User login

Bifidobacteria supplementation regulates newborn immune system

Supplementing breastfed infants with bifidobacteria promotes development of a well-regulated immune system, theoretically reducing risk of immune-mediated conditions like allergies and asthma, according to investigators.

These findings support the importance of early gut colonization with beneficial microbes, an event that may affect the immune system throughout life, reported lead author Bethany M. Henrick, PhD, director of immunology and diagnostics at Evolve Biosystems, Davis, Calif., and adjunct assistant professor at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and colleagues.

“Dysbiosis of the infant gut microbiome is common in modern societies and a likely contributing factor to the increased incidences of immune-mediated disorders,” the investigators wrote in Cell. “Therefore, there is great interest in identifying microbial factors that can support healthier immune system imprinting and hopefully prevent cases of allergy, autoimmunity, and possibly other conditions involving the immune system.”

Prevailing theory suggests that the rising incidence of neonatal intestinal dysbiosis – which is typical in developed countries – may be caused by a variety of factors, including cesarean sections; modern hygiene practices; antibiotics, antiseptics, and other medications; diets high in fat and sugar; and infant formula.

According to Dr. Henrick and colleagues, a healthy gut microbiome plays the greatest role in immunological development during the first 3 months post partum; specifically, a lack of bifidobacteria during this time has been linked with increased risks of autoimmunity and enteric inflammation, although underlying immune mechanisms remain unclear.

Bifidobacteria also exemplify the symbiotic relationship between mothers, babies, and beneficial microbes. The investigators pointed out that breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which humans cannot digest, but are an excellent source of energy for bifidobacteria and other beneficial microbes, giving them a “selective nutritional advantage.”

Bifidobacteria should therefore be common residents within the infant gut, but this is often not now the case, leading Dr. Henrick and colleagues to zero in on the microbe, in hopes of determining the exactly how beneficial bacteria shape immune development.

It is only recently that the necessary knowledge and techniques to perform studies like this one have become available, the investigators wrote, noting a better understanding of cell-regulatory relationships, advances in immune profiling at the systems level, and new technology that allows for profiling small-volume samples from infants.

The present study involved a series of observational experiments and a small interventional trial.

First, the investigators conducted a wide array of blood- and fecal-based longitudinal analyses from 208 infants in Sweden to characterize immune cell expansion and microbiome colonization of the gut, with a focus on bifidobacteria.

Their results showed that infants lacking bifidobacteria, and HMO-utilization genes (which are expressed by bifidobacteria and other beneficial microbes), had higher levels of systemic inflammation, including increased T helper 2 (Th2) and Th17 responses.

“Infants not colonized by Bifidobacteriaceae or in cases where these microbes fail to expand during the first months of life there is evidence of systemic and intestinal inflammation, increased frequencies of activated immune cells, and reduced levels of regulatory cells indicative of systemic immune dysregulation,” the investigators wrote.

The interventional part of the study involved 60 breastfed infants in California. Twenty-nine of the newborns were given 1.8 x 1010 colony-forming units (CFUs) of B. longum subsp. infantis EVC001 daily from postnatal day 7 to day 28, while the remaining 31 infants were given no supplementation.

Fecal samples were collected on day 6 and day 60. At day 60, supplemented infants had high levels of HMO-utilization genes, plus significantly greater alpha diversity (P = .0001; Wilcoxon), compared with controls. Infants receiving EVC001 also had less inflammatory fecal cytokines, suggesting that microbes expressing HMO-utilization genes cause a shift away from proinflammatory Th2 and Th17 responses, and toward Th1.

“It is not the simple presence of bifidobacteria that is responsible for the immune effects but the metabolic partnership between the bacteria and HMOs,” the investigators noted.

According to principal investigator Petter Brodin, MD, PhD, professor of pediatric immunology at Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden, the findings deserve further investigation.

“Our data indicate that substitution with beneficial microbes efficiently metabolizing HMOs could open a way to prevent cases of immune-mediated diseases, but larger, randomized trials aimed at this will be required to determine this potential,” Dr. Brodin said in an interview.

Carolynn Dude, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, agreed that more work is needed.

“While this study provides some insight into the mechanisms that may set up a newborn for poor health outcomes later in life, the data is still very limited, and more long-term follow-up on these infants is needed before recommending any sort of bacterial supplementation to a newborn,” Dr. Dude said in an interview.

Dr. Brodin and colleagues are planning an array of related studies, including larger clinical trials; further investigations into mechanisms of action; comparisons between the present cohort and infants in Kenya, where immune-mediated diseases are rare; and evaluations of vaccine responses and infectious disease susceptibility.

The study was supported by the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, the Marianne & Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, and others. The investigators disclosed relationships with Cytodelics, Scailyte, Kancera, and others. Dr. Dude reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supplementing breastfed infants with bifidobacteria promotes development of a well-regulated immune system, theoretically reducing risk of immune-mediated conditions like allergies and asthma, according to investigators.

These findings support the importance of early gut colonization with beneficial microbes, an event that may affect the immune system throughout life, reported lead author Bethany M. Henrick, PhD, director of immunology and diagnostics at Evolve Biosystems, Davis, Calif., and adjunct assistant professor at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and colleagues.

“Dysbiosis of the infant gut microbiome is common in modern societies and a likely contributing factor to the increased incidences of immune-mediated disorders,” the investigators wrote in Cell. “Therefore, there is great interest in identifying microbial factors that can support healthier immune system imprinting and hopefully prevent cases of allergy, autoimmunity, and possibly other conditions involving the immune system.”

Prevailing theory suggests that the rising incidence of neonatal intestinal dysbiosis – which is typical in developed countries – may be caused by a variety of factors, including cesarean sections; modern hygiene practices; antibiotics, antiseptics, and other medications; diets high in fat and sugar; and infant formula.

According to Dr. Henrick and colleagues, a healthy gut microbiome plays the greatest role in immunological development during the first 3 months post partum; specifically, a lack of bifidobacteria during this time has been linked with increased risks of autoimmunity and enteric inflammation, although underlying immune mechanisms remain unclear.

Bifidobacteria also exemplify the symbiotic relationship between mothers, babies, and beneficial microbes. The investigators pointed out that breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which humans cannot digest, but are an excellent source of energy for bifidobacteria and other beneficial microbes, giving them a “selective nutritional advantage.”

Bifidobacteria should therefore be common residents within the infant gut, but this is often not now the case, leading Dr. Henrick and colleagues to zero in on the microbe, in hopes of determining the exactly how beneficial bacteria shape immune development.

It is only recently that the necessary knowledge and techniques to perform studies like this one have become available, the investigators wrote, noting a better understanding of cell-regulatory relationships, advances in immune profiling at the systems level, and new technology that allows for profiling small-volume samples from infants.

