User login

Workforce Shortage of Pediatric Dermatologists: A Medical Student’s Perspective

Workforce Shortage of Pediatric Dermatologists: A Medical Student’s Perspective

There is a shortage of pediatric dermatologists in the United States, with fewer than 2% of practicing dermatologists specializing in pediatrics.1 Pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate by pediatricians but also is the third most challenging specialty to access, with an average appointment wait time of 92 days.2,3 Another factor leading to increased appointment wait times is the specificity of care required for pediatric patients. Frequently, pediatric patients evaluated by a general dermatologist will be referred to their pediatric dermatology colleagues. As medical students, we were introduced to the field of pediatric dermatology through different avenues—personal experience, research mentorship, or a clinical rotation in medical school. We found ourselves curious about the discrepancy between the supply of and demand for pediatric dermatologists and wondered what could be done to increase awareness of this subspecialty among medical students. We believe this workforce shortage can be ameliorated by improving early exposure to pediatric dermatology. In this article, we explore the existing framework surrounding pediatric dermatology in medical education and offer feasible recommendations and solutions to realistically combat this problem.

Pediatric dermatologists are essential to the greater dermatology community. Pediatric dermatologists receive advanced training in complex pediatric skin conditions that often is lacking in general dermatology residency. A large percentage of pediatric dermatology patients seen in academic medical centers have already been seen by general dermatologists who subsequently referred them to specialty care. In one study, 9.6% (10/108) of practicing pediatric dermatologists noted that their referrals were from general dermatologists.4 In another study, 42% (19/45) of referrals to a multidisciplinary pediatric dermatology-genetics were from general dermatologists.5 Given the shortage of pediatric dermatologists, these referrals undoubtedly overwhelm the system, and the results of these studies underscore the reality that general dermatologists do not necessarily feel adequately trained in complex pediatric conditions, creating an intrinsic need for pediatric dermatologists.

Admani et al6 reported that early mentorship was the single most important factor to 84% (91/109) of survey respondents who pursued pediatric dermatology. Forty percent (40/100) of survey respondents chose their specialty of pediatric dermatology during pediatrics residency, 34% (34/100) during medical school, 17% (17/100) during dermatology residency, and 5% (5/100) during internship, indicating that medical school is a crucial time for recruitment.6 It has been noted in the literature that more medical students matched to dermatology residency from schools with dermatology clerkships built into the curriculum than from schools without dedicated dermatology rotations, suggesting that early clinical exposure to dermatology fields has a predictable influence in matching.7 Currently, only about 10% (15/155) of allopathic medical schools in the United States offer a formal elective in pediatric dermatology via the Association of American Medical College’s Visiting Student Learning Opportunities program.8 When this information was cross-referenced with the most recently matched pediatric dermatology fellowship class (2023-2024), provided by the Fellowship Directors Chair of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, we found that 17% (4/24) of the matched fellows attended one of these 15 medical schools. We also found that the 2023-2024 pediatric dermatology fellowship class had 12 unmatched spots out of 36 total positions nationwide (33%), highlighting a gap in pediatric dermatology care and placing further strain on an already underserved subspecialty. These data suggest that, while dermatologists may decide to pursue pediatric dermatology fellowships during residency, there is an opportunity to foster interest during medical school training and improve the fellowship match rate.

Several medical schools in the United States incorporate pediatric dermatology into their curricula, including lectures in preclinical courses and career panels to pediatric dermatology electives in the third and fourth years. These institutions can serve as models for other medical schools. Within preclinical content, we recommend creating a designated dermatology unit that can incorporate common pediatric dermatology pathologies also seen by general practitioners, such as common childhood rashes, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, seborrheic dermatitis, and acne. Rare pediatric diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa, tuberous sclerosis, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome also may be included in the unit. If schools are not able to offer a stand-alone dermatology preclinical course, this content can be added to the immunology, musculoskeletal, infectious diseases, or genetics courses to account for the multisystemic effects of some of these conditions. Ideally, schools would offer elective exposure to pediatric dermatology during the clinical years of medical school to increase knowledge of the field; for example, pediatric dermatology materials could be included in core clerkships, as much of this content is applicable to the general pediatrics rotation. In particular, a lecture on common rashes in pediatric patients could be given before starting the core pediatric rotation. Additionally, problem-based pediatric dermatology cases could be implemented during the core pediatrics rotation. If students are offered an independent dermatology clinical elective, the already formatted 2- and 4-week basic dermatology courses designed by the American Academy of Dermatology could serve as suggested teaching guides or as self-teaching resources that could complement the dermatology rotation.9,10 Pediatric topics (eg, pediatric cutaneous fungal infections) are included within the American Academy of Dermatology basic dermatology curriculum.8,9

Increasing access to pediatric dermatology resources such as lecture series and mentorship opportunities could further broaden the pediatric dermatology knowledge base of medical students. Within medical school dermatology interest groups, there is an opportunity to have a pediatric dermatology lead to help coordinate lecture series and journal club sessions for interested students. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance have created programs to support students, and we encourage schools to raise awareness of these organizations as well as conference and grant opportunities. These initiatives foster meaningful mentor-mentee relationships, and more medical students may be interested if they are aware of these support networks.

There also may be opportunities to create residency tracks that increase the number of dermatology residency applicants. Programs such as the newly implemented pediatric dermatology track at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University allow medical students who are interested in pursuing pediatric dermatology to have a more focused and linear training path.11,12 Due to the inherent competition in matching into dermatology, we surmise that many students with interest in pediatric dermatology are lost to pediatric residencies. Given the large percentage of pediatric residents who ultimately develop an interest in pediatric dermatology, holding a spot for pediatric dermatology applicants—akin to the combined medical-dermatology spots—may be an avenue to increase the pool of pediatric dermatology fellows.1,6 Another avenue is to encourage the development of first-year pediatric internship tracks that lead directly into dermatology residency, such as newly established programs at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University.11,12

As a group of both aspiring and practicing pediatric dermatologists, we have identified opportunities for formalized education in and early exposure to this subspecialty during medical training instead of leaving the discovery of the field to chance. The gaps in medical education that we have identified have already led us to present potential curricular changes to the medical education committee at our home institution. We hope to inspire the development of strong pediatric dermatology education at the medical school level.

While the solution to the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage is complex and multifaceted, there is a unique opportunity to target medical students through mentorship, access to education, and clinical experiences. We recommend that medical schools implement these educational methods and track the efficacy of these interventions to quantify the predicted association between an increased workforce and early exposure to pediatric dermatology. Addressing a lack of exposure to the field and increasing support of students pursuing pediatric dermatology can help to alleviate the shortage at the earliest point in training.

- Prindaville B, Antaya RJ, Siegfried EC. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12. doi:10.1111/pde.12362

- Wright TS. Update on the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage. Cutis. 2021;108:237-238. doi:10.12788/cutis.0379

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. ediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897. doi:10.1111/pde.13943

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. A survey to assess perceived differences in referral pathways to board-certified pediatric dermatologists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e314-e315. doi:10.1111/pde.12703

- Parker JC, Rangu S, Grand KL, et al. Genetic skin disorders: the value of a multidisciplinary clinic. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185:1159-1167. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.62095

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim SS, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-5.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.004

- Ogidi P, Ahmed F, Cahn BA, et al. Medical schools as gatekeepers: a survey and analysis of factors predicting dermatology residency placement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:490-492. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2021.09.027

- Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO). Accessed May 30, 2025. https://students-residents.aamc.org/visiting-student-learning-opportunities/visiting-student-learning-opportunities-vslo

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AAD Learning Center. Basic dermatology curriculum (2-week rotation). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://learning.aad.org/Listing/Basic-Dermatology-Curriculum-2-Week-Rotation-5395

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AAD Learning Center. Basic dermatology curriculum (4-week rotation). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://learning.aad.org/Public/Catalog/Details.aspx?id=YPssTVIbBO3Zb%2bOuf%2fM7Kg%3d%3d&returnurl=%2fUsers%2fUserOnlineCourse.aspx%3fLearningActivityID%3dYPssTVIbBO3Zb%252bOuf%252fM7Kg%253d%253d

- Penn Medicine Dermatology Residency Training Program. Residency tracks. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://dermatology.upenn.edu/residents/residency-tracks/

- Pediatric Dermatology Residency Track at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Pediatric Track. Accessed May 30, 2025. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/dermatology/education/residency/pediatric-track

There is a shortage of pediatric dermatologists in the United States, with fewer than 2% of practicing dermatologists specializing in pediatrics.1 Pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate by pediatricians but also is the third most challenging specialty to access, with an average appointment wait time of 92 days.2,3 Another factor leading to increased appointment wait times is the specificity of care required for pediatric patients. Frequently, pediatric patients evaluated by a general dermatologist will be referred to their pediatric dermatology colleagues. As medical students, we were introduced to the field of pediatric dermatology through different avenues—personal experience, research mentorship, or a clinical rotation in medical school. We found ourselves curious about the discrepancy between the supply of and demand for pediatric dermatologists and wondered what could be done to increase awareness of this subspecialty among medical students. We believe this workforce shortage can be ameliorated by improving early exposure to pediatric dermatology. In this article, we explore the existing framework surrounding pediatric dermatology in medical education and offer feasible recommendations and solutions to realistically combat this problem.

Pediatric dermatologists are essential to the greater dermatology community. Pediatric dermatologists receive advanced training in complex pediatric skin conditions that often is lacking in general dermatology residency. A large percentage of pediatric dermatology patients seen in academic medical centers have already been seen by general dermatologists who subsequently referred them to specialty care. In one study, 9.6% (10/108) of practicing pediatric dermatologists noted that their referrals were from general dermatologists.4 In another study, 42% (19/45) of referrals to a multidisciplinary pediatric dermatology-genetics were from general dermatologists.5 Given the shortage of pediatric dermatologists, these referrals undoubtedly overwhelm the system, and the results of these studies underscore the reality that general dermatologists do not necessarily feel adequately trained in complex pediatric conditions, creating an intrinsic need for pediatric dermatologists.

Admani et al6 reported that early mentorship was the single most important factor to 84% (91/109) of survey respondents who pursued pediatric dermatology. Forty percent (40/100) of survey respondents chose their specialty of pediatric dermatology during pediatrics residency, 34% (34/100) during medical school, 17% (17/100) during dermatology residency, and 5% (5/100) during internship, indicating that medical school is a crucial time for recruitment.6 It has been noted in the literature that more medical students matched to dermatology residency from schools with dermatology clerkships built into the curriculum than from schools without dedicated dermatology rotations, suggesting that early clinical exposure to dermatology fields has a predictable influence in matching.7 Currently, only about 10% (15/155) of allopathic medical schools in the United States offer a formal elective in pediatric dermatology via the Association of American Medical College’s Visiting Student Learning Opportunities program.8 When this information was cross-referenced with the most recently matched pediatric dermatology fellowship class (2023-2024), provided by the Fellowship Directors Chair of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, we found that 17% (4/24) of the matched fellows attended one of these 15 medical schools. We also found that the 2023-2024 pediatric dermatology fellowship class had 12 unmatched spots out of 36 total positions nationwide (33%), highlighting a gap in pediatric dermatology care and placing further strain on an already underserved subspecialty. These data suggest that, while dermatologists may decide to pursue pediatric dermatology fellowships during residency, there is an opportunity to foster interest during medical school training and improve the fellowship match rate.

Several medical schools in the United States incorporate pediatric dermatology into their curricula, including lectures in preclinical courses and career panels to pediatric dermatology electives in the third and fourth years. These institutions can serve as models for other medical schools. Within preclinical content, we recommend creating a designated dermatology unit that can incorporate common pediatric dermatology pathologies also seen by general practitioners, such as common childhood rashes, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, seborrheic dermatitis, and acne. Rare pediatric diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa, tuberous sclerosis, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome also may be included in the unit. If schools are not able to offer a stand-alone dermatology preclinical course, this content can be added to the immunology, musculoskeletal, infectious diseases, or genetics courses to account for the multisystemic effects of some of these conditions. Ideally, schools would offer elective exposure to pediatric dermatology during the clinical years of medical school to increase knowledge of the field; for example, pediatric dermatology materials could be included in core clerkships, as much of this content is applicable to the general pediatrics rotation. In particular, a lecture on common rashes in pediatric patients could be given before starting the core pediatric rotation. Additionally, problem-based pediatric dermatology cases could be implemented during the core pediatrics rotation. If students are offered an independent dermatology clinical elective, the already formatted 2- and 4-week basic dermatology courses designed by the American Academy of Dermatology could serve as suggested teaching guides or as self-teaching resources that could complement the dermatology rotation.9,10 Pediatric topics (eg, pediatric cutaneous fungal infections) are included within the American Academy of Dermatology basic dermatology curriculum.8,9

Increasing access to pediatric dermatology resources such as lecture series and mentorship opportunities could further broaden the pediatric dermatology knowledge base of medical students. Within medical school dermatology interest groups, there is an opportunity to have a pediatric dermatology lead to help coordinate lecture series and journal club sessions for interested students. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance have created programs to support students, and we encourage schools to raise awareness of these organizations as well as conference and grant opportunities. These initiatives foster meaningful mentor-mentee relationships, and more medical students may be interested if they are aware of these support networks.

There also may be opportunities to create residency tracks that increase the number of dermatology residency applicants. Programs such as the newly implemented pediatric dermatology track at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University allow medical students who are interested in pursuing pediatric dermatology to have a more focused and linear training path.11,12 Due to the inherent competition in matching into dermatology, we surmise that many students with interest in pediatric dermatology are lost to pediatric residencies. Given the large percentage of pediatric residents who ultimately develop an interest in pediatric dermatology, holding a spot for pediatric dermatology applicants—akin to the combined medical-dermatology spots—may be an avenue to increase the pool of pediatric dermatology fellows.1,6 Another avenue is to encourage the development of first-year pediatric internship tracks that lead directly into dermatology residency, such as newly established programs at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University.11,12

As a group of both aspiring and practicing pediatric dermatologists, we have identified opportunities for formalized education in and early exposure to this subspecialty during medical training instead of leaving the discovery of the field to chance. The gaps in medical education that we have identified have already led us to present potential curricular changes to the medical education committee at our home institution. We hope to inspire the development of strong pediatric dermatology education at the medical school level.

While the solution to the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage is complex and multifaceted, there is a unique opportunity to target medical students through mentorship, access to education, and clinical experiences. We recommend that medical schools implement these educational methods and track the efficacy of these interventions to quantify the predicted association between an increased workforce and early exposure to pediatric dermatology. Addressing a lack of exposure to the field and increasing support of students pursuing pediatric dermatology can help to alleviate the shortage at the earliest point in training.

