User login

Things We Do for No Reason™: Calculating a “Corrected Calcium” Level

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old man for evaluation of acute pyelonephritis; the patient’s medical history is significant for chronic kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome. The patient endorses moderate flank pain upon palpation. Initial serum laboratory studies reveal an albumin level of 1.5 g/dL and a calcium level of 10.0 mg/dL. A repeat serum calcium assessment produces similar results. The hospitalist corrects calcium for albumin concentration by applying the most common formula (Payne’s formula), which results in a corrected calcium value of 12 mg/dL. The hospitalist then starts the patient on intravenous (IV) fluids to treat hypercalcemia and obtains serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels.

BACKGROUND

Our skeletons bind, with phosphate, nearly 99% of the body’s calcium, the most abundant mineral in our body. The remaining 1% of calcium (approximately 9-10.5 mg/dL) circulates in the blood. Approximately 40% of serum calcium is bound to albumin, with a smaller percentage bound to lactate and citrate. The remaining 4.5 to 5.5 mg/dL circulates unbound as free (ie, ionized) calcium (iCa).1 Calcium has many fundamental intra- and extracellular functions. Physiologic calcium homeostasis is maintained by parathyroid hormone and vitamin D.2 The amount of circulating iCa, rather than total plasma calcium, determines the many biologic effects of plasma calcium.

In the hospital setting, clinicians commonly encounter patients with derangements in calcium homeostasis.3 True hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia has significant clinical manifestations, including generalized fatigue, nephrolithiasis, cardiac arrhythmias, and, potentially, death. Thus, clinical practice requires correct and accurate assessment of serum calcium levels.1

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK CALCULATING A “CORRECTED CALCIUM” LEVEL IS HELPFUL

Although measuring biologically active calcium (ie, iCa) is the gold standard for assessing calcium levels, laboratories struggle to obtain a direct, accurate measurement of iCa due to the special handling and time constraints required to process samples.4 As a result, metabolic laboratory panels typically report the more easily measured total calcium, the sum of iCa and bound calcium.5 Changes in albumin levels, however, do not affect iCa levels. Since calcium has less available albumin for binding, hypoalbuminemia should theoretically decrease the amount of bound calcium and lead to a decreased reported total calcium. Therefore, a patient’s total calcium level may appear low even though their iCa is normal, which can lead to an incorrect diagnosis of hypocalcemia or overestimate of the extent of existing hypocalcemia. Moreover, these lower reported calcium levels can falsely report normocalcemia in patients with hypercalcemia or underestimate the extent of the patient’s hypercalcemia.

For years physicians have attempted to account for the underestimate in total calcium due to hypoalbuminemia by calculating a “corrected” calcium. The correction formulas use total calcium and serum albumin to estimate the expected iCa. Refinements to the original formula, developed by Payne et al in 1973, have resulted in the most commonly utilized formula today: corrected calcium = (0.8 x [normal albumin – patient’s albumin]) + serum calcium.6,7 Many commonly used clinical-decision resources recommend correcting serum calcium concentrations in patients with hypoalbuminemia.6

WHY CALCULATING A CORRECTED CALCIUM FOR ALBUMIN IS UNNECESSARY

While calculating corrected calcium should theoretically provide a more accurate estimate of physiologically active iCa in patients with hypoalbuminemia,4 the commonly used correction equations become less accurate as hypoalbuminemia worsens.8 Payne et al derived the original formula from 200 patients using a single laboratory; however, subsequent retrospective studies have not supported the use of albumin-corrected calcium calculations to estimate the iCa.4,9-11 For example, although Payne’s corrected calcium equations assume a constant relationship between albumin and calcium binding throughout all serum-albumin concentrations, studies have shown that as albumin falls, more calcium ions bind to each available gram of albumin. Payne’s assumption results in an overestimation of the total serum calcium after correction as compared to the iCa.8 In comparison, uncorrected total serum calcium assays more accurately reflect both the change in albumin binding that occurs with alterations in albumin concentration and the unchanged free calcium ions. Studies demonstrate superior correlation between iCa and uncorrected total calcium.4,9-11

Several large retrospective studies revealed the poor in vivo accuracy of equations used to correct calcium for albumin. In one study, Uppsala University Sweden researchers reviewed the laboratory records of more than 20,000 hospitalized patients from 2005 to 2013.9 This group compared seven corrected calcium formulas to direct measurements of iCa. All of the correction equations correlated poorly with iCa based on their intraclass correlation (ICC), a descriptive statistic for units that have been sorted into groups. (ICC describes how strongly the units in each group correlate or resemble each other—eg, the closer an ICC is to 1, the stronger the correlation is between each unit in the group.) ICC for the correcting equations ranged from 0.45-0.81. The formulas used to calculate corrected calcium levels performed especially poorly in patients with hypoalbuminemia. In this same patient population, the total serum calcium correlated well with directly assessed iCa, with an ICC of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.84-0.86). Moreover, the uncorrected total calcium classified the patient’s calcium level correctly in 82% of cases.

A second study of 5,500 patients in Australia comparing total and adjusted calcium with iCa similarly demonstrated that corrected calcium inaccurately predicts calcium status.10 Findings from this study showed that corrected calcium values correlated with iCa in only 55% to 65% of samples, but uncorrected total calcium correlated with iCa in 70% to 80% of samples. Notably, in patients with renal failure and/or serum albumin concentrations <3 g/dL, formulas used to correct calcium overestimated calcium levels when compared to directly assessed iCa. Correction formulas performed on serum albumin concentrations >3 g/dL correlated better with iCa (65%-77%), effectively negating the utility of the correction formulas.

Another large retrospective observational study from Norway reviewed laboratory data from more than 6,500 hospitalized and clinic patients.11 In this study, researchers calculated corrected calcium using several different albumin-adjusted formulas and compared results to laboratory-assessed iCa. As compared to corrected calcium, uncorrected total calcium more accurately determined clinically relevant free calcium.

Finally, a Canadian research group analyzed time-matched calcium, albumin, and iCa samples from 678 patients.4 They calculated each patient’s corrected calcium values using Payne’s formula. Results of this study showed that corrected calcium predicted iCa outcomes less reliably than uncorrected total calcium (ICC, 0.73 for corrected calcium vs 0.78 for uncorrected calcium).

Utilizing corrected calcium formulas in patients with hypoalbuminemia can overestimate serum calcium, resulting in false-positive findings and an incorrect diagnosis of hypercalcemia or normocalcemia.12 Incorrectly diagnosing hypercalcemia by using correction formulas prompts management that can lead to iatrogenic harm. Hypoalbuminemia is often associated with hepatic or renal disease. In this patient population, standard treatment of hypercalcemia with volume resuscitation (typically 2 to 4 L) and potentially IV loop diuretics will cause clinically significant volume overload and could worsen renal dysfunction.13 Notably, some of the correction formulas utilized in the studies discussed here performed well in hypercalcemic patients, particularly in those with preserved renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Importantly, correction formulas can mask true hypocalcemia or the true severity of hypocalcemia. Applying correction formulas in patients with clinically significant hypocalcemia and hypoalbuminemia can make hospitalists believe that the calcium levels are normal or not as clinically significant as they first seemed. This can lead to the withholding of appropriate treatment.12

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Based on the available literature, uncorrected total calcium values more accurately assess biologically active calcium. If a more certain calcium value will affect clinical outcomes, clinicians should obtain a direct measurement of iCa.4,9-11 Therefore, clinicians should assess iCa irrespective of the uncorrected serum calcium level in patients who are critically ill or who have known hypoparathyroidism or other derangements in iCa.14 Since iCa levels also fluctuate with pH, samples must be processed quickly and kept cool to slow blood cell metabolism, which alters pH levels.4 Using bedside point-of-care blood gas analyzers to obtain iCa removes a large logistical obstacle to obtaining an accurate iCa. Serum electrolyte interpretation with a properly calibrated point-of-care analyzer correlates well with a traditional laboratory analyzer.15

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Use serum calcium testing routinely to evaluate calcium homeostasis.

- Do not use corrected calcium equations to estimate total calcium.

- If a more accurate measurement of calcium will change medical management, obtain a direct iCa.

- Obtain a direct iCa measurement in critically ill patents and in patients with known hypoparathyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, or other derangements in calcium homeostasis.

- Do not order a serum albumin test to assess calcium levels.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our clinical scenario, this patient did not have true hypercalcemia and experienced unnecessary evaluation and treatment. Multiple retrospective clinical trials do not support the practice of using corrected calcium equations to correct for serum albumin derangements.4,9-11 Hospitalists should therefore avoid the temptation to calculate a corrected calcium level in patients with hypoalbuminemia. For patients with clinically significant total serum hypocalcemia or hypercalcemia, they should consider obtaining an iCa assay to better determine the true physiologic impact.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing [email protected]

1. Peacock M. Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5 Suppl 1:S23-S30. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.05910809

2. Brown EM. Extracellular Ca2+ sensing, regulation of parathyroid cell function, and role of Ca2+ and other ions as extracellular (first) messengers. Physiol Rev. 1991;71(2):371-411. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.371

3. Aishah AB, Foo YN. A retrospective study of serum calcium levels in a hospital population in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 1995;50(3):246-249.

