User login

Too high: Can you ID pot-induced psychosis?

The youngest patient with cannabis-induced psychosis (CIP) whom Karen Randall, DO, has treated was a 7-year-old boy. She remembers the screaming, the yelling, the uncontrollable rage.

Dr. Randall is an emergency medicine physician at Southern Colorado Emergency Medicine Associates, a group practice in Pueblo, Colo. She treats youth for cannabis-related medical problems in the emergency department an average of two or three times per shift, she said.

Colorado legalized the recreational use of cannabis for adults older than 21 in 2012. Since then, Dr. Randall said, she has noticed an uptick in cannabis use among youth, as well as an increase in CIP, a syndrome that can be indistinguishable from other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia in the emergency department. But the two conditions require different approaches to care.

“You can’t differentiate unless you know the patient,” Dr. Randall said in an interview.

In 2019, 37% of high school students in the United States reported ever using marijuana, and 22% reported use in the past 30 days. Rates remained steady in 2020 following increases in 2018 and 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC also found that 8% of 8th graders, 19% of 10th graders, and 22% of 12th graders reported vaping marijuana in the past year.

Clinicians in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized say they have noticed an increase in young patients with psychiatric problems – especially after consumption of cannabis products in high doses., which often begin to present in adolescence.

How to differentiate

CIP is characterized by delusions and hallucinations and sometimes anxiety, disorganized thoughts, paranoia, dissociation, and changes in mood and behavior. Symptoms typically last for a couple hours and do not require specific treatment, although they can persist, depending on a patient’s tolerance and the dose of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) they have consumed. Research suggests that the higher the dose and concentration of the drug consumed, the more likely a person will develop symptoms of psychosis.

Diagnosis requires gathering information on previous bipolar disorder or schizophrenia diagnosis, prescriptions for mental illness indications, whether there is a family history of mental illness, and whether the patient recently started using marijuana. In some cases, marijuana use might exacerbate or unmask mental illness.

If symptoms of CIP resolve, and usually they do, clinicians can recommend that patients abstain from cannabis going forward, and psychosis would not need further treatment, according to Divya Singh, MD, a psychiatrist at Banner Behavioral Health Hospital in Scottsdale, Ariz., where recreational cannabis became legal in 2020.

“When I have limited information, especially in the first couple of days, I err on the side of safety,” Dr. Singh said.

Psychosis is the combination of symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized behavior, but it is not a disorder in itself. Rather, it is the primary symptom of schizophrenia and other chronic psychiatric illnesses.

Schizophrenia can be diagnosed only after a patient presents with signs of disturbance for at least 6 months, according to guidelines in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Dr. Singh said a diagnosis of schizophrenia cannot be made in a one-off interaction.

If the patient is younger than 24 years and has no family history of mental illness, a full recovery is likely if the patient abstains from marijuana, he said. But if the patient does have a family history, “the chances of them having a full-blown mental illness is very high,” Dr. Singh said.

If a patient reports that he or she has recently started using marijuana and was previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, Dr. Singh said he generally prescribes medications such as lithium or quetiapine and refers the patient to services such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. He also advises against continuing use of cannabis.

“Cannabis can result in people requiring a higher dose of medication than they took before,” Dr. Singh said. “If they were stable on 600 mg of lithium before, they might need more and may never be able to lower the dose in some cases, even after the acute episode.”

The science of cannabis

As of March 2023, 21 states and the District of Columbia permit the recreational use of marijuana, according to the Congressional Research Service. Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia allow medicinal use of marijuana, and 10 states allow “limited access to medical cannabis,” defined as low-THC cannabis or cannabidiol (CBD) oil.

THC is the main psychoactive compound in cannabis. It creates a high feeling after binding with receptors in the brain that control pain and mood. CBD is another chemical found in cannabis, but it does not create a high.

Some research suggests cannabinoids may help reduce anxiety, reduce inflammation, relieve pain, control nausea, reduce cancer cells, slow the growth of tumor cells, relax tight muscles, and stimulate appetite.

The drug also carries risks, according to Mayo Clinic. Use of marijuana is linked to mental health problems in teens and adults, such as depression, social anxiety, and temporary psychosis, and long-lasting mental disorders, such as schizophrenia.

In the worst cases, CIP can persist for weeks or months – long after a negative drug test – and sometimes does not subside at all, according to Ken Finn, MD, president and founder of Springs Rehabilitation, PC, a pain medicine practice in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Dr. Finn, the co–vice president of the International Academy on the Science and Impact of Cannabis, which opposes making the drug more accessible, said educating health care providers is an urgent need.

Studies are mixed on whether the legalization of cannabis has led to more cases of CIP.

A 2021 study found that experiences of psychosis among users of cannabis jumped 2.5-fold between 2001 and 2013. But a study published earlier this year of more than 63 million medical claims from 2003 to 2017 found no statistically significant difference in rates of psychosis-related diagnoses or prescribed antipsychotics in states that have legalized medical or recreational cannabis compared with states where cannabis is still illegal. However, a secondary analysis did find that rates of psychosis-related diagnoses increased significantly among men, people aged 55-64 years, and Asian adults in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized.

Complicating matters, researchers say, is the question of causality. Cannabis may exacerbate or trigger psychosis, but people with an underlying psychological illness may also be more likely to use cannabis.

Dr. Finn said clinicians in Colorado and other states with legalization laws are seeing more patients with CIP. As more states consider legalizing recreational marijuana, he expects the data will reflect what doctors experience on the ground.

Cannabis-induced “psychosis is complicated and likely underdiagnosed,” Dr. Finn said.

Talking to teens

Clinicians outside the emergency department can play a role in aiding young people at risk for CIP. Primary care physicians, for instance, might explain to young patients that the brain only becomes fully developed at roughly age 26, after which the long-term health consequences of using cannabis become less likely. According to the CDC, using cannabis before age 18 can change how the brain builds connections and can impair attention, memory, and learning.

Dr. Singh takes a harm reduction approach when he engages with a patient who is forthcoming about substance use.

“If I see an 18-year-old, I tell them to abstain,” he said. “I tell them if they are ever going to use it, to use it after 26.”

Clinicians also should understand dosages to provide the optimal guidance to their patients who use cannabis.

“People often have no idea how much cannabis they are taking,” especially when using vape cartridges, Dr. Singh said. “If you don’t know, you can’t tell patients about the harms – and if you tell them the wrong information, they will write you off.”

Dr. Singh said he advises his patients to avoid using cannabis vapes or dabbing pens. Both can contain much higher levels of THC than dried flower or edible forms of the drug. He also says patients should stick with low concentrations and use products that contain CBD, which some studies have shown has a protective effect against CIP, although other studies have found that CBD can induce anxiety.

He also tells patients to buy from legal dispensaries and to avoid buying street products that may have methamphetamine or fentanyl mixed in.

Despite the risks, Dr. Singh said legalization can reduce the stigma associated with cannabis use and may prompt patients to be honest with their clinicians. Dr. Singh recalled a 28-year-old patient who was using cannabis to alleviate her arthritic pain. She also was taking a transplant medication, which carried potential side effects of delirium, generalized anxiety disorder, and hallucinosis. After doubling her THC dose, the patient experienced severe anxiety and paranoia.

Dr. Singh’s patient paid him a visit and asked for help. Dr. Singh told her to reduce the dose and to keep track of how she felt. If she continued to feel anxious and paranoid, he recommended that she switch to CBD instead.

“I think education and knowledge is liberating,” Dr. Singh said. “Legalization and frank conversations help people understand how to use a product – and right now, I think that’s lacking.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The youngest patient with cannabis-induced psychosis (CIP) whom Karen Randall, DO, has treated was a 7-year-old boy. She remembers the screaming, the yelling, the uncontrollable rage.

Dr. Randall is an emergency medicine physician at Southern Colorado Emergency Medicine Associates, a group practice in Pueblo, Colo. She treats youth for cannabis-related medical problems in the emergency department an average of two or three times per shift, she said.

Colorado legalized the recreational use of cannabis for adults older than 21 in 2012. Since then, Dr. Randall said, she has noticed an uptick in cannabis use among youth, as well as an increase in CIP, a syndrome that can be indistinguishable from other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia in the emergency department. But the two conditions require different approaches to care.

