User login

Hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops remain unvaccinated

, according to data analyzed by The Washington Post.

Overall, the military’s vaccination rate has climbed since August, when the Pentagon announced that COVID-19 immunization would become mandatory for the nation’s 2.1 million troops, the newspaper reported. Acting on a directive from President Joe Biden, leaders said exemptions would be rare and unvaccinated service members would face consequences.

But compliance has varied across the services, the newspaper found. About 90% of the active-duty Navy is fully vaccinated, compared with 76% of the active-duty Marine Corps. Both have a November 28 deadline to show proof of full vaccination.

About 81% of the active-duty Air Force is fully vaccinated, leaving more than 60,000 personnel about 3 weeks to get a shot before a November 2 deadline.

Military officials said the variance in vaccination rates is related to the different deadlines, the newspaper reported. As the dates approach, most troops are expected to meet the order.

At the same time, some deadlines are spaced farther out, with the Army Reserve and National Guard required to be fully vaccinated by next summer. About 40% of the Army Reserve and 38% of the National Guard are fully vaccinated. Combined, they account for a quarter of the U.S. military and 40% of the COVID-19 deaths among service members.

“The Army’s policy is incentivizing inaction until the latest possible date,” Katherine Kuzminski, a military policy expert at the Center for a New American Security, told the Post.“The way we’ve seen the virus evolve tells us looking out to June 30 may need to be reconsidered,” she said.

COVID-19 deaths have surged in some of the services in recent months, the newspaper reported. More military personnel died from COVID-19 in September than in all of 2020. None of those who died were fully vaccinated.

Throughout the pandemic, more than 246,000 COVID-19 cases have been reported among service members, according to the latest data from the Defense Department. More than 2,200 have been hospitalized, and 62 personnel died, including 32 in August and September.

For the Army Reserve and National Guard, the June deadline allows “necessary time to update records and process exemption requests,” Lt. Col. Terence Kelley, an Army spokesman, told the Post.

Lt. Col. Kelley noted that the extended date reflects how large the groups are, compared to the other services and their military reserves, as well as the broad geographic distribution of its members. Still, vaccine mandates will apply.

“We expect all unvaccinated soldiers to receive the vaccine as soon as possible,” Lt. Col. Kelley said. “Individual soldiers are required to receive the vaccine when available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to data analyzed by The Washington Post.

Overall, the military’s vaccination rate has climbed since August, when the Pentagon announced that COVID-19 immunization would become mandatory for the nation’s 2.1 million troops, the newspaper reported. Acting on a directive from President Joe Biden, leaders said exemptions would be rare and unvaccinated service members would face consequences.

But compliance has varied across the services, the newspaper found. About 90% of the active-duty Navy is fully vaccinated, compared with 76% of the active-duty Marine Corps. Both have a November 28 deadline to show proof of full vaccination.

About 81% of the active-duty Air Force is fully vaccinated, leaving more than 60,000 personnel about 3 weeks to get a shot before a November 2 deadline.

Military officials said the variance in vaccination rates is related to the different deadlines, the newspaper reported. As the dates approach, most troops are expected to meet the order.

At the same time, some deadlines are spaced farther out, with the Army Reserve and National Guard required to be fully vaccinated by next summer. About 40% of the Army Reserve and 38% of the National Guard are fully vaccinated. Combined, they account for a quarter of the U.S. military and 40% of the COVID-19 deaths among service members.

“The Army’s policy is incentivizing inaction until the latest possible date,” Katherine Kuzminski, a military policy expert at the Center for a New American Security, told the Post.“The way we’ve seen the virus evolve tells us looking out to June 30 may need to be reconsidered,” she said.

COVID-19 deaths have surged in some of the services in recent months, the newspaper reported. More military personnel died from COVID-19 in September than in all of 2020. None of those who died were fully vaccinated.

Throughout the pandemic, more than 246,000 COVID-19 cases have been reported among service members, according to the latest data from the Defense Department. More than 2,200 have been hospitalized, and 62 personnel died, including 32 in August and September.

For the Army Reserve and National Guard, the June deadline allows “necessary time to update records and process exemption requests,” Lt. Col. Terence Kelley, an Army spokesman, told the Post.

Lt. Col. Kelley noted that the extended date reflects how large the groups are, compared to the other services and their military reserves, as well as the broad geographic distribution of its members. Still, vaccine mandates will apply.

“We expect all unvaccinated soldiers to receive the vaccine as soon as possible,” Lt. Col. Kelley said. “Individual soldiers are required to receive the vaccine when available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to data analyzed by The Washington Post.

Overall, the military’s vaccination rate has climbed since August, when the Pentagon announced that COVID-19 immunization would become mandatory for the nation’s 2.1 million troops, the newspaper reported. Acting on a directive from President Joe Biden, leaders said exemptions would be rare and unvaccinated service members would face consequences.

But compliance has varied across the services, the newspaper found. About 90% of the active-duty Navy is fully vaccinated, compared with 76% of the active-duty Marine Corps. Both have a November 28 deadline to show proof of full vaccination.

About 81% of the active-duty Air Force is fully vaccinated, leaving more than 60,000 personnel about 3 weeks to get a shot before a November 2 deadline.

Military officials said the variance in vaccination rates is related to the different deadlines, the newspaper reported. As the dates approach, most troops are expected to meet the order.

At the same time, some deadlines are spaced farther out, with the Army Reserve and National Guard required to be fully vaccinated by next summer. About 40% of the Army Reserve and 38% of the National Guard are fully vaccinated. Combined, they account for a quarter of the U.S. military and 40% of the COVID-19 deaths among service members.

“The Army’s policy is incentivizing inaction until the latest possible date,” Katherine Kuzminski, a military policy expert at the Center for a New American Security, told the Post.“The way we’ve seen the virus evolve tells us looking out to June 30 may need to be reconsidered,” she said.

COVID-19 deaths have surged in some of the services in recent months, the newspaper reported. More military personnel died from COVID-19 in September than in all of 2020. None of those who died were fully vaccinated.

Throughout the pandemic, more than 246,000 COVID-19 cases have been reported among service members, according to the latest data from the Defense Department. More than 2,200 have been hospitalized, and 62 personnel died, including 32 in August and September.

For the Army Reserve and National Guard, the June deadline allows “necessary time to update records and process exemption requests,” Lt. Col. Terence Kelley, an Army spokesman, told the Post.

Lt. Col. Kelley noted that the extended date reflects how large the groups are, compared to the other services and their military reserves, as well as the broad geographic distribution of its members. Still, vaccine mandates will apply.

