User login

Update on high-grade vulvar interepithelial neoplasia

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

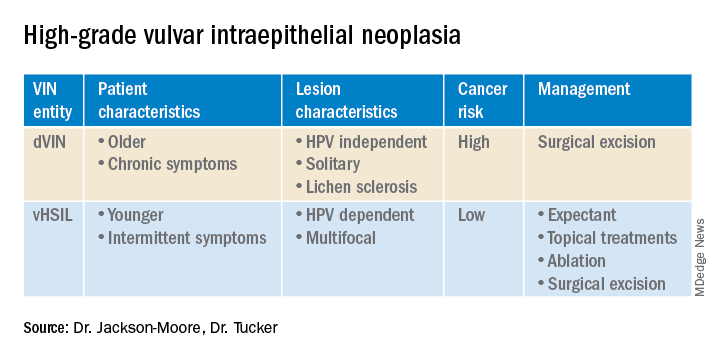

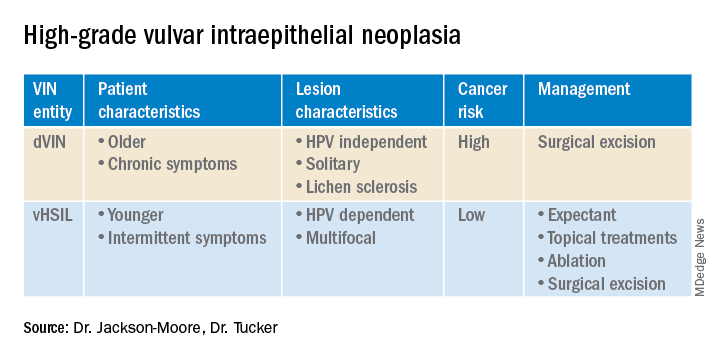

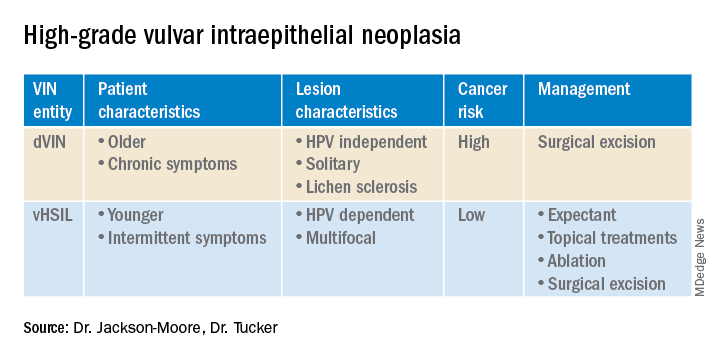

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

Vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCC) comprise approximately 90% of all vulvar malignancies. Unlike cervical SCC, which are predominantly human papilloma virus (HPV) positive, only a minority of VSCC are HPV positive – on the order of 15%-25% of cases. Most cases occur in the setting of lichen sclerosus and are HPV negative.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory dermatitis typically involving the anogenital area, which in some cases can become seriously distorted (e.g. atrophy of the labia minora, clitoral phimosis, and introital stenosis). Although most cases are diagnosed in postmenopausal women, LS can affect women of any age. The true prevalence of lichen sclerosus is unknown. Recent studies have shown a prevalence of 1 in 60; among older women, it can even be as high as 1 in 30. While lichen sclerosus is a pruriginous condition, it is often asymptomatic. It is not considered a premalignant condition. The diagnosis is clinical; however, suspicious lesions (erosions/ulcerations, hyperkeratosis, pigmented areas, ecchymosis, warty or papular lesions), particularly when recalcitrant to adequate first-line therapy, should be biopsied.

VSCC arises from precursor lesions or high-grade vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease nomenclature classifies high-grade VIN into high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) and differentiated VIN (dVIN). Most patients with high-grade VIN are diagnosed with HSIL or usual type VIN. A preponderance of these lesions (75%-85%) are HPV positive, predominantly HPV 16. Vulvar HSIL (vHSIL) lesions affect younger women. The lesions tend to be multifocal and extensive. On the other hand, dVIN typically affects older women and commonly develops as a solitary lesion. While dVIN accounts for only a small subset of patients with high-grade VIN, these lesions are HPV negative and associated with lichen sclerosus.

Both disease entities, vHSIL and dVIN, are increasing in incidence. There is a higher risk and shortened period of progression to cancer in patients with dVIN compared to HSIL. The cancer risk of vHSIL is relatively low. The 10-year cumulative VSCC risk reported in the literature is 10.3%; 9.7% for vHSIL and 50% for dVIN. Patients with vHSIL could benefit from less aggressive treatment modalities.

Patients present with a constellation of signs such as itching, pain, burning, bleeding, and discharge. Chronic symptoms portend HPV-independent lesions associated with lichen sclerosus while episodic signs are suggestive of HPV-positive lesions.

The recurrence risk of high-grade VIN is 46%-70%. Risk factors for recurrence include age greater than 50, immunosuppression, metasynchronous HSIL, and multifocal lesions. Recurrences occur in up to 50% of women who have undergone surgery. For those who undergo surgical treatment for high-grade VIN, recurrence is more common in the setting of positive margins, underlying lichen sclerosis, persistent HPV infection, and immunosuppression.

Management of high-grade VIN is determined by the lesion characteristics, patient characteristics, and medical expertise. Given the risk of progression of high-grade VIN to cancer and risk of underlying cancer, surgical therapy is typically recommended. The treatment of choice is surgical excision in cases of dVIN. Surgical treatments include CO2 laser ablation, wide local excision, and vulvectomy. Women who undergo surgical treatment for vHSIL have about a 50% chance of the condition recurring 1 year later, irrespective of whether treatment is by surgical excision or laser vaporization.

