User login

Fremanezumab may be effective in reversion of chronic to episodic migraine

Key clinical point: Along with its efficacy as a migraine preventive treatment, fremanezumab demonstrates the potential benefit for reversion from chronic migraine (CM) to episodic migraine (EM).

Major finding: The rates of reversion from CM to EM were higher in patients treated with fremanezumab vs. those treated with placebo, when reversion was defined either as an average of less than 15 headache days per month during the 3-month treatment period (quarterly: 50.5%; P = .108 and monthly: 53.7%; P = .012 vs. placebo: 44.5%) or, more stringently, as less than 15 headache days per month at months 1, 2, and 3 (quarterly: 31.2%; P = .008 and monthly: 33.7%; P = .001 vs. placebo: 22.4%).

Study details: The findings are based on a post hoc analysis of the HALO CM trial. Patients with CM (n=1,088) were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 treatment groups (fremanezumab quarterly, n=376; fremanezumab monthly, n=379; or placebo, n=375).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel. Some study investigators reported being an employee of Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc., receiving honoraria from, and/or consulting for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Headache. 2020 Nov 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13997.

Key clinical point: Along with its efficacy as a migraine preventive treatment, fremanezumab demonstrates the potential benefit for reversion from chronic migraine (CM) to episodic migraine (EM).

Major finding: The rates of reversion from CM to EM were higher in patients treated with fremanezumab vs. those treated with placebo, when reversion was defined either as an average of less than 15 headache days per month during the 3-month treatment period (quarterly: 50.5%; P = .108 and monthly: 53.7%; P = .012 vs. placebo: 44.5%) or, more stringently, as less than 15 headache days per month at months 1, 2, and 3 (quarterly: 31.2%; P = .008 and monthly: 33.7%; P = .001 vs. placebo: 22.4%).

Study details: The findings are based on a post hoc analysis of the HALO CM trial. Patients with CM (n=1,088) were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 treatment groups (fremanezumab quarterly, n=376; fremanezumab monthly, n=379; or placebo, n=375).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel. Some study investigators reported being an employee of Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc., receiving honoraria from, and/or consulting for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Headache. 2020 Nov 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13997.

Key clinical point: Along with its efficacy as a migraine preventive treatment, fremanezumab demonstrates the potential benefit for reversion from chronic migraine (CM) to episodic migraine (EM).

Major finding: The rates of reversion from CM to EM were higher in patients treated with fremanezumab vs. those treated with placebo, when reversion was defined either as an average of less than 15 headache days per month during the 3-month treatment period (quarterly: 50.5%; P = .108 and monthly: 53.7%; P = .012 vs. placebo: 44.5%) or, more stringently, as less than 15 headache days per month at months 1, 2, and 3 (quarterly: 31.2%; P = .008 and monthly: 33.7%; P = .001 vs. placebo: 22.4%).

Study details: The findings are based on a post hoc analysis of the HALO CM trial. Patients with CM (n=1,088) were randomly assigned to 1 of the 3 treatment groups (fremanezumab quarterly, n=376; fremanezumab monthly, n=379; or placebo, n=375).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel. Some study investigators reported being an employee of Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc., receiving honoraria from, and/or consulting for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Source: Lipton RB et al. Headache. 2020 Nov 11. doi: 10.1111/head.13997.

Monoclonal antibody combo treatment reduces viral load in mild to moderate COVID-19

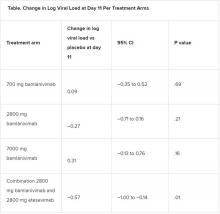

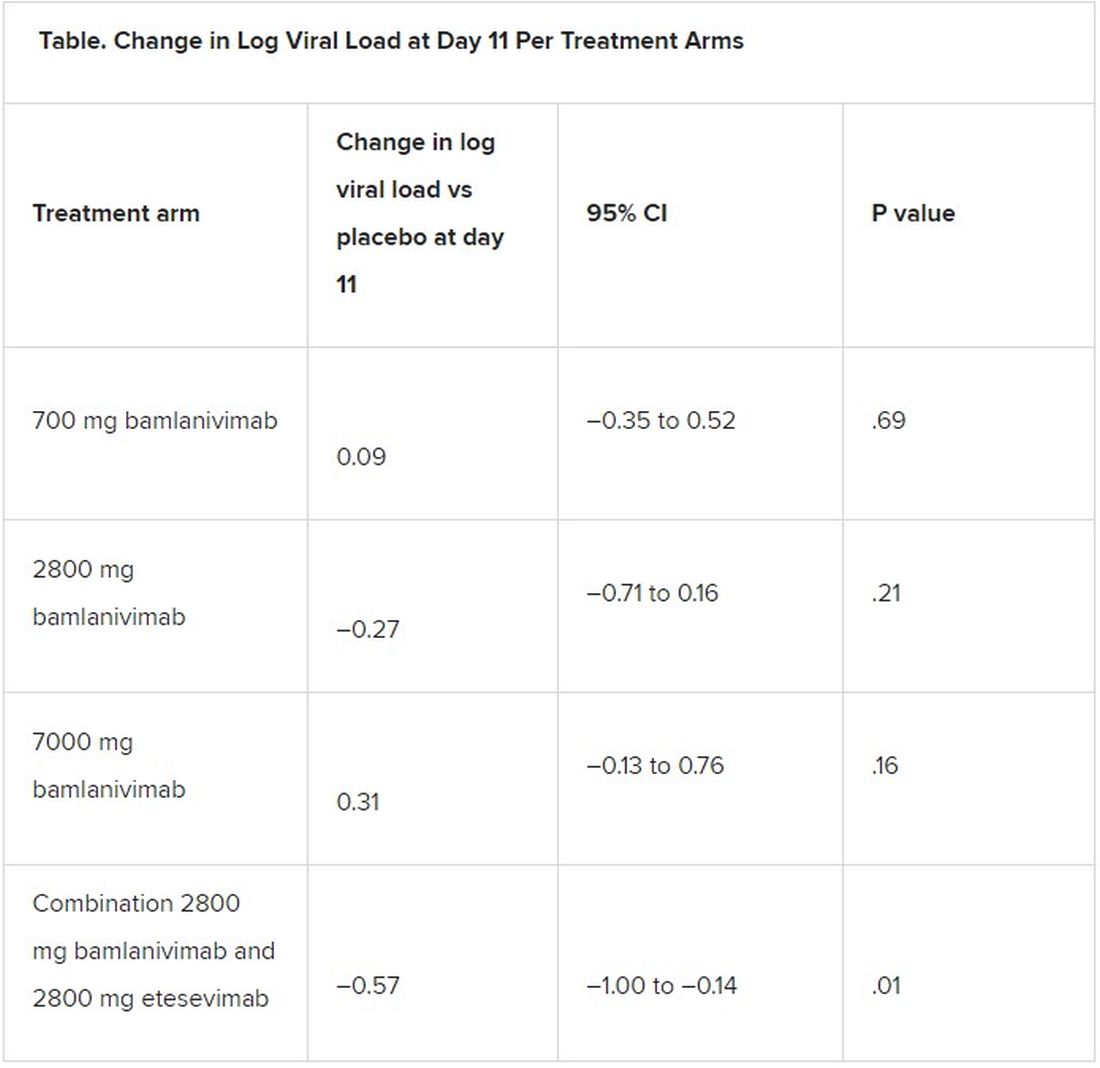

A combination treatment of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies bamlanivimab and etesevimab was associated with a statistically significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 at day 11 compared with placebo among nonhospitalized patients who had mild to moderate COVID-19, new data indicate.

However, bamlanivimab alone in three different single-infusion doses showed no significant reduction in viral load, compared with placebo, according to the phase 2/3 study by Robert L. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the Baylor University Medical Center and the Baylor Scott & White Research Institute, both in Dallas, and colleagues.

