User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Sick call

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

They call me and I go.

– William Carlos Williams

I never get sick. I’ve never had the flu. When everyone’s got a cold, I’m somehow immune. The last time I threw up was June 29th, 1980. You see, I work out almost daily, eat vegan, and sleep plenty. I drink gallons of pressed juice and throw down a few high-quality supplements. Yes, I’m that guy: The one who never gets sick. Well, I was anyway.

I am no longer that guy since our little girl became a supersocial little toddler. My undefeated welterweight “never-sick” title has been obliterated by multiple knockouts. One was a wicked adenovirus that broke the no-vomit streak. At one point, I lay on the luxury gray tile bathroom floor hoping to go unconscious to make the nausea stop. I actually called out sick that day. Then with a nasty COVID-despite-vaccine infection. I called out again. Later with a hacking lower respiratory – RSV?! – bug. Called out. All of which our 2-year-old blonde, curly-haired vector transmitted to me with remarkable efficiency.

In fact, That’s saying a lot. Our docs, like most, don’t call out sick.

We physicians have legendary stamina. Compared with other professionals, we are no less likely to become ill but a whopping 80% less likely to call out sick.

Presenteeism is our physician version of Omerta, a code of honor to never give in even at the expense of our, or our family’s, health and well-being. Every medical student is regaled with stories of physicians getting an IV before rounds or finishing clinic after their water broke. Why? In part it’s an indoctrination into this thing of ours we call Medicine: An elitist club that admits only those able to pass O-chem and hold diarrhea. But it is also because our medical system is so brittle that the slightest bend causes it to shatter. When I cancel a clinic, patients who have waited weeks for their spot have to be sent home. And for critical cases or those patients who don’t get the message, my already slammed colleagues have to cram the unlucky ones in between already-scheduled appointments. The guilt induced by inconveniencing our colleagues and our patients is more potent than dry heaves. And so we go. Suck it up. Sip ginger ale. Load up on acetaminophen. Carry on. This harms not only us, but also patients whom we put in the path of transmission. We become terrible 2-year-olds.

Of course, it’s not always easy to tell if you’re sick enough to stay home. But the stigma of calling out is so great that we often show up no matter what symptoms. A recent Medscape survey of physicians found that 85% said they had come to work sick in 2022.

We can do better. Perhaps creating sick-leave protocols could help? For example, if you have a fever above 100.4, have contact with someone positive for influenza, are unable to take POs, etc. then stay home. So might building rolling slack into schedules to accommodate the inevitable physician illness, parenting emergency, or death of an beloved uncle. And if there is one thing artificial intelligence could help us with, it would be smart scheduling. Can’t we build algorithms for anticipating and absorbing these predictable events? I’d take that over an AI skin cancer detector any day. Yet this year we’ll struggle through the cold and flu (and COVID) season again and nothing will have changed.

Our daughter hasn’t had hand, foot, and mouth disease yet. It’s not a question of if, but rather when she, and her mom and I, will get it. I hope it happens on a Friday so that my Monday clinic will be bearable when I show up.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at [email protected]

Higher metal contact allergy rates found in metalworkers

a systematic review and meta-analysis reports.

“Metal allergy to all three metals was significantly more common in European metalworkers with dermatitis attending patch test clinics as compared to ESSCA [European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies] data, indicating a relationship to occupational exposures,” senior study author Jeanne D. Johansen, MD, professor, department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen wrote in Contact Dermatitis. “However, confounders could not be accounted for.”

How common is metal allergy in metalworkers?

Occupational hand eczema is known to be common in metalworkers. Touching oils, greases, metals, leather gloves, rubber materials, and metalworking fluids as they repeatedly cut, shape, and process raw metals and minerals derived from ore mining exposes metalworkers to allergens and skin irritants, the authors wrote. But the prevalence of allergy to certain metals has not been well characterized.

So they searched PubMed for full-text studies in English that reported metal allergy prevalence in metalworkers, from the database’s inception through April 2022.

They included studies with absolute numbers or proportions of metal allergy to cobalt, chromium, or nickel, in all metalworkers with suspected allergic contact dermatitis who attended outpatient clinics or who worked at metalworking plants participating in workplace studies.

The researchers performed a random-effects meta-analysis to calculate the pooled prevalence of metal allergy. Because 85%-90% of metalworkers in Denmark are male, they compared the estimates they found with ESSCA data on 13,382 consecutively patch-tested males with dermatitis between 2015 and 2018.

Of the 1,667 records they screened, they analyzed data from 29 that met their inclusion criteria: 22 patient studies and 7 workplace studies involving 5,691 patients overall from 22 studies from Europe, 5 studies from Asia, and 1 from Africa. Regarding European metalworkers, the authors found:

- Pooled proportions of allergy in European metalworkers with dermatitis referred to patch test clinics were 8.2% to cobalt (95% confidence interval, 5.3%-11.7%), 8.0% to chromium (95% CI, 5.1%-11.4%), and 11.0% to nickel (95% CI, 7.3%-15.4%).

- In workplace studies, the pooled proportions of allergy in unselected European metalworkers were 4.9% to cobalt, (95% CI, 2.4%-8.1%), 5.2% to chromium (95% CI, 1.0% - 12.6%), and 7.6% to nickel (95% CI, 3.8%-12.6%).

- By comparison, ESSCA data on metal allergy prevalence showed 3.9% allergic to cobalt (95% CI, 3.6%-4.2%), 4.4% allergic to chromium (95% CI, 4.1%-4.8%), and 6.7% allergic to nickel (95% CI, 6.3%-7.0%).

- Data on sex, age, body piercings, and atopic dermatitis were scant.

Thorough histories, protective regulations and equipment

Providers need to ask their dermatitis patients about current and past occupations and hobbies, and employers need to provide employees with equipment that protects them from exposure, Kelly Tyler, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“Repeated exposure to an allergen is required for sensitization to develop,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the study. “Metalworkers, who are continually exposed to metals and metalworking fluids, have a higher risk of allergic contact dermatitis to cobalt, chromium, and nickel.”

“The primary treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is preventing continued exposure to the allergen,” she added. “This study highlights the importance of asking about metal or metalworking fluid in the workplace and of elucidating whether the employer is providing appropriate protective gear.”

To prevent occupational dermatitis, workplaces need to apply regulatory measures and provide their employees with protective equipment, Dr. Tyler advised.

“Body piercings are a common sensitizer in patients with metal allergy, and the prevalence of body piercings among metalworkers was not included in the study,” she noted.

The results of the study may not be generalizable to patients in the United States, she added, because regulations and requirements to provide protective gear here may differ.

“Taking a thorough patient history is crucial when investigating potential causes of dermatitis, especially in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Tyler urged.

Funding and conflict-of-interest details were not provided. Dr. Tyler reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a systematic review and meta-analysis reports.

“Metal allergy to all three metals was significantly more common in European metalworkers with dermatitis attending patch test clinics as compared to ESSCA [European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies] data, indicating a relationship to occupational exposures,” senior study author Jeanne D. Johansen, MD, professor, department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen wrote in Contact Dermatitis. “However, confounders could not be accounted for.”

How common is metal allergy in metalworkers?

Occupational hand eczema is known to be common in metalworkers. Touching oils, greases, metals, leather gloves, rubber materials, and metalworking fluids as they repeatedly cut, shape, and process raw metals and minerals derived from ore mining exposes metalworkers to allergens and skin irritants, the authors wrote. But the prevalence of allergy to certain metals has not been well characterized.

So they searched PubMed for full-text studies in English that reported metal allergy prevalence in metalworkers, from the database’s inception through April 2022.

They included studies with absolute numbers or proportions of metal allergy to cobalt, chromium, or nickel, in all metalworkers with suspected allergic contact dermatitis who attended outpatient clinics or who worked at metalworking plants participating in workplace studies.

The researchers performed a random-effects meta-analysis to calculate the pooled prevalence of metal allergy. Because 85%-90% of metalworkers in Denmark are male, they compared the estimates they found with ESSCA data on 13,382 consecutively patch-tested males with dermatitis between 2015 and 2018.

Of the 1,667 records they screened, they analyzed data from 29 that met their inclusion criteria: 22 patient studies and 7 workplace studies involving 5,691 patients overall from 22 studies from Europe, 5 studies from Asia, and 1 from Africa. Regarding European metalworkers, the authors found:

- Pooled proportions of allergy in European metalworkers with dermatitis referred to patch test clinics were 8.2% to cobalt (95% confidence interval, 5.3%-11.7%), 8.0% to chromium (95% CI, 5.1%-11.4%), and 11.0% to nickel (95% CI, 7.3%-15.4%).

- In workplace studies, the pooled proportions of allergy in unselected European metalworkers were 4.9% to cobalt, (95% CI, 2.4%-8.1%), 5.2% to chromium (95% CI, 1.0% - 12.6%), and 7.6% to nickel (95% CI, 3.8%-12.6%).

- By comparison, ESSCA data on metal allergy prevalence showed 3.9% allergic to cobalt (95% CI, 3.6%-4.2%), 4.4% allergic to chromium (95% CI, 4.1%-4.8%), and 6.7% allergic to nickel (95% CI, 6.3%-7.0%).

- Data on sex, age, body piercings, and atopic dermatitis were scant.

Thorough histories, protective regulations and equipment

Providers need to ask their dermatitis patients about current and past occupations and hobbies, and employers need to provide employees with equipment that protects them from exposure, Kelly Tyler, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“Repeated exposure to an allergen is required for sensitization to develop,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the study. “Metalworkers, who are continually exposed to metals and metalworking fluids, have a higher risk of allergic contact dermatitis to cobalt, chromium, and nickel.”

“The primary treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is preventing continued exposure to the allergen,” she added. “This study highlights the importance of asking about metal or metalworking fluid in the workplace and of elucidating whether the employer is providing appropriate protective gear.”

To prevent occupational dermatitis, workplaces need to apply regulatory measures and provide their employees with protective equipment, Dr. Tyler advised.

“Body piercings are a common sensitizer in patients with metal allergy, and the prevalence of body piercings among metalworkers was not included in the study,” she noted.

