User login

Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma and Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma: A Case Series

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

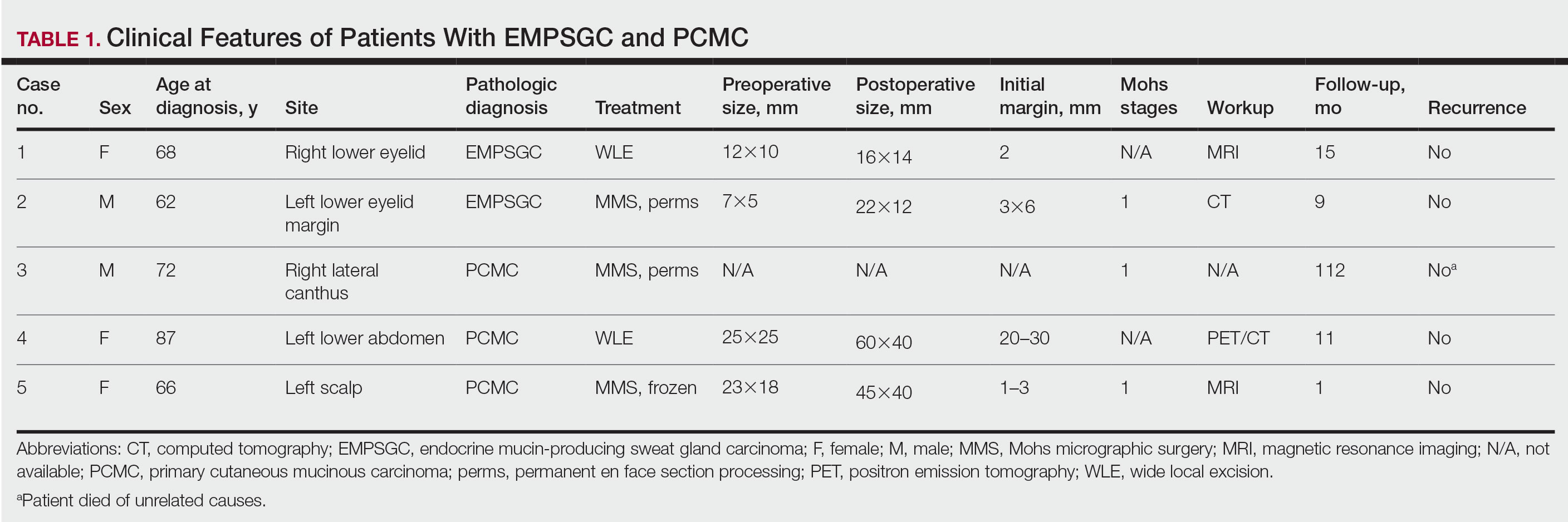

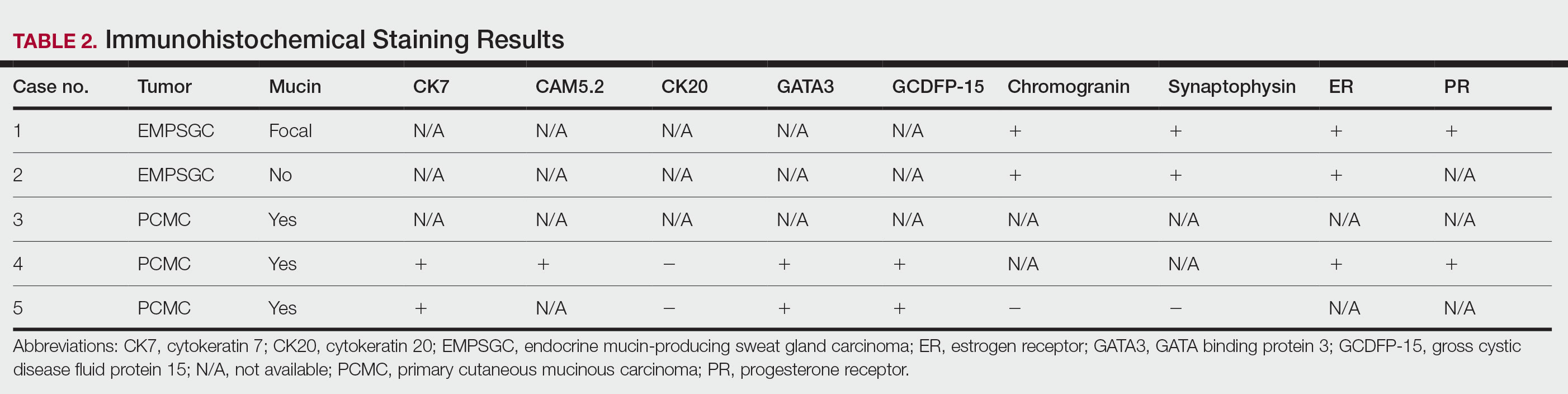

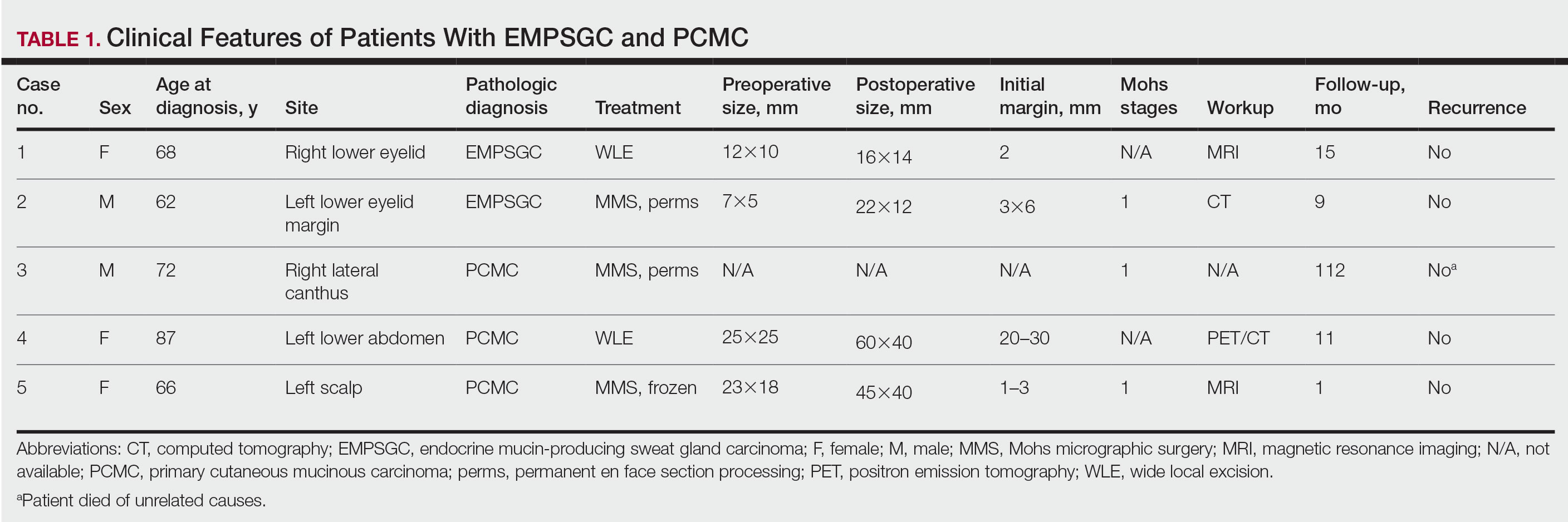

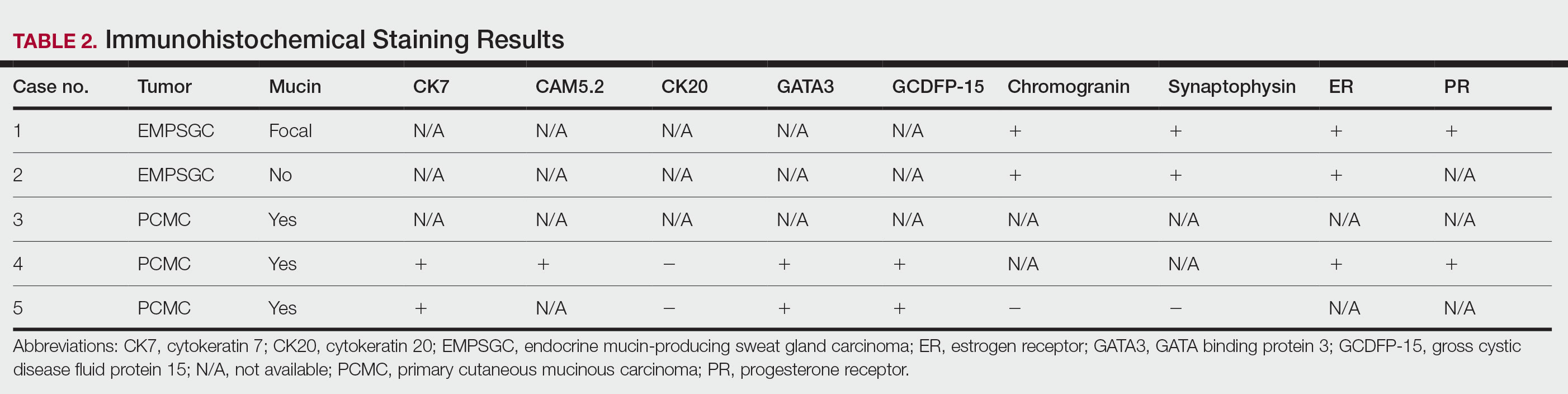

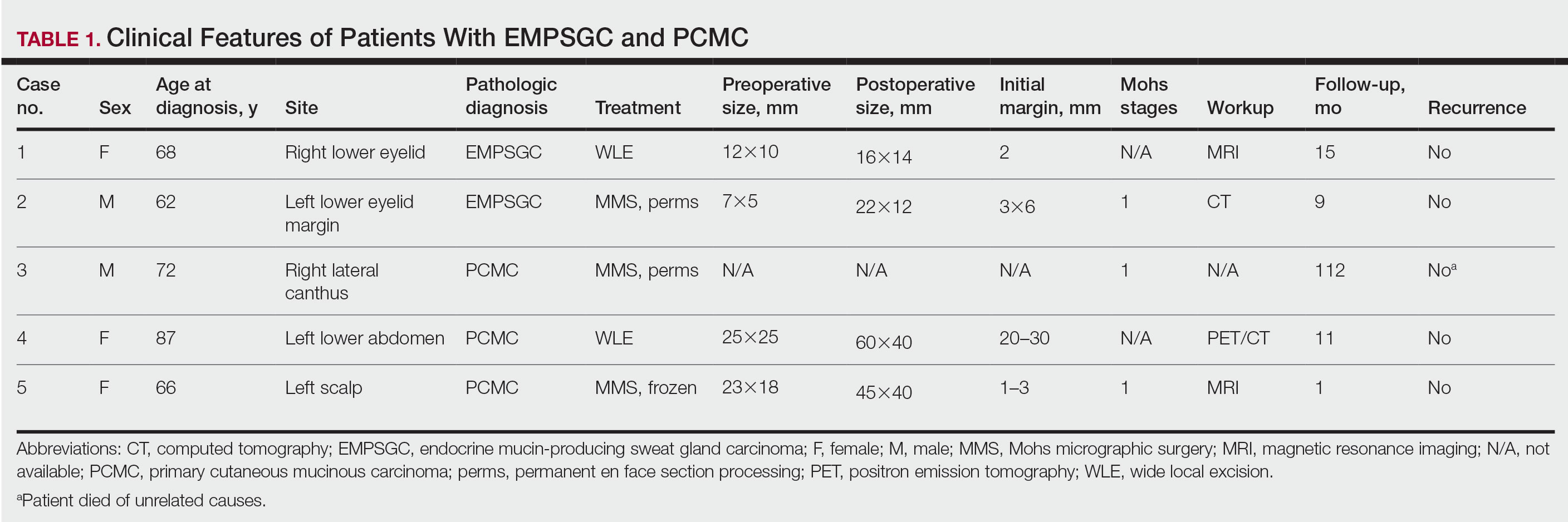

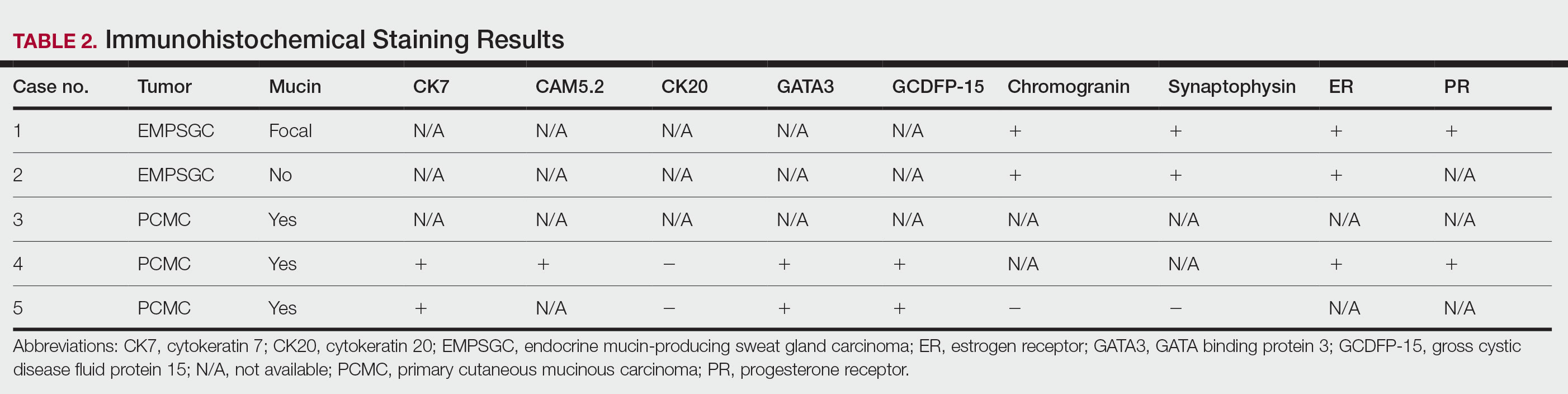

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

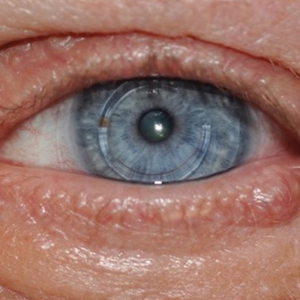

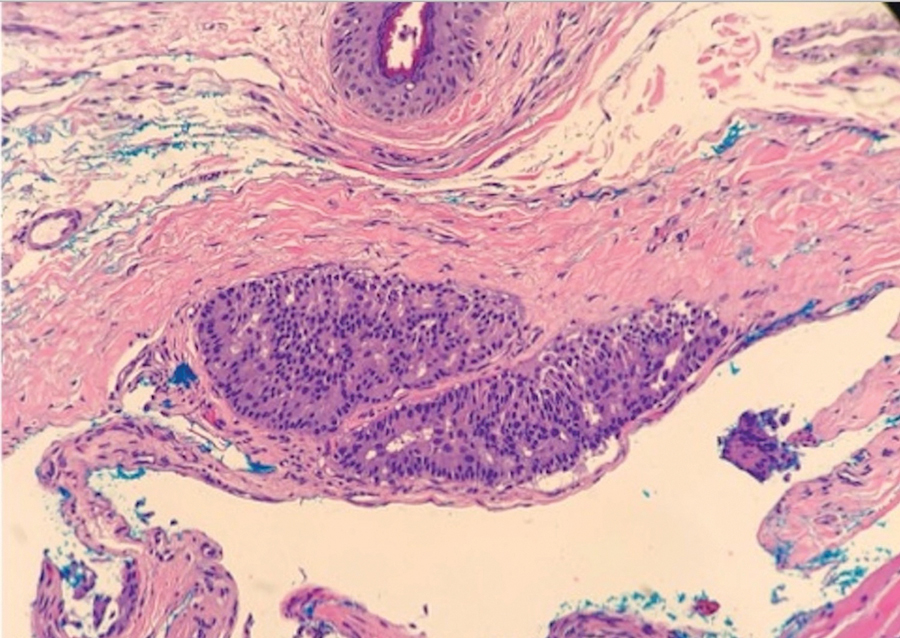

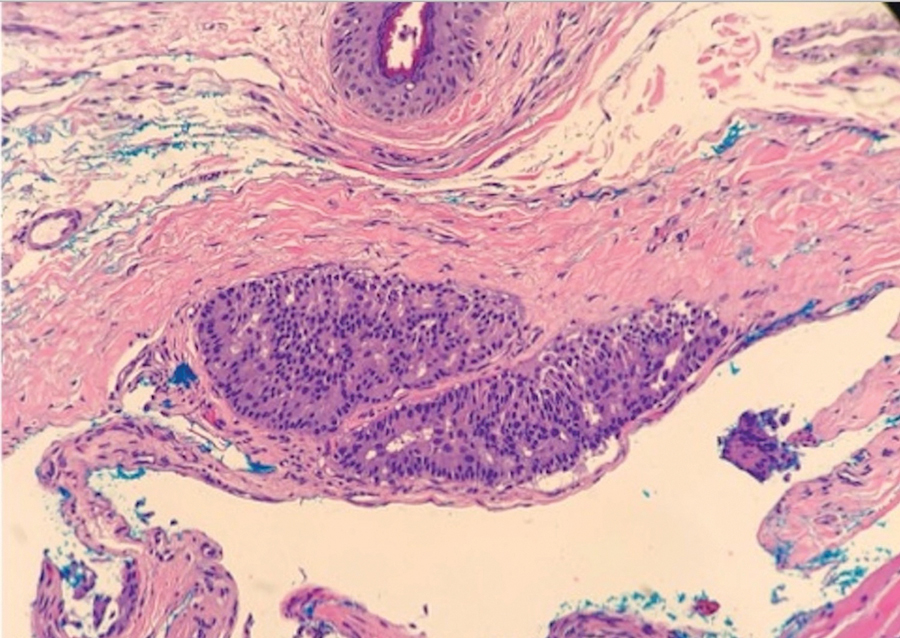

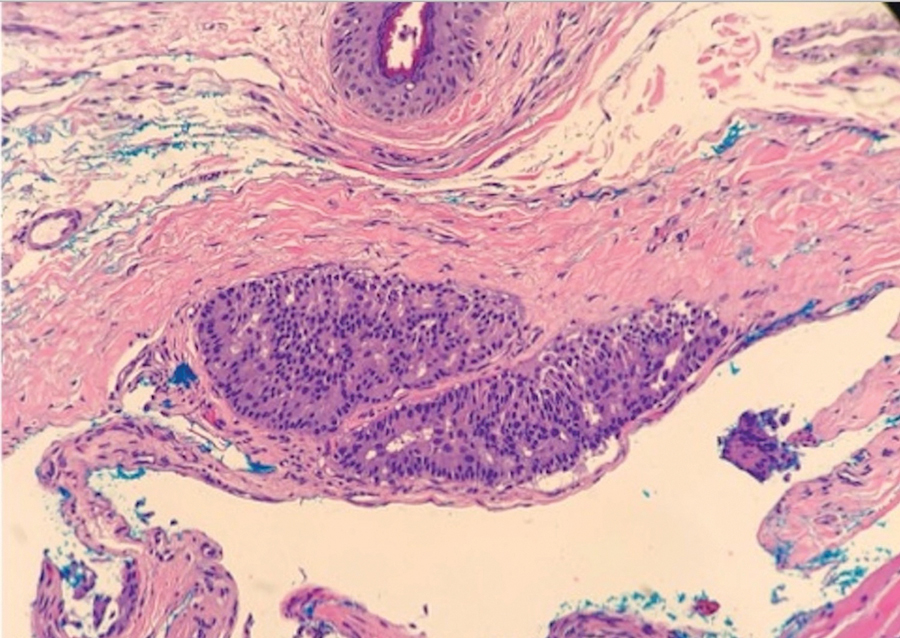

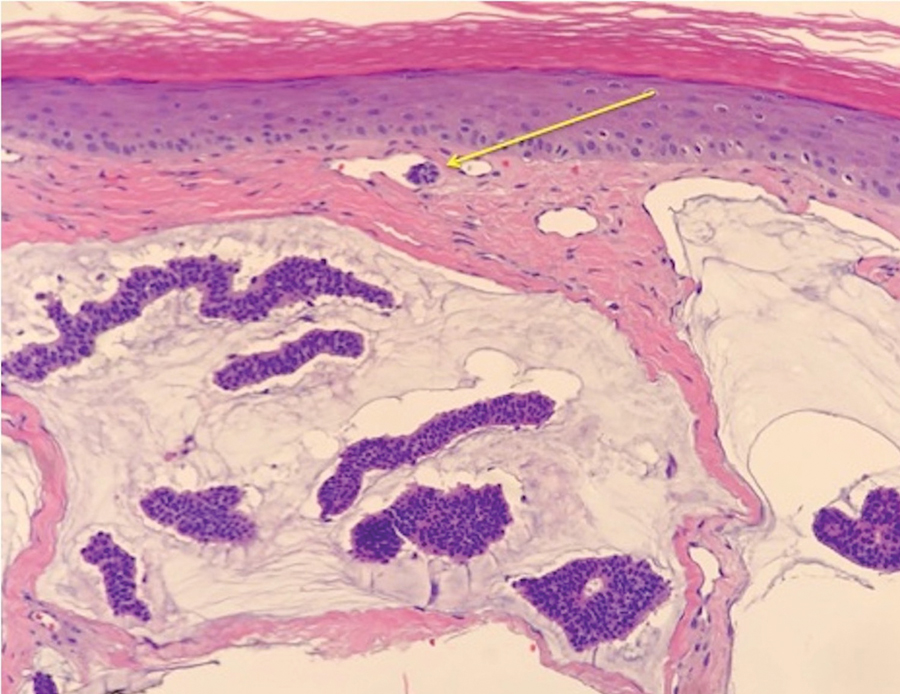

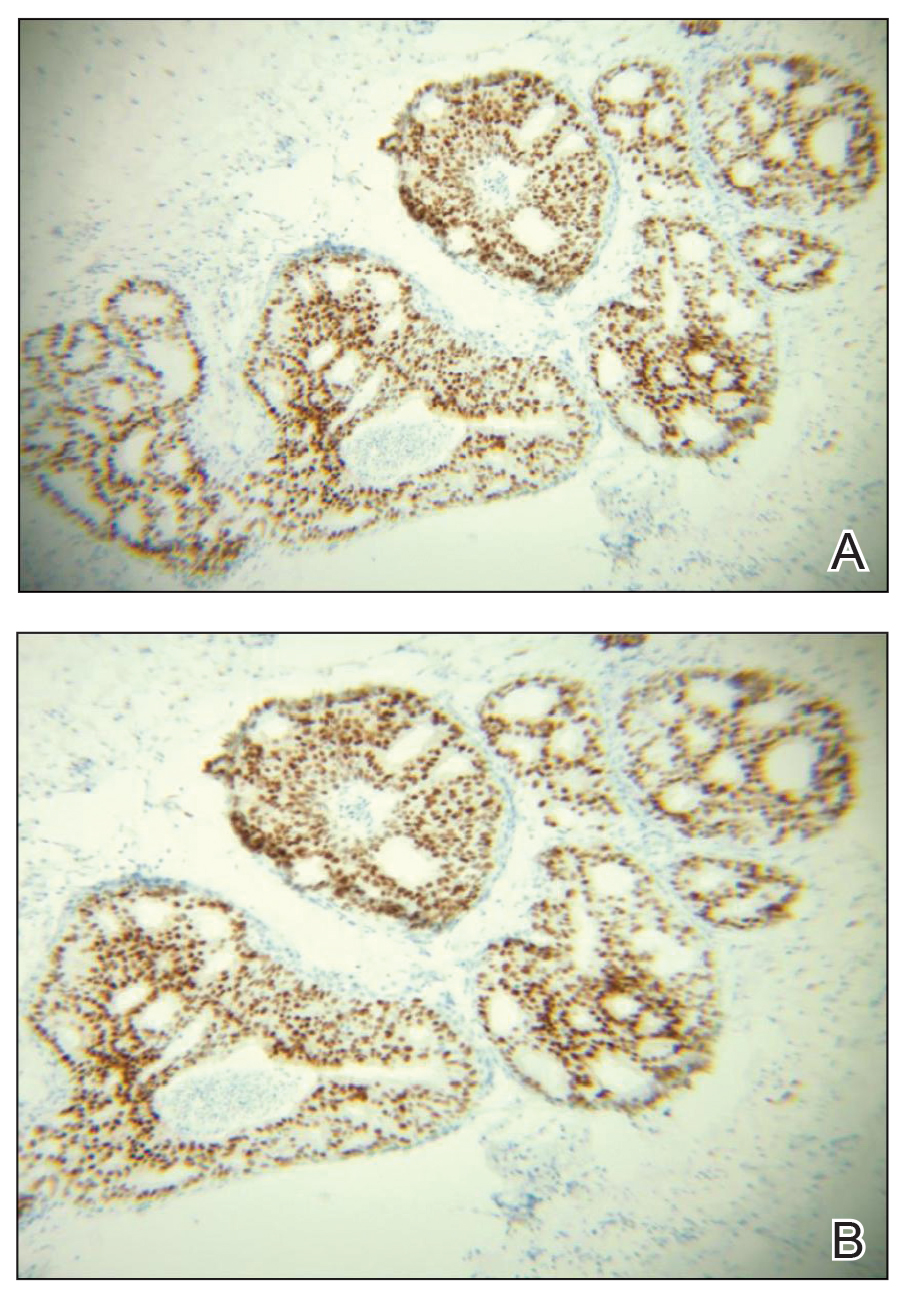

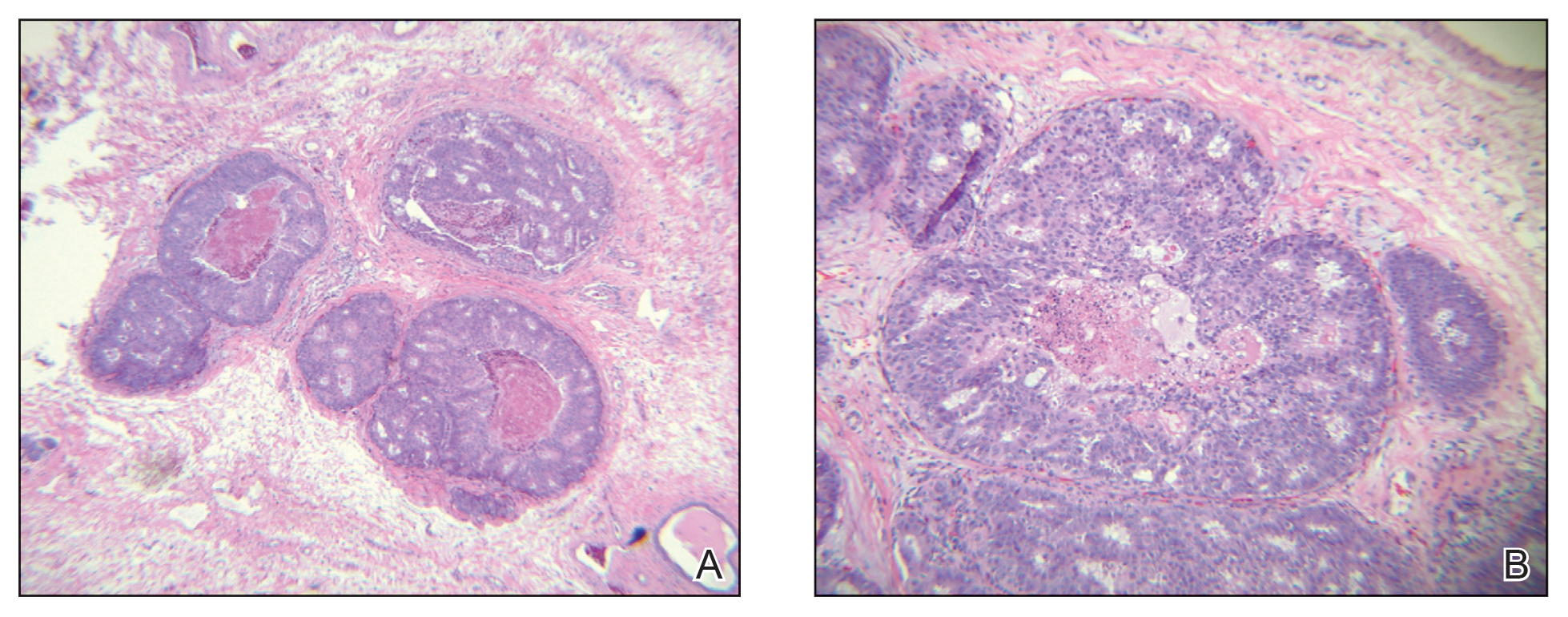

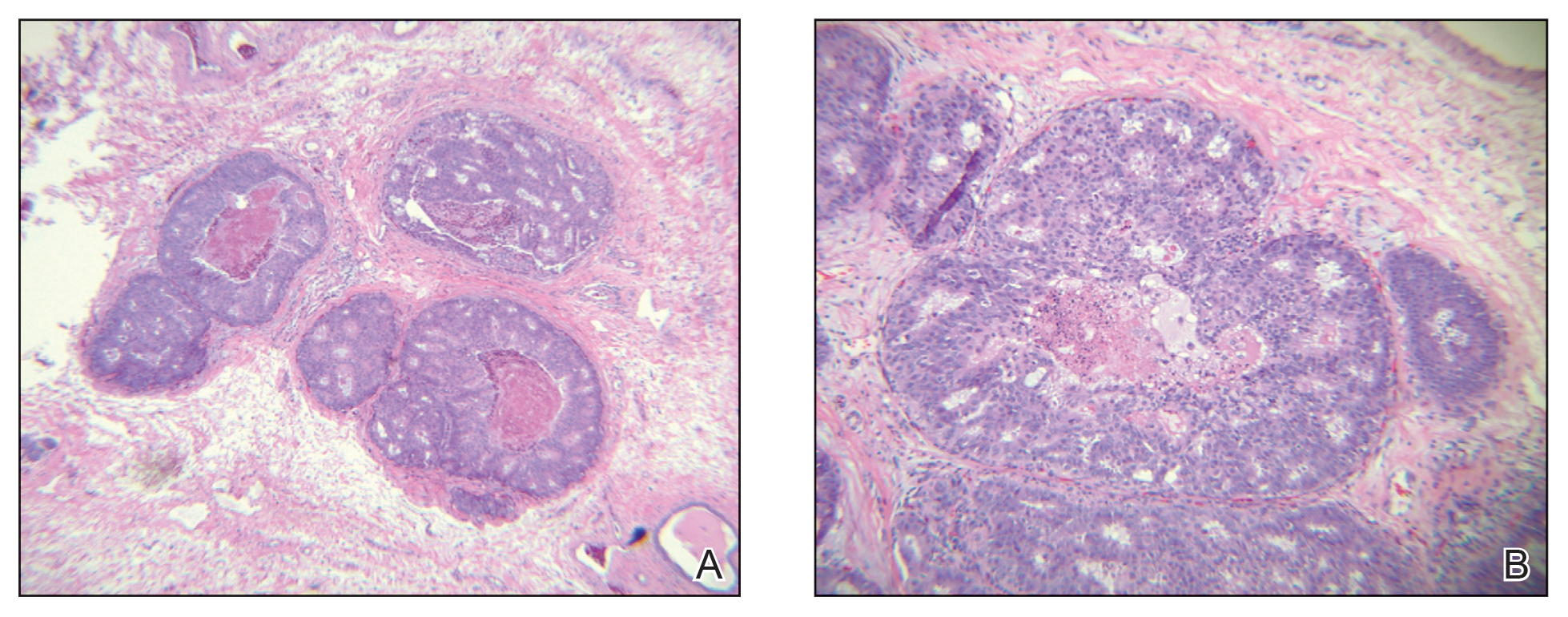

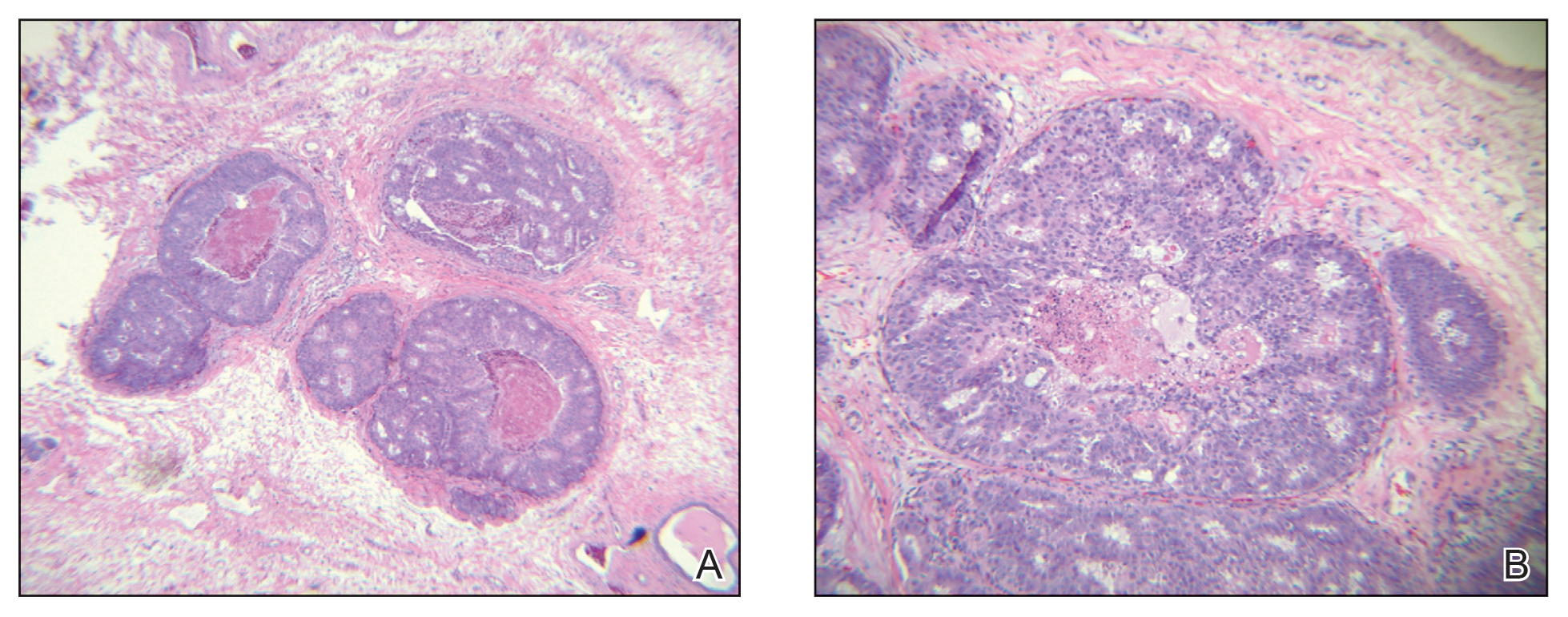

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

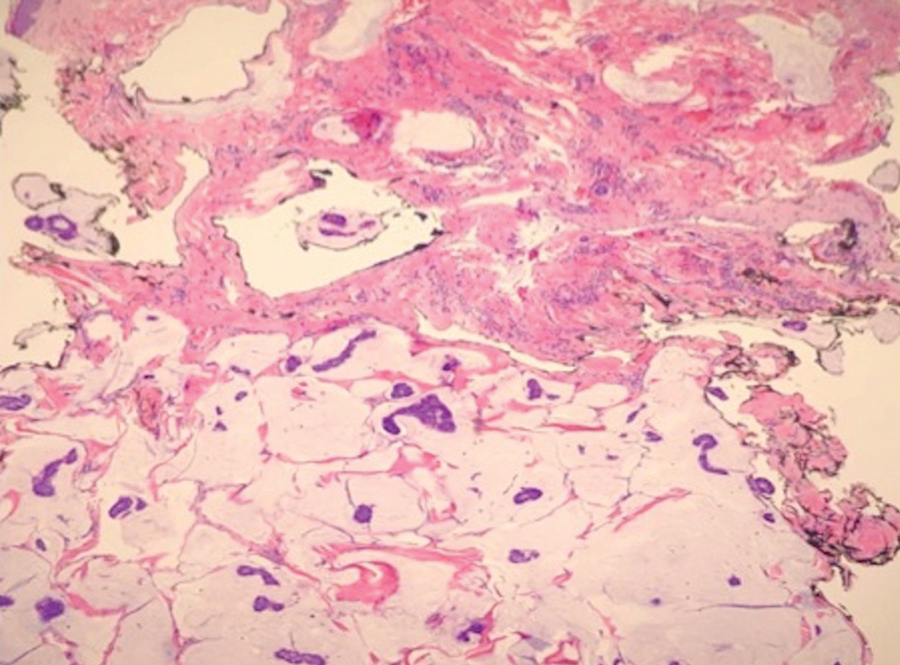

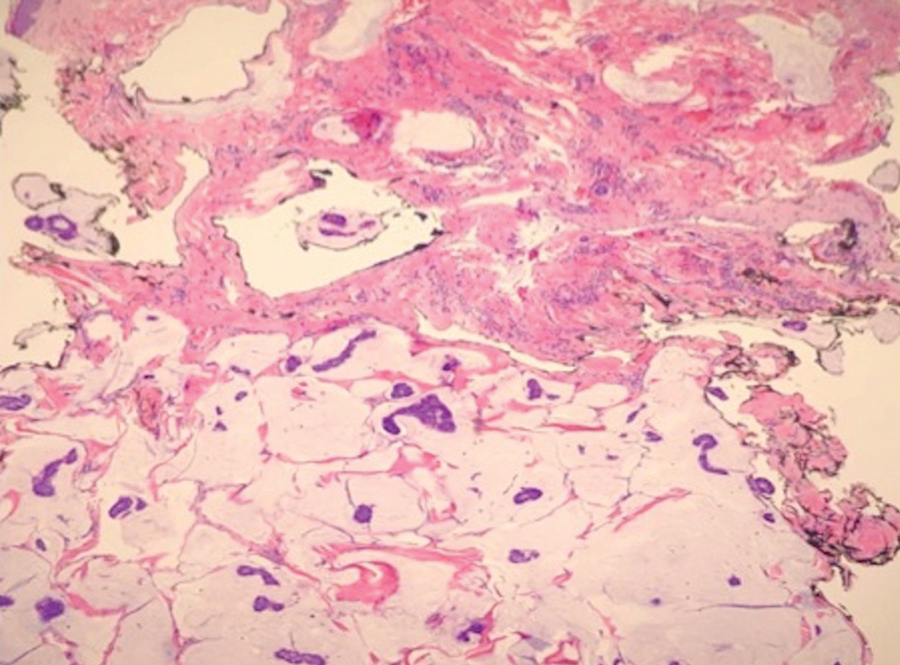

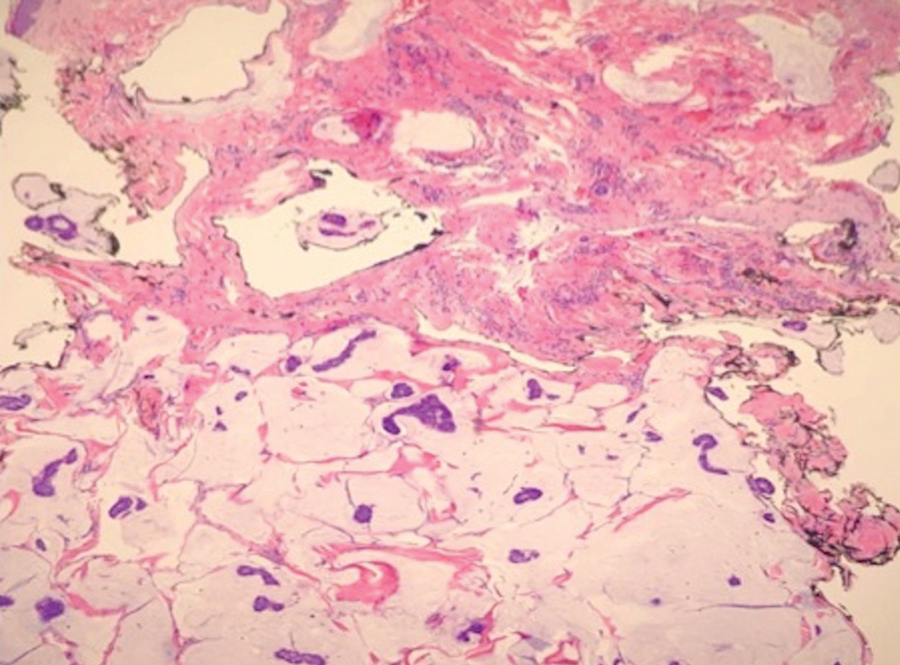

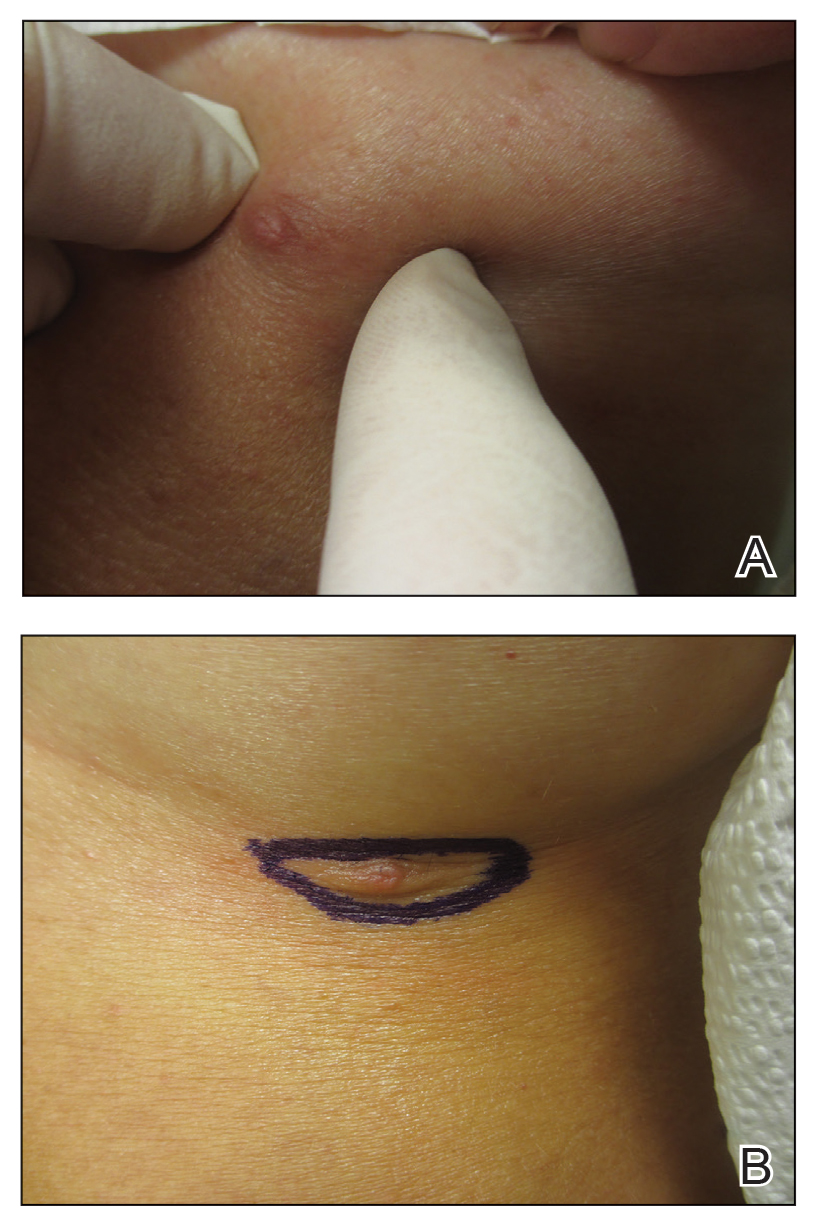

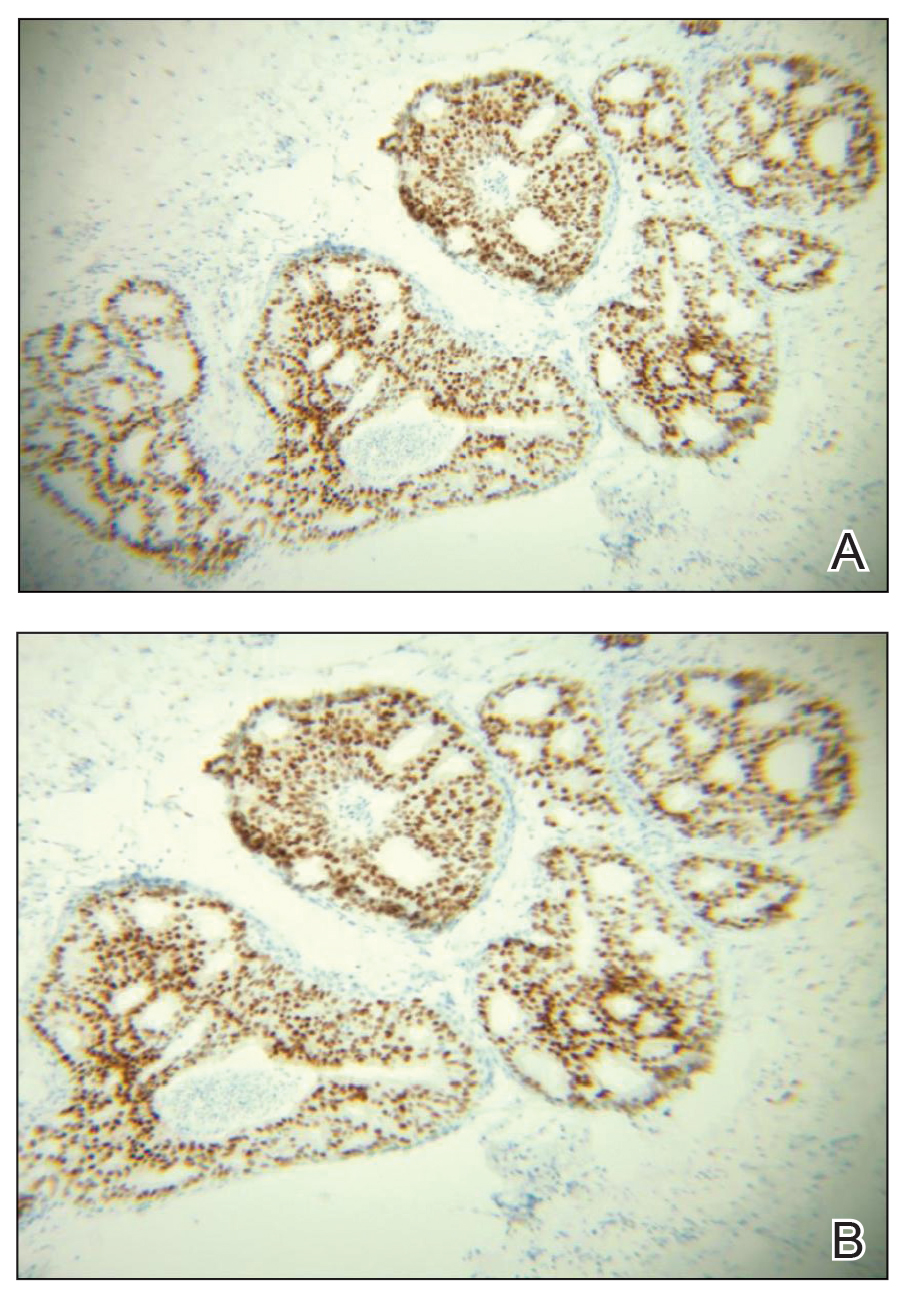

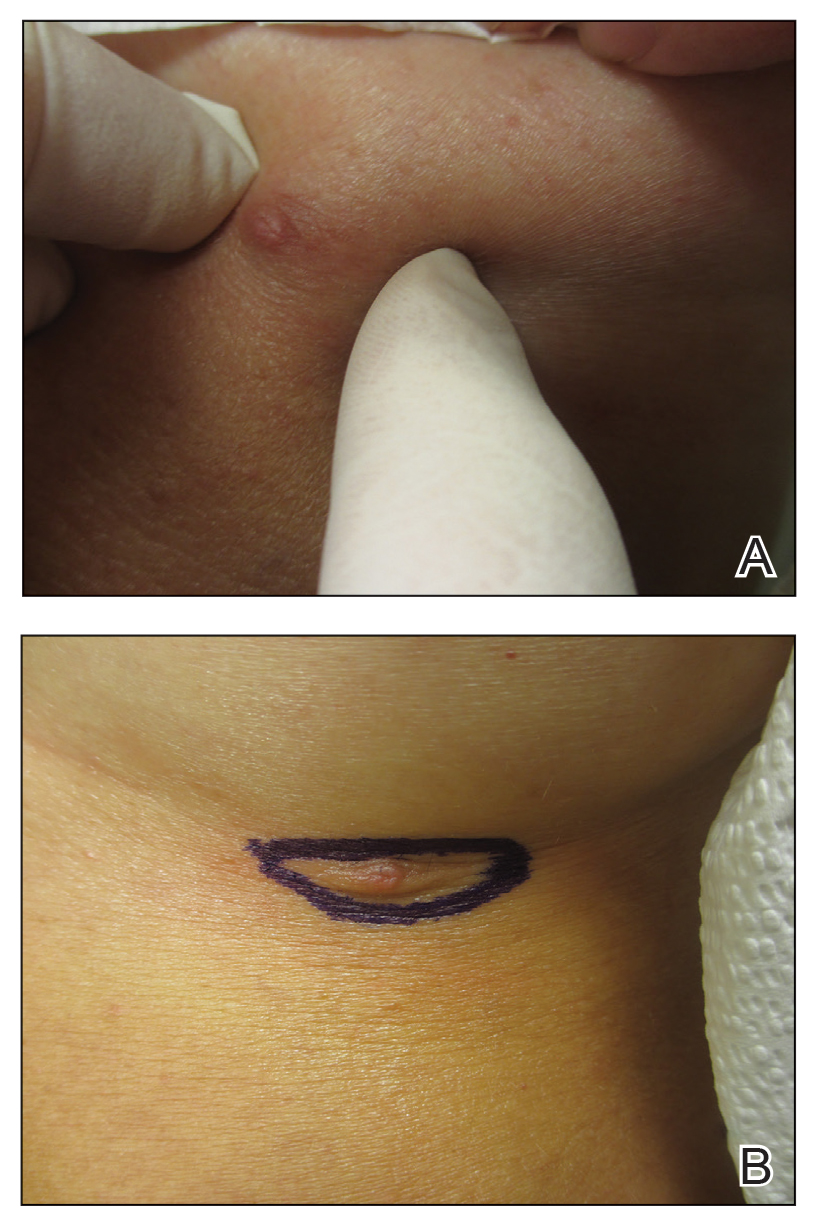

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

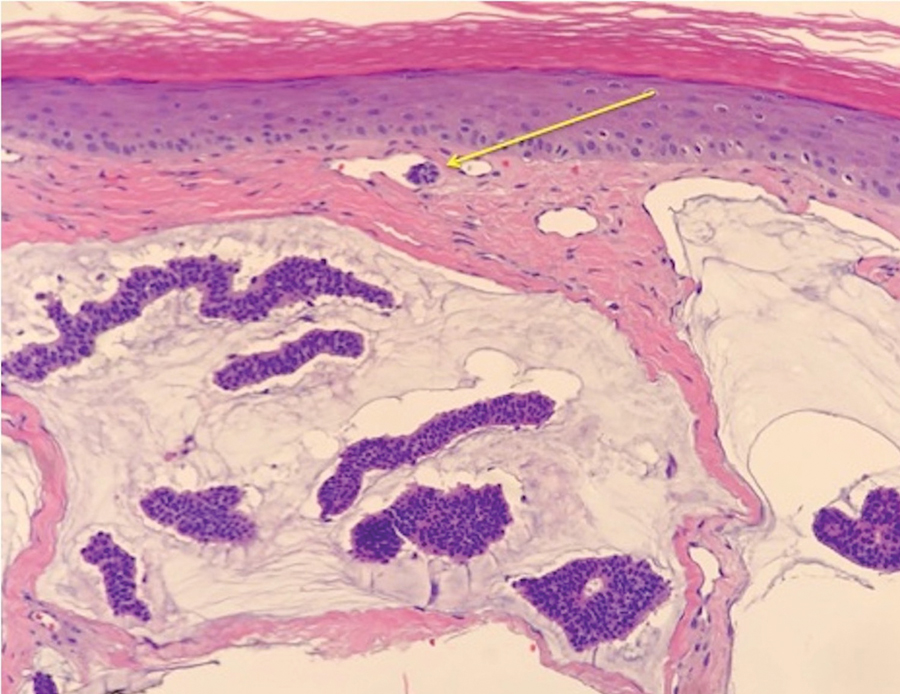

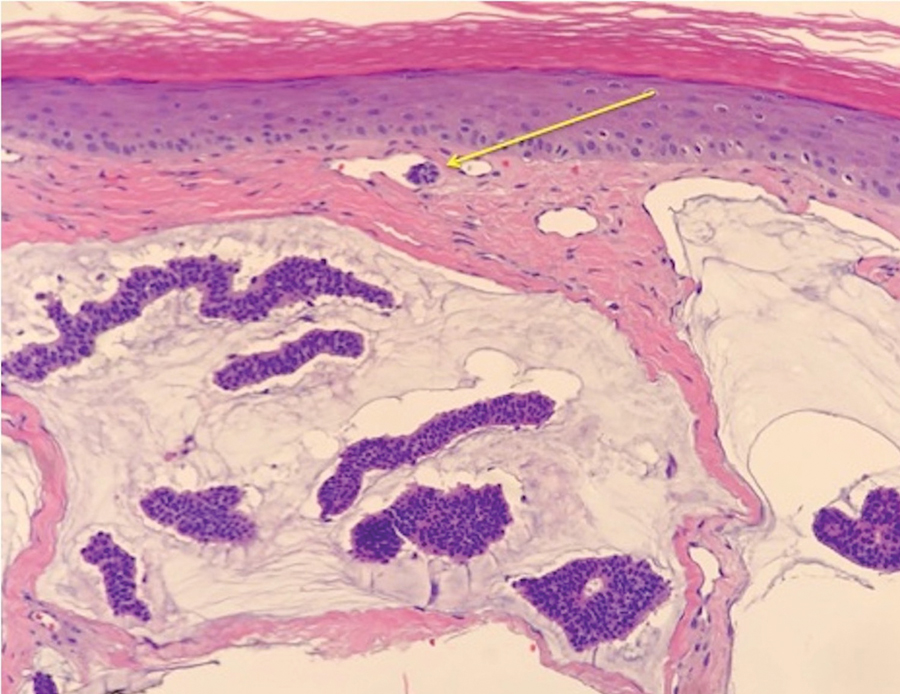

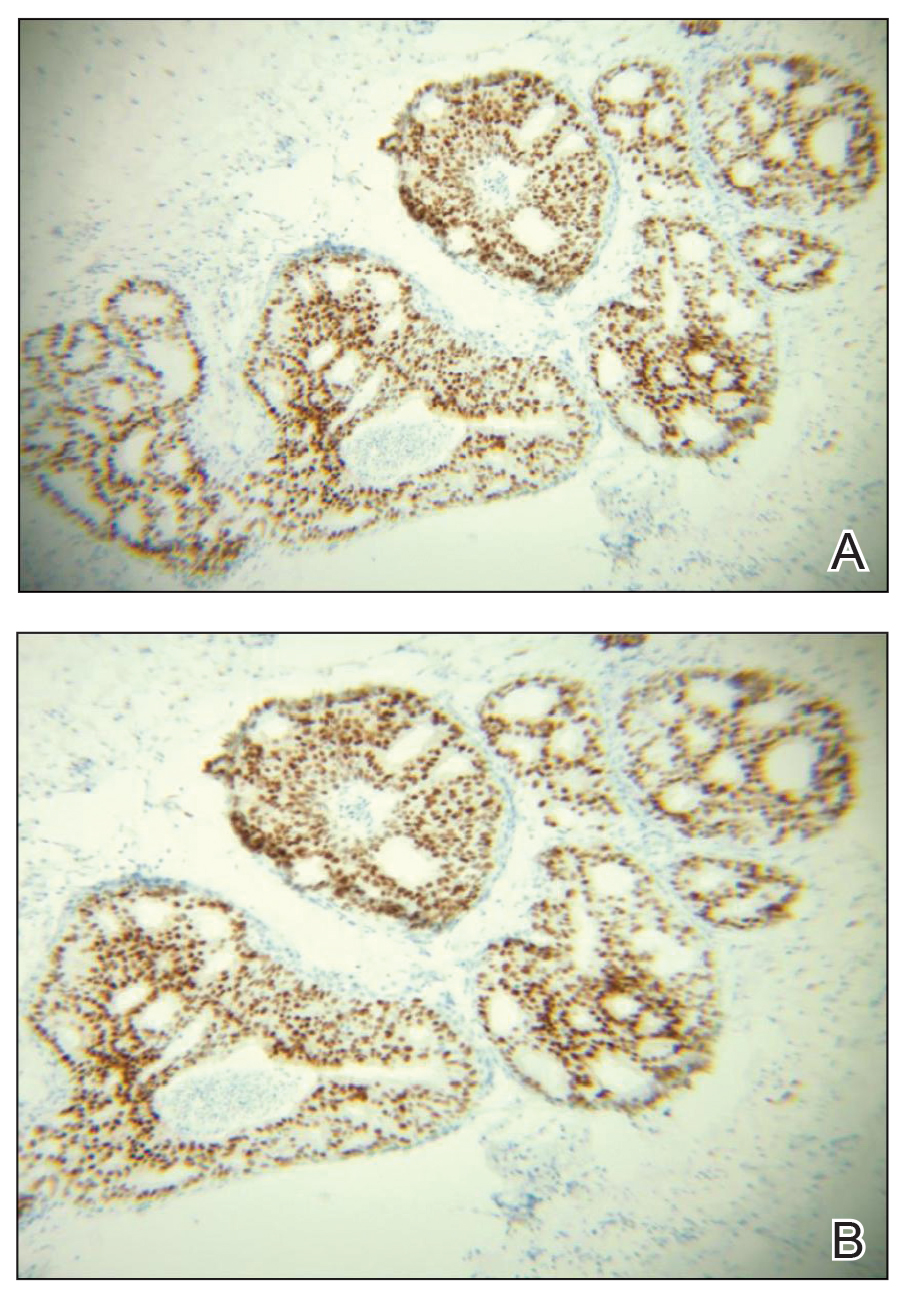

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

Practice Points

- Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma are rare low-grade neoplasms thought to arise from apocrine glands that are morphologically and immunohistochemically analogous to ductal carcinoma in situ and mucinous carcinoma of the breast, respectively.

- Management involves a metastatic workup and either wide local excision with margins greater than 5 mm or Mohs micrographic surgery in anatomically sensitive areas.

High rate of subsequent cancers in MCC

.

In a cohort of 6,146 patients with a first primary MCC, a total of 725 (11.8%) developed subsequent primary cancers. For solid tumors, the risk was highest for cutaneous melanoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma, while for hematologic cancers, the risk was increased for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“Our study does confirm that patients with MCC are at higher risk for developing other cancers,” study author Lisa C. Zaba, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology and director of the Merkel cell carcinoma multidisciplinary clinic, Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Center, said in an interview. “MCC is a highly malignant cancer with a 40% recurrence risk.”

Because of this high risk, Dr. Zaba noted that patients with MCC get frequent surveillance with both imaging studies (PET-CT and CT) as well as frequent visits in clinic with MCC experts. “Specifically, a patient with MCC is imaged and seen in clinic every 3-6 months for the first 3 years after diagnosis, and every 6-12 months thereafter for up to 5 years,” she said. “Interestingly, this high level of surveillance may be one reason that we find so many cancers in patients who have been diagnosed with MCC, compared to the general population.”

The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

With the death of “Margaritaville” singer Jimmy Buffett, who recently died of MCC 4 years after his diagnosis, this rare, aggressive skin cancer has been put in the spotlight. Survival has been increasing, primarily because of the advent of immunotherapy, and the authors note that it is therefore imperative to better understand the risk of subsequent primary tumors to inform screening and treatment recommendations.

In this cohort study, Dr. Zaba and colleagues identified 6,146 patients from 17 registries of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program who had been diagnosed with a first primary cutaneous MCC between 2000 and 2018.

