User login

Radiologically Isolated Syndrome: A condition that often precedes an MS diagnosis in children

Naila Makhani, MD completed medical school training at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada). This was followed by a residency in child neurology and fellowship in MS and other demyelinating diseases at the University of Toronto and The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Canada). Concurrent with fellowship training, Dr. Makhani obtained a Masters’ degree in public health from Harvard University. Dr. Makhani is the Director of the Pediatric MS Program at Yale and the lead investigator of a multi-center international study examining outcomes following the radiologically isolated syndrome in children.

Q1. Could you please provide an overview of Radiologically Isolated Syndrome ?

A1. Radiologically Isolated Syndrome (RIS) was first described in adults in 2009. Since then it has also been increasingly recognized and diagnosed in children. RIS is diagnosed after an MRI of the brain that the patient has sought for reasons other than suspected multiple sclerosis-- for instance, for evaluation of head trauma or headache. However, unexpectedly or incidentally, the patient’s MRI shows the typical findings that we see in multiple sclerosis, even in the absence of any typical clinical symptoms. RIS is generally considered a rare syndrome.

Q2. You created Yale Medicine’s Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis program which advocates for the eradication of MS. What criteria defines a rare disease? Does RIS meet these criteria? And if so, how?

A2. The criteria for a rare disease vary, depending on the reference. In the US, a rare disease is defined as a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people, in total, across the country. By contrast, in Europe, a disease is considered rare if it affects fewer than one in every 2,000 people within the country’s population.

In the case of RIS, especially in children, we suspect that this is a rare condition, but we don't know for sure, as there have been very few population-based studies. There is one large study that was conducted in Europe that found one case of RIS among approximately 5,000 otherwise healthy children, who were between 7 and 14 years of age. I think that's our best estimate of the overall prevalence of RIS in children. Using that finding, it likely would qualify as a rare condition, although, as I said, we really don't know for sure, as the prevalence may vary among different populations or age groups.

Q3. How do you investigate and manage RIS in children? What are some of the challenges?

A3. For children with radiologically isolated syndrome, we usually undertake a comprehensive workup. This includes a detailed clinical neurological exam to ensure that there are no abnormalities that would, for instance, suggest a misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis or an alternative diagnosis. In addition to the brain MRI, we usually obtain an MRI of the spinal cord to determine whether there is any spinal cord involvement. We also obtain blood tests. We often analyze spinal fluid as well, primarily to exclude other alternative processes that may explain the MRI findings. A key challenge in this field is that there are currently no formal guidelines for the investigation and management of children with RIS. Collaborations within the pediatric MS community are needed to develop such consensus approaches to standardize care.

Q4. What are the most significant risk factors that indicate children with RIS could one day develop multiple sclerosis?

A4.This is an area of active research within our group. So far, we've found that approximately 42% of children with RIS develop multiple sclerosis in the future; on average, two years following their first abnormal MRI. Therefore, this is a high-risk group for developing multiple sclerosis in the future. Thus far, we've determined that in children with RIS, it is the presence of abnormal spinal cord imaging and an abnormality in spinal fluid – namely, the presence of oligoclonal bands – that are likely the predictors of whether these children could develop MS in the future. a child’s possible development

Q5. Based on your recent studies, are there data in children highlighting the potential for higher prevalence in one population over another?

A5. Thus far, population-based studies assessing RIS, especially in children, have been rare and thus far have not identified particular subgroups with increased prevalence. We do know that the prevalence of multiple sclerosis varies across different age groups and across gender. Whether such associations are also present for RIS is an area of active research.

de Mol CL, Bruijstens AL, Jansen PR, Dremmen M, Wong Y, van der Lugt A, White T, Neuteboom RF.Mult Scler. 2021 Oct;27(11):1790-1793. doi: 10.1177/1352458521989220. Epub 2021 Jan 22.PMID: 33480814

2. Radiologically isolated syndrome in children: Clinical and radiologic outcomes.

Makhani N, Lebrun C, Siva A, Brassat D, Carra Dallière C, de Seze J, Du W, Durand Dubief F, Kantarci O, Langille M, Narula S, Pelletier J, Rojas JI, Shapiro ED, Stone RT, Tintoré M, Uygunoglu U, Vermersch P, Wassmer E, Okuda DT, Pelletier D.Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017 Sep 25;4(6):e395. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000395. eCollection 2017 Nov.PMID: 28959703

Makhani N, Lebrun C, Siva A, Narula S, Wassmer E, Brassat D, Brenton JN, Cabre P, Carra Dallière C, de Seze J, Durand Dubief F, Inglese M, Langille M, Mathey G, Neuteboom RF, Pelletier J, Pohl D, Reich DS, Ignacio Rojas J, Shabanova V, Shapiro ED, Stone RT, Tenembaum S, Tintoré M, Uygunoglu U, Vargas W, Venkateswaren S, Vermersch P, Kantarci O, Okuda DT, Pelletier D; Observatoire Francophone de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP), Société Francophone de la Sclérose en Plaques (SFSEP), the Radiologically Isolated Syndrome Consortium (RISC) and the Pediatric Radiologically Isolated Syndrome Consortium (PARIS).Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019 Mar 20;5(1):2055217319836664. doi: 10.1177/2055217319836664. eCollection 2019 Jan-Mar.PMID: 30915227

Naila Makhani, MD completed medical school training at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada). This was followed by a residency in child neurology and fellowship in MS and other demyelinating diseases at the University of Toronto and The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Canada). Concurrent with fellowship training, Dr. Makhani obtained a Masters’ degree in public health from Harvard University. Dr. Makhani is the Director of the Pediatric MS Program at Yale and the lead investigator of a multi-center international study examining outcomes following the radiologically isolated syndrome in children.

Q1. Could you please provide an overview of Radiologically Isolated Syndrome ?

A1. Radiologically Isolated Syndrome (RIS) was first described in adults in 2009. Since then it has also been increasingly recognized and diagnosed in children. RIS is diagnosed after an MRI of the brain that the patient has sought for reasons other than suspected multiple sclerosis-- for instance, for evaluation of head trauma or headache. However, unexpectedly or incidentally, the patient’s MRI shows the typical findings that we see in multiple sclerosis, even in the absence of any typical clinical symptoms. RIS is generally considered a rare syndrome.

Q2. You created Yale Medicine’s Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis program which advocates for the eradication of MS. What criteria defines a rare disease? Does RIS meet these criteria? And if so, how?

A2. The criteria for a rare disease vary, depending on the reference. In the US, a rare disease is defined as a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people, in total, across the country. By contrast, in Europe, a disease is considered rare if it affects fewer than one in every 2,000 people within the country’s population.

In the case of RIS, especially in children, we suspect that this is a rare condition, but we don't know for sure, as there have been very few population-based studies. There is one large study that was conducted in Europe that found one case of RIS among approximately 5,000 otherwise healthy children, who were between 7 and 14 years of age. I think that's our best estimate of the overall prevalence of RIS in children. Using that finding, it likely would qualify as a rare condition, although, as I said, we really don't know for sure, as the prevalence may vary among different populations or age groups.

Q3. How do you investigate and manage RIS in children? What are some of the challenges?

A3. For children with radiologically isolated syndrome, we usually undertake a comprehensive workup. This includes a detailed clinical neurological exam to ensure that there are no abnormalities that would, for instance, suggest a misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis or an alternative diagnosis. In addition to the brain MRI, we usually obtain an MRI of the spinal cord to determine whether there is any spinal cord involvement. We also obtain blood tests. We often analyze spinal fluid as well, primarily to exclude other alternative processes that may explain the MRI findings. A key challenge in this field is that there are currently no formal guidelines for the investigation and management of children with RIS. Collaborations within the pediatric MS community are needed to develop such consensus approaches to standardize care.

Q4. What are the most significant risk factors that indicate children with RIS could one day develop multiple sclerosis?

A4.This is an area of active research within our group. So far, we've found that approximately 42% of children with RIS develop multiple sclerosis in the future; on average, two years following their first abnormal MRI. Therefore, this is a high-risk group for developing multiple sclerosis in the future. Thus far, we've determined that in children with RIS, it is the presence of abnormal spinal cord imaging and an abnormality in spinal fluid – namely, the presence of oligoclonal bands – that are likely the predictors of whether these children could develop MS in the future. a child’s possible development

Q5. Based on your recent studies, are there data in children highlighting the potential for higher prevalence in one population over another?

A5. Thus far, population-based studies assessing RIS, especially in children, have been rare and thus far have not identified particular subgroups with increased prevalence. We do know that the prevalence of multiple sclerosis varies across different age groups and across gender. Whether such associations are also present for RIS is an area of active research.

Naila Makhani, MD completed medical school training at the University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada). This was followed by a residency in child neurology and fellowship in MS and other demyelinating diseases at the University of Toronto and The Hospital for Sick Children (Toronto, Canada). Concurrent with fellowship training, Dr. Makhani obtained a Masters’ degree in public health from Harvard University. Dr. Makhani is the Director of the Pediatric MS Program at Yale and the lead investigator of a multi-center international study examining outcomes following the radiologically isolated syndrome in children.

Q1. Could you please provide an overview of Radiologically Isolated Syndrome ?

A1. Radiologically Isolated Syndrome (RIS) was first described in adults in 2009. Since then it has also been increasingly recognized and diagnosed in children. RIS is diagnosed after an MRI of the brain that the patient has sought for reasons other than suspected multiple sclerosis-- for instance, for evaluation of head trauma or headache. However, unexpectedly or incidentally, the patient’s MRI shows the typical findings that we see in multiple sclerosis, even in the absence of any typical clinical symptoms. RIS is generally considered a rare syndrome.

Q2. You created Yale Medicine’s Pediatric Multiple Sclerosis program which advocates for the eradication of MS. What criteria defines a rare disease? Does RIS meet these criteria? And if so, how?

A2. The criteria for a rare disease vary, depending on the reference. In the US, a rare disease is defined as a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people, in total, across the country. By contrast, in Europe, a disease is considered rare if it affects fewer than one in every 2,000 people within the country’s population.

In the case of RIS, especially in children, we suspect that this is a rare condition, but we don't know for sure, as there have been very few population-based studies. There is one large study that was conducted in Europe that found one case of RIS among approximately 5,000 otherwise healthy children, who were between 7 and 14 years of age. I think that's our best estimate of the overall prevalence of RIS in children. Using that finding, it likely would qualify as a rare condition, although, as I said, we really don't know for sure, as the prevalence may vary among different populations or age groups.

Q3. How do you investigate and manage RIS in children? What are some of the challenges?

A3. For children with radiologically isolated syndrome, we usually undertake a comprehensive workup. This includes a detailed clinical neurological exam to ensure that there are no abnormalities that would, for instance, suggest a misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis or an alternative diagnosis. In addition to the brain MRI, we usually obtain an MRI of the spinal cord to determine whether there is any spinal cord involvement. We also obtain blood tests. We often analyze spinal fluid as well, primarily to exclude other alternative processes that may explain the MRI findings. A key challenge in this field is that there are currently no formal guidelines for the investigation and management of children with RIS. Collaborations within the pediatric MS community are needed to develop such consensus approaches to standardize care.

Q4. What are the most significant risk factors that indicate children with RIS could one day develop multiple sclerosis?

A4.This is an area of active research within our group. So far, we've found that approximately 42% of children with RIS develop multiple sclerosis in the future; on average, two years following their first abnormal MRI. Therefore, this is a high-risk group for developing multiple sclerosis in the future. Thus far, we've determined that in children with RIS, it is the presence of abnormal spinal cord imaging and an abnormality in spinal fluid – namely, the presence of oligoclonal bands – that are likely the predictors of whether these children could develop MS in the future. a child’s possible development

Q5. Based on your recent studies, are there data in children highlighting the potential for higher prevalence in one population over another?

A5. Thus far, population-based studies assessing RIS, especially in children, have been rare and thus far have not identified particular subgroups with increased prevalence. We do know that the prevalence of multiple sclerosis varies across different age groups and across gender. Whether such associations are also present for RIS is an area of active research.

de Mol CL, Bruijstens AL, Jansen PR, Dremmen M, Wong Y, van der Lugt A, White T, Neuteboom RF.Mult Scler. 2021 Oct;27(11):1790-1793. doi: 10.1177/1352458521989220. Epub 2021 Jan 22.PMID: 33480814

2. Radiologically isolated syndrome in children: Clinical and radiologic outcomes.

Makhani N, Lebrun C, Siva A, Brassat D, Carra Dallière C, de Seze J, Du W, Durand Dubief F, Kantarci O, Langille M, Narula S, Pelletier J, Rojas JI, Shapiro ED, Stone RT, Tintoré M, Uygunoglu U, Vermersch P, Wassmer E, Okuda DT, Pelletier D.Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017 Sep 25;4(6):e395. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000395. eCollection 2017 Nov.PMID: 28959703

Makhani N, Lebrun C, Siva A, Narula S, Wassmer E, Brassat D, Brenton JN, Cabre P, Carra Dallière C, de Seze J, Durand Dubief F, Inglese M, Langille M, Mathey G, Neuteboom RF, Pelletier J, Pohl D, Reich DS, Ignacio Rojas J, Shabanova V, Shapiro ED, Stone RT, Tenembaum S, Tintoré M, Uygunoglu U, Vargas W, Venkateswaren S, Vermersch P, Kantarci O, Okuda DT, Pelletier D; Observatoire Francophone de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP), Société Francophone de la Sclérose en Plaques (SFSEP), the Radiologically Isolated Syndrome Consortium (RISC) and the Pediatric Radiologically Isolated Syndrome Consortium (PARIS).Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019 Mar 20;5(1):2055217319836664. doi: 10.1177/2055217319836664. eCollection 2019 Jan-Mar.PMID: 30915227

de Mol CL, Bruijstens AL, Jansen PR, Dremmen M, Wong Y, van der Lugt A, White T, Neuteboom RF.Mult Scler. 2021 Oct;27(11):1790-1793. doi: 10.1177/1352458521989220. Epub 2021 Jan 22.PMID: 33480814

2. Radiologically isolated syndrome in children: Clinical and radiologic outcomes.

Makhani N, Lebrun C, Siva A, Brassat D, Carra Dallière C, de Seze J, Du W, Durand Dubief F, Kantarci O, Langille M, Narula S, Pelletier J, Rojas JI, Shapiro ED, Stone RT, Tintoré M, Uygunoglu U, Vermersch P, Wassmer E, Okuda DT, Pelletier D.Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017 Sep 25;4(6):e395. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000395. eCollection 2017 Nov.PMID: 28959703

Makhani N, Lebrun C, Siva A, Narula S, Wassmer E, Brassat D, Brenton JN, Cabre P, Carra Dallière C, de Seze J, Durand Dubief F, Inglese M, Langille M, Mathey G, Neuteboom RF, Pelletier J, Pohl D, Reich DS, Ignacio Rojas J, Shabanova V, Shapiro ED, Stone RT, Tenembaum S, Tintoré M, Uygunoglu U, Vargas W, Venkateswaren S, Vermersch P, Kantarci O, Okuda DT, Pelletier D; Observatoire Francophone de la Sclérose en Plaques (OFSEP), Société Francophone de la Sclérose en Plaques (SFSEP), the Radiologically Isolated Syndrome Consortium (RISC) and the Pediatric Radiologically Isolated Syndrome Consortium (PARIS).Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2019 Mar 20;5(1):2055217319836664. doi: 10.1177/2055217319836664. eCollection 2019 Jan-Mar.PMID: 30915227

Vitamin D and omega-3 supplements reduce autoimmune disease risk

For those of us who cannot sit in the sun and fish all day, the next best thing for preventing autoimmune diseases may be supplementation with vitamin D and fish oil-derived omega-3 fatty acids, results of a large prospective randomized trial suggest.

