User login

Microsensor perfectly distinguished coagulopathy patients from controls

SAN DIEGO – Using less than a drop of blood, a portable microsensor provided a comprehensive coagulation profile in less than 15 minutes and perfectly distinguished various coagulopathies from normal blood samples – handily beating the results with both activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT).

Dubbed ClotChip, the disposable device detects coagulation factors and platelet activity using dielectric spectroscopy, Evi X. Stavrou, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The development points the way for comprehensive, rapid, point-of-care assessment of critically ill or severely injured patients and those who need ongoing monitoring to evaluate response to anticoagulant therapy, she added.

Existing point-of-care coagulation assays have several shortcomings, Dr. Stavrou, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said during a press briefing at the conference. They are relatively insensitive, fail to measure platelet activity, or are only approved for specific subgroups of patients, such as those on warfarin, she specified.

To develop an alternative, Dr. Stavrou and her associates added a parallel-plate capacitive sensing structure to an inexpensive, disposable microfluidic biochip designed to test 9 microliters (less than one drop) of blood. They built the microsensor from biocompatible and chemically inert materials to minimize the chances of artificial contact activation.

To test the device, the researchers used calcium dichloride to induce coagulation in whole blood samples from 11 controls with normal aPTT and PT values. Time curves of output from the microsensor showed that coagulation consistently peaked within 4.5 to 6 minutes.

Next, the investigators tested blood from 12 patients with coagulopathies, including hemophilia A, hemophilia B, acquired von Willebrand factor defect, and congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia. These samples all yielded abnormal curves, with prolonged times to peak that ranged between 7 and 15 minutes – significantly exceeding those of healthy controls (P = .0002).

By plotting rates of true positives against rates of true negatives, the researchers obtained areas under the receiver operating curves of 100% for ClotChip, 78% for aPTT, and 57% for PT. In other words, ClotChip correctly identified all cases and controls in this small patient cohort, which neither aPTT or PT did.

Finally, the researchers used the microsensor to measure coagulation activity in normal blood samples that they treated with prostaglandin E2 to inhibit platelet aggregation. Normalized permittivity (an electrical measure) was significantly lower than in untreated control samples (P = .03), but time to peak values were the same in both groups. This finding confirms that the chip can identify abnormal platelet function, Dr. Stavrou said. “ClotChip is sensitive to the complete hemostasis process, exhibits better sensitivity and specificity than conventional coagulation assays, and discriminates between coagulation and platelet defects,” she concluded.

The investigators are recruiting volunteers for an expanded round of testing for the device, and are working to optimize construction to further enhance its sensitivity.

Dr. Stavrou and her coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Using less than a drop of blood, a portable microsensor provided a comprehensive coagulation profile in less than 15 minutes and perfectly distinguished various coagulopathies from normal blood samples – handily beating the results with both activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT).

Dubbed ClotChip, the disposable device detects coagulation factors and platelet activity using dielectric spectroscopy, Evi X. Stavrou, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The development points the way for comprehensive, rapid, point-of-care assessment of critically ill or severely injured patients and those who need ongoing monitoring to evaluate response to anticoagulant therapy, she added.

Existing point-of-care coagulation assays have several shortcomings, Dr. Stavrou, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said during a press briefing at the conference. They are relatively insensitive, fail to measure platelet activity, or are only approved for specific subgroups of patients, such as those on warfarin, she specified.

To develop an alternative, Dr. Stavrou and her associates added a parallel-plate capacitive sensing structure to an inexpensive, disposable microfluidic biochip designed to test 9 microliters (less than one drop) of blood. They built the microsensor from biocompatible and chemically inert materials to minimize the chances of artificial contact activation.

To test the device, the researchers used calcium dichloride to induce coagulation in whole blood samples from 11 controls with normal aPTT and PT values. Time curves of output from the microsensor showed that coagulation consistently peaked within 4.5 to 6 minutes.

Next, the investigators tested blood from 12 patients with coagulopathies, including hemophilia A, hemophilia B, acquired von Willebrand factor defect, and congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia. These samples all yielded abnormal curves, with prolonged times to peak that ranged between 7 and 15 minutes – significantly exceeding those of healthy controls (P = .0002).

By plotting rates of true positives against rates of true negatives, the researchers obtained areas under the receiver operating curves of 100% for ClotChip, 78% for aPTT, and 57% for PT. In other words, ClotChip correctly identified all cases and controls in this small patient cohort, which neither aPTT or PT did.

Finally, the researchers used the microsensor to measure coagulation activity in normal blood samples that they treated with prostaglandin E2 to inhibit platelet aggregation. Normalized permittivity (an electrical measure) was significantly lower than in untreated control samples (P = .03), but time to peak values were the same in both groups. This finding confirms that the chip can identify abnormal platelet function, Dr. Stavrou said. “ClotChip is sensitive to the complete hemostasis process, exhibits better sensitivity and specificity than conventional coagulation assays, and discriminates between coagulation and platelet defects,” she concluded.

The investigators are recruiting volunteers for an expanded round of testing for the device, and are working to optimize construction to further enhance its sensitivity.

Dr. Stavrou and her coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Using less than a drop of blood, a portable microsensor provided a comprehensive coagulation profile in less than 15 minutes and perfectly distinguished various coagulopathies from normal blood samples – handily beating the results with both activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and prothrombin time (PT).

Dubbed ClotChip, the disposable device detects coagulation factors and platelet activity using dielectric spectroscopy, Evi X. Stavrou, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. The development points the way for comprehensive, rapid, point-of-care assessment of critically ill or severely injured patients and those who need ongoing monitoring to evaluate response to anticoagulant therapy, she added.

Existing point-of-care coagulation assays have several shortcomings, Dr. Stavrou, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said during a press briefing at the conference. They are relatively insensitive, fail to measure platelet activity, or are only approved for specific subgroups of patients, such as those on warfarin, she specified.

To develop an alternative, Dr. Stavrou and her associates added a parallel-plate capacitive sensing structure to an inexpensive, disposable microfluidic biochip designed to test 9 microliters (less than one drop) of blood. They built the microsensor from biocompatible and chemically inert materials to minimize the chances of artificial contact activation.

To test the device, the researchers used calcium dichloride to induce coagulation in whole blood samples from 11 controls with normal aPTT and PT values. Time curves of output from the microsensor showed that coagulation consistently peaked within 4.5 to 6 minutes.

Next, the investigators tested blood from 12 patients with coagulopathies, including hemophilia A, hemophilia B, acquired von Willebrand factor defect, and congenital hypodysfibrinogenemia. These samples all yielded abnormal curves, with prolonged times to peak that ranged between 7 and 15 minutes – significantly exceeding those of healthy controls (P = .0002).

By plotting rates of true positives against rates of true negatives, the researchers obtained areas under the receiver operating curves of 100% for ClotChip, 78% for aPTT, and 57% for PT. In other words, ClotChip correctly identified all cases and controls in this small patient cohort, which neither aPTT or PT did.

Finally, the researchers used the microsensor to measure coagulation activity in normal blood samples that they treated with prostaglandin E2 to inhibit platelet aggregation. Normalized permittivity (an electrical measure) was significantly lower than in untreated control samples (P = .03), but time to peak values were the same in both groups. This finding confirms that the chip can identify abnormal platelet function, Dr. Stavrou said. “ClotChip is sensitive to the complete hemostasis process, exhibits better sensitivity and specificity than conventional coagulation assays, and discriminates between coagulation and platelet defects,” she concluded.

The investigators are recruiting volunteers for an expanded round of testing for the device, and are working to optimize construction to further enhance its sensitivity.

Dr. Stavrou and her coinvestigators had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ASH 2016

Key clinical point: A prototype point-of-care microsensor perfectly distinguished patients with various coagulopathies from healthy controls.

Major finding: The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 100%, compared with 78% for aPTT and 59% for PT.

Data source: Oral and poster sessions at ASH 2016.

Disclosures: None of the investigators had relevant financial disclosures.

RSV is top cause of severe respiratory disease in preterm infants

Respiratory syncytial virus is the number one virus causing severe lower respiratory disease in preterm infants, while those of younger age and those exposed to young children are at greatest risk, Eric A. F. Simões, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and his coauthors reported in the Nov. 29 edition of PLOS ONE.

“These data demonstrate that higher risk for 32 to 35 wGA [weeks gestational age] infants can be easily identified by age or birth month and significant exposure to other young children,” they wrote. “These infants would benefit from targeted efforts to prevent severe RSV disease.”

The overall rates of lower respiratory infections per 100 infant-seasons – a season being 5 months of observation from November 1 to March 31 in 2009-2010 or 2010-2011 – were 13.7 for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), 2.9 for adenovirus, 1.7 for parainfluenza virus type 2, 1.3 for human metapneumovirus, and 0.3 for parainfluenza virus type 2 (PLoS One. 2016 Nov 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166226).

Infants who had been exposed to young children, either through attending day care or living with non–multiple birth preschool-age siblings, had a twofold higher risk of RSV and human metapneumovirus, and a 3.3-fold greater risk of adenovirus.

The youngest infants showed the highest rate of hospitalizations with RSV: the incidence ranged from 8.2 per 100 infant season in those aged less than 1 month to 2.3 per 100 infant seasons in those aged 10 months of age. Similarly, the incidence of admission to ICU was significantly higher among younger infants.

Infants born in May, before the RSV season, had a much lower incidence of hospitalization, compared with those born in the height of RSV season in February. ICU admission rates also were higher among those born in February, compared with those born in May.

The highest overall rates of hospitalization with RSV – 19 per 100 infant-seasons – were among those born in February, and also those who were exposed to other young children.

“The current results are unique in that they provide continuous age-based risk models for outpatient and inpatient disease for infants with and without young child exposure,” wrote Dr. Simões and his coauthors.

They argued that their findings refute earlier suggestions that the rate of RSV infection in preterm infants is similar to the rate in term infants, and suggested that the limitations of their study may have even underestimated the incidence in preterm babies.

The study was supported by AstraZeneca, parent company of MedImmune. Two authors declared grant support and research funding from AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of MedImmune and now contractor to AstraZeneca. One author was a current employee of AstraZeneca and holds stock options. Two authors also declared funding and consultancies with AbbVie.

Respiratory syncytial virus is the number one virus causing severe lower respiratory disease in preterm infants, while those of younger age and those exposed to young children are at greatest risk, Eric A. F. Simões, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and his coauthors reported in the Nov. 29 edition of PLOS ONE.

“These data demonstrate that higher risk for 32 to 35 wGA [weeks gestational age] infants can be easily identified by age or birth month and significant exposure to other young children,” they wrote. “These infants would benefit from targeted efforts to prevent severe RSV disease.”

The overall rates of lower respiratory infections per 100 infant-seasons – a season being 5 months of observation from November 1 to March 31 in 2009-2010 or 2010-2011 – were 13.7 for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), 2.9 for adenovirus, 1.7 for parainfluenza virus type 2, 1.3 for human metapneumovirus, and 0.3 for parainfluenza virus type 2 (PLoS One. 2016 Nov 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166226).

Infants who had been exposed to young children, either through attending day care or living with non–multiple birth preschool-age siblings, had a twofold higher risk of RSV and human metapneumovirus, and a 3.3-fold greater risk of adenovirus.

The youngest infants showed the highest rate of hospitalizations with RSV: the incidence ranged from 8.2 per 100 infant season in those aged less than 1 month to 2.3 per 100 infant seasons in those aged 10 months of age. Similarly, the incidence of admission to ICU was significantly higher among younger infants.

Infants born in May, before the RSV season, had a much lower incidence of hospitalization, compared with those born in the height of RSV season in February. ICU admission rates also were higher among those born in February, compared with those born in May.

The highest overall rates of hospitalization with RSV – 19 per 100 infant-seasons – were among those born in February, and also those who were exposed to other young children.

“The current results are unique in that they provide continuous age-based risk models for outpatient and inpatient disease for infants with and without young child exposure,” wrote Dr. Simões and his coauthors.

They argued that their findings refute earlier suggestions that the rate of RSV infection in preterm infants is similar to the rate in term infants, and suggested that the limitations of their study may have even underestimated the incidence in preterm babies.

The study was supported by AstraZeneca, parent company of MedImmune. Two authors declared grant support and research funding from AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of MedImmune and now contractor to AstraZeneca. One author was a current employee of AstraZeneca and holds stock options. Two authors also declared funding and consultancies with AbbVie.

Respiratory syncytial virus is the number one virus causing severe lower respiratory disease in preterm infants, while those of younger age and those exposed to young children are at greatest risk, Eric A. F. Simões, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and his coauthors reported in the Nov. 29 edition of PLOS ONE.

“These data demonstrate that higher risk for 32 to 35 wGA [weeks gestational age] infants can be easily identified by age or birth month and significant exposure to other young children,” they wrote. “These infants would benefit from targeted efforts to prevent severe RSV disease.”

The overall rates of lower respiratory infections per 100 infant-seasons – a season being 5 months of observation from November 1 to March 31 in 2009-2010 or 2010-2011 – were 13.7 for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), 2.9 for adenovirus, 1.7 for parainfluenza virus type 2, 1.3 for human metapneumovirus, and 0.3 for parainfluenza virus type 2 (PLoS One. 2016 Nov 29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166226).

Infants who had been exposed to young children, either through attending day care or living with non–multiple birth preschool-age siblings, had a twofold higher risk of RSV and human metapneumovirus, and a 3.3-fold greater risk of adenovirus.

The youngest infants showed the highest rate of hospitalizations with RSV: the incidence ranged from 8.2 per 100 infant season in those aged less than 1 month to 2.3 per 100 infant seasons in those aged 10 months of age. Similarly, the incidence of admission to ICU was significantly higher among younger infants.

Infants born in May, before the RSV season, had a much lower incidence of hospitalization, compared with those born in the height of RSV season in February. ICU admission rates also were higher among those born in February, compared with those born in May.

The highest overall rates of hospitalization with RSV – 19 per 100 infant-seasons – were among those born in February, and also those who were exposed to other young children.

“The current results are unique in that they provide continuous age-based risk models for outpatient and inpatient disease for infants with and without young child exposure,” wrote Dr. Simões and his coauthors.

They argued that their findings refute earlier suggestions that the rate of RSV infection in preterm infants is similar to the rate in term infants, and suggested that the limitations of their study may have even underestimated the incidence in preterm babies.

The study was supported by AstraZeneca, parent company of MedImmune. Two authors declared grant support and research funding from AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of MedImmune and now contractor to AstraZeneca. One author was a current employee of AstraZeneca and holds stock options. Two authors also declared funding and consultancies with AbbVie.

FROM PLOS ONE

Key clinical point: Respiratory syncytial virus is the leading viral cause of severe lower respiratory disease in preterm infants, with those of younger age and those exposed to young children at greatest risk.

Major finding: The rates of lower respiratory infections per 100 infant-seasons were 13.7 for RSV, 2.9 for adenovirus, 1.7 for parainfluenza virus type 2, and 1.3 for human metapneumovirus.

Data source: The prospective RSV Respiratory Events Among Preterm Infants Outcomes and Risk Tracking (REPORT) study, in 1,642 preterm infants with medically attended acute respiratory illness.

Disclosures: The study was supported by AstraZeneca, parent company of MedImmune. Two authors declared grant support and research funding from AstraZeneca, one author was a former employee of AstraZeneca, and one author was a former employee of MedImmune and now contractor to AstraZeneca. One author was a current employee of AstraZeneca and holds stock options. Two authors also declared funding and consultancies with AbbVie.

Presume parents want HPV vaccines for tweens

Clinics in which providers presented human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as an assumed part of tween health care had a 5% increase in HPV vaccination coverage, compared with clinics that did not receive “announcement” training, based on data from a parallel-group, randomized trial of 30 pediatric and family medicine clinics in North Carolina.

Many providers hesitate to recommend HPV vaccination for 11- to 12-year-olds for a number of reasons, including lack of time and anticipation of a lengthy conversation about sex, wrote Noel T. Brewer, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and his colleagues.

At 6 months after the training period, 17,173 children aged 11-12 years and 37,796 children aged 13-17 years were seen at the clinics. Overall, clinics that underwent announcement training increased HPV vaccine initiation for 11- and 12-year-olds by 5.4% over the control clinics. Clinics that received conversation training showed no significant increase in vaccine initiation, compared with controls. Intervention groups did not differ from the controls in terms of other ages (adolescents aged 13-17 years) or other immunization coverage, including HPV series completion, Tdap, and meningococcal vaccines.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the collection of data from a single Southeastern state that may not be generalizable to other areas, the researchers noted. The results, however, “support training providers to use announcements as an approach to address low HPV vaccination uptake in primary care clinics,” especially at the recommended ages for routine vaccination, Dr. Brewer and his associates said.

Read the full study here (Pediatrics 2016;139:e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764).

Clinics in which providers presented human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as an assumed part of tween health care had a 5% increase in HPV vaccination coverage, compared with clinics that did not receive “announcement” training, based on data from a parallel-group, randomized trial of 30 pediatric and family medicine clinics in North Carolina.

Many providers hesitate to recommend HPV vaccination for 11- to 12-year-olds for a number of reasons, including lack of time and anticipation of a lengthy conversation about sex, wrote Noel T. Brewer, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and his colleagues.

At 6 months after the training period, 17,173 children aged 11-12 years and 37,796 children aged 13-17 years were seen at the clinics. Overall, clinics that underwent announcement training increased HPV vaccine initiation for 11- and 12-year-olds by 5.4% over the control clinics. Clinics that received conversation training showed no significant increase in vaccine initiation, compared with controls. Intervention groups did not differ from the controls in terms of other ages (adolescents aged 13-17 years) or other immunization coverage, including HPV series completion, Tdap, and meningococcal vaccines.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the collection of data from a single Southeastern state that may not be generalizable to other areas, the researchers noted. The results, however, “support training providers to use announcements as an approach to address low HPV vaccination uptake in primary care clinics,” especially at the recommended ages for routine vaccination, Dr. Brewer and his associates said.

Read the full study here (Pediatrics 2016;139:e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764).

Clinics in which providers presented human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination as an assumed part of tween health care had a 5% increase in HPV vaccination coverage, compared with clinics that did not receive “announcement” training, based on data from a parallel-group, randomized trial of 30 pediatric and family medicine clinics in North Carolina.

Many providers hesitate to recommend HPV vaccination for 11- to 12-year-olds for a number of reasons, including lack of time and anticipation of a lengthy conversation about sex, wrote Noel T. Brewer, PhD, of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and his colleagues.

At 6 months after the training period, 17,173 children aged 11-12 years and 37,796 children aged 13-17 years were seen at the clinics. Overall, clinics that underwent announcement training increased HPV vaccine initiation for 11- and 12-year-olds by 5.4% over the control clinics. Clinics that received conversation training showed no significant increase in vaccine initiation, compared with controls. Intervention groups did not differ from the controls in terms of other ages (adolescents aged 13-17 years) or other immunization coverage, including HPV series completion, Tdap, and meningococcal vaccines.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the collection of data from a single Southeastern state that may not be generalizable to other areas, the researchers noted. The results, however, “support training providers to use announcements as an approach to address low HPV vaccination uptake in primary care clinics,” especially at the recommended ages for routine vaccination, Dr. Brewer and his associates said.

Read the full study here (Pediatrics 2016;139:e20161764. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1764).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Beyond Salary—Are You Happy With Your Work?

Would you say you're satisfied with your job? If you had to do it all over again, what—if anything—would you change? We asked, you answered! Here are the results of our first annual Job Satisfaction Survey, including a comprehensive list of the nonmonetary benefits you deem most important.

Would you say you're satisfied with your job? If you had to do it all over again, what—if anything—would you change? We asked, you answered! Here are the results of our first annual Job Satisfaction Survey, including a comprehensive list of the nonmonetary benefits you deem most important.

Would you say you're satisfied with your job? If you had to do it all over again, what—if anything—would you change? We asked, you answered! Here are the results of our first annual Job Satisfaction Survey, including a comprehensive list of the nonmonetary benefits you deem most important.

Critical Care Commentary

According to IBM, over 2 quintillion bytes of data are generated every day (that’s a 2 with 18 zeros!), with over 90% of the data in the world today generated in the past 2 years alone.

In our private lives, much of this information is generated through online shopping, web surfing, and popular websites such as Facebook and Twitter. Companies are making incredible efforts to collect these data and to use it to improve how they relate to customers and, ultimately, to make more money. For example, companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Netflix collect enormous amounts of data and then use algorithms to provide real-time suggestions for what their customers might want to rent, buy, or click on. These algorithms, which companies use for anything from predicting customer behavior to facial recognition, were developed in the field of machine learning, a branch of computer science that focuses on how to learn from data.

Big data and critical care

Although the “big data” revolution has proliferated across the private sector, medicine has been slow to utilize the data we painstakingly collect in hospitals every day in order to improve patient care.

Clinicians typically rely on their intuition and the few clinical trials that their patients would have been included in to make decisions, and evidence-based clinical decision support tools are often not available or not used. The tools and scores we have at our disposal are often oversimplified so that they can be calculated by hand and usually rely on the clinician to manually gather information from the electronic health record (EHR) to calculate the score. However, this is starting to change. From partnerships between IBM Watson and hospitals, to groups developing and implementing clinical decision support tools in the EHR, it is clear that hospitals are becoming increasingly interested in learning from and using the enormous amount of data that are just sitting in the hospital records.

Although there are many areas in medicine that stand to benefit from harnessing the data available in the EHR to improve patient care, critical care should be one of the specialties that benefits the most. With the variety and frequency of monitoring that critically ill patients receive, there are large swaths of data available to collect, analyze, and harness to improve patient care. The current glut of information results in data overload and alarm fatigue for today’s clinicians, but intelligent use of these data holds promise for making care safer and more efficient and effective.

Groups have already begun using these data to develop tools to identify patients with ARDS (Herasevich V, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35[6]:1018-23), patients at risk of adverse drug reactions (Harinstein LM, et al. J Crit Care. 2012;27[3]:242-9), and those with sepsis (Tafelski S, et al. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1605-16).

Furthermore, groups have begun “crowdsourcing” critical care problems by making large datasets publicly available, such as the Multi-parameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC) database, which now holds clinical data from over 40,000 ICU stays from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Continued efforts to utilize data from patients in the ICU have the potential to revolutionize the care in hospitals today.

An important area of critical care that has seen a rapid rise in the use of EHR data to create decision support tools is in the early detection of critical illness. Given that many in-hospital cardiac arrests occur outside the ICU and delays in transferring critically ill patients to the ICU increase morbidity and mortality (Churpek MM, et al. J Hosp Med. 2016;11[11]:757-62), detecting critical illness early is incredibly important.

For millennia, clinicians have relied on their intuition and experience to determine which patients have a poor prognosis or need increased levels of care. In the 1990s, rapid response teams (RRTs) were developed, with the goal of identifying and treating critical illness earlier. Along with them came early warning scores, which are objective tools that typically use vital sign abnormalities to detect patients at high risk of clinical deterioration. RRTs and the early warning scores used to activate them have proliferated around the world, including in the United States, and scores like the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) are available for automatic calculation in the EHR.

However, taking a tool such as the MEWS that can easily be calculated by hand and making our expensive EHRs calculate it is a lot like buying a Ferrari just to drive it around the parking lot. There is no reason to limit our decision support tools to simple algorithms with only a few variables, especially when patients’ lives are at stake.

Several groups around the country have, therefore, begun to utilize other variables in the EHR, such as laboratory values, to create integrated decision support tools for the early identification of critical illness. For example, Kollef and colleagues developed a statistical model to identify critical illness and implemented it on the wards to activate their RRT, which resulted in decreased lengths of stay in the intervention group (Kollef MH, et al. J Hosp Med. 2014;9[7]:424-9).

Escobar et al. developed a model to predict ICU transfer or non-DNR deaths in the Kaiser system and found it to be more accurate than the MEWS in a validation cohort (Escobar GJ, et al. J Hosp Med. 2012;7[5]:388-95). A clinical trial of their system is ongoing.

Finally, our group developed a model called eCART in a multicenter study of over 250,000 patients and has since implemented it in our hospital. An early “black-box” study found that eCART detected more patients who went on to experience a cardiac arrest or ICU transfer than our usual care RRT and it did so 24 hours earlier (Kang MA, et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44[8]:1468-73). These scores and many more will likely become commonplace in hospitals to provide an objective and accurate way to identify critically ill patients earlier, which may result in decreased preventable morbidity and mortality.

Future directions

There are several important future directions at the intersection of big data and critical care.

First, efforts to collect, store, and share the highly granular data in the ICU are paramount for successful and generalizable research collaborations. Although there are often institutional barriers to data sharing to surmount, efforts such as the MIMIC database provide a roadmap for how ICU data can be shared and problems “crowdsourced” in order to allow researchers access to these data for high quality research.

Second, efforts to fuse randomized controlled trials with big data, such as randomized, embedded, multifactorial, adaptive platform (REMAP) trials, have the potential to greatly enhance the way trials are done in the future. REMAP trials would be embedded in the EHR, provide the ability to study multiple therapies at once, and adapt the randomization scheme to ensure that patients are not harmed by interventions that are clearly detrimental while the study is ongoing (Angus DC. JAMA. 2015;314[8]:767-8).

Finally, it is important that we move beyond the classic statistical methods that are commonly used to develop decision support tools and increase our use of more modern machine learning techniques that companies in the private sector use every day. For example, our group found that classic regression methods were the least accurate of all the methods we studied for detecting clinical deterioration on the wards (Churpek MM, et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44[2]:368-74). In the future, methods such as the random forest and neural network should become commonplace in the critical care literature.

The big data revolution is here, both in our private lives and in the hospital. The future will bring continued efforts to use data to identify critical illness earlier, improve the care of patients in the ICU, and implement smarter and more efficient clinical trials. This should rapidly increase the generation and utilization of new knowledge and will have a profound impact on the way we care for critically ill patients.

Dr. Churpek is assistant professor, section of pulmonary and critical care medicine, department of medicine at University of Chicago.

Editor’s comment

Why should busy ICU clinicians bother with big data? Isn’t this simply a “flash in the pan” phenomenon that has sprung up in the aftermath of the electronic medical records (EMRs) mandated by the Affordable Care Act? Are concerns valid that clinical data–based algorithms will lead to an endless stream of alerts akin to the ubiquitous pop-up ads for mortgage refinancing, herbal Viagra, and online gambling that has resulted from commercial data mining?

In this Critical Care Commentary, Dr. Matthew Churpek convincingly outlines the potential inherent in the big data generated by our collective ICUs. These benefits are manifesting themselves not just in the data populated within the EMR – but also in the novel ways we can now design and execute studies. And for those who aren’t yet convinced, recall that payers already use the treasure trove of information within our EMRs against us in the forms of self-serving quality metrics, punitive reimbursement, and unvalidated hospital comparison sites.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP, is the editor of the Critical Care Commentary section of CHEST Physician.

According to IBM, over 2 quintillion bytes of data are generated every day (that’s a 2 with 18 zeros!), with over 90% of the data in the world today generated in the past 2 years alone.

In our private lives, much of this information is generated through online shopping, web surfing, and popular websites such as Facebook and Twitter. Companies are making incredible efforts to collect these data and to use it to improve how they relate to customers and, ultimately, to make more money. For example, companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Netflix collect enormous amounts of data and then use algorithms to provide real-time suggestions for what their customers might want to rent, buy, or click on. These algorithms, which companies use for anything from predicting customer behavior to facial recognition, were developed in the field of machine learning, a branch of computer science that focuses on how to learn from data.

Big data and critical care

Although the “big data” revolution has proliferated across the private sector, medicine has been slow to utilize the data we painstakingly collect in hospitals every day in order to improve patient care.

Clinicians typically rely on their intuition and the few clinical trials that their patients would have been included in to make decisions, and evidence-based clinical decision support tools are often not available or not used. The tools and scores we have at our disposal are often oversimplified so that they can be calculated by hand and usually rely on the clinician to manually gather information from the electronic health record (EHR) to calculate the score. However, this is starting to change. From partnerships between IBM Watson and hospitals, to groups developing and implementing clinical decision support tools in the EHR, it is clear that hospitals are becoming increasingly interested in learning from and using the enormous amount of data that are just sitting in the hospital records.

Although there are many areas in medicine that stand to benefit from harnessing the data available in the EHR to improve patient care, critical care should be one of the specialties that benefits the most. With the variety and frequency of monitoring that critically ill patients receive, there are large swaths of data available to collect, analyze, and harness to improve patient care. The current glut of information results in data overload and alarm fatigue for today’s clinicians, but intelligent use of these data holds promise for making care safer and more efficient and effective.

Groups have already begun using these data to develop tools to identify patients with ARDS (Herasevich V, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35[6]:1018-23), patients at risk of adverse drug reactions (Harinstein LM, et al. J Crit Care. 2012;27[3]:242-9), and those with sepsis (Tafelski S, et al. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1605-16).

Furthermore, groups have begun “crowdsourcing” critical care problems by making large datasets publicly available, such as the Multi-parameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC) database, which now holds clinical data from over 40,000 ICU stays from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Continued efforts to utilize data from patients in the ICU have the potential to revolutionize the care in hospitals today.

An important area of critical care that has seen a rapid rise in the use of EHR data to create decision support tools is in the early detection of critical illness. Given that many in-hospital cardiac arrests occur outside the ICU and delays in transferring critically ill patients to the ICU increase morbidity and mortality (Churpek MM, et al. J Hosp Med. 2016;11[11]:757-62), detecting critical illness early is incredibly important.

For millennia, clinicians have relied on their intuition and experience to determine which patients have a poor prognosis or need increased levels of care. In the 1990s, rapid response teams (RRTs) were developed, with the goal of identifying and treating critical illness earlier. Along with them came early warning scores, which are objective tools that typically use vital sign abnormalities to detect patients at high risk of clinical deterioration. RRTs and the early warning scores used to activate them have proliferated around the world, including in the United States, and scores like the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) are available for automatic calculation in the EHR.

However, taking a tool such as the MEWS that can easily be calculated by hand and making our expensive EHRs calculate it is a lot like buying a Ferrari just to drive it around the parking lot. There is no reason to limit our decision support tools to simple algorithms with only a few variables, especially when patients’ lives are at stake.

Several groups around the country have, therefore, begun to utilize other variables in the EHR, such as laboratory values, to create integrated decision support tools for the early identification of critical illness. For example, Kollef and colleagues developed a statistical model to identify critical illness and implemented it on the wards to activate their RRT, which resulted in decreased lengths of stay in the intervention group (Kollef MH, et al. J Hosp Med. 2014;9[7]:424-9).

Escobar et al. developed a model to predict ICU transfer or non-DNR deaths in the Kaiser system and found it to be more accurate than the MEWS in a validation cohort (Escobar GJ, et al. J Hosp Med. 2012;7[5]:388-95). A clinical trial of their system is ongoing.

Finally, our group developed a model called eCART in a multicenter study of over 250,000 patients and has since implemented it in our hospital. An early “black-box” study found that eCART detected more patients who went on to experience a cardiac arrest or ICU transfer than our usual care RRT and it did so 24 hours earlier (Kang MA, et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44[8]:1468-73). These scores and many more will likely become commonplace in hospitals to provide an objective and accurate way to identify critically ill patients earlier, which may result in decreased preventable morbidity and mortality.

Future directions

There are several important future directions at the intersection of big data and critical care.

First, efforts to collect, store, and share the highly granular data in the ICU are paramount for successful and generalizable research collaborations. Although there are often institutional barriers to data sharing to surmount, efforts such as the MIMIC database provide a roadmap for how ICU data can be shared and problems “crowdsourced” in order to allow researchers access to these data for high quality research.

Second, efforts to fuse randomized controlled trials with big data, such as randomized, embedded, multifactorial, adaptive platform (REMAP) trials, have the potential to greatly enhance the way trials are done in the future. REMAP trials would be embedded in the EHR, provide the ability to study multiple therapies at once, and adapt the randomization scheme to ensure that patients are not harmed by interventions that are clearly detrimental while the study is ongoing (Angus DC. JAMA. 2015;314[8]:767-8).

Finally, it is important that we move beyond the classic statistical methods that are commonly used to develop decision support tools and increase our use of more modern machine learning techniques that companies in the private sector use every day. For example, our group found that classic regression methods were the least accurate of all the methods we studied for detecting clinical deterioration on the wards (Churpek MM, et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44[2]:368-74). In the future, methods such as the random forest and neural network should become commonplace in the critical care literature.

The big data revolution is here, both in our private lives and in the hospital. The future will bring continued efforts to use data to identify critical illness earlier, improve the care of patients in the ICU, and implement smarter and more efficient clinical trials. This should rapidly increase the generation and utilization of new knowledge and will have a profound impact on the way we care for critically ill patients.

Dr. Churpek is assistant professor, section of pulmonary and critical care medicine, department of medicine at University of Chicago.

Editor’s comment

Why should busy ICU clinicians bother with big data? Isn’t this simply a “flash in the pan” phenomenon that has sprung up in the aftermath of the electronic medical records (EMRs) mandated by the Affordable Care Act? Are concerns valid that clinical data–based algorithms will lead to an endless stream of alerts akin to the ubiquitous pop-up ads for mortgage refinancing, herbal Viagra, and online gambling that has resulted from commercial data mining?

In this Critical Care Commentary, Dr. Matthew Churpek convincingly outlines the potential inherent in the big data generated by our collective ICUs. These benefits are manifesting themselves not just in the data populated within the EMR – but also in the novel ways we can now design and execute studies. And for those who aren’t yet convinced, recall that payers already use the treasure trove of information within our EMRs against us in the forms of self-serving quality metrics, punitive reimbursement, and unvalidated hospital comparison sites.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP, is the editor of the Critical Care Commentary section of CHEST Physician.

According to IBM, over 2 quintillion bytes of data are generated every day (that’s a 2 with 18 zeros!), with over 90% of the data in the world today generated in the past 2 years alone.

In our private lives, much of this information is generated through online shopping, web surfing, and popular websites such as Facebook and Twitter. Companies are making incredible efforts to collect these data and to use it to improve how they relate to customers and, ultimately, to make more money. For example, companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Netflix collect enormous amounts of data and then use algorithms to provide real-time suggestions for what their customers might want to rent, buy, or click on. These algorithms, which companies use for anything from predicting customer behavior to facial recognition, were developed in the field of machine learning, a branch of computer science that focuses on how to learn from data.

Big data and critical care

Although the “big data” revolution has proliferated across the private sector, medicine has been slow to utilize the data we painstakingly collect in hospitals every day in order to improve patient care.

Clinicians typically rely on their intuition and the few clinical trials that their patients would have been included in to make decisions, and evidence-based clinical decision support tools are often not available or not used. The tools and scores we have at our disposal are often oversimplified so that they can be calculated by hand and usually rely on the clinician to manually gather information from the electronic health record (EHR) to calculate the score. However, this is starting to change. From partnerships between IBM Watson and hospitals, to groups developing and implementing clinical decision support tools in the EHR, it is clear that hospitals are becoming increasingly interested in learning from and using the enormous amount of data that are just sitting in the hospital records.

Although there are many areas in medicine that stand to benefit from harnessing the data available in the EHR to improve patient care, critical care should be one of the specialties that benefits the most. With the variety and frequency of monitoring that critically ill patients receive, there are large swaths of data available to collect, analyze, and harness to improve patient care. The current glut of information results in data overload and alarm fatigue for today’s clinicians, but intelligent use of these data holds promise for making care safer and more efficient and effective.

Groups have already begun using these data to develop tools to identify patients with ARDS (Herasevich V, et al. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35[6]:1018-23), patients at risk of adverse drug reactions (Harinstein LM, et al. J Crit Care. 2012;27[3]:242-9), and those with sepsis (Tafelski S, et al. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1605-16).

Furthermore, groups have begun “crowdsourcing” critical care problems by making large datasets publicly available, such as the Multi-parameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC) database, which now holds clinical data from over 40,000 ICU stays from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Continued efforts to utilize data from patients in the ICU have the potential to revolutionize the care in hospitals today.

An important area of critical care that has seen a rapid rise in the use of EHR data to create decision support tools is in the early detection of critical illness. Given that many in-hospital cardiac arrests occur outside the ICU and delays in transferring critically ill patients to the ICU increase morbidity and mortality (Churpek MM, et al. J Hosp Med. 2016;11[11]:757-62), detecting critical illness early is incredibly important.

For millennia, clinicians have relied on their intuition and experience to determine which patients have a poor prognosis or need increased levels of care. In the 1990s, rapid response teams (RRTs) were developed, with the goal of identifying and treating critical illness earlier. Along with them came early warning scores, which are objective tools that typically use vital sign abnormalities to detect patients at high risk of clinical deterioration. RRTs and the early warning scores used to activate them have proliferated around the world, including in the United States, and scores like the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) are available for automatic calculation in the EHR.

However, taking a tool such as the MEWS that can easily be calculated by hand and making our expensive EHRs calculate it is a lot like buying a Ferrari just to drive it around the parking lot. There is no reason to limit our decision support tools to simple algorithms with only a few variables, especially when patients’ lives are at stake.

Several groups around the country have, therefore, begun to utilize other variables in the EHR, such as laboratory values, to create integrated decision support tools for the early identification of critical illness. For example, Kollef and colleagues developed a statistical model to identify critical illness and implemented it on the wards to activate their RRT, which resulted in decreased lengths of stay in the intervention group (Kollef MH, et al. J Hosp Med. 2014;9[7]:424-9).

Escobar et al. developed a model to predict ICU transfer or non-DNR deaths in the Kaiser system and found it to be more accurate than the MEWS in a validation cohort (Escobar GJ, et al. J Hosp Med. 2012;7[5]:388-95). A clinical trial of their system is ongoing.

Finally, our group developed a model called eCART in a multicenter study of over 250,000 patients and has since implemented it in our hospital. An early “black-box” study found that eCART detected more patients who went on to experience a cardiac arrest or ICU transfer than our usual care RRT and it did so 24 hours earlier (Kang MA, et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44[8]:1468-73). These scores and many more will likely become commonplace in hospitals to provide an objective and accurate way to identify critically ill patients earlier, which may result in decreased preventable morbidity and mortality.

Future directions

There are several important future directions at the intersection of big data and critical care.

First, efforts to collect, store, and share the highly granular data in the ICU are paramount for successful and generalizable research collaborations. Although there are often institutional barriers to data sharing to surmount, efforts such as the MIMIC database provide a roadmap for how ICU data can be shared and problems “crowdsourced” in order to allow researchers access to these data for high quality research.

Second, efforts to fuse randomized controlled trials with big data, such as randomized, embedded, multifactorial, adaptive platform (REMAP) trials, have the potential to greatly enhance the way trials are done in the future. REMAP trials would be embedded in the EHR, provide the ability to study multiple therapies at once, and adapt the randomization scheme to ensure that patients are not harmed by interventions that are clearly detrimental while the study is ongoing (Angus DC. JAMA. 2015;314[8]:767-8).

Finally, it is important that we move beyond the classic statistical methods that are commonly used to develop decision support tools and increase our use of more modern machine learning techniques that companies in the private sector use every day. For example, our group found that classic regression methods were the least accurate of all the methods we studied for detecting clinical deterioration on the wards (Churpek MM, et al. Crit Care Med. 2016;44[2]:368-74). In the future, methods such as the random forest and neural network should become commonplace in the critical care literature.

The big data revolution is here, both in our private lives and in the hospital. The future will bring continued efforts to use data to identify critical illness earlier, improve the care of patients in the ICU, and implement smarter and more efficient clinical trials. This should rapidly increase the generation and utilization of new knowledge and will have a profound impact on the way we care for critically ill patients.

Dr. Churpek is assistant professor, section of pulmonary and critical care medicine, department of medicine at University of Chicago.

Editor’s comment

Why should busy ICU clinicians bother with big data? Isn’t this simply a “flash in the pan” phenomenon that has sprung up in the aftermath of the electronic medical records (EMRs) mandated by the Affordable Care Act? Are concerns valid that clinical data–based algorithms will lead to an endless stream of alerts akin to the ubiquitous pop-up ads for mortgage refinancing, herbal Viagra, and online gambling that has resulted from commercial data mining?

In this Critical Care Commentary, Dr. Matthew Churpek convincingly outlines the potential inherent in the big data generated by our collective ICUs. These benefits are manifesting themselves not just in the data populated within the EMR – but also in the novel ways we can now design and execute studies. And for those who aren’t yet convinced, recall that payers already use the treasure trove of information within our EMRs against us in the forms of self-serving quality metrics, punitive reimbursement, and unvalidated hospital comparison sites.

Lee E. Morrow, MD, FCCP, is the editor of the Critical Care Commentary section of CHEST Physician.

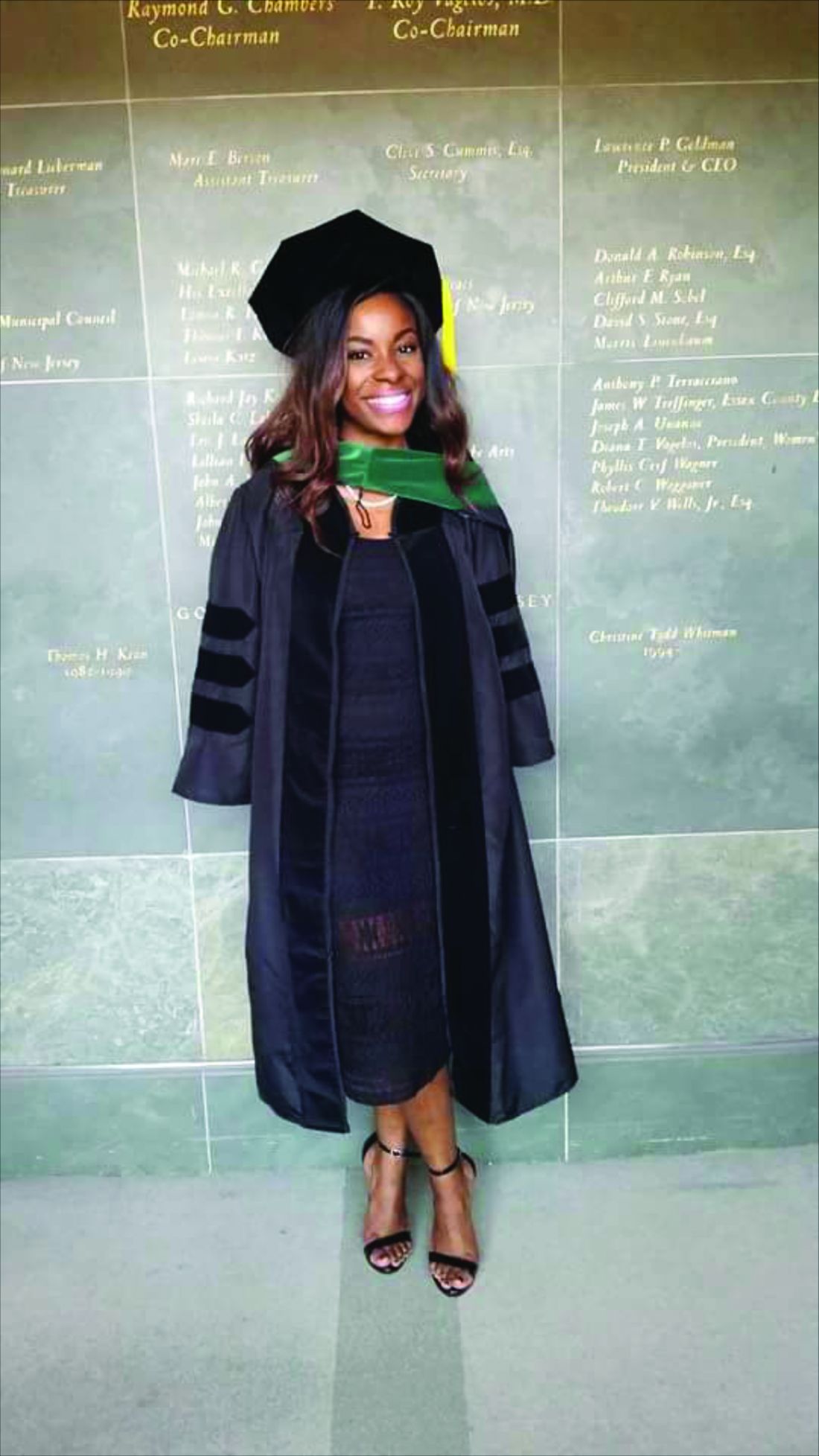

My journey into pulmonary-critical care medicine

Growing up was not easy. Camden, an inner city in southern New Jersey, is known for its abject poverty, constant violence, and drug trafficking and has been notoriously labeled as one of the “most dangerous cities in the US.” It is a daunting place for many, but home for me. My story is one of a single mother high school dropout with eight children, who worked tirelessly to provide my siblings and me with more advantageous circumstances than she had.

They say “home is where the heart is.” I guess this old statement holds true in my case when I think of why I choose to return to Camden for my residency training at Cooper Hospital. Driving to work in Camden is always a memorable event for me. With every corner and bend in the city, I get a short trip down memory lane. I remember fondly walking to the corner store to buy candy with quarters that my sisters and I dredged up from our couch cushions.

Sundays were my favorite days growing up. We all woke up very early with the singular purpose of getting ready for church. As a child, I loved the attention we all gave each other, especially on Sundays. My siblings and I squabbled and played pranks on each other all morning to my mother’s displeasure, but, somehow, we always made it to church on time, dressed in our Sunday best. After church, our home was filled with hours of laughter, good food, and games only children knew how to play. Our house was always a second home to other kids from our block and friends of my mother who stopped by to try her famous chicken dishes. The days always had the feel of a fun holiday, like Halloween, or Christmas without the lights. It is important that people don’t see Camden as a stereotype, as it has more to offer than murder stories, stray cats, and drug dealing. I am a product of this city.

Embarking on pulmonary-critical care medicine is my next chapter. I see the scourge of pulmonary disease in my internal medicine clinic and am looking forward to arming myself with the knowledge to ease my patients’ burdens. Furthermore, I relish the opportunity to learn how to organize a chaos-filled room into an efficient, harmonized resuscitation situation. The process encourages teamwork, mindfulness, and empathy while being a scientist for the sickest patients in the hospital. These are all fundamental qualities I’ve strived to develop over my maturation as an internal medicine resident and traits I’ve also gained through my various life experiences. I am certain that no other field of medicine would better position me to serve in the broadest sense as a clinician, and I am sure that my life experiences will complement my scientific skill set.

It is said that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Who knew that someday, I would be able to help repay Camden for nurturing me as a child. I am ready for my new challenges and to embark on this new, pulmonary-critical care medicine chapter in my life.

Dr. Lee is an internal medicine resident at Cooper University Hospital at Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ.

Editor’s Note

Dr. Lee’s thoughtful piece about why she chose to go into pulmonary–critical care medicine is both inspiring and insightful. She deserves commendation for her willingness to share her story, and I am humbled by her words.

Nitin Puri, MD, FCCP, is the editor of the Pulmonary Perspectives section of CHEST Physician.

Growing up was not easy. Camden, an inner city in southern New Jersey, is known for its abject poverty, constant violence, and drug trafficking and has been notoriously labeled as one of the “most dangerous cities in the US.” It is a daunting place for many, but home for me. My story is one of a single mother high school dropout with eight children, who worked tirelessly to provide my siblings and me with more advantageous circumstances than she had.

They say “home is where the heart is.” I guess this old statement holds true in my case when I think of why I choose to return to Camden for my residency training at Cooper Hospital. Driving to work in Camden is always a memorable event for me. With every corner and bend in the city, I get a short trip down memory lane. I remember fondly walking to the corner store to buy candy with quarters that my sisters and I dredged up from our couch cushions.

Sundays were my favorite days growing up. We all woke up very early with the singular purpose of getting ready for church. As a child, I loved the attention we all gave each other, especially on Sundays. My siblings and I squabbled and played pranks on each other all morning to my mother’s displeasure, but, somehow, we always made it to church on time, dressed in our Sunday best. After church, our home was filled with hours of laughter, good food, and games only children knew how to play. Our house was always a second home to other kids from our block and friends of my mother who stopped by to try her famous chicken dishes. The days always had the feel of a fun holiday, like Halloween, or Christmas without the lights. It is important that people don’t see Camden as a stereotype, as it has more to offer than murder stories, stray cats, and drug dealing. I am a product of this city.

Embarking on pulmonary-critical care medicine is my next chapter. I see the scourge of pulmonary disease in my internal medicine clinic and am looking forward to arming myself with the knowledge to ease my patients’ burdens. Furthermore, I relish the opportunity to learn how to organize a chaos-filled room into an efficient, harmonized resuscitation situation. The process encourages teamwork, mindfulness, and empathy while being a scientist for the sickest patients in the hospital. These are all fundamental qualities I’ve strived to develop over my maturation as an internal medicine resident and traits I’ve also gained through my various life experiences. I am certain that no other field of medicine would better position me to serve in the broadest sense as a clinician, and I am sure that my life experiences will complement my scientific skill set.

It is said that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Who knew that someday, I would be able to help repay Camden for nurturing me as a child. I am ready for my new challenges and to embark on this new, pulmonary-critical care medicine chapter in my life.

Dr. Lee is an internal medicine resident at Cooper University Hospital at Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ.

Editor’s Note

Dr. Lee’s thoughtful piece about why she chose to go into pulmonary–critical care medicine is both inspiring and insightful. She deserves commendation for her willingness to share her story, and I am humbled by her words.

Nitin Puri, MD, FCCP, is the editor of the Pulmonary Perspectives section of CHEST Physician.

Growing up was not easy. Camden, an inner city in southern New Jersey, is known for its abject poverty, constant violence, and drug trafficking and has been notoriously labeled as one of the “most dangerous cities in the US.” It is a daunting place for many, but home for me. My story is one of a single mother high school dropout with eight children, who worked tirelessly to provide my siblings and me with more advantageous circumstances than she had.

They say “home is where the heart is.” I guess this old statement holds true in my case when I think of why I choose to return to Camden for my residency training at Cooper Hospital. Driving to work in Camden is always a memorable event for me. With every corner and bend in the city, I get a short trip down memory lane. I remember fondly walking to the corner store to buy candy with quarters that my sisters and I dredged up from our couch cushions.

Sundays were my favorite days growing up. We all woke up very early with the singular purpose of getting ready for church. As a child, I loved the attention we all gave each other, especially on Sundays. My siblings and I squabbled and played pranks on each other all morning to my mother’s displeasure, but, somehow, we always made it to church on time, dressed in our Sunday best. After church, our home was filled with hours of laughter, good food, and games only children knew how to play. Our house was always a second home to other kids from our block and friends of my mother who stopped by to try her famous chicken dishes. The days always had the feel of a fun holiday, like Halloween, or Christmas without the lights. It is important that people don’t see Camden as a stereotype, as it has more to offer than murder stories, stray cats, and drug dealing. I am a product of this city.

Embarking on pulmonary-critical care medicine is my next chapter. I see the scourge of pulmonary disease in my internal medicine clinic and am looking forward to arming myself with the knowledge to ease my patients’ burdens. Furthermore, I relish the opportunity to learn how to organize a chaos-filled room into an efficient, harmonized resuscitation situation. The process encourages teamwork, mindfulness, and empathy while being a scientist for the sickest patients in the hospital. These are all fundamental qualities I’ve strived to develop over my maturation as an internal medicine resident and traits I’ve also gained through my various life experiences. I am certain that no other field of medicine would better position me to serve in the broadest sense as a clinician, and I am sure that my life experiences will complement my scientific skill set.

It is said that a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step. Who knew that someday, I would be able to help repay Camden for nurturing me as a child. I am ready for my new challenges and to embark on this new, pulmonary-critical care medicine chapter in my life.

Dr. Lee is an internal medicine resident at Cooper University Hospital at Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ.

Editor’s Note

Dr. Lee’s thoughtful piece about why she chose to go into pulmonary–critical care medicine is both inspiring and insightful. She deserves commendation for her willingness to share her story, and I am humbled by her words.

Nitin Puri, MD, FCCP, is the editor of the Pulmonary Perspectives section of CHEST Physician.

This Month in CHEST: Editor’s Picks

Oral Macrolide Therapy Following Short-term Combination Antibiotic Treatment of Mycobacterium massiliense Lung Disease. By Dr. Won-Jung Koh, et al.

Impact of Acute Changes in CPAP Flow Route in Sleep Apnea Treatment. By Dr. R. G. Andrade, et al.

Endobronchial Ultrasound: Clinical Uses and Professional Reimbursements. By Dr. T. R. Gildea and Dr. K. Nicolacakis.

Chronic Cough Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. P. J. Kahrilas, et al., on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Oral Macrolide Therapy Following Short-term Combination Antibiotic Treatment of Mycobacterium massiliense Lung Disease. By Dr. Won-Jung Koh, et al.

Impact of Acute Changes in CPAP Flow Route in Sleep Apnea Treatment. By Dr. R. G. Andrade, et al.

Endobronchial Ultrasound: Clinical Uses and Professional Reimbursements. By Dr. T. R. Gildea and Dr. K. Nicolacakis.

Chronic Cough Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. P. J. Kahrilas, et al., on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

Oral Macrolide Therapy Following Short-term Combination Antibiotic Treatment of Mycobacterium massiliense Lung Disease. By Dr. Won-Jung Koh, et al.

Impact of Acute Changes in CPAP Flow Route in Sleep Apnea Treatment. By Dr. R. G. Andrade, et al.

Endobronchial Ultrasound: Clinical Uses and Professional Reimbursements. By Dr. T. R. Gildea and Dr. K. Nicolacakis.

Chronic Cough Due to Gastroesophageal Reflux in Adults: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. By Dr. P. J. Kahrilas, et al., on behalf of the CHEST Expert Cough Panel.

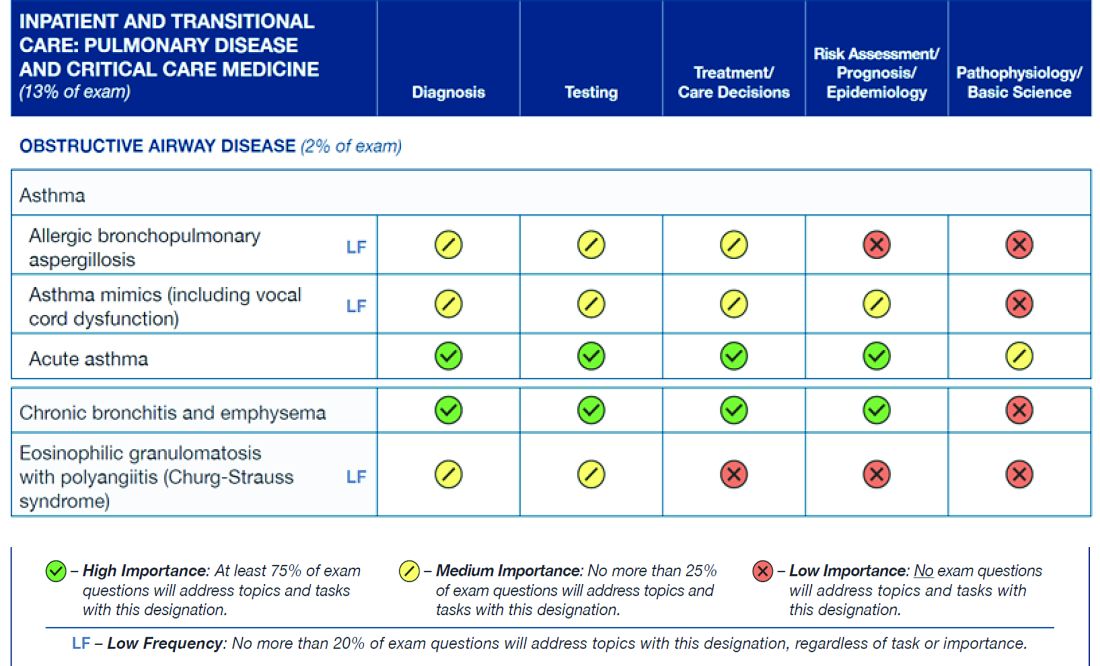

ABIM Pulmonary Medicine Board urges participation in survey

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has emailed diplomates a survey regarding the blueprint for the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) pulmonary exam.

This survey relates to the content of the exam, as opposed to a prior survey that asked diplomates for their opinion about new proposals for 2- and 5-year cycles for the exam.

Participating in the survey gives diplomates a voice in determining the content of the MOC exam for pulmonary medicine. If enough individuals participate in the survey and the data support changing the distribution of exam content, it is very likely that ABIM will make improvements to the MOC exam.

The figure below illustrates the information provided by diplomates that ABIM used to help them decide the exam content for the Hospital Medicine exam.

Diplomates can find the survey when they log into their respective homepages on the ABIM website at www.abim.org. The survey does not need to be completed in one sitting, but rather can be done one section at a time. It takes approximately 15 minutes to finish each section.

A link to the survey is located in the My Reminders tab.

This is a great opportunity for individuals to make their voices heard.

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has emailed diplomates a survey regarding the blueprint for the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) pulmonary exam.

This survey relates to the content of the exam, as opposed to a prior survey that asked diplomates for their opinion about new proposals for 2- and 5-year cycles for the exam.

Participating in the survey gives diplomates a voice in determining the content of the MOC exam for pulmonary medicine. If enough individuals participate in the survey and the data support changing the distribution of exam content, it is very likely that ABIM will make improvements to the MOC exam.

The figure below illustrates the information provided by diplomates that ABIM used to help them decide the exam content for the Hospital Medicine exam.

Diplomates can find the survey when they log into their respective homepages on the ABIM website at www.abim.org. The survey does not need to be completed in one sitting, but rather can be done one section at a time. It takes approximately 15 minutes to finish each section.

A link to the survey is located in the My Reminders tab.

This is a great opportunity for individuals to make their voices heard.

The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has emailed diplomates a survey regarding the blueprint for the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) pulmonary exam.

This survey relates to the content of the exam, as opposed to a prior survey that asked diplomates for their opinion about new proposals for 2- and 5-year cycles for the exam.

Participating in the survey gives diplomates a voice in determining the content of the MOC exam for pulmonary medicine. If enough individuals participate in the survey and the data support changing the distribution of exam content, it is very likely that ABIM will make improvements to the MOC exam.

The figure below illustrates the information provided by diplomates that ABIM used to help them decide the exam content for the Hospital Medicine exam.

Diplomates can find the survey when they log into their respective homepages on the ABIM website at www.abim.org. The survey does not need to be completed in one sitting, but rather can be done one section at a time. It takes approximately 15 minutes to finish each section.

A link to the survey is located in the My Reminders tab.

This is a great opportunity for individuals to make their voices heard.

Update on NAMDRC Activities

The NAMDRC annual meeting will be held March 23-25, 2017, at the Meritage Resort in Napa, California. A variety of excellent speakers and topics of interest to the pulmonary, sleep, and critical care medicine community will be presented, including presentations on the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, pulmonary hypertension in interstitial lung disease, use of big-data in critical care medicine, cardiovascular risk in obstructive sleep apnea, as well as talks on ICD-10 coding, and updates on practice management and on regulatory topics in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Finally, Dr. Mark Kelley, a visiting scholar at the Harvard Business School, will present a special lecture on “What do consumers really value in health care?” Meeting details and a registration form can be found at NAMDRC.org.

The costs of starting a pulmonary rehabilitation program are capital intensive and, generally, only hospitals can afford the start-up and ongoing costs, making pulmonary rehabilitation almost always a hospital service. Cost data from CMS demonstrate that the vast majority of billing for pulmonary rehab comes from hospitals and not from physician practices. By stopping the use of hospital-based clinic billing for new or expanded pulmonary rehabilitation services, this has the likely result of severely limiting the development of new pulmonary rehabilitation programs. If the new site of the rehabilitation program is more than 250 yards away, the hospital must bill under the physician fee schedule for reimbursement. No health care enterprise is likely to expand rehabilitation into new venues with such low reimbursement. The real shame in this scenario is that pulmonary rehabilitation is an effective and very low cost intervention for patients with COPD, and its future is largely being threatened by low reimbursement – making it unattractive for hospitals to open new programs in new space they may have purchased.

What is the fix? NAMDRC has discussed this problem with CMS, pointing out the large likely negative impact on pulmonary rehabilitation. We discussed a possible exemption for pulmonary rehabilitation. The final rule does afford an additional comment period, and we anticipate further discussions with CMS. It is also likely that the American Hospital Association, strongly opposed to this new rule, may seek a legislative fix.

A final area of activity is our ongoing discussion with CMS about updating the archaic guidelines created by CMS that govern how patients can be prescribed a bilevel positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy device for different forms of hypoventilation. The guidelines have been so complicated to follow that many clinicians, often at the request of a durable medical equipment company, have obtained home ventilators for patients for whom it was difficult to get a bilevel PAP. To be sure, hypoventilation disorders are complicated. The different patient types have somewhat different equipment pathways but all are overly complicated and are real barriers to getting these patients the necessary ventilatory equipment, which usually can be a bilevel PAP device. The home ventilator pathway has been easier to use to get therapy provided so many physicians have followed it, but it is also a lot more expensive. However, as of October 2015, CMS has effectively shut down the home ventilator pathway unless the patient has an indwelling invasive airway (i.e., a tracheotomy tube). NAMDRC, working with other sister societies, patient organizations, and others, has developed a strategy to oppose this draconian step. We hope to move CMS in a more rational direction regarding ventilator therapy for a variety of patients with hypoventilation. This work is complicated, but we are determined to do our utmost to bring a contemporary approach to this important area of therapy.

The NAMDRC annual meeting will be held March 23-25, 2017, at the Meritage Resort in Napa, California. A variety of excellent speakers and topics of interest to the pulmonary, sleep, and critical care medicine community will be presented, including presentations on the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome, pulmonary hypertension in interstitial lung disease, use of big-data in critical care medicine, cardiovascular risk in obstructive sleep apnea, as well as talks on ICD-10 coding, and updates on practice management and on regulatory topics in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. Finally, Dr. Mark Kelley, a visiting scholar at the Harvard Business School, will present a special lecture on “What do consumers really value in health care?” Meeting details and a registration form can be found at NAMDRC.org.

The costs of starting a pulmonary rehabilitation program are capital intensive and, generally, only hospitals can afford the start-up and ongoing costs, making pulmonary rehabilitation almost always a hospital service. Cost data from CMS demonstrate that the vast majority of billing for pulmonary rehab comes from hospitals and not from physician practices. By stopping the use of hospital-based clinic billing for new or expanded pulmonary rehabilitation services, this has the likely result of severely limiting the development of new pulmonary rehabilitation programs. If the new site of the rehabilitation program is more than 250 yards away, the hospital must bill under the physician fee schedule for reimbursement. No health care enterprise is likely to expand rehabilitation into new venues with such low reimbursement. The real shame in this scenario is that pulmonary rehabilitation is an effective and very low cost intervention for patients with COPD, and its future is largely being threatened by low reimbursement – making it unattractive for hospitals to open new programs in new space they may have purchased.

What is the fix? NAMDRC has discussed this problem with CMS, pointing out the large likely negative impact on pulmonary rehabilitation. We discussed a possible exemption for pulmonary rehabilitation. The final rule does afford an additional comment period, and we anticipate further discussions with CMS. It is also likely that the American Hospital Association, strongly opposed to this new rule, may seek a legislative fix.

A final area of activity is our ongoing discussion with CMS about updating the archaic guidelines created by CMS that govern how patients can be prescribed a bilevel positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy device for different forms of hypoventilation. The guidelines have been so complicated to follow that many clinicians, often at the request of a durable medical equipment company, have obtained home ventilators for patients for whom it was difficult to get a bilevel PAP. To be sure, hypoventilation disorders are complicated. The different patient types have somewhat different equipment pathways but all are overly complicated and are real barriers to getting these patients the necessary ventilatory equipment, which usually can be a bilevel PAP device. The home ventilator pathway has been easier to use to get therapy provided so many physicians have followed it, but it is also a lot more expensive. However, as of October 2015, CMS has effectively shut down the home ventilator pathway unless the patient has an indwelling invasive airway (i.e., a tracheotomy tube). NAMDRC, working with other sister societies, patient organizations, and others, has developed a strategy to oppose this draconian step. We hope to move CMS in a more rational direction regarding ventilator therapy for a variety of patients with hypoventilation. This work is complicated, but we are determined to do our utmost to bring a contemporary approach to this important area of therapy.