There is a shortage of pediatric dermatologists in the United States, with fewer than 2% of practicing dermatologists specializing in pediatrics.1 Pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate by pediatricians but also is the third most challenging specialty to access, with an average appointment wait time of 92 days.2,3 Another factor leading to increased appointment wait times is the specificity of care required for pediatric patients. Frequently, pediatric patients evaluated by a general dermatologist will be referred to their pediatric dermatology colleagues. As medical students, we were introduced to the field of pediatric dermatology through different avenues—personal experience, research mentorship, or a clinical rotation in medical school. We found ourselves curious about the discrepancy between the supply of and demand for pediatric dermatologists and wondered what could be done to increase awareness of this subspecialty among medical students. We believe this workforce shortage can be ameliorated by improving early exposure to pediatric dermatology. In this article, we explore the existing framework surrounding pediatric dermatology in medical education and offer feasible recommendations and solutions to realistically combat this problem.

Pediatric dermatologists are essential to the greater dermatology community. Pediatric dermatologists receive advanced training in complex pediatric skin conditions that often is lacking in general dermatology residency. A large percentage of pediatric dermatology patients seen in academic medical centers have already been seen by general dermatologists who subsequently referred them to specialty care. In one study, 9.6% (10/108) of practicing pediatric dermatologists noted that their referrals were from general dermatologists.4 In another study, 42% (19/45) of referrals to a multidisciplinary pediatric dermatology-genetics were from general dermatologists.5 Given the shortage of pediatric dermatologists, these referrals undoubtedly overwhelm the system, and the results of these studies underscore the reality that general dermatologists do not necessarily feel adequately trained in complex pediatric conditions, creating an intrinsic need for pediatric dermatologists.

Admani et al6 reported that early mentorship was the single most important factor to 84% (91/109) of survey respondents who pursued pediatric dermatology. Forty percent (40/100) of survey respondents chose their specialty of pediatric dermatology during pediatrics residency, 34% (34/100) during medical school, 17% (17/100) during dermatology residency, and 5% (5/100) during internship, indicating that medical school is a crucial time for recruitment.6 It has been noted in the literature that more medical students matched to dermatology residency from schools with dermatology clerkships built into the curriculum than from schools without dedicated dermatology rotations, suggesting that early clinical exposure to dermatology fields has a predictable influence in matching.7 Currently, only about 10% (15/155) of allopathic medical schools in the United States offer a formal elective in pediatric dermatology via the Association of American Medical College’s Visiting Student Learning Opportunities program.8 When this information was cross-referenced with the most recently matched pediatric dermatology fellowship class (2023-2024), provided by the Fellowship Directors Chair of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, we found that 17% (4/24) of the matched fellows attended one of these 15 medical schools. We also found that the 2023-2024 pediatric dermatology fellowship class had 12 unmatched spots out of 36 total positions nationwide (33%), highlighting a gap in pediatric dermatology care and placing further strain on an already underserved subspecialty. These data suggest that, while dermatologists may decide to pursue pediatric dermatology fellowships during residency, there is an opportunity to foster interest during medical school training and improve the fellowship match rate.

Several medical schools in the United States incorporate pediatric dermatology into their curricula, including lectures in preclinical courses and career panels to pediatric dermatology electives in the third and fourth years. These institutions can serve as models for other medical schools. Within preclinical content, we recommend creating a designated dermatology unit that can incorporate common pediatric dermatology pathologies also seen by general practitioners, such as common childhood rashes, atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, seborrheic dermatitis, and acne. Rare pediatric diseases such as epidermolysis bullosa, tuberous sclerosis, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome also may be included in the unit. If schools are not able to offer a stand-alone dermatology preclinical course, this content can be added to the immunology, musculoskeletal, infectious diseases, or genetics courses to account for the multisystemic effects of some of these conditions. Ideally, schools would offer elective exposure to pediatric dermatology during the clinical years of medical school to increase knowledge of the field; for example, pediatric dermatology materials could be included in core clerkships, as much of this content is applicable to the general pediatrics rotation. In particular, a lecture on common rashes in pediatric patients could be given before starting the core pediatric rotation. Additionally, problem-based pediatric dermatology cases could be implemented during the core pediatrics rotation. If students are offered an independent dermatology clinical elective, the already formatted 2- and 4-week basic dermatology courses designed by the American Academy of Dermatology could serve as suggested teaching guides or as self-teaching resources that could complement the dermatology rotation.9,10 Pediatric topics (eg, pediatric cutaneous fungal infections) are included within the American Academy of Dermatology basic dermatology curriculum.8,9

Increasing access to pediatric dermatology resources such as lecture series and mentorship opportunities could further broaden the pediatric dermatology knowledge base of medical students. Within medical school dermatology interest groups, there is an opportunity to have a pediatric dermatology lead to help coordinate lecture series and journal club sessions for interested students. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology and the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance have created programs to support students, and we encourage schools to raise awareness of these organizations as well as conference and grant opportunities. These initiatives foster meaningful mentor-mentee relationships, and more medical students may be interested if they are aware of these support networks.

There also may be opportunities to create residency tracks that increase the number of dermatology residency applicants. Programs such as the newly implemented pediatric dermatology track at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University allow medical students who are interested in pursuing pediatric dermatology to have a more focused and linear training path.11,12 Due to the inherent competition in matching into dermatology, we surmise that many students with interest in pediatric dermatology are lost to pediatric residencies. Given the large percentage of pediatric residents who ultimately develop an interest in pediatric dermatology, holding a spot for pediatric dermatology applicants—akin to the combined medical-dermatology spots—may be an avenue to increase the pool of pediatric dermatology fellows.1,6 Another avenue is to encourage the development of first-year pediatric internship tracks that lead directly into dermatology residency, such as newly established programs at the University of Pennsylvania and New York University.11,12

As a group of both aspiring and practicing pediatric dermatologists, we have identified opportunities for formalized education in and early exposure to this subspecialty during medical training instead of leaving the discovery of the field to chance. The gaps in medical education that we have identified have already led us to present potential curricular changes to the medical education committee at our home institution. We hope to inspire the development of strong pediatric dermatology education at the medical school level.

While the solution to the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage is complex and multifaceted, there is a unique opportunity to target medical students through mentorship, access to education, and clinical experiences. We recommend that medical schools implement these educational methods and track the efficacy of these interventions to quantify the predicted association between an increased workforce and early exposure to pediatric dermatology. Addressing a lack of exposure to the field and increasing support of students pursuing pediatric dermatology can help to alleviate the shortage at the earliest point in training.

- Prindaville B, Antaya RJ, Siegfried EC. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12. doi:10.1111/pde.12362

- Wright TS. Update on the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage. Cutis. 2021;108:237-238. doi:10.12788/cutis.0379

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. ediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897. doi:10.1111/pde.13943

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. A survey to assess perceived differences in referral pathways to board-certified pediatric dermatologists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e314-e315. doi:10.1111/pde.12703

- Parker JC, Rangu S, Grand KL, et al. Genetic skin disorders: the value of a multidisciplinary clinic. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185:1159-1167. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.62095

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim SS, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-5.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.004

- Ogidi P, Ahmed F, Cahn BA, et al. Medical schools as gatekeepers: a survey and analysis of factors predicting dermatology residency placement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:490-492. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2021.09.027

- Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO). Accessed May 30, 2025. https://students-residents.aamc.org/visiting-student-learning-opportunities/visiting-student-learning-opportunities-vslo

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AAD Learning Center. Basic dermatology curriculum (2-week rotation). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://learning.aad.org/Listing/Basic-Dermatology-Curriculum-2-Week-Rotation-5395

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AAD Learning Center. Basic dermatology curriculum (4-week rotation). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://learning.aad.org/Public/Catalog/Details.aspx?id=YPssTVIbBO3Zb%2bOuf%2fM7Kg%3d%3d&returnurl=%2fUsers%2fUserOnlineCourse.aspx%3fLearningActivityID%3dYPssTVIbBO3Zb%252bOuf%252fM7Kg%253d%253d

- Penn Medicine Dermatology Residency Training Program. Residency tracks. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://dermatology.upenn.edu/residents/residency-tracks/

- Pediatric Dermatology Residency Track at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Pediatric Track. Accessed May 30, 2025. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/dermatology/education/residency/pediatric-track

- Prindaville B, Antaya RJ, Siegfried EC. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12. doi:10.1111/pde.12362

- Wright TS. Update on the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage. Cutis. 2021;108:237-238. doi:10.12788/cutis.0379

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. ediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897. doi:10.1111/pde.13943

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. A survey to assess perceived differences in referral pathways to board-certified pediatric dermatologists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e314-e315. doi:10.1111/pde.12703

- Parker JC, Rangu S, Grand KL, et al. Genetic skin disorders: the value of a multidisciplinary clinic. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185:1159-1167. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.62095

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim SS, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-5.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.10.004

- Ogidi P, Ahmed F, Cahn BA, et al. Medical schools as gatekeepers: a survey and analysis of factors predicting dermatology residency placement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:490-492. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2021.09.027

- Visiting Student Learning Opportunities (VSLO). Accessed May 30, 2025. https://students-residents.aamc.org/visiting-student-learning-opportunities/visiting-student-learning-opportunities-vslo

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AAD Learning Center. Basic dermatology curriculum (2-week rotation). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://learning.aad.org/Listing/Basic-Dermatology-Curriculum-2-Week-Rotation-5395

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AAD Learning Center. Basic dermatology curriculum (4-week rotation). Accessed May 12, 2025. https://learning.aad.org/Public/Catalog/Details.aspx?id=YPssTVIbBO3Zb%2bOuf%2fM7Kg%3d%3d&returnurl=%2fUsers%2fUserOnlineCourse.aspx%3fLearningActivityID%3dYPssTVIbBO3Zb%252bOuf%252fM7Kg%253d%253d

- Penn Medicine Dermatology Residency Training Program. Residency tracks. Accessed May 12, 2025. https://dermatology.upenn.edu/residents/residency-tracks/

- Pediatric Dermatology Residency Track at NYU Grossman School of Medicine. Pediatric Track. Accessed May 30, 2025. https://med.nyu.edu/departments-institutes/dermatology/education/residency/pediatric-track

Workforce Shortage of Pediatric Dermatologists: A Medical Student’s Perspective

Workforce Shortage of Pediatric Dermatologists: A Medical Student’s Perspective

PRACTICE POINTS

- Addressing a lack of exposure to pediatric dermatology in medical school and increasing support for students who are interested in the field can help alleviate the shortage of physicians at the earliest point in training.

- Increasing access to pediatric dermatology resources, such as lecture series and mentorship opportunities, could further broaden the medical student knowledge base.

- There is an opportunity to create residency tracks that increase the number of dermatology residency applicants who are medical students interested in pursuing pediatric dermatology.

Eruptive Erythematous Papules on the Forearms

Eruptive Erythematous Papules on the Forearms

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Eruptive Syringoma

Syringomas are small, benign, often asymptomatic eccrine tumors that originate in the intraepidermal portion of eccrine sweat ducts.1 Clinically, they present as multiple symmetric white-to-yellow or discrete flesh-colored papules measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter, often located on the face (most commonly on the eyelids), with a greater prevalence in middle-aged women. Occasionally, they manifest in other locations such as the cheeks, chest, axillae, abdomen, and groin.2

In 1987, Friedman and Butler3 developed a classification system categorizing syringomas into 4 clinical subtypes: familial syringoma, localized syringoma, Down syndrome–related syringoma, and generalized syringoma. The fourth subtype includes the variant of eruptive syringoma,3 a rare clinical manifestation that often develops before or during puberty with several flesh-colored or lightly pigmented papules on the neck, anterior chest, upper abdomen, axillae, periumbilical region, and/or genital region.1,4,5 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, although it has been linked to abnormal proliferation of sweat glands due to an underlying local inflammatory process.6

Acral distribution of syringomas is a rare variant that can manifest as part of generalized eruptive syringoma with consequent involvement of the arms and other areas.5,7 There are limited case reports on eruptive syringomas with predominant acral distribution.8 Compared to classic syringomas, the acral variant is associated with an older age of onset as well as a similar prevalence between men and women.9 Acral eruptive syringoma (AES) usually is isolated to the distal arms and legs. The most commonly affected region is the anterior surface of the forearms, although involvement of the dorsal hands, wrists, and feet also has been reported.10-16

The first known case of AES, which was reported in 1977, described eruptive syringomas on the dorsal hands of a healthy 31-year-old man.17 Several cases have been reported since then, mostly in patients aged 30 to 60 years, with predominant involvement of the dorsal hands and forearms.18-24 A review of Embase as well as PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms syringoma OR eccrine ductal tumor and eruptive OR acral OR arms OR forearms OR extremities identified 19 reported cases of AES between 1977 and 2023. For the reported AES cases, the mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 45.1 years (15.96 years), with patient ages ranging from 19 to 76 years. Notably, most cases occurred in individuals aged between 30 and 60 years, which deviates from the typical age of onset of localized syringomas, commonly seen during puberty or early adulthood.

Currently, AES is categorized within the clinical presentation of eruptive syringoma. Nevertheless, some authors have proposed classifying it as a distinct fifth clinical group due to specific features that distinguish it from generalized eruptive syringoma.9 This reclassification has considerable implications for the differential diagnosis, particularly because exclusive acral involvement poses a substantial diagnostic challenge and often requires histologic confirmation.

