User login

Tramadol use for noncancer pain linked with increased hip fracture risk

The risk of hip fracture was higher among patients treated with tramadol for chronic noncancer pain than among those treated with other commonly used NSAIDs in a large population-based cohort in the United Kingdom.

The incidence of hip fracture over a 12-month period among 293,912 propensity score-matched tramadol and codeine recipients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database during 2000-2017 was 3.7 vs. 2.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio for hip fracture, 1.28), Jie Wei, PhD, of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China, and colleagues reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Hip fracture incidence per 1,000 person-years was also higher in propensity score–matched cohorts of patients receiving tramadol vs. naproxen (2.9 vs. 1.7; HR, 1.69), ibuprofen (3.4 vs. 2.0; HR, 1.65), celecoxib (3.4 vs. 1.8; HR, 1.85), or etoricoxib (2.9 vs. 1.5; HR, 1.96), the investigators found.

Tramadol is considered a weak opioid and is commonly used for the treatment of pain based on a lower perceived risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects versus NSAIDs, and of addiction and respiratory depression versus traditional opioids, they explained. Several professional organizations also have “strongly or conditionally recommended tramadol” as a first- or second-line treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

The potential mechanisms for the association between tramadol and hip fracture require further study, but “[c]onsidering the significant impact of hip fracture on morbidity, mortality, and health care costs, our results point to the need to consider tramadol’s associated risk of fracture in clinical practice and treatment guidelines,” they concluded.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central South University. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wei J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Feb 5. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3935.

The risk of hip fracture was higher among patients treated with tramadol for chronic noncancer pain than among those treated with other commonly used NSAIDs in a large population-based cohort in the United Kingdom.

The incidence of hip fracture over a 12-month period among 293,912 propensity score-matched tramadol and codeine recipients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database during 2000-2017 was 3.7 vs. 2.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio for hip fracture, 1.28), Jie Wei, PhD, of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China, and colleagues reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Hip fracture incidence per 1,000 person-years was also higher in propensity score–matched cohorts of patients receiving tramadol vs. naproxen (2.9 vs. 1.7; HR, 1.69), ibuprofen (3.4 vs. 2.0; HR, 1.65), celecoxib (3.4 vs. 1.8; HR, 1.85), or etoricoxib (2.9 vs. 1.5; HR, 1.96), the investigators found.

Tramadol is considered a weak opioid and is commonly used for the treatment of pain based on a lower perceived risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects versus NSAIDs, and of addiction and respiratory depression versus traditional opioids, they explained. Several professional organizations also have “strongly or conditionally recommended tramadol” as a first- or second-line treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

The potential mechanisms for the association between tramadol and hip fracture require further study, but “[c]onsidering the significant impact of hip fracture on morbidity, mortality, and health care costs, our results point to the need to consider tramadol’s associated risk of fracture in clinical practice and treatment guidelines,” they concluded.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central South University. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wei J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Feb 5. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3935.

The risk of hip fracture was higher among patients treated with tramadol for chronic noncancer pain than among those treated with other commonly used NSAIDs in a large population-based cohort in the United Kingdom.

The incidence of hip fracture over a 12-month period among 293,912 propensity score-matched tramadol and codeine recipients in The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database during 2000-2017 was 3.7 vs. 2.9 per 1,000 person-years, respectively (hazard ratio for hip fracture, 1.28), Jie Wei, PhD, of Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China, and colleagues reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Hip fracture incidence per 1,000 person-years was also higher in propensity score–matched cohorts of patients receiving tramadol vs. naproxen (2.9 vs. 1.7; HR, 1.69), ibuprofen (3.4 vs. 2.0; HR, 1.65), celecoxib (3.4 vs. 1.8; HR, 1.85), or etoricoxib (2.9 vs. 1.5; HR, 1.96), the investigators found.

Tramadol is considered a weak opioid and is commonly used for the treatment of pain based on a lower perceived risk of serious cardiovascular and gastrointestinal effects versus NSAIDs, and of addiction and respiratory depression versus traditional opioids, they explained. Several professional organizations also have “strongly or conditionally recommended tramadol” as a first- or second-line treatment for conditions such as osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, and chronic low back pain.

The potential mechanisms for the association between tramadol and hip fracture require further study, but “[c]onsidering the significant impact of hip fracture on morbidity, mortality, and health care costs, our results point to the need to consider tramadol’s associated risk of fracture in clinical practice and treatment guidelines,” they concluded.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of Central South University. The authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wei J et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Feb 5. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3935.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

FDA approves novel pandemic influenza vaccine

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first and only adjuvanted, cell-based pandemic vaccine to provide active immunization against the influenza A virus H5N1 strain.

Influenza A (H5N1) monovalent vaccine, adjuvanted (Audenz, Seqirus) is for use in individuals aged 6 months and older. It’s designed to be rapidly deployed to help protect the U.S. population and can be stockpiled for first responders in the event of a pandemic.

The vaccine and formulated prefilled syringes used in the vaccine are produced in a state-of-the-art production facility built and supported through a multiyear public-private partnership between Seqirus and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

“Pandemic influenza viruses can be deadly and spread rapidly, making production of safe, effective vaccines essential in saving lives,” BARDA Director Rick Bright, PhD, said in a company news release.

“With this licensure – the latest FDA-approved vaccine to prevent H5N1 influenza — we celebrate a decade-long partnership to achieve health security goals set by the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza and the 2019 Executive Order to speed the availability of influenza vaccine. Ultimately, this latest licensure means we can protect more people in an influenza pandemic,” said Bright.

“The approval of Audenz represents a key advance in influenza prevention and pandemic preparedness, combining leading-edge, cell-based manufacturing and adjuvant technologies,” Russell Basser, MD, chief scientist and senior vice president of research and development at Seqirus, said in the news release. “This pandemic influenza vaccine exemplifies our commitment to developing innovative technologies that can help provide rapid response during a pandemic emergency.”

Audenz had FDA fast track designation, a process designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs to treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first and only adjuvanted, cell-based pandemic vaccine to provide active immunization against the influenza A virus H5N1 strain.

Influenza A (H5N1) monovalent vaccine, adjuvanted (Audenz, Seqirus) is for use in individuals aged 6 months and older. It’s designed to be rapidly deployed to help protect the U.S. population and can be stockpiled for first responders in the event of a pandemic.

The vaccine and formulated prefilled syringes used in the vaccine are produced in a state-of-the-art production facility built and supported through a multiyear public-private partnership between Seqirus and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

“Pandemic influenza viruses can be deadly and spread rapidly, making production of safe, effective vaccines essential in saving lives,” BARDA Director Rick Bright, PhD, said in a company news release.

“With this licensure – the latest FDA-approved vaccine to prevent H5N1 influenza — we celebrate a decade-long partnership to achieve health security goals set by the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza and the 2019 Executive Order to speed the availability of influenza vaccine. Ultimately, this latest licensure means we can protect more people in an influenza pandemic,” said Bright.

“The approval of Audenz represents a key advance in influenza prevention and pandemic preparedness, combining leading-edge, cell-based manufacturing and adjuvant technologies,” Russell Basser, MD, chief scientist and senior vice president of research and development at Seqirus, said in the news release. “This pandemic influenza vaccine exemplifies our commitment to developing innovative technologies that can help provide rapid response during a pandemic emergency.”

Audenz had FDA fast track designation, a process designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs to treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first and only adjuvanted, cell-based pandemic vaccine to provide active immunization against the influenza A virus H5N1 strain.

Influenza A (H5N1) monovalent vaccine, adjuvanted (Audenz, Seqirus) is for use in individuals aged 6 months and older. It’s designed to be rapidly deployed to help protect the U.S. population and can be stockpiled for first responders in the event of a pandemic.

The vaccine and formulated prefilled syringes used in the vaccine are produced in a state-of-the-art production facility built and supported through a multiyear public-private partnership between Seqirus and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

“Pandemic influenza viruses can be deadly and spread rapidly, making production of safe, effective vaccines essential in saving lives,” BARDA Director Rick Bright, PhD, said in a company news release.

“With this licensure – the latest FDA-approved vaccine to prevent H5N1 influenza — we celebrate a decade-long partnership to achieve health security goals set by the National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza and the 2019 Executive Order to speed the availability of influenza vaccine. Ultimately, this latest licensure means we can protect more people in an influenza pandemic,” said Bright.

“The approval of Audenz represents a key advance in influenza prevention and pandemic preparedness, combining leading-edge, cell-based manufacturing and adjuvant technologies,” Russell Basser, MD, chief scientist and senior vice president of research and development at Seqirus, said in the news release. “This pandemic influenza vaccine exemplifies our commitment to developing innovative technologies that can help provide rapid response during a pandemic emergency.”

Audenz had FDA fast track designation, a process designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs to treat serious conditions and fill an unmet medical need.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Stimulant Medication Prescribing Practices Within a VA Health Care System

Dispensing of prescription stimulant medications, such as methylphenidate or amphetamine salts, has been expanding at a rapid rate over the past 2 decades. An astounding 58 million stimulant medications were prescribed in 2014.1,2 Adults now exceed youths in the proportion of prescribed stimulant medications.1,3

Off-label use of prescription stimulant medications, such as for performance enhancement, fatigue management, weight loss, medication-assisted therapy for stimulant use disorders, and adjunctive treatment for certain depressive disorders, is reported to be ≥ 40% of total stimulant use and is much more common in adults.1 A 2017 study assessing risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among veterans prescribed stimulant medications within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) reported off-label use in nearly 3 of every 5 incident users in 2012.4 Off-label use also is significantly more common when prescribed by nonpsychiatric physicians compared with that of psychiatrists.1

One study assessing stimulant prescribing from 2006 to 2009 found that nearly 60% of adults were prescribed stimulant medications by nonpsychiatrist physicians, and only 34% of those adults prescribed a stimulant by a nonpsychiatrist physician had a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).5 Findings from managed care plans covering years from 2000 to 2004 were similar, concluding that 30% of the adult patients who were prescribed methylphenidate had at least 1 medical claim with a diagnosis of ADHD.6 Of the approximately 16 million adults prescribed stimulant medications in 2017, > 5 million of them reported stimulant misuse.3 Much attention has been focused on misuse of stimulant medications by youths and young adults, but new information suggests that increased monitoring is needed among the US adult population. Per the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Academic Detailing Stimulant Dashboard, as of October 2018 the national average of veterans with a documented substance use disorder (SUD) who are also prescribed stimulant medications through the VHA exceeds 20%, < 50% have an annual urine drug screen (UDS), and > 10% are coprescribed opioids and benzodiazepines.The percentage of veterans prescribed stimulant medications in the presence of a SUD has increased over the past decade, with a reported 8.7% incidence in 2002 increasing to 14.3% in 2012.4

There are currently no protocols, prescribing restrictions, or required monitoring parameters in place for prescription stimulant use within the Lexington VA Health Care System (LVAHCS). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prescribing practices at LVAHCS of stimulant medications and identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of this drug class.

Methods

This study was a single-center quality improvement project evaluating the prescribing practices of stimulant medications within LVAHCS and exempt from institutional review board approval. Veterans were included in the study if they were prescribed amphetamine salts, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamphetamine, or methylphenidate between January 1, 2018 and June 30, 2018; however, the veterans’ entire stimulant use history was assessed. Exclusion criteria included duration of use of < 2 months or < 2 prescriptions filled during the study period. Data for veterans who met the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria were collected via chart review and Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio.

Collected data included age, gender, stimulant regimen (drug name, dose, frequency), indication and duration of use, prescriber name and specialty, prescribing origin of initial stimulant medication, and whether stimulant use predated military service. Monitoring of stimulant medications was assessed via UDS at least annually, query of the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) at least quarterly, and average time between follow-up appointments with stimulant prescriber.

Monitoring parameters were assessed from January 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018, as it was felt that the 6-month study period would be too narrow to accurately assess monitoring trends. Mental health diagnoses, ADHD diagnostic testing if applicable, documented SUD or stimulant misuse past or present, and concomitant central nervous system (CNS) depressant use also were collected. CNS depressants evaluated were those that have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects and included benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, opioids, gabapentin/pregabalin, Z-hypnotics, and muscle relaxants.

Results

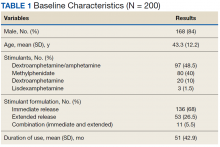

The majority of participants were male (168/200) with an average age of 43.3 years. Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine was the most used stimulant (48.5%), followed by methylphenidate (40%), and dextroamphetamine (10%). Lisdexamphetamine was the least used stimulant, likely due to its formulary-restricted status within this facility. An extended release (ER) formulation was utilized in 1 of 4 participants, with 1 of 20 participants prescribed a combination of immediate release (IR) and ER formulations. Duration of use ranged from 3 months to 14 years, with an average duration of 4 years (Table 1).

Nearly 40% of participants reported an origin of stimulant initiation outside of LVAHCS. Fourteen percent of participants were started on prescription stimulant medications while active-duty service members. Stimulant medications were initiated at another VA facility in 10.5% of instances, and 15% of participants reported being prescribed stimulant medications by a civilian prescriber prior to receiving them at LVAHCS. Seventy-four of 79 (93.6%) participants with an origin of stimulant prescription outside of LVAHCS reported a US Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for use.

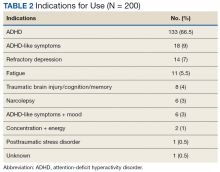

Stimulant medications were used for FDA-approved indications (ADHD and narcolepsy) in 69.5% of participants. Note, this included patients who maintained an ADHD diagnosis in their medical record even if it was not substantiated with diagnostic testing. Of the participants reporting ADHD as an indication for stimulant use, diagnostic testing was conducted at LVAHCS to confirm an ADHD diagnosis in 58.6% (78/133) participants; 20.5% (16/78) of these diagnostic tests did not support the diagnosis of ADHD. All documented indications for use can be found in Table 2.

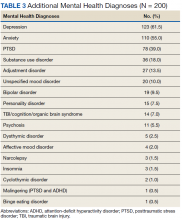

As expected, the most common indication was ADHD (66.5%), followed by ADHD-like symptoms (9%), refractory depression (7%), and fatigue (5.5%). Fourteen percent of participants had ≥ 1 change in indication for use, with some participants having up to 4 different documented indications while being prescribed stimulant medications. Twelve percent of participants were either denied stimulant initiation, or current stimulant medications were discontinued by one health provider and were restarted by another following a prescriber change. Aside from indication for stimulant use, 90% of participants had at least one additional mental health diagnosis. The rate of all mental health diagnoses documented in the medical record problem list can be found in Table 3.

A UDS was collected at least annually in 37% of participants. A methylphenidate confirmatory screen was ordered to assess adherence in just 2 (2.5%) participants prescribed methylphenidate. While actively prescribed stimulant medications, PDMP was queried quarterly in 26% of participants. Time to follow-up with the prescriber ranged from 1 to 15 months, and 40% of participants had follow-up at least quarterly. Instance of SUD, either active or in remission, differed when searched via problem list (36/200) and prescriber documentation (63/200). The most common SUD was alcohol use disorder (13%), followed by cannabis use disorder (5%), polysubstance use disorder (5%), opioid use disorder (4.5%), stimulant use disorder (2.5%), and sedative use disorder (1%). Twenty-five participants currently prescribed stimulant medications had stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. Fifty-four percent of participants were prescribed at least 1 CNS depressant considered to have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects. Opioids were most common (23%), followed by muscle relaxants (15.5%), benzodiazepines (15%), antipsychotics (13%), gabapentin/pregabalin (12%), and Z-hypnotics (12%).

Discussion

The source of the initial stimulant prescription was assessed. The majority of veterans had received medical care prior to receiving care at LVAHCS, whether on active duty, from another VA facility throughout the country, or by a private civilian prescriber. The origin of initial stimulant medication and indication for stimulant medication use were patient reported. Requiring medical records from civilian providers prior to continuing stimulant medication is prescriber-dependent and was not available for all participants.

As expected, the majority of participants

The reasons for discontinuation included a positive UDS result for cocaine, psychosis, broken narcotic contract, ADHD diagnosis not supported by psychological testing, chronic bipolar disorder secondary to stimulant use, diversion, stimulant misuse, and lack of indication for use. There also were a handful of veterans whose VA prescribers declined to initiate prescription stimulant medications for various reasons, so the veteran sought care from a civilian prescriber who prescribed stimulant medications, then returned to the VA for medication management, and stimulant medications were continued. Fourteen percent (28/200) of participants had multiple indications for use at some point during stimulant medication therapy. Eight of those were a reasonable change from ADHD to ADHD-like symptoms when diagnosis was not substantiated by testing. The cause of other changes in indication for use was not well documented and often unclear. One veteran had 4 different indications for use documented in the medical record, often changing with each change in prescriber. It appeared that the most recent prescriber was uncertain of the actual indication for use but did not want to discontinue the medication. This prescriber documented that the stimulant medication should continue for presumed ADHD/mood/fatigue/cognitive dysfunction, which were all of the indications documented by the veteran’s previous prescribers.

Reasons for Discontinuation

ADHD was the most prominent indication for use, although the indication was changed to ADHD-like symptoms in several veterans for whom diagnostic testing did not support the ADHD diagnosis. Seventy-eight of 133 veterans prescribed stimulant medications for ADHD received diagnostic testing via a psychologist at LVAHCS. For the 11 veterans who had testing after stimulant initiation, a stimulant-free period was required prior to testing to ensure an accurate diagnosis. For 21% of veterans, the ADHD diagnosis was unsubstantiated by formal testing; however, all of these veterans continued stimulant medication use. For 1 veteran, the psychologist performing the testing documented new diagnoses, including moderate to severe stimulant use disorder and malingering both for PTSD and ADHD. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, “prescriber-hopping,” and unsupported ADHD diagnosis results warrant a conversation about expectations for transitions of care regarding stimulant medications, not only from outside to inside LVAHCS, but from prescriber to prescriber within the facility.

In some cases, stimulant medications were discontinued by a prescriber secondary to a worsening of another mental health condition. More than half of the participants in this study had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Whether or not anxiety predated stimulant use or whether the use of stimulant medications contributed to the diagnosis and thus the addition of an additional CNS depressant to treat anxiety may be an area of research for future consideration. Although bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and SUD are not contraindications for use of stimulant medications, caution must be used in patients with these diagnoses. Prescribers must weigh risks vs benefits as well as perform close monitoring during use. Similarly, one might look further into stimulant medications prescribed for fatigue and assess the role of any simultaneously prescribed CNS depressants. Is the stimulant being used to treat the adverse effect (AE) of another medication? In 2 documented instances in this study, a psychologist conducted diagnostic testing who reported that the veteran did not meet the criteria for ADHD but that a stimulant may help counteract the iatrogenic effect of anticonvulsants. In both instances stimulant use continued.

Prescription Monitoring

Polysubstance use disorder (5%) was the third most common SUD recorded among study participants. The majority of those with polysubstance use disorder reported abuse/misuse of illicit or prescribed stimulants. Stimulant abuse/misuse was documented in 25 of 200 (12.5%) study participants. In several instances, abuse/misuse was detected by the LVAHCS delivery coordination pharmacist who tracks patterns of early fill requests and prescriptions reported lost/stolen. This pharmacist may request that the prescriber obtain PDMP query, UDS, or pill count if concerning patterns are noted. Lisdexamphetamine is a formulary-restricted medication at LVAHCS, but it was noted to be approved for use when prescribers requested an abuse-deterrent formulation. Investigators noticed a trend in veterans whose prescriptions exceeded the recommended maximum dosage also having stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. The highest documented total daily dose in this study was 120-mg amphetamine salts IR for ADHD, compared with the normal recommended dosing range of 5 to 40 mg/d for the same indication.

Various modalities were used to monitor participants but less than half of veterans had an annual UDS, quarterly PDMP query, and quarterly prescriber follow-up. PDMP queries and prescriber follow-up was assessed quarterly as would be reasonable given that private sector practitioners may issue multiple prescriptions authorizing the patient to receive up to a 90-day supply.7 Prescriber follow-up ranged from 1 to 15 months. A longer time to follow-up was seen more frequently in stimulant medications prescribed by primary care as compared with that of mental health.

Clinical Practice Protocol

Data from this study were collected with the intent to identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a facility-specific clinical practice protocol (CPP) for stimulant prescribing. It may also be beneficial to formulate a chronic stimulant management agreement between patient and prescriber to provide informed consent and clear expectations prior to stimulant medication initiation.

A CPP could be used to establish stimulant prescribing rules within a facility, which may limit who can prescribe stimulant medications or include a review process and/or required documentation in the medical record when being prescribed outside of specified dosing range and indications for use designated in the CPP or other evidence-based guidelines. Transition of care was found to be an area of opportunity in this study, which could be mitigated with the requirement of a baseline assessment prior to stimulant initiation with the expectation that it be completed regardless of prior prescription stimulant medication use. There was a lack of consistent monitoring for participants in this study, which may be improved if required monitoring parameters and frequency were provided for prescribers. For example, monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure was not assessed in this study, but a CPP may include monitoring vital signs before and after each dose change and every 6 months, per recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ADHD Diagnosis and Management guideline published in 2018.8The CPP may list the responsibilities of all those involved in the prescribing of stimulant medications, such as mental health service leadership, prescribers, nursing staff, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, and other mental health staff. For prescribers this may include a thorough baseline assessment and criteria for use that must be met prior to stimulant initiation, documentation that must be included in the medical record and required monitoring during stimulant treatment, and expectations for increased monitoring and/or termination of treatment with nonadherence, diversion, or abuse/misuse.

The responsibilities of pharmacists may include establishing criteria for use of nonformulary and restricted agents as well as completion of nonformulary/restricted requests, reviewing dosages that exceed the recommended FDA daily maximum, reviewing uncommon off-label uses of stimulant medications, review and document early fill requests, potential nonadherence, potential drug-seeking behavior, and communication of the following information to the primary prescriber. For other mental health staff this may include documenting any reported AEs of the medication, referring the patient to their prescriber or pharmacist for any medication questions or concerns, and assessment of effectiveness and/or worsening behavior during patient contact.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the way that data were pulled from patient charts. For example, only 3/200 participants in this study had insomnia per diagnosis codes, whereas that number was substantially higher when chart review was used to assess active prescriptions for sleep aids or documented complaints of insomnia in prescriber progress notes. For this same reason, rates of SUDs must be interpreted with caution as well. SUD diagnosis, both current and in remission were taken into account during data collection. Per diagnosis codes, 36 (18%) veterans in this study had a history of SUD, but this number was higher (31.5%) during chart review. The majority of discrepancies were found when participants reported a history of SUD to the prescriber, but this information was not captured via the problem list or encounter codes. What some may consider a minor omission in documentation can have a large impact on patient care as it is unlikely that prescribers have adequate administrative time to complete a chart review in order to find a complete past medical history as was required of investigators in this study. For this reason, incomplete provider documentation and human error that can occur as a result of a retrospective chart review were also identified as study limitations.

Conclusion

Our data show that there is still substantial room for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, prescriber-hopping, and unsupported ADHD diagnosis resulting from formal diagnostic testing warrant a review in the processes for transition of care regarding stimulant medications, both within and outside of this facility. A lack of consistent monitoring was also identified in this study. One of the most appreciable areas of opportunity resulting from this study is the need for consistency in both the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a CPP for stimulant prescribing as well as a chronic stimulant management agreement to provide clear expectations for patients and prescribers prior to and during prescription stimulant use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tori Wilhoit, PharmD candidate, and Dana Fischer, PharmD candidate, for their participation in data collection and Courtney Eatmon, PharmD, BCPP, for her general administrative support throughout this study.

1. Safer DJ. Recent trends in stimulant usage. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(6):471-477.

2. Christopher Jones; US Food and Drug Administration. The opioid epidemic overview and a look to the future. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/OpioidConference/2Jones_OPIOIDEPIDEMICOVERVIEW.pdf. Published June 12, 2015. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, Johnson K, Jones CM. Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):741-755.

4. Westover AN, Nakonezney PA, Halm EA, Adinoff B. Risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among incident users of prescribed stimulant medications in the Veterans Administration. Addiction. 2018;113(5):857-867.

5. Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Greenhill LL. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulant medications in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):43-50.

6. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Zhang HF, and Wan GJ. Continuity in methylphenidate treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13(7): 570-577.

7. 21 CFR § 1306.12

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 87. Leicester, United Kingdom: British Psychological Society; 2018.

Dispensing of prescription stimulant medications, such as methylphenidate or amphetamine salts, has been expanding at a rapid rate over the past 2 decades. An astounding 58 million stimulant medications were prescribed in 2014.1,2 Adults now exceed youths in the proportion of prescribed stimulant medications.1,3

Off-label use of prescription stimulant medications, such as for performance enhancement, fatigue management, weight loss, medication-assisted therapy for stimulant use disorders, and adjunctive treatment for certain depressive disorders, is reported to be ≥ 40% of total stimulant use and is much more common in adults.1 A 2017 study assessing risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among veterans prescribed stimulant medications within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) reported off-label use in nearly 3 of every 5 incident users in 2012.4 Off-label use also is significantly more common when prescribed by nonpsychiatric physicians compared with that of psychiatrists.1

One study assessing stimulant prescribing from 2006 to 2009 found that nearly 60% of adults were prescribed stimulant medications by nonpsychiatrist physicians, and only 34% of those adults prescribed a stimulant by a nonpsychiatrist physician had a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).5 Findings from managed care plans covering years from 2000 to 2004 were similar, concluding that 30% of the adult patients who were prescribed methylphenidate had at least 1 medical claim with a diagnosis of ADHD.6 Of the approximately 16 million adults prescribed stimulant medications in 2017, > 5 million of them reported stimulant misuse.3 Much attention has been focused on misuse of stimulant medications by youths and young adults, but new information suggests that increased monitoring is needed among the US adult population. Per the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Academic Detailing Stimulant Dashboard, as of October 2018 the national average of veterans with a documented substance use disorder (SUD) who are also prescribed stimulant medications through the VHA exceeds 20%, < 50% have an annual urine drug screen (UDS), and > 10% are coprescribed opioids and benzodiazepines.The percentage of veterans prescribed stimulant medications in the presence of a SUD has increased over the past decade, with a reported 8.7% incidence in 2002 increasing to 14.3% in 2012.4

There are currently no protocols, prescribing restrictions, or required monitoring parameters in place for prescription stimulant use within the Lexington VA Health Care System (LVAHCS). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prescribing practices at LVAHCS of stimulant medications and identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of this drug class.

Methods

This study was a single-center quality improvement project evaluating the prescribing practices of stimulant medications within LVAHCS and exempt from institutional review board approval. Veterans were included in the study if they were prescribed amphetamine salts, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamphetamine, or methylphenidate between January 1, 2018 and June 30, 2018; however, the veterans’ entire stimulant use history was assessed. Exclusion criteria included duration of use of < 2 months or < 2 prescriptions filled during the study period. Data for veterans who met the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria were collected via chart review and Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio.

Collected data included age, gender, stimulant regimen (drug name, dose, frequency), indication and duration of use, prescriber name and specialty, prescribing origin of initial stimulant medication, and whether stimulant use predated military service. Monitoring of stimulant medications was assessed via UDS at least annually, query of the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) at least quarterly, and average time between follow-up appointments with stimulant prescriber.

Monitoring parameters were assessed from January 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018, as it was felt that the 6-month study period would be too narrow to accurately assess monitoring trends. Mental health diagnoses, ADHD diagnostic testing if applicable, documented SUD or stimulant misuse past or present, and concomitant central nervous system (CNS) depressant use also were collected. CNS depressants evaluated were those that have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects and included benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, opioids, gabapentin/pregabalin, Z-hypnotics, and muscle relaxants.

Results

The majority of participants were male (168/200) with an average age of 43.3 years. Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine was the most used stimulant (48.5%), followed by methylphenidate (40%), and dextroamphetamine (10%). Lisdexamphetamine was the least used stimulant, likely due to its formulary-restricted status within this facility. An extended release (ER) formulation was utilized in 1 of 4 participants, with 1 of 20 participants prescribed a combination of immediate release (IR) and ER formulations. Duration of use ranged from 3 months to 14 years, with an average duration of 4 years (Table 1).

Nearly 40% of participants reported an origin of stimulant initiation outside of LVAHCS. Fourteen percent of participants were started on prescription stimulant medications while active-duty service members. Stimulant medications were initiated at another VA facility in 10.5% of instances, and 15% of participants reported being prescribed stimulant medications by a civilian prescriber prior to receiving them at LVAHCS. Seventy-four of 79 (93.6%) participants with an origin of stimulant prescription outside of LVAHCS reported a US Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for use.

Stimulant medications were used for FDA-approved indications (ADHD and narcolepsy) in 69.5% of participants. Note, this included patients who maintained an ADHD diagnosis in their medical record even if it was not substantiated with diagnostic testing. Of the participants reporting ADHD as an indication for stimulant use, diagnostic testing was conducted at LVAHCS to confirm an ADHD diagnosis in 58.6% (78/133) participants; 20.5% (16/78) of these diagnostic tests did not support the diagnosis of ADHD. All documented indications for use can be found in Table 2.

As expected, the most common indication was ADHD (66.5%), followed by ADHD-like symptoms (9%), refractory depression (7%), and fatigue (5.5%). Fourteen percent of participants had ≥ 1 change in indication for use, with some participants having up to 4 different documented indications while being prescribed stimulant medications. Twelve percent of participants were either denied stimulant initiation, or current stimulant medications were discontinued by one health provider and were restarted by another following a prescriber change. Aside from indication for stimulant use, 90% of participants had at least one additional mental health diagnosis. The rate of all mental health diagnoses documented in the medical record problem list can be found in Table 3.

A UDS was collected at least annually in 37% of participants. A methylphenidate confirmatory screen was ordered to assess adherence in just 2 (2.5%) participants prescribed methylphenidate. While actively prescribed stimulant medications, PDMP was queried quarterly in 26% of participants. Time to follow-up with the prescriber ranged from 1 to 15 months, and 40% of participants had follow-up at least quarterly. Instance of SUD, either active or in remission, differed when searched via problem list (36/200) and prescriber documentation (63/200). The most common SUD was alcohol use disorder (13%), followed by cannabis use disorder (5%), polysubstance use disorder (5%), opioid use disorder (4.5%), stimulant use disorder (2.5%), and sedative use disorder (1%). Twenty-five participants currently prescribed stimulant medications had stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. Fifty-four percent of participants were prescribed at least 1 CNS depressant considered to have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects. Opioids were most common (23%), followed by muscle relaxants (15.5%), benzodiazepines (15%), antipsychotics (13%), gabapentin/pregabalin (12%), and Z-hypnotics (12%).

Discussion

The source of the initial stimulant prescription was assessed. The majority of veterans had received medical care prior to receiving care at LVAHCS, whether on active duty, from another VA facility throughout the country, or by a private civilian prescriber. The origin of initial stimulant medication and indication for stimulant medication use were patient reported. Requiring medical records from civilian providers prior to continuing stimulant medication is prescriber-dependent and was not available for all participants.

As expected, the majority of participants

The reasons for discontinuation included a positive UDS result for cocaine, psychosis, broken narcotic contract, ADHD diagnosis not supported by psychological testing, chronic bipolar disorder secondary to stimulant use, diversion, stimulant misuse, and lack of indication for use. There also were a handful of veterans whose VA prescribers declined to initiate prescription stimulant medications for various reasons, so the veteran sought care from a civilian prescriber who prescribed stimulant medications, then returned to the VA for medication management, and stimulant medications were continued. Fourteen percent (28/200) of participants had multiple indications for use at some point during stimulant medication therapy. Eight of those were a reasonable change from ADHD to ADHD-like symptoms when diagnosis was not substantiated by testing. The cause of other changes in indication for use was not well documented and often unclear. One veteran had 4 different indications for use documented in the medical record, often changing with each change in prescriber. It appeared that the most recent prescriber was uncertain of the actual indication for use but did not want to discontinue the medication. This prescriber documented that the stimulant medication should continue for presumed ADHD/mood/fatigue/cognitive dysfunction, which were all of the indications documented by the veteran’s previous prescribers.

Reasons for Discontinuation

ADHD was the most prominent indication for use, although the indication was changed to ADHD-like symptoms in several veterans for whom diagnostic testing did not support the ADHD diagnosis. Seventy-eight of 133 veterans prescribed stimulant medications for ADHD received diagnostic testing via a psychologist at LVAHCS. For the 11 veterans who had testing after stimulant initiation, a stimulant-free period was required prior to testing to ensure an accurate diagnosis. For 21% of veterans, the ADHD diagnosis was unsubstantiated by formal testing; however, all of these veterans continued stimulant medication use. For 1 veteran, the psychologist performing the testing documented new diagnoses, including moderate to severe stimulant use disorder and malingering both for PTSD and ADHD. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, “prescriber-hopping,” and unsupported ADHD diagnosis results warrant a conversation about expectations for transitions of care regarding stimulant medications, not only from outside to inside LVAHCS, but from prescriber to prescriber within the facility.

In some cases, stimulant medications were discontinued by a prescriber secondary to a worsening of another mental health condition. More than half of the participants in this study had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Whether or not anxiety predated stimulant use or whether the use of stimulant medications contributed to the diagnosis and thus the addition of an additional CNS depressant to treat anxiety may be an area of research for future consideration. Although bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and SUD are not contraindications for use of stimulant medications, caution must be used in patients with these diagnoses. Prescribers must weigh risks vs benefits as well as perform close monitoring during use. Similarly, one might look further into stimulant medications prescribed for fatigue and assess the role of any simultaneously prescribed CNS depressants. Is the stimulant being used to treat the adverse effect (AE) of another medication? In 2 documented instances in this study, a psychologist conducted diagnostic testing who reported that the veteran did not meet the criteria for ADHD but that a stimulant may help counteract the iatrogenic effect of anticonvulsants. In both instances stimulant use continued.

Prescription Monitoring

Polysubstance use disorder (5%) was the third most common SUD recorded among study participants. The majority of those with polysubstance use disorder reported abuse/misuse of illicit or prescribed stimulants. Stimulant abuse/misuse was documented in 25 of 200 (12.5%) study participants. In several instances, abuse/misuse was detected by the LVAHCS delivery coordination pharmacist who tracks patterns of early fill requests and prescriptions reported lost/stolen. This pharmacist may request that the prescriber obtain PDMP query, UDS, or pill count if concerning patterns are noted. Lisdexamphetamine is a formulary-restricted medication at LVAHCS, but it was noted to be approved for use when prescribers requested an abuse-deterrent formulation. Investigators noticed a trend in veterans whose prescriptions exceeded the recommended maximum dosage also having stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. The highest documented total daily dose in this study was 120-mg amphetamine salts IR for ADHD, compared with the normal recommended dosing range of 5 to 40 mg/d for the same indication.

Various modalities were used to monitor participants but less than half of veterans had an annual UDS, quarterly PDMP query, and quarterly prescriber follow-up. PDMP queries and prescriber follow-up was assessed quarterly as would be reasonable given that private sector practitioners may issue multiple prescriptions authorizing the patient to receive up to a 90-day supply.7 Prescriber follow-up ranged from 1 to 15 months. A longer time to follow-up was seen more frequently in stimulant medications prescribed by primary care as compared with that of mental health.

Clinical Practice Protocol

Data from this study were collected with the intent to identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a facility-specific clinical practice protocol (CPP) for stimulant prescribing. It may also be beneficial to formulate a chronic stimulant management agreement between patient and prescriber to provide informed consent and clear expectations prior to stimulant medication initiation.

A CPP could be used to establish stimulant prescribing rules within a facility, which may limit who can prescribe stimulant medications or include a review process and/or required documentation in the medical record when being prescribed outside of specified dosing range and indications for use designated in the CPP or other evidence-based guidelines. Transition of care was found to be an area of opportunity in this study, which could be mitigated with the requirement of a baseline assessment prior to stimulant initiation with the expectation that it be completed regardless of prior prescription stimulant medication use. There was a lack of consistent monitoring for participants in this study, which may be improved if required monitoring parameters and frequency were provided for prescribers. For example, monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure was not assessed in this study, but a CPP may include monitoring vital signs before and after each dose change and every 6 months, per recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ADHD Diagnosis and Management guideline published in 2018.8The CPP may list the responsibilities of all those involved in the prescribing of stimulant medications, such as mental health service leadership, prescribers, nursing staff, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, and other mental health staff. For prescribers this may include a thorough baseline assessment and criteria for use that must be met prior to stimulant initiation, documentation that must be included in the medical record and required monitoring during stimulant treatment, and expectations for increased monitoring and/or termination of treatment with nonadherence, diversion, or abuse/misuse.

The responsibilities of pharmacists may include establishing criteria for use of nonformulary and restricted agents as well as completion of nonformulary/restricted requests, reviewing dosages that exceed the recommended FDA daily maximum, reviewing uncommon off-label uses of stimulant medications, review and document early fill requests, potential nonadherence, potential drug-seeking behavior, and communication of the following information to the primary prescriber. For other mental health staff this may include documenting any reported AEs of the medication, referring the patient to their prescriber or pharmacist for any medication questions or concerns, and assessment of effectiveness and/or worsening behavior during patient contact.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the way that data were pulled from patient charts. For example, only 3/200 participants in this study had insomnia per diagnosis codes, whereas that number was substantially higher when chart review was used to assess active prescriptions for sleep aids or documented complaints of insomnia in prescriber progress notes. For this same reason, rates of SUDs must be interpreted with caution as well. SUD diagnosis, both current and in remission were taken into account during data collection. Per diagnosis codes, 36 (18%) veterans in this study had a history of SUD, but this number was higher (31.5%) during chart review. The majority of discrepancies were found when participants reported a history of SUD to the prescriber, but this information was not captured via the problem list or encounter codes. What some may consider a minor omission in documentation can have a large impact on patient care as it is unlikely that prescribers have adequate administrative time to complete a chart review in order to find a complete past medical history as was required of investigators in this study. For this reason, incomplete provider documentation and human error that can occur as a result of a retrospective chart review were also identified as study limitations.

Conclusion

Our data show that there is still substantial room for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, prescriber-hopping, and unsupported ADHD diagnosis resulting from formal diagnostic testing warrant a review in the processes for transition of care regarding stimulant medications, both within and outside of this facility. A lack of consistent monitoring was also identified in this study. One of the most appreciable areas of opportunity resulting from this study is the need for consistency in both the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a CPP for stimulant prescribing as well as a chronic stimulant management agreement to provide clear expectations for patients and prescribers prior to and during prescription stimulant use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tori Wilhoit, PharmD candidate, and Dana Fischer, PharmD candidate, for their participation in data collection and Courtney Eatmon, PharmD, BCPP, for her general administrative support throughout this study.

Dispensing of prescription stimulant medications, such as methylphenidate or amphetamine salts, has been expanding at a rapid rate over the past 2 decades. An astounding 58 million stimulant medications were prescribed in 2014.1,2 Adults now exceed youths in the proportion of prescribed stimulant medications.1,3

Off-label use of prescription stimulant medications, such as for performance enhancement, fatigue management, weight loss, medication-assisted therapy for stimulant use disorders, and adjunctive treatment for certain depressive disorders, is reported to be ≥ 40% of total stimulant use and is much more common in adults.1 A 2017 study assessing risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among veterans prescribed stimulant medications within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) reported off-label use in nearly 3 of every 5 incident users in 2012.4 Off-label use also is significantly more common when prescribed by nonpsychiatric physicians compared with that of psychiatrists.1

One study assessing stimulant prescribing from 2006 to 2009 found that nearly 60% of adults were prescribed stimulant medications by nonpsychiatrist physicians, and only 34% of those adults prescribed a stimulant by a nonpsychiatrist physician had a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).5 Findings from managed care plans covering years from 2000 to 2004 were similar, concluding that 30% of the adult patients who were prescribed methylphenidate had at least 1 medical claim with a diagnosis of ADHD.6 Of the approximately 16 million adults prescribed stimulant medications in 2017, > 5 million of them reported stimulant misuse.3 Much attention has been focused on misuse of stimulant medications by youths and young adults, but new information suggests that increased monitoring is needed among the US adult population. Per the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Academic Detailing Stimulant Dashboard, as of October 2018 the national average of veterans with a documented substance use disorder (SUD) who are also prescribed stimulant medications through the VHA exceeds 20%, < 50% have an annual urine drug screen (UDS), and > 10% are coprescribed opioids and benzodiazepines.The percentage of veterans prescribed stimulant medications in the presence of a SUD has increased over the past decade, with a reported 8.7% incidence in 2002 increasing to 14.3% in 2012.4

There are currently no protocols, prescribing restrictions, or required monitoring parameters in place for prescription stimulant use within the Lexington VA Health Care System (LVAHCS). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the prescribing practices at LVAHCS of stimulant medications and identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of this drug class.

Methods

This study was a single-center quality improvement project evaluating the prescribing practices of stimulant medications within LVAHCS and exempt from institutional review board approval. Veterans were included in the study if they were prescribed amphetamine salts, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamphetamine, or methylphenidate between January 1, 2018 and June 30, 2018; however, the veterans’ entire stimulant use history was assessed. Exclusion criteria included duration of use of < 2 months or < 2 prescriptions filled during the study period. Data for veterans who met the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria were collected via chart review and Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio.

Collected data included age, gender, stimulant regimen (drug name, dose, frequency), indication and duration of use, prescriber name and specialty, prescribing origin of initial stimulant medication, and whether stimulant use predated military service. Monitoring of stimulant medications was assessed via UDS at least annually, query of the prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) at least quarterly, and average time between follow-up appointments with stimulant prescriber.

Monitoring parameters were assessed from January 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018, as it was felt that the 6-month study period would be too narrow to accurately assess monitoring trends. Mental health diagnoses, ADHD diagnostic testing if applicable, documented SUD or stimulant misuse past or present, and concomitant central nervous system (CNS) depressant use also were collected. CNS depressants evaluated were those that have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects and included benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, opioids, gabapentin/pregabalin, Z-hypnotics, and muscle relaxants.

Results

The majority of participants were male (168/200) with an average age of 43.3 years. Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine was the most used stimulant (48.5%), followed by methylphenidate (40%), and dextroamphetamine (10%). Lisdexamphetamine was the least used stimulant, likely due to its formulary-restricted status within this facility. An extended release (ER) formulation was utilized in 1 of 4 participants, with 1 of 20 participants prescribed a combination of immediate release (IR) and ER formulations. Duration of use ranged from 3 months to 14 years, with an average duration of 4 years (Table 1).

Nearly 40% of participants reported an origin of stimulant initiation outside of LVAHCS. Fourteen percent of participants were started on prescription stimulant medications while active-duty service members. Stimulant medications were initiated at another VA facility in 10.5% of instances, and 15% of participants reported being prescribed stimulant medications by a civilian prescriber prior to receiving them at LVAHCS. Seventy-four of 79 (93.6%) participants with an origin of stimulant prescription outside of LVAHCS reported a US Federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for use.

Stimulant medications were used for FDA-approved indications (ADHD and narcolepsy) in 69.5% of participants. Note, this included patients who maintained an ADHD diagnosis in their medical record even if it was not substantiated with diagnostic testing. Of the participants reporting ADHD as an indication for stimulant use, diagnostic testing was conducted at LVAHCS to confirm an ADHD diagnosis in 58.6% (78/133) participants; 20.5% (16/78) of these diagnostic tests did not support the diagnosis of ADHD. All documented indications for use can be found in Table 2.

As expected, the most common indication was ADHD (66.5%), followed by ADHD-like symptoms (9%), refractory depression (7%), and fatigue (5.5%). Fourteen percent of participants had ≥ 1 change in indication for use, with some participants having up to 4 different documented indications while being prescribed stimulant medications. Twelve percent of participants were either denied stimulant initiation, or current stimulant medications were discontinued by one health provider and were restarted by another following a prescriber change. Aside from indication for stimulant use, 90% of participants had at least one additional mental health diagnosis. The rate of all mental health diagnoses documented in the medical record problem list can be found in Table 3.

A UDS was collected at least annually in 37% of participants. A methylphenidate confirmatory screen was ordered to assess adherence in just 2 (2.5%) participants prescribed methylphenidate. While actively prescribed stimulant medications, PDMP was queried quarterly in 26% of participants. Time to follow-up with the prescriber ranged from 1 to 15 months, and 40% of participants had follow-up at least quarterly. Instance of SUD, either active or in remission, differed when searched via problem list (36/200) and prescriber documentation (63/200). The most common SUD was alcohol use disorder (13%), followed by cannabis use disorder (5%), polysubstance use disorder (5%), opioid use disorder (4.5%), stimulant use disorder (2.5%), and sedative use disorder (1%). Twenty-five participants currently prescribed stimulant medications had stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. Fifty-four percent of participants were prescribed at least 1 CNS depressant considered to have abuse potential or significant psychotropic effects. Opioids were most common (23%), followed by muscle relaxants (15.5%), benzodiazepines (15%), antipsychotics (13%), gabapentin/pregabalin (12%), and Z-hypnotics (12%).

Discussion

The source of the initial stimulant prescription was assessed. The majority of veterans had received medical care prior to receiving care at LVAHCS, whether on active duty, from another VA facility throughout the country, or by a private civilian prescriber. The origin of initial stimulant medication and indication for stimulant medication use were patient reported. Requiring medical records from civilian providers prior to continuing stimulant medication is prescriber-dependent and was not available for all participants.

As expected, the majority of participants

The reasons for discontinuation included a positive UDS result for cocaine, psychosis, broken narcotic contract, ADHD diagnosis not supported by psychological testing, chronic bipolar disorder secondary to stimulant use, diversion, stimulant misuse, and lack of indication for use. There also were a handful of veterans whose VA prescribers declined to initiate prescription stimulant medications for various reasons, so the veteran sought care from a civilian prescriber who prescribed stimulant medications, then returned to the VA for medication management, and stimulant medications were continued. Fourteen percent (28/200) of participants had multiple indications for use at some point during stimulant medication therapy. Eight of those were a reasonable change from ADHD to ADHD-like symptoms when diagnosis was not substantiated by testing. The cause of other changes in indication for use was not well documented and often unclear. One veteran had 4 different indications for use documented in the medical record, often changing with each change in prescriber. It appeared that the most recent prescriber was uncertain of the actual indication for use but did not want to discontinue the medication. This prescriber documented that the stimulant medication should continue for presumed ADHD/mood/fatigue/cognitive dysfunction, which were all of the indications documented by the veteran’s previous prescribers.

Reasons for Discontinuation

ADHD was the most prominent indication for use, although the indication was changed to ADHD-like symptoms in several veterans for whom diagnostic testing did not support the ADHD diagnosis. Seventy-eight of 133 veterans prescribed stimulant medications for ADHD received diagnostic testing via a psychologist at LVAHCS. For the 11 veterans who had testing after stimulant initiation, a stimulant-free period was required prior to testing to ensure an accurate diagnosis. For 21% of veterans, the ADHD diagnosis was unsubstantiated by formal testing; however, all of these veterans continued stimulant medication use. For 1 veteran, the psychologist performing the testing documented new diagnoses, including moderate to severe stimulant use disorder and malingering both for PTSD and ADHD. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, “prescriber-hopping,” and unsupported ADHD diagnosis results warrant a conversation about expectations for transitions of care regarding stimulant medications, not only from outside to inside LVAHCS, but from prescriber to prescriber within the facility.

In some cases, stimulant medications were discontinued by a prescriber secondary to a worsening of another mental health condition. More than half of the participants in this study had an anxiety disorder diagnosis. Whether or not anxiety predated stimulant use or whether the use of stimulant medications contributed to the diagnosis and thus the addition of an additional CNS depressant to treat anxiety may be an area of research for future consideration. Although bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, psychosis, and SUD are not contraindications for use of stimulant medications, caution must be used in patients with these diagnoses. Prescribers must weigh risks vs benefits as well as perform close monitoring during use. Similarly, one might look further into stimulant medications prescribed for fatigue and assess the role of any simultaneously prescribed CNS depressants. Is the stimulant being used to treat the adverse effect (AE) of another medication? In 2 documented instances in this study, a psychologist conducted diagnostic testing who reported that the veteran did not meet the criteria for ADHD but that a stimulant may help counteract the iatrogenic effect of anticonvulsants. In both instances stimulant use continued.

Prescription Monitoring

Polysubstance use disorder (5%) was the third most common SUD recorded among study participants. The majority of those with polysubstance use disorder reported abuse/misuse of illicit or prescribed stimulants. Stimulant abuse/misuse was documented in 25 of 200 (12.5%) study participants. In several instances, abuse/misuse was detected by the LVAHCS delivery coordination pharmacist who tracks patterns of early fill requests and prescriptions reported lost/stolen. This pharmacist may request that the prescriber obtain PDMP query, UDS, or pill count if concerning patterns are noted. Lisdexamphetamine is a formulary-restricted medication at LVAHCS, but it was noted to be approved for use when prescribers requested an abuse-deterrent formulation. Investigators noticed a trend in veterans whose prescriptions exceeded the recommended maximum dosage also having stimulant abuse/misuse documented in their medical record. The highest documented total daily dose in this study was 120-mg amphetamine salts IR for ADHD, compared with the normal recommended dosing range of 5 to 40 mg/d for the same indication.

Various modalities were used to monitor participants but less than half of veterans had an annual UDS, quarterly PDMP query, and quarterly prescriber follow-up. PDMP queries and prescriber follow-up was assessed quarterly as would be reasonable given that private sector practitioners may issue multiple prescriptions authorizing the patient to receive up to a 90-day supply.7 Prescriber follow-up ranged from 1 to 15 months. A longer time to follow-up was seen more frequently in stimulant medications prescribed by primary care as compared with that of mental health.

Clinical Practice Protocol

Data from this study were collected with the intent to identify opportunities for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a facility-specific clinical practice protocol (CPP) for stimulant prescribing. It may also be beneficial to formulate a chronic stimulant management agreement between patient and prescriber to provide informed consent and clear expectations prior to stimulant medication initiation.

A CPP could be used to establish stimulant prescribing rules within a facility, which may limit who can prescribe stimulant medications or include a review process and/or required documentation in the medical record when being prescribed outside of specified dosing range and indications for use designated in the CPP or other evidence-based guidelines. Transition of care was found to be an area of opportunity in this study, which could be mitigated with the requirement of a baseline assessment prior to stimulant initiation with the expectation that it be completed regardless of prior prescription stimulant medication use. There was a lack of consistent monitoring for participants in this study, which may be improved if required monitoring parameters and frequency were provided for prescribers. For example, monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure was not assessed in this study, but a CPP may include monitoring vital signs before and after each dose change and every 6 months, per recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ADHD Diagnosis and Management guideline published in 2018.8The CPP may list the responsibilities of all those involved in the prescribing of stimulant medications, such as mental health service leadership, prescribers, nursing staff, pharmacists, social workers, psychologists, and other mental health staff. For prescribers this may include a thorough baseline assessment and criteria for use that must be met prior to stimulant initiation, documentation that must be included in the medical record and required monitoring during stimulant treatment, and expectations for increased monitoring and/or termination of treatment with nonadherence, diversion, or abuse/misuse.

The responsibilities of pharmacists may include establishing criteria for use of nonformulary and restricted agents as well as completion of nonformulary/restricted requests, reviewing dosages that exceed the recommended FDA daily maximum, reviewing uncommon off-label uses of stimulant medications, review and document early fill requests, potential nonadherence, potential drug-seeking behavior, and communication of the following information to the primary prescriber. For other mental health staff this may include documenting any reported AEs of the medication, referring the patient to their prescriber or pharmacist for any medication questions or concerns, and assessment of effectiveness and/or worsening behavior during patient contact.

Limitations

One limitation of this study was the way that data were pulled from patient charts. For example, only 3/200 participants in this study had insomnia per diagnosis codes, whereas that number was substantially higher when chart review was used to assess active prescriptions for sleep aids or documented complaints of insomnia in prescriber progress notes. For this same reason, rates of SUDs must be interpreted with caution as well. SUD diagnosis, both current and in remission were taken into account during data collection. Per diagnosis codes, 36 (18%) veterans in this study had a history of SUD, but this number was higher (31.5%) during chart review. The majority of discrepancies were found when participants reported a history of SUD to the prescriber, but this information was not captured via the problem list or encounter codes. What some may consider a minor omission in documentation can have a large impact on patient care as it is unlikely that prescribers have adequate administrative time to complete a chart review in order to find a complete past medical history as was required of investigators in this study. For this reason, incomplete provider documentation and human error that can occur as a result of a retrospective chart review were also identified as study limitations.

Conclusion

Our data show that there is still substantial room for improvement in the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. The rate of stimulant prescribing inconsistency, prescriber-hopping, and unsupported ADHD diagnosis resulting from formal diagnostic testing warrant a review in the processes for transition of care regarding stimulant medications, both within and outside of this facility. A lack of consistent monitoring was also identified in this study. One of the most appreciable areas of opportunity resulting from this study is the need for consistency in both the prescribing and monitoring of stimulant medications. From the above results investigators concluded that this facility may benefit from implementation of a CPP for stimulant prescribing as well as a chronic stimulant management agreement to provide clear expectations for patients and prescribers prior to and during prescription stimulant use.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tori Wilhoit, PharmD candidate, and Dana Fischer, PharmD candidate, for their participation in data collection and Courtney Eatmon, PharmD, BCPP, for her general administrative support throughout this study.

1. Safer DJ. Recent trends in stimulant usage. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(6):471-477.

2. Christopher Jones; US Food and Drug Administration. The opioid epidemic overview and a look to the future. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/OpioidConference/2Jones_OPIOIDEPIDEMICOVERVIEW.pdf. Published June 12, 2015. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, Johnson K, Jones CM. Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):741-755.

4. Westover AN, Nakonezney PA, Halm EA, Adinoff B. Risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among incident users of prescribed stimulant medications in the Veterans Administration. Addiction. 2018;113(5):857-867.

5. Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Greenhill LL. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulant medications in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):43-50.

6. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Zhang HF, and Wan GJ. Continuity in methylphenidate treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13(7): 570-577.

7. 21 CFR § 1306.12

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 87. Leicester, United Kingdom: British Psychological Society; 2018.

1. Safer DJ. Recent trends in stimulant usage. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(6):471-477.

2. Christopher Jones; US Food and Drug Administration. The opioid epidemic overview and a look to the future. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/OpioidConference/2Jones_OPIOIDEPIDEMICOVERVIEW.pdf. Published June 12, 2015. Accessed January 16, 2020.

3. Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, Johnson K, Jones CM. Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):741-755.

4. Westover AN, Nakonezney PA, Halm EA, Adinoff B. Risk of amphetamine use disorder and mortality among incident users of prescribed stimulant medications in the Veterans Administration. Addiction. 2018;113(5):857-867.

5. Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Greenhill LL. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulant medications in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):43-50.

6. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Zhang HF, and Wan GJ. Continuity in methylphenidate treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Manag Care Pharm. 2007;13(7): 570-577.

7. 21 CFR § 1306.12

8. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management of ADHD in children, young people and adults. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 87. Leicester, United Kingdom: British Psychological Society; 2018.

Lenvatinib/pembrolizumab has good activity in advanced RCC, other solid tumors

A combination of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor lenvatinib (Lenvima) and the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was safe and showed promising activity against advanced renal cell carcinoma and other solid tumors in a phase 1b/2 study.

Overall response rates (ORR) at 24 weeks ranged from 63% for patients with advanced renal cell carcinomas (RCC) to 25% for patients with urothelial cancers, reported Matthew H. Taylor, MD, of Knight Cancer Institute at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, and colleagues.

The findings from this study sparked additional clinical trials for patients with gastric cancer, gastroesophageal cancer, and differentiated thyroid cancer, and set the stage for larger phase 3 trials in patients with advanced RCC, endometrial cancer, malignant melanoma, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

“In the future, we also plan to study lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with RCC who have had disease progression after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors,” they wrote. The report was published in Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Lenvatinib is a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with action against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors 1-3, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptors 1-4, platelet-derived growth factor receptors alpha and the RET and KIT kinases.

“Preclinical and clinical studies suggest that modulation of VEGF-mediated immune suppression via angiogenesis inhibition could potentially augment the immunotherapeutic activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors,” the investigators wrote.

They reported results from the dose finding (1b) phase including 13 patients and initial phase 2 expansion cohorts with a total of 124 patients.

The maximum tolerated dose of lenvatinib in combination with pembrolizumab was established as 20 mg/day.