User login

Freezing breast cancer to death avoids surgery: Why not further along?

In the United States, cryoablation or freezing tissue to death is a primary treatment option for a variety of cancers, including those originating in or spread to the bone, cervix, eye, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, prostate, and skin.

Cryoablation for prostate cancer, one of the most common cancers in men, was first approved in the 1990s.

But unlike in Europe, this nonsurgical approach is not approved for breast cancer in the United States; it is one of the most common cancers in women.

So why is this approach still experimental for breast cancer?

“I don’t know,” answered cryoablation researcher Richard Fine, MD, of West Cancer Center in Germantown, Tenn., when asked by this news organization.

“It’s very interesting how slow the [Food and Drug Administration] is in approving devices for breast cancer [when compared with] other cancers,” he said.

New clinical data

Perhaps new clinical data will eventually lead to approval of this nonsurgical technique for use in low-risk breast cancer. However, the related trial had a controversial design that might discourage uptake by practitioners if it is approved, said an expert not involved in the study.

Nevertheless, the new data show that cryoablation can be an effective treatment for small, low-risk, early-stage breast cancers in older patients.

The findings come from ICE-3, a multicenter single-arm study of cryoablation in 194 such patients with mean follow-up of roughly 3 years.

It used liquid nitrogen-based cryoablation technology from IceCure Medical Ltd., an Israeli company and the study sponsor.

The results show that 2.06% (n = 4) of patients had a recurrence in the same breast, which is “basically the same” as lumpectomy, the surgical standard for this patient group, said Dr. Fine, the lead investigator on the trial.

These are interim data, Dr. Fine said at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting, held virtually.

The primary outcome is the 5-year recurrence rate, and this is the first-ever cryoablation trial that does not involve follow-up surgery, he said.

Cryoablation, which delivers a gas to a tumor via a thin needle-like probe that is guided by ultrasound, has multiple advantages over surgery, Dr. Fine said.

“The noninvasive procedure is fast, painless, and can be delivered under local anesthesia in a doctor’s office. Recovery time is minimal and cosmetic outcomes are excellent with little loss of breast tissue and no scarring,” he said in a meeting press statement.

The potential market for cryoablation in breast cancer is large, as it is intended for tumors ≤1.5 cm, which comprise approximately 60%-70% of stage 1 breast cancers that are hormone receptor–positive (HR+), and HER2-negative (HER2–), Dr. Fine said in an interview.

Cryoablation is part of a logical, de-escalation of breast cancer care, he added. “We have moved from radical mastectomy to modified mastectomy to lumpectomy – so the next step in that evolution is ablative technology, which is ‘nonsurgical.’ ”

There are other experimental ablative treatments for breast cancer including high-frequency ultrasound and laser, but cryoablation is the furthest along in development.

Cryoablation as a primary cancer treatment was first approved for coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for localized prostate cancer in 1999.

But the concept extends back to 1845, when English physician James Arnott first used iced salt solutions (about –20 °C or – 4 °F) to induce tissue necrosis, reducing tumor size and ameliorating pain. Because the crude cryogen needed to be applied topically, the pioneering technique was limited to breast and cervical cancers because of their accessibility.

Not likely to show superiority

The new study’s population was composed of women aged 60 years or older (mean of 75 years) with unifocal invasive ductal cancers measuring ≤1.5 cm or less that were all low-grade, HR+, and HER2–, as noted.

The liquid nitrogen–based cryoablation consisted of a freeze-thaw-freeze cycle that totals 20-40 minutes, with freezing temperatures targeting the tumor area and turning it into an “ice ball.”

That ice ball eventually surrounds the tumor, creating a “lethal zone,” and thus a margin in which no cancer exists, akin to surgery, said Dr. Fine.

There were no significant device-related adverse events or complications reported, say the investigators. Most of the adverse events were minor and included bruising, localized edema, minor skin freeze burn, rash, minor bleeding from needle insertion, minor local hematoma, skin induration, minor infection, and pruritis.

Two of 15 patients who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsies had a positive sentinel node. At the discretion of their treating physician, 27 patients underwent adjuvant radiation, 1 patient received chemotherapy, and 148 began endocrine therapy. More than 95% of the patients and 98% of physicians reported satisfaction from the cosmetic results during follow-up visits.

Because not all patients underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy and adjuvant radiation, there is likely to be controversy about this approach, suggested Deanna J. Attai, MD, a breast surgeon at the University of California, Los Angeles, and past president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons, who was asked for comment.

“We have studies that [indicate that] these treatments don’t add significant benefit [in this patient population] but there still is this hesitation [to forgo them],” she told this news organization.

“The patients in this study were exceedingly low risk,” she emphasized.

“Is 5 years enough to assess recurrence rates? The answer is probably no. Recurrences or distant metastases are more likely to happen 10-20 years later.”

Thus, it will be difficult to show that cryoablation is superior to surgery, she said.

“You can show that cryoablation is not inferior to lumpectomy alone – which allows patients to avoid the operating room,” Dr. Attai summarized.

The surgical mindset and breast cancer

Dr. Attai, who was not involved in the current trial, was an investigator in an earlier single-arm cooperative group study of cryoablation for breast cancer, which had the rate of complete tumor ablation as the primary outcome. The study, known as the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1072 trial, enrolled 99 patients, all of whom underwent ablation followed by surgery. The study reported results in 2014 but was very slow to develop, she observed.

“I did my first training in 2004 and I don’t think the study opened for several years after that. I think there’s been a lot of hesitation to change the mindset that every cancer needs to be removed surgically,” Dr. Attai stated.

“When you put breast cancer in the context of the other organs, we are lagging behind a bit [with cryoablation],” she added.

“I don’t want to go there but … the innovation for male diseases and procedures sometimes surpasses that of women’s diseases,” she said.

But she also defended her fellow practitioners. “There’s been tremendous changes in management over the 27 years I’ve been in practice,” she said, citing the movement from mastectomy to lumpectomy as one of multiple big changes.

The disparity between the development of cryoablation for breast and prostate cancer is a mystery when you contemplate the potential side effects, Dr. Fine observed. “There’s not a lot of vital structures inside the breast, so you don’t have risks that you have with the prostate, including urinary incontinence and impotence.”

As a next move, the American Society of Breast Surgeons is planning to establish a cryoablation registry and aims to enroll 50 sites and 500 patients who are aged 55-85 years; for those aged 65-70, radiation therapy will be required, said Dr. Fine.

Currently, cryoablation for breast cancer is allowed only in a clinical trial, so a registry would expand usage considerably, he said.

However, cryoablation, including from IceCure, has FDA clearance for ablating cancerous tissue in general (but not breast cancer specifically).

Dr. Attai hopes the field is ready for the nonsurgical approach.

“Halsted died in 1922 and the Halsted radical mastectomy really didn’t start to fall out of favor until the 1950s, 1960,” said Dr. Attai, referring to Dr William Halsted, who pioneered the procedure in the 1890s. “I would hope we are better at speeding up our progress. Changing the surgical mindset takes time,” she said.

Dr. Fine was an investigator in the ICE3 trial, which is funded by IceCure Medical. Dr. Attai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, cryoablation or freezing tissue to death is a primary treatment option for a variety of cancers, including those originating in or spread to the bone, cervix, eye, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, prostate, and skin.

Cryoablation for prostate cancer, one of the most common cancers in men, was first approved in the 1990s.

But unlike in Europe, this nonsurgical approach is not approved for breast cancer in the United States; it is one of the most common cancers in women.

So why is this approach still experimental for breast cancer?

“I don’t know,” answered cryoablation researcher Richard Fine, MD, of West Cancer Center in Germantown, Tenn., when asked by this news organization.

“It’s very interesting how slow the [Food and Drug Administration] is in approving devices for breast cancer [when compared with] other cancers,” he said.

New clinical data

Perhaps new clinical data will eventually lead to approval of this nonsurgical technique for use in low-risk breast cancer. However, the related trial had a controversial design that might discourage uptake by practitioners if it is approved, said an expert not involved in the study.

Nevertheless, the new data show that cryoablation can be an effective treatment for small, low-risk, early-stage breast cancers in older patients.

The findings come from ICE-3, a multicenter single-arm study of cryoablation in 194 such patients with mean follow-up of roughly 3 years.

It used liquid nitrogen-based cryoablation technology from IceCure Medical Ltd., an Israeli company and the study sponsor.

The results show that 2.06% (n = 4) of patients had a recurrence in the same breast, which is “basically the same” as lumpectomy, the surgical standard for this patient group, said Dr. Fine, the lead investigator on the trial.

These are interim data, Dr. Fine said at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting, held virtually.

The primary outcome is the 5-year recurrence rate, and this is the first-ever cryoablation trial that does not involve follow-up surgery, he said.

Cryoablation, which delivers a gas to a tumor via a thin needle-like probe that is guided by ultrasound, has multiple advantages over surgery, Dr. Fine said.

“The noninvasive procedure is fast, painless, and can be delivered under local anesthesia in a doctor’s office. Recovery time is minimal and cosmetic outcomes are excellent with little loss of breast tissue and no scarring,” he said in a meeting press statement.

The potential market for cryoablation in breast cancer is large, as it is intended for tumors ≤1.5 cm, which comprise approximately 60%-70% of stage 1 breast cancers that are hormone receptor–positive (HR+), and HER2-negative (HER2–), Dr. Fine said in an interview.

Cryoablation is part of a logical, de-escalation of breast cancer care, he added. “We have moved from radical mastectomy to modified mastectomy to lumpectomy – so the next step in that evolution is ablative technology, which is ‘nonsurgical.’ ”

There are other experimental ablative treatments for breast cancer including high-frequency ultrasound and laser, but cryoablation is the furthest along in development.

Cryoablation as a primary cancer treatment was first approved for coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for localized prostate cancer in 1999.

But the concept extends back to 1845, when English physician James Arnott first used iced salt solutions (about –20 °C or – 4 °F) to induce tissue necrosis, reducing tumor size and ameliorating pain. Because the crude cryogen needed to be applied topically, the pioneering technique was limited to breast and cervical cancers because of their accessibility.

