User login

A COVID-19 Clinical Management Committee to Standardize Care in a 2-Hospital System

From the Department of Medicine (Drs. Meisenberg, Muganlinskaya, Sharma, Amjadi, Arnold, Barnes, Clance, Khalil, Miller, Mooradian, O’Connell, Patel, Press, Samaras, Shanmugam, Tavadze, and Thompson), Department of Pharmacy (Drs. Jiang, Jarawan, Sheth, and Trinh), Department of Nursing (Dr. Ohnmacht), and Department of Women and Children’s Services (Dr. Raji), Luminis Health, Annapolis, MD, and Lanham, MD.

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenge for hospital medical staffs worldwide due to high volumes of patients acutely ill with novel syndromes and prevailing uncertainty regarding optimum supportive and therapeutic interventions. Additionally, the response to this crisis was driven by a plethora of nontraditional information sources, such as email chains, websites, non–peer-reviewed preprints, and press releases. Care patterns became idiosyncratic and often incorporated unproven interventions driven by these nontraditional information sources. This report evaluates the efforts of a health system to create and empower a multidisciplinary committee to develop, implement, and monitor evidence-based, standardized protocols for patients with COVID-19.

Methods: This report describes the composition of the committee, its scope, and its important interactions with the health system pharmacy and therapeutics committee, research teams, and other work groups planning other aspects of COVID-19 management. It illustrates how the committee was used to demonstrate for trainees the process and value of critically examining evidence, even in a chaotic environment.

Results: Data show successful interventions in reducing excessive ordering of certain laboratory tests, reduction of nonrecommended therapies, and rapid uptake of evidence-based or guidelines-supported interventions.

Conclusions: A multidisciplinary committee dedicated solely to planning, implementing, and monitoring standard approaches that eventually became evidence-based decision-making led to an improved focus on treatment options and outcomes for COVID-19 patients. Data presented illustrate the attainable success that is both adaptable and suitable for similar emergencies in the future.

Keywords: COVID-19; clinical management; pharmacy and therapeutics; treatment; therapy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread to nearly all countries, carrying with it high morbidity, mortality, and severe impacts on both well-developed and less-well-developed health systems. Media reports of chaos within overwhelmed hospitals have been prominent.1,2 As of January 5, 2022, SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 295 million people globally and directly caused the death of more than 5.4 million,3 though this number is likely an undercount even in countries with well-developed mortality tracking.4

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital-based medical teams have been confronted with a flood of severely ill patients with novel syndromes. Initially, there were no standards for therapy or supportive care except for treatments borrowed from similar syndromes. In the setting of high volumes, high acuity, and public dismay, it is unsurprising that the usual deliberative methods for weighing evidence and initiating interventions were often pushed aside in favor of the solace of active intervention.5 In this milieu of limited evidence, there was a lamentable, if understandable, tendency to seek guidance from “nontraditional” sources,6 including email chains from colleagues, hospital websites, non–peer-reviewed manuscripts, advanced publication by medical journals,7 and nonscientific media presentations. In many localities, practitioners responded in idiosyncratic ways. For example, findings of high cytokine levels in COVID-19,8 along with reports of in-vitro antiviral activity with drugs like hydroxychloroquine against both SARS9 and SARS-CoV-2,10 drove laboratory test ordering and therapeutic interventions, respectively, carving shortcuts into the traditional clinical trial–dependent standards. Clinical trial results eventually emerged.11COVID-19 created a clinical dilemma for hospital medical staffs in terms of how to organize, standardize, and rapidly adapt to a flood of new information. In this report, we describe how 1 health system responded to these challenges by forming a COVID-19 Clinical Management Committee (CCMC) and empowering this interdisciplinary team to review evidence, create and adjust order sets, educate practitioners, oversee care, and collaborate across teams addressing other aspects of the COVID-19 response.

Program Overview

Health System Description

Luminis Health is a health system with 2 acute care hospitals that was formed in 2019 just before the start of the pandemic. Anne Arundel Medical Center (hospital A) is a 385-bed teaching hospital in Annapolis, MD. It has more than 23 000 discharges annually. Patients with COVID-19 were cared for by either an internal medicine teaching service or nonteaching hospitalist services on cohorted nursing units. Doctor’s Community Medical Center, in Lanham, MD (hospital B), is a 206-bed acute care hospital with more than 10 350 annual discharges. COVID-19 patients were cared for by hospitalist groups, initially in noncohorted units with transition to cohorted nursing units after a few months. The medical staffs are generally distinct, with different leadership structures, though the Luminis Health Department of Medicine has oversight responsibilities at both hospitals. More than 47 physicians attended COVID-19 patients at hospital A (with medical residents) and 30 individual physicians at hospital B, respectively, including intensivists. The nursing and pharmacy staffs are distinct, but there is a shared oversight Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee.

The 2 hospitals had distinct electronic medical records (EMR) until January 2021, when hospital B adopted the same EMR as hospital A (Epic).

Mission and Formation of CCMC

In order to coordinate the therapeutic approach across the health system, it was important for the CCMC to be designated by the health system P&T committee as an official subcommittee so that decisions on restrictions of medications and/or new or revised order sets could be rapidly initiated across the system without waiting for the subsequent P&T meetings. The full committee retained oversight of the CCMC. Some P&T members were also on the CCMC.

The committee reviewed new reports in medical journals and prepublication servers and consulted recommendations of professional societies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 guidelines, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Society of Critical Care Medicine, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA), among other sources.

Composition of the CCMC

Physician leaders from both hospitals in the following specialties were solicited for participation: critical care, epidemiology, hospital medicine (internal medicine), emergency medicine, infectious diseases, nephrology, women and children’s services, and medical informatics. Specialists in other areas, such as hematology, were invited for topic-specific discussions. Hospital pharmacists with different specialties and nursing leadership were essential contributors. The committee members were expected to use various communication channels to inform frontline clinicians of new care standards and the existence of new order sets, which were embedded in the EMR.

Clinical Research

An important connection for the CCMC was with theCOVID-19 clinical research team. Three members of the research team were also members of the CCMC. All new study proposals for therapeutics were discussed with the CCMC as they were being considered by the research team. In this way, feedback on the feasibility and acceptance of new study opportunities could be discussed with the CCMC. Occasionally, CCMC decisions impacted clinical research accrual strategies. For example, new data from randomized trials about tocilizumab1,2 demonstrated benefits in some subsets of patients and resulted in a recommendation for use by the NIH guideline committee in these populations.1 The CCMC quickly adopted this recommendation, which required a reprioritization of clinical research enrollment for studies testing other immune-modulating agents. This important dialogue was mediated within the CCMC.

Guideline Distribution, Reinforcement, and Platform for Feedback

New guidelines were disseminated to clinicians via daily brief patient huddles held on COVID units, with participation by nursing and pharmacy, and by weekly meetings with hospitalist leaders and frontline hospital physicians. Order sets and guidelines were maintained on the intranet. Adherence was reinforced by unit-based and central pharmacists. Order sets, including admission order sets, could be created only by designated informatics personnel, thus enforcing standardization. Feedback on the utility of the order sets was obtained during the weekly meetings or huddles, as described above. To ensure a sense of transparency, physicians who had interest in commenting on a particular therapy, or who wished to discuss a particular manuscript, news article, or website, were invited to attend CCMC meetings.

Scope of CCMC

In order to be effective and timely, we limited the scope of our work to the report to the inpatient therapeutic environment, allowing other committees to work on other aspects of the pandemic response. In addition to issuing guidance and creating order sets to direct clinical practice, the CCMC also monitored COVID-19 therapeutic shortages15,16 and advised on prioritization of such treatments as convalescent plasma, remdesivir (prioritization and duration of therapy, 5 vs 10 days), baricitinib, and tocilizumab, depending upon the location of the patient (critical care or not). The CCMC was not involved in the management of non–COVID-19 shortages brought about by supply chain deficiencies.

