User login

Disparities of Cutaneous Malignancies in the US Military

Occupational sun exposure is a well-known risk factor for the development of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). In addition to sun exposure, US military personnel may face other risk factors such as lack of access to adequate sun protection, work in equatorial latitudes, and increased exposure to carcinogens. In one study, fewer than 30% of surveyed soldiers reported regular sunscreen use during deployment and reported the face, neck, and upper extremities were unprotected at least 70% of the time.1 Skin cancer risk factors that are more common in military service members include inadequate sunscreen access, insufficient sun protection, harsh weather conditions, more immediate safety concerns than sun protection, and male gender. A higher incidence of melanoma and NMSC has been correlated with the more common demographics of US veterans such as male sex, older age, and White race.2

Although not uncommon in both civilian and military populations, we present the case of a military service member who developed skin cancer at an early age potentially due to occupational sun exposure. We also provide a review of the literature to examine the risk factors and incidence of melanoma and NMSC in US military personnel and veterans and provide recommendations for skin cancer prevention, screening, and intervention in the military population.

Case Report

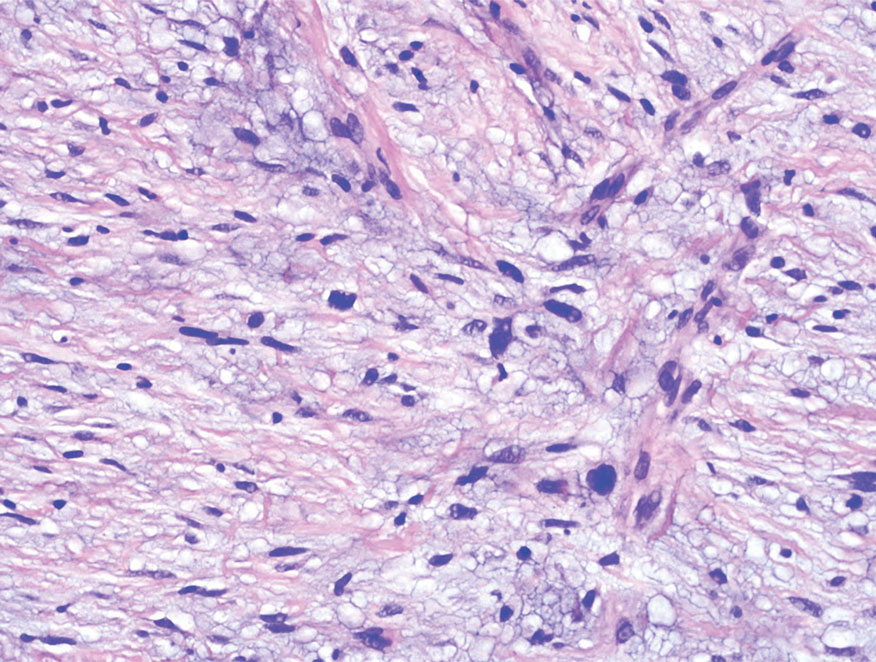

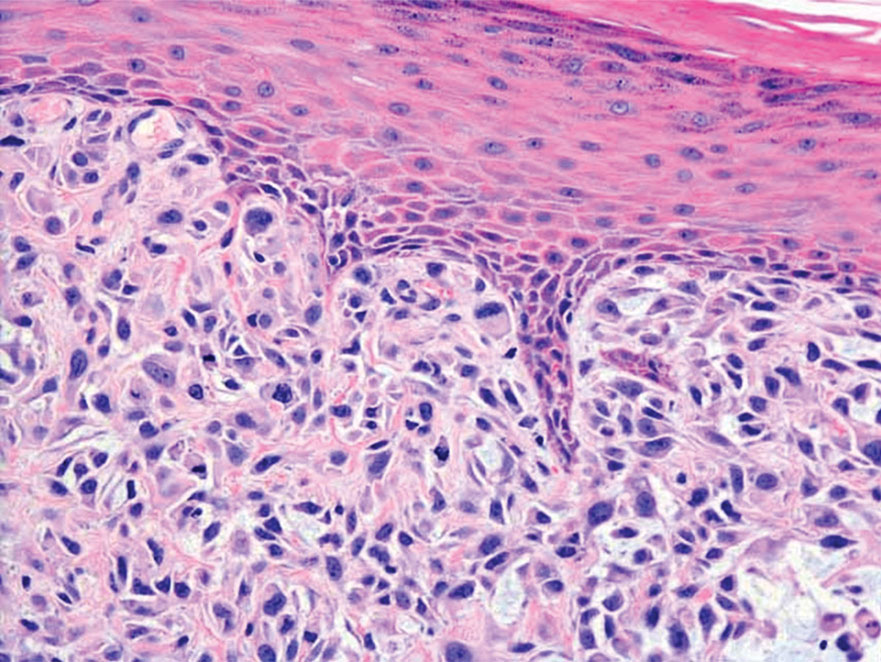

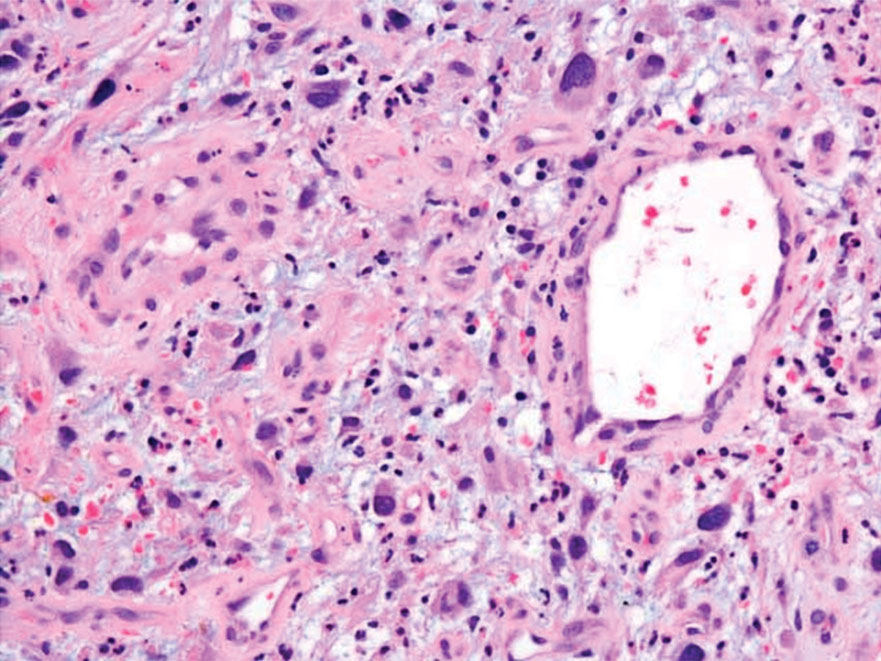

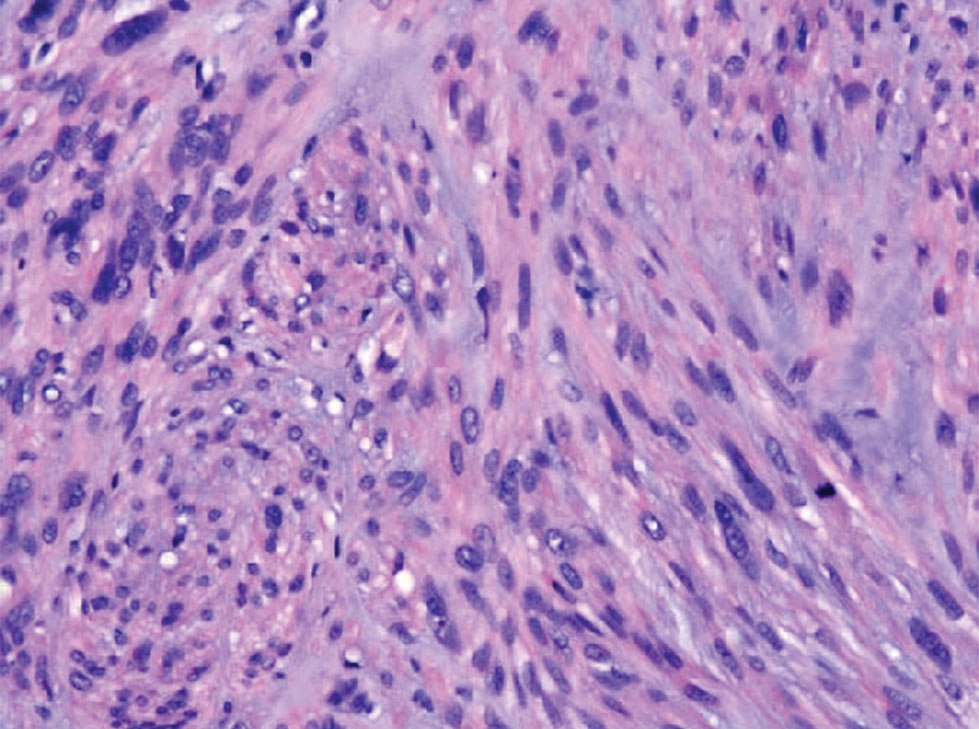

A 37-year-old White active-duty male service member in the US Navy (USN) presented with a nonhealing lesion on the nose of 2 years’ duration that had been gradually growing and bleeding for several weeks. He participated in several sea deployments while onboard a naval destroyer over his 10-year military career. He did not routinely use sunscreen during his deployments. His personal and family medical history lacked risk factors for skin cancer other than his skin tone and frequent sun exposure.