Not likely to show superiority

The new study’s population was composed of women aged 60 years or older (mean of 75 years) with unifocal invasive ductal cancers measuring ≤1.5 cm or less that were all low-grade, HR+, and HER2–, as noted.

The liquid nitrogen–based cryoablation consisted of a freeze-thaw-freeze cycle that totals 20-40 minutes, with freezing temperatures targeting the tumor area and turning it into an “ice ball.”

That ice ball eventually surrounds the tumor, creating a “lethal zone,” and thus a margin in which no cancer exists, akin to surgery, said Dr. Fine.

There were no significant device-related adverse events or complications reported, say the investigators. Most of the adverse events were minor and included bruising, localized edema, minor skin freeze burn, rash, minor bleeding from needle insertion, minor local hematoma, skin induration, minor infection, and pruritis.

Two of 15 patients who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsies had a positive sentinel node. At the discretion of their treating physician, 27 patients underwent adjuvant radiation, 1 patient received chemotherapy, and 148 began endocrine therapy. More than 95% of the patients and 98% of physicians reported satisfaction from the cosmetic results during follow-up visits.

Because not all patients underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy and adjuvant radiation, there is likely to be controversy about this approach, suggested Deanna J. Attai, MD, a breast surgeon at the University of California, Los Angeles, and past president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons, who was asked for comment.

“We have studies that [indicate that] these treatments don’t add significant benefit [in this patient population] but there still is this hesitation [to forgo them],” she told this news organization.

“The patients in this study were exceedingly low risk,” she emphasized.

“Is 5 years enough to assess recurrence rates? The answer is probably no. Recurrences or distant metastases are more likely to happen 10-20 years later.”

Thus, it will be difficult to show that cryoablation is superior to surgery, she said.

“You can show that cryoablation is not inferior to lumpectomy alone – which allows patients to avoid the operating room,” Dr. Attai summarized.

The surgical mindset and breast cancer

Dr. Attai, who was not involved in the current trial, was an investigator in an earlier single-arm cooperative group study of cryoablation for breast cancer, which had the rate of complete tumor ablation as the primary outcome. The study, known as the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1072 trial, enrolled 99 patients, all of whom underwent ablation followed by surgery. The study reported results in 2014 but was very slow to develop, she observed.

“I did my first training in 2004 and I don’t think the study opened for several years after that. I think there’s been a lot of hesitation to change the mindset that every cancer needs to be removed surgically,” Dr. Attai stated.

“When you put breast cancer in the context of the other organs, we are lagging behind a bit [with cryoablation],” she added.

“I don’t want to go there but … the innovation for male diseases and procedures sometimes surpasses that of women’s diseases,” she said.

But she also defended her fellow practitioners. “There’s been tremendous changes in management over the 27 years I’ve been in practice,” she said, citing the movement from mastectomy to lumpectomy as one of multiple big changes.

The disparity between the development of cryoablation for breast and prostate cancer is a mystery when you contemplate the potential side effects, Dr. Fine observed. “There’s not a lot of vital structures inside the breast, so you don’t have risks that you have with the prostate, including urinary incontinence and impotence.”

As a next move, the American Society of Breast Surgeons is planning to establish a cryoablation registry and aims to enroll 50 sites and 500 patients who are aged 55-85 years; for those aged 65-70, radiation therapy will be required, said Dr. Fine.

Currently, cryoablation for breast cancer is allowed only in a clinical trial, so a registry would expand usage considerably, he said.

However, cryoablation, including from IceCure, has FDA clearance for ablating cancerous tissue in general (but not breast cancer specifically).

Dr. Attai hopes the field is ready for the nonsurgical approach.

“Halsted died in 1922 and the Halsted radical mastectomy really didn’t start to fall out of favor until the 1950s, 1960,” said Dr. Attai, referring to Dr William Halsted, who pioneered the procedure in the 1890s. “I would hope we are better at speeding up our progress. Changing the surgical mindset takes time,” she said.

Dr. Fine was an investigator in the ICE3 trial, which is funded by IceCure Medical. Dr. Attai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, cryoablation or freezing tissue to death is a primary treatment option for a variety of cancers, including those originating in or spread to the bone, cervix, eye, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, prostate, and skin.

Cryoablation for prostate cancer, one of the most common cancers in men, was first approved in the 1990s.

But unlike in Europe, this nonsurgical approach is not approved for breast cancer in the United States; it is one of the most common cancers in women.

So why is this approach still experimental for breast cancer?

“I don’t know,” answered cryoablation researcher Richard Fine, MD, of West Cancer Center in Germantown, Tenn., when asked by this news organization.

“It’s very interesting how slow the [Food and Drug Administration] is in approving devices for breast cancer [when compared with] other cancers,” he said.

New clinical data

Perhaps new clinical data will eventually lead to approval of this nonsurgical technique for use in low-risk breast cancer. However, the related trial had a controversial design that might discourage uptake by practitioners if it is approved, said an expert not involved in the study.

Nevertheless, the new data show that cryoablation can be an effective treatment for small, low-risk, early-stage breast cancers in older patients.

The findings come from ICE-3, a multicenter single-arm study of cryoablation in 194 such patients with mean follow-up of roughly 3 years.

It used liquid nitrogen-based cryoablation technology from IceCure Medical Ltd., an Israeli company and the study sponsor.

The results show that 2.06% (n = 4) of patients had a recurrence in the same breast, which is “basically the same” as lumpectomy, the surgical standard for this patient group, said Dr. Fine, the lead investigator on the trial.

These are interim data, Dr. Fine said at the American Society of Breast Surgeons annual meeting, held virtually.

The primary outcome is the 5-year recurrence rate, and this is the first-ever cryoablation trial that does not involve follow-up surgery, he said.

Cryoablation, which delivers a gas to a tumor via a thin needle-like probe that is guided by ultrasound, has multiple advantages over surgery, Dr. Fine said.

“The noninvasive procedure is fast, painless, and can be delivered under local anesthesia in a doctor’s office. Recovery time is minimal and cosmetic outcomes are excellent with little loss of breast tissue and no scarring,” he said in a meeting press statement.

The potential market for cryoablation in breast cancer is large, as it is intended for tumors ≤1.5 cm, which comprise approximately 60%-70% of stage 1 breast cancers that are hormone receptor–positive (HR+), and HER2-negative (HER2–), Dr. Fine said in an interview.

Cryoablation is part of a logical, de-escalation of breast cancer care, he added. “We have moved from radical mastectomy to modified mastectomy to lumpectomy – so the next step in that evolution is ablative technology, which is ‘nonsurgical.’ ”

There are other experimental ablative treatments for breast cancer including high-frequency ultrasound and laser, but cryoablation is the furthest along in development.

Cryoablation as a primary cancer treatment was first approved for coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for localized prostate cancer in 1999.

But the concept extends back to 1845, when English physician James Arnott first used iced salt solutions (about –20 °C or – 4 °F) to induce tissue necrosis, reducing tumor size and ameliorating pain. Because the crude cryogen needed to be applied topically, the pioneering technique was limited to breast and cervical cancers because of their accessibility.

Not likely to show superiority

The new study’s population was composed of women aged 60 years or older (mean of 75 years) with unifocal invasive ductal cancers measuring ≤1.5 cm or less that were all low-grade, HR+, and HER2–, as noted.

The liquid nitrogen–based cryoablation consisted of a freeze-thaw-freeze cycle that totals 20-40 minutes, with freezing temperatures targeting the tumor area and turning it into an “ice ball.”

That ice ball eventually surrounds the tumor, creating a “lethal zone,” and thus a margin in which no cancer exists, akin to surgery, said Dr. Fine.

There were no significant device-related adverse events or complications reported, say the investigators. Most of the adverse events were minor and included bruising, localized edema, minor skin freeze burn, rash, minor bleeding from needle insertion, minor local hematoma, skin induration, minor infection, and pruritis.

Two of 15 patients who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsies had a positive sentinel node. At the discretion of their treating physician, 27 patients underwent adjuvant radiation, 1 patient received chemotherapy, and 148 began endocrine therapy. More than 95% of the patients and 98% of physicians reported satisfaction from the cosmetic results during follow-up visits.

Because not all patients underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy and adjuvant radiation, there is likely to be controversy about this approach, suggested Deanna J. Attai, MD, a breast surgeon at the University of California, Los Angeles, and past president of the American Society of Breast Surgeons, who was asked for comment.

“We have studies that [indicate that] these treatments don’t add significant benefit [in this patient population] but there still is this hesitation [to forgo them],” she told this news organization.

“The patients in this study were exceedingly low risk,” she emphasized.

“Is 5 years enough to assess recurrence rates? The answer is probably no. Recurrences or distant metastases are more likely to happen 10-20 years later.”

Thus, it will be difficult to show that cryoablation is superior to surgery, she said.

“You can show that cryoablation is not inferior to lumpectomy alone – which allows patients to avoid the operating room,” Dr. Attai summarized.

The surgical mindset and breast cancer

Dr. Attai, who was not involved in the current trial, was an investigator in an earlier single-arm cooperative group study of cryoablation for breast cancer, which had the rate of complete tumor ablation as the primary outcome. The study, known as the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1072 trial, enrolled 99 patients, all of whom underwent ablation followed by surgery. The study reported results in 2014 but was very slow to develop, she observed.

“I did my first training in 2004 and I don’t think the study opened for several years after that. I think there’s been a lot of hesitation to change the mindset that every cancer needs to be removed surgically,” Dr. Attai stated.

“When you put breast cancer in the context of the other organs, we are lagging behind a bit [with cryoablation],” she added.

“I don’t want to go there but … the innovation for male diseases and procedures sometimes surpasses that of women’s diseases,” she said.

But she also defended her fellow practitioners. “There’s been tremendous changes in management over the 27 years I’ve been in practice,” she said, citing the movement from mastectomy to lumpectomy as one of multiple big changes.

