User login

COVID-19 tied to spike in suspected suicide attempts by girls

Suspected suicide attempts by teenage girls have increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data released today by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among children and adolescents aged 12-17 years, the average weekly number of emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts was 22.3% higher during summer 2020 and 39.1% higher during winter 2021 than during the corresponding periods in 2019.

The increase was most evident among young girls.

Between Feb. 21 and March 20, 2021, the number of ED visits for suspected suicide attempts was about 51% higher among girls aged 12-17 years than during the same period in 2019. Among boys aged 12-17 years, ED visits for suspected suicide attempts increased 4%, the CDC reports.

“Young persons might represent a group at high risk because they might have been particularly affected by mitigation measures, such as physical distancing (including a lack of connectedness to schools, teachers, and peers); barriers to mental health treatment; increases in substance use; and anxiety about family health and economic problems, which are all risk factors for suicide,” write the authors, led by Ellen Yard, PhD, with the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

In addition, the findings from this study suggest there has been “more severe distress among young females than has been identified in previous reports during the pandemic, reinforcing the need for increased attention to, and prevention for, this population,” they point out.

The results were published June 11 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The findings are based on data for ED visits for suspected suicide from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, which includes about 71% of the nation’s EDs in 49 states (all except Hawaii) and the District of Columbia.

Earlier data reported by the CDC showed that the proportion of mental health–related ED visits among children and adolescents aged 12-17 years increased by 31% during 2020, compared with 2019.

‘Time for action is now’

These new findings underscore the “enormous impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on our country’s overall emotional wellbeing, especially among young people,” the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (Action Alliance) Media Messaging Work Group said in a statement responding to the newly released data.

“Just as we have taken steps to protect our physical health throughout the pandemic, we must also take steps to protect our mental and emotional health,” the group says.

The data, the group says, specifically speak to the importance of improving suicide care both during and after ED visits by scaling up the adoption of best practices, such as the Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe and Best Practices in Care Transitions for Individuals with Suicide Risk: Inpatient Care to Outpatient Care.

“These and other evidence-based best practices must be adopted by health care systems nationwide to ensure safe, effective suicide care for all,” the group says.

“However, health care systems cannot address this issue alone. Suicide is a complex public health issue that also requires a comprehensive, community-based approach to addressing it. We must ensure suicide prevention is infused into a variety of community-based settings – such as schools, workplaces, and places of worship – to ensure people are connected with prevention activities and resources before a crisis occurs,” the group says.

It also highlights the crucial role of social connectedness as a protective factor against suicide.

“Research indicates that a sense of belonging and social connectedness improves physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Everyone can play a role in being there for each other and helping to build resiliency. Having real, honest conversations about our own mental health opens the door for connection and social support,” the group says.

It calls on leaders from all sectors and industries to make suicide prevention “a national priority by becoming engaged in the issue and bringing resources to bear. The time for action is now.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Suspected suicide attempts by teenage girls have increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data released today by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among children and adolescents aged 12-17 years, the average weekly number of emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts was 22.3% higher during summer 2020 and 39.1% higher during winter 2021 than during the corresponding periods in 2019.

The increase was most evident among young girls.

Between Feb. 21 and March 20, 2021, the number of ED visits for suspected suicide attempts was about 51% higher among girls aged 12-17 years than during the same period in 2019. Among boys aged 12-17 years, ED visits for suspected suicide attempts increased 4%, the CDC reports.

“Young persons might represent a group at high risk because they might have been particularly affected by mitigation measures, such as physical distancing (including a lack of connectedness to schools, teachers, and peers); barriers to mental health treatment; increases in substance use; and anxiety about family health and economic problems, which are all risk factors for suicide,” write the authors, led by Ellen Yard, PhD, with the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

In addition, the findings from this study suggest there has been “more severe distress among young females than has been identified in previous reports during the pandemic, reinforcing the need for increased attention to, and prevention for, this population,” they point out.

The results were published June 11 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The findings are based on data for ED visits for suspected suicide from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, which includes about 71% of the nation’s EDs in 49 states (all except Hawaii) and the District of Columbia.

Earlier data reported by the CDC showed that the proportion of mental health–related ED visits among children and adolescents aged 12-17 years increased by 31% during 2020, compared with 2019.

‘Time for action is now’

These new findings underscore the “enormous impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on our country’s overall emotional wellbeing, especially among young people,” the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (Action Alliance) Media Messaging Work Group said in a statement responding to the newly released data.

“Just as we have taken steps to protect our physical health throughout the pandemic, we must also take steps to protect our mental and emotional health,” the group says.

The data, the group says, specifically speak to the importance of improving suicide care both during and after ED visits by scaling up the adoption of best practices, such as the Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe and Best Practices in Care Transitions for Individuals with Suicide Risk: Inpatient Care to Outpatient Care.

“These and other evidence-based best practices must be adopted by health care systems nationwide to ensure safe, effective suicide care for all,” the group says.

“However, health care systems cannot address this issue alone. Suicide is a complex public health issue that also requires a comprehensive, community-based approach to addressing it. We must ensure suicide prevention is infused into a variety of community-based settings – such as schools, workplaces, and places of worship – to ensure people are connected with prevention activities and resources before a crisis occurs,” the group says.

It also highlights the crucial role of social connectedness as a protective factor against suicide.

“Research indicates that a sense of belonging and social connectedness improves physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Everyone can play a role in being there for each other and helping to build resiliency. Having real, honest conversations about our own mental health opens the door for connection and social support,” the group says.

It calls on leaders from all sectors and industries to make suicide prevention “a national priority by becoming engaged in the issue and bringing resources to bear. The time for action is now.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Suspected suicide attempts by teenage girls have increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data released today by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Among children and adolescents aged 12-17 years, the average weekly number of emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts was 22.3% higher during summer 2020 and 39.1% higher during winter 2021 than during the corresponding periods in 2019.

The increase was most evident among young girls.

Between Feb. 21 and March 20, 2021, the number of ED visits for suspected suicide attempts was about 51% higher among girls aged 12-17 years than during the same period in 2019. Among boys aged 12-17 years, ED visits for suspected suicide attempts increased 4%, the CDC reports.

“Young persons might represent a group at high risk because they might have been particularly affected by mitigation measures, such as physical distancing (including a lack of connectedness to schools, teachers, and peers); barriers to mental health treatment; increases in substance use; and anxiety about family health and economic problems, which are all risk factors for suicide,” write the authors, led by Ellen Yard, PhD, with the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

In addition, the findings from this study suggest there has been “more severe distress among young females than has been identified in previous reports during the pandemic, reinforcing the need for increased attention to, and prevention for, this population,” they point out.

The results were published June 11 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The findings are based on data for ED visits for suspected suicide from the National Syndromic Surveillance Program, which includes about 71% of the nation’s EDs in 49 states (all except Hawaii) and the District of Columbia.

Earlier data reported by the CDC showed that the proportion of mental health–related ED visits among children and adolescents aged 12-17 years increased by 31% during 2020, compared with 2019.

‘Time for action is now’

These new findings underscore the “enormous impact the COVID-19 pandemic is having on our country’s overall emotional wellbeing, especially among young people,” the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention (Action Alliance) Media Messaging Work Group said in a statement responding to the newly released data.

“Just as we have taken steps to protect our physical health throughout the pandemic, we must also take steps to protect our mental and emotional health,” the group says.

The data, the group says, specifically speak to the importance of improving suicide care both during and after ED visits by scaling up the adoption of best practices, such as the Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe and Best Practices in Care Transitions for Individuals with Suicide Risk: Inpatient Care to Outpatient Care.