4. Steen O, Clase C, Don-Wauchope A. Corrected calcium formula in routine clinical use does not accurately reflect ionized calcium in hospital patients. Can J Gen Int Med. 2016;11(3):14-21. https://doi.org/10.22374/cjgim.v11i3.150

5. Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, Milner JR. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J. 1973;4(5893):643-646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5893.643

6. Shane E. Diagnostic approach to hypercalcemia. UpToDate website. Updated August 31, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnostic-approach-to-hypercalcemia

7. Ladenson JH, Lewis JW, Boyd JC. Failure of total calcium corrected for protein, albumin, and pH to correctly assess free calcium status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;46(6):986-993. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-46-6-986

8. Besarab A, Caro JF. Increased absolute calcium binding to albumin in hypoalbuminaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1981;34(12):1368-1374. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.34.12.1368

9. Ridefelt P, Helmersson-Karlqvist J. Albumin adjustment of total calcium does not improve the estimation of calcium status. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77(6):442-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2017.1336568

10. Smith JD, Wilson S, Schneider HG. Misclassification of calcium status based on albumin-adjusted calcium: studies in a tertiary hospital setting. Clin Chem. 2018;64(12):1713-1722. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.291377

11. Lian IA, Åsberg A. Should total calcium be adjusted for albumin? A retrospective observational study of laboratory data from central Norway. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e017703. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017703

12. Bowers GN Jr, Brassard C, Sena SF. Measurement of ionized calcium in serum with ion-selective electrodes: a mature technology that can meet the daily service needs. Clin Chem. 1986;32(8)1437-1447.

13. Myburgh JA. Fluid resuscitation in acute medicine: what is the current situation? J Intern Med. 2015;277(1):58-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12326

14. Aberegg SK. Ionized calcium in the ICU: should it be measured and corrected? Chest. 2016;149(3):846-855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.001

15. Mirzazadeh M, Morovat A, James T, Smith I, Kirby J, Shine B. Point-of-care testing of electrolytes and calcium using blood gas analysers: it is time we trusted the results. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(3):181-186. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2015-204669

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old man for evaluation of acute pyelonephritis; the patient’s medical history is significant for chronic kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome. The patient endorses moderate flank pain upon palpation. Initial serum laboratory studies reveal an albumin level of 1.5 g/dL and a calcium level of 10.0 mg/dL. A repeat serum calcium assessment produces similar results. The hospitalist corrects calcium for albumin concentration by applying the most common formula (Payne’s formula), which results in a corrected calcium value of 12 mg/dL. The hospitalist then starts the patient on intravenous (IV) fluids to treat hypercalcemia and obtains serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels.

BACKGROUND

Our skeletons bind, with phosphate, nearly 99% of the body’s calcium, the most abundant mineral in our body. The remaining 1% of calcium (approximately 9-10.5 mg/dL) circulates in the blood. Approximately 40% of serum calcium is bound to albumin, with a smaller percentage bound to lactate and citrate. The remaining 4.5 to 5.5 mg/dL circulates unbound as free (ie, ionized) calcium (iCa).1 Calcium has many fundamental intra- and extracellular functions. Physiologic calcium homeostasis is maintained by parathyroid hormone and vitamin D.2 The amount of circulating iCa, rather than total plasma calcium, determines the many biologic effects of plasma calcium.

In the hospital setting, clinicians commonly encounter patients with derangements in calcium homeostasis.3 True hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia has significant clinical manifestations, including generalized fatigue, nephrolithiasis, cardiac arrhythmias, and, potentially, death. Thus, clinical practice requires correct and accurate assessment of serum calcium levels.1

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK CALCULATING A “CORRECTED CALCIUM” LEVEL IS HELPFUL

Although measuring biologically active calcium (ie, iCa) is the gold standard for assessing calcium levels, laboratories struggle to obtain a direct, accurate measurement of iCa due to the special handling and time constraints required to process samples.4 As a result, metabolic laboratory panels typically report the more easily measured total calcium, the sum of iCa and bound calcium.5 Changes in albumin levels, however, do not affect iCa levels. Since calcium has less available albumin for binding, hypoalbuminemia should theoretically decrease the amount of bound calcium and lead to a decreased reported total calcium. Therefore, a patient’s total calcium level may appear low even though their iCa is normal, which can lead to an incorrect diagnosis of hypocalcemia or overestimate of the extent of existing hypocalcemia. Moreover, these lower reported calcium levels can falsely report normocalcemia in patients with hypercalcemia or underestimate the extent of the patient’s hypercalcemia.

For years physicians have attempted to account for the underestimate in total calcium due to hypoalbuminemia by calculating a “corrected” calcium. The correction formulas use total calcium and serum albumin to estimate the expected iCa. Refinements to the original formula, developed by Payne et al in 1973, have resulted in the most commonly utilized formula today: corrected calcium = (0.8 x [normal albumin – patient’s albumin]) + serum calcium.6,7 Many commonly used clinical-decision resources recommend correcting serum calcium concentrations in patients with hypoalbuminemia.6

WHY CALCULATING A CORRECTED CALCIUM FOR ALBUMIN IS UNNECESSARY

While calculating corrected calcium should theoretically provide a more accurate estimate of physiologically active iCa in patients with hypoalbuminemia,4 the commonly used correction equations become less accurate as hypoalbuminemia worsens.8 Payne et al derived the original formula from 200 patients using a single laboratory; however, subsequent retrospective studies have not supported the use of albumin-corrected calcium calculations to estimate the iCa.4,9-11 For example, although Payne’s corrected calcium equations assume a constant relationship between albumin and calcium binding throughout all serum-albumin concentrations, studies have shown that as albumin falls, more calcium ions bind to each available gram of albumin. Payne’s assumption results in an overestimation of the total serum calcium after correction as compared to the iCa.8 In comparison, uncorrected total serum calcium assays more accurately reflect both the change in albumin binding that occurs with alterations in albumin concentration and the unchanged free calcium ions. Studies demonstrate superior correlation between iCa and uncorrected total calcium.4,9-11

Several large retrospective studies revealed the poor in vivo accuracy of equations used to correct calcium for albumin. In one study, Uppsala University Sweden researchers reviewed the laboratory records of more than 20,000 hospitalized patients from 2005 to 2013.9 This group compared seven corrected calcium formulas to direct measurements of iCa. All of the correction equations correlated poorly with iCa based on their intraclass correlation (ICC), a descriptive statistic for units that have been sorted into groups. (ICC describes how strongly the units in each group correlate or resemble each other—eg, the closer an ICC is to 1, the stronger the correlation is between each unit in the group.) ICC for the correcting equations ranged from 0.45-0.81. The formulas used to calculate corrected calcium levels performed especially poorly in patients with hypoalbuminemia. In this same patient population, the total serum calcium correlated well with directly assessed iCa, with an ICC of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.84-0.86). Moreover, the uncorrected total calcium classified the patient’s calcium level correctly in 82% of cases.

A second study of 5,500 patients in Australia comparing total and adjusted calcium with iCa similarly demonstrated that corrected calcium inaccurately predicts calcium status.10 Findings from this study showed that corrected calcium values correlated with iCa in only 55% to 65% of samples, but uncorrected total calcium correlated with iCa in 70% to 80% of samples. Notably, in patients with renal failure and/or serum albumin concentrations <3 g/dL, formulas used to correct calcium overestimated calcium levels when compared to directly assessed iCa. Correction formulas performed on serum albumin concentrations >3 g/dL correlated better with iCa (65%-77%), effectively negating the utility of the correction formulas.

Another large retrospective observational study from Norway reviewed laboratory data from more than 6,500 hospitalized and clinic patients.11 In this study, researchers calculated corrected calcium using several different albumin-adjusted formulas and compared results to laboratory-assessed iCa. As compared to corrected calcium, uncorrected total calcium more accurately determined clinically relevant free calcium.

Finally, a Canadian research group analyzed time-matched calcium, albumin, and iCa samples from 678 patients.4 They calculated each patient’s corrected calcium values using Payne’s formula. Results of this study showed that corrected calcium predicted iCa outcomes less reliably than uncorrected total calcium (ICC, 0.73 for corrected calcium vs 0.78 for uncorrected calcium).

