User login

Osteoporosis linked to increased risk of hearing loss

Women with osteoporosis, low bone density, or a previous vertebral fracture show significant increases in the risk of hearing loss compared to those without osteoporosis, according to a new study with more than 3 decades of follow-up.

The use of bisphosphonate therapy did not alter the risk, the researchers found.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large longitudinal study to evaluate the relations of bone density, bisphosphonate use, fractures, and risk of hearing loss,” reported Sharon Curhan, MD, and colleagues in research published online in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society.

“In this large nationwide longitudinal study of nearly 144,000 women with up to 34 years of follow-up, we found that osteoporosis or low bone density was independently associated with higher risk of incident moderate or worse hearing loss,” the authors wrote.

“The magnitude of the elevated risk was similar among women who did and did not use bisphosphonates,” they added.

Participants were from the nurses’ health study and NHS II

With recent research suggesting a potential link between bisphosphonate use and prevention of noise-induced hearing loss in mice, Dr. Curhan, of the Channing Division of Network Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues turned to the large longitudinal cohorts of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), conducted from 1982 to 2016, and the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II), from 1995 to 2017.

In total, the primary analysis included 60,821 women in the NHS and 83,078 in the NHS II.

Women in the NHS were aged 36-61 years at baseline and 70-95 years at the end of follow-up, while in the NHS II, women were aged 31-48 years at baseline and 53-70 years at the end of follow-up.

After multivariate adjustment for key factors including age, race/ethnicity, oral hormone use, and a variety of other factors, women in the NHS with osteoporosis had an increased risk of moderate or worse hearing loss, as self-reported every 2 years, compared to those without osteoporosis (relative risk, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.19).

And in the NHS II, which also included data on low bone density, the risk of self-reported hearing loss was higher among those with osteoporosis or low bone density (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.40).

No significant differences were observed in hearing loss risk based on whether women were treated with bisphosphonates, with the mean duration of use of the medication being 5.8 years in the NHS and 3.4 years in the NHS II.

Those who sustained a vertebral fracture also had a higher risk of hearing loss in both studies (NHS: RR, 1.31; NHS II: RR, 1.39).

However, the increased risk of hearing loss was not observed with hip fracture.

“Our findings of up to a 40% higher risk among women with vertebral fracture, but not hip fracture, were intriguing and merit further study,” the authors noted.

“The discordant findings between these skeletal sites may reflect differences in composition and metabolism of bones in the spine and hip and could provide insight into the pathophysiological changes in the ear that may lead to hearing loss,” they added.

Audiometric subanalysis

In an analysis of a subcohort of 3,749 women looking at audiometric thresholds for a more precise measure of hearing loss, women with osteoporosis or low bone density continued to show significantly worse hearing loss when treated with bisphosphonates compared to those without osteoporosis or low bone density.

However, there were no significant hearing loss differences among those with osteoporosis who did not take bisphosphonates versus those without osteoporosis.

The authors speculate that the use of bisphosphonates could have been indicative of more severe osteoporosis, hence the poorer audiometric thresholds.

In an interview, Dr. Curhan said the details of bisphosphonate use, such as type and duration, and their role in hearing loss should be further evaluated.

“Possibly, a potential influence of bisphosphonates on the relation of osteoporosis and hearing loss in humans may depend on the type, dose, and timing of bisphosphonate administration,” she observed. “This is an important question for further study.”

Mechanisms: Bone loss may extend to ear structures

In terms of the mechanisms linking osteoporosis itself to hearing loss, the authors noted that bone loss, in addition to compromising more prominent skeletal sites, could logically extend to bone-related structures in the ear.

“Bone mass at peripheral sites is correlated with bone mass at central sites, such as hip and spine, with correlation coefficients between 0.6 and 0.7,” they explained. “Plausibly, systemic bone demineralization could involve the temporal bone, the otic capsule, and the middle ear ossicles.”

They noted that hearing loss has been linked to other pathologic bone disorders, including otosclerosis and Paget disease.

Furthermore, imbalances in bone formation and resorption in osteoporosis may lead to alterations in ionic metabolism, which can lead to hearing loss.

Looking ahead, Dr. Curhan and colleagues plan to further examine whether calcium and vitamin D, which are associated with the prevention of osteoporosis, have a role in preventing hearing loss.

In the meantime, the findings underscore that clinicians treating patients with osteoporosis should routinely check patients’ hearing, Dr. Curhan said.

“Undetected and untreated hearing loss can adversely impact social interactions, physical and mental well-being, and daily life,” she said.

“Early detection of hearing loss offers greater opportunity for successful management and to learn strategies for rehabilitation and prevention of further progression.”

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with osteoporosis, low bone density, or a previous vertebral fracture show significant increases in the risk of hearing loss compared to those without osteoporosis, according to a new study with more than 3 decades of follow-up.

The use of bisphosphonate therapy did not alter the risk, the researchers found.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large longitudinal study to evaluate the relations of bone density, bisphosphonate use, fractures, and risk of hearing loss,” reported Sharon Curhan, MD, and colleagues in research published online in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society.

“In this large nationwide longitudinal study of nearly 144,000 women with up to 34 years of follow-up, we found that osteoporosis or low bone density was independently associated with higher risk of incident moderate or worse hearing loss,” the authors wrote.

“The magnitude of the elevated risk was similar among women who did and did not use bisphosphonates,” they added.

Participants were from the nurses’ health study and NHS II

With recent research suggesting a potential link between bisphosphonate use and prevention of noise-induced hearing loss in mice, Dr. Curhan, of the Channing Division of Network Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues turned to the large longitudinal cohorts of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), conducted from 1982 to 2016, and the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II), from 1995 to 2017.

In total, the primary analysis included 60,821 women in the NHS and 83,078 in the NHS II.

Women in the NHS were aged 36-61 years at baseline and 70-95 years at the end of follow-up, while in the NHS II, women were aged 31-48 years at baseline and 53-70 years at the end of follow-up.

After multivariate adjustment for key factors including age, race/ethnicity, oral hormone use, and a variety of other factors, women in the NHS with osteoporosis had an increased risk of moderate or worse hearing loss, as self-reported every 2 years, compared to those without osteoporosis (relative risk, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.19).

And in the NHS II, which also included data on low bone density, the risk of self-reported hearing loss was higher among those with osteoporosis or low bone density (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.40).

No significant differences were observed in hearing loss risk based on whether women were treated with bisphosphonates, with the mean duration of use of the medication being 5.8 years in the NHS and 3.4 years in the NHS II.

Those who sustained a vertebral fracture also had a higher risk of hearing loss in both studies (NHS: RR, 1.31; NHS II: RR, 1.39).

However, the increased risk of hearing loss was not observed with hip fracture.

“Our findings of up to a 40% higher risk among women with vertebral fracture, but not hip fracture, were intriguing and merit further study,” the authors noted.

“The discordant findings between these skeletal sites may reflect differences in composition and metabolism of bones in the spine and hip and could provide insight into the pathophysiological changes in the ear that may lead to hearing loss,” they added.

Audiometric subanalysis

In an analysis of a subcohort of 3,749 women looking at audiometric thresholds for a more precise measure of hearing loss, women with osteoporosis or low bone density continued to show significantly worse hearing loss when treated with bisphosphonates compared to those without osteoporosis or low bone density.

However, there were no significant hearing loss differences among those with osteoporosis who did not take bisphosphonates versus those without osteoporosis.

The authors speculate that the use of bisphosphonates could have been indicative of more severe osteoporosis, hence the poorer audiometric thresholds.

In an interview, Dr. Curhan said the details of bisphosphonate use, such as type and duration, and their role in hearing loss should be further evaluated.

“Possibly, a potential influence of bisphosphonates on the relation of osteoporosis and hearing loss in humans may depend on the type, dose, and timing of bisphosphonate administration,” she observed. “This is an important question for further study.”

Mechanisms: Bone loss may extend to ear structures

In terms of the mechanisms linking osteoporosis itself to hearing loss, the authors noted that bone loss, in addition to compromising more prominent skeletal sites, could logically extend to bone-related structures in the ear.

“Bone mass at peripheral sites is correlated with bone mass at central sites, such as hip and spine, with correlation coefficients between 0.6 and 0.7,” they explained. “Plausibly, systemic bone demineralization could involve the temporal bone, the otic capsule, and the middle ear ossicles.”

They noted that hearing loss has been linked to other pathologic bone disorders, including otosclerosis and Paget disease.

Furthermore, imbalances in bone formation and resorption in osteoporosis may lead to alterations in ionic metabolism, which can lead to hearing loss.

Looking ahead, Dr. Curhan and colleagues plan to further examine whether calcium and vitamin D, which are associated with the prevention of osteoporosis, have a role in preventing hearing loss.

In the meantime, the findings underscore that clinicians treating patients with osteoporosis should routinely check patients’ hearing, Dr. Curhan said.

“Undetected and untreated hearing loss can adversely impact social interactions, physical and mental well-being, and daily life,” she said.

“Early detection of hearing loss offers greater opportunity for successful management and to learn strategies for rehabilitation and prevention of further progression.”

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with osteoporosis, low bone density, or a previous vertebral fracture show significant increases in the risk of hearing loss compared to those without osteoporosis, according to a new study with more than 3 decades of follow-up.