Endpoints were the ratio of observed to expected number of cases of subsequent cancer (Standardized incidence ratio, or SIR) and the excess risk.

Overall, there was an elevated risk of developing a subsequent primary cancer after being diagnosed with MCC (SIR, 1.28; excess risk, 57.25 per 10,000 person-years). This included the risk for all solid tumors including liver (SIR, 1.92; excess risk, 2.77 per 10,000 person-years), pancreas (SIR, 1.65; excess risk, 4.55 per 10,000 person-years), cutaneous melanoma (SIR, 2.36; excess risk, 15.27 per 10,000 person-years), and kidney (SIR, 1.64; excess risk, 3.83 per 10,000 person-years).

There was also a higher risk of developing papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (SIR, 5.26; excess risk, 6.16 per 10,000 person-years).

The risk of developing hematological cancers after MCC was also increased, especially for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (SIR, 2.62; excess risk, 15.48 per 10,000 person-years) and myelodysplastic syndrome (SIR, 2.17; excess risk, 2.73 per 10,000 person-years).

The risk for developing subsequent tumors, including melanoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, remained significant for up to 10 years, while the risk for developing PTC and kidney cancers remained for up to 5 years.

“After 3-5 years, when a MCC patient’s risk of MCC recurrence drops below 2%, we do not currently have guidelines in place for additional cancer screening,” Dr. Zaba said. “Regarding patient education, patients with MCC are educated to let us know if they experience any symptoms of cancer between visits, including unintentional weight loss, night sweats, headaches that increasingly worsen, or growing lumps or bumps. These symptoms may occur in a multitude of cancers and not just MCC.”