“You can’t differentiate unless you know the patient,” Dr. Randall said in an interview.

In 2019, 37% of high school students in the United States reported ever using marijuana, and 22% reported use in the past 30 days. Rates remained steady in 2020 following increases in 2018 and 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC also found that 8% of 8th graders, 19% of 10th graders, and 22% of 12th graders reported vaping marijuana in the past year.

Clinicians in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized say they have noticed an increase in young patients with psychiatric problems – especially after consumption of cannabis products in high doses., which often begin to present in adolescence.

How to differentiate

CIP is characterized by delusions and hallucinations and sometimes anxiety, disorganized thoughts, paranoia, dissociation, and changes in mood and behavior. Symptoms typically last for a couple hours and do not require specific treatment, although they can persist, depending on a patient’s tolerance and the dose of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) they have consumed. Research suggests that the higher the dose and concentration of the drug consumed, the more likely a person will develop symptoms of psychosis.

Diagnosis requires gathering information on previous bipolar disorder or schizophrenia diagnosis, prescriptions for mental illness indications, whether there is a family history of mental illness, and whether the patient recently started using marijuana. In some cases, marijuana use might exacerbate or unmask mental illness.

If symptoms of CIP resolve, and usually they do, clinicians can recommend that patients abstain from cannabis going forward, and psychosis would not need further treatment, according to Divya Singh, MD, a psychiatrist at Banner Behavioral Health Hospital in Scottsdale, Ariz., where recreational cannabis became legal in 2020.

“When I have limited information, especially in the first couple of days, I err on the side of safety,” Dr. Singh said.

Psychosis is the combination of symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized behavior, but it is not a disorder in itself. Rather, it is the primary symptom of schizophrenia and other chronic psychiatric illnesses.

Schizophrenia can be diagnosed only after a patient presents with signs of disturbance for at least 6 months, according to guidelines in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Dr. Singh said a diagnosis of schizophrenia cannot be made in a one-off interaction.

If the patient is younger than 24 years and has no family history of mental illness, a full recovery is likely if the patient abstains from marijuana, he said. But if the patient does have a family history, “the chances of them having a full-blown mental illness is very high,” Dr. Singh said.

If a patient reports that he or she has recently started using marijuana and was previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, Dr. Singh said he generally prescribes medications such as lithium or quetiapine and refers the patient to services such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. He also advises against continuing use of cannabis.

“Cannabis can result in people requiring a higher dose of medication than they took before,” Dr. Singh said. “If they were stable on 600 mg of lithium before, they might need more and may never be able to lower the dose in some cases, even after the acute episode.”

The science of cannabis

As of March 2023, 21 states and the District of Columbia permit the recreational use of marijuana, according to the Congressional Research Service. Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia allow medicinal use of marijuana, and 10 states allow “limited access to medical cannabis,” defined as low-THC cannabis or cannabidiol (CBD) oil.

THC is the main psychoactive compound in cannabis. It creates a high feeling after binding with receptors in the brain that control pain and mood. CBD is another chemical found in cannabis, but it does not create a high.

Some research suggests cannabinoids may help reduce anxiety, reduce inflammation, relieve pain, control nausea, reduce cancer cells, slow the growth of tumor cells, relax tight muscles, and stimulate appetite.

The drug also carries risks, according to Mayo Clinic. Use of marijuana is linked to mental health problems in teens and adults, such as depression, social anxiety, and temporary psychosis, and long-lasting mental disorders, such as schizophrenia.

In the worst cases, CIP can persist for weeks or months – long after a negative drug test – and sometimes does not subside at all, according to Ken Finn, MD, president and founder of Springs Rehabilitation, PC, a pain medicine practice in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Dr. Finn, the co–vice president of the International Academy on the Science and Impact of Cannabis, which opposes making the drug more accessible, said educating health care providers is an urgent need.

Studies are mixed on whether the legalization of cannabis has led to more cases of CIP.

A 2021 study found that experiences of psychosis among users of cannabis jumped 2.5-fold between 2001 and 2013. But a study published earlier this year of more than 63 million medical claims from 2003 to 2017 found no statistically significant difference in rates of psychosis-related diagnoses or prescribed antipsychotics in states that have legalized medical or recreational cannabis compared with states where cannabis is still illegal. However, a secondary analysis did find that rates of psychosis-related diagnoses increased significantly among men, people aged 55-64 years, and Asian adults in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized.

Complicating matters, researchers say, is the question of causality. Cannabis may exacerbate or trigger psychosis, but people with an underlying psychological illness may also be more likely to use cannabis.

Dr. Finn said clinicians in Colorado and other states with legalization laws are seeing more patients with CIP. As more states consider legalizing recreational marijuana, he expects the data will reflect what doctors experience on the ground.

Cannabis-induced “psychosis is complicated and likely underdiagnosed,” Dr. Finn said.

Talking to teens

Clinicians outside the emergency department can play a role in aiding young people at risk for CIP. Primary care physicians, for instance, might explain to young patients that the brain only becomes fully developed at roughly age 26, after which the long-term health consequences of using cannabis become less likely. According to the CDC, using cannabis before age 18 can change how the brain builds connections and can impair attention, memory, and learning.

Dr. Singh takes a harm reduction approach when he engages with a patient who is forthcoming about substance use.

“If I see an 18-year-old, I tell them to abstain,” he said. “I tell them if they are ever going to use it, to use it after 26.”

Clinicians also should understand dosages to provide the optimal guidance to their patients who use cannabis.

“People often have no idea how much cannabis they are taking,” especially when using vape cartridges, Dr. Singh said. “If you don’t know, you can’t tell patients about the harms – and if you tell them the wrong information, they will write you off.”

Dr. Singh said he advises his patients to avoid using cannabis vapes or dabbing pens. Both can contain much higher levels of THC than dried flower or edible forms of the drug. He also says patients should stick with low concentrations and use products that contain CBD, which some studies have shown has a protective effect against CIP, although other studies have found that CBD can induce anxiety.

He also tells patients to buy from legal dispensaries and to avoid buying street products that may have methamphetamine or fentanyl mixed in.

Despite the risks, Dr. Singh said legalization can reduce the stigma associated with cannabis use and may prompt patients to be honest with their clinicians. Dr. Singh recalled a 28-year-old patient who was using cannabis to alleviate her arthritic pain. She also was taking a transplant medication, which carried potential side effects of delirium, generalized anxiety disorder, and hallucinosis. After doubling her THC dose, the patient experienced severe anxiety and paranoia.

Dr. Singh’s patient paid him a visit and asked for help. Dr. Singh told her to reduce the dose and to keep track of how she felt. If she continued to feel anxious and paranoid, he recommended that she switch to CBD instead.

“I think education and knowledge is liberating,” Dr. Singh said. “Legalization and frank conversations help people understand how to use a product – and right now, I think that’s lacking.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The youngest patient with cannabis-induced psychosis (CIP) whom Karen Randall, DO, has treated was a 7-year-old boy. She remembers the screaming, the yelling, the uncontrollable rage.

Dr. Randall is an emergency medicine physician at Southern Colorado Emergency Medicine Associates, a group practice in Pueblo, Colo. She treats youth for cannabis-related medical problems in the emergency department an average of two or three times per shift, she said.

Colorado legalized the recreational use of cannabis for adults older than 21 in 2012. Since then, Dr. Randall said, she has noticed an uptick in cannabis use among youth, as well as an increase in CIP, a syndrome that can be indistinguishable from other psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia in the emergency department. But the two conditions require different approaches to care.

“You can’t differentiate unless you know the patient,” Dr. Randall said in an interview.

In 2019, 37% of high school students in the United States reported ever using marijuana, and 22% reported use in the past 30 days. Rates remained steady in 2020 following increases in 2018 and 2019, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC also found that 8% of 8th graders, 19% of 10th graders, and 22% of 12th graders reported vaping marijuana in the past year.

Clinicians in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized say they have noticed an increase in young patients with psychiatric problems – especially after consumption of cannabis products in high doses., which often begin to present in adolescence.