The results of the study may not be generalizable to patients in the United States, she added, because regulations and requirements to provide protective gear here may differ.

“Taking a thorough patient history is crucial when investigating potential causes of dermatitis, especially in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Tyler urged.

Funding and conflict-of-interest details were not provided. Dr. Tyler reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a systematic review and meta-analysis reports.

“Metal allergy to all three metals was significantly more common in European metalworkers with dermatitis attending patch test clinics as compared to ESSCA [European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies] data, indicating a relationship to occupational exposures,” senior study author Jeanne D. Johansen, MD, professor, department of dermatology and allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark, and colleagues at the University of Copenhagen wrote in Contact Dermatitis. “However, confounders could not be accounted for.”

How common is metal allergy in metalworkers?

Occupational hand eczema is known to be common in metalworkers. Touching oils, greases, metals, leather gloves, rubber materials, and metalworking fluids as they repeatedly cut, shape, and process raw metals and minerals derived from ore mining exposes metalworkers to allergens and skin irritants, the authors wrote. But the prevalence of allergy to certain metals has not been well characterized.

So they searched PubMed for full-text studies in English that reported metal allergy prevalence in metalworkers, from the database’s inception through April 2022.

They included studies with absolute numbers or proportions of metal allergy to cobalt, chromium, or nickel, in all metalworkers with suspected allergic contact dermatitis who attended outpatient clinics or who worked at metalworking plants participating in workplace studies.

The researchers performed a random-effects meta-analysis to calculate the pooled prevalence of metal allergy. Because 85%-90% of metalworkers in Denmark are male, they compared the estimates they found with ESSCA data on 13,382 consecutively patch-tested males with dermatitis between 2015 and 2018.

Of the 1,667 records they screened, they analyzed data from 29 that met their inclusion criteria: 22 patient studies and 7 workplace studies involving 5,691 patients overall from 22 studies from Europe, 5 studies from Asia, and 1 from Africa. Regarding European metalworkers, the authors found:

- Pooled proportions of allergy in European metalworkers with dermatitis referred to patch test clinics were 8.2% to cobalt (95% confidence interval, 5.3%-11.7%), 8.0% to chromium (95% CI, 5.1%-11.4%), and 11.0% to nickel (95% CI, 7.3%-15.4%).

- In workplace studies, the pooled proportions of allergy in unselected European metalworkers were 4.9% to cobalt, (95% CI, 2.4%-8.1%), 5.2% to chromium (95% CI, 1.0% - 12.6%), and 7.6% to nickel (95% CI, 3.8%-12.6%).

- By comparison, ESSCA data on metal allergy prevalence showed 3.9% allergic to cobalt (95% CI, 3.6%-4.2%), 4.4% allergic to chromium (95% CI, 4.1%-4.8%), and 6.7% allergic to nickel (95% CI, 6.3%-7.0%).

- Data on sex, age, body piercings, and atopic dermatitis were scant.

Thorough histories, protective regulations and equipment

Providers need to ask their dermatitis patients about current and past occupations and hobbies, and employers need to provide employees with equipment that protects them from exposure, Kelly Tyler, MD, associate professor of dermatology, Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said in an interview.

“Repeated exposure to an allergen is required for sensitization to develop,” said Dr. Tyler, who was not involved in the study. “Metalworkers, who are continually exposed to metals and metalworking fluids, have a higher risk of allergic contact dermatitis to cobalt, chromium, and nickel.”

“The primary treatment for allergic contact dermatitis is preventing continued exposure to the allergen,” she added. “This study highlights the importance of asking about metal or metalworking fluid in the workplace and of elucidating whether the employer is providing appropriate protective gear.”

To prevent occupational dermatitis, workplaces need to apply regulatory measures and provide their employees with protective equipment, Dr. Tyler advised.

“Body piercings are a common sensitizer in patients with metal allergy, and the prevalence of body piercings among metalworkers was not included in the study,” she noted.

The results of the study may not be generalizable to patients in the United States, she added, because regulations and requirements to provide protective gear here may differ.

“Taking a thorough patient history is crucial when investigating potential causes of dermatitis, especially in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis,” Dr. Tyler urged.

Funding and conflict-of-interest details were not provided. Dr. Tyler reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CONTACT DERMATITIS

Give bacterial diversity a chance: The antibiotic dichotomy

What’s the opposite of an antibiotic?

Everyone knows that LOTME loves a good dichotomy: yin/yang, good/evil, heads/tails, particle/wave, peanut butter/jelly. They’re all great. We’re also big fans of microbiomes, particularly the gut microbiome. But what if we could combine the two? A healthy and nutritious story about the gut microbiome, with a dash of added dichotomy for flavor. Is such a thing even possible? Let’s find out.

First, we need an antibiotic, a drug designed to fight bacterial infections. If you’ve got strep throat, otitis media, or bubonic plague, there’s a good chance you will receive an antibiotic. That antibiotic will kill the bad bacteria that are making you sick, but it will also kill a lot of the good bacteria that inhabit your gut microbiome, which results in side effects like bloating and diarrhea.

It comes down to diversity, explained Elisa Marroquin, PhD, of Texas Christian University (Go Horned Frogs!): “In a human community, we need people that have different professions because we don’t all know how to do every single job. And so the same happens with bacteria. We need lots of different gut bacteria that know how to do different things.”

She and her colleagues reviewed 29 studies published over the last 7 years and found a way to preserve the diversity of a human gut microbiome that’s dealing with an antibiotic. Their solution? Prescribe a probiotic.

The way to fight the effects of stopping a bacterial infection is to provide food for what are, basically, other bacterial infections. Antibiotic/probiotic is a prescription for dichotomy, and it means we managed to combine gut microbiomes with a dichotomy. And you didn’t think we could do it.

The earphone of hearing aids

It’s estimated that up to 75% of people who need hearing aids don’t wear them. Why? Well, there’s the social stigma about not wanting to appear too old, and then there’s the cost factor.

Is there a cheaper, less stigmatizing option to amplify hearing? The answer, according to otolaryngologist Yen-fu Cheng, MD, of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and associates, is wireless earphones. AirPods, if you want to be brand specific.

Airpods can be on the more expensive side – running about $129 for AirPods 2 and $249 for AirPods Pro – but when compared with premium hearing aids ($10,000), or even basic aids (about $1,500), the Apple products come off inexpensive after all.

The team tested the premium and basic hearing aids against the AirPods 2 and the AirPod Pro using Apple’s Live Listen feature, which helps amplify sound through the company’s wireless earphones and iPhones and was initially designed to assist people with normal hearing in situations such as birdwatching.

The AirPods Pro worked just as well as the basic hearing aid but not quite as well as the premium hearing aid in a quiet setting, while the AirPods 2 performed the worst. When tested in a noisy setting, the AirPods Pro was pretty comparable to the premium hearing aid, as long as the noise came from a lateral direction. Neither of the AirPod models did as well as the hearing aids with head-on noises.

Wireless earbuds may not be the perfect solution from a clinical standpoint, but they’re a good start for people who don’t have access to hearing aids, Dr. Cheng noted.

So who says headphones damage your hearing? They might actually help.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the computer my soul to keep

Radiation is the boring hazard of space travel. No one dies in a space horror movie because they’ve been slowly exposed to too much cosmic radiation. It’s always “thrown out the airlock” this and “eaten by a xenomorph” that.

Radiation, however, is not something that can be ignored, but it turns out that a potential solution is another science fiction staple: artificial hibernation. Generally in sci-fi, hibernation is a plot convenience to get people from point A to point B in a ship that doesn’t break the laws of physics. Here on Earth, though, it is well known that animals naturally entering a state of torpor during hibernation gain significant resistance to radiation.

The problem, of course, is that humans don’t hibernate, and no matter how hard people who work 100-hour weeks for Elon Musk try, sleeping for months on end is simply something we can’t do. However, a new study shows that it’s possible to induce this torpor state in animals that don’t naturally hibernate. By injecting rats with adenosine 5’-monophosphate monohydrate and keeping them in a room held at 16° C, an international team of scientists successfully induced a synthetic torpor state.

That’s not all they did: The scientists also exposed the hibernating rats to a large dose of radiation approximating that found in deep space. Which isn’t something we’d like to explain to our significant other when we got home from work. “So how was your day?” “Oh, I irradiated a bunch of sleeping rats. … Don’t worry they’re fine!” Which they were. Thanks to the hypoxic and hypothermic state, the tissue was spared damage from the high-energy ion radiation.

Obviously, there’s a big difference between a rat and a human and a lot of work to be done, but the study does show that artificial hibernation is possible. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to fall asleep and wake up light-years away under an alien sky, and we won’t be horrifically mutated or riddled with cancer. If, however, you find yourself in hibernation on your way to Jupiter (or Saturn) to investigate a mysterious black monolith, we suggest sleeping with one eye open and gripping your pillow tight.

What’s the opposite of an antibiotic?

Everyone knows that LOTME loves a good dichotomy: yin/yang, good/evil, heads/tails, particle/wave, peanut butter/jelly. They’re all great. We’re also big fans of microbiomes, particularly the gut microbiome. But what if we could combine the two? A healthy and nutritious story about the gut microbiome, with a dash of added dichotomy for flavor. Is such a thing even possible? Let’s find out.

First, we need an antibiotic, a drug designed to fight bacterial infections. If you’ve got strep throat, otitis media, or bubonic plague, there’s a good chance you will receive an antibiotic. That antibiotic will kill the bad bacteria that are making you sick, but it will also kill a lot of the good bacteria that inhabit your gut microbiome, which results in side effects like bloating and diarrhea.

It comes down to diversity, explained Elisa Marroquin, PhD, of Texas Christian University (Go Horned Frogs!): “In a human community, we need people that have different professions because we don’t all know how to do every single job. And so the same happens with bacteria. We need lots of different gut bacteria that know how to do different things.”

She and her colleagues reviewed 29 studies published over the last 7 years and found a way to preserve the diversity of a human gut microbiome that’s dealing with an antibiotic. Their solution? Prescribe a probiotic.