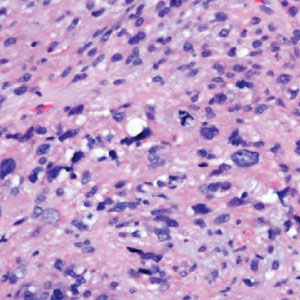

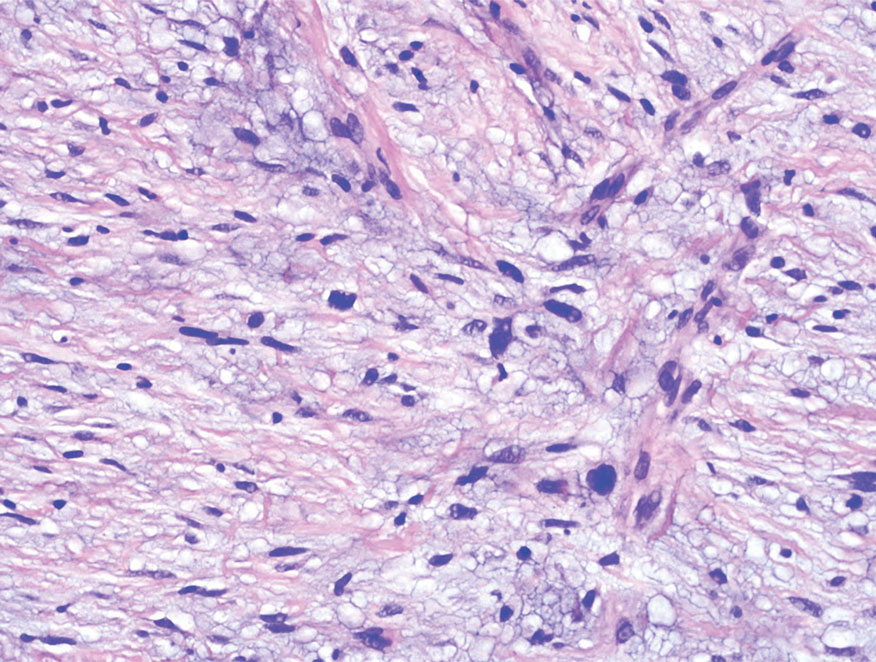

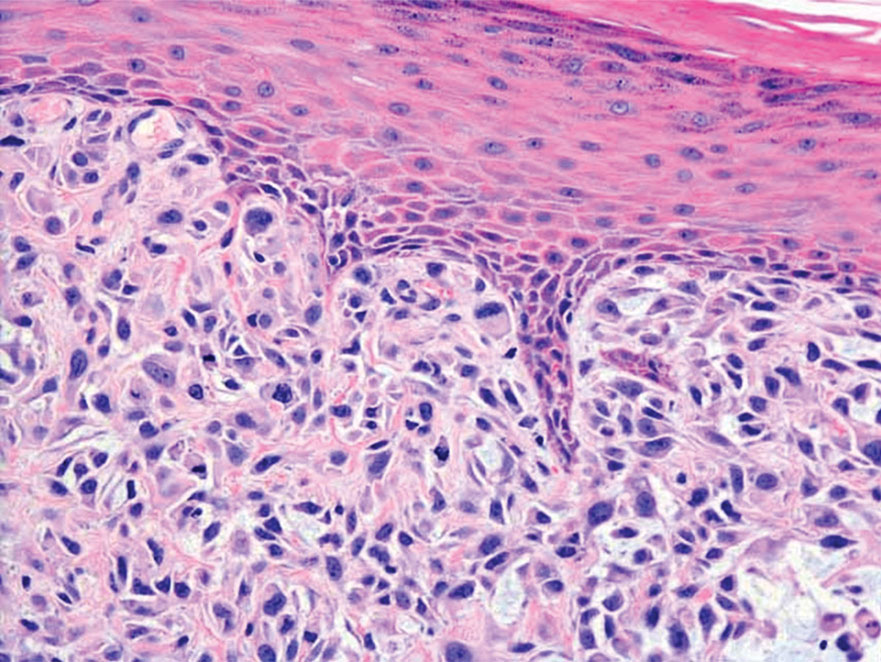

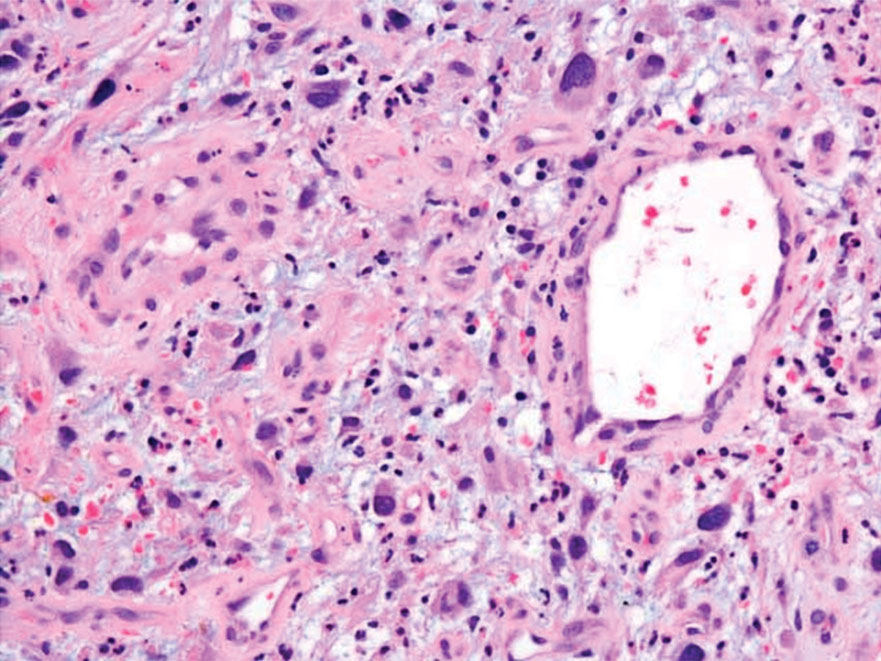

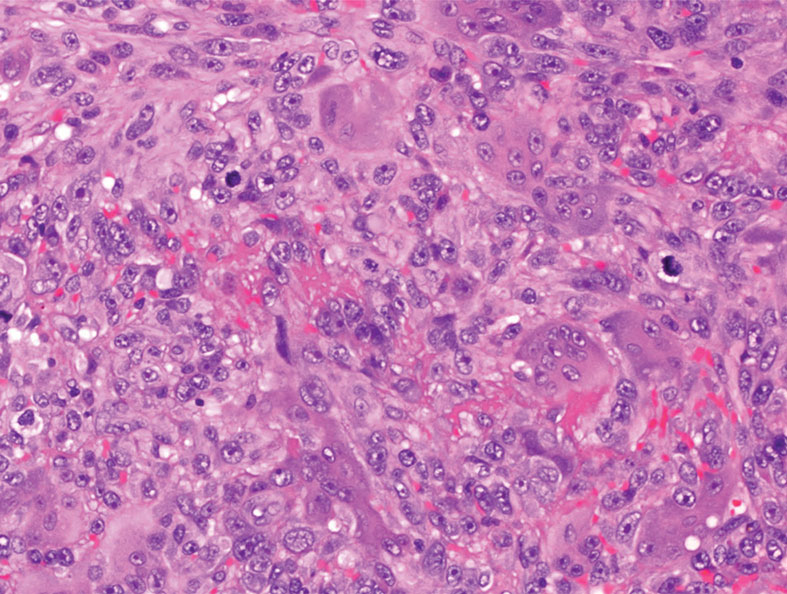

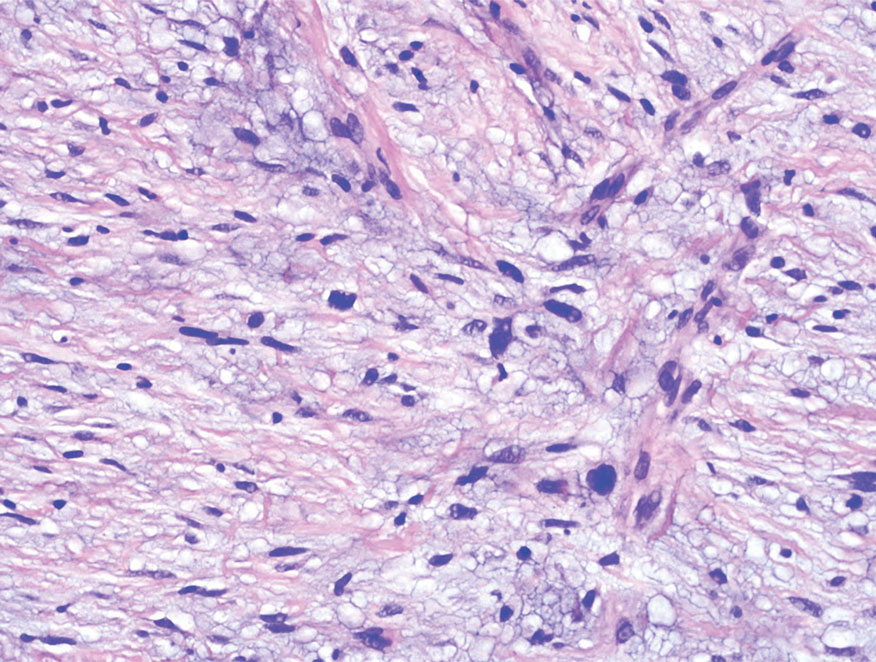

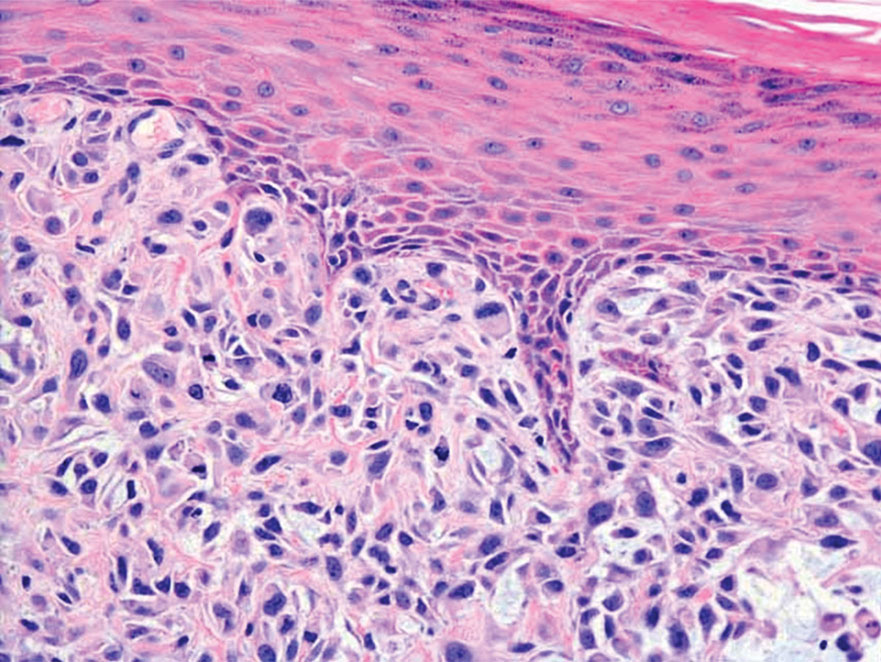

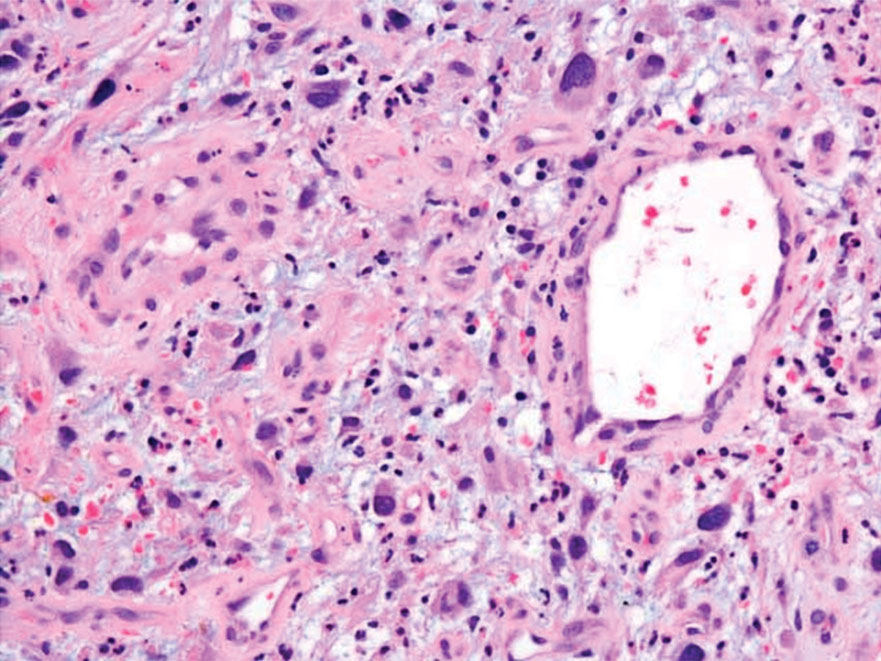

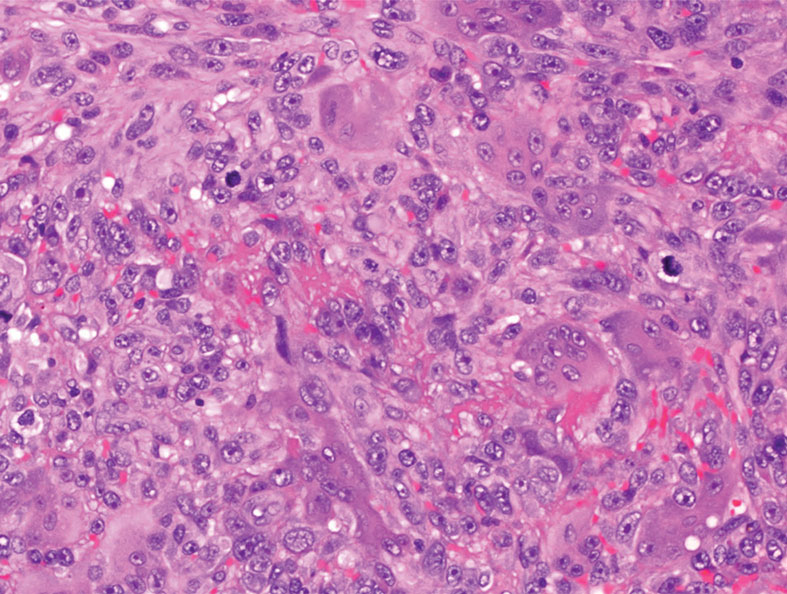

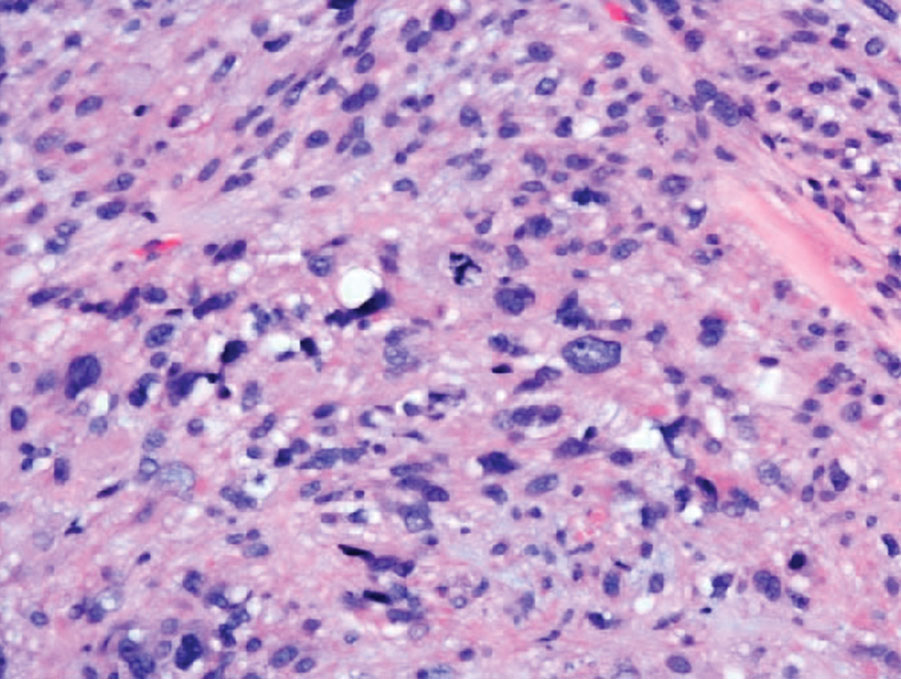

Physical examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated plaque with rolled borders and prominent telangiectases on the mid nasal dorsum. A shave biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery, which required repair with an advancement flap. He currently continues his active-duty service and is preparing for his next overseas deployment.

Literature Review

We conducted a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms skin cancer, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, or sebaceous carcinoma along with military, Army, Navy, Air Force, or veterans. Studies from January 1984 to April 2020 were included in our qualitative review. All articles were reviewed, and those that did not examine skin cancer and the military population in the United States were excluded. Relevant data, such as results of skin cancer incidence or risk factors or insights about developing skin cancer in this affected population, were extracted from the selected publications.

Several studies showed overall increased age-adjusted incidence rates of melanoma and NMSC among military service personnel compared to age-matched controls in the general population.2 A survey of draft-age men during World War II found a slightly higher percentage of respondents with history of melanoma compared to the control group (83% [74/89] vs 76% [49/65]). Of those who had a history of melanoma, 34% (30/89) served in the tropics compared to 6% (4/65) in the control group.3 A tumor registry review found the age-adjusted melanoma incidence rates per 100,000 person-years for White individuals in the military vs the general population was 33.6 vs 27.5 among those aged 45 to 49 years, 49.8 vs 32.2 among those aged 50 to 54 years, and 178.5 vs 39.2 among those aged 55 to 59 years.4 Among published literature reviews, members of the US Air Force (USAF) had the highest rates of melanoma compared to other military branches, with an incidence rate of 7.6 vs 6.3 among USAF males vs Army males and 9.0 vs 5.5 among USAF females vs Army females.4 These findings were further supported by another study showing a higher incidence rate of melanoma in USAF members compared to Army personnel (17.8 vs 9.5) and a 62% greater melanoma incidence in active-duty military personnel compared to the general population when adjusted for age, race, sex, and year of diagnosis.5 Additionally, a meta-analysis reported a standardized incidence ratio of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.9) for malignant melanoma and 1.8 (95% CI, 1.3-2.8) for NMSC among military pilots compared to the general population.6 It is important to note that these data are limited to published peer-reviewed studies within PubMed and may not reflect the true skin cancer incidence.

More comprehensive studies are needed to compare NMSC incidence rates in nonpilot military populations compared to the general population. From 2005 to 2014, the average annual NMSC incidence rate in the USAF was 64.4 per 100,000 person-years, with the highest rate at 97.4 per 100,000 person-years in 2007.7 However, this study did not directly compare military service members to the general population. Service in tropical environments among World War II veterans was associated with an increased risk for NMSC. Sixty-six percent of patients with BCC (n=197) and 68% with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(n=41) were stationed in the Pacific, despite the number and demographics of soldiers deployed to the Pacific and Europe being approximately equal.8 During a 6-month period in 2008, a Combat Dermatology Clinic in Iraq showed 5% (n=129) of visits were for treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs), while 8% of visits (n=205) were related to skin cancer, including BCC, SCC, mycosis fungoides, and melanoma.9 Overall, these studies confirm a higher rate of melanoma in military service members vs the general population and indicate USAF members may be at the greatest risk for developing melanoma and NMSC among the service branches. Further studies are needed to elucidate why this might be the case and should concentrate on demographics, service locations, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, and use of sun-protective measures across each service branch.

Our search yielded no aggregate studies to determine if there is an increased rate of other types of skin cancer in military service members such as Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Gerall et al10 described a case of MAC in a 43-year-old USAF U-2 pilot with a 15-year history of a slow-growing soft-tissue nodule on the cheek. The patient’s young age differed from the typical age of MAC occurrence (ie, 60–70 years), which led to the possibility that his profession contributed to the development of MAC and the relatively young age of onset.10

Etiology of Disease

The results of our literature review indicated that skin cancers are more prevalent among active-duty military personnel and veterans than in the general population; they also suggest that frequent sun exposure and lack of sun protection may be key etiologic factors. In 2015, only 23% of veterans (n=49) reported receiving skin cancer awareness education from the US Military.1 Among soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan (n=212), only 13% reported routine sunscreen use, and

Exposure to UV radiation at higher altitudes (with corresponding higher UV energy) and altered sleep-wake cycles (with resulting altered immune defenses) may contribute to higher rates of melanoma and NMSC among USAF pilots.11 During a 57-minute flight at 30,000-ft altitude, a pilot is exposed to a UVA dose equivalent to 20 minutes inside a tanning booth.12 Although UVB transmission through plastic and glass windshields was reported to be less than 1%, UVA transmission ranged from 0.4% to 53.5%. The UVA dose for a pilot flying a light aircraft in Las Vegas, Nevada, was reported to be 127 μW/cm2 at ground level vs 242 μW/cm2 at a 30,000-ft altitude.12 Therefore, cosmic radiation exposure for military pilots is higher than for commercial pilots, as they fly at higher altitudes. U-2 pilots are exposed to 20 times the cosmic radiation dose at sea level and 10 times the exposure of commercial pilots.10

It currently is unknown why service in the USAF would increase skin cancer risk compared to service in other branches; however, there are some differences between military branches that require further research, including ethnic demographics, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, duty assignment locations, and the hours the military members are asked to work outside with direct sunlight exposure for each branch of service. Environmental exposures may differ based on the military branch gear requirements; for example, when on the flight line or flight deck, USN aircrews are required to wear cranials (helmets), eyewear (visor or goggles), and long-sleeved shirts. When at sea, USN flight crews wear gloves, headgear, goggles, pants, and long-sleeved shirts to identify their duty onboard. All of these measures offer good sun protection and are carried over to the land-based flight lines in the USN and Marine Corps. Neither the Army nor the USAF commonly utilize these practices. Conversely, the USAF does not allow flight line workers including fuelers, maintainers, and aircrew to wear coveralls due to the risk of being blown off, becoming foreign object debris, and being sucked into jet engines. However, in-flight protective gear such as goggles, gloves, and coveralls are worn.12 Perhaps the USAF may attract, recruit, or commission people with inherently more risk for skin cancer (eg, White individuals). How racial and ethnic factors may affect skin cancer incidence in military branches is an area for future research efforts.

Recommendations

Given the considerable increase in risk factors, efforts are needed to reduce the disparity in skin cancer rates between US military personnel and their civilian counterparts through appropriate prevention, screening, and intervention programs.

Prevention—In wartime settings as well as in training and other peacetime activities, active-duty military members cannot avoid harmful midday sun exposure. Additionally, application and reapplication of sunscreen can be challenging. Sunscreen, broad-spectrum lip balm, and wide-brimmed “boonie” hats can be ordered by supply personnel.13 We recommend that a standard sunscreen supply be available to all active-duty military service members. The long-sleeved, tightly woven fabric of military uniforms also can provide protection from the sun but can be difficult to tolerate for extended periods of time in warm climates. Breathable, lightweight, sun-protective clothing is commercially available and could be incorporated into military uniforms.

All service members should be educated about skin cancer risks while addressing common myths and inaccuracies. Fifty percent (n=50) of surveyed veterans thought discussions of skin cancer prevention and safety during basic training could help prevent skin cancer in service members.14 Suggestions from respondents included education about sun exposure consequences, use of graphic images of skin cancer in teaching, providing protective clothing and sunscreen to active-duty military service members, and discussion about sun protection with physicians during annual physicals. When veterans with a history of skin cancer were surveyed about their personal risk for skin cancer, most believed they were at little risk (average perceived risk response score, 2.2 out of 5 [1=no risk; 5=high risk]).14 The majority explained that they did not seek sun protection after warnings of skin cancer risk because they did not think skin cancer would happen to them,14 though the incidence of NMSC in the United States at the time of these surveys was estimated to be 3.5 million per year.14,15 Another study found that only 13% of veterans knew the back is the most common site of melanoma in men.1 The Army Public Health Center has informational fact sheets available online or in dermatologists’ offices that detail correct sunscreen application techniques and how to reduce sun exposure.16,17 However, military service members reported that they prefer physicians to communicate with them directly about skin cancer risks vs reading brochures in physician offices or gaining information from television, radio, military training, or the Internet (4.4 out 5 rating for communication methods of risks associated with skin cancer [1=ineffective; 5=very effective]).14 However, only 27% of nondermatologist physicians counseled or screened their patients on skin cancer or sunscreen yearly, 49% even less frequently, with 24% never counseling or screening at all. Because not all service members may be able to regularly see a dermatologist, efforts should be focused on increasing primary care physician awareness on counseling and screening.18

Early Detection—Military service members should be educated on how to perform skin self-examinations to alert their providers earlier to concerning lesions. The American Academy of Dermatology publishes infographics regarding the ABCDEs of melanoma and how to perform skin self-examinations.19,20 Although the US Preventive Services Task Force concluded there was insufficient evidence to recommend skin self-examination for all adults, the increased risk that military service members and veterans have requires further studies to examine the utility of self-screening in this population.20 Given the evidence of a higher incidence of melanoma in military service members vs the general population after 45 years of age,4 we recommend starting yearly in-person screenings performed by primary care physicians or dermatologists at this age. Ensuring every service member has routine in-office skin examinations can be difficult given the limited number of active-duty military dermatologists. Civilian dermatologists also could be helpful in this respect.

