User login

Skin patterns of COVID-19 vary widely

according to Christine Ko, MD.

“Things are very fluid,” Dr. Ko, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “New studies are coming out daily. Due to the need for rapid dissemination, a lot of the studies are case reports, but there are some nice case series. Another caveat for the literature is that a lot of these cases were not necessarily confirmed with testing for SARS-CoV-2, but some were.”

Dr. Ko framed her remarks largely on a case collection survey of images and clinical data from 375 patients in Spain with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 that was published online April 29, 2020, in the British Journal of Dermatology (doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163). Cutaneous manifestations included early vesicular eruptions mainly on the trunk or limbs (9%), maculopapular (47%) to urticarial lesions (19%) mainly on the trunk, and acral areas of erythema sometimes with vesicles or erosion (perniosis-like) (19%) that seemed to be a later manifestation of COVID-19. Retiform purpura or necrosis (6%) was most concerning in terms of skin disease, with an associated with a mortality of 10%.

On histology, the early vesicular eruptions are typically marked by dyskeratotic keratinocytes, Dr. Ko said, while urticarial lesions are characterized by a mixed dermal infiltrate; maculopapular lesions were a broad category. “There are some case reports that show spongiotic dermatitis or parakeratosis with a lymphocytic infiltrate,” she said. “A caveat to keep in mind is that, although these patients may definitely have COVID-19 and be confirmed to have it by testing, hypersensitivity reactions may be due to the multiple medications they’re on.”

Patients can develop a spectrum of lesions that are suggestive of vascular damage or occlusion, Dr. Ko continued. Livedoid lesions may remain static and not eventuate into necrosis or purpura but will self-resolve. Purpuric lesions and acral gangrene have been described, and these lesions correspond to vascular occlusion on biopsy.

A later manifestation are the so-called “COVID toes” with a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate, as published June 1, 2020, in JAAD Case Reports: (doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011).

“There are patients in the literature that have slightly different pathology, with lymphocytic inflammation as well as occlusion of vessels,” Dr. Ko said. A paper published June 20, 2020, in the British Journal of Dermatology used immunohistochemical staining against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and biopsies of “COVID toes” had positive staining of endothelial cells, supporting the notion that “COVID toes” are a direct manifestation of viral infection (doi: 10.1111/bjd.19327).

“There’s a lot that we still don’t know, and some patterns are going to be outliers,” Dr. Ko concluded. “[As for] determining which skin manifestations are directly from coronavirus infection within the skin, more study is needed and likely time will tell.” She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to her talk.

according to Christine Ko, MD.

“Things are very fluid,” Dr. Ko, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “New studies are coming out daily. Due to the need for rapid dissemination, a lot of the studies are case reports, but there are some nice case series. Another caveat for the literature is that a lot of these cases were not necessarily confirmed with testing for SARS-CoV-2, but some were.”

Dr. Ko framed her remarks largely on a case collection survey of images and clinical data from 375 patients in Spain with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 that was published online April 29, 2020, in the British Journal of Dermatology (doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163). Cutaneous manifestations included early vesicular eruptions mainly on the trunk or limbs (9%), maculopapular (47%) to urticarial lesions (19%) mainly on the trunk, and acral areas of erythema sometimes with vesicles or erosion (perniosis-like) (19%) that seemed to be a later manifestation of COVID-19. Retiform purpura or necrosis (6%) was most concerning in terms of skin disease, with an associated with a mortality of 10%.

On histology, the early vesicular eruptions are typically marked by dyskeratotic keratinocytes, Dr. Ko said, while urticarial lesions are characterized by a mixed dermal infiltrate; maculopapular lesions were a broad category. “There are some case reports that show spongiotic dermatitis or parakeratosis with a lymphocytic infiltrate,” she said. “A caveat to keep in mind is that, although these patients may definitely have COVID-19 and be confirmed to have it by testing, hypersensitivity reactions may be due to the multiple medications they’re on.”

Patients can develop a spectrum of lesions that are suggestive of vascular damage or occlusion, Dr. Ko continued. Livedoid lesions may remain static and not eventuate into necrosis or purpura but will self-resolve. Purpuric lesions and acral gangrene have been described, and these lesions correspond to vascular occlusion on biopsy.

A later manifestation are the so-called “COVID toes” with a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate, as published June 1, 2020, in JAAD Case Reports: (doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011).

“There are patients in the literature that have slightly different pathology, with lymphocytic inflammation as well as occlusion of vessels,” Dr. Ko said. A paper published June 20, 2020, in the British Journal of Dermatology used immunohistochemical staining against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and biopsies of “COVID toes” had positive staining of endothelial cells, supporting the notion that “COVID toes” are a direct manifestation of viral infection (doi: 10.1111/bjd.19327).

“There’s a lot that we still don’t know, and some patterns are going to be outliers,” Dr. Ko concluded. “[As for] determining which skin manifestations are directly from coronavirus infection within the skin, more study is needed and likely time will tell.” She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to her talk.

according to Christine Ko, MD.

“Things are very fluid,” Dr. Ko, professor of dermatology and pathology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “New studies are coming out daily. Due to the need for rapid dissemination, a lot of the studies are case reports, but there are some nice case series. Another caveat for the literature is that a lot of these cases were not necessarily confirmed with testing for SARS-CoV-2, but some were.”

Dr. Ko framed her remarks largely on a case collection survey of images and clinical data from 375 patients in Spain with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 that was published online April 29, 2020, in the British Journal of Dermatology (doi: 10.1111/bjd.19163). Cutaneous manifestations included early vesicular eruptions mainly on the trunk or limbs (9%), maculopapular (47%) to urticarial lesions (19%) mainly on the trunk, and acral areas of erythema sometimes with vesicles or erosion (perniosis-like) (19%) that seemed to be a later manifestation of COVID-19. Retiform purpura or necrosis (6%) was most concerning in terms of skin disease, with an associated with a mortality of 10%.

On histology, the early vesicular eruptions are typically marked by dyskeratotic keratinocytes, Dr. Ko said, while urticarial lesions are characterized by a mixed dermal infiltrate; maculopapular lesions were a broad category. “There are some case reports that show spongiotic dermatitis or parakeratosis with a lymphocytic infiltrate,” she said. “A caveat to keep in mind is that, although these patients may definitely have COVID-19 and be confirmed to have it by testing, hypersensitivity reactions may be due to the multiple medications they’re on.”

Patients can develop a spectrum of lesions that are suggestive of vascular damage or occlusion, Dr. Ko continued. Livedoid lesions may remain static and not eventuate into necrosis or purpura but will self-resolve. Purpuric lesions and acral gangrene have been described, and these lesions correspond to vascular occlusion on biopsy.

A later manifestation are the so-called “COVID toes” with a superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate, as published June 1, 2020, in JAAD Case Reports: (doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.04.011).

“There are patients in the literature that have slightly different pathology, with lymphocytic inflammation as well as occlusion of vessels,” Dr. Ko said. A paper published June 20, 2020, in the British Journal of Dermatology used immunohistochemical staining against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and biopsies of “COVID toes” had positive staining of endothelial cells, supporting the notion that “COVID toes” are a direct manifestation of viral infection (doi: 10.1111/bjd.19327).

“There’s a lot that we still don’t know, and some patterns are going to be outliers,” Dr. Ko concluded. “[As for] determining which skin manifestations are directly from coronavirus infection within the skin, more study is needed and likely time will tell.” She reported having no financial disclosures relevant to her talk.

FROM AAD 20

First validated classification criteria for discoid lupus erythematosus unveiled

The first validated classification criteria for discoid lupus erythematosus has a sensitivity that ranges between 73.9% and 84.1% and a specificity that ranges between 75.9% and 92.9%.

