User login

Irritable Bowel Syndrome Risk in Acne Patients: Implications for Dermatologic Care

To the Editor:

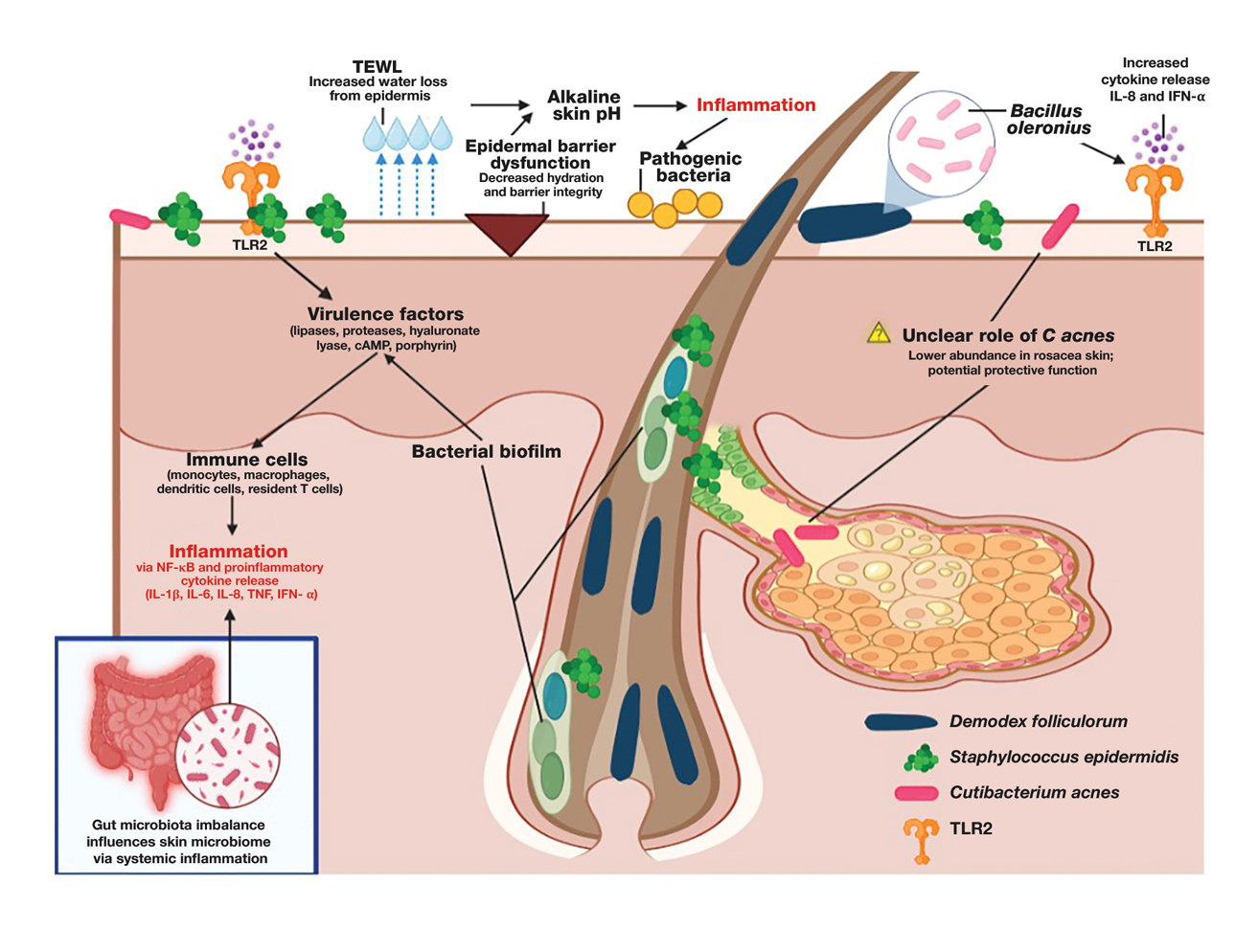

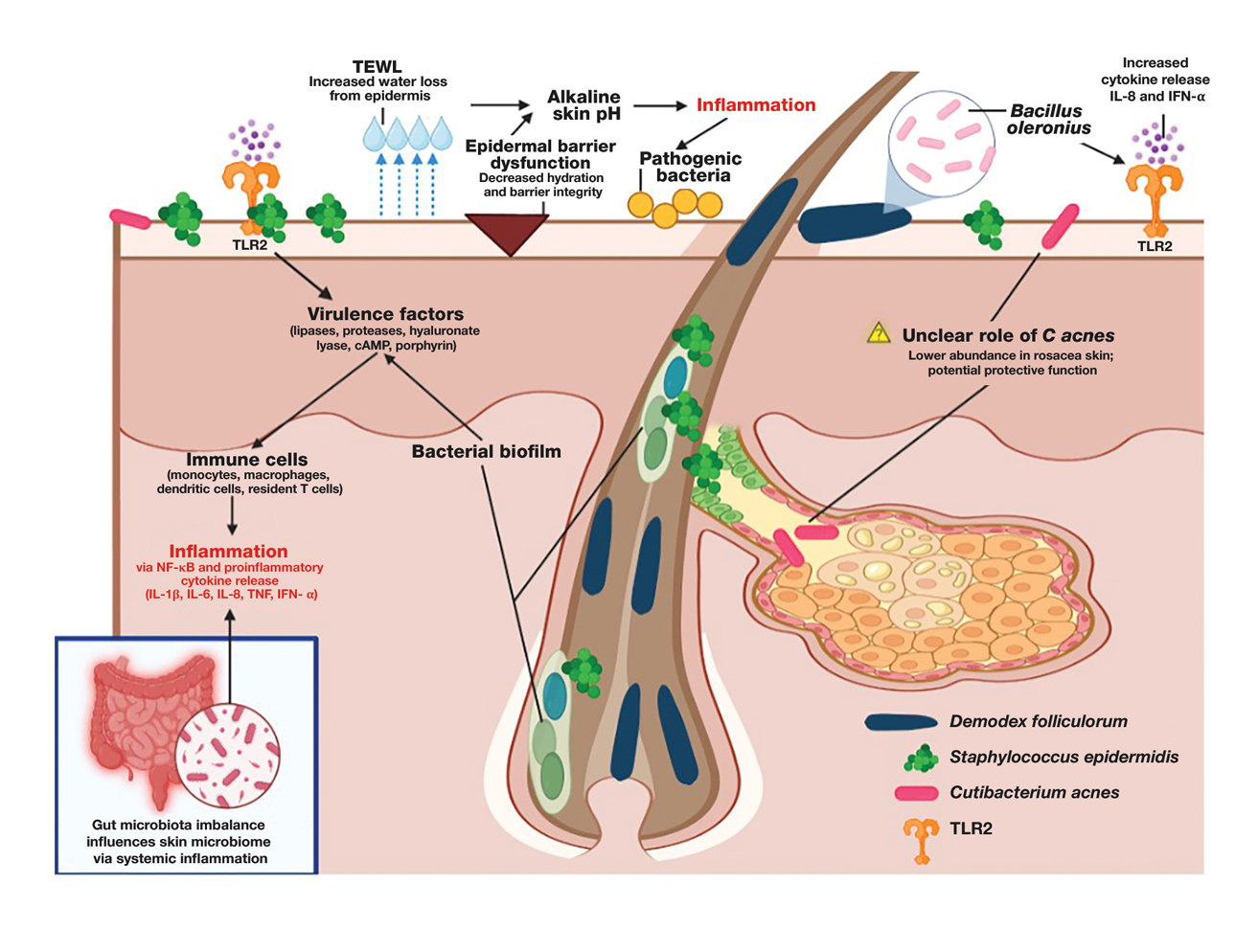

Acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are both associated with microbial dysbiosis and chronic inflammation.1-3 While the prevalence of IBS among patients with acne has been examined previously,4,5 there has been limited focus on the risk for new-onset IBS following acne diagnosis. Current evidence suggests isotretinoin may be associated with a lower risk for IBS compared to oral antibiotics6; however, evidence supporting this association is limited outside these cohorts, highlighting the need for further investigation. In this large-scale study, we sought to investigate the incidence of new-onset IBS among patients with acne compared with healthy controls as well as to evaluate whether oral acne treatments (ie, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin) are associated with new-onset IBS in this population.

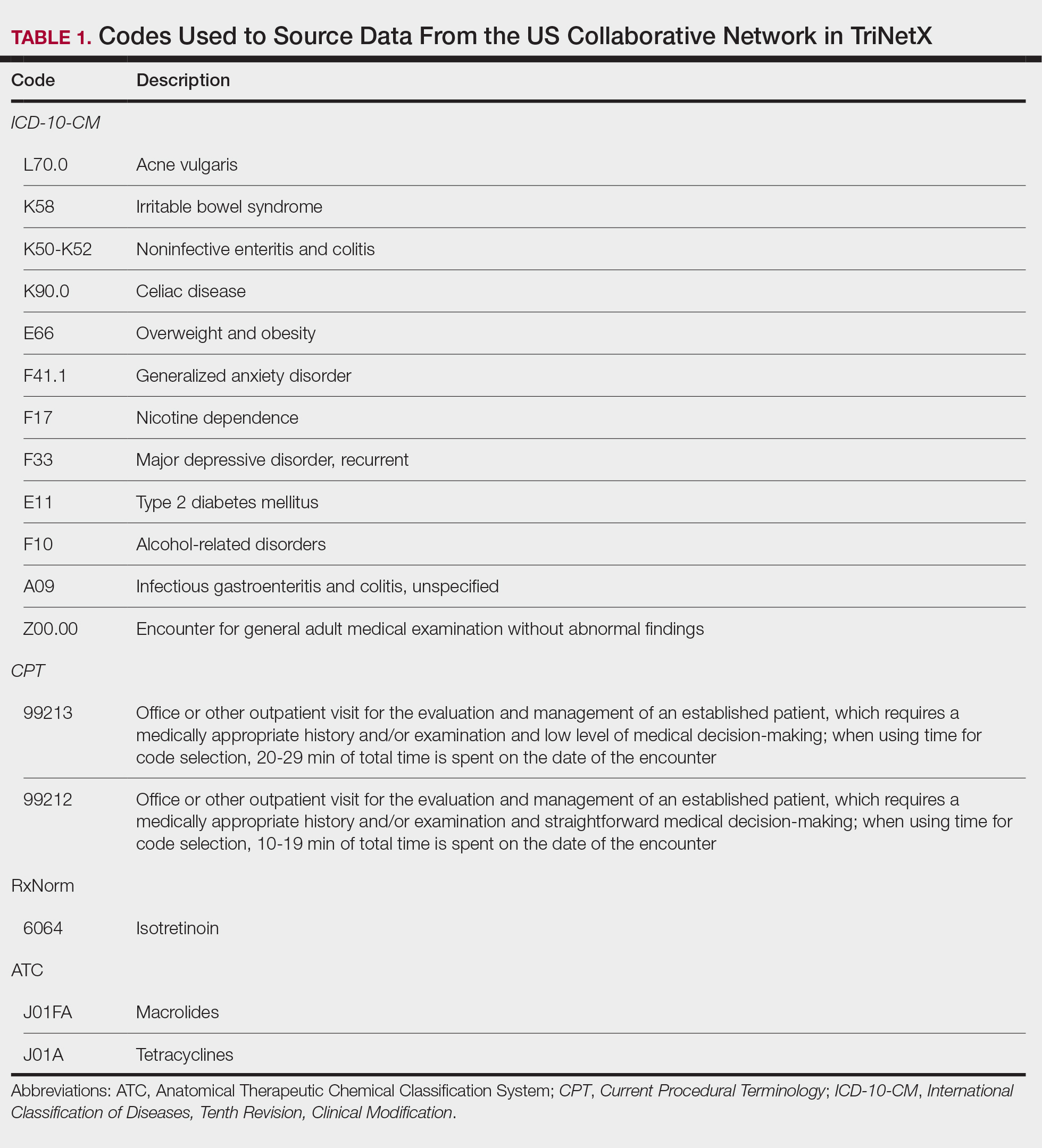

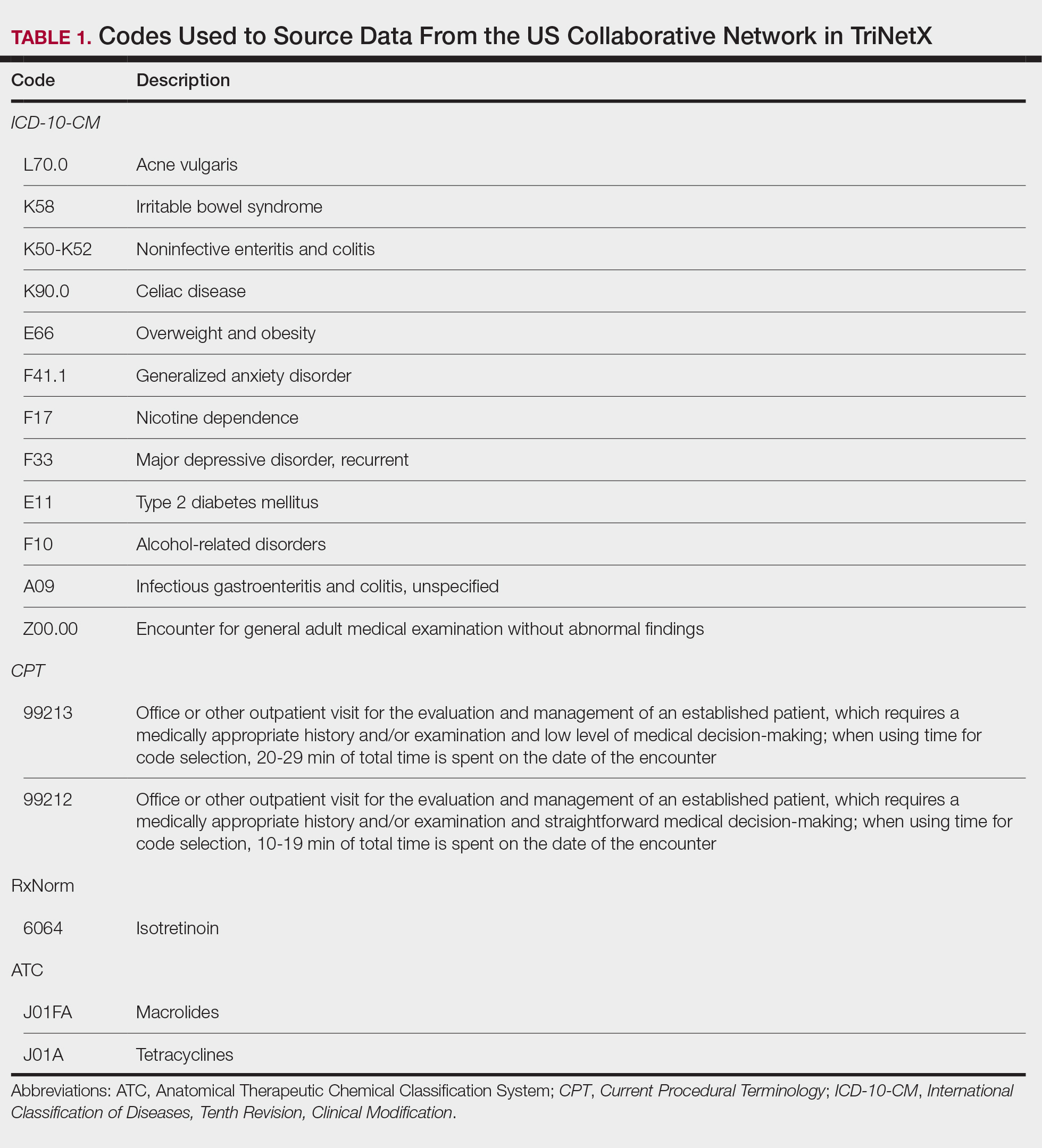

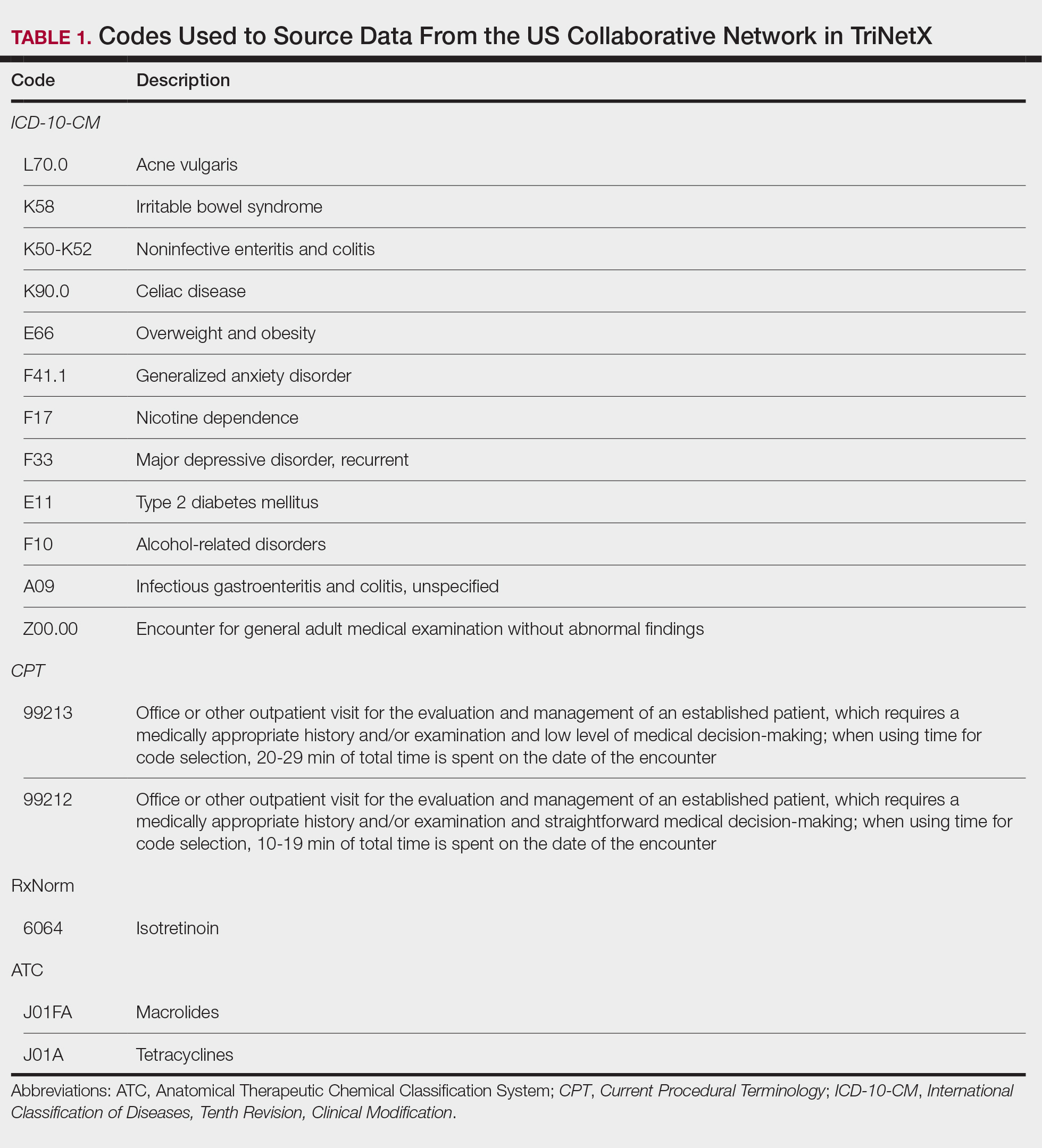

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX from October 2014 to October 2024. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes, and RxNorm codes (Table 1). These codes were selected based on prior literature review, clinical relevance, and their ability to capture diagnoses of acne and IBS as well as relevant exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 90 years. Individuals with a history of IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious gastroenteritis, or celiac disease were excluded from our analysis.

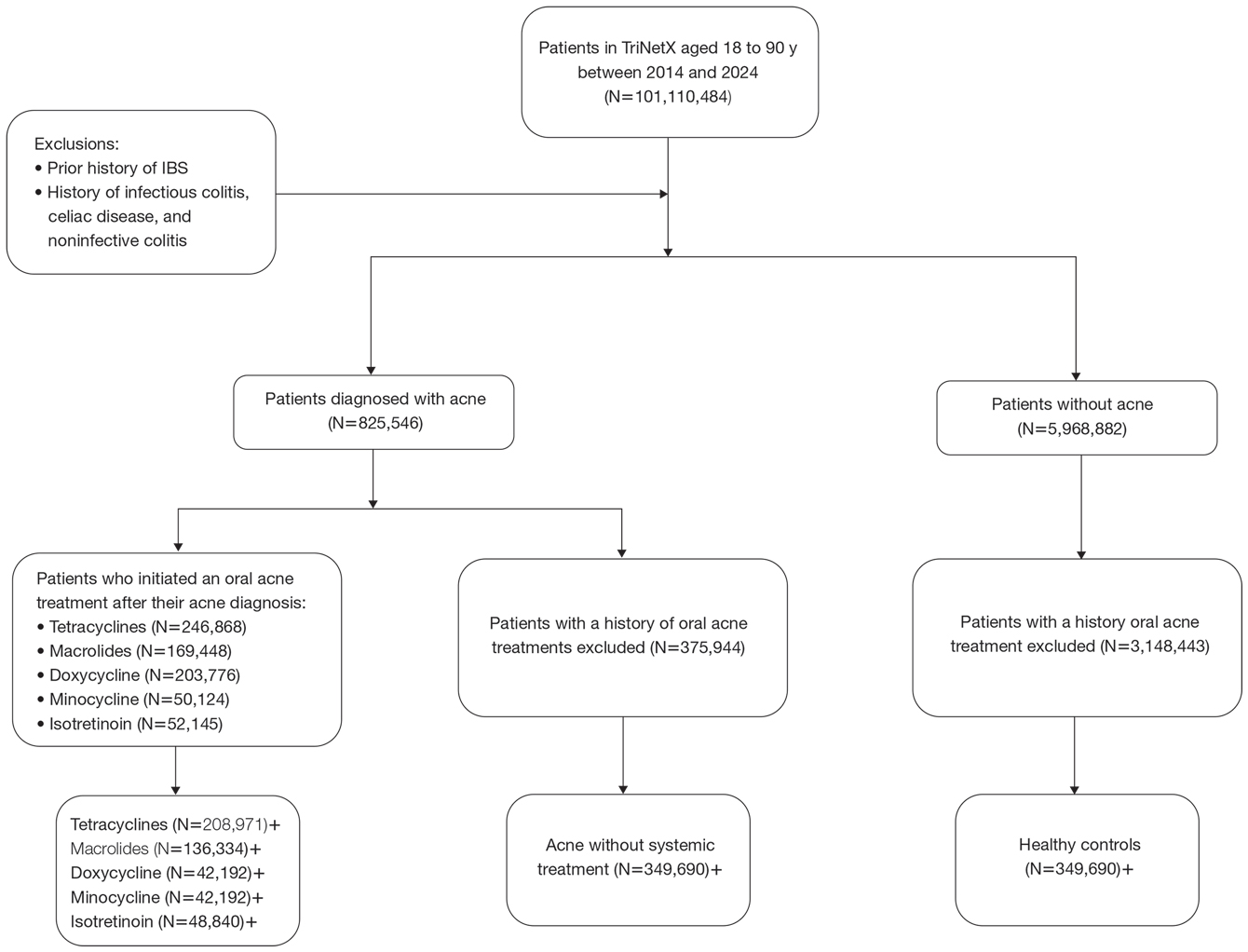

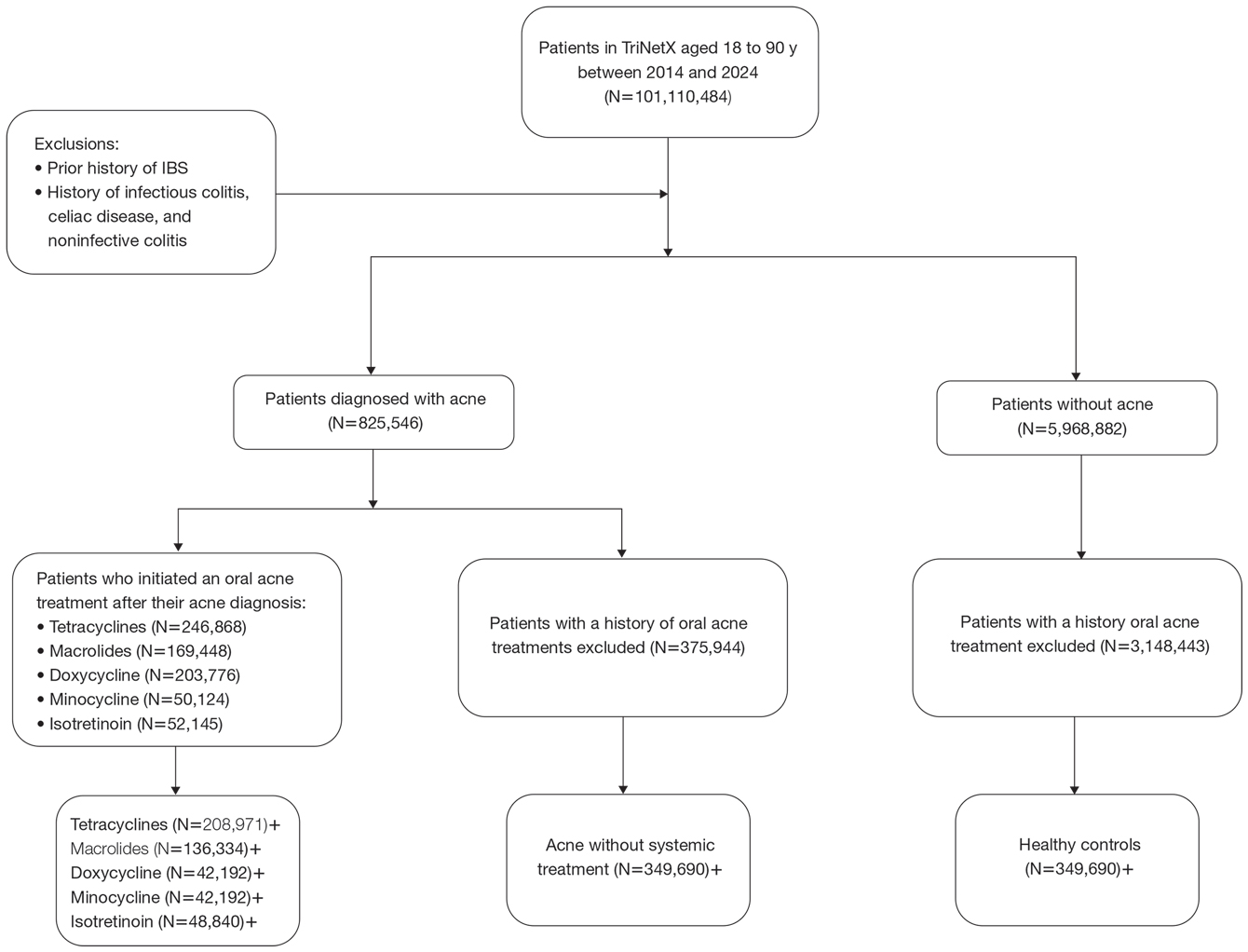

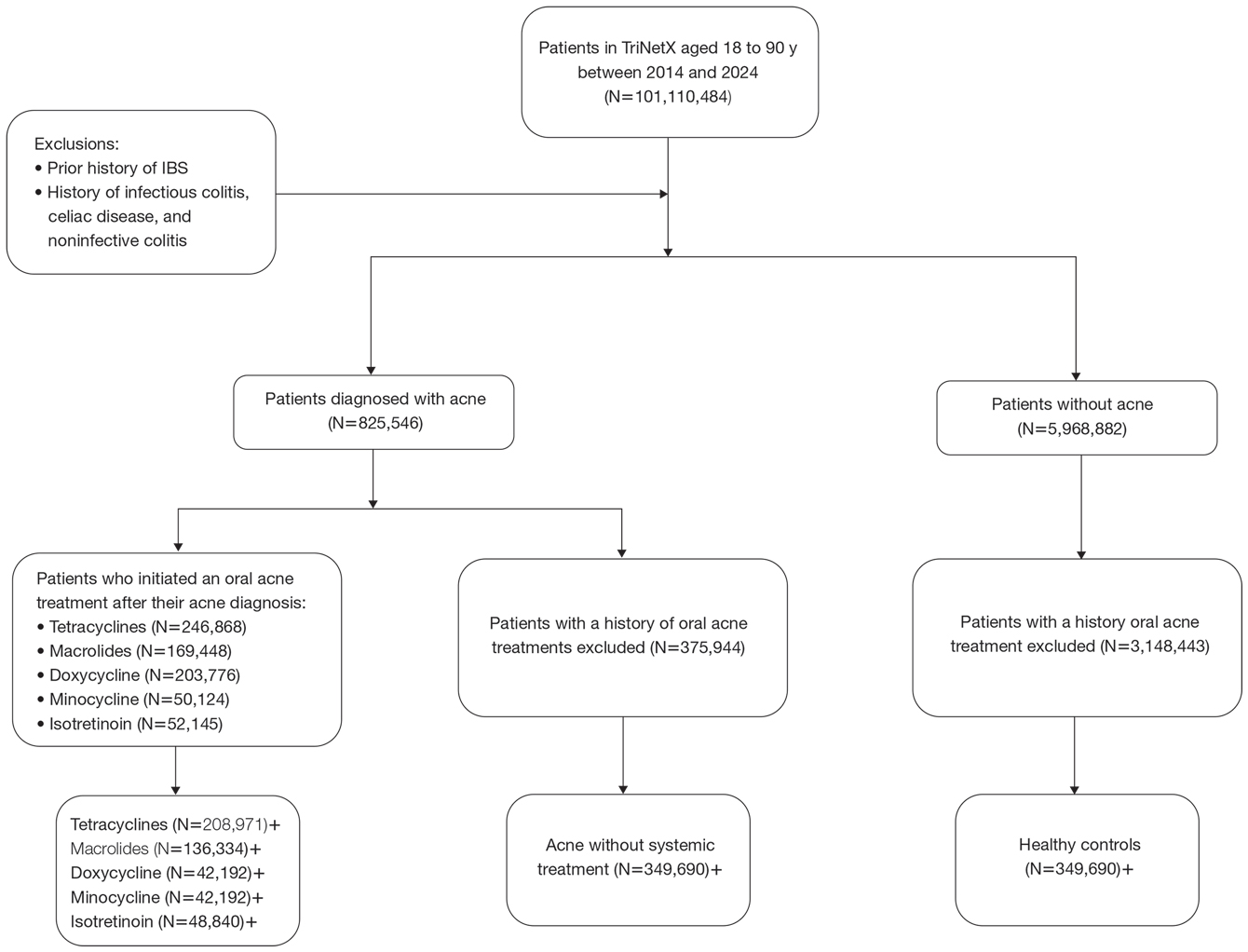

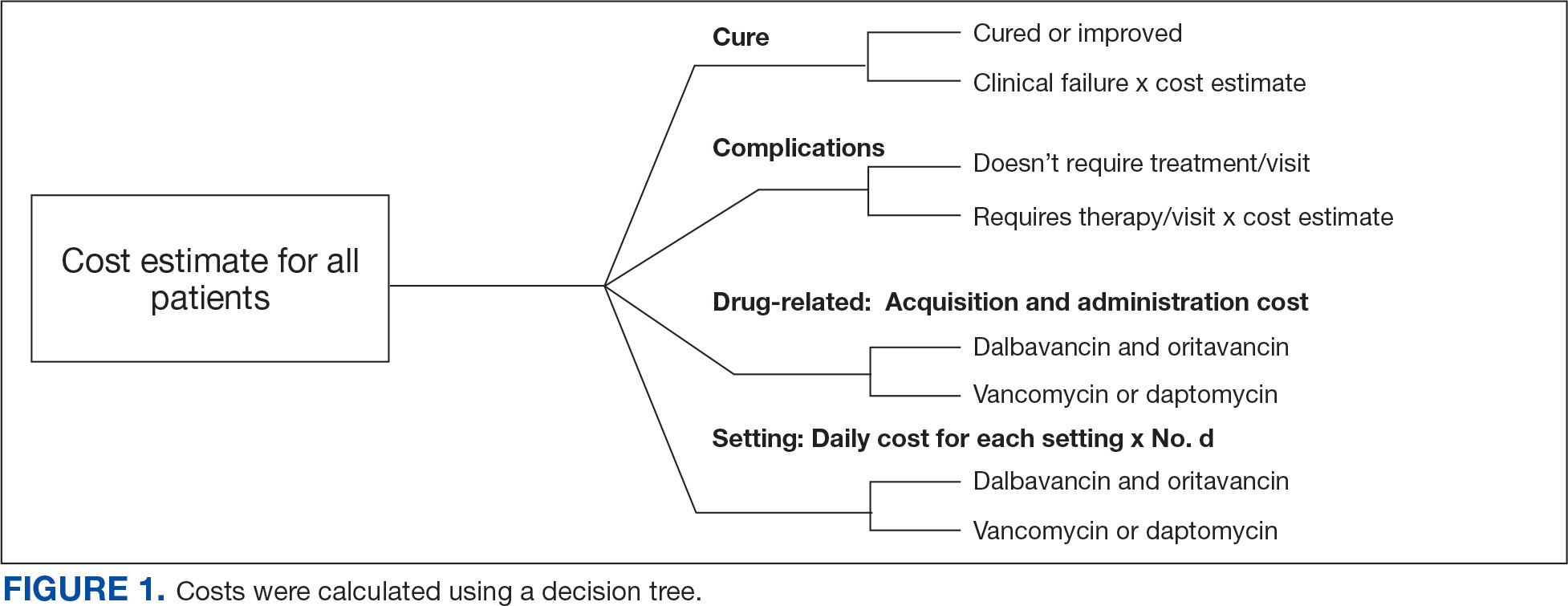

To examine potential associations between acne and IBS, 2 primary cohorts were established: patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications and healthy controls (ie, patients with no history of acne) who had no exposure to systemic acne treatments (Figure). Further, to assess the relationship between oral acne treatments (macrolides, tetracyclines, isotretinoin) and IBS, additional cohorts were created for each therapy and were compared to a cohort of patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications. To control for potential concomitant treatments, patients who had received any systemic treatment other than the specific therapy for their treatment cohort were excluded from our analysis.

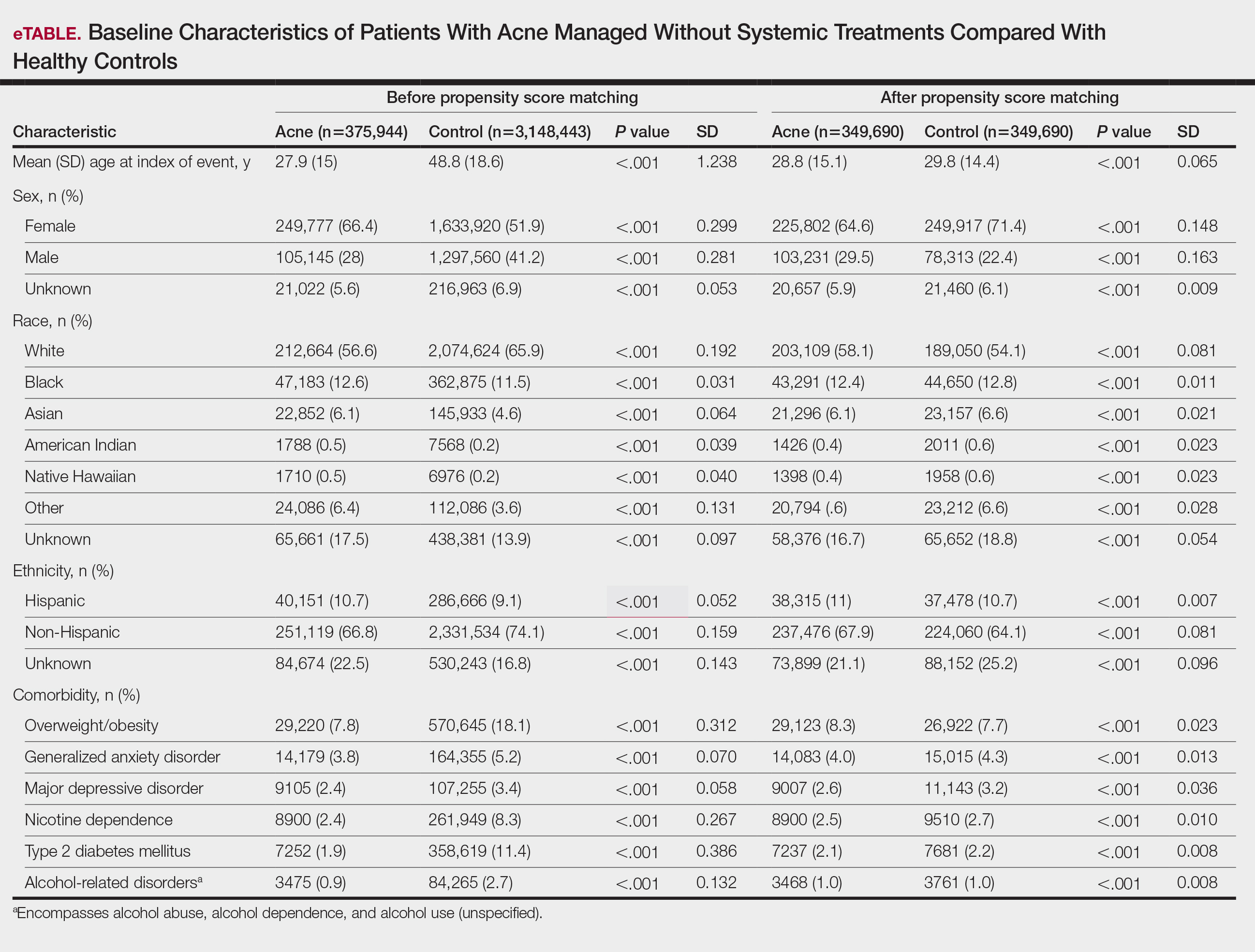

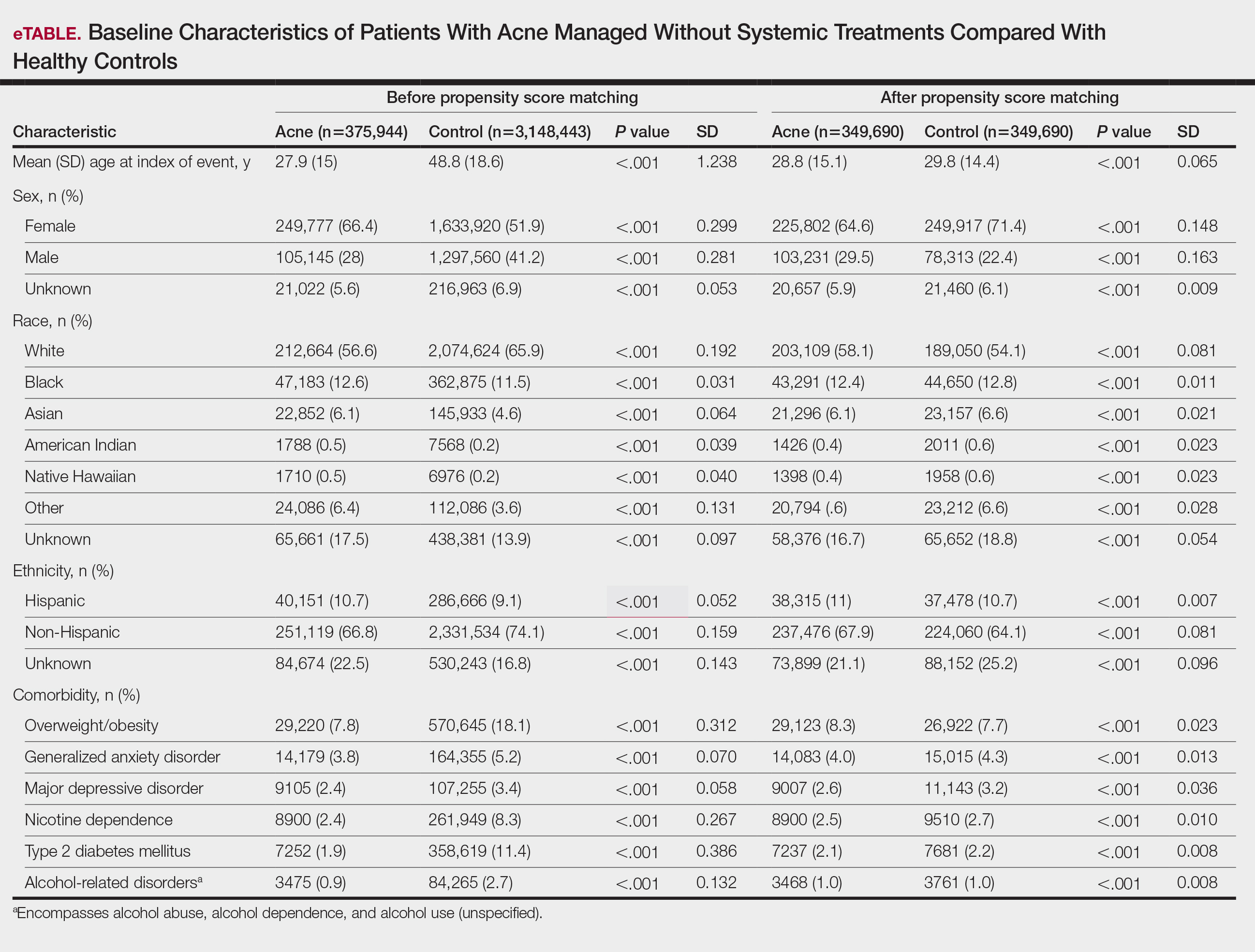

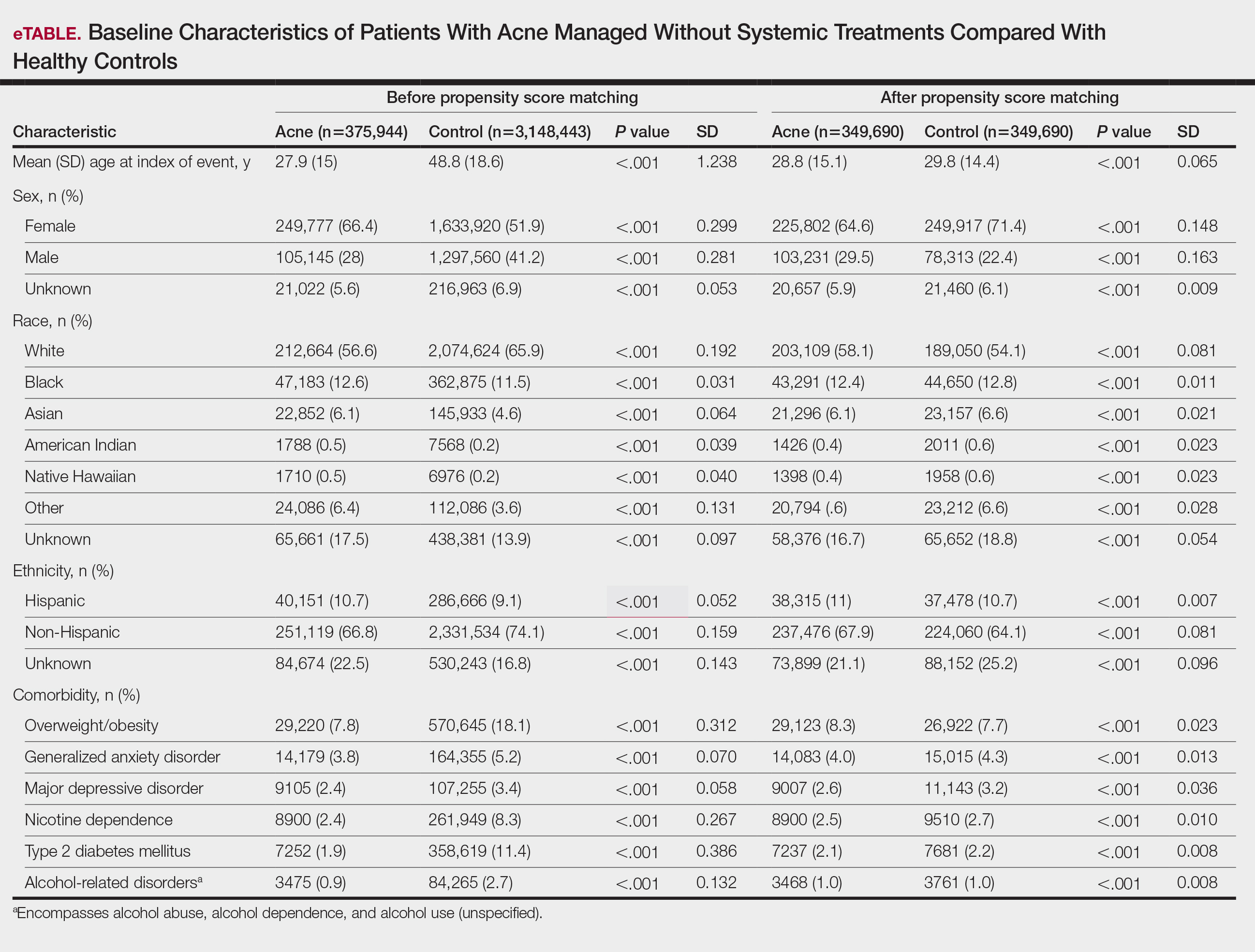

To account for potential confounders, all cohorts were 1:1 propensity score matched by demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, type 2 diabetes, obesity, anxiety, and depression (eTable). Each cohort was followed for 2 years after their index of event: the date of acne diagnosis for the acne cohort, the date of systemic treatment initiation for the treatment cohorts, and the date of the general adult encounter without abnormal findings for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the incidence of IBS, assessed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs.

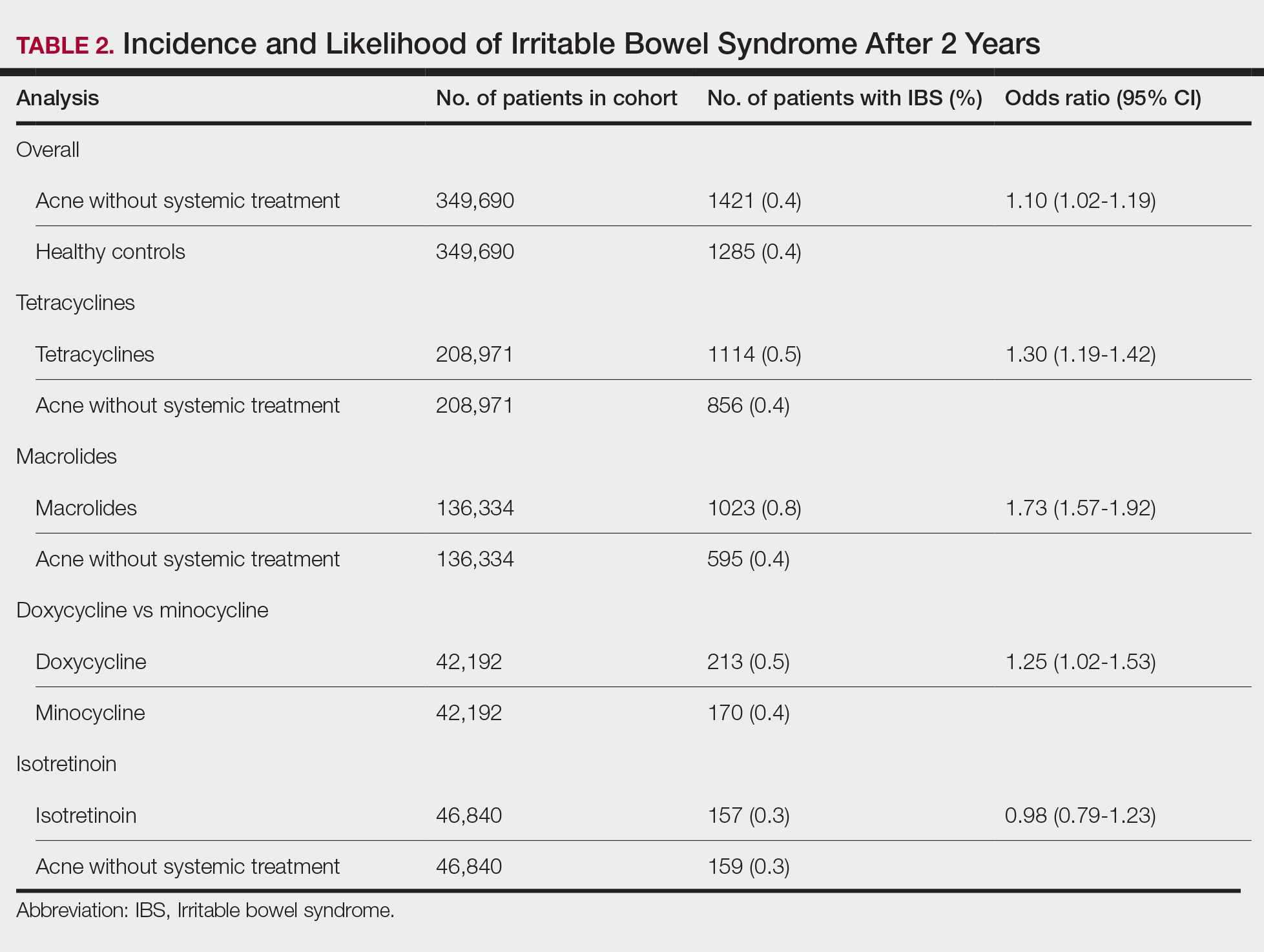

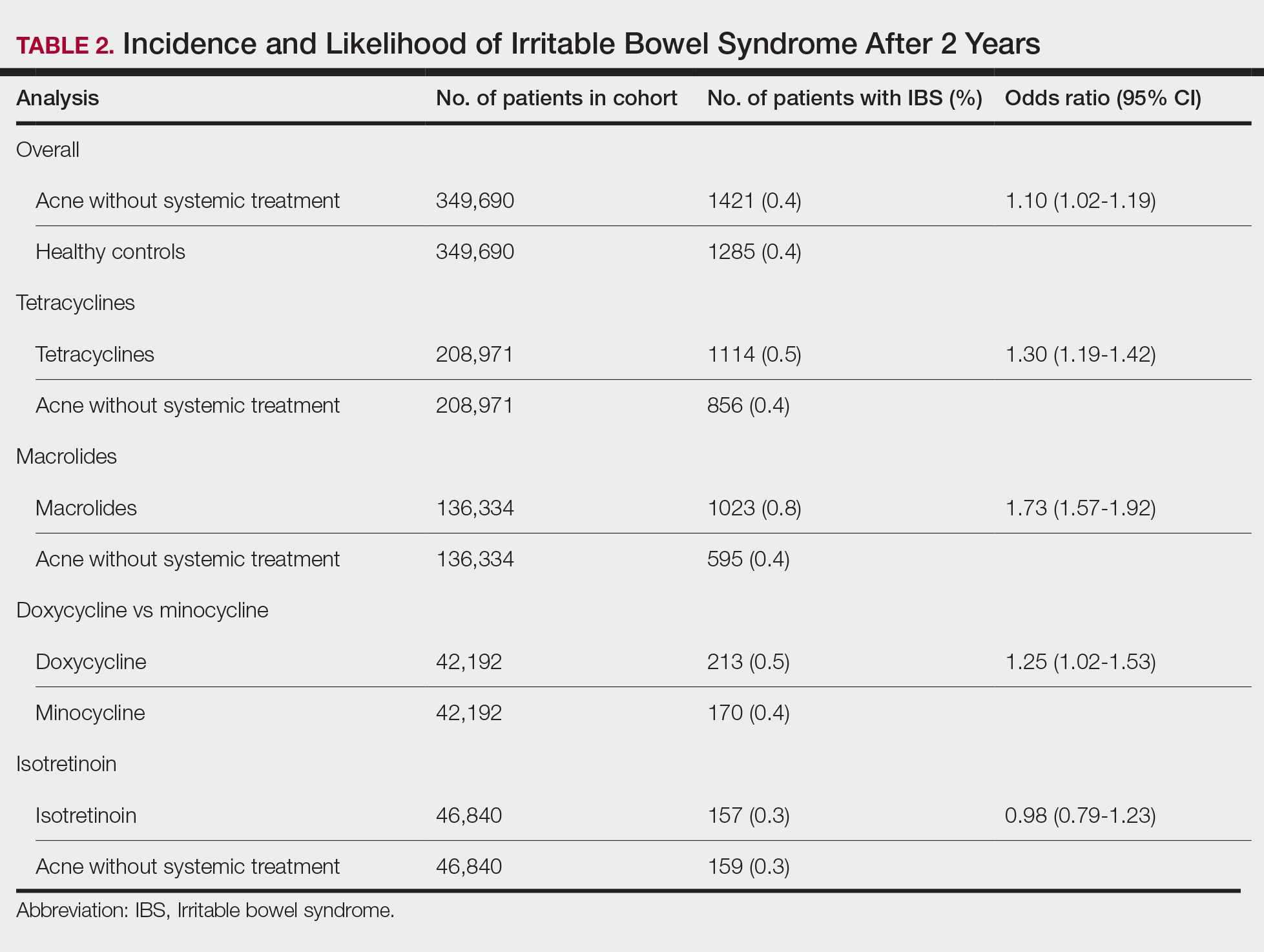

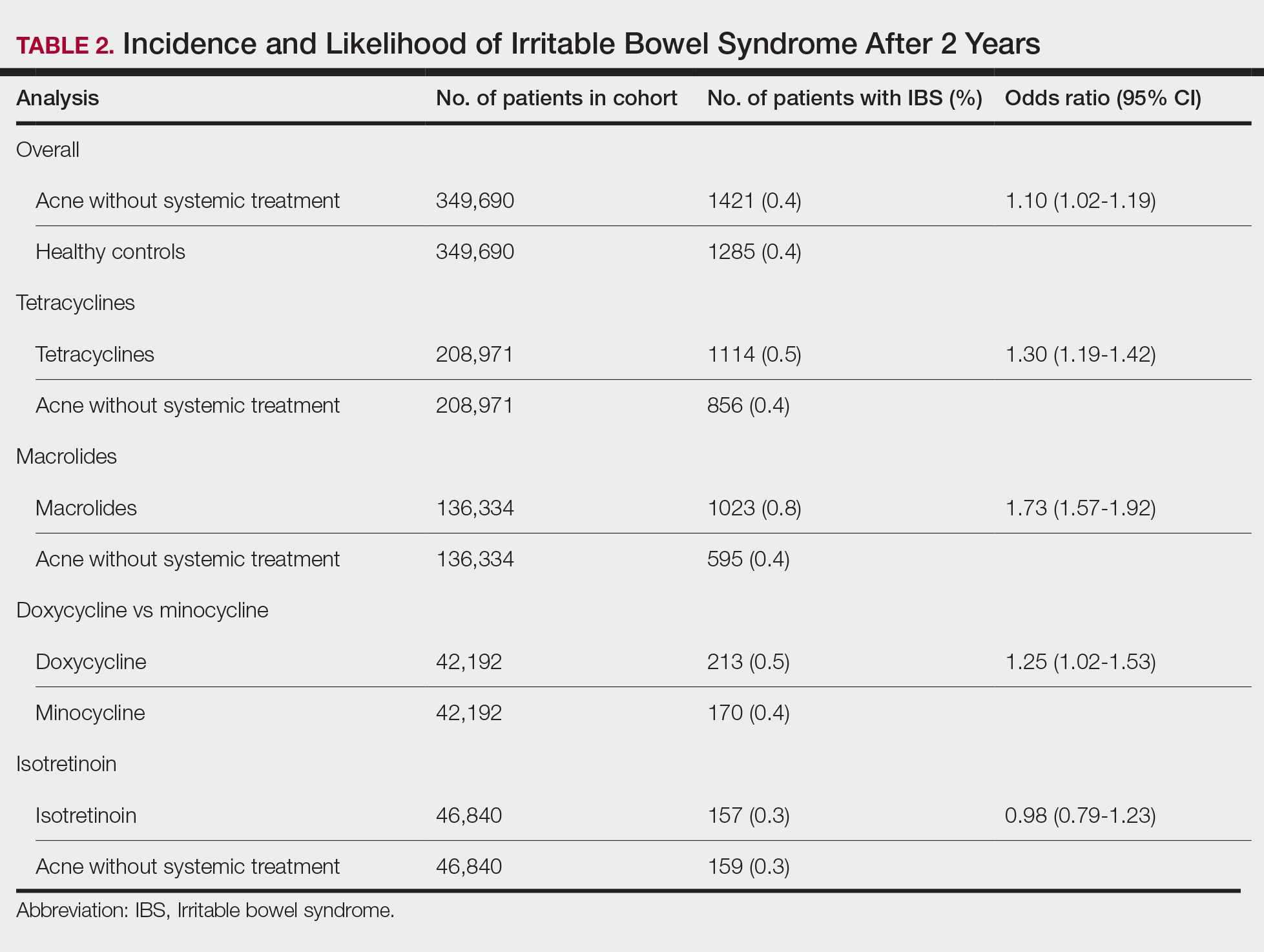

We identified 375,944 patients with acne managed without systemic treatment and 3,148,443 healthy controls who met study criteria. After the 1:1 propensity score match, each cohort included 49,690 patients (eTable). In the 2-year period after acne diagnosis, patients were more likely to develop IBS compared with controls (1421 vs 1285 [OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19])(Table 2). Patients with acne who were treated with tetracyclines (n=208,971) were 30% more likely to develop IBS than those managed without systemic medications (1114 vs 856 [OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19-1.42]). Within the tetracycline cohort, doxycycline-treated patients were 25% more likely to develop IBS compared with those treated with minocycline (213 vs 170 [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.53]). Similarly, the use of macrolides (n=136,334) for acne treatment was significantly associated with an increased risk for IBS (1023 vs 595 [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.57-1.92; P<.0001]) compared with controls. No statistically significant association was observed between isotretinoin and the incidence of IBS (Table 2).

In this large-scale cohort study, acne was associated with an increased likelihood of developing IBS within 2 years of an acne diagnosis compared with healthy controls. While a prior study also identified this association, it had a broader follow-up window ranging from 8 to 10 years.2 In contrast, our analysis specifically quantified the risk within the first 2 years of diagnosis. This distinction suggested potential for earlier IBS onset in patients with acne than has previously been recognized and may serve as an early clinical indicator for IBS risk in this population.

Our findings further suggested an association between oral tetracyclines and macrolides and an increased risk for IBS. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that oral antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota and lead to potential gastrointestinal complications7 and reinforces the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice.

Although isotretinoin initially was surrounded by substantial controversy regarding its potential impact on gut health—particularly in inflammatory bowel disease8—our results do not support an increased risk for IBS among patients with acne who use isotretinoin. These findings challenge previous concerns and align with research suggesting that isotretinoin could be a safer alternative to antibiotic use for eligible patients who have a history of gastrointestinal disorders.6

This study highlights an important but underrecognized link between acne and IBS risk, emphasizing the need for early monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms and careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice. Gastroenterology consultation may be advisable for patients with acne who have persistent gastrointestinal symptoms to facilitate a more integrated, patient-centered approach to care.

Limitations of this study include potential misclassification of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, selection bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease severity, and treatment adherence due to the reliance on electronic health record data.

Our findings build upon prior evidence linking acne and IBS and offer important insights into the timing of this association following acne diagnosis. Future research should explore biological mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis and evaluate targeted interventions to mitigate IBS risk in patients with acne.

Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1

Yu-Wen C, Chun-Ying W, Yi-Ju C. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with acne vulgaris: a population-based retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2025;18:62-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2024.08.022

Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J, et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:783-790. doi:10.2340/00015555-2968

Demirbas¸ A, Elmas ÖF. The relationship between acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:316-320. doi:10.1111/jocd.13481

Daye M, Cihan FG, Is¸ık B, et al. Evaluation of bowel habits in patients with acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14903. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14903

Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. Isotretinoin and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:824-830. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.015

Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, et al. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17-20.

Yu C-L, Chou P-Y, Liang C-S, et al. Isotretinoin exposure and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:721-730. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00765-9

To the Editor:

Acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are both associated with microbial dysbiosis and chronic inflammation.1-3 While the prevalence of IBS among patients with acne has been examined previously,4,5 there has been limited focus on the risk for new-onset IBS following acne diagnosis. Current evidence suggests isotretinoin may be associated with a lower risk for IBS compared to oral antibiotics6; however, evidence supporting this association is limited outside these cohorts, highlighting the need for further investigation. In this large-scale study, we sought to investigate the incidence of new-onset IBS among patients with acne compared with healthy controls as well as to evaluate whether oral acne treatments (ie, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin) are associated with new-onset IBS in this population.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX from October 2014 to October 2024. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes, and RxNorm codes (Table 1). These codes were selected based on prior literature review, clinical relevance, and their ability to capture diagnoses of acne and IBS as well as relevant exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 90 years. Individuals with a history of IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious gastroenteritis, or celiac disease were excluded from our analysis.

To examine potential associations between acne and IBS, 2 primary cohorts were established: patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications and healthy controls (ie, patients with no history of acne) who had no exposure to systemic acne treatments (Figure). Further, to assess the relationship between oral acne treatments (macrolides, tetracyclines, isotretinoin) and IBS, additional cohorts were created for each therapy and were compared to a cohort of patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications. To control for potential concomitant treatments, patients who had received any systemic treatment other than the specific therapy for their treatment cohort were excluded from our analysis.

To account for potential confounders, all cohorts were 1:1 propensity score matched by demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, type 2 diabetes, obesity, anxiety, and depression (eTable). Each cohort was followed for 2 years after their index of event: the date of acne diagnosis for the acne cohort, the date of systemic treatment initiation for the treatment cohorts, and the date of the general adult encounter without abnormal findings for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the incidence of IBS, assessed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs.

We identified 375,944 patients with acne managed without systemic treatment and 3,148,443 healthy controls who met study criteria. After the 1:1 propensity score match, each cohort included 49,690 patients (eTable). In the 2-year period after acne diagnosis, patients were more likely to develop IBS compared with controls (1421 vs 1285 [OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19])(Table 2). Patients with acne who were treated with tetracyclines (n=208,971) were 30% more likely to develop IBS than those managed without systemic medications (1114 vs 856 [OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19-1.42]). Within the tetracycline cohort, doxycycline-treated patients were 25% more likely to develop IBS compared with those treated with minocycline (213 vs 170 [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.53]). Similarly, the use of macrolides (n=136,334) for acne treatment was significantly associated with an increased risk for IBS (1023 vs 595 [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.57-1.92; P<.0001]) compared with controls. No statistically significant association was observed between isotretinoin and the incidence of IBS (Table 2).

In this large-scale cohort study, acne was associated with an increased likelihood of developing IBS within 2 years of an acne diagnosis compared with healthy controls. While a prior study also identified this association, it had a broader follow-up window ranging from 8 to 10 years.2 In contrast, our analysis specifically quantified the risk within the first 2 years of diagnosis. This distinction suggested potential for earlier IBS onset in patients with acne than has previously been recognized and may serve as an early clinical indicator for IBS risk in this population.

Our findings further suggested an association between oral tetracyclines and macrolides and an increased risk for IBS. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that oral antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota and lead to potential gastrointestinal complications7 and reinforces the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice.

Although isotretinoin initially was surrounded by substantial controversy regarding its potential impact on gut health—particularly in inflammatory bowel disease8—our results do not support an increased risk for IBS among patients with acne who use isotretinoin. These findings challenge previous concerns and align with research suggesting that isotretinoin could be a safer alternative to antibiotic use for eligible patients who have a history of gastrointestinal disorders.6

This study highlights an important but underrecognized link between acne and IBS risk, emphasizing the need for early monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms and careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice. Gastroenterology consultation may be advisable for patients with acne who have persistent gastrointestinal symptoms to facilitate a more integrated, patient-centered approach to care.

Limitations of this study include potential misclassification of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, selection bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease severity, and treatment adherence due to the reliance on electronic health record data.

Our findings build upon prior evidence linking acne and IBS and offer important insights into the timing of this association following acne diagnosis. Future research should explore biological mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis and evaluate targeted interventions to mitigate IBS risk in patients with acne.

To the Editor:

Acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are both associated with microbial dysbiosis and chronic inflammation.1-3 While the prevalence of IBS among patients with acne has been examined previously,4,5 there has been limited focus on the risk for new-onset IBS following acne diagnosis. Current evidence suggests isotretinoin may be associated with a lower risk for IBS compared to oral antibiotics6; however, evidence supporting this association is limited outside these cohorts, highlighting the need for further investigation. In this large-scale study, we sought to investigate the incidence of new-onset IBS among patients with acne compared with healthy controls as well as to evaluate whether oral acne treatments (ie, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin) are associated with new-onset IBS in this population.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX from October 2014 to October 2024. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes, and RxNorm codes (Table 1). These codes were selected based on prior literature review, clinical relevance, and their ability to capture diagnoses of acne and IBS as well as relevant exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 90 years. Individuals with a history of IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious gastroenteritis, or celiac disease were excluded from our analysis.

To examine potential associations between acne and IBS, 2 primary cohorts were established: patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications and healthy controls (ie, patients with no history of acne) who had no exposure to systemic acne treatments (Figure). Further, to assess the relationship between oral acne treatments (macrolides, tetracyclines, isotretinoin) and IBS, additional cohorts were created for each therapy and were compared to a cohort of patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications. To control for potential concomitant treatments, patients who had received any systemic treatment other than the specific therapy for their treatment cohort were excluded from our analysis.

To account for potential confounders, all cohorts were 1:1 propensity score matched by demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, type 2 diabetes, obesity, anxiety, and depression (eTable). Each cohort was followed for 2 years after their index of event: the date of acne diagnosis for the acne cohort, the date of systemic treatment initiation for the treatment cohorts, and the date of the general adult encounter without abnormal findings for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the incidence of IBS, assessed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs.

We identified 375,944 patients with acne managed without systemic treatment and 3,148,443 healthy controls who met study criteria. After the 1:1 propensity score match, each cohort included 49,690 patients (eTable). In the 2-year period after acne diagnosis, patients were more likely to develop IBS compared with controls (1421 vs 1285 [OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19])(Table 2). Patients with acne who were treated with tetracyclines (n=208,971) were 30% more likely to develop IBS than those managed without systemic medications (1114 vs 856 [OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19-1.42]). Within the tetracycline cohort, doxycycline-treated patients were 25% more likely to develop IBS compared with those treated with minocycline (213 vs 170 [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.53]). Similarly, the use of macrolides (n=136,334) for acne treatment was significantly associated with an increased risk for IBS (1023 vs 595 [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.57-1.92; P<.0001]) compared with controls. No statistically significant association was observed between isotretinoin and the incidence of IBS (Table 2).

In this large-scale cohort study, acne was associated with an increased likelihood of developing IBS within 2 years of an acne diagnosis compared with healthy controls. While a prior study also identified this association, it had a broader follow-up window ranging from 8 to 10 years.2 In contrast, our analysis specifically quantified the risk within the first 2 years of diagnosis. This distinction suggested potential for earlier IBS onset in patients with acne than has previously been recognized and may serve as an early clinical indicator for IBS risk in this population.

Our findings further suggested an association between oral tetracyclines and macrolides and an increased risk for IBS. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that oral antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota and lead to potential gastrointestinal complications7 and reinforces the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice.

Although isotretinoin initially was surrounded by substantial controversy regarding its potential impact on gut health—particularly in inflammatory bowel disease8—our results do not support an increased risk for IBS among patients with acne who use isotretinoin. These findings challenge previous concerns and align with research suggesting that isotretinoin could be a safer alternative to antibiotic use for eligible patients who have a history of gastrointestinal disorders.6

This study highlights an important but underrecognized link between acne and IBS risk, emphasizing the need for early monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms and careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice. Gastroenterology consultation may be advisable for patients with acne who have persistent gastrointestinal symptoms to facilitate a more integrated, patient-centered approach to care.

Limitations of this study include potential misclassification of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, selection bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease severity, and treatment adherence due to the reliance on electronic health record data.

Our findings build upon prior evidence linking acne and IBS and offer important insights into the timing of this association following acne diagnosis. Future research should explore biological mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis and evaluate targeted interventions to mitigate IBS risk in patients with acne.

Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1

Yu-Wen C, Chun-Ying W, Yi-Ju C. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with acne vulgaris: a population-based retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2025;18:62-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2024.08.022

Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J, et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:783-790. doi:10.2340/00015555-2968

Demirbas¸ A, Elmas ÖF. The relationship between acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:316-320. doi:10.1111/jocd.13481

Daye M, Cihan FG, Is¸ık B, et al. Evaluation of bowel habits in patients with acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14903. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14903

Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. Isotretinoin and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:824-830. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.015

Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, et al. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17-20.

Yu C-L, Chou P-Y, Liang C-S, et al. Isotretinoin exposure and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:721-730. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00765-9

Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1

Yu-Wen C, Chun-Ying W, Yi-Ju C. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with acne vulgaris: a population-based retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2025;18:62-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2024.08.022

Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J, et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:783-790. doi:10.2340/00015555-2968

Demirbas¸ A, Elmas ÖF. The relationship between acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:316-320. doi:10.1111/jocd.13481

Daye M, Cihan FG, Is¸ık B, et al. Evaluation of bowel habits in patients with acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14903. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14903

Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. Isotretinoin and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:824-830. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.015

Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, et al. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17-20.

Yu C-L, Chou P-Y, Liang C-S, et al. Isotretinoin exposure and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:721-730. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00765-9

Consider Cultural Practices and Barriers to Care When Treating Alopecia Areata

The Comparison

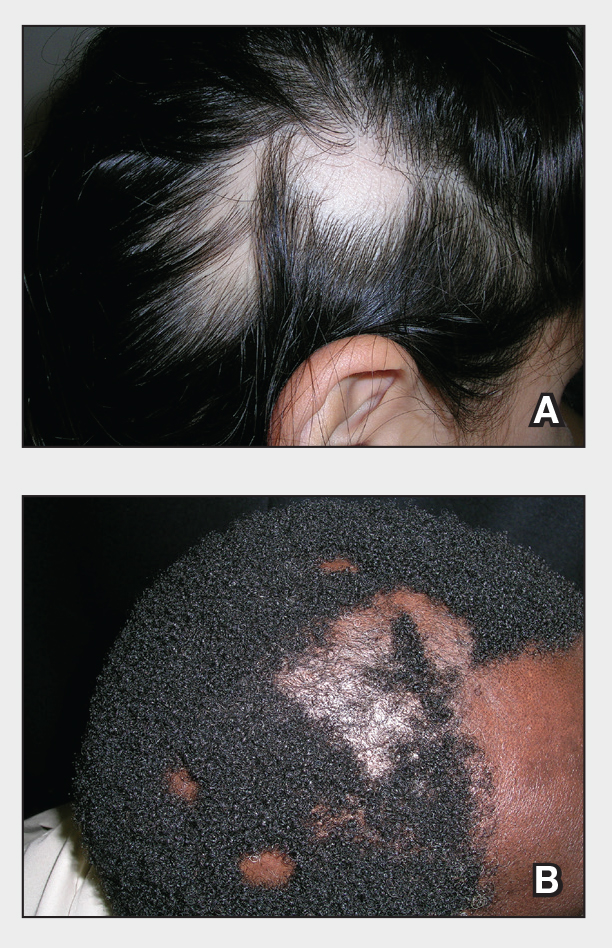

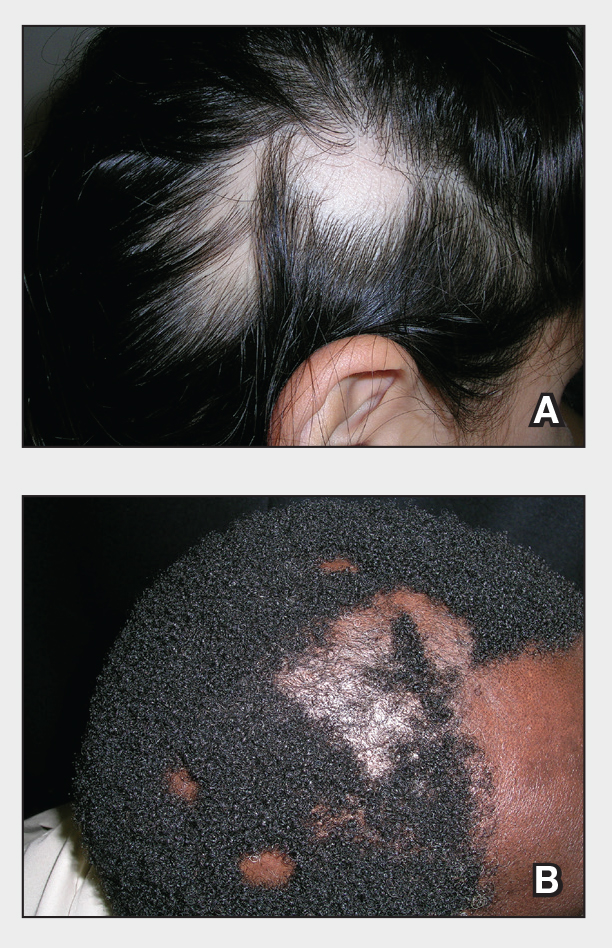

A. Alopecia areata in a young girl with a lighter skin tone. The fine white vellus hairs are signs of regrowth.

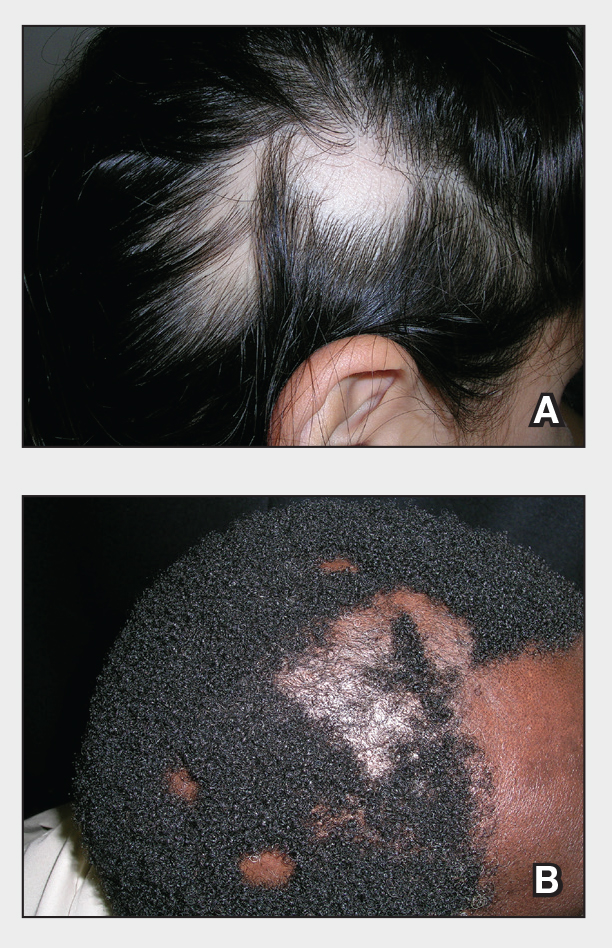

B. Alopecia areata in a 49-year-old man with tightly coiled hair and darker skin tone. Coiled white hairs are noted in the alopecia patches.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune condition characterized by hair loss resulting from a T cell–mediated attack on the hair follicles. It manifests as nonscarring patches of hair loss on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard area as well as more extensive complete loss of scalp and body hair. While AA may affect individuals of any age, most patients develop their first patch(es) of hair loss during childhood.1 The treatment landscape for AA has evolved considerably in recent years, but barriers to access to newer treatments persist.

Epidemiology

Alopecia areata is most prevalent among pediatric and adult individuals of African, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino descent.2-4 In some studies, Black individuals had higher odds and Asian individuals had lower odds of developing AA, while other studies have reported the highest standardized prevalence among Asian individuals.5 In the United States, AA affects about 1.47% of adults and as many as 0.11% of children.6-8 In Black patients, AA often manifests early with a female predominance.5

Alopecia areata frequently is associated with autoimmune comorbidities, the most common being thyroid disease.3,5 In Black patients, AA is associated with more atopic comorbidities, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.5

Key Clinical Features

Alopecia areata clinically manifests similarly across different skin tones; however, in patients with more tightly coiled or curly hair, the extent of scalp hair loss may be underestimated without a full examination. Culturally sensitive approaches to hair and scalp evaluation are essential, especially for Black women, whose hair care practices and scalp conditions may be overlooked or misunderstood during visits to evaluate hair loss. A thoughtful history and gentle examination of the hair and scalp that considers hair texture, cultural practices such as head coverings (eg, headwraps, turbans, hijabs), use of hair adornments (eg, clips, beads, bows), traditional braiding, and use of natural oils or herbal treatments, as well as styling methods including tight hairstyles, use of heat styling tools (eg, flat irons, curling irons), chemical application (eg, straighteners, hair color), and washing or styling frequency can improve diagnostic accuracy and help build trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Classic signs of AA visualized with dermoscopy include yellow and/or black dots on the scalp and exclamation point hairs. The appearance of fine white vellus hairs within the alopecic patches also may indicate early regrowth. On scalp trichoscopy, black dots are more prominent, and yellow dots are less prominent, in individuals with darker skin tones vs lighter skin tones.9

Worth Noting

In addition to a full examination of the scalp, documenting the extent of hair loss using validated severity scales, including the severity of alopecia tool (SALT), alopecia areata severity index (AASI), clinician-reported outcome assessment, and patient-reported outcome measures, can standardize disease severity assessment, facilitate timely insurance or medication approvals, and support objective tracking of treatment response, which may ultimately enhance access to care.10

Prompt treatment of AA is essential. Not surprisingly, patients given a diagnosis of AA may experience considerable emotional and psychological distress—regardless of the extent of the loss.11 Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids and newer and more targeted systemic options, including 3 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors—baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib—for more extensive disease.12 Treatment with intralesional corticosteroids may cause transient hypopigmentation, which may be more noticeable in patients with darker skin tones. Delays in treatment with JAK inhibitors can lead to a less-than-optimal response. Of the 3 JAK inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA, only ritlecitinib is approved for children 12 years and older, leaving a therapeutic gap for younger patients that often leads to uncomfortable scalp injections, delayed or no treatment, off-label use of JAK inhibitors as well as the pairing of off-label dupilumab with oral minoxidil.12

Based on adult data, patients with severe disease and a shorter duration of hair loss (ie, <4 years) tend to respond better to JAK inhibitors than those experiencing hair loss for longer periods. Also, those with more severe AA tend to have poorer outcomes than those with less severe disease.13 If treatment proves less than optimal, wigs and hair pieces may need to be considered. It is worth noting that some insurance companies will cover the cost of wigs for patients when prescribed as cranial prostheses.

Health Disparity Highlight

Health disparities in AA can be influenced by socioeconomic status and access to care. Patients from lower-income backgrounds often face barriers to accessing dermatologic care and treatments such as JAK inhibitors, which may remain inaccessible due to high costs and insurance limitations.14 These barriers can intersect with other factors such as age, sex, and race, potentially exacerbating disparities. Women with skin of color in underserved communities may experience delayed diagnosis, limited treatment options, and greater psychosocial distress from hair loss.14 Addressing these inequities requires advocacy, education for both patients and clinicians, and improved access to treatment to ensure comprehensive care for all patients.

- Kara T, Topkarcı Z. Interactions between posttraumatic stress disorder and alopecia areata in child with trauma exposure: two case reports. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:131-134. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_2_18

- Sy N, Mastacouris N, Strunk A, et al. Overall and racial and ethnic subgroup prevalences of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:419-423.

- Lee H, Jung SJ, Patel AB, et al. Racial characteristics of alopecia areata in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1064-1070.

- Feaster B, McMichael AJ. Epidemiology of alopecia areata in Black patients: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1121-1123.

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:675-682.

- Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:411-418.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1(suppl 1):12-23.

- Karampinis E, Toli O, Georgopoulou KE, et al. Exploring pediatric dermatology in skin of color: focus on dermoscopy. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1604.

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:825-834.

- Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-175.

- Kalil L, Welch D, Heath CR, et al. Systemic therapies for pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1:36-42.

- King BA, Craiglow BG. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:S29-S32.

- Klein EJ, Taiwò D, Kakpovbia E, et al. Disparities in Janus kinase inhibitor access for alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:E155.

- McKenzie PL, Maltenfort M, Bruckner AL, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and incidence of pediatric alopecia areata using electronic health record data. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:547-551. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0351

The Comparison

A. Alopecia areata in a young girl with a lighter skin tone. The fine white vellus hairs are signs of regrowth.

B. Alopecia areata in a 49-year-old man with tightly coiled hair and darker skin tone. Coiled white hairs are noted in the alopecia patches.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune condition characterized by hair loss resulting from a T cell–mediated attack on the hair follicles. It manifests as nonscarring patches of hair loss on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard area as well as more extensive complete loss of scalp and body hair. While AA may affect individuals of any age, most patients develop their first patch(es) of hair loss during childhood.1 The treatment landscape for AA has evolved considerably in recent years, but barriers to access to newer treatments persist.

Epidemiology

Alopecia areata is most prevalent among pediatric and adult individuals of African, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino descent.2-4 In some studies, Black individuals had higher odds and Asian individuals had lower odds of developing AA, while other studies have reported the highest standardized prevalence among Asian individuals.5 In the United States, AA affects about 1.47% of adults and as many as 0.11% of children.6-8 In Black patients, AA often manifests early with a female predominance.5

Alopecia areata frequently is associated with autoimmune comorbidities, the most common being thyroid disease.3,5 In Black patients, AA is associated with more atopic comorbidities, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.5

Key Clinical Features

Alopecia areata clinically manifests similarly across different skin tones; however, in patients with more tightly coiled or curly hair, the extent of scalp hair loss may be underestimated without a full examination. Culturally sensitive approaches to hair and scalp evaluation are essential, especially for Black women, whose hair care practices and scalp conditions may be overlooked or misunderstood during visits to evaluate hair loss. A thoughtful history and gentle examination of the hair and scalp that considers hair texture, cultural practices such as head coverings (eg, headwraps, turbans, hijabs), use of hair adornments (eg, clips, beads, bows), traditional braiding, and use of natural oils or herbal treatments, as well as styling methods including tight hairstyles, use of heat styling tools (eg, flat irons, curling irons), chemical application (eg, straighteners, hair color), and washing or styling frequency can improve diagnostic accuracy and help build trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Classic signs of AA visualized with dermoscopy include yellow and/or black dots on the scalp and exclamation point hairs. The appearance of fine white vellus hairs within the alopecic patches also may indicate early regrowth. On scalp trichoscopy, black dots are more prominent, and yellow dots are less prominent, in individuals with darker skin tones vs lighter skin tones.9

Worth Noting

In addition to a full examination of the scalp, documenting the extent of hair loss using validated severity scales, including the severity of alopecia tool (SALT), alopecia areata severity index (AASI), clinician-reported outcome assessment, and patient-reported outcome measures, can standardize disease severity assessment, facilitate timely insurance or medication approvals, and support objective tracking of treatment response, which may ultimately enhance access to care.10

Prompt treatment of AA is essential. Not surprisingly, patients given a diagnosis of AA may experience considerable emotional and psychological distress—regardless of the extent of the loss.11 Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids and newer and more targeted systemic options, including 3 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors—baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib—for more extensive disease.12 Treatment with intralesional corticosteroids may cause transient hypopigmentation, which may be more noticeable in patients with darker skin tones. Delays in treatment with JAK inhibitors can lead to a less-than-optimal response. Of the 3 JAK inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA, only ritlecitinib is approved for children 12 years and older, leaving a therapeutic gap for younger patients that often leads to uncomfortable scalp injections, delayed or no treatment, off-label use of JAK inhibitors as well as the pairing of off-label dupilumab with oral minoxidil.12

Based on adult data, patients with severe disease and a shorter duration of hair loss (ie, <4 years) tend to respond better to JAK inhibitors than those experiencing hair loss for longer periods. Also, those with more severe AA tend to have poorer outcomes than those with less severe disease.13 If treatment proves less than optimal, wigs and hair pieces may need to be considered. It is worth noting that some insurance companies will cover the cost of wigs for patients when prescribed as cranial prostheses.

Health Disparity Highlight

Health disparities in AA can be influenced by socioeconomic status and access to care. Patients from lower-income backgrounds often face barriers to accessing dermatologic care and treatments such as JAK inhibitors, which may remain inaccessible due to high costs and insurance limitations.14 These barriers can intersect with other factors such as age, sex, and race, potentially exacerbating disparities. Women with skin of color in underserved communities may experience delayed diagnosis, limited treatment options, and greater psychosocial distress from hair loss.14 Addressing these inequities requires advocacy, education for both patients and clinicians, and improved access to treatment to ensure comprehensive care for all patients.

The Comparison

A. Alopecia areata in a young girl with a lighter skin tone. The fine white vellus hairs are signs of regrowth.

B. Alopecia areata in a 49-year-old man with tightly coiled hair and darker skin tone. Coiled white hairs are noted in the alopecia patches.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a common autoimmune condition characterized by hair loss resulting from a T cell–mediated attack on the hair follicles. It manifests as nonscarring patches of hair loss on the scalp, eyebrows, eyelashes, and beard area as well as more extensive complete loss of scalp and body hair. While AA may affect individuals of any age, most patients develop their first patch(es) of hair loss during childhood.1 The treatment landscape for AA has evolved considerably in recent years, but barriers to access to newer treatments persist.

Epidemiology

Alopecia areata is most prevalent among pediatric and adult individuals of African, Asian, or Hispanic/Latino descent.2-4 In some studies, Black individuals had higher odds and Asian individuals had lower odds of developing AA, while other studies have reported the highest standardized prevalence among Asian individuals.5 In the United States, AA affects about 1.47% of adults and as many as 0.11% of children.6-8 In Black patients, AA often manifests early with a female predominance.5

Alopecia areata frequently is associated with autoimmune comorbidities, the most common being thyroid disease.3,5 In Black patients, AA is associated with more atopic comorbidities, including asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis.5

Key Clinical Features

Alopecia areata clinically manifests similarly across different skin tones; however, in patients with more tightly coiled or curly hair, the extent of scalp hair loss may be underestimated without a full examination. Culturally sensitive approaches to hair and scalp evaluation are essential, especially for Black women, whose hair care practices and scalp conditions may be overlooked or misunderstood during visits to evaluate hair loss. A thoughtful history and gentle examination of the hair and scalp that considers hair texture, cultural practices such as head coverings (eg, headwraps, turbans, hijabs), use of hair adornments (eg, clips, beads, bows), traditional braiding, and use of natural oils or herbal treatments, as well as styling methods including tight hairstyles, use of heat styling tools (eg, flat irons, curling irons), chemical application (eg, straighteners, hair color), and washing or styling frequency can improve diagnostic accuracy and help build trust in the patient-provider relationship.

Classic signs of AA visualized with dermoscopy include yellow and/or black dots on the scalp and exclamation point hairs. The appearance of fine white vellus hairs within the alopecic patches also may indicate early regrowth. On scalp trichoscopy, black dots are more prominent, and yellow dots are less prominent, in individuals with darker skin tones vs lighter skin tones.9

Worth Noting

In addition to a full examination of the scalp, documenting the extent of hair loss using validated severity scales, including the severity of alopecia tool (SALT), alopecia areata severity index (AASI), clinician-reported outcome assessment, and patient-reported outcome measures, can standardize disease severity assessment, facilitate timely insurance or medication approvals, and support objective tracking of treatment response, which may ultimately enhance access to care.10

Prompt treatment of AA is essential. Not surprisingly, patients given a diagnosis of AA may experience considerable emotional and psychological distress—regardless of the extent of the loss.11 Treatment options include mid- to high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids and newer and more targeted systemic options, including 3 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors—baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib—for more extensive disease.12 Treatment with intralesional corticosteroids may cause transient hypopigmentation, which may be more noticeable in patients with darker skin tones. Delays in treatment with JAK inhibitors can lead to a less-than-optimal response. Of the 3 JAK inhibitors that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for AA, only ritlecitinib is approved for children 12 years and older, leaving a therapeutic gap for younger patients that often leads to uncomfortable scalp injections, delayed or no treatment, off-label use of JAK inhibitors as well as the pairing of off-label dupilumab with oral minoxidil.12

Based on adult data, patients with severe disease and a shorter duration of hair loss (ie, <4 years) tend to respond better to JAK inhibitors than those experiencing hair loss for longer periods. Also, those with more severe AA tend to have poorer outcomes than those with less severe disease.13 If treatment proves less than optimal, wigs and hair pieces may need to be considered. It is worth noting that some insurance companies will cover the cost of wigs for patients when prescribed as cranial prostheses.

Health Disparity Highlight

Health disparities in AA can be influenced by socioeconomic status and access to care. Patients from lower-income backgrounds often face barriers to accessing dermatologic care and treatments such as JAK inhibitors, which may remain inaccessible due to high costs and insurance limitations.14 These barriers can intersect with other factors such as age, sex, and race, potentially exacerbating disparities. Women with skin of color in underserved communities may experience delayed diagnosis, limited treatment options, and greater psychosocial distress from hair loss.14 Addressing these inequities requires advocacy, education for both patients and clinicians, and improved access to treatment to ensure comprehensive care for all patients.

- Kara T, Topkarcı Z. Interactions between posttraumatic stress disorder and alopecia areata in child with trauma exposure: two case reports. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:131-134. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_2_18

- Sy N, Mastacouris N, Strunk A, et al. Overall and racial and ethnic subgroup prevalences of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:419-423.

- Lee H, Jung SJ, Patel AB, et al. Racial characteristics of alopecia areata in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1064-1070.

- Feaster B, McMichael AJ. Epidemiology of alopecia areata in Black patients: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1121-1123.

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:675-682.

- Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:411-418.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1(suppl 1):12-23.

- Karampinis E, Toli O, Georgopoulou KE, et al. Exploring pediatric dermatology in skin of color: focus on dermoscopy. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1604.

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:825-834.

- Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-175.

- Kalil L, Welch D, Heath CR, et al. Systemic therapies for pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1:36-42.

- King BA, Craiglow BG. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:S29-S32.

- Klein EJ, Taiwò D, Kakpovbia E, et al. Disparities in Janus kinase inhibitor access for alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:E155.

- McKenzie PL, Maltenfort M, Bruckner AL, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and incidence of pediatric alopecia areata using electronic health record data. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:547-551. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0351

- Kara T, Topkarcı Z. Interactions between posttraumatic stress disorder and alopecia areata in child with trauma exposure: two case reports. Int J Trichology. 2018;10:131-134. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_2_18

- Sy N, Mastacouris N, Strunk A, et al. Overall and racial and ethnic subgroup prevalences of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:419-423.

- Lee H, Jung SJ, Patel AB, et al. Racial characteristics of alopecia areata in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1064-1070.

- Feaster B, McMichael AJ. Epidemiology of alopecia areata in Black patients: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1121-1123.

- Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:675-682.

- Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:411-418.

- Adhanom R, Ansbro B, Castelo-Soccio L. Epidemiology of pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1(suppl 1):12-23.

- Karampinis E, Toli O, Georgopoulou KE, et al. Exploring pediatric dermatology in skin of color: focus on dermoscopy. Life (Basel). 2024;14:1604.

- King BA, Senna MM, Ohyama M, et al. Defining severity in alopecia areata: current perspectives and a multidimensional framework. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:825-834.

- Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, et al. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:162-175.

- Kalil L, Welch D, Heath CR, et al. Systemic therapies for pediatric alopecia areata. Pediatr Dermatol. 2025;42 suppl 1:36-42.

- King BA, Craiglow BG. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:S29-S32.

- Klein EJ, Taiwò D, Kakpovbia E, et al. Disparities in Janus kinase inhibitor access for alopecia areata: a retrospective analysis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2024;10:E155.

- McKenzie PL, Maltenfort M, Bruckner AL, et al. Evaluation of the prevalence and incidence of pediatric alopecia areata using electronic health record data. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:547-551. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0351

Erythematous Rash on the Face and Neck

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

In our patient, the erythematous pruritic rash on the face and neck, the lack of systemic symptoms, and her history of atopic dermatitis suggested a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). She underwent patch testing with standard, fragrance, and cosmetic panels in addition to 6 of her personal care products. Her first patch test, which was read on day 2, showed a positive reaction to isopropyl myristate (IPM), a penetration enhancer used in cosmetics, topical medications (eg, tretinoin), and cosmeceuticals. The reading on day 5 showed a 2+ reaction to IPM, which was found in several of her personal care products, including her shampoo, leave-in conditioner, and eczema-calming cream. Isopropyl myristate is used in these products because of its ability to enhance their penetration into the skin and also can be found in commercially used products such as hand sanitizers. The patient was given information on this allergen and how to identify and avoid triggers. At follow-up, the ACD had resolved with avoidance of IPM.

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory skin condition that is triggered by contact with a specific causative agent. There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic; the irritant type is more common (approximately 80% of cases worldwide).1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV (delayed-type) hypersensitivity reaction; common causative agents include shampoos, moisturizers, makeup, certain metals (eg, nickel), fragrances, latex, and certain plants (eg, poison ivy).2 In cases of ACD, a new reaction can develop from exposure to a product that the patient has used for years. It manifests clinically as erythema, pruritus, scaling, and vesicle formation.1 Certain populations, such as those with atopic dermatitis, are more prone to developing ACD due to a breakdown of the skin barrier, frequent use of topical products, and immune dysregulation.1,2 Patch testing performed by dermatologists and allergists is the gold standard for diagnosing ACD.1,3

Annually, allergists, dermatologists, and primary care physicians see thousands of cases of contact dermatitis.1 Early recognition and appropriate treatment can help reduce the severity and duration of symptoms and improve patient outcomes. The main treatment for ACD is identification of the causative agent followed by patient education on how to identify and avoid triggers.2 Once patch testing has been completed, patients can be given access to the American Contact Dermatitis Society’s Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) database (https://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) to help them identify and avoid products that contain triggering allergens.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line pharmacologic treatments for atopic dermatitis.4 When our patient presented with the facial rash, her atopic dermatitis had been well controlled with both dupilumab and topical triamcinolone. The lack of response to previously successful therapies in a new area of involvement made a flare of atopic dermatitis less likely. For flares of ACD after exposure, topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors can help. If needed due to severity, oral corticosteroids also can be used.1

Dermatomyositis is an inflammatory myopathy that has several skin manifestations, including a heliotrope rash and poikiloderma.5 While our patient’s rash covered the periorbital area, she did not have other classic skin findings of dermatomyositis, such as nail-fold capillary changes or poikiloderma in a shawl or holster distribution.6 She also lacked signs of systemic involvement including myositis and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and creatine kinase levels.5

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is characterized by telangiectasias and transient flushing and erythema on the central face.5 Rosacea typically is triggered by temperature changes, alcohol consumption, sun exposure, spicy foods, and stress5 and would be expected to involve the nose, which was not observed in our patient. The fixed nature of our patient’s patches and the absence of telangiectasias also argued against this diagnosis.

The classic cutaneous finding of systemic lupus erythematosus is a malar rash, which appears as erythematous patches or thin plaques across the bridge of the nose and over the cheeks, sparing the nasolabial folds.5 Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with laboratory abnormalities, such as positive antinuclear antibodies and elevated CRP and ESR levels.5 Our patient had notable sparing of the nose, negative antinuclear antibodies, and normal CRP and ESR levels, making systemic lupus erythematosus unlikely. Systemic lupus erythematosus also can manifest with photosensitivity,7 and involvement of the submental skin in our patient argued against a photosensitive eruption.

- Nassau S, Fonacier L. Allergic contact dermatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:61-76. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.08.012

- Fonacier LS, Sher JM. Allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:9-12. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.03.018

- Uyesugi BA, Sheehan MP. Patch testing pearls. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:110-118. doi:10.1007/s12016-018-8715-y

- Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(suppl 2):52. doi:10.1186/s13223-018-0281-6

- Naji S. Malar rash. StatPearls. Updated September 4, 2023. Accessed June 30, 2025. https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/24661

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302. doi:10.1007 /s12016-015-8496-5

- Hannon CW, McCourt C, Lima HC, et al. Interventions for cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3(3):CD007478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007478.pub2

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

In our patient, the erythematous pruritic rash on the face and neck, the lack of systemic symptoms, and her history of atopic dermatitis suggested a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). She underwent patch testing with standard, fragrance, and cosmetic panels in addition to 6 of her personal care products. Her first patch test, which was read on day 2, showed a positive reaction to isopropyl myristate (IPM), a penetration enhancer used in cosmetics, topical medications (eg, tretinoin), and cosmeceuticals. The reading on day 5 showed a 2+ reaction to IPM, which was found in several of her personal care products, including her shampoo, leave-in conditioner, and eczema-calming cream. Isopropyl myristate is used in these products because of its ability to enhance their penetration into the skin and also can be found in commercially used products such as hand sanitizers. The patient was given information on this allergen and how to identify and avoid triggers. At follow-up, the ACD had resolved with avoidance of IPM.

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory skin condition that is triggered by contact with a specific causative agent. There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic; the irritant type is more common (approximately 80% of cases worldwide).1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV (delayed-type) hypersensitivity reaction; common causative agents include shampoos, moisturizers, makeup, certain metals (eg, nickel), fragrances, latex, and certain plants (eg, poison ivy).2 In cases of ACD, a new reaction can develop from exposure to a product that the patient has used for years. It manifests clinically as erythema, pruritus, scaling, and vesicle formation.1 Certain populations, such as those with atopic dermatitis, are more prone to developing ACD due to a breakdown of the skin barrier, frequent use of topical products, and immune dysregulation.1,2 Patch testing performed by dermatologists and allergists is the gold standard for diagnosing ACD.1,3

Annually, allergists, dermatologists, and primary care physicians see thousands of cases of contact dermatitis.1 Early recognition and appropriate treatment can help reduce the severity and duration of symptoms and improve patient outcomes. The main treatment for ACD is identification of the causative agent followed by patient education on how to identify and avoid triggers.2 Once patch testing has been completed, patients can be given access to the American Contact Dermatitis Society’s Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) database (https://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) to help them identify and avoid products that contain triggering allergens.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line pharmacologic treatments for atopic dermatitis.4 When our patient presented with the facial rash, her atopic dermatitis had been well controlled with both dupilumab and topical triamcinolone. The lack of response to previously successful therapies in a new area of involvement made a flare of atopic dermatitis less likely. For flares of ACD after exposure, topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors can help. If needed due to severity, oral corticosteroids also can be used.1

Dermatomyositis is an inflammatory myopathy that has several skin manifestations, including a heliotrope rash and poikiloderma.5 While our patient’s rash covered the periorbital area, she did not have other classic skin findings of dermatomyositis, such as nail-fold capillary changes or poikiloderma in a shawl or holster distribution.6 She also lacked signs of systemic involvement including myositis and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and creatine kinase levels.5

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is characterized by telangiectasias and transient flushing and erythema on the central face.5 Rosacea typically is triggered by temperature changes, alcohol consumption, sun exposure, spicy foods, and stress5 and would be expected to involve the nose, which was not observed in our patient. The fixed nature of our patient’s patches and the absence of telangiectasias also argued against this diagnosis.

The classic cutaneous finding of systemic lupus erythematosus is a malar rash, which appears as erythematous patches or thin plaques across the bridge of the nose and over the cheeks, sparing the nasolabial folds.5 Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with laboratory abnormalities, such as positive antinuclear antibodies and elevated CRP and ESR levels.5 Our patient had notable sparing of the nose, negative antinuclear antibodies, and normal CRP and ESR levels, making systemic lupus erythematosus unlikely. Systemic lupus erythematosus also can manifest with photosensitivity,7 and involvement of the submental skin in our patient argued against a photosensitive eruption.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

In our patient, the erythematous pruritic rash on the face and neck, the lack of systemic symptoms, and her history of atopic dermatitis suggested a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). She underwent patch testing with standard, fragrance, and cosmetic panels in addition to 6 of her personal care products. Her first patch test, which was read on day 2, showed a positive reaction to isopropyl myristate (IPM), a penetration enhancer used in cosmetics, topical medications (eg, tretinoin), and cosmeceuticals. The reading on day 5 showed a 2+ reaction to IPM, which was found in several of her personal care products, including her shampoo, leave-in conditioner, and eczema-calming cream. Isopropyl myristate is used in these products because of its ability to enhance their penetration into the skin and also can be found in commercially used products such as hand sanitizers. The patient was given information on this allergen and how to identify and avoid triggers. At follow-up, the ACD had resolved with avoidance of IPM.

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory skin condition that is triggered by contact with a specific causative agent. There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic; the irritant type is more common (approximately 80% of cases worldwide).1 Allergic contact dermatitis is a type IV (delayed-type) hypersensitivity reaction; common causative agents include shampoos, moisturizers, makeup, certain metals (eg, nickel), fragrances, latex, and certain plants (eg, poison ivy).2 In cases of ACD, a new reaction can develop from exposure to a product that the patient has used for years. It manifests clinically as erythema, pruritus, scaling, and vesicle formation.1 Certain populations, such as those with atopic dermatitis, are more prone to developing ACD due to a breakdown of the skin barrier, frequent use of topical products, and immune dysregulation.1,2 Patch testing performed by dermatologists and allergists is the gold standard for diagnosing ACD.1,3

Annually, allergists, dermatologists, and primary care physicians see thousands of cases of contact dermatitis.1 Early recognition and appropriate treatment can help reduce the severity and duration of symptoms and improve patient outcomes. The main treatment for ACD is identification of the causative agent followed by patient education on how to identify and avoid triggers.2 Once patch testing has been completed, patients can be given access to the American Contact Dermatitis Society’s Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) database (https://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) to help them identify and avoid products that contain triggering allergens.

Topical corticosteroids are the first-line pharmacologic treatments for atopic dermatitis.4 When our patient presented with the facial rash, her atopic dermatitis had been well controlled with both dupilumab and topical triamcinolone. The lack of response to previously successful therapies in a new area of involvement made a flare of atopic dermatitis less likely. For flares of ACD after exposure, topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors can help. If needed due to severity, oral corticosteroids also can be used.1

Dermatomyositis is an inflammatory myopathy that has several skin manifestations, including a heliotrope rash and poikiloderma.5 While our patient’s rash covered the periorbital area, she did not have other classic skin findings of dermatomyositis, such as nail-fold capillary changes or poikiloderma in a shawl or holster distribution.6 She also lacked signs of systemic involvement including myositis and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and creatine kinase levels.5

Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea is characterized by telangiectasias and transient flushing and erythema on the central face.5 Rosacea typically is triggered by temperature changes, alcohol consumption, sun exposure, spicy foods, and stress5 and would be expected to involve the nose, which was not observed in our patient. The fixed nature of our patient’s patches and the absence of telangiectasias also argued against this diagnosis.

The classic cutaneous finding of systemic lupus erythematosus is a malar rash, which appears as erythematous patches or thin plaques across the bridge of the nose and over the cheeks, sparing the nasolabial folds.5 Systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with laboratory abnormalities, such as positive antinuclear antibodies and elevated CRP and ESR levels.5 Our patient had notable sparing of the nose, negative antinuclear antibodies, and normal CRP and ESR levels, making systemic lupus erythematosus unlikely. Systemic lupus erythematosus also can manifest with photosensitivity,7 and involvement of the submental skin in our patient argued against a photosensitive eruption.

- Nassau S, Fonacier L. Allergic contact dermatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:61-76. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.08.012

- Fonacier LS, Sher JM. Allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:9-12. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.03.018

- Uyesugi BA, Sheehan MP. Patch testing pearls. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:110-118. doi:10.1007/s12016-018-8715-y

- Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(suppl 2):52. doi:10.1186/s13223-018-0281-6

- Naji S. Malar rash. StatPearls. Updated September 4, 2023. Accessed June 30, 2025. https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/24661

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302. doi:10.1007 /s12016-015-8496-5

- Hannon CW, McCourt C, Lima HC, et al. Interventions for cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3(3):CD007478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007478.pub2

- Nassau S, Fonacier L. Allergic contact dermatitis. Med Clin North Am. 2020;104:61-76. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2019.08.012

- Fonacier LS, Sher JM. Allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:9-12. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2014.03.018

- Uyesugi BA, Sheehan MP. Patch testing pearls. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56:110-118. doi:10.1007/s12016-018-8715-y

- Kapur S, Watson W, Carr S. Atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(suppl 2):52. doi:10.1186/s13223-018-0281-6

- Naji S. Malar rash. StatPearls. Updated September 4, 2023. Accessed June 30, 2025. https://www.statpearls.com/point-of-care/24661

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302. doi:10.1007 /s12016-015-8496-5

- Hannon CW, McCourt C, Lima HC, et al. Interventions for cutaneous disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;3(3):CD007478. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007478.pub2

A 23-year-old woman with atopic dermatitis and seasonal allergic rhinitis presented to the dermatology department with an erythematous pruritic rash of 1 year’s duration involving the forehead, periorbital and submental skin, and neck. The patient’s atopic dermatitis was stable and had been well controlled with dupilumab and topical triamcinolone as needed for flares. The patient denied any other symptoms including fever, fatigue, and muscle weakness. Physical examination of the hands and nails revealed no abnormalities. She was treated with topical triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% without improvement. Short-term prednisone tapers fully resolved the rash, but it recurred within 5 days after discontinuation of prednisone. Results of testing for rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and antistreptolysin O antibodies were unremarkable.

Spironolactone for Acne: Practical Strategies for Optimal Clinical Outcomes

Spironolactone for Acne: Practical Strategies for Optimal Clinical Outcomes

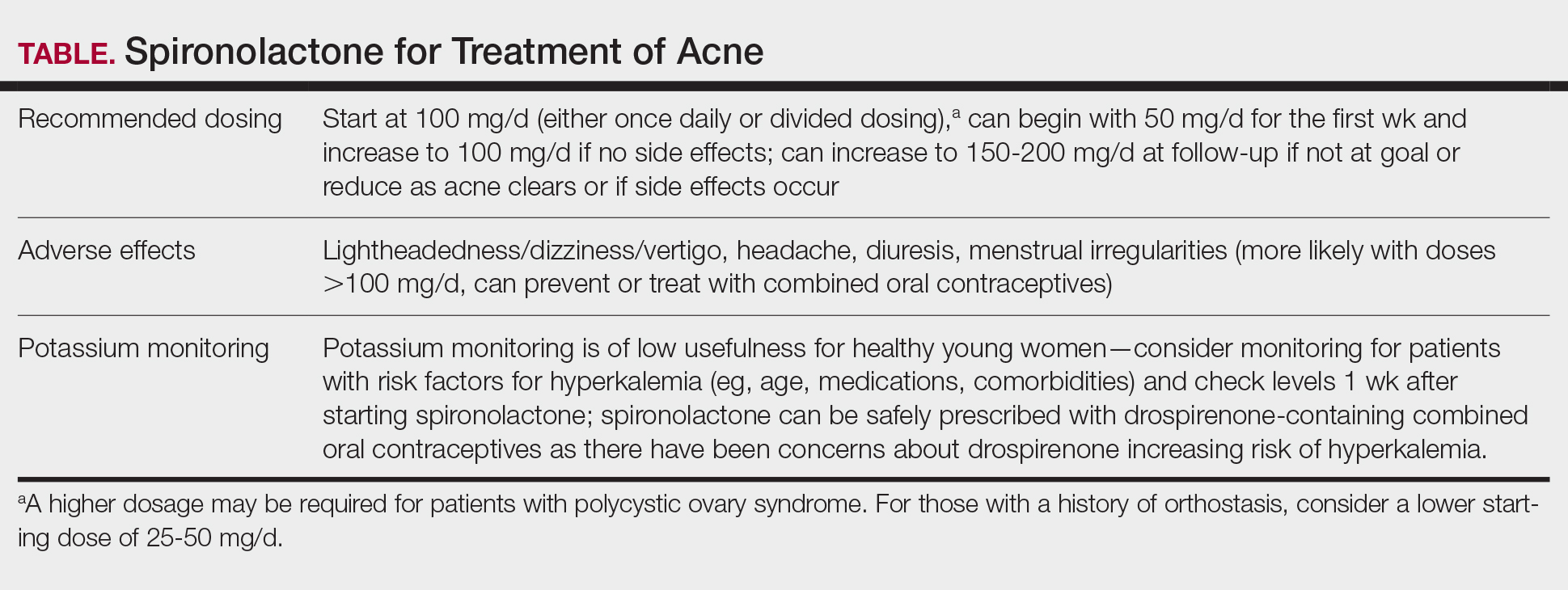

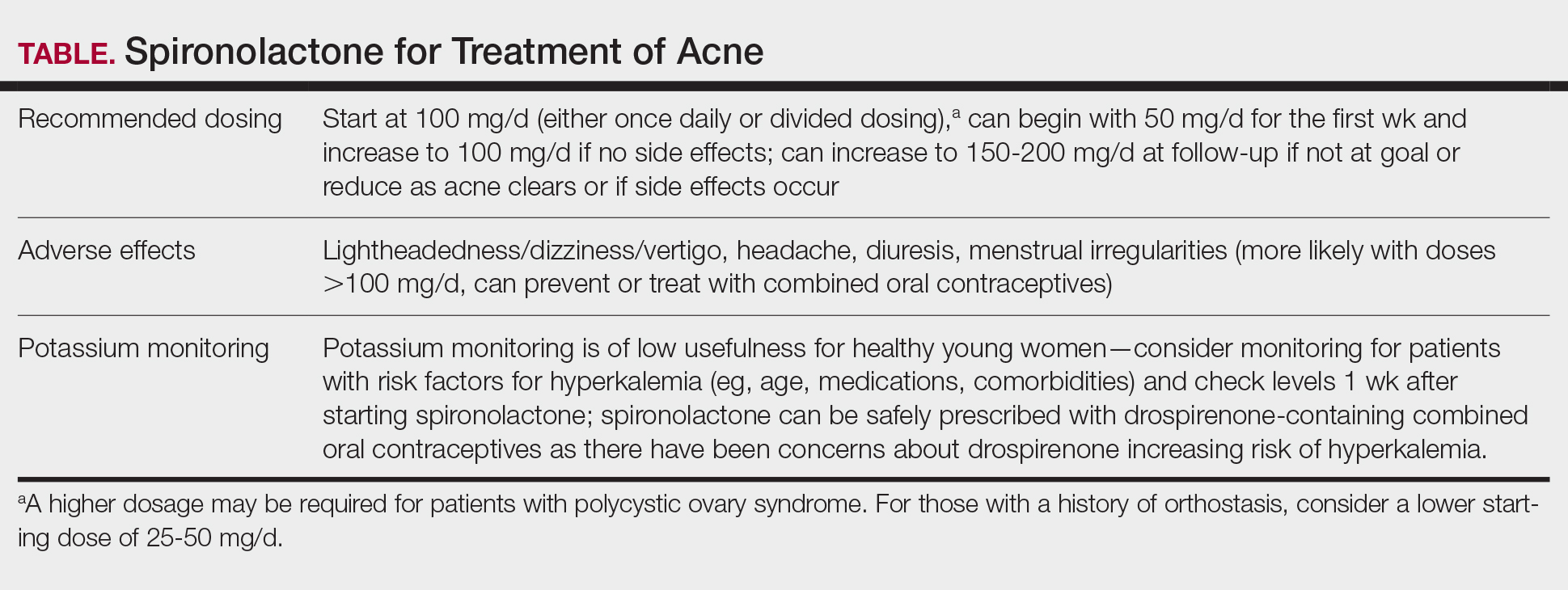

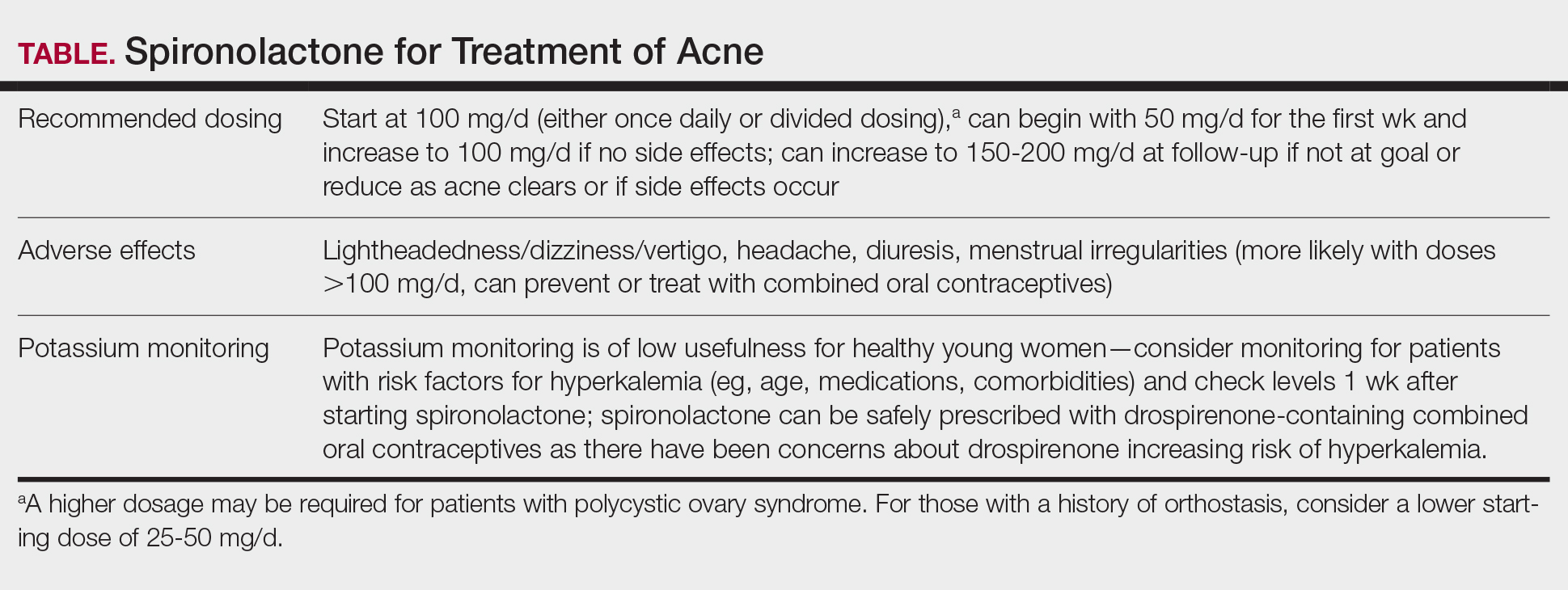

Spironolactone is increasingly used off label for acne treatment and is now being prescribed for women with acne at a frequency similar to oral antibiotics.1,2 In this article, we provide an overview of spironolactone use for acne treatment and discuss recent clinical trials and practical strategies for patient selection, dosing, adverse effect management, and monitoring (Table).

History and Mechanism of Action

Because sebaceous gland activity is an important component of acne pathogenesis and is regulated by androgens,3 there has long been interest in identifying treatment strategies that can target the role of hormones in activating the sebaceous gland. In the 1980s, it became apparent that spironolactone, originally developed as a potassium-sparing diuretic, also might possess antiandrogenic properties that could be useful in the treatment of acne.4 Spironolactone has been found to decrease testosterone production, inhibit testosterone and dihydrotestosterone binding to androgen receptors,5-8 and block 5α-reductase receptors of the sebaceous glands of skin.9

In 1984, Goodfellow et al10 conducted a trial in which 36 male and female patients with severe acne were randomized to placebo or spironolactone doses ranging from 50 to 200 mg/d. They found that spironolactone resulted in dose-dependent reductions of sebum production as well as improvement in patient- and clinician-reported assessments of acne. In 1986, another placebo-controlled crossover trial by Muhlemann et al11 provided further support for the effectiveness of spironolactone for acne. This trial randomized 21 women to placebo or spironolactone 200 mg/d and found that spironolactone was associated with statistically significant (P<.001) improvements in acne lesion counts.

Recent Observational Studies and Trials

Following these early trials, several large case series have been published describing the successful use of spironolactone for acne, including a 2020 retrospective case series from the Mayo Clinic describing 395 patients.12 The investigators found that almost 66% of patients had a complete response and almost 85% had a complete response or a partial response greater than 50%. They also found that the median time to initial response and maximal response were 3 and 5 months, respectively, and that efficacy was observed across acne subtypes, including for nodulocystic acne.12 In addition, a 2021 case series describing 403 patients treated with spironolactone found that approximately 80% had reduction or complete clearance of acne, with improvements observed for both facial and truncal acne. In this cohort, doses of 100 to 150 mg/d typically were the most successful.13 A case series of 80 adolescent females also highlighted the efficacy of spironolactone in younger populations.14

Adding to these observational data, the multicenter, phase 3, double-blind Spironolactone for Adult Female Acne (SAFA) trial included 410 women (mean age, 29.2 years) who were randomized to receive either placebo or intervention (spironolactone 50 mg/d until week 6 and 100 mg/d until week 24).15 At 24 weeks, greater improvement in quality of life and participant self-assessed improvement were observed in the spironolactone group. In addition, at 12 weeks, rates of success were higher in the spironolactone group using the Investigator Global Assessment score (adjusted odds ratio 5.18 [95% CI, 2.18- 12.28]). Those randomized to receive spironolactone also had lower rates of oral antibiotic use at 52 weeks than the placebo group did (5.8% vs 13.5%, respectively).

In the SAFA trial, spironolactone was well tolerated; the most common adverse effects relative to placebo were lightheadedness (19% for spironolactone vs 12% for placebo) and headache (20% for spironolactone vs 12% for placebo). Notably, more than 95% of patients were able to increase from 50 mg/d to 100 mg/d at week 6, with greater than 90% tolerating 100 mg/d. As observational data suggest that spironolactone takes 3 to 5 months to reach peak efficacy, these findings provide further support that starting at a dose of at least 100 mg/d is likely optimal for most patients.16

A Potential Alternative to Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics such as tetracyclines have long played a central role in the treatment of acne and remain a first-line treatment option.17 In addition, many of these antibiotic courses exceed 6 months in duration.1 In fact, dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics per capita than any other specialty1,18-20; however, this can be associated with the development of antibiotic resistance,21,22 as well as other antibiotic-associated complications, including inflammatory bowel disease,23 pharyngitis,24 Clostridium difficile infections, and cancer.25-29

In addition to these concerns, many patients may prefer nonantibiotic alternatives to oral antibiotics, with more than 75% preferring a nonantibiotic option if available. For female patients with acne, antiandrogens such as spironolactone have been suggested as a potential alternative.30 A 10-year retrospective study of female patients with acne found that those who had ever received hormonal therapy (ie, spironolactone or a combined oral contraceptive) received fewer cumulative days of oral antibiotics than those who did not (226 days vs 302 days, respectively).31 In addition, while oral antibiotics were the most common initial therapy prescribed for patients, as they progressed through their treatment course, more patients ended up on hormonal therapy than oral antibiotics. This study suggests that hormonal therapy such as spironolactone could represent an alternative to the use of systemic antibiotics.31

Further supporting the role of spironolactone as an alternative to oral antibiotics, a 2018 analysis of claims data found that spironolactone may have similar effectiveness to oral antibiotics for the treatment of acne.32 After adjusting for age and topical retinoid and oral contraceptive use, this study found that there was no significant difference in the odds of being prescribed a different systemic treatment within 1 year (ie, treatment failure) among those starting spironolactone vs those starting oral tetracycline-class antibiotics as their initial therapy for acne.

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial (Female Acne Spironolactone vs doxyCycline Efficacy [FASCE]) also evaluated the comparative effectiveness of doxycycline 100 mg/d for 3 months followed by an oral placebo for 3 months vs spironolactone 150 mg/d for 6 months among 133 adult women with acne. This study found that spironolactone had statistically significantly greater rates of Investigator Global Assessment treatment success after 6 months (odds ratio 2.87 [95% CI, 1.38-5.99; P=.007]).33 Since spironolactone historically has been prescribed less often than oral antibiotics for women with acne, these findings support spironolactone as an underutilized treatment alternative. The ongoing Spironolactone versus Doxycycline for Acne: A Comparative Effectiveness, Noninferiority Evaluation trial—a 16-week, blinded trial comparing 100 mg/d doses of both drugs—should provide additional evidence regarding the relative role of spironolactone and oral antibiotics in the management of acne.34

Ultimately, the decision to use spironolactone or other treatments such as oral antibiotics should be based on shared decision making between clinician and patient. Spironolactone has a relatively slow onset of efficacy, and other options such as oral antibiotics might be preferred by those looking for more immediate results; however, as women with acne often have activity that persists into adulthood, spironolactone might be preferable as a long-term maintenance therapy to avoid complications of prolonged antibiotic use.35 Comorbidities also will influence the optimal choice of therapy (eg, spironolactone might be preferred in someone with inflammatory bowel disease, and oral antibiotics might be preferred in someone with orthostatic hypotension).

Patient Selection

Acne occurring along the lower face or jawline in adult women sometimes is referred to as hormonal acne, but this dogma is not particularly evidence based. An observational study of 374 patients found that almost 90% of adult women had acne involving multiple facial zones with a spectrum of facial acne severity similar to that in adolescents.36 Only a small subset of these patients (11.2%) had acne localized solely to the mandibular area. In addition, acne along the lower face is not predictive of hyperandrogenism (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome).37 Antiandrogen therapies such as spironolactone and clascoterone are effective in both men and women with acne10,38 and in adolescents and adults, suggesting that hormones play a fundamental role in all acne and that addressing this mechanism can be useful broadly. Therefore, hormonal therapies such as spironolactone should not be restricted to only adult women with acne along the lower face.

While spironolactone can be effective for acne treatment in any age group, it may be most effective for adult women with acne. In the SAFA trial, prespecified subgroup analyses showed a statistically significant (P=.005) interaction term for age (categorized as <25 years and ≥25 years), which suggested that spironolactone might be a more effective treatment for women 25 years and older.15 In addition, subgroup analyses in the aforementioned 2018 analysis of claims data found that spironolactone was more effective relative to oral antibiotics in adults vs adolescents.32 Despite these limitations, several case series have highlighted that spironolactone is effective among adolescent populations with acne. A case series of spironolactone use in 73 patients aged 19 years or younger found that 68% of patients demonstrated resolution or improvement in their acne after spironolactone treatment.39 Another case series among 80 adolescent females reported 80% of patients experiencing improvement of their acne.14

For those with more severe acne, spironolactone can be combined with other complementary treatment approaches such as topicals, oral antibiotics, or procedural modalities.40

Dosing

We recommend starting spironolactone at a dose of 100 mg/d (the patient can take 50 mg/d for 1 week, then increase to 100 mg/d if there are no adverse effects at the lower dose). In the 1984 trial by Goodfellow et al,10 participants were randomized to doses of 50 mg/d, 100 mg/d, 150 mg/d, and 200 mg/d. In this trial, efficacy assessed by objective and subjective outcomes did not plateau until doses of 100 mg/d to 150 mg/d. In addition, a case series of 403 patients found that the most successful dosage of spironolactone generally was 100 mg/d or higher.13 Most of the patients who were started at this dosage either stayed at this level or escalated, whereas patients who started at lower dosages (25-75 mg/d) frequently increased their dosage over time. The SAFA trial also highlighted that most patients can tolerate a spironolactone dose of 100 mg/d.15 For specific populations, such as patients with polycystic ovary syndrome, a higher dose (mean dosage of 143 mg/d) may be required for efficacy.41 Given the slow onset of efficacy, typically taking 3 to 5 months, and the low rate of adverse effects, we believe the optimal starting dose is 100 mg/s to 150 mg/d. If adverse effects occur or lesions clear, then the dosage may be reduced.

Adverse Effects