The present study involved a series of observational experiments and a small interventional trial.

First, the investigators conducted a wide array of blood- and fecal-based longitudinal analyses from 208 infants in Sweden to characterize immune cell expansion and microbiome colonization of the gut, with a focus on bifidobacteria.

Their results showed that infants lacking bifidobacteria, and HMO-utilization genes (which are expressed by bifidobacteria and other beneficial microbes), had higher levels of systemic inflammation, including increased T helper 2 (Th2) and Th17 responses.

“Infants not colonized by Bifidobacteriaceae or in cases where these microbes fail to expand during the first months of life there is evidence of systemic and intestinal inflammation, increased frequencies of activated immune cells, and reduced levels of regulatory cells indicative of systemic immune dysregulation,” the investigators wrote.

The interventional part of the study involved 60 breastfed infants in California. Twenty-nine of the newborns were given 1.8 x 1010 colony-forming units (CFUs) of B. longum subsp. infantis EVC001 daily from postnatal day 7 to day 28, while the remaining 31 infants were given no supplementation.

Fecal samples were collected on day 6 and day 60. At day 60, supplemented infants had high levels of HMO-utilization genes, plus significantly greater alpha diversity (P = .0001; Wilcoxon), compared with controls. Infants receiving EVC001 also had less inflammatory fecal cytokines, suggesting that microbes expressing HMO-utilization genes cause a shift away from proinflammatory Th2 and Th17 responses, and toward Th1.

“It is not the simple presence of bifidobacteria that is responsible for the immune effects but the metabolic partnership between the bacteria and HMOs,” the investigators noted.

According to principal investigator Petter Brodin, MD, PhD, professor of pediatric immunology at Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden, the findings deserve further investigation.

“Our data indicate that substitution with beneficial microbes efficiently metabolizing HMOs could open a way to prevent cases of immune-mediated diseases, but larger, randomized trials aimed at this will be required to determine this potential,” Dr. Brodin said in an interview.

Carolynn Dude, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, agreed that more work is needed.

“While this study provides some insight into the mechanisms that may set up a newborn for poor health outcomes later in life, the data is still very limited, and more long-term follow-up on these infants is needed before recommending any sort of bacterial supplementation to a newborn,” Dr. Dude said in an interview.

Dr. Brodin and colleagues are planning an array of related studies, including larger clinical trials; further investigations into mechanisms of action; comparisons between the present cohort and infants in Kenya, where immune-mediated diseases are rare; and evaluations of vaccine responses and infectious disease susceptibility.

The study was supported by the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, the Marianne & Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, and others. The investigators disclosed relationships with Cytodelics, Scailyte, Kancera, and others. Dr. Dude reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Supplementing breastfed infants with bifidobacteria promotes development of a well-regulated immune system, theoretically reducing risk of immune-mediated conditions like allergies and asthma, according to investigators.

These findings support the importance of early gut colonization with beneficial microbes, an event that may affect the immune system throughout life, reported lead author Bethany M. Henrick, PhD, director of immunology and diagnostics at Evolve Biosystems, Davis, Calif., and adjunct assistant professor at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and colleagues.

“Dysbiosis of the infant gut microbiome is common in modern societies and a likely contributing factor to the increased incidences of immune-mediated disorders,” the investigators wrote in Cell. “Therefore, there is great interest in identifying microbial factors that can support healthier immune system imprinting and hopefully prevent cases of allergy, autoimmunity, and possibly other conditions involving the immune system.”

Prevailing theory suggests that the rising incidence of neonatal intestinal dysbiosis – which is typical in developed countries – may be caused by a variety of factors, including cesarean sections; modern hygiene practices; antibiotics, antiseptics, and other medications; diets high in fat and sugar; and infant formula.

According to Dr. Henrick and colleagues, a healthy gut microbiome plays the greatest role in immunological development during the first 3 months post partum; specifically, a lack of bifidobacteria during this time has been linked with increased risks of autoimmunity and enteric inflammation, although underlying immune mechanisms remain unclear.

Bifidobacteria also exemplify the symbiotic relationship between mothers, babies, and beneficial microbes. The investigators pointed out that breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), which humans cannot digest, but are an excellent source of energy for bifidobacteria and other beneficial microbes, giving them a “selective nutritional advantage.”

Bifidobacteria should therefore be common residents within the infant gut, but this is often not now the case, leading Dr. Henrick and colleagues to zero in on the microbe, in hopes of determining the exactly how beneficial bacteria shape immune development.

It is only recently that the necessary knowledge and techniques to perform studies like this one have become available, the investigators wrote, noting a better understanding of cell-regulatory relationships, advances in immune profiling at the systems level, and new technology that allows for profiling small-volume samples from infants.

The present study involved a series of observational experiments and a small interventional trial.

First, the investigators conducted a wide array of blood- and fecal-based longitudinal analyses from 208 infants in Sweden to characterize immune cell expansion and microbiome colonization of the gut, with a focus on bifidobacteria.

Their results showed that infants lacking bifidobacteria, and HMO-utilization genes (which are expressed by bifidobacteria and other beneficial microbes), had higher levels of systemic inflammation, including increased T helper 2 (Th2) and Th17 responses.

“Infants not colonized by Bifidobacteriaceae or in cases where these microbes fail to expand during the first months of life there is evidence of systemic and intestinal inflammation, increased frequencies of activated immune cells, and reduced levels of regulatory cells indicative of systemic immune dysregulation,” the investigators wrote.

The interventional part of the study involved 60 breastfed infants in California. Twenty-nine of the newborns were given 1.8 x 1010 colony-forming units (CFUs) of B. longum subsp. infantis EVC001 daily from postnatal day 7 to day 28, while the remaining 31 infants were given no supplementation.

Fecal samples were collected on day 6 and day 60. At day 60, supplemented infants had high levels of HMO-utilization genes, plus significantly greater alpha diversity (P = .0001; Wilcoxon), compared with controls. Infants receiving EVC001 also had less inflammatory fecal cytokines, suggesting that microbes expressing HMO-utilization genes cause a shift away from proinflammatory Th2 and Th17 responses, and toward Th1.

“It is not the simple presence of bifidobacteria that is responsible for the immune effects but the metabolic partnership between the bacteria and HMOs,” the investigators noted.

According to principal investigator Petter Brodin, MD, PhD, professor of pediatric immunology at Karolinska Institutet, Solna, Sweden, the findings deserve further investigation.

“Our data indicate that substitution with beneficial microbes efficiently metabolizing HMOs could open a way to prevent cases of immune-mediated diseases, but larger, randomized trials aimed at this will be required to determine this potential,” Dr. Brodin said in an interview.

