User login

Pandemic seems to impact lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis

The two-center study showed a 38% decrease in new lung cancer diagnoses during the pandemic. Patients diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) during the pandemic had more severe disease than patients diagnosed prepandemic, but cases of SCLC were not more severe during the pandemic. Still, the 30-day mortality rate nearly doubled for both NSCLC and SCLC patients during the pandemic.

“The prioritization of the health care system towards COVID-19 patients has led to drastic changes in cancer management that could interfere with the initial diagnosis of lung cancer, resulting in delayed treatment and worse outcomes,” said Roxana Reyes, MD, of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. “Delay of cancer treatment is associated with increased mortality.”

Dr. Reyes and colleagues conducted a retrospective study of the impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of new lung cancer cases, disease severity, and clinical outcomes. Dr. Reyes reported the group’s findings at the 2020 World Conference on Lung Cancer (Abstract 3700), which was rescheduled for January 2021.

Study details

Dr. Reyes and colleagues compared data from two tertiary hospitals in Spain in the first 6 months of 2020 with data from the same period in 2019. Spain was one of the countries most affected by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic.

The study’s primary endpoint was differences by period in the number of new lung cancer cases and disease severity. A secondary endpoint was 30-day mortality rate by period and histology.

The study included 162 patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer – 100 diagnosed before the pandemic began and 62 diagnosed during the pandemic. Overall, 68% of patients had NSCLC, and 32% had SCLC.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the prepandemic and pandemic groups, except for the proportion of nonsmokers. Twice as many patients diagnosed during the pandemic were nonsmokers (16% vs. 8%).

Differences by time period and subtype

During the pandemic, there was a 38% reduction in all lung cancer diagnoses, a 36% reduction in NSCLC diagnoses, and a 42% reduction in SCLC diagnoses.

Respiratory symptoms were more common during the pandemic for both NSCLC (30% vs. 23%) and SCLC (32% vs. 24%).

Cases of NSCLC diagnosed during the pandemic were more severe, but SCLC cases were not.

In the NSCLC cohort, symptomatic disease was more common during the pandemic (74% vs. 63%), as were advanced disease (58% vs. 46%), more than two metastatic sites (16% vs. 12%), oncologic emergencies (7% vs. 3%), hospitalization (21% vs. 18%), and death during hospitalization (44% vs. 17%).

For SCLC, symptomatic disease was less common during the pandemic (74% vs. 79%), as were advanced disease (52% vs. 67%), more than two metastatic sites (26% vs. 36%), oncologic emergencies (5% vs. 12%), hospitalization (21% vs. 33%), and death during hospitalization (0% vs. 18%).

Nevertheless, the 30-day mortality rate almost doubled during the pandemic for both NSCLC (49% vs. 25%) and SCLC (32% vs. 18%).

For both subtypes together, the median overall survival was 6.7 months during the pandemic and 7.9 months before the pandemic.

Implications and next steps

“In our descriptive study, lung cancer diagnosis is being affected during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Reyes said. “Fewer new lung cancer cases were diagnosed during COVID-19.”

Some patients with acute respiratory infections who tested negative for COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic may have had undiagnosed lung cancer, noted Matthew Peters, MD, of Concord Repatriation General Hospital and Macquarie University Hospital, both in Sydney, who was not involved in this study.

“They receive a negative result and think their problem is reduced but wonder why they still have a cough,” Dr. Peters said. “The various lockdowns and social distancing reduced the diagnosis of respiratory viral illnesses that often result in an accidental diagnosis of lung cancer. As time goes by, we will recapture harvesting of accidental diagnosis of lung cancer and provide curative treatments.”

Dr. Reyes emphasized that strategies for maintaining cancer diagnoses need to be implemented during the pandemic. She also noted that this study is ongoing, with the goal of assessing the long-term impact of COVID-19.

Dr. Reyes disclosed relationships with Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She did not disclose funding for this study. Dr. Peters disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Takeda.

The two-center study showed a 38% decrease in new lung cancer diagnoses during the pandemic. Patients diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) during the pandemic had more severe disease than patients diagnosed prepandemic, but cases of SCLC were not more severe during the pandemic. Still, the 30-day mortality rate nearly doubled for both NSCLC and SCLC patients during the pandemic.

“The prioritization of the health care system towards COVID-19 patients has led to drastic changes in cancer management that could interfere with the initial diagnosis of lung cancer, resulting in delayed treatment and worse outcomes,” said Roxana Reyes, MD, of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. “Delay of cancer treatment is associated with increased mortality.”

Dr. Reyes and colleagues conducted a retrospective study of the impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of new lung cancer cases, disease severity, and clinical outcomes. Dr. Reyes reported the group’s findings at the 2020 World Conference on Lung Cancer (Abstract 3700), which was rescheduled for January 2021.

Study details

Dr. Reyes and colleagues compared data from two tertiary hospitals in Spain in the first 6 months of 2020 with data from the same period in 2019. Spain was one of the countries most affected by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic.

The study’s primary endpoint was differences by period in the number of new lung cancer cases and disease severity. A secondary endpoint was 30-day mortality rate by period and histology.

The study included 162 patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer – 100 diagnosed before the pandemic began and 62 diagnosed during the pandemic. Overall, 68% of patients had NSCLC, and 32% had SCLC.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the prepandemic and pandemic groups, except for the proportion of nonsmokers. Twice as many patients diagnosed during the pandemic were nonsmokers (16% vs. 8%).

Differences by time period and subtype

During the pandemic, there was a 38% reduction in all lung cancer diagnoses, a 36% reduction in NSCLC diagnoses, and a 42% reduction in SCLC diagnoses.

Respiratory symptoms were more common during the pandemic for both NSCLC (30% vs. 23%) and SCLC (32% vs. 24%).

Cases of NSCLC diagnosed during the pandemic were more severe, but SCLC cases were not.

In the NSCLC cohort, symptomatic disease was more common during the pandemic (74% vs. 63%), as were advanced disease (58% vs. 46%), more than two metastatic sites (16% vs. 12%), oncologic emergencies (7% vs. 3%), hospitalization (21% vs. 18%), and death during hospitalization (44% vs. 17%).

For SCLC, symptomatic disease was less common during the pandemic (74% vs. 79%), as were advanced disease (52% vs. 67%), more than two metastatic sites (26% vs. 36%), oncologic emergencies (5% vs. 12%), hospitalization (21% vs. 33%), and death during hospitalization (0% vs. 18%).

Nevertheless, the 30-day mortality rate almost doubled during the pandemic for both NSCLC (49% vs. 25%) and SCLC (32% vs. 18%).

For both subtypes together, the median overall survival was 6.7 months during the pandemic and 7.9 months before the pandemic.

Implications and next steps

“In our descriptive study, lung cancer diagnosis is being affected during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Reyes said. “Fewer new lung cancer cases were diagnosed during COVID-19.”

Some patients with acute respiratory infections who tested negative for COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic may have had undiagnosed lung cancer, noted Matthew Peters, MD, of Concord Repatriation General Hospital and Macquarie University Hospital, both in Sydney, who was not involved in this study.

“They receive a negative result and think their problem is reduced but wonder why they still have a cough,” Dr. Peters said. “The various lockdowns and social distancing reduced the diagnosis of respiratory viral illnesses that often result in an accidental diagnosis of lung cancer. As time goes by, we will recapture harvesting of accidental diagnosis of lung cancer and provide curative treatments.”

Dr. Reyes emphasized that strategies for maintaining cancer diagnoses need to be implemented during the pandemic. She also noted that this study is ongoing, with the goal of assessing the long-term impact of COVID-19.

Dr. Reyes disclosed relationships with Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She did not disclose funding for this study. Dr. Peters disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Takeda.

The two-center study showed a 38% decrease in new lung cancer diagnoses during the pandemic. Patients diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) during the pandemic had more severe disease than patients diagnosed prepandemic, but cases of SCLC were not more severe during the pandemic. Still, the 30-day mortality rate nearly doubled for both NSCLC and SCLC patients during the pandemic.

“The prioritization of the health care system towards COVID-19 patients has led to drastic changes in cancer management that could interfere with the initial diagnosis of lung cancer, resulting in delayed treatment and worse outcomes,” said Roxana Reyes, MD, of Hospital Clínic de Barcelona. “Delay of cancer treatment is associated with increased mortality.”

Dr. Reyes and colleagues conducted a retrospective study of the impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of new lung cancer cases, disease severity, and clinical outcomes. Dr. Reyes reported the group’s findings at the 2020 World Conference on Lung Cancer (Abstract 3700), which was rescheduled for January 2021.

Study details

Dr. Reyes and colleagues compared data from two tertiary hospitals in Spain in the first 6 months of 2020 with data from the same period in 2019. Spain was one of the countries most affected by COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic.

The study’s primary endpoint was differences by period in the number of new lung cancer cases and disease severity. A secondary endpoint was 30-day mortality rate by period and histology.

The study included 162 patients newly diagnosed with lung cancer – 100 diagnosed before the pandemic began and 62 diagnosed during the pandemic. Overall, 68% of patients had NSCLC, and 32% had SCLC.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the prepandemic and pandemic groups, except for the proportion of nonsmokers. Twice as many patients diagnosed during the pandemic were nonsmokers (16% vs. 8%).

Differences by time period and subtype

During the pandemic, there was a 38% reduction in all lung cancer diagnoses, a 36% reduction in NSCLC diagnoses, and a 42% reduction in SCLC diagnoses.

Respiratory symptoms were more common during the pandemic for both NSCLC (30% vs. 23%) and SCLC (32% vs. 24%).

Cases of NSCLC diagnosed during the pandemic were more severe, but SCLC cases were not.

In the NSCLC cohort, symptomatic disease was more common during the pandemic (74% vs. 63%), as were advanced disease (58% vs. 46%), more than two metastatic sites (16% vs. 12%), oncologic emergencies (7% vs. 3%), hospitalization (21% vs. 18%), and death during hospitalization (44% vs. 17%).

For SCLC, symptomatic disease was less common during the pandemic (74% vs. 79%), as were advanced disease (52% vs. 67%), more than two metastatic sites (26% vs. 36%), oncologic emergencies (5% vs. 12%), hospitalization (21% vs. 33%), and death during hospitalization (0% vs. 18%).

Nevertheless, the 30-day mortality rate almost doubled during the pandemic for both NSCLC (49% vs. 25%) and SCLC (32% vs. 18%).

For both subtypes together, the median overall survival was 6.7 months during the pandemic and 7.9 months before the pandemic.

Implications and next steps

“In our descriptive study, lung cancer diagnosis is being affected during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Reyes said. “Fewer new lung cancer cases were diagnosed during COVID-19.”

Some patients with acute respiratory infections who tested negative for COVID-19 during the first 6 months of the pandemic may have had undiagnosed lung cancer, noted Matthew Peters, MD, of Concord Repatriation General Hospital and Macquarie University Hospital, both in Sydney, who was not involved in this study.

“They receive a negative result and think their problem is reduced but wonder why they still have a cough,” Dr. Peters said. “The various lockdowns and social distancing reduced the diagnosis of respiratory viral illnesses that often result in an accidental diagnosis of lung cancer. As time goes by, we will recapture harvesting of accidental diagnosis of lung cancer and provide curative treatments.”

Dr. Reyes emphasized that strategies for maintaining cancer diagnoses need to be implemented during the pandemic. She also noted that this study is ongoing, with the goal of assessing the long-term impact of COVID-19.

Dr. Reyes disclosed relationships with Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She did not disclose funding for this study. Dr. Peters disclosed relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Takeda.

FROM WCLC 2020

Plant-based or keto diet? Novel study yields surprising results

For appetite control, a low-fat, plant-based diet has advantages over a low-carbohydrate, animal-based ketogenic diet, although the keto diet wins when it comes to keeping post-meal glucose and insulin levels in check, new research suggests.

In a highly controlled crossover study conducted at the National Institutes of Health, people consumed fewer daily calories when on a low-fat, plant-based diet, but their insulin and blood glucose levels were higher than when they followed a low-carbohydrate, animal-based diet.

“There is this somewhat-outdated idea now that higher-fat diets, because they have more calories per gram, tend to make people overeat – something called the passive overconsumption model,” senior investigator Kevin Hall, PhD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, said in an interview.

The other more popular model these days, he explained, is the carbohydrate-insulin model, which holds that following a diet high in carbohydrates and sugar that causes insulin levels to spike will increase hunger and cause a person to overeat.

In this study, Dr. Hall and colleagues tested these two hypotheses head to head.

“The short answer is that we got exactly the opposite predictions from the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. In other words, instead of making people eat more and gaining weight and body fat, they actually ended up eating less on that diet and losing body fat compared to the higher-fat diet,” Dr. Hall said.

“Yet, the passive overconsumption model also failed, because despite them eating a very energy-dense diet and high fat, they didn’t gain weight and gain body fat. And so both of these models of why people overeat and gain weight seem to be inadequate in our study,” he said. “This suggests that things are a little bit more complicated.”

The study was published online Jan. 21, 2021 in Nature Medicine.

Pros and cons to both diets

For the study, the researchers housed 20 healthy adults who did not have diabetes for 4 continuous weeks at the NIH Clinical Center. The mean age of the participants was 29.9 years, and the mean body mass index was 27.8 kg/m2.

The participants were randomly allocated to consume ad libitum either a plant-based, low-fat diet (10.3% fat, 75.2% carbohydrate) with low-energy density (about 1 kcal/g−1), or an animal-based, ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet (75.8% fat, 10.0% carbohydrate) with high energy density (about 2 kcal/g−1) for 2 weeks. They then crossed over to the alternate diet for 2 weeks.

Both diets contained about 14% protein and were matched for total calories, although the low-carb diet had twice as many calories per gram of food than the low-fat diet. Participants could eat what and however much they chose of the meals they were given.

One participant withdrew, owing to hypoglycemia during the low-carbohydrate diet phase. For the primary outcome, the researchers compared mean daily ad libitum energy intake between each 2-week diet period.

They found that energy intake from the low-fat diet was reduced by approximately 550-700 kcal/d−1, compared with the low-carbohydrate keto diet. Yet, despite the large differences in calorie intake, participants reported no differences in hunger, enjoyment of meals, or fullness between the two diets.

Participants lost weight on both diets (about 1-2 kg on average), but only the low-fat diet led to a significant loss of body fat.

“Interestingly, our findings suggest benefits to both diets, at least in the short term,” Dr. Hall said in a news release.

“While the low-fat, plant-based diet helps curb appetite, the animal-based, low-carb diet resulted in lower and more steady insulin and glucose levels. We don’t yet know if these differences would be sustained over the long term,” he said.

Dr. Hall added that it’s important to note that the study was not designed to make diet recommendations for weight loss, and the results might have been different had the participants been actively trying to lose weight.

“In fact, they didn’t even know what the study was about; we just said we want you to eat the two diets, and we’re going to see what happens in your body either as you eat as much or as little as you want,” he said.

“It’s a bit of a mixed bag in terms of which diet might be better for an individual. I think you can interpret this study as that there are positives and negatives for both diets,” Dr. Hall said.

Diet ‘tribes’

In a comment, Taylor Wallace, PhD, adjunct professor, department of nutrition and food studies, George Mason University, Fairfax, Va., said it’s important to note that “a ‘low-carb diet’ has yet to be defined, and many definitions exist.

“We really need a standard definition of what constitutes ‘low-carb’ so that studies can be designed and evaluated in a consistent manner. It’s problematic because, without a standard definition, the ‘diet tribe’ researchers (keto versus plant-based) always seem to find the answer that is in their own favor,” Dr. Wallace said. “This study does seem to use less than 20 grams of carbs per day, which in my mind is pretty low carb.”

Perhaps the most important caveat, he added, is that, in the real world, “most people don’t adhere to these very strict diets – not even for 2 weeks.”

The study was supported by the NIDDK Intramural Research Program, with additional NIH support from a National Institute of Nursing Research grant. One author has received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products, serves on the scientific advisory council for Kerry Taste and Nutrition, and is part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbott Nutrition, Nestec, and Danone. Dr. Hall and the other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace is principal and CEO of the Think Healthy Group, editor of the Journal of Dietary Supplements, and deputy editor of the Journal of the American College of Nutrition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For appetite control, a low-fat, plant-based diet has advantages over a low-carbohydrate, animal-based ketogenic diet, although the keto diet wins when it comes to keeping post-meal glucose and insulin levels in check, new research suggests.

In a highly controlled crossover study conducted at the National Institutes of Health, people consumed fewer daily calories when on a low-fat, plant-based diet, but their insulin and blood glucose levels were higher than when they followed a low-carbohydrate, animal-based diet.

“There is this somewhat-outdated idea now that higher-fat diets, because they have more calories per gram, tend to make people overeat – something called the passive overconsumption model,” senior investigator Kevin Hall, PhD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, said in an interview.

The other more popular model these days, he explained, is the carbohydrate-insulin model, which holds that following a diet high in carbohydrates and sugar that causes insulin levels to spike will increase hunger and cause a person to overeat.

In this study, Dr. Hall and colleagues tested these two hypotheses head to head.

“The short answer is that we got exactly the opposite predictions from the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. In other words, instead of making people eat more and gaining weight and body fat, they actually ended up eating less on that diet and losing body fat compared to the higher-fat diet,” Dr. Hall said.

“Yet, the passive overconsumption model also failed, because despite them eating a very energy-dense diet and high fat, they didn’t gain weight and gain body fat. And so both of these models of why people overeat and gain weight seem to be inadequate in our study,” he said. “This suggests that things are a little bit more complicated.”

The study was published online Jan. 21, 2021 in Nature Medicine.

Pros and cons to both diets

For the study, the researchers housed 20 healthy adults who did not have diabetes for 4 continuous weeks at the NIH Clinical Center. The mean age of the participants was 29.9 years, and the mean body mass index was 27.8 kg/m2.

The participants were randomly allocated to consume ad libitum either a plant-based, low-fat diet (10.3% fat, 75.2% carbohydrate) with low-energy density (about 1 kcal/g−1), or an animal-based, ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet (75.8% fat, 10.0% carbohydrate) with high energy density (about 2 kcal/g−1) for 2 weeks. They then crossed over to the alternate diet for 2 weeks.

Both diets contained about 14% protein and were matched for total calories, although the low-carb diet had twice as many calories per gram of food than the low-fat diet. Participants could eat what and however much they chose of the meals they were given.

One participant withdrew, owing to hypoglycemia during the low-carbohydrate diet phase. For the primary outcome, the researchers compared mean daily ad libitum energy intake between each 2-week diet period.

They found that energy intake from the low-fat diet was reduced by approximately 550-700 kcal/d−1, compared with the low-carbohydrate keto diet. Yet, despite the large differences in calorie intake, participants reported no differences in hunger, enjoyment of meals, or fullness between the two diets.

Participants lost weight on both diets (about 1-2 kg on average), but only the low-fat diet led to a significant loss of body fat.

“Interestingly, our findings suggest benefits to both diets, at least in the short term,” Dr. Hall said in a news release.

“While the low-fat, plant-based diet helps curb appetite, the animal-based, low-carb diet resulted in lower and more steady insulin and glucose levels. We don’t yet know if these differences would be sustained over the long term,” he said.

Dr. Hall added that it’s important to note that the study was not designed to make diet recommendations for weight loss, and the results might have been different had the participants been actively trying to lose weight.

“In fact, they didn’t even know what the study was about; we just said we want you to eat the two diets, and we’re going to see what happens in your body either as you eat as much or as little as you want,” he said.

“It’s a bit of a mixed bag in terms of which diet might be better for an individual. I think you can interpret this study as that there are positives and negatives for both diets,” Dr. Hall said.

Diet ‘tribes’

In a comment, Taylor Wallace, PhD, adjunct professor, department of nutrition and food studies, George Mason University, Fairfax, Va., said it’s important to note that “a ‘low-carb diet’ has yet to be defined, and many definitions exist.

“We really need a standard definition of what constitutes ‘low-carb’ so that studies can be designed and evaluated in a consistent manner. It’s problematic because, without a standard definition, the ‘diet tribe’ researchers (keto versus plant-based) always seem to find the answer that is in their own favor,” Dr. Wallace said. “This study does seem to use less than 20 grams of carbs per day, which in my mind is pretty low carb.”

Perhaps the most important caveat, he added, is that, in the real world, “most people don’t adhere to these very strict diets – not even for 2 weeks.”

The study was supported by the NIDDK Intramural Research Program, with additional NIH support from a National Institute of Nursing Research grant. One author has received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products, serves on the scientific advisory council for Kerry Taste and Nutrition, and is part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbott Nutrition, Nestec, and Danone. Dr. Hall and the other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace is principal and CEO of the Think Healthy Group, editor of the Journal of Dietary Supplements, and deputy editor of the Journal of the American College of Nutrition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For appetite control, a low-fat, plant-based diet has advantages over a low-carbohydrate, animal-based ketogenic diet, although the keto diet wins when it comes to keeping post-meal glucose and insulin levels in check, new research suggests.

In a highly controlled crossover study conducted at the National Institutes of Health, people consumed fewer daily calories when on a low-fat, plant-based diet, but their insulin and blood glucose levels were higher than when they followed a low-carbohydrate, animal-based diet.

“There is this somewhat-outdated idea now that higher-fat diets, because they have more calories per gram, tend to make people overeat – something called the passive overconsumption model,” senior investigator Kevin Hall, PhD, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, said in an interview.

The other more popular model these days, he explained, is the carbohydrate-insulin model, which holds that following a diet high in carbohydrates and sugar that causes insulin levels to spike will increase hunger and cause a person to overeat.

In this study, Dr. Hall and colleagues tested these two hypotheses head to head.

“The short answer is that we got exactly the opposite predictions from the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. In other words, instead of making people eat more and gaining weight and body fat, they actually ended up eating less on that diet and losing body fat compared to the higher-fat diet,” Dr. Hall said.

“Yet, the passive overconsumption model also failed, because despite them eating a very energy-dense diet and high fat, they didn’t gain weight and gain body fat. And so both of these models of why people overeat and gain weight seem to be inadequate in our study,” he said. “This suggests that things are a little bit more complicated.”

The study was published online Jan. 21, 2021 in Nature Medicine.

Pros and cons to both diets

For the study, the researchers housed 20 healthy adults who did not have diabetes for 4 continuous weeks at the NIH Clinical Center. The mean age of the participants was 29.9 years, and the mean body mass index was 27.8 kg/m2.

The participants were randomly allocated to consume ad libitum either a plant-based, low-fat diet (10.3% fat, 75.2% carbohydrate) with low-energy density (about 1 kcal/g−1), or an animal-based, ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet (75.8% fat, 10.0% carbohydrate) with high energy density (about 2 kcal/g−1) for 2 weeks. They then crossed over to the alternate diet for 2 weeks.

Both diets contained about 14% protein and were matched for total calories, although the low-carb diet had twice as many calories per gram of food than the low-fat diet. Participants could eat what and however much they chose of the meals they were given.

One participant withdrew, owing to hypoglycemia during the low-carbohydrate diet phase. For the primary outcome, the researchers compared mean daily ad libitum energy intake between each 2-week diet period.

They found that energy intake from the low-fat diet was reduced by approximately 550-700 kcal/d−1, compared with the low-carbohydrate keto diet. Yet, despite the large differences in calorie intake, participants reported no differences in hunger, enjoyment of meals, or fullness between the two diets.

Participants lost weight on both diets (about 1-2 kg on average), but only the low-fat diet led to a significant loss of body fat.

“Interestingly, our findings suggest benefits to both diets, at least in the short term,” Dr. Hall said in a news release.

“While the low-fat, plant-based diet helps curb appetite, the animal-based, low-carb diet resulted in lower and more steady insulin and glucose levels. We don’t yet know if these differences would be sustained over the long term,” he said.

Dr. Hall added that it’s important to note that the study was not designed to make diet recommendations for weight loss, and the results might have been different had the participants been actively trying to lose weight.

“In fact, they didn’t even know what the study was about; we just said we want you to eat the two diets, and we’re going to see what happens in your body either as you eat as much or as little as you want,” he said.

“It’s a bit of a mixed bag in terms of which diet might be better for an individual. I think you can interpret this study as that there are positives and negatives for both diets,” Dr. Hall said.

Diet ‘tribes’

In a comment, Taylor Wallace, PhD, adjunct professor, department of nutrition and food studies, George Mason University, Fairfax, Va., said it’s important to note that “a ‘low-carb diet’ has yet to be defined, and many definitions exist.

“We really need a standard definition of what constitutes ‘low-carb’ so that studies can be designed and evaluated in a consistent manner. It’s problematic because, without a standard definition, the ‘diet tribe’ researchers (keto versus plant-based) always seem to find the answer that is in their own favor,” Dr. Wallace said. “This study does seem to use less than 20 grams of carbs per day, which in my mind is pretty low carb.”

Perhaps the most important caveat, he added, is that, in the real world, “most people don’t adhere to these very strict diets – not even for 2 weeks.”

The study was supported by the NIDDK Intramural Research Program, with additional NIH support from a National Institute of Nursing Research grant. One author has received reimbursement for speaking at conferences sponsored by companies selling nutritional products, serves on the scientific advisory council for Kerry Taste and Nutrition, and is part of an academic consortium that has received research funding from Abbott Nutrition, Nestec, and Danone. Dr. Hall and the other authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace is principal and CEO of the Think Healthy Group, editor of the Journal of Dietary Supplements, and deputy editor of the Journal of the American College of Nutrition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Consensus statement issued on retinoids for ichthyosis, disorders of cornification

Clinicians using advised the authors of a new consensus statement.

In the statement, published in Pediatric Dermatology, they also addressed the effects of topical and systemic retinoid use on bone, eye, cardiovascular, and mental health, and the risks some retinoids pose to reproductive health.

Many patients with these chronic conditions, driven by multiple genetic mutations, respond to topical and/or systemic retinoids. However, to date, no specific guidance has addressed the safety, efficacy, or overall precautions for their use in the pediatric population, one of the statement authors, Moise L. Levy, MD, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Texas at Austin, said in an interview.

Dr. Levy was one of the physicians on the multidisciplinary panel, The Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Use of Retinoids in Ichthyosis Work Group, formed to devise best practice recommendations on the use of retinoids in the management of ichthyoses and other cornification disorders in children and adolescents. The panel conducted an extensive evidence-based literature review and met in person to arrive at their conclusions. Representation from the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) was also key to this work. “Additionally, the teratogenic effects of retinoids prompted examination of gynecologic considerations and the role of the iPLEDGE program in the United States on patient access to isotretinoin,” the authors wrote.

Retinoid effects, dosing

“Both topical and systemic retinoids can improve scaling in patients with select forms of ichthyosis,” and some subtypes of disease respond better to treatment than others, they noted. Oral or topical retinoids are known to improve cases of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (select genotypes), Sjögren-Larsson syndrome, ichthyosis follicularis–alopecia-photophobia syndromes and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, harlequin ichthyosis, ichthyosis with confetti, and other subtypes.

Comparatively, they added, there are no data on the use of retinoids, or data showing no improvement with retinoids for several ichthyosis subtypes, including congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects, CHIME syndrome, Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis-sclerosing cholangitis, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome, MEDNIK syndrome, peeling skin disease, Refsum syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy though the response to such cases may vary.

Retinoids may worsen conditions that lead to peeling or skin fragility, atopic diathesis, or excessive desquamation, “and should be used with caution,” the authors advised.

Pediatric and adult patients with moderate to severe disease and significant functional or psychological impairment “should be offered the opportunity to make a benefit/risk assessment of treatment” with a systemic retinoid, they added, noting that topical retinoids have a lower risk profile and may be a better choice for milder disease.

Clinicians should aim for the lowest dose possible “that will achieve and maintain the desired therapeutic effect with acceptable mucocutaneous and systemic toxicities,” the panel recommended. Lower doses work especially well in patients with epidermolytic ichthyoses and erythrokeratodermia variabilis.

“Given the cutaneous and extracutaneous toxicities of oral retinoids, lower doses were found to achieve the most acceptable risk-benefit result. Few individuals now receive more than 1 mg/kg per day of isotretinoin or 0.5 mg/kg per day of acitretin,” according to the panel.

Dosing decisions call for a group conversation between physicians, patients and caregivers, addressing skin care, comfort and appearance issues, risk of adverse effects, and tolerance of the therapy.

Retinoid effects on organs

The impact of retinoids on the body varies by organ system, type of therapy and dosage. Dose and duration of therapy, for example, help determine the toxic effects of retinoids on bone. “Long-term use of systemic retinoids in ichthyosis/DOC is associated with skeletal concerns,” noted the authors, adding that clinicians should still consider this therapeutic approach if there is a strong clinical case for using it in a patient.

Children on long-term systemic therapy should undergo a series of tests and evaluations for bone monitoring, including an annual growth assessment. The group also recommended a baseline skeletal radiographic survey when children are on long-term systemic retinoid therapy, repeated after 3-5 years or when symptoms are present. Clinicians should also inquire about diet and discuss with patients factors that impact susceptibility to retinoid bone toxicity, such as genetic risk, diet and physical activity.

They also recommended monitoring patients taking systemic retinoids for psychiatric symptoms.

Adolescents of childbearing potential using systemic retinoids, who are sexually active, should receive counseling about contraceptive options, and should use two forms of contraception, including one highly effective method, the statement advises.

In the United States, all patients and prescribers of isotretinoin must comply with iPLEDGE guidelines; the statement addresses the issue that iPLEDGE was not designed for long-term use of isotretinoin in patients with ichthyosis, and “imposes a significant burden” in this group.

Other practice gaps and unmet needs in this area of study were discussed, calling for a closer examination of optimal timing of therapy initiation, and the adverse effects of long-term retinoid treatment. “The work, as a whole, is a starting point for these important management issues,” said Dr. Levy.

Unrestricted educational grants from Sun Pharmaceuticals and FIRST funded this effort. Dr. Levy’s disclosed serving on the advisory board and as a consultant for Cassiopea, Regeneron, and UCB, and an investigator for Fibrocell, Galderma, Janssen, and Pfizer. The other authors disclosed serving as investigators, advisers, consultants, and/or other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

Clinicians using advised the authors of a new consensus statement.

In the statement, published in Pediatric Dermatology, they also addressed the effects of topical and systemic retinoid use on bone, eye, cardiovascular, and mental health, and the risks some retinoids pose to reproductive health.

Many patients with these chronic conditions, driven by multiple genetic mutations, respond to topical and/or systemic retinoids. However, to date, no specific guidance has addressed the safety, efficacy, or overall precautions for their use in the pediatric population, one of the statement authors, Moise L. Levy, MD, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Texas at Austin, said in an interview.

Dr. Levy was one of the physicians on the multidisciplinary panel, The Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Use of Retinoids in Ichthyosis Work Group, formed to devise best practice recommendations on the use of retinoids in the management of ichthyoses and other cornification disorders in children and adolescents. The panel conducted an extensive evidence-based literature review and met in person to arrive at their conclusions. Representation from the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) was also key to this work. “Additionally, the teratogenic effects of retinoids prompted examination of gynecologic considerations and the role of the iPLEDGE program in the United States on patient access to isotretinoin,” the authors wrote.

Retinoid effects, dosing

“Both topical and systemic retinoids can improve scaling in patients with select forms of ichthyosis,” and some subtypes of disease respond better to treatment than others, they noted. Oral or topical retinoids are known to improve cases of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (select genotypes), Sjögren-Larsson syndrome, ichthyosis follicularis–alopecia-photophobia syndromes and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, harlequin ichthyosis, ichthyosis with confetti, and other subtypes.

Comparatively, they added, there are no data on the use of retinoids, or data showing no improvement with retinoids for several ichthyosis subtypes, including congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects, CHIME syndrome, Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis-sclerosing cholangitis, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome, MEDNIK syndrome, peeling skin disease, Refsum syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy though the response to such cases may vary.

Retinoids may worsen conditions that lead to peeling or skin fragility, atopic diathesis, or excessive desquamation, “and should be used with caution,” the authors advised.

Pediatric and adult patients with moderate to severe disease and significant functional or psychological impairment “should be offered the opportunity to make a benefit/risk assessment of treatment” with a systemic retinoid, they added, noting that topical retinoids have a lower risk profile and may be a better choice for milder disease.

Clinicians should aim for the lowest dose possible “that will achieve and maintain the desired therapeutic effect with acceptable mucocutaneous and systemic toxicities,” the panel recommended. Lower doses work especially well in patients with epidermolytic ichthyoses and erythrokeratodermia variabilis.

“Given the cutaneous and extracutaneous toxicities of oral retinoids, lower doses were found to achieve the most acceptable risk-benefit result. Few individuals now receive more than 1 mg/kg per day of isotretinoin or 0.5 mg/kg per day of acitretin,” according to the panel.

Dosing decisions call for a group conversation between physicians, patients and caregivers, addressing skin care, comfort and appearance issues, risk of adverse effects, and tolerance of the therapy.

Retinoid effects on organs

The impact of retinoids on the body varies by organ system, type of therapy and dosage. Dose and duration of therapy, for example, help determine the toxic effects of retinoids on bone. “Long-term use of systemic retinoids in ichthyosis/DOC is associated with skeletal concerns,” noted the authors, adding that clinicians should still consider this therapeutic approach if there is a strong clinical case for using it in a patient.

Children on long-term systemic therapy should undergo a series of tests and evaluations for bone monitoring, including an annual growth assessment. The group also recommended a baseline skeletal radiographic survey when children are on long-term systemic retinoid therapy, repeated after 3-5 years or when symptoms are present. Clinicians should also inquire about diet and discuss with patients factors that impact susceptibility to retinoid bone toxicity, such as genetic risk, diet and physical activity.

They also recommended monitoring patients taking systemic retinoids for psychiatric symptoms.

Adolescents of childbearing potential using systemic retinoids, who are sexually active, should receive counseling about contraceptive options, and should use two forms of contraception, including one highly effective method, the statement advises.

In the United States, all patients and prescribers of isotretinoin must comply with iPLEDGE guidelines; the statement addresses the issue that iPLEDGE was not designed for long-term use of isotretinoin in patients with ichthyosis, and “imposes a significant burden” in this group.

Other practice gaps and unmet needs in this area of study were discussed, calling for a closer examination of optimal timing of therapy initiation, and the adverse effects of long-term retinoid treatment. “The work, as a whole, is a starting point for these important management issues,” said Dr. Levy.

Unrestricted educational grants from Sun Pharmaceuticals and FIRST funded this effort. Dr. Levy’s disclosed serving on the advisory board and as a consultant for Cassiopea, Regeneron, and UCB, and an investigator for Fibrocell, Galderma, Janssen, and Pfizer. The other authors disclosed serving as investigators, advisers, consultants, and/or other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

Clinicians using advised the authors of a new consensus statement.

In the statement, published in Pediatric Dermatology, they also addressed the effects of topical and systemic retinoid use on bone, eye, cardiovascular, and mental health, and the risks some retinoids pose to reproductive health.

Many patients with these chronic conditions, driven by multiple genetic mutations, respond to topical and/or systemic retinoids. However, to date, no specific guidance has addressed the safety, efficacy, or overall precautions for their use in the pediatric population, one of the statement authors, Moise L. Levy, MD, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Texas at Austin, said in an interview.

Dr. Levy was one of the physicians on the multidisciplinary panel, The Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance Use of Retinoids in Ichthyosis Work Group, formed to devise best practice recommendations on the use of retinoids in the management of ichthyoses and other cornification disorders in children and adolescents. The panel conducted an extensive evidence-based literature review and met in person to arrive at their conclusions. Representation from the Foundation for Ichthyosis and Related Skin Types (FIRST) was also key to this work. “Additionally, the teratogenic effects of retinoids prompted examination of gynecologic considerations and the role of the iPLEDGE program in the United States on patient access to isotretinoin,” the authors wrote.

Retinoid effects, dosing

“Both topical and systemic retinoids can improve scaling in patients with select forms of ichthyosis,” and some subtypes of disease respond better to treatment than others, they noted. Oral or topical retinoids are known to improve cases of congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma (select genotypes), Sjögren-Larsson syndrome, ichthyosis follicularis–alopecia-photophobia syndromes and keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome, erythrokeratodermia variabilis, harlequin ichthyosis, ichthyosis with confetti, and other subtypes.

Comparatively, they added, there are no data on the use of retinoids, or data showing no improvement with retinoids for several ichthyosis subtypes, including congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects, CHIME syndrome, Conradi-Hünermann-Happle syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis syndrome, ichthyosis-hypotrichosis-sclerosing cholangitis, ichthyosis prematurity syndrome, MEDNIK syndrome, peeling skin disease, Refsum syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy though the response to such cases may vary.

Retinoids may worsen conditions that lead to peeling or skin fragility, atopic diathesis, or excessive desquamation, “and should be used with caution,” the authors advised.

Pediatric and adult patients with moderate to severe disease and significant functional or psychological impairment “should be offered the opportunity to make a benefit/risk assessment of treatment” with a systemic retinoid, they added, noting that topical retinoids have a lower risk profile and may be a better choice for milder disease.

Clinicians should aim for the lowest dose possible “that will achieve and maintain the desired therapeutic effect with acceptable mucocutaneous and systemic toxicities,” the panel recommended. Lower doses work especially well in patients with epidermolytic ichthyoses and erythrokeratodermia variabilis.

“Given the cutaneous and extracutaneous toxicities of oral retinoids, lower doses were found to achieve the most acceptable risk-benefit result. Few individuals now receive more than 1 mg/kg per day of isotretinoin or 0.5 mg/kg per day of acitretin,” according to the panel.

Dosing decisions call for a group conversation between physicians, patients and caregivers, addressing skin care, comfort and appearance issues, risk of adverse effects, and tolerance of the therapy.

Retinoid effects on organs

The impact of retinoids on the body varies by organ system, type of therapy and dosage. Dose and duration of therapy, for example, help determine the toxic effects of retinoids on bone. “Long-term use of systemic retinoids in ichthyosis/DOC is associated with skeletal concerns,” noted the authors, adding that clinicians should still consider this therapeutic approach if there is a strong clinical case for using it in a patient.

Children on long-term systemic therapy should undergo a series of tests and evaluations for bone monitoring, including an annual growth assessment. The group also recommended a baseline skeletal radiographic survey when children are on long-term systemic retinoid therapy, repeated after 3-5 years or when symptoms are present. Clinicians should also inquire about diet and discuss with patients factors that impact susceptibility to retinoid bone toxicity, such as genetic risk, diet and physical activity.

They also recommended monitoring patients taking systemic retinoids for psychiatric symptoms.

Adolescents of childbearing potential using systemic retinoids, who are sexually active, should receive counseling about contraceptive options, and should use two forms of contraception, including one highly effective method, the statement advises.

In the United States, all patients and prescribers of isotretinoin must comply with iPLEDGE guidelines; the statement addresses the issue that iPLEDGE was not designed for long-term use of isotretinoin in patients with ichthyosis, and “imposes a significant burden” in this group.

Other practice gaps and unmet needs in this area of study were discussed, calling for a closer examination of optimal timing of therapy initiation, and the adverse effects of long-term retinoid treatment. “The work, as a whole, is a starting point for these important management issues,” said Dr. Levy.

Unrestricted educational grants from Sun Pharmaceuticals and FIRST funded this effort. Dr. Levy’s disclosed serving on the advisory board and as a consultant for Cassiopea, Regeneron, and UCB, and an investigator for Fibrocell, Galderma, Janssen, and Pfizer. The other authors disclosed serving as investigators, advisers, consultants, and/or other relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Adalimumab enhances primary wound closure after HS surgery

, a pilot study suggests.

“Our experience suggests that under the effects of treatment with adalimumab, wound healing disorders with primary wound closure occur less often. And primary wound closure offers advantages over secondary wound healing: shorter length of inpatient stay, lower morbidity, fewer functional problems, and better quality of life,” Gefion Girbig, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She noted that primary wound closure following surgery for HS is controversial. For example, current German guidelines recommend complete surgical excision of HS lesions, followed by secondary wound healing; the guidelines advise against primary wound closure. But those guidelines were issued back in 2012, years before adalimumab (Humira) achieved regulatory approval as the first and to date only medication indicated for treatment of HS.

Experts agree that while adalimumab has been a difference maker for many patients with HS, surgery is still often necessary. And many surgeons prefer secondary wound healing in HS. That’s because healing by first intention has historically often resulted in complications involving wound healing disorders and infection. These complications necessitate loosening of the primary closure to permit further wound healing by second intention, with a resultant prolonged healing time, explained Dr. Girbig, of the Institute for Health Sciences Research in Dermatology and Nursing at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

She and her coinvestigators hypothesized that the disordered wound healing is a consequence of the underlying inflammatory disease that lies at the core of HS, and that quelling the inflammation with adalimumab for at least 6 months before performing surgery with primary closure while the anti-TNF therapy continues would reduce the incidence of wound healing disorders.

This was borne out in the group’s small observational pilot study. It included 10 patients with HS who underwent surgery only after at least 6 months on adalimumab. Six had surgery for axillary HS and four for inguinal disease. Only 2 of the 10 developed a wound healing disorder. Both had surgical reconstruction in the inguinal area. Neither case involved infection. Surgical management entailed opening part of the suture to allow simultaneous secondary wound closure.

This 20% incidence of disordered wound healing when primary closure was carried out while systemic inflammation was controlled via adalimumab is markedly lower than rates reported using primary closure without adalimumab. Dr. Girbig and her coinvestigators are now conducting a larger controlled study to confirm their findings.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

, a pilot study suggests.

“Our experience suggests that under the effects of treatment with adalimumab, wound healing disorders with primary wound closure occur less often. And primary wound closure offers advantages over secondary wound healing: shorter length of inpatient stay, lower morbidity, fewer functional problems, and better quality of life,” Gefion Girbig, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She noted that primary wound closure following surgery for HS is controversial. For example, current German guidelines recommend complete surgical excision of HS lesions, followed by secondary wound healing; the guidelines advise against primary wound closure. But those guidelines were issued back in 2012, years before adalimumab (Humira) achieved regulatory approval as the first and to date only medication indicated for treatment of HS.

Experts agree that while adalimumab has been a difference maker for many patients with HS, surgery is still often necessary. And many surgeons prefer secondary wound healing in HS. That’s because healing by first intention has historically often resulted in complications involving wound healing disorders and infection. These complications necessitate loosening of the primary closure to permit further wound healing by second intention, with a resultant prolonged healing time, explained Dr. Girbig, of the Institute for Health Sciences Research in Dermatology and Nursing at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

She and her coinvestigators hypothesized that the disordered wound healing is a consequence of the underlying inflammatory disease that lies at the core of HS, and that quelling the inflammation with adalimumab for at least 6 months before performing surgery with primary closure while the anti-TNF therapy continues would reduce the incidence of wound healing disorders.

This was borne out in the group’s small observational pilot study. It included 10 patients with HS who underwent surgery only after at least 6 months on adalimumab. Six had surgery for axillary HS and four for inguinal disease. Only 2 of the 10 developed a wound healing disorder. Both had surgical reconstruction in the inguinal area. Neither case involved infection. Surgical management entailed opening part of the suture to allow simultaneous secondary wound closure.

This 20% incidence of disordered wound healing when primary closure was carried out while systemic inflammation was controlled via adalimumab is markedly lower than rates reported using primary closure without adalimumab. Dr. Girbig and her coinvestigators are now conducting a larger controlled study to confirm their findings.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

, a pilot study suggests.

“Our experience suggests that under the effects of treatment with adalimumab, wound healing disorders with primary wound closure occur less often. And primary wound closure offers advantages over secondary wound healing: shorter length of inpatient stay, lower morbidity, fewer functional problems, and better quality of life,” Gefion Girbig, MD, said at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

She noted that primary wound closure following surgery for HS is controversial. For example, current German guidelines recommend complete surgical excision of HS lesions, followed by secondary wound healing; the guidelines advise against primary wound closure. But those guidelines were issued back in 2012, years before adalimumab (Humira) achieved regulatory approval as the first and to date only medication indicated for treatment of HS.

Experts agree that while adalimumab has been a difference maker for many patients with HS, surgery is still often necessary. And many surgeons prefer secondary wound healing in HS. That’s because healing by first intention has historically often resulted in complications involving wound healing disorders and infection. These complications necessitate loosening of the primary closure to permit further wound healing by second intention, with a resultant prolonged healing time, explained Dr. Girbig, of the Institute for Health Sciences Research in Dermatology and Nursing at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (Germany).

She and her coinvestigators hypothesized that the disordered wound healing is a consequence of the underlying inflammatory disease that lies at the core of HS, and that quelling the inflammation with adalimumab for at least 6 months before performing surgery with primary closure while the anti-TNF therapy continues would reduce the incidence of wound healing disorders.

This was borne out in the group’s small observational pilot study. It included 10 patients with HS who underwent surgery only after at least 6 months on adalimumab. Six had surgery for axillary HS and four for inguinal disease. Only 2 of the 10 developed a wound healing disorder. Both had surgical reconstruction in the inguinal area. Neither case involved infection. Surgical management entailed opening part of the suture to allow simultaneous secondary wound closure.

This 20% incidence of disordered wound healing when primary closure was carried out while systemic inflammation was controlled via adalimumab is markedly lower than rates reported using primary closure without adalimumab. Dr. Girbig and her coinvestigators are now conducting a larger controlled study to confirm their findings.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Hypochlorous acid is a valuable adjunctive treatment in AD

, Joseph F. Fowler, MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually this year.

“I definitely like hypochlorous acid products to reduce microbial load and improve itching,” said Dr. Fowler, a dermatologist at the University of Louisville (Ky.). “It’s certainly a useful adjunct – not your primary treatment – in managing atopic dermatitis, especially when infected.”

Topical stabilized hypochlorous acid for use on the skin is commercially available over the counter in gel and liquid spray forms. It’s not bleach, which is sodium hypochlorite. In fact, for use on the skin, hypochlorous acid is better than bleach, since it doesn’t stain dark clothes, it’s nonirritating, and it doesn’t smell like bleach.

“We’re not entirely sure why it has an anti-itch effect, but that might partly be due to its inhibition of mast cell degranulation. It stops the mast cell from releasing its itch-o-genic properties into the skin. It also inhibits phospholipase A2, resulting in reduction of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, which may also account for the anti-itch effect,” Dr. Fowler said.

Hypochlorous acid has a powerful antimicrobial effect. It is highly effective at rapidly killing a broad range of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, including Staphylococcus aureus, a pathogen of particular relevance in AD. After the Environmental Protection Agency added hypochlorous acid to its list of disinfectants known to be effective against coronavirus, commercial interest in the use of hypochlorous acid in higher concentrations as a disinfectant in office buildings, hospitals, and for other large-scale applications has ballooned. The product, made via a process involving electrolyzation of water, is inexpensive. It’s also nontoxic: It’s not perceived by the immune system as foreign, since hypochlorous acid is produced during the human innate immune response.

Dr. Fowler reported serving as a consultant to and on the speakers bureau for SmartPractice, and receiving research funding from Asana, Edesa Biotech, J&J, and Novartis.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, Joseph F. Fowler, MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually this year.

“I definitely like hypochlorous acid products to reduce microbial load and improve itching,” said Dr. Fowler, a dermatologist at the University of Louisville (Ky.). “It’s certainly a useful adjunct – not your primary treatment – in managing atopic dermatitis, especially when infected.”

Topical stabilized hypochlorous acid for use on the skin is commercially available over the counter in gel and liquid spray forms. It’s not bleach, which is sodium hypochlorite. In fact, for use on the skin, hypochlorous acid is better than bleach, since it doesn’t stain dark clothes, it’s nonirritating, and it doesn’t smell like bleach.

“We’re not entirely sure why it has an anti-itch effect, but that might partly be due to its inhibition of mast cell degranulation. It stops the mast cell from releasing its itch-o-genic properties into the skin. It also inhibits phospholipase A2, resulting in reduction of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, which may also account for the anti-itch effect,” Dr. Fowler said.

Hypochlorous acid has a powerful antimicrobial effect. It is highly effective at rapidly killing a broad range of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, including Staphylococcus aureus, a pathogen of particular relevance in AD. After the Environmental Protection Agency added hypochlorous acid to its list of disinfectants known to be effective against coronavirus, commercial interest in the use of hypochlorous acid in higher concentrations as a disinfectant in office buildings, hospitals, and for other large-scale applications has ballooned. The product, made via a process involving electrolyzation of water, is inexpensive. It’s also nontoxic: It’s not perceived by the immune system as foreign, since hypochlorous acid is produced during the human innate immune response.

Dr. Fowler reported serving as a consultant to and on the speakers bureau for SmartPractice, and receiving research funding from Asana, Edesa Biotech, J&J, and Novartis.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, Joseph F. Fowler, MD, said at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar, held virtually this year.

“I definitely like hypochlorous acid products to reduce microbial load and improve itching,” said Dr. Fowler, a dermatologist at the University of Louisville (Ky.). “It’s certainly a useful adjunct – not your primary treatment – in managing atopic dermatitis, especially when infected.”

Topical stabilized hypochlorous acid for use on the skin is commercially available over the counter in gel and liquid spray forms. It’s not bleach, which is sodium hypochlorite. In fact, for use on the skin, hypochlorous acid is better than bleach, since it doesn’t stain dark clothes, it’s nonirritating, and it doesn’t smell like bleach.

“We’re not entirely sure why it has an anti-itch effect, but that might partly be due to its inhibition of mast cell degranulation. It stops the mast cell from releasing its itch-o-genic properties into the skin. It also inhibits phospholipase A2, resulting in reduction of leukotrienes and prostaglandins, which may also account for the anti-itch effect,” Dr. Fowler said.

Hypochlorous acid has a powerful antimicrobial effect. It is highly effective at rapidly killing a broad range of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, including Staphylococcus aureus, a pathogen of particular relevance in AD. After the Environmental Protection Agency added hypochlorous acid to its list of disinfectants known to be effective against coronavirus, commercial interest in the use of hypochlorous acid in higher concentrations as a disinfectant in office buildings, hospitals, and for other large-scale applications has ballooned. The product, made via a process involving electrolyzation of water, is inexpensive. It’s also nontoxic: It’s not perceived by the immune system as foreign, since hypochlorous acid is produced during the human innate immune response.

Dr. Fowler reported serving as a consultant to and on the speakers bureau for SmartPractice, and receiving research funding from Asana, Edesa Biotech, J&J, and Novartis.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

An Unusual Presentation of Cutaneous Metastatic Lobular Breast Carcinoma

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of new widespread lesions that developed over a period of months. The eruption was asymptomatic and consisted of numerous bumpy lesions that reportedly started on the patient’s neck and progressively spread to involve the trunk. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored, firm nodules scattered across the upper back, neck, and chest (Figure 1). Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy also was noted. Upon questioning regarding family history of malignancy, the patient reported that her brother had been diagnosed with colon cancer. Although she was not up to date on age-appropriate malignancy screenings, she did report having a diagnostic mammogram 1 year prior that revealed a suspicious lesion on the left breast. A repeat mammogram of the left breast 6 months later was read as unremarkable.

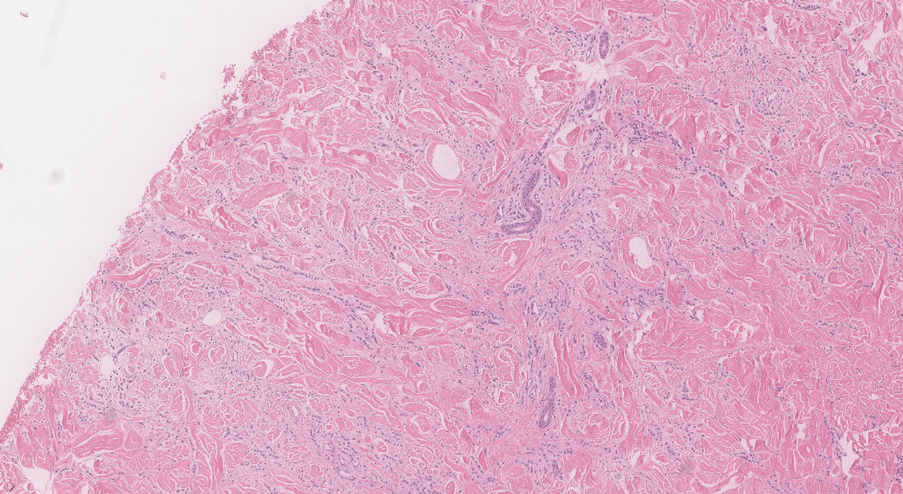

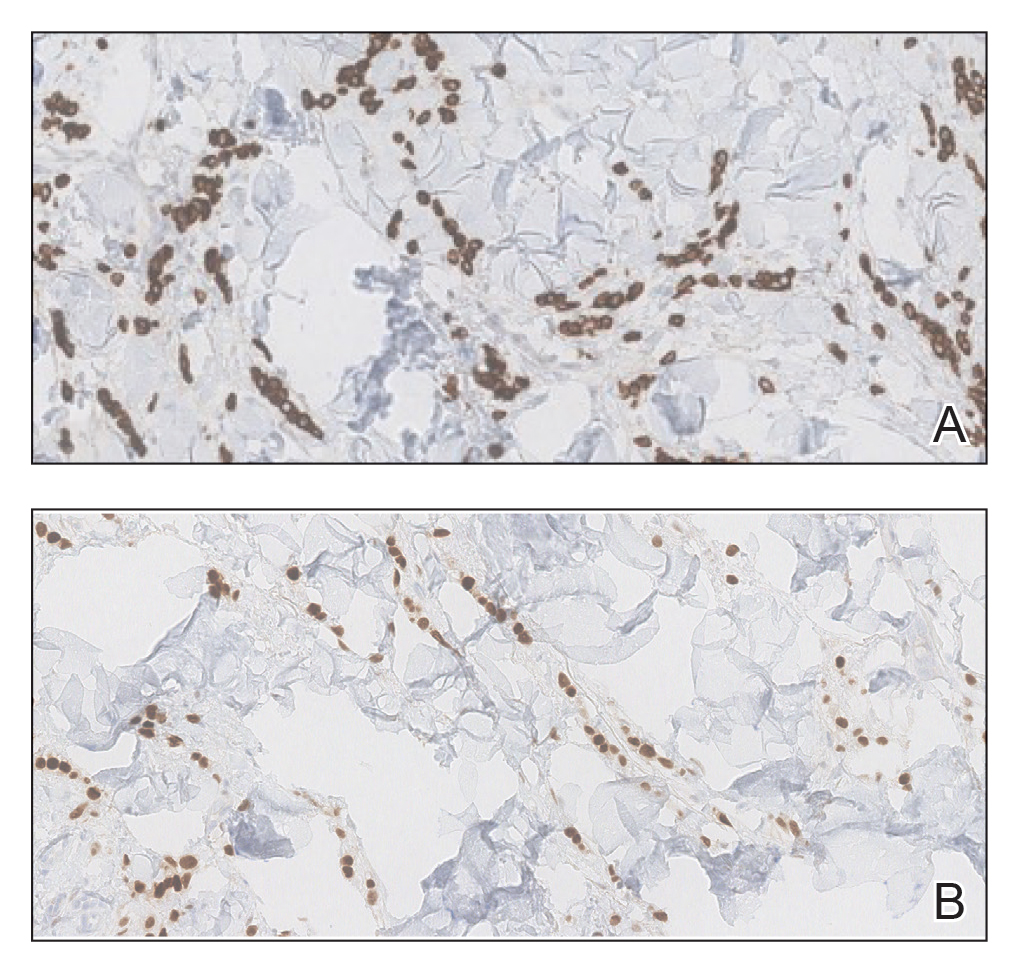

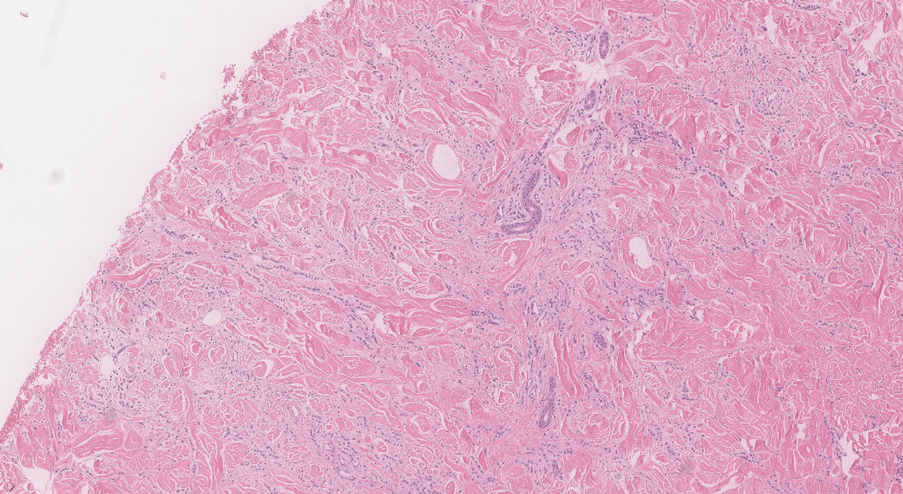

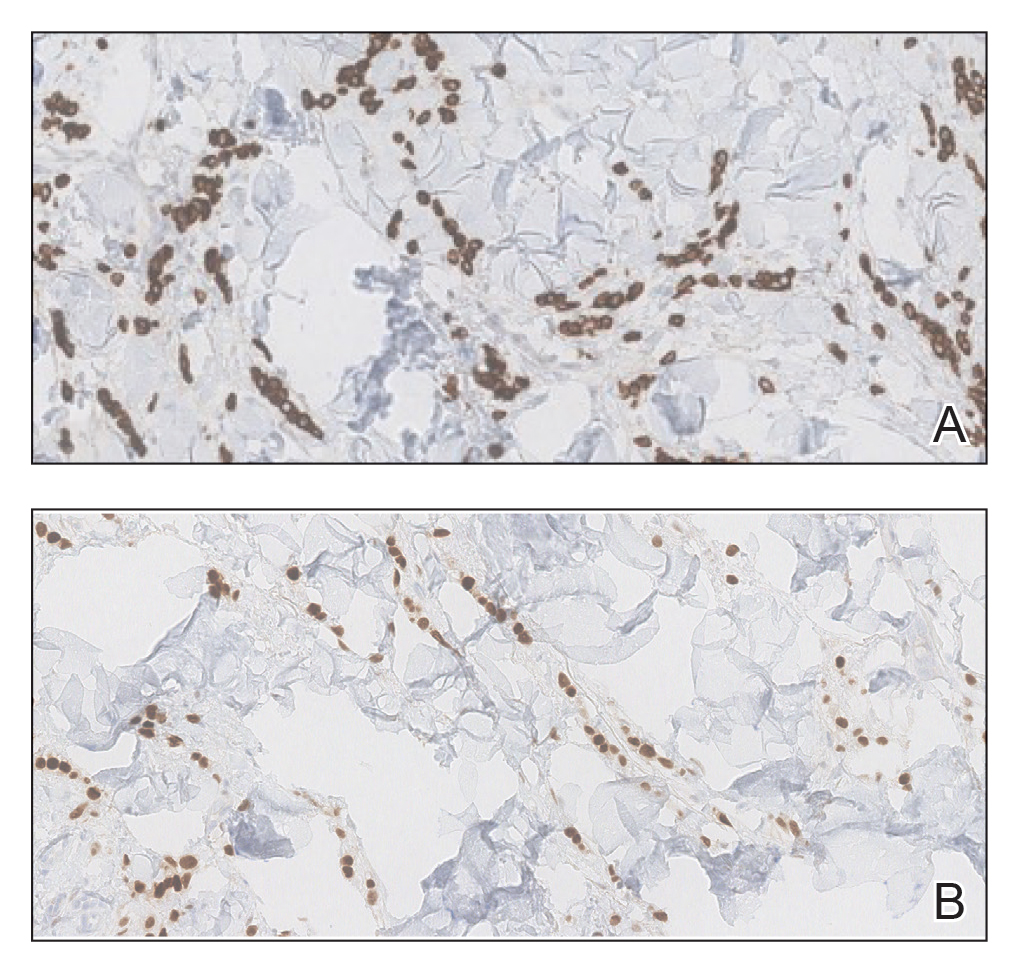

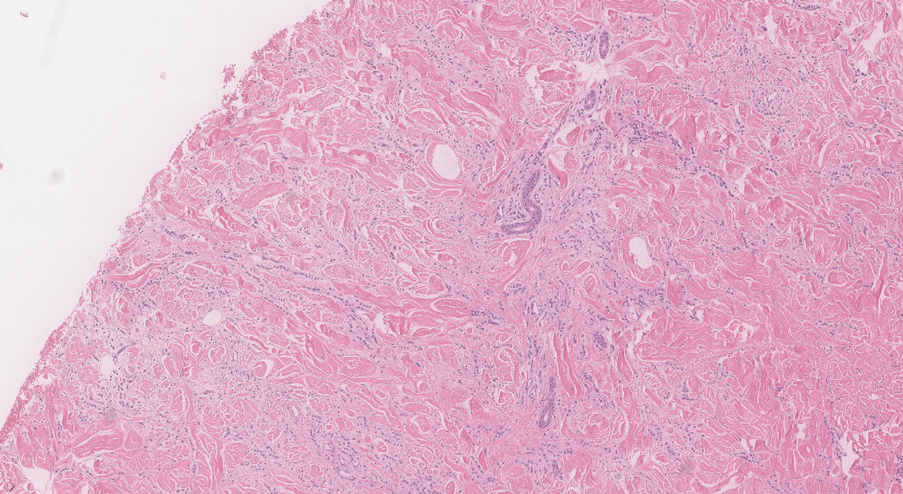

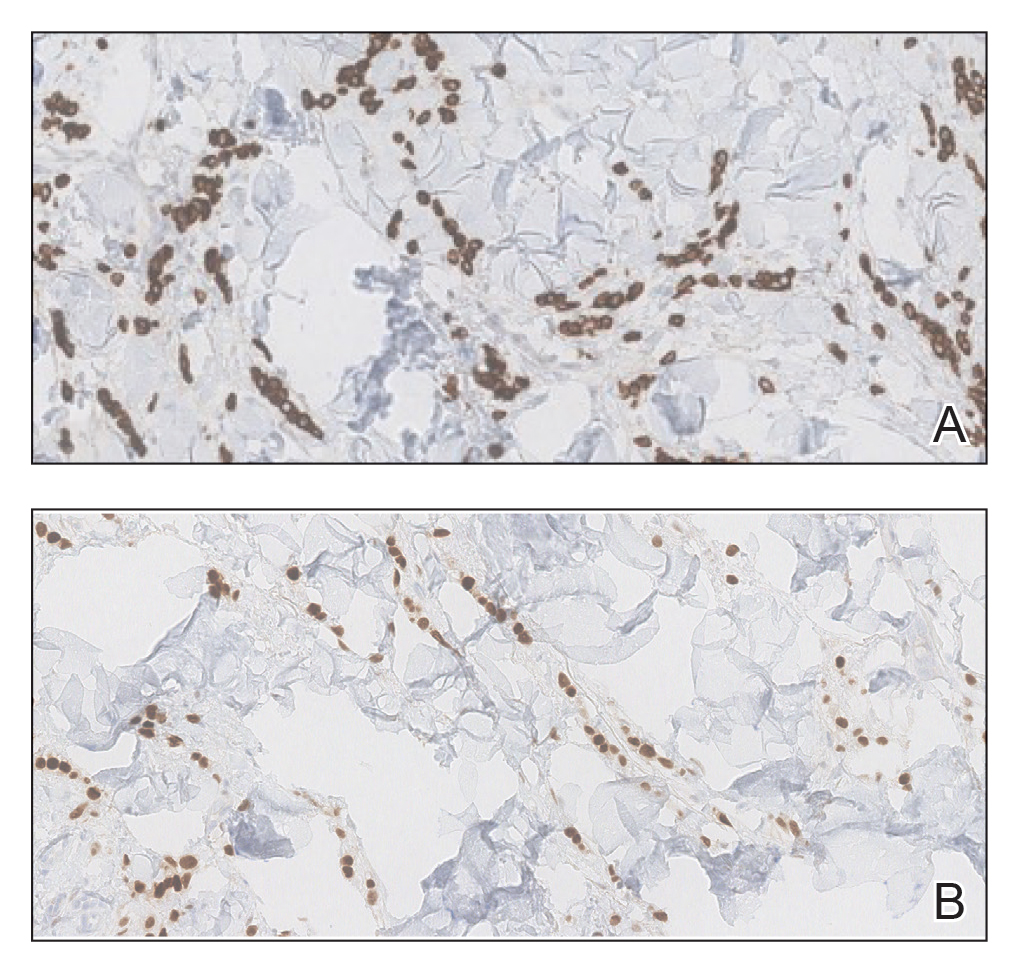

Two 3-mm representative punch biopsies were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a basket-weave stratum corneum with underlying epidermal atrophy. A relatively monomorphic epithelioid cell infiltrate extending from the superficial reticular dermis into the deep dermis and displaying an open chromatin pattern and pink cytoplasm was observed, as well as dermal collagen thickening. Linear, single-filing cells along with focal irregular nests and scattered cells were observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A), epithelial membrane antigen, and estrogen receptor (Figure 3B) along with gross cystic disease fluid protein 15; focal progesterone receptor positivity also was present. Cytokeratin 20, cytokeratin 5/6, carcinoembryonic antigen, p63, CDX2, paired box gene 8, thyroid transcription factor 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu stains were negative. Findings identified in both biopsies were consistent with metastatic cutaneous lobular breast carcinoma.

A complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panels were within normal limits, aside from a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level. Breast ultrasonography was unremarkable. Stereotactic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 9.4-cm mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast as well as enlarged lymph nodes 2.2 cm from the left axilla. A subsequent bone scan demonstrated focal activity in the left lateral fourth rib, left costochondral junction, and right anterolateral fifth rib—it was unclear whether these lesions were metastatic or secondary to trauma from a fall the patient reportedly had sustained 2 weeks prior. Lumbar MRI without gadolinium contrast revealed extensive abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity of osseous structures consistent with osseous metastasis.

Subsequent diagnostic bilateral breast ultrasonography and percutaneous left lymph node biopsy revealed pathology consistent with metastatic lobular breast carcinoma with near total effacement of the lymph node and extracapsular extension concordant with previous MRI findings. The mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast that previously was observed on MRI was not identifiable on this ultrasound. It was recommended that the patient pursue MRI-guided breast biopsy to have the breast lesion further characterized. She was referred to surgical oncology at a tertiary center for management; however, the patient was lost to follow-up, and there are no records available indicating the patient pursued any treatment. Although we were unable to confirm the patient’s breast lesion that previously was seen on MRI was the cause of the metastatic disease, the overall clinical picture supported metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

Comment

Tumor metastasis to the skin accounts for approximately 2% of all skin cancers5 and typically is observed in advanced stages of cancer. In women, breast carcinoma is the most common type of cancer to exhibit this behavior.2 Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common histologic subtype of breast cancer overall,6,7 and breast adenocarcinomas, including lobular and ductal breast carcinomas, are the most common histologic subtypes to exhibit metastatic cutaneous lesions.8

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma represents approximately 10% of invasive breast cancer cases. Compared to invasive ductal carcinoma, there tends to be a delay in diagnosis often leading to larger tumor sizes relative to the former upon detection and with lymph node invasion. These findings may be explained by the greater difficulty of detecting invasive lobular carcinomas by mammography and clinical breast examination compared to invasive ductal carcinomas.9-11 Additionally, invasive lobular carcinomas are more likely to be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors compared to invasive ductal carcinomas,12 which also was consistent in our case.

Cutaneous metastases of breast cancer most commonly are found on the anterior chest wall and can present as a wide spectrum of lesions, with nodules as the most common primary dermatologic manifestation.13 Cutaneous metastatic lesions commonly have been described as firm, mobile, round or oval, solitary or grouped nodules. The color of the nodules varies and may be flesh-colored, brown, blue, black, pink, and/or red-brown. The lesions often are asymptomatic but may ulcerate.2

In our case, the distribution of lesions was a unique aspect that is not typical of most cases of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma. The nodules appeared more scattered and involved multiple body regions, including the back, neck, and chest. Although cutaneous breast cancer metastases have been documented to extend to these body regions, a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and metastatic breast cancer suggested that it is uncommon for these multiple areas to be simultaneously affected.4,14 Rather, the more common clinical presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma is as a solitary nodule or group of nodules localized to a single anatomic region.14

Another notable feature of our case was the rapid development of the cutaneous lesions relative to the primary tumor. This patient developed diffuse lesions over a period of several months, and given that her mammogram performed the previous year was negative for any abnormalities, one could suggest that the metastatic lesions developed less than a year from onset of the primary tumor. A previous study involving 41 patients with a known clinical primary visceral malignancy (ie, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, kidney, thyroid, prostate, or ovarian origin) found that it takes approximately 3 years on average for cutaneous metastases to develop from the onset of cancer diagnosis (range, 1–177 months).14 In the aforementioned study, 94% of patients had stage III or IV disease at time of skin metastasis, with the majority of those demonstrating stage IV disease. However, it also is possible that these breast tumors evaded detection or were too small to be identified on prior imaging.14 A review of our patient’s medical records did not indicate documentation of any visual or palpable breast changes prior to the onset of the clinically detected metastatic nodules.

Conclusion

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining ultimately yielded the diagnosis of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma in our patient. Providers should be aware of the varying clinical presentations that may arise in the setting of cutaneous metastasis. When faced with lesions suspicious for cutaneous metastasis, biopsy is warranted to determine the correct diagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Upon diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, prompt coordination with the primary care provider and appropriate referral to multidisciplinary teams is necessary. Clinical providers also should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with cutaneous metastasis who have a history of normal malignancy screenings.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. a retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, et al. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289:1421-1424.

- Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2773-2780.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Dixon J, Anderson R, Page D, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcioma of the breast. Histopathology. 1982;6:149-161.

- Yeatman T, Cantor AB, Smith TJ, et al. Tumor biology of infiltrating lobular carcinoma: implications for management. Ann Surg. 1995;222:549-559.

- Silverstein M, Lewinski BS, Waisman JR, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma: is it different from infiltrating duct carcinoma? Cancer. 1994;73:1673-1677.

- Li CI, Uribe DJ, Daling JR. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1046-1052.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol. 2000;9:143-148.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report