User login

Breakfast Based on Whey Protein May Help Manage Type 2 Diabetes

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - A breakfast rich in whey protein may help people with type 2 diabetes manage their illness better, new research from Israel suggests.

"Whey protein, a byproduct of cheese manufacturing, lowers postprandial glycemia more than other protein sources," said lead author Dr. Daniela Jakubowicz from Wolfson Medical Center at Tel Aviv University."

We found that in type 2 diabetes, increasing protein content at breakfast has a greater impact on weight loss, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), satiety and postprandial glycemia when the protein source is whey protein, compared with other protein sources, such as eggs, tuna and soy," she told Reuters Health by email.

Dr. Jakubowicz and her group presented their findings April 1 at ENDO 2016, the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society, in Boston.

They randomly assigned 48 overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes to one of three isocaloric diets. Over 12 weeks, everyone ate a large breakfast, a medium-sized lunch and a small dinner, but the amount and source of each group's breakfast proteins differed.

At breakfast, the 17 participants in the whey group ate 36 g of protein as part of a whey protein shake consisting of 40% carbohydrate, 40% protein and 20% fat. The 16 participants in the high-protein group ate 36 g of protein in the form of eggs, tuna and cheese (40% carbs; 40% protein; 20% fat). The 15 in the high-carbohydrate group ate 13 g of protein in ready-to-eat cereals (65% carbs; 15% protein; 20% fat).

All three diets included a 660 kcal breakfast, a 567 cal lunch and a 276 cal dinner, with the same composition at lunch and dinner.

After 12 weeks, the participants in the whey protein group lost the most weight (7.6 kg vs. 6.1 kg for participants in the high-protein group and 3.5 kg for those in the high-carbohydrate group (p<0.0001).

Participants on the whey protein diet were less hungry during the day and had lower glucose spikes after meals compared with those on the other two diets.

The drop in HbA1C was 11.5% in the whey group, 7.7% in the protein group and 4.6% in the carbohydrate group (p<0.0001). Compared with the carbohydrate group, the percentage drop in HbA1c was greater by 41% in the protein group and by 64% in the whey group (p<0.0001).

"Whey protein was consumed only at breakfast; however, the improvement of glucose, insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) was also observed after lunch and dinner. The mechanism of this persistent beneficial effect of whey protein needs further research," Dr. Jakubowicz said.

Co-author Dr. Julio Wainstein, also at Wolfson Medical Center, added by email, "Usually, patients with type 2 diabetes are treated with a combination of several antidiabetic drugs to achieve adequate glucose regulation and decrease HbA1c. Whey protein should be considered an important adjuvant in the management of type 2 diabetes."

"Furthermore," Dr. Wainstein added, "it is possible that by adding whey protein to the diet, glucose regulation might be achieved with less medication, which is a valuable advantage in type 2 diabetes treatment."

The study had no commercial funding, and the authors declared no conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - A breakfast rich in whey protein may help people with type 2 diabetes manage their illness better, new research from Israel suggests.

"Whey protein, a byproduct of cheese manufacturing, lowers postprandial glycemia more than other protein sources," said lead author Dr. Daniela Jakubowicz from Wolfson Medical Center at Tel Aviv University."

We found that in type 2 diabetes, increasing protein content at breakfast has a greater impact on weight loss, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), satiety and postprandial glycemia when the protein source is whey protein, compared with other protein sources, such as eggs, tuna and soy," she told Reuters Health by email.

Dr. Jakubowicz and her group presented their findings April 1 at ENDO 2016, the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society, in Boston.

They randomly assigned 48 overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes to one of three isocaloric diets. Over 12 weeks, everyone ate a large breakfast, a medium-sized lunch and a small dinner, but the amount and source of each group's breakfast proteins differed.

At breakfast, the 17 participants in the whey group ate 36 g of protein as part of a whey protein shake consisting of 40% carbohydrate, 40% protein and 20% fat. The 16 participants in the high-protein group ate 36 g of protein in the form of eggs, tuna and cheese (40% carbs; 40% protein; 20% fat). The 15 in the high-carbohydrate group ate 13 g of protein in ready-to-eat cereals (65% carbs; 15% protein; 20% fat).

All three diets included a 660 kcal breakfast, a 567 cal lunch and a 276 cal dinner, with the same composition at lunch and dinner.

After 12 weeks, the participants in the whey protein group lost the most weight (7.6 kg vs. 6.1 kg for participants in the high-protein group and 3.5 kg for those in the high-carbohydrate group (p<0.0001).

Participants on the whey protein diet were less hungry during the day and had lower glucose spikes after meals compared with those on the other two diets.

The drop in HbA1C was 11.5% in the whey group, 7.7% in the protein group and 4.6% in the carbohydrate group (p<0.0001). Compared with the carbohydrate group, the percentage drop in HbA1c was greater by 41% in the protein group and by 64% in the whey group (p<0.0001).

"Whey protein was consumed only at breakfast; however, the improvement of glucose, insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) was also observed after lunch and dinner. The mechanism of this persistent beneficial effect of whey protein needs further research," Dr. Jakubowicz said.

Co-author Dr. Julio Wainstein, also at Wolfson Medical Center, added by email, "Usually, patients with type 2 diabetes are treated with a combination of several antidiabetic drugs to achieve adequate glucose regulation and decrease HbA1c. Whey protein should be considered an important adjuvant in the management of type 2 diabetes."

"Furthermore," Dr. Wainstein added, "it is possible that by adding whey protein to the diet, glucose regulation might be achieved with less medication, which is a valuable advantage in type 2 diabetes treatment."

The study had no commercial funding, and the authors declared no conflicts of interest.

NEW YORK (Reuters Health) - A breakfast rich in whey protein may help people with type 2 diabetes manage their illness better, new research from Israel suggests.

"Whey protein, a byproduct of cheese manufacturing, lowers postprandial glycemia more than other protein sources," said lead author Dr. Daniela Jakubowicz from Wolfson Medical Center at Tel Aviv University."

We found that in type 2 diabetes, increasing protein content at breakfast has a greater impact on weight loss, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), satiety and postprandial glycemia when the protein source is whey protein, compared with other protein sources, such as eggs, tuna and soy," she told Reuters Health by email.

Dr. Jakubowicz and her group presented their findings April 1 at ENDO 2016, the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society, in Boston.

They randomly assigned 48 overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes to one of three isocaloric diets. Over 12 weeks, everyone ate a large breakfast, a medium-sized lunch and a small dinner, but the amount and source of each group's breakfast proteins differed.

At breakfast, the 17 participants in the whey group ate 36 g of protein as part of a whey protein shake consisting of 40% carbohydrate, 40% protein and 20% fat. The 16 participants in the high-protein group ate 36 g of protein in the form of eggs, tuna and cheese (40% carbs; 40% protein; 20% fat). The 15 in the high-carbohydrate group ate 13 g of protein in ready-to-eat cereals (65% carbs; 15% protein; 20% fat).

All three diets included a 660 kcal breakfast, a 567 cal lunch and a 276 cal dinner, with the same composition at lunch and dinner.

After 12 weeks, the participants in the whey protein group lost the most weight (7.6 kg vs. 6.1 kg for participants in the high-protein group and 3.5 kg for those in the high-carbohydrate group (p<0.0001).

Participants on the whey protein diet were less hungry during the day and had lower glucose spikes after meals compared with those on the other two diets.

The drop in HbA1C was 11.5% in the whey group, 7.7% in the protein group and 4.6% in the carbohydrate group (p<0.0001). Compared with the carbohydrate group, the percentage drop in HbA1c was greater by 41% in the protein group and by 64% in the whey group (p<0.0001).

"Whey protein was consumed only at breakfast; however, the improvement of glucose, insulin and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) was also observed after lunch and dinner. The mechanism of this persistent beneficial effect of whey protein needs further research," Dr. Jakubowicz said.

