User login

Discharges Against Medical Advice

Patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA) for a variety of reasons. The AMA rate is approximately 1% nationally but substantially higher at safety-net hospitals and has rapidly increased over the past decade.1-5 The principle that patients have the right to make choices about their healthcare, up to and including whether to leave the hospital against the advice of medical staff, is well-established law and a foundation of medical ethics.6 In practice, however, AMA discharges are often emotionally charged for both patients and providers, and, in the high-stress setting of AMA discharge, providers may be confused about their roles.7-9

The demographics of patients who leave AMA have been well described. Compared with conventionally discharged patients, AMA patients are younger, more likely to be male, and more likely a marginalized ethnic or racial minority.10-14 Patients with mental illnesses and addiction issues are overrepresented in AMA discharges, and complicated capacity assessments and limited resources may strain providers.7,8,15,16 Studies have repeatedly shown higher rates of readmission and mortality for AMA patients than for conventionally discharged patients.17-21 Whether AMA discharge is a marker for other prognostic factors that bode poorly for patients or contributes to negative outcomes, data suggest this group of patients is vulnerable, having mortality rates up to 40% higher 1 year after discharge, relative to conventionally discharged patients.12

Several models of standardized best practice approaches for AMA have been proposed by bioethicists.6,22,23 Although details of these approaches vary, all involve assessing the patient’s decision-making capacity, clarifying the risks of AMA discharge, addressing factors that might be prompting the discharge, formulating an alternative outpatient treatment plan or “next best” option, and documenting extensively. A recent study found patients often gave advance warning of an AMA discharge, but physicians rarely prepared by arranging follow-up care.8 The investigators hypothesized that providers might not have known what they were permitted to arrange for AMA patients, or might have thought that providing “second best” options went against their principles. The investigators noted that nurses might have become aware of AMA risk sooner than physicians did but could not act on this awareness by preparing medications and arranging follow-up.

Translating models of best practice care for AMA patients into clinical practice requires buy-in from bedside providers, not just bioethicists. Given the study findings that providers have misconceptions about their roles in the AMA discharge,7 it is prudent to investigate providers’ current practices, beliefs, and concerns about AMA discharges before introducing a new approach.

The present authors conducted a mixed-methods cross-sectional study of the state of AMA discharges at Highland Hospital (Oakland, California), a 236-bed county hospital and trauma center serving a primarily underserved urban patient population. The aim of this study was to assess current provider practices for AMA discharges and provider perceptions and knowledge about AMA discharges, ultimately to help direct future educational interventions with medical providers or hospital policy changes needed to improve the quality of AMA discharges.

METHODS

Phase 1 of this study involved identifying AMA patients through a review of data from Highland Hospital’s electronic medical records for 2014. These data included discharge status (eg, AMA vs other discharge types). The hospital’s floor clerk distinguishes between absent without official leave (AWOL; the patient leaves without notifying a provider) and AMA discharge. Discharges designated AWOL were excluded from the analyses.

In phase 2, a structured chart review (Appendix A) was performed for all patients identified during phase 1 as being discharged AMA in 2014. In these reviews, further assessment was made of patient and visit characteristics in hospitalizations that ended in AMA discharge, and of providers’ documentation of AMA discharges—that is, whether several factors were documented (capacity; predischarge indication that patient might leave AMA; reason for AMA; and indications that discharge medications, transportation, and follow-up were arranged). These visit factors were reviewed because the literature has identified them as being important markers for AMA discharge safety.6,8 Two research assistants, under the guidance of Dr. Stearns, reviewed the charts. To ensure agreement across chart reviews with respect to subjective questions (eg, whether capacity was adequately documented), the group reviewed the first 10 consecutive charts together; there was full agreement on how to classify the data of interest. Throughout the study, whenever a research assistant asked how to classify particular patient data, Dr. Stearns reviewed the data, and the research team made a decision together. Additional data, for AMA patients and for all patients admitted to Highland Hospital, were obtained from the hospital’s data warehouse, which pools data from within the health system.

Phase 3 involved surveying healthcare providers who were involved in patient care on the internal medicine and trauma surgery services at the hospital. These providers were selected because chart review revealed that the vast majority of patients who left AMA in 2014 were on one of these services. Surveys (Appendix B) asked participant providers to identify their role at the hospital, to provide a self-assessment of competence in various aspects of AMA discharge, to voice opinions about provider responsibilities in arranging follow-up for AMA patients, and to make suggestions about the AMA process. The authors designed these surveys, which included questions about aspects of care that have been highlighted in the AMA discharge literature as being important for AMA discharge safety.6,8,22,23 Surveys were distributed to providers at internal medicine and trauma surgery department meetings and nursing conferences. Data (without identifying information) were analyzed, and survey responses kept anonymous.

The Alameda Health System Institutional Review Board approved this project. Providers were given the option of writing their name and contact information at the top of the survey in order to be entered into a drawing to receive a prize for completion.

We performed statistical analyses of the patient charts and physician survey data using Stata (version 14.0, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas). We analyzed both patient- and encounter-level data. In demographic analyses, this approach prevented duplicate counting of patients who left AMA multiple times. Patient-level analyses compared the demographic characteristics of AMA patients and patients discharged conventionally from the hospital in 2014. In addition, patients with either 1 or multiple AMA discharges were compared to identify characteristics that might be linked to highest risk of recurrent AMA discharge in the hope that early identification of these patients might facilitate providers’ early awareness and preparation for follow-up care or hospitalization alternatives. We used ANOVAs for continuous variables and tests of proportions for categorical variables. On the encounter level, analyses examined data about each admission (eg, AMA forms signed, follow-up arrangements made, capacity documented, etc.) for all AMA discharges. We employed chi square tests to identify variations in healthcare provider survey responses. A P value < 0.05 was used as the significance cut-off point.

Staged logistic regression analyses, adjusted for demographic characteristics, were performed to assess the association between risk of leaving AMA (yes or no) and demographic characteristics and the association between risk of leaving AMA more than once (yes or no) and health-related characteristics.

RESULTS

Demographic, Clinical, and Utilization Characteristics

Of the 12,036 Highland Hospital admissions in 2014, 319 (2.7%) ended with an AMA discharge. Of the 8207 individual patients discharged, 268 left AMA once, and 29 left AMA multiple times. Further review of the Admissions, Discharges, and Transfers Report generated from the electronic medical record revealed that 15 AWOL discharges were misclassified as AMA discharges.

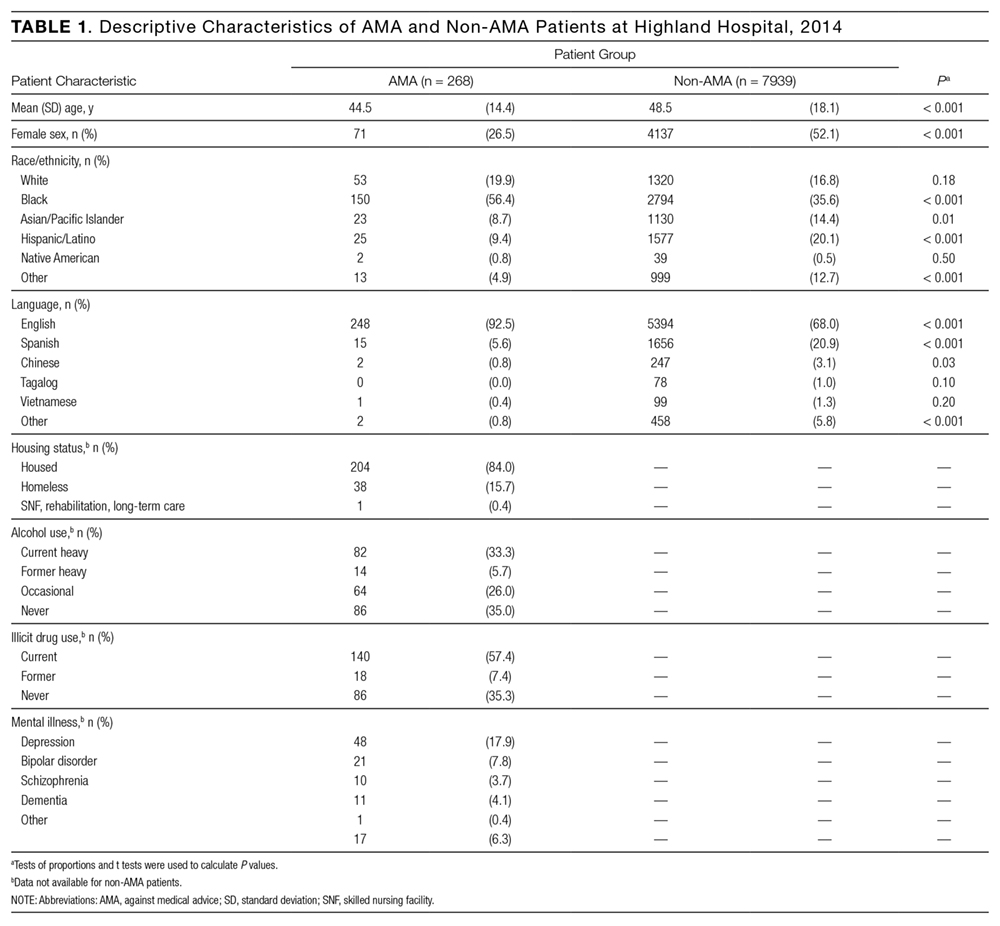

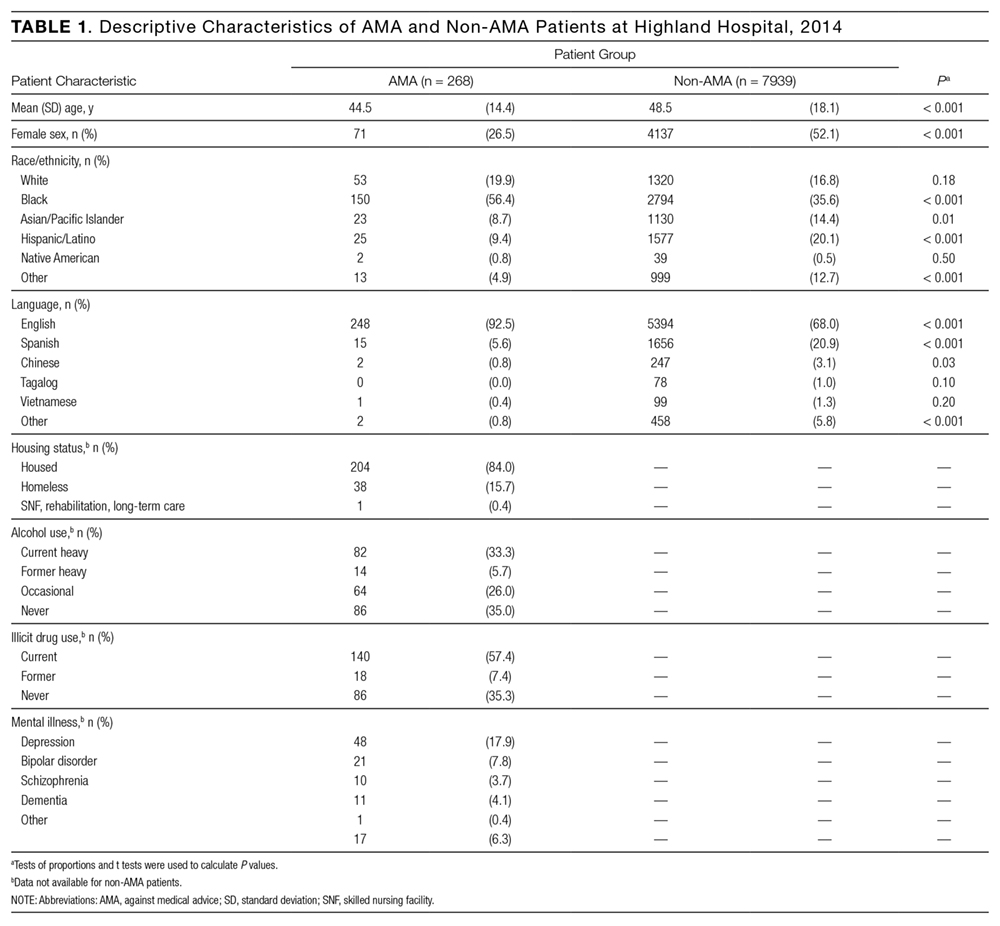

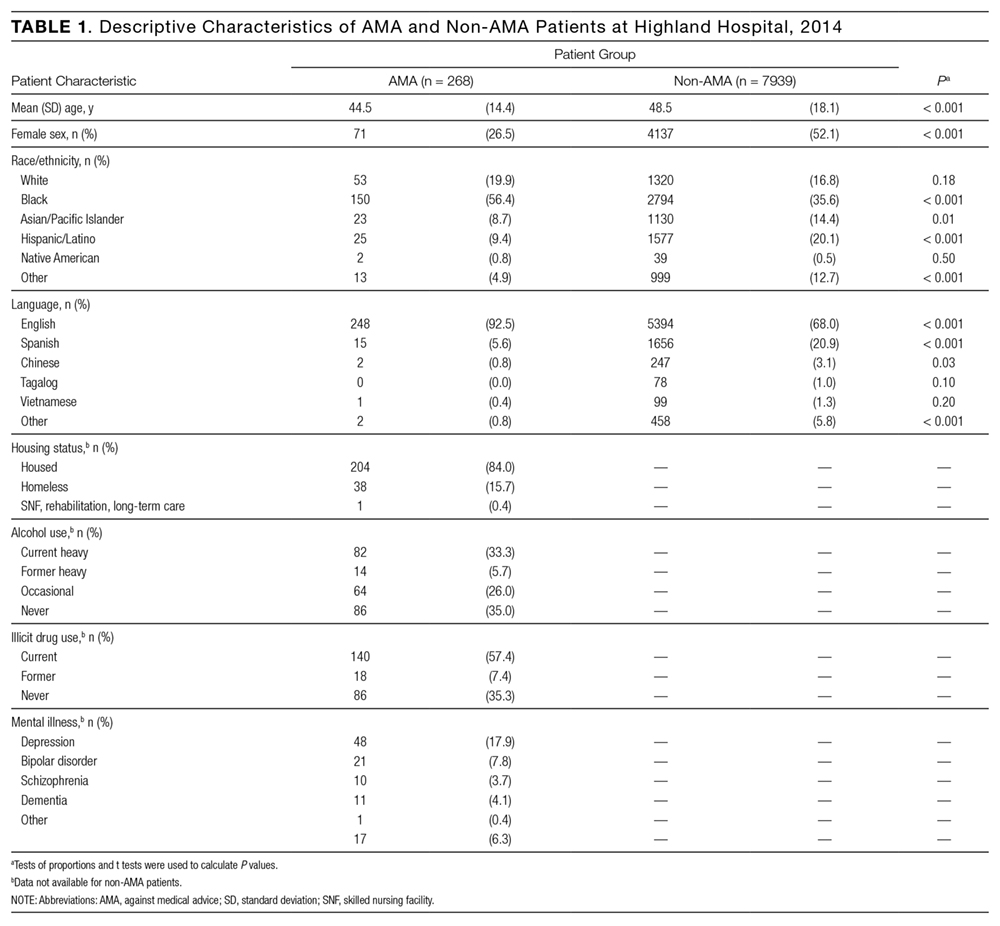

Compared with patients discharged conventionally, AMA patients were significantly younger; more likely to be male, to self-identify as Black/African American, and to be English-speaking; and less likely to self-identify as Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic/Latino or to be Chinese- or Spanish-speaking (Table 1). They were also more likely than all patients admitted to Highland to be homeless (15.7% vs 8.7%; P < 0.01). Multivariate regression analysis revealed persistent age and sex disparities, but racial disparities were mitigated in adjusted analyses (Appendix C). Language disparities persisted only for Spanish speakers, who had a significantly lower rate of AMA discharge, even in adjusted analyses.

The majority of AMA patients were on the internal medicine service (63.5%) or the trauma surgery service (24.8%). Regarding admission diagnosis, 17.2% of AMA patients were admitted for infections, 5.0% for drug or alcohol intoxication or withdrawal, 38.9% for acute noninfectious illnesses, 16.7% for decompensation of chronic disease, 18.4% for injuries or trauma, and 3.8% for pregnancy complications or labor. Compared with patients who left AMA once, patients who left AMA multiple times had higher rates of heavy alcohol use (53.9% vs 30.9%; P = 0.01) and illicit drug use (88.5% vs 53.7%; P < 0.001) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, the increased odds of leaving AMA more than once persisted for current heavy illicit drug users compared with patients who had never engaged in illicit drug use.

Discharge Characteristics and Documentation

Providers documented a patient’s plan to leave AMA before actual discharge 17.3% of the time. The documented plan to leave had to indicate that the patient was actually considering leaving. For example, “Patient is eager to go home” was not enough to qualify as a plan, but “Patient is thinking of leaving” qualified. For 84.3% of AMA discharges, the hospital’s AMA form was signed and was included in the medical record. Documentation showed that medications were prescribed for AMA patients 21.4% of the time, follow-up was arranged 25.7% of the time, and follow-up was pending arrangement 14.8% of the time. The majority of AMA patients (71.4%) left during daytime hours. In 29.6% of AMA discharges, providers documented AMA patients had decision-making capacity.

Readmission After AMA Discharge

Of the 268 AMA patients, 67.7% were not readmitted within the 6 months after AMA, 24.5% had 1 or 2 readmissions, and the rest had 3 or more readmissions (1 patient had 15). In addition, 35.8% returned to the emergency department within 30 days, and 16.4% were readmitted within 30 days. In 2014, the hospital’s overall 30-day readmission rate was 10.8%. Of the patients readmitted within 6 months after AMA, 23.5% left AMA again at the next visit, 9.4% left AWOL, and 67.1% were discharged conventionally.

Drivers of Premature Discharge

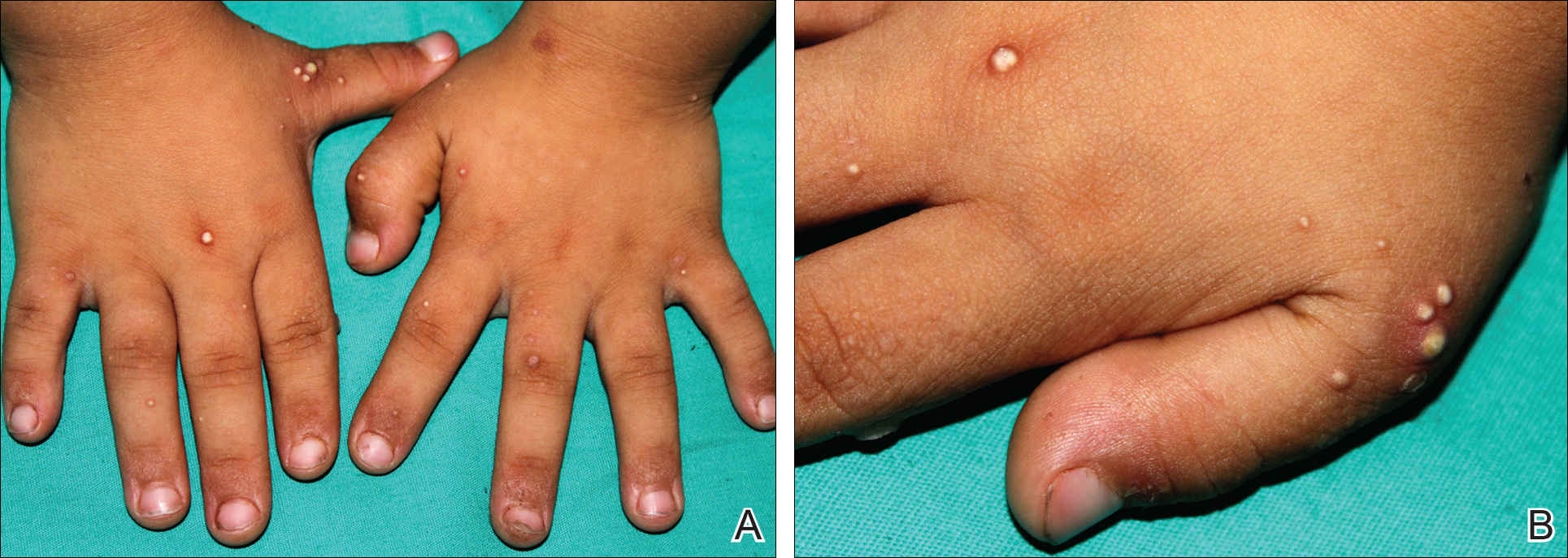

Qualitative analysis of the 35.5% of patient charts documenting a reason for leaving the hospital revealed 3 broad, interrelated themes (Figure 1). The first theme, dissatisfaction with hospital care, included chart notations such as “His wife couldn’t sleep in the hospital room” and “Not satisfied with all-liquid diet.” The second theme, urgent personal issues, included comments such as “He has a very important court date for his children” and “He needed to take care of immigration forms.” The third theme, mental health and substance abuse issues, included notations such as “He wants to go smoke” and “Severe anxiety and prison flashbacks.”

Provider Self-Assessment and Beliefs

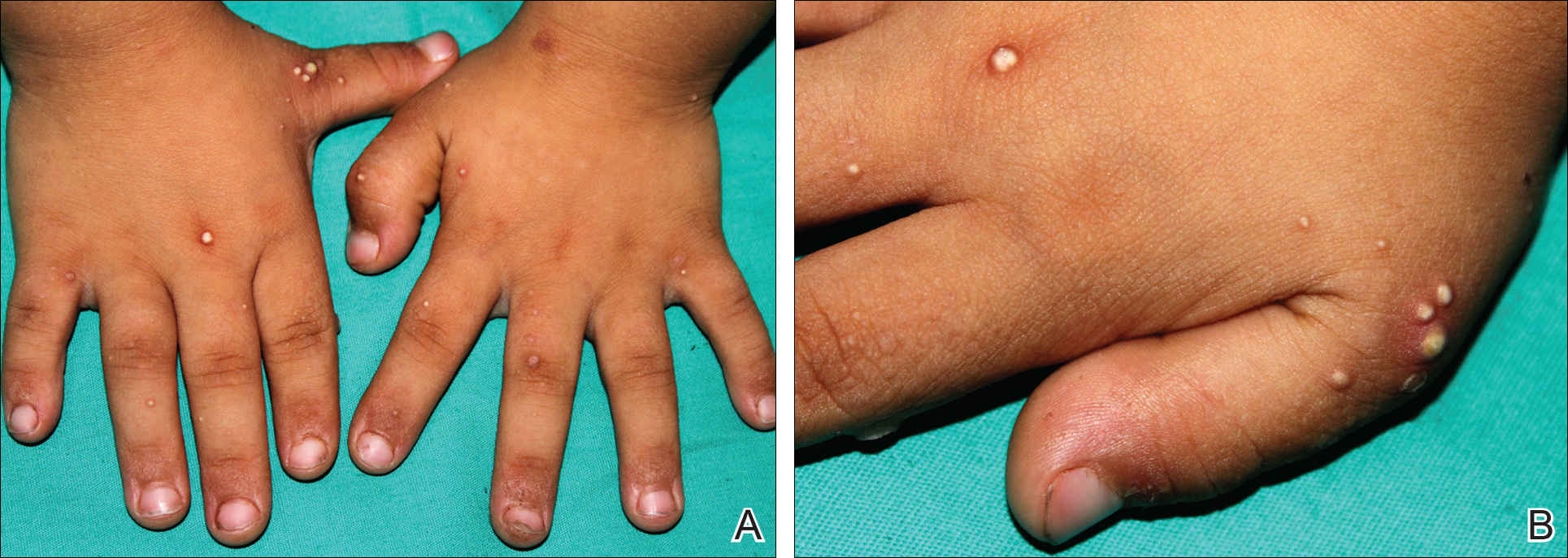

The survey was completed by 178 healthcare providers: 49.4% registered nurses, 19.1% trainee physicians, 20.8% attending physicians, and 10.7% other providers, including chaplains, social workers, and clerks. Regarding self-assessment of competency in AMA discharges, 94% of providers agreed they were comfortable assessing capacity, and 94% agreed they were comfortable talking with patients about the risks of leaving AMA (Figure 2). Nurses were more likely than trainee physicians to agree they knew what to do for patients who lacked capacity (74% vs 49%; P = 0.02). Most providers (70%) agreed they usually knew why their patients were leaving AMA; in this self-assessment, there were no significant differences between types of providers.

Regarding follow-up, attending physicians and trainee physicians demonstrated more agreement than nurses that AMA patients should receive medications and follow-up (94% and 84% vs 64%; P < 0.05). Nurses were more likely than attending physicians to say patients should lose their rights to hospital follow-up because of leaving AMA (38% vs 6%; P < 0.01). A minority of providers (37%) agreed transportation should be arranged. Addiction was the most common driver of AMA discharge (35%), followed by familial obligations (19%), dissatisfaction with hospital care (16%), and financial concerns (15%).

DISCUSSION

The demographic characteristics of AMA patients in this study are similar to those identified in other studies, showing overrepresentation of young male patients.12,14 Homeless patients were also overrepresented in the AMA discharge population at Highland Hospital—a finding that has not been consistently reported in prior studies, and that warrants further examination. In adjusted analyses, Spanish speakers had a lower rate of AMA discharge, and there were no racial variations. This is consistent with another study’s finding: that racial disparities in AMA discharge rates were largely attributable to confounders.24 Language differences may result from failure of staff to fully explain the option of AMA discharge to non-English speakers, or from fear of immigration consequences after AMA discharge. Further investigation of patient experiences is needed to identify factors that contribute to demographic variations in AMA discharge rates.25,26

Of the patients who left AMA multiple times, nearly all were actively using illicit drugs. In a recent study conducted at a safety-net hospital in Vancouver, Canada, 43% of patients with illicit drug use and at least 1 hospitalization left AMA at least once during the 6-year study period.11 Many factors might explain this correlation—addiction itself, poor pain control for patients with addiction issues, fears about incarceration, and poor treatment of drug users by healthcare staff.15 Although the medical literature highlights deficits in pain control for patients addicted to opiates, proposed solutions are sparse and focus on perioperative pain control and physician prescribing practices.27,28 At safety-net hospitals in which addiction is a factor in many hospitalizations, there is opportunity for new research in inpatient pain control for patients with substance dependence. In addition, harm reduction strategies—such as methadone maintenance for hospitalized patients with opiate dependence and abscess clinics as hospitalization alternatives for injection-associated infection treatment—may be key in improving safety for patients.11,15,29

Comparing the provider survey and chart review results highlights discordance between provider beliefs and clinical practice. Healthcare providers at Highland Hospital considered themselves competent in assessing capacity and talking with patients about the risks of AMA discharge. In practice, however, capacity was documented in less than a third of AMA discharges. Although the majority of providers thought medications and follow-up should be arranged for patients, arrangements were seldom made. This may be partially attributable to limited resources for making these arrangements. Average time to “third next available” primary care appointment within the county health system that includes Highland was 44.6 days for established patients during the period of study; for new primary care patients, the average wait for an appointment was 2 to 3 months. Highland has a same-day clinic, but inpatient providers are discouraged from using it as a postdischarge clinic for patients who would be better served in primary care. Medications and transportation are easily arranged during daytime hours but are not immediately available at night. In addition, some of this discrepancy may be attributable to the limited documentation rather than to provider failure to achieve their own benchmarks of quality care for AMA patients.

Documentation in AMA discharges is key for multiple reasons. Most AMA patients in this study signed an AMA form, and it could be that the rate of documenting decision-making capacity was low because providers thought a signed AMA form was adequate documentation of capacity and informed consent. In numerous court cases, however, these forms were found to be insufficient evidence of informed consent (lacking other supportive documentation) and possibly to go against the public good.30 In addition, high rates of repeat emergency department visits and readmissions for AMA patients, demonstrated here and in other studies, highlight the importance of careful documentation in informing subsequent providers about hospital returnees’ ongoing issues.17-19

This study also demonstrated differences between nurses and physicians in their beliefs about arranging follow-up for AMA patients. Nurses were less likely than physicians to think follow-up arrangements should be made for AMA patients and more likely to say these patients should lose the right to follow-up because of the AMA discharge. For conventional discharges, nurses provide patients with significantly more discharge education than interns or hospitalists do.31 This discrepancy highlights an urgent need for the education and involvement of nurses as stakeholders in the challenging AMA discharge process. Although the percentage of physicians who thought they were not obligated to provide medications and arrange follow-up for AMA patients was lower than the percentage of nurses, these beliefs contradict best practice guidelines for AMA discharges,22,23 and this finding calls attention to the need for interventions to improve adherence to professional and ethical guidelines in this aspect of clinical practice.

Providers showed a lack of familiarity with practice guidelines regarding certain aspects of the AMA discharge process. For example, most providers thought they should not have to arrange transportation for AMA patients, even though both the California Hospital Association Guidelines and the Highland Hospital internal policy on AMA discharges recommend arranging appropriate transportation.32 This finding suggests a need for educational interventions to ensure providers are informed about state and hospital policies, and a need to include both physicians and nurses in policymaking so theory can be tied to practice.

This study was limited to a single center with healthcare provider and patient populations that might not be generalizable to other settings. In the retrospective chart review, the authors were limited to information documented in the medical record, which might not accurately reflect the AMA discharge process. As they surveyed a limited number of social workers, case managers, and others who play an important role in the AMA discharge process, their data may lack varying viewpoints.

Overall, these data suggest providers at this county hospital generally agreed in principle with the best practice guidelines proposed by bioethicists for AMA discharges. In practice, however, providers were not reliably following these guidelines. Future interventions—including provider education on best practice guidelines for AMA discharge, provider involvement in policymaking, supportive templates for guiding documentation of AMA discharges, and improving access to follow-up care—will be key in improving the safety and health outcomes of AMA patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelly Aguilar, Kethia Chheng, Irene Yen, and the Research Advancement and Coordination Initiative at Alameda Health System for important contributions to this project.

Disclosures

Highland Hospital Department of Medicine internal grant 2015.23 helped fund this research. A portion of the data was presented as a poster at the University of California San Francisco Health Disparities Symposium; October 2015; San Francisco, CA. Two posters from the data were presented at Hospital Medicine 2016, March 2016; San Diego, CA.

1. Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594-602. PubMed

2. Stranges E, Wier L, Merrill C, Steiner C. Hospitalizations in which Patients Leave the Hospital against Medical Advice (AMA), 2007. HCUP Statistical Brief #78. August 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb78.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2016. PubMed

3. Devitt PJ, Devitt AC, Dewan M. Does identifying a discharge as “against medical advice” confer legal protection? J Fam Pract. 2000;49(3):224-227. PubMed

4. O’Hara D, Hart W, McDonald I. Leaving hospital against medical advice. J Qual Clin Pract. 1996;16(3):157-164. PubMed

5. Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2204-2208. PubMed

6. Clark MA, Abbott JT, Adyanthaya T. Ethics seminars: a best-practice approach to navigating the against-medical-advice discharge. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(9):1050-1057. PubMed

7. Windish DM, Ratanawongsa N. Providers’ perceptions of relationships and professional roles when caring for patients who leave the hospital against medical advice. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1698-1707. PubMed

8. Edwards J, Markert R, Bricker D. Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):574-577. PubMed

9. Alfandre DJ. “I’m going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255-260. PubMed

10. Katzenellenbogen JM, Sanfilippo FM, Hobbs MS, et al. Voting with their feet—predictors of discharge against medical advice in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal ischaemic heart disease inpatients in Western Australia: an analytic study using data linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:330. PubMed

11. Ti L, Milloy MJ, Buxton J, et al. Factors associated with leaving hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141594. PubMed

12. Yong TY, Fok JS, Hakendorf P, Ben-Tovim D, Thompson CH, Li JY. Characteristics and outcomes of discharges against medical advice among hospitalised patients. Intern Med J. 2013;43(7):798-802. PubMed

13. Tabatabaei SM, Sargazi Moakhar Z, Behmanesh Pour F, Shaare Mollashahi S, Zaboli M. Hospitalized pregnant women who leave against medical advice: attributes and reasons. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):128-138. PubMed

14. Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325-327. PubMed

15. Ti L, Ti L. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e53-e59. PubMed

16. Targum SD, Capodanno AE, Hoffman HA, Foudraine C. An intervention to reduce the rate of hospital discharges against medical advice. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(5):657-659. PubMed

17. Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24459. PubMed

18. Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926-929. PubMed

19. Garland A, Ramsey CD, Fransoo R, et al. Rates of readmission and death associated with leaving hospital against medical advice: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2013;185(14):1207-1214. PubMed

20. Hwang SW, Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? CMAJ. 2003;168(4):417-420. PubMed

21. Onukwugha E, Mullins CD, Loh FE, Saunders E, Shaya FT, Weir MR. Readmissions after unauthorized discharges in the cardiovascular setting. Med Care. 2011;49(2):215-224. PubMed

22. Alfandre D. Reconsidering against medical advice discharges: embracing patient-centeredness to promote high quality care and a renewed research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(12):1657-1662. PubMed

23. Berger JT. Discharge against medical advice: ethical considerations and professional obligations. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):403-408. PubMed

24. Franks P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K. Discharges against medical advice: are race/ethnicity predictors? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):955-960. PubMed

25. Hicks LS, Ayanian JZ, Orav EJ, et al. Is hospital service associated with racial and ethnic disparities in experiences with hospital care? Am J Med. 2005;118(5):529-535. PubMed

26. Hicks LS, Tovar DA, Orav EJ, Johnson PA. Experiences with hospital care: perspectives of black and Hispanic patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1234-1240. PubMed

27. McCreaddie M, Lyons I, Watt D, et al. Routines and rituals: a grounded theory of the pain management of drug users in acute care settings. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19-20):2730-2740. PubMed

28. Carroll IR, Angst MS, Clark JD. Management of perioperative pain in patients chronically consuming opioids. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(6):576-591. PubMed

29. Chan AC, Palepu A, Guh DP, et al. HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospital against medical advice: the mitigating role of methadone and social support. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(1):56-59. PubMed

30. Levy F, Mareiniss DP, Iacovelli C. The importance of a proper against-medical-advice (AMA) discharge: how signing out AMA may create significant liability protection for providers. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(3):516-520. PubMed

31. Ashbrook L, Mourad M, Sehgal N. Communicating discharge instructions to patients: a survey of nurse, intern, and hospitalist practices. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):36-41. PubMed

32. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Title 22, California Code of Regulations, §70707.3.

Patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA) for a variety of reasons. The AMA rate is approximately 1% nationally but substantially higher at safety-net hospitals and has rapidly increased over the past decade.1-5 The principle that patients have the right to make choices about their healthcare, up to and including whether to leave the hospital against the advice of medical staff, is well-established law and a foundation of medical ethics.6 In practice, however, AMA discharges are often emotionally charged for both patients and providers, and, in the high-stress setting of AMA discharge, providers may be confused about their roles.7-9

The demographics of patients who leave AMA have been well described. Compared with conventionally discharged patients, AMA patients are younger, more likely to be male, and more likely a marginalized ethnic or racial minority.10-14 Patients with mental illnesses and addiction issues are overrepresented in AMA discharges, and complicated capacity assessments and limited resources may strain providers.7,8,15,16 Studies have repeatedly shown higher rates of readmission and mortality for AMA patients than for conventionally discharged patients.17-21 Whether AMA discharge is a marker for other prognostic factors that bode poorly for patients or contributes to negative outcomes, data suggest this group of patients is vulnerable, having mortality rates up to 40% higher 1 year after discharge, relative to conventionally discharged patients.12

Several models of standardized best practice approaches for AMA have been proposed by bioethicists.6,22,23 Although details of these approaches vary, all involve assessing the patient’s decision-making capacity, clarifying the risks of AMA discharge, addressing factors that might be prompting the discharge, formulating an alternative outpatient treatment plan or “next best” option, and documenting extensively. A recent study found patients often gave advance warning of an AMA discharge, but physicians rarely prepared by arranging follow-up care.8 The investigators hypothesized that providers might not have known what they were permitted to arrange for AMA patients, or might have thought that providing “second best” options went against their principles. The investigators noted that nurses might have become aware of AMA risk sooner than physicians did but could not act on this awareness by preparing medications and arranging follow-up.

Translating models of best practice care for AMA patients into clinical practice requires buy-in from bedside providers, not just bioethicists. Given the study findings that providers have misconceptions about their roles in the AMA discharge,7 it is prudent to investigate providers’ current practices, beliefs, and concerns about AMA discharges before introducing a new approach.

The present authors conducted a mixed-methods cross-sectional study of the state of AMA discharges at Highland Hospital (Oakland, California), a 236-bed county hospital and trauma center serving a primarily underserved urban patient population. The aim of this study was to assess current provider practices for AMA discharges and provider perceptions and knowledge about AMA discharges, ultimately to help direct future educational interventions with medical providers or hospital policy changes needed to improve the quality of AMA discharges.

METHODS

Phase 1 of this study involved identifying AMA patients through a review of data from Highland Hospital’s electronic medical records for 2014. These data included discharge status (eg, AMA vs other discharge types). The hospital’s floor clerk distinguishes between absent without official leave (AWOL; the patient leaves without notifying a provider) and AMA discharge. Discharges designated AWOL were excluded from the analyses.

In phase 2, a structured chart review (Appendix A) was performed for all patients identified during phase 1 as being discharged AMA in 2014. In these reviews, further assessment was made of patient and visit characteristics in hospitalizations that ended in AMA discharge, and of providers’ documentation of AMA discharges—that is, whether several factors were documented (capacity; predischarge indication that patient might leave AMA; reason for AMA; and indications that discharge medications, transportation, and follow-up were arranged). These visit factors were reviewed because the literature has identified them as being important markers for AMA discharge safety.6,8 Two research assistants, under the guidance of Dr. Stearns, reviewed the charts. To ensure agreement across chart reviews with respect to subjective questions (eg, whether capacity was adequately documented), the group reviewed the first 10 consecutive charts together; there was full agreement on how to classify the data of interest. Throughout the study, whenever a research assistant asked how to classify particular patient data, Dr. Stearns reviewed the data, and the research team made a decision together. Additional data, for AMA patients and for all patients admitted to Highland Hospital, were obtained from the hospital’s data warehouse, which pools data from within the health system.

Phase 3 involved surveying healthcare providers who were involved in patient care on the internal medicine and trauma surgery services at the hospital. These providers were selected because chart review revealed that the vast majority of patients who left AMA in 2014 were on one of these services. Surveys (Appendix B) asked participant providers to identify their role at the hospital, to provide a self-assessment of competence in various aspects of AMA discharge, to voice opinions about provider responsibilities in arranging follow-up for AMA patients, and to make suggestions about the AMA process. The authors designed these surveys, which included questions about aspects of care that have been highlighted in the AMA discharge literature as being important for AMA discharge safety.6,8,22,23 Surveys were distributed to providers at internal medicine and trauma surgery department meetings and nursing conferences. Data (without identifying information) were analyzed, and survey responses kept anonymous.

The Alameda Health System Institutional Review Board approved this project. Providers were given the option of writing their name and contact information at the top of the survey in order to be entered into a drawing to receive a prize for completion.

We performed statistical analyses of the patient charts and physician survey data using Stata (version 14.0, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas). We analyzed both patient- and encounter-level data. In demographic analyses, this approach prevented duplicate counting of patients who left AMA multiple times. Patient-level analyses compared the demographic characteristics of AMA patients and patients discharged conventionally from the hospital in 2014. In addition, patients with either 1 or multiple AMA discharges were compared to identify characteristics that might be linked to highest risk of recurrent AMA discharge in the hope that early identification of these patients might facilitate providers’ early awareness and preparation for follow-up care or hospitalization alternatives. We used ANOVAs for continuous variables and tests of proportions for categorical variables. On the encounter level, analyses examined data about each admission (eg, AMA forms signed, follow-up arrangements made, capacity documented, etc.) for all AMA discharges. We employed chi square tests to identify variations in healthcare provider survey responses. A P value < 0.05 was used as the significance cut-off point.

Staged logistic regression analyses, adjusted for demographic characteristics, were performed to assess the association between risk of leaving AMA (yes or no) and demographic characteristics and the association between risk of leaving AMA more than once (yes or no) and health-related characteristics.

RESULTS

Demographic, Clinical, and Utilization Characteristics

Of the 12,036 Highland Hospital admissions in 2014, 319 (2.7%) ended with an AMA discharge. Of the 8207 individual patients discharged, 268 left AMA once, and 29 left AMA multiple times. Further review of the Admissions, Discharges, and Transfers Report generated from the electronic medical record revealed that 15 AWOL discharges were misclassified as AMA discharges.

Compared with patients discharged conventionally, AMA patients were significantly younger; more likely to be male, to self-identify as Black/African American, and to be English-speaking; and less likely to self-identify as Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic/Latino or to be Chinese- or Spanish-speaking (Table 1). They were also more likely than all patients admitted to Highland to be homeless (15.7% vs 8.7%; P < 0.01). Multivariate regression analysis revealed persistent age and sex disparities, but racial disparities were mitigated in adjusted analyses (Appendix C). Language disparities persisted only for Spanish speakers, who had a significantly lower rate of AMA discharge, even in adjusted analyses.

The majority of AMA patients were on the internal medicine service (63.5%) or the trauma surgery service (24.8%). Regarding admission diagnosis, 17.2% of AMA patients were admitted for infections, 5.0% for drug or alcohol intoxication or withdrawal, 38.9% for acute noninfectious illnesses, 16.7% for decompensation of chronic disease, 18.4% for injuries or trauma, and 3.8% for pregnancy complications or labor. Compared with patients who left AMA once, patients who left AMA multiple times had higher rates of heavy alcohol use (53.9% vs 30.9%; P = 0.01) and illicit drug use (88.5% vs 53.7%; P < 0.001) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, the increased odds of leaving AMA more than once persisted for current heavy illicit drug users compared with patients who had never engaged in illicit drug use.

Discharge Characteristics and Documentation

Providers documented a patient’s plan to leave AMA before actual discharge 17.3% of the time. The documented plan to leave had to indicate that the patient was actually considering leaving. For example, “Patient is eager to go home” was not enough to qualify as a plan, but “Patient is thinking of leaving” qualified. For 84.3% of AMA discharges, the hospital’s AMA form was signed and was included in the medical record. Documentation showed that medications were prescribed for AMA patients 21.4% of the time, follow-up was arranged 25.7% of the time, and follow-up was pending arrangement 14.8% of the time. The majority of AMA patients (71.4%) left during daytime hours. In 29.6% of AMA discharges, providers documented AMA patients had decision-making capacity.

Readmission After AMA Discharge

Of the 268 AMA patients, 67.7% were not readmitted within the 6 months after AMA, 24.5% had 1 or 2 readmissions, and the rest had 3 or more readmissions (1 patient had 15). In addition, 35.8% returned to the emergency department within 30 days, and 16.4% were readmitted within 30 days. In 2014, the hospital’s overall 30-day readmission rate was 10.8%. Of the patients readmitted within 6 months after AMA, 23.5% left AMA again at the next visit, 9.4% left AWOL, and 67.1% were discharged conventionally.

Drivers of Premature Discharge

Qualitative analysis of the 35.5% of patient charts documenting a reason for leaving the hospital revealed 3 broad, interrelated themes (Figure 1). The first theme, dissatisfaction with hospital care, included chart notations such as “His wife couldn’t sleep in the hospital room” and “Not satisfied with all-liquid diet.” The second theme, urgent personal issues, included comments such as “He has a very important court date for his children” and “He needed to take care of immigration forms.” The third theme, mental health and substance abuse issues, included notations such as “He wants to go smoke” and “Severe anxiety and prison flashbacks.”

Provider Self-Assessment and Beliefs

The survey was completed by 178 healthcare providers: 49.4% registered nurses, 19.1% trainee physicians, 20.8% attending physicians, and 10.7% other providers, including chaplains, social workers, and clerks. Regarding self-assessment of competency in AMA discharges, 94% of providers agreed they were comfortable assessing capacity, and 94% agreed they were comfortable talking with patients about the risks of leaving AMA (Figure 2). Nurses were more likely than trainee physicians to agree they knew what to do for patients who lacked capacity (74% vs 49%; P = 0.02). Most providers (70%) agreed they usually knew why their patients were leaving AMA; in this self-assessment, there were no significant differences between types of providers.

Regarding follow-up, attending physicians and trainee physicians demonstrated more agreement than nurses that AMA patients should receive medications and follow-up (94% and 84% vs 64%; P < 0.05). Nurses were more likely than attending physicians to say patients should lose their rights to hospital follow-up because of leaving AMA (38% vs 6%; P < 0.01). A minority of providers (37%) agreed transportation should be arranged. Addiction was the most common driver of AMA discharge (35%), followed by familial obligations (19%), dissatisfaction with hospital care (16%), and financial concerns (15%).

DISCUSSION

The demographic characteristics of AMA patients in this study are similar to those identified in other studies, showing overrepresentation of young male patients.12,14 Homeless patients were also overrepresented in the AMA discharge population at Highland Hospital—a finding that has not been consistently reported in prior studies, and that warrants further examination. In adjusted analyses, Spanish speakers had a lower rate of AMA discharge, and there were no racial variations. This is consistent with another study’s finding: that racial disparities in AMA discharge rates were largely attributable to confounders.24 Language differences may result from failure of staff to fully explain the option of AMA discharge to non-English speakers, or from fear of immigration consequences after AMA discharge. Further investigation of patient experiences is needed to identify factors that contribute to demographic variations in AMA discharge rates.25,26

Of the patients who left AMA multiple times, nearly all were actively using illicit drugs. In a recent study conducted at a safety-net hospital in Vancouver, Canada, 43% of patients with illicit drug use and at least 1 hospitalization left AMA at least once during the 6-year study period.11 Many factors might explain this correlation—addiction itself, poor pain control for patients with addiction issues, fears about incarceration, and poor treatment of drug users by healthcare staff.15 Although the medical literature highlights deficits in pain control for patients addicted to opiates, proposed solutions are sparse and focus on perioperative pain control and physician prescribing practices.27,28 At safety-net hospitals in which addiction is a factor in many hospitalizations, there is opportunity for new research in inpatient pain control for patients with substance dependence. In addition, harm reduction strategies—such as methadone maintenance for hospitalized patients with opiate dependence and abscess clinics as hospitalization alternatives for injection-associated infection treatment—may be key in improving safety for patients.11,15,29

Comparing the provider survey and chart review results highlights discordance between provider beliefs and clinical practice. Healthcare providers at Highland Hospital considered themselves competent in assessing capacity and talking with patients about the risks of AMA discharge. In practice, however, capacity was documented in less than a third of AMA discharges. Although the majority of providers thought medications and follow-up should be arranged for patients, arrangements were seldom made. This may be partially attributable to limited resources for making these arrangements. Average time to “third next available” primary care appointment within the county health system that includes Highland was 44.6 days for established patients during the period of study; for new primary care patients, the average wait for an appointment was 2 to 3 months. Highland has a same-day clinic, but inpatient providers are discouraged from using it as a postdischarge clinic for patients who would be better served in primary care. Medications and transportation are easily arranged during daytime hours but are not immediately available at night. In addition, some of this discrepancy may be attributable to the limited documentation rather than to provider failure to achieve their own benchmarks of quality care for AMA patients.

Documentation in AMA discharges is key for multiple reasons. Most AMA patients in this study signed an AMA form, and it could be that the rate of documenting decision-making capacity was low because providers thought a signed AMA form was adequate documentation of capacity and informed consent. In numerous court cases, however, these forms were found to be insufficient evidence of informed consent (lacking other supportive documentation) and possibly to go against the public good.30 In addition, high rates of repeat emergency department visits and readmissions for AMA patients, demonstrated here and in other studies, highlight the importance of careful documentation in informing subsequent providers about hospital returnees’ ongoing issues.17-19

This study also demonstrated differences between nurses and physicians in their beliefs about arranging follow-up for AMA patients. Nurses were less likely than physicians to think follow-up arrangements should be made for AMA patients and more likely to say these patients should lose the right to follow-up because of the AMA discharge. For conventional discharges, nurses provide patients with significantly more discharge education than interns or hospitalists do.31 This discrepancy highlights an urgent need for the education and involvement of nurses as stakeholders in the challenging AMA discharge process. Although the percentage of physicians who thought they were not obligated to provide medications and arrange follow-up for AMA patients was lower than the percentage of nurses, these beliefs contradict best practice guidelines for AMA discharges,22,23 and this finding calls attention to the need for interventions to improve adherence to professional and ethical guidelines in this aspect of clinical practice.

Providers showed a lack of familiarity with practice guidelines regarding certain aspects of the AMA discharge process. For example, most providers thought they should not have to arrange transportation for AMA patients, even though both the California Hospital Association Guidelines and the Highland Hospital internal policy on AMA discharges recommend arranging appropriate transportation.32 This finding suggests a need for educational interventions to ensure providers are informed about state and hospital policies, and a need to include both physicians and nurses in policymaking so theory can be tied to practice.

This study was limited to a single center with healthcare provider and patient populations that might not be generalizable to other settings. In the retrospective chart review, the authors were limited to information documented in the medical record, which might not accurately reflect the AMA discharge process. As they surveyed a limited number of social workers, case managers, and others who play an important role in the AMA discharge process, their data may lack varying viewpoints.

Overall, these data suggest providers at this county hospital generally agreed in principle with the best practice guidelines proposed by bioethicists for AMA discharges. In practice, however, providers were not reliably following these guidelines. Future interventions—including provider education on best practice guidelines for AMA discharge, provider involvement in policymaking, supportive templates for guiding documentation of AMA discharges, and improving access to follow-up care—will be key in improving the safety and health outcomes of AMA patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelly Aguilar, Kethia Chheng, Irene Yen, and the Research Advancement and Coordination Initiative at Alameda Health System for important contributions to this project.

Disclosures

Highland Hospital Department of Medicine internal grant 2015.23 helped fund this research. A portion of the data was presented as a poster at the University of California San Francisco Health Disparities Symposium; October 2015; San Francisco, CA. Two posters from the data were presented at Hospital Medicine 2016, March 2016; San Diego, CA.

Patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA) for a variety of reasons. The AMA rate is approximately 1% nationally but substantially higher at safety-net hospitals and has rapidly increased over the past decade.1-5 The principle that patients have the right to make choices about their healthcare, up to and including whether to leave the hospital against the advice of medical staff, is well-established law and a foundation of medical ethics.6 In practice, however, AMA discharges are often emotionally charged for both patients and providers, and, in the high-stress setting of AMA discharge, providers may be confused about their roles.7-9

The demographics of patients who leave AMA have been well described. Compared with conventionally discharged patients, AMA patients are younger, more likely to be male, and more likely a marginalized ethnic or racial minority.10-14 Patients with mental illnesses and addiction issues are overrepresented in AMA discharges, and complicated capacity assessments and limited resources may strain providers.7,8,15,16 Studies have repeatedly shown higher rates of readmission and mortality for AMA patients than for conventionally discharged patients.17-21 Whether AMA discharge is a marker for other prognostic factors that bode poorly for patients or contributes to negative outcomes, data suggest this group of patients is vulnerable, having mortality rates up to 40% higher 1 year after discharge, relative to conventionally discharged patients.12

Several models of standardized best practice approaches for AMA have been proposed by bioethicists.6,22,23 Although details of these approaches vary, all involve assessing the patient’s decision-making capacity, clarifying the risks of AMA discharge, addressing factors that might be prompting the discharge, formulating an alternative outpatient treatment plan or “next best” option, and documenting extensively. A recent study found patients often gave advance warning of an AMA discharge, but physicians rarely prepared by arranging follow-up care.8 The investigators hypothesized that providers might not have known what they were permitted to arrange for AMA patients, or might have thought that providing “second best” options went against their principles. The investigators noted that nurses might have become aware of AMA risk sooner than physicians did but could not act on this awareness by preparing medications and arranging follow-up.

Translating models of best practice care for AMA patients into clinical practice requires buy-in from bedside providers, not just bioethicists. Given the study findings that providers have misconceptions about their roles in the AMA discharge,7 it is prudent to investigate providers’ current practices, beliefs, and concerns about AMA discharges before introducing a new approach.

The present authors conducted a mixed-methods cross-sectional study of the state of AMA discharges at Highland Hospital (Oakland, California), a 236-bed county hospital and trauma center serving a primarily underserved urban patient population. The aim of this study was to assess current provider practices for AMA discharges and provider perceptions and knowledge about AMA discharges, ultimately to help direct future educational interventions with medical providers or hospital policy changes needed to improve the quality of AMA discharges.

METHODS

Phase 1 of this study involved identifying AMA patients through a review of data from Highland Hospital’s electronic medical records for 2014. These data included discharge status (eg, AMA vs other discharge types). The hospital’s floor clerk distinguishes between absent without official leave (AWOL; the patient leaves without notifying a provider) and AMA discharge. Discharges designated AWOL were excluded from the analyses.

In phase 2, a structured chart review (Appendix A) was performed for all patients identified during phase 1 as being discharged AMA in 2014. In these reviews, further assessment was made of patient and visit characteristics in hospitalizations that ended in AMA discharge, and of providers’ documentation of AMA discharges—that is, whether several factors were documented (capacity; predischarge indication that patient might leave AMA; reason for AMA; and indications that discharge medications, transportation, and follow-up were arranged). These visit factors were reviewed because the literature has identified them as being important markers for AMA discharge safety.6,8 Two research assistants, under the guidance of Dr. Stearns, reviewed the charts. To ensure agreement across chart reviews with respect to subjective questions (eg, whether capacity was adequately documented), the group reviewed the first 10 consecutive charts together; there was full agreement on how to classify the data of interest. Throughout the study, whenever a research assistant asked how to classify particular patient data, Dr. Stearns reviewed the data, and the research team made a decision together. Additional data, for AMA patients and for all patients admitted to Highland Hospital, were obtained from the hospital’s data warehouse, which pools data from within the health system.

Phase 3 involved surveying healthcare providers who were involved in patient care on the internal medicine and trauma surgery services at the hospital. These providers were selected because chart review revealed that the vast majority of patients who left AMA in 2014 were on one of these services. Surveys (Appendix B) asked participant providers to identify their role at the hospital, to provide a self-assessment of competence in various aspects of AMA discharge, to voice opinions about provider responsibilities in arranging follow-up for AMA patients, and to make suggestions about the AMA process. The authors designed these surveys, which included questions about aspects of care that have been highlighted in the AMA discharge literature as being important for AMA discharge safety.6,8,22,23 Surveys were distributed to providers at internal medicine and trauma surgery department meetings and nursing conferences. Data (without identifying information) were analyzed, and survey responses kept anonymous.

The Alameda Health System Institutional Review Board approved this project. Providers were given the option of writing their name and contact information at the top of the survey in order to be entered into a drawing to receive a prize for completion.

We performed statistical analyses of the patient charts and physician survey data using Stata (version 14.0, Stata Corp., College Station, Texas). We analyzed both patient- and encounter-level data. In demographic analyses, this approach prevented duplicate counting of patients who left AMA multiple times. Patient-level analyses compared the demographic characteristics of AMA patients and patients discharged conventionally from the hospital in 2014. In addition, patients with either 1 or multiple AMA discharges were compared to identify characteristics that might be linked to highest risk of recurrent AMA discharge in the hope that early identification of these patients might facilitate providers’ early awareness and preparation for follow-up care or hospitalization alternatives. We used ANOVAs for continuous variables and tests of proportions for categorical variables. On the encounter level, analyses examined data about each admission (eg, AMA forms signed, follow-up arrangements made, capacity documented, etc.) for all AMA discharges. We employed chi square tests to identify variations in healthcare provider survey responses. A P value < 0.05 was used as the significance cut-off point.

Staged logistic regression analyses, adjusted for demographic characteristics, were performed to assess the association between risk of leaving AMA (yes or no) and demographic characteristics and the association between risk of leaving AMA more than once (yes or no) and health-related characteristics.

RESULTS

Demographic, Clinical, and Utilization Characteristics

Of the 12,036 Highland Hospital admissions in 2014, 319 (2.7%) ended with an AMA discharge. Of the 8207 individual patients discharged, 268 left AMA once, and 29 left AMA multiple times. Further review of the Admissions, Discharges, and Transfers Report generated from the electronic medical record revealed that 15 AWOL discharges were misclassified as AMA discharges.

Compared with patients discharged conventionally, AMA patients were significantly younger; more likely to be male, to self-identify as Black/African American, and to be English-speaking; and less likely to self-identify as Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic/Latino or to be Chinese- or Spanish-speaking (Table 1). They were also more likely than all patients admitted to Highland to be homeless (15.7% vs 8.7%; P < 0.01). Multivariate regression analysis revealed persistent age and sex disparities, but racial disparities were mitigated in adjusted analyses (Appendix C). Language disparities persisted only for Spanish speakers, who had a significantly lower rate of AMA discharge, even in adjusted analyses.

The majority of AMA patients were on the internal medicine service (63.5%) or the trauma surgery service (24.8%). Regarding admission diagnosis, 17.2% of AMA patients were admitted for infections, 5.0% for drug or alcohol intoxication or withdrawal, 38.9% for acute noninfectious illnesses, 16.7% for decompensation of chronic disease, 18.4% for injuries or trauma, and 3.8% for pregnancy complications or labor. Compared with patients who left AMA once, patients who left AMA multiple times had higher rates of heavy alcohol use (53.9% vs 30.9%; P = 0.01) and illicit drug use (88.5% vs 53.7%; P < 0.001) (Table 2). In multivariate analyses, the increased odds of leaving AMA more than once persisted for current heavy illicit drug users compared with patients who had never engaged in illicit drug use.

Discharge Characteristics and Documentation

Providers documented a patient’s plan to leave AMA before actual discharge 17.3% of the time. The documented plan to leave had to indicate that the patient was actually considering leaving. For example, “Patient is eager to go home” was not enough to qualify as a plan, but “Patient is thinking of leaving” qualified. For 84.3% of AMA discharges, the hospital’s AMA form was signed and was included in the medical record. Documentation showed that medications were prescribed for AMA patients 21.4% of the time, follow-up was arranged 25.7% of the time, and follow-up was pending arrangement 14.8% of the time. The majority of AMA patients (71.4%) left during daytime hours. In 29.6% of AMA discharges, providers documented AMA patients had decision-making capacity.

Readmission After AMA Discharge

Of the 268 AMA patients, 67.7% were not readmitted within the 6 months after AMA, 24.5% had 1 or 2 readmissions, and the rest had 3 or more readmissions (1 patient had 15). In addition, 35.8% returned to the emergency department within 30 days, and 16.4% were readmitted within 30 days. In 2014, the hospital’s overall 30-day readmission rate was 10.8%. Of the patients readmitted within 6 months after AMA, 23.5% left AMA again at the next visit, 9.4% left AWOL, and 67.1% were discharged conventionally.

Drivers of Premature Discharge

Qualitative analysis of the 35.5% of patient charts documenting a reason for leaving the hospital revealed 3 broad, interrelated themes (Figure 1). The first theme, dissatisfaction with hospital care, included chart notations such as “His wife couldn’t sleep in the hospital room” and “Not satisfied with all-liquid diet.” The second theme, urgent personal issues, included comments such as “He has a very important court date for his children” and “He needed to take care of immigration forms.” The third theme, mental health and substance abuse issues, included notations such as “He wants to go smoke” and “Severe anxiety and prison flashbacks.”

Provider Self-Assessment and Beliefs

The survey was completed by 178 healthcare providers: 49.4% registered nurses, 19.1% trainee physicians, 20.8% attending physicians, and 10.7% other providers, including chaplains, social workers, and clerks. Regarding self-assessment of competency in AMA discharges, 94% of providers agreed they were comfortable assessing capacity, and 94% agreed they were comfortable talking with patients about the risks of leaving AMA (Figure 2). Nurses were more likely than trainee physicians to agree they knew what to do for patients who lacked capacity (74% vs 49%; P = 0.02). Most providers (70%) agreed they usually knew why their patients were leaving AMA; in this self-assessment, there were no significant differences between types of providers.

Regarding follow-up, attending physicians and trainee physicians demonstrated more agreement than nurses that AMA patients should receive medications and follow-up (94% and 84% vs 64%; P < 0.05). Nurses were more likely than attending physicians to say patients should lose their rights to hospital follow-up because of leaving AMA (38% vs 6%; P < 0.01). A minority of providers (37%) agreed transportation should be arranged. Addiction was the most common driver of AMA discharge (35%), followed by familial obligations (19%), dissatisfaction with hospital care (16%), and financial concerns (15%).

DISCUSSION

The demographic characteristics of AMA patients in this study are similar to those identified in other studies, showing overrepresentation of young male patients.12,14 Homeless patients were also overrepresented in the AMA discharge population at Highland Hospital—a finding that has not been consistently reported in prior studies, and that warrants further examination. In adjusted analyses, Spanish speakers had a lower rate of AMA discharge, and there were no racial variations. This is consistent with another study’s finding: that racial disparities in AMA discharge rates were largely attributable to confounders.24 Language differences may result from failure of staff to fully explain the option of AMA discharge to non-English speakers, or from fear of immigration consequences after AMA discharge. Further investigation of patient experiences is needed to identify factors that contribute to demographic variations in AMA discharge rates.25,26

Of the patients who left AMA multiple times, nearly all were actively using illicit drugs. In a recent study conducted at a safety-net hospital in Vancouver, Canada, 43% of patients with illicit drug use and at least 1 hospitalization left AMA at least once during the 6-year study period.11 Many factors might explain this correlation—addiction itself, poor pain control for patients with addiction issues, fears about incarceration, and poor treatment of drug users by healthcare staff.15 Although the medical literature highlights deficits in pain control for patients addicted to opiates, proposed solutions are sparse and focus on perioperative pain control and physician prescribing practices.27,28 At safety-net hospitals in which addiction is a factor in many hospitalizations, there is opportunity for new research in inpatient pain control for patients with substance dependence. In addition, harm reduction strategies—such as methadone maintenance for hospitalized patients with opiate dependence and abscess clinics as hospitalization alternatives for injection-associated infection treatment—may be key in improving safety for patients.11,15,29

Comparing the provider survey and chart review results highlights discordance between provider beliefs and clinical practice. Healthcare providers at Highland Hospital considered themselves competent in assessing capacity and talking with patients about the risks of AMA discharge. In practice, however, capacity was documented in less than a third of AMA discharges. Although the majority of providers thought medications and follow-up should be arranged for patients, arrangements were seldom made. This may be partially attributable to limited resources for making these arrangements. Average time to “third next available” primary care appointment within the county health system that includes Highland was 44.6 days for established patients during the period of study; for new primary care patients, the average wait for an appointment was 2 to 3 months. Highland has a same-day clinic, but inpatient providers are discouraged from using it as a postdischarge clinic for patients who would be better served in primary care. Medications and transportation are easily arranged during daytime hours but are not immediately available at night. In addition, some of this discrepancy may be attributable to the limited documentation rather than to provider failure to achieve their own benchmarks of quality care for AMA patients.

Documentation in AMA discharges is key for multiple reasons. Most AMA patients in this study signed an AMA form, and it could be that the rate of documenting decision-making capacity was low because providers thought a signed AMA form was adequate documentation of capacity and informed consent. In numerous court cases, however, these forms were found to be insufficient evidence of informed consent (lacking other supportive documentation) and possibly to go against the public good.30 In addition, high rates of repeat emergency department visits and readmissions for AMA patients, demonstrated here and in other studies, highlight the importance of careful documentation in informing subsequent providers about hospital returnees’ ongoing issues.17-19

This study also demonstrated differences between nurses and physicians in their beliefs about arranging follow-up for AMA patients. Nurses were less likely than physicians to think follow-up arrangements should be made for AMA patients and more likely to say these patients should lose the right to follow-up because of the AMA discharge. For conventional discharges, nurses provide patients with significantly more discharge education than interns or hospitalists do.31 This discrepancy highlights an urgent need for the education and involvement of nurses as stakeholders in the challenging AMA discharge process. Although the percentage of physicians who thought they were not obligated to provide medications and arrange follow-up for AMA patients was lower than the percentage of nurses, these beliefs contradict best practice guidelines for AMA discharges,22,23 and this finding calls attention to the need for interventions to improve adherence to professional and ethical guidelines in this aspect of clinical practice.

Providers showed a lack of familiarity with practice guidelines regarding certain aspects of the AMA discharge process. For example, most providers thought they should not have to arrange transportation for AMA patients, even though both the California Hospital Association Guidelines and the Highland Hospital internal policy on AMA discharges recommend arranging appropriate transportation.32 This finding suggests a need for educational interventions to ensure providers are informed about state and hospital policies, and a need to include both physicians and nurses in policymaking so theory can be tied to practice.

This study was limited to a single center with healthcare provider and patient populations that might not be generalizable to other settings. In the retrospective chart review, the authors were limited to information documented in the medical record, which might not accurately reflect the AMA discharge process. As they surveyed a limited number of social workers, case managers, and others who play an important role in the AMA discharge process, their data may lack varying viewpoints.

Overall, these data suggest providers at this county hospital generally agreed in principle with the best practice guidelines proposed by bioethicists for AMA discharges. In practice, however, providers were not reliably following these guidelines. Future interventions—including provider education on best practice guidelines for AMA discharge, provider involvement in policymaking, supportive templates for guiding documentation of AMA discharges, and improving access to follow-up care—will be key in improving the safety and health outcomes of AMA patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kelly Aguilar, Kethia Chheng, Irene Yen, and the Research Advancement and Coordination Initiative at Alameda Health System for important contributions to this project.

Disclosures

Highland Hospital Department of Medicine internal grant 2015.23 helped fund this research. A portion of the data was presented as a poster at the University of California San Francisco Health Disparities Symposium; October 2015; San Francisco, CA. Two posters from the data were presented at Hospital Medicine 2016, March 2016; San Diego, CA.

1. Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594-602. PubMed

2. Stranges E, Wier L, Merrill C, Steiner C. Hospitalizations in which Patients Leave the Hospital against Medical Advice (AMA), 2007. HCUP Statistical Brief #78. August 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb78.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2016. PubMed

3. Devitt PJ, Devitt AC, Dewan M. Does identifying a discharge as “against medical advice” confer legal protection? J Fam Pract. 2000;49(3):224-227. PubMed

4. O’Hara D, Hart W, McDonald I. Leaving hospital against medical advice. J Qual Clin Pract. 1996;16(3):157-164. PubMed

5. Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2204-2208. PubMed

6. Clark MA, Abbott JT, Adyanthaya T. Ethics seminars: a best-practice approach to navigating the against-medical-advice discharge. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(9):1050-1057. PubMed

7. Windish DM, Ratanawongsa N. Providers’ perceptions of relationships and professional roles when caring for patients who leave the hospital against medical advice. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1698-1707. PubMed

8. Edwards J, Markert R, Bricker D. Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):574-577. PubMed

9. Alfandre DJ. “I’m going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255-260. PubMed

10. Katzenellenbogen JM, Sanfilippo FM, Hobbs MS, et al. Voting with their feet—predictors of discharge against medical advice in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal ischaemic heart disease inpatients in Western Australia: an analytic study using data linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:330. PubMed

11. Ti L, Milloy MJ, Buxton J, et al. Factors associated with leaving hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141594. PubMed

12. Yong TY, Fok JS, Hakendorf P, Ben-Tovim D, Thompson CH, Li JY. Characteristics and outcomes of discharges against medical advice among hospitalised patients. Intern Med J. 2013;43(7):798-802. PubMed

13. Tabatabaei SM, Sargazi Moakhar Z, Behmanesh Pour F, Shaare Mollashahi S, Zaboli M. Hospitalized pregnant women who leave against medical advice: attributes and reasons. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):128-138. PubMed

14. Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325-327. PubMed

15. Ti L, Ti L. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e53-e59. PubMed

16. Targum SD, Capodanno AE, Hoffman HA, Foudraine C. An intervention to reduce the rate of hospital discharges against medical advice. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(5):657-659. PubMed

17. Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24459. PubMed

18. Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926-929. PubMed

19. Garland A, Ramsey CD, Fransoo R, et al. Rates of readmission and death associated with leaving hospital against medical advice: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2013;185(14):1207-1214. PubMed

20. Hwang SW, Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? CMAJ. 2003;168(4):417-420. PubMed

21. Onukwugha E, Mullins CD, Loh FE, Saunders E, Shaya FT, Weir MR. Readmissions after unauthorized discharges in the cardiovascular setting. Med Care. 2011;49(2):215-224. PubMed

22. Alfandre D. Reconsidering against medical advice discharges: embracing patient-centeredness to promote high quality care and a renewed research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(12):1657-1662. PubMed

23. Berger JT. Discharge against medical advice: ethical considerations and professional obligations. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):403-408. PubMed

24. Franks P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K. Discharges against medical advice: are race/ethnicity predictors? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):955-960. PubMed

25. Hicks LS, Ayanian JZ, Orav EJ, et al. Is hospital service associated with racial and ethnic disparities in experiences with hospital care? Am J Med. 2005;118(5):529-535. PubMed

26. Hicks LS, Tovar DA, Orav EJ, Johnson PA. Experiences with hospital care: perspectives of black and Hispanic patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1234-1240. PubMed

27. McCreaddie M, Lyons I, Watt D, et al. Routines and rituals: a grounded theory of the pain management of drug users in acute care settings. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19-20):2730-2740. PubMed

28. Carroll IR, Angst MS, Clark JD. Management of perioperative pain in patients chronically consuming opioids. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(6):576-591. PubMed

29. Chan AC, Palepu A, Guh DP, et al. HIV-positive injection drug users who leave the hospital against medical advice: the mitigating role of methadone and social support. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(1):56-59. PubMed

30. Levy F, Mareiniss DP, Iacovelli C. The importance of a proper against-medical-advice (AMA) discharge: how signing out AMA may create significant liability protection for providers. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(3):516-520. PubMed

31. Ashbrook L, Mourad M, Sehgal N. Communicating discharge instructions to patients: a survey of nurse, intern, and hospitalist practices. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(1):36-41. PubMed

32. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Title 22, California Code of Regulations, §70707.3.

1. Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594-602. PubMed

2. Stranges E, Wier L, Merrill C, Steiner C. Hospitalizations in which Patients Leave the Hospital against Medical Advice (AMA), 2007. HCUP Statistical Brief #78. August 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb78.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2016. PubMed

3. Devitt PJ, Devitt AC, Dewan M. Does identifying a discharge as “against medical advice” confer legal protection? J Fam Pract. 2000;49(3):224-227. PubMed

4. O’Hara D, Hart W, McDonald I. Leaving hospital against medical advice. J Qual Clin Pract. 1996;16(3):157-164. PubMed

5. Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2204-2208. PubMed

6. Clark MA, Abbott JT, Adyanthaya T. Ethics seminars: a best-practice approach to navigating the against-medical-advice discharge. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(9):1050-1057. PubMed

7. Windish DM, Ratanawongsa N. Providers’ perceptions of relationships and professional roles when caring for patients who leave the hospital against medical advice. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1698-1707. PubMed

8. Edwards J, Markert R, Bricker D. Discharge against medical advice: how often do we intervene? J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):574-577. PubMed

9. Alfandre DJ. “I’m going home”: discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255-260. PubMed

10. Katzenellenbogen JM, Sanfilippo FM, Hobbs MS, et al. Voting with their feet—predictors of discharge against medical advice in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal ischaemic heart disease inpatients in Western Australia: an analytic study using data linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:330. PubMed

11. Ti L, Milloy MJ, Buxton J, et al. Factors associated with leaving hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0141594. PubMed

12. Yong TY, Fok JS, Hakendorf P, Ben-Tovim D, Thompson CH, Li JY. Characteristics and outcomes of discharges against medical advice among hospitalised patients. Intern Med J. 2013;43(7):798-802. PubMed

13. Tabatabaei SM, Sargazi Moakhar Z, Behmanesh Pour F, Shaare Mollashahi S, Zaboli M. Hospitalized pregnant women who leave against medical advice: attributes and reasons. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(1):128-138. PubMed

14. Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325-327. PubMed

15. Ti L, Ti L. Leaving the hospital against medical advice among people who use illicit drugs: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e53-e59. PubMed

16. Targum SD, Capodanno AE, Hoffman HA, Foudraine C. An intervention to reduce the rate of hospital discharges against medical advice. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(5):657-659. PubMed

17. Choi M, Kim H, Qian H, Palepu A. Readmission rates of patients discharged against medical advice: a matched cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24459. PubMed

18. Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926-929. PubMed

19. Garland A, Ramsey CD, Fransoo R, et al. Rates of readmission and death associated with leaving hospital against medical advice: a population-based study. CMAJ. 2013;185(14):1207-1214. PubMed

20. Hwang SW, Li J, Gupta R, Chien V, Martin RE. What happens to patients who leave hospital against medical advice? CMAJ. 2003;168(4):417-420. PubMed

21. Onukwugha E, Mullins CD, Loh FE, Saunders E, Shaya FT, Weir MR. Readmissions after unauthorized discharges in the cardiovascular setting. Med Care. 2011;49(2):215-224. PubMed

22. Alfandre D. Reconsidering against medical advice discharges: embracing patient-centeredness to promote high quality care and a renewed research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(12):1657-1662. PubMed

23. Berger JT. Discharge against medical advice: ethical considerations and professional obligations. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):403-408. PubMed

24. Franks P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K. Discharges against medical advice: are race/ethnicity predictors? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):955-960. PubMed

25. Hicks LS, Ayanian JZ, Orav EJ, et al. Is hospital service associated with racial and ethnic disparities in experiences with hospital care? Am J Med. 2005;118(5):529-535. PubMed

26. Hicks LS, Tovar DA, Orav EJ, Johnson PA. Experiences with hospital care: perspectives of black and Hispanic patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(8):1234-1240. PubMed