User login

FDA approves Yuflyma as ninth adalimumab biosimilar

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the biosimilar adalimumab-aaty (Yuflyma) in a citrate-free, high-concentration formulation, the manufacturer, Celltrion USA, announced today. It is the ninth biosimilar of adalimumab (Humira) to be approved in the United States.

Yuflyma is approved for the treatment of adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. It is also approved for polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis for patients aged 2 years or older, as well as for Crohn’s disease in adults and in pediatric patients aged 6 years or older.

The formulation was approved on the basis of a comprehensive data package of analytic, preclinical, and clinical studies, according to Celltrion USA, “demonstrating that Yuflyma is comparable to the reference product Humira in terms of efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity up to 24 weeks and 1 year following treatment.”

The company conducted a double-blind, randomized phase 3 trial that compared switching from reference adalimumab to Yuflyma with continuing either reference adalimumab or Yuflyma for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. In that trial, the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, safety, and immunogenicity of Yuflyma and reference adalimumab were comparable after 1 year of treatment, including after switching from reference adalimumab to Yuflyma.

“Currently, more than 80% of patients treated with Humira in the United States rely on a high-concentration and citrate-free formulation of this medication. The availability of a high-concentration and citrate-free formulation adalimumab biosimilar provides an important treatment option for patients with inflammatory diseases who benefit from this effective therapy,” said Jonathan Kay, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, in the press release.

The citrate-free formulation is thought to lead to less pain on injection.

Yuflyma will be available in prefilled syringe and autoinjector administration options.

Celltrion USA plans to market the drug in the United States in July 2023. Following the initial launch of 40 mg/0.4 mL, the company plans to launch dose forms of 80 mg/0.8 mL and 20 mg/0.2 mL.

Celltrion USA is also seeking an interchangeability designation from the FDA following the completion of an interchangeability trial of 366 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The interchangeability designation would mean that patients successfully switched from Humira to Yuflyma multiple times in the trial. The interchangeability designation would allow pharmacists to autosubstitute Humira with Yuflyma. In these cases, individual state laws control how and whether physicians will be notified of this switch.

If interchangeability is approved for Yuflyma, which the company tentatively expects in the fourth quarter of 2024, it would be just the third interchangeable biosimilar approved by the FDA overall and the second adalimumab biosimilar to be designated as such, after adalimumab-adbm (Cyltezo) in October 2021.

Yuflyma was approved in Canada in December 2021 for 10 indications: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, adult ulcerative colitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, plaque psoriasis, adult uveitis, and pediatric uveitis.

In February 2022, the European Commission granted marketing authorization for Yuflyma across those 10 indications, as well as for nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis, pediatric plaque psoriasis, and pediatric Crohn’s disease.

In April 2022, Celltrion USA signed a licensing agreement with AbbVie, the manufacturer of Humira. Under that agreement, Celltrion will pay royalties to AbbVie on sales of their individual biosimilars, and AbbVie agreed to drop all patent litigation.

The full prescribing information for Yuflyma is available here.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the biosimilar adalimumab-aaty (Yuflyma) in a citrate-free, high-concentration formulation, the manufacturer, Celltrion USA, announced today. It is the ninth biosimilar of adalimumab (Humira) to be approved in the United States.

Yuflyma is approved for the treatment of adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. It is also approved for polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis for patients aged 2 years or older, as well as for Crohn’s disease in adults and in pediatric patients aged 6 years or older.

The formulation was approved on the basis of a comprehensive data package of analytic, preclinical, and clinical studies, according to Celltrion USA, “demonstrating that Yuflyma is comparable to the reference product Humira in terms of efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity up to 24 weeks and 1 year following treatment.”

The company conducted a double-blind, randomized phase 3 trial that compared switching from reference adalimumab to Yuflyma with continuing either reference adalimumab or Yuflyma for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. In that trial, the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, safety, and immunogenicity of Yuflyma and reference adalimumab were comparable after 1 year of treatment, including after switching from reference adalimumab to Yuflyma.

“Currently, more than 80% of patients treated with Humira in the United States rely on a high-concentration and citrate-free formulation of this medication. The availability of a high-concentration and citrate-free formulation adalimumab biosimilar provides an important treatment option for patients with inflammatory diseases who benefit from this effective therapy,” said Jonathan Kay, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, in the press release.

The citrate-free formulation is thought to lead to less pain on injection.

Yuflyma will be available in prefilled syringe and autoinjector administration options.

Celltrion USA plans to market the drug in the United States in July 2023. Following the initial launch of 40 mg/0.4 mL, the company plans to launch dose forms of 80 mg/0.8 mL and 20 mg/0.2 mL.

Celltrion USA is also seeking an interchangeability designation from the FDA following the completion of an interchangeability trial of 366 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The interchangeability designation would mean that patients successfully switched from Humira to Yuflyma multiple times in the trial. The interchangeability designation would allow pharmacists to autosubstitute Humira with Yuflyma. In these cases, individual state laws control how and whether physicians will be notified of this switch.

If interchangeability is approved for Yuflyma, which the company tentatively expects in the fourth quarter of 2024, it would be just the third interchangeable biosimilar approved by the FDA overall and the second adalimumab biosimilar to be designated as such, after adalimumab-adbm (Cyltezo) in October 2021.

Yuflyma was approved in Canada in December 2021 for 10 indications: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, adult ulcerative colitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, plaque psoriasis, adult uveitis, and pediatric uveitis.

In February 2022, the European Commission granted marketing authorization for Yuflyma across those 10 indications, as well as for nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis, pediatric plaque psoriasis, and pediatric Crohn’s disease.

In April 2022, Celltrion USA signed a licensing agreement with AbbVie, the manufacturer of Humira. Under that agreement, Celltrion will pay royalties to AbbVie on sales of their individual biosimilars, and AbbVie agreed to drop all patent litigation.

The full prescribing information for Yuflyma is available here.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved the biosimilar adalimumab-aaty (Yuflyma) in a citrate-free, high-concentration formulation, the manufacturer, Celltrion USA, announced today. It is the ninth biosimilar of adalimumab (Humira) to be approved in the United States.

Yuflyma is approved for the treatment of adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, plaque psoriasis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. It is also approved for polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis for patients aged 2 years or older, as well as for Crohn’s disease in adults and in pediatric patients aged 6 years or older.

The formulation was approved on the basis of a comprehensive data package of analytic, preclinical, and clinical studies, according to Celltrion USA, “demonstrating that Yuflyma is comparable to the reference product Humira in terms of efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity up to 24 weeks and 1 year following treatment.”

The company conducted a double-blind, randomized phase 3 trial that compared switching from reference adalimumab to Yuflyma with continuing either reference adalimumab or Yuflyma for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. In that trial, the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, safety, and immunogenicity of Yuflyma and reference adalimumab were comparable after 1 year of treatment, including after switching from reference adalimumab to Yuflyma.

“Currently, more than 80% of patients treated with Humira in the United States rely on a high-concentration and citrate-free formulation of this medication. The availability of a high-concentration and citrate-free formulation adalimumab biosimilar provides an important treatment option for patients with inflammatory diseases who benefit from this effective therapy,” said Jonathan Kay, MD, of the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, in the press release.

The citrate-free formulation is thought to lead to less pain on injection.

Yuflyma will be available in prefilled syringe and autoinjector administration options.

Celltrion USA plans to market the drug in the United States in July 2023. Following the initial launch of 40 mg/0.4 mL, the company plans to launch dose forms of 80 mg/0.8 mL and 20 mg/0.2 mL.

Celltrion USA is also seeking an interchangeability designation from the FDA following the completion of an interchangeability trial of 366 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. The interchangeability designation would mean that patients successfully switched from Humira to Yuflyma multiple times in the trial. The interchangeability designation would allow pharmacists to autosubstitute Humira with Yuflyma. In these cases, individual state laws control how and whether physicians will be notified of this switch.

If interchangeability is approved for Yuflyma, which the company tentatively expects in the fourth quarter of 2024, it would be just the third interchangeable biosimilar approved by the FDA overall and the second adalimumab biosimilar to be designated as such, after adalimumab-adbm (Cyltezo) in October 2021.

Yuflyma was approved in Canada in December 2021 for 10 indications: rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, adult Crohn’s disease, adult ulcerative colitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, plaque psoriasis, adult uveitis, and pediatric uveitis.

In February 2022, the European Commission granted marketing authorization for Yuflyma across those 10 indications, as well as for nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis, pediatric plaque psoriasis, and pediatric Crohn’s disease.

In April 2022, Celltrion USA signed a licensing agreement with AbbVie, the manufacturer of Humira. Under that agreement, Celltrion will pay royalties to AbbVie on sales of their individual biosimilars, and AbbVie agreed to drop all patent litigation.

The full prescribing information for Yuflyma is available here.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An Evaluation of Spin in the Abstracts of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses on the Treatment of Psoriasis: A Cross-sectional Analysis

Psoriasis is an inflammatory autoimmune skin condition that affects approximately 125 million individuals worldwide, with approximately 8 million patients in the United States.1 Psoriasis not only involves a cosmetic component but also comprises other comorbidities, such as psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatric disorders, that can influence patient quality of life.2-4 In addition, the costs associated with psoriasis are substantial, with an estimated economic burden of $35.2 billion in the United States in 2015.5 Given the prevalence of psoriasis and its many effects on patients, it is important that providers have high-quality evidence regarding efficacious treatment options.

Systematic reviews, which compile all available evidence on a subject to answer a specific question, represent the gold standard of research.6 However, studies have demonstrated that when referencing research literature, physicians tend to read only the abstract of a study rather than the entire article.7,8 A study by Marcelo et al8 showed that residents at a tertiary care center answered clinical questions using only the abstract of a paper 69% of the time. Based on these findings, it is imperative that the results of systematic reviews be accurately reported in their abstracts because they can influence patient care.

Referencing only the abstracts of systematic reviews can be problematic if the abstract contains spin. Spin is a form of reporting that inappropriately highlights the benefits of a treatment with greater emphasis than what is shown by the results.9 Research has identified the presence of spin in the abstracts of randomized controlled trials.10-12 For example, Cooper et al10 found that 70% (33/47) of abstracts in otolaryngology randomized controlled trials contained spin. Additionally, Arthur et al11 and Austin et al12 had similar findings within abstracts of orthopedic and obesity trials, where 44.8% (112/250) and 46.7% (21/45) contained spin, respectively. Ottwell et al13 found that the presence of spin in abstracts is not limited to randomized controlled trials; they demonstrated that the abstracts of nearly one-third (31% [11/36]) of systematic reviews focused on the treatment of acne vulgaris contained spin.

In our study, we aimed to evaluate the presence of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews focused on the treatment of psoriasis.

Methods

Reproducibility and Reporting—Our study did not meet the regulatory definition for human subjects research per the US Code of Federal Regulations because the study did not involve human research subjects. The study also was not subject to review by the institutional review board. Our protocol, data set, analysis scripts, extraction forms, and other material related to the study have been placed on Open Science Framework to provide transparency and ensure reproducibility. To further allow for analytic reproducibility, our data set was given to an independent laboratory and reanalyzed with a masked approach. Our study was carried out alongside other studies assessing spin in systematic reviews regarding different specialties and disease states. Because these studies were similar in design, this methodology also has been reported elsewhere. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)14 and the guidelines for meta-epidemiological studies developed by Murad and Wang15 were used in drafting this article.