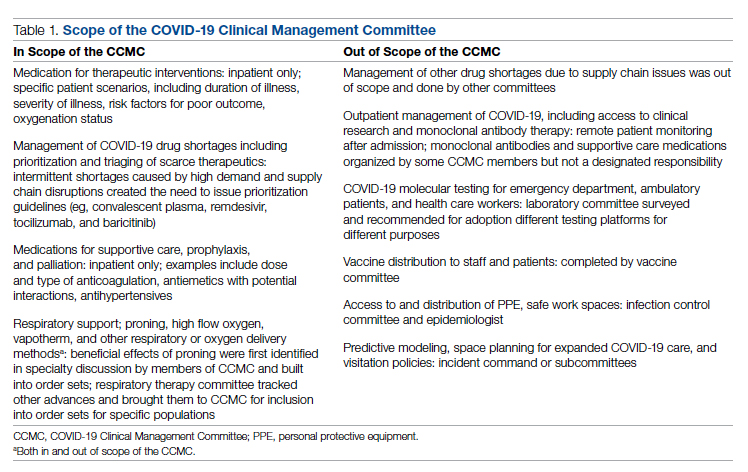

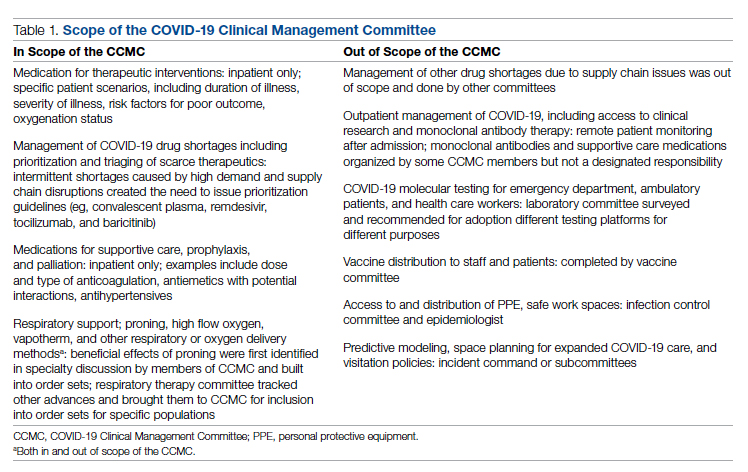

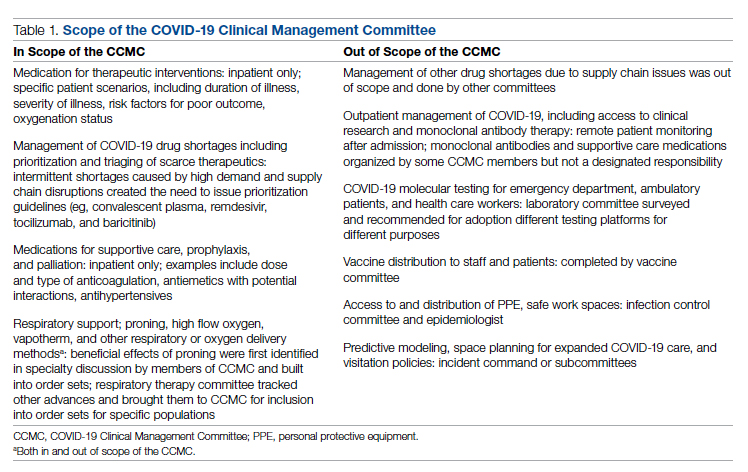

Table 1 shows some aspects of the health system pandemic-response planning and the committee workforce that undertook that work. Though many items were out of scope for the CCMC, members of the CCMC did participate in the planning work of these other committees and therefore stayed connected to this complementary work.

A Teaching Opportunity About Making Thoughtful Choices

Another important feature of the CCMC was the contributions of residents from both pharmacy and internal medicine. The purpose and operations of the committee were recognized as an opportunity to involve learners in a curriculum based on Kern’s 6-step approach.17 Though the problem identification and general needs assessment were easily defined, the targeted needs assessment, extracted from individual and group interviews with learners and the committee members, pointed at the need to learn how to assess and analyze a rapidly growing body of literature on several relevant clinical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. To achieve goals and objectives, residents were assigned to present current literature on a particular intervention during a committee meeting, specifically commenting on the merit or deficiencies of the study design, the strength of the data, and applicability to the local context with a recommendation. Prior to the presentations, the residents worked with faculty to identify the best studies or systematic analyses with potential to alter current practices. We thus used the CCMC process as a teaching tool about evidence-based medicine and the dilemma of clinical equipoise. This was imperative, since trainees thrust into the COVID-19 response have often keenly observed a movement away from deliberative decision-making.18 Indeed, including residents in the process of deliberative responses to COVID-19 addresses a recent call to adjust medical education during COVID-19 to “adapt curriculum to current issues in real time.”19

Interventions and Therapies Considered

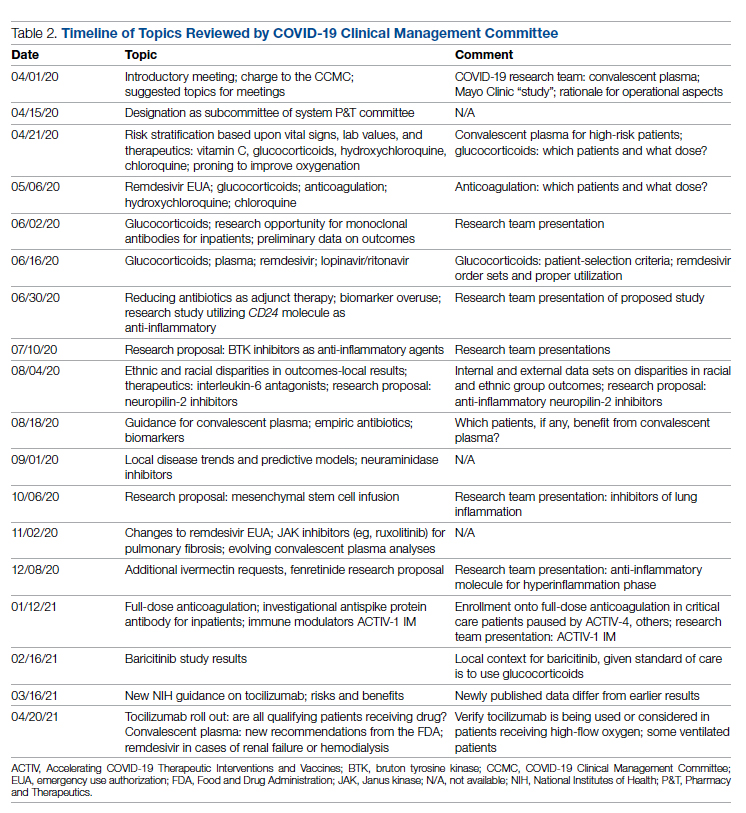

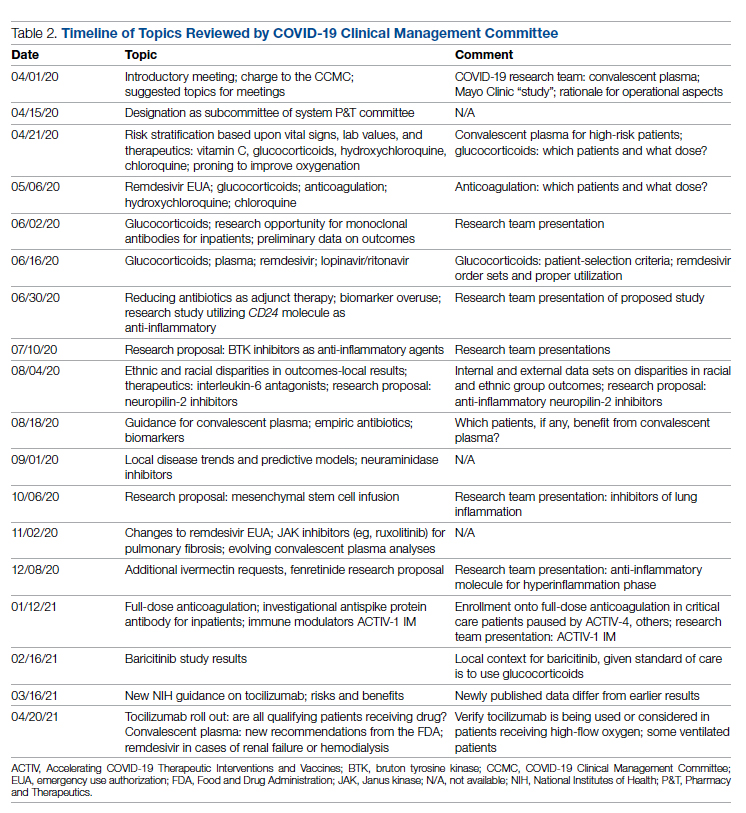

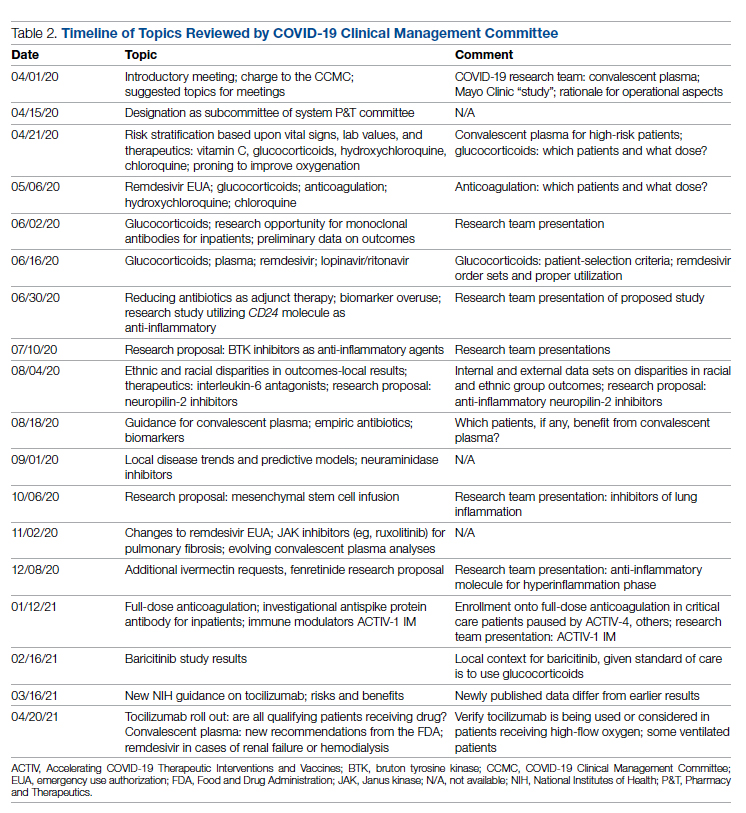

Table 2 shows the topics reviewed by the CCMC. By the time of the first meeting, nonstandardization of care was already a source of concern for clinicians. Dialogue often continued outside of the formal meetings. Many topics were considered more than once as new guidance developed, changes to EUAs occurred, and new data or new publicity arose.

Methods

The Human Protections Administrator determined that this work constituted “quality improvement, and not research” and was therefore exempt from institutional review board review.

Quantitative Analysis

All admitted patients from March 10, 2020, through April 20, 2021, were considered in the quantitative aspects of this report except as noted. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were identified by searching our internal data base using diagnostic codes. Patient admissions with the following diagnostic codes were included (prior to April 1, 2020): J12.89, J20.8, J40, J22, J98.8, J80, each with the additional code of B97.29. After April 1, 2020, the guideline for coding COVID-19 was U07.1.

Descriptive statistics were used to measure utilization rates of certain medications and laboratory tests of interest over time. These data were adjusted for number of unique admissions. In a few cases, not all data elements were available from both hospitals due to differences in the EMR.