Teleconsultation, teledermoscopy, or store-and-forward imaging services for concerning lesions could be utilized when in-person consultations with a dermatologist are not feasible or cannot be performed in a timely manner. From 2004 to 2012, 40% of 10,817 teleconsultations were dermatology consultations from deployed or remote environments.21 Teleconsultation can be performed via email through the global military teleconsultation portal.22 These methods can lead to earlier detection of skin cancer rather than delaying evaluation for an in-person consultation.23

Intervention—High-risk patients who have been diagnosed with NMSC or many AKs should consider oral, procedural, or topical chemoprevention to reduce the risk for additional skin cancers as both primary and secondary prevention. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of 386 individuals with a history of 2 or more NMSCs, participants were randomly assigned to receive either 500 mg of nicotinamide twice daily or placebo for 12 months. Compared to the placebo group, the nicotinamide group had a 23% lower rate of new NMSCs and an 11% lower rate of new AKs at 12 months.24 The use of acitretin also has been studied in transplant recipients for the chemoprevention of NMSC. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of renal transplant recipients with more than 10 AKs randomized to receive either 30 mg/d of acitretin or placebo for 6 months, 11% of the acitretin group reported a new NMSC compared to 47% in the placebo group.25 An open-label study of 27 renal transplant recipients treated with methyl-esterified aminolevulinic acid–photodynamic therapy and red light demonstrated an increased mean time to occurrence of an AK, SCC, BCC, keratoacanthoma, or wart from 6.8 months in untreated areas compared to 9.6 months in treated areas.25 In active-duty locations where access to red and blue light sources is unavailable, the use of daylight photodynamic therapy can be considered, as it does not require any special equipment. Topical treatments such as 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod can be used for treatment and chemoprevention of NMSC. In a follow-up study from the Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial, patients who applied 5-fluorouracil cream 5% twice daily to the face and ears for 4 weeks had a 75% risk reduction in developing SCC requiring surgery compared to the control group for the first year after treatment.26,27

Final Thoughts

Focusing on the efforts we propose can help the US Military expand their prevention, screening, and intervention programs for skin cancer in service members. Further research can then be performed to determine which programs have the greatest impact on rates of skin cancer among military and veteran personnel. Given these higher incidences and risk of exposure for skin cancer among service members, the various services may consider mandating sunscreen use as part of the uniform to prevent skin cancer. To maximize effectiveness, these efforts to prevent the development of skin cancer among military and veteran personnel should be adopted nationally.

- Powers JG, Patel NA, Powers EM, et al. Skin cancer risk factors and preventative behaviors among United States military veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2871-2873.

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192.

- Brown J, Kopf AW, Rigel DS, et al. Malignant melanoma in World War II veterans. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:661-663.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the U.S. Military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:318-323.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, et al. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179:247-253.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in pilots and cabin crew: UV measurements in flying airplanes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:450-452.

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Ramani ML, Bennett RG. High prevalence of skin cancer in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:733-737.

- Henning JS, Firoz, BF. Combat dermatology: the prevalence of skin disease in a deployed dermatology clinic in Iraq. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:210-214.

- Gerall CD, Sippel MR, Yracheta JL, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a rare, commonly misdiagnosed malignancy. Mil Med. 2019;184:948-950.

- Wilkison B, Wong E. Skin cancer in military pilots: a special population with special risk factors. Cutis. 2017;100:218-220.

- Proctor SP, Heaton KJ, Smith KW, et al. The Occupational JP8 Neuroepidemiology Study (OJENES): repeated workday exposure and central nervous system functioning among US Air Force personnel. Neurotoxicology. 2011;32:799-808.

- Soldiers protect themselves from skin cancer. US Army website. Published February 28, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.army.mil/article/17601/soldiers_protect_themselves_from_skin_cancer

- Fisher V, Lee D, McGrath J, et al. Veterans speak up: current warnings on skin cancer miss the target, suggestions for improvement. Mil Med. 2015;180:892-897.

- Rogers HW, Weinstick MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Sun safety. Army Public Health Center website. Updated June 6, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/topics/discond/hipss/Pages/Sun-Safety.aspx

- Outdoor ultraviolet radiation hazards and protection. Army Public Health Center website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/OutdoorUltravioletRadiationHazardsandProtection_FS_24-017-1115.pdf

- Saraiya M, Frank E, Elon L, et al. Personal and clinical skin cancer prevention practices of US women physicians. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:633-642.

- What to look for: ABCDEs of melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/at-risk/abcdes

- Detect skin cancer: how to perform a skin self-exam. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/check-skin

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the US military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353.

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:2034-2039.

- Day WG, Shirvastava V, Roman JW. Synchronous teledermoscopy in military treatment facilities. Mil Med. 2020;185:1334-1337.

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

- Bavinck JN, Tieben LM, Van der Woude FJ, et al. Prevention of skin cancer and reduction of keratotic skin lesions during acitretin therapy in renal transplant recipients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1933-1938.

- Wulf HC, Pavel S, Stender I, et al. Topical photodynamic therapy for prevention of new skin lesions in renal transplant recipients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:25-28.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al; Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial (VAKCC) Group. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

Occupational sun exposure is a well-known risk factor for the development of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). In addition to sun exposure, US military personnel may face other risk factors such as lack of access to adequate sun protection, work in equatorial latitudes, and increased exposure to carcinogens. In one study, fewer than 30% of surveyed soldiers reported regular sunscreen use during deployment and reported the face, neck, and upper extremities were unprotected at least 70% of the time.1 Skin cancer risk factors that are more common in military service members include inadequate sunscreen access, insufficient sun protection, harsh weather conditions, more immediate safety concerns than sun protection, and male gender. A higher incidence of melanoma and NMSC has been correlated with the more common demographics of US veterans such as male sex, older age, and White race.2

Although not uncommon in both civilian and military populations, we present the case of a military service member who developed skin cancer at an early age potentially due to occupational sun exposure. We also provide a review of the literature to examine the risk factors and incidence of melanoma and NMSC in US military personnel and veterans and provide recommendations for skin cancer prevention, screening, and intervention in the military population.

Case Report

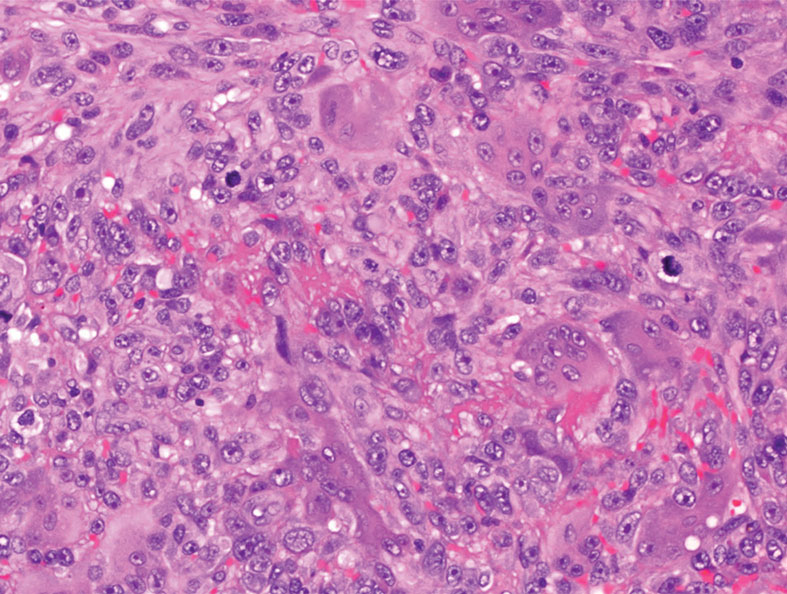

A 37-year-old White active-duty male service member in the US Navy (USN) presented with a nonhealing lesion on the nose of 2 years’ duration that had been gradually growing and bleeding for several weeks. He participated in several sea deployments while onboard a naval destroyer over his 10-year military career. He did not routinely use sunscreen during his deployments. His personal and family medical history lacked risk factors for skin cancer other than his skin tone and frequent sun exposure.

Physical examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated plaque with rolled borders and prominent telangiectases on the mid nasal dorsum. A shave biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery, which required repair with an advancement flap. He currently continues his active-duty service and is preparing for his next overseas deployment.

Literature Review

We conducted a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms skin cancer, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, or sebaceous carcinoma along with military, Army, Navy, Air Force, or veterans. Studies from January 1984 to April 2020 were included in our qualitative review. All articles were reviewed, and those that did not examine skin cancer and the military population in the United States were excluded. Relevant data, such as results of skin cancer incidence or risk factors or insights about developing skin cancer in this affected population, were extracted from the selected publications.

Several studies showed overall increased age-adjusted incidence rates of melanoma and NMSC among military service personnel compared to age-matched controls in the general population.2 A survey of draft-age men during World War II found a slightly higher percentage of respondents with history of melanoma compared to the control group (83% [74/89] vs 76% [49/65]). Of those who had a history of melanoma, 34% (30/89) served in the tropics compared to 6% (4/65) in the control group.3 A tumor registry review found the age-adjusted melanoma incidence rates per 100,000 person-years for White individuals in the military vs the general population was 33.6 vs 27.5 among those aged 45 to 49 years, 49.8 vs 32.2 among those aged 50 to 54 years, and 178.5 vs 39.2 among those aged 55 to 59 years.4 Among published literature reviews, members of the US Air Force (USAF) had the highest rates of melanoma compared to other military branches, with an incidence rate of 7.6 vs 6.3 among USAF males vs Army males and 9.0 vs 5.5 among USAF females vs Army females.4 These findings were further supported by another study showing a higher incidence rate of melanoma in USAF members compared to Army personnel (17.8 vs 9.5) and a 62% greater melanoma incidence in active-duty military personnel compared to the general population when adjusted for age, race, sex, and year of diagnosis.5 Additionally, a meta-analysis reported a standardized incidence ratio of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.9) for malignant melanoma and 1.8 (95% CI, 1.3-2.8) for NMSC among military pilots compared to the general population.6 It is important to note that these data are limited to published peer-reviewed studies within PubMed and may not reflect the true skin cancer incidence.

More comprehensive studies are needed to compare NMSC incidence rates in nonpilot military populations compared to the general population. From 2005 to 2014, the average annual NMSC incidence rate in the USAF was 64.4 per 100,000 person-years, with the highest rate at 97.4 per 100,000 person-years in 2007.7 However, this study did not directly compare military service members to the general population. Service in tropical environments among World War II veterans was associated with an increased risk for NMSC. Sixty-six percent of patients with BCC (n=197) and 68% with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(n=41) were stationed in the Pacific, despite the number and demographics of soldiers deployed to the Pacific and Europe being approximately equal.8 During a 6-month period in 2008, a Combat Dermatology Clinic in Iraq showed 5% (n=129) of visits were for treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs), while 8% of visits (n=205) were related to skin cancer, including BCC, SCC, mycosis fungoides, and melanoma.9 Overall, these studies confirm a higher rate of melanoma in military service members vs the general population and indicate USAF members may be at the greatest risk for developing melanoma and NMSC among the service branches. Further studies are needed to elucidate why this might be the case and should concentrate on demographics, service locations, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, and use of sun-protective measures across each service branch.

Our search yielded no aggregate studies to determine if there is an increased rate of other types of skin cancer in military service members such as Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Gerall et al10 described a case of MAC in a 43-year-old USAF U-2 pilot with a 15-year history of a slow-growing soft-tissue nodule on the cheek. The patient’s young age differed from the typical age of MAC occurrence (ie, 60–70 years), which led to the possibility that his profession contributed to the development of MAC and the relatively young age of onset.10

Etiology of Disease

The results of our literature review indicated that skin cancers are more prevalent among active-duty military personnel and veterans than in the general population; they also suggest that frequent sun exposure and lack of sun protection may be key etiologic factors. In 2015, only 23% of veterans (n=49) reported receiving skin cancer awareness education from the US Military.1 Among soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan (n=212), only 13% reported routine sunscreen use, and

Exposure to UV radiation at higher altitudes (with corresponding higher UV energy) and altered sleep-wake cycles (with resulting altered immune defenses) may contribute to higher rates of melanoma and NMSC among USAF pilots.11 During a 57-minute flight at 30,000-ft altitude, a pilot is exposed to a UVA dose equivalent to 20 minutes inside a tanning booth.12 Although UVB transmission through plastic and glass windshields was reported to be less than 1%, UVA transmission ranged from 0.4% to 53.5%. The UVA dose for a pilot flying a light aircraft in Las Vegas, Nevada, was reported to be 127 μW/cm2 at ground level vs 242 μW/cm2 at a 30,000-ft altitude.12 Therefore, cosmic radiation exposure for military pilots is higher than for commercial pilots, as they fly at higher altitudes. U-2 pilots are exposed to 20 times the cosmic radiation dose at sea level and 10 times the exposure of commercial pilots.10

It currently is unknown why service in the USAF would increase skin cancer risk compared to service in other branches; however, there are some differences between military branches that require further research, including ethnic demographics, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, duty assignment locations, and the hours the military members are asked to work outside with direct sunlight exposure for each branch of service. Environmental exposures may differ based on the military branch gear requirements; for example, when on the flight line or flight deck, USN aircrews are required to wear cranials (helmets), eyewear (visor or goggles), and long-sleeved shirts. When at sea, USN flight crews wear gloves, headgear, goggles, pants, and long-sleeved shirts to identify their duty onboard. All of these measures offer good sun protection and are carried over to the land-based flight lines in the USN and Marine Corps. Neither the Army nor the USAF commonly utilize these practices. Conversely, the USAF does not allow flight line workers including fuelers, maintainers, and aircrew to wear coveralls due to the risk of being blown off, becoming foreign object debris, and being sucked into jet engines. However, in-flight protective gear such as goggles, gloves, and coveralls are worn.12 Perhaps the USAF may attract, recruit, or commission people with inherently more risk for skin cancer (eg, White individuals). How racial and ethnic factors may affect skin cancer incidence in military branches is an area for future research efforts.

Recommendations

Given the considerable increase in risk factors, efforts are needed to reduce the disparity in skin cancer rates between US military personnel and their civilian counterparts through appropriate prevention, screening, and intervention programs.

Prevention—In wartime settings as well as in training and other peacetime activities, active-duty military members cannot avoid harmful midday sun exposure. Additionally, application and reapplication of sunscreen can be challenging. Sunscreen, broad-spectrum lip balm, and wide-brimmed “boonie” hats can be ordered by supply personnel.13 We recommend that a standard sunscreen supply be available to all active-duty military service members. The long-sleeved, tightly woven fabric of military uniforms also can provide protection from the sun but can be difficult to tolerate for extended periods of time in warm climates. Breathable, lightweight, sun-protective clothing is commercially available and could be incorporated into military uniforms.

All service members should be educated about skin cancer risks while addressing common myths and inaccuracies. Fifty percent (n=50) of surveyed veterans thought discussions of skin cancer prevention and safety during basic training could help prevent skin cancer in service members.14 Suggestions from respondents included education about sun exposure consequences, use of graphic images of skin cancer in teaching, providing protective clothing and sunscreen to active-duty military service members, and discussion about sun protection with physicians during annual physicals. When veterans with a history of skin cancer were surveyed about their personal risk for skin cancer, most believed they were at little risk (average perceived risk response score, 2.2 out of 5 [1=no risk; 5=high risk]).14 The majority explained that they did not seek sun protection after warnings of skin cancer risk because they did not think skin cancer would happen to them,14 though the incidence of NMSC in the United States at the time of these surveys was estimated to be 3.5 million per year.14,15 Another study found that only 13% of veterans knew the back is the most common site of melanoma in men.1 The Army Public Health Center has informational fact sheets available online or in dermatologists’ offices that detail correct sunscreen application techniques and how to reduce sun exposure.16,17 However, military service members reported that they prefer physicians to communicate with them directly about skin cancer risks vs reading brochures in physician offices or gaining information from television, radio, military training, or the Internet (4.4 out 5 rating for communication methods of risks associated with skin cancer [1=ineffective; 5=very effective]).14 However, only 27% of nondermatologist physicians counseled or screened their patients on skin cancer or sunscreen yearly, 49% even less frequently, with 24% never counseling or screening at all. Because not all service members may be able to regularly see a dermatologist, efforts should be focused on increasing primary care physician awareness on counseling and screening.18

Early Detection—Military service members should be educated on how to perform skin self-examinations to alert their providers earlier to concerning lesions. The American Academy of Dermatology publishes infographics regarding the ABCDEs of melanoma and how to perform skin self-examinations.19,20 Although the US Preventive Services Task Force concluded there was insufficient evidence to recommend skin self-examination for all adults, the increased risk that military service members and veterans have requires further studies to examine the utility of self-screening in this population.20 Given the evidence of a higher incidence of melanoma in military service members vs the general population after 45 years of age,4 we recommend starting yearly in-person screenings performed by primary care physicians or dermatologists at this age. Ensuring every service member has routine in-office skin examinations can be difficult given the limited number of active-duty military dermatologists. Civilian dermatologists also could be helpful in this respect.

Teleconsultation, teledermoscopy, or store-and-forward imaging services for concerning lesions could be utilized when in-person consultations with a dermatologist are not feasible or cannot be performed in a timely manner. From 2004 to 2012, 40% of 10,817 teleconsultations were dermatology consultations from deployed or remote environments.21 Teleconsultation can be performed via email through the global military teleconsultation portal.22 These methods can lead to earlier detection of skin cancer rather than delaying evaluation for an in-person consultation.23

Intervention—High-risk patients who have been diagnosed with NMSC or many AKs should consider oral, procedural, or topical chemoprevention to reduce the risk for additional skin cancers as both primary and secondary prevention. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of 386 individuals with a history of 2 or more NMSCs, participants were randomly assigned to receive either 500 mg of nicotinamide twice daily or placebo for 12 months. Compared to the placebo group, the nicotinamide group had a 23% lower rate of new NMSCs and an 11% lower rate of new AKs at 12 months.24 The use of acitretin also has been studied in transplant recipients for the chemoprevention of NMSC. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of renal transplant recipients with more than 10 AKs randomized to receive either 30 mg/d of acitretin or placebo for 6 months, 11% of the acitretin group reported a new NMSC compared to 47% in the placebo group.25 An open-label study of 27 renal transplant recipients treated with methyl-esterified aminolevulinic acid–photodynamic therapy and red light demonstrated an increased mean time to occurrence of an AK, SCC, BCC, keratoacanthoma, or wart from 6.8 months in untreated areas compared to 9.6 months in treated areas.25 In active-duty locations where access to red and blue light sources is unavailable, the use of daylight photodynamic therapy can be considered, as it does not require any special equipment. Topical treatments such as 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod can be used for treatment and chemoprevention of NMSC. In a follow-up study from the Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial, patients who applied 5-fluorouracil cream 5% twice daily to the face and ears for 4 weeks had a 75% risk reduction in developing SCC requiring surgery compared to the control group for the first year after treatment.26,27

Final Thoughts

Focusing on the efforts we propose can help the US Military expand their prevention, screening, and intervention programs for skin cancer in service members. Further research can then be performed to determine which programs have the greatest impact on rates of skin cancer among military and veteran personnel. Given these higher incidences and risk of exposure for skin cancer among service members, the various services may consider mandating sunscreen use as part of the uniform to prevent skin cancer. To maximize effectiveness, these efforts to prevent the development of skin cancer among military and veteran personnel should be adopted nationally.

Occupational sun exposure is a well-known risk factor for the development of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC). In addition to sun exposure, US military personnel may face other risk factors such as lack of access to adequate sun protection, work in equatorial latitudes, and increased exposure to carcinogens. In one study, fewer than 30% of surveyed soldiers reported regular sunscreen use during deployment and reported the face, neck, and upper extremities were unprotected at least 70% of the time.1 Skin cancer risk factors that are more common in military service members include inadequate sunscreen access, insufficient sun protection, harsh weather conditions, more immediate safety concerns than sun protection, and male gender. A higher incidence of melanoma and NMSC has been correlated with the more common demographics of US veterans such as male sex, older age, and White race.2

Although not uncommon in both civilian and military populations, we present the case of a military service member who developed skin cancer at an early age potentially due to occupational sun exposure. We also provide a review of the literature to examine the risk factors and incidence of melanoma and NMSC in US military personnel and veterans and provide recommendations for skin cancer prevention, screening, and intervention in the military population.

Case Report

A 37-year-old White active-duty male service member in the US Navy (USN) presented with a nonhealing lesion on the nose of 2 years’ duration that had been gradually growing and bleeding for several weeks. He participated in several sea deployments while onboard a naval destroyer over his 10-year military career. He did not routinely use sunscreen during his deployments. His personal and family medical history lacked risk factors for skin cancer other than his skin tone and frequent sun exposure.

Physical examination revealed a 1-cm ulcerated plaque with rolled borders and prominent telangiectases on the mid nasal dorsum. A shave biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis of nodular basal cell carcinoma (BCC). The patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery, which required repair with an advancement flap. He currently continues his active-duty service and is preparing for his next overseas deployment.

Literature Review

We conducted a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms skin cancer, melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, or sebaceous carcinoma along with military, Army, Navy, Air Force, or veterans. Studies from January 1984 to April 2020 were included in our qualitative review. All articles were reviewed, and those that did not examine skin cancer and the military population in the United States were excluded. Relevant data, such as results of skin cancer incidence or risk factors or insights about developing skin cancer in this affected population, were extracted from the selected publications.

Several studies showed overall increased age-adjusted incidence rates of melanoma and NMSC among military service personnel compared to age-matched controls in the general population.2 A survey of draft-age men during World War II found a slightly higher percentage of respondents with history of melanoma compared to the control group (83% [74/89] vs 76% [49/65]). Of those who had a history of melanoma, 34% (30/89) served in the tropics compared to 6% (4/65) in the control group.3 A tumor registry review found the age-adjusted melanoma incidence rates per 100,000 person-years for White individuals in the military vs the general population was 33.6 vs 27.5 among those aged 45 to 49 years, 49.8 vs 32.2 among those aged 50 to 54 years, and 178.5 vs 39.2 among those aged 55 to 59 years.4 Among published literature reviews, members of the US Air Force (USAF) had the highest rates of melanoma compared to other military branches, with an incidence rate of 7.6 vs 6.3 among USAF males vs Army males and 9.0 vs 5.5 among USAF females vs Army females.4 These findings were further supported by another study showing a higher incidence rate of melanoma in USAF members compared to Army personnel (17.8 vs 9.5) and a 62% greater melanoma incidence in active-duty military personnel compared to the general population when adjusted for age, race, sex, and year of diagnosis.5 Additionally, a meta-analysis reported a standardized incidence ratio of 1.4 (95% CI, 1.1-1.9) for malignant melanoma and 1.8 (95% CI, 1.3-2.8) for NMSC among military pilots compared to the general population.6 It is important to note that these data are limited to published peer-reviewed studies within PubMed and may not reflect the true skin cancer incidence.

More comprehensive studies are needed to compare NMSC incidence rates in nonpilot military populations compared to the general population. From 2005 to 2014, the average annual NMSC incidence rate in the USAF was 64.4 per 100,000 person-years, with the highest rate at 97.4 per 100,000 person-years in 2007.7 However, this study did not directly compare military service members to the general population. Service in tropical environments among World War II veterans was associated with an increased risk for NMSC. Sixty-six percent of patients with BCC (n=197) and 68% with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)(n=41) were stationed in the Pacific, despite the number and demographics of soldiers deployed to the Pacific and Europe being approximately equal.8 During a 6-month period in 2008, a Combat Dermatology Clinic in Iraq showed 5% (n=129) of visits were for treatment of actinic keratoses (AKs), while 8% of visits (n=205) were related to skin cancer, including BCC, SCC, mycosis fungoides, and melanoma.9 Overall, these studies confirm a higher rate of melanoma in military service members vs the general population and indicate USAF members may be at the greatest risk for developing melanoma and NMSC among the service branches. Further studies are needed to elucidate why this might be the case and should concentrate on demographics, service locations, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, and use of sun-protective measures across each service branch.

Our search yielded no aggregate studies to determine if there is an increased rate of other types of skin cancer in military service members such as Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC). Gerall et al10 described a case of MAC in a 43-year-old USAF U-2 pilot with a 15-year history of a slow-growing soft-tissue nodule on the cheek. The patient’s young age differed from the typical age of MAC occurrence (ie, 60–70 years), which led to the possibility that his profession contributed to the development of MAC and the relatively young age of onset.10

Etiology of Disease

The results of our literature review indicated that skin cancers are more prevalent among active-duty military personnel and veterans than in the general population; they also suggest that frequent sun exposure and lack of sun protection may be key etiologic factors. In 2015, only 23% of veterans (n=49) reported receiving skin cancer awareness education from the US Military.1 Among soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan (n=212), only 13% reported routine sunscreen use, and

Exposure to UV radiation at higher altitudes (with corresponding higher UV energy) and altered sleep-wake cycles (with resulting altered immune defenses) may contribute to higher rates of melanoma and NMSC among USAF pilots.11 During a 57-minute flight at 30,000-ft altitude, a pilot is exposed to a UVA dose equivalent to 20 minutes inside a tanning booth.12 Although UVB transmission through plastic and glass windshields was reported to be less than 1%, UVA transmission ranged from 0.4% to 53.5%. The UVA dose for a pilot flying a light aircraft in Las Vegas, Nevada, was reported to be 127 μW/cm2 at ground level vs 242 μW/cm2 at a 30,000-ft altitude.12 Therefore, cosmic radiation exposure for military pilots is higher than for commercial pilots, as they fly at higher altitudes. U-2 pilots are exposed to 20 times the cosmic radiation dose at sea level and 10 times the exposure of commercial pilots.10

It currently is unknown why service in the USAF would increase skin cancer risk compared to service in other branches; however, there are some differences between military branches that require further research, including ethnic demographics, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, duty assignment locations, and the hours the military members are asked to work outside with direct sunlight exposure for each branch of service. Environmental exposures may differ based on the military branch gear requirements; for example, when on the flight line or flight deck, USN aircrews are required to wear cranials (helmets), eyewear (visor or goggles), and long-sleeved shirts. When at sea, USN flight crews wear gloves, headgear, goggles, pants, and long-sleeved shirts to identify their duty onboard. All of these measures offer good sun protection and are carried over to the land-based flight lines in the USN and Marine Corps. Neither the Army nor the USAF commonly utilize these practices. Conversely, the USAF does not allow flight line workers including fuelers, maintainers, and aircrew to wear coveralls due to the risk of being blown off, becoming foreign object debris, and being sucked into jet engines. However, in-flight protective gear such as goggles, gloves, and coveralls are worn.12 Perhaps the USAF may attract, recruit, or commission people with inherently more risk for skin cancer (eg, White individuals). How racial and ethnic factors may affect skin cancer incidence in military branches is an area for future research efforts.

Recommendations

Given the considerable increase in risk factors, efforts are needed to reduce the disparity in skin cancer rates between US military personnel and their civilian counterparts through appropriate prevention, screening, and intervention programs.

Prevention—In wartime settings as well as in training and other peacetime activities, active-duty military members cannot avoid harmful midday sun exposure. Additionally, application and reapplication of sunscreen can be challenging. Sunscreen, broad-spectrum lip balm, and wide-brimmed “boonie” hats can be ordered by supply personnel.13 We recommend that a standard sunscreen supply be available to all active-duty military service members. The long-sleeved, tightly woven fabric of military uniforms also can provide protection from the sun but can be difficult to tolerate for extended periods of time in warm climates. Breathable, lightweight, sun-protective clothing is commercially available and could be incorporated into military uniforms.

All service members should be educated about skin cancer risks while addressing common myths and inaccuracies. Fifty percent (n=50) of surveyed veterans thought discussions of skin cancer prevention and safety during basic training could help prevent skin cancer in service members.14 Suggestions from respondents included education about sun exposure consequences, use of graphic images of skin cancer in teaching, providing protective clothing and sunscreen to active-duty military service members, and discussion about sun protection with physicians during annual physicals. When veterans with a history of skin cancer were surveyed about their personal risk for skin cancer, most believed they were at little risk (average perceived risk response score, 2.2 out of 5 [1=no risk; 5=high risk]).14 The majority explained that they did not seek sun protection after warnings of skin cancer risk because they did not think skin cancer would happen to them,14 though the incidence of NMSC in the United States at the time of these surveys was estimated to be 3.5 million per year.14,15 Another study found that only 13% of veterans knew the back is the most common site of melanoma in men.1 The Army Public Health Center has informational fact sheets available online or in dermatologists’ offices that detail correct sunscreen application techniques and how to reduce sun exposure.16,17 However, military service members reported that they prefer physicians to communicate with them directly about skin cancer risks vs reading brochures in physician offices or gaining information from television, radio, military training, or the Internet (4.4 out 5 rating for communication methods of risks associated with skin cancer [1=ineffective; 5=very effective]).14 However, only 27% of nondermatologist physicians counseled or screened their patients on skin cancer or sunscreen yearly, 49% even less frequently, with 24% never counseling or screening at all. Because not all service members may be able to regularly see a dermatologist, efforts should be focused on increasing primary care physician awareness on counseling and screening.18

Early Detection—Military service members should be educated on how to perform skin self-examinations to alert their providers earlier to concerning lesions. The American Academy of Dermatology publishes infographics regarding the ABCDEs of melanoma and how to perform skin self-examinations.19,20 Although the US Preventive Services Task Force concluded there was insufficient evidence to recommend skin self-examination for all adults, the increased risk that military service members and veterans have requires further studies to examine the utility of self-screening in this population.20 Given the evidence of a higher incidence of melanoma in military service members vs the general population after 45 years of age,4 we recommend starting yearly in-person screenings performed by primary care physicians or dermatologists at this age. Ensuring every service member has routine in-office skin examinations can be difficult given the limited number of active-duty military dermatologists. Civilian dermatologists also could be helpful in this respect.

Teleconsultation, teledermoscopy, or store-and-forward imaging services for concerning lesions could be utilized when in-person consultations with a dermatologist are not feasible or cannot be performed in a timely manner. From 2004 to 2012, 40% of 10,817 teleconsultations were dermatology consultations from deployed or remote environments.21 Teleconsultation can be performed via email through the global military teleconsultation portal.22 These methods can lead to earlier detection of skin cancer rather than delaying evaluation for an in-person consultation.23

Intervention—High-risk patients who have been diagnosed with NMSC or many AKs should consider oral, procedural, or topical chemoprevention to reduce the risk for additional skin cancers as both primary and secondary prevention. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of 386 individuals with a history of 2 or more NMSCs, participants were randomly assigned to receive either 500 mg of nicotinamide twice daily or placebo for 12 months. Compared to the placebo group, the nicotinamide group had a 23% lower rate of new NMSCs and an 11% lower rate of new AKs at 12 months.24 The use of acitretin also has been studied in transplant recipients for the chemoprevention of NMSC. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial of renal transplant recipients with more than 10 AKs randomized to receive either 30 mg/d of acitretin or placebo for 6 months, 11% of the acitretin group reported a new NMSC compared to 47% in the placebo group.25 An open-label study of 27 renal transplant recipients treated with methyl-esterified aminolevulinic acid–photodynamic therapy and red light demonstrated an increased mean time to occurrence of an AK, SCC, BCC, keratoacanthoma, or wart from 6.8 months in untreated areas compared to 9.6 months in treated areas.25 In active-duty locations where access to red and blue light sources is unavailable, the use of daylight photodynamic therapy can be considered, as it does not require any special equipment. Topical treatments such as 5-fluorouracil and imiquimod can be used for treatment and chemoprevention of NMSC. In a follow-up study from the Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial, patients who applied 5-fluorouracil cream 5% twice daily to the face and ears for 4 weeks had a 75% risk reduction in developing SCC requiring surgery compared to the control group for the first year after treatment.26,27

Final Thoughts

Focusing on the efforts we propose can help the US Military expand their prevention, screening, and intervention programs for skin cancer in service members. Further research can then be performed to determine which programs have the greatest impact on rates of skin cancer among military and veteran personnel. Given these higher incidences and risk of exposure for skin cancer among service members, the various services may consider mandating sunscreen use as part of the uniform to prevent skin cancer. To maximize effectiveness, these efforts to prevent the development of skin cancer among military and veteran personnel should be adopted nationally.

- Powers JG, Patel NA, Powers EM, et al. Skin cancer risk factors and preventative behaviors among United States military veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2871-2873.

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192.

- Brown J, Kopf AW, Rigel DS, et al. Malignant melanoma in World War II veterans. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:661-663.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the U.S. Military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:318-323.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, et al. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179:247-253.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in pilots and cabin crew: UV measurements in flying airplanes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:450-452.

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Ramani ML, Bennett RG. High prevalence of skin cancer in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:733-737.

- Henning JS, Firoz, BF. Combat dermatology: the prevalence of skin disease in a deployed dermatology clinic in Iraq. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:210-214.

- Gerall CD, Sippel MR, Yracheta JL, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a rare, commonly misdiagnosed malignancy. Mil Med. 2019;184:948-950.

- Wilkison B, Wong E. Skin cancer in military pilots: a special population with special risk factors. Cutis. 2017;100:218-220.

- Proctor SP, Heaton KJ, Smith KW, et al. The Occupational JP8 Neuroepidemiology Study (OJENES): repeated workday exposure and central nervous system functioning among US Air Force personnel. Neurotoxicology. 2011;32:799-808.

- Soldiers protect themselves from skin cancer. US Army website. Published February 28, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.army.mil/article/17601/soldiers_protect_themselves_from_skin_cancer

- Fisher V, Lee D, McGrath J, et al. Veterans speak up: current warnings on skin cancer miss the target, suggestions for improvement. Mil Med. 2015;180:892-897.

- Rogers HW, Weinstick MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Sun safety. Army Public Health Center website. Updated June 6, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/topics/discond/hipss/Pages/Sun-Safety.aspx

- Outdoor ultraviolet radiation hazards and protection. Army Public Health Center website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/OutdoorUltravioletRadiationHazardsandProtection_FS_24-017-1115.pdf

- Saraiya M, Frank E, Elon L, et al. Personal and clinical skin cancer prevention practices of US women physicians. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:633-642.

- What to look for: ABCDEs of melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/at-risk/abcdes

- Detect skin cancer: how to perform a skin self-exam. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/check-skin

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the US military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353.

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:2034-2039.

- Day WG, Shirvastava V, Roman JW. Synchronous teledermoscopy in military treatment facilities. Mil Med. 2020;185:1334-1337.

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

- Bavinck JN, Tieben LM, Van der Woude FJ, et al. Prevention of skin cancer and reduction of keratotic skin lesions during acitretin therapy in renal transplant recipients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1933-1938.

