User login

CDC finds cluster of newborns with late VKDB

Photo by Bertrand Devouard

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified a

small group of newborns in Tennessee with late vitamin K deficiency

bleeding (VKDB).

The agency reported 4 cases of late VKDB, a

serious but preventable bleeding disorder that can cause intracranial

hemorrhage, neurological deficits, and death.

In each case, the newborn’s parents

declined a vitamin K injection at birth, mainly because they were

uninformed about the risk of late VKBD.

Preliminary findings of the CDC’s investigation, in collaboration with the Tennessee Department of Health, appear in the current issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“Not giving vitamin K at birth is an emerging trend that can have devastating outcomes for infants and their families,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. “Ensuring that every newborn receives a vitamin K injection at birth is critical to protect infants.”

Between February and September of this year, 4 cases of late VKDB were diagnosed at a hospital in Nashville, Tennessee.

Three of the infants experienced intracranial hemorrhage, and the fourth had gastrointestinal bleeding. None of the patients had received a vitamin K injection at birth.

Fortunately, all of the infants survived. The patient with gastrointestinal bleeding has made a full recovery. And the 3 infants with intracranial hemorrhage are being followed by neurologists.

One patient has an apparent gross motor deficit, but it seems the others do not. However, all of the patients are still less than 1 year of age, so the full impact of VKDB might only become apparent with time.

The infants’ parents said they declined vitamin K prophylaxis for a number of reasons, including concern about an increased risk of leukemia, the belief that the injection was unnecessary, and a desire to minimize the newborn’s exposure to “toxins.”

Concern about the increased risk of leukemia associated with vitamin K prophylaxis was initially generated by a report published in 1992, but the finding has not been replicated in subsequent studies.

In all cases, parents were uninformed or insufficiently informed about the risk of late VKDB. Most parents only learned about the possibility of late VKDB after their infants developed the condition.

These findings illustrate the importance of educating parents about vitamin K prophylaxis, said Lauren Marcewicz, MD, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

A vitamin K injection at birth has been standard practice in the US since it was first recommended as prophylaxis for late VKDB by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1961.

The late form of VKDB can develop in infants 2 weeks to 6 months of age who did not receive a vitamin K injection and do not have enough vitamin K-dependent proteins in their bodies to allow normal blood clotting. If untreated, this can cause intracranial hemorrhage, which may lead to neurological problems and can be fatal.

The risk for developing late VKDB has been estimated at 81 times greater among infants who do not receive a vitamin K injection at birth than in infants who do receive it.

The CDC said it is currently working with the Tennessee Department of Health to determine if other cases of late VKDB occurred in the state in recent years.

In addition, a case-control study is underway to assess whether any additional risk factors might contribute to the development of late VKDB in children who do not receive vitamin K prophylaxis. ![]()

Photo by Bertrand Devouard

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified a

small group of newborns in Tennessee with late vitamin K deficiency

bleeding (VKDB).

The agency reported 4 cases of late VKDB, a

serious but preventable bleeding disorder that can cause intracranial

hemorrhage, neurological deficits, and death.

In each case, the newborn’s parents

declined a vitamin K injection at birth, mainly because they were

uninformed about the risk of late VKBD.

Preliminary findings of the CDC’s investigation, in collaboration with the Tennessee Department of Health, appear in the current issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“Not giving vitamin K at birth is an emerging trend that can have devastating outcomes for infants and their families,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. “Ensuring that every newborn receives a vitamin K injection at birth is critical to protect infants.”

Between February and September of this year, 4 cases of late VKDB were diagnosed at a hospital in Nashville, Tennessee.

Three of the infants experienced intracranial hemorrhage, and the fourth had gastrointestinal bleeding. None of the patients had received a vitamin K injection at birth.

Fortunately, all of the infants survived. The patient with gastrointestinal bleeding has made a full recovery. And the 3 infants with intracranial hemorrhage are being followed by neurologists.

One patient has an apparent gross motor deficit, but it seems the others do not. However, all of the patients are still less than 1 year of age, so the full impact of VKDB might only become apparent with time.

The infants’ parents said they declined vitamin K prophylaxis for a number of reasons, including concern about an increased risk of leukemia, the belief that the injection was unnecessary, and a desire to minimize the newborn’s exposure to “toxins.”

Concern about the increased risk of leukemia associated with vitamin K prophylaxis was initially generated by a report published in 1992, but the finding has not been replicated in subsequent studies.

In all cases, parents were uninformed or insufficiently informed about the risk of late VKDB. Most parents only learned about the possibility of late VKDB after their infants developed the condition.

These findings illustrate the importance of educating parents about vitamin K prophylaxis, said Lauren Marcewicz, MD, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

A vitamin K injection at birth has been standard practice in the US since it was first recommended as prophylaxis for late VKDB by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1961.

The late form of VKDB can develop in infants 2 weeks to 6 months of age who did not receive a vitamin K injection and do not have enough vitamin K-dependent proteins in their bodies to allow normal blood clotting. If untreated, this can cause intracranial hemorrhage, which may lead to neurological problems and can be fatal.

The risk for developing late VKDB has been estimated at 81 times greater among infants who do not receive a vitamin K injection at birth than in infants who do receive it.

The CDC said it is currently working with the Tennessee Department of Health to determine if other cases of late VKDB occurred in the state in recent years.

In addition, a case-control study is underway to assess whether any additional risk factors might contribute to the development of late VKDB in children who do not receive vitamin K prophylaxis. ![]()

Photo by Bertrand Devouard

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified a

small group of newborns in Tennessee with late vitamin K deficiency

bleeding (VKDB).

The agency reported 4 cases of late VKDB, a

serious but preventable bleeding disorder that can cause intracranial

hemorrhage, neurological deficits, and death.

In each case, the newborn’s parents

declined a vitamin K injection at birth, mainly because they were

uninformed about the risk of late VKBD.

Preliminary findings of the CDC’s investigation, in collaboration with the Tennessee Department of Health, appear in the current issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“Not giving vitamin K at birth is an emerging trend that can have devastating outcomes for infants and their families,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, MD. “Ensuring that every newborn receives a vitamin K injection at birth is critical to protect infants.”

Between February and September of this year, 4 cases of late VKDB were diagnosed at a hospital in Nashville, Tennessee.

Three of the infants experienced intracranial hemorrhage, and the fourth had gastrointestinal bleeding. None of the patients had received a vitamin K injection at birth.

Fortunately, all of the infants survived. The patient with gastrointestinal bleeding has made a full recovery. And the 3 infants with intracranial hemorrhage are being followed by neurologists.

One patient has an apparent gross motor deficit, but it seems the others do not. However, all of the patients are still less than 1 year of age, so the full impact of VKDB might only become apparent with time.

The infants’ parents said they declined vitamin K prophylaxis for a number of reasons, including concern about an increased risk of leukemia, the belief that the injection was unnecessary, and a desire to minimize the newborn’s exposure to “toxins.”

Concern about the increased risk of leukemia associated with vitamin K prophylaxis was initially generated by a report published in 1992, but the finding has not been replicated in subsequent studies.

In all cases, parents were uninformed or insufficiently informed about the risk of late VKDB. Most parents only learned about the possibility of late VKDB after their infants developed the condition.

These findings illustrate the importance of educating parents about vitamin K prophylaxis, said Lauren Marcewicz, MD, of the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities.

A vitamin K injection at birth has been standard practice in the US since it was first recommended as prophylaxis for late VKDB by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1961.

The late form of VKDB can develop in infants 2 weeks to 6 months of age who did not receive a vitamin K injection and do not have enough vitamin K-dependent proteins in their bodies to allow normal blood clotting. If untreated, this can cause intracranial hemorrhage, which may lead to neurological problems and can be fatal.

The risk for developing late VKDB has been estimated at 81 times greater among infants who do not receive a vitamin K injection at birth than in infants who do receive it.

The CDC said it is currently working with the Tennessee Department of Health to determine if other cases of late VKDB occurred in the state in recent years.