Case fatality rate was calculated based upon whether the patient died or was admitted to inpatient hospice as a result of COVID-19. Four patients transferred out of hospital A and 18 transferred out of hospital B were censored from case-fatality-rate determination.

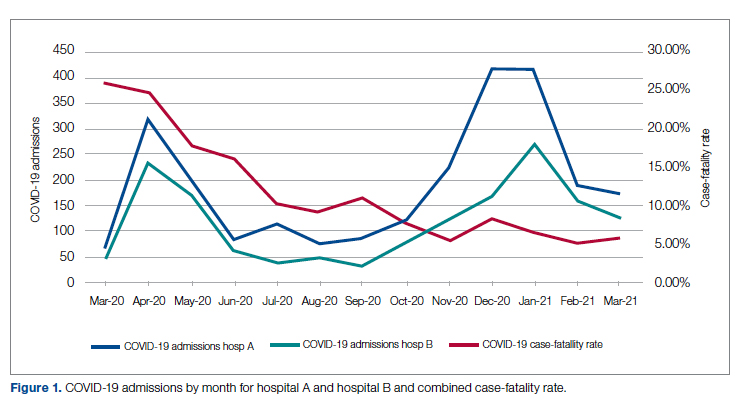

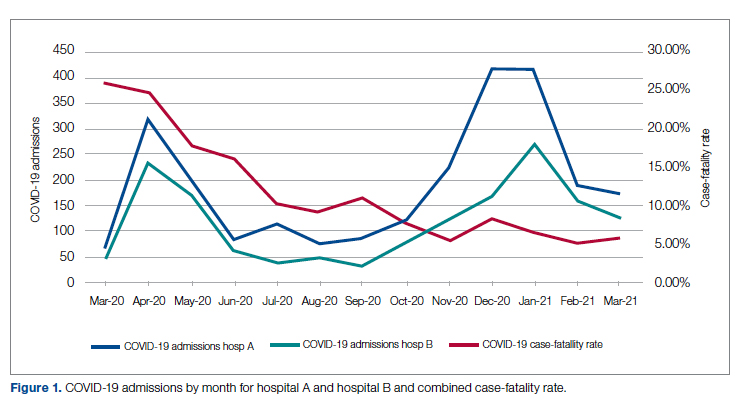

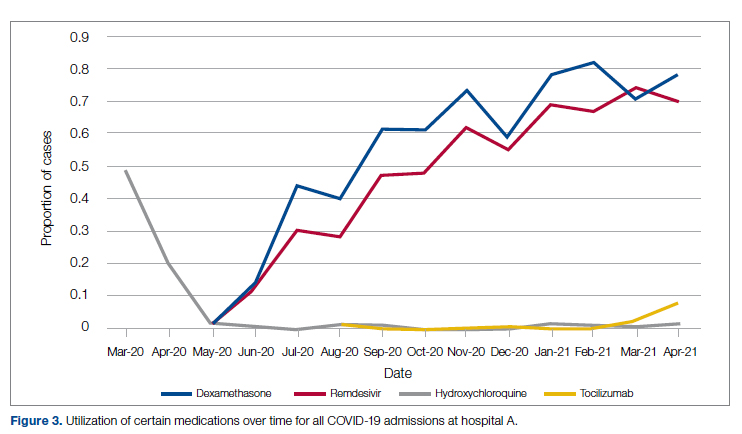

Figure 1 shows the number of admissions for each acute care hospital in the health system and the combined COVID-19 case-fatality rate over time.

Results

A total of 5955 consecutive COVID-19 patients admitted from March 10, 2020, through April 30, 2021, were analyzed. Patients with International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes J12.89. J20.8, J40, J22, J98.8, J80, each with the additional code of B97.29 (or the code UO7.1 after April 1, 2020), were included in the analysis. The median age of admitted patients was 65 years (range 19-91 years). Using the NIH classification system for severity,20 the distribution of severity during the first 24 hours after the time of hospital admission was as follows: asymptomatic/presymptomatic, 0.5%; mild illness, 5.3%; moderate illness, 37.1%; severe illness, 55.5%; and critical illness, 1.1%.

The impact of the CCMC can be estimated by looking at care patterns over time. Since the work of the CCMC was aimed at influencing and standardizing physician ordering and therapy choices through order set creation and other forms of oversight, we measured the use of the CCMC-approved order sets at both hospitals and the use of certain laboratory tests and therapies that the CCMC sought either to limit or increase. These counts were adjusted for number of unique COVID-19 admissions. But the limits of the case collection tool meant it also collected cases that were not eligible for some of the interventions. For example, COVID-19 admissions without hypoxemia would not have been eligible for remdesivir or glucocorticoids. When admitted, some patients were already on steroids for other medical indications and did not receive the prescribed dexamethasone dose that we measured in pharmacy databases. Similarly, a few patients were hospitalized for indications unrelated to COVID-19, such as surgery or childbirth, and were found to be SARS-CoV-2-positive on routine screening.

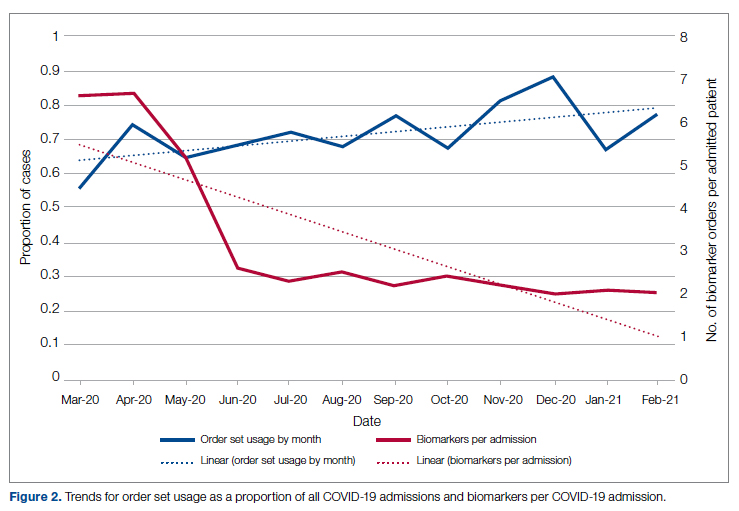

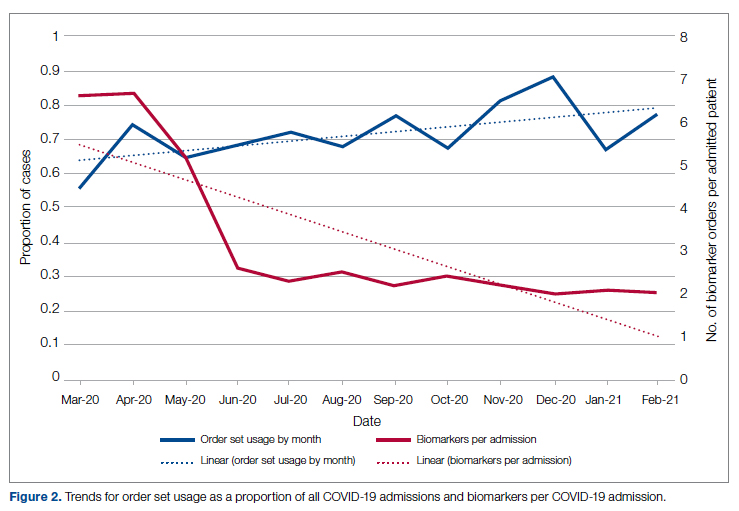

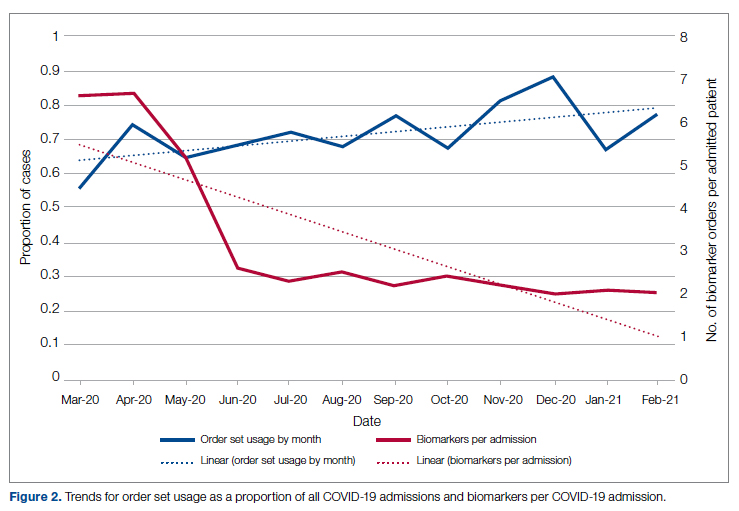

Figure 2 shows the utilization of CCMC-approved standard COVID-19 admission order sets as a proportion of all COVID-19 admissions over time. The trend reveals a modest increase in usage (R2 = 0.34), but these data do not reflect the progressive build of content into order sets over time. One of the goals of the order sets was to standardize and reduce the ordering of certain biomarkers: C-reactive protein, serum ferritin, and D-dimer, which were ordered frequently in many early patients. Orders for these 3 laboratory tests are combined and expressed as an average number of labs per COVID-19 admission in Figure 2. A downward trend, with an R2 value of 0.65, is suggestive of impact from the order sets, though other explanations are possible.

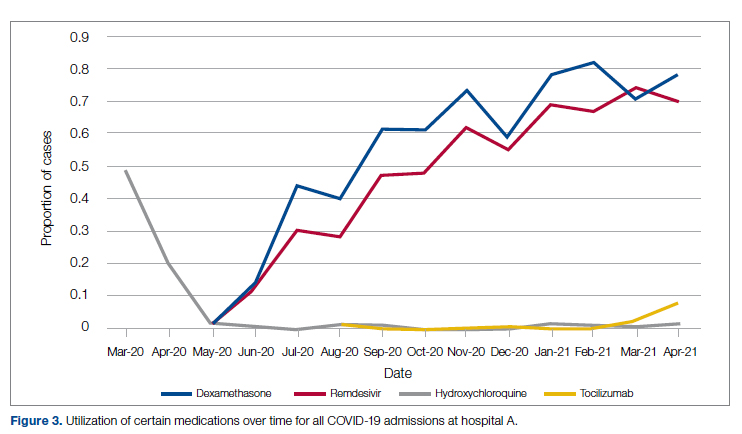

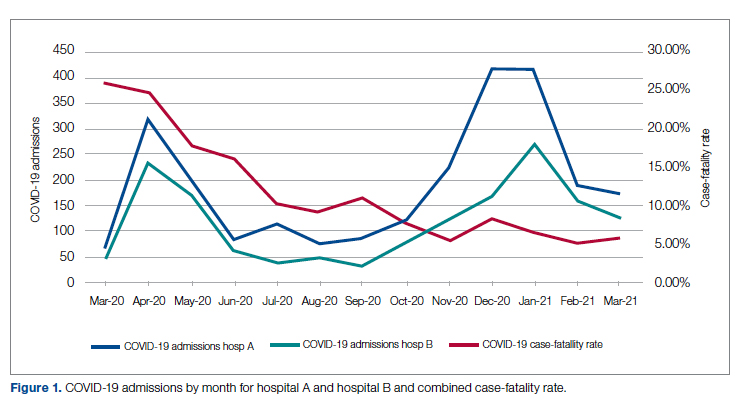

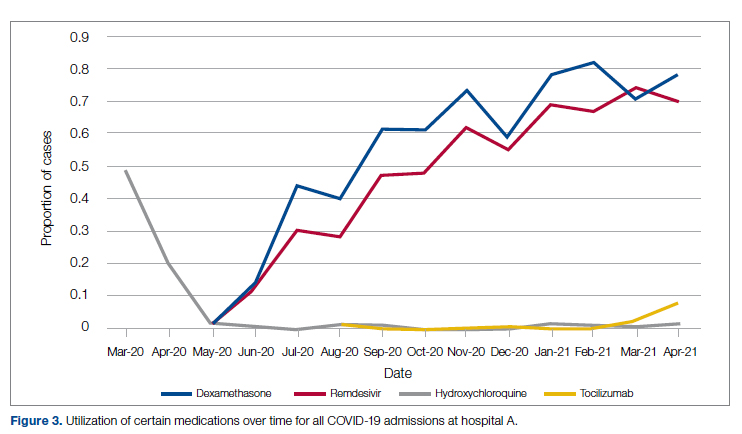

Medication guidance was also a goal of the CCMC, simultaneously discouraging poorly supported interventions and driving uptake of the recommended evidence-based interventions in appropriate patients. Figure 3 shows the utilization pattern for some drugs of interest over the course of the pandemic, specifically the proportion of patients receiving at least 1 dose of medication among all COVID-19 admissions by month. (Data for hospital B was excluded from this analysis because it did not include all admitted patients.)

Hydroxychloroquine, which enjoyed a wave of popularity early on during the pandemic, was a target of successful order stewardship through the CCMC. Use of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 therapeutic option after the first 2 months of the pandemic stopped, and subsequent use at low levels likely represented continuation therapy for outpatients who took hydroxychloroquine for rheumatologic indications.

Dexamethasone, as used in the RECOVERY trial,21 had a swift uptake among physicians after it was incorporated into order sets and its use encouraged. Similarly, uptake was immediate for remdesivir when, in May 2020, preliminary reports showed at least some benefits, confirmed by later analysis,22 and it received an FDA EUA.

Our data also show successful stewardship of the interleukin-6 antagonist toclilizumab, which was discouraged early on by the CCMC due to lack of data or negative results. But in March 2021, with new studies releasing data12,13 and new recommendations14 for its use in some subsets of patients with COVID-19, this drug was encouraged in appropriate subsets. A new order set with qualifying indications was prepared by the CCMC and new educational efforts made to encourage its use in appropriate patients.

Ivermectin was nonformulary at the start of the pandemic. This drug enjoyed much publicity from media sources and was promoted by certain physicians and on websites,23 based on in-vitro activity against coronaviruses. Eventually, the World Health Organization24 and the FDA25 found it necessary to issue advisory statements to the public against its use outside of clinical trials. The CCMC had requests from physicians to incorporate ivermectin but declined to add it to the formulary and recommended not approving nonformulary requests due to lack of data. As a result, ivermectin was not used at either hospital.

Discussion

COVID-19 represents many challenges to health systems all over the world. For Luminis Health, the high volume of acutely ill patients with novel syndromes was a particular challenge for the hospital-based care teams. A flood of information from preprints, press releases, preliminary reports, and many other nontraditional sources made deliberative management decisions difficult for individual physicians. Much commentary has appeared around the phenomenon but with less practical advice about how to make day-to-day care decisions at a time of scientific uncertainty and intense pressure to intervene.26,27 The CCMC was designed to overcome the information management dilemma. The need to coordinate, standardize, and oversee care was necessary given the large number of physicians who cared for COVID-19 patients on inpatient services.

It should be noted that creating order sets and issuing guidance is necessary, but not sufficient, to achieve our goals of being updated and consistent. This is especially true with large cadres of health care workers attending COVID-19 patients. Guidelines and recommendations were reinforced by unit-based oversight and stewardship from pharmacy and other leaders who constituted the CCMC.

The reduction in COVID-19 mortality over time experienced in this health care system was not unique and cannot necessarily be attributed to standardization of care. Similar improvements in mortality have been reported at many US hospitals in aggregate.28 Many other factors, including changes in patient characteristics, may be responsible for reduction in mortality over time.

Throughout this report we have relied upon an implicit assumption that standardization of medical therapeutics is desirable and leads to better outcomes as compared with allowing unlimited empiricism by individual physicians, either consultants or hospitalists. Our program represents a single health system with 2 acute care hospitals located 25 miles apart and which thus were similarly impacted by the different phases of the pandemic. Generalizability to health systems either smaller or larger, or in different geographical areas, has not been established. Data limitations have already been discussed.

We did not measure user satisfaction with the program either from physicians or nurses. However, the high rate of compliance suggests general agreement with the content and process.

We cannot definitively ascribe reduction in utilization of some nonrecommended treatments and increased utilization of the recommended therapies to the work of the CCMC. Individual physicians may have made these adjustments on their own or under the influence of other sources.

Finally, it should be noted that the mission to rapidly respond to data from well-conducted trials might be thwarted by too rigid a process or a committee’s lack of a sense of urgency. Organizing a committee and then empowering it to act is no guarantee of success; commitment to the mission is.

Conclusion

COVID-19 represented a challenge to medical staffs everywhere, inundating them with high volumes of acutely ill patients presenting with unfamiliar syndromes. Initial responses were characterized by idiosyncratic management approaches based on nontraditional sources of opinion and influences.

This report describes how a complex medical system brought order and standardization through a deliberative, but urgent, multidisciplinary committee with responsibility for planning, implementing, and monitoring standard approaches that eventually became evidence based. The composition of the committee and its scope of influence, limited to inpatient management, were important elements of success, allowing for better focus on the many treatment decisions. The important connection between the management committee and the system P&T committee, the clinical research effort, and teaching programs in both medicine and pharmacy are offered as exemplars of coordination. The data presented show success in achieving standardized, guideline-directed care. The approach is adoptable and suitable for similar emergencies in the future.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Gary Scabis, Kip Waite, John Moxley, Angela Clubb, and David Woodley for their assistance in gathering data. We express appreciation and admiration for all our colleagues at the bedside.

Corresponding author: Barry R. Meisenberg, MD, Department of Medicine, Luminis Health, 2001 Medical Pkwy, Annapolis, MD 21401; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gettleman J, Raj S, Kumar H. India’s health system cracks under the strain as coronavirus cases surge. The New York Times. April 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/21/world/asia/india-coronavirus-oxygen.html

2. Rappleye H, Lehren AW, Strickler L, Fitzpatrick S. ‘This system is doomed’: doctors, nurses sound off in NBC News coronavirus survey. NBC News. March 20, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/system-doomed-doctors-nurses-sound-nbc-news-coronavirus-survey-n1164841

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

4. Fineberg HV. The toll of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1502-1503. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.20019

5. Meisenberg BR. Medical staffs response to COVID-19 ‘data’: have we misplaced our skeptic’s eye? Am J Med. 2021;134(2):151-152. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.09.013

6. McMahon JH, Lydeamore MH, Stewardson AJ. Bringing evidence from press release to the clinic in the era of COVID-19. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(3):547-549. doi:10.1093/jac/dkaa506

7. Rubin EJ, Baden LR, Morrissey S, Campion EW. Medical journals and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):866. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001329

8. Liu F, Li L, Xu M, et al. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104370. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370

9. Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2:69. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-2-69

10. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269-271. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

11. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2030-2040. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022926

12. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial [preprint]. February 11, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.02.11.21249258 https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.11.21249258v1

13. REMAP-CAP Investigators. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1491-1502. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2100433

14. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 treatment guidelines: interleukin-6 inhibitors. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immunomodulators/interleukin-6-inhibitors/

15. Deana C, Vetrugno L, Tonizzo A, et al. Drug supply during COVID-19 pandemic: remember not to run with your tank empty. Hosp Pharm. 2021;56(5):405-407. doi:10.1177/0018578720931749

16. Choe J, Crane M, Greene J, et al. The Pandemic and the Supply Chain: Addressing Gaps in Pharmaceutical Production and Distribution. Johns Hopkins University, November 2020. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/affiliated-programs/johns-hopkins-drug-access-and-affordability-initiative/publications/Pandemic_Supply_Chain.pdf

17. Kern DE. Overview: a six-step approach to curriculum development. In: Kern DE, Thornton PA, Hughes MT, eds. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. 3rd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

18. Rice TW, Janz DR. In defense of evidence-based medicine for the treatment of COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(7):787-789. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-325IP

19. Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033-1034. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14136

20. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 treatment guidelines: clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/clinical-spectrum/

21. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693-704. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

22. Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—final report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1813-1826. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2007764

23. Jiminez D. Ivermectin and Covid-19: how a cheap antiparasitic became political. April 19, 2021. https://www.pharmaceutical-technology.com/features/ivermectin-covid-19-antiparasitic-political/

24. World Health Organization. WHO advises that ivermectin only be used to treat COVID-19 within clinical trials. March 31, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-advises-that-ivermectin-only-be-used-to-treat-covid-19-within-clinical-trials

25. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Why you should not use ivermectin to treat or prevent COVID-19. March 5, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/why-you-should-not-use-ivermectin-treat-or-prevent-covid-19

26. Seymour CW, McCreary EK, Stegenga J. Sensible medicine-balancing intervention and inaction during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(18):1827-1828. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.20271

27. Flanagin A, Fontanarosa PB, Bauchner H. Preprints involving medical research—do the benefits outweigh the challenges? JAMA. 2020;324(18):1840-1843. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.20674

28. Asch DA, Shells NE, Islam N, et al. Variation in US hospital mortality rates for patients admitted with COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):471-478. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8193

From the Department of Medicine (Drs. Meisenberg, Muganlinskaya, Sharma, Amjadi, Arnold, Barnes, Clance, Khalil, Miller, Mooradian, O’Connell, Patel, Press, Samaras, Shanmugam, Tavadze, and Thompson), Department of Pharmacy (Drs. Jiang, Jarawan, Sheth, and Trinh), Department of Nursing (Dr. Ohnmacht), and Department of Women and Children’s Services (Dr. Raji), Luminis Health, Annapolis, MD, and Lanham, MD.

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenge for hospital medical staffs worldwide due to high volumes of patients acutely ill with novel syndromes and prevailing uncertainty regarding optimum supportive and therapeutic interventions. Additionally, the response to this crisis was driven by a plethora of nontraditional information sources, such as email chains, websites, non–peer-reviewed preprints, and press releases. Care patterns became idiosyncratic and often incorporated unproven interventions driven by these nontraditional information sources. This report evaluates the efforts of a health system to create and empower a multidisciplinary committee to develop, implement, and monitor evidence-based, standardized protocols for patients with COVID-19.

Methods: This report describes the composition of the committee, its scope, and its important interactions with the health system pharmacy and therapeutics committee, research teams, and other work groups planning other aspects of COVID-19 management. It illustrates how the committee was used to demonstrate for trainees the process and value of critically examining evidence, even in a chaotic environment.

Results: Data show successful interventions in reducing excessive ordering of certain laboratory tests, reduction of nonrecommended therapies, and rapid uptake of evidence-based or guidelines-supported interventions.

Conclusions: A multidisciplinary committee dedicated solely to planning, implementing, and monitoring standard approaches that eventually became evidence-based decision-making led to an improved focus on treatment options and outcomes for COVID-19 patients. Data presented illustrate the attainable success that is both adaptable and suitable for similar emergencies in the future.

Keywords: COVID-19; clinical management; pharmacy and therapeutics; treatment; therapy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread to nearly all countries, carrying with it high morbidity, mortality, and severe impacts on both well-developed and less-well-developed health systems. Media reports of chaos within overwhelmed hospitals have been prominent.1,2 As of January 5, 2022, SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 295 million people globally and directly caused the death of more than 5.4 million,3 though this number is likely an undercount even in countries with well-developed mortality tracking.4

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital-based medical teams have been confronted with a flood of severely ill patients with novel syndromes. Initially, there were no standards for therapy or supportive care except for treatments borrowed from similar syndromes. In the setting of high volumes, high acuity, and public dismay, it is unsurprising that the usual deliberative methods for weighing evidence and initiating interventions were often pushed aside in favor of the solace of active intervention.5 In this milieu of limited evidence, there was a lamentable, if understandable, tendency to seek guidance from “nontraditional” sources,6 including email chains from colleagues, hospital websites, non–peer-reviewed manuscripts, advanced publication by medical journals,7 and nonscientific media presentations. In many localities, practitioners responded in idiosyncratic ways. For example, findings of high cytokine levels in COVID-19,8 along with reports of in-vitro antiviral activity with drugs like hydroxychloroquine against both SARS9 and SARS-CoV-2,10 drove laboratory test ordering and therapeutic interventions, respectively, carving shortcuts into the traditional clinical trial–dependent standards. Clinical trial results eventually emerged.11COVID-19 created a clinical dilemma for hospital medical staffs in terms of how to organize, standardize, and rapidly adapt to a flood of new information. In this report, we describe how 1 health system responded to these challenges by forming a COVID-19 Clinical Management Committee (CCMC) and empowering this interdisciplinary team to review evidence, create and adjust order sets, educate practitioners, oversee care, and collaborate across teams addressing other aspects of the COVID-19 response.

Program Overview

Health System Description

Luminis Health is a health system with 2 acute care hospitals that was formed in 2019 just before the start of the pandemic. Anne Arundel Medical Center (hospital A) is a 385-bed teaching hospital in Annapolis, MD. It has more than 23 000 discharges annually. Patients with COVID-19 were cared for by either an internal medicine teaching service or nonteaching hospitalist services on cohorted nursing units. Doctor’s Community Medical Center, in Lanham, MD (hospital B), is a 206-bed acute care hospital with more than 10 350 annual discharges. COVID-19 patients were cared for by hospitalist groups, initially in noncohorted units with transition to cohorted nursing units after a few months. The medical staffs are generally distinct, with different leadership structures, though the Luminis Health Department of Medicine has oversight responsibilities at both hospitals. More than 47 physicians attended COVID-19 patients at hospital A (with medical residents) and 30 individual physicians at hospital B, respectively, including intensivists. The nursing and pharmacy staffs are distinct, but there is a shared oversight Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee.

The 2 hospitals had distinct electronic medical records (EMR) until January 2021, when hospital B adopted the same EMR as hospital A (Epic).

Mission and Formation of CCMC

In order to coordinate the therapeutic approach across the health system, it was important for the CCMC to be designated by the health system P&T committee as an official subcommittee so that decisions on restrictions of medications and/or new or revised order sets could be rapidly initiated across the system without waiting for the subsequent P&T meetings. The full committee retained oversight of the CCMC. Some P&T members were also on the CCMC.

The committee reviewed new reports in medical journals and prepublication servers and consulted recommendations of professional societies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 guidelines, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Society of Critical Care Medicine, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA), among other sources.

Composition of the CCMC

Physician leaders from both hospitals in the following specialties were solicited for participation: critical care, epidemiology, hospital medicine (internal medicine), emergency medicine, infectious diseases, nephrology, women and children’s services, and medical informatics. Specialists in other areas, such as hematology, were invited for topic-specific discussions. Hospital pharmacists with different specialties and nursing leadership were essential contributors. The committee members were expected to use various communication channels to inform frontline clinicians of new care standards and the existence of new order sets, which were embedded in the EMR.

Clinical Research

An important connection for the CCMC was with theCOVID-19 clinical research team. Three members of the research team were also members of the CCMC. All new study proposals for therapeutics were discussed with the CCMC as they were being considered by the research team. In this way, feedback on the feasibility and acceptance of new study opportunities could be discussed with the CCMC. Occasionally, CCMC decisions impacted clinical research accrual strategies. For example, new data from randomized trials about tocilizumab1,2 demonstrated benefits in some subsets of patients and resulted in a recommendation for use by the NIH guideline committee in these populations.1 The CCMC quickly adopted this recommendation, which required a reprioritization of clinical research enrollment for studies testing other immune-modulating agents. This important dialogue was mediated within the CCMC.

Guideline Distribution, Reinforcement, and Platform for Feedback

New guidelines were disseminated to clinicians via daily brief patient huddles held on COVID units, with participation by nursing and pharmacy, and by weekly meetings with hospitalist leaders and frontline hospital physicians. Order sets and guidelines were maintained on the intranet. Adherence was reinforced by unit-based and central pharmacists. Order sets, including admission order sets, could be created only by designated informatics personnel, thus enforcing standardization. Feedback on the utility of the order sets was obtained during the weekly meetings or huddles, as described above. To ensure a sense of transparency, physicians who had interest in commenting on a particular therapy, or who wished to discuss a particular manuscript, news article, or website, were invited to attend CCMC meetings.

Scope of CCMC

In order to be effective and timely, we limited the scope of our work to the report to the inpatient therapeutic environment, allowing other committees to work on other aspects of the pandemic response. In addition to issuing guidance and creating order sets to direct clinical practice, the CCMC also monitored COVID-19 therapeutic shortages15,16 and advised on prioritization of such treatments as convalescent plasma, remdesivir (prioritization and duration of therapy, 5 vs 10 days), baricitinib, and tocilizumab, depending upon the location of the patient (critical care or not). The CCMC was not involved in the management of non–COVID-19 shortages brought about by supply chain deficiencies.

Table 1 shows some aspects of the health system pandemic-response planning and the committee workforce that undertook that work. Though many items were out of scope for the CCMC, members of the CCMC did participate in the planning work of these other committees and therefore stayed connected to this complementary work.

A Teaching Opportunity About Making Thoughtful Choices

Another important feature of the CCMC was the contributions of residents from both pharmacy and internal medicine. The purpose and operations of the committee were recognized as an opportunity to involve learners in a curriculum based on Kern’s 6-step approach.17 Though the problem identification and general needs assessment were easily defined, the targeted needs assessment, extracted from individual and group interviews with learners and the committee members, pointed at the need to learn how to assess and analyze a rapidly growing body of literature on several relevant clinical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. To achieve goals and objectives, residents were assigned to present current literature on a particular intervention during a committee meeting, specifically commenting on the merit or deficiencies of the study design, the strength of the data, and applicability to the local context with a recommendation. Prior to the presentations, the residents worked with faculty to identify the best studies or systematic analyses with potential to alter current practices. We thus used the CCMC process as a teaching tool about evidence-based medicine and the dilemma of clinical equipoise. This was imperative, since trainees thrust into the COVID-19 response have often keenly observed a movement away from deliberative decision-making.18 Indeed, including residents in the process of deliberative responses to COVID-19 addresses a recent call to adjust medical education during COVID-19 to “adapt curriculum to current issues in real time.”19

Interventions and Therapies Considered

Table 2 shows the topics reviewed by the CCMC. By the time of the first meeting, nonstandardization of care was already a source of concern for clinicians. Dialogue often continued outside of the formal meetings. Many topics were considered more than once as new guidance developed, changes to EUAs occurred, and new data or new publicity arose.

Methods

The Human Protections Administrator determined that this work constituted “quality improvement, and not research” and was therefore exempt from institutional review board review.

Quantitative Analysis

All admitted patients from March 10, 2020, through April 20, 2021, were considered in the quantitative aspects of this report except as noted. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were identified by searching our internal data base using diagnostic codes. Patient admissions with the following diagnostic codes were included (prior to April 1, 2020): J12.89, J20.8, J40, J22, J98.8, J80, each with the additional code of B97.29. After April 1, 2020, the guideline for coding COVID-19 was U07.1.

Descriptive statistics were used to measure utilization rates of certain medications and laboratory tests of interest over time. These data were adjusted for number of unique admissions. In a few cases, not all data elements were available from both hospitals due to differences in the EMR.

Case fatality rate was calculated based upon whether the patient died or was admitted to inpatient hospice as a result of COVID-19. Four patients transferred out of hospital A and 18 transferred out of hospital B were censored from case-fatality-rate determination.

Figure 1 shows the number of admissions for each acute care hospital in the health system and the combined COVID-19 case-fatality rate over time.

Results

A total of 5955 consecutive COVID-19 patients admitted from March 10, 2020, through April 30, 2021, were analyzed. Patients with International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes J12.89. J20.8, J40, J22, J98.8, J80, each with the additional code of B97.29 (or the code UO7.1 after April 1, 2020), were included in the analysis. The median age of admitted patients was 65 years (range 19-91 years). Using the NIH classification system for severity,20 the distribution of severity during the first 24 hours after the time of hospital admission was as follows: asymptomatic/presymptomatic, 0.5%; mild illness, 5.3%; moderate illness, 37.1%; severe illness, 55.5%; and critical illness, 1.1%.

The impact of the CCMC can be estimated by looking at care patterns over time. Since the work of the CCMC was aimed at influencing and standardizing physician ordering and therapy choices through order set creation and other forms of oversight, we measured the use of the CCMC-approved order sets at both hospitals and the use of certain laboratory tests and therapies that the CCMC sought either to limit or increase. These counts were adjusted for number of unique COVID-19 admissions. But the limits of the case collection tool meant it also collected cases that were not eligible for some of the interventions. For example, COVID-19 admissions without hypoxemia would not have been eligible for remdesivir or glucocorticoids. When admitted, some patients were already on steroids for other medical indications and did not receive the prescribed dexamethasone dose that we measured in pharmacy databases. Similarly, a few patients were hospitalized for indications unrelated to COVID-19, such as surgery or childbirth, and were found to be SARS-CoV-2-positive on routine screening.

Figure 2 shows the utilization of CCMC-approved standard COVID-19 admission order sets as a proportion of all COVID-19 admissions over time. The trend reveals a modest increase in usage (R2 = 0.34), but these data do not reflect the progressive build of content into order sets over time. One of the goals of the order sets was to standardize and reduce the ordering of certain biomarkers: C-reactive protein, serum ferritin, and D-dimer, which were ordered frequently in many early patients. Orders for these 3 laboratory tests are combined and expressed as an average number of labs per COVID-19 admission in Figure 2. A downward trend, with an R2 value of 0.65, is suggestive of impact from the order sets, though other explanations are possible.

Medication guidance was also a goal of the CCMC, simultaneously discouraging poorly supported interventions and driving uptake of the recommended evidence-based interventions in appropriate patients. Figure 3 shows the utilization pattern for some drugs of interest over the course of the pandemic, specifically the proportion of patients receiving at least 1 dose of medication among all COVID-19 admissions by month. (Data for hospital B was excluded from this analysis because it did not include all admitted patients.)

Hydroxychloroquine, which enjoyed a wave of popularity early on during the pandemic, was a target of successful order stewardship through the CCMC. Use of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 therapeutic option after the first 2 months of the pandemic stopped, and subsequent use at low levels likely represented continuation therapy for outpatients who took hydroxychloroquine for rheumatologic indications.

Dexamethasone, as used in the RECOVERY trial,21 had a swift uptake among physicians after it was incorporated into order sets and its use encouraged. Similarly, uptake was immediate for remdesivir when, in May 2020, preliminary reports showed at least some benefits, confirmed by later analysis,22 and it received an FDA EUA.

Our data also show successful stewardship of the interleukin-6 antagonist toclilizumab, which was discouraged early on by the CCMC due to lack of data or negative results. But in March 2021, with new studies releasing data12,13 and new recommendations14 for its use in some subsets of patients with COVID-19, this drug was encouraged in appropriate subsets. A new order set with qualifying indications was prepared by the CCMC and new educational efforts made to encourage its use in appropriate patients.

Ivermectin was nonformulary at the start of the pandemic. This drug enjoyed much publicity from media sources and was promoted by certain physicians and on websites,23 based on in-vitro activity against coronaviruses. Eventually, the World Health Organization24 and the FDA25 found it necessary to issue advisory statements to the public against its use outside of clinical trials. The CCMC had requests from physicians to incorporate ivermectin but declined to add it to the formulary and recommended not approving nonformulary requests due to lack of data. As a result, ivermectin was not used at either hospital.

Discussion

COVID-19 represents many challenges to health systems all over the world. For Luminis Health, the high volume of acutely ill patients with novel syndromes was a particular challenge for the hospital-based care teams. A flood of information from preprints, press releases, preliminary reports, and many other nontraditional sources made deliberative management decisions difficult for individual physicians. Much commentary has appeared around the phenomenon but with less practical advice about how to make day-to-day care decisions at a time of scientific uncertainty and intense pressure to intervene.26,27 The CCMC was designed to overcome the information management dilemma. The need to coordinate, standardize, and oversee care was necessary given the large number of physicians who cared for COVID-19 patients on inpatient services.

It should be noted that creating order sets and issuing guidance is necessary, but not sufficient, to achieve our goals of being updated and consistent. This is especially true with large cadres of health care workers attending COVID-19 patients. Guidelines and recommendations were reinforced by unit-based oversight and stewardship from pharmacy and other leaders who constituted the CCMC.

The reduction in COVID-19 mortality over time experienced in this health care system was not unique and cannot necessarily be attributed to standardization of care. Similar improvements in mortality have been reported at many US hospitals in aggregate.28 Many other factors, including changes in patient characteristics, may be responsible for reduction in mortality over time.

Throughout this report we have relied upon an implicit assumption that standardization of medical therapeutics is desirable and leads to better outcomes as compared with allowing unlimited empiricism by individual physicians, either consultants or hospitalists. Our program represents a single health system with 2 acute care hospitals located 25 miles apart and which thus were similarly impacted by the different phases of the pandemic. Generalizability to health systems either smaller or larger, or in different geographical areas, has not been established. Data limitations have already been discussed.

We did not measure user satisfaction with the program either from physicians or nurses. However, the high rate of compliance suggests general agreement with the content and process.

We cannot definitively ascribe reduction in utilization of some nonrecommended treatments and increased utilization of the recommended therapies to the work of the CCMC. Individual physicians may have made these adjustments on their own or under the influence of other sources.

Finally, it should be noted that the mission to rapidly respond to data from well-conducted trials might be thwarted by too rigid a process or a committee’s lack of a sense of urgency. Organizing a committee and then empowering it to act is no guarantee of success; commitment to the mission is.

Conclusion

COVID-19 represented a challenge to medical staffs everywhere, inundating them with high volumes of acutely ill patients presenting with unfamiliar syndromes. Initial responses were characterized by idiosyncratic management approaches based on nontraditional sources of opinion and influences.

This report describes how a complex medical system brought order and standardization through a deliberative, but urgent, multidisciplinary committee with responsibility for planning, implementing, and monitoring standard approaches that eventually became evidence based. The composition of the committee and its scope of influence, limited to inpatient management, were important elements of success, allowing for better focus on the many treatment decisions. The important connection between the management committee and the system P&T committee, the clinical research effort, and teaching programs in both medicine and pharmacy are offered as exemplars of coordination. The data presented show success in achieving standardized, guideline-directed care. The approach is adoptable and suitable for similar emergencies in the future.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Gary Scabis, Kip Waite, John Moxley, Angela Clubb, and David Woodley for their assistance in gathering data. We express appreciation and admiration for all our colleagues at the bedside.

Corresponding author: Barry R. Meisenberg, MD, Department of Medicine, Luminis Health, 2001 Medical Pkwy, Annapolis, MD 21401; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Medicine (Drs. Meisenberg, Muganlinskaya, Sharma, Amjadi, Arnold, Barnes, Clance, Khalil, Miller, Mooradian, O’Connell, Patel, Press, Samaras, Shanmugam, Tavadze, and Thompson), Department of Pharmacy (Drs. Jiang, Jarawan, Sheth, and Trinh), Department of Nursing (Dr. Ohnmacht), and Department of Women and Children’s Services (Dr. Raji), Luminis Health, Annapolis, MD, and Lanham, MD.