Utilizing corrected calcium formulas in patients with hypoalbuminemia can overestimate serum calcium, resulting in false-positive findings and an incorrect diagnosis of hypercalcemia or normocalcemia.12 Incorrectly diagnosing hypercalcemia by using correction formulas prompts management that can lead to iatrogenic harm. Hypoalbuminemia is often associated with hepatic or renal disease. In this patient population, standard treatment of hypercalcemia with volume resuscitation (typically 2 to 4 L) and potentially IV loop diuretics will cause clinically significant volume overload and could worsen renal dysfunction.13 Notably, some of the correction formulas utilized in the studies discussed here performed well in hypercalcemic patients, particularly in those with preserved renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Importantly, correction formulas can mask true hypocalcemia or the true severity of hypocalcemia. Applying correction formulas in patients with clinically significant hypocalcemia and hypoalbuminemia can make hospitalists believe that the calcium levels are normal or not as clinically significant as they first seemed. This can lead to the withholding of appropriate treatment.12

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Based on the available literature, uncorrected total calcium values more accurately assess biologically active calcium. If a more certain calcium value will affect clinical outcomes, clinicians should obtain a direct measurement of iCa.4,9-11 Therefore, clinicians should assess iCa irrespective of the uncorrected serum calcium level in patients who are critically ill or who have known hypoparathyroidism or other derangements in iCa.14 Since iCa levels also fluctuate with pH, samples must be processed quickly and kept cool to slow blood cell metabolism, which alters pH levels.4 Using bedside point-of-care blood gas analyzers to obtain iCa removes a large logistical obstacle to obtaining an accurate iCa. Serum electrolyte interpretation with a properly calibrated point-of-care analyzer correlates well with a traditional laboratory analyzer.15

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Use serum calcium testing routinely to evaluate calcium homeostasis.

- Do not use corrected calcium equations to estimate total calcium.

- If a more accurate measurement of calcium will change medical management, obtain a direct iCa.

- Obtain a direct iCa measurement in critically ill patents and in patients with known hypoparathyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, or other derangements in calcium homeostasis.

- Do not order a serum albumin test to assess calcium levels.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our clinical scenario, this patient did not have true hypercalcemia and experienced unnecessary evaluation and treatment. Multiple retrospective clinical trials do not support the practice of using corrected calcium equations to correct for serum albumin derangements.4,9-11 Hospitalists should therefore avoid the temptation to calculate a corrected calcium level in patients with hypoalbuminemia. For patients with clinically significant total serum hypocalcemia or hypercalcemia, they should consider obtaining an iCa assay to better determine the true physiologic impact.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing [email protected]

Inspired by the ABIM Foundation’s Choosing Wisely® campaign, the “Things We Do for No Reason™” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices that have become common parts of hospital care but may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent clear-cut conclusions or clinical practice standards but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion.

CLINICAL SCENARIO

A hospitalist admits a 75-year-old man for evaluation of acute pyelonephritis; the patient’s medical history is significant for chronic kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome. The patient endorses moderate flank pain upon palpation. Initial serum laboratory studies reveal an albumin level of 1.5 g/dL and a calcium level of 10.0 mg/dL. A repeat serum calcium assessment produces similar results. The hospitalist corrects calcium for albumin concentration by applying the most common formula (Payne’s formula), which results in a corrected calcium value of 12 mg/dL. The hospitalist then starts the patient on intravenous (IV) fluids to treat hypercalcemia and obtains serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and parathyroid hormone levels.

BACKGROUND

Our skeletons bind, with phosphate, nearly 99% of the body’s calcium, the most abundant mineral in our body. The remaining 1% of calcium (approximately 9-10.5 mg/dL) circulates in the blood. Approximately 40% of serum calcium is bound to albumin, with a smaller percentage bound to lactate and citrate. The remaining 4.5 to 5.5 mg/dL circulates unbound as free (ie, ionized) calcium (iCa).1 Calcium has many fundamental intra- and extracellular functions. Physiologic calcium homeostasis is maintained by parathyroid hormone and vitamin D.2 The amount of circulating iCa, rather than total plasma calcium, determines the many biologic effects of plasma calcium.

In the hospital setting, clinicians commonly encounter patients with derangements in calcium homeostasis.3 True hypercalcemia or hypocalcemia has significant clinical manifestations, including generalized fatigue, nephrolithiasis, cardiac arrhythmias, and, potentially, death. Thus, clinical practice requires correct and accurate assessment of serum calcium levels.1

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK CALCULATING A “CORRECTED CALCIUM” LEVEL IS HELPFUL

Although measuring biologically active calcium (ie, iCa) is the gold standard for assessing calcium levels, laboratories struggle to obtain a direct, accurate measurement of iCa due to the special handling and time constraints required to process samples.4 As a result, metabolic laboratory panels typically report the more easily measured total calcium, the sum of iCa and bound calcium.5 Changes in albumin levels, however, do not affect iCa levels. Since calcium has less available albumin for binding, hypoalbuminemia should theoretically decrease the amount of bound calcium and lead to a decreased reported total calcium. Therefore, a patient’s total calcium level may appear low even though their iCa is normal, which can lead to an incorrect diagnosis of hypocalcemia or overestimate of the extent of existing hypocalcemia. Moreover, these lower reported calcium levels can falsely report normocalcemia in patients with hypercalcemia or underestimate the extent of the patient’s hypercalcemia.

For years physicians have attempted to account for the underestimate in total calcium due to hypoalbuminemia by calculating a “corrected” calcium. The correction formulas use total calcium and serum albumin to estimate the expected iCa. Refinements to the original formula, developed by Payne et al in 1973, have resulted in the most commonly utilized formula today: corrected calcium = (0.8 x [normal albumin – patient’s albumin]) + serum calcium.6,7 Many commonly used clinical-decision resources recommend correcting serum calcium concentrations in patients with hypoalbuminemia.6

WHY CALCULATING A CORRECTED CALCIUM FOR ALBUMIN IS UNNECESSARY

While calculating corrected calcium should theoretically provide a more accurate estimate of physiologically active iCa in patients with hypoalbuminemia,4 the commonly used correction equations become less accurate as hypoalbuminemia worsens.8 Payne et al derived the original formula from 200 patients using a single laboratory; however, subsequent retrospective studies have not supported the use of albumin-corrected calcium calculations to estimate the iCa.4,9-11 For example, although Payne’s corrected calcium equations assume a constant relationship between albumin and calcium binding throughout all serum-albumin concentrations, studies have shown that as albumin falls, more calcium ions bind to each available gram of albumin. Payne’s assumption results in an overestimation of the total serum calcium after correction as compared to the iCa.8 In comparison, uncorrected total serum calcium assays more accurately reflect both the change in albumin binding that occurs with alterations in albumin concentration and the unchanged free calcium ions. Studies demonstrate superior correlation between iCa and uncorrected total calcium.4,9-11

Several large retrospective studies revealed the poor in vivo accuracy of equations used to correct calcium for albumin. In one study, Uppsala University Sweden researchers reviewed the laboratory records of more than 20,000 hospitalized patients from 2005 to 2013.9 This group compared seven corrected calcium formulas to direct measurements of iCa. All of the correction equations correlated poorly with iCa based on their intraclass correlation (ICC), a descriptive statistic for units that have been sorted into groups. (ICC describes how strongly the units in each group correlate or resemble each other—eg, the closer an ICC is to 1, the stronger the correlation is between each unit in the group.) ICC for the correcting equations ranged from 0.45-0.81. The formulas used to calculate corrected calcium levels performed especially poorly in patients with hypoalbuminemia. In this same patient population, the total serum calcium correlated well with directly assessed iCa, with an ICC of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.84-0.86). Moreover, the uncorrected total calcium classified the patient’s calcium level correctly in 82% of cases.

A second study of 5,500 patients in Australia comparing total and adjusted calcium with iCa similarly demonstrated that corrected calcium inaccurately predicts calcium status.10 Findings from this study showed that corrected calcium values correlated with iCa in only 55% to 65% of samples, but uncorrected total calcium correlated with iCa in 70% to 80% of samples. Notably, in patients with renal failure and/or serum albumin concentrations <3 g/dL, formulas used to correct calcium overestimated calcium levels when compared to directly assessed iCa. Correction formulas performed on serum albumin concentrations >3 g/dL correlated better with iCa (65%-77%), effectively negating the utility of the correction formulas.

Another large retrospective observational study from Norway reviewed laboratory data from more than 6,500 hospitalized and clinic patients.11 In this study, researchers calculated corrected calcium using several different albumin-adjusted formulas and compared results to laboratory-assessed iCa. As compared to corrected calcium, uncorrected total calcium more accurately determined clinically relevant free calcium.

Finally, a Canadian research group analyzed time-matched calcium, albumin, and iCa samples from 678 patients.4 They calculated each patient’s corrected calcium values using Payne’s formula. Results of this study showed that corrected calcium predicted iCa outcomes less reliably than uncorrected total calcium (ICC, 0.73 for corrected calcium vs 0.78 for uncorrected calcium).