Since surgery can be associated with disfigurement and sexual dysfunction, alternatives to surgery should be considered in cases of vHSIL. The potential for effect on sexual function should be part of preoperative counseling and treatment. Women treated for VIN often experience increased inhibition of sexual excitement and increased inhibition of orgasm. One study found that in women undergoing vulvar excision for VIN, the impairment was found to be psychological in nature. Overall, the studies of sexual effect from treatment of VIN have found that women do not return to their pretreatment sexual function. However, the optimal management of vHSIL has not been determined. Nonsurgical options include topical therapies (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, cidofovir, and interferon) and nonpharmacologic treatments, such as photodynamic therapy.

Imiquimod, a topical immune modulator, is the most studied pharmacologic treatment of vHSIL. The drug induces secretion of cytokines, creating an immune response that clears the HPV infection. Imiquimod is safe and well tolerated. The clinical response rate varies between 35% and 81%. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of imiquimod and the treatment was found to be noninferior to surgery. Adverse events differed, with local pain following surgical treatment and local pruritus and erythema associated with imiquimod use. Some patients did not respond to imiquimod; it was thought by the authors of the study that specific immunological factors affect the clinical response.

In conclusion, high-grade VIN is a heterogeneous disease made up of two distinct disease entities with rising incidence. In contrast to dVIN, the cancer risk is low for patients with vHSIL. Treatment should be driven by the clinical characteristics of the vulvar lesions, patients’ preferences, sexual activity, and compliance. Future directions include risk stratification of patients with vHSIL who are most likely to benefit from topical treatments, thus reducing overtreatment. Molecular biomarkers that could identify dVIN at an early stage are needed.

Dr. Jackson-Moore is associate professor in gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tucker is assistant professor of gynecologic oncology at the university.

References

Cendejas BR et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar;212(3):291-7.

Lebreton M et al. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020 Nov;49(9):101801.

Thuijs NB et al. Int J Cancer. 2021 Jan 1;148(1):90-8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33198. .

Trutnovsky G et al. Lancet. 2022 May 7;399(10337):1790-8. Erratum in: Lancet. 2022 Oct 8;400(10359):1194.

FDA approves first-ever agent to delay type 1 diabetes onset

“Today’s approval of a first-in-class therapy adds an important new treatment option for certain at-risk patients,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the Division of Diabetes, Lipid Disorders, and Obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “The drug’s potential to delay clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes may provide patients with months to years without the burdens of disease.”

The agent, which interferes with T-cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, is the first disease-modifying therapy for impeding progression of type 1 diabetes. It is administered by intravenous infusion once daily for 14 consecutive days.

The specific indication is “to delay the onset of stage 3 type 1 diabetes in adults and pediatric patients 8 years and older who currently have stage 2 type 1 diabetes.” In type 1 diabetes staging, adopted in 2015, stage 1 is defined as the presence of beta cell autoimmunity with two or more islet autoantibodies with normoglycemia, stage 2 is beta-cell autoimmunity with dysglycemia yet asymptomatic, and stage 3 is the onset of symptomatic type 1 diabetes.

Stage 2 type 1 diabetes is associated with a nearly 100% lifetime risk of progression to clinical (stage 3) type 1 diabetes and a 75% risk of developing the condition within 5 years.

The FDA had previously rejected teplizumab for this indication in July 2021, despite a prior endorsement from an advisory panel in May 2021.

Now, with the FDA approval, Provention Bio cofounder and CEO Ashleigh Palmer said in a statement, “This is a historic occasion for the T1D community and a paradigm shifting breakthrough ... It cannot be emphasized enough how precious a delay in the onset of stage 3 T1D can be from a patient and family perspective; more time to live without and, when necessary, prepare for the burdens, complications, and risks associated with stage 3 disease.”

T1D onset delayed by 2 years

In 2019, a pivotal phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 76 at-risk children and adults aged 8 years and older showed that a single 14-day treatment of daily intravenous infusions of teplizumab in 44 patients resulted in a significant median 2-year delay to onset of clinical type 1 diabetes compared with 32 who received placebo.

Those “game changer” data were presented at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) annual meeting in June 2019 and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Three-year data were presented at the June 2020 ADA meeting and published in March 2021 in Science Translational Medicine, by Emily K. Sims, MD, department of pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues.

At a median follow-up of 923 days, 50% of those randomly assigned to teplizumab remained diabetes free, compared with 22% of those who received placebo infusions (hazard ratio, 0.457; P = .01). The teplizumab group had a greater average C-peptide area under the curve compared with placebo, reflecting improved beta-cell function (1.96 vs. 1.68 pmol/mL; P = .006).

C-peptide levels declined over time in the placebo group but stabilized in those receiving teplizumab (P = .0015).

“The mid-range time from randomization to stage 3 type 1 diabetes diagnosis was 50 months for the patients who received Tzield and 25 months for those who received a placebo. This represents a statistically significant delay in the development of stage 3 type 1 diabetes,” according to the FDA statement.

The most common side effects of Tzield include lymphopenia (73% teplizumab vs. 6% placebo), rash (36% vs. 0%), leukopenia (221% vs. 0%), and headache (11% vs. 6%). Label warnings and precautions include monitoring for cytokine release syndrome, risk for serious infections, and avoidance of live, inactivated, and mRNA vaccines.

This approval is likely to accelerate discussion about universal autoantibody screening. Currently, most individuals identified as having preclinical type 1 diabetes are first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes identified through the federally funded TrialNet program. In December 2020, the type 1 diabetes research and advocacy organization JDRF began offering a $55 home blood test to screen for the antibodies, and other screening programs have been launched in the United States and Europe.

Previous studies have examined cost-effectiveness of universal screening in children and the optimal ages that such screening should take place.

In October, Provention Bio announced a co-promotion agreement with Sanofi for the U.S. launch of Tzield for delay in onset of clinical T1D in at-risk individuals. Provention Bio offers financial assistance options (e.g., copay assistance) to eligible patients for out-of-pocket costs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Today’s approval of a first-in-class therapy adds an important new treatment option for certain at-risk patients,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the Division of Diabetes, Lipid Disorders, and Obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “The drug’s potential to delay clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes may provide patients with months to years without the burdens of disease.”

The agent, which interferes with T-cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, is the first disease-modifying therapy for impeding progression of type 1 diabetes. It is administered by intravenous infusion once daily for 14 consecutive days.

