User login

Home Phototherapy During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Office-based phototherapy practices have closed or are operating below capacity because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Social distancing measures to reduce virus transmission are a significant driving factor.1-3 In the age of biologics, other options requiring fewer patient visits are available, such as UVB phototherapy. UV phototherapy is considered first line when more than 10% of the body surface area is affected.4 Although phototherapy often is performed in the office, it also may be delivered at home.2 Home-based phototherapy is safe, effective, and similar in cost to office-based phototherapy.4 Currently, there are limited COVID-19–specific guidelines for home-based phototherapy.

The risks and sequelae of COVID-19 are still being investigated, with cases varying by location. As such, local and national public health recommendations are evolving. Dermatologists must make individualized decisions about practice services, as local restrictions differ. As office-based phototherapy services may struggle to implement mitigation strategies, home-based phototherapy is an increasingly viable treatment option.1,4,5 Patient benefits of home therapy include improved treatment compliance; greater patient satisfaction; reduced travel/waiting time; and reduced long-term cost, including co-pays, depending on insurance coverage.2,4

We aim to provide recommendations on home-based phototherapy during the pandemic. Throughout the decision-making process, careful consideration of safety, risks, benefits, and treatment options for physicians, staff, and patients will be vital to the successful implementation of home-based phototherapy. Our recommendations are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

Considerations for Physicians

Physicians should take the following steps when assessing if home phototherapy is an option for each patient.1,2,4

• Determine patient eligibility for phototherapy treatment if currently not on phototherapy

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Review patient history of treatment compliance

• Determine insurance coverage and consider exclusion criteria

• Review prior treatments

• Provide education on side effects

• Provide education on signs of adequate treatment response

• Indicate the type of UV light and unit on the prescription

• Consider whether the patient is in the maintenance or initiation phase when providing recommendations

• Work with the supplier if the light therapy unit is denied by submitting an appeal or prescribing a different unit

• Follow up with telemedicine to assess treatment effectiveness and monitor for adverse effects

Considerations for Patients

Counsel patients to weigh the risks and benefits of home phototherapy prescription and usage.1,2,4

• Evaluate cost

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Ensure a complete understanding of treatment schedule

• Properly utilize protective equipment (eg, genital shields for men, eye shields for all)

• Avoid sharing phototherapy units with household members

• Disinfect and maintain units

• Maintain proper ventilation of spaces

• Maintain treatment log

• Attend follow-up

Treatment Alternatives

For patients with severe psoriasis, there are alternative treatments to office and home phototherapy. Biologics, immunosuppressive therapies, and other treatment options may be considered on a case-by-case basis.3,4,6 Currently, recommendations for the risk of COVID-19 with biologics or systemic immunosuppressive therapies remains inconsistent and should be carefully considered when providing alternative treatments.7-11

Final Thoughts

As restrictions are lifted according to local public health measures, prepandemic office phototherapy practices may resume operations. Home phototherapy is a practical and effective alternative for treatment of psoriasis when access to the office setting is limited.

- Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287-288.

Anderson KL, Feldman SR. A guide to prescribing home phototherapy for patients with psoriasis: the appropriate patient, the type of unit, the treatment regimen, and the potential obstacles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:868.E1-878.E1. - Palmore TN, Smith BA. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): infection control in health care and home settings. UpToDate. Updated January 7, 2021. Accessed January 25, 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-infection-control-in-health-care-and-home-settings

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Sadeghinia A, Daneshpazhooh M. Immunosuppressive drugs for patients with psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic era. a review [published online November 3, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020:E14498. doi:10.1111/dth.14498

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13475.

- Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217-1218.

- Mehta P, Ciurtin C, Scully M, et al. JAK inhibitors in COVID-19: the need for vigilance regarding increased inherent thrombotic risk. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001919.

- Walz L, Cohen AJ, Rebaza AP, et al. JAK-inhibitor and type I interferon ability to produce favorable clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:47.

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al. COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:292-294.

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Naldi L, et al. Incidence rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis receiving biological treatment: a Northern Italy experience [published online November 5, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.032

Office-based phototherapy practices have closed or are operating below capacity because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Social distancing measures to reduce virus transmission are a significant driving factor.1-3 In the age of biologics, other options requiring fewer patient visits are available, such as UVB phototherapy. UV phototherapy is considered first line when more than 10% of the body surface area is affected.4 Although phototherapy often is performed in the office, it also may be delivered at home.2 Home-based phototherapy is safe, effective, and similar in cost to office-based phototherapy.4 Currently, there are limited COVID-19–specific guidelines for home-based phototherapy.

The risks and sequelae of COVID-19 are still being investigated, with cases varying by location. As such, local and national public health recommendations are evolving. Dermatologists must make individualized decisions about practice services, as local restrictions differ. As office-based phototherapy services may struggle to implement mitigation strategies, home-based phototherapy is an increasingly viable treatment option.1,4,5 Patient benefits of home therapy include improved treatment compliance; greater patient satisfaction; reduced travel/waiting time; and reduced long-term cost, including co-pays, depending on insurance coverage.2,4

We aim to provide recommendations on home-based phototherapy during the pandemic. Throughout the decision-making process, careful consideration of safety, risks, benefits, and treatment options for physicians, staff, and patients will be vital to the successful implementation of home-based phototherapy. Our recommendations are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

Considerations for Physicians

Physicians should take the following steps when assessing if home phototherapy is an option for each patient.1,2,4

• Determine patient eligibility for phototherapy treatment if currently not on phototherapy

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Review patient history of treatment compliance

• Determine insurance coverage and consider exclusion criteria

• Review prior treatments

• Provide education on side effects

• Provide education on signs of adequate treatment response

• Indicate the type of UV light and unit on the prescription

• Consider whether the patient is in the maintenance or initiation phase when providing recommendations

• Work with the supplier if the light therapy unit is denied by submitting an appeal or prescribing a different unit

• Follow up with telemedicine to assess treatment effectiveness and monitor for adverse effects

Considerations for Patients

Counsel patients to weigh the risks and benefits of home phototherapy prescription and usage.1,2,4

• Evaluate cost

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Ensure a complete understanding of treatment schedule

• Properly utilize protective equipment (eg, genital shields for men, eye shields for all)

• Avoid sharing phototherapy units with household members

• Disinfect and maintain units

• Maintain proper ventilation of spaces

• Maintain treatment log

• Attend follow-up

Treatment Alternatives

For patients with severe psoriasis, there are alternative treatments to office and home phototherapy. Biologics, immunosuppressive therapies, and other treatment options may be considered on a case-by-case basis.3,4,6 Currently, recommendations for the risk of COVID-19 with biologics or systemic immunosuppressive therapies remains inconsistent and should be carefully considered when providing alternative treatments.7-11

Final Thoughts

As restrictions are lifted according to local public health measures, prepandemic office phototherapy practices may resume operations. Home phototherapy is a practical and effective alternative for treatment of psoriasis when access to the office setting is limited.

Office-based phototherapy practices have closed or are operating below capacity because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1 Social distancing measures to reduce virus transmission are a significant driving factor.1-3 In the age of biologics, other options requiring fewer patient visits are available, such as UVB phototherapy. UV phototherapy is considered first line when more than 10% of the body surface area is affected.4 Although phototherapy often is performed in the office, it also may be delivered at home.2 Home-based phototherapy is safe, effective, and similar in cost to office-based phototherapy.4 Currently, there are limited COVID-19–specific guidelines for home-based phototherapy.

The risks and sequelae of COVID-19 are still being investigated, with cases varying by location. As such, local and national public health recommendations are evolving. Dermatologists must make individualized decisions about practice services, as local restrictions differ. As office-based phototherapy services may struggle to implement mitigation strategies, home-based phototherapy is an increasingly viable treatment option.1,4,5 Patient benefits of home therapy include improved treatment compliance; greater patient satisfaction; reduced travel/waiting time; and reduced long-term cost, including co-pays, depending on insurance coverage.2,4

We aim to provide recommendations on home-based phototherapy during the pandemic. Throughout the decision-making process, careful consideration of safety, risks, benefits, and treatment options for physicians, staff, and patients will be vital to the successful implementation of home-based phototherapy. Our recommendations are based on maximizing benefits and minimizing risks.

Considerations for Physicians

Physicians should take the following steps when assessing if home phototherapy is an option for each patient.1,2,4

• Determine patient eligibility for phototherapy treatment if currently not on phototherapy

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Review patient history of treatment compliance

• Determine insurance coverage and consider exclusion criteria

• Review prior treatments

• Provide education on side effects

• Provide education on signs of adequate treatment response

• Indicate the type of UV light and unit on the prescription

• Consider whether the patient is in the maintenance or initiation phase when providing recommendations

• Work with the supplier if the light therapy unit is denied by submitting an appeal or prescribing a different unit

• Follow up with telemedicine to assess treatment effectiveness and monitor for adverse effects

Considerations for Patients

Counsel patients to weigh the risks and benefits of home phototherapy prescription and usage.1,2,4

• Evaluate cost

• Carefully review patient and provider requirements for home phototherapy supplier

• Ensure a complete understanding of treatment schedule

• Properly utilize protective equipment (eg, genital shields for men, eye shields for all)

• Avoid sharing phototherapy units with household members

• Disinfect and maintain units

• Maintain proper ventilation of spaces

• Maintain treatment log

• Attend follow-up

Treatment Alternatives

For patients with severe psoriasis, there are alternative treatments to office and home phototherapy. Biologics, immunosuppressive therapies, and other treatment options may be considered on a case-by-case basis.3,4,6 Currently, recommendations for the risk of COVID-19 with biologics or systemic immunosuppressive therapies remains inconsistent and should be carefully considered when providing alternative treatments.7-11

Final Thoughts

As restrictions are lifted according to local public health measures, prepandemic office phototherapy practices may resume operations. Home phototherapy is a practical and effective alternative for treatment of psoriasis when access to the office setting is limited.

- Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287-288.

Anderson KL, Feldman SR. A guide to prescribing home phototherapy for patients with psoriasis: the appropriate patient, the type of unit, the treatment regimen, and the potential obstacles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:868.E1-878.E1. - Palmore TN, Smith BA. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): infection control in health care and home settings. UpToDate. Updated January 7, 2021. Accessed January 25, 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-infection-control-in-health-care-and-home-settings

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Sadeghinia A, Daneshpazhooh M. Immunosuppressive drugs for patients with psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic era. a review [published online November 3, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020:E14498. doi:10.1111/dth.14498

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13475.

- Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217-1218.

- Mehta P, Ciurtin C, Scully M, et al. JAK inhibitors in COVID-19: the need for vigilance regarding increased inherent thrombotic risk. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001919.

- Walz L, Cohen AJ, Rebaza AP, et al. JAK-inhibitor and type I interferon ability to produce favorable clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:47.

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al. COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:292-294.

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Naldi L, et al. Incidence rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis receiving biological treatment: a Northern Italy experience [published online November 5, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.032

- Lim HW, Feldman SR, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Recommendations for phototherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:287-288.

Anderson KL, Feldman SR. A guide to prescribing home phototherapy for patients with psoriasis: the appropriate patient, the type of unit, the treatment regimen, and the potential obstacles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:868.E1-878.E1. - Palmore TN, Smith BA. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): infection control in health care and home settings. UpToDate. Updated January 7, 2021. Accessed January 25, 2021.https://www.uptodate.com/contents/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-infection-control-in-health-care-and-home-settings

- Koek MB, Buskens E, van Weelden H, et al. Home versus outpatient ultraviolet B phototherapy for mild to severe psoriasis: pragmatic multicentre randomised controlled non-inferiority trial (PLUTO study). BMJ. 2009;338:b1542.

- Sadeghinia A, Daneshpazhooh M. Immunosuppressive drugs for patients with psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic era. a review [published online November 3, 2020]. Dermatol Ther. 2020:E14498. doi:10.1111/dth.14498

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13475.

- Lebwohl M, Rivera-Oyola R, Murrell DF. Should biologics for psoriasis be interrupted in the era of COVID-19? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1217-1218.

- Mehta P, Ciurtin C, Scully M, et al. JAK inhibitors in COVID-19: the need for vigilance regarding increased inherent thrombotic risk. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001919.

- Walz L, Cohen AJ, Rebaza AP, et al. JAK-inhibitor and type I interferon ability to produce favorable clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:47.

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al. COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:292-294.

- Gisondi P, Piaserico S, Naldi L, et al. Incidence rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis receiving biological treatment: a Northern Italy experience [published online November 5, 2020]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.032

Practice Points

- Home phototherapy is a safe and effective option for patients with psoriasis during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

- Although a consensus has not been reached with systemic immunosuppressive therapies for patients with psoriasis and the risk of COVID-19, we continue to recommend caution and careful monitoring of clinical outcomes for patients.

What’s Eating You? Black Butterfly (Hylesia nigricans)

The order Lepidoptera (phylum Arthropoda, class Hexapoda) is comprised of moths and butterflies.1 Lepidopterism refers to a range of adverse medical conditions resulting from contact with these insects, typically during the caterpillar (larval) stage. It involves multiple pathologic mechanisms, including direct toxicity of venom and mechanical irritant effects.2 Erucism has been defined as any reaction caused by contact with caterpillars or any reaction limited to the skin caused by contact with caterpillars, butterflies, or moths. Lepidopterism can mean any reaction to caterpillars or moths, referring only to reactions from contact with scales or hairs from adult moths or butterflies, or referring only to cases with systemic signs and symptoms (eg, rhinoconjunctival or asthmatic symptoms, angioedema and anaphylaxis, hemorrhagic diathesis) with or without cutaneous findings, resulting from contact with any lepidopteran source.1 Strictly speaking, erucism should refer to any reaction from caterpillars and lepidopterism to reactions from moths or butterflies. Because reactions to both larval and adult lepidoptera can cause a variety of either cutaneous and/or systemic symptoms, classifying reactions into erucism or lepidopterism is only of academic interest.1

We report a documented case of lepidopterism in a patient with acute cutaneous lesions following exposure to an adult-stage black butterfly (Hylesia nigricans).

