User login

'Cardio-obstetrics' tied to better outcome in pregnancy with CVD

A multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team-based care model may help improve cardiovascular care for pregnant women with cardiovascular disease (CVD), according to a recent study.

“We sought to describe clinical characteristics, maternal and fetal outcomes, and cardiovascular readmissions in a cohort of pregnant women with underlying CVD followed by a cardio-obstetrics team,” wrote Ella Magun, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and coauthors. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a retrospective cohort analysis involving 306 pregnant women with CVD, who were treated at a quaternary care hospital in New York City.

They defined cardio-obstetrics as a team-based collaborative approach to maternal care that includes maternal fetal medicine, cardiology, anesthesiology, neonatology, nursing, social work, and pharmacy.

More than half of the women in the cohort (53%) were Hispanic and Latino, and 74% were receiving Medicaid, suggesting low socioeconomic status. Key outcomes of interest were cardiovascular readmissions at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year. Secondary endpoints included maternal death, need for a left ventricular assist device or heart transplantation, and fetal demise.

The most frequently observed forms of CVD were arrhythmias (29%), cardiomyopathy (24%), congenital heart disease (24%), valvular disease (16%), and coronary artery disease (4%). The median Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPREG II) score was 3, and 43% of women had a CARPREG II score of 4 or higher.

After a median follow-up of 2.6 years, the 30-day and 90-day cardiovascular readmission rates were 1.9% and 4.6%, which was lower than the national 30-day postpartum rate of readmission (3.6%). One maternal death (0.3%) occurred within a year of delivery (woman with Eisenmenger syndrome).

“Despite high CARPREG II scores in this patient population, we found low rates of maternal and fetal complications with a low rate of 30- and 90-day readmissions following delivery,” the researchers wrote.

Experts weigh in

“We’re seeing widely increasing interest in the implementation of cardio-obstetrics models for multidisciplinary collaborative care and initial studies suggest these team-based models improve pregnancy and postpartum outcomes for women with cardiac disease,” said Lisa M. Hollier, MD, past president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dr. Magun and colleagues acknowledged that a key limitation of the present study was the retrospective, single-center design.

“With program expansions over the next 2-3 years, I expect to see an increasing number of prospective studies with larger sample sizes evaluating the impact of cardio-obstetrics teams on maternal morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Hollier said.

“These findings suggest that our cardio-obstetrics program may help provide improved cardiovascular care to an otherwise underserved population,” the authors concluded.

In an editorial accompanying the reports, Pamela Ouyang, MBBS, and Garima Sharma, MD, wrote that, although this study wasn’t designed to assess the benefit of cardio-obstetric teams relative to standard of care, its implementation of a multidisciplinary team-based care model showed excellent long-term outcomes.

The importance of coordinated postpartum follow-up with both cardiologists and obstetricians is becoming increasingly recognized, especially for women with poor pregnancy outcomes and with CVD that arises during pregnancy, such as pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection and peripartum cardiomyopathy, wrote Dr. Ouyang and Dr. Sharma, both with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“I’m very excited about the growing recognition of the importance of cardio-obstetrics and the emergence of many of these models of care at various institutions,” Melinda Davis, MD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

“Over the next few years, I expect we will see several studies that show the benefits of the cardio-obstetrics model of care,” she explained. “Multicenter collaboration will be very important for learning about the optimal way to manage high-risk conditions during pregnancy.”

No funding sources were reported. The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Magun E et al. JACC. 2020 Nov 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.071.

A multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team-based care model may help improve cardiovascular care for pregnant women with cardiovascular disease (CVD), according to a recent study.

“We sought to describe clinical characteristics, maternal and fetal outcomes, and cardiovascular readmissions in a cohort of pregnant women with underlying CVD followed by a cardio-obstetrics team,” wrote Ella Magun, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and coauthors. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a retrospective cohort analysis involving 306 pregnant women with CVD, who were treated at a quaternary care hospital in New York City.

They defined cardio-obstetrics as a team-based collaborative approach to maternal care that includes maternal fetal medicine, cardiology, anesthesiology, neonatology, nursing, social work, and pharmacy.

More than half of the women in the cohort (53%) were Hispanic and Latino, and 74% were receiving Medicaid, suggesting low socioeconomic status. Key outcomes of interest were cardiovascular readmissions at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year. Secondary endpoints included maternal death, need for a left ventricular assist device or heart transplantation, and fetal demise.

The most frequently observed forms of CVD were arrhythmias (29%), cardiomyopathy (24%), congenital heart disease (24%), valvular disease (16%), and coronary artery disease (4%). The median Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPREG II) score was 3, and 43% of women had a CARPREG II score of 4 or higher.

After a median follow-up of 2.6 years, the 30-day and 90-day cardiovascular readmission rates were 1.9% and 4.6%, which was lower than the national 30-day postpartum rate of readmission (3.6%). One maternal death (0.3%) occurred within a year of delivery (woman with Eisenmenger syndrome).

“Despite high CARPREG II scores in this patient population, we found low rates of maternal and fetal complications with a low rate of 30- and 90-day readmissions following delivery,” the researchers wrote.

Experts weigh in

“We’re seeing widely increasing interest in the implementation of cardio-obstetrics models for multidisciplinary collaborative care and initial studies suggest these team-based models improve pregnancy and postpartum outcomes for women with cardiac disease,” said Lisa M. Hollier, MD, past president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dr. Magun and colleagues acknowledged that a key limitation of the present study was the retrospective, single-center design.

“With program expansions over the next 2-3 years, I expect to see an increasing number of prospective studies with larger sample sizes evaluating the impact of cardio-obstetrics teams on maternal morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Hollier said.

“These findings suggest that our cardio-obstetrics program may help provide improved cardiovascular care to an otherwise underserved population,” the authors concluded.

In an editorial accompanying the reports, Pamela Ouyang, MBBS, and Garima Sharma, MD, wrote that, although this study wasn’t designed to assess the benefit of cardio-obstetric teams relative to standard of care, its implementation of a multidisciplinary team-based care model showed excellent long-term outcomes.

The importance of coordinated postpartum follow-up with both cardiologists and obstetricians is becoming increasingly recognized, especially for women with poor pregnancy outcomes and with CVD that arises during pregnancy, such as pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection and peripartum cardiomyopathy, wrote Dr. Ouyang and Dr. Sharma, both with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“I’m very excited about the growing recognition of the importance of cardio-obstetrics and the emergence of many of these models of care at various institutions,” Melinda Davis, MD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

“Over the next few years, I expect we will see several studies that show the benefits of the cardio-obstetrics model of care,” she explained. “Multicenter collaboration will be very important for learning about the optimal way to manage high-risk conditions during pregnancy.”

No funding sources were reported. The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Magun E et al. JACC. 2020 Nov 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.071.

A multidisciplinary cardio-obstetrics team-based care model may help improve cardiovascular care for pregnant women with cardiovascular disease (CVD), according to a recent study.

“We sought to describe clinical characteristics, maternal and fetal outcomes, and cardiovascular readmissions in a cohort of pregnant women with underlying CVD followed by a cardio-obstetrics team,” wrote Ella Magun, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and coauthors. Their report is in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The researchers reported the outcomes of a retrospective cohort analysis involving 306 pregnant women with CVD, who were treated at a quaternary care hospital in New York City.

They defined cardio-obstetrics as a team-based collaborative approach to maternal care that includes maternal fetal medicine, cardiology, anesthesiology, neonatology, nursing, social work, and pharmacy.

More than half of the women in the cohort (53%) were Hispanic and Latino, and 74% were receiving Medicaid, suggesting low socioeconomic status. Key outcomes of interest were cardiovascular readmissions at 30 days, 90 days, and 1 year. Secondary endpoints included maternal death, need for a left ventricular assist device or heart transplantation, and fetal demise.