How to differentiate

CIP is characterized by delusions and hallucinations and sometimes anxiety, disorganized thoughts, paranoia, dissociation, and changes in mood and behavior. Symptoms typically last for a couple hours and do not require specific treatment, although they can persist, depending on a patient’s tolerance and the dose of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) they have consumed. Research suggests that the higher the dose and concentration of the drug consumed, the more likely a person will develop symptoms of psychosis.

Diagnosis requires gathering information on previous bipolar disorder or schizophrenia diagnosis, prescriptions for mental illness indications, whether there is a family history of mental illness, and whether the patient recently started using marijuana. In some cases, marijuana use might exacerbate or unmask mental illness.

If symptoms of CIP resolve, and usually they do, clinicians can recommend that patients abstain from cannabis going forward, and psychosis would not need further treatment, according to Divya Singh, MD, a psychiatrist at Banner Behavioral Health Hospital in Scottsdale, Ariz., where recreational cannabis became legal in 2020.

“When I have limited information, especially in the first couple of days, I err on the side of safety,” Dr. Singh said.

Psychosis is the combination of symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized behavior, but it is not a disorder in itself. Rather, it is the primary symptom of schizophrenia and other chronic psychiatric illnesses.

Schizophrenia can be diagnosed only after a patient presents with signs of disturbance for at least 6 months, according to guidelines in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Dr. Singh said a diagnosis of schizophrenia cannot be made in a one-off interaction.

If the patient is younger than 24 years and has no family history of mental illness, a full recovery is likely if the patient abstains from marijuana, he said. But if the patient does have a family history, “the chances of them having a full-blown mental illness is very high,” Dr. Singh said.

If a patient reports that he or she has recently started using marijuana and was previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, Dr. Singh said he generally prescribes medications such as lithium or quetiapine and refers the patient to services such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. He also advises against continuing use of cannabis.

“Cannabis can result in people requiring a higher dose of medication than they took before,” Dr. Singh said. “If they were stable on 600 mg of lithium before, they might need more and may never be able to lower the dose in some cases, even after the acute episode.”

The science of cannabis

As of March 2023, 21 states and the District of Columbia permit the recreational use of marijuana, according to the Congressional Research Service. Thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia allow medicinal use of marijuana, and 10 states allow “limited access to medical cannabis,” defined as low-THC cannabis or cannabidiol (CBD) oil.

THC is the main psychoactive compound in cannabis. It creates a high feeling after binding with receptors in the brain that control pain and mood. CBD is another chemical found in cannabis, but it does not create a high.

Some research suggests cannabinoids may help reduce anxiety, reduce inflammation, relieve pain, control nausea, reduce cancer cells, slow the growth of tumor cells, relax tight muscles, and stimulate appetite.

The drug also carries risks, according to Mayo Clinic. Use of marijuana is linked to mental health problems in teens and adults, such as depression, social anxiety, and temporary psychosis, and long-lasting mental disorders, such as schizophrenia.

In the worst cases, CIP can persist for weeks or months – long after a negative drug test – and sometimes does not subside at all, according to Ken Finn, MD, president and founder of Springs Rehabilitation, PC, a pain medicine practice in Colorado Springs, Colo.

Dr. Finn, the co–vice president of the International Academy on the Science and Impact of Cannabis, which opposes making the drug more accessible, said educating health care providers is an urgent need.

Studies are mixed on whether the legalization of cannabis has led to more cases of CIP.

A 2021 study found that experiences of psychosis among users of cannabis jumped 2.5-fold between 2001 and 2013. But a study published earlier this year of more than 63 million medical claims from 2003 to 2017 found no statistically significant difference in rates of psychosis-related diagnoses or prescribed antipsychotics in states that have legalized medical or recreational cannabis compared with states where cannabis is still illegal. However, a secondary analysis did find that rates of psychosis-related diagnoses increased significantly among men, people aged 55-64 years, and Asian adults in states where recreational marijuana has been legalized.

Complicating matters, researchers say, is the question of causality. Cannabis may exacerbate or trigger psychosis, but people with an underlying psychological illness may also be more likely to use cannabis.

Dr. Finn said clinicians in Colorado and other states with legalization laws are seeing more patients with CIP. As more states consider legalizing recreational marijuana, he expects the data will reflect what doctors experience on the ground.

Cannabis-induced “psychosis is complicated and likely underdiagnosed,” Dr. Finn said.

Talking to teens

Clinicians outside the emergency department can play a role in aiding young people at risk for CIP. Primary care physicians, for instance, might explain to young patients that the brain only becomes fully developed at roughly age 26, after which the long-term health consequences of using cannabis become less likely. According to the CDC, using cannabis before age 18 can change how the brain builds connections and can impair attention, memory, and learning.

Dr. Singh takes a harm reduction approach when he engages with a patient who is forthcoming about substance use.

“If I see an 18-year-old, I tell them to abstain,” he said. “I tell them if they are ever going to use it, to use it after 26.”

Clinicians also should understand dosages to provide the optimal guidance to their patients who use cannabis.

“People often have no idea how much cannabis they are taking,” especially when using vape cartridges, Dr. Singh said. “If you don’t know, you can’t tell patients about the harms – and if you tell them the wrong information, they will write you off.”

Dr. Singh said he advises his patients to avoid using cannabis vapes or dabbing pens. Both can contain much higher levels of THC than dried flower or edible forms of the drug. He also says patients should stick with low concentrations and use products that contain CBD, which some studies have shown has a protective effect against CIP, although other studies have found that CBD can induce anxiety.

He also tells patients to buy from legal dispensaries and to avoid buying street products that may have methamphetamine or fentanyl mixed in.

Despite the risks, Dr. Singh said legalization can reduce the stigma associated with cannabis use and may prompt patients to be honest with their clinicians. Dr. Singh recalled a 28-year-old patient who was using cannabis to alleviate her arthritic pain. She also was taking a transplant medication, which carried potential side effects of delirium, generalized anxiety disorder, and hallucinosis. After doubling her THC dose, the patient experienced severe anxiety and paranoia.

Dr. Singh’s patient paid him a visit and asked for help. Dr. Singh told her to reduce the dose and to keep track of how she felt. If she continued to feel anxious and paranoid, he recommended that she switch to CBD instead.

“I think education and knowledge is liberating,” Dr. Singh said. “Legalization and frank conversations help people understand how to use a product – and right now, I think that’s lacking.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pretransfer visits with pediatric and adult rheumatologists smooth adolescent transition

NEW ORLEANS – Implementing a pediatric transition program in which a patient meets with both their pediatric and soon-to-be adult rheumatologist during a visit before formal transition resulted in less time setting up the first adult visit, according to research presented at the Pediatric Rheumatology Symposium.

The presentation was one of two that focused on ways to improve the transition from pediatric to adult care for rheumatology patients. The other, a poster from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, took the first steps toward learning what factors can help predict a successful transition.

“This period of transitioning from pediatric to adult care, both rheumatology specific and otherwise, is a high-risk time,” John M. Bridges, MD, a fourth-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told attendees. “There are changes in insurance coverage, employment, geographic mobility, and shifting responsibilities between parents and children in the setting of a still-developing frontal lobe that contribute to the risk of this period. Risks include disease flare, and then organ damage, as well as issues with decreasing medication and therapy, adherence, unscheduled care utilization, and increasing loss to follow-up.”

Dr. Bridges developed a structured transition program called the Bridge to Adult Care from Childhood for Young Adults with Rheumatic Disease (BACC YARD) aimed at improving the pediatric transition period. The analysis he presented focused specifically on reducing loss to follow-up by introducing a pretransfer visit with both rheumatologists. The patient first meets with their pediatric rheumatologist.

During that visit, the adult rheumatologist attends and discusses the patient’s history and current therapy with the pediatric rheumatologist before entering the patient’s room and having “a brief introductory conversation, a sort of verbal handoff and handshake, in front of the patient,” Dr. Bridges explained. “Then I assume responsibility for this patient and their next visit is to see me, both proverbially and literally down the street at the adulthood rheumatology clinic, where this patient becomes a part of my continuity cohort.”

Bridges entered patients from this BACC YARD cohort into an observational registry that included their dual provider pretransfer visit and a posttransfer visit, occurring between July 2020 and May 2022. He compared these patients with a historical control cohort of 45 patients from March 2018 to March 2020, who had at least two pediatric rheumatology visits prior to their transfer to adult care and no documentation of outside rheumatology visits during the study period. Specifically, he examined at the requested and actual interval between patients’ final pediatric rheumatology visit and their first adult rheumatology visit.

The intervention cohort included 86 patients, mostly female (73%), with a median age of 20. About two-thirds were White (65%) and one-third (34%) were Black. One patient was Asian, and 7% were Hispanic. Just over half the patients had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (58%), and 30% had lupus and related connective tissue diseases. The other patients had vasculitis, uveitis, inflammatory myopathy, relapsing polychondritis, morphea, or syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever.

A total of 8% of these patients had previously been lost to follow-up at Children’s of Alabama before they re-established rheumatology care at UAB, and 3.5% came from a pediatric rheumatologist from somewhere other than Children’s of Alabama but established adult care at UAB through the BACC YARD program. Among the remaining patients, 65% (n = 56) had both a dual provider pretransfer visit and a posttransfer visit.

The BACC YARD patients requested their next rheumatology visit (the first adult one) a median 119 days after their last pediatric visit, and the actual time until that visit was a median 141 days (P < .05). By comparison, the 45 patients in the historical control group had a median 261 days between their last pediatric visit and their first adult visit (P < .001). The median days between visits was shorter for those with JIA (129 days) and lupus (119 days) than for patients with other conditions (149 days).

Bridges acknowledged that the study was limited by the small size of the cohort and potential contextual factors related to individual patients’ circumstances.

“We’re continuing to make iterative changes to this process to try to continue to improve the transition and its outcomes in this cohort,” Dr. Bridges said.

Aimee Hersh, MD, an associate professor of pediatric rheumatology and division chief of pediatric rheumatology at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Hospital, both in Salt Lake City, attended the presentation and noted that the University of Utah has a very similar transfer program.

“I think one of the challenges of that model, and our model, is that you have to have a very specific type of physician who is both [medical-pediatrics] trained and has a specific interest in transition,” Dr. Hersh said in an interview. She noted that the adult rheumatologist at her institution didn’t train in pediatric rheumatology but did complete a meds-peds residency. “So if you can find an adult rheumatologist who can do something similar, can see older adolescent patients and serve as that transition bridge, then I think it is feasible.”

For practices that don’t have the resources for this kind of program, Dr. Hersh recommended the Got Transition program, which provides transition guidance that can be applied to any adolescent population with chronic illness.

The other study, led by Kristiana Nasto, BS, a third-year medical student at Baylor College of Medicine, reported on the findings from one aspect of a program also developed to improve the transition from pediatric to adult care for rheumatology patients. It included periodic self-reported evaluation using the validated Adolescent Assessment of Preparation for Transition (ADAPT) survey. As the first step to better understanding the factors that can predict successful transition, the researchers surveyed returning patients with any rheumatologic diagnosis, aged 14 years and older, between July 2021 and November 2022.

Since the survey was automated through the electronic medical record, patients and their caregivers could respond during in-person or virtual visit check-in. The researchers calculated three composite scores out of 100 for self-management, prescription management, and transfer planning, using responses from the ADAPT survey. Among 462 patients who returned 670 surveys, 87% provided surveys that could be scored for at least one composite score. Most respondents were female (75%), White (69%), non-Hispanic (64%), English speaking (90%), and aged 14-17 years (83%).

The overall average score for self-management from 401 respondents was 35. For prescription management, the average score was 59 from 288 respondents, and the average transfer planning score was 17 from 367 respondents. Self-management and transfer planning scores both improved with age (P = .0001). Self-management scores rose from an average of 20 at age 14 to an average of 64 at age 18 and older. Transfer planning scores increased from an average of 1 at age 14 to an average of 49 at age 18 and older. Prescription management scores remained high across all ages, from an average of 59 at age 14 to an average score of 66 at age 18 and older (P = .044). Although the scores did not statistically vary by age or race, Hispanic patients did score higher in self-management with an average of 44.5, compared with 31 among other patients (P = .0001).

Only 21% of patients completed two surveys, and 8.4% completed all three surveys. The average time between the first and second surveys was 4 months, during which there was no statistically significant change in self-management or prescription management scores, but transfer planning scores did increase from 14 to 21 (P = .008) among the 90 patients who completed those surveys.

The researchers concluded from their analysis that “participation in the transition pathway can rapidly improve transfer planning scores, [but] opportunities remain to improve readiness in all domains.” The researchers are in the process of developing Spanish-language surveys.

No external funding was noted for either study. Dr. Bridges, Dr. Hersh, and Ms. Nasto reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS – Implementing a pediatric transition program in which a patient meets with both their pediatric and soon-to-be adult rheumatologist during a visit before formal transition resulted in less time setting up the first adult visit, according to research presented at the Pediatric Rheumatology Symposium.

The presentation was one of two that focused on ways to improve the transition from pediatric to adult care for rheumatology patients. The other, a poster from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, took the first steps toward learning what factors can help predict a successful transition.

“This period of transitioning from pediatric to adult care, both rheumatology specific and otherwise, is a high-risk time,” John M. Bridges, MD, a fourth-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told attendees. “There are changes in insurance coverage, employment, geographic mobility, and shifting responsibilities between parents and children in the setting of a still-developing frontal lobe that contribute to the risk of this period. Risks include disease flare, and then organ damage, as well as issues with decreasing medication and therapy, adherence, unscheduled care utilization, and increasing loss to follow-up.”

Dr. Bridges developed a structured transition program called the Bridge to Adult Care from Childhood for Young Adults with Rheumatic Disease (BACC YARD) aimed at improving the pediatric transition period. The analysis he presented focused specifically on reducing loss to follow-up by introducing a pretransfer visit with both rheumatologists. The patient first meets with their pediatric rheumatologist.

During that visit, the adult rheumatologist attends and discusses the patient’s history and current therapy with the pediatric rheumatologist before entering the patient’s room and having “a brief introductory conversation, a sort of verbal handoff and handshake, in front of the patient,” Dr. Bridges explained. “Then I assume responsibility for this patient and their next visit is to see me, both proverbially and literally down the street at the adulthood rheumatology clinic, where this patient becomes a part of my continuity cohort.”

Bridges entered patients from this BACC YARD cohort into an observational registry that included their dual provider pretransfer visit and a posttransfer visit, occurring between July 2020 and May 2022. He compared these patients with a historical control cohort of 45 patients from March 2018 to March 2020, who had at least two pediatric rheumatology visits prior to their transfer to adult care and no documentation of outside rheumatology visits during the study period. Specifically, he examined at the requested and actual interval between patients’ final pediatric rheumatology visit and their first adult rheumatology visit.

The intervention cohort included 86 patients, mostly female (73%), with a median age of 20. About two-thirds were White (65%) and one-third (34%) were Black. One patient was Asian, and 7% were Hispanic. Just over half the patients had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (58%), and 30% had lupus and related connective tissue diseases. The other patients had vasculitis, uveitis, inflammatory myopathy, relapsing polychondritis, morphea, or syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever.

A total of 8% of these patients had previously been lost to follow-up at Children’s of Alabama before they re-established rheumatology care at UAB, and 3.5% came from a pediatric rheumatologist from somewhere other than Children’s of Alabama but established adult care at UAB through the BACC YARD program. Among the remaining patients, 65% (n = 56) had both a dual provider pretransfer visit and a posttransfer visit.

The BACC YARD patients requested their next rheumatology visit (the first adult one) a median 119 days after their last pediatric visit, and the actual time until that visit was a median 141 days (P < .05). By comparison, the 45 patients in the historical control group had a median 261 days between their last pediatric visit and their first adult visit (P < .001). The median days between visits was shorter for those with JIA (129 days) and lupus (119 days) than for patients with other conditions (149 days).

Bridges acknowledged that the study was limited by the small size of the cohort and potential contextual factors related to individual patients’ circumstances.

“We’re continuing to make iterative changes to this process to try to continue to improve the transition and its outcomes in this cohort,” Dr. Bridges said.

Aimee Hersh, MD, an associate professor of pediatric rheumatology and division chief of pediatric rheumatology at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Hospital, both in Salt Lake City, attended the presentation and noted that the University of Utah has a very similar transfer program.

“I think one of the challenges of that model, and our model, is that you have to have a very specific type of physician who is both [medical-pediatrics] trained and has a specific interest in transition,” Dr. Hersh said in an interview. She noted that the adult rheumatologist at her institution didn’t train in pediatric rheumatology but did complete a meds-peds residency. “So if you can find an adult rheumatologist who can do something similar, can see older adolescent patients and serve as that transition bridge, then I think it is feasible.”

For practices that don’t have the resources for this kind of program, Dr. Hersh recommended the Got Transition program, which provides transition guidance that can be applied to any adolescent population with chronic illness.

The other study, led by Kristiana Nasto, BS, a third-year medical student at Baylor College of Medicine, reported on the findings from one aspect of a program also developed to improve the transition from pediatric to adult care for rheumatology patients. It included periodic self-reported evaluation using the validated Adolescent Assessment of Preparation for Transition (ADAPT) survey. As the first step to better understanding the factors that can predict successful transition, the researchers surveyed returning patients with any rheumatologic diagnosis, aged 14 years and older, between July 2021 and November 2022.

Since the survey was automated through the electronic medical record, patients and their caregivers could respond during in-person or virtual visit check-in. The researchers calculated three composite scores out of 100 for self-management, prescription management, and transfer planning, using responses from the ADAPT survey. Among 462 patients who returned 670 surveys, 87% provided surveys that could be scored for at least one composite score. Most respondents were female (75%), White (69%), non-Hispanic (64%), English speaking (90%), and aged 14-17 years (83%).

The overall average score for self-management from 401 respondents was 35. For prescription management, the average score was 59 from 288 respondents, and the average transfer planning score was 17 from 367 respondents. Self-management and transfer planning scores both improved with age (P = .0001). Self-management scores rose from an average of 20 at age 14 to an average of 64 at age 18 and older. Transfer planning scores increased from an average of 1 at age 14 to an average of 49 at age 18 and older. Prescription management scores remained high across all ages, from an average of 59 at age 14 to an average score of 66 at age 18 and older (P = .044). Although the scores did not statistically vary by age or race, Hispanic patients did score higher in self-management with an average of 44.5, compared with 31 among other patients (P = .0001).

Only 21% of patients completed two surveys, and 8.4% completed all three surveys. The average time between the first and second surveys was 4 months, during which there was no statistically significant change in self-management or prescription management scores, but transfer planning scores did increase from 14 to 21 (P = .008) among the 90 patients who completed those surveys.

The researchers concluded from their analysis that “participation in the transition pathway can rapidly improve transfer planning scores, [but] opportunities remain to improve readiness in all domains.” The researchers are in the process of developing Spanish-language surveys.

No external funding was noted for either study. Dr. Bridges, Dr. Hersh, and Ms. Nasto reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS – Implementing a pediatric transition program in which a patient meets with both their pediatric and soon-to-be adult rheumatologist during a visit before formal transition resulted in less time setting up the first adult visit, according to research presented at the Pediatric Rheumatology Symposium.

The presentation was one of two that focused on ways to improve the transition from pediatric to adult care for rheumatology patients. The other, a poster from researchers at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, took the first steps toward learning what factors can help predict a successful transition.

“This period of transitioning from pediatric to adult care, both rheumatology specific and otherwise, is a high-risk time,” John M. Bridges, MD, a fourth-year pediatric rheumatology fellow at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, told attendees. “There are changes in insurance coverage, employment, geographic mobility, and shifting responsibilities between parents and children in the setting of a still-developing frontal lobe that contribute to the risk of this period. Risks include disease flare, and then organ damage, as well as issues with decreasing medication and therapy, adherence, unscheduled care utilization, and increasing loss to follow-up.”

Dr. Bridges developed a structured transition program called the Bridge to Adult Care from Childhood for Young Adults with Rheumatic Disease (BACC YARD) aimed at improving the pediatric transition period. The analysis he presented focused specifically on reducing loss to follow-up by introducing a pretransfer visit with both rheumatologists. The patient first meets with their pediatric rheumatologist.

During that visit, the adult rheumatologist attends and discusses the patient’s history and current therapy with the pediatric rheumatologist before entering the patient’s room and having “a brief introductory conversation, a sort of verbal handoff and handshake, in front of the patient,” Dr. Bridges explained. “Then I assume responsibility for this patient and their next visit is to see me, both proverbially and literally down the street at the adulthood rheumatology clinic, where this patient becomes a part of my continuity cohort.”

Bridges entered patients from this BACC YARD cohort into an observational registry that included their dual provider pretransfer visit and a posttransfer visit, occurring between July 2020 and May 2022. He compared these patients with a historical control cohort of 45 patients from March 2018 to March 2020, who had at least two pediatric rheumatology visits prior to their transfer to adult care and no documentation of outside rheumatology visits during the study period. Specifically, he examined at the requested and actual interval between patients’ final pediatric rheumatology visit and their first adult rheumatology visit.

The intervention cohort included 86 patients, mostly female (73%), with a median age of 20. About two-thirds were White (65%) and one-third (34%) were Black. One patient was Asian, and 7% were Hispanic. Just over half the patients had juvenile idiopathic arthritis (58%), and 30% had lupus and related connective tissue diseases. The other patients had vasculitis, uveitis, inflammatory myopathy, relapsing polychondritis, morphea, or syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever.

A total of 8% of these patients had previously been lost to follow-up at Children’s of Alabama before they re-established rheumatology care at UAB, and 3.5% came from a pediatric rheumatologist from somewhere other than Children’s of Alabama but established adult care at UAB through the BACC YARD program. Among the remaining patients, 65% (n = 56) had both a dual provider pretransfer visit and a posttransfer visit.

The BACC YARD patients requested their next rheumatology visit (the first adult one) a median 119 days after their last pediatric visit, and the actual time until that visit was a median 141 days (P < .05). By comparison, the 45 patients in the historical control group had a median 261 days between their last pediatric visit and their first adult visit (P < .001). The median days between visits was shorter for those with JIA (129 days) and lupus (119 days) than for patients with other conditions (149 days).

Bridges acknowledged that the study was limited by the small size of the cohort and potential contextual factors related to individual patients’ circumstances.

“We’re continuing to make iterative changes to this process to try to continue to improve the transition and its outcomes in this cohort,” Dr. Bridges said.

Aimee Hersh, MD, an associate professor of pediatric rheumatology and division chief of pediatric rheumatology at the University of Utah and Primary Children’s Hospital, both in Salt Lake City, attended the presentation and noted that the University of Utah has a very similar transfer program.

“I think one of the challenges of that model, and our model, is that you have to have a very specific type of physician who is both [medical-pediatrics] trained and has a specific interest in transition,” Dr. Hersh said in an interview. She noted that the adult rheumatologist at her institution didn’t train in pediatric rheumatology but did complete a meds-peds residency. “So if you can find an adult rheumatologist who can do something similar, can see older adolescent patients and serve as that transition bridge, then I think it is feasible.”

For practices that don’t have the resources for this kind of program, Dr. Hersh recommended the Got Transition program, which provides transition guidance that can be applied to any adolescent population with chronic illness.

The other study, led by Kristiana Nasto, BS, a third-year medical student at Baylor College of Medicine, reported on the findings from one aspect of a program also developed to improve the transition from pediatric to adult care for rheumatology patients. It included periodic self-reported evaluation using the validated Adolescent Assessment of Preparation for Transition (ADAPT) survey. As the first step to better understanding the factors that can predict successful transition, the researchers surveyed returning patients with any rheumatologic diagnosis, aged 14 years and older, between July 2021 and November 2022.

Since the survey was automated through the electronic medical record, patients and their caregivers could respond during in-person or virtual visit check-in. The researchers calculated three composite scores out of 100 for self-management, prescription management, and transfer planning, using responses from the ADAPT survey. Among 462 patients who returned 670 surveys, 87% provided surveys that could be scored for at least one composite score. Most respondents were female (75%), White (69%), non-Hispanic (64%), English speaking (90%), and aged 14-17 years (83%).

The overall average score for self-management from 401 respondents was 35. For prescription management, the average score was 59 from 288 respondents, and the average transfer planning score was 17 from 367 respondents. Self-management and transfer planning scores both improved with age (P = .0001). Self-management scores rose from an average of 20 at age 14 to an average of 64 at age 18 and older. Transfer planning scores increased from an average of 1 at age 14 to an average of 49 at age 18 and older. Prescription management scores remained high across all ages, from an average of 59 at age 14 to an average score of 66 at age 18 and older (P = .044). Although the scores did not statistically vary by age or race, Hispanic patients did score higher in self-management with an average of 44.5, compared with 31 among other patients (P = .0001).

Only 21% of patients completed two surveys, and 8.4% completed all three surveys. The average time between the first and second surveys was 4 months, during which there was no statistically significant change in self-management or prescription management scores, but transfer planning scores did increase from 14 to 21 (P = .008) among the 90 patients who completed those surveys.

The researchers concluded from their analysis that “participation in the transition pathway can rapidly improve transfer planning scores, [but] opportunities remain to improve readiness in all domains.” The researchers are in the process of developing Spanish-language surveys.

No external funding was noted for either study. Dr. Bridges, Dr. Hersh, and Ms. Nasto reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT PRSYM 2023

Autism: Is it in the water?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

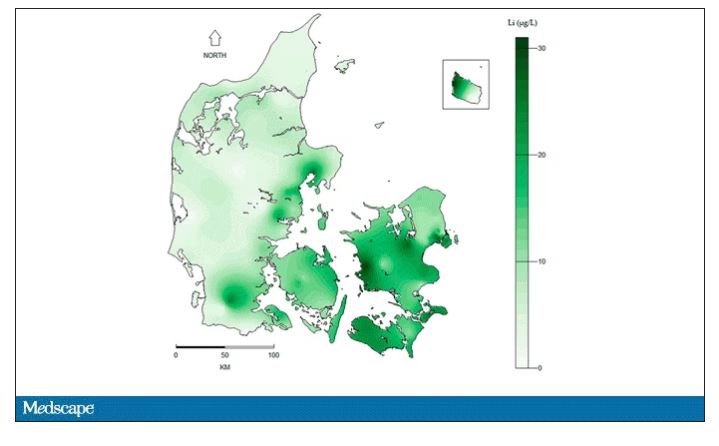

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

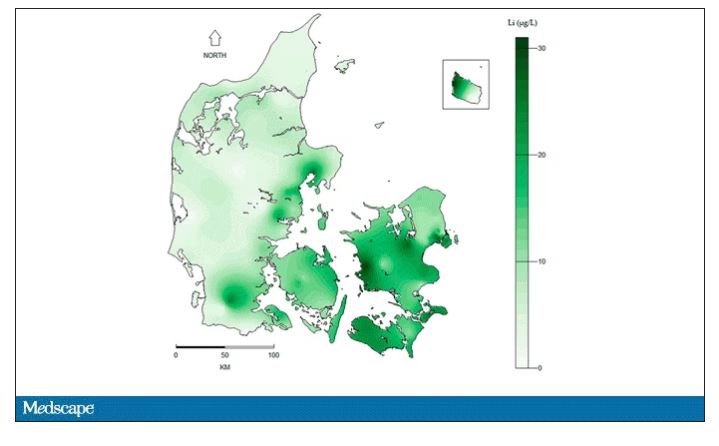