Case Report

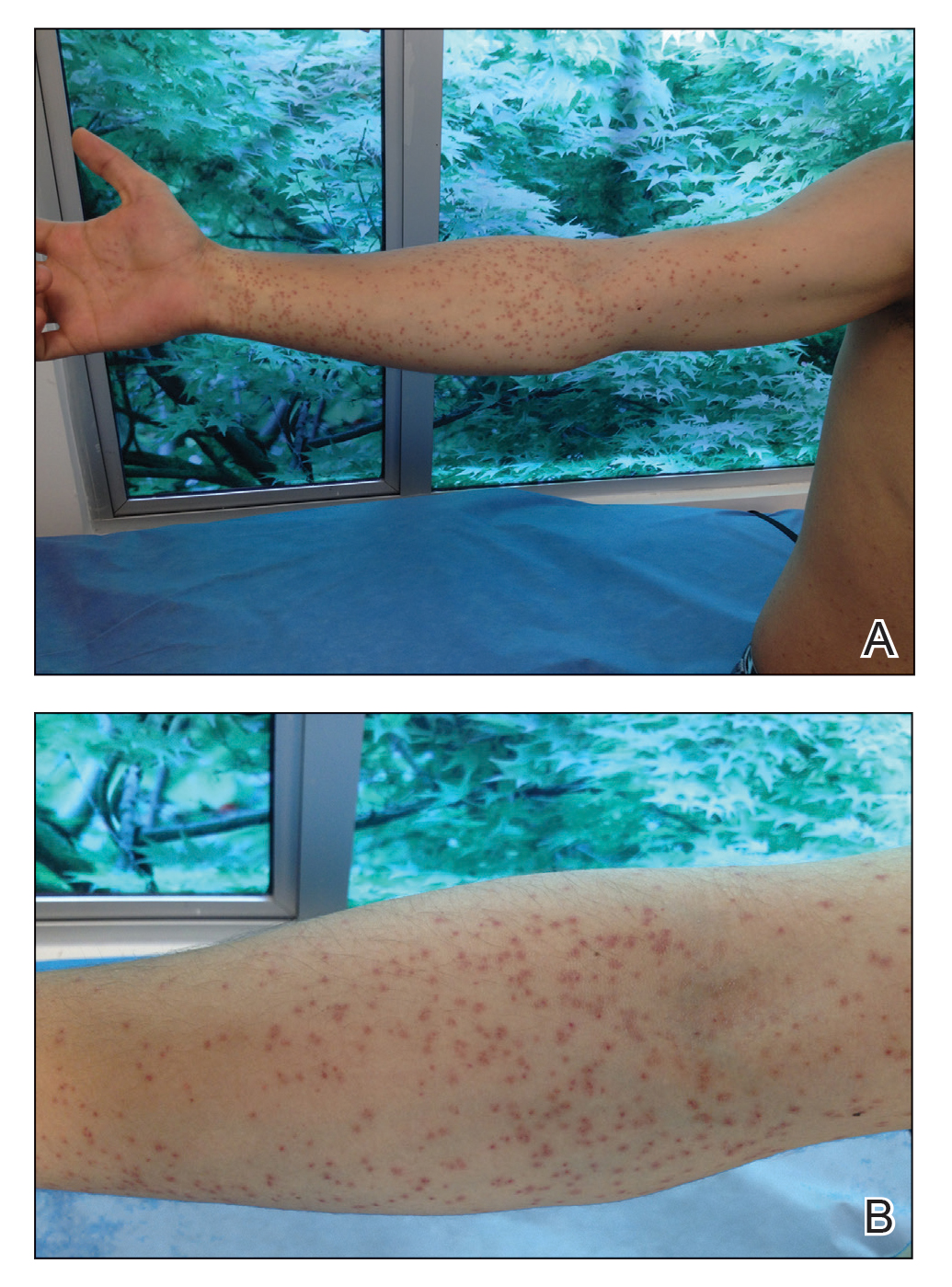

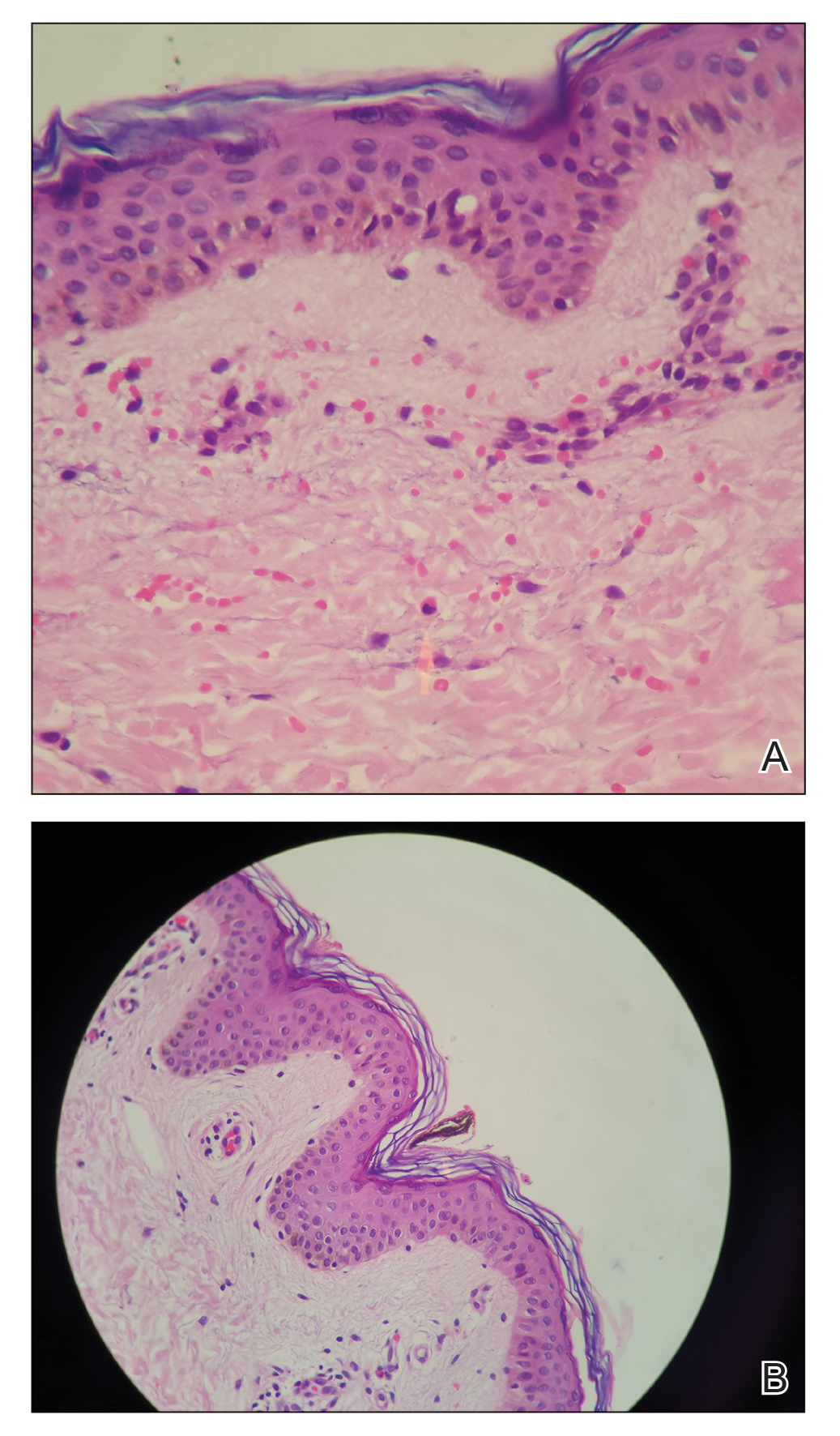

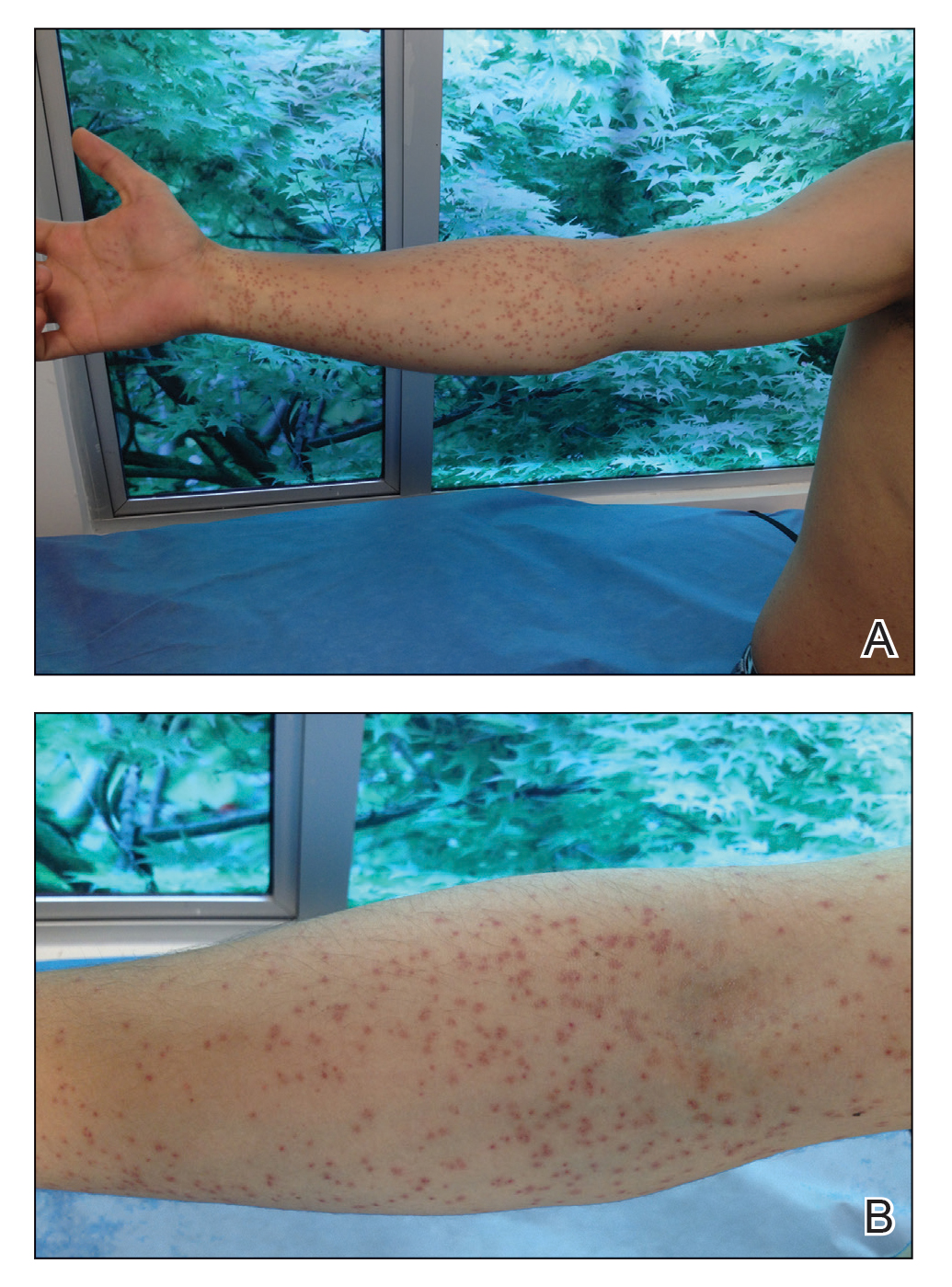

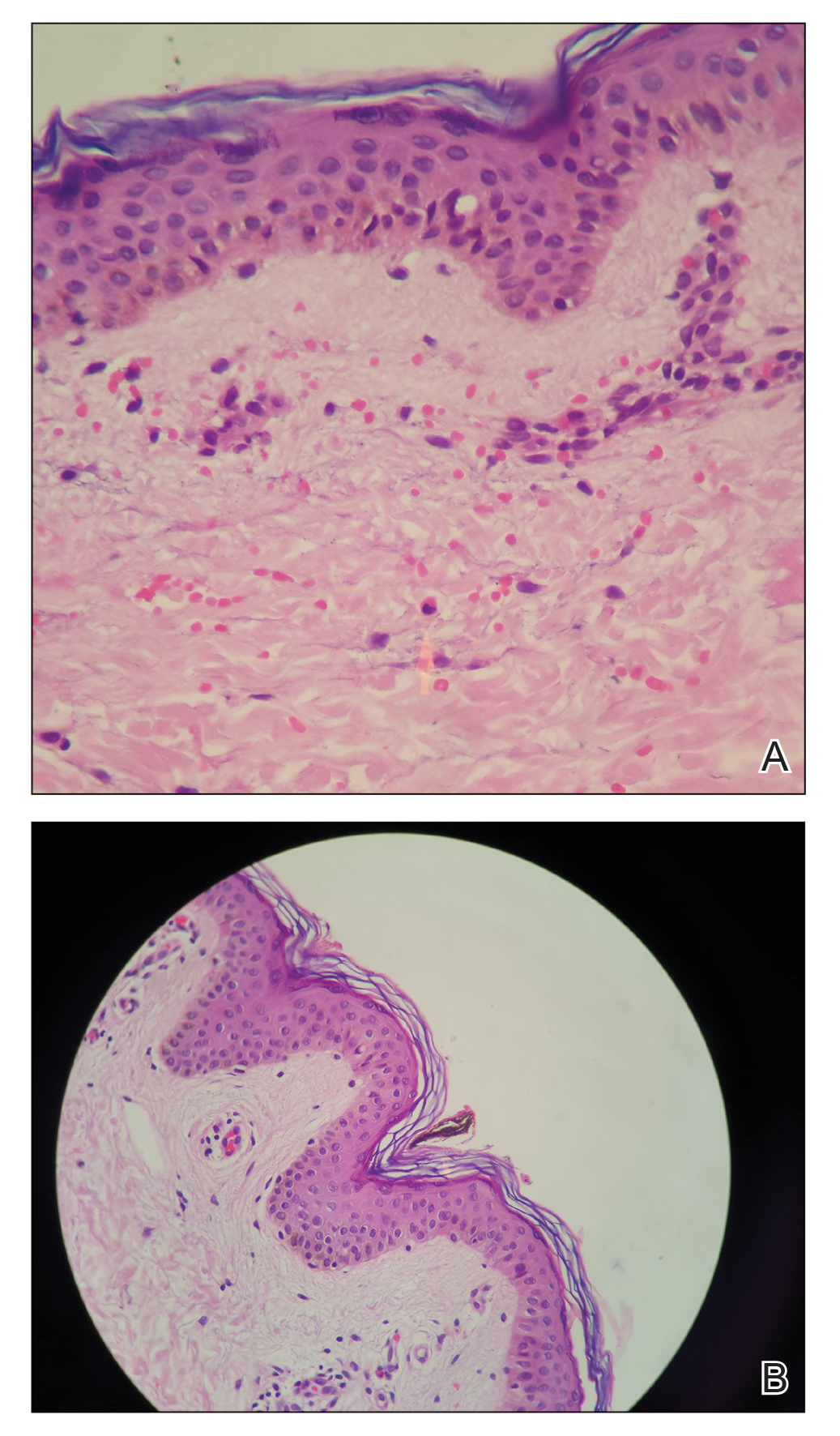

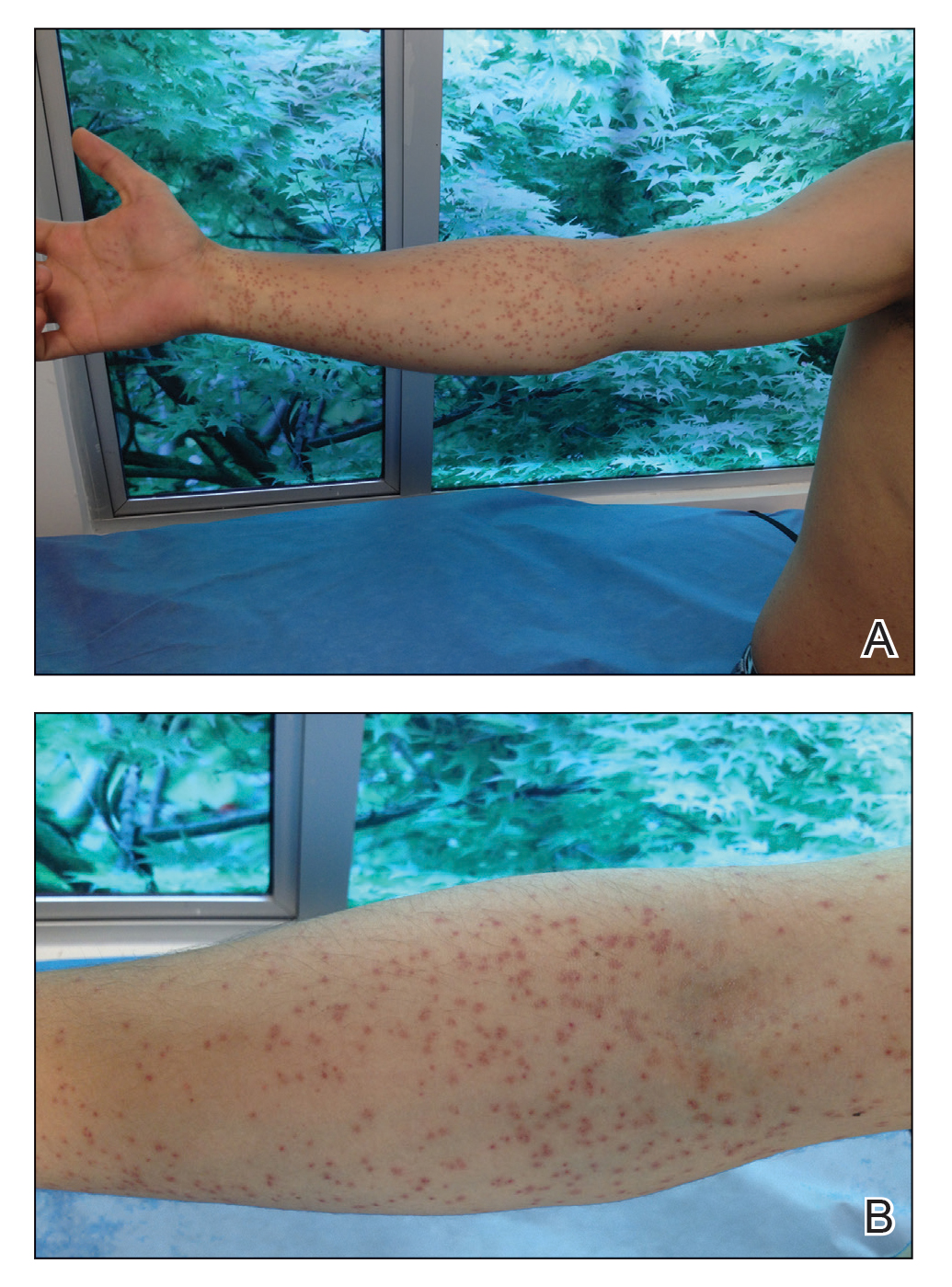

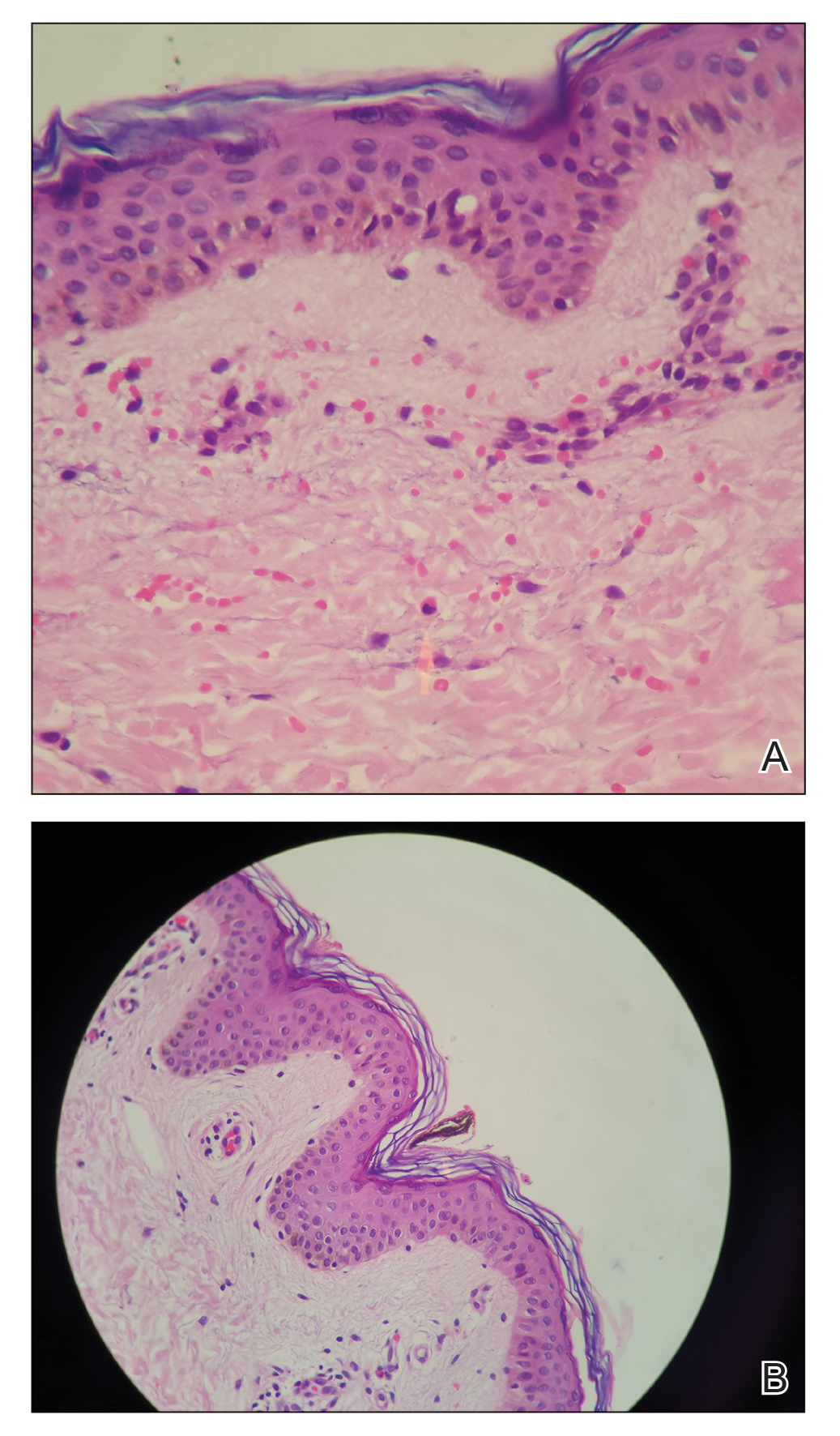

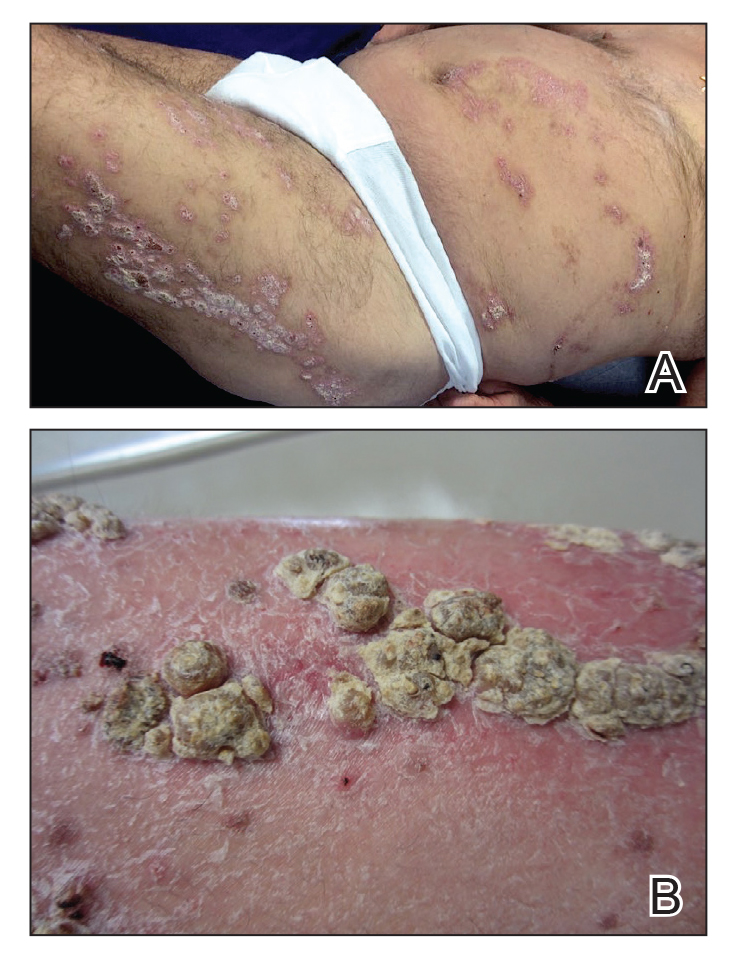

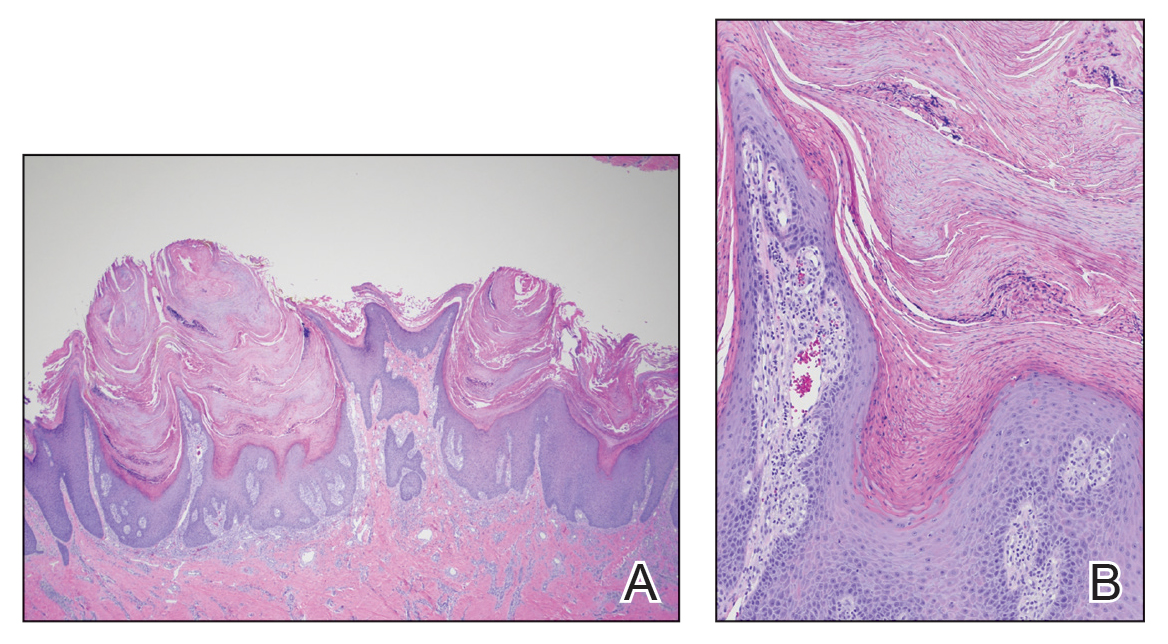

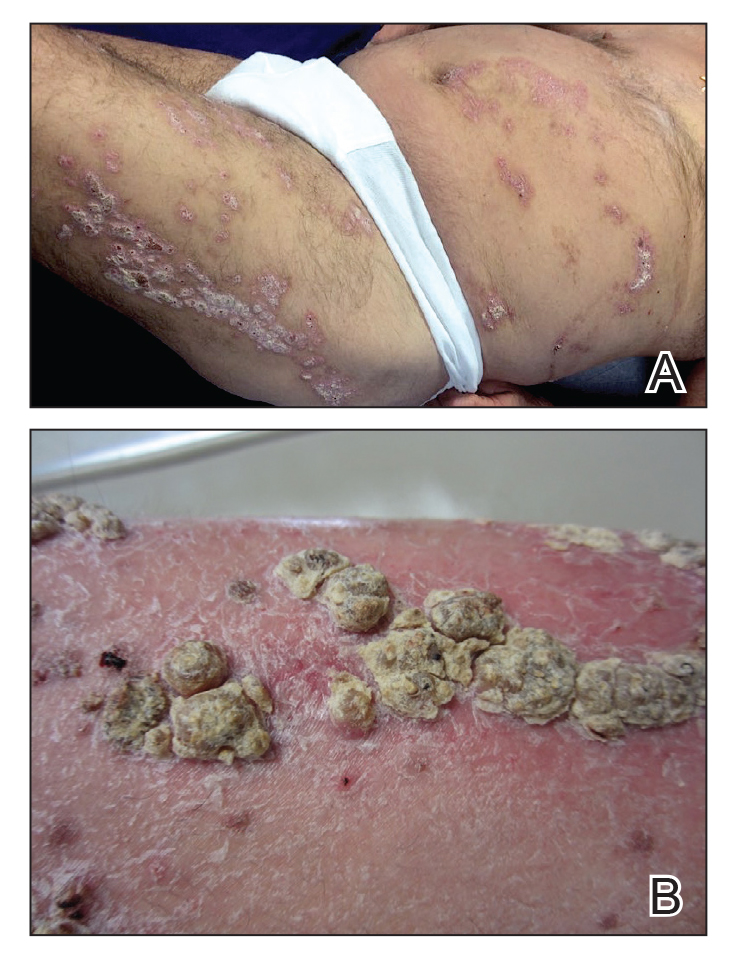

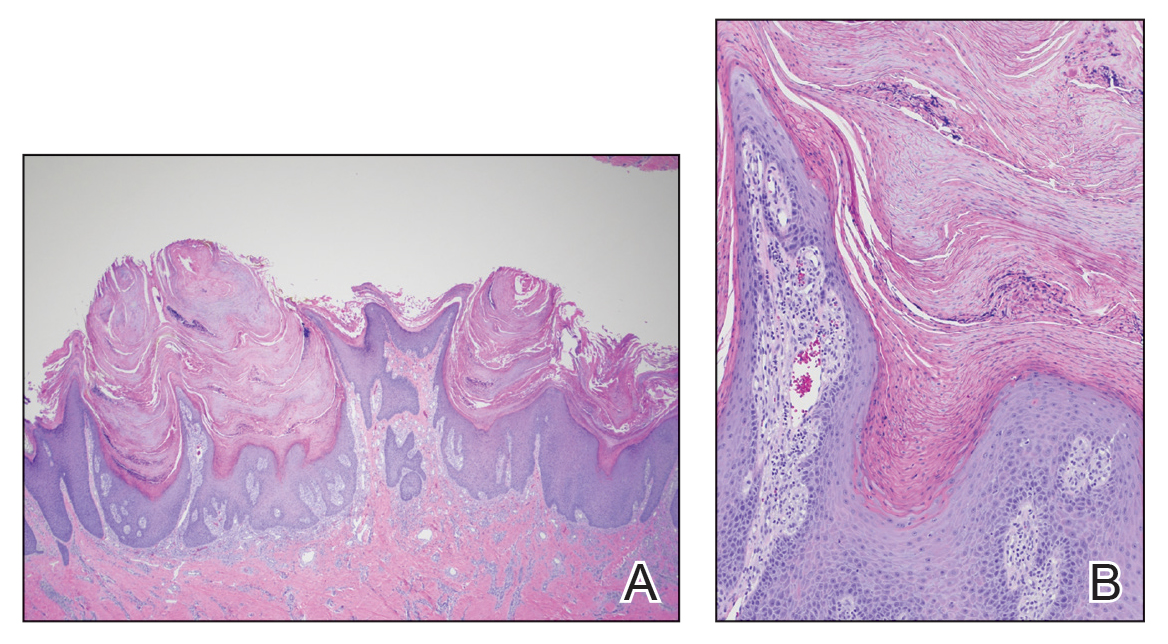

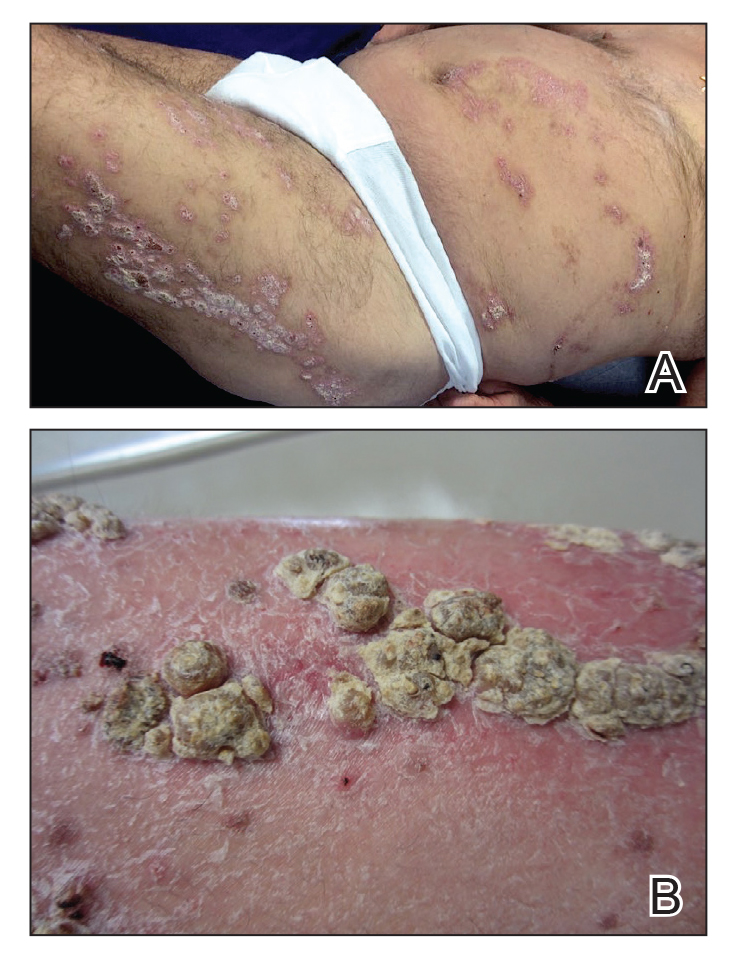

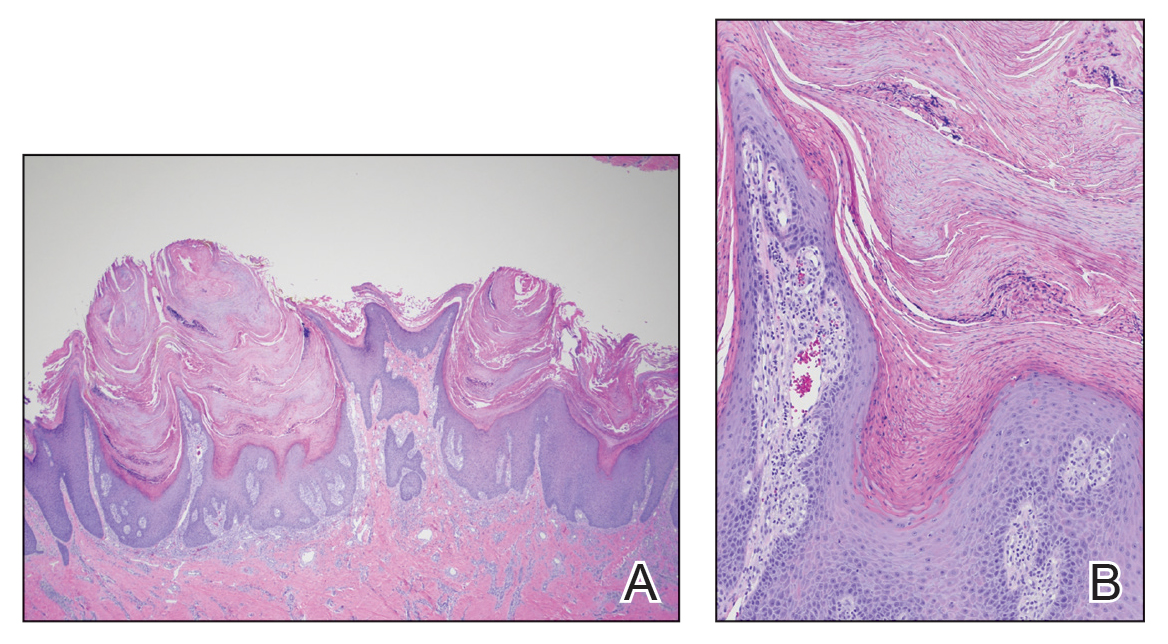

A 21-year-old oil well worker presented with pruritic skin lesions on the right arm and flank of 3 hours’ duration. He reported that a black butterfly had perched on his arm while he was working and left a considerable number of small yellowish hairs on the skin, after which an intense pruritus and skin lesions began to develop. He denied other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous 1- to 2-mm, nonconfluent, erythematous and edematous papules on the right forearm, arm (Figure 1A), and flank. Some abrasions of the skin due to scratching and crusting were noted (Figure 1B). A skin biopsy from the right arm showed a superficial perivascular dermatitis with a mixed infiltrate of polymorphonuclear predominance with eosinophils (Figure 2A). Importantly, a structure resembling an urticating spicule was identified in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B); spicules are located on the abdomen of arthropods and are associated with an inflammatory response in human skin.