The disparity between the development of cryoablation for breast and prostate cancer is a mystery when you contemplate the potential side effects, Dr. Fine observed. “There’s not a lot of vital structures inside the breast, so you don’t have risks that you have with the prostate, including urinary incontinence and impotence.”

As a next move, the American Society of Breast Surgeons is planning to establish a cryoablation registry and aims to enroll 50 sites and 500 patients who are aged 55-85 years; for those aged 65-70, radiation therapy will be required, said Dr. Fine.

Currently, cryoablation for breast cancer is allowed only in a clinical trial, so a registry would expand usage considerably, he said.

However, cryoablation, including from IceCure, has FDA clearance for ablating cancerous tissue in general (but not breast cancer specifically).

Dr. Attai hopes the field is ready for the nonsurgical approach.

“Halsted died in 1922 and the Halsted radical mastectomy really didn’t start to fall out of favor until the 1950s, 1960,” said Dr. Attai, referring to Dr William Halsted, who pioneered the procedure in the 1890s. “I would hope we are better at speeding up our progress. Changing the surgical mindset takes time,” she said.

Dr. Fine was an investigator in the ICE3 trial, which is funded by IceCure Medical. Dr. Attai has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Converging to build for tomorrow

Last month we converged virtually for our annual conference, SHM Converge – the second time since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. We are thankful for innovations and advancements in technology that have allowed the world, including SHM, to continue connecting us all together. And yet, 18 months in, having forged new roads, experienced unique and life-changing events, we long for the in-person human connection that allows us to share a common experience. At a time of imperatives in our world – a global pandemic, systemic racism, and deep geopolitical divides – more than ever, we need to converge. Isolation only festers, deepening our divisions and conflicts.

In high school, I read Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” and clung to the notion of diverging roads and choosing the road less traveled. Like most young people, my years since reading the poem were filled with attempts at forging new paths and experiencing great things – and yet, always feeling unaccomplished. Was Oscar Wilde right when he wrote: “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life?” After all, these past 18 months, we have shared in the traumas of our times, and still, we remain isolated and alone. Our diverse experiences have been real, both tragic and heroic, from east to west, city to country, black to white, and red to blue.

At SHM, it’s time to converge and face the great challenges of our lifetime. A deadly pandemic continues to rage around the world, bringing unprecedented human suffering and loss of lives. In its wake, this pandemic also laid bare the ugly face of systemic racism, brought our deepest divisions to the surface – all threatening the very fabric of our society. This pandemic has been a stress test for health care systems, revealing our vulnerabilities and expanding the chasm of care between urban and rural communities, all in turn worsening our growing health disparities. This moment needs convergence to rekindle connection and solidarity.

Scholars do not interpret “The Road Not Taken” as a recommendation to take the road less traveled. Instead, it is a suggestion that the diverging roads lead to a common place having been “worn about the same” as they “equally lay.” It is true that our roads are unique and shape our lives, but so, too, does the destination and common place our roads lead us to. At that common place, during these taxing times, SHM enables hospitalists to tackle these great challenges.

For over 2 decades of dynamic changes in health care, SHM has been the workshop where hospitalists converged to sharpen clinical skills, improve quality and safety, develop acute care models inside and outside of hospitals, advocate for better health policy and blaze new trails. Though the issues evolved, and new ones emerge, today is no different.

Indeed, this is an historic time. This weighted moment meets us at the crossroads. A moment that demands synergy, cooperation, and creativity. A dynamic change to health care policy, advances in care innovation, renewed prioritization of public health, and rich national discourse on our social fabric; hospitalists are essential to every one of those conversations. SHM has evolved to meet our growing needs, equipping hospitalists with tools to engage at every level, and most importantly, enabled us to find our common place.

Where do we go now? I suggest we continue to take the roads not taken and at the destination, build the map of tomorrow, together.

Dr. Siy is division medical director, hospital specialties, in the departments of hospital medicine and community senior and palliative care at HealthPartners in Bloomington, Minn. He is the new president of SHM.

Last month we converged virtually for our annual conference, SHM Converge – the second time since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. We are thankful for innovations and advancements in technology that have allowed the world, including SHM, to continue connecting us all together. And yet, 18 months in, having forged new roads, experienced unique and life-changing events, we long for the in-person human connection that allows us to share a common experience. At a time of imperatives in our world – a global pandemic, systemic racism, and deep geopolitical divides – more than ever, we need to converge. Isolation only festers, deepening our divisions and conflicts.

In high school, I read Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” and clung to the notion of diverging roads and choosing the road less traveled. Like most young people, my years since reading the poem were filled with attempts at forging new paths and experiencing great things – and yet, always feeling unaccomplished. Was Oscar Wilde right when he wrote: “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life?” After all, these past 18 months, we have shared in the traumas of our times, and still, we remain isolated and alone. Our diverse experiences have been real, both tragic and heroic, from east to west, city to country, black to white, and red to blue.

At SHM, it’s time to converge and face the great challenges of our lifetime. A deadly pandemic continues to rage around the world, bringing unprecedented human suffering and loss of lives. In its wake, this pandemic also laid bare the ugly face of systemic racism, brought our deepest divisions to the surface – all threatening the very fabric of our society. This pandemic has been a stress test for health care systems, revealing our vulnerabilities and expanding the chasm of care between urban and rural communities, all in turn worsening our growing health disparities. This moment needs convergence to rekindle connection and solidarity.

Scholars do not interpret “The Road Not Taken” as a recommendation to take the road less traveled. Instead, it is a suggestion that the diverging roads lead to a common place having been “worn about the same” as they “equally lay.” It is true that our roads are unique and shape our lives, but so, too, does the destination and common place our roads lead us to. At that common place, during these taxing times, SHM enables hospitalists to tackle these great challenges.

For over 2 decades of dynamic changes in health care, SHM has been the workshop where hospitalists converged to sharpen clinical skills, improve quality and safety, develop acute care models inside and outside of hospitals, advocate for better health policy and blaze new trails. Though the issues evolved, and new ones emerge, today is no different.

Indeed, this is an historic time. This weighted moment meets us at the crossroads. A moment that demands synergy, cooperation, and creativity. A dynamic change to health care policy, advances in care innovation, renewed prioritization of public health, and rich national discourse on our social fabric; hospitalists are essential to every one of those conversations. SHM has evolved to meet our growing needs, equipping hospitalists with tools to engage at every level, and most importantly, enabled us to find our common place.

Where do we go now? I suggest we continue to take the roads not taken and at the destination, build the map of tomorrow, together.

Dr. Siy is division medical director, hospital specialties, in the departments of hospital medicine and community senior and palliative care at HealthPartners in Bloomington, Minn. He is the new president of SHM.

Last month we converged virtually for our annual conference, SHM Converge – the second time since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. We are thankful for innovations and advancements in technology that have allowed the world, including SHM, to continue connecting us all together. And yet, 18 months in, having forged new roads, experienced unique and life-changing events, we long for the in-person human connection that allows us to share a common experience. At a time of imperatives in our world – a global pandemic, systemic racism, and deep geopolitical divides – more than ever, we need to converge. Isolation only festers, deepening our divisions and conflicts.

In high school, I read Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” and clung to the notion of diverging roads and choosing the road less traveled. Like most young people, my years since reading the poem were filled with attempts at forging new paths and experiencing great things – and yet, always feeling unaccomplished. Was Oscar Wilde right when he wrote: “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life?” After all, these past 18 months, we have shared in the traumas of our times, and still, we remain isolated and alone. Our diverse experiences have been real, both tragic and heroic, from east to west, city to country, black to white, and red to blue.

At SHM, it’s time to converge and face the great challenges of our lifetime. A deadly pandemic continues to rage around the world, bringing unprecedented human suffering and loss of lives. In its wake, this pandemic also laid bare the ugly face of systemic racism, brought our deepest divisions to the surface – all threatening the very fabric of our society. This pandemic has been a stress test for health care systems, revealing our vulnerabilities and expanding the chasm of care between urban and rural communities, all in turn worsening our growing health disparities. This moment needs convergence to rekindle connection and solidarity.

Scholars do not interpret “The Road Not Taken” as a recommendation to take the road less traveled. Instead, it is a suggestion that the diverging roads lead to a common place having been “worn about the same” as they “equally lay.” It is true that our roads are unique and shape our lives, but so, too, does the destination and common place our roads lead us to. At that common place, during these taxing times, SHM enables hospitalists to tackle these great challenges.

For over 2 decades of dynamic changes in health care, SHM has been the workshop where hospitalists converged to sharpen clinical skills, improve quality and safety, develop acute care models inside and outside of hospitals, advocate for better health policy and blaze new trails. Though the issues evolved, and new ones emerge, today is no different.

Indeed, this is an historic time. This weighted moment meets us at the crossroads. A moment that demands synergy, cooperation, and creativity. A dynamic change to health care policy, advances in care innovation, renewed prioritization of public health, and rich national discourse on our social fabric; hospitalists are essential to every one of those conversations. SHM has evolved to meet our growing needs, equipping hospitalists with tools to engage at every level, and most importantly, enabled us to find our common place.

Where do we go now? I suggest we continue to take the roads not taken and at the destination, build the map of tomorrow, together.

Dr. Siy is division medical director, hospital specialties, in the departments of hospital medicine and community senior and palliative care at HealthPartners in Bloomington, Minn. He is the new president of SHM.

New biomarkers may predict interstitial lung disease progression in patients with systemic sclerosis

Quantitative assessment of the extent of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis and levels of certain proteins in bronchoalveolar lavage samples have potential for predicting mortality and disease progression, according to two analyses of data from the Scleroderma Lung Study I and II.

The analyses, presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, aim to improve current prognostic abilities in patients with systemic sclerosis–interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD). Although forced vital capacity is commonly used as a biomarker for survival in many SSc-ILD trials, other factors can affect FVC, such as respiratory muscle weakness and skin fibrosis. Further, FVC correlates poorly with patient-reported outcomes, explained first author Elizabeth Volkmann, MD, director of the scleroderma program at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the founder and codirector of the UCLA connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease program.