In addition, a case-control study is underway to assess whether any additional risk factors might contribute to the development of late VKDB in children who do not receive vitamin K prophylaxis. ![]()

Evaluating an Academic Hospitalist Service

Improving quality while reducing costs remains important for hospitals across the United States, including the approximately 150 hospitals that are part of the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system.[1, 2] The field of hospital medicine has grown rapidly, leading to predictions that the majority of inpatient care in the United States eventually will be delivered by hospitalists.[3, 4] In 2010, 57% of US hospitals had hospitalists on staff, including 87% of hospitals with 200 beds,[5] and nearly 80% of VA hospitals.[6]

The demand for hospitalists within teaching hospitals has grown in part as a response to the mandate to reduce residency work hours.[7] Furthermore, previous research has found that hospitalist care is associated with modest reductions in length of stay (LOS) and weak but inconsistent differences in quality.[8] The educational effect of hospitalists has been far less examined. The limited number of studies published to date suggests that hospitalists may improve resident learning and house‐officer satisfaction in academic medical centers and community teaching hospitals[9, 10, 11] and provide positive experiences for medical students12,13; however, Wachter et al reported no significant changes in clinical outcomes or patient, faculty, and house‐staff satisfaction in a newly designed hospital medicine service in San Francisco.[14] Additionally, whether using hospitalists influences nurse‐physician communication[15] is unknown.

Recognizing the limited and sometimes conflicting evidence about the hospitalist model, we report the results of a 3‐year quasi‐experimental evaluation of the experience at our medical center with academic hospitalists. As part of a VA Systems Redesign Improvement Capability Grantknown as the Hospital Outcomes Program of Excellence (HOPE) Initiativewe created a hospitalist‐based medicine team focused on quality improvement, medical education, and patient outcomes.

METHODS

Setting and Design

The main hospital of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, located in Ann Arbor, Michigan, operates 105 acute‐care beds and 40 extended‐care beds. At the time of this evaluation, the medicine service consisted of 4 internal medicine teamsGold, Silver, Burgundy, and Yelloweach of which was responsible for admitting patients on a rotating basis every fourth day, with limited numbers of admissions occurring between each team's primary admitting day. Each team is led by an attending physician, a board‐certified (or board‐eligible) general internist or subspecialist who is also a faculty member at the University of Michigan Medical School. Each team has a senior medical resident, 2 to 3 interns, and 3 to 5 medical students (mostly third‐year students). In total, there are approximately 50 senior medical residents, 60 interns, and 170 medical students who rotate through the medicine service each year. Traditional rounding involves the medical students and interns receiving sign‐out from the overnight team in the morning, then pre‐rounding on each patient by obtaining an interval history, performing an exam, and checking any test results. A tentative plan of care is formed with the senior medical resident, usually by discussing each patient very quickly in the team room. Attending rounds are then conducted, with the physician team visiting each patient one by one to review and plan all aspects of care in detail. When time allows, small segments of teaching may occur during these attending work rounds. This system had been in place for >20 years.

Resulting in part from a grant received from the VA Systems Redesign Central Office (ie, the HOPE Initiative), the Gold team was modified in July 2009 and an academic hospitalist (S.S.) was assigned to head this team. Specific hospitalists were selected by the Associate Chief of Medicine (S.S.) and the Chief of Medicine (R.H.M.) to serve as Gold team attendings on a regular basis. The other teams continued to be overseen by the Chief of Medicine, and the Gold team remained within the medicine service. Characteristics of the Gold and nonGold team attendings can be found in Table 1. The 3 other teams initially were noninterventional concurrent control groups. However, during the second year of the evaluation, the Silver team adopted some of the initiatives as a result of the preliminary findings observed on Gold. Specifically, in the second year of the evaluation, approximately 42% of attendings on the Silver team were from the Gold team. This increased in the third year to 67% of coverage by Gold team attendings on the Silver team. The evaluation of the Gold team ended in June 2012.

| Characteristic | Gold Team | Non‐Gold Teams |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of attendings | 14 | 57 |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 79 | 58 |

| Female | 21 | 42 |

| Median years postresidency (range) | 10 (130) | 7 (141) |

| Subspecialists, % | 14 | 40 |

| Median days on service per year (range) | 53 (574) | 30 (592) |

The clinical interventions implemented on the Gold team were quality‐improvement work and were therefore exempt from institutional review board review. Human subjects' approval was, however, received to conduct interviews as part of a qualitative assessment.

Clinical Interventions

Several interventions involving the clinical care delivered were introduced on the Gold team, with a focus on improving communication among healthcare workers (Table 2).

| Clinical Interventions | Educational Interventions |

|---|---|

| Modified structure of attending rounds | Modified structure of attending rounds |

| Circle of Concern rounds | Attending reading list |

| Clinical Care Coordinator | Nifty Fifty reading list for learners |

| Regular attending team meetings | Website to provide expectations to learners |

| Two‐month per year commitment by attendings |

Structure of Attending Rounds

The structure of morning rounds was modified on the Gold team. Similar to the traditional structure, medical students and interns on the Gold team receive sign‐out from the overnight team in the morning. However, interns and students may or may not conduct pre‐rounds on each patient. The majority of time between sign‐out and the arrival of the attending physician is spent on work rounds. The senior resident leads rounds with the interns and students, discussing each patient while focusing on overnight events and current symptoms, new physical‐examination findings, and laboratory and test data. The plan of care to be presented to the attending is then formulated with the senior resident. The attending physician then leads Circle of Concern rounds with an expanded team, including a charge nurse, a clinical pharmacist, and a nurse Clinical Care Coordinator. Attending rounds tend to use an E‐AP format: significant Events overnight are discussed, followed by an Assessment & Plan by problem for the top active problems. Using this model, the attendings are able to focus more on teaching and discussing the patient plan than in the traditional model (in which the learner presents the details of the subjective, objective, laboratory, and radiographic data, with limited time left for the assessment and plan for each problem).

Circle of Concern Rounds

Suzanne Gordon described the Circle of Concern in her book Nursing Against the Odds.[16] From her observations, she noted that physicians typically form a circle to discuss patient care during rounds. The circle expands when another physician joins the group; however, the circle does not similarly expand to include nurses when they approach the group. Instead, nurses typically remain on the periphery, listening silently or trying to communicate to physicians' backs.[16] Thus, to promote nurse‐physician communication, Circle of Concern rounds were formally introduced on the Gold team. Each morning, the charge nurse rounds with the team and is encouraged to bring up nursing concerns. The inpatient clinical pharmacist is also included 2 to 3 times per week to help provide education to residents and students and perform medication reconciliation.

Clinical Care Coordinator

The role of the nurse Clinical Care Coordinatoralso introduced on the Gold teamis to provide continuity of patient care, facilitate interdisciplinary communication, facilitate patient discharge, ensure appropriate appointments are scheduled, communicate with the ambulatory care service to ensure proper transition between inpatient and outpatient care, and help educate residents and students on VA procedures and resources.

Regular Gold Team Meetings

All Gold team attendings are expected to dedicate 2 months per year to inpatient service (divided into half‐month blocks), instead of the average 1 month per year for attendings on the other teams. The Gold team attendings, unlike the other teams, also attend bimonthly meetings to discuss strategies for running the team.

Educational Interventions

Given the high number of learners on the medicine service, we wanted to enhance the educational experience for our learners. We thus implemented various interventions, in addition to the change in the structure of rounds, as described below.

Reading List for Learners: The Nifty Fifty

Because reading about clinical medicine is an integral part of medical education, we make explicit our expectation that residents and students read something clinically relevant every day. To promote this, we have provided a Nifty Fifty reading list of key articles. The PDF of each article is provided, along with a brief summary highlighting key points.

Reading List for Gold Attendings and Support Staff

To promote a common understanding of leadership techniques, management books are provided to Gold attending physicians and other members of the team (eg, Care Coordinator, nurse researcher, systems redesign engineer). One book is discussed at each Gold team meeting (Table 3), with participants taking turns leading the discussion.

| Book Title | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| The One Minute Manager | Ken Blanchard and Spencer Johnson |

| Good to Great | Jim Collins |

| Good to Great and the Social Sectors | Jim Collins |

| The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right | Atul Gawande |

| The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable | Patrick Lencioni |

| Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In | Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton |

| The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done | Peter Drucker |

| A Sense of Urgency | John Kotter |

| The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World's Toughest Problems | Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin |

| On the Mend: Revolutionizing Healthcare to Save Lives and Transform the Industry | John Toussaint and Roger Gerard |

| Outliers: The Story of Success | Malcolm Gladwell |

| Nursing Against the Odds: How Health Care Cost Cutting, Media Stereotypes, and Medical Hubris Undermine Nurses and Patient Care | Suzanne Gordon |

| How the Mighty Fall and Why Some Companies Never Give In | Jim Collins |

| What the Best College Teachers Do | Ken Bain |

| The Creative Destruction of Medicine | Eric Topol |

| What Got You Here Won't Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful! | Marshall Goldsmith |

Website

A HOPE Initiative website was created (

Qualitative Assessment

To evaluate our efforts, we conducted a thorough qualitative assessment during the third year of the program. A total of 35 semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with patients and staff from all levels of the organization, including senior leadership. The qualitative assessment was led by research staff from the Center for Clinical Management Research, who were minimally involved in the redesign effort and could provide an unbiased view of the initiative. Field notes from the semistructured interviews were analyzed, with themes developed using a descriptive approach and through discussion by a multidisciplinary team, which included building team consensus on findings that were supported by clear evidence in the data.[17]

Quantitative Outcome Measures

Clinical Outcomes

To determine if our communication and educational interventions had an impact on patient care, we used hospital administrative data to evaluate admission rates, LOS, and readmission rates for all 4 of the medicine teams. Additional clinical measures were assessed as needed. For example, we monitored the impact of the clinical pharmacist during a 4‐week pilot study by asking the Clinical Care Coordinator to track the proportion of patient encounters (n=170) in which the clinical pharmacist changed management or provided education to team members. Additionally, 2 staff surveys were conducted. The first survey focused on healthcare‐worker communication and was given to inpatient nurses and physicians (including attendings, residents, and medical students) who were recently on an inpatient medical service rotation. The survey included questions from previously validated communication measures,[18, 19, 20] as well as study‐specific questions. The second survey evaluated the new role of the Clinical Care Coordinator (Appendix). Both physicians and nurses who interacted with the Gold team's Clinical Care Coordinator were asked to complete this survey.

