User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Crohn’s disease research goes to the dogs

Why it might be better to be a dog person

Here’s that old debate again: Dogs or cats? You probably have your own opinion, but research presented at this year’s Digestive Disease Week may have tipped the scale by showing that children who lived with dogs may be less likely to have Crohn’s disease as adults.

The research was done by having approximately 4,300 people closely related to patients with Crohn’s disease fill out an environmental questionnaire. Using these data, the research team looked into environmental factors such as size of the families, where the home was, how many bathrooms the homes had, and quality of drinking water.

The researchers found that those who had or were exposed to dogs between the ages of 5 and 15 years were more likely to have healthy gut permeability and balanced microbes, which increased their protection against Crohn’s disease.

“Our study seems to add to others that have explored the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ which suggests that the lack of exposure to microbes early in life may lead to lack of immune regulation toward environmental microbes,” senior author Williams Turpin, PhD, said in the written statement.

The researchers aren’t sure why they didn’t get the same findings with cats, but Dr. Turpin theorized that dog owners tend to be outside more with their dogs or live in places with more green space, which are good protectors against Crohn’s disease.

It’s all good for dog owners, but do their pets’ parasites make you more attractive? Just more fuel for the ongoing debate.

Come for the history, stay for the fossilized parasites

Another week, another analysis of old British poop. LOTME really is your one-stop shop for all the important, hard-hitting news about historic parasites. You’re welcome, Internet.

The news this week is from Stonehenge, which is apparently kind of a big deal. Rocks in a circle, celestial calendar, cultural significance, whatever. We’re not here to talk about rocks. We’re here to talk about, uh, rocks. Smaller rocks. Specifically, coprolites, which are essentially poop turned into a rock. (Though now we’re imagining Stonehenge made out of fossilized poop rocks. Would it still be a big tourist destination? We can see both sides of the argument on that one.)

Archaeologists from the University of Cambridge have conducted an analysis of coprolites from Durrington Walls, a Neolithic settlement just a few kilometers from Stonehenge. The town dates to the same time that Stonehenge was constructed, and it’s believed that the residents were responsible for building the landmark. These coprolites, depending on what’s inside, can tell us a lot about how the builders of Stonehenge lived and, more specifically, how they ate.

In this case, the coprolites of one human and three dogs contained capillariid worm eggs. These worms come from cows, and when a human is typically infected, the eggs embed in the liver and do not pass through the body. Finding them in excrement indicates that the people were eating raw cow organs and feeding leftovers to their dogs. This is interesting, because a preponderance of pottery and cooking implements also found at the site indicates that the residents of Durrington Walls were spit-roasting or boiling their beef and pork. So the meat was cooked, but not the organs. That is an interesting dietary decision, ancient British people. Then again, modern British cuisine exists. At least now we know where they got it from.

This new research raises one other very important question: When are we going to get a full-on guided tour of all the important coprolite sites in Britain? They’ve clearly got plenty of them, and the tourist demand for ancient parasites must be sky-high. Come on, capitalism, follow through on this. We’d go.

Everyone lies: Food intake edition

Do you have any patients on special diets? Do you ask them if they are following those diets? Don’t bother, because they’re lying. Everyone lies about the food they eat. Everyone. Obese people lie, and nonobese people lie.

Investigators at the University of Essex in England asked 221 adults to keep food diaries, and then they checked on energy consumption by analyzing radioactive water levels in the participants’ urine over a 10-day period.

Underreporting of food consumption was rampant, even among those who were not obese. The obese subjects did underreport by a greater extent (1,200 calories per day) than did those who were not obese, who were off by only 800 calories, but the obese participants burned about 400 calories more each day than did the nonobese, so the difference was a wash.

Everyone ended up underreporting their calorie consumption by an average of about 900 calories, and the investigators were good enough to provide some food equivalents, tops on the list being three MacDonald’s cheeseburgers.

“Public health recommendations have historically relied heavily on self-reported energy intake values,” senior author Gavin Sandercock, PhD, said in a EurekAlert statement, and “recognising that the measures of energy intake are incorrect might result in the setting of more realistic targets.”

Maybe you can be more realistic with your patients, too. Go ahead and ask Mr. Smith about the burger sticking out of his coat pocket, because there are probably two more you can’t see. We’ve each got 900 calories hiding on us somewhere. Ours is usually pizza.

The art of the gallbladder

Ever thought you would see a portrait of a gallbladder hanging up in a gallery? Not just an artist’s rendition, but an actual photo from an actual patient? Well, you can at the Soloway Gallery in Brooklyn, N.Y., at least until June 12.

The artist? K.C. Joseph, MD, a general surgeon from St. Marie, Pa., who died in 2015. His daughter Melissa is the curator of the show and told ARTnews about the interesting connection her father had with art and surgery.

In 2010, Dr. Joseph gave his daughter a box of photos and said “Make me a famous artist,” she recalled. At first, “I was like, ‘These are weird,’ and then I put them under my bed for 10 years.”

Apparently he had been making art with his patients’ organs for about 15 years and had a system in which he put each one together. Before a surgery Dr. Joseph would make a note card with the patient’s name handwritten in calligraphy with a couple of pages taken out of the magazine from the waiting room as the backdrop. Afterward, when the patient was in recovery, the removed organ would be placed among the pages and the name card. A photo was taken with the same endoscope that was used for the procedure.

After the show’s debut, people reached out expressing their love for their photos. “I wish, before he died, I had asked him more questions about it,” Ms. Joseph told ARTnews. “I’m regretting it so much now, kicking myself.”

Who gets to take home an artsy photo of their gallbladder after getting it removed? Not us, that’s who. Each collage is a one-of-a-kind piece. They definitely should be framed and shown in an art gallery. Oh, right. Never mind.

Why it might be better to be a dog person

Here’s that old debate again: Dogs or cats? You probably have your own opinion, but research presented at this year’s Digestive Disease Week may have tipped the scale by showing that children who lived with dogs may be less likely to have Crohn’s disease as adults.

The research was done by having approximately 4,300 people closely related to patients with Crohn’s disease fill out an environmental questionnaire. Using these data, the research team looked into environmental factors such as size of the families, where the home was, how many bathrooms the homes had, and quality of drinking water.

The researchers found that those who had or were exposed to dogs between the ages of 5 and 15 years were more likely to have healthy gut permeability and balanced microbes, which increased their protection against Crohn’s disease.

“Our study seems to add to others that have explored the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ which suggests that the lack of exposure to microbes early in life may lead to lack of immune regulation toward environmental microbes,” senior author Williams Turpin, PhD, said in the written statement.

The researchers aren’t sure why they didn’t get the same findings with cats, but Dr. Turpin theorized that dog owners tend to be outside more with their dogs or live in places with more green space, which are good protectors against Crohn’s disease.

It’s all good for dog owners, but do their pets’ parasites make you more attractive? Just more fuel for the ongoing debate.

Come for the history, stay for the fossilized parasites

Another week, another analysis of old British poop. LOTME really is your one-stop shop for all the important, hard-hitting news about historic parasites. You’re welcome, Internet.

The news this week is from Stonehenge, which is apparently kind of a big deal. Rocks in a circle, celestial calendar, cultural significance, whatever. We’re not here to talk about rocks. We’re here to talk about, uh, rocks. Smaller rocks. Specifically, coprolites, which are essentially poop turned into a rock. (Though now we’re imagining Stonehenge made out of fossilized poop rocks. Would it still be a big tourist destination? We can see both sides of the argument on that one.)

Archaeologists from the University of Cambridge have conducted an analysis of coprolites from Durrington Walls, a Neolithic settlement just a few kilometers from Stonehenge. The town dates to the same time that Stonehenge was constructed, and it’s believed that the residents were responsible for building the landmark. These coprolites, depending on what’s inside, can tell us a lot about how the builders of Stonehenge lived and, more specifically, how they ate.

In this case, the coprolites of one human and three dogs contained capillariid worm eggs. These worms come from cows, and when a human is typically infected, the eggs embed in the liver and do not pass through the body. Finding them in excrement indicates that the people were eating raw cow organs and feeding leftovers to their dogs. This is interesting, because a preponderance of pottery and cooking implements also found at the site indicates that the residents of Durrington Walls were spit-roasting or boiling their beef and pork. So the meat was cooked, but not the organs. That is an interesting dietary decision, ancient British people. Then again, modern British cuisine exists. At least now we know where they got it from.

This new research raises one other very important question: When are we going to get a full-on guided tour of all the important coprolite sites in Britain? They’ve clearly got plenty of them, and the tourist demand for ancient parasites must be sky-high. Come on, capitalism, follow through on this. We’d go.

Everyone lies: Food intake edition

Do you have any patients on special diets? Do you ask them if they are following those diets? Don’t bother, because they’re lying. Everyone lies about the food they eat. Everyone. Obese people lie, and nonobese people lie.

Investigators at the University of Essex in England asked 221 adults to keep food diaries, and then they checked on energy consumption by analyzing radioactive water levels in the participants’ urine over a 10-day period.

Underreporting of food consumption was rampant, even among those who were not obese. The obese subjects did underreport by a greater extent (1,200 calories per day) than did those who were not obese, who were off by only 800 calories, but the obese participants burned about 400 calories more each day than did the nonobese, so the difference was a wash.

Everyone ended up underreporting their calorie consumption by an average of about 900 calories, and the investigators were good enough to provide some food equivalents, tops on the list being three MacDonald’s cheeseburgers.

“Public health recommendations have historically relied heavily on self-reported energy intake values,” senior author Gavin Sandercock, PhD, said in a EurekAlert statement, and “recognising that the measures of energy intake are incorrect might result in the setting of more realistic targets.”

Maybe you can be more realistic with your patients, too. Go ahead and ask Mr. Smith about the burger sticking out of his coat pocket, because there are probably two more you can’t see. We’ve each got 900 calories hiding on us somewhere. Ours is usually pizza.

The art of the gallbladder

Ever thought you would see a portrait of a gallbladder hanging up in a gallery? Not just an artist’s rendition, but an actual photo from an actual patient? Well, you can at the Soloway Gallery in Brooklyn, N.Y., at least until June 12.

The artist? K.C. Joseph, MD, a general surgeon from St. Marie, Pa., who died in 2015. His daughter Melissa is the curator of the show and told ARTnews about the interesting connection her father had with art and surgery.

In 2010, Dr. Joseph gave his daughter a box of photos and said “Make me a famous artist,” she recalled. At first, “I was like, ‘These are weird,’ and then I put them under my bed for 10 years.”

Apparently he had been making art with his patients’ organs for about 15 years and had a system in which he put each one together. Before a surgery Dr. Joseph would make a note card with the patient’s name handwritten in calligraphy with a couple of pages taken out of the magazine from the waiting room as the backdrop. Afterward, when the patient was in recovery, the removed organ would be placed among the pages and the name card. A photo was taken with the same endoscope that was used for the procedure.

After the show’s debut, people reached out expressing their love for their photos. “I wish, before he died, I had asked him more questions about it,” Ms. Joseph told ARTnews. “I’m regretting it so much now, kicking myself.”

Who gets to take home an artsy photo of their gallbladder after getting it removed? Not us, that’s who. Each collage is a one-of-a-kind piece. They definitely should be framed and shown in an art gallery. Oh, right. Never mind.

Why it might be better to be a dog person

Here’s that old debate again: Dogs or cats? You probably have your own opinion, but research presented at this year’s Digestive Disease Week may have tipped the scale by showing that children who lived with dogs may be less likely to have Crohn’s disease as adults.

The research was done by having approximately 4,300 people closely related to patients with Crohn’s disease fill out an environmental questionnaire. Using these data, the research team looked into environmental factors such as size of the families, where the home was, how many bathrooms the homes had, and quality of drinking water.

The researchers found that those who had or were exposed to dogs between the ages of 5 and 15 years were more likely to have healthy gut permeability and balanced microbes, which increased their protection against Crohn’s disease.

“Our study seems to add to others that have explored the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ which suggests that the lack of exposure to microbes early in life may lead to lack of immune regulation toward environmental microbes,” senior author Williams Turpin, PhD, said in the written statement.

The researchers aren’t sure why they didn’t get the same findings with cats, but Dr. Turpin theorized that dog owners tend to be outside more with their dogs or live in places with more green space, which are good protectors against Crohn’s disease.

It’s all good for dog owners, but do their pets’ parasites make you more attractive? Just more fuel for the ongoing debate.

Come for the history, stay for the fossilized parasites

Another week, another analysis of old British poop. LOTME really is your one-stop shop for all the important, hard-hitting news about historic parasites. You’re welcome, Internet.

The news this week is from Stonehenge, which is apparently kind of a big deal. Rocks in a circle, celestial calendar, cultural significance, whatever. We’re not here to talk about rocks. We’re here to talk about, uh, rocks. Smaller rocks. Specifically, coprolites, which are essentially poop turned into a rock. (Though now we’re imagining Stonehenge made out of fossilized poop rocks. Would it still be a big tourist destination? We can see both sides of the argument on that one.)

Archaeologists from the University of Cambridge have conducted an analysis of coprolites from Durrington Walls, a Neolithic settlement just a few kilometers from Stonehenge. The town dates to the same time that Stonehenge was constructed, and it’s believed that the residents were responsible for building the landmark. These coprolites, depending on what’s inside, can tell us a lot about how the builders of Stonehenge lived and, more specifically, how they ate.

