User login

Merkel Cell Carcinoma in a Vein Graft Donor Site

Case Report

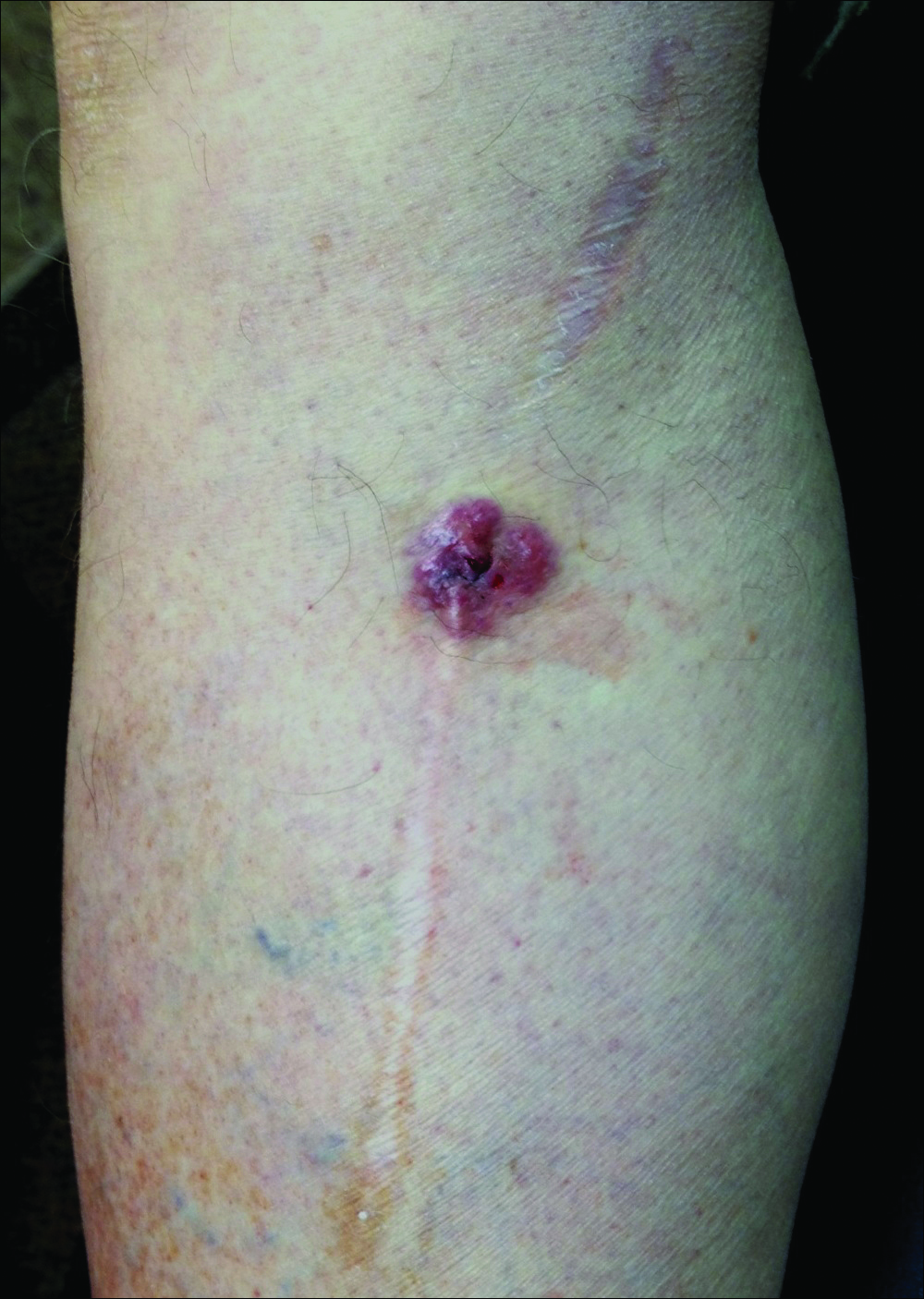

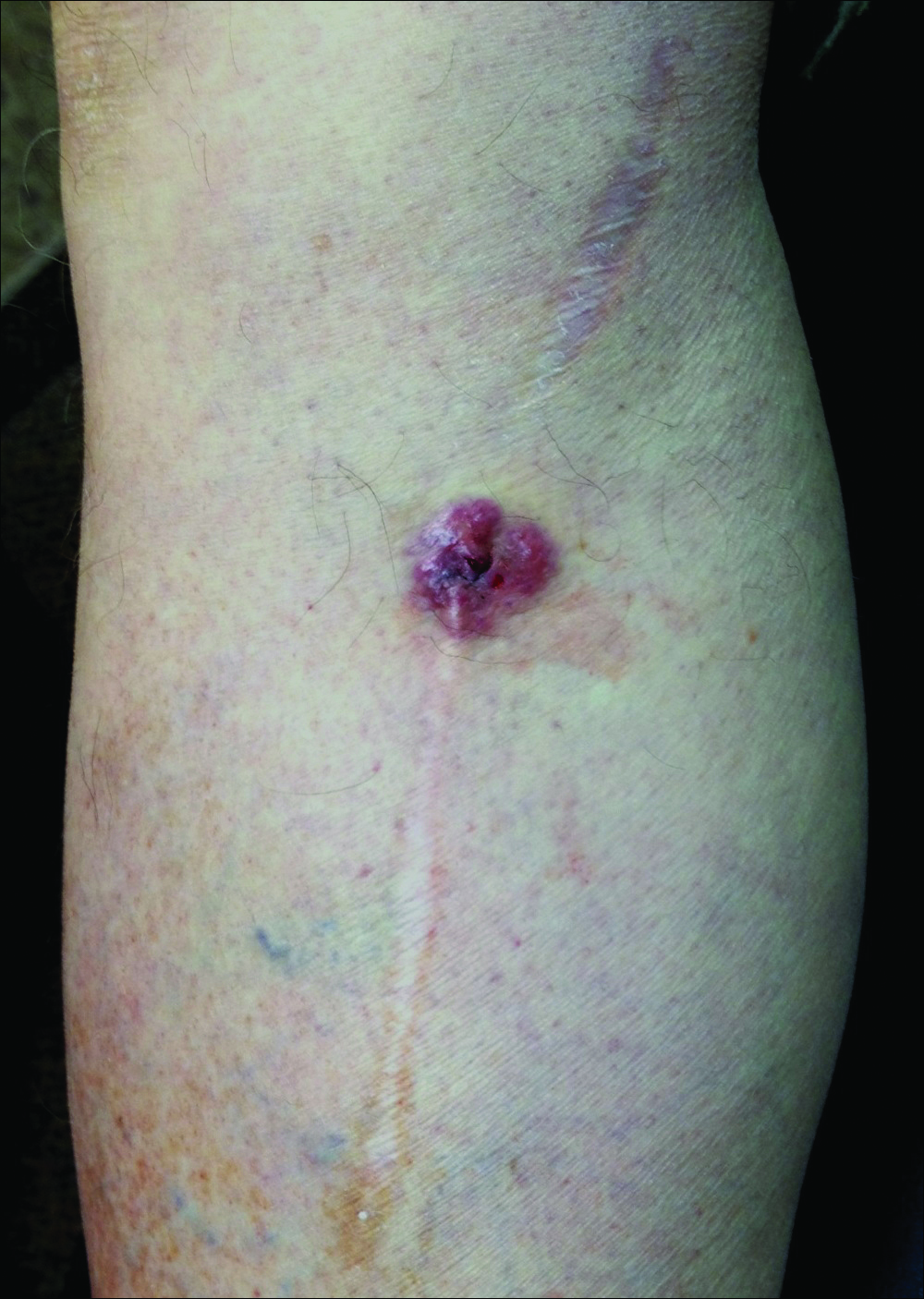

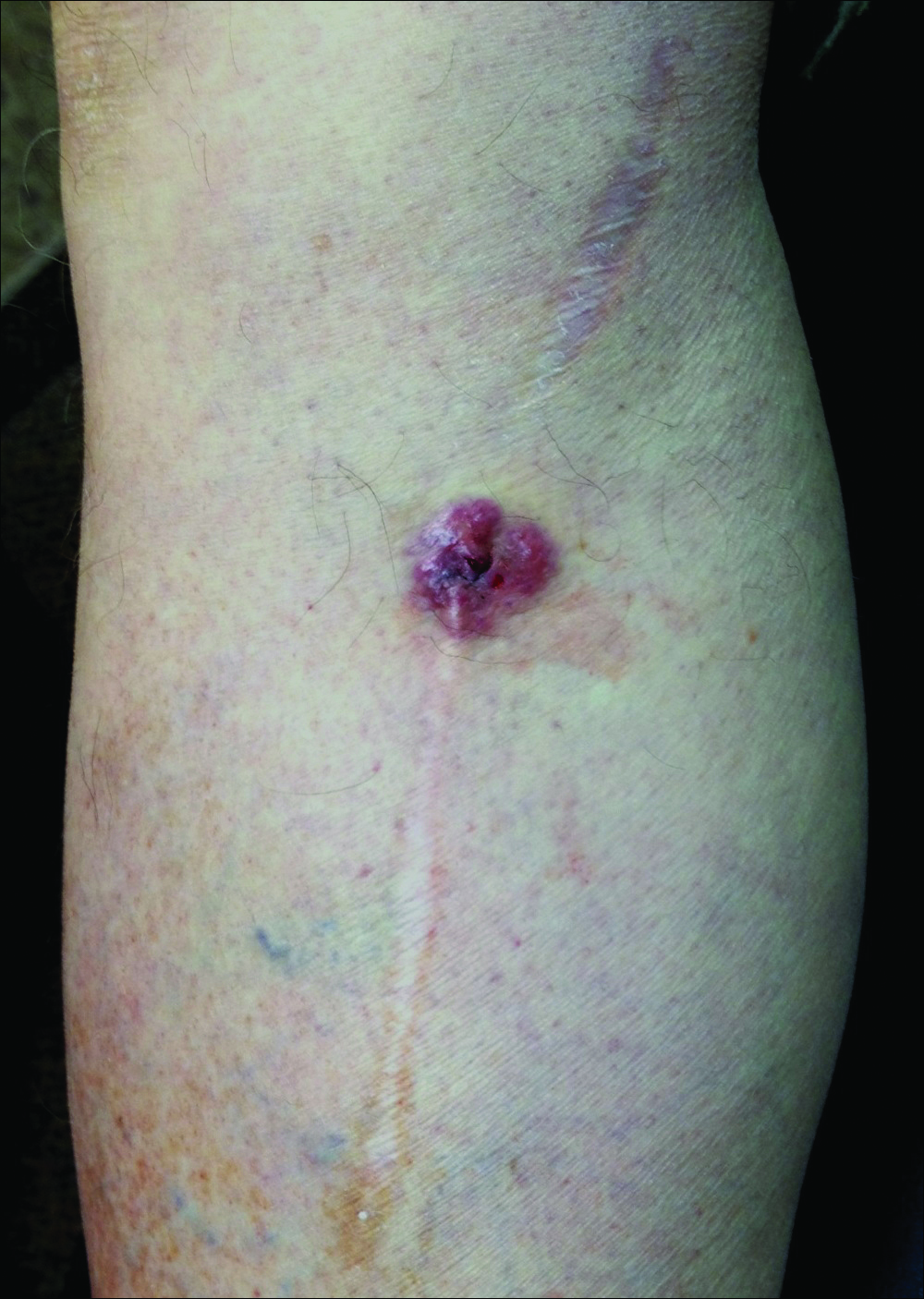

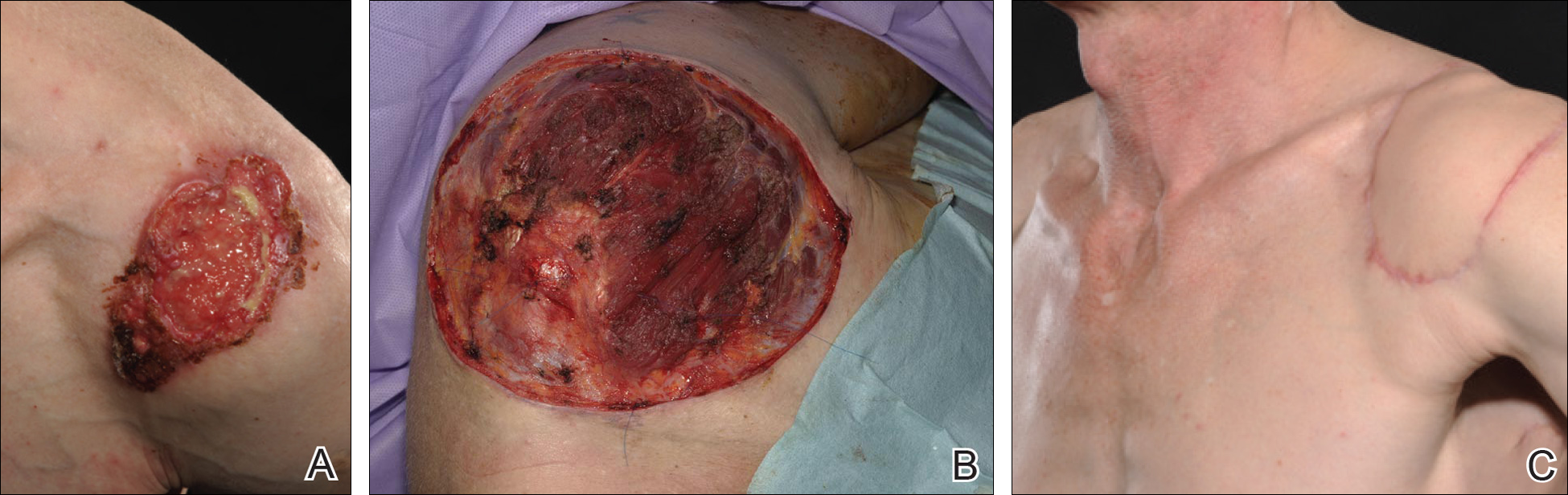

A 70-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease presented with a growing lesion on the right leg of 1 year’s duration. The lesion developed at a vein graft donor site for a coronary artery bypass that had been performed 18 years prior to presentation. The patient reported that the lesion was sensitive to touch. Physical examination revealed a 27-mm, firm, violaceous plaque on the medial aspect of the right upper shin (Figure 1). Mild pitting edema also was noted on both lower legs but was more prominent on the right leg. A 6-mm punch biopsy was performed.