“These and other evidence-based best practices must be adopted by health care systems nationwide to ensure safe, effective suicide care for all,” the group says.

“However, health care systems cannot address this issue alone. Suicide is a complex public health issue that also requires a comprehensive, community-based approach to addressing it. We must ensure suicide prevention is infused into a variety of community-based settings – such as schools, workplaces, and places of worship – to ensure people are connected with prevention activities and resources before a crisis occurs,” the group says.

It also highlights the crucial role of social connectedness as a protective factor against suicide.

“Research indicates that a sense of belonging and social connectedness improves physical, mental, and emotional wellbeing. Everyone can play a role in being there for each other and helping to build resiliency. Having real, honest conversations about our own mental health opens the door for connection and social support,” the group says.

It calls on leaders from all sectors and industries to make suicide prevention “a national priority by becoming engaged in the issue and bringing resources to bear. The time for action is now.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Remove sex designation from public part of birth certificates, AMA advises

Requiring the designation can lead to discrimination and unnecessary burden on individuals whose current gender identity does not align with their designation at birth when they register for school or sports, adopt, get married, or request personal records.

A person’s sex designation at birth would still be submitted to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Live Birth for medical, public health, and statistical use only, report authors note.

Willie Underwood III, MD, MSc, author of Board Report 15, explained in reference committee testimony that a standard certificate of live birth is critical for uniformly collecting and processing data, but birth certificates are issued by the government to individuals.

Ten states allow gender-neutral designation

According to the report, 48 states (Tennessee and Ohio are the exceptions) and the District of Columbia allow people to amend their sex designation on their birth certificate to reflect their gender identities, but only 10 states allow for a gender-neutral designation, usually “X,” on birth certificates. The U.S. Department of State does not currently offer an option for a gender-neutral designation on U.S. passports.

“Assigning sex using binary variables in the public portion of the birth certificate fails to recognize the medical spectrum of gender identity,” Dr. Underwood said, and it can be used to discriminate.

Jeremy Toler, MD, a delegate from GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality, testified that there is precedent for information to be removed from the public portion of the birth certificates. And much data is collected for each live birth that doesn’t show up on individuals’ birth certificates, he noted.

Dr. Toler said transgender, gender nonbinary, and individuals with differences in sex development can be placed at a disadvantage by the sex label on the birth certificate.

“We unfortunately still live in a world where it is unsafe in many cases for one’s gender to vary from the sex assigned at birth,” Dr. Toler said.

Not having this data on the widely used form will reduce unnecessary reliance on sex as a stand-in for gender, he said, and would “serve as an equalizer” since policies differ by state.

Robert Jackson, MD, an alternate delegate from the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, spoke against the measure.

“We as physicians need to report things accurately,” Dr. Jackson said. “All through medical school, residency, and specialty training we were supposed to delegate all of the physical findings of the patient we’re taking care of. I think when the child is born, they do have physical characteristics either male or female, and I think that probably should be on the public record. That’s just my personal opinion.”

Sarah Mae Smith, MD, delegate from California, speaking on behalf of the Women Physicians Section, said removing the sex designation is important for moving toward gender equity.

“We need to recognize [that] gender is not a binary but a spectrum,” she said. “Obligating our patients to jump through numerous administrative hoops to identify as who they are based on a sex assigned at birth primarily on genitalia is not only unnecessary but actively deleterious to their health.”

Race was once public on birth certificates

She noted that the report mentions that previously, information on the race of a person’s parents was included on the public portion of the birth certificate and that information was recognized to facilitate discrimination.

“Thankfully, a change was made to obviate at least that avenue for discriminatory practices,” she said. “Now, likewise, the information on sex assigned at birth is being used to undermine the rights of our transgender, intersex, and nonbinary patients.”

Arlene Seid, MD, MPH, an alternate delegate from the American Association of Public Health Physicians, said the resolution protects the aggregate data “without the discrimination associated with the individual data.”

Sex no longer has a role to play in the jobs people do, she noted, and the designation shouldn’t have to be evaluated for something like a job interview.

“Our society doesn’t need it on an individual basis for most of what occurs in public life,” Dr. Seid said.

Dr. Underwood, Dr. Toler, Dr. Jackson, Dr. Smith, and Dr. Seid declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Requiring the designation can lead to discrimination and unnecessary burden on individuals whose current gender identity does not align with their designation at birth when they register for school or sports, adopt, get married, or request personal records.

A person’s sex designation at birth would still be submitted to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Live Birth for medical, public health, and statistical use only, report authors note.

Willie Underwood III, MD, MSc, author of Board Report 15, explained in reference committee testimony that a standard certificate of live birth is critical for uniformly collecting and processing data, but birth certificates are issued by the government to individuals.

Ten states allow gender-neutral designation

According to the report, 48 states (Tennessee and Ohio are the exceptions) and the District of Columbia allow people to amend their sex designation on their birth certificate to reflect their gender identities, but only 10 states allow for a gender-neutral designation, usually “X,” on birth certificates. The U.S. Department of State does not currently offer an option for a gender-neutral designation on U.S. passports.

“Assigning sex using binary variables in the public portion of the birth certificate fails to recognize the medical spectrum of gender identity,” Dr. Underwood said, and it can be used to discriminate.

Jeremy Toler, MD, a delegate from GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality, testified that there is precedent for information to be removed from the public portion of the birth certificates. And much data is collected for each live birth that doesn’t show up on individuals’ birth certificates, he noted.

Dr. Toler said transgender, gender nonbinary, and individuals with differences in sex development can be placed at a disadvantage by the sex label on the birth certificate.

“We unfortunately still live in a world where it is unsafe in many cases for one’s gender to vary from the sex assigned at birth,” Dr. Toler said.

Not having this data on the widely used form will reduce unnecessary reliance on sex as a stand-in for gender, he said, and would “serve as an equalizer” since policies differ by state.

Robert Jackson, MD, an alternate delegate from the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, spoke against the measure.

“We as physicians need to report things accurately,” Dr. Jackson said. “All through medical school, residency, and specialty training we were supposed to delegate all of the physical findings of the patient we’re taking care of. I think when the child is born, they do have physical characteristics either male or female, and I think that probably should be on the public record. That’s just my personal opinion.”

Sarah Mae Smith, MD, delegate from California, speaking on behalf of the Women Physicians Section, said removing the sex designation is important for moving toward gender equity.

“We need to recognize [that] gender is not a binary but a spectrum,” she said. “Obligating our patients to jump through numerous administrative hoops to identify as who they are based on a sex assigned at birth primarily on genitalia is not only unnecessary but actively deleterious to their health.”

Race was once public on birth certificates

She noted that the report mentions that previously, information on the race of a person’s parents was included on the public portion of the birth certificate and that information was recognized to facilitate discrimination.

“Thankfully, a change was made to obviate at least that avenue for discriminatory practices,” she said. “Now, likewise, the information on sex assigned at birth is being used to undermine the rights of our transgender, intersex, and nonbinary patients.”

Arlene Seid, MD, MPH, an alternate delegate from the American Association of Public Health Physicians, said the resolution protects the aggregate data “without the discrimination associated with the individual data.”

Sex no longer has a role to play in the jobs people do, she noted, and the designation shouldn’t have to be evaluated for something like a job interview.

“Our society doesn’t need it on an individual basis for most of what occurs in public life,” Dr. Seid said.

