User login

How to Discuss Lifestyle Modifications in MASLD

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

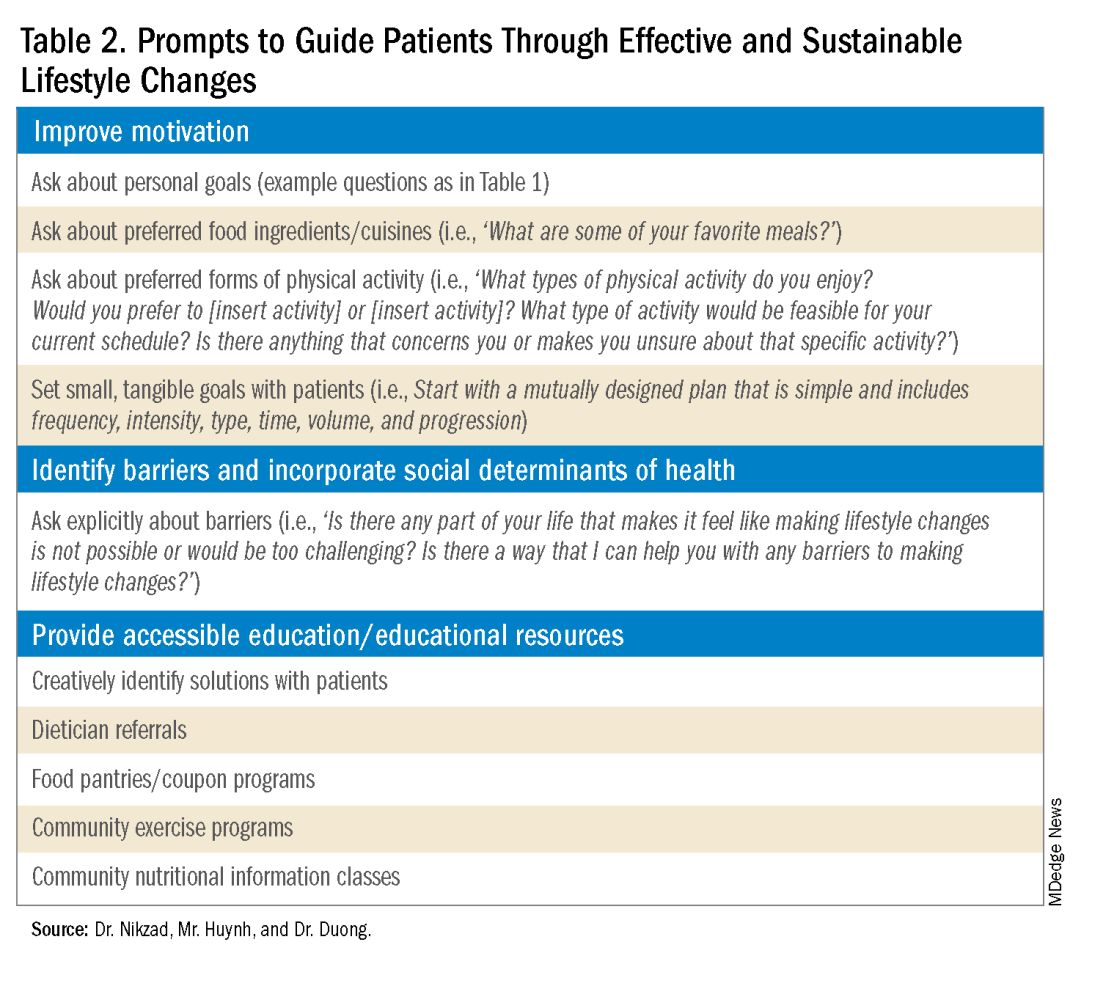

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

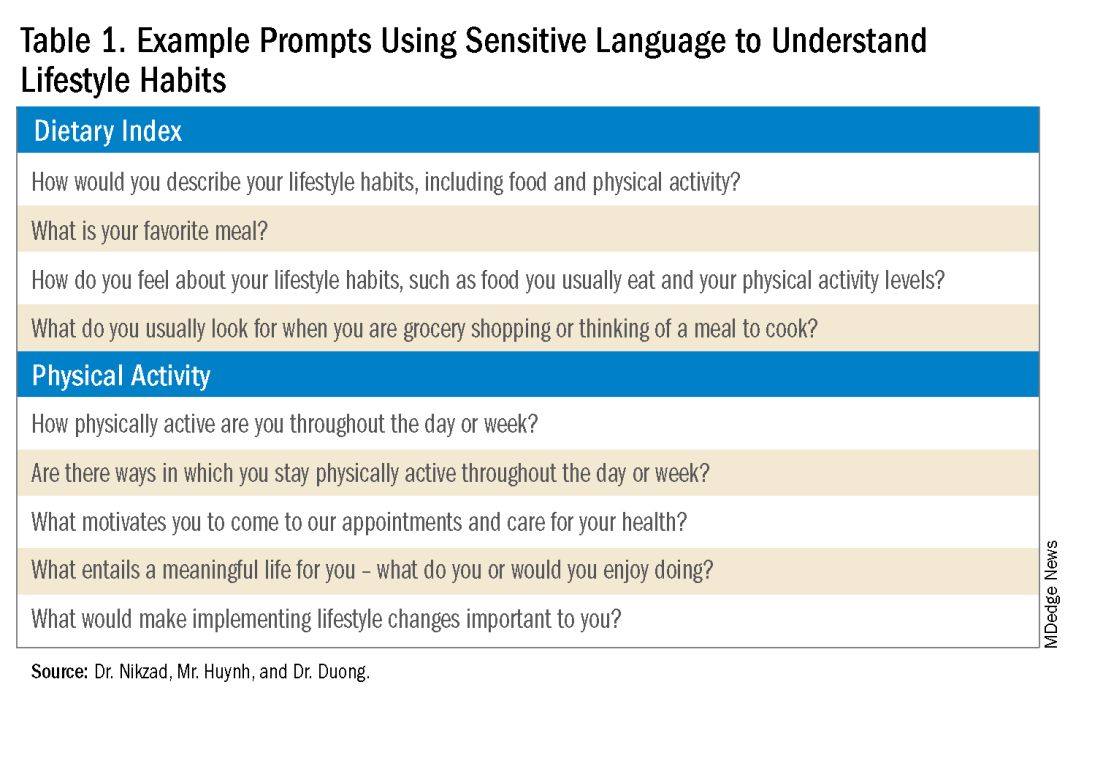

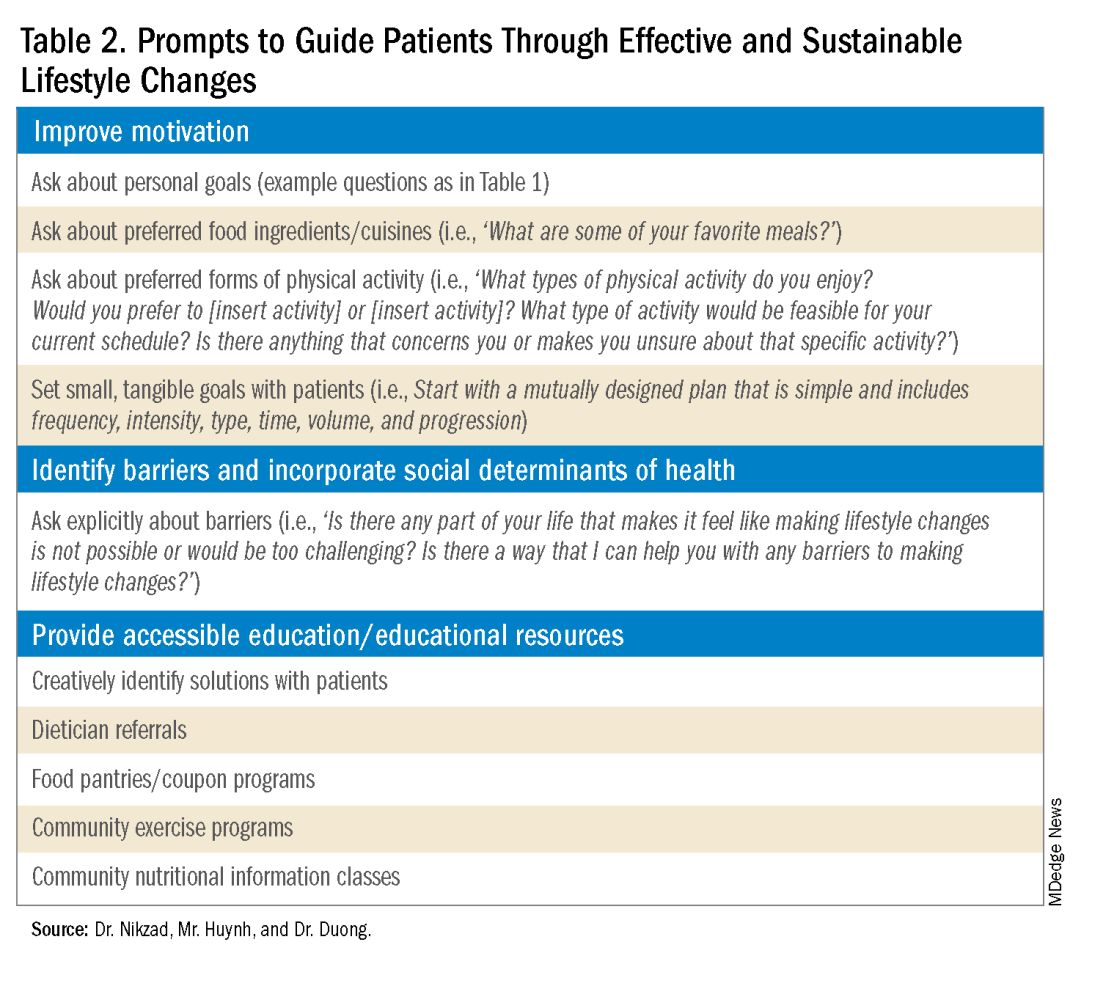

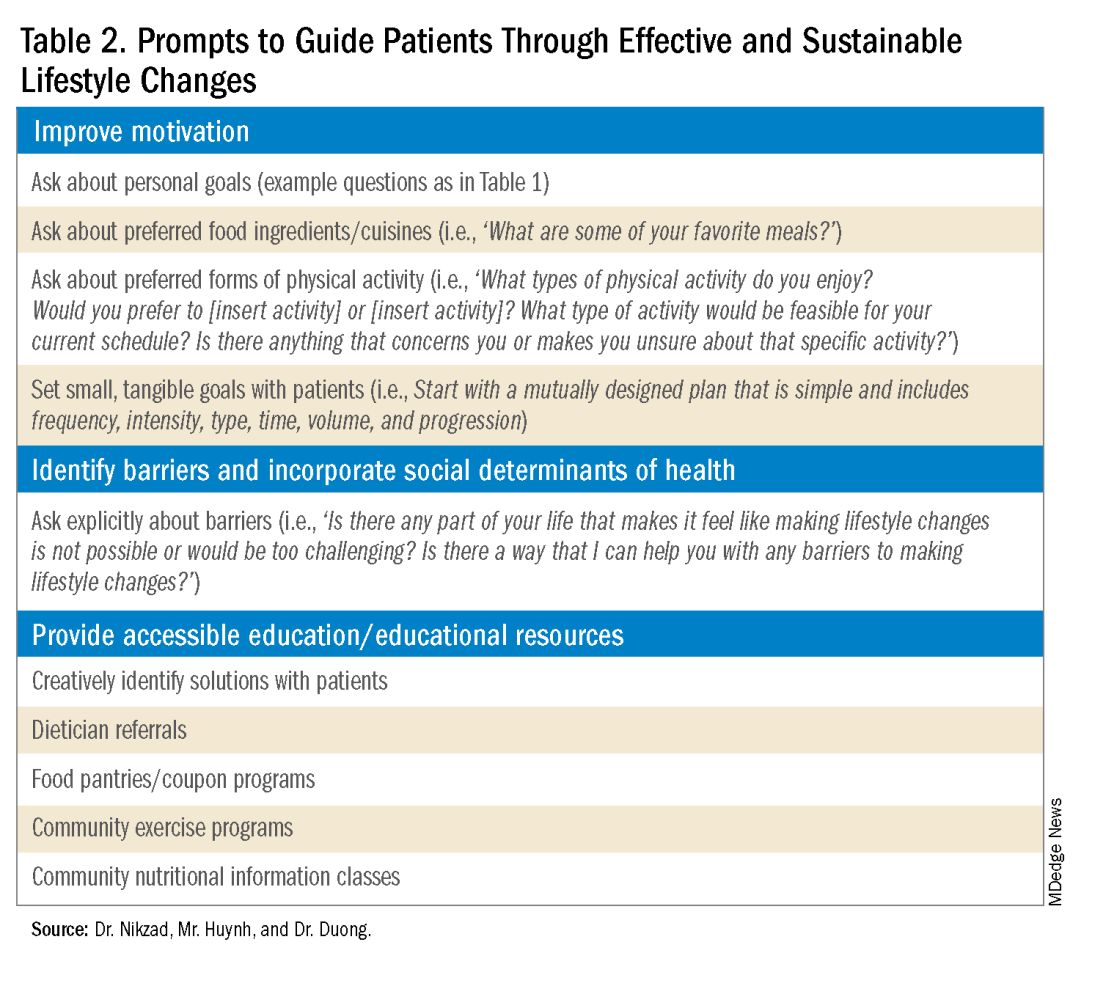

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

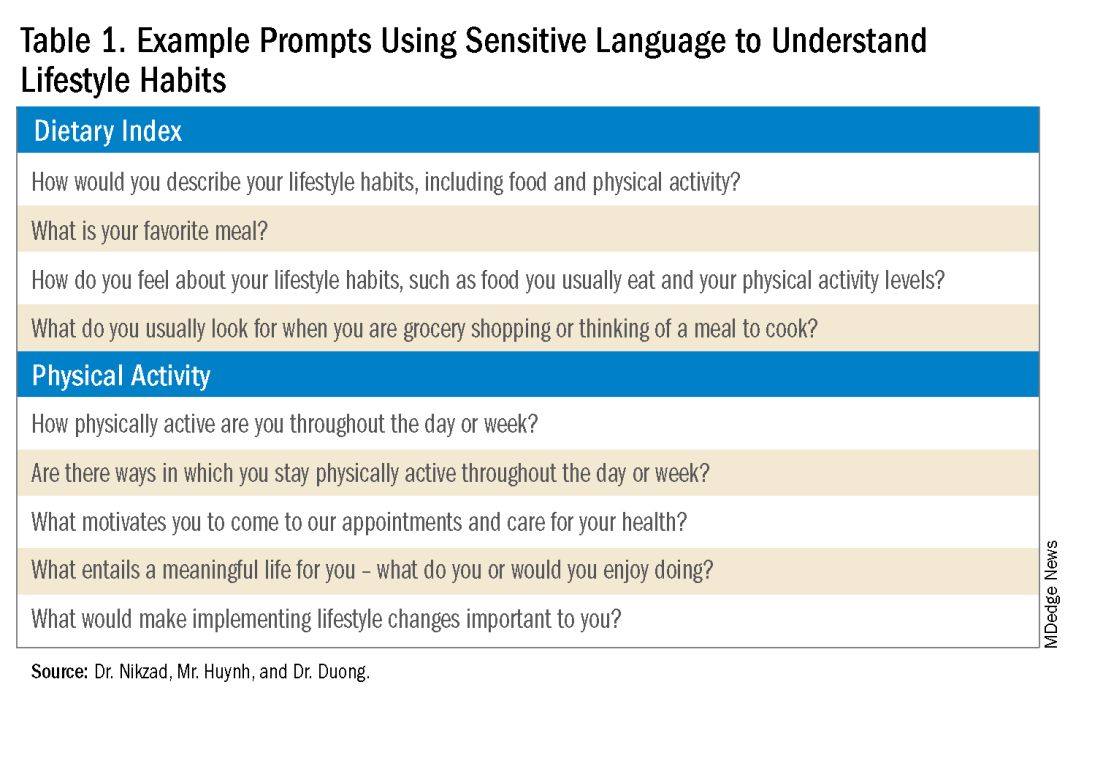

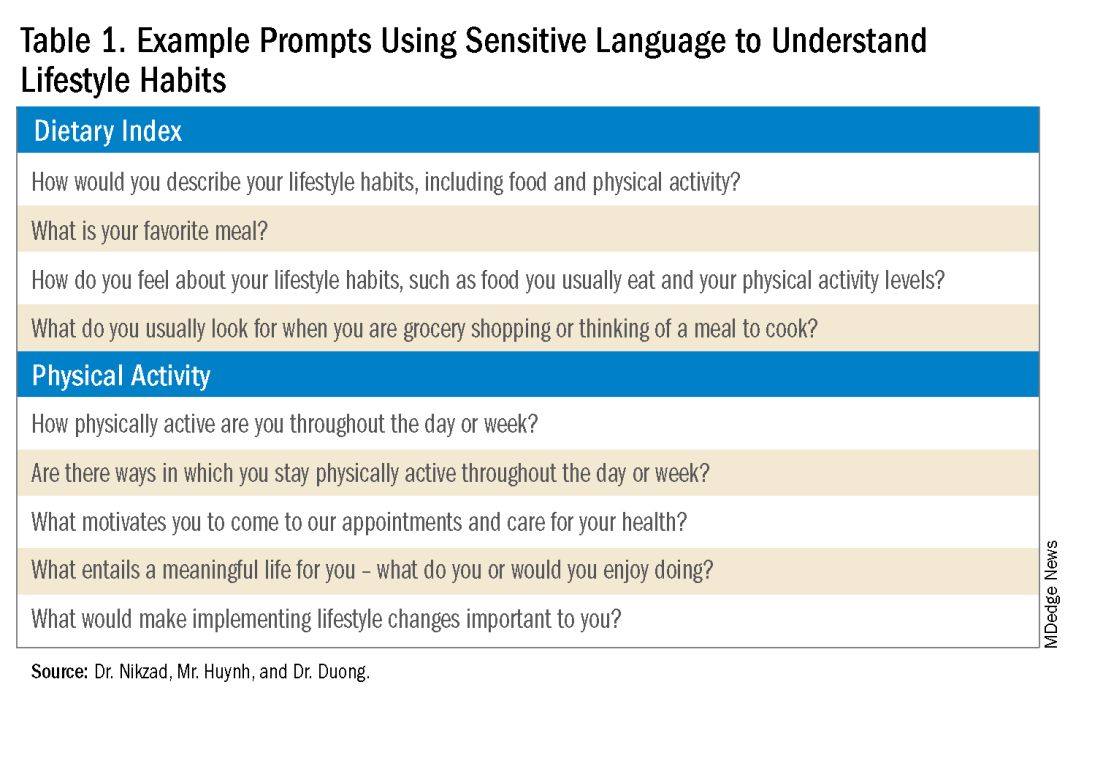

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a spectrum of hepatic disorders closely linked to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and obesity.1 An increasingly prevalent cause of liver disease and liver-related deaths worldwide, MASLD affects at least 38% of the global population.2 The immense burden of MASLD and its complications demands attention and action from the medical community.

Lifestyle modifications involving weight management and dietary composition adjustments are the foundation of addressing MASLD, with a critical emphasis on early intervention.3 Healthy dietary indices and weight loss can lower enzyme levels, reduce hepatic fat content, improve insulin resistance, and overall, reduce the risk of MASLD.3 Given the abundance of literature that exists on the benefits