User login

Joint effort: CBD not just innocent bystander in weed

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

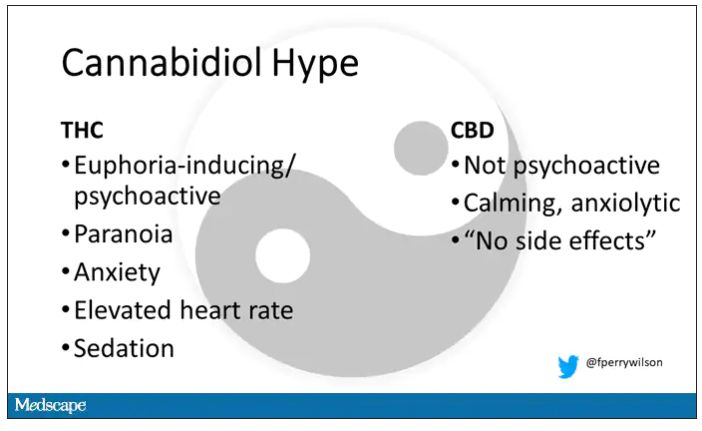

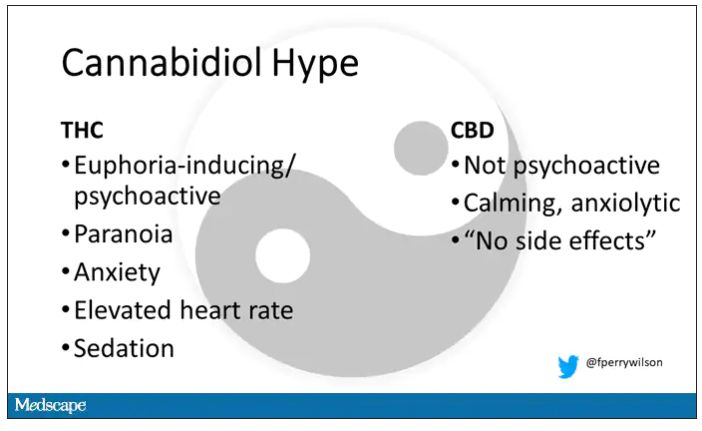

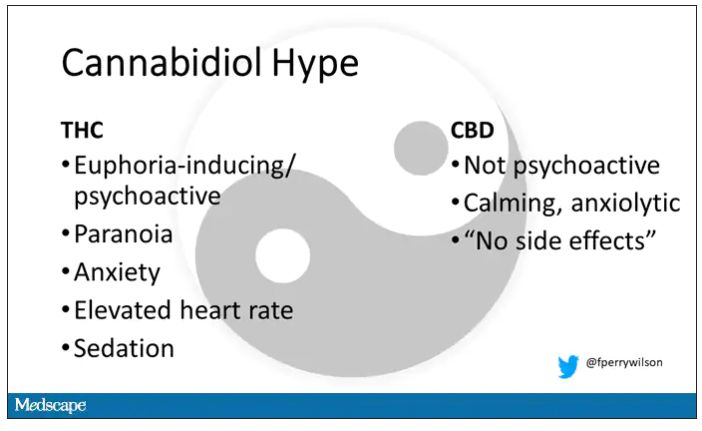

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

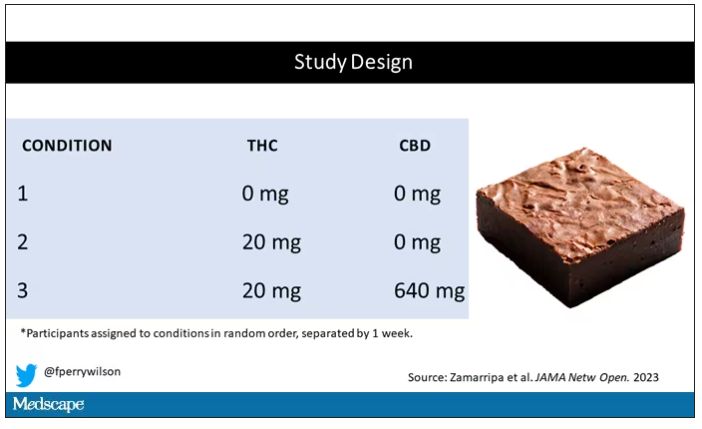

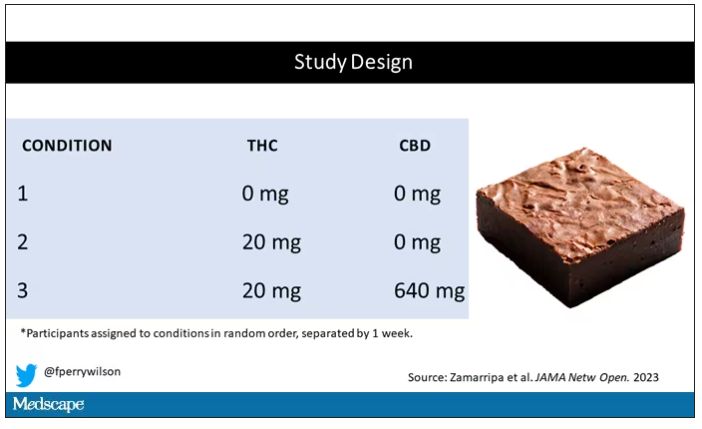

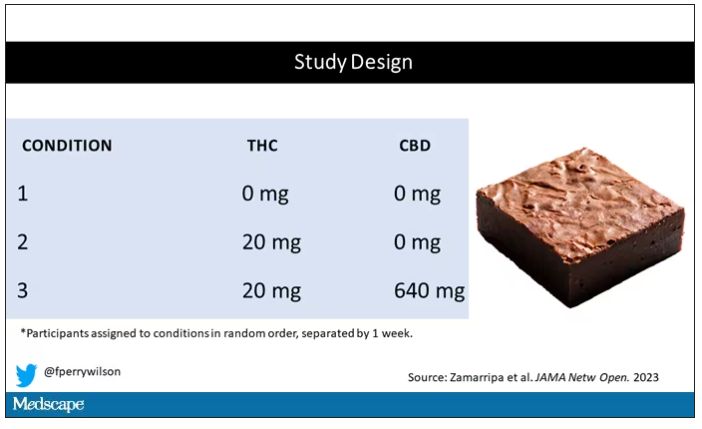

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

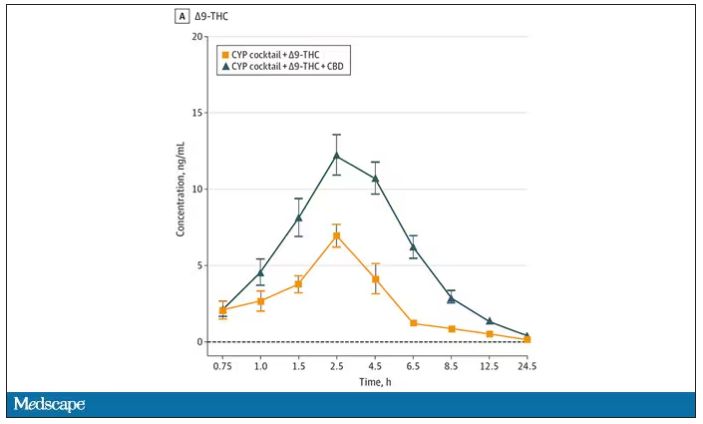

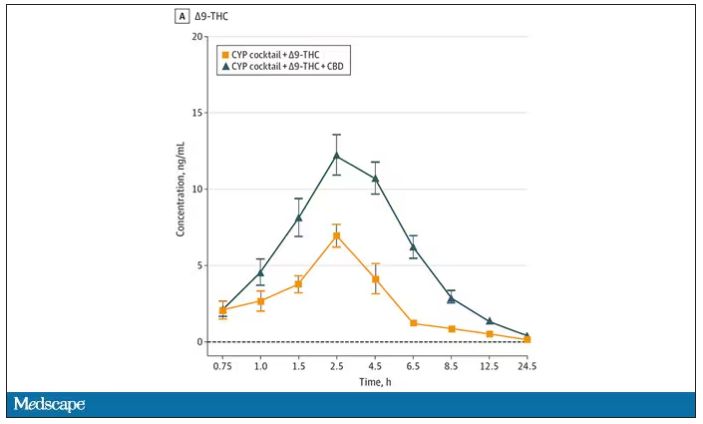

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

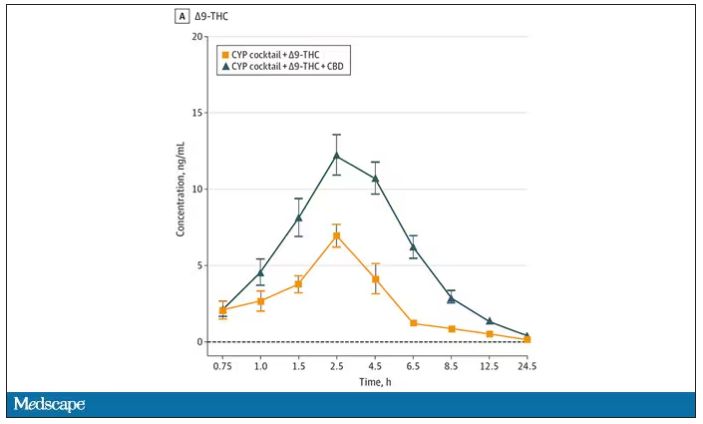

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