The way to fight the effects of stopping a bacterial infection is to provide food for what are, basically, other bacterial infections. Antibiotic/probiotic is a prescription for dichotomy, and it means we managed to combine gut microbiomes with a dichotomy. And you didn’t think we could do it.

The earphone of hearing aids

It’s estimated that up to 75% of people who need hearing aids don’t wear them. Why? Well, there’s the social stigma about not wanting to appear too old, and then there’s the cost factor.

Is there a cheaper, less stigmatizing option to amplify hearing? The answer, according to otolaryngologist Yen-fu Cheng, MD, of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and associates, is wireless earphones. AirPods, if you want to be brand specific.

Airpods can be on the more expensive side – running about $129 for AirPods 2 and $249 for AirPods Pro – but when compared with premium hearing aids ($10,000), or even basic aids (about $1,500), the Apple products come off inexpensive after all.

The team tested the premium and basic hearing aids against the AirPods 2 and the AirPod Pro using Apple’s Live Listen feature, which helps amplify sound through the company’s wireless earphones and iPhones and was initially designed to assist people with normal hearing in situations such as birdwatching.

The AirPods Pro worked just as well as the basic hearing aid but not quite as well as the premium hearing aid in a quiet setting, while the AirPods 2 performed the worst. When tested in a noisy setting, the AirPods Pro was pretty comparable to the premium hearing aid, as long as the noise came from a lateral direction. Neither of the AirPod models did as well as the hearing aids with head-on noises.

Wireless earbuds may not be the perfect solution from a clinical standpoint, but they’re a good start for people who don’t have access to hearing aids, Dr. Cheng noted.

So who says headphones damage your hearing? They might actually help.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the computer my soul to keep

Radiation is the boring hazard of space travel. No one dies in a space horror movie because they’ve been slowly exposed to too much cosmic radiation. It’s always “thrown out the airlock” this and “eaten by a xenomorph” that.

Radiation, however, is not something that can be ignored, but it turns out that a potential solution is another science fiction staple: artificial hibernation. Generally in sci-fi, hibernation is a plot convenience to get people from point A to point B in a ship that doesn’t break the laws of physics. Here on Earth, though, it is well known that animals naturally entering a state of torpor during hibernation gain significant resistance to radiation.

The problem, of course, is that humans don’t hibernate, and no matter how hard people who work 100-hour weeks for Elon Musk try, sleeping for months on end is simply something we can’t do. However, a new study shows that it’s possible to induce this torpor state in animals that don’t naturally hibernate. By injecting rats with adenosine 5’-monophosphate monohydrate and keeping them in a room held at 16° C, an international team of scientists successfully induced a synthetic torpor state.

That’s not all they did: The scientists also exposed the hibernating rats to a large dose of radiation approximating that found in deep space. Which isn’t something we’d like to explain to our significant other when we got home from work. “So how was your day?” “Oh, I irradiated a bunch of sleeping rats. … Don’t worry they’re fine!” Which they were. Thanks to the hypoxic and hypothermic state, the tissue was spared damage from the high-energy ion radiation.

Obviously, there’s a big difference between a rat and a human and a lot of work to be done, but the study does show that artificial hibernation is possible. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to fall asleep and wake up light-years away under an alien sky, and we won’t be horrifically mutated or riddled with cancer. If, however, you find yourself in hibernation on your way to Jupiter (or Saturn) to investigate a mysterious black monolith, we suggest sleeping with one eye open and gripping your pillow tight.

What’s the opposite of an antibiotic?

Everyone knows that LOTME loves a good dichotomy: yin/yang, good/evil, heads/tails, particle/wave, peanut butter/jelly. They’re all great. We’re also big fans of microbiomes, particularly the gut microbiome. But what if we could combine the two? A healthy and nutritious story about the gut microbiome, with a dash of added dichotomy for flavor. Is such a thing even possible? Let’s find out.

First, we need an antibiotic, a drug designed to fight bacterial infections. If you’ve got strep throat, otitis media, or bubonic plague, there’s a good chance you will receive an antibiotic. That antibiotic will kill the bad bacteria that are making you sick, but it will also kill a lot of the good bacteria that inhabit your gut microbiome, which results in side effects like bloating and diarrhea.

It comes down to diversity, explained Elisa Marroquin, PhD, of Texas Christian University (Go Horned Frogs!): “In a human community, we need people that have different professions because we don’t all know how to do every single job. And so the same happens with bacteria. We need lots of different gut bacteria that know how to do different things.”

She and her colleagues reviewed 29 studies published over the last 7 years and found a way to preserve the diversity of a human gut microbiome that’s dealing with an antibiotic. Their solution? Prescribe a probiotic.

The way to fight the effects of stopping a bacterial infection is to provide food for what are, basically, other bacterial infections. Antibiotic/probiotic is a prescription for dichotomy, and it means we managed to combine gut microbiomes with a dichotomy. And you didn’t think we could do it.

The earphone of hearing aids

It’s estimated that up to 75% of people who need hearing aids don’t wear them. Why? Well, there’s the social stigma about not wanting to appear too old, and then there’s the cost factor.

Is there a cheaper, less stigmatizing option to amplify hearing? The answer, according to otolaryngologist Yen-fu Cheng, MD, of Taipei Veterans General Hospital and associates, is wireless earphones. AirPods, if you want to be brand specific.

Airpods can be on the more expensive side – running about $129 for AirPods 2 and $249 for AirPods Pro – but when compared with premium hearing aids ($10,000), or even basic aids (about $1,500), the Apple products come off inexpensive after all.

The team tested the premium and basic hearing aids against the AirPods 2 and the AirPod Pro using Apple’s Live Listen feature, which helps amplify sound through the company’s wireless earphones and iPhones and was initially designed to assist people with normal hearing in situations such as birdwatching.

The AirPods Pro worked just as well as the basic hearing aid but not quite as well as the premium hearing aid in a quiet setting, while the AirPods 2 performed the worst. When tested in a noisy setting, the AirPods Pro was pretty comparable to the premium hearing aid, as long as the noise came from a lateral direction. Neither of the AirPod models did as well as the hearing aids with head-on noises.

Wireless earbuds may not be the perfect solution from a clinical standpoint, but they’re a good start for people who don’t have access to hearing aids, Dr. Cheng noted.

So who says headphones damage your hearing? They might actually help.

Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray the computer my soul to keep

Radiation is the boring hazard of space travel. No one dies in a space horror movie because they’ve been slowly exposed to too much cosmic radiation. It’s always “thrown out the airlock” this and “eaten by a xenomorph” that.

Radiation, however, is not something that can be ignored, but it turns out that a potential solution is another science fiction staple: artificial hibernation. Generally in sci-fi, hibernation is a plot convenience to get people from point A to point B in a ship that doesn’t break the laws of physics. Here on Earth, though, it is well known that animals naturally entering a state of torpor during hibernation gain significant resistance to radiation.

The problem, of course, is that humans don’t hibernate, and no matter how hard people who work 100-hour weeks for Elon Musk try, sleeping for months on end is simply something we can’t do. However, a new study shows that it’s possible to induce this torpor state in animals that don’t naturally hibernate. By injecting rats with adenosine 5’-monophosphate monohydrate and keeping them in a room held at 16° C, an international team of scientists successfully induced a synthetic torpor state.

That’s not all they did: The scientists also exposed the hibernating rats to a large dose of radiation approximating that found in deep space. Which isn’t something we’d like to explain to our significant other when we got home from work. “So how was your day?” “Oh, I irradiated a bunch of sleeping rats. … Don’t worry they’re fine!” Which they were. Thanks to the hypoxic and hypothermic state, the tissue was spared damage from the high-energy ion radiation.

Obviously, there’s a big difference between a rat and a human and a lot of work to be done, but the study does show that artificial hibernation is possible. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to fall asleep and wake up light-years away under an alien sky, and we won’t be horrifically mutated or riddled with cancer. If, however, you find yourself in hibernation on your way to Jupiter (or Saturn) to investigate a mysterious black monolith, we suggest sleeping with one eye open and gripping your pillow tight.

Is there a doctor on the plane? Tips for providing in-flight assistance

In most cases, passengers on an airline flight are representative of the general population, which means that anyone could have an emergency at any time.