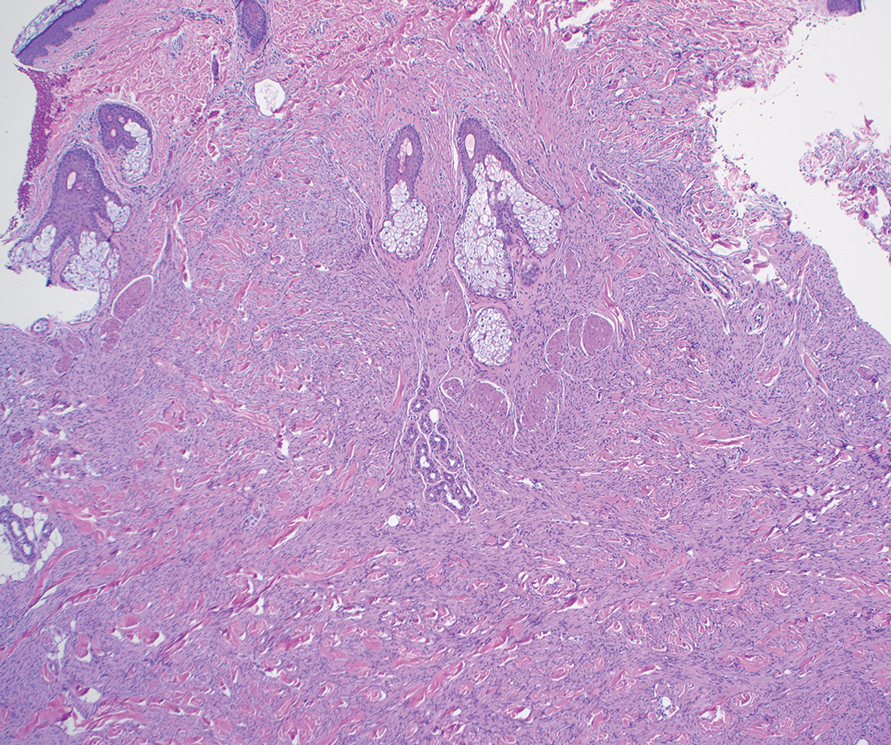

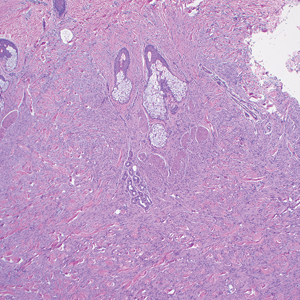

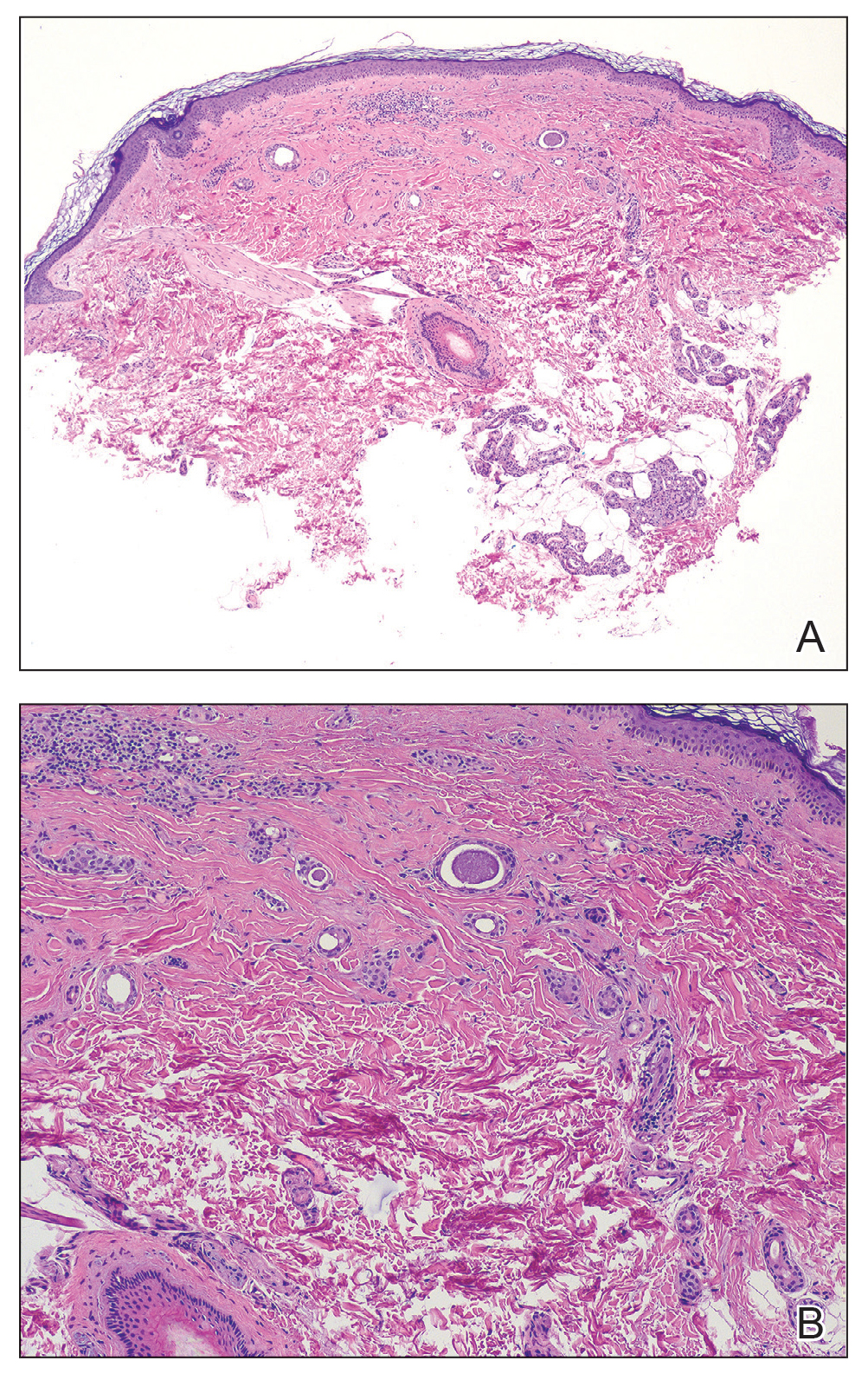

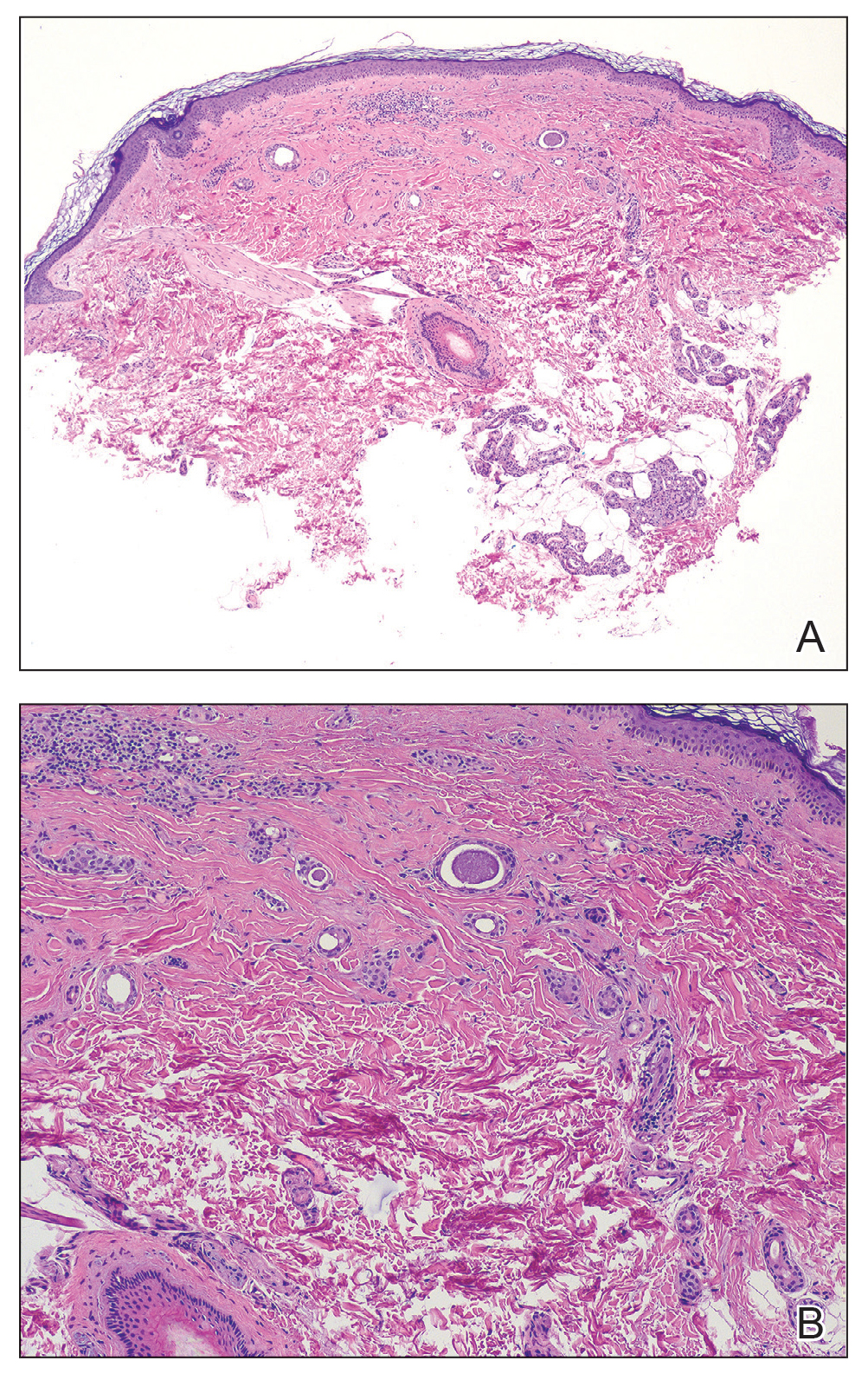

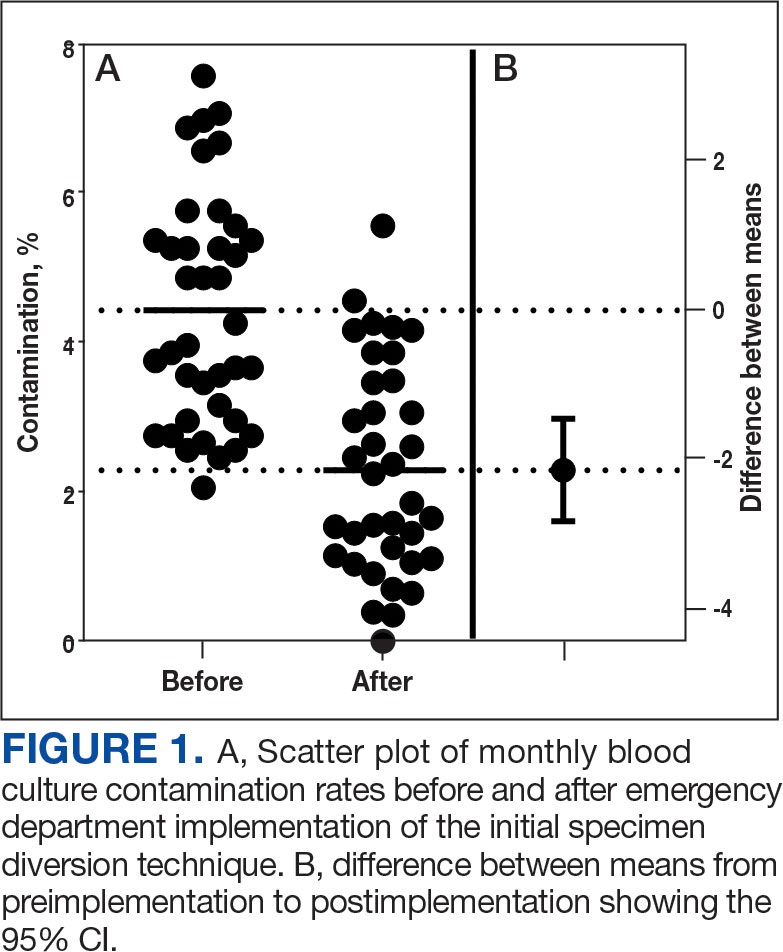

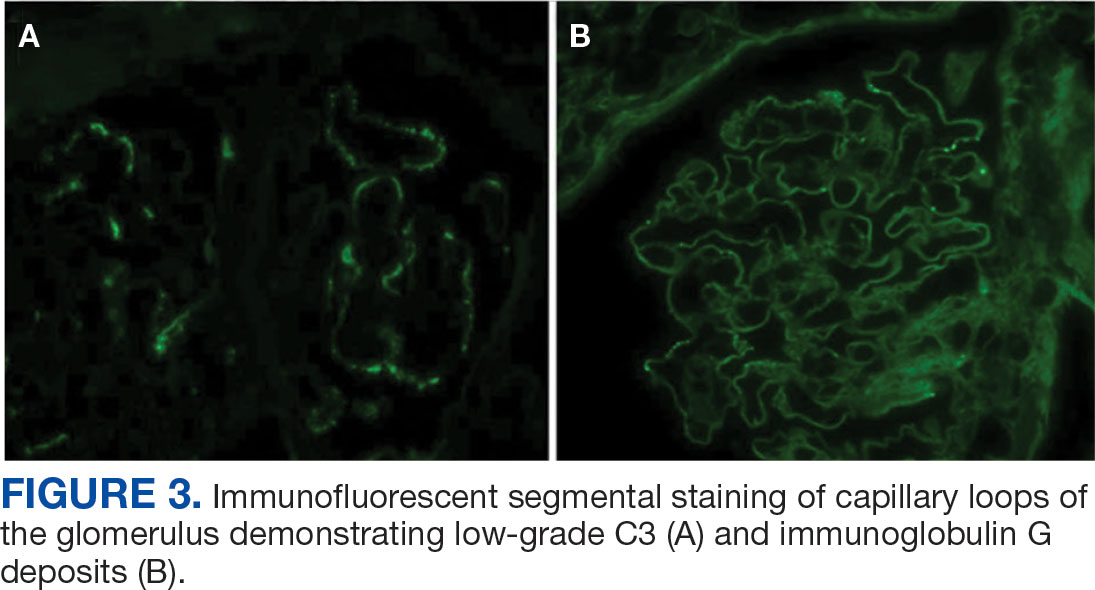

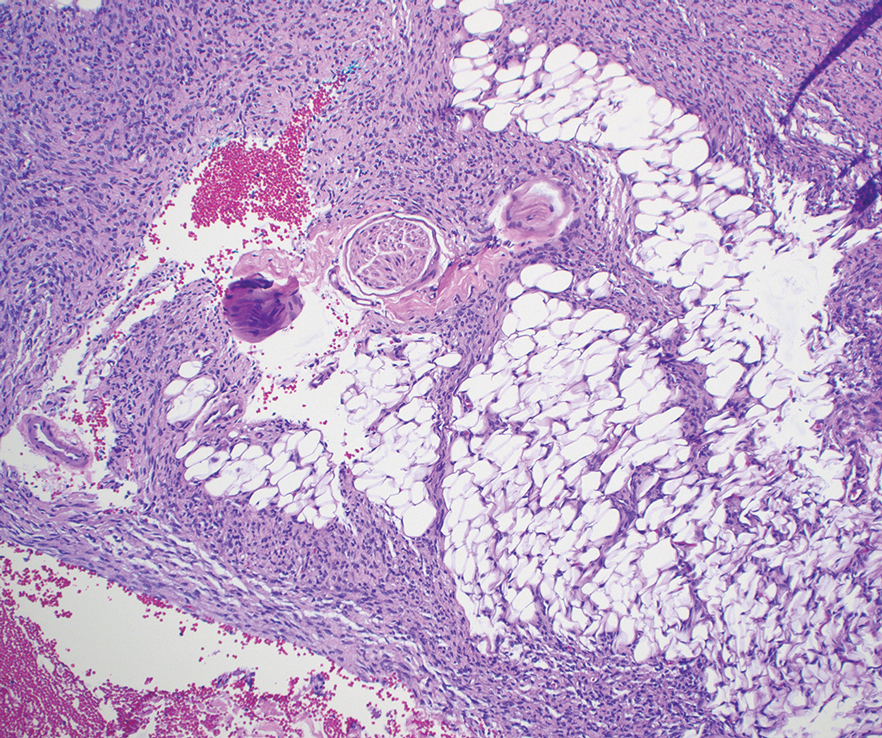

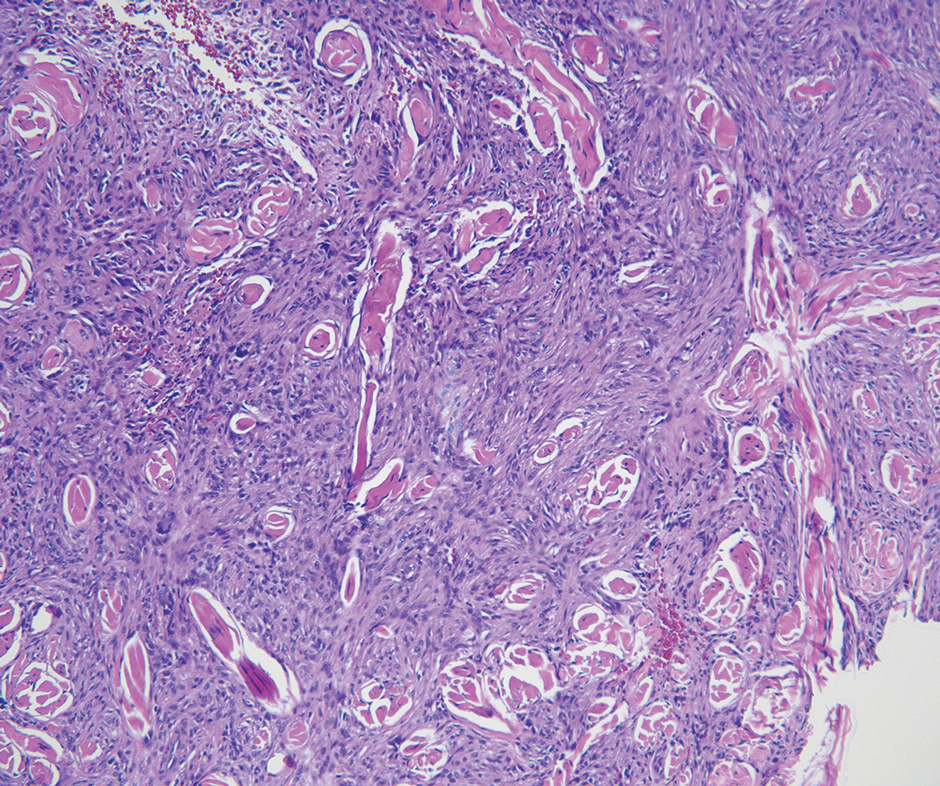

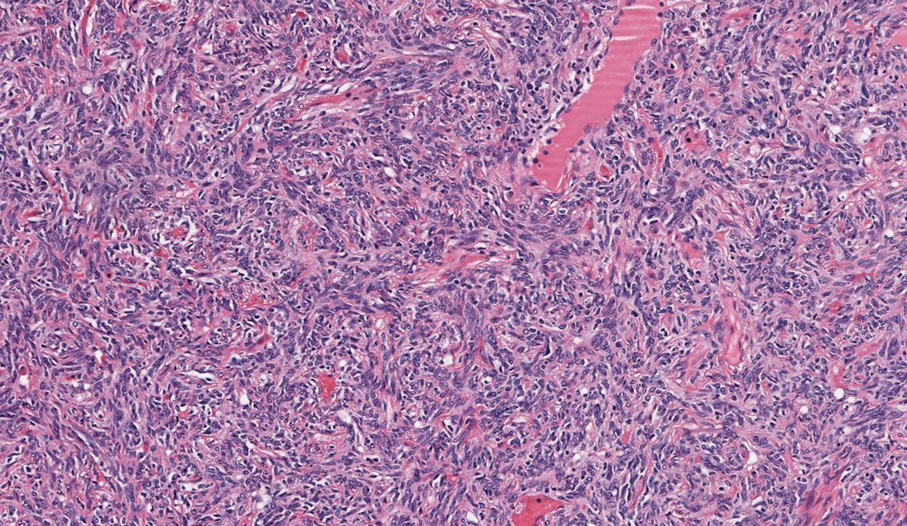

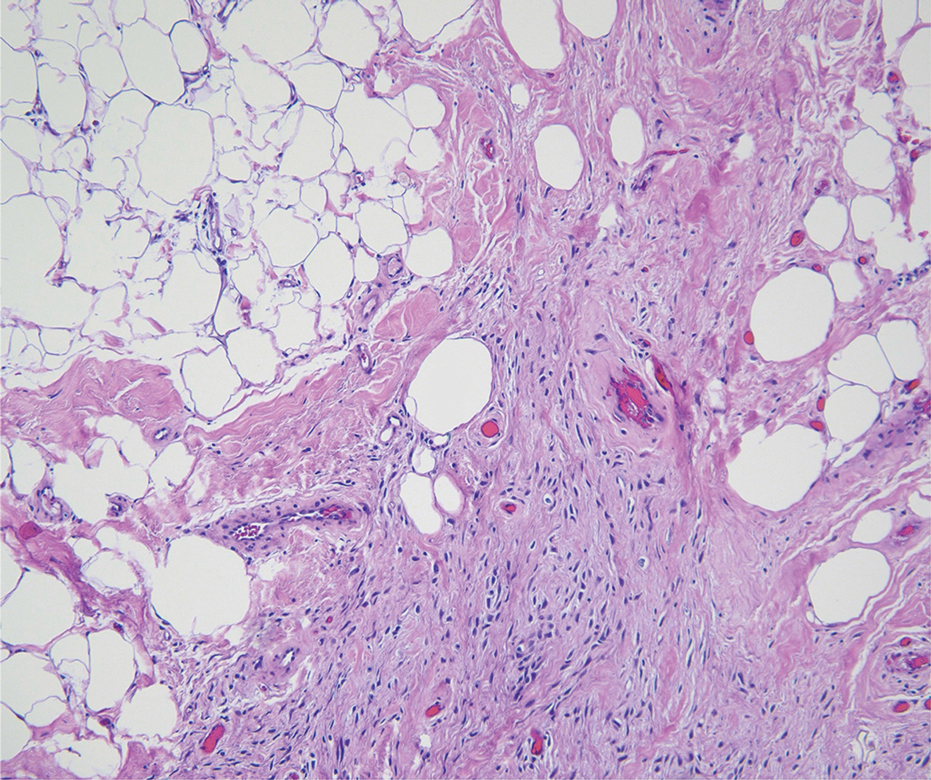

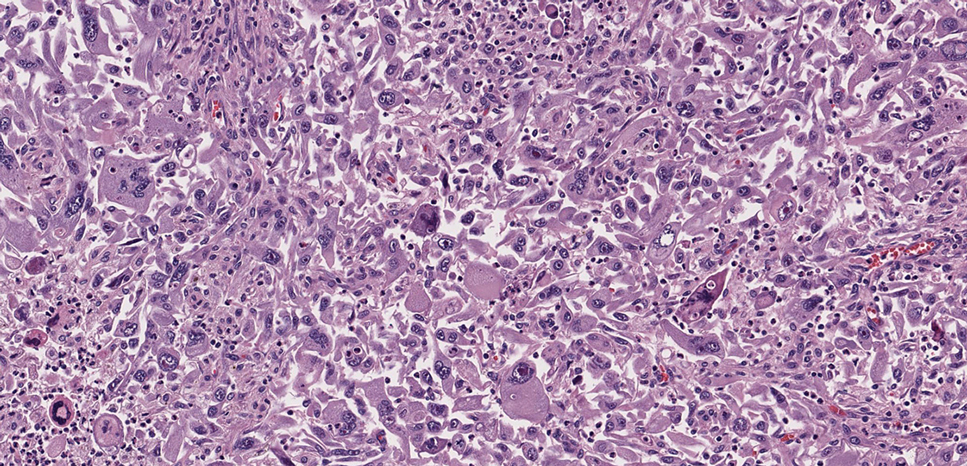