Among nearly 26,000 adults enrolled in a randomized trial designed primarily to study the effects of vitamin D and omega-3 supplementation on incident cancer and cardiovascular disease, 5, and 5 years of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation was associated with an 18% reduction in confirmed and probable incident autoimmune diseases, reported Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“The clinical importance of these results is very high, given that these are nontoxic, well-tolerated supplements, and that there are no other known effective therapies to reduce the incidence of autoimmune diseases,” she said during the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“People do have to take the supplements a long time to start to see the reduction in risk, especially for vitamin D, but they make biological sense, and autoimmune diseases develop slowly over time, so taking it today isn’t going to reduce risk of developing something tomorrow,” Dr. Costenbader said in an interview.

“These supplements have other health benefits. Obviously, fish oil is anti-inflammatory, and vitamin D is good for osteoporosis prevention, especially in our patients who take glucocorticoids. People who are otherwise healthy and have a family history of autoimmune disease might also consider starting to take these supplements,” she said.

After watching her presentation, session co-moderator Gregg Silverman, MD, from the NYU Langone School of Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the study, commented “I’m going to [nutrition store] GNC to get some vitamins.”

When asked for comment, the other session moderator, Tracy Frech, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, said, “I think Dr. Costenbader’s work is very important and her presentation excellent. My current practice is replacement of vitamin D in all autoimmune disease patients with low levels and per bone health guidelines. Additionally, I discuss omega-3 supplementation with Sjögren’s [syndrome] patients as a consideration.”

Evidence base

Dr. Costenbader noted that in a 2013 observational study from France, vitamin D derived through ultraviolet (UV) light exposure was associated with a lower risk for incident Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis, and in two analyses of data in 2014 from the Nurses’ Health Study, both high plasma levels of 25-OH vitamin D and geographic residence in areas of high UV exposure were associated with a decreased incidence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Other observational studies have supported omega-3 fatty acids for their anti-inflammatory properties, including a 2005 Danish prospective cohort study showing a lower risk for RA in participants who reported higher levels of fatty fish intake. In a separate study conducted in 2017, healthy volunteers with higher omega-3 fatty acid/total lipid proportions in red blood cell membranes had a lower prevalence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies and rheumatoid factor and a lower incidence of progression to inflammatory arthritis, she said.

Ancillary study

Despite the evidence, however, there have been no prospective randomized trials to test the effects of either vitamin D or omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on the incidence of autoimmune disease over time.

To rectify this, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues piggybacked an ancillary study onto the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which had primary outcomes of cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence.

A total of 25,871 participants were enrolled, including 12,786 men aged 50 and older, and 13,085 women aged 55 and older.

The study had a 2 x 2 factorial design, with patients randomly assigned to vitamin D 2,000 IU/day or placebo, and then further randomized to either 1 g/day omega-3 fatty acids or placebo in both the vitamin D and placebo primary randomization arms.

At baseline 16,956 participants were assayed for 25-OH vitamin D and plasma omega 3 index, the ratio of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to total fatty acids. Participants self-reported baseline and all incident autoimmune diseases annually, with the reports confirmed by medical record review and disease criteria whenever possible.

Results

At 5 years of follow-up, confirmed incident autoimmune diseases had occurred in 123 patients in the active vitamin D group, compared with 155 in the placebo vitamin D group, translating into a hazard ratio (HR) for vitamin D of 0.78 (P = .045).

In the active omega-3 arm, 130 participants developed an autoimmune disease, compared with 148 in the placebo omega-3 arm, which translated into a nonsignificant HR of 0.85.

There was no statistical interaction between the two supplements. The investigators did observe an interaction between vitamin D and body mass index, with the effect stronger among participants with low BMI (P = .02). There also was an interaction between omega-3 fatty acids with a family history of autoimmune disease (P = .03).

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, and other supplement arm, vitamin D alone was associated with an HR for incident autoimmune disease of 0.68 (P = .02), omega-3 alone was associated with a nonsignificant HR of 0.74, and the combination was associated with an HR of 0.69 (P = .03).

Dr. Costenbader and colleagues acknowledged that the study was limited by the lack of a high-risk or nutritionally-deficient population, where the effects of supplementation might be larger; the restriction of the sample to older adults; and to the difficulty of confirming incident autoimmune thyroid disease from patient reports.

Cheryl Koehn, an arthritis patient advocate from Vancouver, Canada, who was not involved in the study, commented in the “chat” section of the presentation that her rheumatologist “has recommended vitamin D for years now. Says basically everyone north of Boston is vitamin D deficient. I take 1,000 IU per day. Been taking it for years.” Ms. Koehn is the founder and president of Arthritis Consumer Experts, a website that provides education to those with arthritis.

“Agreed. I tell every patient to take vitamin D supplement,” commented Fatma Dedeoglu, MD, a rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For those of us who cannot sit in the sun and fish all day, the next best thing for preventing autoimmune diseases may be supplementation with vitamin D and fish oil-derived omega-3 fatty acids, results of a large prospective randomized trial suggest.

Among nearly 26,000 adults enrolled in a randomized trial designed primarily to study the effects of vitamin D and omega-3 supplementation on incident cancer and cardiovascular disease, 5, and 5 years of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation was associated with an 18% reduction in confirmed and probable incident autoimmune diseases, reported Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“The clinical importance of these results is very high, given that these are nontoxic, well-tolerated supplements, and that there are no other known effective therapies to reduce the incidence of autoimmune diseases,” she said during the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“People do have to take the supplements a long time to start to see the reduction in risk, especially for vitamin D, but they make biological sense, and autoimmune diseases develop slowly over time, so taking it today isn’t going to reduce risk of developing something tomorrow,” Dr. Costenbader said in an interview.

“These supplements have other health benefits. Obviously, fish oil is anti-inflammatory, and vitamin D is good for osteoporosis prevention, especially in our patients who take glucocorticoids. People who are otherwise healthy and have a family history of autoimmune disease might also consider starting to take these supplements,” she said.

After watching her presentation, session co-moderator Gregg Silverman, MD, from the NYU Langone School of Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the study, commented “I’m going to [nutrition store] GNC to get some vitamins.”

When asked for comment, the other session moderator, Tracy Frech, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, said, “I think Dr. Costenbader’s work is very important and her presentation excellent. My current practice is replacement of vitamin D in all autoimmune disease patients with low levels and per bone health guidelines. Additionally, I discuss omega-3 supplementation with Sjögren’s [syndrome] patients as a consideration.”

Evidence base

Dr. Costenbader noted that in a 2013 observational study from France, vitamin D derived through ultraviolet (UV) light exposure was associated with a lower risk for incident Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis, and in two analyses of data in 2014 from the Nurses’ Health Study, both high plasma levels of 25-OH vitamin D and geographic residence in areas of high UV exposure were associated with a decreased incidence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Other observational studies have supported omega-3 fatty acids for their anti-inflammatory properties, including a 2005 Danish prospective cohort study showing a lower risk for RA in participants who reported higher levels of fatty fish intake. In a separate study conducted in 2017, healthy volunteers with higher omega-3 fatty acid/total lipid proportions in red blood cell membranes had a lower prevalence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies and rheumatoid factor and a lower incidence of progression to inflammatory arthritis, she said.

Ancillary study

Despite the evidence, however, there have been no prospective randomized trials to test the effects of either vitamin D or omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on the incidence of autoimmune disease over time.

To rectify this, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues piggybacked an ancillary study onto the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which had primary outcomes of cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence.

A total of 25,871 participants were enrolled, including 12,786 men aged 50 and older, and 13,085 women aged 55 and older.

The study had a 2 x 2 factorial design, with patients randomly assigned to vitamin D 2,000 IU/day or placebo, and then further randomized to either 1 g/day omega-3 fatty acids or placebo in both the vitamin D and placebo primary randomization arms.

At baseline 16,956 participants were assayed for 25-OH vitamin D and plasma omega 3 index, the ratio of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to total fatty acids. Participants self-reported baseline and all incident autoimmune diseases annually, with the reports confirmed by medical record review and disease criteria whenever possible.

Results

At 5 years of follow-up, confirmed incident autoimmune diseases had occurred in 123 patients in the active vitamin D group, compared with 155 in the placebo vitamin D group, translating into a hazard ratio (HR) for vitamin D of 0.78 (P = .045).

In the active omega-3 arm, 130 participants developed an autoimmune disease, compared with 148 in the placebo omega-3 arm, which translated into a nonsignificant HR of 0.85.

There was no statistical interaction between the two supplements. The investigators did observe an interaction between vitamin D and body mass index, with the effect stronger among participants with low BMI (P = .02). There also was an interaction between omega-3 fatty acids with a family history of autoimmune disease (P = .03).

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, and other supplement arm, vitamin D alone was associated with an HR for incident autoimmune disease of 0.68 (P = .02), omega-3 alone was associated with a nonsignificant HR of 0.74, and the combination was associated with an HR of 0.69 (P = .03).

Dr. Costenbader and colleagues acknowledged that the study was limited by the lack of a high-risk or nutritionally-deficient population, where the effects of supplementation might be larger; the restriction of the sample to older adults; and to the difficulty of confirming incident autoimmune thyroid disease from patient reports.

Cheryl Koehn, an arthritis patient advocate from Vancouver, Canada, who was not involved in the study, commented in the “chat” section of the presentation that her rheumatologist “has recommended vitamin D for years now. Says basically everyone north of Boston is vitamin D deficient. I take 1,000 IU per day. Been taking it for years.” Ms. Koehn is the founder and president of Arthritis Consumer Experts, a website that provides education to those with arthritis.

“Agreed. I tell every patient to take vitamin D supplement,” commented Fatma Dedeoglu, MD, a rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For those of us who cannot sit in the sun and fish all day, the next best thing for preventing autoimmune diseases may be supplementation with vitamin D and fish oil-derived omega-3 fatty acids, results of a large prospective randomized trial suggest.

Among nearly 26,000 adults enrolled in a randomized trial designed primarily to study the effects of vitamin D and omega-3 supplementation on incident cancer and cardiovascular disease, 5, and 5 years of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation was associated with an 18% reduction in confirmed and probable incident autoimmune diseases, reported Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“The clinical importance of these results is very high, given that these are nontoxic, well-tolerated supplements, and that there are no other known effective therapies to reduce the incidence of autoimmune diseases,” she said during the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“People do have to take the supplements a long time to start to see the reduction in risk, especially for vitamin D, but they make biological sense, and autoimmune diseases develop slowly over time, so taking it today isn’t going to reduce risk of developing something tomorrow,” Dr. Costenbader said in an interview.

“These supplements have other health benefits. Obviously, fish oil is anti-inflammatory, and vitamin D is good for osteoporosis prevention, especially in our patients who take glucocorticoids. People who are otherwise healthy and have a family history of autoimmune disease might also consider starting to take these supplements,” she said.

After watching her presentation, session co-moderator Gregg Silverman, MD, from the NYU Langone School of Medicine in New York, who was not involved in the study, commented “I’m going to [nutrition store] GNC to get some vitamins.”

When asked for comment, the other session moderator, Tracy Frech, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, said, “I think Dr. Costenbader’s work is very important and her presentation excellent. My current practice is replacement of vitamin D in all autoimmune disease patients with low levels and per bone health guidelines. Additionally, I discuss omega-3 supplementation with Sjögren’s [syndrome] patients as a consideration.”

Evidence base

Dr. Costenbader noted that in a 2013 observational study from France, vitamin D derived through ultraviolet (UV) light exposure was associated with a lower risk for incident Crohn’s disease but not ulcerative colitis, and in two analyses of data in 2014 from the Nurses’ Health Study, both high plasma levels of 25-OH vitamin D and geographic residence in areas of high UV exposure were associated with a decreased incidence of rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Other observational studies have supported omega-3 fatty acids for their anti-inflammatory properties, including a 2005 Danish prospective cohort study showing a lower risk for RA in participants who reported higher levels of fatty fish intake. In a separate study conducted in 2017, healthy volunteers with higher omega-3 fatty acid/total lipid proportions in red blood cell membranes had a lower prevalence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies and rheumatoid factor and a lower incidence of progression to inflammatory arthritis, she said.

Ancillary study

Despite the evidence, however, there have been no prospective randomized trials to test the effects of either vitamin D or omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on the incidence of autoimmune disease over time.

To rectify this, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues piggybacked an ancillary study onto the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which had primary outcomes of cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence.

A total of 25,871 participants were enrolled, including 12,786 men aged 50 and older, and 13,085 women aged 55 and older.

The study had a 2 x 2 factorial design, with patients randomly assigned to vitamin D 2,000 IU/day or placebo, and then further randomized to either 1 g/day omega-3 fatty acids or placebo in both the vitamin D and placebo primary randomization arms.

At baseline 16,956 participants were assayed for 25-OH vitamin D and plasma omega 3 index, the ratio of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to total fatty acids. Participants self-reported baseline and all incident autoimmune diseases annually, with the reports confirmed by medical record review and disease criteria whenever possible.

Results

At 5 years of follow-up, confirmed incident autoimmune diseases had occurred in 123 patients in the active vitamin D group, compared with 155 in the placebo vitamin D group, translating into a hazard ratio (HR) for vitamin D of 0.78 (P = .045).

In the active omega-3 arm, 130 participants developed an autoimmune disease, compared with 148 in the placebo omega-3 arm, which translated into a nonsignificant HR of 0.85.

There was no statistical interaction between the two supplements. The investigators did observe an interaction between vitamin D and body mass index, with the effect stronger among participants with low BMI (P = .02). There also was an interaction between omega-3 fatty acids with a family history of autoimmune disease (P = .03).

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, and other supplement arm, vitamin D alone was associated with an HR for incident autoimmune disease of 0.68 (P = .02), omega-3 alone was associated with a nonsignificant HR of 0.74, and the combination was associated with an HR of 0.69 (P = .03).

Dr. Costenbader and colleagues acknowledged that the study was limited by the lack of a high-risk or nutritionally-deficient population, where the effects of supplementation might be larger; the restriction of the sample to older adults; and to the difficulty of confirming incident autoimmune thyroid disease from patient reports.

Cheryl Koehn, an arthritis patient advocate from Vancouver, Canada, who was not involved in the study, commented in the “chat” section of the presentation that her rheumatologist “has recommended vitamin D for years now. Says basically everyone north of Boston is vitamin D deficient. I take 1,000 IU per day. Been taking it for years.” Ms. Koehn is the founder and president of Arthritis Consumer Experts, a website that provides education to those with arthritis.

“Agreed. I tell every patient to take vitamin D supplement,” commented Fatma Dedeoglu, MD, a rheumatologist at Boston Children’s Hospital.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACR 2021

Liquid biopsy in metastatic breast cancer management: Where does it stand in clinical practice?

Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for characterizing tumor biology and guiding therapeutic decisions, but liquid biopsies — blood analyses that allow oncologists to detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the blood — are increasingly demonstrating their value. Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two liquid biopsy tests, Guardant360 CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx, that can identify more than 300 cancer-related genes in the blood. In 2019, the FDA also approved the first companion diagnostic test, therascreen, to pinpoint PIK3CA gene mutations in patients’ ctDNA and determine whether patients should receive the PI3K inhibitor alpelisib along with fulvestrant.

Here’s an overview of how liquid biopsy is being used in monitoring MBC progression and treatment — and what some oncologists think of it.

What we do and don’t know

“Identifying a patient’s targetable mutations, most notably PIK3CA mutations, is currently the main use of liquid biopsy,” said Pedram Razavi, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist who leads the liquid biopsy program for breast cancer at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center in New York City. “Patients who come to MSK are offered a tumor and liquid biopsy at the time of metastatic diagnosis as part of the standard of care.”

Liquid and tissue biopsy analyses can provide a more complete picture of a patient’s condition. Whereas tissue biopsy allows oncologists to target a more saturated sample of the cancer ecosystem and a wider array of biomarkers, liquid biopsy offers important advantages as well, including a less invasive way to sequence a sample, monitor patients’ treatment response, or track tumor evolution. Liquid biopsy also provides a bigger picture view of tumor heterogeneity by pooling information from many tumor locations as opposed to one.

But, cautioned Yuan Yuan, MD, PhD, liquid biopsy technology is not always sensitive enough to detect CTCs, ctDNA, or all relevant mutations. “When you collect a small tube of blood, you’re essentially trying to catch a small fish in a big sea and wading through a lot of background noise,” said Dr. Yuan, medical oncologist at City of Hope, a comprehensive cancer center in Los Angeles County. “The results may be hard to interpret or come back inconclusive.”

And although emerging data suggest that liquid biopsy provides important insights about tumor dynamics — including mapping disease progression, predicting survival, and even detecting signs of cancer recurrence before metastasis develops — the tool has limited utility in clinical practice outside of identifying sensitivity to various therapies or drugs.

“Right now, a lot of research is being done to understand how to use CTC and ctDNA in particular as a means of surveillance in breast cancer, but we’re still in the beginning stages of applying that outside of clinical trials,” said Joseph A. Sparano, MD, deputy director of the Tisch Cancer Institute and chief of the division of hematology and medical oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

Personalizing treatment

The companion diagnostic test therascreen marked the beginning stages of using liquid biopsy to match treatments to genetic abnormalities in MBC. The SOLAR-1 phase 3 trial, which led to the approval of alpelisib and therascreen, found that the PI3K inhibitor plus fulvestrant almost doubled progression-free survival (PFS) (11 months vs 5.7 months in placebo-fulvestrant group) in patients with PIK3CA-mutated, HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

More recent studies have shown that liquid biopsy tests can also identify ESR1 mutations and predict responses to inhibitors that target AKT1 and HER2. Investigators presenting at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting reported that next-generation sequencing of ctDNA in patients with HR-positive MBC, HER-positive MBC, or triple-negative breast cancer detected ESR1 mutations in 14% of patients (71 of 501). Moreover, ESR1 mutations were found only in HR-positive patients who had already received endocrine therapy. (The study also examined PIK3CA mutations, which occurred in about one third of patients). A more in-depth look revealed that ESR1 mutations were strongly associated with liver and bone metastases and that mutations along specific codons negatively affected overall survival (OS) and PFS: codons 537 and 538 for OS and codons 380 and 536 for PFS.

According to Debasish Tripathy, MD, professor and chairman of the department of breast medical oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, in addition to tumor sequencing, “liquid biopsy has become a great research tool to track patients in real time and predict, for instance, who will respond to a treatment and identify emerging resistance.”

In terms of predicting responses to treatment, the plasmaMATCH trial assessed ctDNA in 1,034 patients with advanced breast cancer for mutations in ESR1, HER2, and AKT1 using digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Guardant360. Results showed that 357 (34.5%) of these patients had potentially targetable aberrations, including 222 patients with ESR1 mutations, 36 patients with HER2 mutations, and 30 patients with AKT1 mutations.

Agreement between digital droplet PCR and Guardant360 testing was 96%-99%, and liquid biopsy showed 93% sensitivity compared with tumor samples. The investigators also used liquid biopsy findings to match patients’ mutations to targeted treatments: fulvestrant for those with ESR1 mutations, neratinib for HER2 (ERBB2) mutations, and the selective AKT inhibitor capivasertib for estrogen receptor–positive tumors with AKT1 mutations.

Overall, the investigators concluded that ctDNA testing offers “accurate tumor genotyping” in line with tissue-based testing and is ready for routine clinical practice to identify common as well as rare genetic alterations, such as HER2 and AKT1 mutations, that affect only about 5% of patients with advanced disease.

Predicting survival and recurrence

A particularly promising area for liquid biopsy is its usefulness in helping to predict survival outcomes and monitor patients for early signs of recurrence before metastasis occurs. But the data to support this are still in their infancy.

A highly cited study, published over 15 years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that patients with MBC who had five or more CTCs per 7.5 mL of whole blood before receiving first-line therapy exhibited significantly shorter median PFS (2.7 vs 7.0 months) and OS (10 vs > 18 months) compared with patients with fewer than five CTCs. Subsequent analyses performed more than a decade later, including a meta-analysis published last year, helped validate these early findings that levels of CTCs detected in the blood independently and strongly predicted PFS and OS in patients with MBC.

In addition, ctDNA can provide important information about patients’ survival odds. In a retrospective study published last year, investigators tracked changes in ctDNA in 291 plasma samples from 84 patients with locally advanced breast cancer who participated in the I-SPY trial. Patients who remained ctDNA-positive after 3 weeks of neoadjuvant chemotherapy were significantly more likely to have residual disease after completing their treatment compared with patients who cleared ctDNA at that early stage (83% for those with nonpathologic complete response vs 52%). Notably, the presence of ctDNA between therapy initiation and completion was associated with a significantly greater risk for metastatic recurrence, whereas clearance of ctDNA after neoadjuvant therapy was linked to improved survival.

“The study is important because it highlights how tracking circulating ctDNA status in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer can expose a patient’s risk for distant metastasis,” said Dr. Yuan. But, she added, “I think the biggest attraction of liquid biopsy will be the ability to detect molecular disease even before imaging can, and identify who has a high risk for recurrence.”

Dr. Razavi agreed that the potential to prevent metastasis by finding minimal residual disease (MRD) is the most exciting area of liquid biopsy research. “If we can find tumor DNA early before tumors have a chance to establish themselves, we could potentially change the trajectory of the disease for patients,” he said.

Several studies suggest that monitoring patients’ ctDNA levels after neoadjuvant treatment and surgery may help predict their risk for relapse and progression to metastatic disease. A 2015 analysis, which followed 20 patients with breast cancer after surgery, found that ctDNA monitoring accurately differentiated those who ultimately developed metastatic disease from those who didn’t (sensitivity, 93%; specificity, 100%) and detected metastatic disease 11 months earlier, on average, than imaging did. Another 2015 study found that the presence of ctDNA in plasma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery predicted metastatic relapse a median of almost 8 months before clinical detection. Other recent data show the power of ultrasensitive blood tests to detect MRD and potentially find metastatic disease early.

Although an increasing number of studies show that ctDNA and CTCs are prognostic for breast cancer recurrence, a major question remains: For patients with ctDNA or CTCs but no overt disease after imaging, will initiating therapy prevent or delay the development of metastatic disease?

“We still have to do those clinical trials to determine whether detecting MRD and treating patients early actually positively affects their survival and quality of life,” Dr. Razavi said.

Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for characterizing tumor biology and guiding therapeutic decisions, but liquid biopsies — blood analyses that allow oncologists to detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the blood — are increasingly demonstrating their value. Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two liquid biopsy tests, Guardant360 CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx, that can identify more than 300 cancer-related genes in the blood. In 2019, the FDA also approved the first companion diagnostic test, therascreen, to pinpoint PIK3CA gene mutations in patients’ ctDNA and determine whether patients should receive the PI3K inhibitor alpelisib along with fulvestrant.

Here’s an overview of how liquid biopsy is being used in monitoring MBC progression and treatment — and what some oncologists think of it.

What we do and don’t know

“Identifying a patient’s targetable mutations, most notably PIK3CA mutations, is currently the main use of liquid biopsy,” said Pedram Razavi, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist who leads the liquid biopsy program for breast cancer at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center in New York City. “Patients who come to MSK are offered a tumor and liquid biopsy at the time of metastatic diagnosis as part of the standard of care.”