The use of bisphosphonate therapy did not alter the risk, the researchers found.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large longitudinal study to evaluate the relations of bone density, bisphosphonate use, fractures, and risk of hearing loss,” reported Sharon Curhan, MD, and colleagues in research published online in the Journal of the American Geriatric Society.

“In this large nationwide longitudinal study of nearly 144,000 women with up to 34 years of follow-up, we found that osteoporosis or low bone density was independently associated with higher risk of incident moderate or worse hearing loss,” the authors wrote.

“The magnitude of the elevated risk was similar among women who did and did not use bisphosphonates,” they added.

Participants were from the nurses’ health study and NHS II

With recent research suggesting a potential link between bisphosphonate use and prevention of noise-induced hearing loss in mice, Dr. Curhan, of the Channing Division of Network Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues turned to the large longitudinal cohorts of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), conducted from 1982 to 2016, and the Nurses’ Health Study II (NHS II), from 1995 to 2017.

In total, the primary analysis included 60,821 women in the NHS and 83,078 in the NHS II.

Women in the NHS were aged 36-61 years at baseline and 70-95 years at the end of follow-up, while in the NHS II, women were aged 31-48 years at baseline and 53-70 years at the end of follow-up.

After multivariate adjustment for key factors including age, race/ethnicity, oral hormone use, and a variety of other factors, women in the NHS with osteoporosis had an increased risk of moderate or worse hearing loss, as self-reported every 2 years, compared to those without osteoporosis (relative risk, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.19).

And in the NHS II, which also included data on low bone density, the risk of self-reported hearing loss was higher among those with osteoporosis or low bone density (RR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.40).

No significant differences were observed in hearing loss risk based on whether women were treated with bisphosphonates, with the mean duration of use of the medication being 5.8 years in the NHS and 3.4 years in the NHS II.

Those who sustained a vertebral fracture also had a higher risk of hearing loss in both studies (NHS: RR, 1.31; NHS II: RR, 1.39).

However, the increased risk of hearing loss was not observed with hip fracture.

“Our findings of up to a 40% higher risk among women with vertebral fracture, but not hip fracture, were intriguing and merit further study,” the authors noted.

“The discordant findings between these skeletal sites may reflect differences in composition and metabolism of bones in the spine and hip and could provide insight into the pathophysiological changes in the ear that may lead to hearing loss,” they added.

Audiometric subanalysis

In an analysis of a subcohort of 3,749 women looking at audiometric thresholds for a more precise measure of hearing loss, women with osteoporosis or low bone density continued to show significantly worse hearing loss when treated with bisphosphonates compared to those without osteoporosis or low bone density.

However, there were no significant hearing loss differences among those with osteoporosis who did not take bisphosphonates versus those without osteoporosis.

The authors speculate that the use of bisphosphonates could have been indicative of more severe osteoporosis, hence the poorer audiometric thresholds.

In an interview, Dr. Curhan said the details of bisphosphonate use, such as type and duration, and their role in hearing loss should be further evaluated.

“Possibly, a potential influence of bisphosphonates on the relation of osteoporosis and hearing loss in humans may depend on the type, dose, and timing of bisphosphonate administration,” she observed. “This is an important question for further study.”

Mechanisms: Bone loss may extend to ear structures

In terms of the mechanisms linking osteoporosis itself to hearing loss, the authors noted that bone loss, in addition to compromising more prominent skeletal sites, could logically extend to bone-related structures in the ear.

“Bone mass at peripheral sites is correlated with bone mass at central sites, such as hip and spine, with correlation coefficients between 0.6 and 0.7,” they explained. “Plausibly, systemic bone demineralization could involve the temporal bone, the otic capsule, and the middle ear ossicles.”

They noted that hearing loss has been linked to other pathologic bone disorders, including otosclerosis and Paget disease.

Furthermore, imbalances in bone formation and resorption in osteoporosis may lead to alterations in ionic metabolism, which can lead to hearing loss.

Looking ahead, Dr. Curhan and colleagues plan to further examine whether calcium and vitamin D, which are associated with the prevention of osteoporosis, have a role in preventing hearing loss.

In the meantime, the findings underscore that clinicians treating patients with osteoporosis should routinely check patients’ hearing, Dr. Curhan said.

“Undetected and untreated hearing loss can adversely impact social interactions, physical and mental well-being, and daily life,” she said.

“Early detection of hearing loss offers greater opportunity for successful management and to learn strategies for rehabilitation and prevention of further progression.”

The study received support from the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Combination therapy may benefit patients with migraine

, according to a large retrospective analysis. The results lend hope that the combination may be synergistic, according to Andrew Blumenfeld, MD, director of the Headache Center of Southern California in Carlsbad. Dr. Blumenfeld presented at the American Headache Society’s 2021 annual meeting. The study was published online April 21 in Pain Therapy.

The retrospective analysis showed a 4-day reduction in headache days per month. In contrast, in the pivotal study for erenumab, the most commonly used anti-CGRP antibody among subjects in the study, showed a 2-day benefit in a subanalysis of patients who had failed at least two oral preventives.

There is mechanistic evidence to suggest the two therapies could be synergistic. OnabotulinumtoxinA is believed to inhibit the release of CGRP, and antibodies reduce CGRP levels. OnabotulinumtoxinA prevents activation of C-fibers in the trigeminal sensory afferents, but does not affect A-delta fibers.

On the other hand, most data indicate that the anti-CGRP antibody fremanezumab prevents activation of A-delta but not C-fibers, and a recent review argues that CGRP antibody nonresponders may have migraines driven by C-fibers or other pathways. “Thus, concomitant use of medications blocking the activation of meningeal C-fibers may provide a synergistic effect on the trigeminal nociceptive pathway,” the authors wrote.

Study finding match clinical practice

The results of the new study strengthen the case that the combination is effective, though proof would require prospective, randomized trials. “I think that it really gives credibility to what we are seeing in practice, which is that combined therapy often is much better than therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA alone, said Deborah Friedman, MD, MPH, who was asked to comment on the findings. Dr. Friedman is professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Texas, Dallas.

The extra 4 migraine-free days per month is a significant benefit, said Stewart Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “It’s an extra month and a half of no disability per year, and that’s on top of what onabotulinumtoxinA does. So it’s really a very important clinical finding,” Dr. Tepper said in an interview.

Many insurance companies refuse to pay for the combination therapy, despite the fact that relatively few migraine patients would likely seek it out, according to Dr. Friedman. “It’s just kind of a shame,” she said.

Insurance companies often object that the combination therapy is experimental, despite the widespread use of combination therapies in migraine. “It’s no more experimental in my opinion than any other combination of medications that we use. For people that have severe migraine, we use combination therapy all the time,” said Dr. Friedman.

Improvements with combination therapy

The study was a chart review of 257 patients who started on onabotulinumtoxinA and later initiated anti-CGRP antibody therapy. A total of 104 completed four visits after initiation of anti-CGRP antibody therapy (completers). Before starting any therapy, patients reported an average of 21 headache days per month in the overall group, and 22 among completers. That frequency dropped to 12 in both groups after onabotulinumtoxinA therapy (overall group difference, –9 days; 95% confidence interval, –8 to –11 days; completers group difference, –10; 95% CI, –7 to –12 days).

A total of 77.8% of subjects in the overall cohort took erenumab, 16.3% took galcanezumab, and 5.8% took fremanezumab. In the completers cohort, the percentages were 84.5%, 10.7%, and 4.9%, respectively.

Compared with baseline, both completers and noncompleters had clinically significant improvements in disability, as measured by at least a 5-point improvement in Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score at the 3-month visit (–5.8 for completers and –6.3 for the overall cohort group), the 6-month visit (–6.6 and –11.1), the 9-month visit (–8.3 and –6.1), and 1 year (–12.7 and –8.4).

At the first visit, 33.0% of completers had at least a 5-point reduction in MIDAS, as did 36.0% of the overall cohort group, and the trend continued at 6 months (39.8% and 45.1%), 9 months (43.7% and 43.7%), and at 1 year (45.3% and 44.8%).

The study was funded by Allergan. Dr. Blumenfeld has served on advisory boards for Aeon, AbbVie, Amgen, Alder, Biohaven, Teva, Supernus, Promius, Eaglet, and Lilly, and has received funding for speaking from AbbVie, Amgen, Pernix, Supernus, Depomed, Avanir, Promius, Teva, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Theranica. Dr. Tepper has consulted for Teva. Dr. Friedman has been on the advisory board for Allergan, Amgen, Lundbeck, Eli Lilly, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, and has received grant support from Allergan and Eli Lilly.

, according to a large retrospective analysis. The results lend hope that the combination may be synergistic, according to Andrew Blumenfeld, MD, director of the Headache Center of Southern California in Carlsbad. Dr. Blumenfeld presented at the American Headache Society’s 2021 annual meeting. The study was published online April 21 in Pain Therapy.

The retrospective analysis showed a 4-day reduction in headache days per month. In contrast, in the pivotal study for erenumab, the most commonly used anti-CGRP antibody among subjects in the study, showed a 2-day benefit in a subanalysis of patients who had failed at least two oral preventives.

There is mechanistic evidence to suggest the two therapies could be synergistic. OnabotulinumtoxinA is believed to inhibit the release of CGRP, and antibodies reduce CGRP levels. OnabotulinumtoxinA prevents activation of C-fibers in the trigeminal sensory afferents, but does not affect A-delta fibers.

