User login

The importance of family acceptance for LGBTQ youth

It is well established that LGBTQ individuals experience more health disparities compared with their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts. In general, LGBTQ adolescents and young adults have higher levels of depression, suicide attempts, and substance use than those of their heterosexual peers. However, a key protective factor is family acceptance and support. By encouraging families to modify and change behaviors that are experienced by their LGBTQ children as rejecting and to engage in supportive and affirming behaviors, providers can help families to decrease risk and promote healthy outcomes for LGBTQ youth and young adults.

We all know that a supportive family can make a difference for any child, but this is especially true for LGBTQ youth and is critical during a pandemic when young people are confined with families and separated from peers and supportive adults outside the home. Several research studies show that family support can improve outcomes related to suicide, depression, homelessness, drug use, and HIV in LGBTQ young people. Family acceptance improves health outcomes, while rejection undermines family relationships and worsens both health and other serious outcomes such as homelessness and placement in custodial care. Pediatricians can help their patients by educating parents and caregivers with LGBTQ children about the critical role of family support – both those who see themselves as accepting and those who believe that being gay or transgender is wrong and are struggling with parenting a child who identifies as LGBTQ or who is gender diverse.

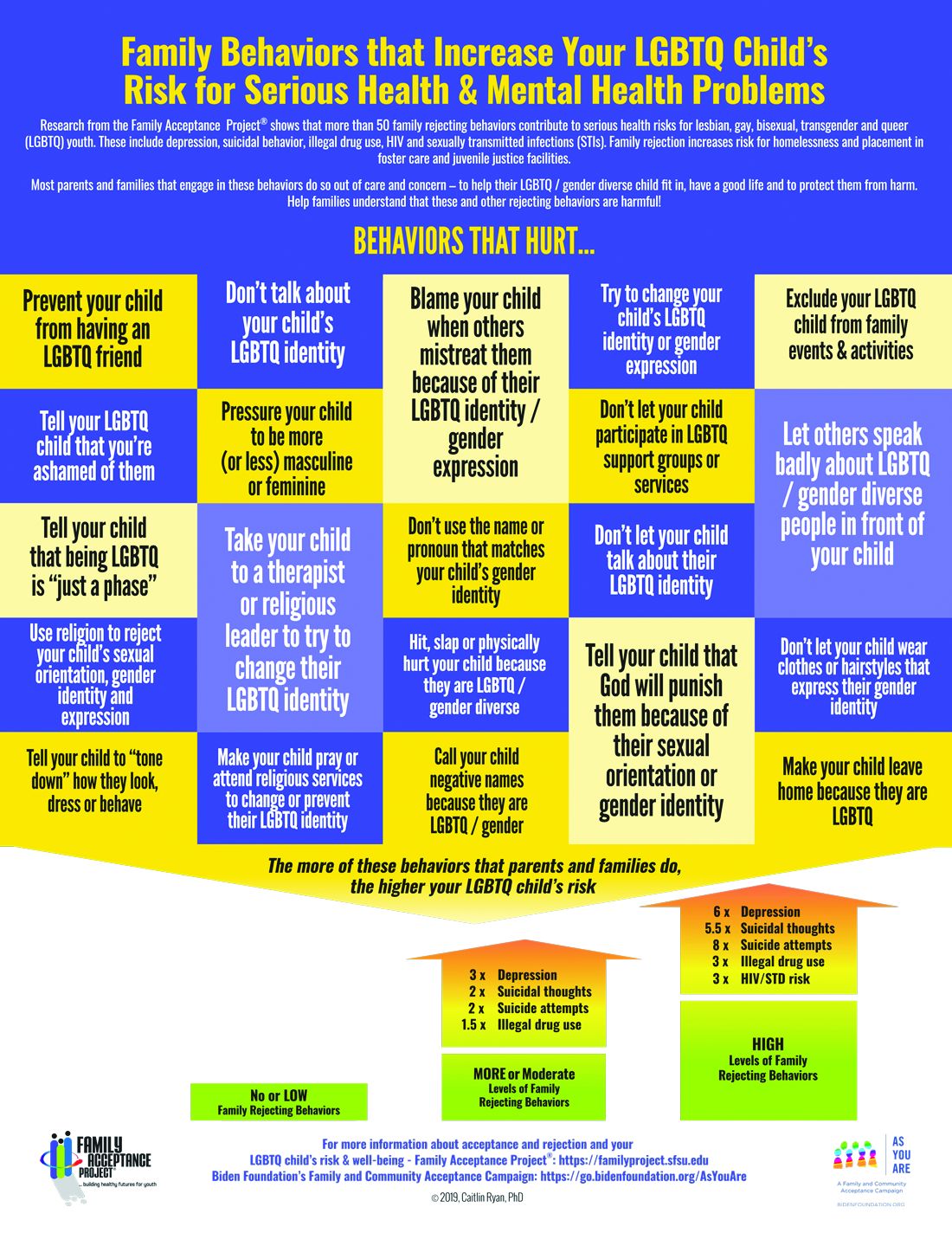

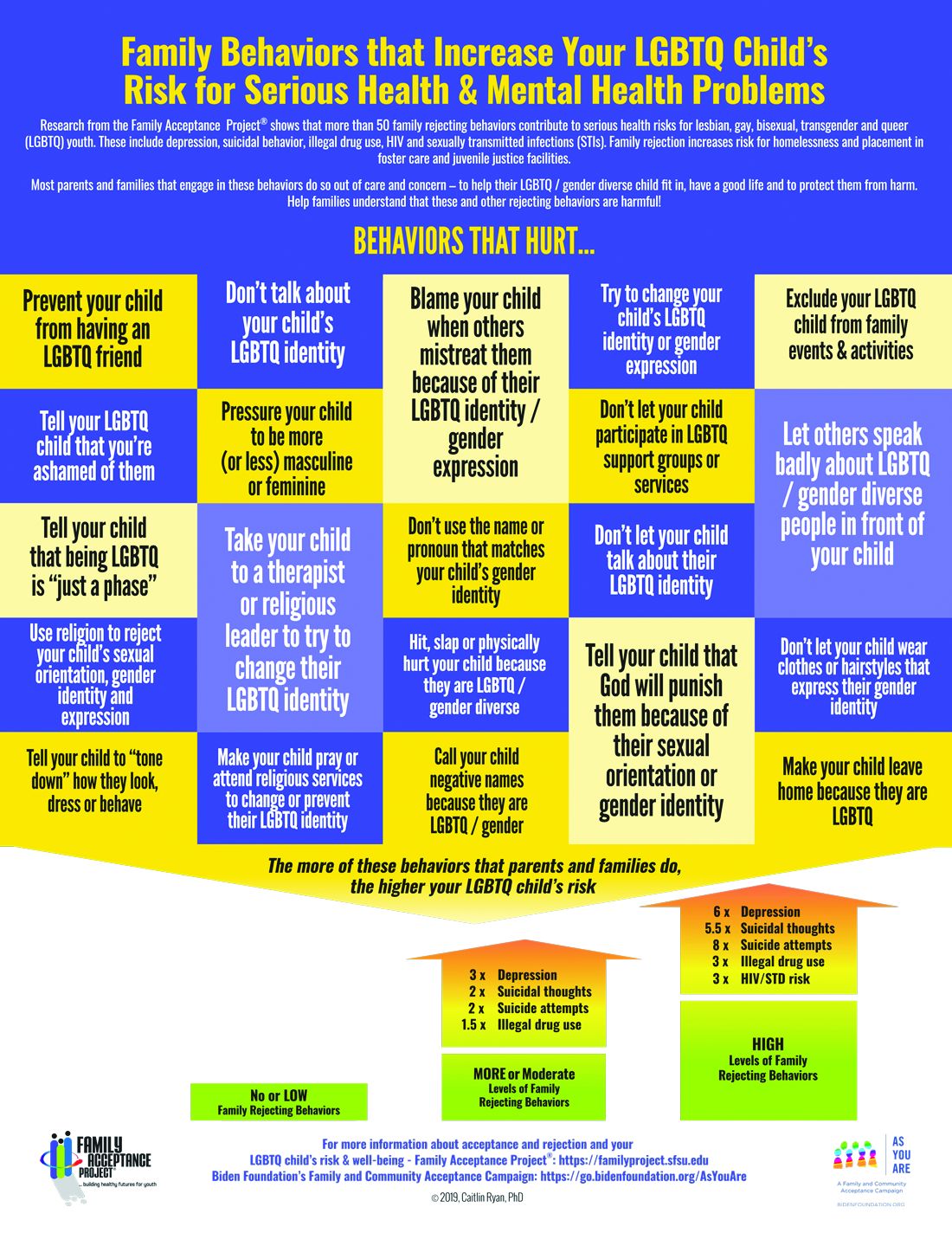

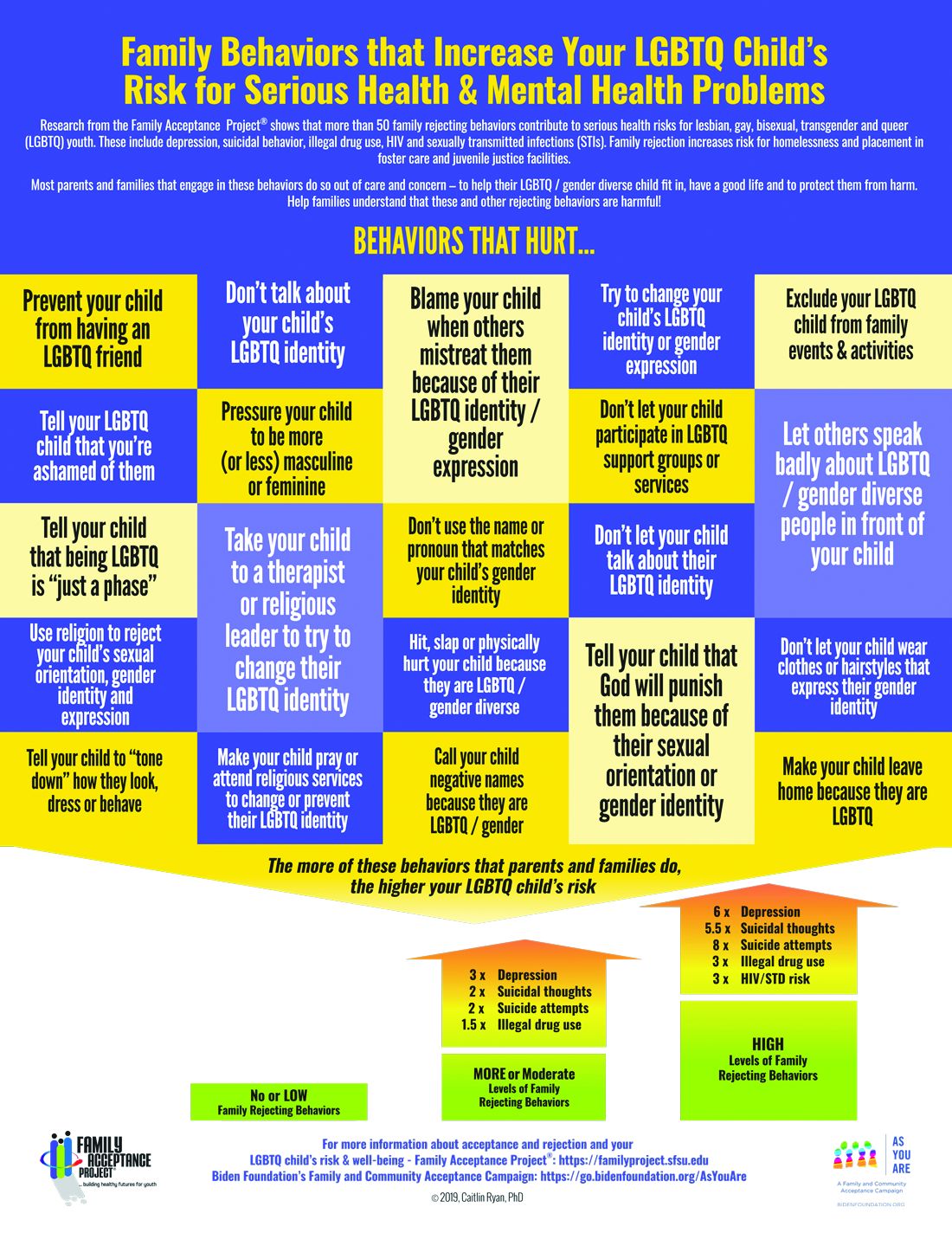

The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families, developed the first evidence-informed family support model, and has published a range of studies and evidence-based resources that demonstrate the harm caused by family rejection, validate the importance of family acceptance, and provide guidance to increase family support. FAP’s research found that parents and caregivers that engage in rejecting behaviors are typically motivated by care and concern and by trying to protect their children from harm. They believe such behaviors will help their LGBTQ children fit in, have a good life, meet cultural and religious expectations, and be respected by others.1 FAP’s research identified and measured more than 50 rejecting behaviors that parents and caregivers use to respond to their LGBTQ children. Some of these commonly expressed rejecting behaviors include ridiculing and making disparaging comments about their child and other LGBTQ people; excluding them from family activities; blaming their child when others mistreat them because they are LGBTQ; blocking access to LGBTQ resources including friends, support groups, and activities; and trying to change their child’s sexual orientation and gender identity.2 LGBTQ youth experience these and other such behaviors as hurtful, harmful, and traumatic and may feel that they need to hide or repress their identity which can affect their self-esteem, increase isolation, depression, and risky behaviors.3 Providers working with families of LGBTQ youth should focus on shared goals, such as reducing risk and having a happy, healthy child. Most parents love their children and fear for their well-being. However, many are uninformed about their child’s gender identity and sexual orientation and don’t know how to nurture and support them.

In FAP’s initial study, LGB young people who reported higher levels of family rejection had substantially higher rates of attempted suicide, depression, illegal drug use, and unprotected sex.4 These rates were even more significant among Latino gay and bisexual men.4 Those who are rejected by family are less likely to want to have a family or to be parents themselves5 and have lower educational and income levels.6

To reduce risk, pediatricians should ask LGBTQ patients about family rejecting behaviors and help parents and caregivers to identify and understand the effect of such behaviors to reduce health risks and conflict that can lead to running away, expulsion, and removal from the home. Even decreasing rejecting behaviors to moderate levels can significantly improve negative outcomes.5

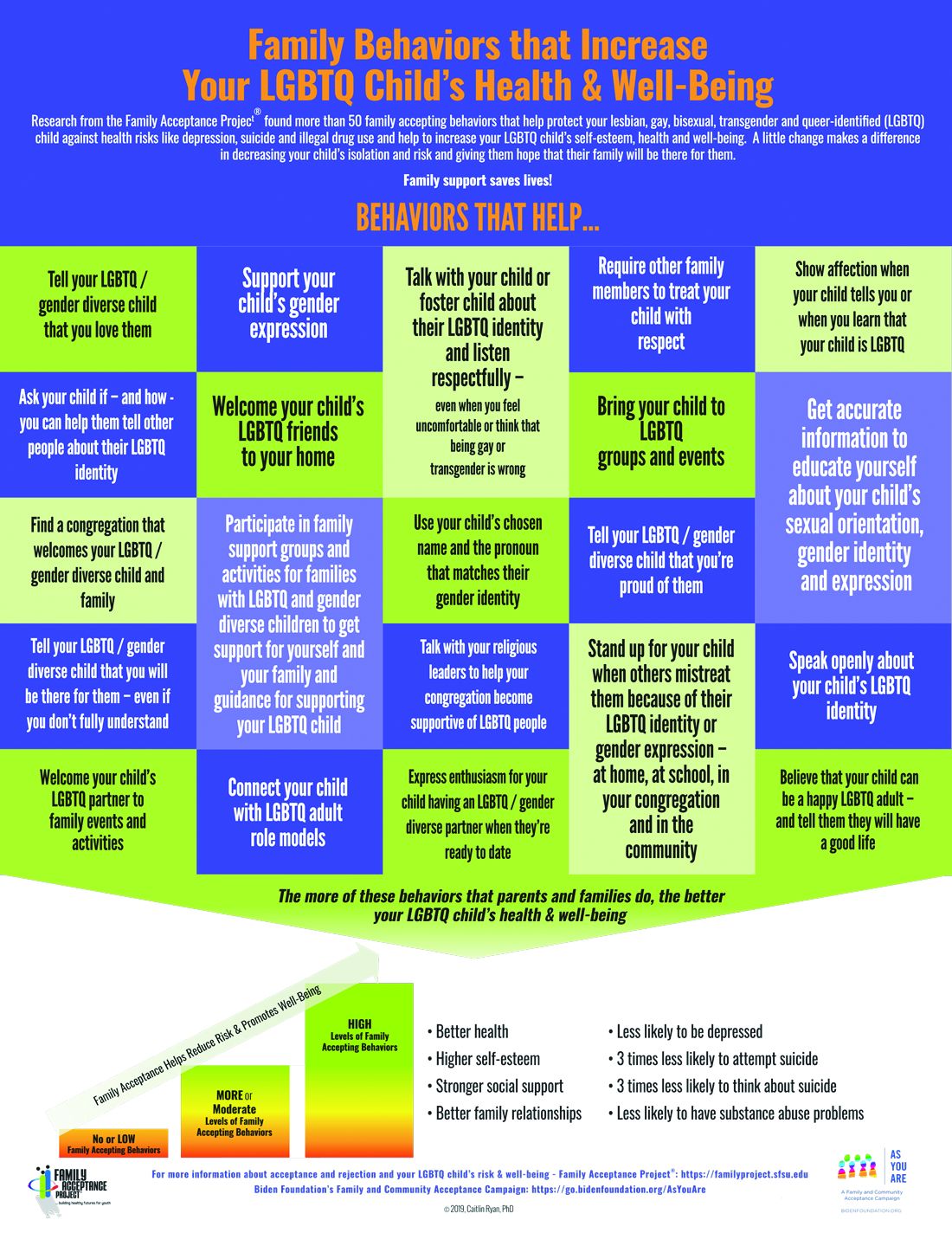

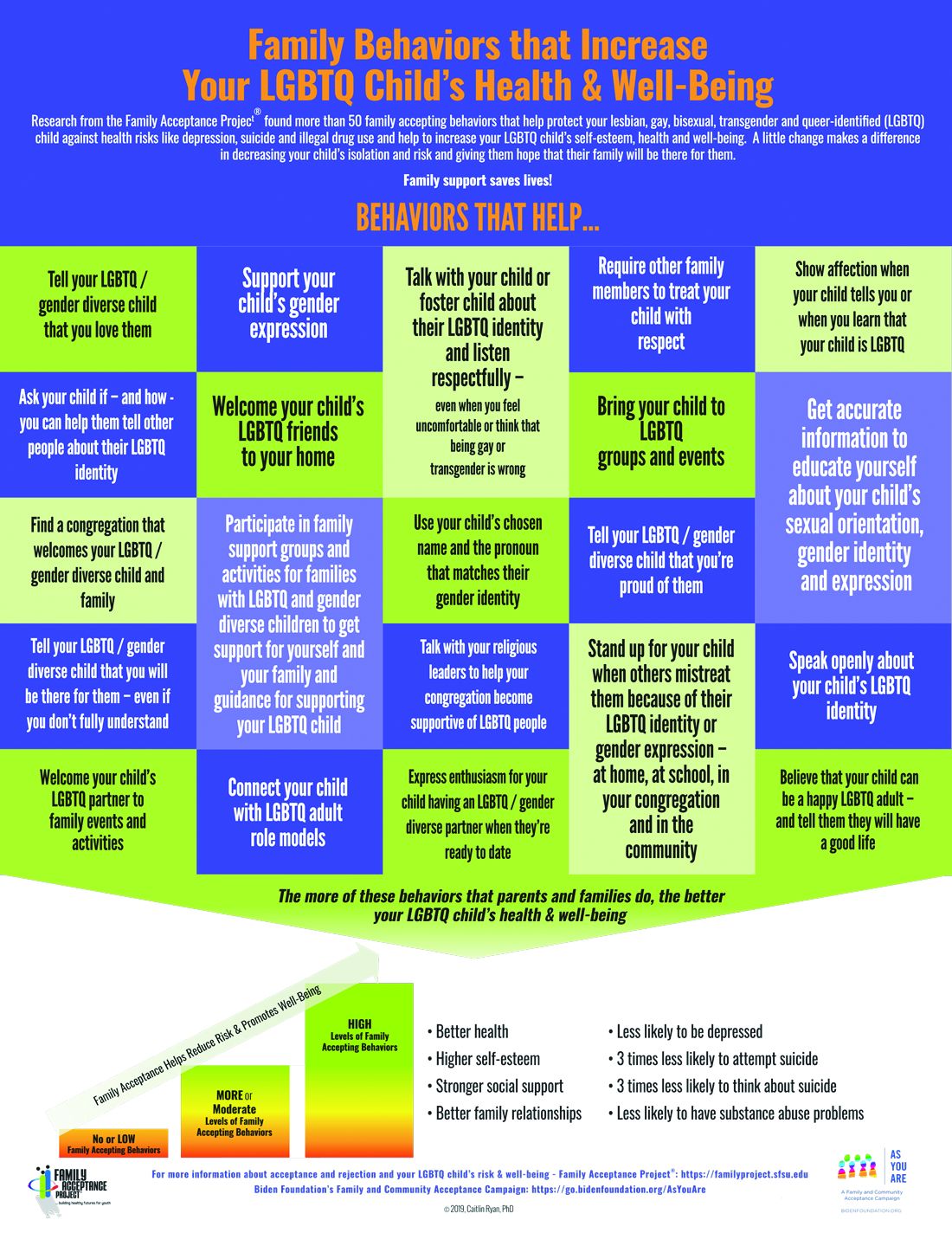

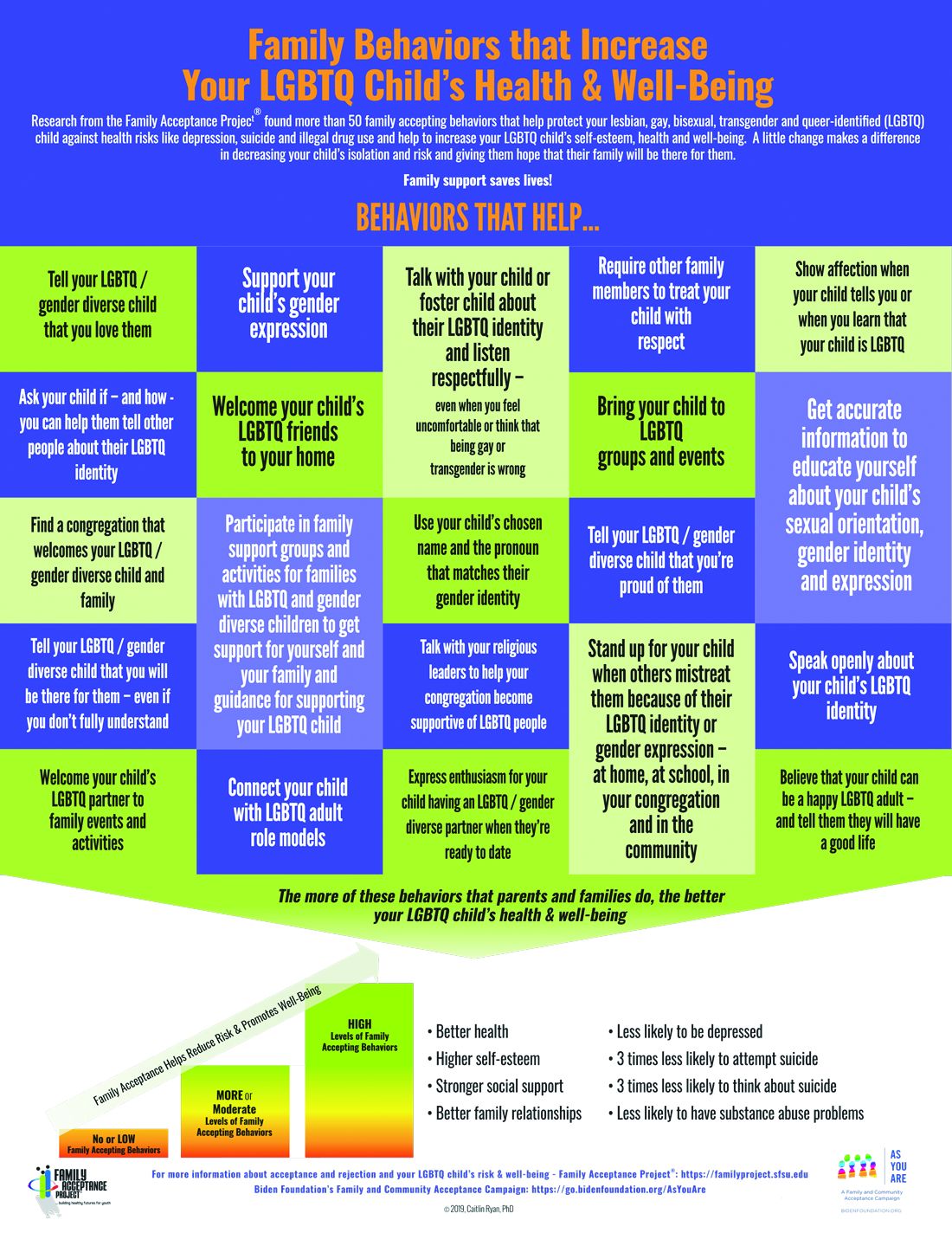

Caitlin Ryan, PhD, and her team also identified and measured more than 50 family accepting behaviors that help protect against risk and promote well-being. They found that young adults who experience high levels of family acceptance during adolescence report significantly higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health with much lower levels of depression, suicidality, and substance abuse.7 Family accepting and supportive behaviors include talking with the child about their LGBTQ identity; advocating for their LGBTQ child when others mistreat them; requiring other family members to treat their LGBTQ child with respect; and supporting their child’s gender identity.5 FAP has developed an evidence-informed family support model and multilingual educational resources for families, providers, youth and religious leaders to decrease rejection and increase family support. These are available in print copies and for download at familyproject.sfsu.edu.

In addition, Dr. Ryan and colleagues1,4,8 recommend the following guidance for providers:

- Ask LGBTQ adolescents about family reactions to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression, and refer to LGBTQ community support programs and for supportive counseling, as needed.

- Identify LGBTQ community support programs and online resources to educate parents about how to help their children. Parents need culturally relevant peer support to help decrease rejection and increase family support.

- Advise parents that negative reactions to their adolescent’s LGBTQ identity may negatively impact their child’s health and mental health while supportive and affirming reactions promote well-being.

- Advise parents and caregivers to modify and change family rejecting behaviors that increase their child’s risk for suicide, depression, substance abuse ,and risky sexual behaviors.

- Expand anticipatory guidance to include information on the need for support and the link between family rejection and negative health problems.

- Provide guidance on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of normative child development during well-baby and early childhood care.

- Use FAP’s multilingual family education booklets and Healthy Futures poster series in family and patient education and provide these materials in clinical and community settings. FAP’s Healthy Futures posters include a poster guidance, a version on family acceptance, a version on family rejection and a family acceptance version for conservative families and settings. They are available in camera-ready art in four sizes in English and Spanish and are forthcoming in five Asian languages: familyproject.sfsu.edu/poster.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Resources

• Family Acceptance Project – consultation and training; evidence-based educational materials for families, providers, religious leaders and youth.

• PFLAG – peer support for parents and friends with LGBTQ children in all states and several other countries.

References

1. Ryan C. Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 2014;23(2):331-44.

2. Ryan C. Healthy Futures Poster Series – Family Accepting & Rejecting Behaviors That Impact LGBTQ Children’s Health & Well-Being. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2019.

3. Ryan C. Family Acceptance Project: Culturally grounded framework for supporting LGBTQ children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2019;58(10):S58-9.

4. Ryan C et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346-52.

5. Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2009.

6. Ryan C et al. Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental health and adjustment. J Homosexuality. 2020;67(2):159-73.

7. Ryan C et al. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2010;23(4):205-13. 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A Practitioner’s Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. In: Administration SAaMhS, ed. Vol PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: HHS Publication; 2014.

It is well established that LGBTQ individuals experience more health disparities compared with their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts. In general, LGBTQ adolescents and young adults have higher levels of depression, suicide attempts, and substance use than those of their heterosexual peers. However, a key protective factor is family acceptance and support. By encouraging families to modify and change behaviors that are experienced by their LGBTQ children as rejecting and to engage in supportive and affirming behaviors, providers can help families to decrease risk and promote healthy outcomes for LGBTQ youth and young adults.

We all know that a supportive family can make a difference for any child, but this is especially true for LGBTQ youth and is critical during a pandemic when young people are confined with families and separated from peers and supportive adults outside the home. Several research studies show that family support can improve outcomes related to suicide, depression, homelessness, drug use, and HIV in LGBTQ young people. Family acceptance improves health outcomes, while rejection undermines family relationships and worsens both health and other serious outcomes such as homelessness and placement in custodial care. Pediatricians can help their patients by educating parents and caregivers with LGBTQ children about the critical role of family support – both those who see themselves as accepting and those who believe that being gay or transgender is wrong and are struggling with parenting a child who identifies as LGBTQ or who is gender diverse.

The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families, developed the first evidence-informed family support model, and has published a range of studies and evidence-based resources that demonstrate the harm caused by family rejection, validate the importance of family acceptance, and provide guidance to increase family support. FAP’s research found that parents and caregivers that engage in rejecting behaviors are typically motivated by care and concern and by trying to protect their children from harm. They believe such behaviors will help their LGBTQ children fit in, have a good life, meet cultural and religious expectations, and be respected by others.1 FAP’s research identified and measured more than 50 rejecting behaviors that parents and caregivers use to respond to their LGBTQ children. Some of these commonly expressed rejecting behaviors include ridiculing and making disparaging comments about their child and other LGBTQ people; excluding them from family activities; blaming their child when others mistreat them because they are LGBTQ; blocking access to LGBTQ resources including friends, support groups, and activities; and trying to change their child’s sexual orientation and gender identity.2 LGBTQ youth experience these and other such behaviors as hurtful, harmful, and traumatic and may feel that they need to hide or repress their identity which can affect their self-esteem, increase isolation, depression, and risky behaviors.3 Providers working with families of LGBTQ youth should focus on shared goals, such as reducing risk and having a happy, healthy child. Most parents love their children and fear for their well-being. However, many are uninformed about their child’s gender identity and sexual orientation and don’t know how to nurture and support them.

In FAP’s initial study, LGB young people who reported higher levels of family rejection had substantially higher rates of attempted suicide, depression, illegal drug use, and unprotected sex.4 These rates were even more significant among Latino gay and bisexual men.4 Those who are rejected by family are less likely to want to have a family or to be parents themselves5 and have lower educational and income levels.6

To reduce risk, pediatricians should ask LGBTQ patients about family rejecting behaviors and help parents and caregivers to identify and understand the effect of such behaviors to reduce health risks and conflict that can lead to running away, expulsion, and removal from the home. Even decreasing rejecting behaviors to moderate levels can significantly improve negative outcomes.5

Caitlin Ryan, PhD, and her team also identified and measured more than 50 family accepting behaviors that help protect against risk and promote well-being. They found that young adults who experience high levels of family acceptance during adolescence report significantly higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health with much lower levels of depression, suicidality, and substance abuse.7 Family accepting and supportive behaviors include talking with the child about their LGBTQ identity; advocating for their LGBTQ child when others mistreat them; requiring other family members to treat their LGBTQ child with respect; and supporting their child’s gender identity.5 FAP has developed an evidence-informed family support model and multilingual educational resources for families, providers, youth and religious leaders to decrease rejection and increase family support. These are available in print copies and for download at familyproject.sfsu.edu.

In addition, Dr. Ryan and colleagues1,4,8 recommend the following guidance for providers:

- Ask LGBTQ adolescents about family reactions to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression, and refer to LGBTQ community support programs and for supportive counseling, as needed.

- Identify LGBTQ community support programs and online resources to educate parents about how to help their children. Parents need culturally relevant peer support to help decrease rejection and increase family support.

- Advise parents that negative reactions to their adolescent’s LGBTQ identity may negatively impact their child’s health and mental health while supportive and affirming reactions promote well-being.

- Advise parents and caregivers to modify and change family rejecting behaviors that increase their child’s risk for suicide, depression, substance abuse ,and risky sexual behaviors.

- Expand anticipatory guidance to include information on the need for support and the link between family rejection and negative health problems.

- Provide guidance on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of normative child development during well-baby and early childhood care.

- Use FAP’s multilingual family education booklets and Healthy Futures poster series in family and patient education and provide these materials in clinical and community settings. FAP’s Healthy Futures posters include a poster guidance, a version on family acceptance, a version on family rejection and a family acceptance version for conservative families and settings. They are available in camera-ready art in four sizes in English and Spanish and are forthcoming in five Asian languages: familyproject.sfsu.edu/poster.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Resources

• Family Acceptance Project – consultation and training; evidence-based educational materials for families, providers, religious leaders and youth.

• PFLAG – peer support for parents and friends with LGBTQ children in all states and several other countries.

References

1. Ryan C. Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 2014;23(2):331-44.

2. Ryan C. Healthy Futures Poster Series – Family Accepting & Rejecting Behaviors That Impact LGBTQ Children’s Health & Well-Being. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2019.

3. Ryan C. Family Acceptance Project: Culturally grounded framework for supporting LGBTQ children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2019;58(10):S58-9.

4. Ryan C et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346-52.

5. Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2009.

6. Ryan C et al. Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental health and adjustment. J Homosexuality. 2020;67(2):159-73.

7. Ryan C et al. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2010;23(4):205-13. 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A Practitioner’s Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. In: Administration SAaMhS, ed. Vol PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: HHS Publication; 2014.

It is well established that LGBTQ individuals experience more health disparities compared with their cisgender, heterosexual counterparts. In general, LGBTQ adolescents and young adults have higher levels of depression, suicide attempts, and substance use than those of their heterosexual peers. However, a key protective factor is family acceptance and support. By encouraging families to modify and change behaviors that are experienced by their LGBTQ children as rejecting and to engage in supportive and affirming behaviors, providers can help families to decrease risk and promote healthy outcomes for LGBTQ youth and young adults.

We all know that a supportive family can make a difference for any child, but this is especially true for LGBTQ youth and is critical during a pandemic when young people are confined with families and separated from peers and supportive adults outside the home. Several research studies show that family support can improve outcomes related to suicide, depression, homelessness, drug use, and HIV in LGBTQ young people. Family acceptance improves health outcomes, while rejection undermines family relationships and worsens both health and other serious outcomes such as homelessness and placement in custodial care. Pediatricians can help their patients by educating parents and caregivers with LGBTQ children about the critical role of family support – both those who see themselves as accepting and those who believe that being gay or transgender is wrong and are struggling with parenting a child who identifies as LGBTQ or who is gender diverse.

The Family Acceptance Project (FAP) at San Francisco State University conducted the first research on LGBTQ youth and families, developed the first evidence-informed family support model, and has published a range of studies and evidence-based resources that demonstrate the harm caused by family rejection, validate the importance of family acceptance, and provide guidance to increase family support. FAP’s research found that parents and caregivers that engage in rejecting behaviors are typically motivated by care and concern and by trying to protect their children from harm. They believe such behaviors will help their LGBTQ children fit in, have a good life, meet cultural and religious expectations, and be respected by others.1 FAP’s research identified and measured more than 50 rejecting behaviors that parents and caregivers use to respond to their LGBTQ children. Some of these commonly expressed rejecting behaviors include ridiculing and making disparaging comments about their child and other LGBTQ people; excluding them from family activities; blaming their child when others mistreat them because they are LGBTQ; blocking access to LGBTQ resources including friends, support groups, and activities; and trying to change their child’s sexual orientation and gender identity.2 LGBTQ youth experience these and other such behaviors as hurtful, harmful, and traumatic and may feel that they need to hide or repress their identity which can affect their self-esteem, increase isolation, depression, and risky behaviors.3 Providers working with families of LGBTQ youth should focus on shared goals, such as reducing risk and having a happy, healthy child. Most parents love their children and fear for their well-being. However, many are uninformed about their child’s gender identity and sexual orientation and don’t know how to nurture and support them.

In FAP’s initial study, LGB young people who reported higher levels of family rejection had substantially higher rates of attempted suicide, depression, illegal drug use, and unprotected sex.4 These rates were even more significant among Latino gay and bisexual men.4 Those who are rejected by family are less likely to want to have a family or to be parents themselves5 and have lower educational and income levels.6

To reduce risk, pediatricians should ask LGBTQ patients about family rejecting behaviors and help parents and caregivers to identify and understand the effect of such behaviors to reduce health risks and conflict that can lead to running away, expulsion, and removal from the home. Even decreasing rejecting behaviors to moderate levels can significantly improve negative outcomes.5

Caitlin Ryan, PhD, and her team also identified and measured more than 50 family accepting behaviors that help protect against risk and promote well-being. They found that young adults who experience high levels of family acceptance during adolescence report significantly higher levels of self-esteem, social support, and general health with much lower levels of depression, suicidality, and substance abuse.7 Family accepting and supportive behaviors include talking with the child about their LGBTQ identity; advocating for their LGBTQ child when others mistreat them; requiring other family members to treat their LGBTQ child with respect; and supporting their child’s gender identity.5 FAP has developed an evidence-informed family support model and multilingual educational resources for families, providers, youth and religious leaders to decrease rejection and increase family support. These are available in print copies and for download at familyproject.sfsu.edu.

In addition, Dr. Ryan and colleagues1,4,8 recommend the following guidance for providers:

- Ask LGBTQ adolescents about family reactions to their sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression, and refer to LGBTQ community support programs and for supportive counseling, as needed.

- Identify LGBTQ community support programs and online resources to educate parents about how to help their children. Parents need culturally relevant peer support to help decrease rejection and increase family support.

- Advise parents that negative reactions to their adolescent’s LGBTQ identity may negatively impact their child’s health and mental health while supportive and affirming reactions promote well-being.

- Advise parents and caregivers to modify and change family rejecting behaviors that increase their child’s risk for suicide, depression, substance abuse ,and risky sexual behaviors.

- Expand anticipatory guidance to include information on the need for support and the link between family rejection and negative health problems.

- Provide guidance on sexual orientation and gender identity as part of normative child development during well-baby and early childhood care.

- Use FAP’s multilingual family education booklets and Healthy Futures poster series in family and patient education and provide these materials in clinical and community settings. FAP’s Healthy Futures posters include a poster guidance, a version on family acceptance, a version on family rejection and a family acceptance version for conservative families and settings. They are available in camera-ready art in four sizes in English and Spanish and are forthcoming in five Asian languages: familyproject.sfsu.edu/poster.

Dr. Lawlis is assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, and an adolescent medicine specialist at OU Children’s. She has no relevant financial disclosures.

Resources

• Family Acceptance Project – consultation and training; evidence-based educational materials for families, providers, religious leaders and youth.

• PFLAG – peer support for parents and friends with LGBTQ children in all states and several other countries.

References

1. Ryan C. Generating a revolution in prevention, wellness & care for LGBT children & youth. Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 2014;23(2):331-44.

2. Ryan C. Healthy Futures Poster Series – Family Accepting & Rejecting Behaviors That Impact LGBTQ Children’s Health & Well-Being. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2019.

3. Ryan C. Family Acceptance Project: Culturally grounded framework for supporting LGBTQ children and youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2019;58(10):S58-9.

4. Ryan C et al. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346-52.

5. Ryan C. Supportive families, healthy children: Helping families with lesbian, gay, bisexual & transgender children. In: Family Acceptance Project Marian Wright Edelman Institute SFSU, ed. San Francisco, CA2009.

6. Ryan C et al. Parent-initiated sexual orientation change efforts with LGBT adolescents: Implications for young adult mental health and adjustment. J Homosexuality. 2020;67(2):159-73.

7. Ryan C et al. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nursing. 2010;23(4):205-13. 8. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. A Practitioner’s Guide: Helping Families to Support Their LGBT Children. In: Administration SAaMhS, ed. Vol PEP14-LGBTKIDS. Rockville, MD: HHS Publication; 2014.

Checkpoint inhibitors’ ‘big picture’ safety shown with preexisting autoimmune diseases

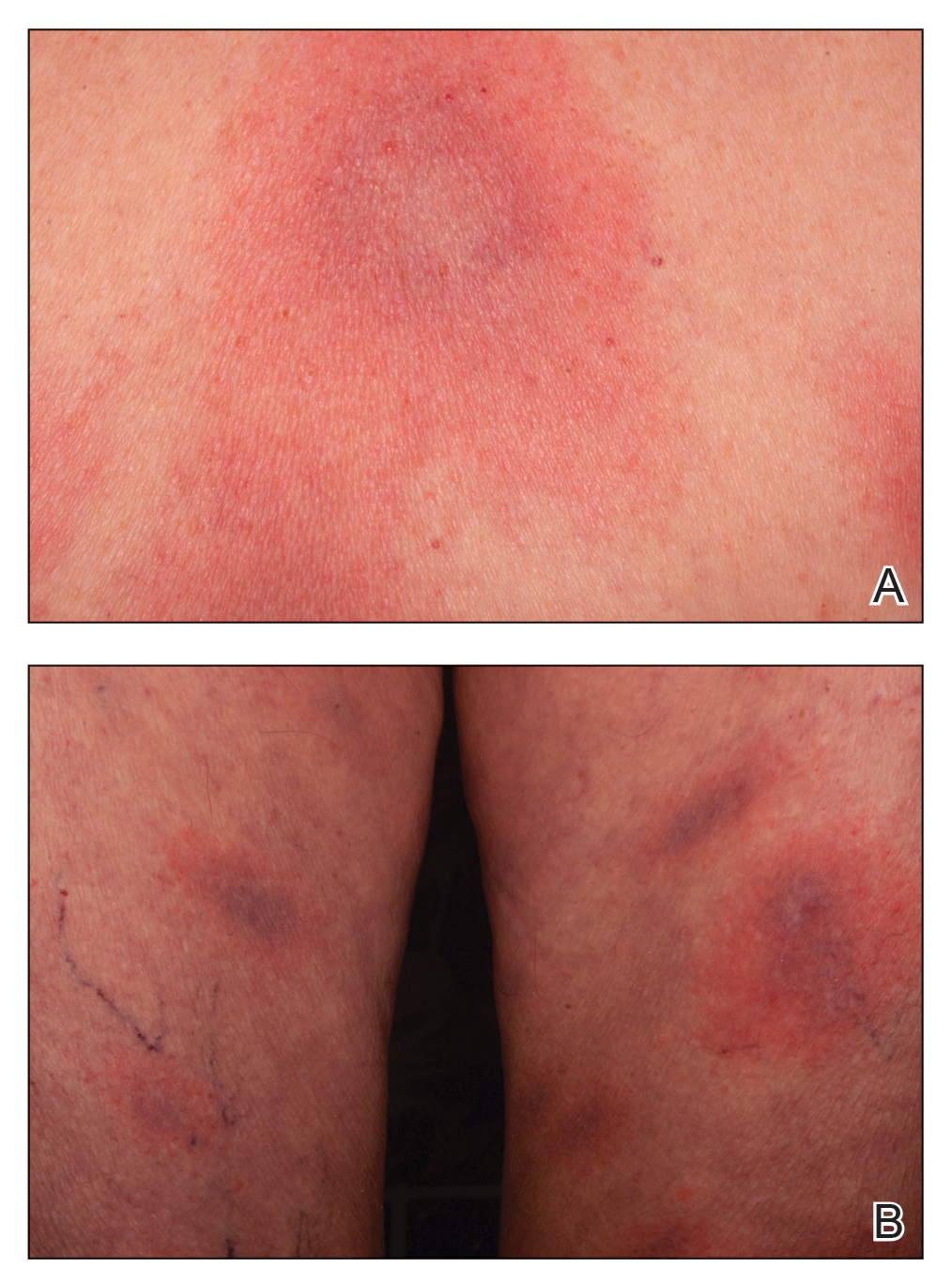

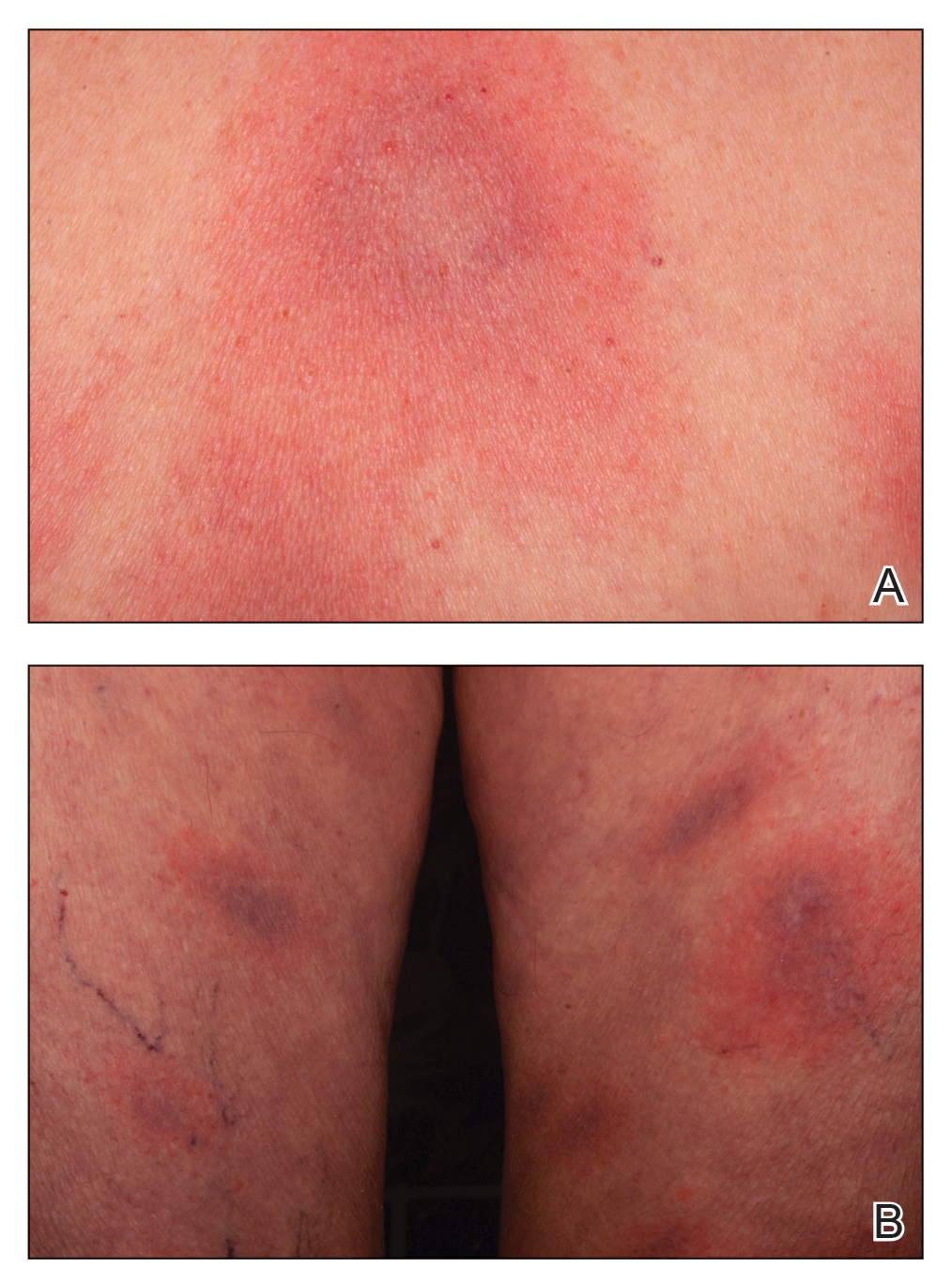

Patients with advanced melanoma and preexisting autoimmune diseases (AIDs) who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) responded well and did not suffer more grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events than patients without an AID, a new study finds, although some concerns were raised regarding patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to bridge this knowledge gap by presenting ‘real-world’ data on the safety and efficacy of ICI on a national scale,” wrote Monique K. van der Kooij, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center and coauthors. The study was published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

To investigate ICI use and response among this specific subset of melanoma patients, the researchers launched a nationwide cohort study set in the Netherlands. Data were gathered via the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR), in which 4,367 patients with advanced melanoma were enrolled between July 2013 and July 2018.

Within that cohort, 415 (9.5%) had preexisting AIDs. Nearly 55% had rheumatologic AIDs (n = 227) – which included RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, sarcoidosis, and vasculitis – with the next most frequent being endocrine AID (n = 143) and IBD (n = 55). Patients with AID were older than patients without (67 vs. 63 years) and were more likely to be female (53% vs. 41%).

The ICIs used in the study included anti-CTLA4 (ipilimumab), anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) (nivolumab or pembrolizumab), or a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab. Of the patients with AID, 55% (n = 228) were treated with ICI, compared with 58% of patients without AID. A total of 87 AID patients were treated with anti-CTLA4, 187 received anti-PD-1, and 34 received the combination. The combination was not readily available in the Netherlands until 2017, the authors stated, acknowledging that it may be wise to revisit its effects in the coming years.

Incidence of immune-related adverse events

The incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) grade 3 and above for patients with and without AID who were given anti-CTLA4 was 30%. The incidence rate of irAEs was also similar for patients with (17%; 95% confidence interval, 12%-23%) and without (13%; 95% CI, 12%-15%) AID on anti-PD-1. Patients with AIDs who took anti-PD-1 therapy discontinued it more often because of toxicity than did the patients without AIDs.

The combination group had irAE incidence rates of 44% (95% CI, 27%-62%) for patients with AID, compared with 48% (95% CI, 43%-53%) for patients without AIDs. Overall, no patients with AIDs on ICIs died of toxicity, compared with three deaths among patients without AID on anti-CTLA4, five deaths among patients on anti-PD-1, and one patient on the combination.

Patients with IBD had a notably higher risk of anti-PD-1–induced colitis (19%; 95% CI, 7%-37%), compared with patients with other AIDs (3%; 95% CI, 0%-6%) and patients without AIDs (2%; 95% CI, 2%-3%). IBD patients were also more likely than all other groups on ICIs to stop treatment because of toxicity, leading the researchers to note that “close monitoring in patients with IBD is advised.”

Overall survival after diagnosis was similar in patients with AIDs (median, 13 months; 95% CI, 10-16 months) and without (median, 14 months; 95% CI, 13-15 months), as was the objective response rate to anti-CTLA4 treatment (10% vs. 16%), anti-PD-1 treatment (40% vs. 44%), and combination therapy (39% vs. 43%).

Study largely bypasses the effects of checkpoint inhibitors on RA patients

“For detail, you can’t look to this study,” Anne R. Bass, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, said in an interview. “But for a big-picture look at ‘how safe are checkpoint inhibitors,’ I think it’s an important one.”

Dr. Bass noted that the investigators lumped certain elements together and bypassed others, including their focus on grade 3 or higher adverse events. That was a decision the authors themselves recognized as a potential limitation of their research.

“Understandably, they were worried about life-threatening adverse events, and that’s fine,” she said. But for patients with arthritis who flare, their events are usually grade 2 or even grade 1 and therefore not captured or analyzed in the study. “This does not really address the risk of flare in an RA patient.”

She also questioned their grouping of AIDs, with a bevy of rheumatic diseases categorized as one cluster and the “other” group being particularly broad in its inclusion of “all AIDs not listed” – though only eight patients were placed into that group.

That said, the researchers relied on an oncology database, not one aimed at AID or adverse events. “The numbers are so much bigger than any other study in this area that’s been done,” she said. “It’s both a strength and a weakness of this kind of database.”

Indeed, the authors considered their use of nationwide, population-based data from the DMTR a benefit, calling it “a strength of our approach.”

The DMTR was funded by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche Nederland, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Pierre Fabre via the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing.

Patients with advanced melanoma and preexisting autoimmune diseases (AIDs) who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) responded well and did not suffer more grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events than patients without an AID, a new study finds, although some concerns were raised regarding patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to bridge this knowledge gap by presenting ‘real-world’ data on the safety and efficacy of ICI on a national scale,” wrote Monique K. van der Kooij, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center and coauthors. The study was published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

To investigate ICI use and response among this specific subset of melanoma patients, the researchers launched a nationwide cohort study set in the Netherlands. Data were gathered via the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR), in which 4,367 patients with advanced melanoma were enrolled between July 2013 and July 2018.

Within that cohort, 415 (9.5%) had preexisting AIDs. Nearly 55% had rheumatologic AIDs (n = 227) – which included RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, sarcoidosis, and vasculitis – with the next most frequent being endocrine AID (n = 143) and IBD (n = 55). Patients with AID were older than patients without (67 vs. 63 years) and were more likely to be female (53% vs. 41%).

The ICIs used in the study included anti-CTLA4 (ipilimumab), anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) (nivolumab or pembrolizumab), or a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab. Of the patients with AID, 55% (n = 228) were treated with ICI, compared with 58% of patients without AID. A total of 87 AID patients were treated with anti-CTLA4, 187 received anti-PD-1, and 34 received the combination. The combination was not readily available in the Netherlands until 2017, the authors stated, acknowledging that it may be wise to revisit its effects in the coming years.

Incidence of immune-related adverse events

The incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) grade 3 and above for patients with and without AID who were given anti-CTLA4 was 30%. The incidence rate of irAEs was also similar for patients with (17%; 95% confidence interval, 12%-23%) and without (13%; 95% CI, 12%-15%) AID on anti-PD-1. Patients with AIDs who took anti-PD-1 therapy discontinued it more often because of toxicity than did the patients without AIDs.

The combination group had irAE incidence rates of 44% (95% CI, 27%-62%) for patients with AID, compared with 48% (95% CI, 43%-53%) for patients without AIDs. Overall, no patients with AIDs on ICIs died of toxicity, compared with three deaths among patients without AID on anti-CTLA4, five deaths among patients on anti-PD-1, and one patient on the combination.

Patients with IBD had a notably higher risk of anti-PD-1–induced colitis (19%; 95% CI, 7%-37%), compared with patients with other AIDs (3%; 95% CI, 0%-6%) and patients without AIDs (2%; 95% CI, 2%-3%). IBD patients were also more likely than all other groups on ICIs to stop treatment because of toxicity, leading the researchers to note that “close monitoring in patients with IBD is advised.”

Overall survival after diagnosis was similar in patients with AIDs (median, 13 months; 95% CI, 10-16 months) and without (median, 14 months; 95% CI, 13-15 months), as was the objective response rate to anti-CTLA4 treatment (10% vs. 16%), anti-PD-1 treatment (40% vs. 44%), and combination therapy (39% vs. 43%).

Study largely bypasses the effects of checkpoint inhibitors on RA patients

“For detail, you can’t look to this study,” Anne R. Bass, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, said in an interview. “But for a big-picture look at ‘how safe are checkpoint inhibitors,’ I think it’s an important one.”

Dr. Bass noted that the investigators lumped certain elements together and bypassed others, including their focus on grade 3 or higher adverse events. That was a decision the authors themselves recognized as a potential limitation of their research.

“Understandably, they were worried about life-threatening adverse events, and that’s fine,” she said. But for patients with arthritis who flare, their events are usually grade 2 or even grade 1 and therefore not captured or analyzed in the study. “This does not really address the risk of flare in an RA patient.”

She also questioned their grouping of AIDs, with a bevy of rheumatic diseases categorized as one cluster and the “other” group being particularly broad in its inclusion of “all AIDs not listed” – though only eight patients were placed into that group.

That said, the researchers relied on an oncology database, not one aimed at AID or adverse events. “The numbers are so much bigger than any other study in this area that’s been done,” she said. “It’s both a strength and a weakness of this kind of database.”

Indeed, the authors considered their use of nationwide, population-based data from the DMTR a benefit, calling it “a strength of our approach.”

The DMTR was funded by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche Nederland, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Pierre Fabre via the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing.

Patients with advanced melanoma and preexisting autoimmune diseases (AIDs) who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) responded well and did not suffer more grade 3 or higher immune-related adverse events than patients without an AID, a new study finds, although some concerns were raised regarding patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to bridge this knowledge gap by presenting ‘real-world’ data on the safety and efficacy of ICI on a national scale,” wrote Monique K. van der Kooij, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center and coauthors. The study was published online in Annals of Internal Medicine.

To investigate ICI use and response among this specific subset of melanoma patients, the researchers launched a nationwide cohort study set in the Netherlands. Data were gathered via the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR), in which 4,367 patients with advanced melanoma were enrolled between July 2013 and July 2018.

Within that cohort, 415 (9.5%) had preexisting AIDs. Nearly 55% had rheumatologic AIDs (n = 227) – which included RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma, sarcoidosis, and vasculitis – with the next most frequent being endocrine AID (n = 143) and IBD (n = 55). Patients with AID were older than patients without (67 vs. 63 years) and were more likely to be female (53% vs. 41%).

The ICIs used in the study included anti-CTLA4 (ipilimumab), anti–programmed death 1 (PD-1) (nivolumab or pembrolizumab), or a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab. Of the patients with AID, 55% (n = 228) were treated with ICI, compared with 58% of patients without AID. A total of 87 AID patients were treated with anti-CTLA4, 187 received anti-PD-1, and 34 received the combination. The combination was not readily available in the Netherlands until 2017, the authors stated, acknowledging that it may be wise to revisit its effects in the coming years.

Incidence of immune-related adverse events

The incidence of immune-related adverse events (irAEs) grade 3 and above for patients with and without AID who were given anti-CTLA4 was 30%. The incidence rate of irAEs was also similar for patients with (17%; 95% confidence interval, 12%-23%) and without (13%; 95% CI, 12%-15%) AID on anti-PD-1. Patients with AIDs who took anti-PD-1 therapy discontinued it more often because of toxicity than did the patients without AIDs.

The combination group had irAE incidence rates of 44% (95% CI, 27%-62%) for patients with AID, compared with 48% (95% CI, 43%-53%) for patients without AIDs. Overall, no patients with AIDs on ICIs died of toxicity, compared with three deaths among patients without AID on anti-CTLA4, five deaths among patients on anti-PD-1, and one patient on the combination.

Patients with IBD had a notably higher risk of anti-PD-1–induced colitis (19%; 95% CI, 7%-37%), compared with patients with other AIDs (3%; 95% CI, 0%-6%) and patients without AIDs (2%; 95% CI, 2%-3%). IBD patients were also more likely than all other groups on ICIs to stop treatment because of toxicity, leading the researchers to note that “close monitoring in patients with IBD is advised.”

Overall survival after diagnosis was similar in patients with AIDs (median, 13 months; 95% CI, 10-16 months) and without (median, 14 months; 95% CI, 13-15 months), as was the objective response rate to anti-CTLA4 treatment (10% vs. 16%), anti-PD-1 treatment (40% vs. 44%), and combination therapy (39% vs. 43%).

Study largely bypasses the effects of checkpoint inhibitors on RA patients

“For detail, you can’t look to this study,” Anne R. Bass, MD, of the division of rheumatology at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, said in an interview. “But for a big-picture look at ‘how safe are checkpoint inhibitors,’ I think it’s an important one.”

Dr. Bass noted that the investigators lumped certain elements together and bypassed others, including their focus on grade 3 or higher adverse events. That was a decision the authors themselves recognized as a potential limitation of their research.

“Understandably, they were worried about life-threatening adverse events, and that’s fine,” she said. But for patients with arthritis who flare, their events are usually grade 2 or even grade 1 and therefore not captured or analyzed in the study. “This does not really address the risk of flare in an RA patient.”

She also questioned their grouping of AIDs, with a bevy of rheumatic diseases categorized as one cluster and the “other” group being particularly broad in its inclusion of “all AIDs not listed” – though only eight patients were placed into that group.

That said, the researchers relied on an oncology database, not one aimed at AID or adverse events. “The numbers are so much bigger than any other study in this area that’s been done,” she said. “It’s both a strength and a weakness of this kind of database.”

Indeed, the authors considered their use of nationwide, population-based data from the DMTR a benefit, calling it “a strength of our approach.”

The DMTR was funded by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Roche Nederland, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Pierre Fabre via the Dutch Institute for Clinical Auditing.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Child ‘Mis’behavior – What’s ‘mis’ing?

“What kind of parent are you? Why don’t you straighten him out!” rants the woman being jostled in the grocery store by your patient. “Easy for you to say,” thinks your patient’s frazzled and now insulted parent.

Blaming the parent for an out-of-control child has historically been a common refrain of neighbors, relatives, and even strangers. But considering child behavior as resulting from both parent and child factors is central to the current transactional model of child development. In this model, mismatch of the parent’s and child’s response patterns is seen as setting them up for chronically rough interactions around parent requests/demands. A parent escalating quickly from a briefly stated request to a tirade may create more tension paired with an anxious child who takes time to act, for example. Once a parent (and ultimately the child) recognize patterns in what leads to conflict, they can become more proactive in predicting and negotiating these situations. Ross Greene, PhD, explains this in his book “The Explosive Child,” calling the method Collaborative Problem Solving (now Collaborative & Proactive Solutions or CPS).

While there are general principles parents can use to modify what they consider “mis”behaviors, these methods often do not account for the “missing” skills of the individual child (and parent) predisposing to those “mis”takes. Thinking of misbehaviors as being because of a kind of “learning disability” in the child rather than willful defiance can help cool off interactions by instead focusing on solving the underlying problem.

What kinds of “gaps in skills” set a child up for defiant or explosive reactions? If you think about what features of children, and parent-child relationships are associated with harmonious interactions this becomes evident. Children over 3 who are patient, easygoing, flexible or adaptable, and good at transitions and problem-solving can delay gratification and tolerate frustration, regulate their emotions, explain their desires, and multitask. They are better at reading the parent’s needs and intent and tend to interpret requests as positive or at least neutral and are more likely to comply with parent requests without a fuss.

What? No kid you know is great at all of these? These skills, at best variable, develop with maturation. Some are part of temperament, considered normal variation in personality. For example, so-called difficult temperament includes low adaptability, high-intensity reactions, low regularity, tendency to withdraw, and negative mood. But in the extreme, weaknesses in these skills are core to or comorbid with diagnosable mental health disorders. Defiance and irritable responses are criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and less severe categories called aggressive/oppositional problem or variation. ODD is often found in children diagnosed with ADHD (65%), Tourette’s (15%-65%), depression (70% if severe), bipolar disorder (85%), OCD, anxiety (45%), autism, and language-processing disorders (55%), or trauma. These conditions variably include lower emotion regulation, poorer executive functioning including poor task shifting and impulsivity, obsessiveness, lower expressive and receptive communication skills, and less social awareness that facilitates harmonious problem solving.

The basic components of the CPS approach to addressing parent-child conflict sound intuitive but defining them clearly is important when families are stuck. There are three levels of plans. If the problem is an emergency or nonnegotiable, e.g., child hurting the cat, it may call for Plan A – parent-imposed solutions, sometimes with consequences or rewards. As children mature, Plan A should be used less frequently. If solving the problem is not a top life priority, Plan C – postponing action, may be appropriate. Plan C highlights that behavior change is a long-term project and “picking your fights” is important.

The biggest value of CPS for resolving behavior problems comes from intermediate Plan B. In Plan B the first step of problem solving for parents facing child defiance or upset is to empathically and nonjudgmentally figure out the child’s concern. Questions such as “I’ve noticed that when I remind you that it is trash night you start shouting. What’s up with that?” then patiently asking about the who, what, where, and when of their concern and checking to ensure understanding. Specificity is important as well as noting times when the reaction occurs or not.

Once the child’s concern is clear, e.g., feeling that the demand to take out the trash now interrupts his games during the only time his friends are online, the parents should echo the child’s concern then express their own concern about how the behavior is affecting them and others, potentially including the child; e.g., mother is so upset by the shouting that she can’t sleep, and worry that the child is not learning responsibility, and then checking for child understanding.

Finally, the parent invites brainstorming for a solution that addresses both of their concerns, first asking the child for suggestions, aiming for a strategy that is realistic and specific. Children reluctant to make suggestions may need more time and the parent may be wondering “if there is a way for both of our concerns to be addressed.” Solutions chosen are then tried for several weeks, success tracked, and needed changes negotiated.

For parents, using a collaborative approach to dealing with their child’s behavior takes skills they may not have at the moment, or ever. Especially under the stresses of COVID-19 lockdown, taking a step back from an encounter to consider lack of a skill to turn off the video game promptly when a Zoom meeting starts is challenging. Parents may also genetically share the child’s predisposing ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, or weakness in communication or social sensitivity.

Sometimes part of the solution for a conflict is for the parent to reduce expectations. This requires understanding and accepting the child’s cognitive or emotional limitations. Reducing expectations is ideally done before a request rather than by giving in after it, which reinforces protests. For authoritarian adults rigid in their belief that parents are boss, changing expectations can be tough and can feel like losing control or failing as a leader. One benefit of working with a CPS coach (see livesinthebalance.org or ThinkKids.org) is to help parents identify their own limitations.

Predicting the types of demands that tend to create conflict, such as to act immediately or be flexible about options, allows parents to prioritize those requests for calmer moments or when there is more time for discussion. Reviewing a checklist of common gaps in skills and creating a list of expectations and triggers that are difficult for the child helps the family be more proactive in developing solutions. Authors of CPS have validated a checklist of skill deficits, “Thinking Skills Inventory,” to facilitate detection of gaps that is educational plus useful for planning specific solutions.

CPS has been shown in randomized trials with both parent groups and in home counseling to be as effective as Parent Training in reducing oppositional behavior and reducing maternal stress, with effects lasting even longer.

CPS Plan B notably has no reward or punishment components as it assumes the child wants to behave acceptably but can’t; has the “will but not the skill.” When skill deficits are worked around the child is satisfied with complying and pleasing the parents. The idea of a “function” of the misbehavior for the child of gaining attention or reward or avoiding consequences is reinterpreted as serving to communicate the problem the child is having trouble in meeting the parent’s demand. When the parent understands and helps the child solve the problem his/her misbehavior is no longer needed. A benefit of the communication and mutual problem solving used in CPS is on not only improving behavior but empowering parents and children, building parental empathy, and improving child skills.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication is as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

Greene RW et al. A transactional model of oppositional behavior: Underpinnings of the Collaborative Problem Solving approach. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):67-75.

“What kind of parent are you? Why don’t you straighten him out!” rants the woman being jostled in the grocery store by your patient. “Easy for you to say,” thinks your patient’s frazzled and now insulted parent.

Blaming the parent for an out-of-control child has historically been a common refrain of neighbors, relatives, and even strangers. But considering child behavior as resulting from both parent and child factors is central to the current transactional model of child development. In this model, mismatch of the parent’s and child’s response patterns is seen as setting them up for chronically rough interactions around parent requests/demands. A parent escalating quickly from a briefly stated request to a tirade may create more tension paired with an anxious child who takes time to act, for example. Once a parent (and ultimately the child) recognize patterns in what leads to conflict, they can become more proactive in predicting and negotiating these situations. Ross Greene, PhD, explains this in his book “The Explosive Child,” calling the method Collaborative Problem Solving (now Collaborative & Proactive Solutions or CPS).

While there are general principles parents can use to modify what they consider “mis”behaviors, these methods often do not account for the “missing” skills of the individual child (and parent) predisposing to those “mis”takes. Thinking of misbehaviors as being because of a kind of “learning disability” in the child rather than willful defiance can help cool off interactions by instead focusing on solving the underlying problem.

What kinds of “gaps in skills” set a child up for defiant or explosive reactions? If you think about what features of children, and parent-child relationships are associated with harmonious interactions this becomes evident. Children over 3 who are patient, easygoing, flexible or adaptable, and good at transitions and problem-solving can delay gratification and tolerate frustration, regulate their emotions, explain their desires, and multitask. They are better at reading the parent’s needs and intent and tend to interpret requests as positive or at least neutral and are more likely to comply with parent requests without a fuss.

What? No kid you know is great at all of these? These skills, at best variable, develop with maturation. Some are part of temperament, considered normal variation in personality. For example, so-called difficult temperament includes low adaptability, high-intensity reactions, low regularity, tendency to withdraw, and negative mood. But in the extreme, weaknesses in these skills are core to or comorbid with diagnosable mental health disorders. Defiance and irritable responses are criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and less severe categories called aggressive/oppositional problem or variation. ODD is often found in children diagnosed with ADHD (65%), Tourette’s (15%-65%), depression (70% if severe), bipolar disorder (85%), OCD, anxiety (45%), autism, and language-processing disorders (55%), or trauma. These conditions variably include lower emotion regulation, poorer executive functioning including poor task shifting and impulsivity, obsessiveness, lower expressive and receptive communication skills, and less social awareness that facilitates harmonious problem solving.

The basic components of the CPS approach to addressing parent-child conflict sound intuitive but defining them clearly is important when families are stuck. There are three levels of plans. If the problem is an emergency or nonnegotiable, e.g., child hurting the cat, it may call for Plan A – parent-imposed solutions, sometimes with consequences or rewards. As children mature, Plan A should be used less frequently. If solving the problem is not a top life priority, Plan C – postponing action, may be appropriate. Plan C highlights that behavior change is a long-term project and “picking your fights” is important.

The biggest value of CPS for resolving behavior problems comes from intermediate Plan B. In Plan B the first step of problem solving for parents facing child defiance or upset is to empathically and nonjudgmentally figure out the child’s concern. Questions such as “I’ve noticed that when I remind you that it is trash night you start shouting. What’s up with that?” then patiently asking about the who, what, where, and when of their concern and checking to ensure understanding. Specificity is important as well as noting times when the reaction occurs or not.

Once the child’s concern is clear, e.g., feeling that the demand to take out the trash now interrupts his games during the only time his friends are online, the parents should echo the child’s concern then express their own concern about how the behavior is affecting them and others, potentially including the child; e.g., mother is so upset by the shouting that she can’t sleep, and worry that the child is not learning responsibility, and then checking for child understanding.

Finally, the parent invites brainstorming for a solution that addresses both of their concerns, first asking the child for suggestions, aiming for a strategy that is realistic and specific. Children reluctant to make suggestions may need more time and the parent may be wondering “if there is a way for both of our concerns to be addressed.” Solutions chosen are then tried for several weeks, success tracked, and needed changes negotiated.

For parents, using a collaborative approach to dealing with their child’s behavior takes skills they may not have at the moment, or ever. Especially under the stresses of COVID-19 lockdown, taking a step back from an encounter to consider lack of a skill to turn off the video game promptly when a Zoom meeting starts is challenging. Parents may also genetically share the child’s predisposing ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, or weakness in communication or social sensitivity.

Sometimes part of the solution for a conflict is for the parent to reduce expectations. This requires understanding and accepting the child’s cognitive or emotional limitations. Reducing expectations is ideally done before a request rather than by giving in after it, which reinforces protests. For authoritarian adults rigid in their belief that parents are boss, changing expectations can be tough and can feel like losing control or failing as a leader. One benefit of working with a CPS coach (see livesinthebalance.org or ThinkKids.org) is to help parents identify their own limitations.

Predicting the types of demands that tend to create conflict, such as to act immediately or be flexible about options, allows parents to prioritize those requests for calmer moments or when there is more time for discussion. Reviewing a checklist of common gaps in skills and creating a list of expectations and triggers that are difficult for the child helps the family be more proactive in developing solutions. Authors of CPS have validated a checklist of skill deficits, “Thinking Skills Inventory,” to facilitate detection of gaps that is educational plus useful for planning specific solutions.

CPS has been shown in randomized trials with both parent groups and in home counseling to be as effective as Parent Training in reducing oppositional behavior and reducing maternal stress, with effects lasting even longer.

CPS Plan B notably has no reward or punishment components as it assumes the child wants to behave acceptably but can’t; has the “will but not the skill.” When skill deficits are worked around the child is satisfied with complying and pleasing the parents. The idea of a “function” of the misbehavior for the child of gaining attention or reward or avoiding consequences is reinterpreted as serving to communicate the problem the child is having trouble in meeting the parent’s demand. When the parent understands and helps the child solve the problem his/her misbehavior is no longer needed. A benefit of the communication and mutual problem solving used in CPS is on not only improving behavior but empowering parents and children, building parental empathy, and improving child skills.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication is as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

Greene RW et al. A transactional model of oppositional behavior: Underpinnings of the Collaborative Problem Solving approach. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):67-75.

“What kind of parent are you? Why don’t you straighten him out!” rants the woman being jostled in the grocery store by your patient. “Easy for you to say,” thinks your patient’s frazzled and now insulted parent.

Blaming the parent for an out-of-control child has historically been a common refrain of neighbors, relatives, and even strangers. But considering child behavior as resulting from both parent and child factors is central to the current transactional model of child development. In this model, mismatch of the parent’s and child’s response patterns is seen as setting them up for chronically rough interactions around parent requests/demands. A parent escalating quickly from a briefly stated request to a tirade may create more tension paired with an anxious child who takes time to act, for example. Once a parent (and ultimately the child) recognize patterns in what leads to conflict, they can become more proactive in predicting and negotiating these situations. Ross Greene, PhD, explains this in his book “The Explosive Child,” calling the method Collaborative Problem Solving (now Collaborative & Proactive Solutions or CPS).

While there are general principles parents can use to modify what they consider “mis”behaviors, these methods often do not account for the “missing” skills of the individual child (and parent) predisposing to those “mis”takes. Thinking of misbehaviors as being because of a kind of “learning disability” in the child rather than willful defiance can help cool off interactions by instead focusing on solving the underlying problem.

What kinds of “gaps in skills” set a child up for defiant or explosive reactions? If you think about what features of children, and parent-child relationships are associated with harmonious interactions this becomes evident. Children over 3 who are patient, easygoing, flexible or adaptable, and good at transitions and problem-solving can delay gratification and tolerate frustration, regulate their emotions, explain their desires, and multitask. They are better at reading the parent’s needs and intent and tend to interpret requests as positive or at least neutral and are more likely to comply with parent requests without a fuss.

What? No kid you know is great at all of these? These skills, at best variable, develop with maturation. Some are part of temperament, considered normal variation in personality. For example, so-called difficult temperament includes low adaptability, high-intensity reactions, low regularity, tendency to withdraw, and negative mood. But in the extreme, weaknesses in these skills are core to or comorbid with diagnosable mental health disorders. Defiance and irritable responses are criteria for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and less severe categories called aggressive/oppositional problem or variation. ODD is often found in children diagnosed with ADHD (65%), Tourette’s (15%-65%), depression (70% if severe), bipolar disorder (85%), OCD, anxiety (45%), autism, and language-processing disorders (55%), or trauma. These conditions variably include lower emotion regulation, poorer executive functioning including poor task shifting and impulsivity, obsessiveness, lower expressive and receptive communication skills, and less social awareness that facilitates harmonious problem solving.

The basic components of the CPS approach to addressing parent-child conflict sound intuitive but defining them clearly is important when families are stuck. There are three levels of plans. If the problem is an emergency or nonnegotiable, e.g., child hurting the cat, it may call for Plan A – parent-imposed solutions, sometimes with consequences or rewards. As children mature, Plan A should be used less frequently. If solving the problem is not a top life priority, Plan C – postponing action, may be appropriate. Plan C highlights that behavior change is a long-term project and “picking your fights” is important.

The biggest value of CPS for resolving behavior problems comes from intermediate Plan B. In Plan B the first step of problem solving for parents facing child defiance or upset is to empathically and nonjudgmentally figure out the child’s concern. Questions such as “I’ve noticed that when I remind you that it is trash night you start shouting. What’s up with that?” then patiently asking about the who, what, where, and when of their concern and checking to ensure understanding. Specificity is important as well as noting times when the reaction occurs or not.

Once the child’s concern is clear, e.g., feeling that the demand to take out the trash now interrupts his games during the only time his friends are online, the parents should echo the child’s concern then express their own concern about how the behavior is affecting them and others, potentially including the child; e.g., mother is so upset by the shouting that she can’t sleep, and worry that the child is not learning responsibility, and then checking for child understanding.

Finally, the parent invites brainstorming for a solution that addresses both of their concerns, first asking the child for suggestions, aiming for a strategy that is realistic and specific. Children reluctant to make suggestions may need more time and the parent may be wondering “if there is a way for both of our concerns to be addressed.” Solutions chosen are then tried for several weeks, success tracked, and needed changes negotiated.

For parents, using a collaborative approach to dealing with their child’s behavior takes skills they may not have at the moment, or ever. Especially under the stresses of COVID-19 lockdown, taking a step back from an encounter to consider lack of a skill to turn off the video game promptly when a Zoom meeting starts is challenging. Parents may also genetically share the child’s predisposing ADHD, anxiety, depression, OCD, or weakness in communication or social sensitivity.

Sometimes part of the solution for a conflict is for the parent to reduce expectations. This requires understanding and accepting the child’s cognitive or emotional limitations. Reducing expectations is ideally done before a request rather than by giving in after it, which reinforces protests. For authoritarian adults rigid in their belief that parents are boss, changing expectations can be tough and can feel like losing control or failing as a leader. One benefit of working with a CPS coach (see livesinthebalance.org or ThinkKids.org) is to help parents identify their own limitations.

Predicting the types of demands that tend to create conflict, such as to act immediately or be flexible about options, allows parents to prioritize those requests for calmer moments or when there is more time for discussion. Reviewing a checklist of common gaps in skills and creating a list of expectations and triggers that are difficult for the child helps the family be more proactive in developing solutions. Authors of CPS have validated a checklist of skill deficits, “Thinking Skills Inventory,” to facilitate detection of gaps that is educational plus useful for planning specific solutions.

CPS has been shown in randomized trials with both parent groups and in home counseling to be as effective as Parent Training in reducing oppositional behavior and reducing maternal stress, with effects lasting even longer.

CPS Plan B notably has no reward or punishment components as it assumes the child wants to behave acceptably but can’t; has the “will but not the skill.” When skill deficits are worked around the child is satisfied with complying and pleasing the parents. The idea of a “function” of the misbehavior for the child of gaining attention or reward or avoiding consequences is reinterpreted as serving to communicate the problem the child is having trouble in meeting the parent’s demand. When the parent understands and helps the child solve the problem his/her misbehavior is no longer needed. A benefit of the communication and mutual problem solving used in CPS is on not only improving behavior but empowering parents and children, building parental empathy, and improving child skills.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS. She has no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication is as a paid expert to MDedge News. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

Greene RW et al. A transactional model of oppositional behavior: Underpinnings of the Collaborative Problem Solving approach. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):67-75.

More Americans hospitalized, readmitted for heart failure

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”

As reported online Feb. 10 in JAMA Cardiology, notable sex differences were found in hospitalization, with higher rates per 1,000 persons among men.

In contrast, a 2020 report on HF trends in the VA system showed a 2% decrease in unadjusted 30-day readmissions from 2007 to 2017 and a decline in the adjusted 30-day readmission risk.

The present study did not risk-adjust readmission risk and included a population that was 51% male, compared with about 98% male in the VA, the investigators noted.

“The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction,” they wrote.

The analysis was based on data from the Nationwide Readmission Database, which included 35,197,725 hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8,273,270 primary HF hospitalizations from January 2010 to December 2017.

A single primary HF admission occurred in 5,092,626 unique patients and 1,269,109 had two or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 years.

The administrative database did not include clinical data, so it wasn’t possible to differentiate between HF with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, the authors noted. Patient race and ethnicity data also were not available.

“Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women,” the investigators concluded.

One coauthor reporting receiving personal fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, CHF Solutions, Edwards Lifesciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Medtronic, Merck, and Novartis. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Overall primary HF hospitalization rates per 1,000 adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013, and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017.

Rates of unique patient visits for HF were also on the way down – falling from 3.4 in 2010 to 3.2 in 2013 and 2014 – before climbing to 3.8 in 2017.

Similar trends were observed for rates of postdischarge HF readmissions (from 1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (from 0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017).

“We should be emphasizing the things we know work to reduce heart failure hospitalization, which is, No. 1, prevention,” senior author Boback Ziaeian, MD, PhD, said in an interview.

Comorbidities that can lead to heart failure crept up over the study period, such that by 2017, hypertension was present in 91.4% of patients, diabetes in 48.9%, and lipid disorders in 53.1%, up from 76.5%, 44.9%, and 40.4%, respectively, in 2010. Half of all patients had coronary artery disease at both time points. Renal disease shot up from 45.9% to 60.6% by 2017.

“If we did a better job of controlling our known risk factors, we would really cut down on the incidence of heart failure being developed and then, among those estimated 6.6 million heart failure patients, we need to get them on our cornerstone therapies,” said Dr. Ziaeian, of the Veterans Affairts Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have shown clear efficacy and safety in trials like DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced, provide a “huge opportunity” to add on to standard therapies, he noted. Competition for VA contracts has brought the price down to about $50 a month for veterans, compared with a cash price of about $500-$600 a month.

Yet in routine practice, only 8% of veterans with HF at his center are on an SGLT2 inhibitor, compared with 80% on ACE inhibitors or beta blockers, observed Dr. Ziaeian. “This medication has been indicated for the last year and a half and we’re only at 8% in a system where we have pretty easy access to medications.”