User login

The impact of loss of income and medicine costs on the financial burden for cancer patients in Australia

Background The cost of medicines may prove prohibitive for some cancer patients, potentially reducing the ability of a health system to fully deliver best practice care.

Objective To identify nonuse or nonpurchase of cancer-related medicines due to cost, and to describe the perceived financial burden of such medicines and associated patient characteristics.

Methods A cross-sectional pen-and-paper questionnaire was completed by oncology outpatients at 2 hospitals in Australia; 1 in regional New South Wales and 1 in metropolitan Victoria.

Results Almost 1 in 10 study participants had used over-the-counter medicines rather than prescribed medicines for cancer and obtained some but not all of the medicines prescribed in relation to their cancer. 63% of the sample reported some level of financial burden associated with obtaining these medicines, with 34% reporting a moderate or heavy financial burden. 11.8% reported using alternatives to prescribed medicines. People reporting reduced income after being diagnosed with cancer had almost 4 times the odds (OR, 3.73; 95% CI, 1.1-12.1) of reporting a heavy or extreme financial burden associated with prescribed medicines for cancer.

Limitations Study response rate, narrow survey population, self-reported survey used.

Conclusion This study identifies that a number of cancer patients, especially those with a reduced income after their diagnosis, experience financial burden associated with the purchase of medicines and that some go as far as to not use or to not purchase medicines. It seems likely that limiting the cost of medicines for cancer may improve patient ability to fully participate in the intended treatment.

Funding Cancer Council NSW, National Health and Medical Research Council, and Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background The cost of medicines may prove prohibitive for some cancer patients, potentially reducing the ability of a health system to fully deliver best practice care.

Objective To identify nonuse or nonpurchase of cancer-related medicines due to cost, and to describe the perceived financial burden of such medicines and associated patient characteristics.

Methods A cross-sectional pen-and-paper questionnaire was completed by oncology outpatients at 2 hospitals in Australia; 1 in regional New South Wales and 1 in metropolitan Victoria.

Results Almost 1 in 10 study participants had used over-the-counter medicines rather than prescribed medicines for cancer and obtained some but not all of the medicines prescribed in relation to their cancer. 63% of the sample reported some level of financial burden associated with obtaining these medicines, with 34% reporting a moderate or heavy financial burden. 11.8% reported using alternatives to prescribed medicines. People reporting reduced income after being diagnosed with cancer had almost 4 times the odds (OR, 3.73; 95% CI, 1.1-12.1) of reporting a heavy or extreme financial burden associated with prescribed medicines for cancer.

Limitations Study response rate, narrow survey population, self-reported survey used.

Conclusion This study identifies that a number of cancer patients, especially those with a reduced income after their diagnosis, experience financial burden associated with the purchase of medicines and that some go as far as to not use or to not purchase medicines. It seems likely that limiting the cost of medicines for cancer may improve patient ability to fully participate in the intended treatment.

Funding Cancer Council NSW, National Health and Medical Research Council, and Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background The cost of medicines may prove prohibitive for some cancer patients, potentially reducing the ability of a health system to fully deliver best practice care.

Objective To identify nonuse or nonpurchase of cancer-related medicines due to cost, and to describe the perceived financial burden of such medicines and associated patient characteristics.

Methods A cross-sectional pen-and-paper questionnaire was completed by oncology outpatients at 2 hospitals in Australia; 1 in regional New South Wales and 1 in metropolitan Victoria.

Results Almost 1 in 10 study participants had used over-the-counter medicines rather than prescribed medicines for cancer and obtained some but not all of the medicines prescribed in relation to their cancer. 63% of the sample reported some level of financial burden associated with obtaining these medicines, with 34% reporting a moderate or heavy financial burden. 11.8% reported using alternatives to prescribed medicines. People reporting reduced income after being diagnosed with cancer had almost 4 times the odds (OR, 3.73; 95% CI, 1.1-12.1) of reporting a heavy or extreme financial burden associated with prescribed medicines for cancer.

Limitations Study response rate, narrow survey population, self-reported survey used.

Conclusion This study identifies that a number of cancer patients, especially those with a reduced income after their diagnosis, experience financial burden associated with the purchase of medicines and that some go as far as to not use or to not purchase medicines. It seems likely that limiting the cost of medicines for cancer may improve patient ability to fully participate in the intended treatment.

Funding Cancer Council NSW, National Health and Medical Research Council, and Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Adolescent and young adult perceptions of cancer survivor care and supportive programming

Background Improvements in cancer therapy have led to an increasing number of adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of childhood cancers. Many survivors have ongoing needs for support and information that are not being met.

Objective To conduct a program evaluation to identify AYAs’ perceptions of survivor care services.

Methods Using a community-based approach, 157 AYA childhood cancer survivors (aged 15-30 years) completed a program evaluation survey to assess perceptions of the importance of survivor patient care services and supportive programming using a Likert scale (1, Not At All Important; 2, Of Little Importance; 3, Somewhat Important; 4, Important; 5, Very Important).

Results Receipt of a medical summary was ranked as the most important survivor patient care service (mean, 4.5; SD, 0.91). 70% of respondents reported interest in late-effects education. Informational mailings were the most valued form of supportive programming and were endorsed by 62% of AYAs. Older survivors were more likely to value workshops (P = .01-0.05), whereas those aged 19-22 years valued weekend retreats (P < .01) and social activities (P < .01). Survivors of brain/CNS tumors were more likely to value social activities (P = .03) and support groups (P = .03), compared with leukemia survivors.

Limitations Contact information from the hospital tumor registry was used, which limited the number of correct addresses.

Conclusion The greatest care needs reported by AYA survivors of childhood cancer are services such as generation of a medical summary, late-effects education, and survivor-focused follow-up care, which are provided through cancer survivor programs. Development of additional programming to engage and further educate and encourage AYA survivors will be important to reinforce their adherence with survivor care throughout adulthood.

Funding/Sponsorship LiveStrong Community Based Participatory Research Planning Grant

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Improvements in cancer therapy have led to an increasing number of adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of childhood cancers. Many survivors have ongoing needs for support and information that are not being met.

Objective To conduct a program evaluation to identify AYAs’ perceptions of survivor care services.

Methods Using a community-based approach, 157 AYA childhood cancer survivors (aged 15-30 years) completed a program evaluation survey to assess perceptions of the importance of survivor patient care services and supportive programming using a Likert scale (1, Not At All Important; 2, Of Little Importance; 3, Somewhat Important; 4, Important; 5, Very Important).

Results Receipt of a medical summary was ranked as the most important survivor patient care service (mean, 4.5; SD, 0.91). 70% of respondents reported interest in late-effects education. Informational mailings were the most valued form of supportive programming and were endorsed by 62% of AYAs. Older survivors were more likely to value workshops (P = .01-0.05), whereas those aged 19-22 years valued weekend retreats (P < .01) and social activities (P < .01). Survivors of brain/CNS tumors were more likely to value social activities (P = .03) and support groups (P = .03), compared with leukemia survivors.

Limitations Contact information from the hospital tumor registry was used, which limited the number of correct addresses.

Conclusion The greatest care needs reported by AYA survivors of childhood cancer are services such as generation of a medical summary, late-effects education, and survivor-focused follow-up care, which are provided through cancer survivor programs. Development of additional programming to engage and further educate and encourage AYA survivors will be important to reinforce their adherence with survivor care throughout adulthood.

Funding/Sponsorship LiveStrong Community Based Participatory Research Planning Grant

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Improvements in cancer therapy have led to an increasing number of adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of childhood cancers. Many survivors have ongoing needs for support and information that are not being met.

Objective To conduct a program evaluation to identify AYAs’ perceptions of survivor care services.