Weighing in on the study, Jeffrey M. Farma, MD, interim chair, department of surgical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, noted that MCC is considered to be high risk because of its chances of recurring after surgical resection or spreading to lymph nodes or other areas of the body. “There are approximately 3,000 new cases of melanoma a year in the U.S., and it is 40 times rarer than melanoma,” he said. “Patients are usually diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma later in life, and the tumors have been associated with sun exposure and immunosuppression and have also been associated with the polyomavirus.”

That said, however, he emphasized that great strides have been made in treatment. “These tumors are very sensitive to radiation, and we generally treat earlier-stage MCC with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy,” said Dr. Farma. “More recently we have had a lot of success with the use of immunotherapy to treat more advanced MCC.”

Dr. Zaba reported receiving grants from the Kuni Foundation outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Author Eleni Linos, MD, DrPH, MPH, is supported by grant K24AR075060 from the National Institutes of Health. No other outside funding was reported. Dr. Farma had no disclosures.

.

In a cohort of 6,146 patients with a first primary MCC, a total of 725 (11.8%) developed subsequent primary cancers. For solid tumors, the risk was highest for cutaneous melanoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma, while for hematologic cancers, the risk was increased for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“Our study does confirm that patients with MCC are at higher risk for developing other cancers,” study author Lisa C. Zaba, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology and director of the Merkel cell carcinoma multidisciplinary clinic, Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Center, said in an interview. “MCC is a highly malignant cancer with a 40% recurrence risk.”

