User login

Hearing loss tied to decline in physical functioning

published online in JAMA Network Open.

Hearing loss is associated with slower gait and, in particular, worse balance, the data suggest.

“Because hearing impairment is amenable to prevention and management, it potentially serves as a target for interventions to slow physical decline with aging,” the researchers said.

To examine how hearing impairment relates to physical function in older adults, Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, MD, PhD, MHS, a researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

ARIC initially enrolled more than 15,000 adults in Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, and North Carolina between 1987 and 1989. In the present study, the researchers focused on data from 2,956 participants who attended a study visit between 2016 and 2017, during which researchers assessed their hearing using pure tone audiometry.

Hearing-study participants had an average age of 79 years, about 58% were women, and 80% were White. Approximately 33% of the participants had normal hearing, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% had moderate hearing impairment, and 4% had severe hearing impairment.

Participants had also undergone assessment of physical functioning at study visits between 2011 and 2019, including a fast-paced 2-minute walk test to measure their walking endurance. Another assessment, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), tests balance, gait speed, and chair stands (seated participants stand up and sit back down five times as quickly as possible while their arms are crossed).

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and colleagues found that severe hearing impairment was associated with a lower average SPPB score compared with normal hearing in a regression analysis. Specifically, compared with those with normal hearing, participants with severe hearing impairment were more likely to have low scores on the SPPB (odds ratio, 2.72), balance (OR, 2.72), and gait speed (OR, 2.16).

However, hearing impairment was not significantly associated with the chair stand test results. The researchers note that chair stands may rely more on strength, whereas balance and gait speed may rely more on coordination and movement.

The team also found that people with worse hearing tended to walk a shorter distance during the 2-minute walk test. Compared with participants with normal hearing, participants with moderate hearing impairment walked 2.81 meters less and those with severe hearing impairment walked 5.31 meters less on average, after adjustment for variables including age, sex, and health conditions.

Participants with hearing impairment also tended to have faster declines in physical function over time.

Various mechanisms could explain associations between hearing and physical function, the authors said. For example, an underlying condition such as cardiovascular disease might affect both hearing and physical function. Damage to the inner ear could affect vestibular and auditory systems at the same time. In addition, hearing impairment may relate to cognition, depression, or social isolation, which could influence physical activity.

“Age-related hearing loss is traditionally seen as a barrier for communication,” Dr. Martinez-Amezcua told this news organization. “In the past decade, research on the consequences of hearing loss has identified it as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Our findings contribute to our understanding of other negative outcomes associated with hearing loss.”

Randomized clinical trials are the best way to assess whether addressing hearing loss might improve physical function, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said. “Currently there is one clinical trial (ACHIEVE) that will, among other outcomes, study the impact of hearing aids on cognitive and physical function,” he said.

Although interventions may not reverse hearing loss, hearing rehabilitation strategies, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, may help, he added. Educating caregivers and changing a person’s environment can also reduce the effects hearing loss has on daily life, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said.

“We rely so much in our sense of vision for activities of daily living that we tend to underestimate how important hearing is, and the consequences of hearing loss go beyond having trouble communicating with someone,” he said.

This study and prior research “raise the intriguing idea that hearing may provide essential information to the neural circuits underpinning movement in our environment and that correction for hearing loss may help promote physical well-being,” Willa D. Brenowitz, PhD, MPH, and Margaret I. Wallhagen, PhD, GNP-BC, both at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying commentary. “While this hypothesis is appealing and warrants further investigation, there are multiple other potential explanations of such an association, including potential sources of bias that may affect observational studies such as this one.”

Beyond treating hearing loss, interventions such as physical therapy or tai chi may benefit patients, they suggested.

Because many changes occur during older age, it can be difficult to understand which factor is influencing another, Dr. Brenowitz said in an interview. There are potentially relevant mechanisms through which hearing could affect cognition and physical functioning. Still another explanation could be that some people are “aging in a faster way” than others, Dr. Brenowitz said.

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and a coauthor disclosed receiving sponsorship from the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health. Another author, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD, directs the research center, which is partly funded by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Lin also disclosed personal fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Caption Call. One author serves on a scientific advisory board for Shoebox and Good Machine Studio.

Dr. Wallhagen has served on the board of trustees of the Hearing Loss Association of America and is a member of the board of the Hearing Loss Association of America–California. Dr. Wallhagen also received funding for a pilot project on the impact of hearing loss on communication in the context of chronic serious illness from the National Palliative Care Research Center outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published online in JAMA Network Open.

Hearing loss is associated with slower gait and, in particular, worse balance, the data suggest.

“Because hearing impairment is amenable to prevention and management, it potentially serves as a target for interventions to slow physical decline with aging,” the researchers said.

To examine how hearing impairment relates to physical function in older adults, Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, MD, PhD, MHS, a researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

ARIC initially enrolled more than 15,000 adults in Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, and North Carolina between 1987 and 1989. In the present study, the researchers focused on data from 2,956 participants who attended a study visit between 2016 and 2017, during which researchers assessed their hearing using pure tone audiometry.

Hearing-study participants had an average age of 79 years, about 58% were women, and 80% were White. Approximately 33% of the participants had normal hearing, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% had moderate hearing impairment, and 4% had severe hearing impairment.

Participants had also undergone assessment of physical functioning at study visits between 2011 and 2019, including a fast-paced 2-minute walk test to measure their walking endurance. Another assessment, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), tests balance, gait speed, and chair stands (seated participants stand up and sit back down five times as quickly as possible while their arms are crossed).

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and colleagues found that severe hearing impairment was associated with a lower average SPPB score compared with normal hearing in a regression analysis. Specifically, compared with those with normal hearing, participants with severe hearing impairment were more likely to have low scores on the SPPB (odds ratio, 2.72), balance (OR, 2.72), and gait speed (OR, 2.16).

However, hearing impairment was not significantly associated with the chair stand test results. The researchers note that chair stands may rely more on strength, whereas balance and gait speed may rely more on coordination and movement.

The team also found that people with worse hearing tended to walk a shorter distance during the 2-minute walk test. Compared with participants with normal hearing, participants with moderate hearing impairment walked 2.81 meters less and those with severe hearing impairment walked 5.31 meters less on average, after adjustment for variables including age, sex, and health conditions.

Participants with hearing impairment also tended to have faster declines in physical function over time.

Various mechanisms could explain associations between hearing and physical function, the authors said. For example, an underlying condition such as cardiovascular disease might affect both hearing and physical function. Damage to the inner ear could affect vestibular and auditory systems at the same time. In addition, hearing impairment may relate to cognition, depression, or social isolation, which could influence physical activity.

“Age-related hearing loss is traditionally seen as a barrier for communication,” Dr. Martinez-Amezcua told this news organization. “In the past decade, research on the consequences of hearing loss has identified it as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Our findings contribute to our understanding of other negative outcomes associated with hearing loss.”

Randomized clinical trials are the best way to assess whether addressing hearing loss might improve physical function, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said. “Currently there is one clinical trial (ACHIEVE) that will, among other outcomes, study the impact of hearing aids on cognitive and physical function,” he said.

Although interventions may not reverse hearing loss, hearing rehabilitation strategies, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, may help, he added. Educating caregivers and changing a person’s environment can also reduce the effects hearing loss has on daily life, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said.

“We rely so much in our sense of vision for activities of daily living that we tend to underestimate how important hearing is, and the consequences of hearing loss go beyond having trouble communicating with someone,” he said.

This study and prior research “raise the intriguing idea that hearing may provide essential information to the neural circuits underpinning movement in our environment and that correction for hearing loss may help promote physical well-being,” Willa D. Brenowitz, PhD, MPH, and Margaret I. Wallhagen, PhD, GNP-BC, both at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying commentary. “While this hypothesis is appealing and warrants further investigation, there are multiple other potential explanations of such an association, including potential sources of bias that may affect observational studies such as this one.”

Beyond treating hearing loss, interventions such as physical therapy or tai chi may benefit patients, they suggested.

Because many changes occur during older age, it can be difficult to understand which factor is influencing another, Dr. Brenowitz said in an interview. There are potentially relevant mechanisms through which hearing could affect cognition and physical functioning. Still another explanation could be that some people are “aging in a faster way” than others, Dr. Brenowitz said.

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and a coauthor disclosed receiving sponsorship from the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health. Another author, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD, directs the research center, which is partly funded by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Lin also disclosed personal fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Caption Call. One author serves on a scientific advisory board for Shoebox and Good Machine Studio.

Dr. Wallhagen has served on the board of trustees of the Hearing Loss Association of America and is a member of the board of the Hearing Loss Association of America–California. Dr. Wallhagen also received funding for a pilot project on the impact of hearing loss on communication in the context of chronic serious illness from the National Palliative Care Research Center outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published online in JAMA Network Open.

Hearing loss is associated with slower gait and, in particular, worse balance, the data suggest.

“Because hearing impairment is amenable to prevention and management, it potentially serves as a target for interventions to slow physical decline with aging,” the researchers said.

To examine how hearing impairment relates to physical function in older adults, Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, MD, PhD, MHS, a researcher in the department of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues analyzed data from the ongoing Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study.

ARIC initially enrolled more than 15,000 adults in Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, and North Carolina between 1987 and 1989. In the present study, the researchers focused on data from 2,956 participants who attended a study visit between 2016 and 2017, during which researchers assessed their hearing using pure tone audiometry.

Hearing-study participants had an average age of 79 years, about 58% were women, and 80% were White. Approximately 33% of the participants had normal hearing, 40% had mild hearing impairment, 23% had moderate hearing impairment, and 4% had severe hearing impairment.

Participants had also undergone assessment of physical functioning at study visits between 2011 and 2019, including a fast-paced 2-minute walk test to measure their walking endurance. Another assessment, the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), tests balance, gait speed, and chair stands (seated participants stand up and sit back down five times as quickly as possible while their arms are crossed).

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and colleagues found that severe hearing impairment was associated with a lower average SPPB score compared with normal hearing in a regression analysis. Specifically, compared with those with normal hearing, participants with severe hearing impairment were more likely to have low scores on the SPPB (odds ratio, 2.72), balance (OR, 2.72), and gait speed (OR, 2.16).

However, hearing impairment was not significantly associated with the chair stand test results. The researchers note that chair stands may rely more on strength, whereas balance and gait speed may rely more on coordination and movement.

The team also found that people with worse hearing tended to walk a shorter distance during the 2-minute walk test. Compared with participants with normal hearing, participants with moderate hearing impairment walked 2.81 meters less and those with severe hearing impairment walked 5.31 meters less on average, after adjustment for variables including age, sex, and health conditions.

Participants with hearing impairment also tended to have faster declines in physical function over time.

Various mechanisms could explain associations between hearing and physical function, the authors said. For example, an underlying condition such as cardiovascular disease might affect both hearing and physical function. Damage to the inner ear could affect vestibular and auditory systems at the same time. In addition, hearing impairment may relate to cognition, depression, or social isolation, which could influence physical activity.

“Age-related hearing loss is traditionally seen as a barrier for communication,” Dr. Martinez-Amezcua told this news organization. “In the past decade, research on the consequences of hearing loss has identified it as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia. Our findings contribute to our understanding of other negative outcomes associated with hearing loss.”

Randomized clinical trials are the best way to assess whether addressing hearing loss might improve physical function, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said. “Currently there is one clinical trial (ACHIEVE) that will, among other outcomes, study the impact of hearing aids on cognitive and physical function,” he said.

Although interventions may not reverse hearing loss, hearing rehabilitation strategies, including hearing aids and cochlear implants, may help, he added. Educating caregivers and changing a person’s environment can also reduce the effects hearing loss has on daily life, Dr. Martinez-Amezcua said.