Liquid and tissue biopsy analyses can provide a more complete picture of a patient’s condition. Whereas tissue biopsy allows oncologists to target a more saturated sample of the cancer ecosystem and a wider array of biomarkers, liquid biopsy offers important advantages as well, including a less invasive way to sequence a sample, monitor patients’ treatment response, or track tumor evolution. Liquid biopsy also provides a bigger picture view of tumor heterogeneity by pooling information from many tumor locations as opposed to one.

But, cautioned Yuan Yuan, MD, PhD, liquid biopsy technology is not always sensitive enough to detect CTCs, ctDNA, or all relevant mutations. “When you collect a small tube of blood, you’re essentially trying to catch a small fish in a big sea and wading through a lot of background noise,” said Dr. Yuan, medical oncologist at City of Hope, a comprehensive cancer center in Los Angeles County. “The results may be hard to interpret or come back inconclusive.”

And although emerging data suggest that liquid biopsy provides important insights about tumor dynamics — including mapping disease progression, predicting survival, and even detecting signs of cancer recurrence before metastasis develops — the tool has limited utility in clinical practice outside of identifying sensitivity to various therapies or drugs.

“Right now, a lot of research is being done to understand how to use CTC and ctDNA in particular as a means of surveillance in breast cancer, but we’re still in the beginning stages of applying that outside of clinical trials,” said Joseph A. Sparano, MD, deputy director of the Tisch Cancer Institute and chief of the division of hematology and medical oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

Personalizing treatment

The companion diagnostic test therascreen marked the beginning stages of using liquid biopsy to match treatments to genetic abnormalities in MBC. The SOLAR-1 phase 3 trial, which led to the approval of alpelisib and therascreen, found that the PI3K inhibitor plus fulvestrant almost doubled progression-free survival (PFS) (11 months vs 5.7 months in placebo-fulvestrant group) in patients with PIK3CA-mutated, HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

More recent studies have shown that liquid biopsy tests can also identify ESR1 mutations and predict responses to inhibitors that target AKT1 and HER2. Investigators presenting at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting reported that next-generation sequencing of ctDNA in patients with HR-positive MBC, HER-positive MBC, or triple-negative breast cancer detected ESR1 mutations in 14% of patients (71 of 501). Moreover, ESR1 mutations were found only in HR-positive patients who had already received endocrine therapy. (The study also examined PIK3CA mutations, which occurred in about one third of patients). A more in-depth look revealed that ESR1 mutations were strongly associated with liver and bone metastases and that mutations along specific codons negatively affected overall survival (OS) and PFS: codons 537 and 538 for OS and codons 380 and 536 for PFS.

According to Debasish Tripathy, MD, professor and chairman of the department of breast medical oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, in addition to tumor sequencing, “liquid biopsy has become a great research tool to track patients in real time and predict, for instance, who will respond to a treatment and identify emerging resistance.”

In terms of predicting responses to treatment, the plasmaMATCH trial assessed ctDNA in 1,034 patients with advanced breast cancer for mutations in ESR1, HER2, and AKT1 using digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Guardant360. Results showed that 357 (34.5%) of these patients had potentially targetable aberrations, including 222 patients with ESR1 mutations, 36 patients with HER2 mutations, and 30 patients with AKT1 mutations.

Agreement between digital droplet PCR and Guardant360 testing was 96%-99%, and liquid biopsy showed 93% sensitivity compared with tumor samples. The investigators also used liquid biopsy findings to match patients’ mutations to targeted treatments: fulvestrant for those with ESR1 mutations, neratinib for HER2 (ERBB2) mutations, and the selective AKT inhibitor capivasertib for estrogen receptor–positive tumors with AKT1 mutations.

Overall, the investigators concluded that ctDNA testing offers “accurate tumor genotyping” in line with tissue-based testing and is ready for routine clinical practice to identify common as well as rare genetic alterations, such as HER2 and AKT1 mutations, that affect only about 5% of patients with advanced disease.

Predicting survival and recurrence

A particularly promising area for liquid biopsy is its usefulness in helping to predict survival outcomes and monitor patients for early signs of recurrence before metastasis occurs. But the data to support this are still in their infancy.

A highly cited study, published over 15 years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that patients with MBC who had five or more CTCs per 7.5 mL of whole blood before receiving first-line therapy exhibited significantly shorter median PFS (2.7 vs 7.0 months) and OS (10 vs > 18 months) compared with patients with fewer than five CTCs. Subsequent analyses performed more than a decade later, including a meta-analysis published last year, helped validate these early findings that levels of CTCs detected in the blood independently and strongly predicted PFS and OS in patients with MBC.

In addition, ctDNA can provide important information about patients’ survival odds. In a retrospective study published last year, investigators tracked changes in ctDNA in 291 plasma samples from 84 patients with locally advanced breast cancer who participated in the I-SPY trial. Patients who remained ctDNA-positive after 3 weeks of neoadjuvant chemotherapy were significantly more likely to have residual disease after completing their treatment compared with patients who cleared ctDNA at that early stage (83% for those with nonpathologic complete response vs 52%). Notably, the presence of ctDNA between therapy initiation and completion was associated with a significantly greater risk for metastatic recurrence, whereas clearance of ctDNA after neoadjuvant therapy was linked to improved survival.

“The study is important because it highlights how tracking circulating ctDNA status in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer can expose a patient’s risk for distant metastasis,” said Dr. Yuan. But, she added, “I think the biggest attraction of liquid biopsy will be the ability to detect molecular disease even before imaging can, and identify who has a high risk for recurrence.”

Dr. Razavi agreed that the potential to prevent metastasis by finding minimal residual disease (MRD) is the most exciting area of liquid biopsy research. “If we can find tumor DNA early before tumors have a chance to establish themselves, we could potentially change the trajectory of the disease for patients,” he said.

Several studies suggest that monitoring patients’ ctDNA levels after neoadjuvant treatment and surgery may help predict their risk for relapse and progression to metastatic disease. A 2015 analysis, which followed 20 patients with breast cancer after surgery, found that ctDNA monitoring accurately differentiated those who ultimately developed metastatic disease from those who didn’t (sensitivity, 93%; specificity, 100%) and detected metastatic disease 11 months earlier, on average, than imaging did. Another 2015 study found that the presence of ctDNA in plasma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery predicted metastatic relapse a median of almost 8 months before clinical detection. Other recent data show the power of ultrasensitive blood tests to detect MRD and potentially find metastatic disease early.

Although an increasing number of studies show that ctDNA and CTCs are prognostic for breast cancer recurrence, a major question remains: For patients with ctDNA or CTCs but no overt disease after imaging, will initiating therapy prevent or delay the development of metastatic disease?

“We still have to do those clinical trials to determine whether detecting MRD and treating patients early actually positively affects their survival and quality of life,” Dr. Razavi said.

Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for characterizing tumor biology and guiding therapeutic decisions, but liquid biopsies — blood analyses that allow oncologists to detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the blood — are increasingly demonstrating their value. Last year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two liquid biopsy tests, Guardant360 CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx, that can identify more than 300 cancer-related genes in the blood. In 2019, the FDA also approved the first companion diagnostic test, therascreen, to pinpoint PIK3CA gene mutations in patients’ ctDNA and determine whether patients should receive the PI3K inhibitor alpelisib along with fulvestrant.

Here’s an overview of how liquid biopsy is being used in monitoring MBC progression and treatment — and what some oncologists think of it.

What we do and don’t know

“Identifying a patient’s targetable mutations, most notably PIK3CA mutations, is currently the main use of liquid biopsy,” said Pedram Razavi, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist who leads the liquid biopsy program for breast cancer at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center in New York City. “Patients who come to MSK are offered a tumor and liquid biopsy at the time of metastatic diagnosis as part of the standard of care.”

Liquid and tissue biopsy analyses can provide a more complete picture of a patient’s condition. Whereas tissue biopsy allows oncologists to target a more saturated sample of the cancer ecosystem and a wider array of biomarkers, liquid biopsy offers important advantages as well, including a less invasive way to sequence a sample, monitor patients’ treatment response, or track tumor evolution. Liquid biopsy also provides a bigger picture view of tumor heterogeneity by pooling information from many tumor locations as opposed to one.

But, cautioned Yuan Yuan, MD, PhD, liquid biopsy technology is not always sensitive enough to detect CTCs, ctDNA, or all relevant mutations. “When you collect a small tube of blood, you’re essentially trying to catch a small fish in a big sea and wading through a lot of background noise,” said Dr. Yuan, medical oncologist at City of Hope, a comprehensive cancer center in Los Angeles County. “The results may be hard to interpret or come back inconclusive.”

And although emerging data suggest that liquid biopsy provides important insights about tumor dynamics — including mapping disease progression, predicting survival, and even detecting signs of cancer recurrence before metastasis develops — the tool has limited utility in clinical practice outside of identifying sensitivity to various therapies or drugs.

“Right now, a lot of research is being done to understand how to use CTC and ctDNA in particular as a means of surveillance in breast cancer, but we’re still in the beginning stages of applying that outside of clinical trials,” said Joseph A. Sparano, MD, deputy director of the Tisch Cancer Institute and chief of the division of hematology and medical oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

Personalizing treatment

The companion diagnostic test therascreen marked the beginning stages of using liquid biopsy to match treatments to genetic abnormalities in MBC. The SOLAR-1 phase 3 trial, which led to the approval of alpelisib and therascreen, found that the PI3K inhibitor plus fulvestrant almost doubled progression-free survival (PFS) (11 months vs 5.7 months in placebo-fulvestrant group) in patients with PIK3CA-mutated, HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer.

More recent studies have shown that liquid biopsy tests can also identify ESR1 mutations and predict responses to inhibitors that target AKT1 and HER2. Investigators presenting at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting reported that next-generation sequencing of ctDNA in patients with HR-positive MBC, HER-positive MBC, or triple-negative breast cancer detected ESR1 mutations in 14% of patients (71 of 501). Moreover, ESR1 mutations were found only in HR-positive patients who had already received endocrine therapy. (The study also examined PIK3CA mutations, which occurred in about one third of patients). A more in-depth look revealed that ESR1 mutations were strongly associated with liver and bone metastases and that mutations along specific codons negatively affected overall survival (OS) and PFS: codons 537 and 538 for OS and codons 380 and 536 for PFS.

According to Debasish Tripathy, MD, professor and chairman of the department of breast medical oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, in addition to tumor sequencing, “liquid biopsy has become a great research tool to track patients in real time and predict, for instance, who will respond to a treatment and identify emerging resistance.”

In terms of predicting responses to treatment, the plasmaMATCH trial assessed ctDNA in 1,034 patients with advanced breast cancer for mutations in ESR1, HER2, and AKT1 using digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Guardant360. Results showed that 357 (34.5%) of these patients had potentially targetable aberrations, including 222 patients with ESR1 mutations, 36 patients with HER2 mutations, and 30 patients with AKT1 mutations.

Agreement between digital droplet PCR and Guardant360 testing was 96%-99%, and liquid biopsy showed 93% sensitivity compared with tumor samples. The investigators also used liquid biopsy findings to match patients’ mutations to targeted treatments: fulvestrant for those with ESR1 mutations, neratinib for HER2 (ERBB2) mutations, and the selective AKT inhibitor capivasertib for estrogen receptor–positive tumors with AKT1 mutations.

Overall, the investigators concluded that ctDNA testing offers “accurate tumor genotyping” in line with tissue-based testing and is ready for routine clinical practice to identify common as well as rare genetic alterations, such as HER2 and AKT1 mutations, that affect only about 5% of patients with advanced disease.

Predicting survival and recurrence

A particularly promising area for liquid biopsy is its usefulness in helping to predict survival outcomes and monitor patients for early signs of recurrence before metastasis occurs. But the data to support this are still in their infancy.

A highly cited study, published over 15 years ago in the New England Journal of Medicine, found that patients with MBC who had five or more CTCs per 7.5 mL of whole blood before receiving first-line therapy exhibited significantly shorter median PFS (2.7 vs 7.0 months) and OS (10 vs > 18 months) compared with patients with fewer than five CTCs. Subsequent analyses performed more than a decade later, including a meta-analysis published last year, helped validate these early findings that levels of CTCs detected in the blood independently and strongly predicted PFS and OS in patients with MBC.

In addition, ctDNA can provide important information about patients’ survival odds. In a retrospective study published last year, investigators tracked changes in ctDNA in 291 plasma samples from 84 patients with locally advanced breast cancer who participated in the I-SPY trial. Patients who remained ctDNA-positive after 3 weeks of neoadjuvant chemotherapy were significantly more likely to have residual disease after completing their treatment compared with patients who cleared ctDNA at that early stage (83% for those with nonpathologic complete response vs 52%). Notably, the presence of ctDNA between therapy initiation and completion was associated with a significantly greater risk for metastatic recurrence, whereas clearance of ctDNA after neoadjuvant therapy was linked to improved survival.

“The study is important because it highlights how tracking circulating ctDNA status in neoadjuvant-treated breast cancer can expose a patient’s risk for distant metastasis,” said Dr. Yuan. But, she added, “I think the biggest attraction of liquid biopsy will be the ability to detect molecular disease even before imaging can, and identify who has a high risk for recurrence.”

Dr. Razavi agreed that the potential to prevent metastasis by finding minimal residual disease (MRD) is the most exciting area of liquid biopsy research. “If we can find tumor DNA early before tumors have a chance to establish themselves, we could potentially change the trajectory of the disease for patients,” he said.

Several studies suggest that monitoring patients’ ctDNA levels after neoadjuvant treatment and surgery may help predict their risk for relapse and progression to metastatic disease. A 2015 analysis, which followed 20 patients with breast cancer after surgery, found that ctDNA monitoring accurately differentiated those who ultimately developed metastatic disease from those who didn’t (sensitivity, 93%; specificity, 100%) and detected metastatic disease 11 months earlier, on average, than imaging did. Another 2015 study found that the presence of ctDNA in plasma after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgery predicted metastatic relapse a median of almost 8 months before clinical detection. Other recent data show the power of ultrasensitive blood tests to detect MRD and potentially find metastatic disease early.

Although an increasing number of studies show that ctDNA and CTCs are prognostic for breast cancer recurrence, a major question remains: For patients with ctDNA or CTCs but no overt disease after imaging, will initiating therapy prevent or delay the development of metastatic disease?

“We still have to do those clinical trials to determine whether detecting MRD and treating patients early actually positively affects their survival and quality of life,” Dr. Razavi said.

Artificial Intelligence: Review of Current and Future Applications in Medicine

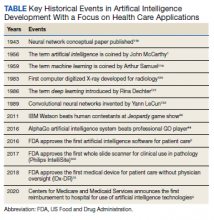

Artificial Intelligence (AI) was first described in 1956 and refers to machines having the ability to learn as they receive and process information, resulting in the ability to “think” like humans.1 AI’s impact in medicine is increasing; currently, at least 29 AI medical devices and algorithms are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in a variety of areas, including radiograph interpretation, managing glucose levels in patients with diabetes mellitus, analyzing electrocardiograms (ECGs), and diagnosing sleep disorders among others.2 Significantly, in 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the first reimbursement to hospitals for an AI platform, a model for early detection of strokes.3 AI is rapidly becoming an integral part of health care, and its role will only increase in the future (Table).

As knowledge in medicine is expanding exponentially, AI has great potential to assist with handling complex patient care data. The concept of exponential growth is not a natural one. As Bini described, with exponential growth the volume of knowledge amassed over the past 10 years will now occur in perhaps only 1 year.1 Likewise, equivalent advances over the past year may take just a few months. This phenomenon is partly due to the law of accelerating returns, which states that advances feed on themselves, continually increasing the rate of further advances.4 The volume of medical data doubles every 2 to 5 years.5 Fortunately, the field of AI is growing exponentially as well and can help health care practitioners (HCPs) keep pace, allowing the continued delivery of effective health care.