Utilizing corrected calcium formulas in patients with hypoalbuminemia can overestimate serum calcium, resulting in false-positive findings and an incorrect diagnosis of hypercalcemia or normocalcemia.12 Incorrectly diagnosing hypercalcemia by using correction formulas prompts management that can lead to iatrogenic harm. Hypoalbuminemia is often associated with hepatic or renal disease. In this patient population, standard treatment of hypercalcemia with volume resuscitation (typically 2 to 4 L) and potentially IV loop diuretics will cause clinically significant volume overload and could worsen renal dysfunction.13 Notably, some of the correction formulas utilized in the studies discussed here performed well in hypercalcemic patients, particularly in those with preserved renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Importantly, correction formulas can mask true hypocalcemia or the true severity of hypocalcemia. Applying correction formulas in patients with clinically significant hypocalcemia and hypoalbuminemia can make hospitalists believe that the calcium levels are normal or not as clinically significant as they first seemed. This can lead to the withholding of appropriate treatment.12

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

Based on the available literature, uncorrected total calcium values more accurately assess biologically active calcium. If a more certain calcium value will affect clinical outcomes, clinicians should obtain a direct measurement of iCa.4,9-11 Therefore, clinicians should assess iCa irrespective of the uncorrected serum calcium level in patients who are critically ill or who have known hypoparathyroidism or other derangements in iCa.14 Since iCa levels also fluctuate with pH, samples must be processed quickly and kept cool to slow blood cell metabolism, which alters pH levels.4 Using bedside point-of-care blood gas analyzers to obtain iCa removes a large logistical obstacle to obtaining an accurate iCa. Serum electrolyte interpretation with a properly calibrated point-of-care analyzer correlates well with a traditional laboratory analyzer.15

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Use serum calcium testing routinely to evaluate calcium homeostasis.

- Do not use corrected calcium equations to estimate total calcium.

- If a more accurate measurement of calcium will change medical management, obtain a direct iCa.

- Obtain a direct iCa measurement in critically ill patents and in patients with known hypoparathyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, or other derangements in calcium homeostasis.

- Do not order a serum albumin test to assess calcium levels.

CONCLUSION

Returning to our clinical scenario, this patient did not have true hypercalcemia and experienced unnecessary evaluation and treatment. Multiple retrospective clinical trials do not support the practice of using corrected calcium equations to correct for serum albumin derangements.4,9-11 Hospitalists should therefore avoid the temptation to calculate a corrected calcium level in patients with hypoalbuminemia. For patients with clinically significant total serum hypocalcemia or hypercalcemia, they should consider obtaining an iCa assay to better determine the true physiologic impact.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason™”? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason™” topics by emailing [email protected]

1. Peacock M. Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5 Suppl 1:S23-S30. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.05910809

2. Brown EM. Extracellular Ca2+ sensing, regulation of parathyroid cell function, and role of Ca2+ and other ions as extracellular (first) messengers. Physiol Rev. 1991;71(2):371-411. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.371

3. Aishah AB, Foo YN. A retrospective study of serum calcium levels in a hospital population in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 1995;50(3):246-249.

4. Steen O, Clase C, Don-Wauchope A. Corrected calcium formula in routine clinical use does not accurately reflect ionized calcium in hospital patients. Can J Gen Int Med. 2016;11(3):14-21. https://doi.org/10.22374/cjgim.v11i3.150

5. Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, Milner JR. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J. 1973;4(5893):643-646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5893.643

6. Shane E. Diagnostic approach to hypercalcemia. UpToDate website. Updated August 31, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnostic-approach-to-hypercalcemia

7. Ladenson JH, Lewis JW, Boyd JC. Failure of total calcium corrected for protein, albumin, and pH to correctly assess free calcium status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;46(6):986-993. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-46-6-986

8. Besarab A, Caro JF. Increased absolute calcium binding to albumin in hypoalbuminaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1981;34(12):1368-1374. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.34.12.1368

9. Ridefelt P, Helmersson-Karlqvist J. Albumin adjustment of total calcium does not improve the estimation of calcium status. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77(6):442-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2017.1336568

10. Smith JD, Wilson S, Schneider HG. Misclassification of calcium status based on albumin-adjusted calcium: studies in a tertiary hospital setting. Clin Chem. 2018;64(12):1713-1722. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.291377

11. Lian IA, Åsberg A. Should total calcium be adjusted for albumin? A retrospective observational study of laboratory data from central Norway. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e017703. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017703

12. Bowers GN Jr, Brassard C, Sena SF. Measurement of ionized calcium in serum with ion-selective electrodes: a mature technology that can meet the daily service needs. Clin Chem. 1986;32(8)1437-1447.

13. Myburgh JA. Fluid resuscitation in acute medicine: what is the current situation? J Intern Med. 2015;277(1):58-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12326

14. Aberegg SK. Ionized calcium in the ICU: should it be measured and corrected? Chest. 2016;149(3):846-855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.001

15. Mirzazadeh M, Morovat A, James T, Smith I, Kirby J, Shine B. Point-of-care testing of electrolytes and calcium using blood gas analysers: it is time we trusted the results. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(3):181-186. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2015-204669

1. Peacock M. Calcium metabolism in health and disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5 Suppl 1:S23-S30. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.05910809

2. Brown EM. Extracellular Ca2+ sensing, regulation of parathyroid cell function, and role of Ca2+ and other ions as extracellular (first) messengers. Physiol Rev. 1991;71(2):371-411. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.371

3. Aishah AB, Foo YN. A retrospective study of serum calcium levels in a hospital population in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 1995;50(3):246-249.

4. Steen O, Clase C, Don-Wauchope A. Corrected calcium formula in routine clinical use does not accurately reflect ionized calcium in hospital patients. Can J Gen Int Med. 2016;11(3):14-21. https://doi.org/10.22374/cjgim.v11i3.150

5. Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, Milner JR. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J. 1973;4(5893):643-646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5893.643

6. Shane E. Diagnostic approach to hypercalcemia. UpToDate website. Updated August 31, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diagnostic-approach-to-hypercalcemia

7. Ladenson JH, Lewis JW, Boyd JC. Failure of total calcium corrected for protein, albumin, and pH to correctly assess free calcium status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1978;46(6):986-993. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-46-6-986

8. Besarab A, Caro JF. Increased absolute calcium binding to albumin in hypoalbuminaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1981;34(12):1368-1374. https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.34.12.1368

9. Ridefelt P, Helmersson-Karlqvist J. Albumin adjustment of total calcium does not improve the estimation of calcium status. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2017;77(6):442-447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365513.2017.1336568

10. Smith JD, Wilson S, Schneider HG. Misclassification of calcium status based on albumin-adjusted calcium: studies in a tertiary hospital setting. Clin Chem. 2018;64(12):1713-1722. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.291377

11. Lian IA, Åsberg A. Should total calcium be adjusted for albumin? A retrospective observational study of laboratory data from central Norway. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e017703. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017703

12. Bowers GN Jr, Brassard C, Sena SF. Measurement of ionized calcium in serum with ion-selective electrodes: a mature technology that can meet the daily service needs. Clin Chem. 1986;32(8)1437-1447.

13. Myburgh JA. Fluid resuscitation in acute medicine: what is the current situation? J Intern Med. 2015;277(1):58-68. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12326

14. Aberegg SK. Ionized calcium in the ICU: should it be measured and corrected? Chest. 2016;149(3):846-855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.001

15. Mirzazadeh M, Morovat A, James T, Smith I, Kirby J, Shine B. Point-of-care testing of electrolytes and calcium using blood gas analysers: it is time we trusted the results. Emerg Med J. 2016;33(3):181-186. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2015-204669

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Pediatric Conditions Requiring Minimal Intervention or Observation After Interfacility Transfer

Regionalization of pediatric acute care is increasing across the United States, with rates of interfacility transfer for general medical conditions in children similar to those of high-risk conditions in adults.1 The inability for children to receive definitive care (ie, care provided to conclusively manage a patient’s condition without requiring an interfacility transfer) within their local community has implications on public health as well as family function and financial burden.1,2 Previous studies demonstrated that 30% to 80% of interfacility transfers are potentially unnecessary,3-6 as indicated by a high proportion of short lengths of stay after transfer.

To highlight conditions that referring hospitals may prioritize for pediatric capacity building, we aimed to identify the most common medical diagnoses among pediatric transfer patients that did not require advanced evaluation or intervention and that had high rates of discharge within 1 day of interfacility transfer.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, which contains administrative data from 48 geographically diverse US children’s hospitals.

We included children <18 years old who were transferred to a participating PHIS hospital in 2019, including emergency department (ED), observation, and inpatient encounters. We identified patients through the source-of-admission code labeled as “transfer.”

For each diagnosis, we determined the number of transfers and frequency of rapid discharge, defined as either discharge from the ED without admission or admission and discharge within 1 day from a general inpatient unit. As discharge times are not reliably available in PHIS, all patients discharged on the day of transfer or the following calendar day were identified as rapid discharge. Medical complexity was determined through applying the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA).8

For descriptive statistics, we calculated means for normally distributed variables, medians for continuous variables with nonnormal distributions, and percentages for binary variables. Comparisons were made using t-tests and chi-square tests.

This study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 286,905 transfers into participating PHIS hospitals in 2019. Of these, 89,519 (31.2%) were excluded (Appendix Table 2), leaving 197,386 (68.6%) transfers. Patients discharged within 1 day were more likely to have public or unknown insurance (65.1% vs 61.5%, P < 0.01), to have no co-occurring chronic conditions (60.2% vs 28.5%, P < 0.01), and to reside within the Northeast (35.0% vs 11.0%, P < 0.01) (Appendix Table 3).

The most common medical diagnoses among these transfers included acute bronchiolitis (4.3% of all interfacility transfers, n = 8,425), chemotherapy (4.0%, n = 7,819), and asthma (3.3%, n = 6,430) (Appendix Table 4); 45.9% of bronchiolitis, 15.0% of chemotherapy, and 67.4% of asthma transfers were rapidly discharged.

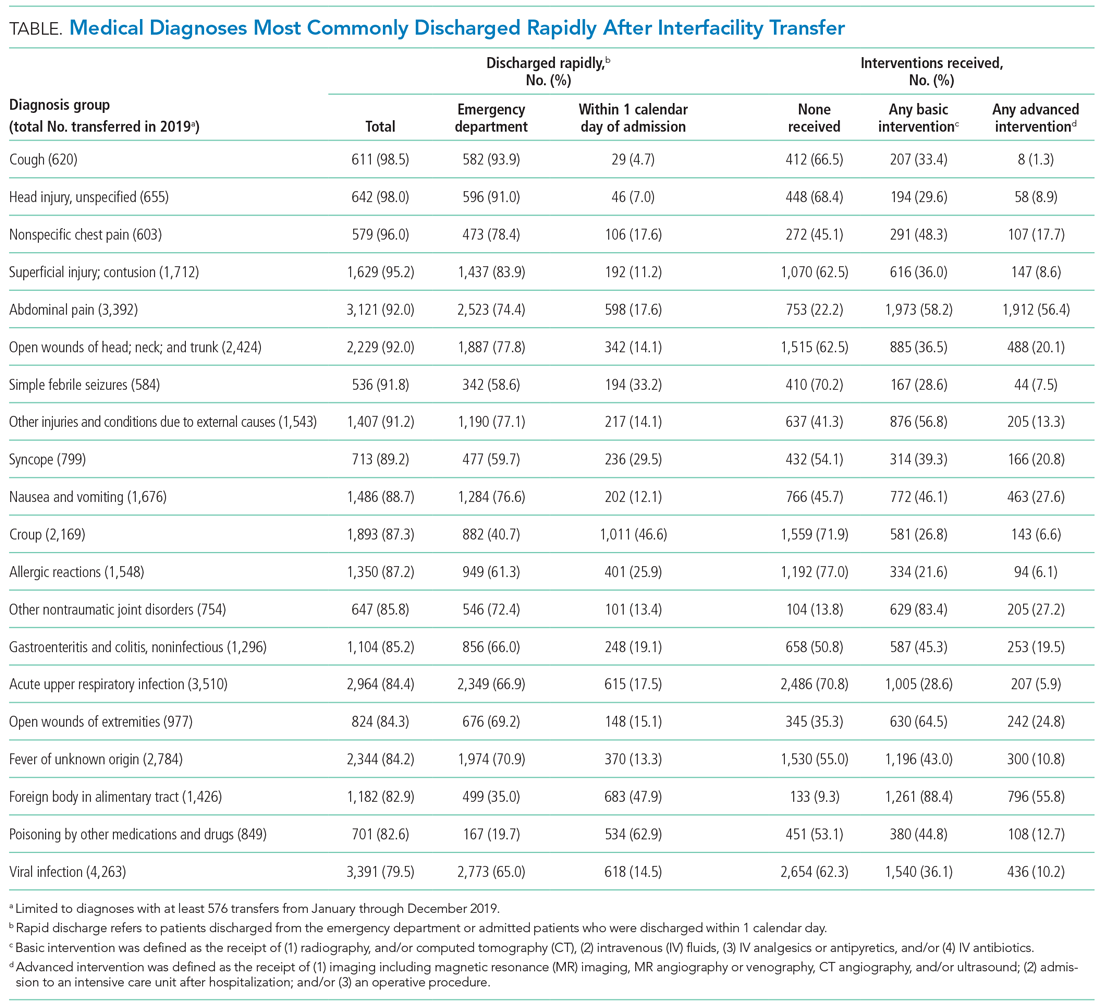

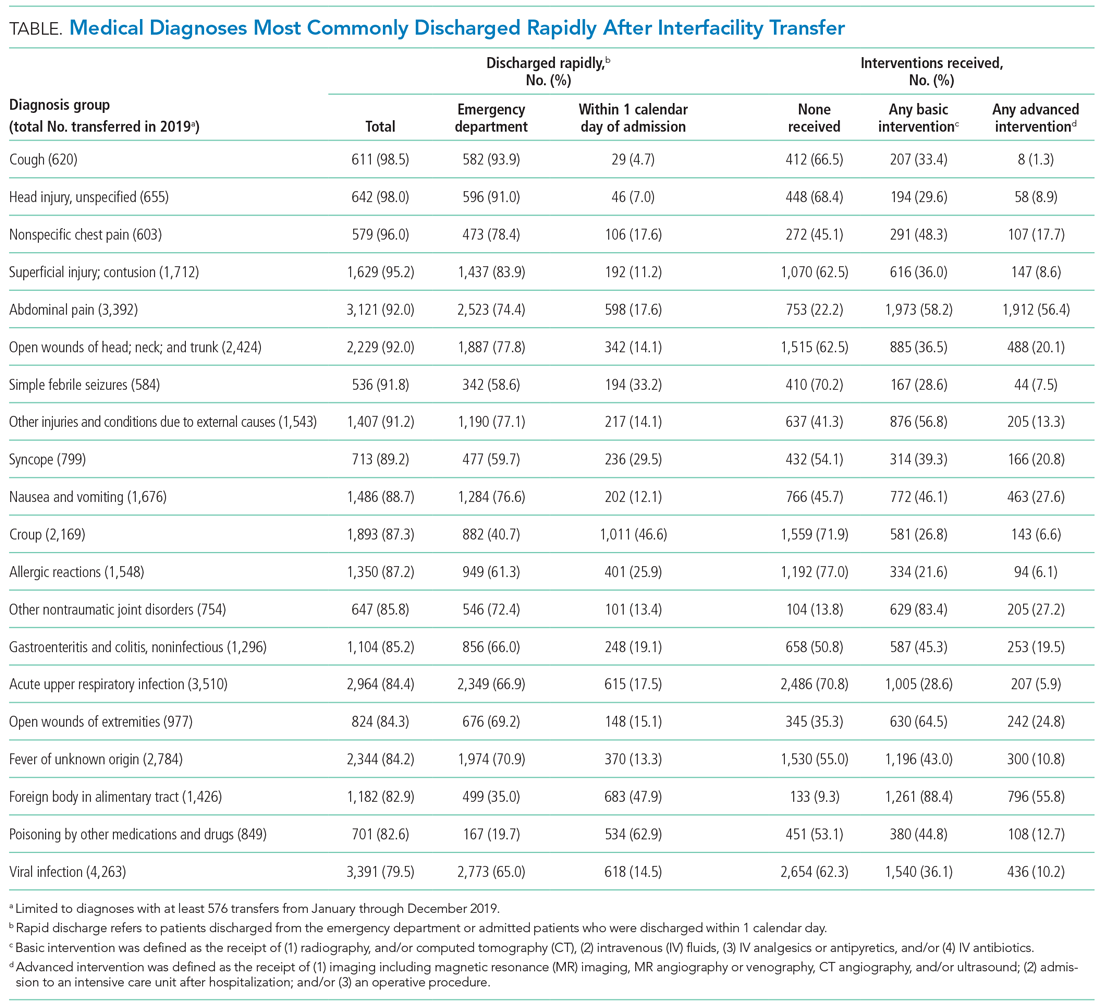

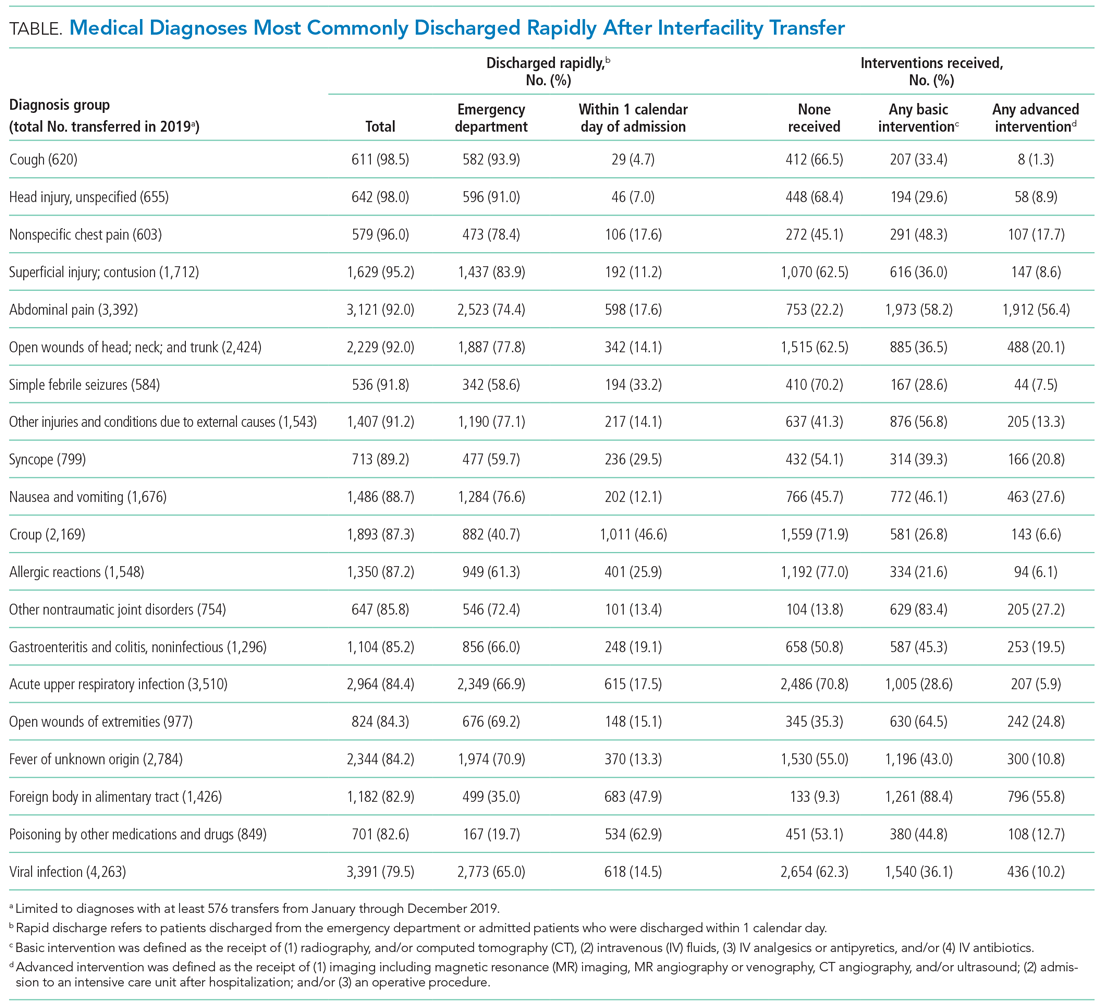

The Table shows the medical conditions among transfers that most frequently experienced rapid discharge (primary surgical diagnoses are presented in Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We have identified medical conditions that not only had high rates of rapid discharge after transfer, but also received minimal intervention from the accepting institution. Although bronchiolitis and chemotherapy were the most common conditions for which patients were transferred, the range of severity varied widely, with more than 50% of bronchiolitis and 85% of chemotherapy transfers requiring hospitalization for longer than 1 day

Identifying conditions as potential targets to reduce the number of interfacility transfers requires balancing a hospital’s capacity (or lack thereof) for pediatric admissions, perceived risk of decompensation, referring provider discomfort, and parental preference.9-11

The rapid upscale of telehealth may provide a unique opportunity to support the provision of pediatric care within local communities.12,13

Building infrastructure to prevent interfacility transfers may improve healthcare access for children in rural areas proportionately more than children in urban areas. Children in rural communities experience significantly higher rates of interfacility transfers than children in urban areas.14 This increases financial burden and causes additional distress and inconvenience for families.15 With constraints in staffing capacity, equipment, and finances, identifying a subset of medical conditions is a critical initial step to inform the design of targeted interventions to support pediatric healthcare delivery in local communities and avoid costly transfers, although it is not the wholesale solution. Additional utilization of tools such as informed shared decision-making resources and implementation of pediatric-specific protocols likely represent additional necessary steps.

Our study has several limitations. Because we used administrative data, there is a risk of misclassifying diagnoses. We attempted to mitigate this by using a standard ICD-10-based, pediatric-specific grouper.

CONCLUSION

Our exploration of pediatric interfacility transfers that experienced rapid discharge with minimal intervention provides a building block to support the provision of definitive pediatric care in non-pediatric hospitals and represents a step towards addressing limited access to care in general hospitals.

1. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):e171096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1096

2. Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13923

3. Richard KR, Glisson KL, Shah N, et al. Predictors of potentially unnecessary transfers to pediatric emergency departments. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0307

4. Gattu RK, Teshome G, Cai L, Wright C, Lichenstein R. Interhospital pediatric patient transfers-factors influencing rapid disposition after transfer. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000061

5. Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1819

6. Rosenthal JL, Lieng MK, Marcin JP, Romano PS. Profiling pediatric potentially avoidable transfers using procedure and diagnosis codes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 19;10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777

7. Pediatric clinical classification system (PECCS) codes. Children’s Hospital Association. December 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

8. Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

