User login

Why VADS is gaining ground in pediatrics

The miniaturization of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices has launched the era of continuous-flow VAD support in pediatric patients, and the trend may accelerate with the introduction of a continuous-flow device designed specifically for small children. In an expert opinion in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Iki Adachi, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said the emerging science of continuous-flow VADs in children promises to solve problems like device size mismatch, hospital-only VADs, and chronic therapy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Oct;154:1358-61). “With ongoing device miniaturization, enthusiasm has been growing among pediatric physicians for the use of continuous-flow VADs in children,” Dr. Adachi said. He noted the introduction of a continuous-flow device for small children, the Infant Jarvik 2015, “may further accelerate the trend.”

Dr. Adachi cited PediMACS reports that stated that more than half of the long-term devices now registered are continuous-flow devices, and that continuous-flow VADs comprised 62% of all durable VAD implants in the third quarter of 2016. “With the encouraging results recorded to date, the use of continuous-flow devices in the pediatric population is rapidly increasing,” he said.

Miniaturization has addressed the problem of size mismatch when using continuous-flow VAD devices in children, he said, noting that use of the Infant Jarvik device may be expanded even further to children as small at 8 kg or less. The PumpKIN trial(Pumps for Kids, Infants, and Neonates), which is evaluating the Infant Jarvik 2015 vs. the Berlin Heart EXCOR, could provide answers on the feasibility of continuous-flow VADs in small children.

“Based on experience with the chronic animal model, I believe that the Infant Jarvik device will properly fit the patients included in the trial,” he said.

Continuous-flow VAD in children also holds potential for managing these patients outside the hospital setting. “Outpatient management of children with continuous-flow VADs has been shown to be feasible,” he said, adding that the PediMACS registry has reported that only 45% of patients have been managed this way. “Nonetheless, with maturation of the pediatric field, outpatient management will become routine rather than the exception,” he said.

Greater use of continuous-flow VADs also may create opportunities to improve the status and suitability for transplantation of children with severe heart failure, he said. He gave as an example his group’s practice at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, which is to deactivate patients on the transplant wait list for 3 months once they start continuous-flow VAD support. “A postoperative ‘grace period’ affords protected opportunities for both physical and psychological recovery,” he said. This timeout of sorts also affords the care team time to assess the myocardium for possible functional recovery.

In patients who are not good candidates for transplantation, durable continuous-flow VADs may provide chronic therapy, and in time, these patients may become suitable transplant candidates, said Dr. Adachi. “Bypassing such an unfavorable period for transplantation with prolonged VAD support may be a reasonable approach,” he said.

Patients with failing single-ventricle circulation also may benefit from VAD support, although the challenges facing this population are more profound than in other groups, Dr. Adachi said. VAD support for single-ventricle disease is sparse, but these patients require careful evaluation of the nature of their condition. “If systolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of circulatory failure, then VAD support for the failing systemic ventricle will likely improve hemodynamics,” said Dr. Adachi. VAD support also could help the patient move through the various stages of palliation.

“Again, the emphasis is not just on simply keeping the patient alive until a donor organ becomes available; rather, attention is refocused on overall health beyond survival, which may eventually affect transplantation candidacy and even post transplantation outcome,” Dr. Adachi concluded.

Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare, and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

The miniaturization of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices has launched the era of continuous-flow VAD support in pediatric patients, and the trend may accelerate with the introduction of a continuous-flow device designed specifically for small children. In an expert opinion in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Iki Adachi, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said the emerging science of continuous-flow VADs in children promises to solve problems like device size mismatch, hospital-only VADs, and chronic therapy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Oct;154:1358-61). “With ongoing device miniaturization, enthusiasm has been growing among pediatric physicians for the use of continuous-flow VADs in children,” Dr. Adachi said. He noted the introduction of a continuous-flow device for small children, the Infant Jarvik 2015, “may further accelerate the trend.”

Dr. Adachi cited PediMACS reports that stated that more than half of the long-term devices now registered are continuous-flow devices, and that continuous-flow VADs comprised 62% of all durable VAD implants in the third quarter of 2016. “With the encouraging results recorded to date, the use of continuous-flow devices in the pediatric population is rapidly increasing,” he said.

Miniaturization has addressed the problem of size mismatch when using continuous-flow VAD devices in children, he said, noting that use of the Infant Jarvik device may be expanded even further to children as small at 8 kg or less. The PumpKIN trial(Pumps for Kids, Infants, and Neonates), which is evaluating the Infant Jarvik 2015 vs. the Berlin Heart EXCOR, could provide answers on the feasibility of continuous-flow VADs in small children.

“Based on experience with the chronic animal model, I believe that the Infant Jarvik device will properly fit the patients included in the trial,” he said.

Continuous-flow VAD in children also holds potential for managing these patients outside the hospital setting. “Outpatient management of children with continuous-flow VADs has been shown to be feasible,” he said, adding that the PediMACS registry has reported that only 45% of patients have been managed this way. “Nonetheless, with maturation of the pediatric field, outpatient management will become routine rather than the exception,” he said.

Greater use of continuous-flow VADs also may create opportunities to improve the status and suitability for transplantation of children with severe heart failure, he said. He gave as an example his group’s practice at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, which is to deactivate patients on the transplant wait list for 3 months once they start continuous-flow VAD support. “A postoperative ‘grace period’ affords protected opportunities for both physical and psychological recovery,” he said. This timeout of sorts also affords the care team time to assess the myocardium for possible functional recovery.

In patients who are not good candidates for transplantation, durable continuous-flow VADs may provide chronic therapy, and in time, these patients may become suitable transplant candidates, said Dr. Adachi. “Bypassing such an unfavorable period for transplantation with prolonged VAD support may be a reasonable approach,” he said.

Patients with failing single-ventricle circulation also may benefit from VAD support, although the challenges facing this population are more profound than in other groups, Dr. Adachi said. VAD support for single-ventricle disease is sparse, but these patients require careful evaluation of the nature of their condition. “If systolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of circulatory failure, then VAD support for the failing systemic ventricle will likely improve hemodynamics,” said Dr. Adachi. VAD support also could help the patient move through the various stages of palliation.

“Again, the emphasis is not just on simply keeping the patient alive until a donor organ becomes available; rather, attention is refocused on overall health beyond survival, which may eventually affect transplantation candidacy and even post transplantation outcome,” Dr. Adachi concluded.

Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare, and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

The miniaturization of continuous-flow ventricular assist devices has launched the era of continuous-flow VAD support in pediatric patients, and the trend may accelerate with the introduction of a continuous-flow device designed specifically for small children. In an expert opinion in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Iki Adachi, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said the emerging science of continuous-flow VADs in children promises to solve problems like device size mismatch, hospital-only VADs, and chronic therapy (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 Oct;154:1358-61). “With ongoing device miniaturization, enthusiasm has been growing among pediatric physicians for the use of continuous-flow VADs in children,” Dr. Adachi said. He noted the introduction of a continuous-flow device for small children, the Infant Jarvik 2015, “may further accelerate the trend.”

Dr. Adachi cited PediMACS reports that stated that more than half of the long-term devices now registered are continuous-flow devices, and that continuous-flow VADs comprised 62% of all durable VAD implants in the third quarter of 2016. “With the encouraging results recorded to date, the use of continuous-flow devices in the pediatric population is rapidly increasing,” he said.

Miniaturization has addressed the problem of size mismatch when using continuous-flow VAD devices in children, he said, noting that use of the Infant Jarvik device may be expanded even further to children as small at 8 kg or less. The PumpKIN trial(Pumps for Kids, Infants, and Neonates), which is evaluating the Infant Jarvik 2015 vs. the Berlin Heart EXCOR, could provide answers on the feasibility of continuous-flow VADs in small children.

“Based on experience with the chronic animal model, I believe that the Infant Jarvik device will properly fit the patients included in the trial,” he said.

Continuous-flow VAD in children also holds potential for managing these patients outside the hospital setting. “Outpatient management of children with continuous-flow VADs has been shown to be feasible,” he said, adding that the PediMACS registry has reported that only 45% of patients have been managed this way. “Nonetheless, with maturation of the pediatric field, outpatient management will become routine rather than the exception,” he said.

Greater use of continuous-flow VADs also may create opportunities to improve the status and suitability for transplantation of children with severe heart failure, he said. He gave as an example his group’s practice at Houston’s Texas Children’s Hospital, which is to deactivate patients on the transplant wait list for 3 months once they start continuous-flow VAD support. “A postoperative ‘grace period’ affords protected opportunities for both physical and psychological recovery,” he said. This timeout of sorts also affords the care team time to assess the myocardium for possible functional recovery.

In patients who are not good candidates for transplantation, durable continuous-flow VADs may provide chronic therapy, and in time, these patients may become suitable transplant candidates, said Dr. Adachi. “Bypassing such an unfavorable period for transplantation with prolonged VAD support may be a reasonable approach,” he said.

Patients with failing single-ventricle circulation also may benefit from VAD support, although the challenges facing this population are more profound than in other groups, Dr. Adachi said. VAD support for single-ventricle disease is sparse, but these patients require careful evaluation of the nature of their condition. “If systolic dysfunction is the predominant cause of circulatory failure, then VAD support for the failing systemic ventricle will likely improve hemodynamics,” said Dr. Adachi. VAD support also could help the patient move through the various stages of palliation.

“Again, the emphasis is not just on simply keeping the patient alive until a donor organ becomes available; rather, attention is refocused on overall health beyond survival, which may eventually affect transplantation candidacy and even post transplantation outcome,” Dr. Adachi concluded.

Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare, and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Advances in continuous-flow ventricular assist devices (VADs) promise a paradigm shift in pediatrics.

Major finding: Device miniaturization is solving problems such as size mismatch, inpatients on VADs, and chronic therapy.

Data source: Expert opinion drawing on PediMACS reports and published trials of continuous-flow VAD.

Disclosures: Dr. Adachi serves as a consultant and proctor for Berlin Heart and HeartWare and as a consultant for the New England Research Institute related to the PumpKIN trial.

Obesity-Related Cancer Is on the Rise

Overweight and obesity are associated with an increased risk of 13 types of cancer—and those cancers account for about 40% of all cancers diagnosed in 2014, according to the CDC.

The 13 cancers are meningioma, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, multiple myeloma, kidney, uterine, ovarian, thyroid, breast, liver, gallbladder, upper stomach, pancreas, and colorectal. About 630,000 people were diagnosed with 1 of those cancers in 2014; 2 in 3 cancers were in adults aged 50 to 74 years. In 2013-2014, about 2 of every 3 American adults were overweight or obese.

Related: The Impact of Obesity on Simvastatin for Lowering LDL-C Among Veterans

Overall, the rate of new cancer cases has been on the decline since the 1990s, the report says, but increases in overweight- and obesity-related cancers “are likely slowing this progress.” Obesity-related cancers (not including colorectal cancer, which declined by 23%) increased by 7% between 2005 and 2014, while the rates of nonobesity–related cancers declined 13%.

Health care providers can help, the CDC says, by counseling patients on healthy weight and its role in cancer prevention, referring obese patients to intensive management programs and connecting patients and their families to community services that give them easier access to healthful food. The National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/index.htm) funds cancer coalitions across the U.S., which include strategies to prevent and control overweight and obesity.

Related: The Impact of Obesity on the Recovery of Patients With Cancer

“When people ask me if there’s a cure for cancer, I say, ‘Yes, good health is the best prescription for preventing chronic diseases, including cancer,” said Lisa Richardson, MD, director of CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. That means, she says, giving people the information they need to make healthy choices where they live, work, learn, and play.

Overweight and obesity are associated with an increased risk of 13 types of cancer—and those cancers account for about 40% of all cancers diagnosed in 2014, according to the CDC.

The 13 cancers are meningioma, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, multiple myeloma, kidney, uterine, ovarian, thyroid, breast, liver, gallbladder, upper stomach, pancreas, and colorectal. About 630,000 people were diagnosed with 1 of those cancers in 2014; 2 in 3 cancers were in adults aged 50 to 74 years. In 2013-2014, about 2 of every 3 American adults were overweight or obese.

Related: The Impact of Obesity on Simvastatin for Lowering LDL-C Among Veterans

Overall, the rate of new cancer cases has been on the decline since the 1990s, the report says, but increases in overweight- and obesity-related cancers “are likely slowing this progress.” Obesity-related cancers (not including colorectal cancer, which declined by 23%) increased by 7% between 2005 and 2014, while the rates of nonobesity–related cancers declined 13%.

Health care providers can help, the CDC says, by counseling patients on healthy weight and its role in cancer prevention, referring obese patients to intensive management programs and connecting patients and their families to community services that give them easier access to healthful food. The National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/index.htm) funds cancer coalitions across the U.S., which include strategies to prevent and control overweight and obesity.

Related: The Impact of Obesity on the Recovery of Patients With Cancer

“When people ask me if there’s a cure for cancer, I say, ‘Yes, good health is the best prescription for preventing chronic diseases, including cancer,” said Lisa Richardson, MD, director of CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. That means, she says, giving people the information they need to make healthy choices where they live, work, learn, and play.

Overweight and obesity are associated with an increased risk of 13 types of cancer—and those cancers account for about 40% of all cancers diagnosed in 2014, according to the CDC.

The 13 cancers are meningioma, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, multiple myeloma, kidney, uterine, ovarian, thyroid, breast, liver, gallbladder, upper stomach, pancreas, and colorectal. About 630,000 people were diagnosed with 1 of those cancers in 2014; 2 in 3 cancers were in adults aged 50 to 74 years. In 2013-2014, about 2 of every 3 American adults were overweight or obese.

Related: The Impact of Obesity on Simvastatin for Lowering LDL-C Among Veterans

Overall, the rate of new cancer cases has been on the decline since the 1990s, the report says, but increases in overweight- and obesity-related cancers “are likely slowing this progress.” Obesity-related cancers (not including colorectal cancer, which declined by 23%) increased by 7% between 2005 and 2014, while the rates of nonobesity–related cancers declined 13%.

Health care providers can help, the CDC says, by counseling patients on healthy weight and its role in cancer prevention, referring obese patients to intensive management programs and connecting patients and their families to community services that give them easier access to healthful food. The National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/index.htm) funds cancer coalitions across the U.S., which include strategies to prevent and control overweight and obesity.

Related: The Impact of Obesity on the Recovery of Patients With Cancer

“When people ask me if there’s a cure for cancer, I say, ‘Yes, good health is the best prescription for preventing chronic diseases, including cancer,” said Lisa Richardson, MD, director of CDC’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. That means, she says, giving people the information they need to make healthy choices where they live, work, learn, and play.

Team identifies HSCs that rapidly reconstitute hematopoiesis

Researchers say they have identified a subpopulation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that immediately contributes to long-term, multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution after transplant.

These HSCs were discovered in macaques, but the cells are similar to a subset of HSCs found in humans.

The researchers found the 2 sets of cells behaved identically when tested in vitro.

The team believes their findings will increase the efficiency of future efforts for HSC transplants, gene therapies, and gene editing.

Hans-Peter Kiem, MD, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers performed HSC transplants in pig-tailed macaques, following hundreds of thousands of cells immediately after transplant and over the course of 7.5 years.

Previous reports had suggested that successive waves of progenitor cells expand and contract to establish the new bone marrow after transplant.

However, Dr Kiem and his colleagues homed in on a distinct group of HSCs that took hold early after transplant and went on to produce all cell lineages that constitute a complete blood system.

“These findings came as a surprise,” Dr Kiem said. “We had thought that there were multiple types of blood stem cells that take on different roles in rebuilding a blood and immune system. This population does it all.”

The population is a subset of CD34+ cells expressing CD90 and lacking CD45RA markers.

“The gold standard target cell population for stem cell gene therapy are cells with the marker CD34,” said study author Stefan Radtke, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“But we used 2 additional markers to further distinguish the population from the other blood stem cells.”

The researchers noted that the CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs started repopulating the hematopoietic system within 10 days of being infused in macaques undergoing transplant.

A year later, the researchers found strong molecular traces of the cells, suggesting they were responsible for the ongoing maintenance of the newly transplanted system.

The team also determined the minimum numbers of CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs that were necessary for successful transplant (defined as sustained neutrophil and platelet recovery).

And the researchers found similar gene expression profiles between macaque and human CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs.

The team therefore believes these findings could have implications for HSC transplants in humans.

The researchers are now working to move their findings into the clinic with the hopes of integrating them in ongoing clinical trials. The team is currently looking for commercial partners. ![]()

Researchers say they have identified a subpopulation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that immediately contributes to long-term, multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution after transplant.

These HSCs were discovered in macaques, but the cells are similar to a subset of HSCs found in humans.

The researchers found the 2 sets of cells behaved identically when tested in vitro.

The team believes their findings will increase the efficiency of future efforts for HSC transplants, gene therapies, and gene editing.

Hans-Peter Kiem, MD, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers performed HSC transplants in pig-tailed macaques, following hundreds of thousands of cells immediately after transplant and over the course of 7.5 years.

Previous reports had suggested that successive waves of progenitor cells expand and contract to establish the new bone marrow after transplant.

However, Dr Kiem and his colleagues homed in on a distinct group of HSCs that took hold early after transplant and went on to produce all cell lineages that constitute a complete blood system.

“These findings came as a surprise,” Dr Kiem said. “We had thought that there were multiple types of blood stem cells that take on different roles in rebuilding a blood and immune system. This population does it all.”

The population is a subset of CD34+ cells expressing CD90 and lacking CD45RA markers.

“The gold standard target cell population for stem cell gene therapy are cells with the marker CD34,” said study author Stefan Radtke, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“But we used 2 additional markers to further distinguish the population from the other blood stem cells.”

The researchers noted that the CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs started repopulating the hematopoietic system within 10 days of being infused in macaques undergoing transplant.

A year later, the researchers found strong molecular traces of the cells, suggesting they were responsible for the ongoing maintenance of the newly transplanted system.

The team also determined the minimum numbers of CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs that were necessary for successful transplant (defined as sustained neutrophil and platelet recovery).

And the researchers found similar gene expression profiles between macaque and human CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs.

The team therefore believes these findings could have implications for HSC transplants in humans.

The researchers are now working to move their findings into the clinic with the hopes of integrating them in ongoing clinical trials. The team is currently looking for commercial partners. ![]()

Researchers say they have identified a subpopulation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that immediately contributes to long-term, multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution after transplant.

These HSCs were discovered in macaques, but the cells are similar to a subset of HSCs found in humans.

The researchers found the 2 sets of cells behaved identically when tested in vitro.

The team believes their findings will increase the efficiency of future efforts for HSC transplants, gene therapies, and gene editing.

Hans-Peter Kiem, MD, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers performed HSC transplants in pig-tailed macaques, following hundreds of thousands of cells immediately after transplant and over the course of 7.5 years.

Previous reports had suggested that successive waves of progenitor cells expand and contract to establish the new bone marrow after transplant.

However, Dr Kiem and his colleagues homed in on a distinct group of HSCs that took hold early after transplant and went on to produce all cell lineages that constitute a complete blood system.

“These findings came as a surprise,” Dr Kiem said. “We had thought that there were multiple types of blood stem cells that take on different roles in rebuilding a blood and immune system. This population does it all.”

The population is a subset of CD34+ cells expressing CD90 and lacking CD45RA markers.

“The gold standard target cell population for stem cell gene therapy are cells with the marker CD34,” said study author Stefan Radtke, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

“But we used 2 additional markers to further distinguish the population from the other blood stem cells.”

The researchers noted that the CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs started repopulating the hematopoietic system within 10 days of being infused in macaques undergoing transplant.

A year later, the researchers found strong molecular traces of the cells, suggesting they were responsible for the ongoing maintenance of the newly transplanted system.

The team also determined the minimum numbers of CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs that were necessary for successful transplant (defined as sustained neutrophil and platelet recovery).

And the researchers found similar gene expression profiles between macaque and human CD34+ CD45RA- CD90+ HSCs.

The team therefore believes these findings could have implications for HSC transplants in humans.

The researchers are now working to move their findings into the clinic with the hopes of integrating them in ongoing clinical trials. The team is currently looking for commercial partners. ![]()

FDA grants product breakthrough designation for MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation to GSK2857916, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) monoclonal antibody conjugated to the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin-F via a non-cleavable linker.

The designation is for GSK2857916 as monotherapy for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) who have failed at least 3 prior lines of therapy, including an anti-CD38 antibody, and who are refractory to a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

The designation is based on results from a phase 1, dose-escalation and expansion study in patients with relapsed/refractory MM, irrespective of BCMA expression (NCT02064387).

Data from this ongoing trial are scheduled to be presented December 11 in an oral presentation at the 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in Atlanta, Georgia.

GSK2857916 has also received orphan drug designation from the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as well as PRIME designation from the EMA.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions. The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

Orphan and PRIME designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. The designation qualifies a drug’s sponsor for various development incentives of the Orphan Drug Act, including tax credits for qualified clinical testing and 7 years of market exclusivity.

In Europe, sponsors who obtain orphan designation for a potential new medicine benefit from a range of incentives, including protocol assistance, access to the centralized procedure, 10 years of market exclusivity, and fee reductions.

The EMA grants PRIME designation to enhance support for the development of medicines that target an unmet medical need. The designation is based on enhanced interaction between sponsor companies and the EMA to optimize development plans and speed up evaluation so these medicines can reach patients earlier. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation to GSK2857916, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) monoclonal antibody conjugated to the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin-F via a non-cleavable linker.

The designation is for GSK2857916 as monotherapy for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) who have failed at least 3 prior lines of therapy, including an anti-CD38 antibody, and who are refractory to a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

The designation is based on results from a phase 1, dose-escalation and expansion study in patients with relapsed/refractory MM, irrespective of BCMA expression (NCT02064387).

Data from this ongoing trial are scheduled to be presented December 11 in an oral presentation at the 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in Atlanta, Georgia.

GSK2857916 has also received orphan drug designation from the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as well as PRIME designation from the EMA.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions. The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

Orphan and PRIME designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. The designation qualifies a drug’s sponsor for various development incentives of the Orphan Drug Act, including tax credits for qualified clinical testing and 7 years of market exclusivity.

In Europe, sponsors who obtain orphan designation for a potential new medicine benefit from a range of incentives, including protocol assistance, access to the centralized procedure, 10 years of market exclusivity, and fee reductions.

The EMA grants PRIME designation to enhance support for the development of medicines that target an unmet medical need. The designation is based on enhanced interaction between sponsor companies and the EMA to optimize development plans and speed up evaluation so these medicines can reach patients earlier. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation to GSK2857916, an anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) monoclonal antibody conjugated to the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin-F via a non-cleavable linker.

The designation is for GSK2857916 as monotherapy for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) who have failed at least 3 prior lines of therapy, including an anti-CD38 antibody, and who are refractory to a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

The designation is based on results from a phase 1, dose-escalation and expansion study in patients with relapsed/refractory MM, irrespective of BCMA expression (NCT02064387).

Data from this ongoing trial are scheduled to be presented December 11 in an oral presentation at the 59th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) in Atlanta, Georgia.

GSK2857916 has also received orphan drug designation from the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) as well as PRIME designation from the EMA.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions. The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

Orphan and PRIME designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to therapies intended to treat conditions that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. The designation qualifies a drug’s sponsor for various development incentives of the Orphan Drug Act, including tax credits for qualified clinical testing and 7 years of market exclusivity.

In Europe, sponsors who obtain orphan designation for a potential new medicine benefit from a range of incentives, including protocol assistance, access to the centralized procedure, 10 years of market exclusivity, and fee reductions.

The EMA grants PRIME designation to enhance support for the development of medicines that target an unmet medical need. The designation is based on enhanced interaction between sponsor companies and the EMA to optimize development plans and speed up evaluation so these medicines can reach patients earlier. ![]()

Cancer patients prefer computer-free interactions

SAN DIEGO—A new study suggests patients with advanced cancer may prefer doctors who do not use a computer while communicating with them.

Most of the 120 patients studied said they preferred face-to-face consultations in which a doctor used a notepad rather than a computer.

Doctors who did not use a computer were perceived as more compassionate, communicative, and professional.

These findings were presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 26*).

“To our knowledge, this is the only study that compares exam room interactions between people with advanced cancer and their physicians, with or without a computer present,” said study investigator Ali Haider, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

For this study, Dr Haider and his colleagues enrolled 120 patients with localized, recurrent, or metastatic disease. The patients’ median ECOG performance status was 2.

All patients were English speakers, they had a median age of 58 (range, 44-66), and 55% were female. Sixty-seven percent of patients were white, 18% were Hispanic, 13% were African American, and 2% were “other.” Forty-one percent of patients had completed college.

According to the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, patients’ median pain score was 5 (range, 2-7), and their median fatigue score was 4 (range, 3-7). According to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, patients’ median anxiety score was 6 (range, 4-8), and their median depression score was 6 (range, 4-9).

The intervention

The investigators randomly assigned patients to watch different videos showing doctor-patient interactions with and without computer use. The team had filmed 4 short videos that featured actors playing the parts of doctor and patient.

All study participants were blinded to the hypothesis of the study. The actors were carefully scripted and used the same gestures, expressions, and other nonverbal communication in each video to minimize bias.

Video 1 involved Doctor A in a face-to-face consultation with just a notepad in hand, and Video 2 involved Doctor A in a consultation using a computer.

Video 3 involved Doctor B in a face-to-face consultation with just a notepad in hand, and Video 4 involved Doctor B in a consultation using a computer.

Doctors A and B looked similar, which was intended to minimize bias.

After viewing their first video, patients completed a validated questionnaire rating the doctor’s communication skills, professionalism, and compassion.

Subsequently, each group was assigned to a video topic (face-to-face or computer) they had not viewed previously featuring the doctor they had not viewed in the first video.

A follow-up questionnaire was given after this round of viewing, and the patients were also asked to rate their overall physician preference.

Results

After the first round of viewing, the patients gave better ratings to doctors (A or B) in the face-to-face videos than in the computer videos. Face-to-face doctors were rated significantly higher for compassion (P=0.0003), communication skills (P=0.0012), and professionalism (P=0.0001).

After patients had watched both videos, doctors in the face-to-face videos still had better scores for compassion, communication, and professionalism (P<0.001 for all).

Most patients (72%) said they preferred the face-to-face consultation, while 8% said they preferred the computer consultation, and 20% said they had no preference.

Dr Haider said a possible explanation for these findings is that patients with serious chronic illnesses might value undivided attention from their physicians, and patients might perceive providers using computers as more distracted or multitasking during visits.

“We know that having a good rapport with patients can be extremely beneficial for their health,” Dr Haider said. “Patients with advanced disease need the cues that come with direct interaction to help them along with their care.”

However, Dr Haider also noted that additional research is needed to confirm these results. And he said perceptions might be different in a younger population with higher computer literacy. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

SAN DIEGO—A new study suggests patients with advanced cancer may prefer doctors who do not use a computer while communicating with them.

Most of the 120 patients studied said they preferred face-to-face consultations in which a doctor used a notepad rather than a computer.

Doctors who did not use a computer were perceived as more compassionate, communicative, and professional.

These findings were presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 26*).

“To our knowledge, this is the only study that compares exam room interactions between people with advanced cancer and their physicians, with or without a computer present,” said study investigator Ali Haider, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

For this study, Dr Haider and his colleagues enrolled 120 patients with localized, recurrent, or metastatic disease. The patients’ median ECOG performance status was 2.

All patients were English speakers, they had a median age of 58 (range, 44-66), and 55% were female. Sixty-seven percent of patients were white, 18% were Hispanic, 13% were African American, and 2% were “other.” Forty-one percent of patients had completed college.

According to the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, patients’ median pain score was 5 (range, 2-7), and their median fatigue score was 4 (range, 3-7). According to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, patients’ median anxiety score was 6 (range, 4-8), and their median depression score was 6 (range, 4-9).

The intervention

The investigators randomly assigned patients to watch different videos showing doctor-patient interactions with and without computer use. The team had filmed 4 short videos that featured actors playing the parts of doctor and patient.

All study participants were blinded to the hypothesis of the study. The actors were carefully scripted and used the same gestures, expressions, and other nonverbal communication in each video to minimize bias.

Video 1 involved Doctor A in a face-to-face consultation with just a notepad in hand, and Video 2 involved Doctor A in a consultation using a computer.

Video 3 involved Doctor B in a face-to-face consultation with just a notepad in hand, and Video 4 involved Doctor B in a consultation using a computer.

Doctors A and B looked similar, which was intended to minimize bias.

After viewing their first video, patients completed a validated questionnaire rating the doctor’s communication skills, professionalism, and compassion.

Subsequently, each group was assigned to a video topic (face-to-face or computer) they had not viewed previously featuring the doctor they had not viewed in the first video.

A follow-up questionnaire was given after this round of viewing, and the patients were also asked to rate their overall physician preference.

Results

After the first round of viewing, the patients gave better ratings to doctors (A or B) in the face-to-face videos than in the computer videos. Face-to-face doctors were rated significantly higher for compassion (P=0.0003), communication skills (P=0.0012), and professionalism (P=0.0001).

After patients had watched both videos, doctors in the face-to-face videos still had better scores for compassion, communication, and professionalism (P<0.001 for all).

Most patients (72%) said they preferred the face-to-face consultation, while 8% said they preferred the computer consultation, and 20% said they had no preference.

Dr Haider said a possible explanation for these findings is that patients with serious chronic illnesses might value undivided attention from their physicians, and patients might perceive providers using computers as more distracted or multitasking during visits.

“We know that having a good rapport with patients can be extremely beneficial for their health,” Dr Haider said. “Patients with advanced disease need the cues that come with direct interaction to help them along with their care.”

However, Dr Haider also noted that additional research is needed to confirm these results. And he said perceptions might be different in a younger population with higher computer literacy. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

SAN DIEGO—A new study suggests patients with advanced cancer may prefer doctors who do not use a computer while communicating with them.

Most of the 120 patients studied said they preferred face-to-face consultations in which a doctor used a notepad rather than a computer.

Doctors who did not use a computer were perceived as more compassionate, communicative, and professional.

These findings were presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 26*).

“To our knowledge, this is the only study that compares exam room interactions between people with advanced cancer and their physicians, with or without a computer present,” said study investigator Ali Haider, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

For this study, Dr Haider and his colleagues enrolled 120 patients with localized, recurrent, or metastatic disease. The patients’ median ECOG performance status was 2.

All patients were English speakers, they had a median age of 58 (range, 44-66), and 55% were female. Sixty-seven percent of patients were white, 18% were Hispanic, 13% were African American, and 2% were “other.” Forty-one percent of patients had completed college.

According to the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System, patients’ median pain score was 5 (range, 2-7), and their median fatigue score was 4 (range, 3-7). According to the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, patients’ median anxiety score was 6 (range, 4-8), and their median depression score was 6 (range, 4-9).

The intervention

The investigators randomly assigned patients to watch different videos showing doctor-patient interactions with and without computer use. The team had filmed 4 short videos that featured actors playing the parts of doctor and patient.

All study participants were blinded to the hypothesis of the study. The actors were carefully scripted and used the same gestures, expressions, and other nonverbal communication in each video to minimize bias.

Video 1 involved Doctor A in a face-to-face consultation with just a notepad in hand, and Video 2 involved Doctor A in a consultation using a computer.

Video 3 involved Doctor B in a face-to-face consultation with just a notepad in hand, and Video 4 involved Doctor B in a consultation using a computer.

Doctors A and B looked similar, which was intended to minimize bias.

After viewing their first video, patients completed a validated questionnaire rating the doctor’s communication skills, professionalism, and compassion.

Subsequently, each group was assigned to a video topic (face-to-face or computer) they had not viewed previously featuring the doctor they had not viewed in the first video.

A follow-up questionnaire was given after this round of viewing, and the patients were also asked to rate their overall physician preference.

Results

After the first round of viewing, the patients gave better ratings to doctors (A or B) in the face-to-face videos than in the computer videos. Face-to-face doctors were rated significantly higher for compassion (P=0.0003), communication skills (P=0.0012), and professionalism (P=0.0001).

After patients had watched both videos, doctors in the face-to-face videos still had better scores for compassion, communication, and professionalism (P<0.001 for all).

Most patients (72%) said they preferred the face-to-face consultation, while 8% said they preferred the computer consultation, and 20% said they had no preference.

Dr Haider said a possible explanation for these findings is that patients with serious chronic illnesses might value undivided attention from their physicians, and patients might perceive providers using computers as more distracted or multitasking during visits.

“We know that having a good rapport with patients can be extremely beneficial for their health,” Dr Haider said. “Patients with advanced disease need the cues that come with direct interaction to help them along with their care.”

However, Dr Haider also noted that additional research is needed to confirm these results. And he said perceptions might be different in a younger population with higher computer literacy. ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from the presentation.

Acute Management of Severe Asymptomatic Hypertension

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Patient history; what to ask

- Cardiovascular risk factors

- Disposition pathway

- Oral medications

Approximately one in three US adults, or about 75 million people, have high blood pressure (BP), which has been defined as a BP of 140/90 mm Hg or higher.1 Unfortunately, only about half (54%) of those affected have their condition under optimal control.1 From an epidemiologic standpoint, hypertension has the distinction of being the most common chronic condition in the US, affecting about 54% of persons ages 55 to 64 and about 73% of those 75 and older.2,3 It is the number one reason patients schedule office visits with physicians; it accounts for the most prescriptions; and it is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke, as well as a significant contributor to mortality throughout the world.4

HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY VS EMERGENCY

Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies account for approximately 27% of all medical emergencies and 2% to 3% of all annual visits to the emergency department (ED).5 Hypertensive urgency, or severe asymptomatic hypertension, is a common complaint in urgent care clinics and primary care offices as well. It is often defined as a systolic BP (SBP) of ≥ 160 mm Hg and/or a diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 100 mm Hg with no associated end-organ damage.5-7 Patients may experience hypertensive urgency if they have been noncompliant with their antihypertensive drug regimen; present with pain; have white-coat hypertension or anxiety; or use recreational drugs (eg, sympathomimetics).5,8-10

Alternatively, hypertensive emergency, also known as hypertensive crisis, is generally defined as elevated BP > 180/120 mm Hg. Equally important, it is associated with signs, symptoms, or laboratory values indicative of target end-organ damage, such as cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction (MI), aortic dissection, acute left ventricular failure, acute pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, acute mental status changes (hypertensive encephalopathy), and eclampsia.5,7,8,11,12

Determining appropriate management for patients with hypertensive urgency is controversial among clinicians. Practice patterns range from full screening and “rule-outs”—with prompt initiation of antihypertensive agents, regardless of whether the patient is symptomatic—to sending the patient home with minimal screening, laboratory testing, or treatment.

This article offers a guided approach to managing patients with hypertensive urgency in a logical fashion, based on risk stratification, thereby avoiding both extremes (extensive unnecessary workup or discharge without workup resulting in adverse outcomes). It is vital to differentiate between patients with hypertensive emergency, in which BP should be lowered in minutes, and patients with hypertensive urgency, in which BP can be lowered more slowly.12

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Normally, when BP increases, blood vessel diameter changes in response; this autoregulation serves to limit damage. However, when BP increases abruptly, the body’s ability to hemodynamically calibrate to such a rapid change is impeded, thus allowing for potential end-organ damage.5,12 The increased vascular resistance observed in many patients with hypertension appears to be an autoregulatory process that helps to maintain a normal or viable level of tissue blood flow and organ perfusion despite the increased BP, rather than a primary cause of the hypertension.13

The exact physiology of hypertensive urgencies is not clearly understood, because of the multifactorial nature of the process. One leading theory is that circulating humoral vasoconstrictors cause an abrupt increase in systemic vascular resistance, which in turn causes mechanical shear stress to the endothelial wall. This endothelial damage promotes more vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation, and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which thereby increases release of angiotensin II and various cytokines.14

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL

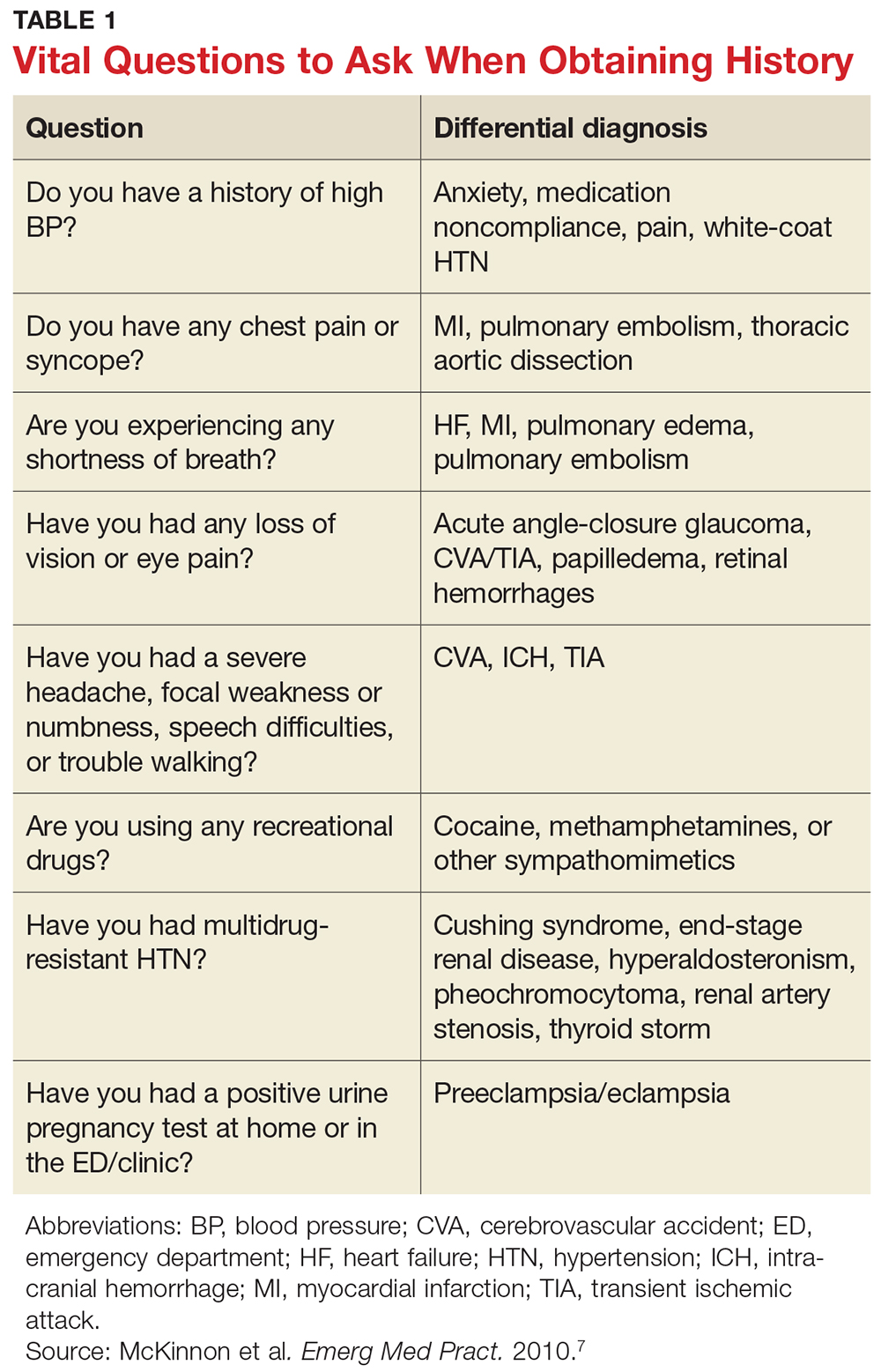

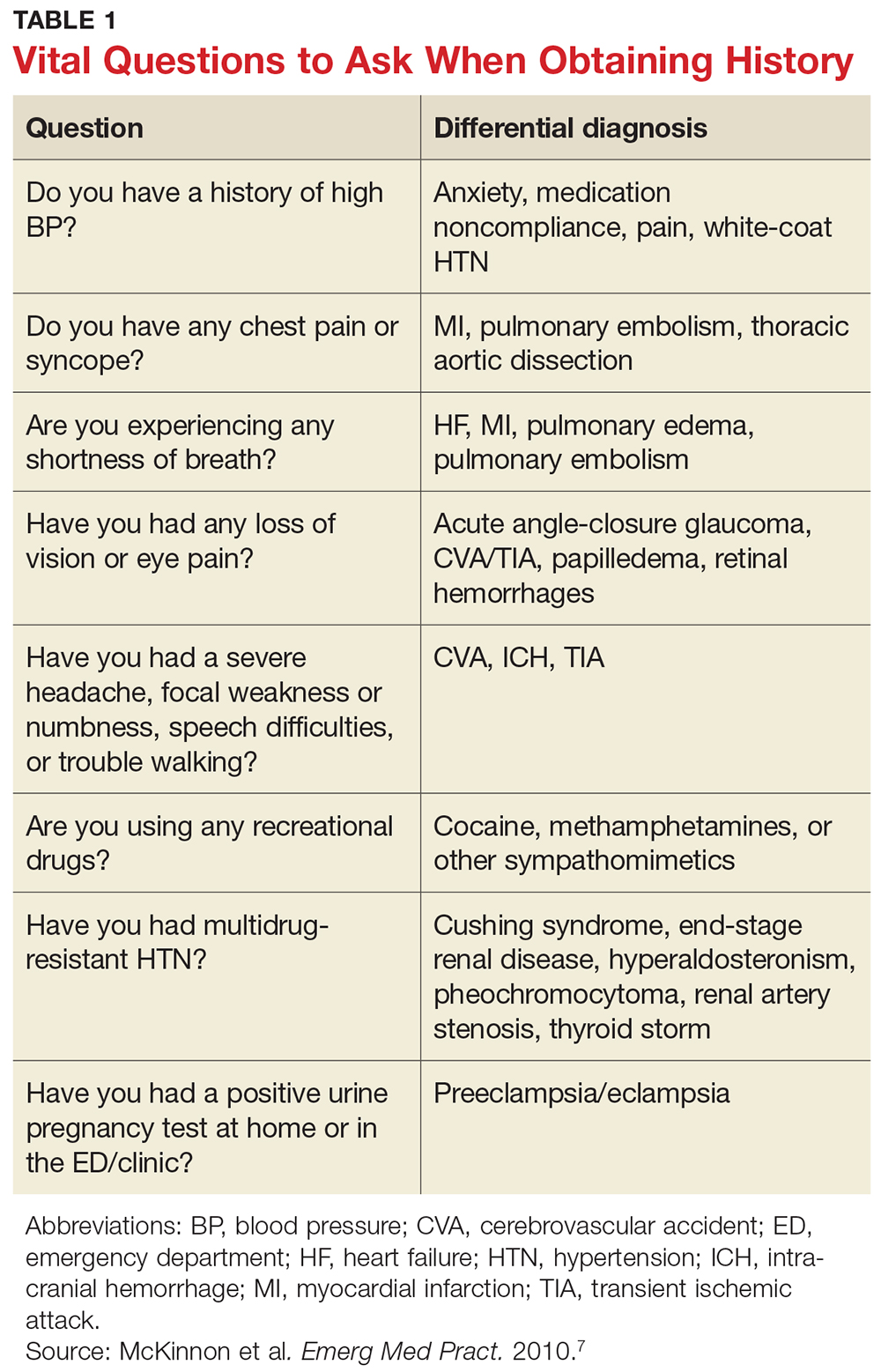

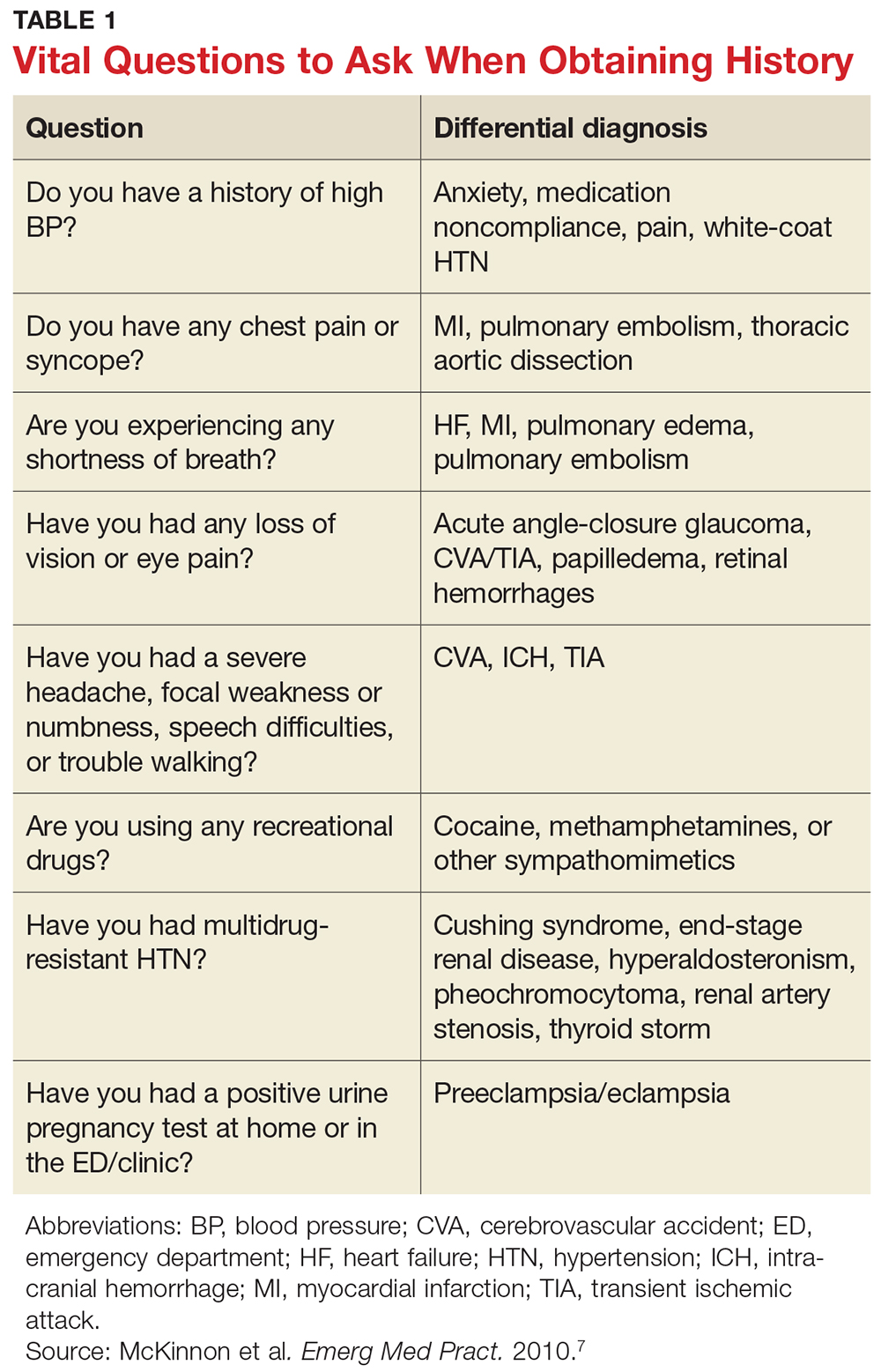

A detailed medical history is of utmost importance in distinguishing patients who present with asymptomatic hypertensive urgency from those experiencing a hypertensive emergency. In addition, obtain a full medication list, including any nutritional supplements or illicit drugs the patient may be taking. Question the patient regarding medication adherence; some may not be taking antihypertensive agents as prescribed or may have altered the dosing frequency in an effort to extend the duration of their prescription.5,8 Table 1 lists pertinent questions to ask at presentation; the answers will dictate who needs further workup and possible admission as well as who will require screening for end-organ damage.7

The physical exam should focus primarily on a thorough cardiopulmonary and neurologic examination, as well as funduscopic examination, if needed. A complete set of vital signs should be recorded upon the patient’s arrival to the ED or clinic and should be repeated on the opposite arm for verification. Beginning with the eyes, conduct a thorough funduscopic examination to evaluate for papilledema or hemorrhages.5 During the cardiopulmonary exam, attention should be focused on signs of congestive heart failure and/or pulmonary edema, such as increased jugular vein distension, an S3 gallop, peripheral edema, and pulmonary rales. The neurologic exam is essential in evaluating for cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or intracranial hemorrhage. A full cranial nerve examination is necessary, in addition to motor and sensory testing, at minimum.5,9

RISK STRATIFICATION

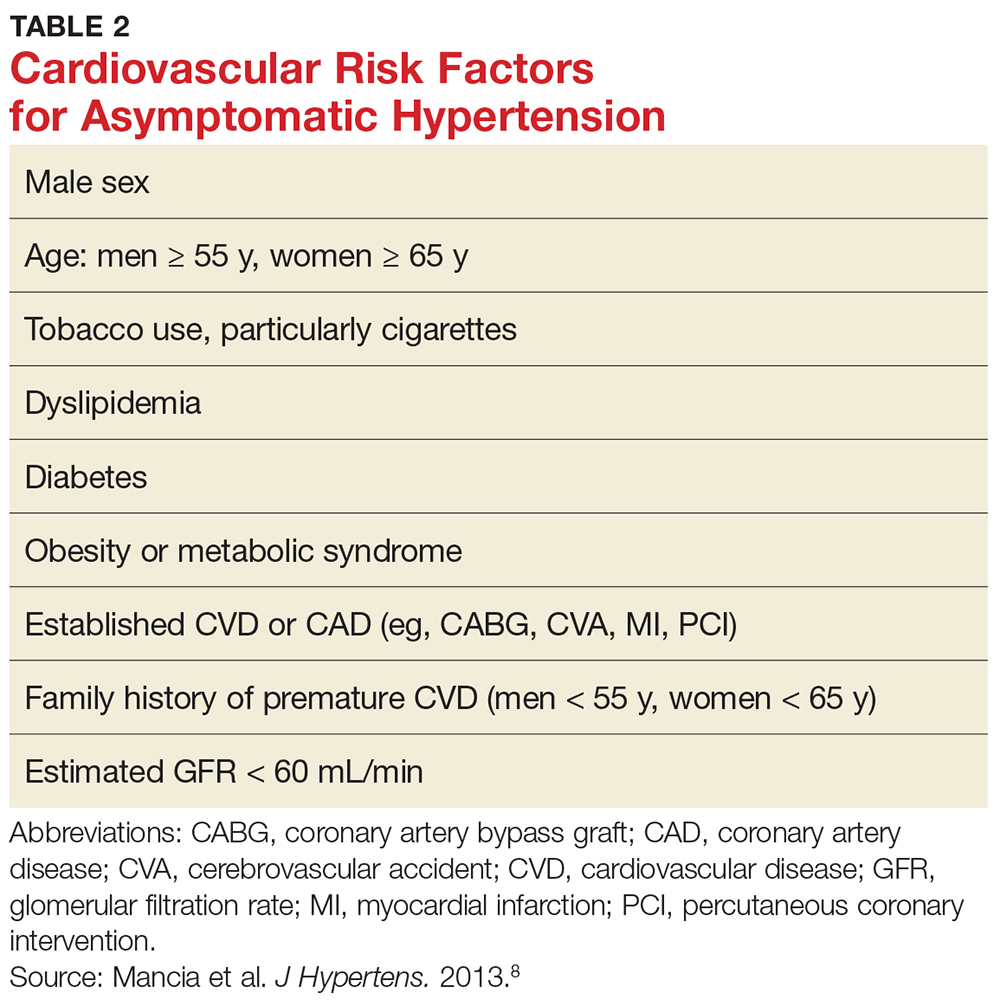

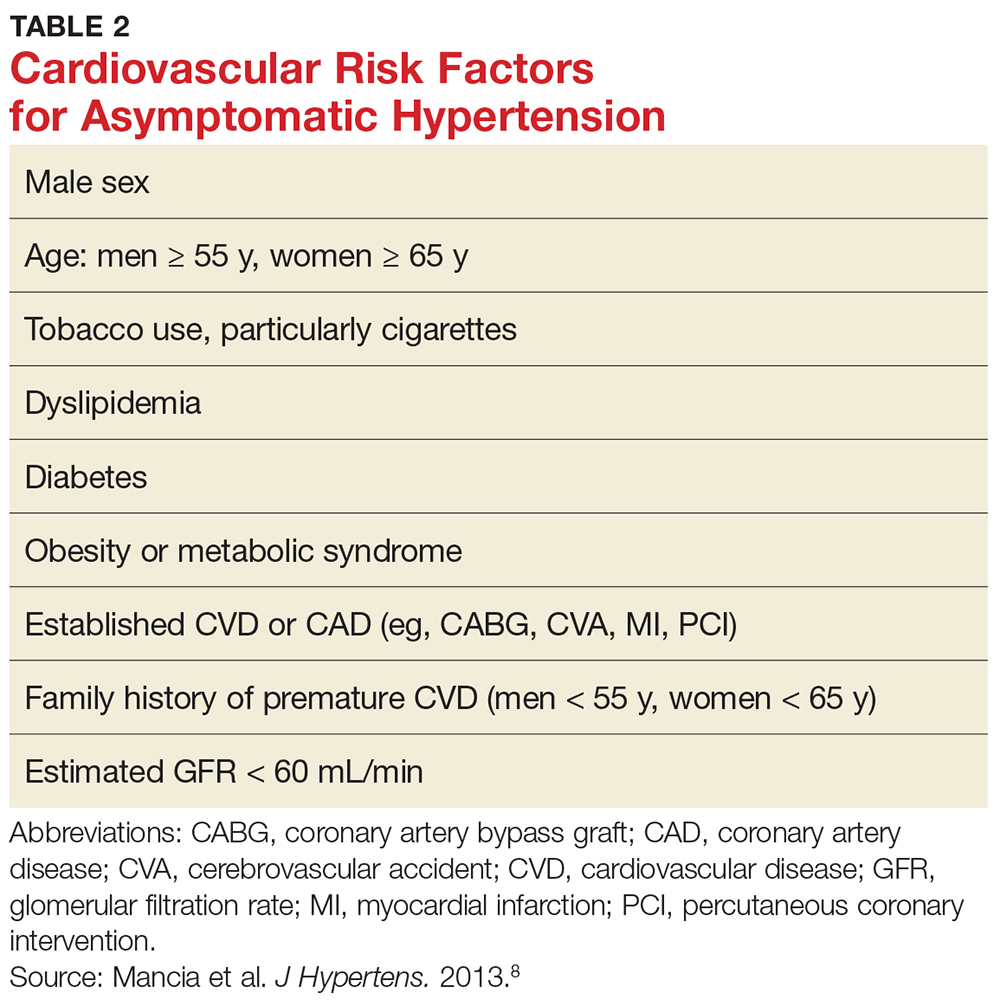

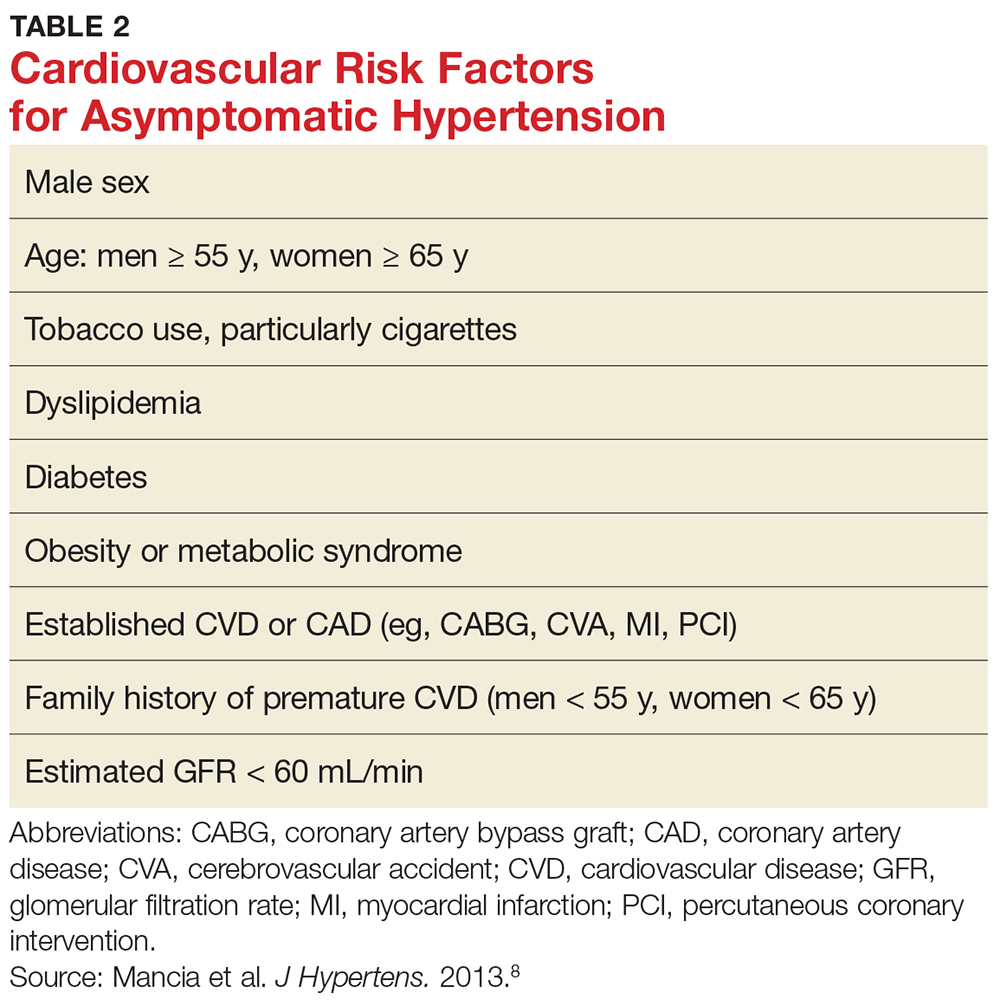

According to the 2013 Task Force of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), several risk factors contribute to overall cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic patients presenting with severe hypertension (see Table 2).8 This report has been monumental in linking grades of hypertension directly to cardiovascular risk factors, but it differs from that recently published by the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8), which offers evidence-based guidelines for the management of high BP in the general population of adults (with some modifications for individuals with diabetes or chronic kidney disease or of black ethnicity).15

According to the ESH/ESC study, patients with one or two risk factors who have grade 1 hypertension (SBP 140-159 mm Hg) are at moderate risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and patients with grade 2 (SBP 160-179 mm Hg) or grade 3 (SBP ≥ 180 mm Hg) hypertension are at moderate-to-high risk and high risk, respectively.8 Patients with three or more risk factors, or who already have end-organ damage, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease, enter the high-risk category for CVD even at grade 1 hypertension.8

These cardiovascular risk factors can and should be used as guidelines for deciding who needs further screening and who may have benign causes of severe hypertension (eg, white-coat hypertension, anxiety) that can be managed safely in an outpatient setting. In the author’s opinion, patients with known cardiovascular risk factors, those with signs or symptoms of end-organ damage, and those with test results suggestive of end-organ damage should have a more immediate treatment strategy initiated.

Numerous observational studies have shown a direct relationship between systemic hypertension and CVD risk in men and women of various ages, races, and ethnicities, regardless of other risk factors for CVD.12 In patients with diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension is a strong predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and of progressive nephropathy leading to chronic kidney disease.8

SCREENING

Results from the following tests may provide useful clues in the workup of a patient with hypertensive urgency.

Basic metabolic panel. Many EDs and primary care offices offer point-of-care testing that can typically give a rapid (< 10 min) result of a basic metabolic panel. This useful, quick screening tool can identify renal failure due to chronic untreated hypertension, acute renal failure, or other disease states that cause electrolyte abnormalities such as hyperaldosteronism (hypertension with hypokalemia) or Cushing syndrome (hypertension with hypernatremia and hyperkalemia).7

Cardiac enzymes. Measurement of cardiac troponins (T or I) may provide confirmatory evidence of myocardial necrosis within two to three hours of suspected acute MI.16,17 These tests are now available in most EDs and some clinics with point-of-care testing. A variety of current guidelines advocate repeat cardiac enzyme measurements at various time points, depending on results of initial testing and concomitant risk factors. These protocols vary by facility.

ECG. Obtaining an ECG is another quick, easy, and useful way to screen patients presenting with severe hypertensive urgency. Evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy suggests an increased risk for MI, stroke, heart failure, and sudden death.7,18-20 The Cornell criteria of summing the R wave in aVL and the S wave in V3, with a cutoff of 2.8 mV in men and 2.0 mV in women, has been shown to be the best predictor of future cardiovascular mortality.7 While an isolated finding of left ventricular hypertrophy on an ECG—in and of itself—may have limited value for an individual patient, this finding coupled with other risk factors may alter the provider’s assessment.

Chest radiograph. A chest radiograph can be helpful when used in conjunction with physical exam findings that suggest pulmonary edema and cardiomegaly.7 Widened mediastinum and tortuous aorta may also be evident on chest x-ray, necessitating further workup and imaging.

Urinalysis. In a patient presenting with asymptomatic hypertensive urgency, a urine dipstick result that shows new-onset proteinuria, while not definitive for diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, may certainly prove helpful in the patient’s workup.5,13

Urine drug screen. In patients without a history of hypertension who present with asymptomatic hypertensive urgency, the urine drug screen may ascertain exposure to cocaine, amphetamine, or phencyclidine.

Pregnancy test. A pregnancy test is essential for any female patient of childbearing age presenting to the ED, and a positive result may be concerning for preeclampsia in a hypertensive patient with no prior history of the condition.7

TREATMENT

Knowing who to treat and when is a vast area of debate among emergency and primary care providers. Patients with hypertension who have established risk factors are known to have worse outcomes than those who may be otherwise healthy. Some clinicians believe that patients presenting with hypertensive urgency should be discharged home without screening and/or treatment. However, because uncontrolled severe hypertension can lead to acute complications (eg, MI, cerebrovascular accident), in practice, many providers are unwilling to send the patient home without workup.12 The patient’s condition must be viewed in the context of the entire disease spectrum, including risk factors.

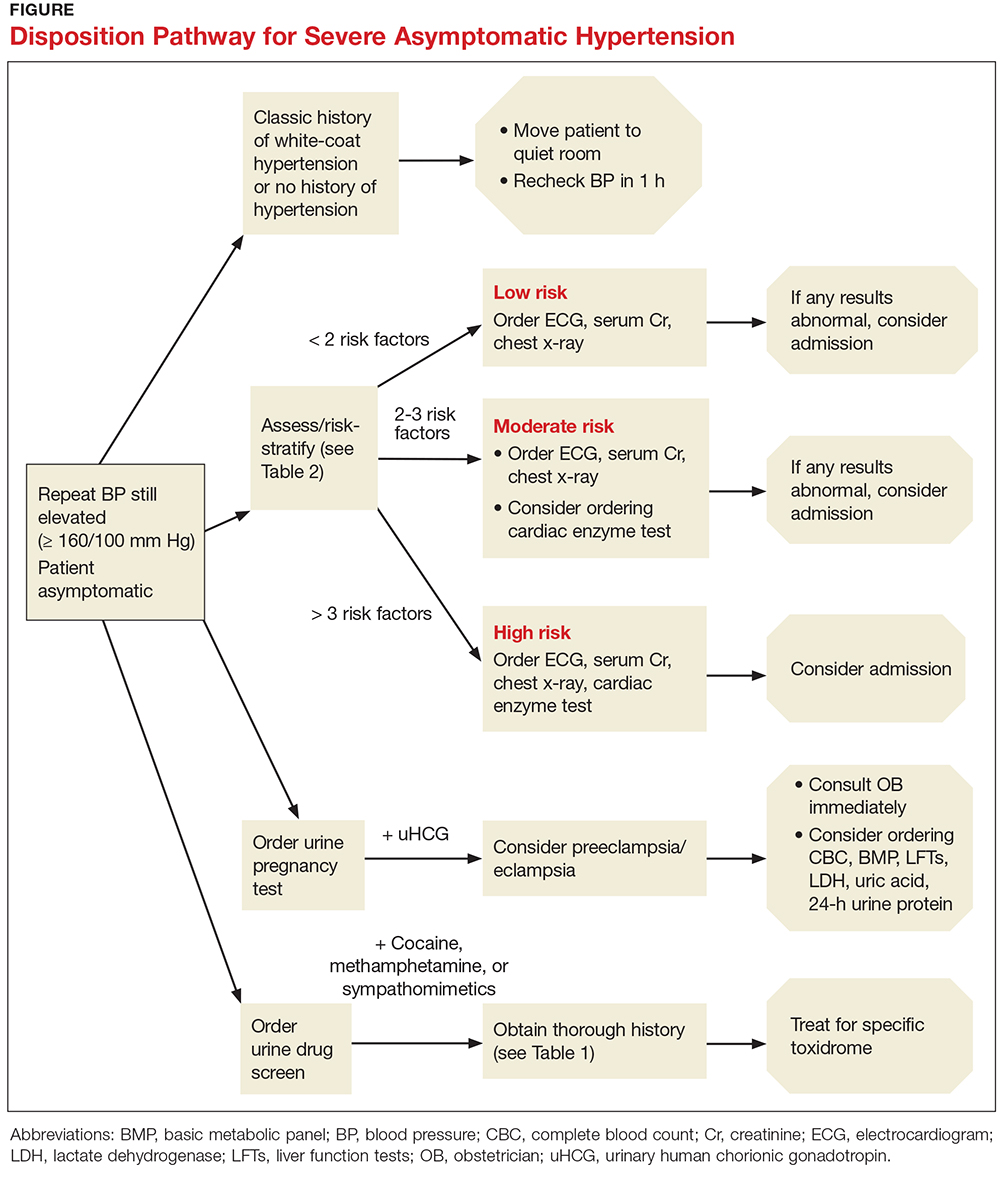

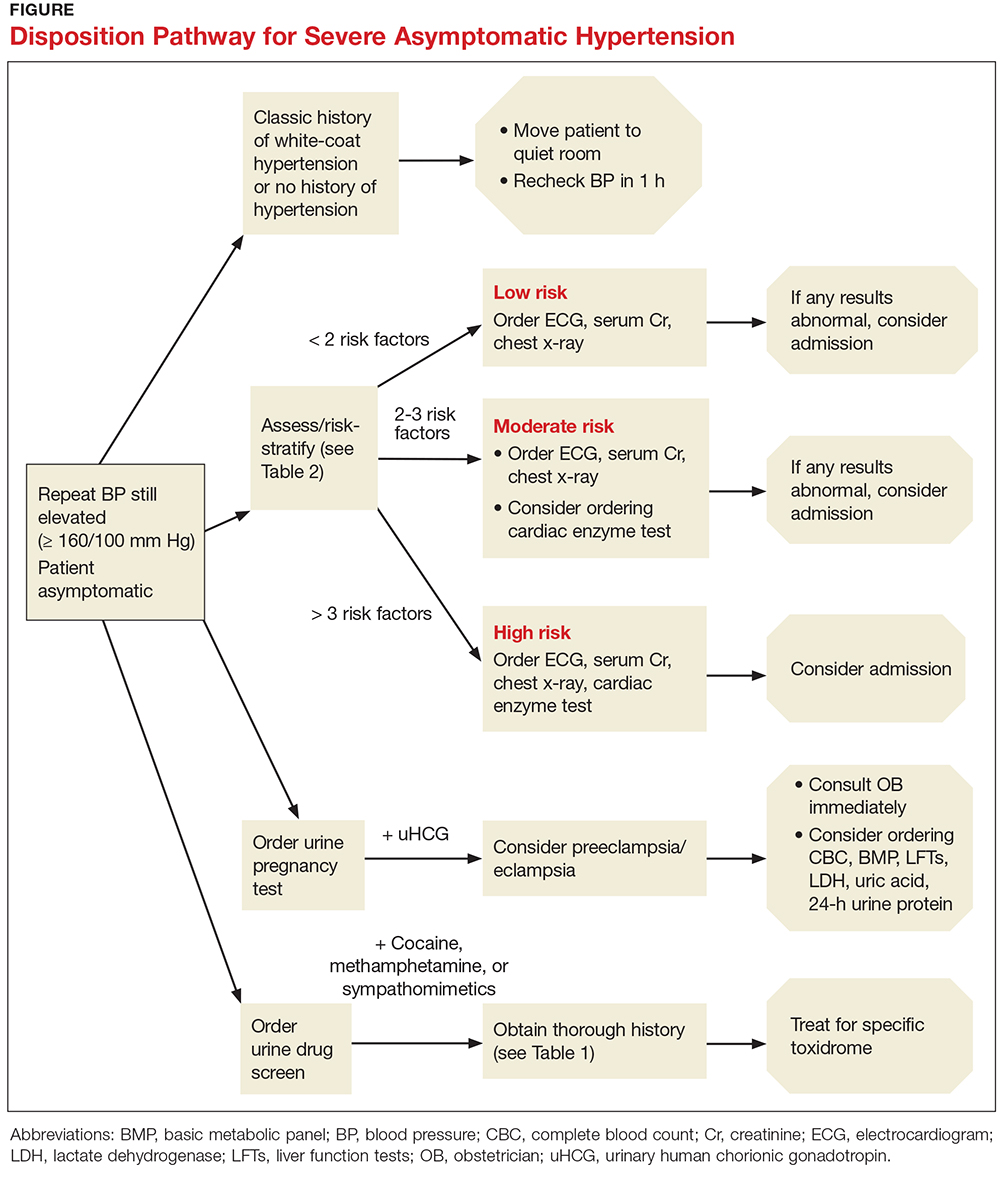

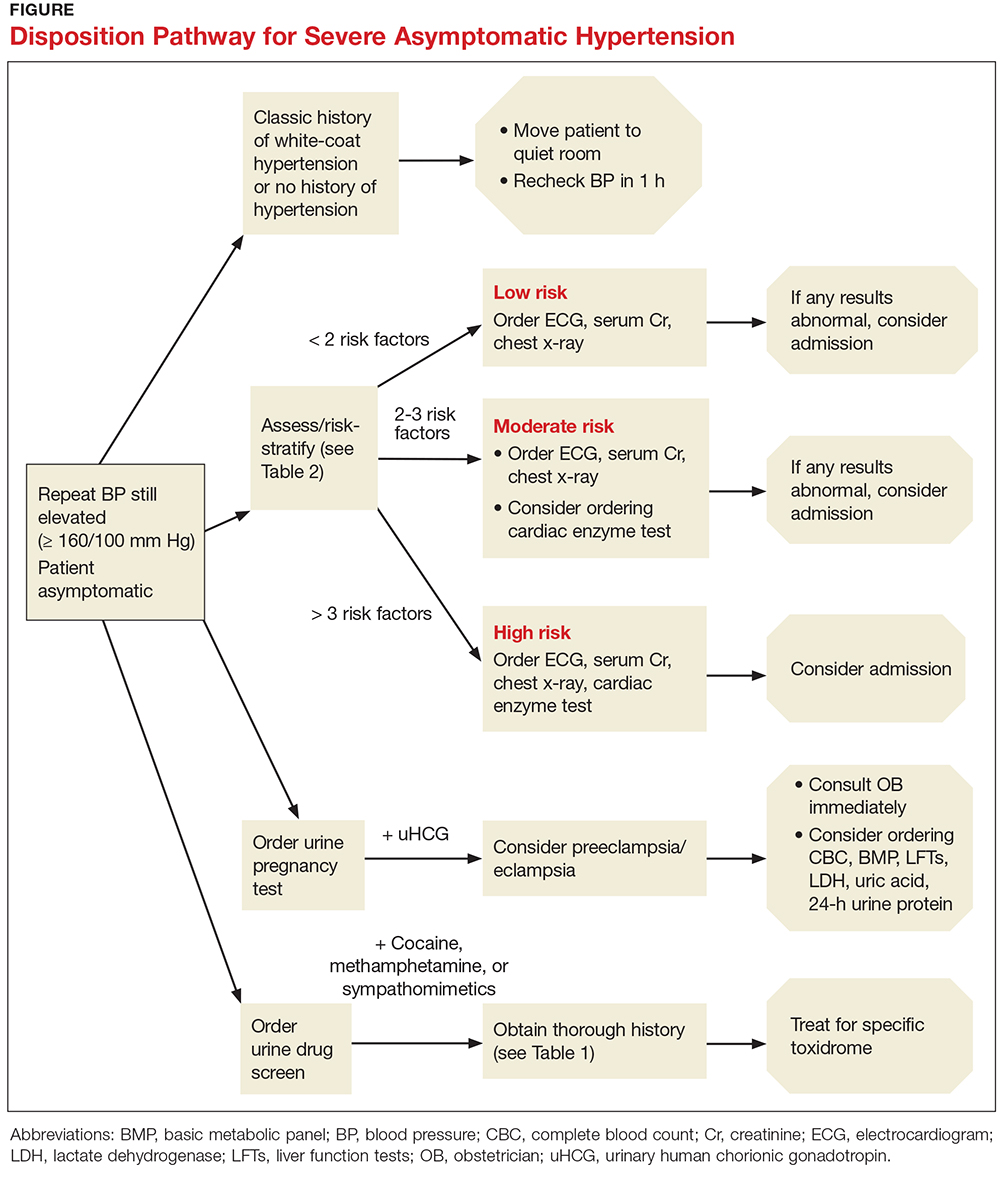

The Figure offers a disposition pathway of recommendations based on risk stratification as well as screening tools for some of the less common causes of hypertensive urgency. Regardless of the results of screening tests or the decision to treat, affected patients require close primary care follow-up. Many of these patients may need further testing and careful management of their BP medication regimen.

How to treat

For patients with severe asymptomatic hypertension, if the history, physical, and screening tests do not show evidence of end-organ damage, BP can be controlled within 24 to 48 hours.5,10,11,21 In adults with hypertensive urgency, the most reasonable goal is to reduce the BP to ≤ 160/100 mm Hg5-7; however, the mean arterial pressure should not be lowered by more than 25% within the first two to three hours.13

Patients at high risk for imminent neurovascular, cardiovascular, renovascular, or pulmonary events should have their BP lowered over a period of hours, not minutes. In fact, there is evidence that rapid lowering of BP in asymptomatic patients may cause adverse outcomes.6 For example, in patients with acute ischemic stroke, increases in cerebral perfusion pressure promote an increase in vascular resistance—but decreasing the cerebral perfusion pressure abruptly will thereby decrease the cerebral blood flow, potentially causing cerebral ischemia or a worsening of the stroke.9,14

Treatment options

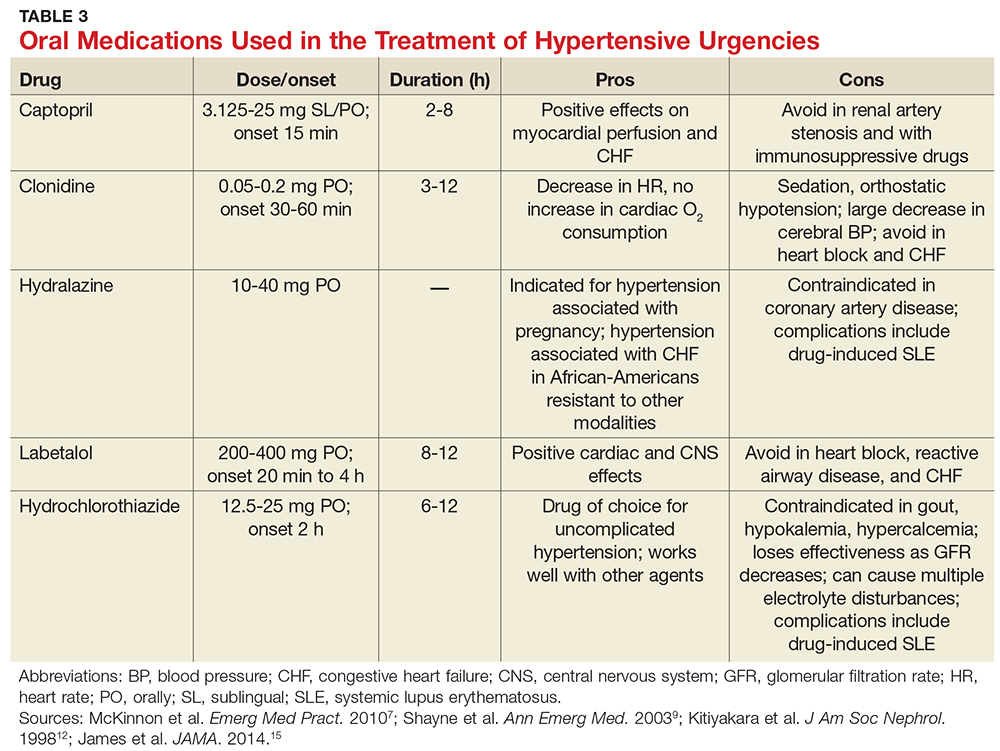

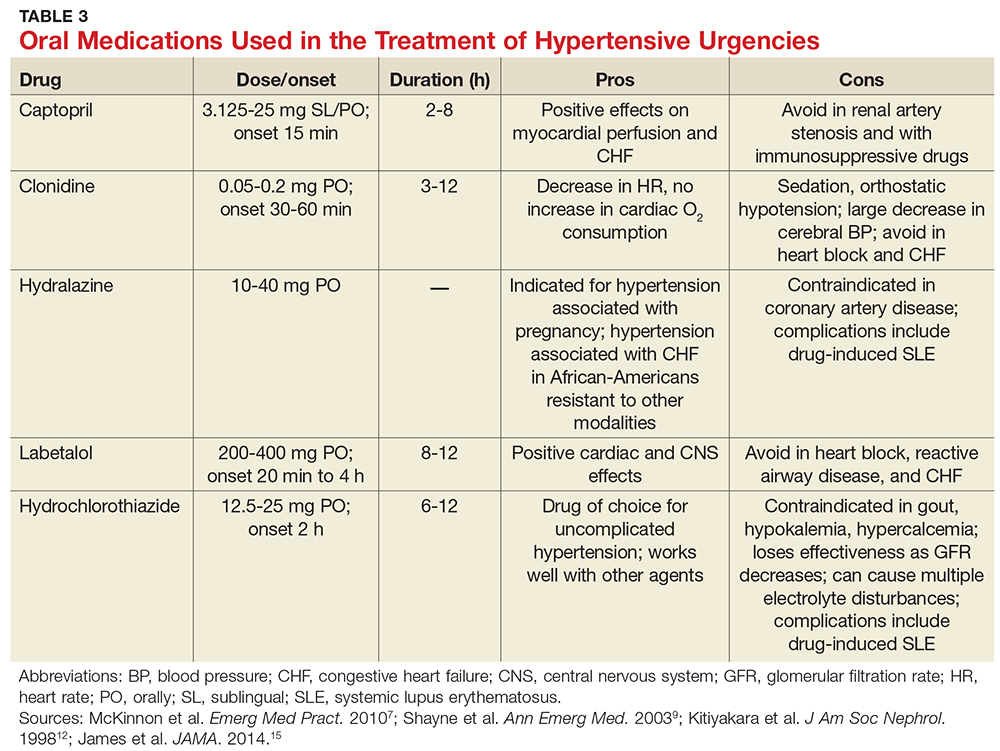

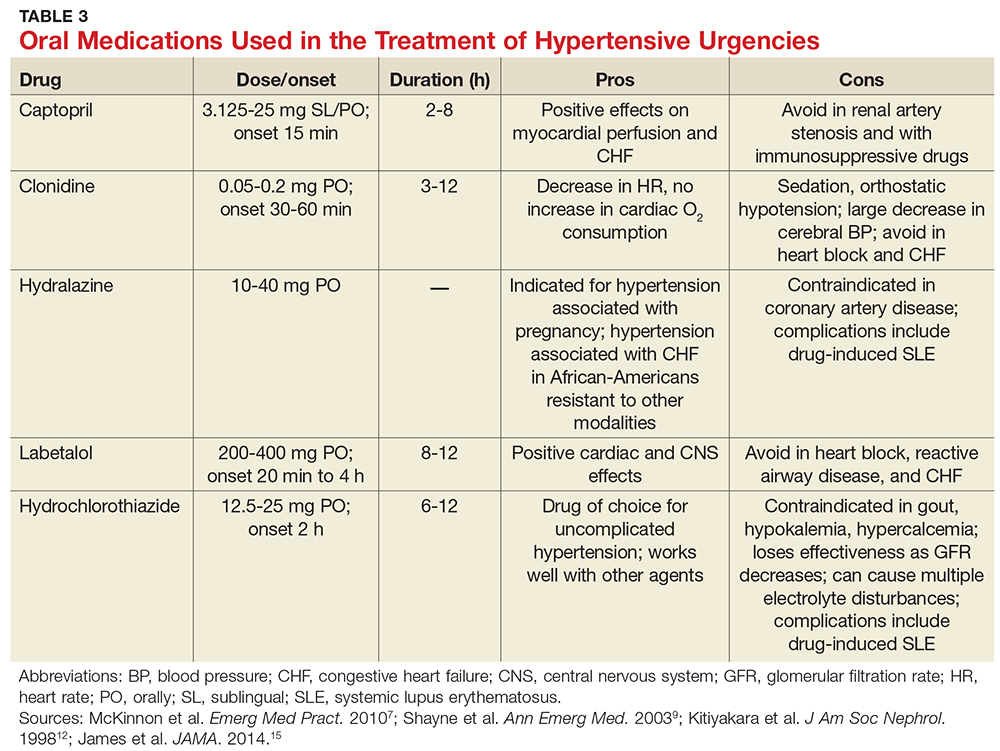

A broad spectrum of therapeutic options has proven helpful in lowering BP over a short period of time, including oral captopril, clonidine, hydralazine, labetalol, and hydrochlorothiazide (see Table 3).7,9,12,15 Nifedipine is contraindicated because of the abrupt and often unpredictable reduction in BP and associated myocardial ischemia, especially in patients with MI or left ventricular hypertrophy.14,22,23 In cases of hypertensive urgency secondary to cocaine abuse, benzodiazepines would be the drug of choice and ß-blockers should be avoided due to the risk for coronary vasoconstriction.7

For patients with previously treated hypertension, the following options are reasonable: Increase the dose of the current antihypertensive medication; add another agent; reinstitute prior antihypertensive medications in nonadherent patients; or add a diuretic.

In patients with previously untreated hypertension, no clear evidence supports using one particular agent over another. However, initial treatment options that are generally considered safe include an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker, a calcium channel blocker, or a thiazide diuretic.15 A few examples of medications within these categories include lisinopril (10 mg PO qd), losartan (50 mg PO qd), amlodipine (2.5 mg PO qd), or hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg PO qd).

Close follow-up is essential when an antihypertensive medication is started or reinstituted. Encourage the patient to reestablish care with their primary care provider (if you do not fill that role). You may need to refer the patient to a new provider or, in some cases, have the patient return to the ED for a repeat BP check.

CONCLUSION

The challenges of managing patients with hypertensive urgency are complicated by low follow-up rates with primary physicians, difficulty in obtaining referrals and follow-up for the patient, and hesitancy of providers to start patients on new BP medications. This article clarifies a well-defined algorithm for how to screen and risk-stratify patients who present to the ED or primary care office with hypertensive urgency.

1. CDC. High blood pressure fact sheet. www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/data_statistics/fact_sheets/fs_bloodpressure.htm. Accessed September 26, 2017.

2. Decker WW, Godwin SA, Hess EP, et al; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Asymptomatic Hypertension in the ED. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients with asymptomatic hypertension in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47(3):237-249.

3. CDC. High blood pressure facts. www.cdc.gov/bloodpressure/facts.htm. Accessed October 19, 2017.

4. World Health Organization. Global Health Risks: Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf. Accessed October 19, 2017.

5. Stewart DL, Feinstein SE, Colgan R. Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies. Prim Care. 2006;33(3):613-623.

6. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Shih RD, et al; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(1):59-68.

7. McKinnon M, O’Neill JM. Hypertension in the emergency department: treat now, later, or not at all. Emerg Med Pract. 2010;12(6):1-22.

8. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens. 2013;31(7): 1281-1357.

9. Shayne PH, Pitts SR. Severely increased blood pressure in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41(4): 513-529.

10. Aggarwal M, Khan IA. Hypertensive crisis: hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24(1):135-146.

11. Houston MC. The comparative effects of clonidine hydrochloride and nifedipine in the treatment of hypertensive crises. Am Heart J. 1998;115(1 pt 1):152-159.

12. Kitiyakara C, Guaman NJ. Malignant hypertension and hypertensive emergencies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(1):133-142.

13. Elliott WJ. Hypertensive emergencies. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17(2):435-451.

14. Papadopoulos DP, Mourouzis I, Thomopoulos C, et al. Hypertension crisis. Blood Press. 2010;19(6):328-336.

15. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520.

16. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):868-877.

17. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):858-867.

18. Ghali JK, Kadakia S, Cooper RS, Liao YL. Impact of left ventricular hypertrophy on ventricular arrhythmias in the absence of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(6):1277-1282.

19. Bang CN, Soliman EZ, Simpson LM, et al. Electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy predicts cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertensive patients: the ALLHAT study. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30(9):914-922.

20. Hsieh BP, Pham MX, Froelicher VF. Prognostic value of electrocardiographic criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J. 2005;150(1):161-167.

21. Kinsella K, Baraff LJ. Initiation of therapy for asymptomatic hypertension in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54(6):791-792.

22. O’Mailia JJ, Sander GE, Giles TD. Nifedipine-associated myocardial ischemia or infarction in the treatment of hypertensive urgencies. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(2):185-186.

23. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, Kowey P. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-1331.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Patient history; what to ask

- Cardiovascular risk factors

- Disposition pathway

- Oral medications

Approximately one in three US adults, or about 75 million people, have high blood pressure (BP), which has been defined as a BP of 140/90 mm Hg or higher.1 Unfortunately, only about half (54%) of those affected have their condition under optimal control.1 From an epidemiologic standpoint, hypertension has the distinction of being the most common chronic condition in the US, affecting about 54% of persons ages 55 to 64 and about 73% of those 75 and older.2,3 It is the number one reason patients schedule office visits with physicians; it accounts for the most prescriptions; and it is a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke, as well as a significant contributor to mortality throughout the world.4

HYPERTENSIVE URGENCY VS EMERGENCY

Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies account for approximately 27% of all medical emergencies and 2% to 3% of all annual visits to the emergency department (ED).5 Hypertensive urgency, or severe asymptomatic hypertension, is a common complaint in urgent care clinics and primary care offices as well. It is often defined as a systolic BP (SBP) of ≥ 160 mm Hg and/or a diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 100 mm Hg with no associated end-organ damage.5-7 Patients may experience hypertensive urgency if they have been noncompliant with their antihypertensive drug regimen; present with pain; have white-coat hypertension or anxiety; or use recreational drugs (eg, sympathomimetics).5,8-10

Alternatively, hypertensive emergency, also known as hypertensive crisis, is generally defined as elevated BP > 180/120 mm Hg. Equally important, it is associated with signs, symptoms, or laboratory values indicative of target end-organ damage, such as cerebrovascular accident, myocardial infarction (MI), aortic dissection, acute left ventricular failure, acute pulmonary edema, acute renal failure, acute mental status changes (hypertensive encephalopathy), and eclampsia.5,7,8,11,12

Determining appropriate management for patients with hypertensive urgency is controversial among clinicians. Practice patterns range from full screening and “rule-outs”—with prompt initiation of antihypertensive agents, regardless of whether the patient is symptomatic—to sending the patient home with minimal screening, laboratory testing, or treatment.

This article offers a guided approach to managing patients with hypertensive urgency in a logical fashion, based on risk stratification, thereby avoiding both extremes (extensive unnecessary workup or discharge without workup resulting in adverse outcomes). It is vital to differentiate between patients with hypertensive emergency, in which BP should be lowered in minutes, and patients with hypertensive urgency, in which BP can be lowered more slowly.12

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Normally, when BP increases, blood vessel diameter changes in response; this autoregulation serves to limit damage. However, when BP increases abruptly, the body’s ability to hemodynamically calibrate to such a rapid change is impeded, thus allowing for potential end-organ damage.5,12 The increased vascular resistance observed in many patients with hypertension appears to be an autoregulatory process that helps to maintain a normal or viable level of tissue blood flow and organ perfusion despite the increased BP, rather than a primary cause of the hypertension.13

The exact physiology of hypertensive urgencies is not clearly understood, because of the multifactorial nature of the process. One leading theory is that circulating humoral vasoconstrictors cause an abrupt increase in systemic vascular resistance, which in turn causes mechanical shear stress to the endothelial wall. This endothelial damage promotes more vasoconstriction, platelet aggregation, and activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which thereby increases release of angiotensin II and various cytokines.14

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL

A detailed medical history is of utmost importance in distinguishing patients who present with asymptomatic hypertensive urgency from those experiencing a hypertensive emergency. In addition, obtain a full medication list, including any nutritional supplements or illicit drugs the patient may be taking. Question the patient regarding medication adherence; some may not be taking antihypertensive agents as prescribed or may have altered the dosing frequency in an effort to extend the duration of their prescription.5,8 Table 1 lists pertinent questions to ask at presentation; the answers will dictate who needs further workup and possible admission as well as who will require screening for end-organ damage.7

The physical exam should focus primarily on a thorough cardiopulmonary and neurologic examination, as well as funduscopic examination, if needed. A complete set of vital signs should be recorded upon the patient’s arrival to the ED or clinic and should be repeated on the opposite arm for verification. Beginning with the eyes, conduct a thorough funduscopic examination to evaluate for papilledema or hemorrhages.5 During the cardiopulmonary exam, attention should be focused on signs of congestive heart failure and/or pulmonary edema, such as increased jugular vein distension, an S3 gallop, peripheral edema, and pulmonary rales. The neurologic exam is essential in evaluating for cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or intracranial hemorrhage. A full cranial nerve examination is necessary, in addition to motor and sensory testing, at minimum.5,9

RISK STRATIFICATION

According to the 2013 Task Force of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), several risk factors contribute to overall cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic patients presenting with severe hypertension (see Table 2).8 This report has been monumental in linking grades of hypertension directly to cardiovascular risk factors, but it differs from that recently published by the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8), which offers evidence-based guidelines for the management of high BP in the general population of adults (with some modifications for individuals with diabetes or chronic kidney disease or of black ethnicity).15

According to the ESH/ESC study, patients with one or two risk factors who have grade 1 hypertension (SBP 140-159 mm Hg) are at moderate risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and patients with grade 2 (SBP 160-179 mm Hg) or grade 3 (SBP ≥ 180 mm Hg) hypertension are at moderate-to-high risk and high risk, respectively.8 Patients with three or more risk factors, or who already have end-organ damage, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease, enter the high-risk category for CVD even at grade 1 hypertension.8

These cardiovascular risk factors can and should be used as guidelines for deciding who needs further screening and who may have benign causes of severe hypertension (eg, white-coat hypertension, anxiety) that can be managed safely in an outpatient setting. In the author’s opinion, patients with known cardiovascular risk factors, those with signs or symptoms of end-organ damage, and those with test results suggestive of end-organ damage should have a more immediate treatment strategy initiated.

Numerous observational studies have shown a direct relationship between systemic hypertension and CVD risk in men and women of various ages, races, and ethnicities, regardless of other risk factors for CVD.12 In patients with diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension is a strong predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and of progressive nephropathy leading to chronic kidney disease.8

SCREENING

Results from the following tests may provide useful clues in the workup of a patient with hypertensive urgency.

Basic metabolic panel. Many EDs and primary care offices offer point-of-care testing that can typically give a rapid (< 10 min) result of a basic metabolic panel. This useful, quick screening tool can identify renal failure due to chronic untreated hypertension, acute renal failure, or other disease states that cause electrolyte abnormalities such as hyperaldosteronism (hypertension with hypokalemia) or Cushing syndrome (hypertension with hypernatremia and hyperkalemia).7

Cardiac enzymes. Measurement of cardiac troponins (T or I) may provide confirmatory evidence of myocardial necrosis within two to three hours of suspected acute MI.16,17 These tests are now available in most EDs and some clinics with point-of-care testing. A variety of current guidelines advocate repeat cardiac enzyme measurements at various time points, depending on results of initial testing and concomitant risk factors. These protocols vary by facility.

ECG. Obtaining an ECG is another quick, easy, and useful way to screen patients presenting with severe hypertensive urgency. Evidence of left ventricular hypertrophy suggests an increased risk for MI, stroke, heart failure, and sudden death.7,18-20 The Cornell criteria of summing the R wave in aVL and the S wave in V3, with a cutoff of 2.8 mV in men and 2.0 mV in women, has been shown to be the best predictor of future cardiovascular mortality.7 While an isolated finding of left ventricular hypertrophy on an ECG—in and of itself—may have limited value for an individual patient, this finding coupled with other risk factors may alter the provider’s assessment.

Chest radiograph. A chest radiograph can be helpful when used in conjunction with physical exam findings that suggest pulmonary edema and cardiomegaly.7 Widened mediastinum and tortuous aorta may also be evident on chest x-ray, necessitating further workup and imaging.

Urinalysis. In a patient presenting with asymptomatic hypertensive urgency, a urine dipstick result that shows new-onset proteinuria, while not definitive for diagnosis of nephrotic syndrome, may certainly prove helpful in the patient’s workup.5,13

Urine drug screen. In patients without a history of hypertension who present with asymptomatic hypertensive urgency, the urine drug screen may ascertain exposure to cocaine, amphetamine, or phencyclidine.

Pregnancy test. A pregnancy test is essential for any female patient of childbearing age presenting to the ED, and a positive result may be concerning for preeclampsia in a hypertensive patient with no prior history of the condition.7

TREATMENT

Knowing who to treat and when is a vast area of debate among emergency and primary care providers. Patients with hypertension who have established risk factors are known to have worse outcomes than those who may be otherwise healthy. Some clinicians believe that patients presenting with hypertensive urgency should be discharged home without screening and/or treatment. However, because uncontrolled severe hypertension can lead to acute complications (eg, MI, cerebrovascular accident), in practice, many providers are unwilling to send the patient home without workup.12 The patient’s condition must be viewed in the context of the entire disease spectrum, including risk factors.