“We rely so much in our sense of vision for activities of daily living that we tend to underestimate how important hearing is, and the consequences of hearing loss go beyond having trouble communicating with someone,” he said.

This study and prior research “raise the intriguing idea that hearing may provide essential information to the neural circuits underpinning movement in our environment and that correction for hearing loss may help promote physical well-being,” Willa D. Brenowitz, PhD, MPH, and Margaret I. Wallhagen, PhD, GNP-BC, both at the University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an accompanying commentary. “While this hypothesis is appealing and warrants further investigation, there are multiple other potential explanations of such an association, including potential sources of bias that may affect observational studies such as this one.”

Beyond treating hearing loss, interventions such as physical therapy or tai chi may benefit patients, they suggested.

Because many changes occur during older age, it can be difficult to understand which factor is influencing another, Dr. Brenowitz said in an interview. There are potentially relevant mechanisms through which hearing could affect cognition and physical functioning. Still another explanation could be that some people are “aging in a faster way” than others, Dr. Brenowitz said.

Dr. Martinez-Amezcua and a coauthor disclosed receiving sponsorship from the Cochlear Center for Hearing and Public Health. Another author, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD, directs the research center, which is partly funded by a philanthropic gift from Cochlear to the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Lin also disclosed personal fees from Frequency Therapeutics and Caption Call. One author serves on a scientific advisory board for Shoebox and Good Machine Studio.

Dr. Wallhagen has served on the board of trustees of the Hearing Loss Association of America and is a member of the board of the Hearing Loss Association of America–California. Dr. Wallhagen also received funding for a pilot project on the impact of hearing loss on communication in the context of chronic serious illness from the National Palliative Care Research Center outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AAP updates guidance for return to sports and physical activities

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

5-year-old boy • calf pain • fever • cough & rhinitis • Dx?

THE CASE

A 5-year-old previously healthy white boy presented to clinic with bilateral calf pain and refusal to bear weight since awakening that morning. Associated symptoms included a 3-day history of generalized fatigue, subjective fevers, cough, congestion, and rhinitis. The night prior to presentation, he showed no symptoms of gait abnormalities, muscle pain, or weakness. There was no history of similar symptoms, trauma, overexertion, foreign travel, or family history of musculoskeletal disease. He was fully immunized, except for the annual influenza vaccine. He was not taking any medications. This case occurred before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective findings included fever of 101 °F, refusal to bear weight, and symmetrical bilateral tenderness to palpation of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex. Pain was elicited with passive dorsiflexion. There was no erythema, edema, or sensory deficits, and the distal leg compartments were soft. There was normal range of motion of the hips, knees, and ankles. Dorsalis pedis pulses were 2+, and patella reflexes were 2/4 bilaterally.

Lab results included a white blood cell count of 2500/μL (normal range, 4500 to 11,000/μL);absolute neutrophil count, 900/μL (1500 to 8000/μL); platelet count, 131,000/μL (150,000 to 450,000/μL); creatine kinase level, 869 IU/L (22 to 198 U/L); and aspartate aminotransferase level, 116 U/L (8 to 33 U/L). A rapid influenza swab was positive for influenza B. Plain films of the bilateral hips and lower extremities were unremarkable. C-reactive protein (CRP) level, urinalysis, and renal function tests were within normal limits. Creatine kinase (CK) level peaked (1935 U/L; normal range, 22 to 198 U/L) within the first 24 hours of presentation and then trended down.

The Diagnosis

The patient’s sudden onset of symmetrical bilateral calf pain in the setting of an upper respiratory tract infection was extremely suspicious for benign acute childhood myositis (BACM). Lab work and radiologic evaluation were performed to rule out more ominous causes of refusal to bear weight. The suspicion of BACM was further validated by influenza B serology, an elevated CK, and a normal CRP.

Discussion

BACM was first described by Lundberg in 1957.1 The overall incidence and prevalence are unclear.2 A viral prodrome involving rhinorrhea, low-grade fever, sore throat, cough, and malaise typically precedes bilateral calf pain by 3 days.2-4 Myositis symptoms typically last for 4 days.3 While several infectious etiologies have been linked to this condition, influenza B has the greatest association.5,6

❚ Patient population. BACM occurs predominately in school-aged children (6-8 years old) and has a male-to-female ratio of 2:1.3,5,6 In a retrospective study of 219 children, BACM was strongly associated with male gender and ages 6 to 9 years.3 In another retrospective study of 54 children,80% of patients were male, and the mean age was 7.3 years.5

❚ Key symptoms and differential. The distinguishing feature of BACM is bilateral symmetric gastrocnemius-soleus tenderness.2,4 Additionally, the lack of neurologic symptoms is an important differentiator, as long as refusal to bear weight is not mistaken for weakness.6 These features help to distinguish BACM from other items in the differential, including trauma, Guillain-Barre syndrome, osteomyelitis, malignancy, deep vein thrombosis, and inherited musculoskeletal disorders.2

Continue to: Labratory evaluation...

❚ Laboratory evaluation will often show mild neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and mild elevation in CK.7,8 CRP is typically normal.4,7,9 In a retrospective study of 28 admissions for BACM from 2001 to 2012, common findings included leukopenia (35%), neutropenia (25%), and thrombocytopenia (21%). The median CK value was 4181 U/L.4 In another analysis of BACM cases, mean CK was 1872 U/L.5

❚ Biopsy is unnecessary; however, calf muscle samples from 11 of 12 children with suspected BACM due to influenza B infection were consistent with patchy necrosis without significant myositis.10

❚ Complications. Rhabdomyolysis, although rare, has been reported with BACM. In 1 analysis, 10 of 316 patients with influenza-associated myositis developed rhabdomyolysis; 8 experienced renal failure. Rhabdomyolysis was 4 times more likely to occur in girls, and 86% of cases were associated with influenza A.6 Common manifestations of rhabdomyolysis associated with influenza include diffuse myopathy, gross hematuria, and myoglobinuria.6

❚ Treatment is mainly supportive.4,8,9 Antivirals typically are not indicated, as the bilateral calf pain manifests during the recovery phase of the illness.4,9,11 BACM is self-limited and should resolve within 3 days of myositis manifestation.2 Patients should follow up in 2 to 3 weeks to verify symptom resolution.2

If muscle pain, swelling, and tenderness worsen, further work-up is indicated. In more severe cases, including those involving renal failure, intensive care management and even dialysis may be necessary.4,6

❚ Our patient was hospitalized due to fever in the setting of neutropenia. Ultimately, he was treated with acetaminophen and intravenous fluids for mild dehydration and elevated CK levels. He was discharged home after 3 days, at which time he had complete resolution of pain and was able to resume normal activities.

The Takeaway

Benign acute childhood myositis is a self-limited disorder with an excellent prognosis. It has a typical presentation and therefore should be a clinical diagnosis; however, investigative studies may be warranted to rule out more ominous causes. Reassurance to family that the condition should self-resolve in a few days is important. Close follow-up should be scheduled to ensure resolution of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas A. Rathjen, DO, William Beaumont Army Medical Center, Department of Soldier and Family Care, 11335 SSG Sims Street, Fort Bliss, TX 79918; nicholas.a.rathjen@gmail. com

- Lundberg A. Myalgia cruris epidemica. Acta Paediatr. 1957;46:18-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1957.tb08627.x

- Magee H, Goldman RD. Viral myositis in children. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:365-368.

- Mall S, Buchholz U, Tibussek D, et al. A large outbreak of influenza B-associated benign acute childhood myositis in Germany, 2007/2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e142-e146. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318217e356

- Santos JA, Albuquerque C, Lito D, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: an alarming condition with an excellent prognosis! Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1418-1419. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.08.022

- Rosenberg T, Heitner S, Scolnik D, et al. Outcome of benign acute childhood myositis: the experience of 2 large tertiary care pediatric hospitals. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:400-402. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000830

- Agyeman P, Duppenthaler A, Heininger U, et al. Influenza-associated myositis in children. Infection. 2004;32:199-203. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4003-2

- Mackay MT, Kornberg AJ, Shield LK, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: laboratory and clinical features. Neurology. 1999;53:2127-2131. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2127

- Neocleous C, Spanou C, Mpampalis E, et al. Unnecessary diagnostic investigations in benign acute childhood myositis: a case series report. Scott Med J. 2012;57:182. doi: 10.1258/smj.2012.012023

- Felipe Cavagnaro SM, Alejandra Aird G, Ingrid Harwardt R, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: clinical series and literature review. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2017;88:268-274. doi: 10.1016/j.rchipe.2016.07.002

- Bove KE, Hilton PK, Partin J, et al. Morphology of acute myopathy associated with influenza B infection. Pediatric Pathology. 1983;1:51-66. https://doi.org/10.3109/15513818309048284

- Koliou M, Hadjiloizou S, Ourani S, et al. A case of benign acute childhood myositis associated with influenza A (HINI) virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:193-195. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03064.x

THE CASE

A 5-year-old previously healthy white boy presented to clinic with bilateral calf pain and refusal to bear weight since awakening that morning. Associated symptoms included a 3-day history of generalized fatigue, subjective fevers, cough, congestion, and rhinitis. The night prior to presentation, he showed no symptoms of gait abnormalities, muscle pain, or weakness. There was no history of similar symptoms, trauma, overexertion, foreign travel, or family history of musculoskeletal disease. He was fully immunized, except for the annual influenza vaccine. He was not taking any medications. This case occurred before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective findings included fever of 101 °F, refusal to bear weight, and symmetrical bilateral tenderness to palpation of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex. Pain was elicited with passive dorsiflexion. There was no erythema, edema, or sensory deficits, and the distal leg compartments were soft. There was normal range of motion of the hips, knees, and ankles. Dorsalis pedis pulses were 2+, and patella reflexes were 2/4 bilaterally.

Lab results included a white blood cell count of 2500/μL (normal range, 4500 to 11,000/μL);absolute neutrophil count, 900/μL (1500 to 8000/μL); platelet count, 131,000/μL (150,000 to 450,000/μL); creatine kinase level, 869 IU/L (22 to 198 U/L); and aspartate aminotransferase level, 116 U/L (8 to 33 U/L). A rapid influenza swab was positive for influenza B. Plain films of the bilateral hips and lower extremities were unremarkable. C-reactive protein (CRP) level, urinalysis, and renal function tests were within normal limits. Creatine kinase (CK) level peaked (1935 U/L; normal range, 22 to 198 U/L) within the first 24 hours of presentation and then trended down.

The Diagnosis

The patient’s sudden onset of symmetrical bilateral calf pain in the setting of an upper respiratory tract infection was extremely suspicious for benign acute childhood myositis (BACM). Lab work and radiologic evaluation were performed to rule out more ominous causes of refusal to bear weight. The suspicion of BACM was further validated by influenza B serology, an elevated CK, and a normal CRP.

Discussion

BACM was first described by Lundberg in 1957.1 The overall incidence and prevalence are unclear.2 A viral prodrome involving rhinorrhea, low-grade fever, sore throat, cough, and malaise typically precedes bilateral calf pain by 3 days.2-4 Myositis symptoms typically last for 4 days.3 While several infectious etiologies have been linked to this condition, influenza B has the greatest association.5,6

❚ Patient population. BACM occurs predominately in school-aged children (6-8 years old) and has a male-to-female ratio of 2:1.3,5,6 In a retrospective study of 219 children, BACM was strongly associated with male gender and ages 6 to 9 years.3 In another retrospective study of 54 children,80% of patients were male, and the mean age was 7.3 years.5

❚ Key symptoms and differential. The distinguishing feature of BACM is bilateral symmetric gastrocnemius-soleus tenderness.2,4 Additionally, the lack of neurologic symptoms is an important differentiator, as long as refusal to bear weight is not mistaken for weakness.6 These features help to distinguish BACM from other items in the differential, including trauma, Guillain-Barre syndrome, osteomyelitis, malignancy, deep vein thrombosis, and inherited musculoskeletal disorders.2

Continue to: Labratory evaluation...

❚ Laboratory evaluation will often show mild neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and mild elevation in CK.7,8 CRP is typically normal.4,7,9 In a retrospective study of 28 admissions for BACM from 2001 to 2012, common findings included leukopenia (35%), neutropenia (25%), and thrombocytopenia (21%). The median CK value was 4181 U/L.4 In another analysis of BACM cases, mean CK was 1872 U/L.5

❚ Biopsy is unnecessary; however, calf muscle samples from 11 of 12 children with suspected BACM due to influenza B infection were consistent with patchy necrosis without significant myositis.10

❚ Complications. Rhabdomyolysis, although rare, has been reported with BACM. In 1 analysis, 10 of 316 patients with influenza-associated myositis developed rhabdomyolysis; 8 experienced renal failure. Rhabdomyolysis was 4 times more likely to occur in girls, and 86% of cases were associated with influenza A.6 Common manifestations of rhabdomyolysis associated with influenza include diffuse myopathy, gross hematuria, and myoglobinuria.6

❚ Treatment is mainly supportive.4,8,9 Antivirals typically are not indicated, as the bilateral calf pain manifests during the recovery phase of the illness.4,9,11 BACM is self-limited and should resolve within 3 days of myositis manifestation.2 Patients should follow up in 2 to 3 weeks to verify symptom resolution.2

If muscle pain, swelling, and tenderness worsen, further work-up is indicated. In more severe cases, including those involving renal failure, intensive care management and even dialysis may be necessary.4,6

❚ Our patient was hospitalized due to fever in the setting of neutropenia. Ultimately, he was treated with acetaminophen and intravenous fluids for mild dehydration and elevated CK levels. He was discharged home after 3 days, at which time he had complete resolution of pain and was able to resume normal activities.

The Takeaway

Benign acute childhood myositis is a self-limited disorder with an excellent prognosis. It has a typical presentation and therefore should be a clinical diagnosis; however, investigative studies may be warranted to rule out more ominous causes. Reassurance to family that the condition should self-resolve in a few days is important. Close follow-up should be scheduled to ensure resolution of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas A. Rathjen, DO, William Beaumont Army Medical Center, Department of Soldier and Family Care, 11335 SSG Sims Street, Fort Bliss, TX 79918; nicholas.a.rathjen@gmail. com

THE CASE

A 5-year-old previously healthy white boy presented to clinic with bilateral calf pain and refusal to bear weight since awakening that morning. Associated symptoms included a 3-day history of generalized fatigue, subjective fevers, cough, congestion, and rhinitis. The night prior to presentation, he showed no symptoms of gait abnormalities, muscle pain, or weakness. There was no history of similar symptoms, trauma, overexertion, foreign travel, or family history of musculoskeletal disease. He was fully immunized, except for the annual influenza vaccine. He was not taking any medications. This case occurred before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective findings included fever of 101 °F, refusal to bear weight, and symmetrical bilateral tenderness to palpation of the gastrocnemius-soleus complex. Pain was elicited with passive dorsiflexion. There was no erythema, edema, or sensory deficits, and the distal leg compartments were soft. There was normal range of motion of the hips, knees, and ankles. Dorsalis pedis pulses were 2+, and patella reflexes were 2/4 bilaterally.

Lab results included a white blood cell count of 2500/μL (normal range, 4500 to 11,000/μL);absolute neutrophil count, 900/μL (1500 to 8000/μL); platelet count, 131,000/μL (150,000 to 450,000/μL); creatine kinase level, 869 IU/L (22 to 198 U/L); and aspartate aminotransferase level, 116 U/L (8 to 33 U/L). A rapid influenza swab was positive for influenza B. Plain films of the bilateral hips and lower extremities were unremarkable. C-reactive protein (CRP) level, urinalysis, and renal function tests were within normal limits. Creatine kinase (CK) level peaked (1935 U/L; normal range, 22 to 198 U/L) within the first 24 hours of presentation and then trended down.

The Diagnosis

The patient’s sudden onset of symmetrical bilateral calf pain in the setting of an upper respiratory tract infection was extremely suspicious for benign acute childhood myositis (BACM). Lab work and radiologic evaluation were performed to rule out more ominous causes of refusal to bear weight. The suspicion of BACM was further validated by influenza B serology, an elevated CK, and a normal CRP.

Discussion

BACM was first described by Lundberg in 1957.1 The overall incidence and prevalence are unclear.2 A viral prodrome involving rhinorrhea, low-grade fever, sore throat, cough, and malaise typically precedes bilateral calf pain by 3 days.2-4 Myositis symptoms typically last for 4 days.3 While several infectious etiologies have been linked to this condition, influenza B has the greatest association.5,6

❚ Patient population. BACM occurs predominately in school-aged children (6-8 years old) and has a male-to-female ratio of 2:1.3,5,6 In a retrospective study of 219 children, BACM was strongly associated with male gender and ages 6 to 9 years.3 In another retrospective study of 54 children,80% of patients were male, and the mean age was 7.3 years.5

❚ Key symptoms and differential. The distinguishing feature of BACM is bilateral symmetric gastrocnemius-soleus tenderness.2,4 Additionally, the lack of neurologic symptoms is an important differentiator, as long as refusal to bear weight is not mistaken for weakness.6 These features help to distinguish BACM from other items in the differential, including trauma, Guillain-Barre syndrome, osteomyelitis, malignancy, deep vein thrombosis, and inherited musculoskeletal disorders.2

Continue to: Labratory evaluation...

❚ Laboratory evaluation will often show mild neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and mild elevation in CK.7,8 CRP is typically normal.4,7,9 In a retrospective study of 28 admissions for BACM from 2001 to 2012, common findings included leukopenia (35%), neutropenia (25%), and thrombocytopenia (21%). The median CK value was 4181 U/L.4 In another analysis of BACM cases, mean CK was 1872 U/L.5

❚ Biopsy is unnecessary; however, calf muscle samples from 11 of 12 children with suspected BACM due to influenza B infection were consistent with patchy necrosis without significant myositis.10

❚ Complications. Rhabdomyolysis, although rare, has been reported with BACM. In 1 analysis, 10 of 316 patients with influenza-associated myositis developed rhabdomyolysis; 8 experienced renal failure. Rhabdomyolysis was 4 times more likely to occur in girls, and 86% of cases were associated with influenza A.6 Common manifestations of rhabdomyolysis associated with influenza include diffuse myopathy, gross hematuria, and myoglobinuria.6

❚ Treatment is mainly supportive.4,8,9 Antivirals typically are not indicated, as the bilateral calf pain manifests during the recovery phase of the illness.4,9,11 BACM is self-limited and should resolve within 3 days of myositis manifestation.2 Patients should follow up in 2 to 3 weeks to verify symptom resolution.2

If muscle pain, swelling, and tenderness worsen, further work-up is indicated. In more severe cases, including those involving renal failure, intensive care management and even dialysis may be necessary.4,6

❚ Our patient was hospitalized due to fever in the setting of neutropenia. Ultimately, he was treated with acetaminophen and intravenous fluids for mild dehydration and elevated CK levels. He was discharged home after 3 days, at which time he had complete resolution of pain and was able to resume normal activities.

The Takeaway

Benign acute childhood myositis is a self-limited disorder with an excellent prognosis. It has a typical presentation and therefore should be a clinical diagnosis; however, investigative studies may be warranted to rule out more ominous causes. Reassurance to family that the condition should self-resolve in a few days is important. Close follow-up should be scheduled to ensure resolution of symptoms.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nicholas A. Rathjen, DO, William Beaumont Army Medical Center, Department of Soldier and Family Care, 11335 SSG Sims Street, Fort Bliss, TX 79918; nicholas.a.rathjen@gmail. com

- Lundberg A. Myalgia cruris epidemica. Acta Paediatr. 1957;46:18-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1957.tb08627.x

- Magee H, Goldman RD. Viral myositis in children. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:365-368.

- Mall S, Buchholz U, Tibussek D, et al. A large outbreak of influenza B-associated benign acute childhood myositis in Germany, 2007/2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e142-e146. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318217e356

- Santos JA, Albuquerque C, Lito D, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: an alarming condition with an excellent prognosis! Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1418-1419. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.08.022

- Rosenberg T, Heitner S, Scolnik D, et al. Outcome of benign acute childhood myositis: the experience of 2 large tertiary care pediatric hospitals. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:400-402. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000830

- Agyeman P, Duppenthaler A, Heininger U, et al. Influenza-associated myositis in children. Infection. 2004;32:199-203. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4003-2

- Mackay MT, Kornberg AJ, Shield LK, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: laboratory and clinical features. Neurology. 1999;53:2127-2131. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2127

- Neocleous C, Spanou C, Mpampalis E, et al. Unnecessary diagnostic investigations in benign acute childhood myositis: a case series report. Scott Med J. 2012;57:182. doi: 10.1258/smj.2012.012023

- Felipe Cavagnaro SM, Alejandra Aird G, Ingrid Harwardt R, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: clinical series and literature review. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2017;88:268-274. doi: 10.1016/j.rchipe.2016.07.002

- Bove KE, Hilton PK, Partin J, et al. Morphology of acute myopathy associated with influenza B infection. Pediatric Pathology. 1983;1:51-66. https://doi.org/10.3109/15513818309048284

- Koliou M, Hadjiloizou S, Ourani S, et al. A case of benign acute childhood myositis associated with influenza A (HINI) virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:193-195. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03064.x

- Lundberg A. Myalgia cruris epidemica. Acta Paediatr. 1957;46:18-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1957.tb08627.x

- Magee H, Goldman RD. Viral myositis in children. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:365-368.

- Mall S, Buchholz U, Tibussek D, et al. A large outbreak of influenza B-associated benign acute childhood myositis in Germany, 2007/2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e142-e146. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318217e356

- Santos JA, Albuquerque C, Lito D, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: an alarming condition with an excellent prognosis! Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:1418-1419. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.08.022

- Rosenberg T, Heitner S, Scolnik D, et al. Outcome of benign acute childhood myositis: the experience of 2 large tertiary care pediatric hospitals. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:400-402. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000830

- Agyeman P, Duppenthaler A, Heininger U, et al. Influenza-associated myositis in children. Infection. 2004;32:199-203. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4003-2

- Mackay MT, Kornberg AJ, Shield LK, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: laboratory and clinical features. Neurology. 1999;53:2127-2131. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2127

- Neocleous C, Spanou C, Mpampalis E, et al. Unnecessary diagnostic investigations in benign acute childhood myositis: a case series report. Scott Med J. 2012;57:182. doi: 10.1258/smj.2012.012023

- Felipe Cavagnaro SM, Alejandra Aird G, Ingrid Harwardt R, et al. Benign acute childhood myositis: clinical series and literature review. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2017;88:268-274. doi: 10.1016/j.rchipe.2016.07.002

- Bove KE, Hilton PK, Partin J, et al. Morphology of acute myopathy associated with influenza B infection. Pediatric Pathology. 1983;1:51-66. https://doi.org/10.3109/15513818309048284

- Koliou M, Hadjiloizou S, Ourani S, et al. A case of benign acute childhood myositis associated with influenza A (HINI) virus infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2010;16:193-195. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03064.x

Osteoporosis management: Use a goal-oriented, individualized approach

Recommendations for care are evolving, with increasingly sophisticated screening and diagnostic tools and a broadening array of treatment options.

As the population of older adults rises, primary osteoporosis has become a problem of public health significance, resulting in more than 2 million fractures and $19 billion in related costs annually in the United States.1 Despite the availability of effective primary and secondary preventive measures, many older adults do not receive adequate information on bone health from their primary care provider.2 Initiation of osteoporosis treatment is low even among patients who have had an osteoporotic fracture: Fewer than one-quarter of older adults with hip fracture have begun taking osteoporosis medication within 12 months of hospital discharge.3

In this overview of osteoporosis care, we provide information on how to evaluate and manage older adults in primary care settings who are at risk of, or have been given a diagnosis of, primary osteoporosis. The guidance that we offer reflects the most recent updates and recommendations by relevant professional societies.1,4-7

The nature and scope of an urgent problem

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone structure that causes bone fragility and increases the risk of fracture.8 Operationally, it is defined by the World Health Organization as a bone mineral density (BMD) score below 2.5 SD from the mean value for a young White woman (ie, T-score ≤ –2.5).9 Primary osteoporosis is age related and occurs mostly in postmenopausal women and older men, affecting 25% of women and 5% of men ≥ 65 years.10

An osteoporotic fracture is particularly devastating in an older adult because it can cause pain, reduced mobility, depression, and social isolation and can increase the risk of related mortality.1 The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates that 20% of older adults who sustain a hip fracture die within 1 year due to complications of the fracture itself or surgical repair.1 Therefore, it is of paramount importance to identify patients who are at increased risk of fracture and intervene early.

Clinical manifestations

Osteoporosis does not have a primary presentation; rather, disease manifests clinically when a patient develops complications. Often, a fragility fracture is the first sign in an older person.11

A fracture is the most important complication of osteoporosis and can result from low-trauma injury or a fall from standing height—thus, the term “fragility fracture.” Osteoporotic fractures commonly involve the vertebra, hip, and wrist. Hip and extremity fractures can result in limited or lost mobility and depression. Vertebral fractures can be asymptomatic or result in kyphosis and loss of height. Fractures can give rise to pain.