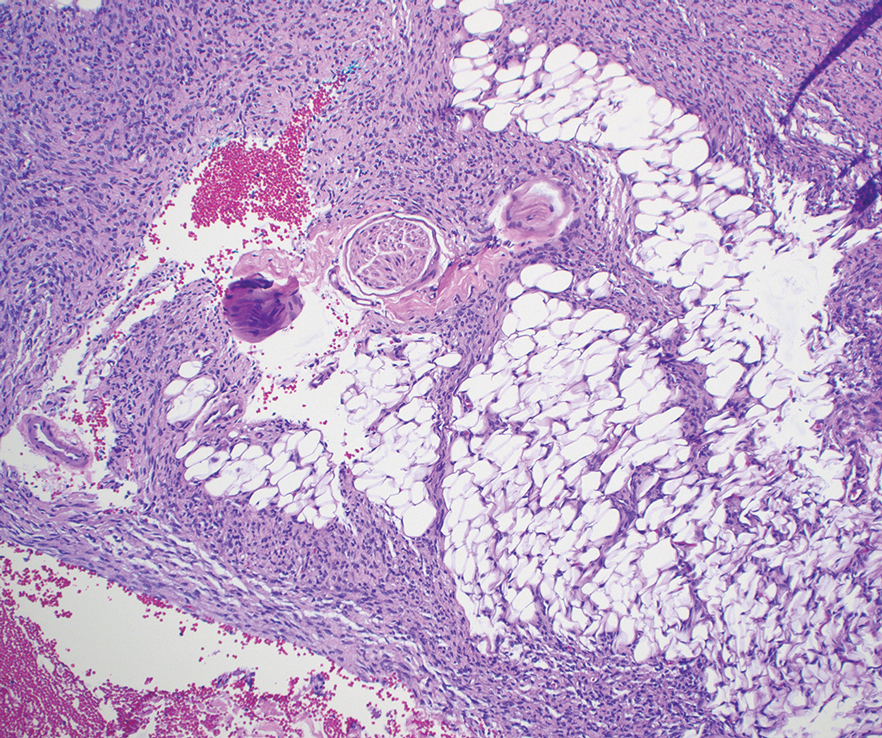

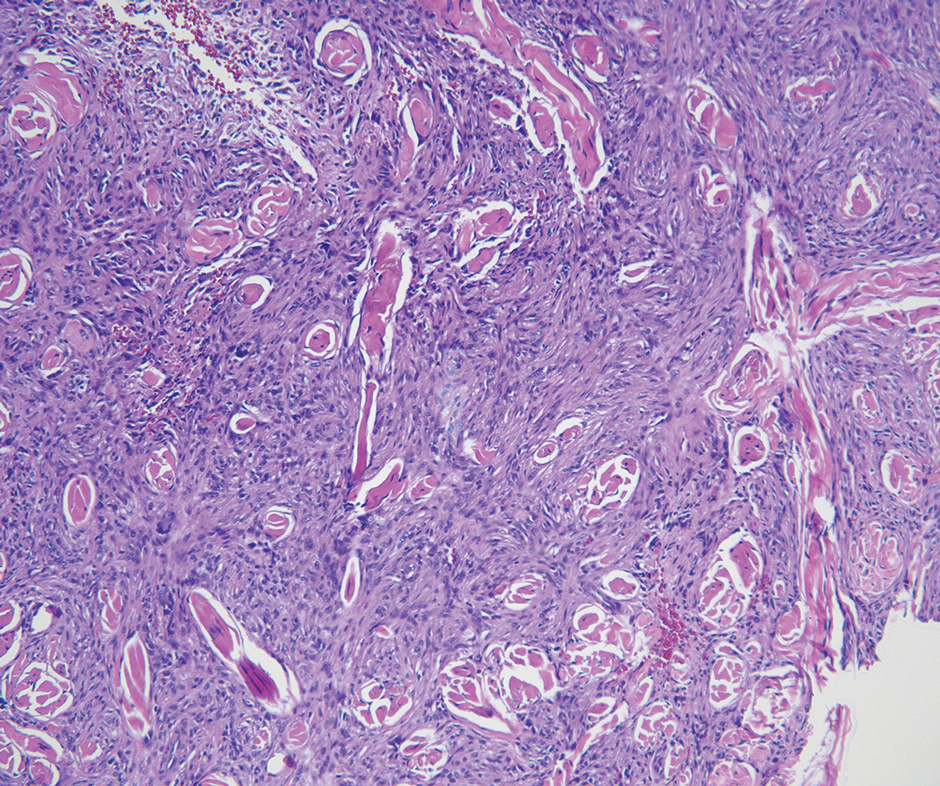

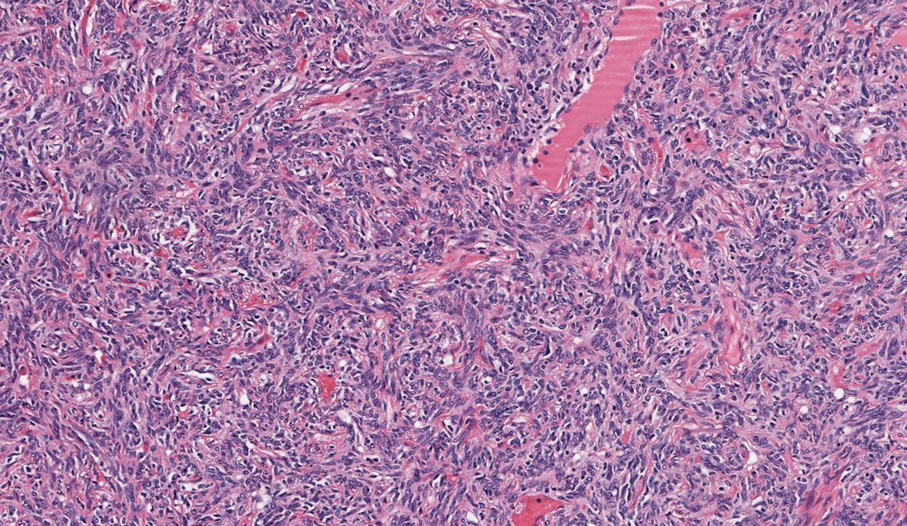

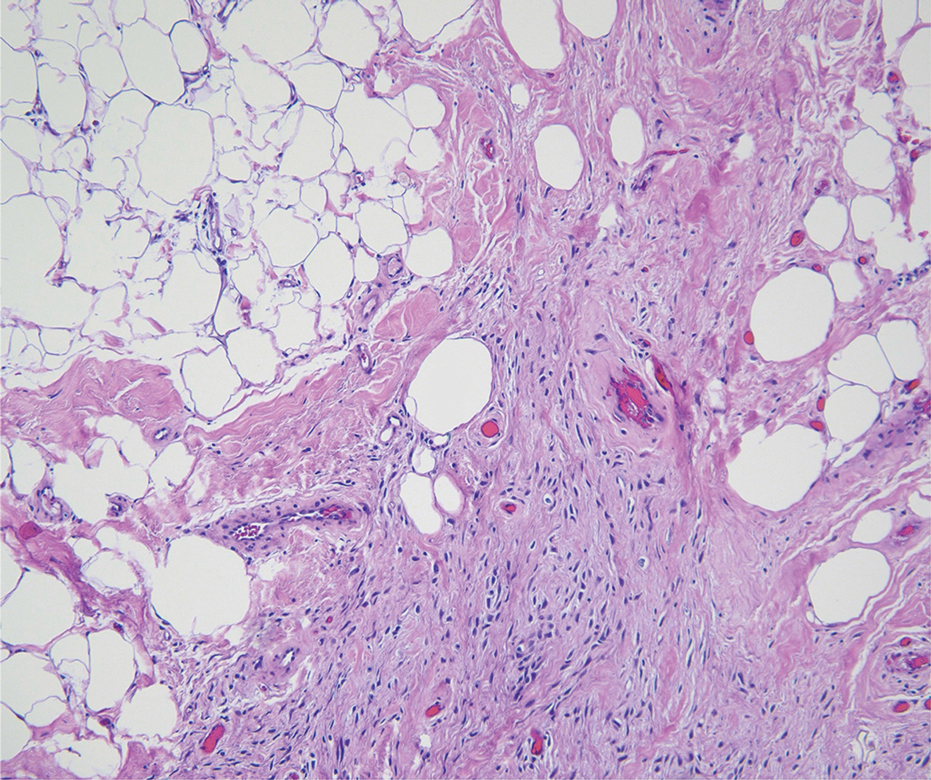

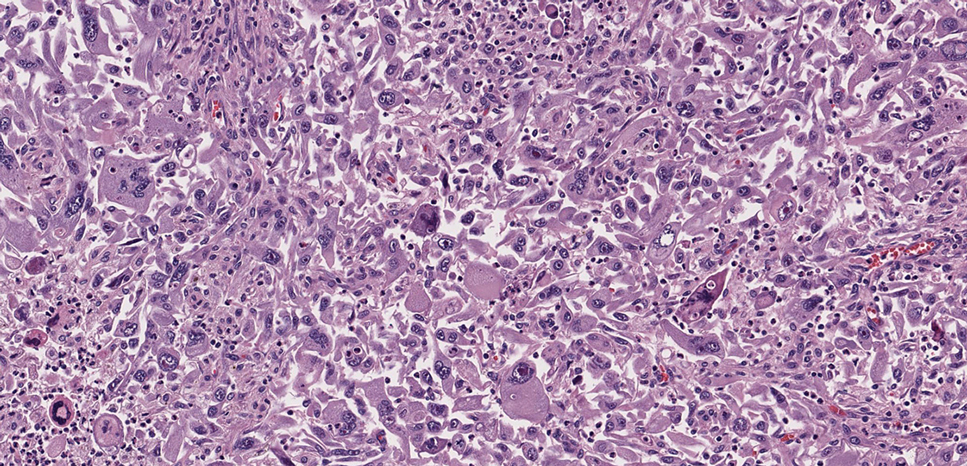

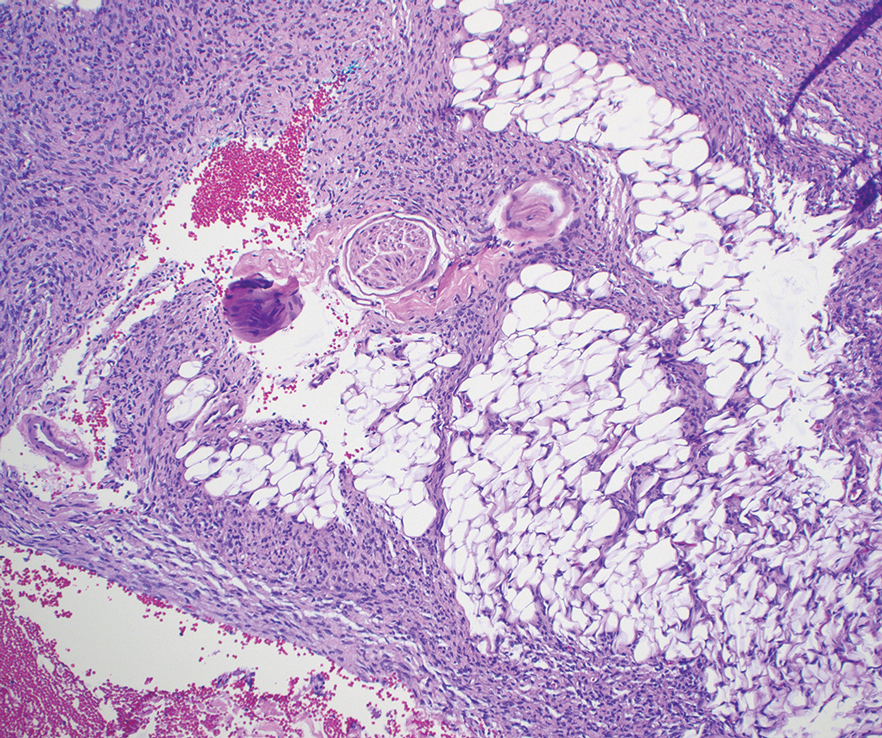

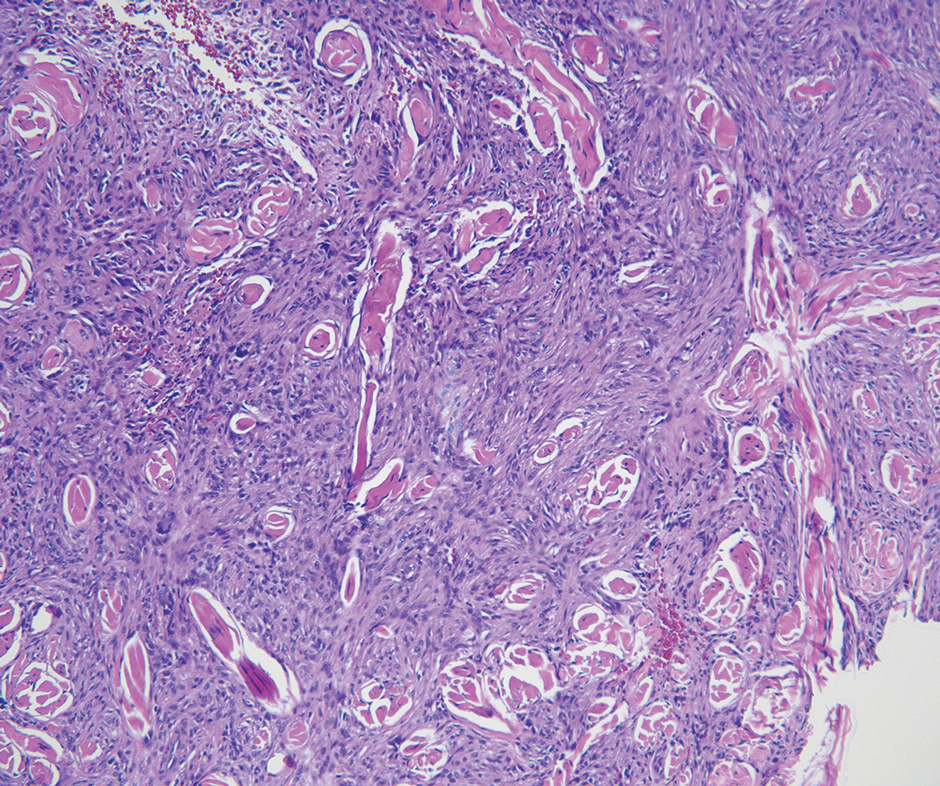

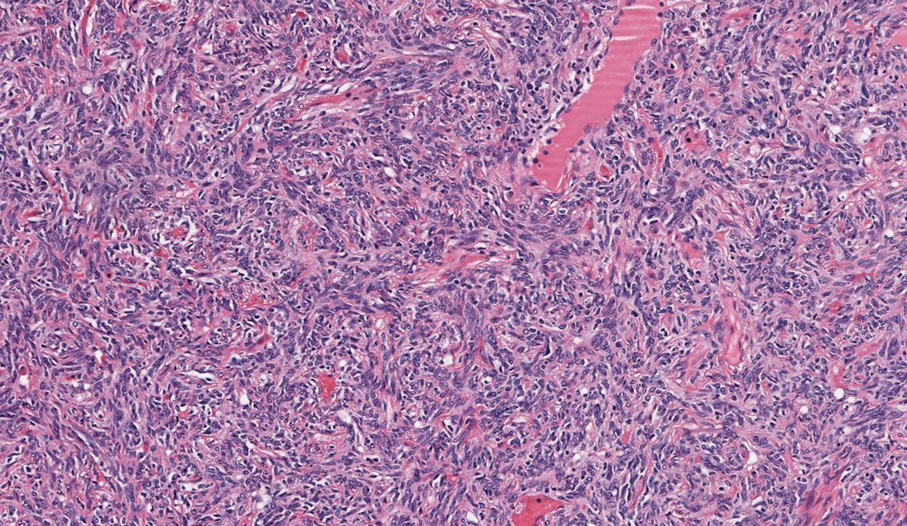

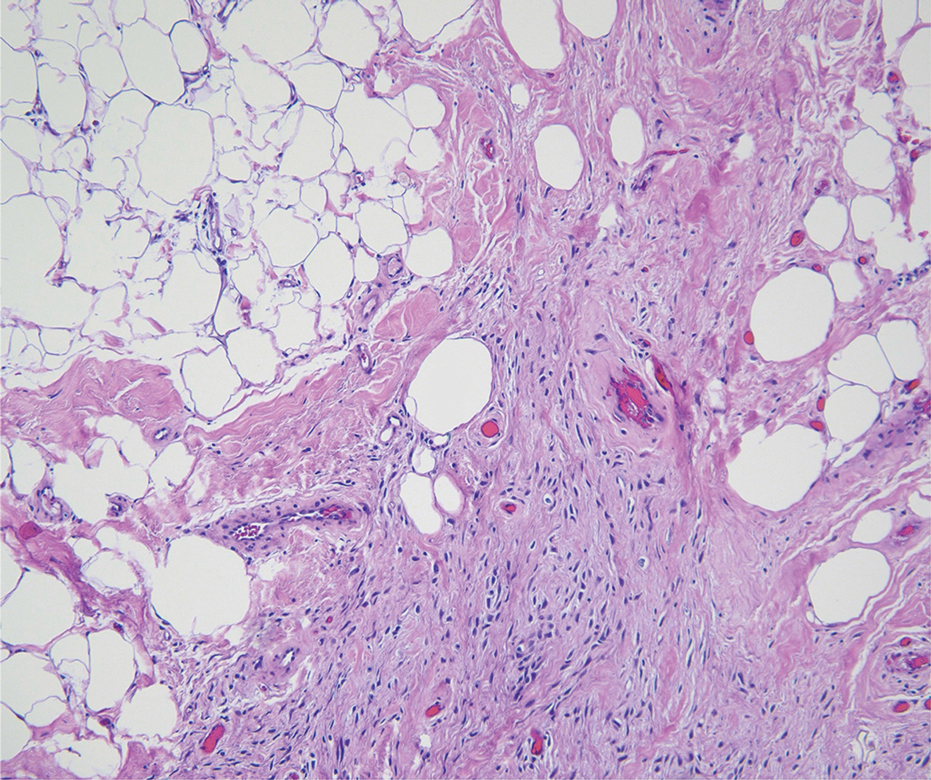

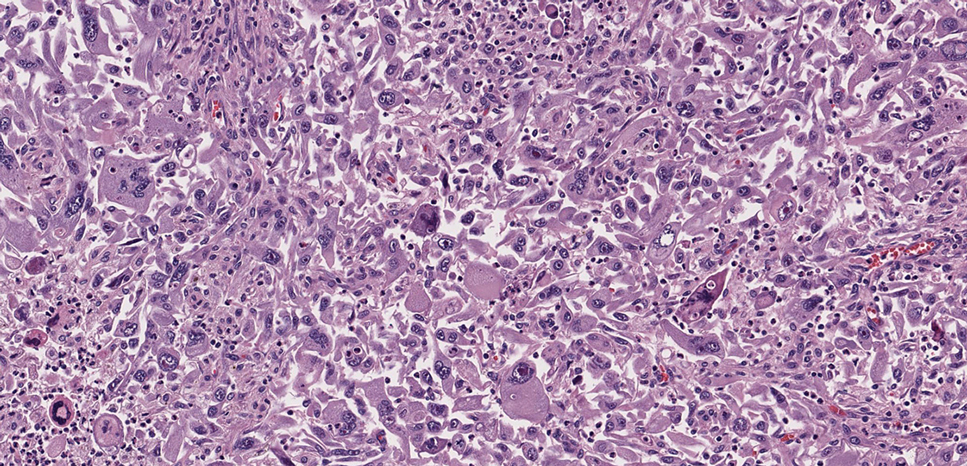

As shown in the Figure, histopathologic examination revealed tubular structures in the upper dermis with characteristic comma-shaped extensions. Some of these structures were lined with cuboidal cells and contained eosinophilic material within the lumen. There was no involvement of the epidermis or deeper dermis. The histologic features were consistent with syringoma, which is distinguished by its predominant involvement of the upper dermis and the presence of enlarged, dilated eccrine ducts, as observed in our case.