Because of this high risk, Dr. Zaba noted that patients with MCC get frequent surveillance with both imaging studies (PET-CT and CT) as well as frequent visits in clinic with MCC experts. “Specifically, a patient with MCC is imaged and seen in clinic every 3-6 months for the first 3 years after diagnosis, and every 6-12 months thereafter for up to 5 years,” she said. “Interestingly, this high level of surveillance may be one reason that we find so many cancers in patients who have been diagnosed with MCC, compared to the general population.”

The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

With the death of “Margaritaville” singer Jimmy Buffett, who recently died of MCC 4 years after his diagnosis, this rare, aggressive skin cancer has been put in the spotlight. Survival has been increasing, primarily because of the advent of immunotherapy, and the authors note that it is therefore imperative to better understand the risk of subsequent primary tumors to inform screening and treatment recommendations.

In this cohort study, Dr. Zaba and colleagues identified 6,146 patients from 17 registries of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program who had been diagnosed with a first primary cutaneous MCC between 2000 and 2018.

Endpoints were the ratio of observed to expected number of cases of subsequent cancer (Standardized incidence ratio, or SIR) and the excess risk.

Overall, there was an elevated risk of developing a subsequent primary cancer after being diagnosed with MCC (SIR, 1.28; excess risk, 57.25 per 10,000 person-years). This included the risk for all solid tumors including liver (SIR, 1.92; excess risk, 2.77 per 10,000 person-years), pancreas (SIR, 1.65; excess risk, 4.55 per 10,000 person-years), cutaneous melanoma (SIR, 2.36; excess risk, 15.27 per 10,000 person-years), and kidney (SIR, 1.64; excess risk, 3.83 per 10,000 person-years).

There was also a higher risk of developing papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (SIR, 5.26; excess risk, 6.16 per 10,000 person-years).

The risk of developing hematological cancers after MCC was also increased, especially for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (SIR, 2.62; excess risk, 15.48 per 10,000 person-years) and myelodysplastic syndrome (SIR, 2.17; excess risk, 2.73 per 10,000 person-years).

The risk for developing subsequent tumors, including melanoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, remained significant for up to 10 years, while the risk for developing PTC and kidney cancers remained for up to 5 years.

“After 3-5 years, when a MCC patient’s risk of MCC recurrence drops below 2%, we do not currently have guidelines in place for additional cancer screening,” Dr. Zaba said. “Regarding patient education, patients with MCC are educated to let us know if they experience any symptoms of cancer between visits, including unintentional weight loss, night sweats, headaches that increasingly worsen, or growing lumps or bumps. These symptoms may occur in a multitude of cancers and not just MCC.”

Weighing in on the study, Jeffrey M. Farma, MD, interim chair, department of surgical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, noted that MCC is considered to be high risk because of its chances of recurring after surgical resection or spreading to lymph nodes or other areas of the body. “There are approximately 3,000 new cases of melanoma a year in the U.S., and it is 40 times rarer than melanoma,” he said. “Patients are usually diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma later in life, and the tumors have been associated with sun exposure and immunosuppression and have also been associated with the polyomavirus.”

That said, however, he emphasized that great strides have been made in treatment. “These tumors are very sensitive to radiation, and we generally treat earlier-stage MCC with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy,” said Dr. Farma. “More recently we have had a lot of success with the use of immunotherapy to treat more advanced MCC.”

Dr. Zaba reported receiving grants from the Kuni Foundation outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Author Eleni Linos, MD, DrPH, MPH, is supported by grant K24AR075060 from the National Institutes of Health. No other outside funding was reported. Dr. Farma had no disclosures.

.

In a cohort of 6,146 patients with a first primary MCC, a total of 725 (11.8%) developed subsequent primary cancers. For solid tumors, the risk was highest for cutaneous melanoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma, while for hematologic cancers, the risk was increased for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

“Our study does confirm that patients with MCC are at higher risk for developing other cancers,” study author Lisa C. Zaba, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology and director of the Merkel cell carcinoma multidisciplinary clinic, Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Center, said in an interview. “MCC is a highly malignant cancer with a 40% recurrence risk.”

Because of this high risk, Dr. Zaba noted that patients with MCC get frequent surveillance with both imaging studies (PET-CT and CT) as well as frequent visits in clinic with MCC experts. “Specifically, a patient with MCC is imaged and seen in clinic every 3-6 months for the first 3 years after diagnosis, and every 6-12 months thereafter for up to 5 years,” she said. “Interestingly, this high level of surveillance may be one reason that we find so many cancers in patients who have been diagnosed with MCC, compared to the general population.”

The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

With the death of “Margaritaville” singer Jimmy Buffett, who recently died of MCC 4 years after his diagnosis, this rare, aggressive skin cancer has been put in the spotlight. Survival has been increasing, primarily because of the advent of immunotherapy, and the authors note that it is therefore imperative to better understand the risk of subsequent primary tumors to inform screening and treatment recommendations.

In this cohort study, Dr. Zaba and colleagues identified 6,146 patients from 17 registries of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program who had been diagnosed with a first primary cutaneous MCC between 2000 and 2018.

Endpoints were the ratio of observed to expected number of cases of subsequent cancer (Standardized incidence ratio, or SIR) and the excess risk.

Overall, there was an elevated risk of developing a subsequent primary cancer after being diagnosed with MCC (SIR, 1.28; excess risk, 57.25 per 10,000 person-years). This included the risk for all solid tumors including liver (SIR, 1.92; excess risk, 2.77 per 10,000 person-years), pancreas (SIR, 1.65; excess risk, 4.55 per 10,000 person-years), cutaneous melanoma (SIR, 2.36; excess risk, 15.27 per 10,000 person-years), and kidney (SIR, 1.64; excess risk, 3.83 per 10,000 person-years).

There was also a higher risk of developing papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) (SIR, 5.26; excess risk, 6.16 per 10,000 person-years).

The risk of developing hematological cancers after MCC was also increased, especially for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (SIR, 2.62; excess risk, 15.48 per 10,000 person-years) and myelodysplastic syndrome (SIR, 2.17; excess risk, 2.73 per 10,000 person-years).

The risk for developing subsequent tumors, including melanoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, remained significant for up to 10 years, while the risk for developing PTC and kidney cancers remained for up to 5 years.

“After 3-5 years, when a MCC patient’s risk of MCC recurrence drops below 2%, we do not currently have guidelines in place for additional cancer screening,” Dr. Zaba said. “Regarding patient education, patients with MCC are educated to let us know if they experience any symptoms of cancer between visits, including unintentional weight loss, night sweats, headaches that increasingly worsen, or growing lumps or bumps. These symptoms may occur in a multitude of cancers and not just MCC.”

Weighing in on the study, Jeffrey M. Farma, MD, interim chair, department of surgical oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, noted that MCC is considered to be high risk because of its chances of recurring after surgical resection or spreading to lymph nodes or other areas of the body. “There are approximately 3,000 new cases of melanoma a year in the U.S., and it is 40 times rarer than melanoma,” he said. “Patients are usually diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma later in life, and the tumors have been associated with sun exposure and immunosuppression and have also been associated with the polyomavirus.”

That said, however, he emphasized that great strides have been made in treatment. “These tumors are very sensitive to radiation, and we generally treat earlier-stage MCC with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy,” said Dr. Farma. “More recently we have had a lot of success with the use of immunotherapy to treat more advanced MCC.”

Dr. Zaba reported receiving grants from the Kuni Foundation outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported. Author Eleni Linos, MD, DrPH, MPH, is supported by grant K24AR075060 from the National Institutes of Health. No other outside funding was reported. Dr. Farma had no disclosures.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Can skin bleaching lead to cancer?

SINGAPORE –

This question was posed by Ousmane Faye, MD, PhD, director general of Mali’s Bamako Dermatology Hospital, at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Dr. Faye explored the issue during a hot topics session at the meeting, prefacing that it was an important question to ask because “in West Africa, skin bleaching is very common.”

“There are many local names” for skin bleaching, he said. “For example, in Senegal, it’s called xessal; in Mali and Ivory Coast, its name is caco; in South Africa, there are many names, like ukutsheyisa.”

Skin bleaching refers to the cosmetic misuse of topical agents to change one’s natural skin color. It’s a centuries-old practice that people, mainly women, adopt “to increase attractiveness and self-esteem,” explained Dr. Faye.

To demonstrate how pervasive skin bleaching is on the continent, he presented a slide that summarized figures from six studies spanning the past 2 decades. Prevalence ranged from 25% in Mali (based on a 1993 survey of 210 women) to a high of 79.25% in Benin (from a sample size of 511 women in 2019). In other studies of women in Burkina Faso and Togo, the figures were 44.3% and 58.9%, respectively. The most recently conducted study, which involved 2,689 Senegalese women and was published in 2022, found that nearly 6 in 10 (59.2%) respondents used skin-lightening products.

But skin bleaching isn’t just limited to Africa, said session moderator Omar Lupi, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, when approached for an independent comment. “It’s a traditional practice around the world. Maybe not in the developed countries, but it’s quite common in Africa, in South America, and in Asia.”

His sentiments are echoed in a meta-analysis that was published in the International Journal of Dermatology in 2019. The work examined 68 studies involving more than 67,000 people across Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America. It found that the pooled lifetime prevalence of skin bleaching was 27.7% (95% confidence interval, 19.6-37.5; P < .01).

“This is an important and interesting topic because our world is shrinking,” Dr. Lupi told this news organization. “Even in countries that don’t have bleaching as a common situation, we now have patients who are migrating from one part [of the world] to another, so bleaching is something that can knock on your door and you need to be prepared.”

Misuse leads to complications

The issue is pertinent to dermatologists because skin bleaching is associated with a wide range of complications. Take, for example, topical steroids, which are the most common products used for bleaching, said Dr. Faye in his talk.

“Clobetasol can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) function,” he said, referring to the body’s main stress response system. “It can also foster skin infection, including bacterial, fungal, viral, and parasitic infection.”

In addition, topical steroids that are misused as skin lighteners have been reported to cause stretch marks, skin atrophy, inflammatory acne, and even metabolic disorders such as diabetes and hypertension, said Dr. Faye.

To further his point, he cited a 2021 prospective case-control study conducted across five sub-Saharan countries, which found that the use of “voluntary cosmetic depigmentation” significantly increased a person’s risk for necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.19-3.73; P = .0226).

Similarly, mercury, another substance found in products commonly used to bleach skin, has been associated with problems ranging from rashes to renal toxicity. And because it’s so incredibly harmful, mercury is also known to cause neurologic abnormalities.

Apart from causing certain conditions, prolonged use of skin-lightening products can change the way existing diseases present themselves as well as their severity, added Dr. Faye.

An increased risk

But what about skin bleaching’s link with cancer? “Skin cancer on Black skin is uncommon, yet it occurs in skin-bleaching women,” said Dr. Faye.

“Since 2000, we have had some cases of skin cancer associated with skin bleaching,” he continued, adding that squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent type of cancer observed.

If you look at what’s been published on the topic so far, you’ll see that “all the cases of skin cancer are located over the neck or some exposed area when skin bleaching products are used for more than 10 years,” said Dr. Faye. “And most of the time, the age of the patient ranges from 30 to 60 years.”

The first known case in Africa was reported in a 58-year-old woman from Ghana, who had been using skin bleaching products for close to 30 years. The patient presented with tumors on her face, neck, and arms.

Dr. Faye then proceeded to share more than 10 such carcinoma cases. “These previous reports strongly suggest a relationship between skin bleaching and skin cancers,” said Dr. Faye.

Indeed, there have been reports and publications in the literature that support his observation, including one last year, which found that use of the tyrosinase inhibitor hydroquinone was associated with approximately a threefold increased risk for skin cancer.

For some, including Brazil’s Dr. Lupi, Dr. Faye’s talk was enlightening: “I didn’t know about this relationship [of bleaching] with skin cancer, it was something new for me.”

But the prevalence of SCC is very low, compared with that of skin bleaching, Dr. Faye acknowledged. Moreover, the cancer observed in the cases reported could have resulted from a number of reasons, including exposure to harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun and genetic predisposition in addition to the use of bleaching products such as hydroquinone. “Other causes of skin cancer are not excluded,” he said.

To further explore the link between skin bleaching and cancer, “we need case-control studies to provide more evidence,” he added. Until then, dermatologists “should keep on promoting messages” to prevent SCC from occurring. This includes encouraging the use of proper sun protection in addition to discouraging the practice of skin bleaching, which still persists despite more than 10 African nations banning the use of toxic skin-lightening products.

Dr. Faye and Dr. Lupi report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SINGAPORE –

This question was posed by Ousmane Faye, MD, PhD, director general of Mali’s Bamako Dermatology Hospital, at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Dr. Faye explored the issue during a hot topics session at the meeting, prefacing that it was an important question to ask because “in West Africa, skin bleaching is very common.”

“There are many local names” for skin bleaching, he said. “For example, in Senegal, it’s called xessal; in Mali and Ivory Coast, its name is caco; in South Africa, there are many names, like ukutsheyisa.”

Skin bleaching refers to the cosmetic misuse of topical agents to change one’s natural skin color. It’s a centuries-old practice that people, mainly women, adopt “to increase attractiveness and self-esteem,” explained Dr. Faye.

To demonstrate how pervasive skin bleaching is on the continent, he presented a slide that summarized figures from six studies spanning the past 2 decades. Prevalence ranged from 25% in Mali (based on a 1993 survey of 210 women) to a high of 79.25% in Benin (from a sample size of 511 women in 2019). In other studies of women in Burkina Faso and Togo, the figures were 44.3% and 58.9%, respectively. The most recently conducted study, which involved 2,689 Senegalese women and was published in 2022, found that nearly 6 in 10 (59.2%) respondents used skin-lightening products.

But skin bleaching isn’t just limited to Africa, said session moderator Omar Lupi, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, when approached for an independent comment. “It’s a traditional practice around the world. Maybe not in the developed countries, but it’s quite common in Africa, in South America, and in Asia.”

His sentiments are echoed in a meta-analysis that was published in the International Journal of Dermatology in 2019. The work examined 68 studies involving more than 67,000 people across Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America. It found that the pooled lifetime prevalence of skin bleaching was 27.7% (95% confidence interval, 19.6-37.5; P < .01).

“This is an important and interesting topic because our world is shrinking,” Dr. Lupi told this news organization. “Even in countries that don’t have bleaching as a common situation, we now have patients who are migrating from one part [of the world] to another, so bleaching is something that can knock on your door and you need to be prepared.”

Misuse leads to complications

The issue is pertinent to dermatologists because skin bleaching is associated with a wide range of complications. Take, for example, topical steroids, which are the most common products used for bleaching, said Dr. Faye in his talk.

“Clobetasol can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) function,” he said, referring to the body’s main stress response system. “It can also foster skin infection, including bacterial, fungal, viral, and parasitic infection.”

In addition, topical steroids that are misused as skin lighteners have been reported to cause stretch marks, skin atrophy, inflammatory acne, and even metabolic disorders such as diabetes and hypertension, said Dr. Faye.

To further his point, he cited a 2021 prospective case-control study conducted across five sub-Saharan countries, which found that the use of “voluntary cosmetic depigmentation” significantly increased a person’s risk for necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.19-3.73; P = .0226).

Similarly, mercury, another substance found in products commonly used to bleach skin, has been associated with problems ranging from rashes to renal toxicity. And because it’s so incredibly harmful, mercury is also known to cause neurologic abnormalities.

Apart from causing certain conditions, prolonged use of skin-lightening products can change the way existing diseases present themselves as well as their severity, added Dr. Faye.

An increased risk

But what about skin bleaching’s link with cancer? “Skin cancer on Black skin is uncommon, yet it occurs in skin-bleaching women,” said Dr. Faye.

“Since 2000, we have had some cases of skin cancer associated with skin bleaching,” he continued, adding that squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent type of cancer observed.

If you look at what’s been published on the topic so far, you’ll see that “all the cases of skin cancer are located over the neck or some exposed area when skin bleaching products are used for more than 10 years,” said Dr. Faye. “And most of the time, the age of the patient ranges from 30 to 60 years.”

The first known case in Africa was reported in a 58-year-old woman from Ghana, who had been using skin bleaching products for close to 30 years. The patient presented with tumors on her face, neck, and arms.

Dr. Faye then proceeded to share more than 10 such carcinoma cases. “These previous reports strongly suggest a relationship between skin bleaching and skin cancers,” said Dr. Faye.

Indeed, there have been reports and publications in the literature that support his observation, including one last year, which found that use of the tyrosinase inhibitor hydroquinone was associated with approximately a threefold increased risk for skin cancer.

For some, including Brazil’s Dr. Lupi, Dr. Faye’s talk was enlightening: “I didn’t know about this relationship [of bleaching] with skin cancer, it was something new for me.”

But the prevalence of SCC is very low, compared with that of skin bleaching, Dr. Faye acknowledged. Moreover, the cancer observed in the cases reported could have resulted from a number of reasons, including exposure to harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun and genetic predisposition in addition to the use of bleaching products such as hydroquinone. “Other causes of skin cancer are not excluded,” he said.

To further explore the link between skin bleaching and cancer, “we need case-control studies to provide more evidence,” he added. Until then, dermatologists “should keep on promoting messages” to prevent SCC from occurring. This includes encouraging the use of proper sun protection in addition to discouraging the practice of skin bleaching, which still persists despite more than 10 African nations banning the use of toxic skin-lightening products.

Dr. Faye and Dr. Lupi report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SINGAPORE –

This question was posed by Ousmane Faye, MD, PhD, director general of Mali’s Bamako Dermatology Hospital, at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Dr. Faye explored the issue during a hot topics session at the meeting, prefacing that it was an important question to ask because “in West Africa, skin bleaching is very common.”

“There are many local names” for skin bleaching, he said. “For example, in Senegal, it’s called xessal; in Mali and Ivory Coast, its name is caco; in South Africa, there are many names, like ukutsheyisa.”

Skin bleaching refers to the cosmetic misuse of topical agents to change one’s natural skin color. It’s a centuries-old practice that people, mainly women, adopt “to increase attractiveness and self-esteem,” explained Dr. Faye.

To demonstrate how pervasive skin bleaching is on the continent, he presented a slide that summarized figures from six studies spanning the past 2 decades. Prevalence ranged from 25% in Mali (based on a 1993 survey of 210 women) to a high of 79.25% in Benin (from a sample size of 511 women in 2019). In other studies of women in Burkina Faso and Togo, the figures were 44.3% and 58.9%, respectively. The most recently conducted study, which involved 2,689 Senegalese women and was published in 2022, found that nearly 6 in 10 (59.2%) respondents used skin-lightening products.

But skin bleaching isn’t just limited to Africa, said session moderator Omar Lupi, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, when approached for an independent comment. “It’s a traditional practice around the world. Maybe not in the developed countries, but it’s quite common in Africa, in South America, and in Asia.”

His sentiments are echoed in a meta-analysis that was published in the International Journal of Dermatology in 2019. The work examined 68 studies involving more than 67,000 people across Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America. It found that the pooled lifetime prevalence of skin bleaching was 27.7% (95% confidence interval, 19.6-37.5; P < .01).

“This is an important and interesting topic because our world is shrinking,” Dr. Lupi told this news organization. “Even in countries that don’t have bleaching as a common situation, we now have patients who are migrating from one part [of the world] to another, so bleaching is something that can knock on your door and you need to be prepared.”

Misuse leads to complications

The issue is pertinent to dermatologists because skin bleaching is associated with a wide range of complications. Take, for example, topical steroids, which are the most common products used for bleaching, said Dr. Faye in his talk.

“Clobetasol can suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) function,” he said, referring to the body’s main stress response system. “It can also foster skin infection, including bacterial, fungal, viral, and parasitic infection.”

In addition, topical steroids that are misused as skin lighteners have been reported to cause stretch marks, skin atrophy, inflammatory acne, and even metabolic disorders such as diabetes and hypertension, said Dr. Faye.

To further his point, he cited a 2021 prospective case-control study conducted across five sub-Saharan countries, which found that the use of “voluntary cosmetic depigmentation” significantly increased a person’s risk for necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs (odds ratio, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.19-3.73; P = .0226).

Similarly, mercury, another substance found in products commonly used to bleach skin, has been associated with problems ranging from rashes to renal toxicity. And because it’s so incredibly harmful, mercury is also known to cause neurologic abnormalities.

Apart from causing certain conditions, prolonged use of skin-lightening products can change the way existing diseases present themselves as well as their severity, added Dr. Faye.

An increased risk

But what about skin bleaching’s link with cancer? “Skin cancer on Black skin is uncommon, yet it occurs in skin-bleaching women,” said Dr. Faye.

“Since 2000, we have had some cases of skin cancer associated with skin bleaching,” he continued, adding that squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the most frequent type of cancer observed.

If you look at what’s been published on the topic so far, you’ll see that “all the cases of skin cancer are located over the neck or some exposed area when skin bleaching products are used for more than 10 years,” said Dr. Faye. “And most of the time, the age of the patient ranges from 30 to 60 years.”

The first known case in Africa was reported in a 58-year-old woman from Ghana, who had been using skin bleaching products for close to 30 years. The patient presented with tumors on her face, neck, and arms.

Dr. Faye then proceeded to share more than 10 such carcinoma cases. “These previous reports strongly suggest a relationship between skin bleaching and skin cancers,” said Dr. Faye.

Indeed, there have been reports and publications in the literature that support his observation, including one last year, which found that use of the tyrosinase inhibitor hydroquinone was associated with approximately a threefold increased risk for skin cancer.

For some, including Brazil’s Dr. Lupi, Dr. Faye’s talk was enlightening: “I didn’t know about this relationship [of bleaching] with skin cancer, it was something new for me.”

But the prevalence of SCC is very low, compared with that of skin bleaching, Dr. Faye acknowledged. Moreover, the cancer observed in the cases reported could have resulted from a number of reasons, including exposure to harmful ultraviolet rays from the sun and genetic predisposition in addition to the use of bleaching products such as hydroquinone. “Other causes of skin cancer are not excluded,” he said.

To further explore the link between skin bleaching and cancer, “we need case-control studies to provide more evidence,” he added. Until then, dermatologists “should keep on promoting messages” to prevent SCC from occurring. This includes encouraging the use of proper sun protection in addition to discouraging the practice of skin bleaching, which still persists despite more than 10 African nations banning the use of toxic skin-lightening products.

Dr. Faye and Dr. Lupi report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT WCD 2023

Cadaveric Split-Thickness Skin Graft With Partial Guiding Closure for Scalp Defects Extending to the Periosteum

Practice Gap

Scalp defects that extend to or below the periosteum often pose a reconstructive conundrum. Secondary-intention healing is challenging without an intact periosteum, and complex rotational flaps are required in these scenarios.1 For a tumor that is at high risk for recurrence or when adjuvant therapy is necessary, tissue distortion of flaps can make monitoring for recurrence difficult. Similarly, for patients in poor health or who are elderly and have substantial skin atrophy, extensive closure may be undesirable or more technically challenging with a higher risk for adverse events. In these scenarios, additional strategies are necessary to optimize wound healing and cosmesis. A cadaveric split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consisting of biologically active tissue can be used to expedite granulation.2

Technique

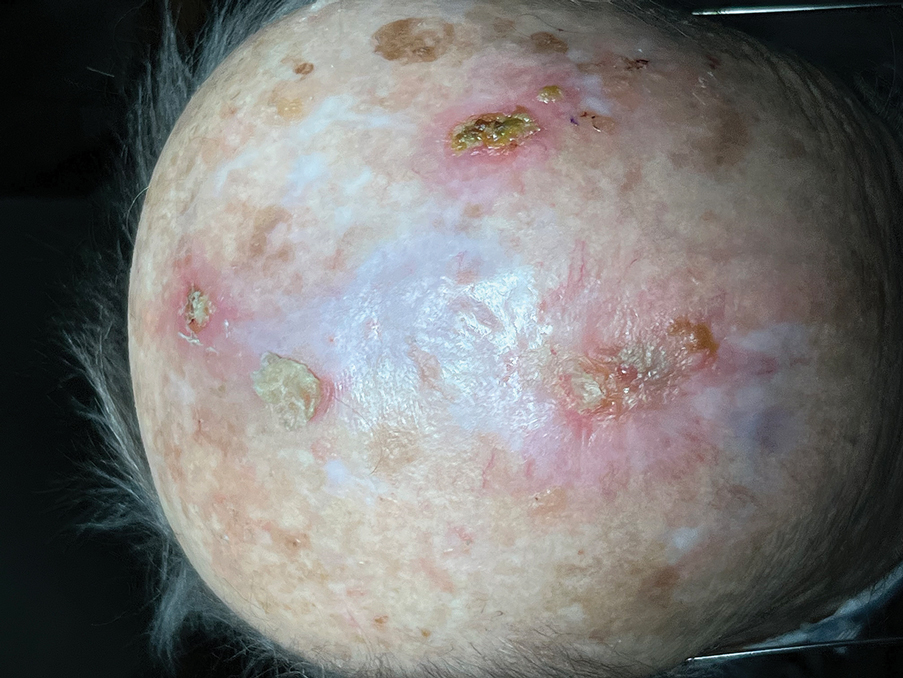

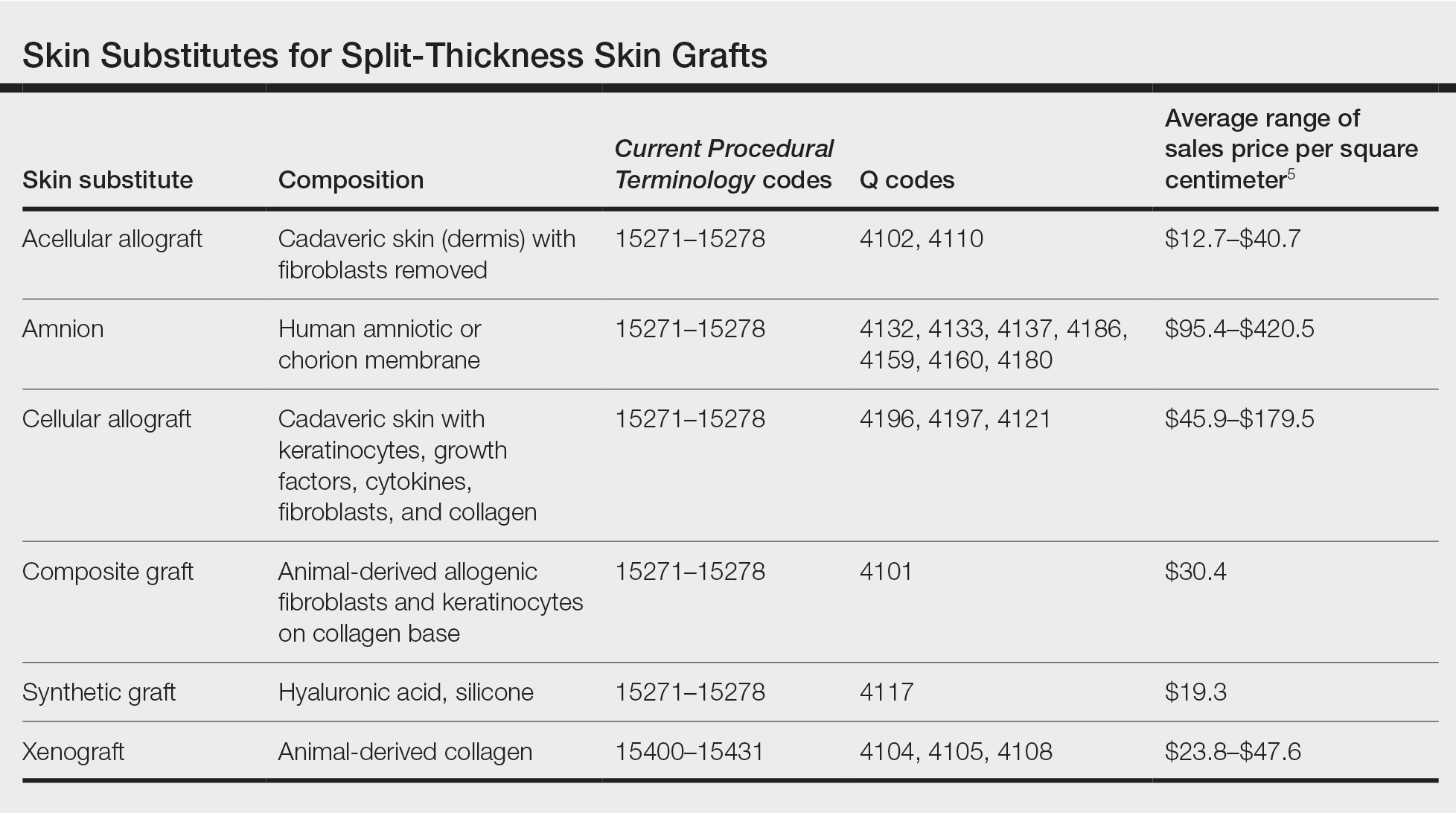

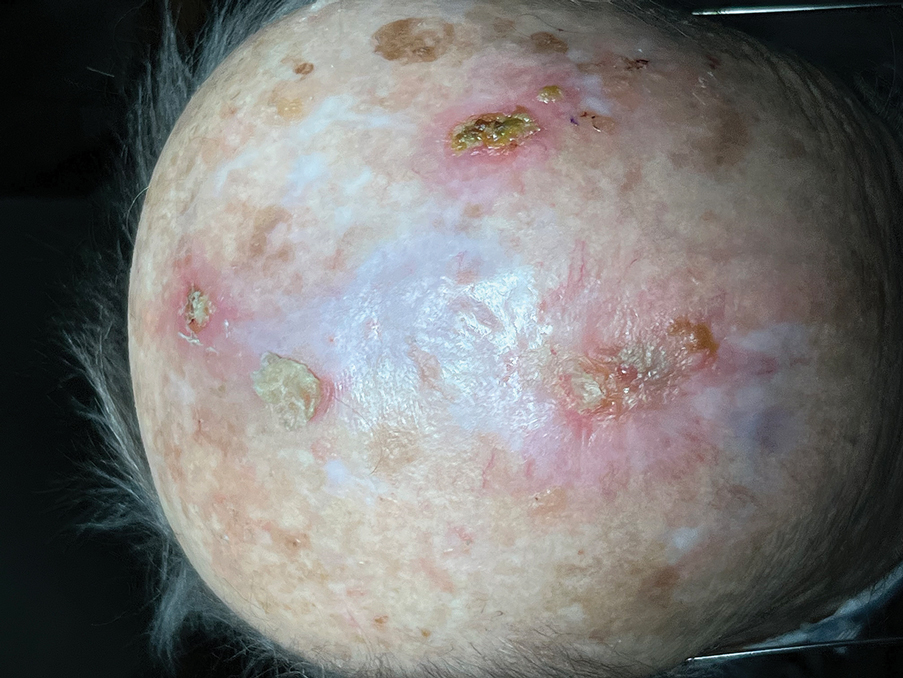

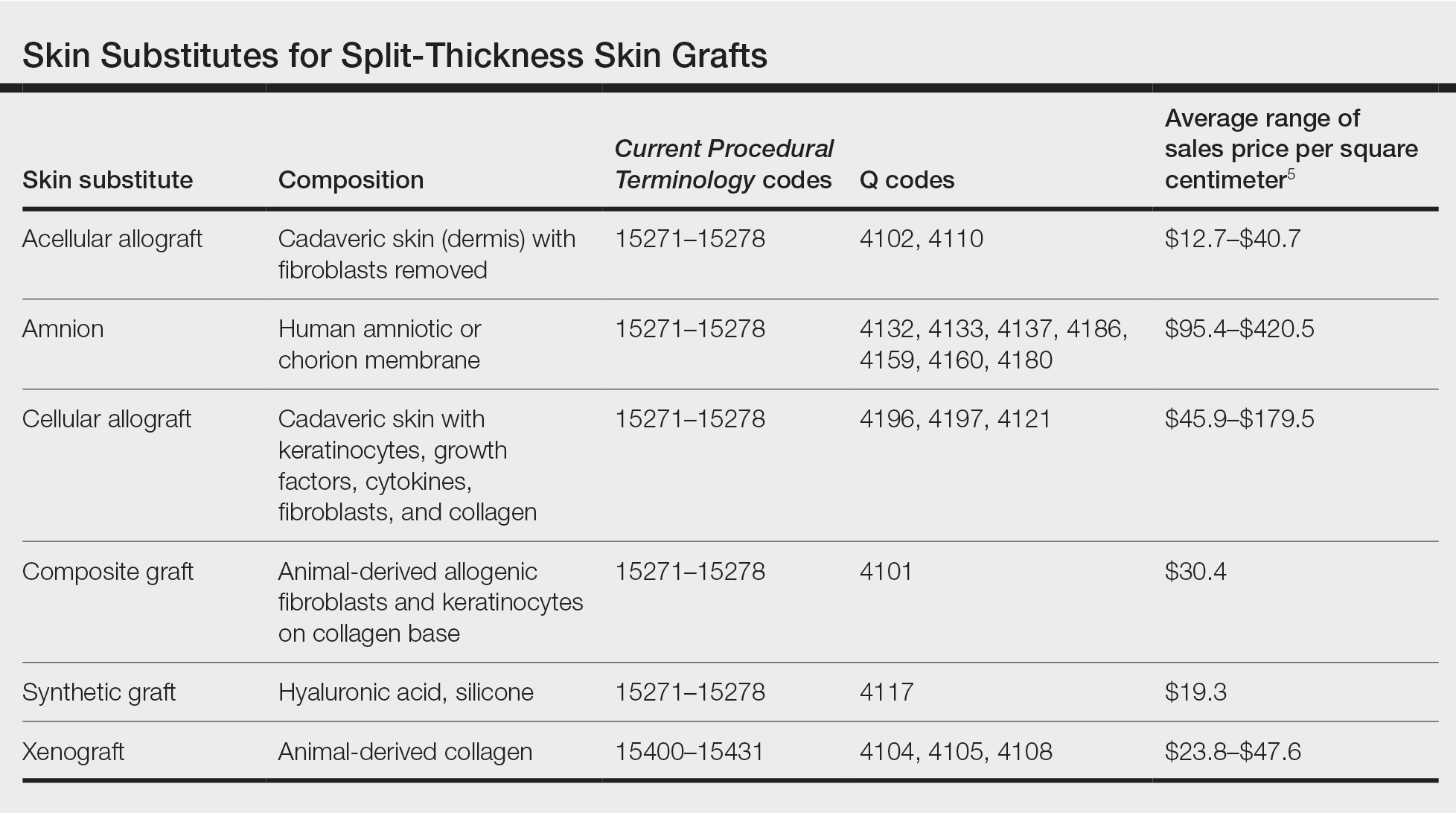

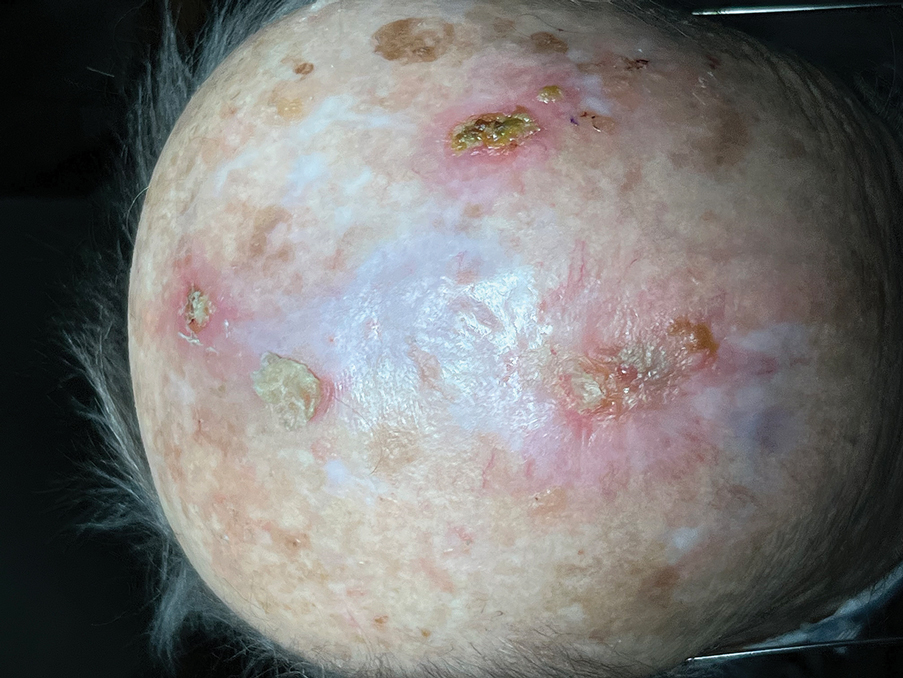

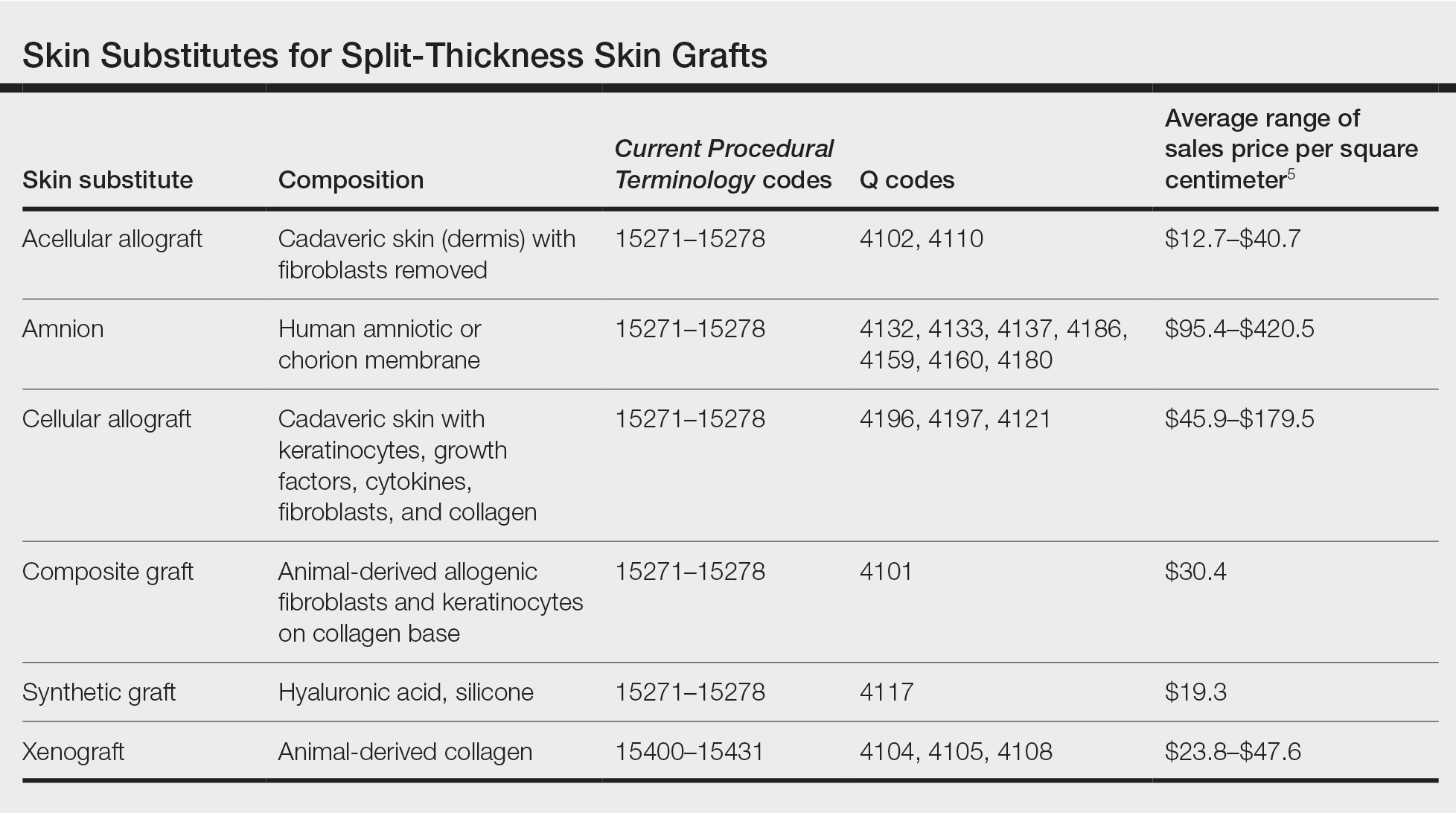

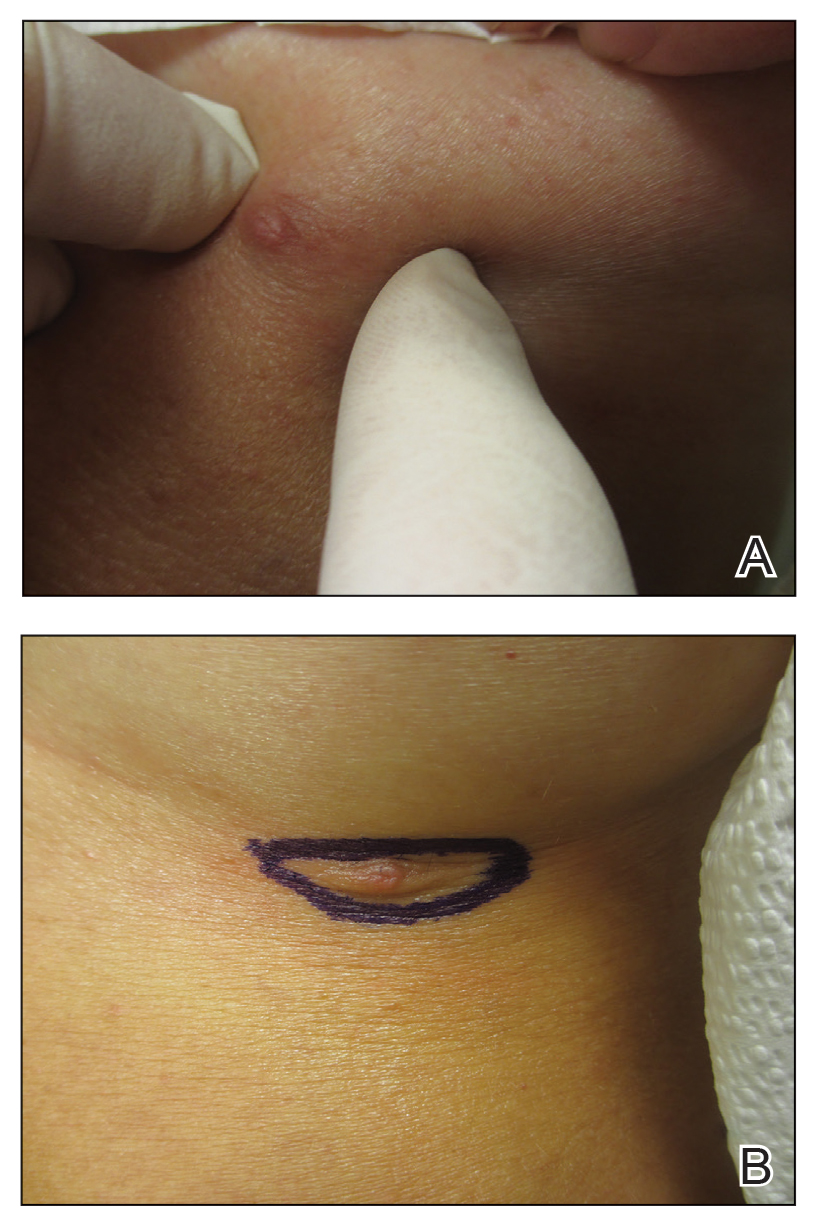

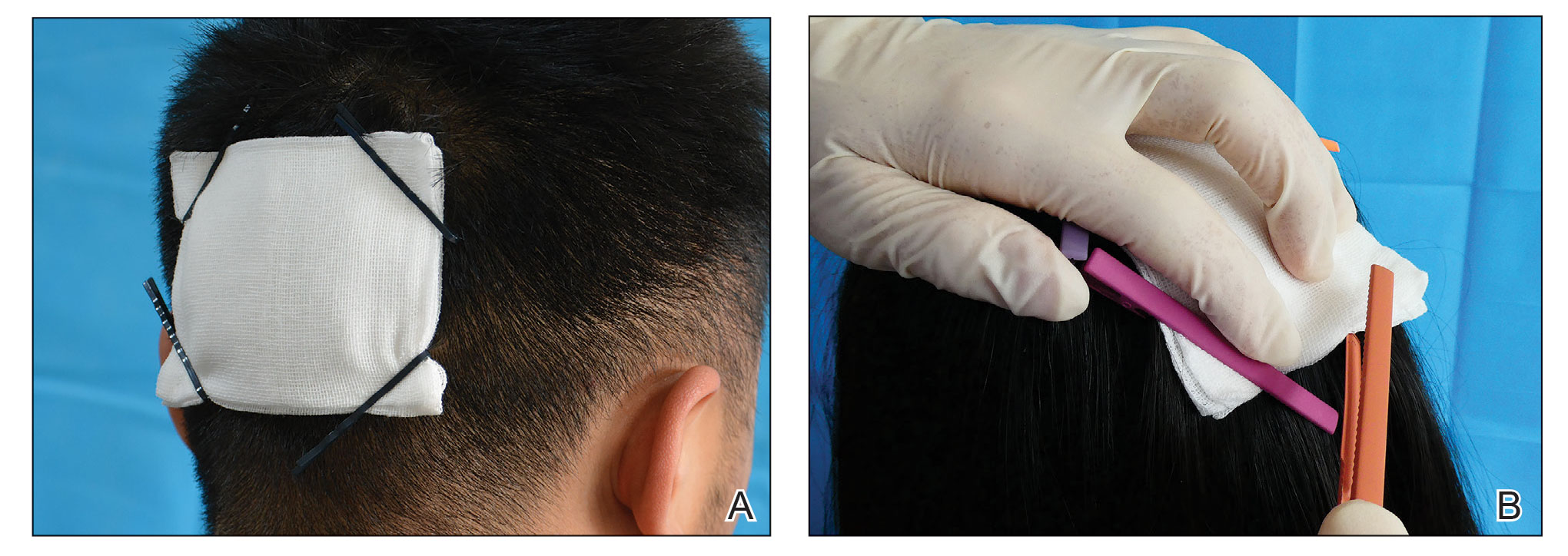

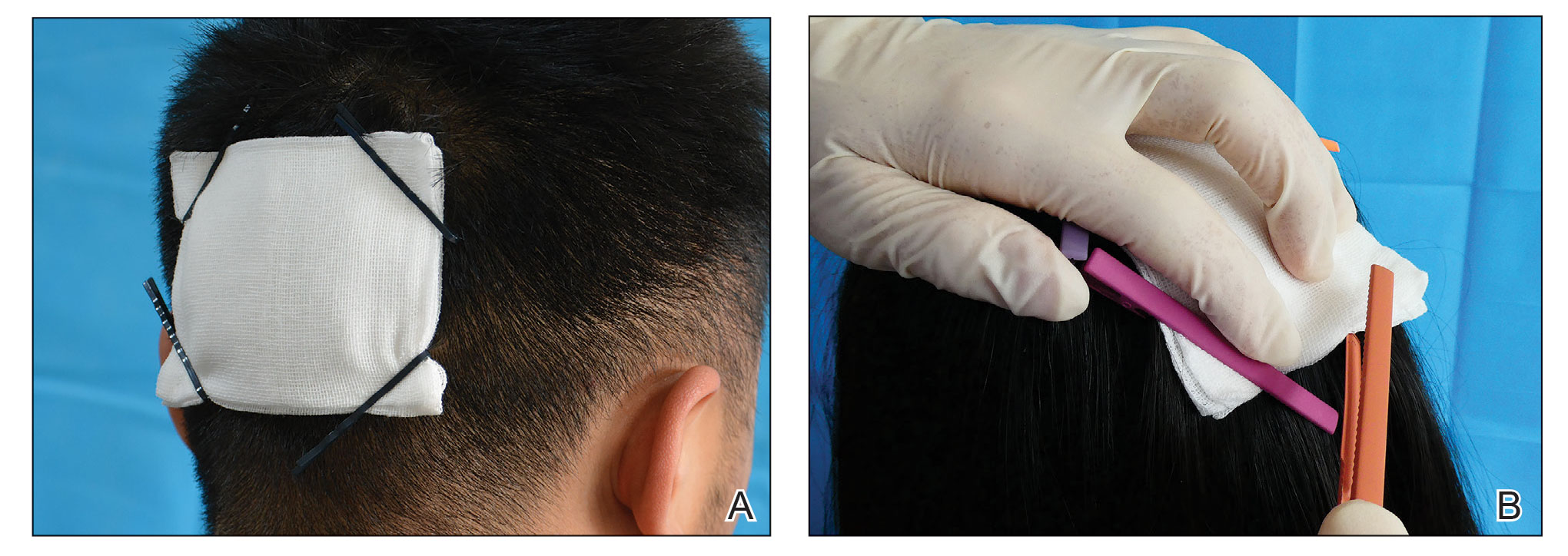

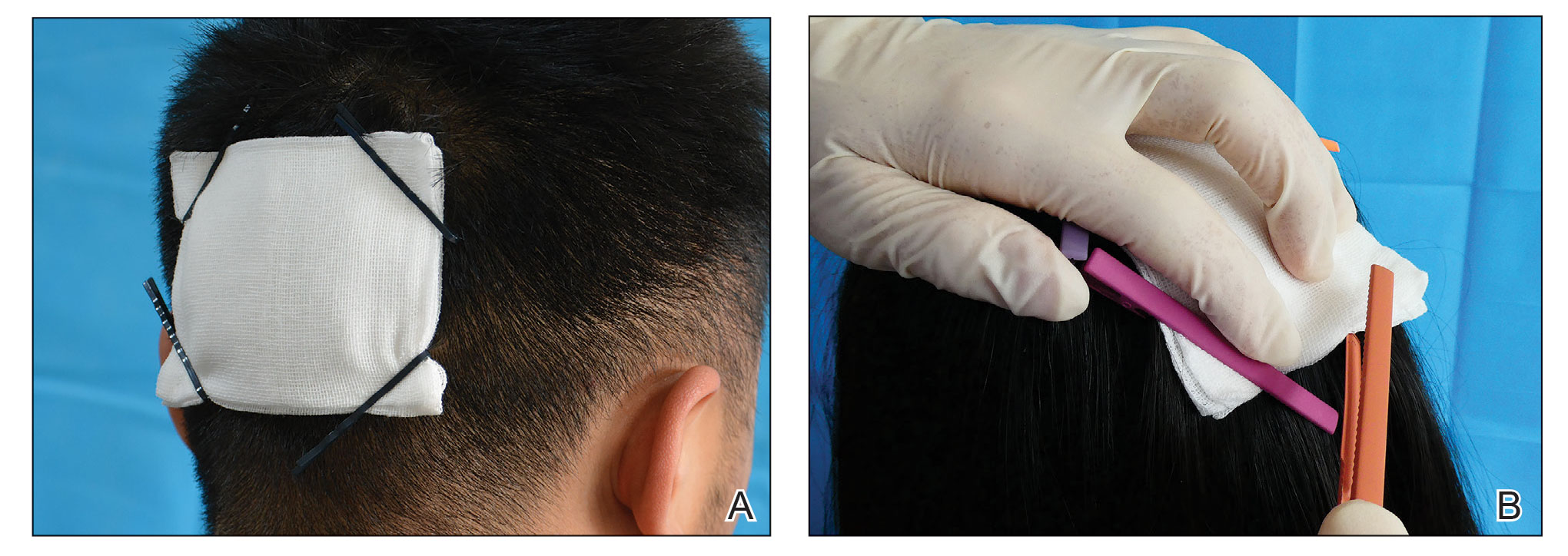

Following tumor clearance on the scalp (Figure 1), wide undermining is performed and 3-0 polyglactin 910 epidermal pulley sutures are placed to partially close the defect. A cadaveric STSG is placed over the remaining exposed periosteum and secured under the pulley sutures (Figure 2). The cadaveric STSG is replaced at 1-week intervals. At 4 weeks, sutures typically are removed. The cadaveric STSG is used until the exposed periosteum is fully granulated and the surgeon decides that granulation arrest is unlikely. The wound then heals by unassisted granulation. This approach provides an excellent final cosmetic outcome while avoiding extensive reconstruction (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

Scalp defects requiring closure are common for dermatologic surgeons. Several techniques to promote tissue granulation in defects that involve exposed periosteum have been reported, including (1) creation of small holes with a scalpel or chisel to access cortical circulation and (2) using laser modalities to stimulate granulation (eg, an erbium:YAG or CO2 laser).3,4 Although direct comparative studies are needed, the cadaveric STSG provides an approach that increases tissue granulation but does not require more invasive techniques or equipment.

Autologous STSGs need a wound bed and can fail with an exposed periosteum. Furthermore, an autologous STSG that survives may leave an unsightly, hypopigmented, depressed defect. When a defect involves the periosteum and a primary closure or flap is not ideal, a skin substitute may be an option.

Skin substitutes, including cadaveric STSG, generally are classified as bioengineered skin equivalents, amniotic tissue, or cadaveric bioproducts (Table). Unlike autologous grafts, these skin substitutes can provide rapid coverage of the defect and do not require a highly vascularized wound bed.6 They also minimize the inflammatory response and potentially improve the final cosmetic outcome by improving granulation rather than immediate STSG closure creating a step-off in deep wounds.6

Cadaveric STSGs also have been used in nonhealing ulcerations; diabetic foot ulcers; and ulcerations in which muscle, tendon, or bone are exposed, demonstrating induction of wound healing with superior scar quality and skin function.2,7,8 The utility of the cadaveric STSG is further highlighted by its potential to reduce costs9 compared to bioengineered skin substitutes, though considerable variability exists in pricing (Table).

Consider using a cadaveric STSG with a guiding closure in cases in which there is concern for delayed or absent tissue granulation or when monitoring for recurrence is essential.

- Jibbe A, Tolkachjov SN. An efficient single-layer suture technique for large scalp flaps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E395-E396. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.062

- Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Magliaro A, et al. Cadaveric skin grafts may greatly increase the healing rate of recalcitrant ulcers when used both alone and in combination with split-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:169-179. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001990

- Valesky EM, Vogl T, Kaufmann R, et al. Trepanation or complete removal of the outer table of the calvarium for granulation induction: the erbium:YAG laser as an alternative to the rose head burr. Dermatology. 2015;230:276-281. doi:10.1159/000368749

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH. Scalpel-made holes on exposed scalp bone to promote second intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.020

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 2023 ASP Pricing. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/asp-pricing-files

- Shores JT, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Skin substitutes and alternatives: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(9 Pt 1):493-508. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000288217.83128.f3

- Li X, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Human acellular dermal matrix allograft: a randomized, controlled human trial for the long-term evaluation of patients with extensive burns. Burns. 2015;41:689-699. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.12.007

- Juhasz I, Kiss B, Lukacs L, et al. Long-term followup of dermal substitution with acellular dermal implant in burns and postburn scar corrections. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:210150. doi:10.1155/2010/210150

- Towler MA, Rush EW, Richardson MK, et al. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (Apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (TheraSkin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006

Practice Gap

Scalp defects that extend to or below the periosteum often pose a reconstructive conundrum. Secondary-intention healing is challenging without an intact periosteum, and complex rotational flaps are required in these scenarios.1 For a tumor that is at high risk for recurrence or when adjuvant therapy is necessary, tissue distortion of flaps can make monitoring for recurrence difficult. Similarly, for patients in poor health or who are elderly and have substantial skin atrophy, extensive closure may be undesirable or more technically challenging with a higher risk for adverse events. In these scenarios, additional strategies are necessary to optimize wound healing and cosmesis. A cadaveric split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consisting of biologically active tissue can be used to expedite granulation.2

Technique

Following tumor clearance on the scalp (Figure 1), wide undermining is performed and 3-0 polyglactin 910 epidermal pulley sutures are placed to partially close the defect. A cadaveric STSG is placed over the remaining exposed periosteum and secured under the pulley sutures (Figure 2). The cadaveric STSG is replaced at 1-week intervals. At 4 weeks, sutures typically are removed. The cadaveric STSG is used until the exposed periosteum is fully granulated and the surgeon decides that granulation arrest is unlikely. The wound then heals by unassisted granulation. This approach provides an excellent final cosmetic outcome while avoiding extensive reconstruction (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

Scalp defects requiring closure are common for dermatologic surgeons. Several techniques to promote tissue granulation in defects that involve exposed periosteum have been reported, including (1) creation of small holes with a scalpel or chisel to access cortical circulation and (2) using laser modalities to stimulate granulation (eg, an erbium:YAG or CO2 laser).3,4 Although direct comparative studies are needed, the cadaveric STSG provides an approach that increases tissue granulation but does not require more invasive techniques or equipment.

Autologous STSGs need a wound bed and can fail with an exposed periosteum. Furthermore, an autologous STSG that survives may leave an unsightly, hypopigmented, depressed defect. When a defect involves the periosteum and a primary closure or flap is not ideal, a skin substitute may be an option.

Skin substitutes, including cadaveric STSG, generally are classified as bioengineered skin equivalents, amniotic tissue, or cadaveric bioproducts (Table). Unlike autologous grafts, these skin substitutes can provide rapid coverage of the defect and do not require a highly vascularized wound bed.6 They also minimize the inflammatory response and potentially improve the final cosmetic outcome by improving granulation rather than immediate STSG closure creating a step-off in deep wounds.6

Cadaveric STSGs also have been used in nonhealing ulcerations; diabetic foot ulcers; and ulcerations in which muscle, tendon, or bone are exposed, demonstrating induction of wound healing with superior scar quality and skin function.2,7,8 The utility of the cadaveric STSG is further highlighted by its potential to reduce costs9 compared to bioengineered skin substitutes, though considerable variability exists in pricing (Table).

Consider using a cadaveric STSG with a guiding closure in cases in which there is concern for delayed or absent tissue granulation or when monitoring for recurrence is essential.

Practice Gap

Scalp defects that extend to or below the periosteum often pose a reconstructive conundrum. Secondary-intention healing is challenging without an intact periosteum, and complex rotational flaps are required in these scenarios.1 For a tumor that is at high risk for recurrence or when adjuvant therapy is necessary, tissue distortion of flaps can make monitoring for recurrence difficult. Similarly, for patients in poor health or who are elderly and have substantial skin atrophy, extensive closure may be undesirable or more technically challenging with a higher risk for adverse events. In these scenarios, additional strategies are necessary to optimize wound healing and cosmesis. A cadaveric split-thickness skin graft (STSG) consisting of biologically active tissue can be used to expedite granulation.2

Technique

Following tumor clearance on the scalp (Figure 1), wide undermining is performed and 3-0 polyglactin 910 epidermal pulley sutures are placed to partially close the defect. A cadaveric STSG is placed over the remaining exposed periosteum and secured under the pulley sutures (Figure 2). The cadaveric STSG is replaced at 1-week intervals. At 4 weeks, sutures typically are removed. The cadaveric STSG is used until the exposed periosteum is fully granulated and the surgeon decides that granulation arrest is unlikely. The wound then heals by unassisted granulation. This approach provides an excellent final cosmetic outcome while avoiding extensive reconstruction (Figure 3).

Practice Implications

Scalp defects requiring closure are common for dermatologic surgeons. Several techniques to promote tissue granulation in defects that involve exposed periosteum have been reported, including (1) creation of small holes with a scalpel or chisel to access cortical circulation and (2) using laser modalities to stimulate granulation (eg, an erbium:YAG or CO2 laser).3,4 Although direct comparative studies are needed, the cadaveric STSG provides an approach that increases tissue granulation but does not require more invasive techniques or equipment.

Autologous STSGs need a wound bed and can fail with an exposed periosteum. Furthermore, an autologous STSG that survives may leave an unsightly, hypopigmented, depressed defect. When a defect involves the periosteum and a primary closure or flap is not ideal, a skin substitute may be an option.

Skin substitutes, including cadaveric STSG, generally are classified as bioengineered skin equivalents, amniotic tissue, or cadaveric bioproducts (Table). Unlike autologous grafts, these skin substitutes can provide rapid coverage of the defect and do not require a highly vascularized wound bed.6 They also minimize the inflammatory response and potentially improve the final cosmetic outcome by improving granulation rather than immediate STSG closure creating a step-off in deep wounds.6

Cadaveric STSGs also have been used in nonhealing ulcerations; diabetic foot ulcers; and ulcerations in which muscle, tendon, or bone are exposed, demonstrating induction of wound healing with superior scar quality and skin function.2,7,8 The utility of the cadaveric STSG is further highlighted by its potential to reduce costs9 compared to bioengineered skin substitutes, though considerable variability exists in pricing (Table).

Consider using a cadaveric STSG with a guiding closure in cases in which there is concern for delayed or absent tissue granulation or when monitoring for recurrence is essential.

- Jibbe A, Tolkachjov SN. An efficient single-layer suture technique for large scalp flaps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E395-E396. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.062

- Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Magliaro A, et al. Cadaveric skin grafts may greatly increase the healing rate of recalcitrant ulcers when used both alone and in combination with split-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:169-179. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001990

- Valesky EM, Vogl T, Kaufmann R, et al. Trepanation or complete removal of the outer table of the calvarium for granulation induction: the erbium:YAG laser as an alternative to the rose head burr. Dermatology. 2015;230:276-281. doi:10.1159/000368749

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH. Scalpel-made holes on exposed scalp bone to promote second intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.020

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 2023 ASP Pricing. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/asp-pricing-files

- Shores JT, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Skin substitutes and alternatives: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(9 Pt 1):493-508. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000288217.83128.f3

- Li X, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Human acellular dermal matrix allograft: a randomized, controlled human trial for the long-term evaluation of patients with extensive burns. Burns. 2015;41:689-699. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.12.007

- Juhasz I, Kiss B, Lukacs L, et al. Long-term followup of dermal substitution with acellular dermal implant in burns and postburn scar corrections. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:210150. doi:10.1155/2010/210150

- Towler MA, Rush EW, Richardson MK, et al. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (Apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (TheraSkin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006

- Jibbe A, Tolkachjov SN. An efficient single-layer suture technique for large scalp flaps. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:E395-E396. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.062

- Mosti G, Mattaliano V, Magliaro A, et al. Cadaveric skin grafts may greatly increase the healing rate of recalcitrant ulcers when used both alone and in combination with split-thickness skin grafts. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:169-179. doi:10.1097/dss.0000000000001990

- Valesky EM, Vogl T, Kaufmann R, et al. Trepanation or complete removal of the outer table of the calvarium for granulation induction: the erbium:YAG laser as an alternative to the rose head burr. Dermatology. 2015;230:276-281. doi:10.1159/000368749

- Drosou A, Trieu D, Goldberg LH. Scalpel-made holes on exposed scalp bone to promote second intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:387-388. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.020

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. April 2023 ASP Pricing. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-part-b-drug-average-sales-price/asp-pricing-files

- Shores JT, Gabriel A, Gupta S. Skin substitutes and alternatives: a review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20(9 Pt 1):493-508. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000288217.83128.f3

- Li X, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Human acellular dermal matrix allograft: a randomized, controlled human trial for the long-term evaluation of patients with extensive burns. Burns. 2015;41:689-699. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2014.12.007

- Juhasz I, Kiss B, Lukacs L, et al. Long-term followup of dermal substitution with acellular dermal implant in burns and postburn scar corrections. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:210150. doi:10.1155/2010/210150

- Towler MA, Rush EW, Richardson MK, et al. Randomized, prospective, blinded-enrollment, head-to-head venous leg ulcer healing trial comparing living, bioengineered skin graft substitute (Apligraf) with living, cryopreserved, human skin allograft (TheraSkin). Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2018;35:357-365. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2018.02.006

Mohs found to confer survival benefit in localized Merkel cell carcinoma

results from a national retrospective cohort study suggest.