Dr. Underwood, Dr. Toler, Dr. Jackson, Dr. Smith, and Dr. Seid declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Requiring the designation can lead to discrimination and unnecessary burden on individuals whose current gender identity does not align with their designation at birth when they register for school or sports, adopt, get married, or request personal records.

A person’s sex designation at birth would still be submitted to the U.S. Standard Certificate of Live Birth for medical, public health, and statistical use only, report authors note.

Willie Underwood III, MD, MSc, author of Board Report 15, explained in reference committee testimony that a standard certificate of live birth is critical for uniformly collecting and processing data, but birth certificates are issued by the government to individuals.

Ten states allow gender-neutral designation

According to the report, 48 states (Tennessee and Ohio are the exceptions) and the District of Columbia allow people to amend their sex designation on their birth certificate to reflect their gender identities, but only 10 states allow for a gender-neutral designation, usually “X,” on birth certificates. The U.S. Department of State does not currently offer an option for a gender-neutral designation on U.S. passports.

“Assigning sex using binary variables in the public portion of the birth certificate fails to recognize the medical spectrum of gender identity,” Dr. Underwood said, and it can be used to discriminate.

Jeremy Toler, MD, a delegate from GLMA: Health Professionals Advancing LGBTQ Equality, testified that there is precedent for information to be removed from the public portion of the birth certificates. And much data is collected for each live birth that doesn’t show up on individuals’ birth certificates, he noted.

Dr. Toler said transgender, gender nonbinary, and individuals with differences in sex development can be placed at a disadvantage by the sex label on the birth certificate.

“We unfortunately still live in a world where it is unsafe in many cases for one’s gender to vary from the sex assigned at birth,” Dr. Toler said.

Not having this data on the widely used form will reduce unnecessary reliance on sex as a stand-in for gender, he said, and would “serve as an equalizer” since policies differ by state.

Robert Jackson, MD, an alternate delegate from the American Academy of Cosmetic Surgery, spoke against the measure.

“We as physicians need to report things accurately,” Dr. Jackson said. “All through medical school, residency, and specialty training we were supposed to delegate all of the physical findings of the patient we’re taking care of. I think when the child is born, they do have physical characteristics either male or female, and I think that probably should be on the public record. That’s just my personal opinion.”

Sarah Mae Smith, MD, delegate from California, speaking on behalf of the Women Physicians Section, said removing the sex designation is important for moving toward gender equity.

“We need to recognize [that] gender is not a binary but a spectrum,” she said. “Obligating our patients to jump through numerous administrative hoops to identify as who they are based on a sex assigned at birth primarily on genitalia is not only unnecessary but actively deleterious to their health.”

Race was once public on birth certificates

She noted that the report mentions that previously, information on the race of a person’s parents was included on the public portion of the birth certificate and that information was recognized to facilitate discrimination.

“Thankfully, a change was made to obviate at least that avenue for discriminatory practices,” she said. “Now, likewise, the information on sex assigned at birth is being used to undermine the rights of our transgender, intersex, and nonbinary patients.”

Arlene Seid, MD, MPH, an alternate delegate from the American Association of Public Health Physicians, said the resolution protects the aggregate data “without the discrimination associated with the individual data.”

Sex no longer has a role to play in the jobs people do, she noted, and the designation shouldn’t have to be evaluated for something like a job interview.

“Our society doesn’t need it on an individual basis for most of what occurs in public life,” Dr. Seid said.

Dr. Underwood, Dr. Toler, Dr. Jackson, Dr. Smith, and Dr. Seid declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

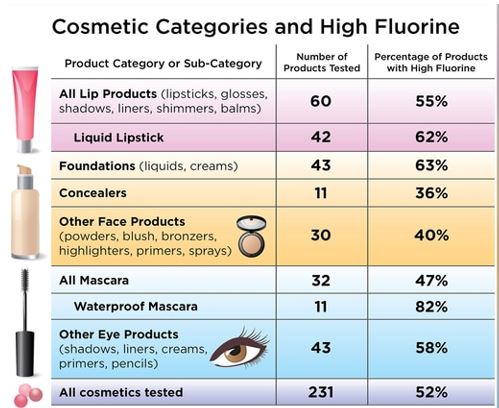

Toxic chemicals found in many cosmetics

People may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic chemicals from their cosmetic products, a new study suggests.

– per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Many of these chemicals were not included on the product labels, making it difficult for consumers to consciously avoid them.

“This study is very helpful for elucidating the PFAS content of different types of cosmetics in the U.S. and Canadian markets,” said Elsie Sunderland, PhD, an environmental scientist who was not involved with the study.

“Previously, all the data had been collected in Europe, and this study shows we are dealing with similar problems in the North American marketplace,” said Dr. Sunderland, a professor of environmental chemistry at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

PFAS are a class of chemicals used in a variety of consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and water-repellent clothing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are added to cosmetics to make the products more durable and spreadable, researchers said in the study.

“[PFAS] are added to change the properties of surfaces, to make them nonstick or resistant to stay in water or oils,” said study coauthor Tom Bruton, PhD, senior scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in Berkeley, Calif. “The concerning thing about cosmetics is that these are products that you’re applying to your skin and face every day, so there’s the skin absorption route that’s of concern, but also incidental ingestion of cosmetics is also a concern as well.”

The CDC says some of the potential health effects of PFAS exposure includes increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, changes in liver enzymes, decreased vaccine response in children, and a higher risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women.

“PFAS are a large class of chemicals. In humans, exposure to some of these chemicals has been associated with impaired immune function, certain cancers, increased risks of diabetes, obesity and endocrine disruption,” Dr. Sunderland said. “They appear to be harmful to every major organ system in the human body.”

For the current study, published online in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Dr. Bruton and colleagues purchased 231 cosmetic products in the United States and Canada from retailers such as Ulta Beauty, Sephora, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond. They then screened them for fluorine.Three-quarters of waterproof mascara samples contained high fluorine concentrations, as did nearly two-thirds of foundations and liquid lipsticks, and more than half of the eye and lip products tested.

The authors found that different categories of makeup tended to have higher or lower fluorine concentrations. “High fluorine levels were found in products commonly advertised as ‘wear-resistant’ to water and oils or ‘long-lasting,’ including foundations, liquid lipsticks, and waterproof mascaras,” Dr. Bruton and colleagues wrote.

When they further analyzed a subset of 29 products to determine what types of chemicals were present, they found that each cosmetic product contained at least 4 PFAS, with one product containing 13.The PFAS substances found included some that break down into other chemicals that are known to be highly toxic and environmentally harmful.

“It’s concerning that some of the products we tested appear to be intentionally using PFAS, but not listing those ingredients on the label,” Dr. Bruton said. “I do think that it is helpful for consumers to read labels, but beyond that, there’s not a lot of ways that consumers themselves can solve this problem. ... We think that the industry needs to be more proactive about moving away from this group of chemicals.”

Dr. Sunderland said a resource people can use when trying to avoid PFAS is the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that maintains an extensive database of cosmetics and personal care products.

“At this point, there is very little regulatory activity related to PFAS in cosmetics,” Dr. Sunderland said. “The best thing to happen now would be for consumers to indicate that they prefer products without PFAS and to demand better transparency in product ingredient lists.”

A similar study done in 2018 by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency found high levels of PFAS in nearly one-third of the cosmetics products it tested.

People can also be exposed to PFAS by eating or drinking contaminated food or water and through food packaging. Dr. Sunderland said some wild foods like seafood are known to accumulate these compounds in the environment.