Findings from the Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) study were published online Jan. 21 in JAMA. The results represent findings through Oct. 6, 2020.

BLAZE-1 was funded by Eli Lilly, which makes both of the antispike neutralizing antibodies. The trial was conducted at 49 U.S. centers and included 613 outpatients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had one or more mild to moderate symptoms.

Patients were randomized to one of five groups (four treatment groups and a placebo control), and researchers analyzed between-group differences.

All four treatment arms suggest a trend toward reduction in viral load, which was the primary endpoint of the trial, but only the combination showed a statistically significant reduction.

The average age of patients was 44.7 years, 54.6% were female, 42.5% were Hispanic, and 67.1% had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19 (aged ≥55 years, body mass index of at least 30, or relevant comorbidity such as hypertension).

Among secondary outcomes, there were no consistent differences between the monotherapy groups or the combination group versus placebo for the other measures of viral load or clinical symptom scores.

The proportion of patients who had COVID-19–related hospitalizations or ED visits was 5.8% (nine events) for placebo; 1.0% (one event) for the 700-mg group; 1.9% (two events) for 2,800 mg; 2.0% (two events) for 7,000 mg; and 0.9% (one event) for combination treatment.

“Combining these two neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in clinical use may enhance viral load reduction and decrease treatment-emergent resistant variants,” the authors concluded.

Safety profile comparison

As for adverse events, immediate hypersensitivity reactions were reported in nine patients (six bamlanivimab, two combination treatment, and one placebo). No deaths occurred during the study.

Serious adverse events unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 infection or considered related to the study drug occurred in 0% (0/309) of patients in the bamlanivimab monotherapy groups; in 0.9% (1/112) of patients in the combination group; and in 0.6% (1/156) of patients in the placebo group.

The serious adverse event in the combination group was a urinary tract infection deemed unrelated to the study drug, the authors wrote.

The two most frequently reported side effects were nausea (3.0% for the 700-mg group; 3.7% for the 2,800-mg group; 5.0% for the 7,000-mg group; 3.6% for the combination group; and 3.8% for the placebo group) and diarrhea (1.0%, 1.9%, 5.9%, 0.9%, and 4.5%, respectively).

The authors included in the study’s limitations that the primary endpoint at day 11 may have been too late to best detect treatment effects.

“All patients, including those who received placebo, demonstrated substantial viral reduction by day 11,” they noted. “An earlier time point like day 3 or day 7 could possibly have been more appropriate to measure viral load.”

Currently, only remdesivir has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating COVID-19, but convalescent plasma and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies have been granted emergency-use authorization.

In an accompanying editor’s note, Preeti N. Malani, MD, with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and associate editor of JAMA, and Robert M. Golub, MD, deputy editor of JAMA, pointed out that these results differ from an earlier interim analysis of BLAZE-1 data.

A previous publication by Peter Chen, MD, with the department of medicine at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, compared the three monotherapy groups (no combination group) with placebo, and in that study the 2,800-mg dose of bamlanivimab versus placebo achieved statistical significance for reduction in viral load from baseline at day 11, whereas the other two doses did not.

The editors explain that, in the study by Dr. Chen, “Follow-up for the placebo group was incomplete at the time of the database lock on Sept. 5, 2020. In the final analysis reported in the current article, the database was locked on Oct. 6, 2020, and the longer follow-up for the placebo group, which is now complete, resulted in changes in the primary outcome among that group.”

They concluded: “The comparison of the monotherapy groups against the final results for the placebo group led to changes in the effect sizes,” and the statistical significance of the 2,800-mg group was erased.

The editors pointed out that monoclonal antibodies are likely to benefit certain patients but definitive answers regarding which patients will benefit and under what circumstances will likely take more time than clinicians have to make decisions on treatment.

Meanwhile, as this news organization reported, the United States has spent $375 million on bamlanivimab and $450 million on Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, with the promise to spend billions more.

However, 80% of the 660,000 doses delivered by the two companies are still sitting on shelves, federal officials said in a press briefing last week, because of doubts about efficacy, lack of resources for infusion centers, and questions on reimbursement.

“While the world waits for widespread administration of effective vaccines and additional data on treatments, local efforts should work to improve testing access and turnaround time and reduce logistical barriers to ensure that monoclonal therapies can be provided to patients who are most likely to benefit,” Dr. Malani and Dr. Golub wrote.

This trial was sponsored and funded by Eli Lilly. Dr. Gottlieb disclosed personal fees and nonfinancial support (medication for another trial) from Gilead Sciences and serving on an advisory board for Sentinel. Several coauthors have financial ties to Eli Lilly. Dr. Malani reported serving on the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Preventive Monoclonal Antibody data and safety monitoring board but was not compensated. Dr. Golub disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A combination treatment of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies bamlanivimab and etesevimab was associated with a statistically significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 at day 11 compared with placebo among nonhospitalized patients who had mild to moderate COVID-19, new data indicate.

However, bamlanivimab alone in three different single-infusion doses showed no significant reduction in viral load, compared with placebo, according to the phase 2/3 study by Robert L. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the Baylor University Medical Center and the Baylor Scott & White Research Institute, both in Dallas, and colleagues.

Findings from the Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) study were published online Jan. 21 in JAMA. The results represent findings through Oct. 6, 2020.

BLAZE-1 was funded by Eli Lilly, which makes both of the antispike neutralizing antibodies. The trial was conducted at 49 U.S. centers and included 613 outpatients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had one or more mild to moderate symptoms.

Patients were randomized to one of five groups (four treatment groups and a placebo control), and researchers analyzed between-group differences.

All four treatment arms suggest a trend toward reduction in viral load, which was the primary endpoint of the trial, but only the combination showed a statistically significant reduction.

The average age of patients was 44.7 years, 54.6% were female, 42.5% were Hispanic, and 67.1% had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19 (aged ≥55 years, body mass index of at least 30, or relevant comorbidity such as hypertension).

Among secondary outcomes, there were no consistent differences between the monotherapy groups or the combination group versus placebo for the other measures of viral load or clinical symptom scores.

The proportion of patients who had COVID-19–related hospitalizations or ED visits was 5.8% (nine events) for placebo; 1.0% (one event) for the 700-mg group; 1.9% (two events) for 2,800 mg; 2.0% (two events) for 7,000 mg; and 0.9% (one event) for combination treatment.

“Combining these two neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in clinical use may enhance viral load reduction and decrease treatment-emergent resistant variants,” the authors concluded.

Safety profile comparison

As for adverse events, immediate hypersensitivity reactions were reported in nine patients (six bamlanivimab, two combination treatment, and one placebo). No deaths occurred during the study.

Serious adverse events unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 infection or considered related to the study drug occurred in 0% (0/309) of patients in the bamlanivimab monotherapy groups; in 0.9% (1/112) of patients in the combination group; and in 0.6% (1/156) of patients in the placebo group.

The serious adverse event in the combination group was a urinary tract infection deemed unrelated to the study drug, the authors wrote.

The two most frequently reported side effects were nausea (3.0% for the 700-mg group; 3.7% for the 2,800-mg group; 5.0% for the 7,000-mg group; 3.6% for the combination group; and 3.8% for the placebo group) and diarrhea (1.0%, 1.9%, 5.9%, 0.9%, and 4.5%, respectively).

The authors included in the study’s limitations that the primary endpoint at day 11 may have been too late to best detect treatment effects.

“All patients, including those who received placebo, demonstrated substantial viral reduction by day 11,” they noted. “An earlier time point like day 3 or day 7 could possibly have been more appropriate to measure viral load.”

Currently, only remdesivir has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating COVID-19, but convalescent plasma and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies have been granted emergency-use authorization.

In an accompanying editor’s note, Preeti N. Malani, MD, with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and associate editor of JAMA, and Robert M. Golub, MD, deputy editor of JAMA, pointed out that these results differ from an earlier interim analysis of BLAZE-1 data.

A previous publication by Peter Chen, MD, with the department of medicine at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, compared the three monotherapy groups (no combination group) with placebo, and in that study the 2,800-mg dose of bamlanivimab versus placebo achieved statistical significance for reduction in viral load from baseline at day 11, whereas the other two doses did not.

The editors explain that, in the study by Dr. Chen, “Follow-up for the placebo group was incomplete at the time of the database lock on Sept. 5, 2020. In the final analysis reported in the current article, the database was locked on Oct. 6, 2020, and the longer follow-up for the placebo group, which is now complete, resulted in changes in the primary outcome among that group.”

They concluded: “The comparison of the monotherapy groups against the final results for the placebo group led to changes in the effect sizes,” and the statistical significance of the 2,800-mg group was erased.

The editors pointed out that monoclonal antibodies are likely to benefit certain patients but definitive answers regarding which patients will benefit and under what circumstances will likely take more time than clinicians have to make decisions on treatment.

Meanwhile, as this news organization reported, the United States has spent $375 million on bamlanivimab and $450 million on Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, with the promise to spend billions more.

However, 80% of the 660,000 doses delivered by the two companies are still sitting on shelves, federal officials said in a press briefing last week, because of doubts about efficacy, lack of resources for infusion centers, and questions on reimbursement.

“While the world waits for widespread administration of effective vaccines and additional data on treatments, local efforts should work to improve testing access and turnaround time and reduce logistical barriers to ensure that monoclonal therapies can be provided to patients who are most likely to benefit,” Dr. Malani and Dr. Golub wrote.

This trial was sponsored and funded by Eli Lilly. Dr. Gottlieb disclosed personal fees and nonfinancial support (medication for another trial) from Gilead Sciences and serving on an advisory board for Sentinel. Several coauthors have financial ties to Eli Lilly. Dr. Malani reported serving on the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Preventive Monoclonal Antibody data and safety monitoring board but was not compensated. Dr. Golub disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A combination treatment of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies bamlanivimab and etesevimab was associated with a statistically significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 at day 11 compared with placebo among nonhospitalized patients who had mild to moderate COVID-19, new data indicate.

However, bamlanivimab alone in three different single-infusion doses showed no significant reduction in viral load, compared with placebo, according to the phase 2/3 study by Robert L. Gottlieb, MD, PhD, of the Baylor University Medical Center and the Baylor Scott & White Research Institute, both in Dallas, and colleagues.

Findings from the Blocking Viral Attachment and Cell Entry with SARS-CoV-2 Neutralizing Antibodies (BLAZE-1) study were published online Jan. 21 in JAMA. The results represent findings through Oct. 6, 2020.

BLAZE-1 was funded by Eli Lilly, which makes both of the antispike neutralizing antibodies. The trial was conducted at 49 U.S. centers and included 613 outpatients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had one or more mild to moderate symptoms.

Patients were randomized to one of five groups (four treatment groups and a placebo control), and researchers analyzed between-group differences.

All four treatment arms suggest a trend toward reduction in viral load, which was the primary endpoint of the trial, but only the combination showed a statistically significant reduction.

The average age of patients was 44.7 years, 54.6% were female, 42.5% were Hispanic, and 67.1% had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19 (aged ≥55 years, body mass index of at least 30, or relevant comorbidity such as hypertension).

Among secondary outcomes, there were no consistent differences between the monotherapy groups or the combination group versus placebo for the other measures of viral load or clinical symptom scores.

The proportion of patients who had COVID-19–related hospitalizations or ED visits was 5.8% (nine events) for placebo; 1.0% (one event) for the 700-mg group; 1.9% (two events) for 2,800 mg; 2.0% (two events) for 7,000 mg; and 0.9% (one event) for combination treatment.

“Combining these two neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in clinical use may enhance viral load reduction and decrease treatment-emergent resistant variants,” the authors concluded.

Safety profile comparison

As for adverse events, immediate hypersensitivity reactions were reported in nine patients (six bamlanivimab, two combination treatment, and one placebo). No deaths occurred during the study.

Serious adverse events unrelated to SARS-CoV-2 infection or considered related to the study drug occurred in 0% (0/309) of patients in the bamlanivimab monotherapy groups; in 0.9% (1/112) of patients in the combination group; and in 0.6% (1/156) of patients in the placebo group.

The serious adverse event in the combination group was a urinary tract infection deemed unrelated to the study drug, the authors wrote.

The two most frequently reported side effects were nausea (3.0% for the 700-mg group; 3.7% for the 2,800-mg group; 5.0% for the 7,000-mg group; 3.6% for the combination group; and 3.8% for the placebo group) and diarrhea (1.0%, 1.9%, 5.9%, 0.9%, and 4.5%, respectively).

The authors included in the study’s limitations that the primary endpoint at day 11 may have been too late to best detect treatment effects.

“All patients, including those who received placebo, demonstrated substantial viral reduction by day 11,” they noted. “An earlier time point like day 3 or day 7 could possibly have been more appropriate to measure viral load.”

Currently, only remdesivir has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating COVID-19, but convalescent plasma and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies have been granted emergency-use authorization.

In an accompanying editor’s note, Preeti N. Malani, MD, with the division of infectious diseases at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and associate editor of JAMA, and Robert M. Golub, MD, deputy editor of JAMA, pointed out that these results differ from an earlier interim analysis of BLAZE-1 data.

A previous publication by Peter Chen, MD, with the department of medicine at Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, compared the three monotherapy groups (no combination group) with placebo, and in that study the 2,800-mg dose of bamlanivimab versus placebo achieved statistical significance for reduction in viral load from baseline at day 11, whereas the other two doses did not.

The editors explain that, in the study by Dr. Chen, “Follow-up for the placebo group was incomplete at the time of the database lock on Sept. 5, 2020. In the final analysis reported in the current article, the database was locked on Oct. 6, 2020, and the longer follow-up for the placebo group, which is now complete, resulted in changes in the primary outcome among that group.”

They concluded: “The comparison of the monotherapy groups against the final results for the placebo group led to changes in the effect sizes,” and the statistical significance of the 2,800-mg group was erased.

The editors pointed out that monoclonal antibodies are likely to benefit certain patients but definitive answers regarding which patients will benefit and under what circumstances will likely take more time than clinicians have to make decisions on treatment.

Meanwhile, as this news organization reported, the United States has spent $375 million on bamlanivimab and $450 million on Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody cocktail of casirivimab plus imdevimab, with the promise to spend billions more.

However, 80% of the 660,000 doses delivered by the two companies are still sitting on shelves, federal officials said in a press briefing last week, because of doubts about efficacy, lack of resources for infusion centers, and questions on reimbursement.

“While the world waits for widespread administration of effective vaccines and additional data on treatments, local efforts should work to improve testing access and turnaround time and reduce logistical barriers to ensure that monoclonal therapies can be provided to patients who are most likely to benefit,” Dr. Malani and Dr. Golub wrote.

This trial was sponsored and funded by Eli Lilly. Dr. Gottlieb disclosed personal fees and nonfinancial support (medication for another trial) from Gilead Sciences and serving on an advisory board for Sentinel. Several coauthors have financial ties to Eli Lilly. Dr. Malani reported serving on the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Preventive Monoclonal Antibody data and safety monitoring board but was not compensated. Dr. Golub disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Severe renal arteriosclerosis may indicate cardiovascular risk in lupus nephritis

Severe renal arteriosclerosis was associated with a ninefold increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with lupus nephritis, based on data from an observational study of 189 individuals.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has traditionally been thought to be a late complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but this has been challenged in recent population-based studies of patients with SLE and lupus nephritis (LN) that indicated an early and increased risk of ASCVD at the time of diagnosis. However, it is unclear which early risk factors may predispose patients to ASCVD, Shivani Garg, MD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and colleagues wrote in a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

In patients with IgA nephropathy and renal transplantation, previous studies have shown that severe renal arteriosclerosis (r-ASCL) based on kidney biopsies at the time of diagnosis predicts ASCVD, but “a few studies including LN biopsies failed to report a similar association between the presence of severe r-ASCL and ASCVD occurrence,” possibly because of underreporting of r-ASCL. Dr. Garg and colleagues also noted the problem of underreporting of r-ASCL in their own previous study of its prevalence in LN patients at the time of diagnosis.

To get a more detailed view of how r-ASCL may be linked to early occurrence of ASCVD in LN patients, Dr. Garg and coauthors identified 189 consecutive patients with incident LN who underwent diagnostic biopsies between 1994 and 2017. The median age of the patients was 25 years, 78% were women, and 73% were white. The researchers developed a composite score for r-ASCL severity based on reported and overread biopsies.

Overall, 31% of the patients had any reported r-ASCL, and 7% had moderate-severe r-ASCL. After incorporating systematically reexamined r-ASCL grades, the prevalence of any and moderate-severe r-ASCL increased to 39% and 12%, respectively.

Based on their composite of reported and overread r-ASCL grade, severe r-ASCL in diagnostic LN biopsies was associated with a ninefold increased risk of ASCVD.

The researchers identified 22 incident ASCVD events over an 11-year follow-up for an overall 12% incidence of ASCVD in LN. ASCVD was defined as ischemic heart disease (including myocardial infarction, coronary artery revascularization, abnormal stress test, abnormal angiogram, and events documented by a cardiologist); stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA); and peripheral vascular disease. Incident ASCVD was defined as the first ASCVD event between 1 and 10 years after LN diagnosis.

The most common ASCVD events were stroke or TIA (12 patients), events related to ischemic heart disease (7 patients), and events related to peripheral vascular disease (3 patients).

Lack of statin use

The researchers also hypothesized that the presence of gaps in statin use among eligible LN patients would be present in their study population. “Among the 20 patients with incident ASCVD events after LN diagnosis in our cohort, none was on statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis,” the researchers said, noting that current guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism (now known as the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) recommend initiating statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis in all patients who have hyperlipidemia and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage ≥3. “Further, 11 patients (55%) met high-risk criteria (hyperlipidemia and CKD stage ≥3) to implement statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis, yet only one patient (9%) was initiated on statin therapy.” In addition, patients with stage 3 or higher CKD were more likely to develop ASCVD than patients without stage 3 or higher CKD, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the majority white study population, the ability to overread only 25% of the biopsies, and the lack of data on the potential role of chronic lesions in ASCVD, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the use of a validated LN cohort, and the data provide “the basis to establish severe composite r-ASCL as a predictor of ASCVD events using a larger sample size in different cohorts,” they said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Severe renal arteriosclerosis was associated with a ninefold increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with lupus nephritis, based on data from an observational study of 189 individuals.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has traditionally been thought to be a late complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but this has been challenged in recent population-based studies of patients with SLE and lupus nephritis (LN) that indicated an early and increased risk of ASCVD at the time of diagnosis. However, it is unclear which early risk factors may predispose patients to ASCVD, Shivani Garg, MD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and colleagues wrote in a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

In patients with IgA nephropathy and renal transplantation, previous studies have shown that severe renal arteriosclerosis (r-ASCL) based on kidney biopsies at the time of diagnosis predicts ASCVD, but “a few studies including LN biopsies failed to report a similar association between the presence of severe r-ASCL and ASCVD occurrence,” possibly because of underreporting of r-ASCL. Dr. Garg and colleagues also noted the problem of underreporting of r-ASCL in their own previous study of its prevalence in LN patients at the time of diagnosis.

To get a more detailed view of how r-ASCL may be linked to early occurrence of ASCVD in LN patients, Dr. Garg and coauthors identified 189 consecutive patients with incident LN who underwent diagnostic biopsies between 1994 and 2017. The median age of the patients was 25 years, 78% were women, and 73% were white. The researchers developed a composite score for r-ASCL severity based on reported and overread biopsies.

Overall, 31% of the patients had any reported r-ASCL, and 7% had moderate-severe r-ASCL. After incorporating systematically reexamined r-ASCL grades, the prevalence of any and moderate-severe r-ASCL increased to 39% and 12%, respectively.

Based on their composite of reported and overread r-ASCL grade, severe r-ASCL in diagnostic LN biopsies was associated with a ninefold increased risk of ASCVD.

The researchers identified 22 incident ASCVD events over an 11-year follow-up for an overall 12% incidence of ASCVD in LN. ASCVD was defined as ischemic heart disease (including myocardial infarction, coronary artery revascularization, abnormal stress test, abnormal angiogram, and events documented by a cardiologist); stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA); and peripheral vascular disease. Incident ASCVD was defined as the first ASCVD event between 1 and 10 years after LN diagnosis.

The most common ASCVD events were stroke or TIA (12 patients), events related to ischemic heart disease (7 patients), and events related to peripheral vascular disease (3 patients).

Lack of statin use

The researchers also hypothesized that the presence of gaps in statin use among eligible LN patients would be present in their study population. “Among the 20 patients with incident ASCVD events after LN diagnosis in our cohort, none was on statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis,” the researchers said, noting that current guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism (now known as the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) recommend initiating statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis in all patients who have hyperlipidemia and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage ≥3. “Further, 11 patients (55%) met high-risk criteria (hyperlipidemia and CKD stage ≥3) to implement statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis, yet only one patient (9%) was initiated on statin therapy.” In addition, patients with stage 3 or higher CKD were more likely to develop ASCVD than patients without stage 3 or higher CKD, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the majority white study population, the ability to overread only 25% of the biopsies, and the lack of data on the potential role of chronic lesions in ASCVD, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the use of a validated LN cohort, and the data provide “the basis to establish severe composite r-ASCL as a predictor of ASCVD events using a larger sample size in different cohorts,” they said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Severe renal arteriosclerosis was associated with a ninefold increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with lupus nephritis, based on data from an observational study of 189 individuals.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) has traditionally been thought to be a late complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), but this has been challenged in recent population-based studies of patients with SLE and lupus nephritis (LN) that indicated an early and increased risk of ASCVD at the time of diagnosis. However, it is unclear which early risk factors may predispose patients to ASCVD, Shivani Garg, MD, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and colleagues wrote in a study published in Arthritis Care & Research.

In patients with IgA nephropathy and renal transplantation, previous studies have shown that severe renal arteriosclerosis (r-ASCL) based on kidney biopsies at the time of diagnosis predicts ASCVD, but “a few studies including LN biopsies failed to report a similar association between the presence of severe r-ASCL and ASCVD occurrence,” possibly because of underreporting of r-ASCL. Dr. Garg and colleagues also noted the problem of underreporting of r-ASCL in their own previous study of its prevalence in LN patients at the time of diagnosis.

To get a more detailed view of how r-ASCL may be linked to early occurrence of ASCVD in LN patients, Dr. Garg and coauthors identified 189 consecutive patients with incident LN who underwent diagnostic biopsies between 1994 and 2017. The median age of the patients was 25 years, 78% were women, and 73% were white. The researchers developed a composite score for r-ASCL severity based on reported and overread biopsies.

Overall, 31% of the patients had any reported r-ASCL, and 7% had moderate-severe r-ASCL. After incorporating systematically reexamined r-ASCL grades, the prevalence of any and moderate-severe r-ASCL increased to 39% and 12%, respectively.

Based on their composite of reported and overread r-ASCL grade, severe r-ASCL in diagnostic LN biopsies was associated with a ninefold increased risk of ASCVD.

The researchers identified 22 incident ASCVD events over an 11-year follow-up for an overall 12% incidence of ASCVD in LN. ASCVD was defined as ischemic heart disease (including myocardial infarction, coronary artery revascularization, abnormal stress test, abnormal angiogram, and events documented by a cardiologist); stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA); and peripheral vascular disease. Incident ASCVD was defined as the first ASCVD event between 1 and 10 years after LN diagnosis.

The most common ASCVD events were stroke or TIA (12 patients), events related to ischemic heart disease (7 patients), and events related to peripheral vascular disease (3 patients).

Lack of statin use

The researchers also hypothesized that the presence of gaps in statin use among eligible LN patients would be present in their study population. “Among the 20 patients with incident ASCVD events after LN diagnosis in our cohort, none was on statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis,” the researchers said, noting that current guidelines from the American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism (now known as the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology) recommend initiating statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis in all patients who have hyperlipidemia and chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage ≥3. “Further, 11 patients (55%) met high-risk criteria (hyperlipidemia and CKD stage ≥3) to implement statin therapy at the time of LN diagnosis, yet only one patient (9%) was initiated on statin therapy.” In addition, patients with stage 3 or higher CKD were more likely to develop ASCVD than patients without stage 3 or higher CKD, they said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the majority white study population, the ability to overread only 25% of the biopsies, and the lack of data on the potential role of chronic lesions in ASCVD, the researchers noted. However, the results were strengthened by the use of a validated LN cohort, and the data provide “the basis to establish severe composite r-ASCL as a predictor of ASCVD events using a larger sample size in different cohorts,” they said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Type of Alzheimer’s disease with intact memory offers new research paths

They also show some differences in neuropathology to typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, raising hopes of discovering novel mechanisms that might protect against memory loss in typical forms of the disease.

“We are discovering that Alzheimer’s disease has more than one form. While the typical patient with Alzheimer’s disease will have impaired memory, patients with primary progressive aphasia linked to Alzheimer’s disease are quite different. They have problems with language – they know what they want to say but can’t find the words – but their memory is intact,” said lead author Marsel Mesulam, MD.

“We have found that these patients still show the same levels of neurofibrillary tangles which destroy neurons in the memory part of the brain as typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, but in patients with primary progressive aphasia Alzheimer’s the nondominant side of this part of the brain showed less atrophy,” added Dr. Mesulam, who is director of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease at Northwestern University, Chicago. “It appears that these patients are more resilient to the effects of the neurofibrillary tangles.”

The researchers also found that two biomarkers that are established risk factors in typical Alzheimer’s disease do not appear to be risk factors for the primary progressive aphasia (PPA) form of the condition.

“These observations suggest that there are mechanisms that may protect the brain from Alzheimer’s-type damage. Studying these patients with this primary progressive aphasia form of Alzheimer’s disease may give us clues as to where to look for these mechanisms that may lead to new treatments for the memory loss associated with typical Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Mesulam commented.

The study was published online in the Jan. 13 issue of Neurology.

PPA is diagnosed when language impairment emerges on a background of preserved memory and behavior, with about 40% of cases representing atypical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers explained.

“While we knew that the memories of people with primary progressive aphasia were not affected at first, we did not know if they maintained their memory functioning over years,” Dr. Mesulam noted.

The current study aimed to investigate whether the memory preservation in PPA linked to Alzheimer’s disease is a consistent core feature or a transient finding confined to initial presentation, and to explore the underlying pathology of the condition.

The researchers searched their database to identify patients with PPA with autopsy or biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease, who also had at least two consecutive visits during which language and memory assessment had been obtained with the same tests. The study included 17 patients with the PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease who compared with 14 patients who had typical Alzheimer’s disease with memory loss.

The authors pointed out that characterization of memory in patients with PPA is challenging because most tests use word lists, and thus patients may fail the test because of their language impairments. To address this issue, they included patients with PPA who had undergone memory tests involving recalling pictures of common objects.

Patients with typical Alzheimer’s disease underwent similar tests but used a list of common words.

A second round of tests was conducted in the primary progressive aphasia group an average of 2.4 years later and in the typical Alzheimer’s disease group an average of 1.7 years later.

Brain scans were also available for the patients with PPA, as well as postmortem evaluations for eight of the PPA cases and all the typical Alzheimer’s disease cases.

Results showed that patients with PPA had no decline in their memory skills when they took the tests a second time. At that point, they had been showing symptoms of the disorder for an average of 6 years. In contrast, their language skills declined significantly during the same period. For typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, verbal memory and language skills declined with equal severity during the study.

Postmortem results showed that the two groups had comparable degrees of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the medial temporal lobe – the main area of the brain affected in dementia.

However, MRI scans showed that patients with PPA had an asymmetrical atrophy of the dominant (left) hemisphere with sparing of the right sided medial temporal lobe, indicating a lack of neurodegeneration in the nondominant hemisphere, despite the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

It was also found that the patients with PPA had significantly lower prevalence of two factors strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease – TDP-43 pathology and APOE ε4 positivity – than the typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

The authors concluded that “primary progressive aphasia Alzheimer’s syndrome offers unique opportunities for exploring the biological foundations of these phenomena that interactively modulate the impact of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology on cognitive function.”

‘Preservation of cognition is the holy grail’

In an accompanying editorial, Seyed Ahmad Sajjadi, MD, University of California, Irvine; Sharon Ash, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and Stefano Cappa, MD, University School for Advanced Studies, Pavia, Italy, said these findings have important implications, “as ultimately, preservation of cognition is the holy grail of research in this area.”

They pointed out that the current observations imply “an uncoupling of neurodegeneration and pathology” in patients with PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease, adding that “it seems reasonable to conclude that neurodegeneration, and not mere presence of pathology, is what correlates with clinical presentation in these patients.”

The editorialists noted that the study has some limitations: the sample size is relatively small, not all patients with PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease underwent autopsy, MRI was only available for the aphasia group, and the two groups had different memory tests for comparison of their recognition memory.

But they concluded that this study “provides important insights about the potential reasons for differential vulnerability of the neural substrate of memory in those with different clinical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, the Davee Foundation, and the Jeanine Jones Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

They also show some differences in neuropathology to typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, raising hopes of discovering novel mechanisms that might protect against memory loss in typical forms of the disease.

“We are discovering that Alzheimer’s disease has more than one form. While the typical patient with Alzheimer’s disease will have impaired memory, patients with primary progressive aphasia linked to Alzheimer’s disease are quite different. They have problems with language – they know what they want to say but can’t find the words – but their memory is intact,” said lead author Marsel Mesulam, MD.

“We have found that these patients still show the same levels of neurofibrillary tangles which destroy neurons in the memory part of the brain as typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, but in patients with primary progressive aphasia Alzheimer’s the nondominant side of this part of the brain showed less atrophy,” added Dr. Mesulam, who is director of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease at Northwestern University, Chicago. “It appears that these patients are more resilient to the effects of the neurofibrillary tangles.”

The researchers also found that two biomarkers that are established risk factors in typical Alzheimer’s disease do not appear to be risk factors for the primary progressive aphasia (PPA) form of the condition.

“These observations suggest that there are mechanisms that may protect the brain from Alzheimer’s-type damage. Studying these patients with this primary progressive aphasia form of Alzheimer’s disease may give us clues as to where to look for these mechanisms that may lead to new treatments for the memory loss associated with typical Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Mesulam commented.

The study was published online in the Jan. 13 issue of Neurology.

PPA is diagnosed when language impairment emerges on a background of preserved memory and behavior, with about 40% of cases representing atypical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers explained.

“While we knew that the memories of people with primary progressive aphasia were not affected at first, we did not know if they maintained their memory functioning over years,” Dr. Mesulam noted.

The current study aimed to investigate whether the memory preservation in PPA linked to Alzheimer’s disease is a consistent core feature or a transient finding confined to initial presentation, and to explore the underlying pathology of the condition.

The researchers searched their database to identify patients with PPA with autopsy or biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease, who also had at least two consecutive visits during which language and memory assessment had been obtained with the same tests. The study included 17 patients with the PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease who compared with 14 patients who had typical Alzheimer’s disease with memory loss.

The authors pointed out that characterization of memory in patients with PPA is challenging because most tests use word lists, and thus patients may fail the test because of their language impairments. To address this issue, they included patients with PPA who had undergone memory tests involving recalling pictures of common objects.

Patients with typical Alzheimer’s disease underwent similar tests but used a list of common words.

A second round of tests was conducted in the primary progressive aphasia group an average of 2.4 years later and in the typical Alzheimer’s disease group an average of 1.7 years later.

Brain scans were also available for the patients with PPA, as well as postmortem evaluations for eight of the PPA cases and all the typical Alzheimer’s disease cases.

Results showed that patients with PPA had no decline in their memory skills when they took the tests a second time. At that point, they had been showing symptoms of the disorder for an average of 6 years. In contrast, their language skills declined significantly during the same period. For typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, verbal memory and language skills declined with equal severity during the study.

Postmortem results showed that the two groups had comparable degrees of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the medial temporal lobe – the main area of the brain affected in dementia.

However, MRI scans showed that patients with PPA had an asymmetrical atrophy of the dominant (left) hemisphere with sparing of the right sided medial temporal lobe, indicating a lack of neurodegeneration in the nondominant hemisphere, despite the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

It was also found that the patients with PPA had significantly lower prevalence of two factors strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease – TDP-43 pathology and APOE ε4 positivity – than the typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

The authors concluded that “primary progressive aphasia Alzheimer’s syndrome offers unique opportunities for exploring the biological foundations of these phenomena that interactively modulate the impact of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology on cognitive function.”

‘Preservation of cognition is the holy grail’

In an accompanying editorial, Seyed Ahmad Sajjadi, MD, University of California, Irvine; Sharon Ash, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and Stefano Cappa, MD, University School for Advanced Studies, Pavia, Italy, said these findings have important implications, “as ultimately, preservation of cognition is the holy grail of research in this area.”

They pointed out that the current observations imply “an uncoupling of neurodegeneration and pathology” in patients with PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease, adding that “it seems reasonable to conclude that neurodegeneration, and not mere presence of pathology, is what correlates with clinical presentation in these patients.”

The editorialists noted that the study has some limitations: the sample size is relatively small, not all patients with PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease underwent autopsy, MRI was only available for the aphasia group, and the two groups had different memory tests for comparison of their recognition memory.

But they concluded that this study “provides important insights about the potential reasons for differential vulnerability of the neural substrate of memory in those with different clinical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, the Davee Foundation, and the Jeanine Jones Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

They also show some differences in neuropathology to typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, raising hopes of discovering novel mechanisms that might protect against memory loss in typical forms of the disease.

“We are discovering that Alzheimer’s disease has more than one form. While the typical patient with Alzheimer’s disease will have impaired memory, patients with primary progressive aphasia linked to Alzheimer’s disease are quite different. They have problems with language – they know what they want to say but can’t find the words – but their memory is intact,” said lead author Marsel Mesulam, MD.

“We have found that these patients still show the same levels of neurofibrillary tangles which destroy neurons in the memory part of the brain as typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, but in patients with primary progressive aphasia Alzheimer’s the nondominant side of this part of the brain showed less atrophy,” added Dr. Mesulam, who is director of the Mesulam Center for Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer’s Disease at Northwestern University, Chicago. “It appears that these patients are more resilient to the effects of the neurofibrillary tangles.”

The researchers also found that two biomarkers that are established risk factors in typical Alzheimer’s disease do not appear to be risk factors for the primary progressive aphasia (PPA) form of the condition.

“These observations suggest that there are mechanisms that may protect the brain from Alzheimer’s-type damage. Studying these patients with this primary progressive aphasia form of Alzheimer’s disease may give us clues as to where to look for these mechanisms that may lead to new treatments for the memory loss associated with typical Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Mesulam commented.

The study was published online in the Jan. 13 issue of Neurology.

PPA is diagnosed when language impairment emerges on a background of preserved memory and behavior, with about 40% of cases representing atypical manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers explained.

“While we knew that the memories of people with primary progressive aphasia were not affected at first, we did not know if they maintained their memory functioning over years,” Dr. Mesulam noted.

The current study aimed to investigate whether the memory preservation in PPA linked to Alzheimer’s disease is a consistent core feature or a transient finding confined to initial presentation, and to explore the underlying pathology of the condition.

The researchers searched their database to identify patients with PPA with autopsy or biomarker evidence of Alzheimer’s disease, who also had at least two consecutive visits during which language and memory assessment had been obtained with the same tests. The study included 17 patients with the PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease who compared with 14 patients who had typical Alzheimer’s disease with memory loss.

The authors pointed out that characterization of memory in patients with PPA is challenging because most tests use word lists, and thus patients may fail the test because of their language impairments. To address this issue, they included patients with PPA who had undergone memory tests involving recalling pictures of common objects.

Patients with typical Alzheimer’s disease underwent similar tests but used a list of common words.

A second round of tests was conducted in the primary progressive aphasia group an average of 2.4 years later and in the typical Alzheimer’s disease group an average of 1.7 years later.

Brain scans were also available for the patients with PPA, as well as postmortem evaluations for eight of the PPA cases and all the typical Alzheimer’s disease cases.

Results showed that patients with PPA had no decline in their memory skills when they took the tests a second time. At that point, they had been showing symptoms of the disorder for an average of 6 years. In contrast, their language skills declined significantly during the same period. For typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease, verbal memory and language skills declined with equal severity during the study.

Postmortem results showed that the two groups had comparable degrees of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in the medial temporal lobe – the main area of the brain affected in dementia.

However, MRI scans showed that patients with PPA had an asymmetrical atrophy of the dominant (left) hemisphere with sparing of the right sided medial temporal lobe, indicating a lack of neurodegeneration in the nondominant hemisphere, despite the presence of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

It was also found that the patients with PPA had significantly lower prevalence of two factors strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease – TDP-43 pathology and APOE ε4 positivity – than the typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

The authors concluded that “primary progressive aphasia Alzheimer’s syndrome offers unique opportunities for exploring the biological foundations of these phenomena that interactively modulate the impact of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology on cognitive function.”

‘Preservation of cognition is the holy grail’

In an accompanying editorial, Seyed Ahmad Sajjadi, MD, University of California, Irvine; Sharon Ash, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; and Stefano Cappa, MD, University School for Advanced Studies, Pavia, Italy, said these findings have important implications, “as ultimately, preservation of cognition is the holy grail of research in this area.”

They pointed out that the current observations imply “an uncoupling of neurodegeneration and pathology” in patients with PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease, adding that “it seems reasonable to conclude that neurodegeneration, and not mere presence of pathology, is what correlates with clinical presentation in these patients.”

The editorialists noted that the study has some limitations: the sample size is relatively small, not all patients with PPA-type Alzheimer’s disease underwent autopsy, MRI was only available for the aphasia group, and the two groups had different memory tests for comparison of their recognition memory.

But they concluded that this study “provides important insights about the potential reasons for differential vulnerability of the neural substrate of memory in those with different clinical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease pathology.”

The study was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Communication Disorders, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute on Aging, the Davee Foundation, and the Jeanine Jones Fund.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Expert panel addresses gaps in acne guidelines

A distinguished .

“The challenge with acne guidelines is they mainly focus on facial acne and they’re informed by randomized controlled trials which are conducted over a relatively short period of time. Given that acne is a chronic disease, this actually produces a lack of clarity on multiple issues, including things like truncal acne, treatment escalation and de-escalation, maintenance therapy, patient perspective, and longitudinal management,” Alison Layton, MBChB, said in presenting the findings of the Personalizing Acne: Consensus of Experts (PACE) panel at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The PACE panel highlighted two key unmet needs in acne care as the dearth of guidance on how to implement patient-centered management in clinical practice, and the absence of high-quality evidence on how best to handle long-term maintenance therapy: When to initiate it, the best regimens, and when to escalate, switch, or de-escalate it, added Dr. Layton, a dermatologist at Hull York Medical School, Heslington, England, and associate medical director for research and development at Harrogate and District National Health Service Foundation Trust.

Most of the 13 dermatologists on the PACE panel were coauthors of the current U.S., European, or Canadian acne guidelines, so they are closely familiar with the guidelines’ strengths and shortcomings. For example, the American contingent includes Linda Stein Gold, MD, Detroit; Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, New Brunswick, NJ; Julie C. Harper, MD, Birmingham, Ala.; and Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, of Georgia, all members of the work group that created the current American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.

Strong points of the current guidelines are the high-quality, evidence-based recommendations on initial treatment of facial acne. However, a major weakness of existing guidelines is reflected in the fact that well over 40% of patients relapse after acne therapy, and these relapses can significantly impair quality of life and productivity, said Dr. Layton, one of several PACE panelists who coauthored the current European Dermatology Forum acne guidelines.

The PACE panel utilized a modified Delphi approach to reach consensus on their recommendations. Ten panelists rated current practice guidelines as “somewhat useful” for informing long-term management, two dermatologists deemed existing guidelines “not at all useful” in this regard, and one declined to answer the question.

“None of us felt the guidelines were very useful,” Dr. Layton noted.

It will take time, money, and research commitment to generate compelling data on best practices for long-term maintenance therapy for acne. Other areas in sore need of high-quality studies to improve the evidence-based care of acne include the appropriate length of antibiotic therapy for acne and how to effectively combine topical agents with oral antibiotics to support appropriate use of antimicrobials. In the meantime, the PACE group plans to issue interim practical consensus recommendations to beef up existing guidelines.

With regard to practical recommendations to improve patient-centered care, there was strong consensus among the panelists that acne management in certain patient subgroups requires special attention. These subgroups include patients with darker skin phototypes, heavy exercisers, transgender patients and patients with hormonal conditions, pregnant or breast-feeding women, patients with psychiatric issues, and children under age 10.

PACE panelists agreed that a physician-patient discussion about long-term treatment expectations is “paramount” to effective patient-centered management.

“To ensure a positive consultation experience, physicians should prioritize discussion of efficacy expectations, including timelines and treatment duration,” Dr. Layton continued.

Other key topics to address in promoting patient-centered management of acne include discussion of medication adverse effects and tolerability, application technique for topical treatments, the importance of adherence, and recommendations regarding a daily skin care routine, according to the PACE group.

Dr. Layton reported serving as a consultant to Galderma, which funded the PACE project, as well as half a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

A distinguished .

“The challenge with acne guidelines is they mainly focus on facial acne and they’re informed by randomized controlled trials which are conducted over a relatively short period of time. Given that acne is a chronic disease, this actually produces a lack of clarity on multiple issues, including things like truncal acne, treatment escalation and de-escalation, maintenance therapy, patient perspective, and longitudinal management,” Alison Layton, MBChB, said in presenting the findings of the Personalizing Acne: Consensus of Experts (PACE) panel at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The PACE panel highlighted two key unmet needs in acne care as the dearth of guidance on how to implement patient-centered management in clinical practice, and the absence of high-quality evidence on how best to handle long-term maintenance therapy: When to initiate it, the best regimens, and when to escalate, switch, or de-escalate it, added Dr. Layton, a dermatologist at Hull York Medical School, Heslington, England, and associate medical director for research and development at Harrogate and District National Health Service Foundation Trust.

Most of the 13 dermatologists on the PACE panel were coauthors of the current U.S., European, or Canadian acne guidelines, so they are closely familiar with the guidelines’ strengths and shortcomings. For example, the American contingent includes Linda Stein Gold, MD, Detroit; Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, New Brunswick, NJ; Julie C. Harper, MD, Birmingham, Ala.; and Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, of Georgia, all members of the work group that created the current American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.

Strong points of the current guidelines are the high-quality, evidence-based recommendations on initial treatment of facial acne. However, a major weakness of existing guidelines is reflected in the fact that well over 40% of patients relapse after acne therapy, and these relapses can significantly impair quality of life and productivity, said Dr. Layton, one of several PACE panelists who coauthored the current European Dermatology Forum acne guidelines.

The PACE panel utilized a modified Delphi approach to reach consensus on their recommendations. Ten panelists rated current practice guidelines as “somewhat useful” for informing long-term management, two dermatologists deemed existing guidelines “not at all useful” in this regard, and one declined to answer the question.

“None of us felt the guidelines were very useful,” Dr. Layton noted.

It will take time, money, and research commitment to generate compelling data on best practices for long-term maintenance therapy for acne. Other areas in sore need of high-quality studies to improve the evidence-based care of acne include the appropriate length of antibiotic therapy for acne and how to effectively combine topical agents with oral antibiotics to support appropriate use of antimicrobials. In the meantime, the PACE group plans to issue interim practical consensus recommendations to beef up existing guidelines.

With regard to practical recommendations to improve patient-centered care, there was strong consensus among the panelists that acne management in certain patient subgroups requires special attention. These subgroups include patients with darker skin phototypes, heavy exercisers, transgender patients and patients with hormonal conditions, pregnant or breast-feeding women, patients with psychiatric issues, and children under age 10.

PACE panelists agreed that a physician-patient discussion about long-term treatment expectations is “paramount” to effective patient-centered management.

“To ensure a positive consultation experience, physicians should prioritize discussion of efficacy expectations, including timelines and treatment duration,” Dr. Layton continued.

Other key topics to address in promoting patient-centered management of acne include discussion of medication adverse effects and tolerability, application technique for topical treatments, the importance of adherence, and recommendations regarding a daily skin care routine, according to the PACE group.

Dr. Layton reported serving as a consultant to Galderma, which funded the PACE project, as well as half a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

A distinguished .

“The challenge with acne guidelines is they mainly focus on facial acne and they’re informed by randomized controlled trials which are conducted over a relatively short period of time. Given that acne is a chronic disease, this actually produces a lack of clarity on multiple issues, including things like truncal acne, treatment escalation and de-escalation, maintenance therapy, patient perspective, and longitudinal management,” Alison Layton, MBChB, said in presenting the findings of the Personalizing Acne: Consensus of Experts (PACE) panel at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The PACE panel highlighted two key unmet needs in acne care as the dearth of guidance on how to implement patient-centered management in clinical practice, and the absence of high-quality evidence on how best to handle long-term maintenance therapy: When to initiate it, the best regimens, and when to escalate, switch, or de-escalate it, added Dr. Layton, a dermatologist at Hull York Medical School, Heslington, England, and associate medical director for research and development at Harrogate and District National Health Service Foundation Trust.

Most of the 13 dermatologists on the PACE panel were coauthors of the current U.S., European, or Canadian acne guidelines, so they are closely familiar with the guidelines’ strengths and shortcomings. For example, the American contingent includes Linda Stein Gold, MD, Detroit; Hilary E. Baldwin, MD, New Brunswick, NJ; Julie C. Harper, MD, Birmingham, Ala.; and Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, of Georgia, all members of the work group that created the current American Academy of Dermatology guidelines.

Strong points of the current guidelines are the high-quality, evidence-based recommendations on initial treatment of facial acne. However, a major weakness of existing guidelines is reflected in the fact that well over 40% of patients relapse after acne therapy, and these relapses can significantly impair quality of life and productivity, said Dr. Layton, one of several PACE panelists who coauthored the current European Dermatology Forum acne guidelines.

The PACE panel utilized a modified Delphi approach to reach consensus on their recommendations. Ten panelists rated current practice guidelines as “somewhat useful” for informing long-term management, two dermatologists deemed existing guidelines “not at all useful” in this regard, and one declined to answer the question.

“None of us felt the guidelines were very useful,” Dr. Layton noted.

It will take time, money, and research commitment to generate compelling data on best practices for long-term maintenance therapy for acne. Other areas in sore need of high-quality studies to improve the evidence-based care of acne include the appropriate length of antibiotic therapy for acne and how to effectively combine topical agents with oral antibiotics to support appropriate use of antimicrobials. In the meantime, the PACE group plans to issue interim practical consensus recommendations to beef up existing guidelines.

With regard to practical recommendations to improve patient-centered care, there was strong consensus among the panelists that acne management in certain patient subgroups requires special attention. These subgroups include patients with darker skin phototypes, heavy exercisers, transgender patients and patients with hormonal conditions, pregnant or breast-feeding women, patients with psychiatric issues, and children under age 10.

PACE panelists agreed that a physician-patient discussion about long-term treatment expectations is “paramount” to effective patient-centered management.

“To ensure a positive consultation experience, physicians should prioritize discussion of efficacy expectations, including timelines and treatment duration,” Dr. Layton continued.

Other key topics to address in promoting patient-centered management of acne include discussion of medication adverse effects and tolerability, application technique for topical treatments, the importance of adherence, and recommendations regarding a daily skin care routine, according to the PACE group.

Dr. Layton reported serving as a consultant to Galderma, which funded the PACE project, as well as half a dozen other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Colonoscopy prep suggestions for those who hate it

A 61-year-old man is seen for a primary care visit. He has a history of colonic polyps (tubular adenoma) on two previous colonoscopies (at age 50 and 55). He has been on an appropriate 5-year schedule, but is overdue for his colonoscopy. He did not follow up with messages from his gastroenterologist for scheduling his colonoscopy last year. He explains he really hates the whole preparation for colonoscopy, but does realize he needs to follow up, and is willing to do so now. What do you recommend for colonoscopy prep?

A) Diet as usual until 5 p.m. day before, then clear liquid diet. Start GoLYTELY (1 gallon) night before procedure.

B) Low-fiber diet X2 days, clear liquid diet day before procedure, GoLYTELY (1 gallon) night before procedure.

C) Low residue diet X3 days, SUPREP the night before the procedure.

D) Low residue diet X2 days, followed by clear liquid diet the day before the procedure, SUPREP the night before the procedure.

It is common for patients to be reluctant to follow recommendations for colonoscopy due to dreading the prep. I would recommend choice C here, as the least difficult bowel preparation for colonoscopy.

Gastroenterologists are usually the ones to recommend the bowel prep that they want their patients to follow.

Major diet change for several days before colonoscopy is difficult for many patients. Standard advice is that patients eat only low-fiber foods starting 3 days before the procedure. Patients are advised to switch to a completely clear liquid diet 1-2 days before the colonoscopy.

Are there more tolerable diets to offer patients?

Soweid and colleagues randomized 200 patients to a low residue diet for the three meals the day before colonoscopy vs. clear liquid diet.1 The low residue diet allowed patients to eat meat, eggs, cheese, bread, rice, and ice cream. Not surprisingly, patients tolerated the low residue diet better with statistically significantly less nausea, vomiting, weakness, headache, sleep difficulties, and hunger. The patients in the low residue diet group also had better bowel prep than did those in the clear liquid diet group (81% vs. 52%, P less than 0.001).1

In a recent meta- analysis, low residue diets were comparable to clear liquid diets in regard to adequacy of bowel prep and for detection of polyps.2 Patients who followed low residue diets had statistically significantly less headaches, nausea, vomiting, and hunger. Very importantly, patients who followed low residue diets showed an increased willingness to repeat it, compared with those who followed a clear liquid diet (P less than .005; odds ratio, 2.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.28-3.89).2

What alternatives to GoLYTELY exist?

Another part of the bowel prep that patients struggle with is drinking a gallon of GoLYTELY (polyethylene glycol/electrolytes). Drinking that amount of this nasty stuff is never welcome.

There are a number of lower-volume alternatives that are as effective as GoLYTELY. Sarvepalli and colleagues did a retrospective study of 75,874 patients who had a colonoscopy in the Cleveland Clinic health system.3 The choice of bowel prep was not associated with adenoma detection.

Patients who lower volume preparations (2 quarts) SUPREP, MoviPrep, Osmoprep and HalfLytely had varying results of rates of inadequate bowel prep compared with patients who took GoLYTELY. Results for patients taking SUPREP and MoviPrep were statistically significantly better than for patients taking GoLYTELY. Results for patients taking OsmoPrep were not statistically different from those for patients taking GoLYTELY. Rates of inadequate bowel prep were statistically higher, meaning worse, for patients taking HalfLytely vs. patients taking GoLYTELY.3

Gu and colleagues did a prospective study of bowel prep outcomes from 4,339 colonoscopies, involving 75 different endoscopists.4 There was a wide range of bowel preps used, including low- and high-volume bowel preps. The low-volume preparations, SUPREP (P less than .001), MoviPrep (P less than .004) and MiraLAX with Gatorade (P less than .001), were superior to GoLYTELY for bowel cleansing. This was based on scoring via the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale. All were better tolerated than GoLYTELY.

Myth: All patients need a clear liquid diet and GoLYTELY for their bowel prep.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. Soweid AM et al. A randomized single-blind trial of standard diet versus fiber-free diet with polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution for colonoscopy preparation. Endoscopy 2010;42:633-8.

2. Zhang X et al. Low-[residue] diet versus clear-liquid diet for bowel preparation before colonoscopy: meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020 Sep;92(3):508-18.

3. Sarvepalli S et al. Comparative effectiveness of commercial bowel preparations in ambulatory patients presenting for screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2020 Jul 20. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06492-z.

4. Gu P et al. Comparing the real-world effectiveness of competing colonoscopy preparations: results of a prospective trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(2):305-14.

A 61-year-old man is seen for a primary care visit. He has a history of colonic polyps (tubular adenoma) on two previous colonoscopies (at age 50 and 55). He has been on an appropriate 5-year schedule, but is overdue for his colonoscopy. He did not follow up with messages from his gastroenterologist for scheduling his colonoscopy last year. He explains he really hates the whole preparation for colonoscopy, but does realize he needs to follow up, and is willing to do so now. What do you recommend for colonoscopy prep?

A) Diet as usual until 5 p.m. day before, then clear liquid diet. Start GoLYTELY (1 gallon) night before procedure.

B) Low-fiber diet X2 days, clear liquid diet day before procedure, GoLYTELY (1 gallon) night before procedure.

C) Low residue diet X3 days, SUPREP the night before the procedure.

D) Low residue diet X2 days, followed by clear liquid diet the day before the procedure, SUPREP the night before the procedure.

It is common for patients to be reluctant to follow recommendations for colonoscopy due to dreading the prep. I would recommend choice C here, as the least difficult bowel preparation for colonoscopy.

Gastroenterologists are usually the ones to recommend the bowel prep that they want their patients to follow.

Major diet change for several days before colonoscopy is difficult for many patients. Standard advice is that patients eat only low-fiber foods starting 3 days before the procedure. Patients are advised to switch to a completely clear liquid diet 1-2 days before the colonoscopy.

Are there more tolerable diets to offer patients?

Soweid and colleagues randomized 200 patients to a low residue diet for the three meals the day before colonoscopy vs. clear liquid diet.1 The low residue diet allowed patients to eat meat, eggs, cheese, bread, rice, and ice cream. Not surprisingly, patients tolerated the low residue diet better with statistically significantly less nausea, vomiting, weakness, headache, sleep difficulties, and hunger. The patients in the low residue diet group also had better bowel prep than did those in the clear liquid diet group (81% vs. 52%, P less than 0.001).1