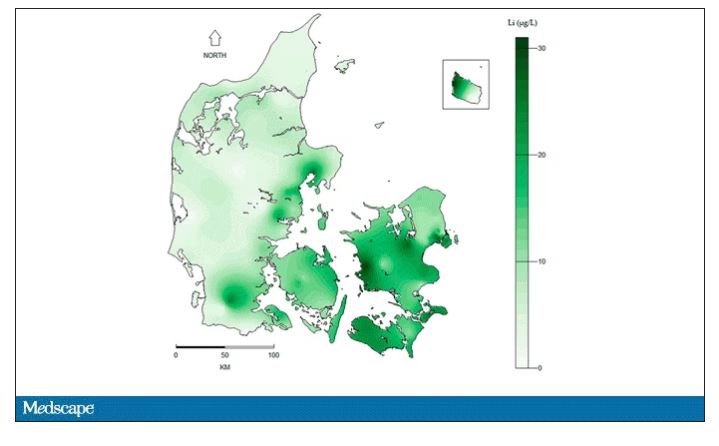

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

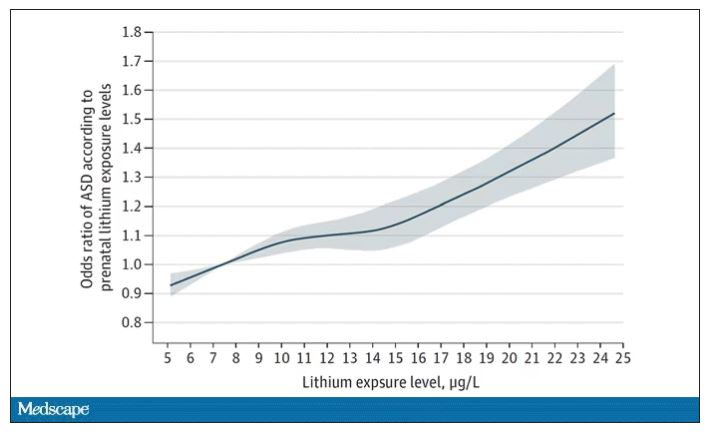

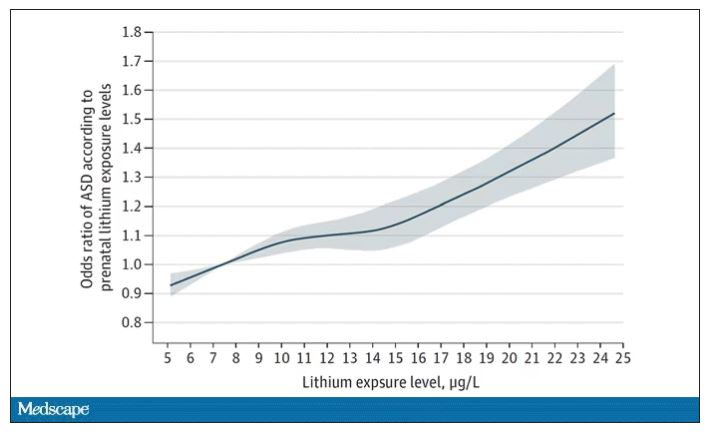

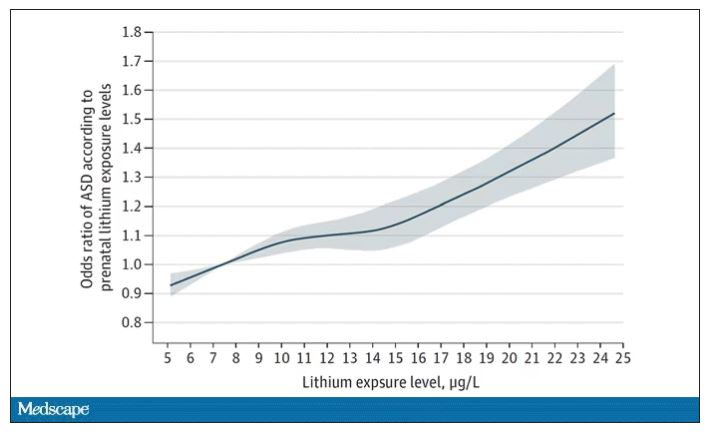

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

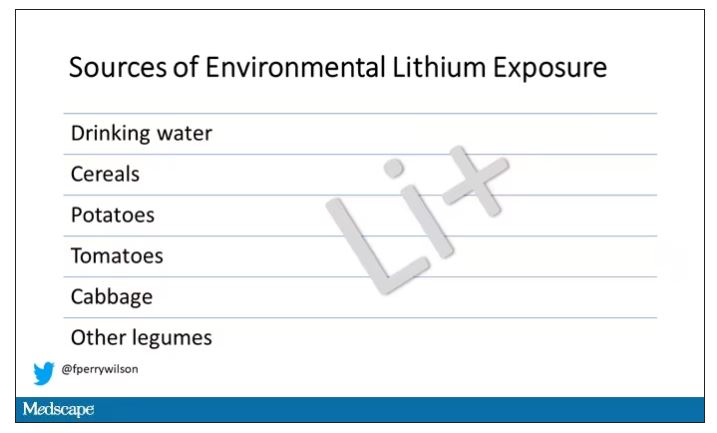

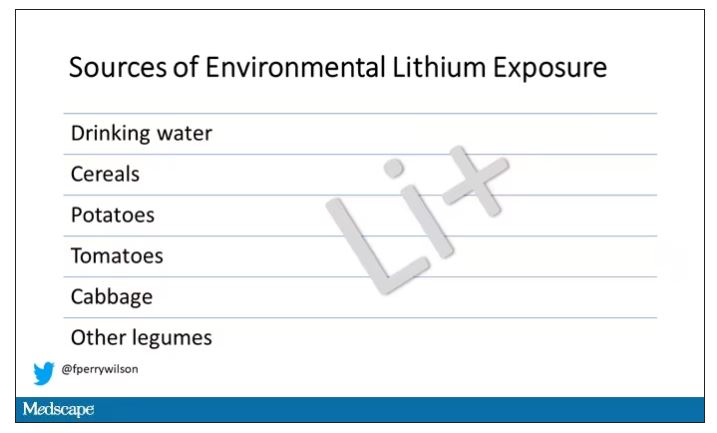

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

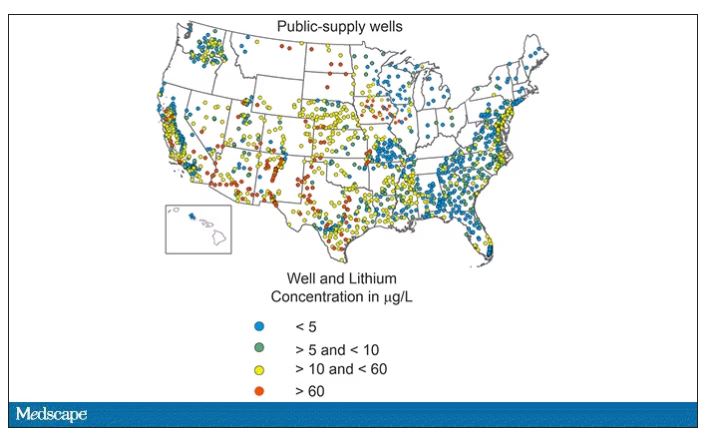

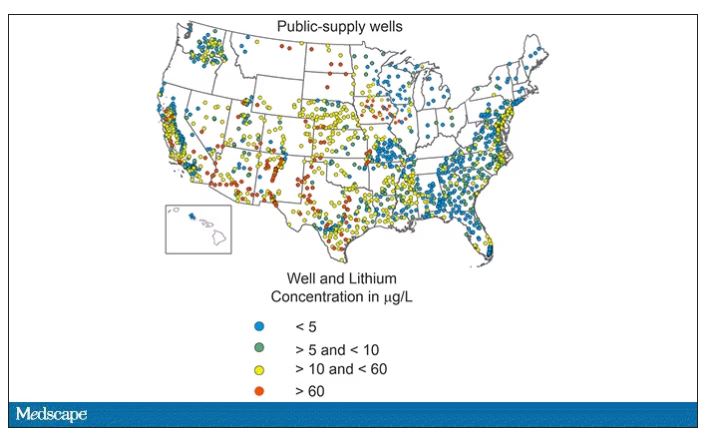

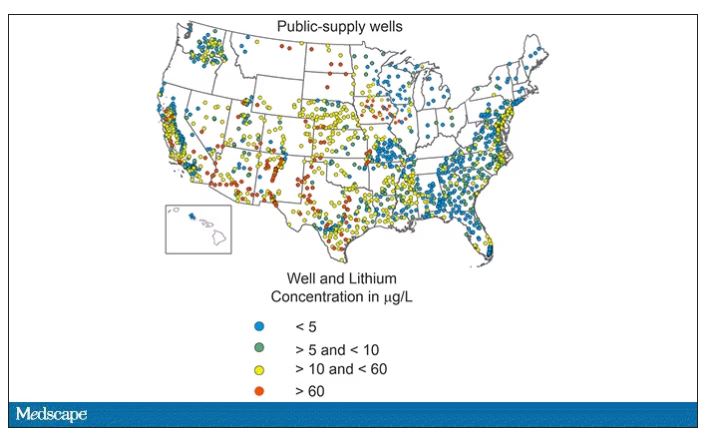

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

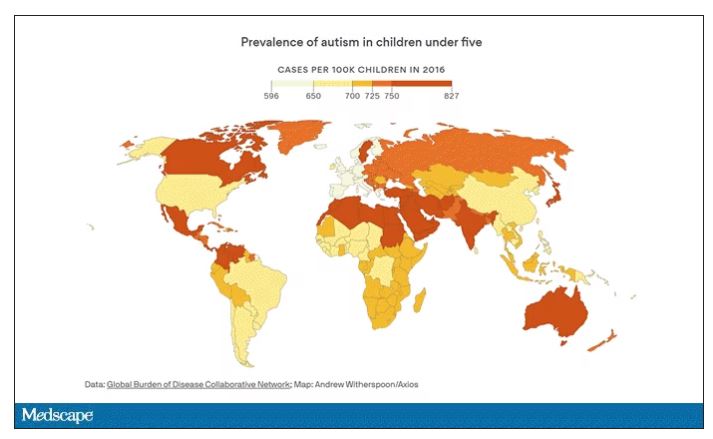

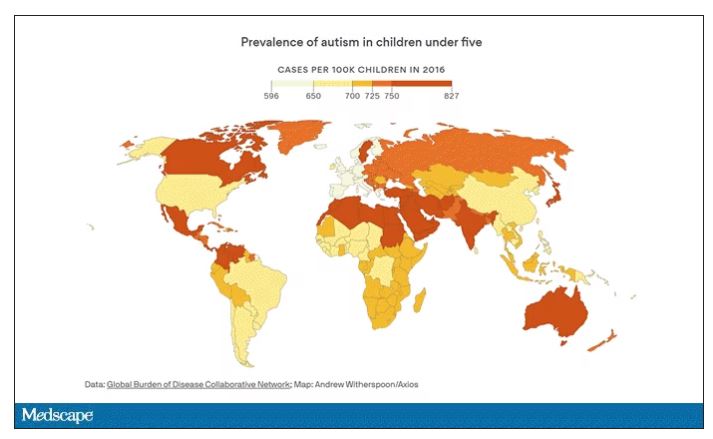

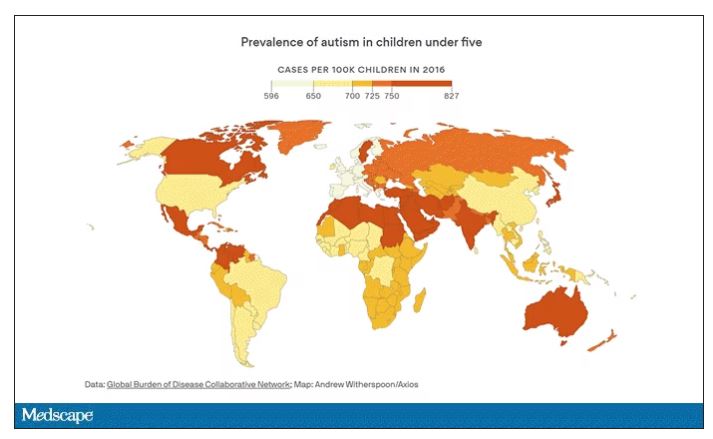

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Few diseases have stymied explanation like autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We know that the prevalence has been increasing dramatically, but we aren’t quite sure whether that is because of more screening and awareness or more fundamental changes. We know that much of the risk appears to be genetic, but there may be 1,000 genes involved in the syndrome. We know that certain environmental exposures, like pollution, might increase the risk – perhaps on a susceptible genetic background – but we’re not really sure which exposures are most harmful.

So, the search continues, across all domains of inquiry from cell culture to large epidemiologic analyses. And this week, a new player enters the field, and, as they say, it’s something in the water.

We’re talking about this paper, by Zeyan Liew and colleagues, appearing in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using the incredibly robust health data infrastructure in Denmark, the researchers were able to identify 8,842 children born between 2000 and 2013 with ASD and matched each one to five control kids of the same sex and age without autism.

They then mapped the location the mothers of these kids lived while they were pregnant – down to 5 meters resolution, actually – to groundwater lithium levels.

Once that was done, the analysis was straightforward. Would moms who were pregnant in areas with higher groundwater lithium levels be more likely to have kids with ASD?

The results show a rather steady and consistent association between higher lithium levels in groundwater and the prevalence of ASD in children.

We’re not talking huge numbers, but moms who lived in the areas of the highest quartile of lithium were about 46% more likely to have a child with ASD. That’s a relative risk, of course – this would be like an increase from 1 in 100 kids to 1.5 in 100 kids. But still, it’s intriguing.

But the case is far from closed here.

Groundwater concentration of lithium and the amount of lithium a pregnant mother ingests are not the same thing. It does turn out that virtually all drinking water in Denmark comes from groundwater sources – but not all lithium comes from drinking water. There are plenty of dietary sources of lithium as well. And, of course, there is medical lithium, but we’ll get to that in a second.

First, let’s talk about those lithium measurements. They were taken in 2013 – after all these kids were born. The authors acknowledge this limitation but show a high correlation between measured levels in 2013 and earlier measured levels from prior studies, suggesting that lithium levels in a given area are quite constant over time. That’s great – but if lithium levels are constant over time, this study does nothing to shed light on why autism diagnoses seem to be increasing.

Let’s put some numbers to the lithium concentrations the authors examined. The average was about 12 mcg/L.

As a reminder, a standard therapeutic dose of lithium used for bipolar disorder is like 600 mg. That means you’d need to drink more than 2,500 of those 5-gallon jugs that sit on your water cooler, per day, to approximate the dose you’d get from a lithium tablet. Of course, small doses can still cause toxicity – but I wanted to put this in perspective.

Also, we have some data on pregnant women who take medical lithium. An analysis of nine studies showed that first-trimester lithium use may be associated with congenital malformations – particularly some specific heart malformations – and some birth complications. But three of four separate studies looking at longer-term neurodevelopmental outcomes did not find any effect on development, attainment of milestones, or IQ. One study of 15 kids exposed to medical lithium in utero did note minor neurologic dysfunction in one child and a low verbal IQ in another – but that’s a very small study.

Of course, lithium levels vary around the world as well. The U.S. Geological Survey examined lithium content in groundwater in the United States, as you can see here.

Our numbers are pretty similar to Denmark’s – in the 0-60 range. But an area in the Argentine Andes has levels as high as 1,600 mcg/L. A study of 194 babies from that area found higher lithium exposure was associated with lower fetal size, but I haven’t seen follow-up on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The point is that there is a lot of variability here. It would be really interesting to map groundwater lithium levels to autism rates around the world. As a teaser, I will point out that, if you look at worldwide autism rates, you may be able to convince yourself that they are higher in more arid climates, and arid climates tend to have more groundwater lithium. But I’m really reaching here. More work needs to be done.

And I hope it is done quickly. Lithium is in the midst of becoming a very important commodity thanks to the shift to electric vehicles. While we can hope that recycling will claim most of those batteries at the end of their life, some will escape reclamation and potentially put more lithium into the drinking water. I’d like to know how risky that is before it happens.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, “How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t”, is available now.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children ate more fruits and vegetables during longer meals: Study

Adding 10 minutes to family mealtimes increased children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables by approximately one portion, based on data from 50 parent-child dyads.

Family meals are known to affect children’s food choices and preferences and can be an effective setting for improving children’s nutrition, wrote Mattea Dallacker, PhD, of the University of Mannheim, Germany, and colleagues.

However, the effect of extending meal duration on increasing fruit and vegetable intake in particular has not been examined, they said.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers provided two free evening meals to 50 parent-child dyads under each of two different conditions. The control condition was defined by the families as a regular family mealtime duration (an average meal was 20.83 minutes), while the intervention was an average meal time 10 minutes (50%) longer. The age of the parents ranged from 22 to 55 years, with a mean of 43 years; 72% of the parent participants were mothers. The children’s ages ranged from 6 to 11 years, with a mean of 8 years, with approximately equal numbers of boys and girls.

The study was conducted in a family meal laboratory setting in Berlin, and groups were randomized to the longer or shorter meal setting first. The primary outcome was the total number of pieces of fruit and vegetables eaten by the child as part of each of the two meals.

Both meals were the “typical German evening meal of sliced bread, cold cuts of cheese and meat, and bite-sized pieces of fruits and vegetables,” followed by a dessert course of chocolate pudding or fruit yogurt and cookies, the researchers wrote. Beverages were water and one sugar-sweetened beverage; the specific foods and beverages were based on the child’s preferences, reported in an online preassessment, and the foods were consistent for the longer and shorter meals. All participants were asked not to eat for 2 hours prior to arriving for their meals at the laboratory.

During longer meals, children ate an average of seven additional bite-sized pieces of fruits and vegetables, which translates to approximately a full portion (defined as 100 g, such as a medium apple), the researchers wrote. The difference was significant compared with the shorter meals for fruits (P = .01) and vegetables (P < .001).

A piece of fruit was approximately 10 grams (6-10 g for grapes and tangerine segments; 10-14 g for cherry tomatoes; and 9-11 g for apple, banana, carrot, or cucumber). Other foods served with the meals included cheese, meats, butter, and sweet spreads.

Children also ate more slowly (defined as fewer bites per minute) during the longer meals, and they reported significantly greater satiety after the longer meals (P < .001 for both). The consumption of bread and cold cuts was similar for the two meal settings.

“Higher intake of fruits and vegetables during longer meals cannot be explained by longer exposure to food alone; otherwise, an increased intake of bread and cold cuts would have occurred,” the researchers wrote in their discussion. “One possible explanation is that the fruits and vegetables were cut into bite-sized pieces, making them convenient to eat.”

Further analysis showed that during the longer meals, more fruits and vegetables were consumed overall, but more vegetables were eaten from the start of the meal, while the additional fruit was eaten during the additional time at the end.

The findings were limited by several factors, primarily use of a laboratory setting that does not generalize to natural eating environments, the researchers noted. Other potential limitations included the effect of a video cameras on desirable behaviors and the limited ethnic and socioeconomic diversity of the study population, they said. The results were strengthened by the within-dyad study design that allowed for control of factors such as video observation, but more research is needed with more diverse groups and across longer time frames, the researchers said.

However, the results suggest that adding 10 minutes to a family mealtime can yield significant improvements in children’s diets, they said. They suggested strategies including playing music chosen by the child/children and setting rules that everyone must remain at the table for a certain length of time, with fruits and vegetables available on the table.

“If the effects of this simple, inexpensive, and low-threshold intervention prove stable over time, it could contribute to addressing a major public health problem,” the researchers concluded.

Findings intriguing, more data needed

The current study is important because food and vegetable intake in the majority of children falls below the recommended daily allowance, Karalyn Kinsella, MD, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn., said in an interview.

The key take-home message for clinicians is the continued need to stress the importance of family meals, said Dr. Kinsella. “Many children continue to be overbooked with activities, and it may be rare for many families to sit down together for a meal for any length of time.”

Don’t discount the potential effect of a longer school lunch on children’s fruit and vegetable consumption as well, she added. “Advocating for longer lunch time is important, as many kids report not being able to finish their lunch at school.”

The current study was limited by being conducted in a lab setting, which may have influenced children’s desire for different foods, “also they had fewer distractions, and were being offered favorite foods,” said Dr. Kinsella.

Looking ahead, “it would be interesting to see if this result carried over to nonpreferred fruits and veggies and made any difference for picky eaters,” she said.

The study received no outside funding. The open-access publication of the study (but not the study itself) was supported by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development Library Open Access Fund. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kinsella had no financial conflicts to disclose and serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

Adding 10 minutes to family mealtimes increased children’s consumption of fruits and vegetables by approximately one portion, based on data from 50 parent-child dyads.

Family meals are known to affect children’s food choices and preferences and can be an effective setting for improving children’s nutrition, wrote Mattea Dallacker, PhD, of the University of Mannheim, Germany, and colleagues.

However, the effect of extending meal duration on increasing fruit and vegetable intake in particular has not been examined, they said.