“There are examples of contaminated biosolids leading to accumulation of PFAS in vegetables and milk,” Dr. Sunderland explained. “Food packaging is another concern because it can also result in PFAS accumulation in the foods we eat.”

Although it’s difficult to avoid PFAS altogether, the CDC suggests lowering exposure rates by avoiding contaminated water and food. If you’re not sure if your water is contaminated, you should ask your local or state health and environmental quality departments for fish or water advisories in your area.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

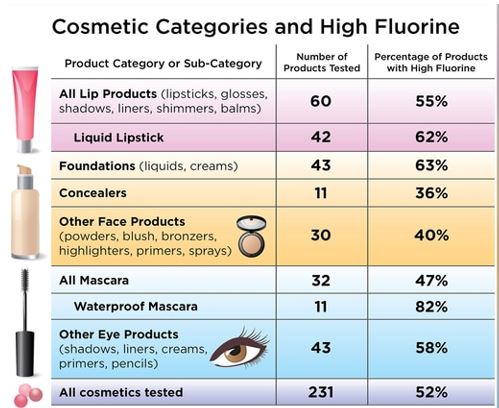

People may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic chemicals from their cosmetic products, a new study suggests.

– per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Many of these chemicals were not included on the product labels, making it difficult for consumers to consciously avoid them.

“This study is very helpful for elucidating the PFAS content of different types of cosmetics in the U.S. and Canadian markets,” said Elsie Sunderland, PhD, an environmental scientist who was not involved with the study.

“Previously, all the data had been collected in Europe, and this study shows we are dealing with similar problems in the North American marketplace,” said Dr. Sunderland, a professor of environmental chemistry at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

PFAS are a class of chemicals used in a variety of consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and water-repellent clothing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are added to cosmetics to make the products more durable and spreadable, researchers said in the study.

“[PFAS] are added to change the properties of surfaces, to make them nonstick or resistant to stay in water or oils,” said study coauthor Tom Bruton, PhD, senior scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in Berkeley, Calif. “The concerning thing about cosmetics is that these are products that you’re applying to your skin and face every day, so there’s the skin absorption route that’s of concern, but also incidental ingestion of cosmetics is also a concern as well.”

The CDC says some of the potential health effects of PFAS exposure includes increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, changes in liver enzymes, decreased vaccine response in children, and a higher risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women.

“PFAS are a large class of chemicals. In humans, exposure to some of these chemicals has been associated with impaired immune function, certain cancers, increased risks of diabetes, obesity and endocrine disruption,” Dr. Sunderland said. “They appear to be harmful to every major organ system in the human body.”

For the current study, published online in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Dr. Bruton and colleagues purchased 231 cosmetic products in the United States and Canada from retailers such as Ulta Beauty, Sephora, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond. They then screened them for fluorine.Three-quarters of waterproof mascara samples contained high fluorine concentrations, as did nearly two-thirds of foundations and liquid lipsticks, and more than half of the eye and lip products tested.

The authors found that different categories of makeup tended to have higher or lower fluorine concentrations. “High fluorine levels were found in products commonly advertised as ‘wear-resistant’ to water and oils or ‘long-lasting,’ including foundations, liquid lipsticks, and waterproof mascaras,” Dr. Bruton and colleagues wrote.

When they further analyzed a subset of 29 products to determine what types of chemicals were present, they found that each cosmetic product contained at least 4 PFAS, with one product containing 13.The PFAS substances found included some that break down into other chemicals that are known to be highly toxic and environmentally harmful.

“It’s concerning that some of the products we tested appear to be intentionally using PFAS, but not listing those ingredients on the label,” Dr. Bruton said. “I do think that it is helpful for consumers to read labels, but beyond that, there’s not a lot of ways that consumers themselves can solve this problem. ... We think that the industry needs to be more proactive about moving away from this group of chemicals.”

Dr. Sunderland said a resource people can use when trying to avoid PFAS is the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that maintains an extensive database of cosmetics and personal care products.

“At this point, there is very little regulatory activity related to PFAS in cosmetics,” Dr. Sunderland said. “The best thing to happen now would be for consumers to indicate that they prefer products without PFAS and to demand better transparency in product ingredient lists.”

A similar study done in 2018 by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency found high levels of PFAS in nearly one-third of the cosmetics products it tested.

People can also be exposed to PFAS by eating or drinking contaminated food or water and through food packaging. Dr. Sunderland said some wild foods like seafood are known to accumulate these compounds in the environment.

“There are examples of contaminated biosolids leading to accumulation of PFAS in vegetables and milk,” Dr. Sunderland explained. “Food packaging is another concern because it can also result in PFAS accumulation in the foods we eat.”

Although it’s difficult to avoid PFAS altogether, the CDC suggests lowering exposure rates by avoiding contaminated water and food. If you’re not sure if your water is contaminated, you should ask your local or state health and environmental quality departments for fish or water advisories in your area.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

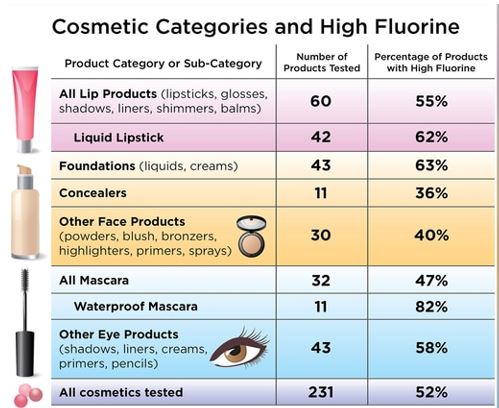

People may be absorbing and ingesting potentially toxic chemicals from their cosmetic products, a new study suggests.

– per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Many of these chemicals were not included on the product labels, making it difficult for consumers to consciously avoid them.

“This study is very helpful for elucidating the PFAS content of different types of cosmetics in the U.S. and Canadian markets,” said Elsie Sunderland, PhD, an environmental scientist who was not involved with the study.

“Previously, all the data had been collected in Europe, and this study shows we are dealing with similar problems in the North American marketplace,” said Dr. Sunderland, a professor of environmental chemistry at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston.

PFAS are a class of chemicals used in a variety of consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, stain-resistant carpeting, and water-repellent clothing, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are added to cosmetics to make the products more durable and spreadable, researchers said in the study.

“[PFAS] are added to change the properties of surfaces, to make them nonstick or resistant to stay in water or oils,” said study coauthor Tom Bruton, PhD, senior scientist at the Green Science Policy Institute in Berkeley, Calif. “The concerning thing about cosmetics is that these are products that you’re applying to your skin and face every day, so there’s the skin absorption route that’s of concern, but also incidental ingestion of cosmetics is also a concern as well.”

The CDC says some of the potential health effects of PFAS exposure includes increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, changes in liver enzymes, decreased vaccine response in children, and a higher risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia in pregnant women.

“PFAS are a large class of chemicals. In humans, exposure to some of these chemicals has been associated with impaired immune function, certain cancers, increased risks of diabetes, obesity and endocrine disruption,” Dr. Sunderland said. “They appear to be harmful to every major organ system in the human body.”

For the current study, published online in Environmental Science & Technology Letters, Dr. Bruton and colleagues purchased 231 cosmetic products in the United States and Canada from retailers such as Ulta Beauty, Sephora, Target, and Bed Bath & Beyond. They then screened them for fluorine.Three-quarters of waterproof mascara samples contained high fluorine concentrations, as did nearly two-thirds of foundations and liquid lipsticks, and more than half of the eye and lip products tested.

The authors found that different categories of makeup tended to have higher or lower fluorine concentrations. “High fluorine levels were found in products commonly advertised as ‘wear-resistant’ to water and oils or ‘long-lasting,’ including foundations, liquid lipsticks, and waterproof mascaras,” Dr. Bruton and colleagues wrote.

When they further analyzed a subset of 29 products to determine what types of chemicals were present, they found that each cosmetic product contained at least 4 PFAS, with one product containing 13.The PFAS substances found included some that break down into other chemicals that are known to be highly toxic and environmentally harmful.

“It’s concerning that some of the products we tested appear to be intentionally using PFAS, but not listing those ingredients on the label,” Dr. Bruton said. “I do think that it is helpful for consumers to read labels, but beyond that, there’s not a lot of ways that consumers themselves can solve this problem. ... We think that the industry needs to be more proactive about moving away from this group of chemicals.”

Dr. Sunderland said a resource people can use when trying to avoid PFAS is the Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit organization that maintains an extensive database of cosmetics and personal care products.

“At this point, there is very little regulatory activity related to PFAS in cosmetics,” Dr. Sunderland said. “The best thing to happen now would be for consumers to indicate that they prefer products without PFAS and to demand better transparency in product ingredient lists.”

A similar study done in 2018 by the Danish Environmental Protection Agency found high levels of PFAS in nearly one-third of the cosmetics products it tested.

People can also be exposed to PFAS by eating or drinking contaminated food or water and through food packaging. Dr. Sunderland said some wild foods like seafood are known to accumulate these compounds in the environment.

“There are examples of contaminated biosolids leading to accumulation of PFAS in vegetables and milk,” Dr. Sunderland explained. “Food packaging is another concern because it can also result in PFAS accumulation in the foods we eat.”

Although it’s difficult to avoid PFAS altogether, the CDC suggests lowering exposure rates by avoiding contaminated water and food. If you’re not sure if your water is contaminated, you should ask your local or state health and environmental quality departments for fish or water advisories in your area.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Watchdog group demands removal of FDA leaders after aducanumab approval

In a letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, Michael A. Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, said: “The FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab for anyone with Alzheimer’s disease, regardless of severity, showed a stunning disregard for science, eviscerated the agency’s standards for approving new drugs, and ranks as one of the most irresponsible and egregious decisions in the history of the agency.”

Public Citizen urged Mr. Becerra to seek the resignations or the removal of the three FDA officials it said were most responsible for the approval – Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Director Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD; and CDER’s Office of Neuroscience Director Billy Dunn, MD.

“This decision is a disastrous blow to the agency’s credibility, public health, and the financial sustainability of the Medicare program,” writes Dr. Carome, noting that Biogen said it would charge $56,000 annually for the infusion.

Aaron Kesselheim, MD, one of three FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs advisory committee members who resigned in the wake of the approval, agreed with Public Citizen that the agency’s credibility is suffering.

“The aducanumab decision is the worst example yet of the FDA’s movement away from its high standards,” Dr. Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Harvard colleague Jerry Avorn, MD, wrote in the New York Times on June 15.

“As physicians, we know well that Alzheimer’s disease is a terrible condition,” they wrote. However, they added, “approving a drug that has such poor evidence that it works and causes such worrisome side effects is not the solution.”

In his resignation letter, Dr. Kesselheim said he had also been dismayed by the agency’s 2016 approval of eteplirsen (Exondys 51, Sarepta Therapeutics) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. In both the eteplirsen and aducanumab approvals, the agency went against its advisers’ recommendations, Dr. Kesselheim said.

Advocates who backed approval decry cost

Aducanumab had a rocky road to approval but had unwavering backing from the Alzheimer’s Association and at least one other organization, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s.

The Alzheimer’s Association was particularly outspoken in its support and, in March, was accused of potential conflict of interest by Public Citizen and several neurologists because the association accepted at least $1.4 million from Biogen and its partner Eisai since fiscal year 2018.

The association applauded the FDA approval but, a few days later, expressed outrage over the $56,000-a-year price tag.

“This price is simply unacceptable,” the Alzheimer’s Association said in the statement. “For many, this price will pose an insurmountable barrier to access, it complicates and jeopardizes sustainable access to this treatment, and may further deepen issues of health equity,” the association said, adding, “We call on Biogen to change this price.”

UsAgainstAlzheimer’s also expressed concerns about access, even before it knew aducanumab’s price.

“Shockingly, Medicare does not reimburse patients for the expensive PET scans important to determine whether someone is appropriate for this drug,” noted George Vradenburg, chairman and cofounder of the group, in a June 7 statement. “We intend to work with Biogen and Medicare to make access to this drug affordable for every American who needs it,” Mr. Vradenburg said.

Dr. Carome said the advocates’ complaints were hard to fathom.

“This should not have come as a surprise to anyone,” Dr. Carome said, adding that “it’s essentially the ballpark figure the company threw out weeks ago.”

“Fifty-six-thousand-dollars is particularly egregiously overpriced for a drug that doesn’t work,” Dr. Carome said. “If the [Alzheimer’s Association] truly finds this objectionable, hopefully they’ll stop accepting money from Biogen and its partner Eisai,” he added.

“The Alzheimer’s Association is recognizing that the genie is out of the bottle and that they are going to have trouble reining in the inevitable run-away costs,” said Mike Greicius, MD, MPH, associate professor of neurology at Stanford University’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Stanford, California.

“In addition to the eye-popping annual cost that Biogen has invented, I hope the Alzheimer’s Association is also concerned about the dangerously loose and broad FDA labeling which does not require screening for amyloid-positivity and does not restrict use to the milder forms of disease studied in the Phase 3 trials,” Dr. Greicius said.

Another advocacy group, Patients For Affordable Drugs, commended the Alzheimer’s Association. Its statement “was nothing short of courageous, especially in light of the Alzheimer’s Association’s reliance on funding from drug corporations, including Biogen,” said David Mitchell, a cancer patient and founder of Patients For Affordable Drugs, in a statement.

Mr. Mitchell said his members “stand with the Alzheimer’s Association in its denunciation of the price set by Biogen” and called for a new law that would allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, Michael A. Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, said: “The FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab for anyone with Alzheimer’s disease, regardless of severity, showed a stunning disregard for science, eviscerated the agency’s standards for approving new drugs, and ranks as one of the most irresponsible and egregious decisions in the history of the agency.”

Public Citizen urged Mr. Becerra to seek the resignations or the removal of the three FDA officials it said were most responsible for the approval – Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Director Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD; and CDER’s Office of Neuroscience Director Billy Dunn, MD.

“This decision is a disastrous blow to the agency’s credibility, public health, and the financial sustainability of the Medicare program,” writes Dr. Carome, noting that Biogen said it would charge $56,000 annually for the infusion.

Aaron Kesselheim, MD, one of three FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs advisory committee members who resigned in the wake of the approval, agreed with Public Citizen that the agency’s credibility is suffering.

“The aducanumab decision is the worst example yet of the FDA’s movement away from its high standards,” Dr. Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Harvard colleague Jerry Avorn, MD, wrote in the New York Times on June 15.

“As physicians, we know well that Alzheimer’s disease is a terrible condition,” they wrote. However, they added, “approving a drug that has such poor evidence that it works and causes such worrisome side effects is not the solution.”

In his resignation letter, Dr. Kesselheim said he had also been dismayed by the agency’s 2016 approval of eteplirsen (Exondys 51, Sarepta Therapeutics) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. In both the eteplirsen and aducanumab approvals, the agency went against its advisers’ recommendations, Dr. Kesselheim said.