Treatment of syringomas often is challenging due to the high rate of recurrence and the risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Since the condition is benign, treatment typically is pursued for aesthetic reasons. Various therapeutic approaches have been reported, each with diverse response rates. The most common method involves surgical intervention, either with electrodesiccation or CO2 laser—both of which have shown satisfactory resolution of lesions without recurrence at 1-year follow-up, with no major scarring reported.25,26 Alternatively, topical management with retinoids daily over a 4-month period leads to flattening of the tumors with no further appearance of new lesions.27 Despite the availability of numerous management options, establishing a first-line treatment remains controversial due to the high risk for recurrence and the variability in the number and location of lesions among individual patients. In our case, given the benign nature of syringomas, the asymptomatic nature of the lesions, the involvement of noncritical aesthetic areas, and the limited response to noninvasive therapeutic options, the patient was informed of the diagnosis, and no further pharmacologic or surgical intervention was pursued.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234-1240.E9. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2015.12.006

- Resende C, Araújo C, Santos R, et al. Late-onset of eruptive syringomas: a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3 suppl 1):239-241. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153899

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Avhad G, Ghuge P, Jerajani HR. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:214. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.152586

- Ning WV, Bashey S, Cole C, et al. Multiple eruptive syringomas on the penis. Cutis. 2019;103:E15-E16.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Jamalipour M, Heidarpour M, Rajabi P. Generalized eruptive syringomas. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:65-67. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.48992

- Mohaghegh F, Amiri A, Fatemi Naeini F, et al. Acral eruptive syringoma: an unusual presentation with misdiagnosis. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:5416285. doi:10.1155/2020/5416285

- Valdivielso-Ramos M, de la Cueva P, Gimeno M, et al. Acral syringomas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:458-460.

- Patel K, Lundgren AD, Ahmed AM, et al. Disseminated syringomas of the upper extremities in a young woman. Cureus. 2018;10:E3619. doi:10.7759/cureus.3619

- Balci DD, Atik E, Altintas S. Coexistence of acral syringomas and multiple trichoepitheliomas on the face. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:169-171. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.08011

- Martín-García RF, Muñoz CM. Acral syringomas presenting as a photosensitive papular eruption. Cutis. 2006;77:33-36.

- Varas-Meis E, Prada-García C, Samaniego-González E, et al. Acral syringomas associated with hematological neoplasm. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:136. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.192961

- Berbis P, Fabre JF, Jancovici E, et al. Late-onset syringomas of the upper extremities associated with a carcinoid tumor. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:848-849.

- Metze D, Jurecka W, Gebhart W. Disseminated syringomas of the upper extremities. case history and immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Dermatologica. 1990;180:228-235. doi:10.1159/000248036

- Gómez-de Castro C, Vivanco Allende B, García-García B. Multiple acral syringomas. siringomas acrales múltiples. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109:834-836. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2017.10.014

- Hughes PS, Apisarnthanarax P. Acral syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1435-1436.

- Asai Y, Ishii M, Hamada T. Acral syringoma: electron microscopic studies on its origin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:64-68.

- van den Broek H, Lundquist CD. Syringomas of the upper extremities with onset in the sixth decade. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982,6:534-536. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(82)80368-X

- Garcia C, Krunic AL, Grichnik J, et al. Multiple acral syringomata with uniform involvement of the hands and feet. Cutis. 1997;59:213-214, 216.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Iglesias Sancho M, Serra Llobet J, Salleras Redonnet M, et al. Siringomas disem- inados de inicio acral, aparecidos en la octava década. Actas Dermosifiliofr. 1999;90:253-257.

- Muniesa C, Fortuño Y, Moreno A, et al. Papules on the dorsum of the fingers. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:812-813. doi:10.1016 /S1578-2190(08)70371-8

- Koh MJ. Multiple acral syringomas involving the hands. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E438. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03462.x

- Karam P, Benedetto AV. Syringomas: new approach to an old technique. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:219-220. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362 .1996.tb01647.x

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08111.x

- Gómez MI, Pérez B, Azaña JM, et al. Eruptive syringoma: treatment with topical tretinoin. Dermatology. 2009;189:105-106. doi:10.1159/000246803

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Eruptive Syringoma

Syringomas are small, benign, often asymptomatic eccrine tumors that originate in the intraepidermal portion of eccrine sweat ducts.1 Clinically, they present as multiple symmetric white-to-yellow or discrete flesh-colored papules measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter, often located on the face (most commonly on the eyelids), with a greater prevalence in middle-aged women. Occasionally, they manifest in other locations such as the cheeks, chest, axillae, abdomen, and groin.2

In 1987, Friedman and Butler3 developed a classification system categorizing syringomas into 4 clinical subtypes: familial syringoma, localized syringoma, Down syndrome–related syringoma, and generalized syringoma. The fourth subtype includes the variant of eruptive syringoma,3 a rare clinical manifestation that often develops before or during puberty with several flesh-colored or lightly pigmented papules on the neck, anterior chest, upper abdomen, axillae, periumbilical region, and/or genital region.1,4,5 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, although it has been linked to abnormal proliferation of sweat glands due to an underlying local inflammatory process.6

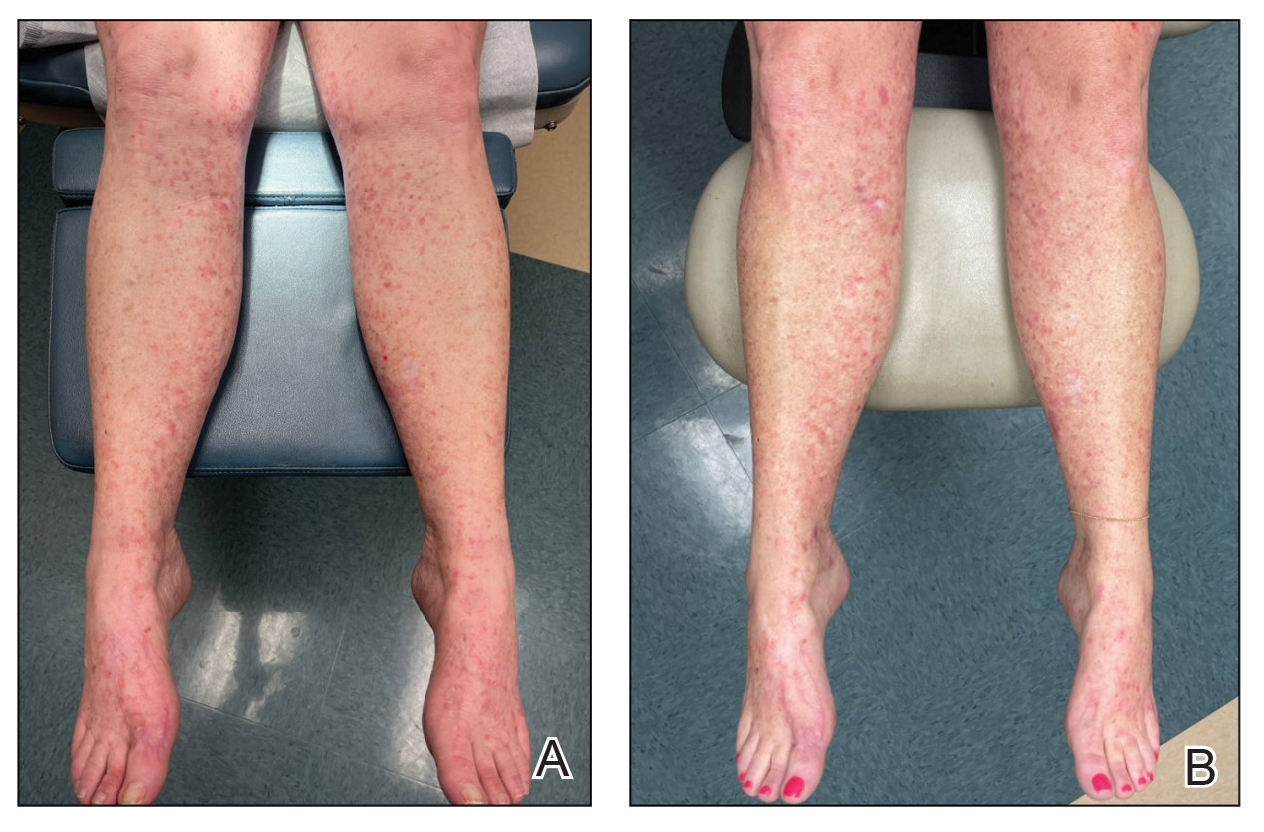

Acral distribution of syringomas is a rare variant that can manifest as part of generalized eruptive syringoma with consequent involvement of the arms and other areas.5,7 There are limited case reports on eruptive syringomas with predominant acral distribution.8 Compared to classic syringomas, the acral variant is associated with an older age of onset as well as a similar prevalence between men and women.9 Acral eruptive syringoma (AES) usually is isolated to the distal arms and legs. The most commonly affected region is the anterior surface of the forearms, although involvement of the dorsal hands, wrists, and feet also has been reported.10-16

The first known case of AES, which was reported in 1977, described eruptive syringomas on the dorsal hands of a healthy 31-year-old man.17 Several cases have been reported since then, mostly in patients aged 30 to 60 years, with predominant involvement of the dorsal hands and forearms.18-24 A review of Embase as well as PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms syringoma OR eccrine ductal tumor and eruptive OR acral OR arms OR forearms OR extremities identified 19 reported cases of AES between 1977 and 2023. For the reported AES cases, the mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 45.1 years (15.96 years), with patient ages ranging from 19 to 76 years. Notably, most cases occurred in individuals aged between 30 and 60 years, which deviates from the typical age of onset of localized syringomas, commonly seen during puberty or early adulthood.

Currently, AES is categorized within the clinical presentation of eruptive syringoma. Nevertheless, some authors have proposed classifying it as a distinct fifth clinical group due to specific features that distinguish it from generalized eruptive syringoma.9 This reclassification has considerable implications for the differential diagnosis, particularly because exclusive acral involvement poses a substantial diagnostic challenge and often requires histologic confirmation.

As shown in the Figure, histopathologic examination revealed tubular structures in the upper dermis with characteristic comma-shaped extensions. Some of these structures were lined with cuboidal cells and contained eosinophilic material within the lumen. There was no involvement of the epidermis or deeper dermis. The histologic features were consistent with syringoma, which is distinguished by its predominant involvement of the upper dermis and the presence of enlarged, dilated eccrine ducts, as observed in our case.

Treatment of syringomas often is challenging due to the high rate of recurrence and the risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Since the condition is benign, treatment typically is pursued for aesthetic reasons. Various therapeutic approaches have been reported, each with diverse response rates. The most common method involves surgical intervention, either with electrodesiccation or CO2 laser—both of which have shown satisfactory resolution of lesions without recurrence at 1-year follow-up, with no major scarring reported.25,26 Alternatively, topical management with retinoids daily over a 4-month period leads to flattening of the tumors with no further appearance of new lesions.27 Despite the availability of numerous management options, establishing a first-line treatment remains controversial due to the high risk for recurrence and the variability in the number and location of lesions among individual patients. In our case, given the benign nature of syringomas, the asymptomatic nature of the lesions, the involvement of noncritical aesthetic areas, and the limited response to noninvasive therapeutic options, the patient was informed of the diagnosis, and no further pharmacologic or surgical intervention was pursued.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Acral Eruptive Syringoma

Syringomas are small, benign, often asymptomatic eccrine tumors that originate in the intraepidermal portion of eccrine sweat ducts.1 Clinically, they present as multiple symmetric white-to-yellow or discrete flesh-colored papules measuring 1 to 3 mm in diameter, often located on the face (most commonly on the eyelids), with a greater prevalence in middle-aged women. Occasionally, they manifest in other locations such as the cheeks, chest, axillae, abdomen, and groin.2

In 1987, Friedman and Butler3 developed a classification system categorizing syringomas into 4 clinical subtypes: familial syringoma, localized syringoma, Down syndrome–related syringoma, and generalized syringoma. The fourth subtype includes the variant of eruptive syringoma,3 a rare clinical manifestation that often develops before or during puberty with several flesh-colored or lightly pigmented papules on the neck, anterior chest, upper abdomen, axillae, periumbilical region, and/or genital region.1,4,5 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, although it has been linked to abnormal proliferation of sweat glands due to an underlying local inflammatory process.6

Acral distribution of syringomas is a rare variant that can manifest as part of generalized eruptive syringoma with consequent involvement of the arms and other areas.5,7 There are limited case reports on eruptive syringomas with predominant acral distribution.8 Compared to classic syringomas, the acral variant is associated with an older age of onset as well as a similar prevalence between men and women.9 Acral eruptive syringoma (AES) usually is isolated to the distal arms and legs. The most commonly affected region is the anterior surface of the forearms, although involvement of the dorsal hands, wrists, and feet also has been reported.10-16

The first known case of AES, which was reported in 1977, described eruptive syringomas on the dorsal hands of a healthy 31-year-old man.17 Several cases have been reported since then, mostly in patients aged 30 to 60 years, with predominant involvement of the dorsal hands and forearms.18-24 A review of Embase as well as PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms syringoma OR eccrine ductal tumor and eruptive OR acral OR arms OR forearms OR extremities identified 19 reported cases of AES between 1977 and 2023. For the reported AES cases, the mean (SD) age at diagnosis was 45.1 years (15.96 years), with patient ages ranging from 19 to 76 years. Notably, most cases occurred in individuals aged between 30 and 60 years, which deviates from the typical age of onset of localized syringomas, commonly seen during puberty or early adulthood.

Currently, AES is categorized within the clinical presentation of eruptive syringoma. Nevertheless, some authors have proposed classifying it as a distinct fifth clinical group due to specific features that distinguish it from generalized eruptive syringoma.9 This reclassification has considerable implications for the differential diagnosis, particularly because exclusive acral involvement poses a substantial diagnostic challenge and often requires histologic confirmation.

As shown in the Figure, histopathologic examination revealed tubular structures in the upper dermis with characteristic comma-shaped extensions. Some of these structures were lined with cuboidal cells and contained eosinophilic material within the lumen. There was no involvement of the epidermis or deeper dermis. The histologic features were consistent with syringoma, which is distinguished by its predominant involvement of the upper dermis and the presence of enlarged, dilated eccrine ducts, as observed in our case.