9. Rosenthal JL, Okumura MJ, Hernandez L, Li ST, Rehm RS. Interfacility transfers to general pediatric floors: a qualitative study exploring the role of communication. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):692-699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.003

10. Rosenthal JL, Li ST, Hernandez L, Alvarez M, Rehm RS, Okumura MJ. Familial caregiver and physician perceptions of the family-physician interactions during interfacility transfers. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):344-351. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0017

11. Peebles ER, Miller MR, Lynch TP, Tijssen JA. Factors associated with discharge home after transfer to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(9):650-655. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001098

12. Labarbera JM, Ellenby MS, Bouressa P, Burrell J, Flori HR, Marcin JP. The impact of telemedicine intensivist support and a pediatric hospitalist program on a community hospital. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0303

13. Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.013

14. Michelson KA, Hudgins JD, Lyons TW, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG, Finkelstein JA. Trends in capability of hospitals to provide definitive acute care for children: 2008 to 2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2203

15. Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Miller SL, Torner JC. Potentially avoidable pediatric interfacility transfer is a costly burden for rural families: a cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):885-894. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12972

Regionalization of pediatric acute care is increasing across the United States, with rates of interfacility transfer for general medical conditions in children similar to those of high-risk conditions in adults.1 The inability for children to receive definitive care (ie, care provided to conclusively manage a patient’s condition without requiring an interfacility transfer) within their local community has implications on public health as well as family function and financial burden.1,2 Previous studies demonstrated that 30% to 80% of interfacility transfers are potentially unnecessary,3-6 as indicated by a high proportion of short lengths of stay after transfer.

To highlight conditions that referring hospitals may prioritize for pediatric capacity building, we aimed to identify the most common medical diagnoses among pediatric transfer patients that did not require advanced evaluation or intervention and that had high rates of discharge within 1 day of interfacility transfer.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, which contains administrative data from 48 geographically diverse US children’s hospitals.

We included children <18 years old who were transferred to a participating PHIS hospital in 2019, including emergency department (ED), observation, and inpatient encounters. We identified patients through the source-of-admission code labeled as “transfer.”

For each diagnosis, we determined the number of transfers and frequency of rapid discharge, defined as either discharge from the ED without admission or admission and discharge within 1 day from a general inpatient unit. As discharge times are not reliably available in PHIS, all patients discharged on the day of transfer or the following calendar day were identified as rapid discharge. Medical complexity was determined through applying the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA).8

For descriptive statistics, we calculated means for normally distributed variables, medians for continuous variables with nonnormal distributions, and percentages for binary variables. Comparisons were made using t-tests and chi-square tests.

This study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 286,905 transfers into participating PHIS hospitals in 2019. Of these, 89,519 (31.2%) were excluded (Appendix Table 2), leaving 197,386 (68.6%) transfers. Patients discharged within 1 day were more likely to have public or unknown insurance (65.1% vs 61.5%, P < 0.01), to have no co-occurring chronic conditions (60.2% vs 28.5%, P < 0.01), and to reside within the Northeast (35.0% vs 11.0%, P < 0.01) (Appendix Table 3).

The most common medical diagnoses among these transfers included acute bronchiolitis (4.3% of all interfacility transfers, n = 8,425), chemotherapy (4.0%, n = 7,819), and asthma (3.3%, n = 6,430) (Appendix Table 4); 45.9% of bronchiolitis, 15.0% of chemotherapy, and 67.4% of asthma transfers were rapidly discharged.