Educational Outcomes

To assess the educational interventions, we used learner evaluations of attendings, by both residents and medical students, and standardized internal medicine National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examination (or shelf) scores for third‐year medical students. A separate evaluation of medical student perceptions of the rounding structure introduced on the Gold team using survey design has already been published.[21]

Statistical Analyses

Data from all sources were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Outliers for the LOS variable were removed from the analysis. Means and frequency distributions were examined for all variables. Student t tests and [2] tests of independence were used to compare data between groups. Multivariable linear regression models controlling for time (preintervention vs postintervention) were used to assess the effect of the HOPE Initiative on patient LOS and readmission rates. In all cases, 2‐tailed P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Role of the Funding Source

The VA Office of Systems Redesign provided funding but was not involved in the design or conduct of the study, data analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Clinical Outcomes

Patient Outcomes

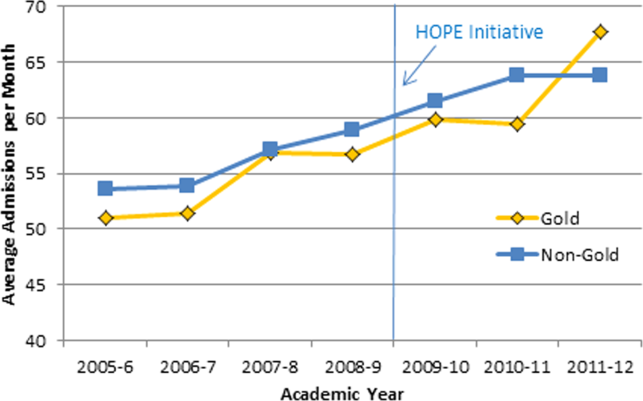

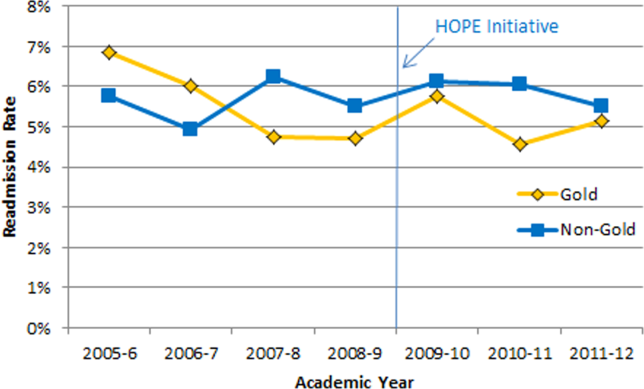

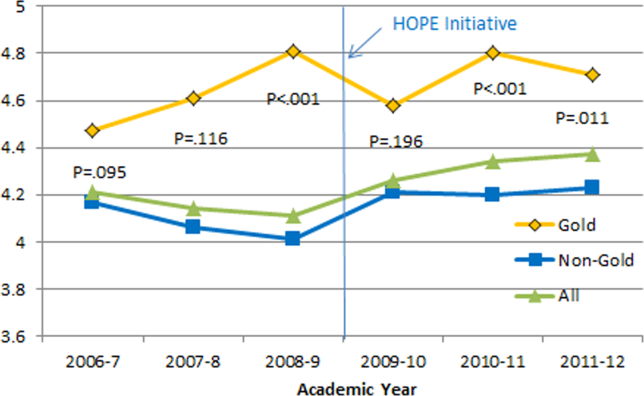

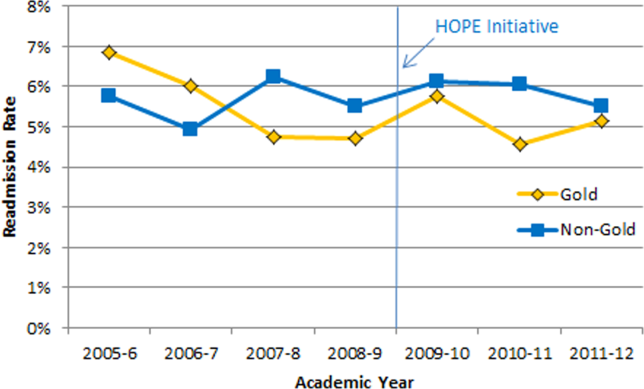

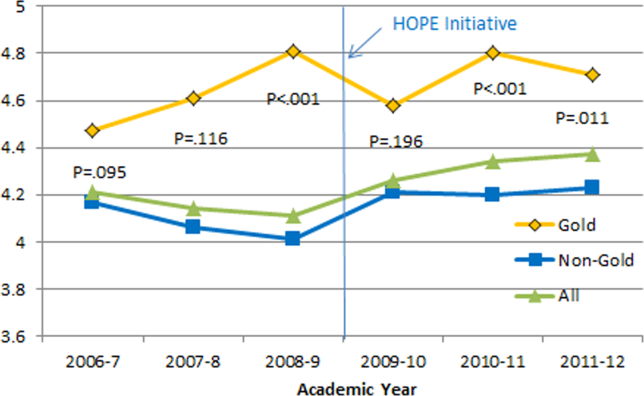

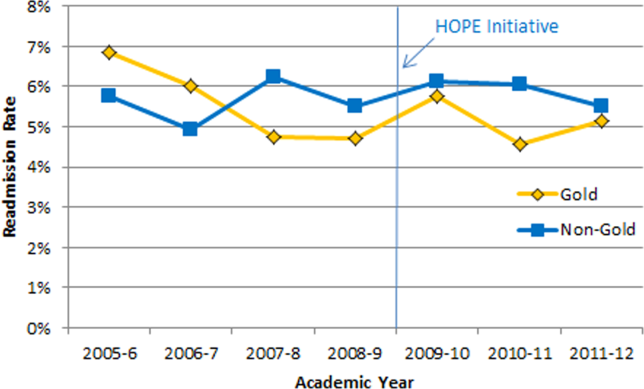

Our multivariable linear regression analysis, controlling for time, showed a significant reduction in LOS of approximately 0.3 days on all teams after the HOPE Initiative began (P=0.004). There were no significant differences between the Gold and non‐Gold teams in the multivariate models when controlling for time for any of the patient‐outcome measures. The number of admissions increased for all 4 medical teams (Figure 1), but, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, the readmission rates for all teams remained relatively stable over this same period of time.

Clinical Pharmacist on Gold Team Rounds

The inpatient clinical pharmacist changed the management plan for 22% of the patients seen on rounds. Contributions from the clinical pharmacist included adjusting the dosing of ordered medication and correcting medication reconciliation. Education and pharmaceutical information was provided to the team in another 6% of the 170 consecutive patient encounters evaluated.

Perception of Circle of Concern Rounds

Circle of Concern rounds were generally well‐received by both nurses and physicians. In a healthcare‐worker communication survey, completed by 38 physicians (62% response rate) and 48 nurses (54% response rate), the majority of both physicians (83%) and nurses (68%) felt Circle of Concern rounds improved communication.

