User login

Review of Ethnoracial Representation in Clinical Trials (Phases 1 Through 4) of Atopic Dermatitis Therapies

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

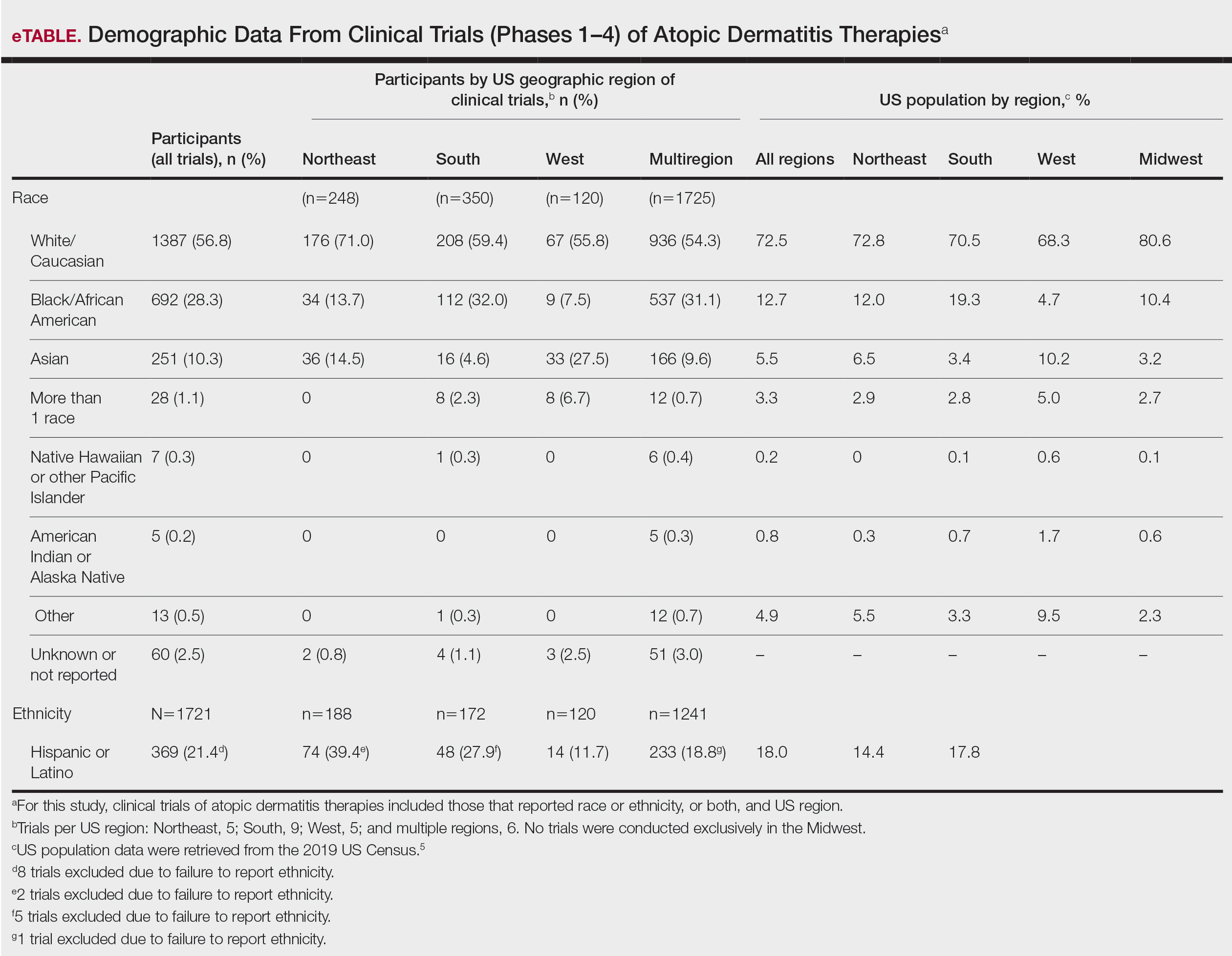

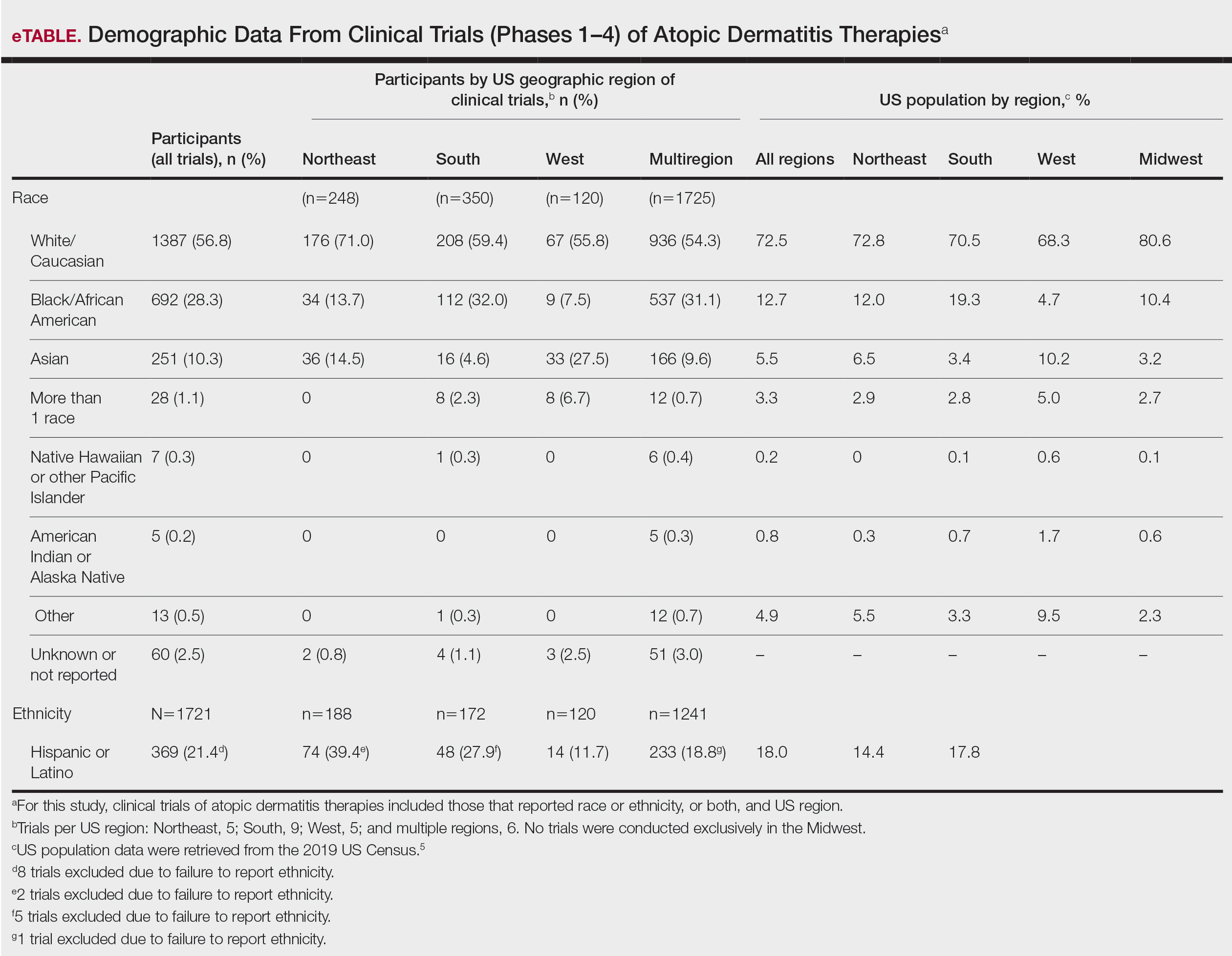

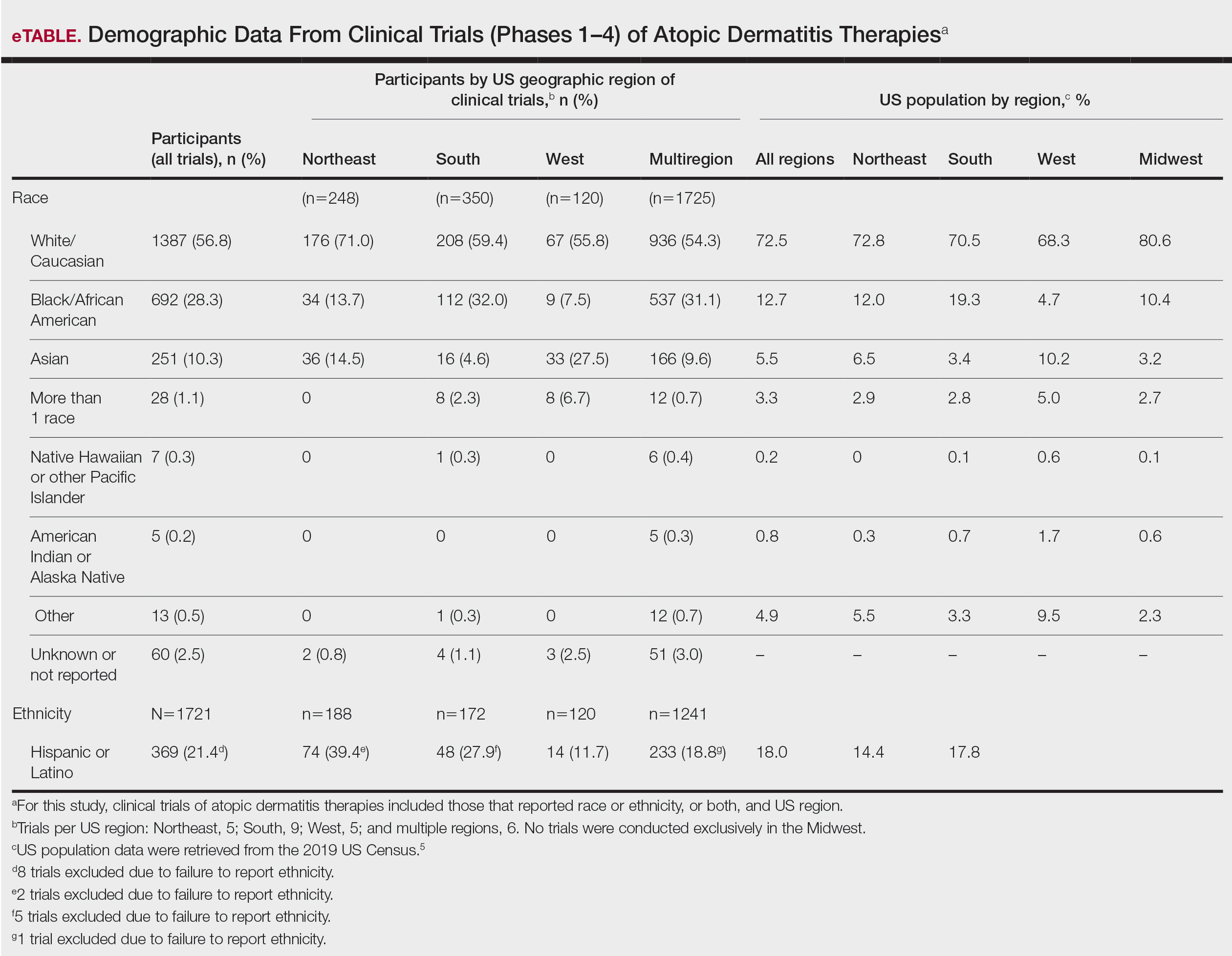

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

Practice Points

- Although minority groups are disproportionally affected by atopic dermatitis (AD), they may be underrepresented in clinical trials for AD in the United States.

- Equal representation among ethnoracial groups in clinical trials is important to allow for a more thorough investigation of the efficacy of treatments for AD.

When Are Inpatient and Emergency Dermatologic Consultations Appropriate?

There are limited clinical data concerning inpatient and emergency department (ED) dermatologic consultations. The indications for these consultations vary widely, but in one study (N=271), it was found that 21% of inpatient consultations were for contact dermatitis and 10% were for drug eruptions.1 In the same study, 77% of patients who required a dermatology consultation eventually were given a different diagnosis or change in treatment after consultation. For example, of all consultations for suspected cellulitis, only 10% were confirmed after dermatology evaluation.1

Hospitalists and emergency physicians continue to struggle with the assessment of dermatologic conditions, often consulting dermatology whenever a patient has a “rash” or skin concern. Dermatology is still not emphasized in medical education and often is taught to most medical students in an abbreviated fashion, which results in physicians feeling ill-equipped to deal with any dermatologic condition—either mundane or potentially life-threatening. A study in 2016 showed that a monthly lecture series given to hospitalists over the course of 5 years did not improve diagnostic accuracy in patients who were admitted with skin manifestations.2 This further shows that there is a need for dermatologic experts in the hospital.

We need to develop better guidelines for physicians in the ED and on inpatient units to guide them on appropriate use of dermatologic consultation outside the ambulatory office and the clinic. A 2013 study showed that patients often were discharged immediately after a dermatologic consultation, furthering our hypothesis that many inpatient consultations can be delayed until after discharge.3

In an era in which medical costs are soaring and there is constant surveillance for ways to reduce costs without impairing quality of care, limiting unnecessary specialty consultations should be embraced. In 2009, $1.8 billion in Medicare claims was paid for dermatology-related admissions.3 A substantial savings to Medicare consulting fees for certain diagnoses, such as cellulitis or contact dermatitis, could be realized if patients were referred