In this report, we review common terminology, principles, and general applications of AI, followed by current and potential applications of AI for selected medical specialties. Finally, we discuss AI’s future in health care, along with potential risks and pitfalls.

AI Overview

AI refers to machine programs that can “learn” or think based on past experiences. This functionality contrasts with simple rules-based programming available to health care for years. An example of rules-based programming is the warfarindosing.org website developed by Barnes-Jewish Hospital at Washington University Medical Center, which guides initial warfarin dosing.6,7 The prescriber inputs detailed patient information, including age, sex, height, weight, tobacco history, medications, laboratory results, and genotype if available. The application then calculates recommended warfarin dosing regimens to avoid over- or underanticoagulation. While the dosing algorithm may be complex, it depends entirely on preprogrammed rules. The program does not learn to reach its conclusions and recommendations from patient data.

In contrast, one of the most common subsets of AI is machine learning (ML). ML describes a program that “learns from experience and improves its performance as it learns.”1 With ML, the computer is initially provided with a training data set—data with known outcomes or labels. Because the initial data are input from known samples, this type of AI is known as supervised learning.8-10 As an example, we recently reported using ML to diagnose various types of cancer from pathology slides.11 In one experiment, we captured images of colon adenocarcinoma and normal colon (these 2 groups represent the training data set). Unlike traditional programming, we did not define characteristics that would differentiate colon cancer from normal; rather, the machine learned these characteristics independently by assessing the labeled images provided. A second data set (the validation data set) was used to evaluate the program and fine-tune the ML training model’s parameters. Finally, the program was presented with new images of cancer and normal cases for final assessment of accuracy (test data set). Our program learned to recognize differences from the images provided and was able to differentiate normal and cancer images with > 95% accuracy.

Advances in computer processing have allowed for the development of artificial neural networks (ANNs). While there are several types of ANNs, the most common types used for image classification and segmentation are known as convolutional neural networks (CNNs).9,12-14 The programs are designed to work similar to the human brain, specifically the visual cortex.15,16 As data are acquired, they are processed by various layers in the program. Much like neurons in the brain, one layer decides whether to advance information to the next.13,14 CNNs can be many layers deep, leading to the term deep learning: “computational models that are composed of multiple processing layers to learn representations of data with multiple levels of abstraction.”1,13,17

ANNs can process larger volumes of data. This advance has led to the development of unstructured or unsupervised learning. With this type of learning, imputing defined features (ie, predetermined answers) of the training data set described above is no longer required.1,8,10,14 The advantage of unsupervised learning is that the program can be presented raw data and extract meaningful interpretation without human input, often with less bias than may exist with supervised learning.1,18 If shown enough data, the program can extract relevant features to make conclusions independently without predefined definitions, potentially uncovering markers not previously known. For example, several studies have used unsupervised learning to search patient data to assess readmission risks of patients with congestive heart failure.10,19,20 AI compiled features independently and not previously defined, predicting patients at greater risk for readmission superior to traditional methods.

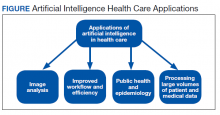

A more detailed description of the various terminologies and techniques of AI is beyond the scope of this review.9,10,17,21 However, in this basic overview, we describe 4 general areas that AI impacts health care (Figure).

Health Care Applications

Image analysis has seen the most AI health care applications.8,15 AI has shown potential in interpreting many types of medical images, including pathology slides, radiographs of various types, retina and other eye scans, and photographs of skin lesions. Many studies have demonstrated that AI can interpret these images as accurately as or even better than experienced clinicians.9,13,22-29 Studies have suggested AI interpretation of radiographs may better distinguish patients infected with COVID-19 from other causes of pneumonia, and AI interpretation of pathology slides may detect specific genetic mutations not previously identified without additional molecular tests.11,14,23,24,30-32

The second area in which AI can impact health care is improving workflow and efficiency. AI has improved surgery scheduling, saving significant revenue, and decreased patient wait times for appointments.1 AI can screen and triage radiographs, allowing attention to be directed to critical patients. This use would be valuable in many busy clinical settings, such as the recent COVID-19 pandemic.8,23 Similarly, AI can screen retina images to prioritize urgent conditions.25 AI has improved pathologists’ efficiency when used to detect breast metastases.33 Finally, AI may reduce medical errors, thereby ensuring patient safety.8,9,34

A third health care benefit of AI is in public health and epidemiology. AI can assist with clinical decision-making and diagnoses in low-income countries and areas with limited health care resources and personnel.25,29 AI can improve identification of infectious outbreaks, such as tuberculosis, malaria, dengue fever, and influenza.29,35-40 AI has been used to predict transmission patterns of the Zika virus and the current COVID-19 pandemic.41,42 Applications can stratify the risk of outbreaks based on multiple factors, including age, income, race, atypical geographic clusters, and seasonal factors like rainfall and temperature.35,36,38,43 AI has been used to assess morbidity and mortality, such as predicting disease severity with malaria and identifying treatment failures in tuberculosis.29

Finally, AI can dramatically impact health care due to processing large data sets or disconnected volumes of patient information—so-called big data.44-46 An example is the widespread use of electronic health records (EHRs) such as the Computerized Patient Record System used in Veteran Affairs medical centers (VAMCs). Much of patient information exists in written text: HCP notes, laboratory and radiology reports, medication records, etc. Natural language processing (NLP) allows platforms to sort through extensive volumes of data on complex patients at rates much faster than human capability, which has great potential to assist with diagnosis and treatment decisions.9

Medical literature is being produced at rates that exceed our ability to digest. More than 200,000 cancer-related articles were published in 2019 alone.14 NLP capabilities of AI have the potential to rapidly sort through this extensive medical literature and relate specific verbiage in patient records guiding therapy.46 IBM Watson, a supercomputer based on ML and NLP, demonstrates this concept with many potential applications, only some of which relate to health care.1,9 Watson has an oncology component to assimilate multiple aspects of patient care, including clinical notes, pathology results, radiograph findings, staging, and a tumor’s genetic profile. It coordinates these inputs from the EHR and mines medical literature and research databases to recommend treatment options.1,46 AI can assess and compile far greater patient data and therapeutic options than would be feasible by individual clinicians, thus providing customized patient care.47 Watson has partnered with numerous medical centers, including MD Anderson Cancer Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, with variable success.44,47-49 While the full potential of Watson appears not yet realized, these AI-driven approaches will likely play an important role in leveraging the hidden value in the expanding volume of health care information.

Medical Specialty Applications

Radiology

Currently > 70% of FDA-approved AI medical devices are in the field of radiology.2 Most radiology departments have used AI-friendly digital imaging for years, such as the picture archiving and communication systems used by numerous health care systems, including VAMCs.2,15 Gray-scale images common in radiology lend themselves to standardization, although AI is not limited to black-and- white image interpretation.15

An abundance of literature describes plain radiograph interpretation using AI. One FDA-approved platform improved X-ray diagnosis of wrist fractures when used by emergency medicine clinicians.2,50 AI has been applied to chest X-ray (CXR) interpretation of many conditions, including pneumonia, tuberculosis, malignant lung lesions, and COVID-19.23,25,28,44,51-53 For example, Nam and colleagues suggested AI is better at diagnosing malignant pulmonary nodules from CXRs than are trained radiologists.28

In addition to plain radiographs, AI has been applied to many other imaging technologies, including ultrasounds, positron emission tomography, mammograms, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).15,26,44,48,54-56 A large study demonstrated that ML platforms significantly reduced the time to diagnose intracranial hemorrhages on CT and identified subtle hemorrhages missed by radiologists.55 Other studies have claimed that AI programs may be better than radiologists in detecting cancer in screening mammograms, and 3 FDA-approved devices focus on mammogram interpretation.2,15,54,57 There is also great interest in MRI applications to detect and predict prognosis for breast cancer based on imaging findings.21,56