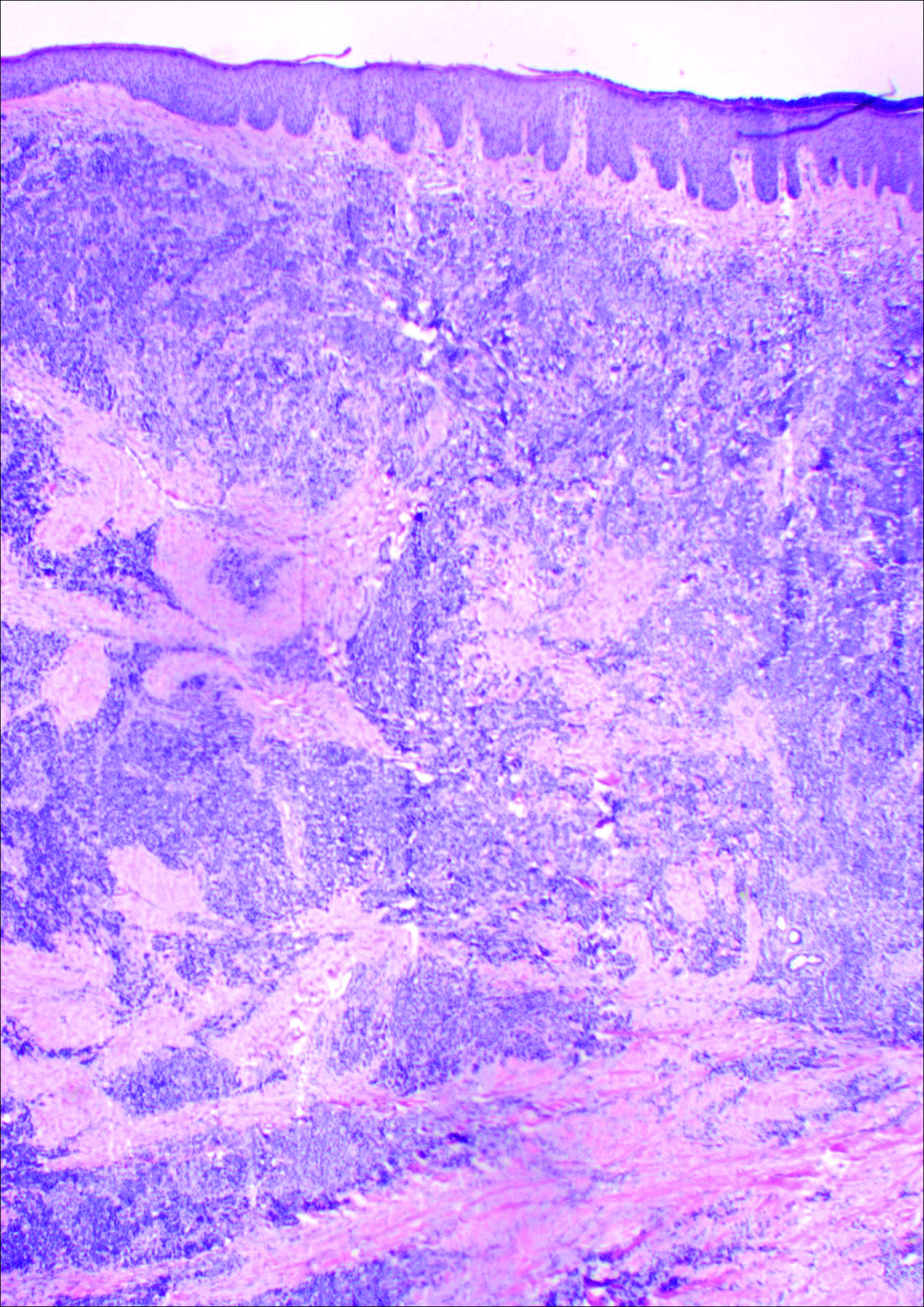

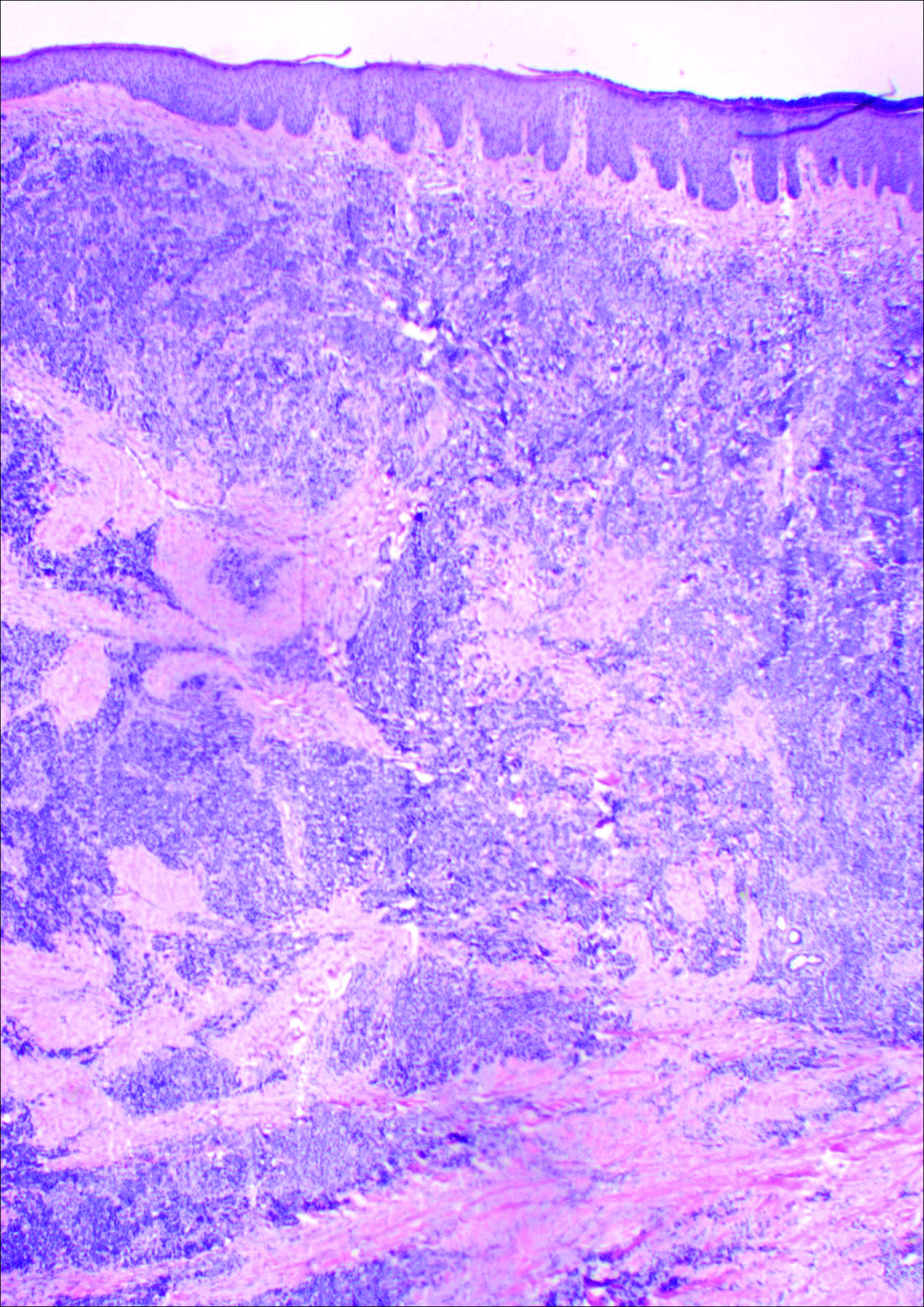

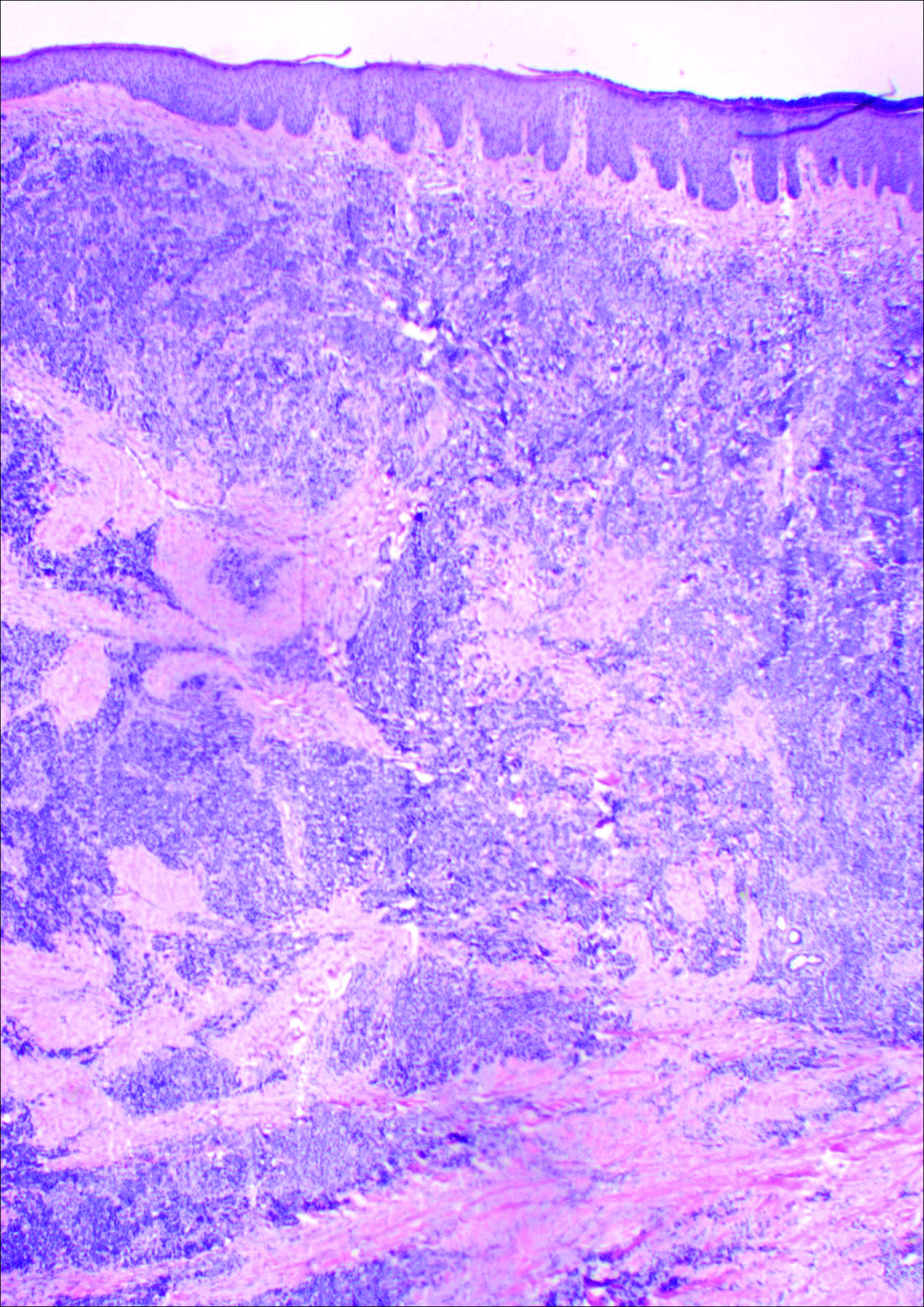

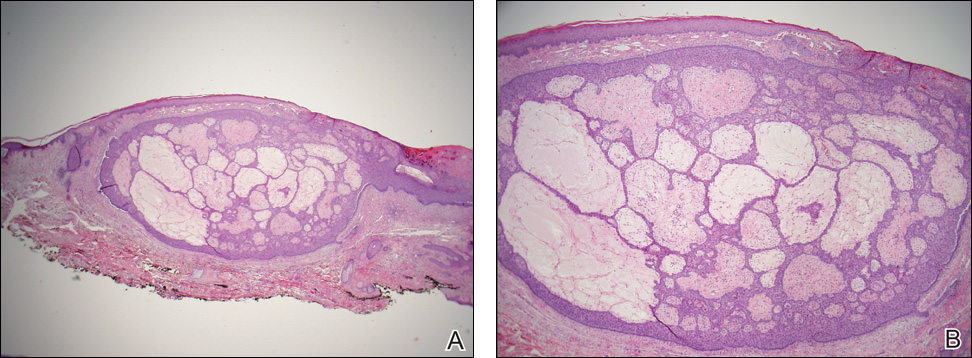

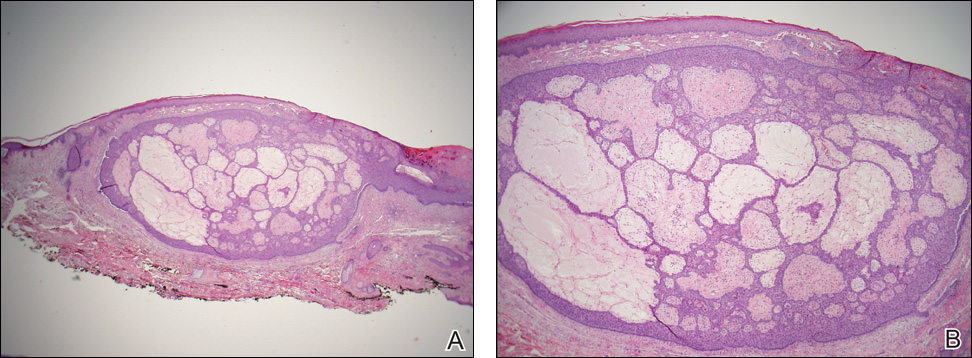

Histology showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by intermediate-sized atypical blue cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 2). The tumor exhibited moderate cytologic atypia with occasional mitotic figures, and lymphovascular invasion was present. Staining for CD3 was negative within the tumor, but a few reactive lymphocytes were highlighted at the periphery. Staining for CD20 and CD30 was negative. Strong and diffuse staining for cyto-keratin 20 and pan-cytokeratin was noted within the tumor with the distinctive perinuclear pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Staining for cytokeratin 7 was negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin were strongly and diffusely positive within the tumor, consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

The patient was found to have stage IIA (T2N0M0) MCC. Computed tomography completed for staging showed no evidence of metastasis. Wide local excision of the lesion was performed. Margins were negative, as was a right inguinal sentinel lymph node dissection. Because of the size of the tumor and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, radiation therapy at the primary tumor site was recommended. Local radiation treatment (200 cGy daily) was administered for a total dose of 5000 cGy over 5 weeks. The patient currently is free of recurrence or metastases and is being followed by the oncology, surgery, and dermatology departments.

Comment

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but immunosuppression and UV radiation, possibly through its immunosuppressive effects, appear to be contributing factors. More recently, the Merkel cell polyomavirus has been linked to MCC in approximately 80% of cases.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma is more common in individuals with fair skin, and the average age at diagnosis is 69 years.1 Patients typically present with an asymptomatic, firm, erythematous or violaceous, dome-shaped nodule or a small indurated plaque, most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck followed by the upper and lower extremities including the hands, feet, ankles, and wrists. Fifteen percent to 20% of MCCs develop on the legs and feet.1 Our patient presented with an MCC that developed on the right shin at a vein graft donor site.

The development of a cutaneous malignancy in a chronic wound (also known as a Marjolin ulcer) is a rare but well-recognized process. These malignancies occur in previously traumatized or chronically inflamed wounds and have been found to occur most commonly in chronic burn wounds, especially in ungrafted full-thickness burns. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the most common malignancies to arise in chronic wounds, but basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, adenoacanthomas, liposarcomas, and osteosarcomas also have been reported.3 There also have been a few reports of MCC associated with Bowen disease that developed in burn wounds.4 These malignancies generally occur years after injury (average, 35.5 years), but there have been reports of keratoacanthomas developing as early as 3 weeks after injury.5,6

In some reports, malignancies in skin graft donor sites are differentiated from Marjolin ulcers, as the former appear in healed surgical wounds rather than in chronic unstable wounds and tend to occur sooner (ie, in weeks to months after graft harvesting).7,8 The development of these malignancies in graft donor sites is not as well recognized and has been reported in donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs), full-thickness skin grafts, tendon grafts, and bone grafts. In addition to malignancies that arise de novo, some develop due to metastatic and iatrogenic spread. The majority of reported malignancies in tendon and bone graft donor sites have been due to metastasis or iatrogenic spread.9-14

Iatrogenic implantation of tumor cells is a well-recognized phenomenon. Hussain et al10 reported a case of implantation of SCC in an STSG donor site, most likely due to direct seeding from a hollow needle used to infiltrate local anesthetic in the tumor area and the STSG. In this case, metastasis could not be completely ruled out.10 There also have been reports of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, scirrhous carcinoma of the breast, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma thought to be implanted at bone graft donor sites.14-17 Iatrogenic spread of malignancies can occur through seeding from contaminated gloves or instruments such as hollow bore needles or trocar placement in laparoscopic surgery.11 Airborne spread also may be possible, as viable melanoma cells have been detected in electrocautery plume in mice.13

Metastatic malignancies including metastases from SCC, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, and osteosarcoma also have been reported to develop in graft donor sites.11,13,18,19 Many malignancies thought to have developed from iatrogenic seeding may actually be from metastasis either by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. A possible contributing factor may be surgery-induced immunosuppression, which has been linked to increased tumor metastasis formation.20 Surgery or trauma have been shown to have an effect on cellular components of the immune system, causing changes such as a shift in T lymphocytes toward immune-suppressive T lymphocytes and impaired function of natural killer cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.20 The suppression of cell-mediated immunity has been shown to decrease over days to weeks in the postoperative period.21 In addition to surgery- or trauma-induced immunosuppression, the risk for metastasis may increase due to increased vascular, including lymphatic, flow toward a skin graft donor site.13,16 Furthermore, trauma predisposes areas to a hypercoagulable state with increased sludging as well as increased platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, which may lead to localization of metastatic lesions.22 All of these factors could potentially work simultaneously to induce the development of metastasis in graft donor sites.

We found that SCCs and keratoacanthomas, which may be a variant of SCC, are among the only primary malignancies that have been reported to develop in skin graft donor sites.6-8 Malignancies in these donor sites appear to develop sooner than those found in chronic wounds and are reported to develop within weeks to several months postoperatively, even in as few as 2 weeks.6,8 Tamir et al6 reported 2 keratoacanthomas that developed simultaneously in a burn scar and STSG donor site. The investigators believed it could be a sign of reduced immune surveillance in the 2 affected areas.6 It has been hypothesized that one cause of local immune suppression in Marjolin ulcers could be due to poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue, which would prevent delivery of antigens and stimulated lymphocytes.23 Haik et al7 considered this possibility when discussing a case of SCC that developed at the site of an STSG. The authors did not feel it applied, however, as the donor site had only undergone a single skin harvesting procedure.7 Ponnuvelu et al8 felt that inflammation was the underlying etiology behind the 2 cases they reported of SCCs that developed in STSG donor sites. The inflammation associated with tumors has many of the same processes involved in wound healing (eg, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis). Ponnuvelu et al8 hypothesized that the local inflammation caused by graft harvesting produced an ideal environment for early carcinogenesis. Although in chronic wounds it is believed that continual repair and regeneration in recurrent ulceration contributes to neoplastic initiation, it is thought that even a single injury may lead to malignant change, which may be because prior actinic damage or another cause has made the area more susceptible to these changes.24,25 Surgery-induced immunosuppression also may play a role in development of primary malignancies in graft donor sites.

There have been a few reports of SCCs and basal cell carcinomas occurring in other surgical scars that healed without complications.24,26-28 Similar to the malignancies in graft donor sites, some authors differentiate malignancies that occur in surgical scars that heal without complications from Marjolin ulcers, as they do not occur in chronically irritated wounds. These malignancies have been reported in scars from sternotomies, an infertility procedure, hair transplantation, thyroidectomy, colostomy, cleft lip repair, inguinal hernia repair, and paraumbilical laparoscopic port site. The time between surgery and diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 9 months to 67 years.24,26-28 The development of malignancies in these surgical scars may be due to local immunosuppression, possibly from decreased lymphatic flow; additionally, the inflammation in wound healing may provide the ideal environment for carcinogenesis. Trauma in areas already susceptible to malignant change could be a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Our patient developed an MCC in a vein graft donor site 18 years after vein harvesting. It was likely a primary tumor, as vein harvesting was done for coronary artery bypass graft. There was no evidence of any other lesions on physical examination or computed tomography, making it doubtful that an MCC serving as a primary lesion for seeding or metastasis was present. If such a lesion had been present at that time, it would likely have spread well before the time of presentation to our clinic due to the fast doubling time and high rate of metastasis characteristic of MCCs, further lessening the possibility of metastasis or implantation.

The extended length of time from procedure to lesion development in our patient is much longer than for other reported malignancies in graft donor sites, but the reported time for malignancies in other postsurgical scars is more varied. Regardless of whether the MCC in our patient is classified as a Marjolin ulcer, the pathogenesis is unclear. It is thought that a single injury could lead to malignant change in predisposed skin. Our patient’s legs did not have any evidence of prior actinic damage; however, it is likely that he had local immune suppression, which may have made him more susceptible to these changes. It is unlikely that surgery-induced immunosuppression played a role in our patient, as specific cellular components of the immune system only appear to be affected over days to weeks in the postoperative period. Although poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue leading to decreased immune surveillance is not generally thought to contribute to malignancies in most surgical scars, our patient underwent vein harvesting. Chronic edema commonly occurs after vein harvesting and is believed to be due to trauma to the lymphatics. Local immune suppression also may have led to increased susceptibility to infection by the MCC polyomavirus, which has been found to be associated with many MCCs. In addition, the area may have been more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to changes from inflammation from wound healing. We suspect together these factors contributed to the development of our patient’s MCC. Although rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for the development of malignancy.

- Swann MH, Yoon J. Merkel cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:51-56.

- Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-149.

- Kadir AR. Burn scar neoplasm. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2007;20:185-188.

- Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:680-689.

- Guenther N, Menenakos C, Braumann C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on a skin graft 64 years after primary injury. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:27.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:870-871.

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893.

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MF, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169.

- Bekar A, Kahveci R, Tolunay S, et al. Metastatic gliosarcoma mass extension to a donor fascia lata graft harvest site by tumor cell contamination. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:719-721.

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692.

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Serrano-Ortega S, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega del Olmo RM, et al. Melanoma metastasis in donor site of full-thickness skin graft. Dermatology. 2000;201:377-378.

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266.

- Yip KM, Lin J, Kumta SM. A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. a case report. Int Orthop. 1996;20:389-391.

- Dias RG, Abudu A, Carter SR, et al. Tumour transfer to bone graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature of the mechanism of seeding. Sarcoma. 2000;4:57-59.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419.

- Singh C, Ibrahim S, Pang KS, et al. Implantation metastasis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11:94-96.

- Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993;80:366.

- Yamasaki O, Terao K, Asagoe K, et al. Koebner phenomenon on skin graft donor site in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:584-586.

- Hogan BV, Peter MB, Shenoy HG, et al. Surgery induced immunosuppression. Surgeon. 2011;9:38-43.

- Neeman E, Ben-Eliyahu S. The perioperative period and promotion of cancer metastasis: new outlooks on mediating mechanisms and immune involvement. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):32-40.

- Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Trauma as a cause of localization of blood-borne metastases: preventive effect of heparin and fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1965;161:97-102.

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683.

- Korula R, Hughes CF. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a sternotomy scar. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:667-669.

- Kennedy CTC, Burd DAR, Creamer D. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 2. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:28.1-28.94.

- Durrani AJ, Miller RJ, Davies M. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a laparoscopic port site scar at the umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:348-350.

- Kotwal S, Madaan S, Prescott S, et al. Unusual squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum arising from a well healed, innocuous scar of an infertility procedure: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:17-19.

- Ozyazgan I, Kontas O. Previous injuries or scars as risk factors for the development of basal cell carcinoma. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38:11-15.

Case Report

A 70-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease presented with a growing lesion on the right leg of 1 year’s duration. The lesion developed at a vein graft donor site for a coronary artery bypass that had been performed 18 years prior to presentation. The patient reported that the lesion was sensitive to touch. Physical examination revealed a 27-mm, firm, violaceous plaque on the medial aspect of the right upper shin (Figure 1). Mild pitting edema also was noted on both lower legs but was more prominent on the right leg. A 6-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Histology showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by intermediate-sized atypical blue cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 2). The tumor exhibited moderate cytologic atypia with occasional mitotic figures, and lymphovascular invasion was present. Staining for CD3 was negative within the tumor, but a few reactive lymphocytes were highlighted at the periphery. Staining for CD20 and CD30 was negative. Strong and diffuse staining for cyto-keratin 20 and pan-cytokeratin was noted within the tumor with the distinctive perinuclear pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Staining for cytokeratin 7 was negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin were strongly and diffusely positive within the tumor, consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

The patient was found to have stage IIA (T2N0M0) MCC. Computed tomography completed for staging showed no evidence of metastasis. Wide local excision of the lesion was performed. Margins were negative, as was a right inguinal sentinel lymph node dissection. Because of the size of the tumor and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, radiation therapy at the primary tumor site was recommended. Local radiation treatment (200 cGy daily) was administered for a total dose of 5000 cGy over 5 weeks. The patient currently is free of recurrence or metastases and is being followed by the oncology, surgery, and dermatology departments.

Comment

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but immunosuppression and UV radiation, possibly through its immunosuppressive effects, appear to be contributing factors. More recently, the Merkel cell polyomavirus has been linked to MCC in approximately 80% of cases.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma is more common in individuals with fair skin, and the average age at diagnosis is 69 years.1 Patients typically present with an asymptomatic, firm, erythematous or violaceous, dome-shaped nodule or a small indurated plaque, most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck followed by the upper and lower extremities including the hands, feet, ankles, and wrists. Fifteen percent to 20% of MCCs develop on the legs and feet.1 Our patient presented with an MCC that developed on the right shin at a vein graft donor site.

The development of a cutaneous malignancy in a chronic wound (also known as a Marjolin ulcer) is a rare but well-recognized process. These malignancies occur in previously traumatized or chronically inflamed wounds and have been found to occur most commonly in chronic burn wounds, especially in ungrafted full-thickness burns. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the most common malignancies to arise in chronic wounds, but basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, adenoacanthomas, liposarcomas, and osteosarcomas also have been reported.3 There also have been a few reports of MCC associated with Bowen disease that developed in burn wounds.4 These malignancies generally occur years after injury (average, 35.5 years), but there have been reports of keratoacanthomas developing as early as 3 weeks after injury.5,6

In some reports, malignancies in skin graft donor sites are differentiated from Marjolin ulcers, as the former appear in healed surgical wounds rather than in chronic unstable wounds and tend to occur sooner (ie, in weeks to months after graft harvesting).7,8 The development of these malignancies in graft donor sites is not as well recognized and has been reported in donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs), full-thickness skin grafts, tendon grafts, and bone grafts. In addition to malignancies that arise de novo, some develop due to metastatic and iatrogenic spread. The majority of reported malignancies in tendon and bone graft donor sites have been due to metastasis or iatrogenic spread.9-14

Iatrogenic implantation of tumor cells is a well-recognized phenomenon. Hussain et al10 reported a case of implantation of SCC in an STSG donor site, most likely due to direct seeding from a hollow needle used to infiltrate local anesthetic in the tumor area and the STSG. In this case, metastasis could not be completely ruled out.10 There also have been reports of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, scirrhous carcinoma of the breast, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma thought to be implanted at bone graft donor sites.14-17 Iatrogenic spread of malignancies can occur through seeding from contaminated gloves or instruments such as hollow bore needles or trocar placement in laparoscopic surgery.11 Airborne spread also may be possible, as viable melanoma cells have been detected in electrocautery plume in mice.13

Metastatic malignancies including metastases from SCC, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, and osteosarcoma also have been reported to develop in graft donor sites.11,13,18,19 Many malignancies thought to have developed from iatrogenic seeding may actually be from metastasis either by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. A possible contributing factor may be surgery-induced immunosuppression, which has been linked to increased tumor metastasis formation.20 Surgery or trauma have been shown to have an effect on cellular components of the immune system, causing changes such as a shift in T lymphocytes toward immune-suppressive T lymphocytes and impaired function of natural killer cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.20 The suppression of cell-mediated immunity has been shown to decrease over days to weeks in the postoperative period.21 In addition to surgery- or trauma-induced immunosuppression, the risk for metastasis may increase due to increased vascular, including lymphatic, flow toward a skin graft donor site.13,16 Furthermore, trauma predisposes areas to a hypercoagulable state with increased sludging as well as increased platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, which may lead to localization of metastatic lesions.22 All of these factors could potentially work simultaneously to induce the development of metastasis in graft donor sites.

We found that SCCs and keratoacanthomas, which may be a variant of SCC, are among the only primary malignancies that have been reported to develop in skin graft donor sites.6-8 Malignancies in these donor sites appear to develop sooner than those found in chronic wounds and are reported to develop within weeks to several months postoperatively, even in as few as 2 weeks.6,8 Tamir et al6 reported 2 keratoacanthomas that developed simultaneously in a burn scar and STSG donor site. The investigators believed it could be a sign of reduced immune surveillance in the 2 affected areas.6 It has been hypothesized that one cause of local immune suppression in Marjolin ulcers could be due to poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue, which would prevent delivery of antigens and stimulated lymphocytes.23 Haik et al7 considered this possibility when discussing a case of SCC that developed at the site of an STSG. The authors did not feel it applied, however, as the donor site had only undergone a single skin harvesting procedure.7 Ponnuvelu et al8 felt that inflammation was the underlying etiology behind the 2 cases they reported of SCCs that developed in STSG donor sites. The inflammation associated with tumors has many of the same processes involved in wound healing (eg, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis). Ponnuvelu et al8 hypothesized that the local inflammation caused by graft harvesting produced an ideal environment for early carcinogenesis. Although in chronic wounds it is believed that continual repair and regeneration in recurrent ulceration contributes to neoplastic initiation, it is thought that even a single injury may lead to malignant change, which may be because prior actinic damage or another cause has made the area more susceptible to these changes.24,25 Surgery-induced immunosuppression also may play a role in development of primary malignancies in graft donor sites.

There have been a few reports of SCCs and basal cell carcinomas occurring in other surgical scars that healed without complications.24,26-28 Similar to the malignancies in graft donor sites, some authors differentiate malignancies that occur in surgical scars that heal without complications from Marjolin ulcers, as they do not occur in chronically irritated wounds. These malignancies have been reported in scars from sternotomies, an infertility procedure, hair transplantation, thyroidectomy, colostomy, cleft lip repair, inguinal hernia repair, and paraumbilical laparoscopic port site. The time between surgery and diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 9 months to 67 years.24,26-28 The development of malignancies in these surgical scars may be due to local immunosuppression, possibly from decreased lymphatic flow; additionally, the inflammation in wound healing may provide the ideal environment for carcinogenesis. Trauma in areas already susceptible to malignant change could be a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Our patient developed an MCC in a vein graft donor site 18 years after vein harvesting. It was likely a primary tumor, as vein harvesting was done for coronary artery bypass graft. There was no evidence of any other lesions on physical examination or computed tomography, making it doubtful that an MCC serving as a primary lesion for seeding or metastasis was present. If such a lesion had been present at that time, it would likely have spread well before the time of presentation to our clinic due to the fast doubling time and high rate of metastasis characteristic of MCCs, further lessening the possibility of metastasis or implantation.

The extended length of time from procedure to lesion development in our patient is much longer than for other reported malignancies in graft donor sites, but the reported time for malignancies in other postsurgical scars is more varied. Regardless of whether the MCC in our patient is classified as a Marjolin ulcer, the pathogenesis is unclear. It is thought that a single injury could lead to malignant change in predisposed skin. Our patient’s legs did not have any evidence of prior actinic damage; however, it is likely that he had local immune suppression, which may have made him more susceptible to these changes. It is unlikely that surgery-induced immunosuppression played a role in our patient, as specific cellular components of the immune system only appear to be affected over days to weeks in the postoperative period. Although poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue leading to decreased immune surveillance is not generally thought to contribute to malignancies in most surgical scars, our patient underwent vein harvesting. Chronic edema commonly occurs after vein harvesting and is believed to be due to trauma to the lymphatics. Local immune suppression also may have led to increased susceptibility to infection by the MCC polyomavirus, which has been found to be associated with many MCCs. In addition, the area may have been more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to changes from inflammation from wound healing. We suspect together these factors contributed to the development of our patient’s MCC. Although rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for the development of malignancy.

Case Report

A 70-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease presented with a growing lesion on the right leg of 1 year’s duration. The lesion developed at a vein graft donor site for a coronary artery bypass that had been performed 18 years prior to presentation. The patient reported that the lesion was sensitive to touch. Physical examination revealed a 27-mm, firm, violaceous plaque on the medial aspect of the right upper shin (Figure 1). Mild pitting edema also was noted on both lower legs but was more prominent on the right leg. A 6-mm punch biopsy was performed.

Histology showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by intermediate-sized atypical blue cells with scant cytoplasm (Figure 2). The tumor exhibited moderate cytologic atypia with occasional mitotic figures, and lymphovascular invasion was present. Staining for CD3 was negative within the tumor, but a few reactive lymphocytes were highlighted at the periphery. Staining for CD20 and CD30 was negative. Strong and diffuse staining for cyto-keratin 20 and pan-cytokeratin was noted within the tumor with the distinctive perinuclear pattern characteristic of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Staining for cytokeratin 7 was negative. Synaptophysin and chromogranin were strongly and diffusely positive within the tumor, consistent with a diagnosis of MCC.

The patient was found to have stage IIA (T2N0M0) MCC. Computed tomography completed for staging showed no evidence of metastasis. Wide local excision of the lesion was performed. Margins were negative, as was a right inguinal sentinel lymph node dissection. Because of the size of the tumor and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, radiation therapy at the primary tumor site was recommended. Local radiation treatment (200 cGy daily) was administered for a total dose of 5000 cGy over 5 weeks. The patient currently is free of recurrence or metastases and is being followed by the oncology, surgery, and dermatology departments.

Comment

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare aggressive cutaneous malignancy. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, but immunosuppression and UV radiation, possibly through its immunosuppressive effects, appear to be contributing factors. More recently, the Merkel cell polyomavirus has been linked to MCC in approximately 80% of cases.1,2

Merkel cell carcinoma is more common in individuals with fair skin, and the average age at diagnosis is 69 years.1 Patients typically present with an asymptomatic, firm, erythematous or violaceous, dome-shaped nodule or a small indurated plaque, most commonly on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck followed by the upper and lower extremities including the hands, feet, ankles, and wrists. Fifteen percent to 20% of MCCs develop on the legs and feet.1 Our patient presented with an MCC that developed on the right shin at a vein graft donor site.

The development of a cutaneous malignancy in a chronic wound (also known as a Marjolin ulcer) is a rare but well-recognized process. These malignancies occur in previously traumatized or chronically inflamed wounds and have been found to occur most commonly in chronic burn wounds, especially in ungrafted full-thickness burns. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are the most common malignancies to arise in chronic wounds, but basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, melanomas, malignant fibrous histiocytomas, adenoacanthomas, liposarcomas, and osteosarcomas also have been reported.3 There also have been a few reports of MCC associated with Bowen disease that developed in burn wounds.4 These malignancies generally occur years after injury (average, 35.5 years), but there have been reports of keratoacanthomas developing as early as 3 weeks after injury.5,6

In some reports, malignancies in skin graft donor sites are differentiated from Marjolin ulcers, as the former appear in healed surgical wounds rather than in chronic unstable wounds and tend to occur sooner (ie, in weeks to months after graft harvesting).7,8 The development of these malignancies in graft donor sites is not as well recognized and has been reported in donor sites for split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs), full-thickness skin grafts, tendon grafts, and bone grafts. In addition to malignancies that arise de novo, some develop due to metastatic and iatrogenic spread. The majority of reported malignancies in tendon and bone graft donor sites have been due to metastasis or iatrogenic spread.9-14

Iatrogenic implantation of tumor cells is a well-recognized phenomenon. Hussain et al10 reported a case of implantation of SCC in an STSG donor site, most likely due to direct seeding from a hollow needle used to infiltrate local anesthetic in the tumor area and the STSG. In this case, metastasis could not be completely ruled out.10 There also have been reports of osteosarcoma, ameloblastoma, scirrhous carcinoma of the breast, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma thought to be implanted at bone graft donor sites.14-17 Iatrogenic spread of malignancies can occur through seeding from contaminated gloves or instruments such as hollow bore needles or trocar placement in laparoscopic surgery.11 Airborne spread also may be possible, as viable melanoma cells have been detected in electrocautery plume in mice.13

Metastatic malignancies including metastases from SCC, adenocarcinoma, melanoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, angiosarcoma, and osteosarcoma also have been reported to develop in graft donor sites.11,13,18,19 Many malignancies thought to have developed from iatrogenic seeding may actually be from metastasis either by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. A possible contributing factor may be surgery-induced immunosuppression, which has been linked to increased tumor metastasis formation.20 Surgery or trauma have been shown to have an effect on cellular components of the immune system, causing changes such as a shift in T lymphocytes toward immune-suppressive T lymphocytes and impaired function of natural killer cells, neutrophils, and macrophages.20 The suppression of cell-mediated immunity has been shown to decrease over days to weeks in the postoperative period.21 In addition to surgery- or trauma-induced immunosuppression, the risk for metastasis may increase due to increased vascular, including lymphatic, flow toward a skin graft donor site.13,16 Furthermore, trauma predisposes areas to a hypercoagulable state with increased sludging as well as increased platelet counts and fibrinogen levels, which may lead to localization of metastatic lesions.22 All of these factors could potentially work simultaneously to induce the development of metastasis in graft donor sites.

We found that SCCs and keratoacanthomas, which may be a variant of SCC, are among the only primary malignancies that have been reported to develop in skin graft donor sites.6-8 Malignancies in these donor sites appear to develop sooner than those found in chronic wounds and are reported to develop within weeks to several months postoperatively, even in as few as 2 weeks.6,8 Tamir et al6 reported 2 keratoacanthomas that developed simultaneously in a burn scar and STSG donor site. The investigators believed it could be a sign of reduced immune surveillance in the 2 affected areas.6 It has been hypothesized that one cause of local immune suppression in Marjolin ulcers could be due to poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue, which would prevent delivery of antigens and stimulated lymphocytes.23 Haik et al7 considered this possibility when discussing a case of SCC that developed at the site of an STSG. The authors did not feel it applied, however, as the donor site had only undergone a single skin harvesting procedure.7 Ponnuvelu et al8 felt that inflammation was the underlying etiology behind the 2 cases they reported of SCCs that developed in STSG donor sites. The inflammation associated with tumors has many of the same processes involved in wound healing (eg, cellular proliferation, angiogenesis). Ponnuvelu et al8 hypothesized that the local inflammation caused by graft harvesting produced an ideal environment for early carcinogenesis. Although in chronic wounds it is believed that continual repair and regeneration in recurrent ulceration contributes to neoplastic initiation, it is thought that even a single injury may lead to malignant change, which may be because prior actinic damage or another cause has made the area more susceptible to these changes.24,25 Surgery-induced immunosuppression also may play a role in development of primary malignancies in graft donor sites.

There have been a few reports of SCCs and basal cell carcinomas occurring in other surgical scars that healed without complications.24,26-28 Similar to the malignancies in graft donor sites, some authors differentiate malignancies that occur in surgical scars that heal without complications from Marjolin ulcers, as they do not occur in chronically irritated wounds. These malignancies have been reported in scars from sternotomies, an infertility procedure, hair transplantation, thyroidectomy, colostomy, cleft lip repair, inguinal hernia repair, and paraumbilical laparoscopic port site. The time between surgery and diagnosis of malignancy ranged from 9 months to 67 years.24,26-28 The development of malignancies in these surgical scars may be due to local immunosuppression, possibly from decreased lymphatic flow; additionally, the inflammation in wound healing may provide the ideal environment for carcinogenesis. Trauma in areas already susceptible to malignant change could be a contributing factor.

Conclusion

Our patient developed an MCC in a vein graft donor site 18 years after vein harvesting. It was likely a primary tumor, as vein harvesting was done for coronary artery bypass graft. There was no evidence of any other lesions on physical examination or computed tomography, making it doubtful that an MCC serving as a primary lesion for seeding or metastasis was present. If such a lesion had been present at that time, it would likely have spread well before the time of presentation to our clinic due to the fast doubling time and high rate of metastasis characteristic of MCCs, further lessening the possibility of metastasis or implantation.

The extended length of time from procedure to lesion development in our patient is much longer than for other reported malignancies in graft donor sites, but the reported time for malignancies in other postsurgical scars is more varied. Regardless of whether the MCC in our patient is classified as a Marjolin ulcer, the pathogenesis is unclear. It is thought that a single injury could lead to malignant change in predisposed skin. Our patient’s legs did not have any evidence of prior actinic damage; however, it is likely that he had local immune suppression, which may have made him more susceptible to these changes. It is unlikely that surgery-induced immunosuppression played a role in our patient, as specific cellular components of the immune system only appear to be affected over days to weeks in the postoperative period. Although poor lymphatic regeneration in scar tissue leading to decreased immune surveillance is not generally thought to contribute to malignancies in most surgical scars, our patient underwent vein harvesting. Chronic edema commonly occurs after vein harvesting and is believed to be due to trauma to the lymphatics. Local immune suppression also may have led to increased susceptibility to infection by the MCC polyomavirus, which has been found to be associated with many MCCs. In addition, the area may have been more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to changes from inflammation from wound healing. We suspect together these factors contributed to the development of our patient’s MCC. Although rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for the development of malignancy.

- Swann MH, Yoon J. Merkel cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:51-56.

- Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-149.

- Kadir AR. Burn scar neoplasm. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2007;20:185-188.

- Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:680-689.

- Guenther N, Menenakos C, Braumann C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on a skin graft 64 years after primary injury. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:27.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:870-871.

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893.

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MF, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169.

- Bekar A, Kahveci R, Tolunay S, et al. Metastatic gliosarcoma mass extension to a donor fascia lata graft harvest site by tumor cell contamination. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:719-721.

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692.

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Serrano-Ortega S, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega del Olmo RM, et al. Melanoma metastasis in donor site of full-thickness skin graft. Dermatology. 2000;201:377-378.

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266.

- Yip KM, Lin J, Kumta SM. A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. a case report. Int Orthop. 1996;20:389-391.

- Dias RG, Abudu A, Carter SR, et al. Tumour transfer to bone graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature of the mechanism of seeding. Sarcoma. 2000;4:57-59.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419.

- Singh C, Ibrahim S, Pang KS, et al. Implantation metastasis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11:94-96.

- Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993;80:366.

- Yamasaki O, Terao K, Asagoe K, et al. Koebner phenomenon on skin graft donor site in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:584-586.

- Hogan BV, Peter MB, Shenoy HG, et al. Surgery induced immunosuppression. Surgeon. 2011;9:38-43.

- Neeman E, Ben-Eliyahu S. The perioperative period and promotion of cancer metastasis: new outlooks on mediating mechanisms and immune involvement. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):32-40.

- Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Trauma as a cause of localization of blood-borne metastases: preventive effect of heparin and fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1965;161:97-102.

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683.

- Korula R, Hughes CF. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a sternotomy scar. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:667-669.

- Kennedy CTC, Burd DAR, Creamer D. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 2. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:28.1-28.94.

- Durrani AJ, Miller RJ, Davies M. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a laparoscopic port site scar at the umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:348-350.

- Kotwal S, Madaan S, Prescott S, et al. Unusual squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum arising from a well healed, innocuous scar of an infertility procedure: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:17-19.

- Ozyazgan I, Kontas O. Previous injuries or scars as risk factors for the development of basal cell carcinoma. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38:11-15.

- Swann MH, Yoon J. Merkel cell carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:51-56.

- Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC. Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:141-149.

- Kadir AR. Burn scar neoplasm. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2007;20:185-188.

- Walsh NM. Primary neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma of the skin: morphologic diversity and implications thereof. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:680-689.

- Guenther N, Menenakos C, Braumann C, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising on a skin graft 64 years after primary injury. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:27.

- Tamir G, Morgenstern S, Ben-Amitay D, et al. Synchronous appearance of keratoacanthomas in burn scar and skin graft donor site shortly after injury. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:870-871.

- Haik J, Georgiou I, Farber N, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. Burns. 2008;34:891-893.

- Ponnuvelu G, Ng MF, Connolly CM, et al. Inflammation to skin malignancy, time to rethink the link: SCC in skin graft donor sites. Surgeon. 2011;9:168-169.

- Bekar A, Kahveci R, Tolunay S, et al. Metastatic gliosarcoma mass extension to a donor fascia lata graft harvest site by tumor cell contamination. World Neurosurg. 2010;73:719-721.

- Hussain A, Ekwobi C, Watson S. Metastatic implantation squamous cell carcinoma in a split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:690-692.

- May JT, Patil YJ. Keratoacanthoma-type squamous cell carcinoma developing in a skin graft donor site after tumor extirpation at a distant site. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E11-E13.

- Serrano-Ortega S, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega del Olmo RM, et al. Melanoma metastasis in donor site of full-thickness skin graft. Dermatology. 2000;201:377-378.

- Wright H, McKinnell TH, Dunkin C. Recurrence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma at remote limb donor site. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1265-1266.

- Yip KM, Lin J, Kumta SM. A pelvic osteosarcoma with metastasis to the donor site of the bone graft. a case report. Int Orthop. 1996;20:389-391.

- Dias RG, Abudu A, Carter SR, et al. Tumour transfer to bone graft donor site: a case report and review of the literature of the mechanism of seeding. Sarcoma. 2000;4:57-59.

- Neilson D, Emerson DJ, Dunn L. Squamous cell carcinoma of skin developing in a skin graft donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1988;41:417-419.

- Singh C, Ibrahim S, Pang KS, et al. Implantation metastasis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2003;11:94-96.

- Enion DS, Scott MJ, Gouldesbrough D. Cutaneous metastasis from a malignant fibrous histiocytoma to a limb skin graft donor site. Br J Surg. 1993;80:366.

- Yamasaki O, Terao K, Asagoe K, et al. Koebner phenomenon on skin graft donor site in cutaneous angiosarcoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:584-586.

- Hogan BV, Peter MB, Shenoy HG, et al. Surgery induced immunosuppression. Surgeon. 2011;9:38-43.

- Neeman E, Ben-Eliyahu S. The perioperative period and promotion of cancer metastasis: new outlooks on mediating mechanisms and immune involvement. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(suppl):32-40.

- Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Trauma as a cause of localization of blood-borne metastases: preventive effect of heparin and fibrinolysin. Ann Surg. 1965;161:97-102.

- Hammond JS, Thomsen S, Ward CG. Scar carcinoma arising acutely in a skin graft donor site. J Trauma. 1987;27:681-683.

- Korula R, Hughes CF. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a sternotomy scar. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;51:667-669.

- Kennedy CTC, Burd DAR, Creamer D. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, et al, eds. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. Vol 2. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010:28.1-28.94.

- Durrani AJ, Miller RJ, Davies M. Basal cell carcinoma arising in a laparoscopic port site scar at the umbilicus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:348-350.

- Kotwal S, Madaan S, Prescott S, et al. Unusual squamous cell carcinoma of the scrotum arising from a well healed, innocuous scar of an infertility procedure: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:17-19.

- Ozyazgan I, Kontas O. Previous injuries or scars as risk factors for the development of basal cell carcinoma. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2004;38:11-15.

Practice Points

- Malignancies (both primary and metastatic) can develop in graft donor sites including donor sites for split-thickness skin, full-thickness skin, tendon, bone, and vein grafts.

- Primary malignancies that develop in graft donor sites may be distinct from malignancies that develop in chronic wounds, as the former occur in healed surgical wounds and tend to occur sooner after injury (ie, weeks to months after graft harvesting versus years).

- Although the occurrence is rare, graft donor sites should be examined periodically for development of malignancies.

Highlights From the 2016 AAN Annual Meeting

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Irregular, Smooth, Pink Plaque on the Back

The Diagnosis: Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) was first described in 19531 and was thought to be premalignant as evidenced by the proposed name premalignant fibroepithelial tumor of the skin. This neoplasm now is largely believed to represent a rare form of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Typical presentation is a smooth, flesh-colored or pink plaque or nodule.2 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus has a predilection for the lumbosacral back, though the groin also has been reported as a common site of incidence.1,3 Similar to other BCCs, it is seen in older individuals, typically those older than 50 years.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of FeP can be difficult. The differential diagnosis of FeP can include acrochordon, amelanotic melanoma, compound nevus, hemangioma, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceous, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.5 Dermoscopic evaluation can aid in the diagnosis. A vascular network composed of fine arborizing vessels with or without dotted vessels and white streaks are characteristic findings of FeP. Patients with pigment also demonstrate structureless gray-brown areas and gray-blue dots.6

Biopsy with subsequent histopathologic evaluation confirms the diagnosis of FeP. The characteristic microscopic findings of thin eosinophilic epithelial strands with eccrine ducts anastomosing in an abundant fibromyxoid stroma with collections of basophilic cells located at the ends of the epithelial strands were demonstrated in our patient’s histopathologic specimen (Figure). The histologic appearance is similar to syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro. Recognition of basaloid nests, which often demonstrate retraction, and mitotic activity can differentiate FeP from syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro.7

Treatment of FeP is largely the same as other BCCs including destruction by electrodesiccation and curettage or complete removal by surgical excision. Several studies have demonstrated effective treatment of nonaggressive BCCs with curettage alone and subjectively reported improved cosmesis compared to electrodesiccation and curettage.8-10 Although methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy has demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy for superficial and nodular BCCs,11 a case report utilizing the same modality for FeP did not provide adequate response.12 However, adequate data are not available to assess potential use of this less invasive therapy.

- Pinkus H. Premalignant fibroepithelial tumors of skin. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67:598-615.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Barr RJ, Herten RJ, Stone OJ. Multiple premalignant fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 1978;21:335-337.

- Betti R, Inselvini E, Carducci M, et al. Age and site prevalence of histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:174-176.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presenting as a sessile thigh nodule. Skinmed. 2003;2:385-387.

- Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Broganelli P, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1318-1322.

- Schadt CR, Boyd AS. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma with co-existent squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):71-74.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, et al. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1039-1045.

- McDaniel WE. Therapy for basal cell epitheliomas by curettage only. further study. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:901-903.

- Reymann F. 15 Years’ experience with treatment of basal cell carcinomas of the skin with curettage. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1985;120:56-59.

- Fai D, Arpaia N, Romano I, et al. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancers: a retrospective analysis of response in 462 patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:281-285.

- Park MY, Kim YC. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: poor response to topical photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:133-134.

The Diagnosis: Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) was first described in 19531 and was thought to be premalignant as evidenced by the proposed name premalignant fibroepithelial tumor of the skin. This neoplasm now is largely believed to represent a rare form of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Typical presentation is a smooth, flesh-colored or pink plaque or nodule.2 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus has a predilection for the lumbosacral back, though the groin also has been reported as a common site of incidence.1,3 Similar to other BCCs, it is seen in older individuals, typically those older than 50 years.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of FeP can be difficult. The differential diagnosis of FeP can include acrochordon, amelanotic melanoma, compound nevus, hemangioma, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceous, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.5 Dermoscopic evaluation can aid in the diagnosis. A vascular network composed of fine arborizing vessels with or without dotted vessels and white streaks are characteristic findings of FeP. Patients with pigment also demonstrate structureless gray-brown areas and gray-blue dots.6

Biopsy with subsequent histopathologic evaluation confirms the diagnosis of FeP. The characteristic microscopic findings of thin eosinophilic epithelial strands with eccrine ducts anastomosing in an abundant fibromyxoid stroma with collections of basophilic cells located at the ends of the epithelial strands were demonstrated in our patient’s histopathologic specimen (Figure). The histologic appearance is similar to syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro. Recognition of basaloid nests, which often demonstrate retraction, and mitotic activity can differentiate FeP from syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro.7

Treatment of FeP is largely the same as other BCCs including destruction by electrodesiccation and curettage or complete removal by surgical excision. Several studies have demonstrated effective treatment of nonaggressive BCCs with curettage alone and subjectively reported improved cosmesis compared to electrodesiccation and curettage.8-10 Although methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy has demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy for superficial and nodular BCCs,11 a case report utilizing the same modality for FeP did not provide adequate response.12 However, adequate data are not available to assess potential use of this less invasive therapy.

The Diagnosis: Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP) was first described in 19531 and was thought to be premalignant as evidenced by the proposed name premalignant fibroepithelial tumor of the skin. This neoplasm now is largely believed to represent a rare form of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Typical presentation is a smooth, flesh-colored or pink plaque or nodule.2 Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus has a predilection for the lumbosacral back, though the groin also has been reported as a common site of incidence.1,3 Similar to other BCCs, it is seen in older individuals, typically those older than 50 years.3,4

Clinical diagnosis of FeP can be difficult. The differential diagnosis of FeP can include acrochordon, amelanotic melanoma, compound nevus, hemangioma, neurofibroma, nevus sebaceous, pyogenic granuloma, and seborrheic keratosis.5 Dermoscopic evaluation can aid in the diagnosis. A vascular network composed of fine arborizing vessels with or without dotted vessels and white streaks are characteristic findings of FeP. Patients with pigment also demonstrate structureless gray-brown areas and gray-blue dots.6

Biopsy with subsequent histopathologic evaluation confirms the diagnosis of FeP. The characteristic microscopic findings of thin eosinophilic epithelial strands with eccrine ducts anastomosing in an abundant fibromyxoid stroma with collections of basophilic cells located at the ends of the epithelial strands were demonstrated in our patient’s histopathologic specimen (Figure). The histologic appearance is similar to syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro. Recognition of basaloid nests, which often demonstrate retraction, and mitotic activity can differentiate FeP from syringofibroadenoma of Mascaro.7

Treatment of FeP is largely the same as other BCCs including destruction by electrodesiccation and curettage or complete removal by surgical excision. Several studies have demonstrated effective treatment of nonaggressive BCCs with curettage alone and subjectively reported improved cosmesis compared to electrodesiccation and curettage.8-10 Although methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy has demonstrated some therapeutic efficacy for superficial and nodular BCCs,11 a case report utilizing the same modality for FeP did not provide adequate response.12 However, adequate data are not available to assess potential use of this less invasive therapy.

- Pinkus H. Premalignant fibroepithelial tumors of skin. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67:598-615.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Barr RJ, Herten RJ, Stone OJ. Multiple premalignant fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 1978;21:335-337.

- Betti R, Inselvini E, Carducci M, et al. Age and site prevalence of histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:174-176.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presenting as a sessile thigh nodule. Skinmed. 2003;2:385-387.

- Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Broganelli P, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1318-1322.

- Schadt CR, Boyd AS. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma with co-existent squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):71-74.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, et al. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1039-1045.

- McDaniel WE. Therapy for basal cell epitheliomas by curettage only. further study. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:901-903.

- Reymann F. 15 Years’ experience with treatment of basal cell carcinomas of the skin with curettage. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1985;120:56-59.

- Fai D, Arpaia N, Romano I, et al. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancers: a retrospective analysis of response in 462 patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:281-285.

- Park MY, Kim YC. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: poor response to topical photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:133-134.

- Pinkus H. Premalignant fibroepithelial tumors of skin. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1953;67:598-615.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Barr RJ, Herten RJ, Stone OJ. Multiple premalignant fibroepitheliomas of Pinkus: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 1978;21:335-337.

- Betti R, Inselvini E, Carducci M, et al. Age and site prevalence of histologic subtypes of basal cell carcinomas. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:174-176.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus presenting as a sessile thigh nodule. Skinmed. 2003;2:385-387.

- Zalaudek I, Ferrara G, Broganelli P, et al. Dermoscopy patterns of fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1318-1322.

- Schadt CR, Boyd AS. Eccrine syringofibroadenoma with co-existent squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):71-74.

- Barlow JO, Zalla MJ, Kyle A, et al. Treatment of basal cell carcinoma with curettage alone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1039-1045.

- McDaniel WE. Therapy for basal cell epitheliomas by curettage only. further study. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:901-903.

- Reymann F. 15 Years’ experience with treatment of basal cell carcinomas of the skin with curettage. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1985;120:56-59.

- Fai D, Arpaia N, Romano I, et al. Methyl-aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratoses and non-melanoma skin cancers: a retrospective analysis of response in 462 patients. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2009;144:281-285.

- Park MY, Kim YC. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: poor response to topical photodynamic therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:133-134.

If a Chronic Wound Does Not Heal, Biopsy It: A Clinical Lesson on Underlying Malignancies

To the Editor:

Experience, subjective opinion, and relationships with patients are cornerstones of general practice but also can be pitfalls. It is common for a late-presenting patient to offer a seemingly rational explanation for a long-standing lesion. Unless an objective analysis of the clinical problem is undertaken, it can be easy to embark on an incorrect treatment pathway for the patient’s condition.

One of the luxuries of specialist hospital medicine or surgery is the ability to focus on a narrow range of clinical problems, which makes it easier to spot the anomaly, as long as it is within the purview of the practitioner. We report 2 cases of skin malignancies that were assumed to be chronic wounds of benign etiology.

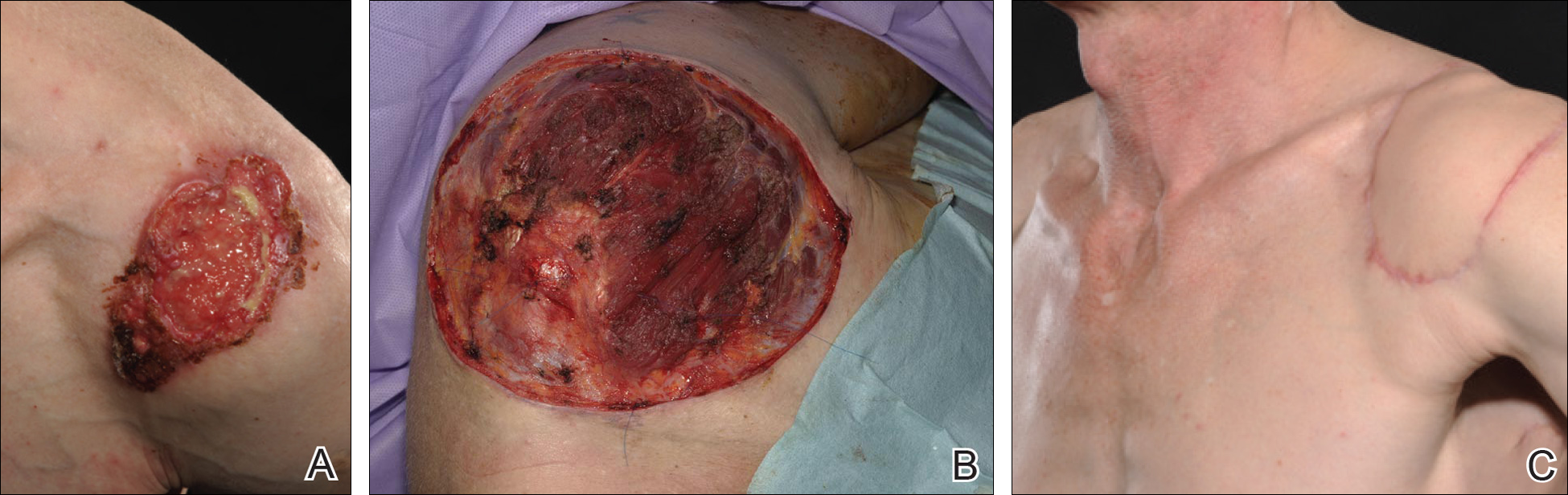

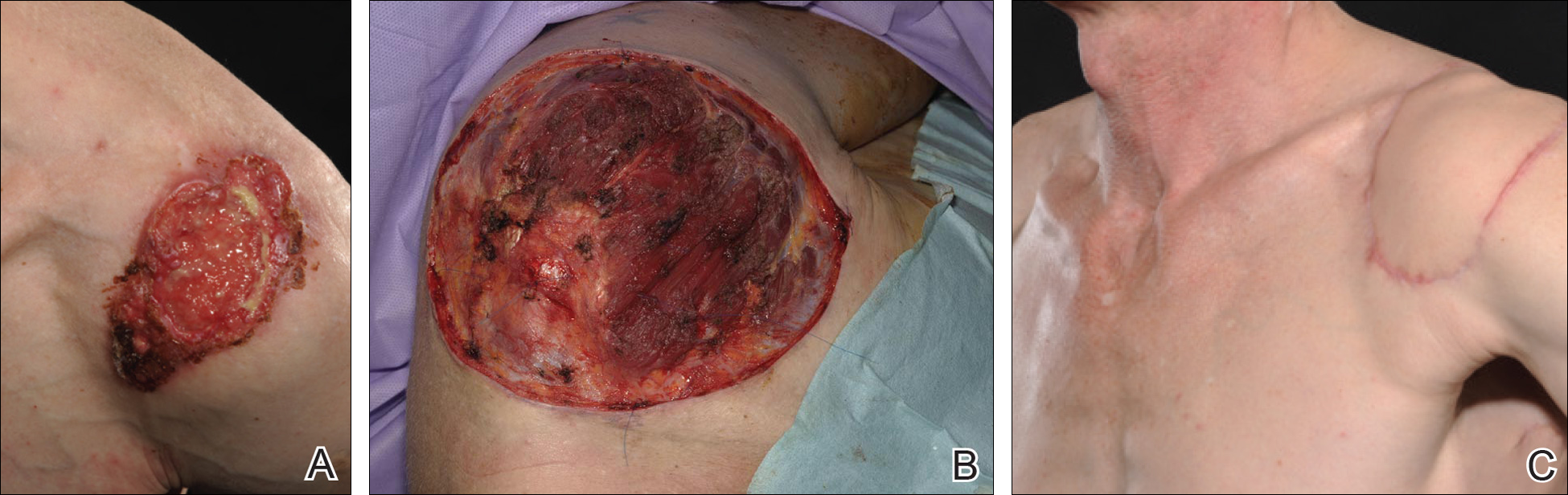

A 63-year-old builder was referred by his general practitioner with a chronic wound on the right forearm of 4 years’ duration. His medical history included psoriasis, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner suggested possible incidental origin following a prior trauma or a psoriatic-related lesion. The patient reported that the lesion did not resemble prior psoriatic lesions and it had deteriorated substantially over the last 2 years. Furthermore, a small ulcer was starting to develop on the left forearm. Further advice was requested by the general practitioner regarding wound dressings. On examination a sloughy ulcer measuring 8.5×7.5 cm had eroded to expose necrotic tendons with surrounding induration and cellulitis (Figure 1A). In addition, a psoriatic lesion was found on the left forearm (Figure 1B). There were no palpable axillary lymph nodes. Clinical suspicion, incision biopsies, and subsequent histology confirmed cutaneous CD4+ T-cell lymphoma. This case was reviewed at a multidisciplinary team meeting and referred to the hematology-oncology department. The patient subsequently underwent chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin and radiotherapy over a period of 5 months. An elective right forearm amputation was planned due to erosion of the ulcer through tendons down to bone (Figure 2).

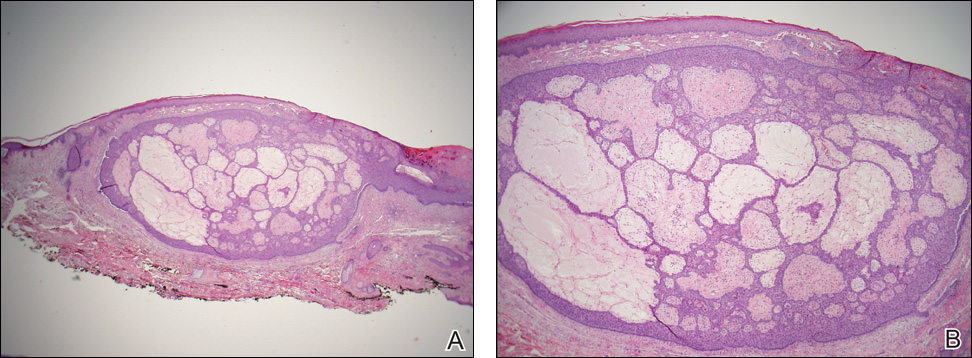

A 48-year-old Latvian lorry driver was referred by his general practitioner with a chronic wound on the left shoulder of 6 years’ duration. His medical history included a partial gastrectomy for a peptic ulcer 18 years prior, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner included a partial gastrectomy for a peptic ulcer 18 years prior, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner suggested the etiology was a burn from a hot metal rod 6 years prior. Advice was sought regarding dressings and suitability for a possible skin graft. Physical examination showed a 4.5×10-cm ulcer fixed to the underlying tissue on the anterior aspect of the left shoulder with no evidence of infection or presence of a foreign body (Figure 3A). Clinical suspicion, incision biopsies, and subsequent histology confirmed a highly infiltrative/morphoeic, partly nodular, and partly diffuse basal cell carcinoma (BCC) that measured 92 mm in diameter extending to the subcutis with no involvement of muscle or perineural or vascular invasion. The patient underwent wide local excision of the BCC with frozen section control. The BCC had eroded into the deltoid muscle and to the periosteum of the clavicle (Figure 3B). The defect was reconstructed with a pedicled muscle-sparing latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap. The patient presented for follow-up months following reconstruction with an uneventful recovery (Figure 3C).

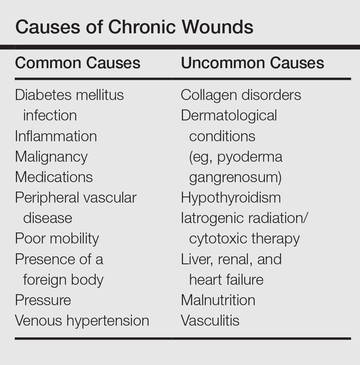

These 2 cases highlight easy pitfalls for an unsuspecting clinician. Although both cases had alternative plausible explanations, they proved to be cutaneous malignancies. The powerful message these cases send is that long-standing chronic wounds should be biopsied to exclude malignancy. Some of the other common underlying causes of wounds that may prevent healing are highlighted in the Table. Vascular insufficiency usually presents in characteristic patterns with a good clinical history and associated signs and findings on investigation. A foreign body, which can be anything from an orthopedic metal implant to a retained stitch from surgery or nonmedical material, may be the culprit and may be identified from a thorough medical history or appropriate imaging.

Infection is another possible explanation of a nonhealing wound. On the face, an underlying dental abscess with a sinus tracking from the root of the tooth to the skin of the cheek or jaw may be the source. Elsewhere on the body, chronic osteomyelitis may be the cause, which may be from any infective origin from Staphylococcus aureus to tuberculosis, and will most commonly present with a discharging sinus but also may present with a nonspecific ulcer.

Chronic wounds also may not heal because of a multitude of patient factors such as poor nutrition, diabetes mellitus, medication (eg, steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), other inflammatory causes, and poor mobility. Chronic wounds represent a substantial burden to patients, health care professionals, and the health care system. In the United States alone, they affect 5.7 million patients and cost an estimated $20 billion.1 Approximately 1% of the Western population will present with leg ulceration at some point in their lives.2

Physical examination of ulcers in any clinical setting can be difficult. We postulate that it can be made more difficult at times in primary care because the patient may add confounding elements for consideration or seemingly plausible explanations. However, whenever possible, a physician should ask, “Could there possibly be an underlying malignancy here?” If there is any chance of malignancy despite plausible explanations being offered, the lesion should be biopsied.

- Branski LK, Gauglitz GG, Herndon DN, et al. A review of gene and stem cell therapy in cutaneous wound healing [published online July 7, 2008]. Burns. 2009;35:171-180.

- Callam MJ. Prevalence of chronic leg ulceration and severe chronic venous disease in western countries. Phlebology. 1992;7(suppl 1):6-12.

To the Editor:

Experience, subjective opinion, and relationships with patients are cornerstones of general practice but also can be pitfalls. It is common for a late-presenting patient to offer a seemingly rational explanation for a long-standing lesion. Unless an objective analysis of the clinical problem is undertaken, it can be easy to embark on an incorrect treatment pathway for the patient’s condition.

One of the luxuries of specialist hospital medicine or surgery is the ability to focus on a narrow range of clinical problems, which makes it easier to spot the anomaly, as long as it is within the purview of the practitioner. We report 2 cases of skin malignancies that were assumed to be chronic wounds of benign etiology.

A 63-year-old builder was referred by his general practitioner with a chronic wound on the right forearm of 4 years’ duration. His medical history included psoriasis, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner suggested possible incidental origin following a prior trauma or a psoriatic-related lesion. The patient reported that the lesion did not resemble prior psoriatic lesions and it had deteriorated substantially over the last 2 years. Furthermore, a small ulcer was starting to develop on the left forearm. Further advice was requested by the general practitioner regarding wound dressings. On examination a sloughy ulcer measuring 8.5×7.5 cm had eroded to expose necrotic tendons with surrounding induration and cellulitis (Figure 1A). In addition, a psoriatic lesion was found on the left forearm (Figure 1B). There were no palpable axillary lymph nodes. Clinical suspicion, incision biopsies, and subsequent histology confirmed cutaneous CD4+ T-cell lymphoma. This case was reviewed at a multidisciplinary team meeting and referred to the hematology-oncology department. The patient subsequently underwent chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin and radiotherapy over a period of 5 months. An elective right forearm amputation was planned due to erosion of the ulcer through tendons down to bone (Figure 2).

A 48-year-old Latvian lorry driver was referred by his general practitioner with a chronic wound on the left shoulder of 6 years’ duration. His medical history included a partial gastrectomy for a peptic ulcer 18 years prior, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner included a partial gastrectomy for a peptic ulcer 18 years prior, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner suggested the etiology was a burn from a hot metal rod 6 years prior. Advice was sought regarding dressings and suitability for a possible skin graft. Physical examination showed a 4.5×10-cm ulcer fixed to the underlying tissue on the anterior aspect of the left shoulder with no evidence of infection or presence of a foreign body (Figure 3A). Clinical suspicion, incision biopsies, and subsequent histology confirmed a highly infiltrative/morphoeic, partly nodular, and partly diffuse basal cell carcinoma (BCC) that measured 92 mm in diameter extending to the subcutis with no involvement of muscle or perineural or vascular invasion. The patient underwent wide local excision of the BCC with frozen section control. The BCC had eroded into the deltoid muscle and to the periosteum of the clavicle (Figure 3B). The defect was reconstructed with a pedicled muscle-sparing latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap. The patient presented for follow-up months following reconstruction with an uneventful recovery (Figure 3C).

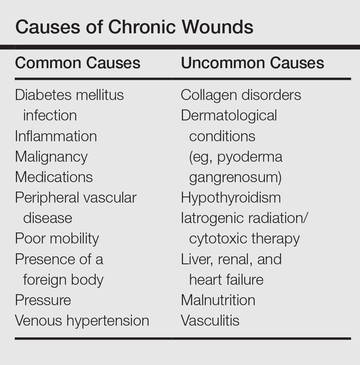

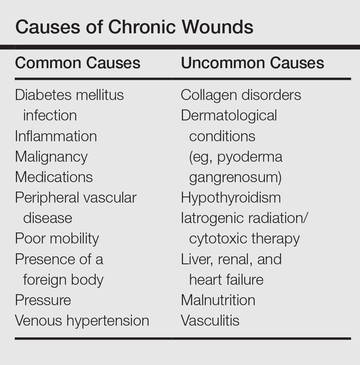

These 2 cases highlight easy pitfalls for an unsuspecting clinician. Although both cases had alternative plausible explanations, they proved to be cutaneous malignancies. The powerful message these cases send is that long-standing chronic wounds should be biopsied to exclude malignancy. Some of the other common underlying causes of wounds that may prevent healing are highlighted in the Table. Vascular insufficiency usually presents in characteristic patterns with a good clinical history and associated signs and findings on investigation. A foreign body, which can be anything from an orthopedic metal implant to a retained stitch from surgery or nonmedical material, may be the culprit and may be identified from a thorough medical history or appropriate imaging.

Infection is another possible explanation of a nonhealing wound. On the face, an underlying dental abscess with a sinus tracking from the root of the tooth to the skin of the cheek or jaw may be the source. Elsewhere on the body, chronic osteomyelitis may be the cause, which may be from any infective origin from Staphylococcus aureus to tuberculosis, and will most commonly present with a discharging sinus but also may present with a nonspecific ulcer.

Chronic wounds also may not heal because of a multitude of patient factors such as poor nutrition, diabetes mellitus, medication (eg, steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), other inflammatory causes, and poor mobility. Chronic wounds represent a substantial burden to patients, health care professionals, and the health care system. In the United States alone, they affect 5.7 million patients and cost an estimated $20 billion.1 Approximately 1% of the Western population will present with leg ulceration at some point in their lives.2

Physical examination of ulcers in any clinical setting can be difficult. We postulate that it can be made more difficult at times in primary care because the patient may add confounding elements for consideration or seemingly plausible explanations. However, whenever possible, a physician should ask, “Could there possibly be an underlying malignancy here?” If there is any chance of malignancy despite plausible explanations being offered, the lesion should be biopsied.

To the Editor:

Experience, subjective opinion, and relationships with patients are cornerstones of general practice but also can be pitfalls. It is common for a late-presenting patient to offer a seemingly rational explanation for a long-standing lesion. Unless an objective analysis of the clinical problem is undertaken, it can be easy to embark on an incorrect treatment pathway for the patient’s condition.

One of the luxuries of specialist hospital medicine or surgery is the ability to focus on a narrow range of clinical problems, which makes it easier to spot the anomaly, as long as it is within the purview of the practitioner. We report 2 cases of skin malignancies that were assumed to be chronic wounds of benign etiology.

A 63-year-old builder was referred by his general practitioner with a chronic wound on the right forearm of 4 years’ duration. His medical history included psoriasis, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner suggested possible incidental origin following a prior trauma or a psoriatic-related lesion. The patient reported that the lesion did not resemble prior psoriatic lesions and it had deteriorated substantially over the last 2 years. Furthermore, a small ulcer was starting to develop on the left forearm. Further advice was requested by the general practitioner regarding wound dressings. On examination a sloughy ulcer measuring 8.5×7.5 cm had eroded to expose necrotic tendons with surrounding induration and cellulitis (Figure 1A). In addition, a psoriatic lesion was found on the left forearm (Figure 1B). There were no palpable axillary lymph nodes. Clinical suspicion, incision biopsies, and subsequent histology confirmed cutaneous CD4+ T-cell lymphoma. This case was reviewed at a multidisciplinary team meeting and referred to the hematology-oncology department. The patient subsequently underwent chemotherapy with liposomal doxorubicin and radiotherapy over a period of 5 months. An elective right forearm amputation was planned due to erosion of the ulcer through tendons down to bone (Figure 2).

A 48-year-old Latvian lorry driver was referred by his general practitioner with a chronic wound on the left shoulder of 6 years’ duration. His medical history included a partial gastrectomy for a peptic ulcer 18 years prior, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner included a partial gastrectomy for a peptic ulcer 18 years prior, and he did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or use of immunosuppressants. The general practitioner suggested the etiology was a burn from a hot metal rod 6 years prior. Advice was sought regarding dressings and suitability for a possible skin graft. Physical examination showed a 4.5×10-cm ulcer fixed to the underlying tissue on the anterior aspect of the left shoulder with no evidence of infection or presence of a foreign body (Figure 3A). Clinical suspicion, incision biopsies, and subsequent histology confirmed a highly infiltrative/morphoeic, partly nodular, and partly diffuse basal cell carcinoma (BCC) that measured 92 mm in diameter extending to the subcutis with no involvement of muscle or perineural or vascular invasion. The patient underwent wide local excision of the BCC with frozen section control. The BCC had eroded into the deltoid muscle and to the periosteum of the clavicle (Figure 3B). The defect was reconstructed with a pedicled muscle-sparing latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap. The patient presented for follow-up months following reconstruction with an uneventful recovery (Figure 3C).

These 2 cases highlight easy pitfalls for an unsuspecting clinician. Although both cases had alternative plausible explanations, they proved to be cutaneous malignancies. The powerful message these cases send is that long-standing chronic wounds should be biopsied to exclude malignancy. Some of the other common underlying causes of wounds that may prevent healing are highlighted in the Table. Vascular insufficiency usually presents in characteristic patterns with a good clinical history and associated signs and findings on investigation. A foreign body, which can be anything from an orthopedic metal implant to a retained stitch from surgery or nonmedical material, may be the culprit and may be identified from a thorough medical history or appropriate imaging.

Infection is another possible explanation of a nonhealing wound. On the face, an underlying dental abscess with a sinus tracking from the root of the tooth to the skin of the cheek or jaw may be the source. Elsewhere on the body, chronic osteomyelitis may be the cause, which may be from any infective origin from Staphylococcus aureus to tuberculosis, and will most commonly present with a discharging sinus but also may present with a nonspecific ulcer.