User login

Pulmonary Embolism Ruled Out in Error

A 28-year-old man presented to a Maryland hospital emergency department (ED) with a two-day history of low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, and dizziness. He was also tachycardic and significantly hypoxic. After an hour’s wait, the patient saw an emergency physician, who noted complaints of weakness, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness. The differential diagnosis included pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary embolism (PE).

After an ECG, chest x-ray, and blood work, the emergency physician diagnosed pneumonia and renal insufficiency. The patient was admitted but within eight hours of arrival at the ED was transferred to another hospital. The admitting physician at the second hospital did not evaluate the patient on admission.

Almost five hours later, the patient got out of bed and collapsed in the presence of his wife. A code was called, but the man never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead about 90 minutes later. An autopsy confirmed a PE as the cause of death.

Plaintiff for the decedent alleged negligence in the clinicians’ failure to diagnose and treat the PE. The plaintiff claimed that with proper treatment, the patient would have survived.

The defendants argued that there was no negligence involved and that heparin therapy would not have prevented the patient’s death.

What was the outcome? >>

OUTCOME

According to a published account, a $6.1 million verdict was returned.

COMMENT

This is a substantial verdict, reflecting the jury’s revulsion at the loss of a 28-year-old patient. His initial presentation of low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, and dizziness with tachycardia and hypoxia could be consistent with either pneumonia or PE. The facts as presented render the chest x-ray findings and the magnitude of hypoxia unclear. We also are not told whether any specific risk factors existed to make PE more likely, nor whether there was evidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during presentation or at autopsy.

Diagnosing PE can be difficult. However, jurors confronted with a case involving a fatal PE may be led to believe that the diagnosis is straightforward and should never be missed. Plaintiff’s counsel will argue that the patient “would be standing here today” in a fully functional status if the diagnosis had been made.

Here, presumptively, the chest films and chest auscultation were suggestive of pneumonia and led the clinician, who actively considered PE, to ultimately exclude the possibility. It is not clear why the patient was transferred and not formally evaluated upon arrival at the second hospital, but the facts indicate that the patient was “significantly hypoxic.” This should have entailed close monitoring by the receiving clinician, irrespective of the diagnosis.

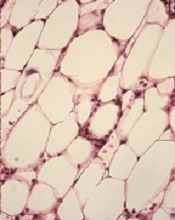

The pathophysiology of PE is straightforward—but the presentation is often variable and nonspecific and the diagnosis tricky. Thus, for the clinician confronted with a hypoxic patient, it is important to consider this diagnosis early and thoroughly. Evaluate for risk factors: hypercoagulability, as in cases of malignancy, estrogen use, pregnancy, antiphospholipid syndrome (Hughes syndrome), or genomic mutations (eg, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin mutation, factor VIII mutations, protein C and protein S deficiency); venous stasis; and vascular endothelial damage, as possibly occasioned by hypertension or atherosclerotic disease.

In addition, it is important to confirm the presence or absence of a DVT. Follow evidence-based rules, such as the Wells score, to guide decision making. In Wells scoring, points are assigned for each of seven criteria, allowing the patient to be categorized by high, moderate, or low probability for PE. The Wells scoring criteria comprise

• Suspected DVT (3 points)

• PE the most likely diagnosis, or equally likely as a second diagnosis (3 points)

• Tachycardia (heart rate > 100 beats/min; 1.5 points)

• Immobilization for at least three days or surgery within the previous four weeks (1.5 points)

• History of DVT or PE (1.5 points)

• Hemoptysis (1 point)

• Malignancy with treatment within previous six months (1 point)

Patients with a total score exceeding 6 points are considered high-probability for PE and should undergo multidetector CT. Those with a score of 2 to 6 have moderate probability and should undergo high-sensitivity d-dimer testing; negative d-dimer results exclude PE and positive results warrant multidetector CT and lower-extremity ultrasound. In low-probability patients (Wells score below 2) with negative d-dimer results, PE is excluded; if d-dimer results are positive, multidetector CT should be ordered.

IN SUM

Extensive discussion of clinical predictive rules, diagnostic modalities, and treatment is beyond the scope of this comment. But clinicians should apply evidence-based decision-making rules to establish a diagnosis. And it should be apparent that hypoxic patients warrant close monitoring—particularly when a change of provider, service, or institution occurs. —DML

A 28-year-old man presented to a Maryland hospital emergency department (ED) with a two-day history of low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, and dizziness. He was also tachycardic and significantly hypoxic. After an hour’s wait, the patient saw an emergency physician, who noted complaints of weakness, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness. The differential diagnosis included pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary embolism (PE).

After an ECG, chest x-ray, and blood work, the emergency physician diagnosed pneumonia and renal insufficiency. The patient was admitted but within eight hours of arrival at the ED was transferred to another hospital. The admitting physician at the second hospital did not evaluate the patient on admission.

Almost five hours later, the patient got out of bed and collapsed in the presence of his wife. A code was called, but the man never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead about 90 minutes later. An autopsy confirmed a PE as the cause of death.

Plaintiff for the decedent alleged negligence in the clinicians’ failure to diagnose and treat the PE. The plaintiff claimed that with proper treatment, the patient would have survived.

The defendants argued that there was no negligence involved and that heparin therapy would not have prevented the patient’s death.

What was the outcome? >>

OUTCOME

According to a published account, a $6.1 million verdict was returned.

COMMENT

This is a substantial verdict, reflecting the jury’s revulsion at the loss of a 28-year-old patient. His initial presentation of low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, and dizziness with tachycardia and hypoxia could be consistent with either pneumonia or PE. The facts as presented render the chest x-ray findings and the magnitude of hypoxia unclear. We also are not told whether any specific risk factors existed to make PE more likely, nor whether there was evidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during presentation or at autopsy.

Diagnosing PE can be difficult. However, jurors confronted with a case involving a fatal PE may be led to believe that the diagnosis is straightforward and should never be missed. Plaintiff’s counsel will argue that the patient “would be standing here today” in a fully functional status if the diagnosis had been made.

Here, presumptively, the chest films and chest auscultation were suggestive of pneumonia and led the clinician, who actively considered PE, to ultimately exclude the possibility. It is not clear why the patient was transferred and not formally evaluated upon arrival at the second hospital, but the facts indicate that the patient was “significantly hypoxic.” This should have entailed close monitoring by the receiving clinician, irrespective of the diagnosis.

The pathophysiology of PE is straightforward—but the presentation is often variable and nonspecific and the diagnosis tricky. Thus, for the clinician confronted with a hypoxic patient, it is important to consider this diagnosis early and thoroughly. Evaluate for risk factors: hypercoagulability, as in cases of malignancy, estrogen use, pregnancy, antiphospholipid syndrome (Hughes syndrome), or genomic mutations (eg, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin mutation, factor VIII mutations, protein C and protein S deficiency); venous stasis; and vascular endothelial damage, as possibly occasioned by hypertension or atherosclerotic disease.

In addition, it is important to confirm the presence or absence of a DVT. Follow evidence-based rules, such as the Wells score, to guide decision making. In Wells scoring, points are assigned for each of seven criteria, allowing the patient to be categorized by high, moderate, or low probability for PE. The Wells scoring criteria comprise

• Suspected DVT (3 points)

• PE the most likely diagnosis, or equally likely as a second diagnosis (3 points)

• Tachycardia (heart rate > 100 beats/min; 1.5 points)

• Immobilization for at least three days or surgery within the previous four weeks (1.5 points)

• History of DVT or PE (1.5 points)

• Hemoptysis (1 point)

• Malignancy with treatment within previous six months (1 point)

Patients with a total score exceeding 6 points are considered high-probability for PE and should undergo multidetector CT. Those with a score of 2 to 6 have moderate probability and should undergo high-sensitivity d-dimer testing; negative d-dimer results exclude PE and positive results warrant multidetector CT and lower-extremity ultrasound. In low-probability patients (Wells score below 2) with negative d-dimer results, PE is excluded; if d-dimer results are positive, multidetector CT should be ordered.

IN SUM

Extensive discussion of clinical predictive rules, diagnostic modalities, and treatment is beyond the scope of this comment. But clinicians should apply evidence-based decision-making rules to establish a diagnosis. And it should be apparent that hypoxic patients warrant close monitoring—particularly when a change of provider, service, or institution occurs. —DML

A 28-year-old man presented to a Maryland hospital emergency department (ED) with a two-day history of low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, and dizziness. He was also tachycardic and significantly hypoxic. After an hour’s wait, the patient saw an emergency physician, who noted complaints of weakness, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness. The differential diagnosis included pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary embolism (PE).

After an ECG, chest x-ray, and blood work, the emergency physician diagnosed pneumonia and renal insufficiency. The patient was admitted but within eight hours of arrival at the ED was transferred to another hospital. The admitting physician at the second hospital did not evaluate the patient on admission.

Almost five hours later, the patient got out of bed and collapsed in the presence of his wife. A code was called, but the man never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead about 90 minutes later. An autopsy confirmed a PE as the cause of death.

Plaintiff for the decedent alleged negligence in the clinicians’ failure to diagnose and treat the PE. The plaintiff claimed that with proper treatment, the patient would have survived.

The defendants argued that there was no negligence involved and that heparin therapy would not have prevented the patient’s death.

What was the outcome? >>

OUTCOME

According to a published account, a $6.1 million verdict was returned.

COMMENT

This is a substantial verdict, reflecting the jury’s revulsion at the loss of a 28-year-old patient. His initial presentation of low-grade fever, nonproductive cough, and dizziness with tachycardia and hypoxia could be consistent with either pneumonia or PE. The facts as presented render the chest x-ray findings and the magnitude of hypoxia unclear. We also are not told whether any specific risk factors existed to make PE more likely, nor whether there was evidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during presentation or at autopsy.

Diagnosing PE can be difficult. However, jurors confronted with a case involving a fatal PE may be led to believe that the diagnosis is straightforward and should never be missed. Plaintiff’s counsel will argue that the patient “would be standing here today” in a fully functional status if the diagnosis had been made.

Here, presumptively, the chest films and chest auscultation were suggestive of pneumonia and led the clinician, who actively considered PE, to ultimately exclude the possibility. It is not clear why the patient was transferred and not formally evaluated upon arrival at the second hospital, but the facts indicate that the patient was “significantly hypoxic.” This should have entailed close monitoring by the receiving clinician, irrespective of the diagnosis.

The pathophysiology of PE is straightforward—but the presentation is often variable and nonspecific and the diagnosis tricky. Thus, for the clinician confronted with a hypoxic patient, it is important to consider this diagnosis early and thoroughly. Evaluate for risk factors: hypercoagulability, as in cases of malignancy, estrogen use, pregnancy, antiphospholipid syndrome (Hughes syndrome), or genomic mutations (eg, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin mutation, factor VIII mutations, protein C and protein S deficiency); venous stasis; and vascular endothelial damage, as possibly occasioned by hypertension or atherosclerotic disease.

In addition, it is important to confirm the presence or absence of a DVT. Follow evidence-based rules, such as the Wells score, to guide decision making. In Wells scoring, points are assigned for each of seven criteria, allowing the patient to be categorized by high, moderate, or low probability for PE. The Wells scoring criteria comprise

• Suspected DVT (3 points)

• PE the most likely diagnosis, or equally likely as a second diagnosis (3 points)

• Tachycardia (heart rate > 100 beats/min; 1.5 points)

• Immobilization for at least three days or surgery within the previous four weeks (1.5 points)

• History of DVT or PE (1.5 points)

• Hemoptysis (1 point)

• Malignancy with treatment within previous six months (1 point)

Patients with a total score exceeding 6 points are considered high-probability for PE and should undergo multidetector CT. Those with a score of 2 to 6 have moderate probability and should undergo high-sensitivity d-dimer testing; negative d-dimer results exclude PE and positive results warrant multidetector CT and lower-extremity ultrasound. In low-probability patients (Wells score below 2) with negative d-dimer results, PE is excluded; if d-dimer results are positive, multidetector CT should be ordered.

IN SUM

Extensive discussion of clinical predictive rules, diagnostic modalities, and treatment is beyond the scope of this comment. But clinicians should apply evidence-based decision-making rules to establish a diagnosis. And it should be apparent that hypoxic patients warrant close monitoring—particularly when a change of provider, service, or institution occurs. —DML

Autonomy vs abuse: Can a patient choose a new power of attorney?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

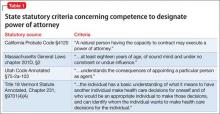

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8

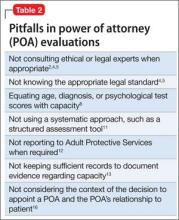

People who have good marital or parent-child relationships are more likely to select loved ones as their POAs.9 Family members who have not previously served as surrogates or have not had talked with their loved ones about their preferences feel less confident exercising the duties of a POA.10 An evaluation, therefore, should consider the prior relationship between the designator and proposed surrogate, and particularly whether these parties have discussed the designator’s health care preferences. Table 2 lists potential pitfalls in POA evaluations.2,4,5,8,11-13,16

Responding to abuse

Accompanying the request for Dr. P’s evaluation were reports that the current POA had been stealing the patient’s funds. Financial exploitation of older people is not a rare phenomenon.14,15 Yet only about 1 in 25 cases is reported,16,17 and physicians discover as few as 2% of all reported cases.15

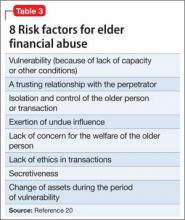

Many variables—the stress of the situation,8 pre-existing relationship dynamics,18 and caregiver psychopathology11—lead POAs to exploit their designator. Sometimes, family members believe that they are entitled to a relative’s money because of real or imagined transgressions19 or because they regard themselves as eventual heirs to their relative’s estate.16 Some designated POAs use designators’ funds simply because they need money. Kemp and Mosqueda20 have developed an evaluation framework for assessing possible financial abuse (Table 3).

Although reporting financial abuse can strain alliances between patients and their families, psychiatrists bear a responsibility to look out for the welfare of their older patients.8 Indeed, all 50 states have elder abuse statutes, most of which mandate reporting by physicians.21

Suspicion of financial abuse could indicate the need to evaluate the susceptible person’s capacity to make financial decisions.12 Depending on the patient’s circumstances and medical problems, further steps might include:

• contacting proper authorities, such as Adult Protective Services or the Department of Human Services

• contacting local law enforcement

• instituting procedures for emergency guardianship

• arranging for more in-home services for the patient or recommending a higher level of care

• developing a treatment plan for the patient’s medical and psychiatric problems

• communicating with other trusted family members.12,18

Bottom Line

Evaluating the capacity to appoint a power of attorney (POA) often requires awareness of social systems, family dynamics, and legal requirements, combined with the psychiatric data from a systematic individual assessment. Evaluating psychiatrists should understand what type of POA is being considered and the applicable legal standards in the jurisdictions where they work.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Black PG, Derse AR, Derrington S, et al. Can a patient designate his doctor as his proxy decision maker? Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):986-990.

2. Pope TM. Legal fundamentals of surrogate decision making. Chest. 2012;141(4):1074-1081.

3. Araj V. Types of power of attorney: which POA is right for me? http://www.quickenloans.com/blog/types-power-attorney-poa#4zvT8F58fd6zVb2v.99. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2015.

4. Moye J, Sabatino CP, Weintraub Brendel R. Evaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):326-336.

5. Whitman R. Capacity for lifetime and estate planning. Penn State L Rev. 2013;117(4):1061-1080.

6. Duke v Kindred Healthcare Operating, Inc., 2011 WL 864321 (Tenn. Ct. App).

7. Soliman S. Evaluating older adults’ capacity and need for guardianship. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):39-42,52-53,A.

8. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consensus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1319-1324.

9. Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-life planning in a family context: does relationship quality affect whether (and with whom) older adults plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):586-592.

10. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2281-2286.

11. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):297-304.

12. Horning SM, Wilkins SS, Dhanani S, et al. A case of elder abuse and undue influence: assessment and treatment from a geriatric interdisciplinary team. Clin Case Stud. 2013;12:373-387.

13. Lui VW, Chiu CC, Ko RS, et al. The principle of assessing mental capacity for enduring power of attorney. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(1):59-62.

14. Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, et al. National Elder Mistreatment Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

15. Wilber KH, Reynolds SL. Introducing a framework for defining financial abuse of the elderly. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1996;8(2):61-80.

16. Mukherjee D. Financial exploitation of older adults in rural settings: a family perspective. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013; 25(5):425-437.

17. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://nyceac.com/wp-content/ uploads/2011/05/UndertheRadar051211.pdf. Published May 16, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2015.

18. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. Exploitation of the elderly: undue influence as a form of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr. 2005;13(2):28-36.

19. Kemp B, Liao S. Elder financial abuse: tips for the medical director. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(9):591-593.

20. Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: an evaluation framework and supporting evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1123-1127.

21. Stiegel S, Klem E. Reporting requirements: provisions and citations in Adult Protective Services laws, by state. http:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/ aging/docs/MandatoryReportingProvisionsChart. authcheckdam.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 9, 2015.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8

People who have good marital or parent-child relationships are more likely to select loved ones as their POAs.9 Family members who have not previously served as surrogates or have not had talked with their loved ones about their preferences feel less confident exercising the duties of a POA.10 An evaluation, therefore, should consider the prior relationship between the designator and proposed surrogate, and particularly whether these parties have discussed the designator’s health care preferences. Table 2 lists potential pitfalls in POA evaluations.2,4,5,8,11-13,16

Responding to abuse

Accompanying the request for Dr. P’s evaluation were reports that the current POA had been stealing the patient’s funds. Financial exploitation of older people is not a rare phenomenon.14,15 Yet only about 1 in 25 cases is reported,16,17 and physicians discover as few as 2% of all reported cases.15

Many variables—the stress of the situation,8 pre-existing relationship dynamics,18 and caregiver psychopathology11—lead POAs to exploit their designator. Sometimes, family members believe that they are entitled to a relative’s money because of real or imagined transgressions19 or because they regard themselves as eventual heirs to their relative’s estate.16 Some designated POAs use designators’ funds simply because they need money. Kemp and Mosqueda20 have developed an evaluation framework for assessing possible financial abuse (Table 3).

Although reporting financial abuse can strain alliances between patients and their families, psychiatrists bear a responsibility to look out for the welfare of their older patients.8 Indeed, all 50 states have elder abuse statutes, most of which mandate reporting by physicians.21

Suspicion of financial abuse could indicate the need to evaluate the susceptible person’s capacity to make financial decisions.12 Depending on the patient’s circumstances and medical problems, further steps might include:

• contacting proper authorities, such as Adult Protective Services or the Department of Human Services

• contacting local law enforcement

• instituting procedures for emergency guardianship

• arranging for more in-home services for the patient or recommending a higher level of care

• developing a treatment plan for the patient’s medical and psychiatric problems

• communicating with other trusted family members.12,18

Bottom Line

Evaluating the capacity to appoint a power of attorney (POA) often requires awareness of social systems, family dynamics, and legal requirements, combined with the psychiatric data from a systematic individual assessment. Evaluating psychiatrists should understand what type of POA is being considered and the applicable legal standards in the jurisdictions where they work.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the hospital where I serve as the psychiatric consultant, a medical team asked me to evaluate a patient’s capacity to designate a new power of attorney (POA) for health care. The patient’s relatives want the change because they think the current POA—also a relative—is stealing the patient’s funds. The contentious family situation made me wonder: What legal risks might I face after I assess the patient’s capacity to choose a new POA?

Submitted by “Dr. P”

As America’s population ages, situations like the one Dr. P has encountered will become more common. Many variables—time constraints, patients’ cognitive impairments, lack of prior relationships with patients, complex medical situations, and strained family dynamics— can make these clinical situations complex and daunting.

Dr. P realizes that feuding relatives can redirect their anger toward a well-meaning physician who might appear to take sides in a dispute. Yet staying silent isn’t a good option, either: If the patient is being mistreated or abused, Dr. P may have a duty to initiate appropriate protective action.

In this article, we’ll respond to Dr. P’s question by examining these topics:

• what a POA is and the rationale for having one

• standards for capacity to choose a POA

• characteristics and dynamics of potential surrogates

• responding to possible elder abuse.

Surrogate decision-makers

People can lose their decision-making capacity because of dementia, acute or chronic illness, or sudden injury. Although autonomy and respecting decisions of mentally capable people are paramount American values, our legal system has several mechanisms that can be activated on behalf of people who have lost their decision-making capabilities.

When a careful evaluation suggests that a patient cannot make informed medical decisions, one solution is to turn to a surrogate decision-maker whom the patient previously has designated to act on his (her) behalf, should he (she) become incapacitated. A surrogate can make decisions based on the incapacitated person’s current utterances (eg, expressions of pain), previously expressed wishes about what should happen under certain circumstances, or the surrogate’s judgment of the person’s best interest.1

States have varied legal frameworks for establishing surrogacy and refer to a surrogate using terms such as proxy, agent, attorney-in-fact, and power of attorney.2 POA responsibilities can encompass a broad array of decision-making tasks or can be limited, for example, to handling banking transactions or managing estate planning.3,4 A POA can be “durable” and grant lasting power regardless of disability, or “springing” and operational only when the designator has lost capacity.

A health care POA designates a substitute decision-maker for medical care. The Patient Self-Determination Act and the Joint Commission obligate health care professionals to follow the decisions made by a legally valid POA. Generally, providers who follow a surrogate’s decision in good faith have legal immunity, but they must challenge a surrogate’s decision if it deviates widely from usual protocol.2

Legal standards

Dr. P received a consultation request that asked whether a patient with compromised medical decision-making powers nonetheless had the current capacity to choose a new POA.

To evaluate the patient’s capacity to designate a new POA, Dr. P must know what having this capacity means. What determines if someone has the capacity to designate a POA is a legal matter, and unless Dr. P is sure what the laws in her state say about this, she should consult a lawyer who can explain the jurisdiction’s applicable legal standards to her.5

The law generally presumes that adults are competent to make health care decisions, including decisions about appointing a POA.5 The law also recognizes that people with cognitive impairments or mental illnesses still can be competent to appoint POAs.4

Most states don’t have statutes that define the capacity to appoint a health care POA. In these jurisdictions, courts may apply standards similar to those concerning competence to enter into a contract.6Table 1 describes criteria in 4 states that do have statutory provisions concerning competence to designate a health care POA.

Approaching the evaluation

Before evaluating a person’s capacity to designate a POA, you should first understand the person’s medical condition and learn what powers the surrogate would have. A detailed description of the evaluation process lies beyond the scope of this article. For more information, please consult the structured interviews described by Moye et al4 and Soliman’s guide to the evaluation process.7

In addition to examining the patient’s psychological status and cognitive capacity, you also might have to consider contextual variables, such as:

• potential risks of not allowing the appointment of POA, including a delay in needed care

• the person’s relationship to the proposed POA

• possible power imbalances or evidence of coercion

• how the person would benefit from having the POA.8

People who have good marital or parent-child relationships are more likely to select loved ones as their POAs.9 Family members who have not previously served as surrogates or have not had talked with their loved ones about their preferences feel less confident exercising the duties of a POA.10 An evaluation, therefore, should consider the prior relationship between the designator and proposed surrogate, and particularly whether these parties have discussed the designator’s health care preferences. Table 2 lists potential pitfalls in POA evaluations.2,4,5,8,11-13,16

Responding to abuse

Accompanying the request for Dr. P’s evaluation were reports that the current POA had been stealing the patient’s funds. Financial exploitation of older people is not a rare phenomenon.14,15 Yet only about 1 in 25 cases is reported,16,17 and physicians discover as few as 2% of all reported cases.15

Many variables—the stress of the situation,8 pre-existing relationship dynamics,18 and caregiver psychopathology11—lead POAs to exploit their designator. Sometimes, family members believe that they are entitled to a relative’s money because of real or imagined transgressions19 or because they regard themselves as eventual heirs to their relative’s estate.16 Some designated POAs use designators’ funds simply because they need money. Kemp and Mosqueda20 have developed an evaluation framework for assessing possible financial abuse (Table 3).

Although reporting financial abuse can strain alliances between patients and their families, psychiatrists bear a responsibility to look out for the welfare of their older patients.8 Indeed, all 50 states have elder abuse statutes, most of which mandate reporting by physicians.21

Suspicion of financial abuse could indicate the need to evaluate the susceptible person’s capacity to make financial decisions.12 Depending on the patient’s circumstances and medical problems, further steps might include:

• contacting proper authorities, such as Adult Protective Services or the Department of Human Services

• contacting local law enforcement

• instituting procedures for emergency guardianship

• arranging for more in-home services for the patient or recommending a higher level of care

• developing a treatment plan for the patient’s medical and psychiatric problems

• communicating with other trusted family members.12,18

Bottom Line

Evaluating the capacity to appoint a power of attorney (POA) often requires awareness of social systems, family dynamics, and legal requirements, combined with the psychiatric data from a systematic individual assessment. Evaluating psychiatrists should understand what type of POA is being considered and the applicable legal standards in the jurisdictions where they work.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Black PG, Derse AR, Derrington S, et al. Can a patient designate his doctor as his proxy decision maker? Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):986-990.

2. Pope TM. Legal fundamentals of surrogate decision making. Chest. 2012;141(4):1074-1081.

3. Araj V. Types of power of attorney: which POA is right for me? http://www.quickenloans.com/blog/types-power-attorney-poa#4zvT8F58fd6zVb2v.99. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2015.

4. Moye J, Sabatino CP, Weintraub Brendel R. Evaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):326-336.

5. Whitman R. Capacity for lifetime and estate planning. Penn State L Rev. 2013;117(4):1061-1080.

6. Duke v Kindred Healthcare Operating, Inc., 2011 WL 864321 (Tenn. Ct. App).

7. Soliman S. Evaluating older adults’ capacity and need for guardianship. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):39-42,52-53,A.

8. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consensus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1319-1324.

9. Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-life planning in a family context: does relationship quality affect whether (and with whom) older adults plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):586-592.

10. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2281-2286.

11. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):297-304.

12. Horning SM, Wilkins SS, Dhanani S, et al. A case of elder abuse and undue influence: assessment and treatment from a geriatric interdisciplinary team. Clin Case Stud. 2013;12:373-387.

13. Lui VW, Chiu CC, Ko RS, et al. The principle of assessing mental capacity for enduring power of attorney. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(1):59-62.

14. Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, et al. National Elder Mistreatment Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

15. Wilber KH, Reynolds SL. Introducing a framework for defining financial abuse of the elderly. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1996;8(2):61-80.

16. Mukherjee D. Financial exploitation of older adults in rural settings: a family perspective. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013; 25(5):425-437.

17. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://nyceac.com/wp-content/ uploads/2011/05/UndertheRadar051211.pdf. Published May 16, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2015.

18. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. Exploitation of the elderly: undue influence as a form of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr. 2005;13(2):28-36.

19. Kemp B, Liao S. Elder financial abuse: tips for the medical director. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(9):591-593.

20. Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: an evaluation framework and supporting evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1123-1127.

21. Stiegel S, Klem E. Reporting requirements: provisions and citations in Adult Protective Services laws, by state. http:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/ aging/docs/MandatoryReportingProvisionsChart. authcheckdam.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 9, 2015.

1. Black PG, Derse AR, Derrington S, et al. Can a patient designate his doctor as his proxy decision maker? Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):986-990.

2. Pope TM. Legal fundamentals of surrogate decision making. Chest. 2012;141(4):1074-1081.

3. Araj V. Types of power of attorney: which POA is right for me? http://www.quickenloans.com/blog/types-power-attorney-poa#4zvT8F58fd6zVb2v.99. Published December 29, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2015.

4. Moye J, Sabatino CP, Weintraub Brendel R. Evaluation of the capacity to appoint a healthcare proxy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(4):326-336.

5. Whitman R. Capacity for lifetime and estate planning. Penn State L Rev. 2013;117(4):1061-1080.

6. Duke v Kindred Healthcare Operating, Inc., 2011 WL 864321 (Tenn. Ct. App).

7. Soliman S. Evaluating older adults’ capacity and need for guardianship. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(4):39-42,52-53,A.

8. Katona C, Chiu E, Adelman S, et al. World psychiatric association section of old age psychiatry consensus statement on ethics and capacity in older people with mental disorders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(12):1319-1324.

9. Carr D, Moorman SM, Boerner K. End-of-life planning in a family context: does relationship quality affect whether (and with whom) older adults plan? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(4):586-592.

10. Majesko A, Hong SY, Weissfeld L, et al. Identifying family members who may struggle in the role of surrogate decision maker. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2281-2286.

11. Fulmer T, Guadagno L, Bitondo Dyer C, et al. Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):297-304.

12. Horning SM, Wilkins SS, Dhanani S, et al. A case of elder abuse and undue influence: assessment and treatment from a geriatric interdisciplinary team. Clin Case Stud. 2013;12:373-387.

13. Lui VW, Chiu CC, Ko RS, et al. The principle of assessing mental capacity for enduring power of attorney. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(1):59-62.

14. Acierno R, Hernandez-Tejada M, Muzzy W, et al. National Elder Mistreatment Study. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

15. Wilber KH, Reynolds SL. Introducing a framework for defining financial abuse of the elderly. J Elder Abuse Negl. 1996;8(2):61-80.

16. Mukherjee D. Financial exploitation of older adults in rural settings: a family perspective. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2013; 25(5):425-437.

17. Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Inc., Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, New York City Department for the Aging. Under the Radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study. http://nyceac.com/wp-content/ uploads/2011/05/UndertheRadar051211.pdf. Published May 16, 2011. Accessed January 10, 2015.

18. Hall RCW, Hall RCW, Chapman MJ. Exploitation of the elderly: undue influence as a form of elder abuse. Clin Geriatr. 2005;13(2):28-36.

19. Kemp B, Liao S. Elder financial abuse: tips for the medical director. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(9):591-593.

20. Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: an evaluation framework and supporting evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1123-1127.

21. Stiegel S, Klem E. Reporting requirements: provisions and citations in Adult Protective Services laws, by state. http:// www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/migrated/ aging/docs/MandatoryReportingProvisionsChart. authcheckdam.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed January 9, 2015.

Telepsychiatry: Ready to consider a different kind of practice?

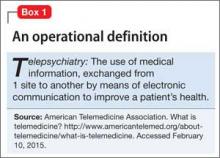

Too few psychiatrists. A growing number of patients. A new federal law, technological advances, and a generational shift in the way people communicate. Add them together and you have the perfect environment for telepsychiatry—the remote practice of psychiatry by means of telemedicine—to take root (Box 1). Although telepsychiatry has, in various forms, been around since the 1950s,1 only recently has it expanded into almost all areas of psychiatric practice.

Here are some observations from my daily work on why I see this method of delivering mental health care is poised to expand in 2015 and beyond. Does telepsychiatry make sense for you?

Lack of supply is a big driver

There are simply not enough psychiatrists where they are needed, which is the primary driver of the expansion of telepsychiatry. With 77% of counties in the United States reporting a shortage of psychiatrists2 and the “graying” of the psychiatric workforce,3 a more efficient way to make use of a psychiatrist’s time is needed. Telepsychiatry eliminates travel time and allows psychiatrists to visit distant sites virtually.

The shortage of psychiatric practitioners that we see today is only going to become worse. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 includes mental health care and substance abuse treatment among its 10 essential benefits; just as important, new rules arising from the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 limit restrictions on access to mental health care when insurance provides such coverage.4 These legislative initiatives likely will lead to increased demand for psychiatrists in all care settings—from outpatient consults to acute inpatient admissions.

Why so attractive an option?

The shortage of psychiatrists creates limitations on access to care. Fortunately, telemedicine has entered a new age, ushered in by widely available teleconferencing technology. Specialists from dermatology to surgery currently are using telemedicine; psychiatry is a good fit for telemedicine because of (1) the limited amount of “touch” required to make a psychiatric assessment, (2) significant improvements in video quality in recent years, and (3) a decrease in the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist.

A generation raised on the Internet is entering the health care marketplace. These consumers and clinicians are accustomed to using video for many daily activities, and they seek health information from the Web. Visiting a psychiatrist through teleconferencing isn’t strange or alienating to this generation; their comfort with technology allows them to have intimate exchanges on video.

Subspecialty particulars

The earliest adopters, not surprisingly, are in areas where the strain of shortage has been felt most, with pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatrists leading the way. In these fields, a substantial literature supports the use of telepsychiatry from a number of practice perspectives.

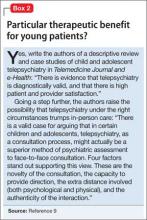

Pediatric psychiatry. The literature shows that children, families, and clinicians are, on the whole, satisfied with telepsychiatry.5 Children and adolescents who have been shown to benefit from telepsychiatry include those with depression,6 posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.7 Based on a case series, some authors have asserted that telepsychiatry might be preferable to in-person treatment (Box 2).8

Geriatric psychiatry. Research shows that geriatric patients, who are most likely to feel threatened by new technology, accept telepsychiatry visits.9 For psychiatrists treating geriatric patients, telepsychiatry can significantly lower costs by cutting commuting10 and make more accessible for patients whose age makes them unable to drive.

Correctional psychiatry. Clinicians working in correctional psychiatry have been at the forefront of experimentation with telepsychiatry. The technology is a natural fit for this setting:

• Prisons often are located in remote locations.

• Psychiatrists can be reluctant to provide on-site services because of safety concerns.

With correctional telepsychiatry, not only are patient outcomes comparable with in-person psychiatry, but the cost of delivering care can be significantly lower.11 With the U.S. Department of Justice reporting that 50% of inmates have a diagnosable mental disorder, including substance abuse,12 the need for access to a psychiatrist in the correctional system is acute.

Telepsychiatry can confidently be provided in a number of settings:

• emergency rooms

• nursing homes

• offices of primary care physicians

• in-home care.

Clinical services in these settings have been offered, studied, and reviewed.13

Can confidentiality and security be assured?

As with any new medical tool, the risk and benefits must be weighed care fully. The most obvious risk is to privacy. Telepsychiatry visits, like all patient encounters, must be secure and confidential. Given the growing suspicion among the public and professionals who use computers that all data are at risk, clinicians must take appropriate cautions and, at the same time, warn patients of the risks. Readily available videoconferencing software, such as Skype, does not provide the level of security that patients expect from health care providers.14

Other common concerns about telepsychiatry are stable access to videoconferencing and the safety from hackers of necessary hardware. Medical device companies have created hardware and software for use in telepsychiatry that provide a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant high-quality, stable, videoconferencing visit.

Do patients benefit?

Clinically, patients have fared well when they receive care through telepsychiatry. In some studies, however, clinicians have expressed some dissatisfaction with the technology13— understandable, given the value that psychiatry traditionally has put on sitting with the patient. As Knoedler15 described it, making the switch to telepsychiatry from in-person contact can engender loneliness in some physicians; not only is patient contact shifted to videoconferencing, but the psychiatrist loses the supportive environment of a busy clinical practice. Knoedler also pointed out that, on the other hand, telepsychiatry offers practitioners the opportunity to evaluate and treat people who otherwise would not have mental health care.

Obstacles—practical, knotty ones

Reimbursement and licensing. These are 2 pressing problems of telepsychiatry, although recent policy developments will help expand telepsychiatry and make it more appealing to physicians:

• Medicare reimburses for telepsychiatry in non-metropolitan areas.

• In 41 states, Medicaid has included telepsychiatry as a benefit.16

• Nine states offer a specific medical license for practicing telepsychiatry17 (in the remaining states, a full medical license must be obtained before one can provide telemedicine services).

• The Joint Commission has included language in its regulations that could expedite privileging of telepsychiatrists.18

Even with such advancements, problems with licensure, credentialing, privacy, security, confidentiality, informed consent, and professional liability remain.19 I urge you to do your research on these key areas before plunging in.

Changes to models of care. The risk that telepsychiatry poses to various models of care has to be considered. Telepsychiatry is a dramatic innovation, but it should be used to support only high-quality, evidence-based care to which patients are entitled.20 With new technology—as with new medications—use must be carefully monitored and scrutinized.

Although evidence of the value of telepsychiatry is growing, many methods of long-distance practice are still in their infancy. Data must be collected and poor outcomes assessed honestly to ensure that the “more-good-than-harm” mandate is met.

Good reasons to call this shift ‘inevitable’

The future of telepsychiatry includes expansion into new areas of practice. The move to providing services to patients where they happen to be—at work or home— seems inevitable:

• In rural areas, practitioners can communicate with patients so that they are cared for in their homes, without the expense of transportation.

• Employers can invest in workplace health clinics that use telemedicine services to reduce absenteeism.

• For psychiatrists, the ability to provide services to patients across a wide region, from a single convenient location, and at lower cost is an attractive prospect.

To conclude: telepsychiatry holds potential to provide greater reimbursement and improved quality of life for psychiatrists and patients: It allows physicians to choose where they live and work, and limits the number of unreimbursed commutes, and gives patients access to psychiatric care locally, without disruptive travel and delays.

Bottom Line

The exchange of medical information from 1 site to another by means of electronic communication has great potential to improve the health of patients and to alleviate the shortage of psychiatric practitioners across regions and settings. Pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatry stand to benefit because of the nature of the patients and locations.

Related Resources

• American Telemedicine Association. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. http://www. americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-video-based-online-mental-health-services. pdf?sfvrsn=6. Published May 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

• Freudenberg N, Yellowlees PM. Telepsychiatry as part of a comprehensive care plan. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(12):964-968.

• Kornbluh R. Telepsychiatry is a tool that we must exploit. Clinical Psychiatry News. August 7, 2014. http://www. clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/home/article/telepsychiatry-is-a-tool-that-we-must-exploit/28c87bec298e0aa208309fa 9bc48dedc.html.

• University of Colorado Denver. Telemental Health Guide. http:// www.tmhguide.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Kornbluh reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

2. Konrad TR, Ellis AR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of need for mental health professionals in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1307-1314.

3. Vernon DJ, Salsberg E, Erikson C, et al. Planning the future mental health workforce: with progress on coverage, what role will psychiatrists play? Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):187-192.

4. Carrns A. Understanding new rules that widen mental health coverage. The New York Times. http://www. nytimes.com/2014/01/10/your-money/understanding-new-rules-that-widen-mental-health-coverage.html. Published January 9, 2014. Accessed February 10, 2015.

5. Myers KM, Valentine JM, Melzer SM. Feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of telepsychiatry for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1493-1496.

6. Nelson EL, Barnard M, Cain S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemed J E Health. 2003;9(1):49-55.

7. Boydell KM, Hodgins M, Pignatiello A, et al. Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: a scoping review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(2):87-99.

8. Pakyurek M, Yellowlees P, Hilty D. The child and adolescent telepsychiatry consultation: can it be a more effective clinical process for certain patients than conventional practice? Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(3):289-292.

9. Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, et al. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):285-286.

10. Rabinowitz T, Murphy KM, Amour JL, et al. Benefits of a telepsychiatry consultation service for rural nursing home residents. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(1):34-40.

11. Deslich SA, Thistlethwaite T, Coustasse A. Telepsychiatry in correctional facilities: using technology to improve access and decrease costs of mental health care in underserved populations. Perm J. 2013;17(3):80-86.

12. James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji. pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Hilty DN, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444-454.

14. Maheu MM, Mcmenamin J. Telepsychiatry: the perils of using skype. Psychiatric Times. http://www. psychiatrictimes.com/blog/telepsychiatry-perils-using-skype. Published March 28, 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

15. Knoedler DW. Telepsychiatry: first week in the trenches. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ blogs/couch-crisis/telepsychiatry-first-week-trenches. Published January 22, 2014. Accessed February 15, 2015.

16. Secure Telehealth. Medicaid reimburses for telehealth in 41 states. http://www.securetelehealth.com/medicaid-reimbursement.html. Updated January 15, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Federation of State Medical Boards. Telemedicine overview: Board-by-Board approach. http://library.fsmb.org/pdf/ grpol_telemedicine_licensure.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

18. Joint Commission Perspectives. Accepted: final revisions to telemedicine standards. http://www.jointcommission. org/assets/1/6/Revisions_telemedicine_standards.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed February 10, 2015.

19. Hyler SE, Gangure DP. Legal and ethical challenges in telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):272-276.

20. Kornbluh RA. Staying true to the mission: adapting telepsychiatry to a new environment. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):482-483.

Too few psychiatrists. A growing number of patients. A new federal law, technological advances, and a generational shift in the way people communicate. Add them together and you have the perfect environment for telepsychiatry—the remote practice of psychiatry by means of telemedicine—to take root (Box 1). Although telepsychiatry has, in various forms, been around since the 1950s,1 only recently has it expanded into almost all areas of psychiatric practice.

Here are some observations from my daily work on why I see this method of delivering mental health care is poised to expand in 2015 and beyond. Does telepsychiatry make sense for you?

Lack of supply is a big driver

There are simply not enough psychiatrists where they are needed, which is the primary driver of the expansion of telepsychiatry. With 77% of counties in the United States reporting a shortage of psychiatrists2 and the “graying” of the psychiatric workforce,3 a more efficient way to make use of a psychiatrist’s time is needed. Telepsychiatry eliminates travel time and allows psychiatrists to visit distant sites virtually.

The shortage of psychiatric practitioners that we see today is only going to become worse. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 includes mental health care and substance abuse treatment among its 10 essential benefits; just as important, new rules arising from the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 limit restrictions on access to mental health care when insurance provides such coverage.4 These legislative initiatives likely will lead to increased demand for psychiatrists in all care settings—from outpatient consults to acute inpatient admissions.

Why so attractive an option?

The shortage of psychiatrists creates limitations on access to care. Fortunately, telemedicine has entered a new age, ushered in by widely available teleconferencing technology. Specialists from dermatology to surgery currently are using telemedicine; psychiatry is a good fit for telemedicine because of (1) the limited amount of “touch” required to make a psychiatric assessment, (2) significant improvements in video quality in recent years, and (3) a decrease in the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist.

A generation raised on the Internet is entering the health care marketplace. These consumers and clinicians are accustomed to using video for many daily activities, and they seek health information from the Web. Visiting a psychiatrist through teleconferencing isn’t strange or alienating to this generation; their comfort with technology allows them to have intimate exchanges on video.

Subspecialty particulars

The earliest adopters, not surprisingly, are in areas where the strain of shortage has been felt most, with pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatrists leading the way. In these fields, a substantial literature supports the use of telepsychiatry from a number of practice perspectives.

Pediatric psychiatry. The literature shows that children, families, and clinicians are, on the whole, satisfied with telepsychiatry.5 Children and adolescents who have been shown to benefit from telepsychiatry include those with depression,6 posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.7 Based on a case series, some authors have asserted that telepsychiatry might be preferable to in-person treatment (Box 2).8

Geriatric psychiatry. Research shows that geriatric patients, who are most likely to feel threatened by new technology, accept telepsychiatry visits.9 For psychiatrists treating geriatric patients, telepsychiatry can significantly lower costs by cutting commuting10 and make more accessible for patients whose age makes them unable to drive.

Correctional psychiatry. Clinicians working in correctional psychiatry have been at the forefront of experimentation with telepsychiatry. The technology is a natural fit for this setting:

• Prisons often are located in remote locations.

• Psychiatrists can be reluctant to provide on-site services because of safety concerns.

With correctional telepsychiatry, not only are patient outcomes comparable with in-person psychiatry, but the cost of delivering care can be significantly lower.11 With the U.S. Department of Justice reporting that 50% of inmates have a diagnosable mental disorder, including substance abuse,12 the need for access to a psychiatrist in the correctional system is acute.

Telepsychiatry can confidently be provided in a number of settings:

• emergency rooms

• nursing homes

• offices of primary care physicians

• in-home care.

Clinical services in these settings have been offered, studied, and reviewed.13

Can confidentiality and security be assured?

As with any new medical tool, the risk and benefits must be weighed care fully. The most obvious risk is to privacy. Telepsychiatry visits, like all patient encounters, must be secure and confidential. Given the growing suspicion among the public and professionals who use computers that all data are at risk, clinicians must take appropriate cautions and, at the same time, warn patients of the risks. Readily available videoconferencing software, such as Skype, does not provide the level of security that patients expect from health care providers.14

Other common concerns about telepsychiatry are stable access to videoconferencing and the safety from hackers of necessary hardware. Medical device companies have created hardware and software for use in telepsychiatry that provide a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant high-quality, stable, videoconferencing visit.

Do patients benefit?

Clinically, patients have fared well when they receive care through telepsychiatry. In some studies, however, clinicians have expressed some dissatisfaction with the technology13— understandable, given the value that psychiatry traditionally has put on sitting with the patient. As Knoedler15 described it, making the switch to telepsychiatry from in-person contact can engender loneliness in some physicians; not only is patient contact shifted to videoconferencing, but the psychiatrist loses the supportive environment of a busy clinical practice. Knoedler also pointed out that, on the other hand, telepsychiatry offers practitioners the opportunity to evaluate and treat people who otherwise would not have mental health care.

Obstacles—practical, knotty ones

Reimbursement and licensing. These are 2 pressing problems of telepsychiatry, although recent policy developments will help expand telepsychiatry and make it more appealing to physicians:

• Medicare reimburses for telepsychiatry in non-metropolitan areas.

• In 41 states, Medicaid has included telepsychiatry as a benefit.16

• Nine states offer a specific medical license for practicing telepsychiatry17 (in the remaining states, a full medical license must be obtained before one can provide telemedicine services).

• The Joint Commission has included language in its regulations that could expedite privileging of telepsychiatrists.18

Even with such advancements, problems with licensure, credentialing, privacy, security, confidentiality, informed consent, and professional liability remain.19 I urge you to do your research on these key areas before plunging in.

Changes to models of care. The risk that telepsychiatry poses to various models of care has to be considered. Telepsychiatry is a dramatic innovation, but it should be used to support only high-quality, evidence-based care to which patients are entitled.20 With new technology—as with new medications—use must be carefully monitored and scrutinized.

Although evidence of the value of telepsychiatry is growing, many methods of long-distance practice are still in their infancy. Data must be collected and poor outcomes assessed honestly to ensure that the “more-good-than-harm” mandate is met.

Good reasons to call this shift ‘inevitable’

The future of telepsychiatry includes expansion into new areas of practice. The move to providing services to patients where they happen to be—at work or home— seems inevitable:

• In rural areas, practitioners can communicate with patients so that they are cared for in their homes, without the expense of transportation.

• Employers can invest in workplace health clinics that use telemedicine services to reduce absenteeism.

• For psychiatrists, the ability to provide services to patients across a wide region, from a single convenient location, and at lower cost is an attractive prospect.

To conclude: telepsychiatry holds potential to provide greater reimbursement and improved quality of life for psychiatrists and patients: It allows physicians to choose where they live and work, and limits the number of unreimbursed commutes, and gives patients access to psychiatric care locally, without disruptive travel and delays.

Bottom Line

The exchange of medical information from 1 site to another by means of electronic communication has great potential to improve the health of patients and to alleviate the shortage of psychiatric practitioners across regions and settings. Pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatry stand to benefit because of the nature of the patients and locations.

Related Resources

• American Telemedicine Association. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. http://www. americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-video-based-online-mental-health-services. pdf?sfvrsn=6. Published May 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

• Freudenberg N, Yellowlees PM. Telepsychiatry as part of a comprehensive care plan. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(12):964-968.

• Kornbluh R. Telepsychiatry is a tool that we must exploit. Clinical Psychiatry News. August 7, 2014. http://www. clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/home/article/telepsychiatry-is-a-tool-that-we-must-exploit/28c87bec298e0aa208309fa 9bc48dedc.html.

• University of Colorado Denver. Telemental Health Guide. http:// www.tmhguide.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Kornbluh reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Too few psychiatrists. A growing number of patients. A new federal law, technological advances, and a generational shift in the way people communicate. Add them together and you have the perfect environment for telepsychiatry—the remote practice of psychiatry by means of telemedicine—to take root (Box 1). Although telepsychiatry has, in various forms, been around since the 1950s,1 only recently has it expanded into almost all areas of psychiatric practice.

Here are some observations from my daily work on why I see this method of delivering mental health care is poised to expand in 2015 and beyond. Does telepsychiatry make sense for you?

Lack of supply is a big driver

There are simply not enough psychiatrists where they are needed, which is the primary driver of the expansion of telepsychiatry. With 77% of counties in the United States reporting a shortage of psychiatrists2 and the “graying” of the psychiatric workforce,3 a more efficient way to make use of a psychiatrist’s time is needed. Telepsychiatry eliminates travel time and allows psychiatrists to visit distant sites virtually.

The shortage of psychiatric practitioners that we see today is only going to become worse. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 includes mental health care and substance abuse treatment among its 10 essential benefits; just as important, new rules arising from the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 limit restrictions on access to mental health care when insurance provides such coverage.4 These legislative initiatives likely will lead to increased demand for psychiatrists in all care settings—from outpatient consults to acute inpatient admissions.

Why so attractive an option?

The shortage of psychiatrists creates limitations on access to care. Fortunately, telemedicine has entered a new age, ushered in by widely available teleconferencing technology. Specialists from dermatology to surgery currently are using telemedicine; psychiatry is a good fit for telemedicine because of (1) the limited amount of “touch” required to make a psychiatric assessment, (2) significant improvements in video quality in recent years, and (3) a decrease in the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist.

A generation raised on the Internet is entering the health care marketplace. These consumers and clinicians are accustomed to using video for many daily activities, and they seek health information from the Web. Visiting a psychiatrist through teleconferencing isn’t strange or alienating to this generation; their comfort with technology allows them to have intimate exchanges on video.

Subspecialty particulars

The earliest adopters, not surprisingly, are in areas where the strain of shortage has been felt most, with pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatrists leading the way. In these fields, a substantial literature supports the use of telepsychiatry from a number of practice perspectives.

Pediatric psychiatry. The literature shows that children, families, and clinicians are, on the whole, satisfied with telepsychiatry.5 Children and adolescents who have been shown to benefit from telepsychiatry include those with depression,6 posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.7 Based on a case series, some authors have asserted that telepsychiatry might be preferable to in-person treatment (Box 2).8

Geriatric psychiatry. Research shows that geriatric patients, who are most likely to feel threatened by new technology, accept telepsychiatry visits.9 For psychiatrists treating geriatric patients, telepsychiatry can significantly lower costs by cutting commuting10 and make more accessible for patients whose age makes them unable to drive.

Correctional psychiatry. Clinicians working in correctional psychiatry have been at the forefront of experimentation with telepsychiatry. The technology is a natural fit for this setting:

• Prisons often are located in remote locations.

• Psychiatrists can be reluctant to provide on-site services because of safety concerns.

With correctional telepsychiatry, not only are patient outcomes comparable with in-person psychiatry, but the cost of delivering care can be significantly lower.11 With the U.S. Department of Justice reporting that 50% of inmates have a diagnosable mental disorder, including substance abuse,12 the need for access to a psychiatrist in the correctional system is acute.

Telepsychiatry can confidently be provided in a number of settings:

• emergency rooms

• nursing homes

• offices of primary care physicians