Co-author Dr. Julio Wainstein, also at Wolfson Medical Center, added by email, "Usually, patients with type 2 diabetes are treated with a combination of several antidiabetic drugs to achieve adequate glucose regulation and decrease HbA1c. Whey protein should be considered an important adjuvant in the management of type 2 diabetes."

"Furthermore," Dr. Wainstein added, "it is possible that by adding whey protein to the diet, glucose regulation might be achieved with less medication, which is a valuable advantage in type 2 diabetes treatment."

The study had no commercial funding, and the authors declared no conflicts of interest.

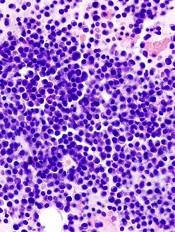

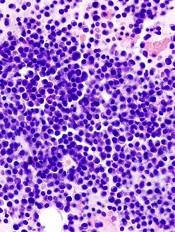

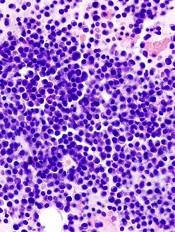

Combo could improve treatment of MM, team says

multiple myeloma

Combining a calcineurin inhibitor and a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor could improve the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

The team found that MM cells express high levels of the protein phosphatase PPP3CA, a subunit of calcineurin.

And combining the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 with the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat suppressed MM cell growth in vitro and decreased tumor growth in mouse models of MM.

Yoichi Imai, MD, PhD, of Tokyo Women’s Medical University in Japan, and colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JCI Insight.

First, the team observed increased PPP3CA expression in MM cell lines and MM cells isolated from patients with advanced disease.

Then, the researchers found that panobinostat reduced PPP3CA expression in MM cell lines. And further investigation revealed that the drug induced degradation of PPP3CA through HSP90 inhibition.

When the team knocked down PPP3CA in MM cells, they observed a reduction in cell growth. And when they overexpressed PPP3CA, they observed enhanced MM cell growth.

The researchers noted that FK506 inhibits the association between PPP3CA and calcineurin B. Unfortunately, FK506 alone did not suppress the growth of MM cells in vitro.

However, when FK506 was given with panobinostat or the HDAC inhibitor ACY-1215, the researchers observed a greater reduction in MM cell growth than with either HDAC inhibitor alone.

Panobinostat and FK506 reduced the growth of MM cells that were t(4;14)-positive (KMS-11, KMS-18, and KMS-26) and t(4;14)-negative (U266 and KMS-12PE) more effectively than panobinostat alone.

In mice with MM, those treated with FK506 alone had tumor sizes similar to control mice. However, mice treated with panobinostat saw a decrease in tumor size. And this effect was enhanced by the addition of FK506.

The researchers observed reduced PPP3CA expression, enhanced histone H3 acetylation, and cleavage of caspase-3 in samples from panobinostat-treated mice. And FK506 augmented panobinostat-induced apoptosis.

The team said these results suggest that FK506 enhances the antimyeloma effect of panobinostat through PPP3CA reduction, which supports the importance of calcineurin in the pathogenesis of MM. ![]()

multiple myeloma

Combining a calcineurin inhibitor and a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor could improve the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

The team found that MM cells express high levels of the protein phosphatase PPP3CA, a subunit of calcineurin.

And combining the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 with the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat suppressed MM cell growth in vitro and decreased tumor growth in mouse models of MM.

Yoichi Imai, MD, PhD, of Tokyo Women’s Medical University in Japan, and colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JCI Insight.

First, the team observed increased PPP3CA expression in MM cell lines and MM cells isolated from patients with advanced disease.

Then, the researchers found that panobinostat reduced PPP3CA expression in MM cell lines. And further investigation revealed that the drug induced degradation of PPP3CA through HSP90 inhibition.

When the team knocked down PPP3CA in MM cells, they observed a reduction in cell growth. And when they overexpressed PPP3CA, they observed enhanced MM cell growth.

The researchers noted that FK506 inhibits the association between PPP3CA and calcineurin B. Unfortunately, FK506 alone did not suppress the growth of MM cells in vitro.

However, when FK506 was given with panobinostat or the HDAC inhibitor ACY-1215, the researchers observed a greater reduction in MM cell growth than with either HDAC inhibitor alone.

Panobinostat and FK506 reduced the growth of MM cells that were t(4;14)-positive (KMS-11, KMS-18, and KMS-26) and t(4;14)-negative (U266 and KMS-12PE) more effectively than panobinostat alone.

In mice with MM, those treated with FK506 alone had tumor sizes similar to control mice. However, mice treated with panobinostat saw a decrease in tumor size. And this effect was enhanced by the addition of FK506.

The researchers observed reduced PPP3CA expression, enhanced histone H3 acetylation, and cleavage of caspase-3 in samples from panobinostat-treated mice. And FK506 augmented panobinostat-induced apoptosis.

The team said these results suggest that FK506 enhances the antimyeloma effect of panobinostat through PPP3CA reduction, which supports the importance of calcineurin in the pathogenesis of MM. ![]()

multiple myeloma

Combining a calcineurin inhibitor and a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor could improve the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

The team found that MM cells express high levels of the protein phosphatase PPP3CA, a subunit of calcineurin.

And combining the calcineurin inhibitor FK506 with the HDAC inhibitor panobinostat suppressed MM cell growth in vitro and decreased tumor growth in mouse models of MM.

Yoichi Imai, MD, PhD, of Tokyo Women’s Medical University in Japan, and colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in JCI Insight.

First, the team observed increased PPP3CA expression in MM cell lines and MM cells isolated from patients with advanced disease.

Then, the researchers found that panobinostat reduced PPP3CA expression in MM cell lines. And further investigation revealed that the drug induced degradation of PPP3CA through HSP90 inhibition.

When the team knocked down PPP3CA in MM cells, they observed a reduction in cell growth. And when they overexpressed PPP3CA, they observed enhanced MM cell growth.

The researchers noted that FK506 inhibits the association between PPP3CA and calcineurin B. Unfortunately, FK506 alone did not suppress the growth of MM cells in vitro.

However, when FK506 was given with panobinostat or the HDAC inhibitor ACY-1215, the researchers observed a greater reduction in MM cell growth than with either HDAC inhibitor alone.

Panobinostat and FK506 reduced the growth of MM cells that were t(4;14)-positive (KMS-11, KMS-18, and KMS-26) and t(4;14)-negative (U266 and KMS-12PE) more effectively than panobinostat alone.

In mice with MM, those treated with FK506 alone had tumor sizes similar to control mice. However, mice treated with panobinostat saw a decrease in tumor size. And this effect was enhanced by the addition of FK506.

The researchers observed reduced PPP3CA expression, enhanced histone H3 acetylation, and cleavage of caspase-3 in samples from panobinostat-treated mice. And FK506 augmented panobinostat-induced apoptosis.

The team said these results suggest that FK506 enhances the antimyeloma effect of panobinostat through PPP3CA reduction, which supports the importance of calcineurin in the pathogenesis of MM. ![]()

Drug corrects anemia in CKD patients

The investigational therapy roxadustat can effectively treat anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not on dialysis, according to a phase 2 study.

Roxadustat increased and maintained hemoglobin levels and decreased hepcidin levels in these patients, who had not received previous treatment with

erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and were treated with roxadustat regardless of their baseline iron repletion status.

In addition, researchers said there were no serious adverse events related to roxadustat.

Robert Provenzano, MD, of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan, and his colleagues reported these results in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was sponsored by FibroGen, Inc., the company developing roxadustat in collaboration with AstraZeneca.

Roxadustat (FG-4592) is an oral, small-molecule inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase activity. HIF is a transcription factor that induces the natural physiological response to conditions of low oxygen, “turning on” erythropoiesis and other protective pathways.

In this randomized, phase 2 study of roxadustat, 145 patients with anemia (hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL at baseline) and non-dialysis CKD were randomized into 1 of 6 cohorts of approximately 24 patients.

The cohorts had varying roxadustat starting doses (tiered weight and fixed amounts) and frequencies (2 and 3 times weekly), followed by hemoglobin maintenance with roxadustat 1 to 3 times weekly. The treatment duration was 16 or 24 weeks.

Results

Of the 143 patients evaluable for efficacy, 92% achieved a hemoglobin response—defined as a hemoglobin increase of > 1.0 g/dL from baseline and a hemoglobin of > 11.0 g/dL by the end of treatment (up to 16 weeks of treatment in 47 patients, and up to 24 weeks of treatment in 96 patients).

Generally, patients in all cohorts who received higher starting doses of roxadustat demonstrated earlier achievement of the hemoglobin response.

Roxadustat increased hemoglobin independently of the patients’ baseline iron repletion and inflammatory status, as measured by baseline C–reactive protein levels. Intravenous iron was not permitted throughout the study period, and 52.4% of patients were iron-replete at baseline.

Over 16 weeks of treatment, roxadustat decreased hepcidin levels by 16.9% (P=0.004), maintained reticulocyte hemoglobin content, and increased hemoglobin by a mean (±SD) of 1.83 (±0.09) g/dL (P<0.001).

After 8 weeks of roxadustat, total cholesterol levels decreased by a mean (±SD) of 26 (±30) mg/dL (P<0.001).

“In this study, anemia correction was achieved under a range of treatment options, including tiered-weight as well as fixed-starting-dose strategies,” Dr Provenzano said. “Correction of anemia and maintenance of hemoglobin response were seen at different dose frequencies—2 or 3 times weekly for achievement of hemoglobin response; 1, 2, or 3 times weekly for maintenance.”

“Secondary analyses showing decreases in hepcidin and increased iron utilization, as well as reductions in total cholesterol levels, suggest roxadustat consistently affects these parameters.”

Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 80% of all patients.

The most common events that occurred in more than 5% of patients were nausea (9.7%), diarrhea (8.3%), constipation (6.2%), vomiting (5.5%), peripheral edema (12.4%), urinary tract infection (9.7%), nasopharyngitis (9.0%), sinusitis (5.5%), dizziness (6.2%), headache (5.5%), and hypertension (7.6%). ![]()

The investigational therapy roxadustat can effectively treat anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not on dialysis, according to a phase 2 study.

Roxadustat increased and maintained hemoglobin levels and decreased hepcidin levels in these patients, who had not received previous treatment with

erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and were treated with roxadustat regardless of their baseline iron repletion status.

In addition, researchers said there were no serious adverse events related to roxadustat.

Robert Provenzano, MD, of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan, and his colleagues reported these results in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was sponsored by FibroGen, Inc., the company developing roxadustat in collaboration with AstraZeneca.

Roxadustat (FG-4592) is an oral, small-molecule inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase activity. HIF is a transcription factor that induces the natural physiological response to conditions of low oxygen, “turning on” erythropoiesis and other protective pathways.

In this randomized, phase 2 study of roxadustat, 145 patients with anemia (hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL at baseline) and non-dialysis CKD were randomized into 1 of 6 cohorts of approximately 24 patients.

The cohorts had varying roxadustat starting doses (tiered weight and fixed amounts) and frequencies (2 and 3 times weekly), followed by hemoglobin maintenance with roxadustat 1 to 3 times weekly. The treatment duration was 16 or 24 weeks.

Results

Of the 143 patients evaluable for efficacy, 92% achieved a hemoglobin response—defined as a hemoglobin increase of > 1.0 g/dL from baseline and a hemoglobin of > 11.0 g/dL by the end of treatment (up to 16 weeks of treatment in 47 patients, and up to 24 weeks of treatment in 96 patients).

Generally, patients in all cohorts who received higher starting doses of roxadustat demonstrated earlier achievement of the hemoglobin response.

Roxadustat increased hemoglobin independently of the patients’ baseline iron repletion and inflammatory status, as measured by baseline C–reactive protein levels. Intravenous iron was not permitted throughout the study period, and 52.4% of patients were iron-replete at baseline.

Over 16 weeks of treatment, roxadustat decreased hepcidin levels by 16.9% (P=0.004), maintained reticulocyte hemoglobin content, and increased hemoglobin by a mean (±SD) of 1.83 (±0.09) g/dL (P<0.001).

After 8 weeks of roxadustat, total cholesterol levels decreased by a mean (±SD) of 26 (±30) mg/dL (P<0.001).

“In this study, anemia correction was achieved under a range of treatment options, including tiered-weight as well as fixed-starting-dose strategies,” Dr Provenzano said. “Correction of anemia and maintenance of hemoglobin response were seen at different dose frequencies—2 or 3 times weekly for achievement of hemoglobin response; 1, 2, or 3 times weekly for maintenance.”

“Secondary analyses showing decreases in hepcidin and increased iron utilization, as well as reductions in total cholesterol levels, suggest roxadustat consistently affects these parameters.”

Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 80% of all patients.

The most common events that occurred in more than 5% of patients were nausea (9.7%), diarrhea (8.3%), constipation (6.2%), vomiting (5.5%), peripheral edema (12.4%), urinary tract infection (9.7%), nasopharyngitis (9.0%), sinusitis (5.5%), dizziness (6.2%), headache (5.5%), and hypertension (7.6%). ![]()

The investigational therapy roxadustat can effectively treat anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) who are not on dialysis, according to a phase 2 study.

Roxadustat increased and maintained hemoglobin levels and decreased hepcidin levels in these patients, who had not received previous treatment with

erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and were treated with roxadustat regardless of their baseline iron repletion status.

In addition, researchers said there were no serious adverse events related to roxadustat.

Robert Provenzano, MD, of St. John Hospital and Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan, and his colleagues reported these results in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The study was sponsored by FibroGen, Inc., the company developing roxadustat in collaboration with AstraZeneca.

Roxadustat (FG-4592) is an oral, small-molecule inhibitor of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylase activity. HIF is a transcription factor that induces the natural physiological response to conditions of low oxygen, “turning on” erythropoiesis and other protective pathways.

In this randomized, phase 2 study of roxadustat, 145 patients with anemia (hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL at baseline) and non-dialysis CKD were randomized into 1 of 6 cohorts of approximately 24 patients.

The cohorts had varying roxadustat starting doses (tiered weight and fixed amounts) and frequencies (2 and 3 times weekly), followed by hemoglobin maintenance with roxadustat 1 to 3 times weekly. The treatment duration was 16 or 24 weeks.

Results

Of the 143 patients evaluable for efficacy, 92% achieved a hemoglobin response—defined as a hemoglobin increase of > 1.0 g/dL from baseline and a hemoglobin of > 11.0 g/dL by the end of treatment (up to 16 weeks of treatment in 47 patients, and up to 24 weeks of treatment in 96 patients).

Generally, patients in all cohorts who received higher starting doses of roxadustat demonstrated earlier achievement of the hemoglobin response.

Roxadustat increased hemoglobin independently of the patients’ baseline iron repletion and inflammatory status, as measured by baseline C–reactive protein levels. Intravenous iron was not permitted throughout the study period, and 52.4% of patients were iron-replete at baseline.

Over 16 weeks of treatment, roxadustat decreased hepcidin levels by 16.9% (P=0.004), maintained reticulocyte hemoglobin content, and increased hemoglobin by a mean (±SD) of 1.83 (±0.09) g/dL (P<0.001).

After 8 weeks of roxadustat, total cholesterol levels decreased by a mean (±SD) of 26 (±30) mg/dL (P<0.001).