On the other hand, most data indicate that the anti-CGRP antibody fremanezumab prevents activation of A-delta but not C-fibers, and a recent review argues that CGRP antibody nonresponders may have migraines driven by C-fibers or other pathways. “Thus, concomitant use of medications blocking the activation of meningeal C-fibers may provide a synergistic effect on the trigeminal nociceptive pathway,” the authors wrote.

Study finding match clinical practice

The results of the new study strengthen the case that the combination is effective, though proof would require prospective, randomized trials. “I think that it really gives credibility to what we are seeing in practice, which is that combined therapy often is much better than therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA alone, said Deborah Friedman, MD, MPH, who was asked to comment on the findings. Dr. Friedman is professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Texas, Dallas.

The extra 4 migraine-free days per month is a significant benefit, said Stewart Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “It’s an extra month and a half of no disability per year, and that’s on top of what onabotulinumtoxinA does. So it’s really a very important clinical finding,” Dr. Tepper said in an interview.

Many insurance companies refuse to pay for the combination therapy, despite the fact that relatively few migraine patients would likely seek it out, according to Dr. Friedman. “It’s just kind of a shame,” she said.

Insurance companies often object that the combination therapy is experimental, despite the widespread use of combination therapies in migraine. “It’s no more experimental in my opinion than any other combination of medications that we use. For people that have severe migraine, we use combination therapy all the time,” said Dr. Friedman.

Improvements with combination therapy

The study was a chart review of 257 patients who started on onabotulinumtoxinA and later initiated anti-CGRP antibody therapy. A total of 104 completed four visits after initiation of anti-CGRP antibody therapy (completers). Before starting any therapy, patients reported an average of 21 headache days per month in the overall group, and 22 among completers. That frequency dropped to 12 in both groups after onabotulinumtoxinA therapy (overall group difference, –9 days; 95% confidence interval, –8 to –11 days; completers group difference, –10; 95% CI, –7 to –12 days).

A total of 77.8% of subjects in the overall cohort took erenumab, 16.3% took galcanezumab, and 5.8% took fremanezumab. In the completers cohort, the percentages were 84.5%, 10.7%, and 4.9%, respectively.

Compared with baseline, both completers and noncompleters had clinically significant improvements in disability, as measured by at least a 5-point improvement in Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score at the 3-month visit (–5.8 for completers and –6.3 for the overall cohort group), the 6-month visit (–6.6 and –11.1), the 9-month visit (–8.3 and –6.1), and 1 year (–12.7 and –8.4).

At the first visit, 33.0% of completers had at least a 5-point reduction in MIDAS, as did 36.0% of the overall cohort group, and the trend continued at 6 months (39.8% and 45.1%), 9 months (43.7% and 43.7%), and at 1 year (45.3% and 44.8%).

The study was funded by Allergan. Dr. Blumenfeld has served on advisory boards for Aeon, AbbVie, Amgen, Alder, Biohaven, Teva, Supernus, Promius, Eaglet, and Lilly, and has received funding for speaking from AbbVie, Amgen, Pernix, Supernus, Depomed, Avanir, Promius, Teva, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Theranica. Dr. Tepper has consulted for Teva. Dr. Friedman has been on the advisory board for Allergan, Amgen, Lundbeck, Eli Lilly, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, and has received grant support from Allergan and Eli Lilly.

, according to a large retrospective analysis. The results lend hope that the combination may be synergistic, according to Andrew Blumenfeld, MD, director of the Headache Center of Southern California in Carlsbad. Dr. Blumenfeld presented at the American Headache Society’s 2021 annual meeting. The study was published online April 21 in Pain Therapy.

The retrospective analysis showed a 4-day reduction in headache days per month. In contrast, in the pivotal study for erenumab, the most commonly used anti-CGRP antibody among subjects in the study, showed a 2-day benefit in a subanalysis of patients who had failed at least two oral preventives.

There is mechanistic evidence to suggest the two therapies could be synergistic. OnabotulinumtoxinA is believed to inhibit the release of CGRP, and antibodies reduce CGRP levels. OnabotulinumtoxinA prevents activation of C-fibers in the trigeminal sensory afferents, but does not affect A-delta fibers.

On the other hand, most data indicate that the anti-CGRP antibody fremanezumab prevents activation of A-delta but not C-fibers, and a recent review argues that CGRP antibody nonresponders may have migraines driven by C-fibers or other pathways. “Thus, concomitant use of medications blocking the activation of meningeal C-fibers may provide a synergistic effect on the trigeminal nociceptive pathway,” the authors wrote.

Study finding match clinical practice

The results of the new study strengthen the case that the combination is effective, though proof would require prospective, randomized trials. “I think that it really gives credibility to what we are seeing in practice, which is that combined therapy often is much better than therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA alone, said Deborah Friedman, MD, MPH, who was asked to comment on the findings. Dr. Friedman is professor of neurology and ophthalmology at the University of Texas, Dallas.

The extra 4 migraine-free days per month is a significant benefit, said Stewart Tepper, MD, professor of neurology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H. “It’s an extra month and a half of no disability per year, and that’s on top of what onabotulinumtoxinA does. So it’s really a very important clinical finding,” Dr. Tepper said in an interview.

Many insurance companies refuse to pay for the combination therapy, despite the fact that relatively few migraine patients would likely seek it out, according to Dr. Friedman. “It’s just kind of a shame,” she said.

Insurance companies often object that the combination therapy is experimental, despite the widespread use of combination therapies in migraine. “It’s no more experimental in my opinion than any other combination of medications that we use. For people that have severe migraine, we use combination therapy all the time,” said Dr. Friedman.

Improvements with combination therapy

The study was a chart review of 257 patients who started on onabotulinumtoxinA and later initiated anti-CGRP antibody therapy. A total of 104 completed four visits after initiation of anti-CGRP antibody therapy (completers). Before starting any therapy, patients reported an average of 21 headache days per month in the overall group, and 22 among completers. That frequency dropped to 12 in both groups after onabotulinumtoxinA therapy (overall group difference, –9 days; 95% confidence interval, –8 to –11 days; completers group difference, –10; 95% CI, –7 to –12 days).

A total of 77.8% of subjects in the overall cohort took erenumab, 16.3% took galcanezumab, and 5.8% took fremanezumab. In the completers cohort, the percentages were 84.5%, 10.7%, and 4.9%, respectively.

Compared with baseline, both completers and noncompleters had clinically significant improvements in disability, as measured by at least a 5-point improvement in Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score at the 3-month visit (–5.8 for completers and –6.3 for the overall cohort group), the 6-month visit (–6.6 and –11.1), the 9-month visit (–8.3 and –6.1), and 1 year (–12.7 and –8.4).

At the first visit, 33.0% of completers had at least a 5-point reduction in MIDAS, as did 36.0% of the overall cohort group, and the trend continued at 6 months (39.8% and 45.1%), 9 months (43.7% and 43.7%), and at 1 year (45.3% and 44.8%).

The study was funded by Allergan. Dr. Blumenfeld has served on advisory boards for Aeon, AbbVie, Amgen, Alder, Biohaven, Teva, Supernus, Promius, Eaglet, and Lilly, and has received funding for speaking from AbbVie, Amgen, Pernix, Supernus, Depomed, Avanir, Promius, Teva, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, and Theranica. Dr. Tepper has consulted for Teva. Dr. Friedman has been on the advisory board for Allergan, Amgen, Lundbeck, Eli Lilly, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, and has received grant support from Allergan and Eli Lilly.

FROM AHS 2021

Improving racial and gender equity in pediatric HM programs

Converge 2021 session

Racial and Gender Equity in Your PHM Program

Presenters

Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, and Vanessa N. Durand, DO, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Ganem, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and director of pediatric hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, and Dr. Durand, assistant professor of pediatrics at Drexel University and pediatric hospitalist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, presented an engaging session regarding gender equity in the workplace during SHM Converge 2021.

Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand first presented data to illustrate the gender equity problem. They touched on the mental burden underrepresented minorities face professionally. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand discussed cognitive biases, defined allyship, sponsorship, and mentorship and shared how to distinguish between the three. They concluded their session with concrete ways to narrow gaps in equity in hospital medicine programs.

The highlights of this session included evidence-based “best-practices” that pediatric hospital medicine divisions can adopt. One important theme was regarding metrics. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand shared how important it is to evaluate divisions for pay and diversity gaps. Armed with these data, programs can be more effective in developing solutions. Some solutions provided by the presenters included “blind” interviews where traditional “cognitive metrics” (i.e., board scores) are not shared with interviewers to minimize anchoring and confirmation biases. Instead, interviewers should focus on the experiences and attributes of the job that the applicant can hopefully embody. This could be accomplished using a holistic review tool from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

One of the most powerful ideas shared in this session was a quote from a Harvard student shown in a video regarding bias and racism where he said, “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscious stupidity.” Changes will only happen if we make them happen.

Key takeaways

- Racial and gender equity are problems that are undeniable, even in pediatrics.

- Be wary of conscious biases and the mental burden placed unfairly on underrepresented minorities in your institution.

- Becoming an amplifier, a sponsor, or a champion are ways to make a small individual difference.