“Discoid lupus erythematosus [DLE] is the most common type of chronic cutaneous lupus,” lead study author Scott A. Elman, MD, said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s one of the most potentially disfiguring forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus [CLE], which can lead to scarring, hair loss, and dyspigmentation if not treated early or promptly. It has a significant impact on patient quality of life and there are currently no classification criteria for DLE, which has led to problematic heterogeneity in observational and interventional research efforts. As there is increasing interest in drug development programs for CLE and DLE, there is a need to develop classification criteria.”

Dr. Elman, of the Harvard combined medicine-dermatology training program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, pointed out that classification criteria are the standard definitions that are primarily intended to enroll uniform cohorts for research. “These emphasize high specificity, whereas diagnostic criteria reflect a more broad and variable set of features of a given disease, and therefore require a higher sensitivity,” he explained. “While classification criteria are not synonymous with diagnostic criteria, they typically mirror the list of criteria that are used for diagnosis.”

In 2017, Dr. Elman and colleagues generated an item list of 12 potential classification criteria using an international Delphi consensus process: 5 criteria represented disease morphology, 2 represented discoid lupus location, and 5 represented histopathology (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;77[2]:261-7). The purpose of the current study, which was presented as a late-breaking abstract, was to validate the proposed classification criteria in a multicenter, international trial. “The point is to be able to differentiate between discoid lupus and its disease mimickers, which could be confused in enrollment in clinical trials,” he said.

At nine participating sites, patients were identified at clinical visits as having either DLE or a DLE mimicker. After each visit, dermatologists determined if morphological features were present. One dermatopathologist at each site reviewed pathology, if available, to see if the histopathologic features were present. Diagnosis by clinical features and dermatopathology were tabulated and presented as counts and percentages. Clinical features among those with and without DLE were calculated and compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The researchers used best subsets logistic regression analysis to identify candidate models.

A total of 215 patients were enrolled: 94 that were consistent with DLE and 121 that were consistent with a DLE mimicker. Most cases (83%) were from North America, 11% were from Asia, and 6% were from Europe. Only 86 cases (40%) had biopsies for dermatopathology review.

The following clinical features were found to be more commonly associated with DLE, compared with DLE mimickers: atrophic scarring (83% vs. 24%; P < .001), dyspigmentation (84% vs. 55%; P < .001), follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging (43% vs. 11%; P < .001), scarring alopecia (61% vs. 21%; P < .001), location in the conchal bowl (49% vs. 10%; P < .001), preference for the head and neck (87% vs. 49%; P < .001), and erythematous to violaceous in color (93% vs. 85%, a nonsignificant difference; P = .09).

When histopathological items were assessed, the following features were found to be more commonly associated with DLE, compared with DLE mimickers: interface/vacuolar dermatitis (83% vs. 53%; P = .004), perivascular and/or periappendageal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (95% vs. 84%, a nonsignificant difference; P = .18), follicular keratin plugs (57% vs. 20%; P < .001), mucin deposition (73% vs. 39%; P = .002), and basement membrane thickening (57% vs. 14%; P < .001).

“There was good agreement between the diagnoses made by dermatologists and dermatopathologists, with a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 0.83,” Dr. Elman added. “Similarly, in many of the cases, the dermatopathologists and the dermatologists felt confident in their diagnosis.”

For the final model, the researchers excluded patients who had any missing data as well as those who had a diagnosis that was uncertain. This left 200 cases in the final model. Clinical variables associated with DLE were: atrophic scarring (odds ratio, 8.70; P < .001), location in the conchal bowl (OR, 6.80; P < .001), preference for head and neck (OR, 9.41; P < .001), dyspigmentation (OR, 3.23; P = .020), follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging (OR, 2.94; P = .054), and erythematous to violaceous in color (OR, 3.44; P = .056). The area under the curve for the model was 0.91.

According to Dr. Elman, the final model is a points-based model with 3 points assigned to atrophic scarring, 2 points assigned to location in the conchal bowl, 2 points assigned to preference for head and neck, 1 point assigned to dyspigmentation, 1 point assigned to follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging, and 1 point assigned to erythematous to violaceous in color. A score of 5 or greater yields a classification as DLE with 84.1% sensitivity and 75.9% specificity, while a score of 7 or greater yields a 73.9% sensitivity and 92.9% specificity.

Dr. Elman acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that information related to histopathology was not included in the final model. “This was a result of having only 40% of cases with relevant dermatopathology,” he said. “This limited our ability to meaningfully incorporate these items into a classification criteria set. However, with the data we’ve collected, efforts are under way to make a DLE-specific histopathology classification criteria.”

Another limitation is that the researchers relied on expert diagnosis as the preferred option. “Similarly, many of the cases came from large referral centers, and no demographic data were obtained, so this limits the generalizability of our study,” he said.

Dr. Elman reported having no financial disclosures.

The first validated classification criteria for discoid lupus erythematosus has a sensitivity that ranges between 73.9% and 84.1% and a specificity that ranges between 75.9% and 92.9%.

“Discoid lupus erythematosus [DLE] is the most common type of chronic cutaneous lupus,” lead study author Scott A. Elman, MD, said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s one of the most potentially disfiguring forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus [CLE], which can lead to scarring, hair loss, and dyspigmentation if not treated early or promptly. It has a significant impact on patient quality of life and there are currently no classification criteria for DLE, which has led to problematic heterogeneity in observational and interventional research efforts. As there is increasing interest in drug development programs for CLE and DLE, there is a need to develop classification criteria.”

Dr. Elman, of the Harvard combined medicine-dermatology training program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, pointed out that classification criteria are the standard definitions that are primarily intended to enroll uniform cohorts for research. “These emphasize high specificity, whereas diagnostic criteria reflect a more broad and variable set of features of a given disease, and therefore require a higher sensitivity,” he explained. “While classification criteria are not synonymous with diagnostic criteria, they typically mirror the list of criteria that are used for diagnosis.”

In 2017, Dr. Elman and colleagues generated an item list of 12 potential classification criteria using an international Delphi consensus process: 5 criteria represented disease morphology, 2 represented discoid lupus location, and 5 represented histopathology (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;77[2]:261-7). The purpose of the current study, which was presented as a late-breaking abstract, was to validate the proposed classification criteria in a multicenter, international trial. “The point is to be able to differentiate between discoid lupus and its disease mimickers, which could be confused in enrollment in clinical trials,” he said.

At nine participating sites, patients were identified at clinical visits as having either DLE or a DLE mimicker. After each visit, dermatologists determined if morphological features were present. One dermatopathologist at each site reviewed pathology, if available, to see if the histopathologic features were present. Diagnosis by clinical features and dermatopathology were tabulated and presented as counts and percentages. Clinical features among those with and without DLE were calculated and compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The researchers used best subsets logistic regression analysis to identify candidate models.

A total of 215 patients were enrolled: 94 that were consistent with DLE and 121 that were consistent with a DLE mimicker. Most cases (83%) were from North America, 11% were from Asia, and 6% were from Europe. Only 86 cases (40%) had biopsies for dermatopathology review.

The following clinical features were found to be more commonly associated with DLE, compared with DLE mimickers: atrophic scarring (83% vs. 24%; P < .001), dyspigmentation (84% vs. 55%; P < .001), follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging (43% vs. 11%; P < .001), scarring alopecia (61% vs. 21%; P < .001), location in the conchal bowl (49% vs. 10%; P < .001), preference for the head and neck (87% vs. 49%; P < .001), and erythematous to violaceous in color (93% vs. 85%, a nonsignificant difference; P = .09).

