User login

Nomogram predicts conversion of first demyelinating event to definite MS

Baseline and follow-up data from a prospective, multinational cohort of more than 3,000 patients with clinically isolated events allowed researchers to develop an accurate prognostic nomogram to calculate an individual’s risk for conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis at 12 months.

“Identification of patient, disease, and examination factors associated with higher probability of second attack in clinical practice may enable clinicians to flag patients that could benefit from more intensive follow-up and consideration of early DMD [disease-modifying drug] treatment intervention, facilitating more favorable patient outcomes,” wrote Tim Spelman, PhD, and his associates.

Risk of relapse was decreased when clinically isolated syndrome was diagnosed later, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.9 for every 5 additional years of age. Other risk factors for earlier relapse include higher Expanded Disability Status Scale score at the onset of the first demyelinating event, DMD exposure prior to the first attack, multiple brain and spinal MRI criteria, and oligoclonal bands.

“These results corroborate and extend prior, albeit smaller, studies observing similar sets of predictors of clinical conversion probability,” Dr. Spelman and his coauthors wrote.

The predictive nomogram had a concordance index of 0.81 between the 12-month estimated and observed conversion probabilities.

“While our own internal validation suggested good performance, both an additional training-validation approach and an external validation through the application of the nomogram to a separate MS data set or population are required to confirm the generalizability of the nomogram,” they wrote.

Read the full study in Multiple Sclerosis Journal (2016 Nov 24. doi: 10.1177/1352458516679893).

Baseline and follow-up data from a prospective, multinational cohort of more than 3,000 patients with clinically isolated events allowed researchers to develop an accurate prognostic nomogram to calculate an individual’s risk for conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis at 12 months.

“Identification of patient, disease, and examination factors associated with higher probability of second attack in clinical practice may enable clinicians to flag patients that could benefit from more intensive follow-up and consideration of early DMD [disease-modifying drug] treatment intervention, facilitating more favorable patient outcomes,” wrote Tim Spelman, PhD, and his associates.

Risk of relapse was decreased when clinically isolated syndrome was diagnosed later, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.9 for every 5 additional years of age. Other risk factors for earlier relapse include higher Expanded Disability Status Scale score at the onset of the first demyelinating event, DMD exposure prior to the first attack, multiple brain and spinal MRI criteria, and oligoclonal bands.

“These results corroborate and extend prior, albeit smaller, studies observing similar sets of predictors of clinical conversion probability,” Dr. Spelman and his coauthors wrote.

The predictive nomogram had a concordance index of 0.81 between the 12-month estimated and observed conversion probabilities.

“While our own internal validation suggested good performance, both an additional training-validation approach and an external validation through the application of the nomogram to a separate MS data set or population are required to confirm the generalizability of the nomogram,” they wrote.

Read the full study in Multiple Sclerosis Journal (2016 Nov 24. doi: 10.1177/1352458516679893).

Baseline and follow-up data from a prospective, multinational cohort of more than 3,000 patients with clinically isolated events allowed researchers to develop an accurate prognostic nomogram to calculate an individual’s risk for conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis at 12 months.

“Identification of patient, disease, and examination factors associated with higher probability of second attack in clinical practice may enable clinicians to flag patients that could benefit from more intensive follow-up and consideration of early DMD [disease-modifying drug] treatment intervention, facilitating more favorable patient outcomes,” wrote Tim Spelman, PhD, and his associates.

Risk of relapse was decreased when clinically isolated syndrome was diagnosed later, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.9 for every 5 additional years of age. Other risk factors for earlier relapse include higher Expanded Disability Status Scale score at the onset of the first demyelinating event, DMD exposure prior to the first attack, multiple brain and spinal MRI criteria, and oligoclonal bands.

“These results corroborate and extend prior, albeit smaller, studies observing similar sets of predictors of clinical conversion probability,” Dr. Spelman and his coauthors wrote.

The predictive nomogram had a concordance index of 0.81 between the 12-month estimated and observed conversion probabilities.

“While our own internal validation suggested good performance, both an additional training-validation approach and an external validation through the application of the nomogram to a separate MS data set or population are required to confirm the generalizability of the nomogram,” they wrote.

Read the full study in Multiple Sclerosis Journal (2016 Nov 24. doi: 10.1177/1352458516679893).

FROM MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS JOURNAL

Lower analgesic use after robotic pelvic surgery

Postoperative use of both opioid and nonopioid analgesics was lower after robotic surgery than after laparotomy for endometrial cancer, according to a report published in Gynecologic Oncology.

Researchers assessed the use of postoperative pain medication in a single-center retrospective study involving 340 consecutive robotically assisted surgeries for endometrial cancer during a 6-year period. The mean patient age was 65 years, and more than one-third of the women were aged 70 or older. Slightly more than half were obese, and 19% were morbidly obese, said Jeremie Abitbol, PhD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, Montreal, and his associates.

This benefit in the use of pain medication occurred regardless of the patient’s obesity status or age, which is particularly helpful in view of the increased risk of adverse events in these two patient populations, Dr. Abitbol and his associates reported (Gynecol Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1016/jgyno.2016.11.014).

The direct costs associated with postoperative analgesia also were commensurately lower for robotically assisted surgery ($2.52 per day) than for laparotomy ($7.89 per day).

This study was supported by grants from the Israel Cancer Research Foundation, the Gloria’s Girls Fund, the Levi Family Fund, and the Weekend to End Women’s Cancers. Dr. Abitbol reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of his associates reported receiving a grant from Intuitive Surgical.

Postoperative use of both opioid and nonopioid analgesics was lower after robotic surgery than after laparotomy for endometrial cancer, according to a report published in Gynecologic Oncology.

Researchers assessed the use of postoperative pain medication in a single-center retrospective study involving 340 consecutive robotically assisted surgeries for endometrial cancer during a 6-year period. The mean patient age was 65 years, and more than one-third of the women were aged 70 or older. Slightly more than half were obese, and 19% were morbidly obese, said Jeremie Abitbol, PhD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, Montreal, and his associates.

This benefit in the use of pain medication occurred regardless of the patient’s obesity status or age, which is particularly helpful in view of the increased risk of adverse events in these two patient populations, Dr. Abitbol and his associates reported (Gynecol Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1016/jgyno.2016.11.014).

The direct costs associated with postoperative analgesia also were commensurately lower for robotically assisted surgery ($2.52 per day) than for laparotomy ($7.89 per day).

This study was supported by grants from the Israel Cancer Research Foundation, the Gloria’s Girls Fund, the Levi Family Fund, and the Weekend to End Women’s Cancers. Dr. Abitbol reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of his associates reported receiving a grant from Intuitive Surgical.

Postoperative use of both opioid and nonopioid analgesics was lower after robotic surgery than after laparotomy for endometrial cancer, according to a report published in Gynecologic Oncology.

Researchers assessed the use of postoperative pain medication in a single-center retrospective study involving 340 consecutive robotically assisted surgeries for endometrial cancer during a 6-year period. The mean patient age was 65 years, and more than one-third of the women were aged 70 or older. Slightly more than half were obese, and 19% were morbidly obese, said Jeremie Abitbol, PhD, of the division of gynecologic oncology, Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, Montreal, and his associates.

This benefit in the use of pain medication occurred regardless of the patient’s obesity status or age, which is particularly helpful in view of the increased risk of adverse events in these two patient populations, Dr. Abitbol and his associates reported (Gynecol Oncol. 2016. doi: 10.1016/jgyno.2016.11.014).

The direct costs associated with postoperative analgesia also were commensurately lower for robotically assisted surgery ($2.52 per day) than for laparotomy ($7.89 per day).

This study was supported by grants from the Israel Cancer Research Foundation, the Gloria’s Girls Fund, the Levi Family Fund, and the Weekend to End Women’s Cancers. Dr. Abitbol reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of his associates reported receiving a grant from Intuitive Surgical.

FROM GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Postoperative use of both opioid and nonopioid analgesics was lower after robotic surgery than after laparotomy for endometrial cancer.

Major finding: The robotic surgery cohort required significantly less opioids (12 mg vs. 71 mg), acetaminophen (2,151 mg vs. 4,810 mg), ibuprofen (377 mg vs. 1,892 mg), and naproxen (393 mg vs 1,470 mg), compared with an historical cohort of 59 women who underwent laparotomy.

Data source: A single-center retrospective cohort study involving 340 consecutive robotically assisted pelvic surgeries during a 6-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by grants from the Israel Cancer Research Foundation, the Gloria’s Girls Fund, the Levi Family Fund, and the Weekend to End Women’s Cancers. Dr. Abitbol reported having no relevant financial disclosures; one of his associates reported receiving a grant from Intuitive Surgical.

Few drug-resistant epilepsy patients recruitable for trials of new AEDs

HOUSTON – Fewer than 8% of adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy would have been recruitable for recent phase II and III trials of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), results from a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore a need to rethink how phase II and III trials of AEDs are conducted, Bernhard J. Steinhoff, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In spite of the marketing of numerous new antiepileptic drugs, the percentage of drug-resistant epilepsies has remained almost unchanged,” said Dr. Steinhoff of the Kork (Germany) Epilepsy Center. “I am not aware that anybody involved in the issue of clinical trials with AEDs addressed the problem [of] whether the pivotal trials really cover the patients the new AEDs are developed for: namely, patients with drug-resistant epilepsies. Every time we start with a new drug after licensing, we realize that we have no clue whether this drug will be appropriate for our difficult-to-treat patients. We wondered whether the design of the usual phase II and III randomized controlled trials covers an acceptable percentage of AED-resistant epilepsy patients.”

“The result was frightening because less than 10% [of patients] would have been covered by the trials,” Dr. Steinhoff said. “Therefore, we suggest that a bad trials strategy may be responsible for the fact that the percentage of drug-resistant patients has not been markedly reduced by more than 15 new AEDs that were introduced during the recent years.” He added that pivotal trials with new AEDs “show superiority over placebo as add-on in an extremely limited group of difficult-to-treat patients. After licensing and marketing, we start to learn whether a new AED is appropriate for our drug-resistant patients.”

Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial conflicts.

HOUSTON – Fewer than 8% of adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy would have been recruitable for recent phase II and III trials of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), results from a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore a need to rethink how phase II and III trials of AEDs are conducted, Bernhard J. Steinhoff, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In spite of the marketing of numerous new antiepileptic drugs, the percentage of drug-resistant epilepsies has remained almost unchanged,” said Dr. Steinhoff of the Kork (Germany) Epilepsy Center. “I am not aware that anybody involved in the issue of clinical trials with AEDs addressed the problem [of] whether the pivotal trials really cover the patients the new AEDs are developed for: namely, patients with drug-resistant epilepsies. Every time we start with a new drug after licensing, we realize that we have no clue whether this drug will be appropriate for our difficult-to-treat patients. We wondered whether the design of the usual phase II and III randomized controlled trials covers an acceptable percentage of AED-resistant epilepsy patients.”

“The result was frightening because less than 10% [of patients] would have been covered by the trials,” Dr. Steinhoff said. “Therefore, we suggest that a bad trials strategy may be responsible for the fact that the percentage of drug-resistant patients has not been markedly reduced by more than 15 new AEDs that were introduced during the recent years.” He added that pivotal trials with new AEDs “show superiority over placebo as add-on in an extremely limited group of difficult-to-treat patients. After licensing and marketing, we start to learn whether a new AED is appropriate for our drug-resistant patients.”

Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial conflicts.

HOUSTON – Fewer than 8% of adult patients with drug-resistant epilepsy would have been recruitable for recent phase II and III trials of new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), results from a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore a need to rethink how phase II and III trials of AEDs are conducted, Bernhard J. Steinhoff, MD, said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “In spite of the marketing of numerous new antiepileptic drugs, the percentage of drug-resistant epilepsies has remained almost unchanged,” said Dr. Steinhoff of the Kork (Germany) Epilepsy Center. “I am not aware that anybody involved in the issue of clinical trials with AEDs addressed the problem [of] whether the pivotal trials really cover the patients the new AEDs are developed for: namely, patients with drug-resistant epilepsies. Every time we start with a new drug after licensing, we realize that we have no clue whether this drug will be appropriate for our difficult-to-treat patients. We wondered whether the design of the usual phase II and III randomized controlled trials covers an acceptable percentage of AED-resistant epilepsy patients.”

“The result was frightening because less than 10% [of patients] would have been covered by the trials,” Dr. Steinhoff said. “Therefore, we suggest that a bad trials strategy may be responsible for the fact that the percentage of drug-resistant patients has not been markedly reduced by more than 15 new AEDs that were introduced during the recent years.” He added that pivotal trials with new AEDs “show superiority over placebo as add-on in an extremely limited group of difficult-to-treat patients. After licensing and marketing, we start to learn whether a new AED is appropriate for our drug-resistant patients.”

Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial conflicts.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Only 7.4% of patients would have fulfilled the inclusion criteria of five phase II and III trials of new AEDs.

Data source: A review of 216 outpatients with drug-resistant epilepsies.

Disclosures: Medical writing was funded by an unrestricted grant from UCB. Dr. Steinhoff reported having no financial disclosures.

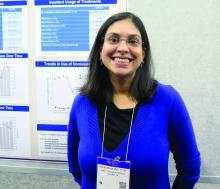

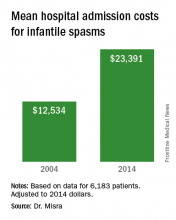

Wide variation seen in treatment of infantile spasms

HOUSTON – The types of diagnostic tests ordered and medication used for treatment of infantile spasms vary considerably, a large study of children’s hospitals showed.

“Children with infantile spasms often require extensive diagnostic work-up to determine etiology, expensive medications for treatment, and hospitalization during the initiation of certain therapies,” researchers led by Sunita N. Misra, MD, PhD, wrote in an abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “The common diagnostic studies and therapies have evolved over the last several decades.”

The researchers collected patient demographics, hospital length of stay, hospital admission cost, use of various diagnostic studies (such as lumbar puncture, brain MRI, and EEG), and medications used for infantile spasms (including antiepileptic drugs, corticotropin, and steroids). Cost data, calculated as a ratio of cost to charges, were collected and adjusted to 2014 dollars.

A total of 6,183 patients were included in the analysis and their average age of infantile-spasm diagnosis was 9 months. The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%). Medications were started during inpatient hospitalization in two-thirds of patients, with 33% starting on corticotropin; 29% on topiramate; and fewer than 10% of patients on an oral or intravenous steroid, zonisamide, or vigabatrin (Sabril). Use of corticotropin decreased over time, while use of oral steroids trended upwards. “We were surprised that one-third of patients did not have a medication initiated as an inpatient, given the studies showing earlier use of effective therapy has better outcomes,” Dr. Misra said in an interview in advance of the meeting.

“The cost of taking care of children with infantile spasms has increased over the study period 2004-2014,” Dr. Misra said. “Although we identified a few contributors to rising cost, there are probably other factors that need to be considered in future studies.” She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that it only identified cost associated with the initial admission. “Several of the diagnostic studies and medications may be initiated as an outpatient, for which we do not have the data,” she said.

Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The types of diagnostic tests ordered and medication used for treatment of infantile spasms vary considerably, a large study of children’s hospitals showed.

“Children with infantile spasms often require extensive diagnostic work-up to determine etiology, expensive medications for treatment, and hospitalization during the initiation of certain therapies,” researchers led by Sunita N. Misra, MD, PhD, wrote in an abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “The common diagnostic studies and therapies have evolved over the last several decades.”

The researchers collected patient demographics, hospital length of stay, hospital admission cost, use of various diagnostic studies (such as lumbar puncture, brain MRI, and EEG), and medications used for infantile spasms (including antiepileptic drugs, corticotropin, and steroids). Cost data, calculated as a ratio of cost to charges, were collected and adjusted to 2014 dollars.

A total of 6,183 patients were included in the analysis and their average age of infantile-spasm diagnosis was 9 months. The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%). Medications were started during inpatient hospitalization in two-thirds of patients, with 33% starting on corticotropin; 29% on topiramate; and fewer than 10% of patients on an oral or intravenous steroid, zonisamide, or vigabatrin (Sabril). Use of corticotropin decreased over time, while use of oral steroids trended upwards. “We were surprised that one-third of patients did not have a medication initiated as an inpatient, given the studies showing earlier use of effective therapy has better outcomes,” Dr. Misra said in an interview in advance of the meeting.

“The cost of taking care of children with infantile spasms has increased over the study period 2004-2014,” Dr. Misra said. “Although we identified a few contributors to rising cost, there are probably other factors that need to be considered in future studies.” She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that it only identified cost associated with the initial admission. “Several of the diagnostic studies and medications may be initiated as an outpatient, for which we do not have the data,” she said.

Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The types of diagnostic tests ordered and medication used for treatment of infantile spasms vary considerably, a large study of children’s hospitals showed.

“Children with infantile spasms often require extensive diagnostic work-up to determine etiology, expensive medications for treatment, and hospitalization during the initiation of certain therapies,” researchers led by Sunita N. Misra, MD, PhD, wrote in an abstract presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “The common diagnostic studies and therapies have evolved over the last several decades.”

The researchers collected patient demographics, hospital length of stay, hospital admission cost, use of various diagnostic studies (such as lumbar puncture, brain MRI, and EEG), and medications used for infantile spasms (including antiepileptic drugs, corticotropin, and steroids). Cost data, calculated as a ratio of cost to charges, were collected and adjusted to 2014 dollars.

A total of 6,183 patients were included in the analysis and their average age of infantile-spasm diagnosis was 9 months. The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%). Medications were started during inpatient hospitalization in two-thirds of patients, with 33% starting on corticotropin; 29% on topiramate; and fewer than 10% of patients on an oral or intravenous steroid, zonisamide, or vigabatrin (Sabril). Use of corticotropin decreased over time, while use of oral steroids trended upwards. “We were surprised that one-third of patients did not have a medication initiated as an inpatient, given the studies showing earlier use of effective therapy has better outcomes,” Dr. Misra said in an interview in advance of the meeting.

“The cost of taking care of children with infantile spasms has increased over the study period 2004-2014,” Dr. Misra said. “Although we identified a few contributors to rising cost, there are probably other factors that need to be considered in future studies.” She acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its retrospective design and the fact that it only identified cost associated with the initial admission. “Several of the diagnostic studies and medications may be initiated as an outpatient, for which we do not have the data,” she said.

Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The most common diagnostic test ordered was EEG (76%), followed by brain imaging (57%), organic acids (38%), and lumbar puncture (17%).

Data source: Retrospective analysis of data on 6,183 patients with infantile spasms between 2004 and 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Misra reported having no financial disclosures.

The plan-do-study-act cycle and data display

This month’s column is the second in a series of three articles written by a group from Toronto and Houston. The series imagined that a community of gastroenterologists set out to improve the adenoma detection rates of physicians in their practice. The first article described the design and launch of the project. This month, Dr. Bollegala and her colleagues explain the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle of improvement within a small practice. The PDSA cycle is a fundamental component of successful quality improvement initiatives; it allows a group to systematically analyze what works and what doesn’t. The focus of this article is squarely on small community practices (still the majority of gastrointestinal practices nationally), so its relevance is high. PDSA cycles are small, narrowly focused projects that can be accomplished by all as we strive to improve our care of the patients we serve. Next month, we will learn how to embed a quality initiative within our practices so sustained improvement can be seen.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Article 1 of our series focused on the emergence of the adenoma detection rate (ADR) as a quality indicator for colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening programs.1 A target ADR of 25% has been established by several national gastroenterology societies and serves as a focus area for those seeking to develop quality improvement (QI) initiatives aimed at reducing the interval incidence of colorectal cancer.2 In this series, you are a community-based urban general gastroenterologist interested in improving your current group ADR of 19% to the established target of 25% for each individual endoscopist within the group over a 12-month period.

This article focuses on a clinician-friendly description of the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle, a key construct within the Model for Improvement framework for QI initiatives. It also describes the importance and key elements of QI data reporting, including the run chart. All core concepts will be framed within the series example of the development of an institutional QI initiative for ADR improvement.

Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle

Conventional scientific research in health care generally is based on large-scale projects, performed over long periods of time and producing aggregate data analyzed through summary statistics. QI-related research, as it relates to PDSA, in contrast, is characterized by smaller-scale projects performed over shorter periods of time, with iterative protocols to accommodate local context and therefore optimize intervention success. As such, the framework for their development, implementation, and continual modification requires a conceptual and methodologic shift.

The PDSA cycle is characterized by four key steps. The first step is to plan. This step involves addressing the following questions: 1) what are we trying to accomplish? (aim); 2) how will we know that a change is an improvement? (measure); and 3) what changes can we make that will lead to improvement? (change). Additional considerations include ensuring that the stated goal is attainable, relevant, and that the timeline is feasible. An important aspect of the plan stage is gaining an understanding for the current local context, key participants and their roles, and areas in which performance is excelling or is challenged. This understanding is critical to conceptually linking the identified problem with its proposed solution. Formulating an impact prediction allows subsequent learning and adaptation.

The second step is to do. This step involves execution of the identified plan over a specified period of time. It also involves rigorous qualitative and quantitative data collection, allowing the research team to assess change and document unexpected events. The identification of an implementation leader or champion to ensure protocol adherence, effective communication among team members, and coordinate accurate data collection can be critical for overall success.

The third step is to study. This step requires evaluating whether a change in the outcome measure has occurred, which intervention was successful, and whether an identified change is sustained over time. It also requires interpretation of change within the local context, specifically with respect to unintended consequences, unanticipated events, and the sustainability of any gains. To interpret study findings appropriately, feedback with involved process members, endoscopists, and/or other stakeholder groups may be necessary. This can be important for explaining the results of each cycle, identifying protocol modifications for future cycles, and optimizing the opportunity for success. Studying the data generated by a QI initiative requires clear and accurate data display and rules for interpretation.

The fourth step is to act. This final step allows team members to reflect on the results generated and decide whether the same intervention should be continued, modified, or changed, thereby incorporating lessons learned from previous PDSA cycles (Figure 1).3

Despite these challenges, the PDSA framework allows for small-scale and fast-paced initiative testing that reduces patient and institutional risk while minimizing the commitment of resources.4,7 Successful cycles improve stakeholder confidence in the probability for success with larger-scale implementation.

In our series example, step 1 of the PDSA cycle, plan, can be described as follows: Aim: increase the ADR of all group endoscopists to 25% over a 12-month period. Measure: Outcome: the proportion of endoscopists at your institution with an ADR greater than 25%; process – withdrawal time; balancing – staff satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and procedure time. Change: Successive cycles will institute the following: audible timers to ensure adequate withdrawal time, publication of an endoscopist-specific composite score, and training to improve inspection technique.8

In step 2 of the PDSA cycle, do, a physician member of the gastroenterology division incorporates QI into their job description and leads a change team charged with PDSA cycle 1. An administrative assistant calculates the endoscopist-specific ADRs for that month. Documentation of related events for this cycle such as unexpected physician absence, delays in polyp histology reporting, and so forth, is performed.

In step 3 of the PDSA cycle, study, the data generated will be represented on a run chart plotting the proportion of endoscopists with an ADR greater than 25% on the y-axis, and time (in monthly intervals) on the x-axis. This will be described in further detail in a later section.

In the final step of the PDSA cycle, act, continuation and modification of the tested changes can be represented as follows.

Displaying data

The documentation, analysis, and interpretation of data generated by multiple PDSA cycles must be displayed accurately and succinctly. The run chart has been developed as a simple technique for identifying nonrandom patterns (that is, signals), which allows QI researchers to determine the impact of each cycle of change and the stability of that change over a given time period.9 This often is contrasted with conventional statistical approaches that aggregate data and perform summary statistical comparisons at static time points. Instead, the run chart allows for an appreciation of the dynamic nature of PDSA-driven process manipulation and resulting outcome changes.

Correct interpretation of the presented data requires an understanding of common cause variation (CCV) and special cause variation (SCV). CCV occurs randomly and is present in all health care processes. It can never be eliminated completely. SCV, in contrast, is the result of external factors that are imposed on normal processes. For example, the introduction of audible timers within endoscopy rooms to ensure adequate withdrawal time may result in an increase in the ADR. The relatively stable ADR measured in both the pre-intervention and postintervention periods are subject to CCV. However, the postintervention increase in ADR is the result of SCV.10

As shown in Figure 2, the horizontal axis shows the time scale and spans the entire duration of the intervention period. The y-axis shows the outcome measure of interest. A horizontal line representing the median is shown.9 A goal line also may be depicted. Annotations to indicate the implementation of change or other important events (such as unintended consequences or unexpected events) also may be added to facilitate data interpretation.

Shift: at least six consecutive data points above or below the median line are needed (points on the median line are skipped).9 To assess a shift appropriately, at least 10 data points are required.

Trend: at least five consecutive data points all increasing in value or all decreasing in value are needed (numerically equivalent points are skipped).9

Runs: a run refers to a series of data points on one side of the median.9 If a random pattern of data points exists on the run chart, there should be an appropriate number of runs on either side of the median. Values outside of this indicate a higher probability of a nonrandom pattern.9,11

Astronomic point: this refers to a data point that subjectively is found to be obviously different from the rest and prompts consideration of the events that led to this.9

Although straightforward to construct and interpret for clinicians without statistical training, the run chart has specific limitations. It is ideal for the display of early data but cannot be used to determine its durability.9 In addition, a run chart does not reflect discrete data with no clear median.

The example run chart in Figure 2 shows that there is a shift in data points from below the median to above the median, ultimately achieving 100% group adherence to the ADR target of greater than 25%. There are only two runs for a total of 12 data points within the 12-month study period, indicating that there is a 5% or less probability that this is a random pattern.11 It appears that our interventions have resulted in incremental improvements in the ADR to exceed the target level in a nonrandom fashion. Although the cumulative effect of these interventions has been successful, it is difficult to predict the durability of this change moving forward. In addition, it would be difficult to select only a single intervention, of the many trialed, that would result in a sustained ADR of 25% or greater.

Summary and next steps

This article selectively reviews the process of change framed by the PDSA cycle. We also discuss the role of data display and interpretation using a run chart. The final article in this series will cover how to sustain change and support a culture of continuous improvement.

References

1. Corley, D.A., Jensen, C.D., Marks, A.R., et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-306.

2. Cohen, J., Schoenfeld, P., Park, W., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53.

3. Module 5: Improvement Cycle. (2013). Available at: http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/book/export/html/326. Accessed Feb. 1, 2016.

4. Taylor, M.J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):290-8.

5. Davidoff, F., Batalden, P., Stevens, D. et al. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:i3-9.

6. Ogrinc, G., Mooney, S., Estrada, C., et al. The SQUIRE (standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:i13-32.

7. Nelson, E.C., Batalden, B.P., Godfrey, M.M. Quality by design: a clinical microsystems approach. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco; 2007.

8. Coe, S.G.C.J., Diehl, N.N., Wallace, M.B. An endoscopic quality improvement program improves detection of colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):219-26.

9. Perla, R.J., Provost, L.P., Murray, S.K. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51.

10. Neuhauser, D., Provost, L., Bergman, B. The meaning of variation to healthcare managers, clinical and health-services researchers, and individual patients. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:i36-40.

11. Swed, F.S. Eisenhart, C. Tables for testing randomness of grouping in a sequence of alternatives. Ann Math Statist. 1943;14:66-87

Dr. Bollegala is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Women’s College Hospital; Dr. Mosko is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, and the Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation; Dr. Bernstein is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre; Dr. Brahmania is in the Toronto Center for Liver Diseases, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University Health Network; Dr. Liu is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University Health Network; Dr. Steinhart is at Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine and Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation; Dr. Silver is in the division of nephrology, St. Michael’s Hospital; Dr. Bell is in the division of internal medicine, department of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital; Dr. Nguyen is at Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine; Dr. Weizman is at the Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine, and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation. All are at the University of Toronto. Dr. Patel is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. The authors disclose no conflicts.

This month’s column is the second in a series of three articles written by a group from Toronto and Houston. The series imagined that a community of gastroenterologists set out to improve the adenoma detection rates of physicians in their practice. The first article described the design and launch of the project. This month, Dr. Bollegala and her colleagues explain the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle of improvement within a small practice. The PDSA cycle is a fundamental component of successful quality improvement initiatives; it allows a group to systematically analyze what works and what doesn’t. The focus of this article is squarely on small community practices (still the majority of gastrointestinal practices nationally), so its relevance is high. PDSA cycles are small, narrowly focused projects that can be accomplished by all as we strive to improve our care of the patients we serve. Next month, we will learn how to embed a quality initiative within our practices so sustained improvement can be seen.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Article 1 of our series focused on the emergence of the adenoma detection rate (ADR) as a quality indicator for colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening programs.1 A target ADR of 25% has been established by several national gastroenterology societies and serves as a focus area for those seeking to develop quality improvement (QI) initiatives aimed at reducing the interval incidence of colorectal cancer.2 In this series, you are a community-based urban general gastroenterologist interested in improving your current group ADR of 19% to the established target of 25% for each individual endoscopist within the group over a 12-month period.

This article focuses on a clinician-friendly description of the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle, a key construct within the Model for Improvement framework for QI initiatives. It also describes the importance and key elements of QI data reporting, including the run chart. All core concepts will be framed within the series example of the development of an institutional QI initiative for ADR improvement.

Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle

Conventional scientific research in health care generally is based on large-scale projects, performed over long periods of time and producing aggregate data analyzed through summary statistics. QI-related research, as it relates to PDSA, in contrast, is characterized by smaller-scale projects performed over shorter periods of time, with iterative protocols to accommodate local context and therefore optimize intervention success. As such, the framework for their development, implementation, and continual modification requires a conceptual and methodologic shift.

The PDSA cycle is characterized by four key steps. The first step is to plan. This step involves addressing the following questions: 1) what are we trying to accomplish? (aim); 2) how will we know that a change is an improvement? (measure); and 3) what changes can we make that will lead to improvement? (change). Additional considerations include ensuring that the stated goal is attainable, relevant, and that the timeline is feasible. An important aspect of the plan stage is gaining an understanding for the current local context, key participants and their roles, and areas in which performance is excelling or is challenged. This understanding is critical to conceptually linking the identified problem with its proposed solution. Formulating an impact prediction allows subsequent learning and adaptation.

The second step is to do. This step involves execution of the identified plan over a specified period of time. It also involves rigorous qualitative and quantitative data collection, allowing the research team to assess change and document unexpected events. The identification of an implementation leader or champion to ensure protocol adherence, effective communication among team members, and coordinate accurate data collection can be critical for overall success.

The third step is to study. This step requires evaluating whether a change in the outcome measure has occurred, which intervention was successful, and whether an identified change is sustained over time. It also requires interpretation of change within the local context, specifically with respect to unintended consequences, unanticipated events, and the sustainability of any gains. To interpret study findings appropriately, feedback with involved process members, endoscopists, and/or other stakeholder groups may be necessary. This can be important for explaining the results of each cycle, identifying protocol modifications for future cycles, and optimizing the opportunity for success. Studying the data generated by a QI initiative requires clear and accurate data display and rules for interpretation.

The fourth step is to act. This final step allows team members to reflect on the results generated and decide whether the same intervention should be continued, modified, or changed, thereby incorporating lessons learned from previous PDSA cycles (Figure 1).3

Despite these challenges, the PDSA framework allows for small-scale and fast-paced initiative testing that reduces patient and institutional risk while minimizing the commitment of resources.4,7 Successful cycles improve stakeholder confidence in the probability for success with larger-scale implementation.

In our series example, step 1 of the PDSA cycle, plan, can be described as follows: Aim: increase the ADR of all group endoscopists to 25% over a 12-month period. Measure: Outcome: the proportion of endoscopists at your institution with an ADR greater than 25%; process – withdrawal time; balancing – staff satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and procedure time. Change: Successive cycles will institute the following: audible timers to ensure adequate withdrawal time, publication of an endoscopist-specific composite score, and training to improve inspection technique.8

In step 2 of the PDSA cycle, do, a physician member of the gastroenterology division incorporates QI into their job description and leads a change team charged with PDSA cycle 1. An administrative assistant calculates the endoscopist-specific ADRs for that month. Documentation of related events for this cycle such as unexpected physician absence, delays in polyp histology reporting, and so forth, is performed.

In step 3 of the PDSA cycle, study, the data generated will be represented on a run chart plotting the proportion of endoscopists with an ADR greater than 25% on the y-axis, and time (in monthly intervals) on the x-axis. This will be described in further detail in a later section.

In the final step of the PDSA cycle, act, continuation and modification of the tested changes can be represented as follows.

Displaying data

The documentation, analysis, and interpretation of data generated by multiple PDSA cycles must be displayed accurately and succinctly. The run chart has been developed as a simple technique for identifying nonrandom patterns (that is, signals), which allows QI researchers to determine the impact of each cycle of change and the stability of that change over a given time period.9 This often is contrasted with conventional statistical approaches that aggregate data and perform summary statistical comparisons at static time points. Instead, the run chart allows for an appreciation of the dynamic nature of PDSA-driven process manipulation and resulting outcome changes.

Correct interpretation of the presented data requires an understanding of common cause variation (CCV) and special cause variation (SCV). CCV occurs randomly and is present in all health care processes. It can never be eliminated completely. SCV, in contrast, is the result of external factors that are imposed on normal processes. For example, the introduction of audible timers within endoscopy rooms to ensure adequate withdrawal time may result in an increase in the ADR. The relatively stable ADR measured in both the pre-intervention and postintervention periods are subject to CCV. However, the postintervention increase in ADR is the result of SCV.10

As shown in Figure 2, the horizontal axis shows the time scale and spans the entire duration of the intervention period. The y-axis shows the outcome measure of interest. A horizontal line representing the median is shown.9 A goal line also may be depicted. Annotations to indicate the implementation of change or other important events (such as unintended consequences or unexpected events) also may be added to facilitate data interpretation.

Shift: at least six consecutive data points above or below the median line are needed (points on the median line are skipped).9 To assess a shift appropriately, at least 10 data points are required.

Trend: at least five consecutive data points all increasing in value or all decreasing in value are needed (numerically equivalent points are skipped).9

Runs: a run refers to a series of data points on one side of the median.9 If a random pattern of data points exists on the run chart, there should be an appropriate number of runs on either side of the median. Values outside of this indicate a higher probability of a nonrandom pattern.9,11

Astronomic point: this refers to a data point that subjectively is found to be obviously different from the rest and prompts consideration of the events that led to this.9

Although straightforward to construct and interpret for clinicians without statistical training, the run chart has specific limitations. It is ideal for the display of early data but cannot be used to determine its durability.9 In addition, a run chart does not reflect discrete data with no clear median.

The example run chart in Figure 2 shows that there is a shift in data points from below the median to above the median, ultimately achieving 100% group adherence to the ADR target of greater than 25%. There are only two runs for a total of 12 data points within the 12-month study period, indicating that there is a 5% or less probability that this is a random pattern.11 It appears that our interventions have resulted in incremental improvements in the ADR to exceed the target level in a nonrandom fashion. Although the cumulative effect of these interventions has been successful, it is difficult to predict the durability of this change moving forward. In addition, it would be difficult to select only a single intervention, of the many trialed, that would result in a sustained ADR of 25% or greater.

Summary and next steps

This article selectively reviews the process of change framed by the PDSA cycle. We also discuss the role of data display and interpretation using a run chart. The final article in this series will cover how to sustain change and support a culture of continuous improvement.

References

1. Corley, D.A., Jensen, C.D., Marks, A.R., et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-306.

2. Cohen, J., Schoenfeld, P., Park, W., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53.

3. Module 5: Improvement Cycle. (2013). Available at: http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/book/export/html/326. Accessed Feb. 1, 2016.

4. Taylor, M.J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):290-8.

5. Davidoff, F., Batalden, P., Stevens, D. et al. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:i3-9.

6. Ogrinc, G., Mooney, S., Estrada, C., et al. The SQUIRE (standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:i13-32.

7. Nelson, E.C., Batalden, B.P., Godfrey, M.M. Quality by design: a clinical microsystems approach. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco; 2007.

8. Coe, S.G.C.J., Diehl, N.N., Wallace, M.B. An endoscopic quality improvement program improves detection of colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):219-26.

9. Perla, R.J., Provost, L.P., Murray, S.K. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51.

10. Neuhauser, D., Provost, L., Bergman, B. The meaning of variation to healthcare managers, clinical and health-services researchers, and individual patients. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:i36-40.

11. Swed, F.S. Eisenhart, C. Tables for testing randomness of grouping in a sequence of alternatives. Ann Math Statist. 1943;14:66-87

Dr. Bollegala is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Women’s College Hospital; Dr. Mosko is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, and the Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation; Dr. Bernstein is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre; Dr. Brahmania is in the Toronto Center for Liver Diseases, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University Health Network; Dr. Liu is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University Health Network; Dr. Steinhart is at Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine and Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation; Dr. Silver is in the division of nephrology, St. Michael’s Hospital; Dr. Bell is in the division of internal medicine, department of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital; Dr. Nguyen is at Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine; Dr. Weizman is at the Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine, and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation. All are at the University of Toronto. Dr. Patel is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. The authors disclose no conflicts.

This month’s column is the second in a series of three articles written by a group from Toronto and Houston. The series imagined that a community of gastroenterologists set out to improve the adenoma detection rates of physicians in their practice. The first article described the design and launch of the project. This month, Dr. Bollegala and her colleagues explain the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle of improvement within a small practice. The PDSA cycle is a fundamental component of successful quality improvement initiatives; it allows a group to systematically analyze what works and what doesn’t. The focus of this article is squarely on small community practices (still the majority of gastrointestinal practices nationally), so its relevance is high. PDSA cycles are small, narrowly focused projects that can be accomplished by all as we strive to improve our care of the patients we serve. Next month, we will learn how to embed a quality initiative within our practices so sustained improvement can be seen.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Article 1 of our series focused on the emergence of the adenoma detection rate (ADR) as a quality indicator for colonoscopy-based colorectal cancer screening programs.1 A target ADR of 25% has been established by several national gastroenterology societies and serves as a focus area for those seeking to develop quality improvement (QI) initiatives aimed at reducing the interval incidence of colorectal cancer.2 In this series, you are a community-based urban general gastroenterologist interested in improving your current group ADR of 19% to the established target of 25% for each individual endoscopist within the group over a 12-month period.

This article focuses on a clinician-friendly description of the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle, a key construct within the Model for Improvement framework for QI initiatives. It also describes the importance and key elements of QI data reporting, including the run chart. All core concepts will be framed within the series example of the development of an institutional QI initiative for ADR improvement.

Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle

Conventional scientific research in health care generally is based on large-scale projects, performed over long periods of time and producing aggregate data analyzed through summary statistics. QI-related research, as it relates to PDSA, in contrast, is characterized by smaller-scale projects performed over shorter periods of time, with iterative protocols to accommodate local context and therefore optimize intervention success. As such, the framework for their development, implementation, and continual modification requires a conceptual and methodologic shift.

The PDSA cycle is characterized by four key steps. The first step is to plan. This step involves addressing the following questions: 1) what are we trying to accomplish? (aim); 2) how will we know that a change is an improvement? (measure); and 3) what changes can we make that will lead to improvement? (change). Additional considerations include ensuring that the stated goal is attainable, relevant, and that the timeline is feasible. An important aspect of the plan stage is gaining an understanding for the current local context, key participants and their roles, and areas in which performance is excelling or is challenged. This understanding is critical to conceptually linking the identified problem with its proposed solution. Formulating an impact prediction allows subsequent learning and adaptation.

The second step is to do. This step involves execution of the identified plan over a specified period of time. It also involves rigorous qualitative and quantitative data collection, allowing the research team to assess change and document unexpected events. The identification of an implementation leader or champion to ensure protocol adherence, effective communication among team members, and coordinate accurate data collection can be critical for overall success.

The third step is to study. This step requires evaluating whether a change in the outcome measure has occurred, which intervention was successful, and whether an identified change is sustained over time. It also requires interpretation of change within the local context, specifically with respect to unintended consequences, unanticipated events, and the sustainability of any gains. To interpret study findings appropriately, feedback with involved process members, endoscopists, and/or other stakeholder groups may be necessary. This can be important for explaining the results of each cycle, identifying protocol modifications for future cycles, and optimizing the opportunity for success. Studying the data generated by a QI initiative requires clear and accurate data display and rules for interpretation.

The fourth step is to act. This final step allows team members to reflect on the results generated and decide whether the same intervention should be continued, modified, or changed, thereby incorporating lessons learned from previous PDSA cycles (Figure 1).3

Despite these challenges, the PDSA framework allows for small-scale and fast-paced initiative testing that reduces patient and institutional risk while minimizing the commitment of resources.4,7 Successful cycles improve stakeholder confidence in the probability for success with larger-scale implementation.

In our series example, step 1 of the PDSA cycle, plan, can be described as follows: Aim: increase the ADR of all group endoscopists to 25% over a 12-month period. Measure: Outcome: the proportion of endoscopists at your institution with an ADR greater than 25%; process – withdrawal time; balancing – staff satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and procedure time. Change: Successive cycles will institute the following: audible timers to ensure adequate withdrawal time, publication of an endoscopist-specific composite score, and training to improve inspection technique.8

In step 2 of the PDSA cycle, do, a physician member of the gastroenterology division incorporates QI into their job description and leads a change team charged with PDSA cycle 1. An administrative assistant calculates the endoscopist-specific ADRs for that month. Documentation of related events for this cycle such as unexpected physician absence, delays in polyp histology reporting, and so forth, is performed.

In step 3 of the PDSA cycle, study, the data generated will be represented on a run chart plotting the proportion of endoscopists with an ADR greater than 25% on the y-axis, and time (in monthly intervals) on the x-axis. This will be described in further detail in a later section.

In the final step of the PDSA cycle, act, continuation and modification of the tested changes can be represented as follows.

Displaying data

The documentation, analysis, and interpretation of data generated by multiple PDSA cycles must be displayed accurately and succinctly. The run chart has been developed as a simple technique for identifying nonrandom patterns (that is, signals), which allows QI researchers to determine the impact of each cycle of change and the stability of that change over a given time period.9 This often is contrasted with conventional statistical approaches that aggregate data and perform summary statistical comparisons at static time points. Instead, the run chart allows for an appreciation of the dynamic nature of PDSA-driven process manipulation and resulting outcome changes.

Correct interpretation of the presented data requires an understanding of common cause variation (CCV) and special cause variation (SCV). CCV occurs randomly and is present in all health care processes. It can never be eliminated completely. SCV, in contrast, is the result of external factors that are imposed on normal processes. For example, the introduction of audible timers within endoscopy rooms to ensure adequate withdrawal time may result in an increase in the ADR. The relatively stable ADR measured in both the pre-intervention and postintervention periods are subject to CCV. However, the postintervention increase in ADR is the result of SCV.10

As shown in Figure 2, the horizontal axis shows the time scale and spans the entire duration of the intervention period. The y-axis shows the outcome measure of interest. A horizontal line representing the median is shown.9 A goal line also may be depicted. Annotations to indicate the implementation of change or other important events (such as unintended consequences or unexpected events) also may be added to facilitate data interpretation.

Shift: at least six consecutive data points above or below the median line are needed (points on the median line are skipped).9 To assess a shift appropriately, at least 10 data points are required.

Trend: at least five consecutive data points all increasing in value or all decreasing in value are needed (numerically equivalent points are skipped).9

Runs: a run refers to a series of data points on one side of the median.9 If a random pattern of data points exists on the run chart, there should be an appropriate number of runs on either side of the median. Values outside of this indicate a higher probability of a nonrandom pattern.9,11

Astronomic point: this refers to a data point that subjectively is found to be obviously different from the rest and prompts consideration of the events that led to this.9

Although straightforward to construct and interpret for clinicians without statistical training, the run chart has specific limitations. It is ideal for the display of early data but cannot be used to determine its durability.9 In addition, a run chart does not reflect discrete data with no clear median.

The example run chart in Figure 2 shows that there is a shift in data points from below the median to above the median, ultimately achieving 100% group adherence to the ADR target of greater than 25%. There are only two runs for a total of 12 data points within the 12-month study period, indicating that there is a 5% or less probability that this is a random pattern.11 It appears that our interventions have resulted in incremental improvements in the ADR to exceed the target level in a nonrandom fashion. Although the cumulative effect of these interventions has been successful, it is difficult to predict the durability of this change moving forward. In addition, it would be difficult to select only a single intervention, of the many trialed, that would result in a sustained ADR of 25% or greater.

Summary and next steps

This article selectively reviews the process of change framed by the PDSA cycle. We also discuss the role of data display and interpretation using a run chart. The final article in this series will cover how to sustain change and support a culture of continuous improvement.

References

1. Corley, D.A., Jensen, C.D., Marks, A.R., et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1298-306.

2. Cohen, J., Schoenfeld, P., Park, W., et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:31-53.

3. Module 5: Improvement Cycle. (2013). Available at: http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/book/export/html/326. Accessed Feb. 1, 2016.

4. Taylor, M.J., McNicholas, C., Nicolay, C., et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(4):290-8.

5. Davidoff, F., Batalden, P., Stevens, D. et al. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:i3-9.

6. Ogrinc, G., Mooney, S., Estrada, C., et al. The SQUIRE (standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:i13-32.

7. Nelson, E.C., Batalden, B.P., Godfrey, M.M. Quality by design: a clinical microsystems approach. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco; 2007.

8. Coe, S.G.C.J., Diehl, N.N., Wallace, M.B. An endoscopic quality improvement program improves detection of colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(2):219-26.

9. Perla, R.J., Provost, L.P., Murray, S.K. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:46-51.

10. Neuhauser, D., Provost, L., Bergman, B. The meaning of variation to healthcare managers, clinical and health-services researchers, and individual patients. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:i36-40.

11. Swed, F.S. Eisenhart, C. Tables for testing randomness of grouping in a sequence of alternatives. Ann Math Statist. 1943;14:66-87

Dr. Bollegala is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Women’s College Hospital; Dr. Mosko is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, and the Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation; Dr. Bernstein is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre; Dr. Brahmania is in the Toronto Center for Liver Diseases, division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University Health Network; Dr. Liu is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, University Health Network; Dr. Steinhart is at Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine and Institute of Health Policy, Management, and Evaluation; Dr. Silver is in the division of nephrology, St. Michael’s Hospital; Dr. Bell is in the division of internal medicine, department of medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital; Dr. Nguyen is at Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine; Dr. Weizman is at the Mount Sinai Hospital Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, department of medicine, and Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation. All are at the University of Toronto. Dr. Patel is in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, department of medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Herbal medicine can reduce pain, fatigue in SCD patients

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.

The gastrointestinal symptoms were most likely dose-related from an excipient of SCD-101, Dr Gillette said.

He and his colleagues found no significant side effects after 28 days of dosing, and there were no dose reductions or interruptions due to drug-related AEs.

There were also no laboratory or electrocardiogram abnormalities.

“Almost all pain AEs stopped by day 13 in 22 of 23 patients,” Dr Gillette said.

“And unexpectedly, patients began to report that they slept better and had improved energy and cognition,” he noted.

Six patients in the 2200 and 4400 mg BID cohorts reported reduced fatigue as measured by the PROMIS fatigue questionnaire.

And 2 patients with ankle ulcers in the 2 highest dose cohorts reported improved healing.

Two weeks after treatment stopped, patients were almost back to baseline in terms of their chronic pain and fatigue levels, Dr Gillette said.

A parallel design, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of the 2750 mg TID dose is ongoing.

Future studies include a crossover-design, exploratory study of the 2750 mg TID dose and a phase 2 parallel design study of the 2200 mg BID and 2750 mg TID doses.

While the researchers are uncertain about the mechanism of action of SCD-101, they hypothesize that its effects could be due to increased vascular flow, increased oxygen delivery, or a reduction in inflammation.

“This is a promising drug potentially for low-income countries or middle-income countries elsewhere in the world where gene therapy and transplant are really not that feasible,” Dr Gillette said.

Research for this study was supported in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Convention Center, site of

the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting

SAN DIEGO—Results of a phase 1 study suggest that SCD-101, a botanical extract based on an herbal medicine used in Nigeria to treat sickle cell disease (SCD), can reduce pain and fatigue in people with SCD.

The anti-sickling drug also improves the shape of red blood cells but doesn’t produce a change in hemoglobin, according to researchers.

Peter Gillette, MD, of SUNY Downstate in Brooklyn, New York, reported these results at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 121*).

A 6-month phase 2b study conducted previously in Nigeria showed that the herbal medicine Niprisan reduced pain crises and school absenteeism and raised hemoglobin levels compared to placebo.

Based on this study and positive preclinical activity, Dr Gillette and his colleagues undertook a phase 1 study to determine the safety of escalating doses of SCD-101.

Dr Gillette pointed out that Niprisan had been produced commercially in Nigeria but was later removed by the government from the commercial market because of production problems.

The researchers evaluated 23 patients with homozygous SCD or S/beta0 thalassemia.

Patients were aged 18 to 55 years with hemoglobin F of 15% or less and hemoglobin levels between 6.0 and 9.5 g/dL.

Patients could not have had hydroxyurea treatment within 6 months of enrollment, red blood cell transfusion within 3 months, or hospitalization within 4 weeks.

Patients received SCD-101 orally for 28 days administered 2 times daily (BID) or 3 times daily (TID). Doses were 550 mg BID, 1100 mg BID, 2200 mg BID, 4400 mg BID, and 2750 mg TID.

Dr Gillette explained that by distributing the highest dose 3 times over the course of a day, the researchers were able to decrease the side effects of bloating and flatulence on the highest dose.

“Interestingly, with the dose-distributed TID, we found that the hemoglobin had increased by 10%,” he said. “In other words, it appears that the effects are very short-acting, and that by going from a Q12 to a Q8 dosage, the hemoglobin suddenly looks like it might be significant, although this is not a significant change.”

Laboratory outcomes included hemoglobin and hemolysis (LDH, bilirubin, and reticulocyte measurements). Patient-reported outcomes included pain and fatigue.

The most common adverse events (AEs) were pain, flatulence, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and headache.

Seven patients in the 2200 mg BID and 4400 mg BID cohorts had dose-related bloating, gas, flatulence or diarrhea, which subsided in a few days.

Patients in the 2750 mg TID cohort did not experience gas side effects.