User login

CKD-EPI eGFR formula surpasses alternatives in young adults

PHILADELPHIA –

The two alternative formulas for calculating eGFR, the CKiD U25 (Chronic Kidney Disease in Children under 25) and the European Kidney Function Consortium equations, showed higher levels of bias that resulted in underestimates of kidney function, particularly in younger adults 18-25 years old and in those with higher eGFR values, Leslie A. Inker, MD, said at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

However, for young adults with a history of childhood CKD and especially for those who continue under the care of pediatric clinicians even after they become young adults, use of the CKiD U25 equation, remains a reasonable option, said Dr. Inker, professor and director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. The CKiD U25 equation is intended for people aged 1-25 years and came out in late 2020.

Pediatric nephrologists use the CKiD U25 but the results of the 2021 CKD-EPI race-free equation is what U.S. clinical labs routinely report for people aged 18 or older. “Our findings support the current practice of pediatric nephrologists” who may opt to use the CKiD U25 even when a patient turns 18 years or older, Dr. Inker said in an interview.

But the new results also support the current practice of U.S. labs, which is to focus on calculating eGFR in anyone at least 18 years old using the 2021 equation developed by the CKD-EPI, work led by Dr. Inker. The new findings confirm routine use of the 2021 CKD-EPI equation in adults as young as 18 years old, especially when they’re having their eGFR calculated for the first time, she said.

Discontinuity changing from CKiD U25 to CKD-EPI is ‘not huge’

“It’s important to understand that the 2021 CKD-EPI equation works in young adults,” noted Josef Coresh, MD, PhD, professor of clinical epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who collaborated on both the current study and on developing the 2021 CKD-EPI equation.

The new data show that the discontinuity in eGFR produced by switching from the CKiD U25 formula to the 2021 CKD-EPI formula “is not huge, maybe about 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 higher. People should focus on the new baseline and subsequent trends, not the modest difference between equations,” Dr. Coresh advised in an interview.

The study run by Dr. Inker and her associates used 1,491 people aged 18-40 years and enrolled in a cohort created by the CKD-EPI. They compared measured GFR levels in each subject with the estimates generated by the 2021 race-free CKD-EPI equation, the CKiD U25 equation, and a third equation developed by the EKFC and introduced in 2021.

Less bias with the 2021 CKD-EPI equation

The researchers compared the three eGFR equations with their respective measured GFR values by two metrics: bias, defined as the median difference between measured and estimated GFR; and the percentage of eGFR values that fell within 30% of the corresponding measured GFR value.

The results showed that bias was lowest using the 2021 CKD-EPI equation, with an overall median difference of 0.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This compared with median differences of 7.2 with the CKiD U25 equation and 4.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with the EKFC equation. The disparity in bias was greatest among those with eGFR values in the range of 60-90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and was also greatest for those 18-25 years old.

The CKD-EPI equation results also showed the greatest consistency of bias across the entire 18- to 40-year-old range. Between-group differences were small for the percentage of eGFR values that fell within 30% of measured GFR, with all three equations scoring in the range of 88%-90%.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Inker is a consultant to Diamtrix and her department receives research funding from Chinook, Omeros, Reata, and Tricida. Dr. Coresh is a consultant to Healthy.io and SomaLogic and he has an ownership interest in Healthy.io.

PHILADELPHIA –

The two alternative formulas for calculating eGFR, the CKiD U25 (Chronic Kidney Disease in Children under 25) and the European Kidney Function Consortium equations, showed higher levels of bias that resulted in underestimates of kidney function, particularly in younger adults 18-25 years old and in those with higher eGFR values, Leslie A. Inker, MD, said at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

However, for young adults with a history of childhood CKD and especially for those who continue under the care of pediatric clinicians even after they become young adults, use of the CKiD U25 equation, remains a reasonable option, said Dr. Inker, professor and director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. The CKiD U25 equation is intended for people aged 1-25 years and came out in late 2020.

Pediatric nephrologists use the CKiD U25 but the results of the 2021 CKD-EPI race-free equation is what U.S. clinical labs routinely report for people aged 18 or older. “Our findings support the current practice of pediatric nephrologists” who may opt to use the CKiD U25 even when a patient turns 18 years or older, Dr. Inker said in an interview.

But the new results also support the current practice of U.S. labs, which is to focus on calculating eGFR in anyone at least 18 years old using the 2021 equation developed by the CKD-EPI, work led by Dr. Inker. The new findings confirm routine use of the 2021 CKD-EPI equation in adults as young as 18 years old, especially when they’re having their eGFR calculated for the first time, she said.

Discontinuity changing from CKiD U25 to CKD-EPI is ‘not huge’

“It’s important to understand that the 2021 CKD-EPI equation works in young adults,” noted Josef Coresh, MD, PhD, professor of clinical epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who collaborated on both the current study and on developing the 2021 CKD-EPI equation.

The new data show that the discontinuity in eGFR produced by switching from the CKiD U25 formula to the 2021 CKD-EPI formula “is not huge, maybe about 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 higher. People should focus on the new baseline and subsequent trends, not the modest difference between equations,” Dr. Coresh advised in an interview.

The study run by Dr. Inker and her associates used 1,491 people aged 18-40 years and enrolled in a cohort created by the CKD-EPI. They compared measured GFR levels in each subject with the estimates generated by the 2021 race-free CKD-EPI equation, the CKiD U25 equation, and a third equation developed by the EKFC and introduced in 2021.

Less bias with the 2021 CKD-EPI equation

The researchers compared the three eGFR equations with their respective measured GFR values by two metrics: bias, defined as the median difference between measured and estimated GFR; and the percentage of eGFR values that fell within 30% of the corresponding measured GFR value.

The results showed that bias was lowest using the 2021 CKD-EPI equation, with an overall median difference of 0.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This compared with median differences of 7.2 with the CKiD U25 equation and 4.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with the EKFC equation. The disparity in bias was greatest among those with eGFR values in the range of 60-90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and was also greatest for those 18-25 years old.

The CKD-EPI equation results also showed the greatest consistency of bias across the entire 18- to 40-year-old range. Between-group differences were small for the percentage of eGFR values that fell within 30% of measured GFR, with all three equations scoring in the range of 88%-90%.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Inker is a consultant to Diamtrix and her department receives research funding from Chinook, Omeros, Reata, and Tricida. Dr. Coresh is a consultant to Healthy.io and SomaLogic and he has an ownership interest in Healthy.io.

PHILADELPHIA –

The two alternative formulas for calculating eGFR, the CKiD U25 (Chronic Kidney Disease in Children under 25) and the European Kidney Function Consortium equations, showed higher levels of bias that resulted in underestimates of kidney function, particularly in younger adults 18-25 years old and in those with higher eGFR values, Leslie A. Inker, MD, said at Kidney Week 2023, organized by the American Society of Nephrology.

However, for young adults with a history of childhood CKD and especially for those who continue under the care of pediatric clinicians even after they become young adults, use of the CKiD U25 equation, remains a reasonable option, said Dr. Inker, professor and director of the Kidney and Blood Pressure Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. The CKiD U25 equation is intended for people aged 1-25 years and came out in late 2020.

Pediatric nephrologists use the CKiD U25 but the results of the 2021 CKD-EPI race-free equation is what U.S. clinical labs routinely report for people aged 18 or older. “Our findings support the current practice of pediatric nephrologists” who may opt to use the CKiD U25 even when a patient turns 18 years or older, Dr. Inker said in an interview.

But the new results also support the current practice of U.S. labs, which is to focus on calculating eGFR in anyone at least 18 years old using the 2021 equation developed by the CKD-EPI, work led by Dr. Inker. The new findings confirm routine use of the 2021 CKD-EPI equation in adults as young as 18 years old, especially when they’re having their eGFR calculated for the first time, she said.

Discontinuity changing from CKiD U25 to CKD-EPI is ‘not huge’

“It’s important to understand that the 2021 CKD-EPI equation works in young adults,” noted Josef Coresh, MD, PhD, professor of clinical epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who collaborated on both the current study and on developing the 2021 CKD-EPI equation.

The new data show that the discontinuity in eGFR produced by switching from the CKiD U25 formula to the 2021 CKD-EPI formula “is not huge, maybe about 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 higher. People should focus on the new baseline and subsequent trends, not the modest difference between equations,” Dr. Coresh advised in an interview.

The study run by Dr. Inker and her associates used 1,491 people aged 18-40 years and enrolled in a cohort created by the CKD-EPI. They compared measured GFR levels in each subject with the estimates generated by the 2021 race-free CKD-EPI equation, the CKiD U25 equation, and a third equation developed by the EKFC and introduced in 2021.

Less bias with the 2021 CKD-EPI equation

The researchers compared the three eGFR equations with their respective measured GFR values by two metrics: bias, defined as the median difference between measured and estimated GFR; and the percentage of eGFR values that fell within 30% of the corresponding measured GFR value.