Treatment of syringomas often is challenging due to the high rate of recurrence and the risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Since the condition is benign, treatment typically is pursued for aesthetic reasons. Various therapeutic approaches have been reported, each with diverse response rates. The most common method involves surgical intervention, either with electrodesiccation or CO2 laser—both of which have shown satisfactory resolution of lesions without recurrence at 1-year follow-up, with no major scarring reported.25,26 Alternatively, topical management with retinoids daily over a 4-month period leads to flattening of the tumors with no further appearance of new lesions.27 Despite the availability of numerous management options, establishing a first-line treatment remains controversial due to the high risk for recurrence and the variability in the number and location of lesions among individual patients. In our case, given the benign nature of syringomas, the asymptomatic nature of the lesions, the involvement of noncritical aesthetic areas, and the limited response to noninvasive therapeutic options, the patient was informed of the diagnosis, and no further pharmacologic or surgical intervention was pursued.

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234-1240.E9. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2015.12.006

- Resende C, Araújo C, Santos R, et al. Late-onset of eruptive syringomas: a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3 suppl 1):239-241. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153899

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Avhad G, Ghuge P, Jerajani HR. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:214. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.152586

- Ning WV, Bashey S, Cole C, et al. Multiple eruptive syringomas on the penis. Cutis. 2019;103:E15-E16.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Jamalipour M, Heidarpour M, Rajabi P. Generalized eruptive syringomas. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:65-67. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.48992

- Mohaghegh F, Amiri A, Fatemi Naeini F, et al. Acral eruptive syringoma: an unusual presentation with misdiagnosis. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:5416285. doi:10.1155/2020/5416285

- Valdivielso-Ramos M, de la Cueva P, Gimeno M, et al. Acral syringomas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:458-460.

- Patel K, Lundgren AD, Ahmed AM, et al. Disseminated syringomas of the upper extremities in a young woman. Cureus. 2018;10:E3619. doi:10.7759/cureus.3619

- Balci DD, Atik E, Altintas S. Coexistence of acral syringomas and multiple trichoepitheliomas on the face. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:169-171. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.08011

- Martín-García RF, Muñoz CM. Acral syringomas presenting as a photosensitive papular eruption. Cutis. 2006;77:33-36.

- Varas-Meis E, Prada-García C, Samaniego-González E, et al. Acral syringomas associated with hematological neoplasm. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:136. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.192961

- Berbis P, Fabre JF, Jancovici E, et al. Late-onset syringomas of the upper extremities associated with a carcinoid tumor. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:848-849.

- Metze D, Jurecka W, Gebhart W. Disseminated syringomas of the upper extremities. case history and immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Dermatologica. 1990;180:228-235. doi:10.1159/000248036

- Gómez-de Castro C, Vivanco Allende B, García-García B. Multiple acral syringomas. siringomas acrales múltiples. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109:834-836. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2017.10.014

- Hughes PS, Apisarnthanarax P. Acral syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1435-1436.

- Asai Y, Ishii M, Hamada T. Acral syringoma: electron microscopic studies on its origin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:64-68.

- van den Broek H, Lundquist CD. Syringomas of the upper extremities with onset in the sixth decade. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982,6:534-536. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(82)80368-X

- Garcia C, Krunic AL, Grichnik J, et al. Multiple acral syringomata with uniform involvement of the hands and feet. Cutis. 1997;59:213-214, 216.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Iglesias Sancho M, Serra Llobet J, Salleras Redonnet M, et al. Siringomas disem- inados de inicio acral, aparecidos en la octava década. Actas Dermosifiliofr. 1999;90:253-257.

- Muniesa C, Fortuño Y, Moreno A, et al. Papules on the dorsum of the fingers. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:812-813. doi:10.1016 /S1578-2190(08)70371-8

- Koh MJ. Multiple acral syringomas involving the hands. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E438. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03462.x

- Karam P, Benedetto AV. Syringomas: new approach to an old technique. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:219-220. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362 .1996.tb01647.x

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08111.x

- Gómez MI, Pérez B, Azaña JM, et al. Eruptive syringoma: treatment with topical tretinoin. Dermatology. 2009;189:105-106. doi:10.1159/000246803

- Williams K, Shinkai K. Evaluation and management of the patient with multiple syringomas: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1234-1240.E9. doi:10.1016 /j.jaad.2015.12.006

- Resende C, Araújo C, Santos R, et al. Late-onset of eruptive syringomas: a diagnostic challenge. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(3 suppl 1):239-241. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153899

- Friedman SJ, Butler DF. Syringoma presenting as milia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:310-314.

- Avhad G, Ghuge P, Jerajani HR. Generalized eruptive syringoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:214. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.152586

- Ning WV, Bashey S, Cole C, et al. Multiple eruptive syringomas on the penis. Cutis. 2019;103:E15-E16.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Jamalipour M, Heidarpour M, Rajabi P. Generalized eruptive syringomas. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:65-67. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.48992

- Mohaghegh F, Amiri A, Fatemi Naeini F, et al. Acral eruptive syringoma: an unusual presentation with misdiagnosis. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:5416285. doi:10.1155/2020/5416285

- Valdivielso-Ramos M, de la Cueva P, Gimeno M, et al. Acral syringomas. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2010;101:458-460.

- Patel K, Lundgren AD, Ahmed AM, et al. Disseminated syringomas of the upper extremities in a young woman. Cureus. 2018;10:E3619. doi:10.7759/cureus.3619

- Balci DD, Atik E, Altintas S. Coexistence of acral syringomas and multiple trichoepitheliomas on the face. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:169-171. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.08011

- Martín-García RF, Muñoz CM. Acral syringomas presenting as a photosensitive papular eruption. Cutis. 2006;77:33-36.

- Varas-Meis E, Prada-García C, Samaniego-González E, et al. Acral syringomas associated with hematological neoplasm. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:136. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.192961

- Berbis P, Fabre JF, Jancovici E, et al. Late-onset syringomas of the upper extremities associated with a carcinoid tumor. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:848-849.

- Metze D, Jurecka W, Gebhart W. Disseminated syringomas of the upper extremities. case history and immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Dermatologica. 1990;180:228-235. doi:10.1159/000248036

- Gómez-de Castro C, Vivanco Allende B, García-García B. Multiple acral syringomas. siringomas acrales múltiples. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2018;109:834-836. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2017.10.014

- Hughes PS, Apisarnthanarax P. Acral syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1435-1436.

- Asai Y, Ishii M, Hamada T. Acral syringoma: electron microscopic studies on its origin. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:64-68.

- van den Broek H, Lundquist CD. Syringomas of the upper extremities with onset in the sixth decade. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982,6:534-536. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(82)80368-X

- Garcia C, Krunic AL, Grichnik J, et al. Multiple acral syringomata with uniform involvement of the hands and feet. Cutis. 1997;59:213-214, 216.

- Patrizi A, Neri I, Marzaduri S, et al. Syringoma: a review of twenty-nine cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:460-462.

- Iglesias Sancho M, Serra Llobet J, Salleras Redonnet M, et al. Siringomas disem- inados de inicio acral, aparecidos en la octava década. Actas Dermosifiliofr. 1999;90:253-257.

- Muniesa C, Fortuño Y, Moreno A, et al. Papules on the dorsum of the fingers. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008;99:812-813. doi:10.1016 /S1578-2190(08)70371-8

- Koh MJ. Multiple acral syringomas involving the hands. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E438. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03462.x

- Karam P, Benedetto AV. Syringomas: new approach to an old technique. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:219-220. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362 .1996.tb01647.x

- Wang JI, Roenigk HH. Treatment of multiple facial syringomas with the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:136-139. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08111.x

- Gómez MI, Pérez B, Azaña JM, et al. Eruptive syringoma: treatment with topical tretinoin. Dermatology. 2009;189:105-106. doi:10.1159/000246803

Eruptive Erythematous Papules on the Forearms

Eruptive Erythematous Papules on the Forearms

A 44-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with multiple eruptive, nonconfluent, erythematous papules on the anterior forearms of 2 years’ duration. The patient’s medical history was notable for right-sided testicular cancer diagnosed in childhood and 3 excised basal cell carcinomas, the most recent of which was concurrent with the present case. The patient denied any recent pruritus, exposure to irritants, or use of over-the-counter medications. Physical examination was remarkable for numerous monomorphic, symmetric, nonconfluent, flesh-colored to slightly pigmented papules on the dorsal aspect of the forearms. No involvement of the fingers or lower extremities was observed. Two punch biopsies of representative lesions on the right and left forearms were taken. Histopathologic examination revealed eccrine ductal proliferations lined by cuboidal cells embedded within bundles of sclerotic collagen.

Actinic Keratosis Treatment With Diclofenac Gel 1%

Actinic Keratosis Treatment With Diclofenac Gel 1%

To the Editor:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are keratinocyte neoplasms that manifest as rough, scaly, erythematous papules with ill-defined borders (commonly known as precancers) and develop due to long-term UV light exposure.1 They must be treated promptly due to the risk for progression to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). One US Department of Veterans Affairs study reported that 0.6% of AKs progress to SCC in 1 year and 2.6% progressed to SCC in 4 years.2 In 10% of AKs that will progress to SCC, one study reported progression in approximately 2 years.3

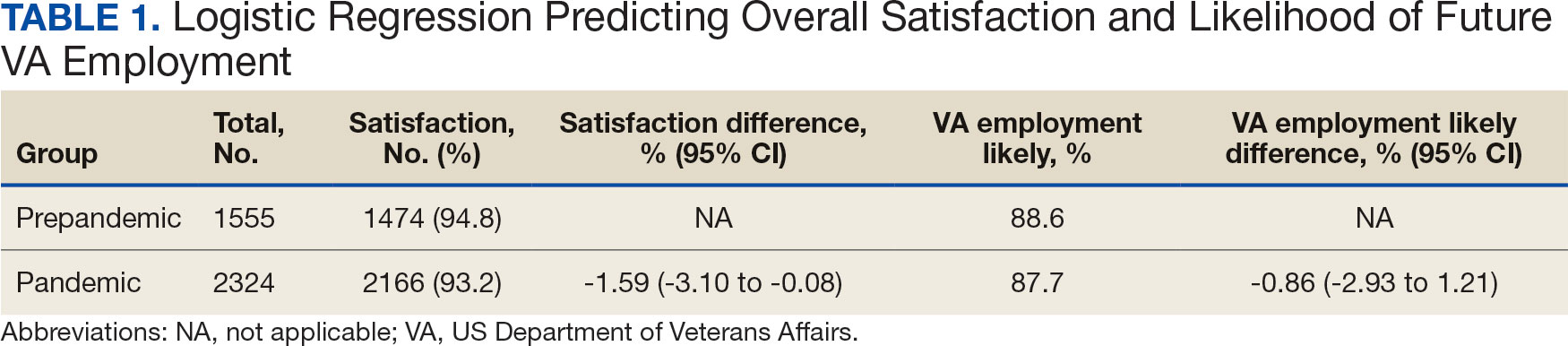

The risk for progression also increases in patients with multiple AKs; the risk is 4-fold higher in patients with 6 to 20 AKs and 11-fold higher in patients with more than 20 AKs.4 Common treatment options include lesion-directed therapies such as cryotherapy, laser therapy, surgery, and curettage, as well as field-directed therapies such as topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), diclofenac gel 3%, chemical peeling, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).4 When diclofenac gel is chosen as a treatment modality, it is commonly prescribed in the 3% formulation. Diclofenac gel 3% has been shown to be effective in the treatment of AKs,5,6 but diclofenac gel 1% has not been well described in the literature. We report the case of a patient with AKs on the lower legs who was treated with diclofenac gel after other therapies failed.

