User login

Helping patients process sexual harassment

Years ago, after the revelation of sexual predations of male members of the U.S. Navy upon their female underlings, the Navy announced a “zero tolerance” policy. I, then the chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Women, was invited to address a meeting of top Naval officers. They seemed dismayed when I told them that zero tolerance was just the beginning. Declarations that certain behaviors are unacceptable are facile, flimsy, and ultimately disingenuous substitutes for the infinitely more difficult task of monitoring and policing forbidden behaviors and protecting potential and actual victims.

The United States, I pointed out, has a zero tolerance policy on murder but still has to maintain a large force of police officers, detectives, judges, and prison guards to enforce that policy. The Navy had to have a similar approach to sexual assaults. Judging from the recent reports of female members of the military, that hasn’t happened.

Clarity in the law

Unwanted physical intrusion by one adult on another is against the law in the United States. Then why do we need laws specifically banning rape? In addition to the fact that rape, unlike any other assault, can result in conception, sexual assault is recognized as a particularly and uniquely evil and damaging invasion and degradation.

Although there are cultural differences about responsibility for rape, and whether marriage obviates a woman’s right to refuse sexual contact, there is little or no dispute about the need to recognize rape as a distinct, degrading, and particularly heinous attack. It is, therefore, no surprise that people who are raped feel soiled, shamed, and degraded. Those feelings are exacerbated by centuries of shifting responsibility for sexual assault, whether forced intercourse or other unwanted sexual behavior, from the perpetrator onto the victim.

The shifting of blame has been rejected in theory, but it very much persists in actuality. Who among us does not wonder how the victim was dressed or why (s)he was on that street, at that party, in that man’s room? Other forms of harassment echo the motivations of rape – to demonstrate the unanswerable power to degrade – and result in similar psychological responses.

The recent media revelations have lumped physical assault together with unwanted touching, sexual acts undergone as a result of psychological coercion, unwanted exposure to perpetrators’ genitalia and masturbation, and offensive sexual requests and comments. All of those acts are wrong, but they are not equivalent. An elderly man in a wheelchair grabbing an adult woman’s buttocks is not in the same category as an adult man sexually assaulting an underage girl.

What is the genesis of all this misbehavior? It’s not just about sex; it’s about sex and power. For many men, bragging about sexual conquests and making derogatory remarks about women’s physical appearance demonstrate machismo – define maleness.

It is not surprising that such comments are called “locker room talk”; sports are macho displays as well. Physically violating sexual boundaries is just the talk put into action. And macho works. Last November, more than 40% of female voters in the United States voted for the candidate who reportedly cheated on at least one of his three wives, bragged about unwanted sexual assault, and has been credibly accused of many other illegal and/or inappropriate behaviors.

Where does it end?

What is going to be the result of all this hullabaloo? The list of convincingly accused perpetrators grows by the day. Sexism and sexual misbehavior are endemic in every sphere of human endeavor, up to and including, of course, the clergy, who are meant to be models and protectors of virtue. The scope of recent revelations may be unusual, but revelations about one sector or another have happened every few years: the military, clergy, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, academia. What would happen if all the sexual misbehavior were to be revealed, and the perpetrators removed from their leadership and management positions? Would we have a film industry, a financial industry, a legislature? I saw a headline somewhere: “He’s always indispensable; you never are.” The argument, or myth, of indispensability is a powerful protection for powerful individuals. The powerful are too powerful to tolerate mass expulsions. Already, Congress has resorted to the time-honored and demonstrably useless response: training. Others among the accused report that they are undergoing treatment of sex addiction, a diagnosis our profession has wisely discarded, and for which there was no effective treatment.

Sex, while not addictive, does have a role in sexual misbehavior. Through the ages, women’s reproductive hormones have been a focus of social and medical attention, as the source of unpleasant behaviors, and, in fact, psychopathology: premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression. Little or no attention has been paid to the problematic psychosocial effects of male reproductive hormones. In addition to the offensive behaviors currently in the headlines, there is the behavior of adolescent males. Isn’t reckless driving related to the pubertal influx of testosterone (Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30[3]:319-45)? This gender discrepancy deserves scientific and social attention.

What can psychiatrists do to help women (and men) who are affected by sexual misbehavior? This is a difficult problem. What would help most victims, of any injustice, most would be to confront those responsible, and see them removed from positions of power and otherwise punished. However, the recent reports of seemingly swift and severe responses are misleading. The responsible journalists who have reported these cases have, in most cases, devoted months to finding victimized women, persuading them to go public, and corroborating their accounts. The perpetrators, even when complaints have been made, have gone unpunished, and often been promoted, for years or even decades. Women who complain often are subject to employer retaliation.

So a treating psychiatrist is left with less-than-satisfactory recommendations and responses. The most important intervention is to identify and counter the patient’s inaccurate and damaging assumptions: that she was responsible, that she should and could have refused to tolerate the misbehavior, that she has been left tainted, impure. Some social groups and families will have reinforced the latter feeling. The remainder of the psychiatric intervention will be focused on the patient’s particular symptoms – of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, or depression – and the relationship between her symptoms, history, and psychodynamics. Group therapy or other support by women who have faced similar abuse may be helpful. I’m afraid that we will continue to have many such patients to treat.

Dr. Stotland, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is professor of psychiatry, and obstetrics and gynecology, at Rush Medical College, Chicago. She has written numerous articles and books, including “Cutting Edge Medicine: What Psychiatrists Need to Know” (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2002).

Years ago, after the revelation of sexual predations of male members of the U.S. Navy upon their female underlings, the Navy announced a “zero tolerance” policy. I, then the chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Women, was invited to address a meeting of top Naval officers. They seemed dismayed when I told them that zero tolerance was just the beginning. Declarations that certain behaviors are unacceptable are facile, flimsy, and ultimately disingenuous substitutes for the infinitely more difficult task of monitoring and policing forbidden behaviors and protecting potential and actual victims.

The United States, I pointed out, has a zero tolerance policy on murder but still has to maintain a large force of police officers, detectives, judges, and prison guards to enforce that policy. The Navy had to have a similar approach to sexual assaults. Judging from the recent reports of female members of the military, that hasn’t happened.

Clarity in the law

Unwanted physical intrusion by one adult on another is against the law in the United States. Then why do we need laws specifically banning rape? In addition to the fact that rape, unlike any other assault, can result in conception, sexual assault is recognized as a particularly and uniquely evil and damaging invasion and degradation.

Although there are cultural differences about responsibility for rape, and whether marriage obviates a woman’s right to refuse sexual contact, there is little or no dispute about the need to recognize rape as a distinct, degrading, and particularly heinous attack. It is, therefore, no surprise that people who are raped feel soiled, shamed, and degraded. Those feelings are exacerbated by centuries of shifting responsibility for sexual assault, whether forced intercourse or other unwanted sexual behavior, from the perpetrator onto the victim.

The shifting of blame has been rejected in theory, but it very much persists in actuality. Who among us does not wonder how the victim was dressed or why (s)he was on that street, at that party, in that man’s room? Other forms of harassment echo the motivations of rape – to demonstrate the unanswerable power to degrade – and result in similar psychological responses.

The recent media revelations have lumped physical assault together with unwanted touching, sexual acts undergone as a result of psychological coercion, unwanted exposure to perpetrators’ genitalia and masturbation, and offensive sexual requests and comments. All of those acts are wrong, but they are not equivalent. An elderly man in a wheelchair grabbing an adult woman’s buttocks is not in the same category as an adult man sexually assaulting an underage girl.

What is the genesis of all this misbehavior? It’s not just about sex; it’s about sex and power. For many men, bragging about sexual conquests and making derogatory remarks about women’s physical appearance demonstrate machismo – define maleness.

It is not surprising that such comments are called “locker room talk”; sports are macho displays as well. Physically violating sexual boundaries is just the talk put into action. And macho works. Last November, more than 40% of female voters in the United States voted for the candidate who reportedly cheated on at least one of his three wives, bragged about unwanted sexual assault, and has been credibly accused of many other illegal and/or inappropriate behaviors.

Where does it end?

What is going to be the result of all this hullabaloo? The list of convincingly accused perpetrators grows by the day. Sexism and sexual misbehavior are endemic in every sphere of human endeavor, up to and including, of course, the clergy, who are meant to be models and protectors of virtue. The scope of recent revelations may be unusual, but revelations about one sector or another have happened every few years: the military, clergy, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, academia. What would happen if all the sexual misbehavior were to be revealed, and the perpetrators removed from their leadership and management positions? Would we have a film industry, a financial industry, a legislature? I saw a headline somewhere: “He’s always indispensable; you never are.” The argument, or myth, of indispensability is a powerful protection for powerful individuals. The powerful are too powerful to tolerate mass expulsions. Already, Congress has resorted to the time-honored and demonstrably useless response: training. Others among the accused report that they are undergoing treatment of sex addiction, a diagnosis our profession has wisely discarded, and for which there was no effective treatment.

Sex, while not addictive, does have a role in sexual misbehavior. Through the ages, women’s reproductive hormones have been a focus of social and medical attention, as the source of unpleasant behaviors, and, in fact, psychopathology: premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression. Little or no attention has been paid to the problematic psychosocial effects of male reproductive hormones. In addition to the offensive behaviors currently in the headlines, there is the behavior of adolescent males. Isn’t reckless driving related to the pubertal influx of testosterone (Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30[3]:319-45)? This gender discrepancy deserves scientific and social attention.

What can psychiatrists do to help women (and men) who are affected by sexual misbehavior? This is a difficult problem. What would help most victims, of any injustice, most would be to confront those responsible, and see them removed from positions of power and otherwise punished. However, the recent reports of seemingly swift and severe responses are misleading. The responsible journalists who have reported these cases have, in most cases, devoted months to finding victimized women, persuading them to go public, and corroborating their accounts. The perpetrators, even when complaints have been made, have gone unpunished, and often been promoted, for years or even decades. Women who complain often are subject to employer retaliation.

So a treating psychiatrist is left with less-than-satisfactory recommendations and responses. The most important intervention is to identify and counter the patient’s inaccurate and damaging assumptions: that she was responsible, that she should and could have refused to tolerate the misbehavior, that she has been left tainted, impure. Some social groups and families will have reinforced the latter feeling. The remainder of the psychiatric intervention will be focused on the patient’s particular symptoms – of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, or depression – and the relationship between her symptoms, history, and psychodynamics. Group therapy or other support by women who have faced similar abuse may be helpful. I’m afraid that we will continue to have many such patients to treat.

Dr. Stotland, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is professor of psychiatry, and obstetrics and gynecology, at Rush Medical College, Chicago. She has written numerous articles and books, including “Cutting Edge Medicine: What Psychiatrists Need to Know” (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2002).

Years ago, after the revelation of sexual predations of male members of the U.S. Navy upon their female underlings, the Navy announced a “zero tolerance” policy. I, then the chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Women, was invited to address a meeting of top Naval officers. They seemed dismayed when I told them that zero tolerance was just the beginning. Declarations that certain behaviors are unacceptable are facile, flimsy, and ultimately disingenuous substitutes for the infinitely more difficult task of monitoring and policing forbidden behaviors and protecting potential and actual victims.

The United States, I pointed out, has a zero tolerance policy on murder but still has to maintain a large force of police officers, detectives, judges, and prison guards to enforce that policy. The Navy had to have a similar approach to sexual assaults. Judging from the recent reports of female members of the military, that hasn’t happened.

Clarity in the law

Unwanted physical intrusion by one adult on another is against the law in the United States. Then why do we need laws specifically banning rape? In addition to the fact that rape, unlike any other assault, can result in conception, sexual assault is recognized as a particularly and uniquely evil and damaging invasion and degradation.

Although there are cultural differences about responsibility for rape, and whether marriage obviates a woman’s right to refuse sexual contact, there is little or no dispute about the need to recognize rape as a distinct, degrading, and particularly heinous attack. It is, therefore, no surprise that people who are raped feel soiled, shamed, and degraded. Those feelings are exacerbated by centuries of shifting responsibility for sexual assault, whether forced intercourse or other unwanted sexual behavior, from the perpetrator onto the victim.

The shifting of blame has been rejected in theory, but it very much persists in actuality. Who among us does not wonder how the victim was dressed or why (s)he was on that street, at that party, in that man’s room? Other forms of harassment echo the motivations of rape – to demonstrate the unanswerable power to degrade – and result in similar psychological responses.

The recent media revelations have lumped physical assault together with unwanted touching, sexual acts undergone as a result of psychological coercion, unwanted exposure to perpetrators’ genitalia and masturbation, and offensive sexual requests and comments. All of those acts are wrong, but they are not equivalent. An elderly man in a wheelchair grabbing an adult woman’s buttocks is not in the same category as an adult man sexually assaulting an underage girl.

What is the genesis of all this misbehavior? It’s not just about sex; it’s about sex and power. For many men, bragging about sexual conquests and making derogatory remarks about women’s physical appearance demonstrate machismo – define maleness.

It is not surprising that such comments are called “locker room talk”; sports are macho displays as well. Physically violating sexual boundaries is just the talk put into action. And macho works. Last November, more than 40% of female voters in the United States voted for the candidate who reportedly cheated on at least one of his three wives, bragged about unwanted sexual assault, and has been credibly accused of many other illegal and/or inappropriate behaviors.

Where does it end?

What is going to be the result of all this hullabaloo? The list of convincingly accused perpetrators grows by the day. Sexism and sexual misbehavior are endemic in every sphere of human endeavor, up to and including, of course, the clergy, who are meant to be models and protectors of virtue. The scope of recent revelations may be unusual, but revelations about one sector or another have happened every few years: the military, clergy, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, academia. What would happen if all the sexual misbehavior were to be revealed, and the perpetrators removed from their leadership and management positions? Would we have a film industry, a financial industry, a legislature? I saw a headline somewhere: “He’s always indispensable; you never are.” The argument, or myth, of indispensability is a powerful protection for powerful individuals. The powerful are too powerful to tolerate mass expulsions. Already, Congress has resorted to the time-honored and demonstrably useless response: training. Others among the accused report that they are undergoing treatment of sex addiction, a diagnosis our profession has wisely discarded, and for which there was no effective treatment.

Sex, while not addictive, does have a role in sexual misbehavior. Through the ages, women’s reproductive hormones have been a focus of social and medical attention, as the source of unpleasant behaviors, and, in fact, psychopathology: premenstrual dysphoric disorder, postpartum depression. Little or no attention has been paid to the problematic psychosocial effects of male reproductive hormones. In addition to the offensive behaviors currently in the headlines, there is the behavior of adolescent males. Isn’t reckless driving related to the pubertal influx of testosterone (Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30[3]:319-45)? This gender discrepancy deserves scientific and social attention.

What can psychiatrists do to help women (and men) who are affected by sexual misbehavior? This is a difficult problem. What would help most victims, of any injustice, most would be to confront those responsible, and see them removed from positions of power and otherwise punished. However, the recent reports of seemingly swift and severe responses are misleading. The responsible journalists who have reported these cases have, in most cases, devoted months to finding victimized women, persuading them to go public, and corroborating their accounts. The perpetrators, even when complaints have been made, have gone unpunished, and often been promoted, for years or even decades. Women who complain often are subject to employer retaliation.

So a treating psychiatrist is left with less-than-satisfactory recommendations and responses. The most important intervention is to identify and counter the patient’s inaccurate and damaging assumptions: that she was responsible, that she should and could have refused to tolerate the misbehavior, that she has been left tainted, impure. Some social groups and families will have reinforced the latter feeling. The remainder of the psychiatric intervention will be focused on the patient’s particular symptoms – of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, or depression – and the relationship between her symptoms, history, and psychodynamics. Group therapy or other support by women who have faced similar abuse may be helpful. I’m afraid that we will continue to have many such patients to treat.

Dr. Stotland, past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is professor of psychiatry, and obstetrics and gynecology, at Rush Medical College, Chicago. She has written numerous articles and books, including “Cutting Edge Medicine: What Psychiatrists Need to Know” (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2002).

Retinal changes may reflect brain changes in preclinical Alzheimer’s

BOSTON – Changes in the retina seem to mirror changes that begin to reshape the brain in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

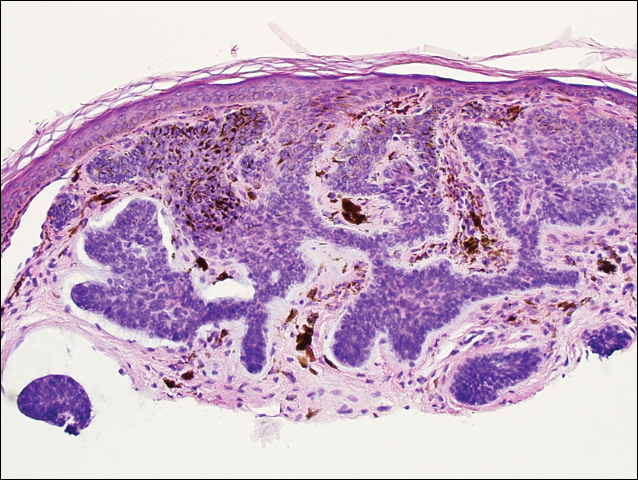

Manifested as a reduction in volume in the retinal nerve fiber layer, these changes appear to track the aggregation of beta amyloid brain plaques well before cognitive problems arise – and can be easily measured with a piece of equipment already in many optometry offices, Peter J. Snyder, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“If we are lucky enough to live past age 45, then it’s a given that we’re all going to develop some presbyopia. So we all have to go to the optometrist sometime, and that may become a point of entry for broad screening and to track changes over time, to keep an eye on at-risk patients, and to refer those with retinal changes that fit the preclinical AD profile to specialty care for more comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.”

The retina begins to form in the third week of embryologic life, arising from the neural tube cells that also form the brain and spinal cord. It makes sense then that very early neuronal changes in Alzheimer’s disease could be occurring in the retina as well, said Dr. Snyder, professor of neurology and surgery (ophthalmology) at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, Providence.

“The retina is really a protrusion of the brain, and it is part and parcel of the central nervous system. In terms of the neuronal structure, the retina develops in layers with very specific cell types that are neurochemically and physiologically the same as the nervous tissue in the brain. That’s why it is, potentially, literally a window that could let us see what’s happening in the brain in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Other researchers have explored amyloid in the lens and retina as a possible early Alzheimer’s identification tool. But Dr. Snyder’s study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal association between neuronal changes in the eye and amyloid burden in the brain among clinically normal subjects.

For 27 months, he followed 56 people who had normal cognition but were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints. All subjects had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone underwent an amyloid PET scan at baseline. Of the cohort, 15 had PET imaging evidence of abnormal beta-amyloid protein aggregation in the neocortex. This group was deemed to have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the remainder served as a control group.

Dr. Snyder imaged each subject’s retinas twice – once at baseline and once at 27 months, when everyone underwent a second amyloid PET scan as well. He examined the retina with spectral domain optical coherence tomography, a relatively new method of imaging the retina.

These scanners are becoming increasingly more common in optometry practices, Dr. Snyder said. “Graduate optometrists tell me they would not want to be in a practice without one.” The scanners are typically used to detect retinal and ocular changes associated with diabetes, macular degeneration, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

Dr. Snyder used the scanner to examine the optic nerve head and macula at both baseline and 27 months in his cohort. He was looking for volumetric changes in several of the retinal layers: the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), macular RNFL (mRNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and inner nuclear layer (INL). He also computed changes in total retinal volume.

Even at baseline, he found a significant difference between the groups. Among the amyloid-positive subjects, the inner plexiform layer was slightly larger in volume. “This seems a bit counterintuitive, but I think it suggests that there may be some inflammatory processes going on in this early stage and that we are catching that inflammation.”

Dr. Snyder noted that this finding has recently been replicated by an independent research group in Perth, Australia – with a much larger sample of participants – and will be reported at international conferences this coming year.

At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in the preclinical AD group than in the control group. There was also a volume reduction in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

In a multivariate linear regression model that controlled for age and total amyloid burden, the mean volume change in the macular retinal nerve fiber layer accounted for about 10% of the variation in PET binding to brain amyloid by 27 months. Volume reductions in all the other layers appeared to be associated only with age, representing normal age-related changes in the eye.

Dr. Snyder said this volume loss in the retinal nerve fiber layer probably represents early demyelination and/or degeneration of the axons coursing from the cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer, which project to the optic nerve head.

“This finding in the retina appears analogous, and possibly directly related to, a similar loss of white matter that is readily observable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, patients are beginning to experience both cholinergic changes in the basal forebrain and the abnormal aggregation of fibrillar beta-amyloid plaques. I don’t know to what extent these changes are mechanistically dependent on each other, but they appear to also be happening, in the earliest stages of the disease course, in the retina.”

There is a lot of work left to be done before retinal scanning could be employed as a risk-assessment tool, however. With every new biomarker – and especially with imaging – the ability to measure change occurs far in advance of an understanding of what those changes mean, and how to judge them accurately.

“Every time we have a major advance in imaging, the technical engineering breakthroughs precede our detailed understanding of what we’re looking at and what to measure. This is where we are right now with retinal imaging. Biologically, it makes sense to be looking at this as a marker of risk in those who are clinically healthy, and maybe later as a marker of disease progression. But there is a lot of work to be done here yet.”

Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – Changes in the retina seem to mirror changes that begin to reshape the brain in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Manifested as a reduction in volume in the retinal nerve fiber layer, these changes appear to track the aggregation of beta amyloid brain plaques well before cognitive problems arise – and can be easily measured with a piece of equipment already in many optometry offices, Peter J. Snyder, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“If we are lucky enough to live past age 45, then it’s a given that we’re all going to develop some presbyopia. So we all have to go to the optometrist sometime, and that may become a point of entry for broad screening and to track changes over time, to keep an eye on at-risk patients, and to refer those with retinal changes that fit the preclinical AD profile to specialty care for more comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.”

The retina begins to form in the third week of embryologic life, arising from the neural tube cells that also form the brain and spinal cord. It makes sense then that very early neuronal changes in Alzheimer’s disease could be occurring in the retina as well, said Dr. Snyder, professor of neurology and surgery (ophthalmology) at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, Providence.

“The retina is really a protrusion of the brain, and it is part and parcel of the central nervous system. In terms of the neuronal structure, the retina develops in layers with very specific cell types that are neurochemically and physiologically the same as the nervous tissue in the brain. That’s why it is, potentially, literally a window that could let us see what’s happening in the brain in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Other researchers have explored amyloid in the lens and retina as a possible early Alzheimer’s identification tool. But Dr. Snyder’s study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal association between neuronal changes in the eye and amyloid burden in the brain among clinically normal subjects.

For 27 months, he followed 56 people who had normal cognition but were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints. All subjects had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone underwent an amyloid PET scan at baseline. Of the cohort, 15 had PET imaging evidence of abnormal beta-amyloid protein aggregation in the neocortex. This group was deemed to have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the remainder served as a control group.

Dr. Snyder imaged each subject’s retinas twice – once at baseline and once at 27 months, when everyone underwent a second amyloid PET scan as well. He examined the retina with spectral domain optical coherence tomography, a relatively new method of imaging the retina.

These scanners are becoming increasingly more common in optometry practices, Dr. Snyder said. “Graduate optometrists tell me they would not want to be in a practice without one.” The scanners are typically used to detect retinal and ocular changes associated with diabetes, macular degeneration, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

Dr. Snyder used the scanner to examine the optic nerve head and macula at both baseline and 27 months in his cohort. He was looking for volumetric changes in several of the retinal layers: the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), macular RNFL (mRNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and inner nuclear layer (INL). He also computed changes in total retinal volume.

Even at baseline, he found a significant difference between the groups. Among the amyloid-positive subjects, the inner plexiform layer was slightly larger in volume. “This seems a bit counterintuitive, but I think it suggests that there may be some inflammatory processes going on in this early stage and that we are catching that inflammation.”

Dr. Snyder noted that this finding has recently been replicated by an independent research group in Perth, Australia – with a much larger sample of participants – and will be reported at international conferences this coming year.

At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in the preclinical AD group than in the control group. There was also a volume reduction in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

In a multivariate linear regression model that controlled for age and total amyloid burden, the mean volume change in the macular retinal nerve fiber layer accounted for about 10% of the variation in PET binding to brain amyloid by 27 months. Volume reductions in all the other layers appeared to be associated only with age, representing normal age-related changes in the eye.

Dr. Snyder said this volume loss in the retinal nerve fiber layer probably represents early demyelination and/or degeneration of the axons coursing from the cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer, which project to the optic nerve head.

“This finding in the retina appears analogous, and possibly directly related to, a similar loss of white matter that is readily observable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, patients are beginning to experience both cholinergic changes in the basal forebrain and the abnormal aggregation of fibrillar beta-amyloid plaques. I don’t know to what extent these changes are mechanistically dependent on each other, but they appear to also be happening, in the earliest stages of the disease course, in the retina.”

There is a lot of work left to be done before retinal scanning could be employed as a risk-assessment tool, however. With every new biomarker – and especially with imaging – the ability to measure change occurs far in advance of an understanding of what those changes mean, and how to judge them accurately.

“Every time we have a major advance in imaging, the technical engineering breakthroughs precede our detailed understanding of what we’re looking at and what to measure. This is where we are right now with retinal imaging. Biologically, it makes sense to be looking at this as a marker of risk in those who are clinically healthy, and maybe later as a marker of disease progression. But there is a lot of work to be done here yet.”

Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

BOSTON – Changes in the retina seem to mirror changes that begin to reshape the brain in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease.

Manifested as a reduction in volume in the retinal nerve fiber layer, these changes appear to track the aggregation of beta amyloid brain plaques well before cognitive problems arise – and can be easily measured with a piece of equipment already in many optometry offices, Peter J. Snyder, PhD, said at the Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease conference.

“If we are lucky enough to live past age 45, then it’s a given that we’re all going to develop some presbyopia. So we all have to go to the optometrist sometime, and that may become a point of entry for broad screening and to track changes over time, to keep an eye on at-risk patients, and to refer those with retinal changes that fit the preclinical AD profile to specialty care for more comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.”

The retina begins to form in the third week of embryologic life, arising from the neural tube cells that also form the brain and spinal cord. It makes sense then that very early neuronal changes in Alzheimer’s disease could be occurring in the retina as well, said Dr. Snyder, professor of neurology and surgery (ophthalmology) at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University, Providence.

“The retina is really a protrusion of the brain, and it is part and parcel of the central nervous system. In terms of the neuronal structure, the retina develops in layers with very specific cell types that are neurochemically and physiologically the same as the nervous tissue in the brain. That’s why it is, potentially, literally a window that could let us see what’s happening in the brain in early Alzheimer’s disease.”

Other researchers have explored amyloid in the lens and retina as a possible early Alzheimer’s identification tool. But Dr. Snyder’s study is the first to demonstrate a longitudinal association between neuronal changes in the eye and amyloid burden in the brain among clinically normal subjects.

For 27 months, he followed 56 people who had normal cognition but were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints. All subjects had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone underwent an amyloid PET scan at baseline. Of the cohort, 15 had PET imaging evidence of abnormal beta-amyloid protein aggregation in the neocortex. This group was deemed to have preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, while the remainder served as a control group.

Dr. Snyder imaged each subject’s retinas twice – once at baseline and once at 27 months, when everyone underwent a second amyloid PET scan as well. He examined the retina with spectral domain optical coherence tomography, a relatively new method of imaging the retina.

These scanners are becoming increasingly more common in optometry practices, Dr. Snyder said. “Graduate optometrists tell me they would not want to be in a practice without one.” The scanners are typically used to detect retinal and ocular changes associated with diabetes, macular degeneration, glaucoma and multiple sclerosis.

Dr. Snyder used the scanner to examine the optic nerve head and macula at both baseline and 27 months in his cohort. He was looking for volumetric changes in several of the retinal layers: the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (pRNFL), macular RNFL (mRNFL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), outer nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), and inner nuclear layer (INL). He also computed changes in total retinal volume.

Even at baseline, he found a significant difference between the groups. Among the amyloid-positive subjects, the inner plexiform layer was slightly larger in volume. “This seems a bit counterintuitive, but I think it suggests that there may be some inflammatory processes going on in this early stage and that we are catching that inflammation.”

Dr. Snyder noted that this finding has recently been replicated by an independent research group in Perth, Australia – with a much larger sample of participants – and will be reported at international conferences this coming year.

At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in the preclinical AD group than in the control group. There was also a volume reduction in the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer, although the between-group difference was not statistically significant.

In a multivariate linear regression model that controlled for age and total amyloid burden, the mean volume change in the macular retinal nerve fiber layer accounted for about 10% of the variation in PET binding to brain amyloid by 27 months. Volume reductions in all the other layers appeared to be associated only with age, representing normal age-related changes in the eye.

Dr. Snyder said this volume loss in the retinal nerve fiber layer probably represents early demyelination and/or degeneration of the axons coursing from the cell bodies in the ganglion cell layer, which project to the optic nerve head.

“This finding in the retina appears analogous, and possibly directly related to, a similar loss of white matter that is readily observable in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. At the same time, patients are beginning to experience both cholinergic changes in the basal forebrain and the abnormal aggregation of fibrillar beta-amyloid plaques. I don’t know to what extent these changes are mechanistically dependent on each other, but they appear to also be happening, in the earliest stages of the disease course, in the retina.”

There is a lot of work left to be done before retinal scanning could be employed as a risk-assessment tool, however. With every new biomarker – and especially with imaging – the ability to measure change occurs far in advance of an understanding of what those changes mean, and how to judge them accurately.

“Every time we have a major advance in imaging, the technical engineering breakthroughs precede our detailed understanding of what we’re looking at and what to measure. This is where we are right now with retinal imaging. Biologically, it makes sense to be looking at this as a marker of risk in those who are clinically healthy, and maybe later as a marker of disease progression. But there is a lot of work to be done here yet.”

Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

[email protected]

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT CTAD

Key clinical point: Retinal scans might eventually be an easy, noninvasive, and inexpensive way to tag people who may be at elevated risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Major finding: At 27 months, both the total retinal volume and the macular retinal nerve fiber layer volume were significantly lower in 15 patients in the preclinical AD group than in the 41 patients in the control group.

Data source: A follow-up study of 56 people who had at least one parent with Alzheimer’s disease and were beginning to experience subjective memory complaints.

Disclosures: Dr. Snyder’s project was funded in part by a research award from Pfizer, with PET imaging supported in part by a grant from Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. He has no financial ties to the company, or other financial interest related to the study.

Swarm and suspicion leadership

During your career, you serve as staff member and leader to many different professional groups. Some are collaborative, collegial, and supportive. Others are competitive, antagonistic, or even combative. What are the benefits and downsides of each of these cultures and what can you do, as a hospitalist leader, to influence the character of your workplace?

The field of “game theory” provides insights into the distinction. The first questions to ask are “What is the game you are playing?” and then “Who is the competition?” In a “winner-takes-all” scenario, such as a sporting event, each team seeks strategic advantage over the other team. In baseball terms, the winner gets more points when at bat and denies more points when on the field. However, when competing as a team, winning together requires collaboration to build strategy, execute plays, and reach victory. You compete against the other team and collaborate within your own team.

Scientists who study negotiation strategies and conflict resolution find that collaborative groups spend less time countering one another and, instead, investing that same effort into building constructive outcomes, a force multiplier.

In the winner-takes-all model, the baseball team that gets “outs,” makes plays, and advances team members to home plate, wins. If there is contest within the team, players invest that same effort into seeking their own gain at the expense of others. Benefits derived from shared effort are shunned in favor of benefits accrued to one player over the other. It is a distinction between “I won” versus “We won.”

Hospital medicine is not a win/lose sport, yet over the years, hospitalists have shared with me that their institution or group at times feels like a competitive field with winners and losers. If this distinction is placed on a continuum, what factors encourage a more collaborative environment and what factors do the opposite, toward the adversarial side of the continuum? It makes a substantive difference in the interactions and accomplishments that a group achieves.

My colleagues and I at Harvard study leaders in times of crisis. A crisis makes apparent what is often more subtle during routine times. Our study of leaders in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombings was among our most revealing.

During most crises, an operational leader is designated to oversee the whole of the response. This is an individual with organizational authority and subject-matter expertise appropriate to the situation at hand. In Boston, however, there were so many different jurisdictions – federal, state, and local – and so many different agencies, that no one leader stood above the others. They worked in a remarkably collaborative fashion. While the bombings themselves were tragic, the response itself was a success: All who survived the initial blasts lived, a function of remarkable emergency care, distribution to hospitals, and good medical care. The perpetrators were caught in 102 hours, and “Boston Strong” reflected a genuine city resilience.

These leaders worked together in ways that we had rarely seen before. What we discovered was a phenomenon we call “swarm leadership,” inspired by the ways ants, bees, and termites engage in collective work and decision making. These creatures have clear lines of communication and structures for judgment calls, often about food sources, nesting locations, and threats.

There are five principles of swarm leadership:

- Unity of mission – In Boston, that was to “save lives,” and it motivated and activated the whole of the response.

- Generosity of spirit and action – Across the community, people were eager to assist in the response.

- Everyone stayed in their own lanes of responsibility and helped others succeed in theirs – There were law enforcement, medical, and resilience activities and the theme across the leaders was “how can I help make you a success?”

- No ego and no blame – There was a level of emotional intelligence and maturity among the leaders.

- A foundation of trusting relations – These leaders had known one another for years and, though the decisions were tough, they were confident in the motives and actions of the others.

While the discovery emerged from our crisis research, the findings equally apply to other, more routine work and interactions. Conduct your own assessment. Have you worked in groups in which these principles of swarm leadership characterized the experience? People were focused on a shared mission: They were available to assist one another; accomplished their work in ways that were respectful and supportive of their different responsibilities; did not claim undue credit or swipe at each another; and knew one another well enough to trust the others’ actions and motives.

The flip side of this continuum of collaboration and competition we term “suspicion leadership.” This is characterized by selfish ambitions; narcissistic actions; grabs for authority and resources; credit taking for the good and accusations for the bad; and an environment of mistrust and back stabbing.

Leaders influence the tone and tenor of their own group’s interactions as well as interactions among different working groups. As role models, if they articulate and demonstrate a mission that others can rally around, they forge that critical unity of mission. By contrast, suspicion leaders make it clear that “it is all about me and my priorities.” There is much work to be done, and swarm leaders ensure that people have the resources, autonomy, and support necessary to get the job done. On the other end, the work environment is burdened by the uncertainties about who does what and who is responsible. Swarm leaders are focused on “we” and suspicion leaders are caught up on “me.” There is no trust when people are suspicious of one another. Much can be accomplished when people believe in themselves, their colleagues, and the reasons that bring them together.

As a hospitalist leader, you influence where on this continuum your group will lie. It is your choice to be a role model for the principles of swarm, encouraging the same among others. When those principles become the beacons by which you work and relate, you will find an environment that inspires people to be and to do their best.

In the next column, how to build trust within your teams.

Dr. Marcus is director, Program on Health Care Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston.

During your career, you serve as staff member and leader to many different professional groups. Some are collaborative, collegial, and supportive. Others are competitive, antagonistic, or even combative. What are the benefits and downsides of each of these cultures and what can you do, as a hospitalist leader, to influence the character of your workplace?

The field of “game theory” provides insights into the distinction. The first questions to ask are “What is the game you are playing?” and then “Who is the competition?” In a “winner-takes-all” scenario, such as a sporting event, each team seeks strategic advantage over the other team. In baseball terms, the winner gets more points when at bat and denies more points when on the field. However, when competing as a team, winning together requires collaboration to build strategy, execute plays, and reach victory. You compete against the other team and collaborate within your own team.

Scientists who study negotiation strategies and conflict resolution find that collaborative groups spend less time countering one another and, instead, investing that same effort into building constructive outcomes, a force multiplier.

In the winner-takes-all model, the baseball team that gets “outs,” makes plays, and advances team members to home plate, wins. If there is contest within the team, players invest that same effort into seeking their own gain at the expense of others. Benefits derived from shared effort are shunned in favor of benefits accrued to one player over the other. It is a distinction between “I won” versus “We won.”

Hospital medicine is not a win/lose sport, yet over the years, hospitalists have shared with me that their institution or group at times feels like a competitive field with winners and losers. If this distinction is placed on a continuum, what factors encourage a more collaborative environment and what factors do the opposite, toward the adversarial side of the continuum? It makes a substantive difference in the interactions and accomplishments that a group achieves.

My colleagues and I at Harvard study leaders in times of crisis. A crisis makes apparent what is often more subtle during routine times. Our study of leaders in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombings was among our most revealing.

During most crises, an operational leader is designated to oversee the whole of the response. This is an individual with organizational authority and subject-matter expertise appropriate to the situation at hand. In Boston, however, there were so many different jurisdictions – federal, state, and local – and so many different agencies, that no one leader stood above the others. They worked in a remarkably collaborative fashion. While the bombings themselves were tragic, the response itself was a success: All who survived the initial blasts lived, a function of remarkable emergency care, distribution to hospitals, and good medical care. The perpetrators were caught in 102 hours, and “Boston Strong” reflected a genuine city resilience.

These leaders worked together in ways that we had rarely seen before. What we discovered was a phenomenon we call “swarm leadership,” inspired by the ways ants, bees, and termites engage in collective work and decision making. These creatures have clear lines of communication and structures for judgment calls, often about food sources, nesting locations, and threats.

There are five principles of swarm leadership:

- Unity of mission – In Boston, that was to “save lives,” and it motivated and activated the whole of the response.

- Generosity of spirit and action – Across the community, people were eager to assist in the response.

- Everyone stayed in their own lanes of responsibility and helped others succeed in theirs – There were law enforcement, medical, and resilience activities and the theme across the leaders was “how can I help make you a success?”

- No ego and no blame – There was a level of emotional intelligence and maturity among the leaders.

- A foundation of trusting relations – These leaders had known one another for years and, though the decisions were tough, they were confident in the motives and actions of the others.

While the discovery emerged from our crisis research, the findings equally apply to other, more routine work and interactions. Conduct your own assessment. Have you worked in groups in which these principles of swarm leadership characterized the experience? People were focused on a shared mission: They were available to assist one another; accomplished their work in ways that were respectful and supportive of their different responsibilities; did not claim undue credit or swipe at each another; and knew one another well enough to trust the others’ actions and motives.

The flip side of this continuum of collaboration and competition we term “suspicion leadership.” This is characterized by selfish ambitions; narcissistic actions; grabs for authority and resources; credit taking for the good and accusations for the bad; and an environment of mistrust and back stabbing.

Leaders influence the tone and tenor of their own group’s interactions as well as interactions among different working groups. As role models, if they articulate and demonstrate a mission that others can rally around, they forge that critical unity of mission. By contrast, suspicion leaders make it clear that “it is all about me and my priorities.” There is much work to be done, and swarm leaders ensure that people have the resources, autonomy, and support necessary to get the job done. On the other end, the work environment is burdened by the uncertainties about who does what and who is responsible. Swarm leaders are focused on “we” and suspicion leaders are caught up on “me.” There is no trust when people are suspicious of one another. Much can be accomplished when people believe in themselves, their colleagues, and the reasons that bring them together.

As a hospitalist leader, you influence where on this continuum your group will lie. It is your choice to be a role model for the principles of swarm, encouraging the same among others. When those principles become the beacons by which you work and relate, you will find an environment that inspires people to be and to do their best.

In the next column, how to build trust within your teams.

Dr. Marcus is director, Program on Health Care Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston.

During your career, you serve as staff member and leader to many different professional groups. Some are collaborative, collegial, and supportive. Others are competitive, antagonistic, or even combative. What are the benefits and downsides of each of these cultures and what can you do, as a hospitalist leader, to influence the character of your workplace?

The field of “game theory” provides insights into the distinction. The first questions to ask are “What is the game you are playing?” and then “Who is the competition?” In a “winner-takes-all” scenario, such as a sporting event, each team seeks strategic advantage over the other team. In baseball terms, the winner gets more points when at bat and denies more points when on the field. However, when competing as a team, winning together requires collaboration to build strategy, execute plays, and reach victory. You compete against the other team and collaborate within your own team.

Scientists who study negotiation strategies and conflict resolution find that collaborative groups spend less time countering one another and, instead, investing that same effort into building constructive outcomes, a force multiplier.

In the winner-takes-all model, the baseball team that gets “outs,” makes plays, and advances team members to home plate, wins. If there is contest within the team, players invest that same effort into seeking their own gain at the expense of others. Benefits derived from shared effort are shunned in favor of benefits accrued to one player over the other. It is a distinction between “I won” versus “We won.”

Hospital medicine is not a win/lose sport, yet over the years, hospitalists have shared with me that their institution or group at times feels like a competitive field with winners and losers. If this distinction is placed on a continuum, what factors encourage a more collaborative environment and what factors do the opposite, toward the adversarial side of the continuum? It makes a substantive difference in the interactions and accomplishments that a group achieves.

My colleagues and I at Harvard study leaders in times of crisis. A crisis makes apparent what is often more subtle during routine times. Our study of leaders in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombings was among our most revealing.

During most crises, an operational leader is designated to oversee the whole of the response. This is an individual with organizational authority and subject-matter expertise appropriate to the situation at hand. In Boston, however, there were so many different jurisdictions – federal, state, and local – and so many different agencies, that no one leader stood above the others. They worked in a remarkably collaborative fashion. While the bombings themselves were tragic, the response itself was a success: All who survived the initial blasts lived, a function of remarkable emergency care, distribution to hospitals, and good medical care. The perpetrators were caught in 102 hours, and “Boston Strong” reflected a genuine city resilience.

These leaders worked together in ways that we had rarely seen before. What we discovered was a phenomenon we call “swarm leadership,” inspired by the ways ants, bees, and termites engage in collective work and decision making. These creatures have clear lines of communication and structures for judgment calls, often about food sources, nesting locations, and threats.

There are five principles of swarm leadership:

- Unity of mission – In Boston, that was to “save lives,” and it motivated and activated the whole of the response.

- Generosity of spirit and action – Across the community, people were eager to assist in the response.

- Everyone stayed in their own lanes of responsibility and helped others succeed in theirs – There were law enforcement, medical, and resilience activities and the theme across the leaders was “how can I help make you a success?”

- No ego and no blame – There was a level of emotional intelligence and maturity among the leaders.

- A foundation of trusting relations – These leaders had known one another for years and, though the decisions were tough, they were confident in the motives and actions of the others.

While the discovery emerged from our crisis research, the findings equally apply to other, more routine work and interactions. Conduct your own assessment. Have you worked in groups in which these principles of swarm leadership characterized the experience? People were focused on a shared mission: They were available to assist one another; accomplished their work in ways that were respectful and supportive of their different responsibilities; did not claim undue credit or swipe at each another; and knew one another well enough to trust the others’ actions and motives.

The flip side of this continuum of collaboration and competition we term “suspicion leadership.” This is characterized by selfish ambitions; narcissistic actions; grabs for authority and resources; credit taking for the good and accusations for the bad; and an environment of mistrust and back stabbing.

Leaders influence the tone and tenor of their own group’s interactions as well as interactions among different working groups. As role models, if they articulate and demonstrate a mission that others can rally around, they forge that critical unity of mission. By contrast, suspicion leaders make it clear that “it is all about me and my priorities.” There is much work to be done, and swarm leaders ensure that people have the resources, autonomy, and support necessary to get the job done. On the other end, the work environment is burdened by the uncertainties about who does what and who is responsible. Swarm leaders are focused on “we” and suspicion leaders are caught up on “me.” There is no trust when people are suspicious of one another. Much can be accomplished when people believe in themselves, their colleagues, and the reasons that bring them together.

As a hospitalist leader, you influence where on this continuum your group will lie. It is your choice to be a role model for the principles of swarm, encouraging the same among others. When those principles become the beacons by which you work and relate, you will find an environment that inspires people to be and to do their best.

In the next column, how to build trust within your teams.

Dr. Marcus is director, Program on Health Care Negotiation and Conflict Resolution, at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston.

Urge PAs to Join New SVS Section

SVS members, please remember to urge your physician assistants -- and other PAs you know who work in a vascular setting -- to apply to become charter members of the new SVS section created for them. The first step is becoming an affiliate member of the SVS. For our new charter PA members, SVS is waiving the application fee. For more information, email [email protected] or call the SVS Membership Department at 312-334-2313.

We welcome nurses and nurse practitioners as well. Please consider becoming a part of the Society for Vascular Nursing, which makes its management home at SVS.

SVS members, please remember to urge your physician assistants -- and other PAs you know who work in a vascular setting -- to apply to become charter members of the new SVS section created for them. The first step is becoming an affiliate member of the SVS. For our new charter PA members, SVS is waiving the application fee. For more information, email [email protected] or call the SVS Membership Department at 312-334-2313.

We welcome nurses and nurse practitioners as well. Please consider becoming a part of the Society for Vascular Nursing, which makes its management home at SVS.

SVS members, please remember to urge your physician assistants -- and other PAs you know who work in a vascular setting -- to apply to become charter members of the new SVS section created for them. The first step is becoming an affiliate member of the SVS. For our new charter PA members, SVS is waiving the application fee. For more information, email [email protected] or call the SVS Membership Department at 312-334-2313.

We welcome nurses and nurse practitioners as well. Please consider becoming a part of the Society for Vascular Nursing, which makes its management home at SVS.

With CHIP in limbo, here are five takeaways on the congressional impasse

Two months past its deadline, Congress has yet to fund the Children’s Health Insurance Program, leaving several states scrambling for cash.

Lawmakers grappling with the failed repeal of the Affordable Care Act allowed authorization of the program to lapse on Sept. 30. Although CHIP has always had broad bipartisan support, the House and Senate cannot agree on how to continue federal funding. And the Trump administration has been mostly silent on the issue.

CHIP benefits 9 million children nationwide and 370,000 pregnant women a year. It helps lower- and middle-income families who otherwise earn too much to be eligible for Medicaid. Like Medicaid, CHIP is paid for with state and federal funds, but the federal government covers close to 90% of the cost.

To keep the program going, states with unspent federal CHIP money have seen their excess sent to a handful of states running low on funds. But that is a bureaucratic Band-Aid; some large states are warning families they may not be able to rely on CHIP for much longer.

All told, the CMS has given out $1.2 billion in redistribution dollars since October. To keep the program going would cost the federal government $8.5 billion over 5 years, the Congressional Budget Office estimates.

Dec. 2 marked the 25th anniversary of Pennsylvania approving the original CHIP program, which served as a model for the national law, established in 1997. Since then, CHIP has been left in the fiscal lurch only once before. In 2007, CHIP went several weeks without funding authorization from Congress.

Here’s a quick look at what the shortfall may mean to daily life.

1. Are any kids hurting because Congress has failed to fund CHIP?

No. But states such as California will run out of money within weeks. That state alone accounts for nearly 15% of all children benefiting from CHIP. Without federal money, state programs could freeze enrollment or suspend operation.

2. What are states doing since Congress missed the deadline?

Most states are doing little except looking for other unspent federal funds or asking the federal government to send some unspent funds from other states. But some, such as Colorado, are sending warning letters to beneficiaries to tell them that the program could soon end and to look for alternatives. This could mean exploring the ACA marketplace for coverage or researching if a child qualifies for Medicaid.

Colorado said it has only enough CHIP funding to last through January and then the program, without federal dollars, will end.

Arizona officials announced Nov. 30 that it will use Medicaid funding to fill in the shortage of CHIP dollars to extend the life of its CHIP program.

Virginia officials plan to send out a similar notice to parents of CHIP members by early December.

Minnesota is keeping CHIP alive by paying the federal share with state funds.

In Oregon, Democratic Gov. Kate Brown recently said that she is ready to spend $35 million in state funds to keep CHIP running through December.

Nevada announced on Nov. 30 it had been approved for extra funding from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services – nearly $5.7 million – which could keep CHIP alive through December and possibly January.

California, which leads the nation in CHIP enrollment, has received the lion’s share of CMS redistribution funds since October: nearly $692 million.

“Approximately 98% of the 1.3 million population now covered using CHIP funding would continue to receive coverage under the Medicaid program because of a legal obligation to cover them through September 2019,” said California Medicaid/CHIP spokesman Tony Cava. “If CHIP is not reauthorized, the governor and Legislature would need to deliberate on how best to address the population no longer eligible for federal CHIP funding.”

3. When is Congress likely to act?

Not sure. CHIP reauthorization could be included in an appropriations bill that Congress must pass to fund the government into 2018. (Congress now has funded the government through Dec. 8.) A “continuing resolution” bill would have to be approved by then to avert a government shutdown.

4. If CHIP is so popular among Republicans and Democrats, what’s the problem?

There is little debate about its worth and value, but the momentum on CHIP was lost amid disagreements over the Affordable Care Act. The House did extend authorization with a vote – mostly along party lines – on Nov. 3. The Senate itself has yet to vote. The Senate Finance Committee on Oct. 3 approved a bipartisan bill to extend the program for 5 years.

The sticking point is not whether to keep CHIP running but how to raise the cash needed. The House agreed to charge higher premiums to wealthier Medicare beneficiaries, cut money from the ACA’s preventive health fund and shorten the grace period for ACA enrollees who fail to make monthly premium payments.

Like the House bill, the Senate committee bill eliminated an ACA provision to increase CHIP matching funds – to states – by 23%. The increased funding would continue through fiscal year 2019 and fall to 11.5 percent in fiscal year 2020. It would be cut entirely in the following fiscal year.

5. How does CHIP differ based on where you live?

CHIP income eligibility levels vary by state. About 90% of children who qualify are from families earning 200% of poverty or less ($40,840 for a family of three). CHIP covers children up to age 19. But states have the option to cover pregnant women, and 18 states plus the District of Columbia do so.

Some states call CHIP by different names. For example, it is known as Hoosier Healthwise in Indiana, PeachCare for Kids in Georgia and KidsCare in Arizona.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Two months past its deadline, Congress has yet to fund the Children’s Health Insurance Program, leaving several states scrambling for cash.

Lawmakers grappling with the failed repeal of the Affordable Care Act allowed authorization of the program to lapse on Sept. 30. Although CHIP has always had broad bipartisan support, the House and Senate cannot agree on how to continue federal funding. And the Trump administration has been mostly silent on the issue.

CHIP benefits 9 million children nationwide and 370,000 pregnant women a year. It helps lower- and middle-income families who otherwise earn too much to be eligible for Medicaid. Like Medicaid, CHIP is paid for with state and federal funds, but the federal government covers close to 90% of the cost.

To keep the program going, states with unspent federal CHIP money have seen their excess sent to a handful of states running low on funds. But that is a bureaucratic Band-Aid; some large states are warning families they may not be able to rely on CHIP for much longer.

All told, the CMS has given out $1.2 billion in redistribution dollars since October. To keep the program going would cost the federal government $8.5 billion over 5 years, the Congressional Budget Office estimates.

Dec. 2 marked the 25th anniversary of Pennsylvania approving the original CHIP program, which served as a model for the national law, established in 1997. Since then, CHIP has been left in the fiscal lurch only once before. In 2007, CHIP went several weeks without funding authorization from Congress.

Here’s a quick look at what the shortfall may mean to daily life.

1. Are any kids hurting because Congress has failed to fund CHIP?

No. But states such as California will run out of money within weeks. That state alone accounts for nearly 15% of all children benefiting from CHIP. Without federal money, state programs could freeze enrollment or suspend operation.

2. What are states doing since Congress missed the deadline?

Most states are doing little except looking for other unspent federal funds or asking the federal government to send some unspent funds from other states. But some, such as Colorado, are sending warning letters to beneficiaries to tell them that the program could soon end and to look for alternatives. This could mean exploring the ACA marketplace for coverage or researching if a child qualifies for Medicaid.

Colorado said it has only enough CHIP funding to last through January and then the program, without federal dollars, will end.

Arizona officials announced Nov. 30 that it will use Medicaid funding to fill in the shortage of CHIP dollars to extend the life of its CHIP program.

Virginia officials plan to send out a similar notice to parents of CHIP members by early December.

Minnesota is keeping CHIP alive by paying the federal share with state funds.

In Oregon, Democratic Gov. Kate Brown recently said that she is ready to spend $35 million in state funds to keep CHIP running through December.

Nevada announced on Nov. 30 it had been approved for extra funding from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services – nearly $5.7 million – which could keep CHIP alive through December and possibly January.

California, which leads the nation in CHIP enrollment, has received the lion’s share of CMS redistribution funds since October: nearly $692 million.

“Approximately 98% of the 1.3 million population now covered using CHIP funding would continue to receive coverage under the Medicaid program because of a legal obligation to cover them through September 2019,” said California Medicaid/CHIP spokesman Tony Cava. “If CHIP is not reauthorized, the governor and Legislature would need to deliberate on how best to address the population no longer eligible for federal CHIP funding.”

3. When is Congress likely to act?

Not sure. CHIP reauthorization could be included in an appropriations bill that Congress must pass to fund the government into 2018. (Congress now has funded the government through Dec. 8.) A “continuing resolution” bill would have to be approved by then to avert a government shutdown.

4. If CHIP is so popular among Republicans and Democrats, what’s the problem?

There is little debate about its worth and value, but the momentum on CHIP was lost amid disagreements over the Affordable Care Act. The House did extend authorization with a vote – mostly along party lines – on Nov. 3. The Senate itself has yet to vote. The Senate Finance Committee on Oct. 3 approved a bipartisan bill to extend the program for 5 years.

The sticking point is not whether to keep CHIP running but how to raise the cash needed. The House agreed to charge higher premiums to wealthier Medicare beneficiaries, cut money from the ACA’s preventive health fund and shorten the grace period for ACA enrollees who fail to make monthly premium payments.

Like the House bill, the Senate committee bill eliminated an ACA provision to increase CHIP matching funds – to states – by 23%. The increased funding would continue through fiscal year 2019 and fall to 11.5 percent in fiscal year 2020. It would be cut entirely in the following fiscal year.

5. How does CHIP differ based on where you live?

CHIP income eligibility levels vary by state. About 90% of children who qualify are from families earning 200% of poverty or less ($40,840 for a family of three). CHIP covers children up to age 19. But states have the option to cover pregnant women, and 18 states plus the District of Columbia do so.

Some states call CHIP by different names. For example, it is known as Hoosier Healthwise in Indiana, PeachCare for Kids in Georgia and KidsCare in Arizona.

KHN’s coverage of children’s health care issues is supported in part by the Heising-Simons Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Two months past its deadline, Congress has yet to fund the Children’s Health Insurance Program, leaving several states scrambling for cash.

Lawmakers grappling with the failed repeal of the Affordable Care Act allowed authorization of the program to lapse on Sept. 30. Although CHIP has always had broad bipartisan support, the House and Senate cannot agree on how to continue federal funding. And the Trump administration has been mostly silent on the issue.

CHIP benefits 9 million children nationwide and 370,000 pregnant women a year. It helps lower- and middle-income families who otherwise earn too much to be eligible for Medicaid. Like Medicaid, CHIP is paid for with state and federal funds, but the federal government covers close to 90% of the cost.

To keep the program going, states with unspent federal CHIP money have seen their excess sent to a handful of states running low on funds. But that is a bureaucratic Band-Aid; some large states are warning families they may not be able to rely on CHIP for much longer.

All told, the CMS has given out $1.2 billion in redistribution dollars since October. To keep the program going would cost the federal government $8.5 billion over 5 years, the Congressional Budget Office estimates.

Dec. 2 marked the 25th anniversary of Pennsylvania approving the original CHIP program, which served as a model for the national law, established in 1997. Since then, CHIP has been left in the fiscal lurch only once before. In 2007, CHIP went several weeks without funding authorization from Congress.

Here’s a quick look at what the shortfall may mean to daily life.

1. Are any kids hurting because Congress has failed to fund CHIP?

No. But states such as California will run out of money within weeks. That state alone accounts for nearly 15% of all children benefiting from CHIP. Without federal money, state programs could freeze enrollment or suspend operation.

2. What are states doing since Congress missed the deadline?

Most states are doing little except looking for other unspent federal funds or asking the federal government to send some unspent funds from other states. But some, such as Colorado, are sending warning letters to beneficiaries to tell them that the program could soon end and to look for alternatives. This could mean exploring the ACA marketplace for coverage or researching if a child qualifies for Medicaid.

Colorado said it has only enough CHIP funding to last through January and then the program, without federal dollars, will end.

Arizona officials announced Nov. 30 that it will use Medicaid funding to fill in the shortage of CHIP dollars to extend the life of its CHIP program.

Virginia officials plan to send out a similar notice to parents of CHIP members by early December.

Minnesota is keeping CHIP alive by paying the federal share with state funds.

In Oregon, Democratic Gov. Kate Brown recently said that she is ready to spend $35 million in state funds to keep CHIP running through December.