The Table shows the medical conditions among transfers that most frequently experienced rapid discharge (primary surgical diagnoses are presented in Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We have identified medical conditions that not only had high rates of rapid discharge after transfer, but also received minimal intervention from the accepting institution. Although bronchiolitis and chemotherapy were the most common conditions for which patients were transferred, the range of severity varied widely, with more than 50% of bronchiolitis and 85% of chemotherapy transfers requiring hospitalization for longer than 1 day

Identifying conditions as potential targets to reduce the number of interfacility transfers requires balancing a hospital’s capacity (or lack thereof) for pediatric admissions, perceived risk of decompensation, referring provider discomfort, and parental preference.9-11

The rapid upscale of telehealth may provide a unique opportunity to support the provision of pediatric care within local communities.12,13

Building infrastructure to prevent interfacility transfers may improve healthcare access for children in rural areas proportionately more than children in urban areas. Children in rural communities experience significantly higher rates of interfacility transfers than children in urban areas.14 This increases financial burden and causes additional distress and inconvenience for families.15 With constraints in staffing capacity, equipment, and finances, identifying a subset of medical conditions is a critical initial step to inform the design of targeted interventions to support pediatric healthcare delivery in local communities and avoid costly transfers, although it is not the wholesale solution. Additional utilization of tools such as informed shared decision-making resources and implementation of pediatric-specific protocols likely represent additional necessary steps.

Our study has several limitations. Because we used administrative data, there is a risk of misclassifying diagnoses. We attempted to mitigate this by using a standard ICD-10-based, pediatric-specific grouper.

CONCLUSION

Our exploration of pediatric interfacility transfers that experienced rapid discharge with minimal intervention provides a building block to support the provision of definitive pediatric care in non-pediatric hospitals and represents a step towards addressing limited access to care in general hospitals.

Regionalization of pediatric acute care is increasing across the United States, with rates of interfacility transfer for general medical conditions in children similar to those of high-risk conditions in adults.1 The inability for children to receive definitive care (ie, care provided to conclusively manage a patient’s condition without requiring an interfacility transfer) within their local community has implications on public health as well as family function and financial burden.1,2 Previous studies demonstrated that 30% to 80% of interfacility transfers are potentially unnecessary,3-6 as indicated by a high proportion of short lengths of stay after transfer.

To highlight conditions that referring hospitals may prioritize for pediatric capacity building, we aimed to identify the most common medical diagnoses among pediatric transfer patients that did not require advanced evaluation or intervention and that had high rates of discharge within 1 day of interfacility transfer.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional, descriptive study using the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database, which contains administrative data from 48 geographically diverse US children’s hospitals.

We included children <18 years old who were transferred to a participating PHIS hospital in 2019, including emergency department (ED), observation, and inpatient encounters. We identified patients through the source-of-admission code labeled as “transfer.”

For each diagnosis, we determined the number of transfers and frequency of rapid discharge, defined as either discharge from the ED without admission or admission and discharge within 1 day from a general inpatient unit. As discharge times are not reliably available in PHIS, all patients discharged on the day of transfer or the following calendar day were identified as rapid discharge. Medical complexity was determined through applying the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA).8

For descriptive statistics, we calculated means for normally distributed variables, medians for continuous variables with nonnormal distributions, and percentages for binary variables. Comparisons were made using t-tests and chi-square tests.

This study was approved by the Seattle Children’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

We identified 286,905 transfers into participating PHIS hospitals in 2019. Of these, 89,519 (31.2%) were excluded (Appendix Table 2), leaving 197,386 (68.6%) transfers. Patients discharged within 1 day were more likely to have public or unknown insurance (65.1% vs 61.5%, P < 0.01), to have no co-occurring chronic conditions (60.2% vs 28.5%, P < 0.01), and to reside within the Northeast (35.0% vs 11.0%, P < 0.01) (Appendix Table 3).

The most common medical diagnoses among these transfers included acute bronchiolitis (4.3% of all interfacility transfers, n = 8,425), chemotherapy (4.0%, n = 7,819), and asthma (3.3%, n = 6,430) (Appendix Table 4); 45.9% of bronchiolitis, 15.0% of chemotherapy, and 67.4% of asthma transfers were rapidly discharged.

The Table shows the medical conditions among transfers that most frequently experienced rapid discharge (primary surgical diagnoses are presented in Appendix Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We have identified medical conditions that not only had high rates of rapid discharge after transfer, but also received minimal intervention from the accepting institution. Although bronchiolitis and chemotherapy were the most common conditions for which patients were transferred, the range of severity varied widely, with more than 50% of bronchiolitis and 85% of chemotherapy transfers requiring hospitalization for longer than 1 day

Identifying conditions as potential targets to reduce the number of interfacility transfers requires balancing a hospital’s capacity (or lack thereof) for pediatric admissions, perceived risk of decompensation, referring provider discomfort, and parental preference.9-11

The rapid upscale of telehealth may provide a unique opportunity to support the provision of pediatric care within local communities.12,13

Building infrastructure to prevent interfacility transfers may improve healthcare access for children in rural areas proportionately more than children in urban areas. Children in rural communities experience significantly higher rates of interfacility transfers than children in urban areas.14 This increases financial burden and causes additional distress and inconvenience for families.15 With constraints in staffing capacity, equipment, and finances, identifying a subset of medical conditions is a critical initial step to inform the design of targeted interventions to support pediatric healthcare delivery in local communities and avoid costly transfers, although it is not the wholesale solution. Additional utilization of tools such as informed shared decision-making resources and implementation of pediatric-specific protocols likely represent additional necessary steps.

Our study has several limitations. Because we used administrative data, there is a risk of misclassifying diagnoses. We attempted to mitigate this by using a standard ICD-10-based, pediatric-specific grouper.

CONCLUSION

Our exploration of pediatric interfacility transfers that experienced rapid discharge with minimal intervention provides a building block to support the provision of definitive pediatric care in non-pediatric hospitals and represents a step towards addressing limited access to care in general hospitals.

1. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):e171096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1096

2. Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13923

3. Richard KR, Glisson KL, Shah N, et al. Predictors of potentially unnecessary transfers to pediatric emergency departments. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0307

4. Gattu RK, Teshome G, Cai L, Wright C, Lichenstein R. Interhospital pediatric patient transfers-factors influencing rapid disposition after transfer. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000061

5. Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1819

6. Rosenthal JL, Lieng MK, Marcin JP, Romano PS. Profiling pediatric potentially avoidable transfers using procedure and diagnosis codes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 19;10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777

7. Pediatric clinical classification system (PECCS) codes. Children’s Hospital Association. December 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

8. Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

9. Rosenthal JL, Okumura MJ, Hernandez L, Li ST, Rehm RS. Interfacility transfers to general pediatric floors: a qualitative study exploring the role of communication. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):692-699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.003

10. Rosenthal JL, Li ST, Hernandez L, Alvarez M, Rehm RS, Okumura MJ. Familial caregiver and physician perceptions of the family-physician interactions during interfacility transfers. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):344-351. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0017

11. Peebles ER, Miller MR, Lynch TP, Tijssen JA. Factors associated with discharge home after transfer to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(9):650-655. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001098

12. Labarbera JM, Ellenby MS, Bouressa P, Burrell J, Flori HR, Marcin JP. The impact of telemedicine intensivist support and a pediatric hospitalist program on a community hospital. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0303

13. Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.013

14. Michelson KA, Hudgins JD, Lyons TW, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG, Finkelstein JA. Trends in capability of hospitals to provide definitive acute care for children: 2008 to 2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2203

15. Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Miller SL, Torner JC. Potentially avoidable pediatric interfacility transfer is a costly burden for rural families: a cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):885-894. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12972

1. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):e171096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1096

2. Mumford V, Baysari MT, Kalinin D, et al. Measuring the financial and productivity burden of paediatric hospitalisation on the wider family network. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(9):987-996. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.13923

3. Richard KR, Glisson KL, Shah N, et al. Predictors of potentially unnecessary transfers to pediatric emergency departments. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(5):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0307

4. Gattu RK, Teshome G, Cai L, Wright C, Lichenstein R. Interhospital pediatric patient transfers-factors influencing rapid disposition after transfer. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000061

5. Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):83-92. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1819

6. Rosenthal JL, Lieng MK, Marcin JP, Romano PS. Profiling pediatric potentially avoidable transfers using procedure and diagnosis codes. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019 Mar 19;10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001777

7. Pediatric clinical classification system (PECCS) codes. Children’s Hospital Association. December 11, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2021. https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Research-and-Data/Pediatric-Data-and-Trends/2020/Pediatric-Clinical-Classification-System-PECCS

8. Simon TD, Haaland W, Hawley K, Lambka K, Mangione-Smith R. Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(5):577-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

9. Rosenthal JL, Okumura MJ, Hernandez L, Li ST, Rehm RS. Interfacility transfers to general pediatric floors: a qualitative study exploring the role of communication. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(7):692-699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.003

10. Rosenthal JL, Li ST, Hernandez L, Alvarez M, Rehm RS, Okumura MJ. Familial caregiver and physician perceptions of the family-physician interactions during interfacility transfers. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):344-351. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0017

11. Peebles ER, Miller MR, Lynch TP, Tijssen JA. Factors associated with discharge home after transfer to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(9):650-655. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001098