Objective: The COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenge for hospital medical staffs worldwide due to high volumes of patients acutely ill with novel syndromes and prevailing uncertainty regarding optimum supportive and therapeutic interventions. Additionally, the response to this crisis was driven by a plethora of nontraditional information sources, such as email chains, websites, non–peer-reviewed preprints, and press releases. Care patterns became idiosyncratic and often incorporated unproven interventions driven by these nontraditional information sources. This report evaluates the efforts of a health system to create and empower a multidisciplinary committee to develop, implement, and monitor evidence-based, standardized protocols for patients with COVID-19.

Methods: This report describes the composition of the committee, its scope, and its important interactions with the health system pharmacy and therapeutics committee, research teams, and other work groups planning other aspects of COVID-19 management. It illustrates how the committee was used to demonstrate for trainees the process and value of critically examining evidence, even in a chaotic environment.

Results: Data show successful interventions in reducing excessive ordering of certain laboratory tests, reduction of nonrecommended therapies, and rapid uptake of evidence-based or guidelines-supported interventions.

Conclusions: A multidisciplinary committee dedicated solely to planning, implementing, and monitoring standard approaches that eventually became evidence-based decision-making led to an improved focus on treatment options and outcomes for COVID-19 patients. Data presented illustrate the attainable success that is both adaptable and suitable for similar emergencies in the future.

Keywords: COVID-19; clinical management; pharmacy and therapeutics; treatment; therapy.

The COVID-19 pandemic has spread to nearly all countries, carrying with it high morbidity, mortality, and severe impacts on both well-developed and less-well-developed health systems. Media reports of chaos within overwhelmed hospitals have been prominent.1,2 As of January 5, 2022, SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 295 million people globally and directly caused the death of more than 5.4 million,3 though this number is likely an undercount even in countries with well-developed mortality tracking.4

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, hospital-based medical teams have been confronted with a flood of severely ill patients with novel syndromes. Initially, there were no standards for therapy or supportive care except for treatments borrowed from similar syndromes. In the setting of high volumes, high acuity, and public dismay, it is unsurprising that the usual deliberative methods for weighing evidence and initiating interventions were often pushed aside in favor of the solace of active intervention.5 In this milieu of limited evidence, there was a lamentable, if understandable, tendency to seek guidance from “nontraditional” sources,6 including email chains from colleagues, hospital websites, non–peer-reviewed manuscripts, advanced publication by medical journals,7 and nonscientific media presentations. In many localities, practitioners responded in idiosyncratic ways. For example, findings of high cytokine levels in COVID-19,8 along with reports of in-vitro antiviral activity with drugs like hydroxychloroquine against both SARS9 and SARS-CoV-2,10 drove laboratory test ordering and therapeutic interventions, respectively, carving shortcuts into the traditional clinical trial–dependent standards. Clinical trial results eventually emerged.11COVID-19 created a clinical dilemma for hospital medical staffs in terms of how to organize, standardize, and rapidly adapt to a flood of new information. In this report, we describe how 1 health system responded to these challenges by forming a COVID-19 Clinical Management Committee (CCMC) and empowering this interdisciplinary team to review evidence, create and adjust order sets, educate practitioners, oversee care, and collaborate across teams addressing other aspects of the COVID-19 response.

Program Overview

Health System Description

Luminis Health is a health system with 2 acute care hospitals that was formed in 2019 just before the start of the pandemic. Anne Arundel Medical Center (hospital A) is a 385-bed teaching hospital in Annapolis, MD. It has more than 23 000 discharges annually. Patients with COVID-19 were cared for by either an internal medicine teaching service or nonteaching hospitalist services on cohorted nursing units. Doctor’s Community Medical Center, in Lanham, MD (hospital B), is a 206-bed acute care hospital with more than 10 350 annual discharges. COVID-19 patients were cared for by hospitalist groups, initially in noncohorted units with transition to cohorted nursing units after a few months. The medical staffs are generally distinct, with different leadership structures, though the Luminis Health Department of Medicine has oversight responsibilities at both hospitals. More than 47 physicians attended COVID-19 patients at hospital A (with medical residents) and 30 individual physicians at hospital B, respectively, including intensivists. The nursing and pharmacy staffs are distinct, but there is a shared oversight Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) Committee.

The 2 hospitals had distinct electronic medical records (EMR) until January 2021, when hospital B adopted the same EMR as hospital A (Epic).

Mission and Formation of CCMC

In order to coordinate the therapeutic approach across the health system, it was important for the CCMC to be designated by the health system P&T committee as an official subcommittee so that decisions on restrictions of medications and/or new or revised order sets could be rapidly initiated across the system without waiting for the subsequent P&T meetings. The full committee retained oversight of the CCMC. Some P&T members were also on the CCMC.

The committee reviewed new reports in medical journals and prepublication servers and consulted recommendations of professional societies, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 guidelines, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Society of Critical Care Medicine, and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA), among other sources.

Composition of the CCMC

Physician leaders from both hospitals in the following specialties were solicited for participation: critical care, epidemiology, hospital medicine (internal medicine), emergency medicine, infectious diseases, nephrology, women and children’s services, and medical informatics. Specialists in other areas, such as hematology, were invited for topic-specific discussions. Hospital pharmacists with different specialties and nursing leadership were essential contributors. The committee members were expected to use various communication channels to inform frontline clinicians of new care standards and the existence of new order sets, which were embedded in the EMR.

Clinical Research

An important connection for the CCMC was with theCOVID-19 clinical research team. Three members of the research team were also members of the CCMC. All new study proposals for therapeutics were discussed with the CCMC as they were being considered by the research team. In this way, feedback on the feasibility and acceptance of new study opportunities could be discussed with the CCMC. Occasionally, CCMC decisions impacted clinical research accrual strategies. For example, new data from randomized trials about tocilizumab1,2 demonstrated benefits in some subsets of patients and resulted in a recommendation for use by the NIH guideline committee in these populations.1 The CCMC quickly adopted this recommendation, which required a reprioritization of clinical research enrollment for studies testing other immune-modulating agents. This important dialogue was mediated within the CCMC.

Guideline Distribution, Reinforcement, and Platform for Feedback

New guidelines were disseminated to clinicians via daily brief patient huddles held on COVID units, with participation by nursing and pharmacy, and by weekly meetings with hospitalist leaders and frontline hospital physicians. Order sets and guidelines were maintained on the intranet. Adherence was reinforced by unit-based and central pharmacists. Order sets, including admission order sets, could be created only by designated informatics personnel, thus enforcing standardization. Feedback on the utility of the order sets was obtained during the weekly meetings or huddles, as described above. To ensure a sense of transparency, physicians who had interest in commenting on a particular therapy, or who wished to discuss a particular manuscript, news article, or website, were invited to attend CCMC meetings.

Scope of CCMC

In order to be effective and timely, we limited the scope of our work to the report to the inpatient therapeutic environment, allowing other committees to work on other aspects of the pandemic response. In addition to issuing guidance and creating order sets to direct clinical practice, the CCMC also monitored COVID-19 therapeutic shortages15,16 and advised on prioritization of such treatments as convalescent plasma, remdesivir (prioritization and duration of therapy, 5 vs 10 days), baricitinib, and tocilizumab, depending upon the location of the patient (critical care or not). The CCMC was not involved in the management of non–COVID-19 shortages brought about by supply chain deficiencies.

Table 1 shows some aspects of the health system pandemic-response planning and the committee workforce that undertook that work. Though many items were out of scope for the CCMC, members of the CCMC did participate in the planning work of these other committees and therefore stayed connected to this complementary work.

A Teaching Opportunity About Making Thoughtful Choices

Another important feature of the CCMC was the contributions of residents from both pharmacy and internal medicine. The purpose and operations of the committee were recognized as an opportunity to involve learners in a curriculum based on Kern’s 6-step approach.17 Though the problem identification and general needs assessment were easily defined, the targeted needs assessment, extracted from individual and group interviews with learners and the committee members, pointed at the need to learn how to assess and analyze a rapidly growing body of literature on several relevant clinical aspects of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. To achieve goals and objectives, residents were assigned to present current literature on a particular intervention during a committee meeting, specifically commenting on the merit or deficiencies of the study design, the strength of the data, and applicability to the local context with a recommendation. Prior to the presentations, the residents worked with faculty to identify the best studies or systematic analyses with potential to alter current practices. We thus used the CCMC process as a teaching tool about evidence-based medicine and the dilemma of clinical equipoise. This was imperative, since trainees thrust into the COVID-19 response have often keenly observed a movement away from deliberative decision-making.18 Indeed, including residents in the process of deliberative responses to COVID-19 addresses a recent call to adjust medical education during COVID-19 to “adapt curriculum to current issues in real time.”19

Interventions and Therapies Considered

Table 2 shows the topics reviewed by the CCMC. By the time of the first meeting, nonstandardization of care was already a source of concern for clinicians. Dialogue often continued outside of the formal meetings. Many topics were considered more than once as new guidance developed, changes to EUAs occurred, and new data or new publicity arose.

Methods

The Human Protections Administrator determined that this work constituted “quality improvement, and not research” and was therefore exempt from institutional review board review.

Quantitative Analysis

All admitted patients from March 10, 2020, through April 20, 2021, were considered in the quantitative aspects of this report except as noted. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 were identified by searching our internal data base using diagnostic codes. Patient admissions with the following diagnostic codes were included (prior to April 1, 2020): J12.89, J20.8, J40, J22, J98.8, J80, each with the additional code of B97.29. After April 1, 2020, the guideline for coding COVID-19 was U07.1.

Descriptive statistics were used to measure utilization rates of certain medications and laboratory tests of interest over time. These data were adjusted for number of unique admissions. In a few cases, not all data elements were available from both hospitals due to differences in the EMR.

Case fatality rate was calculated based upon whether the patient died or was admitted to inpatient hospice as a result of COVID-19. Four patients transferred out of hospital A and 18 transferred out of hospital B were censored from case-fatality-rate determination.

Figure 1 shows the number of admissions for each acute care hospital in the health system and the combined COVID-19 case-fatality rate over time.