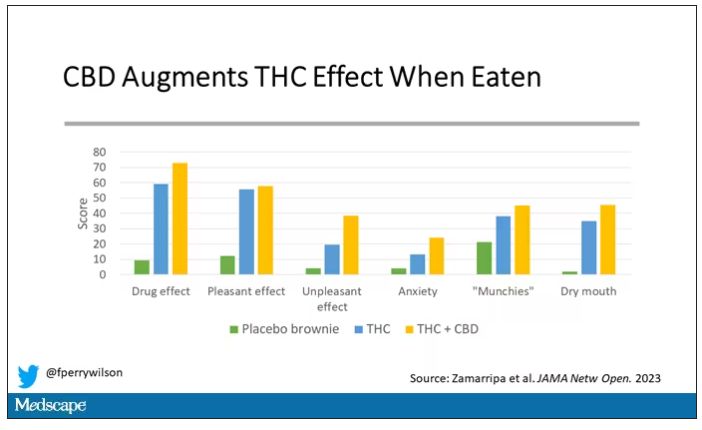

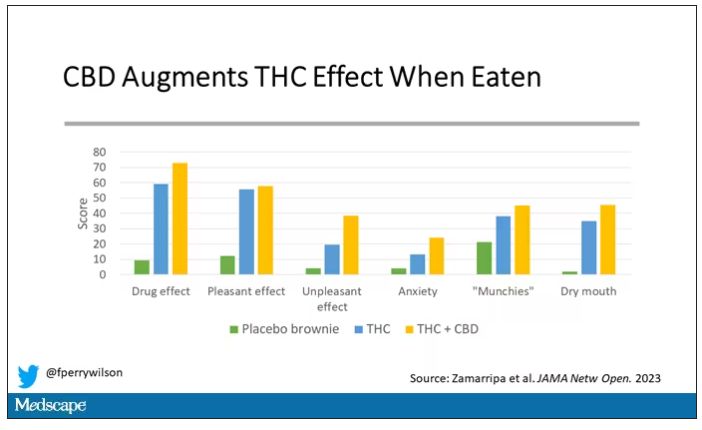

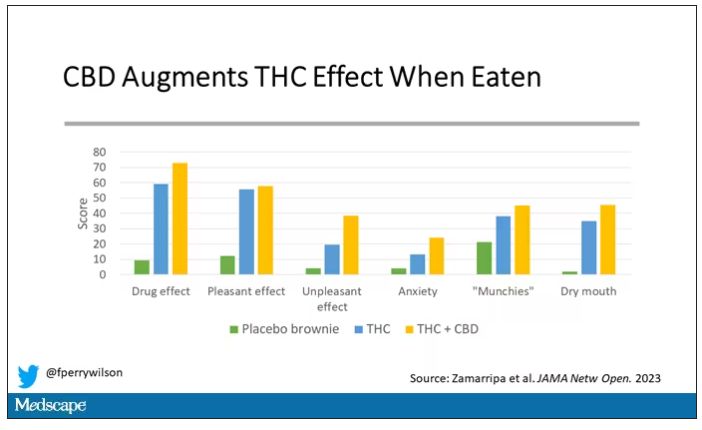

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

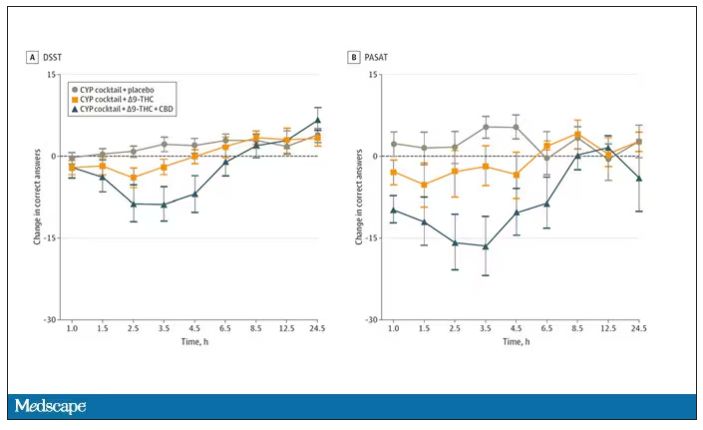

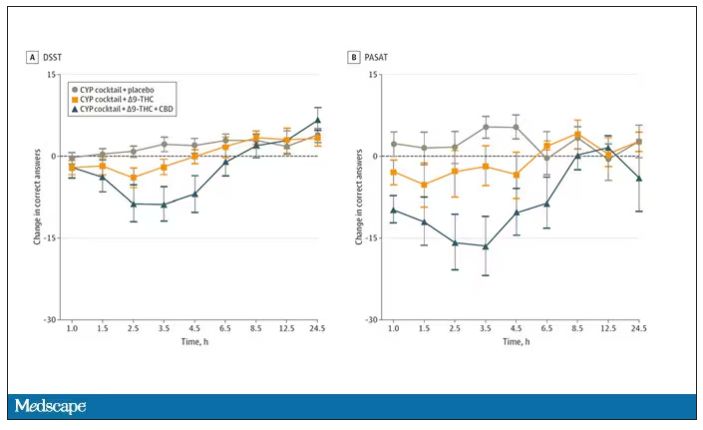

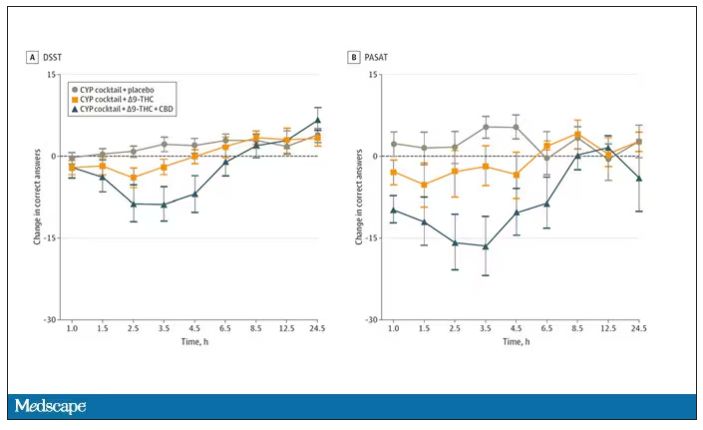

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

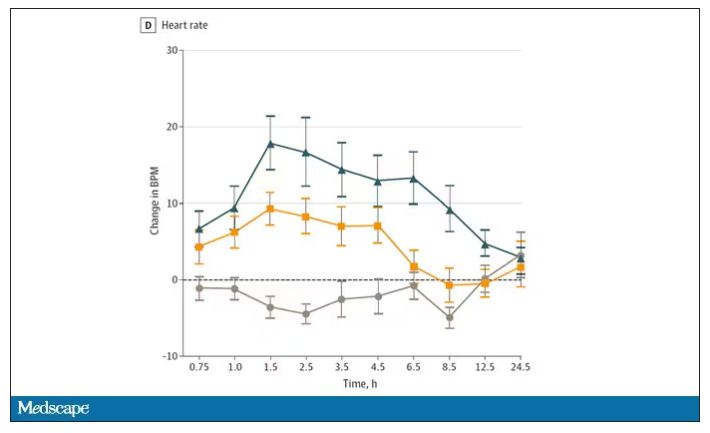

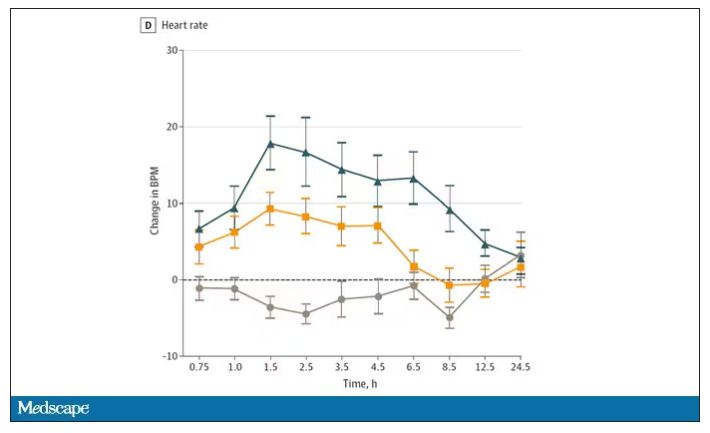

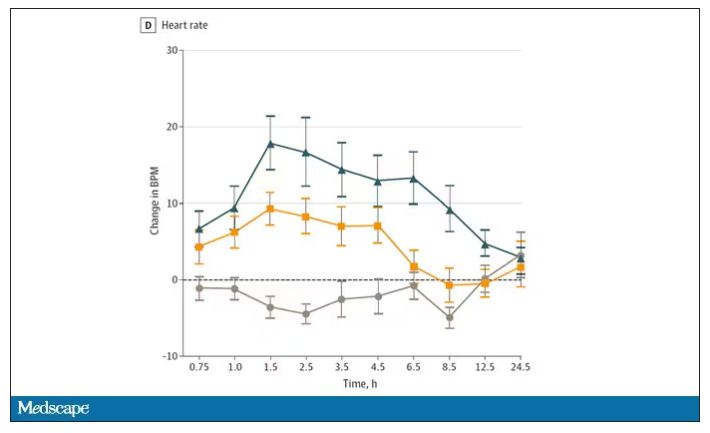

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

UnitedHealthcare tried to deny coverage to a chronically ill patient. He fought back, exposing the insurer’s inner workings.