In this case, the coprolites of one human and three dogs contained capillariid worm eggs. These worms come from cows, and when a human is typically infected, the eggs embed in the liver and do not pass through the body. Finding them in excrement indicates that the people were eating raw cow organs and feeding leftovers to their dogs. This is interesting, because a preponderance of pottery and cooking implements also found at the site indicates that the residents of Durrington Walls were spit-roasting or boiling their beef and pork. So the meat was cooked, but not the organs. That is an interesting dietary decision, ancient British people. Then again, modern British cuisine exists. At least now we know where they got it from.

This new research raises one other very important question: When are we going to get a full-on guided tour of all the important coprolite sites in Britain? They’ve clearly got plenty of them, and the tourist demand for ancient parasites must be sky-high. Come on, capitalism, follow through on this. We’d go.

Everyone lies: Food intake edition

Do you have any patients on special diets? Do you ask them if they are following those diets? Don’t bother, because they’re lying. Everyone lies about the food they eat. Everyone. Obese people lie, and nonobese people lie.

Investigators at the University of Essex in England asked 221 adults to keep food diaries, and then they checked on energy consumption by analyzing radioactive water levels in the participants’ urine over a 10-day period.

Underreporting of food consumption was rampant, even among those who were not obese. The obese subjects did underreport by a greater extent (1,200 calories per day) than did those who were not obese, who were off by only 800 calories, but the obese participants burned about 400 calories more each day than did the nonobese, so the difference was a wash.

Everyone ended up underreporting their calorie consumption by an average of about 900 calories, and the investigators were good enough to provide some food equivalents, tops on the list being three MacDonald’s cheeseburgers.

“Public health recommendations have historically relied heavily on self-reported energy intake values,” senior author Gavin Sandercock, PhD, said in a EurekAlert statement, and “recognising that the measures of energy intake are incorrect might result in the setting of more realistic targets.”

Maybe you can be more realistic with your patients, too. Go ahead and ask Mr. Smith about the burger sticking out of his coat pocket, because there are probably two more you can’t see. We’ve each got 900 calories hiding on us somewhere. Ours is usually pizza.

The art of the gallbladder

Ever thought you would see a portrait of a gallbladder hanging up in a gallery? Not just an artist’s rendition, but an actual photo from an actual patient? Well, you can at the Soloway Gallery in Brooklyn, N.Y., at least until June 12.

The artist? K.C. Joseph, MD, a general surgeon from St. Marie, Pa., who died in 2015. His daughter Melissa is the curator of the show and told ARTnews about the interesting connection her father had with art and surgery.

In 2010, Dr. Joseph gave his daughter a box of photos and said “Make me a famous artist,” she recalled. At first, “I was like, ‘These are weird,’ and then I put them under my bed for 10 years.”

Apparently he had been making art with his patients’ organs for about 15 years and had a system in which he put each one together. Before a surgery Dr. Joseph would make a note card with the patient’s name handwritten in calligraphy with a couple of pages taken out of the magazine from the waiting room as the backdrop. Afterward, when the patient was in recovery, the removed organ would be placed among the pages and the name card. A photo was taken with the same endoscope that was used for the procedure.

After the show’s debut, people reached out expressing their love for their photos. “I wish, before he died, I had asked him more questions about it,” Ms. Joseph told ARTnews. “I’m regretting it so much now, kicking myself.”

Who gets to take home an artsy photo of their gallbladder after getting it removed? Not us, that’s who. Each collage is a one-of-a-kind piece. They definitely should be framed and shown in an art gallery. Oh, right. Never mind.

Manufacturer announces FDA approval for molluscum treatment delayed

Pharmaceuticals, which is developing the product.

VP-102 is a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been evaluated in phase 3 studies of patients with molluscum aged 2 years and older. It features a visualization agent so the person applying the drug can see which lesions have been treated. It also contains a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children.

According to a press release from Verrica, the only deficiency listed in the FDA’s complete response letter stemmed from a general reinspection of Sterling Pharmaceuticals Services, which manufactures Verrica’s bulk solution drug product. Although none of the issues identified by the FDA during the reinspection were specific to the manufacturing of VP-102, FDA policy prevents approval of a new drug application when a contract manufacturing organization has an unresolved classification status or is placed on “official action indicated” status.

According to the press release, Verrica will “continue to work collaboratively” with the FDA to bring VP-102 to the market as soon as possible. The company has completed phase 2 studies of VP-102 for the treatment of common warts and for the treatment of external genital warts, the release said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pharmaceuticals, which is developing the product.

VP-102 is a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been evaluated in phase 3 studies of patients with molluscum aged 2 years and older. It features a visualization agent so the person applying the drug can see which lesions have been treated. It also contains a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children.

According to a press release from Verrica, the only deficiency listed in the FDA’s complete response letter stemmed from a general reinspection of Sterling Pharmaceuticals Services, which manufactures Verrica’s bulk solution drug product. Although none of the issues identified by the FDA during the reinspection were specific to the manufacturing of VP-102, FDA policy prevents approval of a new drug application when a contract manufacturing organization has an unresolved classification status or is placed on “official action indicated” status.

According to the press release, Verrica will “continue to work collaboratively” with the FDA to bring VP-102 to the market as soon as possible. The company has completed phase 2 studies of VP-102 for the treatment of common warts and for the treatment of external genital warts, the release said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pharmaceuticals, which is developing the product.

VP-102 is a proprietary drug-device combination of cantharidin 0.7% administered through a single-use precision applicator, which has been evaluated in phase 3 studies of patients with molluscum aged 2 years and older. It features a visualization agent so the person applying the drug can see which lesions have been treated. It also contains a bittering agent to mitigate oral ingestion by children.

According to a press release from Verrica, the only deficiency listed in the FDA’s complete response letter stemmed from a general reinspection of Sterling Pharmaceuticals Services, which manufactures Verrica’s bulk solution drug product. Although none of the issues identified by the FDA during the reinspection were specific to the manufacturing of VP-102, FDA policy prevents approval of a new drug application when a contract manufacturing organization has an unresolved classification status or is placed on “official action indicated” status.

According to the press release, Verrica will “continue to work collaboratively” with the FDA to bring VP-102 to the market as soon as possible. The company has completed phase 2 studies of VP-102 for the treatment of common warts and for the treatment of external genital warts, the release said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pemphigus Vulgaris Aggravated: Rifampicin Found at the Scene of the Crime