Dr. Volkmann presented two studies that investigated the potential of radiographic and protein biomarkers for predicting mortality and identifying patients at risk for ILD progression. The biomarkers may also help to identify patients who would benefit most from immunosuppressive therapy.

The first study found that tracking the quantitative extent of ILD (QILD) over time with high-resolution CT (HRCT) predicted poorer outcomes and could therefore act as a surrogate endpoint for mortality among patients with SSc-ILD. The other study identified associations between specific proteins from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and the likelihood of ILD progression, although some associations were treatment dependent.

Jacob M. van Laar, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), who was not involved in the study, found the results intriguing and noted the importance of further validation in research before these biomarkers are considered for clinical use.

“It would be wonderful if we can tailor therapy based on BAL biomarkers in the future, as clinicians often struggle to decide on selection, timing, and duration of immunosuppressive treatment,” Dr. van Laar told this news organization. “This has become even more relevant with the introduction of new drugs such as nintedanib.”

Extent of ILD progression as a surrogate for mortality

Scleroderma Lung Study I involved 158 patients with SSc-ILD who were randomly assigned to receive either cyclophosphamide or placebo for 12 months. Scleroderma Lung Study II included 142 patients with SSc-ILD who were randomly assigned to receive either mycophenolate for 24 months or cyclophosphamide for 12 months followed by placebo for 12 months.

The researchers calculated QILD in the whole lung at baseline, at 12 months in the first trial, and at 24 months in the second trial. However, only 82 participants from the first trial and 90 participants from the second trial underwent HRCT. Demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the two groups on follow-up scans.

Follow-up continued for 12 years for patients in the first trial and 8 years in the second. The researchers compared survival rates between the 41% of participants from the first study and 31% of participants from the second study who had poorer QILD scores (at least a 2% increase) with the participants who had stable or improved scores (less than 2% increase).

Participants from both trials had significantly poorer long-term survival if their QILD scores had increased by at least 2% at follow-up (P = .01 for I; P = .019 for II). The association was no longer significant after adjustment for baseline FVC, age, and modified Rodnan skin score in the first trial (hazard ratio, 1.98; P = .089), but it remained significant for participants of the second trial (HR, 3.86; P = .014).

“Data from two independent trial cohorts demonstrated that radiographic progression of SSc-ILD at 1 and 2 years is associated with worse long-term survival,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees.

However, FVC did not significantly predict risk of mortality in either trial.

“To me, the most striking finding from the first study was that change in QILD performed better as a predictor of survival than change in FVC,” Dr. van Laar said in an interview. “This indicates QILD is fit for purpose and worth including in future clinical trials.”

Limitations of the study included lack of HRCT for all participants in the trials and the difference in timing (1 year and 2 years) of HRCT assessment between the two trials. The greater hazard ratio for worsened QILD in the second trial may suggest that assessment at 2 years provides more reliable data as a biomarker, Dr. Volkmann said.

“QILD may represent a better proxy for how a patient feels, functions, and survives than FVC,” she said.

Treatment-dependent biomarkers for worsening lung fibrosis

In the second study, the researchers looked for any associations between changes in the radiographic extent of SSc-ILD and 68 proteins from BAL.

“Being able to risk-stratify patients with interstitial lung disease at the time of diagnosis and predict which patients are likely to have a stable versus progressive disease course is critical for making important treatment decisions for these patients,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees.

The second study she presented involved Scleroderma Lung Study I. Of the 158 participants, 144 underwent a bronchoscopy, yielding BAL protein samples from 103 participants. The researchers determined the extent of radiographic fibrosis in the whole lung with quantitative imaging analysis of HRCT of the chest at baseline and 12 months.

Although the researchers identified several statistically significant associations between certain proteins and changes in radiographic fibrosis, “baseline protein levels were differentially associated with the course of ILD based on treatment status,” she told attendees.

For example, increased levels of the following proteins were linked to poor radiographic fibrosis scores for patients who received placebo:

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- Interleukin-1

- Monocyte chemoattractant protein–3

- Chemokine ligand–5

- Transforming growth factor–beta

- Hepatocyte growth factor

- Stem cell factor

- IL-4

- TGF-alpha

Yet increases in these proteins predicted improvement in radiographic fibrosis in patients who had taken cyclophosphamide.

Independently of treatment, the researchers also identified an association between higher levels of fractalkine and poorer radiographic fibrosis scores and between higher IL-7 levels and improved radiographic fibrosis scores.

After adjusting for treatment arm and baseline severity of ILD, significant associations remained between change in radiographic fibrosis score and IL-1, MCP-3, surfactant protein C, IL-7 and CCL-5 levels.

“Biomarker discovery is really central to our ability to risk stratify patients with SSc-ILD,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees. “Understanding how biomarkers predict outcomes in treated and untreated patients may improve personalized medicine to patients with SSc-ILD and could also reveal novel treatment targets.”

Dr. van Laar said in an interview that this study’s biggest strength lay in its large sample size and in the comprehensiveness of the biomarkers studied.

“The findings are interesting from a research perspective and potentially relevant for clinical practice, but the utility of measuring biomarkers in BAL should be further studied for predictive value on clinical endpoints,” Dr. van Laar said. “BAL is an invasive procedure [that] is not routinely done.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Volkmann has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and received grant funding from Corbus, Forbius, and Kadmon. Dr. van Laar has received grant funding or personal fees from Arthrogen, Arxx Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gesynta, Leadiant, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Sanofi, and Thermofisher.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Quantitative assessment of the extent of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis and levels of certain proteins in bronchoalveolar lavage samples have potential for predicting mortality and disease progression, according to two analyses of data from the Scleroderma Lung Study I and II.

The analyses, presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, aim to improve current prognostic abilities in patients with systemic sclerosis–interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD). Although forced vital capacity is commonly used as a biomarker for survival in many SSc-ILD trials, other factors can affect FVC, such as respiratory muscle weakness and skin fibrosis. Further, FVC correlates poorly with patient-reported outcomes, explained first author Elizabeth Volkmann, MD, director of the scleroderma program at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the founder and codirector of the UCLA connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease program.

Dr. Volkmann presented two studies that investigated the potential of radiographic and protein biomarkers for predicting mortality and identifying patients at risk for ILD progression. The biomarkers may also help to identify patients who would benefit most from immunosuppressive therapy.

The first study found that tracking the quantitative extent of ILD (QILD) over time with high-resolution CT (HRCT) predicted poorer outcomes and could therefore act as a surrogate endpoint for mortality among patients with SSc-ILD. The other study identified associations between specific proteins from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and the likelihood of ILD progression, although some associations were treatment dependent.

Jacob M. van Laar, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), who was not involved in the study, found the results intriguing and noted the importance of further validation in research before these biomarkers are considered for clinical use.

“It would be wonderful if we can tailor therapy based on BAL biomarkers in the future, as clinicians often struggle to decide on selection, timing, and duration of immunosuppressive treatment,” Dr. van Laar told this news organization. “This has become even more relevant with the introduction of new drugs such as nintedanib.”

Extent of ILD progression as a surrogate for mortality

Scleroderma Lung Study I involved 158 patients with SSc-ILD who were randomly assigned to receive either cyclophosphamide or placebo for 12 months. Scleroderma Lung Study II included 142 patients with SSc-ILD who were randomly assigned to receive either mycophenolate for 24 months or cyclophosphamide for 12 months followed by placebo for 12 months.

The researchers calculated QILD in the whole lung at baseline, at 12 months in the first trial, and at 24 months in the second trial. However, only 82 participants from the first trial and 90 participants from the second trial underwent HRCT. Demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the two groups on follow-up scans.

Follow-up continued for 12 years for patients in the first trial and 8 years in the second. The researchers compared survival rates between the 41% of participants from the first study and 31% of participants from the second study who had poorer QILD scores (at least a 2% increase) with the participants who had stable or improved scores (less than 2% increase).

Participants from both trials had significantly poorer long-term survival if their QILD scores had increased by at least 2% at follow-up (P = .01 for I; P = .019 for II). The association was no longer significant after adjustment for baseline FVC, age, and modified Rodnan skin score in the first trial (hazard ratio, 1.98; P = .089), but it remained significant for participants of the second trial (HR, 3.86; P = .014).

“Data from two independent trial cohorts demonstrated that radiographic progression of SSc-ILD at 1 and 2 years is associated with worse long-term survival,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees.

However, FVC did not significantly predict risk of mortality in either trial.

“To me, the most striking finding from the first study was that change in QILD performed better as a predictor of survival than change in FVC,” Dr. van Laar said in an interview. “This indicates QILD is fit for purpose and worth including in future clinical trials.”

Limitations of the study included lack of HRCT for all participants in the trials and the difference in timing (1 year and 2 years) of HRCT assessment between the two trials. The greater hazard ratio for worsened QILD in the second trial may suggest that assessment at 2 years provides more reliable data as a biomarker, Dr. Volkmann said.

“QILD may represent a better proxy for how a patient feels, functions, and survives than FVC,” she said.

Treatment-dependent biomarkers for worsening lung fibrosis

In the second study, the researchers looked for any associations between changes in the radiographic extent of SSc-ILD and 68 proteins from BAL.

“Being able to risk-stratify patients with interstitial lung disease at the time of diagnosis and predict which patients are likely to have a stable versus progressive disease course is critical for making important treatment decisions for these patients,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees.

The second study she presented involved Scleroderma Lung Study I. Of the 158 participants, 144 underwent a bronchoscopy, yielding BAL protein samples from 103 participants. The researchers determined the extent of radiographic fibrosis in the whole lung with quantitative imaging analysis of HRCT of the chest at baseline and 12 months.

Although the researchers identified several statistically significant associations between certain proteins and changes in radiographic fibrosis, “baseline protein levels were differentially associated with the course of ILD based on treatment status,” she told attendees.

For example, increased levels of the following proteins were linked to poor radiographic fibrosis scores for patients who received placebo:

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- Interleukin-1

- Monocyte chemoattractant protein–3

- Chemokine ligand–5

- Transforming growth factor–beta

- Hepatocyte growth factor

- Stem cell factor

- IL-4

- TGF-alpha

Yet increases in these proteins predicted improvement in radiographic fibrosis in patients who had taken cyclophosphamide.