Methods Using a community-based approach, 157 AYA childhood cancer survivors (aged 15-30 years) completed a program evaluation survey to assess perceptions of the importance of survivor patient care services and supportive programming using a Likert scale (1, Not At All Important; 2, Of Little Importance; 3, Somewhat Important; 4, Important; 5, Very Important).

Results Receipt of a medical summary was ranked as the most important survivor patient care service (mean, 4.5; SD, 0.91). 70% of respondents reported interest in late-effects education. Informational mailings were the most valued form of supportive programming and were endorsed by 62% of AYAs. Older survivors were more likely to value workshops (P = .01-0.05), whereas those aged 19-22 years valued weekend retreats (P < .01) and social activities (P < .01). Survivors of brain/CNS tumors were more likely to value social activities (P = .03) and support groups (P = .03), compared with leukemia survivors.

Limitations Contact information from the hospital tumor registry was used, which limited the number of correct addresses.

Conclusion The greatest care needs reported by AYA survivors of childhood cancer are services such as generation of a medical summary, late-effects education, and survivor-focused follow-up care, which are provided through cancer survivor programs. Development of additional programming to engage and further educate and encourage AYA survivors will be important to reinforce their adherence with survivor care throughout adulthood.

Funding/Sponsorship LiveStrong Community Based Participatory Research Planning Grant

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Hereditary cancer testing in patients with ovarian cancer using a 25-gene panel

Symptoms, unmet need, and quality of life among recent breast cancer survivors

Background Assessing patient quality of life (QoL) apart from symptoms and unmet need may miss important concerns for which remediation is possible. Therapeutic advances have improved survival among breast cancer patients, and 89% can expect to survive for longer than 5 years. However, the price is lasting physical and psychosocial symptoms. Education regarding the value of symptom reduction may be needed for breast cancer survivors and their providers.

Objective To examine the unmet needs for symptom management and the relationships between unmet needs, symptom burden, and patient QoL.

Method Eligibility included nonmetastatic breast cancer survivors who had been treated less than a year before the study and attendance at a survivorship appointment. QoL was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 (scale, 0 [Did Not Experience] to 5 [As Bad As Possible]), and 19 symptoms were evaluated. Participants reported unmet need for assistance for each symptom experienced.

Results 164 primarily white, middle-aged, early-stage survivors of breast cancer were recruited. Physical and Mental QoL were similar to national norms. Survivors reported an average of 11.5 symptoms, most commonly Fatigue, Insomnia, Hot Flashes, Joint Pain, but reported unmet need for fewer symptoms (mean, 2.6). Weight Gain, Joint Pain, Numbness were most likely to result in unmet need. Both Physical and Mental QoL were negatively associated with number of symptoms (r = -.46 and -.41, respectively) and unmet needs (r = -.17 and -.41, respectively).

Limitations Cross-sectional sample of consecutive patients from a single clinical site.

Conclusion Symptoms are common among recent survivors of breast cancer, as are unmet needs, but to a lesser extent. Both have a negative impact on Physical and Mental health QoL.

Funding Translational Center of Excellence in Breast Cancer at the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Assessing patient quality of life (QoL) apart from symptoms and unmet need may miss important concerns for which remediation is possible. Therapeutic advances have improved survival among breast cancer patients, and 89% can expect to survive for longer than 5 years. However, the price is lasting physical and psychosocial symptoms. Education regarding the value of symptom reduction may be needed for breast cancer survivors and their providers.

Objective To examine the unmet needs for symptom management and the relationships between unmet needs, symptom burden, and patient QoL.

Method Eligibility included nonmetastatic breast cancer survivors who had been treated less than a year before the study and attendance at a survivorship appointment. QoL was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 (scale, 0 [Did Not Experience] to 5 [As Bad As Possible]), and 19 symptoms were evaluated. Participants reported unmet need for assistance for each symptom experienced.

Results 164 primarily white, middle-aged, early-stage survivors of breast cancer were recruited. Physical and Mental QoL were similar to national norms. Survivors reported an average of 11.5 symptoms, most commonly Fatigue, Insomnia, Hot Flashes, Joint Pain, but reported unmet need for fewer symptoms (mean, 2.6). Weight Gain, Joint Pain, Numbness were most likely to result in unmet need. Both Physical and Mental QoL were negatively associated with number of symptoms (r = -.46 and -.41, respectively) and unmet needs (r = -.17 and -.41, respectively).

Limitations Cross-sectional sample of consecutive patients from a single clinical site.

Conclusion Symptoms are common among recent survivors of breast cancer, as are unmet needs, but to a lesser extent. Both have a negative impact on Physical and Mental health QoL.

Funding Translational Center of Excellence in Breast Cancer at the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Assessing patient quality of life (QoL) apart from symptoms and unmet need may miss important concerns for which remediation is possible. Therapeutic advances have improved survival among breast cancer patients, and 89% can expect to survive for longer than 5 years. However, the price is lasting physical and psychosocial symptoms. Education regarding the value of symptom reduction may be needed for breast cancer survivors and their providers.

Objective To examine the unmet needs for symptom management and the relationships between unmet needs, symptom burden, and patient QoL.

Method Eligibility included nonmetastatic breast cancer survivors who had been treated less than a year before the study and attendance at a survivorship appointment. QoL was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 (scale, 0 [Did Not Experience] to 5 [As Bad As Possible]), and 19 symptoms were evaluated. Participants reported unmet need for assistance for each symptom experienced.

Results 164 primarily white, middle-aged, early-stage survivors of breast cancer were recruited. Physical and Mental QoL were similar to national norms. Survivors reported an average of 11.5 symptoms, most commonly Fatigue, Insomnia, Hot Flashes, Joint Pain, but reported unmet need for fewer symptoms (mean, 2.6). Weight Gain, Joint Pain, Numbness were most likely to result in unmet need. Both Physical and Mental QoL were negatively associated with number of symptoms (r = -.46 and -.41, respectively) and unmet needs (r = -.17 and -.41, respectively).

Limitations Cross-sectional sample of consecutive patients from a single clinical site.

Conclusion Symptoms are common among recent survivors of breast cancer, as are unmet needs, but to a lesser extent. Both have a negative impact on Physical and Mental health QoL.

Funding Translational Center of Excellence in Breast Cancer at the Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Canada reduces restrictions for blood donation

Photo by Marja Helander

Canadian Blood Services has made several changes to its blood donor policies in an attempt to broaden the pool of eligible donors in the country.

The agency has eliminated the upper age limit for donating blood, and donors over the age of 71 no longer need to have their physician fill out an assessment form before donating.

People with a history of most cancers are now eligible to donate blood if they have been cancer-free for 5 years.

However, this change does not apply to those with a history of hematologic malignancies.

People who have recently received most vaccines, such as a flu shot, will no longer need to wait 2 days before donating blood.

People who were born in or lived in some African countries (Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger, and Nigeria) are now eligible to donate blood. According to Canadian Blood Services, HIV testing performed on blood donors can now detect HIV strains found in these countries.

Canadian Blood Services has also revised geographic deferrals affecting Western Europe based on scientific evidence that indicates the risk of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease has decreased since January 2008.

People who spent 5 years or more in Western Europe since 1980 are deferred from donating blood, but Canadian Blood Services is now including an end date of 2007. People who reached the 5-year limit in Western Europe after 2007 are now eligible to donate.

“Canadian Blood Services regularly reviews the criteria used to determine if someone is eligible to donate blood, including geographic and age restrictions, based on new scientific information,” said Mindy Goldman, medical director of donor and clinical services with Canadian Blood Services.

“These restrictions are no longer necessary. We estimate that about 3000 people who try to donate each year but cannot will now be eligible to donate due to these changes.”

The complete policy changes are available at www.blood.ca/en/blood/recent-changes-donation-criteria. ![]()

Photo by Marja Helander

Canadian Blood Services has made several changes to its blood donor policies in an attempt to broaden the pool of eligible donors in the country.

The agency has eliminated the upper age limit for donating blood, and donors over the age of 71 no longer need to have their physician fill out an assessment form before donating.

People with a history of most cancers are now eligible to donate blood if they have been cancer-free for 5 years.

However, this change does not apply to those with a history of hematologic malignancies.

People who have recently received most vaccines, such as a flu shot, will no longer need to wait 2 days before donating blood.

People who were born in or lived in some African countries (Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger, and Nigeria) are now eligible to donate blood. According to Canadian Blood Services, HIV testing performed on blood donors can now detect HIV strains found in these countries.

Canadian Blood Services has also revised geographic deferrals affecting Western Europe based on scientific evidence that indicates the risk of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease has decreased since January 2008.

People who spent 5 years or more in Western Europe since 1980 are deferred from donating blood, but Canadian Blood Services is now including an end date of 2007. People who reached the 5-year limit in Western Europe after 2007 are now eligible to donate.

“Canadian Blood Services regularly reviews the criteria used to determine if someone is eligible to donate blood, including geographic and age restrictions, based on new scientific information,” said Mindy Goldman, medical director of donor and clinical services with Canadian Blood Services.

“These restrictions are no longer necessary. We estimate that about 3000 people who try to donate each year but cannot will now be eligible to donate due to these changes.”

The complete policy changes are available at www.blood.ca/en/blood/recent-changes-donation-criteria. ![]()

Photo by Marja Helander

Canadian Blood Services has made several changes to its blood donor policies in an attempt to broaden the pool of eligible donors in the country.

The agency has eliminated the upper age limit for donating blood, and donors over the age of 71 no longer need to have their physician fill out an assessment form before donating.

People with a history of most cancers are now eligible to donate blood if they have been cancer-free for 5 years.

However, this change does not apply to those with a history of hematologic malignancies.

People who have recently received most vaccines, such as a flu shot, will no longer need to wait 2 days before donating blood.

People who were born in or lived in some African countries (Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Niger, and Nigeria) are now eligible to donate blood. According to Canadian Blood Services, HIV testing performed on blood donors can now detect HIV strains found in these countries.

Canadian Blood Services has also revised geographic deferrals affecting Western Europe based on scientific evidence that indicates the risk of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease has decreased since January 2008.

People who spent 5 years or more in Western Europe since 1980 are deferred from donating blood, but Canadian Blood Services is now including an end date of 2007. People who reached the 5-year limit in Western Europe after 2007 are now eligible to donate.

“Canadian Blood Services regularly reviews the criteria used to determine if someone is eligible to donate blood, including geographic and age restrictions, based on new scientific information,” said Mindy Goldman, medical director of donor and clinical services with Canadian Blood Services.

“These restrictions are no longer necessary. We estimate that about 3000 people who try to donate each year but cannot will now be eligible to donate due to these changes.”

The complete policy changes are available at www.blood.ca/en/blood/recent-changes-donation-criteria. ![]()

Delirium in advanced cancer may go undetected

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study indicates that delirium is relatively frequent and underdiagnosed in patients with advanced cancer visiting the emergency department.

The research showed that delirium was similarly common among older and younger patients.

According to researchers, this suggests that, in the setting of advanced cancer, all patients should be considered at higher risk for delirium.

The researchers reported their findings in Cancer.

For this study, the team assessed a random sample of 243 advanced cancer patients who presented to the emergency department. They were 19 to 89 years old.

All patients were assessed with 2 methods: the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) to screen for delirium and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) to measure delirium severity (mild ≤15, moderate 16-22, and severe ≥23).

In all, 22 patients (9%) had CAM-positive delirium and a median MDAS score of 14. Among CAM-positive patients, delirium was mild in 18 (82%) and moderate in 4 (18%) according to the MDAS.

Of the 99 patients age 65 and older, 10 (10%) had CAM-positive delirium, compared with 12 (8%) of 144 patients younger than 65.

Emergency department physicians failed to detect delirium in 9 (41%) CAM-positive delirious patients.

“We found evidence of delirium in 1 of every 10 patients with advanced cancer who are treated in the emergency department,” said study author Knox Todd, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Given that we could only study patients who were able to give consent to enter our study, even 10% is likely to be a low estimate. We also identified many psychoactive medications that could have contributed to delirium, and sharing this information with treating oncologists may help them avoid such complications in the next patient they treat.” ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study indicates that delirium is relatively frequent and underdiagnosed in patients with advanced cancer visiting the emergency department.

The research showed that delirium was similarly common among older and younger patients.

According to researchers, this suggests that, in the setting of advanced cancer, all patients should be considered at higher risk for delirium.

The researchers reported their findings in Cancer.

For this study, the team assessed a random sample of 243 advanced cancer patients who presented to the emergency department. They were 19 to 89 years old.

All patients were assessed with 2 methods: the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) to screen for delirium and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) to measure delirium severity (mild ≤15, moderate 16-22, and severe ≥23).

In all, 22 patients (9%) had CAM-positive delirium and a median MDAS score of 14. Among CAM-positive patients, delirium was mild in 18 (82%) and moderate in 4 (18%) according to the MDAS.

Of the 99 patients age 65 and older, 10 (10%) had CAM-positive delirium, compared with 12 (8%) of 144 patients younger than 65.

Emergency department physicians failed to detect delirium in 9 (41%) CAM-positive delirious patients.

“We found evidence of delirium in 1 of every 10 patients with advanced cancer who are treated in the emergency department,” said study author Knox Todd, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Given that we could only study patients who were able to give consent to enter our study, even 10% is likely to be a low estimate. We also identified many psychoactive medications that could have contributed to delirium, and sharing this information with treating oncologists may help them avoid such complications in the next patient they treat.” ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study indicates that delirium is relatively frequent and underdiagnosed in patients with advanced cancer visiting the emergency department.

The research showed that delirium was similarly common among older and younger patients.

According to researchers, this suggests that, in the setting of advanced cancer, all patients should be considered at higher risk for delirium.

The researchers reported their findings in Cancer.

For this study, the team assessed a random sample of 243 advanced cancer patients who presented to the emergency department. They were 19 to 89 years old.

All patients were assessed with 2 methods: the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) to screen for delirium and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) to measure delirium severity (mild ≤15, moderate 16-22, and severe ≥23).

In all, 22 patients (9%) had CAM-positive delirium and a median MDAS score of 14. Among CAM-positive patients, delirium was mild in 18 (82%) and moderate in 4 (18%) according to the MDAS.

Of the 99 patients age 65 and older, 10 (10%) had CAM-positive delirium, compared with 12 (8%) of 144 patients younger than 65.

Emergency department physicians failed to detect delirium in 9 (41%) CAM-positive delirious patients.

“We found evidence of delirium in 1 of every 10 patients with advanced cancer who are treated in the emergency department,” said study author Knox Todd, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“Given that we could only study patients who were able to give consent to enter our study, even 10% is likely to be a low estimate. We also identified many psychoactive medications that could have contributed to delirium, and sharing this information with treating oncologists may help them avoid such complications in the next patient they treat.” ![]()

Severe pruritus • crusted lesions affecting face, extremities, and trunk • hepatitis C virus carrier • Dx?

THE CASE

An 85-year-old woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for a 9-month history of severe pruritus and crusted lesions on her face, extremities, and trunk. She had been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection one year ago and was not taking any medication. The patient, who had been living with her family, had visited various clinics for her complaints and was diagnosed as having contact dermatitis and senile pruritus. She was prescribed topical mometasone furoate and moisturizers.

After 6 months of using this therapy, widespread grey-white plaques and minimal excoriation appeared on her face, scalp, and trunk. This was diagnosed as psoriasis, and the patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids, which she used for 9 months until she came to our clinic. She said the lesions regressed minimally with the topical corticosteroids, but did not fully clear.

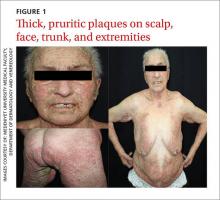

Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythema and grey-white, cohesive, thick, pruritic plaques on her scalp, face, trunk, and bilateral extremities (FIGURE 1). A punch biopsy specimen was taken from the border of a plaque on her trunk.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A complete blood cell count and wide biochemistry panel, including tumor markers and viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), were normal. The patient had lymphadenopathy in her posterior cervical, bilateral preauricular, and bilateral inguinal regions.

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiotic edema in the epidermis, and vesiculation and mites in the stratum corneum. The dermal changes consisted of perivascular and diffuse cell infiltrates that were mainly mononuclear cells and eosinophilic granulocytes.

Based on the dermatologic examination and the histopathologic findings, we diagnosed the patient with crusted (Norwegian) scabies.

DISCUSSION

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies is a rare, highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by the presence of millions of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mites in the epidermis.1 This variant of scabies can affect individuals of any age, gender, or race.2 It was first described by Boeck and Danielssen in 1848 in Norway and was named Norwegian scabies by von Hebra in 1862.3 In 2010, more than 200 cases of crusted scabies were reported in the literature.4

Crusted scabies is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, such as the elderly, those who’ve had solid organ transplantation, and those with HIV, malignancy, or malnutrition. Crusted scabies may also occur in patients with decreased sensory function (such as those with leprosy) or decreased ability to scratch, intellectual disabilities, and in those who use biologic agents or systemic/topical corticosteroids.4-8

Crusted scabies is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in children and the elderly, because of complications such as secondary bacterial infections and sepsis.1,3 Widespread inflammation may also cause erythroderma, which can lead to metabolic disorders.

Distinguish it from other pruritic papulosquamous diseases

The differential diagnosis for crusted scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, cutaneous lymphoma, Darier disease, and adverse drug reactions.9 Crusted scabies can be differentiated from these other diagnoses by its clinical presentation and histopathological examination.

Crusted scabies is characterized by hyperkeratosis and wart-like crusts that are due to extreme proliferation of mites in the stratum corneum of the epidermis.2 Lesions are usually localized on acral sites (especially the hands), although the entire body, including the face and the scalp, can be involved.1 Psoriasiform or bullous pemphigoid-like eruptions have also been reported in the literature.5,9

Our patient presented with widespread erythema and psoriasiform grey-white crusts on her scalp, face, chest, periareolar region, and extremities. In addition, she did not have an immunosuppressant disease or medication history.

However, the fact that our patient was using topical corticosteroids for so long explained the extent of her condition. Topical corticosteroids have been linked to scabies incognito.10 Topical or systemic corticosteroid use for long periods of time may alter the skin immune system by suppressing cellular immunity, thereby reducing the inflammatory response. This may lead to progression of the regular variant of scabies to crusted scabies, as our patient had.

Topical treatments, oral ivermectin proven to be effective

Topical keratolytics, permethrin 5%, lindane 1%, crotamiton 10%, sulfur ointment (5%-10%), malathion 0.5%, benzyl benzoate (10%-25%), oral ivermectin (2 doses of 200 mcg/kg/dose), and systemic antihistamines are appropriate therapies.3 While oral ivermectin is effective, it is not available in Turkey.

Because of our patient’s hepatic disorder, we opted for a topical, rather than a systemic, treatment and recommended repeated applications of topical permethrin. Repeated treatment with topical permethrin is often sufficient in patients who are unable to take systemic therapy. In fact, Binic et al4 reported a case in which an elderly patient with crusted scabies (who had previously been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids) responded well to repeated topical treatment with lindane 1%, 25% benzyl benzoate, and 10% precipitated sulfur.

Our patient. We prescribed topical 5% permethrin lotion for our patient to apply to her entire body 4 times a week and advised her to wash her clothing and bed linens at 140° F. She was scheduled for biweekly check-ups. We also advised the patient’s family to use the same topical therapy 2 times per week because crusted scabies is highly contagious. One month later, our patient’s lesions had resolved (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Early diagnosis and treatment of crusted scabies is important, both for the treatment of the patient and to stop the spread of the disease. Although rare, crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-term pruritic papulosquamous diseases, and the possibility of an atypical presentation in all patients should be considered—whether their immunity is compromised or not. Scabies should also be considered in patients with a positive family history of the disease and in those with chronic pruritus that is unresponsive to topical therapies.

1. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012;1423-1426.

2. Subramaniam G, Kaliaperumal K, Duraipandian J, et al. Norwegian scabies in a malnourished young adult: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:349-351.

3. Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Binic I, Jankovic A, Jovanovic D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191.

5. Ramachandran V, Shankar EM, Devaleenal B, et al. Atypically distributed cutaneous lesions of Norwegian scabies in an HIV-positive man in South India: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:82.

6. Lai YC, Teng CJ, Chen PC, et al. Unusual scalp crusted scabies in an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patient. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:77-78.

7. Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e138-e139.

8. Marlière V, Roul S, Labrèze C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124.

9. Goyal NN, Wong GA. Psoriasis or crusted scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:211-212.

10. Kim KJ, Roh KH, Choi JH, et al. Scabies incognito presenting as urticaria pigmentosa in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:409-411.

THE CASE

An 85-year-old woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for a 9-month history of severe pruritus and crusted lesions on her face, extremities, and trunk. She had been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection one year ago and was not taking any medication. The patient, who had been living with her family, had visited various clinics for her complaints and was diagnosed as having contact dermatitis and senile pruritus. She was prescribed topical mometasone furoate and moisturizers.

After 6 months of using this therapy, widespread grey-white plaques and minimal excoriation appeared on her face, scalp, and trunk. This was diagnosed as psoriasis, and the patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids, which she used for 9 months until she came to our clinic. She said the lesions regressed minimally with the topical corticosteroids, but did not fully clear.

Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythema and grey-white, cohesive, thick, pruritic plaques on her scalp, face, trunk, and bilateral extremities (FIGURE 1). A punch biopsy specimen was taken from the border of a plaque on her trunk.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A complete blood cell count and wide biochemistry panel, including tumor markers and viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), were normal. The patient had lymphadenopathy in her posterior cervical, bilateral preauricular, and bilateral inguinal regions.

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiotic edema in the epidermis, and vesiculation and mites in the stratum corneum. The dermal changes consisted of perivascular and diffuse cell infiltrates that were mainly mononuclear cells and eosinophilic granulocytes.

Based on the dermatologic examination and the histopathologic findings, we diagnosed the patient with crusted (Norwegian) scabies.

DISCUSSION

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies is a rare, highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by the presence of millions of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mites in the epidermis.1 This variant of scabies can affect individuals of any age, gender, or race.2 It was first described by Boeck and Danielssen in 1848 in Norway and was named Norwegian scabies by von Hebra in 1862.3 In 2010, more than 200 cases of crusted scabies were reported in the literature.4

Crusted scabies is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, such as the elderly, those who’ve had solid organ transplantation, and those with HIV, malignancy, or malnutrition. Crusted scabies may also occur in patients with decreased sensory function (such as those with leprosy) or decreased ability to scratch, intellectual disabilities, and in those who use biologic agents or systemic/topical corticosteroids.4-8

Crusted scabies is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in children and the elderly, because of complications such as secondary bacterial infections and sepsis.1,3 Widespread inflammation may also cause erythroderma, which can lead to metabolic disorders.

Distinguish it from other pruritic papulosquamous diseases

The differential diagnosis for crusted scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, cutaneous lymphoma, Darier disease, and adverse drug reactions.9 Crusted scabies can be differentiated from these other diagnoses by its clinical presentation and histopathological examination.

Crusted scabies is characterized by hyperkeratosis and wart-like crusts that are due to extreme proliferation of mites in the stratum corneum of the epidermis.2 Lesions are usually localized on acral sites (especially the hands), although the entire body, including the face and the scalp, can be involved.1 Psoriasiform or bullous pemphigoid-like eruptions have also been reported in the literature.5,9

Our patient presented with widespread erythema and psoriasiform grey-white crusts on her scalp, face, chest, periareolar region, and extremities. In addition, she did not have an immunosuppressant disease or medication history.

However, the fact that our patient was using topical corticosteroids for so long explained the extent of her condition. Topical corticosteroids have been linked to scabies incognito.10 Topical or systemic corticosteroid use for long periods of time may alter the skin immune system by suppressing cellular immunity, thereby reducing the inflammatory response. This may lead to progression of the regular variant of scabies to crusted scabies, as our patient had.

Topical treatments, oral ivermectin proven to be effective

Topical keratolytics, permethrin 5%, lindane 1%, crotamiton 10%, sulfur ointment (5%-10%), malathion 0.5%, benzyl benzoate (10%-25%), oral ivermectin (2 doses of 200 mcg/kg/dose), and systemic antihistamines are appropriate therapies.3 While oral ivermectin is effective, it is not available in Turkey.

Because of our patient’s hepatic disorder, we opted for a topical, rather than a systemic, treatment and recommended repeated applications of topical permethrin. Repeated treatment with topical permethrin is often sufficient in patients who are unable to take systemic therapy. In fact, Binic et al4 reported a case in which an elderly patient with crusted scabies (who had previously been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids) responded well to repeated topical treatment with lindane 1%, 25% benzyl benzoate, and 10% precipitated sulfur.

Our patient. We prescribed topical 5% permethrin lotion for our patient to apply to her entire body 4 times a week and advised her to wash her clothing and bed linens at 140° F. She was scheduled for biweekly check-ups. We also advised the patient’s family to use the same topical therapy 2 times per week because crusted scabies is highly contagious. One month later, our patient’s lesions had resolved (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Early diagnosis and treatment of crusted scabies is important, both for the treatment of the patient and to stop the spread of the disease. Although rare, crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-term pruritic papulosquamous diseases, and the possibility of an atypical presentation in all patients should be considered—whether their immunity is compromised or not. Scabies should also be considered in patients with a positive family history of the disease and in those with chronic pruritus that is unresponsive to topical therapies.

THE CASE

An 85-year-old woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for a 9-month history of severe pruritus and crusted lesions on her face, extremities, and trunk. She had been diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection one year ago and was not taking any medication. The patient, who had been living with her family, had visited various clinics for her complaints and was diagnosed as having contact dermatitis and senile pruritus. She was prescribed topical mometasone furoate and moisturizers.

After 6 months of using this therapy, widespread grey-white plaques and minimal excoriation appeared on her face, scalp, and trunk. This was diagnosed as psoriasis, and the patient was prescribed topical corticosteroids, which she used for 9 months until she came to our clinic. She said the lesions regressed minimally with the topical corticosteroids, but did not fully clear.

Dermatologic examination revealed widespread erythema and grey-white, cohesive, thick, pruritic plaques on her scalp, face, trunk, and bilateral extremities (FIGURE 1). A punch biopsy specimen was taken from the border of a plaque on her trunk.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A complete blood cell count and wide biochemistry panel, including tumor markers and viral serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), were normal. The patient had lymphadenopathy in her posterior cervical, bilateral preauricular, and bilateral inguinal regions.

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and spongiotic edema in the epidermis, and vesiculation and mites in the stratum corneum. The dermal changes consisted of perivascular and diffuse cell infiltrates that were mainly mononuclear cells and eosinophilic granulocytes.

Based on the dermatologic examination and the histopathologic findings, we diagnosed the patient with crusted (Norwegian) scabies.

DISCUSSION

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies is a rare, highly contagious form of scabies that is characterized by the presence of millions of Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis mites in the epidermis.1 This variant of scabies can affect individuals of any age, gender, or race.2 It was first described by Boeck and Danielssen in 1848 in Norway and was named Norwegian scabies by von Hebra in 1862.3 In 2010, more than 200 cases of crusted scabies were reported in the literature.4

Crusted scabies is usually seen in immunocompromised patients, such as the elderly, those who’ve had solid organ transplantation, and those with HIV, malignancy, or malnutrition. Crusted scabies may also occur in patients with decreased sensory function (such as those with leprosy) or decreased ability to scratch, intellectual disabilities, and in those who use biologic agents or systemic/topical corticosteroids.4-8

Crusted scabies is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, especially in children and the elderly, because of complications such as secondary bacterial infections and sepsis.1,3 Widespread inflammation may also cause erythroderma, which can lead to metabolic disorders.

Distinguish it from other pruritic papulosquamous diseases

The differential diagnosis for crusted scabies includes psoriasis, eczema, cutaneous lymphoma, Darier disease, and adverse drug reactions.9 Crusted scabies can be differentiated from these other diagnoses by its clinical presentation and histopathological examination.

Crusted scabies is characterized by hyperkeratosis and wart-like crusts that are due to extreme proliferation of mites in the stratum corneum of the epidermis.2 Lesions are usually localized on acral sites (especially the hands), although the entire body, including the face and the scalp, can be involved.1 Psoriasiform or bullous pemphigoid-like eruptions have also been reported in the literature.5,9

Our patient presented with widespread erythema and psoriasiform grey-white crusts on her scalp, face, chest, periareolar region, and extremities. In addition, she did not have an immunosuppressant disease or medication history.

However, the fact that our patient was using topical corticosteroids for so long explained the extent of her condition. Topical corticosteroids have been linked to scabies incognito.10 Topical or systemic corticosteroid use for long periods of time may alter the skin immune system by suppressing cellular immunity, thereby reducing the inflammatory response. This may lead to progression of the regular variant of scabies to crusted scabies, as our patient had.

Topical treatments, oral ivermectin proven to be effective

Topical keratolytics, permethrin 5%, lindane 1%, crotamiton 10%, sulfur ointment (5%-10%), malathion 0.5%, benzyl benzoate (10%-25%), oral ivermectin (2 doses of 200 mcg/kg/dose), and systemic antihistamines are appropriate therapies.3 While oral ivermectin is effective, it is not available in Turkey.

Because of our patient’s hepatic disorder, we opted for a topical, rather than a systemic, treatment and recommended repeated applications of topical permethrin. Repeated treatment with topical permethrin is often sufficient in patients who are unable to take systemic therapy. In fact, Binic et al4 reported a case in which an elderly patient with crusted scabies (who had previously been treated with systemic and topical corticosteroids) responded well to repeated topical treatment with lindane 1%, 25% benzyl benzoate, and 10% precipitated sulfur.

Our patient. We prescribed topical 5% permethrin lotion for our patient to apply to her entire body 4 times a week and advised her to wash her clothing and bed linens at 140° F. She was scheduled for biweekly check-ups. We also advised the patient’s family to use the same topical therapy 2 times per week because crusted scabies is highly contagious. One month later, our patient’s lesions had resolved (FIGURE 2).

THE TAKEAWAY

Early diagnosis and treatment of crusted scabies is important, both for the treatment of the patient and to stop the spread of the disease. Although rare, crusted scabies should be included in the differential diagnosis of long-term pruritic papulosquamous diseases, and the possibility of an atypical presentation in all patients should be considered—whether their immunity is compromised or not. Scabies should also be considered in patients with a positive family history of the disease and in those with chronic pruritus that is unresponsive to topical therapies.

1. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012;1423-1426.

2. Subramaniam G, Kaliaperumal K, Duraipandian J, et al. Norwegian scabies in a malnourished young adult: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:349-351.

3. Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Binic I, Jankovic A, Jovanovic D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191.

5. Ramachandran V, Shankar EM, Devaleenal B, et al. Atypically distributed cutaneous lesions of Norwegian scabies in an HIV-positive man in South India: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:82.

6. Lai YC, Teng CJ, Chen PC, et al. Unusual scalp crusted scabies in an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patient. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:77-78.

7. Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e138-e139.

8. Marlière V, Roul S, Labrèze C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124.

9. Goyal NN, Wong GA. Psoriasis or crusted scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:211-212.

10. Kim KJ, Roh KH, Choi JH, et al. Scabies incognito presenting as urticaria pigmentosa in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:409-411.

1. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG, Morrell DS. Infestations. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, et al, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2012;1423-1426.

2. Subramaniam G, Kaliaperumal K, Duraipandian J, et al. Norwegian scabies in a malnourished young adult: a case report. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:349-351.

3. Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

4. Binic I, Jankovic A, Jovanovic D, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies following systemic and topical corticosteroid therapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:188-191.

5. Ramachandran V, Shankar EM, Devaleenal B, et al. Atypically distributed cutaneous lesions of Norwegian scabies in an HIV-positive man in South India: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:82.

6. Lai YC, Teng CJ, Chen PC, et al. Unusual scalp crusted scabies in an adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma patient. Ups J Med Sci. 2011;116:77-78.

7. Saillard C, Darrieux L, Safa G. Crusted scabies complicates etanercept therapy in a patient with severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:e138-e139.

8. Marlière V, Roul S, Labrèze C, et al. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies induced by use of topical corticosteroids and treated successfully with ivermectin. J Pediatr. 1999;135:122-124.

9. Goyal NN, Wong GA. Psoriasis or crusted scabies. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:211-212.

10. Kim KJ, Roh KH, Choi JH, et al. Scabies incognito presenting as urticaria pigmentosa in an infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:409-411.

Swollen right hand and forearm • minor trauma to hand • previous diagnosis of cellulitis • Dx?

THE CASE

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to our hospital with a swollen right hand. The patient noted that she had closed her hand in a car door one week earlier, causing minor trauma to the right third metacarpophalangeal joint. Shortly after injuring her hand, she’d sought care at an outpatient facility, where she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and a prescription for an oral antibiotic. The swelling, however, worsened, prompting her visit to our hospital. She was admitted for further work-up and started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

Her family history included a sister with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. The patient denied oral contraceptive use or a personal history of malignancy. On physical examination, her right hand and forearm were swollen, tender, and erythematous.

THE DIAGNOSIS

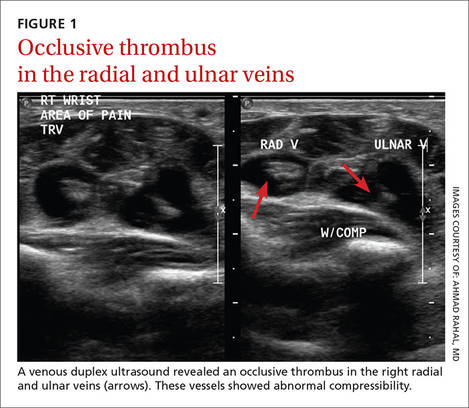

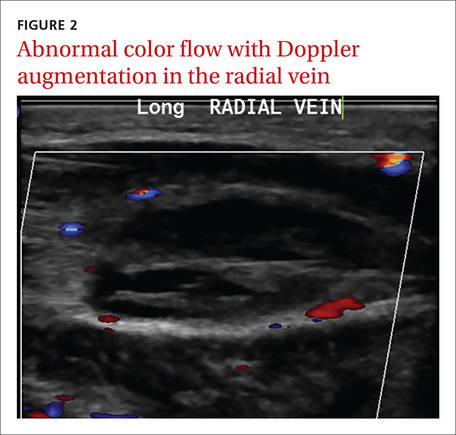

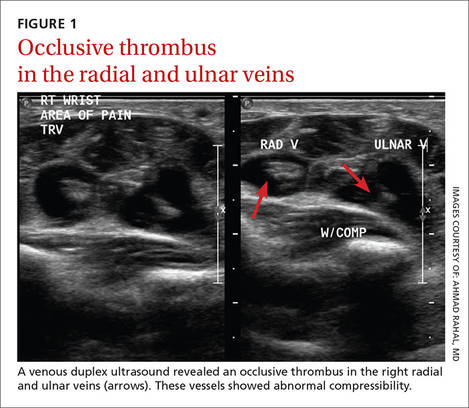

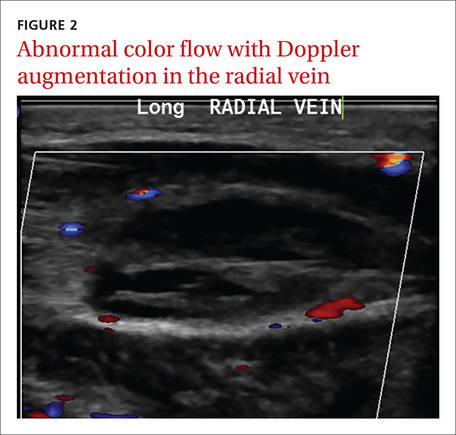

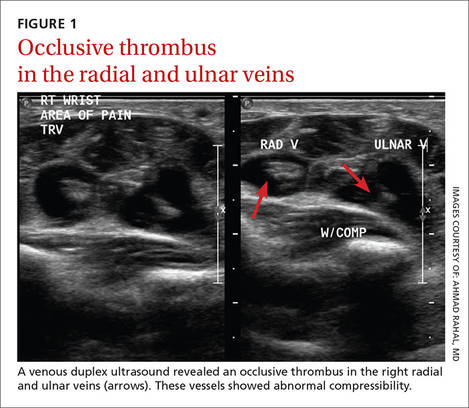

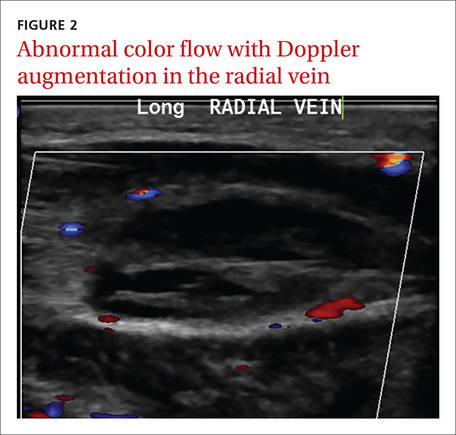

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and complete metabolic panel. The patient’s sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 65 mm/hr and 110 mg/L, respectively. The patient was not improving on IV antibiotics, so we performed a right upper extremity venous duplex ultrasound. The ultrasound showed an occlusive thrombus in the right ulnar and radial veins (FIGURES 1 AND 2), and we diagnosed the patient with upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT). (The timing of the diagnosis, relative to the injury to the patient’s hand, appeared to have been coincidental.)

Further work-up revealed normal complement C3 and C4 tests, as well as negative antinuclear, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, and anticardiolipin antibody tests. Similarly, a factor II DNA analysis was negative. However, the patient was positive for the factor V Leiden heterozygous mutation.

|

|

DISCUSSION

More than 350,000 people are diagnosed with DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in the United States each year.1 Up to 4% of all DVTs involve the upper extremities.2 Secondary UEDVT, which occurs in patients with central venous catheters, malignancies, and thrombophilia, accounts for the majority of UEDVT cases; primary UEDVT is less common.3

Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that hypercoagulability is a risk factor for lower extremity DVT, but few data exist on the role of coagulation abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT. The prevalence of clotting abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT ranges from 8% to 43%.4,5 Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia. Patients with heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation have a 7-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.6

Héron and colleagues7 reported that 16 of 51 patients with at least one clotting abnormality had primary UEDVT. Factor V Leiden was found in 5 of those patients (20%). Interestingly, 3 of the 5 carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation were older than 45 years. Our patient was 63, which was consistent with these findings.

Malignancy is also an important risk factor for UEDVT.8,9 In patients with a DVT in an unusual location, age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings are strongly recommended. (Our patient had undergone a colonoscopy 8 years earlier, which was normal. She’d also had a recent mammogram and Pap smear, which were normal, as well.)

It’s often difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and UEDVT

The differential diagnosis for UEDVT includes effort thrombosis (also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome) and cellulitis.

Effort thrombosis usually occurs in young, otherwise healthy individuals and almost exclusively in the axillary and subclavian veins. Our patient’s age and a venous duplex ultrasound ruled out any thrombosis in these locations.

Distinguishing cellulitis from UEDVT based on clinical features can be difficult. In both conditions, the limb is swollen and painful and the skin is warm and erythematous. As a result, each condition is often misdiagnosed as the other.

But there are features that distinguish the 2. In patients with UEDVT, you’re likely to see limb pain and a palpable cord (a hard, thickened palpable vein along the line of the deep veins). On the other hand, patients with cellulitis tend to have more systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes, as well as skin breakdown, ulcers, and pus.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that the initial evaluation for patients with suspected UEDVT be a combined modality ultrasound (compression with either Doppler or color Doppler) rather than D-dimer or venography.10 Quickly arriving at a proper diagnosis is critical, given that up to one-third of patients with UEDVT will develop a PE.7 Other complications include superior vena cava syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis, thoracic duct obstruction, and brachial plexopathy.11

Treat with anticoagulants for no longer than 3 months

The ACCP also recommends that patients who have UEDVT that isn’t associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer be treated with anticoagulation for no longer than 3 months.10

Our patient was started on enoxaparin and warfarin. After 5 days at our hospital, she was taken off the enoxaparin and discharged home on warfarin 5 mg/d. The swelling completely resolved one week later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Ulnar and radial DVT in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation is a rare condition. UEDVT should be included in the differential diagnosis for cellulitis whenever the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Factor V Leiden mutation appears to be a risk factor in UEDVT and testing for it should be considered.

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.

2. Sawyer GA, Hayda R. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis following humeral shaft fracture. Orthopedics. 2011;34:141.

3. Leebeek FW, Stadhouders NA, van Stein D, et al. Hypercoagulability states in upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:15-19.

4. Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57-62.

5. Ruggeri M, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. Low prevalence of thrombophilic coagulation defects in patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper limbs. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:191-194.

6. Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107:e94-e97.

7. Héron E, Lozinguez O, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Hypercoagulable states in primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:382-386.

8. Linnemann B, Meister F, Schwonberg J, et al; MAISTHRO registry. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Results from the MAISTHRO registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:440-446.

9. Monreal M, Lafoz E, Ruiz J, et al. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;99:280-283.

10. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e152S-e184S.

11. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB 4th. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943.

THE CASE

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to our hospital with a swollen right hand. The patient noted that she had closed her hand in a car door one week earlier, causing minor trauma to the right third metacarpophalangeal joint. Shortly after injuring her hand, she’d sought care at an outpatient facility, where she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and a prescription for an oral antibiotic. The swelling, however, worsened, prompting her visit to our hospital. She was admitted for further work-up and started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

Her family history included a sister with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. The patient denied oral contraceptive use or a personal history of malignancy. On physical examination, her right hand and forearm were swollen, tender, and erythematous.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and complete metabolic panel. The patient’s sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 65 mm/hr and 110 mg/L, respectively. The patient was not improving on IV antibiotics, so we performed a right upper extremity venous duplex ultrasound. The ultrasound showed an occlusive thrombus in the right ulnar and radial veins (FIGURES 1 AND 2), and we diagnosed the patient with upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT). (The timing of the diagnosis, relative to the injury to the patient’s hand, appeared to have been coincidental.)

Further work-up revealed normal complement C3 and C4 tests, as well as negative antinuclear, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, and anticardiolipin antibody tests. Similarly, a factor II DNA analysis was negative. However, the patient was positive for the factor V Leiden heterozygous mutation.

|

|

DISCUSSION

More than 350,000 people are diagnosed with DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in the United States each year.1 Up to 4% of all DVTs involve the upper extremities.2 Secondary UEDVT, which occurs in patients with central venous catheters, malignancies, and thrombophilia, accounts for the majority of UEDVT cases; primary UEDVT is less common.3

Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that hypercoagulability is a risk factor for lower extremity DVT, but few data exist on the role of coagulation abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT. The prevalence of clotting abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT ranges from 8% to 43%.4,5 Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia. Patients with heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation have a 7-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.6

Héron and colleagues7 reported that 16 of 51 patients with at least one clotting abnormality had primary UEDVT. Factor V Leiden was found in 5 of those patients (20%). Interestingly, 3 of the 5 carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation were older than 45 years. Our patient was 63, which was consistent with these findings.

Malignancy is also an important risk factor for UEDVT.8,9 In patients with a DVT in an unusual location, age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings are strongly recommended. (Our patient had undergone a colonoscopy 8 years earlier, which was normal. She’d also had a recent mammogram and Pap smear, which were normal, as well.)

It’s often difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and UEDVT

The differential diagnosis for UEDVT includes effort thrombosis (also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome) and cellulitis.

Effort thrombosis usually occurs in young, otherwise healthy individuals and almost exclusively in the axillary and subclavian veins. Our patient’s age and a venous duplex ultrasound ruled out any thrombosis in these locations.

Distinguishing cellulitis from UEDVT based on clinical features can be difficult. In both conditions, the limb is swollen and painful and the skin is warm and erythematous. As a result, each condition is often misdiagnosed as the other.

But there are features that distinguish the 2. In patients with UEDVT, you’re likely to see limb pain and a palpable cord (a hard, thickened palpable vein along the line of the deep veins). On the other hand, patients with cellulitis tend to have more systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes, as well as skin breakdown, ulcers, and pus.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that the initial evaluation for patients with suspected UEDVT be a combined modality ultrasound (compression with either Doppler or color Doppler) rather than D-dimer or venography.10 Quickly arriving at a proper diagnosis is critical, given that up to one-third of patients with UEDVT will develop a PE.7 Other complications include superior vena cava syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis, thoracic duct obstruction, and brachial plexopathy.11

Treat with anticoagulants for no longer than 3 months

The ACCP also recommends that patients who have UEDVT that isn’t associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer be treated with anticoagulation for no longer than 3 months.10

Our patient was started on enoxaparin and warfarin. After 5 days at our hospital, she was taken off the enoxaparin and discharged home on warfarin 5 mg/d. The swelling completely resolved one week later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Ulnar and radial DVT in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation is a rare condition. UEDVT should be included in the differential diagnosis for cellulitis whenever the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Factor V Leiden mutation appears to be a risk factor in UEDVT and testing for it should be considered.

THE CASE

A 63-year-old woman with a history of hyperlipidemia presented to our hospital with a swollen right hand. The patient noted that she had closed her hand in a car door one week earlier, causing minor trauma to the right third metacarpophalangeal joint. Shortly after injuring her hand, she’d sought care at an outpatient facility, where she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and a prescription for an oral antibiotic. The swelling, however, worsened, prompting her visit to our hospital. She was admitted for further work-up and started on intravenous (IV) antibiotics.

Her family history included a sister with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. The patient denied oral contraceptive use or a personal history of malignancy. On physical examination, her right hand and forearm were swollen, tender, and erythematous.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Laboratory data showed a normal complete blood count and complete metabolic panel. The patient’s sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were elevated at 65 mm/hr and 110 mg/L, respectively. The patient was not improving on IV antibiotics, so we performed a right upper extremity venous duplex ultrasound. The ultrasound showed an occlusive thrombus in the right ulnar and radial veins (FIGURES 1 AND 2), and we diagnosed the patient with upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (UEDVT). (The timing of the diagnosis, relative to the injury to the patient’s hand, appeared to have been coincidental.)

Further work-up revealed normal complement C3 and C4 tests, as well as negative antinuclear, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-Smith, and anticardiolipin antibody tests. Similarly, a factor II DNA analysis was negative. However, the patient was positive for the factor V Leiden heterozygous mutation.

|

|

DISCUSSION

More than 350,000 people are diagnosed with DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE) in the United States each year.1 Up to 4% of all DVTs involve the upper extremities.2 Secondary UEDVT, which occurs in patients with central venous catheters, malignancies, and thrombophilia, accounts for the majority of UEDVT cases; primary UEDVT is less common.3

Large epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that hypercoagulability is a risk factor for lower extremity DVT, but few data exist on the role of coagulation abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT. The prevalence of clotting abnormalities in patients with primary UEDVT ranges from 8% to 43%.4,5 Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of inherited thrombophilia. Patients with heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation have a 7-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis.6

Héron and colleagues7 reported that 16 of 51 patients with at least one clotting abnormality had primary UEDVT. Factor V Leiden was found in 5 of those patients (20%). Interestingly, 3 of the 5 carriers of the factor V Leiden mutation were older than 45 years. Our patient was 63, which was consistent with these findings.

Malignancy is also an important risk factor for UEDVT.8,9 In patients with a DVT in an unusual location, age- and sex-appropriate cancer screenings are strongly recommended. (Our patient had undergone a colonoscopy 8 years earlier, which was normal. She’d also had a recent mammogram and Pap smear, which were normal, as well.)

It’s often difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and UEDVT

The differential diagnosis for UEDVT includes effort thrombosis (also known as Paget-Schroetter syndrome) and cellulitis.

Effort thrombosis usually occurs in young, otherwise healthy individuals and almost exclusively in the axillary and subclavian veins. Our patient’s age and a venous duplex ultrasound ruled out any thrombosis in these locations.

Distinguishing cellulitis from UEDVT based on clinical features can be difficult. In both conditions, the limb is swollen and painful and the skin is warm and erythematous. As a result, each condition is often misdiagnosed as the other.

But there are features that distinguish the 2. In patients with UEDVT, you’re likely to see limb pain and a palpable cord (a hard, thickened palpable vein along the line of the deep veins). On the other hand, patients with cellulitis tend to have more systemic symptoms, such as fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes, as well as skin breakdown, ulcers, and pus.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) recommends that the initial evaluation for patients with suspected UEDVT be a combined modality ultrasound (compression with either Doppler or color Doppler) rather than D-dimer or venography.10 Quickly arriving at a proper diagnosis is critical, given that up to one-third of patients with UEDVT will develop a PE.7 Other complications include superior vena cava syndrome, septic thrombophlebitis, thoracic duct obstruction, and brachial plexopathy.11

Treat with anticoagulants for no longer than 3 months

The ACCP also recommends that patients who have UEDVT that isn’t associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer be treated with anticoagulation for no longer than 3 months.10

Our patient was started on enoxaparin and warfarin. After 5 days at our hospital, she was taken off the enoxaparin and discharged home on warfarin 5 mg/d. The swelling completely resolved one week later.

THE TAKEAWAY

Ulnar and radial DVT in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation is a rare condition. UEDVT should be included in the differential diagnosis for cellulitis whenever the diagnosis is uncertain or the patient doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Factor V Leiden mutation appears to be a risk factor in UEDVT and testing for it should be considered.

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.

2. Sawyer GA, Hayda R. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis following humeral shaft fracture. Orthopedics. 2011;34:141.

3. Leebeek FW, Stadhouders NA, van Stein D, et al. Hypercoagulability states in upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:15-19.

4. Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57-62.

5. Ruggeri M, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. Low prevalence of thrombophilic coagulation defects in patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper limbs. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:191-194.

6. Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107:e94-e97.

7. Héron E, Lozinguez O, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Hypercoagulable states in primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:382-386.

8. Linnemann B, Meister F, Schwonberg J, et al; MAISTHRO registry. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Results from the MAISTHRO registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:440-446.

9. Monreal M, Lafoz E, Ruiz J, et al. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;99:280-283.

10. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e152S-e184S.

11. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB 4th. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943.

1. Office of the Surgeon General (US); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44178/. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General (US); 2008.

2. Sawyer GA, Hayda R. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis following humeral shaft fracture. Orthopedics. 2011;34:141.

3. Leebeek FW, Stadhouders NA, van Stein D, et al. Hypercoagulability states in upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis. Am J Hematol. 2001;67:15-19.

4. Prandoni P, Polistena P, Bernardi E, et al. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Risk factors, diagnosis, and complications. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:57-62.

5. Ruggeri M, Castaman G, Tosetto A, et al. Low prevalence of thrombophilic coagulation defects in patients with deep vein thrombosis of the upper limbs. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8:191-194.

6. Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Cardiology patient page. Factor V Leiden. Circulation. 2003;107:e94-e97.

7. Héron E, Lozinguez O, Alhenc-Gelas M, et al. Hypercoagulable states in primary upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:382-386.

8. Linnemann B, Meister F, Schwonberg J, et al; MAISTHRO registry. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Results from the MAISTHRO registry. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100:440-446.

9. Monreal M, Lafoz E, Ruiz J, et al. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. A prospective study. Chest. 1991;99:280-283.

10. Holbrook A, Schulman S, Witt DM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Evidence-based management of anticoagulant therapy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e152S-e184S.

11. Becker DM, Philbrick JT, Walker FB 4th. Axillary and subclavian venous thrombosis. Prognosis and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1934-1943.

Multivisceral resection for growing teratoma syndrome: overcoming pessimism

Growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) is a rare condition seen in patients with germ-cell tumors (GCT) who present with enlarging masses during or after appropriate chemotherapy with normalized serum markers.1 Three defining criteria for GTS are: a persistently growing tumor mass or evolving new mass during or after chemotherapy, normalization of tumor markers, and presence of only mature teratoma in the resected specimen on the final histopathological examination.1 Growing teratomas lack the metastatic potential; however, their relentless local growth causes compression and infiltration of adjacent organs, which produces symptoms.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Growing teratoma syndrome (GTS) is a rare condition seen in patients with germ-cell tumors (GCT) who present with enlarging masses during or after appropriate chemotherapy with normalized serum markers.1 Three defining criteria for GTS are: a persistently growing tumor mass or evolving new mass during or after chemotherapy, normalization of tumor markers, and presence of only mature teratoma in the resected specimen on the final histopathological examination.1 Growing teratomas lack the metastatic potential; however, their relentless local growth causes compression and infiltration of adjacent organs, which produces symptoms.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.