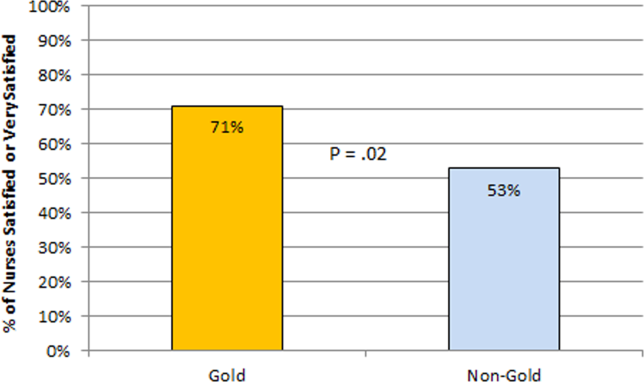

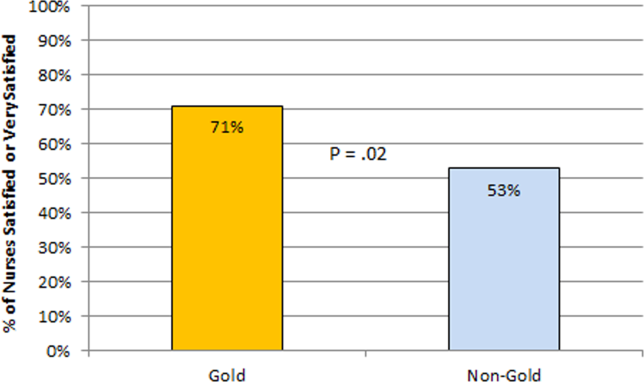

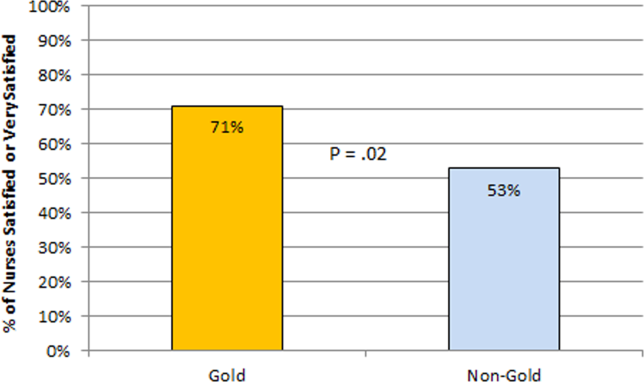

Nurse Perception of Communication

The healthcare‐worker communication survey asked inpatient nurses to rate communication between nurses and physicians on each of the 4 medicine teams. Significantly more nurses were satisfied with communication with the Gold team (71%) compared with the other 3 medicine teams (53%; P=0.02) (Figure 4).

Perception of the Clinical Care Coordinator

In total, 20 physicians (87% response rate) and 10 nurses (56% response rate) completed the Clinical Care Coordinator survey. The physician results were overwhelmingly positive: 100% were satisfied or very satisfied with the role; 100% felt each team should have a Clinical Care Coordinator; and 100% agreed or strongly agreed that the Clinical Care Coordinator ensures that appropriate follow‐up is arranged, provides continuity of care, assists with interdisciplinary communication, and helps facilitate discharge. The majority of nurses was also satisfied or very satisfied with the Clinical Care Coordinator role and felt each team should have one.

Educational Outcomes

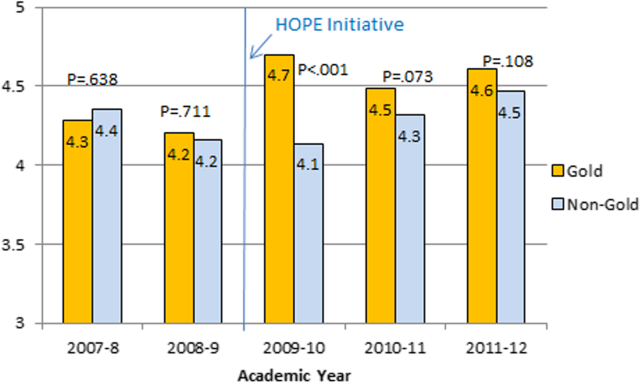

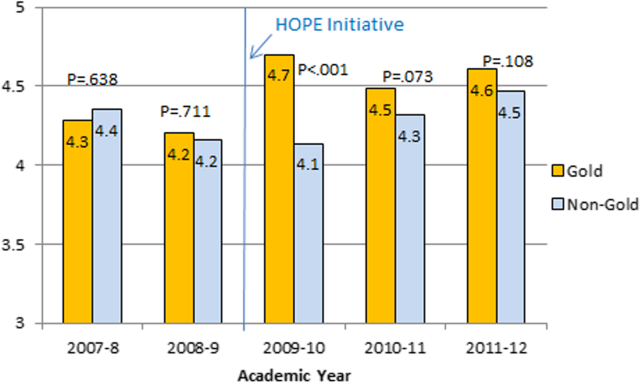

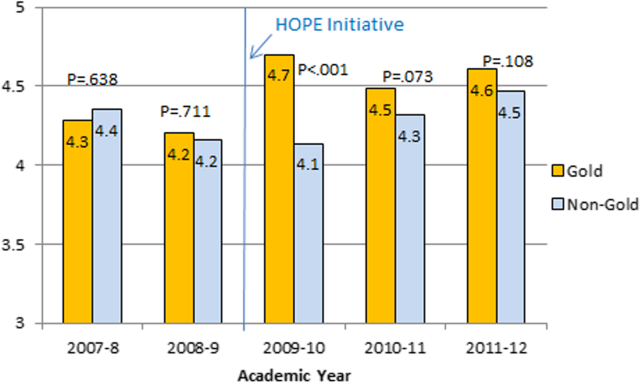

House Officer Evaluation of Attendings

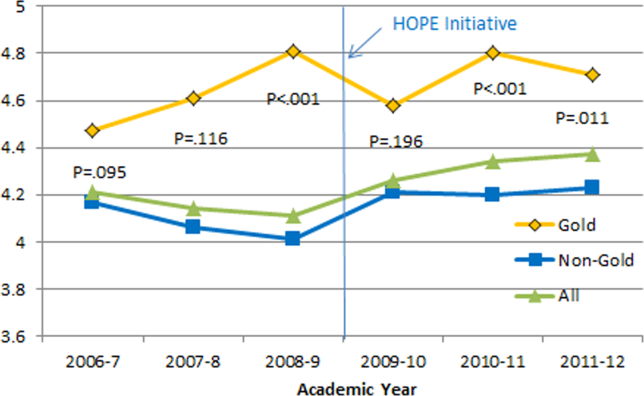

Monthly evaluations of attending physicians by house officers (Figure 5) revealed that prior to the HOPE Initiative, little differences were observed between teams, as would be expected because attending assignment was largely random. After the intervention date of July 2009, however, significant differences were noted, with Gold team attendings receiving significantly higher teaching evaluations immediately after the introduction of the HOPE Initiative. Although ratings for Gold attendings remained more favorable, the difference was no longer statistically significant in the second and third year of the initiative, likely due to Gold attendings serving on other medicine teams, which contributed to an improvement in ratings of all attendings.

Medical Student Evaluation of Attendings

Monthly evaluations of attending physicians by third‐year medical students (Figure 6) revealed differences between the Gold attendings and all others, with the attendings that joined the Gold team in 2009 receiving higher teaching evaluations even before the HOPE Initiative started. However, this difference remained statistically significant in years 2 and 3 postinitiative, despite the addition of 4 new junior attendings.

Medical Student Medicine Shelf Scores

The national average on the shelf exam, which reflects learning after the internal medicine third‐year clerkship, has ranged from 75 to 78 for the past several years, with University of Michigan students averaging significantly higher scores prior to and after the HOPE Initiative. However, following the HOPE Initiative, third‐year medical students on the Gold team scored significantly higher on the shelf exam compared with their colleagues on the non‐Gold teams (84 vs 82; P=0.006). This difference in the shelf exam scores, although small, is statistically significant. It represents a measurable improvement in shelf scores in our system and demonstrates the potential educational benefit for the students. Over this same time period, scores on the United States Medical Licensing Exam, given to medical students at the beginning of their third year, remained stable (233 preHOPE Initiative; 234 postHOPE Initiative).

