User login

CKD: Risk Before, Diet After

Q) In my admitting orders for a CKD patient, I wrote for a “renal diet.” However, the nephrology practitioners changed it to a DASH diet. What is the difference? Why would they not want a “renal diet”?

The answer to this question is: It depends—on the patient, his/her comorbidities, and the need for dialysis treatments (and if so, what type he/she is receiving). Renal diet is a general term used to refer to medical nutrition therapy (MNT) given to a patient with CKD. Each of the five stages of CKD has its own specific MNT requirements.

The MNT for CKD patients often involves modification of the following nutrients: protein, sodium, potassium, phosphorus, and sometimes fluid. The complexity of this therapy often confuses health care professionals when a CKD patient is admitted to the hospital. Let’s examine each nutrient modification to understand optimal nutrition for CKD patients.

Protein. As kidneys fail to excrete urea, protein metabolism is compromised. Thus, in CKD stages 1 and 2, the general recommendations for protein intake are 0.8 to 1.4 g/kg/d. As a patient progresses into CKD stages 3 and 4, these recommendations decrease to 0.6 to 0.8 g/kg/d. In addition, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommend that at least 50% of that protein intake be of high biological value (eg, foods of animal origin, soy proteins, dairy, legumes, and nuts and nut butters).2

Why the wide range in protein intake? Needs vary depending on the patient’s comorbidities and nutritional status. Patients with greater need (eg, documented malnutrition, infections, or wounds) will require more protein than those without documented catabolic stress. Additionally, protein needs are based on weight, making it crucial to obtain an accurate weight. When managing a very overweight or underweight patient, an appropriate standard body weight must be calculated. This assessment should be done by a registered dietitian (RD).

Also, renal replacement therapies, once introduced, sharply increase protein needs. Hemodialysis (HD) can account for free amino acid losses of 5 to 20 g per treatment. Peritoneal dialysis (PD) can result in albumin losses of 5 to 15 g/d.2 As a result, protein needs in HD and PD patients are about 1.2 g/kg/d of standard body weight. It has been reported that 30% to 50% of patients are not consuming these amounts, placing them at risk for malnutrition and a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality.2

Sodium. In CKD stages 1 to 4, dietary sodium intake should be less than 2,400 mg/d. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and a Mediterranean diet have been associated with reduced risk for decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and better blood pressure control.3 Both of these diets can be employed, especially in the beginning stages of CKD. But as CKD progresses and urine output declines, recommendations for sodium intake for both HD and PD patients decrease to 2,000 mg/d. In an anuric patient, 2,000 mg/d is the maximum.2

Potassium. As kidney function declines, potassium retention occurs. In CKD stages 1 to 4, potassium restriction is not employed unless the serum level rises above normal.2 The addition of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker to the medication regimen necessitates close monitoring of potassium levels. Potassium allowance for HD varies according to the patient’s urine output and can range from 2 to 4 g/d. PD patients generally can tolerate 3 to 4 g/d of potassium without becoming hyperkalemic, as potassium is well cleared with PD.2

Continue for further examinations >>

Phosphorus. Mineral bone abnormalities begin early in the course of CKD and lead to high-turnover bone disease, adynamic bone disease, fractures, and soft-tissue calcification. Careful monitoring of calcium, intact parathyroid hormone, and phosphorus levels is required throughout all stages of CKD, with hyperphosphatemia of particular concern.

In CKD stages 1 and 2, dietary phosphorus should be limited to maintain a normal serum level.2 As CKD progresses and phosphorus retention increases, 800 to 1,000 mg/d or 10 to 12 mg of phosphorus per gram of protein should be prescribed.

Even with the limitation of dietary phosphorus, phosphate-binding medications may be required to control serum phosphorus in later CKD stages and in HD and PD patients.2 Limiting dietary phosphorus can be difficult for patients because of inorganic phosphate salt additives widely found in canned and processed foods; they are also added to dark colas and to meats and poultry to act as preservatives and improve flavor and texture. Phosphorus additives are 100% bioavailable and therefore more readily absorbed than organic phosphorus.4

Fluid. Lastly, CKD patients need to think about their fluid intake. HD patients with a urine output of > 1,000 mL/24-h period will be allowed up to 2,000 mL/d of fluid. (A 12-oz canned drink is 355 mL.) Those with less than 1,000 mL of urine output will be allowed 1,000 to 1,500 mL/d, with anuric patients capped at 1,000 mL/d. PD patients are allowed 1,000 to 3,000 mL/d depending on urine output and overall status.2 Patients should also be reminded that foods such as soup and gelatin are counted in their fluid allowance.

The complexities of the “renal diet” make patient education by an RD critical. However, a recent article suggested that MNT for CKD patients is underutilized, with limited referrals and lack of education for primary care providers and RDs cited as reasons.5 This is mystifying considering that Medicare will pay for RD services for CKD patients.

The National Kidney Disease Education Program, in association with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, has developed free professional and patient education materials to address this need; they are available at http://nkdep.nih.gov/.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. McMahon GM, Preis SR, Hwang S-J, Fox CS. Mid-adulthood risk factor profiles for CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Jun 26; [Epub ahead of print].

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A Clinical Guide to Nutrition Care in Kidney Disease. 2nd ed. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2013.

3. Crews DC. Chronic kidney disease and access to healthful foods. ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):11.

4. Moe SM. Phosphate additives in food: you are what you eat—but shouldn’t you know that? ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):8.

5. Narva A, Norton J. Medical nutrition therapy for CKD. ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):7.

Q) In my admitting orders for a CKD patient, I wrote for a “renal diet.” However, the nephrology practitioners changed it to a DASH diet. What is the difference? Why would they not want a “renal diet”?

The answer to this question is: It depends—on the patient, his/her comorbidities, and the need for dialysis treatments (and if so, what type he/she is receiving). Renal diet is a general term used to refer to medical nutrition therapy (MNT) given to a patient with CKD. Each of the five stages of CKD has its own specific MNT requirements.

The MNT for CKD patients often involves modification of the following nutrients: protein, sodium, potassium, phosphorus, and sometimes fluid. The complexity of this therapy often confuses health care professionals when a CKD patient is admitted to the hospital. Let’s examine each nutrient modification to understand optimal nutrition for CKD patients.

Protein. As kidneys fail to excrete urea, protein metabolism is compromised. Thus, in CKD stages 1 and 2, the general recommendations for protein intake are 0.8 to 1.4 g/kg/d. As a patient progresses into CKD stages 3 and 4, these recommendations decrease to 0.6 to 0.8 g/kg/d. In addition, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommend that at least 50% of that protein intake be of high biological value (eg, foods of animal origin, soy proteins, dairy, legumes, and nuts and nut butters).2

Why the wide range in protein intake? Needs vary depending on the patient’s comorbidities and nutritional status. Patients with greater need (eg, documented malnutrition, infections, or wounds) will require more protein than those without documented catabolic stress. Additionally, protein needs are based on weight, making it crucial to obtain an accurate weight. When managing a very overweight or underweight patient, an appropriate standard body weight must be calculated. This assessment should be done by a registered dietitian (RD).

Also, renal replacement therapies, once introduced, sharply increase protein needs. Hemodialysis (HD) can account for free amino acid losses of 5 to 20 g per treatment. Peritoneal dialysis (PD) can result in albumin losses of 5 to 15 g/d.2 As a result, protein needs in HD and PD patients are about 1.2 g/kg/d of standard body weight. It has been reported that 30% to 50% of patients are not consuming these amounts, placing them at risk for malnutrition and a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality.2

Sodium. In CKD stages 1 to 4, dietary sodium intake should be less than 2,400 mg/d. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and a Mediterranean diet have been associated with reduced risk for decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and better blood pressure control.3 Both of these diets can be employed, especially in the beginning stages of CKD. But as CKD progresses and urine output declines, recommendations for sodium intake for both HD and PD patients decrease to 2,000 mg/d. In an anuric patient, 2,000 mg/d is the maximum.2

Potassium. As kidney function declines, potassium retention occurs. In CKD stages 1 to 4, potassium restriction is not employed unless the serum level rises above normal.2 The addition of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker to the medication regimen necessitates close monitoring of potassium levels. Potassium allowance for HD varies according to the patient’s urine output and can range from 2 to 4 g/d. PD patients generally can tolerate 3 to 4 g/d of potassium without becoming hyperkalemic, as potassium is well cleared with PD.2

Continue for further examinations >>

Phosphorus. Mineral bone abnormalities begin early in the course of CKD and lead to high-turnover bone disease, adynamic bone disease, fractures, and soft-tissue calcification. Careful monitoring of calcium, intact parathyroid hormone, and phosphorus levels is required throughout all stages of CKD, with hyperphosphatemia of particular concern.

In CKD stages 1 and 2, dietary phosphorus should be limited to maintain a normal serum level.2 As CKD progresses and phosphorus retention increases, 800 to 1,000 mg/d or 10 to 12 mg of phosphorus per gram of protein should be prescribed.

Even with the limitation of dietary phosphorus, phosphate-binding medications may be required to control serum phosphorus in later CKD stages and in HD and PD patients.2 Limiting dietary phosphorus can be difficult for patients because of inorganic phosphate salt additives widely found in canned and processed foods; they are also added to dark colas and to meats and poultry to act as preservatives and improve flavor and texture. Phosphorus additives are 100% bioavailable and therefore more readily absorbed than organic phosphorus.4

Fluid. Lastly, CKD patients need to think about their fluid intake. HD patients with a urine output of > 1,000 mL/24-h period will be allowed up to 2,000 mL/d of fluid. (A 12-oz canned drink is 355 mL.) Those with less than 1,000 mL of urine output will be allowed 1,000 to 1,500 mL/d, with anuric patients capped at 1,000 mL/d. PD patients are allowed 1,000 to 3,000 mL/d depending on urine output and overall status.2 Patients should also be reminded that foods such as soup and gelatin are counted in their fluid allowance.

The complexities of the “renal diet” make patient education by an RD critical. However, a recent article suggested that MNT for CKD patients is underutilized, with limited referrals and lack of education for primary care providers and RDs cited as reasons.5 This is mystifying considering that Medicare will pay for RD services for CKD patients.

The National Kidney Disease Education Program, in association with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, has developed free professional and patient education materials to address this need; they are available at http://nkdep.nih.gov/.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. McMahon GM, Preis SR, Hwang S-J, Fox CS. Mid-adulthood risk factor profiles for CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Jun 26; [Epub ahead of print].

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A Clinical Guide to Nutrition Care in Kidney Disease. 2nd ed. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2013.

3. Crews DC. Chronic kidney disease and access to healthful foods. ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):11.

4. Moe SM. Phosphate additives in food: you are what you eat—but shouldn’t you know that? ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):8.

5. Narva A, Norton J. Medical nutrition therapy for CKD. ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):7.

Q) In my admitting orders for a CKD patient, I wrote for a “renal diet.” However, the nephrology practitioners changed it to a DASH diet. What is the difference? Why would they not want a “renal diet”?

The answer to this question is: It depends—on the patient, his/her comorbidities, and the need for dialysis treatments (and if so, what type he/she is receiving). Renal diet is a general term used to refer to medical nutrition therapy (MNT) given to a patient with CKD. Each of the five stages of CKD has its own specific MNT requirements.

The MNT for CKD patients often involves modification of the following nutrients: protein, sodium, potassium, phosphorus, and sometimes fluid. The complexity of this therapy often confuses health care professionals when a CKD patient is admitted to the hospital. Let’s examine each nutrient modification to understand optimal nutrition for CKD patients.

Protein. As kidneys fail to excrete urea, protein metabolism is compromised. Thus, in CKD stages 1 and 2, the general recommendations for protein intake are 0.8 to 1.4 g/kg/d. As a patient progresses into CKD stages 3 and 4, these recommendations decrease to 0.6 to 0.8 g/kg/d. In addition, the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics recommend that at least 50% of that protein intake be of high biological value (eg, foods of animal origin, soy proteins, dairy, legumes, and nuts and nut butters).2

Why the wide range in protein intake? Needs vary depending on the patient’s comorbidities and nutritional status. Patients with greater need (eg, documented malnutrition, infections, or wounds) will require more protein than those without documented catabolic stress. Additionally, protein needs are based on weight, making it crucial to obtain an accurate weight. When managing a very overweight or underweight patient, an appropriate standard body weight must be calculated. This assessment should be done by a registered dietitian (RD).

Also, renal replacement therapies, once introduced, sharply increase protein needs. Hemodialysis (HD) can account for free amino acid losses of 5 to 20 g per treatment. Peritoneal dialysis (PD) can result in albumin losses of 5 to 15 g/d.2 As a result, protein needs in HD and PD patients are about 1.2 g/kg/d of standard body weight. It has been reported that 30% to 50% of patients are not consuming these amounts, placing them at risk for malnutrition and a higher incidence of morbidity and mortality.2

Sodium. In CKD stages 1 to 4, dietary sodium intake should be less than 2,400 mg/d. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and a Mediterranean diet have been associated with reduced risk for decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and better blood pressure control.3 Both of these diets can be employed, especially in the beginning stages of CKD. But as CKD progresses and urine output declines, recommendations for sodium intake for both HD and PD patients decrease to 2,000 mg/d. In an anuric patient, 2,000 mg/d is the maximum.2

Potassium. As kidney function declines, potassium retention occurs. In CKD stages 1 to 4, potassium restriction is not employed unless the serum level rises above normal.2 The addition of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker to the medication regimen necessitates close monitoring of potassium levels. Potassium allowance for HD varies according to the patient’s urine output and can range from 2 to 4 g/d. PD patients generally can tolerate 3 to 4 g/d of potassium without becoming hyperkalemic, as potassium is well cleared with PD.2

Continue for further examinations >>

Phosphorus. Mineral bone abnormalities begin early in the course of CKD and lead to high-turnover bone disease, adynamic bone disease, fractures, and soft-tissue calcification. Careful monitoring of calcium, intact parathyroid hormone, and phosphorus levels is required throughout all stages of CKD, with hyperphosphatemia of particular concern.

In CKD stages 1 and 2, dietary phosphorus should be limited to maintain a normal serum level.2 As CKD progresses and phosphorus retention increases, 800 to 1,000 mg/d or 10 to 12 mg of phosphorus per gram of protein should be prescribed.

Even with the limitation of dietary phosphorus, phosphate-binding medications may be required to control serum phosphorus in later CKD stages and in HD and PD patients.2 Limiting dietary phosphorus can be difficult for patients because of inorganic phosphate salt additives widely found in canned and processed foods; they are also added to dark colas and to meats and poultry to act as preservatives and improve flavor and texture. Phosphorus additives are 100% bioavailable and therefore more readily absorbed than organic phosphorus.4

Fluid. Lastly, CKD patients need to think about their fluid intake. HD patients with a urine output of > 1,000 mL/24-h period will be allowed up to 2,000 mL/d of fluid. (A 12-oz canned drink is 355 mL.) Those with less than 1,000 mL of urine output will be allowed 1,000 to 1,500 mL/d, with anuric patients capped at 1,000 mL/d. PD patients are allowed 1,000 to 3,000 mL/d depending on urine output and overall status.2 Patients should also be reminded that foods such as soup and gelatin are counted in their fluid allowance.

The complexities of the “renal diet” make patient education by an RD critical. However, a recent article suggested that MNT for CKD patients is underutilized, with limited referrals and lack of education for primary care providers and RDs cited as reasons.5 This is mystifying considering that Medicare will pay for RD services for CKD patients.

The National Kidney Disease Education Program, in association with the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, has developed free professional and patient education materials to address this need; they are available at http://nkdep.nih.gov/.

Luanne DiGuglielmo, MS, RD, CSR

DaVita Summit Renal Center

Mountainside, New Jersey

REFERENCES

1. McMahon GM, Preis SR, Hwang S-J, Fox CS. Mid-adulthood risk factor profiles for CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Jun 26; [Epub ahead of print].

2. Byham-Gray L, Stover J, Wiesen K. A Clinical Guide to Nutrition Care in Kidney Disease. 2nd ed. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics; 2013.

3. Crews DC. Chronic kidney disease and access to healthful foods. ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):11.

4. Moe SM. Phosphate additives in food: you are what you eat—but shouldn’t you know that? ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):8.

5. Narva A, Norton J. Medical nutrition therapy for CKD. ASN Kidney News. 2014;6(5):7.

Prescribing Statins for Patients With ACS? No Need to Wait

PRACTICE CHANGER

Prescribe a high-dose statin before any patient with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); it may be reasonable to extend this to patients being evaluated for ACS.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to the emergency department with chest pain and is diagnosed with ACS. He is scheduled to have PCI within the next 24 hours. When should you start him on a statin?

Statins are the mainstay pharmaceutical treatment for hyperlipidemia and are used for primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease and stroke.2,3 Well known for their cholesterol-lowering effect, they also offer benefits independent of lipids, including improving endothelial function, decreasing oxidative stress, and decreasing vascular inflammation.4-6

Compared to patients with stable angina, those with ACS experience markedly higher rates of coronary events, especially immediately before and after PCI and during the subsequent 30 days.1 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the management of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) advocate starting statins before patients are discharged from the hospital, but they don’t specify precisely when.7

Considering the higher risk for coronary events before and after PCI and statins’ pleiotropic effects, it is reasonable to investigate the optimal time to start statins in patients with ACS.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Meta-analysis shows statins before PCI cut risk for MI

Navarese et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patients with ACS who received statins before or after PCI (statins group) with those who received low-dose or no statins (control group). The authors searched PubMed, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and CINAHL databases as well as key conference proceedings for studies published before November 2013. Using reasonable inclusion and exclusion criteria and appropriate statistical methods, they analyzed the results of 20 randomized controlled trials that included 8,750 patients. Four studies enrolled only patients with ST elevation MI (STEMI), eight were restricted to NSTEMI, and the remaining eight studies enrolled patients with any type of MI or unstable angina.

For patients who were started on a statin before PCI, the mean timing of administration was 0.53 days before. For those started after PCI, the average time to administration was 3.18 days after.

Administering statins before PCI resulted in a greater reduction in the odds of MI than did starting them afterward. Whether administered before or after PCI, statins reduced the incidence of MIs. The overall 30-day incidence of MIs was 3.4% (123 of 3,621) in the statins group and 5% (179 of 3,577) in the control group. This resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 1.6% (number needed to treat = 62.5) and a 33% reduction of the odds of MI (odds ratio [OR] = 0.67). There was also a trend toward reduced mortality in the statin group (OR = 0.66).

In addition, administering statins before PCI resulted in a greater reduction in the odds of MI at 30 days (OR = 0.38) than starting them post-PCI (OR = 0.85) when compared to the controls. The difference between the pre-PCI OR and the post-PCI OR was statistically significant; these findings persisted past 30 days.

WHAT’S NEW

Early statin administration is most effective

According to ACC/AHA guidelines, all patients with ACS should be receiving a statin by the time they are discharged. However, when to start the statin is not specified. This meta-analysis is the first report to show that administering a statin before PCI can significantly reduce the risk for subsequent MI.

Next page: Caveats and challenges >>

CAVEATS

Benefits might vary with different statins

The studies evaluated in this meta-analysis used various statins and dosing regimens, which could have affected the results. However, sensitivity analyses found similar benefits across different types of statins. In addition, most of the included trials used high doses of statins, which minimized the potential discrepancy in outcomes from various dosing regimens. And while the included studies were not perfect, Navarese et al1 used reasonable methods to identify potential biases.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

No barriers to earlier start

Implementing this intervention may be as simple as editing a standard order. This meta-analysis also suggests that the earlier the intervention, the greater the benefit, which may be an argument for starting a statin when a patient first presents for evaluation for ACS, since the associated risks are quite low. We believe it would be beneficial if the next update of the ACC/AHA guidelines7 included this recommendation.

REFERENCES

1. Navarese EP, Kowalewski M, Andreotti F, et al. Meta-analysis of time-related benefits of statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1753-1764.

2. Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Use of lipid lowering drugs for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:983-986.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Liao JK. Beyond lipid lowering: the role of statins in vascular protection. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86:5-18.

5. Li J, Li JJ, He JG, et al. Atorvastatin decreases C-reactive protein-induced inflammatory response in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:8-14.

6. Tandon V, Bano G, Khajuria V, et al. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005; 37:77-85.

7. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57: e215-e367.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(12):735, 738.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Prescribe a high-dose statin before any patient with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); it may be reasonable to extend this to patients being evaluated for ACS.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to the emergency department with chest pain and is diagnosed with ACS. He is scheduled to have PCI within the next 24 hours. When should you start him on a statin?

Statins are the mainstay pharmaceutical treatment for hyperlipidemia and are used for primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease and stroke.2,3 Well known for their cholesterol-lowering effect, they also offer benefits independent of lipids, including improving endothelial function, decreasing oxidative stress, and decreasing vascular inflammation.4-6

Compared to patients with stable angina, those with ACS experience markedly higher rates of coronary events, especially immediately before and after PCI and during the subsequent 30 days.1 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the management of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) advocate starting statins before patients are discharged from the hospital, but they don’t specify precisely when.7

Considering the higher risk for coronary events before and after PCI and statins’ pleiotropic effects, it is reasonable to investigate the optimal time to start statins in patients with ACS.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Meta-analysis shows statins before PCI cut risk for MI

Navarese et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patients with ACS who received statins before or after PCI (statins group) with those who received low-dose or no statins (control group). The authors searched PubMed, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and CINAHL databases as well as key conference proceedings for studies published before November 2013. Using reasonable inclusion and exclusion criteria and appropriate statistical methods, they analyzed the results of 20 randomized controlled trials that included 8,750 patients. Four studies enrolled only patients with ST elevation MI (STEMI), eight were restricted to NSTEMI, and the remaining eight studies enrolled patients with any type of MI or unstable angina.

For patients who were started on a statin before PCI, the mean timing of administration was 0.53 days before. For those started after PCI, the average time to administration was 3.18 days after.

Administering statins before PCI resulted in a greater reduction in the odds of MI than did starting them afterward. Whether administered before or after PCI, statins reduced the incidence of MIs. The overall 30-day incidence of MIs was 3.4% (123 of 3,621) in the statins group and 5% (179 of 3,577) in the control group. This resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 1.6% (number needed to treat = 62.5) and a 33% reduction of the odds of MI (odds ratio [OR] = 0.67). There was also a trend toward reduced mortality in the statin group (OR = 0.66).

In addition, administering statins before PCI resulted in a greater reduction in the odds of MI at 30 days (OR = 0.38) than starting them post-PCI (OR = 0.85) when compared to the controls. The difference between the pre-PCI OR and the post-PCI OR was statistically significant; these findings persisted past 30 days.

WHAT’S NEW

Early statin administration is most effective

According to ACC/AHA guidelines, all patients with ACS should be receiving a statin by the time they are discharged. However, when to start the statin is not specified. This meta-analysis is the first report to show that administering a statin before PCI can significantly reduce the risk for subsequent MI.

Next page: Caveats and challenges >>

CAVEATS

Benefits might vary with different statins

The studies evaluated in this meta-analysis used various statins and dosing regimens, which could have affected the results. However, sensitivity analyses found similar benefits across different types of statins. In addition, most of the included trials used high doses of statins, which minimized the potential discrepancy in outcomes from various dosing regimens. And while the included studies were not perfect, Navarese et al1 used reasonable methods to identify potential biases.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

No barriers to earlier start

Implementing this intervention may be as simple as editing a standard order. This meta-analysis also suggests that the earlier the intervention, the greater the benefit, which may be an argument for starting a statin when a patient first presents for evaluation for ACS, since the associated risks are quite low. We believe it would be beneficial if the next update of the ACC/AHA guidelines7 included this recommendation.

REFERENCES

1. Navarese EP, Kowalewski M, Andreotti F, et al. Meta-analysis of time-related benefits of statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1753-1764.

2. Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Use of lipid lowering drugs for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:983-986.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Liao JK. Beyond lipid lowering: the role of statins in vascular protection. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86:5-18.

5. Li J, Li JJ, He JG, et al. Atorvastatin decreases C-reactive protein-induced inflammatory response in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:8-14.

6. Tandon V, Bano G, Khajuria V, et al. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005; 37:77-85.

7. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57: e215-e367.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(12):735, 738.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Prescribe a high-dose statin before any patient with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); it may be reasonable to extend this to patients being evaluated for ACS.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a meta-analysis1

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to the emergency department with chest pain and is diagnosed with ACS. He is scheduled to have PCI within the next 24 hours. When should you start him on a statin?

Statins are the mainstay pharmaceutical treatment for hyperlipidemia and are used for primary and secondary prevention of coronary artery disease and stroke.2,3 Well known for their cholesterol-lowering effect, they also offer benefits independent of lipids, including improving endothelial function, decreasing oxidative stress, and decreasing vascular inflammation.4-6

Compared to patients with stable angina, those with ACS experience markedly higher rates of coronary events, especially immediately before and after PCI and during the subsequent 30 days.1 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for the management of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) advocate starting statins before patients are discharged from the hospital, but they don’t specify precisely when.7

Considering the higher risk for coronary events before and after PCI and statins’ pleiotropic effects, it is reasonable to investigate the optimal time to start statins in patients with ACS.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

Meta-analysis shows statins before PCI cut risk for MI

Navarese et al1 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing the clinical outcomes of patients with ACS who received statins before or after PCI (statins group) with those who received low-dose or no statins (control group). The authors searched PubMed, Cochrane, Google Scholar, and CINAHL databases as well as key conference proceedings for studies published before November 2013. Using reasonable inclusion and exclusion criteria and appropriate statistical methods, they analyzed the results of 20 randomized controlled trials that included 8,750 patients. Four studies enrolled only patients with ST elevation MI (STEMI), eight were restricted to NSTEMI, and the remaining eight studies enrolled patients with any type of MI or unstable angina.

For patients who were started on a statin before PCI, the mean timing of administration was 0.53 days before. For those started after PCI, the average time to administration was 3.18 days after.

Administering statins before PCI resulted in a greater reduction in the odds of MI than did starting them afterward. Whether administered before or after PCI, statins reduced the incidence of MIs. The overall 30-day incidence of MIs was 3.4% (123 of 3,621) in the statins group and 5% (179 of 3,577) in the control group. This resulted in an absolute risk reduction of 1.6% (number needed to treat = 62.5) and a 33% reduction of the odds of MI (odds ratio [OR] = 0.67). There was also a trend toward reduced mortality in the statin group (OR = 0.66).

In addition, administering statins before PCI resulted in a greater reduction in the odds of MI at 30 days (OR = 0.38) than starting them post-PCI (OR = 0.85) when compared to the controls. The difference between the pre-PCI OR and the post-PCI OR was statistically significant; these findings persisted past 30 days.

WHAT’S NEW

Early statin administration is most effective

According to ACC/AHA guidelines, all patients with ACS should be receiving a statin by the time they are discharged. However, when to start the statin is not specified. This meta-analysis is the first report to show that administering a statin before PCI can significantly reduce the risk for subsequent MI.

Next page: Caveats and challenges >>

CAVEATS

Benefits might vary with different statins

The studies evaluated in this meta-analysis used various statins and dosing regimens, which could have affected the results. However, sensitivity analyses found similar benefits across different types of statins. In addition, most of the included trials used high doses of statins, which minimized the potential discrepancy in outcomes from various dosing regimens. And while the included studies were not perfect, Navarese et al1 used reasonable methods to identify potential biases.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

No barriers to earlier start

Implementing this intervention may be as simple as editing a standard order. This meta-analysis also suggests that the earlier the intervention, the greater the benefit, which may be an argument for starting a statin when a patient first presents for evaluation for ACS, since the associated risks are quite low. We believe it would be beneficial if the next update of the ACC/AHA guidelines7 included this recommendation.

REFERENCES

1. Navarese EP, Kowalewski M, Andreotti F, et al. Meta-analysis of time-related benefits of statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1753-1764.

2. Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Use of lipid lowering drugs for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:983-986.

3. The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349-1357.

4. Liao JK. Beyond lipid lowering: the role of statins in vascular protection. Int J Cardiol. 2002;86:5-18.

5. Li J, Li JJ, He JG, et al. Atorvastatin decreases C-reactive protein-induced inflammatory response in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB pathway. Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;28:8-14.

6. Tandon V, Bano G, Khajuria V, et al. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005; 37:77-85.

7. Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57: e215-e367.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2014. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(12):735, 738.

Pain Out of Proportion to a Fracture

A 57-year-old woman sustained an injury to her left shoulder during a fall down stairs. She presented to the emergency department, where a physician ordered x-rays that a radiologist interpreted as depicting a simple fracture.

The patient claimed that the radiologist misread the x-rays and that the emergency medicine (EM) physician failed to realize her pain was out of proportion to a fracture. She said the EM physician should have ordered additional tests and sought a radiologic consult. The patient contended that she had actually dislocated her shoulder and that the delay in treatment caused her condition to worsen, leaving her unable to use her left hand.

In addition to the radiologist and the EM physician, two nurses were named as defendants. The plaintiff maintained that they had failed to notify the physician when her condition deteriorated.

OUTCOME

A $2.75 million settlement was reached. The hospital, the EM physician, and the nurses were responsible for $1.5 million and the radiologist, $1.25 million.

Continue for David M. Lang's comments >>

COMMENT

Although complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS, formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) is not specifically mentioned in this case synopsis, the size of the settlement suggests that it was likely claimed as the resulting injury. CRPS is frequently a source of litigation.

Relatively minor trauma can lead to CRPS; why only certain patients subsequently develop the syndrome, however, is a mystery. What is certain is that CRPS is recognized as one of the most painful conditions known to humankind. Once it develops, the syndrome can result in constant, debilitating pain, the loss of a limb, and near-total decay of a patient’s quality of life.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys are quick to claim negligence and substantial damages for these patients, with their sad, compelling stories. Because the underlying pathophysiology of CRPS is unclear, liability is often hotly debated, with cases difficult to defend.

Malpractice cases generally involve two elements: liability (the presence and magnitude of the error) and damages (the severity of the injury and impact on life). CRPS cases are often considered “damages” cases, because while liability may be uncertain, the patient’s damages are very clear. An understandingly sympathetic jury panel sees the unfortunate patient’s red, swollen, misshapen limb, hears the story of the patient’s ever-present, exquisite pain, and (based largely on human emotion) infers negligence based on the magnitude of the patient’s suffering.

In this case, the patient sustained a shoulder injury in a fall that was initially treated as a fracture (presumptively proximal) but later determined to be a dislocation. Management of the injury was not described, but we can assume that if a fracture was diagnosed, the shoulder joint was immobilized. The plaintiff did not claim that there were any diminished neurovascular findings at the time of injury. We are not told whether follow-up was arranged for the patient, what the final, full diagnosis was (eg, fracture/anterior dislocation of the proximal humerus), or when/if the shoulder was actively reduced.

Under these circumstances, what could a bedside clinician have done differently? The most prominent element is the report of “pain out of proportion to the diagnosis.” When confronted with pain that seems out of proportion to a limb injury, stop and review the case. Be sure to consider occult or evolving neurovascular injury (eg, compartment syndrome, brachial plexus injury). Seek consultation and a second opinion in cases involving pain that seems intractable and out of proportion.

One quick word about pain and drug-seeking behavior. Many of us are all too familiar with patients who overstate their symptoms to obtain narcotic pain medications. Will you encounter drug seekers who embellish their level of pain to obtain narcotics? You know the answer to that question.

But it is necessary to take an injured patient’s claim of pain as stated. Don’t view yourself as “wrong” or “fooled” if patients misstate their level of pain and you respond accordingly. In many cases, there is no way to differentiate between genuine manifestations of pain and gamesmanship. To attempt to do so is dangerous because it may lead you to dismiss a patient with genuine pain for fear of being “fooled.” Don’t. Few situations will irritate a jury more than a patient with genuine pathology who is wrongly considered a “drug seeker.” Take patients at face value and act appropriately if substance misuse is later discovered.

In this case, recognition of out-of-control pain may have resulted in an orthopedic consultation. At minimum, that would demonstrate that the patient’s pain was taken seriously and the clinicians acted with due concern for her. —DML

A 57-year-old woman sustained an injury to her left shoulder during a fall down stairs. She presented to the emergency department, where a physician ordered x-rays that a radiologist interpreted as depicting a simple fracture.

The patient claimed that the radiologist misread the x-rays and that the emergency medicine (EM) physician failed to realize her pain was out of proportion to a fracture. She said the EM physician should have ordered additional tests and sought a radiologic consult. The patient contended that she had actually dislocated her shoulder and that the delay in treatment caused her condition to worsen, leaving her unable to use her left hand.

In addition to the radiologist and the EM physician, two nurses were named as defendants. The plaintiff maintained that they had failed to notify the physician when her condition deteriorated.

OUTCOME

A $2.75 million settlement was reached. The hospital, the EM physician, and the nurses were responsible for $1.5 million and the radiologist, $1.25 million.

Continue for David M. Lang's comments >>

COMMENT

Although complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS, formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) is not specifically mentioned in this case synopsis, the size of the settlement suggests that it was likely claimed as the resulting injury. CRPS is frequently a source of litigation.

Relatively minor trauma can lead to CRPS; why only certain patients subsequently develop the syndrome, however, is a mystery. What is certain is that CRPS is recognized as one of the most painful conditions known to humankind. Once it develops, the syndrome can result in constant, debilitating pain, the loss of a limb, and near-total decay of a patient’s quality of life.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys are quick to claim negligence and substantial damages for these patients, with their sad, compelling stories. Because the underlying pathophysiology of CRPS is unclear, liability is often hotly debated, with cases difficult to defend.

Malpractice cases generally involve two elements: liability (the presence and magnitude of the error) and damages (the severity of the injury and impact on life). CRPS cases are often considered “damages” cases, because while liability may be uncertain, the patient’s damages are very clear. An understandingly sympathetic jury panel sees the unfortunate patient’s red, swollen, misshapen limb, hears the story of the patient’s ever-present, exquisite pain, and (based largely on human emotion) infers negligence based on the magnitude of the patient’s suffering.

In this case, the patient sustained a shoulder injury in a fall that was initially treated as a fracture (presumptively proximal) but later determined to be a dislocation. Management of the injury was not described, but we can assume that if a fracture was diagnosed, the shoulder joint was immobilized. The plaintiff did not claim that there were any diminished neurovascular findings at the time of injury. We are not told whether follow-up was arranged for the patient, what the final, full diagnosis was (eg, fracture/anterior dislocation of the proximal humerus), or when/if the shoulder was actively reduced.

Under these circumstances, what could a bedside clinician have done differently? The most prominent element is the report of “pain out of proportion to the diagnosis.” When confronted with pain that seems out of proportion to a limb injury, stop and review the case. Be sure to consider occult or evolving neurovascular injury (eg, compartment syndrome, brachial plexus injury). Seek consultation and a second opinion in cases involving pain that seems intractable and out of proportion.

One quick word about pain and drug-seeking behavior. Many of us are all too familiar with patients who overstate their symptoms to obtain narcotic pain medications. Will you encounter drug seekers who embellish their level of pain to obtain narcotics? You know the answer to that question.

But it is necessary to take an injured patient’s claim of pain as stated. Don’t view yourself as “wrong” or “fooled” if patients misstate their level of pain and you respond accordingly. In many cases, there is no way to differentiate between genuine manifestations of pain and gamesmanship. To attempt to do so is dangerous because it may lead you to dismiss a patient with genuine pain for fear of being “fooled.” Don’t. Few situations will irritate a jury more than a patient with genuine pathology who is wrongly considered a “drug seeker.” Take patients at face value and act appropriately if substance misuse is later discovered.

In this case, recognition of out-of-control pain may have resulted in an orthopedic consultation. At minimum, that would demonstrate that the patient’s pain was taken seriously and the clinicians acted with due concern for her. —DML

A 57-year-old woman sustained an injury to her left shoulder during a fall down stairs. She presented to the emergency department, where a physician ordered x-rays that a radiologist interpreted as depicting a simple fracture.

The patient claimed that the radiologist misread the x-rays and that the emergency medicine (EM) physician failed to realize her pain was out of proportion to a fracture. She said the EM physician should have ordered additional tests and sought a radiologic consult. The patient contended that she had actually dislocated her shoulder and that the delay in treatment caused her condition to worsen, leaving her unable to use her left hand.

In addition to the radiologist and the EM physician, two nurses were named as defendants. The plaintiff maintained that they had failed to notify the physician when her condition deteriorated.

OUTCOME

A $2.75 million settlement was reached. The hospital, the EM physician, and the nurses were responsible for $1.5 million and the radiologist, $1.25 million.

Continue for David M. Lang's comments >>

COMMENT

Although complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS, formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) is not specifically mentioned in this case synopsis, the size of the settlement suggests that it was likely claimed as the resulting injury. CRPS is frequently a source of litigation.

Relatively minor trauma can lead to CRPS; why only certain patients subsequently develop the syndrome, however, is a mystery. What is certain is that CRPS is recognized as one of the most painful conditions known to humankind. Once it develops, the syndrome can result in constant, debilitating pain, the loss of a limb, and near-total decay of a patient’s quality of life.

Plaintiffs’ attorneys are quick to claim negligence and substantial damages for these patients, with their sad, compelling stories. Because the underlying pathophysiology of CRPS is unclear, liability is often hotly debated, with cases difficult to defend.

Malpractice cases generally involve two elements: liability (the presence and magnitude of the error) and damages (the severity of the injury and impact on life). CRPS cases are often considered “damages” cases, because while liability may be uncertain, the patient’s damages are very clear. An understandingly sympathetic jury panel sees the unfortunate patient’s red, swollen, misshapen limb, hears the story of the patient’s ever-present, exquisite pain, and (based largely on human emotion) infers negligence based on the magnitude of the patient’s suffering.

In this case, the patient sustained a shoulder injury in a fall that was initially treated as a fracture (presumptively proximal) but later determined to be a dislocation. Management of the injury was not described, but we can assume that if a fracture was diagnosed, the shoulder joint was immobilized. The plaintiff did not claim that there were any diminished neurovascular findings at the time of injury. We are not told whether follow-up was arranged for the patient, what the final, full diagnosis was (eg, fracture/anterior dislocation of the proximal humerus), or when/if the shoulder was actively reduced.

Under these circumstances, what could a bedside clinician have done differently? The most prominent element is the report of “pain out of proportion to the diagnosis.” When confronted with pain that seems out of proportion to a limb injury, stop and review the case. Be sure to consider occult or evolving neurovascular injury (eg, compartment syndrome, brachial plexus injury). Seek consultation and a second opinion in cases involving pain that seems intractable and out of proportion.

One quick word about pain and drug-seeking behavior. Many of us are all too familiar with patients who overstate their symptoms to obtain narcotic pain medications. Will you encounter drug seekers who embellish their level of pain to obtain narcotics? You know the answer to that question.

But it is necessary to take an injured patient’s claim of pain as stated. Don’t view yourself as “wrong” or “fooled” if patients misstate their level of pain and you respond accordingly. In many cases, there is no way to differentiate between genuine manifestations of pain and gamesmanship. To attempt to do so is dangerous because it may lead you to dismiss a patient with genuine pain for fear of being “fooled.” Don’t. Few situations will irritate a jury more than a patient with genuine pathology who is wrongly considered a “drug seeker.” Take patients at face value and act appropriately if substance misuse is later discovered.

In this case, recognition of out-of-control pain may have resulted in an orthopedic consultation. At minimum, that would demonstrate that the patient’s pain was taken seriously and the clinicians acted with due concern for her. —DML

Varying cutoffs of vitamin D add confusion to field

Efforts to reach agreement on how vitamin D deficiency is defined are complicated by the fact that the cutoff points used in reports from clinical laboratories vary widely.

“I think reporting is a great problem because primary care physicians are very hurried,” Dr. John F. Aloia said at a public conference on vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. “When you look at the laboratory report, what you get is a column that’s normal and another column that’s low or high. The choice of the laboratories to choose their own cutpoints is really a problem. The other part of that reporting is using the low level of normal in a range at the RDA [recommended daily allowance].”

In its recently updated recommendations on vitamin D screening, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force noted that variability between serum vitamin D assay methods “and between laboratories using the same methods may range from 10% to 20%, and classification of samples as ‘deficient’ or ‘nondeficient’ may vary by 4% to 32%, depending on which assay is used. Another factor that may complicate interpretation is that 25-(OH)D may act as a negative acute-phase reactant and its levels may decrease in response to inflammation. Lastly, whether common laboratory reference ranges are appropriate for all ethnic groups is unclear.”

Trying to exert influence on what ranges of serum vitamin D laboratories are using in reporting data “is an issue,” said Dr. Aloia, director of the Bone Mineral Research Center at Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, N.Y., and professor of medicine at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University. “A laboratory can report anything it chooses to. For instance, the American College of Pathology and other [professional organizations] don’t have the responsibility for [the cut-offs in] those reports.”

Dr. Aloia favors translating the reporting of vitamin D levels based on something like Z scores, “so when you see lab reports, some of them will have a paragraph of explanation to guide the physician,” he explained. “We’re going to need that. We have to move away from just [a] cutpoint range and the lower level of the range being the RDA.”

Dr. Roger Bouillon, professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of Leuven (Belgium), supports a threshold of 20 ng/mL serum vitamin D in adults. “I don’t like a range [of vitamin D]; they just need to have a level above 20 ng/mL. For me, a threshold is the best strategy on a population basis.”

During an open comment session, attendee Dr. Neil C. Binkley expressed concern over applying Z-score principles to the vitamin D field. “I love bone density measurement,” said Dr. Binkley, codirector of the Osteoporosis Clinical Center & Research Program at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and past president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. “The T-score was in fact an advance in the field. But I can’t tell you how strongly I would urge you to not consider T-scores or Z-scores or something like that in the vitamin D field. Rather, I would urge that we do a better job at measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D so our laboratories agree and have concise guidance for primary care. If you choose to go into the probability realm and the Z-scores, it is going to be a disaster.”

The presenters reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

Efforts to reach agreement on how vitamin D deficiency is defined are complicated by the fact that the cutoff points used in reports from clinical laboratories vary widely.

“I think reporting is a great problem because primary care physicians are very hurried,” Dr. John F. Aloia said at a public conference on vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. “When you look at the laboratory report, what you get is a column that’s normal and another column that’s low or high. The choice of the laboratories to choose their own cutpoints is really a problem. The other part of that reporting is using the low level of normal in a range at the RDA [recommended daily allowance].”

In its recently updated recommendations on vitamin D screening, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force noted that variability between serum vitamin D assay methods “and between laboratories using the same methods may range from 10% to 20%, and classification of samples as ‘deficient’ or ‘nondeficient’ may vary by 4% to 32%, depending on which assay is used. Another factor that may complicate interpretation is that 25-(OH)D may act as a negative acute-phase reactant and its levels may decrease in response to inflammation. Lastly, whether common laboratory reference ranges are appropriate for all ethnic groups is unclear.”

Trying to exert influence on what ranges of serum vitamin D laboratories are using in reporting data “is an issue,” said Dr. Aloia, director of the Bone Mineral Research Center at Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, N.Y., and professor of medicine at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University. “A laboratory can report anything it chooses to. For instance, the American College of Pathology and other [professional organizations] don’t have the responsibility for [the cut-offs in] those reports.”

Dr. Aloia favors translating the reporting of vitamin D levels based on something like Z scores, “so when you see lab reports, some of them will have a paragraph of explanation to guide the physician,” he explained. “We’re going to need that. We have to move away from just [a] cutpoint range and the lower level of the range being the RDA.”

Dr. Roger Bouillon, professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of Leuven (Belgium), supports a threshold of 20 ng/mL serum vitamin D in adults. “I don’t like a range [of vitamin D]; they just need to have a level above 20 ng/mL. For me, a threshold is the best strategy on a population basis.”

During an open comment session, attendee Dr. Neil C. Binkley expressed concern over applying Z-score principles to the vitamin D field. “I love bone density measurement,” said Dr. Binkley, codirector of the Osteoporosis Clinical Center & Research Program at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and past president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. “The T-score was in fact an advance in the field. But I can’t tell you how strongly I would urge you to not consider T-scores or Z-scores or something like that in the vitamin D field. Rather, I would urge that we do a better job at measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D so our laboratories agree and have concise guidance for primary care. If you choose to go into the probability realm and the Z-scores, it is going to be a disaster.”

The presenters reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

Efforts to reach agreement on how vitamin D deficiency is defined are complicated by the fact that the cutoff points used in reports from clinical laboratories vary widely.

“I think reporting is a great problem because primary care physicians are very hurried,” Dr. John F. Aloia said at a public conference on vitamin D sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. “When you look at the laboratory report, what you get is a column that’s normal and another column that’s low or high. The choice of the laboratories to choose their own cutpoints is really a problem. The other part of that reporting is using the low level of normal in a range at the RDA [recommended daily allowance].”

In its recently updated recommendations on vitamin D screening, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force noted that variability between serum vitamin D assay methods “and between laboratories using the same methods may range from 10% to 20%, and classification of samples as ‘deficient’ or ‘nondeficient’ may vary by 4% to 32%, depending on which assay is used. Another factor that may complicate interpretation is that 25-(OH)D may act as a negative acute-phase reactant and its levels may decrease in response to inflammation. Lastly, whether common laboratory reference ranges are appropriate for all ethnic groups is unclear.”

Trying to exert influence on what ranges of serum vitamin D laboratories are using in reporting data “is an issue,” said Dr. Aloia, director of the Bone Mineral Research Center at Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, N.Y., and professor of medicine at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University. “A laboratory can report anything it chooses to. For instance, the American College of Pathology and other [professional organizations] don’t have the responsibility for [the cut-offs in] those reports.”

Dr. Aloia favors translating the reporting of vitamin D levels based on something like Z scores, “so when you see lab reports, some of them will have a paragraph of explanation to guide the physician,” he explained. “We’re going to need that. We have to move away from just [a] cutpoint range and the lower level of the range being the RDA.”

Dr. Roger Bouillon, professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of Leuven (Belgium), supports a threshold of 20 ng/mL serum vitamin D in adults. “I don’t like a range [of vitamin D]; they just need to have a level above 20 ng/mL. For me, a threshold is the best strategy on a population basis.”

During an open comment session, attendee Dr. Neil C. Binkley expressed concern over applying Z-score principles to the vitamin D field. “I love bone density measurement,” said Dr. Binkley, codirector of the Osteoporosis Clinical Center & Research Program at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and past president of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. “The T-score was in fact an advance in the field. But I can’t tell you how strongly I would urge you to not consider T-scores or Z-scores or something like that in the vitamin D field. Rather, I would urge that we do a better job at measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D so our laboratories agree and have concise guidance for primary care. If you choose to go into the probability realm and the Z-scores, it is going to be a disaster.”

The presenters reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

FROM AN NIH PUBLIC CONFERENCE ON VITAMIN D

A step away from immediate umbilical cord clamping

The common practice of immediate cord clamping, which generally means clamping within 15-20 seconds after birth, was fueled by efforts to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, a leading cause of maternal death worldwide. Immediate clamping was part of a full active management intervention recommended in 2007 by the World Health Organization, along with the use of uterotonics (generally oxytocin) immediately after birth and controlled cord traction to quickly deliver the placenta.

Adoption of the WHO-recommended “active management during the third stage of labor” (AMTSL) worked, leading to a 70% reduction in postpartum hemorrhage and a 60% reduction in blood transfusion over passive management. However, it appears that immediate cord clamping has not played an important role in these reductions. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that early clamping does not impact the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (> 1000 cc or > 500 cc), nor does it impact the need for manual removal of the placenta or the need for blood transfusion.

Instead, the critical component of the AMTSL package appears to be administration of a uterotonic, as reported in a large WHO-directed multicenter clinical trial published in 2012. The study also found that women who received controlled cord traction bled an average of 11 cc less – an insignificant difference – than did women who delivered their placentas by their own effort. Moreover, they had a third stage of labor that was an average of 6 minutes shorter (Lancet 2012;379:1721-7).

With assurance that the timing of umbilical cord clamping does not impact maternal outcomes, investigators have begun to look more at the impact of immediate versus delayed cord clamping on the health of the baby.

Thus far, the issues in this arena are a bit more complicated than on the maternal side. There are indications, however, that slight delays in umbilical cord clamping may be beneficial for the newborn – particularly for preterm infants, who appear in systemic reviews to have a nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage when clamping is delayed.

Timing in term infants

The theoretical benefits of delayed cord clamping include increased neonatal blood volume (improved perfusion and decreased organ injury), more time for spontaneous breathing (reduced risks of resuscitation and a smoother transition of cardiopulmonary and cerebral circulation), and increased stem cells for the infant (anti-inflammatory, neurotropic, and neuroprotective effects).

Theoretically, delayed clamping will increase the infant’s iron stores and lower the incidence of iron deficiency anemia during infancy. This is particularly relevant in developing countries, where up to 50% of infants have anemia by 1 year of age. Anemia is consistently associated with abnormal neurodevelopment, and treatment may not always reverse developmental issues.

On the negative side, delayed clamping is associated with theoretical concerns about hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice, hypothermia, polycythemia, and delays in the bonding of infants and mothers.

For term infants, our best reading on the benefits and risks of delayed umbilical cord clamping comes from a 2013 Cochrane systematic review that assessed results from 15 randomized controlled trials involving 3,911 women and infant pairs. Early cord clamping was generally carried out within 60 seconds of birth, whereas delayed cord clamping involved clamping the umbilical cord more than 1 minute after birth or when cord pulsation has ceased.

The review found that delayed clamping was associated with a significantly higher neonatal hemoglobin concentration at 24-48 hours postpartum (a weighted mean difference of 2 g/dL) and increased iron reserves up to 6 months after birth. Infants in the early clamping group were more than twice as likely to be iron deficient at 3-6 months compared with infants whose cord clamping was delayed (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;7:CD004074)

There were no significant differences between early and late clamping in neonatal mortality or for most other neonatal morbidity outcomes. Delayed clamping also did not increase the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage, blood loss, or reduced hemoglobin levels in mothers.

The downside to delayed cord clamping was an increased risk of jaundice requiring phototherapy. Infants in the later cord clamping group were 40% more likely to need phototherapy – a difference that equates to 3% of infants in the early clamping group and 5% of infants in the late clamping group.

Data were insufficient in the Cochrane review to draw reliable conclusions about the comparative effects on other short-term outcomes such as symptomatic polycythemia, respiratory problems, hypothermia, and infection, as data were limited on long-term outcomes.

In practice, this means that the risk of jaundice must be weighed against the risk of iron deficiency. In developed countries we have the resources both to increase iron stores of infants and to provide phototherapy. While the WHO recommends umbilical cord clamping after 1-3 minutes to improve an infant’s iron status, I do not believe the evidence is strong enough to universally adopt such delayed cord clamping in the United States.

Considering the risks of jaundice and the relative infrequency of iron deficiency in the United States, we should not routinely delay clamping for term infants at this point.

A recent committee opinion developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (No. 543, December 2012) captures this view by concluding that “insufficient evidence exists to support or to refute the benefits from delayed umbilical cord clamping for term infants that are born in settings with rich resources.” Although the ACOG opinion preceded the Cochrane review, the committee, of which I was a member, reviewed much of the same literature.

Timing in preterm infants

Preterm neonates are at increased risk of temperature dysregulation, hypotension, and the need for rapid initial pediatric care and blood transfusion. The increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants is possibly related to the increased risk of hypotension.

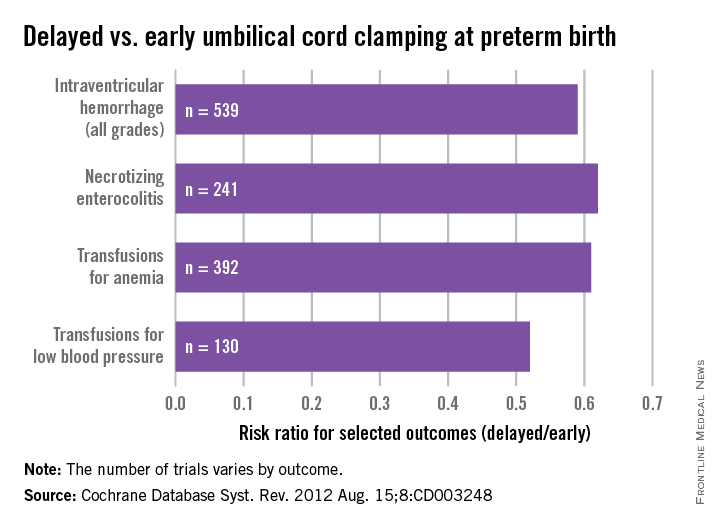

As with term infants, a 2012 Cochrane systematic review offers good insight on our current knowledge. This review of umbilical cord clamping at preterm birth covers 15 studies that included 738 infants delivered between 24 and 36 weeks of gestation. The timing of umbilical cord clamping ranged from 25 seconds to a maximum of 180 seconds (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012;8:CD003248).

Delayed cord clamping was associated with fewer transfusions for anemia or low blood pressure, less intraventricular hemorrhage of all grades (relative risk 0.59), and a lower risk for necrotizing enterocolitis (relative risk 0.62), compared with immediate clamping.

While there were no clear differences with respect to severe intraventricular hemorrhage (grades 3-4), the nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage overall among deliveries with delayed clamping was significant enough to prompt ACOG to conclude that delayed cord clamping should be considered for preterm infants. This reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage appears to be the single most important benefit, based on current findings.

The data on cord clamping in preterm infants are suggestive of benefit, but are not robust. The studies published thus far have been small, and many of them, as the 2012 Cochrane review points out, involved incomplete reporting and wide confidence intervals. Moreover, just as with the studies on term infants, there has been a lack of long-term follow-up in most of the published trials.

When considering delayed cord clamping in preterm infants, as the ACOG Committee Opinion recommends, I urge focusing on earlier gestational ages. Allowing more placental transfusion at births that occur at or after 36 weeks of gestation may not make much sense because by that point the risk of intraventricular hemorrhage is almost nonexistent.

Our practice and the future

At our institution, births that occur at less than 32 weeks of gestation are eligible for delayed umbilical cord clamping, usually at 30-45 seconds after birth. The main contraindications are placental abruption and multiples.

We do not perform any milking or stripping of the umbilical cord, as the risks are unknown and it is not yet clear whether such practices are equivalent to delayed cord clamping. Compared with delayed cord clamping, which is a natural passive transfusion of placental blood to the infant, milking and stripping are not physiologic.

Additional data from an ongoing large international multicenter study, the Australian Placental Transfusion Study, may resolve some of the current controversy. This study is evaluating the cord clamping in neonates < 30 weeks’ gestation. Another study ongoing in Europe should also provide more information.

These studies – and other trials that are larger and longer than the trials published thus far – are necessary to evaluate long-term outcomes and to establish the ideal timing for umbilical cord clamping. Research is also needed to evaluate the management of the third stage of labor relative to umbilical cord clamping as well as the timing in relation to the initiation of voluntary or assisted ventilation.

Dr. Macones said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Macones is the Mitchell and Elaine Yanow Professor and Chair, and director of the division of maternal-fetal medicine and ultrasound in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University, St. Louis.

The common practice of immediate cord clamping, which generally means clamping within 15-20 seconds after birth, was fueled by efforts to reduce the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, a leading cause of maternal death worldwide. Immediate clamping was part of a full active management intervention recommended in 2007 by the World Health Organization, along with the use of uterotonics (generally oxytocin) immediately after birth and controlled cord traction to quickly deliver the placenta.

Adoption of the WHO-recommended “active management during the third stage of labor” (AMTSL) worked, leading to a 70% reduction in postpartum hemorrhage and a 60% reduction in blood transfusion over passive management. However, it appears that immediate cord clamping has not played an important role in these reductions. Several randomized controlled trials have shown that early clamping does not impact the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (> 1000 cc or > 500 cc), nor does it impact the need for manual removal of the placenta or the need for blood transfusion.

Instead, the critical component of the AMTSL package appears to be administration of a uterotonic, as reported in a large WHO-directed multicenter clinical trial published in 2012. The study also found that women who received controlled cord traction bled an average of 11 cc less – an insignificant difference – than did women who delivered their placentas by their own effort. Moreover, they had a third stage of labor that was an average of 6 minutes shorter (Lancet 2012;379:1721-7).

With assurance that the timing of umbilical cord clamping does not impact maternal outcomes, investigators have begun to look more at the impact of immediate versus delayed cord clamping on the health of the baby.

Thus far, the issues in this arena are a bit more complicated than on the maternal side. There are indications, however, that slight delays in umbilical cord clamping may be beneficial for the newborn – particularly for preterm infants, who appear in systemic reviews to have a nearly 50% reduction in intraventricular hemorrhage when clamping is delayed.

Timing in term infants