Based on the patient’s history of butterfly exposure, clinical presentation of the lesions, and histopathologic findings demonstrating the presence of the spicules, the diagnosis of lepidopterism was confirmed. The patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids for 1 week with complete resolution of the lesions.

Comment

Epidemiology of Envenomation

Although many tropical insects carry infectious diseases, cutaneous injury can occur by other mechanisms, such as dermatitis caused by contact with the skin (erucism or lepidopterism). Caterpillar envenomation is common, but this phenomenon rarely has been studied due to few reported cases, which hinders a complete understanding of the problem.3

The order Lepidoptera comprises 2 suborders: Rhopalocera, with adult specimens that fly during the daytime (butterflies), and Heterocera, which are largely nocturnal (moths). The stages of development include egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult (imago), constituting a holometabolic life cycle.4 Adult butterflies and moths represent the reproductive stage of lepidoptera.

The pathology of lepidopterism is attributed to contact with fluids such as hemolymph and secretions from the spicules, with histamine being identified as the main causative component.3 During the reproductive stage, female insects approach light sources and release clouds of bristles from their abdomens that can penetrate human skin and cause an irritating dermatitis.5 Lepidopterism can occur following contact with bristles from insects of the Hylesia genus (Saturniidae family), such as in our patient.3,6 Epidemic outbreaks have been reported in several countries, mainly Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela.5 The patient was located in Colombia, a country without any reported cases of lepidopterism from the black butterfly (H nigricans). Cutaneous reactions to lepidoptera insects come in many forms, most commonly presenting as a mild stinging reaction with a papular eruption, pruritic urticarial papules and plaques, or scaly erythematous papules and plaques in exposed areas.7

Histopathologic Findings

The histology of lepidoptera exposure is nonspecific, typically demonstrating epidermal edema, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and eosinophils. Epidermal necrosis and vasculitis rarely are seen. Embedded spines from Hylesia insects have been described.7 The histopathologic examination generally reveals a foreign body reaction in addition to granulomas.3

Therapy

The use of oral antihistamines is indicated for the control of pruritus, and topical treatment with cold compresses, baths, and corticosteroid creams is recommended.3,8,9

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient with lepidopterism, a rare entity confirmed histologically with documentation of a spicule in the stratum corneum in the patient’s biopsy. Changes due to urbanization and industrialization have a closer relationship with various animal species that are pathogenic to humans; therefore, we encourage dermatologists to be aware of these diseases.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:666.

- Redd JT, Voorhees RE, Török TJ. Outbreak of lepidopterism at a Boy Scout camp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:952-955.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, et al. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I. Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.

- Cardoso AEC, Haddad V Jr. Accidents caused by lepidopterans (moth larvae and adult): study on the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:571-578.

- Salomón AD, Simón D, Rimoldi JC, et al. Lepidopterism due to the butterfly Hylesia nigricans. preventive research-intervention in Buenos Aires. Medicina (B Aires). 2005;65:241-246.

- Moreira SC, Lima JC, Silva L, et al. Description of an outbreak of lepidopterism (dermatitis associated with contact with moths) among sailors in Salvador, State of Bahia. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:591-593.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:666.

- Maier H, Spiegel W, Kinaciyan T, et al. The oak processionary caterpillar as the cause of an epidemic airborne disease: survey and analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:990-997.

- Herrera-Chaumont C, Sojo-Milano M, Pérez-Ybarra LM. Knowledge and practices on lepidopterism by Hylesia metabus (Cramer, 1775)(Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) in Yaguaraparo parish, Sucre state, northeastern Venezuela. Revista Biomédica. 2016;27:11-23.

The order Lepidoptera (phylum Arthropoda, class Hexapoda) is comprised of moths and butterflies.1 Lepidopterism refers to a range of adverse medical conditions resulting from contact with these insects, typically during the caterpillar (larval) stage. It involves multiple pathologic mechanisms, including direct toxicity of venom and mechanical irritant effects.2 Erucism has been defined as any reaction caused by contact with caterpillars or any reaction limited to the skin caused by contact with caterpillars, butterflies, or moths. Lepidopterism can mean any reaction to caterpillars or moths, referring only to reactions from contact with scales or hairs from adult moths or butterflies, or referring only to cases with systemic signs and symptoms (eg, rhinoconjunctival or asthmatic symptoms, angioedema and anaphylaxis, hemorrhagic diathesis) with or without cutaneous findings, resulting from contact with any lepidopteran source.1 Strictly speaking, erucism should refer to any reaction from caterpillars and lepidopterism to reactions from moths or butterflies. Because reactions to both larval and adult lepidoptera can cause a variety of either cutaneous and/or systemic symptoms, classifying reactions into erucism or lepidopterism is only of academic interest.1

We report a documented case of lepidopterism in a patient with acute cutaneous lesions following exposure to an adult-stage black butterfly (Hylesia nigricans).

Case Report

A 21-year-old oil well worker presented with pruritic skin lesions on the right arm and flank of 3 hours’ duration. He reported that a black butterfly had perched on his arm while he was working and left a considerable number of small yellowish hairs on the skin, after which an intense pruritus and skin lesions began to develop. He denied other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous 1- to 2-mm, nonconfluent, erythematous and edematous papules on the right forearm, arm (Figure 1A), and flank. Some abrasions of the skin due to scratching and crusting were noted (Figure 1B). A skin biopsy from the right arm showed a superficial perivascular dermatitis with a mixed infiltrate of polymorphonuclear predominance with eosinophils (Figure 2A). Importantly, a structure resembling an urticating spicule was identified in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B); spicules are located on the abdomen of arthropods and are associated with an inflammatory response in human skin.

Based on the patient’s history of butterfly exposure, clinical presentation of the lesions, and histopathologic findings demonstrating the presence of the spicules, the diagnosis of lepidopterism was confirmed. The patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids for 1 week with complete resolution of the lesions.

Comment

Epidemiology of Envenomation

Although many tropical insects carry infectious diseases, cutaneous injury can occur by other mechanisms, such as dermatitis caused by contact with the skin (erucism or lepidopterism). Caterpillar envenomation is common, but this phenomenon rarely has been studied due to few reported cases, which hinders a complete understanding of the problem.3

The order Lepidoptera comprises 2 suborders: Rhopalocera, with adult specimens that fly during the daytime (butterflies), and Heterocera, which are largely nocturnal (moths). The stages of development include egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult (imago), constituting a holometabolic life cycle.4 Adult butterflies and moths represent the reproductive stage of lepidoptera.

The pathology of lepidopterism is attributed to contact with fluids such as hemolymph and secretions from the spicules, with histamine being identified as the main causative component.3 During the reproductive stage, female insects approach light sources and release clouds of bristles from their abdomens that can penetrate human skin and cause an irritating dermatitis.5 Lepidopterism can occur following contact with bristles from insects of the Hylesia genus (Saturniidae family), such as in our patient.3,6 Epidemic outbreaks have been reported in several countries, mainly Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela.5 The patient was located in Colombia, a country without any reported cases of lepidopterism from the black butterfly (H nigricans). Cutaneous reactions to lepidoptera insects come in many forms, most commonly presenting as a mild stinging reaction with a papular eruption, pruritic urticarial papules and plaques, or scaly erythematous papules and plaques in exposed areas.7

Histopathologic Findings

The histology of lepidoptera exposure is nonspecific, typically demonstrating epidermal edema, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and eosinophils. Epidermal necrosis and vasculitis rarely are seen. Embedded spines from Hylesia insects have been described.7 The histopathologic examination generally reveals a foreign body reaction in addition to granulomas.3

Therapy

The use of oral antihistamines is indicated for the control of pruritus, and topical treatment with cold compresses, baths, and corticosteroid creams is recommended.3,8,9

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient with lepidopterism, a rare entity confirmed histologically with documentation of a spicule in the stratum corneum in the patient’s biopsy. Changes due to urbanization and industrialization have a closer relationship with various animal species that are pathogenic to humans; therefore, we encourage dermatologists to be aware of these diseases.

The order Lepidoptera (phylum Arthropoda, class Hexapoda) is comprised of moths and butterflies.1 Lepidopterism refers to a range of adverse medical conditions resulting from contact with these insects, typically during the caterpillar (larval) stage. It involves multiple pathologic mechanisms, including direct toxicity of venom and mechanical irritant effects.2 Erucism has been defined as any reaction caused by contact with caterpillars or any reaction limited to the skin caused by contact with caterpillars, butterflies, or moths. Lepidopterism can mean any reaction to caterpillars or moths, referring only to reactions from contact with scales or hairs from adult moths or butterflies, or referring only to cases with systemic signs and symptoms (eg, rhinoconjunctival or asthmatic symptoms, angioedema and anaphylaxis, hemorrhagic diathesis) with or without cutaneous findings, resulting from contact with any lepidopteran source.1 Strictly speaking, erucism should refer to any reaction from caterpillars and lepidopterism to reactions from moths or butterflies. Because reactions to both larval and adult lepidoptera can cause a variety of either cutaneous and/or systemic symptoms, classifying reactions into erucism or lepidopterism is only of academic interest.1

We report a documented case of lepidopterism in a patient with acute cutaneous lesions following exposure to an adult-stage black butterfly (Hylesia nigricans).

Case Report

A 21-year-old oil well worker presented with pruritic skin lesions on the right arm and flank of 3 hours’ duration. He reported that a black butterfly had perched on his arm while he was working and left a considerable number of small yellowish hairs on the skin, after which an intense pruritus and skin lesions began to develop. He denied other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed numerous 1- to 2-mm, nonconfluent, erythematous and edematous papules on the right forearm, arm (Figure 1A), and flank. Some abrasions of the skin due to scratching and crusting were noted (Figure 1B). A skin biopsy from the right arm showed a superficial perivascular dermatitis with a mixed infiltrate of polymorphonuclear predominance with eosinophils (Figure 2A). Importantly, a structure resembling an urticating spicule was identified in the stratum corneum (Figure 2B); spicules are located on the abdomen of arthropods and are associated with an inflammatory response in human skin.

Based on the patient’s history of butterfly exposure, clinical presentation of the lesions, and histopathologic findings demonstrating the presence of the spicules, the diagnosis of lepidopterism was confirmed. The patient was treated with oral antihistamines and topical steroids for 1 week with complete resolution of the lesions.

Comment

Epidemiology of Envenomation

Although many tropical insects carry infectious diseases, cutaneous injury can occur by other mechanisms, such as dermatitis caused by contact with the skin (erucism or lepidopterism). Caterpillar envenomation is common, but this phenomenon rarely has been studied due to few reported cases, which hinders a complete understanding of the problem.3

The order Lepidoptera comprises 2 suborders: Rhopalocera, with adult specimens that fly during the daytime (butterflies), and Heterocera, which are largely nocturnal (moths). The stages of development include egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa (chrysalis), and adult (imago), constituting a holometabolic life cycle.4 Adult butterflies and moths represent the reproductive stage of lepidoptera.

The pathology of lepidopterism is attributed to contact with fluids such as hemolymph and secretions from the spicules, with histamine being identified as the main causative component.3 During the reproductive stage, female insects approach light sources and release clouds of bristles from their abdomens that can penetrate human skin and cause an irritating dermatitis.5 Lepidopterism can occur following contact with bristles from insects of the Hylesia genus (Saturniidae family), such as in our patient.3,6 Epidemic outbreaks have been reported in several countries, mainly Argentina, Brazil, and Venezuela.5 The patient was located in Colombia, a country without any reported cases of lepidopterism from the black butterfly (H nigricans). Cutaneous reactions to lepidoptera insects come in many forms, most commonly presenting as a mild stinging reaction with a papular eruption, pruritic urticarial papules and plaques, or scaly erythematous papules and plaques in exposed areas.7

Histopathologic Findings

The histology of lepidoptera exposure is nonspecific, typically demonstrating epidermal edema, superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, and eosinophils. Epidermal necrosis and vasculitis rarely are seen. Embedded spines from Hylesia insects have been described.7 The histopathologic examination generally reveals a foreign body reaction in addition to granulomas.3

Therapy

The use of oral antihistamines is indicated for the control of pruritus, and topical treatment with cold compresses, baths, and corticosteroid creams is recommended.3,8,9

Conclusion

We report the case of a patient with lepidopterism, a rare entity confirmed histologically with documentation of a spicule in the stratum corneum in the patient’s biopsy. Changes due to urbanization and industrialization have a closer relationship with various animal species that are pathogenic to humans; therefore, we encourage dermatologists to be aware of these diseases.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:666.

- Redd JT, Voorhees RE, Török TJ. Outbreak of lepidopterism at a Boy Scout camp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:952-955.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, et al. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I. Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.

- Cardoso AEC, Haddad V Jr. Accidents caused by lepidopterans (moth larvae and adult): study on the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:571-578.

- Salomón AD, Simón D, Rimoldi JC, et al. Lepidopterism due to the butterfly Hylesia nigricans. preventive research-intervention in Buenos Aires. Medicina (B Aires). 2005;65:241-246.

- Moreira SC, Lima JC, Silva L, et al. Description of an outbreak of lepidopterism (dermatitis associated with contact with moths) among sailors in Salvador, State of Bahia. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:591-593.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:666.

- Maier H, Spiegel W, Kinaciyan T, et al. The oak processionary caterpillar as the cause of an epidemic airborne disease: survey and analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:990-997.

- Herrera-Chaumont C, Sojo-Milano M, Pérez-Ybarra LM. Knowledge and practices on lepidopterism by Hylesia metabus (Cramer, 1775)(Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) in Yaguaraparo parish, Sucre state, northeastern Venezuela. Revista Biomédica. 2016;27:11-23.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part I. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:666.

- Redd JT, Voorhees RE, Török TJ. Outbreak of lepidopterism at a Boy Scout camp. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:952-955.

- Haddad V Jr, Cardoso JL, Lupi O, et al. Tropical dermatology: venomous arthropods and human skin: part I. Insecta. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:331.

- Cardoso AEC, Haddad V Jr. Accidents caused by lepidopterans (moth larvae and adult): study on the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects. An Bras Dermatol. 2005;80:571-578.

- Salomón AD, Simón D, Rimoldi JC, et al. Lepidopterism due to the butterfly Hylesia nigricans. preventive research-intervention in Buenos Aires. Medicina (B Aires). 2005;65:241-246.

- Moreira SC, Lima JC, Silva L, et al. Description of an outbreak of lepidopterism (dermatitis associated with contact with moths) among sailors in Salvador, State of Bahia. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40:591-593.

- Hossler EW. Caterpillars and moths: part II. dermatologic manifestations of encounters with Lepidoptera. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:666.

- Maier H, Spiegel W, Kinaciyan T, et al. The oak processionary caterpillar as the cause of an epidemic airborne disease: survey and analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:990-997.

- Herrera-Chaumont C, Sojo-Milano M, Pérez-Ybarra LM. Knowledge and practices on lepidopterism by Hylesia metabus (Cramer, 1775)(Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) in Yaguaraparo parish, Sucre state, northeastern Venezuela. Revista Biomédica. 2016;27:11-23.

Practice Points

- When contact with caterpillars, butterflies, or moths occurs, patients should be advised not to rub or scratch the area or attempt to remove or crush the insect with a bare hand, as this may further spread irritating setae or spines.

- Careful removal of the larva with forceps or a similar instrument, combined with tape stripping of the area and immediate washing with soap and water, can be effective in minimizing exposure.

- Contaminated clothing should be removed and laundered thoroughly.

Translating the 2020 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis With Systemic Nonbiologics to Clinical Practice

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing skin condition characterized by keratinocyte hyperproliferation and a chronic inflammatory cascade. Therefore, controlling inflammatory responses with systemic medications is beneficial in managing psoriatic lesions and their accompanying symptoms, especially in disease inadequately controlled by topicals. Ease of drug administration and treatment availability are benefits that systemic nonbiologic therapies may have over biologic therapies.

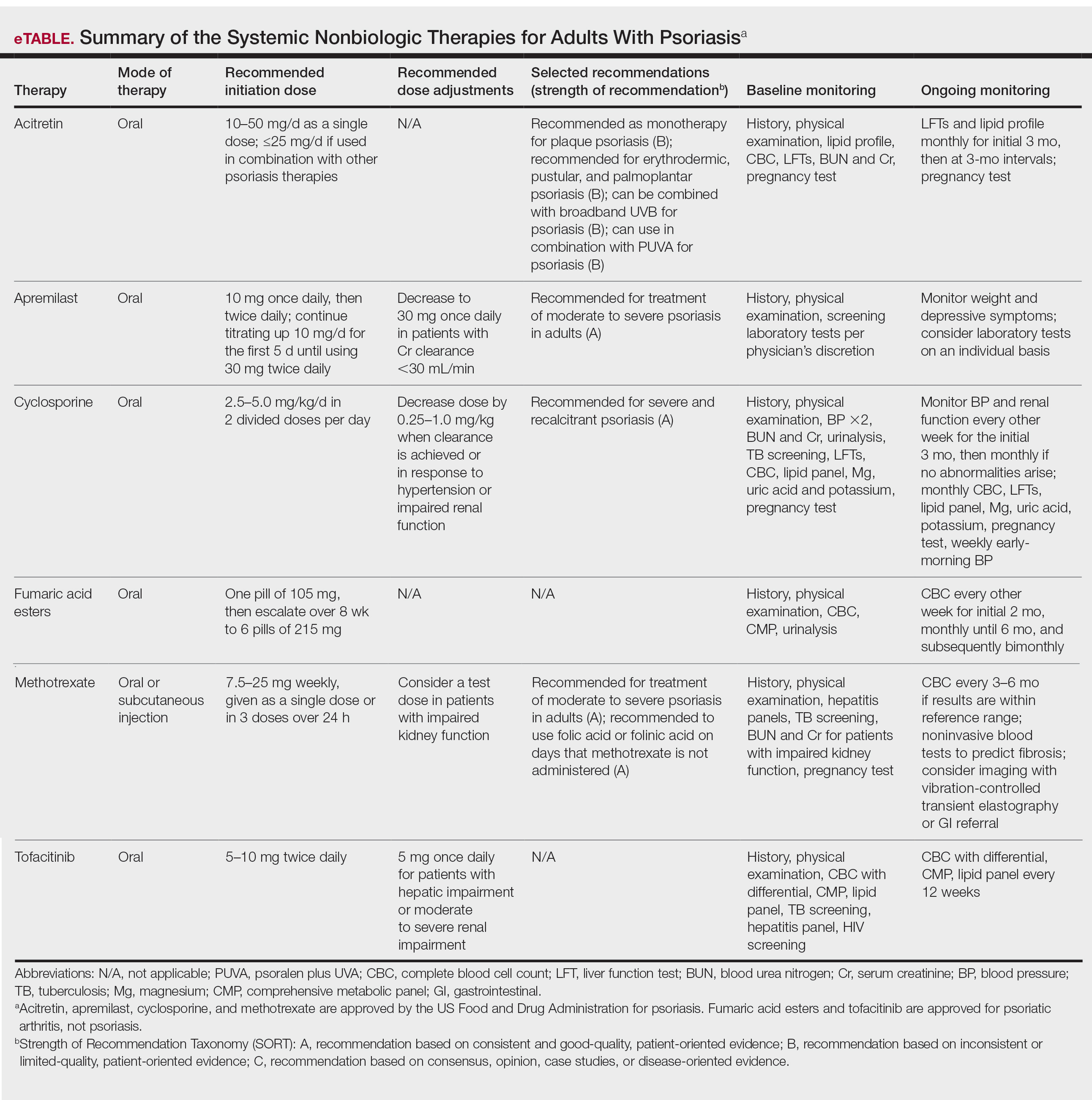

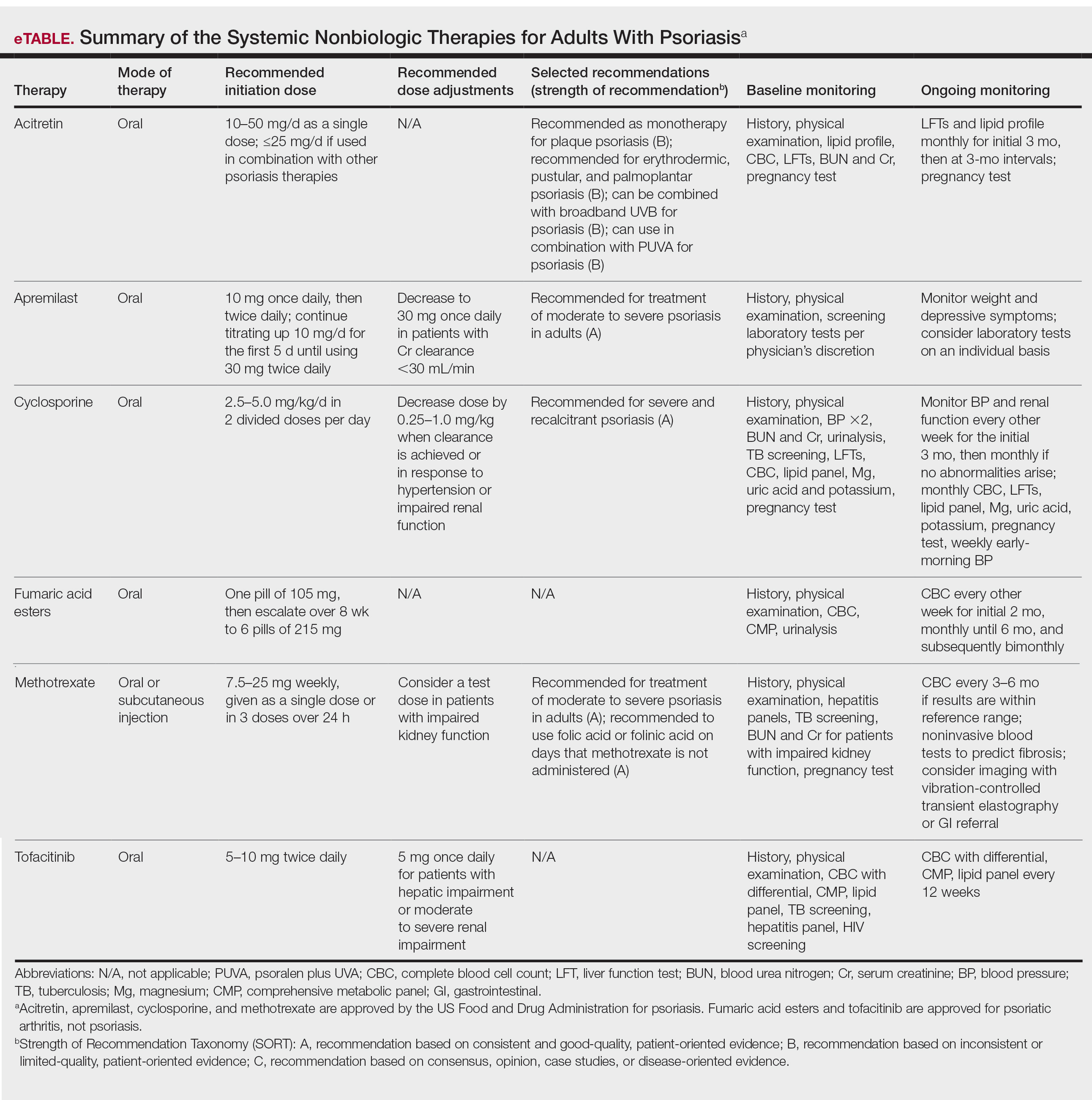

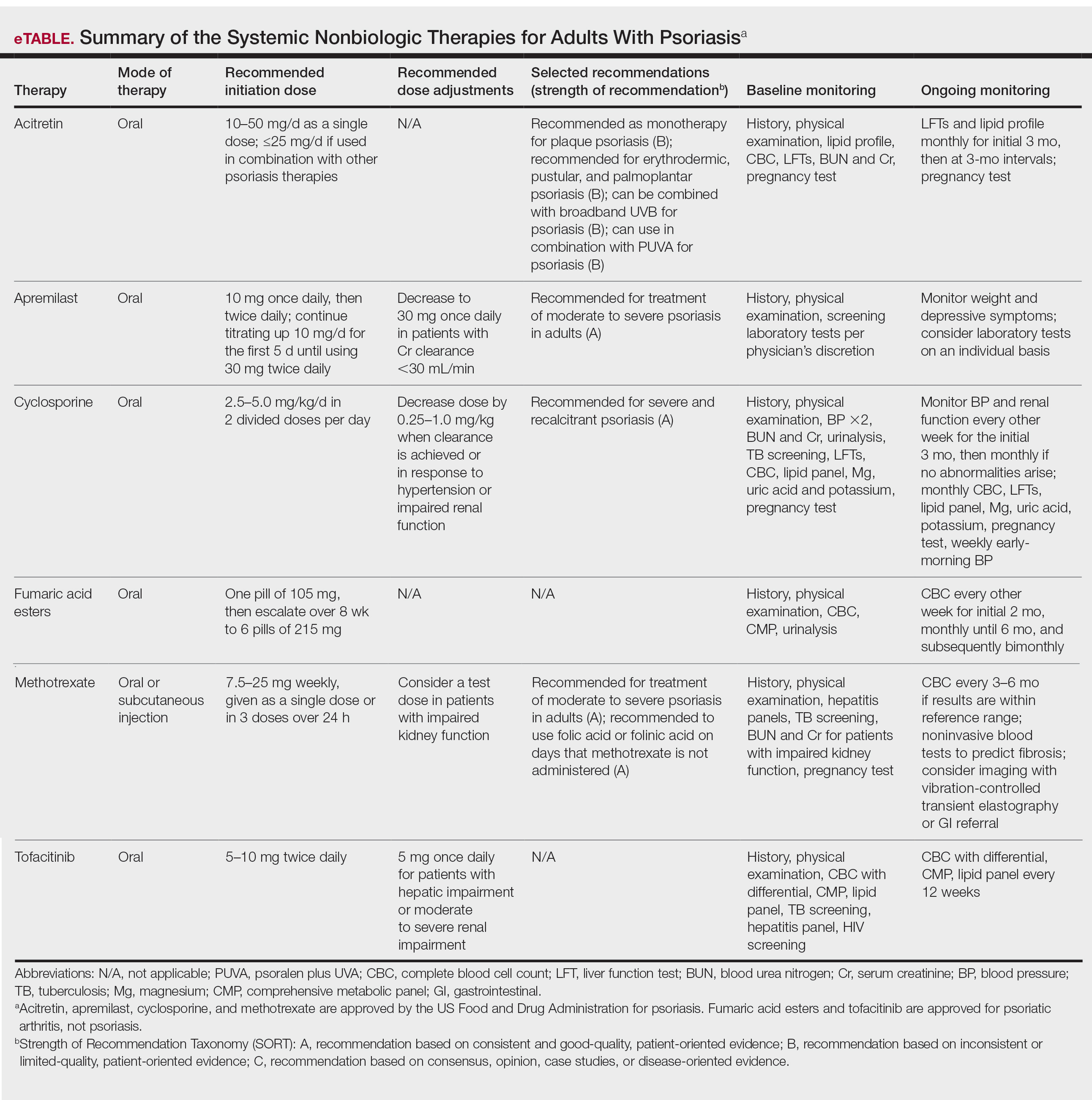

In 2020, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with systemic nonbiologic therapies.1 Dosing, efficacy, toxicity, drug-related interactions, and contraindications are addressed alongside evidence-based treatment recommendations. This review addresses current recommendations for systemic nonbiologics in psoriasis with a focus on the treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, and methotrexate (eTable). Fumaric acid esters and tofacitinib are FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis but not for plaque psoriasis. Additional long-term safety analyses of tofacitinib for plaque psoriasis were requested by the FDA. Dimethyl fumarate is approved by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of psoriasis and is among the first-line systemic treatments used in Germany.2

Selecting a Systemic Nonbiologic Agent

Methotrexate and apremilast have a strength level A recommendation for treating moderate to severe psoriasis in adults. However, methotrexate is less effective than biologic agents, including adalimumab and infliximab, for cutaneous psoriasis. Methotrexate is believed to improve psoriasis because of its direct immunosuppressive effect and inhibition of lymphoid cell proliferation. It typically is administered orally but can be administered subcutaneously for decreased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects. Compliance with close laboratory monitoring and lifestyle modifications, such as contraceptive use (because of teratogenicity) and alcohol cessation (because of the risk of liver damage) are essential in patients using methotrexate.

Apremilast, the most recently FDA-approved oral systemic medication for psoriasis, inhibits phosphodiesterase 4, subsequently decreasing inflammatory responses involving helper T cells TH1 and TH17 as well as type 1 interferon pathways. Apremilast is particularly effective in treating psoriasis with scalp and palmoplantar involvement.3 Additionally, it has an encouraging safety profile and is favorable in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Among the 4 oral agents, cyclosporine has the quickest onset of effect and has a strength level A recommendation for treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis. Because of its high-risk profile, it is recommended for short periods of time, acute flares, or during transitions to safer long-term treatment. Patients with multiple comorbidities should avoid cyclosporine as a treatment option.

Acitretin, an FDA-approved oral retinoid, is an optimal treatment option for immunosuppressed patients or patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy because it is not immunosuppressive.4 Unlike cyclosporine, acitretin is less helpful for acute flares because it takes 3 to 6 months to reach peak therapeutic response for treating plaque psoriasis. Similar to cyclosporine, acitretin can be recommended for severe psoriatic variants of erythrodermic, generalized pustular, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Acitretin has been reported to be more effective and have a more rapid onset of action in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis than in plaque psoriasis.5

Patient Comorbidities

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common comorbidity that affects treatment choice. Patients with coexisting PsA could be treated with apremilast, as it is approved for both psoriasis and PsA. In a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial, American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at weeks 16 and 52 was achieved by significantly more patients on apremilast at 20 mg twice daily (BID)(P=.0166) or 30 mg BID (P=.0001) than placebo.6 Although not FDA approved for PsA, methotrexate has been shown to improve concomitant PsA of the peripheral joints in patients with psoriasis. Furthermore, a trial of methotrexate has shown considerable improvements in PsA symptoms in patients with psoriasis—a 62.7% decrease in proportion of patients with dactylitis, 25.7% decrease in enthesitis, and improvements in ACR outcomes (ACR20 in 40.8%, ACR50 in 18.8%, and ACR70 in 8.6%, with 22.4% achieving minimal disease activity).7

Prior to starting a systemic medication for psoriasis, it is necessary to discuss effects on pregnancy and fertility. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate and acitretin use because of the drugs’ teratogenicity. Fetal death and fetal abnormalities have been reported with methotrexate use in pregnant women.8 Bone, central nervous system, auditory, ocular, and cardiovascular fetal abnormalities have been reported with maternal acitretin use.9 Breastfeeding also is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate use, as methotrexate passes into breastmilk in small quantities. Patients taking acitretin also are strongly discouraged from nursing because of the long half-life (168 days) of etretinate, a reverse metabolism product of acitretin that is increased in the presence of alcohol. Women should wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate for complete drug clearance before conceiving compared to 3 years in women who have discontinued acitretin.8,10 Men also are recommended to wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate before attempting to conceive, as its effect on male spermatogenesis and teratogenicity is unclear. Acitretin has no documented teratogenic effect in men. For women planning to become pregnant, apremilast and cyclosporine can be continued throughout pregnancy on an individual basis. The benefit of apremilast should be weighed against its potential risk to the fetus. There is no evidence of teratogenicity of apremilast at doses of 20 mg/kg daily.11 Current research regarding cyclosporine use in pregnancy only exists in transplant patients and has revealed higher rates of prematurity and lower birth weight without teratogenic effects.10,12 The risks and benefits of continuing cyclosporine while nursing should be evaluated, as cyclosporine (and ethanol-methanol components used in some formulations) is detectable in breast milk.

Drug Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to a specific systemic nonbiologic medication is a contraindication to its use and is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate. Other absolute contraindications to methotrexate are pregnancy and nursing, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease, chronic liver disease, immunodeficiency, and cytopenia. Contraindications to acitretin include pregnancy, severely impaired liver and kidney function, and chronic abnormally elevated lipid levels. There are no additional contraindications for apremilast, but patients must be informed of the risk for depression before initiating therapy. Cyclosporine is contraindicated in patients with prior psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) treatment or radiation therapy, abnormal renal function, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled and active infections, and a history of systemic malignancy. Live vaccines should be avoided in patients on cyclosporine, and caution is advised when cyclosporine is prescribed for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Pretreatment Screening

Because of drug interactions, a detailed medication history is essential prior to starting any systemic medication for psoriasis. Apremilast and cyclosporine are metabolized by cytochrome P450 and therefore are more susceptible to drug-related interactions. Cyclosporine use can affect levels of other medications that are metabolized by cytochrome P450, such as statins, calcium channel blockers, and warfarin. Similarly, acitretin’s metabolism is affected by drugs that interfere with cytochrome P450. Additionally, screening laboratory tests are needed before initiating systemic nonbiologic agents for psoriasis, with the exception of apremilast.

Prior to initiating methotrexate treatment, patients may require tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C screening tests, depending on their risk factors. A baseline liver fibrosis assessment is recommended because of the potential of hepatotoxicity in patients receiving methotrexate. Noninvasive serology tests utilized to evaluate the presence of pre-existing liver disease include Fibrosis-4, FibroMeter, FibroSure, and Hepascore. Patients with impaired renal function have an increased predisposition to methotrexate-induced hematologic toxicity. Thus, it is necessary to administer a test dose of methotrexate in these patients followed by a complete blood cell count (CBC) 5 to 7 days later. An unremarkable CBC after the test dose suggests the absence of myelosuppression, and methotrexate dosage can be increased weekly. Patients on methotrexate also must receive folate supplementation to reduce the risk for adverse effects during treatment.

Patients considering cyclosporine must undergo screening for family and personal history of renal disease. Prior to initiating treatment, patients require 2 blood pressure measurements, hepatitis screening, TB screening, urinalysis, serum creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid profile, bilirubin, and liver function tests (LFTs). A pregnancy test also is warranted for women of childbearing potential (WOCP).

Patients receiving acitretin should receive screening laboratory tests consisting of fasting cholesterol and triglycerides, CBC, renal function tests, LFTs, and a pregnancy test, if applicable.

After baseline evaluations, the selected oral systemic can be initiated using specific dosing regimens to ensure optimal drug efficacy and reduce incidence of adverse effects (eTable).

Monitoring During Active Treatment

Physicians need to counsel patients on potential adverse effects of their medications. Because of its relatively safe profile among the systemic nonbiologic agents, apremilast requires the least monitoring during treatment. There is no required routine laboratory monitoring for patients using apremilast, though testing may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. However, weight should be regularly measured in patients on apremilast. In a phase 3 clinical trial of patients with psoriasis, 12% of patients on apremilast experienced a 5% to 10% weight loss compared to 5% of patients on placebo.11,13 Thus, it is recommended that physicians consider discontinuing apremilast in patients with a weight loss of more than 5% from baseline, especially if it may lead to other unfavorable health effects. Because depression is reported among 1% of patients on apremilast, close monitoring for new or worsening symptoms of depression should be performed during treatment.11,13 To avoid common GI side effects, apremilast is initiated at 10 mg/d and is increased by 10 mg/d over the first 5 days to a final dose of 30 mg BID. Elderly patients in particular should be cautioned about the risk of dehydration associated with GI side effects. Patients with severe renal impairment (Cr clearance, <30 mL/min) should use apremilast at a dosage of 30 mg once daily.

For patients on methotrexate, laboratory monitoring is essential after each dose increase. It also is important for physicians to obtain regular blood work to assess for hematologic abnormalities and hepatoxicity. Patients with risk factors such as renal insufficiency, increased age, hypoalbuminemia, alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver disease, and methotrexate dosing errors, as well as those prone to drug-related interactions, must be monitored closely for pancytopenia.14,15 The protocol for screening for methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity during treatment depends on patient risk factors. Risk factors for hepatoxicity include history of or current alcohol abuse, abnormal LFTs, personal or family history of liver disease, diabetes, obesity, use of other hepatotoxic drugs, and hyperlipidemia.16 In patients without blood work abnormalities, CBC and LFTs can be performed every 3 to 6 months. Patients with abnormally elevated LFTs require repeat blood work every 2 to 4 weeks. Persistent elevations in LFTs require further evaluation by a GI specialist. After a cumulative dose of 3.5 to 4 g, patients should receive a GI referral and further studies (such as vibration-controlled transient elastography or liver biopsy) to assess for liver fibrosis. Patients with signs of stage 3 liver fibrosis are recommended to discontinue methotrexate and switch to another medication for psoriasis. For patients with impaired renal function, periodic BUN and Cr monitoring are needed. Common adverse effects of methotrexate include diarrhea, nausea, and anorexia, which can be mitigated by taking methotrexate with food or lowering the dosage.8 Patients on methotrexate should be monitored for rare but potential risks of infection and reactivation of latent TB, hepatitis, and lymphoma. To reduce the incidence of methotrexate toxicity from drug interactions, a review of current medications at each follow-up visit is recommended.

Nephrotoxicity and hypertension are the most common adverse effects of cyclosporine. It is important to monitor BUN and Cr biweekly for the initial 3 months, then at monthly intervals if there are no persistent abnormalities. Patients also must receive monthly CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid panel, serum bilirubin, and LFTs to monitor for adverse effects.17 Physicians should obtain regular pregnancy tests in WOCP. Weekly monitoring of early-morning blood pressure is recommended for patients on cyclosporine to detect early cyclosporine-induced nephrotoxicity. Hypertension on 2 separate occasions warrants a reduction in cyclosporine dosage or an addition of a calcium channel blocker for blood pressure control. Dose reduction also should be performed in patients with an increase in Cr above baseline greater than 25%.17 If Cr level is persistently elevated or if blood pressure does not normalize to lower than 140/90 after dose reduction, cyclosporine should be immediately discontinued. Patients on cyclosporine for more than a year warrant an annual estimation of glomerular filtration rate because of irreversible kidney damage associated with long-term use. A systematic review of patients treated with cyclosporine for more than 2 years found that at least 50% of patients experienced a 30% increase in Cr above baseline.18

Patients taking acitretin should be monitored for hyperlipidemia, the most common laboratory abnormality seen in 25% to 50% of patients.19 Fasting lipid panel and LFTs should be performed monthly for the initial 3 months on acitretin, then at 3-month intervals. Lifestyle changes should be encouraged to reduce hyperlipidemia, and fibrates may be given to treat elevated triglyceride levels, the most common type of hyperlipidemia seen with acitretin. Acitretin-induced toxic hepatitis is a rare occurrence that warrants immediate discontinuation of the medication.20 Monthly pregnancy tests must be performed in WOCP.

Combination Therapy

For apremilast, there is anecdotal evidence supporting its use in conjunction with phototherapy or biologics in some cases, but no high-quality data.21 On the other hand, using combination therapy with other systemic therapies can reduce adverse effects and decrease the amount of medication needed to achieve psoriasis clearance. Methotrexate used with etanercept, for example, has been more effective than methotrexate monotherapy in treating psoriasis, which has been attributed to a methotrexate-mediated reduction in the production of antidrug antibodies.22,23

Methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin have synergistic effects when used with phototherapy. Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy combined with methotrexate is more effective in clearing psoriasis than methotrexate or NB-UVB phototherapy alone. Similarly, acitretin and PUVA combination therapy is more effective than acitretin or PUVA phototherapy alone. Combination regimens of acitretin and broadband UVB phototherapy, acitretin and NB-UVB phototherapy, and acitretin and PUVA phototherapy also have been more effective than individual modalities alone. Combination therapy reduces the cumulative doses of both therapies and reduces the frequency and duration of phototherapy needed for psoriatic clearance.24 In acitretin combination therapy with UVB phototherapy, the recommended regimen is 2 weeks of acitretin monotherapy followed by UVB phototherapy. For patients with an inadequate response to UVB phototherapy, the UVB dose can be reduced by 30% to 50%, and acitretin 25 mg/d can be added to phototherapy treatment. Acitretin-UVB combination therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of UVB-induced erythema seen in UVB monotherapy. Similarly, the risk of squamous cell carcinoma is reduced in acitretin-PUVA combination therapy compared to PUVA monotherapy.25

The timing of phototherapy in combination with systemic nonbiologic agents is critical. Phototherapy used simultaneously with cyclosporine is contraindicated owing to increased risk of photocarcinogenesis, whereas phototherapy used in sequence with cyclosporine is well tolerated and effective. Furthermore, cyclosporine 3 mg/kg/d for 4 weeks followed by a rapid cyclosporine taper and initiation of NB-UVB phototherapy demonstrated resolution of psoriasis with fewer NB-UVB treatments and less UVB exposure than NB-UVB therapy alone.26

Final Thoughts

The FDA-approved systemic nonbiologic agents are accessible and effective treatment options for adults with widespread or inadequately controlled psoriasis. Selecting the ideal therapy requires careful consideration of medication toxicity, contraindications, monitoring requirements, and patient comorbidities. The AAD-NPF guidelines guide dermatologists in prescribing systemic nonbiologic treatments in adults with psoriasis. Utilizing these recommendations in combination with clinician judgment will help patients achieve safe and optimal psoriasis clearance.

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486.

- Mrowietz U, Barker J, Boehncke WH, et al. Clinical use of dimethyl fumarate in moderate-to-severe plaque-type psoriasis: a European expert consensus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(suppl 3):3-14.

- Van Voorhees AS, Gold LS, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of apremilast in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis of the scalp: results of a phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:96-103.

- Buccheri L, Katchen BR, Karter AJ, et al. Acitretin therapy is effective for psoriasis associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:711-715.

- Ormerod AD, Campalani E, Goodfield MJD. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines on the efficacy and use of acitretin in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:952-963.

- Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Longterm (52-week) results of a phase III randomized, controlled trial of apremilast in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:479-488.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Antares Pharma, Inc. Otrexup PFS (methotrexate) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised June 2019. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/204824s009lbl.pdf

- David M, Hodak E, Lowe NJ. Adverse effects of retinoids. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1988;3:273-288.

- Stiefel Laboratories, Inc. Soriatane (acitretin) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised September 2017. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/019821s028lbl.pdf

- Celgene Corporation. Otezla (apremilast) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Revised March 2014. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205437s000lbl.pdf

- Ghanem ME, El-Baghdadi LA, Badawy AM, et al. Pregnancy outcome after renal allograft transplantation: 15 years experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;121:178-181.

- Zerilli T, Ocheretyaner E. Apremilast (Otezla): A new oral treatment for adults with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. P T. 2015;40:495-500.

- Kivity S, Zafrir Y, Loebstein R, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for low dose methotrexate toxicity: a cohort of 28 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:1109-1113.

- Boffa MJ, Chalmers RJ. Methotrexate for psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:399-408.

- Rosenberg P, Urwitz H, Johannesson A, et al. Psoriasis patients with diabetes type 2 are at high risk of developing liver fibrosis during methotrexate treatment. J Hepatol. 2007;46:1111-1118.

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. Sandimmune (cyclosporine) [package insert]. US Food and Drug Administration website. Published 2015. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/050573s041,050574s051,050625s055lbl.pdf

- Maza A, Montaudie H, Sbidian E, et al. Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: a systematic review on treatment modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in non-plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 2):19-27.

- Yamauchi PS, Rizk D, Kormilli T, et al. Systemic retinoids. In: Weinstein GD, Gottlieb AB, eds. Therapy of Moderate-to-Severe Psoriasis. Marcel Dekker; 2003:137-150.

- van Ditzhuijsen TJ, van Haelst UJ, van Dooren-Greebe RJ, et al. Severe hepatotoxic reaction with progression to cirrhosis after use of a novel retinoid (acitretin). J Hepatol. 1990;11:185-188.

- AbuHilal M, Walsh S, Shear N. Use of apremilast in combination with other therapies for treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:313-316.

- Gottlieb AB, Langley RG, Strober BE, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the addition of methotrexate to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:649-657.

- Cronstein BN. Methotrexate BAFFles anti-drug antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:505-506.

- Lebwohl M, Drake L, Menter A, et al. Consensus conference: acitretin in combination with UVB or PUVA in the treatment of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:544-553.

- Nijsten TE, Stern RS. Oral retinoid use reduces cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma risk in patients with psoriasis treated with psoralen-UVA: a nested cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:644-650.

- Calzavara-Pinton P, Leone G, Venturini M, et al. A comparative non randomized study of narrow-band (NB) (312 +/- 2 nm) UVB phototherapy versus sequential therapy with oral administration of low-dose cyclosporin A and NB-UVB phototherapy in patients with severe psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:470-473.

Psoriasis is a chronic relapsing skin condition characterized by keratinocyte hyperproliferation and a chronic inflammatory cascade. Therefore, controlling inflammatory responses with systemic medications is beneficial in managing psoriatic lesions and their accompanying symptoms, especially in disease inadequately controlled by topicals. Ease of drug administration and treatment availability are benefits that systemic nonbiologic therapies may have over biologic therapies.

In 2020, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) published guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with systemic nonbiologic therapies.1 Dosing, efficacy, toxicity, drug-related interactions, and contraindications are addressed alongside evidence-based treatment recommendations. This review addresses current recommendations for systemic nonbiologics in psoriasis with a focus on the treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): acitretin, apremilast, cyclosporine, and methotrexate (eTable). Fumaric acid esters and tofacitinib are FDA approved for psoriatic arthritis but not for plaque psoriasis. Additional long-term safety analyses of tofacitinib for plaque psoriasis were requested by the FDA. Dimethyl fumarate is approved by the European Medicines Agency for treatment of psoriasis and is among the first-line systemic treatments used in Germany.2

Selecting a Systemic Nonbiologic Agent

Methotrexate and apremilast have a strength level A recommendation for treating moderate to severe psoriasis in adults. However, methotrexate is less effective than biologic agents, including adalimumab and infliximab, for cutaneous psoriasis. Methotrexate is believed to improve psoriasis because of its direct immunosuppressive effect and inhibition of lymphoid cell proliferation. It typically is administered orally but can be administered subcutaneously for decreased gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects. Compliance with close laboratory monitoring and lifestyle modifications, such as contraceptive use (because of teratogenicity) and alcohol cessation (because of the risk of liver damage) are essential in patients using methotrexate.

Apremilast, the most recently FDA-approved oral systemic medication for psoriasis, inhibits phosphodiesterase 4, subsequently decreasing inflammatory responses involving helper T cells TH1 and TH17 as well as type 1 interferon pathways. Apremilast is particularly effective in treating psoriasis with scalp and palmoplantar involvement.3 Additionally, it has an encouraging safety profile and is favorable in patients with multiple comorbidities.

Among the 4 oral agents, cyclosporine has the quickest onset of effect and has a strength level A recommendation for treating severe and recalcitrant psoriasis. Because of its high-risk profile, it is recommended for short periods of time, acute flares, or during transitions to safer long-term treatment. Patients with multiple comorbidities should avoid cyclosporine as a treatment option.

Acitretin, an FDA-approved oral retinoid, is an optimal treatment option for immunosuppressed patients or patients with HIV on antiretroviral therapy because it is not immunosuppressive.4 Unlike cyclosporine, acitretin is less helpful for acute flares because it takes 3 to 6 months to reach peak therapeutic response for treating plaque psoriasis. Similar to cyclosporine, acitretin can be recommended for severe psoriatic variants of erythrodermic, generalized pustular, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Acitretin has been reported to be more effective and have a more rapid onset of action in erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis than in plaque psoriasis.5

Patient Comorbidities

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a common comorbidity that affects treatment choice. Patients with coexisting PsA could be treated with apremilast, as it is approved for both psoriasis and PsA. In a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial, American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20 response at weeks 16 and 52 was achieved by significantly more patients on apremilast at 20 mg twice daily (BID)(P=.0166) or 30 mg BID (P=.0001) than placebo.6 Although not FDA approved for PsA, methotrexate has been shown to improve concomitant PsA of the peripheral joints in patients with psoriasis. Furthermore, a trial of methotrexate has shown considerable improvements in PsA symptoms in patients with psoriasis—a 62.7% decrease in proportion of patients with dactylitis, 25.7% decrease in enthesitis, and improvements in ACR outcomes (ACR20 in 40.8%, ACR50 in 18.8%, and ACR70 in 8.6%, with 22.4% achieving minimal disease activity).7

Prior to starting a systemic medication for psoriasis, it is necessary to discuss effects on pregnancy and fertility. Pregnancy is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate and acitretin use because of the drugs’ teratogenicity. Fetal death and fetal abnormalities have been reported with methotrexate use in pregnant women.8 Bone, central nervous system, auditory, ocular, and cardiovascular fetal abnormalities have been reported with maternal acitretin use.9 Breastfeeding also is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate use, as methotrexate passes into breastmilk in small quantities. Patients taking acitretin also are strongly discouraged from nursing because of the long half-life (168 days) of etretinate, a reverse metabolism product of acitretin that is increased in the presence of alcohol. Women should wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate for complete drug clearance before conceiving compared to 3 years in women who have discontinued acitretin.8,10 Men also are recommended to wait 3 months after discontinuing methotrexate before attempting to conceive, as its effect on male spermatogenesis and teratogenicity is unclear. Acitretin has no documented teratogenic effect in men. For women planning to become pregnant, apremilast and cyclosporine can be continued throughout pregnancy on an individual basis. The benefit of apremilast should be weighed against its potential risk to the fetus. There is no evidence of teratogenicity of apremilast at doses of 20 mg/kg daily.11 Current research regarding cyclosporine use in pregnancy only exists in transplant patients and has revealed higher rates of prematurity and lower birth weight without teratogenic effects.10,12 The risks and benefits of continuing cyclosporine while nursing should be evaluated, as cyclosporine (and ethanol-methanol components used in some formulations) is detectable in breast milk.

Drug Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to a specific systemic nonbiologic medication is a contraindication to its use and is an absolute contraindication for methotrexate. Other absolute contraindications to methotrexate are pregnancy and nursing, alcoholism, alcoholic liver disease, chronic liver disease, immunodeficiency, and cytopenia. Contraindications to acitretin include pregnancy, severely impaired liver and kidney function, and chronic abnormally elevated lipid levels. There are no additional contraindications for apremilast, but patients must be informed of the risk for depression before initiating therapy. Cyclosporine is contraindicated in patients with prior psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) treatment or radiation therapy, abnormal renal function, uncontrolled hypertension, uncontrolled and active infections, and a history of systemic malignancy. Live vaccines should be avoided in patients on cyclosporine, and caution is advised when cyclosporine is prescribed for patients with poorly controlled diabetes.

Pretreatment Screening

Because of drug interactions, a detailed medication history is essential prior to starting any systemic medication for psoriasis. Apremilast and cyclosporine are metabolized by cytochrome P450 and therefore are more susceptible to drug-related interactions. Cyclosporine use can affect levels of other medications that are metabolized by cytochrome P450, such as statins, calcium channel blockers, and warfarin. Similarly, acitretin’s metabolism is affected by drugs that interfere with cytochrome P450. Additionally, screening laboratory tests are needed before initiating systemic nonbiologic agents for psoriasis, with the exception of apremilast.

Prior to initiating methotrexate treatment, patients may require tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B, and hepatitis C screening tests, depending on their risk factors. A baseline liver fibrosis assessment is recommended because of the potential of hepatotoxicity in patients receiving methotrexate. Noninvasive serology tests utilized to evaluate the presence of pre-existing liver disease include Fibrosis-4, FibroMeter, FibroSure, and Hepascore. Patients with impaired renal function have an increased predisposition to methotrexate-induced hematologic toxicity. Thus, it is necessary to administer a test dose of methotrexate in these patients followed by a complete blood cell count (CBC) 5 to 7 days later. An unremarkable CBC after the test dose suggests the absence of myelosuppression, and methotrexate dosage can be increased weekly. Patients on methotrexate also must receive folate supplementation to reduce the risk for adverse effects during treatment.

Patients considering cyclosporine must undergo screening for family and personal history of renal disease. Prior to initiating treatment, patients require 2 blood pressure measurements, hepatitis screening, TB screening, urinalysis, serum creatinine (Cr), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), CBC, potassium and magnesium levels, uric acid levels, lipid profile, bilirubin, and liver function tests (LFTs). A pregnancy test also is warranted for women of childbearing potential (WOCP).

Patients receiving acitretin should receive screening laboratory tests consisting of fasting cholesterol and triglycerides, CBC, renal function tests, LFTs, and a pregnancy test, if applicable.

After baseline evaluations, the selected oral systemic can be initiated using specific dosing regimens to ensure optimal drug efficacy and reduce incidence of adverse effects (eTable).

Monitoring During Active Treatment

Physicians need to counsel patients on potential adverse effects of their medications. Because of its relatively safe profile among the systemic nonbiologic agents, apremilast requires the least monitoring during treatment. There is no required routine laboratory monitoring for patients using apremilast, though testing may be pursued at the clinician’s discretion. However, weight should be regularly measured in patients on apremilast. In a phase 3 clinical trial of patients with psoriasis, 12% of patients on apremilast experienced a 5% to 10% weight loss compared to 5% of patients on placebo.11,13 Thus, it is recommended that physicians consider discontinuing apremilast in patients with a weight loss of more than 5% from baseline, especially if it may lead to other unfavorable health effects. Because depression is reported among 1% of patients on apremilast, close monitoring for new or worsening symptoms of depression should be performed during treatment.11,13 To avoid common GI side effects, apremilast is initiated at 10 mg/d and is increased by 10 mg/d over the first 5 days to a final dose of 30 mg BID. Elderly patients in particular should be cautioned about the risk of dehydration associated with GI side effects. Patients with severe renal impairment (Cr clearance, <30 mL/min) should use apremilast at a dosage of 30 mg once daily.

For patients on methotrexate, laboratory monitoring is essential after each dose increase. It also is important for physicians to obtain regular blood work to assess for hematologic abnormalities and hepatoxicity. Patients with risk factors such as renal insufficiency, increased age, hypoalbuminemia, alcohol abuse and alcoholic liver disease, and methotrexate dosing errors, as well as those prone to drug-related interactions, must be monitored closely for pancytopenia.14,15 The protocol for screening for methotrexate-induced hepatotoxicity during treatment depends on patient risk factors. Risk factors for hepatoxicity include history of or current alcohol abuse, abnormal LFTs, personal or family history of liver disease, diabetes, obesity, use of other hepatotoxic drugs, and hyperlipidemia.16 In patients without blood work abnormalities, CBC and LFTs can be performed every 3 to 6 months. Patients with abnormally elevated LFTs require repeat blood work every 2 to 4 weeks. Persistent elevations in LFTs require further evaluation by a GI specialist. After a cumulative dose of 3.5 to 4 g, patients should receive a GI referral and further studies (such as vibration-controlled transient elastography or liver biopsy) to assess for liver fibrosis. Patients with signs of stage 3 liver fibrosis are recommended to discontinue methotrexate and switch to another medication for psoriasis. For patients with impaired renal function, periodic BUN and Cr monitoring are needed. Common adverse effects of methotrexate include diarrhea, nausea, and anorexia, which can be mitigated by taking methotrexate with food or lowering the dosage.8 Patients on methotrexate should be monitored for rare but potential risks of infection and reactivation of latent TB, hepatitis, and lymphoma. To reduce the incidence of methotrexate toxicity from drug interactions, a review of current medications at each follow-up visit is recommended.