When histopathological items were assessed, the following features were found to be more commonly associated with DLE, compared with DLE mimickers: interface/vacuolar dermatitis (83% vs. 53%; P = .004), perivascular and/or periappendageal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (95% vs. 84%, a nonsignificant difference; P = .18), follicular keratin plugs (57% vs. 20%; P < .001), mucin deposition (73% vs. 39%; P = .002), and basement membrane thickening (57% vs. 14%; P < .001).

“There was good agreement between the diagnoses made by dermatologists and dermatopathologists, with a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 0.83,” Dr. Elman added. “Similarly, in many of the cases, the dermatopathologists and the dermatologists felt confident in their diagnosis.”

For the final model, the researchers excluded patients who had any missing data as well as those who had a diagnosis that was uncertain. This left 200 cases in the final model. Clinical variables associated with DLE were: atrophic scarring (odds ratio, 8.70; P < .001), location in the conchal bowl (OR, 6.80; P < .001), preference for head and neck (OR, 9.41; P < .001), dyspigmentation (OR, 3.23; P = .020), follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging (OR, 2.94; P = .054), and erythematous to violaceous in color (OR, 3.44; P = .056). The area under the curve for the model was 0.91.

According to Dr. Elman, the final model is a points-based model with 3 points assigned to atrophic scarring, 2 points assigned to location in the conchal bowl, 2 points assigned to preference for head and neck, 1 point assigned to dyspigmentation, 1 point assigned to follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging, and 1 point assigned to erythematous to violaceous in color. A score of 5 or greater yields a classification as DLE with 84.1% sensitivity and 75.9% specificity, while a score of 7 or greater yields a 73.9% sensitivity and 92.9% specificity.

Dr. Elman acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that information related to histopathology was not included in the final model. “This was a result of having only 40% of cases with relevant dermatopathology,” he said. “This limited our ability to meaningfully incorporate these items into a classification criteria set. However, with the data we’ve collected, efforts are under way to make a DLE-specific histopathology classification criteria.”

Another limitation is that the researchers relied on expert diagnosis as the preferred option. “Similarly, many of the cases came from large referral centers, and no demographic data were obtained, so this limits the generalizability of our study,” he said.

Dr. Elman reported having no financial disclosures.

The first validated classification criteria for discoid lupus erythematosus has a sensitivity that ranges between 73.9% and 84.1% and a specificity that ranges between 75.9% and 92.9%.

“Discoid lupus erythematosus [DLE] is the most common type of chronic cutaneous lupus,” lead study author Scott A. Elman, MD, said during the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s one of the most potentially disfiguring forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus [CLE], which can lead to scarring, hair loss, and dyspigmentation if not treated early or promptly. It has a significant impact on patient quality of life and there are currently no classification criteria for DLE, which has led to problematic heterogeneity in observational and interventional research efforts. As there is increasing interest in drug development programs for CLE and DLE, there is a need to develop classification criteria.”

Dr. Elman, of the Harvard combined medicine-dermatology training program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, pointed out that classification criteria are the standard definitions that are primarily intended to enroll uniform cohorts for research. “These emphasize high specificity, whereas diagnostic criteria reflect a more broad and variable set of features of a given disease, and therefore require a higher sensitivity,” he explained. “While classification criteria are not synonymous with diagnostic criteria, they typically mirror the list of criteria that are used for diagnosis.”

In 2017, Dr. Elman and colleagues generated an item list of 12 potential classification criteria using an international Delphi consensus process: 5 criteria represented disease morphology, 2 represented discoid lupus location, and 5 represented histopathology (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Aug 1;77[2]:261-7). The purpose of the current study, which was presented as a late-breaking abstract, was to validate the proposed classification criteria in a multicenter, international trial. “The point is to be able to differentiate between discoid lupus and its disease mimickers, which could be confused in enrollment in clinical trials,” he said.

At nine participating sites, patients were identified at clinical visits as having either DLE or a DLE mimicker. After each visit, dermatologists determined if morphological features were present. One dermatopathologist at each site reviewed pathology, if available, to see if the histopathologic features were present. Diagnosis by clinical features and dermatopathology were tabulated and presented as counts and percentages. Clinical features among those with and without DLE were calculated and compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. The researchers used best subsets logistic regression analysis to identify candidate models.

A total of 215 patients were enrolled: 94 that were consistent with DLE and 121 that were consistent with a DLE mimicker. Most cases (83%) were from North America, 11% were from Asia, and 6% were from Europe. Only 86 cases (40%) had biopsies for dermatopathology review.

The following clinical features were found to be more commonly associated with DLE, compared with DLE mimickers: atrophic scarring (83% vs. 24%; P < .001), dyspigmentation (84% vs. 55%; P < .001), follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging (43% vs. 11%; P < .001), scarring alopecia (61% vs. 21%; P < .001), location in the conchal bowl (49% vs. 10%; P < .001), preference for the head and neck (87% vs. 49%; P < .001), and erythematous to violaceous in color (93% vs. 85%, a nonsignificant difference; P = .09).

When histopathological items were assessed, the following features were found to be more commonly associated with DLE, compared with DLE mimickers: interface/vacuolar dermatitis (83% vs. 53%; P = .004), perivascular and/or periappendageal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (95% vs. 84%, a nonsignificant difference; P = .18), follicular keratin plugs (57% vs. 20%; P < .001), mucin deposition (73% vs. 39%; P = .002), and basement membrane thickening (57% vs. 14%; P < .001).

“There was good agreement between the diagnoses made by dermatologists and dermatopathologists, with a Cohen’s kappa statistic of 0.83,” Dr. Elman added. “Similarly, in many of the cases, the dermatopathologists and the dermatologists felt confident in their diagnosis.”

For the final model, the researchers excluded patients who had any missing data as well as those who had a diagnosis that was uncertain. This left 200 cases in the final model. Clinical variables associated with DLE were: atrophic scarring (odds ratio, 8.70; P < .001), location in the conchal bowl (OR, 6.80; P < .001), preference for head and neck (OR, 9.41; P < .001), dyspigmentation (OR, 3.23; P = .020), follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging (OR, 2.94; P = .054), and erythematous to violaceous in color (OR, 3.44; P = .056). The area under the curve for the model was 0.91.

According to Dr. Elman, the final model is a points-based model with 3 points assigned to atrophic scarring, 2 points assigned to location in the conchal bowl, 2 points assigned to preference for head and neck, 1 point assigned to dyspigmentation, 1 point assigned to follicular hyperkeratosis/plugging, and 1 point assigned to erythematous to violaceous in color. A score of 5 or greater yields a classification as DLE with 84.1% sensitivity and 75.9% specificity, while a score of 7 or greater yields a 73.9% sensitivity and 92.9% specificity.

Dr. Elman acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that information related to histopathology was not included in the final model. “This was a result of having only 40% of cases with relevant dermatopathology,” he said. “This limited our ability to meaningfully incorporate these items into a classification criteria set. However, with the data we’ve collected, efforts are under way to make a DLE-specific histopathology classification criteria.”

Another limitation is that the researchers relied on expert diagnosis as the preferred option. “Similarly, many of the cases came from large referral centers, and no demographic data were obtained, so this limits the generalizability of our study,” he said.

Dr. Elman reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM AAD 20

In scleroderma, GERD questionnaires are essential tools

Every rheumatologist ought to be comfortable in using a validated gastrointestinal symptom scale for evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with scleroderma, Tracy M. Frech, MD, declared at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

About 90% of scleroderma patients will develop GI tract involvement during the course of their connective tissue disease. And while any portion of the GI tract from esophagus to anus can be involved, the most common GI manifestation is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), affecting up to 90% of scleroderma patients, observed Dr. Frech, a rheumatologist and director of the systemic sclerosis clinic at the University of Utah and the George E. Wahlen Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Salt Lake City.

“It is essential to ask scleroderma patients questions in order to understand their gastrointestinal tract symptoms. The questionnaires are really critical for us to grade the severity and then properly order tests,” she explained. “The goal is symptom identification, ideally with minimal time burden and at no cost, to guide decisions that move our patients’ care forward.”

Three of the most useful validated instruments for assessment of GERD symptoms in scleroderma patients in routine clinical practice are the GerdQ, the University of California, Los Angeles, Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium GI Tract Questionnaire (UCLA GIT) 2.0 reflux scale, and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) reflux scale.

The GerdQ is a six-item, self-administered questionnaire in which patients specify how many days in the past week they have experienced heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, sleep interference, upper abdominal pain, and need for medication. A free online tool is available for calculating the likelihood of having GERD based upon GerdQ score. A score of 8 or more points out of a possible 18 has the highest sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of GERD.

The UCLA GIT 2.0 – the most commonly used instrument for GI symptom assessment in scleroderma patients – includes 34 items. It takes 6-8 minutes to complete the whole thing, but patients being assessed for GERD only need answer the eight GERD-specific questions. Six of these eight questions are the same as in the GerdQ. One of the two extra questions asks about difficulty in swallowing solid food, which if answered affirmatively warrants early referral to a gastroenterologist. The other question inquires about any food triggers for the reflux, providing an opportunity for a rheumatologist to educate the patient about the importance of avoiding acidic foods, such as tomatoes, and other food and drink generally considered healthy but which actually exacerbate GERD.

The National Institutes of Health PROMIS scale, the newest of the three instruments, is a 60-item questionnaire; however, only 20 questions relate to reflux and dysphagia and are thus germane to a focused GERD assessment in scleroderma.

When a clinical diagnosis of GERD is made in a scleroderma patient based upon symptoms elicited by questionnaire, guidelines recommend a trial of empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy and behavioral interventions, such as raising the head of the bed, in order to confirm the diagnosis. If the patient reports feeling better after these basic interventions, the diagnosis is confirmed. If not, it’s time to make a referral to a gastroenterologist for specialized care, Dr. Frech said.

Dr. Frech was a coinvestigator in an international, prospective, longitudinal study of patient-reported outcomes measures in 116 patients with scleroderma and GERD. All study participants had to complete the UCLA GIT 2.0, the PROMIS reflux scale, and a third patient-reported GERD measure both before and after the therapeutic intervention. The UCLA GIT 2.0 and PROMIS instruments demonstrated similarly robust sensitivity for identifying changes in GERD symptoms after therapeutic intervention.

“It doesn’t really matter what questionnaire we’re using,” according to the rheumatologist. “But I will point out that there is significant overlap in symptoms among GERD, gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia, and eosinophilic esophagitis, all of which cause symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. So we don’t want to ask these questions just once, we want to make an intervention and then reask the questions to ensure that we’re continuously moving forward with the gastrointestinal tract management plan.”

Dr. Frech reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

Every rheumatologist ought to be comfortable in using a validated gastrointestinal symptom scale for evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with scleroderma, Tracy M. Frech, MD, declared at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

About 90% of scleroderma patients will develop GI tract involvement during the course of their connective tissue disease. And while any portion of the GI tract from esophagus to anus can be involved, the most common GI manifestation is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), affecting up to 90% of scleroderma patients, observed Dr. Frech, a rheumatologist and director of the systemic sclerosis clinic at the University of Utah and the George E. Wahlen Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Salt Lake City.

“It is essential to ask scleroderma patients questions in order to understand their gastrointestinal tract symptoms. The questionnaires are really critical for us to grade the severity and then properly order tests,” she explained. “The goal is symptom identification, ideally with minimal time burden and at no cost, to guide decisions that move our patients’ care forward.”

Three of the most useful validated instruments for assessment of GERD symptoms in scleroderma patients in routine clinical practice are the GerdQ, the University of California, Los Angeles, Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium GI Tract Questionnaire (UCLA GIT) 2.0 reflux scale, and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) reflux scale.

The GerdQ is a six-item, self-administered questionnaire in which patients specify how many days in the past week they have experienced heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, sleep interference, upper abdominal pain, and need for medication. A free online tool is available for calculating the likelihood of having GERD based upon GerdQ score. A score of 8 or more points out of a possible 18 has the highest sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of GERD.

The UCLA GIT 2.0 – the most commonly used instrument for GI symptom assessment in scleroderma patients – includes 34 items. It takes 6-8 minutes to complete the whole thing, but patients being assessed for GERD only need answer the eight GERD-specific questions. Six of these eight questions are the same as in the GerdQ. One of the two extra questions asks about difficulty in swallowing solid food, which if answered affirmatively warrants early referral to a gastroenterologist. The other question inquires about any food triggers for the reflux, providing an opportunity for a rheumatologist to educate the patient about the importance of avoiding acidic foods, such as tomatoes, and other food and drink generally considered healthy but which actually exacerbate GERD.

The National Institutes of Health PROMIS scale, the newest of the three instruments, is a 60-item questionnaire; however, only 20 questions relate to reflux and dysphagia and are thus germane to a focused GERD assessment in scleroderma.

When a clinical diagnosis of GERD is made in a scleroderma patient based upon symptoms elicited by questionnaire, guidelines recommend a trial of empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy and behavioral interventions, such as raising the head of the bed, in order to confirm the diagnosis. If the patient reports feeling better after these basic interventions, the diagnosis is confirmed. If not, it’s time to make a referral to a gastroenterologist for specialized care, Dr. Frech said.

Dr. Frech was a coinvestigator in an international, prospective, longitudinal study of patient-reported outcomes measures in 116 patients with scleroderma and GERD. All study participants had to complete the UCLA GIT 2.0, the PROMIS reflux scale, and a third patient-reported GERD measure both before and after the therapeutic intervention. The UCLA GIT 2.0 and PROMIS instruments demonstrated similarly robust sensitivity for identifying changes in GERD symptoms after therapeutic intervention.

“It doesn’t really matter what questionnaire we’re using,” according to the rheumatologist. “But I will point out that there is significant overlap in symptoms among GERD, gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia, and eosinophilic esophagitis, all of which cause symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. So we don’t want to ask these questions just once, we want to make an intervention and then reask the questions to ensure that we’re continuously moving forward with the gastrointestinal tract management plan.”

Dr. Frech reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

Every rheumatologist ought to be comfortable in using a validated gastrointestinal symptom scale for evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with scleroderma, Tracy M. Frech, MD, declared at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

About 90% of scleroderma patients will develop GI tract involvement during the course of their connective tissue disease. And while any portion of the GI tract from esophagus to anus can be involved, the most common GI manifestation is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), affecting up to 90% of scleroderma patients, observed Dr. Frech, a rheumatologist and director of the systemic sclerosis clinic at the University of Utah and the George E. Wahlen Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Salt Lake City.

“It is essential to ask scleroderma patients questions in order to understand their gastrointestinal tract symptoms. The questionnaires are really critical for us to grade the severity and then properly order tests,” she explained. “The goal is symptom identification, ideally with minimal time burden and at no cost, to guide decisions that move our patients’ care forward.”

Three of the most useful validated instruments for assessment of GERD symptoms in scleroderma patients in routine clinical practice are the GerdQ, the University of California, Los Angeles, Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium GI Tract Questionnaire (UCLA GIT) 2.0 reflux scale, and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) reflux scale.

The GerdQ is a six-item, self-administered questionnaire in which patients specify how many days in the past week they have experienced heartburn, regurgitation, nausea, sleep interference, upper abdominal pain, and need for medication. A free online tool is available for calculating the likelihood of having GERD based upon GerdQ score. A score of 8 or more points out of a possible 18 has the highest sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of GERD.

The UCLA GIT 2.0 – the most commonly used instrument for GI symptom assessment in scleroderma patients – includes 34 items. It takes 6-8 minutes to complete the whole thing, but patients being assessed for GERD only need answer the eight GERD-specific questions. Six of these eight questions are the same as in the GerdQ. One of the two extra questions asks about difficulty in swallowing solid food, which if answered affirmatively warrants early referral to a gastroenterologist. The other question inquires about any food triggers for the reflux, providing an opportunity for a rheumatologist to educate the patient about the importance of avoiding acidic foods, such as tomatoes, and other food and drink generally considered healthy but which actually exacerbate GERD.

The National Institutes of Health PROMIS scale, the newest of the three instruments, is a 60-item questionnaire; however, only 20 questions relate to reflux and dysphagia and are thus germane to a focused GERD assessment in scleroderma.

When a clinical diagnosis of GERD is made in a scleroderma patient based upon symptoms elicited by questionnaire, guidelines recommend a trial of empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy and behavioral interventions, such as raising the head of the bed, in order to confirm the diagnosis. If the patient reports feeling better after these basic interventions, the diagnosis is confirmed. If not, it’s time to make a referral to a gastroenterologist for specialized care, Dr. Frech said.

Dr. Frech was a coinvestigator in an international, prospective, longitudinal study of patient-reported outcomes measures in 116 patients with scleroderma and GERD. All study participants had to complete the UCLA GIT 2.0, the PROMIS reflux scale, and a third patient-reported GERD measure both before and after the therapeutic intervention. The UCLA GIT 2.0 and PROMIS instruments demonstrated similarly robust sensitivity for identifying changes in GERD symptoms after therapeutic intervention.

“It doesn’t really matter what questionnaire we’re using,” according to the rheumatologist. “But I will point out that there is significant overlap in symptoms among GERD, gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia, and eosinophilic esophagitis, all of which cause symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation. So we don’t want to ask these questions just once, we want to make an intervention and then reask the questions to ensure that we’re continuously moving forward with the gastrointestinal tract management plan.”

Dr. Frech reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

FROM SOTA 2020

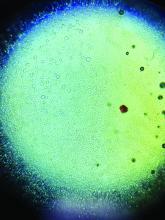

Newborn ear lesion

This lesion was diagnosed as an accessory tragus. Although sometimes called a preauricular skin tag, it is more aptly named accessory tragus since it arises embryonically along with the tragus from the first branchial arch. It usually is slightly anterior to the ear and can be seen unilaterally or bilaterally. The lesions usually feel firm to palpation due to an underlying cartilaginous component.

While this finding can be seen in congenital syndromes—most commonly oculoauriculovertebral syndrome (also known as Goldenhar syndrome)—it usually occurs in isolation. If there are no other abnormalities on exam to suggest a congenital syndrome, no additional work-up is necessary.

Concerns have been raised about a possible association with decreased hearing. Routine hearing screens are performed in the United States and this child’s screen was normal, so no further investigation for inner ear abnormalities was warranted.

These lesions usually are asymptomatic (unless traumatized). If removal is desired, it is important to remove the cartilaginous component, which can be deep and require additional dissection rather than simple transection at the base. Incomplete removal of the cartilage can cause chondritis, impede skin healing, and lead to infection.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Bahrani B, Khachemoune A. Review of accessory tragus with highlights of its associated syndromes. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1442-1446.

This lesion was diagnosed as an accessory tragus. Although sometimes called a preauricular skin tag, it is more aptly named accessory tragus since it arises embryonically along with the tragus from the first branchial arch. It usually is slightly anterior to the ear and can be seen unilaterally or bilaterally. The lesions usually feel firm to palpation due to an underlying cartilaginous component.

While this finding can be seen in congenital syndromes—most commonly oculoauriculovertebral syndrome (also known as Goldenhar syndrome)—it usually occurs in isolation. If there are no other abnormalities on exam to suggest a congenital syndrome, no additional work-up is necessary.

Concerns have been raised about a possible association with decreased hearing. Routine hearing screens are performed in the United States and this child’s screen was normal, so no further investigation for inner ear abnormalities was warranted.

These lesions usually are asymptomatic (unless traumatized). If removal is desired, it is important to remove the cartilaginous component, which can be deep and require additional dissection rather than simple transection at the base. Incomplete removal of the cartilage can cause chondritis, impede skin healing, and lead to infection.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

This lesion was diagnosed as an accessory tragus. Although sometimes called a preauricular skin tag, it is more aptly named accessory tragus since it arises embryonically along with the tragus from the first branchial arch. It usually is slightly anterior to the ear and can be seen unilaterally or bilaterally. The lesions usually feel firm to palpation due to an underlying cartilaginous component.

While this finding can be seen in congenital syndromes—most commonly oculoauriculovertebral syndrome (also known as Goldenhar syndrome)—it usually occurs in isolation. If there are no other abnormalities on exam to suggest a congenital syndrome, no additional work-up is necessary.

Concerns have been raised about a possible association with decreased hearing. Routine hearing screens are performed in the United States and this child’s screen was normal, so no further investigation for inner ear abnormalities was warranted.

These lesions usually are asymptomatic (unless traumatized). If removal is desired, it is important to remove the cartilaginous component, which can be deep and require additional dissection rather than simple transection at the base. Incomplete removal of the cartilage can cause chondritis, impede skin healing, and lead to infection.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Bahrani B, Khachemoune A. Review of accessory tragus with highlights of its associated syndromes. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1442-1446.

Bahrani B, Khachemoune A. Review of accessory tragus with highlights of its associated syndromes. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1442-1446.

Eczema may increase lymphoma risk, cohort studies suggest

according to two matched longitudinal cohort studies from England and Denmark.

“In this study, no evidence was found that people with atopic eczema are at increased risk of most cancers. An exception is the observed association between atopic eczema and lymphoma, particularly NHL, [which] increased with eczema severity,” Kathryn E. Mansfield, PhD, wrote in JAMA Dermatology. Adjusted hazard ratios for NHL in the English cohort were 1.06 (99% CI, 0.90-1.25) for mild atopic eczema, 1.24 (99% CI, 1.04-1.48) for moderate eczema, and 2.08 (99% CI, 1.42-3.04) for severe eczema, reported Dr. Mansfield of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and associates.

Past studies of a possible link between atopic eczema and cancer have produced conflicting evidence, which might reflect “two competing theories” – that cancer risk falls with greater immune surveillance, and that cancer risk rises with immune stimulation, the researchers wrote. Immunosuppressive treatment and an impaired skin barrier might also increase the risk of cancer, but the evidence is conflicting.

For the study, they analyzed electronic health records linked with hospital admissions and death records in England and national health registry data from Denmark. The English cohort included 471,970 adults with atopic eczema and 2,239,775 adults without atopic eczema. The Danish cohort was composed of individuals of any age, including 44,945 who had eczema and with 445,673 who did not. Participants were matched based on factors such as age, sex, and primary care practice. The researchers excluded individuals with a history of cancer, apart from nonmelanoma skin cancer or keratinocyte cancer. (For analyses of skin cancer risk, they also excluded individuals with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.)

Overall, there was “little evidence” for a link between atopic eczema and cancer (adjusted hazard ratio in England, 1.04; 99% CI, 1.02-1.06; aHR in Denmark, 1.05; 99% CI, 0.95-1.16) or for most specific types of cancer, the investigators wrote.