Independently of treatment, the researchers also identified an association between higher levels of fractalkine and poorer radiographic fibrosis scores and between higher IL-7 levels and improved radiographic fibrosis scores.

After adjusting for treatment arm and baseline severity of ILD, significant associations remained between change in radiographic fibrosis score and IL-1, MCP-3, surfactant protein C, IL-7 and CCL-5 levels.

“Biomarker discovery is really central to our ability to risk stratify patients with SSc-ILD,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees. “Understanding how biomarkers predict outcomes in treated and untreated patients may improve personalized medicine to patients with SSc-ILD and could also reveal novel treatment targets.”

Dr. van Laar said in an interview that this study’s biggest strength lay in its large sample size and in the comprehensiveness of the biomarkers studied.

“The findings are interesting from a research perspective and potentially relevant for clinical practice, but the utility of measuring biomarkers in BAL should be further studied for predictive value on clinical endpoints,” Dr. van Laar said. “BAL is an invasive procedure [that] is not routinely done.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Volkmann has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and received grant funding from Corbus, Forbius, and Kadmon. Dr. van Laar has received grant funding or personal fees from Arthrogen, Arxx Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gesynta, Leadiant, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Sanofi, and Thermofisher.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Quantitative assessment of the extent of interstitial lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis and levels of certain proteins in bronchoalveolar lavage samples have potential for predicting mortality and disease progression, according to two analyses of data from the Scleroderma Lung Study I and II.

The analyses, presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, aim to improve current prognostic abilities in patients with systemic sclerosis–interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD). Although forced vital capacity is commonly used as a biomarker for survival in many SSc-ILD trials, other factors can affect FVC, such as respiratory muscle weakness and skin fibrosis. Further, FVC correlates poorly with patient-reported outcomes, explained first author Elizabeth Volkmann, MD, director of the scleroderma program at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the founder and codirector of the UCLA connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease program.

Dr. Volkmann presented two studies that investigated the potential of radiographic and protein biomarkers for predicting mortality and identifying patients at risk for ILD progression. The biomarkers may also help to identify patients who would benefit most from immunosuppressive therapy.

The first study found that tracking the quantitative extent of ILD (QILD) over time with high-resolution CT (HRCT) predicted poorer outcomes and could therefore act as a surrogate endpoint for mortality among patients with SSc-ILD. The other study identified associations between specific proteins from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and the likelihood of ILD progression, although some associations were treatment dependent.

Jacob M. van Laar, MD, PhD, professor of rheumatology at the University Medical Center Utrecht (the Netherlands), who was not involved in the study, found the results intriguing and noted the importance of further validation in research before these biomarkers are considered for clinical use.

“It would be wonderful if we can tailor therapy based on BAL biomarkers in the future, as clinicians often struggle to decide on selection, timing, and duration of immunosuppressive treatment,” Dr. van Laar told this news organization. “This has become even more relevant with the introduction of new drugs such as nintedanib.”

Extent of ILD progression as a surrogate for mortality

Scleroderma Lung Study I involved 158 patients with SSc-ILD who were randomly assigned to receive either cyclophosphamide or placebo for 12 months. Scleroderma Lung Study II included 142 patients with SSc-ILD who were randomly assigned to receive either mycophenolate for 24 months or cyclophosphamide for 12 months followed by placebo for 12 months.

The researchers calculated QILD in the whole lung at baseline, at 12 months in the first trial, and at 24 months in the second trial. However, only 82 participants from the first trial and 90 participants from the second trial underwent HRCT. Demographic and disease characteristics were similar between the two groups on follow-up scans.

Follow-up continued for 12 years for patients in the first trial and 8 years in the second. The researchers compared survival rates between the 41% of participants from the first study and 31% of participants from the second study who had poorer QILD scores (at least a 2% increase) with the participants who had stable or improved scores (less than 2% increase).

Participants from both trials had significantly poorer long-term survival if their QILD scores had increased by at least 2% at follow-up (P = .01 for I; P = .019 for II). The association was no longer significant after adjustment for baseline FVC, age, and modified Rodnan skin score in the first trial (hazard ratio, 1.98; P = .089), but it remained significant for participants of the second trial (HR, 3.86; P = .014).

“Data from two independent trial cohorts demonstrated that radiographic progression of SSc-ILD at 1 and 2 years is associated with worse long-term survival,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees.

However, FVC did not significantly predict risk of mortality in either trial.

“To me, the most striking finding from the first study was that change in QILD performed better as a predictor of survival than change in FVC,” Dr. van Laar said in an interview. “This indicates QILD is fit for purpose and worth including in future clinical trials.”

Limitations of the study included lack of HRCT for all participants in the trials and the difference in timing (1 year and 2 years) of HRCT assessment between the two trials. The greater hazard ratio for worsened QILD in the second trial may suggest that assessment at 2 years provides more reliable data as a biomarker, Dr. Volkmann said.

“QILD may represent a better proxy for how a patient feels, functions, and survives than FVC,” she said.

Treatment-dependent biomarkers for worsening lung fibrosis

In the second study, the researchers looked for any associations between changes in the radiographic extent of SSc-ILD and 68 proteins from BAL.

“Being able to risk-stratify patients with interstitial lung disease at the time of diagnosis and predict which patients are likely to have a stable versus progressive disease course is critical for making important treatment decisions for these patients,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees.

The second study she presented involved Scleroderma Lung Study I. Of the 158 participants, 144 underwent a bronchoscopy, yielding BAL protein samples from 103 participants. The researchers determined the extent of radiographic fibrosis in the whole lung with quantitative imaging analysis of HRCT of the chest at baseline and 12 months.

Although the researchers identified several statistically significant associations between certain proteins and changes in radiographic fibrosis, “baseline protein levels were differentially associated with the course of ILD based on treatment status,” she told attendees.

For example, increased levels of the following proteins were linked to poor radiographic fibrosis scores for patients who received placebo:

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- Interleukin-1

- Monocyte chemoattractant protein–3

- Chemokine ligand–5

- Transforming growth factor–beta

- Hepatocyte growth factor

- Stem cell factor

- IL-4

- TGF-alpha

Yet increases in these proteins predicted improvement in radiographic fibrosis in patients who had taken cyclophosphamide.

Independently of treatment, the researchers also identified an association between higher levels of fractalkine and poorer radiographic fibrosis scores and between higher IL-7 levels and improved radiographic fibrosis scores.

After adjusting for treatment arm and baseline severity of ILD, significant associations remained between change in radiographic fibrosis score and IL-1, MCP-3, surfactant protein C, IL-7 and CCL-5 levels.

“Biomarker discovery is really central to our ability to risk stratify patients with SSc-ILD,” Dr. Volkmann told attendees. “Understanding how biomarkers predict outcomes in treated and untreated patients may improve personalized medicine to patients with SSc-ILD and could also reveal novel treatment targets.”

Dr. van Laar said in an interview that this study’s biggest strength lay in its large sample size and in the comprehensiveness of the biomarkers studied.

“The findings are interesting from a research perspective and potentially relevant for clinical practice, but the utility of measuring biomarkers in BAL should be further studied for predictive value on clinical endpoints,” Dr. van Laar said. “BAL is an invasive procedure [that] is not routinely done.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Volkmann has consulted for Boehringer Ingelheim and received grant funding from Corbus, Forbius, and Kadmon. Dr. van Laar has received grant funding or personal fees from Arthrogen, Arxx Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Gesynta, Leadiant, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Sanofi, and Thermofisher.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