“We expect all unvaccinated soldiers to receive the vaccine as soon as possible,” Lt. Col. Kelley said. “Individual soldiers are required to receive the vaccine when available.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with recurrent UTIs express fear, frustration

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.

“Here in our female pelvic medicine reconstructive urology clinic at Cedars-Sinai and at UCLA, we see many women who are referred for evaluation of rUTIs who are very frustrated with their care,” Victoria Scott, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

“So with these focus groups, we saw an opportunity to explore why women are so frustrated and to try and improve the care delivered,” she added.

Findings from the study were published online Sept. 1 in The Journal of Urology.

“There is a need for physicians to modify management strategies ... and to devote more research efforts to improving nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as management strategies that better empower patients,” the authors wrote.

Six focus groups

Four or five participants were included in each of the six focus groups – a total of 29 women. All participants reported a history of symptomatic, culture-proven UTI episodes. They had experienced two or more infections in 6 months or three or more infections within 1 year. Women were predominantly White. Most were employed part- or full-time and held a college degree.

From a qualitative analysis of all focus group transcripts, two main themes emerged:

- The negative impact of taking antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of rUTIs.

- Resentment of the medical profession for the way it managed rUTIs.

The researchers found that participants had a good understanding of the deleterious effects from inappropriate antibiotic use, largely gleaned from media sources and the Internet. “Numerous women stated that they had reached such a level of concern about antibiotics that they would resist taking them for prevention or treatment of infections,” Dr. Scott and colleagues pointed out.

These concerns centered around the risk of developing resistance to antibiotics and the ill effects that antibiotics can have on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary microbiomes. Several women reported that they had developed Clostridium difficile infections after taking antibiotics; one of the patients required hospitalization for the infection.

Women also reported concerns that they had been given an antibiotic needlessly for symptoms that might have been caused by a genitourinary condition other than a UTI. They also reported feeling resentful toward practitioners, particularly if they felt the practitioner was overprescribing antibiotics. Some had resorted to consultations with alternative practitioners, such as herbalists. “A second concern discussed by participants was the feeling of being ignored by physicians,” the authors observed.

In this regard, the women felt that their physicians underestimated the burden that rUTIs had on their lives and the detrimental effect that repeated infections had on their relationships, work, and overall quality of life. “These perceptions led to a prevalent mistrust of physicians,” the investigators wrote. This prompted many women to insist that the medical community devote more effort to the development of nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of UTIs.

Improved management strategies

Asked how physicians might improve their management of rUTIs, Dr. Scott shared a number of suggestions. Cardinal rule No. 1: Have the patient undergo a urinalysis to make sure she does have a UTI. “There is a subset of patients among women with rUTIs who come in with a diagnosis of an rUTI but who really have not had documentation of more than one positive urine culture,” Dr. Scott noted. Such a history suggests that they do not have an rUTI.

It’s imperative that physicians rule out commonly misdiagnosed disorders, such as overactive bladder, as a cause of the patient’s symptoms. Symptoms of overactive bladder and rUTIs often overlap. While waiting for results from the urinalysis to confirm or rule out a UTI, young and healthy women may be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen, which can help ameliorate symptoms.

Because UTIs are frequently self-limiting, Dr. Scott and others have found that for young, otherwise healthy women, NSAIDs alone can often resolve symptoms of the UTI without use of an antibiotic. For relatively severe symptoms, a urinary analgesic, such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium), may soothe the lining of the urinary tract and relieve pain. Cystex is an over-the-counter urinary analgesic that women can procure themselves, Dr. Scott added.

If an antibiotic is indicated, those most commonly prescribed for a single episode of acute cystitis are nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (Bactrim). For recurrent UTIs, “patients are a bit more complicated,” Dr. Scott admitted. “I think the best practice is to look back at a woman’s prior urine culture and select an antibiotic that showed good sensitivity in the last positive urine test,” she said.

Prevention starts with behavioral strategies, such as voiding after sexual intercourse and wiping from front to back following urination to avoid introducing fecal bacteria into the urethra. Evidence suggests that premenopausal women who drink at least 1.5 L of water a day have significantly fewer UTI episodes, Dr. Scott noted. There is also “pretty good” evidence that cranberry supplements (not juice) can prevent rUTIs. Use of cranberry supplements is supported by the American Urological Association (conditional recommendation; evidence level of grade C).

For peri- and postmenopausal women, vaginal estrogen may be effective. It’s use for UTI prevention is well supported by the literature. Although not as well supported by evidence, some women find that a supplement such as D-mannose may prevent or treat UTIs by causing bacteria to bind to it rather than to the bladder wall. Probiotics are another possibility, she noted. Empathy can’t hurt, she added.

“A common theme among satisfied women was the sentiment that their physicians understood their problems and had a system in place to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment for UTI episodes,” the authors emphasized.

“[Such attitudes] highlight the need to investigate each patient’s experience and perceptions to allow for shared decision making regarding the management of rUTIs,” they wrote.

Further commentary

Asked to comment on the findings, editorialist Michelle Van Kuiken, MD, assistant professor of urology, University of California, San Francisco, acknowledged that there is not a lot of good evidence to support many of the strategies recommended by the American Urological Association to prevent and treat rUTIs, but she often follows these recommendations anyway. “The one statement in the guidelines that is the most supported by evidence is the use of cranberry supplements, and I do routinely recommended daily use of some form of concentrated cranberry supplements for all of my patients with rUTIs,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Van Kuiken said that vaginal estrogen is a very good option for all postmenopausal women who suffer from rUTIs and that there is growing acceptance of its use for this and other indications. There is some evidence to support D-mannose as well, although it’s not that robust, she acknowledged.

She said the evidence supporting the use of probiotics for this indication is very thin. She does not routinely recommend them for rUTIs, although they are not inherently harmful. “I think for a lot of women who have rUTIs, it can be pretty debilitating and upsetting for them – it can impact travel plans, work, and social events,” Dr. Van Kuiken said.

“Until we develop better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, validating women’s experiences and concerns with rUTI while limiting unnecessary antibiotics remains our best option,” she wrote.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Van Kuiken have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.

“Here in our female pelvic medicine reconstructive urology clinic at Cedars-Sinai and at UCLA, we see many women who are referred for evaluation of rUTIs who are very frustrated with their care,” Victoria Scott, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

“So with these focus groups, we saw an opportunity to explore why women are so frustrated and to try and improve the care delivered,” she added.

Findings from the study were published online Sept. 1 in The Journal of Urology.

“There is a need for physicians to modify management strategies ... and to devote more research efforts to improving nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as management strategies that better empower patients,” the authors wrote.