Carolynn Dude, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the division of maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, agreed that more work is needed.

“While this study provides some insight into the mechanisms that may set up a newborn for poor health outcomes later in life, the data is still very limited, and more long-term follow-up on these infants is needed before recommending any sort of bacterial supplementation to a newborn,” Dr. Dude said in an interview.

Dr. Brodin and colleagues are planning an array of related studies, including larger clinical trials; further investigations into mechanisms of action; comparisons between the present cohort and infants in Kenya, where immune-mediated diseases are rare; and evaluations of vaccine responses and infectious disease susceptibility.

The study was supported by the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council, the Marianne & Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, and others. The investigators disclosed relationships with Cytodelics, Scailyte, Kancera, and others. Dr. Dude reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM CELL

AI-based software demonstrates accuracy in diagnosis of autism

A software program based on artificial intelligence (AI) is effective for distinguishing young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from those with other conditions, according to results of a pivotal trial presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

The AI-based software, which will be submitted to regulatory approval as a device, employs an algorithm that assembles inputs from a caregiver questionnaire, a video, and a clinician questionnaire, according to Sharief Taraman, MD, a pediatric neurologist at CHOC, a pediatric health care system in Orange County, Calif.

Although the device could be employed in a variety of settings, it is envisioned for use by primary care physicians. This will circumvent the need for specialist evaluation except in challenging cases. Currently, nearly all children with ASD are diagnosed in specialty care, according to data cited by Dr. Taraman.

“The lack of diagnostic tools for ASD in primary care settings contributes to an average delay of 3 years between first parental concern and diagnosis and to long wait lists for specialty evaluation,” he reported at the virtual meeting, presented by MedscapeLive.

When used with clinical judgment and criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), the data from the trial suggest the diagnostic tool in the hands of primary care physicians “could efficiently and accurately assess ASD in children 18 to 72 months old,” said Dr. Taraman, also an associate clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.*

The AI-assisted software was evaluated in 425 children at 14 sites in 6 states. The study population was reflective of U.S. demographics. Although only 36% of the children were female, this is consistent with ASD prevalence. Only 60% of the subjects were White. Nearly 30% were Black or Latinx and other populations, such as those of Asian heritage, were represented.

Children between the ages of 18 and 72 months were eligible if both a caregiver and a health care professional were concerned that the child had ASD. About the same time that a caregiver completed a 20-item questionnaire and the primary care physician completed a 15-item questionnaire on a mobile device, the caregiver uploaded two videos of 1-2 minutes in length.

This information, along with a 33-item questionnaire completed by an analyst of the submitted videos, was then processed by the software algorithm. It provided a patient status of positive or negative for ASD, or it concluded that the status was indeterminate.

“To reduce the risk of false classifications, the indeterminate status was included as a safety feature,” Dr. Taraman explained. However, Dr. Taraman considers an indeterminate designation potentially actionable. Rather than a negative result, this status suggests a complex neurodevelopmental disorder and indicates the need for further evaluation.

The reference standard diagnosis, completed in all participants in this study, was a specialist evaluation completed independently by two experts. The presence or absence of ASD was confirmed if the experts agreed. If they did not, a third specialist made the final determination.

In comparison to the specialist determinations, all were correctly classified except for one child, in which the software was determined to have made a false-negative diagnosis. A diagnosis of ASD was reached in 29% of the study participants.

For those with a determinate designation, the sensitivity was 98.4% and the specificity was 78.9%. This translated into positive predictive and negative predictive values of 80.8% and 98.3%, respectively.

Of those identified as indeterminate by the AI-assisted algorithm, 91% were ultimately considered by specialist evaluation to have complex issues. In this group, ASD was part of the complex clinical picture in 20%. The others had non-ASD neurodevelopmental conditions, according to Dr. Taraman.

When the accuracy was evaluated across ages, ethnicity, and factors such as parent education or family income, the tool performed consistently, Dr. Taraman reported. This is important, he said, because the presence or absence of ASD is misdiagnosed in many underserved populations.

The focus on developing a methodology specific for use in primary care was based on evidence that the delay in the diagnosis of ASD is attributable to long wait times for specialty evaluations.

“There will never be enough specialists. There is a need for a way to streamline the diagnosis of ASD,” Dr. Taraman maintained. This is helpful not only to parents concerned about their children, he said, but also there are data to suggest that early intervention improves outcomes.

A specialist in ASD, Paul Carbone, MD, medical director of the child development program at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, agreed. He said early diagnosis and intervention should be a goal.

“Reducing the age of ASD diagnosis is a priority because early entry into autism-specific interventions is a strong predictor of optimal developmental outcomes for children,” Dr. Carbone said.

Although he is not familiar with this experimental AI-assisted diagnostic program, he has published on the feasibility of ASD diagnosis at the primary care level. In his study, Dr. Carbone examined the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) as one of several methodologies that might be considered.

Diagnosis of ASD “can be achieved through systematic processes within primary care that facilitate universal development surveillance and autism screening followed by prompt and timely diagnostic evaluations of at-risk children,” Dr. Carbone said.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Taraman reported a financial relationship with Cognoa, the company that is developing the ASD software for clinical use. Dr. Carbone reported that he has no conflicts of interest.

*Updated, 7/7/21

A software program based on artificial intelligence (AI) is effective for distinguishing young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from those with other conditions, according to results of a pivotal trial presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

The AI-based software, which will be submitted to regulatory approval as a device, employs an algorithm that assembles inputs from a caregiver questionnaire, a video, and a clinician questionnaire, according to Sharief Taraman, MD, a pediatric neurologist at CHOC, a pediatric health care system in Orange County, Calif.

Although the device could be employed in a variety of settings, it is envisioned for use by primary care physicians. This will circumvent the need for specialist evaluation except in challenging cases. Currently, nearly all children with ASD are diagnosed in specialty care, according to data cited by Dr. Taraman.

“The lack of diagnostic tools for ASD in primary care settings contributes to an average delay of 3 years between first parental concern and diagnosis and to long wait lists for specialty evaluation,” he reported at the virtual meeting, presented by MedscapeLive.

When used with clinical judgment and criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), the data from the trial suggest the diagnostic tool in the hands of primary care physicians “could efficiently and accurately assess ASD in children 18 to 72 months old,” said Dr. Taraman, also an associate clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.*

The AI-assisted software was evaluated in 425 children at 14 sites in 6 states. The study population was reflective of U.S. demographics. Although only 36% of the children were female, this is consistent with ASD prevalence. Only 60% of the subjects were White. Nearly 30% were Black or Latinx and other populations, such as those of Asian heritage, were represented.

