User login

Antibiotics may prolong PFS in HCC patients on immunotherapy

Response rates and overall survival (OS), on the other hand, did not seem to be affected by antibiotic administration, according to investigator Petros Fessas, MD, of Imperial College London.

Dr. Fessas and colleagues presented these findings in a poster at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract 485).

Dr. Fessas noted that, in other cancers, antibiotics have been shown to reduce both response and survival rates after ICI.

To assess the impact of early antibiotic exposure on ICI efficacy in HCC, Dr. Fessas and colleagues examined data from 449 patients treated at 12 centers in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

The patients’ median age was 65 years, and 79.1% were men. Nearly three-quarters (73.3%) were cirrhotic (60.4% because of viral hepatitis), 79.9% were Child-Pugh class A, 72.4% were Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C, and 79% had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1.

Response and survival results

The investigators compared outcomes between patients with and without antibiotic exposure in the early immunotherapy period (EIOP) 30 days before and after ICI initiation.

In all, 170 patients (37.9%) received antibiotics in the EIOP. There were no differences in response rates, disease control rates, or median OS between patients who received antibiotics and those who did not.

The objective response rate was 20.2% in patients who received antibiotics in the EIOP and 16.1% in patients who did not (P = .2808). Disease control rates were 63.1% and 55.4%, respectively (P = .1144). The median OS was 15.3 months and 15.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-1.21; P = .6275).

The median PFS, however, was significantly longer in patients who received antibiotics than in patients who did not – 6.1 months and 3.7 months, respectively (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60-0.93; P = .0135).

To overcome possible bias introduced by misclassification of patients who received antibiotics but discontinued immunotherapy within 30 days of initiation, the investigators conducted a landmark selection analysis among only those patients with a median follow-up for PFS of 30 days or longer (n = 402). This analysis confirmed the prior findings.

“Antibiotic exposure in the 30 days before or after immune checkpoint initiation in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with prolonged progression-free survival,” Dr. Fessas concluded.

He added that a key question for future research is to discover the immune-microbiologic determinants of response to initiation of ICIs.

Positive effect surprising

“My group has shown that antibiotic therapy is normally detrimental in patients with cancer,” investigator David J. Pinato, MD, PhD, of Imperial College London, said in an interview. “So we were very surprised to see a positive effect on PFS.”

He added that the new findings should be interpreted with caution.

“My feeling is that, unlike with many other malignancies, the gut microbiome is heavily involved in the progression of the cirrhosis that pre-dates HCC onset,” he said.

That would suggest the relationship between antibiotics and perturbation of the gut microbiome is dictated by something more than changes in antitumor immune tolerance, he added.

“Overall, I think the interplay is more complex in HCC: cirrhosis/cancer/microbiome, not just microbiome/cancer as in many other tumors,” Dr. Pinato said. “So we are looking at microbial determinants of response in HCC patients undergoing ICI therapy, and we are hopeful to see some more mechanistic evidence behind this association.”

Dr. Pinato disclosed relationships with ViiV Healthcare, Bayer Healthcare, Bristol Myers Squibb, Mina Therapeutics, Eisai, Roche, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Fessas reported having no conflicts of interest. No funding source for the study was disclosed.

Response rates and overall survival (OS), on the other hand, did not seem to be affected by antibiotic administration, according to investigator Petros Fessas, MD, of Imperial College London.

Dr. Fessas and colleagues presented these findings in a poster at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract 485).

Dr. Fessas noted that, in other cancers, antibiotics have been shown to reduce both response and survival rates after ICI.

To assess the impact of early antibiotic exposure on ICI efficacy in HCC, Dr. Fessas and colleagues examined data from 449 patients treated at 12 centers in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

The patients’ median age was 65 years, and 79.1% were men. Nearly three-quarters (73.3%) were cirrhotic (60.4% because of viral hepatitis), 79.9% were Child-Pugh class A, 72.4% were Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C, and 79% had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1.

Response and survival results

The investigators compared outcomes between patients with and without antibiotic exposure in the early immunotherapy period (EIOP) 30 days before and after ICI initiation.

In all, 170 patients (37.9%) received antibiotics in the EIOP. There were no differences in response rates, disease control rates, or median OS between patients who received antibiotics and those who did not.

The objective response rate was 20.2% in patients who received antibiotics in the EIOP and 16.1% in patients who did not (P = .2808). Disease control rates were 63.1% and 55.4%, respectively (P = .1144). The median OS was 15.3 months and 15.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-1.21; P = .6275).

The median PFS, however, was significantly longer in patients who received antibiotics than in patients who did not – 6.1 months and 3.7 months, respectively (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60-0.93; P = .0135).

To overcome possible bias introduced by misclassification of patients who received antibiotics but discontinued immunotherapy within 30 days of initiation, the investigators conducted a landmark selection analysis among only those patients with a median follow-up for PFS of 30 days or longer (n = 402). This analysis confirmed the prior findings.

“Antibiotic exposure in the 30 days before or after immune checkpoint initiation in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with prolonged progression-free survival,” Dr. Fessas concluded.

He added that a key question for future research is to discover the immune-microbiologic determinants of response to initiation of ICIs.

Positive effect surprising

“My group has shown that antibiotic therapy is normally detrimental in patients with cancer,” investigator David J. Pinato, MD, PhD, of Imperial College London, said in an interview. “So we were very surprised to see a positive effect on PFS.”

He added that the new findings should be interpreted with caution.

“My feeling is that, unlike with many other malignancies, the gut microbiome is heavily involved in the progression of the cirrhosis that pre-dates HCC onset,” he said.

That would suggest the relationship between antibiotics and perturbation of the gut microbiome is dictated by something more than changes in antitumor immune tolerance, he added.

“Overall, I think the interplay is more complex in HCC: cirrhosis/cancer/microbiome, not just microbiome/cancer as in many other tumors,” Dr. Pinato said. “So we are looking at microbial determinants of response in HCC patients undergoing ICI therapy, and we are hopeful to see some more mechanistic evidence behind this association.”

Dr. Pinato disclosed relationships with ViiV Healthcare, Bayer Healthcare, Bristol Myers Squibb, Mina Therapeutics, Eisai, Roche, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Fessas reported having no conflicts of interest. No funding source for the study was disclosed.

Response rates and overall survival (OS), on the other hand, did not seem to be affected by antibiotic administration, according to investigator Petros Fessas, MD, of Imperial College London.

Dr. Fessas and colleagues presented these findings in a poster at the American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting 2021: Week 1 (Abstract 485).

Dr. Fessas noted that, in other cancers, antibiotics have been shown to reduce both response and survival rates after ICI.

To assess the impact of early antibiotic exposure on ICI efficacy in HCC, Dr. Fessas and colleagues examined data from 449 patients treated at 12 centers in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

The patients’ median age was 65 years, and 79.1% were men. Nearly three-quarters (73.3%) were cirrhotic (60.4% because of viral hepatitis), 79.9% were Child-Pugh class A, 72.4% were Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C, and 79% had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1.

Response and survival results

The investigators compared outcomes between patients with and without antibiotic exposure in the early immunotherapy period (EIOP) 30 days before and after ICI initiation.

In all, 170 patients (37.9%) received antibiotics in the EIOP. There were no differences in response rates, disease control rates, or median OS between patients who received antibiotics and those who did not.

The objective response rate was 20.2% in patients who received antibiotics in the EIOP and 16.1% in patients who did not (P = .2808). Disease control rates were 63.1% and 55.4%, respectively (P = .1144). The median OS was 15.3 months and 15.4 months, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.93; 95% confidence interval, 0.72-1.21; P = .6275).

The median PFS, however, was significantly longer in patients who received antibiotics than in patients who did not – 6.1 months and 3.7 months, respectively (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.60-0.93; P = .0135).

To overcome possible bias introduced by misclassification of patients who received antibiotics but discontinued immunotherapy within 30 days of initiation, the investigators conducted a landmark selection analysis among only those patients with a median follow-up for PFS of 30 days or longer (n = 402). This analysis confirmed the prior findings.

“Antibiotic exposure in the 30 days before or after immune checkpoint initiation in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with prolonged progression-free survival,” Dr. Fessas concluded.

He added that a key question for future research is to discover the immune-microbiologic determinants of response to initiation of ICIs.

Positive effect surprising

“My group has shown that antibiotic therapy is normally detrimental in patients with cancer,” investigator David J. Pinato, MD, PhD, of Imperial College London, said in an interview. “So we were very surprised to see a positive effect on PFS.”

He added that the new findings should be interpreted with caution.

“My feeling is that, unlike with many other malignancies, the gut microbiome is heavily involved in the progression of the cirrhosis that pre-dates HCC onset,” he said.

That would suggest the relationship between antibiotics and perturbation of the gut microbiome is dictated by something more than changes in antitumor immune tolerance, he added.

“Overall, I think the interplay is more complex in HCC: cirrhosis/cancer/microbiome, not just microbiome/cancer as in many other tumors,” Dr. Pinato said. “So we are looking at microbial determinants of response in HCC patients undergoing ICI therapy, and we are hopeful to see some more mechanistic evidence behind this association.”

Dr. Pinato disclosed relationships with ViiV Healthcare, Bayer Healthcare, Bristol Myers Squibb, Mina Therapeutics, Eisai, Roche, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Fessas reported having no conflicts of interest. No funding source for the study was disclosed.

FROM AACR 2021

CLL patients: Diagnostic difficulties, treatment confusion with COVID-19

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients present significant problems with regard to COVID-19 disease, according to a literature review by Yousef Roosta, MD, of Urmia (Iran) University of Medical Sciences, and colleagues.

Diagnostic interaction between CLL and COVID-19 provides a major challenge. CLL patients have a lower rate of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG development, and evidence shows worse therapeutic outcomes in these patients, according to study published in Leukemia Research Reports.

The researchers assessed 20 retrieved articles, 11 of which examined patients with CLL and with concomitant COVID-19; and 9 articles were designed as prospective or retrospective case series of such patients. The studies were assessed qualitatively by the QUADAS-2 tool.

Troubling results

Although the overall prevalence of CLL and COVID-19 concurrence was low, at 0.6% (95% confidence interval 0.5%-0.7%) according to the meta-analysis, the results showed some special challenges in the diagnosis and care of these patients.

Diagnostic difficulties are a unique problem. Lymphopenia is common in patients with COVID-19, while lymphocytosis may be considered a transient or even rare finding. The interplay between the two diseases is sometimes very misleading for specialists, and in patients with lymphocytosis, the diagnosis of CLL may be completely ignored, according to the researchers. They added that when performing a diagnostic approach for concurrent COVID-19 and CLL, due to differences in the amount and type of immune response, “relying on serological testing, and especially the evaluation of the anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels may not be beneficial,” they indicated.

In addition, studies showed unacceptable therapeutic outcome in patients with concurrent CLL and COVID-19, with mortality ranging from 33% to 41.7%, showing a need to revise current treatment protocols, according to the authors. In one study, 85.7% of surviving patients showed a considerable decrease in functional class and significant fatigue, with such a poor prognosis occurring more commonly in the elderly.

With regard to treatment, “it is quite obvious that despite the use of current standard protocols, the prognosis of these patients will be much worse than the prognosis of CLL patients with no evidence of COVID-19. Even in the first-line treatment protocol for these patients, there is no agreement in combination therapy with selected CLL drugs along with management protocols of COVID-19 patients,” the researchers stated.

“[The] different hematological behaviors of two diseases might mimic the detection of COVID-19 in the CLL state and vise versa. Also, due to the low level of immune response against SARS-CoV-2 in CLL patients, both scheduled immunological-based diagnosis and treatment may fail,” the researchers added.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients present significant problems with regard to COVID-19 disease, according to a literature review by Yousef Roosta, MD, of Urmia (Iran) University of Medical Sciences, and colleagues.

Diagnostic interaction between CLL and COVID-19 provides a major challenge. CLL patients have a lower rate of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG development, and evidence shows worse therapeutic outcomes in these patients, according to study published in Leukemia Research Reports.

The researchers assessed 20 retrieved articles, 11 of which examined patients with CLL and with concomitant COVID-19; and 9 articles were designed as prospective or retrospective case series of such patients. The studies were assessed qualitatively by the QUADAS-2 tool.

Troubling results

Although the overall prevalence of CLL and COVID-19 concurrence was low, at 0.6% (95% confidence interval 0.5%-0.7%) according to the meta-analysis, the results showed some special challenges in the diagnosis and care of these patients.

Diagnostic difficulties are a unique problem. Lymphopenia is common in patients with COVID-19, while lymphocytosis may be considered a transient or even rare finding. The interplay between the two diseases is sometimes very misleading for specialists, and in patients with lymphocytosis, the diagnosis of CLL may be completely ignored, according to the researchers. They added that when performing a diagnostic approach for concurrent COVID-19 and CLL, due to differences in the amount and type of immune response, “relying on serological testing, and especially the evaluation of the anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels may not be beneficial,” they indicated.

In addition, studies showed unacceptable therapeutic outcome in patients with concurrent CLL and COVID-19, with mortality ranging from 33% to 41.7%, showing a need to revise current treatment protocols, according to the authors. In one study, 85.7% of surviving patients showed a considerable decrease in functional class and significant fatigue, with such a poor prognosis occurring more commonly in the elderly.

With regard to treatment, “it is quite obvious that despite the use of current standard protocols, the prognosis of these patients will be much worse than the prognosis of CLL patients with no evidence of COVID-19. Even in the first-line treatment protocol for these patients, there is no agreement in combination therapy with selected CLL drugs along with management protocols of COVID-19 patients,” the researchers stated.

“[The] different hematological behaviors of two diseases might mimic the detection of COVID-19 in the CLL state and vise versa. Also, due to the low level of immune response against SARS-CoV-2 in CLL patients, both scheduled immunological-based diagnosis and treatment may fail,” the researchers added.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients present significant problems with regard to COVID-19 disease, according to a literature review by Yousef Roosta, MD, of Urmia (Iran) University of Medical Sciences, and colleagues.

Diagnostic interaction between CLL and COVID-19 provides a major challenge. CLL patients have a lower rate of anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG development, and evidence shows worse therapeutic outcomes in these patients, according to study published in Leukemia Research Reports.

The researchers assessed 20 retrieved articles, 11 of which examined patients with CLL and with concomitant COVID-19; and 9 articles were designed as prospective or retrospective case series of such patients. The studies were assessed qualitatively by the QUADAS-2 tool.

Troubling results

Although the overall prevalence of CLL and COVID-19 concurrence was low, at 0.6% (95% confidence interval 0.5%-0.7%) according to the meta-analysis, the results showed some special challenges in the diagnosis and care of these patients.

Diagnostic difficulties are a unique problem. Lymphopenia is common in patients with COVID-19, while lymphocytosis may be considered a transient or even rare finding. The interplay between the two diseases is sometimes very misleading for specialists, and in patients with lymphocytosis, the diagnosis of CLL may be completely ignored, according to the researchers. They added that when performing a diagnostic approach for concurrent COVID-19 and CLL, due to differences in the amount and type of immune response, “relying on serological testing, and especially the evaluation of the anti–SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels may not be beneficial,” they indicated.

In addition, studies showed unacceptable therapeutic outcome in patients with concurrent CLL and COVID-19, with mortality ranging from 33% to 41.7%, showing a need to revise current treatment protocols, according to the authors. In one study, 85.7% of surviving patients showed a considerable decrease in functional class and significant fatigue, with such a poor prognosis occurring more commonly in the elderly.

With regard to treatment, “it is quite obvious that despite the use of current standard protocols, the prognosis of these patients will be much worse than the prognosis of CLL patients with no evidence of COVID-19. Even in the first-line treatment protocol for these patients, there is no agreement in combination therapy with selected CLL drugs along with management protocols of COVID-19 patients,” the researchers stated.

“[The] different hematological behaviors of two diseases might mimic the detection of COVID-19 in the CLL state and vise versa. Also, due to the low level of immune response against SARS-CoV-2 in CLL patients, both scheduled immunological-based diagnosis and treatment may fail,” the researchers added.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH REPORTS

Eating more fat may boost borderline low testosterone

Low-fat diets appear to decrease testosterone levels in men, but further randomized, controlled trials are needed to confirm this effect, the authors of a meta-analysis of six small intervention studies concluded.

A total of 206 healthy men with normal testosterone received a high-fat diet followed by a low-fat diet (or vice versa), and their mean total testosterone levels were 10%-15% lower (but still in the normal range) during the low-fat diet.

The study by registered nutritionist Joseph Whittaker, MSc, University of Worcester (England), and statistician Kexin Wu, MSc, University of Warwick, Coventry, England, was published online in the Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

“I think our results are consistent and fairly strong, but they are not strong enough to give blanket recommendations,” Mr. Whittaker said in an interview.

However, “if somebody has low testosterone, particularly borderline, they could try increasing their fat intake, maybe on a Mediterranean diet,” he said, and see if that works to increase their testosterone by 60 ng/dL, the weighted mean difference in total testosterone levels between the low-fat versus high-fat diet interventions in this meta-analysis.

“A Mediterranean diet is a good way to increase ‘healthy fats,’ mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which will likely decrease cardiovascular disease risk, and boost testosterone at the same time,” Mr. Whittaker noted.

Olive oil has been shown to boost testosterone more than butter, and it also reduces CVD, he continued. Nuts are high in “healthy fats” and consistently decrease CVD and mortality and may boost testosterone. Other sources of “good fat” in a healthy diet include avocado, and red meat and poultry in moderation.

“It is controversial, but our results also indicate that foods with saturated fatty acids may boost testosterone,” he added, noting however that such foods are also associated with an increase in cholesterol.

Is waning testosterone explained by leaner diet?

Men need healthy testosterone levels for good physical performance, mental health, and sexual health, and low levels are associated with a higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease, according to a statement about this research issued by the University of Worcester.

Although testosterone levels do decline with advancing age, there has also been an additional age-independent and persistent decline in testosterone levels that began roughly after nutrition guidelines began recommending a lower-fat diet in 1965.

Fat consumption dropped from 45% of the diet in 1965 to 35% of the diet in 1991, and stayed around that lower level through to 2011.

However, it is not clear if this decrease in dietary fat intake might explain part of the concurrent decline in men’s testosterone levels.

Mr. Whittaker and Mr. Wu conducted a systematic literature review and identified six crossover intervention studies that compared testosterone levels during low-fat versus high-fat diets – Dorgan 1996, Wang 2005, Hamalainen 1984, Hill 1980, Reed 1987, and Hill 1979 – and then they combined these studies in a meta-analysis.

Five studies each enrolled 6-43 healthy men from North America, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia, and the sixth study (Hill 1980) enrolled 34 healthy men from North America and 39 farm laborers from South Africa.

Overall, on average, the men were aged 34-54 years and slightly overweight (a mean body mass index of roughly 27 kg/m2) with normal testosterone (i.e., >300 ng/dL, based on the 2018 American Urological Association guidelines criteria).

Most men received a high-fat diet (40% of calories from fat) first, followed by a low-fat diet (on average 20% of calories from fat; range, 7%-25%), but the subgroup of men from South Africa received the low-fat diet first.

To put this into context, U.K. guidelines recommend a fat intake of less than 35% of daily calories, and U.S. guidelines recommend a fat intake of 20%-35% of daily calories.

The low-and high-fat interventions ranged from 2 to 10 weeks.

Lowest testosterone levels with low-fat vegetarian diets

Overall, on average, the men’s total testosterone was 475 mg/dL when they were consuming a low-fat diet and 532 mg/dL when they were consuming a high-fat diet.

However, the South African men had higher testosterone levels when they consumed a low-fat diet. This suggests that “men with European ancestry may experience a greater decrease in testosterone in response to a low-fat diet,” the researchers wrote.

The decrease in total testosterone in the low-fat versus high-fat diet was largest (26%) in the two studies of men who consumed a vegetarian diet (Hill 1979 and Hill 1980). These diets may have been low in zinc, since a marginal zinc deficiency has been shown to decrease total testosterone, Mr. Whittaker and Mr. Wu speculated.

The meta-analysis also showed that levels of free testosterone, urinary testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone declined during the low-fat diet, whereas levels of luteinizing hormone or sex hormone binding globulin were similar with both diets.

Men with low testosterone and overweight, obesity

What nutritional advice should practitioners give to men who have low testosterone and overweight/obesity?

“If you are very overweight, losing weight is going to dramatically improve your testosterone,” Mr. Whittaker said.

However, proponents of various diets are often in stark disagreement about the merits of a low-fat versus low-carbohydrate diet to lose weight.

“In general,” he continued, “the literature shows low-carb (high-fat) diets are better for weight loss [although many will disagree with that statement].”

Although nutrition guidelines have stressed the importance of limiting fat intake, fat in the diet is also associated with lower triglyceride levels and blood pressure and higher HDL cholesterol levels, and now in this study, higher testosterone levels.

More research needed

The researchers acknowledge study limitations: The meta-analysis included just a few small studies with heterogeneous designs and findings, and there was possible bias from confounding variables.

“Ideally, we would like to see a few more studies to confirm our results,” Mr. Whittaker said in the statement. “However, these studies may never come; normally researchers want to find new results, not replicate old ones. In the meantime, men with low testosterone would be wise to avoid low-fat diets.”

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-fat diets appear to decrease testosterone levels in men, but further randomized, controlled trials are needed to confirm this effect, the authors of a meta-analysis of six small intervention studies concluded.

A total of 206 healthy men with normal testosterone received a high-fat diet followed by a low-fat diet (or vice versa), and their mean total testosterone levels were 10%-15% lower (but still in the normal range) during the low-fat diet.

The study by registered nutritionist Joseph Whittaker, MSc, University of Worcester (England), and statistician Kexin Wu, MSc, University of Warwick, Coventry, England, was published online in the Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

“I think our results are consistent and fairly strong, but they are not strong enough to give blanket recommendations,” Mr. Whittaker said in an interview.

However, “if somebody has low testosterone, particularly borderline, they could try increasing their fat intake, maybe on a Mediterranean diet,” he said, and see if that works to increase their testosterone by 60 ng/dL, the weighted mean difference in total testosterone levels between the low-fat versus high-fat diet interventions in this meta-analysis.

“A Mediterranean diet is a good way to increase ‘healthy fats,’ mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which will likely decrease cardiovascular disease risk, and boost testosterone at the same time,” Mr. Whittaker noted.

Olive oil has been shown to boost testosterone more than butter, and it also reduces CVD, he continued. Nuts are high in “healthy fats” and consistently decrease CVD and mortality and may boost testosterone. Other sources of “good fat” in a healthy diet include avocado, and red meat and poultry in moderation.

“It is controversial, but our results also indicate that foods with saturated fatty acids may boost testosterone,” he added, noting however that such foods are also associated with an increase in cholesterol.

Is waning testosterone explained by leaner diet?

Men need healthy testosterone levels for good physical performance, mental health, and sexual health, and low levels are associated with a higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease, according to a statement about this research issued by the University of Worcester.

Although testosterone levels do decline with advancing age, there has also been an additional age-independent and persistent decline in testosterone levels that began roughly after nutrition guidelines began recommending a lower-fat diet in 1965.

Fat consumption dropped from 45% of the diet in 1965 to 35% of the diet in 1991, and stayed around that lower level through to 2011.

However, it is not clear if this decrease in dietary fat intake might explain part of the concurrent decline in men’s testosterone levels.

Mr. Whittaker and Mr. Wu conducted a systematic literature review and identified six crossover intervention studies that compared testosterone levels during low-fat versus high-fat diets – Dorgan 1996, Wang 2005, Hamalainen 1984, Hill 1980, Reed 1987, and Hill 1979 – and then they combined these studies in a meta-analysis.

Five studies each enrolled 6-43 healthy men from North America, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia, and the sixth study (Hill 1980) enrolled 34 healthy men from North America and 39 farm laborers from South Africa.

Overall, on average, the men were aged 34-54 years and slightly overweight (a mean body mass index of roughly 27 kg/m2) with normal testosterone (i.e., >300 ng/dL, based on the 2018 American Urological Association guidelines criteria).

Most men received a high-fat diet (40% of calories from fat) first, followed by a low-fat diet (on average 20% of calories from fat; range, 7%-25%), but the subgroup of men from South Africa received the low-fat diet first.

To put this into context, U.K. guidelines recommend a fat intake of less than 35% of daily calories, and U.S. guidelines recommend a fat intake of 20%-35% of daily calories.

The low-and high-fat interventions ranged from 2 to 10 weeks.

Lowest testosterone levels with low-fat vegetarian diets

Overall, on average, the men’s total testosterone was 475 mg/dL when they were consuming a low-fat diet and 532 mg/dL when they were consuming a high-fat diet.

However, the South African men had higher testosterone levels when they consumed a low-fat diet. This suggests that “men with European ancestry may experience a greater decrease in testosterone in response to a low-fat diet,” the researchers wrote.

The decrease in total testosterone in the low-fat versus high-fat diet was largest (26%) in the two studies of men who consumed a vegetarian diet (Hill 1979 and Hill 1980). These diets may have been low in zinc, since a marginal zinc deficiency has been shown to decrease total testosterone, Mr. Whittaker and Mr. Wu speculated.

The meta-analysis also showed that levels of free testosterone, urinary testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone declined during the low-fat diet, whereas levels of luteinizing hormone or sex hormone binding globulin were similar with both diets.

Men with low testosterone and overweight, obesity

What nutritional advice should practitioners give to men who have low testosterone and overweight/obesity?

“If you are very overweight, losing weight is going to dramatically improve your testosterone,” Mr. Whittaker said.

However, proponents of various diets are often in stark disagreement about the merits of a low-fat versus low-carbohydrate diet to lose weight.

“In general,” he continued, “the literature shows low-carb (high-fat) diets are better for weight loss [although many will disagree with that statement].”

Although nutrition guidelines have stressed the importance of limiting fat intake, fat in the diet is also associated with lower triglyceride levels and blood pressure and higher HDL cholesterol levels, and now in this study, higher testosterone levels.

More research needed

The researchers acknowledge study limitations: The meta-analysis included just a few small studies with heterogeneous designs and findings, and there was possible bias from confounding variables.

“Ideally, we would like to see a few more studies to confirm our results,” Mr. Whittaker said in the statement. “However, these studies may never come; normally researchers want to find new results, not replicate old ones. In the meantime, men with low testosterone would be wise to avoid low-fat diets.”

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Low-fat diets appear to decrease testosterone levels in men, but further randomized, controlled trials are needed to confirm this effect, the authors of a meta-analysis of six small intervention studies concluded.

A total of 206 healthy men with normal testosterone received a high-fat diet followed by a low-fat diet (or vice versa), and their mean total testosterone levels were 10%-15% lower (but still in the normal range) during the low-fat diet.

The study by registered nutritionist Joseph Whittaker, MSc, University of Worcester (England), and statistician Kexin Wu, MSc, University of Warwick, Coventry, England, was published online in the Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

“I think our results are consistent and fairly strong, but they are not strong enough to give blanket recommendations,” Mr. Whittaker said in an interview.

However, “if somebody has low testosterone, particularly borderline, they could try increasing their fat intake, maybe on a Mediterranean diet,” he said, and see if that works to increase their testosterone by 60 ng/dL, the weighted mean difference in total testosterone levels between the low-fat versus high-fat diet interventions in this meta-analysis.

“A Mediterranean diet is a good way to increase ‘healthy fats,’ mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, which will likely decrease cardiovascular disease risk, and boost testosterone at the same time,” Mr. Whittaker noted.

Olive oil has been shown to boost testosterone more than butter, and it also reduces CVD, he continued. Nuts are high in “healthy fats” and consistently decrease CVD and mortality and may boost testosterone. Other sources of “good fat” in a healthy diet include avocado, and red meat and poultry in moderation.

“It is controversial, but our results also indicate that foods with saturated fatty acids may boost testosterone,” he added, noting however that such foods are also associated with an increase in cholesterol.

Is waning testosterone explained by leaner diet?

Men need healthy testosterone levels for good physical performance, mental health, and sexual health, and low levels are associated with a higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease, according to a statement about this research issued by the University of Worcester.

Although testosterone levels do decline with advancing age, there has also been an additional age-independent and persistent decline in testosterone levels that began roughly after nutrition guidelines began recommending a lower-fat diet in 1965.

Fat consumption dropped from 45% of the diet in 1965 to 35% of the diet in 1991, and stayed around that lower level through to 2011.

However, it is not clear if this decrease in dietary fat intake might explain part of the concurrent decline in men’s testosterone levels.

Mr. Whittaker and Mr. Wu conducted a systematic literature review and identified six crossover intervention studies that compared testosterone levels during low-fat versus high-fat diets – Dorgan 1996, Wang 2005, Hamalainen 1984, Hill 1980, Reed 1987, and Hill 1979 – and then they combined these studies in a meta-analysis.

Five studies each enrolled 6-43 healthy men from North America, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia, and the sixth study (Hill 1980) enrolled 34 healthy men from North America and 39 farm laborers from South Africa.

Overall, on average, the men were aged 34-54 years and slightly overweight (a mean body mass index of roughly 27 kg/m2) with normal testosterone (i.e., >300 ng/dL, based on the 2018 American Urological Association guidelines criteria).

Most men received a high-fat diet (40% of calories from fat) first, followed by a low-fat diet (on average 20% of calories from fat; range, 7%-25%), but the subgroup of men from South Africa received the low-fat diet first.

To put this into context, U.K. guidelines recommend a fat intake of less than 35% of daily calories, and U.S. guidelines recommend a fat intake of 20%-35% of daily calories.

The low-and high-fat interventions ranged from 2 to 10 weeks.

Lowest testosterone levels with low-fat vegetarian diets

Overall, on average, the men’s total testosterone was 475 mg/dL when they were consuming a low-fat diet and 532 mg/dL when they were consuming a high-fat diet.

However, the South African men had higher testosterone levels when they consumed a low-fat diet. This suggests that “men with European ancestry may experience a greater decrease in testosterone in response to a low-fat diet,” the researchers wrote.

The decrease in total testosterone in the low-fat versus high-fat diet was largest (26%) in the two studies of men who consumed a vegetarian diet (Hill 1979 and Hill 1980). These diets may have been low in zinc, since a marginal zinc deficiency has been shown to decrease total testosterone, Mr. Whittaker and Mr. Wu speculated.

The meta-analysis also showed that levels of free testosterone, urinary testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone declined during the low-fat diet, whereas levels of luteinizing hormone or sex hormone binding globulin were similar with both diets.

Men with low testosterone and overweight, obesity

What nutritional advice should practitioners give to men who have low testosterone and overweight/obesity?

“If you are very overweight, losing weight is going to dramatically improve your testosterone,” Mr. Whittaker said.

However, proponents of various diets are often in stark disagreement about the merits of a low-fat versus low-carbohydrate diet to lose weight.

“In general,” he continued, “the literature shows low-carb (high-fat) diets are better for weight loss [although many will disagree with that statement].”

Although nutrition guidelines have stressed the importance of limiting fat intake, fat in the diet is also associated with lower triglyceride levels and blood pressure and higher HDL cholesterol levels, and now in this study, higher testosterone levels.

More research needed

The researchers acknowledge study limitations: The meta-analysis included just a few small studies with heterogeneous designs and findings, and there was possible bias from confounding variables.

“Ideally, we would like to see a few more studies to confirm our results,” Mr. Whittaker said in the statement. “However, these studies may never come; normally researchers want to find new results, not replicate old ones. In the meantime, men with low testosterone would be wise to avoid low-fat diets.”

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

How often should we check EKGs in patients starting antipsychotic medications?

Determining relative risk with available data

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

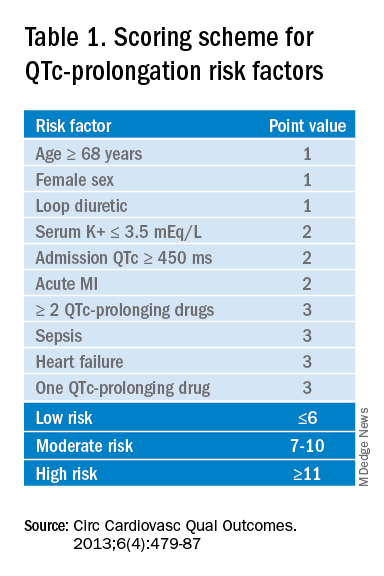

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

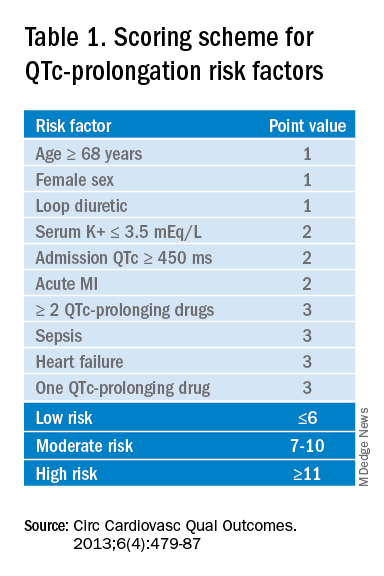

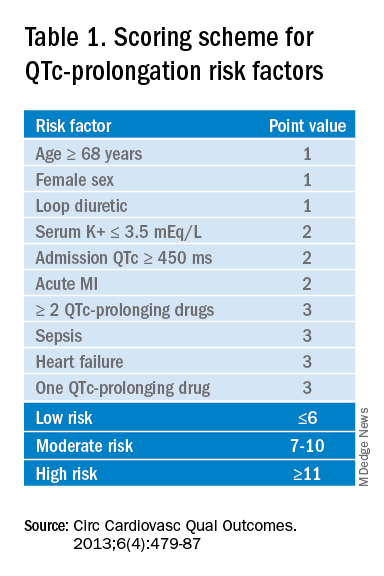

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

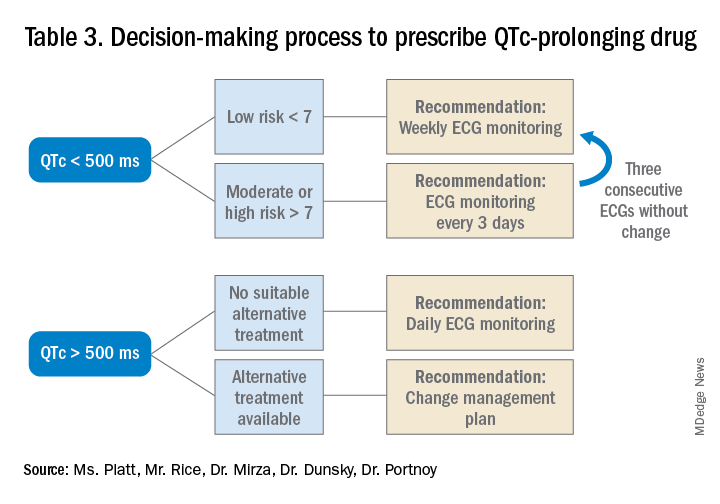

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

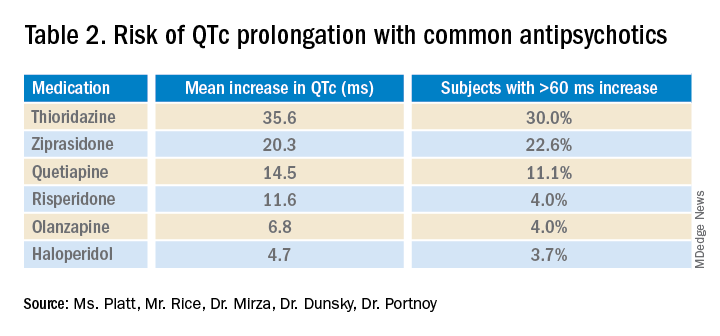

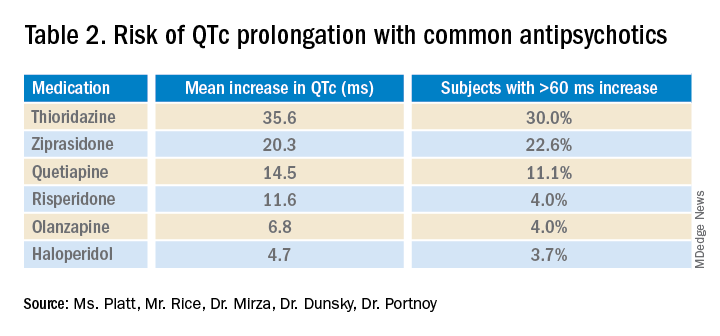

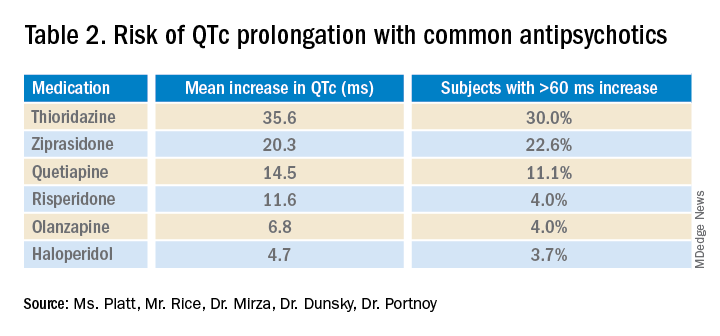

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

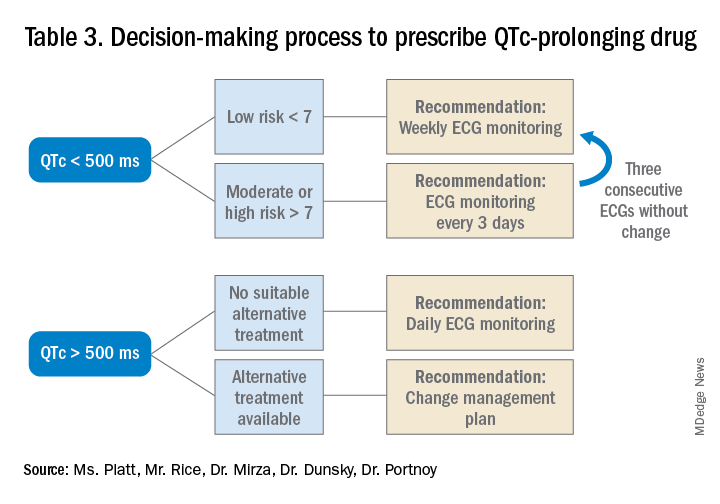

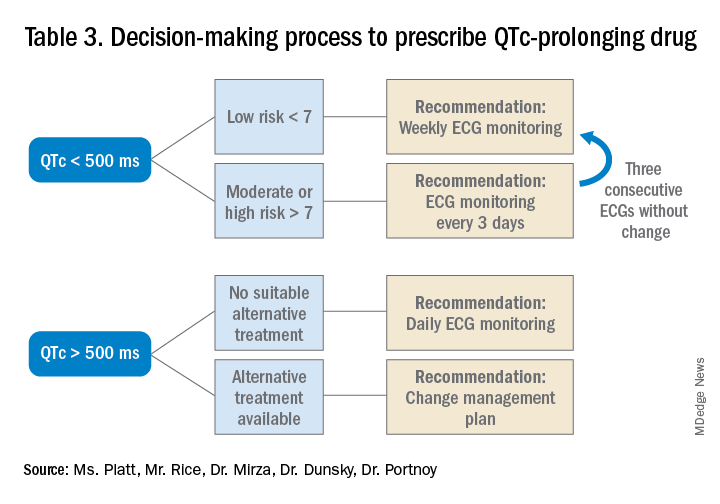

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Determining relative risk with available data

Determining relative risk with available data

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.