- Wulf HC, Pavel S, Stender I, et al. Topical photodynamic therapy for prevention of new skin lesions in renal transplant recipients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:25-28.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al; Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial (VAKCC) Group. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

- Powers JG, Patel NA, Powers EM, et al. Skin cancer risk factors and preventative behaviors among United States military veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2871-2873.

- Riemenschneider K, Liu J, Powers JG. Skin cancer in the military: a systematic review of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence, prevention, and screening among active duty and veteran personnel. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:1185-1192.

- Brown J, Kopf AW, Rigel DS, et al. Malignant melanoma in World War II veterans. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:661-663.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the U.S. Military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:318-323.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, et al. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000-2007. Mil Med. 2014;179:247-253.

- Sanlorenzo M, Vujic I, Posch C, et al. The risk of melanoma in pilots and cabin crew: UV measurements in flying airplanes. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:450-452.

- Lee T, Taubman SB, Williams VF. Incident diagnoses of non-melanoma skin cancer, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005-2014. MSMR. 2016;23:2-6.

- Ramani ML, Bennett RG. High prevalence of skin cancer in World War II servicemen stationed in the Pacific theater. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:733-737.

- Henning JS, Firoz, BF. Combat dermatology: the prevalence of skin disease in a deployed dermatology clinic in Iraq. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:210-214.

- Gerall CD, Sippel MR, Yracheta JL, et al. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a rare, commonly misdiagnosed malignancy. Mil Med. 2019;184:948-950.

- Wilkison B, Wong E. Skin cancer in military pilots: a special population with special risk factors. Cutis. 2017;100:218-220.

- Proctor SP, Heaton KJ, Smith KW, et al. The Occupational JP8 Neuroepidemiology Study (OJENES): repeated workday exposure and central nervous system functioning among US Air Force personnel. Neurotoxicology. 2011;32:799-808.

- Soldiers protect themselves from skin cancer. US Army website. Published February 28, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.army.mil/article/17601/soldiers_protect_themselves_from_skin_cancer

- Fisher V, Lee D, McGrath J, et al. Veterans speak up: current warnings on skin cancer miss the target, suggestions for improvement. Mil Med. 2015;180:892-897.

- Rogers HW, Weinstick MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Sun safety. Army Public Health Center website. Updated June 6, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/topics/discond/hipss/Pages/Sun-Safety.aspx

- Outdoor ultraviolet radiation hazards and protection. Army Public Health Center website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/OutdoorUltravioletRadiationHazardsandProtection_FS_24-017-1115.pdf

- Saraiya M, Frank E, Elon L, et al. Personal and clinical skin cancer prevention practices of US women physicians. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:633-642.

- What to look for: ABCDEs of melanoma. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/at-risk/abcdes

- Detect skin cancer: how to perform a skin self-exam. American Academy of Dermatology website. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/find/check-skin

- Hwang JS, Lappan CM, Sperling LC, et al. Utilization of telemedicine in the US military in a deployed setting. Mil Med. 2014;179:1347-1353.

- Bartling SJ, Rivard SC, Meyerle JH. Melanoma in an active duty marine. Mil Med. 2017;182:2034-2039.

- Day WG, Shirvastava V, Roman JW. Synchronous teledermoscopy in military treatment facilities. Mil Med. 2020;185:1334-1337.

- Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

- Bavinck JN, Tieben LM, Van der Woude FJ, et al. Prevention of skin cancer and reduction of keratotic skin lesions during acitretin therapy in renal transplant recipients: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1933-1938.

- Wulf HC, Pavel S, Stender I, et al. Topical photodynamic therapy for prevention of new skin lesions in renal transplant recipients. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:25-28.

- Weinstock MA, Thwin SS, Siegel JA, et al; Veterans Affairs Keratinocyte Carcinoma Chemoprevention Trial (VAKCC) Group. Chemoprevention of basal and squamous cell carcinoma with a single course of fluorouracil, 5%, cream: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:167-174.

Practice Points

- Skin cancer is more prevalent among military personnel and veterans, especially those in the US Air Force. Frequent and/or prolonged sun exposure and lack of sun protection may be key factors.

- Future research should compare the prevalence of skin cancer in nonpilot military populations to the general US population; explore racial and ethnic differences by military branch and their influence on skin cancers; analyze each branch’s sun-protective measures, uniform wear and personal protective equipment standards, duty assignment locations, and the hours the military members are asked to work outside with direct sunlight exposure; and explore the effects of appropriate military skin cancer intervention and screening programs.

Association of BRAF V600E Status of Incident Melanoma and Risk for a Second Primary Malignancy: A Population-Based Study

The incidence of cutaneous melanoma in the United States has increased in the last 30 years, with the American Cancer Society estimating that 99,780 new melanomas will be diagnosed and 7650 melanoma-related deaths will occur in 2022.1 Patients with melanoma have an increased risk for developing a second primary melanoma or other malignancy, such as salivary gland, small intestine, breast, prostate, renal, or thyroid cancer, but most commonly nonmelanoma skin cancer.2,3 The incidence rate of melanoma among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1970 through 2009 has already been described for various age groups4-7; however, the incidence of a second primary malignancy, including melanoma, within these incident cohorts remains unknown.

Mutations in the BRAF oncogene occur in approximately 50% of melanomas.8,9

Although the BRAF mutation event in melanoma is sporadic and should not necessarily affect the development of an unrelated malignancy, we hypothesized that the exposures that may have predisposed a particular individual to a BRAF-mutated melanoma also may have a higher chance of predisposing that individual to the development of another primary malignancy. In this population-based study, we aimed to determine whether the specific melanoma feature of mutant BRAF V600E expression was associated with the development of a second primary malignancy.

Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center (both in Rochester, Minnesota). The reporting of this study is compliant with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement.15

Patient Selection and BRAF Assessment—The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) links comprehensive health care records for virtually all residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, across different medical providers. The REP provides an index of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, tracks timelines and outcomes of individuals and their medical conditions, and is ideal for population-based studies.

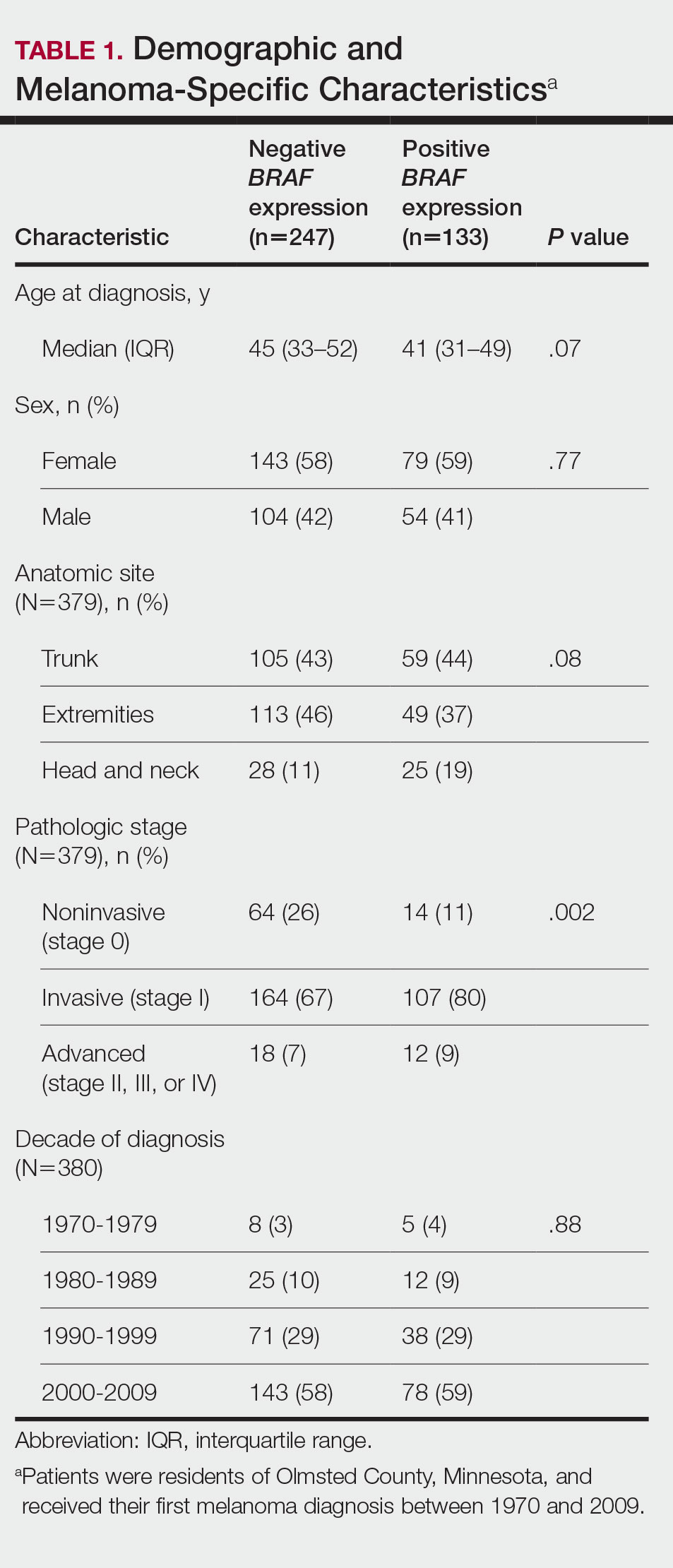

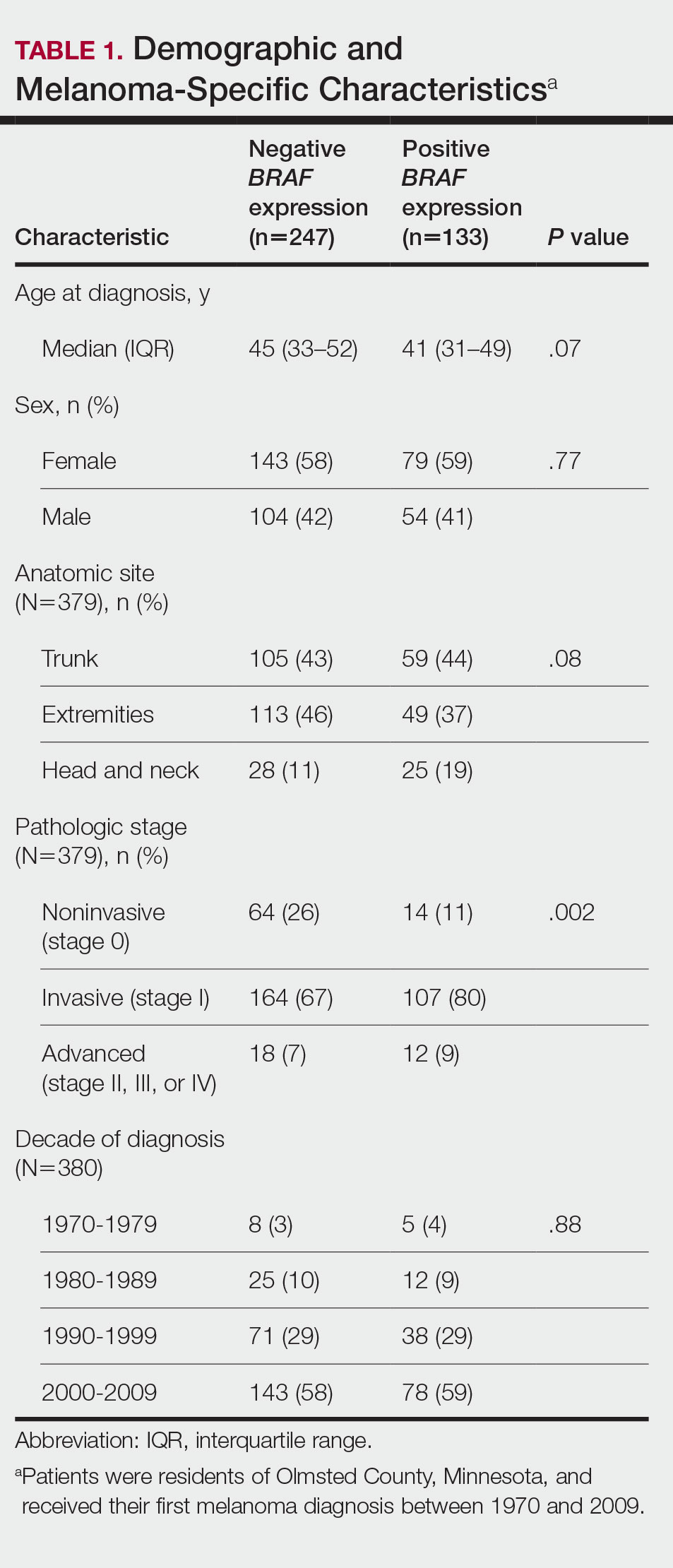

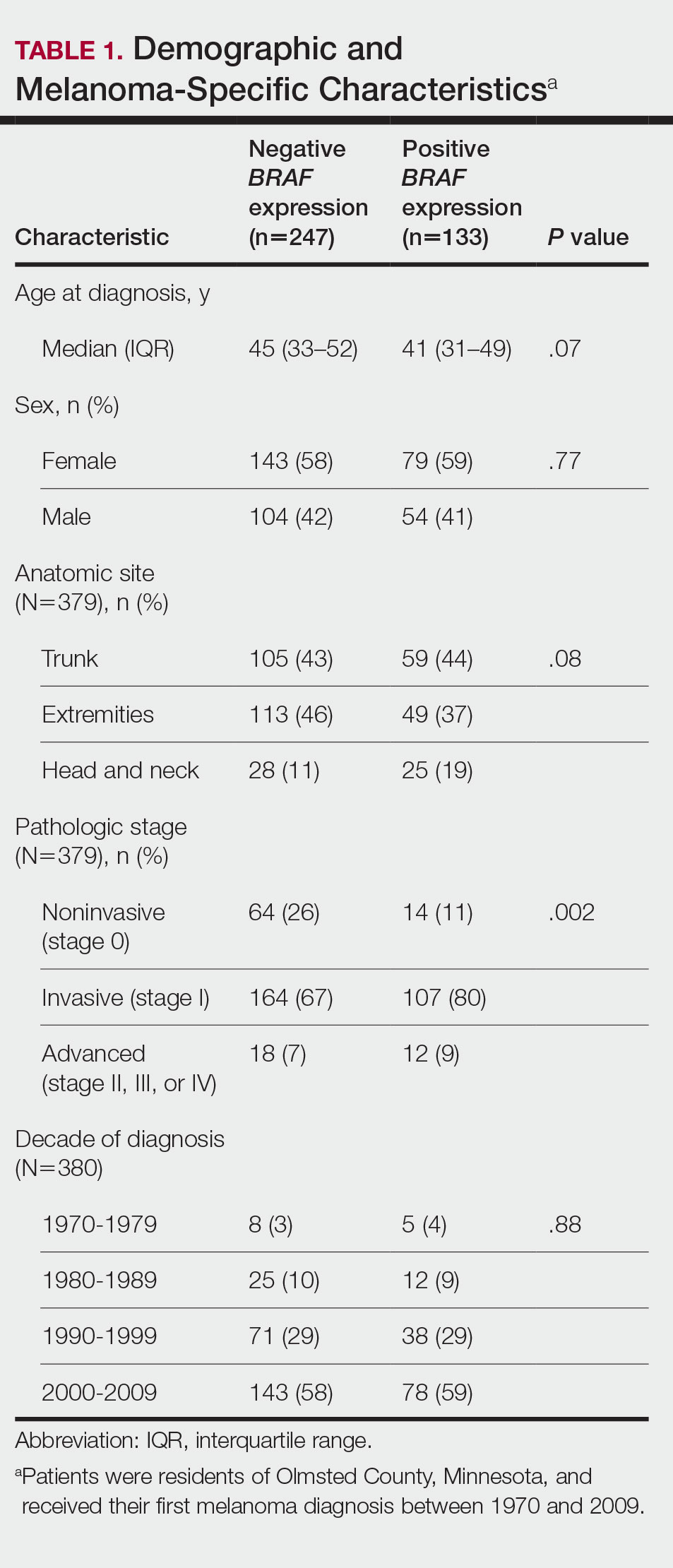

We obtained a list of all residents of Olmsted County aged 18 to 60 years who had a melanoma diagnosed according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, from January 1, 1970, through December 30, 2009; these cohorts have been analyzed previously.4-7 Of the 638 individuals identified, 380 had a melanoma tissue block on file at Mayo Clinic with enough tumor present in available tissue blocks for BRAF assessment. All specimens were reviewed by a board-certified dermatopathologist (J.S.L.) to confirm the diagnosis of melanoma. Tissue blocks were recut, and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained for BRAF V600E (Spring Bioscience Corporation). BRAF-stained specimens and the associated hematoxylin and eosin−stained slides were reviewed. Melanocyte cytoplasmic staining for BRAF was graded as negative if no staining was evident. BRAF was graded as positive if focal or partial staining was observed (<50% of tumor or low BRAF expression) or if diffuse staining was evident (>50% of tumor or high BRAF expression).

Using resources of the REP, we confirmed patients’ residency status in Olmsted County at the time of diagnosis of the incident melanoma. Patients who denied access to their medical records for research purposes were excluded. We used the complete record of each patient to confirm the date of diagnosis of the incident melanoma. Baseline characteristics of patients and their incident melanomas (eg, anatomic site and pathologic stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification) were obtained. When only the Clark level was included in the dermatopathology report, the corresponding Breslow thickness was extrapolated from the Clark level,18 and the pathologic stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification (7th edition) was determined.

For our study, specific diagnostic codes—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revisions; Hospital International Classification of Diseases Adaptation19; and Berkson16—were applied across individual records to identify all second primary malignancies using the resources of the REP. The diagnosis date, morphology, and anatomic location of second primary malignancies were confirmed from examination of the clinical records.

Statistical Analysis—Baseline characteristics were compared by BRAF V600E expression using Wilcoxon rank sum and χ2 tests. The rate of developing a second primary malignancy at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after the incident malignant melanoma was estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The duration of follow-up was calculated from the incident melanoma date to the second primary malignancy date or the last follow-up date. Patients with a history of the malignancy of interest, except skin cancers, before the incident melanoma date were excluded because it was not possible to distinguish between recurrence of a prior malignancy and a second primary malignancy. Associations of BRAF V600E expression with the development of a second primary malignancy were evaluated with Cox proportional hazards regression models and summarized with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs; all associations were adjusted for potential confounders such as age at the incident melanoma, year of the incident melanoma, and sex.

Results

Cumulative Incidence of Second Primary Melanoma—Of 133 patients with positive BRAF V600E expression, we identified 14 (10.5%), 1 (0.8%), and 1 (0.8%) who had 1, 2, and 4 subsequent melanomas, respectively. Of the 247 patients with negative BRAF V600E expression, we identified 15 (6%), 4 (1.6%), 2 (0.8%), and 1 (0.4%) patients who had 1, 2, 3, and 4 subsequent melanomas, respectively; BRAF V600E expression was not associated with the number of subsequent melanomas (P=.37; Wilcoxon rank sum test). The cumulative incidences of developing a second primary melanoma (n=38 among the 380 patients studied) at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after the incident melanoma were 5.3%, 7.6%, 8.1%, and 14.6%, respectively.