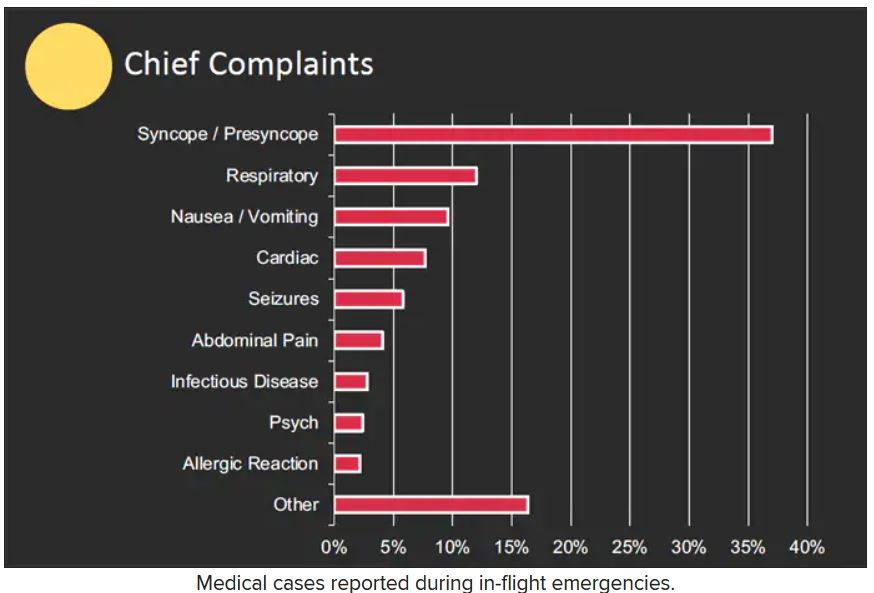

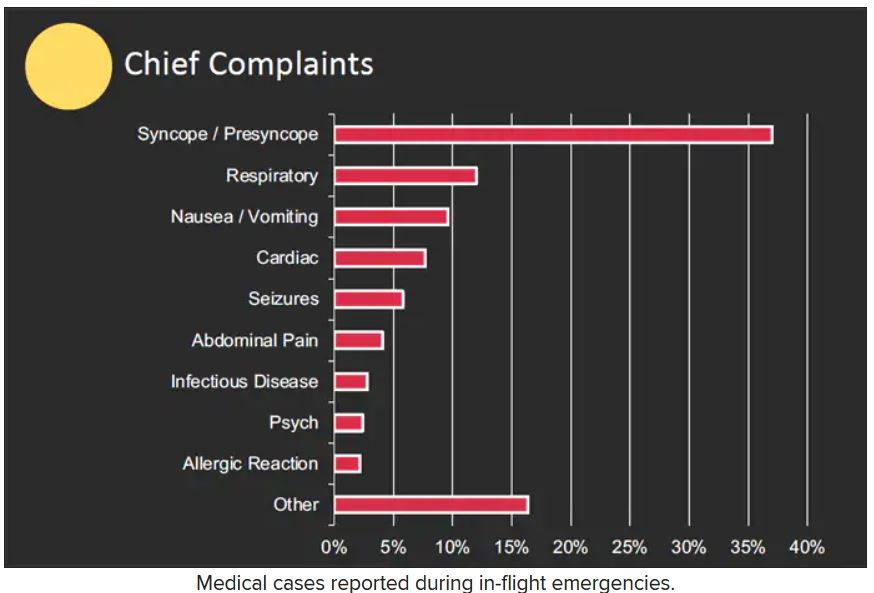

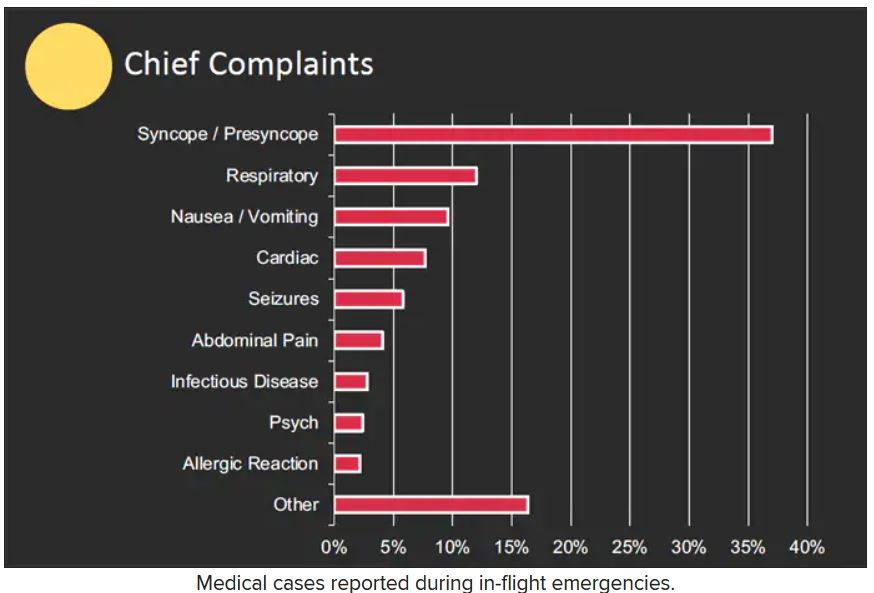

as determined on the basis of in-flight medical emergencies that resulted in calls to a physician-directed medical communications center, said Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH of Integrative Emergency Services, Dallas–Fort Worth, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The study authors reviewed records of 11,920 in-flight medical emergencies between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 31, 2010. The data showed that physician passengers provided medical assistance in nearly half of in-flight emergencies (48.1%) and that flights were diverted because of the emergency in 7.3% of cases.

The majority of the in-flight emergencies involved syncope or presyncope (37.4% of cases), followed by respiratory symptoms (12.1%) and nausea or vomiting (9.5%), according to the study.

When a physician is faced with an in-flight emergency, the medical team includes the physician himself, medical ground control, and the flight attendants, said Dr. Ho. Requirements may vary among airlines, but all flight attendants will be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or basic life support, as well as use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Physician call centers (medical ground control) can provide additional assistance remotely, she said.

The in-flight medical bag

Tools in a physician’s in-flight toolbox start with the first-aid kit. Airplanes also have an emergency medical kit (EMK), an oxygen tank, and an AED.

The minimum EMK contents are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, said Dr. Ho. The standard equipment includes a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer, and three sizes of oropharyngeal airways. Other items include self-inflating manual resuscitation devices and CPR masks in thee sizes, alcohol sponges, gloves, adhesive tape, scissors, a tourniquet, as well as saline solution, needles, syringes, and an intravenous administration set consisting of tubing and two Y connectors.

An EMK also should contain the following medications: nonnarcotic analgesic tablets, antihistamine tablets, an injectable antihistamine, atropine, aspirin tablets, a bronchodilator, and epinephrine (both 1:1000; 1 injectable cc and 1:10,000; two injectable cc). Nitroglycerin tablets and 5 cc of 20 mg/mL injectable cardiac lidocaine are part of the mandated kit as well, according to Dr. Ho.

Some airlines carry additional supplies on all their flights, said Dr. Ho. Notably, American Airlines and British Airways carry EpiPens for adults and children, as well as opioid reversal medication (naloxone) and glucose for managing low blood sugar. American Airlines and Delta stock antiemetics, and Delta also carries naloxone. British Airways is unique in stocking additional cardiac medications, both oral and injectable.

How to handle an in-flight emergency

Physicians should always carry a copy of their medical license when traveling for documentation by the airline if they assist in a medical emergency during a flight, Dr. Ho emphasized. “Staff” personnel should be used. These include the flight attendants, medical ground control, and other passengers who might have useful skills, such as nursing, the ability to perform CPR, or therapy/counseling to calm a frightened patient. If needed, “crowdsource additional supplies from passengers,” such as a glucometer or pulse oximeter.

Legal lessons

Physicians are not obligated to assist during an in-flight medical emergency, said Dr. Ho. Legal jurisdiction can vary. In the United States, a bystander who assists in an emergency is generally protected by Good Samaritan laws; for international airlines, the laws may vary; those where the airline is based usually apply.

The Aviation Medical Assistance Act, passed in 1998, protects individuals from being sued for negligence while providing medical assistance, “unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct,” Dr. Ho noted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act also protects the airline itself “if the carrier in good faith believes that the passenger is a medically qualified individual.”

Dr. Ho disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In most cases, passengers on an airline flight are representative of the general population, which means that anyone could have an emergency at any time.

as determined on the basis of in-flight medical emergencies that resulted in calls to a physician-directed medical communications center, said Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH of Integrative Emergency Services, Dallas–Fort Worth, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The study authors reviewed records of 11,920 in-flight medical emergencies between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 31, 2010. The data showed that physician passengers provided medical assistance in nearly half of in-flight emergencies (48.1%) and that flights were diverted because of the emergency in 7.3% of cases.

The majority of the in-flight emergencies involved syncope or presyncope (37.4% of cases), followed by respiratory symptoms (12.1%) and nausea or vomiting (9.5%), according to the study.

When a physician is faced with an in-flight emergency, the medical team includes the physician himself, medical ground control, and the flight attendants, said Dr. Ho. Requirements may vary among airlines, but all flight attendants will be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or basic life support, as well as use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Physician call centers (medical ground control) can provide additional assistance remotely, she said.

The in-flight medical bag

Tools in a physician’s in-flight toolbox start with the first-aid kit. Airplanes also have an emergency medical kit (EMK), an oxygen tank, and an AED.

The minimum EMK contents are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, said Dr. Ho. The standard equipment includes a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer, and three sizes of oropharyngeal airways. Other items include self-inflating manual resuscitation devices and CPR masks in thee sizes, alcohol sponges, gloves, adhesive tape, scissors, a tourniquet, as well as saline solution, needles, syringes, and an intravenous administration set consisting of tubing and two Y connectors.

An EMK also should contain the following medications: nonnarcotic analgesic tablets, antihistamine tablets, an injectable antihistamine, atropine, aspirin tablets, a bronchodilator, and epinephrine (both 1:1000; 1 injectable cc and 1:10,000; two injectable cc). Nitroglycerin tablets and 5 cc of 20 mg/mL injectable cardiac lidocaine are part of the mandated kit as well, according to Dr. Ho.

Some airlines carry additional supplies on all their flights, said Dr. Ho. Notably, American Airlines and British Airways carry EpiPens for adults and children, as well as opioid reversal medication (naloxone) and glucose for managing low blood sugar. American Airlines and Delta stock antiemetics, and Delta also carries naloxone. British Airways is unique in stocking additional cardiac medications, both oral and injectable.

How to handle an in-flight emergency

Physicians should always carry a copy of their medical license when traveling for documentation by the airline if they assist in a medical emergency during a flight, Dr. Ho emphasized. “Staff” personnel should be used. These include the flight attendants, medical ground control, and other passengers who might have useful skills, such as nursing, the ability to perform CPR, or therapy/counseling to calm a frightened patient. If needed, “crowdsource additional supplies from passengers,” such as a glucometer or pulse oximeter.

Legal lessons

Physicians are not obligated to assist during an in-flight medical emergency, said Dr. Ho. Legal jurisdiction can vary. In the United States, a bystander who assists in an emergency is generally protected by Good Samaritan laws; for international airlines, the laws may vary; those where the airline is based usually apply.

The Aviation Medical Assistance Act, passed in 1998, protects individuals from being sued for negligence while providing medical assistance, “unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct,” Dr. Ho noted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act also protects the airline itself “if the carrier in good faith believes that the passenger is a medically qualified individual.”

Dr. Ho disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In most cases, passengers on an airline flight are representative of the general population, which means that anyone could have an emergency at any time.

as determined on the basis of in-flight medical emergencies that resulted in calls to a physician-directed medical communications center, said Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH of Integrative Emergency Services, Dallas–Fort Worth, in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Emergency Physicians.

The study authors reviewed records of 11,920 in-flight medical emergencies between Jan. 1, 2008, and Oct. 31, 2010. The data showed that physician passengers provided medical assistance in nearly half of in-flight emergencies (48.1%) and that flights were diverted because of the emergency in 7.3% of cases.

The majority of the in-flight emergencies involved syncope or presyncope (37.4% of cases), followed by respiratory symptoms (12.1%) and nausea or vomiting (9.5%), according to the study.

When a physician is faced with an in-flight emergency, the medical team includes the physician himself, medical ground control, and the flight attendants, said Dr. Ho. Requirements may vary among airlines, but all flight attendants will be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or basic life support, as well as use of automated external defibrillators (AEDs).

Physician call centers (medical ground control) can provide additional assistance remotely, she said.

The in-flight medical bag

Tools in a physician’s in-flight toolbox start with the first-aid kit. Airplanes also have an emergency medical kit (EMK), an oxygen tank, and an AED.

The minimum EMK contents are mandated by the Federal Aviation Administration, said Dr. Ho. The standard equipment includes a stethoscope, a sphygmomanometer, and three sizes of oropharyngeal airways. Other items include self-inflating manual resuscitation devices and CPR masks in thee sizes, alcohol sponges, gloves, adhesive tape, scissors, a tourniquet, as well as saline solution, needles, syringes, and an intravenous administration set consisting of tubing and two Y connectors.

An EMK also should contain the following medications: nonnarcotic analgesic tablets, antihistamine tablets, an injectable antihistamine, atropine, aspirin tablets, a bronchodilator, and epinephrine (both 1:1000; 1 injectable cc and 1:10,000; two injectable cc). Nitroglycerin tablets and 5 cc of 20 mg/mL injectable cardiac lidocaine are part of the mandated kit as well, according to Dr. Ho.

Some airlines carry additional supplies on all their flights, said Dr. Ho. Notably, American Airlines and British Airways carry EpiPens for adults and children, as well as opioid reversal medication (naloxone) and glucose for managing low blood sugar. American Airlines and Delta stock antiemetics, and Delta also carries naloxone. British Airways is unique in stocking additional cardiac medications, both oral and injectable.

How to handle an in-flight emergency

Physicians should always carry a copy of their medical license when traveling for documentation by the airline if they assist in a medical emergency during a flight, Dr. Ho emphasized. “Staff” personnel should be used. These include the flight attendants, medical ground control, and other passengers who might have useful skills, such as nursing, the ability to perform CPR, or therapy/counseling to calm a frightened patient. If needed, “crowdsource additional supplies from passengers,” such as a glucometer or pulse oximeter.

Legal lessons

Physicians are not obligated to assist during an in-flight medical emergency, said Dr. Ho. Legal jurisdiction can vary. In the United States, a bystander who assists in an emergency is generally protected by Good Samaritan laws; for international airlines, the laws may vary; those where the airline is based usually apply.

The Aviation Medical Assistance Act, passed in 1998, protects individuals from being sued for negligence while providing medical assistance, “unless the individual, while rendering such assistance, is guilty of gross negligence of willful misconduct,” Dr. Ho noted. The Aviation Medical Assistance Act also protects the airline itself “if the carrier in good faith believes that the passenger is a medically qualified individual.”

Dr. Ho disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACEP 2022

Psoriasiform Dermatitis Associated With the Moderna COVID-19 Messenger RNA Vaccine

To the Editor:

The Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine was authorized for use on December 18, 2020, with the second dose beginning on January 15, 2021.1-3 Some individuals who received the Moderna vaccine experienced an intense rash known as “COVID arm,” a harmless but bothersome adverse effect that typically appears within a week and is a localized and transient immunogenic response.4 COVID arm differs from most vaccine adverse effects. The rash emerges not immediately but 5 to 9 days after the initial dose—on average, 1 week later. Apart from being itchy, the rash does not appear to be harmful and is not a reason to hesitate getting vaccinated.

Dermatologists and allergists have been studying this adverse effect, which has been formally termed delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. Of potential clinical consequence is that the efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be harmed if postvaccination dermal reactions necessitate systemic corticosteroid therapy. Because this vaccine stimulates an immune response as viral RNA integrates in cells secondary to production of the spike protein of the virus, the skin may be affected secondarily and manifestations of any underlying disease may be aggravated.5 We report a patient who developed a psoriasiform dermatitis after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine.

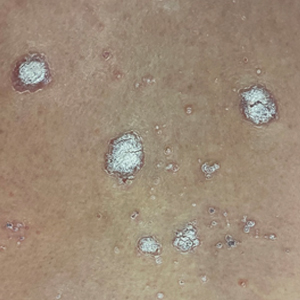

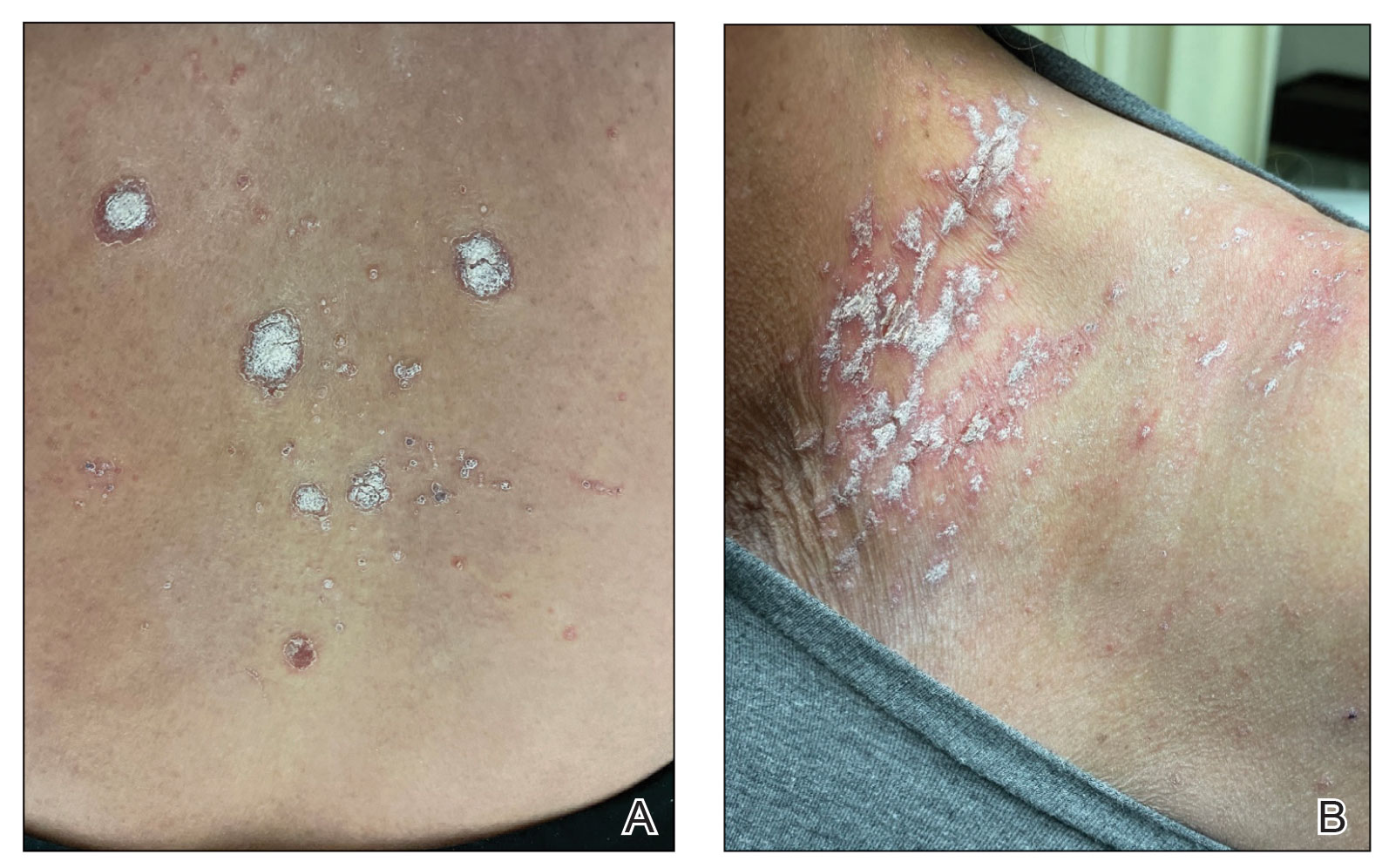

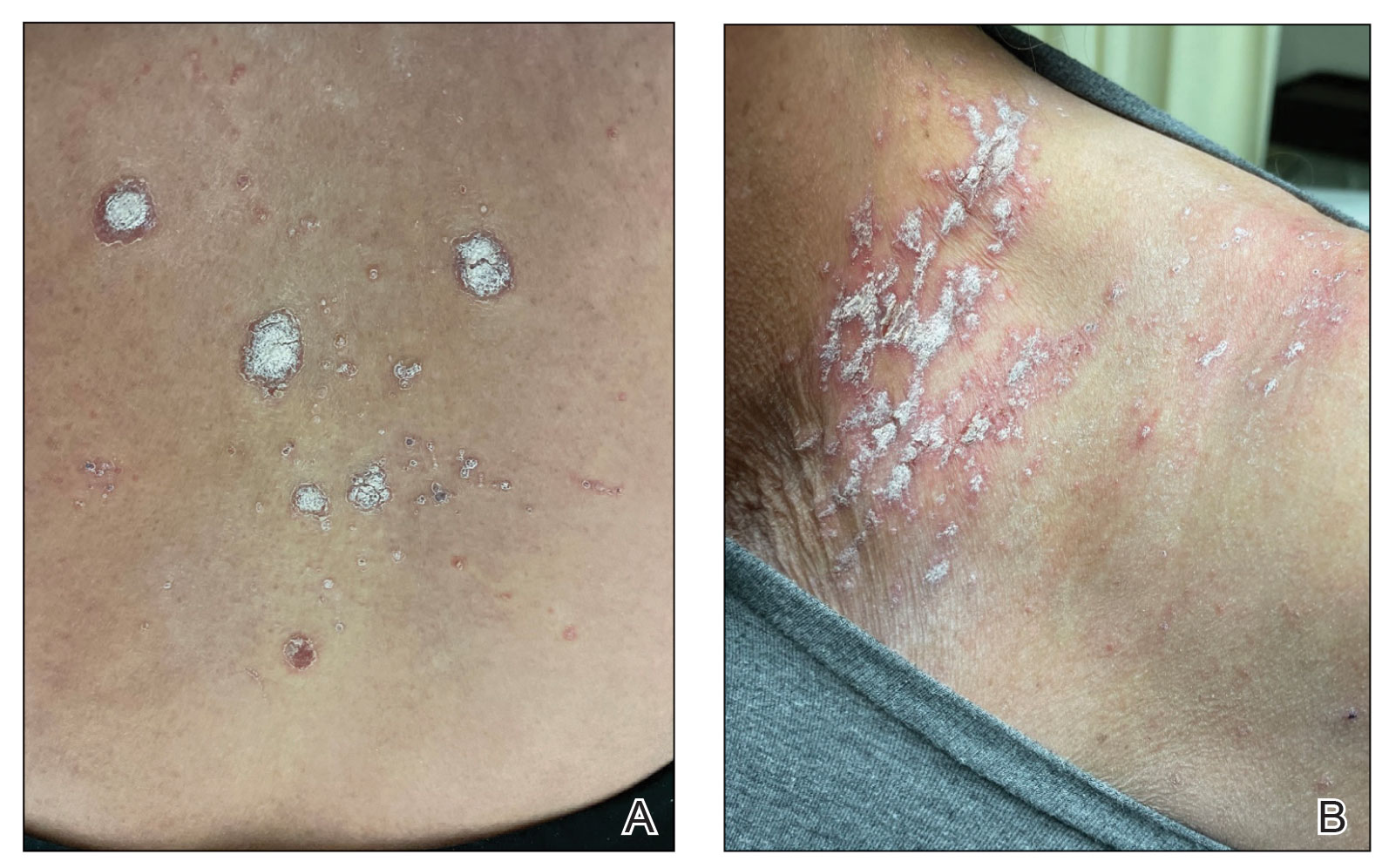

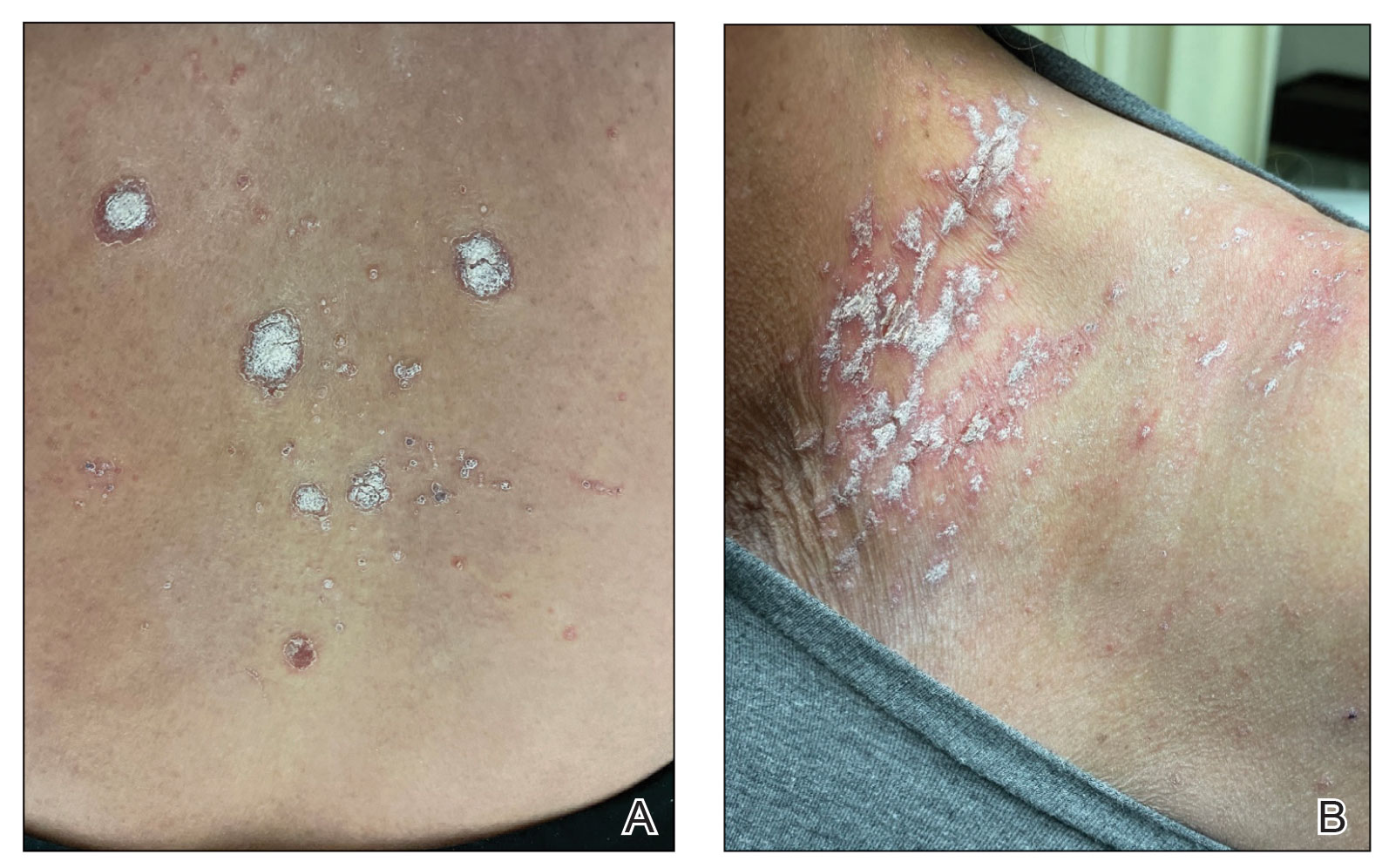

A 65-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician because of the severity of psoriasiform dermatitis that developed 5 days after she received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The patient had a medical history of Sjögren syndrome. Her medication history was negative, and her family history was negative for autoimmune disease. Physical examination by primary care revealed an erythematous scaly rash with plaques and papules on the neck and back (Figure 1). The patient presented again to primary care 2 days later with swollen, painful, discolored digits (Figure 2) and a stiff, sore neck.

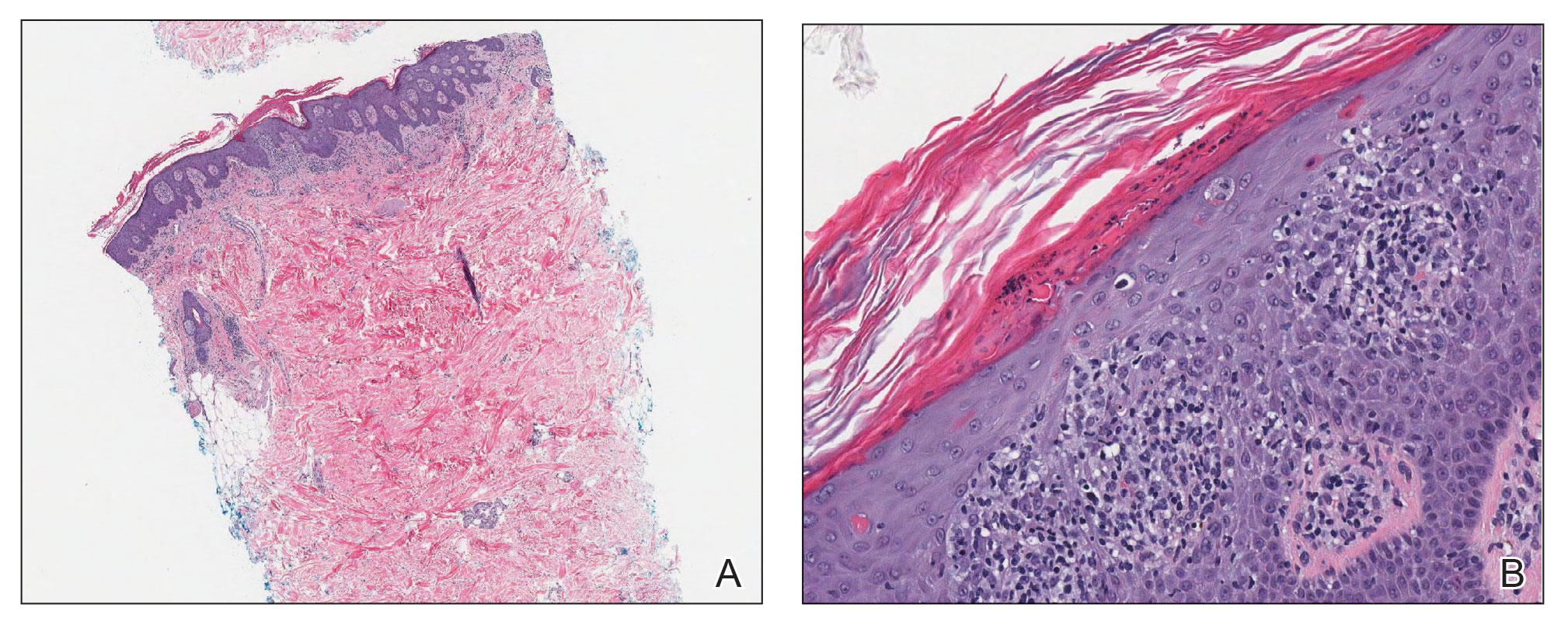

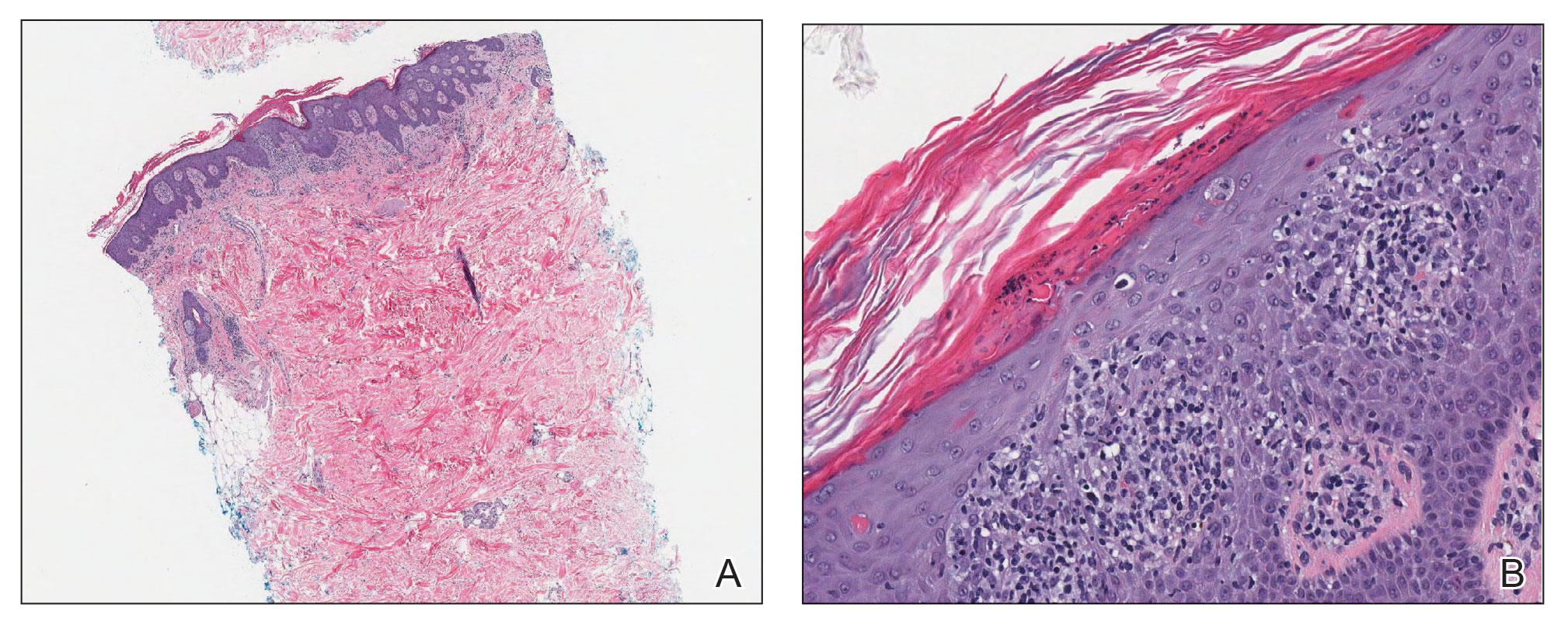

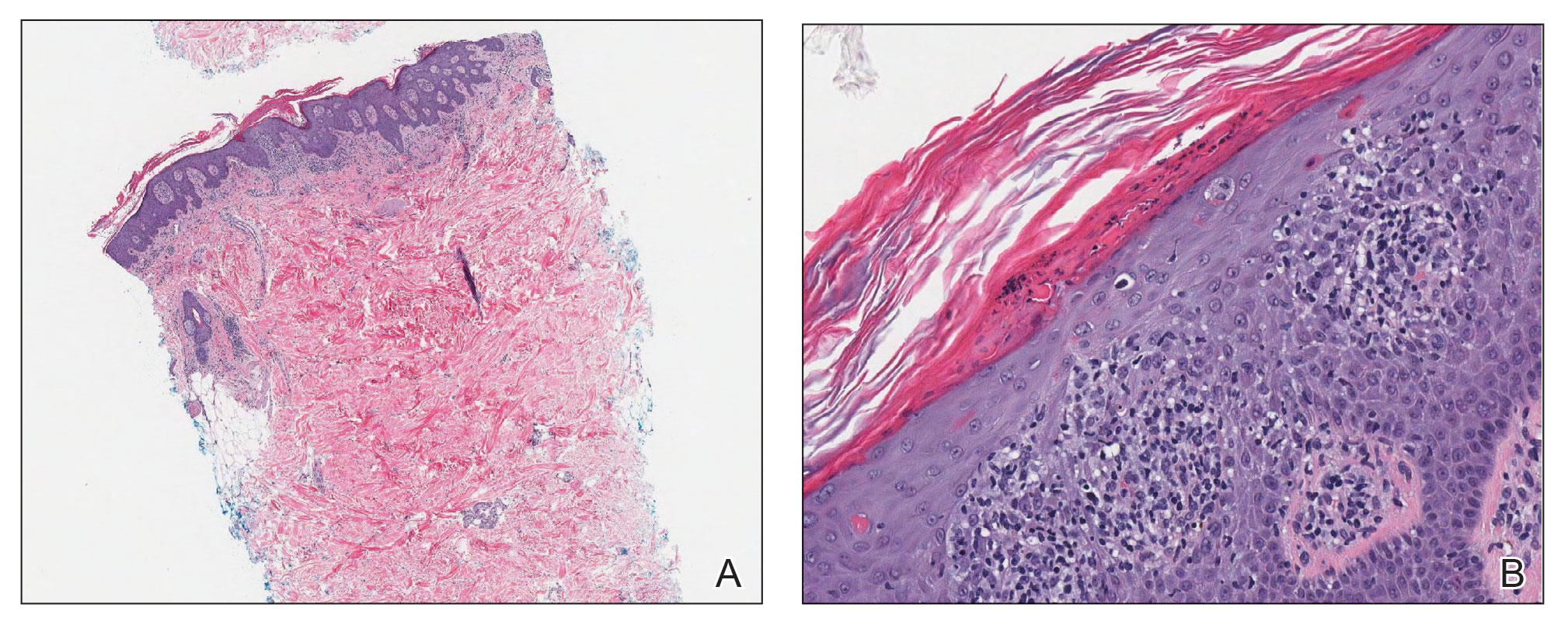

Laboratory results were positive for anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B. A complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and assays of rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide were within reference range. A biopsy of a lesion on the back showed psoriasiform dermatitis with confluent parakeratosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes. There was superficial perivascular inflammation with rare eosinophils (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids. The rash resolved in 1 week. She did not receive the second dose due to the rash.

Two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna—have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 The safety profile of the mRNA-1273 vaccine for the median 2-month follow-up showed no safety concerns.3 Minor localized adverse effects (eg, pain, redness, swelling) have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain, also were seen somewhat more often with the vaccines than with placebo; most such effects occurred 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.3,6,7 The frequency of unsolicited adverse events and serious adverse events reported during the 28-day period after vaccination generally was similar among participants in the vaccine and placebo groups.3

There are 2 types of reactions to COVID-19 vaccination: immediate and delayed. Immediate reactions usually are due to anaphylaxis, requiring prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to stop rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. Delayed reactions include localized reactions, such as urticaria and benign exanthema; serum sickness and serum sickness–like reactions; fever; and rare skin, organ, and neurologic sequelae.1,6-8

Cutaneous manifestations, present in 16% to 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, are considered one of the most common extraglandular presentations of the syndrome. They are classified as nonvascular (eg, xerosis, angular cheilitis, eyelid dermatitis, annular erythema) and vascular (eg, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis).9-11 Our patient did not have any of those findings. She had not taken any medications before the rash appeared, thereby ruling out a drug reaction.

The differential for our patient included post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash, which is not typical with Escherichia coli infection but is described with infection with Chlamydia species and Salmonella species. Moreover, post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash appear mostly on the palms and soles. Systemic lupus erythematosus–like rashes have a different histology and appear on sun-exposed areas; our patient’s rash was found mainly on unexposed areas.12

Because our patient received the Moderna vaccine 5 days before the rash appeared and later developed swelling of the digits with morning stiffness, a delayed serum sickness–like reaction secondary to COVID-19 vaccination was possible.3,6

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna incorporate a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery of mRNA. This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, thus prolonging half-life. The presence of lipid polyethylene glycol 2000 in mRNA vaccines has led to concern that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis.6

COVID-19 antigens can give rise to varying clinical manifestations that are directly related to viral tissue damage or are indirectly induced by the antiviral immune response.13,14 Hyperactivation of the immune system to eradicate COVID-19 may trigger autoimmunity; several immune-mediated disorders have been described in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dermal manifestations include cutaneous rash and vasculitis.13-16 Crucial immunologic steps occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection that may link autoimmunity to COVID-19.13,14 In preliminary published data on the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine on 45 trial enrollees, 3 did not receive the second dose of vaccination, including 1 who developed urticaria on both legs 5 days after the first dose.1

Introduction of viral RNA can induce autoimmunity that can be explained by various phenomena, including epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, cryptic antigen, and bystander activation. Remarkably, more than one-third of immunogenic proteins in SARS-CoV-2 have potentially problematic homology to proteins that are key to the human adaptive immune system.5

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 seems to induce organ injury through alternative mechanisms beyond direct viral infection, including immunologic injury. In some situations, hyperactivation of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA can result in autoimmune disease. COVID-19 has been associated with immune-mediated systemic or organ-selective manifestations, some of which fulfill the diagnostic or classification criteria of specific autoimmune diseases. It is unclear whether those medical disorders are the result of transitory postinfectious epiphenomena.5

A few studies have shown that patients with rheumatic disease have an incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 that is similar to the general population. A similar pattern has been detected in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, even among patients with an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.5,17 Furthermore, exacerbation of preexisting rheumatic symptoms may be due to hyperactivation of antiviral pathways in a person with an autoimmune disease.17-19 The findings in our patient suggested a direct role for the vaccine in skin manifestations, rather than for reactivation or development of new systemic autoimmune processes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination has been described20; however, the case patient did not have a history of psoriasis. The mechanism(s) of such exacerbation remain unclear; COVID-19 vaccine–induced helper T cells (TH17) may play a role.21 Other skin manifestations encountered following COVID-19 vaccination include lichen planus, leukocytoclastic vasculitic rash, erythema multiforme–like rash, and pityriasis rosea–like rash.22-25 The immune mechanisms of these manifestations remain unclear.

The clinical presentation of delayed vaccination reactions can be attributed to the timing of symptoms and, in this case, the immune-mediated background of a psoriasiform reaction. Although adverse reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine are rare, more individuals should be studied after vaccination to confirm and better understand this phenomenon.

- Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, et al; . An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1920-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, et al; . Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427-2438. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2028436

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al; COVE Study Group. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403-416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389

- Weise E. ‘COVID arm’ rash seen after Moderna vaccine annoying but harmless, doctors say. USA Today. January 27, 2021. Accessed September 4, 2022. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/01/27/covid-arm-moderna-vaccine-rash-harmless-side-effect-doctors-say/4277725001/

- Talotta R, Robertson E. Autoimmunity as the comet tail of COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:3621-3644. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3621

- Castells MC, Phillips EJ. Maintaining safety with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:643-649. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2035343

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al; . Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603-2615. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

- Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ interim recommendation for allocating initial supplies of COVID-19 vaccine—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1857-1859. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1

- Roguedas AM, Misery L, Sassolas B, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of primary Sjögren’s syndrome are underestimated. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22:632-636.

- Katayama I. Dry skin manifestations in Sjögren syndrome and atopic dermatitis related to aberrant sudomotor function in inflammatory allergic skin diseases. Allergol Int. 2018;67:448-454. doi:10.1016/j.alit.2018.07.001

- Generali E, Costanzo A, Mainetti C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal manifestations of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;53:357-370. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8639-y

- Chanprapaph K, Tankunakorn J, Suchonwanit P, et al. Dermatologic manifestations, histologic features and disease progression among cutaneous lupus erythematosus subtypes: a prospective observational study in Asians. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:131-147. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00471-y

- Ortega-Quijano D, Jimenez-Cauhe J, Selda-Enriquez G, et al. Algorithm for the classification of COVID-19 rashes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e103-e104. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.034

- Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1236520. doi:10.1155/2020/1236520

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:75-81. doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:739-743. doi:10.1111/ijd.14937

- Dellavance A, Coelho Andrade LE. Immunologic derangement preceding clinical autoimmunity. Lupus. 2014;23:1305-1308. doi:10.1177/0961203314531346

- Parodi A, Gasparini G, Cozzani E. Could antiphospholipid antibodies contribute to coagulopathy in COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:e249. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.003

- Zhou Y, Han T, Chen J, et al. Clinical and autoimmune characteristics of severe and critical cases of COVID-19. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:1077-1086. doi:10.1111/cts.12805

- Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:812010. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.812010

- Rouai M, Slimane MB, Sassi W, et al. Pustular rash triggered by Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022:e15465. doi:10.1111/dth.15465

- Altun E, Kuzucular E. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15279. doi:10.1111/dth.15279

- Buckley JE, Landis LN, Rapini RP. Pityriasis rosea-like rash after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: a case report and review of the literature. JAAD Int. 2022;7:164-168. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.01.009

- Gökçek GE, Öksüm Solak E, Çölgeçen E. Pityriasis rosea like eruption: a dermatological manifestation of Coronavac-COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:e15256. doi:10.1111/dth.15256

- Kim MJ, Kim JW, Kim MS, et al. Generalized erythema multiforme-like skin rash following the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:e98-e100. doi:10.1111/jdv.17757

To the Editor:

The Moderna COVID-19 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine was authorized for use on December 18, 2020, with the second dose beginning on January 15, 2021.1-3 Some individuals who received the Moderna vaccine experienced an intense rash known as “COVID arm,” a harmless but bothersome adverse effect that typically appears within a week and is a localized and transient immunogenic response.4 COVID arm differs from most vaccine adverse effects. The rash emerges not immediately but 5 to 9 days after the initial dose—on average, 1 week later. Apart from being itchy, the rash does not appear to be harmful and is not a reason to hesitate getting vaccinated.

Dermatologists and allergists have been studying this adverse effect, which has been formally termed delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity. Of potential clinical consequence is that the efficacy of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine may be harmed if postvaccination dermal reactions necessitate systemic corticosteroid therapy. Because this vaccine stimulates an immune response as viral RNA integrates in cells secondary to production of the spike protein of the virus, the skin may be affected secondarily and manifestations of any underlying disease may be aggravated.5 We report a patient who developed a psoriasiform dermatitis after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine.

A 65-year-old woman presented to her primary care physician because of the severity of psoriasiform dermatitis that developed 5 days after she received the first dose of the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The patient had a medical history of Sjögren syndrome. Her medication history was negative, and her family history was negative for autoimmune disease. Physical examination by primary care revealed an erythematous scaly rash with plaques and papules on the neck and back (Figure 1). The patient presented again to primary care 2 days later with swollen, painful, discolored digits (Figure 2) and a stiff, sore neck.

Laboratory results were positive for anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B. A complete blood cell count; comprehensive metabolic panel; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and assays of rheumatoid factor, C-reactive protein, and anti–cyclic citrullinated peptide were within reference range. A biopsy of a lesion on the back showed psoriasiform dermatitis with confluent parakeratosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes. There was superficial perivascular inflammation with rare eosinophils (Figure 3).

The patient was treated with a course of systemic corticosteroids. The rash resolved in 1 week. She did not receive the second dose due to the rash.

Two mRNA COVID-19 vaccines—Pfizer BioNTech and Moderna—have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 The safety profile of the mRNA-1273 vaccine for the median 2-month follow-up showed no safety concerns.3 Minor localized adverse effects (eg, pain, redness, swelling) have been observed more frequently with the vaccines than with placebo. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, headache, and muscle and joint pain, also were seen somewhat more often with the vaccines than with placebo; most such effects occurred 24 to 48 hours after vaccination.3,6,7 The frequency of unsolicited adverse events and serious adverse events reported during the 28-day period after vaccination generally was similar among participants in the vaccine and placebo groups.3

There are 2 types of reactions to COVID-19 vaccination: immediate and delayed. Immediate reactions usually are due to anaphylaxis, requiring prompt recognition and treatment with epinephrine to stop rapid progression of life-threatening symptoms. Delayed reactions include localized reactions, such as urticaria and benign exanthema; serum sickness and serum sickness–like reactions; fever; and rare skin, organ, and neurologic sequelae.1,6-8

Cutaneous manifestations, present in 16% to 50% of patients with Sjögren syndrome, are considered one of the most common extraglandular presentations of the syndrome. They are classified as nonvascular (eg, xerosis, angular cheilitis, eyelid dermatitis, annular erythema) and vascular (eg, Raynaud phenomenon, vasculitis).9-11 Our patient did not have any of those findings. She had not taken any medications before the rash appeared, thereby ruling out a drug reaction.

The differential for our patient included post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash, which is not typical with Escherichia coli infection but is described with infection with Chlamydia species and Salmonella species. Moreover, post–urinary tract infection immune-reactive arthritis and rash appear mostly on the palms and soles. Systemic lupus erythematosus–like rashes have a different histology and appear on sun-exposed areas; our patient’s rash was found mainly on unexposed areas.12

Because our patient received the Moderna vaccine 5 days before the rash appeared and later developed swelling of the digits with morning stiffness, a delayed serum sickness–like reaction secondary to COVID-19 vaccination was possible.3,6

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna incorporate a lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system that prevents rapid enzymatic degradation of mRNA and facilitates in vivo delivery of mRNA. This lipid-based nanoparticle carrier system is further stabilized by a polyethylene glycol 2000 lipid conjugate that provides a hydrophilic layer, thus prolonging half-life. The presence of lipid polyethylene glycol 2000 in mRNA vaccines has led to concern that this component could be implicated in anaphylaxis.6

COVID-19 antigens can give rise to varying clinical manifestations that are directly related to viral tissue damage or are indirectly induced by the antiviral immune response.13,14 Hyperactivation of the immune system to eradicate COVID-19 may trigger autoimmunity; several immune-mediated disorders have been described in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Dermal manifestations include cutaneous rash and vasculitis.13-16 Crucial immunologic steps occur during SARS-CoV-2 infection that may link autoimmunity to COVID-19.13,14 In preliminary published data on the efficacy of the Moderna vaccine on 45 trial enrollees, 3 did not receive the second dose of vaccination, including 1 who developed urticaria on both legs 5 days after the first dose.1

Introduction of viral RNA can induce autoimmunity that can be explained by various phenomena, including epitope spreading, molecular mimicry, cryptic antigen, and bystander activation. Remarkably, more than one-third of immunogenic proteins in SARS-CoV-2 have potentially problematic homology to proteins that are key to the human adaptive immune system.5

Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 seems to induce organ injury through alternative mechanisms beyond direct viral infection, including immunologic injury. In some situations, hyperactivation of the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RNA can result in autoimmune disease. COVID-19 has been associated with immune-mediated systemic or organ-selective manifestations, some of which fulfill the diagnostic or classification criteria of specific autoimmune diseases. It is unclear whether those medical disorders are the result of transitory postinfectious epiphenomena.5

A few studies have shown that patients with rheumatic disease have an incidence and prevalence of COVID-19 that is similar to the general population. A similar pattern has been detected in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates, even among patients with an autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.5,17 Furthermore, exacerbation of preexisting rheumatic symptoms may be due to hyperactivation of antiviral pathways in a person with an autoimmune disease.17-19 The findings in our patient suggested a direct role for the vaccine in skin manifestations, rather than for reactivation or development of new systemic autoimmune processes, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination has been described20; however, the case patient did not have a history of psoriasis. The mechanism(s) of such exacerbation remain unclear; COVID-19 vaccine–induced helper T cells (TH17) may play a role.21 Other skin manifestations encountered following COVID-19 vaccination include lichen planus, leukocytoclastic vasculitic rash, erythema multiforme–like rash, and pityriasis rosea–like rash.22-25 The immune mechanisms of these manifestations remain unclear.

The clinical presentation of delayed vaccination reactions can be attributed to the timing of symptoms and, in this case, the immune-mediated background of a psoriasiform reaction. Although adverse reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine are rare, more individuals should be studied after vaccination to confirm and better understand this phenomenon.

To the Editor: