User login

MD-IQ only

Factor XI inhibitors: The promise of a truly safe anticoagulant?

The quest to find an anticoagulant that can prevent strokes, cardiovascular events, and venous thrombosis without significantly increasing risk of bleeding is something of a holy grail in cardiovascular medicine. Could the latest focus of interest in this field – the factor XI inhibitors – be the long–sought-after answer?

Topline results from the largest study so far of a factor XI inhibitor – released on Sep. 18 – are indeed very encouraging. The phase 2 AZALEA-TIMI 71 study was stopped early because of an “overwhelming” reduction in major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding shown with the factor XI inhibitor abelacimab (Anthos), compared with apixaban for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib).

Very few other data from this study have yet been released. Full results are due to be presented at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association in November. Researchers in the field are optimistic that this new class of drugs may allow millions more patients who are at risk of thrombotic events but are concerned about bleeding risk to be treated, with a consequent reduction in strokes and possibly cardiovascular events as well.

Why factor XI?

In natural physiology, there are two ongoing processes: hemostasis – a set of actions that cause bleeding to stop after an injury – and thrombosis – a pathologic clotting process in which thrombus is formed and causes a stroke, MI, or deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

In patients prone to pathologic clotting, such as those with AFib, the balance of these two processes has shifted toward thrombosis, so anticoagulants are used to reduce the thrombotic risks. For many years, the only available oral anticoagulant was warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist that was very effective at preventing strokes but that comes with a high risk for bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and fatal bleeding.

The introduction of the direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) a few years ago was a step forward in that these drugs have been shown to be as effective as warfarin but are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, particularly of ICH and fatal bleeding. But they still cause bleeding, and concerns over that risk of bleeding prevent millions of patients from taking these drugs and receiving protection against stroke.

John Alexander, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., a researcher active in this area, notes that “while the DOACs cause less bleeding than warfarin, they still cause two or three times more bleeding than placebo, and there is a huge, unmet need for safer anticoagulants that don’t cause as much bleeding. We are hopeful that factor XI inhibitors might be those anticoagulants.”

The lead investigator the AZALEA study, Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained why it is thought that factor XI inhibitors may be different.

“There’s a lot of different clotting factors, and most of them converge in a central pathway. The problem, therefore, with anticoagulants used to date that block one of these factors is that they prevent clotting but also cause bleeding.

“It has been discovered that factor XI has a really unique position in the cascade of how our body forms clots in that it seems to be important in clot formation, but it doesn’t seem to play a major role in our ability to heal and repair blood vessels.”

Another doctor involved in the field, Manesh Patel, MD, chief of cardiology at Duke University Medical Center, added, “We think that factor XI inhibitors may prevent the pathologic formation of thrombosis while allowing formation of thrombus for natural hemostasis to prevent bleeding. That is why they are so promising.”

This correlates with epidemiologic data suggesting that patients with a genetic factor XI deficiency have low rates of stroke and MI but don’t appear to bleed spontaneously, Dr. Patel notes.

Candidates in development

The pharmaceutical industry is on the case with several factor XI inhibitors now in clinical development. At present, three main candidates lead the field. These are abelacimab (Anthos), a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month; and two small molecules, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer), which are both given orally.

Phase 3 trials of these three factor XI inhibitors have recently started for a variety of thrombotic indications, including the prevention of stroke in patients with AFib, prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with ischemic stroke, and prevention of future cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Dr. Alexander, who has been involved in clinical trials of both milvexian and asundexian, commented: “We have pretty good data from a number of phase 2 trials now that these factor XI inhibitors at the doses used in these studies cause a lot less bleeding than therapeutic doses of DOACs and low-molecular-weight heparins.”

He pointed out that, in addition to the AZALEA trial with abelacimab, the phase 2 PACIFIC program of studies has shown less bleeding with asundexian than with apixaban in patients with AFib and a similar amount of bleeding as placebo in ACS/stroke patients on top of antiplatelet therapy. Milvexian has also shown similar results in the AXIOMATIC program of studies.

Dr. Ruff noted that the biggest need for new anticoagulants in general is in the AFib population. “Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common medical conditions in the world. Approximately one in every three people will develop AFib in their lifetime, and it is associated with more than a fivefold increased risk of stroke. But up to half of patients with AFib currently do not take anticoagulants because of concerns about bleeding risks, so these patients are being left unprotected from stroke risk.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that the AZALEA study was the largest and longest study of a factor XI inhibitor to date; 1,287 patients were followed for a median of 2 years.

“This was the first trial of long-term administration of factor XI inhibitor against a full-dose DOAC, and it was stopped because of an overwhelming reduction in a major bleeding with abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban,” he noted. “That is very encouraging. It looks like our quest to develop a safe anticoagulant with much lower rates of bleeding, compared with standard of care, seems to have been borne out. I think the field is very excited that we may finally have something that protects patients from thrombosis whilst being much safer than current agents.”

While all this sounds very promising, for these drugs to be successful, in addition to reducing bleeding risk, they will also have to be effective at preventing strokes and other thrombotic events.

“While we are pretty sure that factor XI inhibitors will cause less bleeding than current anticoagulants, what is unknown still is how effective they will be at preventing pathologic blood clots,” Dr. Alexander points out.

“We have some data from studies of these drugs in DVT prophylaxis after orthopedic surgery which suggest that they are effective in preventing blood clots in that scenario. But we don’t know yet about whether they can prevent pathologic blood clots that occur in AFib patients or in poststroke or post-ACS patients. Phase 3 studies are now underway with these three leading drug candidates which will answer some of these questions.”

Dr. Patel agrees that the efficacy data in the phase 3 trials will be key to the success of these drugs. “That is a very important part of the puzzle that is still missing,” he says.

Dr. Ruff notes that the AZALEA study will provide some data on efficacy. “But we already know that in the orthopedic surgery trials there was a 70%-80% reduction in VTE with abelacimab (at the 150-mg dose going forward) vs. prophylactic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin. And we know from the DOACs that the doses preventing clots on the venous side also translated into preventing strokes on the [AFib] side. So that is very encouraging,” Dr. Ruff adds.

Potential indications

The three leading factor XI inhibitors have slightly different phase 3 development programs.

Dr. Ruff notes that not every agent is being investigated in phase 3 trials for all the potential indications, but all three are going for the AFib indication. “This is by far the biggest population, the biggest market, and the biggest clinical need for these agents,” he says.

While the milvexian and asundexian trials are using an active comparator – pitting the factor XI inhibitors against apixaban in AFib patients – the Anthos LILAC trial is taking a slightly different approach and is comparing abelacimab with placebo in patients with AFib who are not currently taking an anticoagulant because of concerns about bleeding risk.

Janssen/BMS is conducting two other phase 3 trials of milvexian in their LIBREXIA phase 3 program. Those trials involve poststroke patients and ACS patients. Bayer is also involved in a poststroke trial of asundexian as part of its OCEANIC phase 3 program.

Dr. Ruff points out that anticoagulants currently do not have a large role in the poststroke or post-ACS population. “But the hope is that, if factor XI inhibitors are so safe, then there will be more enthusiasm about using an anticoagulant on top of antiplatelet therapy, which is the cornerstone of therapy in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

In addition to its phase 3 LILAC study in patients with AFib, Anthos is conducting two major phase 3 trials with abelacimab for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.

Dr. Ruff notes that the indication of postsurgery or general prevention of VTE is not being pursued at present.

“The orthopedic surgery studies were done mainly for dose finding and proof of principle reasons,” he explains. “In orthopedic surgery the window for anticoagulation is quite short – a few weeks or months. And for the prevention of recurrent VTE in general in the community, those people are at a relatively low risk of bleeding, so there may not be much advantage of the factor XI inhibitors, whereas AFib patients and those with stroke or ACS are usually older and have a much higher bleeding risk. I think this is where the advantages of an anticoagulant with a lower bleeding risk are most needed.”

Dr. Alexander points out that to date anticoagulants have shown more efficacy in venous clotting, which appears to be more dependent on coagulation factors and less dependent on platelets. “Atrial fibrillation is a mix between venous and arterial clotting, but it has more similarities to venous, so I think AFib is a place where new anticoagulants such as the factor XI inhibitors are more likely to have success,” he suggests.

“So far, anticoagulants have had a less clear long-term role in the poststroke and post-ACS populations, so these indications may be a more difficult goal,” he added.

The phase 3 studies are just starting and will take a few years before results are known.

Differences between the agents

The three factor XI inhibitors also have some differences. Dr. Ruff points out that most important will be the safety and efficacy of the drugs in phase 3 trials.

“Early data suggest that the various agents being developed may not have equal inhibition of factor XI. The monoclonal antibody abelacimab may produce a higher degree of inhibition than the small molecules. But we don’t know if that matters or not – whether we need to achieve a certain threshold to prevent stroke. The efficacy and safety data from the phase 3 trials are what will primarily guide use.”

There are also differences in formulations and dosage. Abelacimab is administered by subcutaneous injection once a month and has a long duration of activity, whereas the small molecules are taken orally and their duration of action is much shorter.

Dr. Ruff notes: “If these drugs cause bleeding, having a long-acting drug like abelacimab could be a disadvantage because we wouldn’t be able to stop it. But if they are very safe with regard to bleeding, then having the drug hang around for a long time is not necessarily a disadvantage, and it may improve compliance. These older patients often miss doses, and with a shorter-acting drug, that will mean they will be unprotected from stroke risk for a period of time, so there is a trade-off here.”

Dr. Ruff says that the AZALEA phase 2 study will provide some data on patients being managed around procedures. “The hope is that these drugs are so safe that they will not have to be stopped for procedures. And then the compliance issue of a once-a-month dosing would be an advantage.”

Dr. Patel says he believes there is a place for different formations. “Some patients may prefer a once-monthly injection; others will prefer a daily tablet. It may come down to patient preference, but a lot will depend on the study results with the different agents,” he commented.

What effect could these drugs have?

If these drugs do show efficacy in these phase 3 trials, what difference will they make to clinical practice? The potential appears to be very large.

“If these drugs are as effective at preventing strokes as DOACs, they will be a huge breakthrough, and there is good reason to think they would replace the DOACs,” Dr. Alexander says. “It would be a really big deal to have an anticoagulant that causes almost no bleeding and could prevent clots as well as the DOACs. This would enable a lot more patients to receive protection against stroke.”

Dr. Alexander believes the surgery studies are hopeful. “They show that the factor XI inhibitors are doing something to prevent blood clots. The big question is whether they are as effective as what we already have for the prevention of stroke and if not, what is the trade-off with bleeding?”

He points out that, even if the factor XI inhibitors are not as effective as DOACs but are found to be much safer, they might still have a potential clinical role, especially for those patients who currently do not take an anticoagulant because of concerns regarding bleeding.

But Dr. Patel points out that there is always the issue of costs with new drugs. “New drugs are always expensive. The DOACS are just about to become generic, and there will inevitably be concerns about access to an expensive new therapy.”

Dr. Alexander adds: “Yes, costs could be an issue, but a safer drug will definitely help to get more patients treated and in preventing more strokes, which would be a great thing.”

Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an adviser to Bayer (asundexian) and Janssen (milvexian). Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer. Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AFib executive committee for BMS/Janssen, and has been on an advisory board for Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The quest to find an anticoagulant that can prevent strokes, cardiovascular events, and venous thrombosis without significantly increasing risk of bleeding is something of a holy grail in cardiovascular medicine. Could the latest focus of interest in this field – the factor XI inhibitors – be the long–sought-after answer?

Topline results from the largest study so far of a factor XI inhibitor – released on Sep. 18 – are indeed very encouraging. The phase 2 AZALEA-TIMI 71 study was stopped early because of an “overwhelming” reduction in major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding shown with the factor XI inhibitor abelacimab (Anthos), compared with apixaban for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib).

Very few other data from this study have yet been released. Full results are due to be presented at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association in November. Researchers in the field are optimistic that this new class of drugs may allow millions more patients who are at risk of thrombotic events but are concerned about bleeding risk to be treated, with a consequent reduction in strokes and possibly cardiovascular events as well.

Why factor XI?

In natural physiology, there are two ongoing processes: hemostasis – a set of actions that cause bleeding to stop after an injury – and thrombosis – a pathologic clotting process in which thrombus is formed and causes a stroke, MI, or deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

In patients prone to pathologic clotting, such as those with AFib, the balance of these two processes has shifted toward thrombosis, so anticoagulants are used to reduce the thrombotic risks. For many years, the only available oral anticoagulant was warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist that was very effective at preventing strokes but that comes with a high risk for bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and fatal bleeding.

The introduction of the direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) a few years ago was a step forward in that these drugs have been shown to be as effective as warfarin but are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, particularly of ICH and fatal bleeding. But they still cause bleeding, and concerns over that risk of bleeding prevent millions of patients from taking these drugs and receiving protection against stroke.

John Alexander, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., a researcher active in this area, notes that “while the DOACs cause less bleeding than warfarin, they still cause two or three times more bleeding than placebo, and there is a huge, unmet need for safer anticoagulants that don’t cause as much bleeding. We are hopeful that factor XI inhibitors might be those anticoagulants.”

The lead investigator the AZALEA study, Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained why it is thought that factor XI inhibitors may be different.

“There’s a lot of different clotting factors, and most of them converge in a central pathway. The problem, therefore, with anticoagulants used to date that block one of these factors is that they prevent clotting but also cause bleeding.

“It has been discovered that factor XI has a really unique position in the cascade of how our body forms clots in that it seems to be important in clot formation, but it doesn’t seem to play a major role in our ability to heal and repair blood vessels.”

Another doctor involved in the field, Manesh Patel, MD, chief of cardiology at Duke University Medical Center, added, “We think that factor XI inhibitors may prevent the pathologic formation of thrombosis while allowing formation of thrombus for natural hemostasis to prevent bleeding. That is why they are so promising.”

This correlates with epidemiologic data suggesting that patients with a genetic factor XI deficiency have low rates of stroke and MI but don’t appear to bleed spontaneously, Dr. Patel notes.

Candidates in development

The pharmaceutical industry is on the case with several factor XI inhibitors now in clinical development. At present, three main candidates lead the field. These are abelacimab (Anthos), a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month; and two small molecules, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer), which are both given orally.

Phase 3 trials of these three factor XI inhibitors have recently started for a variety of thrombotic indications, including the prevention of stroke in patients with AFib, prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with ischemic stroke, and prevention of future cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Dr. Alexander, who has been involved in clinical trials of both milvexian and asundexian, commented: “We have pretty good data from a number of phase 2 trials now that these factor XI inhibitors at the doses used in these studies cause a lot less bleeding than therapeutic doses of DOACs and low-molecular-weight heparins.”

He pointed out that, in addition to the AZALEA trial with abelacimab, the phase 2 PACIFIC program of studies has shown less bleeding with asundexian than with apixaban in patients with AFib and a similar amount of bleeding as placebo in ACS/stroke patients on top of antiplatelet therapy. Milvexian has also shown similar results in the AXIOMATIC program of studies.

Dr. Ruff noted that the biggest need for new anticoagulants in general is in the AFib population. “Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common medical conditions in the world. Approximately one in every three people will develop AFib in their lifetime, and it is associated with more than a fivefold increased risk of stroke. But up to half of patients with AFib currently do not take anticoagulants because of concerns about bleeding risks, so these patients are being left unprotected from stroke risk.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that the AZALEA study was the largest and longest study of a factor XI inhibitor to date; 1,287 patients were followed for a median of 2 years.

“This was the first trial of long-term administration of factor XI inhibitor against a full-dose DOAC, and it was stopped because of an overwhelming reduction in a major bleeding with abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban,” he noted. “That is very encouraging. It looks like our quest to develop a safe anticoagulant with much lower rates of bleeding, compared with standard of care, seems to have been borne out. I think the field is very excited that we may finally have something that protects patients from thrombosis whilst being much safer than current agents.”

While all this sounds very promising, for these drugs to be successful, in addition to reducing bleeding risk, they will also have to be effective at preventing strokes and other thrombotic events.

“While we are pretty sure that factor XI inhibitors will cause less bleeding than current anticoagulants, what is unknown still is how effective they will be at preventing pathologic blood clots,” Dr. Alexander points out.

“We have some data from studies of these drugs in DVT prophylaxis after orthopedic surgery which suggest that they are effective in preventing blood clots in that scenario. But we don’t know yet about whether they can prevent pathologic blood clots that occur in AFib patients or in poststroke or post-ACS patients. Phase 3 studies are now underway with these three leading drug candidates which will answer some of these questions.”

Dr. Patel agrees that the efficacy data in the phase 3 trials will be key to the success of these drugs. “That is a very important part of the puzzle that is still missing,” he says.

Dr. Ruff notes that the AZALEA study will provide some data on efficacy. “But we already know that in the orthopedic surgery trials there was a 70%-80% reduction in VTE with abelacimab (at the 150-mg dose going forward) vs. prophylactic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin. And we know from the DOACs that the doses preventing clots on the venous side also translated into preventing strokes on the [AFib] side. So that is very encouraging,” Dr. Ruff adds.

Potential indications

The three leading factor XI inhibitors have slightly different phase 3 development programs.

Dr. Ruff notes that not every agent is being investigated in phase 3 trials for all the potential indications, but all three are going for the AFib indication. “This is by far the biggest population, the biggest market, and the biggest clinical need for these agents,” he says.

While the milvexian and asundexian trials are using an active comparator – pitting the factor XI inhibitors against apixaban in AFib patients – the Anthos LILAC trial is taking a slightly different approach and is comparing abelacimab with placebo in patients with AFib who are not currently taking an anticoagulant because of concerns about bleeding risk.

Janssen/BMS is conducting two other phase 3 trials of milvexian in their LIBREXIA phase 3 program. Those trials involve poststroke patients and ACS patients. Bayer is also involved in a poststroke trial of asundexian as part of its OCEANIC phase 3 program.

Dr. Ruff points out that anticoagulants currently do not have a large role in the poststroke or post-ACS population. “But the hope is that, if factor XI inhibitors are so safe, then there will be more enthusiasm about using an anticoagulant on top of antiplatelet therapy, which is the cornerstone of therapy in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

In addition to its phase 3 LILAC study in patients with AFib, Anthos is conducting two major phase 3 trials with abelacimab for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.

Dr. Ruff notes that the indication of postsurgery or general prevention of VTE is not being pursued at present.

“The orthopedic surgery studies were done mainly for dose finding and proof of principle reasons,” he explains. “In orthopedic surgery the window for anticoagulation is quite short – a few weeks or months. And for the prevention of recurrent VTE in general in the community, those people are at a relatively low risk of bleeding, so there may not be much advantage of the factor XI inhibitors, whereas AFib patients and those with stroke or ACS are usually older and have a much higher bleeding risk. I think this is where the advantages of an anticoagulant with a lower bleeding risk are most needed.”

Dr. Alexander points out that to date anticoagulants have shown more efficacy in venous clotting, which appears to be more dependent on coagulation factors and less dependent on platelets. “Atrial fibrillation is a mix between venous and arterial clotting, but it has more similarities to venous, so I think AFib is a place where new anticoagulants such as the factor XI inhibitors are more likely to have success,” he suggests.

“So far, anticoagulants have had a less clear long-term role in the poststroke and post-ACS populations, so these indications may be a more difficult goal,” he added.

The phase 3 studies are just starting and will take a few years before results are known.

Differences between the agents

The three factor XI inhibitors also have some differences. Dr. Ruff points out that most important will be the safety and efficacy of the drugs in phase 3 trials.

“Early data suggest that the various agents being developed may not have equal inhibition of factor XI. The monoclonal antibody abelacimab may produce a higher degree of inhibition than the small molecules. But we don’t know if that matters or not – whether we need to achieve a certain threshold to prevent stroke. The efficacy and safety data from the phase 3 trials are what will primarily guide use.”

There are also differences in formulations and dosage. Abelacimab is administered by subcutaneous injection once a month and has a long duration of activity, whereas the small molecules are taken orally and their duration of action is much shorter.

Dr. Ruff notes: “If these drugs cause bleeding, having a long-acting drug like abelacimab could be a disadvantage because we wouldn’t be able to stop it. But if they are very safe with regard to bleeding, then having the drug hang around for a long time is not necessarily a disadvantage, and it may improve compliance. These older patients often miss doses, and with a shorter-acting drug, that will mean they will be unprotected from stroke risk for a period of time, so there is a trade-off here.”

Dr. Ruff says that the AZALEA phase 2 study will provide some data on patients being managed around procedures. “The hope is that these drugs are so safe that they will not have to be stopped for procedures. And then the compliance issue of a once-a-month dosing would be an advantage.”

Dr. Patel says he believes there is a place for different formations. “Some patients may prefer a once-monthly injection; others will prefer a daily tablet. It may come down to patient preference, but a lot will depend on the study results with the different agents,” he commented.

What effect could these drugs have?

If these drugs do show efficacy in these phase 3 trials, what difference will they make to clinical practice? The potential appears to be very large.

“If these drugs are as effective at preventing strokes as DOACs, they will be a huge breakthrough, and there is good reason to think they would replace the DOACs,” Dr. Alexander says. “It would be a really big deal to have an anticoagulant that causes almost no bleeding and could prevent clots as well as the DOACs. This would enable a lot more patients to receive protection against stroke.”

Dr. Alexander believes the surgery studies are hopeful. “They show that the factor XI inhibitors are doing something to prevent blood clots. The big question is whether they are as effective as what we already have for the prevention of stroke and if not, what is the trade-off with bleeding?”

He points out that, even if the factor XI inhibitors are not as effective as DOACs but are found to be much safer, they might still have a potential clinical role, especially for those patients who currently do not take an anticoagulant because of concerns regarding bleeding.

But Dr. Patel points out that there is always the issue of costs with new drugs. “New drugs are always expensive. The DOACS are just about to become generic, and there will inevitably be concerns about access to an expensive new therapy.”

Dr. Alexander adds: “Yes, costs could be an issue, but a safer drug will definitely help to get more patients treated and in preventing more strokes, which would be a great thing.”

Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an adviser to Bayer (asundexian) and Janssen (milvexian). Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer. Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AFib executive committee for BMS/Janssen, and has been on an advisory board for Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The quest to find an anticoagulant that can prevent strokes, cardiovascular events, and venous thrombosis without significantly increasing risk of bleeding is something of a holy grail in cardiovascular medicine. Could the latest focus of interest in this field – the factor XI inhibitors – be the long–sought-after answer?

Topline results from the largest study so far of a factor XI inhibitor – released on Sep. 18 – are indeed very encouraging. The phase 2 AZALEA-TIMI 71 study was stopped early because of an “overwhelming” reduction in major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding shown with the factor XI inhibitor abelacimab (Anthos), compared with apixaban for patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib).

Very few other data from this study have yet been released. Full results are due to be presented at the scientific sessions of the American Heart Association in November. Researchers in the field are optimistic that this new class of drugs may allow millions more patients who are at risk of thrombotic events but are concerned about bleeding risk to be treated, with a consequent reduction in strokes and possibly cardiovascular events as well.

Why factor XI?

In natural physiology, there are two ongoing processes: hemostasis – a set of actions that cause bleeding to stop after an injury – and thrombosis – a pathologic clotting process in which thrombus is formed and causes a stroke, MI, or deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

In patients prone to pathologic clotting, such as those with AFib, the balance of these two processes has shifted toward thrombosis, so anticoagulants are used to reduce the thrombotic risks. For many years, the only available oral anticoagulant was warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist that was very effective at preventing strokes but that comes with a high risk for bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and fatal bleeding.

The introduction of the direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) a few years ago was a step forward in that these drugs have been shown to be as effective as warfarin but are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, particularly of ICH and fatal bleeding. But they still cause bleeding, and concerns over that risk of bleeding prevent millions of patients from taking these drugs and receiving protection against stroke.

John Alexander, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., a researcher active in this area, notes that “while the DOACs cause less bleeding than warfarin, they still cause two or three times more bleeding than placebo, and there is a huge, unmet need for safer anticoagulants that don’t cause as much bleeding. We are hopeful that factor XI inhibitors might be those anticoagulants.”

The lead investigator the AZALEA study, Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained why it is thought that factor XI inhibitors may be different.

“There’s a lot of different clotting factors, and most of them converge in a central pathway. The problem, therefore, with anticoagulants used to date that block one of these factors is that they prevent clotting but also cause bleeding.

“It has been discovered that factor XI has a really unique position in the cascade of how our body forms clots in that it seems to be important in clot formation, but it doesn’t seem to play a major role in our ability to heal and repair blood vessels.”

Another doctor involved in the field, Manesh Patel, MD, chief of cardiology at Duke University Medical Center, added, “We think that factor XI inhibitors may prevent the pathologic formation of thrombosis while allowing formation of thrombus for natural hemostasis to prevent bleeding. That is why they are so promising.”

This correlates with epidemiologic data suggesting that patients with a genetic factor XI deficiency have low rates of stroke and MI but don’t appear to bleed spontaneously, Dr. Patel notes.

Candidates in development

The pharmaceutical industry is on the case with several factor XI inhibitors now in clinical development. At present, three main candidates lead the field. These are abelacimab (Anthos), a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month; and two small molecules, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer), which are both given orally.

Phase 3 trials of these three factor XI inhibitors have recently started for a variety of thrombotic indications, including the prevention of stroke in patients with AFib, prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with ischemic stroke, and prevention of future cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Dr. Alexander, who has been involved in clinical trials of both milvexian and asundexian, commented: “We have pretty good data from a number of phase 2 trials now that these factor XI inhibitors at the doses used in these studies cause a lot less bleeding than therapeutic doses of DOACs and low-molecular-weight heparins.”

He pointed out that, in addition to the AZALEA trial with abelacimab, the phase 2 PACIFIC program of studies has shown less bleeding with asundexian than with apixaban in patients with AFib and a similar amount of bleeding as placebo in ACS/stroke patients on top of antiplatelet therapy. Milvexian has also shown similar results in the AXIOMATIC program of studies.

Dr. Ruff noted that the biggest need for new anticoagulants in general is in the AFib population. “Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common medical conditions in the world. Approximately one in every three people will develop AFib in their lifetime, and it is associated with more than a fivefold increased risk of stroke. But up to half of patients with AFib currently do not take anticoagulants because of concerns about bleeding risks, so these patients are being left unprotected from stroke risk.”

Dr. Ruff pointed out that the AZALEA study was the largest and longest study of a factor XI inhibitor to date; 1,287 patients were followed for a median of 2 years.

“This was the first trial of long-term administration of factor XI inhibitor against a full-dose DOAC, and it was stopped because of an overwhelming reduction in a major bleeding with abelacimab, compared with rivaroxaban,” he noted. “That is very encouraging. It looks like our quest to develop a safe anticoagulant with much lower rates of bleeding, compared with standard of care, seems to have been borne out. I think the field is very excited that we may finally have something that protects patients from thrombosis whilst being much safer than current agents.”

While all this sounds very promising, for these drugs to be successful, in addition to reducing bleeding risk, they will also have to be effective at preventing strokes and other thrombotic events.

“While we are pretty sure that factor XI inhibitors will cause less bleeding than current anticoagulants, what is unknown still is how effective they will be at preventing pathologic blood clots,” Dr. Alexander points out.

“We have some data from studies of these drugs in DVT prophylaxis after orthopedic surgery which suggest that they are effective in preventing blood clots in that scenario. But we don’t know yet about whether they can prevent pathologic blood clots that occur in AFib patients or in poststroke or post-ACS patients. Phase 3 studies are now underway with these three leading drug candidates which will answer some of these questions.”

Dr. Patel agrees that the efficacy data in the phase 3 trials will be key to the success of these drugs. “That is a very important part of the puzzle that is still missing,” he says.

Dr. Ruff notes that the AZALEA study will provide some data on efficacy. “But we already know that in the orthopedic surgery trials there was a 70%-80% reduction in VTE with abelacimab (at the 150-mg dose going forward) vs. prophylactic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin. And we know from the DOACs that the doses preventing clots on the venous side also translated into preventing strokes on the [AFib] side. So that is very encouraging,” Dr. Ruff adds.

Potential indications

The three leading factor XI inhibitors have slightly different phase 3 development programs.

Dr. Ruff notes that not every agent is being investigated in phase 3 trials for all the potential indications, but all three are going for the AFib indication. “This is by far the biggest population, the biggest market, and the biggest clinical need for these agents,” he says.

While the milvexian and asundexian trials are using an active comparator – pitting the factor XI inhibitors against apixaban in AFib patients – the Anthos LILAC trial is taking a slightly different approach and is comparing abelacimab with placebo in patients with AFib who are not currently taking an anticoagulant because of concerns about bleeding risk.

Janssen/BMS is conducting two other phase 3 trials of milvexian in their LIBREXIA phase 3 program. Those trials involve poststroke patients and ACS patients. Bayer is also involved in a poststroke trial of asundexian as part of its OCEANIC phase 3 program.

Dr. Ruff points out that anticoagulants currently do not have a large role in the poststroke or post-ACS population. “But the hope is that, if factor XI inhibitors are so safe, then there will be more enthusiasm about using an anticoagulant on top of antiplatelet therapy, which is the cornerstone of therapy in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

In addition to its phase 3 LILAC study in patients with AFib, Anthos is conducting two major phase 3 trials with abelacimab for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.

Dr. Ruff notes that the indication of postsurgery or general prevention of VTE is not being pursued at present.

“The orthopedic surgery studies were done mainly for dose finding and proof of principle reasons,” he explains. “In orthopedic surgery the window for anticoagulation is quite short – a few weeks or months. And for the prevention of recurrent VTE in general in the community, those people are at a relatively low risk of bleeding, so there may not be much advantage of the factor XI inhibitors, whereas AFib patients and those with stroke or ACS are usually older and have a much higher bleeding risk. I think this is where the advantages of an anticoagulant with a lower bleeding risk are most needed.”

Dr. Alexander points out that to date anticoagulants have shown more efficacy in venous clotting, which appears to be more dependent on coagulation factors and less dependent on platelets. “Atrial fibrillation is a mix between venous and arterial clotting, but it has more similarities to venous, so I think AFib is a place where new anticoagulants such as the factor XI inhibitors are more likely to have success,” he suggests.

“So far, anticoagulants have had a less clear long-term role in the poststroke and post-ACS populations, so these indications may be a more difficult goal,” he added.

The phase 3 studies are just starting and will take a few years before results are known.

Differences between the agents

The three factor XI inhibitors also have some differences. Dr. Ruff points out that most important will be the safety and efficacy of the drugs in phase 3 trials.

“Early data suggest that the various agents being developed may not have equal inhibition of factor XI. The monoclonal antibody abelacimab may produce a higher degree of inhibition than the small molecules. But we don’t know if that matters or not – whether we need to achieve a certain threshold to prevent stroke. The efficacy and safety data from the phase 3 trials are what will primarily guide use.”

There are also differences in formulations and dosage. Abelacimab is administered by subcutaneous injection once a month and has a long duration of activity, whereas the small molecules are taken orally and their duration of action is much shorter.

Dr. Ruff notes: “If these drugs cause bleeding, having a long-acting drug like abelacimab could be a disadvantage because we wouldn’t be able to stop it. But if they are very safe with regard to bleeding, then having the drug hang around for a long time is not necessarily a disadvantage, and it may improve compliance. These older patients often miss doses, and with a shorter-acting drug, that will mean they will be unprotected from stroke risk for a period of time, so there is a trade-off here.”

Dr. Ruff says that the AZALEA phase 2 study will provide some data on patients being managed around procedures. “The hope is that these drugs are so safe that they will not have to be stopped for procedures. And then the compliance issue of a once-a-month dosing would be an advantage.”

Dr. Patel says he believes there is a place for different formations. “Some patients may prefer a once-monthly injection; others will prefer a daily tablet. It may come down to patient preference, but a lot will depend on the study results with the different agents,” he commented.

What effect could these drugs have?

If these drugs do show efficacy in these phase 3 trials, what difference will they make to clinical practice? The potential appears to be very large.

“If these drugs are as effective at preventing strokes as DOACs, they will be a huge breakthrough, and there is good reason to think they would replace the DOACs,” Dr. Alexander says. “It would be a really big deal to have an anticoagulant that causes almost no bleeding and could prevent clots as well as the DOACs. This would enable a lot more patients to receive protection against stroke.”

Dr. Alexander believes the surgery studies are hopeful. “They show that the factor XI inhibitors are doing something to prevent blood clots. The big question is whether they are as effective as what we already have for the prevention of stroke and if not, what is the trade-off with bleeding?”

He points out that, even if the factor XI inhibitors are not as effective as DOACs but are found to be much safer, they might still have a potential clinical role, especially for those patients who currently do not take an anticoagulant because of concerns regarding bleeding.

But Dr. Patel points out that there is always the issue of costs with new drugs. “New drugs are always expensive. The DOACS are just about to become generic, and there will inevitably be concerns about access to an expensive new therapy.”

Dr. Alexander adds: “Yes, costs could be an issue, but a safer drug will definitely help to get more patients treated and in preventing more strokes, which would be a great thing.”

Dr. Patel has received grants from and acts as an adviser to Bayer (asundexian) and Janssen (milvexian). Dr. Alexander receives research funding from Bayer. Dr. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AFib executive committee for BMS/Janssen, and has been on an advisory board for Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

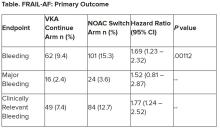

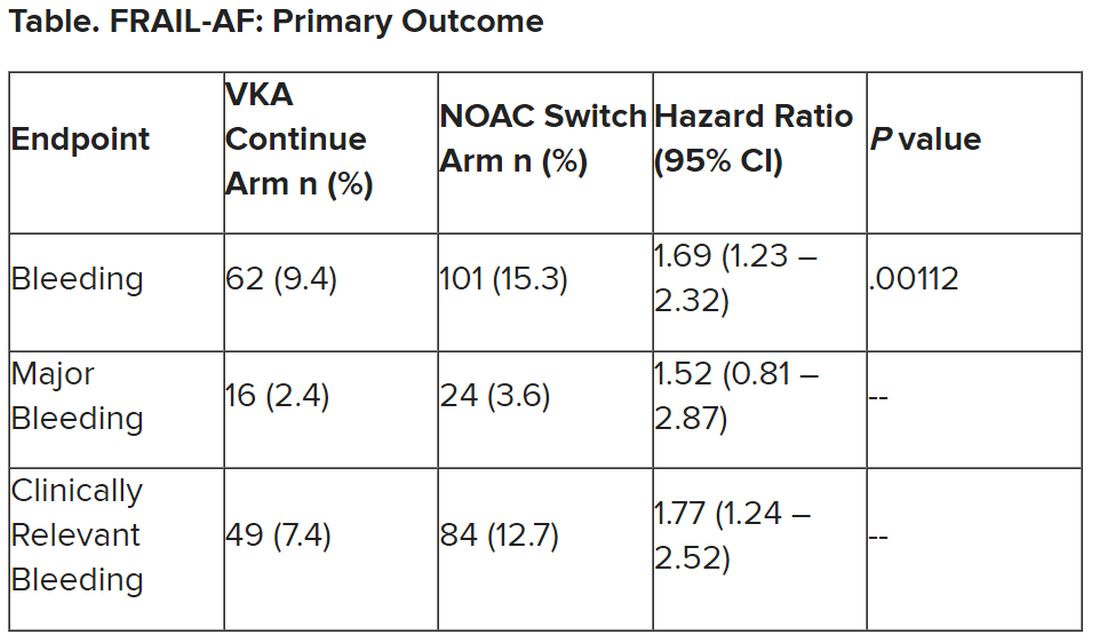

Steady VKA therapy beats switch to NOAC in frail AFib patients: FRAIL-AF

Switching frail patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) from anticoagulation therapy with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) resulted in more bleeding without any reduction in thromboembolic complications or all-cause mortality, randomized trial results show.

The study, FRAIL-AF, is the first randomized NOAC trial to exclusively include frail older patients, said lead author Linda P.T. Joosten, MD, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and these unexpected findings provide evidence that goes beyond what is currently available.

“Data from the FRAIL-AF trial showed that switching from a VKA to a NOAC should not be considered without a clear indication in frail older patients with AF[ib], as switching to a NOAC leads to 69% more bleeding,” she concluded, without any benefit on secondary clinical endpoints, including thromboembolic events and all-cause mortality.

“The results turned out different than we expected,” Dr. Joosten said. “The hypothesis of this superiority trial was that switching from VKA therapy to a NOAC would result in less bleeding. However, we observed the opposite. After the interim analysis, the data and safety monitoring board advised to stop inclusion because switching from a VKA to a NOAC was clearly contraindicated with a hazard ratio of 1.69 and a highly significant P value of .001.”

Results of FRAIL-AF were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published online in the journal Circulation.

Session moderator Renate B. Schnabel, MD, interventional cardiologist with University Heart & Vascular Center Hamburg (Germany), congratulated the researchers on these “astonishing” data.

“The thing I want to emphasize here is that, in the absence of randomized controlled trial data, we should be very cautious in extrapolating data from the landmark trials to populations not enrolled in those, and to rely on observational data only,” Dr. Schnabel told Dr. Joosten. “We need randomized controlled trials that sometimes give astonishing results.”

Frailty a clinical syndrome

Frailty is “a lot more than just aging, multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy,” Dr. Joosten explained. “It’s really a clinical syndrome, with people with a high biological vulnerability, dependency on significant others, and a reduced capacity to resist stressors, all leading to a reduced homeostatic reserve.”

Frailty is common in the community, with a prevalence of about 12%, she noted, “and even more important, AF[ib] in frail older people is very common, with a prevalence of 18%. And “without any doubt, we have to adequately anticoagulate frail AF[ib] patients, as they have a high stroke risk, with an incidence of 12.4% per year,” Dr. Joosten noted, compared with 3.9% per year among nonfrail AFib patients.

NOACs are preferred over VKAs in nonfrail AFib patients, after four major trials, RE-LY with dabigatran, ROCKET-AF with rivaroxaban, ARISTOTLE with apixaban, and ENGAGE-AF with edoxaban, showed that NOAC treatment resulted in less major bleeding while stroke risk was comparable with treatment with warfarin, she noted.

The 2023 European Heart Rhythm Association consensus document on management of arrhythmias in frailty syndrome concludes that the advantages of NOACs relative to VKAs are “likely consistent” in frail and nonfrail AFib patients, but the level of evidence is low.

So it’s unknown if NOACs are preferred over VKAs in frail AFib patients, “and it’s even more questionable whether patients on VKAs should switch to NOAC therapy,” Dr. Joosten said.

This new trial aimed to answer the question of whether switching frail AFib patients currently managed on a VKA to a NOAC would reduce bleeding. FRAIL-AF was a pragmatic, multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Older AFib patients were deemed frail if they were aged 75 years or older and had a score of 3 or more on the validated Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI). Patients with a glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or with valvular AFib were excluded.

Eligible patients were then assigned randomly to switch from their international normalized ratio (INR)–guided VKA treatment with either 1 mg acenocoumarol or 3 mg phenprocoumon, to a NOAC, or to continue VKA treatment. They were followed for 12 months for the primary outcome – major bleeding or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding complication, whichever came first – accounting for death as a competing risk.

A total of 1,330 patients were randomly assigned between January 2018 and June 2022. Their mean age was 83 years, and they had a median GFI of 4. After randomization, 6 patients in the switch-to-NOAC arm, and 1 in the continue-VKA arm were found to have exclusion criteria, so in the end, 662 patients were switched from a VKA to NOAC, while 661 continued on VKA therapy. The choice of NOAC was made by the treating physician.

Major bleeding was defined as a fatal bleeding; bleeding in a critical area or organ; bleeding leading to transfusion; and/or bleeding leading to a fall in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL (1.24 mmol/L) or more. Nonmajor bleeding was bleeding not considered major but requiring face-to-face consultation, hospitalization or increased level of care, or medical intervention.

After a prespecified futility analysis planned after 163 primary outcome events, the trial was halted when it was seen that there were 101 primary outcome events in the switch arm compared to 62 in the continue arm, Dr. Joosten said. The difference appeared to be driven by clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding.

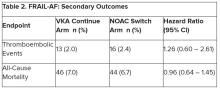

Secondary outcomes of thromboembolic events and all-cause mortality were similar between the groups.

Completely different patients

Discussant at the meeting for the presentation was Isabelle C. Van Gelder, MD, University Medical Centre Groningen (the Netherlands). She said the results are important and relevant because it “provides data on an important gap of knowledge in our AF[ib] guidelines, and a note for all the cardiologists – this study was not done in the hospital. This trial was done in general practitioner practices, so that’s important to consider.”

Comparing FRAIL-AF patients with those of the four previous NOAC trials, “you see that enormous difference in age,” with an average age of 83 years versus 70-73 years in those trials. “These are completely different patients than have been included previously,” she said.

That GFI score of 4 or more includes patients on four or more different types of medication, as well as memory complaints, an inability to walk around the house, and problems with vision or hearing.

The finding of a 69% increase in bleeding with NOACs in FRAIL-AF was “completely unexpected, and I think that we as cardiologists and as NOAC believers did not expect it at all, but it is as clear as it is.” The curves don’t diverge immediately, but rather after 3 months or thereafter, “so it has nothing to do with the switching process. So why did it occur?”

The Netherlands has dedicated thrombosis services that might improve time in therapeutic range for VKA patients, but there is no real difference in TTRs in FRAIL-AF versus the other NOAC trials, Dr. Van Gelder noted.

The most likely suspect in her view is frailty itself, in particular the tendency for patients to be on a high number of medications. A previous study showed, for example, that polypharmacy could be used as a proxy for the effect of frailty on bleeding risk; patients on 10 or more medications had a higher risk for bleeding on treatment with rivaroxaban versus those on 4 or fewer medications.

“Therefore, in my view, why was there such a high risk of bleeding? It’s because these are other patients than we are normally used to treat, we as cardiologists,” although general practitioners see these patients all the time. “It’s all about frailty.”

NOACs are still relatively new drugs, with possible unknown interactions, she added. Because of their frailty and polypharmacy, these patients may benefit from INR control, Dr. Van Gelder speculated. “Therefore, I agree with them that we should be careful; if such old, frail patients survive on VKA, do not change medications and do not switch!”

The study was supported by the Dutch government with additional and unrestricted educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer, Bayer, and Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Joosten reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Van Gelder reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Switching frail patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) from anticoagulation therapy with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) resulted in more bleeding without any reduction in thromboembolic complications or all-cause mortality, randomized trial results show.

The study, FRAIL-AF, is the first randomized NOAC trial to exclusively include frail older patients, said lead author Linda P.T. Joosten, MD, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and these unexpected findings provide evidence that goes beyond what is currently available.

“Data from the FRAIL-AF trial showed that switching from a VKA to a NOAC should not be considered without a clear indication in frail older patients with AF[ib], as switching to a NOAC leads to 69% more bleeding,” she concluded, without any benefit on secondary clinical endpoints, including thromboembolic events and all-cause mortality.

“The results turned out different than we expected,” Dr. Joosten said. “The hypothesis of this superiority trial was that switching from VKA therapy to a NOAC would result in less bleeding. However, we observed the opposite. After the interim analysis, the data and safety monitoring board advised to stop inclusion because switching from a VKA to a NOAC was clearly contraindicated with a hazard ratio of 1.69 and a highly significant P value of .001.”

Results of FRAIL-AF were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published online in the journal Circulation.

Session moderator Renate B. Schnabel, MD, interventional cardiologist with University Heart & Vascular Center Hamburg (Germany), congratulated the researchers on these “astonishing” data.

“The thing I want to emphasize here is that, in the absence of randomized controlled trial data, we should be very cautious in extrapolating data from the landmark trials to populations not enrolled in those, and to rely on observational data only,” Dr. Schnabel told Dr. Joosten. “We need randomized controlled trials that sometimes give astonishing results.”

Frailty a clinical syndrome

Frailty is “a lot more than just aging, multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy,” Dr. Joosten explained. “It’s really a clinical syndrome, with people with a high biological vulnerability, dependency on significant others, and a reduced capacity to resist stressors, all leading to a reduced homeostatic reserve.”

Frailty is common in the community, with a prevalence of about 12%, she noted, “and even more important, AF[ib] in frail older people is very common, with a prevalence of 18%. And “without any doubt, we have to adequately anticoagulate frail AF[ib] patients, as they have a high stroke risk, with an incidence of 12.4% per year,” Dr. Joosten noted, compared with 3.9% per year among nonfrail AFib patients.

NOACs are preferred over VKAs in nonfrail AFib patients, after four major trials, RE-LY with dabigatran, ROCKET-AF with rivaroxaban, ARISTOTLE with apixaban, and ENGAGE-AF with edoxaban, showed that NOAC treatment resulted in less major bleeding while stroke risk was comparable with treatment with warfarin, she noted.

The 2023 European Heart Rhythm Association consensus document on management of arrhythmias in frailty syndrome concludes that the advantages of NOACs relative to VKAs are “likely consistent” in frail and nonfrail AFib patients, but the level of evidence is low.

So it’s unknown if NOACs are preferred over VKAs in frail AFib patients, “and it’s even more questionable whether patients on VKAs should switch to NOAC therapy,” Dr. Joosten said.

This new trial aimed to answer the question of whether switching frail AFib patients currently managed on a VKA to a NOAC would reduce bleeding. FRAIL-AF was a pragmatic, multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Older AFib patients were deemed frail if they were aged 75 years or older and had a score of 3 or more on the validated Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI). Patients with a glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or with valvular AFib were excluded.

Eligible patients were then assigned randomly to switch from their international normalized ratio (INR)–guided VKA treatment with either 1 mg acenocoumarol or 3 mg phenprocoumon, to a NOAC, or to continue VKA treatment. They were followed for 12 months for the primary outcome – major bleeding or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding complication, whichever came first – accounting for death as a competing risk.

A total of 1,330 patients were randomly assigned between January 2018 and June 2022. Their mean age was 83 years, and they had a median GFI of 4. After randomization, 6 patients in the switch-to-NOAC arm, and 1 in the continue-VKA arm were found to have exclusion criteria, so in the end, 662 patients were switched from a VKA to NOAC, while 661 continued on VKA therapy. The choice of NOAC was made by the treating physician.

Major bleeding was defined as a fatal bleeding; bleeding in a critical area or organ; bleeding leading to transfusion; and/or bleeding leading to a fall in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL (1.24 mmol/L) or more. Nonmajor bleeding was bleeding not considered major but requiring face-to-face consultation, hospitalization or increased level of care, or medical intervention.

After a prespecified futility analysis planned after 163 primary outcome events, the trial was halted when it was seen that there were 101 primary outcome events in the switch arm compared to 62 in the continue arm, Dr. Joosten said. The difference appeared to be driven by clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding.

Secondary outcomes of thromboembolic events and all-cause mortality were similar between the groups.

Completely different patients

Discussant at the meeting for the presentation was Isabelle C. Van Gelder, MD, University Medical Centre Groningen (the Netherlands). She said the results are important and relevant because it “provides data on an important gap of knowledge in our AF[ib] guidelines, and a note for all the cardiologists – this study was not done in the hospital. This trial was done in general practitioner practices, so that’s important to consider.”

Comparing FRAIL-AF patients with those of the four previous NOAC trials, “you see that enormous difference in age,” with an average age of 83 years versus 70-73 years in those trials. “These are completely different patients than have been included previously,” she said.

That GFI score of 4 or more includes patients on four or more different types of medication, as well as memory complaints, an inability to walk around the house, and problems with vision or hearing.

The finding of a 69% increase in bleeding with NOACs in FRAIL-AF was “completely unexpected, and I think that we as cardiologists and as NOAC believers did not expect it at all, but it is as clear as it is.” The curves don’t diverge immediately, but rather after 3 months or thereafter, “so it has nothing to do with the switching process. So why did it occur?”

The Netherlands has dedicated thrombosis services that might improve time in therapeutic range for VKA patients, but there is no real difference in TTRs in FRAIL-AF versus the other NOAC trials, Dr. Van Gelder noted.

The most likely suspect in her view is frailty itself, in particular the tendency for patients to be on a high number of medications. A previous study showed, for example, that polypharmacy could be used as a proxy for the effect of frailty on bleeding risk; patients on 10 or more medications had a higher risk for bleeding on treatment with rivaroxaban versus those on 4 or fewer medications.

“Therefore, in my view, why was there such a high risk of bleeding? It’s because these are other patients than we are normally used to treat, we as cardiologists,” although general practitioners see these patients all the time. “It’s all about frailty.”

NOACs are still relatively new drugs, with possible unknown interactions, she added. Because of their frailty and polypharmacy, these patients may benefit from INR control, Dr. Van Gelder speculated. “Therefore, I agree with them that we should be careful; if such old, frail patients survive on VKA, do not change medications and do not switch!”

The study was supported by the Dutch government with additional and unrestricted educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer, Bayer, and Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Joosten reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Van Gelder reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Switching frail patients with atrial fibrillation (AFib) from anticoagulation therapy with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) to a novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) resulted in more bleeding without any reduction in thromboembolic complications or all-cause mortality, randomized trial results show.

The study, FRAIL-AF, is the first randomized NOAC trial to exclusively include frail older patients, said lead author Linda P.T. Joosten, MD, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care in Utrecht, the Netherlands, and these unexpected findings provide evidence that goes beyond what is currently available.

“Data from the FRAIL-AF trial showed that switching from a VKA to a NOAC should not be considered without a clear indication in frail older patients with AF[ib], as switching to a NOAC leads to 69% more bleeding,” she concluded, without any benefit on secondary clinical endpoints, including thromboembolic events and all-cause mortality.

“The results turned out different than we expected,” Dr. Joosten said. “The hypothesis of this superiority trial was that switching from VKA therapy to a NOAC would result in less bleeding. However, we observed the opposite. After the interim analysis, the data and safety monitoring board advised to stop inclusion because switching from a VKA to a NOAC was clearly contraindicated with a hazard ratio of 1.69 and a highly significant P value of .001.”

Results of FRAIL-AF were presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and published online in the journal Circulation.

Session moderator Renate B. Schnabel, MD, interventional cardiologist with University Heart & Vascular Center Hamburg (Germany), congratulated the researchers on these “astonishing” data.

“The thing I want to emphasize here is that, in the absence of randomized controlled trial data, we should be very cautious in extrapolating data from the landmark trials to populations not enrolled in those, and to rely on observational data only,” Dr. Schnabel told Dr. Joosten. “We need randomized controlled trials that sometimes give astonishing results.”

Frailty a clinical syndrome

Frailty is “a lot more than just aging, multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy,” Dr. Joosten explained. “It’s really a clinical syndrome, with people with a high biological vulnerability, dependency on significant others, and a reduced capacity to resist stressors, all leading to a reduced homeostatic reserve.”

Frailty is common in the community, with a prevalence of about 12%, she noted, “and even more important, AF[ib] in frail older people is very common, with a prevalence of 18%. And “without any doubt, we have to adequately anticoagulate frail AF[ib] patients, as they have a high stroke risk, with an incidence of 12.4% per year,” Dr. Joosten noted, compared with 3.9% per year among nonfrail AFib patients.

NOACs are preferred over VKAs in nonfrail AFib patients, after four major trials, RE-LY with dabigatran, ROCKET-AF with rivaroxaban, ARISTOTLE with apixaban, and ENGAGE-AF with edoxaban, showed that NOAC treatment resulted in less major bleeding while stroke risk was comparable with treatment with warfarin, she noted.

The 2023 European Heart Rhythm Association consensus document on management of arrhythmias in frailty syndrome concludes that the advantages of NOACs relative to VKAs are “likely consistent” in frail and nonfrail AFib patients, but the level of evidence is low.

So it’s unknown if NOACs are preferred over VKAs in frail AFib patients, “and it’s even more questionable whether patients on VKAs should switch to NOAC therapy,” Dr. Joosten said.

This new trial aimed to answer the question of whether switching frail AFib patients currently managed on a VKA to a NOAC would reduce bleeding. FRAIL-AF was a pragmatic, multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Older AFib patients were deemed frail if they were aged 75 years or older and had a score of 3 or more on the validated Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI). Patients with a glomerular filtration rate of less than 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or with valvular AFib were excluded.

Eligible patients were then assigned randomly to switch from their international normalized ratio (INR)–guided VKA treatment with either 1 mg acenocoumarol or 3 mg phenprocoumon, to a NOAC, or to continue VKA treatment. They were followed for 12 months for the primary outcome – major bleeding or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding complication, whichever came first – accounting for death as a competing risk.

A total of 1,330 patients were randomly assigned between January 2018 and June 2022. Their mean age was 83 years, and they had a median GFI of 4. After randomization, 6 patients in the switch-to-NOAC arm, and 1 in the continue-VKA arm were found to have exclusion criteria, so in the end, 662 patients were switched from a VKA to NOAC, while 661 continued on VKA therapy. The choice of NOAC was made by the treating physician.

Major bleeding was defined as a fatal bleeding; bleeding in a critical area or organ; bleeding leading to transfusion; and/or bleeding leading to a fall in hemoglobin level of 2 g/dL (1.24 mmol/L) or more. Nonmajor bleeding was bleeding not considered major but requiring face-to-face consultation, hospitalization or increased level of care, or medical intervention.

After a prespecified futility analysis planned after 163 primary outcome events, the trial was halted when it was seen that there were 101 primary outcome events in the switch arm compared to 62 in the continue arm, Dr. Joosten said. The difference appeared to be driven by clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding.

Secondary outcomes of thromboembolic events and all-cause mortality were similar between the groups.

Completely different patients

Discussant at the meeting for the presentation was Isabelle C. Van Gelder, MD, University Medical Centre Groningen (the Netherlands). She said the results are important and relevant because it “provides data on an important gap of knowledge in our AF[ib] guidelines, and a note for all the cardiologists – this study was not done in the hospital. This trial was done in general practitioner practices, so that’s important to consider.”

Comparing FRAIL-AF patients with those of the four previous NOAC trials, “you see that enormous difference in age,” with an average age of 83 years versus 70-73 years in those trials. “These are completely different patients than have been included previously,” she said.

That GFI score of 4 or more includes patients on four or more different types of medication, as well as memory complaints, an inability to walk around the house, and problems with vision or hearing.

The finding of a 69% increase in bleeding with NOACs in FRAIL-AF was “completely unexpected, and I think that we as cardiologists and as NOAC believers did not expect it at all, but it is as clear as it is.” The curves don’t diverge immediately, but rather after 3 months or thereafter, “so it has nothing to do with the switching process. So why did it occur?”

The Netherlands has dedicated thrombosis services that might improve time in therapeutic range for VKA patients, but there is no real difference in TTRs in FRAIL-AF versus the other NOAC trials, Dr. Van Gelder noted.

The most likely suspect in her view is frailty itself, in particular the tendency for patients to be on a high number of medications. A previous study showed, for example, that polypharmacy could be used as a proxy for the effect of frailty on bleeding risk; patients on 10 or more medications had a higher risk for bleeding on treatment with rivaroxaban versus those on 4 or fewer medications.

“Therefore, in my view, why was there such a high risk of bleeding? It’s because these are other patients than we are normally used to treat, we as cardiologists,” although general practitioners see these patients all the time. “It’s all about frailty.”

NOACs are still relatively new drugs, with possible unknown interactions, she added. Because of their frailty and polypharmacy, these patients may benefit from INR control, Dr. Van Gelder speculated. “Therefore, I agree with them that we should be careful; if such old, frail patients survive on VKA, do not change medications and do not switch!”

The study was supported by the Dutch government with additional and unrestricted educational grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS-Pfizer, Bayer, and Daiichi Sankyo. Dr. Joosten reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Van Gelder reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2023

Medicare announces 10 drugs targeted for price cuts in 2026

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.