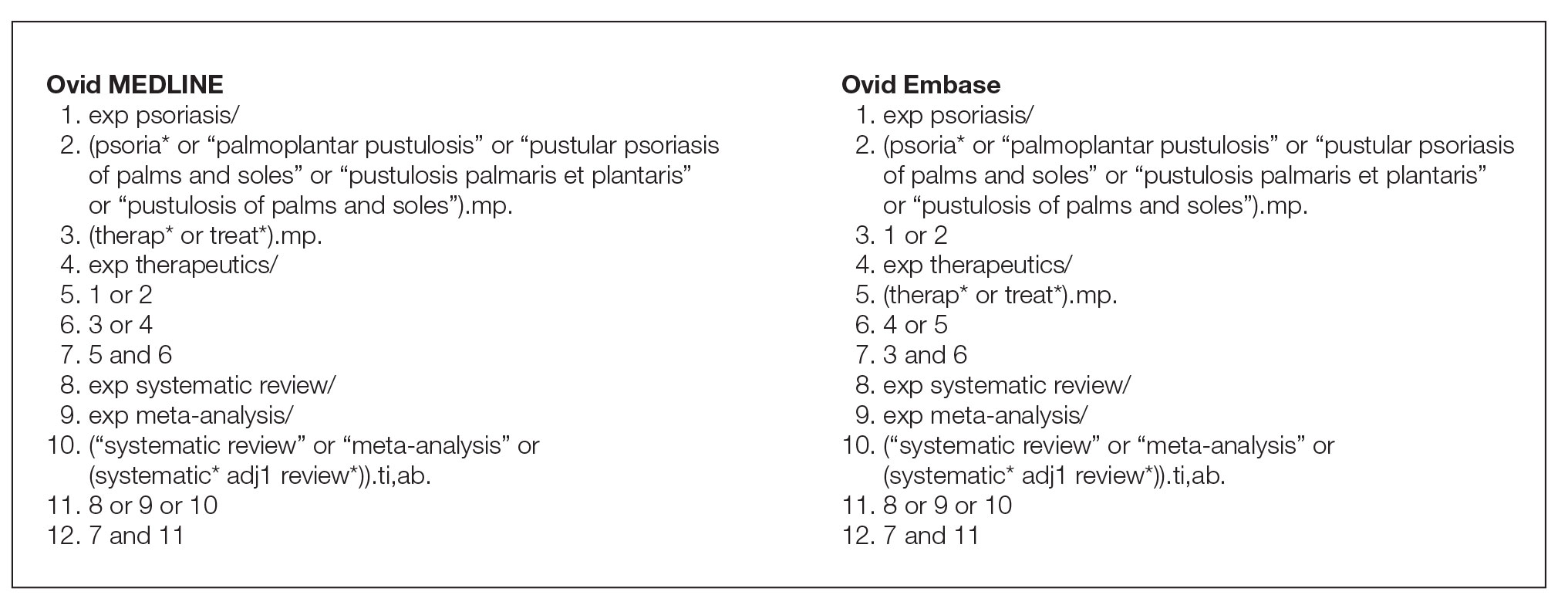

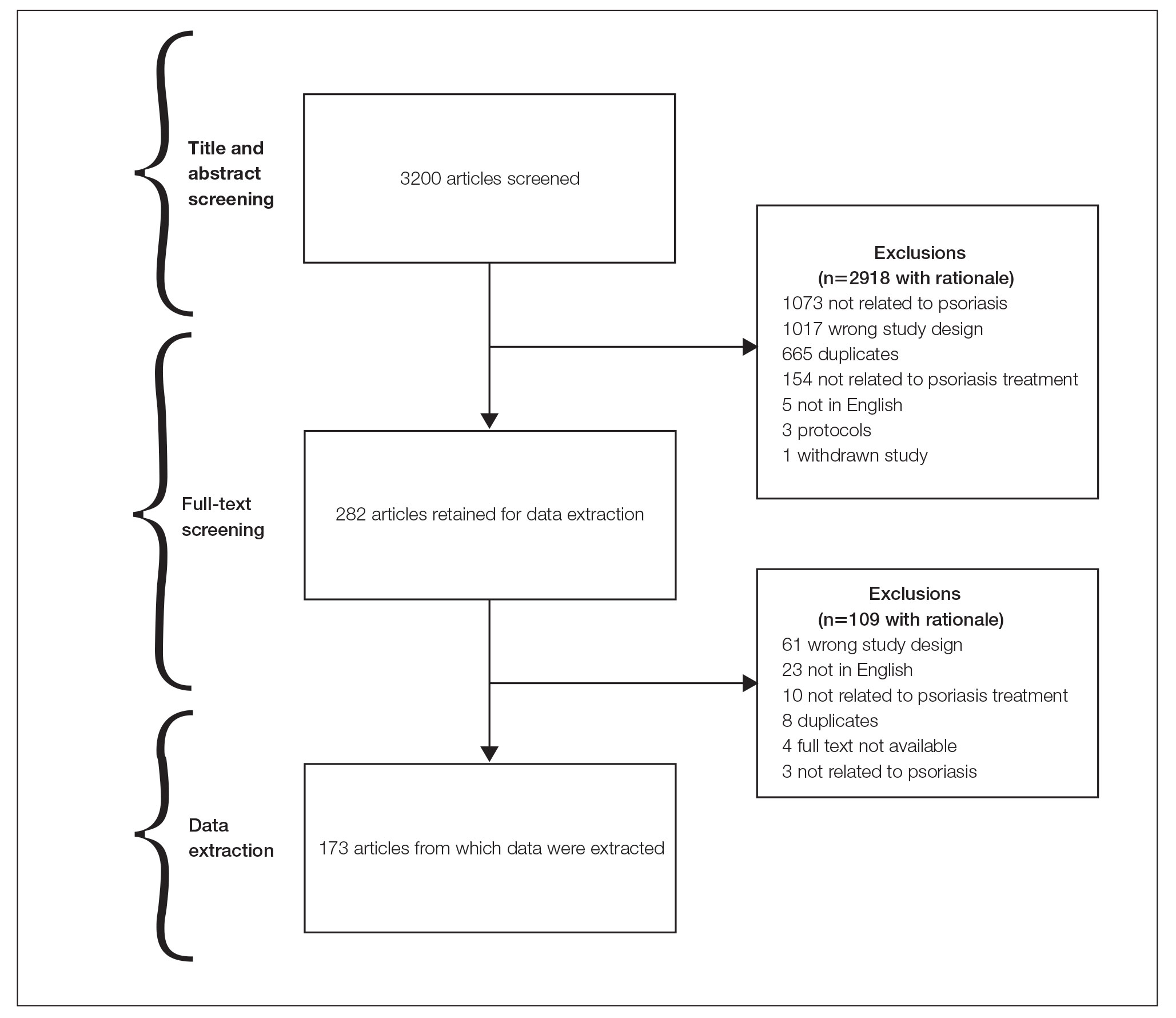

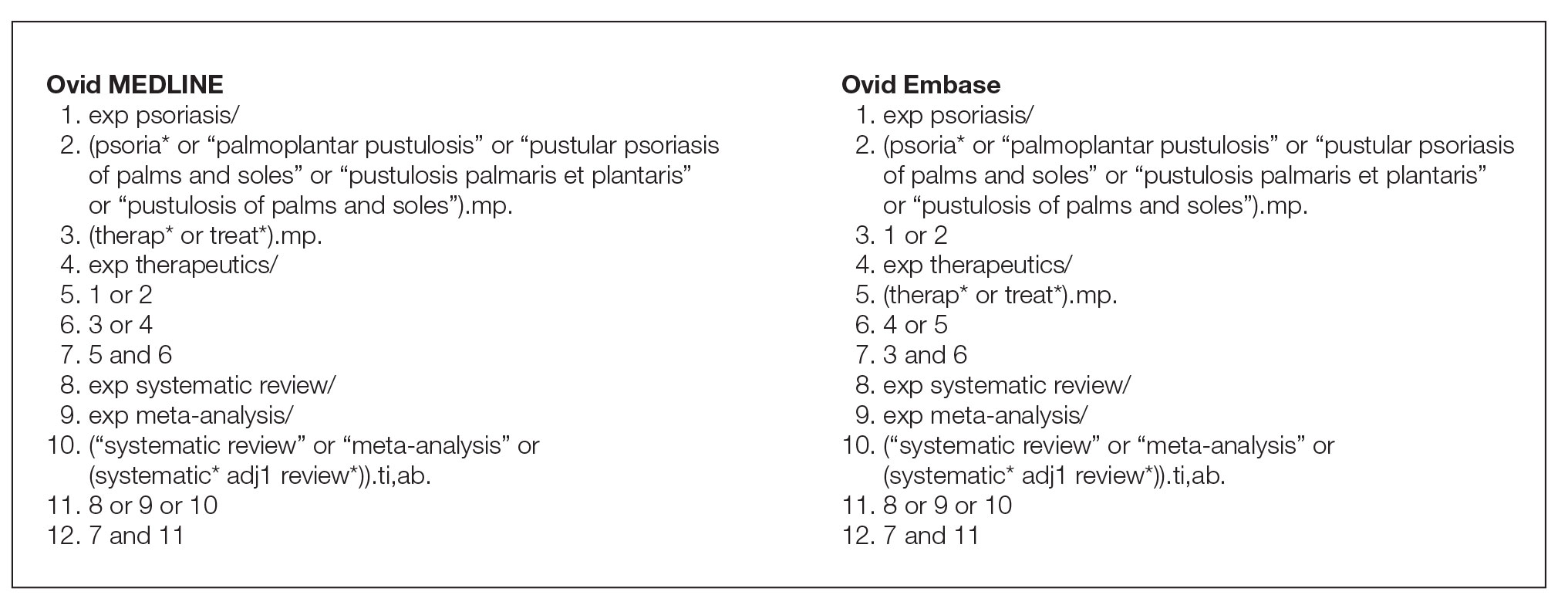

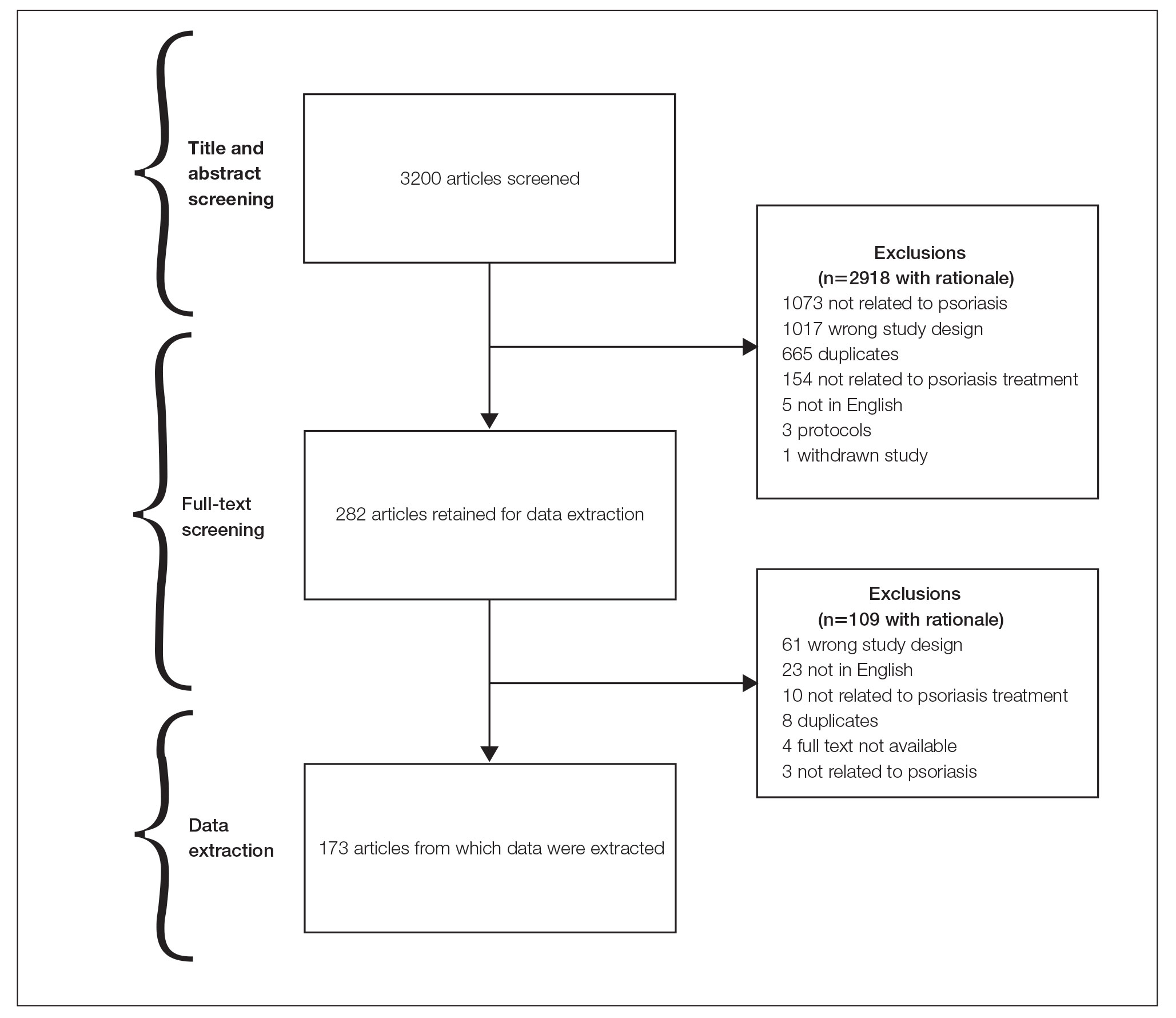

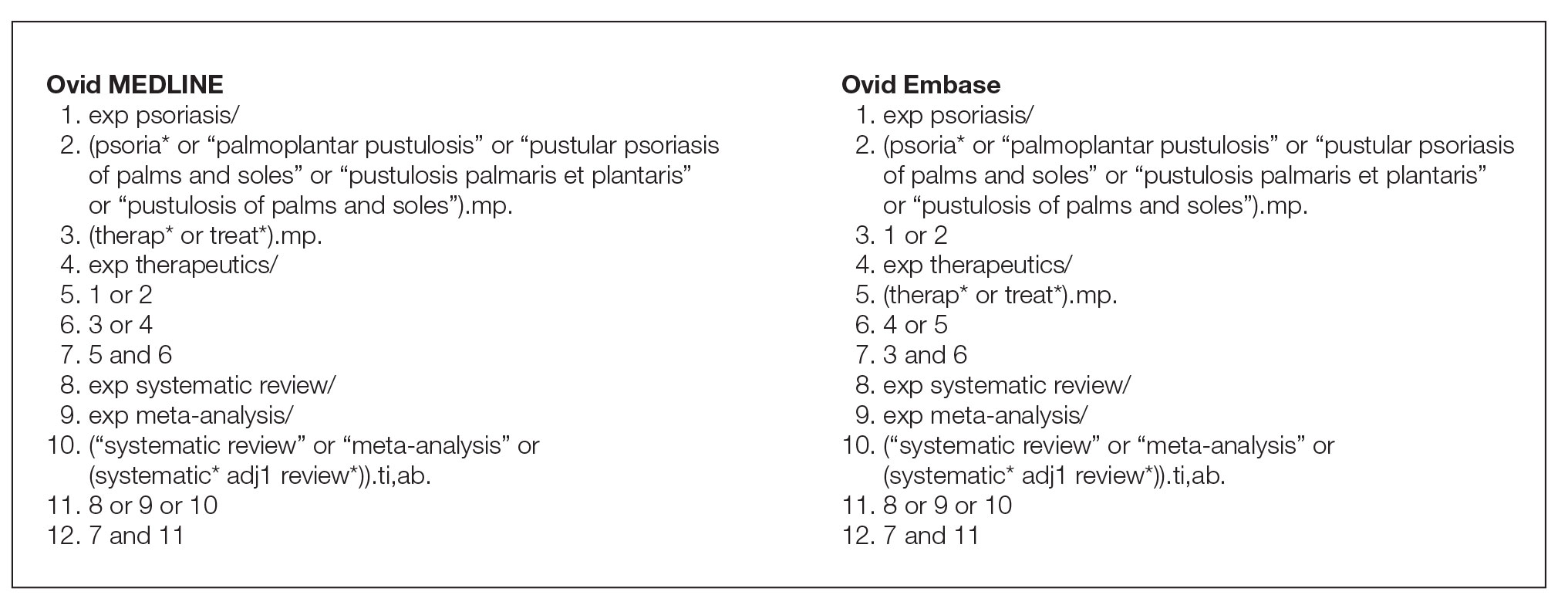

Search Strategy—The search strategies for the MEDLINE (Ovid) and Embase (Ovid) databases were created by a systematic review librarian (D.N.W.) to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses regarding treatments for psoriasis (Figure 1). The searches were performed on June 2, 2020, and uploaded to Rayyan, a systematic review screening platform.16 After duplicates were removed, the records were screened for eligibility by 2 authors (C.H. and A.L.) using the titles and abstracts. Screening was conducted independently while each of these authors was masked to the other’s results; disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Eligibility Criteria—An article had to meet the following criteria for inclusion in our study: (1) be a systematic review with or without a meta-analysis; (2) relate to the treatment of psoriasis; and (3) be written in English and include human patients only. The PRISMA definition of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was applied.17

Training—Various training occurred throughout our study to ensure understanding of each step and mitigate subjectivity. Before beginning screening, 2 investigators (C.H. and A.L.) completed the Introduction to Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis course offered by Johns Hopkins University.18 They also underwent 2 days of online and in-person training on the definition and interpretation of the 9 most severe types of spin found in the abstracts of systematic reviews as defined by Yavchitz et al.9 Finally, they were trained to use A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) to appraise the methodological quality of each systematic review. Our protocol contained an outline of all training modules used.