Advocates who backed approval decry cost

Aducanumab had a rocky road to approval but had unwavering backing from the Alzheimer’s Association and at least one other organization, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s.

The Alzheimer’s Association was particularly outspoken in its support and, in March, was accused of potential conflict of interest by Public Citizen and several neurologists because the association accepted at least $1.4 million from Biogen and its partner Eisai since fiscal year 2018.

The association applauded the FDA approval but, a few days later, expressed outrage over the $56,000-a-year price tag.

“This price is simply unacceptable,” the Alzheimer’s Association said in the statement. “For many, this price will pose an insurmountable barrier to access, it complicates and jeopardizes sustainable access to this treatment, and may further deepen issues of health equity,” the association said, adding, “We call on Biogen to change this price.”

UsAgainstAlzheimer’s also expressed concerns about access, even before it knew aducanumab’s price.

“Shockingly, Medicare does not reimburse patients for the expensive PET scans important to determine whether someone is appropriate for this drug,” noted George Vradenburg, chairman and cofounder of the group, in a June 7 statement. “We intend to work with Biogen and Medicare to make access to this drug affordable for every American who needs it,” Mr. Vradenburg said.

Dr. Carome said the advocates’ complaints were hard to fathom.

“This should not have come as a surprise to anyone,” Dr. Carome said, adding that “it’s essentially the ballpark figure the company threw out weeks ago.”

“Fifty-six-thousand-dollars is particularly egregiously overpriced for a drug that doesn’t work,” Dr. Carome said. “If the [Alzheimer’s Association] truly finds this objectionable, hopefully they’ll stop accepting money from Biogen and its partner Eisai,” he added.

“The Alzheimer’s Association is recognizing that the genie is out of the bottle and that they are going to have trouble reining in the inevitable run-away costs,” said Mike Greicius, MD, MPH, associate professor of neurology at Stanford University’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Stanford, California.

“In addition to the eye-popping annual cost that Biogen has invented, I hope the Alzheimer’s Association is also concerned about the dangerously loose and broad FDA labeling which does not require screening for amyloid-positivity and does not restrict use to the milder forms of disease studied in the Phase 3 trials,” Dr. Greicius said.

Another advocacy group, Patients For Affordable Drugs, commended the Alzheimer’s Association. Its statement “was nothing short of courageous, especially in light of the Alzheimer’s Association’s reliance on funding from drug corporations, including Biogen,” said David Mitchell, a cancer patient and founder of Patients For Affordable Drugs, in a statement.

Mr. Mitchell said his members “stand with the Alzheimer’s Association in its denunciation of the price set by Biogen” and called for a new law that would allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a letter to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra, Michael A. Carome, MD, director of Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, said: “The FDA’s decision to approve aducanumab for anyone with Alzheimer’s disease, regardless of severity, showed a stunning disregard for science, eviscerated the agency’s standards for approving new drugs, and ranks as one of the most irresponsible and egregious decisions in the history of the agency.”

Public Citizen urged Mr. Becerra to seek the resignations or the removal of the three FDA officials it said were most responsible for the approval – Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) Director Patrizia Cavazzoni, MD; and CDER’s Office of Neuroscience Director Billy Dunn, MD.

“This decision is a disastrous blow to the agency’s credibility, public health, and the financial sustainability of the Medicare program,” writes Dr. Carome, noting that Biogen said it would charge $56,000 annually for the infusion.

Aaron Kesselheim, MD, one of three FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs advisory committee members who resigned in the wake of the approval, agreed with Public Citizen that the agency’s credibility is suffering.

“The aducanumab decision is the worst example yet of the FDA’s movement away from its high standards,” Dr. Kesselheim, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Harvard colleague Jerry Avorn, MD, wrote in the New York Times on June 15.

“As physicians, we know well that Alzheimer’s disease is a terrible condition,” they wrote. However, they added, “approving a drug that has such poor evidence that it works and causes such worrisome side effects is not the solution.”

In his resignation letter, Dr. Kesselheim said he had also been dismayed by the agency’s 2016 approval of eteplirsen (Exondys 51, Sarepta Therapeutics) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. In both the eteplirsen and aducanumab approvals, the agency went against its advisers’ recommendations, Dr. Kesselheim said.

Advocates who backed approval decry cost

Aducanumab had a rocky road to approval but had unwavering backing from the Alzheimer’s Association and at least one other organization, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s.

The Alzheimer’s Association was particularly outspoken in its support and, in March, was accused of potential conflict of interest by Public Citizen and several neurologists because the association accepted at least $1.4 million from Biogen and its partner Eisai since fiscal year 2018.

The association applauded the FDA approval but, a few days later, expressed outrage over the $56,000-a-year price tag.

“This price is simply unacceptable,” the Alzheimer’s Association said in the statement. “For many, this price will pose an insurmountable barrier to access, it complicates and jeopardizes sustainable access to this treatment, and may further deepen issues of health equity,” the association said, adding, “We call on Biogen to change this price.”

UsAgainstAlzheimer’s also expressed concerns about access, even before it knew aducanumab’s price.

“Shockingly, Medicare does not reimburse patients for the expensive PET scans important to determine whether someone is appropriate for this drug,” noted George Vradenburg, chairman and cofounder of the group, in a June 7 statement. “We intend to work with Biogen and Medicare to make access to this drug affordable for every American who needs it,” Mr. Vradenburg said.

Dr. Carome said the advocates’ complaints were hard to fathom.

“This should not have come as a surprise to anyone,” Dr. Carome said, adding that “it’s essentially the ballpark figure the company threw out weeks ago.”

“Fifty-six-thousand-dollars is particularly egregiously overpriced for a drug that doesn’t work,” Dr. Carome said. “If the [Alzheimer’s Association] truly finds this objectionable, hopefully they’ll stop accepting money from Biogen and its partner Eisai,” he added.

“The Alzheimer’s Association is recognizing that the genie is out of the bottle and that they are going to have trouble reining in the inevitable run-away costs,” said Mike Greicius, MD, MPH, associate professor of neurology at Stanford University’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Stanford, California.

“In addition to the eye-popping annual cost that Biogen has invented, I hope the Alzheimer’s Association is also concerned about the dangerously loose and broad FDA labeling which does not require screening for amyloid-positivity and does not restrict use to the milder forms of disease studied in the Phase 3 trials,” Dr. Greicius said.

Another advocacy group, Patients For Affordable Drugs, commended the Alzheimer’s Association. Its statement “was nothing short of courageous, especially in light of the Alzheimer’s Association’s reliance on funding from drug corporations, including Biogen,” said David Mitchell, a cancer patient and founder of Patients For Affordable Drugs, in a statement.

Mr. Mitchell said his members “stand with the Alzheimer’s Association in its denunciation of the price set by Biogen” and called for a new law that would allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Incorporating self-care, wellness into routines can prevent doctors’ burnout

Gradually, we are emerging from the chaos, isolation, and anxiety of COVID-19. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adjusts its recommendations and vaccinations become more widely available, our communities are beginning to return to normalcy. We are encouraged to put aside our masks if vaccinated and rejoin society, to venture out with less hesitancy and anxiety. As family and friends reunite, memories of confusion, frustration, and fear are beginning to fade to black. Despite the prevailing belief that we should move on, look forward, and remember the past to safeguard our future, remnants of the pandemic remain.

Unvaccinated individuals, notably children under the age of 12, are quite significant in number. The use of telehealth is now standard practice.