Six focus groups

Four or five participants were included in each of the six focus groups – a total of 29 women. All participants reported a history of symptomatic, culture-proven UTI episodes. They had experienced two or more infections in 6 months or three or more infections within 1 year. Women were predominantly White. Most were employed part- or full-time and held a college degree.

From a qualitative analysis of all focus group transcripts, two main themes emerged:

- The negative impact of taking antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of rUTIs.

- Resentment of the medical profession for the way it managed rUTIs.

The researchers found that participants had a good understanding of the deleterious effects from inappropriate antibiotic use, largely gleaned from media sources and the Internet. “Numerous women stated that they had reached such a level of concern about antibiotics that they would resist taking them for prevention or treatment of infections,” Dr. Scott and colleagues pointed out.

These concerns centered around the risk of developing resistance to antibiotics and the ill effects that antibiotics can have on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary microbiomes. Several women reported that they had developed Clostridium difficile infections after taking antibiotics; one of the patients required hospitalization for the infection.

Women also reported concerns that they had been given an antibiotic needlessly for symptoms that might have been caused by a genitourinary condition other than a UTI. They also reported feeling resentful toward practitioners, particularly if they felt the practitioner was overprescribing antibiotics. Some had resorted to consultations with alternative practitioners, such as herbalists. “A second concern discussed by participants was the feeling of being ignored by physicians,” the authors observed.

In this regard, the women felt that their physicians underestimated the burden that rUTIs had on their lives and the detrimental effect that repeated infections had on their relationships, work, and overall quality of life. “These perceptions led to a prevalent mistrust of physicians,” the investigators wrote. This prompted many women to insist that the medical community devote more effort to the development of nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of UTIs.

Improved management strategies

Asked how physicians might improve their management of rUTIs, Dr. Scott shared a number of suggestions. Cardinal rule No. 1: Have the patient undergo a urinalysis to make sure she does have a UTI. “There is a subset of patients among women with rUTIs who come in with a diagnosis of an rUTI but who really have not had documentation of more than one positive urine culture,” Dr. Scott noted. Such a history suggests that they do not have an rUTI.

It’s imperative that physicians rule out commonly misdiagnosed disorders, such as overactive bladder, as a cause of the patient’s symptoms. Symptoms of overactive bladder and rUTIs often overlap. While waiting for results from the urinalysis to confirm or rule out a UTI, young and healthy women may be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen, which can help ameliorate symptoms.

Because UTIs are frequently self-limiting, Dr. Scott and others have found that for young, otherwise healthy women, NSAIDs alone can often resolve symptoms of the UTI without use of an antibiotic. For relatively severe symptoms, a urinary analgesic, such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium), may soothe the lining of the urinary tract and relieve pain. Cystex is an over-the-counter urinary analgesic that women can procure themselves, Dr. Scott added.

If an antibiotic is indicated, those most commonly prescribed for a single episode of acute cystitis are nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (Bactrim). For recurrent UTIs, “patients are a bit more complicated,” Dr. Scott admitted. “I think the best practice is to look back at a woman’s prior urine culture and select an antibiotic that showed good sensitivity in the last positive urine test,” she said.

Prevention starts with behavioral strategies, such as voiding after sexual intercourse and wiping from front to back following urination to avoid introducing fecal bacteria into the urethra. Evidence suggests that premenopausal women who drink at least 1.5 L of water a day have significantly fewer UTI episodes, Dr. Scott noted. There is also “pretty good” evidence that cranberry supplements (not juice) can prevent rUTIs. Use of cranberry supplements is supported by the American Urological Association (conditional recommendation; evidence level of grade C).

For peri- and postmenopausal women, vaginal estrogen may be effective. It’s use for UTI prevention is well supported by the literature. Although not as well supported by evidence, some women find that a supplement such as D-mannose may prevent or treat UTIs by causing bacteria to bind to it rather than to the bladder wall. Probiotics are another possibility, she noted. Empathy can’t hurt, she added.

“A common theme among satisfied women was the sentiment that their physicians understood their problems and had a system in place to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment for UTI episodes,” the authors emphasized.

“[Such attitudes] highlight the need to investigate each patient’s experience and perceptions to allow for shared decision making regarding the management of rUTIs,” they wrote.

Further commentary

Asked to comment on the findings, editorialist Michelle Van Kuiken, MD, assistant professor of urology, University of California, San Francisco, acknowledged that there is not a lot of good evidence to support many of the strategies recommended by the American Urological Association to prevent and treat rUTIs, but she often follows these recommendations anyway. “The one statement in the guidelines that is the most supported by evidence is the use of cranberry supplements, and I do routinely recommended daily use of some form of concentrated cranberry supplements for all of my patients with rUTIs,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Van Kuiken said that vaginal estrogen is a very good option for all postmenopausal women who suffer from rUTIs and that there is growing acceptance of its use for this and other indications. There is some evidence to support D-mannose as well, although it’s not that robust, she acknowledged.

She said the evidence supporting the use of probiotics for this indication is very thin. She does not routinely recommend them for rUTIs, although they are not inherently harmful. “I think for a lot of women who have rUTIs, it can be pretty debilitating and upsetting for them – it can impact travel plans, work, and social events,” Dr. Van Kuiken said.

“Until we develop better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, validating women’s experiences and concerns with rUTI while limiting unnecessary antibiotics remains our best option,” she wrote.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Van Kuiken have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fear of antibiotic overuse and frustration with physicians who prescribe them too freely are key sentiments expressed by women with recurrent urinary tract infections (rUTIs), according to findings from a study involving six focus groups.

“Here in our female pelvic medicine reconstructive urology clinic at Cedars-Sinai and at UCLA, we see many women who are referred for evaluation of rUTIs who are very frustrated with their care,” Victoria Scott, MD, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

“So with these focus groups, we saw an opportunity to explore why women are so frustrated and to try and improve the care delivered,” she added.

Findings from the study were published online Sept. 1 in The Journal of Urology.

“There is a need for physicians to modify management strategies ... and to devote more research efforts to improving nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections, as well as management strategies that better empower patients,” the authors wrote.

Six focus groups

Four or five participants were included in each of the six focus groups – a total of 29 women. All participants reported a history of symptomatic, culture-proven UTI episodes. They had experienced two or more infections in 6 months or three or more infections within 1 year. Women were predominantly White. Most were employed part- or full-time and held a college degree.

From a qualitative analysis of all focus group transcripts, two main themes emerged:

- The negative impact of taking antibiotics for the prevention and treatment of rUTIs.

- Resentment of the medical profession for the way it managed rUTIs.

