User login

Infectious diseases ‘giant’ John Bartlett: His ‘impact will endure’

The cause of death was not immediately disclosed.

Dr. Bartlett is remembered by colleagues for his wide range of infectious disease expertise, an ability to repeatedly predict emerging issues in the field, and for inspiring students and trainees to choose the same specialty.

“What I consistently found so extraordinary about John was his excitement for ID – the whole field. He had a wonderful sixth sense about what was going to be the next ‘big thing,’” Paul Edward Sax, MD, clinical director of the Infectious Disease Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, told this news organization.

“He thoroughly absorbed the emerging research on the topic and then provided the most wonderful clinical summaries,” Dr. Sax said. “His range of expert content areas was unbelievably broad.” Dr. Bartlett was “a true ID polymath.”

Dr. Bartlett was “a giant in the field of infectious diseases,” David Lee Thomas, MD, MPH, said in an interview. He agreed that Dr. Bartlett was a visionary who could anticipate the most exciting developments in the specialty.

Dr. Bartlett also “led the efforts to combat the foes, from HIV to antimicrobial resistance,” said Dr. Thomas, director of the division of infectious diseases and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

A pioneer in HIV research and care

Dr. Bartlett’s early research focused on anaerobic pulmonary and other infections, Bacteroides fragilis pathogenesis, and colitis caused by Clostridioides difficile.

Shortly after joining Johns Hopkins in 1980, he focused on HIV/AIDS research and caring for people with HIV. Dr. Bartlett led clinical trials of new treatments and developed years of HIV clinical treatment guidelines.

“Back when most hospitals, university medical centers, and ID divisions were running away from the AIDS epidemic, John took it on, both as a scientific priority and a moral imperative,” Dr. Sax writes in a blog post for NEJM Journal Watch. “With the help of Frank Polk and the Hopkins president, he established an outpatient AIDS clinic and an inpatient AIDS ward – both of which were way ahead of their time.”

In the same post, Dr. Sax points out that Dr. Bartlett was an expert in multiple areas – any one of which could be a sole career focus. “How many ID doctors are true experts in all of the following distinct topics? HIV, Clostridium difficile, respiratory tract infections, antimicrobial resistance, and anaerobic pulmonary infections.” Dr. Sax writes.

Expertise that defined an era

In a piece reviewing the long history of infectious disease medicine at Johns Hopkins published in Clinical Infectious Diseases in 2014, Paul Auwaerter, MD, and colleagues describe his tenure at the institution from 1980 to 2006 as “The Bartlett Era,” notable for the many advances he spearheaded.

“It is nearly impossible to find someone trained in infectious diseases in the past 30 years who has not been impacted by John Bartlett,” Dr. Auwaerter and colleagues note. “His tireless devotion to scholarship, teaching, and patient care remains an inspiration to his faculty members at Johns Hopkins, his colleagues, and coworkers around the world.”

Dr. Bartlett was not only a faculty member in the division of infectious diseases, he also helped establish it. When he joined Johns Hopkins, the infectious disease department featured just three faculty members with a research budget of less than $285,000. By the time he left 26 years later, the division had 44 faculty members on tenure track and a research budget exceeding $40 million.

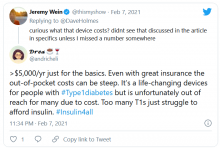

Sharing memories via social media

Reactions to Dr. Bartlett’s passing on Twitter were swift.

“We have lost one of the greatest physicians I have ever met or had the privilege to learn from. Saddened to hear of Dr. John G. Bartlett’s passing. He inspired so many, including me, to choose the field of infectious diseases,” David Fisk, MD, infectious disease specialist in Santa Barbara, Calif., wrote on Twitter.

“John Bartlett just died – a true visionary and the classic ‘Renaissance’ person in clinical ID. Such a nice guy, too! His IDSA/IDWeek literature summaries (among other things) were amazing. We’ll miss him!” Dr. Sax tweeted on Jan. 19.

A colleague at Johns Hopkins, transplant infectious disease specialist Shmuel Shoham, MD, shared an anecdote about Dr. Bartlett on Twitter: “Year ago. My office is across from his. I ask him what he is doing. He tells me he is reviewing a file from the Vatican to adjudicate whether a miracle happened. True story.”

Infectious disease specialist Graeme Forrest, MBBS, also shared a story about Dr. Bartlett via Twitter. “He described to me in 2001 how the U.S. model of health care would not cope with a pandemic or serious bioterror attack as it’s not connected to disseminate information. How prescient from 20 years ago.”

Dr. Bartlett shared his expertise at many national and international infectious disease conferences over the years. He also authored 470 articles, 282 book chapters, and 61 editions of 14 books.

Dr. Bartlett was also a regular contributor to this news organization. For example, he shared his expertise in perspective pieces that addressed priorities in antibiotic stewardship, upcoming infectious disease predictions, and critical infectious disease topics in a three-part series.

Dr. Bartlett’s education includes a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., in 1959 and an MD from Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, N.Y., in 1963. He did his first 2 years of residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

He also served as an Army captain from 1965 to 1967, treating patients in fever wards in Vietnam. He then returned to the United States to finish his internal medicine training at the University of Alabama in 1968.

Dr. Bartlett completed his fellowship in infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1975, he joined the faculty at Tufts University, Boston.

Leaving a legacy

Dr. Bartlett’s influence will likely live on in many ways at Johns Hopkins.

“John is a larger-than-life legend whose impact will endure and after whom we are so proud to have named our clinical service, The Bartlett Specialty Practice,” Dr. Thomas said.

The specialty practice clinic named for him has 23 exam rooms and features multidisciplinary care for people with HIV, hepatitis, bone infections, general infectious diseases, and more. Furthermore, friends, family, and colleagues joined forces to create the “Dr. John G. Bartlett HIV/AIDS Fund.”

They note that it is “only appropriate that we honor him by creating an endowment that will provide support for young trainees and junior faculty in the division, helping them transition to their independent careers.”

In addition to all his professional accomplishments, “He was also a genuinely nice person, approachable and humble,” Dr. Sax said. “We really lost a great one!”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The cause of death was not immediately disclosed.

Dr. Bartlett is remembered by colleagues for his wide range of infectious disease expertise, an ability to repeatedly predict emerging issues in the field, and for inspiring students and trainees to choose the same specialty.

“What I consistently found so extraordinary about John was his excitement for ID – the whole field. He had a wonderful sixth sense about what was going to be the next ‘big thing,’” Paul Edward Sax, MD, clinical director of the Infectious Disease Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, told this news organization.

“He thoroughly absorbed the emerging research on the topic and then provided the most wonderful clinical summaries,” Dr. Sax said. “His range of expert content areas was unbelievably broad.” Dr. Bartlett was “a true ID polymath.”

Dr. Bartlett was “a giant in the field of infectious diseases,” David Lee Thomas, MD, MPH, said in an interview. He agreed that Dr. Bartlett was a visionary who could anticipate the most exciting developments in the specialty.

Dr. Bartlett also “led the efforts to combat the foes, from HIV to antimicrobial resistance,” said Dr. Thomas, director of the division of infectious diseases and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

A pioneer in HIV research and care

Dr. Bartlett’s early research focused on anaerobic pulmonary and other infections, Bacteroides fragilis pathogenesis, and colitis caused by Clostridioides difficile.

Shortly after joining Johns Hopkins in 1980, he focused on HIV/AIDS research and caring for people with HIV. Dr. Bartlett led clinical trials of new treatments and developed years of HIV clinical treatment guidelines.

“Back when most hospitals, university medical centers, and ID divisions were running away from the AIDS epidemic, John took it on, both as a scientific priority and a moral imperative,” Dr. Sax writes in a blog post for NEJM Journal Watch. “With the help of Frank Polk and the Hopkins president, he established an outpatient AIDS clinic and an inpatient AIDS ward – both of which were way ahead of their time.”

In the same post, Dr. Sax points out that Dr. Bartlett was an expert in multiple areas – any one of which could be a sole career focus. “How many ID doctors are true experts in all of the following distinct topics? HIV, Clostridium difficile, respiratory tract infections, antimicrobial resistance, and anaerobic pulmonary infections.” Dr. Sax writes.

Expertise that defined an era

In a piece reviewing the long history of infectious disease medicine at Johns Hopkins published in Clinical Infectious Diseases in 2014, Paul Auwaerter, MD, and colleagues describe his tenure at the institution from 1980 to 2006 as “The Bartlett Era,” notable for the many advances he spearheaded.

“It is nearly impossible to find someone trained in infectious diseases in the past 30 years who has not been impacted by John Bartlett,” Dr. Auwaerter and colleagues note. “His tireless devotion to scholarship, teaching, and patient care remains an inspiration to his faculty members at Johns Hopkins, his colleagues, and coworkers around the world.”

Dr. Bartlett was not only a faculty member in the division of infectious diseases, he also helped establish it. When he joined Johns Hopkins, the infectious disease department featured just three faculty members with a research budget of less than $285,000. By the time he left 26 years later, the division had 44 faculty members on tenure track and a research budget exceeding $40 million.

Sharing memories via social media

Reactions to Dr. Bartlett’s passing on Twitter were swift.

“We have lost one of the greatest physicians I have ever met or had the privilege to learn from. Saddened to hear of Dr. John G. Bartlett’s passing. He inspired so many, including me, to choose the field of infectious diseases,” David Fisk, MD, infectious disease specialist in Santa Barbara, Calif., wrote on Twitter.

“John Bartlett just died – a true visionary and the classic ‘Renaissance’ person in clinical ID. Such a nice guy, too! His IDSA/IDWeek literature summaries (among other things) were amazing. We’ll miss him!” Dr. Sax tweeted on Jan. 19.

A colleague at Johns Hopkins, transplant infectious disease specialist Shmuel Shoham, MD, shared an anecdote about Dr. Bartlett on Twitter: “Year ago. My office is across from his. I ask him what he is doing. He tells me he is reviewing a file from the Vatican to adjudicate whether a miracle happened. True story.”

Infectious disease specialist Graeme Forrest, MBBS, also shared a story about Dr. Bartlett via Twitter. “He described to me in 2001 how the U.S. model of health care would not cope with a pandemic or serious bioterror attack as it’s not connected to disseminate information. How prescient from 20 years ago.”

Dr. Bartlett shared his expertise at many national and international infectious disease conferences over the years. He also authored 470 articles, 282 book chapters, and 61 editions of 14 books.

Dr. Bartlett was also a regular contributor to this news organization. For example, he shared his expertise in perspective pieces that addressed priorities in antibiotic stewardship, upcoming infectious disease predictions, and critical infectious disease topics in a three-part series.

Dr. Bartlett’s education includes a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., in 1959 and an MD from Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, N.Y., in 1963. He did his first 2 years of residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

He also served as an Army captain from 1965 to 1967, treating patients in fever wards in Vietnam. He then returned to the United States to finish his internal medicine training at the University of Alabama in 1968.

Dr. Bartlett completed his fellowship in infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1975, he joined the faculty at Tufts University, Boston.

Leaving a legacy

Dr. Bartlett’s influence will likely live on in many ways at Johns Hopkins.

“John is a larger-than-life legend whose impact will endure and after whom we are so proud to have named our clinical service, The Bartlett Specialty Practice,” Dr. Thomas said.

The specialty practice clinic named for him has 23 exam rooms and features multidisciplinary care for people with HIV, hepatitis, bone infections, general infectious diseases, and more. Furthermore, friends, family, and colleagues joined forces to create the “Dr. John G. Bartlett HIV/AIDS Fund.”

They note that it is “only appropriate that we honor him by creating an endowment that will provide support for young trainees and junior faculty in the division, helping them transition to their independent careers.”

In addition to all his professional accomplishments, “He was also a genuinely nice person, approachable and humble,” Dr. Sax said. “We really lost a great one!”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The cause of death was not immediately disclosed.

Dr. Bartlett is remembered by colleagues for his wide range of infectious disease expertise, an ability to repeatedly predict emerging issues in the field, and for inspiring students and trainees to choose the same specialty.

“What I consistently found so extraordinary about John was his excitement for ID – the whole field. He had a wonderful sixth sense about what was going to be the next ‘big thing,’” Paul Edward Sax, MD, clinical director of the Infectious Disease Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, told this news organization.

“He thoroughly absorbed the emerging research on the topic and then provided the most wonderful clinical summaries,” Dr. Sax said. “His range of expert content areas was unbelievably broad.” Dr. Bartlett was “a true ID polymath.”

Dr. Bartlett was “a giant in the field of infectious diseases,” David Lee Thomas, MD, MPH, said in an interview. He agreed that Dr. Bartlett was a visionary who could anticipate the most exciting developments in the specialty.

Dr. Bartlett also “led the efforts to combat the foes, from HIV to antimicrobial resistance,” said Dr. Thomas, director of the division of infectious diseases and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

A pioneer in HIV research and care

Dr. Bartlett’s early research focused on anaerobic pulmonary and other infections, Bacteroides fragilis pathogenesis, and colitis caused by Clostridioides difficile.

Shortly after joining Johns Hopkins in 1980, he focused on HIV/AIDS research and caring for people with HIV. Dr. Bartlett led clinical trials of new treatments and developed years of HIV clinical treatment guidelines.

“Back when most hospitals, university medical centers, and ID divisions were running away from the AIDS epidemic, John took it on, both as a scientific priority and a moral imperative,” Dr. Sax writes in a blog post for NEJM Journal Watch. “With the help of Frank Polk and the Hopkins president, he established an outpatient AIDS clinic and an inpatient AIDS ward – both of which were way ahead of their time.”

In the same post, Dr. Sax points out that Dr. Bartlett was an expert in multiple areas – any one of which could be a sole career focus. “How many ID doctors are true experts in all of the following distinct topics? HIV, Clostridium difficile, respiratory tract infections, antimicrobial resistance, and anaerobic pulmonary infections.” Dr. Sax writes.

Expertise that defined an era

In a piece reviewing the long history of infectious disease medicine at Johns Hopkins published in Clinical Infectious Diseases in 2014, Paul Auwaerter, MD, and colleagues describe his tenure at the institution from 1980 to 2006 as “The Bartlett Era,” notable for the many advances he spearheaded.

“It is nearly impossible to find someone trained in infectious diseases in the past 30 years who has not been impacted by John Bartlett,” Dr. Auwaerter and colleagues note. “His tireless devotion to scholarship, teaching, and patient care remains an inspiration to his faculty members at Johns Hopkins, his colleagues, and coworkers around the world.”

Dr. Bartlett was not only a faculty member in the division of infectious diseases, he also helped establish it. When he joined Johns Hopkins, the infectious disease department featured just three faculty members with a research budget of less than $285,000. By the time he left 26 years later, the division had 44 faculty members on tenure track and a research budget exceeding $40 million.

Sharing memories via social media

Reactions to Dr. Bartlett’s passing on Twitter were swift.

“We have lost one of the greatest physicians I have ever met or had the privilege to learn from. Saddened to hear of Dr. John G. Bartlett’s passing. He inspired so many, including me, to choose the field of infectious diseases,” David Fisk, MD, infectious disease specialist in Santa Barbara, Calif., wrote on Twitter.

“John Bartlett just died – a true visionary and the classic ‘Renaissance’ person in clinical ID. Such a nice guy, too! His IDSA/IDWeek literature summaries (among other things) were amazing. We’ll miss him!” Dr. Sax tweeted on Jan. 19.

A colleague at Johns Hopkins, transplant infectious disease specialist Shmuel Shoham, MD, shared an anecdote about Dr. Bartlett on Twitter: “Year ago. My office is across from his. I ask him what he is doing. He tells me he is reviewing a file from the Vatican to adjudicate whether a miracle happened. True story.”

Infectious disease specialist Graeme Forrest, MBBS, also shared a story about Dr. Bartlett via Twitter. “He described to me in 2001 how the U.S. model of health care would not cope with a pandemic or serious bioterror attack as it’s not connected to disseminate information. How prescient from 20 years ago.”

Dr. Bartlett shared his expertise at many national and international infectious disease conferences over the years. He also authored 470 articles, 282 book chapters, and 61 editions of 14 books.

Dr. Bartlett was also a regular contributor to this news organization. For example, he shared his expertise in perspective pieces that addressed priorities in antibiotic stewardship, upcoming infectious disease predictions, and critical infectious disease topics in a three-part series.

Dr. Bartlett’s education includes a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., in 1959 and an MD from Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, N.Y., in 1963. He did his first 2 years of residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

He also served as an Army captain from 1965 to 1967, treating patients in fever wards in Vietnam. He then returned to the United States to finish his internal medicine training at the University of Alabama in 1968.

Dr. Bartlett completed his fellowship in infectious diseases at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1975, he joined the faculty at Tufts University, Boston.

Leaving a legacy

Dr. Bartlett’s influence will likely live on in many ways at Johns Hopkins.

“John is a larger-than-life legend whose impact will endure and after whom we are so proud to have named our clinical service, The Bartlett Specialty Practice,” Dr. Thomas said.

The specialty practice clinic named for him has 23 exam rooms and features multidisciplinary care for people with HIV, hepatitis, bone infections, general infectious diseases, and more. Furthermore, friends, family, and colleagues joined forces to create the “Dr. John G. Bartlett HIV/AIDS Fund.”

They note that it is “only appropriate that we honor him by creating an endowment that will provide support for young trainees and junior faculty in the division, helping them transition to their independent careers.”

In addition to all his professional accomplishments, “He was also a genuinely nice person, approachable and humble,” Dr. Sax said. “We really lost a great one!”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adjuvant nivolumab: A new standard of care in high-risk MIUC?

The trial enrolled patients regardless of tumor PD-L1 status and receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The median disease-free survival was 21.0 months among patients given adjuvant nivolumab, almost double the 10.9 months among counterparts given placebo. Unsurprisingly, treatment-related adverse events were more common with nivolumab, but health-related quality of life was similar to that with placebo.

“Nivolumab is the first systemic immunotherapy to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in outcomes when administered as adjuvant therapy to patients with MIUC,” said study investigator Dean F. Bajorin, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“These results support nivolumab monotherapy as a new standard of care in the adjuvant setting for patients with high-risk MIUC after radical surgery regardless of PD-L1 status and prior neoadjuvant chemotherapy,” Dr. Bajorin said when presenting the results at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 391).

Trial details

The international, phase 3 trial enrolled 709 patients who had undergone radical surgery for high-risk MIUC of the bladder, ureter, or renal pelvis.

By intention, about 20% of the trial population had upper-tract disease, Dr. Bajorin noted. Roughly 43% had received cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 40% had tumors that were positive for PD-L1 (defined as ≥1% expression).

The patients were randomized evenly to receive up to 1 year of adjuvant nivolumab or placebo on a double-blind basis.

At a median follow-up of about 20 months, the trial met its primary endpoint, showing significant prolongation of disease-free survival in the intention-to-treat population with nivolumab versus placebo – a median of 21.0 months and 10.9 months, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.70; P < .001).

In subgroup analyses by disease site, benefit appeared restricted to patients with bladder tumors, although this finding is only hypothesis generating, Dr. Bajorin said.

The gain in disease-free survival was greater when analysis was restricted to the patients whose tumors were positive for PD-L1. The median disease-free survival was not reached in the nivolumab group and was 10.8 months in the placebo group (HR, 0.53; P < .001).

Nivolumab also netted significantly better non–urothelial tract recurrence-free survival (an endpoint that excludes common, non–life-threatening second primary urothelial cancers) and distant metastasis–free survival, both in the entire intention-to-treat population and in the subset with PD-L1–positive tumors.

Patients in the nivolumab group had a higher rate of grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events (17.9% vs. 7.2%), mainly caused by higher rates of increased amylase levels and lipase levels. But there was no deterioration in health-related quality of life as compared with placebo.

The most common grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events with nivolumab that were potentially immune mediated were diarrhea (0.9%), colitis (0.9%), and pneumonitis (0.9%), including two deaths in patients with treatment-related pneumonitis.

Awaited findings

Overall survival and biomarker data will require longer follow-up, Dr. Bajorin acknowledged. He defended the choice of disease-free survival as the trial’s primary endpoint, noting that it was selected after discussions with regulators when the trial was designed about 7 years ago.

“We believe that disease-free survival is an appropriate endpoint, that there are a lot of symptoms associated with metastasis in this disease. This is a devastating, symptomatic disease when it’s metastatic,” he elaborated, adding that this fact was also a driver behind selection of the other efficacy endpoints.

“I think that, as we follow this study further, we will see that disease-free survival – like it has in other studies in urothelial cancer – can translate into an overall survival benefit as well,” Dr. Bajorin said.

“This study is one of the most important in the last 5 years,” commented session cochair James M. McKiernan, MD, of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

Some questions do arise when comparing the trial’s findings against those of other adjuvant trials in MIUC, he observed in an interview. In addition, it was noteworthy that the benefit of nivolumab was greatest among patients with PD-L1–positive tumors and those who had received neoadjuvant cisplatin.

Nonetheless, “I agree with the overall conclusion of the trial, and these data will establish a new standard of care,” Dr. McKiernan concluded. “The absence of overall survival data is not concerning for me, but we will all await that endpoint.”

The trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Bajorin disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and several other companies. Dr. McKiernan disclosed a relationship with miR Scientific.

The trial enrolled patients regardless of tumor PD-L1 status and receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The median disease-free survival was 21.0 months among patients given adjuvant nivolumab, almost double the 10.9 months among counterparts given placebo. Unsurprisingly, treatment-related adverse events were more common with nivolumab, but health-related quality of life was similar to that with placebo.

“Nivolumab is the first systemic immunotherapy to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in outcomes when administered as adjuvant therapy to patients with MIUC,” said study investigator Dean F. Bajorin, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“These results support nivolumab monotherapy as a new standard of care in the adjuvant setting for patients with high-risk MIUC after radical surgery regardless of PD-L1 status and prior neoadjuvant chemotherapy,” Dr. Bajorin said when presenting the results at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 391).

Trial details

The international, phase 3 trial enrolled 709 patients who had undergone radical surgery for high-risk MIUC of the bladder, ureter, or renal pelvis.

By intention, about 20% of the trial population had upper-tract disease, Dr. Bajorin noted. Roughly 43% had received cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 40% had tumors that were positive for PD-L1 (defined as ≥1% expression).

The patients were randomized evenly to receive up to 1 year of adjuvant nivolumab or placebo on a double-blind basis.

At a median follow-up of about 20 months, the trial met its primary endpoint, showing significant prolongation of disease-free survival in the intention-to-treat population with nivolumab versus placebo – a median of 21.0 months and 10.9 months, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.70; P < .001).

In subgroup analyses by disease site, benefit appeared restricted to patients with bladder tumors, although this finding is only hypothesis generating, Dr. Bajorin said.

The gain in disease-free survival was greater when analysis was restricted to the patients whose tumors were positive for PD-L1. The median disease-free survival was not reached in the nivolumab group and was 10.8 months in the placebo group (HR, 0.53; P < .001).

Nivolumab also netted significantly better non–urothelial tract recurrence-free survival (an endpoint that excludes common, non–life-threatening second primary urothelial cancers) and distant metastasis–free survival, both in the entire intention-to-treat population and in the subset with PD-L1–positive tumors.

Patients in the nivolumab group had a higher rate of grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events (17.9% vs. 7.2%), mainly caused by higher rates of increased amylase levels and lipase levels. But there was no deterioration in health-related quality of life as compared with placebo.

The most common grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events with nivolumab that were potentially immune mediated were diarrhea (0.9%), colitis (0.9%), and pneumonitis (0.9%), including two deaths in patients with treatment-related pneumonitis.

Awaited findings

Overall survival and biomarker data will require longer follow-up, Dr. Bajorin acknowledged. He defended the choice of disease-free survival as the trial’s primary endpoint, noting that it was selected after discussions with regulators when the trial was designed about 7 years ago.

“We believe that disease-free survival is an appropriate endpoint, that there are a lot of symptoms associated with metastasis in this disease. This is a devastating, symptomatic disease when it’s metastatic,” he elaborated, adding that this fact was also a driver behind selection of the other efficacy endpoints.

“I think that, as we follow this study further, we will see that disease-free survival – like it has in other studies in urothelial cancer – can translate into an overall survival benefit as well,” Dr. Bajorin said.

“This study is one of the most important in the last 5 years,” commented session cochair James M. McKiernan, MD, of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

Some questions do arise when comparing the trial’s findings against those of other adjuvant trials in MIUC, he observed in an interview. In addition, it was noteworthy that the benefit of nivolumab was greatest among patients with PD-L1–positive tumors and those who had received neoadjuvant cisplatin.

Nonetheless, “I agree with the overall conclusion of the trial, and these data will establish a new standard of care,” Dr. McKiernan concluded. “The absence of overall survival data is not concerning for me, but we will all await that endpoint.”

The trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Bajorin disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and several other companies. Dr. McKiernan disclosed a relationship with miR Scientific.

The trial enrolled patients regardless of tumor PD-L1 status and receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The median disease-free survival was 21.0 months among patients given adjuvant nivolumab, almost double the 10.9 months among counterparts given placebo. Unsurprisingly, treatment-related adverse events were more common with nivolumab, but health-related quality of life was similar to that with placebo.

“Nivolumab is the first systemic immunotherapy to demonstrate a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in outcomes when administered as adjuvant therapy to patients with MIUC,” said study investigator Dean F. Bajorin, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“These results support nivolumab monotherapy as a new standard of care in the adjuvant setting for patients with high-risk MIUC after radical surgery regardless of PD-L1 status and prior neoadjuvant chemotherapy,” Dr. Bajorin said when presenting the results at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 391).

Trial details

The international, phase 3 trial enrolled 709 patients who had undergone radical surgery for high-risk MIUC of the bladder, ureter, or renal pelvis.

By intention, about 20% of the trial population had upper-tract disease, Dr. Bajorin noted. Roughly 43% had received cisplatin-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and 40% had tumors that were positive for PD-L1 (defined as ≥1% expression).

The patients were randomized evenly to receive up to 1 year of adjuvant nivolumab or placebo on a double-blind basis.

At a median follow-up of about 20 months, the trial met its primary endpoint, showing significant prolongation of disease-free survival in the intention-to-treat population with nivolumab versus placebo – a median of 21.0 months and 10.9 months, respectively (hazard ratio, 0.70; P < .001).

In subgroup analyses by disease site, benefit appeared restricted to patients with bladder tumors, although this finding is only hypothesis generating, Dr. Bajorin said.

The gain in disease-free survival was greater when analysis was restricted to the patients whose tumors were positive for PD-L1. The median disease-free survival was not reached in the nivolumab group and was 10.8 months in the placebo group (HR, 0.53; P < .001).

Nivolumab also netted significantly better non–urothelial tract recurrence-free survival (an endpoint that excludes common, non–life-threatening second primary urothelial cancers) and distant metastasis–free survival, both in the entire intention-to-treat population and in the subset with PD-L1–positive tumors.

Patients in the nivolumab group had a higher rate of grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events (17.9% vs. 7.2%), mainly caused by higher rates of increased amylase levels and lipase levels. But there was no deterioration in health-related quality of life as compared with placebo.

The most common grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events with nivolumab that were potentially immune mediated were diarrhea (0.9%), colitis (0.9%), and pneumonitis (0.9%), including two deaths in patients with treatment-related pneumonitis.

Awaited findings

Overall survival and biomarker data will require longer follow-up, Dr. Bajorin acknowledged. He defended the choice of disease-free survival as the trial’s primary endpoint, noting that it was selected after discussions with regulators when the trial was designed about 7 years ago.

“We believe that disease-free survival is an appropriate endpoint, that there are a lot of symptoms associated with metastasis in this disease. This is a devastating, symptomatic disease when it’s metastatic,” he elaborated, adding that this fact was also a driver behind selection of the other efficacy endpoints.

“I think that, as we follow this study further, we will see that disease-free survival – like it has in other studies in urothelial cancer – can translate into an overall survival benefit as well,” Dr. Bajorin said.

“This study is one of the most important in the last 5 years,” commented session cochair James M. McKiernan, MD, of the Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York.

Some questions do arise when comparing the trial’s findings against those of other adjuvant trials in MIUC, he observed in an interview. In addition, it was noteworthy that the benefit of nivolumab was greatest among patients with PD-L1–positive tumors and those who had received neoadjuvant cisplatin.

Nonetheless, “I agree with the overall conclusion of the trial, and these data will establish a new standard of care,” Dr. McKiernan concluded. “The absence of overall survival data is not concerning for me, but we will all await that endpoint.”

The trial was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Bajorin disclosed relationships with Bristol-Myers Squibb and several other companies. Dr. McKiernan disclosed a relationship with miR Scientific.

FROM GUCS 2021

TITAN: Final results confirm apalutamide benefit in mCSPC

At a median follow-up of 44 months, the median overall survival (OS) was not reached in patients who received apalutamide plus standard androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), but the median OS was 52.2 months in patients who received placebo plus ADT.

“In the final analysis, the risk of death with apalutamide was reduced by 35%, with a hazard ratio of 0.65 and P value of less than .0001. This was similar to the hazard ratio of 0.67 in the primary analysis of TITAN, despite an almost 40% crossover rate from the placebo group to the apalutamide,” said Kim N. Chi, MD, a medical oncologist at BC Cancer Vancouver Prostate Centre.

Dr. Chi reported these results at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancer Symposium (Abstract 11).

Study details

The international, double-blind TITAN trial compared apalutamide (240 mg daily) with placebo, both added to standard ADT, in 1,052 patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, including those with high- and low-volume disease, prior docetaxel use, prior treatment for localized disease, and prior ADT for no more than 6 months.

At the primary analysis, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019, the dual primary endpoints of radiographic progression-free survival and OS met statistical significance at a median follow up of 22.7 months.

At the final analysis, the median treatment duration was 39.3 months for the apalutamide arm, 20.2 months for the placebo arm, and 15.4 months for patients who crossed over from placebo to apalutamide.

After adjusting for crossover, the effect of apalutamide on OS increased (HR, 0.52), indicating a reduction in the risk of death by 48% versus placebo, Dr. Chi said. He noted that the treatment effect on OS favored apalutamide in both high- and low-volume disease.

“Treatment with apalutamide also significantly prolonged second progression-free survival on next subsequent therapy and delayed development of castration resistance,” Dr. Chi said.

The median second progression-free survival was 44.0 months in the placebo arm and was not reached in the apalutamide arm. The median time to castration resistance was 11.4 months in the placebo arm and was not reached in the apalutamide arm.

Health-related quality of life was also maintained in the apalutamide group throughout the study and did not differ from the placebo group. Safety was consistent with previous reports.

“Importantly, the cumulative incidence of treatment-related falls, fracture, and fatigue was similar between groups, as was the cumulative incidence of treatment-related adverse events and serious adverse events,” Dr. Chi said.

An increased incidence of any-grade rash that was seen in the apalutamide group was expected but plateaued after about 6 months.

“These results confirm the favorable risk-benefit profile of apalutamide,” Dr. Chi concluded.

Implications for practice

The study results raise questions about how to best incorporate the findings into practice, including how to use docetaxel or other androgen receptor inhibitors in treatment strategies for this patient population and if they should be used in high-volume patients, said Elisabeth Heath, MD, session cochair and associate director of translational science at Wayne State University in Detroit.

Dr. Chi said a number of studies over the past 5 years have demonstrated OS benefit when combining ADT with additional therapy.

“Really, this should be considered the standard of care,” he said. “However, real-world studies ... suggest that only a minority of patients are actually receiving this additional therapy.”

Although there are challenges with comparing outcomes across studies to determine which treatments to use, the TITAN data reinforce apalutamide plus ADT as a good option, including in high-volume patients, Dr. Chi said.

Funding for TITAN was provided by Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Chi and Dr. Heath disclosed relationships with Janssen and many other companies. [email protected]

At a median follow-up of 44 months, the median overall survival (OS) was not reached in patients who received apalutamide plus standard androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), but the median OS was 52.2 months in patients who received placebo plus ADT.

“In the final analysis, the risk of death with apalutamide was reduced by 35%, with a hazard ratio of 0.65 and P value of less than .0001. This was similar to the hazard ratio of 0.67 in the primary analysis of TITAN, despite an almost 40% crossover rate from the placebo group to the apalutamide,” said Kim N. Chi, MD, a medical oncologist at BC Cancer Vancouver Prostate Centre.

Dr. Chi reported these results at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancer Symposium (Abstract 11).

Study details

The international, double-blind TITAN trial compared apalutamide (240 mg daily) with placebo, both added to standard ADT, in 1,052 patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, including those with high- and low-volume disease, prior docetaxel use, prior treatment for localized disease, and prior ADT for no more than 6 months.

At the primary analysis, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019, the dual primary endpoints of radiographic progression-free survival and OS met statistical significance at a median follow up of 22.7 months.

At the final analysis, the median treatment duration was 39.3 months for the apalutamide arm, 20.2 months for the placebo arm, and 15.4 months for patients who crossed over from placebo to apalutamide.

After adjusting for crossover, the effect of apalutamide on OS increased (HR, 0.52), indicating a reduction in the risk of death by 48% versus placebo, Dr. Chi said. He noted that the treatment effect on OS favored apalutamide in both high- and low-volume disease.

“Treatment with apalutamide also significantly prolonged second progression-free survival on next subsequent therapy and delayed development of castration resistance,” Dr. Chi said.

The median second progression-free survival was 44.0 months in the placebo arm and was not reached in the apalutamide arm. The median time to castration resistance was 11.4 months in the placebo arm and was not reached in the apalutamide arm.

Health-related quality of life was also maintained in the apalutamide group throughout the study and did not differ from the placebo group. Safety was consistent with previous reports.

“Importantly, the cumulative incidence of treatment-related falls, fracture, and fatigue was similar between groups, as was the cumulative incidence of treatment-related adverse events and serious adverse events,” Dr. Chi said.

An increased incidence of any-grade rash that was seen in the apalutamide group was expected but plateaued after about 6 months.

“These results confirm the favorable risk-benefit profile of apalutamide,” Dr. Chi concluded.

Implications for practice

The study results raise questions about how to best incorporate the findings into practice, including how to use docetaxel or other androgen receptor inhibitors in treatment strategies for this patient population and if they should be used in high-volume patients, said Elisabeth Heath, MD, session cochair and associate director of translational science at Wayne State University in Detroit.

Dr. Chi said a number of studies over the past 5 years have demonstrated OS benefit when combining ADT with additional therapy.

“Really, this should be considered the standard of care,” he said. “However, real-world studies ... suggest that only a minority of patients are actually receiving this additional therapy.”

Although there are challenges with comparing outcomes across studies to determine which treatments to use, the TITAN data reinforce apalutamide plus ADT as a good option, including in high-volume patients, Dr. Chi said.

Funding for TITAN was provided by Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Chi and Dr. Heath disclosed relationships with Janssen and many other companies. [email protected]

At a median follow-up of 44 months, the median overall survival (OS) was not reached in patients who received apalutamide plus standard androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), but the median OS was 52.2 months in patients who received placebo plus ADT.

“In the final analysis, the risk of death with apalutamide was reduced by 35%, with a hazard ratio of 0.65 and P value of less than .0001. This was similar to the hazard ratio of 0.67 in the primary analysis of TITAN, despite an almost 40% crossover rate from the placebo group to the apalutamide,” said Kim N. Chi, MD, a medical oncologist at BC Cancer Vancouver Prostate Centre.

Dr. Chi reported these results at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancer Symposium (Abstract 11).

Study details

The international, double-blind TITAN trial compared apalutamide (240 mg daily) with placebo, both added to standard ADT, in 1,052 patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer, including those with high- and low-volume disease, prior docetaxel use, prior treatment for localized disease, and prior ADT for no more than 6 months.

At the primary analysis, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019, the dual primary endpoints of radiographic progression-free survival and OS met statistical significance at a median follow up of 22.7 months.

At the final analysis, the median treatment duration was 39.3 months for the apalutamide arm, 20.2 months for the placebo arm, and 15.4 months for patients who crossed over from placebo to apalutamide.

After adjusting for crossover, the effect of apalutamide on OS increased (HR, 0.52), indicating a reduction in the risk of death by 48% versus placebo, Dr. Chi said. He noted that the treatment effect on OS favored apalutamide in both high- and low-volume disease.

“Treatment with apalutamide also significantly prolonged second progression-free survival on next subsequent therapy and delayed development of castration resistance,” Dr. Chi said.

The median second progression-free survival was 44.0 months in the placebo arm and was not reached in the apalutamide arm. The median time to castration resistance was 11.4 months in the placebo arm and was not reached in the apalutamide arm.

Health-related quality of life was also maintained in the apalutamide group throughout the study and did not differ from the placebo group. Safety was consistent with previous reports.

“Importantly, the cumulative incidence of treatment-related falls, fracture, and fatigue was similar between groups, as was the cumulative incidence of treatment-related adverse events and serious adverse events,” Dr. Chi said.

An increased incidence of any-grade rash that was seen in the apalutamide group was expected but plateaued after about 6 months.

“These results confirm the favorable risk-benefit profile of apalutamide,” Dr. Chi concluded.

Implications for practice

The study results raise questions about how to best incorporate the findings into practice, including how to use docetaxel or other androgen receptor inhibitors in treatment strategies for this patient population and if they should be used in high-volume patients, said Elisabeth Heath, MD, session cochair and associate director of translational science at Wayne State University in Detroit.

Dr. Chi said a number of studies over the past 5 years have demonstrated OS benefit when combining ADT with additional therapy.

“Really, this should be considered the standard of care,” he said. “However, real-world studies ... suggest that only a minority of patients are actually receiving this additional therapy.”

Although there are challenges with comparing outcomes across studies to determine which treatments to use, the TITAN data reinforce apalutamide plus ADT as a good option, including in high-volume patients, Dr. Chi said.

Funding for TITAN was provided by Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Chi and Dr. Heath disclosed relationships with Janssen and many other companies. [email protected]

FROM GUCS 2021

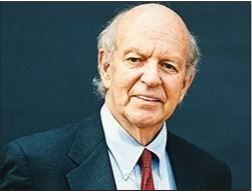

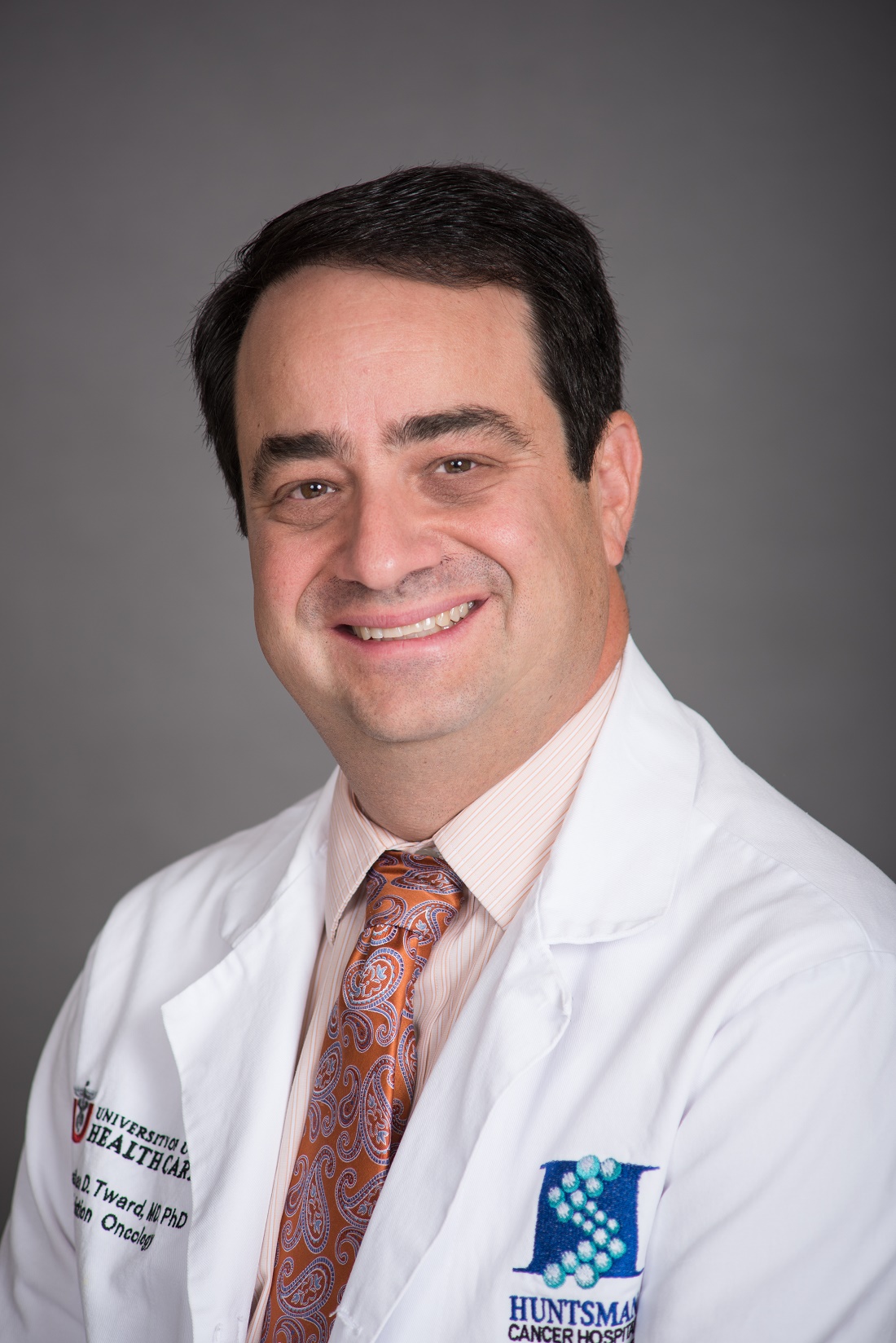

CCR score can guide treatment decisions after radiation in prostate cancer

The score can identify patients in whom the risk of metastasis after dose-escalated radiation is so small that adding ADT no longer makes clinical sense, according to investigator Jonathan Tward, MD, PhD, of the Genitourinary Cancer Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

His group’s study, which included 741 patients, showed that, below a CCR score of 2.112, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 4.2% with radiation therapy (RT) alone and 3.9% with the addition of ADT.

“Whether you have RT alone, RT plus any duration of ADT, insufficient duration ADT, or sufficient ADT duration by guideline standard, the risk of metastasis never exceeds 5% at 10 years” even in high- and very-high-risk men, Dr. Tward said.

He and his team found that half the men in their study with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, 20% with high-risk disease, and 5% with very-high-risk disease scored below the CCR threshold.

This implies that, for many men, ADT after radiation “adds unnecessary morbidity for an extremely small absolute risk reduction in metastasis-free survival,” Dr. Tward said at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, where he presented the findings (Abstract 195).

Value of CCR

The CCR score tells you if the relative metastasis risk reduction with ADT after radiation – about 50% based on clinical trials – translates to an absolute risk reduction that would matter, Dr. Tward said in an interview.

“Each patient has in their own mind what that risk reduction is that works for them,” he added.

For some patients, a 1%-2% drop in absolute risk is worth it, he said, but most patients wouldn’t be willing to endure the side effects of hormone therapy if the absolute benefit is less than 5%.

The CCR score is a validated prognosticator of metastasis and death in localized prostate cancer. It’s an amalgam of traditional clinical risk factors from the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and the cell-cycle progression (CCP) score, which measures expression of cell-cycle proliferation genes for a sense of how quickly tumor cells are dividing.

The CCP test is available commercially as Prolaris. It is used mostly to make the call between active surveillance and treatment, Dr. Tward explained, “but I had a hunch this off-the-shelf test would be very good at” helping with ADT decisions after radiation.

‘Uncomfortable’ findings, barriers to acceptance

“People are going to be very uncomfortable with these findings because it’s been ingrained in our heads for the past 20-30 years that you must use hormone therapy with high-risk prostate cancer, and you should use hormone therapy with intermediate risk,” Dr. Tward said.

“It took me a while to believe my own data, but we have used this test for several years to help men decide if they would like to have hormone therapy after radiation. Patients clearly benefit from this information,” he said.

The 2.112 cut point for CCR was determined from a prior study that was presented at GUCS 2020 (Abstract 346) and recently accepted for publication.

In the validation study Dr. Tward presented at GUCS 2021, 70% of patients had intermediate-risk disease, and 30% had high- or very-high-risk disease according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria.

All 741 patients received RT equivalent to at least 75.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, with 84% getting or exceeding 79.2 Gy. About half the men (53%) had ADT after RT.

Genetic testing was done on stored biopsy samples years after the men were treated. Half of them were below the CCR threshold of 2.112. For those above it, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 25.3%.

CCR outperformed CCP alone, CAPRA alone, and NCCN risk groupings for predicting metastasis risk after RT.

Though this validation study was “successful,” additional research is needed, according to study discussant Richard Valicenti, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“Widespread acceptance for routine use faces challenges since no biomarker has been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcome,” Dr. Valicenti said. “Clearly, the CCR score may provide highly precise, personalized estimates and justifies testing in tiered and appropriately powered noninferiority studies according to NCCN risk groups. We eagerly await the completion and reporting of such trials so that we have a more personalized approach to treating men with prostate cancer.”

The current study was funded by Myriad Genetics, the company that developed the Prolaris test. Dr. Tward disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. Dr. Valicenti has no disclosures.

The score can identify patients in whom the risk of metastasis after dose-escalated radiation is so small that adding ADT no longer makes clinical sense, according to investigator Jonathan Tward, MD, PhD, of the Genitourinary Cancer Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

His group’s study, which included 741 patients, showed that, below a CCR score of 2.112, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 4.2% with radiation therapy (RT) alone and 3.9% with the addition of ADT.

“Whether you have RT alone, RT plus any duration of ADT, insufficient duration ADT, or sufficient ADT duration by guideline standard, the risk of metastasis never exceeds 5% at 10 years” even in high- and very-high-risk men, Dr. Tward said.

He and his team found that half the men in their study with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, 20% with high-risk disease, and 5% with very-high-risk disease scored below the CCR threshold.

This implies that, for many men, ADT after radiation “adds unnecessary morbidity for an extremely small absolute risk reduction in metastasis-free survival,” Dr. Tward said at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, where he presented the findings (Abstract 195).

Value of CCR

The CCR score tells you if the relative metastasis risk reduction with ADT after radiation – about 50% based on clinical trials – translates to an absolute risk reduction that would matter, Dr. Tward said in an interview.

“Each patient has in their own mind what that risk reduction is that works for them,” he added.

For some patients, a 1%-2% drop in absolute risk is worth it, he said, but most patients wouldn’t be willing to endure the side effects of hormone therapy if the absolute benefit is less than 5%.

The CCR score is a validated prognosticator of metastasis and death in localized prostate cancer. It’s an amalgam of traditional clinical risk factors from the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and the cell-cycle progression (CCP) score, which measures expression of cell-cycle proliferation genes for a sense of how quickly tumor cells are dividing.

The CCP test is available commercially as Prolaris. It is used mostly to make the call between active surveillance and treatment, Dr. Tward explained, “but I had a hunch this off-the-shelf test would be very good at” helping with ADT decisions after radiation.

‘Uncomfortable’ findings, barriers to acceptance

“People are going to be very uncomfortable with these findings because it’s been ingrained in our heads for the past 20-30 years that you must use hormone therapy with high-risk prostate cancer, and you should use hormone therapy with intermediate risk,” Dr. Tward said.

“It took me a while to believe my own data, but we have used this test for several years to help men decide if they would like to have hormone therapy after radiation. Patients clearly benefit from this information,” he said.

The 2.112 cut point for CCR was determined from a prior study that was presented at GUCS 2020 (Abstract 346) and recently accepted for publication.

In the validation study Dr. Tward presented at GUCS 2021, 70% of patients had intermediate-risk disease, and 30% had high- or very-high-risk disease according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria.

All 741 patients received RT equivalent to at least 75.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, with 84% getting or exceeding 79.2 Gy. About half the men (53%) had ADT after RT.

Genetic testing was done on stored biopsy samples years after the men were treated. Half of them were below the CCR threshold of 2.112. For those above it, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 25.3%.

CCR outperformed CCP alone, CAPRA alone, and NCCN risk groupings for predicting metastasis risk after RT.

Though this validation study was “successful,” additional research is needed, according to study discussant Richard Valicenti, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“Widespread acceptance for routine use faces challenges since no biomarker has been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcome,” Dr. Valicenti said. “Clearly, the CCR score may provide highly precise, personalized estimates and justifies testing in tiered and appropriately powered noninferiority studies according to NCCN risk groups. We eagerly await the completion and reporting of such trials so that we have a more personalized approach to treating men with prostate cancer.”

The current study was funded by Myriad Genetics, the company that developed the Prolaris test. Dr. Tward disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. Dr. Valicenti has no disclosures.

The score can identify patients in whom the risk of metastasis after dose-escalated radiation is so small that adding ADT no longer makes clinical sense, according to investigator Jonathan Tward, MD, PhD, of the Genitourinary Cancer Center at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

His group’s study, which included 741 patients, showed that, below a CCR score of 2.112, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 4.2% with radiation therapy (RT) alone and 3.9% with the addition of ADT.

“Whether you have RT alone, RT plus any duration of ADT, insufficient duration ADT, or sufficient ADT duration by guideline standard, the risk of metastasis never exceeds 5% at 10 years” even in high- and very-high-risk men, Dr. Tward said.

He and his team found that half the men in their study with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, 20% with high-risk disease, and 5% with very-high-risk disease scored below the CCR threshold.

This implies that, for many men, ADT after radiation “adds unnecessary morbidity for an extremely small absolute risk reduction in metastasis-free survival,” Dr. Tward said at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium, where he presented the findings (Abstract 195).

Value of CCR

The CCR score tells you if the relative metastasis risk reduction with ADT after radiation – about 50% based on clinical trials – translates to an absolute risk reduction that would matter, Dr. Tward said in an interview.

“Each patient has in their own mind what that risk reduction is that works for them,” he added.

For some patients, a 1%-2% drop in absolute risk is worth it, he said, but most patients wouldn’t be willing to endure the side effects of hormone therapy if the absolute benefit is less than 5%.

The CCR score is a validated prognosticator of metastasis and death in localized prostate cancer. It’s an amalgam of traditional clinical risk factors from the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score and the cell-cycle progression (CCP) score, which measures expression of cell-cycle proliferation genes for a sense of how quickly tumor cells are dividing.

The CCP test is available commercially as Prolaris. It is used mostly to make the call between active surveillance and treatment, Dr. Tward explained, “but I had a hunch this off-the-shelf test would be very good at” helping with ADT decisions after radiation.

‘Uncomfortable’ findings, barriers to acceptance

“People are going to be very uncomfortable with these findings because it’s been ingrained in our heads for the past 20-30 years that you must use hormone therapy with high-risk prostate cancer, and you should use hormone therapy with intermediate risk,” Dr. Tward said.

“It took me a while to believe my own data, but we have used this test for several years to help men decide if they would like to have hormone therapy after radiation. Patients clearly benefit from this information,” he said.

The 2.112 cut point for CCR was determined from a prior study that was presented at GUCS 2020 (Abstract 346) and recently accepted for publication.

In the validation study Dr. Tward presented at GUCS 2021, 70% of patients had intermediate-risk disease, and 30% had high- or very-high-risk disease according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network criteria.

All 741 patients received RT equivalent to at least 75.6 Gy at 1.8 Gy per fraction, with 84% getting or exceeding 79.2 Gy. About half the men (53%) had ADT after RT.

Genetic testing was done on stored biopsy samples years after the men were treated. Half of them were below the CCR threshold of 2.112. For those above it, the 10-year risk of metastasis was 25.3%.

CCR outperformed CCP alone, CAPRA alone, and NCCN risk groupings for predicting metastasis risk after RT.

Though this validation study was “successful,” additional research is needed, according to study discussant Richard Valicenti, MD, of the University of California, Davis.

“Widespread acceptance for routine use faces challenges since no biomarker has been prospectively tested or shown to improve long-term outcome,” Dr. Valicenti said. “Clearly, the CCR score may provide highly precise, personalized estimates and justifies testing in tiered and appropriately powered noninferiority studies according to NCCN risk groups. We eagerly await the completion and reporting of such trials so that we have a more personalized approach to treating men with prostate cancer.”

The current study was funded by Myriad Genetics, the company that developed the Prolaris test. Dr. Tward disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Bayer, Blue Earth Diagnostics, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck. Dr. Valicenti has no disclosures.

FROM GUCS 2021

Liquid vs. tissue biopsy in advanced prostate cancer: Why not both?

The type and frequency of genomic alterations observed were largely similar in ctDNA and tissue, and there was high concordance for BRCA1/2 alterations. Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of ctDNA detected more acquired resistance alterations, which included novel androgen receptor (AR)–activating variants. In fact, alterations in nine genes were significantly enriched in ctDNA, but some of these alterations may be attributable to clonal hematopoiesis and not the tumor.

Still, the researchers concluded that CGP of ctDNA could complement tissue-based CGP.

“This is the largest study of mCRPC plasma samples conducted to date, and CGP of ctDNA recapitulated the genomic landscape detected in tissue biopsies,” said investigator Hanna Tukachinsky, PhD, from Foundation Medicine, the company that developed the liquid biopsy tests used in this study.

“The large percentage of patients with rich genomic signal from ctDNA and the sensitive, specific detection of BRCA1/2 alterations position liquid biopsy as a compelling clinical complement to tissue CGP for patients with mCRPC.”

Dr. Tukachinsky presented results from this study at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 25). The results were also published in Clinical Cancer Research, but the following data are from the meeting presentation.

ctDNA profiling proves feasible, comparable

CGP was performed on 3,334 liquid biopsy samples and 2,006 tissue samples from patients with mCRPC, including patients in the TRITON2 and TRITON3 trials.

The plasma samples were profiled using FoundationACT, which had a panel of 62 genes, or FoundationOne Liquid CDx, which had a panel of 70 genes.

Most of the liquid biopsy samples – 94% – had detectable ctDNA, and the median ctDNA fraction was 7.5%.

“One of the most important findings in this study is the fact that the majority of patients with advanced prostate cancer – 94% of them – have abundant ctDNA,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

“The overall landscape we detected in ctDNA highly resembles landscapes reported in tissue-based CGP studies of mCRPC,” she added.

ctDNA results showed a high percentage of TP53 and AR alterations, as well as alterations in DNA repair genes (ATM, CHEK2, BRCA2, and CDK12), PI3 kinase components (PTEN, PIK3CA, and AKT1), and WNT components (APC and CTNNB1).

“It should be noted that the two assays did not bait for TMPRSS2-ERT fusions or SPOP ... and we’re missing homozygous deletions, which affects the frequency we detect PTEN, RB1, and BRCA alterations,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

When the researchers compared results from the 3,334 liquid biopsy samples and the 2,006 tissue samples, they found that most genes were altered at similar rates.

However, nine genes were significantly enriched in ctDNA – AR, TP53, ATM, CHEK2, NF1, TERT, JAK2, IDH2, and GNAS.

Dr. Tukachinsky noted that JAK2, GNAS, and IDH2 alterations are rarely detected in mCRPC tissue and are likely attributable to clonal hematopoiesis. Alterations in TERT and NF1, as well as some of the alterations in ATM and CHEK2, might also be attributed to clonal hematopoiesis, she added.

Rare and novel AR alterations

“ctDNA detected more acquired resistance genomic alterations than tissue, including novel and rare AR-activating variants,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

She noted that F877L/T878A, a compound mutant that has been shown to confer synergistic resistance to enzalutamide, was found in 11 patients.

Similarly, “completely novel” in-frame mutations spanning residues H875 to T878 were found in 11 patients, and each shifted S885 into the T878 position.

“Although these require more experiments to prove that they are activating, their repeated appearance in different patients with mCRPC and alignment of the serine residues is highly suggestive that they are activating,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

The researchers also found, in 160 patients, AR rearrangements that truncate the reading frame just after exon 3 to yield a receptor with an intact DNA binding domain but without a ligand binding domain.

“These truncated receptors have been demonstrated to confer resistance to AR signaling inhibitors and drive transcription of the AR target genes,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

BRCA1/2: High concordance

To further assess concordance between ctDNA and tissue, Dr. Tukachinsky and colleagues evaluated a subset of 837 patients with matched tissue and liquid biopsies.

The researchers observed high concordance in BRCA1/2 short variants and rearrangements. The positive percent agreement was 93.1%, the negative percent agreement was 97.4%, and the overall percent agreement was 97.0%.

There were 5 patients in whom BRCA1/2 alterations were detected in tissue but not ctDNA, and there were 20 patients in whom BRCA1/2 alterations were detected in ctDNA but not tissue.

The false negatives could be the result of low ctDNA fraction, a minor clone, or filtering out by post analytics, said study discussant Silke Gillessen, MD, of the Institute of Oncology of Southern Switzerland in Bellinzona. She also postulated that the false positives could be explained by clonal hematopoiesis or metastases from a subclone.

Implications for practice

This study showed that liquid and tissue biopsies can perform comparably in identifying patients with BRCA1/2 variants who may benefit from PARP inhibition, Dr. Tukachinsky noted. Additionally, ctDNA revealed novel AR variants that may be driving resistance to AR-signaling inhibitors. However, the presence of alterations that may derive from clonal hematopoiesis suggests ctDNA results should be interpreted with some caution, she added.

“NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines have recently changed to include liquid biopsy as an option. There’s definitely some skepticism about liquid biopsy …. That said, liquid biopsy is also a pretty powerful tool,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

“We are not advocating liquid biopsy over tissue. In the cases where tissue’s not available, or if you have a primary, in some cases, liquid could serve as a good complement to give you the full picture of what’s going on in the tumor,” she added.

“For the time being, tissue will still be our gold standard,” Dr. Gillessen said. “And if we can’t get the tissue tested, that will be then maybe a point for the liquid biopsy.”

Dr. Tukachinsky’s research was funded by Foundation Medicine and Clovis Oncology. She and her colleagues disclosed relationships with both companies and a range of other companies. Dr. Gillessen disclosed relationships with Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, and several other companies as well as a patent for a biomarker method (WO 3752009138392 A1).

The type and frequency of genomic alterations observed were largely similar in ctDNA and tissue, and there was high concordance for BRCA1/2 alterations. Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of ctDNA detected more acquired resistance alterations, which included novel androgen receptor (AR)–activating variants. In fact, alterations in nine genes were significantly enriched in ctDNA, but some of these alterations may be attributable to clonal hematopoiesis and not the tumor.

Still, the researchers concluded that CGP of ctDNA could complement tissue-based CGP.

“This is the largest study of mCRPC plasma samples conducted to date, and CGP of ctDNA recapitulated the genomic landscape detected in tissue biopsies,” said investigator Hanna Tukachinsky, PhD, from Foundation Medicine, the company that developed the liquid biopsy tests used in this study.

“The large percentage of patients with rich genomic signal from ctDNA and the sensitive, specific detection of BRCA1/2 alterations position liquid biopsy as a compelling clinical complement to tissue CGP for patients with mCRPC.”

Dr. Tukachinsky presented results from this study at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 25). The results were also published in Clinical Cancer Research, but the following data are from the meeting presentation.

ctDNA profiling proves feasible, comparable

CGP was performed on 3,334 liquid biopsy samples and 2,006 tissue samples from patients with mCRPC, including patients in the TRITON2 and TRITON3 trials.

The plasma samples were profiled using FoundationACT, which had a panel of 62 genes, or FoundationOne Liquid CDx, which had a panel of 70 genes.

Most of the liquid biopsy samples – 94% – had detectable ctDNA, and the median ctDNA fraction was 7.5%.

“One of the most important findings in this study is the fact that the majority of patients with advanced prostate cancer – 94% of them – have abundant ctDNA,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

“The overall landscape we detected in ctDNA highly resembles landscapes reported in tissue-based CGP studies of mCRPC,” she added.

ctDNA results showed a high percentage of TP53 and AR alterations, as well as alterations in DNA repair genes (ATM, CHEK2, BRCA2, and CDK12), PI3 kinase components (PTEN, PIK3CA, and AKT1), and WNT components (APC and CTNNB1).

“It should be noted that the two assays did not bait for TMPRSS2-ERT fusions or SPOP ... and we’re missing homozygous deletions, which affects the frequency we detect PTEN, RB1, and BRCA alterations,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

When the researchers compared results from the 3,334 liquid biopsy samples and the 2,006 tissue samples, they found that most genes were altered at similar rates.

However, nine genes were significantly enriched in ctDNA – AR, TP53, ATM, CHEK2, NF1, TERT, JAK2, IDH2, and GNAS.

Dr. Tukachinsky noted that JAK2, GNAS, and IDH2 alterations are rarely detected in mCRPC tissue and are likely attributable to clonal hematopoiesis. Alterations in TERT and NF1, as well as some of the alterations in ATM and CHEK2, might also be attributed to clonal hematopoiesis, she added.

Rare and novel AR alterations

“ctDNA detected more acquired resistance genomic alterations than tissue, including novel and rare AR-activating variants,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

She noted that F877L/T878A, a compound mutant that has been shown to confer synergistic resistance to enzalutamide, was found in 11 patients.

Similarly, “completely novel” in-frame mutations spanning residues H875 to T878 were found in 11 patients, and each shifted S885 into the T878 position.

“Although these require more experiments to prove that they are activating, their repeated appearance in different patients with mCRPC and alignment of the serine residues is highly suggestive that they are activating,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

The researchers also found, in 160 patients, AR rearrangements that truncate the reading frame just after exon 3 to yield a receptor with an intact DNA binding domain but without a ligand binding domain.

“These truncated receptors have been demonstrated to confer resistance to AR signaling inhibitors and drive transcription of the AR target genes,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

BRCA1/2: High concordance

To further assess concordance between ctDNA and tissue, Dr. Tukachinsky and colleagues evaluated a subset of 837 patients with matched tissue and liquid biopsies.

The researchers observed high concordance in BRCA1/2 short variants and rearrangements. The positive percent agreement was 93.1%, the negative percent agreement was 97.4%, and the overall percent agreement was 97.0%.

There were 5 patients in whom BRCA1/2 alterations were detected in tissue but not ctDNA, and there were 20 patients in whom BRCA1/2 alterations were detected in ctDNA but not tissue.

The false negatives could be the result of low ctDNA fraction, a minor clone, or filtering out by post analytics, said study discussant Silke Gillessen, MD, of the Institute of Oncology of Southern Switzerland in Bellinzona. She also postulated that the false positives could be explained by clonal hematopoiesis or metastases from a subclone.

Implications for practice

This study showed that liquid and tissue biopsies can perform comparably in identifying patients with BRCA1/2 variants who may benefit from PARP inhibition, Dr. Tukachinsky noted. Additionally, ctDNA revealed novel AR variants that may be driving resistance to AR-signaling inhibitors. However, the presence of alterations that may derive from clonal hematopoiesis suggests ctDNA results should be interpreted with some caution, she added.

“NCCN [National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines have recently changed to include liquid biopsy as an option. There’s definitely some skepticism about liquid biopsy …. That said, liquid biopsy is also a pretty powerful tool,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

“We are not advocating liquid biopsy over tissue. In the cases where tissue’s not available, or if you have a primary, in some cases, liquid could serve as a good complement to give you the full picture of what’s going on in the tumor,” she added.

“For the time being, tissue will still be our gold standard,” Dr. Gillessen said. “And if we can’t get the tissue tested, that will be then maybe a point for the liquid biopsy.”

Dr. Tukachinsky’s research was funded by Foundation Medicine and Clovis Oncology. She and her colleagues disclosed relationships with both companies and a range of other companies. Dr. Gillessen disclosed relationships with Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, and several other companies as well as a patent for a biomarker method (WO 3752009138392 A1).

The type and frequency of genomic alterations observed were largely similar in ctDNA and tissue, and there was high concordance for BRCA1/2 alterations. Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of ctDNA detected more acquired resistance alterations, which included novel androgen receptor (AR)–activating variants. In fact, alterations in nine genes were significantly enriched in ctDNA, but some of these alterations may be attributable to clonal hematopoiesis and not the tumor.

Still, the researchers concluded that CGP of ctDNA could complement tissue-based CGP.

“This is the largest study of mCRPC plasma samples conducted to date, and CGP of ctDNA recapitulated the genomic landscape detected in tissue biopsies,” said investigator Hanna Tukachinsky, PhD, from Foundation Medicine, the company that developed the liquid biopsy tests used in this study.

“The large percentage of patients with rich genomic signal from ctDNA and the sensitive, specific detection of BRCA1/2 alterations position liquid biopsy as a compelling clinical complement to tissue CGP for patients with mCRPC.”

Dr. Tukachinsky presented results from this study at the 2021 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium (Abstract 25). The results were also published in Clinical Cancer Research, but the following data are from the meeting presentation.

ctDNA profiling proves feasible, comparable

CGP was performed on 3,334 liquid biopsy samples and 2,006 tissue samples from patients with mCRPC, including patients in the TRITON2 and TRITON3 trials.

The plasma samples were profiled using FoundationACT, which had a panel of 62 genes, or FoundationOne Liquid CDx, which had a panel of 70 genes.

Most of the liquid biopsy samples – 94% – had detectable ctDNA, and the median ctDNA fraction was 7.5%.

“One of the most important findings in this study is the fact that the majority of patients with advanced prostate cancer – 94% of them – have abundant ctDNA,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

“The overall landscape we detected in ctDNA highly resembles landscapes reported in tissue-based CGP studies of mCRPC,” she added.

ctDNA results showed a high percentage of TP53 and AR alterations, as well as alterations in DNA repair genes (ATM, CHEK2, BRCA2, and CDK12), PI3 kinase components (PTEN, PIK3CA, and AKT1), and WNT components (APC and CTNNB1).

“It should be noted that the two assays did not bait for TMPRSS2-ERT fusions or SPOP ... and we’re missing homozygous deletions, which affects the frequency we detect PTEN, RB1, and BRCA alterations,” Dr. Tukachinsky said.

When the researchers compared results from the 3,334 liquid biopsy samples and the 2,006 tissue samples, they found that most genes were altered at similar rates.

However, nine genes were significantly enriched in ctDNA – AR, TP53, ATM, CHEK2, NF1, TERT, JAK2, IDH2, and GNAS.

Dr. Tukachinsky noted that JAK2, GNAS, and IDH2 alterations are rarely detected in mCRPC tissue and are likely attributable to clonal hematopoiesis. Alterations in TERT and NF1, as well as some of the alterations in ATM and CHEK2, might also be attributed to clonal hematopoiesis, she added.