12. Labarbera JM, Ellenby MS, Bouressa P, Burrell J, Flori HR, Marcin JP. The impact of telemedicine intensivist support and a pediatric hospitalist program on a community hospital. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(10):760-766. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2012.0303

13. Haynes SC, Dharmar M, Hill BC, et al. The impact of telemedicine on transfer rates of newborns at rural community hospitals. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(5):636-641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.013

14. Michelson KA, Hudgins JD, Lyons TW, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG, Finkelstein JA. Trends in capability of hospitals to provide definitive acute care for children: 2008 to 2016. Pediatrics. 2020;145(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-2203

15. Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane DM, Miller SL, Torner JC. Potentially avoidable pediatric interfacility transfer is a costly burden for rural families: a cohort study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(8):885-894. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12972

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and Observation Hospitalizations

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) was designed to improve quality and safety for traditional Medicare beneficiaries.1 Since 2012, the program has reduced payments to institutions with excess inpatient rehospitalizations within 30 days of an index inpatient stay for targeted medical conditions. Observation hospitalizations, billed as outpatient and covered under Medicare Part B, are not counted as index or 30-day rehospitalizations under HRRP methods. Historically, observation occurred almost exclusively in observation units. Now, observation hospitalizations commonly occur on hospital wards, even in intensive care units, and are often clinically indistinguishable from inpatient hospitalizations billed under Medicare Part A.2 The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) state that beneficiaries expected to need 2 or more midnights of hospital care should generally be considered inpatients, yet observation hospitalizations commonly exceed 2 midnights.3,4

The increasing use of observation hospitalizations5,6 raises questions about its impact on HRRP measurements. While observation hospitalizations have been studied as part of 30-day follow-up (numerator) to index inpatient hospitalizations,5,6 little is known about how observation hospitalizations impact rates when they are factored in as both index stays (denominator) and in the 30-day rehospitalization rate (numerator).2,7 We analyzed the complete combinations of observation and inpatient hospitalizations, including observation as index hospitalization, rehospitalization, or both, to determine HRRP impact.

METHODS

Study Cohort

Medicare fee-for-service standard claim files for all beneficiaries (100% population file version) were used to examine qualifying index inpatient and observation hospitalizations between January 1, 2014, and November 30, 2014, as well as 30-day inpatient and observation rehospitalizations. We used CMS’s 30-day methodology, including previously described standard exclusions (Appendix Figure),8 except for the aforementioned inclusion of observation hospitalizations. Observation hospitalizations were identified using established methods,3,9,10 excluding those observation encounters coded with revenue center code 0761 only3,10 in order to be most conservative in identifying observation hospitalizations (Appendix Figure). These methods assign hospitalization type (observation or inpatient) based on the final (billed) status. The terms hospitalization and rehospitalization refer to both inpatient and observation encounters. The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program

Index HRRP admissions for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and pneumonia were examined as a prespecified subgroup.1,11 Coronary artery bypass grafting, total hip replacement, and total knee replacement were excluded in this analysis, as no crosswalk exists between International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes and Current Procedural Terminology codes for these surgical conditions.11

Analysis

Analyses were conducted at the encounter level, consistent with CMS methods.8 Descriptive statistics were used to summarize index and 30-day outcomes.

RESULTS

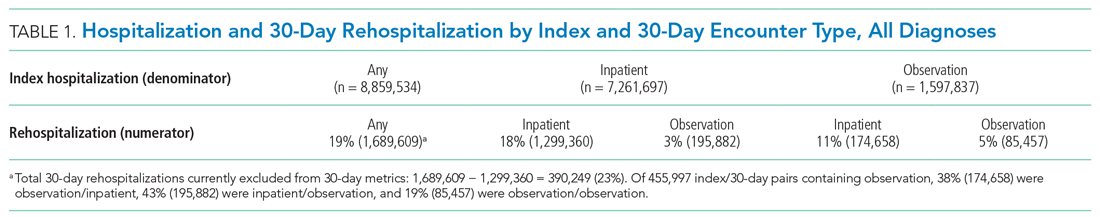

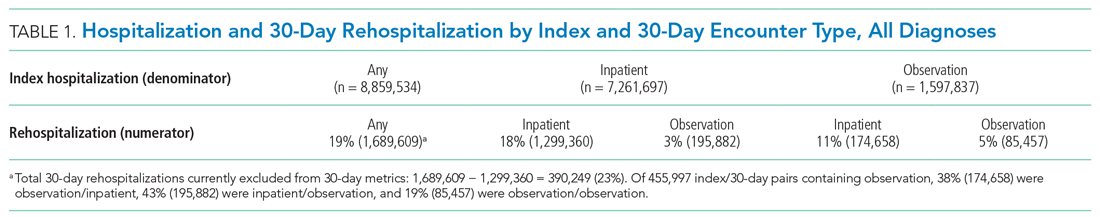

Of 8,859,534 index hospitalizations for any reason or diagnosis, 1,597,837 (18%) were observation and 7,261,697 (82%) were inpatient. Including all hospitalizations, 23% (390,249/1,689,609) of rehospitalizations were excluded from readmission measurement by virtue of the index hospitalization and/or 30-day rehospitalization being observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

For the subgroup of HRRP conditions, 418,923 (11%) and 3,387,849 (89%) of 3,806,772 index hospitalizations were observation and inpatient, respectively. Including HRRP conditions only, 18% (155,553/876,033) of rehospitalizations were excluded from HRRP reporting owing to observation hospitalization as index, 30-day outcome, or both. Of 188,430 index/30-day pairs containing observation, 34% (63,740) were observation/inpatient, 53% (100,343) were inpatient/observation, and 13% (24,347) were observation/observation (Table 1 and Table 2).

DISCUSSION

By ignoring observation hospitalizations in 30-day HRRP quality metrics, nearly one of five potential rehospitalizations is missed. Observation hospitalizations commonly occur as either the index event or 30-day outcome, so accurately determining 30-day HRRP rates must include observation in both positions. Given hospital variability in observation use,3,7 these findings are critically important to accurately understand rehospitalization risk and indicate that HRRP may not be fulfilling its intended purpose.

Including all hospitalizations for any diagnosis, we found that observation and inpatient hospitalizations commonly occur within 30 days of each other. Nearly one in four hospitalization/rehospitalization pairs include observation as index, 30-day rehospitalization, or both. Although not directly related to HRRP metrics, these data demonstrate the growing importance and presence of outpatient (observation) hospitalizations in the Medicare program.

Our study adds to the evolving body of literature investigating quality measures under a two-tiered hospital system where inpatient hospitalizations are counted and observation hospitalizations are not. Figueroa and colleagues12 found that improvements in avoidable admission rates for patients with ambulatory care–sensitive conditions were largely attributable to a shift from counted inpatient to uncounted observation hospitalizations. In other words, hospitalizations were still occurring, but were not being tallied due to outpatient (observation) classification. Zuckerman et al5 and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)6 concluded that readmissions improvements recognized by the HRRP were not explained by a shift to more observation hospitalizations following an index inpatient hospitalization; however, both studies included observation hospitalizations as part of 30-day rehospitalization (numerator) only, not also as part of index hospitalizations (denominator). Our study confirms the importance of including observation hospitalizations in both the index (denominator) and 30-day (numerator) rehospitalization positions to determine the full impact of observation hospitalizations on Medicare’s HRRP metrics.

Our study has limitations. We focused on nonsurgical HRRP conditions, which may have impacted our findings. Additionally, some authors have suggested including emergency department (ED) visits in rehospitalization studies.7 Although ED visits occur at hospitals, they are not hospitalizations; we excluded them as a first step. Had we included ED visits, encounters excluded from HRRP measurements would have increased, suggesting that our findings, while sizeable, are likely conservative. Additionally, we could not determine the merits or medical necessity of hospitalizations (inpatient or outpatient observation), but this is an inherent limitation in a large claims dataset like this one. Finally, we only included a single year of data in this analysis, and it is possible that additional years of data would show different trends. However, we have no reason to believe the study year to be an aberrant year; if anything, observation rates have increased since 2014,6 again pointing out that while our findings are sizable, they are likely conservative. Future research could include additional years of data to confirm even greater proportions of rehospitalizations exempt from HRRP over time due to observation hospitalizations as index and/or 30-day events.

Outpatient observation hospitalizations can occur anywhere in the hospital and are often clinically similar to inpatient hospitalizations, yet observation hospitalizations are essentially invisible under inpatient quality metrics. Requiring the HRRP to include observation hospitalizations is the most obvious solution, but this could require major regulatory and legislative change11,13—change that would fix a metric but fail to address broad policy concerns inherent in the two-tiered observation and inpatient billing distinction. Instead, CMS and Congress might consider this an opportunity to address the oxymoron of “outpatient hospitalizations” by engaging in comprehensive observation reform.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Accessed March 12, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program