Qualitative Assessment

Qualitative data collected as part of our evaluation of the HOPE Initiative also suggested that nurse‐physician communication had improved since the start of the project. In particular, they reported positively on the Gold team in general, the Circle of Concern rounds, and the Clinical Care Coordinator (Table 4).

| Staff Type | Statement1 |

|---|---|

| |

| Nurse | [Gold is] above and beyond other [teams]. Other teams don't run as smoothly. |

| Nurse | There has been a difference in communication [on Gold]. You can tell the difference in how they communicate with staff. We know the Clinical Care Coordinator or charge nurse is rounding with that team, so there is more communication. |

| Nurse | The most important thing that has improved communication is the Circle of Concern rounds. |

| Physician | [The Gold Clinical Care Coordinator] expedites care, not only what to do but who to call. She can convey the urgency. On rounds she is able to break off, put in an order, place a call, talk to a patient. Things that we would do at 11 AM she gets to at 9 AM. A couple of hours may not seem like much, but sometimes it can make the difference between things happening that day instead of the next. |

| Physician | The Clinical Care Coordinator is completely indispensable. Major benefit to providing care to Veterans. |

| Physician | I like to think Gold has lifted all of the teams to a higher level. |

| Medical student | It may be due to personalities vs the Gold [team] itself, but there is more emphasis on best practices. Are we following guidelines even if it is not related to the primary reason for admission? |

| Medical student | Gold is very collegial and nurses/physicians know one another by name. Physicians request rather than order; this sets a good example to me on how to approach the nurses. |

| Chief resident | [Gold attendings] encourage senior residents to take charge and run the team, although the attending is there for back‐up and support. This provides great learning for the residents. Interns and medical students also are affected because they have to step up their game as well. |

DISCUSSION

Within academic medical centers, hospitalists are expected to care for patients, teach, and help improve the quality and efficiency of hospital‐based care.[7] The Department of Veterans Affairs runs the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, with approximately 80% of VA hospitals having hospital medicine programs. Overall, one‐third of US residents perform part of their residency training at a VA hospital.[22, 23] Thus, the effects of a system‐wide change at a VA hospital may have implications throughout the country. We studied one such intervention. Our primary findings are that we were able to improve communication and learner education with minimal effects on patient outcomes. While overall LOS decreased slightly postintervention, after taking into account secular trends, readmission rates did not.

We are not the first to evaluate a hospital medicine team using a quasi‐experimental design. For example, Meltzer and colleagues evaluated a hospitalist program at the University of Chicago Medical Center and found that, by the second year of operation, hospitalist care was associated with significantly shorter LOS (0.49 days), reduced costs, and decreased mortality.[24] Auerbach also evaluated a newly created hospital medicine service, finding decreased LOS (0.61 days), lower costs, and lower risk of mortality by the second year of the program.[25]

Improving nurse‐physician communication is considered important for avoiding medical error,[26] yet there has been limited empirical study of methods to improve communication within the medical profession.[27] Based both on our surveys and qualitative interviews, healthcare‐worker communication appeared to improve on the Gold team during the study. A key component of this improvement is likely related to instituting Circle of Concern rounds, in which nurses joined the medical team during attending rounds. Such an intervention likely helped to address organizational silence[28] and enhance the psychological safety of the nursing staff, because the attending physician was proactive about soliciting the input of nurses during rounds.[29] Such leader inclusivenesswords and deeds exhibited by leaders that invite and appreciate others' contributionscan aid interdisciplinary teams in overcoming the negative effects of status differences, thereby promoting collaboration.[29] The inclusion of nurses on rounds is also relationship‐building, which Gotlib Conn and colleagues found was important to improved interprofessional communication and collaboration.[30] In the future, using a tool such as the Teamwork Effectiveness Assessment Module (TEAM) developed by the American Board of Internal Medicine[31] could provide further evaluation of the impact on interprofessional teamwork and communication.

The focus on learner education, though evaluated in prior studies, is also novel. One previous survey of medical students showed that engaging students in substantive discussions is associated with greater student satisfaction.[32] Another survey of medical students found that attendings who were enthusiastic about teaching, inspired confidence in knowledge and skills, provided useful feedback, and encouraged increased student responsibility were viewed as more effective teachers.[33] No previous study that we are aware of, however, has looked at actual educational outcomes, such as shelf scores. The National Board of Medical Examiners reports that the Medicine subject exam is scaled to have a mean of 70 and a standard deviation of 8.[34] Thus, a mean increase in score of 2 points is small, but not trivial. This shows improvement in a hard educational outcome. Additionally, 2 points, although small in the context of total score and standard deviation, may make a substantial difference to an individual student in terms of overall grade, and, thus, residency applications. Our finding that third‐year medical students on the Gold team performed significantly better than University of Michigan third‐year medical students on other teams is an intriguing finding that warrants confirmation. On the other hand, this finding is consistent with a previous report evaluating learner satisfaction in which Bodnar et al found improved ratings of quantity and quality of teaching on teams with a nontraditional structure (Gold team).[21] Moreover, despite relatively few studies, the reason underlying the educational benefit of hospitalists should surprise few. The hospitalist model ensures that learners are supervised by physicians who are experts in the care of hospitalized patients.[35] Hospitalists hired at teaching hospitals to work on services with learners are generally chosen because they possess superior educational skills.[7]

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, our study focused on a single academically affiliated VA hospital. As other VA hospitals are pursuing a similar approach (eg, the Houston and Detroit VA medical centers), replicating our results will be important. Second, the VA system, although the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, has unique characteristicssuch as an integrated electronic health record and predominantly male patient populationthat may make generalizations to the larger US healthcare system challenging. Third, there was a slightly lower response rate among nurses on a few of the surveys to evaluate our efforts; however, this rate of response is standard at our facility. Finally, our evaluation lacks an empirical measure of healthcare‐worker communication, such as incident reports.

Despite these limitations, our results have important implications. Using both quantitative and qualitative assessment, we found that academic hospitalists have the ability to improve healthcare‐worker communication and enhance learner education without increasing LOS. These findings are directly applicable to VA medical centers and potentially applicable to other academic medical centers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, Edward Kennedy, MS, and Andrew Hickner, MSI, for help with preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosures: This work was funded by a US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Systems Redesign Improvement Capability grant. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Saint reports receiving travel reimbursement for giving invited talks at the Society of Hospital Medicine's National Meeting, as well as serving on the advisory boards of Doximity and Jvion.

APPENDIX

Survey to Evaluate the Care Coordinator Position

| Yes | No | Not Sure | |

| Q1. Are you familiar with the role of the Care Coordinator on the Gold Service (Susan Lee)? | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the statements below.

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Don't Know | |

| Q2. The Care Coordinator ensures that appropriate primary care follow‐up and any other appropriate services are arranged. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q3. The Care Coordinator provides continuity of patient care on the Gold Service. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q4. The Care Coordinator helps educate House Officers and Medical Students on VA processes (e.g., CPRS). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q5. The Care Coordinator assists with interdisciplinary communication between the medical team and other services (e.g., nursing, ambulatory care, pharmacy, social work) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q6. The Care Coordinator helps facilitate patient discharge. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q7. The Care Coordinator initiates communication with the ambulatory care teams to coordinate care. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Yes | No | |

| Q8. Are you a physician (attending or resident), or medical student who has been on more than one medical team at the VA (Gold, Silver, Burgundy, or Yellow)? | 1 | 2 |

If no, please skip to Q13

If yes, comparing your experience on the Gold Service (with the Care Coordinator) to your experience on any of the other services (Silver, Burgundy, or Yellow):

| Not at All | Very Little | Somewhat | To a Great Extent | |

| Q9. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator affect patient care? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q10. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator improve patient flow? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q11. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator assist with education? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q12. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator contribute to attending rounds? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Yes | No | |

| Q13. Do you work [as a nurse] in ambulatory care? | 1 | 2 |

If no, please skip to Q17.

If yes, comparing your experience with the Gold Service (with the Care Coordinator) to the other services (Silver, Burgundy, or Yellow):

| Not at All | Very Little | Somewhat | To a Great Extent | |

| Q14. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator improve coordination of care between inpatient and outpatient services? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q15. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator help identify high risk patients who require follow‐up? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q16. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator ensure follow‐up appointments are scheduled? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Yes | No | Not Sure | |

| Q17. Do you think each medical team should have a Care Coordinator? | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Q18. Are there any additional tasks or duties you think would improve the effectiveness of the Care Coordinator? |

| Very Satisfied | Satisfied | Neutral | Dissatisfied | Very Dissatisfied | |

| Q19. Overall how satisfied are you with the role of the Care Coordinator on the Gold Service? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q20. Do you have any other comments about the role of the Care Coordinator? |

| Q21. What is your position? |

| 1. Physician (attending or resident) or medical student |

| 2. Nurse (inpatient or ambulatory care) |

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2001.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- . Growth in care provided by hospitalists. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2789–2791.

- American Hospital Association. AHA Annual Survey of Hospitals, 2010. Chicago, IL: Health Forum, LLC; 2010.

- , , , . Preventing hospital‐acquired infections: a national survey of practices reported by U.S. hospitals in 2005 and 2009. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(7):773–779.

- , . Hospitalists in teaching hospitals: opportunities but not without danger. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):392–393.

- , . Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Med. 2011;9:58.

- , , , . Effect of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee educational experiences: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):490–498.

- , , , , , . Resident satisfaction on an academic hospitalist service: time to teach. Am J Med. 2002;112(7):597–601.

- , , , et al. The positive impact of initiation of hospitalist clinician educators. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):293–301.

- , . Third‐year medical students' evaluation of hospitalist and nonhospitalist faculty during the inpatient portion of their pediatrics clerkships. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(1):17–22.

- , , , . Medical student evaluation of the quality of hospitalist and nonhospitalist teaching faculty on inpatient medicine rotations. Acad Med. 2004;79(1):78–82.

- , , , , . Reorganizing an academic medical service: impact on cost, quality, patient satisfaction, and education. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1560–1565.

- . Nurse/physician communication through a sensemaking lens: shifting the paradigm to improve patient safety. Med Care. 2010;48(11):941–946.

- . Nursing Against the Odds: How Health Care Cost Cutting, Media Stereotypes, and Medical Hubris Undermine Nurses and Patient Care. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2005.

- . Focus on research methods: whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340.

- , , , , . Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse‐physician questionnaire. Med Care. 1991;29(8):709–726.

- . Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20(1):176–182.

- . Development of the practice environment scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25(3):176–188.

- , , . Does the structure of inpatient rounds affect medical student education? Int J Med Educ. 2013;4:96–100.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. Medical and Dental Education Program. Available at: http://www.va. gov/oaa/GME_default.asp. Published 2012. Accessed May 08, 2013.

- , . Graduate medical education, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2264–2279.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , , , , . Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):859–865.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- , , . ‘It depends': medical residents' perspectives on working with nurses. Am J Nurs. 2009;109(7):34–44.

- , . Organizational silence: a barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Acad Manage Rev. 2000;25(4):706–725.

- , . Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organiz Behav. 2006;27:941–966.

- , , , , . Interprofessional communication with hospitalist and consultant physicians in general internal medicine: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:437.

- , , , , , . A new tool to give hospitalists feedback to improve interprofessional teamwork and advance patient care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(11):2485–2492.

- , , , , , . Impact of instructional practices on student satisfaction with attendings' teaching in the inpatient component of internal medicine clerkships. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):7–12.

- , . Medical students' perceptions of the elements of effective inpatient teaching by attending physicians and housestaff. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):635–639.

- National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examination Program. Internal Medicine Advanced Clinical Examination, score interpretation guide. Available at: http://www.nbme.org/PDF/SampleScoreReports/Internal_Medicine_ACE_Score_Report.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed September 13, 2013.

- . The impact of hospitalists on medical education and the academic health system. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(4 part 2):364–367.

Improving quality while reducing costs remains important for hospitals across the United States, including the approximately 150 hospitals that are part of the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system.[1, 2] The field of hospital medicine has grown rapidly, leading to predictions that the majority of inpatient care in the United States eventually will be delivered by hospitalists.[3, 4] In 2010, 57% of US hospitals had hospitalists on staff, including 87% of hospitals with 200 beds,[5] and nearly 80% of VA hospitals.[6]

The demand for hospitalists within teaching hospitals has grown in part as a response to the mandate to reduce residency work hours.[7] Furthermore, previous research has found that hospitalist care is associated with modest reductions in length of stay (LOS) and weak but inconsistent differences in quality.[8] The educational effect of hospitalists has been far less examined. The limited number of studies published to date suggests that hospitalists may improve resident learning and house‐officer satisfaction in academic medical centers and community teaching hospitals[9, 10, 11] and provide positive experiences for medical students12,13; however, Wachter et al reported no significant changes in clinical outcomes or patient, faculty, and house‐staff satisfaction in a newly designed hospital medicine service in San Francisco.[14] Additionally, whether using hospitalists influences nurse‐physician communication[15] is unknown.

Recognizing the limited and sometimes conflicting evidence about the hospitalist model, we report the results of a 3‐year quasi‐experimental evaluation of the experience at our medical center with academic hospitalists. As part of a VA Systems Redesign Improvement Capability Grantknown as the Hospital Outcomes Program of Excellence (HOPE) Initiativewe created a hospitalist‐based medicine team focused on quality improvement, medical education, and patient outcomes.

METHODS

Setting and Design

The main hospital of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, located in Ann Arbor, Michigan, operates 105 acute‐care beds and 40 extended‐care beds. At the time of this evaluation, the medicine service consisted of 4 internal medicine teamsGold, Silver, Burgundy, and Yelloweach of which was responsible for admitting patients on a rotating basis every fourth day, with limited numbers of admissions occurring between each team's primary admitting day. Each team is led by an attending physician, a board‐certified (or board‐eligible) general internist or subspecialist who is also a faculty member at the University of Michigan Medical School. Each team has a senior medical resident, 2 to 3 interns, and 3 to 5 medical students (mostly third‐year students). In total, there are approximately 50 senior medical residents, 60 interns, and 170 medical students who rotate through the medicine service each year. Traditional rounding involves the medical students and interns receiving sign‐out from the overnight team in the morning, then pre‐rounding on each patient by obtaining an interval history, performing an exam, and checking any test results. A tentative plan of care is formed with the senior medical resident, usually by discussing each patient very quickly in the team room. Attending rounds are then conducted, with the physician team visiting each patient one by one to review and plan all aspects of care in detail. When time allows, small segments of teaching may occur during these attending work rounds. This system had been in place for >20 years.

Resulting in part from a grant received from the VA Systems Redesign Central Office (ie, the HOPE Initiative), the Gold team was modified in July 2009 and an academic hospitalist (S.S.) was assigned to head this team. Specific hospitalists were selected by the Associate Chief of Medicine (S.S.) and the Chief of Medicine (R.H.M.) to serve as Gold team attendings on a regular basis. The other teams continued to be overseen by the Chief of Medicine, and the Gold team remained within the medicine service. Characteristics of the Gold and nonGold team attendings can be found in Table 1. The 3 other teams initially were noninterventional concurrent control groups. However, during the second year of the evaluation, the Silver team adopted some of the initiatives as a result of the preliminary findings observed on Gold. Specifically, in the second year of the evaluation, approximately 42% of attendings on the Silver team were from the Gold team. This increased in the third year to 67% of coverage by Gold team attendings on the Silver team. The evaluation of the Gold team ended in June 2012.

| Characteristic | Gold Team | Non‐Gold Teams |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of attendings | 14 | 57 |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 79 | 58 |

| Female | 21 | 42 |

| Median years postresidency (range) | 10 (130) | 7 (141) |

| Subspecialists, % | 14 | 40 |

| Median days on service per year (range) | 53 (574) | 30 (592) |

The clinical interventions implemented on the Gold team were quality‐improvement work and were therefore exempt from institutional review board review. Human subjects' approval was, however, received to conduct interviews as part of a qualitative assessment.

Clinical Interventions

Several interventions involving the clinical care delivered were introduced on the Gold team, with a focus on improving communication among healthcare workers (Table 2).

| Clinical Interventions | Educational Interventions |

|---|---|

| Modified structure of attending rounds | Modified structure of attending rounds |

| Circle of Concern rounds | Attending reading list |

| Clinical Care Coordinator | Nifty Fifty reading list for learners |

| Regular attending team meetings | Website to provide expectations to learners |

| Two‐month per year commitment by attendings |

Structure of Attending Rounds

The structure of morning rounds was modified on the Gold team. Similar to the traditional structure, medical students and interns on the Gold team receive sign‐out from the overnight team in the morning. However, interns and students may or may not conduct pre‐rounds on each patient. The majority of time between sign‐out and the arrival of the attending physician is spent on work rounds. The senior resident leads rounds with the interns and students, discussing each patient while focusing on overnight events and current symptoms, new physical‐examination findings, and laboratory and test data. The plan of care to be presented to the attending is then formulated with the senior resident. The attending physician then leads Circle of Concern rounds with an expanded team, including a charge nurse, a clinical pharmacist, and a nurse Clinical Care Coordinator. Attending rounds tend to use an E‐AP format: significant Events overnight are discussed, followed by an Assessment & Plan by problem for the top active problems. Using this model, the attendings are able to focus more on teaching and discussing the patient plan than in the traditional model (in which the learner presents the details of the subjective, objective, laboratory, and radiographic data, with limited time left for the assessment and plan for each problem).

Circle of Concern Rounds

Suzanne Gordon described the Circle of Concern in her book Nursing Against the Odds.[16] From her observations, she noted that physicians typically form a circle to discuss patient care during rounds. The circle expands when another physician joins the group; however, the circle does not similarly expand to include nurses when they approach the group. Instead, nurses typically remain on the periphery, listening silently or trying to communicate to physicians' backs.[16] Thus, to promote nurse‐physician communication, Circle of Concern rounds were formally introduced on the Gold team. Each morning, the charge nurse rounds with the team and is encouraged to bring up nursing concerns. The inpatient clinical pharmacist is also included 2 to 3 times per week to help provide education to residents and students and perform medication reconciliation.