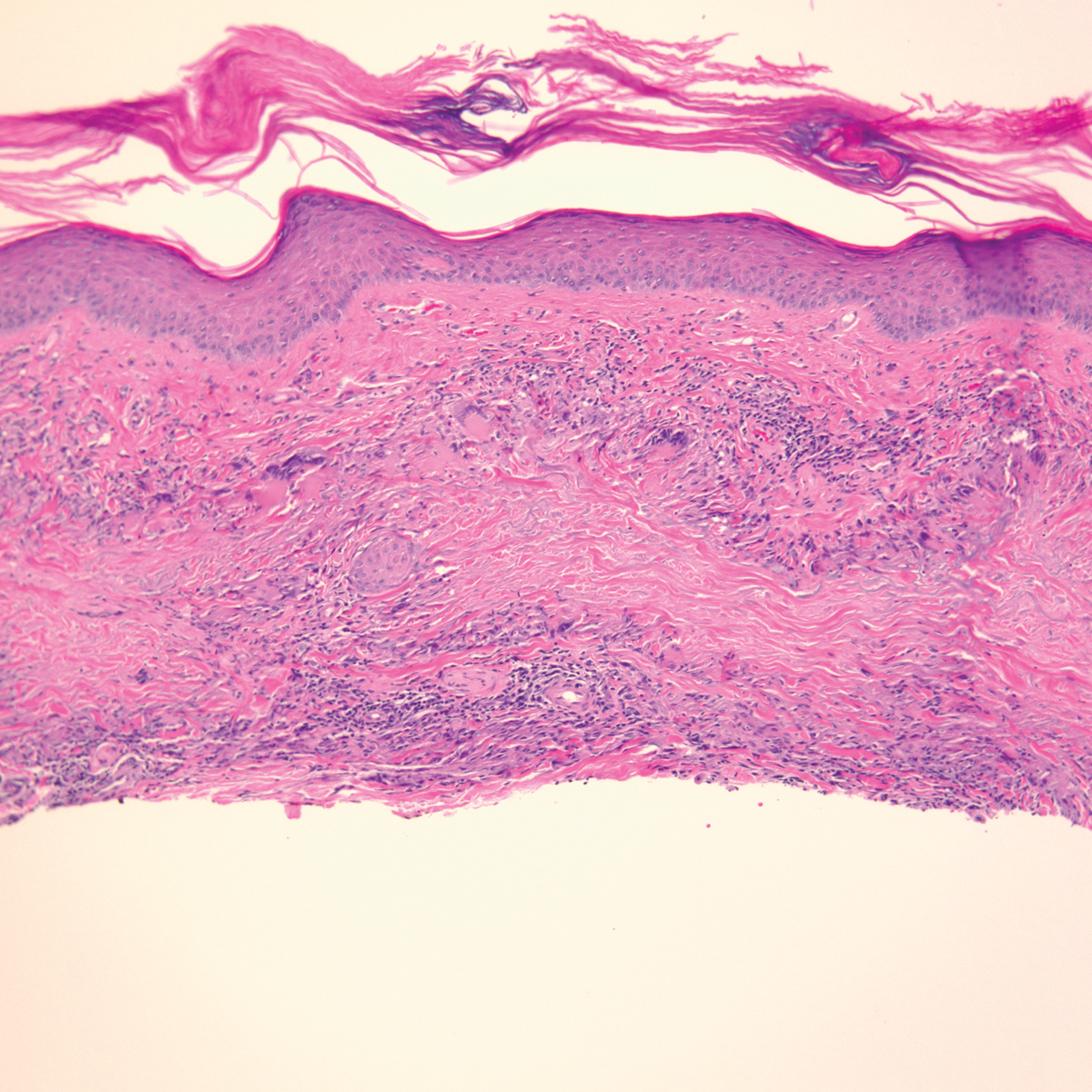

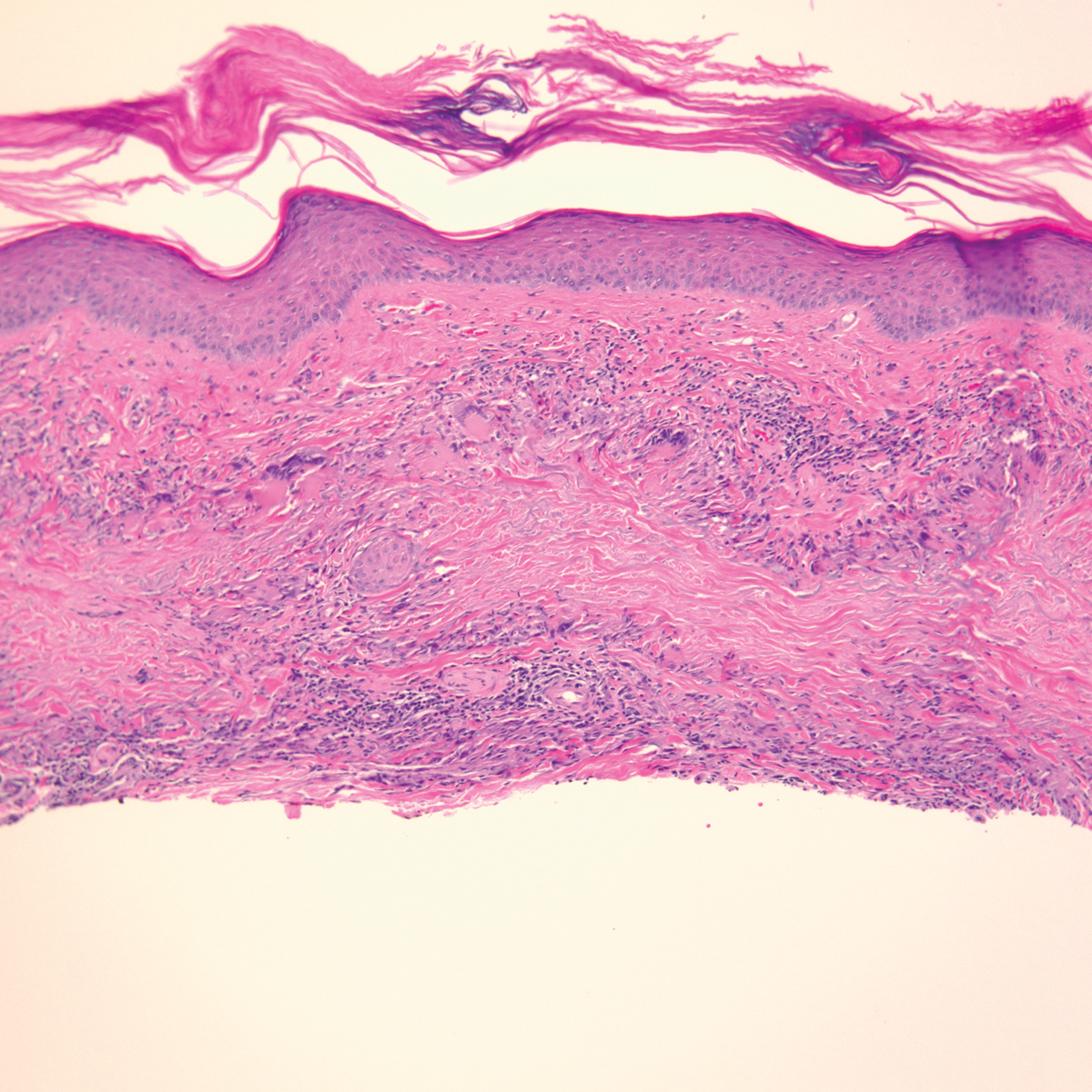

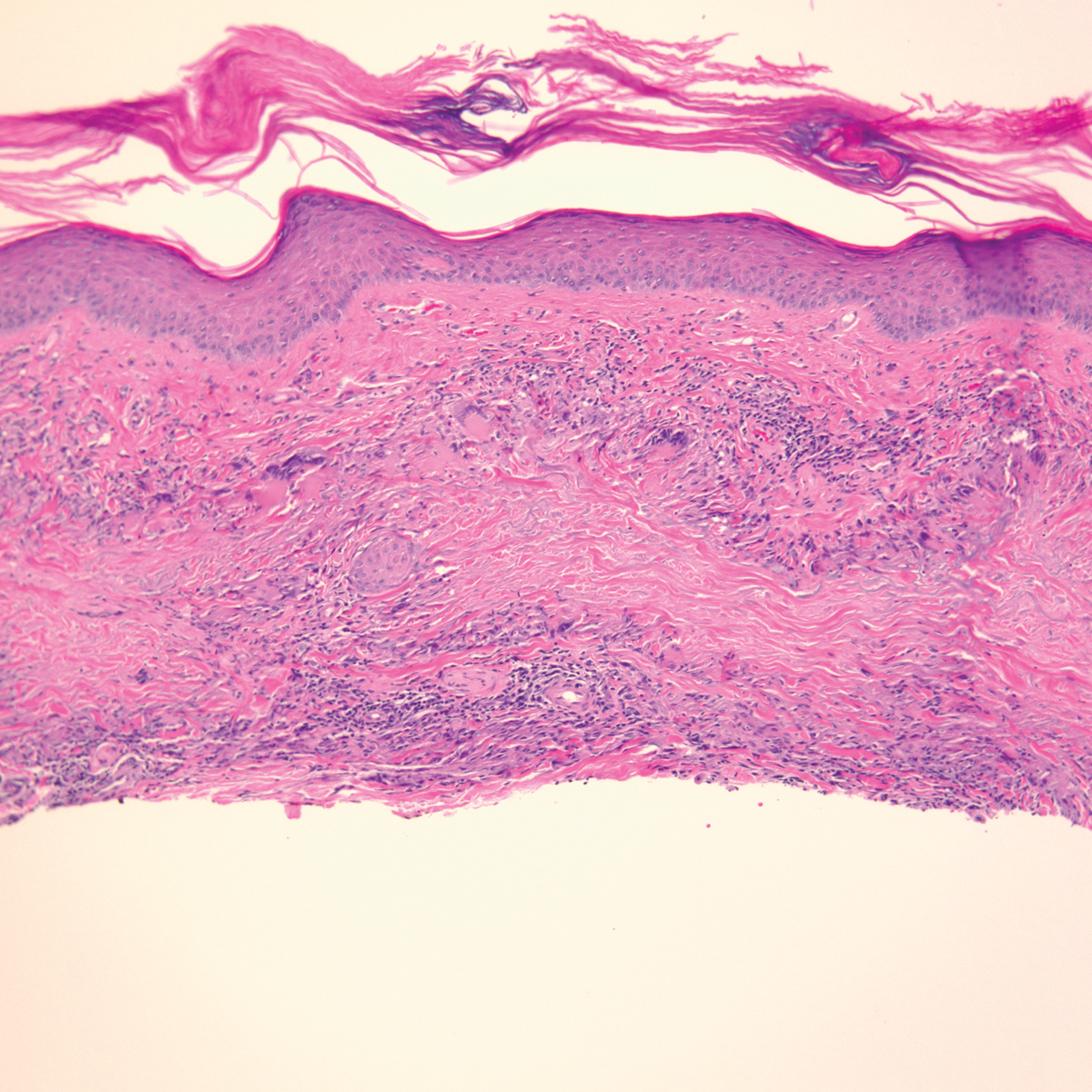

Atopic dermatitis

THE COMPARISON

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-of-pocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

1. McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2019.05.014

2. Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

3. Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

4. Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

THE COMPARISON

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-of-pocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

THE COMPARISON

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-of-pocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

1. McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2019.05.014

2. Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

3. Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

4. Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

1. McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2019.05.014

2. Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2018.10.029

3. Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

4. Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

Argyria From a Topical Home Remedy

To the Editor:

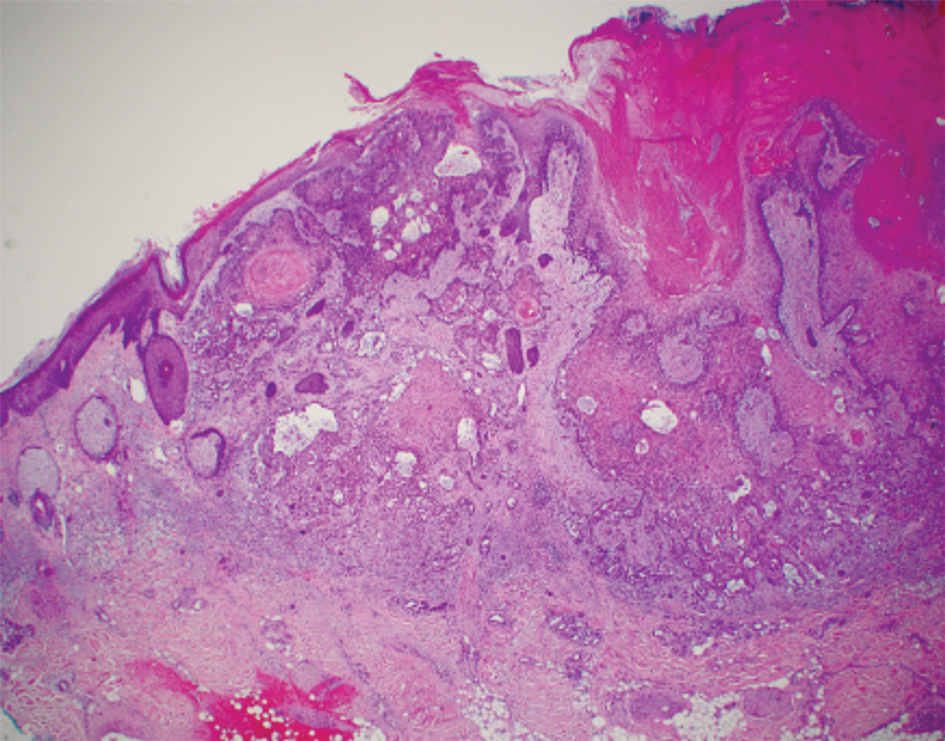

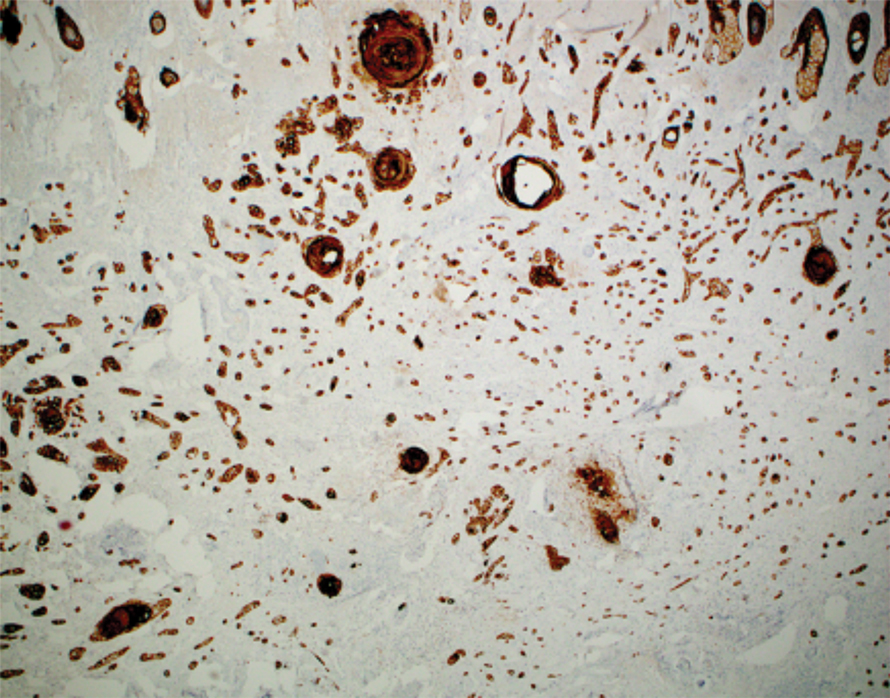

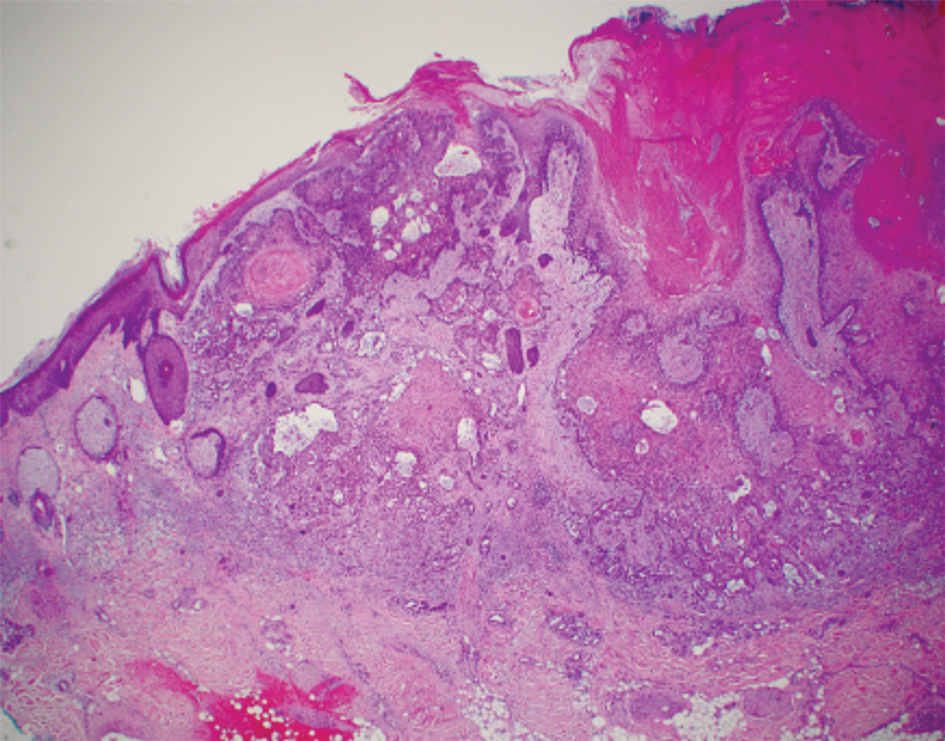

Argyria is a rare disease caused by chronic exposure to products with high silver content (eg, oral ingestion, inhalation, percutaneous absorption). With time, the blood levels of silver surpass the body’s renal and hepatic excretory capacities that lead to silver granules being deposited in the skin and internal organs, including the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.1 The cutaneous deposition results in a blue or blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Intervals of exposure that span from 8 months to 5 years prior to symptom onset have been described in the literature.2 The discoloration that results often is permanent, with no established way of effectively removing silver deposits from the tissue.3

A 22-year-old autistic man, who was completely dependent on his mother’s care, presented to the emergency department with a primary concern of abdominal pain. The mother reported that he was indicating abdominal pain by motioning to his stomach for the last 5 days. The mother also reported he did not have a bowel movement during this time, and she noticed his hands were shaking. Prior to presentation, the mother had given him 2 enemas and had him on a 3-day strict liquid fast consisting of water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, honey, and orange juice. Notably, the mother had a strong history of using naturopathic remedies for treatment of her son’s ailments.

On admission, the patient was stable. There was a 2-point decrease in the patient’s body mass index over the last month. Initial serum electrolytes were highly abnormal with a serum sodium level of 124 mEq/L (reference range, 135–145 mEq/L), blood urea nitrogen of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.77 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74–1.35 mg/dL), and lactic acid of 2.1 mEq/L (reference range, 0.5–1 mEq/L). Serum osmolality was 272 mOsm/kg (reference range, 275–295 mOsm/kg). Urine osmolality was 114 mOsm/kg (reference range, 500–850 mOsm/kg) with a low-normal urine sodium level of 41 mmol/24 hr (reference range, 40–220 mmol/24 hr). Abnormalities were felt to be secondary to malnutrition from the strict liquid diet (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio of 3:1 suggestive of notable protein calorie malnutrition). The patient was given 1 L of normal saline in the emergency department, with further fluids held so as not to increase serum sodium level too rapidly. A regular diet was started.

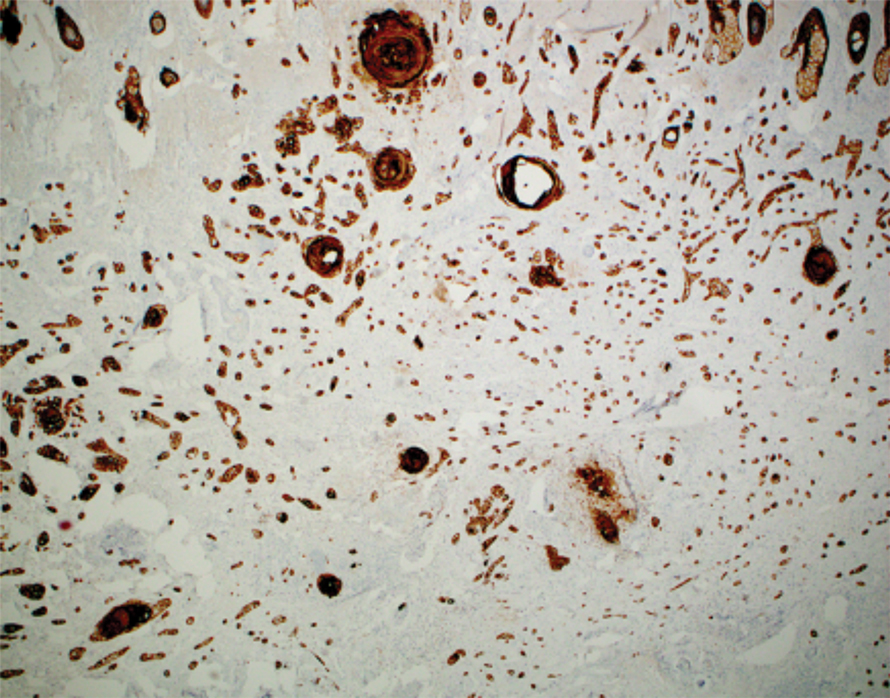

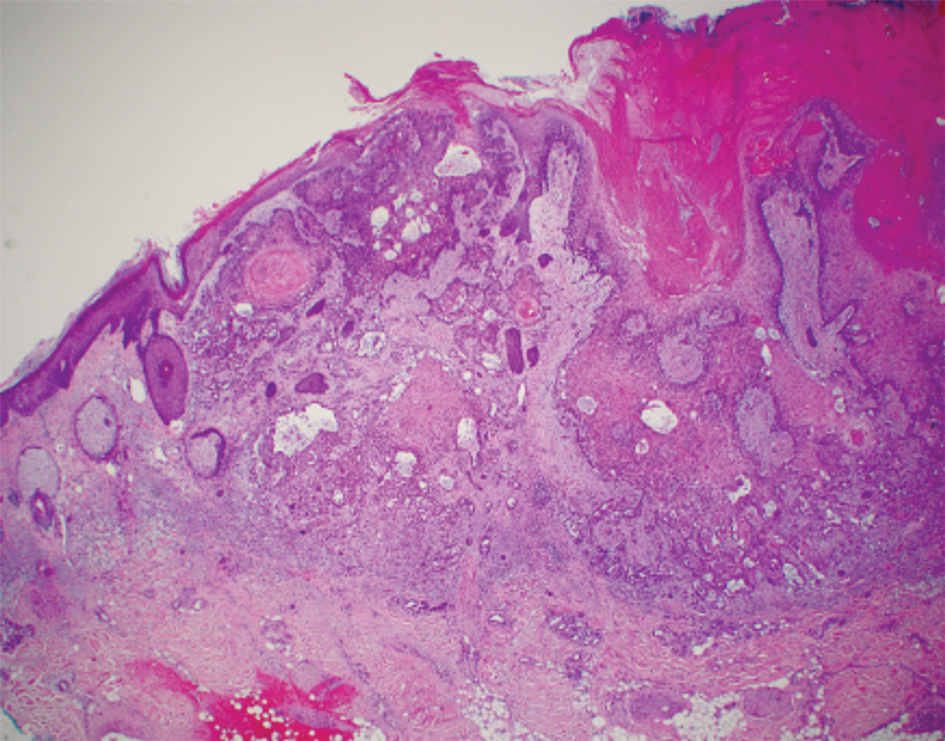

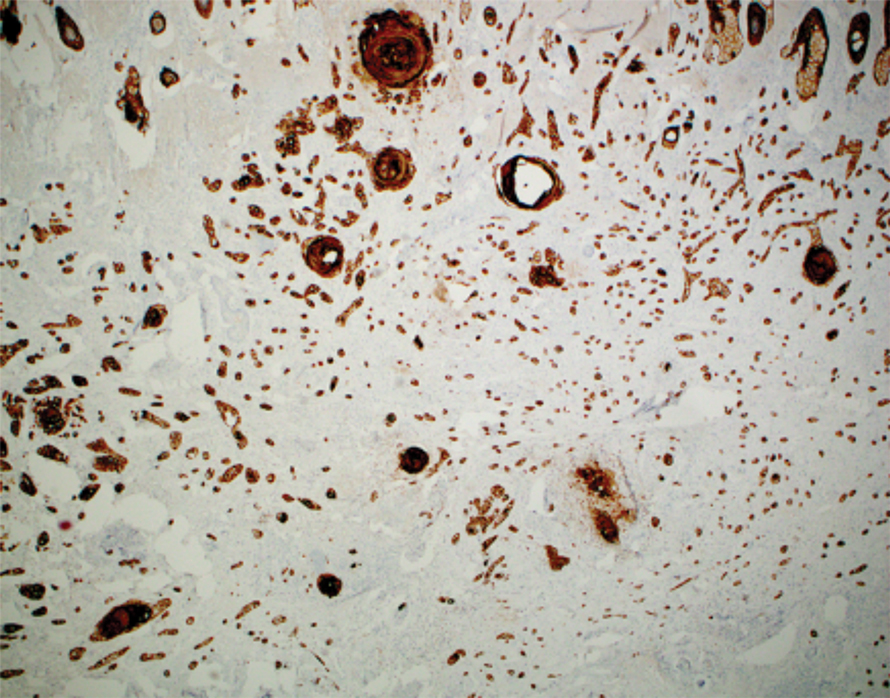

Physical examination revealed dry mucosal membranes but otherwise was unremarkable. Active bowel sounds were noted, as well as a soft, nontender, and nondistended abdomen; however, when examining the patient’s hands for reported shaking, a distinct abnormality of the nails was noticed. The patient had slate blue discoloration of the lunula, along with hyperpigmented violaceous discoloration of the proximal nail bed on all 10 fingernails (Figure 1). No abnormalities were seen on the toenails. The mother had a distinct bluish gray discoloration of the face as well as similar nail findings (Figure 2), strongly suggestive of colloidal silver use. An urgent serum silver level was ordered on the patient as well as a heavy metal panel. The mother was found applying numerous “natural remedies” to the patient’s skin while in the hospital, including a liquid spray and lotion, both in unmarked bottles. At that time, the mother was informed that no external supplements should be applied to her son. The serum silver level was elevated substantially at 94.3 ng/mL (reference range, <1.0 ng/mL). When the mother was confronted, she initially denied use of silver but later admitted to notable silver content in the cream she was applying to her son’s skin. The mother reported that she read online that colloidal silver had been historically used to cure numerous ailments and she was ordering products from an online company. She was counseled on the dangers of both topical application and ingestion of silver, and all supplements were removed from the home.

Argyria is a rare condition caused by chronic exposure to silver and is characterized by a blue-gray pigmentation in the skin and appendages, mucous membranes, and internal organs.4 Clinically, argyria is classified as generalized or localized. Generalized argyria results from ingestion or inhalation of silver compounds, where granules deposit preferentially in sun-exposed areas of skin as well as internal organs, with the highest concentration in the liver, spleen, and adrenal glands; discoloration often is permanent.5 On the contrary, localized argyria results from direct external contact with silver and granules deposited in the hands, eyes, and mucosa.5 Although the exact mechanism of penetration from topical silver remains unknown, it is thought to enter via the eccrine sweat ducts, as histopathology reveals silver granules found in highest concentration surrounding sweat glands in the dermis.6

Initial differential diagnoses for altered nail pigmentation include drug-induced causes, systemic diseases, cyanosis, and exposure to metals.7 The most commonly indicated medications resulting in blue nail pigment changes include antimalarials, minocycline, zidovudine, and phenothiazine. Systemic diseases that may cause blue nail color change include Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, Addison disease, methemoglobinemia, and alkaptonuria.7 Metals include gold, mercury, arsenic, bismuth, lead, and silver.4 After a thorough review of the patient’s medications and lack of support for any underlying disease process, contact with metals, particularly silver, was ranked highly on our differential list. In support of this theory, the mother’s bluish gray facial skin led to high clinical suspicion that she was ingesting colloidal silver and also was exposing her son to silver.

Treatment of argyria is challenging but first and foremost involves discontinuation of the source of chronic silver exposure. Unfortunately, the discoloration of generalized argyria often is permanent. Sunscreen can be used to help prevent any further darkening of pigment. The pigment in localized argyria has been reported to slowly fade with time, and there also have been reports of successful treatment using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.8

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Lencastre A, Lobo M, João A. Argyria—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:413-416.

- Park S-W, Kim J-H, Shin H-T, et al. An effective modality for argyria treatment: Q-switched 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:511-512.

- Molina-Hernandez AI, Diaz-Gonzalez JM, Saeb-Lima M, et al. Argyria after silver nitrate intake: case report and brief review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:520.

- Garcias-Ladaria J, Hernandez-Bel P, Torregrosa-Calatayud JL, et al. Localized cutaneous argyria: a report of 2 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:253-254.

- Kapur N, Landon G, Yu RC. Localized argyria in an antique restorer. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:191-192.

- Kubba A, Kubba R, Batrani M, Pal T. Argyria an unrecognized cause of cutaneous pigmentation in Indian patients: a case series and review of the literature. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:805-811.

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee HK, et al. Successful treatment of argyria using a low-fluence Q-switched 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:751-753.

To the Editor:

Argyria is a rare disease caused by chronic exposure to products with high silver content (eg, oral ingestion, inhalation, percutaneous absorption). With time, the blood levels of silver surpass the body’s renal and hepatic excretory capacities that lead to silver granules being deposited in the skin and internal organs, including the liver, spleen, adrenal glands, and bone marrow.1 The cutaneous deposition results in a blue or blue-gray pigmentation of the skin, mucous membranes, and nails. Intervals of exposure that span from 8 months to 5 years prior to symptom onset have been described in the literature.2 The discoloration that results often is permanent, with no established way of effectively removing silver deposits from the tissue.3

A 22-year-old autistic man, who was completely dependent on his mother’s care, presented to the emergency department with a primary concern of abdominal pain. The mother reported that he was indicating abdominal pain by motioning to his stomach for the last 5 days. The mother also reported he did not have a bowel movement during this time, and she noticed his hands were shaking. Prior to presentation, the mother had given him 2 enemas and had him on a 3-day strict liquid fast consisting of water, lemon juice, cayenne pepper, honey, and orange juice. Notably, the mother had a strong history of using naturopathic remedies for treatment of her son’s ailments.

On admission, the patient was stable. There was a 2-point decrease in the patient’s body mass index over the last month. Initial serum electrolytes were highly abnormal with a serum sodium level of 124 mEq/L (reference range, 135–145 mEq/L), blood urea nitrogen of 3 mg/dL (reference range, 7–20 mg/dL), creatinine of 0.77 mg/dL (reference range, 0.74–1.35 mg/dL), and lactic acid of 2.1 mEq/L (reference range, 0.5–1 mEq/L). Serum osmolality was 272 mOsm/kg (reference range, 275–295 mOsm/kg). Urine osmolality was 114 mOsm/kg (reference range, 500–850 mOsm/kg) with a low-normal urine sodium level of 41 mmol/24 hr (reference range, 40–220 mmol/24 hr). Abnormalities were felt to be secondary to malnutrition from the strict liquid diet (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine ratio of 3:1 suggestive of notable protein calorie malnutrition). The patient was given 1 L of normal saline in the emergency department, with further fluids held so as not to increase serum sodium level too rapidly. A regular diet was started.