of lifestyle modifications on liver and general health outcomes, clinicians should be prepared to have informed, individualized, and culturally concordant conversations with their patients about these modifications. This Short Clinical Review aims to

Initiate the Conversation

Conversations about lifestyle modifications can be challenging and complex. If patients themselves are not initiating conversations about dietary composition and physical activity, then it is important for clinicians to start a productive discussion.

The use of non-stigmatizing, open-ended questions can begin this process. For example, clinicians can consider asking patients: “How would you describe your lifestyle habits, such as foods you usually eat and your physical activity levels? What do you usually look for when you are grocery shopping or thinking of a meal to cook? Are there ways in which you stay physically active throughout the day or week?”4 (see Table 1).

Such questions can provide significant insight into patients’ activity and eating patterns. They also eliminate the utilization of words such as “diet” or “exercise” that may have associated stigma, pressure, or negative connotations.4

Regardless, some patients may not feel prepared or willing to discuss lifestyle modifications during a visit, especially if it is the first clinical encounter when rapport has yet to even be established.4 Lifestyle modifications are implemented at various paces, and patients have their individual timelines for achieving these adjustments. Building rapport with patients and creating spaces in which they feel safe discussing and incorporating changes to various components of their lives can take time. Patients want to trust their providers while being vulnerable. They want to trust that their providers will guide them in what can sometimes be a life altering journey. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge and respect this reality when caring for patients with MASLD. Dr. Duong often utilizes this phrase, “It may seem like you are about to walk through fire, but we are here to walk with you. Remember, what doesn’t challenge you, doesn’t change you.”

Identify Motivators of Engagement

Identifying patients’ motivators of engagement will allow clinicians to guide patients through not only the introduction, but also the maintenance of such changes. Improvements in dietary composition and physical activity are often recommended by clinicians who are inevitably and understandably concerned about the consequences of MASLD. Liver diseases, specifically cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as associated metabolic disorders, are consequences that could result from poorly controlled MASLD. Though these consequences should be conveyed to patients, this tactic may not always serve as an impetus for patients to engage in behavioral changes.5

Clinicians can shed light on motivators by utilizing these suggested prompts: “What motivates you to come to our appointments and care for your health? What entails a meaningful life for you — what do or would you enjoy doing? What would make implementing lifestyle changes important to you?” Patient goals may include “being able to keep up with their grandchildren,” “becoming a runner,” or “providing healthy meals for their families.”5,6 Engagement is more likely to be feasible and sustainable when lifestyle modifications are tied to goals that are personally meaningful and relevant to patients.

Within the realm of physical activity specifically, exercise can be individualized to optimize motivation as well. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training are associated independently with benefits such as weight loss and decreased hepatic adipose content.3 Currently, there is no consensus regarding the optimal type of physical activity for patients with MASLD; therefore, clinicians should encourage patients to personalize physical activity.3 While some patients may prefer aerobic activities such as running and swimming, others may find more fulfillment in weightlifting or high intensity interval training. Furthermore, patients with cardiopulmonary or musculoskeletal health contraindications may be limited to specific types of exercise. It is appropriate and helpful for clinicians to ask patients, “What types of physical activity feel achievable and realistic for you at this time?” If physicians can guide patients with MASLD in identifying types of exercise that are safe and enjoyable, their patients may be more motivated to implement such lifestyle changes.

It is also crucial to recognize that lifestyle changes demand active effort from patients. While sustained improvements in body weight and dietary composition are the foundation of MASLD management, they can initially feel cumbersome and abstract to patients. Physicians can help their patients remain motivated by developing small, tangible goals such as “reducing daily caloric intake by 500 kcal” or “participating in three 30-minute fitness classes per week.” These goals should be developed jointly with patients, primarily to ensure that they are tangible, feasible, and productive.

A Culturally Safe Approach

Additionally, acknowledging a patient’s cultural background can be conducive to incorporating patient-specific care into MASLD management. For example, qualitative studies have shown that people from Mexican heritage traditionally complement dinners with soft drinks. While meal portion sizes vary amongst households, families of Mexican origin believe larger portion sizes may be perceived as healthier than Western diets since their cuisine incorporates more vegetables into each dish.7

Eating rituals should also be considered since some families expect the absence of leftovers on the plate.7 Therefore, it is appropriate to consider questions such as, “What are common ingredients in your culture? What are some of your family traditions when it comes to meals?” By integrating cultural considerations, clinicians can adopt a culturally safe approach, empowering patients to make lifestyle modifications tailored toward their unique social identities. Clinicians should avoid generalizations or stereotypes about cultural values regarding lifestyle practices, as these can vary among individuals.

Identify Barriers to Lifestyle Changes and Social Determinants of Health

Even with delicate language from providers and immense motivation from patients, barriers to lifestyle changes persist. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD perceive a lack of self-efficacy and knowledge as major barriers to adopting lifestyle modifications.8,9 Patients have reported challenges in interpreting nutritional data, identifying caloric intake and portion sizes. Physicians can effectively guide patients through lifestyle changes by identifying each patient’s unique knowledge gap and determining the most effective, accessible form of education. For example, some patients may benefit from jointly interpreting a nutritional label with their healthcare providers, while others may require educational materials and interventions provided by a registered dietitian.

Understanding patients’ professional or other commitments can help physicians further individualize recommendations. Questions such as, “Do you have work or other responsibilities that take up some of your time during the day?” minimize presumptive language about employment status. It can reveal whether patients have schedules that make certain lifestyle changes more challenging than others. For example, a patient who is an overnight delivery associate at a warehouse may have a different routine from another patient who is a family member’s caretaker. This framework allows physicians to build rapport with their patients and ultimately, make lifestyle recommendations that are more accessible.

Though MASLD is driven by inflammation and metabolic dysregulation, social determinants of health play an equally important role in disease development and progression.10 As previously discussed, health literacy can deeply influence patients’ abilities to implement lifestyle changes. Furthermore, economic stability, neighborhood and built environment (i.e., access to fresh produce and sidewalks), community, and social support also impact lifestyle modifications. It is paramount to understand the tangible social factors in which patients live. Such factors can be ascertained by beginning the dialogue with “Which grocery stores do you find most convenient? How do you travel to obtain food/attend community exercise programs?” These questions may offer insight into physical barriers to lifestyle changes. Physicians must utilize an intersectional lens that incorporates patients’ unique circumstances of existence into their individualized health care plans to address MASLD.

Summary

- Communication preferences, cultural backgrounds, and sociocultural contexts of patient existence must be considered when treating a patient with MASLD.

- The utilization of an intersectional and culturally safe approach to communication with patients can lead to more sustainable lifestyle changes and improved health outcomes.

- Equipping and empowering physicians to have meaningful discussions about MASLD is crucial to combating a spectrum of diseases that is rapidly affecting a substantial proportion of patients worldwide.

Dr. Nikzad is based in the Department of Internal Medicine at University of Chicago Medicine (@NewshaN27). Mr. Huynh is a medical student at Stony Brook University Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook, N.Y. (@danielhuynhhh). Dr. Duong is an assistant professor of medicine and transplant hepatologist at Stanford University, Palo Alto, Calif. (@doctornikkid). They have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Mohanty A. MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss. GI & Hepatology News. 2023 Oct. Data Trends 2023:9-13.

2. Wong VW, et al. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036.

3. Zeng J, et al. Therapeutic management of metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2024 Mar. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12525.

4. Berg S. How patients can start—and stick with—key lifestyle changes. AMA Public Health. 2020 Jan.

5. Berg S. 3 ways to get patients engaged in lasting lifestyle change. AMA Diabetes. 2019 Jan.

6. Teixeira PJ, et al. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012 Mar. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-22.

7. Aceves-Martins M, et al. Cultural factors related to childhood and adolescent obesity in Mexico: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes Rev. 2022 Sep. doi: 10.1111/obr.13461.

8. Figueroa G, et al. Low health literacy, lack of knowledge, and self-control hinder healthy lifestyles in diverse patients with steatotic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2024 Feb. doi: 10.1007/s10620-023-08212-9.

9. Wang L, et al. Factors influencing adherence to lifestyle prescriptions among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A qualitative study using the health action process approach framework. Front Public Health. 2023 Mar. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1131827.

10. Andermann A, CLEAR Collaboration. Taking action on the social determinants of health in clinical practice: a framework for health professionals. CMAJ. 2016 Dec. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160177.

Aliens, Ian McShane, and Heart Disease Risk

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

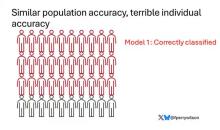

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I was really struggling to think of a good analogy to explain the glaring problem of polygenic risk scores (PRS) this week. But I think I have it now. Go with me on this.

An alien spaceship parks itself, Independence Day style, above a local office building.

But unlike the aliens that gave such a hard time to Will Smith and Brent Spiner, these are benevolent, technologically superior guys. They shine a mysterious green light down on the building and then announce, maybe via telepathy, that 6% of the people in that building will have a heart attack in the next year.

They move on to the next building. “Five percent will have a heart attack in the next year.” And the next, 7%. And the next, 2%.

Let’s assume the aliens are entirely accurate. What do you do with this information?

Most of us would suggest that you find out who was in the buildings with the higher percentages. You check their cholesterol levels, get them to exercise more, do some stress tests, and so on.

But that said, you’d still be spending a lot of money on a bunch of people who were not going to have heart attacks. So, a crack team of spies — in my mind, this is definitely led by a grizzled Ian McShane — infiltrate the alien ship, steal this predictive ray gun, and start pointing it, not at buildings but at people.

In this scenario, one person could have a 10% chance of having a heart attack in the next year. Another person has a 50% chance. The aliens, seeing this, leave us one final message before flying into the great beyond: “No, you guys are doing it wrong.”

This week: The people and companies using an advanced predictive technology, PRS , wrong — and a study that shows just how problematic this is.

We all know that genes play a significant role in our health outcomes. Some diseases (Huntington disease, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, hemochromatosis, and Duchenne muscular dystrophy, for example) are entirely driven by genetic mutations.

The vast majority of chronic diseases we face are not driven by genetics, but they may be enhanced by genetics. Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a prime example. There are clearly environmental risk factors, like smoking, that dramatically increase risk. But there are also genetic underpinnings; about half the risk for CHD comes from genetic variation, according to one study.

But in the case of those common diseases, it’s not one gene that leads to increased risk; it’s the aggregate effect of multiple risk genes, each contributing a small amount of risk to the final total.

The promise of PRS was based on this fact. Take the genome of an individual, identify all the risk genes, and integrate them into some final number that represents your genetic risk of developing CHD.

The way you derive a PRS is take a big group of people and sequence their genomes. Then, you see who develops the disease of interest — in this case, CHD. If the people who develop CHD are more likely to have a particular mutation, that mutation goes in the risk score. Risk scores can integrate tens, hundreds, even thousands of individual mutations to create that final score.

There are literally dozens of PRS for CHD. And there are companies that will calculate yours right now for a reasonable fee.

The accuracy of these scores is assessed at the population level. It’s the alien ray gun thing. Researchers apply the PRS to a big group of people and say 20% of them should develop CHD. If indeed 20% develop CHD, they say the score is accurate. And that’s true.

But what happens next is the problem. Companies and even doctors have been marketing PRS to individuals. And honestly, it sounds amazing. “We’ll use sophisticated techniques to analyze your genetic code and integrate the information to give you your personal risk for CHD.” Or dementia. Or other diseases. A lot of people would want to know this information.

It turns out, though, that this is where the system breaks down. And it is nicely illustrated by this study, appearing November 16 in JAMA.

The authors wanted to see how PRS, which are developed to predict disease in a group of people, work when applied to an individual.

They identified 48 previously published PRS for CHD. They applied those scores to more than 170,000 individuals across multiple genetic databases. And, by and large, the scores worked as advertised, at least across the entire group. The weighted accuracy of all 48 scores was around 78%. They aren’t perfect, of course. We wouldn’t expect them to be, since CHD is not entirely driven by genetics. But 78% accurate isn’t too bad.

But that accuracy is at the population level. At the level of the office building. At the individual level, it was a vastly different story.

This is best illustrated by this plot, which shows the score from 48 different PRS for CHD within the same person. A note here: It is arranged by the publication date of the risk score, but these were all assessed on a single blood sample at a single point in time in this study participant.

The individual scores are all over the map. Using one risk score gives an individual a risk that is near the 99th percentile — a ticking time bomb of CHD. Another score indicates a level of risk at the very bottom of the spectrum — highly reassuring. A bunch of scores fall somewhere in between. In other words, as a doctor, the risk I will discuss with this patient is more strongly determined by which PRS I happen to choose than by his actual genetic risk, whatever that is.

This may seem counterintuitive. All these risk scores were similarly accurate within a population; how can they all give different results to an individual? The answer is simpler than you may think. As long as a given score makes one extra good prediction for each extra bad prediction, its accuracy is not changed.

Let’s imagine we have a population of 40 people.

Risk score model 1 correctly classified 30 of them for 75% accuracy. Great.

Risk score model 2 also correctly classified 30 of our 40 individuals, for 75% accuracy. It’s just a different 30.

Risk score model 3 also correctly classified 30 of 40, but another different 30.

I’ve colored this to show you all the different overlaps. What you can see is that although each score has similar accuracy, the individual people have a bunch of different colors, indicating that some scores worked for them and some didn’t. That’s a real problem.

This has not stopped companies from advertising PRS for all sorts of diseases. Companies are even using PRS to decide which fetuses to implant during IVF therapy, which is a particularly egregiously wrong use of this technology that I have written about before.

How do you fix this? Our aliens tried to warn us. This is not how you are supposed to use this ray gun. You are supposed to use it to identify groups of people at higher risk to direct more resources to that group. That’s really all you can do.

It’s also possible that we need to match the risk score to the individual in a better way. This is likely driven by the fact that risk scores tend to work best in the populations in which they were developed, and many of them were developed in people of largely European ancestry.

It is worth noting that if a PRS had perfect accuracy at the population level, it would also necessarily have perfect accuracy at the individual level. But there aren’t any scores like that. It’s possible that combining various scores may increase the individual accuracy, but that hasn’t been demonstrated yet either.

Look, genetics is and will continue to play a major role in healthcare. At the same time, sequencing entire genomes is a technology that is ripe for hype and thus misuse. Or even abuse. Fundamentally, this JAMA study reminds us that accuracy in a population and accuracy in an individual are not the same. But more deeply, it reminds us that just because a technology is new or cool or expensive doesn’t mean it will work in the clinic.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A Portrait of the Patient

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

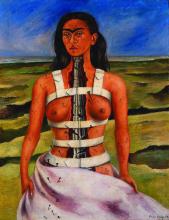

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at [email protected].

The Veteran’s Canon Under Fire

The Veteran’s Canon Under Fire

As Veterans Day approaches, stores and restaurants will offer discounts and free meals to veterans. Children will write thank you letters, and citizens nationwide will raise flags to honor and thank veterans. We can never repay those who lost their life, health, or livelihood in defense of the nation. Since the American Revolution, and in gratitude for that incalculable debt, the US government, on behalf of the American public, has seen fit to grant a host of benefits and services to those who wore the uniform.2,3 Among the best known are health care, burial services, compensation and pensions, home loans, and the GI Bill.

Less recognized yet arguably essential for the fair and consistent provision of these entitlements is a legal principle: the veteran’s canon. A canon is a system of rules or maxims used to interpret legal instruments, such as statutes. They are not rules but serve as a “principle that guides the interpretation of the text.”4 Since I am not a lawyer, I will undoubtedly oversimplify this legal principle, but I hope to get enough right to explain why the veteran’s canon should matter to federal health care professionals.

At its core, the veteran’s canon means that when the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and a veteran have a legal dispute about VA benefits, the courts will give deference to the veteran. Underscoring that any ambiguity in the statute is resolved in the veteran’s favor, the canon is known in legal circles as the Gardner deference. This is a reference to a 1994 case in which a Korean War veteran underwent surgery in a VA facility for a herniated disc he alleged caused pain and weakness in his left lower extremity.5 Gardner argued that federal statutes 38 USC § 1151 underlying corresponding VA regulation 38 CFR § 3.358(c)(3) granted disability benefits to veterans injured during VA treatment. The VA denied the disability claim, contending the regulation restricted compensation to veterans whose injury was the fault of the VA; thus, the disability had to have been the result of negligent treatment or an unforeseen therapeutic accident.5

The case wound its way through various appeals boards and courts until the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) ruled that the statute’s context left no ambiguity, and that any care provided under VA auspices was covered under the statute. What is important for this column is that the justices opined that had ambiguity been present, it would have legally necessitated, “applying the rule that interpretive doubt is to be resolved in the veteran’s favor.”5 In Gardner’s case, the courts reaffirmed nearly 80 years of judicial precedent upholding the veteran’s canon.

Thirty years later, Rudisill v McDonough again questioned the veteran’s canon.6 Educational benefits, namely the GI Bill, were the issue in this case. Rudisill served during 3 different periods in the US Army, totaling 8 years. Two educational programs overlapped during Rudisill’s tenure in the military: the Montgomery GI Bill and Post-9/11 Veterans Educational Assistance Act. Rudisill had used a portion of his Montgomery benefits to fund his undergraduate education and now wished to use the more extensive Post-9/11 assistance to finance his graduate degree. Rudisill and the VA disagreed about when his combined benefits would be capped, either at 36 or 48 months. After working its way through appeals courts, SCOTUS was again called upon for judgment.