Clinical Care Coordinator

The role of the nurse Clinical Care Coordinatoralso introduced on the Gold teamis to provide continuity of patient care, facilitate interdisciplinary communication, facilitate patient discharge, ensure appropriate appointments are scheduled, communicate with the ambulatory care service to ensure proper transition between inpatient and outpatient care, and help educate residents and students on VA procedures and resources.

Regular Gold Team Meetings

All Gold team attendings are expected to dedicate 2 months per year to inpatient service (divided into half‐month blocks), instead of the average 1 month per year for attendings on the other teams. The Gold team attendings, unlike the other teams, also attend bimonthly meetings to discuss strategies for running the team.

Educational Interventions

Given the high number of learners on the medicine service, we wanted to enhance the educational experience for our learners. We thus implemented various interventions, in addition to the change in the structure of rounds, as described below.

Reading List for Learners: The Nifty Fifty

Because reading about clinical medicine is an integral part of medical education, we make explicit our expectation that residents and students read something clinically relevant every day. To promote this, we have provided a Nifty Fifty reading list of key articles. The PDF of each article is provided, along with a brief summary highlighting key points.

Reading List for Gold Attendings and Support Staff

To promote a common understanding of leadership techniques, management books are provided to Gold attending physicians and other members of the team (eg, Care Coordinator, nurse researcher, systems redesign engineer). One book is discussed at each Gold team meeting (Table 3), with participants taking turns leading the discussion.

| Book Title | Author(s) |

|---|---|

| The One Minute Manager | Ken Blanchard and Spencer Johnson |

| Good to Great | Jim Collins |

| Good to Great and the Social Sectors | Jim Collins |

| The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right | Atul Gawande |

| The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable | Patrick Lencioni |

| Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In | Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton |

| The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done | Peter Drucker |

| A Sense of Urgency | John Kotter |

| The Power of Positive Deviance: How Unlikely Innovators Solve the World's Toughest Problems | Richard Pascale, Jerry Sternin, and Monique Sternin |

| On the Mend: Revolutionizing Healthcare to Save Lives and Transform the Industry | John Toussaint and Roger Gerard |

| Outliers: The Story of Success | Malcolm Gladwell |

| Nursing Against the Odds: How Health Care Cost Cutting, Media Stereotypes, and Medical Hubris Undermine Nurses and Patient Care | Suzanne Gordon |

| How the Mighty Fall and Why Some Companies Never Give In | Jim Collins |

| What the Best College Teachers Do | Ken Bain |

| The Creative Destruction of Medicine | Eric Topol |

| What Got You Here Won't Get You There: How Successful People Become Even More Successful! | Marshall Goldsmith |

Website

A HOPE Initiative website was created (

Qualitative Assessment

To evaluate our efforts, we conducted a thorough qualitative assessment during the third year of the program. A total of 35 semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with patients and staff from all levels of the organization, including senior leadership. The qualitative assessment was led by research staff from the Center for Clinical Management Research, who were minimally involved in the redesign effort and could provide an unbiased view of the initiative. Field notes from the semistructured interviews were analyzed, with themes developed using a descriptive approach and through discussion by a multidisciplinary team, which included building team consensus on findings that were supported by clear evidence in the data.[17]

Quantitative Outcome Measures

Clinical Outcomes

To determine if our communication and educational interventions had an impact on patient care, we used hospital administrative data to evaluate admission rates, LOS, and readmission rates for all 4 of the medicine teams. Additional clinical measures were assessed as needed. For example, we monitored the impact of the clinical pharmacist during a 4‐week pilot study by asking the Clinical Care Coordinator to track the proportion of patient encounters (n=170) in which the clinical pharmacist changed management or provided education to team members. Additionally, 2 staff surveys were conducted. The first survey focused on healthcare‐worker communication and was given to inpatient nurses and physicians (including attendings, residents, and medical students) who were recently on an inpatient medical service rotation. The survey included questions from previously validated communication measures,[18, 19, 20] as well as study‐specific questions. The second survey evaluated the new role of the Clinical Care Coordinator (Appendix). Both physicians and nurses who interacted with the Gold team's Clinical Care Coordinator were asked to complete this survey.

Educational Outcomes

To assess the educational interventions, we used learner evaluations of attendings, by both residents and medical students, and standardized internal medicine National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examination (or shelf) scores for third‐year medical students. A separate evaluation of medical student perceptions of the rounding structure introduced on the Gold team using survey design has already been published.[21]

Statistical Analyses

Data from all sources were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Outliers for the LOS variable were removed from the analysis. Means and frequency distributions were examined for all variables. Student t tests and [2] tests of independence were used to compare data between groups. Multivariable linear regression models controlling for time (preintervention vs postintervention) were used to assess the effect of the HOPE Initiative on patient LOS and readmission rates. In all cases, 2‐tailed P values of 0.05 or less were considered statistically significant.

Role of the Funding Source

The VA Office of Systems Redesign provided funding but was not involved in the design or conduct of the study, data analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

RESULTS

Clinical Outcomes

Patient Outcomes

Our multivariable linear regression analysis, controlling for time, showed a significant reduction in LOS of approximately 0.3 days on all teams after the HOPE Initiative began (P=0.004). There were no significant differences between the Gold and non‐Gold teams in the multivariate models when controlling for time for any of the patient‐outcome measures. The number of admissions increased for all 4 medical teams (Figure 1), but, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, the readmission rates for all teams remained relatively stable over this same period of time.

Clinical Pharmacist on Gold Team Rounds

The inpatient clinical pharmacist changed the management plan for 22% of the patients seen on rounds. Contributions from the clinical pharmacist included adjusting the dosing of ordered medication and correcting medication reconciliation. Education and pharmaceutical information was provided to the team in another 6% of the 170 consecutive patient encounters evaluated.

Perception of Circle of Concern Rounds

Circle of Concern rounds were generally well‐received by both nurses and physicians. In a healthcare‐worker communication survey, completed by 38 physicians (62% response rate) and 48 nurses (54% response rate), the majority of both physicians (83%) and nurses (68%) felt Circle of Concern rounds improved communication.

Nurse Perception of Communication

The healthcare‐worker communication survey asked inpatient nurses to rate communication between nurses and physicians on each of the 4 medicine teams. Significantly more nurses were satisfied with communication with the Gold team (71%) compared with the other 3 medicine teams (53%; P=0.02) (Figure 4).

Perception of the Clinical Care Coordinator

In total, 20 physicians (87% response rate) and 10 nurses (56% response rate) completed the Clinical Care Coordinator survey. The physician results were overwhelmingly positive: 100% were satisfied or very satisfied with the role; 100% felt each team should have a Clinical Care Coordinator; and 100% agreed or strongly agreed that the Clinical Care Coordinator ensures that appropriate follow‐up is arranged, provides continuity of care, assists with interdisciplinary communication, and helps facilitate discharge. The majority of nurses was also satisfied or very satisfied with the Clinical Care Coordinator role and felt each team should have one.

Educational Outcomes

House Officer Evaluation of Attendings

Monthly evaluations of attending physicians by house officers (Figure 5) revealed that prior to the HOPE Initiative, little differences were observed between teams, as would be expected because attending assignment was largely random. After the intervention date of July 2009, however, significant differences were noted, with Gold team attendings receiving significantly higher teaching evaluations immediately after the introduction of the HOPE Initiative. Although ratings for Gold attendings remained more favorable, the difference was no longer statistically significant in the second and third year of the initiative, likely due to Gold attendings serving on other medicine teams, which contributed to an improvement in ratings of all attendings.

Medical Student Evaluation of Attendings

Monthly evaluations of attending physicians by third‐year medical students (Figure 6) revealed differences between the Gold attendings and all others, with the attendings that joined the Gold team in 2009 receiving higher teaching evaluations even before the HOPE Initiative started. However, this difference remained statistically significant in years 2 and 3 postinitiative, despite the addition of 4 new junior attendings.

Medical Student Medicine Shelf Scores

The national average on the shelf exam, which reflects learning after the internal medicine third‐year clerkship, has ranged from 75 to 78 for the past several years, with University of Michigan students averaging significantly higher scores prior to and after the HOPE Initiative. However, following the HOPE Initiative, third‐year medical students on the Gold team scored significantly higher on the shelf exam compared with their colleagues on the non‐Gold teams (84 vs 82; P=0.006). This difference in the shelf exam scores, although small, is statistically significant. It represents a measurable improvement in shelf scores in our system and demonstrates the potential educational benefit for the students. Over this same time period, scores on the United States Medical Licensing Exam, given to medical students at the beginning of their third year, remained stable (233 preHOPE Initiative; 234 postHOPE Initiative).