Children between the ages of 18 and 72 months were eligible if both a caregiver and a health care professional were concerned that the child had ASD. About the same time that a caregiver completed a 20-item questionnaire and the primary care physician completed a 15-item questionnaire on a mobile device, the caregiver uploaded two videos of 1-2 minutes in length.

This information, along with a 33-item questionnaire completed by an analyst of the submitted videos, was then processed by the software algorithm. It provided a patient status of positive or negative for ASD, or it concluded that the status was indeterminate.

“To reduce the risk of false classifications, the indeterminate status was included as a safety feature,” Dr. Taraman explained. However, Dr. Taraman considers an indeterminate designation potentially actionable. Rather than a negative result, this status suggests a complex neurodevelopmental disorder and indicates the need for further evaluation.

The reference standard diagnosis, completed in all participants in this study, was a specialist evaluation completed independently by two experts. The presence or absence of ASD was confirmed if the experts agreed. If they did not, a third specialist made the final determination.

In comparison to the specialist determinations, all were correctly classified except for one child, in which the software was determined to have made a false-negative diagnosis. A diagnosis of ASD was reached in 29% of the study participants.

For those with a determinate designation, the sensitivity was 98.4% and the specificity was 78.9%. This translated into positive predictive and negative predictive values of 80.8% and 98.3%, respectively.

Of those identified as indeterminate by the AI-assisted algorithm, 91% were ultimately considered by specialist evaluation to have complex issues. In this group, ASD was part of the complex clinical picture in 20%. The others had non-ASD neurodevelopmental conditions, according to Dr. Taraman.

When the accuracy was evaluated across ages, ethnicity, and factors such as parent education or family income, the tool performed consistently, Dr. Taraman reported. This is important, he said, because the presence or absence of ASD is misdiagnosed in many underserved populations.

The focus on developing a methodology specific for use in primary care was based on evidence that the delay in the diagnosis of ASD is attributable to long wait times for specialty evaluations.

“There will never be enough specialists. There is a need for a way to streamline the diagnosis of ASD,” Dr. Taraman maintained. This is helpful not only to parents concerned about their children, he said, but also there are data to suggest that early intervention improves outcomes.

A specialist in ASD, Paul Carbone, MD, medical director of the child development program at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, agreed. He said early diagnosis and intervention should be a goal.

“Reducing the age of ASD diagnosis is a priority because early entry into autism-specific interventions is a strong predictor of optimal developmental outcomes for children,” Dr. Carbone said.

Although he is not familiar with this experimental AI-assisted diagnostic program, he has published on the feasibility of ASD diagnosis at the primary care level. In his study, Dr. Carbone examined the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) as one of several methodologies that might be considered.

Diagnosis of ASD “can be achieved through systematic processes within primary care that facilitate universal development surveillance and autism screening followed by prompt and timely diagnostic evaluations of at-risk children,” Dr. Carbone said.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Taraman reported a financial relationship with Cognoa, the company that is developing the ASD software for clinical use. Dr. Carbone reported that he has no conflicts of interest.

*Updated, 7/7/21

A software program based on artificial intelligence (AI) is effective for distinguishing young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) from those with other conditions, according to results of a pivotal trial presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

The AI-based software, which will be submitted to regulatory approval as a device, employs an algorithm that assembles inputs from a caregiver questionnaire, a video, and a clinician questionnaire, according to Sharief Taraman, MD, a pediatric neurologist at CHOC, a pediatric health care system in Orange County, Calif.

Although the device could be employed in a variety of settings, it is envisioned for use by primary care physicians. This will circumvent the need for specialist evaluation except in challenging cases. Currently, nearly all children with ASD are diagnosed in specialty care, according to data cited by Dr. Taraman.

“The lack of diagnostic tools for ASD in primary care settings contributes to an average delay of 3 years between first parental concern and diagnosis and to long wait lists for specialty evaluation,” he reported at the virtual meeting, presented by MedscapeLive.

When used with clinical judgment and criteria from the American Psychiatric Association’s 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), the data from the trial suggest the diagnostic tool in the hands of primary care physicians “could efficiently and accurately assess ASD in children 18 to 72 months old,” said Dr. Taraman, also an associate clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of California, Irvine.*

The AI-assisted software was evaluated in 425 children at 14 sites in 6 states. The study population was reflective of U.S. demographics. Although only 36% of the children were female, this is consistent with ASD prevalence. Only 60% of the subjects were White. Nearly 30% were Black or Latinx and other populations, such as those of Asian heritage, were represented.

Children between the ages of 18 and 72 months were eligible if both a caregiver and a health care professional were concerned that the child had ASD. About the same time that a caregiver completed a 20-item questionnaire and the primary care physician completed a 15-item questionnaire on a mobile device, the caregiver uploaded two videos of 1-2 minutes in length.

This information, along with a 33-item questionnaire completed by an analyst of the submitted videos, was then processed by the software algorithm. It provided a patient status of positive or negative for ASD, or it concluded that the status was indeterminate.

“To reduce the risk of false classifications, the indeterminate status was included as a safety feature,” Dr. Taraman explained. However, Dr. Taraman considers an indeterminate designation potentially actionable. Rather than a negative result, this status suggests a complex neurodevelopmental disorder and indicates the need for further evaluation.

The reference standard diagnosis, completed in all participants in this study, was a specialist evaluation completed independently by two experts. The presence or absence of ASD was confirmed if the experts agreed. If they did not, a third specialist made the final determination.

In comparison to the specialist determinations, all were correctly classified except for one child, in which the software was determined to have made a false-negative diagnosis. A diagnosis of ASD was reached in 29% of the study participants.

For those with a determinate designation, the sensitivity was 98.4% and the specificity was 78.9%. This translated into positive predictive and negative predictive values of 80.8% and 98.3%, respectively.

Of those identified as indeterminate by the AI-assisted algorithm, 91% were ultimately considered by specialist evaluation to have complex issues. In this group, ASD was part of the complex clinical picture in 20%. The others had non-ASD neurodevelopmental conditions, according to Dr. Taraman.

When the accuracy was evaluated across ages, ethnicity, and factors such as parent education or family income, the tool performed consistently, Dr. Taraman reported. This is important, he said, because the presence or absence of ASD is misdiagnosed in many underserved populations.

The focus on developing a methodology specific for use in primary care was based on evidence that the delay in the diagnosis of ASD is attributable to long wait times for specialty evaluations.

“There will never be enough specialists. There is a need for a way to streamline the diagnosis of ASD,” Dr. Taraman maintained. This is helpful not only to parents concerned about their children, he said, but also there are data to suggest that early intervention improves outcomes.

A specialist in ASD, Paul Carbone, MD, medical director of the child development program at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, agreed. He said early diagnosis and intervention should be a goal.

“Reducing the age of ASD diagnosis is a priority because early entry into autism-specific interventions is a strong predictor of optimal developmental outcomes for children,” Dr. Carbone said.

Although he is not familiar with this experimental AI-assisted diagnostic program, he has published on the feasibility of ASD diagnosis at the primary care level. In his study, Dr. Carbone examined the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) as one of several methodologies that might be considered.

Diagnosis of ASD “can be achieved through systematic processes within primary care that facilitate universal development surveillance and autism screening followed by prompt and timely diagnostic evaluations of at-risk children,” Dr. Carbone said.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Taraman reported a financial relationship with Cognoa, the company that is developing the ASD software for clinical use. Dr. Carbone reported that he has no conflicts of interest.

*Updated, 7/7/21

FROM CP/AACP PSYCHIATRY UPDATE

Polypharmacy remains common for autism spectrum patients

Approximately one-third of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are prescribed multiple medications to manage comorbidities and symptoms, according to data from a retrospective cohort study of more than 26,000 patients.

“Clinicians caring for patients with ASD are tasked with the challenges of managing the primary disease, as well as co-occurring medical conditions, and coordinating with educational and social service professionals to provide holistic care,” wrote Aliya G. Feroe of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

The medication classes used to treat individuals with ASD include ADHD medications, antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics, and hypnotics, but the prescription rates of these medications in ASD patients have not been examined in large studies, the researchers said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 26,722 individuals with ASD using a United States health care database from Jan. 1, 2014, to Dec. 31, 2019. Data included records of inpatient and outpatient claims, and records of prescriptions filled through commercial pharmacies. Individuals received at least 1 of 24 of the most common medication groups for ASD or comorbidities. The average age of the study participants was 14 years, and 78% were male. Diagnostic codes for ASD were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Over the 6-year study period, approximately one-third of the participants were taking three or more medications at once, ranging from 28.6% to 31.5%. In any 1 year, approximately 41% of children were prescribed a single medication, 17% received two prescriptions, 7.9% received four, and 3.4% received five. Medication changes occurred more frequently within classes than between classes, and reasons for these changes may include patient preference, adverse effects, and cost, the researchers noted.

The overall number of children prescribed particular drugs remained consistent, the researchers noted. “For example, the total number of individuals prescribed methylphenidate shifted from 832 in 2014 to 850 in 2015, 899 in 2016, 863 in 2017, and 838 in 2018,” they wrote.

In 15 of the 24 medication groups included in the study, at least 15% of the individuals had unspecified anxiety disorder, anxiety neurosis, or major depressive disorder; in 11 of the medication groups, at least 15% had some form of ADHD. ADHD prevalence in patients taking stimulants varied based on ADHD type, the researchers said.

The most common comorbidities in patients taking antipsychotics were combined type ADHD (11.6%-17.8%) and anxiety disorder (13.1%-30.1%). The study findings suggest that many clinicians are incorporating medications into ASD management, the researchers said.

“Although there is no medical treatment for the core deficits of social communication and repetitive behavioral patterns in ASD, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that clinicians consider medications in the management of common comorbid conditions, including seizures, ADHD, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and disruptive behavior disorders,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the potential for inconsistent reporting of diagnoses and pharmacy claims, the researchers noted. Other limitations included a lack of direct clinical assessment to validate diagnoses and the absence of validated diagnostic instruments to screen for comorbidities, they added.

“Our findings suggest that clinicians may be increasingly using integrated approaches to treating patients with ASD and co-occurring conditions, and further work is necessary to determine the relative effects of pharmacotherapy vs. behavioral interventions on outcomes in patients with ASD,” the researchers concluded.

Many reasons for multiple medications

“The researchers put in a lot of effort to provide data on a large scale,” Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“The findings illustrate the reality that autistic children are prescribed a lot of medications for a lot of reasons, some of which are not entirely clear,” Dr. Lessin said. The study also reflects the chronic lack of behavioral health services for children, he noted. Many children with ASD are referred for services they are unable to access, he said. “As a result, they see doctors who can only prescribe medications to try to control behavior or symptoms for which the cause is unclear,” and which could be ASD or other comorbidities, he emphasized.

The large sample size strengthens the study findings, but some of the challenges include the use of claims data, which do not indicate how diagnoses were made, said Dr. Lessin. An additional limitation is the fact that many medications for children with autism are used off label, so the specific reason for their use may be unknown, he said.

The take-home message for clinicians is that children with ASD are getting a lot of medications, and pediatricians are not usually responsible for multiple medications,” Dr. Lessin said. Ultimately, the study is “a plea for more research,” to tease out details of what medications are indicated and helpful, he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin serves on the Pediatric News editorial advisory board.

Approximately one-third of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are prescribed multiple medications to manage comorbidities and symptoms, according to data from a retrospective cohort study of more than 26,000 patients.

“Clinicians caring for patients with ASD are tasked with the challenges of managing the primary disease, as well as co-occurring medical conditions, and coordinating with educational and social service professionals to provide holistic care,” wrote Aliya G. Feroe of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

The medication classes used to treat individuals with ASD include ADHD medications, antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics, and hypnotics, but the prescription rates of these medications in ASD patients have not been examined in large studies, the researchers said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 26,722 individuals with ASD using a United States health care database from Jan. 1, 2014, to Dec. 31, 2019. Data included records of inpatient and outpatient claims, and records of prescriptions filled through commercial pharmacies. Individuals received at least 1 of 24 of the most common medication groups for ASD or comorbidities. The average age of the study participants was 14 years, and 78% were male. Diagnostic codes for ASD were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Over the 6-year study period, approximately one-third of the participants were taking three or more medications at once, ranging from 28.6% to 31.5%. In any 1 year, approximately 41% of children were prescribed a single medication, 17% received two prescriptions, 7.9% received four, and 3.4% received five. Medication changes occurred more frequently within classes than between classes, and reasons for these changes may include patient preference, adverse effects, and cost, the researchers noted.

The overall number of children prescribed particular drugs remained consistent, the researchers noted. “For example, the total number of individuals prescribed methylphenidate shifted from 832 in 2014 to 850 in 2015, 899 in 2016, 863 in 2017, and 838 in 2018,” they wrote.

In 15 of the 24 medication groups included in the study, at least 15% of the individuals had unspecified anxiety disorder, anxiety neurosis, or major depressive disorder; in 11 of the medication groups, at least 15% had some form of ADHD. ADHD prevalence in patients taking stimulants varied based on ADHD type, the researchers said.

The most common comorbidities in patients taking antipsychotics were combined type ADHD (11.6%-17.8%) and anxiety disorder (13.1%-30.1%). The study findings suggest that many clinicians are incorporating medications into ASD management, the researchers said.

“Although there is no medical treatment for the core deficits of social communication and repetitive behavioral patterns in ASD, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that clinicians consider medications in the management of common comorbid conditions, including seizures, ADHD, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and disruptive behavior disorders,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the potential for inconsistent reporting of diagnoses and pharmacy claims, the researchers noted. Other limitations included a lack of direct clinical assessment to validate diagnoses and the absence of validated diagnostic instruments to screen for comorbidities, they added.

“Our findings suggest that clinicians may be increasingly using integrated approaches to treating patients with ASD and co-occurring conditions, and further work is necessary to determine the relative effects of pharmacotherapy vs. behavioral interventions on outcomes in patients with ASD,” the researchers concluded.

Many reasons for multiple medications

“The researchers put in a lot of effort to provide data on a large scale,” Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“The findings illustrate the reality that autistic children are prescribed a lot of medications for a lot of reasons, some of which are not entirely clear,” Dr. Lessin said. The study also reflects the chronic lack of behavioral health services for children, he noted. Many children with ASD are referred for services they are unable to access, he said. “As a result, they see doctors who can only prescribe medications to try to control behavior or symptoms for which the cause is unclear,” and which could be ASD or other comorbidities, he emphasized.

The large sample size strengthens the study findings, but some of the challenges include the use of claims data, which do not indicate how diagnoses were made, said Dr. Lessin. An additional limitation is the fact that many medications for children with autism are used off label, so the specific reason for their use may be unknown, he said.

The take-home message for clinicians is that children with ASD are getting a lot of medications, and pediatricians are not usually responsible for multiple medications,” Dr. Lessin said. Ultimately, the study is “a plea for more research,” to tease out details of what medications are indicated and helpful, he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin serves on the Pediatric News editorial advisory board.

Approximately one-third of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are prescribed multiple medications to manage comorbidities and symptoms, according to data from a retrospective cohort study of more than 26,000 patients.

“Clinicians caring for patients with ASD are tasked with the challenges of managing the primary disease, as well as co-occurring medical conditions, and coordinating with educational and social service professionals to provide holistic care,” wrote Aliya G. Feroe of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

The medication classes used to treat individuals with ASD include ADHD medications, antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, anxiolytics, and hypnotics, but the prescription rates of these medications in ASD patients have not been examined in large studies, the researchers said.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics, the researchers identified 26,722 individuals with ASD using a United States health care database from Jan. 1, 2014, to Dec. 31, 2019. Data included records of inpatient and outpatient claims, and records of prescriptions filled through commercial pharmacies. Individuals received at least 1 of 24 of the most common medication groups for ASD or comorbidities. The average age of the study participants was 14 years, and 78% were male. Diagnostic codes for ASD were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision.

Over the 6-year study period, approximately one-third of the participants were taking three or more medications at once, ranging from 28.6% to 31.5%. In any 1 year, approximately 41% of children were prescribed a single medication, 17% received two prescriptions, 7.9% received four, and 3.4% received five. Medication changes occurred more frequently within classes than between classes, and reasons for these changes may include patient preference, adverse effects, and cost, the researchers noted.

The overall number of children prescribed particular drugs remained consistent, the researchers noted. “For example, the total number of individuals prescribed methylphenidate shifted from 832 in 2014 to 850 in 2015, 899 in 2016, 863 in 2017, and 838 in 2018,” they wrote.

In 15 of the 24 medication groups included in the study, at least 15% of the individuals had unspecified anxiety disorder, anxiety neurosis, or major depressive disorder; in 11 of the medication groups, at least 15% had some form of ADHD. ADHD prevalence in patients taking stimulants varied based on ADHD type, the researchers said.

The most common comorbidities in patients taking antipsychotics were combined type ADHD (11.6%-17.8%) and anxiety disorder (13.1%-30.1%). The study findings suggest that many clinicians are incorporating medications into ASD management, the researchers said.

“Although there is no medical treatment for the core deficits of social communication and repetitive behavioral patterns in ASD, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that clinicians consider medications in the management of common comorbid conditions, including seizures, ADHD, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and disruptive behavior disorders,” they said.

The findings were limited by several factors including the potential for inconsistent reporting of diagnoses and pharmacy claims, the researchers noted. Other limitations included a lack of direct clinical assessment to validate diagnoses and the absence of validated diagnostic instruments to screen for comorbidities, they added.

“Our findings suggest that clinicians may be increasingly using integrated approaches to treating patients with ASD and co-occurring conditions, and further work is necessary to determine the relative effects of pharmacotherapy vs. behavioral interventions on outcomes in patients with ASD,” the researchers concluded.

Many reasons for multiple medications

“The researchers put in a lot of effort to provide data on a large scale,” Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“The findings illustrate the reality that autistic children are prescribed a lot of medications for a lot of reasons, some of which are not entirely clear,” Dr. Lessin said. The study also reflects the chronic lack of behavioral health services for children, he noted. Many children with ASD are referred for services they are unable to access, he said. “As a result, they see doctors who can only prescribe medications to try to control behavior or symptoms for which the cause is unclear,” and which could be ASD or other comorbidities, he emphasized.

The large sample size strengthens the study findings, but some of the challenges include the use of claims data, which do not indicate how diagnoses were made, said Dr. Lessin. An additional limitation is the fact that many medications for children with autism are used off label, so the specific reason for their use may be unknown, he said.

The take-home message for clinicians is that children with ASD are getting a lot of medications, and pediatricians are not usually responsible for multiple medications,” Dr. Lessin said. Ultimately, the study is “a plea for more research,” to tease out details of what medications are indicated and helpful, he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin serves on the Pediatric News editorial advisory board.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Children and COVID: Vaccination trends beginning to diverge

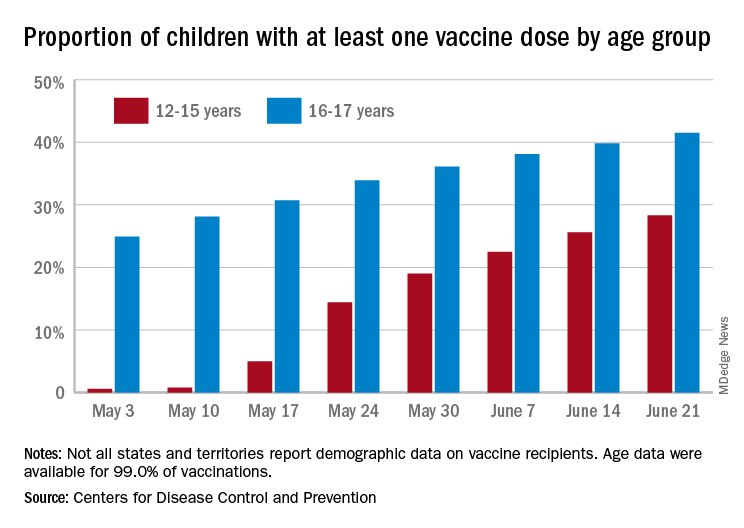

As more adolescents became eligible for a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine since it received approval from the Food and Drug Administration in mid-May, the share of 12- to 15-year-olds considered fully vaccinated rose from 11.4% on June 14 to 17.8% on June 28, an increase of 56%, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker indicated June 22.

For children aged 16-17 years, who have been receiving the vaccine since early April, full vaccination rose by 9.6% in that same week, going from 29.1% on June 14 to 31.9% on June 21. The cumulative numbers for first vaccinations are higher, of course, but are rising more slowly in both age groups: 41.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose by June 21 (up by 4.3%), with the 12- to 15-year-olds at 28.3% (up by 10.5%), based on the CDC data.

Limiting the time frame to just the last 2 weeks, however, shows the opposite of rising among the younger children. During the 2 weeks ending June 7, 17.9% of those initiating a first dose were 12-15 years old, but that 2-week figure slipped to 17.1% as of June 14 and was down to 16.0% on June 21. The older group was slow but steady over that time: 4.8%, 4.7%, and 4.8%, the CDC said. To give those figures some context, those aged 25-39 years represented 23.7% of past-2-week initiations on June 7 and 24.3% on June 21.

Although no COVID-19 vaccine has been approved for children under 12 years, about 0.4% of that age group – just over 167,000 children – have received a first dose and almost 91,000 are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

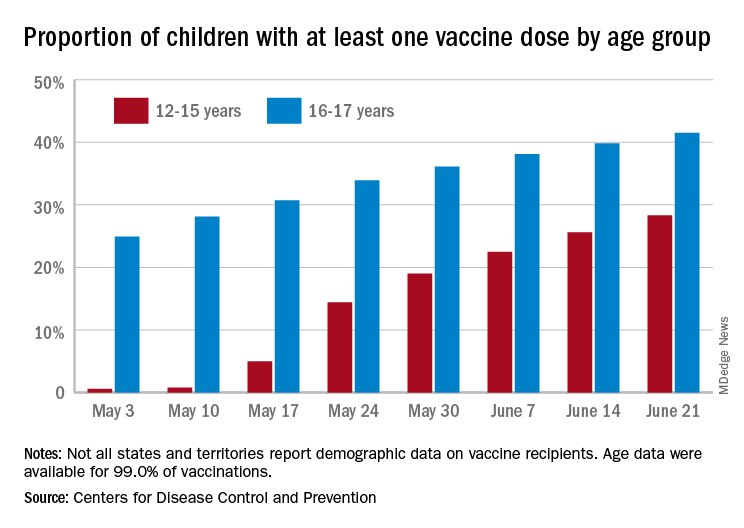

As more adolescents became eligible for a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine since it received approval from the Food and Drug Administration in mid-May, the share of 12- to 15-year-olds considered fully vaccinated rose from 11.4% on June 14 to 17.8% on June 28, an increase of 56%, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker indicated June 22.

For children aged 16-17 years, who have been receiving the vaccine since early April, full vaccination rose by 9.6% in that same week, going from 29.1% on June 14 to 31.9% on June 21. The cumulative numbers for first vaccinations are higher, of course, but are rising more slowly in both age groups: 41.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose by June 21 (up by 4.3%), with the 12- to 15-year-olds at 28.3% (up by 10.5%), based on the CDC data.

Limiting the time frame to just the last 2 weeks, however, shows the opposite of rising among the younger children. During the 2 weeks ending June 7, 17.9% of those initiating a first dose were 12-15 years old, but that 2-week figure slipped to 17.1% as of June 14 and was down to 16.0% on June 21. The older group was slow but steady over that time: 4.8%, 4.7%, and 4.8%, the CDC said. To give those figures some context, those aged 25-39 years represented 23.7% of past-2-week initiations on June 7 and 24.3% on June 21.

Although no COVID-19 vaccine has been approved for children under 12 years, about 0.4% of that age group – just over 167,000 children – have received a first dose and almost 91,000 are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

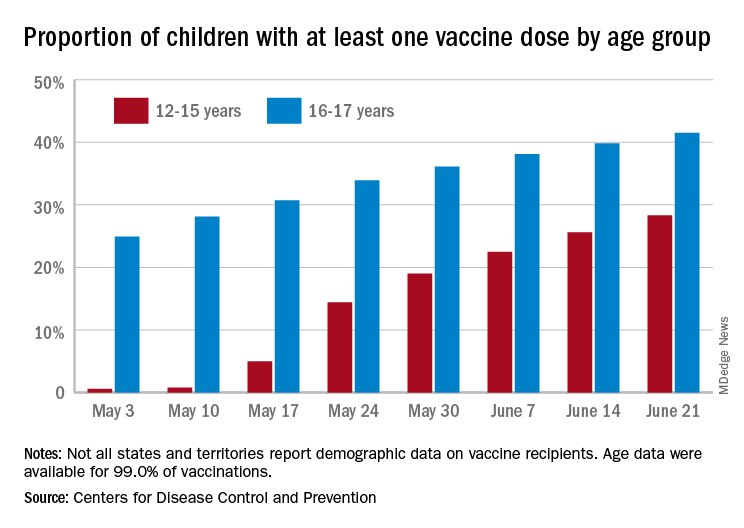

As more adolescents became eligible for a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine since it received approval from the Food and Drug Administration in mid-May, the share of 12- to 15-year-olds considered fully vaccinated rose from 11.4% on June 14 to 17.8% on June 28, an increase of 56%, the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker indicated June 22.

For children aged 16-17 years, who have been receiving the vaccine since early April, full vaccination rose by 9.6% in that same week, going from 29.1% on June 14 to 31.9% on June 21. The cumulative numbers for first vaccinations are higher, of course, but are rising more slowly in both age groups: 41.5% of those aged 16-17 had received at least one dose by June 21 (up by 4.3%), with the 12- to 15-year-olds at 28.3% (up by 10.5%), based on the CDC data.

Limiting the time frame to just the last 2 weeks, however, shows the opposite of rising among the younger children. During the 2 weeks ending June 7, 17.9% of those initiating a first dose were 12-15 years old, but that 2-week figure slipped to 17.1% as of June 14 and was down to 16.0% on June 21. The older group was slow but steady over that time: 4.8%, 4.7%, and 4.8%, the CDC said. To give those figures some context, those aged 25-39 years represented 23.7% of past-2-week initiations on June 7 and 24.3% on June 21.

Although no COVID-19 vaccine has been approved for children under 12 years, about 0.4% of that age group – just over 167,000 children – have received a first dose and almost 91,000 are fully vaccinated, according to CDC data.

AAP updates guidance for return to sports and physical activities

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As pandemic restrictions ease and young athletes once again take to fields, courts, tracks, and rinks, doctors are sharing ways to help them get back to sports safely.

That means taking steps to prevent COVID-19.

It also means trying to avoid sports-related injuries, which may be more likely if young athletes didn’t move around so much during the pandemic.

For adolescents who are eligible, getting a COVID-19 vaccine may be the most important thing they can do, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

“The AAP encourages all people who are eligible to receive the COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it is available,” the organization wrote in updated guidance on returning to sports and physical activity.

“I don’t think it can be overemphasized how important these vaccines are, both for the individual and at the community level,” says Aaron L. Baggish, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Cardiovascular Performance Program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Dr. Baggish, team cardiologist for the New England Patriots, the Boston Bruins, the New England Revolution, U.S. Men’s and Women’s Soccer, and U.S. Rowing, as well as medical director for the Boston Marathon, has studied the effects of COVID-19 on the heart in college athletes and written return-to-play recommendations for athletes of high school age and older.

“Millions of people have received these vaccines from age 12 up,” Dr. Baggish says. “The efficacy continues to look very durable and near complete, and the risk associated with vaccination is incredibly low, to the point where the risk-benefit ratio across the age spectrum, whether you’re athletic or not, strongly favors getting vaccinated. There is really no reason to hold off at this point.”

While outdoor activities are lower-risk for spreading COVID-19 and many people have been vaccinated, masks still should be worn in certain settings, the AAP notes.

“Indoor spaces that are crowded are still high-risk for COVID-19 transmission. And we recognize that not everyone in these settings may be vaccinated,” says Susannah Briskin, MD, lead author of the AAP guidance.

“So for indoor sporting events with spectators, in locker rooms or other small spaces such as a training room, and during shared car rides or school transportation to and from events, individuals should continue to mask,” adds Dr. Briskin, a pediatrician in the Division of Sports Medicine and fellowship director for the Primary Care Sports Medicine program at University Hospitals Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

For outdoor sports, athletes who are not fully vaccinated should be encouraged to wear masks on the sidelines and during group training and competition when they are within 3 feet of others for sustained amounts of time, according to the AAP.

Get back into exercise gradually

In general, athletes who have not been active for more than a month should resume exercise gradually, Dr. Briskin says. Starting at 25% of normal volume and increasing slowly over time – with 10% increases each week – is one rule of thumb.

“Those who have taken a prolonged break from sports are at a higher risk of injury when they return,” she notes. “Families should also be aware of an increased risk for heat-related illness if they are not acclimated.”

Caitlyn Mooney, MD, a team doctor for the University of Texas, San Antonio, has heard reports of doctors seeing more injuries like stress fractures. Some cases may relate to people going from “months of doing nothing to all of a sudden going back to sports,” says Dr. Mooney, who is also a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics and orthopedics at UT Health San Antonio.

“The coaches, the parents, and the athletes themselves really need to keep in mind that it’s not like a regular season,” Dr. Mooney says. She suggests gradually ramping up activity and paying attention to any pain. “That’s a good indicator that maybe you’re going too fast,” she adds.

Athletes should be mindful of other symptoms too when restarting exercise, especially after illness.

It is “very important that any athlete with recent COVID-19 monitor for new symptoms when they return to exercise,” says Jonathan Drezner, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle. “A little fatigue from detraining may be expected, but exertional chest pain deserves more evaluation.”

Dr. Drezner – editor-in-chief of the British Journal of Sports Medicine and team doctor for the Seattle Seahawks – along with Dr. Baggish and colleagues, found a low prevalence of cardiac involvement in a study of more than 3,000 college athletes with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“Any athlete, despite their initial symptom course, who has cardiopulmonary symptoms on return to exercise, particularly chest pain, should see their physician for a comprehensive cardiac evaluation,” Dr. Drezner says. “Cardiac MRI should be reserved for athletes with abnormal testing or when clinical suspicion of myocardial involvement is high.”

If an athlete had COVID-19 with moderate symptoms (such as fever, chills, or a flu-like syndrome) or cardiopulmonary symptoms (such as chest pain or shortness of breath), cardiac testing should be considered, he notes.

These symptoms “were associated with a higher prevalence of cardiac involvement,” Dr. Drezner said in an email. “Testing may include an ECG, echocardiogram (ultrasound), and troponin (blood test).”

For kids who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but do not have symptoms, or their symptoms last less than 4 days, a phone call or telemedicine visit with their doctor may be enough to clear them to play, says Dr. Briskin, who’s also an assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

“This will allow the physician an opportunity to screen for any concerning cardiac signs or symptoms, update the patient’s electronic medical record with the recent COVID-19 infection, and provide appropriate guidance back to exercise,” she adds.

Dr. Baggish, Dr. Briskin, Dr. Mooney, and Dr. Drezner had no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves OTC antihistamine nasal spray

, making it the first nasal antihistamine available over the counter in the United States.

The 0.15% strength of azelastine hydrochloride nasal spray is now approved for nonprescription treatment of seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis in adults and children 6 years of age or older, the agency said. The 0.1% strength remains a prescription product that is indicated in younger children.

The “approval provides individuals an option for a safe and effective nasal antihistamine without requiring the assistance of a health care provider,” Theresa M. Michele, MD, director of the office of nonprescription drugs in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a prepared statement.

The FDA granted the nonprescription approval to Bayer Healthcare LLC, which said in a press release that the nasal spray would be available in national mass retail locations starting in the first quarter of 2022.

Oral antihistamines such as cetirizine (Zyrtec), loratadine (Claritin), and fexofenadine (Allegra) have been on store shelves for years. Azelastine 0.15% will be the first and only over-the-counter antihistamine for indoor and outdoor allergy relief in a nasal formulation, Bayer said.

An over-the-counter nasal antihistamine could be a better option for some allergy sufferers when compared with what is already over the counter, said Tracy Prematta, MD, a private practice allergist in Havertown, Pa.

“In general, I like the nasal antihistamines,” Dr. Prematta said in an interview. “They work quickly, whereas the nasal steroids don’t, and I think a lot of people who go to the drugstore looking for allergy relief are actually looking for something quick-acting.”

However, the cost of the over-the-counter azelastine may play a big role in whether patients go with the prescription or nonprescription option, according to Dr. Prematta.

Bayer has not yet set the price for nonprescription azelastine, a company spokesperson told this news organization.

The change in azelastine approval status happened through a regulatory process called an Rx-to-OTC switch. According to the FDA, products switched to nonprescription status need to have data demonstrating that they are safe and effective as self-medication when used as directed.