- Measure your program’s data and commit to making change using evidence-based actions and assessments aimed at decreasing bias and increasing equity.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic Review. 2021. www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Dr. Singh is a board-certified pediatric hospitalist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, both in Palo Alto, Calif. He is a native Texan living in the San Francisco Bay area with his wife and two young boys. His nonclinical passions include bedside communication and inpatient health care information technology.

Converge 2021 session

Racial and Gender Equity in Your PHM Program

Presenters

Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, and Vanessa N. Durand, DO, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Ganem, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and director of pediatric hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, and Dr. Durand, assistant professor of pediatrics at Drexel University and pediatric hospitalist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, presented an engaging session regarding gender equity in the workplace during SHM Converge 2021.

Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand first presented data to illustrate the gender equity problem. They touched on the mental burden underrepresented minorities face professionally. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand discussed cognitive biases, defined allyship, sponsorship, and mentorship and shared how to distinguish between the three. They concluded their session with concrete ways to narrow gaps in equity in hospital medicine programs.

The highlights of this session included evidence-based “best-practices” that pediatric hospital medicine divisions can adopt. One important theme was regarding metrics. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand shared how important it is to evaluate divisions for pay and diversity gaps. Armed with these data, programs can be more effective in developing solutions. Some solutions provided by the presenters included “blind” interviews where traditional “cognitive metrics” (i.e., board scores) are not shared with interviewers to minimize anchoring and confirmation biases. Instead, interviewers should focus on the experiences and attributes of the job that the applicant can hopefully embody. This could be accomplished using a holistic review tool from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

One of the most powerful ideas shared in this session was a quote from a Harvard student shown in a video regarding bias and racism where he said, “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscious stupidity.” Changes will only happen if we make them happen.

Key takeaways

- Racial and gender equity are problems that are undeniable, even in pediatrics.

- Be wary of conscious biases and the mental burden placed unfairly on underrepresented minorities in your institution.

- Becoming an amplifier, a sponsor, or a champion are ways to make a small individual difference.

- Measure your program’s data and commit to making change using evidence-based actions and assessments aimed at decreasing bias and increasing equity.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic Review. 2021. www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Dr. Singh is a board-certified pediatric hospitalist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, both in Palo Alto, Calif. He is a native Texan living in the San Francisco Bay area with his wife and two young boys. His nonclinical passions include bedside communication and inpatient health care information technology.

Converge 2021 session

Racial and Gender Equity in Your PHM Program

Presenters

Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, and Vanessa N. Durand, DO, FAAP

Session summary

Dr. Ganem, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Texas at Austin and director of pediatric hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, and Dr. Durand, assistant professor of pediatrics at Drexel University and pediatric hospitalist at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Philadelphia, presented an engaging session regarding gender equity in the workplace during SHM Converge 2021.

Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand first presented data to illustrate the gender equity problem. They touched on the mental burden underrepresented minorities face professionally. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand discussed cognitive biases, defined allyship, sponsorship, and mentorship and shared how to distinguish between the three. They concluded their session with concrete ways to narrow gaps in equity in hospital medicine programs.

The highlights of this session included evidence-based “best-practices” that pediatric hospital medicine divisions can adopt. One important theme was regarding metrics. Dr. Ganem and Dr. Durand shared how important it is to evaluate divisions for pay and diversity gaps. Armed with these data, programs can be more effective in developing solutions. Some solutions provided by the presenters included “blind” interviews where traditional “cognitive metrics” (i.e., board scores) are not shared with interviewers to minimize anchoring and confirmation biases. Instead, interviewers should focus on the experiences and attributes of the job that the applicant can hopefully embody. This could be accomplished using a holistic review tool from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

One of the most powerful ideas shared in this session was a quote from a Harvard student shown in a video regarding bias and racism where he said, “Nothing in all the world is more dangerous than sincere ignorance and conscious stupidity.” Changes will only happen if we make them happen.

Key takeaways

- Racial and gender equity are problems that are undeniable, even in pediatrics.

- Be wary of conscious biases and the mental burden placed unfairly on underrepresented minorities in your institution.

- Becoming an amplifier, a sponsor, or a champion are ways to make a small individual difference.

- Measure your program’s data and commit to making change using evidence-based actions and assessments aimed at decreasing bias and increasing equity.

References

Association of American Medical Colleges. Holistic Review. 2021. www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review.

Dr. Singh is a board-certified pediatric hospitalist at Stanford University and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, both in Palo Alto, Calif. He is a native Texan living in the San Francisco Bay area with his wife and two young boys. His nonclinical passions include bedside communication and inpatient health care information technology.

FROM SHM CONVERGE 2021

Schizophrenia meds a key contributor to cognitive impairment

Anticholinergic medication burden from antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychotropics has a cumulative effect of worsening cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia, new research indicates.

“The link between long-term use of anticholinergic medications and cognitive impairment is well-known and growing,” lead researcher Yash Joshi, MD, department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview.

“While this association is relevant for everyone, it is particularly important for those living with schizophrenia, who often struggle with cognitive difficulties conferred by the illness itself,” said Dr. Joshi.

“Brain health in schizophrenia is a game of inches, and even small negative effects on cognitive functioning through anticholinergic medication burden may have large impacts on patients’ lives,” he added.

The study was published online May 14 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

‘Striking’ results

Dr. Joshi and colleagues set out to comprehensively characterize how the cumulative anticholinergic burden from different classes of medications affect cognition in patients with schizophrenia.

They assessed medical records, including all prescribed medications, for 1,120 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

For each participant, prescribed medications were rated and summed using a modified anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) scale. Cognitive functioning was assessed by performance on domains of the Penn Computerized Neurocognitive Battery (PCNB).

The investigators found that 63% of participants had an ACB score of at least 3, which is “striking,” said Dr. Joshi, given that previous studies have shown that an ACB score of 3 in a healthy, older adult is associated with cognitive dysfunction and a 50% increased risk of developing dementia.

About one-quarter of participants had an ACB score of 6 or higher.

Yet, these high ACB scores are not hard to achieve in routine psychiatric care, the researchers note.

For example, a patient taking olanzapine daily to ease symptoms of psychosis would have an ACB score of 3; if hydroxyzine was added for anxiety or insomnia, the patient’s ACB score would rise to 6, they point out.

Lightening the load

Antipsychotics contributed more than half of the anticholinergic burden, while traditional anticholinergics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and benzodiazepines accounted for the remainder.

“It is easy even for well-meaning clinicians to inadvertently contribute to anticholinergic medication burden through routine and appropriate care. The unique finding here is that this burden comes from medications we don’t usually think of as typical anticholinergic agents,” senior author Gregory Light, PhD, with University of California, San Diego, said in a news release.

Anticholinergic medication burden was significantly associated with generalized impairments in cognitive functioning across all cognitive domains on the PCNB with comparable magnitude and after controlling for multiple proxies of functioning or disease severity.

Higher anticholinergic medication burden was associated with worse cognitive performance. The PCNB global cognitive averages for none, low, average, high, and very high anticholinergic burdens were, respectively (in z values), -0.51, -0.70, -0.85, -0.96, and -1.15.

The results suggest “total cumulative anticholinergic burden – rather than anticholinergic burden attributable to a specific antipsychotic or psychotropic medication class – is a key contributor to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia,” the researchers write.

“The results imply that if it is clinically safe and practical,” said Dr. Joshi.

“This may be accomplished by reducing overall polypharmacy or transitioning to equivalent medications with lower overall anticholinergic burden. While ‘traditional’ anticholinergic medications should always be scrutinized, all medications should be carefully evaluated to understand whether they contribute to cumulative anticholinergic medication burden,” he added.

Confirmatory findings

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jessica Gannon, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said the author’s findings “aren’t surprising, but the work that they did was pretty comprehensive [and] further fleshed out some of our concerns about the impact of anticholinergics on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia.”

“We certainly have to use some of these medications for patients, like antipsychotics that do have some anticholinergic burden associated with them. We don’t really have other options,” Dr. Gannon said.

“But certainly I think this calls us to be better stewards of medication in general. And when we prescribe for comorbid conditions, like depression and anxiety, we should be careful in our prescribing practices, try not to prescribe an anticholinergic medication, and, if they have been prescribed, to deprescribe them,” Dr. Gannon added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health; the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation; the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; the VISN-22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Joshi and Dr. Gannon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anticholinergic medication burden from antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychotropics has a cumulative effect of worsening cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia, new research indicates.

“The link between long-term use of anticholinergic medications and cognitive impairment is well-known and growing,” lead researcher Yash Joshi, MD, department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview.

“While this association is relevant for everyone, it is particularly important for those living with schizophrenia, who often struggle with cognitive difficulties conferred by the illness itself,” said Dr. Joshi.

“Brain health in schizophrenia is a game of inches, and even small negative effects on cognitive functioning through anticholinergic medication burden may have large impacts on patients’ lives,” he added.

The study was published online May 14 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

‘Striking’ results

Dr. Joshi and colleagues set out to comprehensively characterize how the cumulative anticholinergic burden from different classes of medications affect cognition in patients with schizophrenia.

They assessed medical records, including all prescribed medications, for 1,120 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

For each participant, prescribed medications were rated and summed using a modified anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) scale. Cognitive functioning was assessed by performance on domains of the Penn Computerized Neurocognitive Battery (PCNB).

The investigators found that 63% of participants had an ACB score of at least 3, which is “striking,” said Dr. Joshi, given that previous studies have shown that an ACB score of 3 in a healthy, older adult is associated with cognitive dysfunction and a 50% increased risk of developing dementia.

About one-quarter of participants had an ACB score of 6 or higher.

Yet, these high ACB scores are not hard to achieve in routine psychiatric care, the researchers note.

For example, a patient taking olanzapine daily to ease symptoms of psychosis would have an ACB score of 3; if hydroxyzine was added for anxiety or insomnia, the patient’s ACB score would rise to 6, they point out.

Lightening the load

Antipsychotics contributed more than half of the anticholinergic burden, while traditional anticholinergics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and benzodiazepines accounted for the remainder.

“It is easy even for well-meaning clinicians to inadvertently contribute to anticholinergic medication burden through routine and appropriate care. The unique finding here is that this burden comes from medications we don’t usually think of as typical anticholinergic agents,” senior author Gregory Light, PhD, with University of California, San Diego, said in a news release.

Anticholinergic medication burden was significantly associated with generalized impairments in cognitive functioning across all cognitive domains on the PCNB with comparable magnitude and after controlling for multiple proxies of functioning or disease severity.

Higher anticholinergic medication burden was associated with worse cognitive performance. The PCNB global cognitive averages for none, low, average, high, and very high anticholinergic burdens were, respectively (in z values), -0.51, -0.70, -0.85, -0.96, and -1.15.

The results suggest “total cumulative anticholinergic burden – rather than anticholinergic burden attributable to a specific antipsychotic or psychotropic medication class – is a key contributor to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia,” the researchers write.

“The results imply that if it is clinically safe and practical,” said Dr. Joshi.

“This may be accomplished by reducing overall polypharmacy or transitioning to equivalent medications with lower overall anticholinergic burden. While ‘traditional’ anticholinergic medications should always be scrutinized, all medications should be carefully evaluated to understand whether they contribute to cumulative anticholinergic medication burden,” he added.

Confirmatory findings

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jessica Gannon, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said the author’s findings “aren’t surprising, but the work that they did was pretty comprehensive [and] further fleshed out some of our concerns about the impact of anticholinergics on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia.”

“We certainly have to use some of these medications for patients, like antipsychotics that do have some anticholinergic burden associated with them. We don’t really have other options,” Dr. Gannon said.

“But certainly I think this calls us to be better stewards of medication in general. And when we prescribe for comorbid conditions, like depression and anxiety, we should be careful in our prescribing practices, try not to prescribe an anticholinergic medication, and, if they have been prescribed, to deprescribe them,” Dr. Gannon added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health; the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation; the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; the VISN-22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Joshi and Dr. Gannon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anticholinergic medication burden from antipsychotics, antidepressants, and other psychotropics has a cumulative effect of worsening cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia, new research indicates.

“The link between long-term use of anticholinergic medications and cognitive impairment is well-known and growing,” lead researcher Yash Joshi, MD, department of psychiatry, University of California, San Diego, said in an interview.

“While this association is relevant for everyone, it is particularly important for those living with schizophrenia, who often struggle with cognitive difficulties conferred by the illness itself,” said Dr. Joshi.

“Brain health in schizophrenia is a game of inches, and even small negative effects on cognitive functioning through anticholinergic medication burden may have large impacts on patients’ lives,” he added.

The study was published online May 14 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

‘Striking’ results

Dr. Joshi and colleagues set out to comprehensively characterize how the cumulative anticholinergic burden from different classes of medications affect cognition in patients with schizophrenia.

They assessed medical records, including all prescribed medications, for 1,120 adults with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

For each participant, prescribed medications were rated and summed using a modified anticholinergic cognitive burden (ACB) scale. Cognitive functioning was assessed by performance on domains of the Penn Computerized Neurocognitive Battery (PCNB).

The investigators found that 63% of participants had an ACB score of at least 3, which is “striking,” said Dr. Joshi, given that previous studies have shown that an ACB score of 3 in a healthy, older adult is associated with cognitive dysfunction and a 50% increased risk of developing dementia.

About one-quarter of participants had an ACB score of 6 or higher.

Yet, these high ACB scores are not hard to achieve in routine psychiatric care, the researchers note.

For example, a patient taking olanzapine daily to ease symptoms of psychosis would have an ACB score of 3; if hydroxyzine was added for anxiety or insomnia, the patient’s ACB score would rise to 6, they point out.

Lightening the load

Antipsychotics contributed more than half of the anticholinergic burden, while traditional anticholinergics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and benzodiazepines accounted for the remainder.

“It is easy even for well-meaning clinicians to inadvertently contribute to anticholinergic medication burden through routine and appropriate care. The unique finding here is that this burden comes from medications we don’t usually think of as typical anticholinergic agents,” senior author Gregory Light, PhD, with University of California, San Diego, said in a news release.

Anticholinergic medication burden was significantly associated with generalized impairments in cognitive functioning across all cognitive domains on the PCNB with comparable magnitude and after controlling for multiple proxies of functioning or disease severity.

Higher anticholinergic medication burden was associated with worse cognitive performance. The PCNB global cognitive averages for none, low, average, high, and very high anticholinergic burdens were, respectively (in z values), -0.51, -0.70, -0.85, -0.96, and -1.15.

The results suggest “total cumulative anticholinergic burden – rather than anticholinergic burden attributable to a specific antipsychotic or psychotropic medication class – is a key contributor to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia,” the researchers write.

“The results imply that if it is clinically safe and practical,” said Dr. Joshi.

“This may be accomplished by reducing overall polypharmacy or transitioning to equivalent medications with lower overall anticholinergic burden. While ‘traditional’ anticholinergic medications should always be scrutinized, all medications should be carefully evaluated to understand whether they contribute to cumulative anticholinergic medication burden,” he added.

Confirmatory findings

Commenting on the study for this news organization, Jessica Gannon, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, said the author’s findings “aren’t surprising, but the work that they did was pretty comprehensive [and] further fleshed out some of our concerns about the impact of anticholinergics on cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia.”

“We certainly have to use some of these medications for patients, like antipsychotics that do have some anticholinergic burden associated with them. We don’t really have other options,” Dr. Gannon said.

“But certainly I think this calls us to be better stewards of medication in general. And when we prescribe for comorbid conditions, like depression and anxiety, we should be careful in our prescribing practices, try not to prescribe an anticholinergic medication, and, if they have been prescribed, to deprescribe them,” Dr. Gannon added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health; the Sidney R. Baer, Jr. Foundation; the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation; the VISN-22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Joshi and Dr. Gannon have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Choosing the right R-CHOP dosage for elderly patients with DLBCL

Physicians often face the choice of whether to treat elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with a full or reduced dose intensity (DI) of R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone + rituximab), according to Edward J. Bataillard of the Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust, London, and colleagues.

To address this issue, the researchers conducted a systematic review assessing the impact of R-CHOP DI on DLBCL survival outcomes, according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines. They found that greater than 80 years of age is an important cutoff for treating patients with a reduced R-CHOP dosage, according to their results, published in Blood Advances (2021;5[9]:2426-37).

Cutoff at 80 years of age

Their final review comprised 13 studies including 5,188 patients. Overall, the lower DI (intended or relative) was associated with inferior survival in seven of nine studies reporting crude survival analyses. In addition, most studies and those larger studies of higher quality showed poorer outcomes associated with reduced R-CHOP DI.

However, in subgroups of patients aged 80 years or more, survival was not consistently affected by the use of lower dosage R-CHOP, according to the researchers.

“We found evidence of improved survival with higher RDIs (up to R-CHOP-21) in those aged < 80 years, but the literature to date does not support full-dose intensity in those 80 years [or older],” they stated.

However, the researchers concluded that: “In the absence of improved options beyond R-CHOP in DLBCL over the past 20 years, prospective studies of DI are warranted, despite the recognized challenges involved.”

Two of the authors reported being previously employed by Roche. A third served as a consultant and adviser and received honoraria from Roche and other pharmaceutical companies. Several authors reported disclosures related to multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Physicians often face the choice of whether to treat elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with a full or reduced dose intensity (DI) of R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone + rituximab), according to Edward J. Bataillard of the Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust, London, and colleagues.

To address this issue, the researchers conducted a systematic review assessing the impact of R-CHOP DI on DLBCL survival outcomes, according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines. They found that greater than 80 years of age is an important cutoff for treating patients with a reduced R-CHOP dosage, according to their results, published in Blood Advances (2021;5[9]:2426-37).

Cutoff at 80 years of age

Their final review comprised 13 studies including 5,188 patients. Overall, the lower DI (intended or relative) was associated with inferior survival in seven of nine studies reporting crude survival analyses. In addition, most studies and those larger studies of higher quality showed poorer outcomes associated with reduced R-CHOP DI.

However, in subgroups of patients aged 80 years or more, survival was not consistently affected by the use of lower dosage R-CHOP, according to the researchers.

“We found evidence of improved survival with higher RDIs (up to R-CHOP-21) in those aged < 80 years, but the literature to date does not support full-dose intensity in those 80 years [or older],” they stated.

However, the researchers concluded that: “In the absence of improved options beyond R-CHOP in DLBCL over the past 20 years, prospective studies of DI are warranted, despite the recognized challenges involved.”

Two of the authors reported being previously employed by Roche. A third served as a consultant and adviser and received honoraria from Roche and other pharmaceutical companies. Several authors reported disclosures related to multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

Physicians often face the choice of whether to treat elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with a full or reduced dose intensity (DI) of R-CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone + rituximab), according to Edward J. Bataillard of the Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service Trust, London, and colleagues.

To address this issue, the researchers conducted a systematic review assessing the impact of R-CHOP DI on DLBCL survival outcomes, according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines. They found that greater than 80 years of age is an important cutoff for treating patients with a reduced R-CHOP dosage, according to their results, published in Blood Advances (2021;5[9]:2426-37).

Cutoff at 80 years of age

Their final review comprised 13 studies including 5,188 patients. Overall, the lower DI (intended or relative) was associated with inferior survival in seven of nine studies reporting crude survival analyses. In addition, most studies and those larger studies of higher quality showed poorer outcomes associated with reduced R-CHOP DI.

However, in subgroups of patients aged 80 years or more, survival was not consistently affected by the use of lower dosage R-CHOP, according to the researchers.

“We found evidence of improved survival with higher RDIs (up to R-CHOP-21) in those aged < 80 years, but the literature to date does not support full-dose intensity in those 80 years [or older],” they stated.

However, the researchers concluded that: “In the absence of improved options beyond R-CHOP in DLBCL over the past 20 years, prospective studies of DI are warranted, despite the recognized challenges involved.”

Two of the authors reported being previously employed by Roche. A third served as a consultant and adviser and received honoraria from Roche and other pharmaceutical companies. Several authors reported disclosures related to multiple other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

Outcomes Following Implementation of a Hospital-Wide, Multicomponent Delirium Care Pathway

Delirium is an acute disturbance in mental status characterized by fluctuations in cognition and attention that affects more than 2.6 million hospitalized older adults in the United States annually, a rate that is expected to increase as the population ages.1-4 Hospital-acquired delirium is associated with poor outcomes, including prolonged hospital length of stay (LOS), loss of independence, cognitive impairment, and even death.5-10 Individuals who develop delirium do poorly after hospital discharge and are more likely to be readmitted within 30 days.11 Approximately 30% to 40% of hospital-acquired delirium cases are preventable.10,12 However, programs designed to prevent delirium and associated complications, such as increased LOS, have demonstrated variable success.12-14 Many studies are limited by small sample sizes, lack of generalizability to different hospitalized patient populations, poor adherence, or reliance on outside funding.12,13,15-18

Delirium prevention programs face several challenges because delirium could be caused by a variety of risk factors and precipitants.19,20 Some risk factors that occur frequently among hospitalized patients can be mitigated, such as sensory impairment, immobility from physical restraints or urinary catheters, and polypharmacy.20,21 Effective delirium care pathways targeting these risk factors must be multifaceted, interdisciplinary, and interprofessional. Accurate risk assessment is critical to allocate resources to high-risk patients. Delirium affects patients in all medical and surgical disciplines, and often is underdiagnosed.19,22 Comprehensive screening is necessary to identify cases early and track outcomes, and educational efforts must reach all providers in the hospital. These challenges require a systematic, pragmatic approach to change.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between a delirium care pathway and clinical outcomes for hospitalized patients. We hypothesized that this program would be associated with reduced hospital LOS, with secondary benefits to hospitalization costs, odds of 30-day readmission, and delirium rates.

METHODS

Study Design

In this retrospective cohort study, we compared clinical outcomes the year before and after implementation of a delirium care pathway across seven hospital units. The study period spanned October 1, 2015, through February 28, 2019. The study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (#13-12500).

Multicomponent Delirium Care Pathway

The delirium care pathway was developed collaboratively among geriatrics, hospital medicine, neurology, anesthesiology, surgery, and psychiatry services, with an interprofessional team of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and physical and occupational therapists. This pathway was implemented in units consecutively, approximately every 4 months in the following order: neurosciences, medicine, cardiology, general surgery, specialty surgery, hematology-oncology, and transplant. The same implementation education protocols were performed in each unit. The pathway consisted of several components targeting delirium prevention and management (Appendix Figure 1 and Appendix Figure 2). Systematic screening for delirium was introduced as part of the multicomponent intervention. Nursing staff assessed each patient’s risk of developing delirium at admission using the AWOL score, a validated delirium prediction tool.23 AWOL consists of: patient Age, spelling “World” backwards correctly, Orientation, and assessment of iLlness severity by the nurse. For patients who spoke a language other than English, spelling of “world” backwards was translated to his or her primary language, or if this was not possible, the task was modified to serial 7s (subtracting 7 from 100 in a serial fashion). This modification has been validated for use in other languages.24 Patients at high risk for delirium based on an AWOL score ≥2 received a multidisciplinary intervention with four components: (1) notifying the primary team by pager and electronic medical record (EMR), (2) a nurse-led, evidence-based, nonpharmacologic multicomponent intervention,25 (3) placement of a delirium order set by the physician, and (4) review of medications by the unit pharmacist who adjusted administration timing to occur during waking hours and placed a note in the EMR notifying the primary team of potentially deliriogenic medications. The delirium order set reinforced the nonpharmacologic multicomponent intervention through a nursing order, placed an automatic consult to occupational therapy, and included options to order physical therapy, order speech/language therapy, obtain vital signs three times daily with minimal night interruptions, remove an indwelling bladder catheter, and prescribe melatonin as a sleep aid.

The bedside nurse screened all patients for active delirium every 12-hour shift using the Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) and entered the results into the EMR.23,26 Capturing NuDESC results in the EMR allowed communication across medical providers as well as monitoring of screening adherence. Each nurse received two in-person trainings in staff meetings and one-to-one instruction during the first week of implementation. All nurses were required to complete a 15-minute training module and had the option of completing an additional 1-hour continuing medical education module. If a patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), delirium was identified through use of the ICU-specific Confusion Assessment Method (CAM-ICU) assessments, which the bedside nurse performed each shift throughout the intervention period.27 Nurses were instructed to call the primary team physician after every positive screen. Before each unit’s implementation start date, physicians with patients on that unit received education through a combination of grand rounds, resident lectures and seminars, and a pocket card on delirium evaluation and management.

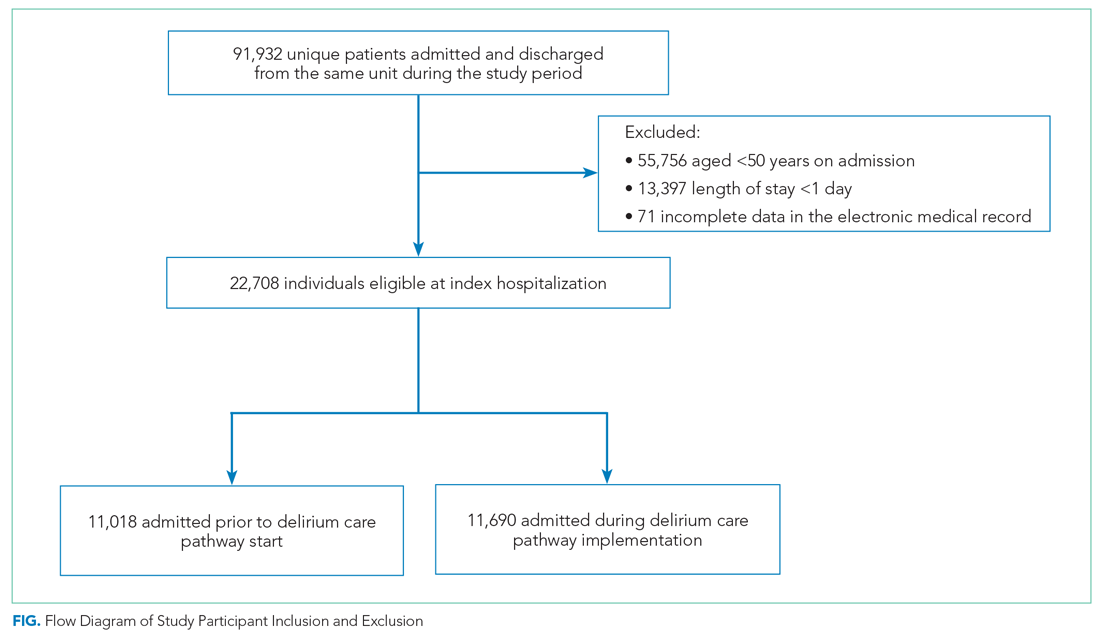

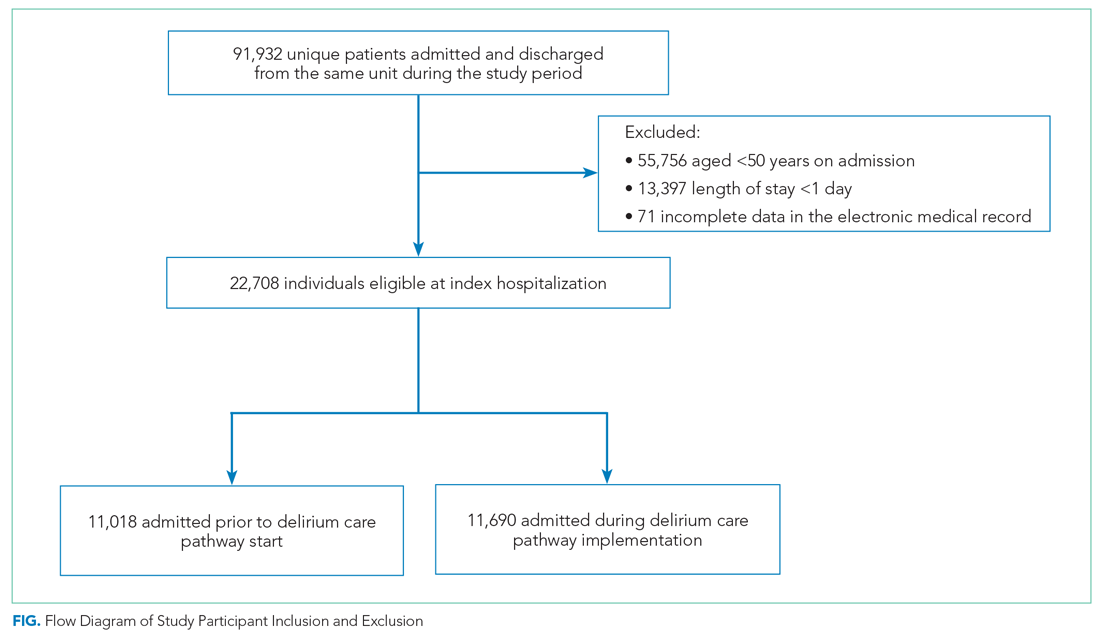

Participants and Eligibility Criteria

We included all patients aged ≥50 years hospitalized for >1 day on each hospital unit (Figure). We included adults aged ≥50 years to maximize the number of participants for this study while also capturing a population at risk for delirium. Because the delirium care pathway was unit-based and the pathway was rolled out sequentially across units, only patients who were admitted to and discharged from the same unit were included to better isolate the effect of the pathway. Patients who were transferred to the ICU were only included if they were discharged from the original unit of admission. Only the first hospitalization was included for patients with multiple hospitalizations during the study period.

Patient Characteristics

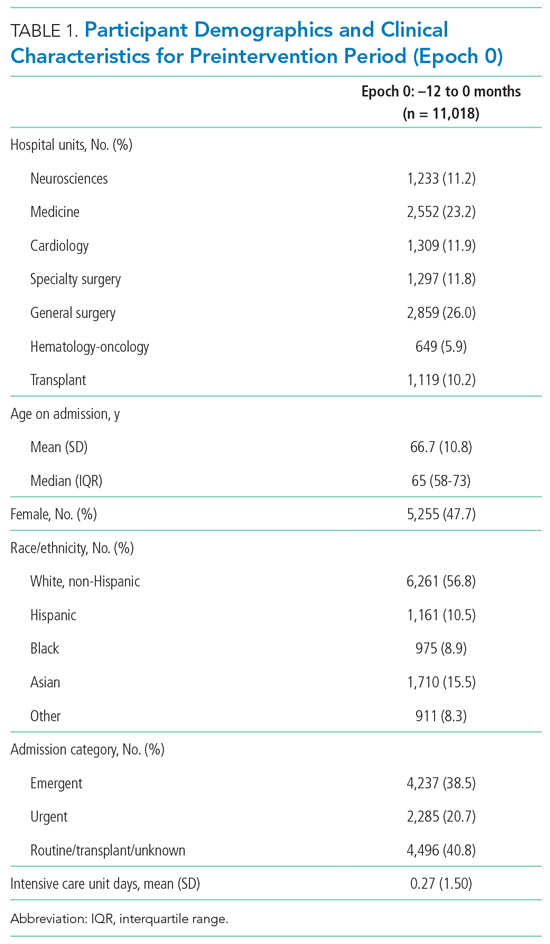

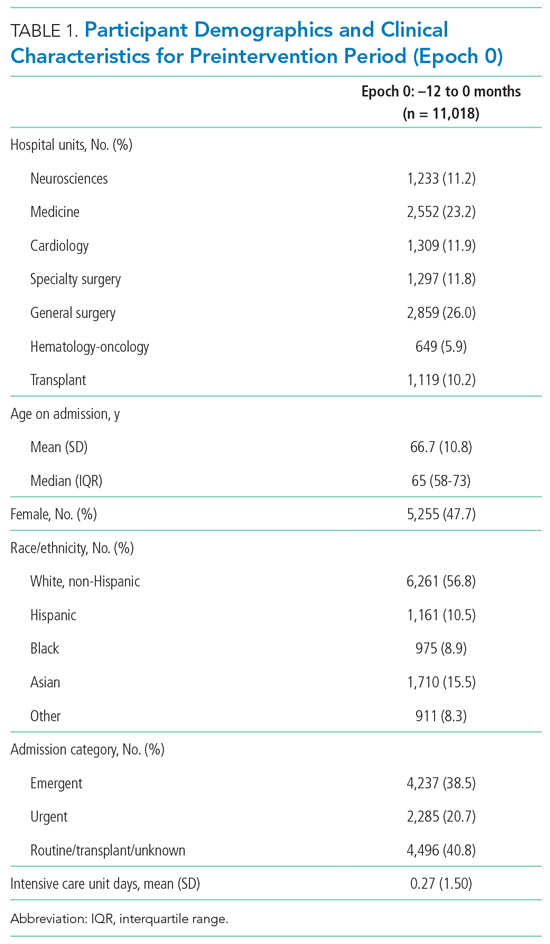

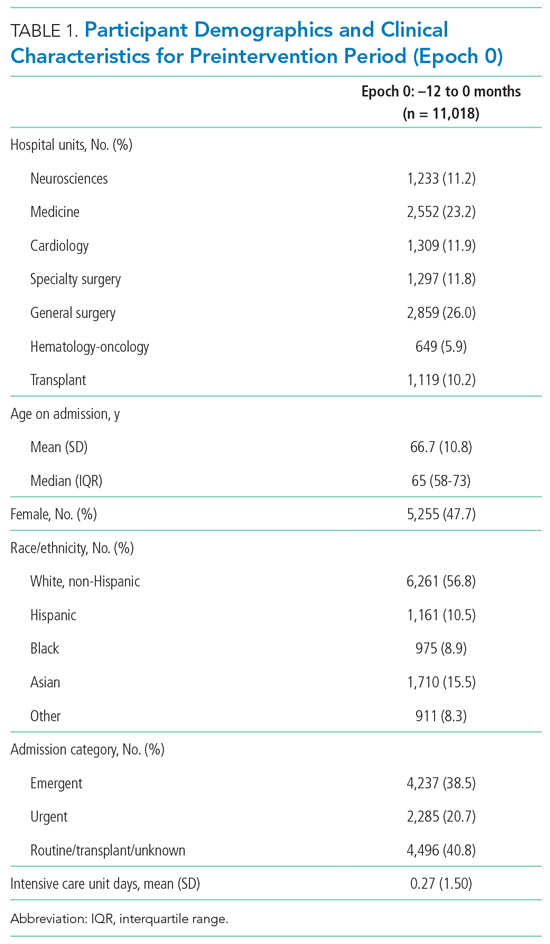

Patient demographics and clinical data were collected after discharge through Clarity and Vizient electronic databases (Table 1 and Table 2). All Elixhauser comorbidities were included except for the following International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10) codes that overlapped with a delirium diagnosis: G31.2, G93.89, G93.9, G94, R41.0, and R41.82 (Appendix Table 1). Severity of illness was obtained from Vizient, which calculates illness severity based on clinical and claims data (Appendix Table 1).

Delirium Metrics

Delirium screening was introduced as part of the multicomponent intervention, and therefore delirium rates before the intervention could not be determined. Trends in delirium prevalence and incidence after the intervention are reported. Prevalent delirium was defined as a single score of ≥2 on the nurse-administered NuDESC or a positive CAM-ICU at any point during the hospital stay. Incident delirium was identified if the first NuDESC score was negative and any subsequent NuDESC or CAM-ICU score was positive.

Outcomes

The primary study outcome was hospital LOS across all participants. Secondary outcomes included total direct cost and odds of 30-day hospital readmission. Readmissions tracked as part of hospital quality reporting were obtained from Vizient and were not captured if they occurred at another hospital. We also examined rates of safety attendant and restraint use during the study period, defined as the number of safety attendant days or restraint days per 1,000 patient days.

Because previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of multicomponent delirium interventions among elderly general medical patients,12 we also investigated these same outcomes in the medicine unit alone.

Statistical Analysis

The date of intervention implementation was determined for each hospital unit, which was defined as time(0) [t(0)]. The 12-month postintervention period was divided into four 3-month epochs to assess for trends. Data were aggregated across the seven units using t(0) as the start date, agnostic to the calendar month. Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected for the 12-months before t(0) and the four 3-month epochs after t(0). Univariate analysis of outcome variables comparing trends across the same epochs were conducted in the same manner, except for the rate of delirium, which was measured after t(0) and therefore could not be compared with the preintervention period.

Multivariable models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, admission category, Elixhauser comorbidities, severity of illness quartile, and number days spent in the ICU. Admission category referred to whether the admission was emergent, urgent, or elective/unknown. Because it took 3 months after t(0) for each unit to reach a delirium screening compliance rate of 90%, the intervention was only considered fully implemented after this period. A ramp-up variable was set to 0 for admissions occurring prior to the intervention to t(0), 1/3 for admissions occurring 1 month post intervention, 2/3 for 2 months post intervention, and 1 for admissions occurring 3 to 12 months post intervention. In this way, the coefficient for the ramp-up variable estimated the postintervention versus preintervention effect. Numerical outcomes (LOS, cost) were log transformed to reduce skewness and analyzed using linear models. Coefficients were back-transformed to provide interpretations as proportional change in the median outcomes.

For LOS and readmission, we assessed secular trends by including admission date and admission date squared, in case the trend was nonlinear, as possible predictors; admission date was the specific date—not time from t(0)—to account for secular trends and allow contemporaneous controls in the analysis. To be conservative, we retained secular terms (first considering the quadratic and then the linear) if P <.10. The categorical outcome (30-day readmission) was analyzed using a logistic model. Count variables (delirium, safety attendants, restraints) were analyzed using Poisson regression models with a log link, and coefficients were back-transformed to provide rate ratio interpretations. Because delirium was not measured before t(0), and because the intervention was considered to take 3 months to become fully effective, baseline delirium rates were defined as those in the first 3 months adjusted by the ramp-up variable. For each outcome we included hospital unit, a ramp-up variable (measuring the pre- vs postintervention effect), and their interaction. If there was no statistically significant interaction, we presented the outcome for all units combined. If the interaction was statistically significant, we looked for consistency across units and reported results for all units combined when consistent, along with site-specific results. If the results were not consistent across the units, we provided site-specific results only. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

Participant Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 22,708 individuals were included in this study, with 11,018 in the preintervention period (Table 1 and Table 2). Most patients were cared for on the general surgery unit (n = 5,899), followed by the medicine unit (n = 4,923). The smallest number of patients were cared for on the hematology-oncology unit (n = 1,709). Across the five epochs, patients were of similar age and sex, and spent a similar number of days in the ICU. The population was diverse with regard to race and ethnicity; there were minor differences in admission category. There were also minor differences in severity of illness and some comorbidities between timepoints (Appendix Table 1).

Delirium Metrics

Delirium prevalence was 13.0% during the first epoch post intervention, followed by 12.0%, 11.7%, and 13.0% in the subsequent epochs (P = .91). Incident delirium occurred in 6.1% of patients during the first epoch post intervention, followed by 5.3%, 5.3%, and 5.8% in the subsequent epochs (P = .63).

Primary Outcome

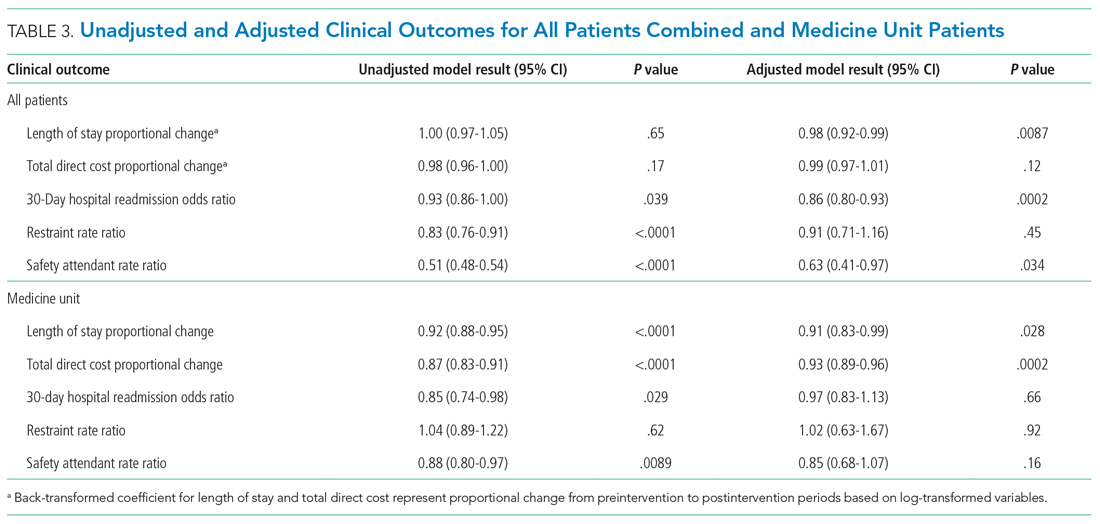

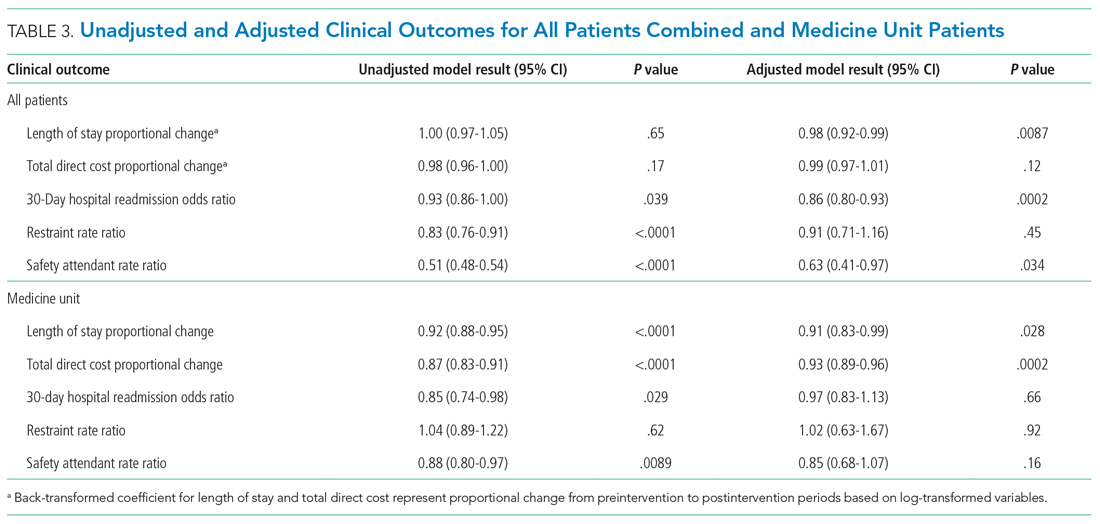

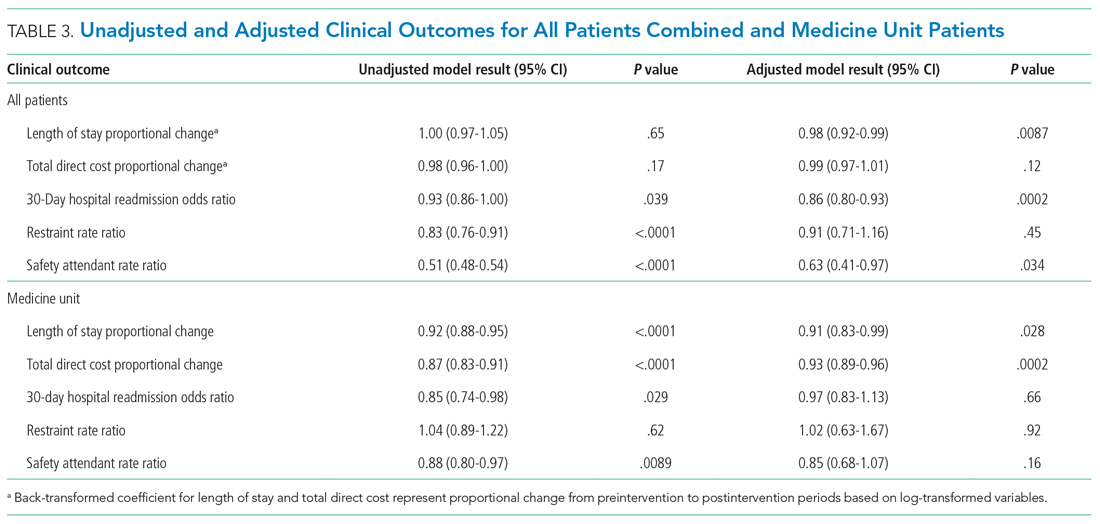

Epoch-level data for LOS before and after the intervention is shown in Appendix Table 2. The mean unadjusted LOS for all units combined did not decrease after the intervention, but in the adjusted model, the mean LOS decreased by 2% after the intervention (P = .0087; Table 3).

Secondary Outcomes

The odds of 30-day readmission decreased by 14% (P = .0002) in the adjusted models for all units combined (Table 3). There was no statistically significant reduction in adjusted total direct hospitalization cost or rate of restraint use. The safety attendant results showed strong effect modification across sites; the site-specific estimates are provided in Appendix Table 3. However, the estimated values all showed reductions, and a number were large and statistically significant.

Medicine Unit Outcomes

On the medicine unit alone, we observed a statistically significant reduction in LOS of 9% after implementation of the delirium care pathway (P = .028) in the adjusted model (Table 3). There was an associated 7% proportional decrease in total direct cost (P = .0002). Reductions in 30-day readmission and safety attendant use did not remain statistically significant in the adjusted models.

DISCUSSION