Qualitative Assessment

Qualitative data collected as part of our evaluation of the HOPE Initiative also suggested that nurse‐physician communication had improved since the start of the project. In particular, they reported positively on the Gold team in general, the Circle of Concern rounds, and the Clinical Care Coordinator (Table 4).

| Staff Type | Statement1 |

|---|---|

| |

| Nurse | [Gold is] above and beyond other [teams]. Other teams don't run as smoothly. |

| Nurse | There has been a difference in communication [on Gold]. You can tell the difference in how they communicate with staff. We know the Clinical Care Coordinator or charge nurse is rounding with that team, so there is more communication. |

| Nurse | The most important thing that has improved communication is the Circle of Concern rounds. |

| Physician | [The Gold Clinical Care Coordinator] expedites care, not only what to do but who to call. She can convey the urgency. On rounds she is able to break off, put in an order, place a call, talk to a patient. Things that we would do at 11 AM she gets to at 9 AM. A couple of hours may not seem like much, but sometimes it can make the difference between things happening that day instead of the next. |

| Physician | The Clinical Care Coordinator is completely indispensable. Major benefit to providing care to Veterans. |

| Physician | I like to think Gold has lifted all of the teams to a higher level. |

| Medical student | It may be due to personalities vs the Gold [team] itself, but there is more emphasis on best practices. Are we following guidelines even if it is not related to the primary reason for admission? |

| Medical student | Gold is very collegial and nurses/physicians know one another by name. Physicians request rather than order; this sets a good example to me on how to approach the nurses. |

| Chief resident | [Gold attendings] encourage senior residents to take charge and run the team, although the attending is there for back‐up and support. This provides great learning for the residents. Interns and medical students also are affected because they have to step up their game as well. |

DISCUSSION

Within academic medical centers, hospitalists are expected to care for patients, teach, and help improve the quality and efficiency of hospital‐based care.[7] The Department of Veterans Affairs runs the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, with approximately 80% of VA hospitals having hospital medicine programs. Overall, one‐third of US residents perform part of their residency training at a VA hospital.[22, 23] Thus, the effects of a system‐wide change at a VA hospital may have implications throughout the country. We studied one such intervention. Our primary findings are that we were able to improve communication and learner education with minimal effects on patient outcomes. While overall LOS decreased slightly postintervention, after taking into account secular trends, readmission rates did not.

We are not the first to evaluate a hospital medicine team using a quasi‐experimental design. For example, Meltzer and colleagues evaluated a hospitalist program at the University of Chicago Medical Center and found that, by the second year of operation, hospitalist care was associated with significantly shorter LOS (0.49 days), reduced costs, and decreased mortality.[24] Auerbach also evaluated a newly created hospital medicine service, finding decreased LOS (0.61 days), lower costs, and lower risk of mortality by the second year of the program.[25]

Improving nurse‐physician communication is considered important for avoiding medical error,[26] yet there has been limited empirical study of methods to improve communication within the medical profession.[27] Based both on our surveys and qualitative interviews, healthcare‐worker communication appeared to improve on the Gold team during the study. A key component of this improvement is likely related to instituting Circle of Concern rounds, in which nurses joined the medical team during attending rounds. Such an intervention likely helped to address organizational silence[28] and enhance the psychological safety of the nursing staff, because the attending physician was proactive about soliciting the input of nurses during rounds.[29] Such leader inclusivenesswords and deeds exhibited by leaders that invite and appreciate others' contributionscan aid interdisciplinary teams in overcoming the negative effects of status differences, thereby promoting collaboration.[29] The inclusion of nurses on rounds is also relationship‐building, which Gotlib Conn and colleagues found was important to improved interprofessional communication and collaboration.[30] In the future, using a tool such as the Teamwork Effectiveness Assessment Module (TEAM) developed by the American Board of Internal Medicine[31] could provide further evaluation of the impact on interprofessional teamwork and communication.

The focus on learner education, though evaluated in prior studies, is also novel. One previous survey of medical students showed that engaging students in substantive discussions is associated with greater student satisfaction.[32] Another survey of medical students found that attendings who were enthusiastic about teaching, inspired confidence in knowledge and skills, provided useful feedback, and encouraged increased student responsibility were viewed as more effective teachers.[33] No previous study that we are aware of, however, has looked at actual educational outcomes, such as shelf scores. The National Board of Medical Examiners reports that the Medicine subject exam is scaled to have a mean of 70 and a standard deviation of 8.[34] Thus, a mean increase in score of 2 points is small, but not trivial. This shows improvement in a hard educational outcome. Additionally, 2 points, although small in the context of total score and standard deviation, may make a substantial difference to an individual student in terms of overall grade, and, thus, residency applications. Our finding that third‐year medical students on the Gold team performed significantly better than University of Michigan third‐year medical students on other teams is an intriguing finding that warrants confirmation. On the other hand, this finding is consistent with a previous report evaluating learner satisfaction in which Bodnar et al found improved ratings of quantity and quality of teaching on teams with a nontraditional structure (Gold team).[21] Moreover, despite relatively few studies, the reason underlying the educational benefit of hospitalists should surprise few. The hospitalist model ensures that learners are supervised by physicians who are experts in the care of hospitalized patients.[35] Hospitalists hired at teaching hospitals to work on services with learners are generally chosen because they possess superior educational skills.[7]

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, our study focused on a single academically affiliated VA hospital. As other VA hospitals are pursuing a similar approach (eg, the Houston and Detroit VA medical centers), replicating our results will be important. Second, the VA system, although the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States, has unique characteristicssuch as an integrated electronic health record and predominantly male patient populationthat may make generalizations to the larger US healthcare system challenging. Third, there was a slightly lower response rate among nurses on a few of the surveys to evaluate our efforts; however, this rate of response is standard at our facility. Finally, our evaluation lacks an empirical measure of healthcare‐worker communication, such as incident reports.

Despite these limitations, our results have important implications. Using both quantitative and qualitative assessment, we found that academic hospitalists have the ability to improve healthcare‐worker communication and enhance learner education without increasing LOS. These findings are directly applicable to VA medical centers and potentially applicable to other academic medical centers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, Edward Kennedy, MS, and Andrew Hickner, MSI, for help with preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosures: This work was funded by a US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Systems Redesign Improvement Capability grant. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Saint reports receiving travel reimbursement for giving invited talks at the Society of Hospital Medicine's National Meeting, as well as serving on the advisory boards of Doximity and Jvion.

APPENDIX

Survey to Evaluate the Care Coordinator Position

| Yes | No | Not Sure | |

| Q1. Are you familiar with the role of the Care Coordinator on the Gold Service (Susan Lee)? | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the statements below.

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Don't Know | |

| Q2. The Care Coordinator ensures that appropriate primary care follow‐up and any other appropriate services are arranged. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q3. The Care Coordinator provides continuity of patient care on the Gold Service. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q4. The Care Coordinator helps educate House Officers and Medical Students on VA processes (e.g., CPRS). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q5. The Care Coordinator assists with interdisciplinary communication between the medical team and other services (e.g., nursing, ambulatory care, pharmacy, social work) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q6. The Care Coordinator helps facilitate patient discharge. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Q7. The Care Coordinator initiates communication with the ambulatory care teams to coordinate care. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Yes | No | |

| Q8. Are you a physician (attending or resident), or medical student who has been on more than one medical team at the VA (Gold, Silver, Burgundy, or Yellow)? | 1 | 2 |

If no, please skip to Q13

If yes, comparing your experience on the Gold Service (with the Care Coordinator) to your experience on any of the other services (Silver, Burgundy, or Yellow):

| Not at All | Very Little | Somewhat | To a Great Extent | |

| Q9. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator affect patient care? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q10. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator improve patient flow? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q11. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator assist with education? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q12. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator contribute to attending rounds? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Yes | No | |

| Q13. Do you work [as a nurse] in ambulatory care? | 1 | 2 |

If no, please skip to Q17.

If yes, comparing your experience with the Gold Service (with the Care Coordinator) to the other services (Silver, Burgundy, or Yellow):

| Not at All | Very Little | Somewhat | To a Great Extent | |

| Q14. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator improve coordination of care between inpatient and outpatient services? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Q15. To what extent does the presence of a Care Coordinator help identify high risk patients who require follow‐up? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |