User login

Black Children With Vitiligo at Increased Risk for Psychiatric Disorders: Study

TOPLINE:

Black children with vitiligo are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, including depression, suicidal ideation, and disruptive behavior disorders, than matched controls who did not have vitiligo, according to a case-control study.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective, single-center, case-control study at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston on 327 Black children with vitiligo and 981 matched controls without vitiligo.

- The average age of participants was 11.7 years, and 62% were girls.

- The study outcome was the prevalence of psychiatric conditions and rates of treatment (pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy) initiation for those conditions.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black children with vitiligo were more likely to be diagnosed with depression (odds ratio [OR], 3.63; P < .001), suicidal ideation (OR, 2.88; P = .005), disruptive behavior disorders (OR, 7.68; P < .001), eating disorders (OR, 15.22; P = .013), generalized anxiety disorder (OR, 2.61; P < .001), and substance abuse (OR, 2.67; P = .011).

- The likelihood of having a psychiatric comorbidity was not significantly different between children with segmental vitiligo and those with generalized vitiligo or between girls and boys.

- Among the patients with vitiligo and psychiatric comorbidities, treatment initiation rates were higher for depression (76.5%), disruptive behavior disorders (82.1%), and eating disorders (100%).

- Treatment initiation rates were lower in patients with vitiligo diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder (55.3%) and substance abuse (61.5%). Treatment was not initiated in 14% patients with suicidal ideation.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pediatric dermatologists have an important role in screening for psychiatric comorbidities, and implementation of appropriate screening tools while treating vitiligo is likely to have a bidirectional positive impact,” the authors wrote, adding: “By better understanding psychiatric comorbidities of African American children with vitiligo, dermatologists can be more aware of pediatric mental health needs and provide appropriate referrals.”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Emily Strouphauer, BSA, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and was published online in JAAD International.

LIMITATIONS:

The study limitations were the retrospective design, small sample size, and heterogeneity in the control group.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Black children with vitiligo are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, including depression, suicidal ideation, and disruptive behavior disorders, than matched controls who did not have vitiligo, according to a case-control study.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective, single-center, case-control study at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston on 327 Black children with vitiligo and 981 matched controls without vitiligo.

- The average age of participants was 11.7 years, and 62% were girls.

- The study outcome was the prevalence of psychiatric conditions and rates of treatment (pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy) initiation for those conditions.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black children with vitiligo were more likely to be diagnosed with depression (odds ratio [OR], 3.63; P < .001), suicidal ideation (OR, 2.88; P = .005), disruptive behavior disorders (OR, 7.68; P < .001), eating disorders (OR, 15.22; P = .013), generalized anxiety disorder (OR, 2.61; P < .001), and substance abuse (OR, 2.67; P = .011).

- The likelihood of having a psychiatric comorbidity was not significantly different between children with segmental vitiligo and those with generalized vitiligo or between girls and boys.

- Among the patients with vitiligo and psychiatric comorbidities, treatment initiation rates were higher for depression (76.5%), disruptive behavior disorders (82.1%), and eating disorders (100%).

- Treatment initiation rates were lower in patients with vitiligo diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder (55.3%) and substance abuse (61.5%). Treatment was not initiated in 14% patients with suicidal ideation.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pediatric dermatologists have an important role in screening for psychiatric comorbidities, and implementation of appropriate screening tools while treating vitiligo is likely to have a bidirectional positive impact,” the authors wrote, adding: “By better understanding psychiatric comorbidities of African American children with vitiligo, dermatologists can be more aware of pediatric mental health needs and provide appropriate referrals.”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Emily Strouphauer, BSA, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and was published online in JAAD International.

LIMITATIONS:

The study limitations were the retrospective design, small sample size, and heterogeneity in the control group.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Black children with vitiligo are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with psychiatric disorders, including depression, suicidal ideation, and disruptive behavior disorders, than matched controls who did not have vitiligo, according to a case-control study.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a retrospective, single-center, case-control study at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston on 327 Black children with vitiligo and 981 matched controls without vitiligo.

- The average age of participants was 11.7 years, and 62% were girls.

- The study outcome was the prevalence of psychiatric conditions and rates of treatment (pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy) initiation for those conditions.

TAKEAWAY:

- Black children with vitiligo were more likely to be diagnosed with depression (odds ratio [OR], 3.63; P < .001), suicidal ideation (OR, 2.88; P = .005), disruptive behavior disorders (OR, 7.68; P < .001), eating disorders (OR, 15.22; P = .013), generalized anxiety disorder (OR, 2.61; P < .001), and substance abuse (OR, 2.67; P = .011).

- The likelihood of having a psychiatric comorbidity was not significantly different between children with segmental vitiligo and those with generalized vitiligo or between girls and boys.

- Among the patients with vitiligo and psychiatric comorbidities, treatment initiation rates were higher for depression (76.5%), disruptive behavior disorders (82.1%), and eating disorders (100%).

- Treatment initiation rates were lower in patients with vitiligo diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder (55.3%) and substance abuse (61.5%). Treatment was not initiated in 14% patients with suicidal ideation.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pediatric dermatologists have an important role in screening for psychiatric comorbidities, and implementation of appropriate screening tools while treating vitiligo is likely to have a bidirectional positive impact,” the authors wrote, adding: “By better understanding psychiatric comorbidities of African American children with vitiligo, dermatologists can be more aware of pediatric mental health needs and provide appropriate referrals.”

SOURCE:

This study was led by Emily Strouphauer, BSA, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and was published online in JAAD International.

LIMITATIONS:

The study limitations were the retrospective design, small sample size, and heterogeneity in the control group.

DISCLOSURES:

The study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parents’ Technology Use May Shape Adolescents’ Mental Health

, according to a new study based in Canada.

In fact, this parental “technoference” is associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity symptoms later in the child’s development, the researchers found.

“We hear a lot about children’s and adolescents’ screen time in the media, but we forget that parents are also on their screens a lot. In fact, past research shows that when parents are with their children, they spend 1 in 3 minutes on a screen,” said lead author Audrey-Ann Deneault, PhD, assistant professor of social psychology at the University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

“We’ve all experienced moments when we’re on the phone and not hearing someone call us or don’t notice something happening right before our eyes,” she said. “We think that’s why it’s important to look at technoference. When parents use screens, they are more likely to miss when their child needs them.”

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Analyzing Parental Technoference

As part of the All Our Families study, Dr. Deneault and colleagues analyzed a cohort of mothers and 1303 emerging adolescents between ages 9 and 11 years in Calgary, with the aim of understanding long-term associations between perceived parental interruptions (or technoference) and their children’s mental health.

Women were recruited during pregnancy between May 2008 and December 2010. For this study, the adolescents were assessed three times — at ages 9 years (in 2020), 10 years (in 2021), and 11 years (in 2021 and 2022). The mothers gave consent for their children to participate, and the children gave assent as well.

During the assessments, the adolescents completed questionnaires about their perceptions of parental technoference and their mental health symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, inattention, and hyperactivity. The study focused on the magnitude of effect sizes rather than statistical significance.

Overall, higher levels of anxiety symptoms at ages 9 and 10 years were prospectively associated with higher levels of perceived parental technoference at ages 10 and 11 years. The effect size was small.

In addition, higher levels of perceived parental technoference at ages 9 and 10 years were prospectively associated with higher levels of hyperactivity at ages 10 and 11 years and higher levels of inattention at age 11 years. There were no significant differences by gender.

“Technoference and youth mental health interact in complex ways. We found that when emerging adolescents have higher rates of anxiety, this can prompt parents to engage in more technoference,” Dr. Deneault said. “This latter bit highlights that parents may be struggling when their youths have mental health difficulties.”

Considering Healthy Changes

The findings call for a multitiered approach, Dr. Deneault said, in which adolescents and parents receive support related to mental health concerns, technology use, and healthy parent-child interactions.

“The key takeaway is that parents’ screen time matters and should begin to be a part of the conversation when we think about child and adolescent mental health,” she said.

Future research should look at the direction of associations between adolescent mental health and parental technoference, as well as underlying mechanisms, specific activities linked to technoference, and different age groups and stages of development, the study authors wrote.

“As a society, we need to understand how parents’ use of technology can interfere or not with youths’ mental health,” said Nicole Letourneau, PhD, a research professor of pediatrics, psychiatry, and community health sciences focused on parent and child health at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Dr. Letourneau, who wasn’t involved in this study, has researched the effects of parental technoference on parent-child relationships and child health and developmental outcomes. She and her colleagues found that parents recognized changes in their child’s behavior.

“Parental support is important for healthy development, and if parents are distracted by their devices, they can miss important but subtle cues that youth are using to signal their needs,” she said. “Given the troubling rise in youth mental health problems, we need to understand potential contributors so we can offer ways to reduce risks and promote youth mental health.”

Communication with parents should be considered as well. For instance, healthcare providers can address the positive and negative aspects of technology use.

“There is enough research out now that we should be more concerned than we currently are about how parents’ own technology habits might influence child and teen well-being. Yet, taking an overall negative lens to parent technology and smartphone habits may not prove very fruitful,” said Brandon McDaniel, PhD, a senior research scientist at the Parkview Mirro Center for Research & Innovation in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Dr. McDaniel, who also wasn’t involved with this study, has researched technoference and associations with child behavior problems, as well as parents’ desires to change phone use. He noted that parents may use their devices for positive reasons, such as finding support from others, regulating their own emotions, and escaping from stress, so they can be more emotionally available for their children soon after using their phone.

“Many parents already feel an immense amount of guilt surrounding smartphone use in the presence of their child,” he said. “I suggest that practitioners address parent technology use in ways that validate parents in their positive uses of technology while helping them identify areas of their tech habits that may be counterproductive for their own or their child’s health and mental health.”

The All Our Families study was supported by an Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions Interdisciplinary Team Grant and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation. The current analysis received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development COVID-19 grant, an Alberta Innovates grant, and a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. Dr. Deneault, Dr. Letourneau, and Dr. McDaniel reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new study based in Canada.

In fact, this parental “technoference” is associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity symptoms later in the child’s development, the researchers found.

“We hear a lot about children’s and adolescents’ screen time in the media, but we forget that parents are also on their screens a lot. In fact, past research shows that when parents are with their children, they spend 1 in 3 minutes on a screen,” said lead author Audrey-Ann Deneault, PhD, assistant professor of social psychology at the University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

“We’ve all experienced moments when we’re on the phone and not hearing someone call us or don’t notice something happening right before our eyes,” she said. “We think that’s why it’s important to look at technoference. When parents use screens, they are more likely to miss when their child needs them.”

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Analyzing Parental Technoference

As part of the All Our Families study, Dr. Deneault and colleagues analyzed a cohort of mothers and 1303 emerging adolescents between ages 9 and 11 years in Calgary, with the aim of understanding long-term associations between perceived parental interruptions (or technoference) and their children’s mental health.

Women were recruited during pregnancy between May 2008 and December 2010. For this study, the adolescents were assessed three times — at ages 9 years (in 2020), 10 years (in 2021), and 11 years (in 2021 and 2022). The mothers gave consent for their children to participate, and the children gave assent as well.

During the assessments, the adolescents completed questionnaires about their perceptions of parental technoference and their mental health symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, inattention, and hyperactivity. The study focused on the magnitude of effect sizes rather than statistical significance.

Overall, higher levels of anxiety symptoms at ages 9 and 10 years were prospectively associated with higher levels of perceived parental technoference at ages 10 and 11 years. The effect size was small.

In addition, higher levels of perceived parental technoference at ages 9 and 10 years were prospectively associated with higher levels of hyperactivity at ages 10 and 11 years and higher levels of inattention at age 11 years. There were no significant differences by gender.

“Technoference and youth mental health interact in complex ways. We found that when emerging adolescents have higher rates of anxiety, this can prompt parents to engage in more technoference,” Dr. Deneault said. “This latter bit highlights that parents may be struggling when their youths have mental health difficulties.”

Considering Healthy Changes

The findings call for a multitiered approach, Dr. Deneault said, in which adolescents and parents receive support related to mental health concerns, technology use, and healthy parent-child interactions.

“The key takeaway is that parents’ screen time matters and should begin to be a part of the conversation when we think about child and adolescent mental health,” she said.

Future research should look at the direction of associations between adolescent mental health and parental technoference, as well as underlying mechanisms, specific activities linked to technoference, and different age groups and stages of development, the study authors wrote.

“As a society, we need to understand how parents’ use of technology can interfere or not with youths’ mental health,” said Nicole Letourneau, PhD, a research professor of pediatrics, psychiatry, and community health sciences focused on parent and child health at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Dr. Letourneau, who wasn’t involved in this study, has researched the effects of parental technoference on parent-child relationships and child health and developmental outcomes. She and her colleagues found that parents recognized changes in their child’s behavior.

“Parental support is important for healthy development, and if parents are distracted by their devices, they can miss important but subtle cues that youth are using to signal their needs,” she said. “Given the troubling rise in youth mental health problems, we need to understand potential contributors so we can offer ways to reduce risks and promote youth mental health.”

Communication with parents should be considered as well. For instance, healthcare providers can address the positive and negative aspects of technology use.

“There is enough research out now that we should be more concerned than we currently are about how parents’ own technology habits might influence child and teen well-being. Yet, taking an overall negative lens to parent technology and smartphone habits may not prove very fruitful,” said Brandon McDaniel, PhD, a senior research scientist at the Parkview Mirro Center for Research & Innovation in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Dr. McDaniel, who also wasn’t involved with this study, has researched technoference and associations with child behavior problems, as well as parents’ desires to change phone use. He noted that parents may use their devices for positive reasons, such as finding support from others, regulating their own emotions, and escaping from stress, so they can be more emotionally available for their children soon after using their phone.

“Many parents already feel an immense amount of guilt surrounding smartphone use in the presence of their child,” he said. “I suggest that practitioners address parent technology use in ways that validate parents in their positive uses of technology while helping them identify areas of their tech habits that may be counterproductive for their own or their child’s health and mental health.”

The All Our Families study was supported by an Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions Interdisciplinary Team Grant and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation. The current analysis received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development COVID-19 grant, an Alberta Innovates grant, and a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. Dr. Deneault, Dr. Letourneau, and Dr. McDaniel reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a new study based in Canada.

In fact, this parental “technoference” is associated with higher levels of inattention and hyperactivity symptoms later in the child’s development, the researchers found.

“We hear a lot about children’s and adolescents’ screen time in the media, but we forget that parents are also on their screens a lot. In fact, past research shows that when parents are with their children, they spend 1 in 3 minutes on a screen,” said lead author Audrey-Ann Deneault, PhD, assistant professor of social psychology at the University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

“We’ve all experienced moments when we’re on the phone and not hearing someone call us or don’t notice something happening right before our eyes,” she said. “We think that’s why it’s important to look at technoference. When parents use screens, they are more likely to miss when their child needs them.”

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

Analyzing Parental Technoference

As part of the All Our Families study, Dr. Deneault and colleagues analyzed a cohort of mothers and 1303 emerging adolescents between ages 9 and 11 years in Calgary, with the aim of understanding long-term associations between perceived parental interruptions (or technoference) and their children’s mental health.

Women were recruited during pregnancy between May 2008 and December 2010. For this study, the adolescents were assessed three times — at ages 9 years (in 2020), 10 years (in 2021), and 11 years (in 2021 and 2022). The mothers gave consent for their children to participate, and the children gave assent as well.

During the assessments, the adolescents completed questionnaires about their perceptions of parental technoference and their mental health symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, inattention, and hyperactivity. The study focused on the magnitude of effect sizes rather than statistical significance.

Overall, higher levels of anxiety symptoms at ages 9 and 10 years were prospectively associated with higher levels of perceived parental technoference at ages 10 and 11 years. The effect size was small.

In addition, higher levels of perceived parental technoference at ages 9 and 10 years were prospectively associated with higher levels of hyperactivity at ages 10 and 11 years and higher levels of inattention at age 11 years. There were no significant differences by gender.

“Technoference and youth mental health interact in complex ways. We found that when emerging adolescents have higher rates of anxiety, this can prompt parents to engage in more technoference,” Dr. Deneault said. “This latter bit highlights that parents may be struggling when their youths have mental health difficulties.”

Considering Healthy Changes

The findings call for a multitiered approach, Dr. Deneault said, in which adolescents and parents receive support related to mental health concerns, technology use, and healthy parent-child interactions.

“The key takeaway is that parents’ screen time matters and should begin to be a part of the conversation when we think about child and adolescent mental health,” she said.

Future research should look at the direction of associations between adolescent mental health and parental technoference, as well as underlying mechanisms, specific activities linked to technoference, and different age groups and stages of development, the study authors wrote.

“As a society, we need to understand how parents’ use of technology can interfere or not with youths’ mental health,” said Nicole Letourneau, PhD, a research professor of pediatrics, psychiatry, and community health sciences focused on parent and child health at the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Dr. Letourneau, who wasn’t involved in this study, has researched the effects of parental technoference on parent-child relationships and child health and developmental outcomes. She and her colleagues found that parents recognized changes in their child’s behavior.

“Parental support is important for healthy development, and if parents are distracted by their devices, they can miss important but subtle cues that youth are using to signal their needs,” she said. “Given the troubling rise in youth mental health problems, we need to understand potential contributors so we can offer ways to reduce risks and promote youth mental health.”

Communication with parents should be considered as well. For instance, healthcare providers can address the positive and negative aspects of technology use.

“There is enough research out now that we should be more concerned than we currently are about how parents’ own technology habits might influence child and teen well-being. Yet, taking an overall negative lens to parent technology and smartphone habits may not prove very fruitful,” said Brandon McDaniel, PhD, a senior research scientist at the Parkview Mirro Center for Research & Innovation in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Dr. McDaniel, who also wasn’t involved with this study, has researched technoference and associations with child behavior problems, as well as parents’ desires to change phone use. He noted that parents may use their devices for positive reasons, such as finding support from others, regulating their own emotions, and escaping from stress, so they can be more emotionally available for their children soon after using their phone.

“Many parents already feel an immense amount of guilt surrounding smartphone use in the presence of their child,” he said. “I suggest that practitioners address parent technology use in ways that validate parents in their positive uses of technology while helping them identify areas of their tech habits that may be counterproductive for their own or their child’s health and mental health.”

The All Our Families study was supported by an Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions Interdisciplinary Team Grant and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation. The current analysis received funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, a Children and Screens: Institute of Digital Media and Child Development COVID-19 grant, an Alberta Innovates grant, and a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. Dr. Deneault, Dr. Letourneau, and Dr. McDaniel reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

How Intermittent Fasting Could Transform Adolescent Obesity

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a 52-week randomized clinical trial at two pediatric centers in Australia that involved 141 adolescents aged 13-17 years with obesity and at least one associated complication.

- Participants were divided into two groups: IER and CER, with three phases: Very low-energy diet (weeks 0-4), intensive intervention (weeks 5-16), and continued intervention/maintenance (weeks 17-52).

- Interventions included a very low-energy diet of 3350 kJ/d (800 kcal/d) for the first 4 weeks, followed by either IER intervention (2500-2950 kJ [600-700 kcal 3 days/wk]) or a daily CER intervention (6000-8000 kJ/d based on age; 1430-1670 kcal/d for teens aged 13-14 years and 1670-1900 kcal/d for teens aged 15-17 years).

- Participants were provided with multivitamins and met with dietitians regularly, with additional support via telephone, text message, or email.

TAKEAWAY:

- Teens in both the IER and CER groups showed a 0.28 reduction in BMI z-scores at 52 weeks with no significant differences between the two.

- The researchers observed no differences in body composition or cardiometabolic outcomes between the IER and CER groups.

- The occurrence of insulin resistance was reduced in both groups at week 16, but this effect was maintained only in the CER group at week 52.

- The study found no significant differences in the occurrence of dyslipidemia or impaired hepatic function between the IER and CER groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings suggest that for adolescents with obesity-associated complications, IER can be incorporated into a behavioral weight management program, providing an option in addition to CER and offering participants more choice,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Natalie B. Lister, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia and was published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS:

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns limited the sample size. Some dietitian visits were conducted via telehealth.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Lister received grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. A coauthor, Louise A. Baur, MBBS, PhD, received speakers’ fees from Novo Nordisk and served as a member of the Eli Lilly Advisory Committee.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a 52-week randomized clinical trial at two pediatric centers in Australia that involved 141 adolescents aged 13-17 years with obesity and at least one associated complication.

- Participants were divided into two groups: IER and CER, with three phases: Very low-energy diet (weeks 0-4), intensive intervention (weeks 5-16), and continued intervention/maintenance (weeks 17-52).

- Interventions included a very low-energy diet of 3350 kJ/d (800 kcal/d) for the first 4 weeks, followed by either IER intervention (2500-2950 kJ [600-700 kcal 3 days/wk]) or a daily CER intervention (6000-8000 kJ/d based on age; 1430-1670 kcal/d for teens aged 13-14 years and 1670-1900 kcal/d for teens aged 15-17 years).

- Participants were provided with multivitamins and met with dietitians regularly, with additional support via telephone, text message, or email.

TAKEAWAY:

- Teens in both the IER and CER groups showed a 0.28 reduction in BMI z-scores at 52 weeks with no significant differences between the two.

- The researchers observed no differences in body composition or cardiometabolic outcomes between the IER and CER groups.

- The occurrence of insulin resistance was reduced in both groups at week 16, but this effect was maintained only in the CER group at week 52.

- The study found no significant differences in the occurrence of dyslipidemia or impaired hepatic function between the IER and CER groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings suggest that for adolescents with obesity-associated complications, IER can be incorporated into a behavioral weight management program, providing an option in addition to CER and offering participants more choice,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Natalie B. Lister, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia and was published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS:

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns limited the sample size. Some dietitian visits were conducted via telehealth.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Lister received grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. A coauthor, Louise A. Baur, MBBS, PhD, received speakers’ fees from Novo Nordisk and served as a member of the Eli Lilly Advisory Committee.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a 52-week randomized clinical trial at two pediatric centers in Australia that involved 141 adolescents aged 13-17 years with obesity and at least one associated complication.

- Participants were divided into two groups: IER and CER, with three phases: Very low-energy diet (weeks 0-4), intensive intervention (weeks 5-16), and continued intervention/maintenance (weeks 17-52).

- Interventions included a very low-energy diet of 3350 kJ/d (800 kcal/d) for the first 4 weeks, followed by either IER intervention (2500-2950 kJ [600-700 kcal 3 days/wk]) or a daily CER intervention (6000-8000 kJ/d based on age; 1430-1670 kcal/d for teens aged 13-14 years and 1670-1900 kcal/d for teens aged 15-17 years).

- Participants were provided with multivitamins and met with dietitians regularly, with additional support via telephone, text message, or email.

TAKEAWAY:

- Teens in both the IER and CER groups showed a 0.28 reduction in BMI z-scores at 52 weeks with no significant differences between the two.

- The researchers observed no differences in body composition or cardiometabolic outcomes between the IER and CER groups.

- The occurrence of insulin resistance was reduced in both groups at week 16, but this effect was maintained only in the CER group at week 52.

- The study found no significant differences in the occurrence of dyslipidemia or impaired hepatic function between the IER and CER groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings suggest that for adolescents with obesity-associated complications, IER can be incorporated into a behavioral weight management program, providing an option in addition to CER and offering participants more choice,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Natalie B. Lister, PhD, of the University of Sydney in Australia and was published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS:

The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdowns limited the sample size. Some dietitian visits were conducted via telehealth.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Lister received grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. A coauthor, Louise A. Baur, MBBS, PhD, received speakers’ fees from Novo Nordisk and served as a member of the Eli Lilly Advisory Committee.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 Booster Vaccine Shortens Menstrual Cycles in Teens

TOPLINE:

The vaccine did not appear to be associated with shifts in menstrual flow, pain, or other symptoms.

METHODOLOGY:

- Reports of menstrual cycle changes following the COVID-19 vaccination began to emerge in early 2021, raising concerns about the impact of the vaccine on menstrual health.

- Researchers conducted a prospective study including 65 adolescent girls (mean age, 17.3 years), of whom 47 had received an initial series of COVID-19 vaccination at least 6 months prior to receiving a booster dose (booster group), and 18 had not received the booster vaccine (control group), two of whom had never received any COVID-19 vaccine, four who had received an initial vaccine but not a booster, and 12 who had received an initial vaccine and booster but more than 6 months prior to the study.

- Menstrual cycle length was measured for three cycles prior to and four cycles after vaccination in the booster group and for seven cycles in the control group.

- Menstrual flow, pain, and stress were measured at baseline and monthly for 3 months post vaccination.

TAKEAWAY:

- Participants in the booster group experienced shorter cycles by an average of 5.35 days after receiving the COVID-19 booster vaccine (P = .03), particularly during the second cycle. In contrast, those in the control group did not experience any changes in the menstrual cycle length.

- Receiving the booster dose in the follicular phase was associated with significantly shorter menstrual cycles, compared with pre-booster cycles (P = .0157).

- Menstrual flow, pain, and other symptoms remained unaffected after the COVID-19 booster vaccination.

- Higher stress levels at baseline were also associated with a shorter length of the menstrual cycle (P = .03) in both groups, regardless of the booster vaccination status.

IN PRACTICE:

“These data are potentially important for counseling parents regarding potential vaccine refusal in the future for their teen daughters,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Laura A. Payne, PhD, from McLean Hospital in Boston, and was published online in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The sample size for the booster and control groups was relatively small and homogeneous. The study did not include the height, weight, birth control use, or other chronic conditions of the participants, which may have influenced the functioning of the menstrual cycle. The control group included a majority of teens who had previously received a vaccine and even a booster, which could have affected results.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. Some authors received consulting fees, travel reimbursements, honoraria, research funding, and royalties from Bayer Healthcare, Mahana Therapeutics, Gates, and Merck, among others.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The vaccine did not appear to be associated with shifts in menstrual flow, pain, or other symptoms.

METHODOLOGY:

- Reports of menstrual cycle changes following the COVID-19 vaccination began to emerge in early 2021, raising concerns about the impact of the vaccine on menstrual health.

- Researchers conducted a prospective study including 65 adolescent girls (mean age, 17.3 years), of whom 47 had received an initial series of COVID-19 vaccination at least 6 months prior to receiving a booster dose (booster group), and 18 had not received the booster vaccine (control group), two of whom had never received any COVID-19 vaccine, four who had received an initial vaccine but not a booster, and 12 who had received an initial vaccine and booster but more than 6 months prior to the study.

- Menstrual cycle length was measured for three cycles prior to and four cycles after vaccination in the booster group and for seven cycles in the control group.

- Menstrual flow, pain, and stress were measured at baseline and monthly for 3 months post vaccination.

TAKEAWAY:

- Participants in the booster group experienced shorter cycles by an average of 5.35 days after receiving the COVID-19 booster vaccine (P = .03), particularly during the second cycle. In contrast, those in the control group did not experience any changes in the menstrual cycle length.

- Receiving the booster dose in the follicular phase was associated with significantly shorter menstrual cycles, compared with pre-booster cycles (P = .0157).

- Menstrual flow, pain, and other symptoms remained unaffected after the COVID-19 booster vaccination.

- Higher stress levels at baseline were also associated with a shorter length of the menstrual cycle (P = .03) in both groups, regardless of the booster vaccination status.

IN PRACTICE:

“These data are potentially important for counseling parents regarding potential vaccine refusal in the future for their teen daughters,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Laura A. Payne, PhD, from McLean Hospital in Boston, and was published online in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The sample size for the booster and control groups was relatively small and homogeneous. The study did not include the height, weight, birth control use, or other chronic conditions of the participants, which may have influenced the functioning of the menstrual cycle. The control group included a majority of teens who had previously received a vaccine and even a booster, which could have affected results.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. Some authors received consulting fees, travel reimbursements, honoraria, research funding, and royalties from Bayer Healthcare, Mahana Therapeutics, Gates, and Merck, among others.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

The vaccine did not appear to be associated with shifts in menstrual flow, pain, or other symptoms.

METHODOLOGY:

- Reports of menstrual cycle changes following the COVID-19 vaccination began to emerge in early 2021, raising concerns about the impact of the vaccine on menstrual health.

- Researchers conducted a prospective study including 65 adolescent girls (mean age, 17.3 years), of whom 47 had received an initial series of COVID-19 vaccination at least 6 months prior to receiving a booster dose (booster group), and 18 had not received the booster vaccine (control group), two of whom had never received any COVID-19 vaccine, four who had received an initial vaccine but not a booster, and 12 who had received an initial vaccine and booster but more than 6 months prior to the study.

- Menstrual cycle length was measured for three cycles prior to and four cycles after vaccination in the booster group and for seven cycles in the control group.

- Menstrual flow, pain, and stress were measured at baseline and monthly for 3 months post vaccination.

TAKEAWAY:

- Participants in the booster group experienced shorter cycles by an average of 5.35 days after receiving the COVID-19 booster vaccine (P = .03), particularly during the second cycle. In contrast, those in the control group did not experience any changes in the menstrual cycle length.

- Receiving the booster dose in the follicular phase was associated with significantly shorter menstrual cycles, compared with pre-booster cycles (P = .0157).

- Menstrual flow, pain, and other symptoms remained unaffected after the COVID-19 booster vaccination.

- Higher stress levels at baseline were also associated with a shorter length of the menstrual cycle (P = .03) in both groups, regardless of the booster vaccination status.

IN PRACTICE:

“These data are potentially important for counseling parents regarding potential vaccine refusal in the future for their teen daughters,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Laura A. Payne, PhD, from McLean Hospital in Boston, and was published online in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

LIMITATIONS:

The sample size for the booster and control groups was relatively small and homogeneous. The study did not include the height, weight, birth control use, or other chronic conditions of the participants, which may have influenced the functioning of the menstrual cycle. The control group included a majority of teens who had previously received a vaccine and even a booster, which could have affected results.

DISCLOSURES:

This study was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. Some authors received consulting fees, travel reimbursements, honoraria, research funding, and royalties from Bayer Healthcare, Mahana Therapeutics, Gates, and Merck, among others.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Identifying Child Abuse Through Oral Health: What Every Clinician Should Know

TOPLINE:

Researchers detail best practices for pediatricians in evaluating dental indications of child abuse and how to work with other physicians to detect and report these incidents.

METHODOLOGY:

- Approximately 323,000 children in the United States were identified as having experienced physical abuse in 2006, the most recent year evaluated, according to the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect.

- One in seven children in the United States are abused or neglected each year; craniofacial, head, face, and neck injuries occur in more than half of child abuse cases.

- Children with orofacial and torso bruising who are younger than age 4 years are at risk for future, more serious abuse.

- Child trafficking survivors are twice as likely to have dental issues due to poor nutrition and inadequate care.

TAKEAWAY:

- In cases of possible oral sexual abuse, physicians should test for sexually transmitted infections and document incidents to support forensic investigations.

- Pediatricians should consult with forensic pediatric dentists or child abuse specialists for assistance in evaluating bite marks or any other indications of abuse.

- If a parent fails to seek treatment for a child’s oral or dental disease after detection, pediatricians should report the case to child protective services regarding concerns of dental neglect.

- Because trafficked children may receive medical or dental care while in captivity, physicians should use screening tools to identify children at risk of trafficking, regardless of gender.

- Physicians should be mindful of having a bias against reporting because of sharing a similar background to the parents or other caregivers of a child who is suspected of experiencing abuse.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pediatric dentists and oral and maxillofacial surgeons, whose advanced education programs include a mandated child abuse curriculum, can provide valuable information and assistance to other health care providers about oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Anupama Rao Tate, DMD, MPH, of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and was published online in Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS:

No limitations were reported.

DISCLOSURES:

Susan A. Fischer-Owens reported financial connections with Colgate. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Researchers detail best practices for pediatricians in evaluating dental indications of child abuse and how to work with other physicians to detect and report these incidents.

METHODOLOGY:

- Approximately 323,000 children in the United States were identified as having experienced physical abuse in 2006, the most recent year evaluated, according to the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect.

- One in seven children in the United States are abused or neglected each year; craniofacial, head, face, and neck injuries occur in more than half of child abuse cases.

- Children with orofacial and torso bruising who are younger than age 4 years are at risk for future, more serious abuse.

- Child trafficking survivors are twice as likely to have dental issues due to poor nutrition and inadequate care.

TAKEAWAY:

- In cases of possible oral sexual abuse, physicians should test for sexually transmitted infections and document incidents to support forensic investigations.

- Pediatricians should consult with forensic pediatric dentists or child abuse specialists for assistance in evaluating bite marks or any other indications of abuse.

- If a parent fails to seek treatment for a child’s oral or dental disease after detection, pediatricians should report the case to child protective services regarding concerns of dental neglect.

- Because trafficked children may receive medical or dental care while in captivity, physicians should use screening tools to identify children at risk of trafficking, regardless of gender.

- Physicians should be mindful of having a bias against reporting because of sharing a similar background to the parents or other caregivers of a child who is suspected of experiencing abuse.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pediatric dentists and oral and maxillofacial surgeons, whose advanced education programs include a mandated child abuse curriculum, can provide valuable information and assistance to other health care providers about oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Anupama Rao Tate, DMD, MPH, of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and was published online in Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS:

No limitations were reported.

DISCLOSURES:

Susan A. Fischer-Owens reported financial connections with Colgate. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Researchers detail best practices for pediatricians in evaluating dental indications of child abuse and how to work with other physicians to detect and report these incidents.

METHODOLOGY:

- Approximately 323,000 children in the United States were identified as having experienced physical abuse in 2006, the most recent year evaluated, according to the Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect.

- One in seven children in the United States are abused or neglected each year; craniofacial, head, face, and neck injuries occur in more than half of child abuse cases.

- Children with orofacial and torso bruising who are younger than age 4 years are at risk for future, more serious abuse.

- Child trafficking survivors are twice as likely to have dental issues due to poor nutrition and inadequate care.

TAKEAWAY:

- In cases of possible oral sexual abuse, physicians should test for sexually transmitted infections and document incidents to support forensic investigations.

- Pediatricians should consult with forensic pediatric dentists or child abuse specialists for assistance in evaluating bite marks or any other indications of abuse.

- If a parent fails to seek treatment for a child’s oral or dental disease after detection, pediatricians should report the case to child protective services regarding concerns of dental neglect.

- Because trafficked children may receive medical or dental care while in captivity, physicians should use screening tools to identify children at risk of trafficking, regardless of gender.

- Physicians should be mindful of having a bias against reporting because of sharing a similar background to the parents or other caregivers of a child who is suspected of experiencing abuse.

IN PRACTICE:

“Pediatric dentists and oral and maxillofacial surgeons, whose advanced education programs include a mandated child abuse curriculum, can provide valuable information and assistance to other health care providers about oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect,” the study authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Anupama Rao Tate, DMD, MPH, of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and was published online in Pediatrics.

LIMITATIONS:

No limitations were reported.

DISCLOSURES:

Susan A. Fischer-Owens reported financial connections with Colgate. No other disclosures were reported.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Timing of iPLEDGE Updates Unclear

iPLEDGE, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–required Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program launched in 2010, aims to manage the risks for the teratogenic acne drug isotretinoin and prevent fetal exposure. But it’s been dogged by issues and controversy, causing difficulties for patients and prescribers.

Late in 2023, there seemed to be a reason for optimism that improvements were coming. On November 30, 2023, the FDA informed isotretinoin manufacturers — known as the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturing Group (IPMG) — that they had 6 months to make five changes to the existing iPLEDGE REMS, addressing the controversies and potentially reducing glitches in the program and minimizing the burden of the program on patients, prescribers, and pharmacies — while maintaining safe use of the drug — and to submit their proposal by May 30, 2024.

The timeline for when an improved program might be in place remains unclear.

An FDA spokesperson, without confirming that the submission was submitted on time, recently said the review timeline once such a submission is received is generally 6 months.

‘Radio Silence’

No official FDA announcement has been made about the timeline, nor has information been forthcoming from the IPMG, and the silence has been frustrating for John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. He chairs the American Academy of Dermatology Association’s IPLEDGE Work Group, which works with both the FDA and IPMG.

He began writing about issues with iPLEDGE about 4 years ago, when he and colleagues suggested, among other changes, simplifying the iPLEDGE contraception requirements in a paper published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri expressed frustration about the lack of information on the status of the iPLEDGE changes. “We’ve been given no timeline [beyond the FDA’s May 30 deadline for the IPMG to respond] of what might happen when. We’ve asked what was submitted. No one will share it with us or tell us anything about it. It’s just radio silence.”

Dr. Barbieri is also frustrated at the lack of response from IPMG. Despite repeated requests to the group to include the dermatologists in the discussions, IPMG has repeatedly declined the help, he said.

IPMG appears to have no dedicated website. No response had been received to an email sent to an address attributed to the group asking if it would share the submission to the FDA.

Currently, isotretinoin, originally marketed as Accutane, is marketed under such brand names as Absorica, Absorica LD, Claravis, Amnesteem, Myorisan, and Zenatane.

Asked for specific information on the proposed changes, an FDA spokesperson said in an August 19 email that “the submission to the FDA from the isotretinoin manufacturers will be a major modification, and the review timeline is generally 6 months. Once approved, the isotretinoin manufacturers will need additional time to implement the changes.”

The spokesperson declined to provide additional information on the status of the IPMG proposal, to share the proposal itself, or to estimate the implementation period.

Reason for Hope?

In response to the comment that the review generally takes 6 months, Dr. Barbieri said it doesn’t give him much hope, adding that “any delay of implementing these reforms is a missed opportunity to improve the care of patients with acne.” He is also hopeful that the FDA will invite some public comment during the review period “so that stakeholders can share their feedback about the proposal to help guide FDA decision-making and ensure effective implementation.”

From Meeting to Mandate

The FDA order for the changes followed a joint meeting of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee in March 2023 about the program requirements. It included feedback from patients and dermatologists and recommendations for changes, with a goal of reducing the burden of the program on patients, pharmacies, and prescribers without compromising patient safety.

The Five Requested Changes

In the November 30 letter, the FDA requested the following from the IPMG:

- Remove the requirement that pregnancy tests be performed in a specially certified lab (such as a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments lab). This would enable the tests to be done in a clinic setting rather than sending patients to a separate lab.

- Allow prescribers the option of letting patients use home pregnancy tests during and after treatment, with steps in place to minimize falsification.

- Remove the waiting period requirement, known as the “19-day lockout,” for patients if they don’t obtain the isotretinoin from the pharmacy within the first 7-day prescription window. Before initiation of isotretinoin, a repeat confirmatory test must be done in a medical setting without any required waiting period.

- Revise the pregnancy registry requirement, removing the objective to document the outcome and associated collection of data for each pregnancy.

- Revise the requirement for prescribers to document patient counseling for those who can’t become pregnant from monthly counseling to counseling at enrollment only. Before each prescription is dispensed, the authorization must verify patient enrollment and prescriber certification. (In December 2021, a new, gender-neutral approach, approved by the FDA, was launched. It places potential patients into two risk categories — those who can become pregnant and those who cannot. Previously, there were three such categories: Females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males.)

Perspective on the Requested Changes

Of the requested changes, “really the most important is eliminating the request for monthly counseling for patients who cannot become pregnant,” Dr. Barbieri said. Because of that requirement, all patients need to have monthly visits with a dermatologist to get the medication refills, “and that creates a logistical barrier,” plus reducing time available for dermatologists to care for other patients with other dermatologic issues.

As for missing the 7-day prescription window, Dr. Barbieri said, in his experience, “it’s almost never the patient’s fault; it’s almost always an insurance problem.”

Dr. Barbieri reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

iPLEDGE, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–required Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program launched in 2010, aims to manage the risks for the teratogenic acne drug isotretinoin and prevent fetal exposure. But it’s been dogged by issues and controversy, causing difficulties for patients and prescribers.

Late in 2023, there seemed to be a reason for optimism that improvements were coming. On November 30, 2023, the FDA informed isotretinoin manufacturers — known as the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturing Group (IPMG) — that they had 6 months to make five changes to the existing iPLEDGE REMS, addressing the controversies and potentially reducing glitches in the program and minimizing the burden of the program on patients, prescribers, and pharmacies — while maintaining safe use of the drug — and to submit their proposal by May 30, 2024.

The timeline for when an improved program might be in place remains unclear.

An FDA spokesperson, without confirming that the submission was submitted on time, recently said the review timeline once such a submission is received is generally 6 months.

‘Radio Silence’

No official FDA announcement has been made about the timeline, nor has information been forthcoming from the IPMG, and the silence has been frustrating for John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. He chairs the American Academy of Dermatology Association’s IPLEDGE Work Group, which works with both the FDA and IPMG.

He began writing about issues with iPLEDGE about 4 years ago, when he and colleagues suggested, among other changes, simplifying the iPLEDGE contraception requirements in a paper published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri expressed frustration about the lack of information on the status of the iPLEDGE changes. “We’ve been given no timeline [beyond the FDA’s May 30 deadline for the IPMG to respond] of what might happen when. We’ve asked what was submitted. No one will share it with us or tell us anything about it. It’s just radio silence.”

Dr. Barbieri is also frustrated at the lack of response from IPMG. Despite repeated requests to the group to include the dermatologists in the discussions, IPMG has repeatedly declined the help, he said.

IPMG appears to have no dedicated website. No response had been received to an email sent to an address attributed to the group asking if it would share the submission to the FDA.

Currently, isotretinoin, originally marketed as Accutane, is marketed under such brand names as Absorica, Absorica LD, Claravis, Amnesteem, Myorisan, and Zenatane.

Asked for specific information on the proposed changes, an FDA spokesperson said in an August 19 email that “the submission to the FDA from the isotretinoin manufacturers will be a major modification, and the review timeline is generally 6 months. Once approved, the isotretinoin manufacturers will need additional time to implement the changes.”

The spokesperson declined to provide additional information on the status of the IPMG proposal, to share the proposal itself, or to estimate the implementation period.

Reason for Hope?

In response to the comment that the review generally takes 6 months, Dr. Barbieri said it doesn’t give him much hope, adding that “any delay of implementing these reforms is a missed opportunity to improve the care of patients with acne.” He is also hopeful that the FDA will invite some public comment during the review period “so that stakeholders can share their feedback about the proposal to help guide FDA decision-making and ensure effective implementation.”

From Meeting to Mandate

The FDA order for the changes followed a joint meeting of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee in March 2023 about the program requirements. It included feedback from patients and dermatologists and recommendations for changes, with a goal of reducing the burden of the program on patients, pharmacies, and prescribers without compromising patient safety.

The Five Requested Changes

In the November 30 letter, the FDA requested the following from the IPMG:

- Remove the requirement that pregnancy tests be performed in a specially certified lab (such as a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments lab). This would enable the tests to be done in a clinic setting rather than sending patients to a separate lab.

- Allow prescribers the option of letting patients use home pregnancy tests during and after treatment, with steps in place to minimize falsification.

- Remove the waiting period requirement, known as the “19-day lockout,” for patients if they don’t obtain the isotretinoin from the pharmacy within the first 7-day prescription window. Before initiation of isotretinoin, a repeat confirmatory test must be done in a medical setting without any required waiting period.

- Revise the pregnancy registry requirement, removing the objective to document the outcome and associated collection of data for each pregnancy.

- Revise the requirement for prescribers to document patient counseling for those who can’t become pregnant from monthly counseling to counseling at enrollment only. Before each prescription is dispensed, the authorization must verify patient enrollment and prescriber certification. (In December 2021, a new, gender-neutral approach, approved by the FDA, was launched. It places potential patients into two risk categories — those who can become pregnant and those who cannot. Previously, there were three such categories: Females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males.)

Perspective on the Requested Changes

Of the requested changes, “really the most important is eliminating the request for monthly counseling for patients who cannot become pregnant,” Dr. Barbieri said. Because of that requirement, all patients need to have monthly visits with a dermatologist to get the medication refills, “and that creates a logistical barrier,” plus reducing time available for dermatologists to care for other patients with other dermatologic issues.

As for missing the 7-day prescription window, Dr. Barbieri said, in his experience, “it’s almost never the patient’s fault; it’s almost always an insurance problem.”

Dr. Barbieri reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

iPLEDGE, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–required Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program launched in 2010, aims to manage the risks for the teratogenic acne drug isotretinoin and prevent fetal exposure. But it’s been dogged by issues and controversy, causing difficulties for patients and prescribers.

Late in 2023, there seemed to be a reason for optimism that improvements were coming. On November 30, 2023, the FDA informed isotretinoin manufacturers — known as the Isotretinoin Products Manufacturing Group (IPMG) — that they had 6 months to make five changes to the existing iPLEDGE REMS, addressing the controversies and potentially reducing glitches in the program and minimizing the burden of the program on patients, prescribers, and pharmacies — while maintaining safe use of the drug — and to submit their proposal by May 30, 2024.

The timeline for when an improved program might be in place remains unclear.

An FDA spokesperson, without confirming that the submission was submitted on time, recently said the review timeline once such a submission is received is generally 6 months.

‘Radio Silence’

No official FDA announcement has been made about the timeline, nor has information been forthcoming from the IPMG, and the silence has been frustrating for John S. Barbieri, MD, MBA, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts. He chairs the American Academy of Dermatology Association’s IPLEDGE Work Group, which works with both the FDA and IPMG.

He began writing about issues with iPLEDGE about 4 years ago, when he and colleagues suggested, among other changes, simplifying the iPLEDGE contraception requirements in a paper published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In an interview, Dr. Barbieri expressed frustration about the lack of information on the status of the iPLEDGE changes. “We’ve been given no timeline [beyond the FDA’s May 30 deadline for the IPMG to respond] of what might happen when. We’ve asked what was submitted. No one will share it with us or tell us anything about it. It’s just radio silence.”

Dr. Barbieri is also frustrated at the lack of response from IPMG. Despite repeated requests to the group to include the dermatologists in the discussions, IPMG has repeatedly declined the help, he said.

IPMG appears to have no dedicated website. No response had been received to an email sent to an address attributed to the group asking if it would share the submission to the FDA.

Currently, isotretinoin, originally marketed as Accutane, is marketed under such brand names as Absorica, Absorica LD, Claravis, Amnesteem, Myorisan, and Zenatane.

Asked for specific information on the proposed changes, an FDA spokesperson said in an August 19 email that “the submission to the FDA from the isotretinoin manufacturers will be a major modification, and the review timeline is generally 6 months. Once approved, the isotretinoin manufacturers will need additional time to implement the changes.”

The spokesperson declined to provide additional information on the status of the IPMG proposal, to share the proposal itself, or to estimate the implementation period.

Reason for Hope?

In response to the comment that the review generally takes 6 months, Dr. Barbieri said it doesn’t give him much hope, adding that “any delay of implementing these reforms is a missed opportunity to improve the care of patients with acne.” He is also hopeful that the FDA will invite some public comment during the review period “so that stakeholders can share their feedback about the proposal to help guide FDA decision-making and ensure effective implementation.”

From Meeting to Mandate

The FDA order for the changes followed a joint meeting of the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and the Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee in March 2023 about the program requirements. It included feedback from patients and dermatologists and recommendations for changes, with a goal of reducing the burden of the program on patients, pharmacies, and prescribers without compromising patient safety.

The Five Requested Changes

In the November 30 letter, the FDA requested the following from the IPMG:

- Remove the requirement that pregnancy tests be performed in a specially certified lab (such as a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments lab). This would enable the tests to be done in a clinic setting rather than sending patients to a separate lab.

- Allow prescribers the option of letting patients use home pregnancy tests during and after treatment, with steps in place to minimize falsification.

- Remove the waiting period requirement, known as the “19-day lockout,” for patients if they don’t obtain the isotretinoin from the pharmacy within the first 7-day prescription window. Before initiation of isotretinoin, a repeat confirmatory test must be done in a medical setting without any required waiting period.

- Revise the pregnancy registry requirement, removing the objective to document the outcome and associated collection of data for each pregnancy.

- Revise the requirement for prescribers to document patient counseling for those who can’t become pregnant from monthly counseling to counseling at enrollment only. Before each prescription is dispensed, the authorization must verify patient enrollment and prescriber certification. (In December 2021, a new, gender-neutral approach, approved by the FDA, was launched. It places potential patients into two risk categories — those who can become pregnant and those who cannot. Previously, there were three such categories: Females of reproductive potential, females not of reproductive potential, and males.)

Perspective on the Requested Changes

Of the requested changes, “really the most important is eliminating the request for monthly counseling for patients who cannot become pregnant,” Dr. Barbieri said. Because of that requirement, all patients need to have monthly visits with a dermatologist to get the medication refills, “and that creates a logistical barrier,” plus reducing time available for dermatologists to care for other patients with other dermatologic issues.

As for missing the 7-day prescription window, Dr. Barbieri said, in his experience, “it’s almost never the patient’s fault; it’s almost always an insurance problem.”

Dr. Barbieri reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer Treatment 101: A Primer for Non-Oncologists

The remaining 700,000 or so often proceed to chemotherapy either immediately or upon cancer recurrence, spread, or newly recognized metastases. “Cures” after that point are rare.

I’m speaking in generalities, understanding that each cancer and each patient is unique.

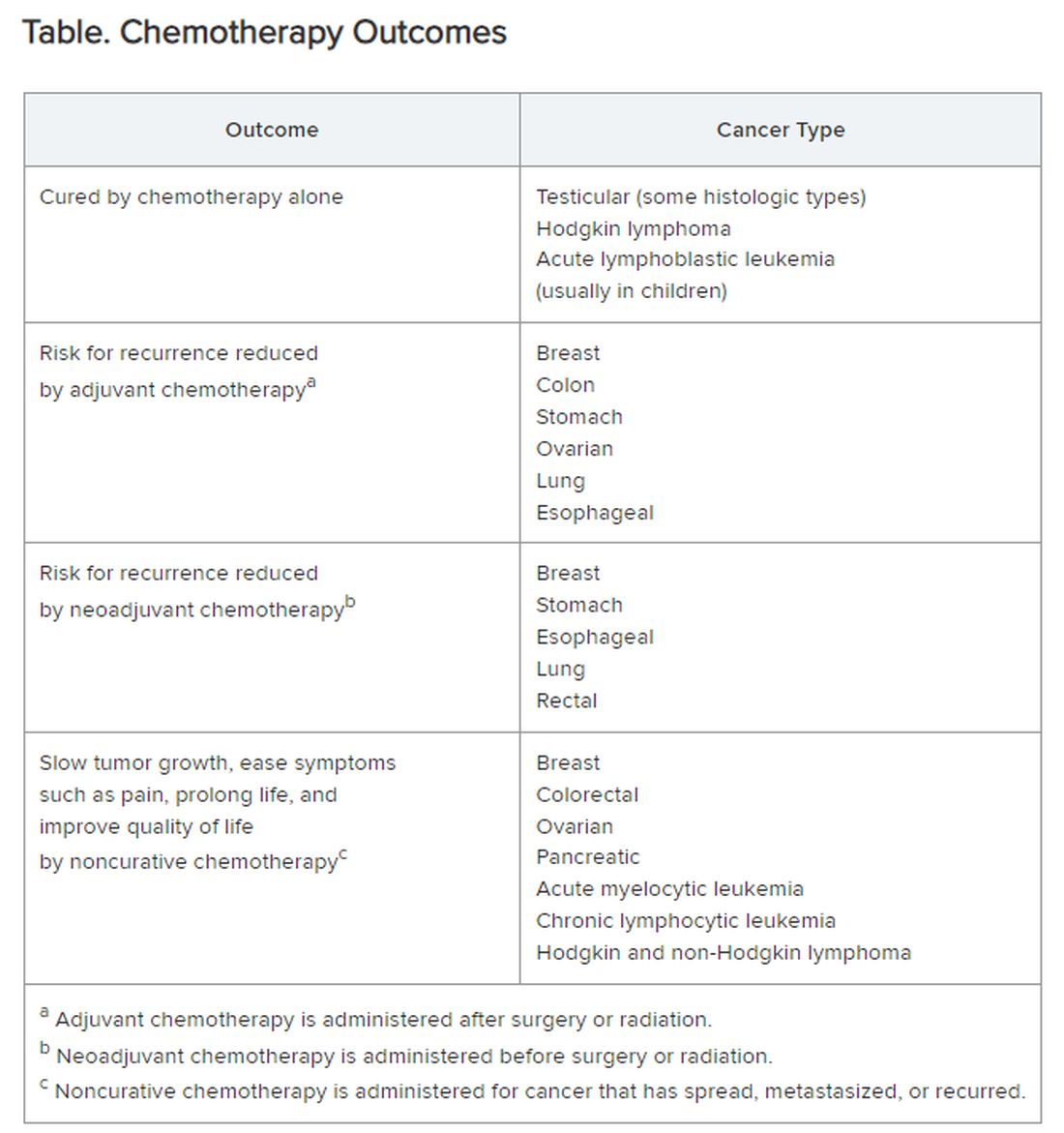

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy alone can cure a small number of cancer types. When added to radiation or surgery, chemotherapy can help to cure a wider range of cancer types. As an add-on, chemotherapy can extend the length and quality of life for many patients with cancer. Since chemotherapy is by definition “toxic,” it can also shorten the duration or harm the quality of life and provide false hope. The Table summarizes what chemotherapy can and cannot achieve in selected cancer types.

Careful, compassionate communication between patient and physician is key. Goals and expectations must be clearly understood.

Organized chemotherapeutic efforts are further categorized as first line, second line, and third line.

First-line treatment. The initial round of recommended chemotherapy for a specific cancer. It is typically considered the most effective treatment for that type and stage of cancer on the basis of current research and clinical trials.

Second-line treatment. This is the treatment used if the first-line chemotherapy doesn’t work as desired. Reasons to switch to second-line chemo include:

- Lack of response (the tumor failed to shrink).

- Progression (the cancer may have grown or spread further).

- Adverse side effects were too severe to continue.

The drugs used in second-line chemo will typically be different from those used in first line, sometimes because cancer cells can develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs over time. Moreover, the goal of second-line chemo may differ from that of first-line therapy. Rather than chiefly aiming for a cure, second-line treatment might focus on slowing cancer growth, managing symptoms, or improving quality of life. Unfortunately, not every type of cancer has a readily available second-line option.

Third-line treatment. Third-line options come into play when both the initial course of chemo (first line) and the subsequent treatment (second line) have failed to achieve remission or control the cancer’s spread. Owing to the progressive nature of advanced cancers, patients might not be eligible or healthy enough for third-line therapy. Depending on cancer type, the patient’s general health, and response to previous treatments, third-line options could include:

- New or different chemotherapy drugs compared with prior lines.

- Surgery to debulk the tumor.

- Radiation for symptom control.

- Targeted therapy: drugs designed to target specific vulnerabilities in cancer cells.

- Immunotherapy: agents that help the body’s immune system fight cancer cells.

- Clinical trials testing new or investigational treatments, which may be applicable at any time, depending on the questions being addressed.

The goals of third-line therapy may shift from aiming for a cure to managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and potentially slowing cancer growth. The decision to pursue third-line therapy involves careful consideration by the doctor and patient, weighing the potential benefits and risks of treatment considering the individual’s overall health and specific situation.

It’s important to have realistic expectations about the potential outcomes of third-line therapy. Although remission may be unlikely, third-line therapy can still play a role in managing the disease.

Navigating advanced cancer treatment is very complex. The patient and physician must together consider detailed explanations and clarifications to set expectations and make informed decisions about care.

Interventions to Consider Earlier

In traditional clinical oncology practice, other interventions are possible, but these may not be offered until treatment has reached the third line:

- Molecular testing.

- Palliation.

- Clinical trials.

- Innovative testing to guide targeted therapy by ascertaining which agents are most likely (or not likely at all) to be effective.

I would argue that the patient’s interests are better served by considering and offering these other interventions much earlier, even before starting first-line chemotherapy.

Molecular testing. The best time for molecular testing of a new malignant tumor is typically at the time of diagnosis. Here’s why:

- Molecular testing helps identify specific genetic mutations in the cancer cells. This information can be crucial for selecting targeted therapies that are most effective against those specific mutations. Early detection allows for the most treatment options. For example, for non–small cell lung cancer, early is best because treatment and outcomes may well be changed by test results.

- Knowing the tumor’s molecular makeup can help determine whether a patient qualifies for clinical trials of new drugs designed for specific mutations.

- Some molecular markers can offer information about the tumor’s aggressiveness and potential for metastasis so that prognosis can be informed.

Molecular testing can be a valuable tool throughout a cancer patient’s journey. With genetically diverse tumors, the initial biopsy might not capture the full picture. Molecular testing of circulating tumor DNA can be used to monitor a patient’s response to treatment and detect potential mutations that might arise during treatment resistance. Retesting after metastasis can provide additional information that can aid in treatment decisions.

Palliative care. The ideal time to discuss palliative care with a patient with cancer is early in the diagnosis and treatment process. Palliative care is not the same as hospice care; it isn’t just about end-of-life. Palliative care focuses on improving a patient’s quality of life throughout cancer treatment. Palliative care specialists can address a wide range of symptoms a patient might experience from cancer or its treatment, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety.