User login

The Wellness Industry: Financially Toxic, Says Ethicist

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

We have many debates and arguments that are swirling around about the out-of-control costs of Medicare. Many people are arguing we’ve got to trim it and cut back, and many people note that we can’t just go on and on with that kind of expenditure.

People look around for savings. Rightly, we can’t go on with the prices that we’re paying. No system could. We’ll bankrupt ourselves if we don’t drive prices down.

There’s another area that is driving up cost where, despite the fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for it, we could capture resources and hopefully shift them back to things like Medicare coverage or the insurance of other efficacious procedures. That area is the wellness industry.

That’s money coming out of people’s pockets that we could hopefully aim at the payment of things that we know work, not seeing the money drain out to cover bunk, nonsense, and charlatanism.

Does any or most of this stuff work? Do anything? Help anybody? No. We are spending money on charlatans and quacks. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which you might think is the agency that could step in and start to get rid of some of this nonsense, is just too overwhelmed trying to track drugs, devices, and vaccines to give much attention to the wellness industry.

What am I talking about specifically? I’m talking about everything from gut probiotics that are sold in sodas to probiotic facial creams and the Goop industry of Gwyneth Paltrow, where you have people buying things like wellness mats or vaginal eggs that are supposed to maintain gynecologic health.

We’re talking about things like PEMF, or pulse electronic magnetic fields, where you buy a machine and expose yourself to mild magnetic pulses. I went online to look them up, and the machines cost $5000-$50,000. There’s no evidence that it works. By the way, the machines are not only out there as being sold for pain relief and many other things to humans, but also they’re being sold for your pets.

That industry is completely out of control. Wellness interventions, whether it’s transcranial magnetism or all manner of supplements that are sold in health food stores, over and over again, we see a world in which wellness is promoted but no data are introduced to show that any of it helps, works, or does anybody any good.

It may not be all that harmful, but it’s certainly financially toxic to many people who end up spending good amounts of money using these things. I think doctors need to ask patients if they are using any of these things, particularly if they have chronic conditions. They’re likely, many of them, to be seduced by online advertisement to get involved with this stuff because it’s preventive or it’ll help treat some condition that they have.

The industry is out of control. We’re trying to figure out how to spend money on things we know work in medicine, and yet we continue to tolerate bunk, nonsense, quackery, and charlatanism, just letting it grow and grow and grow in terms of cost.

That’s money that could go elsewhere. That is money that is being taken out of the pockets of patients. They’re doing things that may even delay medical treatment, which won’t really help them, and they are doing things that perhaps might even interfere with medical care that really is known to be beneficial.

I think it’s time to push for more money for the FDA to regulate the wellness side. I think it’s time for the Federal Trade Commission to go after ads that promise health benefits. I think it’s time to have some honest conversations with patients: What are you using? What are you doing? Tell me about it, and here’s why I think you could probably spend your money in a better way.

Dr. Caplan, director, Division of Medical Ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, disclosed ties with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position). He serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

We have many debates and arguments that are swirling around about the out-of-control costs of Medicare. Many people are arguing we’ve got to trim it and cut back, and many people note that we can’t just go on and on with that kind of expenditure.

People look around for savings. Rightly, we can’t go on with the prices that we’re paying. No system could. We’ll bankrupt ourselves if we don’t drive prices down.

There’s another area that is driving up cost where, despite the fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for it, we could capture resources and hopefully shift them back to things like Medicare coverage or the insurance of other efficacious procedures. That area is the wellness industry.

That’s money coming out of people’s pockets that we could hopefully aim at the payment of things that we know work, not seeing the money drain out to cover bunk, nonsense, and charlatanism.

Does any or most of this stuff work? Do anything? Help anybody? No. We are spending money on charlatans and quacks. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which you might think is the agency that could step in and start to get rid of some of this nonsense, is just too overwhelmed trying to track drugs, devices, and vaccines to give much attention to the wellness industry.

What am I talking about specifically? I’m talking about everything from gut probiotics that are sold in sodas to probiotic facial creams and the Goop industry of Gwyneth Paltrow, where you have people buying things like wellness mats or vaginal eggs that are supposed to maintain gynecologic health.

We’re talking about things like PEMF, or pulse electronic magnetic fields, where you buy a machine and expose yourself to mild magnetic pulses. I went online to look them up, and the machines cost $5000-$50,000. There’s no evidence that it works. By the way, the machines are not only out there as being sold for pain relief and many other things to humans, but also they’re being sold for your pets.

That industry is completely out of control. Wellness interventions, whether it’s transcranial magnetism or all manner of supplements that are sold in health food stores, over and over again, we see a world in which wellness is promoted but no data are introduced to show that any of it helps, works, or does anybody any good.

It may not be all that harmful, but it’s certainly financially toxic to many people who end up spending good amounts of money using these things. I think doctors need to ask patients if they are using any of these things, particularly if they have chronic conditions. They’re likely, many of them, to be seduced by online advertisement to get involved with this stuff because it’s preventive or it’ll help treat some condition that they have.

The industry is out of control. We’re trying to figure out how to spend money on things we know work in medicine, and yet we continue to tolerate bunk, nonsense, quackery, and charlatanism, just letting it grow and grow and grow in terms of cost.

That’s money that could go elsewhere. That is money that is being taken out of the pockets of patients. They’re doing things that may even delay medical treatment, which won’t really help them, and they are doing things that perhaps might even interfere with medical care that really is known to be beneficial.

I think it’s time to push for more money for the FDA to regulate the wellness side. I think it’s time for the Federal Trade Commission to go after ads that promise health benefits. I think it’s time to have some honest conversations with patients: What are you using? What are you doing? Tell me about it, and here’s why I think you could probably spend your money in a better way.

Dr. Caplan, director, Division of Medical Ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, disclosed ties with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position). He serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Hi. I’m Art Caplan. I’m at the Division of Medical Ethics at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City.

We have many debates and arguments that are swirling around about the out-of-control costs of Medicare. Many people are arguing we’ve got to trim it and cut back, and many people note that we can’t just go on and on with that kind of expenditure.

People look around for savings. Rightly, we can’t go on with the prices that we’re paying. No system could. We’ll bankrupt ourselves if we don’t drive prices down.

There’s another area that is driving up cost where, despite the fact that Medicare doesn’t pay for it, we could capture resources and hopefully shift them back to things like Medicare coverage or the insurance of other efficacious procedures. That area is the wellness industry.

That’s money coming out of people’s pockets that we could hopefully aim at the payment of things that we know work, not seeing the money drain out to cover bunk, nonsense, and charlatanism.

Does any or most of this stuff work? Do anything? Help anybody? No. We are spending money on charlatans and quacks. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which you might think is the agency that could step in and start to get rid of some of this nonsense, is just too overwhelmed trying to track drugs, devices, and vaccines to give much attention to the wellness industry.

What am I talking about specifically? I’m talking about everything from gut probiotics that are sold in sodas to probiotic facial creams and the Goop industry of Gwyneth Paltrow, where you have people buying things like wellness mats or vaginal eggs that are supposed to maintain gynecologic health.

We’re talking about things like PEMF, or pulse electronic magnetic fields, where you buy a machine and expose yourself to mild magnetic pulses. I went online to look them up, and the machines cost $5000-$50,000. There’s no evidence that it works. By the way, the machines are not only out there as being sold for pain relief and many other things to humans, but also they’re being sold for your pets.

That industry is completely out of control. Wellness interventions, whether it’s transcranial magnetism or all manner of supplements that are sold in health food stores, over and over again, we see a world in which wellness is promoted but no data are introduced to show that any of it helps, works, or does anybody any good.

It may not be all that harmful, but it’s certainly financially toxic to many people who end up spending good amounts of money using these things. I think doctors need to ask patients if they are using any of these things, particularly if they have chronic conditions. They’re likely, many of them, to be seduced by online advertisement to get involved with this stuff because it’s preventive or it’ll help treat some condition that they have.

The industry is out of control. We’re trying to figure out how to spend money on things we know work in medicine, and yet we continue to tolerate bunk, nonsense, quackery, and charlatanism, just letting it grow and grow and grow in terms of cost.

That’s money that could go elsewhere. That is money that is being taken out of the pockets of patients. They’re doing things that may even delay medical treatment, which won’t really help them, and they are doing things that perhaps might even interfere with medical care that really is known to be beneficial.

I think it’s time to push for more money for the FDA to regulate the wellness side. I think it’s time for the Federal Trade Commission to go after ads that promise health benefits. I think it’s time to have some honest conversations with patients: What are you using? What are you doing? Tell me about it, and here’s why I think you could probably spend your money in a better way.

Dr. Caplan, director, Division of Medical Ethics, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, disclosed ties with Johnson & Johnson’s Panel for Compassionate Drug Use (unpaid position). He serves as a contributing author and adviser for Medscape.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Listeriosis During Pregnancy Can Be Fatal for the Fetus

Listeriosis during pregnancy, when invasive, can be fatal for the fetus, with a rate of fetal loss or neonatal death of 29%, investigators reported in an article alerting clinicians to this condition.

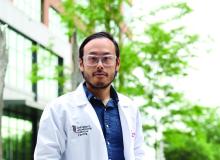

The article was prompted when the Reproductive Infectious Diseases team at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, “received many phone calls from concerned doctors and patients after the plant-based milk recall in early July,” Jeffrey Man Hay Wong, MD, told this news organization. “With such concerns, we updated our British Columbia guidelines for our patients but quickly realized that our recommendations would be useful across the country.”

The article was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Five Key Points

Dr. Wong and colleagues provided the following five points and recommendations:

First, invasive listeriosis (bacteremia or meningitis) in pregnancy can have major fetal consequences, including fetal loss or neonatal death in 29% of cases. Affected patients can be asymptomatic or experience gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or sepsis.

Second, pregnant people should avoid foods at a high risk for Listeria monocytogenes contamination, including unpasteurized dairy products, luncheon meats, refrigerated meat spreads, and prepared salads. They also should stay aware of Health Canada recalls.

Third, it is not necessary to investigate or treat patients who may have ingested contaminated food but are asymptomatic. Listeriosis can present at 2-3 months after exposure because the incubation period can be as long as 70 days.

Fourth, for patients with mild gastroenteritis or flu-like symptoms who may have ingested contaminated food, obtaining blood cultures or starting a 2-week course of oral amoxicillin (500 mg, three times daily) could be considered.

Fifth, for patients with fever and possible exposure to L monocytogenes, blood cultures should be drawn immediately, and high-dose ampicillin should be initiated, along with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring.

“While choosing safer foods in pregnancy is recommended, it is most important to be aware of Health Canada food recalls and pay attention to symptoms if you’ve ingested these foods,” said Dr. Wong. “Working with the BC Centre for Disease Control, our teams are actively monitoring for cases of listeriosis in pregnancy here in British Columbia.

“Thankfully,” he said, “there haven’t been any confirmed cases in British Columbia related to the plant-based milk recall, though the bacteria’s incubation period can be up to 70 days in pregnancy.”

No Increase Suspected

Commenting on the article, Khady Diouf, MD, director of global obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said, “It summarizes the main management, which is based mostly on expert opinion.”

US clinicians also should be reminded about listeriosis in pregnancy, she noted, pointing to “helpful guidance” from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Although the United States similarly experienced a recent listeriosis outbreak resulting from contaminated deli meats, both Dr. Wong and Dr. Diouf said that these outbreaks do not seem to signal an increase in listeriosis cases overall.

“Food-borne listeriosis seems to come in waves,” said Dr. Wong. “At a public health level, we certainly have better surveillance programs for Listeria infections. In 2023, Health Canada updated its Policy on L monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, which emphasizes the good manufacturing practices recommended for food processing environments to identify outbreaks earlier.”

“I think we get these recalls yearly, and this has been the case for as long as I can remember,” Dr. Diouf agreed.

No funding was declared, and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Listeriosis during pregnancy, when invasive, can be fatal for the fetus, with a rate of fetal loss or neonatal death of 29%, investigators reported in an article alerting clinicians to this condition.

The article was prompted when the Reproductive Infectious Diseases team at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, “received many phone calls from concerned doctors and patients after the plant-based milk recall in early July,” Jeffrey Man Hay Wong, MD, told this news organization. “With such concerns, we updated our British Columbia guidelines for our patients but quickly realized that our recommendations would be useful across the country.”

The article was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Five Key Points

Dr. Wong and colleagues provided the following five points and recommendations:

First, invasive listeriosis (bacteremia or meningitis) in pregnancy can have major fetal consequences, including fetal loss or neonatal death in 29% of cases. Affected patients can be asymptomatic or experience gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or sepsis.

Second, pregnant people should avoid foods at a high risk for Listeria monocytogenes contamination, including unpasteurized dairy products, luncheon meats, refrigerated meat spreads, and prepared salads. They also should stay aware of Health Canada recalls.

Third, it is not necessary to investigate or treat patients who may have ingested contaminated food but are asymptomatic. Listeriosis can present at 2-3 months after exposure because the incubation period can be as long as 70 days.

Fourth, for patients with mild gastroenteritis or flu-like symptoms who may have ingested contaminated food, obtaining blood cultures or starting a 2-week course of oral amoxicillin (500 mg, three times daily) could be considered.

Fifth, for patients with fever and possible exposure to L monocytogenes, blood cultures should be drawn immediately, and high-dose ampicillin should be initiated, along with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring.

“While choosing safer foods in pregnancy is recommended, it is most important to be aware of Health Canada food recalls and pay attention to symptoms if you’ve ingested these foods,” said Dr. Wong. “Working with the BC Centre for Disease Control, our teams are actively monitoring for cases of listeriosis in pregnancy here in British Columbia.

“Thankfully,” he said, “there haven’t been any confirmed cases in British Columbia related to the plant-based milk recall, though the bacteria’s incubation period can be up to 70 days in pregnancy.”

No Increase Suspected

Commenting on the article, Khady Diouf, MD, director of global obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said, “It summarizes the main management, which is based mostly on expert opinion.”

US clinicians also should be reminded about listeriosis in pregnancy, she noted, pointing to “helpful guidance” from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Although the United States similarly experienced a recent listeriosis outbreak resulting from contaminated deli meats, both Dr. Wong and Dr. Diouf said that these outbreaks do not seem to signal an increase in listeriosis cases overall.

“Food-borne listeriosis seems to come in waves,” said Dr. Wong. “At a public health level, we certainly have better surveillance programs for Listeria infections. In 2023, Health Canada updated its Policy on L monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, which emphasizes the good manufacturing practices recommended for food processing environments to identify outbreaks earlier.”

“I think we get these recalls yearly, and this has been the case for as long as I can remember,” Dr. Diouf agreed.

No funding was declared, and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Listeriosis during pregnancy, when invasive, can be fatal for the fetus, with a rate of fetal loss or neonatal death of 29%, investigators reported in an article alerting clinicians to this condition.

The article was prompted when the Reproductive Infectious Diseases team at The University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, “received many phone calls from concerned doctors and patients after the plant-based milk recall in early July,” Jeffrey Man Hay Wong, MD, told this news organization. “With such concerns, we updated our British Columbia guidelines for our patients but quickly realized that our recommendations would be useful across the country.”

The article was published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Five Key Points

Dr. Wong and colleagues provided the following five points and recommendations:

First, invasive listeriosis (bacteremia or meningitis) in pregnancy can have major fetal consequences, including fetal loss or neonatal death in 29% of cases. Affected patients can be asymptomatic or experience gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgias, fevers, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or sepsis.

Second, pregnant people should avoid foods at a high risk for Listeria monocytogenes contamination, including unpasteurized dairy products, luncheon meats, refrigerated meat spreads, and prepared salads. They also should stay aware of Health Canada recalls.

Third, it is not necessary to investigate or treat patients who may have ingested contaminated food but are asymptomatic. Listeriosis can present at 2-3 months after exposure because the incubation period can be as long as 70 days.

Fourth, for patients with mild gastroenteritis or flu-like symptoms who may have ingested contaminated food, obtaining blood cultures or starting a 2-week course of oral amoxicillin (500 mg, three times daily) could be considered.

Fifth, for patients with fever and possible exposure to L monocytogenes, blood cultures should be drawn immediately, and high-dose ampicillin should be initiated, along with electronic fetal heart rate monitoring.

“While choosing safer foods in pregnancy is recommended, it is most important to be aware of Health Canada food recalls and pay attention to symptoms if you’ve ingested these foods,” said Dr. Wong. “Working with the BC Centre for Disease Control, our teams are actively monitoring for cases of listeriosis in pregnancy here in British Columbia.

“Thankfully,” he said, “there haven’t been any confirmed cases in British Columbia related to the plant-based milk recall, though the bacteria’s incubation period can be up to 70 days in pregnancy.”

No Increase Suspected

Commenting on the article, Khady Diouf, MD, director of global obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said, “It summarizes the main management, which is based mostly on expert opinion.”

US clinicians also should be reminded about listeriosis in pregnancy, she noted, pointing to “helpful guidance” from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Although the United States similarly experienced a recent listeriosis outbreak resulting from contaminated deli meats, both Dr. Wong and Dr. Diouf said that these outbreaks do not seem to signal an increase in listeriosis cases overall.

“Food-borne listeriosis seems to come in waves,” said Dr. Wong. “At a public health level, we certainly have better surveillance programs for Listeria infections. In 2023, Health Canada updated its Policy on L monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods, which emphasizes the good manufacturing practices recommended for food processing environments to identify outbreaks earlier.”

“I think we get these recalls yearly, and this has been the case for as long as I can remember,” Dr. Diouf agreed.

No funding was declared, and the authors declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

Persistent mood swings

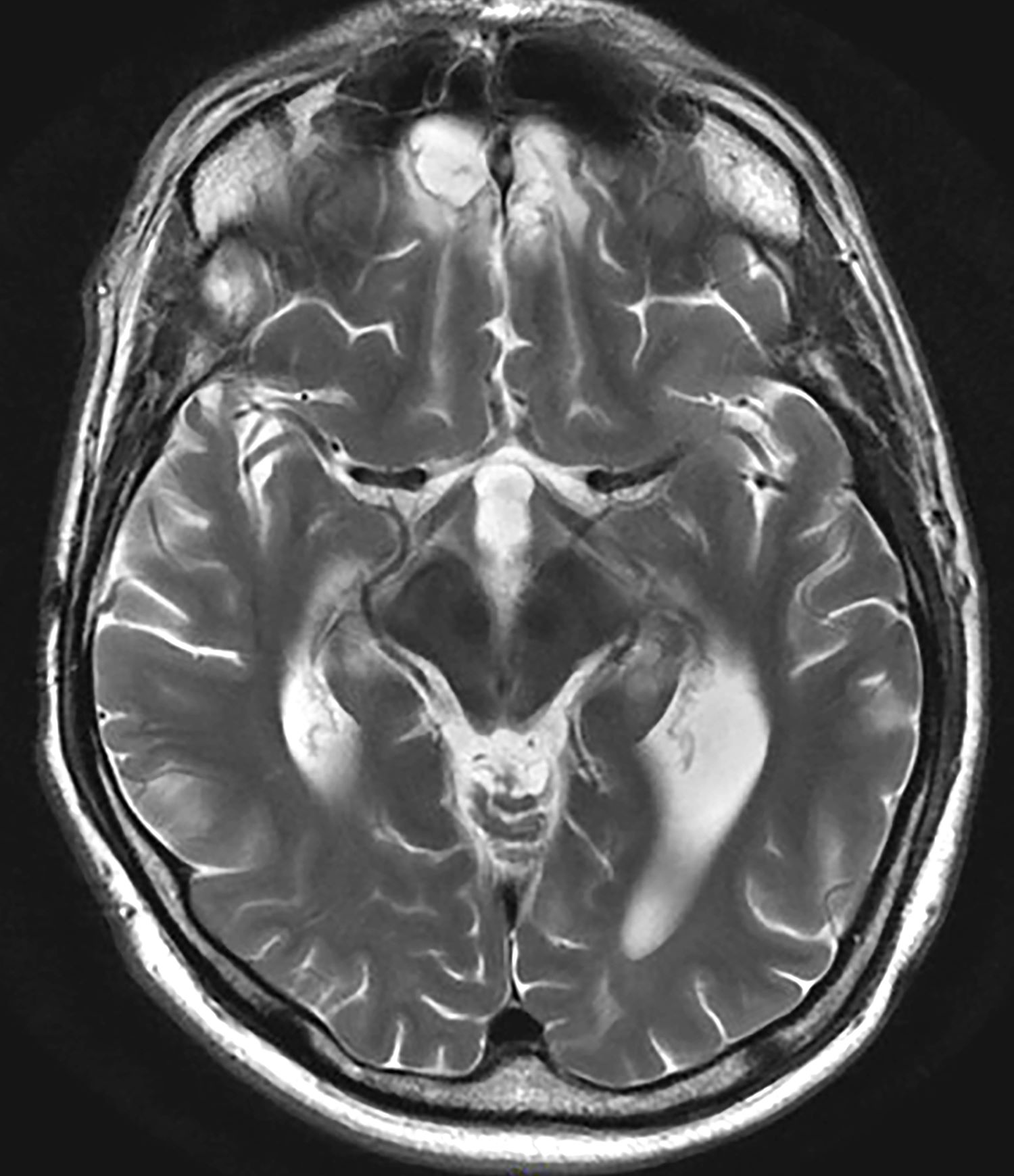

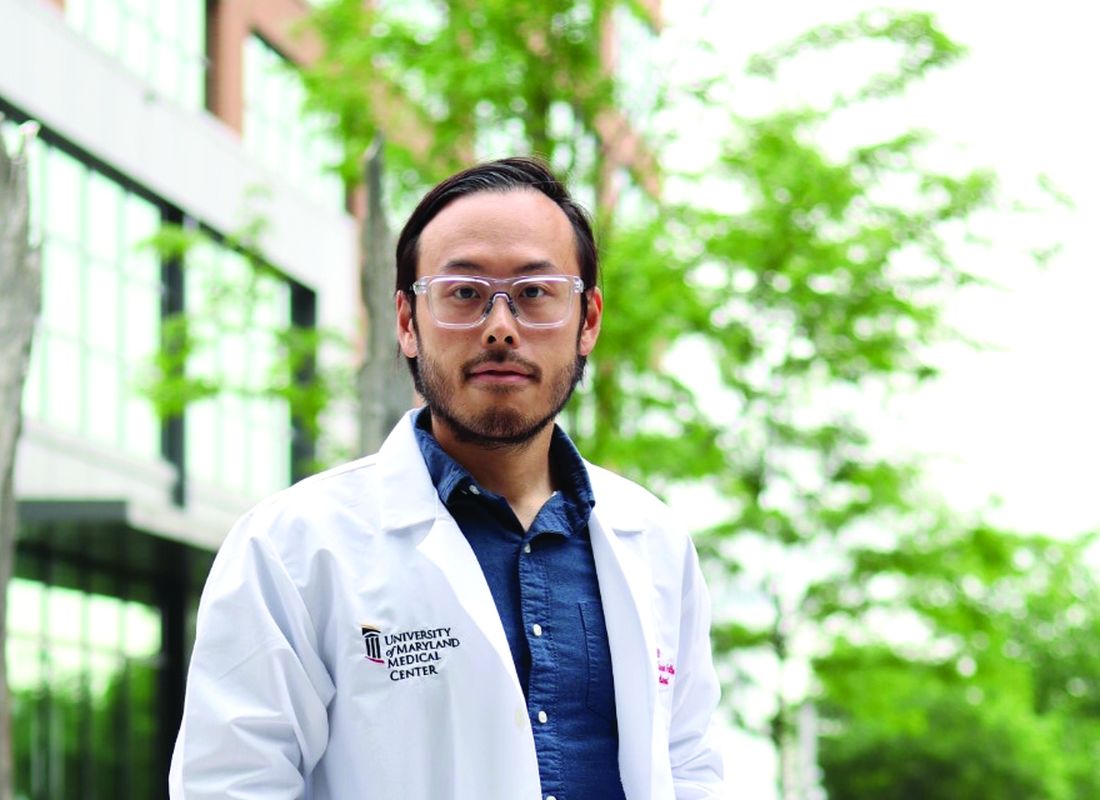

The most likely diagnosis for this patient is veteran posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), given his history of combat exposure and symptoms, such as severe headaches, difficulty concentrating, mood swings, nightmares, flashbacks, increased startle response, and hypervigilance. MRI findings showing significant changes in the limbic system and hippocampal regions support this diagnosis. Other potential diagnoses, like traumatic brain injury, chronic migraine, and major depressive disorder, are less likely because of their inability to account for the full range of his symptoms and specific MRI abnormalities.

PTSD, experienced by a subset of individuals after exposure to life-threatening events, has a lifetime prevalence of 4%-7% and a current prevalence of 1%-3%, with higher rates in older women, those with more trauma, and combat veterans. Nearly half of US veterans are aged 65 or older, many being Vietnam-era veterans at elevated risk for PTSD. Prevalence rates in older veterans range between 1% and 22%.

PTSD is characterized by intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of reminders, hypervigilance, and sleep difficulties, significantly disrupting interpersonal and occupational functioning. Screening tools like the primary care (PC) PTSD-5 and PCL-5, used in primary care settings, are effective for early detection, provisional diagnosis, and monitoring of symptom changes. The clinician-administered PTSD scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is the gold standard for diagnosis, particularly among veterans, with multimethod assessments combining self-report measures and semi-structured interviews recommended for accuracy. The DSM-5 criteria for PTSD diagnosis describe exposure to traumatic events, intrusion symptoms, avoidance behaviors, negative mood, and altered arousal, with symptoms persisting for over a month and causing significant distress or functional impairment.

Research has identified consistent anatomical and functional changes in PTSD patients, such as smaller hippocampi, decreased corpus callosum and prefrontal cortex, increased amygdala reactivity, and decreased prefrontal cortex activity. PTSD, linked to alterations in brain regions involved in fear learning and memory, shows diminished structural integrity in executive function areas, reduced cortical volumes in the cingulate brain cortex and frontal regions, and reduced white matter integrity in key brain pathways. Neuroimaging findings, however, are primarily used for research currently and have yet to be widely implemented in clinical guidelines.

International PTSD treatment guidelines consistently recognize trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs), such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure (PE), and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) as the gold standard. Recent guidelines have expanded the list of recommended treatments: The 2023 Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense guidelines in the United States also endorse therapies like written narrative exposure and brief eclectic therapy. Internationally, guidelines do not perfectly coincide, as the 2018 update from the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) gives the highest recommendations to PE and CPT but rates EMDR slightly lower for military veterans because of limited evidence. Overall, guidelines consistently advocate for trauma-focused psychological interventions as the primary treatment for PTSD.

Guidelines from NICE and the World Health Organization do not recommend medications as the primary treatment; the American Psychiatric Association and the US Department of Veterans Affairs support selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin but advise against benzodiazepines. Inpatient care may be necessary for individuals who pose a danger to themselves or others, or for those with severe PTSD from childhood abuse, to aid in emotional regulation and treatment.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The most likely diagnosis for this patient is veteran posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), given his history of combat exposure and symptoms, such as severe headaches, difficulty concentrating, mood swings, nightmares, flashbacks, increased startle response, and hypervigilance. MRI findings showing significant changes in the limbic system and hippocampal regions support this diagnosis. Other potential diagnoses, like traumatic brain injury, chronic migraine, and major depressive disorder, are less likely because of their inability to account for the full range of his symptoms and specific MRI abnormalities.

PTSD, experienced by a subset of individuals after exposure to life-threatening events, has a lifetime prevalence of 4%-7% and a current prevalence of 1%-3%, with higher rates in older women, those with more trauma, and combat veterans. Nearly half of US veterans are aged 65 or older, many being Vietnam-era veterans at elevated risk for PTSD. Prevalence rates in older veterans range between 1% and 22%.

PTSD is characterized by intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of reminders, hypervigilance, and sleep difficulties, significantly disrupting interpersonal and occupational functioning. Screening tools like the primary care (PC) PTSD-5 and PCL-5, used in primary care settings, are effective for early detection, provisional diagnosis, and monitoring of symptom changes. The clinician-administered PTSD scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is the gold standard for diagnosis, particularly among veterans, with multimethod assessments combining self-report measures and semi-structured interviews recommended for accuracy. The DSM-5 criteria for PTSD diagnosis describe exposure to traumatic events, intrusion symptoms, avoidance behaviors, negative mood, and altered arousal, with symptoms persisting for over a month and causing significant distress or functional impairment.

Research has identified consistent anatomical and functional changes in PTSD patients, such as smaller hippocampi, decreased corpus callosum and prefrontal cortex, increased amygdala reactivity, and decreased prefrontal cortex activity. PTSD, linked to alterations in brain regions involved in fear learning and memory, shows diminished structural integrity in executive function areas, reduced cortical volumes in the cingulate brain cortex and frontal regions, and reduced white matter integrity in key brain pathways. Neuroimaging findings, however, are primarily used for research currently and have yet to be widely implemented in clinical guidelines.

International PTSD treatment guidelines consistently recognize trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs), such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure (PE), and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) as the gold standard. Recent guidelines have expanded the list of recommended treatments: The 2023 Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense guidelines in the United States also endorse therapies like written narrative exposure and brief eclectic therapy. Internationally, guidelines do not perfectly coincide, as the 2018 update from the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) gives the highest recommendations to PE and CPT but rates EMDR slightly lower for military veterans because of limited evidence. Overall, guidelines consistently advocate for trauma-focused psychological interventions as the primary treatment for PTSD.

Guidelines from NICE and the World Health Organization do not recommend medications as the primary treatment; the American Psychiatric Association and the US Department of Veterans Affairs support selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin but advise against benzodiazepines. Inpatient care may be necessary for individuals who pose a danger to themselves or others, or for those with severe PTSD from childhood abuse, to aid in emotional regulation and treatment.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The most likely diagnosis for this patient is veteran posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), given his history of combat exposure and symptoms, such as severe headaches, difficulty concentrating, mood swings, nightmares, flashbacks, increased startle response, and hypervigilance. MRI findings showing significant changes in the limbic system and hippocampal regions support this diagnosis. Other potential diagnoses, like traumatic brain injury, chronic migraine, and major depressive disorder, are less likely because of their inability to account for the full range of his symptoms and specific MRI abnormalities.

PTSD, experienced by a subset of individuals after exposure to life-threatening events, has a lifetime prevalence of 4%-7% and a current prevalence of 1%-3%, with higher rates in older women, those with more trauma, and combat veterans. Nearly half of US veterans are aged 65 or older, many being Vietnam-era veterans at elevated risk for PTSD. Prevalence rates in older veterans range between 1% and 22%.

PTSD is characterized by intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of reminders, hypervigilance, and sleep difficulties, significantly disrupting interpersonal and occupational functioning. Screening tools like the primary care (PC) PTSD-5 and PCL-5, used in primary care settings, are effective for early detection, provisional diagnosis, and monitoring of symptom changes. The clinician-administered PTSD scale for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is the gold standard for diagnosis, particularly among veterans, with multimethod assessments combining self-report measures and semi-structured interviews recommended for accuracy. The DSM-5 criteria for PTSD diagnosis describe exposure to traumatic events, intrusion symptoms, avoidance behaviors, negative mood, and altered arousal, with symptoms persisting for over a month and causing significant distress or functional impairment.

Research has identified consistent anatomical and functional changes in PTSD patients, such as smaller hippocampi, decreased corpus callosum and prefrontal cortex, increased amygdala reactivity, and decreased prefrontal cortex activity. PTSD, linked to alterations in brain regions involved in fear learning and memory, shows diminished structural integrity in executive function areas, reduced cortical volumes in the cingulate brain cortex and frontal regions, and reduced white matter integrity in key brain pathways. Neuroimaging findings, however, are primarily used for research currently and have yet to be widely implemented in clinical guidelines.

International PTSD treatment guidelines consistently recognize trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBTs), such as cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure (PE), and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) as the gold standard. Recent guidelines have expanded the list of recommended treatments: The 2023 Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense guidelines in the United States also endorse therapies like written narrative exposure and brief eclectic therapy. Internationally, guidelines do not perfectly coincide, as the 2018 update from the United Kingdom's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) gives the highest recommendations to PE and CPT but rates EMDR slightly lower for military veterans because of limited evidence. Overall, guidelines consistently advocate for trauma-focused psychological interventions as the primary treatment for PTSD.

Guidelines from NICE and the World Health Organization do not recommend medications as the primary treatment; the American Psychiatric Association and the US Department of Veterans Affairs support selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin but advise against benzodiazepines. Inpatient care may be necessary for individuals who pose a danger to themselves or others, or for those with severe PTSD from childhood abuse, to aid in emotional regulation and treatment.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 35-year-old male veteran presents with a history of severe headaches, difficulty concentrating, and persistent mood swings. He served multiple tours in a combat zone, where he was exposed to several traumatic events, including the loss of close friends. His medical history reveals previous diagnoses of insomnia and anxiety, for which he has been prescribed various medications over the years with limited success. During his clinical evaluation, he describes frequent nightmares and flashbacks related to his time in service. He reports an increased startle response and hypervigilance, often feeling on edge and irritable. A recent MRI of the brain, as shown in the image here, reveals significant changes in the limbic system, with abnormalities in the hippocampal regions. Laboratory tests and physical exams are otherwise unremarkable, but his mental health assessment indicates severe distress, which is affecting his daily functioning and interpersonal relationships.

Hospital to home tracheostomy care

SLEEP MEDICINE NETWORK

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Section

Technological improvement has enhanced our ability to support these patients with complex conditions in their home settings. However, clinical practice guidelines are lacking, and current practice relies on a consensus of expert opinions.1-3

Once a patient who has had a tracheostomy begins transitioning care to home, identifying caregivers is vital.

Caregivers need to be educated on daily tracheostomy care, airway clearance, and ventilator management.

Protocols to standardize this transition, such as the “Trach Trail” protocol, help reduce ICU readmissions with new tracheostomies (P = .05), eliminate predischarge mortality (P = .05), and may decrease ICU length of stay (P = 0.72).4 Standardized protocols for aspects of tracheostomy care, such as the “Go-Bag” from Boston Children’s Hospital, ensure that a consistent approach keeps providers, families, and patients familiar with their equipment and safety procedures, improving outcomes and decreasing tracheostomy-related adverse events.4-6

Understanding the landscape surrounding which equipment companies have trained field respiratory therapists is crucial. Airway clearance is key to improving ventilation and oxygenation and maintaining tracheostomy patency. Knowing the types of airway clearance modalities used for each patient remains critical.

Trach care may look substantially different for some populations, like patients in the neonatal ICU. Trach changes may happen more frequently. Speaking valve times may be gradually increased while planning for possible decannulation. Skin care involving granulation tissue and stoma complications is particularly important for this population. Active infants need well-fitting trach ties to balance enough support to maintain their trach without causing skin breakdown or discomfort. Securing the trach to prevent pulling or dislodgement as infants become more active is crucial as developmental milestones are achieved.

We hope national societies prioritize standardizing care for this vulnerable population while promoting additional high-quality, patient-centered outcomes in research studies. Implementation strategies to promote interprofessional teams to enhance education, communication, and outcomes will reduce health care disparities.

References

1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 161. pp Sherman JM, Davis S, Albamonte-Petrick S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):297-308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats1-00 297-308, 2000

2. Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):6-20. Preprint. Posted online September 18, 2012. PMID: 22990518. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376

3. Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):e16-35. PMID: 27082538; PMCID: PMC5439679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST

4. Cherney RL, Pandian V, Ninan A, et al. The Trach Trail: a systems-based pathway to improve quality of tracheostomy care and interdisciplinary collaboration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):232-243. doi: 10.1177/0194599820917427

5. Brown J. Tracheostomy to noninvasive ventilation: from acute care to home. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.003

6. Kohn J, McKeon M, Munhall D, Blanchette S, Wells S, Watters K. Standardization of pediatric tracheostomy care with “Go-bags.” Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;121:154-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.022

SLEEP MEDICINE NETWORK

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Section

Technological improvement has enhanced our ability to support these patients with complex conditions in their home settings. However, clinical practice guidelines are lacking, and current practice relies on a consensus of expert opinions.1-3

Once a patient who has had a tracheostomy begins transitioning care to home, identifying caregivers is vital.

Caregivers need to be educated on daily tracheostomy care, airway clearance, and ventilator management.

Protocols to standardize this transition, such as the “Trach Trail” protocol, help reduce ICU readmissions with new tracheostomies (P = .05), eliminate predischarge mortality (P = .05), and may decrease ICU length of stay (P = 0.72).4 Standardized protocols for aspects of tracheostomy care, such as the “Go-Bag” from Boston Children’s Hospital, ensure that a consistent approach keeps providers, families, and patients familiar with their equipment and safety procedures, improving outcomes and decreasing tracheostomy-related adverse events.4-6

Understanding the landscape surrounding which equipment companies have trained field respiratory therapists is crucial. Airway clearance is key to improving ventilation and oxygenation and maintaining tracheostomy patency. Knowing the types of airway clearance modalities used for each patient remains critical.

Trach care may look substantially different for some populations, like patients in the neonatal ICU. Trach changes may happen more frequently. Speaking valve times may be gradually increased while planning for possible decannulation. Skin care involving granulation tissue and stoma complications is particularly important for this population. Active infants need well-fitting trach ties to balance enough support to maintain their trach without causing skin breakdown or discomfort. Securing the trach to prevent pulling or dislodgement as infants become more active is crucial as developmental milestones are achieved.

We hope national societies prioritize standardizing care for this vulnerable population while promoting additional high-quality, patient-centered outcomes in research studies. Implementation strategies to promote interprofessional teams to enhance education, communication, and outcomes will reduce health care disparities.

References

1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 161. pp Sherman JM, Davis S, Albamonte-Petrick S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):297-308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats1-00 297-308, 2000

2. Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):6-20. Preprint. Posted online September 18, 2012. PMID: 22990518. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376

3. Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):e16-35. PMID: 27082538; PMCID: PMC5439679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST

4. Cherney RL, Pandian V, Ninan A, et al. The Trach Trail: a systems-based pathway to improve quality of tracheostomy care and interdisciplinary collaboration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):232-243. doi: 10.1177/0194599820917427

5. Brown J. Tracheostomy to noninvasive ventilation: from acute care to home. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.003

6. Kohn J, McKeon M, Munhall D, Blanchette S, Wells S, Watters K. Standardization of pediatric tracheostomy care with “Go-bags.” Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;121:154-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.022

SLEEP MEDICINE NETWORK

Home-Based Mechanical Ventilation and Neuromuscular Section

Technological improvement has enhanced our ability to support these patients with complex conditions in their home settings. However, clinical practice guidelines are lacking, and current practice relies on a consensus of expert opinions.1-3

Once a patient who has had a tracheostomy begins transitioning care to home, identifying caregivers is vital.

Caregivers need to be educated on daily tracheostomy care, airway clearance, and ventilator management.

Protocols to standardize this transition, such as the “Trach Trail” protocol, help reduce ICU readmissions with new tracheostomies (P = .05), eliminate predischarge mortality (P = .05), and may decrease ICU length of stay (P = 0.72).4 Standardized protocols for aspects of tracheostomy care, such as the “Go-Bag” from Boston Children’s Hospital, ensure that a consistent approach keeps providers, families, and patients familiar with their equipment and safety procedures, improving outcomes and decreasing tracheostomy-related adverse events.4-6

Understanding the landscape surrounding which equipment companies have trained field respiratory therapists is crucial. Airway clearance is key to improving ventilation and oxygenation and maintaining tracheostomy patency. Knowing the types of airway clearance modalities used for each patient remains critical.

Trach care may look substantially different for some populations, like patients in the neonatal ICU. Trach changes may happen more frequently. Speaking valve times may be gradually increased while planning for possible decannulation. Skin care involving granulation tissue and stoma complications is particularly important for this population. Active infants need well-fitting trach ties to balance enough support to maintain their trach without causing skin breakdown or discomfort. Securing the trach to prevent pulling or dislodgement as infants become more active is crucial as developmental milestones are achieved.

We hope national societies prioritize standardizing care for this vulnerable population while promoting additional high-quality, patient-centered outcomes in research studies. Implementation strategies to promote interprofessional teams to enhance education, communication, and outcomes will reduce health care disparities.

References

1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 161. pp Sherman JM, Davis S, Albamonte-Petrick S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):297-308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.ats1-00 297-308, 2000

2. Mitchell RB, Hussey HM, Setzen G, et al. Clinical consensus statement: tracheostomy care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(1):6-20. Preprint. Posted online September 18, 2012. PMID: 22990518. doi: 10.1177/0194599812460376

3. Sterni LM, Collaco JM, Baker CD, et al; ATS Pediatric Chronic Home Ventilation Workgroup. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: pediatric chronic home invasive ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):e16-35. PMID: 27082538; PMCID: PMC5439679. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0276ST

4. Cherney RL, Pandian V, Ninan A, et al. The Trach Trail: a systems-based pathway to improve quality of tracheostomy care and interdisciplinary collaboration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(2):232-243. doi: 10.1177/0194599820917427

5. Brown J. Tracheostomy to noninvasive ventilation: from acute care to home. Sleep Med Clin. 2020;15(4):593-598. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2020.08.003

6. Kohn J, McKeon M, Munhall D, Blanchette S, Wells S, Watters K. Standardization of pediatric tracheostomy care with “Go-bags.” Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;121:154-156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.03.022

HALT early recognition is key

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Lung Transplant Section

Hyperammonemia after lung transplantation (HALT) is a rare but serious complication occurring in 1% to 4% of patients with high morbidity and mortality. Early recognition is crucial, as mortality rates can reach 75%.1

HALT arises from excess ammonia production or decreased clearance and is often linked to infections by urea-splitting organisms, including mycoplasma and ureaplasma. Prompt, aggressive treatment is essential and typically includes dietary protein restriction, renal replacement therapy (ideally intermittent hemodialysis), bowel decontamination (lactulose, rifaximin, metronidazole, or neomycin), amino acids (arginine and levocarnitine), nitrogen scavengers (sodium phenylbutyrate or glycerol phenylbutyrate), and empiric antimicrobial coverage for urea-splitting organisms.2 Given concerns for calcineurin inhibitor-induced hyperammonemia, transition to an alternative agent may be considered.

Given the severe risks associated with HALT, vigilance is vital, particularly in intubated and sedated patients where monitoring of neurologic status is more challenging. Protocols may involve routine serum ammonia monitoring, polymerase chain reaction testing for mycoplasma and ureaplasma at the time of transplant or with postoperative bronchoscopy, and empiric antimicrobial treatment. No definitive ammonia threshold exists, but altered sensorium with elevated levels warrants immediate and more aggressive treatment with levels >75 μmol/L. Early testing and symptom recognition can significantly improve survival rates in this potentially devastating condition.

References

1. Leger RF, Silverman MS, Hauck ES, Guvakova KD. Hyperammonemia post lung transplantation: a review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966234. doi:10.1177/1179548420966234

2. Chen C, Bain KB, Luppa JA. Hyperammonemia syndrome after lung transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):678-684. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000868

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Lung Transplant Section

Hyperammonemia after lung transplantation (HALT) is a rare but serious complication occurring in 1% to 4% of patients with high morbidity and mortality. Early recognition is crucial, as mortality rates can reach 75%.1

HALT arises from excess ammonia production or decreased clearance and is often linked to infections by urea-splitting organisms, including mycoplasma and ureaplasma. Prompt, aggressive treatment is essential and typically includes dietary protein restriction, renal replacement therapy (ideally intermittent hemodialysis), bowel decontamination (lactulose, rifaximin, metronidazole, or neomycin), amino acids (arginine and levocarnitine), nitrogen scavengers (sodium phenylbutyrate or glycerol phenylbutyrate), and empiric antimicrobial coverage for urea-splitting organisms.2 Given concerns for calcineurin inhibitor-induced hyperammonemia, transition to an alternative agent may be considered.

Given the severe risks associated with HALT, vigilance is vital, particularly in intubated and sedated patients where monitoring of neurologic status is more challenging. Protocols may involve routine serum ammonia monitoring, polymerase chain reaction testing for mycoplasma and ureaplasma at the time of transplant or with postoperative bronchoscopy, and empiric antimicrobial treatment. No definitive ammonia threshold exists, but altered sensorium with elevated levels warrants immediate and more aggressive treatment with levels >75 μmol/L. Early testing and symptom recognition can significantly improve survival rates in this potentially devastating condition.

References

1. Leger RF, Silverman MS, Hauck ES, Guvakova KD. Hyperammonemia post lung transplantation: a review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966234. doi:10.1177/1179548420966234

2. Chen C, Bain KB, Luppa JA. Hyperammonemia syndrome after lung transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):678-684. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000868

DIFFUSE LUNG DISEASE AND LUNG TRANSPLANT NETWORK

Lung Transplant Section

Hyperammonemia after lung transplantation (HALT) is a rare but serious complication occurring in 1% to 4% of patients with high morbidity and mortality. Early recognition is crucial, as mortality rates can reach 75%.1

HALT arises from excess ammonia production or decreased clearance and is often linked to infections by urea-splitting organisms, including mycoplasma and ureaplasma. Prompt, aggressive treatment is essential and typically includes dietary protein restriction, renal replacement therapy (ideally intermittent hemodialysis), bowel decontamination (lactulose, rifaximin, metronidazole, or neomycin), amino acids (arginine and levocarnitine), nitrogen scavengers (sodium phenylbutyrate or glycerol phenylbutyrate), and empiric antimicrobial coverage for urea-splitting organisms.2 Given concerns for calcineurin inhibitor-induced hyperammonemia, transition to an alternative agent may be considered.

Given the severe risks associated with HALT, vigilance is vital, particularly in intubated and sedated patients where monitoring of neurologic status is more challenging. Protocols may involve routine serum ammonia monitoring, polymerase chain reaction testing for mycoplasma and ureaplasma at the time of transplant or with postoperative bronchoscopy, and empiric antimicrobial treatment. No definitive ammonia threshold exists, but altered sensorium with elevated levels warrants immediate and more aggressive treatment with levels >75 μmol/L. Early testing and symptom recognition can significantly improve survival rates in this potentially devastating condition.

References

1. Leger RF, Silverman MS, Hauck ES, Guvakova KD. Hyperammonemia post lung transplantation: a review. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966234. doi:10.1177/1179548420966234

2. Chen C, Bain KB, Luppa JA. Hyperammonemia syndrome after lung transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):678-684. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000000868

SURMOUNT-OSA Results: ‘Impressive’ in Improving Sleep Apnea

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Akshay B. Jain, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver, Canada, and with me is a very special guest. Today we have Dr. James Kim, a primary care physician working in Calgary, Canada. Both Dr. Kim and I were fortunate to attend the recently concluded American Diabetes Association annual conference in Orlando in June.

We thought we could share with you some of the key learnings that we found very insightful and clinically quite relevant. We were hoping to bring our own conclusion regarding what these findings were, both from a primary care perspective and an endocrinology perspective.

There were so many different studies that, frankly, it was difficult to pick them, but we handpicked a few studies we felt we could do a bit of a deeper dive on, and we’ll talk about each of these studies.

Welcome, Dr. Kim, and thanks for joining us.

James W. Kim, MBBCh, PgDip, MScCH: Thank you so much, Dr Jain. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Jain: Probably the best place to start would be with the SURMOUNT-OSA study. This was highlighted at the American Diabetes Association conference. Essentially, it looked at people who are living with obesity who also had obstructive sleep apnea.

This was a randomized controlled trial where individuals tested either got tirzepatide (trade name, Mounjaro) or placebo treatment. They looked at the change in their apnea-hypopnea index at the end of the study.

This included both people who were using CPAP machines and those who were not using CPAP machines at baseline. We do know that many individuals with sleep apnea may not use these machines.

That was a big reduction.

Dr. Kim, what’s the relevance of this study in primary care?

Dr. Kim: Oh, it’s massive. Obstructive sleep apnea is probably one of the most underdiagnosed yet huge cardiac risk factors that we tend to overlook in primary care. We sometimes say, oh, it’s just sleep apnea; what’s the big deal? We know it’s a big problem. We know that more than 50% of people with type 2 diabetes have obstructive sleep apnea, and some studies have even quoted that 90% of their population cohorts had sleep apnea. This is a big deal.

What do we know so far? We know that obstructive sleep apnea, which I’m just going to call OSA, increases the risk for hypertension, bad cholesterol, and worsening blood glucose in terms of A1c and fasting glucose, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, and eventually cardiovascular death.

We also know that people with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk for OSA. There seems to be a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and OSA. It seems like weight plays the biggest role in terms of developing OSA, and numerous studies have shown this.

Also, thankfully, some of the studies showed that weight loss improves not just OSA but also blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and insulin sensitivities. These have been fascinating. We see these patients every single day. If you think about it in your population, for 50%-90% of the patients to have OSA is a large number. If you haven’t seen a person with OSA this week, you probably missed them, very likely.

Therefore, the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was quite fascinating with, as you mentioned, 50%-60% reduction in the severity of OSA, which is very impressive. Even more impressive, I think, is that for about 50% of the patients on tirzepatide, the OSA improves so much that they may not even need to be on CPAP machines.

Those who were on CPAP may not need to be on CPAP any longer. These are huge data, especially for primary care, because as you mentioned, we see these people every single day.

Dr. Jain: Thanks for pointing that out. Clearly, it’s very clinically relevant. I think the most important takeaway for me from this study was the correlation between weight loss and AHI improvement.

Clearly, it showed that placebo had about a 6% drop in AHI, whereas there was a 60% drop in the tirzepatide group, so you can see that it’s significantly different. The placebo group did not have any significant degree of weight loss, whereas the tirzepatide group had nearly 20% weight loss. This again goes to show that there is a very close correlation between weight loss and improvement in OSA.

What’s very important to note is that we’ve seen this in the past as well. We had seen some of these data with other GLP-1 agents, but the extent of improvement that we have seen in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial is significantly more than what we’ve seen in previous studies. There is a ray of hope now where we have medical management to offer people who are living with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Kim: I want to add that, from a primary care perspective, this study also showed the improvement of the sleep apnea–related symptoms as well. The biggest problem with sleep apnea — or at least what patients’ spouses complain of, is the person snoring too much; it’s a symptom.

It’s the next-day symptoms that really do disturb people, like chronic fatigue. I have numerous patients who say that, once they’ve been treated for sleep apnea, they feel like a brand-new person. They have sudden bursts of energy that they never felt before, and over 50% of these people have huge improvements in the symptoms as well.

This is a huge trial. The only thing that I wish this study included were people with mild obstructive sleep apnea who were symptomatic. I do understand that, with other studies in this population, the data have been conflicting, but it would have been really awesome if they had those patients included. However, it is still a significant study for primary care.

Dr. Jain: That’s a really good point. Fatigue improves and overall quality of life improves. That’s very important from a primary care perspective.

From an endocrinology perspective, we know that management of sleep apnea can often lead to improvement in male hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and insulin resistance. The amount of insulin required, or the number of medications needed for managing diabetes, can improve. Hypertension can improve as well. There are multiple benefits that you can get from appropriate management of sleep apnea.

Thanks, Dr. Kim. We really appreciate your insights on SURMOUNT-OSA.

Dr. Jain is a clinical instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Kim is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary in Alberta. Both disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Akshay B. Jain, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver, Canada, and with me is a very special guest. Today we have Dr. James Kim, a primary care physician working in Calgary, Canada. Both Dr. Kim and I were fortunate to attend the recently concluded American Diabetes Association annual conference in Orlando in June.

We thought we could share with you some of the key learnings that we found very insightful and clinically quite relevant. We were hoping to bring our own conclusion regarding what these findings were, both from a primary care perspective and an endocrinology perspective.

There were so many different studies that, frankly, it was difficult to pick them, but we handpicked a few studies we felt we could do a bit of a deeper dive on, and we’ll talk about each of these studies.

Welcome, Dr. Kim, and thanks for joining us.

James W. Kim, MBBCh, PgDip, MScCH: Thank you so much, Dr Jain. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Jain: Probably the best place to start would be with the SURMOUNT-OSA study. This was highlighted at the American Diabetes Association conference. Essentially, it looked at people who are living with obesity who also had obstructive sleep apnea.

This was a randomized controlled trial where individuals tested either got tirzepatide (trade name, Mounjaro) or placebo treatment. They looked at the change in their apnea-hypopnea index at the end of the study.

This included both people who were using CPAP machines and those who were not using CPAP machines at baseline. We do know that many individuals with sleep apnea may not use these machines.

That was a big reduction.

Dr. Kim, what’s the relevance of this study in primary care?

Dr. Kim: Oh, it’s massive. Obstructive sleep apnea is probably one of the most underdiagnosed yet huge cardiac risk factors that we tend to overlook in primary care. We sometimes say, oh, it’s just sleep apnea; what’s the big deal? We know it’s a big problem. We know that more than 50% of people with type 2 diabetes have obstructive sleep apnea, and some studies have even quoted that 90% of their population cohorts had sleep apnea. This is a big deal.

What do we know so far? We know that obstructive sleep apnea, which I’m just going to call OSA, increases the risk for hypertension, bad cholesterol, and worsening blood glucose in terms of A1c and fasting glucose, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, and eventually cardiovascular death.

We also know that people with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk for OSA. There seems to be a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and OSA. It seems like weight plays the biggest role in terms of developing OSA, and numerous studies have shown this.

Also, thankfully, some of the studies showed that weight loss improves not just OSA but also blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and insulin sensitivities. These have been fascinating. We see these patients every single day. If you think about it in your population, for 50%-90% of the patients to have OSA is a large number. If you haven’t seen a person with OSA this week, you probably missed them, very likely.

Therefore, the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was quite fascinating with, as you mentioned, 50%-60% reduction in the severity of OSA, which is very impressive. Even more impressive, I think, is that for about 50% of the patients on tirzepatide, the OSA improves so much that they may not even need to be on CPAP machines.

Those who were on CPAP may not need to be on CPAP any longer. These are huge data, especially for primary care, because as you mentioned, we see these people every single day.

Dr. Jain: Thanks for pointing that out. Clearly, it’s very clinically relevant. I think the most important takeaway for me from this study was the correlation between weight loss and AHI improvement.

Clearly, it showed that placebo had about a 6% drop in AHI, whereas there was a 60% drop in the tirzepatide group, so you can see that it’s significantly different. The placebo group did not have any significant degree of weight loss, whereas the tirzepatide group had nearly 20% weight loss. This again goes to show that there is a very close correlation between weight loss and improvement in OSA.

What’s very important to note is that we’ve seen this in the past as well. We had seen some of these data with other GLP-1 agents, but the extent of improvement that we have seen in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial is significantly more than what we’ve seen in previous studies. There is a ray of hope now where we have medical management to offer people who are living with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Kim: I want to add that, from a primary care perspective, this study also showed the improvement of the sleep apnea–related symptoms as well. The biggest problem with sleep apnea — or at least what patients’ spouses complain of, is the person snoring too much; it’s a symptom.

It’s the next-day symptoms that really do disturb people, like chronic fatigue. I have numerous patients who say that, once they’ve been treated for sleep apnea, they feel like a brand-new person. They have sudden bursts of energy that they never felt before, and over 50% of these people have huge improvements in the symptoms as well.

This is a huge trial. The only thing that I wish this study included were people with mild obstructive sleep apnea who were symptomatic. I do understand that, with other studies in this population, the data have been conflicting, but it would have been really awesome if they had those patients included. However, it is still a significant study for primary care.

Dr. Jain: That’s a really good point. Fatigue improves and overall quality of life improves. That’s very important from a primary care perspective.

From an endocrinology perspective, we know that management of sleep apnea can often lead to improvement in male hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and insulin resistance. The amount of insulin required, or the number of medications needed for managing diabetes, can improve. Hypertension can improve as well. There are multiple benefits that you can get from appropriate management of sleep apnea.

Thanks, Dr. Kim. We really appreciate your insights on SURMOUNT-OSA.

Dr. Jain is a clinical instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Kim is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary in Alberta. Both disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Akshay B. Jain, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Akshay Jain, an endocrinologist in Vancouver, Canada, and with me is a very special guest. Today we have Dr. James Kim, a primary care physician working in Calgary, Canada. Both Dr. Kim and I were fortunate to attend the recently concluded American Diabetes Association annual conference in Orlando in June.

We thought we could share with you some of the key learnings that we found very insightful and clinically quite relevant. We were hoping to bring our own conclusion regarding what these findings were, both from a primary care perspective and an endocrinology perspective.

There were so many different studies that, frankly, it was difficult to pick them, but we handpicked a few studies we felt we could do a bit of a deeper dive on, and we’ll talk about each of these studies.

Welcome, Dr. Kim, and thanks for joining us.

James W. Kim, MBBCh, PgDip, MScCH: Thank you so much, Dr Jain. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Jain: Probably the best place to start would be with the SURMOUNT-OSA study. This was highlighted at the American Diabetes Association conference. Essentially, it looked at people who are living with obesity who also had obstructive sleep apnea.

This was a randomized controlled trial where individuals tested either got tirzepatide (trade name, Mounjaro) or placebo treatment. They looked at the change in their apnea-hypopnea index at the end of the study.

This included both people who were using CPAP machines and those who were not using CPAP machines at baseline. We do know that many individuals with sleep apnea may not use these machines.

That was a big reduction.

Dr. Kim, what’s the relevance of this study in primary care?

Dr. Kim: Oh, it’s massive. Obstructive sleep apnea is probably one of the most underdiagnosed yet huge cardiac risk factors that we tend to overlook in primary care. We sometimes say, oh, it’s just sleep apnea; what’s the big deal? We know it’s a big problem. We know that more than 50% of people with type 2 diabetes have obstructive sleep apnea, and some studies have even quoted that 90% of their population cohorts had sleep apnea. This is a big deal.

What do we know so far? We know that obstructive sleep apnea, which I’m just going to call OSA, increases the risk for hypertension, bad cholesterol, and worsening blood glucose in terms of A1c and fasting glucose, which eventually leads to myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, stroke, and eventually cardiovascular death.

We also know that people with type 2 diabetes have an increased risk for OSA. There seems to be a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and OSA. It seems like weight plays the biggest role in terms of developing OSA, and numerous studies have shown this.

Also, thankfully, some of the studies showed that weight loss improves not just OSA but also blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose, and insulin sensitivities. These have been fascinating. We see these patients every single day. If you think about it in your population, for 50%-90% of the patients to have OSA is a large number. If you haven’t seen a person with OSA this week, you probably missed them, very likely.

Therefore, the SURMOUNT-OSA trial was quite fascinating with, as you mentioned, 50%-60% reduction in the severity of OSA, which is very impressive. Even more impressive, I think, is that for about 50% of the patients on tirzepatide, the OSA improves so much that they may not even need to be on CPAP machines.

Those who were on CPAP may not need to be on CPAP any longer. These are huge data, especially for primary care, because as you mentioned, we see these people every single day.

Dr. Jain: Thanks for pointing that out. Clearly, it’s very clinically relevant. I think the most important takeaway for me from this study was the correlation between weight loss and AHI improvement.

Clearly, it showed that placebo had about a 6% drop in AHI, whereas there was a 60% drop in the tirzepatide group, so you can see that it’s significantly different. The placebo group did not have any significant degree of weight loss, whereas the tirzepatide group had nearly 20% weight loss. This again goes to show that there is a very close correlation between weight loss and improvement in OSA.

What’s very important to note is that we’ve seen this in the past as well. We had seen some of these data with other GLP-1 agents, but the extent of improvement that we have seen in the SURMOUNT-OSA trial is significantly more than what we’ve seen in previous studies. There is a ray of hope now where we have medical management to offer people who are living with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea.

Dr. Kim: I want to add that, from a primary care perspective, this study also showed the improvement of the sleep apnea–related symptoms as well. The biggest problem with sleep apnea — or at least what patients’ spouses complain of, is the person snoring too much; it’s a symptom.

It’s the next-day symptoms that really do disturb people, like chronic fatigue. I have numerous patients who say that, once they’ve been treated for sleep apnea, they feel like a brand-new person. They have sudden bursts of energy that they never felt before, and over 50% of these people have huge improvements in the symptoms as well.

This is a huge trial. The only thing that I wish this study included were people with mild obstructive sleep apnea who were symptomatic. I do understand that, with other studies in this population, the data have been conflicting, but it would have been really awesome if they had those patients included. However, it is still a significant study for primary care.

Dr. Jain: That’s a really good point. Fatigue improves and overall quality of life improves. That’s very important from a primary care perspective.

From an endocrinology perspective, we know that management of sleep apnea can often lead to improvement in male hypogonadism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and insulin resistance. The amount of insulin required, or the number of medications needed for managing diabetes, can improve. Hypertension can improve as well. There are multiple benefits that you can get from appropriate management of sleep apnea.

Thanks, Dr. Kim. We really appreciate your insights on SURMOUNT-OSA.

Dr. Jain is a clinical instructor, Department of Endocrinology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver. Dr. Kim is a clinical assistant professor, Department of Family Medicine, University of Calgary in Alberta. Both disclosed conflicts of interest with numerous pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

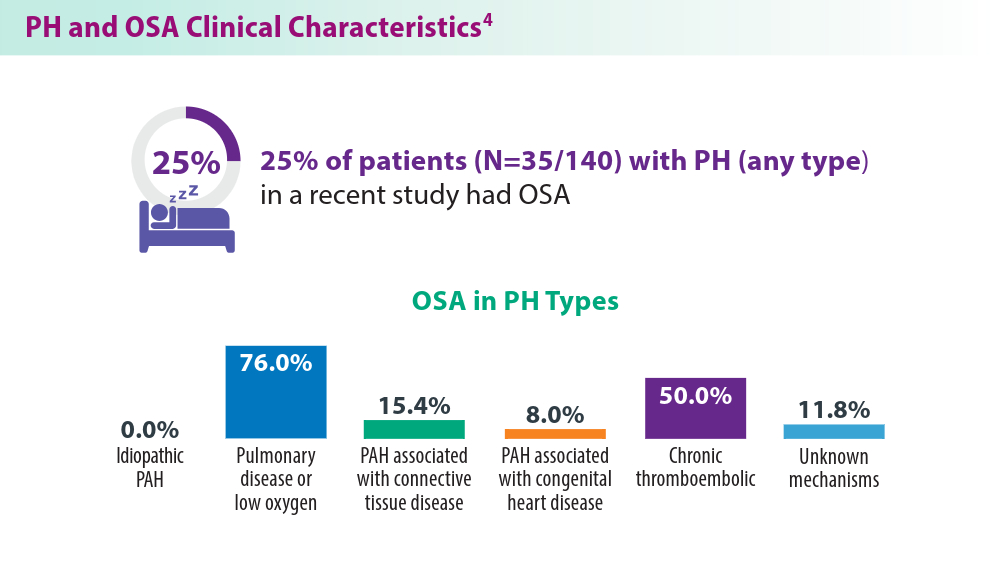

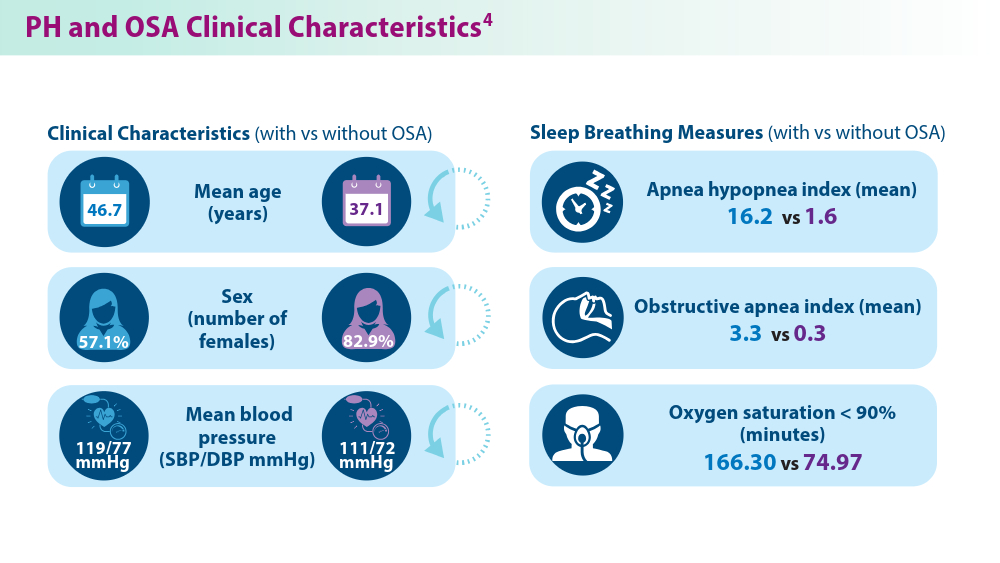

Pulmonary Hypertension: Comorbidities and Novel Therapeutics

- Cullivan S, Gaine S, Sitbon O. New trends in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220211. doi:10.1183/16000617.0211-2022

- Mocumbi A, Humbert M, Saxena A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension [published correction appears in Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):5]. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):1. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00486-7

- Lang IM, Palazzini M. The burden of comorbidities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21(suppl K):K21-K28. doi:10.1093/ eurheartj/suz205

- Yan L, Zhao Z, Zhao Q, et al. The clinical characteristics of patients with pulmonary hypertension combined with obstructive sleep apnoea. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):378. doi:10.1186/s12890-021-01755-5

- Hoeper MM, Badesch DB, Ghofrani HA, et al; for the STELLAR Trial Investigators. Phase 3 trial of sotatercept for treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(16):1478-1490. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2213558

- Grünig E, Jansa P, Fan F, et al. Randomized trial of macitentan/tadalafil single-tablet combination therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83(4):473-484. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.10.045

- Higuchi S, Horinouchi H, Aoki T, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty in the management of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Radiographics. 2022;42(6):1881-1896. doi:10.1148/rg.210102

- Cullivan S, Gaine S, Sitbon O. New trends in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir Rev. 2023;32(167):220211. doi:10.1183/16000617.0211-2022

- Mocumbi A, Humbert M, Saxena A, et al. Pulmonary hypertension [published correction appears in Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):5]. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):1. doi:10.1038/s41572-023-00486-7

- Lang IM, Palazzini M. The burden of comorbidities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2019;21(suppl K):K21-K28. doi:10.1093/ eurheartj/suz205