Case Report

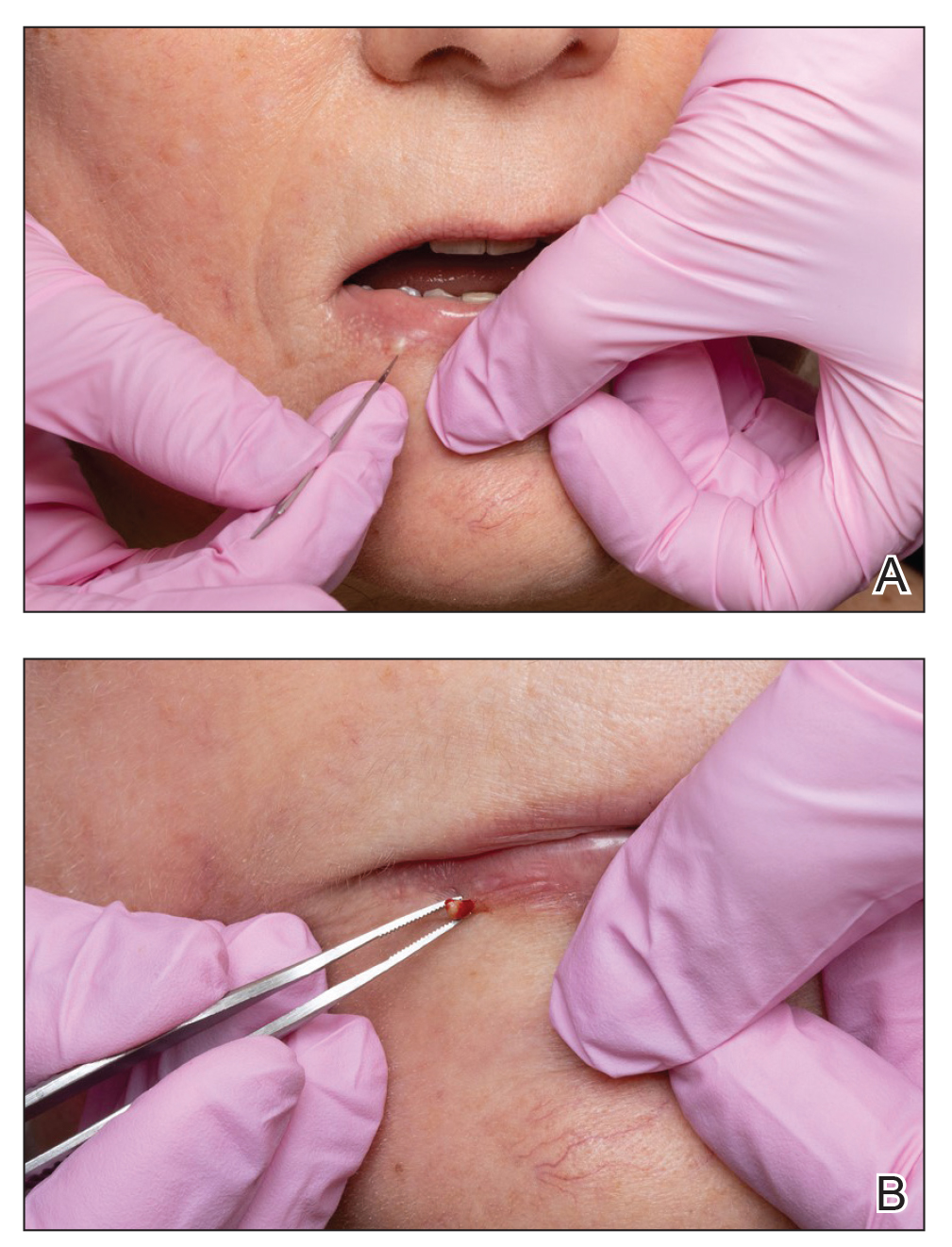

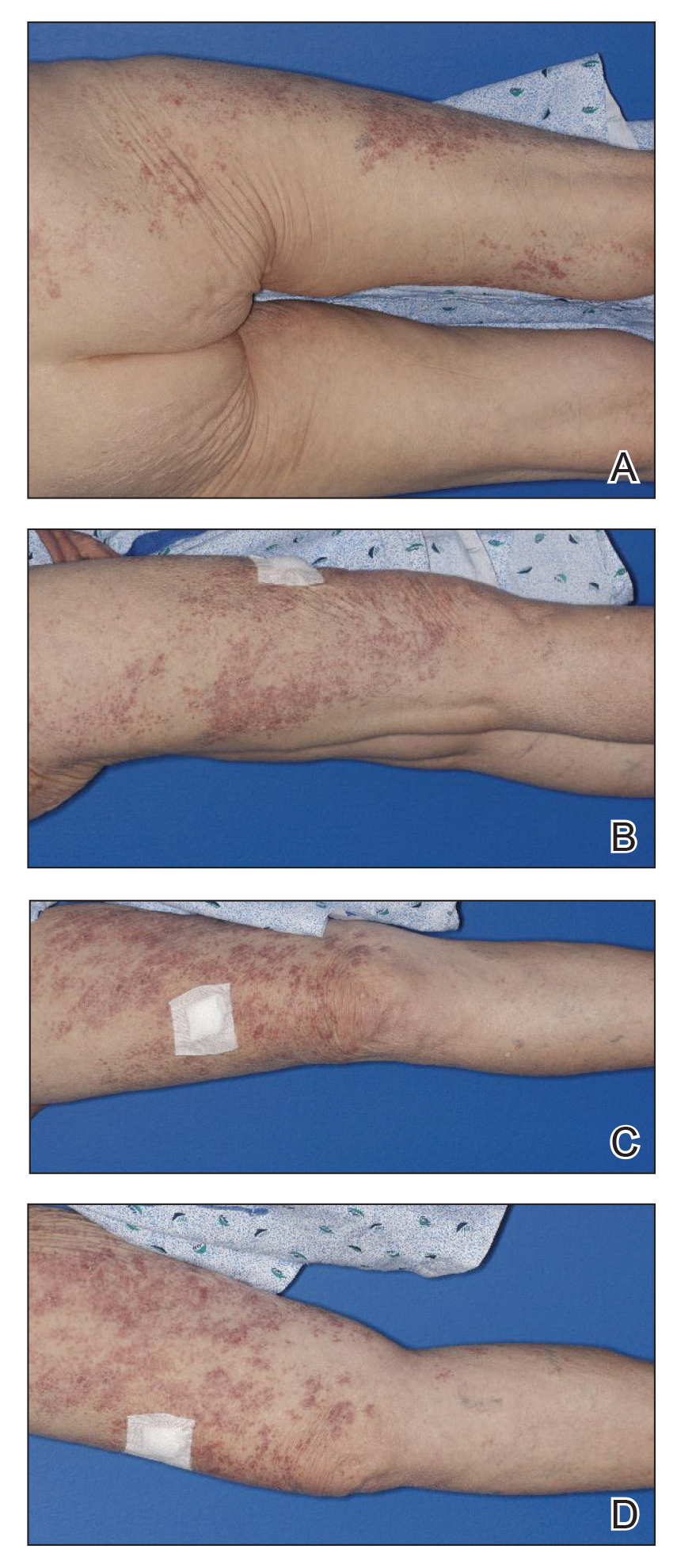

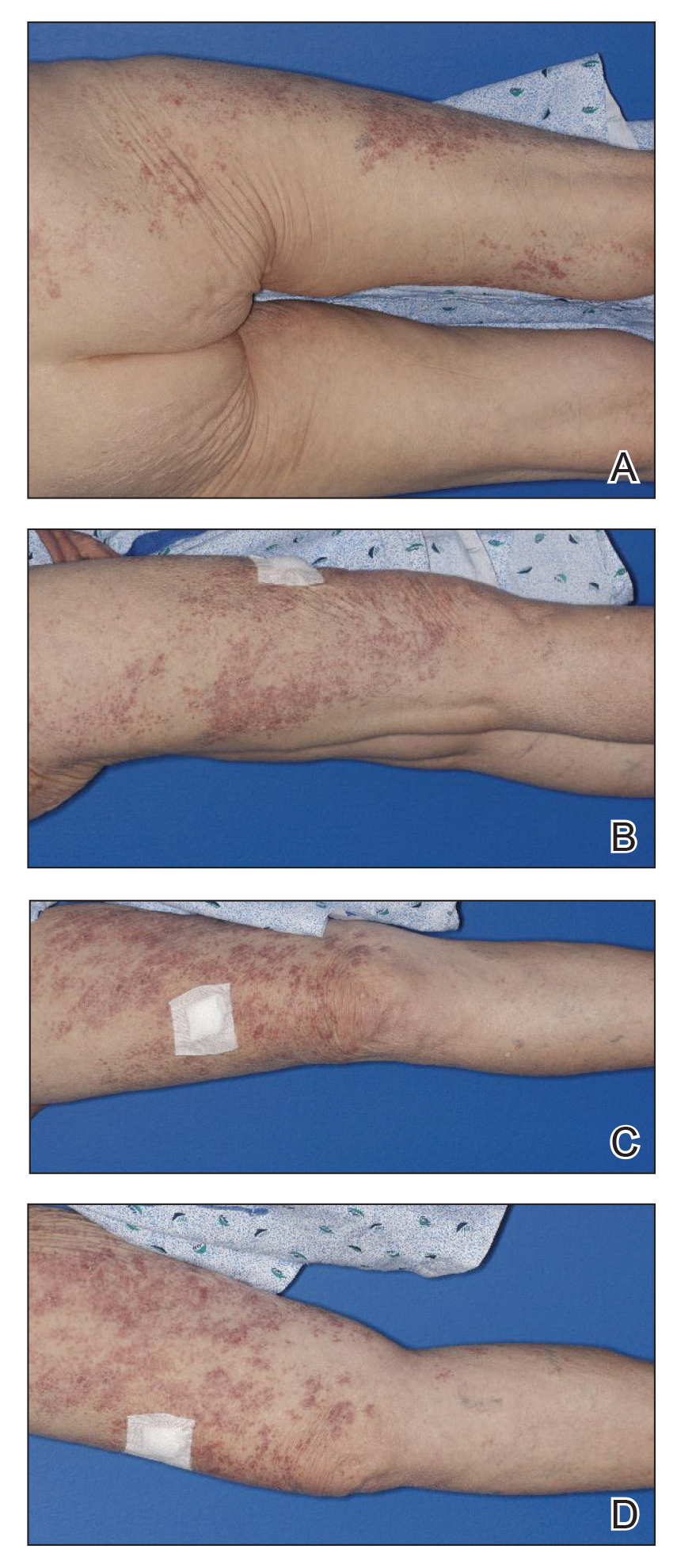

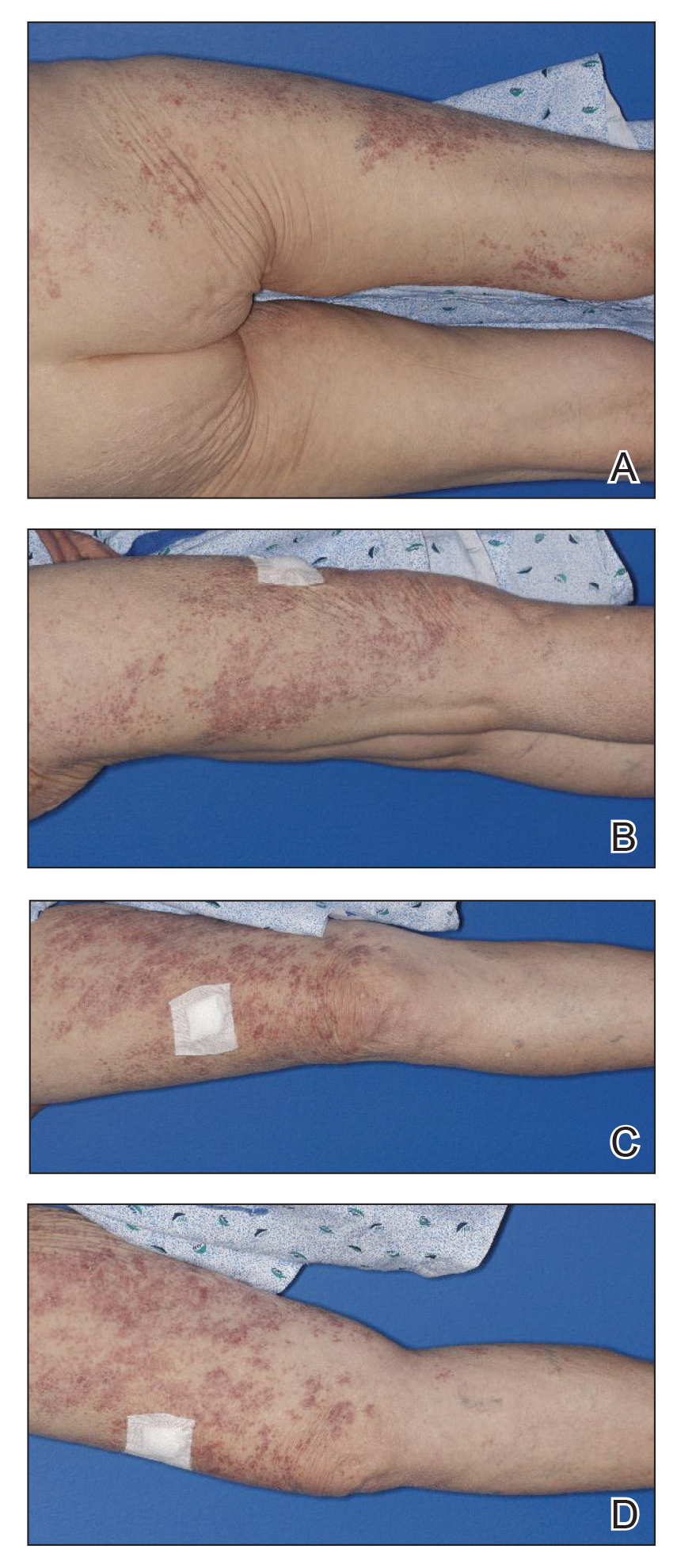

A 60-year-old man presented with eroded areas in the mouth and blistering eruptions on the scalp, face, trunk, arms, and legs. He initially presented to an outside hospital 4 years prior and was treated with oral prednisone 50 mg daily, to which the eruptions responded rapidly; however, following a nearly 5-mg reduction of the dose per week by the patient and irregular oral administration, he experienced several episodes of recurrence, but he could not remember the exact dosage of prednisone he had taken during that period. Subsequently, he was admitted to our hospital because of large areas of erythema and erosions on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.

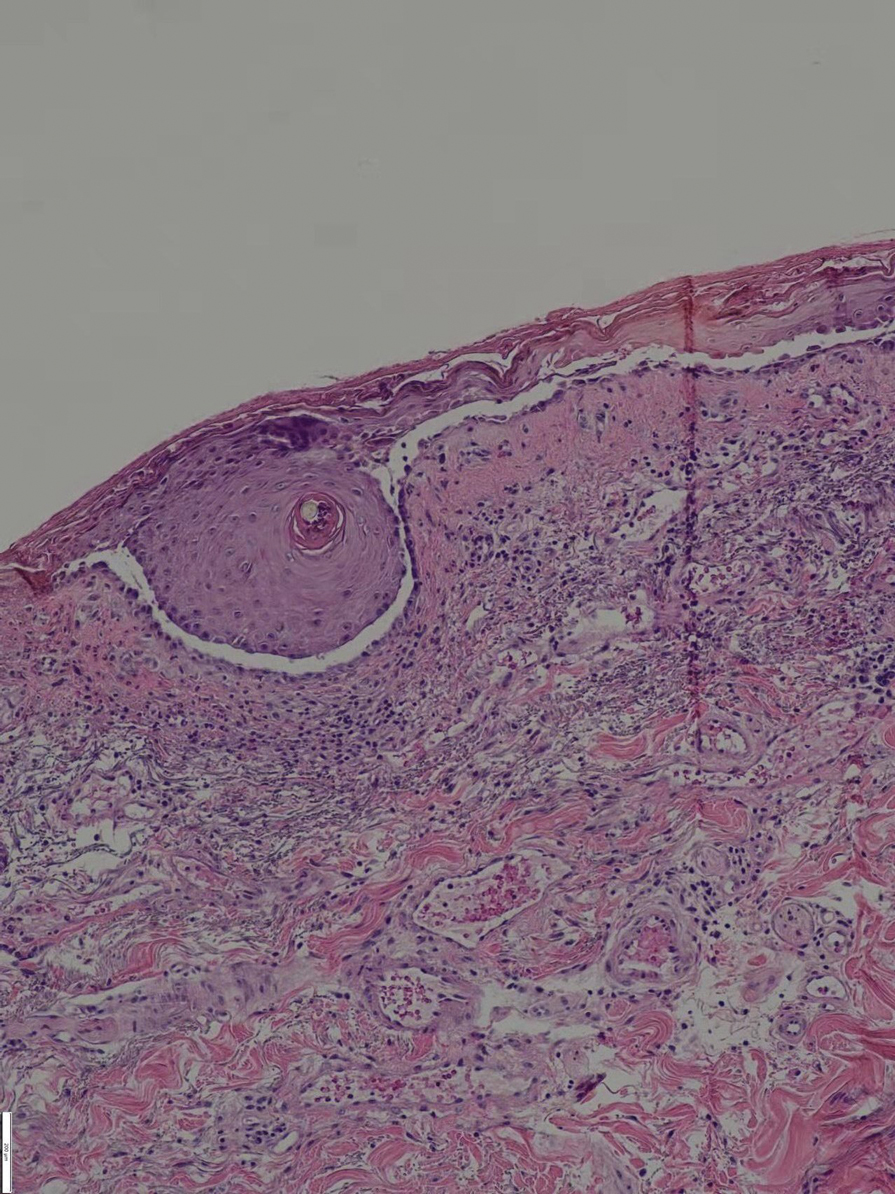

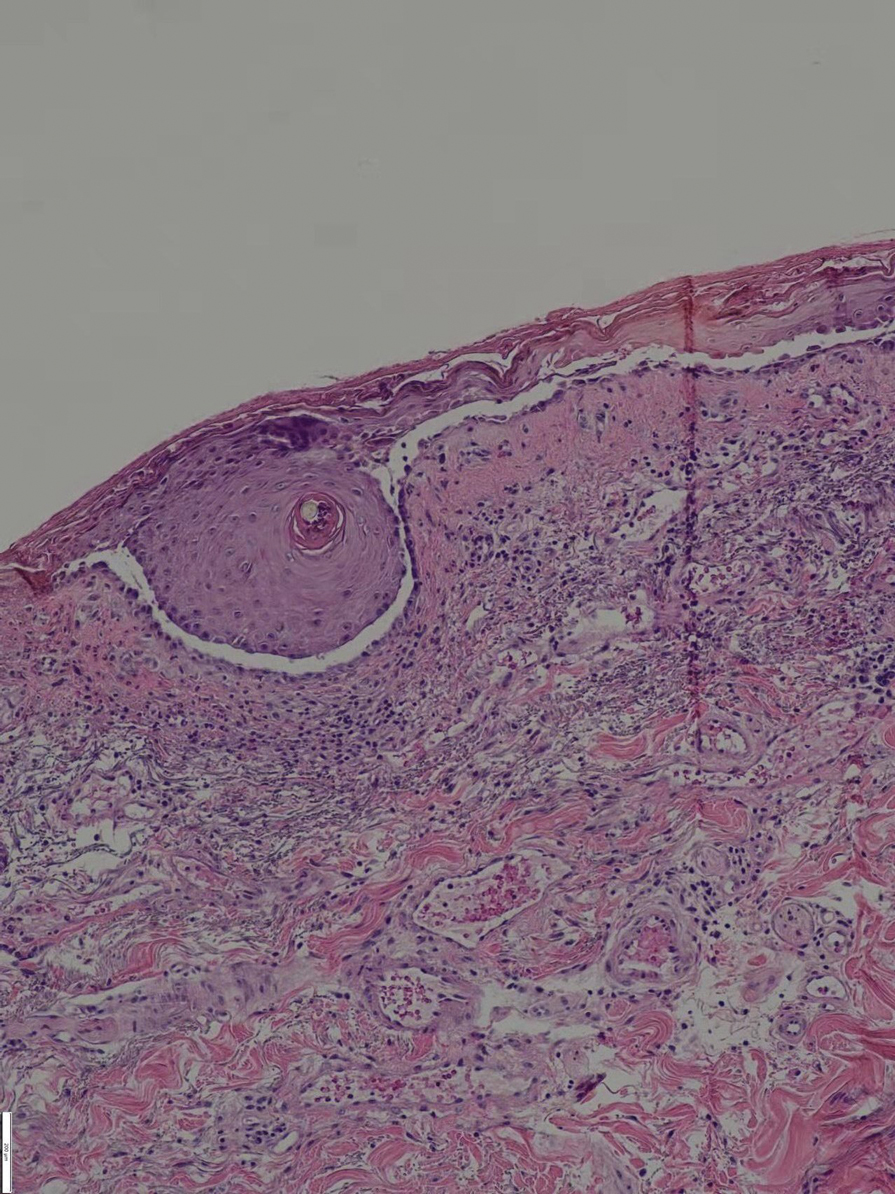

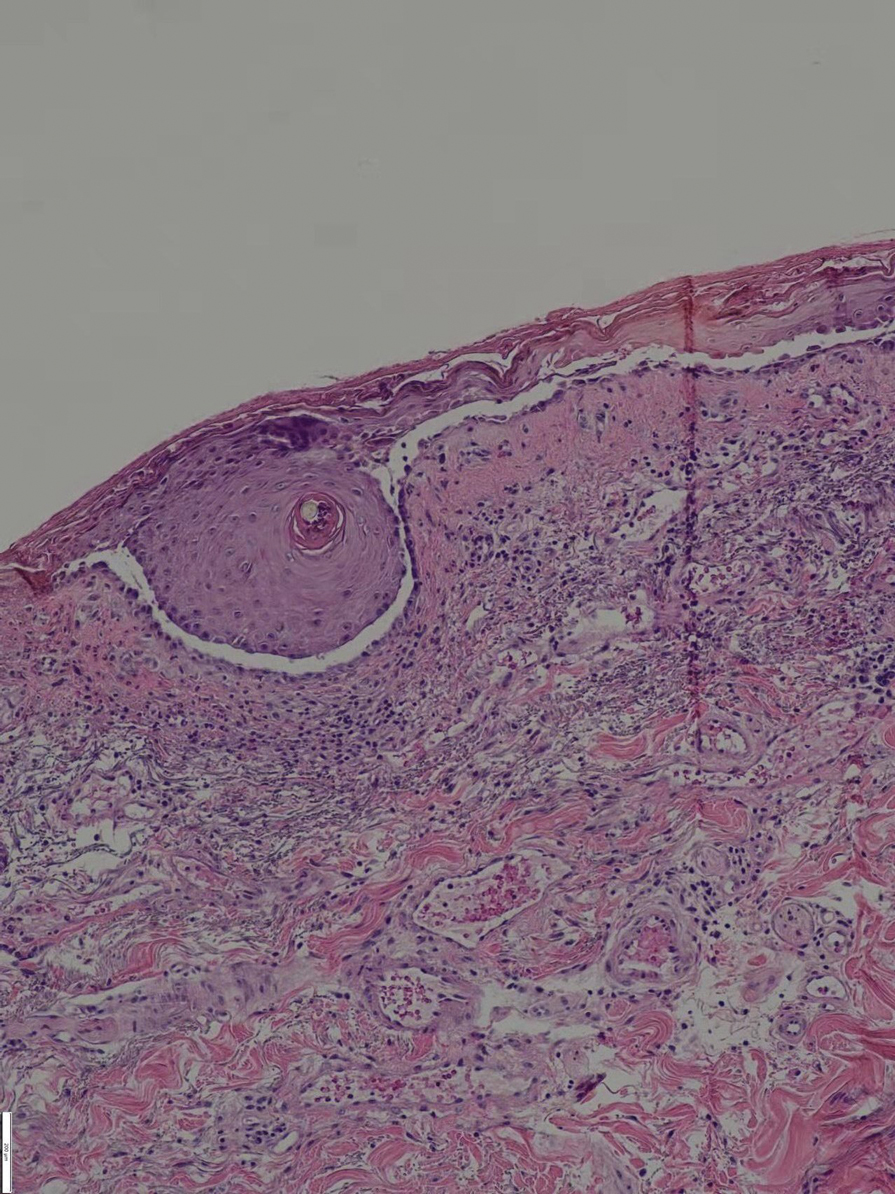

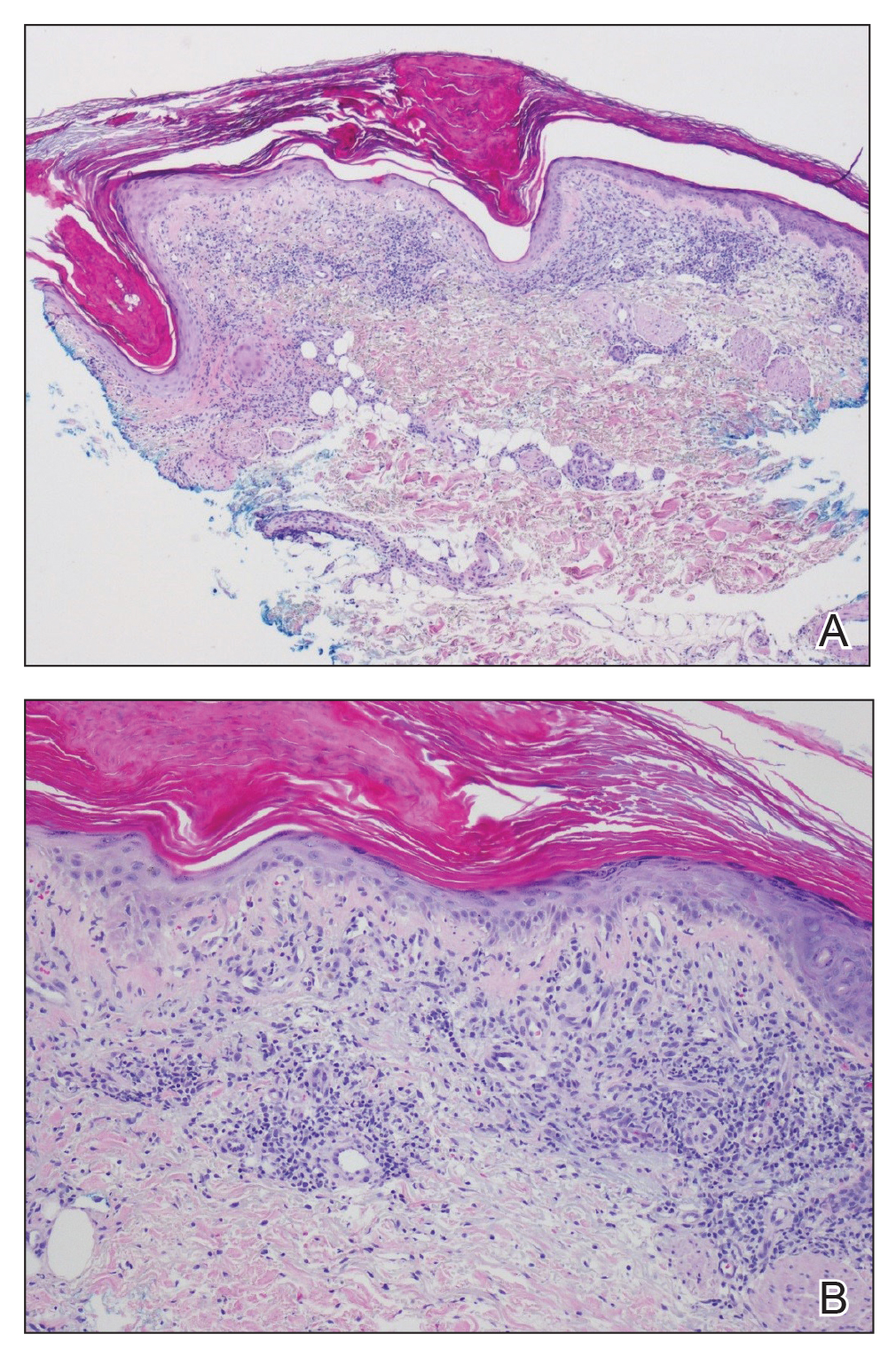

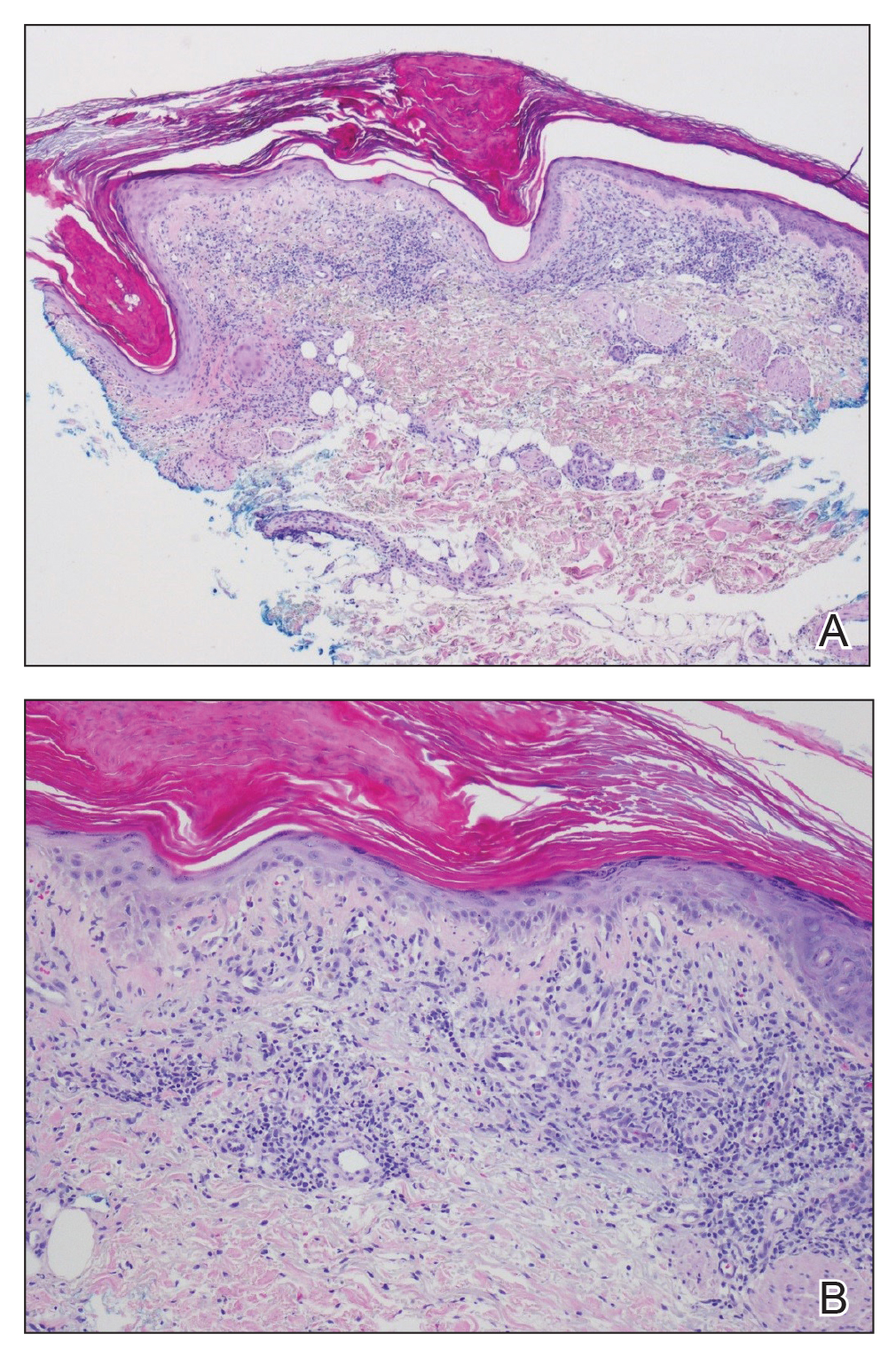

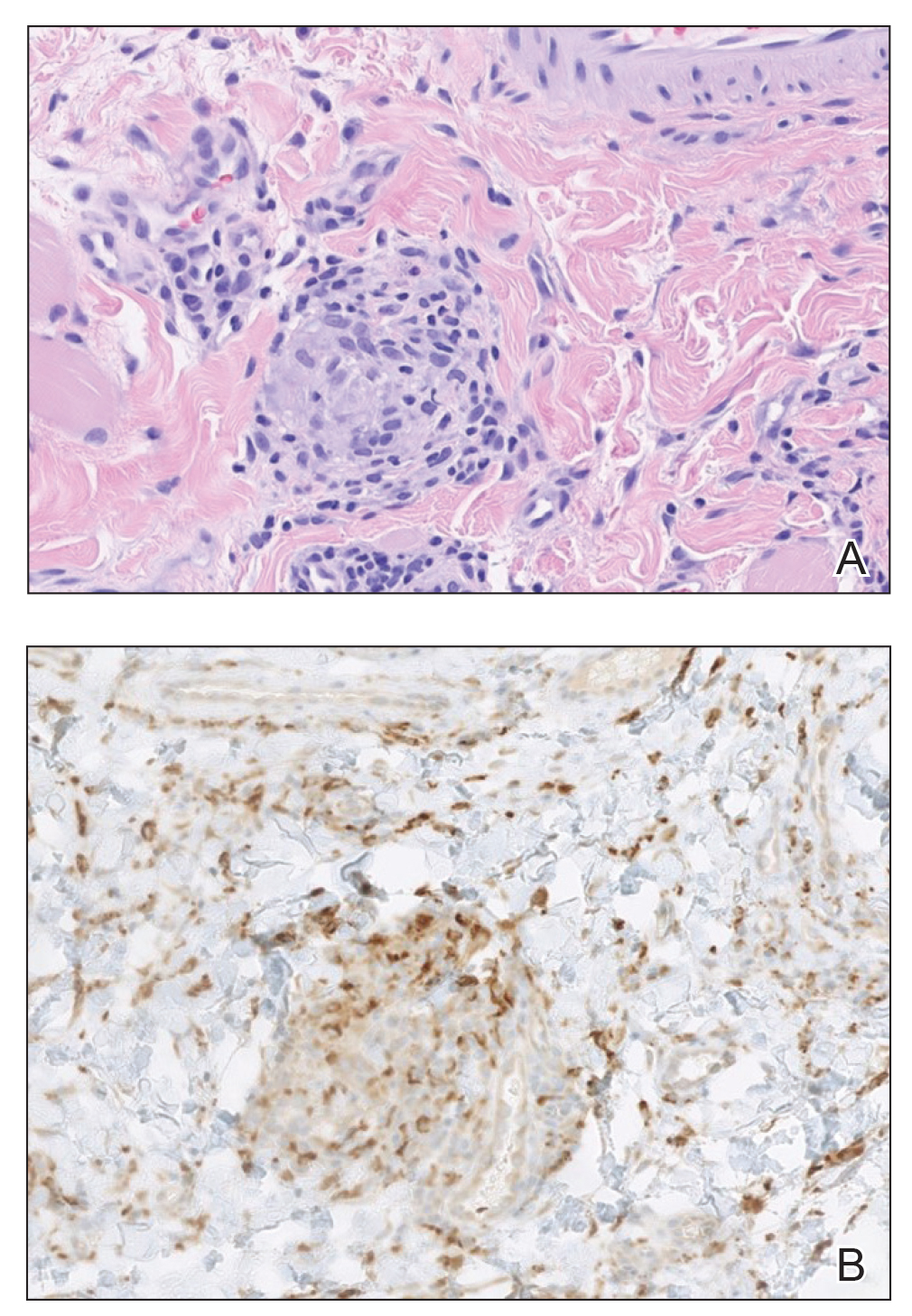

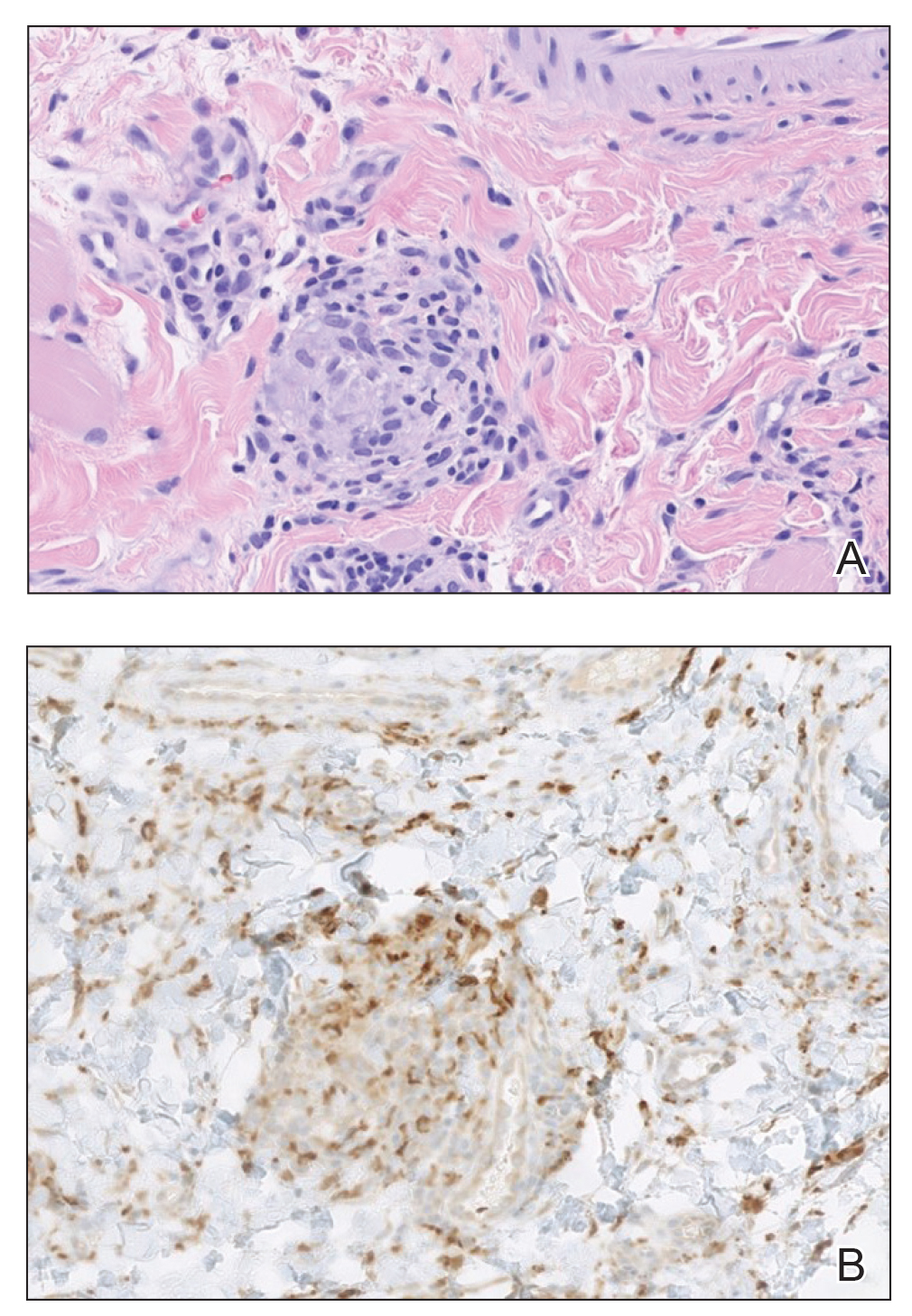

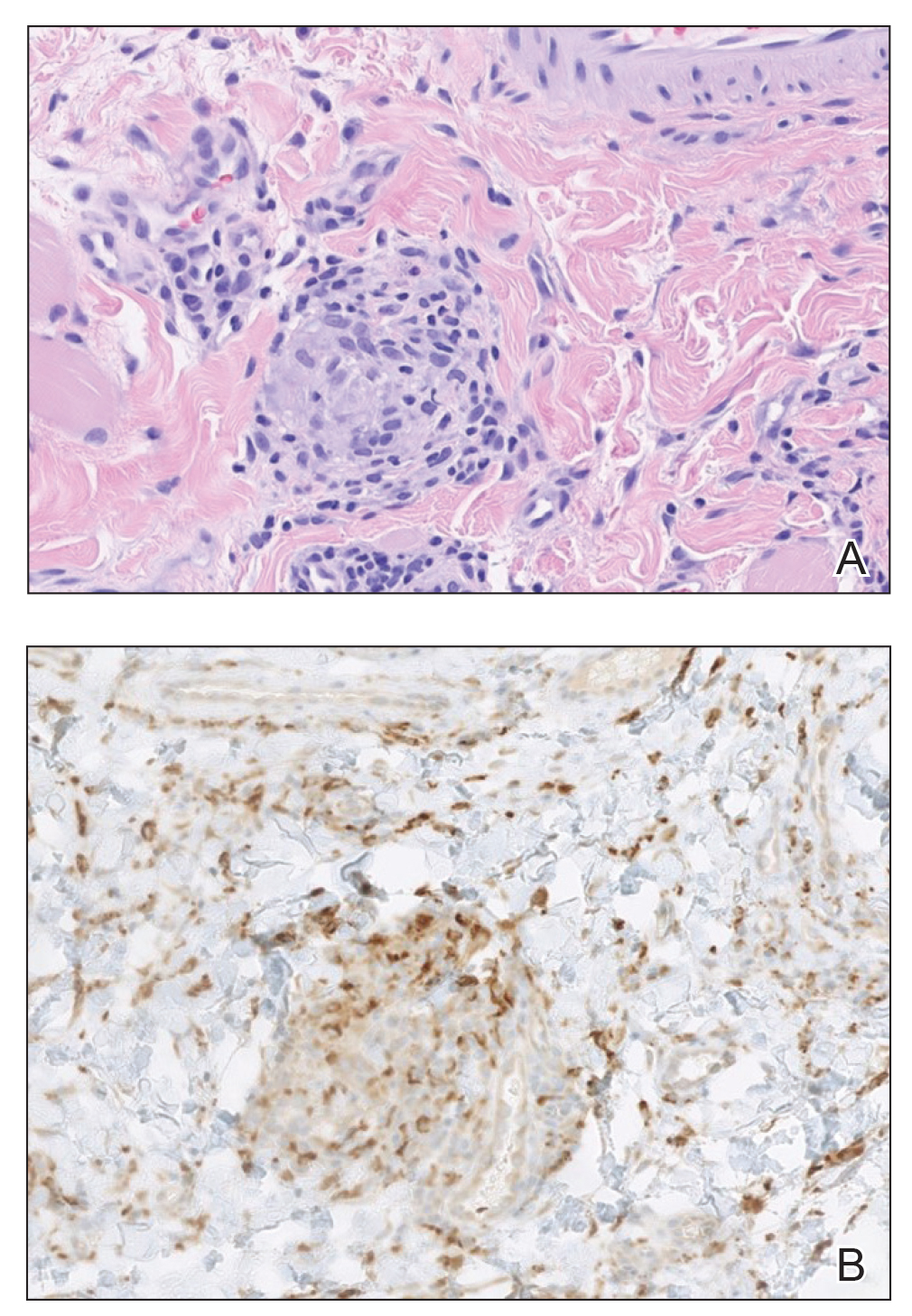

Since starting the prednisone regimen 4 years prior, the patient had experienced onset of hypertension, diabetes, glaucoma, cataracts, optic nerve atrophy, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, and osteoporosis. Biopsy of a new skin lesion

The patient initially was started again prednisone 50 mg daily, to which the skin eruptions responded, and 2 weeks later, the disease was considered controlled. The prednisone dosage was tapered to 20 mg daily 3 months later with no new blister formation. However, 2 weeks later, the patient was diagnosed by a tuberculosis specialist with pulmonary tuberculosis, and a daily regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin was instituted.

Ten days after starting antituberculosis therapy, the patient developed new erythematous blisters that could not be controlled and self-adjusted the prednisone dose to 50 mg daily. Two months later, blister formation continued.

Six months after the initial presentation, the patient returned to our hospital because of uncontrollable rashes (Figure 2). On admission, he had a Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) score of 32 with disease involving 30% of the body surface area. Laboratory testing showed a desmoglein 1 level of 233 U/mL and desmoglein 3 level of 228 U/mL. A tuberculosis specialist from an outside hospital was consulted to evaluate the patient’s condition and assist in treatment. Based on findings from a pulmonary computed tomography scan, which showed the inflammation was considerably absorbed, treatment was adjusted to stop using ethambutol and levofloxacin and continue rifampicin and isoniazid. For the PV, prednisone was titrated upward to 75 mg daily, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 1 g twice daily was added, and IVIG 400 mg/kg daily was administered for 7 days. After 3 weeks, the rash still expanded.

In considering possible interactions between the drugs, we consulted the literature and found reports1-3 that rifampicin accelerated glucocorticoid metabolism, of which the tuberculosis specialist that we consulted was not aware. Therefore, rifampicin was stopped, and the antituberculosis therapy was adjusted to levofloxacin and isoniazid. Meanwhile, the steroid was changed to methylprednisolone 120 mg daily for 3 days, then to 80 mg daily for 2 days.

After 5 days, the rash was controlled with no new development and the patient was discharged. He continued on prednisone 80 mg daily and MMF 1 g twice daily.

At 2-month follow-up, no new rash had developed. The patient had already self-discontinued the MMF for 1 month because it was difficult to obtain at local hospitals. The prednisone was reduced to 40 mg daily. Pulmonary computed tomography showed no signs of reactivation of tuberculosis.

Comment

Drugs that depend on these enzymes for their metabolism are prone to

Rifampicin causes a marked reduction in dose-corrected mycophenolic acid exposure when administered simultaneously with MMF through induction of glucuronidation activity and inhibition of enterohepatic recirculation.5,10In in vitro studies, rifampin and other cytochrome P450 inducers have been identified as potentially useful for increasing the rate of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide (an isomeric analogue of cyclophosphamide) 4-hydroxylation in the human liver in a manner that could have a favorable impact on the clinical pharmacokinetics of these anticancer prodrugs.11 However, clinical analysis of 16 patients indicated that co-administration of ifosfamide with rifampin did not result in changes in the pharmacokinetics of the parent drug or its metabolites.12

The steroids and

Conclusion

In our patient, the use of rifapentine resulted in a recurrence of previously controlled PV and resistance to treatment. The patient’s disease was quickly controlled after discontinuation of rifampicin and with a short-term course of high-dose methylprednisolone and remained stable when the dosages of MMF and prednisone were reduced.

- Miyagawa S, Yamashina Y, Okuchi T, et al. Exacerbation of pemphigus by rifampicin. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:729-732. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb04882.x

- Gange RW, Rhodes EL, Edwards CO, et al. Pemphigus induced by rifampicin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:445-448. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb00849.x

- Bergrem H, Refvem OK. Altered prednisolone pharmacokinetics in patients treated with rifampicin. Acta Med Scand. 1983;213:339-343. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1983.tb03748.x

- McAllister WA, Thompson PJ, Al-Habet SM, et al. Rifampicin reduces effectiveness and bioavailability of prednisolone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:923-925. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6369.923

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106. doi:10.1007/s00403-017-1790-8

- Barman H, Dass R, Duwarah SG. Use of high-dose prednisolone to overcome rifampicin-induced corticosteroid non-responsiveness in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27:157-160. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.174198

- Okey AB, Roberts EA, Harper PA, et al. Induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes: mechanisms and consequences. Clin Biochem. 1986;19:132-141. doi:10.1016/s0009-9120(86)80060-1

- Venkatesan K. Pharmacokinetic interactions with rifampicin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;22:47-65. doi:10.2165/00003088-199222010-00005

- Naesens M, Kuypers DRJ, Streit F, et al. Rifampin induces alterations in mycophenolic acid glucuronidation and elimination: implications for drug exposure in renal allograft recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:509-521. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.08.002

- Kuypers DRJ, Verleden G, Naesens M, et al. Drug interaction between mycophenolate mofetil and rifampin: possible induction of uridine diphosphate–glucuronosyltransferase. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:81-88. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2005.03.004

- Chenhsu RY, Loong CC, Chou MH, et al. Renal allograft dysfunction associated with rifampin–tacrolimus interaction. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:27-31. doi:10.1345/aph.19069

- Douglas JG, McLeod MJ. Pharmacokinetic factors in the modern drug treatment of tuberculosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:127-146. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937020-00003

Case Report

A 60-year-old man presented with eroded areas in the mouth and blistering eruptions on the scalp, face, trunk, arms, and legs. He initially presented to an outside hospital 4 years prior and was treated with oral prednisone 50 mg daily, to which the eruptions responded rapidly; however, following a nearly 5-mg reduction of the dose per week by the patient and irregular oral administration, he experienced several episodes of recurrence, but he could not remember the exact dosage of prednisone he had taken during that period. Subsequently, he was admitted to our hospital because of large areas of erythema and erosions on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.

Since starting the prednisone regimen 4 years prior, the patient had experienced onset of hypertension, diabetes, glaucoma, cataracts, optic nerve atrophy, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, and osteoporosis. Biopsy of a new skin lesion

The patient initially was started again prednisone 50 mg daily, to which the skin eruptions responded, and 2 weeks later, the disease was considered controlled. The prednisone dosage was tapered to 20 mg daily 3 months later with no new blister formation. However, 2 weeks later, the patient was diagnosed by a tuberculosis specialist with pulmonary tuberculosis, and a daily regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin was instituted.

Ten days after starting antituberculosis therapy, the patient developed new erythematous blisters that could not be controlled and self-adjusted the prednisone dose to 50 mg daily. Two months later, blister formation continued.

Six months after the initial presentation, the patient returned to our hospital because of uncontrollable rashes (Figure 2). On admission, he had a Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) score of 32 with disease involving 30% of the body surface area. Laboratory testing showed a desmoglein 1 level of 233 U/mL and desmoglein 3 level of 228 U/mL. A tuberculosis specialist from an outside hospital was consulted to evaluate the patient’s condition and assist in treatment. Based on findings from a pulmonary computed tomography scan, which showed the inflammation was considerably absorbed, treatment was adjusted to stop using ethambutol and levofloxacin and continue rifampicin and isoniazid. For the PV, prednisone was titrated upward to 75 mg daily, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 1 g twice daily was added, and IVIG 400 mg/kg daily was administered for 7 days. After 3 weeks, the rash still expanded.

In considering possible interactions between the drugs, we consulted the literature and found reports1-3 that rifampicin accelerated glucocorticoid metabolism, of which the tuberculosis specialist that we consulted was not aware. Therefore, rifampicin was stopped, and the antituberculosis therapy was adjusted to levofloxacin and isoniazid. Meanwhile, the steroid was changed to methylprednisolone 120 mg daily for 3 days, then to 80 mg daily for 2 days.

After 5 days, the rash was controlled with no new development and the patient was discharged. He continued on prednisone 80 mg daily and MMF 1 g twice daily.

At 2-month follow-up, no new rash had developed. The patient had already self-discontinued the MMF for 1 month because it was difficult to obtain at local hospitals. The prednisone was reduced to 40 mg daily. Pulmonary computed tomography showed no signs of reactivation of tuberculosis.

Comment

Drugs that depend on these enzymes for their metabolism are prone to

Rifampicin causes a marked reduction in dose-corrected mycophenolic acid exposure when administered simultaneously with MMF through induction of glucuronidation activity and inhibition of enterohepatic recirculation.5,10In in vitro studies, rifampin and other cytochrome P450 inducers have been identified as potentially useful for increasing the rate of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide (an isomeric analogue of cyclophosphamide) 4-hydroxylation in the human liver in a manner that could have a favorable impact on the clinical pharmacokinetics of these anticancer prodrugs.11 However, clinical analysis of 16 patients indicated that co-administration of ifosfamide with rifampin did not result in changes in the pharmacokinetics of the parent drug or its metabolites.12

The steroids and

Conclusion

In our patient, the use of rifapentine resulted in a recurrence of previously controlled PV and resistance to treatment. The patient’s disease was quickly controlled after discontinuation of rifampicin and with a short-term course of high-dose methylprednisolone and remained stable when the dosages of MMF and prednisone were reduced.

Case Report

A 60-year-old man presented with eroded areas in the mouth and blistering eruptions on the scalp, face, trunk, arms, and legs. He initially presented to an outside hospital 4 years prior and was treated with oral prednisone 50 mg daily, to which the eruptions responded rapidly; however, following a nearly 5-mg reduction of the dose per week by the patient and irregular oral administration, he experienced several episodes of recurrence, but he could not remember the exact dosage of prednisone he had taken during that period. Subsequently, he was admitted to our hospital because of large areas of erythema and erosions on the scalp, trunk, arms, and legs.

Since starting the prednisone regimen 4 years prior, the patient had experienced onset of hypertension, diabetes, glaucoma, cataracts, optic nerve atrophy, aseptic necrosis of the femoral head, and osteoporosis. Biopsy of a new skin lesion

The patient initially was started again prednisone 50 mg daily, to which the skin eruptions responded, and 2 weeks later, the disease was considered controlled. The prednisone dosage was tapered to 20 mg daily 3 months later with no new blister formation. However, 2 weeks later, the patient was diagnosed by a tuberculosis specialist with pulmonary tuberculosis, and a daily regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and levofloxacin was instituted.

Ten days after starting antituberculosis therapy, the patient developed new erythematous blisters that could not be controlled and self-adjusted the prednisone dose to 50 mg daily. Two months later, blister formation continued.

Six months after the initial presentation, the patient returned to our hospital because of uncontrollable rashes (Figure 2). On admission, he had a Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) score of 32 with disease involving 30% of the body surface area. Laboratory testing showed a desmoglein 1 level of 233 U/mL and desmoglein 3 level of 228 U/mL. A tuberculosis specialist from an outside hospital was consulted to evaluate the patient’s condition and assist in treatment. Based on findings from a pulmonary computed tomography scan, which showed the inflammation was considerably absorbed, treatment was adjusted to stop using ethambutol and levofloxacin and continue rifampicin and isoniazid. For the PV, prednisone was titrated upward to 75 mg daily, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 1 g twice daily was added, and IVIG 400 mg/kg daily was administered for 7 days. After 3 weeks, the rash still expanded.

In considering possible interactions between the drugs, we consulted the literature and found reports1-3 that rifampicin accelerated glucocorticoid metabolism, of which the tuberculosis specialist that we consulted was not aware. Therefore, rifampicin was stopped, and the antituberculosis therapy was adjusted to levofloxacin and isoniazid. Meanwhile, the steroid was changed to methylprednisolone 120 mg daily for 3 days, then to 80 mg daily for 2 days.

After 5 days, the rash was controlled with no new development and the patient was discharged. He continued on prednisone 80 mg daily and MMF 1 g twice daily.

At 2-month follow-up, no new rash had developed. The patient had already self-discontinued the MMF for 1 month because it was difficult to obtain at local hospitals. The prednisone was reduced to 40 mg daily. Pulmonary computed tomography showed no signs of reactivation of tuberculosis.

Comment

Drugs that depend on these enzymes for their metabolism are prone to

Rifampicin causes a marked reduction in dose-corrected mycophenolic acid exposure when administered simultaneously with MMF through induction of glucuronidation activity and inhibition of enterohepatic recirculation.5,10In in vitro studies, rifampin and other cytochrome P450 inducers have been identified as potentially useful for increasing the rate of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide (an isomeric analogue of cyclophosphamide) 4-hydroxylation in the human liver in a manner that could have a favorable impact on the clinical pharmacokinetics of these anticancer prodrugs.11 However, clinical analysis of 16 patients indicated that co-administration of ifosfamide with rifampin did not result in changes in the pharmacokinetics of the parent drug or its metabolites.12

The steroids and

Conclusion

In our patient, the use of rifapentine resulted in a recurrence of previously controlled PV and resistance to treatment. The patient’s disease was quickly controlled after discontinuation of rifampicin and with a short-term course of high-dose methylprednisolone and remained stable when the dosages of MMF and prednisone were reduced.

- Miyagawa S, Yamashina Y, Okuchi T, et al. Exacerbation of pemphigus by rifampicin. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:729-732. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb04882.x

- Gange RW, Rhodes EL, Edwards CO, et al. Pemphigus induced by rifampicin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:445-448. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb00849.x

- Bergrem H, Refvem OK. Altered prednisolone pharmacokinetics in patients treated with rifampicin. Acta Med Scand. 1983;213:339-343. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1983.tb03748.x

- McAllister WA, Thompson PJ, Al-Habet SM, et al. Rifampicin reduces effectiveness and bioavailability of prednisolone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:923-925. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6369.923

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106. doi:10.1007/s00403-017-1790-8

- Barman H, Dass R, Duwarah SG. Use of high-dose prednisolone to overcome rifampicin-induced corticosteroid non-responsiveness in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27:157-160. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.174198

- Okey AB, Roberts EA, Harper PA, et al. Induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes: mechanisms and consequences. Clin Biochem. 1986;19:132-141. doi:10.1016/s0009-9120(86)80060-1

- Venkatesan K. Pharmacokinetic interactions with rifampicin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;22:47-65. doi:10.2165/00003088-199222010-00005

- Naesens M, Kuypers DRJ, Streit F, et al. Rifampin induces alterations in mycophenolic acid glucuronidation and elimination: implications for drug exposure in renal allograft recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:509-521. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.08.002

- Kuypers DRJ, Verleden G, Naesens M, et al. Drug interaction between mycophenolate mofetil and rifampin: possible induction of uridine diphosphate–glucuronosyltransferase. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:81-88. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2005.03.004

- Chenhsu RY, Loong CC, Chou MH, et al. Renal allograft dysfunction associated with rifampin–tacrolimus interaction. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:27-31. doi:10.1345/aph.19069

- Douglas JG, McLeod MJ. Pharmacokinetic factors in the modern drug treatment of tuberculosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:127-146. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937020-00003

- Miyagawa S, Yamashina Y, Okuchi T, et al. Exacerbation of pemphigus by rifampicin. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:729-732. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb04882.x

- Gange RW, Rhodes EL, Edwards CO, et al. Pemphigus induced by rifampicin. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:445-448. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb00849.x

- Bergrem H, Refvem OK. Altered prednisolone pharmacokinetics in patients treated with rifampicin. Acta Med Scand. 1983;213:339-343. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1983.tb03748.x

- McAllister WA, Thompson PJ, Al-Habet SM, et al. Rifampicin reduces effectiveness and bioavailability of prednisolone. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:923-925. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6369.923

- Tavakolpour S. Pemphigus trigger factors: special focus on pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018;310:95-106. doi:10.1007/s00403-017-1790-8

- Barman H, Dass R, Duwarah SG. Use of high-dose prednisolone to overcome rifampicin-induced corticosteroid non-responsiveness in childhood nephrotic syndrome. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27:157-160. doi:10.4103/1319-2442.174198

- Okey AB, Roberts EA, Harper PA, et al. Induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes: mechanisms and consequences. Clin Biochem. 1986;19:132-141. doi:10.1016/s0009-9120(86)80060-1

- Venkatesan K. Pharmacokinetic interactions with rifampicin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1992;22:47-65. doi:10.2165/00003088-199222010-00005

- Naesens M, Kuypers DRJ, Streit F, et al. Rifampin induces alterations in mycophenolic acid glucuronidation and elimination: implications for drug exposure in renal allograft recipients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:509-521. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2006.08.002

- Kuypers DRJ, Verleden G, Naesens M, et al. Drug interaction between mycophenolate mofetil and rifampin: possible induction of uridine diphosphate–glucuronosyltransferase. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:81-88. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2005.03.004

- Chenhsu RY, Loong CC, Chou MH, et al. Renal allograft dysfunction associated with rifampin–tacrolimus interaction. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:27-31. doi:10.1345/aph.19069

- Douglas JG, McLeod MJ. Pharmacokinetic factors in the modern drug treatment of tuberculosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:127-146. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937020-00003

Practice Points

- Long-term use of immunosuppressants requires constant attention for infections, especially latent infections in the body.

- Clinicians should carefully inquire with patients about concomitant diseases and medications used, and be vigilant about drug interactions.

Forceps for Milia Extraction

To the Editor:

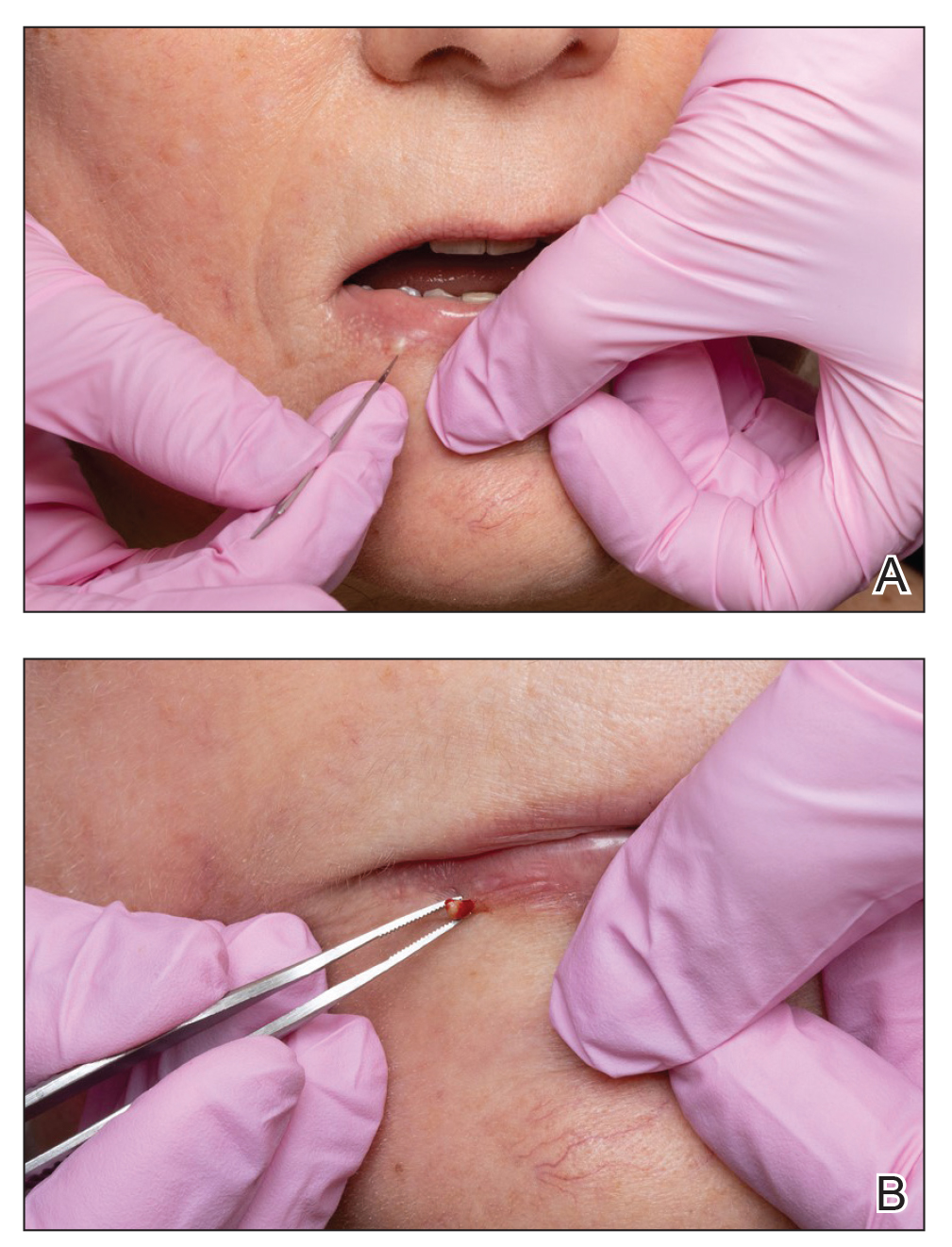

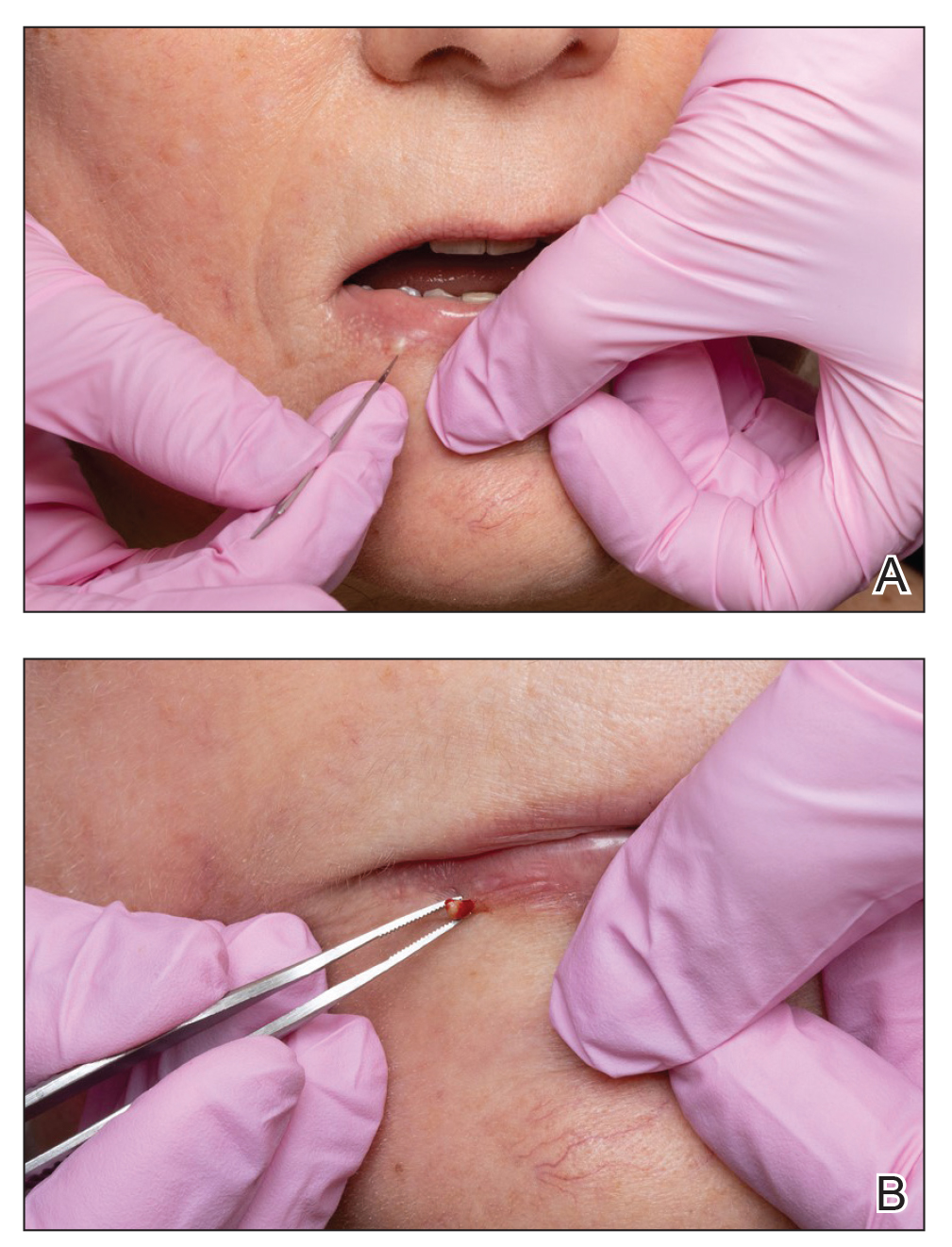

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.

A 74-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic papule on the right lower vermilion border of several years' duration. Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 3-mm, firm, white, dome-shaped papule. Clinical features were most consistent with a benign acquired milium. The patient desired removal for cosmesis. The area was cleaned with an alcohol swab, the surface of the milium was nicked with a No. 11 blade (Figure, A), and then tips of nontoothed Adson forceps were used to gently secure and pinch the base of the papule (Figure, B). The intact cyst was quickly and effortlessly expressed through the epidermal nick. The patient tolerated the procedure well, experiencing minimal pain and bleeding.

Histologically, milia represent infundibular keratin-filled cysts lined with stratified squamous epithelial tissue that contains a granular cell layer. These lesions are classified as primary or secondary; the former represent spontaneous occurrence, and the latter are associated with medications, trauma, or genodermatoses.2 Multiple milia are associated with conditions such as Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, oro-facial-digital syndrome type I, atrichia with papular lesions, pachyonychia congenita type 2, basal cell nevus syndrome, basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and hereditary vitamin D–dependent rickets type 2.5-9 The most common subtype seen in clinical practice includes benign primary milia, which tends to favor the cheeks and eyelids.2

Although these lesions are benign, many patients seek extraction for cosmesis. Milia extraction is a common procedure performed in dermatology clinical practice. Proposed extraction techniques using destructive methods include electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy, and manual methods include nicking the surface of the lesion with a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet and then applying tangential pressure with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Topical retinoids have been proposed as treatment of multiple milia.10 Many of these techniques do not use equipment common to clinical practice, or they fail to stabilize milia in sensitive areas, which makes extraction challenging. We describe a case with a new manual technique that successfully extracts milia in an efficient and safe manner.

- Parlette HL III. Management of cutaneous cysts. In: Wheeland RG, ed. Cutaneous Surgery. WB Saunders; 1994:651-652.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- George DE, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Surgical pearl: evacuation of milia with a paper clip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:326.

- Thami GP, Kaur S, Kanwar AJ. Surgical pearl: enucleation of milia with a disposable hypodermic needle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:602-603.

- Goeteyn M, Geerts ML, Kint A, et al. The Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:337-342.

- Michaëlsson G, Olsson E, Westermark P. The Rombo syndrome: a familial disorder with vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, hypotrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:497-503.

- Gurrieri F, Franco B, Toriello H, et al. Oral-facial-digital syndromes: review and diagnostic guidelines. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:3314-3323.

- Zlotogorski A, Panteleyev AA, Aita VM, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnostic criteria of congenital atrichia with papular lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1662-1665.

- Paller AS, Moore JA, Scher R. Pachyonychia congenita tarda. alate-onset form of pachyonychia congenita. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:701-703.

- Connelly T. Eruptive milia and rapid response to topical tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:816-817.

To the Editor:

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.

A 74-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic papule on the right lower vermilion border of several years' duration. Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 3-mm, firm, white, dome-shaped papule. Clinical features were most consistent with a benign acquired milium. The patient desired removal for cosmesis. The area was cleaned with an alcohol swab, the surface of the milium was nicked with a No. 11 blade (Figure, A), and then tips of nontoothed Adson forceps were used to gently secure and pinch the base of the papule (Figure, B). The intact cyst was quickly and effortlessly expressed through the epidermal nick. The patient tolerated the procedure well, experiencing minimal pain and bleeding.

Histologically, milia represent infundibular keratin-filled cysts lined with stratified squamous epithelial tissue that contains a granular cell layer. These lesions are classified as primary or secondary; the former represent spontaneous occurrence, and the latter are associated with medications, trauma, or genodermatoses.2 Multiple milia are associated with conditions such as Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, oro-facial-digital syndrome type I, atrichia with papular lesions, pachyonychia congenita type 2, basal cell nevus syndrome, basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and hereditary vitamin D–dependent rickets type 2.5-9 The most common subtype seen in clinical practice includes benign primary milia, which tends to favor the cheeks and eyelids.2

Although these lesions are benign, many patients seek extraction for cosmesis. Milia extraction is a common procedure performed in dermatology clinical practice. Proposed extraction techniques using destructive methods include electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy, and manual methods include nicking the surface of the lesion with a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet and then applying tangential pressure with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Topical retinoids have been proposed as treatment of multiple milia.10 Many of these techniques do not use equipment common to clinical practice, or they fail to stabilize milia in sensitive areas, which makes extraction challenging. We describe a case with a new manual technique that successfully extracts milia in an efficient and safe manner.

To the Editor:

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.

A 74-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic papule on the right lower vermilion border of several years' duration. Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 3-mm, firm, white, dome-shaped papule. Clinical features were most consistent with a benign acquired milium. The patient desired removal for cosmesis. The area was cleaned with an alcohol swab, the surface of the milium was nicked with a No. 11 blade (Figure, A), and then tips of nontoothed Adson forceps were used to gently secure and pinch the base of the papule (Figure, B). The intact cyst was quickly and effortlessly expressed through the epidermal nick. The patient tolerated the procedure well, experiencing minimal pain and bleeding.

Histologically, milia represent infundibular keratin-filled cysts lined with stratified squamous epithelial tissue that contains a granular cell layer. These lesions are classified as primary or secondary; the former represent spontaneous occurrence, and the latter are associated with medications, trauma, or genodermatoses.2 Multiple milia are associated with conditions such as Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, oro-facial-digital syndrome type I, atrichia with papular lesions, pachyonychia congenita type 2, basal cell nevus syndrome, basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and hereditary vitamin D–dependent rickets type 2.5-9 The most common subtype seen in clinical practice includes benign primary milia, which tends to favor the cheeks and eyelids.2

Although these lesions are benign, many patients seek extraction for cosmesis. Milia extraction is a common procedure performed in dermatology clinical practice. Proposed extraction techniques using destructive methods include electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy, and manual methods include nicking the surface of the lesion with a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet and then applying tangential pressure with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Topical retinoids have been proposed as treatment of multiple milia.10 Many of these techniques do not use equipment common to clinical practice, or they fail to stabilize milia in sensitive areas, which makes extraction challenging. We describe a case with a new manual technique that successfully extracts milia in an efficient and safe manner.

- Parlette HL III. Management of cutaneous cysts. In: Wheeland RG, ed. Cutaneous Surgery. WB Saunders; 1994:651-652.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- George DE, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Surgical pearl: evacuation of milia with a paper clip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:326.

- Thami GP, Kaur S, Kanwar AJ. Surgical pearl: enucleation of milia with a disposable hypodermic needle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:602-603.

- Goeteyn M, Geerts ML, Kint A, et al. The Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:337-342.

- Michaëlsson G, Olsson E, Westermark P. The Rombo syndrome: a familial disorder with vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, hypotrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:497-503.

- Gurrieri F, Franco B, Toriello H, et al. Oral-facial-digital syndromes: review and diagnostic guidelines. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:3314-3323.