In May 2021, a nurse at UnitedHealthcare called a colleague to share some welcome news about a problem the two had been grappling with for weeks.

United provided the health insurance plan for students at Penn State University. It was a large and potentially lucrative account: lots of young, healthy students paying premiums in, not too many huge medical reimbursements going out.

But Christopher McNaughton suffered from a crippling case of ulcerative colitis – an ailment that caused him to develop severe arthritis, debilitating diarrhea, numbing fatigue, and life-threatening blood clots. His medical bills were running nearly $2 million a year.

United had flagged Mr. McNaughton’s case as a “high dollar account,” and the company was reviewing whether it needed to keep paying for the expensive cocktail of drugs crafted by a Mayo Clinic specialist that had brought Mr. McNaughton’s disease under control after he’d been through years of misery.

On the 2021 phone call, which was recorded by the company, nurse Victoria Kavanaugh told her colleague that a doctor contracted by United to review the case had concluded that Mr. McNaughton’s treatment was “not medically necessary.” Her colleague, Dave Opperman, reacted to the news with a long laugh.

“I knew that was coming,” said Mr. Opperman, who heads up a United subsidiary that brokered the health insurance contract between United and Penn State. “I did too,” Ms. Kavanaugh replied.

Mr. Opperman then complained about Mr. McNaughton’s mother, whom he referred to as “this woman,” for “screaming and yelling” and “throwing tantrums” during calls with United.

The pair agreed that any appeal of the United doctor’s denial of the treatment would be a waste of the family’s time and money.

“We’re still gonna say no,” Mr. Opperman said.

More than 200 million Americans are covered by private health insurance. But data from state and federal regulators shows that insurers reject about 1 in 7 claims for treatment. Many people, faced with fighting insurance companies, simply give up: One study found that Americans file formal appeals on only 0.1% of claims denied by insurers under the Affordable Care Act.

Insurers have wide discretion in crafting what is covered by their policies, beyond some basic services mandated by federal and state law. They often deny claims for services that they deem not “medically necessary.”

When United refused to pay for Mr. McNaughton’s treatment for that reason, his family did something unusual. They fought back with a lawsuit, which uncovered a trove of materials, including internal emails and tape-recorded exchanges among company employees. Those records offer an extraordinary behind-the-scenes look at how one of America’s leading health care insurers relentlessly fought to reduce spending on care, even as its profits rose to record levels.

As United reviewed Mr. McNaughton’s treatment, he and his family were often in the dark about what was happening or their rights. Meanwhile, United employees misrepresented critical findings and ignored warnings from doctors about the risks of altering Mr. McNaughton’s drug plan.

At one point, court records show, United inaccurately reported to Penn State and the family that Mr. McNaughton’s doctor had agreed to lower the doses of his medication. Another time, a doctor paid by United concluded that denying payments for Mr. McNaughton’s treatment could put his health at risk, but the company buried his report and did not consider its findings. The insurer did, however, consider a report submitted by a company doctor who rubber-stamped the recommendation of a United nurse to reject paying for the treatment.

United declined to answer specific questions about the case, even after Mr. McNaughton signed a release provided by the insurer to allow it to discuss details of his interactions with the company. United noted that it ultimately paid for all of Mr. McNaughton’s treatments. In a written response, United spokesperson Maria Gordon Shydlo wrote that the company’s guiding concern was Mr. McNaughton’s well-being.

“Mr. McNaughton’s treatment involves medication dosages that far exceed [Food and Drug Administration] guidelines,” the statement said. “In cases like this, we review treatment plans based on current clinical guidelines to help ensure patient safety.”

But the records reviewed by ProPublica show that United had another, equally urgent goal in dealing with Mr. McNaughton. In emails, officials calculated what Mr. McNaughton was costing them to keep his crippling disease at bay and how much they would save if they forced him to undergo a cheaper treatment that had already failed him. As the family pressed the company to back down, first through Penn State and then through a lawsuit, the United officials handling the case bristled.

“This is just unbelievable,” Ms. Kavanaugh said of Mr. McNaughton’s family in one call to discuss his case. ”They’re just really pushing the envelope, and I’m surprised, like I don’t even know what to say.”

The same meal every day

Now 31, Mr. McNaughton grew up in State College, Pa., just blocks from the Penn State campus. Both of his parents are faculty members at the university.

In the winter of 2014, Mr. McNaughton was halfway through his junior year at Bard College in New York. At 6 feet, 4 inches tall, he was a guard on the basketball team and had started most of the team’s games since the start of his sophomore year. He was majoring in psychology.

When Mr. McNaughton returned to school after the winter holiday break, he started to experience frequent bouts of bloody diarrhea. After just a few days on campus, he went home to State College, where doctors diagnosed him with a severe case of ulcerative colitis.

A chronic inflammatory bowel disease that causes swelling and ulcers in the digestive tract, ulcerative colitis has no cure, and ongoing treatment is needed to alleviate symptoms and prevent serious health complications. The majority of cases produce mild to moderate symptoms. Mr. McNaughton’s case was severe.

Treatments for ulcerative colitis include steroids and special drugs known as biologics that work to reduce inflammation in the large intestine.

Mr. McNaughton, however, failed to get meaningful relief from the drugs his doctors initially prescribed. He was experiencing bloody diarrhea up to 20 times a day, with such severe stomach pain that he spent much of his day curled up on a couch. He had little appetite and lost 50 pounds. Severe anemia left him fatigued. He suffered from other conditions related to his colitis, including crippling arthritis. He was hospitalized several times to treat dangerous blood clots.

For 2 years, in an effort to help alleviate his symptoms, he ate the same meals every day: Rice Chex cereal and scrambled eggs for breakfast, a cup of white rice with plain chicken breast for lunch, and a similar meal for dinner, occasionally swapping in tilapia.

His hometown doctors referred him to a specialist at the University of Pittsburgh, who tried unsuccessfully to bring his disease under control. That doctor ended up referring Mr. McNaughton to Edward V. Loftus Jr., MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which has been ranked as the best gastroenterology hospital in the country every year since 1990 by U.S. News & World Report.

For his first visit with Dr. Loftus in May 2015, Mr. McNaughton and his mother, Janice Light, charted hospitals along the 900-mile drive from Pennsylvania to Minnesota in case they needed medical help along the way.

Mornings were the hardest. Mr. McNaughton often spent several hours in the bathroom at the start of the day. To prepare for his meeting with Dr. Loftus, he set his alarm for 3:30 a.m. so he could be ready for the 7:30 a.m. appointment. Even with that preparation, he had to stop twice to use a bathroom on the 5-minute walk from the hotel to the clinic. When they met, Dr. Loftus looked at Mr. McNaughton and told him that he appeared incapacitated. It was, he told the student, as if Mr. McNaughton were chained to the bathroom, with no outside life. He had not been able to return to school and spent most days indoors, managing his symptoms as best he could.

Mr. McNaughton had tried a number of medications by this point, none of which worked. This pattern would repeat itself during the first couple of years that Dr. Loftus treated him.

In addition to trying to find a treatment that would bring Mr. McNaughton’s colitis into remission, Dr. Loftus wanted to wean him off the steroid prednisone, which he had been taking since his initial diagnosis in 2014. The drug is commonly prescribed to colitis patients to control inflammation, but prolonged use can lead to severe side effects including cataracts, osteoporosis, increased risk of infection, and fatigue. Mr. McNaughton also experienced “moon face,” a side effect caused by the shifting of fat deposits that results in the face becoming puffy and rounder.

In 2018, Dr. Loftus and Mr. McNaughton decided to try an unusual regimen. Many patients with inflammatory bowel diseases such as colitis take a single biologic drug as treatment. Whereas traditional drugs are chemically synthesized, biologics are manufactured in living systems, such as plant or animal cells. A year’s supply of an individual biologic drug can cost up to $500,000. They are often given through infusions in a medical facility, which adds to the cost.

Mr. McNaughton had tried individual biologics, and then two in combination, without much success. He and Dr. Loftus then agreed to try two biologic drugs together at doses well above those recommended by the Food and Drug Administration. The federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates one in five prescriptions written today are for off-label uses.

There are drawbacks to the practice. Since some uses and doses of particular drugs have not been extensively studied, the risks and efficacy of using them off-label are not well known. Also, some drug manufacturers have improperly pushed off-label usage of their products to boost sales despite little or no evidence to support their use in those situations. Like many leading experts and researchers in his field, Dr. Loftus has been paid to do consulting related to the biologic drugs taken by Mr. McNaughton. The payments related to those drugs have ranged from a total of $1,440 in 2020 to $51,235 in 2018. Dr. Loftus said much of his work with pharmaceutical companies was related to conducting clinical trials on new drugs.

In cases of off-label prescribing, patients are depending upon their doctors’ expertise and experience with the drug. “In this case, I was comfortable that the potential benefits to Chris outweighed the risks,” Dr. Loftus said.

There was evidence that the treatment plan for Mr. McNaughton might work, including studies that had found dual biologic therapy to be efficacious and safe. The two drugs he takes, Entyvio and Remicade, have the same purpose – to reduce inflammation in the large intestine – but each works differently in the body. Remicade, marketed by Janssen Biotech, targets a protein that causes inflammation. Entyvio, made by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, works by preventing an excess of white blood cells from entering into the gastrointestinal tract.

As for any suggestion by United doctors that his treatment plan for Mr. McNaughton was out of bounds or dangerous, Dr. Loftus said “my treatment of Chris was not clinically inappropriate – as was shown by Chris’ positive outcome.”

The unusual high-dose combination of two biologic drugs produced a remarkable change in Mr. McNaughton. He no longer had blood in his stool, and his trips to the bathroom were cut from 20 times a day to 3 or 4. He was able to eat different foods and put on weight. He had more energy. He tapered off prednisone.

“If you told me in 2015 that I would be living like this, I would have asked where do I sign up,” Mr. McNaughton said of the change he experienced with the new drug regimen.

When he first started the new treatment, Mr. McNaughton was covered under his family’s plan, and all his bills were paid. Mr. McNaughton enrolled at the university in 2020. Before switching to United’s plan for students, Mr. McNaughton and his parents consulted with a health advocacy service offered to faculty members. A benefits specialist assured them the drugs taken by Mr. McNaughton would be covered by United.

Mr. McNaughton joined the student plan in July 2020, and his infusions that month and the following month were paid for by United. In September, the insurer indicated payment on his claims was “pending,” something it did for his other claims that came in during the rest of the year.

Mr. McNaughton and his family were worried. They called United to make sure there wasn’t a problem; the insurer told them, they said, that it only needed to check his medical records. When the family called again, United told them it had the documentation needed, they said. United, in a court filing last year, said it received two calls from the family and each time indicated that all of the necessary medical records had not yet been received.

In January 2021, Mr. McNaughton received a new explanation of benefits for the prior months. All of the claims for his care, beginning in September, were no longer “pending.” They were stamped “DENIED.” The total outstanding bill for his treatment was $807,086.

When Mr. McNaughton’s mother reached a United customer service representative the next day to ask why bills that had been paid in the summer were being denied for the fall, the representative told her the account was being reviewed because of “a high dollar amount on the claims,” according to a recording of the call.

Misrepresentations

With United refusing to pay, the family was terrified of being stuck with medical bills that would bankrupt them and deprive Mr. McNaughton of treatment that they considered miraculous.

They turned to Penn State for help. Ms. Light and Mr. McNaughton’s father, David McNaughton, hoped their position as faculty members would make the school more willing to intervene on their behalf.

“After more than 30 years on faculty, my husband and I know that this is not how Penn State would want its students to be treated,” Ms. Light wrote to a school official in February 2021.

In response to questions from ProPublica, Penn State spokesperson Lisa Powers wrote that “supporting the health and well-being of our students is always of primary importance” and that “our hearts go out to any student and family impacted by a serious medical condition.” The university, she wrote, does “not comment on students’ individual circumstances or disclose information from their records.” Mr. McNaughton offered to grant Penn State whatever permissions it needed to speak about his case with ProPublica. The school, however, wrote that it would not comment “even if confidentiality has been waived.”

The family appealed to school administrators. Because the effectiveness of biologics wanes in some patients if doses are skipped, Mr. McNaughton and his parents were worried about even a delay in treatment. His doctor wrote that if he missed scheduled infusions of the drugs, there was “a high likelihood they would no longer be effective.”

During a conference call arranged by Penn State officials on March 5, 2021, United agreed to pay for Mr. McNaughton’s care through the end of the plan year that August. Penn State immediately notified the family of the “wonderful news” while also apologizing for “the stress this has caused Chris and your family.”

Behind the scenes, Mr. McNaughton’s review had “gone all the way to the top” at United’s student health plan division, Ms. Kavanaugh, the nurse, said in a recorded conversation.

The family’s relief was short-lived. A month later, United started another review of Mr. McNaughton’s care, overseen by Ms. Kavanaugh, to determine if it would pay for the treatment in the upcoming plan year.

The nurse sent the Mr. McNaughton case to a company called Medical Review Institute of America. Insurers often turn to companies like MRIoA to review coverage decisions involving expensive treatments or specialized care.

Ms. Kavanaugh, who was assigned to a special investigations unit at United, let her feelings about the matter be known in a recorded telephone call with a representative of MRIoA.

“This school apparently is a big client of ours,” she said. She then shared her opinion of Mr. McNaughton’s treatment. “Really this is a case of a kid who’s getting a drug way too much, like too much of a dose,” Ms. Kavanaugh said. She said it was “insane that they would even think that this is reasonable” and “to be honest with you, they’re awfully pushy considering that we are paying through the end of this school year.”

On a call with an outside contractor, the United nurse claimed Mr. McNaughton was on a higher dose of medication than the FDA approved, which is a common practice.

MRIoA sent the case to Vikas Pabby, MD, a gastroenterologist at UCLA Health and a professor at the university’s medical school. His May 2021 review of Mr. McNaughton’s case was just one of more than 300 Dr. Pabby did for MRIoA that month, for which he was paid $23,000 in total, according to a log of his work produced in the lawsuit.

In a May 4, 2021, report, Dr. Pabby concluded Mr. McNaughton’s treatment was not medically necessary, because United’s policies for the two drugs taken by Mr. McNaughton did not support using them in combination.

Insurers spell out what services they cover in plan policies, lengthy documents that can be confusing and difficult to understand. Many policies, such as Mr. McNaughton’s, contain a provision that treatments and procedures must be “medically necessary” in order to be covered. The definition of medically necessary differs by plan. Some don’t even define the term. Mr. McNaughton’s policy contains a five-part definition, including that the treatment must be “in accordance with the standards of good medical policy” and “the most appropriate supply or level of service which can be safely provided.”

Behind the scenes at United, Mr. Opperman and Ms. Kavanaugh agreed that if Mr. McNaughton were to appeal Dr. Pabby’s decision, the insurer would simply rule against him. “I just think it’s a waste of money and time to appeal and send it to another one when we know we’re gonna get the same answer,” Mr. Opperman said, according to a recording in court files. At Mr. Opperman’s urging, United decided to skip the usual appeals process and arrange for Dr. Pabby to have a so-called “peer-to-peer” discussion with Dr. Loftus, the Mayo physician treating Mr. McNaughton. Such a conversation, in which a patient’s doctor talks with an insurance company’s doctor to advocate for the prescribed treatment, usually occurs only after a customer has appealed a denial and the appeal has been rejected.

When Ms. Kavanaugh called Dr. Loftus’ office to set up a conversation with Dr. Pabby, she explained it was an urgent matter and had been requested by Mr. McNaughton. “You know I’ve just gotten to know Christopher,” she explained, although she had never spoken with him. “We’re trying to advocate and help and get this peer-to-peer set up.”

Mr. McNaughton, meanwhile, had no idea at the time that a United doctor had decided his treatment was unnecessary and that the insurer was trying to set up a phone call with his physician.

In the peer-to-peer conversation, Dr. Loftus told Dr. Pabby that Mr. McNaughton had “a very complicated case” and that lower doses had not worked for him, according to an internal MRIoA memo.

Following his conversation with Dr. Loftus, Dr. Pabby created a second report for United. He recommended the insurer pay for both drugs, but at reduced doses. He added new language saying that the safety of using both drugs at the higher levels “is not established.”

When Ms. Kavanaugh shared the May 12 decision from Dr. Pabby with others at United, her boss responded with an email calling it “great news.”

Then Mr. Opperman sent an email that puzzled the McNaughtons.

In it, Mr. Opperman claimed that Dr. Loftus and Dr. Pabby had agreed that Mr. McNaughton should be on significantly lower doses of both drugs. He said Dr. Loftus “will work with the patient to start titrating them down to a normal dose range.” Mr. Opperman wrote that United would cover Mr. McNaughton’s treatment in the coming year, but only at the reduced doses. Mr. Opperman did not respond to emails and phone messages seeking comment.

Mr. McNaughton didn’t believe a word of it. He had already tried and failed treatment with those drugs at lower doses, and it was Dr. Loftus who had upped the doses, leading to his remission from severe colitis.

The only thing that made sense to Mr. McNaughton was that the treatment United said it would now pay for was dramatically cheaper – saving the company at least hundreds of thousands of dollars a year – than his prescribed treatment because it sliced the size of the doses by more than half.

When the family contacted Dr. Loftus for an explanation, they were outraged by what they heard. Dr. Loftus told them that he had never recommended lowering the dosage. In a letter, Dr. Loftus wrote that changing Mr. McNaughton’s treatment “would have serious detrimental effects on both his short term and long term health and could potentially involve life threatening complications. This would ultimately incur far greater medical costs. Chris was on the doses suggested by United Healthcare before, and they were not at all effective.”

It would not be until the lawsuit that it would become clear how Dr. Loftus’ conversations had been so seriously misrepresented.

Under questioning by Mr. McNaughton’s lawyers, Ms. Kavanaugh acknowledged that she was the source of the incorrect claim that Mr. McNaughton’s doctor had agreed to a change in treatment.

“I incorrectly made an assumption that they had come to some sort of agreement,” she said in a deposition last August. “It was my first peer-to-peer. I did not realize that that simply does not occur.”

Ms. Kavanaugh did not respond to emails and telephone messages seeking comment.

When the McNaughtons first learned of Mr. Opperman’s inaccurate report of the phone call with Dr. Loftus, it unnerved them. They started to question if their case would be fairly reviewed.

“When we got the denial and they lied about what Dr. Loftus said, it just hit me that none of this matters,” Mr. McNaughton said. “They will just say or do anything to get rid of me. It delegitimized the entire review process. When I got that denial, I was crushed.”

A buried report

While the family tried to sort out the inaccurate report, United continued putting the McNaughton case in front of more company doctors.

On May 21, 2021, United sent the case to one of its own doctors, Nady Cates, MD, for an additional review. The review was marked “escalated issue.” Dr. Cates is a United medical director, a title used by many insurers for physicians who review cases. It is work he has been doing as an employee of health insurers since 1989 and at United since 2010. He has not practiced medicine since the early 1990s.

Dr. Cates, in a deposition, said he stopped seeing patients because of the long hours involved and because “AIDS was coming around then. I was seeing a lot of military folks who had venereal diseases, and I guess I was concerned about being exposed.” He transitioned to reviewing paperwork for the insurance industry, he said, because “I guess I was a chicken.”

When he had practiced, Dr. Cates said, he hadn’t treated patients with ulcerative colitis and had referred those cases to a gastroenterologist.

He said his review of Mr. McNaughton’s case primarily involved reading a United nurse’s recommendation to deny his care and making sure “that there wasn’t a decimal place that was out of line.” He said he copied and pasted the nurse’s recommendation and typed “agree” on his review of Mr. McNaughton’s case.

Dr. Cates said that he does about a hundred reviews a week. He said that in his reviews he typically checks to see if any medications are prescribed in accordance with the insurer’s guidelines, and if not, he denies it. United’s policies, he said, prevented him from considering that Mr. McNaughton had failed other treatments or that Dr. Loftus was a leading expert in his field.

“You are giving zero weight to the treating doctor’s opinion on the necessity of the treatment regimen?” a lawyer asked Dr. Cates in his deposition. He responded, “Yeah.”

Attempts to contact Dr. Cates for comment were unsuccessful.

At the same time Dr. Cates was looking at Mr. McNaughton’s case, yet another review was underway at MRIoA. United said it sent the case back to MRIoA after the insurer received the letter from Dr. Loftus warning of the life-threatening complications that might occur if the dosages were reduced.

On May 24, 2021, the new report requested by MRIoA arrived. It came to a completely different conclusion than all of the previous reviews.

Nitin Kumar, MD, a gastroenterologist in Illinois, concluded that Mr. McNaughton’s established treatment plan was not only medically necessary and appropriate but that lowering his doses “can result in a lack of effective therapy of Ulcerative Colitis, with complications of uncontrolled disease (including dysplasia leading to colorectal cancer), flare, hospitalization, need for surgery, and toxic megacolon.”

Unlike other doctors who produced reports for United, Dr. Kumar discussed the harm that Mr. McNaughton might suffer if United required him to change his treatment. “His disease is significantly severe, with diagnosis at a young age,” Dr. Kumar wrote. “He has failed every biologic medication class recommended by guidelines. Therefore, guidelines can no longer be applied in this case.” He cited six studies of patients using two biologic drugs together and wrote that they revealed no significant safety issues and found the therapy to be “broadly successful.”

When Ms. Kavanaugh learned of Dr. Kumar’s report, she quickly moved to quash it and get the case returned to Dr. Pabby, according to her deposition.

In a recorded telephone call, Ms. Kavanaugh told an MRIoA representative that “I had asked that this go back through Dr. Pabby, and it went through a different doctor and they had a much different result.” After further discussion, the MRIoA representative agreed to send the case back to Dr. Pabby. “I appreciate that,” Ms. Kavanaugh replied. “I just want to make sure, because, I mean, it’s obviously a very different result than what we’ve been getting on this case.”

MRIoA case notes show that at 7:04 a.m. on May 25, 2021, Dr. Pabby was assigned to take a look at the case for the third time. At 7:27 a.m., the notes indicate, Dr. Pabby again rejected Mr. McNaughton’s treatment plan. While noting it was “difficult to control” Mr. McNaughton’s ulcerative colitis, Dr. Pabby added that his doses “far exceed what is approved by literature” and that the “safety of the requested doses is not supported by literature.”

In a deposition, Ms. Kavanaugh said that after she opened the Kumar report and read that he was supporting Mr. McNaughton’s current treatment plan, she immediately spoke to her supervisor, who told her to call MRIoA and have the case sent back to Dr. Pabby for review.

Ms. Kavanaugh said she didn’t save a copy of the Kumar report, nor did she forward it to anyone at United or to officials at Penn State who had been inquiring about the McNaughton case. “I didn’t because it shouldn’t have existed,” she said. “It should have gone back to Dr. Pabby.”

When asked if the Kumar report caused her any concerns given his warning that Mr. McNaughton risked cancer or hospitalization if his regimen were changed, Ms. Kavanaugh said she didn’t read his full report. “I saw that it was not the correct doctor, I saw the initial outcome and I was asked to send it back,” she said. Ms. Kavanaugh added, “I have a lot of empathy for this member, but it needed to go back to the peer-to-peer reviewer.”

In a court filing, United said Ms. Kavanaugh was correct in insisting that Dr. Pabby conduct the review and that MRIoA confirmed that Dr. Pabby should have been the one doing the review.

The Kumar report was not provided to Mr. McNaughton when his lawyer, Jonathan M. Gesk, first asked United and MRIoA for any reviews of the case. Mr. Gesk discovered it by accident when he was listening to a recorded telephone call produced by United in which Ms. Kavanaugh mentioned a report number Mr. Gesk had not heard before. He then called MRIoA, which confirmed the report existed and eventually provided it to him.

Dr. Pabby asked ProPublica to direct any questions about his involvement in the matter to MRIoA. The company did not respond to questions from ProPublica about the case.

A sense of hopelessness

When Mr. McNaughton enrolled at Penn State in 2020, it brought a sense of normalcy that he had lost when he was first diagnosed with colitis. He still needed monthly hours-long infusions and suffered occasional flare-ups and symptoms, but he was attending classes in person and living a life similar to the one he had before his diagnosis.

It was a striking contrast to the previous 6 years, which he had spent largely confined to his parents’ house in State College. The frequent bouts of diarrhea made it difficult to go out. He didn’t talk much to friends and spent as much time as he could studying potential treatments and reviewing ongoing clinical trials. He tried to keep up with the occasional online course, but his disease made it difficult to make any real progress toward a degree.

United, in correspondence with Mr. McNaughton, noted that its review of his care was “not a treatment decision. Treatment decisions are made between you and your physician.” But by threatening not to pay for his medications, or only to pay for a different regimen, Mr. McNaughton said, United was in fact attempting to dictate his treatment. From his perspective, the insurer was playing doctor, making decisions without ever examining him or even speaking to him.

The idea of changing his treatment or stopping it altogether caused constant worry for Mr. McNaughton, exacerbating his colitis and triggering physical symptoms, according to his doctors. Those included a large ulcer on his leg and welts under his skin on his thighs and shin that made his leg muscles stiff and painful to the point where he couldn’t bend his leg or walk properly. There were daily migraines and severe stomach pain. “I was consumed with this situation,” Mr. McNaughton said. “My path was unconventional, but I was proud of myself for fighting back and finishing school and getting my life back on track. I thought they were singling me out. My biggest fear was going back to the hell.”

Mr. McNaughton said he contemplated suicide on several occasions, dreading a return to a life where he was housebound or hospitalized.

Mr. McNaughton and his parents talked about his possibly moving to Canada where his grandmother lived and seeking treatment there under the nation’s government health plan.

Dr. Loftus connected Mr. McNaughton with a psychologist who specializes in helping patients with chronic digestive diseases.

The psychologist, Tiffany Taft, PsyD, said Mr. McNaughton was not an unusual case. About one in three patients with diseases like colitis suffer from medical trauma or PTSD related to it, she said, often the result of issues related to getting appropriate treatment approved by insurers.

“You get into hopelessness,” she said of the depression that accompanies fighting with insurance companies over care. “They feel like ‘I can’t fix that. I am screwed.’ When you can’t control things with what an insurance company is doing, anxiety, PTSD and depression get mixed together.”

In the case of Mr. McNaughton, Dr. Taft said, he was being treated by one of the best gastroenterologists in the world, was doing well with his treatment, and then was suddenly notified he might be on the hook for nearly a million dollars in medical charges without access to his medications. “It sends you immediately into panic about all these horrific things that could happen,” Dr. Taft said. The physical and mental symptoms Mr. McNaughton suffered after his care was threatened were “triggered” by the stress he experienced, she said.

In early June 2021, United informed Mr. McNaughton in a letter that it would not cover the cost of his treatment regimen in the next academic year, starting in August. The insurer said it would pay only for a treatment plan that called for a significant reduction in the doses of the drugs he took.

United wrote that the decision came after his “records have been reviewed three times and the medical reviewers have concluded that the medication as prescribed does not meet the Medical Necessity requirement of the plan.”

In August 2021, Mr. McNaughton filed a federal lawsuit accusing United of acting in bad faith and unreasonably making treatment decisions based on financial concerns and not what was the best and most effective treatment. It claims United had a duty to find information that supported Mr. McNaughton’s claim for treatment rather than looking for ways to deny coverage.

United, in a court filing, said it did not breach any duty it owed to Mr. McNaughton and acted in good faith. On Sept. 20, 2021, a month after filing the lawsuit, and with United again balking at paying for his treatment, Mr. McNaughton asked a judge to grant a temporary restraining order requiring United to pay for his care. With the looming threat of a court hearing on the motion, United quickly agreed to cover the cost of Mr. McNaughton’s treatment through the end of the 2021-2022 academic year. It also dropped a demand requiring Mr. McNaughton to settle the matter as a condition of the insurer paying for his treatment as prescribed by Dr. Loftus, according to an email sent by United’s lawyer.

The cost of treatment

It is not surprising that insurers are carefully scrutinizing the care of patients treated with biologics, which are among the most expensive medications on the market. Biologics are considered specialty drugs, a class that includes the best-selling Humira, used to treat arthritis. Specialty drug spending in the United States is expected to reach $505 billion in 2023, according to an estimate from Optum, United’s health services division. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, a nonprofit that analyzes the value of drugs, found in 2020 that the biologic drugs used to treat patients like Mr. McNaughton are often effective but overpriced for their therapeutic benefit. To be judged cost-effective by ICER, the biologics should sell at a steep discount to their current market price, the panel found.

A panel convened by ICER to review its analysis cautioned that insurance coverage “should be structured to prevent situations in which patients are forced to choose a treatment approach on the basis of cost.” ICER also found examples where insurance company policies failed to keep pace with updates to clinical practice guidelines based on emerging research.

United officials did not make the cost of treatment an issue when discussing Mr. McNaughton’s care with Penn State administrators or the family.

Bill Truxal, the president of UnitedHealthcare StudentResources, the company’s student health plan division, told a Penn State official that the insurer wanted the “best for the student” and it had “nothing to do with cost,” according to notes the official took of the conversation.

Behind the scenes, however, the price of Mr. McNaughton’s care was front and center at United.

In one email, Mr. Opperman asked about the cost difference if the insurer insisted on paying only for greatly reduced doses of the biologic drugs. Ms. Kavanaugh responded that the insurer had paid $1.1 million in claims for Mr. McNaughton’s care as of the middle of May 2021. If the reduced doses had been in place, the amount would have been cut to $260,218, she wrote.

United was keeping close tabs on Mr. McNaughton at the highest levels of the company. On Aug. 2, 2021, Mr. Opperman notified Mr. Truxal and a United lawyer that Mr. McNaughton “has just purchased the plan again for the 21-22 school year.”

A month later, Ms. Kavanaugh shared another calculation with United executives showing that the insurer spent over $1.7 million on Mr. McNaughton in the prior plan year.

United officials strategized about how to best explain why it was reviewing Mr. McNaughton’s drug regimen, according to an internal email. They pointed to a justification often used by health insurers when denying claims. “As the cost of healthcare continues to climb to soaring heights, it has been determined that a judicious review of these drugs should be included” in order to “make healthcare more affordable for our members,” Ms. Kavanaugh offered as a potential talking point in an April 23, 2021, email.

Three days later, UnitedHealth Group filed an annual statement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission disclosing its pay for top executives in the prior year. Then-CEO David Wichmann was paid $17.9 million in salary and other compensation in 2020. Wichmann retired early the following year, and his total compensation that year exceeded $140 million, according to calculations in a compensation database maintained by the Star Tribune in Minneapolis. The newspaper said the amount was the most paid to an executive in the state since it started tracking pay more than 2 decades ago. About $110 million of that total came from Wichmann exercising stock options accumulated during his stewardship.

The McNaughtons were well aware of the financial situation at United. They looked at publicly available financial results and annual reports. Last year, United reported a profit of $20.1 billion on revenues of $324.2 billion.

When discussing the case with Penn State, Ms. Light said, she told university administrators that United could pay for a year of her son’s treatment using just minutes’ worth of profit.

‘Betrayed’

Mr. McNaughton has been able to continue receiving his infusions for now, anyway. In October, United notified him it was once again reviewing his care, although the insurer quickly reversed course when his lawyer intervened. United, in a court filing, said the review was a mistake and that it had erred in putting Mr. McNaughton’s claims into pending status.

Mr. McNaughton said he is fortunate his parents were employed at the same school he was attending, which was critical in getting the attention of administrators there. But that help had its limits.

In June 2021, just a week after United told Mr. McNaughton it would not cover his treatment plan in the upcoming plan year, Penn State essentially walked away from the matter.

In an email to the McNaughtons and United, Penn State Associate Vice President for Student Affairs Andrea Dowhower wrote that administrators “have observed an unfortunate breakdown in communication” between Mr. McNaughton and his family and the university health insurance plan, “which appears from our perspective to have resulted in a standstill between the two parties.” While she proposed some potential steps to help settle the matter, she wrote that “Penn State’s role in this process is as a resource for students like Chris who, for whatever reason, have experienced difficulty navigating the complex world of health insurance.” The university’s role “is limited,” she wrote, and the school “simply must leave” the issue of the best treatment for Mr. McNaughton to “the appropriate health care professionals.”

In a statement, a Penn State spokesperson wrote that “as a third party in this arrangement, the University’s role is limited and Penn State officials can only help a student manage an issue based on information that a student/family, medical personnel, and/or insurance provider give – with the hope that all information is accurate and that the lines of communication remain open between the insured and the insurer.”

Penn State declined to provide financial information about the plan. However, the university and United share at least one tie that they have not publicly disclosed.

When the McNaughtons first reached out to the university for help, they were referred to the school’s student health insurance coordinator. The official, Heather Klinger, wrote in an email to the family in February 2021 that “I appreciate your trusting me to resolve this for you.”

In April 2022, United began paying Ms. Klinger’s salary, an arrangement which is not noted on the university website. Ms. Klinger appears in the online staff directory on the Penn State University Health Services web page, and has a university phone number, a university address, and a Penn State email listed as her contact. The school said she has maintained a part-time status with the university to allow her to access relevant data systems at both the university and United.

The university said students “benefit” from having a United employee to handle questions about insurance coverage and that the arrangement is “not uncommon” for student health plans.

The family was dismayed to learn that Ms. Klinger was now a full-time employee of United.

“We did feel betrayed,” Ms. Light said. Ms. Klinger did not respond to an email seeking comment.

Mr. McNaughton’s fight to maintain his treatment regimen has come at a cost of time, debilitating stress, and depression. “My biggest fear is realizing I might have to do this every year of my life,” he said.

Mr. McNaughton said one motivation for his lawsuit was to expose how insurers like United make decisions about what care they will pay for and what they will not. The case remains pending, a court docket shows.

He has been accepted to Penn State’s law school. He hopes to become a health care lawyer working for patients who find themselves in situations similar to his.

He plans to re-enroll in the United health care plan when he starts school next fall.

This story was originally published on ProPublica. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive the biggest stories as soon as they’re published.

In May 2021, a nurse at UnitedHealthcare called a colleague to share some welcome news about a problem the two had been grappling with for weeks.

United provided the health insurance plan for students at Penn State University. It was a large and potentially lucrative account: lots of young, healthy students paying premiums in, not too many huge medical reimbursements going out.

But Christopher McNaughton suffered from a crippling case of ulcerative colitis – an ailment that caused him to develop severe arthritis, debilitating diarrhea, numbing fatigue, and life-threatening blood clots. His medical bills were running nearly $2 million a year.

United had flagged Mr. McNaughton’s case as a “high dollar account,” and the company was reviewing whether it needed to keep paying for the expensive cocktail of drugs crafted by a Mayo Clinic specialist that had brought Mr. McNaughton’s disease under control after he’d been through years of misery.

On the 2021 phone call, which was recorded by the company, nurse Victoria Kavanaugh told her colleague that a doctor contracted by United to review the case had concluded that Mr. McNaughton’s treatment was “not medically necessary.” Her colleague, Dave Opperman, reacted to the news with a long laugh.

“I knew that was coming,” said Mr. Opperman, who heads up a United subsidiary that brokered the health insurance contract between United and Penn State. “I did too,” Ms. Kavanaugh replied.

Mr. Opperman then complained about Mr. McNaughton’s mother, whom he referred to as “this woman,” for “screaming and yelling” and “throwing tantrums” during calls with United.

The pair agreed that any appeal of the United doctor’s denial of the treatment would be a waste of the family’s time and money.

“We’re still gonna say no,” Mr. Opperman said.

More than 200 million Americans are covered by private health insurance. But data from state and federal regulators shows that insurers reject about 1 in 7 claims for treatment. Many people, faced with fighting insurance companies, simply give up: One study found that Americans file formal appeals on only 0.1% of claims denied by insurers under the Affordable Care Act.

Insurers have wide discretion in crafting what is covered by their policies, beyond some basic services mandated by federal and state law. They often deny claims for services that they deem not “medically necessary.”

When United refused to pay for Mr. McNaughton’s treatment for that reason, his family did something unusual. They fought back with a lawsuit, which uncovered a trove of materials, including internal emails and tape-recorded exchanges among company employees. Those records offer an extraordinary behind-the-scenes look at how one of America’s leading health care insurers relentlessly fought to reduce spending on care, even as its profits rose to record levels.

As United reviewed Mr. McNaughton’s treatment, he and his family were often in the dark about what was happening or their rights. Meanwhile, United employees misrepresented critical findings and ignored warnings from doctors about the risks of altering Mr. McNaughton’s drug plan.

At one point, court records show, United inaccurately reported to Penn State and the family that Mr. McNaughton’s doctor had agreed to lower the doses of his medication. Another time, a doctor paid by United concluded that denying payments for Mr. McNaughton’s treatment could put his health at risk, but the company buried his report and did not consider its findings. The insurer did, however, consider a report submitted by a company doctor who rubber-stamped the recommendation of a United nurse to reject paying for the treatment.

United declined to answer specific questions about the case, even after Mr. McNaughton signed a release provided by the insurer to allow it to discuss details of his interactions with the company. United noted that it ultimately paid for all of Mr. McNaughton’s treatments. In a written response, United spokesperson Maria Gordon Shydlo wrote that the company’s guiding concern was Mr. McNaughton’s well-being.

“Mr. McNaughton’s treatment involves medication dosages that far exceed [Food and Drug Administration] guidelines,” the statement said. “In cases like this, we review treatment plans based on current clinical guidelines to help ensure patient safety.”

But the records reviewed by ProPublica show that United had another, equally urgent goal in dealing with Mr. McNaughton. In emails, officials calculated what Mr. McNaughton was costing them to keep his crippling disease at bay and how much they would save if they forced him to undergo a cheaper treatment that had already failed him. As the family pressed the company to back down, first through Penn State and then through a lawsuit, the United officials handling the case bristled.

“This is just unbelievable,” Ms. Kavanaugh said of Mr. McNaughton’s family in one call to discuss his case. ”They’re just really pushing the envelope, and I’m surprised, like I don’t even know what to say.”

The same meal every day

Now 31, Mr. McNaughton grew up in State College, Pa., just blocks from the Penn State campus. Both of his parents are faculty members at the university.

In the winter of 2014, Mr. McNaughton was halfway through his junior year at Bard College in New York. At 6 feet, 4 inches tall, he was a guard on the basketball team and had started most of the team’s games since the start of his sophomore year. He was majoring in psychology.

When Mr. McNaughton returned to school after the winter holiday break, he started to experience frequent bouts of bloody diarrhea. After just a few days on campus, he went home to State College, where doctors diagnosed him with a severe case of ulcerative colitis.

A chronic inflammatory bowel disease that causes swelling and ulcers in the digestive tract, ulcerative colitis has no cure, and ongoing treatment is needed to alleviate symptoms and prevent serious health complications. The majority of cases produce mild to moderate symptoms. Mr. McNaughton’s case was severe.

Treatments for ulcerative colitis include steroids and special drugs known as biologics that work to reduce inflammation in the large intestine.

Mr. McNaughton, however, failed to get meaningful relief from the drugs his doctors initially prescribed. He was experiencing bloody diarrhea up to 20 times a day, with such severe stomach pain that he spent much of his day curled up on a couch. He had little appetite and lost 50 pounds. Severe anemia left him fatigued. He suffered from other conditions related to his colitis, including crippling arthritis. He was hospitalized several times to treat dangerous blood clots.

For 2 years, in an effort to help alleviate his symptoms, he ate the same meals every day: Rice Chex cereal and scrambled eggs for breakfast, a cup of white rice with plain chicken breast for lunch, and a similar meal for dinner, occasionally swapping in tilapia.

His hometown doctors referred him to a specialist at the University of Pittsburgh, who tried unsuccessfully to bring his disease under control. That doctor ended up referring Mr. McNaughton to Edward V. Loftus Jr., MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., which has been ranked as the best gastroenterology hospital in the country every year since 1990 by U.S. News & World Report.

For his first visit with Dr. Loftus in May 2015, Mr. McNaughton and his mother, Janice Light, charted hospitals along the 900-mile drive from Pennsylvania to Minnesota in case they needed medical help along the way.

Mornings were the hardest. Mr. McNaughton often spent several hours in the bathroom at the start of the day. To prepare for his meeting with Dr. Loftus, he set his alarm for 3:30 a.m. so he could be ready for the 7:30 a.m. appointment. Even with that preparation, he had to stop twice to use a bathroom on the 5-minute walk from the hotel to the clinic. When they met, Dr. Loftus looked at Mr. McNaughton and told him that he appeared incapacitated. It was, he told the student, as if Mr. McNaughton were chained to the bathroom, with no outside life. He had not been able to return to school and spent most days indoors, managing his symptoms as best he could.

Mr. McNaughton had tried a number of medications by this point, none of which worked. This pattern would repeat itself during the first couple of years that Dr. Loftus treated him.

In addition to trying to find a treatment that would bring Mr. McNaughton’s colitis into remission, Dr. Loftus wanted to wean him off the steroid prednisone, which he had been taking since his initial diagnosis in 2014. The drug is commonly prescribed to colitis patients to control inflammation, but prolonged use can lead to severe side effects including cataracts, osteoporosis, increased risk of infection, and fatigue. Mr. McNaughton also experienced “moon face,” a side effect caused by the shifting of fat deposits that results in the face becoming puffy and rounder.

In 2018, Dr. Loftus and Mr. McNaughton decided to try an unusual regimen. Many patients with inflammatory bowel diseases such as colitis take a single biologic drug as treatment. Whereas traditional drugs are chemically synthesized, biologics are manufactured in living systems, such as plant or animal cells. A year’s supply of an individual biologic drug can cost up to $500,000. They are often given through infusions in a medical facility, which adds to the cost.

Mr. McNaughton had tried individual biologics, and then two in combination, without much success. He and Dr. Loftus then agreed to try two biologic drugs together at doses well above those recommended by the Food and Drug Administration. The federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality estimates one in five prescriptions written today are for off-label uses.

There are drawbacks to the practice. Since some uses and doses of particular drugs have not been extensively studied, the risks and efficacy of using them off-label are not well known. Also, some drug manufacturers have improperly pushed off-label usage of their products to boost sales despite little or no evidence to support their use in those situations. Like many leading experts and researchers in his field, Dr. Loftus has been paid to do consulting related to the biologic drugs taken by Mr. McNaughton. The payments related to those drugs have ranged from a total of $1,440 in 2020 to $51,235 in 2018. Dr. Loftus said much of his work with pharmaceutical companies was related to conducting clinical trials on new drugs.

In cases of off-label prescribing, patients are depending upon their doctors’ expertise and experience with the drug. “In this case, I was comfortable that the potential benefits to Chris outweighed the risks,” Dr. Loftus said.

There was evidence that the treatment plan for Mr. McNaughton might work, including studies that had found dual biologic therapy to be efficacious and safe. The two drugs he takes, Entyvio and Remicade, have the same purpose – to reduce inflammation in the large intestine – but each works differently in the body. Remicade, marketed by Janssen Biotech, targets a protein that causes inflammation. Entyvio, made by Takeda Pharmaceuticals, works by preventing an excess of white blood cells from entering into the gastrointestinal tract.

As for any suggestion by United doctors that his treatment plan for Mr. McNaughton was out of bounds or dangerous, Dr. Loftus said “my treatment of Chris was not clinically inappropriate – as was shown by Chris’ positive outcome.”

The unusual high-dose combination of two biologic drugs produced a remarkable change in Mr. McNaughton. He no longer had blood in his stool, and his trips to the bathroom were cut from 20 times a day to 3 or 4. He was able to eat different foods and put on weight. He had more energy. He tapered off prednisone.

“If you told me in 2015 that I would be living like this, I would have asked where do I sign up,” Mr. McNaughton said of the change he experienced with the new drug regimen.

When he first started the new treatment, Mr. McNaughton was covered under his family’s plan, and all his bills were paid. Mr. McNaughton enrolled at the university in 2020. Before switching to United’s plan for students, Mr. McNaughton and his parents consulted with a health advocacy service offered to faculty members. A benefits specialist assured them the drugs taken by Mr. McNaughton would be covered by United.

Mr. McNaughton joined the student plan in July 2020, and his infusions that month and the following month were paid for by United. In September, the insurer indicated payment on his claims was “pending,” something it did for his other claims that came in during the rest of the year.

Mr. McNaughton and his family were worried. They called United to make sure there wasn’t a problem; the insurer told them, they said, that it only needed to check his medical records. When the family called again, United told them it had the documentation needed, they said. United, in a court filing last year, said it received two calls from the family and each time indicated that all of the necessary medical records had not yet been received.

In January 2021, Mr. McNaughton received a new explanation of benefits for the prior months. All of the claims for his care, beginning in September, were no longer “pending.” They were stamped “DENIED.” The total outstanding bill for his treatment was $807,086.

When Mr. McNaughton’s mother reached a United customer service representative the next day to ask why bills that had been paid in the summer were being denied for the fall, the representative told her the account was being reviewed because of “a high dollar amount on the claims,” according to a recording of the call.

Misrepresentations

With United refusing to pay, the family was terrified of being stuck with medical bills that would bankrupt them and deprive Mr. McNaughton of treatment that they considered miraculous.

They turned to Penn State for help. Ms. Light and Mr. McNaughton’s father, David McNaughton, hoped their position as faculty members would make the school more willing to intervene on their behalf.

“After more than 30 years on faculty, my husband and I know that this is not how Penn State would want its students to be treated,” Ms. Light wrote to a school official in February 2021.

In response to questions from ProPublica, Penn State spokesperson Lisa Powers wrote that “supporting the health and well-being of our students is always of primary importance” and that “our hearts go out to any student and family impacted by a serious medical condition.” The university, she wrote, does “not comment on students’ individual circumstances or disclose information from their records.” Mr. McNaughton offered to grant Penn State whatever permissions it needed to speak about his case with ProPublica. The school, however, wrote that it would not comment “even if confidentiality has been waived.”

The family appealed to school administrators. Because the effectiveness of biologics wanes in some patients if doses are skipped, Mr. McNaughton and his parents were worried about even a delay in treatment. His doctor wrote that if he missed scheduled infusions of the drugs, there was “a high likelihood they would no longer be effective.”

During a conference call arranged by Penn State officials on March 5, 2021, United agreed to pay for Mr. McNaughton’s care through the end of the plan year that August. Penn State immediately notified the family of the “wonderful news” while also apologizing for “the stress this has caused Chris and your family.”

Behind the scenes, Mr. McNaughton’s review had “gone all the way to the top” at United’s student health plan division, Ms. Kavanaugh, the nurse, said in a recorded conversation.

The family’s relief was short-lived. A month later, United started another review of Mr. McNaughton’s care, overseen by Ms. Kavanaugh, to determine if it would pay for the treatment in the upcoming plan year.

The nurse sent the Mr. McNaughton case to a company called Medical Review Institute of America. Insurers often turn to companies like MRIoA to review coverage decisions involving expensive treatments or specialized care.

Ms. Kavanaugh, who was assigned to a special investigations unit at United, let her feelings about the matter be known in a recorded telephone call with a representative of MRIoA.

“This school apparently is a big client of ours,” she said. She then shared her opinion of Mr. McNaughton’s treatment. “Really this is a case of a kid who’s getting a drug way too much, like too much of a dose,” Ms. Kavanaugh said. She said it was “insane that they would even think that this is reasonable” and “to be honest with you, they’re awfully pushy considering that we are paying through the end of this school year.”

On a call with an outside contractor, the United nurse claimed Mr. McNaughton was on a higher dose of medication than the FDA approved, which is a common practice.

MRIoA sent the case to Vikas Pabby, MD, a gastroenterologist at UCLA Health and a professor at the university’s medical school. His May 2021 review of Mr. McNaughton’s case was just one of more than 300 Dr. Pabby did for MRIoA that month, for which he was paid $23,000 in total, according to a log of his work produced in the lawsuit.

In a May 4, 2021, report, Dr. Pabby concluded Mr. McNaughton’s treatment was not medically necessary, because United’s policies for the two drugs taken by Mr. McNaughton did not support using them in combination.

Insurers spell out what services they cover in plan policies, lengthy documents that can be confusing and difficult to understand. Many policies, such as Mr. McNaughton’s, contain a provision that treatments and procedures must be “medically necessary” in order to be covered. The definition of medically necessary differs by plan. Some don’t even define the term. Mr. McNaughton’s policy contains a five-part definition, including that the treatment must be “in accordance with the standards of good medical policy” and “the most appropriate supply or level of service which can be safely provided.”

Behind the scenes at United, Mr. Opperman and Ms. Kavanaugh agreed that if Mr. McNaughton were to appeal Dr. Pabby’s decision, the insurer would simply rule against him. “I just think it’s a waste of money and time to appeal and send it to another one when we know we’re gonna get the same answer,” Mr. Opperman said, according to a recording in court files. At Mr. Opperman’s urging, United decided to skip the usual appeals process and arrange for Dr. Pabby to have a so-called “peer-to-peer” discussion with Dr. Loftus, the Mayo physician treating Mr. McNaughton. Such a conversation, in which a patient’s doctor talks with an insurance company’s doctor to advocate for the prescribed treatment, usually occurs only after a customer has appealed a denial and the appeal has been rejected.

When Ms. Kavanaugh called Dr. Loftus’ office to set up a conversation with Dr. Pabby, she explained it was an urgent matter and had been requested by Mr. McNaughton. “You know I’ve just gotten to know Christopher,” she explained, although she had never spoken with him. “We’re trying to advocate and help and get this peer-to-peer set up.”

Mr. McNaughton, meanwhile, had no idea at the time that a United doctor had decided his treatment was unnecessary and that the insurer was trying to set up a phone call with his physician.

In the peer-to-peer conversation, Dr. Loftus told Dr. Pabby that Mr. McNaughton had “a very complicated case” and that lower doses had not worked for him, according to an internal MRIoA memo.

Following his conversation with Dr. Loftus, Dr. Pabby created a second report for United. He recommended the insurer pay for both drugs, but at reduced doses. He added new language saying that the safety of using both drugs at the higher levels “is not established.”

When Ms. Kavanaugh shared the May 12 decision from Dr. Pabby with others at United, her boss responded with an email calling it “great news.”

Then Mr. Opperman sent an email that puzzled the McNaughtons.

In it, Mr. Opperman claimed that Dr. Loftus and Dr. Pabby had agreed that Mr. McNaughton should be on significantly lower doses of both drugs. He said Dr. Loftus “will work with the patient to start titrating them down to a normal dose range.” Mr. Opperman wrote that United would cover Mr. McNaughton’s treatment in the coming year, but only at the reduced doses. Mr. Opperman did not respond to emails and phone messages seeking comment.

Mr. McNaughton didn’t believe a word of it. He had already tried and failed treatment with those drugs at lower doses, and it was Dr. Loftus who had upped the doses, leading to his remission from severe colitis.

The only thing that made sense to Mr. McNaughton was that the treatment United said it would now pay for was dramatically cheaper – saving the company at least hundreds of thousands of dollars a year – than his prescribed treatment because it sliced the size of the doses by more than half.

When the family contacted Dr. Loftus for an explanation, they were outraged by what they heard. Dr. Loftus told them that he had never recommended lowering the dosage. In a letter, Dr. Loftus wrote that changing Mr. McNaughton’s treatment “would have serious detrimental effects on both his short term and long term health and could potentially involve life threatening complications. This would ultimately incur far greater medical costs. Chris was on the doses suggested by United Healthcare before, and they were not at all effective.”

It would not be until the lawsuit that it would become clear how Dr. Loftus’ conversations had been so seriously misrepresented.

Under questioning by Mr. McNaughton’s lawyers, Ms. Kavanaugh acknowledged that she was the source of the incorrect claim that Mr. McNaughton’s doctor had agreed to a change in treatment.

“I incorrectly made an assumption that they had come to some sort of agreement,” she said in a deposition last August. “It was my first peer-to-peer. I did not realize that that simply does not occur.”

Ms. Kavanaugh did not respond to emails and telephone messages seeking comment.

When the McNaughtons first learned of Mr. Opperman’s inaccurate report of the phone call with Dr. Loftus, it unnerved them. They started to question if their case would be fairly reviewed.

“When we got the denial and they lied about what Dr. Loftus said, it just hit me that none of this matters,” Mr. McNaughton said. “They will just say or do anything to get rid of me. It delegitimized the entire review process. When I got that denial, I was crushed.”

A buried report

While the family tried to sort out the inaccurate report, United continued putting the McNaughton case in front of more company doctors.