The specific indication is “to delay the onset of stage 3 type 1 diabetes in adults and pediatric patients 8 years and older who currently have stage 2 type 1 diabetes.” In type 1 diabetes staging, adopted in 2015, stage 1 is defined as the presence of beta cell autoimmunity with two or more islet autoantibodies with normoglycemia, stage 2 is beta-cell autoimmunity with dysglycemia yet asymptomatic, and stage 3 is the onset of symptomatic type 1 diabetes.

Stage 2 type 1 diabetes is associated with a nearly 100% lifetime risk of progression to clinical (stage 3) type 1 diabetes and a 75% risk of developing the condition within 5 years.

The FDA had previously rejected teplizumab for this indication in July 2021, despite a prior endorsement from an advisory panel in May 2021.

Now, with the FDA approval, Provention Bio cofounder and CEO Ashleigh Palmer said in a statement, “This is a historic occasion for the T1D community and a paradigm shifting breakthrough ... It cannot be emphasized enough how precious a delay in the onset of stage 3 T1D can be from a patient and family perspective; more time to live without and, when necessary, prepare for the burdens, complications, and risks associated with stage 3 disease.”

T1D onset delayed by 2 years

In 2019, a pivotal phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 76 at-risk children and adults aged 8 years and older showed that a single 14-day treatment of daily intravenous infusions of teplizumab in 44 patients resulted in a significant median 2-year delay to onset of clinical type 1 diabetes compared with 32 who received placebo.

Those “game changer” data were presented at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) annual meeting in June 2019 and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Three-year data were presented at the June 2020 ADA meeting and published in March 2021 in Science Translational Medicine, by Emily K. Sims, MD, department of pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues.

At a median follow-up of 923 days, 50% of those randomly assigned to teplizumab remained diabetes free, compared with 22% of those who received placebo infusions (hazard ratio, 0.457; P = .01). The teplizumab group had a greater average C-peptide area under the curve compared with placebo, reflecting improved beta-cell function (1.96 vs. 1.68 pmol/mL; P = .006).

C-peptide levels declined over time in the placebo group but stabilized in those receiving teplizumab (P = .0015).

“The mid-range time from randomization to stage 3 type 1 diabetes diagnosis was 50 months for the patients who received Tzield and 25 months for those who received a placebo. This represents a statistically significant delay in the development of stage 3 type 1 diabetes,” according to the FDA statement.

The most common side effects of Tzield include lymphopenia (73% teplizumab vs. 6% placebo), rash (36% vs. 0%), leukopenia (221% vs. 0%), and headache (11% vs. 6%). Label warnings and precautions include monitoring for cytokine release syndrome, risk for serious infections, and avoidance of live, inactivated, and mRNA vaccines.

This approval is likely to accelerate discussion about universal autoantibody screening. Currently, most individuals identified as having preclinical type 1 diabetes are first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes identified through the federally funded TrialNet program. In December 2020, the type 1 diabetes research and advocacy organization JDRF began offering a $55 home blood test to screen for the antibodies, and other screening programs have been launched in the United States and Europe.

Previous studies have examined cost-effectiveness of universal screening in children and the optimal ages that such screening should take place.

In October, Provention Bio announced a co-promotion agreement with Sanofi for the U.S. launch of Tzield for delay in onset of clinical T1D in at-risk individuals. Provention Bio offers financial assistance options (e.g., copay assistance) to eligible patients for out-of-pocket costs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“Today’s approval of a first-in-class therapy adds an important new treatment option for certain at-risk patients,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the Division of Diabetes, Lipid Disorders, and Obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “The drug’s potential to delay clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes may provide patients with months to years without the burdens of disease.”

The agent, which interferes with T-cell-mediated autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells, is the first disease-modifying therapy for impeding progression of type 1 diabetes. It is administered by intravenous infusion once daily for 14 consecutive days.

The specific indication is “to delay the onset of stage 3 type 1 diabetes in adults and pediatric patients 8 years and older who currently have stage 2 type 1 diabetes.” In type 1 diabetes staging, adopted in 2015, stage 1 is defined as the presence of beta cell autoimmunity with two or more islet autoantibodies with normoglycemia, stage 2 is beta-cell autoimmunity with dysglycemia yet asymptomatic, and stage 3 is the onset of symptomatic type 1 diabetes.

Stage 2 type 1 diabetes is associated with a nearly 100% lifetime risk of progression to clinical (stage 3) type 1 diabetes and a 75% risk of developing the condition within 5 years.

The FDA had previously rejected teplizumab for this indication in July 2021, despite a prior endorsement from an advisory panel in May 2021.

Now, with the FDA approval, Provention Bio cofounder and CEO Ashleigh Palmer said in a statement, “This is a historic occasion for the T1D community and a paradigm shifting breakthrough ... It cannot be emphasized enough how precious a delay in the onset of stage 3 T1D can be from a patient and family perspective; more time to live without and, when necessary, prepare for the burdens, complications, and risks associated with stage 3 disease.”

T1D onset delayed by 2 years

In 2019, a pivotal phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 76 at-risk children and adults aged 8 years and older showed that a single 14-day treatment of daily intravenous infusions of teplizumab in 44 patients resulted in a significant median 2-year delay to onset of clinical type 1 diabetes compared with 32 who received placebo.

Those “game changer” data were presented at the American Diabetes Association (ADA) annual meeting in June 2019 and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Three-year data were presented at the June 2020 ADA meeting and published in March 2021 in Science Translational Medicine, by Emily K. Sims, MD, department of pediatrics, Indiana University, Indianapolis, and colleagues.

At a median follow-up of 923 days, 50% of those randomly assigned to teplizumab remained diabetes free, compared with 22% of those who received placebo infusions (hazard ratio, 0.457; P = .01). The teplizumab group had a greater average C-peptide area under the curve compared with placebo, reflecting improved beta-cell function (1.96 vs. 1.68 pmol/mL; P = .006).

C-peptide levels declined over time in the placebo group but stabilized in those receiving teplizumab (P = .0015).

“The mid-range time from randomization to stage 3 type 1 diabetes diagnosis was 50 months for the patients who received Tzield and 25 months for those who received a placebo. This represents a statistically significant delay in the development of stage 3 type 1 diabetes,” according to the FDA statement.

The most common side effects of Tzield include lymphopenia (73% teplizumab vs. 6% placebo), rash (36% vs. 0%), leukopenia (221% vs. 0%), and headache (11% vs. 6%). Label warnings and precautions include monitoring for cytokine release syndrome, risk for serious infections, and avoidance of live, inactivated, and mRNA vaccines.

This approval is likely to accelerate discussion about universal autoantibody screening. Currently, most individuals identified as having preclinical type 1 diabetes are first-degree relatives of people with type 1 diabetes identified through the federally funded TrialNet program. In December 2020, the type 1 diabetes research and advocacy organization JDRF began offering a $55 home blood test to screen for the antibodies, and other screening programs have been launched in the United States and Europe.

Previous studies have examined cost-effectiveness of universal screening in children and the optimal ages that such screening should take place.

In October, Provention Bio announced a co-promotion agreement with Sanofi for the U.S. launch of Tzield for delay in onset of clinical T1D in at-risk individuals. Provention Bio offers financial assistance options (e.g., copay assistance) to eligible patients for out-of-pocket costs.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New and Improved Devices Add More Therapeutic Options for Treatment of Migraine

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE

gammaCORE is a nVNS device that is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in adolescents and adults, and acute and preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache in adults. It is also cleared to treat chronic cluster headache acutely along with medication. The patient applies gel to the device’s 2 electrical contacts and then locates the vagus nerve on the side of the neck and applies the electrodes to the area that will be treated. Patients can adjust the stimulation’s intensity so that they can barely feel the stimulation; it has not been reported to be painful. nVNS is also an FDA cleared treatment for paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua.

SAVI Dual

The s-TMS (SAVI Dual, formerly called the Spring TMS and the sTMS mini), made by eNeura, is a single-pulse, transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the back of the head to stimulate the occipital lobes in the brain. It was FDA cleared for acute and preventive care of migraine in adolescents over 12 years and for adults in February 2019. The patient holds a handheld magnetic device against their occiput, and when the tool is discharged, a brief magnetic pulse interrupts the pattern of neuronal firing (probably cortical spreading depression) that can trigger migraine and the visual aura associated with migraine in one-third of patients.

Cefaly

The e-TNS (Cefaly) works by external trigeminal nerve stimulation of the supraorbital and trochlear nerves bilaterally in the forehead. It gradually and automatically increases in intensity and can be controlled by the patient. It is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine, and, unlike the other devices, it is sold over the counter without a prescription. According to the company website, there are 3 devices: 1 is for acute treatment, 1 is for preventive treatment, and 1 device has 2 settings for both acute and preventive treatment.

The Studies

While most of the published studies on devices are company-sponsored, these device makers have underwritten numerous, sometimes very well-designed, studies on their products. A review by VanderPluym et al described those studies and their various risks of bias.

There are at least 10 studies on REN published so far. These include 2 randomized, sham-controlled trials looking at pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours after stimulation begins. Another study detailed treatment reports from many patients in which 66.5% experienced pain relief at 2 hours post treatment initiation in half of their treatments. A subgroup of 16% of those patients were prescribed REN by their primary care physicians. Of that group, 77.8% experienced pain relief in half their treatments. That figure was very close to another study that found that 23 of 31 (74.2%) of the study patients treated virtually by non headache providers found relief in 50% of their headaches. REN comes with an education and behavioral medicine app that is used during treatment. A study done by the company shows that when a patient uses the relaxation app along with the standard stimulation, they do considerably better than with stimulation alone.

The eCOT-NS has also been tested in an RCT. At 2 hours, the responder rate was twice as high as in the sham group (66.7% vs 32%). Overall headache relief at 2 hours was higher in the responder group (76% vs 31.6%). In a study collecting real-world data on the efficacy of eCOT-NS in the preventive treatment of migraine (abstract data were presented at the American Headache Society meeting in June 2022), there was a 65.3% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline through 6 months. Treatment reduced MMD by 10.0 (from 15.3 to 5.3—a 76.8% reduction), and reduced acute medication use days (12.5 at baseline to 2.9) at 6 months.

Users of nVNS discussed their experiences with the device, which is the size of a large bar of soap, in a patient registry. They reported 192 attacks, with a mean pain score starting at 2.7 and dropping to 1.3 after 30 minutes. The pain levels of 70% of the attacks dropped to either mild or nonexistent. In a multicenter study on nNVS, 48 patients and 44 sham patients with episodic and chronic cluster headache showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of pain freedom at 15 minutes between the nVNS and sham. There was also no difference in the chronic cluster headache group. But the episodic cluster subgroup showed a difference; nVNS was superior to sham, 48% to 6% (P

The e-TNS device is cleared for treating adults with migraine, acutely and preventively. It received initial clearance in 2017; in 2020, Cefaly Technology received clearance from the FDA to sell its products over the counter. The device, which resembles a large diamond that affixes to the forehead, has received differing reviews between various patient reports (found online at major retailer sites) and study results. In a blinded, intent-to-treat study involving 538 patients, 25.5% of the verum group reported they were pain-free at 2 hours; 18.3% in the sham group reported the same. Additionally, 56.4% of the subjects in the verum group reported they were free of the most bothersome migraine symptoms, as opposed to 42.3% of the sham group.

Adverse Events

The adverse events observed with these devices were, overall, relatively mild, and disappeared once the device was shut off. A few nVNS users said they experienced discomfort at the application site. With REN, 59 of 12,368 patients reported device-related issues; the vast majority were considered mild and consisted mostly of a sensation of warmth under the device. Of the 259 e-TNS users, 8.5% reported minor and reversible occurrences, such as treatment-related discomfort, paresthesia, and burning.

Patients in the Clinic

A few observations from the clinic regarding these devices:

Some devices are easier to use than others. I know this, because at a recent demonstration session in a course for physicians on headache treatment, I agreed to be the person on whom the device was demonstrated. The physician applying the device had difficulty aligning the device’s sensors with the appropriate nerves. Making sure your patients use these devices correctly is essential, and you or your staff should demonstrate their use to the patient. No doubt, this could be time-consuming in some cases, and patients who are reading the device’s instructions while in pain will likely get frustrated if they cannot get the device to work.

Some patients who have failed every medication class can occasionally find partial relief with these devices. One longtime patient of mine came to me severely disabled from chronic migraine and medication overuse headache but was somewhat better with 2 preventive medications. Triptans worked acutely, but she developed nearly every side effect imaginable. I was able to reverse her medication overuse headache, but the gepants, although they worked somewhat, took too long to take effect. We agreed the next step would be to use REN for each migraine attack, combined with acute care medication if necessary. (She uses REN alone for a milder headache and adds a gepant with naproxen if necessary.) She has found using the relaxation module on the REN app increases her chances of eliminating the migraine. She is not pain free all the time, but she appreciates the pain-free intervals.

One chronic cluster patient has relied on subcutaneous sumatriptan and breathing 100% oxygen at 12 liters per minute through a mask over his nose and mouth for acute relief from his headaches. His headache pain can climb from a 3 to a 10 in a matter of minutes. It starts behind and a bit above the right eye where he feels a tremendous pressure building up. He says that at times it feels like a screwdriver has been thrust into his eye and is being turned. Along with the pain, the eye becomes red, the pupil constricts, and the eyelid droops. He also has dripping from the right nostril, which stuffs up when the pain abates. The pain lasts for 1 to 2 hours, then returns 3 to 5 times a day for 5 days a week, on average. The pain never goes away for more than 3 weeks in a year’s time, hence the reason for his chronic cluster headache diagnosis. He is now using nVNS as soon as he feels the pain coming on. If the device does not provide sufficient relief, he uses oxygen or takes the sumatriptan injection.

Some patients who get cluster headaches think of suicide if the pain cannot be stopped; but in my experience, most can become pain free, or at least realize some partial relief from a variety of treatments (sometimes given at the same time).

Doctors often do not think of devices as options, and some doctors think devices do not work even though they have no experience with using them. Devices can give good relief on their own, and when a severe headache needs stronger treatment, medications added to a device usually work better than either treatment alone.

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE

gammaCORE is a nVNS device that is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in adolescents and adults, and acute and preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache in adults. It is also cleared to treat chronic cluster headache acutely along with medication. The patient applies gel to the device’s 2 electrical contacts and then locates the vagus nerve on the side of the neck and applies the electrodes to the area that will be treated. Patients can adjust the stimulation’s intensity so that they can barely feel the stimulation; it has not been reported to be painful. nVNS is also an FDA cleared treatment for paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua.

SAVI Dual

The s-TMS (SAVI Dual, formerly called the Spring TMS and the sTMS mini), made by eNeura, is a single-pulse, transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the back of the head to stimulate the occipital lobes in the brain. It was FDA cleared for acute and preventive care of migraine in adolescents over 12 years and for adults in February 2019. The patient holds a handheld magnetic device against their occiput, and when the tool is discharged, a brief magnetic pulse interrupts the pattern of neuronal firing (probably cortical spreading depression) that can trigger migraine and the visual aura associated with migraine in one-third of patients.

Cefaly

The e-TNS (Cefaly) works by external trigeminal nerve stimulation of the supraorbital and trochlear nerves bilaterally in the forehead. It gradually and automatically increases in intensity and can be controlled by the patient. It is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine, and, unlike the other devices, it is sold over the counter without a prescription. According to the company website, there are 3 devices: 1 is for acute treatment, 1 is for preventive treatment, and 1 device has 2 settings for both acute and preventive treatment.

The Studies

While most of the published studies on devices are company-sponsored, these device makers have underwritten numerous, sometimes very well-designed, studies on their products. A review by VanderPluym et al described those studies and their various risks of bias.

There are at least 10 studies on REN published so far. These include 2 randomized, sham-controlled trials looking at pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours after stimulation begins. Another study detailed treatment reports from many patients in which 66.5% experienced pain relief at 2 hours post treatment initiation in half of their treatments. A subgroup of 16% of those patients were prescribed REN by their primary care physicians. Of that group, 77.8% experienced pain relief in half their treatments. That figure was very close to another study that found that 23 of 31 (74.2%) of the study patients treated virtually by non headache providers found relief in 50% of their headaches. REN comes with an education and behavioral medicine app that is used during treatment. A study done by the company shows that when a patient uses the relaxation app along with the standard stimulation, they do considerably better than with stimulation alone.

The eCOT-NS has also been tested in an RCT. At 2 hours, the responder rate was twice as high as in the sham group (66.7% vs 32%). Overall headache relief at 2 hours was higher in the responder group (76% vs 31.6%). In a study collecting real-world data on the efficacy of eCOT-NS in the preventive treatment of migraine (abstract data were presented at the American Headache Society meeting in June 2022), there was a 65.3% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline through 6 months. Treatment reduced MMD by 10.0 (from 15.3 to 5.3—a 76.8% reduction), and reduced acute medication use days (12.5 at baseline to 2.9) at 6 months.

Users of nVNS discussed their experiences with the device, which is the size of a large bar of soap, in a patient registry. They reported 192 attacks, with a mean pain score starting at 2.7 and dropping to 1.3 after 30 minutes. The pain levels of 70% of the attacks dropped to either mild or nonexistent. In a multicenter study on nNVS, 48 patients and 44 sham patients with episodic and chronic cluster headache showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of pain freedom at 15 minutes between the nVNS and sham. There was also no difference in the chronic cluster headache group. But the episodic cluster subgroup showed a difference; nVNS was superior to sham, 48% to 6% (P

The e-TNS device is cleared for treating adults with migraine, acutely and preventively. It received initial clearance in 2017; in 2020, Cefaly Technology received clearance from the FDA to sell its products over the counter. The device, which resembles a large diamond that affixes to the forehead, has received differing reviews between various patient reports (found online at major retailer sites) and study results. In a blinded, intent-to-treat study involving 538 patients, 25.5% of the verum group reported they were pain-free at 2 hours; 18.3% in the sham group reported the same. Additionally, 56.4% of the subjects in the verum group reported they were free of the most bothersome migraine symptoms, as opposed to 42.3% of the sham group.

Adverse Events

The adverse events observed with these devices were, overall, relatively mild, and disappeared once the device was shut off. A few nVNS users said they experienced discomfort at the application site. With REN, 59 of 12,368 patients reported device-related issues; the vast majority were considered mild and consisted mostly of a sensation of warmth under the device. Of the 259 e-TNS users, 8.5% reported minor and reversible occurrences, such as treatment-related discomfort, paresthesia, and burning.

Patients in the Clinic

A few observations from the clinic regarding these devices:

Some devices are easier to use than others. I know this, because at a recent demonstration session in a course for physicians on headache treatment, I agreed to be the person on whom the device was demonstrated. The physician applying the device had difficulty aligning the device’s sensors with the appropriate nerves. Making sure your patients use these devices correctly is essential, and you or your staff should demonstrate their use to the patient. No doubt, this could be time-consuming in some cases, and patients who are reading the device’s instructions while in pain will likely get frustrated if they cannot get the device to work.

Some patients who have failed every medication class can occasionally find partial relief with these devices. One longtime patient of mine came to me severely disabled from chronic migraine and medication overuse headache but was somewhat better with 2 preventive medications. Triptans worked acutely, but she developed nearly every side effect imaginable. I was able to reverse her medication overuse headache, but the gepants, although they worked somewhat, took too long to take effect. We agreed the next step would be to use REN for each migraine attack, combined with acute care medication if necessary. (She uses REN alone for a milder headache and adds a gepant with naproxen if necessary.) She has found using the relaxation module on the REN app increases her chances of eliminating the migraine. She is not pain free all the time, but she appreciates the pain-free intervals.

One chronic cluster patient has relied on subcutaneous sumatriptan and breathing 100% oxygen at 12 liters per minute through a mask over his nose and mouth for acute relief from his headaches. His headache pain can climb from a 3 to a 10 in a matter of minutes. It starts behind and a bit above the right eye where he feels a tremendous pressure building up. He says that at times it feels like a screwdriver has been thrust into his eye and is being turned. Along with the pain, the eye becomes red, the pupil constricts, and the eyelid droops. He also has dripping from the right nostril, which stuffs up when the pain abates. The pain lasts for 1 to 2 hours, then returns 3 to 5 times a day for 5 days a week, on average. The pain never goes away for more than 3 weeks in a year’s time, hence the reason for his chronic cluster headache diagnosis. He is now using nVNS as soon as he feels the pain coming on. If the device does not provide sufficient relief, he uses oxygen or takes the sumatriptan injection.

Some patients who get cluster headaches think of suicide if the pain cannot be stopped; but in my experience, most can become pain free, or at least realize some partial relief from a variety of treatments (sometimes given at the same time).

Doctors often do not think of devices as options, and some doctors think devices do not work even though they have no experience with using them. Devices can give good relief on their own, and when a severe headache needs stronger treatment, medications added to a device usually work better than either treatment alone.

Since the mid-2010s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved or cleared no fewer than 10 migraine treatments in the form of orals, injectables, nasal sprays, and devices. The medical achievements of the last decade in the field of migraine have been nothing less than stunning for physicians and their patients, whether they relied on off-label medications or those sanctioned by the FDA to treat patients living with migraine.

That said, the newer orals and injectables cannot help everyone living with migraine. The small molecule calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists (gepants) and the monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP ligand or receptor, while well received by patients and physicians alike, have drawbacks for some patients, including lack of efficacy, slow response rate, and adverse events that prevent some patients from taking them. The gepants, which are oral medications—as opposed to the CGRP monoclonal antibody injectables—can occasionally cause enough nausea, drowsiness, and constipation for patients to choose to discontinue their use.

Certain patients have other reasons to shun orals and injectables. Some cannot swallow pills while others fear or do not tolerate injections. Insurance companies limit the quantity of acute care medications, so some patients cannot treat every migraine attack. Then there are those who have failed so many therapies in the past that they will not try the latest one. Consequently, some lie in bed, vomiting until the pain is gone, and some take too many over-the-counter or migraine-specific products, which make migraine symptoms worse if they develop medication overuse headache. And lastly, there are patients who have never walked through a physician’s door to secure a migraine diagnosis and get appropriate treatment.

Non interventional medical devices cleared by the FDA now allow physicians to offer relief to patients with migraine. They work either through various types of electrical neuromodulation to nerves outside the brain or they apply magnetic stimulation to the back of the brain itself to reach pain-associated pathways. A 2019 report on pain management from the US Department of Health and Human Services noted that some randomized control trials (RCTs) and other studies “have demonstrated that noninvasive vagal nerve stimulation can be effective in ameliorating pain in various types of cluster headaches and migraines.”

At least 3 devices, 1 designed to stimulate both the occipital and trigeminal nerves (eCOT-NS, Relivion, Neurolief Ltd), 1 that stimulates the vagus nerve noninvasively (nVNS, gammaCORE, electroCore), and 1 that stimulates peripheral nerves in the upper arm (remote electrical neuromodulation [REN], Nerivio, Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd), are FDA cleared to treat episodic and chronic migraine. nVNS is also cleared to treat migraine, episodic cluster headache acutely, and chronic cluster acutely in connection with medication.

Real-world studies on all migraine treatments, especially the devices, are flooding PubMed. As for a physician’s observation, we will get to that shortly.

The Devices

Nerivio

Theranica Bio-Electronics Ltd makes a REN called Nerivio, which was FDA cleared in January 2021 to treat episodic migraine acutely in adults and adolescents. Studies have shown its effectiveness for chronic migraine patients who are treated acutely, and it has also helped patients with menstrual migraine. The patient wears the device on the upper arm. Sensory fibers, once stimulated in the arm, send an impulse to the brainstem to affect the serotonin- and norepinephrine-modulated descending inhibitory pathway to disrupt incoming pain messaging. Theranica has applied to the FDA for clearance to treat patients with chronic migraine, as well as for prevention.

Relivion

Neurolief Ltd created the external combined occipital and trigeminal nerve stimulation device (eCOT-NS), which stimulates both the occipital and trigeminal nerves. It has multiple output electrodes, which are placed on the forehead to stimulate the trigeminal supraorbital and supratrochlear nerve branches bilaterally, and over the occipital nerves in the back of the head. It is worn like a tiara as it must be in good contact with the forehead and the back of the head simultaneously. It is FDA cleared to treat acute migraine.

gammaCORE

gammaCORE is a nVNS device that is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine in adolescents and adults, and acute and preventive treatment of episodic cluster headache in adults. It is also cleared to treat chronic cluster headache acutely along with medication. The patient applies gel to the device’s 2 electrical contacts and then locates the vagus nerve on the side of the neck and applies the electrodes to the area that will be treated. Patients can adjust the stimulation’s intensity so that they can barely feel the stimulation; it has not been reported to be painful. nVNS is also an FDA cleared treatment for paroxysmal hemicrania and hemicrania continua.

SAVI Dual

The s-TMS (SAVI Dual, formerly called the Spring TMS and the sTMS mini), made by eNeura, is a single-pulse, transcranial magnetic stimulation applied to the back of the head to stimulate the occipital lobes in the brain. It was FDA cleared for acute and preventive care of migraine in adolescents over 12 years and for adults in February 2019. The patient holds a handheld magnetic device against their occiput, and when the tool is discharged, a brief magnetic pulse interrupts the pattern of neuronal firing (probably cortical spreading depression) that can trigger migraine and the visual aura associated with migraine in one-third of patients.

Cefaly

The e-TNS (Cefaly) works by external trigeminal nerve stimulation of the supraorbital and trochlear nerves bilaterally in the forehead. It gradually and automatically increases in intensity and can be controlled by the patient. It is FDA cleared for acute and preventive treatment of migraine, and, unlike the other devices, it is sold over the counter without a prescription. According to the company website, there are 3 devices: 1 is for acute treatment, 1 is for preventive treatment, and 1 device has 2 settings for both acute and preventive treatment.

The Studies

While most of the published studies on devices are company-sponsored, these device makers have underwritten numerous, sometimes very well-designed, studies on their products. A review by VanderPluym et al described those studies and their various risks of bias.

There are at least 10 studies on REN published so far. These include 2 randomized, sham-controlled trials looking at pain freedom and pain relief at 2 hours after stimulation begins. Another study detailed treatment reports from many patients in which 66.5% experienced pain relief at 2 hours post treatment initiation in half of their treatments. A subgroup of 16% of those patients were prescribed REN by their primary care physicians. Of that group, 77.8% experienced pain relief in half their treatments. That figure was very close to another study that found that 23 of 31 (74.2%) of the study patients treated virtually by non headache providers found relief in 50% of their headaches. REN comes with an education and behavioral medicine app that is used during treatment. A study done by the company shows that when a patient uses the relaxation app along with the standard stimulation, they do considerably better than with stimulation alone.

The eCOT-NS has also been tested in an RCT. At 2 hours, the responder rate was twice as high as in the sham group (66.7% vs 32%). Overall headache relief at 2 hours was higher in the responder group (76% vs 31.6%). In a study collecting real-world data on the efficacy of eCOT-NS in the preventive treatment of migraine (abstract data were presented at the American Headache Society meeting in June 2022), there was a 65.3% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMD) from baseline through 6 months. Treatment reduced MMD by 10.0 (from 15.3 to 5.3—a 76.8% reduction), and reduced acute medication use days (12.5 at baseline to 2.9) at 6 months.

Users of nVNS discussed their experiences with the device, which is the size of a large bar of soap, in a patient registry. They reported 192 attacks, with a mean pain score starting at 2.7 and dropping to 1.3 after 30 minutes. The pain levels of 70% of the attacks dropped to either mild or nonexistent. In a multicenter study on nNVS, 48 patients and 44 sham patients with episodic and chronic cluster headache showed no significant difference in the primary endpoint of pain freedom at 15 minutes between the nVNS and sham. There was also no difference in the chronic cluster headache group. But the episodic cluster subgroup showed a difference; nVNS was superior to sham, 48% to 6% (P

The e-TNS device is cleared for treating adults with migraine, acutely and preventively. It received initial clearance in 2017; in 2020, Cefaly Technology received clearance from the FDA to sell its products over the counter. The device, which resembles a large diamond that affixes to the forehead, has received differing reviews between various patient reports (found online at major retailer sites) and study results. In a blinded, intent-to-treat study involving 538 patients, 25.5% of the verum group reported they were pain-free at 2 hours; 18.3% in the sham group reported the same. Additionally, 56.4% of the subjects in the verum group reported they were free of the most bothersome migraine symptoms, as opposed to 42.3% of the sham group.

Adverse Events

The adverse events observed with these devices were, overall, relatively mild, and disappeared once the device was shut off. A few nVNS users said they experienced discomfort at the application site. With REN, 59 of 12,368 patients reported device-related issues; the vast majority were considered mild and consisted mostly of a sensation of warmth under the device. Of the 259 e-TNS users, 8.5% reported minor and reversible occurrences, such as treatment-related discomfort, paresthesia, and burning.

Patients in the Clinic

A few observations from the clinic regarding these devices:

Some devices are easier to use than others. I know this, because at a recent demonstration session in a course for physicians on headache treatment, I agreed to be the person on whom the device was demonstrated. The physician applying the device had difficulty aligning the device’s sensors with the appropriate nerves. Making sure your patients use these devices correctly is essential, and you or your staff should demonstrate their use to the patient. No doubt, this could be time-consuming in some cases, and patients who are reading the device’s instructions while in pain will likely get frustrated if they cannot get the device to work.

Some patients who have failed every medication class can occasionally find partial relief with these devices. One longtime patient of mine came to me severely disabled from chronic migraine and medication overuse headache but was somewhat better with 2 preventive medications. Triptans worked acutely, but she developed nearly every side effect imaginable. I was able to reverse her medication overuse headache, but the gepants, although they worked somewhat, took too long to take effect. We agreed the next step would be to use REN for each migraine attack, combined with acute care medication if necessary. (She uses REN alone for a milder headache and adds a gepant with naproxen if necessary.) She has found using the relaxation module on the REN app increases her chances of eliminating the migraine. She is not pain free all the time, but she appreciates the pain-free intervals.

One chronic cluster patient has relied on subcutaneous sumatriptan and breathing 100% oxygen at 12 liters per minute through a mask over his nose and mouth for acute relief from his headaches. His headache pain can climb from a 3 to a 10 in a matter of minutes. It starts behind and a bit above the right eye where he feels a tremendous pressure building up. He says that at times it feels like a screwdriver has been thrust into his eye and is being turned. Along with the pain, the eye becomes red, the pupil constricts, and the eyelid droops. He also has dripping from the right nostril, which stuffs up when the pain abates. The pain lasts for 1 to 2 hours, then returns 3 to 5 times a day for 5 days a week, on average. The pain never goes away for more than 3 weeks in a year’s time, hence the reason for his chronic cluster headache diagnosis. He is now using nVNS as soon as he feels the pain coming on. If the device does not provide sufficient relief, he uses oxygen or takes the sumatriptan injection.

Some patients who get cluster headaches think of suicide if the pain cannot be stopped; but in my experience, most can become pain free, or at least realize some partial relief from a variety of treatments (sometimes given at the same time).

Doctors often do not think of devices as options, and some doctors think devices do not work even though they have no experience with using them. Devices can give good relief on their own, and when a severe headache needs stronger treatment, medications added to a device usually work better than either treatment alone.

HIV: Greater parental involvement needed with young men who have sex with men

“Take it from me, parents just don’t understand.”

Fresh Prince and D.J. Jazzy Jeff penned this lyric roughly 35 years ago, and coincidentally the HIV/AIDS epidemic has also been with us just as long. But the connection between the two may be highly relevant – that is, if you consider how infrequently parents appear (or have the proper tools) to engage with their gay or bisexual sons to prevent and curb HIV infections.

Currently, YMSM between the ages of 13 and 24 are among the most affected by the ongoing HIV epidemic, with CDC estimates suggesting that, in 2020, this group alone represented about 35% of new diagnoses. At the same time, about half of these HIV infections go undiagnosed. Recent data also suggest that care linkage in this group is similar to adults, but only a third of YMSM start antiretroviral therapy and are retained in care, leading to viral suppression rates as low as 12%.

With a goal to change these discouraging numbers, researchers from George Washington University, Washington, and other institutions conducted a randomized controlled pilot study targeting parents of YMSM to improve both the frequency and quality of communication around sexual health and HIV risk, prevention, and testing.

The findings, which were published online in the journal AIDS and Behavior, highlight the observation that parents could be an essential resource for combating the HIV epidemic, but they’re a resource that’s often underutilized. In fact, after participating in an online offering – PATHS (Parents and Adolescents Talking about Healthy Sexuality) – parents reported significantly greater engagement with their sons, especially around discussions focusing on HIV information and condom use.

“From what we know from the research, parents are uncomfortable talking about sex; they’re not great at talking about it. But when they do and do it effectively, those kids seem to have better health outcomes,” lead author David Huebner, PhD, MPH, associate professor of prevention and community health at George Washington University, said in an interview.

“The goal was to get parents to deliver more messages and engage in more behaviors with their sons that we think are likely to help their sons stay healthy,” he said.

For the pilot study, Huebner and his team recruited 61 parents (95% of whom were mothers) with predominantly high school-aged cisgender sons (median, 16.7-17 years) who had come out as gay or bisexual at least a month prior, whose HIV status was negative or unknown, and who were living at home.

The interventions were strictly parent focused, Dr. Huebner said, noting that the only interaction with the kids involved independent surveys at the start and end of the study that explored parental behavior and engagement.

For the study, parental participants were stratified by son’s age (13-17 or 18-22 years) and then randomly assigned to participate in a web-accessible PATHS intervention (intervention group) or view a 35-minute, documentary-style film that encouraged acceptance of lesbian, gay, or bisexual children (control group),

Parents assigned to the intervention group were asked to engage in their own time with six modules that explored the importance of communication, HIV information, using and acquiring condoms, HIV testing, and as follow-up, a “to-do” list encouraging selection of how they would follow up with their sons about the content. They were also offered the option to participate in supplemental modules on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), anal intercourse, and what to do if a child tested positive for HIV.

“The intervention ... showed strong evidence of being effective at changing the parent behaviors that we hoped to change,” Dr. Huebner explained.

“We got independent reports from parents and kids that showed the same thing: parents were more likely to communicate with their sons about HIV in the 3 months after the intervention and were more likely to help their sons get access to condoms,” he said.

Both of these findings were significant, with parents in the experimental group being almost 10 times more likely to share HIV information with their sons (odds ratio, 9.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-39.99; P < .05) and five times more likely to teach proper condom use (OR, 5.04; 95% CI 1.56-12.46; P < .05), compared with parents receiving the placebo.

“It’s very promising that the initial signals from their intervention do show that parents facilitating the acquisition of information for young men who have sex with men really works,” said Dalmacio Dennis Flores, PhD, ACRN, an assistant professor of nursing in family and community health at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He was not directly involved in the study.

“On the outcomes that matter for us, such as HIV prevention or getting tested, they were able to document that parents receiving guidance on how to have these conversations does result in youth outcomes – something that has been lacking in the literature specifically for this population up until today,” Dr. Flores told this news organization.

Overall, parents engaging in the PATHS intervention showed improvements in skills, attitudes, and behavioral intention toward engagement with their sons, including assisting with HIV testing. However, what about parental involvement in these types of dialogues with children who have not yet come out to their parents?