The results showed that bias was lowest using the 2021 CKD-EPI equation, with an overall median difference of 0.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2. This compared with median differences of 7.2 with the CKiD U25 equation and 4.9 mL/min per 1.73 m2 with the EKFC equation. The disparity in bias was greatest among those with eGFR values in the range of 60-90 mL/min per 1.73 m2 and was also greatest for those 18-25 years old.

The CKD-EPI equation results also showed the greatest consistency of bias across the entire 18- to 40-year-old range. Between-group differences were small for the percentage of eGFR values that fell within 30% of measured GFR, with all three equations scoring in the range of 88%-90%.

The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Inker is a consultant to Diamtrix and her department receives research funding from Chinook, Omeros, Reata, and Tricida. Dr. Coresh is a consultant to Healthy.io and SomaLogic and he has an ownership interest in Healthy.io.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2023

A nurse’s view: Women desperately need information about pelvic floor disorders

Pelvic floor disorders are embarrassing, annoying, painful, and extremely disruptive to a woman’s life, often resulting in depression, anxiety, and a poor self-image. According to a 2021 study, approximately 75% of peripartum women and 68% of postmenopausal women feel insufficiently informed about pelvic floor disorders.1

Consequently, a large majority of women are not seeking care for these disorders. This drives health care costs higher as women wait until their symptoms are unbearable until finally seeking help. Many of these women don’t know they have options.

Who is at risk?

To understand the scope of this growing problem, it is vital to see who is most at risk. Parity, age, body mass index, and race are significant factors, although any woman can have a pelvic floor disorder (PFD).

Urinary incontinence (UI), pelvic floor prolapses (POP), and fecal incontinence (FI) are three of the most common pelvic floor disorders. Pregnancy and childbirth, specifically a vaginal birth, greatly contribute to this population’s risk. In pregnancy, the increase in plasma volume and glomerular filtration rate, along with hormone changes impacting urethral pressure and the growing gravid uterus, cause urinary frequency and nocturia. This can result in urinary incontinence during and after pregnancy.

Indeed, 76% of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum report it 12 years later.1 Third- and fourth-degree lacerations during delivery are uncommon (3.3%), but can cause fecal incontinence, often requiring surgery.1 Independently, all of these symptoms have been correlated with sexual dysfunction and postpartum depression.

One-third of all women and 50% of women over the age of 55 are currently affected by a PFD. Contributing factors include hormone changes with menopause that affect the pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue, prior childbirth and pregnancy, constipation, heavy lifting, prior pelvic surgery, and obesity. These women are vulnerable to pelvic organ prolapse from the weakened pelvic floor muscles. They will often present with a vague complaint of “something is protruding out of my vagina.” These women also present with urinary incontinence or leakage, proclaiming they have to wear a diaper or a pad. Without proper knowledge, aging women think these issues are normal and nothing can be done.

The woman with a BMI above 30 may have damaged tissues supporting the uterus and bladder, weakening those organs, and causing a prolapse. Incontinence is a result of poor muscle and connective tissue of the vagina that support the urethra. Obese women can suffer from both urinary and bowel incontinence. By the year 2030, it is projected that one in two adults will be obese.2 This will greatly impact health care costs.

To date, there is little conclusive evidence on the impact of race on pelvic floor disorders. A study in Scientific Reports did find that Asian women have a significantly lower risk for any PFD.2 Some research has found that Black and Hispanic women have less risk for UI but are at higher risk for FI and other PFDs.3 Understandably, women of certain cultures and demographics may be less likely to report incontinence to their clinicians and may be less informed as well.

What can we do?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has acknowledged the deficiencies and lack of standard care of pelvic health in pregnancy and postpartum.1 There are differences in definitions across clinical practice and in the medical literature. Inconsistent patient reporting of PFD symptoms occurs due to nonstandard methods (questionnaire, interview, physical exam). With the often-short time allotted for visits with health care providers, women may neglect to discuss their symptoms, especially if they have other more pressing matters to address.

At the first OB appointment, a pregnant woman should be given information on what are normal and abnormal symptoms, from the beginning through postpartum. At each visit, she should be given ample opportunity to discuss symptoms of pelvic health. Clinicians should continue assessing, questioning, and discussing treatment options as applicable. Women need to know that early recognition and treatment can have a positive affect on their pelvic health for years to come.

ACOG recommends all postpartum patients see an obstetric provider within 3 weeks of delivery.1 Most are seen at 6 weeks. Pelvic health should be discussed at this final postpartum appointment, including normal and abnormal symptoms within the next few months and beyond.

Regardless of pregnancy status, women need a safe and supportive place to describe their pelvic floor issues. There is a validated questionnaire tool available for postpartum, but one is desperately needed for all women, especially women at risk. A pelvic health assessment must be included in every annual exam.

Women need to know there are multiple treatment modalities including simple exercises, physical therapy, a variety of pessaries, medications, and surgery. Sometimes, all that is needed are a few lifestyle changes: avoiding pushing or straining while urinating or having a bowel movement, maintaining a healthy diet rich in high fiber foods, and drinking plenty of fluids.

The National Public Health Service in the United Kingdom recently announced a government-funded program for pelvic health services to begin in April 2024.4 This program will address the pelvic floor needs, assessment, education and treatment for women after childbirth.

There are multiple clinics in the United States focusing on women’s health that feature urogynecologists – specialists in pelvic floor disorders. These specialists do a thorough health and physical assessment, explain types of pelvic floor disorders, and suggest appropriate treatment options. Most importantly, urogynecologists listen and address a woman’s concerns and fears.

There is no reason for women to feel compromised at any age. We, as health care providers, just need to assess, educate, treat, and follow up.

Ms. Barnett is a registered nurse in the department of obstetrics, Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, Burlingame, Calif. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Madsen AM et al. Recognition and management of pelvic floor disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2021 Sep;48(3):571-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2021.05.009.

2. Kenne KA et al. Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in adult women being seen in a primary care setting and associated risk factors. Sci Rep. 2022 June; (12):9878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13501-w.

3. Nygaard I et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

4. United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care. “National pelvic health service to support women.” 2023 Oct 19.

Pelvic floor disorders are embarrassing, annoying, painful, and extremely disruptive to a woman’s life, often resulting in depression, anxiety, and a poor self-image. According to a 2021 study, approximately 75% of peripartum women and 68% of postmenopausal women feel insufficiently informed about pelvic floor disorders.1

Consequently, a large majority of women are not seeking care for these disorders. This drives health care costs higher as women wait until their symptoms are unbearable until finally seeking help. Many of these women don’t know they have options.

Who is at risk?

To understand the scope of this growing problem, it is vital to see who is most at risk. Parity, age, body mass index, and race are significant factors, although any woman can have a pelvic floor disorder (PFD).

Urinary incontinence (UI), pelvic floor prolapses (POP), and fecal incontinence (FI) are three of the most common pelvic floor disorders. Pregnancy and childbirth, specifically a vaginal birth, greatly contribute to this population’s risk. In pregnancy, the increase in plasma volume and glomerular filtration rate, along with hormone changes impacting urethral pressure and the growing gravid uterus, cause urinary frequency and nocturia. This can result in urinary incontinence during and after pregnancy.

Indeed, 76% of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum report it 12 years later.1 Third- and fourth-degree lacerations during delivery are uncommon (3.3%), but can cause fecal incontinence, often requiring surgery.1 Independently, all of these symptoms have been correlated with sexual dysfunction and postpartum depression.

One-third of all women and 50% of women over the age of 55 are currently affected by a PFD. Contributing factors include hormone changes with menopause that affect the pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue, prior childbirth and pregnancy, constipation, heavy lifting, prior pelvic surgery, and obesity. These women are vulnerable to pelvic organ prolapse from the weakened pelvic floor muscles. They will often present with a vague complaint of “something is protruding out of my vagina.” These women also present with urinary incontinence or leakage, proclaiming they have to wear a diaper or a pad. Without proper knowledge, aging women think these issues are normal and nothing can be done.

The woman with a BMI above 30 may have damaged tissues supporting the uterus and bladder, weakening those organs, and causing a prolapse. Incontinence is a result of poor muscle and connective tissue of the vagina that support the urethra. Obese women can suffer from both urinary and bowel incontinence. By the year 2030, it is projected that one in two adults will be obese.2 This will greatly impact health care costs.

To date, there is little conclusive evidence on the impact of race on pelvic floor disorders. A study in Scientific Reports did find that Asian women have a significantly lower risk for any PFD.2 Some research has found that Black and Hispanic women have less risk for UI but are at higher risk for FI and other PFDs.3 Understandably, women of certain cultures and demographics may be less likely to report incontinence to their clinicians and may be less informed as well.

What can we do?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has acknowledged the deficiencies and lack of standard care of pelvic health in pregnancy and postpartum.1 There are differences in definitions across clinical practice and in the medical literature. Inconsistent patient reporting of PFD symptoms occurs due to nonstandard methods (questionnaire, interview, physical exam). With the often-short time allotted for visits with health care providers, women may neglect to discuss their symptoms, especially if they have other more pressing matters to address.

At the first OB appointment, a pregnant woman should be given information on what are normal and abnormal symptoms, from the beginning through postpartum. At each visit, she should be given ample opportunity to discuss symptoms of pelvic health. Clinicians should continue assessing, questioning, and discussing treatment options as applicable. Women need to know that early recognition and treatment can have a positive affect on their pelvic health for years to come.

ACOG recommends all postpartum patients see an obstetric provider within 3 weeks of delivery.1 Most are seen at 6 weeks. Pelvic health should be discussed at this final postpartum appointment, including normal and abnormal symptoms within the next few months and beyond.

Regardless of pregnancy status, women need a safe and supportive place to describe their pelvic floor issues. There is a validated questionnaire tool available for postpartum, but one is desperately needed for all women, especially women at risk. A pelvic health assessment must be included in every annual exam.

Women need to know there are multiple treatment modalities including simple exercises, physical therapy, a variety of pessaries, medications, and surgery. Sometimes, all that is needed are a few lifestyle changes: avoiding pushing or straining while urinating or having a bowel movement, maintaining a healthy diet rich in high fiber foods, and drinking plenty of fluids.

The National Public Health Service in the United Kingdom recently announced a government-funded program for pelvic health services to begin in April 2024.4 This program will address the pelvic floor needs, assessment, education and treatment for women after childbirth.

There are multiple clinics in the United States focusing on women’s health that feature urogynecologists – specialists in pelvic floor disorders. These specialists do a thorough health and physical assessment, explain types of pelvic floor disorders, and suggest appropriate treatment options. Most importantly, urogynecologists listen and address a woman’s concerns and fears.

There is no reason for women to feel compromised at any age. We, as health care providers, just need to assess, educate, treat, and follow up.

Ms. Barnett is a registered nurse in the department of obstetrics, Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, Burlingame, Calif. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Madsen AM et al. Recognition and management of pelvic floor disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2021 Sep;48(3):571-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2021.05.009.

2. Kenne KA et al. Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in adult women being seen in a primary care setting and associated risk factors. Sci Rep. 2022 June; (12):9878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13501-w.

3. Nygaard I et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

4. United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care. “National pelvic health service to support women.” 2023 Oct 19.

Pelvic floor disorders are embarrassing, annoying, painful, and extremely disruptive to a woman’s life, often resulting in depression, anxiety, and a poor self-image. According to a 2021 study, approximately 75% of peripartum women and 68% of postmenopausal women feel insufficiently informed about pelvic floor disorders.1

Consequently, a large majority of women are not seeking care for these disorders. This drives health care costs higher as women wait until their symptoms are unbearable until finally seeking help. Many of these women don’t know they have options.

Who is at risk?

To understand the scope of this growing problem, it is vital to see who is most at risk. Parity, age, body mass index, and race are significant factors, although any woman can have a pelvic floor disorder (PFD).

Urinary incontinence (UI), pelvic floor prolapses (POP), and fecal incontinence (FI) are three of the most common pelvic floor disorders. Pregnancy and childbirth, specifically a vaginal birth, greatly contribute to this population’s risk. In pregnancy, the increase in plasma volume and glomerular filtration rate, along with hormone changes impacting urethral pressure and the growing gravid uterus, cause urinary frequency and nocturia. This can result in urinary incontinence during and after pregnancy.

Indeed, 76% of women with urinary incontinence at 3 months postpartum report it 12 years later.1 Third- and fourth-degree lacerations during delivery are uncommon (3.3%), but can cause fecal incontinence, often requiring surgery.1 Independently, all of these symptoms have been correlated with sexual dysfunction and postpartum depression.

One-third of all women and 50% of women over the age of 55 are currently affected by a PFD. Contributing factors include hormone changes with menopause that affect the pelvic floor muscles and connective tissue, prior childbirth and pregnancy, constipation, heavy lifting, prior pelvic surgery, and obesity. These women are vulnerable to pelvic organ prolapse from the weakened pelvic floor muscles. They will often present with a vague complaint of “something is protruding out of my vagina.” These women also present with urinary incontinence or leakage, proclaiming they have to wear a diaper or a pad. Without proper knowledge, aging women think these issues are normal and nothing can be done.

The woman with a BMI above 30 may have damaged tissues supporting the uterus and bladder, weakening those organs, and causing a prolapse. Incontinence is a result of poor muscle and connective tissue of the vagina that support the urethra. Obese women can suffer from both urinary and bowel incontinence. By the year 2030, it is projected that one in two adults will be obese.2 This will greatly impact health care costs.

To date, there is little conclusive evidence on the impact of race on pelvic floor disorders. A study in Scientific Reports did find that Asian women have a significantly lower risk for any PFD.2 Some research has found that Black and Hispanic women have less risk for UI but are at higher risk for FI and other PFDs.3 Understandably, women of certain cultures and demographics may be less likely to report incontinence to their clinicians and may be less informed as well.

What can we do?

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has acknowledged the deficiencies and lack of standard care of pelvic health in pregnancy and postpartum.1 There are differences in definitions across clinical practice and in the medical literature. Inconsistent patient reporting of PFD symptoms occurs due to nonstandard methods (questionnaire, interview, physical exam). With the often-short time allotted for visits with health care providers, women may neglect to discuss their symptoms, especially if they have other more pressing matters to address.

At the first OB appointment, a pregnant woman should be given information on what are normal and abnormal symptoms, from the beginning through postpartum. At each visit, she should be given ample opportunity to discuss symptoms of pelvic health. Clinicians should continue assessing, questioning, and discussing treatment options as applicable. Women need to know that early recognition and treatment can have a positive affect on their pelvic health for years to come.

ACOG recommends all postpartum patients see an obstetric provider within 3 weeks of delivery.1 Most are seen at 6 weeks. Pelvic health should be discussed at this final postpartum appointment, including normal and abnormal symptoms within the next few months and beyond.

Regardless of pregnancy status, women need a safe and supportive place to describe their pelvic floor issues. There is a validated questionnaire tool available for postpartum, but one is desperately needed for all women, especially women at risk. A pelvic health assessment must be included in every annual exam.

Women need to know there are multiple treatment modalities including simple exercises, physical therapy, a variety of pessaries, medications, and surgery. Sometimes, all that is needed are a few lifestyle changes: avoiding pushing or straining while urinating or having a bowel movement, maintaining a healthy diet rich in high fiber foods, and drinking plenty of fluids.

The National Public Health Service in the United Kingdom recently announced a government-funded program for pelvic health services to begin in April 2024.4 This program will address the pelvic floor needs, assessment, education and treatment for women after childbirth.

There are multiple clinics in the United States focusing on women’s health that feature urogynecologists – specialists in pelvic floor disorders. These specialists do a thorough health and physical assessment, explain types of pelvic floor disorders, and suggest appropriate treatment options. Most importantly, urogynecologists listen and address a woman’s concerns and fears.

There is no reason for women to feel compromised at any age. We, as health care providers, just need to assess, educate, treat, and follow up.

Ms. Barnett is a registered nurse in the department of obstetrics, Mills-Peninsula Medical Center, Burlingame, Calif. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Madsen AM et al. Recognition and management of pelvic floor disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2021 Sep;48(3):571-84. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2021.05.009.

2. Kenne KA et al. Prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in adult women being seen in a primary care setting and associated risk factors. Sci Rep. 2022 June; (12):9878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13501-w.

3. Nygaard I et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

4. United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care. “National pelvic health service to support women.” 2023 Oct 19.

The easy way to talk about penises

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I mean it. Penis problems are very common and are an early sign that patients could have a cardiac event. Think about it: Clogging the arteries of the heart is called a heart attack; clogging the arteries to the penis is a penis attack, or as doctors like to call it, erectile dysfunction.

The arteries to the penis are only 1 mm in diameter. They develop plaque and clog the circulation long before the 3-mm cardiac arteries. So, it’s very important for primary care doctors to talk to their patients about erection health. And I’ll be honest: It’s easier to talk to patients about how lifestyle is affecting their penis health than it is to discuss how lifestyle affects longevity or prevents cancer. I get a lot of men to quit smoking because I tell them what it’s doing to their penises.

It can be challenging for doctors and patients to talk about penises. It doesn’t come naturally for many of us. If a 20-year-old comes in to my office with his 85-year-old grandfather and they both say their penises aren’t working, how do you figure out what’s going on? Do they even have the same thing wrong with them?

Here’s a fun and helpful tool that I use in my office. It’s called the Erection Hardness Score. It was developed around the time that Viagra came out, in 1998. It’s been game-changing for me to get patients more comfortable talking about their erection issues.

I tell them it’s a 4-number scale. A “1” is no erection at all. A “2” is when it gets harder and larger, but it’s not going to penetrate. A “3” will penetrate, but it’s pretty wobbly. A “4” is that perfect cucumber–porn star erection that everyone is seeking. I have the patient tell me a story. They may say, “When I wake up in the morning, I’m at a 2. When I stimulate myself, I can get up to a 3. When I’m with my partner, sometimes I can get up to a 4.”

This is really helpful because they can talk in numbers. And after I give them treatments such as lifestyle changes, sex therapy, testosterone, a PDE5 inhibitor such as Viagra or Cialis, or an injection, they can come back and tell me how the story has changed. I have an objective measure that shows me how the treatment is affecting their erections. Not only do I feel more confident having those objective measures, but my patients feel more confident in the care that they’re getting, and they feel more comfortable talking to me about the changes. So, I encourage all of you to bring that EHS tool into your office. Show it to patients and get them more comfortable talking about erections.

Dr. Rubin is assistant clinical professor, department of urology, Georgetown University, Washington. She disclosed financial relationships with Absorption Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Endo Pharmaceuticals; has served as a speaker for Sprout; and has received research grant from Maternal Medical.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I mean it. Penis problems are very common and are an early sign that patients could have a cardiac event. Think about it: Clogging the arteries of the heart is called a heart attack; clogging the arteries to the penis is a penis attack, or as doctors like to call it, erectile dysfunction.

The arteries to the penis are only 1 mm in diameter. They develop plaque and clog the circulation long before the 3-mm cardiac arteries. So, it’s very important for primary care doctors to talk to their patients about erection health. And I’ll be honest: It’s easier to talk to patients about how lifestyle is affecting their penis health than it is to discuss how lifestyle affects longevity or prevents cancer. I get a lot of men to quit smoking because I tell them what it’s doing to their penises.

It can be challenging for doctors and patients to talk about penises. It doesn’t come naturally for many of us. If a 20-year-old comes in to my office with his 85-year-old grandfather and they both say their penises aren’t working, how do you figure out what’s going on? Do they even have the same thing wrong with them?

Here’s a fun and helpful tool that I use in my office. It’s called the Erection Hardness Score. It was developed around the time that Viagra came out, in 1998. It’s been game-changing for me to get patients more comfortable talking about their erection issues.

I tell them it’s a 4-number scale. A “1” is no erection at all. A “2” is when it gets harder and larger, but it’s not going to penetrate. A “3” will penetrate, but it’s pretty wobbly. A “4” is that perfect cucumber–porn star erection that everyone is seeking. I have the patient tell me a story. They may say, “When I wake up in the morning, I’m at a 2. When I stimulate myself, I can get up to a 3. When I’m with my partner, sometimes I can get up to a 4.”

This is really helpful because they can talk in numbers. And after I give them treatments such as lifestyle changes, sex therapy, testosterone, a PDE5 inhibitor such as Viagra or Cialis, or an injection, they can come back and tell me how the story has changed. I have an objective measure that shows me how the treatment is affecting their erections. Not only do I feel more confident having those objective measures, but my patients feel more confident in the care that they’re getting, and they feel more comfortable talking to me about the changes. So, I encourage all of you to bring that EHS tool into your office. Show it to patients and get them more comfortable talking about erections.

Dr. Rubin is assistant clinical professor, department of urology, Georgetown University, Washington. She disclosed financial relationships with Absorption Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Endo Pharmaceuticals; has served as a speaker for Sprout; and has received research grant from Maternal Medical.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I mean it. Penis problems are very common and are an early sign that patients could have a cardiac event. Think about it: Clogging the arteries of the heart is called a heart attack; clogging the arteries to the penis is a penis attack, or as doctors like to call it, erectile dysfunction.

The arteries to the penis are only 1 mm in diameter. They develop plaque and clog the circulation long before the 3-mm cardiac arteries. So, it’s very important for primary care doctors to talk to their patients about erection health. And I’ll be honest: It’s easier to talk to patients about how lifestyle is affecting their penis health than it is to discuss how lifestyle affects longevity or prevents cancer. I get a lot of men to quit smoking because I tell them what it’s doing to their penises.

It can be challenging for doctors and patients to talk about penises. It doesn’t come naturally for many of us. If a 20-year-old comes in to my office with his 85-year-old grandfather and they both say their penises aren’t working, how do you figure out what’s going on? Do they even have the same thing wrong with them?

Here’s a fun and helpful tool that I use in my office. It’s called the Erection Hardness Score. It was developed around the time that Viagra came out, in 1998. It’s been game-changing for me to get patients more comfortable talking about their erection issues.

I tell them it’s a 4-number scale. A “1” is no erection at all. A “2” is when it gets harder and larger, but it’s not going to penetrate. A “3” will penetrate, but it’s pretty wobbly. A “4” is that perfect cucumber–porn star erection that everyone is seeking. I have the patient tell me a story. They may say, “When I wake up in the morning, I’m at a 2. When I stimulate myself, I can get up to a 3. When I’m with my partner, sometimes I can get up to a 4.”

This is really helpful because they can talk in numbers. And after I give them treatments such as lifestyle changes, sex therapy, testosterone, a PDE5 inhibitor such as Viagra or Cialis, or an injection, they can come back and tell me how the story has changed. I have an objective measure that shows me how the treatment is affecting their erections. Not only do I feel more confident having those objective measures, but my patients feel more confident in the care that they’re getting, and they feel more comfortable talking to me about the changes. So, I encourage all of you to bring that EHS tool into your office. Show it to patients and get them more comfortable talking about erections.

Dr. Rubin is assistant clinical professor, department of urology, Georgetown University, Washington. She disclosed financial relationships with Absorption Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, and Endo Pharmaceuticals; has served as a speaker for Sprout; and has received research grant from Maternal Medical.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Renewing the dream

The dream of family practice began more than 6 decades ago with a movement toward personal physicians who have “… the feeling of warm personal regard and concern of doctor for patient, the feeling that the doctor treats people, not illnesses ….” The personal family physician helps patients “… not because of the interesting medical problems they may present but because they are human beings in need of help.”1 One of the most influential founders of family medicine, Dr. Gayle Stephens, expounded on this idea in a series of essays that tapped into the intellectual, philosophical, historical, and moral underpinnings of our discipline.2

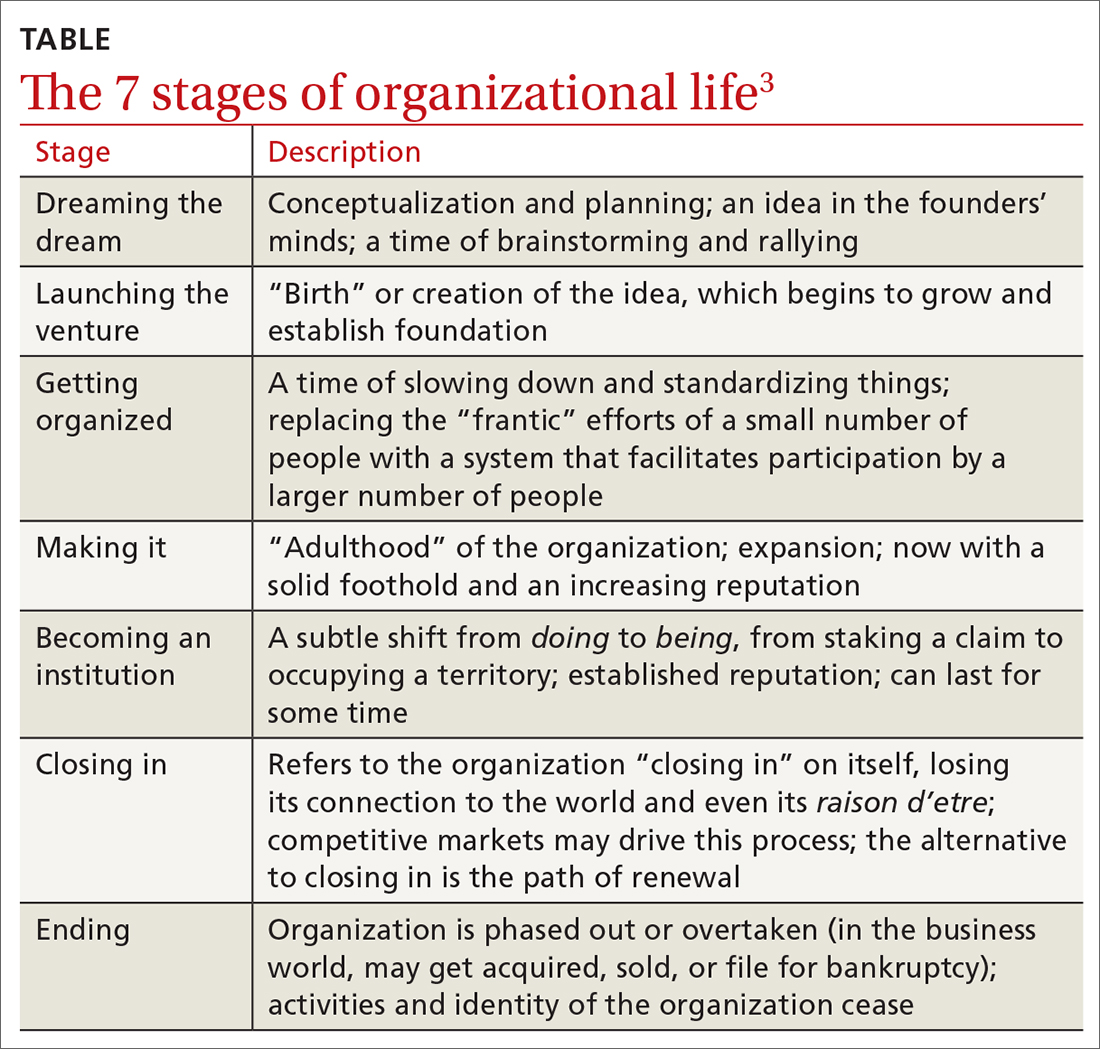

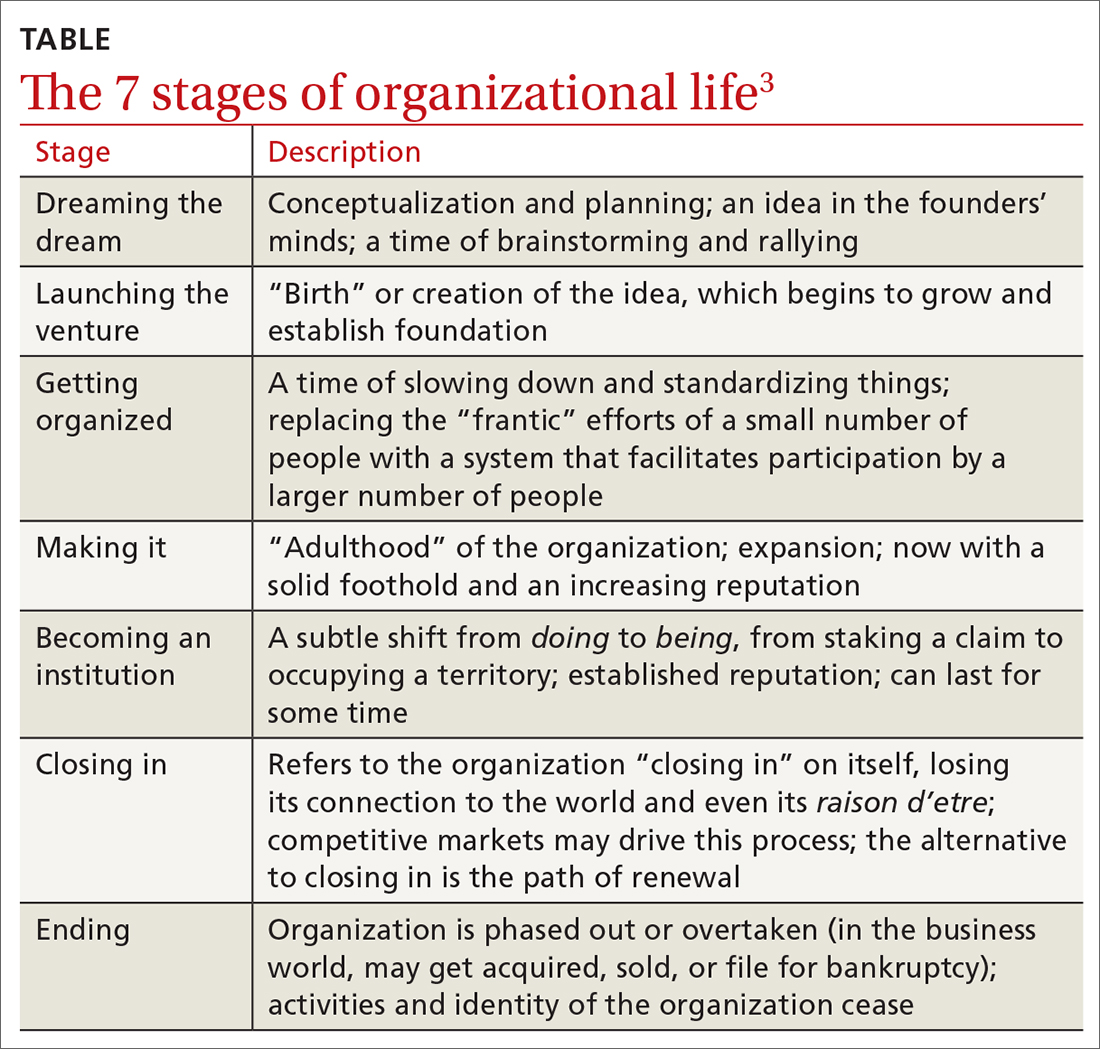

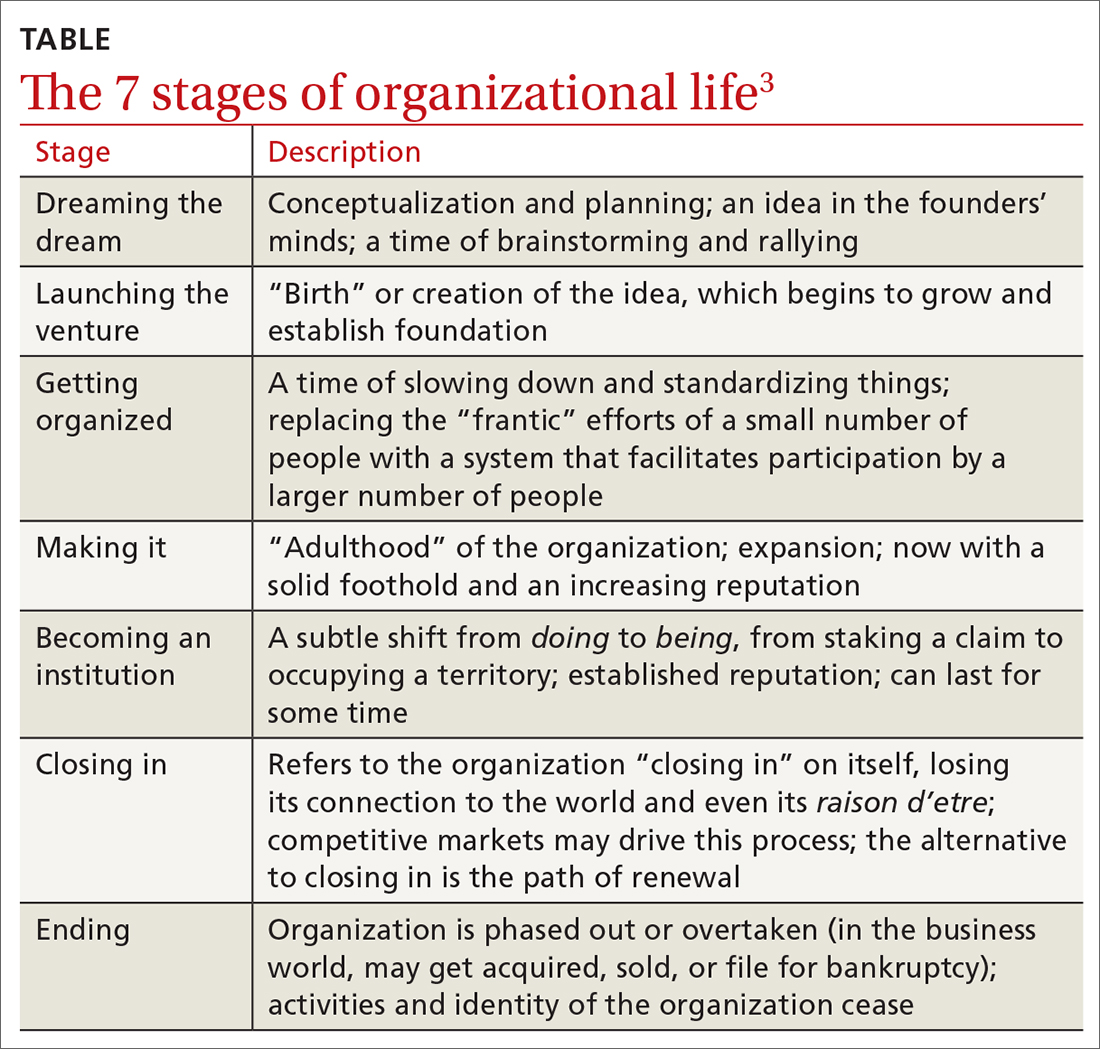

Following the dream and the birth of family medicine—like any organization—its lifecycle can be envisioned as proceeding through the rest of the 7 stages of organizational life (TABLE).3 Now allow me to give you some numbers. There are more than 118,000 family physicians in the United States, 784 family medicine residencies filled by 4530 medical school graduates, more than 150 departments of family medicine, multiple national family medicine organizations, and even a World Organization of Family Doctors.4,5 The American Board of Family Medicine is the second largest medical specialty board in the country. Family doctors make up nearly 40% of our total primary care workforce.6 We launched the venture, got organized, made it. We are an institution.

The threat at the institution stage is that we are on the precipice of “closing in.” Many factors are driving this stage: commoditization in health care, market influences and competition for patients, alternative primary care models, erosion of the patient-physician relationship (partly driven by technology), narrowing scope of care, clinician burnout, and the challenges of implementing value-based care, to name a few. You see what comes next in the TABLE.3 The good news is that there is an alternative to the “natural” progression to the ending stage: the path of renewal.3

In the lifecycle of an organization, the path of renewal starts the cycle anew, with dreaming the dream. I recently had the opportunity to visit Singapore to learn about their health system. Singapore is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. I was impressed with their many innovations, including technological ones, as well as new models of care. However, I was most impressed that the country is betting big on family medicine. Their Ministry of Health has launched an initiative they are calling Healthier SG.7 The goal is for “all Singaporeans to have a trusted and lifelong relationship with [their] family doctor.” Their dream is to bring personal doctoring to everyone in the country to make Singapore healthier.

While their path of renewal is occurring halfway around the world, here at home, our path of renewal has been ignited over the past several years by the work of the Robert Graham Center; the Keystone Conferences; the American Board of Family Medicine; and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, among others.8-11 These organizations are aligning around re-centering on patient-clinician relationships, measuring what is important, care by interprofessional teams, payment reform, professionalism, health equity, improved information technology, and adherence to the best available evidence. We are working toward the solution shop as opposed to the production line.12 We are indeed dreaming a new dream.

While I write about this renewal, I close with an ending. This is the final issue of The Journal of Family Practice. It marks the end of an era of nearly 50 years of publication. The Journal of Family Practice has left a lasting mark, providing generations of clinicians with evidence-based, practical guidance to help care for patients as well as serving as an important venue for scholarly work by the family medicine community. Although I have had the privilege of serving the discipline as an editor-in-chief for only a brief time, I am grateful I had the opportunity. Most of all, I appreciate being on the journey of family medicine with you, renewing the dream together.

The references for this Editorial are available in the online version of the article at www.mdedge.com/familymedicine.

1. Fox TF. The personal doctor and his relation to the hospital. Observations and reflections on some American experiments in general practice by groups. Lancet. 1960;2:743-760.

2. Stephens, GG. The Intellectual Basis of Family Practice. Winter Publishing and Society of Teachers of Family Medicine; 1982.

3. Bridges W, Bridges S. Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change. 4th ed. Da Capo Press; 2016.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician specialty data report. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-us-doctor-medicine-us-md-degree-specialty-2019

5. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2023 match results for family medicine. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.aafp.org/students-residents/residency-program-directors/national-resident-matching-program-results.html

6. Robert Graham Center. Primary Care in the US: A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook2021.pdf

7. Ministry of Health Singapore. What is Healthier SG? Accessed October 25, 2023. www.healthiersg.gov.sg/about/what-is-healthier-sg/

8. The Robert Graham Center. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.graham-center.org/home.html

9. Stange KC. Holding on and letting go: a perspective from the Keystone IV Conference. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:S32-S39.

10. American Board of Family Medicine. Family medicine certification. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.theabfm.org/research-articles/family-medicine-certification?page=1

11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing high-quality primary care. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/implementing-high-quality-primary-care

12. Sinsky CA, Panzer J. The solution shop and the production line—the case for a frameshift for physician practices. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2452-2453.

The dream of family practice began more than 6 decades ago with a movement toward personal physicians who have “… the feeling of warm personal regard and concern of doctor for patient, the feeling that the doctor treats people, not illnesses ….” The personal family physician helps patients “… not because of the interesting medical problems they may present but because they are human beings in need of help.”1 One of the most influential founders of family medicine, Dr. Gayle Stephens, expounded on this idea in a series of essays that tapped into the intellectual, philosophical, historical, and moral underpinnings of our discipline.2

Following the dream and the birth of family medicine—like any organization—its lifecycle can be envisioned as proceeding through the rest of the 7 stages of organizational life (TABLE).3 Now allow me to give you some numbers. There are more than 118,000 family physicians in the United States, 784 family medicine residencies filled by 4530 medical school graduates, more than 150 departments of family medicine, multiple national family medicine organizations, and even a World Organization of Family Doctors.4,5 The American Board of Family Medicine is the second largest medical specialty board in the country. Family doctors make up nearly 40% of our total primary care workforce.6 We launched the venture, got organized, made it. We are an institution.

The threat at the institution stage is that we are on the precipice of “closing in.” Many factors are driving this stage: commoditization in health care, market influences and competition for patients, alternative primary care models, erosion of the patient-physician relationship (partly driven by technology), narrowing scope of care, clinician burnout, and the challenges of implementing value-based care, to name a few. You see what comes next in the TABLE.3 The good news is that there is an alternative to the “natural” progression to the ending stage: the path of renewal.3

In the lifecycle of an organization, the path of renewal starts the cycle anew, with dreaming the dream. I recently had the opportunity to visit Singapore to learn about their health system. Singapore is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. I was impressed with their many innovations, including technological ones, as well as new models of care. However, I was most impressed that the country is betting big on family medicine. Their Ministry of Health has launched an initiative they are calling Healthier SG.7 The goal is for “all Singaporeans to have a trusted and lifelong relationship with [their] family doctor.” Their dream is to bring personal doctoring to everyone in the country to make Singapore healthier.

While their path of renewal is occurring halfway around the world, here at home, our path of renewal has been ignited over the past several years by the work of the Robert Graham Center; the Keystone Conferences; the American Board of Family Medicine; and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, among others.8-11 These organizations are aligning around re-centering on patient-clinician relationships, measuring what is important, care by interprofessional teams, payment reform, professionalism, health equity, improved information technology, and adherence to the best available evidence. We are working toward the solution shop as opposed to the production line.12 We are indeed dreaming a new dream.

While I write about this renewal, I close with an ending. This is the final issue of The Journal of Family Practice. It marks the end of an era of nearly 50 years of publication. The Journal of Family Practice has left a lasting mark, providing generations of clinicians with evidence-based, practical guidance to help care for patients as well as serving as an important venue for scholarly work by the family medicine community. Although I have had the privilege of serving the discipline as an editor-in-chief for only a brief time, I am grateful I had the opportunity. Most of all, I appreciate being on the journey of family medicine with you, renewing the dream together.

The references for this Editorial are available in the online version of the article at www.mdedge.com/familymedicine.

The dream of family practice began more than 6 decades ago with a movement toward personal physicians who have “… the feeling of warm personal regard and concern of doctor for patient, the feeling that the doctor treats people, not illnesses ….” The personal family physician helps patients “… not because of the interesting medical problems they may present but because they are human beings in need of help.”1 One of the most influential founders of family medicine, Dr. Gayle Stephens, expounded on this idea in a series of essays that tapped into the intellectual, philosophical, historical, and moral underpinnings of our discipline.2

Following the dream and the birth of family medicine—like any organization—its lifecycle can be envisioned as proceeding through the rest of the 7 stages of organizational life (TABLE).3 Now allow me to give you some numbers. There are more than 118,000 family physicians in the United States, 784 family medicine residencies filled by 4530 medical school graduates, more than 150 departments of family medicine, multiple national family medicine organizations, and even a World Organization of Family Doctors.4,5 The American Board of Family Medicine is the second largest medical specialty board in the country. Family doctors make up nearly 40% of our total primary care workforce.6 We launched the venture, got organized, made it. We are an institution.

The threat at the institution stage is that we are on the precipice of “closing in.” Many factors are driving this stage: commoditization in health care, market influences and competition for patients, alternative primary care models, erosion of the patient-physician relationship (partly driven by technology), narrowing scope of care, clinician burnout, and the challenges of implementing value-based care, to name a few. You see what comes next in the TABLE.3 The good news is that there is an alternative to the “natural” progression to the ending stage: the path of renewal.3

In the lifecycle of an organization, the path of renewal starts the cycle anew, with dreaming the dream. I recently had the opportunity to visit Singapore to learn about their health system. Singapore is one of the wealthiest countries in the world. I was impressed with their many innovations, including technological ones, as well as new models of care. However, I was most impressed that the country is betting big on family medicine. Their Ministry of Health has launched an initiative they are calling Healthier SG.7 The goal is for “all Singaporeans to have a trusted and lifelong relationship with [their] family doctor.” Their dream is to bring personal doctoring to everyone in the country to make Singapore healthier.

While their path of renewal is occurring halfway around the world, here at home, our path of renewal has been ignited over the past several years by the work of the Robert Graham Center; the Keystone Conferences; the American Board of Family Medicine; and the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, among others.8-11 These organizations are aligning around re-centering on patient-clinician relationships, measuring what is important, care by interprofessional teams, payment reform, professionalism, health equity, improved information technology, and adherence to the best available evidence. We are working toward the solution shop as opposed to the production line.12 We are indeed dreaming a new dream.

While I write about this renewal, I close with an ending. This is the final issue of The Journal of Family Practice. It marks the end of an era of nearly 50 years of publication. The Journal of Family Practice has left a lasting mark, providing generations of clinicians with evidence-based, practical guidance to help care for patients as well as serving as an important venue for scholarly work by the family medicine community. Although I have had the privilege of serving the discipline as an editor-in-chief for only a brief time, I am grateful I had the opportunity. Most of all, I appreciate being on the journey of family medicine with you, renewing the dream together.

The references for this Editorial are available in the online version of the article at www.mdedge.com/familymedicine.

1. Fox TF. The personal doctor and his relation to the hospital. Observations and reflections on some American experiments in general practice by groups. Lancet. 1960;2:743-760.

2. Stephens, GG. The Intellectual Basis of Family Practice. Winter Publishing and Society of Teachers of Family Medicine; 1982.

3. Bridges W, Bridges S. Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change. 4th ed. Da Capo Press; 2016.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician specialty data report. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-us-doctor-medicine-us-md-degree-specialty-2019

5. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2023 match results for family medicine. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.aafp.org/students-residents/residency-program-directors/national-resident-matching-program-results.html

6. Robert Graham Center. Primary Care in the US: A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook2021.pdf

7. Ministry of Health Singapore. What is Healthier SG? Accessed October 25, 2023. www.healthiersg.gov.sg/about/what-is-healthier-sg/

8. The Robert Graham Center. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.graham-center.org/home.html

9. Stange KC. Holding on and letting go: a perspective from the Keystone IV Conference. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:S32-S39.

10. American Board of Family Medicine. Family medicine certification. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.theabfm.org/research-articles/family-medicine-certification?page=1

11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing high-quality primary care. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/implementing-high-quality-primary-care

12. Sinsky CA, Panzer J. The solution shop and the production line—the case for a frameshift for physician practices. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2452-2453.

1. Fox TF. The personal doctor and his relation to the hospital. Observations and reflections on some American experiments in general practice by groups. Lancet. 1960;2:743-760.

2. Stephens, GG. The Intellectual Basis of Family Practice. Winter Publishing and Society of Teachers of Family Medicine; 1982.

3. Bridges W, Bridges S. Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change. 4th ed. Da Capo Press; 2016.

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician specialty data report. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-us-doctor-medicine-us-md-degree-specialty-2019

5. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2023 match results for family medicine. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.aafp.org/students-residents/residency-program-directors/national-resident-matching-program-results.html

6. Robert Graham Center. Primary Care in the US: A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.graham-center.org/content/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/reports/PrimaryCareChartbook2021.pdf

7. Ministry of Health Singapore. What is Healthier SG? Accessed October 25, 2023. www.healthiersg.gov.sg/about/what-is-healthier-sg/

8. The Robert Graham Center. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.graham-center.org/home.html

9. Stange KC. Holding on and letting go: a perspective from the Keystone IV Conference. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:S32-S39.

10. American Board of Family Medicine. Family medicine certification. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.theabfm.org/research-articles/family-medicine-certification?page=1

11. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing high-quality primary care. Accessed October 25, 2023. www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/implementing-high-quality-primary-care

12. Sinsky CA, Panzer J. The solution shop and the production line—the case for a frameshift for physician practices. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2452-2453.

The steep costs of disrupting gut-barrier harmony

An interview with Elena Ivanina, DO, MPH

From Ayurveda to the teachings of Hippocrates, medicine’s earliest traditions advanced a belief that the gut was the foundation of all health and disease. It wasn’t until recently, however, that Western medicine has adopted the notion of gut-barrier dysfunction as a pathologic phenomenon critical to not only digestive health but also chronic allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune disease.

To learn more, Medscape contributor Akash Goel, MD, interviewed Elena Ivanina, DO, MPH, an integrative gastroenterologist, on the role of the gut barrier. Dr. Ivanina is the founder of the Center for Integrative Gut Health and the former director of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She runs the educational platform for all things gut health, gutlove.com.

What is the role of the gut barrier in overall health and disease?

The gut contains the human body’s largest interface between a person and their external environment. The actual interface is at the gut barrier, where there needs to be an ideal homeostasis and selectivity mechanism to allow the absorption of healthy nutrients, but on the other hand prevent the penetration of harmful microbes, food antigens, and other proinflammatory factors and toxins.

The gut barrier is made up of the mucus layer, gut microbiome, epithelial cells, and immune cells in the lamina propria. When this apparatus is disrupted by factors such as infection, low-fiber diet, antibiotics, and alcohol, then it cannot function normally to selectively keep out the harmful intraluminal substances.

Gut-barrier disruption leads to translocation of dangerous intraluminal components, such as bacteria and their components, into the gut wall and, most importantly, exposes the immune system to them. This causes improper immune activation and dysregulation, which has been shown to lead to various diseases, including gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and celiac disease, systemic autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, and metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

Is disruption of this barrier what is usually referred to as “leaky gut”?

Leaky gut is a colloquial term for increased intestinal permeability or intestinal hyperpermeability. In a 2019 review article, Dr. Michael Camilleri exposes leaky gut as a term that can be misleading and confusing to the general population. It calls upon clinicians to have an increased awareness of the potential of barrier dysfunction in diseases, and to consider the barrier as a target for treatment.

Is leaky gut more of a mechanism of underlying chronic disease or is it a disease of its own?

Intestinal permeability is a pathophysiologic process in the gut with certain risk factors that in some conditions has been shown to precede chronic disease. There has not been any convincing evidence that it can be diagnosed and treated as its own entity, but research is ongoing.

In IBD, the Crohn’s and Colitis Canada Genetic, Environmental, Microbial Project research consortium has been studying individuals at increased risk for Crohn’s disease because of a first-degree family member with Crohn’s disease. They found an increased abundance of Ruminococcus torques in the microbiomes of at-risk individuals who went on to develop the disease. R. torques are mucin degraders that induce an increase in other mucin-using bacteria, which can contribute to gut-barrier compromise.

In other studies, patients have been found to have asymptomatic intestinal hyperpermeability years before their diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. This supports understanding more about the potential of intestinal hyperpermeability as its own diagnosis that, if addressed, could possibly prevent disease development.

The many possible sources of gut-barrier disruption

What causes leaky gut, and when should physicians and patients be suspicious if they have it?

There are many risk factors that have been associated with leaky gut in both human studies and animal studies, including acrolein (food toxin), aging, alcohol, antacid drugs, antibiotics, burn injury, chemotherapy, circadian rhythm disruption, corticosteroids, emulsifiers (food additives), strenuous exercise (≥ 2 hours) at 60% VO2 max, starvation, fructose, fructans, gliadin (wheat protein), high-fat diet, high-salt diet, high-sugar diet, hyperglycemia, low-fiber diet, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pesticide, proinflammatory cytokines, psychological stress, radiation, sleep deprivation, smoking, and sweeteners.

Patients may be completely asymptomatic with leaky gut. Physicians should be suspicious if there is a genetic predisposition to chronic disease or if any risk factors are unveiled after assessing diet and lifestyle exposures.

What is the role of the Western diet and processed food consumption in driving disruptions of the gut barrier?

The Western diet reduces gut-barrier mucus thickness, leading to increased gut permeability. People who consume a Western diet typically eat less than 15 grams of fiber per day, which is significantly less than many other cultures, including the hunter-gatherers of Tanzania (Hadza), who get 100 or more grams of fiber a day in their food.

With a fiber-depleted diet, gut microbiota that normally feed on fiber gradually disappear and other commensals shift their metabolism to degrade the gut-barrier mucus layer.

A low-fiber diet also decreases short-chain fatty acid production, which reduces production of mucus and affects tight junction regulation.

Emerging evidence on causality

New evidence is demonstrating that previous functional conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, like functional dyspepsia, are associated with abnormalities to the intestinal barrier. What is the association between conditions like functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with gut-barrier disruption?

Conditions such as functional dyspepsia and IBS are similar in that their pathophysiology is incompletely understood and likely attributable to contributions from many different underlying mechanisms. This makes it difficult for clinicians to explain the condition to patients and often to treat without specific therapeutic targets.

Emerging evidence with new diagnostic tools, such as confocal laser endomicroscopy, has demonstrated altered mucosal barrier function in both conditions.

In patients with IBS who have a suspected food intolerance, studies looking at exposure to the food antigens found that the food caused immediate breaks, increased intervillous spaces, and increased inflammatory cells in the gut mucosa. These changes were associated with patient responses to exclusion diets.

In functional dyspepsia, another study, using confocal laser endomicroscopy, has shown that affected patients have significantly greater epithelial gap density in the duodenum, compared with healthy controls. There was also impaired duodenal-epithelial barrier integrity and evidence of increased cellular pyroptosis in the duodenal mucosa.

These findings suggest that while IBS and functional dyspepsia are still likely multifactorial, there may be a common preclinical state that can be further investigated as far as preventing its development and using it as a therapeutic target.

What diagnostic testing are you using to determine whether patients have disruptions to the gut barrier? Are they validated or more experimental?

There are various testing strategies that have been used in research to diagnose intestinal hyperpermeability. In a 2021 analysis, Dr. Michael Camilleri found that the optimal probes for measuring small intestinal and colonic permeability are the mass excreted of 13C-mannitol at 0-2 hours and lactulose during 2-8 hours or sucralose during 8-24 hours. Studies looking at postinfectious IBS have incorporated elevated urinary lactulose/mannitol ratios. Dr. Alessio Fasano and others have looked at using zonulin as a biomarker of impaired gut-barrier function. These tests are still considered experimental.

Is there an association between alterations in the gut microbiome and gut-barrier disruption?

There is an integral relationship between the gut microbiome and gut-barrier function, and dysbiosis can disrupt gut-barrier functionality.

The microbiota produce a variety of metabolites in close proximity to the gut epithelium, impacting gut-barrier function and immune response. For example, short-chain fatty acids produced by Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Enterobacter, Faecalibacterium, and Roseburia species impact host immune cell differentiation and metabolism as well as influence susceptibility to pathogens.

Studies have shown that sodium butyrate significantly improves epithelial-barrier function. Other experiments have used transplantation of the intestinal microbiota to show that introduction of certain microbial phenotypes can significantly increase gut permeability.

Practical advice for clinicians and patients

How do you advise patients to avoid gut-barrier disruption?

It is important to educate and counsel patients about the long list of risk factors, many of which are closely related to a Western diet and lifestyle, which can increase their risk for leaky gut.

Once one has it, can it be repaired? Can you share a bit about your protocols in general terms?

Many interventions have been shown to improve intestinal permeability. They include berberine, butyrate, caloric restriction and fasting, curcumin, dietary fiber (prebiotics), moderate exercise, fermented food, fish oil, glutamine, quercetin, probiotics, vagus nerve stimulation, vitamin D, and zinc.

Protocols have to be tailored to patients and their risk factors, diet, and lifestyle.

What are some tips from a nutrition and lifestyle standpoint that patients can follow to ensure a robust gut barrier?

It is important to emphasize a high-fiber diet with naturally fermented food, incorporating time-restricted eating, such as eating an early dinner and nothing else before bedtime, a moderate exercise routine, and gut-brain modulation with techniques such as acupuncture that can incorporate vagus nerve stimulation. Limited safe precision supplementation can be discussed on an individual basis based on the patient’s interest, additional testing, and other existing health conditions.

Dr. Akash Goel is a clinical assistant professor of medicine at Weill Cornell in gastroenterology and hepatology. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His work has appeared on networks and publications such as CNN, The New York Times, Time Magazine, and Financial Times. He has a deep interest in nutrition, food as medicine, and the intersection between the gut microbiome and human health.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

An interview with Elena Ivanina, DO, MPH

An interview with Elena Ivanina, DO, MPH

From Ayurveda to the teachings of Hippocrates, medicine’s earliest traditions advanced a belief that the gut was the foundation of all health and disease. It wasn’t until recently, however, that Western medicine has adopted the notion of gut-barrier dysfunction as a pathologic phenomenon critical to not only digestive health but also chronic allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune disease.

To learn more, Medscape contributor Akash Goel, MD, interviewed Elena Ivanina, DO, MPH, an integrative gastroenterologist, on the role of the gut barrier. Dr. Ivanina is the founder of the Center for Integrative Gut Health and the former director of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She runs the educational platform for all things gut health, gutlove.com.

What is the role of the gut barrier in overall health and disease?

The gut contains the human body’s largest interface between a person and their external environment. The actual interface is at the gut barrier, where there needs to be an ideal homeostasis and selectivity mechanism to allow the absorption of healthy nutrients, but on the other hand prevent the penetration of harmful microbes, food antigens, and other proinflammatory factors and toxins.

The gut barrier is made up of the mucus layer, gut microbiome, epithelial cells, and immune cells in the lamina propria. When this apparatus is disrupted by factors such as infection, low-fiber diet, antibiotics, and alcohol, then it cannot function normally to selectively keep out the harmful intraluminal substances.

Gut-barrier disruption leads to translocation of dangerous intraluminal components, such as bacteria and their components, into the gut wall and, most importantly, exposes the immune system to them. This causes improper immune activation and dysregulation, which has been shown to lead to various diseases, including gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and celiac disease, systemic autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis, and metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes.

Is disruption of this barrier what is usually referred to as “leaky gut”?

Leaky gut is a colloquial term for increased intestinal permeability or intestinal hyperpermeability. In a 2019 review article, Dr. Michael Camilleri exposes leaky gut as a term that can be misleading and confusing to the general population. It calls upon clinicians to have an increased awareness of the potential of barrier dysfunction in diseases, and to consider the barrier as a target for treatment.

Is leaky gut more of a mechanism of underlying chronic disease or is it a disease of its own?

Intestinal permeability is a pathophysiologic process in the gut with certain risk factors that in some conditions has been shown to precede chronic disease. There has not been any convincing evidence that it can be diagnosed and treated as its own entity, but research is ongoing.

In IBD, the Crohn’s and Colitis Canada Genetic, Environmental, Microbial Project research consortium has been studying individuals at increased risk for Crohn’s disease because of a first-degree family member with Crohn’s disease. They found an increased abundance of Ruminococcus torques in the microbiomes of at-risk individuals who went on to develop the disease. R. torques are mucin degraders that induce an increase in other mucin-using bacteria, which can contribute to gut-barrier compromise.

In other studies, patients have been found to have asymptomatic intestinal hyperpermeability years before their diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. This supports understanding more about the potential of intestinal hyperpermeability as its own diagnosis that, if addressed, could possibly prevent disease development.

The many possible sources of gut-barrier disruption

What causes leaky gut, and when should physicians and patients be suspicious if they have it?

There are many risk factors that have been associated with leaky gut in both human studies and animal studies, including acrolein (food toxin), aging, alcohol, antacid drugs, antibiotics, burn injury, chemotherapy, circadian rhythm disruption, corticosteroids, emulsifiers (food additives), strenuous exercise (≥ 2 hours) at 60% VO2 max, starvation, fructose, fructans, gliadin (wheat protein), high-fat diet, high-salt diet, high-sugar diet, hyperglycemia, low-fiber diet, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pesticide, proinflammatory cytokines, psychological stress, radiation, sleep deprivation, smoking, and sweeteners.

Patients may be completely asymptomatic with leaky gut. Physicians should be suspicious if there is a genetic predisposition to chronic disease or if any risk factors are unveiled after assessing diet and lifestyle exposures.

What is the role of the Western diet and processed food consumption in driving disruptions of the gut barrier?

The Western diet reduces gut-barrier mucus thickness, leading to increased gut permeability. People who consume a Western diet typically eat less than 15 grams of fiber per day, which is significantly less than many other cultures, including the hunter-gatherers of Tanzania (Hadza), who get 100 or more grams of fiber a day in their food.

With a fiber-depleted diet, gut microbiota that normally feed on fiber gradually disappear and other commensals shift their metabolism to degrade the gut-barrier mucus layer.

A low-fiber diet also decreases short-chain fatty acid production, which reduces production of mucus and affects tight junction regulation.

Emerging evidence on causality

New evidence is demonstrating that previous functional conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, like functional dyspepsia, are associated with abnormalities to the intestinal barrier. What is the association between conditions like functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with gut-barrier disruption?

Conditions such as functional dyspepsia and IBS are similar in that their pathophysiology is incompletely understood and likely attributable to contributions from many different underlying mechanisms. This makes it difficult for clinicians to explain the condition to patients and often to treat without specific therapeutic targets.

Emerging evidence with new diagnostic tools, such as confocal laser endomicroscopy, has demonstrated altered mucosal barrier function in both conditions.

In patients with IBS who have a suspected food intolerance, studies looking at exposure to the food antigens found that the food caused immediate breaks, increased intervillous spaces, and increased inflammatory cells in the gut mucosa. These changes were associated with patient responses to exclusion diets.

In functional dyspepsia, another study, using confocal laser endomicroscopy, has shown that affected patients have significantly greater epithelial gap density in the duodenum, compared with healthy controls. There was also impaired duodenal-epithelial barrier integrity and evidence of increased cellular pyroptosis in the duodenal mucosa.

These findings suggest that while IBS and functional dyspepsia are still likely multifactorial, there may be a common preclinical state that can be further investigated as far as preventing its development and using it as a therapeutic target.

What diagnostic testing are you using to determine whether patients have disruptions to the gut barrier? Are they validated or more experimental?