Results

A total of 5955 consecutive COVID-19 patients admitted from March 10, 2020, through April 30, 2021, were analyzed. Patients with International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes J12.89. J20.8, J40, J22, J98.8, J80, each with the additional code of B97.29 (or the code UO7.1 after April 1, 2020), were included in the analysis. The median age of admitted patients was 65 years (range 19-91 years). Using the NIH classification system for severity,20 the distribution of severity during the first 24 hours after the time of hospital admission was as follows: asymptomatic/presymptomatic, 0.5%; mild illness, 5.3%; moderate illness, 37.1%; severe illness, 55.5%; and critical illness, 1.1%.

The impact of the CCMC can be estimated by looking at care patterns over time. Since the work of the CCMC was aimed at influencing and standardizing physician ordering and therapy choices through order set creation and other forms of oversight, we measured the use of the CCMC-approved order sets at both hospitals and the use of certain laboratory tests and therapies that the CCMC sought either to limit or increase. These counts were adjusted for number of unique COVID-19 admissions. But the limits of the case collection tool meant it also collected cases that were not eligible for some of the interventions. For example, COVID-19 admissions without hypoxemia would not have been eligible for remdesivir or glucocorticoids. When admitted, some patients were already on steroids for other medical indications and did not receive the prescribed dexamethasone dose that we measured in pharmacy databases. Similarly, a few patients were hospitalized for indications unrelated to COVID-19, such as surgery or childbirth, and were found to be SARS-CoV-2-positive on routine screening.

Figure 2 shows the utilization of CCMC-approved standard COVID-19 admission order sets as a proportion of all COVID-19 admissions over time. The trend reveals a modest increase in usage (R2 = 0.34), but these data do not reflect the progressive build of content into order sets over time. One of the goals of the order sets was to standardize and reduce the ordering of certain biomarkers: C-reactive protein, serum ferritin, and D-dimer, which were ordered frequently in many early patients. Orders for these 3 laboratory tests are combined and expressed as an average number of labs per COVID-19 admission in Figure 2. A downward trend, with an R2 value of 0.65, is suggestive of impact from the order sets, though other explanations are possible.

Medication guidance was also a goal of the CCMC, simultaneously discouraging poorly supported interventions and driving uptake of the recommended evidence-based interventions in appropriate patients. Figure 3 shows the utilization pattern for some drugs of interest over the course of the pandemic, specifically the proportion of patients receiving at least 1 dose of medication among all COVID-19 admissions by month. (Data for hospital B was excluded from this analysis because it did not include all admitted patients.)

Hydroxychloroquine, which enjoyed a wave of popularity early on during the pandemic, was a target of successful order stewardship through the CCMC. Use of hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 therapeutic option after the first 2 months of the pandemic stopped, and subsequent use at low levels likely represented continuation therapy for outpatients who took hydroxychloroquine for rheumatologic indications.

Dexamethasone, as used in the RECOVERY trial,21 had a swift uptake among physicians after it was incorporated into order sets and its use encouraged. Similarly, uptake was immediate for remdesivir when, in May 2020, preliminary reports showed at least some benefits, confirmed by later analysis,22 and it received an FDA EUA.

Our data also show successful stewardship of the interleukin-6 antagonist toclilizumab, which was discouraged early on by the CCMC due to lack of data or negative results. But in March 2021, with new studies releasing data12,13 and new recommendations14 for its use in some subsets of patients with COVID-19, this drug was encouraged in appropriate subsets. A new order set with qualifying indications was prepared by the CCMC and new educational efforts made to encourage its use in appropriate patients.

Ivermectin was nonformulary at the start of the pandemic. This drug enjoyed much publicity from media sources and was promoted by certain physicians and on websites,23 based on in-vitro activity against coronaviruses. Eventually, the World Health Organization24 and the FDA25 found it necessary to issue advisory statements to the public against its use outside of clinical trials. The CCMC had requests from physicians to incorporate ivermectin but declined to add it to the formulary and recommended not approving nonformulary requests due to lack of data. As a result, ivermectin was not used at either hospital.

Discussion

COVID-19 represents many challenges to health systems all over the world. For Luminis Health, the high volume of acutely ill patients with novel syndromes was a particular challenge for the hospital-based care teams. A flood of information from preprints, press releases, preliminary reports, and many other nontraditional sources made deliberative management decisions difficult for individual physicians. Much commentary has appeared around the phenomenon but with less practical advice about how to make day-to-day care decisions at a time of scientific uncertainty and intense pressure to intervene.26,27 The CCMC was designed to overcome the information management dilemma. The need to coordinate, standardize, and oversee care was necessary given the large number of physicians who cared for COVID-19 patients on inpatient services.

It should be noted that creating order sets and issuing guidance is necessary, but not sufficient, to achieve our goals of being updated and consistent. This is especially true with large cadres of health care workers attending COVID-19 patients. Guidelines and recommendations were reinforced by unit-based oversight and stewardship from pharmacy and other leaders who constituted the CCMC.

The reduction in COVID-19 mortality over time experienced in this health care system was not unique and cannot necessarily be attributed to standardization of care. Similar improvements in mortality have been reported at many US hospitals in aggregate.28 Many other factors, including changes in patient characteristics, may be responsible for reduction in mortality over time.

Throughout this report we have relied upon an implicit assumption that standardization of medical therapeutics is desirable and leads to better outcomes as compared with allowing unlimited empiricism by individual physicians, either consultants or hospitalists. Our program represents a single health system with 2 acute care hospitals located 25 miles apart and which thus were similarly impacted by the different phases of the pandemic. Generalizability to health systems either smaller or larger, or in different geographical areas, has not been established. Data limitations have already been discussed.

We did not measure user satisfaction with the program either from physicians or nurses. However, the high rate of compliance suggests general agreement with the content and process.

We cannot definitively ascribe reduction in utilization of some nonrecommended treatments and increased utilization of the recommended therapies to the work of the CCMC. Individual physicians may have made these adjustments on their own or under the influence of other sources.

Finally, it should be noted that the mission to rapidly respond to data from well-conducted trials might be thwarted by too rigid a process or a committee’s lack of a sense of urgency. Organizing a committee and then empowering it to act is no guarantee of success; commitment to the mission is.

Conclusion

COVID-19 represented a challenge to medical staffs everywhere, inundating them with high volumes of acutely ill patients presenting with unfamiliar syndromes. Initial responses were characterized by idiosyncratic management approaches based on nontraditional sources of opinion and influences.

This report describes how a complex medical system brought order and standardization through a deliberative, but urgent, multidisciplinary committee with responsibility for planning, implementing, and monitoring standard approaches that eventually became evidence based. The composition of the committee and its scope of influence, limited to inpatient management, were important elements of success, allowing for better focus on the many treatment decisions. The important connection between the management committee and the system P&T committee, the clinical research effort, and teaching programs in both medicine and pharmacy are offered as exemplars of coordination. The data presented show success in achieving standardized, guideline-directed care. The approach is adoptable and suitable for similar emergencies in the future.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank Gary Scabis, Kip Waite, John Moxley, Angela Clubb, and David Woodley for their assistance in gathering data. We express appreciation and admiration for all our colleagues at the bedside.

Corresponding author: Barry R. Meisenberg, MD, Department of Medicine, Luminis Health, 2001 Medical Pkwy, Annapolis, MD 21401; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gettleman J, Raj S, Kumar H. India’s health system cracks under the strain as coronavirus cases surge. The New York Times. April 22, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/21/world/asia/india-coronavirus-oxygen.html

2. Rappleye H, Lehren AW, Strickler L, Fitzpatrick S. ‘This system is doomed’: doctors, nurses sound off in NBC News coronavirus survey. NBC News. March 20, 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/system-doomed-doctors-nurses-sound-nbc-news-coronavirus-survey-n1164841

3. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Accessed January 5, 2022. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

4. Fineberg HV. The toll of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(15):1502-1503. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.20019

5. Meisenberg BR. Medical staffs response to COVID-19 ‘data’: have we misplaced our skeptic’s eye? Am J Med. 2021;134(2):151-152. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.09.013

6. McMahon JH, Lydeamore MH, Stewardson AJ. Bringing evidence from press release to the clinic in the era of COVID-19. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(3):547-549. doi:10.1093/jac/dkaa506

7. Rubin EJ, Baden LR, Morrissey S, Campion EW. Medical journals and the 2019-nCoV outbreak. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(9):866. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001329

8. Liu F, Li L, Xu M, et al. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104370. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370

9. Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2:69. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-2-69

10. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269-271. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

11. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Effect of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2030-2040. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022926

12. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): preliminary results of a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial [preprint]. February 11, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.02.11.21249258 https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.02.11.21249258v1

13. REMAP-CAP Investigators. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists in critically ill patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(16):1491-1502. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2100433

14. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 treatment guidelines: interleukin-6 inhibitors. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immunomodulators/interleukin-6-inhibitors/

15. Deana C, Vetrugno L, Tonizzo A, et al. Drug supply during COVID-19 pandemic: remember not to run with your tank empty. Hosp Pharm. 2021;56(5):405-407. doi:10.1177/0018578720931749

16. Choe J, Crane M, Greene J, et al. The Pandemic and the Supply Chain: Addressing Gaps in Pharmaceutical Production and Distribution. Johns Hopkins University, November 2020. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/affiliated-programs/johns-hopkins-drug-access-and-affordability-initiative/publications/Pandemic_Supply_Chain.pdf

17. Kern DE. Overview: a six-step approach to curriculum development. In: Kern DE, Thornton PA, Hughes MT, eds. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. 3rd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

18. Rice TW, Janz DR. In defense of evidence-based medicine for the treatment of COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(7):787-789. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202004-325IP

19. Lucey CR, Johnston SC. The transformational effects of COVID-19 on medical education. JAMA. 2020;324(11):1033-1034. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.14136

20. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 treatment guidelines: clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/clinical-spectrum/