User login

Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry seed oil) extract

A member of the Ericaceae family, bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) is native to northern Europe and North America, and its fruit is known to contain myriad polyphenols that display potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity.1,2 Also known as European blueberry or whortleberry, this perennial deciduous shrub is also one of the richest sources of the polyphenolic pigments anthocyanins.3-5 Indeed, anthocyanins impart the blue/black color to bilberries and other berries and are thought to be the primary bioactive constituents of berries associated with numerous health benefits.3,6 They are also known to confer anti-allergic, anticancer, and wound healing activity.4 Overall, bilberry has also been reported to exert anti-inflammatory, lipid-lowering, and antimicrobial activity.3 In this column, the focus will be on the chemical constituents and properties of V. myrtillus that indicate potential or applicability for skin care.

Active ingredients of bilberry

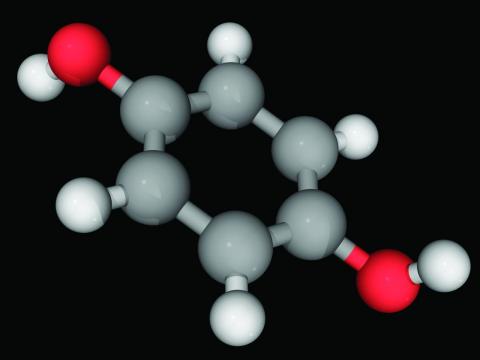

Bilberry seed oil contains unsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid, which exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and contribute to the suppression of tyrosinase. For instance, Ando et al. showed, in 1998, that linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids lighten UV-induced skin hyperpigmentation. Their in vitro experiments using cultured murine melanoma cells and in vivo study of the topical application of either acid to the UV-induced hyperpigmented dorsal skin of guinea pigs revealed pigment-lightening effects that they partly ascribed to inhibited melanin synthesis by active melanocytes and accelerated desquamation of epidermal melanin pigment.7

A 2009 comparative study of the anthocyanin composition as well as antimicrobial and antioxidant activities delivered by bilberry and blueberry fruits and their skins by Burdulis et al. revealed robust functions in both fruits. Cyanidin was found to be an active anthocyanidin in bilberry. Cultivars of both fruits demonstrated antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, with bilberry fruit skin demonstrating potent antiradical activity.8

The anthocyanins of V. myrtillus are reputed to impart protection against cardiovascular disorders, age-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and various degenerative conditions, as well ameliorate neuronal and cognitive brain functions and ocular health.6

In 2012, Bornsek et al. demonstrated that bilberry (and blueberry) anthocyanins function as potent intracellular antioxidants, which may account for their noted health benefits despite relatively low bioavailability.9

Six years later, a chemical composition study of wild bilberry found in Montenegro, Brasanac-Vukanovic et al. determined that chlorogenic acid was the most prevalent phenolic constituent, followed by protocatechuic acid, with resveratrol, isoquercetin, quercetin, and hyperoside also found to be abundant. In vitro assays indicated significant antioxidant activity exhibited by these compounds.10

Activity against allergic contact dermatitis

Yamaura et al. used a mouse model, in 2011, to determine that the anthocyanins from a bilberry extract attenuated various symptoms of chronic allergic contact dermatitis, particularly alleviating pruritus.8 A year later, Yamaura et al. used a BALB/c mouse model of allergic contact dermatitis to compare the antipruritic effect of anthocyanin-rich quality-controlled bilberry extract and anthocyanidin-rich degraded extract. The investigators found that anthocyanins, but not anthocyanidins, derived from bilberry exert an antipruritic effect, likely through their inhibitory action on mast cell degranulation. They concluded that anthocyanin-rich bilberry extract could act as an effective oral supplement to treat pruritic symptoms of skin disorders such as chronic allergic contact dermatitis and atopic dermatitis.11

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity

Bilberries, consumed since ancient times, are reputed to function as potent antioxidants because of a wide array of phenolic constituents, and this fruit is gaining interest for use in pharmaceuticals.12

In 2008, Svobodová et al. assessed possible UVA preventive properties of V. myrtillus fruit extract in a human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT), finding that pre- or posttreatment mitigated UVA-induced harm. They also observed a significant decrease in UVA-caused reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and the prevention or attenuation of UVA-stimulated peroxidation of membrane lipids. Intracellular glutathione was also protected. The investigators attributed the array of cytoprotective effects conferred by V. myrtillus extract primarily to its constituent anthocyanins.2 A year later, they found that the phenolic fraction of V. myrtillus fruits inhibited UVB-induced damage to HaCaT keratinocytes in vitro.13

In 2014, Calò and Marabini used HaCaT keratinocytes to ascertain whether a water-soluble V. myrtillus extract could mitigate UVA- and UVB-induced damage. They found that the extract diminished UVB-induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity at lower doses, decreasing lipid peroxidation but exerting no effect on reactive oxygen species generated by UVB. The extract attenuated genotoxicity induced by UVA as well as ROS and apoptosis. Overall, the investigators concluded that V. myrtillus extract demonstrated antioxidant activity, particularly against UVA exposure.14

Four years later, Bucci et al. developed nanoberries, an ultradeformable liposome carrying V. myrtillus ethanolic extract, and determined that the preparation could penetrate the stratum corneum safely and suggested potential for yielding protection against photodamage.15

Skin preparations

In 2021, Tadic et al. developed an oil-in-water (O/W) cream containing wild bilberry leaf extracts and seed oil. The leaves contained copious phenolic acids (particularly chlorogenic acid), flavonoids (especially isoquercetin), and resveratrol. The seed oil was rife with alpha-linolenic, linoleic, and oleic acids. The investigators conducted an in vivo study over 30 days in 25 healthy volunteers (20 women, 5 men; mean age 23.36 ± 0.64 years). They found that the O/W cream successfully increased stratum corneum hydration, enhanced skin barrier function, and maintained skin pH after topical application. The cream was also well tolerated. In vitro assays also indicated that the bilberry isolates displayed notable antioxidant capacity (stronger in the case of the leaves). Tadic et al. suggested that skin disorders characterized by oxidative stress and/or xerosis may be appropriate targets for topically applied bilberry cream.1

Early in 2022, Ruscinc et al. reported on their efforts to incorporate V. myrtillus extract into a multifunctional sunscreen. In vitro and in vivo tests revealed that while sun protection factor was lowered in the presence of the extract, the samples were safe and photostable. The researchers concluded that further study is necessary to elucidate the effect of V. myrtillus extract on photoprotection.16

V. myrtillus has been consumed by human beings for many generations. Skin care formulations based on this ingredient have not been associated with adverse events. Notably, the Environmental Working Group has rated V. myrtillus (bilberry seed) oil as very safe.17

Summary

While research, particularly in the form of randomized controlled trials, is called for, because the fatty acids it contains have been shown to suppress tyrosinase. Currently, this botanical agent seems to be most suited for sensitive, aging skin and for skin with an uneven tone, particularly postinflammatory pigmentation and melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, an SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Tadic VM et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Mar 16;10(3):465.

2. Svobodová A et al. Biofactors. 2008;33(4):249-66.

3. Chu WK et al. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.), in Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, eds., “Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects,” 2nd ed. (Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2011, Chapter 4).

4. Yamaura K et al. Pharmacognosy Res. 2011 Jul;3(3):173-7.

5. Stefanescu BE et al. Molecules. 2019 May 29;24(11):2046.

6. Smeriglio A et al. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2014;14(7):567-84.

7. Ando H et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998 Jul;290(7):375-81.

8. Burdulis D et al. Acta Pol Pharm. 2009 Jul-Aug;66(4):399-408.

9. Bornsek SM et al. Food Chem. 2012 Oct 15;134(4):1878-84.

10. Brasanac-Vukanovic S et al. Molecules. 2018 Jul 26;23(8):1864.

11. Yamaura K et al. J Food Sci. 2012 Dec;77(12):H262-7.

12. Pires TCSP et al. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(16):1917-28.

13. Svobodová A et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2009 Dec;56(3):196-204.

14. Calò R, Marabini L. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014 Mar 5;132:27-35.

15. Bucci P et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Oct;17(5):889-99.

16. Ruscinc N et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jan 13.

17. Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep website. Vaccinium Myrtillus Bilberry Seed Oil. Accessed October 18, 2022.

A member of the Ericaceae family, bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) is native to northern Europe and North America, and its fruit is known to contain myriad polyphenols that display potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity.1,2 Also known as European blueberry or whortleberry, this perennial deciduous shrub is also one of the richest sources of the polyphenolic pigments anthocyanins.3-5 Indeed, anthocyanins impart the blue/black color to bilberries and other berries and are thought to be the primary bioactive constituents of berries associated with numerous health benefits.3,6 They are also known to confer anti-allergic, anticancer, and wound healing activity.4 Overall, bilberry has also been reported to exert anti-inflammatory, lipid-lowering, and antimicrobial activity.3 In this column, the focus will be on the chemical constituents and properties of V. myrtillus that indicate potential or applicability for skin care.

Active ingredients of bilberry

Bilberry seed oil contains unsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid, which exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and contribute to the suppression of tyrosinase. For instance, Ando et al. showed, in 1998, that linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids lighten UV-induced skin hyperpigmentation. Their in vitro experiments using cultured murine melanoma cells and in vivo study of the topical application of either acid to the UV-induced hyperpigmented dorsal skin of guinea pigs revealed pigment-lightening effects that they partly ascribed to inhibited melanin synthesis by active melanocytes and accelerated desquamation of epidermal melanin pigment.7

A 2009 comparative study of the anthocyanin composition as well as antimicrobial and antioxidant activities delivered by bilberry and blueberry fruits and their skins by Burdulis et al. revealed robust functions in both fruits. Cyanidin was found to be an active anthocyanidin in bilberry. Cultivars of both fruits demonstrated antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, with bilberry fruit skin demonstrating potent antiradical activity.8

The anthocyanins of V. myrtillus are reputed to impart protection against cardiovascular disorders, age-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and various degenerative conditions, as well ameliorate neuronal and cognitive brain functions and ocular health.6

In 2012, Bornsek et al. demonstrated that bilberry (and blueberry) anthocyanins function as potent intracellular antioxidants, which may account for their noted health benefits despite relatively low bioavailability.9

Six years later, a chemical composition study of wild bilberry found in Montenegro, Brasanac-Vukanovic et al. determined that chlorogenic acid was the most prevalent phenolic constituent, followed by protocatechuic acid, with resveratrol, isoquercetin, quercetin, and hyperoside also found to be abundant. In vitro assays indicated significant antioxidant activity exhibited by these compounds.10

Activity against allergic contact dermatitis

Yamaura et al. used a mouse model, in 2011, to determine that the anthocyanins from a bilberry extract attenuated various symptoms of chronic allergic contact dermatitis, particularly alleviating pruritus.8 A year later, Yamaura et al. used a BALB/c mouse model of allergic contact dermatitis to compare the antipruritic effect of anthocyanin-rich quality-controlled bilberry extract and anthocyanidin-rich degraded extract. The investigators found that anthocyanins, but not anthocyanidins, derived from bilberry exert an antipruritic effect, likely through their inhibitory action on mast cell degranulation. They concluded that anthocyanin-rich bilberry extract could act as an effective oral supplement to treat pruritic symptoms of skin disorders such as chronic allergic contact dermatitis and atopic dermatitis.11

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity

Bilberries, consumed since ancient times, are reputed to function as potent antioxidants because of a wide array of phenolic constituents, and this fruit is gaining interest for use in pharmaceuticals.12

In 2008, Svobodová et al. assessed possible UVA preventive properties of V. myrtillus fruit extract in a human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT), finding that pre- or posttreatment mitigated UVA-induced harm. They also observed a significant decrease in UVA-caused reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and the prevention or attenuation of UVA-stimulated peroxidation of membrane lipids. Intracellular glutathione was also protected. The investigators attributed the array of cytoprotective effects conferred by V. myrtillus extract primarily to its constituent anthocyanins.2 A year later, they found that the phenolic fraction of V. myrtillus fruits inhibited UVB-induced damage to HaCaT keratinocytes in vitro.13

In 2014, Calò and Marabini used HaCaT keratinocytes to ascertain whether a water-soluble V. myrtillus extract could mitigate UVA- and UVB-induced damage. They found that the extract diminished UVB-induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity at lower doses, decreasing lipid peroxidation but exerting no effect on reactive oxygen species generated by UVB. The extract attenuated genotoxicity induced by UVA as well as ROS and apoptosis. Overall, the investigators concluded that V. myrtillus extract demonstrated antioxidant activity, particularly against UVA exposure.14

Four years later, Bucci et al. developed nanoberries, an ultradeformable liposome carrying V. myrtillus ethanolic extract, and determined that the preparation could penetrate the stratum corneum safely and suggested potential for yielding protection against photodamage.15

Skin preparations

In 2021, Tadic et al. developed an oil-in-water (O/W) cream containing wild bilberry leaf extracts and seed oil. The leaves contained copious phenolic acids (particularly chlorogenic acid), flavonoids (especially isoquercetin), and resveratrol. The seed oil was rife with alpha-linolenic, linoleic, and oleic acids. The investigators conducted an in vivo study over 30 days in 25 healthy volunteers (20 women, 5 men; mean age 23.36 ± 0.64 years). They found that the O/W cream successfully increased stratum corneum hydration, enhanced skin barrier function, and maintained skin pH after topical application. The cream was also well tolerated. In vitro assays also indicated that the bilberry isolates displayed notable antioxidant capacity (stronger in the case of the leaves). Tadic et al. suggested that skin disorders characterized by oxidative stress and/or xerosis may be appropriate targets for topically applied bilberry cream.1

Early in 2022, Ruscinc et al. reported on their efforts to incorporate V. myrtillus extract into a multifunctional sunscreen. In vitro and in vivo tests revealed that while sun protection factor was lowered in the presence of the extract, the samples were safe and photostable. The researchers concluded that further study is necessary to elucidate the effect of V. myrtillus extract on photoprotection.16

V. myrtillus has been consumed by human beings for many generations. Skin care formulations based on this ingredient have not been associated with adverse events. Notably, the Environmental Working Group has rated V. myrtillus (bilberry seed) oil as very safe.17

Summary

While research, particularly in the form of randomized controlled trials, is called for, because the fatty acids it contains have been shown to suppress tyrosinase. Currently, this botanical agent seems to be most suited for sensitive, aging skin and for skin with an uneven tone, particularly postinflammatory pigmentation and melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, an SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Tadic VM et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Mar 16;10(3):465.

2. Svobodová A et al. Biofactors. 2008;33(4):249-66.

3. Chu WK et al. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.), in Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, eds., “Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects,” 2nd ed. (Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2011, Chapter 4).

4. Yamaura K et al. Pharmacognosy Res. 2011 Jul;3(3):173-7.

5. Stefanescu BE et al. Molecules. 2019 May 29;24(11):2046.

6. Smeriglio A et al. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2014;14(7):567-84.

7. Ando H et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998 Jul;290(7):375-81.

8. Burdulis D et al. Acta Pol Pharm. 2009 Jul-Aug;66(4):399-408.

9. Bornsek SM et al. Food Chem. 2012 Oct 15;134(4):1878-84.

10. Brasanac-Vukanovic S et al. Molecules. 2018 Jul 26;23(8):1864.

11. Yamaura K et al. J Food Sci. 2012 Dec;77(12):H262-7.

12. Pires TCSP et al. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(16):1917-28.

13. Svobodová A et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2009 Dec;56(3):196-204.

14. Calò R, Marabini L. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014 Mar 5;132:27-35.

15. Bucci P et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Oct;17(5):889-99.

16. Ruscinc N et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jan 13.

17. Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep website. Vaccinium Myrtillus Bilberry Seed Oil. Accessed October 18, 2022.

A member of the Ericaceae family, bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) is native to northern Europe and North America, and its fruit is known to contain myriad polyphenols that display potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity.1,2 Also known as European blueberry or whortleberry, this perennial deciduous shrub is also one of the richest sources of the polyphenolic pigments anthocyanins.3-5 Indeed, anthocyanins impart the blue/black color to bilberries and other berries and are thought to be the primary bioactive constituents of berries associated with numerous health benefits.3,6 They are also known to confer anti-allergic, anticancer, and wound healing activity.4 Overall, bilberry has also been reported to exert anti-inflammatory, lipid-lowering, and antimicrobial activity.3 In this column, the focus will be on the chemical constituents and properties of V. myrtillus that indicate potential or applicability for skin care.

Active ingredients of bilberry

Bilberry seed oil contains unsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid, which exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and contribute to the suppression of tyrosinase. For instance, Ando et al. showed, in 1998, that linoleic and alpha-linolenic acids lighten UV-induced skin hyperpigmentation. Their in vitro experiments using cultured murine melanoma cells and in vivo study of the topical application of either acid to the UV-induced hyperpigmented dorsal skin of guinea pigs revealed pigment-lightening effects that they partly ascribed to inhibited melanin synthesis by active melanocytes and accelerated desquamation of epidermal melanin pigment.7

A 2009 comparative study of the anthocyanin composition as well as antimicrobial and antioxidant activities delivered by bilberry and blueberry fruits and their skins by Burdulis et al. revealed robust functions in both fruits. Cyanidin was found to be an active anthocyanidin in bilberry. Cultivars of both fruits demonstrated antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, with bilberry fruit skin demonstrating potent antiradical activity.8

The anthocyanins of V. myrtillus are reputed to impart protection against cardiovascular disorders, age-induced oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and various degenerative conditions, as well ameliorate neuronal and cognitive brain functions and ocular health.6

In 2012, Bornsek et al. demonstrated that bilberry (and blueberry) anthocyanins function as potent intracellular antioxidants, which may account for their noted health benefits despite relatively low bioavailability.9

Six years later, a chemical composition study of wild bilberry found in Montenegro, Brasanac-Vukanovic et al. determined that chlorogenic acid was the most prevalent phenolic constituent, followed by protocatechuic acid, with resveratrol, isoquercetin, quercetin, and hyperoside also found to be abundant. In vitro assays indicated significant antioxidant activity exhibited by these compounds.10

Activity against allergic contact dermatitis

Yamaura et al. used a mouse model, in 2011, to determine that the anthocyanins from a bilberry extract attenuated various symptoms of chronic allergic contact dermatitis, particularly alleviating pruritus.8 A year later, Yamaura et al. used a BALB/c mouse model of allergic contact dermatitis to compare the antipruritic effect of anthocyanin-rich quality-controlled bilberry extract and anthocyanidin-rich degraded extract. The investigators found that anthocyanins, but not anthocyanidins, derived from bilberry exert an antipruritic effect, likely through their inhibitory action on mast cell degranulation. They concluded that anthocyanin-rich bilberry extract could act as an effective oral supplement to treat pruritic symptoms of skin disorders such as chronic allergic contact dermatitis and atopic dermatitis.11

Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity

Bilberries, consumed since ancient times, are reputed to function as potent antioxidants because of a wide array of phenolic constituents, and this fruit is gaining interest for use in pharmaceuticals.12

In 2008, Svobodová et al. assessed possible UVA preventive properties of V. myrtillus fruit extract in a human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT), finding that pre- or posttreatment mitigated UVA-induced harm. They also observed a significant decrease in UVA-caused reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation and the prevention or attenuation of UVA-stimulated peroxidation of membrane lipids. Intracellular glutathione was also protected. The investigators attributed the array of cytoprotective effects conferred by V. myrtillus extract primarily to its constituent anthocyanins.2 A year later, they found that the phenolic fraction of V. myrtillus fruits inhibited UVB-induced damage to HaCaT keratinocytes in vitro.13

In 2014, Calò and Marabini used HaCaT keratinocytes to ascertain whether a water-soluble V. myrtillus extract could mitigate UVA- and UVB-induced damage. They found that the extract diminished UVB-induced cytotoxicity and genotoxicity at lower doses, decreasing lipid peroxidation but exerting no effect on reactive oxygen species generated by UVB. The extract attenuated genotoxicity induced by UVA as well as ROS and apoptosis. Overall, the investigators concluded that V. myrtillus extract demonstrated antioxidant activity, particularly against UVA exposure.14

Four years later, Bucci et al. developed nanoberries, an ultradeformable liposome carrying V. myrtillus ethanolic extract, and determined that the preparation could penetrate the stratum corneum safely and suggested potential for yielding protection against photodamage.15

Skin preparations

In 2021, Tadic et al. developed an oil-in-water (O/W) cream containing wild bilberry leaf extracts and seed oil. The leaves contained copious phenolic acids (particularly chlorogenic acid), flavonoids (especially isoquercetin), and resveratrol. The seed oil was rife with alpha-linolenic, linoleic, and oleic acids. The investigators conducted an in vivo study over 30 days in 25 healthy volunteers (20 women, 5 men; mean age 23.36 ± 0.64 years). They found that the O/W cream successfully increased stratum corneum hydration, enhanced skin barrier function, and maintained skin pH after topical application. The cream was also well tolerated. In vitro assays also indicated that the bilberry isolates displayed notable antioxidant capacity (stronger in the case of the leaves). Tadic et al. suggested that skin disorders characterized by oxidative stress and/or xerosis may be appropriate targets for topically applied bilberry cream.1

Early in 2022, Ruscinc et al. reported on their efforts to incorporate V. myrtillus extract into a multifunctional sunscreen. In vitro and in vivo tests revealed that while sun protection factor was lowered in the presence of the extract, the samples were safe and photostable. The researchers concluded that further study is necessary to elucidate the effect of V. myrtillus extract on photoprotection.16

V. myrtillus has been consumed by human beings for many generations. Skin care formulations based on this ingredient have not been associated with adverse events. Notably, the Environmental Working Group has rated V. myrtillus (bilberry seed) oil as very safe.17

Summary

While research, particularly in the form of randomized controlled trials, is called for, because the fatty acids it contains have been shown to suppress tyrosinase. Currently, this botanical agent seems to be most suited for sensitive, aging skin and for skin with an uneven tone, particularly postinflammatory pigmentation and melasma.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur in Miami. She founded the division of cosmetic dermatology at the University of Miami in 1997. The third edition of her bestselling textbook, “Cosmetic Dermatology,” was published in 2022. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions, an SaaS company used to generate skin care routines in office and as an ecommerce solution. Write to her at [email protected].

References

1. Tadic VM et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021 Mar 16;10(3):465.

2. Svobodová A et al. Biofactors. 2008;33(4):249-66.

3. Chu WK et al. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.), in Benzie IFF, Wachtel-Galor S, eds., “Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects,” 2nd ed. (Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis, 2011, Chapter 4).

4. Yamaura K et al. Pharmacognosy Res. 2011 Jul;3(3):173-7.

5. Stefanescu BE et al. Molecules. 2019 May 29;24(11):2046.

6. Smeriglio A et al. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2014;14(7):567-84.

7. Ando H et al. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998 Jul;290(7):375-81.

8. Burdulis D et al. Acta Pol Pharm. 2009 Jul-Aug;66(4):399-408.

9. Bornsek SM et al. Food Chem. 2012 Oct 15;134(4):1878-84.

10. Brasanac-Vukanovic S et al. Molecules. 2018 Jul 26;23(8):1864.

11. Yamaura K et al. J Food Sci. 2012 Dec;77(12):H262-7.

12. Pires TCSP et al. Curr Pharm Des. 2020;26(16):1917-28.

13. Svobodová A et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2009 Dec;56(3):196-204.

14. Calò R, Marabini L. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014 Mar 5;132:27-35.

15. Bucci P et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Oct;17(5):889-99.

16. Ruscinc N et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jan 13.

17. Environmental Working Group’s Skin Deep website. Vaccinium Myrtillus Bilberry Seed Oil. Accessed October 18, 2022.

Combination of energy-based treatments found to improve Becker’s nevi

Denver – out to 40 weeks, results of a small retrospective case series demonstrated.

During an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, presenting author Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said that NAFR and LHR target the clinically bothersome Becker’s nevi features of hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis via different mechanisms. “NAFR creates microcolumns of thermal injury in the skin, which improves hyperpigmentation,” explained Dr. Kubicki, a 3rd-year dermatology resident at University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston.

“LHR targets follicular melanocytes, which are located more deeply in the dermis,” she said. “This improves hypertrichosis and likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting these melanocytes that are not reached by NAFR.”

Dr. Kubicki and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed 12 patients with Becker’s nevus who underwent a mean of 5.3 NAFR treatments at a single dermatology practice at intervals that ranged between 1 and 4 months. The long-pulsed 755-nm alexandrite laser was used for study participants with skin types I-III, while the long-pulsed 1,064-nm Nd: YAG laser was used for those with skin types IV-VI. Ten of the 12 patients underwent concomitant LHR with one of the two devices and three independent physicians used a 5-point visual analog scale (VAS) to rate clinical photographs. All patients completed a strict pre- and postoperative regimen with either 4% hydroquinone or topical 3% tranexamic acid and broad-spectrum sunscreen and postoperative treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid for 3 days.

The study is the largest known case series of therapy combining 1,550-nm NAFR and LHR for Becker’s nevus patients with skin types III-VI.

After comparing VAS scores at baseline and follow-up, physicians rated the cosmetic appearance of Becker’s nevus as improving by a range of 51%-75%. Two patients did not undergo LHR: one male patient with Becker’s nevus in his beard region, for whom LHR was undesirable, and a second patient with atrichotic Becker’s nevus. These two patients demonstrated improvements in VAS scores of 26%-50% and 76%-99%, respectively.

No long-term adverse events were observed during follow-up, which ranged from 6 to 40 weeks. “We do want more long-term follow-up,” Dr. Kubicki said, noting that there are more data on some patients to extend the follow-up.

She and her coinvestigators concluded that the results show that treatment with a combination of NAFR and LHR safely addresses both hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis in Becker’s nevi. “In addition, LHR likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting follicular melanocytes,” she said. “In our study, we did have one patient experience recurrence of a Becker’s nevus during follow-up, but [the rest] did not, which we considered a success.”

Vincent Richer, MD, a Vancouver-based medical and cosmetic dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized Becker’s nevus as a difficult-to-treat condition that is made even more difficult to treat in skin types III-VI.

“Combining laser hair removal using appropriate wavelengths with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing yielded good clinical results with few recurrences,” he said in an interview with this news organization. “Though it was a small series, it definitely is an interesting option for practicing dermatologists who encounter patients interested in improving the appearance of a Becker’s nevus.”

The researchers reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Richer disclosed that he performs clinical trials for AbbVie/Allergan, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and is a member of advisory boards for Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, and Sanofi. He is also a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, Merz, and Sanofi.

Denver – out to 40 weeks, results of a small retrospective case series demonstrated.

During an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, presenting author Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said that NAFR and LHR target the clinically bothersome Becker’s nevi features of hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis via different mechanisms. “NAFR creates microcolumns of thermal injury in the skin, which improves hyperpigmentation,” explained Dr. Kubicki, a 3rd-year dermatology resident at University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston.

“LHR targets follicular melanocytes, which are located more deeply in the dermis,” she said. “This improves hypertrichosis and likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting these melanocytes that are not reached by NAFR.”

Dr. Kubicki and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed 12 patients with Becker’s nevus who underwent a mean of 5.3 NAFR treatments at a single dermatology practice at intervals that ranged between 1 and 4 months. The long-pulsed 755-nm alexandrite laser was used for study participants with skin types I-III, while the long-pulsed 1,064-nm Nd: YAG laser was used for those with skin types IV-VI. Ten of the 12 patients underwent concomitant LHR with one of the two devices and three independent physicians used a 5-point visual analog scale (VAS) to rate clinical photographs. All patients completed a strict pre- and postoperative regimen with either 4% hydroquinone or topical 3% tranexamic acid and broad-spectrum sunscreen and postoperative treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid for 3 days.

The study is the largest known case series of therapy combining 1,550-nm NAFR and LHR for Becker’s nevus patients with skin types III-VI.

After comparing VAS scores at baseline and follow-up, physicians rated the cosmetic appearance of Becker’s nevus as improving by a range of 51%-75%. Two patients did not undergo LHR: one male patient with Becker’s nevus in his beard region, for whom LHR was undesirable, and a second patient with atrichotic Becker’s nevus. These two patients demonstrated improvements in VAS scores of 26%-50% and 76%-99%, respectively.

No long-term adverse events were observed during follow-up, which ranged from 6 to 40 weeks. “We do want more long-term follow-up,” Dr. Kubicki said, noting that there are more data on some patients to extend the follow-up.

She and her coinvestigators concluded that the results show that treatment with a combination of NAFR and LHR safely addresses both hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis in Becker’s nevi. “In addition, LHR likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting follicular melanocytes,” she said. “In our study, we did have one patient experience recurrence of a Becker’s nevus during follow-up, but [the rest] did not, which we considered a success.”

Vincent Richer, MD, a Vancouver-based medical and cosmetic dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized Becker’s nevus as a difficult-to-treat condition that is made even more difficult to treat in skin types III-VI.

“Combining laser hair removal using appropriate wavelengths with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing yielded good clinical results with few recurrences,” he said in an interview with this news organization. “Though it was a small series, it definitely is an interesting option for practicing dermatologists who encounter patients interested in improving the appearance of a Becker’s nevus.”

The researchers reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Richer disclosed that he performs clinical trials for AbbVie/Allergan, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and is a member of advisory boards for Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, and Sanofi. He is also a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, Merz, and Sanofi.

Denver – out to 40 weeks, results of a small retrospective case series demonstrated.

During an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, presenting author Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said that NAFR and LHR target the clinically bothersome Becker’s nevi features of hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis via different mechanisms. “NAFR creates microcolumns of thermal injury in the skin, which improves hyperpigmentation,” explained Dr. Kubicki, a 3rd-year dermatology resident at University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston.

“LHR targets follicular melanocytes, which are located more deeply in the dermis,” she said. “This improves hypertrichosis and likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting these melanocytes that are not reached by NAFR.”

Dr. Kubicki and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed 12 patients with Becker’s nevus who underwent a mean of 5.3 NAFR treatments at a single dermatology practice at intervals that ranged between 1 and 4 months. The long-pulsed 755-nm alexandrite laser was used for study participants with skin types I-III, while the long-pulsed 1,064-nm Nd: YAG laser was used for those with skin types IV-VI. Ten of the 12 patients underwent concomitant LHR with one of the two devices and three independent physicians used a 5-point visual analog scale (VAS) to rate clinical photographs. All patients completed a strict pre- and postoperative regimen with either 4% hydroquinone or topical 3% tranexamic acid and broad-spectrum sunscreen and postoperative treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid for 3 days.

The study is the largest known case series of therapy combining 1,550-nm NAFR and LHR for Becker’s nevus patients with skin types III-VI.

After comparing VAS scores at baseline and follow-up, physicians rated the cosmetic appearance of Becker’s nevus as improving by a range of 51%-75%. Two patients did not undergo LHR: one male patient with Becker’s nevus in his beard region, for whom LHR was undesirable, and a second patient with atrichotic Becker’s nevus. These two patients demonstrated improvements in VAS scores of 26%-50% and 76%-99%, respectively.

No long-term adverse events were observed during follow-up, which ranged from 6 to 40 weeks. “We do want more long-term follow-up,” Dr. Kubicki said, noting that there are more data on some patients to extend the follow-up.

She and her coinvestigators concluded that the results show that treatment with a combination of NAFR and LHR safely addresses both hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis in Becker’s nevi. “In addition, LHR likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting follicular melanocytes,” she said. “In our study, we did have one patient experience recurrence of a Becker’s nevus during follow-up, but [the rest] did not, which we considered a success.”

Vincent Richer, MD, a Vancouver-based medical and cosmetic dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized Becker’s nevus as a difficult-to-treat condition that is made even more difficult to treat in skin types III-VI.

“Combining laser hair removal using appropriate wavelengths with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing yielded good clinical results with few recurrences,” he said in an interview with this news organization. “Though it was a small series, it definitely is an interesting option for practicing dermatologists who encounter patients interested in improving the appearance of a Becker’s nevus.”

The researchers reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Richer disclosed that he performs clinical trials for AbbVie/Allergan, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and is a member of advisory boards for Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, and Sanofi. He is also a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, Merz, and Sanofi.

AT ASDS 2022

Unusual Bilateral Distribution of Neurofibromatosis Type 5 on the Distal Upper Extremities

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

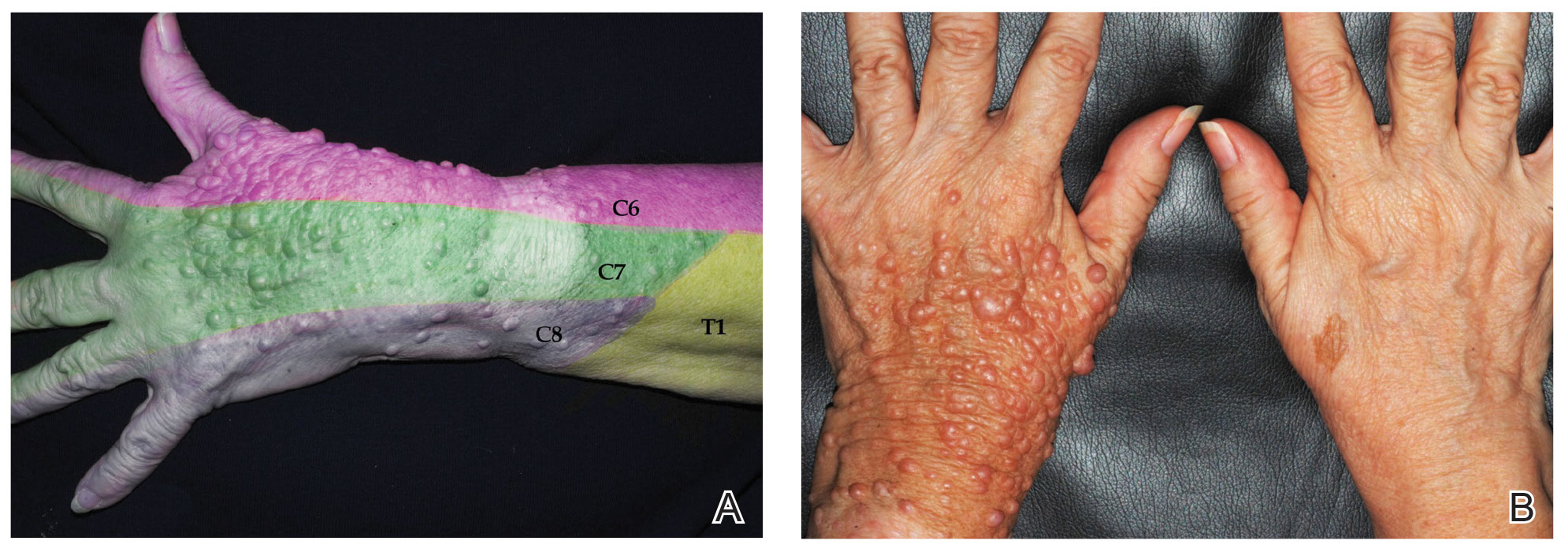

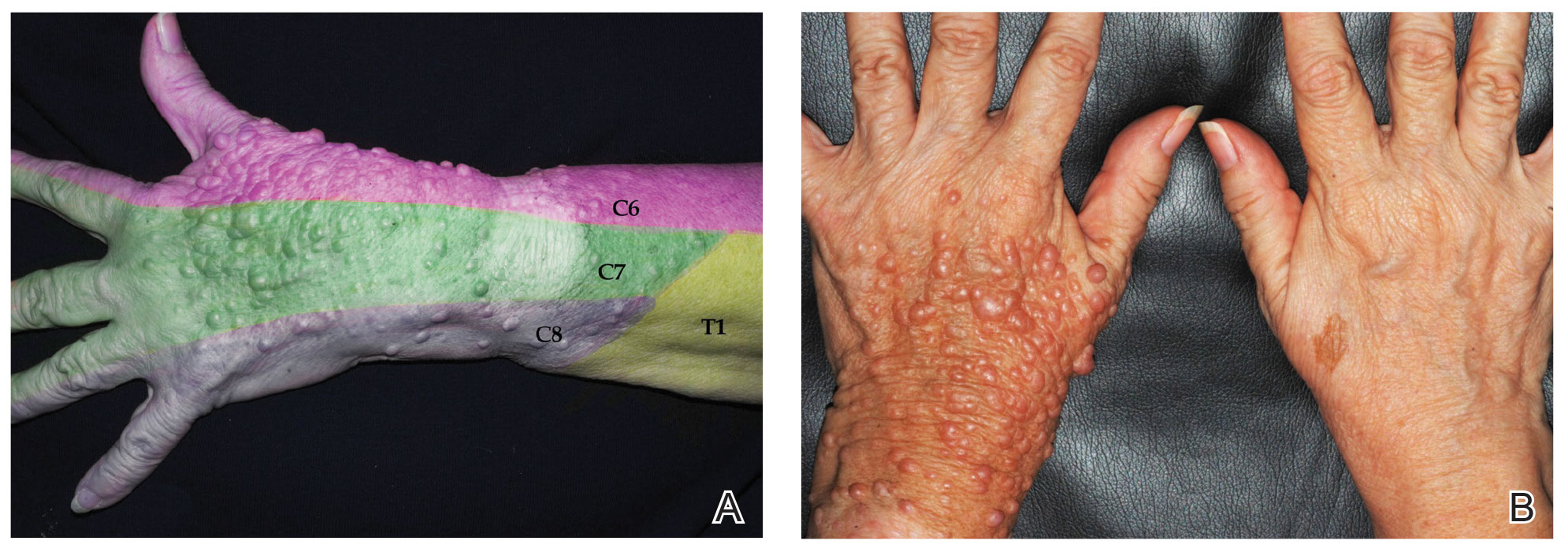

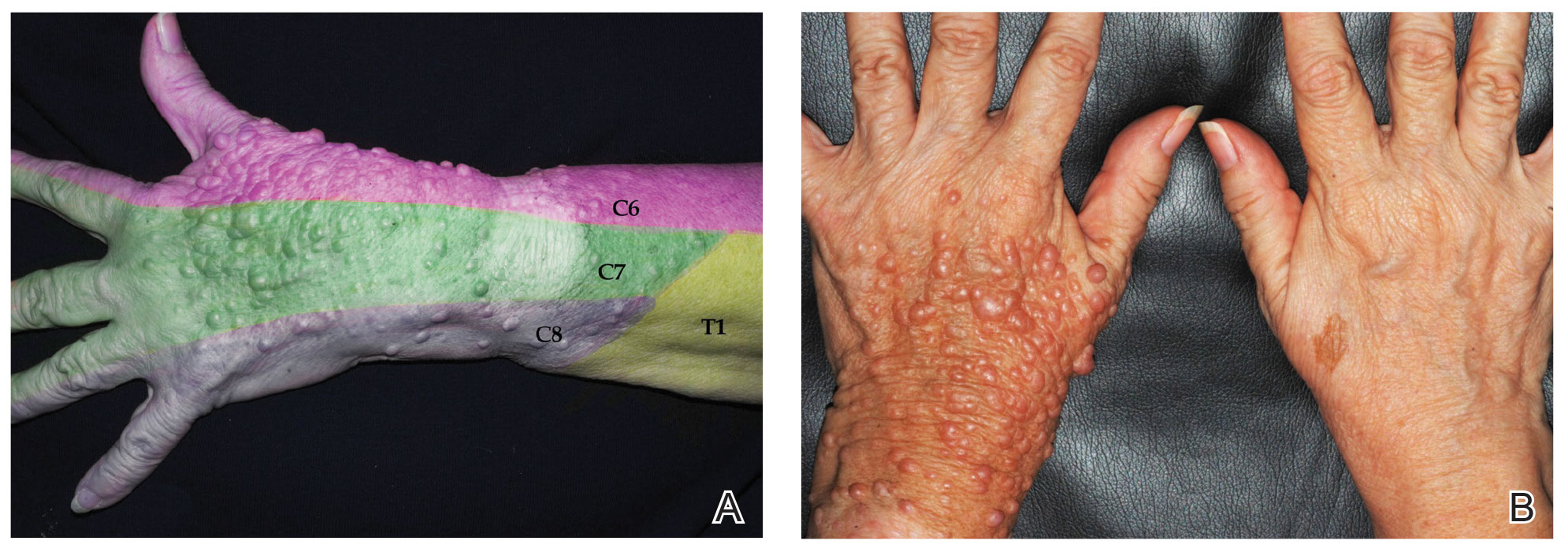

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

Practice Points

- Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosistype 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease).

- Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. This is in contrast to the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells.

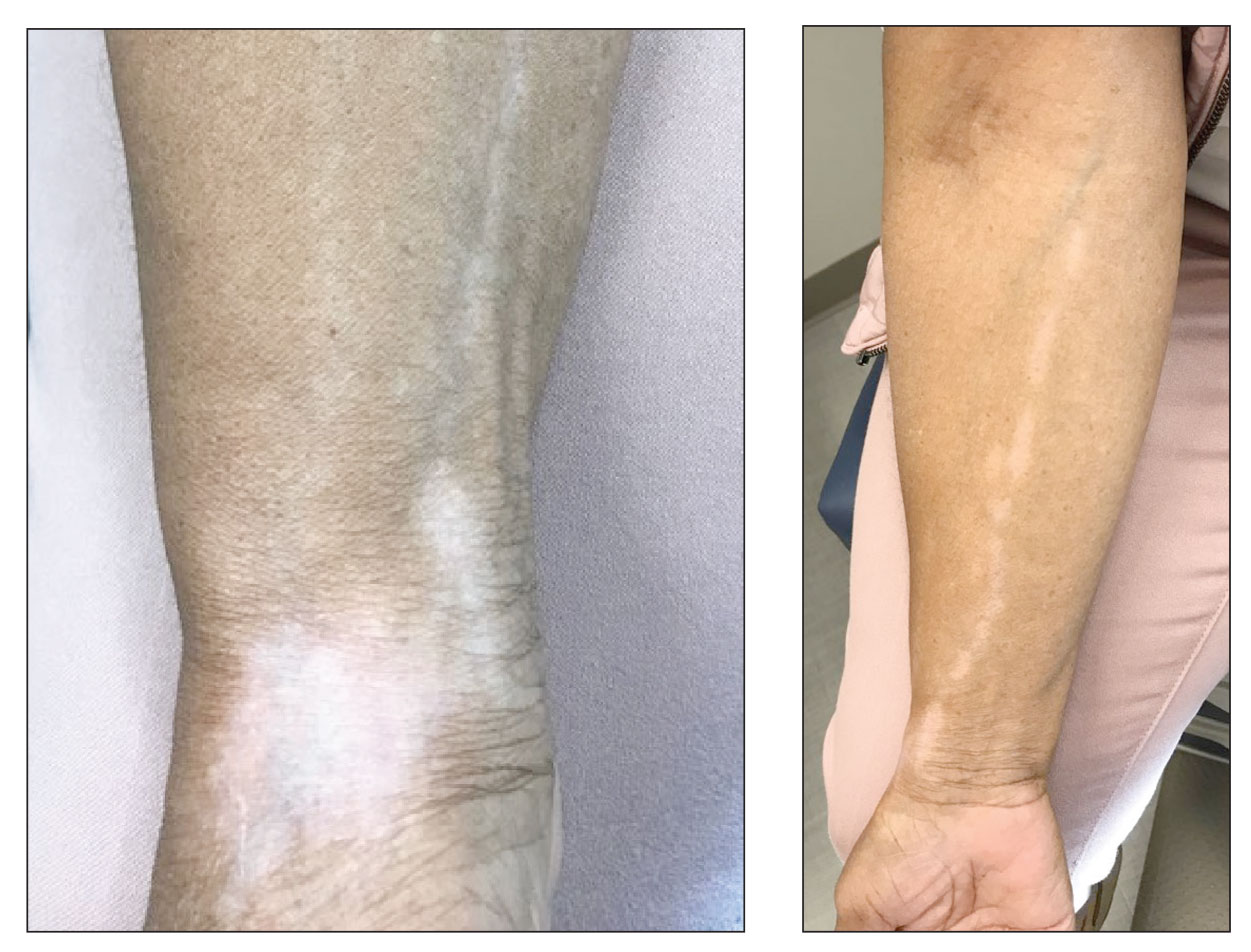

Ruxolitinib repigments many vitiligo-affected body areas

.

Those difficult areas include the hands and feet, said Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, of Université Côte d’Azur and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice (France).

Indeed, a 50% or greater improvement in the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI-50) of the hands and feet was achieved with ruxolitinib cream (Opzelura) in around one-third of patients after 52 weeks’ treatment, and more than half of patients showed improvement in the upper and lower extremities.

During one of the late-breaking news sessions, Dr. Passeron presented a pooled analysis of the Topical Ruxolitinib Evaluation in Vitiligo Study 1 (TRuE-V1) and Study 2 (TruE-V2), which assessed VASI-50 data by body regions.

Similarly positive results were seen on the head and neck and the trunk, with VASI-50 being reached in a respective 68% and 48% of patients after a full year of treatment.

“VASI-50 response rates rose steadily through 52 weeks for both the head and trunk,” said Dr. Passeron. He noted that the trials were initially double-blinded for 24 weeks and that there was a further open-label extension phase through week 52.

In the latter phase, all patients were treated with ruxolitinib; those who originally received a vehicle agent as placebo crossed over to the active treatment.

First FDA-approved treatment for adults and adolescents with vitiligo

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor that has been available for the treatment for atopic dermatitis for more than a year. It was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of vitiligo in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older.

This approval was based on the positive findings of the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which showed that after 24 weeks, 30% of patients treated with ruxolitinib had at least 75% improvement in the facial VASI, compared with 10% of placebo-treated patients.

“These studies demonstrated very nice results, especially on the face, which is the easiest part to repigment in vitiligo,” Dr. Passeron said.

“We know that the location is very important when it comes to repigmentation of vitiligo,” he added. He noted that other body areas, “the extremities, for example, are much more difficult.”

The analysis he presented specifically assessed the effect of ruxolitinib cream on repigmentation in other areas.

Pooled analysis performed

Data from the two TRuE-V trials were pooled. The new analysis included a total of 661 individuals; of those patients, 443 had been treated with topical ruxolitinib, and 218 had received a vehicle cream as a placebo.

For the first 24 weeks, patients received twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream. This was followed by a 28-week extension phase in which everyone was treated with ruxolitinib cream, after which there was a 30-day final follow-up period.

Dr. Passeron reported data by body region for weeks 12, 24, and 52, which showed an increasing percentage of patients with VASI-50.

“We didn’t look at the face; that we know well, that is a very good result,” he said.

The best results were seen for the head and neck. VASI-50 was reached by 28.3%, 45.3%, and 68.1% of patients treated with ruxolitinib cream at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. Corresponding rates for the placebo-crossover group were 19.8%, 23.8%, and 51%.

Repigmentation rates of the hand, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet were about 9%-15% for both ruxolitinib and placebo at 12 weeks, but by 24 weeks, there was a clear increase in repigmentation rates in the ruxolitinib group for all body areas.

The 24-week VASI-50 rates for hand repigmentation were 24.9% for ruxolitinib cream and 14.4% for placebo. Corresponding rates for upper extremity repigmentation were 33.2% and 8.2%; for the trunk, 26.4% and 12.2%; for the lower extremities, 29.5% and 12.2%; and for the feet, 18.5% and 12.5%.

“The results are quite poor at 12 weeks,” Dr. Passeron said. “It’s very important to keep this in mind; it takes time to repigment vitiligo, it takes to 6-24 months. We have to explain to our patients that they will have to wait to see the results.”

Steady improvements, no new safety concerns

Regarding VASI-50 over time, there was a steady increase in total body scores; 47.7% of patients who received ruxolitinib and 23.3% of placebo-treated patients hit this target at 52 weeks.

“And what is also very important to see is that we didn’t reach the plateau,” Dr. Passeron reported.

Similar patterns were seen for all the other body areas. Again there was a suggestion that rates may continue to rise with continued long-term treatment.

“About one-third of the patients reached at least 50% repigmentation after 1 year of treatment in the hands and feet,” Dr. Passeron said. He noted that certain areas, such as the back of the hand or tips of the fingers, may be unresponsive.

“So, we have to also to warn the patient that probably on these areas we have to combine it with other treatment because it remains very, very difficult to treat.”

There were no new safety concerns regarding treatment-emergent adverse events, which were reported in 52% of patients who received ruxolitinib and in 36% of placebo-treated patients.

The most common adverse reactions included COVID-19 (6.1% vs. 3.1%), acne at the application site (5.3% vs. 1.3%), and pruritus at the application site (3.9% vs. 2.7%), although cases were “mild or moderate,” said Dr. Passeron.

An expert’s take-home

“The results of TRuE-V phase 3 studies are encouraging and exciting,” Viktoria Eleftheriadou, MD, MRCP(UK), SCE(Derm), PhD, said in providing an independent comment for this news organization.

“Although ruxolitinib cream is applied on the skin, this novel treatment for vitiligo is not without risks; therefore, careful monitoring of patients who are started on this topical treatment would be prudent,” said Dr. Eleftheriadou, who is a consultant dermatologist for Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust and the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

“I would like to see how many patients achieved VASI-75 or VASI-80 score, which from patients’ perspectives is a more meaningful outcome, as well as how long these results will last for,” she added.

The study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Dr. Passeron has received grants, honoraria, or both from AbbVie, ACM Pharma, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte Corporation, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and UCB. Dr. Passeron is the cofounder of YUKIN Therapeutics and has patents on WNT agonists or GSK2b antagonist for repigmentation of vitiligo and on the use of CXCR3B blockers in vitiligo. Dr. Eleftheriadou is an investigator and trial development group member on the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial (specific), a lead investigator on the pilot HI-Light Vitiligo Trial, and a medical advisory panel member of the Vitiligo Society UK. Dr. Eleftheriadou also provides consultancy services to Incyte and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Those difficult areas include the hands and feet, said Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, of Université Côte d’Azur and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice (France).

Indeed, a 50% or greater improvement in the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI-50) of the hands and feet was achieved with ruxolitinib cream (Opzelura) in around one-third of patients after 52 weeks’ treatment, and more than half of patients showed improvement in the upper and lower extremities.

During one of the late-breaking news sessions, Dr. Passeron presented a pooled analysis of the Topical Ruxolitinib Evaluation in Vitiligo Study 1 (TRuE-V1) and Study 2 (TruE-V2), which assessed VASI-50 data by body regions.

Similarly positive results were seen on the head and neck and the trunk, with VASI-50 being reached in a respective 68% and 48% of patients after a full year of treatment.

“VASI-50 response rates rose steadily through 52 weeks for both the head and trunk,” said Dr. Passeron. He noted that the trials were initially double-blinded for 24 weeks and that there was a further open-label extension phase through week 52.

In the latter phase, all patients were treated with ruxolitinib; those who originally received a vehicle agent as placebo crossed over to the active treatment.

First FDA-approved treatment for adults and adolescents with vitiligo

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor that has been available for the treatment for atopic dermatitis for more than a year. It was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of vitiligo in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older.

This approval was based on the positive findings of the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which showed that after 24 weeks, 30% of patients treated with ruxolitinib had at least 75% improvement in the facial VASI, compared with 10% of placebo-treated patients.

“These studies demonstrated very nice results, especially on the face, which is the easiest part to repigment in vitiligo,” Dr. Passeron said.

“We know that the location is very important when it comes to repigmentation of vitiligo,” he added. He noted that other body areas, “the extremities, for example, are much more difficult.”

The analysis he presented specifically assessed the effect of ruxolitinib cream on repigmentation in other areas.

Pooled analysis performed

Data from the two TRuE-V trials were pooled. The new analysis included a total of 661 individuals; of those patients, 443 had been treated with topical ruxolitinib, and 218 had received a vehicle cream as a placebo.

For the first 24 weeks, patients received twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream. This was followed by a 28-week extension phase in which everyone was treated with ruxolitinib cream, after which there was a 30-day final follow-up period.

Dr. Passeron reported data by body region for weeks 12, 24, and 52, which showed an increasing percentage of patients with VASI-50.

“We didn’t look at the face; that we know well, that is a very good result,” he said.

The best results were seen for the head and neck. VASI-50 was reached by 28.3%, 45.3%, and 68.1% of patients treated with ruxolitinib cream at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. Corresponding rates for the placebo-crossover group were 19.8%, 23.8%, and 51%.

Repigmentation rates of the hand, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet were about 9%-15% for both ruxolitinib and placebo at 12 weeks, but by 24 weeks, there was a clear increase in repigmentation rates in the ruxolitinib group for all body areas.

The 24-week VASI-50 rates for hand repigmentation were 24.9% for ruxolitinib cream and 14.4% for placebo. Corresponding rates for upper extremity repigmentation were 33.2% and 8.2%; for the trunk, 26.4% and 12.2%; for the lower extremities, 29.5% and 12.2%; and for the feet, 18.5% and 12.5%.

“The results are quite poor at 12 weeks,” Dr. Passeron said. “It’s very important to keep this in mind; it takes time to repigment vitiligo, it takes to 6-24 months. We have to explain to our patients that they will have to wait to see the results.”

Steady improvements, no new safety concerns

Regarding VASI-50 over time, there was a steady increase in total body scores; 47.7% of patients who received ruxolitinib and 23.3% of placebo-treated patients hit this target at 52 weeks.

“And what is also very important to see is that we didn’t reach the plateau,” Dr. Passeron reported.

Similar patterns were seen for all the other body areas. Again there was a suggestion that rates may continue to rise with continued long-term treatment.

“About one-third of the patients reached at least 50% repigmentation after 1 year of treatment in the hands and feet,” Dr. Passeron said. He noted that certain areas, such as the back of the hand or tips of the fingers, may be unresponsive.

“So, we have to also to warn the patient that probably on these areas we have to combine it with other treatment because it remains very, very difficult to treat.”

There were no new safety concerns regarding treatment-emergent adverse events, which were reported in 52% of patients who received ruxolitinib and in 36% of placebo-treated patients.

The most common adverse reactions included COVID-19 (6.1% vs. 3.1%), acne at the application site (5.3% vs. 1.3%), and pruritus at the application site (3.9% vs. 2.7%), although cases were “mild or moderate,” said Dr. Passeron.

An expert’s take-home

“The results of TRuE-V phase 3 studies are encouraging and exciting,” Viktoria Eleftheriadou, MD, MRCP(UK), SCE(Derm), PhD, said in providing an independent comment for this news organization.

“Although ruxolitinib cream is applied on the skin, this novel treatment for vitiligo is not without risks; therefore, careful monitoring of patients who are started on this topical treatment would be prudent,” said Dr. Eleftheriadou, who is a consultant dermatologist for Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust and the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

“I would like to see how many patients achieved VASI-75 or VASI-80 score, which from patients’ perspectives is a more meaningful outcome, as well as how long these results will last for,” she added.

The study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Dr. Passeron has received grants, honoraria, or both from AbbVie, ACM Pharma, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte Corporation, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and UCB. Dr. Passeron is the cofounder of YUKIN Therapeutics and has patents on WNT agonists or GSK2b antagonist for repigmentation of vitiligo and on the use of CXCR3B blockers in vitiligo. Dr. Eleftheriadou is an investigator and trial development group member on the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial (specific), a lead investigator on the pilot HI-Light Vitiligo Trial, and a medical advisory panel member of the Vitiligo Society UK. Dr. Eleftheriadou also provides consultancy services to Incyte and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Those difficult areas include the hands and feet, said Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, of Université Côte d’Azur and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice (France).

Indeed, a 50% or greater improvement in the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI-50) of the hands and feet was achieved with ruxolitinib cream (Opzelura) in around one-third of patients after 52 weeks’ treatment, and more than half of patients showed improvement in the upper and lower extremities.

During one of the late-breaking news sessions, Dr. Passeron presented a pooled analysis of the Topical Ruxolitinib Evaluation in Vitiligo Study 1 (TRuE-V1) and Study 2 (TruE-V2), which assessed VASI-50 data by body regions.

Similarly positive results were seen on the head and neck and the trunk, with VASI-50 being reached in a respective 68% and 48% of patients after a full year of treatment.

“VASI-50 response rates rose steadily through 52 weeks for both the head and trunk,” said Dr. Passeron. He noted that the trials were initially double-blinded for 24 weeks and that there was a further open-label extension phase through week 52.

In the latter phase, all patients were treated with ruxolitinib; those who originally received a vehicle agent as placebo crossed over to the active treatment.

First FDA-approved treatment for adults and adolescents with vitiligo

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor that has been available for the treatment for atopic dermatitis for more than a year. It was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of vitiligo in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older.

This approval was based on the positive findings of the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which showed that after 24 weeks, 30% of patients treated with ruxolitinib had at least 75% improvement in the facial VASI, compared with 10% of placebo-treated patients.

“These studies demonstrated very nice results, especially on the face, which is the easiest part to repigment in vitiligo,” Dr. Passeron said.

“We know that the location is very important when it comes to repigmentation of vitiligo,” he added. He noted that other body areas, “the extremities, for example, are much more difficult.”

The analysis he presented specifically assessed the effect of ruxolitinib cream on repigmentation in other areas.

Pooled analysis performed

Data from the two TRuE-V trials were pooled. The new analysis included a total of 661 individuals; of those patients, 443 had been treated with topical ruxolitinib, and 218 had received a vehicle cream as a placebo.

For the first 24 weeks, patients received twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream. This was followed by a 28-week extension phase in which everyone was treated with ruxolitinib cream, after which there was a 30-day final follow-up period.

Dr. Passeron reported data by body region for weeks 12, 24, and 52, which showed an increasing percentage of patients with VASI-50.

“We didn’t look at the face; that we know well, that is a very good result,” he said.

The best results were seen for the head and neck. VASI-50 was reached by 28.3%, 45.3%, and 68.1% of patients treated with ruxolitinib cream at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. Corresponding rates for the placebo-crossover group were 19.8%, 23.8%, and 51%.

Repigmentation rates of the hand, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet were about 9%-15% for both ruxolitinib and placebo at 12 weeks, but by 24 weeks, there was a clear increase in repigmentation rates in the ruxolitinib group for all body areas.