For several years, we were warned about the looming “mental health crisis.” The past year has demonstrated that a crisis no longer looms – it has arrived. Our patients can reveal the vulnerability COVID-19 has wrought – from the devastation of lives lost, supply shortages, loss of employment and financial stability – to a lack of access to computers and thereby, the risk of educational decline. Those factors, coupled with isolation and uncertainty about the future, have led to an influx of individuals with anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders seeking mental health treatment.

Doctors, others suffering

As result of a medical culture guided by the sacred oath to which care, compassion, and dedication held as true in ancient Greece as it does today, the focus centers on those around us – while signs of our own weariness are waved away as “a bad day.” Even though several support groups are readily available to offer a listening ear and mental health physicians who focus on the treatment of health care professionals are becoming more ubiquitous, the vestiges of past doctrine remain.

In this modern age of medical training, there is often as much sacrifice as there is attainment of knowledge. This philosophy is so ingrained that throughout training and practice one may come across colleagues experiencing an abundance of guilt when leave is needed for personal reasons. We are quick to recommend such steps for our patients, family, and friends, but hesitant to consider such for ourselves. Yet, of all the lessons this past year has wrought, the importance of mental health and self-care cannot be overstated. This raises the question:

It is vital to accept our humanity as something not to repair, treat, or overcome but to understand. There is strength and power in vulnerability. If we do not perceive and validate this process within ourselves, how can we do so for others? In other words, the oxygen mask must be placed on us first before we can place it on anyone else – patients or otherwise.

Chiefly and above all else, the importance of identifying individual signs of stress is essential. Where do you hold tension? Are you prone to GI distress or headaches when taxed? Do you tend toward irritability, apathy, or exhaustion?

Once this is determined, it is important to assess your stress on a numerical scale, such as those used for pain. Are you a 5 or an 8? Finally, are there identifiable triggers or reliable alleviators? Is there a time of day or day of the week that is most difficult to manage? Can you anticipate potential stressors? Understanding your triggers, listening to your body, and practicing the language of self is the first step toward wellness.

Following introspection and observation, the next step is inventory. Take stock of your reserves. What replenishes? What depletes? What brings joy? What brings dread? Are there certain activities that mitigate stress? If so, how much time do they entail? Identify your number on a scale and associate that number with specific strategies or techniques. Remember that decompression for a 6 might be excessive for a 4. Furthermore, what is the duration of these feelings? Chronic stressors may incur gradual change verses sudden impact if acute. Through identifying personal signs, devising and using a scale, as well as escalating or de-escalating factors, individuals become more in tune with their bodies and therefore, more likely to intervene before burnout takes hold.

With this process well integrated, one can now consider stylized approaches for stress management. For example, those inclined toward mindfulness practices may find yoga, meditation, and relaxation exercises beneficial. Others may thrive on positive affirmations, gratitude, and thankfulness. While some might find relief in physical activity, be it strenuous or casual, the creative arts might appeal to those who find joy in painting, writing, or doing crafts. In addition, baking, reading, dancing, and/or listening to music might help lift stress.

Along with those discoveries, or in some cases, rediscoveries, basic needs such as dietary habits and nutrition, hydration, and sleep are vital toward emotional regulation, physiological homeostasis, and stress modulation. Remember HALT: Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired, Too hot, Too cold, Sad or Stressed. Those strategies are meant to guide self-care and highlight the importance of allowing time for self-awareness. Imagine yourself as if you are meeting a new patient. Establish rapport, identify symptoms, and explore options for treatment. When we give time to ourselves, we can give time more freely to others. With this in mind, try following the 5-minute wellness check that I formulated:

1. How am I feeling? What am I feeling?

2. Assess HALTS.

3. Identify the number on your scale.

4. Methods of quick de-escalation:

- Designate and schedule personal time.

- Write down daily goals.

- Repeat positive affirmations or write down words of gratitude.

- Use deep breathing exercises.

- Stretch or take a brief walk.

- Engage in mindfulness practices, such as meditation.

Once we develop a habit of monitoring, assessing, and practicing self-care, the process becomes more efficient and effective. Think of the way a seasoned attending can manage workflow with ease, compared with an intern. Recognizing signs and using these strategies routinely can become a quick daily measure of well-being.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with interests in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest.

Gradually, we are emerging from the chaos, isolation, and anxiety of COVID-19. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adjusts its recommendations and vaccinations become more widely available, our communities are beginning to return to normalcy. We are encouraged to put aside our masks if vaccinated and rejoin society, to venture out with less hesitancy and anxiety. As family and friends reunite, memories of confusion, frustration, and fear are beginning to fade to black. Despite the prevailing belief that we should move on, look forward, and remember the past to safeguard our future, remnants of the pandemic remain.

Unvaccinated individuals, notably children under the age of 12, are quite significant in number. The use of telehealth is now standard practice.

For several years, we were warned about the looming “mental health crisis.” The past year has demonstrated that a crisis no longer looms – it has arrived. Our patients can reveal the vulnerability COVID-19 has wrought – from the devastation of lives lost, supply shortages, loss of employment and financial stability – to a lack of access to computers and thereby, the risk of educational decline. Those factors, coupled with isolation and uncertainty about the future, have led to an influx of individuals with anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders seeking mental health treatment.

Doctors, others suffering

As result of a medical culture guided by the sacred oath to which care, compassion, and dedication held as true in ancient Greece as it does today, the focus centers on those around us – while signs of our own weariness are waved away as “a bad day.” Even though several support groups are readily available to offer a listening ear and mental health physicians who focus on the treatment of health care professionals are becoming more ubiquitous, the vestiges of past doctrine remain.

In this modern age of medical training, there is often as much sacrifice as there is attainment of knowledge. This philosophy is so ingrained that throughout training and practice one may come across colleagues experiencing an abundance of guilt when leave is needed for personal reasons. We are quick to recommend such steps for our patients, family, and friends, but hesitant to consider such for ourselves. Yet, of all the lessons this past year has wrought, the importance of mental health and self-care cannot be overstated. This raises the question:

It is vital to accept our humanity as something not to repair, treat, or overcome but to understand. There is strength and power in vulnerability. If we do not perceive and validate this process within ourselves, how can we do so for others? In other words, the oxygen mask must be placed on us first before we can place it on anyone else – patients or otherwise.

Chiefly and above all else, the importance of identifying individual signs of stress is essential. Where do you hold tension? Are you prone to GI distress or headaches when taxed? Do you tend toward irritability, apathy, or exhaustion?

Once this is determined, it is important to assess your stress on a numerical scale, such as those used for pain. Are you a 5 or an 8? Finally, are there identifiable triggers or reliable alleviators? Is there a time of day or day of the week that is most difficult to manage? Can you anticipate potential stressors? Understanding your triggers, listening to your body, and practicing the language of self is the first step toward wellness.

Following introspection and observation, the next step is inventory. Take stock of your reserves. What replenishes? What depletes? What brings joy? What brings dread? Are there certain activities that mitigate stress? If so, how much time do they entail? Identify your number on a scale and associate that number with specific strategies or techniques. Remember that decompression for a 6 might be excessive for a 4. Furthermore, what is the duration of these feelings? Chronic stressors may incur gradual change verses sudden impact if acute. Through identifying personal signs, devising and using a scale, as well as escalating or de-escalating factors, individuals become more in tune with their bodies and therefore, more likely to intervene before burnout takes hold.

With this process well integrated, one can now consider stylized approaches for stress management. For example, those inclined toward mindfulness practices may find yoga, meditation, and relaxation exercises beneficial. Others may thrive on positive affirmations, gratitude, and thankfulness. While some might find relief in physical activity, be it strenuous or casual, the creative arts might appeal to those who find joy in painting, writing, or doing crafts. In addition, baking, reading, dancing, and/or listening to music might help lift stress.

Along with those discoveries, or in some cases, rediscoveries, basic needs such as dietary habits and nutrition, hydration, and sleep are vital toward emotional regulation, physiological homeostasis, and stress modulation. Remember HALT: Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired, Too hot, Too cold, Sad or Stressed. Those strategies are meant to guide self-care and highlight the importance of allowing time for self-awareness. Imagine yourself as if you are meeting a new patient. Establish rapport, identify symptoms, and explore options for treatment. When we give time to ourselves, we can give time more freely to others. With this in mind, try following the 5-minute wellness check that I formulated:

1. How am I feeling? What am I feeling?

2. Assess HALTS.

3. Identify the number on your scale.

4. Methods of quick de-escalation:

- Designate and schedule personal time.

- Write down daily goals.

- Repeat positive affirmations or write down words of gratitude.

- Use deep breathing exercises.

- Stretch or take a brief walk.

- Engage in mindfulness practices, such as meditation.

Once we develop a habit of monitoring, assessing, and practicing self-care, the process becomes more efficient and effective. Think of the way a seasoned attending can manage workflow with ease, compared with an intern. Recognizing signs and using these strategies routinely can become a quick daily measure of well-being.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with interests in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest.

Gradually, we are emerging from the chaos, isolation, and anxiety of COVID-19. As the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adjusts its recommendations and vaccinations become more widely available, our communities are beginning to return to normalcy. We are encouraged to put aside our masks if vaccinated and rejoin society, to venture out with less hesitancy and anxiety. As family and friends reunite, memories of confusion, frustration, and fear are beginning to fade to black. Despite the prevailing belief that we should move on, look forward, and remember the past to safeguard our future, remnants of the pandemic remain.

Unvaccinated individuals, notably children under the age of 12, are quite significant in number. The use of telehealth is now standard practice.

For several years, we were warned about the looming “mental health crisis.” The past year has demonstrated that a crisis no longer looms – it has arrived. Our patients can reveal the vulnerability COVID-19 has wrought – from the devastation of lives lost, supply shortages, loss of employment and financial stability – to a lack of access to computers and thereby, the risk of educational decline. Those factors, coupled with isolation and uncertainty about the future, have led to an influx of individuals with anxiety, depression, and other mood disorders seeking mental health treatment.

Doctors, others suffering

As result of a medical culture guided by the sacred oath to which care, compassion, and dedication held as true in ancient Greece as it does today, the focus centers on those around us – while signs of our own weariness are waved away as “a bad day.” Even though several support groups are readily available to offer a listening ear and mental health physicians who focus on the treatment of health care professionals are becoming more ubiquitous, the vestiges of past doctrine remain.

In this modern age of medical training, there is often as much sacrifice as there is attainment of knowledge. This philosophy is so ingrained that throughout training and practice one may come across colleagues experiencing an abundance of guilt when leave is needed for personal reasons. We are quick to recommend such steps for our patients, family, and friends, but hesitant to consider such for ourselves. Yet, of all the lessons this past year has wrought, the importance of mental health and self-care cannot be overstated. This raises the question:

It is vital to accept our humanity as something not to repair, treat, or overcome but to understand. There is strength and power in vulnerability. If we do not perceive and validate this process within ourselves, how can we do so for others? In other words, the oxygen mask must be placed on us first before we can place it on anyone else – patients or otherwise.

Chiefly and above all else, the importance of identifying individual signs of stress is essential. Where do you hold tension? Are you prone to GI distress or headaches when taxed? Do you tend toward irritability, apathy, or exhaustion?

Once this is determined, it is important to assess your stress on a numerical scale, such as those used for pain. Are you a 5 or an 8? Finally, are there identifiable triggers or reliable alleviators? Is there a time of day or day of the week that is most difficult to manage? Can you anticipate potential stressors? Understanding your triggers, listening to your body, and practicing the language of self is the first step toward wellness.

Following introspection and observation, the next step is inventory. Take stock of your reserves. What replenishes? What depletes? What brings joy? What brings dread? Are there certain activities that mitigate stress? If so, how much time do they entail? Identify your number on a scale and associate that number with specific strategies or techniques. Remember that decompression for a 6 might be excessive for a 4. Furthermore, what is the duration of these feelings? Chronic stressors may incur gradual change verses sudden impact if acute. Through identifying personal signs, devising and using a scale, as well as escalating or de-escalating factors, individuals become more in tune with their bodies and therefore, more likely to intervene before burnout takes hold.

With this process well integrated, one can now consider stylized approaches for stress management. For example, those inclined toward mindfulness practices may find yoga, meditation, and relaxation exercises beneficial. Others may thrive on positive affirmations, gratitude, and thankfulness. While some might find relief in physical activity, be it strenuous or casual, the creative arts might appeal to those who find joy in painting, writing, or doing crafts. In addition, baking, reading, dancing, and/or listening to music might help lift stress.

Along with those discoveries, or in some cases, rediscoveries, basic needs such as dietary habits and nutrition, hydration, and sleep are vital toward emotional regulation, physiological homeostasis, and stress modulation. Remember HALT: Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired, Too hot, Too cold, Sad or Stressed. Those strategies are meant to guide self-care and highlight the importance of allowing time for self-awareness. Imagine yourself as if you are meeting a new patient. Establish rapport, identify symptoms, and explore options for treatment. When we give time to ourselves, we can give time more freely to others. With this in mind, try following the 5-minute wellness check that I formulated:

1. How am I feeling? What am I feeling?

2. Assess HALTS.

3. Identify the number on your scale.

4. Methods of quick de-escalation:

- Designate and schedule personal time.

- Write down daily goals.

- Repeat positive affirmations or write down words of gratitude.

- Use deep breathing exercises.

- Stretch or take a brief walk.

- Engage in mindfulness practices, such as meditation.

Once we develop a habit of monitoring, assessing, and practicing self-care, the process becomes more efficient and effective. Think of the way a seasoned attending can manage workflow with ease, compared with an intern. Recognizing signs and using these strategies routinely can become a quick daily measure of well-being.

Dr. Thomas is a board-certified adult psychiatrist with interests in chronic illness, women’s behavioral health, and minority mental health. She currently practices in North Kingstown and East Providence, R.I. Dr. Thomas has no conflicts of interest.

AMA acknowledges medical education racism of past, vows better future

The report received overwhelming support at the House of Delegates, the AMA’s legislative policy making body, during an online meeting held June 13.

The Council on Medical Education’s report recommends that the AMA acknowledge the harm caused by the Flexner Report, which was issued in 1910 and has since shaped medical education. The Flexner Report caused harm not only to historically Black medical schools, but also to physician workforce diversity and to the clinical outcomes of minority and marginalized patients, according to the medical education advisory body.

The council also recommended conducting a study on medical education with a focus on health equity and racial justice, improving diversity among healthcare workers, and fixing inequitable outcomes from minorities and marginalized patient populations.

The report comes on the heels of the resignation of JAMA editor-in-chief Howard Bauchner, MD, and another high-ranking editor following a February podcast on systemic racism in medicine. The AMA has since released a strategic plan addressing racism and health inequity that has divided membership.

Flexner Report’s effect on physician diversity