In England, however, eczema was associated with a significantly increased risk for noncutaneous lymphoma, with an adjusted HRs of 1.19 (99% CI, 1.07-1.34) for NHL, and 1.48 (99% CI, 1.07-2.04) for Hodgkin lymphoma. Lymphoma risk was highest among adults with severe eczema, defined as those who had been prescribed a systemic treatment for their disease, who had received phototherapy, or who had been referred to a specialist or admitted to a hospital for atopic eczema. Point estimates in the Danish cohort also revealed a higher risk for lymphoma among individuals with moderate to severe atopic eczema, compared with those with eczema, but the 99% CIs crossed 1.0.

The findings highlight the need to be aware of, screen for, and study the pathogenesis of heightened lymphoma risk among patients with atopic eczema, said Shawn Demehri, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology and cancer center, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

“Prospectively collected data from large cohorts of eczema patients is a strength of this study,” he said in an interview. “However, the age range included in the study is suboptimal for assessing cancer as an outcome. The lower incidence of cancer in younger individuals hinders the ability to detect differences in cancer risk between the two groups.” (Approximately 57% of individuals in the English cohort were aged 18-44 years, while approximately 70% of those in the Danish cohort were less than 18 years.)

Understanding how eczema affects the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is an important future direction of research, Dr. Demehri emphasized. “The landscape of atopic eczema therapeutics has dramatically changed in the recent years. It will be very interesting to determine how new biologics impact cancer risk in eczema patients.”

Partial support for the work was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the Royal Society, the Dagmar Marshalls Fund, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Fund. Dr. Mansfield disclosed support from a Wellcome Trust grant. Her coinvestigators disclosed ties to TARGET-DERM, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline, and from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, the British Heart Foundation, Diabetes UK, and IMI Horizon 2020 funding BIOMAP. Dr. Demehri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mansfield KE et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 24. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1948.

according to two matched longitudinal cohort studies from England and Denmark.

“In this study, no evidence was found that people with atopic eczema are at increased risk of most cancers. An exception is the observed association between atopic eczema and lymphoma, particularly NHL, [which] increased with eczema severity,” Kathryn E. Mansfield, PhD, wrote in JAMA Dermatology. Adjusted hazard ratios for NHL in the English cohort were 1.06 (99% CI, 0.90-1.25) for mild atopic eczema, 1.24 (99% CI, 1.04-1.48) for moderate eczema, and 2.08 (99% CI, 1.42-3.04) for severe eczema, reported Dr. Mansfield of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and associates.

Past studies of a possible link between atopic eczema and cancer have produced conflicting evidence, which might reflect “two competing theories” – that cancer risk falls with greater immune surveillance, and that cancer risk rises with immune stimulation, the researchers wrote. Immunosuppressive treatment and an impaired skin barrier might also increase the risk of cancer, but the evidence is conflicting.

For the study, they analyzed electronic health records linked with hospital admissions and death records in England and national health registry data from Denmark. The English cohort included 471,970 adults with atopic eczema and 2,239,775 adults without atopic eczema. The Danish cohort was composed of individuals of any age, including 44,945 who had eczema and with 445,673 who did not. Participants were matched based on factors such as age, sex, and primary care practice. The researchers excluded individuals with a history of cancer, apart from nonmelanoma skin cancer or keratinocyte cancer. (For analyses of skin cancer risk, they also excluded individuals with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.)

Overall, there was “little evidence” for a link between atopic eczema and cancer (adjusted hazard ratio in England, 1.04; 99% CI, 1.02-1.06; aHR in Denmark, 1.05; 99% CI, 0.95-1.16) or for most specific types of cancer, the investigators wrote.

In England, however, eczema was associated with a significantly increased risk for noncutaneous lymphoma, with an adjusted HRs of 1.19 (99% CI, 1.07-1.34) for NHL, and 1.48 (99% CI, 1.07-2.04) for Hodgkin lymphoma. Lymphoma risk was highest among adults with severe eczema, defined as those who had been prescribed a systemic treatment for their disease, who had received phototherapy, or who had been referred to a specialist or admitted to a hospital for atopic eczema. Point estimates in the Danish cohort also revealed a higher risk for lymphoma among individuals with moderate to severe atopic eczema, compared with those with eczema, but the 99% CIs crossed 1.0.

The findings highlight the need to be aware of, screen for, and study the pathogenesis of heightened lymphoma risk among patients with atopic eczema, said Shawn Demehri, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology and cancer center, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

“Prospectively collected data from large cohorts of eczema patients is a strength of this study,” he said in an interview. “However, the age range included in the study is suboptimal for assessing cancer as an outcome. The lower incidence of cancer in younger individuals hinders the ability to detect differences in cancer risk between the two groups.” (Approximately 57% of individuals in the English cohort were aged 18-44 years, while approximately 70% of those in the Danish cohort were less than 18 years.)

Understanding how eczema affects the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is an important future direction of research, Dr. Demehri emphasized. “The landscape of atopic eczema therapeutics has dramatically changed in the recent years. It will be very interesting to determine how new biologics impact cancer risk in eczema patients.”

Partial support for the work was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the Royal Society, the Dagmar Marshalls Fund, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Fund. Dr. Mansfield disclosed support from a Wellcome Trust grant. Her coinvestigators disclosed ties to TARGET-DERM, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline, and from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, the British Heart Foundation, Diabetes UK, and IMI Horizon 2020 funding BIOMAP. Dr. Demehri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mansfield KE et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 24. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1948.

according to two matched longitudinal cohort studies from England and Denmark.

“In this study, no evidence was found that people with atopic eczema are at increased risk of most cancers. An exception is the observed association between atopic eczema and lymphoma, particularly NHL, [which] increased with eczema severity,” Kathryn E. Mansfield, PhD, wrote in JAMA Dermatology. Adjusted hazard ratios for NHL in the English cohort were 1.06 (99% CI, 0.90-1.25) for mild atopic eczema, 1.24 (99% CI, 1.04-1.48) for moderate eczema, and 2.08 (99% CI, 1.42-3.04) for severe eczema, reported Dr. Mansfield of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and associates.

Past studies of a possible link between atopic eczema and cancer have produced conflicting evidence, which might reflect “two competing theories” – that cancer risk falls with greater immune surveillance, and that cancer risk rises with immune stimulation, the researchers wrote. Immunosuppressive treatment and an impaired skin barrier might also increase the risk of cancer, but the evidence is conflicting.

For the study, they analyzed electronic health records linked with hospital admissions and death records in England and national health registry data from Denmark. The English cohort included 471,970 adults with atopic eczema and 2,239,775 adults without atopic eczema. The Danish cohort was composed of individuals of any age, including 44,945 who had eczema and with 445,673 who did not. Participants were matched based on factors such as age, sex, and primary care practice. The researchers excluded individuals with a history of cancer, apart from nonmelanoma skin cancer or keratinocyte cancer. (For analyses of skin cancer risk, they also excluded individuals with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer.)

Overall, there was “little evidence” for a link between atopic eczema and cancer (adjusted hazard ratio in England, 1.04; 99% CI, 1.02-1.06; aHR in Denmark, 1.05; 99% CI, 0.95-1.16) or for most specific types of cancer, the investigators wrote.

In England, however, eczema was associated with a significantly increased risk for noncutaneous lymphoma, with an adjusted HRs of 1.19 (99% CI, 1.07-1.34) for NHL, and 1.48 (99% CI, 1.07-2.04) for Hodgkin lymphoma. Lymphoma risk was highest among adults with severe eczema, defined as those who had been prescribed a systemic treatment for their disease, who had received phototherapy, or who had been referred to a specialist or admitted to a hospital for atopic eczema. Point estimates in the Danish cohort also revealed a higher risk for lymphoma among individuals with moderate to severe atopic eczema, compared with those with eczema, but the 99% CIs crossed 1.0.

The findings highlight the need to be aware of, screen for, and study the pathogenesis of heightened lymphoma risk among patients with atopic eczema, said Shawn Demehri, MD, PhD, of the department of dermatology and cancer center, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, who was not involved in the study.

“Prospectively collected data from large cohorts of eczema patients is a strength of this study,” he said in an interview. “However, the age range included in the study is suboptimal for assessing cancer as an outcome. The lower incidence of cancer in younger individuals hinders the ability to detect differences in cancer risk between the two groups.” (Approximately 57% of individuals in the English cohort were aged 18-44 years, while approximately 70% of those in the Danish cohort were less than 18 years.)

Understanding how eczema affects the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is an important future direction of research, Dr. Demehri emphasized. “The landscape of atopic eczema therapeutics has dramatically changed in the recent years. It will be very interesting to determine how new biologics impact cancer risk in eczema patients.”

Partial support for the work was provided by the Wellcome Trust, the Royal Society, the Dagmar Marshalls Fund, and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsens Fund. Dr. Mansfield disclosed support from a Wellcome Trust grant. Her coinvestigators disclosed ties to TARGET-DERM, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline, and from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, the British Heart Foundation, Diabetes UK, and IMI Horizon 2020 funding BIOMAP. Dr. Demehri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mansfield KE et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jun 24. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1948.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Pilot study shows apremilast effective for severe recurrent canker sores

showed.

“Canker sores [aphthous ulcers] are very common, yet are often not well managed as the diagnosis is not always correctly made,” lead study author Alison J. Bruce, MB, ChB, said in an interview following the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “They’re often mistaken for herpes infection and therefore treated with antiviral therapy. Of the available therapies, several have common side effects or require lab monitoring or are not uniformly effective.”

In their poster abstract, Dr. Bruce, of the division of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues noted that, while no principal etiology has been established for recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), immune up-regulation plays a role in the pathogenesis of the condition. “Attacks of RAS may be precipitated by local trauma, stress, food intake, drugs, hormonal changes and vitamin and trace element deficiencies,” they wrote. “Local and systemic conditions and genetic, immunological and microbial factors all may play a role in the pathogenesis.”

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, down-regulates inflammatory response by modulating expression of tumor necrosis factor–alpha; interferon-gamma; and interleukin-2, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and in July 2019, was approved for treating ulcers associated with Behçet’s disease, in adults.*

For the pilot study, the researchers enrolled 15 patients with RAS to receive apremilast 30 mg twice daily for 15 weeks after 1 week titration. To be eligible for the trial, patients must have had monthly oral ulcers in preceding 6 months, at least two ulcers in previous 4 weeks prior to enrollment at baseline, at least three ulcers during flares, inadequate control with topical therapy, and no evidence of systemic disease. They excluded patients on immune-modulating therapy or systemic steroids, pregnant or breastfeeding women, those with a systemic infection, those with a history of recurrent bacterial, viral, fungal, or mycobacterial infection, those with a history of depression, as well as those with a known malignancy or vitamin deficiencies. Patients were assessed monthly, evaluating number of ulcers, visual analog pain scale, physician’s global assessment and Chronic Oral Mucosal Disease Questionnaire (COMDQ).

Dr. Bruce and colleagues found that, within 4 weeks of therapy, complete clearance of RAS lesions occurred in all patients except one in whom ulcers were reported to be less severe. That patient had considerable reduction in number, size, and duration of oral ulcers. Remission in all patients was sustained during 16 weeks of treatment. COMDQ responses improved considerably from baseline to week 8, and this was continued until week 16.

“Onset of response [to apremilast] was rapid,” Dr. Bruce said. “For many other therapies, patients are counseled that [they] may take several weeks to become effective. Response was also dramatic. Almost all patients had complete remission from their ulcers, compared with other therapies where oftentimes reduction or attenuation is achieved, as opposed to complete resolution. There was a suggestion that a lower dose [of apremilast] may still be effective. This adds to our ‘toolbox’ of therapeutic options.”

The most common adverse effects were nausea/vomiting and headache, but these were mild and tolerable and generally resolved by week 4.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size. “The challenge will most likely be insurance coverage,” Dr. Bruce said. “This is unfortunate, as it would be ideal to offer a safe treatment without the need for monitoring.”

The investigator-initiated study was supported by Celgene. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bruce AJ et al. AAD 20, Abstract 17701.

*Correction 6/23/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the approved indications for apremilast.

showed.

“Canker sores [aphthous ulcers] are very common, yet are often not well managed as the diagnosis is not always correctly made,” lead study author Alison J. Bruce, MB, ChB, said in an interview following the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “They’re often mistaken for herpes infection and therefore treated with antiviral therapy. Of the available therapies, several have common side effects or require lab monitoring or are not uniformly effective.”

In their poster abstract, Dr. Bruce, of the division of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues noted that, while no principal etiology has been established for recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), immune up-regulation plays a role in the pathogenesis of the condition. “Attacks of RAS may be precipitated by local trauma, stress, food intake, drugs, hormonal changes and vitamin and trace element deficiencies,” they wrote. “Local and systemic conditions and genetic, immunological and microbial factors all may play a role in the pathogenesis.”

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, down-regulates inflammatory response by modulating expression of tumor necrosis factor–alpha; interferon-gamma; and interleukin-2, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and in July 2019, was approved for treating ulcers associated with Behçet’s disease, in adults.*

For the pilot study, the researchers enrolled 15 patients with RAS to receive apremilast 30 mg twice daily for 15 weeks after 1 week titration. To be eligible for the trial, patients must have had monthly oral ulcers in preceding 6 months, at least two ulcers in previous 4 weeks prior to enrollment at baseline, at least three ulcers during flares, inadequate control with topical therapy, and no evidence of systemic disease. They excluded patients on immune-modulating therapy or systemic steroids, pregnant or breastfeeding women, those with a systemic infection, those with a history of recurrent bacterial, viral, fungal, or mycobacterial infection, those with a history of depression, as well as those with a known malignancy or vitamin deficiencies. Patients were assessed monthly, evaluating number of ulcers, visual analog pain scale, physician’s global assessment and Chronic Oral Mucosal Disease Questionnaire (COMDQ).

Dr. Bruce and colleagues found that, within 4 weeks of therapy, complete clearance of RAS lesions occurred in all patients except one in whom ulcers were reported to be less severe. That patient had considerable reduction in number, size, and duration of oral ulcers. Remission in all patients was sustained during 16 weeks of treatment. COMDQ responses improved considerably from baseline to week 8, and this was continued until week 16.

“Onset of response [to apremilast] was rapid,” Dr. Bruce said. “For many other therapies, patients are counseled that [they] may take several weeks to become effective. Response was also dramatic. Almost all patients had complete remission from their ulcers, compared with other therapies where oftentimes reduction or attenuation is achieved, as opposed to complete resolution. There was a suggestion that a lower dose [of apremilast] may still be effective. This adds to our ‘toolbox’ of therapeutic options.”

The most common adverse effects were nausea/vomiting and headache, but these were mild and tolerable and generally resolved by week 4.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size. “The challenge will most likely be insurance coverage,” Dr. Bruce said. “This is unfortunate, as it would be ideal to offer a safe treatment without the need for monitoring.”

The investigator-initiated study was supported by Celgene. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bruce AJ et al. AAD 20, Abstract 17701.

*Correction 6/23/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the approved indications for apremilast.

showed.

“Canker sores [aphthous ulcers] are very common, yet are often not well managed as the diagnosis is not always correctly made,” lead study author Alison J. Bruce, MB, ChB, said in an interview following the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “They’re often mistaken for herpes infection and therefore treated with antiviral therapy. Of the available therapies, several have common side effects or require lab monitoring or are not uniformly effective.”

In their poster abstract, Dr. Bruce, of the division of dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues noted that, while no principal etiology has been established for recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS), immune up-regulation plays a role in the pathogenesis of the condition. “Attacks of RAS may be precipitated by local trauma, stress, food intake, drugs, hormonal changes and vitamin and trace element deficiencies,” they wrote. “Local and systemic conditions and genetic, immunological and microbial factors all may play a role in the pathogenesis.”

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, down-regulates inflammatory response by modulating expression of tumor necrosis factor–alpha; interferon-gamma; and interleukin-2, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-23. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, and in July 2019, was approved for treating ulcers associated with Behçet’s disease, in adults.*

For the pilot study, the researchers enrolled 15 patients with RAS to receive apremilast 30 mg twice daily for 15 weeks after 1 week titration. To be eligible for the trial, patients must have had monthly oral ulcers in preceding 6 months, at least two ulcers in previous 4 weeks prior to enrollment at baseline, at least three ulcers during flares, inadequate control with topical therapy, and no evidence of systemic disease. They excluded patients on immune-modulating therapy or systemic steroids, pregnant or breastfeeding women, those with a systemic infection, those with a history of recurrent bacterial, viral, fungal, or mycobacterial infection, those with a history of depression, as well as those with a known malignancy or vitamin deficiencies. Patients were assessed monthly, evaluating number of ulcers, visual analog pain scale, physician’s global assessment and Chronic Oral Mucosal Disease Questionnaire (COMDQ).

Dr. Bruce and colleagues found that, within 4 weeks of therapy, complete clearance of RAS lesions occurred in all patients except one in whom ulcers were reported to be less severe. That patient had considerable reduction in number, size, and duration of oral ulcers. Remission in all patients was sustained during 16 weeks of treatment. COMDQ responses improved considerably from baseline to week 8, and this was continued until week 16.

“Onset of response [to apremilast] was rapid,” Dr. Bruce said. “For many other therapies, patients are counseled that [they] may take several weeks to become effective. Response was also dramatic. Almost all patients had complete remission from their ulcers, compared with other therapies where oftentimes reduction or attenuation is achieved, as opposed to complete resolution. There was a suggestion that a lower dose [of apremilast] may still be effective. This adds to our ‘toolbox’ of therapeutic options.”

The most common adverse effects were nausea/vomiting and headache, but these were mild and tolerable and generally resolved by week 4.

The researchers acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its small sample size. “The challenge will most likely be insurance coverage,” Dr. Bruce said. “This is unfortunate, as it would be ideal to offer a safe treatment without the need for monitoring.”

The investigator-initiated study was supported by Celgene. The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bruce AJ et al. AAD 20, Abstract 17701.

*Correction 6/23/2020: An earlier version of this story misstated the approved indications for apremilast.

FROM AAD 20

Increased hypothyroidism risk seen in young men with HS

Anna Figueiredo, MD, declared at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The surprise about this finding from a large retrospective case-control study stems from the fact that the elevated risk for hypothyroidism didn’t also extend to younger women with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) nor to patients older than 40 years of either gender, explained Dr. Figueiredo of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a retrospective case-control study based on information extracted from a medical records database of more than 8 million Midwestern adults. Among nearly 141,000 dermatology patients with follow-up in the database for at least 1 year, there were 405 HS patients aged 18-40 years and 327 aged 41-89.

In an age-matched comparison with the dermatology patients without HS, the younger HS cohort was at a significant 1.52-fold increased risk for comorbid hypothyroidism. Upon further stratification by sex, only the younger men with HS were at increased risk. Those patients were at 3.95-fold greater risk for having a diagnosis of hypothyroidism than were age-matched younger male dermatology patients.

Both younger and older HS patients were at numerically increased risk for being diagnosed with hyperthyroidism; however, this difference didn’t approach statistical significance because there were so few cases: a total of just eight in the HS population across the full age spectrum.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic inflammatory disease with an estimated prevalence of up to 4% in the United States. Growing evidence suggests it is an immune-mediated disorder because the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) has been approved for treatment of HS.

Thyroid disease is also often autoimmune-mediated, but its relationship with HS hasn’t been extensively examined. A recent meta-analysis of five case-control studies concluded that HS was associated with a 1.36-fold increased risk of thyroid disease; however, the Nepalese investigators didn’t distinguish between hypo- and hyperthyroidism (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb;82[2]:491-3).

Dr. Figueiredo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was without commercial support.

Anna Figueiredo, MD, declared at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The surprise about this finding from a large retrospective case-control study stems from the fact that the elevated risk for hypothyroidism didn’t also extend to younger women with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) nor to patients older than 40 years of either gender, explained Dr. Figueiredo of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a retrospective case-control study based on information extracted from a medical records database of more than 8 million Midwestern adults. Among nearly 141,000 dermatology patients with follow-up in the database for at least 1 year, there were 405 HS patients aged 18-40 years and 327 aged 41-89.

In an age-matched comparison with the dermatology patients without HS, the younger HS cohort was at a significant 1.52-fold increased risk for comorbid hypothyroidism. Upon further stratification by sex, only the younger men with HS were at increased risk. Those patients were at 3.95-fold greater risk for having a diagnosis of hypothyroidism than were age-matched younger male dermatology patients.

Both younger and older HS patients were at numerically increased risk for being diagnosed with hyperthyroidism; however, this difference didn’t approach statistical significance because there were so few cases: a total of just eight in the HS population across the full age spectrum.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic inflammatory disease with an estimated prevalence of up to 4% in the United States. Growing evidence suggests it is an immune-mediated disorder because the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) has been approved for treatment of HS.

Thyroid disease is also often autoimmune-mediated, but its relationship with HS hasn’t been extensively examined. A recent meta-analysis of five case-control studies concluded that HS was associated with a 1.36-fold increased risk of thyroid disease; however, the Nepalese investigators didn’t distinguish between hypo- and hyperthyroidism (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Feb;82[2]:491-3).

Dr. Figueiredo reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was without commercial support.

Anna Figueiredo, MD, declared at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The surprise about this finding from a large retrospective case-control study stems from the fact that the elevated risk for hypothyroidism didn’t also extend to younger women with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) nor to patients older than 40 years of either gender, explained Dr. Figueiredo of the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a retrospective case-control study based on information extracted from a medical records database of more than 8 million Midwestern adults. Among nearly 141,000 dermatology patients with follow-up in the database for at least 1 year, there were 405 HS patients aged 18-40 years and 327 aged 41-89.

In an age-matched comparison with the dermatology patients without HS, the younger HS cohort was at a significant 1.52-fold increased risk for comorbid hypothyroidism. Upon further stratification by sex, only the younger men with HS were at increased risk. Those patients were at 3.95-fold greater risk for having a diagnosis of hypothyroidism than were age-matched younger male dermatology patients.

Both younger and older HS patients were at numerically increased risk for being diagnosed with hyperthyroidism; however, this difference didn’t approach statistical significance because there were so few cases: a total of just eight in the HS population across the full age spectrum.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic inflammatory disease with an estimated prevalence of up to 4% in the United States. Growing evidence suggests it is an immune-mediated disorder because the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab (Humira) has been approved for treatment of HS.