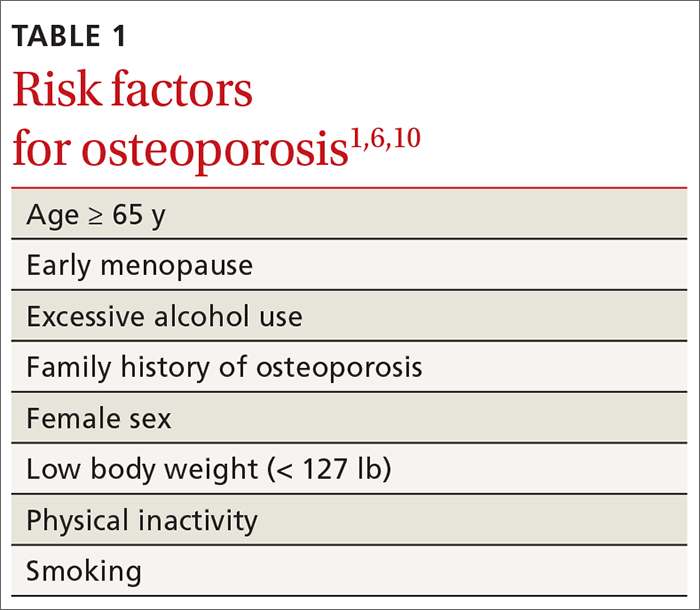

Age and female sexare risk factors

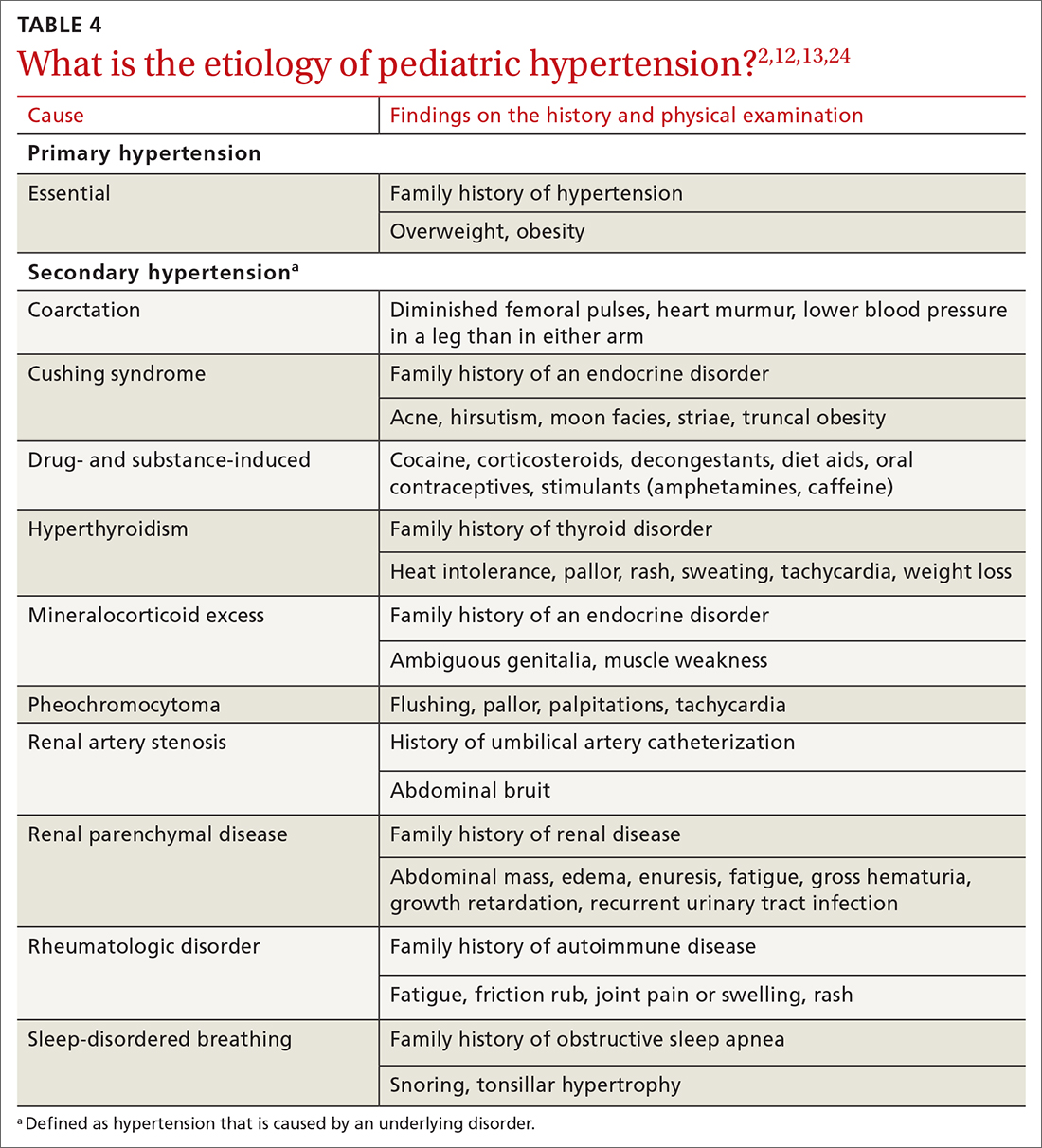

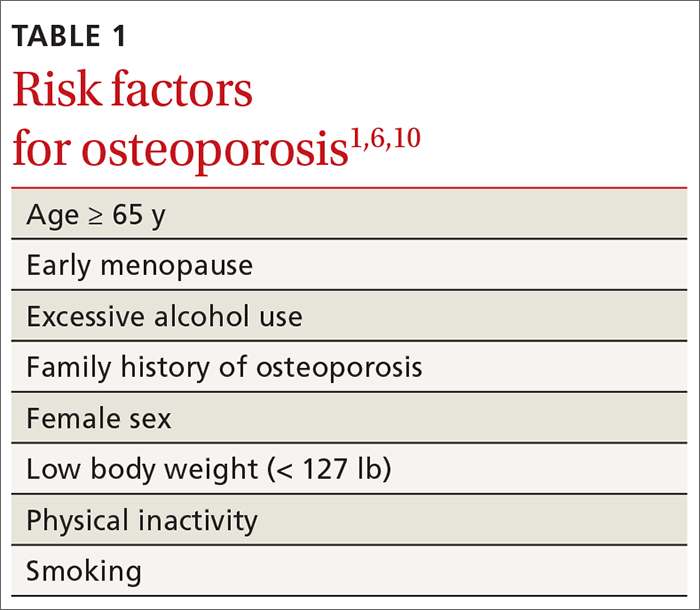

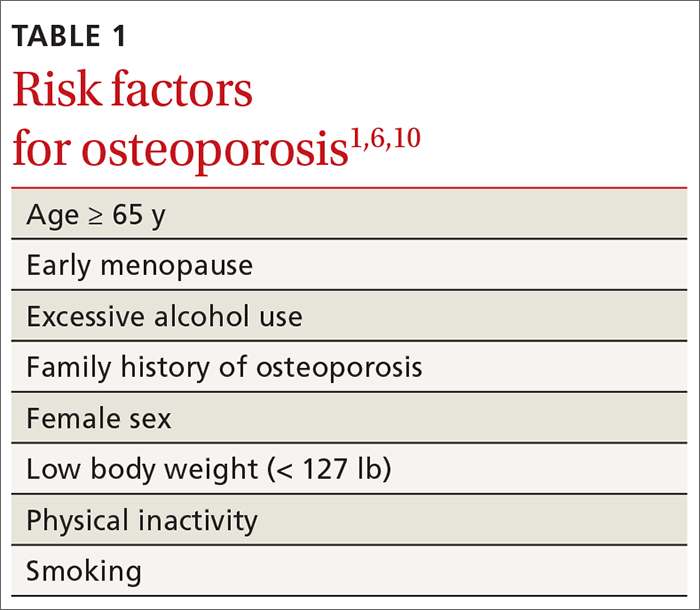

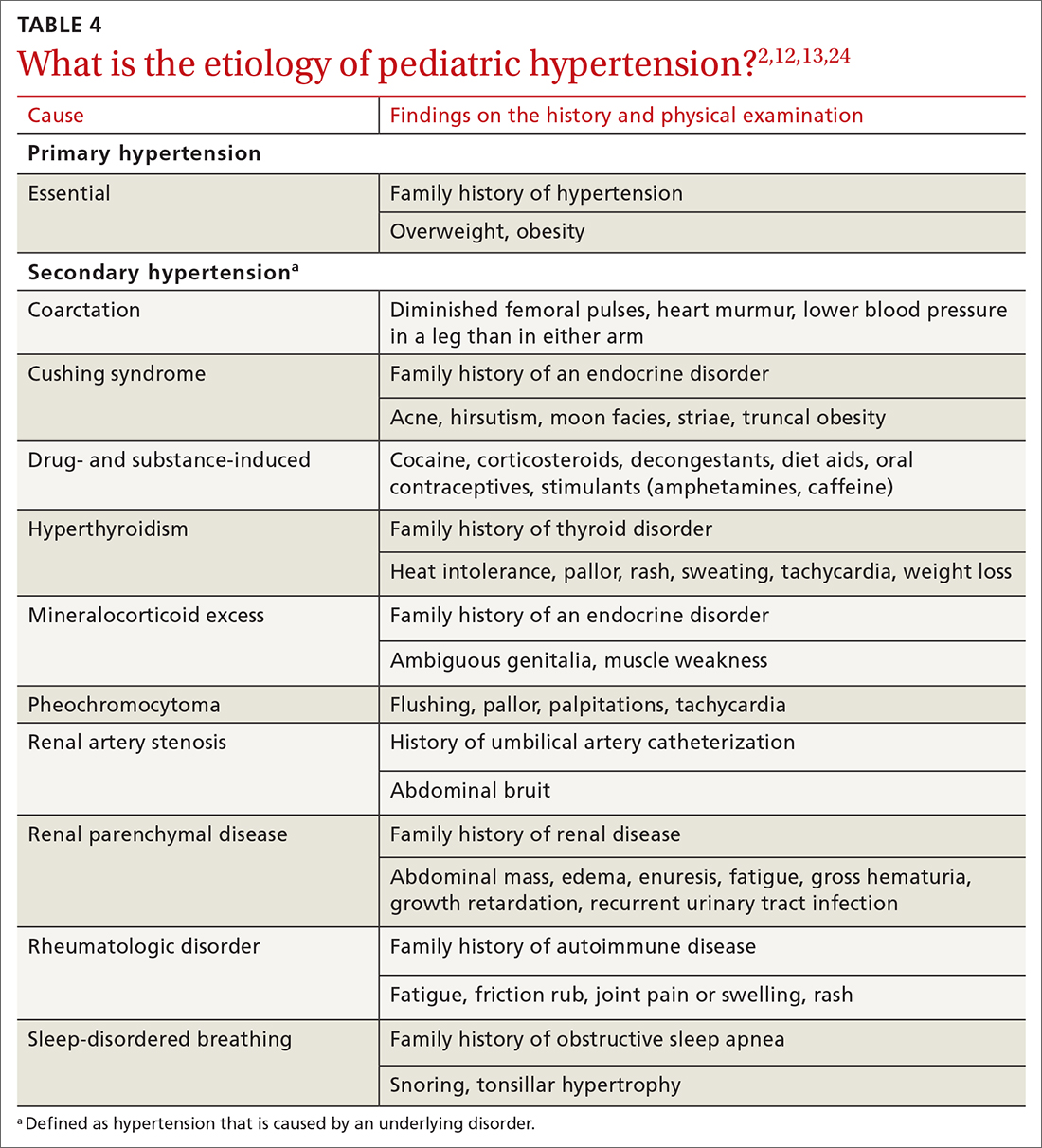

TABLE 11,6,10 lists risk factors associated with osteoporosis. Age is the most important; prevalence of osteoporosis increases with age. Other nonmodifiable risk factors include female sex (the disease appears earlier in women who enter menopause prematurely), family history of osteoporosis, and race and ethnicity. Twenty percent of Asian and non-Hispanic White women > 50 years have osteoporosis.1 A study showed that Mexican Americans are at higher risk of osteoporosis than non-Hispanic Whites; non-Hispanic Blacks are least affected.10

Other risk factors include low body weight (< 127 lb) and a history of fractures after age 50. Behavioral risk factors include smoking, excessive alcohol intake (> 3 drinks/d), poor nutrition, and a sedentary lifestyle.1,6

Continue to: Who should be screened?...

Who should be screened?

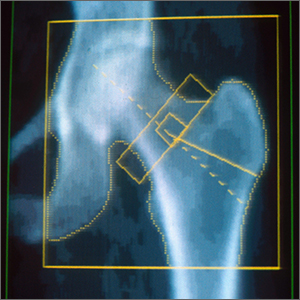

Screening is generally performed with a clinical evaluation and a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan of BMD. Measurement of BMD is generally recommended for screening all women ≥ 65 years and those < 65 years whose 10-year risk of fracture is equivalent to that of a 65-year-old White woman (see “Assessment of fracture risk” later in the article). For men, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening those with a prior fracture or a secondary risk factor for disease.5 However, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends screening all men ≥ 70 years and those 50 to 69 years whose risk profile shows heightened risk.1,4

DXA of the spine and hip is preferred; the distal one-third of the radius (termed “33% radius”) of the nondominant arm can be used when spine and hip BMD cannot be interpreted because of bone changes from the disease process or artifacts, or in certain diseases in which the wrist region shows the earliest change (eg, primary hyperparathyroidism).6,7

Clinical evaluation includes a detailed history, physical examination, laboratory screening, and assessment for risk of fracture.

❚ History. Explore the presence of risk factors, including fractures in adulthood, falls, medication use, alcohol and tobacco use, family history of osteoporosis, and chronic disease.6,7

❚ Physical exam. Assess height, including any loss (> 1.5 in) since the patient’s second or third decade of life; kyphosis; frailty; and balance and mobility problems.4,6,7

❚ Laboratory and imaging studies. Perform basic laboratory testing when DXA is abnormal, including thyroid function, serum calcium, and renal function.6,12 Radiography of the lateral spine might be necessary, especially when there is kyphosis or loss of height. Assess for vertebral fracture, using lateral spine radiography, when vertebral involvement is suspected.6,7

❚ Assessment of fracture risk. Fracture risk can be assessed with any of a number of tools, including:

- Simplified Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE): www.medicalalgorithms.com/simplified-calculated-osteoporosis-risk-estimation-tool

- Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI): www.physio-pedia.com/The_Osteoporosis_Risk_Assessment_Instrument_(ORAI)

- Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS): https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/gye.16.3.245.250?journalCode=igye20

- Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool (OST): www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45516/figure/ch10.f2/

- FRAX tool5: www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX.

The FRAX tool is widely used. It assesses a patient’s 10-year risk of fracture.

Diagnosis is based on these criteria

Diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on any 1 or more of the following criteria6:

- a history of fragility fracture not explained by metabolic bone disease

- T-score ≤ –2.5 (lumbar, hip, femoral neck, or 33% radius)

- a nation-specific FRAX score (in the absence of access to DXA).

❚ Secondary disease. Patients in whom secondary osteoporosis is suspected should undergo laboratory investigation to ascertain the cause; treatment of the underlying pathology might then be required. Evaluation for a secondary cause might include a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, protein electrophoresis and urinary protein electrophoresis (to rule out myeloproliferative and hematologic diseases), and tests of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, serum calcium, alkaline phosphatase, 24-hour urinary calcium, sodium, and creatinine.6,7 Specialized testing for biochemical markers of bone turnover—so-called bone-turnover markers—can be considered as part of the initial evaluation and follow-up, although the tests are not recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (see “Monitoring the efficacy of treatment,” later in the article, for more information about these markers).6

Although BMD by DXA remains the gold standard in screening for and diagnosing osteoporosis, a high rate of fracture is seen in patients with certain diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and ankylosing spondylitis, who have a nonosteoporotic low T-score. This raises concerns about the usefulness of BMD for diagnosing osteoporosis in patients who have one of these diseases.13-16

❚

❚ Trabecular bone score (TBS), a surrogate bone-quality measure that is calculated based on the spine DXA image, has recently been introduced in clinical practice, and can be used to predict fracture risk in conjunction with BMD assessment by DXA and the FRAX score.17 TBS provides an indirect index of the trabecular microarchitecture using pixel gray-level variation in lumbar spine DXA images.18 Three categories of TBS (≤ 1.200, degraded microarchitecture; 1.200-1.350, partially degraded microarchitecture; and > 1.350, normal microarchitecture) have been reported to correspond with a T-score of, respectively, ≤ −2.5; −2.5 to −1.0; and > −1.0.18 TBS can be used only in patients with a body mass index of 15 to 37.5.19,20

There is no recommendation for monitoring bone quality using TBS after osteoporosis treatment. Such monitoring is at the clinician’s discretion for appropriate patients who might not show a risk of fracture, based on BMD measurement.

Continue to: Putting preventive measures into practice...

Putting preventive measures into practice

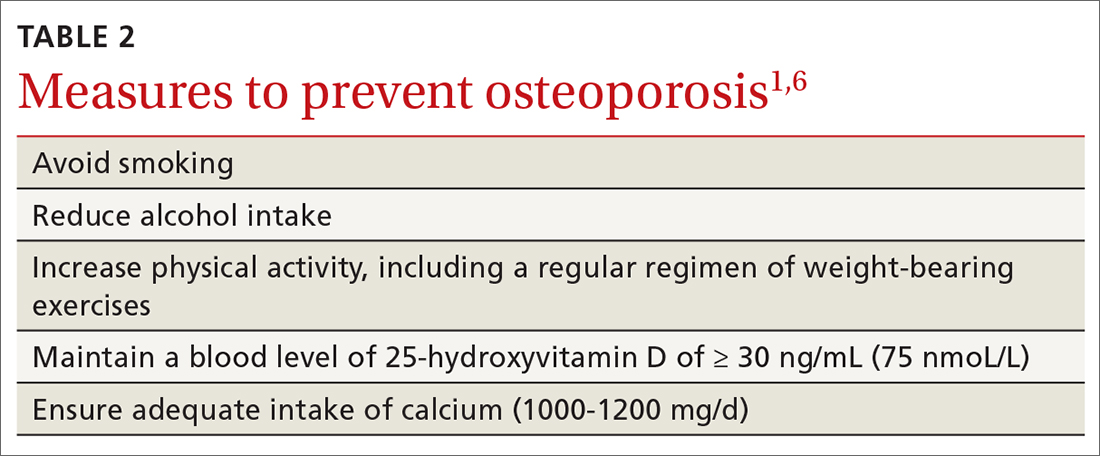

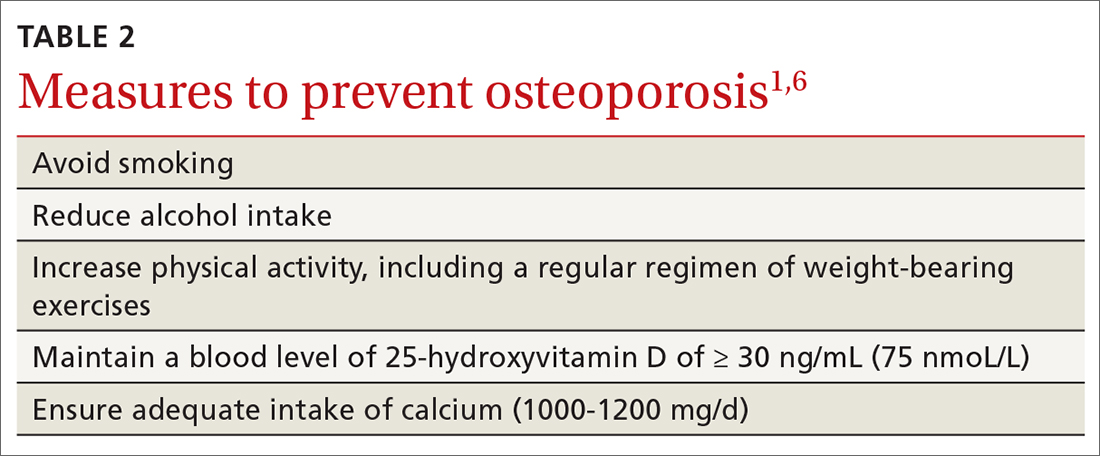

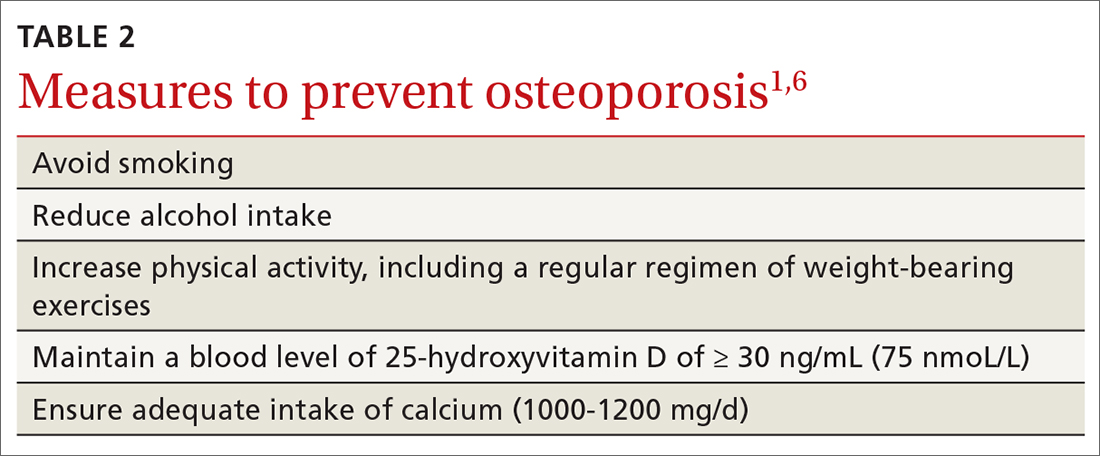

Measures to prevent osteoporosis and preserve bone health (TABLE 21,6) are best started in childhood but can be initiated at any age and maintained through the lifespan. Encourage older adults to adopt dietary and behavioral strategies to improve their bone health and prevent fracture. We recommend the following strategies; take each patient’s individual situation into consideration when electing to adopt any of these measures.

❚ Vitamin D. Consider checking the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and providing supplementation (800-1000 IU daily, the National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends1) as necessary to maintain the level at 30-50 ng/mL.6

❚ Calcium. Encourage a daily dietary calcium intake of 1000-1200 mg. Supplement calcium if you determine that diet does not provide an adequate amount.

❚ Alcohol. Advise patients to limit consumption to < 3 drinks a day.

❚ Tobacco. Advise smoking cessation.

❚ Activity. Encourage an active lifestyle, including regular weight-bearing and balance exercises and resistance exercises such as Pilates, weightlifting, and tai chi. The regimen should be tailored to the patient’s individual situation.

❚ Medical therapy for concomitant illness. When possible, prescribe medications for chronic comorbidities that can also benefit bone health. For example, long-term use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and thiazide diuretics for hypertension are associated with a slower decline in BMD in some populations.21-23

Tailor treatment to patient’s circumstances

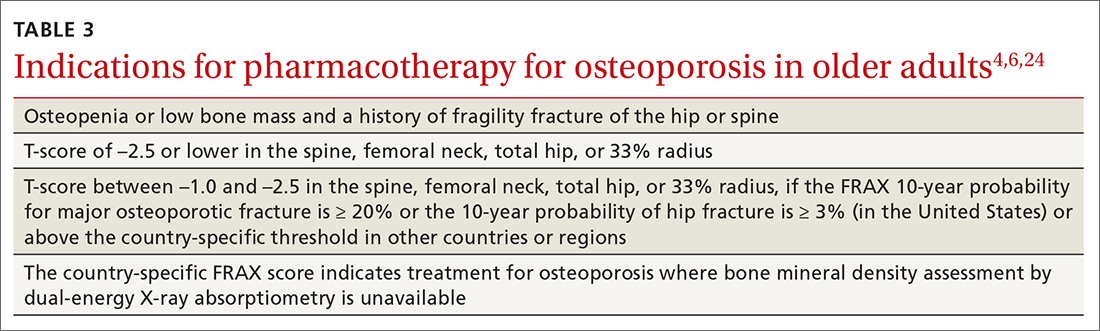

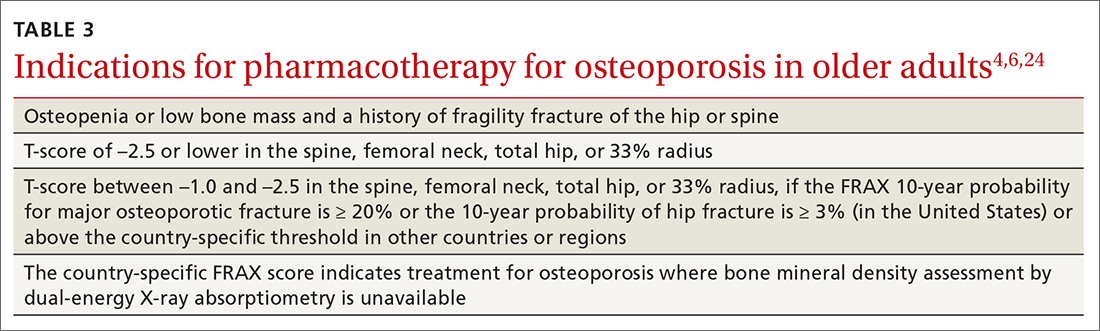

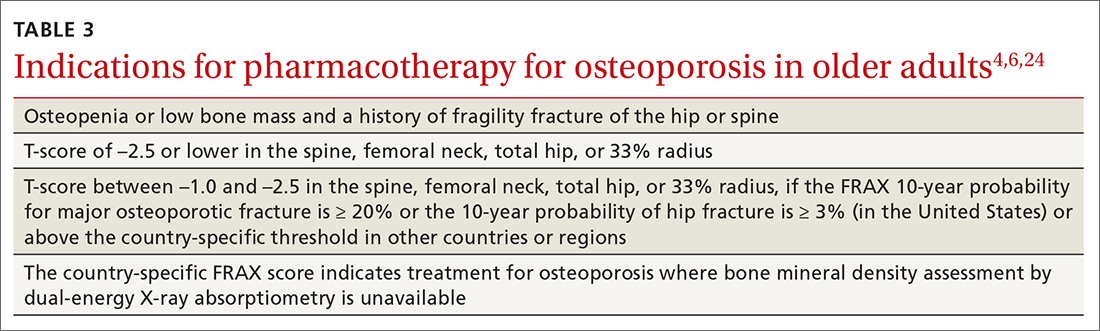

TABLE 34,6,24 describes indications for pharmacotherapy in osteoporosis. Pharmacotherapy is recommended in all cases of osteoporosis and osteopenia when fracture risk is high.24

Generally, you should undertake a discussion with the patient of the relative risks and benefits of treatment, taking into account their values and preferences, to come to a shared decision. Tailoring treatment, based on the patient’s distinctive circumstances, through shared decision-making is key to compliance.25

Pharmacotherapy is not indicated in patients whose risk of fracture is low; however, you should reassess such patients every 2 to 4 years.26 Women with a very high BMD might not need to be retested with DXA any sooner than every 10 to 15 years.

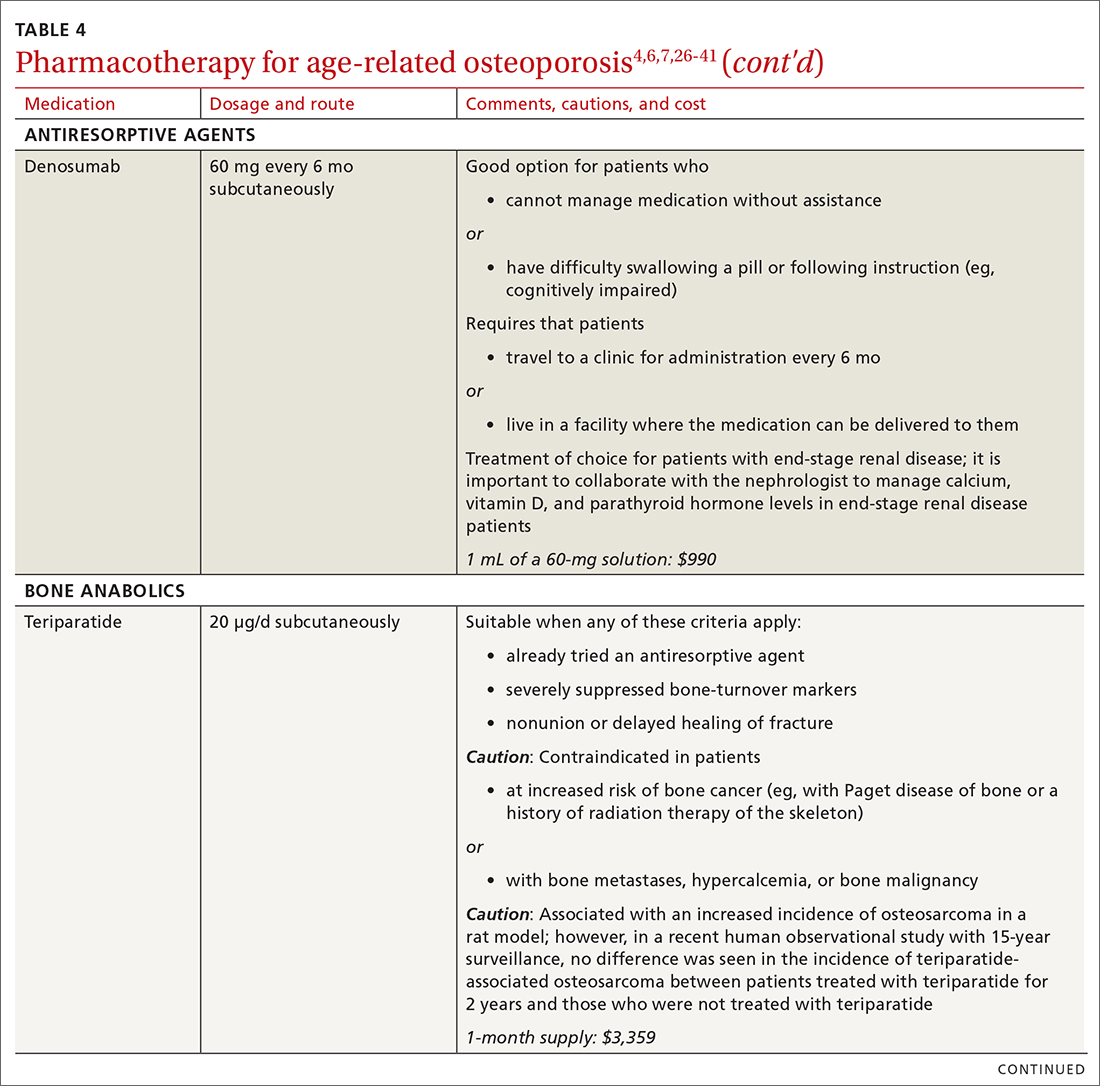

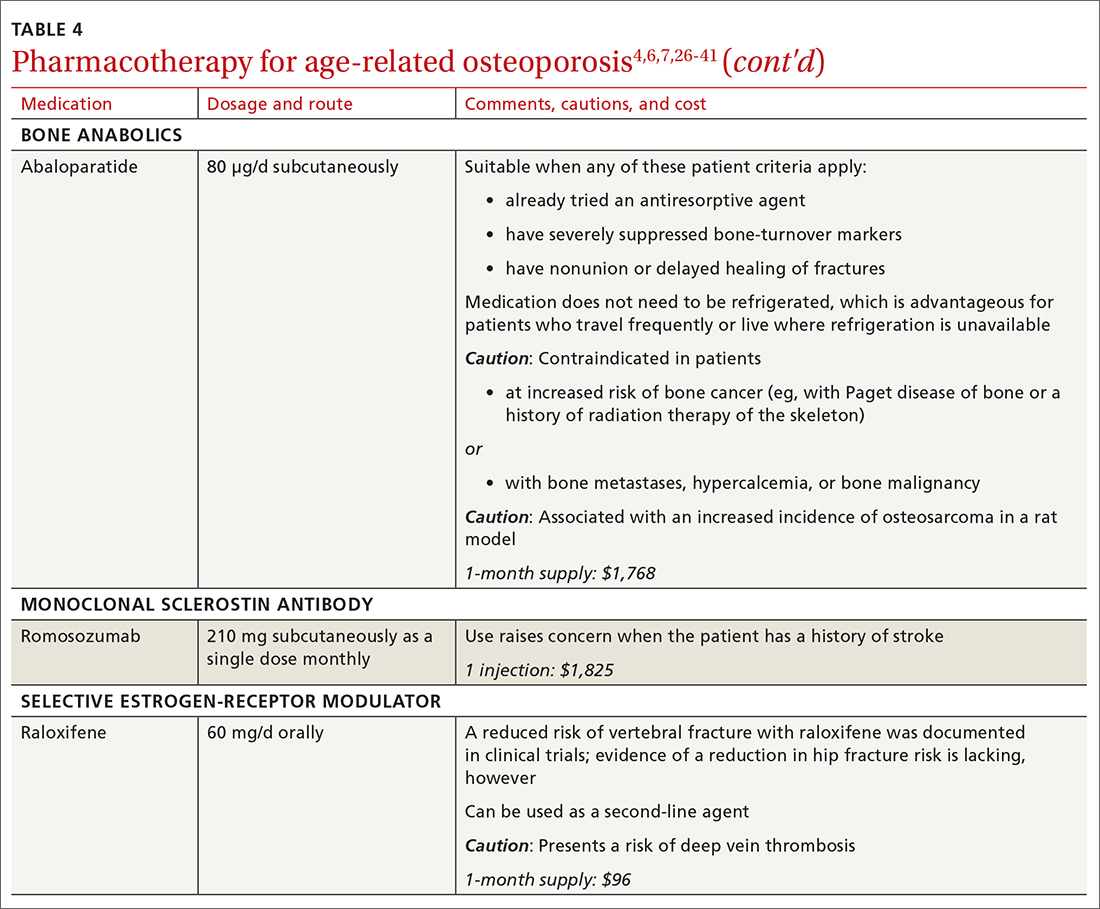

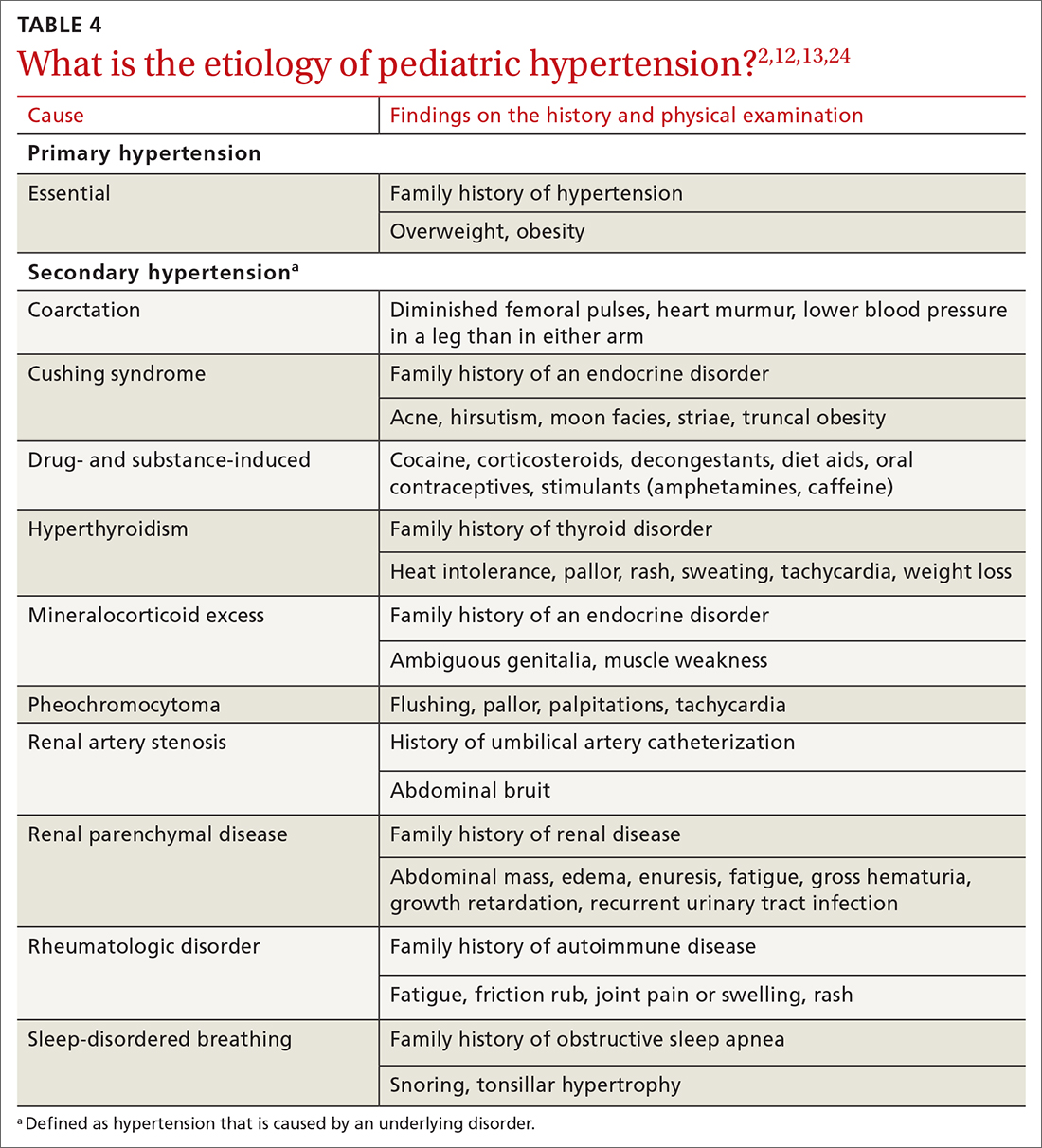

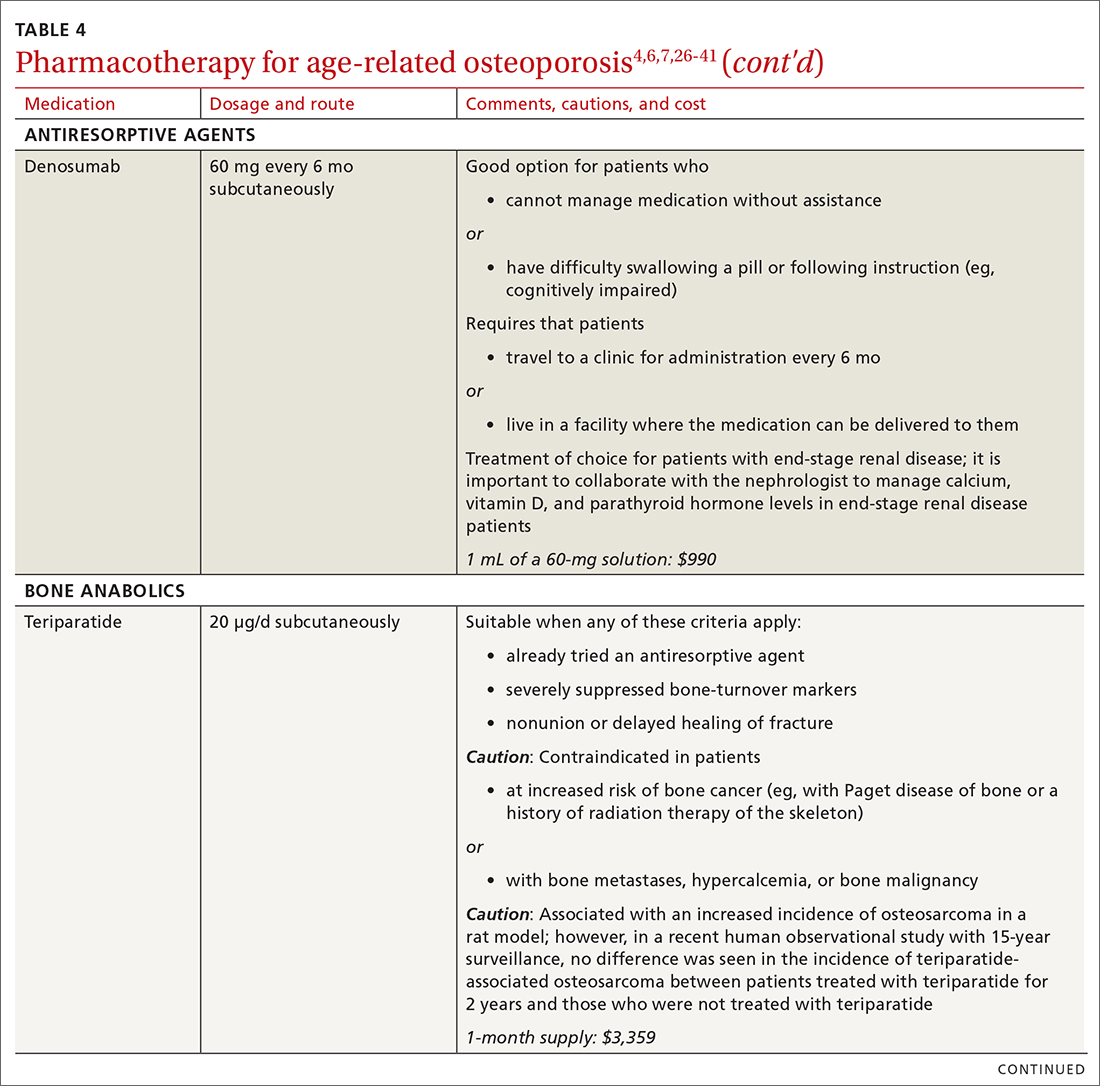

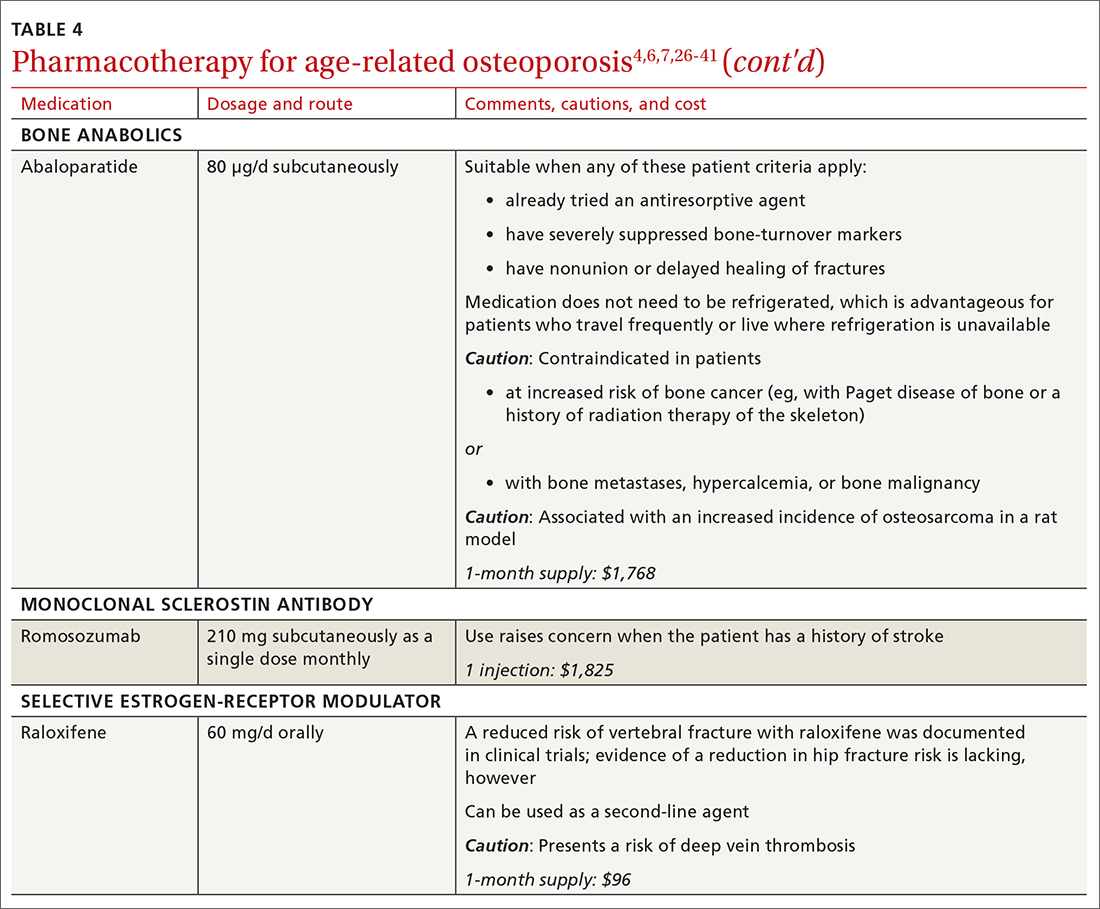

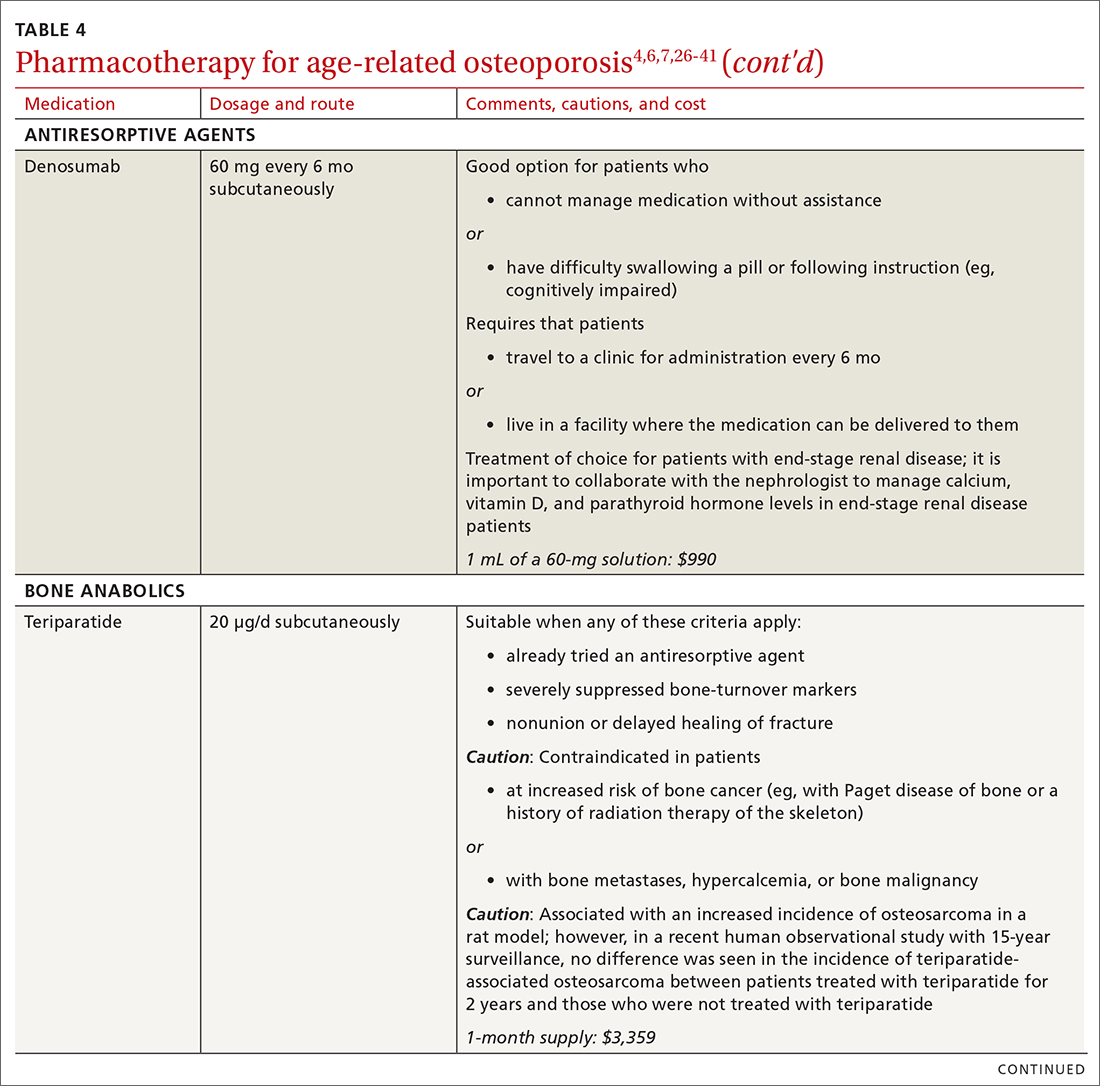

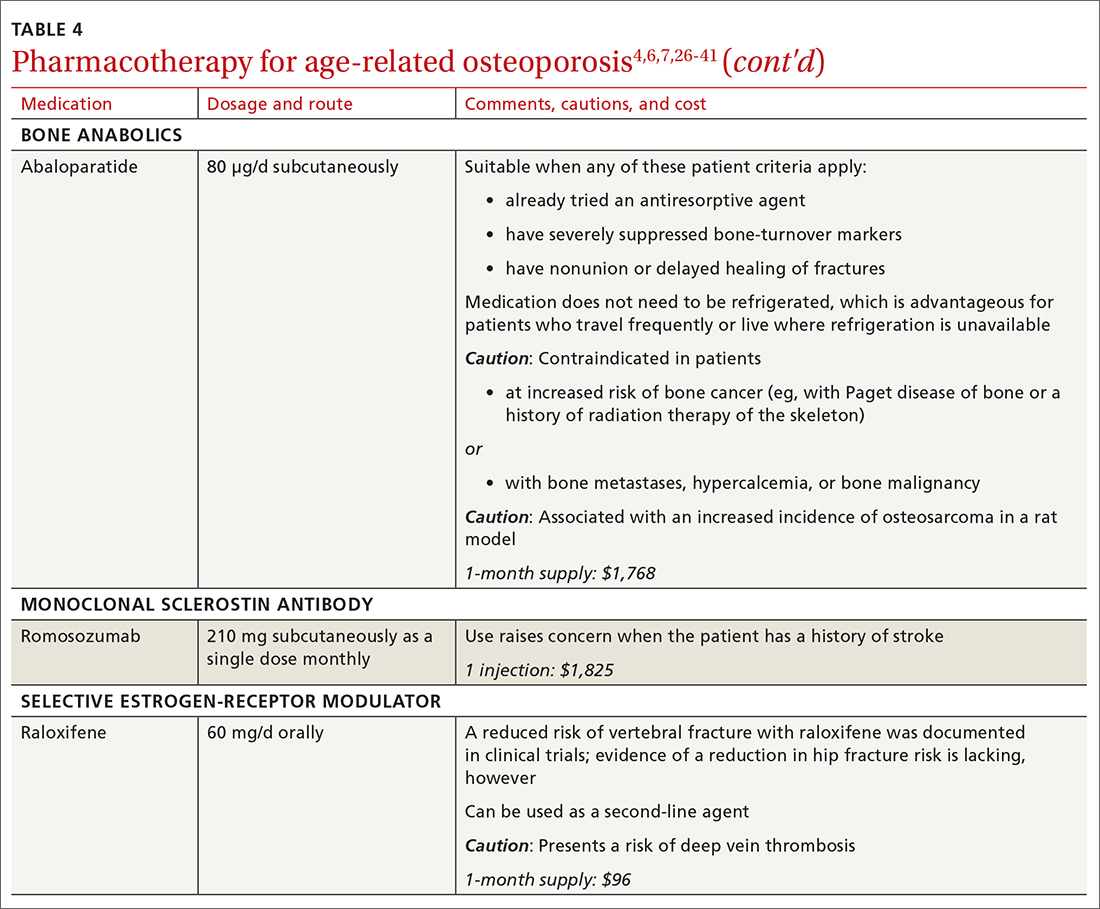

There are 3 main classes of first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for osteoporosis in older adults (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41): antiresorptives (bisphosphonates and denosumab), anabolics (teriparatide and abaloparatide), and a monoclonal sclerostin antibody (romosozumab). (TABLE 44,6,7,26-41 and the discussion in this section also remark on the selective estrogen-receptor modulator raloxifene, which is used in special clinical circumstances but has been removed from the first line of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy.)

❚ Bisphosphonates. Oral bisphosphonates (alendronate, ibandronate, risedronate) can be used as initial treatment in patients with a high risk of fracture.35 Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce fracture risk and improve BMD. When an oral bisphosphonate cannot be tolerated, intravenous zoledronate or ibandronate can be used.41

Patients treated with a bisphosphonate should be assessed for their fracture risk after 3 to 5 years of treatment26; when intravenous zoledronate is given as initial therapy, patients should be assessed after 3 years. After assessment, patients who remain at high risk should continue treatment; those whose fracture risk has decreased to low or moderate should have treatment temporarily suspended (bisphosphonate holiday) for as long as 5 years.26 Patients on bisphosphonate holiday should have their fracture risk assessed at 2- to 4-year intervals.26 Restart treatment if there is an increase in fracture risk (eg, a decrease in BMD) or if a fracture occurs. Bisphosphonates have a prolonged effect on BMD—for many years after treatment is discontinued.27,28

Oral bisphosphonates are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, difficulty swallowing, and gastritis. Rare adverse effects include osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.29

❚ Denosumab, a recombinant human antibody, is a relatively newer antiresorptive for initial treatment. Denosumab, 60 mg, is given subcutaneously every 6 months. The drug can be used when bisphosphonates are contraindicated, the patient finds the bisphosphonate dosing regimen difficult to follow, or the patient is unresponsive to bisphosphonates.

Patients taking denosumab are reassessed every 5 to 10 years to determine whether to continue therapy or change to a new drug. Abrupt discontinuation of therapy can lead to rebound bone loss and increased risk of fracture.30-32 As with bisphosphonates, long-term use can be associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femur fracture.33

There is no recommendation for a drug holiday for denosumab. An increase in, or no loss of, bone density and no new fractures while being treated are signs of effective treatment. There is no guideline for stopping denosumab, unless the patient develops adverse effects.

❚ Bone anabolics. Patients with a very high risk of fracture (eg, who have sustained multiple vertebral fractures), can begin treatment with teriparatide (20 μg/d subcutaneously) or abaloparatide (80 μg/d subcutaneously) for as long as 2 years, followed by treatment with an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate.4,6 Teriparatide can be used in patients who have not responded to an antiresorptive as first-line treatment.

Both abaloparatide and teriparatide might be associated with a risk of osteosarcoma and are contraindicated in patients who are at increased risk of osteosarcoma.36,39,40

❚ Romosozumab, a monoclonal sclerostin antibody, can be used in patients with very high risk of fracture or with multiple vertebral fractures. Romosozumab increases bone formation and reduces bone resorption. It is given monthly, 210 mg subcutaneously, for 1 year. The recommendation is that patients who have completed a course of romosozumab continue with antiresorptive treatment.26

Romosozumab is associated with an increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease, including stroke and myocardial infarction.26

❚ Raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator, is no longer a first-line agent for osteoporosis in older adults34 because of its association with an increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and lethal stroke. However, raloxifene can be used, at 60 mg/d, when bisphosphonates or denosumab are unsuitable. In addition, raloxifene is particularly useful in women with a high risk of breast cancer and in men who are taking a long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for prostate cancer.37,38

Continue to: Influence of chronic...

Influence of chronic diseaseon bone health

Chronic diseases—hypertension, type 2 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and gastroenterologic disorders such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis—are known to affect bone loss that can hasten osteoporosis.16,18,21 Furthermore, medications used to treat chronic diseases are known to affect bone health: Some, such as statins, ACE inhibitors, and hydrochlorothiazide, are bone protective; others, such as steroids, pioglitazone, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, accelerate bone loss.1,14,42,43 It is important to be aware of the effect of a patient’s chronic diseases, and treatments for those diseases, on bone health, to help develop an individualized osteoporosis prevention plan.