The most frequently observed forms of CVD were arrhythmias (29%), cardiomyopathy (24%), congenital heart disease (24%), valvular disease (16%), and coronary artery disease (4%). The median Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPREG II) score was 3, and 43% of women had a CARPREG II score of 4 or higher.

After a median follow-up of 2.6 years, the 30-day and 90-day cardiovascular readmission rates were 1.9% and 4.6%, which was lower than the national 30-day postpartum rate of readmission (3.6%). One maternal death (0.3%) occurred within a year of delivery (woman with Eisenmenger syndrome).

“Despite high CARPREG II scores in this patient population, we found low rates of maternal and fetal complications with a low rate of 30- and 90-day readmissions following delivery,” the researchers wrote.

Experts weigh in

“We’re seeing widely increasing interest in the implementation of cardio-obstetrics models for multidisciplinary collaborative care and initial studies suggest these team-based models improve pregnancy and postpartum outcomes for women with cardiac disease,” said Lisa M. Hollier, MD, past president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and professor at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

Dr. Magun and colleagues acknowledged that a key limitation of the present study was the retrospective, single-center design.

“With program expansions over the next 2-3 years, I expect to see an increasing number of prospective studies with larger sample sizes evaluating the impact of cardio-obstetrics teams on maternal morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Hollier said.

“These findings suggest that our cardio-obstetrics program may help provide improved cardiovascular care to an otherwise underserved population,” the authors concluded.

In an editorial accompanying the reports, Pamela Ouyang, MBBS, and Garima Sharma, MD, wrote that, although this study wasn’t designed to assess the benefit of cardio-obstetric teams relative to standard of care, its implementation of a multidisciplinary team-based care model showed excellent long-term outcomes.

The importance of coordinated postpartum follow-up with both cardiologists and obstetricians is becoming increasingly recognized, especially for women with poor pregnancy outcomes and with CVD that arises during pregnancy, such as pregnancy-associated spontaneous coronary artery dissection and peripartum cardiomyopathy, wrote Dr. Ouyang and Dr. Sharma, both with Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

“I’m very excited about the growing recognition of the importance of cardio-obstetrics and the emergence of many of these models of care at various institutions,” Melinda Davis, MD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said in an interview.

“Over the next few years, I expect we will see several studies that show the benefits of the cardio-obstetrics model of care,” she explained. “Multicenter collaboration will be very important for learning about the optimal way to manage high-risk conditions during pregnancy.”

No funding sources were reported. The authors of this paper disclosed no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Magun E et al. JACC. 2020 Nov 3. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.071.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Probiotic blend may help patients with GI symptoms

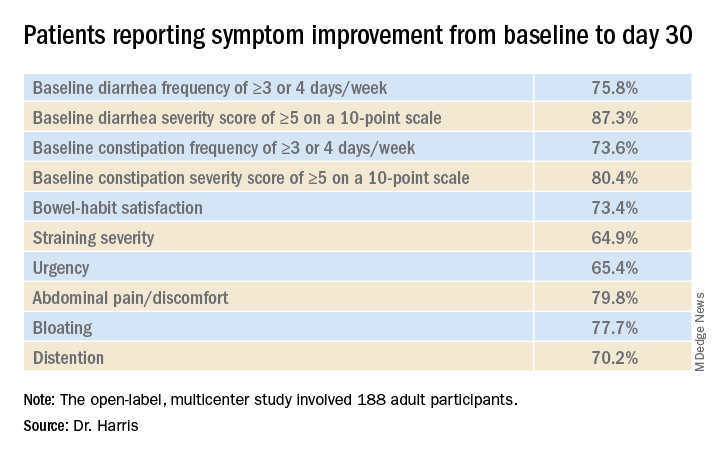

A novel five-strain probiotic blend could provide relief for patients with functional GI disorders, a new study shows.

The combination “improved patient’s functional GI symptoms and displayed a favorable safety profile,” said lead study investigator Lucinda A. Harris, MD, MS, from the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“Results of this study are promising, and additional studies would support the novel probiotic blend’s efficacy, safety, and durability of effect,” said Dr. Harris during her presentation at the virtual American College of Gastroenterology 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Treatment with probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium lactis strains Bl-04, Bi-07, and HN019 and Lactobacillus strains L. acidophilus NCFM and L. paracasei Lpc-37 – administered alone or in multistrain blends – has been shown to improve diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation symptoms in patients with GI disturbances, she reported.

“Multiple pathophysiologic processes may cause functional GI symptoms, including altered gut microbiota,” she said. “The administration of probiotics can impact intestinal microbial balance, thereby contributing to improvement in functional GI symptoms.”

In their study, Dr. Harris and her colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of a five-strain probiotic blend – composed of Bl-04, Bi-07, HN019, NCFM, and Lpc-37 – in people with functional GI disturbances.

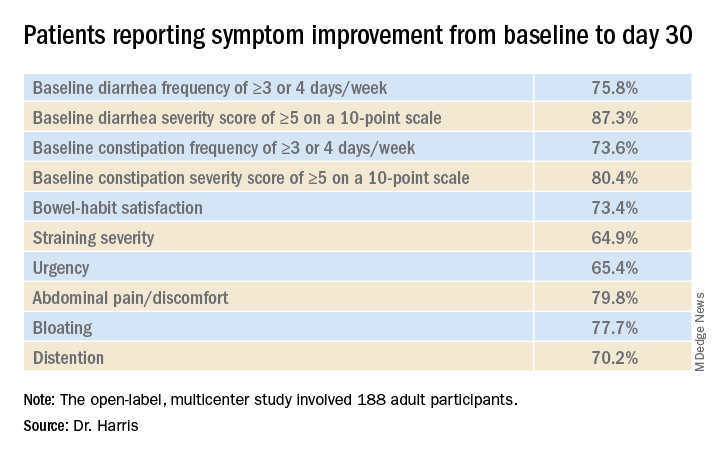

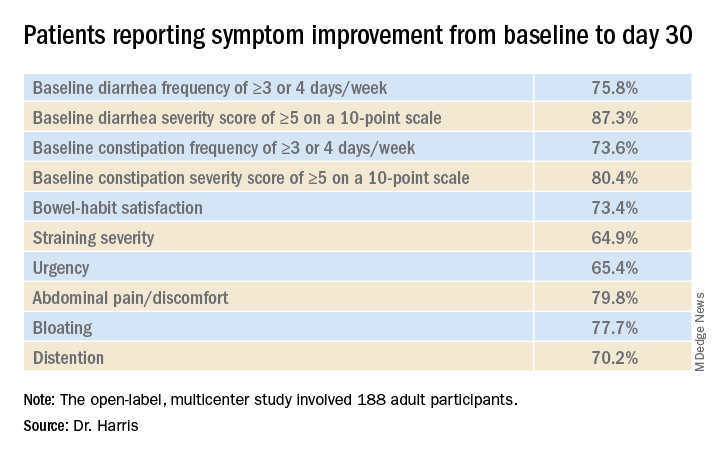

In the open-label, multicenter study, all 188 adult participants (mean age, 44.1 years; 72.3% female) demonstrated symptoms of functional GI disturbances. Each received an oral capsule of the probiotic blend once daily for 30 days.

Patients were assessed at multiple time points: screening (days –15 to –1), baseline (day 1), day 14, day 30, and a follow-up visit (day 42). The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was patient-reported improvement in overall GI well-being at day 30. Secondary outcomes included changes in GI symptoms, assessed with the 11-point GI Health Symptom Questionnaire. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was assessed during all patient visits.

By day 30, 85.1% of patients had achieved the primary endpoint and indicated a positive response when asked about their overall GI well-being. All of the improvements reported at day 30 were generally observed at day 14 as well.

“In addition, we observed a mean decrease in I-FABP [intestinal fatty-acid binding protein] of 32.7% in patients with the highest quartile of baseline I-FABP levels,” Dr. Harris reported.

With respect to tolerability, adverse events were reported by 18.6% of participants and treatment-related adverse events were reported by 8.0%.

“Overall, 35 patients experienced a treatment-emergent adverse event,” she said. “Six patients experienced flatulence and five patients had a cough.” There were no deaths, no serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and no drug-related discontinuations

Placebo effect?

“We know that the biome has a role in modulating a number of physiologic processes, so looking at biomic influence for functional disease makes sense,” said David A. Johnson, MD, from the Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, who was not involved in the study.

However, one of the limitations of this study is the potential for a marked placebo effect, he said in an interview. “When you do an open-label trial in functional diseases, there’s a high placebo rate response. This effect is less pronounced in longer trials, but shorter trials like this one definitely carry the risk of increased placebo responses.”

“Although promising, a randomized control trial evaluating the microbiome as a response to the treatment intervention would be extremely helpful in defining the true role of effect,” he added.

This study was funded by Bausch Health Americas, Inc. Harris reports financial relationships with Allergan, Ironwood, and Takeda. Johnson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships; he writes the Johnson on Gastroenterology blog on Medscape.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel five-strain probiotic blend could provide relief for patients with functional GI disorders, a new study shows.

The combination “improved patient’s functional GI symptoms and displayed a favorable safety profile,” said lead study investigator Lucinda A. Harris, MD, MS, from the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“Results of this study are promising, and additional studies would support the novel probiotic blend’s efficacy, safety, and durability of effect,” said Dr. Harris during her presentation at the virtual American College of Gastroenterology 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Treatment with probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium lactis strains Bl-04, Bi-07, and HN019 and Lactobacillus strains L. acidophilus NCFM and L. paracasei Lpc-37 – administered alone or in multistrain blends – has been shown to improve diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation symptoms in patients with GI disturbances, she reported.

“Multiple pathophysiologic processes may cause functional GI symptoms, including altered gut microbiota,” she said. “The administration of probiotics can impact intestinal microbial balance, thereby contributing to improvement in functional GI symptoms.”

In their study, Dr. Harris and her colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of a five-strain probiotic blend – composed of Bl-04, Bi-07, HN019, NCFM, and Lpc-37 – in people with functional GI disturbances.

In the open-label, multicenter study, all 188 adult participants (mean age, 44.1 years; 72.3% female) demonstrated symptoms of functional GI disturbances. Each received an oral capsule of the probiotic blend once daily for 30 days.

Patients were assessed at multiple time points: screening (days –15 to –1), baseline (day 1), day 14, day 30, and a follow-up visit (day 42). The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was patient-reported improvement in overall GI well-being at day 30. Secondary outcomes included changes in GI symptoms, assessed with the 11-point GI Health Symptom Questionnaire. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was assessed during all patient visits.

By day 30, 85.1% of patients had achieved the primary endpoint and indicated a positive response when asked about their overall GI well-being. All of the improvements reported at day 30 were generally observed at day 14 as well.

“In addition, we observed a mean decrease in I-FABP [intestinal fatty-acid binding protein] of 32.7% in patients with the highest quartile of baseline I-FABP levels,” Dr. Harris reported.

With respect to tolerability, adverse events were reported by 18.6% of participants and treatment-related adverse events were reported by 8.0%.

“Overall, 35 patients experienced a treatment-emergent adverse event,” she said. “Six patients experienced flatulence and five patients had a cough.” There were no deaths, no serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and no drug-related discontinuations

Placebo effect?

“We know that the biome has a role in modulating a number of physiologic processes, so looking at biomic influence for functional disease makes sense,” said David A. Johnson, MD, from the Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, who was not involved in the study.

However, one of the limitations of this study is the potential for a marked placebo effect, he said in an interview. “When you do an open-label trial in functional diseases, there’s a high placebo rate response. This effect is less pronounced in longer trials, but shorter trials like this one definitely carry the risk of increased placebo responses.”

“Although promising, a randomized control trial evaluating the microbiome as a response to the treatment intervention would be extremely helpful in defining the true role of effect,” he added.

This study was funded by Bausch Health Americas, Inc. Harris reports financial relationships with Allergan, Ironwood, and Takeda. Johnson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships; he writes the Johnson on Gastroenterology blog on Medscape.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel five-strain probiotic blend could provide relief for patients with functional GI disorders, a new study shows.

The combination “improved patient’s functional GI symptoms and displayed a favorable safety profile,” said lead study investigator Lucinda A. Harris, MD, MS, from the Mayo Clinic School of Medicine in Scottsdale, Ariz.

“Results of this study are promising, and additional studies would support the novel probiotic blend’s efficacy, safety, and durability of effect,” said Dr. Harris during her presentation at the virtual American College of Gastroenterology 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting.

Treatment with probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium lactis strains Bl-04, Bi-07, and HN019 and Lactobacillus strains L. acidophilus NCFM and L. paracasei Lpc-37 – administered alone or in multistrain blends – has been shown to improve diarrhea, abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation symptoms in patients with GI disturbances, she reported.

“Multiple pathophysiologic processes may cause functional GI symptoms, including altered gut microbiota,” she said. “The administration of probiotics can impact intestinal microbial balance, thereby contributing to improvement in functional GI symptoms.”

In their study, Dr. Harris and her colleagues evaluated the safety and efficacy of a five-strain probiotic blend – composed of Bl-04, Bi-07, HN019, NCFM, and Lpc-37 – in people with functional GI disturbances.

In the open-label, multicenter study, all 188 adult participants (mean age, 44.1 years; 72.3% female) demonstrated symptoms of functional GI disturbances. Each received an oral capsule of the probiotic blend once daily for 30 days.

Patients were assessed at multiple time points: screening (days –15 to –1), baseline (day 1), day 14, day 30, and a follow-up visit (day 42). The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was patient-reported improvement in overall GI well-being at day 30. Secondary outcomes included changes in GI symptoms, assessed with the 11-point GI Health Symptom Questionnaire. The incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events was assessed during all patient visits.

By day 30, 85.1% of patients had achieved the primary endpoint and indicated a positive response when asked about their overall GI well-being. All of the improvements reported at day 30 were generally observed at day 14 as well.

“In addition, we observed a mean decrease in I-FABP [intestinal fatty-acid binding protein] of 32.7% in patients with the highest quartile of baseline I-FABP levels,” Dr. Harris reported.

With respect to tolerability, adverse events were reported by 18.6% of participants and treatment-related adverse events were reported by 8.0%.

“Overall, 35 patients experienced a treatment-emergent adverse event,” she said. “Six patients experienced flatulence and five patients had a cough.” There were no deaths, no serious treatment-emergent adverse events, and no drug-related discontinuations

Placebo effect?

“We know that the biome has a role in modulating a number of physiologic processes, so looking at biomic influence for functional disease makes sense,” said David A. Johnson, MD, from the Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, who was not involved in the study.

However, one of the limitations of this study is the potential for a marked placebo effect, he said in an interview. “When you do an open-label trial in functional diseases, there’s a high placebo rate response. This effect is less pronounced in longer trials, but shorter trials like this one definitely carry the risk of increased placebo responses.”

“Although promising, a randomized control trial evaluating the microbiome as a response to the treatment intervention would be extremely helpful in defining the true role of effect,” he added.

This study was funded by Bausch Health Americas, Inc. Harris reports financial relationships with Allergan, Ironwood, and Takeda. Johnson has disclosed no relevant financial relationships; he writes the Johnson on Gastroenterology blog on Medscape.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 diagnosed on CTA scan in stroke patients

A routine scan used to evaluate some acute stroke patients can also detect SARS-CoV-2 infection in the upper lungs, a new study shows.

“As part of the stroke evaluation workup process, we were able to diagnose COVID-19 at the same time at no extra cost or additional workload,” lead author Charles Esenwa, MD, commented to Medscape Medical News. “This is an objective way to screen for COVID-19 in the acute stroke setting,” he added.

Esenwa is an assistant professor and a stroke neurologist at the Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

He explained that, during the COVID-19 surge earlier this year, assessment of patients with severe acute stroke using computed tomography angiogram (CTA) scans – used to evaluate suitability for endovascular stroke therapy – also showed findings in the upper lung consistent with viral infection in some patients.

“We then assumed that these patients had COVID-19 and took extra precautions to keep them isolated and to protect staff involved in their care. It also allowed us to triage these patients more quickly than waiting for the COVID-19 swab test and arrange the most appropriate care for them,” Esenwa said.

The researchers have now gone back and analyzed their data on acute stroke patients who underwent CTA at their institution during the COVID-19 surge. They found that the changes identified in the lungs were highly specific for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The study was published online on Oct. 29 in Stroke.

“Stroke patients are normally screened for COVID-19 on hospitalization, but the swab test result can take several hours or longer to come back, and it is very useful for us to know if a patient could be infected,” Esenwa noted.

“When we do a CTA, we look at the blood vessels supplying the brain, but the scan also covers the top of the lung, as it starts at the aortic arch. We don’t normally look closely at that area, but we started to notice signs of active lung infection which could have been COVID-19,” he said. “For this paper, we went back to assess how accurate this approach actually was vs. the COVID-19 PCR test.”

The researchers report on 57 patients who presented to three Montefiore Health System hospitals in the Bronx, in New York City, with acute ischemic stroke and who underwent CTA of the head and neck in March and April 2020, the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak there. The patients also underwent PCR testing for COVID-19.

Results showed that 30 patients had a positive COVID-19 test result and that 27 had a negative result. Lung findings highly or very highly suspicious for COVID-19 pneumonia were identified during the CTA scan in 20 (67%) of the COVID-19–positive patients and in two (7%) of the COVID-19–negative patients.

These findings, when used in isolation, yielded a sensitivity of 0.67 and a specificity of 0.93. They had a positive predictive value of 0.19, a negative predictive value of 0.99, and accuracy of 0.92 for the diagnosis of COVID-19.

When apical lung assessment was combined with self-reported clinical symptoms of cough or dyspnea, sensitivity for the diagnosis of COVID-19 for patients presenting to the hospital for acute ischemic stroke increased to 0.83.

“We wondered whether looking at the whole lung would have found better results, but other studies which have done this actually found similar numbers to ours, so we think actually just looking at the top of the lungs, which can be seen in a stroke CTA, may be sufficient,” Esenwa said.

He emphasized the importance of establishing whether an acute stroke patient has COVID-19. “If we had a high suspicion of COVID-19 infection, we would take more precautions during any procedures, such as thrombectomy, and make sure to keep the patient isolated afterwards. It doesn’t necessarily affect the treatment given for stroke, but it affects the safety of the patients and everyone caring for them,” he commented.

Esenwa explained that intubation – which is sometime necessary during thrombectomy – can expose everyone in the room to aerosolized droplets. “So we would take much higher safety precautions if we thought the patient was COVID-19 positive,” he said.

“Early COVID-19 diagnosis also means patients can be given supportive treatment more quickly, admitted to ICU if appropriate, and we can all keep a close eye on pulmonary issues. So having that information is important in many ways,” he added.

Esenwa advises that any medical center that evaluates acute stroke patients for thrombectomy and is experiencing a COVID-19 surge can use this technique as a screening method for COVID-19.

He pointed out that the Montefiore Health System had a very high rate of COVID-19. That part of New York City was one of the worst hit areas of the world, and the CTA approach for identifying COVID-19 has been validated only in areas with such a high local incidence of COVID. If used in an area of lower prevalence, the accuracy would likely be less.

“We don’t know if this approach would work as well at times of low COVID-19 infection, where any lung findings would be more likely to be caused by other conditions, such as pneumonia due to other causes or congestive heart failure. So there would be more false positives,” Esenwa said.

“But when COVID-19 prevalence is high, the lung findings are much more likely to be a sign of COVID-19 infection. As COVID-19 numbers are now rising for a second time, it is likely to become a useful strategy again.”

The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center Institutional Review Board and had no external funding. Esenwa has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A routine scan used to evaluate some acute stroke patients can also detect SARS-CoV-2 infection in the upper lungs, a new study shows.

“As part of the stroke evaluation workup process, we were able to diagnose COVID-19 at the same time at no extra cost or additional workload,” lead author Charles Esenwa, MD, commented to Medscape Medical News. “This is an objective way to screen for COVID-19 in the acute stroke setting,” he added.

Esenwa is an assistant professor and a stroke neurologist at the Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

He explained that, during the COVID-19 surge earlier this year, assessment of patients with severe acute stroke using computed tomography angiogram (CTA) scans – used to evaluate suitability for endovascular stroke therapy – also showed findings in the upper lung consistent with viral infection in some patients.

“We then assumed that these patients had COVID-19 and took extra precautions to keep them isolated and to protect staff involved in their care. It also allowed us to triage these patients more quickly than waiting for the COVID-19 swab test and arrange the most appropriate care for them,” Esenwa said.

The researchers have now gone back and analyzed their data on acute stroke patients who underwent CTA at their institution during the COVID-19 surge. They found that the changes identified in the lungs were highly specific for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The study was published online on Oct. 29 in Stroke.

“Stroke patients are normally screened for COVID-19 on hospitalization, but the swab test result can take several hours or longer to come back, and it is very useful for us to know if a patient could be infected,” Esenwa noted.

“When we do a CTA, we look at the blood vessels supplying the brain, but the scan also covers the top of the lung, as it starts at the aortic arch. We don’t normally look closely at that area, but we started to notice signs of active lung infection which could have been COVID-19,” he said. “For this paper, we went back to assess how accurate this approach actually was vs. the COVID-19 PCR test.”

The researchers report on 57 patients who presented to three Montefiore Health System hospitals in the Bronx, in New York City, with acute ischemic stroke and who underwent CTA of the head and neck in March and April 2020, the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak there. The patients also underwent PCR testing for COVID-19.

Results showed that 30 patients had a positive COVID-19 test result and that 27 had a negative result. Lung findings highly or very highly suspicious for COVID-19 pneumonia were identified during the CTA scan in 20 (67%) of the COVID-19–positive patients and in two (7%) of the COVID-19–negative patients.

These findings, when used in isolation, yielded a sensitivity of 0.67 and a specificity of 0.93. They had a positive predictive value of 0.19, a negative predictive value of 0.99, and accuracy of 0.92 for the diagnosis of COVID-19.

When apical lung assessment was combined with self-reported clinical symptoms of cough or dyspnea, sensitivity for the diagnosis of COVID-19 for patients presenting to the hospital for acute ischemic stroke increased to 0.83.

“We wondered whether looking at the whole lung would have found better results, but other studies which have done this actually found similar numbers to ours, so we think actually just looking at the top of the lungs, which can be seen in a stroke CTA, may be sufficient,” Esenwa said.

He emphasized the importance of establishing whether an acute stroke patient has COVID-19. “If we had a high suspicion of COVID-19 infection, we would take more precautions during any procedures, such as thrombectomy, and make sure to keep the patient isolated afterwards. It doesn’t necessarily affect the treatment given for stroke, but it affects the safety of the patients and everyone caring for them,” he commented.

Esenwa explained that intubation – which is sometime necessary during thrombectomy – can expose everyone in the room to aerosolized droplets. “So we would take much higher safety precautions if we thought the patient was COVID-19 positive,” he said.

“Early COVID-19 diagnosis also means patients can be given supportive treatment more quickly, admitted to ICU if appropriate, and we can all keep a close eye on pulmonary issues. So having that information is important in many ways,” he added.

Esenwa advises that any medical center that evaluates acute stroke patients for thrombectomy and is experiencing a COVID-19 surge can use this technique as a screening method for COVID-19.

He pointed out that the Montefiore Health System had a very high rate of COVID-19. That part of New York City was one of the worst hit areas of the world, and the CTA approach for identifying COVID-19 has been validated only in areas with such a high local incidence of COVID. If used in an area of lower prevalence, the accuracy would likely be less.

“We don’t know if this approach would work as well at times of low COVID-19 infection, where any lung findings would be more likely to be caused by other conditions, such as pneumonia due to other causes or congestive heart failure. So there would be more false positives,” Esenwa said.

“But when COVID-19 prevalence is high, the lung findings are much more likely to be a sign of COVID-19 infection. As COVID-19 numbers are now rising for a second time, it is likely to become a useful strategy again.”

The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center Institutional Review Board and had no external funding. Esenwa has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A routine scan used to evaluate some acute stroke patients can also detect SARS-CoV-2 infection in the upper lungs, a new study shows.

“As part of the stroke evaluation workup process, we were able to diagnose COVID-19 at the same time at no extra cost or additional workload,” lead author Charles Esenwa, MD, commented to Medscape Medical News. “This is an objective way to screen for COVID-19 in the acute stroke setting,” he added.

Esenwa is an assistant professor and a stroke neurologist at the Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City.

He explained that, during the COVID-19 surge earlier this year, assessment of patients with severe acute stroke using computed tomography angiogram (CTA) scans – used to evaluate suitability for endovascular stroke therapy – also showed findings in the upper lung consistent with viral infection in some patients.

“We then assumed that these patients had COVID-19 and took extra precautions to keep them isolated and to protect staff involved in their care. It also allowed us to triage these patients more quickly than waiting for the COVID-19 swab test and arrange the most appropriate care for them,” Esenwa said.

The researchers have now gone back and analyzed their data on acute stroke patients who underwent CTA at their institution during the COVID-19 surge. They found that the changes identified in the lungs were highly specific for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The study was published online on Oct. 29 in Stroke.

“Stroke patients are normally screened for COVID-19 on hospitalization, but the swab test result can take several hours or longer to come back, and it is very useful for us to know if a patient could be infected,” Esenwa noted.

“When we do a CTA, we look at the blood vessels supplying the brain, but the scan also covers the top of the lung, as it starts at the aortic arch. We don’t normally look closely at that area, but we started to notice signs of active lung infection which could have been COVID-19,” he said. “For this paper, we went back to assess how accurate this approach actually was vs. the COVID-19 PCR test.”

The researchers report on 57 patients who presented to three Montefiore Health System hospitals in the Bronx, in New York City, with acute ischemic stroke and who underwent CTA of the head and neck in March and April 2020, the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak there. The patients also underwent PCR testing for COVID-19.

Results showed that 30 patients had a positive COVID-19 test result and that 27 had a negative result. Lung findings highly or very highly suspicious for COVID-19 pneumonia were identified during the CTA scan in 20 (67%) of the COVID-19–positive patients and in two (7%) of the COVID-19–negative patients.

These findings, when used in isolation, yielded a sensitivity of 0.67 and a specificity of 0.93. They had a positive predictive value of 0.19, a negative predictive value of 0.99, and accuracy of 0.92 for the diagnosis of COVID-19.

When apical lung assessment was combined with self-reported clinical symptoms of cough or dyspnea, sensitivity for the diagnosis of COVID-19 for patients presenting to the hospital for acute ischemic stroke increased to 0.83.

“We wondered whether looking at the whole lung would have found better results, but other studies which have done this actually found similar numbers to ours, so we think actually just looking at the top of the lungs, which can be seen in a stroke CTA, may be sufficient,” Esenwa said.

He emphasized the importance of establishing whether an acute stroke patient has COVID-19. “If we had a high suspicion of COVID-19 infection, we would take more precautions during any procedures, such as thrombectomy, and make sure to keep the patient isolated afterwards. It doesn’t necessarily affect the treatment given for stroke, but it affects the safety of the patients and everyone caring for them,” he commented.

Esenwa explained that intubation – which is sometime necessary during thrombectomy – can expose everyone in the room to aerosolized droplets. “So we would take much higher safety precautions if we thought the patient was COVID-19 positive,” he said.

“Early COVID-19 diagnosis also means patients can be given supportive treatment more quickly, admitted to ICU if appropriate, and we can all keep a close eye on pulmonary issues. So having that information is important in many ways,” he added.

Esenwa advises that any medical center that evaluates acute stroke patients for thrombectomy and is experiencing a COVID-19 surge can use this technique as a screening method for COVID-19.

He pointed out that the Montefiore Health System had a very high rate of COVID-19. That part of New York City was one of the worst hit areas of the world, and the CTA approach for identifying COVID-19 has been validated only in areas with such a high local incidence of COVID. If used in an area of lower prevalence, the accuracy would likely be less.

“We don’t know if this approach would work as well at times of low COVID-19 infection, where any lung findings would be more likely to be caused by other conditions, such as pneumonia due to other causes or congestive heart failure. So there would be more false positives,” Esenwa said.

“But when COVID-19 prevalence is high, the lung findings are much more likely to be a sign of COVID-19 infection. As COVID-19 numbers are now rising for a second time, it is likely to become a useful strategy again.”

The study was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center Institutional Review Board and had no external funding. Esenwa has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More mask wearing could save 130,000 US lives by end of February

A cumulative 511,000 lives could be lost from COVID-19 in the United States by the end of February 2021, a new prediction study reveals.

However, if universal mask wearing is adopted — defined as 95% of Americans complying with the protective measure — along with social distancing mandates as warranted, nearly 130,000 of those lives could be saved.

And if even 85% of Americans comply, an additional 95,800 lives would be spared before March of next year, researchers at the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) report.

The study was published online October 23 in Nature Medicine.

“The study is sound and makes the case for mandatory mask policies,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a professor of bioethics at NYU Langone Health in New York City, who frequently provides commentary for Medscape.

Without mandatory mask requirements, he added, “we will see a pandemic slaughter and an overwhelmed healthcare system and workforce.”

The IHME team evaluated COVID-19 data for cases and related deaths between February 1 and September 21. Based on this data, they predicted the likely future of SARS-CoV-2 infections on a state level from September 22, 2020, to February 2021.

An Optimistic Projection

Lead author Robert C. Reiner Jr and colleagues looked at five scenarios. For example, they calculated likely deaths associated with COVID-19 if adoption of mask and social distancing recommendations were nearly universal. They note that Singapore achieved a 95% compliance rate with masks and used this as their “best-case scenario” model.

An estimated 129,574 (range, 85,284–170,867) additional lives could be saved if 95% of Americans wore masks in public, their research reveals. This optimistic scenario includes a “plausible reference” in which any US state reaching 8 COVID-19 deaths per 1 million residents would enact 6 weeks of social distancing mandates (SDMs).

Achieving this level of mask compliance in the United States “could be sufficient to ameliorate the worst effects of epidemic resurgences in many states,” the researchers note.

In contrast, the proportion of Americans wearing masks in public as of September 22 was 49%, according to IHME data.

Universal mask use unlikely

“I’m not a modeling expert, but it is an interesting, and as far as I can judge, well-conducted study which looks, state by state, at what might happen in various scenarios around masking policies going forward — and in particular the effect that mandated masking might have,” Trish Greenhalgh, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

“However, the scenario is a thought experiment. Near-universal mask use is not going to happen in the USA, nor indeed in any individual state, right now, given how emotive the issue has become,” added Greenhalgh, professor in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at Oxford University, UK. She was not affiliated with the study.

“Hence, whilst I am broadly supportive of the science,” she said, “I’m not confident that this paper will be able to change policy.”

Other ‘What if?’ scenarios

The authors also predicted the mortality implications associated with lower adherence to masks, the presence or absence of SDMs, and what could happen if mandates continue to ease at their current rate.

For example, they considered a scenario with less-than-universal mask use in public, 85%, along with SDMs being reinstated based on the mortality rate threshold. In this instance, they found an additional 95,814 (range, 60,731–133,077) lives could be spared by February 28.

Another calculation looked at outcomes if 95% of Americans wore masks going forward without states instituting SDMs at any point. In this case, the researchers predict that 490,437 Americans would die from COVID-19 by February 2021.

A fourth analysis revealed what would happen without greater mask use if the mortality threshold triggered 6 weeks of SDMs as warranted. Under this ‘plausible reference’ calculation, a total 511,373 Americans would die from COVID-19 by the end of February.

A fifth scenario predicted potential mortality if states continue easing SDMs at the current pace. “This is an alternative scenario to the more probable situation where states are expected to respond to an impending health crisis by reinstating some SDMs,” the authors note. The predicted number of American deaths appears more dire in this calculation. The investigators predict cumulative total deaths could reach 1,053,206 (range, 759,693–1,452,397) by the end of February 2021.

The death toll would likely vary among states in this scenario. California, Florida, and Pennsylvania would like account for approximately one third of all deaths.

All the modeling scenarios considered other factors including pneumonia seasonality, mobility, testing rates, and mask use per capita.

“I have seen the IHME study and I agree with the broad conclusions,” Richard Stutt, PhD, of the Epidemiology and Modelling Group at the University of Cambridge, UK, told Medscape Medical News.

“Case numbers are climbing in the US, and without further intervention, there will be a significant number of deaths over the coming months,” he said.

Masks are low cost and widely available, Stutt said. “I am hopeful that even if masks are not widely adopted, we will not see as many deaths as predicted here, as these outbreaks can be significantly reduced by increased social distancing or lockdowns.”

“However this comes at a far higher economic cost than the use of masks, and still requires action,” added Stutt, who authored a study in June that modeled facemasks in combination with “lock-down” measures for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Modeling study results depend on the assumptions researchers make, and the IHME team rightly tested a number of different assumptions, Greenhalgh said.

“The key conclusion,” she added, “is here: ‘The implementation of SDMs as soon as individual states reach a threshold of 8 daily deaths per million could dramatically ameliorate the effects of the disease; achieving near-universal mask use could delay, or in many states, possibly prevent, this threshold from being reached and has the potential to save the most lives while minimizing damage to the economy.’ “

“This is a useful piece of information and I think is borne out by their data,” added Greenhalgh, lead author of an April study on face masks for the public during the pandemic.

You can visit the IHME website for the most current mortality projections.

Caplan, Greenhalgh, and Stutt have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A cumulative 511,000 lives could be lost from COVID-19 in the United States by the end of February 2021, a new prediction study reveals.

However, if universal mask wearing is adopted — defined as 95% of Americans complying with the protective measure — along with social distancing mandates as warranted, nearly 130,000 of those lives could be saved.

And if even 85% of Americans comply, an additional 95,800 lives would be spared before March of next year, researchers at the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) report.

The study was published online October 23 in Nature Medicine.

“The study is sound and makes the case for mandatory mask policies,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a professor of bioethics at NYU Langone Health in New York City, who frequently provides commentary for Medscape.

Without mandatory mask requirements, he added, “we will see a pandemic slaughter and an overwhelmed healthcare system and workforce.”

The IHME team evaluated COVID-19 data for cases and related deaths between February 1 and September 21. Based on this data, they predicted the likely future of SARS-CoV-2 infections on a state level from September 22, 2020, to February 2021.

An Optimistic Projection

Lead author Robert C. Reiner Jr and colleagues looked at five scenarios. For example, they calculated likely deaths associated with COVID-19 if adoption of mask and social distancing recommendations were nearly universal. They note that Singapore achieved a 95% compliance rate with masks and used this as their “best-case scenario” model.

An estimated 129,574 (range, 85,284–170,867) additional lives could be saved if 95% of Americans wore masks in public, their research reveals. This optimistic scenario includes a “plausible reference” in which any US state reaching 8 COVID-19 deaths per 1 million residents would enact 6 weeks of social distancing mandates (SDMs).

Achieving this level of mask compliance in the United States “could be sufficient to ameliorate the worst effects of epidemic resurgences in many states,” the researchers note.

In contrast, the proportion of Americans wearing masks in public as of September 22 was 49%, according to IHME data.

Universal mask use unlikely

“I’m not a modeling expert, but it is an interesting, and as far as I can judge, well-conducted study which looks, state by state, at what might happen in various scenarios around masking policies going forward — and in particular the effect that mandated masking might have,” Trish Greenhalgh, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

“However, the scenario is a thought experiment. Near-universal mask use is not going to happen in the USA, nor indeed in any individual state, right now, given how emotive the issue has become,” added Greenhalgh, professor in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at Oxford University, UK. She was not affiliated with the study.

“Hence, whilst I am broadly supportive of the science,” she said, “I’m not confident that this paper will be able to change policy.”

Other ‘What if?’ scenarios

The authors also predicted the mortality implications associated with lower adherence to masks, the presence or absence of SDMs, and what could happen if mandates continue to ease at their current rate.

For example, they considered a scenario with less-than-universal mask use in public, 85%, along with SDMs being reinstated based on the mortality rate threshold. In this instance, they found an additional 95,814 (range, 60,731–133,077) lives could be spared by February 28.

Another calculation looked at outcomes if 95% of Americans wore masks going forward without states instituting SDMs at any point. In this case, the researchers predict that 490,437 Americans would die from COVID-19 by February 2021.

A fourth analysis revealed what would happen without greater mask use if the mortality threshold triggered 6 weeks of SDMs as warranted. Under this ‘plausible reference’ calculation, a total 511,373 Americans would die from COVID-19 by the end of February.

A fifth scenario predicted potential mortality if states continue easing SDMs at the current pace. “This is an alternative scenario to the more probable situation where states are expected to respond to an impending health crisis by reinstating some SDMs,” the authors note. The predicted number of American deaths appears more dire in this calculation. The investigators predict cumulative total deaths could reach 1,053,206 (range, 759,693–1,452,397) by the end of February 2021.

The death toll would likely vary among states in this scenario. California, Florida, and Pennsylvania would like account for approximately one third of all deaths.

All the modeling scenarios considered other factors including pneumonia seasonality, mobility, testing rates, and mask use per capita.

“I have seen the IHME study and I agree with the broad conclusions,” Richard Stutt, PhD, of the Epidemiology and Modelling Group at the University of Cambridge, UK, told Medscape Medical News.

“Case numbers are climbing in the US, and without further intervention, there will be a significant number of deaths over the coming months,” he said.

Masks are low cost and widely available, Stutt said. “I am hopeful that even if masks are not widely adopted, we will not see as many deaths as predicted here, as these outbreaks can be significantly reduced by increased social distancing or lockdowns.”

“However this comes at a far higher economic cost than the use of masks, and still requires action,” added Stutt, who authored a study in June that modeled facemasks in combination with “lock-down” measures for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Modeling study results depend on the assumptions researchers make, and the IHME team rightly tested a number of different assumptions, Greenhalgh said.

“The key conclusion,” she added, “is here: ‘The implementation of SDMs as soon as individual states reach a threshold of 8 daily deaths per million could dramatically ameliorate the effects of the disease; achieving near-universal mask use could delay, or in many states, possibly prevent, this threshold from being reached and has the potential to save the most lives while minimizing damage to the economy.’ “

“This is a useful piece of information and I think is borne out by their data,” added Greenhalgh, lead author of an April study on face masks for the public during the pandemic.

You can visit the IHME website for the most current mortality projections.

Caplan, Greenhalgh, and Stutt have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A cumulative 511,000 lives could be lost from COVID-19 in the United States by the end of February 2021, a new prediction study reveals.

However, if universal mask wearing is adopted — defined as 95% of Americans complying with the protective measure — along with social distancing mandates as warranted, nearly 130,000 of those lives could be saved.

And if even 85% of Americans comply, an additional 95,800 lives would be spared before March of next year, researchers at the University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) report.

The study was published online October 23 in Nature Medicine.

“The study is sound and makes the case for mandatory mask policies,” said Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a professor of bioethics at NYU Langone Health in New York City, who frequently provides commentary for Medscape.

Without mandatory mask requirements, he added, “we will see a pandemic slaughter and an overwhelmed healthcare system and workforce.”

The IHME team evaluated COVID-19 data for cases and related deaths between February 1 and September 21. Based on this data, they predicted the likely future of SARS-CoV-2 infections on a state level from September 22, 2020, to February 2021.

An Optimistic Projection

Lead author Robert C. Reiner Jr and colleagues looked at five scenarios. For example, they calculated likely deaths associated with COVID-19 if adoption of mask and social distancing recommendations were nearly universal. They note that Singapore achieved a 95% compliance rate with masks and used this as their “best-case scenario” model.

An estimated 129,574 (range, 85,284–170,867) additional lives could be saved if 95% of Americans wore masks in public, their research reveals. This optimistic scenario includes a “plausible reference” in which any US state reaching 8 COVID-19 deaths per 1 million residents would enact 6 weeks of social distancing mandates (SDMs).

Achieving this level of mask compliance in the United States “could be sufficient to ameliorate the worst effects of epidemic resurgences in many states,” the researchers note.

In contrast, the proportion of Americans wearing masks in public as of September 22 was 49%, according to IHME data.

Universal mask use unlikely

“I’m not a modeling expert, but it is an interesting, and as far as I can judge, well-conducted study which looks, state by state, at what might happen in various scenarios around masking policies going forward — and in particular the effect that mandated masking might have,” Trish Greenhalgh, MD, told Medscape Medical News.

“However, the scenario is a thought experiment. Near-universal mask use is not going to happen in the USA, nor indeed in any individual state, right now, given how emotive the issue has become,” added Greenhalgh, professor in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences at Oxford University, UK. She was not affiliated with the study.

“Hence, whilst I am broadly supportive of the science,” she said, “I’m not confident that this paper will be able to change policy.”

Other ‘What if?’ scenarios

The authors also predicted the mortality implications associated with lower adherence to masks, the presence or absence of SDMs, and what could happen if mandates continue to ease at their current rate.

For example, they considered a scenario with less-than-universal mask use in public, 85%, along with SDMs being reinstated based on the mortality rate threshold. In this instance, they found an additional 95,814 (range, 60,731–133,077) lives could be spared by February 28.

Another calculation looked at outcomes if 95% of Americans wore masks going forward without states instituting SDMs at any point. In this case, the researchers predict that 490,437 Americans would die from COVID-19 by February 2021.

A fourth analysis revealed what would happen without greater mask use if the mortality threshold triggered 6 weeks of SDMs as warranted. Under this ‘plausible reference’ calculation, a total 511,373 Americans would die from COVID-19 by the end of February.

A fifth scenario predicted potential mortality if states continue easing SDMs at the current pace. “This is an alternative scenario to the more probable situation where states are expected to respond to an impending health crisis by reinstating some SDMs,” the authors note. The predicted number of American deaths appears more dire in this calculation. The investigators predict cumulative total deaths could reach 1,053,206 (range, 759,693–1,452,397) by the end of February 2021.

The death toll would likely vary among states in this scenario. California, Florida, and Pennsylvania would like account for approximately one third of all deaths.

All the modeling scenarios considered other factors including pneumonia seasonality, mobility, testing rates, and mask use per capita.

“I have seen the IHME study and I agree with the broad conclusions,” Richard Stutt, PhD, of the Epidemiology and Modelling Group at the University of Cambridge, UK, told Medscape Medical News.

“Case numbers are climbing in the US, and without further intervention, there will be a significant number of deaths over the coming months,” he said.

Masks are low cost and widely available, Stutt said. “I am hopeful that even if masks are not widely adopted, we will not see as many deaths as predicted here, as these outbreaks can be significantly reduced by increased social distancing or lockdowns.”

“However this comes at a far higher economic cost than the use of masks, and still requires action,” added Stutt, who authored a study in June that modeled facemasks in combination with “lock-down” measures for managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Modeling study results depend on the assumptions researchers make, and the IHME team rightly tested a number of different assumptions, Greenhalgh said.

“The key conclusion,” she added, “is here: ‘The implementation of SDMs as soon as individual states reach a threshold of 8 daily deaths per million could dramatically ameliorate the effects of the disease; achieving near-universal mask use could delay, or in many states, possibly prevent, this threshold from being reached and has the potential to save the most lives while minimizing damage to the economy.’ “

“This is a useful piece of information and I think is borne out by their data,” added Greenhalgh, lead author of an April study on face masks for the public during the pandemic.

You can visit the IHME website for the most current mortality projections.

Caplan, Greenhalgh, and Stutt have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Novel ‘Wingman’ program cuts suicide risk in Air Force members

A novel program that strengthens bonds, boosts morale, and encourages supportive networks among US Air Force personnel cuts suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms after 1 month, new research shows.

The so-called Wingman-Connect initiative also had a beneficial impact on work performance, and the benefits were apparent at 6-month follow-up.

“This study suggests that group training can teach skills that help with occupational functioning and reduce the likelihood of experiencing elevated depression and suicidal ideation, at least in the short term,” lead author Peter A. Wyman, PhD, professor, department of psychiatry, University of Rochester, New York, told Medscape Medical News.

The study was published online Oct. 21 in JAMA Network Open.

Significant rise in suicide rates

Suicide rates among active duty military populations have increased “significantly” in the past 15 years and have exceeded rates for the general population when comparing groups of the same age and gender, said Wyman.

The study included new personnel who were taking classes at a single training center between October 2017 and October 2019.

The Wingman-Connect intervention involved three 2-hour blocks of group classes that focused on building skills in areas such as healthy relationships and maintaining balance. Group exercises emphasized cohesion, shared purpose, and the value of a healthy unit.

Participants in the stress management group received an overview of the stress response system, information on the effect of stress on health, and cognitive and behavioral strategies to reduce stress.

Primary outcomes included the scores on the suicide scale and the depression inventory of the Computerized Adaptive Test for Mental Health.

The study included 1,485 participants (82.3% men; mean age, 20.9 years). At the 1-month follow-up, participants in Wingman-Connect classes reported less severe suicidal ideation (effect size, −0.23; 95% confidence interval, −39 to −0.09; P = .001) and depressive symptoms (ES, −0.24; 95% CI, −0.41 to −0.08; P = .002).

Unlike most suicide prevention programs, the Wingman intervention didn’t target only high-risk participants. “You’d expect smaller effect sizes” because many people were already doing well, said Wyman.

He noted that the effects at 1 month were similar to other state-of-the-art prevention programs.

Another primary endpoint was self-reported occupational impairment. A poor outcome here, said Wyman, could mean having to repeat a class or falling short of expectations behaviorally or academically.

Investigators found a 50% reduction – from approximately 10% to 5% – among the participants in the Wingman-Connect group who had occupational problems or performance concerns, said Wyman.

About 84% of participants in both study arms participated in the 6-month follow-up. At this time point, Wingman-Connect participants reported significantly lower depressive symptoms (ES, −0.16; 95% CI, −0.34 to −0.02; P = .03), but suicidal ideation severity scores were not significantly lower (ES, −0.13; 95% CI, −0.29 to 0.01; P = .06).

Universally beneficial

A beneficial effect on occupational problems was not evident after 6 months. This suggests that this type of training should be continued in later stages of military careers, said Wyman.

“This is not a one-time inoculation that will likely prevent all future problems,” he said.

Study participants experienced improvements in protective factors such as cohesion, morale, and bonds to classmates. The program was also associated with reduced anxiety and anger.

Overall, the Wingman-Connect group was about 20% less likely than the stress management group to report elevated depression at either follow-up period. In addition, on average, participants in the active intervention group were 19% less likely to have elevated suicidal ideation scores, although the difference was not significant.

The “logical interpretation” of this lack of statistical significance is that because depression was more common than suicidal ideation, “the intervention could have a slightly larger and more lasting effect on depression,” said Wyman.

There was no indication that men or women or those who started out at higher risk experienced greater benefit.

“Overall, the effects seemed to be distributed across airmen, independent of how they started,” said Wyman.

Wyman emphasized the unique nature of the Wingman-Connect program. “It’s universal prevention for all airmen – for those thriving and those struggling,” he said.

“We don’t know who necessarily will become at risk later on, or 6 months later, so it’s important to provide this kind of training for everyone.”

The “key mechanism” by which the program may prevent mental health problems is use of “units of military people working together day to day,” said Wyman.

The study did not reveal whether the intervention reduced suicidal behavior. This, say the authors, will need to be determined in future studies, as will determining which personnel are most likely to benefit.

A ‘particular challenge’

In an accompanying editorial, Roy H. Perlis, MD, department of psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and Stephan D. Fihn, MD, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, noted that suicide represents a “particular challenge” in the military.

This is “because soldiers are placed in extremely stressful situations, often without adequate physical or emotional support.”

The new study “adds to a literature that group-based interventions are effective in reducing depressive symptoms and may have advantages in resource-constrained environments,” they write.

Perlis and Finn note that it remains to be seen whether targeted strategies to reduce suicide “are worthwhile, rather than simply developing better treatments for depression.”

Commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, former military psychiatrist and chair of the department of psychiatry, Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., said the study “is based on quite a sound premise.”

Ritchie referred to the “long history” of research “repeatedly showing that units with good cohesion and morale have fewer difficulties of all kinds.”

However, the current study didn’t investigate the “converse of that,” said Ritchie. “There’s a high likelihood for suicidal ideation among those who are expelled” from the unit for various reasons.

Ritchie noted that a variety of different prevention initiatives have been launched in all military services over the years.

“Often, they have worked for a little while when there’s a champion behind them and there’s a lot of enthusiasm, and then they kind of fade out,” she said.

Ritchie agreed that such initiatives should continue throughout a person’s military career. She noted that suicide risk is elevated during periods of transition, for example, “leaving training base and going to your first duty station,” as well as when approaching retirement.

She appreciated the universal nature of the approach used in the study.

“Often, suicides are in those who have not been identified as high risk,” she said. However, she questioned whether the study’s follow-up period was long enough.

The study was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Wyman, Perlis, and Cameron have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A novel program that strengthens bonds, boosts morale, and encourages supportive networks among US Air Force personnel cuts suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms after 1 month, new research shows.

The so-called Wingman-Connect initiative also had a beneficial impact on work performance, and the benefits were apparent at 6-month follow-up.

“This study suggests that group training can teach skills that help with occupational functioning and reduce the likelihood of experiencing elevated depression and suicidal ideation, at least in the short term,” lead author Peter A. Wyman, PhD, professor, department of psychiatry, University of Rochester, New York, told Medscape Medical News.

The study was published online Oct. 21 in JAMA Network Open.

Significant rise in suicide rates

Suicide rates among active duty military populations have increased “significantly” in the past 15 years and have exceeded rates for the general population when comparing groups of the same age and gender, said Wyman.

The study included new personnel who were taking classes at a single training center between October 2017 and October 2019.

The Wingman-Connect intervention involved three 2-hour blocks of group classes that focused on building skills in areas such as healthy relationships and maintaining balance. Group exercises emphasized cohesion, shared purpose, and the value of a healthy unit.

Participants in the stress management group received an overview of the stress response system, information on the effect of stress on health, and cognitive and behavioral strategies to reduce stress.

Primary outcomes included the scores on the suicide scale and the depression inventory of the Computerized Adaptive Test for Mental Health.

The study included 1,485 participants (82.3% men; mean age, 20.9 years). At the 1-month follow-up, participants in Wingman-Connect classes reported less severe suicidal ideation (effect size, −0.23; 95% confidence interval, −39 to −0.09; P = .001) and depressive symptoms (ES, −0.24; 95% CI, −0.41 to −0.08; P = .002).

Unlike most suicide prevention programs, the Wingman intervention didn’t target only high-risk participants. “You’d expect smaller effect sizes” because many people were already doing well, said Wyman.

He noted that the effects at 1 month were similar to other state-of-the-art prevention programs.

Another primary endpoint was self-reported occupational impairment. A poor outcome here, said Wyman, could mean having to repeat a class or falling short of expectations behaviorally or academically.

Investigators found a 50% reduction – from approximately 10% to 5% – among the participants in the Wingman-Connect group who had occupational problems or performance concerns, said Wyman.

About 84% of participants in both study arms participated in the 6-month follow-up. At this time point, Wingman-Connect participants reported significantly lower depressive symptoms (ES, −0.16; 95% CI, −0.34 to −0.02; P = .03), but suicidal ideation severity scores were not significantly lower (ES, −0.13; 95% CI, −0.29 to 0.01; P = .06).

Universally beneficial

A beneficial effect on occupational problems was not evident after 6 months. This suggests that this type of training should be continued in later stages of military careers, said Wyman.

“This is not a one-time inoculation that will likely prevent all future problems,” he said.

Study participants experienced improvements in protective factors such as cohesion, morale, and bonds to classmates. The program was also associated with reduced anxiety and anger.

Overall, the Wingman-Connect group was about 20% less likely than the stress management group to report elevated depression at either follow-up period. In addition, on average, participants in the active intervention group were 19% less likely to have elevated suicidal ideation scores, although the difference was not significant.

The “logical interpretation” of this lack of statistical significance is that because depression was more common than suicidal ideation, “the intervention could have a slightly larger and more lasting effect on depression,” said Wyman.

There was no indication that men or women or those who started out at higher risk experienced greater benefit.

“Overall, the effects seemed to be distributed across airmen, independent of how they started,” said Wyman.

Wyman emphasized the unique nature of the Wingman-Connect program. “It’s universal prevention for all airmen – for those thriving and those struggling,” he said.

“We don’t know who necessarily will become at risk later on, or 6 months later, so it’s important to provide this kind of training for everyone.”

The “key mechanism” by which the program may prevent mental health problems is use of “units of military people working together day to day,” said Wyman.

The study did not reveal whether the intervention reduced suicidal behavior. This, say the authors, will need to be determined in future studies, as will determining which personnel are most likely to benefit.

A ‘particular challenge’

In an accompanying editorial, Roy H. Perlis, MD, department of psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, and Stephan D. Fihn, MD, department of medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, noted that suicide represents a “particular challenge” in the military.

This is “because soldiers are placed in extremely stressful situations, often without adequate physical or emotional support.”

The new study “adds to a literature that group-based interventions are effective in reducing depressive symptoms and may have advantages in resource-constrained environments,” they write.

Perlis and Finn note that it remains to be seen whether targeted strategies to reduce suicide “are worthwhile, rather than simply developing better treatments for depression.”

Commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, former military psychiatrist and chair of the department of psychiatry, Medstar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, D.C., said the study “is based on quite a sound premise.”

Ritchie referred to the “long history” of research “repeatedly showing that units with good cohesion and morale have fewer difficulties of all kinds.”

However, the current study didn’t investigate the “converse of that,” said Ritchie. “There’s a high likelihood for suicidal ideation among those who are expelled” from the unit for various reasons.

Ritchie noted that a variety of different prevention initiatives have been launched in all military services over the years.

“Often, they have worked for a little while when there’s a champion behind them and there’s a lot of enthusiasm, and then they kind of fade out,” she said.

Ritchie agreed that such initiatives should continue throughout a person’s military career. She noted that suicide risk is elevated during periods of transition, for example, “leaving training base and going to your first duty station,” as well as when approaching retirement.

She appreciated the universal nature of the approach used in the study.

“Often, suicides are in those who have not been identified as high risk,” she said. However, she questioned whether the study’s follow-up period was long enough.

The study was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs. Wyman, Perlis, and Cameron have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.