The researchers found that participants had a good understanding of the deleterious effects from inappropriate antibiotic use, largely gleaned from media sources and the Internet. “Numerous women stated that they had reached such a level of concern about antibiotics that they would resist taking them for prevention or treatment of infections,” Dr. Scott and colleagues pointed out.

These concerns centered around the risk of developing resistance to antibiotics and the ill effects that antibiotics can have on the gastrointestinal and genitourinary microbiomes. Several women reported that they had developed Clostridium difficile infections after taking antibiotics; one of the patients required hospitalization for the infection.

Women also reported concerns that they had been given an antibiotic needlessly for symptoms that might have been caused by a genitourinary condition other than a UTI. They also reported feeling resentful toward practitioners, particularly if they felt the practitioner was overprescribing antibiotics. Some had resorted to consultations with alternative practitioners, such as herbalists. “A second concern discussed by participants was the feeling of being ignored by physicians,” the authors observed.

In this regard, the women felt that their physicians underestimated the burden that rUTIs had on their lives and the detrimental effect that repeated infections had on their relationships, work, and overall quality of life. “These perceptions led to a prevalent mistrust of physicians,” the investigators wrote. This prompted many women to insist that the medical community devote more effort to the development of nonantibiotic options for the prevention and treatment of UTIs.

Improved management strategies

Asked how physicians might improve their management of rUTIs, Dr. Scott shared a number of suggestions. Cardinal rule No. 1: Have the patient undergo a urinalysis to make sure she does have a UTI. “There is a subset of patients among women with rUTIs who come in with a diagnosis of an rUTI but who really have not had documentation of more than one positive urine culture,” Dr. Scott noted. Such a history suggests that they do not have an rUTI.

It’s imperative that physicians rule out commonly misdiagnosed disorders, such as overactive bladder, as a cause of the patient’s symptoms. Symptoms of overactive bladder and rUTIs often overlap. While waiting for results from the urinalysis to confirm or rule out a UTI, young and healthy women may be prescribed a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as naproxen, which can help ameliorate symptoms.

Because UTIs are frequently self-limiting, Dr. Scott and others have found that for young, otherwise healthy women, NSAIDs alone can often resolve symptoms of the UTI without use of an antibiotic. For relatively severe symptoms, a urinary analgesic, such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium), may soothe the lining of the urinary tract and relieve pain. Cystex is an over-the-counter urinary analgesic that women can procure themselves, Dr. Scott added.

If an antibiotic is indicated, those most commonly prescribed for a single episode of acute cystitis are nitrofurantoin and sulfamethoxazole plus trimethoprim (Bactrim). For recurrent UTIs, “patients are a bit more complicated,” Dr. Scott admitted. “I think the best practice is to look back at a woman’s prior urine culture and select an antibiotic that showed good sensitivity in the last positive urine test,” she said.

Prevention starts with behavioral strategies, such as voiding after sexual intercourse and wiping from front to back following urination to avoid introducing fecal bacteria into the urethra. Evidence suggests that premenopausal women who drink at least 1.5 L of water a day have significantly fewer UTI episodes, Dr. Scott noted. There is also “pretty good” evidence that cranberry supplements (not juice) can prevent rUTIs. Use of cranberry supplements is supported by the American Urological Association (conditional recommendation; evidence level of grade C).

For peri- and postmenopausal women, vaginal estrogen may be effective. It’s use for UTI prevention is well supported by the literature. Although not as well supported by evidence, some women find that a supplement such as D-mannose may prevent or treat UTIs by causing bacteria to bind to it rather than to the bladder wall. Probiotics are another possibility, she noted. Empathy can’t hurt, she added.

“A common theme among satisfied women was the sentiment that their physicians understood their problems and had a system in place to allow rapid diagnosis and treatment for UTI episodes,” the authors emphasized.

“[Such attitudes] highlight the need to investigate each patient’s experience and perceptions to allow for shared decision making regarding the management of rUTIs,” they wrote.

Further commentary

Asked to comment on the findings, editorialist Michelle Van Kuiken, MD, assistant professor of urology, University of California, San Francisco, acknowledged that there is not a lot of good evidence to support many of the strategies recommended by the American Urological Association to prevent and treat rUTIs, but she often follows these recommendations anyway. “The one statement in the guidelines that is the most supported by evidence is the use of cranberry supplements, and I do routinely recommended daily use of some form of concentrated cranberry supplements for all of my patients with rUTIs,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Van Kuiken said that vaginal estrogen is a very good option for all postmenopausal women who suffer from rUTIs and that there is growing acceptance of its use for this and other indications. There is some evidence to support D-mannose as well, although it’s not that robust, she acknowledged.

She said the evidence supporting the use of probiotics for this indication is very thin. She does not routinely recommend them for rUTIs, although they are not inherently harmful. “I think for a lot of women who have rUTIs, it can be pretty debilitating and upsetting for them – it can impact travel plans, work, and social events,” Dr. Van Kuiken said.

“Until we develop better diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, validating women’s experiences and concerns with rUTI while limiting unnecessary antibiotics remains our best option,” she wrote.

Dr. Scott and Dr. Van Kuiken have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on respiratory infectious diseases in primary care practice