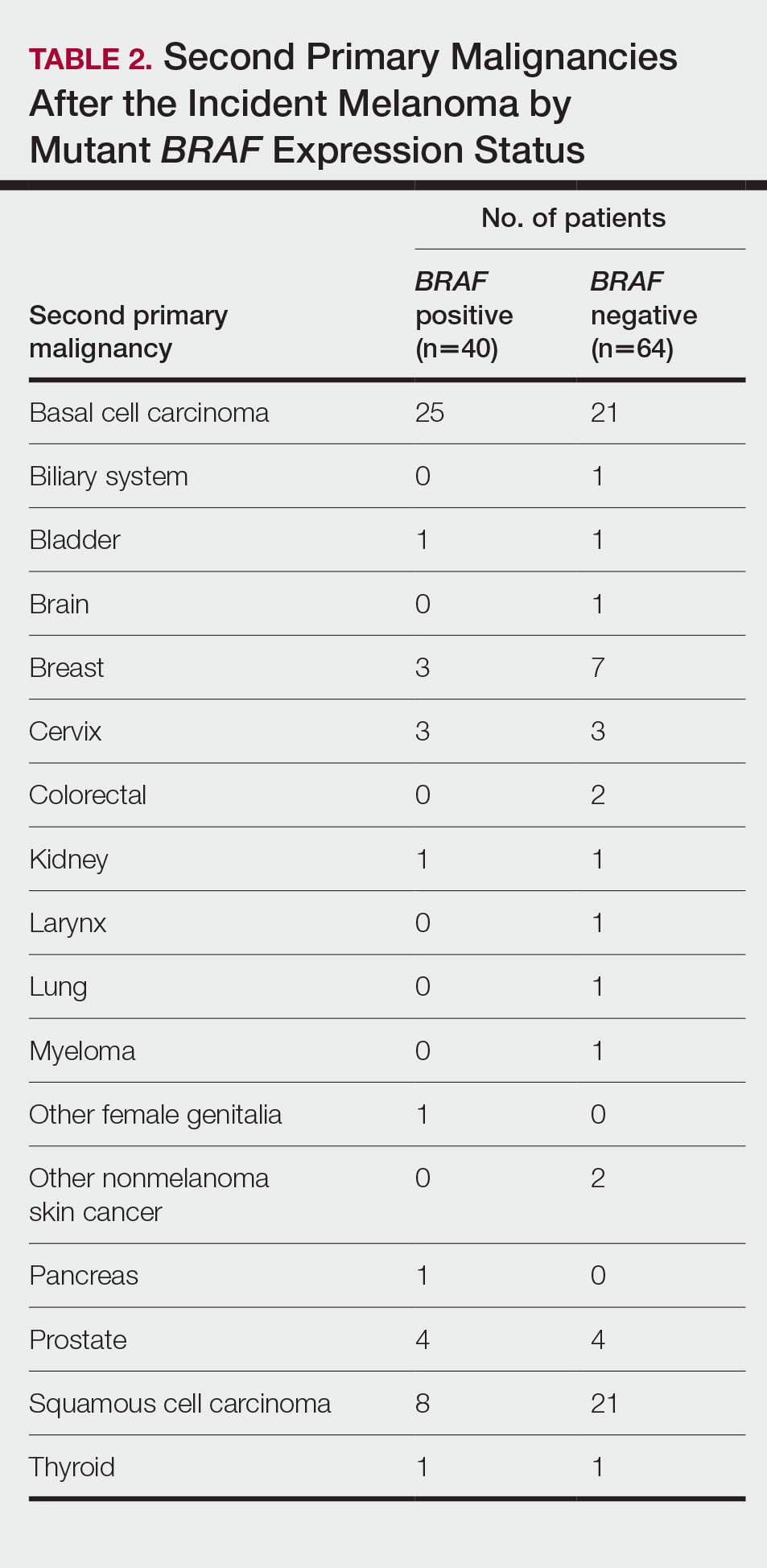

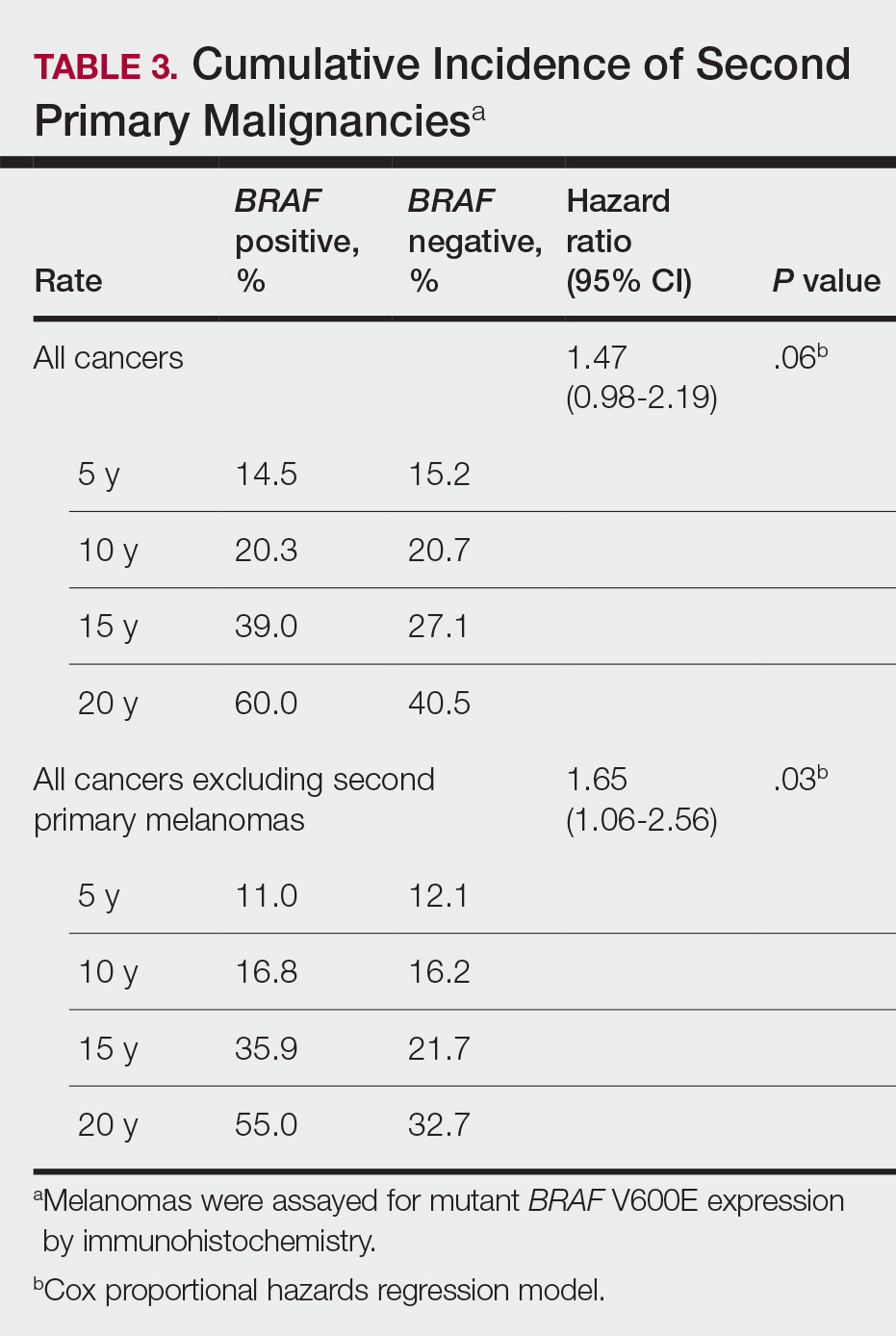

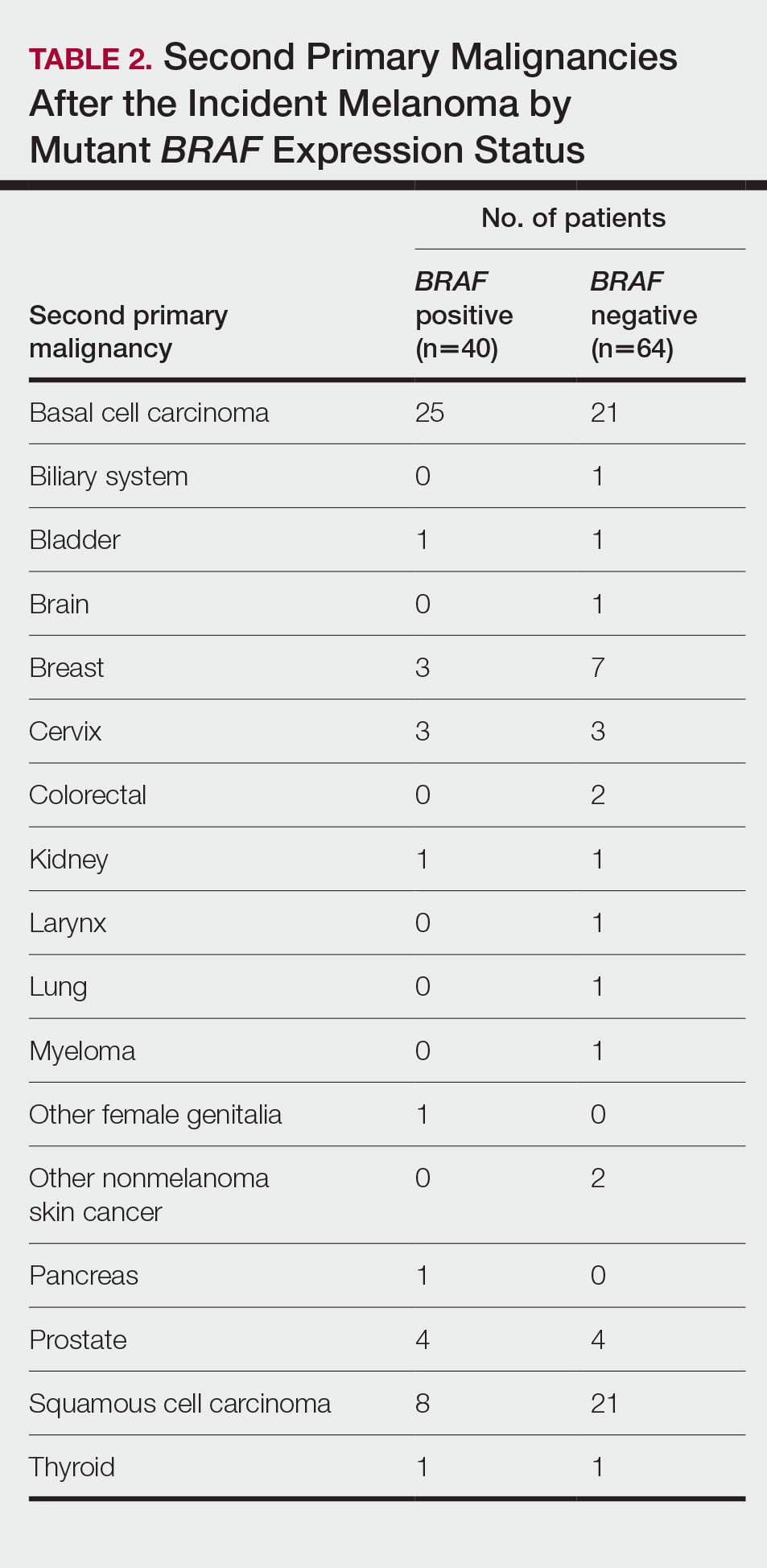

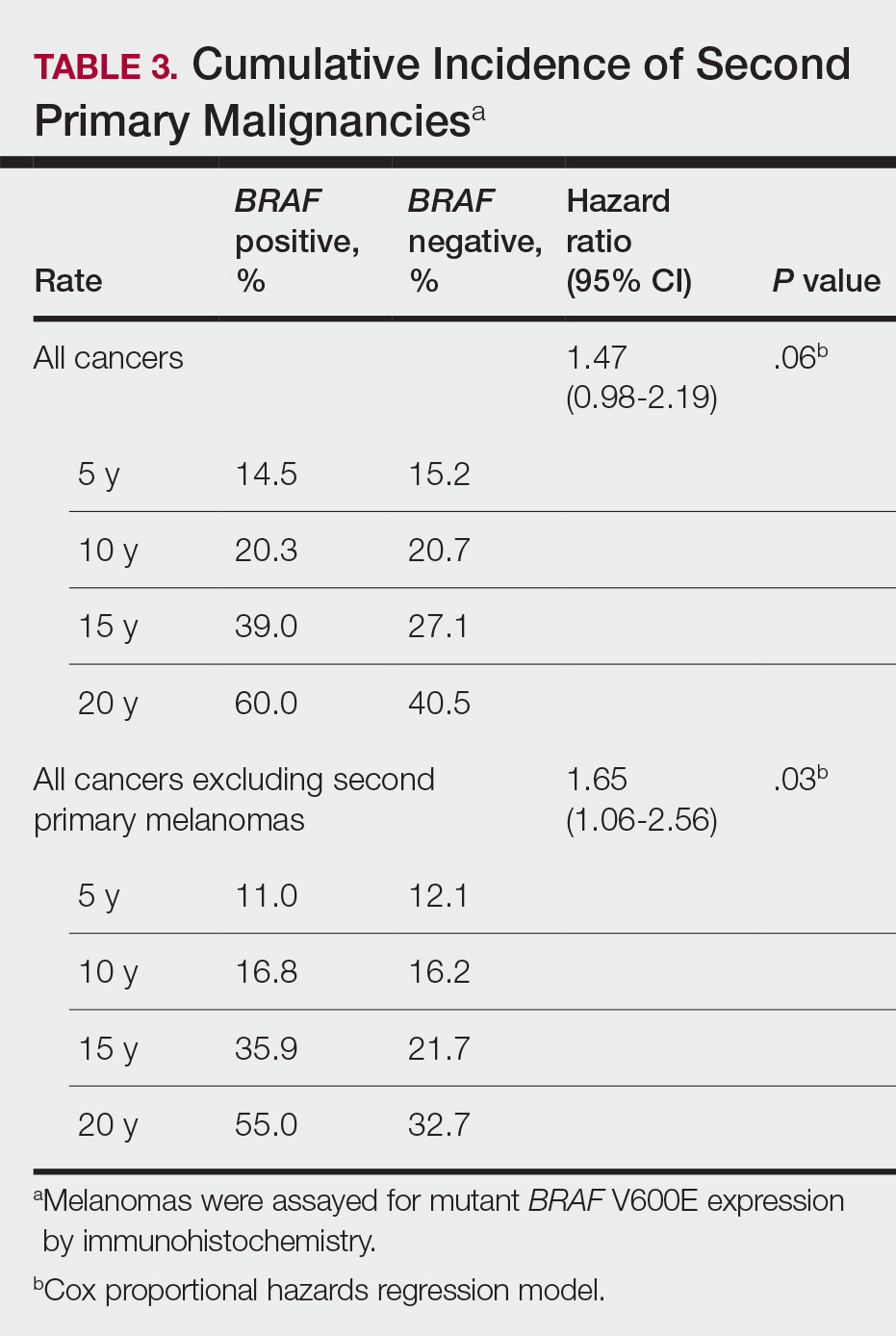

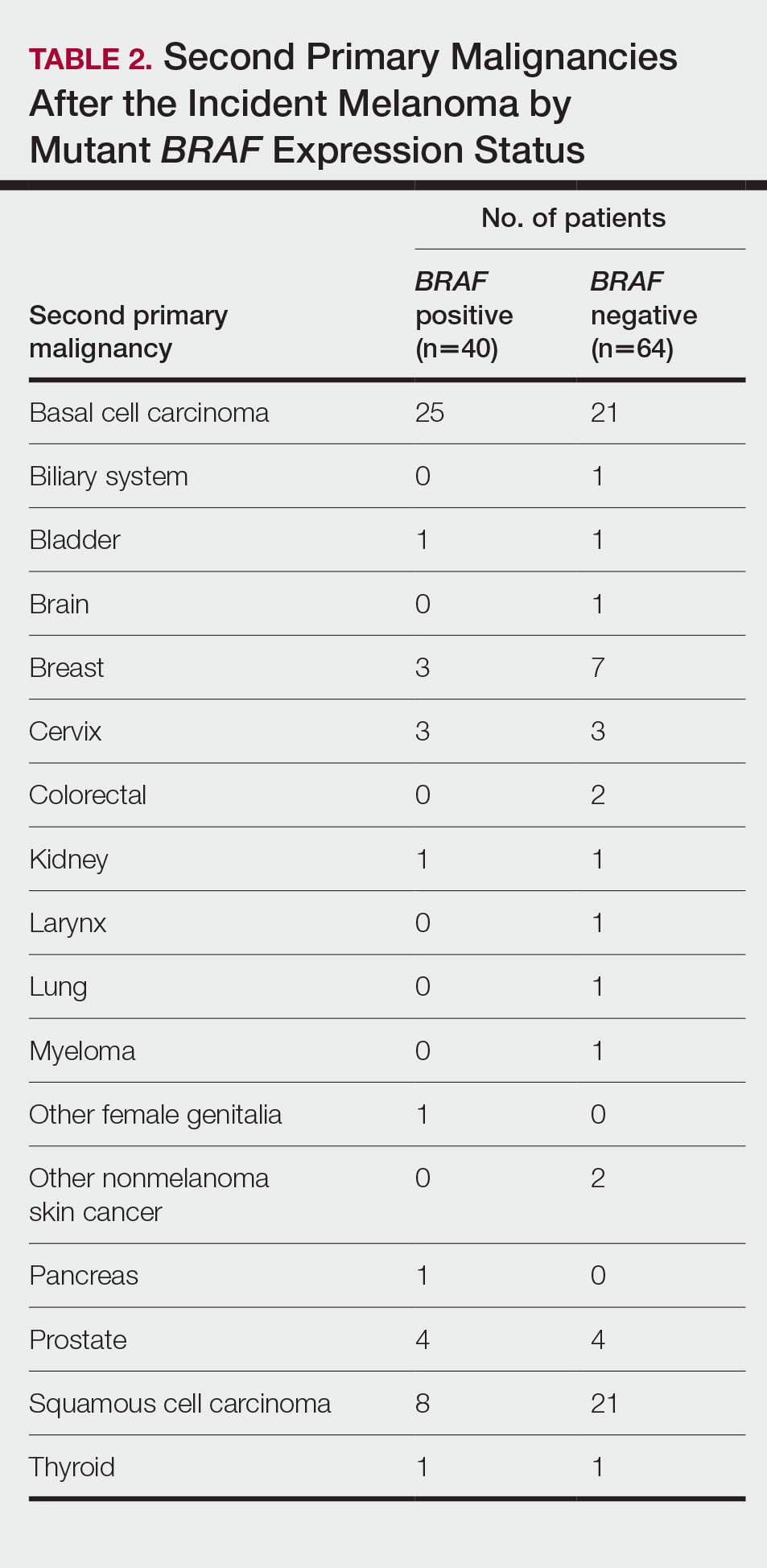

Cumulative Incidence of All Second Primary Malignancies—Of the 380 patients studied, 60 (16%) had at least 1 malignancy diagnosed before the incident melanoma. Of the remaining 320 patients, 104 later had at least 1 malignancy develop, including a second primary melanoma, at a median (IQR) of 8.0 (2.7–16.2) years after the incident melanoma; the 104 patients with at least 1 subsequent malignancy included 40 with BRAF-positive and 64 with BRAF-negative melanomas. The cumulative incidences of developing at least 1 malignancy of any kind at 5, 10, 15, and 20 years after the incident melanoma were 15.0%, 20.5%, 31.2%, and 47.0%, respectively. Table 2 shows the number of patients with at least 1 second primary malignancy after the incident melanoma stratified by BRAF status.

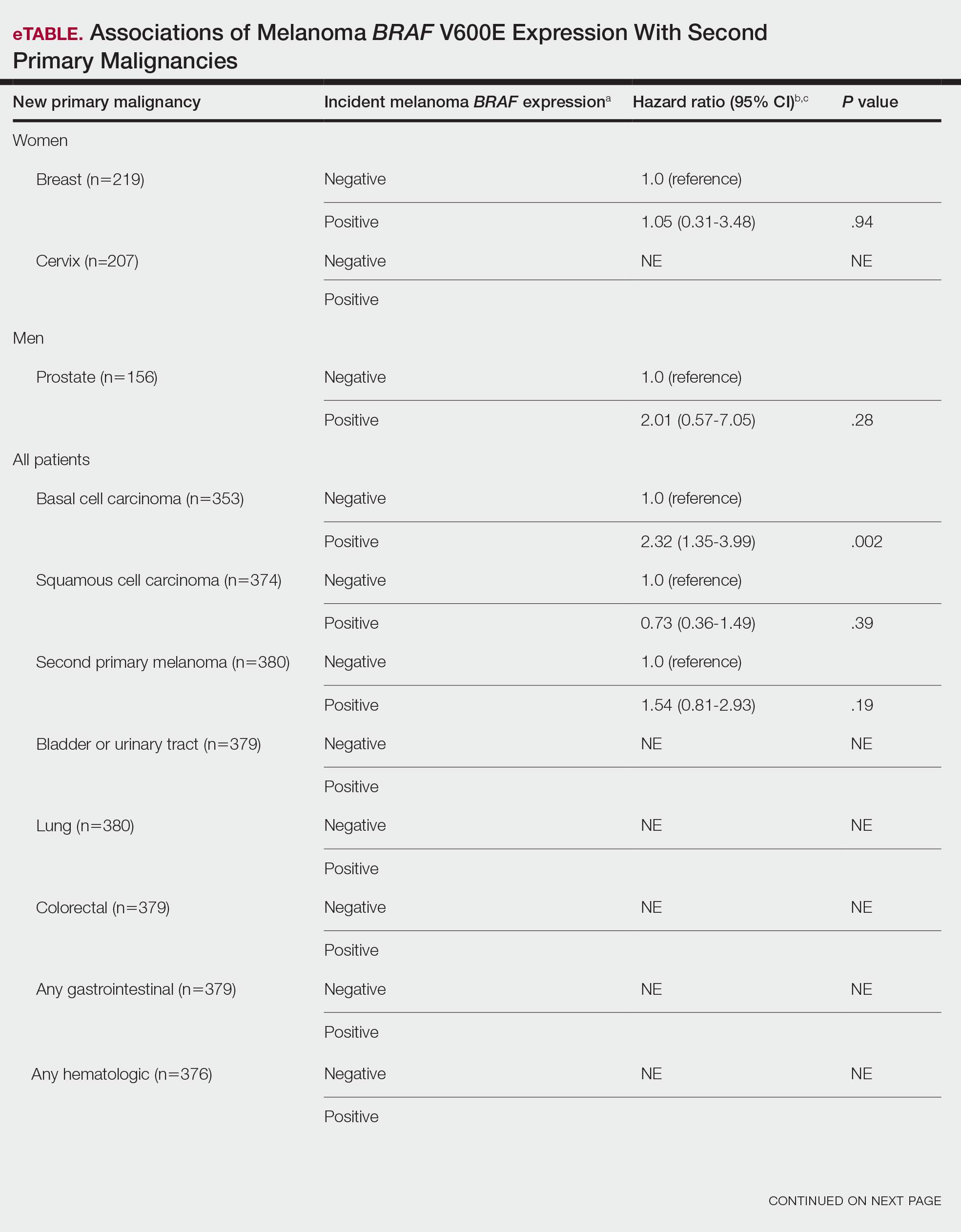

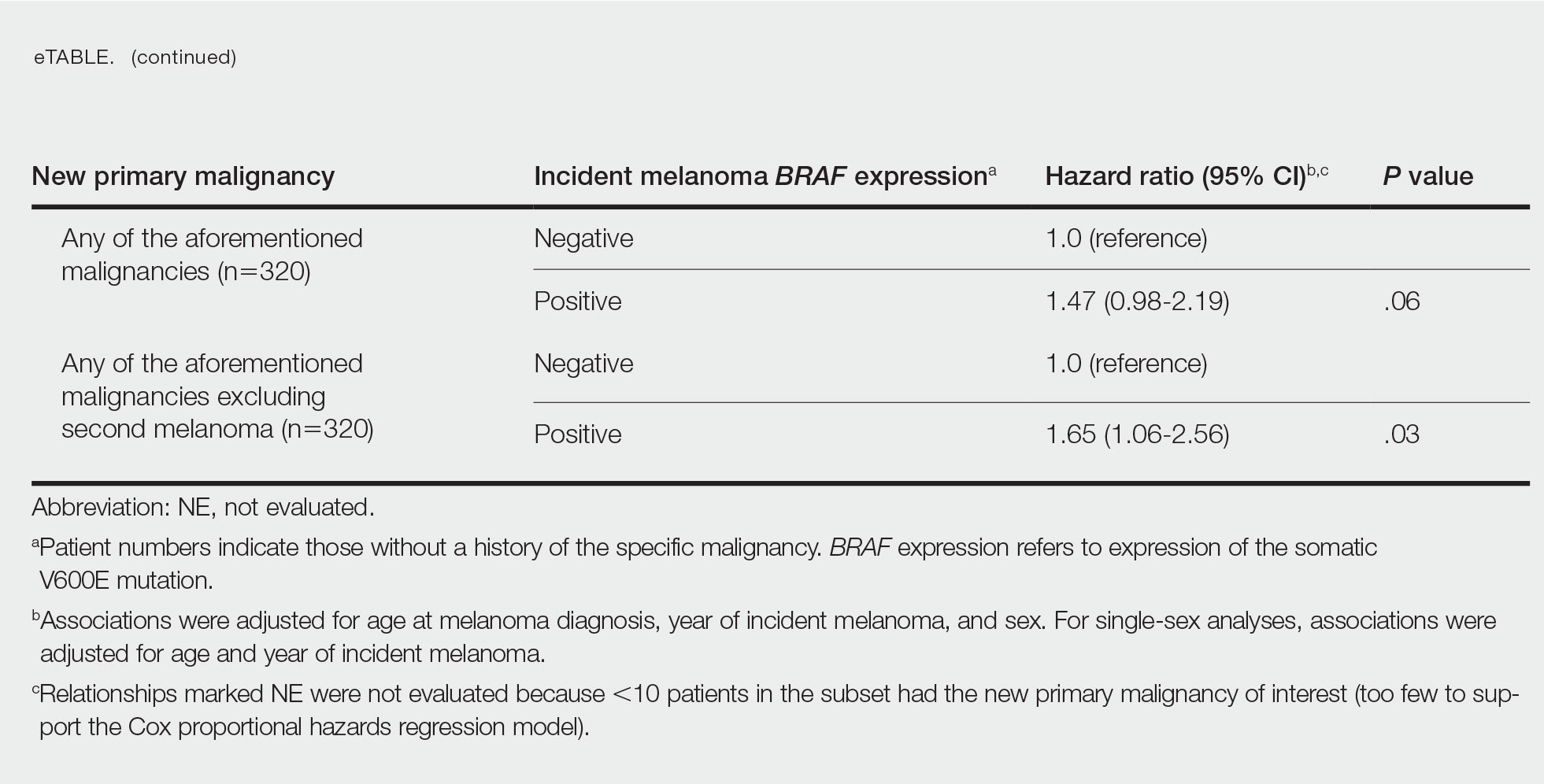

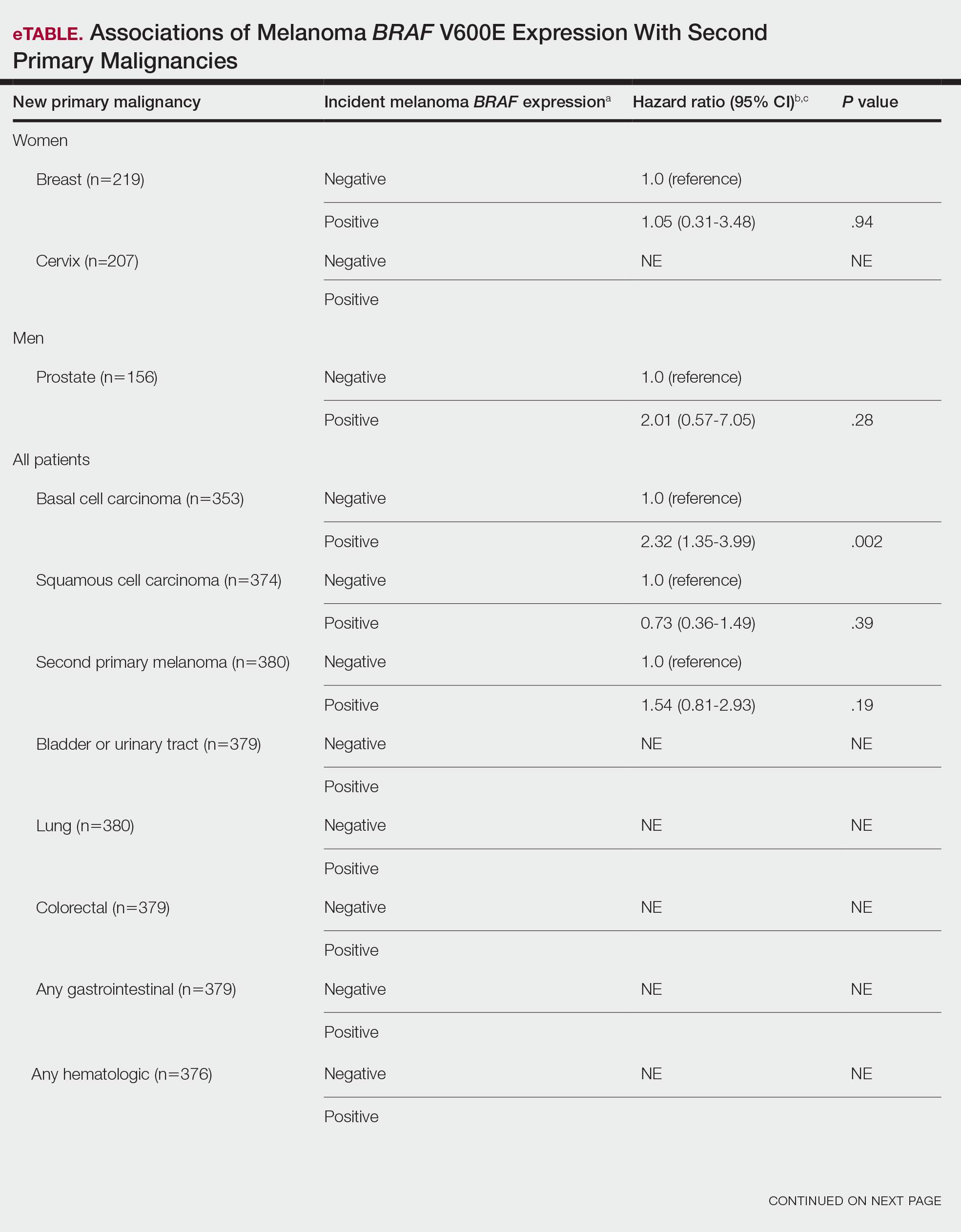

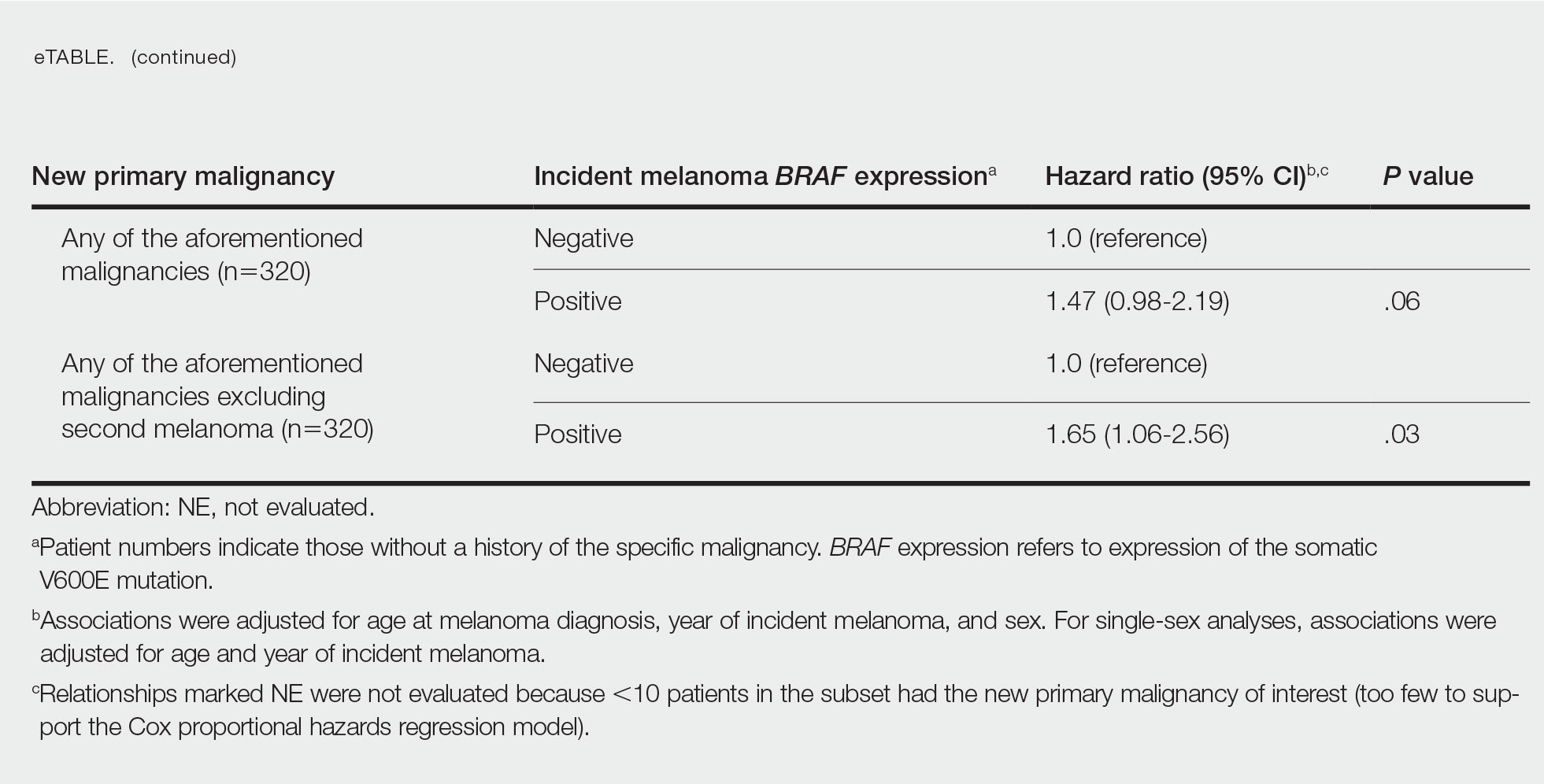

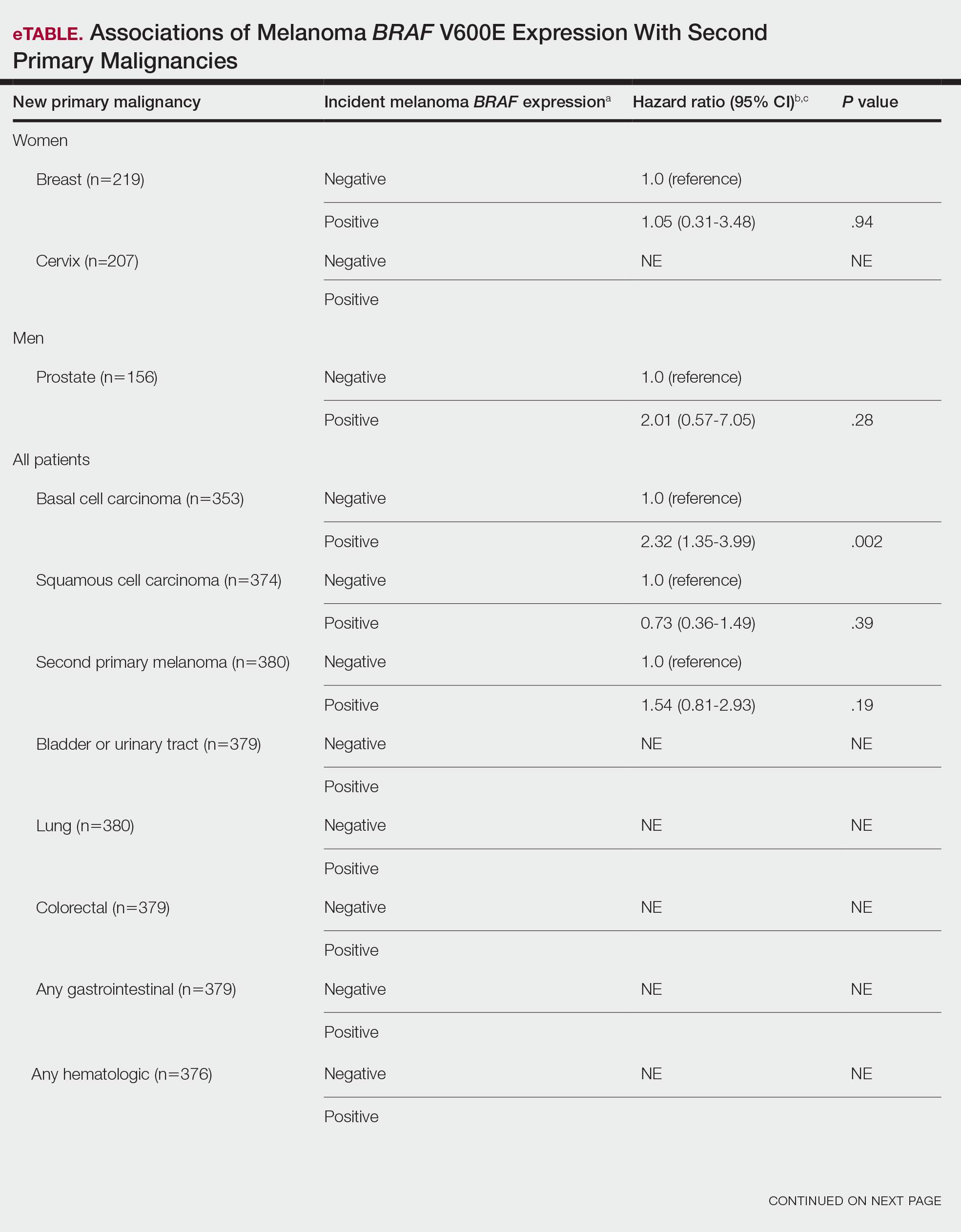

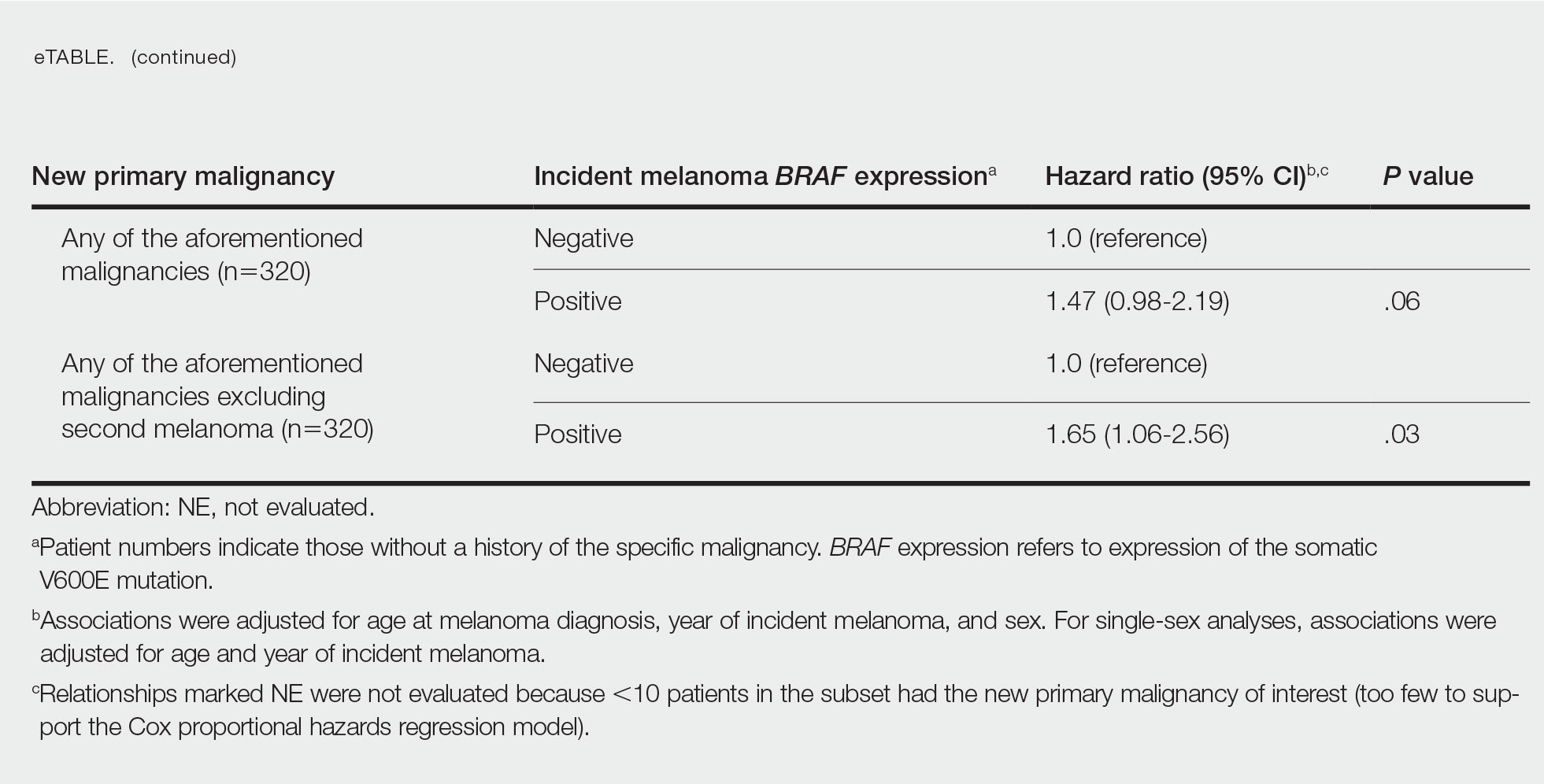

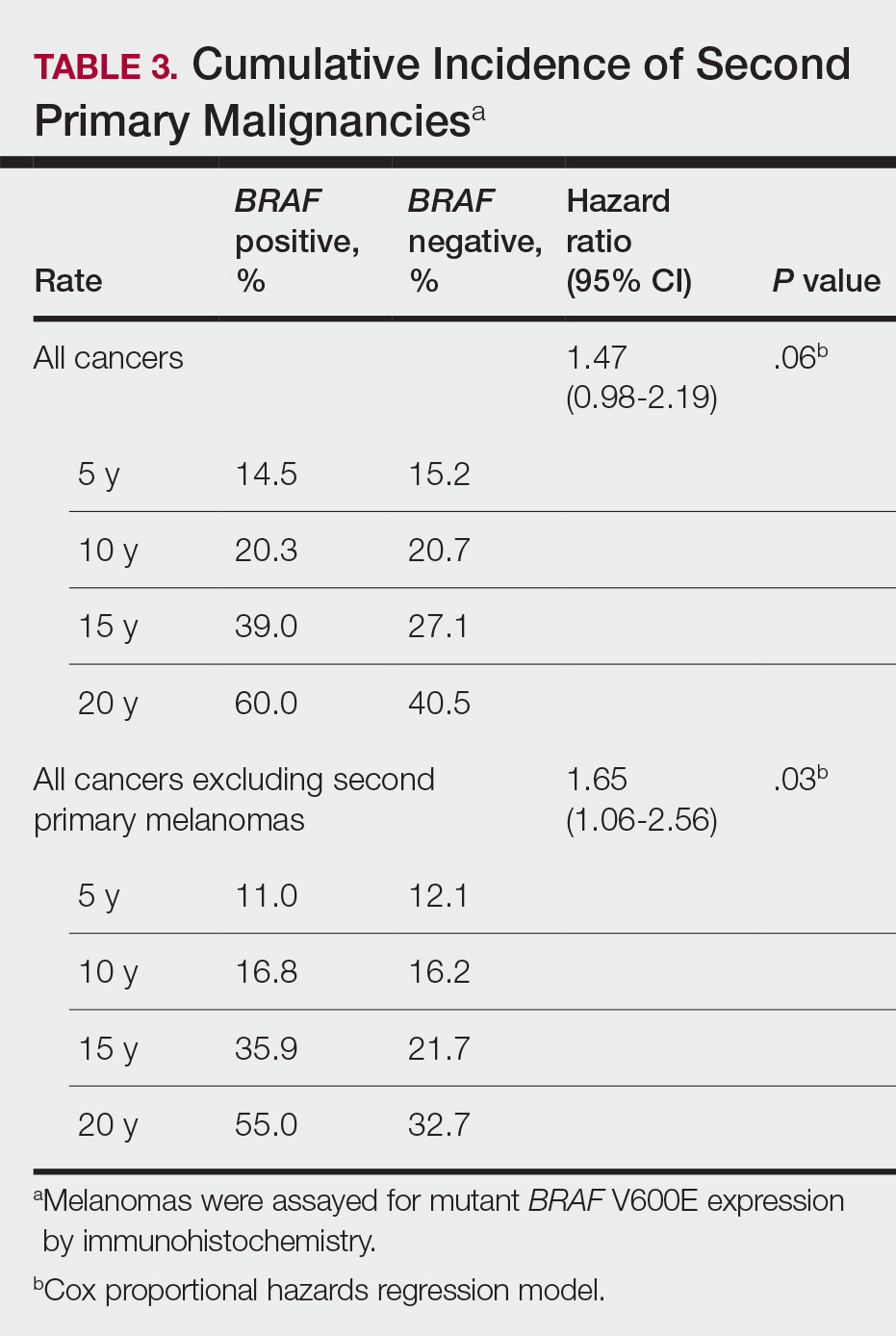

BRAF V600E Expression and Association With Second Primary Malignancy—The eTable shows the associations of mutant BRAF V600E expression status with the development of a new primary malignancy. Malignancies affecting fewer than 10 patients were excluded from the analysis because there were too few events to support the Cox model. Positive BRAF V600E expression was associated with subsequent development of BCCs (HR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.35-3.99; P=.002) and the development of all combined second primary malignancies excluding melanoma (HR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.06-2.56; P=.03). However, BRAF V600E status was no longer a significant factor when all second primary malignancies, including second melanomas, were considered (P=.06). Table 3 shows the 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year cumulative incidences of all second primary malignancies according to mutant BRAF status.

Comment

Association of BRAF V600E Expression With Second Primary Malignancies—BRAF V600E expression of an incident melanoma was associated with the development of all combined second primary malignancies excluding melanoma; however, this association was not statistically significant when second primary melanomas were included. A possible explanation is that individuals with more than 1 primary melanoma possess additional genetic risk—CDKN2A or CDKN4 gene mutations or MC1R variation—that outweighed the effect of BRAF expression in the statistical analysis.

The 5- and 10-year cumulative incidences of all second primary malignancies excluding second primary melanoma were similar between BRAF-positive and BRAF-negative melanoma, but the 15- and 20-year cumulative incidences were greater for the BRAF-positive cohort. This could reflect the association of BRAF expression with BCCs and the increased likelihood of their occurrence with cumulative sun exposure and advancing age. BRAF expression was associated with the development of BCCs, but the reason for this association was unclear. BRAF-mutated melanoma occurs more frequently on sun-protected sites,20 whereas sporadic BCC generally occurs on sun-exposed sites. However, BRAF-mutated melanoma is associated with high levels of ambient UV exposure early in life, particularly birth through 20 years of age,21 and we speculate that such early UV exposure influences the later development of BCCs.

Development of BRAF-Mutated Cancers—It currently is not understood why the same somatic mutation can cause different types of cancer. A recent translational research study showed that in mice models, precursor cells of the pancreas and bile duct responded differently when exposed to PIK3CA and KRAS oncogenes, and tumorigenesis is influenced by specific cooperating genetic events in the tissue microenvironment. Future research investigating these molecular interactions may lead to better understanding of cancer pathogenesis and direct the design of new targeted therapies.22,23

Regarding environmental influences on the development of BRAF-mutated cancers, we found 1 population-based study that identified an association between high iodine content of drinking water and the prevalence of T1799A BRAF papillary thyroid carcinoma in 5 regions in China.24 Another study identified an increased risk for colorectal cancer and nonmelanoma skin cancer in the first-degree relatives of index patients with BRAF V600E colorectal cancer.25 Two studies by institutions in China and Sweden reported the frequency of BRAF mutations in cohorts of patients with melanoma.26,27

Additional studies investigating a possible association between BRAF-mutated melanoma and other cancers with larger numbers of participants than in our study may become more feasible in the future with increased routine genetic testing of biopsied cancers.

Study Limitations—Limitations of this retrospective epidemiologic study include the possibility of ascertainment bias during data collection. We did not account for known risk factors for cancer (eg, excessive sun exposure, smoking).

The main clinical implications from this study are that we do not have enough evidence to recommend BRAF testing for all incident melanomas, and BRAF-mutated melanomas cannot be associated with increased risk for developing other forms of cancer, with the possible exception of BCCs

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware of the risk for a second primary malignancy after an incident melanoma, and we emphasize the importance of long-term cancer surveillance.

Acknowledgment—We thank Ms. Jayne H. Feind (Rochester, Minnesota) for assistance with study coordination.

- American Cancer Society. Key statistics for melanoma skin cancer. Updated January 12, 2022. Accessed August 15, 2022.https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- American Cancer Society. Second Cancers After Melanoma Skin Cancer. Accessed August 19, 2022. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/after-treatment/second-cancers.html

- Spanogle JP, Clarke CA, Aroner S, et al. Risk of second primary malignancies following cutaneous melanoma diagnosis: a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:757-767.

- Olazagasti Lourido JM, Ma JE, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma in the elderly: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1555-1562.

- Reed KB, Brewer JD, Lohse CM, et al. Increasing incidence of melanoma among young adults: an epidemiological study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:328-334.

- Lowe GC, Brewer JD, Peters MS, et al. Incidence of melanoma in the pediatric population: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Pediatr Derm. 2015;32:618-620.