for outpatient assessment and treatment. In a study of 271 consultations, 54 patients also had a skin biopsy, which further increases dollars spent on inpatient care and is (usually) something that can be performed in the outpatient setting.1 In another study, the more common recommended treatments were topical corticosteroids and supportive educational measures for patients and hospital staff,3 which further substantiates that most dermatology consultations are not truly emergent and can wait for outpatient consultation.

In addition, we are dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic in our hospitals and EDs. Many physicians, including dermatologists, would prefer to avoid unnecessary exposure to SARS-CoV-2 on inpatient units and in the ED. It certainly would be preferable to require consultants to come in to evaluate patients only when they truly need to be seen while in the hospital.

There also is limited dermatology training in other specialties, and the dermatology team can help fill this gap with educational programs and one-on-one teaching. Hospital teams have signaled this need, but there has been limited success with multiple teaching opportunities.4

We believe that this need for inpatient dermatology services can be filled with the newer subspecialty of hospital dermatology, which is not commonly present at most hospitals; a reason why the subspecialty has not been more popular is that there are few available data in the form of randomized clinical trials that can guide inpatient dermatologists with the care of rare hospital skin diseases.5 Having a dermatologic hospitalist available might allow for patients to be seen more readily, which ultimately will save lives and health care dollars and would increase real-time teaching and education for house staff, nursing, and attendings at the bedside.

In a 2018 article,6 it was postulated that quicker diagnosis of pseudocellulitis and initiation of antibiotics to treat this condition would save the US health care system $210 million annually. We believe that pseudocellulitis would be best evaluated by inpatient dermatology teams, thereby avoiding costly dermatologic consultations, at an average rate of $138.89.6

Morbilliform drug eruptions are among the most common skin conditions seen in the hospital; approximately 95% of cases are an uncomplicated reaction to a medication or virus. Data show that many of these consultations might be unnecessary.7

Our institution (Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey) is a tertiary hospital that also is connected with a major cancer center. Given this connection, skin eruptions due to chemotherapy and radiation are common. The treatment of drug eruptions, graft-vs-host disease, and other oncologic or drug-related eruptions should be within the scope of practice of our hospitalists, but these cases frequently involve dermatologic consultation.

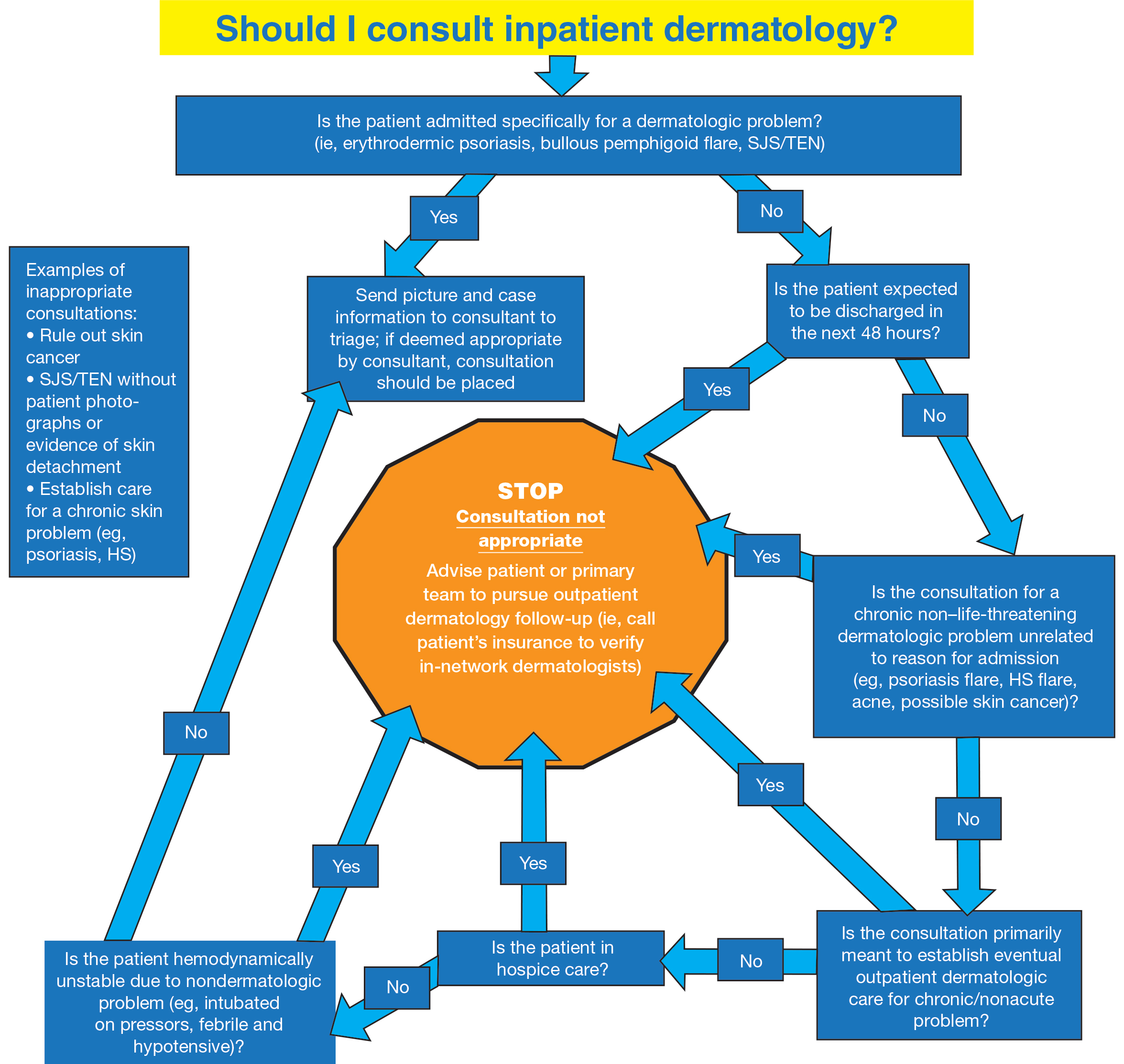

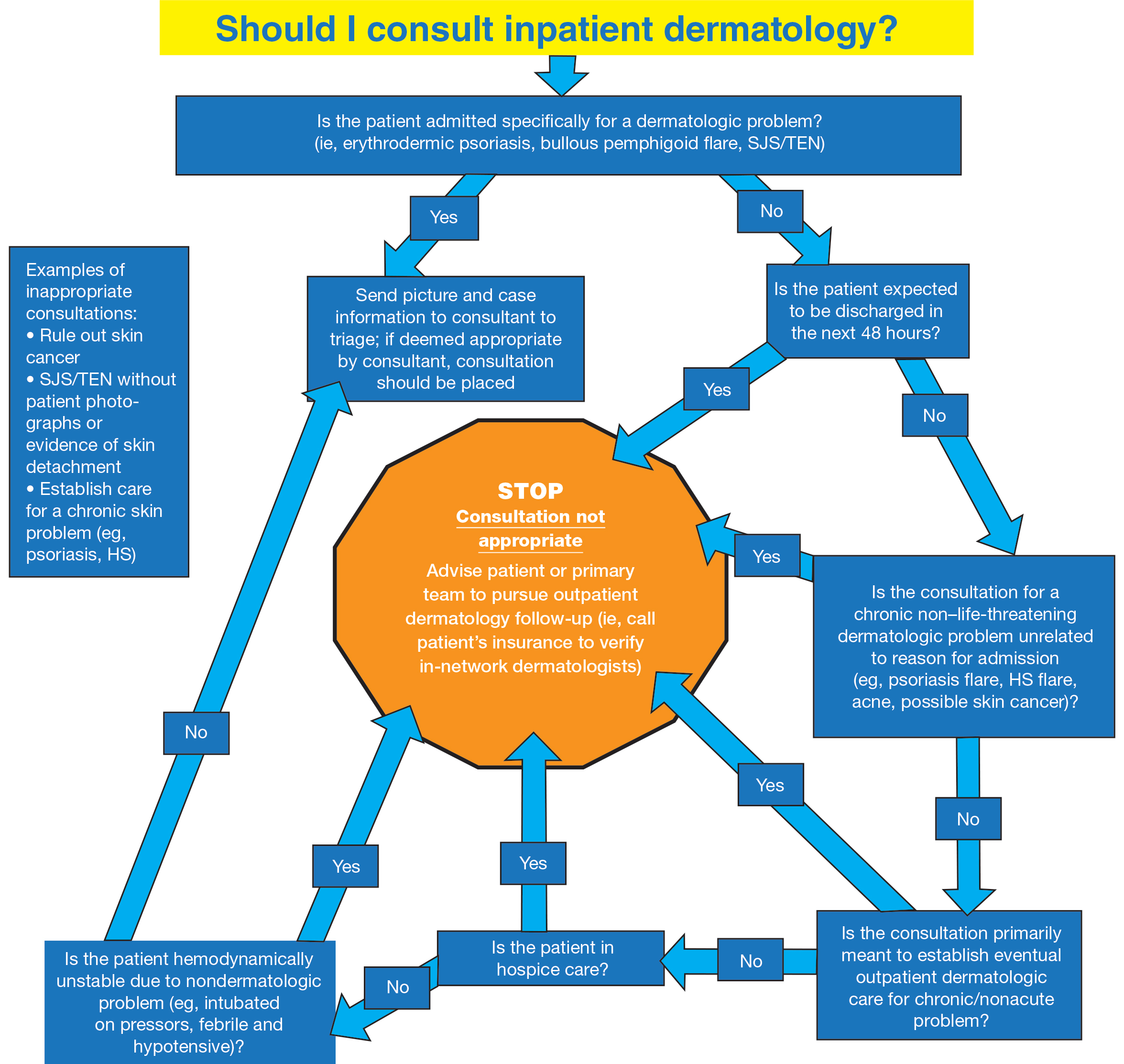

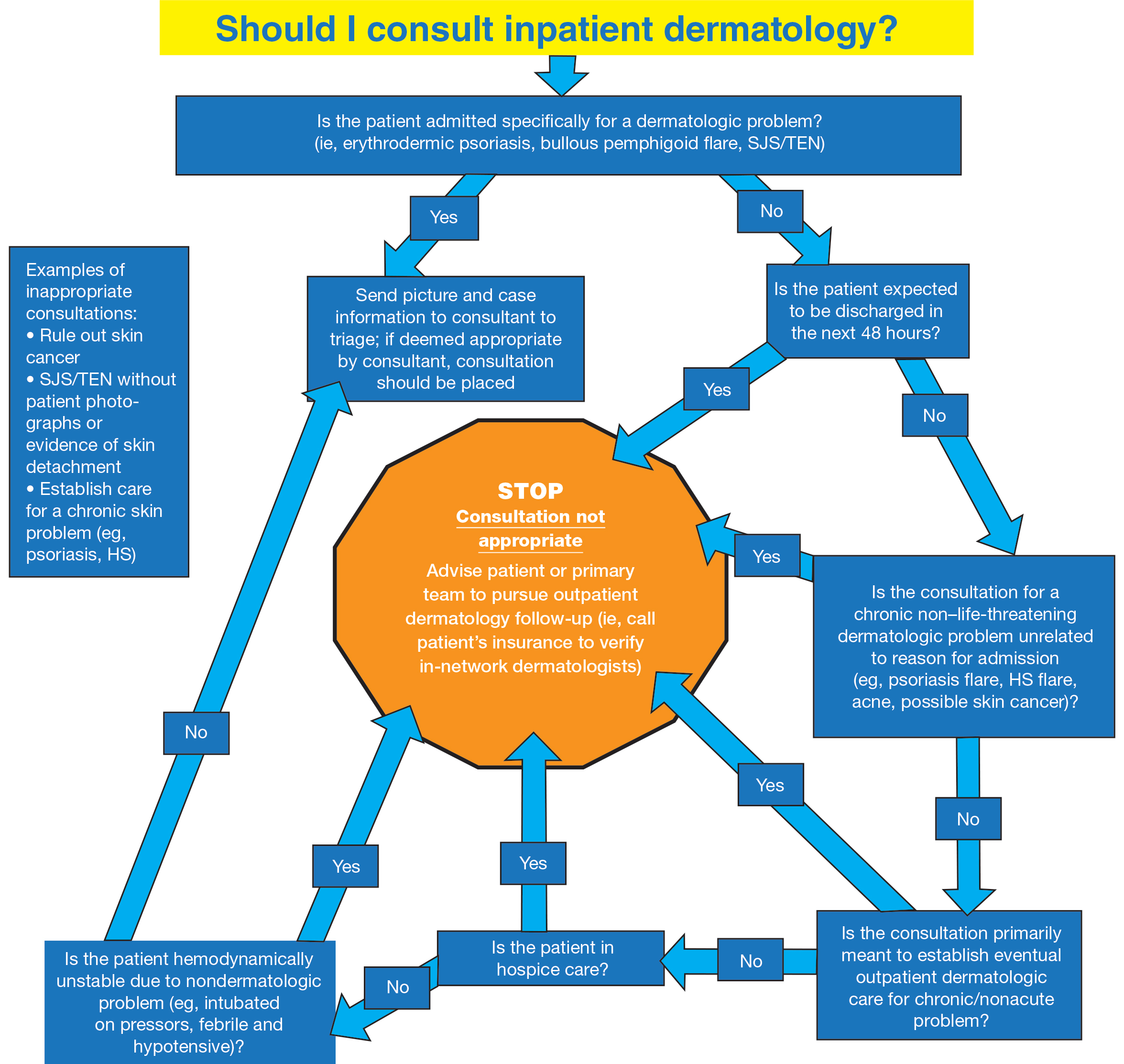

We constructed a consultation flowchart (Figure) to help guide the triage of patients in need of dermatologic evaluation by inpatient teams and possibly to avoid unnecessary consultation fees. The manner in which this—or any flowchart or teaching aid—is conveyed to hospital personnel is critical so that these tools are not perceived as patronizing or confrontational. In our flowchart, we list emergent dermatologic conditions that we believe are appropriate for dermatology consultation including erythrodermic psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid flare, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

We believe that the flowchart can educate inpatient medical teams about appropriate dermatology consultation. Use of the flowchart also may decrease unnecessary consultations, which ultimately will lower health care spending overall.

- Davila M, Christenson LJ, Sontheimer RD. Epidemiology and outcomes of dermatology in-patient consultations in a Midwestern U.S. university hospital. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Beshay A, Liu M, Fox L, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultative programs: a continued need, tools for needs assessment for curriculum development, and a call for new methods of teaching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:769-771. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.017

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Faletsky A, Han JJ, Mostaghimi A. Inpatient dermatology best practice strategies for educating and relaying findings to colleagues. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9:256-260. doi:10.1007/s13671-020-00317-y

- Fox LP. Hospital dermatology, introduction. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:1-2. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2017.015

- Li D, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Biesbroeck LK, Shinohara MM. Inpatient consultative dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1349-1364. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.06.004

There are limited clinical data concerning inpatient and emergency department (ED) dermatologic consultations. The indications for these consultations vary widely, but in one study (N=271), it was found that 21% of inpatient consultations were for contact dermatitis and 10% were for drug eruptions.1 In the same study, 77% of patients who required a dermatology consultation eventually were given a different diagnosis or change in treatment after consultation. For example, of all consultations for suspected cellulitis, only 10% were confirmed after dermatology evaluation.1

Hospitalists and emergency physicians continue to struggle with the assessment of dermatologic conditions, often consulting dermatology whenever a patient has a “rash” or skin concern. Dermatology is still not emphasized in medical education and often is taught to most medical students in an abbreviated fashion, which results in physicians feeling ill-equipped to deal with any dermatologic condition—either mundane or potentially life-threatening. A study in 2016 showed that a monthly lecture series given to hospitalists over the course of 5 years did not improve diagnostic accuracy in patients who were admitted with skin manifestations.2 This further shows that there is a need for dermatologic experts in the hospital.

We need to develop better guidelines for physicians in the ED and on inpatient units to guide them on appropriate use of dermatologic consultation outside the ambulatory office and the clinic. A 2013 study showed that patients often were discharged immediately after a dermatologic consultation, furthering our hypothesis that many inpatient consultations can be delayed until after discharge.3

In an era in which medical costs are soaring and there is constant surveillance for ways to reduce costs without impairing quality of care, limiting unnecessary specialty consultations should be embraced. In 2009, $1.8 billion in Medicare claims was paid for dermatology-related admissions.3 A substantial savings to Medicare consulting fees for certain diagnoses, such as cellulitis or contact dermatitis, could be realized if patients were referred for outpatient assessment and treatment. In a study of 271 consultations, 54 patients also had a skin biopsy, which further increases dollars spent on inpatient care and is (usually) something that can be performed in the outpatient setting.1 In another study, the more common recommended treatments were topical corticosteroids and supportive educational measures for patients and hospital staff,3 which further substantiates that most dermatology consultations are not truly emergent and can wait for outpatient consultation.

In addition, we are dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic in our hospitals and EDs. Many physicians, including dermatologists, would prefer to avoid unnecessary exposure to SARS-CoV-2 on inpatient units and in the ED. It certainly would be preferable to require consultants to come in to evaluate patients only when they truly need to be seen while in the hospital.

There also is limited dermatology training in other specialties, and the dermatology team can help fill this gap with educational programs and one-on-one teaching. Hospital teams have signaled this need, but there has been limited success with multiple teaching opportunities.4

We believe that this need for inpatient dermatology services can be filled with the newer subspecialty of hospital dermatology, which is not commonly present at most hospitals; a reason why the subspecialty has not been more popular is that there are few available data in the form of randomized clinical trials that can guide inpatient dermatologists with the care of rare hospital skin diseases.5 Having a dermatologic hospitalist available might allow for patients to be seen more readily, which ultimately will save lives and health care dollars and would increase real-time teaching and education for house staff, nursing, and attendings at the bedside.

In a 2018 article,6 it was postulated that quicker diagnosis of pseudocellulitis and initiation of antibiotics to treat this condition would save the US health care system $210 million annually. We believe that pseudocellulitis would be best evaluated by inpatient dermatology teams, thereby avoiding costly dermatologic consultations, at an average rate of $138.89.6

Morbilliform drug eruptions are among the most common skin conditions seen in the hospital; approximately 95% of cases are an uncomplicated reaction to a medication or virus. Data show that many of these consultations might be unnecessary.7

Our institution (Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey) is a tertiary hospital that also is connected with a major cancer center. Given this connection, skin eruptions due to chemotherapy and radiation are common. The treatment of drug eruptions, graft-vs-host disease, and other oncologic or drug-related eruptions should be within the scope of practice of our hospitalists, but these cases frequently involve dermatologic consultation.

We constructed a consultation flowchart (Figure) to help guide the triage of patients in need of dermatologic evaluation by inpatient teams and possibly to avoid unnecessary consultation fees. The manner in which this—or any flowchart or teaching aid—is conveyed to hospital personnel is critical so that these tools are not perceived as patronizing or confrontational. In our flowchart, we list emergent dermatologic conditions that we believe are appropriate for dermatology consultation including erythrodermic psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid flare, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

We believe that the flowchart can educate inpatient medical teams about appropriate dermatology consultation. Use of the flowchart also may decrease unnecessary consultations, which ultimately will lower health care spending overall.

There are limited clinical data concerning inpatient and emergency department (ED) dermatologic consultations. The indications for these consultations vary widely, but in one study (N=271), it was found that 21% of inpatient consultations were for contact dermatitis and 10% were for drug eruptions.1 In the same study, 77% of patients who required a dermatology consultation eventually were given a different diagnosis or change in treatment after consultation. For example, of all consultations for suspected cellulitis, only 10% were confirmed after dermatology evaluation.1

Hospitalists and emergency physicians continue to struggle with the assessment of dermatologic conditions, often consulting dermatology whenever a patient has a “rash” or skin concern. Dermatology is still not emphasized in medical education and often is taught to most medical students in an abbreviated fashion, which results in physicians feeling ill-equipped to deal with any dermatologic condition—either mundane or potentially life-threatening. A study in 2016 showed that a monthly lecture series given to hospitalists over the course of 5 years did not improve diagnostic accuracy in patients who were admitted with skin manifestations.2 This further shows that there is a need for dermatologic experts in the hospital.

We need to develop better guidelines for physicians in the ED and on inpatient units to guide them on appropriate use of dermatologic consultation outside the ambulatory office and the clinic. A 2013 study showed that patients often were discharged immediately after a dermatologic consultation, furthering our hypothesis that many inpatient consultations can be delayed until after discharge.3

In an era in which medical costs are soaring and there is constant surveillance for ways to reduce costs without impairing quality of care, limiting unnecessary specialty consultations should be embraced. In 2009, $1.8 billion in Medicare claims was paid for dermatology-related admissions.3 A substantial savings to Medicare consulting fees for certain diagnoses, such as cellulitis or contact dermatitis, could be realized if patients were referred for outpatient assessment and treatment. In a study of 271 consultations, 54 patients also had a skin biopsy, which further increases dollars spent on inpatient care and is (usually) something that can be performed in the outpatient setting.1 In another study, the more common recommended treatments were topical corticosteroids and supportive educational measures for patients and hospital staff,3 which further substantiates that most dermatology consultations are not truly emergent and can wait for outpatient consultation.

In addition, we are dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic in our hospitals and EDs. Many physicians, including dermatologists, would prefer to avoid unnecessary exposure to SARS-CoV-2 on inpatient units and in the ED. It certainly would be preferable to require consultants to come in to evaluate patients only when they truly need to be seen while in the hospital.

There also is limited dermatology training in other specialties, and the dermatology team can help fill this gap with educational programs and one-on-one teaching. Hospital teams have signaled this need, but there has been limited success with multiple teaching opportunities.4

We believe that this need for inpatient dermatology services can be filled with the newer subspecialty of hospital dermatology, which is not commonly present at most hospitals; a reason why the subspecialty has not been more popular is that there are few available data in the form of randomized clinical trials that can guide inpatient dermatologists with the care of rare hospital skin diseases.5 Having a dermatologic hospitalist available might allow for patients to be seen more readily, which ultimately will save lives and health care dollars and would increase real-time teaching and education for house staff, nursing, and attendings at the bedside.

In a 2018 article,6 it was postulated that quicker diagnosis of pseudocellulitis and initiation of antibiotics to treat this condition would save the US health care system $210 million annually. We believe that pseudocellulitis would be best evaluated by inpatient dermatology teams, thereby avoiding costly dermatologic consultations, at an average rate of $138.89.6

Morbilliform drug eruptions are among the most common skin conditions seen in the hospital; approximately 95% of cases are an uncomplicated reaction to a medication or virus. Data show that many of these consultations might be unnecessary.7

Our institution (Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey) is a tertiary hospital that also is connected with a major cancer center. Given this connection, skin eruptions due to chemotherapy and radiation are common. The treatment of drug eruptions, graft-vs-host disease, and other oncologic or drug-related eruptions should be within the scope of practice of our hospitalists, but these cases frequently involve dermatologic consultation.

We constructed a consultation flowchart (Figure) to help guide the triage of patients in need of dermatologic evaluation by inpatient teams and possibly to avoid unnecessary consultation fees. The manner in which this—or any flowchart or teaching aid—is conveyed to hospital personnel is critical so that these tools are not perceived as patronizing or confrontational. In our flowchart, we list emergent dermatologic conditions that we believe are appropriate for dermatology consultation including erythrodermic psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid flare, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis.

We believe that the flowchart can educate inpatient medical teams about appropriate dermatology consultation. Use of the flowchart also may decrease unnecessary consultations, which ultimately will lower health care spending overall.

- Davila M, Christenson LJ, Sontheimer RD. Epidemiology and outcomes of dermatology in-patient consultations in a Midwestern U.S. university hospital. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Beshay A, Liu M, Fox L, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultative programs: a continued need, tools for needs assessment for curriculum development, and a call for new methods of teaching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:769-771. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.017

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Faletsky A, Han JJ, Mostaghimi A. Inpatient dermatology best practice strategies for educating and relaying findings to colleagues. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9:256-260. doi:10.1007/s13671-020-00317-y

- Fox LP. Hospital dermatology, introduction. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:1-2. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2017.015

- Li D, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Biesbroeck LK, Shinohara MM. Inpatient consultative dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1349-1364. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.06.004

- Davila M, Christenson LJ, Sontheimer RD. Epidemiology and outcomes of dermatology in-patient consultations in a Midwestern U.S. university hospital. Dermatol Online J. 2010;16:12.

- Beshay A, Liu M, Fox L, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultative programs: a continued need, tools for needs assessment for curriculum development, and a call for new methods of teaching. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:769-771. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.11.017

- Hu L, Haynes H, Ferrazza D, et al. Impact of specialist consultations on inpatient admissions for dermatology-specific and related DRGs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1477-1482. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2440-2

- Faletsky A, Han JJ, Mostaghimi A. Inpatient dermatology best practice strategies for educating and relaying findings to colleagues. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2020;9:256-260. doi:10.1007/s13671-020-00317-y

- Fox LP. Hospital dermatology, introduction. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:1-2. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2017.015

- Li D, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.6197

- Biesbroeck LK, Shinohara MM. Inpatient consultative dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1349-1364. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.06.004

Practice Points

- Primary inpatient teams should call patients’ insurance companies to verify in-network dermatologists for eventual outpatient follow-up.

- Chronic skin problems (eg, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa) are better cared for in an outpatient setting due to the necessity for follow-up reassessments.

- There remains a need to fill knowledge gaps for common inpatient dermatologic problems that do not necessitate consultations, such as morbilliform drug rash and other chronic and unchanged dermatoses.

Tinted Sunscreens: Consumer Preferences Based on Light, Medium, and Dark Skin Tones

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

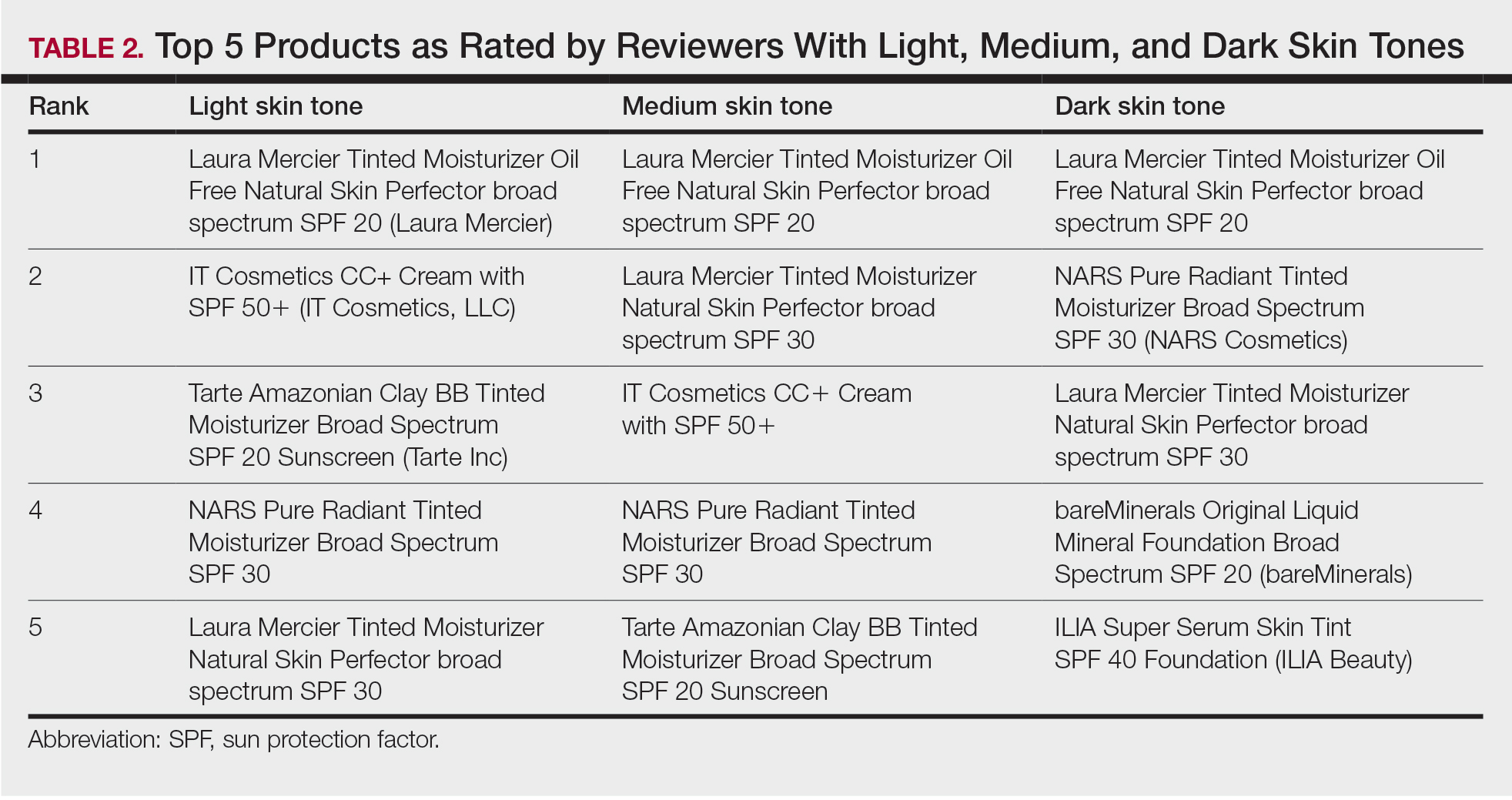

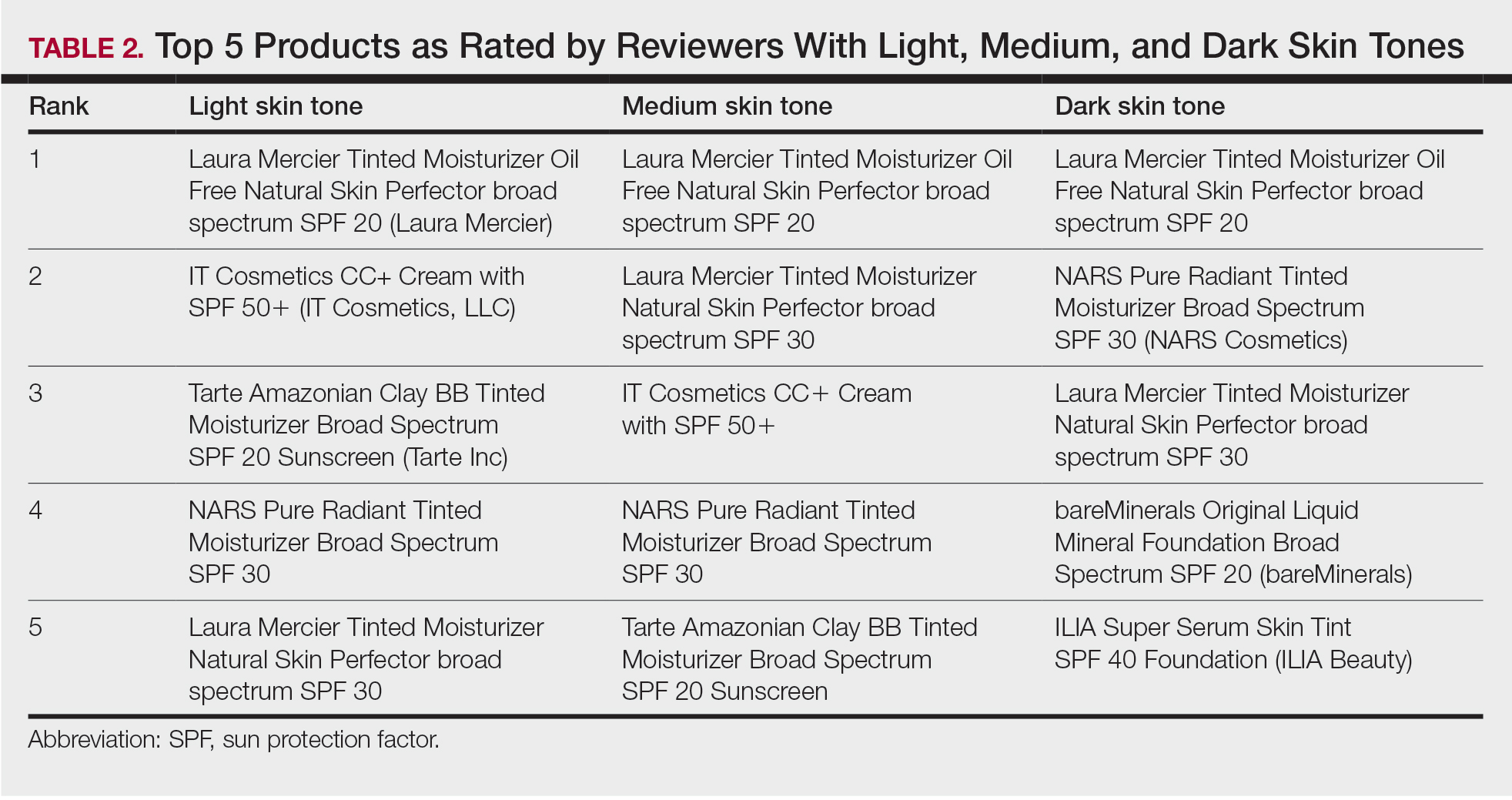

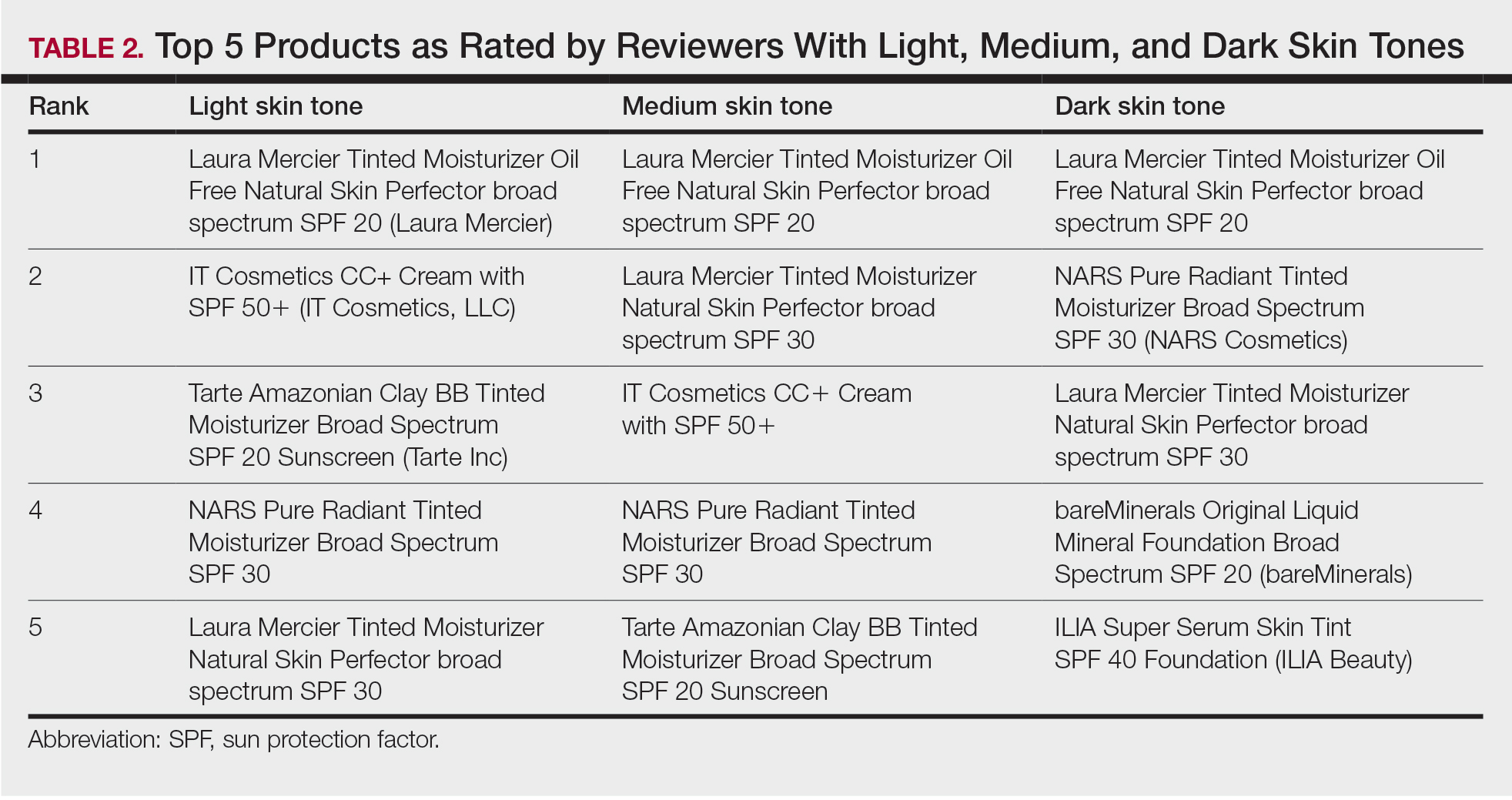

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment

Tone Compatibility—Tinted sunscreens were created to extend the range of photoprotection into the VL spectrum. The goal of TSs is to incorporate pigments that blend in with the natural skin tone, produce a glow, and have an aesthetically pleasing appearance. To accommodate a variety of skin colors, different shades can be obtained by mixing different amounts of yellow, red, and black IO with or without PTD. The pigments and reflective compounds provide color, opacity, and a natural coverage. Our qualitative analysis provides information on the lack of diversity among shades available for TS, especially for darker skin tones. Of the 58 products evaluated, 62% (32/58) only had 1 shade. In our cohort, tone compatibility was the most commonly cited negative feature. Of note, 89% of these comments were from consumers with dark skin tones, and there was a disproportional number of reviews by darker-skinned individuals compared to users with light and medium skin tones. This is of particular importance, as TSs have been shown to protect against dermatoses that disproportionally affect individuals with skin of color. When comparing sunscreen formulations containing IO with regular mineral sunscreens, Dumbuya et al3 found that IO-containing formulations significantly protected against VL-induced pigmentation compared with untreated skin or mineral sunscreen with SPF 50 or higher in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin type IV (P<.001). Similarly, Bernstein et al8 found that exposing patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV to blue-violet light resulted in marked hyperpigmentation that lasted up to 3 months. Visible light elicits immediate and persistent pigment darkening in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin phototype III and above via the photo-oxidation of pre-existing melanin and de novo melanogenesis.9 Tinted sunscreens formulated with IO have been shown to aid in the treatment of melasma and prevent hyperpigmentation in individuals with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.10 Patients with darker skin tones with dermatoses aggravated or induced by VL, such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, may seek photoprotection provided by TS but find the lack of matching shades unappealing. The dearth of shade diversity that matches all skin tones can lead to inequities and disproportionally affect those with darker skin.

Performance—Tinted sunscreen formulations containing IO have been proven effective in protecting against high-energy VL, especially when combined synergistically with ZO.11 Kaye et al12 found that TSs containing IO and the inorganic filters TD or ZO reduced transmittance of VL more effectively than nontinted sunscreens containing TD or ZO alone or products containing organic filters. The decreased VL transmittance in the former is due to synergistic effects of the VL-scattering properties of the TD and the VL absorption properties of the IO. Similarly, Sayre et al13 demonstrated that IO was superior to TD and ZO in attenuating the transmission of VL. Bernstein et al14 found that darker shades containing higher percentages of IO increased the attenuation of VL to 98% compared with lighter shades attenuating 93%. This correlates with the results of prior studies highlighting the potential of TSs in protecting individuals with skin of color.3 In our cohort, comments regarding product performance and protection were mostly positive, claiming that consistent use reduced hyperpigmentation on the skin surface, giving the appearance of a more even skin tone.

Tolerability—Iron oxides are minerals known to be safe, gentle, and nontoxic on the surface of the skin.15 Two case reports of contact dermatitis due to IO have been reported.16,17 Within our cohort, only a few of the comments (6%) described negative product tolerance or compatibility with their skin type. However, it is more likely that these incompatibilities were due to other ingredients in the product or the individuals’ underlying dermatologic conditions.

Cosmetic Elegance—Most of the sunscreens available on the market today contain micronized forms of TD and ZO particles because they have better cosmetic acceptability.18 However, their reduced size compromises the protection provided against VL whereby the addition of IO is of vital importance. According to the RealSelf Sun Safety Report, only 11% of Americans wear sunscreen daily, and 46% never wear sunscreen.19 The most common reasons consumers reported for not wearing sunscreen included not liking how it looks on the skin, forgetting to apply it, and/or believing that application is inconvenient and time-consuming. Currently, TSs have been incorporated into daily-life products such as makeup, moisturizers, and serums, making application for users easy and convenient, decreasing the necessity of using multiple products, and offering the opportunity to choose from different presentations to make decisions for convenience and/or diverse occasions. Products containing IO blend in with the natural skin tone and have an aesthetically pleasing cosmetic appearance. In our cohort, comments regarding cosmetic elegance were highly valued and were present in multiple reviews (45%), with 69% being positive.

Affordability—In our cohort, product price was not predominantly mentioned in consumers’ reviews. However, negative comments regarding affordability were slightly higher than the positive (56% vs 44%). Notably, the mean price of our top recommendations was $42. Higher price was associated with products with a wider range of shades available. Prior studies have found similar results demonstrating that websites with recommendations on sunscreens for patients with skin of color compared with sunscreens for white or fair skin were more likely to recommend more expensive products (median, $14/oz vs $11.3/oz) despite the lower SPF level.20 According to Schneider,21 daily use of the cheapest sunscreen on the head/neck region recommended for white/pale skin ($2/oz) would lead to an annual cost of $61 compared to $182 for darker skin ($6/oz). This showcases the considerable variation in sunscreen prices for both populations that could potentiate disparities and vulnerability in the latter group.

Conclusion

Tinted sunscreens provide both functional and cosmetic benefits and are a safe, effective, and convenient way to protect against high-energy VL. This study suggests that patients with skin of color encounter difficulties in finding matching shades in TS products. These difficulties may stem from the lack of knowledge regarding dark complexions and undertones and the lack of representation of black and brown skin that has persisted in dermatology research journals and textbooks for decades.22 Our study provides important insights to help dermatologists improve their familiarity with the brands and characteristics of TSs geared to patients with all skin tones, including skin of color. Limitations include single-retailer information and inclusion of both highly and poorly rated comments with subjective data, limiting generalizability. The limited selection of shades for darker skin poses a roadblock to proper treatment and prevention. These data represent an area for improvement within the beauty industry and the dermatologic field to deliver culturally sensitive care by being knowledgeable about darker skin tones and TS formulations tailored to people with skin of color.

- McDaniel D, Farris P, Valacchi G. Atmospheric skin aging-contributors and inhibitors. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:124-137.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Dumbuya H, Grimes PE, Lynch S, et al. Impact of iron-oxide containing formulations against visible light-induced skin pigmentation in skin of color individuals. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:712-717.

- Lyons AB, Trullas C, Kohli I, et al. Photoprotection beyond ultraviolet radiation: a review of tinted sunscreens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1393-1397.

- Austin E, Huang A, Adar T, et al. Electronic device generated light increases reactive oxygen species in human fibroblasts [published online February 5, 2018]. Lasers Surg Med. doi:10.1002/lsm.22794

- Randhawa M, Seo I, Liebel F, et al. Visible light induces melanogenesis in human skin through a photoadaptive response. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130949.

- Yeager DG, Lim HW. What’s new in photoprotection: a review of new concepts and controversies. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:149-157.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P. Iron oxides in novel skin care formulations attenuate blue light for enhanced protection against skin damage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:532-537.

- Duteil L, Cardot-Leccia N, Queille-Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light-induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:822-826.

- Ruvolo E, Fair M, Hutson A, et al. Photoprotection against visible light-induced pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:589-595.

- Cohen L, Brodsky MA, Zubair R, et al. Cutaneous interaction with visible light: what do we know. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;S0190-9622(20)30551-X.

- Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, et al. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:351-355.

- Sayre RM, Kollias N, Roberts RL, et al. Physical sunscreens. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1990;41:103-109.

- Bernstein EF, Sarkas HW, Boland P, et al. Beyond sun protection factor: an approach to environmental protection with novel mineral coatings in a vehicle containing a blend of skincare ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:407-415.

- MacLeman E. Why are iron oxides used? Deep Science website. February 10, 2022. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://thedermreview.com/iron-oxides-ci-77491-ci-77492-ci-77499/

- Zugerman C. Contact dermatitis to yellow iron oxide. Contact Dermatitis. 1985;13:107-109.

- Saxena M, Warshaw E, Ahmed DD. Eyelid allergic contact dermatitis to black iron oxide. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001;12:38-39.

- Smijs TG, Pavel S. Titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles in sunscreens: focus on their safety and effectiveness. Nanotechnol Sci Appl. 2011;4:95-112.

- 2020 RealSelf Sun Safety Report: majority of Americans don’t use sunscreen daily. Practical Dermatology. May 6, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://practicaldermatology.com/news/realself-sun-safety-report-majority-of-americans-dont-use-sunscreen-daily

- Song H, Beckles A, Salian P, et al. Sunscreen recommendations for patients with skin of color in the popular press and in the dermatology clinic. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020;7:165-170.

- Schneider J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Nelson B. How dermatology is failing melanoma patients with skin of color: unanswered questions on risk and eye-opening disparities in outcomes are weighing heavily on melanoma patients with darker skin. in this article, part 1 of a 2-part series, we explore the deadly consequences of racism and inequality in cancer care. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128:7-8.

Sunscreen formulations typically protect from UV radiation (290–400 nm), as this is a well-established cause of photodamage, photoaging, and skin cancer.1 However, sunlight also consists of visible (400–700 nm) and infrared (>700 nm) radiation.2 In fact, UV radiation only comprises 5% to 7% of the solar radiation that reaches the surface of the earth, while visible and infrared lights comprise 44% and 53%, respectively.3 Visible light (VL) is the only portion of the solar spectrum visible to the human eye; it penetrates the skin to a depth range of 90 to 750 µm compared to 1.5 to 90 µm for UV radiation.4 Visible light also may come from artificial sources such as light bulbs and digital screens. The rapidly increasing use of smartphones, tablets, laptops, and other digital screens that emit high levels of short-wavelength VL has increased concerns about the safety of these devices. Although blue light exposure from screens is small compared with the amount of exposure from the sun, there is concern about the long-term effects of excessive screen time. Recent studies have demonstrated that exposure to light emitted from electronic devices, even for as little as 1 hour, may cause reactive oxygen species generation, apoptosis, collagen degradation, and necrosis of skin cells.5 Visible light increases tyrosinase activity and induces immediate erythema in light-skinned individuals and long-lasting pigmentation in dark-skinned individuals.4,6

Sunscreens consist of chemical and mineral active ingredients that contain UV filters designed to absorb, scatter, and reflect UV photons with wavelengths up to 380 nm. Historically, traditional options do not protect against the effects induced by VL, as these sunscreens use nanosized particles that help to reduce the white appearance and result in transparency of the product.7 To block VL, the topical agent must be visible. Tinted sunscreens (TSs) are products that combine UV and VL filters. They give a colored base coverage that is achieved by incorporating a blend of black, red, and yellow iron oxides (IOs) and/or pigmentary titanium dioxide (PTD)(ie, titanium dioxide [TD] that is not nanosized). Because TSs offer an instant glow and protect the skin from both sun and artificial light, they have become increasingly popular and have been incorporated into makeup and skin care products to facilitate daily convenient use.

The purpose of this analysis was to study current available options and product factors that may influence consumer preference when choosing a TS based on the reviewer characteristics.

Methods

The keyword sunscreen was searched in the broader category of skin care products on an online supplier of sunscreens (www.sephora.com). This supplier was chosen because, unlike other sources, specific reviewer characteristics regarding underlying skin tone also were available. The search produced 161 results. For the purpose of this analysis, only facial TSs containing IO and/or PTD were included. Each sunscreen was checked by the authors, and 58 sunscreens that met the inclusion criteria were identified and further reviewed. Descriptive data, including formulation, sun protection factor (SPF), ingredient type (chemical or physical), pigments used, shades available, additional benefits, price range, rating, and user reviews, were gathered. The authors extracted these data from the product information on the website, manufacturer claims, ratings, and reviewer comments on each of the listed sunscreens.

For each product, the content of the top 10 most helpful positive and negative reviews as voted by consumers (1160 total reviews, consisting of 1 or more comments) was analyzed. Two authors (H.D.L.G. and P.V.) coded consumer-reported comments for positive and negative descriptors into the categories of cosmetic elegance, performance, skin compatibility and tolerance, tone compatibility, and affordability. Cosmetic elegance was defined as any feature associated with skin sensation (eg, greasy), color (eg, white cast), scent, ability to blend, and overall appearance of the product on the skin. Product performance included SPF, effectiveness in preventing sunburn, coverage, and finish claims (ie, matte, glow, invisible). Skin compatibility and tolerance were represented in the reviewers’ comments and reflected how the product performed in association with underlying dermatologic conditions, skin type, and if there were any side effects such as irritation or allergic reactions. Tone compatibility referred to TS color similarity with users’ skin and shades available for individual products. Affordability reflected consumers’ perceptions of the product price. Comments may be included in multiple categories (eg, a product was noted to blend well on the skin but did not provide enough coverage). Of entries, 10% (116/1160 reviews) were coded by first author (H.D.L.G.) to ensure internal validity. Reviewer characteristics were consistently available and were used to determine the top 5 recommended products for light-, medium-, and dark-skinned individuals based on the number of 5-star ratings in each group. Porcelain, fair, and light were considered light skin tones. Medium, tan, and olive were considered medium skin tones. Deep, dark, and ebony were considered dark skin tones.

Results

Sunscreen Characteristics—Among the 161 screened products, 58 met the inclusion criteria. Four types of formulations were included: lotion, cream, liquid, and powder. Twenty-nine (50%) were creams, followed by lotions (19%), liquids (28%), and powders (3%). More than 79% (46/58) of products had a reported SPF of 30 or higher. Sunscreens with an active physical ingredient—the minerals TD and/or zinc oxide (ZO)—were most common (33/58 [57%]), followed by the chemical sunscreens avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, homosalate, octisalate, and/or octocrylene active ingredients (14/58 [24%]), and a combination of chemical and physical sunscreens (11/58 [19%]). Nearly all products (55/58 [95%]) contained pigmentary IO (red, CI 77491; yellow, CI 77492; black, CI 77499). Notably, only 38% (22/58) of products had more than 1 shade. All products had additional claims associated with being hydrating, having antiaging effects, smoothing texture, minimizing the appearance of pores, softening lines, and/or promoting even skin tone. Traditional physical sunscreens (those containing TD and/or ZO) were more expensive than chemical sunscreens, with a median price of $30. The median review rating was 4.5 of 5 stars, with a median of 2300 customer reviews per product. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

Positive Features of Sunscreens—Based on an analysis of total reviews (N=1160), cosmetic elegance was the most cited positive feature associated with TS products (31%), followed by product performance (10%). Skin compatibility and tolerance (7%), tone compatibility (7%), and affordability (7%) were cited less commonly as positive features. When negative features were cited, consumers mostly noted tone incompatibility (16%) and cosmetic elegance concerns (14%). Product performance (13%) was comparatively cited as a negative feature (Table 1). Exemplary positive comments categorized in cosmetic elegance included the subthemes of rubs in well and natural glow. Exemplary negative comments in cosmetic elegance and tone compatibility categories included the subthemes patchy/dry finish and color mismatch. Table 1 illustrates these findings.

Product Recommendations—The top 5 recommendations of the best TS for each skin tone are listed in Table 2. The mean price of the recommended products was $42 for 1 to 1.9 oz. Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20 (Laura Mercier) was the top product for all 3 groups. Similarly, of 58 products available, the same 5 products—Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Oil Free Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 20, IT Cosmetics CC+ Cream with SPF 50 (IT Cosmetics, LLC), Tarte Amazonian Clay BB Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 20 (Tarte Cosmetics), NARS Pure Radiant Tinted Moisturizer Broad Spectrum SPF 30 (NARS Cosmetics), and Laura Mercier Tinted Moisturizer Natural Skin Perfector broad spectrum SPF 30—were considered the best among consumers of all skin tones, with the addition of 2 different products (bareMinerals Original Liquid Mineral Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 [bareMinerals] and ILIA Super Serum Skin Tint SPF 40 Foundation [ILIA Beauty]) in the dark skin group. Notably, these products were the only ones on Sephora’s website that offered up to 30 (22 on average) different shades.

Comment