“In this study, anemia correction was achieved under a range of treatment options, including tiered-weight as well as fixed-starting-dose strategies,” Dr Provenzano said. “Correction of anemia and maintenance of hemoglobin response were seen at different dose frequencies—2 or 3 times weekly for achievement of hemoglobin response; 1, 2, or 3 times weekly for maintenance.”

“Secondary analyses showing decreases in hepcidin and increased iron utilization, as well as reductions in total cholesterol levels, suggest roxadustat consistently affects these parameters.”

Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 80% of all patients.

The most common events that occurred in more than 5% of patients were nausea (9.7%), diarrhea (8.3%), constipation (6.2%), vomiting (5.5%), peripheral edema (12.4%), urinary tract infection (9.7%), nasopharyngitis (9.0%), sinusitis (5.5%), dizziness (6.2%), headache (5.5%), and hypertension (7.6%). ![]()

A valuable string of PURLs

Since JFP’s launch of the PURL department in November of 2007, 122 PURLs—Priority Updates from the Research Literature—have been published. The Journal of Family Practice is the exclusive publication venue for these items. Because they have stood the test of time and are one of the more popular columns in JFP, I thought it would be worthwhile to describe the rigorous evaluation they undergo before they are published.

Many studies, but few PURLs. Each year, approximately 200,000 new human medical research studies are indexed on PubMed. Very few of these studies are pertinent to family medicine, however, and even fewer provide new patient-oriented evidence for primary care clinicians.

In 2005, the leaders of the Family Physician Inquiries Network (FPIN), which produces another popular JFP column, Clinical Inquiries, set about identifying high-priority research findings relevant to family medicine. A group of family physicians and librarians began combing the research literature monthly to find those rare randomized trials or high-quality observational studies that pertained to our specialty. To qualify as a PURL, a study had to meet 6 criteria. It had to be scientifically valid, relevant to family medicine, applicable in a medical care setting, immediately implementable, clinically meaningful, and practice changing. These criteria still stand today.

Making the cut. When a study is identified as a potential PURL, it is submitted to one of FPIN’s PURL review groups for a critical appraisal and rigorous peer review. If the group cannot convince the PURLs editors that the original research meets all 6 criteria, the study falls by the wayside. Most potential PURLs do not make the cut. I was one of the early PURL “divers,” and I was amazed at how few PURLs existed. Given the emphasis of research on subspecialties and the dearth of primary care research funding in the United States, I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Holding their value. I reviewed all 122 PURLs this week and am proud to say that nearly all still provide highly pertinent, practice-changing information for family physicians and other primary care clinicians. For a quick review of our string of PURLs, go to www.jfponline.com, select “Articles” in the banner, and then “PURLs,” and read the short practice changer box for each one. I guarantee it will be time well spent!

If you would like to become part of the PURLs process, either by nominating or reviewing a PURL, please contact the PURLs Project Manager at [email protected].

Since JFP’s launch of the PURL department in November of 2007, 122 PURLs—Priority Updates from the Research Literature—have been published. The Journal of Family Practice is the exclusive publication venue for these items. Because they have stood the test of time and are one of the more popular columns in JFP, I thought it would be worthwhile to describe the rigorous evaluation they undergo before they are published.

Many studies, but few PURLs. Each year, approximately 200,000 new human medical research studies are indexed on PubMed. Very few of these studies are pertinent to family medicine, however, and even fewer provide new patient-oriented evidence for primary care clinicians.

In 2005, the leaders of the Family Physician Inquiries Network (FPIN), which produces another popular JFP column, Clinical Inquiries, set about identifying high-priority research findings relevant to family medicine. A group of family physicians and librarians began combing the research literature monthly to find those rare randomized trials or high-quality observational studies that pertained to our specialty. To qualify as a PURL, a study had to meet 6 criteria. It had to be scientifically valid, relevant to family medicine, applicable in a medical care setting, immediately implementable, clinically meaningful, and practice changing. These criteria still stand today.

Making the cut. When a study is identified as a potential PURL, it is submitted to one of FPIN’s PURL review groups for a critical appraisal and rigorous peer review. If the group cannot convince the PURLs editors that the original research meets all 6 criteria, the study falls by the wayside. Most potential PURLs do not make the cut. I was one of the early PURL “divers,” and I was amazed at how few PURLs existed. Given the emphasis of research on subspecialties and the dearth of primary care research funding in the United States, I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Holding their value. I reviewed all 122 PURLs this week and am proud to say that nearly all still provide highly pertinent, practice-changing information for family physicians and other primary care clinicians. For a quick review of our string of PURLs, go to www.jfponline.com, select “Articles” in the banner, and then “PURLs,” and read the short practice changer box for each one. I guarantee it will be time well spent!

If you would like to become part of the PURLs process, either by nominating or reviewing a PURL, please contact the PURLs Project Manager at [email protected].

Since JFP’s launch of the PURL department in November of 2007, 122 PURLs—Priority Updates from the Research Literature—have been published. The Journal of Family Practice is the exclusive publication venue for these items. Because they have stood the test of time and are one of the more popular columns in JFP, I thought it would be worthwhile to describe the rigorous evaluation they undergo before they are published.

Many studies, but few PURLs. Each year, approximately 200,000 new human medical research studies are indexed on PubMed. Very few of these studies are pertinent to family medicine, however, and even fewer provide new patient-oriented evidence for primary care clinicians.

In 2005, the leaders of the Family Physician Inquiries Network (FPIN), which produces another popular JFP column, Clinical Inquiries, set about identifying high-priority research findings relevant to family medicine. A group of family physicians and librarians began combing the research literature monthly to find those rare randomized trials or high-quality observational studies that pertained to our specialty. To qualify as a PURL, a study had to meet 6 criteria. It had to be scientifically valid, relevant to family medicine, applicable in a medical care setting, immediately implementable, clinically meaningful, and practice changing. These criteria still stand today.

Making the cut. When a study is identified as a potential PURL, it is submitted to one of FPIN’s PURL review groups for a critical appraisal and rigorous peer review. If the group cannot convince the PURLs editors that the original research meets all 6 criteria, the study falls by the wayside. Most potential PURLs do not make the cut. I was one of the early PURL “divers,” and I was amazed at how few PURLs existed. Given the emphasis of research on subspecialties and the dearth of primary care research funding in the United States, I probably shouldn’t have been surprised.

Holding their value. I reviewed all 122 PURLs this week and am proud to say that nearly all still provide highly pertinent, practice-changing information for family physicians and other primary care clinicians. For a quick review of our string of PURLs, go to www.jfponline.com, select “Articles” in the banner, and then “PURLs,” and read the short practice changer box for each one. I guarantee it will be time well spent!

If you would like to become part of the PURLs process, either by nominating or reviewing a PURL, please contact the PURLs Project Manager at [email protected].

Increased syncopal episodes post surgery • Dx?

THE CASE

A 58-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for recurrent syncopal and near-syncopal events following surgical repair of a left hip fracture. The first syncopal event occurred one day post-surgery shortly after standing and was attributed to orthostatic hypotension. Subsequently, the patient experienced 2 events during her hospital stay. Both events occurred in the upright position and were preceded by lightheadedness, warmth, and diaphoresis. They were short in duration (<30 seconds) with spontaneous and complete recovery. The patient had no associated chest pain or palpitations.

The patient’s past medical history included osteopenia, dyslipidemia, and vasovagal syncope, averaging one to 2 events per year. Given her past history, the physicians caring for her assumed that she was having recurrences of her vasovagal syncope. She was discharged home on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg/d, sodium chloride 1 g tid, enoxaparin 40 mg/d, and acetaminophen and oxycodone as needed for pain.

One week later, the patient experienced another syncopal event at home, prompting her to visit our clinic for further evaluation. On arrival, her vital signs were stable. Her oxygen saturation level was 98%, she was not orthostatic, and her physical exam and blood studies were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed preserved left ventricular function with no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or strain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s revised Geneva Score for pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2 to 5 depending on the heart rate used (66-80 beats per minute), putting her in a low-to-intermediate risk group with an estimated PE prevalence between 8% and 28%.1 Given her recent surgery and the increase in the frequency of her vasovagal events, a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CT-PA) was performed. The CT-PA showed a PE in the lateral and posterior basal subsegmental branches of the right lower lobe. Doppler ultrasound revealed no evidence of acute deep vein thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Syncope may develop in 9% to 19% of patients with PE.2-6 While syncope in patients with PE is often attributed to reduced cardiac filling secondary to massive emboli, it is important to recognize that patients can also present with vasovagal syncope in the absence of massive emboli.

One mechanism for the development of syncope is right ventricular failure with subsequent impairment of left ventricular filling, leading to arterial hypotension. Indeed, the majority of patients with PE and syncope have a massive embolism defined as greater than a 50% reduction in the pulmonary circulation.7 In one study, 60% of patients with PE who presented with syncope had a massive PE compared to 39% of patients presenting without syncope (P=.036).8

Another reported mechanism for syncope in a patient with PE is transient high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block.9 Sudden increases in right-sided pressure can lead to transient right bundle branch block, which may result in complete heart block in the setting of baseline left bundle branch block.

Lastly, patients with PE may develop a vasovagal-like reaction, such as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, which results in transient arterial hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion.10 In such instances, the postulated mechanism is activation of cardiac vagal afferents, which results in an increase in vagal tone and peripheral sympathetic withdrawal leading to hypotension and syncope. It is important to note that this mechanism can occur in the absence of massive PE. In one study, up to 40% of patients with PE and syncope did not have a massive PE, and almost 6% had thrombi only in small branches of the pulmonary artery.8

This patient had isolated subsegmental defects, identified on the CT-PA. The sensitivity of CT-PA to detect subsegmental PE ranges from 53% to 100%.11 While this test has its limitations, the introduction of the multi-detector CT technique has significantly increased the rate of detection with a specificity of 96%.12,13

Was PE the cause of the syncope, or just an incidental finding?

In this case, we believe the CT-PA findings were diagnostic for PE. What is less clear is whether the PE was the cause of the syncope.

Asymptomatic post-operative PE with isolated subsegmental defects has been reported.14-16 When compared to patients with a defect at a segmental or more proximal level, these patients often have less dyspnea, are less likely to be classified as having a high clinical probability of PE, and have a lower prevalence of proximal deep vein thrombosis (3.3% vs 43.8%; P<.0001).17 Therefore, one could argue that the PE finding in our case was incidental. While this is a possibility, we believe the patient’s syncope was due to PE for the following reasons.

First, several investigators have reported transient increases in vagal tone and syncope following PE consistent with a vasovagal-like response.7,18 Therefore, it is possible that the reduction in preload associated with PE triggered a Bezold-Jarisch-like reflex leading to syncope. The patient’s history of vasovagal syncope was certainly indicative of increased susceptibility to reflex-mediated events, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Second, our patient had a cluster of events following surgery compared to the one to 2 events she experienced per year prior to surgery. The increased incidence of events would be an unusual progression of her syncope in the absence of clear triggers, again rendering our hypothesis more plausible.

The patient was admitted to our hospital and started on a higher dose of enoxaparin (60 mg twice daily). She was subsequently discharged home on rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily and midodrine 2.5 mg twice daily in addition to the medications she was already taking. At her 6-week follow-up visit, she reported no recurrences.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case demonstrates that non-massive PE can present as vasovagal syncope. Recognizing that PE could lead to reflex-mediated syncope in the absence of massive emboli, it is important to rule it out in the evaluation of patients with vasovagal syncope when risk factors for PE are present.

1. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

2. Calvo-Romero JM, Pérez-Miranda M, Bureo-Dacal P. Syncope in acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:208-209.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med. 2003;8:257-261.

4. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, et al. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1165-1171.

5. Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature. Heart Lung. 1999;28:342-347.

6. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

7. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1977;238:2509-2511.

8. Duplyakov D, Kurakina E, Pavlova T, et al. Value of syncope in patients with high-to-intermediate risk pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;4:353-358.

9. Wilner C, Garnier-Crussard JP, Huygue De Mahenge A, et al. [Paroxysmal atrioventricular block, cause of syncope in pulmonary embolism. 2 cases]. Presse Med. 1983;12:2987-2989.

10. Frink RJ, James TN. Intracardiac route of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1464-1469.

11. Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:227-232.

12. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317-2327.

13. Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Multidetector CT scan for acute pulmonary embolism: embolic burden and clinical outcome. Chest. 2012;142:1417-1424.

14. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, et al; Evaluation du Scanner Spiralé dans l’Embolie Pulmonaire study group. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360:1914-1920.

15. Simpson RJ Jr, Podolak R, Mangano CA Jr, et al. Vagal syncope during recurrent pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1983;249:390-393.

16. Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1760-1768.

17. Le Gal G, Righini M, Parent F, et al. Diagnosis and management of subsegmental pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:724-731.

18. Eldadah ZA, Najjar SS, Ziegelstein RC. A patient with syncope, only “vagally” related to the heart. Chest. 2000;117:1801-1803.

THE CASE

A 58-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for recurrent syncopal and near-syncopal events following surgical repair of a left hip fracture. The first syncopal event occurred one day post-surgery shortly after standing and was attributed to orthostatic hypotension. Subsequently, the patient experienced 2 events during her hospital stay. Both events occurred in the upright position and were preceded by lightheadedness, warmth, and diaphoresis. They were short in duration (<30 seconds) with spontaneous and complete recovery. The patient had no associated chest pain or palpitations.

The patient’s past medical history included osteopenia, dyslipidemia, and vasovagal syncope, averaging one to 2 events per year. Given her past history, the physicians caring for her assumed that she was having recurrences of her vasovagal syncope. She was discharged home on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg/d, sodium chloride 1 g tid, enoxaparin 40 mg/d, and acetaminophen and oxycodone as needed for pain.

One week later, the patient experienced another syncopal event at home, prompting her to visit our clinic for further evaluation. On arrival, her vital signs were stable. Her oxygen saturation level was 98%, she was not orthostatic, and her physical exam and blood studies were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed preserved left ventricular function with no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or strain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s revised Geneva Score for pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2 to 5 depending on the heart rate used (66-80 beats per minute), putting her in a low-to-intermediate risk group with an estimated PE prevalence between 8% and 28%.1 Given her recent surgery and the increase in the frequency of her vasovagal events, a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CT-PA) was performed. The CT-PA showed a PE in the lateral and posterior basal subsegmental branches of the right lower lobe. Doppler ultrasound revealed no evidence of acute deep vein thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Syncope may develop in 9% to 19% of patients with PE.2-6 While syncope in patients with PE is often attributed to reduced cardiac filling secondary to massive emboli, it is important to recognize that patients can also present with vasovagal syncope in the absence of massive emboli.

One mechanism for the development of syncope is right ventricular failure with subsequent impairment of left ventricular filling, leading to arterial hypotension. Indeed, the majority of patients with PE and syncope have a massive embolism defined as greater than a 50% reduction in the pulmonary circulation.7 In one study, 60% of patients with PE who presented with syncope had a massive PE compared to 39% of patients presenting without syncope (P=.036).8

Another reported mechanism for syncope in a patient with PE is transient high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block.9 Sudden increases in right-sided pressure can lead to transient right bundle branch block, which may result in complete heart block in the setting of baseline left bundle branch block.

Lastly, patients with PE may develop a vasovagal-like reaction, such as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, which results in transient arterial hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion.10 In such instances, the postulated mechanism is activation of cardiac vagal afferents, which results in an increase in vagal tone and peripheral sympathetic withdrawal leading to hypotension and syncope. It is important to note that this mechanism can occur in the absence of massive PE. In one study, up to 40% of patients with PE and syncope did not have a massive PE, and almost 6% had thrombi only in small branches of the pulmonary artery.8

This patient had isolated subsegmental defects, identified on the CT-PA. The sensitivity of CT-PA to detect subsegmental PE ranges from 53% to 100%.11 While this test has its limitations, the introduction of the multi-detector CT technique has significantly increased the rate of detection with a specificity of 96%.12,13

Was PE the cause of the syncope, or just an incidental finding?

In this case, we believe the CT-PA findings were diagnostic for PE. What is less clear is whether the PE was the cause of the syncope.

Asymptomatic post-operative PE with isolated subsegmental defects has been reported.14-16 When compared to patients with a defect at a segmental or more proximal level, these patients often have less dyspnea, are less likely to be classified as having a high clinical probability of PE, and have a lower prevalence of proximal deep vein thrombosis (3.3% vs 43.8%; P<.0001).17 Therefore, one could argue that the PE finding in our case was incidental. While this is a possibility, we believe the patient’s syncope was due to PE for the following reasons.

First, several investigators have reported transient increases in vagal tone and syncope following PE consistent with a vasovagal-like response.7,18 Therefore, it is possible that the reduction in preload associated with PE triggered a Bezold-Jarisch-like reflex leading to syncope. The patient’s history of vasovagal syncope was certainly indicative of increased susceptibility to reflex-mediated events, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Second, our patient had a cluster of events following surgery compared to the one to 2 events she experienced per year prior to surgery. The increased incidence of events would be an unusual progression of her syncope in the absence of clear triggers, again rendering our hypothesis more plausible.

The patient was admitted to our hospital and started on a higher dose of enoxaparin (60 mg twice daily). She was subsequently discharged home on rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily and midodrine 2.5 mg twice daily in addition to the medications she was already taking. At her 6-week follow-up visit, she reported no recurrences.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case demonstrates that non-massive PE can present as vasovagal syncope. Recognizing that PE could lead to reflex-mediated syncope in the absence of massive emboli, it is important to rule it out in the evaluation of patients with vasovagal syncope when risk factors for PE are present.

THE CASE

A 58-year-old woman sought care at our clinic for recurrent syncopal and near-syncopal events following surgical repair of a left hip fracture. The first syncopal event occurred one day post-surgery shortly after standing and was attributed to orthostatic hypotension. Subsequently, the patient experienced 2 events during her hospital stay. Both events occurred in the upright position and were preceded by lightheadedness, warmth, and diaphoresis. They were short in duration (<30 seconds) with spontaneous and complete recovery. The patient had no associated chest pain or palpitations.

The patient’s past medical history included osteopenia, dyslipidemia, and vasovagal syncope, averaging one to 2 events per year. Given her past history, the physicians caring for her assumed that she was having recurrences of her vasovagal syncope. She was discharged home on fludrocortisone 0.1 mg/d, sodium chloride 1 g tid, enoxaparin 40 mg/d, and acetaminophen and oxycodone as needed for pain.

One week later, the patient experienced another syncopal event at home, prompting her to visit our clinic for further evaluation. On arrival, her vital signs were stable. Her oxygen saturation level was 98%, she was not orthostatic, and her physical exam and blood studies were unremarkable. An echocardiogram showed preserved left ventricular function with no evidence of right ventricular dilatation or strain.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s revised Geneva Score for pulmonary embolism (PE) was 2 to 5 depending on the heart rate used (66-80 beats per minute), putting her in a low-to-intermediate risk group with an estimated PE prevalence between 8% and 28%.1 Given her recent surgery and the increase in the frequency of her vasovagal events, a computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CT-PA) was performed. The CT-PA showed a PE in the lateral and posterior basal subsegmental branches of the right lower lobe. Doppler ultrasound revealed no evidence of acute deep vein thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Syncope may develop in 9% to 19% of patients with PE.2-6 While syncope in patients with PE is often attributed to reduced cardiac filling secondary to massive emboli, it is important to recognize that patients can also present with vasovagal syncope in the absence of massive emboli.

One mechanism for the development of syncope is right ventricular failure with subsequent impairment of left ventricular filling, leading to arterial hypotension. Indeed, the majority of patients with PE and syncope have a massive embolism defined as greater than a 50% reduction in the pulmonary circulation.7 In one study, 60% of patients with PE who presented with syncope had a massive PE compared to 39% of patients presenting without syncope (P=.036).8

Another reported mechanism for syncope in a patient with PE is transient high-degree atrioventricular (AV) block.9 Sudden increases in right-sided pressure can lead to transient right bundle branch block, which may result in complete heart block in the setting of baseline left bundle branch block.

Lastly, patients with PE may develop a vasovagal-like reaction, such as the Bezold-Jarisch reflex, which results in transient arterial hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion.10 In such instances, the postulated mechanism is activation of cardiac vagal afferents, which results in an increase in vagal tone and peripheral sympathetic withdrawal leading to hypotension and syncope. It is important to note that this mechanism can occur in the absence of massive PE. In one study, up to 40% of patients with PE and syncope did not have a massive PE, and almost 6% had thrombi only in small branches of the pulmonary artery.8

This patient had isolated subsegmental defects, identified on the CT-PA. The sensitivity of CT-PA to detect subsegmental PE ranges from 53% to 100%.11 While this test has its limitations, the introduction of the multi-detector CT technique has significantly increased the rate of detection with a specificity of 96%.12,13

Was PE the cause of the syncope, or just an incidental finding?

In this case, we believe the CT-PA findings were diagnostic for PE. What is less clear is whether the PE was the cause of the syncope.

Asymptomatic post-operative PE with isolated subsegmental defects has been reported.14-16 When compared to patients with a defect at a segmental or more proximal level, these patients often have less dyspnea, are less likely to be classified as having a high clinical probability of PE, and have a lower prevalence of proximal deep vein thrombosis (3.3% vs 43.8%; P<.0001).17 Therefore, one could argue that the PE finding in our case was incidental. While this is a possibility, we believe the patient’s syncope was due to PE for the following reasons.

First, several investigators have reported transient increases in vagal tone and syncope following PE consistent with a vasovagal-like response.7,18 Therefore, it is possible that the reduction in preload associated with PE triggered a Bezold-Jarisch-like reflex leading to syncope. The patient’s history of vasovagal syncope was certainly indicative of increased susceptibility to reflex-mediated events, thus supporting our hypothesis.

Second, our patient had a cluster of events following surgery compared to the one to 2 events she experienced per year prior to surgery. The increased incidence of events would be an unusual progression of her syncope in the absence of clear triggers, again rendering our hypothesis more plausible.

The patient was admitted to our hospital and started on a higher dose of enoxaparin (60 mg twice daily). She was subsequently discharged home on rivaroxaban 15 mg twice daily and midodrine 2.5 mg twice daily in addition to the medications she was already taking. At her 6-week follow-up visit, she reported no recurrences.

THE TAKEAWAY

This case demonstrates that non-massive PE can present as vasovagal syncope. Recognizing that PE could lead to reflex-mediated syncope in the absence of massive emboli, it is important to rule it out in the evaluation of patients with vasovagal syncope when risk factors for PE are present.

1. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

2. Calvo-Romero JM, Pérez-Miranda M, Bureo-Dacal P. Syncope in acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:208-209.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med. 2003;8:257-261.

4. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, et al. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1165-1171.

5. Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature. Heart Lung. 1999;28:342-347.

6. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

7. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1977;238:2509-2511.

8. Duplyakov D, Kurakina E, Pavlova T, et al. Value of syncope in patients with high-to-intermediate risk pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;4:353-358.

9. Wilner C, Garnier-Crussard JP, Huygue De Mahenge A, et al. [Paroxysmal atrioventricular block, cause of syncope in pulmonary embolism. 2 cases]. Presse Med. 1983;12:2987-2989.

10. Frink RJ, James TN. Intracardiac route of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1464-1469.

11. Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:227-232.

12. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317-2327.

13. Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Multidetector CT scan for acute pulmonary embolism: embolic burden and clinical outcome. Chest. 2012;142:1417-1424.

14. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, et al; Evaluation du Scanner Spiralé dans l’Embolie Pulmonaire study group. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360:1914-1920.

15. Simpson RJ Jr, Podolak R, Mangano CA Jr, et al. Vagal syncope during recurrent pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1983;249:390-393.

16. Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1760-1768.

17. Le Gal G, Righini M, Parent F, et al. Diagnosis and management of subsegmental pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:724-731.

18. Eldadah ZA, Najjar SS, Ziegelstein RC. A patient with syncope, only “vagally” related to the heart. Chest. 2000;117:1801-1803.

1. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:165-171.

2. Calvo-Romero JM, Pérez-Miranda M, Bureo-Dacal P. Syncope in acute pulmonary embolism. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:208-209.

3. Castelli R, Tarsia P, Tantardini C, et al. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism: comparison between patients with syncope as the presenting symptom of pulmonary embolism and patients with pulmonary embolism without syncope. Vasc Med. 2003;8:257-261.

4. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, et al. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1165-1171.

5. Koutkia P, Wachtel TJ. Pulmonary embolism presenting as syncope: case report and review of the literature. Heart Lung. 1999;28:342-347.

6. Torbicki A, Perrier A, Konstantinides S, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2276-2315.

7. Thames MD, Alpert JS, Dalen JE. Syncope in patients with pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1977;238:2509-2511.

8. Duplyakov D, Kurakina E, Pavlova T, et al. Value of syncope in patients with high-to-intermediate risk pulmonary artery embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2015;4:353-358.

9. Wilner C, Garnier-Crussard JP, Huygue De Mahenge A, et al. [Paroxysmal atrioventricular block, cause of syncope in pulmonary embolism. 2 cases]. Presse Med. 1983;12:2987-2989.

10. Frink RJ, James TN. Intracardiac route of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. Am J Physiol. 1971;221:1464-1469.

11. Rathbun SW, Raskob GE, Whitsett TL. Sensitivity and specificity of helical computed tomography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:227-232.

12. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, et al; PIOPED II Investigators. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317-2327.

13. Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Agnelli G, et al. Multidetector CT scan for acute pulmonary embolism: embolic burden and clinical outcome. Chest. 2012;142:1417-1424.

14. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, et al; Evaluation du Scanner Spiralé dans l’Embolie Pulmonaire study group. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002;360:1914-1920.

15. Simpson RJ Jr, Podolak R, Mangano CA Jr, et al. Vagal syncope during recurrent pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1983;249:390-393.

16. Perrier A, Roy PM, Sanchez O, et al. Multidetector-row computed tomography in suspected pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1760-1768.

17. Le Gal G, Righini M, Parent F, et al. Diagnosis and management of subsegmental pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:724-731.

18. Eldadah ZA, Najjar SS, Ziegelstein RC. A patient with syncope, only “vagally” related to the heart. Chest. 2000;117:1801-1803.

Diabetes update: Your guide to the latest ADA standards

Prevention of diabetes, as well as early detection and treatment of both prediabetes and diabetes, is critical to the health of our country. Because evidence-based guidelines are key to our ability to effectively address the nation’s diabetes epidemic, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) updates its “Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes” annually to incorporate new evidence or clarifications.

The 2016 standards,1 available at professional.diabetes.org/jfp, are a valuable resource. Among the latest revisions: an expansion in screening recommendations, a change in the age at which aspirin therapy for women should be considered, and a change in A1C goals for pregnant women with diabetes.

As members of the ADA’s primary care advisory group, we use a question and answer format in the summary that follows to highlight recent revisions and review other recommendations that are of particular relevance to physicians in primary care. It is important to note, however, that ADA recommendations are not intended to preclude clinical judgment and should be applied in the context of excellent medical care.

Diagnosis and screening

Have the 2016 ADA standards changed the way diabetes is diagnosed?

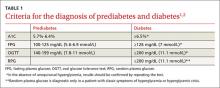

No. The criteria for a diagnosis of diabetes did not change. Diabetes and prediabetes are still screened for and diagnosed with any of the following: a fasting plasma glucose (FPG); a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT); a random plasma glucose >200 mg/dL with symptoms of hyperglycemia; or A1C criteria (TABLE 1).1,2 The wording was changed, however, to make it clear that no one test is preferred over another for diagnosis.

Yes. In addition to screening asymptomatic adults of any age who are overweight or obese and have one or more additional risk factors for diabetes, the 2016 standards recommend screening all adults 45 years and older, regardless of weight.

Is an A1C <7% the recommended treatment goal for everyone with diabetes?

No. An A1C <7% is considered reasonable for most, but not all, nonpregnant adults. In the last few years, the ADA has focused more on individualized targets.

Tighter control (<6.5%)—which is associated with lower rates of eye disease, kidney disease, and nerve damage—may be appropriate for patients who have no significant hypoglycemia, no cardiovascular disease (CVD), a shorter duration of diabetes, or a longer expected lifespan.

Conversely, a higher target (<8%) may be appropriate for patients who are older, have longstanding diabetes, advanced macrovascular or microvascular disease, established complications, or a limited life expectancy.3,4

Pregnancy. The 2016 standards have a new target for pregnant women with diabetes: The ADA previously recommended an A1C <6% for this patient population, but now recommends a target A1C between 6% and 6.5%. This may be tightened or relaxed, however, depending on individual risk of hypoglycemia.

In focusing on individualized targets and hypoglycemia avoidance, the ADA notes that attention must be paid to fasting, pre-meal, and post-meal blood glucose levels to achieve treatment goals. The 2016 standards emphasize the importance of patient-centered diabetes care, aligned with a coordinated, team-based chronic care model.

Diabetes self-management education and support is indicated for those who are newly diagnosed, and should be provided periodically based on glucose control and progression of the disease. All patients should receive education on hypoglycemia risk and treatment.

Prediabetes and prevention

What is prediabetes and what can I do to prevent patients with prediabetes from developing diabetes?

Patients with impaired glucose tolerance, impaired fasting glucose, or an A1C between 5.7% and 6.4% are considered to have prediabetes and are at risk for developing type 2 diabetes.

Family physicians should refer patients with prediabetes to intensive diet, physical activity, and behavioral counseling programs like those based on the Diabetes Prevention Program study (www.niddk.nih.gov/about-niddk/research-areas/diabetes/diabetes-prevention-program-dpp/Pages/default.aspx). Goals should include a minimum 7% weight loss and moderate-intensity physical activity, such as brisk walking, for at least 150 minutes per week.

Lifestyle modification programs have been shown to be very effective in preventing diabetes, with about a 58% reduction in the risk of developing type 2 diabetes after 3 years.5 The 2016 standards added a recommendation that physicians encourage the use of new technology, such as text messaging or smart phone apps, to support such efforts.

Should I consider initiating oral antiglycemics in patients with prediabetes?

Yes. Pharmacologic agents, including metformin, acarbose, and pioglitazone, have been shown to decrease progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes. Thus, antiglycemics should be considered for certain patients. Metformin is especially appropriate for women with a history of gestational diabetes, patients who are younger than 60 years, and those who have a body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2.6

How often should I screen patients with prediabetes?

Patients with prediabetes should be screened annually. Such individuals should also be screened and treated for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors. There is strong evidence that the treatment of obesity can be beneficial for those at any stage of the diabetes spectrum.

Obesity management

What do the 2016 ADA standards recommend for obese patients with diabetes?

With more than two-thirds of Americans either overweight or obese, the ADA added a new section on obesity management and calls on health care providers to:

- weigh patients and calculate and document their BMI at every visit, and

- counsel those who are overweight or obese on the benefits of even modest weight loss.

The ADA recommends a sustained weight loss of 5%, which can improve glycemic control and reduce the need for diabetes medications,7-9 although weight loss of ≥7% is optimal. Physicians are also called on to assess each patient’s readiness to engage in therapeutic lifestyle change to maintain a modest weight loss.

Treatment for obesity can include therapeutic lifestyle change (reduction in calories, increase in physical activity) and behavioral therapy. For refractory patients, pharmacologic therapy and bariatric surgery may be considered.

Interventions should be high-intensity (≥16 sessions in 6 months) and focus on diet, physical activity, and behavioral strategies to achieve a 500 to 750 calorie deficit per day.10 Long-term (≥1 year) comprehensive weight maintenance programs should be prescribed for those who achieve short-term weight loss.11,12 Such programs should provide at least monthly contact and encourage ongoing monitoring of body weight (weekly or more frequently), continued consumption of a reduced-calorie diet, and participation in high levels of physical activity (200 to 300 minutes per week).

Glycemic treatment

What are some of the key factors that distinguish the different type 2 diabetes medications from one another?

An increasing understanding of diabetes pathophysiology has led to a wider array of medications, making treatment more complex than ever. It is important for physicians to have a strong working knowledge of the various classes of antidiabetic agents and the subtleties between drugs in the same class to best individualize treatment.

Here are the highlights of each class of medication listed in the ADA/European Association for the Study of Diabetes algorithm for the management of type 2 diabetes,13 which is available at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/38/1/140/F2.large.jpg):

Metformin is the preferred initial medication for all patients who can tolerate it and have no contraindications. The drug is cost-effective, weight neutral, and has had positive cardiovascular and mortality outcomes in long-term studies. Adverse gastrointestinal (GI) effects, including nausea, diarrhea, and dyspepsia, are common but can be reduced with a slow titration of the drug. Metformin should be used with caution in those with renal disease. The dose should be reduced if the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <45 mL/min/1.73m2 and the drug discontinued if eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Sulfonylureas/meglitinides stimulate insulin secretion in a glucose-independent manner. They are cost-effective and have high efficacy early in the disease and with initial use, but the effect wanes as the disease progresses. This class of drugs is associated with weight gain and hypoglycemia. Second-generation sulfonylureas (glipizide, glimepiride) are recommended; meglitinides are more expensive than sulfonylureas.

Thiazolidinediones work to improve insulin sensitivity in the periphery and have a low risk of hypoglycemia. They have been associated with fluid retention, weight gain, and worsening of pre-existing congestive heart failure, but previous cardiovascular concerns (with rosiglitazone)14 and bladder cancer risks (with pioglitazone)15-17 have been refuted. Thiazolidinediones are contraindicated in those with Class III and IV congestive heart failure, however, and patients taking them require careful monitoring for weight gain, fluid retention, and exacerbation of heart failure.

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4Is) work to reduce the breakdown of endogenous incretin hormones. These oral agents increase insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner; more insulin is secreted when glucose is higher and less when glucose is closer to normal. This means that there is a much lower risk of hypoglycemia when a DPP4I is used as monotherapy.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), which are injectable, also work via incretin hormones and stimulate insulin in a glucose-dependent manner. They are associated with weight loss and low rates of hypoglycemia. Adverse GI effects are common with this class of drugs, but can be reduced by titrating the medication and avoiding overeating. GLP-1RAs can be taken twice daily to once weekly, depending on the specific agent.

Sodium glucose transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2Is) are oral agents and the newest class of antidiabetes drugs. The drugs help block the reabsorption of glucose, thereby lowering glucose levels, blood pressure, and weight in many patients. The most common adverse effects are urinary tract and genital yeast infections. SGLT2Is should not be given to patients with advanced renal disease (chronic kidney disease Stages 3B-5) because they will not be effectively absorbed.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued a warning about the risk of ketoacidosis with these agents,18 and patients should be advised to stop taking them and to seek immediate medical attention if they develop symptoms of ketoacidosis, such as excessive thirst, frequent urination, nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain, weakness or fatigue, shortness of breath, fruity-scented breath, or confusion.

Insulin is eventually needed by most patients with type 2 diabetes who live long enough to see the disease progress. The most common adverse effects are weight gain and hypoglycemia. There are many types of insulin, but only one that is delivered via inhalation—human insulin inhaled powder. Inhaled insulin, however, has the potential for adverse pulmonary effects, including cough and reduction of peak expiratory flow. Therefore, pulmonary function testing is recommended prior to its use.

Treatment goal attainment should be evaluated every 3 months, and treatment titrated at 3-month intervals if goals are not achieved. The ADA/European Association for the Study of Diabetes’ algorithm indicates that patients are likely to need insulin a year after diagnosis if their A1C goal has not been achieved or maintained.13

The following medications are not included in the algorithm but are included in the 2016 standards, and may be helpful for certain patients:

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors delay the absorption of glucose from the proximal to distal GI tract, thereby reducing postprandial hyperglycemia. Flatulence and leakage of stool—the most common adverse effects—have limited their use in the United States.

Bile acid sequestrants (colesevelam) treat both hyperlipidemia and diabetes. The medications work by reducing glucose absorption from the GI tract. They reduce postprandial hyperglycemia, with a low risk of hypoglycemia. Colesevelam’s use is limited, however, because of the number of pills needed (6 daily).

Bromocriptine affects satiety levels via the central nervous system, and is available in a specific formulation for the treatment of diabetes. “First-dose” hypotension, however, is an adverse effect of considerable concern.1

Pramlintide, an injectable amylin mimetic given to patients on prandial insulin, can reduce postprandial glucose levels. The most common adverse effects are upper GI symptoms and hypoglycemia. Due to the adverse effects and the need for an injection with each meal, pramlintide is used infrequently.

Cardiovascular risk reduction

Has the ADA revised its recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management?

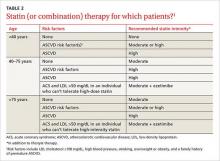

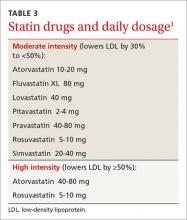

Yes. There have been several changes. The first is in terminology, with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) replacing CVD alone. While new recommendations for statin therapy for adults older than 40 years (TABLE 2)1 were also added, the emphasis remains on therapeutic lifestyle change as an effective treatment for hypertension. These modifications should include at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity per week and, for most patients, a reduction in total calories, saturated fat, and sodium.

It is important to remind patients that to maximize the benefits in terms of treating hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, such changes must be maintained over the long term.

Aspirin therapy. The ADA also revised its recommendation regarding aspirin therapy. Based on new evidence in the treatment of women with ASCVD risk, the standards now call for considering aspirin therapy (75-162 mg/d) in both women and men ≥50 years as a primary prevention strategy for those with type 1 or type 2 diabetes with a 10-year ASCVD risk of >10%. (The previous standards recommended this only for women older than 60 years.)

Antiplatelet therapy is now recommended for patients younger than 50 years with multiple risk factors, and as secondary prevention in those with a history of ASCVD.19-21

Hypertension. The ADA’s recommendations for treating hypertension in patients with diabetes have not changed; the goal remains <140/<90 mm Hg. Lower targets may be appropriate for younger patients, those with albuminuria, and individuals with additional CVD risk factors; however, systolic pressure <130 mm Hg has not been shown to reduce CVD outcomes, and diastolic pressure <70 mm Hg has been associated with higher mortality.22

Optimal medication and lifestyle therapy are important to achieve goals, with avoidance of undue treatment burden. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), but not both, should be included as part of treatment. Other agents, such as a thiazide diuretic, may be needed to achieve individual goals. Serum creatinine/eGFR and serum potassium levels should be monitored with the use of diuretics.