- Zlotogorski A, Panteleyev AA, Aita VM, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnostic criteria of congenital atrichia with papular lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1662-1665.

- Paller AS, Moore JA, Scher R. Pachyonychia congenita tarda. alate-onset form of pachyonychia congenita. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:701-703.

- Connelly T. Eruptive milia and rapid response to topical tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:816-817.

- Parlette HL III. Management of cutaneous cysts. In: Wheeland RG, ed. Cutaneous Surgery. WB Saunders; 1994:651-652.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- George DE, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Surgical pearl: evacuation of milia with a paper clip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:326.

- Thami GP, Kaur S, Kanwar AJ. Surgical pearl: enucleation of milia with a disposable hypodermic needle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:602-603.

- Goeteyn M, Geerts ML, Kint A, et al. The Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:337-342.

- Michaëlsson G, Olsson E, Westermark P. The Rombo syndrome: a familial disorder with vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, hypotrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:497-503.

- Gurrieri F, Franco B, Toriello H, et al. Oral-facial-digital syndromes: review and diagnostic guidelines. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:3314-3323.

- Zlotogorski A, Panteleyev AA, Aita VM, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnostic criteria of congenital atrichia with papular lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1662-1665.

- Paller AS, Moore JA, Scher R. Pachyonychia congenita tarda. alate-onset form of pachyonychia congenita. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:701-703.

- Connelly T. Eruptive milia and rapid response to topical tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:816-817.

Practice Points

- Milia are common benign lesions that are cosmetically undesirable to some patients.

- Although some methods of milia removal can be painful, removal with forceps is quick and effective.

Navigating Motherhood and Dermatology Residency

Motherhood and dermatology residency are both full-time jobs. The thought that a woman must either be superhuman to succeed at both or that success at one must come at the expense of the other is antiquated. With careful navigation and sufficient support, these two roles can complement and heighten one another. The most recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) report showed that nearly 60% of dermatology residents are women,1 with most women in training being of childbearing age. One study showed that female dermatologists were most likely to have children during residency (51% of those surveyed), despite residents reporting more barriers to childbearing at this career stage.2 Trainees thinking of starting a family have many considerations to navigate: timing of pregnancy, maternity leave scheduling, breastfeeding while working, and planning for childcare. For the first time in the history of the specialty, most active dermatologists in practice are women.3 Thus, the future of dermatology requires supportive policies and resources for the successful navigation of these issues by today’s trainees.

Timing of Pregnancy

Timing of pregnancy can be a source of stress to the female dermatology resident. Barriers to childbearing during residency include the perception that women who have children during residency training are less committed to their jobs; concerns of overburdening fellow residents; and fear that residency may need to be extended, thereby delaying the ability to sit for the board examination.2 However, the potential increased risk for infertility in delaying pregnancy adds to the stress of pregnancy planning. A 2016 survey of female physicians (N=327) showed that 24.1% of respondents who had attempted conception were diagnosed with infertility, with an average age at diagnosis of 33.7 years.4 This is higher than the national average, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting that approximately 19% of women aged 15 to 49 years with no prior births experience infertility.5 In a 1992 survey of female physician residents (N=373) who gave birth during residency, 32% indicated that they would not recommend the experience to others; of the 68% who would recommend the experience, one-third encouraged timing delivery to occur in the last 2 months of residency due to benefits of continued insurance coverage, a decrease in clinic responsibilities, and the potential for extended maternity leave during hiatus between jobs.6 Although this may be a good strategy, studying and sitting for board examinations while caring for a newborn right after graduation may be overly difficult for some. The first year of residency was perceived as the most stressful time to be pregnant, with each subsequent year being less problematic.6 Planning pregnancy for delivery near the end of the second year and beginning of the third year of dermatology residency may be a reasonable choice.

Maternity Leave

The Family and Medical Leave Act entitles eligible employees of covered employers to take unpaid, job-protected leave, with 12 workweeks of leave in a 12-month period for the birth of a child and to care for the newborn child within 1 year of birth.7 The actual length of maternity leave taken by most surveyed female dermatologists (n=96) is shorter: 25% (24/96) took less than 4 weeks, 42.7% (41/96) took 4 to 8 weeks, 25% (24/96) took 9 to 12 weeks, and 7.3% (7/96) were able to take more than 12 weeks of maternity leave.2

The American Board of Dermatology implemented a new Resident Leave policy that went into effect July 1, 2021, stipulating that, within certain parameters, time spent away from training for family and parental leave would not exhaust vacation time or require an extension in training. Under this policy, absence from training exceeding 8 weeks (6 weeks leave, plus 2 weeks of vacation) in a given year should be approved only under exceptional circumstances and may necessitate additional training time to ensure that competency requirements are met.8 Although this policy is a step in the right direction, institutional policies still may vary. Dermatology residents planning to start a family during training should consider their plans for fellowship, as taking an extended maternity leave beyond 8 weeks may jeopardize a July fellowship start date.

Lactation and Residency

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for approximately 6 months, with continuation of breastfeeding for 1 year or longer as mutually desired by the mother and infant.9 Successful lactation and achieving breastfeeding goals can be difficult during medical training. A national cross-sectional survey of female residents (N=312) showed that the median total time of breastfeeding and pumping was 9 months, with 74% continuing after 6 months and 13% continuing past 12 months. Of those surveyed, 73% reported residency limited their ability to lactate, and 37% stopped prior to their desired goal.10 As of July 1, 2020, the ACGME requires that residency programs and sponsoring institutions provide clean and private facilities for lactation that have refrigeration capabilities, with proximity appropriate for safe patient care.11 There has been a call to dermatology program leadership to support breastfeeding residents by providing sufficient time and space to pump; a breastfeeding resident will need a 20- to 30-minute break to express milk approximately every 3 hours during the work day.12 One innovative initiative to meet the ACGME lactation requirement reported by the Kansas University Medical Center Graduate Medical Education program (Kansas City, Kansas) was the purchase of wearable breast pumps to loan to residents. The benefits of wearable breast pumps are that they are discreet and can allow mothers to express milk inconspicuously while working, can increase milk supply, require less set up and expression time than traditional pumps, and can allow the mother to manage time more efficiently.13 Breastfeeding plans and goals should be discussed with program leadership before return from leave to strategize and anticipate gaps in clinic scheduling to accommodate the lactating resident.

Planning for Childcare

Resident hours can be long and erratic, making choices for childcare difficult. In one survey of female residents, 61% of married or partnered respondents (n=447) were delaying childbearing, and 46% cited lack of access to childcare as a reason.14 Not all dermatology residents are fortunate enough to match to a program near family, but close family support can be an undeniable asset during childrearing and should be weighed heavily when ranking programs. Options for childcare include relying on a stay-at-home spouse or other family member, a live-in or live-out nanny, part-time babysitters, and daycare. It is crucial to have multiple layers and back-up options for childcare available at any given time when working as a resident. Even with a child enrolled in a full-time daycare and a live-in nanny, a daycare closure due to a COVID-19 exposure or sudden medical emergency in the nanny can still leave unpredicted holes in your childcare plan, leaving the resident to potentially miss work to fill the gap. A survey of residents at one institution showed that the most common backup childcare plan for situations in which either the child or the regular caregiver is ill is for the nontrainee parent or spouse to stay home (45%; n=101), with 25% of respondents staying home to care for a sick child themselves, which clearly has an impact on the hospital. The article proposed implementation of on-site or near-site childcare for residents with extended hours or a 24-hour emergency drop-in availability.15 One institution reported success with the development of a departmentally funded childcare supplementation stipend offered to residents to support daycare costs during the first 6 months of a baby’s life.16

Final Thoughts

Due to the competitiveness of the field, dermatology residents are by nature high performing and academically successful. For a high achiever, the idea of potentially disappointing faculty and colleagues by starting a family during residency can be guilt inducing. Concerns about one’s ability to adequately study the breadth of dermatology while simultaneously raising a child can be distressing; however, there are many ways in which motherhood can hone skills to become a better dermatology resident. Through motherhood one can enhance time management skills, increase efficiency, and improve rapport with pediatric patients and trust with their parents/guardians. A dermatology resident may be her own harshest critic, but it is time that the future generation of dermatologists become their own greatest advocates for establishing supportive policies and resources for the successful navigation of motherhood and dermatology residency.

- ACGME residents and fellows by sex and specialty, 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/interactive-data/acgme-residents-and-fellows-sex-and-specialty-2019

- Mattessich S, Shea K, Whitaker-Worth D. Parenting and female dermatologists’ perceptions of work-life balance. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3:127-130. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.04.001

- Active physicians by sex and specialty, 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges website. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2019

- Stentz NC, Griffith KA, Perkins E, et al. Fertility and childbearing among American female physicians. J Womens Health. 2016;25:1059-1065. doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5638

- Infertility. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Updated March 1, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/infertility/

- Phelan ST. Sources of stress and support for the pregnant resident. Acad Med. 1992;67:408-410. doi:10.1097/00001888-199206000-00014

- Family and Medical Leave Act. US Department of Labor website. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla

- American Board of Dermatology. Effective July 2021: new family leave policy. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.abderm.org/public/announcements/effective-july-2021-new-family-leave-policy.aspx

- Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:E827-E841. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3552

- Peters GW, Kuczmarska-Haas A, Holliday EB, et al. Lactation challenges of resident physicians: results of a national survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:762. doi:10.1186/s12884-020-03436-3

- Common program requirements (residency) sections I-V table of implementation dates. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. Accessed April 21, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidencyImplementationTable.pdf

- Gracey LE, Mathes EF, Shinkai K. Supporting breastfeeding mothers during dermatology residency—challenges and best practices. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:117-118. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3759

- McMillin A, Behravesh B, Byrne P, et al. A GME wearable breast pump program: an innovative method to meet ACGME requirements and federal law. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13:422-423. doi:10.4300/jgme-d-20-01275.1

- Stack SW, Jagsi R, Biermann JS, et al. Childbearing decisions in residency: a multicenter survey of female residents. Acad Med. 2020;95:1550-1557. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000003549

- Snyder RA, Tarpley MJ, Phillips SE, et al. The case for on-site child care in residency training and afterward. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:365-367. doi:10.4300/jgme-d-12-00294.1

- Key LL. Child care supplementation: aid for residents and advantages for residency programs. J Pediatr. 2008;153:449-450. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.05.028

Motherhood and dermatology residency are both full-time jobs. The thought that a woman must either be superhuman to succeed at both or that success at one must come at the expense of the other is antiquated. With careful navigation and sufficient support, these two roles can complement and heighten one another. The most recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) report showed that nearly 60% of dermatology residents are women,1 with most women in training being of childbearing age. One study showed that female dermatologists were most likely to have children during residency (51% of those surveyed), despite residents reporting more barriers to childbearing at this career stage.2 Trainees thinking of starting a family have many considerations to navigate: timing of pregnancy, maternity leave scheduling, breastfeeding while working, and planning for childcare. For the first time in the history of the specialty, most active dermatologists in practice are women.3 Thus, the future of dermatology requires supportive policies and resources for the successful navigation of these issues by today’s trainees.

Timing of Pregnancy

Timing of pregnancy can be a source of stress to the female dermatology resident. Barriers to childbearing during residency include the perception that women who have children during residency training are less committed to their jobs; concerns of overburdening fellow residents; and fear that residency may need to be extended, thereby delaying the ability to sit for the board examination.2 However, the potential increased risk for infertility in delaying pregnancy adds to the stress of pregnancy planning. A 2016 survey of female physicians (N=327) showed that 24.1% of respondents who had attempted conception were diagnosed with infertility, with an average age at diagnosis of 33.7 years.4 This is higher than the national average, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reporting that approximately 19% of women aged 15 to 49 years with no prior births experience infertility.5 In a 1992 survey of female physician residents (N=373) who gave birth during residency, 32% indicated that they would not recommend the experience to others; of the 68% who would recommend the experience, one-third encouraged timing delivery to occur in the last 2 months of residency due to benefits of continued insurance coverage, a decrease in clinic responsibilities, and the potential for extended maternity leave during hiatus between jobs.6 Although this may be a good strategy, studying and sitting for board examinations while caring for a newborn right after graduation may be overly difficult for some. The first year of residency was perceived as the most stressful time to be pregnant, with each subsequent year being less problematic.6 Planning pregnancy for delivery near the end of the second year and beginning of the third year of dermatology residency may be a reasonable choice.

Maternity Leave

The Family and Medical Leave Act entitles eligible employees of covered employers to take unpaid, job-protected leave, with 12 workweeks of leave in a 12-month period for the birth of a child and to care for the newborn child within 1 year of birth.7 The actual length of maternity leave taken by most surveyed female dermatologists (n=96) is shorter: 25% (24/96) took less than 4 weeks, 42.7% (41/96) took 4 to 8 weeks, 25% (24/96) took 9 to 12 weeks, and 7.3% (7/96) were able to take more than 12 weeks of maternity leave.2

The American Board of Dermatology implemented a new Resident Leave policy that went into effect July 1, 2021, stipulating that, within certain parameters, time spent away from training for family and parental leave would not exhaust vacation time or require an extension in training. Under this policy, absence from training exceeding 8 weeks (6 weeks leave, plus 2 weeks of vacation) in a given year should be approved only under exceptional circumstances and may necessitate additional training time to ensure that competency requirements are met.8 Although this policy is a step in the right direction, institutional policies still may vary. Dermatology residents planning to start a family during training should consider their plans for fellowship, as taking an extended maternity leave beyond 8 weeks may jeopardize a July fellowship start date.

Lactation and Residency