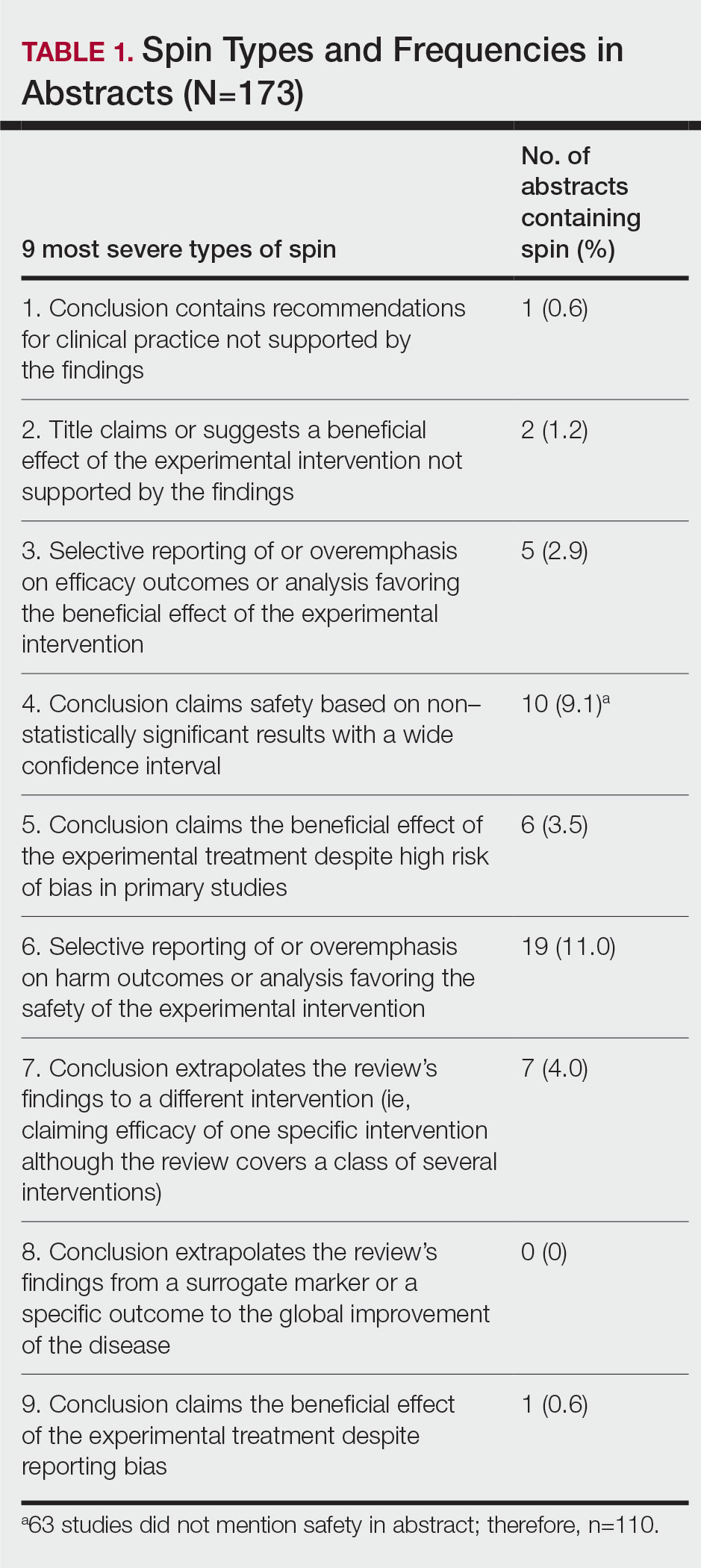

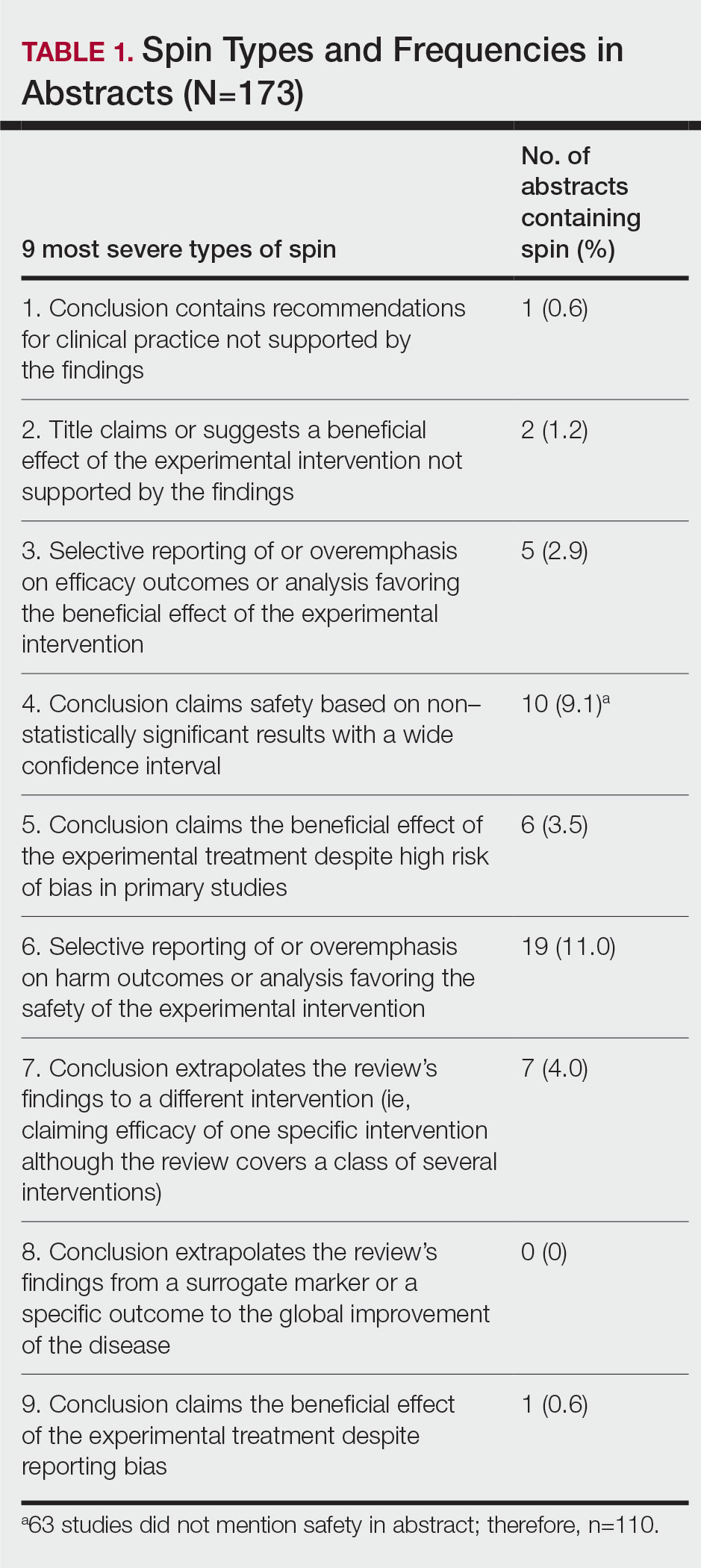

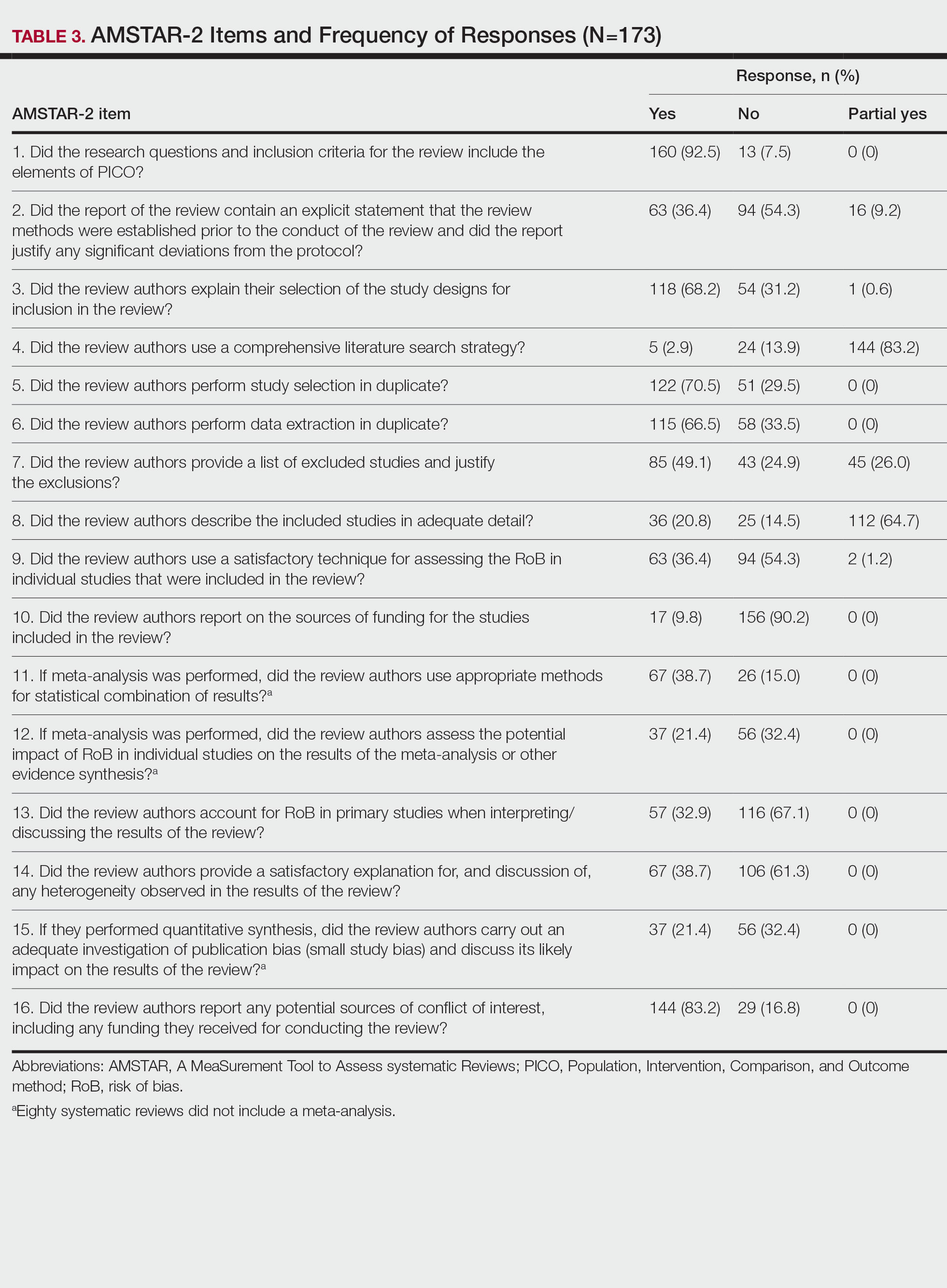

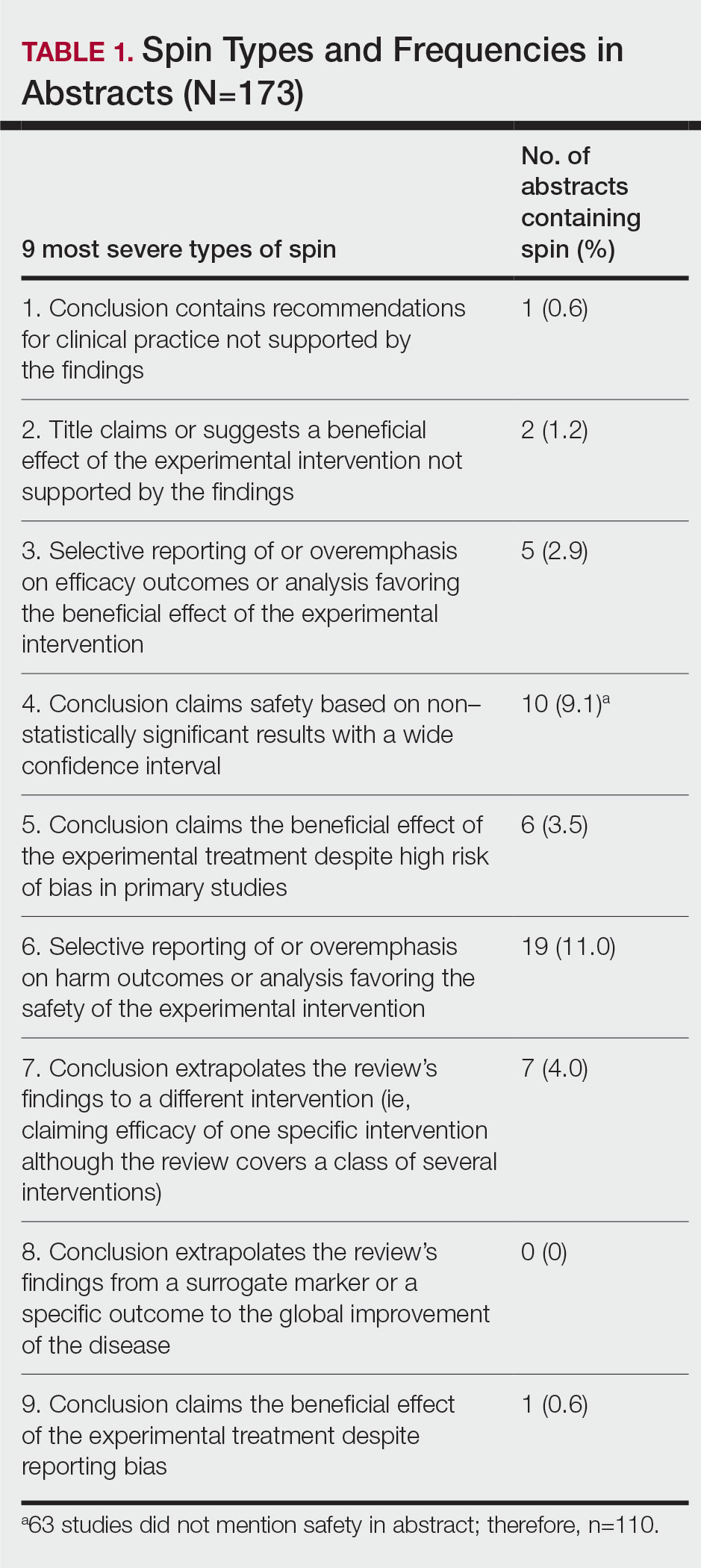

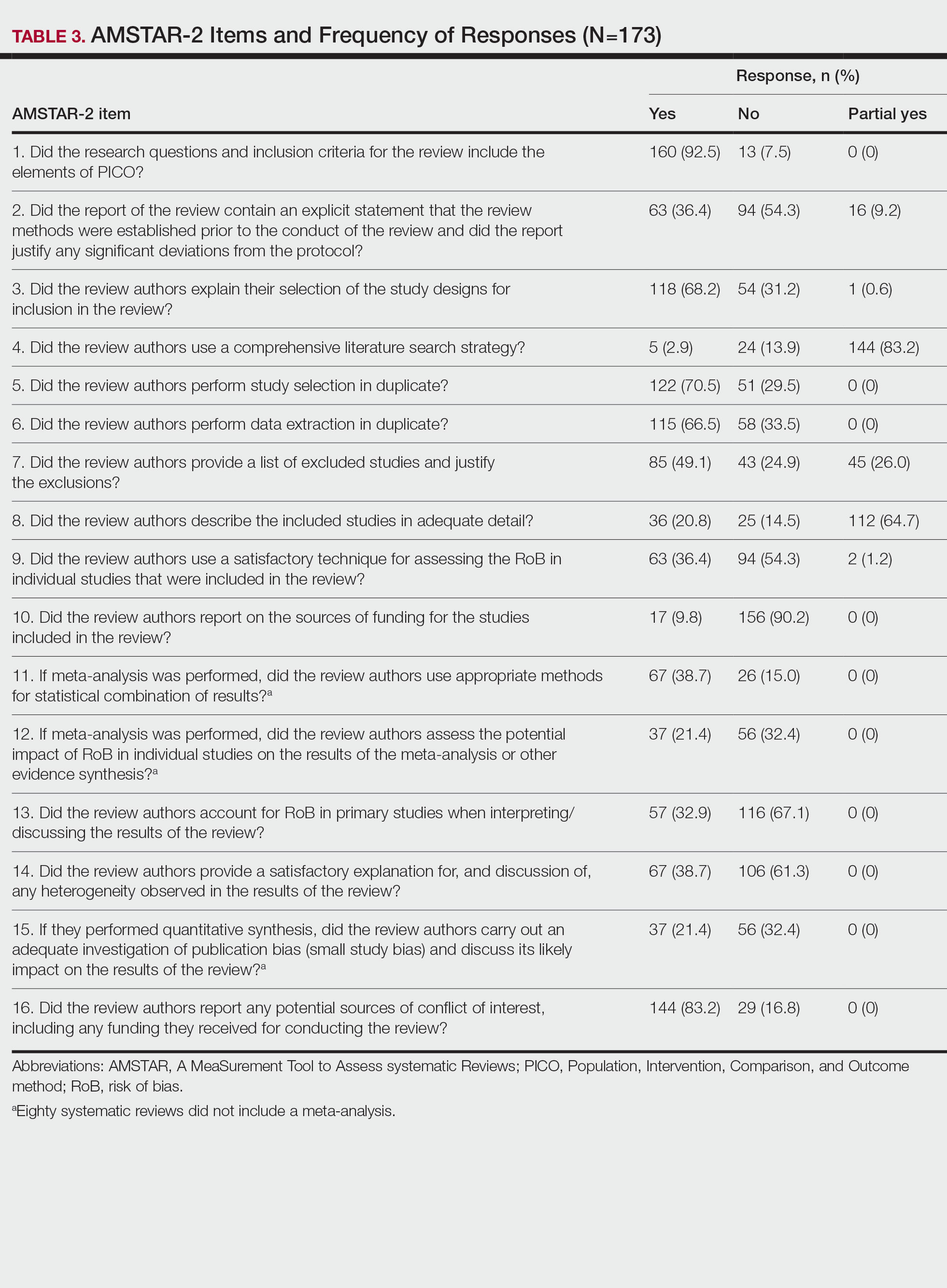

Data Extraction—The investigators (C.H. and A.L.) analyzed included abstracts for the 9 most severe types of spin (Table 1). Data were extracted in a masked duplicate fashion using the Google form. AMSTAR-2 was used to assess systematic reviews for methodological quality. AMSTAR-2 is an appraisal tool consisting of a 16-item checklist for systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Scores range from critically low to high based on the methodological quality of the review. Interrater reliability of AMSTAR-2 scores has been moderate to high across studies. Construct validity coefficients have been high with the original AMSTAR instrument (r=0.91) and the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews instrument (r=0.84).19

During data extraction from each included systematic review, the following additional items were obtained: (1) the date the review was received; (2) intervention type (ie, pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, surgery, light therapy, mixed); (3) the funding source(s) for each systematic review (ie, industry, private, public, none, not mentioned, hospital, a combination of funding not including industry, a combination of funding including industry, other); (4) whether the journal submission guidelines suggested adherence to PRISMA guidelines; (5) whether the review discussed adherence to PRISMA14 or PRISMA for Abstracts20 (PRISMA-A); (6) the publishing journal’s 5-year impact factor; and (6) the country of the systematic review’s origin. When data extraction was complete, investigators (C.H. and A.L.) were unmasked and met to resolve any disagreements by discussion. Two authors (R.O. or M.V.) served as arbiters in the case that an agreement between C.H. and A.L. could not be reached.

Statistical Analysis—Frequencies and percentages were calculated to evaluate the most common types of spin found within systematic reviews and meta-analyses. One author (M.H.) prespecified the possibility of a binary logistic regression and calculated a power analysis to determine sample size, as stated in our protocol. Our final sample size of 173 was not powered to perform the multivariable logistic regression; therefore, we calculated unadjusted odds ratios to enable assessing relationships between the presence of spin in abstracts and the various study characteristics. We used Stata 16.1 for all analyses, and all analytic decisions can be found in our protocol.

Results

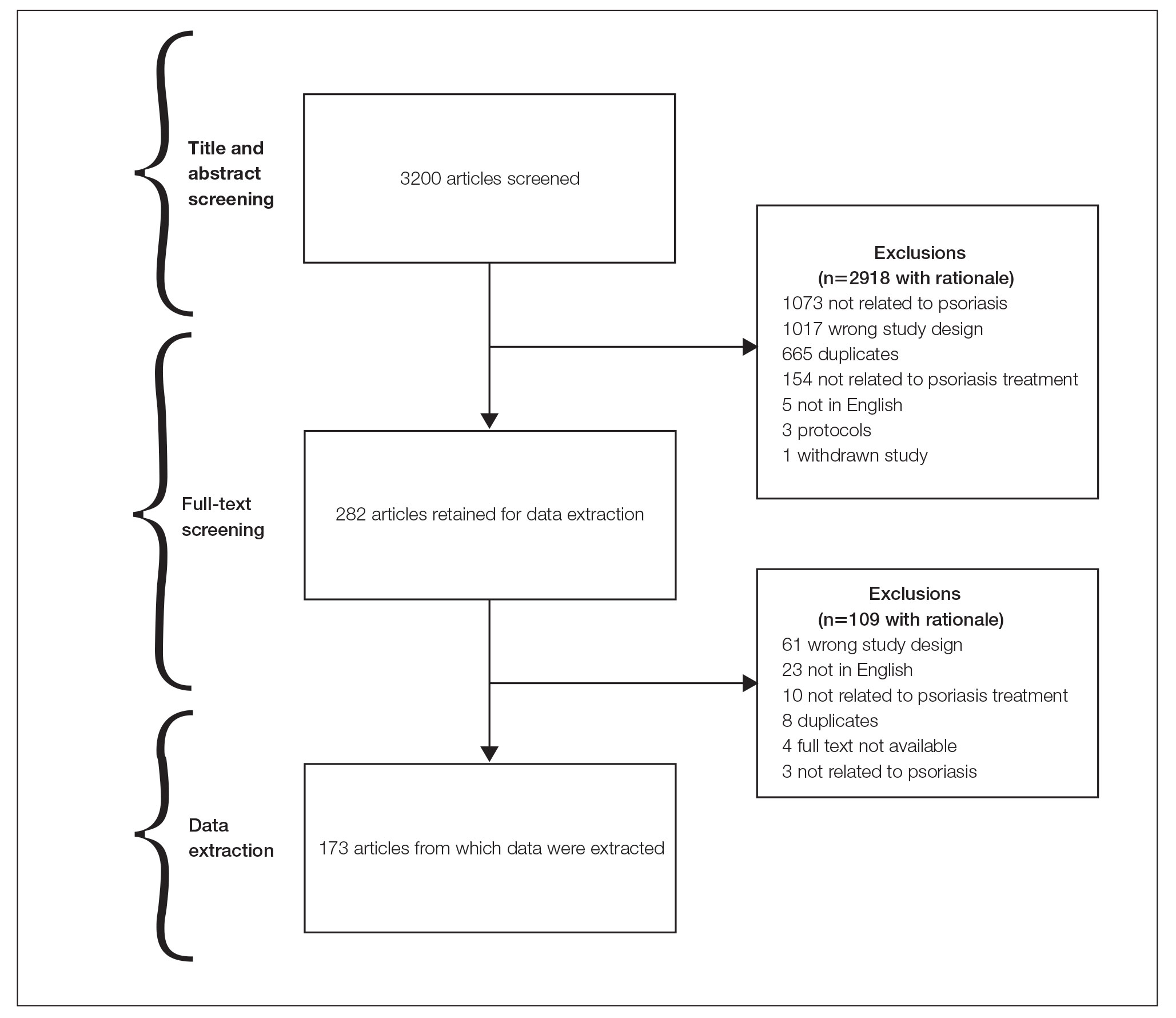

General Characteristics—Our systematic search of MEDLINE and Embase returned 3200 articles, of which 665 were duplicates that were removed. An additional 2253 articles were excluded during initial abstract and title screening, and full-text screening led to the exclusion of another 109 articles. In total, 173 systematic reviews were included for data extraction. Figure 2 illustrates the screening process with the rationale for all exclusions.

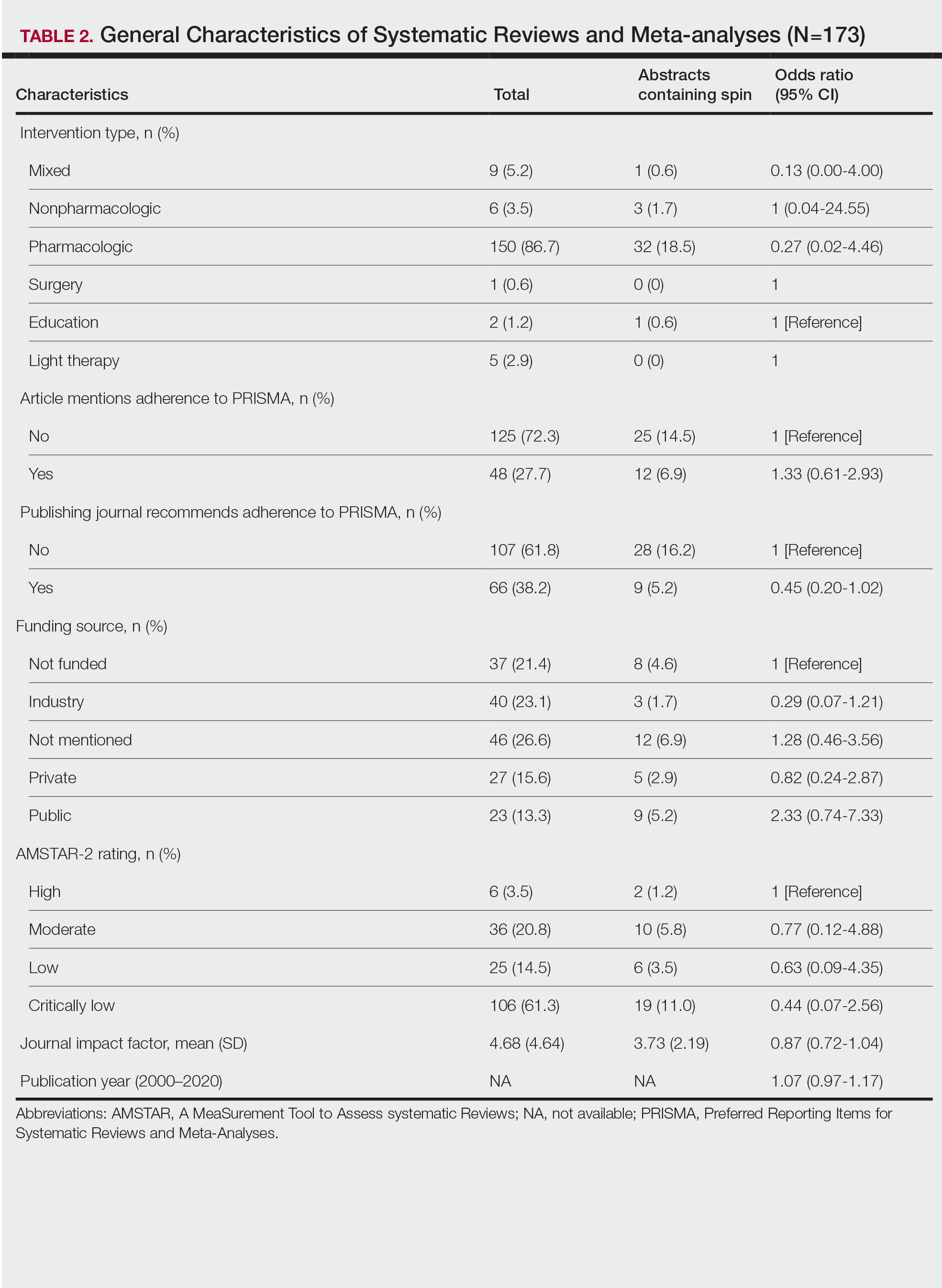

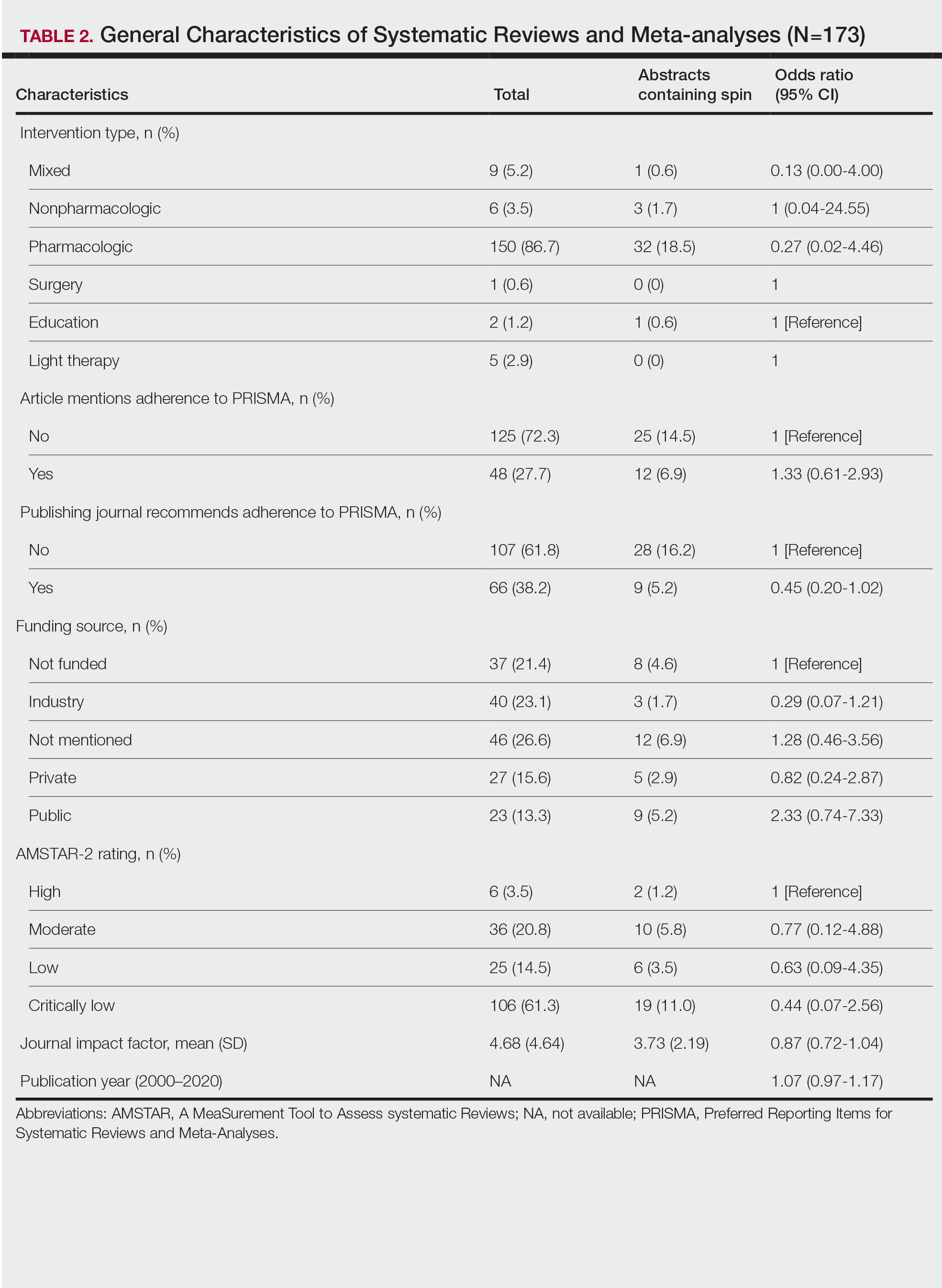

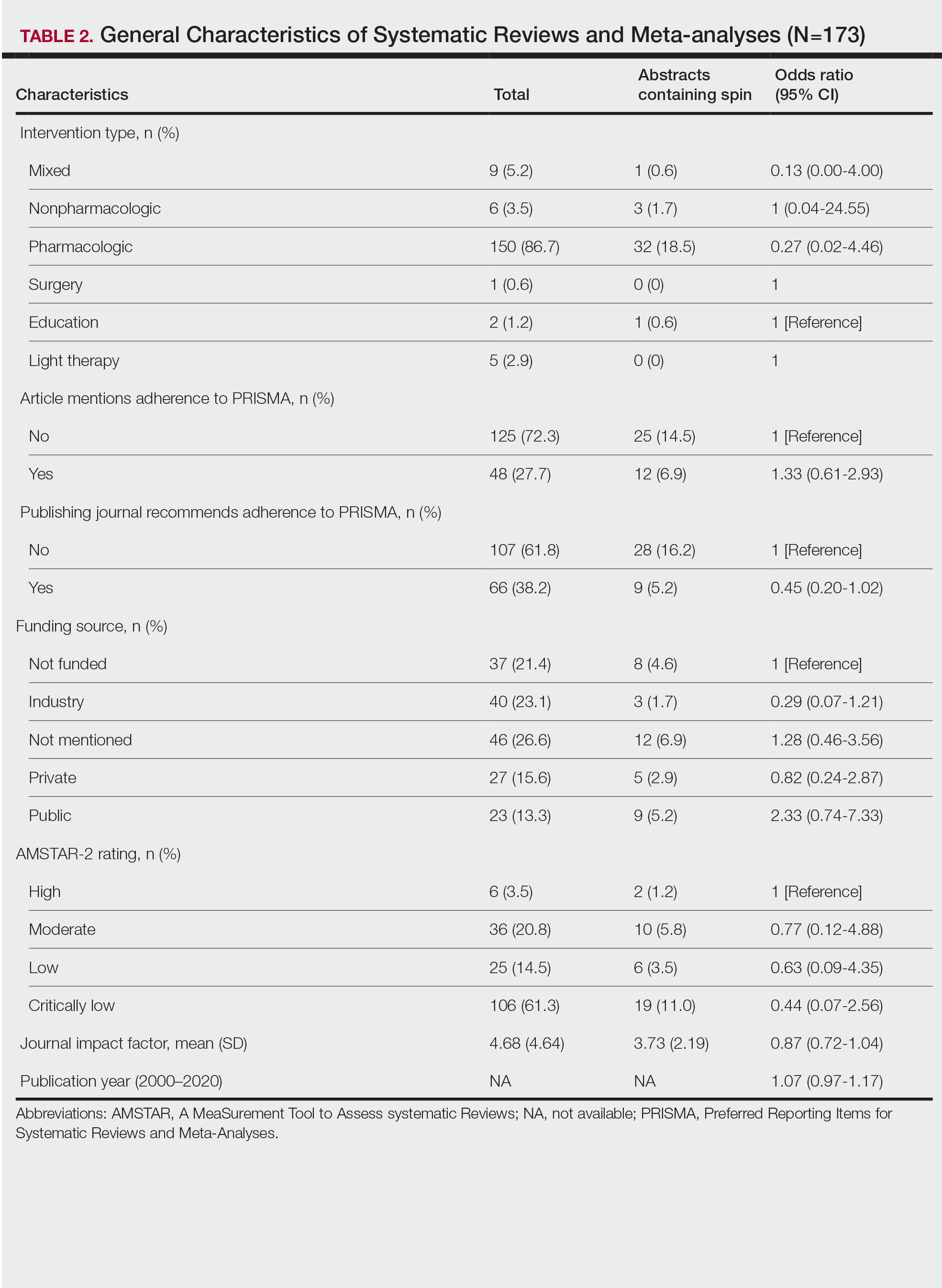

Of the 173 included systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 150 (86.7%) focused on pharmacologic interventions. The majority of studies did not mention adhering to PRISMA guidelines (125/173 [72.3%]), and the publishing journals recommended their authors adhere to PRISMA for only 66 (38.2%) of the included articles. For the articles that received funding (90/173 [52.0%]), industry sources were the most common funding source (40/90 [44.4%]), followed by private (27/90 [30%]) and public funding sources (23/90 [25.6%]). Of the remaining studies, 46 articles did not include a funding statement (46/83 [55.4%]), and 37 studies were not funded (37/83 [44.6%]). The average (SD) 5-year impact factor of our included journals was 4.68 (4.64). Systematic reviews were from 31 different countries. All studies were received by their respective journals between the years 2000 and 2020 (Table 2).

Abstracts Containing Spin—We found that 37 (21.4%) of the abstracts of systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments contained at least 1 type of spin. Some abstracts had more than 1 type; thus, a total of 51 different instances of spin were detected. Spin type 6—selective reporting of or overemphasis on harm outcomes or analysis favoring the safety of the experimental intervention—was the most common type ofspin, found in 19 of 173 abstracts (11.0%). The most severe type of spin—type 1 (conclusion contains recommendations for clinical practice not supported by the findings)—occurred in only 1 abstract (0.6%). Spin type 8 did not occur in any of the abstracts (Table 1). There was no statistically significant association between the presence of spin and any of the study characteristics (Table 2).

AMSTAR Ratings—After using AMSTAR-2 to appraise the included systematic reviews, we found that 6 (3.5%) of the 173 studies could be rated as high; 36 (20.8%) as moderate; 25 (14.5%) as low; and 106 (61.3%) as critically low. Of the 37 abstracts containing spin, 2 (5.4%) had an AMSTAR-2 rating of high, 10 (27%) had a rating of moderate, 6 (16.2%) had a rating of low, and 19 (51.4%) had a rating of critically low (Table 2). No statistically significant associations were seen between abstracts found to have spin and the AMSTAR-2 rating of the review.

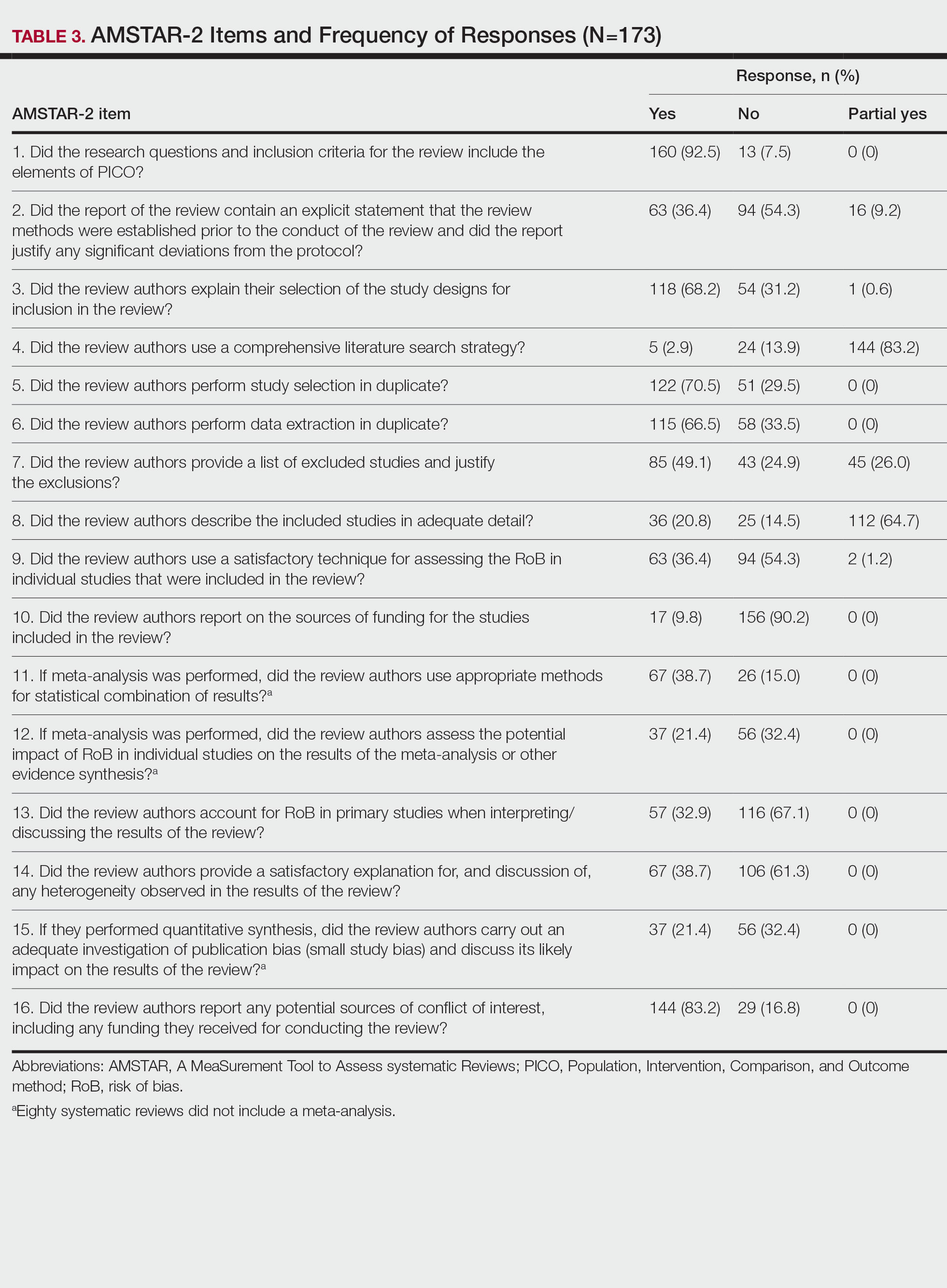

Nearly all (160/173 [92.5%]) of the included reviews were compliant with the inclusion of Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) method. Only 17 of 173 (9.8%) reviews reported funding sources for the studies included. See Table 3 for all AMSTAR-2 items.

Comment

Primary Findings—We evaluated the abstracts of systematic reviews for the treatment of psoriasis and found that more than one-fifth of them contained spin. Our study contributes to the existing literature surrounding spin. Spin in randomized controlled trials is well documented across several fields of medicine, including otolaryngology,10 obesity medicine,12 dermatology,21 anesthesiology,22 psychiatry,23 orthopedics,24 emergency medicine,25 oncology,26 and cardiology.27 More recently, studies have emerged evaluating the presence of spin in systematic reviews. Specific to dermatology, one study found that 74% (84/113) of systematic reviews related to atopic dermatitis treatment contained spin.28 Additionally, Ottwell et al13 identified spin in 31% (11/36) of the systematic reviews related to the treatment of acne vulgaris, which is similar to our results for systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments. When comparing the presence of spin in abstracts of systematic reviews from the field of dermatology with other specialties, dermatology-focused systematic reviews appear to contain more spin in the abstract than systematic reviews focused on tinnitus and glaucoma therapies.29,30 However, systematic reviews from the field of dermatology appear to contain less spin than systematic reviews focused on therapies for lower back pain.31 For example, Nascimento et al31 found that 80% (53/66) of systematic reviews focused on low-back pain treatments contained spin.

Examples of Spin—The most common type of spin found in our study was type 6.9 An example of spin type 6 can be found in an article by Bai et al32 that investigated the short-term efficacy and safety of multiple interleukin inhibitors for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract states, “Risankizumab appeared to have relatively high efficacy and low risk.” However, in the results section, the authors showed that risankizumab had the highest risk of serious adverse events and was ranked highest for discontinuation because of adverse events when compared with other interleukin inhibitors. Here, the presence of spin in the abstract may mislead the reader to accept the “low risk” of risankizumab without understanding the study’s full results.32

Another example of selective reporting of harm outcomes in a systematic review can be found in the article by Wu et al,33 which focused on assessing IL-17 antagonists for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract indicated that IL-17 antagonists should be accepted as safe; however, in the results section, the authors discussed serious safety concerns with brodalumab, including the death of 4 patients from suicide.33 This example of spin type 6 highlights how the overgeneralization of a drug’s safety profile neglects serious harm outcomes that are critical to patient safety. In fact, against the safety claims of Wu et al,33 brodalumab later received a boxed warning from the US Food and Drug Administration after 6 patients died from suicide while receiving the drug, which led to early discontinuation of the trials.34,35 Although studies suggest this relationship is not causal,34-36 the purpose of our study was not to investigate this association but to highlight the importance of this finding. Thus, with this example of spin in mind, we offer recommendations that we believe will improve reporting in abstracts as well as quality of patient care.

Recommendations for Reporting in Abstracts—Regarding the boxed warning37 for brodalumab because of suicidal ideation and behavior, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that prior to prescribing brodalumab, clinicians consider the potential benefits and risks in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal ideation or behavior. However, a clinician would not adequately assess the full risks and benefits when an abstract, such as that for the article by Wu et al,33 contains spin through selectively reporting harm outcomes. Arguably, clinicians could just read the full text; however, research confirms that abstracts often are utilized by clinicians and commonly are used to guide clinical decisions.7,38 It is reasonable that clinicians would use abstracts in this fashion because they provide a quick synopsis of the full article’s findings and are widely available to clinicians who may not have access to article databases. Initiatives are in place to improve the quality of reporting in an abstract, such as PRISMA-A,20 but even this fails to address spin. In fact, it may suggest spin because checklist item 10 of PRISMA-A advises authors of systematic reviews to provide a “general interpretation of the results and important implications.” This item is concerning because it suggests that the authors interpret importance rather than the clinician who prescribes the drug and is ultimately responsible for patient safety. Therefore, we recommend a reform to abstract reporting and an update to PRISMA-A that leads authors to report all benefits and risks encountered instead of reporting what the authors define as important.

Strengths and Limitations—Our study has several strengths as well as limitations. One of these strengths is that our protocol was strictly adhered to; any deviations were noted and added as an amendment. Our protocol, data, and all study artifacts were made freely available online on the Open Science Framework to strengthen reproducibility (https://osf.io/zrxh8/). Investigators underwent training to ensure comprehension of spin and systematic review designs. All data were extracted in masked duplicate fashion per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.39

Regarding limitations, only 2 databases were searched—MEDLINE and Embase. Therefore, our screening process may not have included every available systematic review on the treatment of psoriasis. Journal impact factors may be inaccurate for the systematic reviews that were published earlier in our data date range; however, we attempted to negate this limitation by using a 5-year average. Our study characteristic regarding PRISMA adherence did not account for studies published before the PRISMA statement release; we also could not access prior submission guidelines to determine when a journal began recommending PRISMA adherence. Another limitation of our study was the intrinsic subjectivity behind spin. Some may disagree with our classifications. Finally, our cross-sectional design should not be generalized to study types that are not systematic reviews or published in other journals during different periods.

Conclusion

Evidence of spin was present in many of the abstracts of systematic reviews pertaining to the treatment of psoriasis. Future clinical research should investigate any reporting of spin and search for ways to better reduce spin within literature. Continued research is necessary to evaluate the presence of spin within dermatology and other specialties.

- Psoriasis statistics. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated December 21, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://www.psoriasis.org/content/statistics

- Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082.

- Hu SCS, Lan CCE. Psoriasis and cardiovascular comorbidities: focusing on severe vascular events, cardiovascular risk factors and implications for treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2211.

- Patel N, Nadkarni A, Cardwell LA, et al. Psoriasis, depression, and inflammatory overlap: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:613-620.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

- Gopalakrishnan S, Ganeshkumar P. Systematic reviews and meta‑analysis: understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2013;2:9-14.

- Barry HC, Ebell MH, Shaughnessy AF, et al. Family physicians’ use of medical abstracts to guide decision making: style or substance? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:437-442.

- Marcelo A, Gavino A, Isip-Tan IT, et al. A comparison of the accuracy of clinical decisions based on full-text articles and on journal abstracts alone: a study among residents in a tertiary care hospital. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:48-53.

- Yavchitz A, Ravaud P, Altman DG, et al. A new classification of spin in systematic reviews and meta-analyses was developed and ranked according to the severity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:56-65.

- Cooper CM, Gray HM, Ross AE, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of otolaryngology randomized controlled trials. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:2036-2040.

- Arthur W, Zaaza Z, Checketts JX, et al. Analyzing spin in abstracts of orthopaedic randomized controlled trials with statistically insignificant primary endpoints. Arthroscopy. 2020;36:1443-1450.

- Austin J, Smith C, Natarajan K, et al. Evaluation of spin within abstracts in obesity randomized clinical trials: a cross-sectional review. Clin Obes. 2019;9:E12292.

- Ottwell R, Rogers TC, Michael Anderson J, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on the treatment of acne vulgaris: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR Dermatol. 2020;3:E16978.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:E1000100.

- Murad MH, Wang Z. Guidelines for reporting meta-epidemiological methodology research. Evid Based Med. 2017;22:139-142.

- Rayyan QCRI. Accessed September 10, 2019. https://rayyan.qcri.org/reviews/81224

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647.

- Coursera. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.coursera.org/learn/systematic-review

- Lorenz RC, Matthias K, Pieper D, et al. A psychometric study found AMSTAR 2 to be a valid and moderately reliable appraisal tool. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;114:133-140.

- Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG, et al. PRISMA for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med. 2013;10:E1001419.

- Motosko CC, Ault AK, Kimberly LL, et al. Analysis of spin in the reporting of studies of topical treatments of photoaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:516-522.e12.

- Kinder NC, Weaver MD, Wayant C, et al. Presence of “spin” in the abstracts and titles of anaesthesiology randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:E13-E14.

- Jellison S, Roberts W, Bowers A, et al. Evaluation of spin in abstracts of papers in psychiatry and psychology journals. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2019;5:178-181.

- Checketts JX, Riddle J, Zaaza Z, et al. An evaluation of spin in lower extremity joint trials. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1008-1012.

- Reynolds-Vaughn V, Riddle J, Brown J, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of emergency medicine randomized controlled trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;14:423-431.

- Wayant C, Margalski D, Vaughn K, et al. Evaluation of spin in oncology clinical trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;144:102821.

- Khan MS, Lateef N, Siddiqi TJ, et al. Level and prevalence of spin in published cardiovascular randomized clinical trial reports with statistically nonsignificant primary outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:E192622.

- Lin V, Patel R, Wirtz A, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of atopic dermatitis treatments and interventions. Dermatology. 2021;237:496-505.

- Rucker B, Umbarger E, Ottwell R, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2021;10:1237-1244.

- Okonya O, Lai E, Ottwell R, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of treatments for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2021;30:235-241.

- Nascimento DP, Gonzalez GZ, Araujo AC, et al. Eight out of every ten abstracts of low back pain systematic reviews presented spin and inconsistencies with the full text: an analysis of 66 systematic reviews. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50:17-23.

- Bai F, Li GG, Liu Q, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors brodalumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, ustekinumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:2546161.

- Wu D, Hou SY, Zhao S, et al. Efficacy and safety of interleukin-17 antagonists in patients with plaque psoriasis: a meta-analysis from phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:992-1003.

- Rusta-Sallehy S, Gooderham M, Papp K. Brodalumab: a review of safety. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018;23:1-3.

- Rodrigeuz-Bolanos F, Gooderham M, Papp K. A closer look at the data regarding suicidal ideation and behavior in psoriasis patients: the case of brodalumab. Skin Therapy Lett. 2019;24:1-4.

- Danesh MJ, Kimball AB. Brodalumab and suicidal ideation in the context of a recent economic crisis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:190-192.

- Siliq. Prescribing information. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC; 2017. Accessed May 18, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761032lbl.pdf

- Johnson HL, Fontelo P, Olsen CH, et al. Family nurse practitioner student perception of journal abstract usefulness in clinical decision making: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2013;25:597-603.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

Psoriasis is an inflammatory autoimmune skin condition that affects approximately 125 million individuals worldwide, with approximately 8 million patients in the United States.1 Psoriasis not only involves a cosmetic component but also comprises other comorbidities, such as psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatric disorders, that can influence patient quality of life.2-4 In addition, the costs associated with psoriasis are substantial, with an estimated economic burden of $35.2 billion in the United States in 2015.5 Given the prevalence of psoriasis and its many effects on patients, it is important that providers have high-quality evidence regarding efficacious treatment options.

Systematic reviews, which compile all available evidence on a subject to answer a specific question, represent the gold standard of research.6 However, studies have demonstrated that when referencing research literature, physicians tend to read only the abstract of a study rather than the entire article.7,8 A study by Marcelo et al8 showed that residents at a tertiary care center answered clinical questions using only the abstract of a paper 69% of the time. Based on these findings, it is imperative that the results of systematic reviews be accurately reported in their abstracts because they can influence patient care.

Referencing only the abstracts of systematic reviews can be problematic if the abstract contains spin. Spin is a form of reporting that inappropriately highlights the benefits of a treatment with greater emphasis than what is shown by the results.9 Research has identified the presence of spin in the abstracts of randomized controlled trials.10-12 For example, Cooper et al10 found that 70% (33/47) of abstracts in otolaryngology randomized controlled trials contained spin. Additionally, Arthur et al11 and Austin et al12 had similar findings within abstracts of orthopedic and obesity trials, where 44.8% (112/250) and 46.7% (21/45) contained spin, respectively. Ottwell et al13 found that the presence of spin in abstracts is not limited to randomized controlled trials; they demonstrated that the abstracts of nearly one-third (31% [11/36]) of systematic reviews focused on the treatment of acne vulgaris contained spin.

In our study, we aimed to evaluate the presence of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews focused on the treatment of psoriasis.

Methods

Reproducibility and Reporting—Our study did not meet the regulatory definition for human subjects research per the US Code of Federal Regulations because the study did not involve human research subjects. The study also was not subject to review by the institutional review board. Our protocol, data set, analysis scripts, extraction forms, and other material related to the study have been placed on Open Science Framework to provide transparency and ensure reproducibility. To further allow for analytic reproducibility, our data set was given to an independent laboratory and reanalyzed with a masked approach. Our study was carried out alongside other studies assessing spin in systematic reviews regarding different specialties and disease states. Because these studies were similar in design, this methodology also has been reported elsewhere. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)14 and the guidelines for meta-epidemiological studies developed by Murad and Wang15 were used in drafting this article.

Search Strategy—The search strategies for the MEDLINE (Ovid) and Embase (Ovid) databases were created by a systematic review librarian (D.N.W.) to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses regarding treatments for psoriasis (Figure 1). The searches were performed on June 2, 2020, and uploaded to Rayyan, a systematic review screening platform.16 After duplicates were removed, the records were screened for eligibility by 2 authors (C.H. and A.L.) using the titles and abstracts. Screening was conducted independently while each of these authors was masked to the other’s results; disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Eligibility Criteria—An article had to meet the following criteria for inclusion in our study: (1) be a systematic review with or without a meta-analysis; (2) relate to the treatment of psoriasis; and (3) be written in English and include human patients only. The PRISMA definition of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was applied.17

Training—Various training occurred throughout our study to ensure understanding of each step and mitigate subjectivity. Before beginning screening, 2 investigators (C.H. and A.L.) completed the Introduction to Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis course offered by Johns Hopkins University.18 They also underwent 2 days of online and in-person training on the definition and interpretation of the 9 most severe types of spin found in the abstracts of systematic reviews as defined by Yavchitz et al.9 Finally, they were trained to use A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) to appraise the methodological quality of each systematic review. Our protocol contained an outline of all training modules used.

Data Extraction—The investigators (C.H. and A.L.) analyzed included abstracts for the 9 most severe types of spin (Table 1). Data were extracted in a masked duplicate fashion using the Google form. AMSTAR-2 was used to assess systematic reviews for methodological quality. AMSTAR-2 is an appraisal tool consisting of a 16-item checklist for systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Scores range from critically low to high based on the methodological quality of the review. Interrater reliability of AMSTAR-2 scores has been moderate to high across studies. Construct validity coefficients have been high with the original AMSTAR instrument (r=0.91) and the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews instrument (r=0.84).19

During data extraction from each included systematic review, the following additional items were obtained: (1) the date the review was received; (2) intervention type (ie, pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, surgery, light therapy, mixed); (3) the funding source(s) for each systematic review (ie, industry, private, public, none, not mentioned, hospital, a combination of funding not including industry, a combination of funding including industry, other); (4) whether the journal submission guidelines suggested adherence to PRISMA guidelines; (5) whether the review discussed adherence to PRISMA14 or PRISMA for Abstracts20 (PRISMA-A); (6) the publishing journal’s 5-year impact factor; and (6) the country of the systematic review’s origin. When data extraction was complete, investigators (C.H. and A.L.) were unmasked and met to resolve any disagreements by discussion. Two authors (R.O. or M.V.) served as arbiters in the case that an agreement between C.H. and A.L. could not be reached.

Statistical Analysis—Frequencies and percentages were calculated to evaluate the most common types of spin found within systematic reviews and meta-analyses. One author (M.H.) prespecified the possibility of a binary logistic regression and calculated a power analysis to determine sample size, as stated in our protocol. Our final sample size of 173 was not powered to perform the multivariable logistic regression; therefore, we calculated unadjusted odds ratios to enable assessing relationships between the presence of spin in abstracts and the various study characteristics. We used Stata 16.1 for all analyses, and all analytic decisions can be found in our protocol.

Results

General Characteristics—Our systematic search of MEDLINE and Embase returned 3200 articles, of which 665 were duplicates that were removed. An additional 2253 articles were excluded during initial abstract and title screening, and full-text screening led to the exclusion of another 109 articles. In total, 173 systematic reviews were included for data extraction. Figure 2 illustrates the screening process with the rationale for all exclusions.

Of the 173 included systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 150 (86.7%) focused on pharmacologic interventions. The majority of studies did not mention adhering to PRISMA guidelines (125/173 [72.3%]), and the publishing journals recommended their authors adhere to PRISMA for only 66 (38.2%) of the included articles. For the articles that received funding (90/173 [52.0%]), industry sources were the most common funding source (40/90 [44.4%]), followed by private (27/90 [30%]) and public funding sources (23/90 [25.6%]). Of the remaining studies, 46 articles did not include a funding statement (46/83 [55.4%]), and 37 studies were not funded (37/83 [44.6%]). The average (SD) 5-year impact factor of our included journals was 4.68 (4.64). Systematic reviews were from 31 different countries. All studies were received by their respective journals between the years 2000 and 2020 (Table 2).

Abstracts Containing Spin—We found that 37 (21.4%) of the abstracts of systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments contained at least 1 type of spin. Some abstracts had more than 1 type; thus, a total of 51 different instances of spin were detected. Spin type 6—selective reporting of or overemphasis on harm outcomes or analysis favoring the safety of the experimental intervention—was the most common type ofspin, found in 19 of 173 abstracts (11.0%). The most severe type of spin—type 1 (conclusion contains recommendations for clinical practice not supported by the findings)—occurred in only 1 abstract (0.6%). Spin type 8 did not occur in any of the abstracts (Table 1). There was no statistically significant association between the presence of spin and any of the study characteristics (Table 2).

AMSTAR Ratings—After using AMSTAR-2 to appraise the included systematic reviews, we found that 6 (3.5%) of the 173 studies could be rated as high; 36 (20.8%) as moderate; 25 (14.5%) as low; and 106 (61.3%) as critically low. Of the 37 abstracts containing spin, 2 (5.4%) had an AMSTAR-2 rating of high, 10 (27%) had a rating of moderate, 6 (16.2%) had a rating of low, and 19 (51.4%) had a rating of critically low (Table 2). No statistically significant associations were seen between abstracts found to have spin and the AMSTAR-2 rating of the review.

Nearly all (160/173 [92.5%]) of the included reviews were compliant with the inclusion of Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) method. Only 17 of 173 (9.8%) reviews reported funding sources for the studies included. See Table 3 for all AMSTAR-2 items.

Comment

Primary Findings—We evaluated the abstracts of systematic reviews for the treatment of psoriasis and found that more than one-fifth of them contained spin. Our study contributes to the existing literature surrounding spin. Spin in randomized controlled trials is well documented across several fields of medicine, including otolaryngology,10 obesity medicine,12 dermatology,21 anesthesiology,22 psychiatry,23 orthopedics,24 emergency medicine,25 oncology,26 and cardiology.27 More recently, studies have emerged evaluating the presence of spin in systematic reviews. Specific to dermatology, one study found that 74% (84/113) of systematic reviews related to atopic dermatitis treatment contained spin.28 Additionally, Ottwell et al13 identified spin in 31% (11/36) of the systematic reviews related to the treatment of acne vulgaris, which is similar to our results for systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments. When comparing the presence of spin in abstracts of systematic reviews from the field of dermatology with other specialties, dermatology-focused systematic reviews appear to contain more spin in the abstract than systematic reviews focused on tinnitus and glaucoma therapies.29,30 However, systematic reviews from the field of dermatology appear to contain less spin than systematic reviews focused on therapies for lower back pain.31 For example, Nascimento et al31 found that 80% (53/66) of systematic reviews focused on low-back pain treatments contained spin.

Examples of Spin—The most common type of spin found in our study was type 6.9 An example of spin type 6 can be found in an article by Bai et al32 that investigated the short-term efficacy and safety of multiple interleukin inhibitors for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract states, “Risankizumab appeared to have relatively high efficacy and low risk.” However, in the results section, the authors showed that risankizumab had the highest risk of serious adverse events and was ranked highest for discontinuation because of adverse events when compared with other interleukin inhibitors. Here, the presence of spin in the abstract may mislead the reader to accept the “low risk” of risankizumab without understanding the study’s full results.32

Another example of selective reporting of harm outcomes in a systematic review can be found in the article by Wu et al,33 which focused on assessing IL-17 antagonists for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract indicated that IL-17 antagonists should be accepted as safe; however, in the results section, the authors discussed serious safety concerns with brodalumab, including the death of 4 patients from suicide.33 This example of spin type 6 highlights how the overgeneralization of a drug’s safety profile neglects serious harm outcomes that are critical to patient safety. In fact, against the safety claims of Wu et al,33 brodalumab later received a boxed warning from the US Food and Drug Administration after 6 patients died from suicide while receiving the drug, which led to early discontinuation of the trials.34,35 Although studies suggest this relationship is not causal,34-36 the purpose of our study was not to investigate this association but to highlight the importance of this finding. Thus, with this example of spin in mind, we offer recommendations that we believe will improve reporting in abstracts as well as quality of patient care.

Recommendations for Reporting in Abstracts—Regarding the boxed warning37 for brodalumab because of suicidal ideation and behavior, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that prior to prescribing brodalumab, clinicians consider the potential benefits and risks in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal ideation or behavior. However, a clinician would not adequately assess the full risks and benefits when an abstract, such as that for the article by Wu et al,33 contains spin through selectively reporting harm outcomes. Arguably, clinicians could just read the full text; however, research confirms that abstracts often are utilized by clinicians and commonly are used to guide clinical decisions.7,38 It is reasonable that clinicians would use abstracts in this fashion because they provide a quick synopsis of the full article’s findings and are widely available to clinicians who may not have access to article databases. Initiatives are in place to improve the quality of reporting in an abstract, such as PRISMA-A,20 but even this fails to address spin. In fact, it may suggest spin because checklist item 10 of PRISMA-A advises authors of systematic reviews to provide a “general interpretation of the results and important implications.” This item is concerning because it suggests that the authors interpret importance rather than the clinician who prescribes the drug and is ultimately responsible for patient safety. Therefore, we recommend a reform to abstract reporting and an update to PRISMA-A that leads authors to report all benefits and risks encountered instead of reporting what the authors define as important.

Strengths and Limitations—Our study has several strengths as well as limitations. One of these strengths is that our protocol was strictly adhered to; any deviations were noted and added as an amendment. Our protocol, data, and all study artifacts were made freely available online on the Open Science Framework to strengthen reproducibility (https://osf.io/zrxh8/). Investigators underwent training to ensure comprehension of spin and systematic review designs. All data were extracted in masked duplicate fashion per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.39

Regarding limitations, only 2 databases were searched—MEDLINE and Embase. Therefore, our screening process may not have included every available systematic review on the treatment of psoriasis. Journal impact factors may be inaccurate for the systematic reviews that were published earlier in our data date range; however, we attempted to negate this limitation by using a 5-year average. Our study characteristic regarding PRISMA adherence did not account for studies published before the PRISMA statement release; we also could not access prior submission guidelines to determine when a journal began recommending PRISMA adherence. Another limitation of our study was the intrinsic subjectivity behind spin. Some may disagree with our classifications. Finally, our cross-sectional design should not be generalized to study types that are not systematic reviews or published in other journals during different periods.

Conclusion

Evidence of spin was present in many of the abstracts of systematic reviews pertaining to the treatment of psoriasis. Future clinical research should investigate any reporting of spin and search for ways to better reduce spin within literature. Continued research is necessary to evaluate the presence of spin within dermatology and other specialties.

Psoriasis is an inflammatory autoimmune skin condition that affects approximately 125 million individuals worldwide, with approximately 8 million patients in the United States.1 Psoriasis not only involves a cosmetic component but also comprises other comorbidities, such as psoriatic arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and psychiatric disorders, that can influence patient quality of life.2-4 In addition, the costs associated with psoriasis are substantial, with an estimated economic burden of $35.2 billion in the United States in 2015.5 Given the prevalence of psoriasis and its many effects on patients, it is important that providers have high-quality evidence regarding efficacious treatment options.

Systematic reviews, which compile all available evidence on a subject to answer a specific question, represent the gold standard of research.6 However, studies have demonstrated that when referencing research literature, physicians tend to read only the abstract of a study rather than the entire article.7,8 A study by Marcelo et al8 showed that residents at a tertiary care center answered clinical questions using only the abstract of a paper 69% of the time. Based on these findings, it is imperative that the results of systematic reviews be accurately reported in their abstracts because they can influence patient care.

Referencing only the abstracts of systematic reviews can be problematic if the abstract contains spin. Spin is a form of reporting that inappropriately highlights the benefits of a treatment with greater emphasis than what is shown by the results.9 Research has identified the presence of spin in the abstracts of randomized controlled trials.10-12 For example, Cooper et al10 found that 70% (33/47) of abstracts in otolaryngology randomized controlled trials contained spin. Additionally, Arthur et al11 and Austin et al12 had similar findings within abstracts of orthopedic and obesity trials, where 44.8% (112/250) and 46.7% (21/45) contained spin, respectively. Ottwell et al13 found that the presence of spin in abstracts is not limited to randomized controlled trials; they demonstrated that the abstracts of nearly one-third (31% [11/36]) of systematic reviews focused on the treatment of acne vulgaris contained spin.

In our study, we aimed to evaluate the presence of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews focused on the treatment of psoriasis.

Methods

Reproducibility and Reporting—Our study did not meet the regulatory definition for human subjects research per the US Code of Federal Regulations because the study did not involve human research subjects. The study also was not subject to review by the institutional review board. Our protocol, data set, analysis scripts, extraction forms, and other material related to the study have been placed on Open Science Framework to provide transparency and ensure reproducibility. To further allow for analytic reproducibility, our data set was given to an independent laboratory and reanalyzed with a masked approach. Our study was carried out alongside other studies assessing spin in systematic reviews regarding different specialties and disease states. Because these studies were similar in design, this methodology also has been reported elsewhere. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)14 and the guidelines for meta-epidemiological studies developed by Murad and Wang15 were used in drafting this article.

Search Strategy—The search strategies for the MEDLINE (Ovid) and Embase (Ovid) databases were created by a systematic review librarian (D.N.W.) to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses regarding treatments for psoriasis (Figure 1). The searches were performed on June 2, 2020, and uploaded to Rayyan, a systematic review screening platform.16 After duplicates were removed, the records were screened for eligibility by 2 authors (C.H. and A.L.) using the titles and abstracts. Screening was conducted independently while each of these authors was masked to the other’s results; disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Eligibility Criteria—An article had to meet the following criteria for inclusion in our study: (1) be a systematic review with or without a meta-analysis; (2) relate to the treatment of psoriasis; and (3) be written in English and include human patients only. The PRISMA definition of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was applied.17

Training—Various training occurred throughout our study to ensure understanding of each step and mitigate subjectivity. Before beginning screening, 2 investigators (C.H. and A.L.) completed the Introduction to Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis course offered by Johns Hopkins University.18 They also underwent 2 days of online and in-person training on the definition and interpretation of the 9 most severe types of spin found in the abstracts of systematic reviews as defined by Yavchitz et al.9 Finally, they were trained to use A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) to appraise the methodological quality of each systematic review. Our protocol contained an outline of all training modules used.

Data Extraction—The investigators (C.H. and A.L.) analyzed included abstracts for the 9 most severe types of spin (Table 1). Data were extracted in a masked duplicate fashion using the Google form. AMSTAR-2 was used to assess systematic reviews for methodological quality. AMSTAR-2 is an appraisal tool consisting of a 16-item checklist for systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Scores range from critically low to high based on the methodological quality of the review. Interrater reliability of AMSTAR-2 scores has been moderate to high across studies. Construct validity coefficients have been high with the original AMSTAR instrument (r=0.91) and the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews instrument (r=0.84).19

During data extraction from each included systematic review, the following additional items were obtained: (1) the date the review was received; (2) intervention type (ie, pharmacologic, nonpharmacologic, surgery, light therapy, mixed); (3) the funding source(s) for each systematic review (ie, industry, private, public, none, not mentioned, hospital, a combination of funding not including industry, a combination of funding including industry, other); (4) whether the journal submission guidelines suggested adherence to PRISMA guidelines; (5) whether the review discussed adherence to PRISMA14 or PRISMA for Abstracts20 (PRISMA-A); (6) the publishing journal’s 5-year impact factor; and (6) the country of the systematic review’s origin. When data extraction was complete, investigators (C.H. and A.L.) were unmasked and met to resolve any disagreements by discussion. Two authors (R.O. or M.V.) served as arbiters in the case that an agreement between C.H. and A.L. could not be reached.

Statistical Analysis—Frequencies and percentages were calculated to evaluate the most common types of spin found within systematic reviews and meta-analyses. One author (M.H.) prespecified the possibility of a binary logistic regression and calculated a power analysis to determine sample size, as stated in our protocol. Our final sample size of 173 was not powered to perform the multivariable logistic regression; therefore, we calculated unadjusted odds ratios to enable assessing relationships between the presence of spin in abstracts and the various study characteristics. We used Stata 16.1 for all analyses, and all analytic decisions can be found in our protocol.

Results

General Characteristics—Our systematic search of MEDLINE and Embase returned 3200 articles, of which 665 were duplicates that were removed. An additional 2253 articles were excluded during initial abstract and title screening, and full-text screening led to the exclusion of another 109 articles. In total, 173 systematic reviews were included for data extraction. Figure 2 illustrates the screening process with the rationale for all exclusions.

Of the 173 included systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 150 (86.7%) focused on pharmacologic interventions. The majority of studies did not mention adhering to PRISMA guidelines (125/173 [72.3%]), and the publishing journals recommended their authors adhere to PRISMA for only 66 (38.2%) of the included articles. For the articles that received funding (90/173 [52.0%]), industry sources were the most common funding source (40/90 [44.4%]), followed by private (27/90 [30%]) and public funding sources (23/90 [25.6%]). Of the remaining studies, 46 articles did not include a funding statement (46/83 [55.4%]), and 37 studies were not funded (37/83 [44.6%]). The average (SD) 5-year impact factor of our included journals was 4.68 (4.64). Systematic reviews were from 31 different countries. All studies were received by their respective journals between the years 2000 and 2020 (Table 2).

Abstracts Containing Spin—We found that 37 (21.4%) of the abstracts of systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments contained at least 1 type of spin. Some abstracts had more than 1 type; thus, a total of 51 different instances of spin were detected. Spin type 6—selective reporting of or overemphasis on harm outcomes or analysis favoring the safety of the experimental intervention—was the most common type ofspin, found in 19 of 173 abstracts (11.0%). The most severe type of spin—type 1 (conclusion contains recommendations for clinical practice not supported by the findings)—occurred in only 1 abstract (0.6%). Spin type 8 did not occur in any of the abstracts (Table 1). There was no statistically significant association between the presence of spin and any of the study characteristics (Table 2).

AMSTAR Ratings—After using AMSTAR-2 to appraise the included systematic reviews, we found that 6 (3.5%) of the 173 studies could be rated as high; 36 (20.8%) as moderate; 25 (14.5%) as low; and 106 (61.3%) as critically low. Of the 37 abstracts containing spin, 2 (5.4%) had an AMSTAR-2 rating of high, 10 (27%) had a rating of moderate, 6 (16.2%) had a rating of low, and 19 (51.4%) had a rating of critically low (Table 2). No statistically significant associations were seen between abstracts found to have spin and the AMSTAR-2 rating of the review.

Nearly all (160/173 [92.5%]) of the included reviews were compliant with the inclusion of Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) method. Only 17 of 173 (9.8%) reviews reported funding sources for the studies included. See Table 3 for all AMSTAR-2 items.

Comment

Primary Findings—We evaluated the abstracts of systematic reviews for the treatment of psoriasis and found that more than one-fifth of them contained spin. Our study contributes to the existing literature surrounding spin. Spin in randomized controlled trials is well documented across several fields of medicine, including otolaryngology,10 obesity medicine,12 dermatology,21 anesthesiology,22 psychiatry,23 orthopedics,24 emergency medicine,25 oncology,26 and cardiology.27 More recently, studies have emerged evaluating the presence of spin in systematic reviews. Specific to dermatology, one study found that 74% (84/113) of systematic reviews related to atopic dermatitis treatment contained spin.28 Additionally, Ottwell et al13 identified spin in 31% (11/36) of the systematic reviews related to the treatment of acne vulgaris, which is similar to our results for systematic reviews focused on psoriasis treatments. When comparing the presence of spin in abstracts of systematic reviews from the field of dermatology with other specialties, dermatology-focused systematic reviews appear to contain more spin in the abstract than systematic reviews focused on tinnitus and glaucoma therapies.29,30 However, systematic reviews from the field of dermatology appear to contain less spin than systematic reviews focused on therapies for lower back pain.31 For example, Nascimento et al31 found that 80% (53/66) of systematic reviews focused on low-back pain treatments contained spin.

Examples of Spin—The most common type of spin found in our study was type 6.9 An example of spin type 6 can be found in an article by Bai et al32 that investigated the short-term efficacy and safety of multiple interleukin inhibitors for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract states, “Risankizumab appeared to have relatively high efficacy and low risk.” However, in the results section, the authors showed that risankizumab had the highest risk of serious adverse events and was ranked highest for discontinuation because of adverse events when compared with other interleukin inhibitors. Here, the presence of spin in the abstract may mislead the reader to accept the “low risk” of risankizumab without understanding the study’s full results.32

Another example of selective reporting of harm outcomes in a systematic review can be found in the article by Wu et al,33 which focused on assessing IL-17 antagonists for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. The conclusion of the abstract indicated that IL-17 antagonists should be accepted as safe; however, in the results section, the authors discussed serious safety concerns with brodalumab, including the death of 4 patients from suicide.33 This example of spin type 6 highlights how the overgeneralization of a drug’s safety profile neglects serious harm outcomes that are critical to patient safety. In fact, against the safety claims of Wu et al,33 brodalumab later received a boxed warning from the US Food and Drug Administration after 6 patients died from suicide while receiving the drug, which led to early discontinuation of the trials.34,35 Although studies suggest this relationship is not causal,34-36 the purpose of our study was not to investigate this association but to highlight the importance of this finding. Thus, with this example of spin in mind, we offer recommendations that we believe will improve reporting in abstracts as well as quality of patient care.

Recommendations for Reporting in Abstracts—Regarding the boxed warning37 for brodalumab because of suicidal ideation and behavior, the US Food and Drug Administration recommends that prior to prescribing brodalumab, clinicians consider the potential benefits and risks in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal ideation or behavior. However, a clinician would not adequately assess the full risks and benefits when an abstract, such as that for the article by Wu et al,33 contains spin through selectively reporting harm outcomes. Arguably, clinicians could just read the full text; however, research confirms that abstracts often are utilized by clinicians and commonly are used to guide clinical decisions.7,38 It is reasonable that clinicians would use abstracts in this fashion because they provide a quick synopsis of the full article’s findings and are widely available to clinicians who may not have access to article databases. Initiatives are in place to improve the quality of reporting in an abstract, such as PRISMA-A,20 but even this fails to address spin. In fact, it may suggest spin because checklist item 10 of PRISMA-A advises authors of systematic reviews to provide a “general interpretation of the results and important implications.” This item is concerning because it suggests that the authors interpret importance rather than the clinician who prescribes the drug and is ultimately responsible for patient safety. Therefore, we recommend a reform to abstract reporting and an update to PRISMA-A that leads authors to report all benefits and risks encountered instead of reporting what the authors define as important.

Strengths and Limitations—Our study has several strengths as well as limitations. One of these strengths is that our protocol was strictly adhered to; any deviations were noted and added as an amendment. Our protocol, data, and all study artifacts were made freely available online on the Open Science Framework to strengthen reproducibility (https://osf.io/zrxh8/). Investigators underwent training to ensure comprehension of spin and systematic review designs. All data were extracted in masked duplicate fashion per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.39

Regarding limitations, only 2 databases were searched—MEDLINE and Embase. Therefore, our screening process may not have included every available systematic review on the treatment of psoriasis. Journal impact factors may be inaccurate for the systematic reviews that were published earlier in our data date range; however, we attempted to negate this limitation by using a 5-year average. Our study characteristic regarding PRISMA adherence did not account for studies published before the PRISMA statement release; we also could not access prior submission guidelines to determine when a journal began recommending PRISMA adherence. Another limitation of our study was the intrinsic subjectivity behind spin. Some may disagree with our classifications. Finally, our cross-sectional design should not be generalized to study types that are not systematic reviews or published in other journals during different periods.

Conclusion

Evidence of spin was present in many of the abstracts of systematic reviews pertaining to the treatment of psoriasis. Future clinical research should investigate any reporting of spin and search for ways to better reduce spin within literature. Continued research is necessary to evaluate the presence of spin within dermatology and other specialties.

- Psoriasis statistics. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated December 21, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://www.psoriasis.org/content/statistics

- Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082.

- Hu SCS, Lan CCE. Psoriasis and cardiovascular comorbidities: focusing on severe vascular events, cardiovascular risk factors and implications for treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2211.

- Patel N, Nadkarni A, Cardwell LA, et al. Psoriasis, depression, and inflammatory overlap: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:613-620.

- Brezinski EA, Dhillon JS, Armstrong AW. Economic burden of psoriasis in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:651-658.

- Gopalakrishnan S, Ganeshkumar P. Systematic reviews and meta‑analysis: understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2013;2:9-14.

- Barry HC, Ebell MH, Shaughnessy AF, et al. Family physicians’ use of medical abstracts to guide decision making: style or substance? J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:437-442.

- Marcelo A, Gavino A, Isip-Tan IT, et al. A comparison of the accuracy of clinical decisions based on full-text articles and on journal abstracts alone: a study among residents in a tertiary care hospital. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:48-53.

- Yavchitz A, Ravaud P, Altman DG, et al. A new classification of spin in systematic reviews and meta-analyses was developed and ranked according to the severity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:56-65.

- Cooper CM, Gray HM, Ross AE, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of otolaryngology randomized controlled trials. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:2036-2040.

- Arthur W, Zaaza Z, Checketts JX, et al. Analyzing spin in abstracts of orthopaedic randomized controlled trials with statistically insignificant primary endpoints. Arthroscopy. 2020;36:1443-1450.

- Austin J, Smith C, Natarajan K, et al. Evaluation of spin within abstracts in obesity randomized clinical trials: a cross-sectional review. Clin Obes. 2019;9:E12292.

- Ottwell R, Rogers TC, Michael Anderson J, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on the treatment of acne vulgaris: cross-sectional analysis. JMIR Dermatol. 2020;3:E16978.

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:E1000100.

- Murad MH, Wang Z. Guidelines for reporting meta-epidemiological methodology research. Evid Based Med. 2017;22:139-142.

- Rayyan QCRI. Accessed September 10, 2019. https://rayyan.qcri.org/reviews/81224

- Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;350:g7647.

- Coursera. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Accessed May 18, 2023. https://www.coursera.org/learn/systematic-review

- Lorenz RC, Matthias K, Pieper D, et al. A psychometric study found AMSTAR 2 to be a valid and moderately reliable appraisal tool. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;114:133-140.

- Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG, et al. PRISMA for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med. 2013;10:E1001419.

- Motosko CC, Ault AK, Kimberly LL, et al. Analysis of spin in the reporting of studies of topical treatments of photoaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:516-522.e12.

- Kinder NC, Weaver MD, Wayant C, et al. Presence of “spin” in the abstracts and titles of anaesthesiology randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:E13-E14.

- Jellison S, Roberts W, Bowers A, et al. Evaluation of spin in abstracts of papers in psychiatry and psychology journals. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2019;5:178-181.

- Checketts JX, Riddle J, Zaaza Z, et al. An evaluation of spin in lower extremity joint trials. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:1008-1012.

- Reynolds-Vaughn V, Riddle J, Brown J, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of emergency medicine randomized controlled trials. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;14:423-431.

- Wayant C, Margalski D, Vaughn K, et al. Evaluation of spin in oncology clinical trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2019;144:102821.

- Khan MS, Lateef N, Siddiqi TJ, et al. Level and prevalence of spin in published cardiovascular randomized clinical trial reports with statistically nonsignificant primary outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:E192622.

- Lin V, Patel R, Wirtz A, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of atopic dermatitis treatments and interventions. Dermatology. 2021;237:496-505.

- Rucker B, Umbarger E, Ottwell R, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses focused on tinnitus. Otol Neurotol. 2021;10:1237-1244.

- Okonya O, Lai E, Ottwell R, et al. Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of treatments for glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2021;30:235-241.

- Nascimento DP, Gonzalez GZ, Araujo AC, et al. Eight out of every ten abstracts of low back pain systematic reviews presented spin and inconsistencies with the full text: an analysis of 66 systematic reviews. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020;50:17-23.

- Bai F, Li GG, Liu Q, et al. Short-term efficacy and safety of IL-17, IL-12/23, and IL-23 inhibitors brodalumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, ustekinumab, guselkumab, tildrakizumab, and risankizumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:2546161.

- Wu D, Hou SY, Zhao S, et al. Efficacy and safety of interleukin-17 antagonists in patients with plaque psoriasis: a meta-analysis from phase 3 randomized controlled trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:992-1003.

- Rusta-Sallehy S, Gooderham M, Papp K. Brodalumab: a review of safety. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018;23:1-3.

- Rodrigeuz-Bolanos F, Gooderham M, Papp K. A closer look at the data regarding suicidal ideation and behavior in psoriasis patients: the case of brodalumab. Skin Therapy Lett. 2019;24:1-4.

- Danesh MJ, Kimball AB. Brodalumab and suicidal ideation in the context of a recent economic crisis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:190-192.

- Siliq. Prescribing information. Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC; 2017. Accessed May 18, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761032lbl.pdf

- Johnson HL, Fontelo P, Olsen CH, et al. Family nurse practitioner student perception of journal abstract usefulness in clinical decision making: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2013;25:597-603.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019.

- Psoriasis statistics. National Psoriasis Foundation. Updated December 21, 2022. Accessed March 6, 2023. https://www.psoriasis.org/content/statistics

- Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082.