User login

Cancer genomic data released to public

Photo courtesy of the

National Institute of

General Medical Sciences

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has announced the first public release of cancer genomic data aggregated through the AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE).

The data set includes nearly 19,000 de-identified genomic records collected from patients who were treated at 8 international institutions, making it one of the largest public cancer genomic data sets released to date.

The release includes data for 59 major cancer types, including leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma.

The genomic data and a limited amount of linked clinical data for each patient can be accessed via the AACR Project GENIE cBioPortal or from Sage Bionetworks. (Users must create an account for either site to access the data.)

“We are excited to make publicly available this very large set of clinical-grade, next-generation sequencing data obtained during routine patient care,” said Charles L. Sawyers, MD, AACR Project GENIE Steering Committee chairperson.

“These data were generated as part of routine patient care and, without AACR Project GENIE, they would likely never have been shared with the global cancer research community.”

AACR Project GENIE is a multi-phase, international data-sharing project aimed at catalyzing precision oncology through the development of a registry that aggregates and links clinical-grade cancer genomic data with clinical outcomes from tens of thousands of cancer patients treated at multiple institutions.

The newly released data are fully de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

The data are derived from patients whose tumors were genetically sequenced as part of their care at any of the 8 institutions that participated in the first phase of AACR Project GENIE.

The goal of releasing these data to the cancer research community is to aid new research that will accelerate the pace of progress against cancer.

According to AACR, the data can be used to validate gene signatures of drug response or prognosis, identify new patient populations for drugs that are currently available, and uncover new drug targets and biomarkers.

“I am extremely proud that the American Association for Cancer Research, as the coordinating center for AACR Project GENIE, is delivering on its promise to make these important data publicly available just over a year after unveiling the initiative,” said Margaret Foti, PhD, MD, chief executive officer of the AACR.

To expand the AACR Project GENIE registry, the consortium is accepting applications for new participating centers. Any nonprofit institution that meets certain criteria can submit an application to become a project participant.

For more information on AACR Project GENIE, visit the project website or send an email to [email protected]. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

National Institute of

General Medical Sciences

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has announced the first public release of cancer genomic data aggregated through the AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE).

The data set includes nearly 19,000 de-identified genomic records collected from patients who were treated at 8 international institutions, making it one of the largest public cancer genomic data sets released to date.

The release includes data for 59 major cancer types, including leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma.

The genomic data and a limited amount of linked clinical data for each patient can be accessed via the AACR Project GENIE cBioPortal or from Sage Bionetworks. (Users must create an account for either site to access the data.)

“We are excited to make publicly available this very large set of clinical-grade, next-generation sequencing data obtained during routine patient care,” said Charles L. Sawyers, MD, AACR Project GENIE Steering Committee chairperson.

“These data were generated as part of routine patient care and, without AACR Project GENIE, they would likely never have been shared with the global cancer research community.”

AACR Project GENIE is a multi-phase, international data-sharing project aimed at catalyzing precision oncology through the development of a registry that aggregates and links clinical-grade cancer genomic data with clinical outcomes from tens of thousands of cancer patients treated at multiple institutions.

The newly released data are fully de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

The data are derived from patients whose tumors were genetically sequenced as part of their care at any of the 8 institutions that participated in the first phase of AACR Project GENIE.

The goal of releasing these data to the cancer research community is to aid new research that will accelerate the pace of progress against cancer.

According to AACR, the data can be used to validate gene signatures of drug response or prognosis, identify new patient populations for drugs that are currently available, and uncover new drug targets and biomarkers.

“I am extremely proud that the American Association for Cancer Research, as the coordinating center for AACR Project GENIE, is delivering on its promise to make these important data publicly available just over a year after unveiling the initiative,” said Margaret Foti, PhD, MD, chief executive officer of the AACR.

To expand the AACR Project GENIE registry, the consortium is accepting applications for new participating centers. Any nonprofit institution that meets certain criteria can submit an application to become a project participant.

For more information on AACR Project GENIE, visit the project website or send an email to [email protected]. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

National Institute of

General Medical Sciences

The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) has announced the first public release of cancer genomic data aggregated through the AACR Project Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange (GENIE).

The data set includes nearly 19,000 de-identified genomic records collected from patients who were treated at 8 international institutions, making it one of the largest public cancer genomic data sets released to date.

The release includes data for 59 major cancer types, including leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma.

The genomic data and a limited amount of linked clinical data for each patient can be accessed via the AACR Project GENIE cBioPortal or from Sage Bionetworks. (Users must create an account for either site to access the data.)

“We are excited to make publicly available this very large set of clinical-grade, next-generation sequencing data obtained during routine patient care,” said Charles L. Sawyers, MD, AACR Project GENIE Steering Committee chairperson.

“These data were generated as part of routine patient care and, without AACR Project GENIE, they would likely never have been shared with the global cancer research community.”

AACR Project GENIE is a multi-phase, international data-sharing project aimed at catalyzing precision oncology through the development of a registry that aggregates and links clinical-grade cancer genomic data with clinical outcomes from tens of thousands of cancer patients treated at multiple institutions.

The newly released data are fully de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

The data are derived from patients whose tumors were genetically sequenced as part of their care at any of the 8 institutions that participated in the first phase of AACR Project GENIE.

The goal of releasing these data to the cancer research community is to aid new research that will accelerate the pace of progress against cancer.

According to AACR, the data can be used to validate gene signatures of drug response or prognosis, identify new patient populations for drugs that are currently available, and uncover new drug targets and biomarkers.

“I am extremely proud that the American Association for Cancer Research, as the coordinating center for AACR Project GENIE, is delivering on its promise to make these important data publicly available just over a year after unveiling the initiative,” said Margaret Foti, PhD, MD, chief executive officer of the AACR.

To expand the AACR Project GENIE registry, the consortium is accepting applications for new participating centers. Any nonprofit institution that meets certain criteria can submit an application to become a project participant.

For more information on AACR Project GENIE, visit the project website or send an email to [email protected]. ![]()

FDA lifts full clinical hold on pacritinib

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the full clinical hold placed on all clinical trials conducted under the investigational new drug application for pacritinib, an oral kinase inhibitor being developed as a treatment for myelofibrosis (MF).

The FDA placed the hold on pacritinib trials in February 2016 after results from 2 phase 3 trials, PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2, showed excess mortality in patients who received pacritinib.

Both trials suggested pacritinib can be more effective than the best available therapy for MF.

However, interim overall survival results from PERSIST-2 indicated that pacritinib had a detrimental effect on survival, which was consistent with the results from PERSIST-1.

Due to the full clinical hold, CTI BioPharma withdrew the new drug application for pacritinib while reviewing data from PERSIST-2.

When the FDA enacted the hold, the agency recommended that CTI BioPharma conduct dose-exploration studies for pacritinib, submit final study reports and data sets for PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2, make certain modifications to protocols and study-related documents, and request a meeting with the FDA prior to submitting a response to the full clinical hold.

CTI BioPharma followed the FDA’s recommendations and submitted a response to the hold that included final clinical study reports for PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2 and a protocol for a dose-exploration trial.

The trial, PAC203, should enroll up to approximately 105 patients with primary MF who have failed prior ruxolitinib therapy. The goal is to evaluate the safety and the dose-response relationship for efficacy (spleen volume reduction at 24 weeks) of pacritinib at 3 doses: 100 mg once daily, 100 mg twice daily (BID), and 200 mg BID. The 200 mg BID dose regimen was used in PERSIST-2.

CTI BioPharma said it expects to start the trial in the second quarter of 2017.

“We are pleased to resolve the full clinical hold through working diligently with the FDA to provide a comprehensive response to their requests,” said Richard Love, interim president and chief executive officer of CTI BioPharma.

“We look forward to discussing with the FDA the future development of pacritinib. We believe pacritinib can ultimately address the unmet need of patients with myelofibrosis who are ineligible to receive or are not benefitting from the approved JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, as these patients have limited treatment options.” ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the full clinical hold placed on all clinical trials conducted under the investigational new drug application for pacritinib, an oral kinase inhibitor being developed as a treatment for myelofibrosis (MF).

The FDA placed the hold on pacritinib trials in February 2016 after results from 2 phase 3 trials, PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2, showed excess mortality in patients who received pacritinib.

Both trials suggested pacritinib can be more effective than the best available therapy for MF.

However, interim overall survival results from PERSIST-2 indicated that pacritinib had a detrimental effect on survival, which was consistent with the results from PERSIST-1.

Due to the full clinical hold, CTI BioPharma withdrew the new drug application for pacritinib while reviewing data from PERSIST-2.

When the FDA enacted the hold, the agency recommended that CTI BioPharma conduct dose-exploration studies for pacritinib, submit final study reports and data sets for PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2, make certain modifications to protocols and study-related documents, and request a meeting with the FDA prior to submitting a response to the full clinical hold.

CTI BioPharma followed the FDA’s recommendations and submitted a response to the hold that included final clinical study reports for PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2 and a protocol for a dose-exploration trial.

The trial, PAC203, should enroll up to approximately 105 patients with primary MF who have failed prior ruxolitinib therapy. The goal is to evaluate the safety and the dose-response relationship for efficacy (spleen volume reduction at 24 weeks) of pacritinib at 3 doses: 100 mg once daily, 100 mg twice daily (BID), and 200 mg BID. The 200 mg BID dose regimen was used in PERSIST-2.

CTI BioPharma said it expects to start the trial in the second quarter of 2017.

“We are pleased to resolve the full clinical hold through working diligently with the FDA to provide a comprehensive response to their requests,” said Richard Love, interim president and chief executive officer of CTI BioPharma.

“We look forward to discussing with the FDA the future development of pacritinib. We believe pacritinib can ultimately address the unmet need of patients with myelofibrosis who are ineligible to receive or are not benefitting from the approved JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, as these patients have limited treatment options.” ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the full clinical hold placed on all clinical trials conducted under the investigational new drug application for pacritinib, an oral kinase inhibitor being developed as a treatment for myelofibrosis (MF).

The FDA placed the hold on pacritinib trials in February 2016 after results from 2 phase 3 trials, PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2, showed excess mortality in patients who received pacritinib.

Both trials suggested pacritinib can be more effective than the best available therapy for MF.

However, interim overall survival results from PERSIST-2 indicated that pacritinib had a detrimental effect on survival, which was consistent with the results from PERSIST-1.

Due to the full clinical hold, CTI BioPharma withdrew the new drug application for pacritinib while reviewing data from PERSIST-2.

When the FDA enacted the hold, the agency recommended that CTI BioPharma conduct dose-exploration studies for pacritinib, submit final study reports and data sets for PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2, make certain modifications to protocols and study-related documents, and request a meeting with the FDA prior to submitting a response to the full clinical hold.

CTI BioPharma followed the FDA’s recommendations and submitted a response to the hold that included final clinical study reports for PERSIST-1 and PERSIST-2 and a protocol for a dose-exploration trial.

The trial, PAC203, should enroll up to approximately 105 patients with primary MF who have failed prior ruxolitinib therapy. The goal is to evaluate the safety and the dose-response relationship for efficacy (spleen volume reduction at 24 weeks) of pacritinib at 3 doses: 100 mg once daily, 100 mg twice daily (BID), and 200 mg BID. The 200 mg BID dose regimen was used in PERSIST-2.

CTI BioPharma said it expects to start the trial in the second quarter of 2017.

“We are pleased to resolve the full clinical hold through working diligently with the FDA to provide a comprehensive response to their requests,” said Richard Love, interim president and chief executive officer of CTI BioPharma.

“We look forward to discussing with the FDA the future development of pacritinib. We believe pacritinib can ultimately address the unmet need of patients with myelofibrosis who are ineligible to receive or are not benefitting from the approved JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, as these patients have limited treatment options.” ![]()

Bronchoscopy sedation changes in 2017

A major change in coding for bronchoscopy occurred on January 1, 2017, as moderate (conscious) sedation is now separately identified from the work relative value units (wRVUs) for the bronchoscopy codes. While traditionally the bronchoscopist provided moderate sedation, in recent clinical practice, other individuals often provide the sedation. CMS mandated refinement of separate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes to account for the work of moderate procedural sedation. In the final rule published in November 2016, CMS removed 0.25 wRVUs from many of the bronchoscopy codes to account for the work of moderate sedation. To be reimbursed appropriately, include a moderate sedation CPT code with all bronchoscopy procedures.

Use codes 99151 and 99155 for patients younger than 5 years. For a patient 5 years or older, when the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation, report code 99152 for the initial 15 minutes and 99153 for subsequent time in 15-minute increments. For a patient 5 years or older, when a provider other than the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation, use code 99156 for the initial 15 minutes and 99157 for subsequent time in 15-minute increments. Utilize codes 99156 and 99157 only when a second provider (other than the bronchoscopist) performs moderate sedation in the facility setting (eg, hospital, outpatient hospital/ambulatory surgery center, skilled nursing facility). When the second provider performs these services in the nonfacility setting (eg, physician office, freestanding imaging center), do not report codes 99155, 99156, or 99157. Moderate sedation does not include minimal sedation (anxiolysis), deep sedation, or monitored anesthesia care (00100-01999).

Do not use a moderate sedation code (99151-2 or 99155-6) if providing less than 10 minutes of moderate sedation. As with other time-based codes, use the subsequent codes 99153 and 99157 when moderate sedation lasts 8 minutes or longer than the initial 15 minutes. The time for moderate sedation begins with the administration of the sedating agent and concludes when the continuous face-to-face presence of the bronchoscopist ends after completion of the procedure. Intermittent, re-evaluation of the patient afterward is postservice work and is not included in the time for moderate sedation. For example, if the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation for 25 minutes in a 65-year-old man, report 99152 (for the initial 15 minutes) and 99153 (for the subsequent 10 minutes). If an individual other than the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation for 41 minutes in a 57-year-old woman, use 99156 (for the initial 15 minutes) and two units of 99157 (for the subsequent 26 minutes). If a bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation and reports the appropriate codes after January 1, the 0.25 wRVU change will have no financial impact compared with 2016. If a second provider performs the moderate sedation, expect an approximately $8.72 drop in reimbursement per procedure.

A major change in coding for bronchoscopy occurred on January 1, 2017, as moderate (conscious) sedation is now separately identified from the work relative value units (wRVUs) for the bronchoscopy codes. While traditionally the bronchoscopist provided moderate sedation, in recent clinical practice, other individuals often provide the sedation. CMS mandated refinement of separate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes to account for the work of moderate procedural sedation. In the final rule published in November 2016, CMS removed 0.25 wRVUs from many of the bronchoscopy codes to account for the work of moderate sedation. To be reimbursed appropriately, include a moderate sedation CPT code with all bronchoscopy procedures.

Use codes 99151 and 99155 for patients younger than 5 years. For a patient 5 years or older, when the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation, report code 99152 for the initial 15 minutes and 99153 for subsequent time in 15-minute increments. For a patient 5 years or older, when a provider other than the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation, use code 99156 for the initial 15 minutes and 99157 for subsequent time in 15-minute increments. Utilize codes 99156 and 99157 only when a second provider (other than the bronchoscopist) performs moderate sedation in the facility setting (eg, hospital, outpatient hospital/ambulatory surgery center, skilled nursing facility). When the second provider performs these services in the nonfacility setting (eg, physician office, freestanding imaging center), do not report codes 99155, 99156, or 99157. Moderate sedation does not include minimal sedation (anxiolysis), deep sedation, or monitored anesthesia care (00100-01999).

Do not use a moderate sedation code (99151-2 or 99155-6) if providing less than 10 minutes of moderate sedation. As with other time-based codes, use the subsequent codes 99153 and 99157 when moderate sedation lasts 8 minutes or longer than the initial 15 minutes. The time for moderate sedation begins with the administration of the sedating agent and concludes when the continuous face-to-face presence of the bronchoscopist ends after completion of the procedure. Intermittent, re-evaluation of the patient afterward is postservice work and is not included in the time for moderate sedation. For example, if the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation for 25 minutes in a 65-year-old man, report 99152 (for the initial 15 minutes) and 99153 (for the subsequent 10 minutes). If an individual other than the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation for 41 minutes in a 57-year-old woman, use 99156 (for the initial 15 minutes) and two units of 99157 (for the subsequent 26 minutes). If a bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation and reports the appropriate codes after January 1, the 0.25 wRVU change will have no financial impact compared with 2016. If a second provider performs the moderate sedation, expect an approximately $8.72 drop in reimbursement per procedure.

A major change in coding for bronchoscopy occurred on January 1, 2017, as moderate (conscious) sedation is now separately identified from the work relative value units (wRVUs) for the bronchoscopy codes. While traditionally the bronchoscopist provided moderate sedation, in recent clinical practice, other individuals often provide the sedation. CMS mandated refinement of separate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes to account for the work of moderate procedural sedation. In the final rule published in November 2016, CMS removed 0.25 wRVUs from many of the bronchoscopy codes to account for the work of moderate sedation. To be reimbursed appropriately, include a moderate sedation CPT code with all bronchoscopy procedures.

Use codes 99151 and 99155 for patients younger than 5 years. For a patient 5 years or older, when the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation, report code 99152 for the initial 15 minutes and 99153 for subsequent time in 15-minute increments. For a patient 5 years or older, when a provider other than the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation, use code 99156 for the initial 15 minutes and 99157 for subsequent time in 15-minute increments. Utilize codes 99156 and 99157 only when a second provider (other than the bronchoscopist) performs moderate sedation in the facility setting (eg, hospital, outpatient hospital/ambulatory surgery center, skilled nursing facility). When the second provider performs these services in the nonfacility setting (eg, physician office, freestanding imaging center), do not report codes 99155, 99156, or 99157. Moderate sedation does not include minimal sedation (anxiolysis), deep sedation, or monitored anesthesia care (00100-01999).

Do not use a moderate sedation code (99151-2 or 99155-6) if providing less than 10 minutes of moderate sedation. As with other time-based codes, use the subsequent codes 99153 and 99157 when moderate sedation lasts 8 minutes or longer than the initial 15 minutes. The time for moderate sedation begins with the administration of the sedating agent and concludes when the continuous face-to-face presence of the bronchoscopist ends after completion of the procedure. Intermittent, re-evaluation of the patient afterward is postservice work and is not included in the time for moderate sedation. For example, if the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation for 25 minutes in a 65-year-old man, report 99152 (for the initial 15 minutes) and 99153 (for the subsequent 10 minutes). If an individual other than the bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation for 41 minutes in a 57-year-old woman, use 99156 (for the initial 15 minutes) and two units of 99157 (for the subsequent 26 minutes). If a bronchoscopist provides moderate sedation and reports the appropriate codes after January 1, the 0.25 wRVU change will have no financial impact compared with 2016. If a second provider performs the moderate sedation, expect an approximately $8.72 drop in reimbursement per procedure.

Sleep strategies: Sleep-disordered breathing and pregnancy complications: Emerging data and future directions

Background

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) conditions are characterized by abnormal respiratory patterns and abnormal gas exchange during sleep.1-3 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the most common type of SDB, is characterized by repetitive episodes of airway narrowing during sleep that lead to respiratory disruption, hypoxia, and sleep fragmentation. In reproductive-aged women, epidemiologic studies suggest a 2% to 13% prevalence of OSA.4-6 Pregnancy is associated with changes that promote OSA, such as weight gain and edema of the upper airway.7 Frequent snoring, a common symptom of OSA, is endorsed by 15% to 25% of pregnant women.8-10 Health outcomes that have been linked to SDB in the nonpregnant population, such as hypertension and insulin-resistant diabetes, have clinically relevant correlates in pregnancy (preeclampsia, gestational diabetes).11-13

While several retrospective and cross-sectional studies suggest that SDB may increase the risk of developing hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes during pregnancy,16-18 up until recently, there were limited and conflicting data from prospective observational cohorts in which SDB exposure and pregnancy outcomes have been methodically measured and confounding variables carefully considered.19-21 Louis et al.19 reported on a cohort of 175 obese women and demonstrated that women with SDB (apnea-hypopnea index greater than or equal to 5) were more likely to develop preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3, 9.9). However, two other small studies failed to demonstrate a positive association between SDB and pregnancy-related hypertension, but one suggested a relationship between SDB and gestational diabetes.20,21

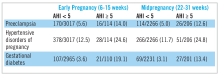

Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy

The Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy (nuMoM2b-SDB) was a prospective cohort study.22,23 Level 3 home sleep tests were performed using a six-channel monitor that was self-applied by the participant twice during pregnancy, first between 60 and 150 weeks of pregnancy and then again between 220 and 310 weeks. An apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of at least 5 was used to define SDB. The study was powered to test the primary hypothesis that SDB occurring in pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes were rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, defined as preeclampsia and prenatal gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Adjustment covariates included maternal age (less than or equal to 21, 22-35, and over 35 years), body mass index (less than 25, 25 to less than 30, greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2), chronic hypertension (yes, no), and, for midpregnancy, rate of weight gain per week between early and midpregnancy assessments, treated as a continuous variable.

Conclusions and future directions

The nuMoM2b data are provocative because sleep apnea is a potentially modifiable risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. While a majority of SDB cases identified during pregnancy were mild, the nuMoM2b data demonstrate that even modest elevations of AHI in pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of developing hypertensive disorders and an increased incidence of gestational diabetes.

Pregnancy is conceivably an ideal scenario in which to better understand the role of SDB treatment as a preventive strategy for reducing cardiometabolic morbidity as the time frame needed to measure incident outcomes after initiating therapy is significantly contracted. However, data regarding the role of OSA treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during pregnancy, both regarding its acceptability to patients and its therapeutic benefit, are extremely limited. Further research is needed to establish whether universal screening for and treating of SDB in pregnancy can mitigate the risks and consequences of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes. However, in the meantime, we have to recognize that as our obstetric patient population is becoming more obese, we will encounter more women with symptomatic SDB in pregnancy. It is well documented that patients with symptomatic SDB, those who report that their snoring leads to chronic sleep disruption and excessive daytime sleepiness, can benefit from CPAP in terms of sleep quality and daytime function. Therefore, in addition to encouraging women already prescribed CPAP to continue their therapy during pregnancy, obstetricians who encounter a patient reporting severe SDB symptoms should refer her to a sleep specialist for further evaluation.

Dr. Facco is assistant professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Women’s Hospital, Magee Women’s Research Institute.

References

1. Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597-619.

2. Park JG, Ramar K, Olson EJ. Updates on definition, consequences, and management of obstructive sleep apnea. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(6):549-54; quiz, 554-5.

3. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan S. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, Ill.: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

4. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 May 1;177(9):1006-14.

5. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230-5.

6. Young T, Finn L, Austin D, Peterson A. Menopausal status and sleep-disordered breathing in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(9):1181-5.

7. Pien GW, Schwab RJ. Sleep disorders during pregnancy. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1405-17.

8. Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm AS, Myllyla VV. Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Med. 2002;3(1):37-42.

9. Pien GW, Fife D, Pack AI, Nkwuo JE, Schwab RJ. Changes in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1299-1305.

10. Facco FL, Kramer J, Ho KH, Zee PC, Grobman WA. Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):77-83.

11. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378-84.

12. Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):521-30.

13. Reichmuth KJ, Austin D, Skatrud JB, Young T. Association of sleep apnea and type II diabetes: A population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(12):1590-5.

14. Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):47-112.

15. Romero R, Badr MS. A role for sleep disorders in pregnancy complications: Challenges and opportunities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):3-11.

16. O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. Pregnancy-onset habitual snoring, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia: Prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(6):487.e1-9

17. Chen YH, Kang JH, Lin CC, Wang IT, Keller JJ, Lin HC. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):136.e1-5.

18. Bourjeily G, Raker CA, Chalhoub M, Miller MA, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(4):849-55.

19. Louis J, Auckley D, Miladinovic B, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with obstructive sleep apnea in obese pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1085-92.

20. Facco FL, Ouyang DW, Zee PC, et al. Implications of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;210(6):559.e1-6.

21. Pien GW, Pack AI, Jackson N, Maislin G, Macones GA, Schwab RJ. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Thorax. 2014;69(4):371-7.

22. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. NuMoM2b Sleep-Disordered Breathing study: Objectives and methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 April;212(4):542.e1–542.e127.

23. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. Association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertensive disorders of pregn ancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. ePub. 2016 Dec 2.

Background

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) conditions are characterized by abnormal respiratory patterns and abnormal gas exchange during sleep.1-3 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the most common type of SDB, is characterized by repetitive episodes of airway narrowing during sleep that lead to respiratory disruption, hypoxia, and sleep fragmentation. In reproductive-aged women, epidemiologic studies suggest a 2% to 13% prevalence of OSA.4-6 Pregnancy is associated with changes that promote OSA, such as weight gain and edema of the upper airway.7 Frequent snoring, a common symptom of OSA, is endorsed by 15% to 25% of pregnant women.8-10 Health outcomes that have been linked to SDB in the nonpregnant population, such as hypertension and insulin-resistant diabetes, have clinically relevant correlates in pregnancy (preeclampsia, gestational diabetes).11-13

While several retrospective and cross-sectional studies suggest that SDB may increase the risk of developing hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes during pregnancy,16-18 up until recently, there were limited and conflicting data from prospective observational cohorts in which SDB exposure and pregnancy outcomes have been methodically measured and confounding variables carefully considered.19-21 Louis et al.19 reported on a cohort of 175 obese women and demonstrated that women with SDB (apnea-hypopnea index greater than or equal to 5) were more likely to develop preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3, 9.9). However, two other small studies failed to demonstrate a positive association between SDB and pregnancy-related hypertension, but one suggested a relationship between SDB and gestational diabetes.20,21

Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy

The Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy (nuMoM2b-SDB) was a prospective cohort study.22,23 Level 3 home sleep tests were performed using a six-channel monitor that was self-applied by the participant twice during pregnancy, first between 60 and 150 weeks of pregnancy and then again between 220 and 310 weeks. An apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of at least 5 was used to define SDB. The study was powered to test the primary hypothesis that SDB occurring in pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes were rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, defined as preeclampsia and prenatal gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Adjustment covariates included maternal age (less than or equal to 21, 22-35, and over 35 years), body mass index (less than 25, 25 to less than 30, greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2), chronic hypertension (yes, no), and, for midpregnancy, rate of weight gain per week between early and midpregnancy assessments, treated as a continuous variable.

Conclusions and future directions

The nuMoM2b data are provocative because sleep apnea is a potentially modifiable risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. While a majority of SDB cases identified during pregnancy were mild, the nuMoM2b data demonstrate that even modest elevations of AHI in pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of developing hypertensive disorders and an increased incidence of gestational diabetes.

Pregnancy is conceivably an ideal scenario in which to better understand the role of SDB treatment as a preventive strategy for reducing cardiometabolic morbidity as the time frame needed to measure incident outcomes after initiating therapy is significantly contracted. However, data regarding the role of OSA treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during pregnancy, both regarding its acceptability to patients and its therapeutic benefit, are extremely limited. Further research is needed to establish whether universal screening for and treating of SDB in pregnancy can mitigate the risks and consequences of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes. However, in the meantime, we have to recognize that as our obstetric patient population is becoming more obese, we will encounter more women with symptomatic SDB in pregnancy. It is well documented that patients with symptomatic SDB, those who report that their snoring leads to chronic sleep disruption and excessive daytime sleepiness, can benefit from CPAP in terms of sleep quality and daytime function. Therefore, in addition to encouraging women already prescribed CPAP to continue their therapy during pregnancy, obstetricians who encounter a patient reporting severe SDB symptoms should refer her to a sleep specialist for further evaluation.

Dr. Facco is assistant professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Women’s Hospital, Magee Women’s Research Institute.

References

1. Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597-619.

2. Park JG, Ramar K, Olson EJ. Updates on definition, consequences, and management of obstructive sleep apnea. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(6):549-54; quiz, 554-5.

3. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan S. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, Ill.: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

4. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 May 1;177(9):1006-14.

5. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230-5.

6. Young T, Finn L, Austin D, Peterson A. Menopausal status and sleep-disordered breathing in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(9):1181-5.

7. Pien GW, Schwab RJ. Sleep disorders during pregnancy. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1405-17.

8. Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm AS, Myllyla VV. Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Med. 2002;3(1):37-42.

9. Pien GW, Fife D, Pack AI, Nkwuo JE, Schwab RJ. Changes in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1299-1305.

10. Facco FL, Kramer J, Ho KH, Zee PC, Grobman WA. Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):77-83.

11. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378-84.

12. Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):521-30.

13. Reichmuth KJ, Austin D, Skatrud JB, Young T. Association of sleep apnea and type II diabetes: A population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(12):1590-5.

14. Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):47-112.

15. Romero R, Badr MS. A role for sleep disorders in pregnancy complications: Challenges and opportunities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):3-11.

16. O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. Pregnancy-onset habitual snoring, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia: Prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(6):487.e1-9

17. Chen YH, Kang JH, Lin CC, Wang IT, Keller JJ, Lin HC. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):136.e1-5.

18. Bourjeily G, Raker CA, Chalhoub M, Miller MA, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(4):849-55.

19. Louis J, Auckley D, Miladinovic B, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with obstructive sleep apnea in obese pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1085-92.

20. Facco FL, Ouyang DW, Zee PC, et al. Implications of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;210(6):559.e1-6.

21. Pien GW, Pack AI, Jackson N, Maislin G, Macones GA, Schwab RJ. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Thorax. 2014;69(4):371-7.

22. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. NuMoM2b Sleep-Disordered Breathing study: Objectives and methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 April;212(4):542.e1–542.e127.

23. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. Association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertensive disorders of pregn ancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. ePub. 2016 Dec 2.

Background

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) conditions are characterized by abnormal respiratory patterns and abnormal gas exchange during sleep.1-3 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the most common type of SDB, is characterized by repetitive episodes of airway narrowing during sleep that lead to respiratory disruption, hypoxia, and sleep fragmentation. In reproductive-aged women, epidemiologic studies suggest a 2% to 13% prevalence of OSA.4-6 Pregnancy is associated with changes that promote OSA, such as weight gain and edema of the upper airway.7 Frequent snoring, a common symptom of OSA, is endorsed by 15% to 25% of pregnant women.8-10 Health outcomes that have been linked to SDB in the nonpregnant population, such as hypertension and insulin-resistant diabetes, have clinically relevant correlates in pregnancy (preeclampsia, gestational diabetes).11-13

While several retrospective and cross-sectional studies suggest that SDB may increase the risk of developing hypertensive disorders and gestational diabetes during pregnancy,16-18 up until recently, there were limited and conflicting data from prospective observational cohorts in which SDB exposure and pregnancy outcomes have been methodically measured and confounding variables carefully considered.19-21 Louis et al.19 reported on a cohort of 175 obese women and demonstrated that women with SDB (apnea-hypopnea index greater than or equal to 5) were more likely to develop preeclampsia (adjusted odds ratio, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.3, 9.9). However, two other small studies failed to demonstrate a positive association between SDB and pregnancy-related hypertension, but one suggested a relationship between SDB and gestational diabetes.20,21

Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy

The Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Sleep-Disordered Breathing Substudy (nuMoM2b-SDB) was a prospective cohort study.22,23 Level 3 home sleep tests were performed using a six-channel monitor that was self-applied by the participant twice during pregnancy, first between 60 and 150 weeks of pregnancy and then again between 220 and 310 weeks. An apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of at least 5 was used to define SDB. The study was powered to test the primary hypothesis that SDB occurring in pregnancy is associated with an increased incidence of preeclampsia. Secondary outcomes were rates of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, defined as preeclampsia and prenatal gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes. Crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Adjustment covariates included maternal age (less than or equal to 21, 22-35, and over 35 years), body mass index (less than 25, 25 to less than 30, greater than or equal to 30 kg/m2), chronic hypertension (yes, no), and, for midpregnancy, rate of weight gain per week between early and midpregnancy assessments, treated as a continuous variable.

Conclusions and future directions

The nuMoM2b data are provocative because sleep apnea is a potentially modifiable risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. While a majority of SDB cases identified during pregnancy were mild, the nuMoM2b data demonstrate that even modest elevations of AHI in pregnancy are associated with an increased risk of developing hypertensive disorders and an increased incidence of gestational diabetes.

Pregnancy is conceivably an ideal scenario in which to better understand the role of SDB treatment as a preventive strategy for reducing cardiometabolic morbidity as the time frame needed to measure incident outcomes after initiating therapy is significantly contracted. However, data regarding the role of OSA treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) during pregnancy, both regarding its acceptability to patients and its therapeutic benefit, are extremely limited. Further research is needed to establish whether universal screening for and treating of SDB in pregnancy can mitigate the risks and consequences of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes. However, in the meantime, we have to recognize that as our obstetric patient population is becoming more obese, we will encounter more women with symptomatic SDB in pregnancy. It is well documented that patients with symptomatic SDB, those who report that their snoring leads to chronic sleep disruption and excessive daytime sleepiness, can benefit from CPAP in terms of sleep quality and daytime function. Therefore, in addition to encouraging women already prescribed CPAP to continue their therapy during pregnancy, obstetricians who encounter a patient reporting severe SDB symptoms should refer her to a sleep specialist for further evaluation.

Dr. Facco is assistant professor, department of obstetrics and gynecology, University of Pittsburgh, Magee-Women’s Hospital, Magee Women’s Research Institute.

References

1. Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: Update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597-619.

2. Park JG, Ramar K, Olson EJ. Updates on definition, consequences, and management of obstructive sleep apnea. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(6):549-54; quiz, 554-5.

3. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan S. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, Ill.: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

4. Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 May 1;177(9):1006-14.

5. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230-5.

6. Young T, Finn L, Austin D, Peterson A. Menopausal status and sleep-disordered breathing in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(9):1181-5.

7. Pien GW, Schwab RJ. Sleep disorders during pregnancy. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1405-17.

8. Hedman C, Pohjasvaara T, Tolonen U, Suhonen-Malm AS, Myllyla VV. Effects of pregnancy on mothers’ sleep. Sleep Med. 2002;3(1):37-42.

9. Pien GW, Fife D, Pack AI, Nkwuo JE, Schwab RJ. Changes in symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy. Sleep. 2005;28(10):1299-1305.

10. Facco FL, Kramer J, Ho KH, Zee PC, Grobman WA. Sleep disturbances in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(1):77-83.

11. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378-84.

12. Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(6):521-30.

13. Reichmuth KJ, Austin D, Skatrud JB, Young T. Association of sleep apnea and type II diabetes: A population-based study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(12):1590-5.

14. Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):47-112.

15. Romero R, Badr MS. A role for sleep disorders in pregnancy complications: Challenges and opportunities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):3-11.

16. O’Brien LM, Bullough AS, Owusu JT, et al. Pregnancy-onset habitual snoring, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia: Prospective cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(6):487.e1-9

17. Chen YH, Kang JH, Lin CC, Wang IT, Keller JJ, Lin HC. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):136.e1-5.

18. Bourjeily G, Raker CA, Chalhoub M, Miller MA, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes of symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(4):849-55.

19. Louis J, Auckley D, Miladinovic B, et al. Perinatal outcomes associated with obstructive sleep apnea in obese pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1085-92.

20. Facco FL, Ouyang DW, Zee PC, et al. Implications of sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;210(6):559.e1-6.

21. Pien GW, Pack AI, Jackson N, Maislin G, Macones GA, Schwab RJ. Risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. Thorax. 2014;69(4):371-7.

22. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. NuMoM2b Sleep-Disordered Breathing study: Objectives and methods. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 April;212(4):542.e1–542.e127.

23. Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, et al. Association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertensive disorders of pregn ancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. ePub. 2016 Dec 2.

NETWORKS: Pneumonia Day, evaluating inhalers, tobacco taxes Chest Infections Clinical Pulmonary Medicine Interprofessional Team

Pneumonia Day: Today is the day to act!

This past November 12, we celebrated “Pneumonia Day,” named for a disease that has little connotation in the real world, because of the perception that we need only a short course of antibiotics to get better. Such is the origin of the term “walking pneumonia,” which emphasizes that we can still walk even while sick with pneumonia.

However, we recently experienced the most important moment of awareness related to this condition, when one of the U.S. presidential candidates became sick with that disease known as “pneumonia.”

Suddenly, the media devoted great interest to explore this condition, as if it were a new outbreak or a rare disease that could potentially kill someone. Even the health-care providers seem to believe that “pneumonia” is not a big deal, ignoring the fact that it is the most common infectious cause of death overall, and that it not only affects children but also the elderly and patients with poor immune systems.

One out of nine patients who are admitted to the hospital for pneumonia may die during the hospitalization, and one out of four patients who get admitted to an ICU may not survive the event.

However, it also highlights that pneumonia is more than just an acute disease, compromising the brain, heart, and kidneys. In the long run, even after surviving the hospitalization for pneumonia, it can kill and cause other well-known complications leading to death, such as myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death.

Please, stop for one moment and ask yourself about your role in preventing pneumonia and pneumonia-related deaths in your communities. The Chest Infections NetWork is here to help you advocate for the common goal of solving this problem.

Steering Committee Member

Delivery makes a difference: Providing inhaled medication to your patients

One might ask why CHEST (American College of Chest Physicians) and Sunovion developed a steering committee of experts in the field of obstructive lung disease to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices of physicians and other health-care professionals related to inhalational medicines and devices. While inhalers are approved by the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation Research (CEDER) as drug and device combination, the process assesses reproducibility and shelf‐life but does not address the real‐world situation that each of us face with individual patients. How often do clinicians consider the characteristics of each delivery system, as well as the medication being delivered? One might be surprised at the answer.

Patients are frequently prescribed several types of devices with different instructions for optimal use. For example, dry powder inhalers often require high flow rates (30-90 L/min) to deaggregate powder pellets into particles less than 5 mcm, while metereddose inhalers require a slow inspiratory flow (less than 30 L/min). Patients who use both types of devices often confuse which inspiratory flow rate to use with which devices, despite proper education and training. This does not even take into consideration the variable number of steps required by various inhalational devices (which can be as few as 3 steps to as many as 12 steps). Additionally, studies demonstrate that peak inspiratory flow rates, inspiratory volumes, and drug deposition in the lungs may be influenced by gender, height, and weight; as well as by the degree of pulmonary reserve and hyperinflation.

Are there data to suggest that these questions impact the care of patients with severe asthma or COPD? I eagerly await the results of the survey.

Steering Committee Member

A California victory for tobacco control

Californians approved Proposition 56, “Cigarette Tax to Fund Healthcare, Tobacco Use Prevention, Research, and Law Enforcement.” This measure increases the excise tax on all forms of tobacco by $2.00. For the first time, it applies to electronic products that vaporize nicotine that were previously only subject to sales tax. This is in addition to federal excise taxes ($1.01) and state and local sales taxes ($0.50 to $0.60). (https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_56,_Tobacco _Tax_Increase_(2016)

When Prop 56 goes into effect April 1, 2017, the average price of a package of cigarettes will increase to at least $7.89. Based on data from the Surgeon General’s report on “Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults,” this tax increase should equate with a fall in smoking rates by about 12%. Youth and young adults are particularly susceptible to price increases, which helps prevent smoking initiation or continuation.

Tobacco-related health-care costs Californians $3.5 billion dollars annually (Official Voter Information Guide, 2016). Funds raised by Prop 56 will be used by state and local health programs such as Medi-Cal to defray the costs of smoking prevention pro

Prop 56 expands on tougher laws implemented in 2016 that expanded the workplace prohibition of smoking, increased fees for tobacco retailers and wholesalers, broadened the definition of smoking to include e-cigarettes, and increased the minimum age to purchase tobacco to 21 years old. Combined, these measures are expected to result in a further decline in tobacco usage in California.

Alan Roth, RRT, MS, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Pneumonia Day: Today is the day to act!

This past November 12, we celebrated “Pneumonia Day,” named for a disease that has little connotation in the real world, because of the perception that we need only a short course of antibiotics to get better. Such is the origin of the term “walking pneumonia,” which emphasizes that we can still walk even while sick with pneumonia.

However, we recently experienced the most important moment of awareness related to this condition, when one of the U.S. presidential candidates became sick with that disease known as “pneumonia.”

Suddenly, the media devoted great interest to explore this condition, as if it were a new outbreak or a rare disease that could potentially kill someone. Even the health-care providers seem to believe that “pneumonia” is not a big deal, ignoring the fact that it is the most common infectious cause of death overall, and that it not only affects children but also the elderly and patients with poor immune systems.

One out of nine patients who are admitted to the hospital for pneumonia may die during the hospitalization, and one out of four patients who get admitted to an ICU may not survive the event.

However, it also highlights that pneumonia is more than just an acute disease, compromising the brain, heart, and kidneys. In the long run, even after surviving the hospitalization for pneumonia, it can kill and cause other well-known complications leading to death, such as myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death.

Please, stop for one moment and ask yourself about your role in preventing pneumonia and pneumonia-related deaths in your communities. The Chest Infections NetWork is here to help you advocate for the common goal of solving this problem.

Steering Committee Member

Delivery makes a difference: Providing inhaled medication to your patients

One might ask why CHEST (American College of Chest Physicians) and Sunovion developed a steering committee of experts in the field of obstructive lung disease to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices of physicians and other health-care professionals related to inhalational medicines and devices. While inhalers are approved by the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation Research (CEDER) as drug and device combination, the process assesses reproducibility and shelf‐life but does not address the real‐world situation that each of us face with individual patients. How often do clinicians consider the characteristics of each delivery system, as well as the medication being delivered? One might be surprised at the answer.

Patients are frequently prescribed several types of devices with different instructions for optimal use. For example, dry powder inhalers often require high flow rates (30-90 L/min) to deaggregate powder pellets into particles less than 5 mcm, while metereddose inhalers require a slow inspiratory flow (less than 30 L/min). Patients who use both types of devices often confuse which inspiratory flow rate to use with which devices, despite proper education and training. This does not even take into consideration the variable number of steps required by various inhalational devices (which can be as few as 3 steps to as many as 12 steps). Additionally, studies demonstrate that peak inspiratory flow rates, inspiratory volumes, and drug deposition in the lungs may be influenced by gender, height, and weight; as well as by the degree of pulmonary reserve and hyperinflation.

Are there data to suggest that these questions impact the care of patients with severe asthma or COPD? I eagerly await the results of the survey.

Steering Committee Member

A California victory for tobacco control

Californians approved Proposition 56, “Cigarette Tax to Fund Healthcare, Tobacco Use Prevention, Research, and Law Enforcement.” This measure increases the excise tax on all forms of tobacco by $2.00. For the first time, it applies to electronic products that vaporize nicotine that were previously only subject to sales tax. This is in addition to federal excise taxes ($1.01) and state and local sales taxes ($0.50 to $0.60). (https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_56,_Tobacco _Tax_Increase_(2016)

When Prop 56 goes into effect April 1, 2017, the average price of a package of cigarettes will increase to at least $7.89. Based on data from the Surgeon General’s report on “Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults,” this tax increase should equate with a fall in smoking rates by about 12%. Youth and young adults are particularly susceptible to price increases, which helps prevent smoking initiation or continuation.

Tobacco-related health-care costs Californians $3.5 billion dollars annually (Official Voter Information Guide, 2016). Funds raised by Prop 56 will be used by state and local health programs such as Medi-Cal to defray the costs of smoking prevention pro

Prop 56 expands on tougher laws implemented in 2016 that expanded the workplace prohibition of smoking, increased fees for tobacco retailers and wholesalers, broadened the definition of smoking to include e-cigarettes, and increased the minimum age to purchase tobacco to 21 years old. Combined, these measures are expected to result in a further decline in tobacco usage in California.

Alan Roth, RRT, MS, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Pneumonia Day: Today is the day to act!

This past November 12, we celebrated “Pneumonia Day,” named for a disease that has little connotation in the real world, because of the perception that we need only a short course of antibiotics to get better. Such is the origin of the term “walking pneumonia,” which emphasizes that we can still walk even while sick with pneumonia.

However, we recently experienced the most important moment of awareness related to this condition, when one of the U.S. presidential candidates became sick with that disease known as “pneumonia.”

Suddenly, the media devoted great interest to explore this condition, as if it were a new outbreak or a rare disease that could potentially kill someone. Even the health-care providers seem to believe that “pneumonia” is not a big deal, ignoring the fact that it is the most common infectious cause of death overall, and that it not only affects children but also the elderly and patients with poor immune systems.

One out of nine patients who are admitted to the hospital for pneumonia may die during the hospitalization, and one out of four patients who get admitted to an ICU may not survive the event.

However, it also highlights that pneumonia is more than just an acute disease, compromising the brain, heart, and kidneys. In the long run, even after surviving the hospitalization for pneumonia, it can kill and cause other well-known complications leading to death, such as myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death.

Please, stop for one moment and ask yourself about your role in preventing pneumonia and pneumonia-related deaths in your communities. The Chest Infections NetWork is here to help you advocate for the common goal of solving this problem.

Steering Committee Member

Delivery makes a difference: Providing inhaled medication to your patients

One might ask why CHEST (American College of Chest Physicians) and Sunovion developed a steering committee of experts in the field of obstructive lung disease to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices of physicians and other health-care professionals related to inhalational medicines and devices. While inhalers are approved by the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation Research (CEDER) as drug and device combination, the process assesses reproducibility and shelf‐life but does not address the real‐world situation that each of us face with individual patients. How often do clinicians consider the characteristics of each delivery system, as well as the medication being delivered? One might be surprised at the answer.

Patients are frequently prescribed several types of devices with different instructions for optimal use. For example, dry powder inhalers often require high flow rates (30-90 L/min) to deaggregate powder pellets into particles less than 5 mcm, while metereddose inhalers require a slow inspiratory flow (less than 30 L/min). Patients who use both types of devices often confuse which inspiratory flow rate to use with which devices, despite proper education and training. This does not even take into consideration the variable number of steps required by various inhalational devices (which can be as few as 3 steps to as many as 12 steps). Additionally, studies demonstrate that peak inspiratory flow rates, inspiratory volumes, and drug deposition in the lungs may be influenced by gender, height, and weight; as well as by the degree of pulmonary reserve and hyperinflation.

Are there data to suggest that these questions impact the care of patients with severe asthma or COPD? I eagerly await the results of the survey.

Steering Committee Member

A California victory for tobacco control

Californians approved Proposition 56, “Cigarette Tax to Fund Healthcare, Tobacco Use Prevention, Research, and Law Enforcement.” This measure increases the excise tax on all forms of tobacco by $2.00. For the first time, it applies to electronic products that vaporize nicotine that were previously only subject to sales tax. This is in addition to federal excise taxes ($1.01) and state and local sales taxes ($0.50 to $0.60). (https://ballotpedia.org/California_Proposition_56,_Tobacco _Tax_Increase_(2016)

When Prop 56 goes into effect April 1, 2017, the average price of a package of cigarettes will increase to at least $7.89. Based on data from the Surgeon General’s report on “Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults,” this tax increase should equate with a fall in smoking rates by about 12%. Youth and young adults are particularly susceptible to price increases, which helps prevent smoking initiation or continuation.

Tobacco-related health-care costs Californians $3.5 billion dollars annually (Official Voter Information Guide, 2016). Funds raised by Prop 56 will be used by state and local health programs such as Medi-Cal to defray the costs of smoking prevention pro

Prop 56 expands on tougher laws implemented in 2016 that expanded the workplace prohibition of smoking, increased fees for tobacco retailers and wholesalers, broadened the definition of smoking to include e-cigarettes, and increased the minimum age to purchase tobacco to 21 years old. Combined, these measures are expected to result in a further decline in tobacco usage in California.

Alan Roth, RRT, MS, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

This month in CHEST : Editor’s picks

Editorial

Spread the Word About CHEST for 2017: Collaboration With Elsevier, Publishing of Guidelines, More Multimedia Content, and Changes for Reviewers and Authors. By Dr. Richard S. Irwin; Dr. John E. Heffner; Jean Rice; Dr. Cynthia T. French; on behalf of the Editorial Leadership Team.

Point Counterpoint Editorial

POINT: Will New Anti-eosinophilic Drugs Be Useful In Asthma Management?

Yes. Dr. P.M. O’Byrne

No. Dr. P. Barnes

Giants in Chest Medicine

Dr. Claude Lenfant. By Dr. E.J. Roccella.

Special Feature

The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. By Dr. F.C. Detterbeck, et al.

Evidence-based MedicineLiberation From Mechanical Ventilation in Critically Ill Adults: Executive Summary of an Official American College of Chest Physicians/American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. By Dr. G.A. Schmidt, et al.

Original ResearchEffect of Procalcitonin Testing on Health-care Utilization and Costs in Critically Ill Patients in the United States. By Dr. R.A. Balk, et al.

Use of Palliative Care in Patients With End-Stage COPD and Receiving Home Oxygen: National Trends and Barriers to Care in the United States. By Dr. B. Rush, et al.

Editorial

Spread the Word About CHEST for 2017: Collaboration With Elsevier, Publishing of Guidelines, More Multimedia Content, and Changes for Reviewers and Authors. By Dr. Richard S. Irwin; Dr. John E. Heffner; Jean Rice; Dr. Cynthia T. French; on behalf of the Editorial Leadership Team.

Point Counterpoint Editorial

POINT: Will New Anti-eosinophilic Drugs Be Useful In Asthma Management?

Yes. Dr. P.M. O’Byrne

No. Dr. P. Barnes

Giants in Chest Medicine

Dr. Claude Lenfant. By Dr. E.J. Roccella.

Special Feature

The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. By Dr. F.C. Detterbeck, et al.

Evidence-based MedicineLiberation From Mechanical Ventilation in Critically Ill Adults: Executive Summary of an Official American College of Chest Physicians/American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. By Dr. G.A. Schmidt, et al.

Original ResearchEffect of Procalcitonin Testing on Health-care Utilization and Costs in Critically Ill Patients in the United States. By Dr. R.A. Balk, et al.

Use of Palliative Care in Patients With End-Stage COPD and Receiving Home Oxygen: National Trends and Barriers to Care in the United States. By Dr. B. Rush, et al.

Editorial

Spread the Word About CHEST for 2017: Collaboration With Elsevier, Publishing of Guidelines, More Multimedia Content, and Changes for Reviewers and Authors. By Dr. Richard S. Irwin; Dr. John E. Heffner; Jean Rice; Dr. Cynthia T. French; on behalf of the Editorial Leadership Team.

Point Counterpoint Editorial

POINT: Will New Anti-eosinophilic Drugs Be Useful In Asthma Management?

Yes. Dr. P.M. O’Byrne

No. Dr. P. Barnes

Giants in Chest Medicine

Dr. Claude Lenfant. By Dr. E.J. Roccella.

Special Feature

The Eighth Edition Lung Cancer Stage Classification. By Dr. F.C. Detterbeck, et al.

Evidence-based MedicineLiberation From Mechanical Ventilation in Critically Ill Adults: Executive Summary of an Official American College of Chest Physicians/American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. By Dr. G.A. Schmidt, et al.

Original ResearchEffect of Procalcitonin Testing on Health-care Utilization and Costs in Critically Ill Patients in the United States. By Dr. R.A. Balk, et al.

Use of Palliative Care in Patients With End-Stage COPD and Receiving Home Oxygen: National Trends and Barriers to Care in the United States. By Dr. B. Rush, et al.

Introducing our new Editorial Board Members

Kidney Disease Progression: How to Calculate Risk

Q)When I diagnose patients with minor kidney disease, they often ask if they will require dialysis. I know it is unlikely, but I wish I could give them a better answer. Can you help me?

The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is understandably concerning for many patients. Being able to estimate CKD progression helps patients gain a better understanding of their condition while allowing clinicians to develop more personalized care plans. Tangri and colleagues developed a model that can be used to predict risk for kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation in patients with stage III to V CKD. This model has been validated in multiple diverse populations in North America and worldwide.1

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (found at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com) uses four variables—age, gender, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR)—to assess two- and five-year risk for kidney failure.1,2 For example

- A 63-year-old woman with a GFR of 45 mL/min and an ACR of 30 mg/g has a 0.4% two-year risk and a 1.3% five-year risk for progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant.1

- Alternatively, a 55-year-old man with a GFR of 38 mL/min and an ACR of 150 mg/g has a 2.9% two-year risk and a 9% five-year risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1

Per proposed thresholds, patients with a score < 5% would be deemed “low risk”; with scores of 5% to 15%, “intermediate risk”; and with scores > 15%, “high risk.”1,2

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation can be incorporated into clinic visits to provide context for lab results. For patients with low risk for progression, optimal care and lifestyle measures can be reinforced. For those with intermediate or high risk, more intensive treatments and appropriate referrals can be initiated. (The National Kidney Foundation advises referral when a patient’s estimated GFR is 20 mL/min or the urine ACR is ≥ 300 mg/g.3) Providing a numeric risk for progression can help alleviate the patient’s uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of CKD. —NDM

Nicole D. McCormick, MS, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

University of Colorado Renal Transplant Clinic, Aurora, Colorado

1. Tangri N, Grams ME, Levey AS, et al. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164-174.

2. Tangri N, Stevens LA, Griffith J, et al. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553-1559.

3. National Kidney Foundation. Renal Replacement Therapy: What the PCP Needs to Know. www.kidney.org/sites/default/files/PCP%20in%20a%20Box%20-%20Module%203.pptx. Accessed December 5, 2016.

Q)When I diagnose patients with minor kidney disease, they often ask if they will require dialysis. I know it is unlikely, but I wish I could give them a better answer. Can you help me?

The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is understandably concerning for many patients. Being able to estimate CKD progression helps patients gain a better understanding of their condition while allowing clinicians to develop more personalized care plans. Tangri and colleagues developed a model that can be used to predict risk for kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation in patients with stage III to V CKD. This model has been validated in multiple diverse populations in North America and worldwide.1

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (found at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com) uses four variables—age, gender, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR)—to assess two- and five-year risk for kidney failure.1,2 For example

- A 63-year-old woman with a GFR of 45 mL/min and an ACR of 30 mg/g has a 0.4% two-year risk and a 1.3% five-year risk for progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant.1

- Alternatively, a 55-year-old man with a GFR of 38 mL/min and an ACR of 150 mg/g has a 2.9% two-year risk and a 9% five-year risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1

Per proposed thresholds, patients with a score < 5% would be deemed “low risk”; with scores of 5% to 15%, “intermediate risk”; and with scores > 15%, “high risk.”1,2

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation can be incorporated into clinic visits to provide context for lab results. For patients with low risk for progression, optimal care and lifestyle measures can be reinforced. For those with intermediate or high risk, more intensive treatments and appropriate referrals can be initiated. (The National Kidney Foundation advises referral when a patient’s estimated GFR is 20 mL/min or the urine ACR is ≥ 300 mg/g.3) Providing a numeric risk for progression can help alleviate the patient’s uncertainty surrounding the diagnosis of CKD. —NDM

Nicole D. McCormick, MS, MBA, NP-C, CCTC

University of Colorado Renal Transplant Clinic, Aurora, Colorado

Q)When I diagnose patients with minor kidney disease, they often ask if they will require dialysis. I know it is unlikely, but I wish I could give them a better answer. Can you help me?

The diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is understandably concerning for many patients. Being able to estimate CKD progression helps patients gain a better understanding of their condition while allowing clinicians to develop more personalized care plans. Tangri and colleagues developed a model that can be used to predict risk for kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation in patients with stage III to V CKD. This model has been validated in multiple diverse populations in North America and worldwide.1

The Kidney Failure Risk Equation (found at www.kidneyfailurerisk.com) uses four variables—age, gender, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR)—to assess two- and five-year risk for kidney failure.1,2 For example

- A 63-year-old woman with a GFR of 45 mL/min and an ACR of 30 mg/g has a 0.4% two-year risk and a 1.3% five-year risk for progression to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplant.1

- Alternatively, a 55-year-old man with a GFR of 38 mL/min and an ACR of 150 mg/g has a 2.9% two-year risk and a 9% five-year risk for progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1

Per proposed thresholds, patients with a score < 5% would be deemed “low risk”; with scores of 5% to 15%, “intermediate risk”; and with scores > 15%, “high risk.”1,2