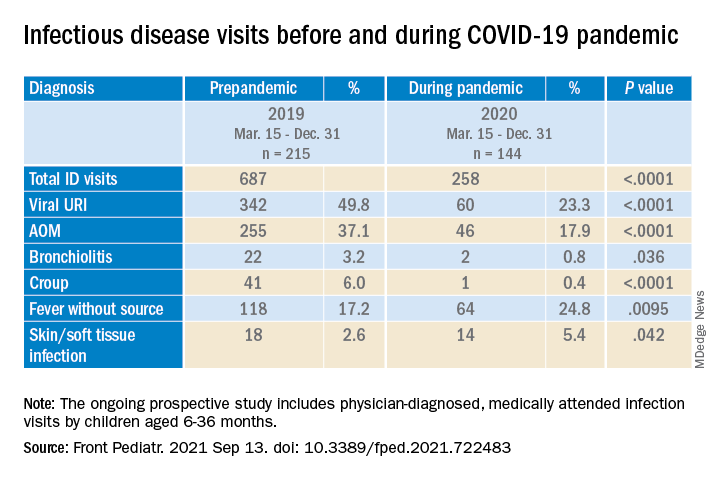

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

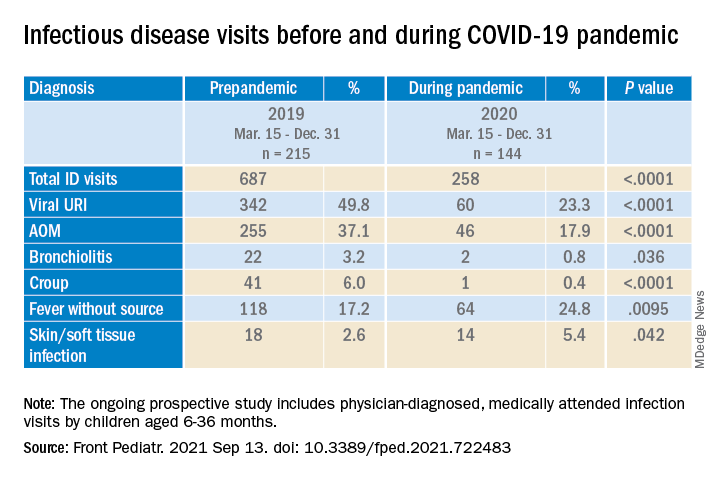

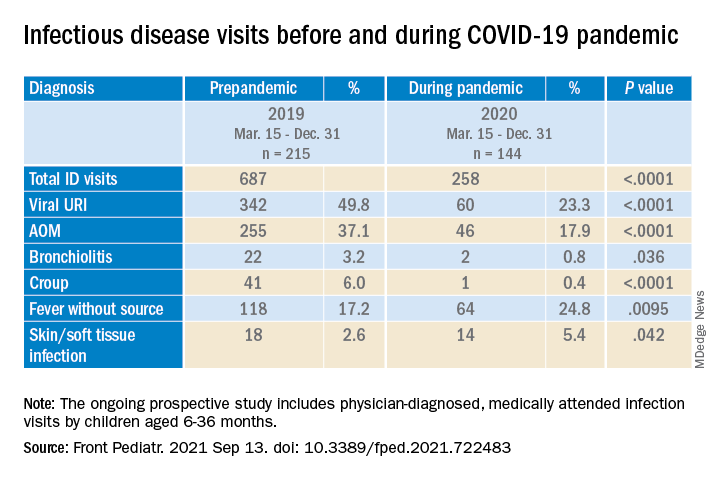

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

A secondary consequence of public health measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 included a concurrent reduction in risk for children to acquire and spread other respiratory viral infectious diseases. In the Rochester, N.Y., area, we had an ongoing prospective study in primary care pediatric practices that afforded an opportunity to assess the effect of the pandemic control measures on all infectious disease illness visits in young children. Specifically, in children aged 6-36 months old, our study was in place when the pandemic began with a primary objective to evaluate the changing epidemiology of acute otitis media (AOM) and nasopharyngeal colonization by potential bacterial respiratory pathogens in community-based primary care pediatric practices. As the public health measures mandated by New York State Department of Health were implemented, we prospectively quantified their effect on physician-diagnosed infectious disease illness visits. The incidence of infectious disease visits by a cohort of young children during the COVID-19 pandemic period March 15, 2020, through Dec. 31, 2020, was compared with the same time frame in the preceding year, 2019.1

Recommendations of the New York State Department of Health for public health, changes in school and day care attendance, and clinical practice during the study time frame

On March 7, 2020, a state of emergency was declared in New York because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All schools were required to close. A mandated order for public use of masks in adults and children more than 2 years of age was enacted. In the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York, where the two primary care pediatric practices reside, complete lockdown was partially lifted on May 15, 2020, and further lifted on June 26, 2020. Almost all regional school districts opened to at least hybrid learning models for all students starting Sept. 8, 2020. On March 6, 2020, video telehealth and telephone call visits were introduced as routine practice. Well-child visits were limited to those less than 2 years of age, then gradually expanded to all ages by late May 2020. During the “stay at home” phase of the New York State lockdown, day care services were considered an essential business. Day care child density was limited. All children less than 2 years old were required to wear a mask while in the facility. Upon arrival, children with any respiratory symptoms or fever were excluded. For the school year commencing September 2020, almost all regional school districts opened to virtual, hybrid, or in-person learning models. Exclusion occurred similar to that of the day care facilities.

Incidence of respiratory infectious disease illnesses

Clinical diagnoses and healthy visits of 144 children from March 15 to Dec. 31, 2020 (beginning of the pandemic) were compared to 215 children during the same months in 2019 (prepandemic). Pediatric SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates trended up alongside community spread. Pediatric practice positivity rates rose from 1.9% in October 2020 to 19% in December 2020.

The table shows the incidence of significantly different infectious disease illness visits in the two study cohorts.

During the pandemic, 258 infection visits occurred among 144 pandemic cohort children, compared with 687 visits among 215 prepandemic cohort children, a 1.8-fold decrease (P < .0001). The proportion of children with visits for AOM (3.7-fold; P < .0001), bronchiolitis (7.4-fold; P = .036), croup (27.5-fold; P < .0001), and viral upper respiratory infection (3.8-fold; P < .0001) decreased significantly. Fever without a source (1.4-fold decrease; P = .009) and skin/soft tissue infection (2.1-fold decrease; P = .042) represented a higher proportion of visits during the pandemic.

Prescription of antibiotics significantly decreased (P < .001) during the pandemic.

Change in care practices

In the prepandemic period, virtual visits, leading to a diagnosis and treatment and referring children to an urgent care or hospital emergency department during regular office hours were rare. During the pandemic, this changed. Significantly increased use of telemedicine visits (P < .0001) and significantly decreased office and urgent care visits (P < .0001) occurred during the pandemic. Telehealth visits peaked the week of April 12, 2020, at 45% of all pediatric visits. In-person illness visits gradually returned to year-to-year volumes in August-September 2020 with school opening. Early in the pandemic, both pediatric offices limited patient encounters to well-child visits in the first 2 years of life to not miss opportunities for childhood vaccinations. However, some parents were reluctant to bring their children to those visits. There was no significant change in frequency of healthy child visits during the pandemic.

To our knowledge, this was the first study from primary care pediatric practices in the United States to analyze the effect on infectious diseases during the first 9 months of the pandemic, including the 6-month time period after the reopening from the first 3 months of lockdown. One prior study from a primary care network in Massachusetts reported significant decreases in respiratory infectious diseases for children aged 0-17 years during the first months of the pandemic during lockdown.2 A study in Tennessee that included hospital emergency department, urgent care, primary care, and retail health clinics also reported respiratory infection diagnoses as well as antibiotic prescription were reduced in the early months of the pandemic.3

Our study shows an overall reduction in frequency of respiratory illness visits in children 6-36 months old during the first 9 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. We learned the value of using technology in the form of virtual visits to render care. Perhaps as the pandemic subsides, many of the hand-washing and sanitizing practices will remain in place and lead to less frequent illness in children in the future. However, there may be temporary negative consequences from the “immune debt” that has occurred from a prolonged time span when children were not becoming infected with respiratory pathogens.4 We will see what unfolds in the future.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director at Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero and Dr. Schulz have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Front Pediatr. 2021;(9)722483:1-8.

2. Hatoun J et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460.

3. Katz SE et al. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021;10(1):62-4.

4. Cohen R et al. Infect. Dis Now. 2021; 51(5)418-23.

Staff education cuts psychotropic drug use in long-term care

The effect of the intervention was transient, possibly because of high staff turnover, according to the investigators in the new randomized, controlled trial.

The findings were presented by Ulla Aalto, MD, PhD, during a session at the European Geriatric Medicine Society annual congress, a hybrid live and online meeting.

There was a significant reduction in the use of psychotropic agents at 6 months in long-term care wards where the nursing staff had undergone a short training session on drug therapy for older patients, but there was no improvement in wards that were randomly assigned to serve as controls, Dr. Aalto, from Helsinki Hospital, reported during the session.

“Future research would be investigating how we could maintain the positive effects that were gained at 6 months but not seen any more at 1 year, and how to implement the good practice in nursing homes by this kind of staff training,” she said.

Heavy drug use

Psychotropic medications are widely used in long-term care settings, but their indiscriminate use or use of the wrong drug for the wrong patient can be harmful. Inappropriate drug use in long-term care settings is also associated with higher costs, Dr. Aalto said.

To see whether a staff-training intervention could reduce drugs use and lower costs, the investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial in assisted living facilities in Helsinki in 2011, with a total of 227 patients 65 years and older.

Long-term care wards were randomly assigned to either an intervention for nursing staff consisting of two 4-hour sessions on good drug-therapy practice for older adults, or to serve as controls (10 wards in each group).

Drug use and costs were monitored at both 6 and 12 months after randomization. Psychotropic drugs included antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics as classified by the World Health Organization. For the purposes of comparison, actual doses were counted and converted into relative proportions of defined daily doses.

The baseline characteristics of patients in each group were generally similar, with a mean age of around 83 years. In each study arm, nearly two-thirds of patients were on at least one psychotropic drug, and of this group, a third had been prescribed 2 or more psychotropic agents.

Nearly half of the patients were on at least one antipsychotic agent and/or antidepressant.

Short-term benefit

As noted before, in the wards randomized to staff training, there was a significant reduction in use of all psychotropics from baseline at 6 months after randomization (P = .045), but there was no change among the control wards.

By 12 months, however, the differences between the intervention and control arms narrowed, and drug use in the intervention arm was no longer significantly lower over baseline.

Drugs costs significantly decreased in the intervention group at 6 months (P = .027) and were numerically but not statistically lower over baseline at 12 months.

In contrast, drug costs in the control arm were numerically (but not statistically) higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up.

Annual drug costs in the intervention group decreased by mean of 12.3 euros ($14.22) whereas costs in the control group increased by a mean of 20.6 euros ($23.81).

“This quite light and feasible intervention succeeded in reducing overall defined daily doses of psychotropics in the short term,” Dr. Aalto said.

The waning of the intervention’s effect on drug use and costs may be caused partly by the high employee turnover rate in long-term care facilities and to the dilution effect, she said, referring to a form of judgment bias in which people tend to devalue diagnostic information when other, nondiagnostic information is also available.

Randomized design

In the question-and-answer session following her presentation, audience member Jesper Ryg, MD, PhD from Odense (Denmark) University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, commented: “It’s a great study, doing a [randomized, controlled trial] on deprescribing, we need more of those.”

“But what we know now is that a lot of studies show it is possible to deprescribe and get less drugs, but do we have any clinical data? Does this deprescribing lead to less falls, did it lead to lower mortality?” he asked.

Dr. Aalto replied that, in an earlier report from this study, investigators showed that harmful medication use was reduced and negative outcomes were reduced.

Another audience member asked why nursing staff were the target of the intervention, given that physicians do the actual drug prescribing.

Dr. Aalto responded: “It is the physician of course who prescribes, but in nursing homes and long-term care, nursing staff is there all the time, and the physicians are kind of consultants who just come there once in a while, so it’s important that the nurses also know about these harmful medications and can bring them to the doctor when he or she arrives there.”

Dr. Aalto and Dr. Ryg had no disclosures.

The effect of the intervention was transient, possibly because of high staff turnover, according to the investigators in the new randomized, controlled trial.

The findings were presented by Ulla Aalto, MD, PhD, during a session at the European Geriatric Medicine Society annual congress, a hybrid live and online meeting.

There was a significant reduction in the use of psychotropic agents at 6 months in long-term care wards where the nursing staff had undergone a short training session on drug therapy for older patients, but there was no improvement in wards that were randomly assigned to serve as controls, Dr. Aalto, from Helsinki Hospital, reported during the session.

“Future research would be investigating how we could maintain the positive effects that were gained at 6 months but not seen any more at 1 year, and how to implement the good practice in nursing homes by this kind of staff training,” she said.

Heavy drug use

Psychotropic medications are widely used in long-term care settings, but their indiscriminate use or use of the wrong drug for the wrong patient can be harmful. Inappropriate drug use in long-term care settings is also associated with higher costs, Dr. Aalto said.

To see whether a staff-training intervention could reduce drugs use and lower costs, the investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial in assisted living facilities in Helsinki in 2011, with a total of 227 patients 65 years and older.

Long-term care wards were randomly assigned to either an intervention for nursing staff consisting of two 4-hour sessions on good drug-therapy practice for older adults, or to serve as controls (10 wards in each group).

Drug use and costs were monitored at both 6 and 12 months after randomization. Psychotropic drugs included antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics as classified by the World Health Organization. For the purposes of comparison, actual doses were counted and converted into relative proportions of defined daily doses.

The baseline characteristics of patients in each group were generally similar, with a mean age of around 83 years. In each study arm, nearly two-thirds of patients were on at least one psychotropic drug, and of this group, a third had been prescribed 2 or more psychotropic agents.

Nearly half of the patients were on at least one antipsychotic agent and/or antidepressant.

Short-term benefit

As noted before, in the wards randomized to staff training, there was a significant reduction in use of all psychotropics from baseline at 6 months after randomization (P = .045), but there was no change among the control wards.

By 12 months, however, the differences between the intervention and control arms narrowed, and drug use in the intervention arm was no longer significantly lower over baseline.

Drugs costs significantly decreased in the intervention group at 6 months (P = .027) and were numerically but not statistically lower over baseline at 12 months.

In contrast, drug costs in the control arm were numerically (but not statistically) higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up.

Annual drug costs in the intervention group decreased by mean of 12.3 euros ($14.22) whereas costs in the control group increased by a mean of 20.6 euros ($23.81).

“This quite light and feasible intervention succeeded in reducing overall defined daily doses of psychotropics in the short term,” Dr. Aalto said.

The waning of the intervention’s effect on drug use and costs may be caused partly by the high employee turnover rate in long-term care facilities and to the dilution effect, she said, referring to a form of judgment bias in which people tend to devalue diagnostic information when other, nondiagnostic information is also available.

Randomized design

In the question-and-answer session following her presentation, audience member Jesper Ryg, MD, PhD from Odense (Denmark) University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, commented: “It’s a great study, doing a [randomized, controlled trial] on deprescribing, we need more of those.”

“But what we know now is that a lot of studies show it is possible to deprescribe and get less drugs, but do we have any clinical data? Does this deprescribing lead to less falls, did it lead to lower mortality?” he asked.

Dr. Aalto replied that, in an earlier report from this study, investigators showed that harmful medication use was reduced and negative outcomes were reduced.

Another audience member asked why nursing staff were the target of the intervention, given that physicians do the actual drug prescribing.

Dr. Aalto responded: “It is the physician of course who prescribes, but in nursing homes and long-term care, nursing staff is there all the time, and the physicians are kind of consultants who just come there once in a while, so it’s important that the nurses also know about these harmful medications and can bring them to the doctor when he or she arrives there.”

Dr. Aalto and Dr. Ryg had no disclosures.

The effect of the intervention was transient, possibly because of high staff turnover, according to the investigators in the new randomized, controlled trial.

The findings were presented by Ulla Aalto, MD, PhD, during a session at the European Geriatric Medicine Society annual congress, a hybrid live and online meeting.

There was a significant reduction in the use of psychotropic agents at 6 months in long-term care wards where the nursing staff had undergone a short training session on drug therapy for older patients, but there was no improvement in wards that were randomly assigned to serve as controls, Dr. Aalto, from Helsinki Hospital, reported during the session.

“Future research would be investigating how we could maintain the positive effects that were gained at 6 months but not seen any more at 1 year, and how to implement the good practice in nursing homes by this kind of staff training,” she said.

Heavy drug use

Psychotropic medications are widely used in long-term care settings, but their indiscriminate use or use of the wrong drug for the wrong patient can be harmful. Inappropriate drug use in long-term care settings is also associated with higher costs, Dr. Aalto said.

To see whether a staff-training intervention could reduce drugs use and lower costs, the investigators conducted a randomized clinical trial in assisted living facilities in Helsinki in 2011, with a total of 227 patients 65 years and older.

Long-term care wards were randomly assigned to either an intervention for nursing staff consisting of two 4-hour sessions on good drug-therapy practice for older adults, or to serve as controls (10 wards in each group).

Drug use and costs were monitored at both 6 and 12 months after randomization. Psychotropic drugs included antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics as classified by the World Health Organization. For the purposes of comparison, actual doses were counted and converted into relative proportions of defined daily doses.

The baseline characteristics of patients in each group were generally similar, with a mean age of around 83 years. In each study arm, nearly two-thirds of patients were on at least one psychotropic drug, and of this group, a third had been prescribed 2 or more psychotropic agents.

Nearly half of the patients were on at least one antipsychotic agent and/or antidepressant.

Short-term benefit

As noted before, in the wards randomized to staff training, there was a significant reduction in use of all psychotropics from baseline at 6 months after randomization (P = .045), but there was no change among the control wards.

By 12 months, however, the differences between the intervention and control arms narrowed, and drug use in the intervention arm was no longer significantly lower over baseline.

Drugs costs significantly decreased in the intervention group at 6 months (P = .027) and were numerically but not statistically lower over baseline at 12 months.

In contrast, drug costs in the control arm were numerically (but not statistically) higher at both 6 and 12 months of follow-up.

Annual drug costs in the intervention group decreased by mean of 12.3 euros ($14.22) whereas costs in the control group increased by a mean of 20.6 euros ($23.81).

“This quite light and feasible intervention succeeded in reducing overall defined daily doses of psychotropics in the short term,” Dr. Aalto said.

The waning of the intervention’s effect on drug use and costs may be caused partly by the high employee turnover rate in long-term care facilities and to the dilution effect, she said, referring to a form of judgment bias in which people tend to devalue diagnostic information when other, nondiagnostic information is also available.

Randomized design

In the question-and-answer session following her presentation, audience member Jesper Ryg, MD, PhD from Odense (Denmark) University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark, also in Odense, commented: “It’s a great study, doing a [randomized, controlled trial] on deprescribing, we need more of those.”

“But what we know now is that a lot of studies show it is possible to deprescribe and get less drugs, but do we have any clinical data? Does this deprescribing lead to less falls, did it lead to lower mortality?” he asked.

Dr. Aalto replied that, in an earlier report from this study, investigators showed that harmful medication use was reduced and negative outcomes were reduced.

Another audience member asked why nursing staff were the target of the intervention, given that physicians do the actual drug prescribing.

Dr. Aalto responded: “It is the physician of course who prescribes, but in nursing homes and long-term care, nursing staff is there all the time, and the physicians are kind of consultants who just come there once in a while, so it’s important that the nurses also know about these harmful medications and can bring them to the doctor when he or she arrives there.”

Dr. Aalto and Dr. Ryg had no disclosures.

FROM EUGMS 2021

Low preconception complement levels linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes in antiphospholipid syndrome

Low serum levels of two complement proteins are linked to worse pregnancy outcomes in women with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), the results of a multicenter study appear to confirm.

The study evaluated preconception complement levels in 260 pregnancies in 197 women who had APS or carried antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), and found that low levels of C3 and C4 in the 6 months prior to pregnancy were associated with several gestational complications and resulted in pregnancy losses.

“This study has validated, on large scale, the possible utility of preconception measurement of C3 and C4 levels to predict pregnancy loss in patients with aPL, even at a high-risk profile,” said study investigator Daniele Lini, MD, of ASST Spedali Civili and the University of Brescia (Italy).

“The tests are easy and cheap to be routinely performed, and they could therefore represent a valid aid to identify women that need particular monitoring and management,” he said at the 14th International Congress on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus held together with the 6th International Congress on Controversies in Rheumatology and Autoimmunity.

aPL and adverse obstetric outcomes

aPL, which include lupus anticoagulant, anti–beta2-glycoprotein 1, and anticardiolipin antibodies, have been shown to induce fetal loss in animal models. Their influence on the outcome of human pregnancies, however, has been less clear, with several studies failing to prove a link between their presence and obstetric complications.

Dr. Lini and coinvestigators conducted a multicenter study involving 11 Italian centers and one Russian center, retrospectively looking for women with primary APS or women who had persistently high levels of aPL but no symptoms who had become pregnant. Of 503 pregnancies, information on complement levels before conception was available for 260, of which 184 had occurred in women with APS and 76 in women with persistently high aPL.

The pregnancies were grouped according to whether there were low (n = 93) or normal (n = 167) levels of C3 and C4 in the last 6 months.

“Women with adverse pregnancy outcomes showed significantly lower preconception complement levels than those with successful pregnancies, without any difference between APS and aPL carriers,” Dr. Lini reported.

Comparing those with low to those with high complement levels, the preterm live birth rate (before 37 weeks’ gestation) was 37% versus 18% (P < .0001).

The full-term live birth rates were a respective 42% and 72% (P < .0001).

The rate of pregnancy loss, which included both abortion and miscarriage, was a respective 21% and 10% (P = .008).

A subgroup analysis focusing on where there was triple aPL positivity found that preconception low C3 and/or C4 levels was associated with an increased rate of pregnancy loss (P = .05). This association disappeared if there was just one or two aPL present.

The researchers found no correlation between complement levels and rates of venous thromboembolism or thrombocytopenia.

Study highlights ‘impact and importance’ of complement in APS

The study indicates “the impact and the importance of complement” in APS, said Yehuda Shoenfeld, MD, the founder and head of the Zabludowicz Center for Autoimmune Diseases at the Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, Israel.

In the early days of understanding APS, said Dr. Shoenfeld, it was thought that complement was not as important as it was in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The importance of raised complement seen in studies of APS would often be discounted or neglected in comparison to SLE.

However, “slowly, slowly” it has been found that “complement [in APS] is activated very similarly to SLE,” Dr. Shoenfeld noted.

“I think that it’s important to assess the component levels,” Dr. Lini said in discussion. “This is needed to be done in the preconception counseling for APS and aPL carrier patients.”

Determining whether there is single, double, or even triple aPL positivity could be useful in guiding clinical decisions.

“If we have triple positivity, that could mean that there may be a more immunologic activation of the system and that it could be useful to administrate hydroxychloroquine [to] those patients who would like to have a pregnancy,” Dr. Lini suggested.

Plus, in those with decreased complement levels, “this could be a very useful tool” to identify where something could go wrong during their pregnancy.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Lini and Dr. Shoenfeld disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low serum levels of two complement proteins are linked to worse pregnancy outcomes in women with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), the results of a multicenter study appear to confirm.

The study evaluated preconception complement levels in 260 pregnancies in 197 women who had APS or carried antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), and found that low levels of C3 and C4 in the 6 months prior to pregnancy were associated with several gestational complications and resulted in pregnancy losses.

“This study has validated, on large scale, the possible utility of preconception measurement of C3 and C4 levels to predict pregnancy loss in patients with aPL, even at a high-risk profile,” said study investigator Daniele Lini, MD, of ASST Spedali Civili and the University of Brescia (Italy).

“The tests are easy and cheap to be routinely performed, and they could therefore represent a valid aid to identify women that need particular monitoring and management,” he said at the 14th International Congress on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus held together with the 6th International Congress on Controversies in Rheumatology and Autoimmunity.

aPL and adverse obstetric outcomes

aPL, which include lupus anticoagulant, anti–beta2-glycoprotein 1, and anticardiolipin antibodies, have been shown to induce fetal loss in animal models. Their influence on the outcome of human pregnancies, however, has been less clear, with several studies failing to prove a link between their presence and obstetric complications.

Dr. Lini and coinvestigators conducted a multicenter study involving 11 Italian centers and one Russian center, retrospectively looking for women with primary APS or women who had persistently high levels of aPL but no symptoms who had become pregnant. Of 503 pregnancies, information on complement levels before conception was available for 260, of which 184 had occurred in women with APS and 76 in women with persistently high aPL.

The pregnancies were grouped according to whether there were low (n = 93) or normal (n = 167) levels of C3 and C4 in the last 6 months.

“Women with adverse pregnancy outcomes showed significantly lower preconception complement levels than those with successful pregnancies, without any difference between APS and aPL carriers,” Dr. Lini reported.

Comparing those with low to those with high complement levels, the preterm live birth rate (before 37 weeks’ gestation) was 37% versus 18% (P < .0001).

The full-term live birth rates were a respective 42% and 72% (P < .0001).

The rate of pregnancy loss, which included both abortion and miscarriage, was a respective 21% and 10% (P = .008).

A subgroup analysis focusing on where there was triple aPL positivity found that preconception low C3 and/or C4 levels was associated with an increased rate of pregnancy loss (P = .05). This association disappeared if there was just one or two aPL present.

The researchers found no correlation between complement levels and rates of venous thromboembolism or thrombocytopenia.

Study highlights ‘impact and importance’ of complement in APS

The study indicates “the impact and the importance of complement” in APS, said Yehuda Shoenfeld, MD, the founder and head of the Zabludowicz Center for Autoimmune Diseases at the Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, Israel.

In the early days of understanding APS, said Dr. Shoenfeld, it was thought that complement was not as important as it was in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The importance of raised complement seen in studies of APS would often be discounted or neglected in comparison to SLE.

However, “slowly, slowly” it has been found that “complement [in APS] is activated very similarly to SLE,” Dr. Shoenfeld noted.

“I think that it’s important to assess the component levels,” Dr. Lini said in discussion. “This is needed to be done in the preconception counseling for APS and aPL carrier patients.”

Determining whether there is single, double, or even triple aPL positivity could be useful in guiding clinical decisions.

“If we have triple positivity, that could mean that there may be a more immunologic activation of the system and that it could be useful to administrate hydroxychloroquine [to] those patients who would like to have a pregnancy,” Dr. Lini suggested.

Plus, in those with decreased complement levels, “this could be a very useful tool” to identify where something could go wrong during their pregnancy.

The study had no outside funding. Dr. Lini and Dr. Shoenfeld disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low serum levels of two complement proteins are linked to worse pregnancy outcomes in women with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), the results of a multicenter study appear to confirm.

The study evaluated preconception complement levels in 260 pregnancies in 197 women who had APS or carried antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL), and found that low levels of C3 and C4 in the 6 months prior to pregnancy were associated with several gestational complications and resulted in pregnancy losses.