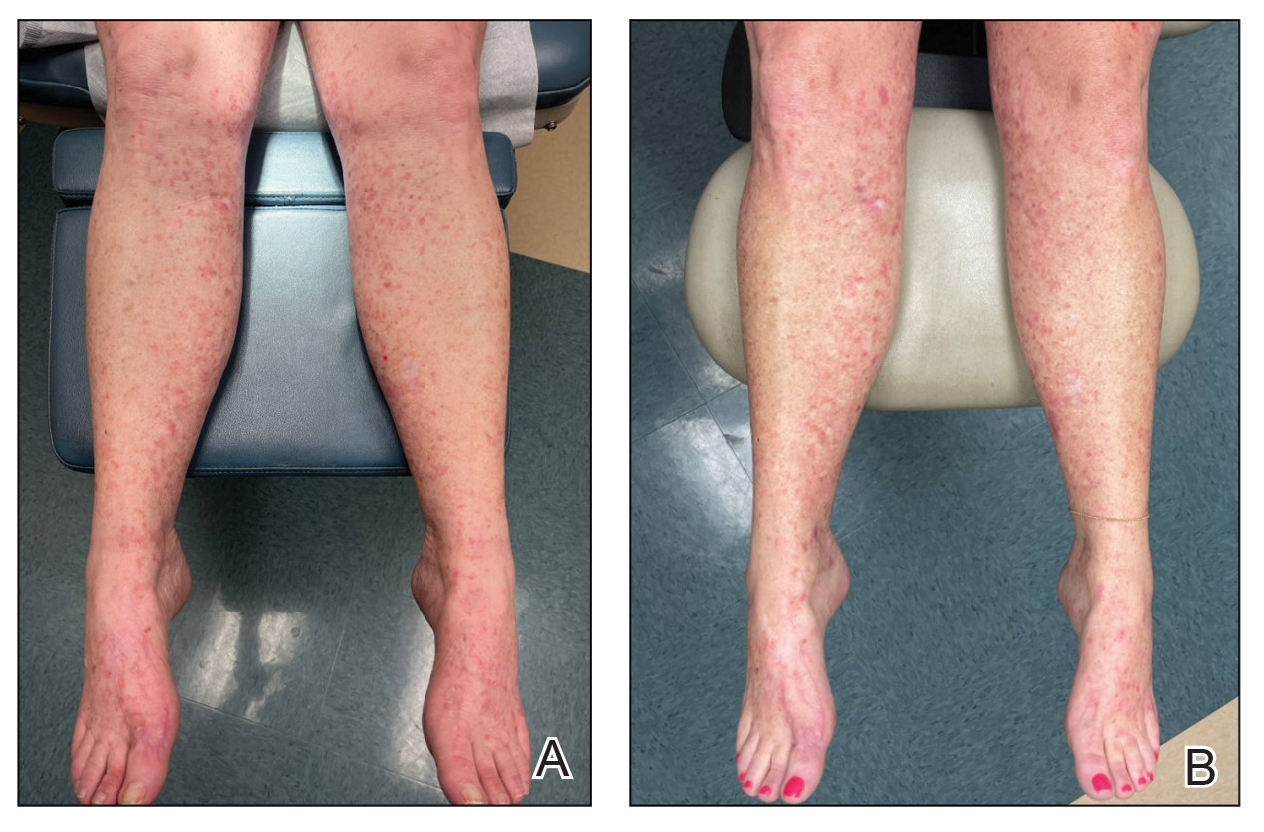

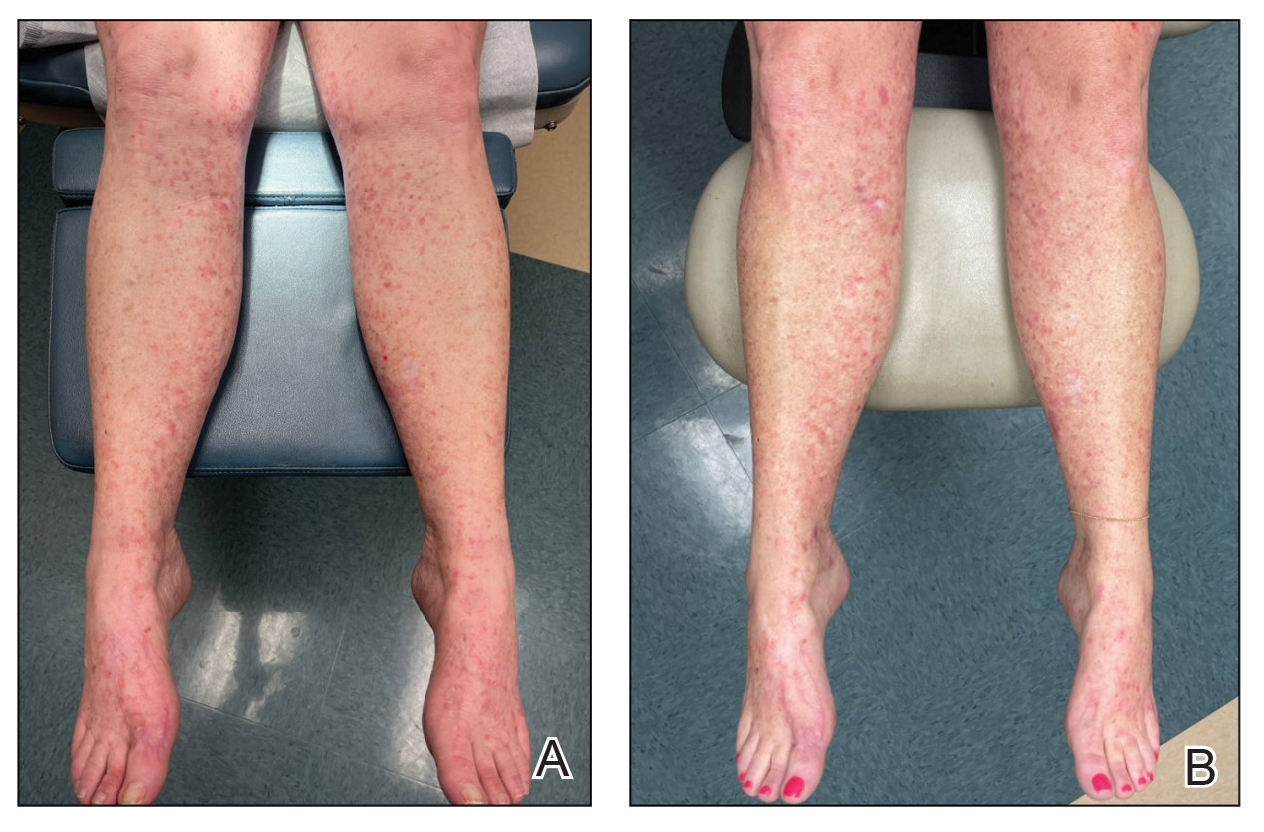

A 55-year-old woman presented for a routine skin check due to a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Her medical history also included palmar hyperhidrosis, disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis, and extensive actinic damage, as well as numerous biopsy-proven AKs. She had been evaluated every 3 months up to presentation due to the frequency of AK development over the past 5 years. The lesions were mainly localized to both lower legs, where the patient had acquired considerable lifetime sun exposure from tanning beds and sunbathing while boating. She also noted exposure to well water as a child, but none of her family members had a similar issue with AKs.

Prior to this visit, the patient had undergone 5 years of therapy for AKs. She initially was treated with multiple courses of topical 5-FU, but she consequently developed severe allergic contact dermatitis. Subsequent treatments included cryotherapy as well as application of tretinoin cream nightly for 2 weeks followed by PDT. She was unable to tolerate the tretinoin, which she reported led to dryness and irritation. She reported mild improvement after her first session of PDT but only minimal improvement after the next session. Ingenol mebutate was then prescribed for topical use on the legs for 2 days, which did not result in improvement. The patient continued to follow up for unresolved AKs on the legs and was prescribed acitretin to help reduce the risk for progression to SCC. At follow-up 3 months later, she reported decreased soreness from AKs after starting the acitretin and, aside from mild dryness, she tolerated the medication well; however, with continued use of acitretin, she began to experience adverse effects 6 months later, including thyroid suppression and hair loss, leading to discontinuation. Instead, 3 months later, she was recommended to start nicotinamide supplementation for prevention of SCC.

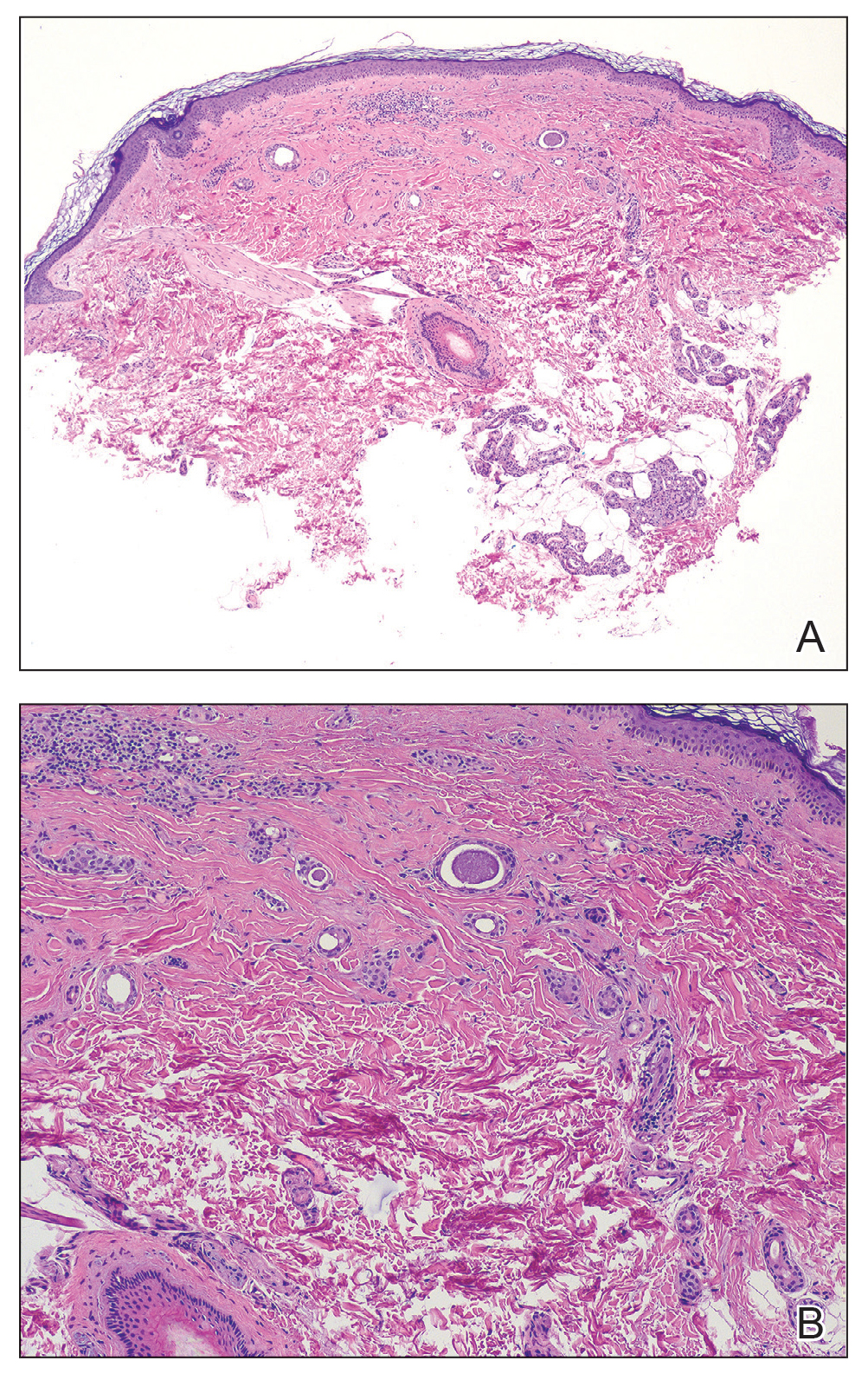

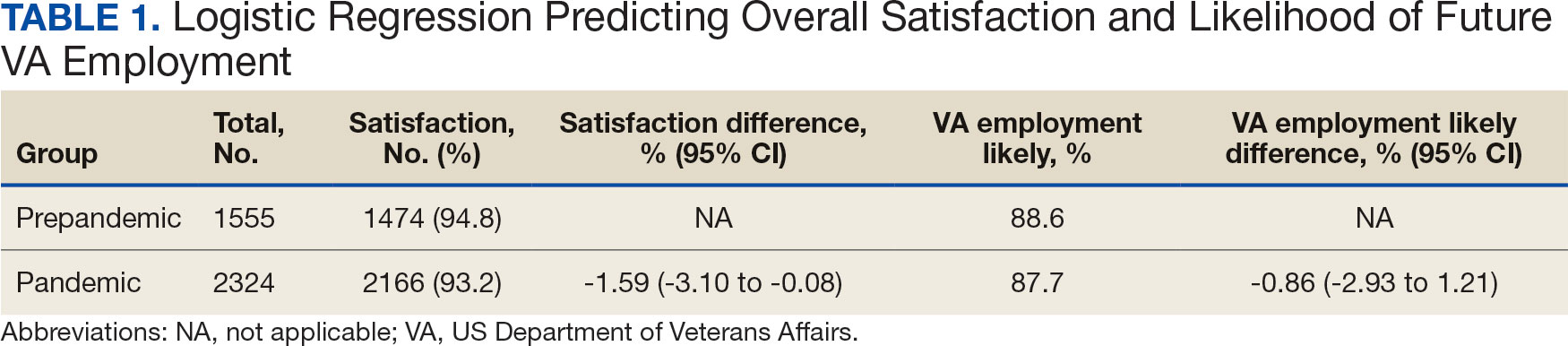

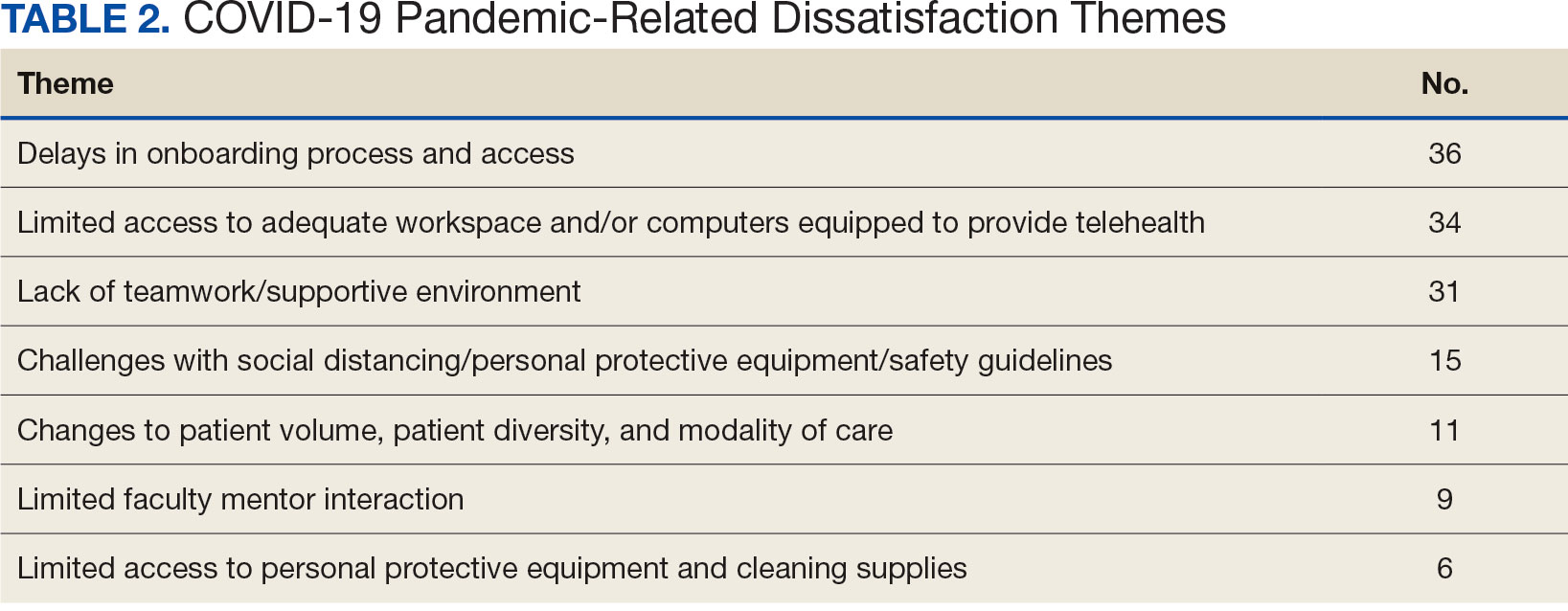

Due to continued AK development (Figure, A), we eventually prescribed diclofenac gel 3% twice daily for both legs 9 months after prescribing nicotinamide. This regimen was cost prohibitive, as the medication was not covered by her insurance and the cost was $300 for one tube. We recommended the patient instead apply the 3% gel to the right leg only due to greater severity of AKs on this leg and over-the-counter diclofenac gel 1% twice daily to the left leg. Approximately 5 months later, she reported a reduction in the discomfort from AKs as well as a reduction in the total number of AKs. She applied the 2 different products as instructed for the first month but did not notice a difference between them. She then continued to apply only the 1% gel on both legs for a total of 8 months with excellent response (Figure, B). At subsequent follow-up visits over a 2-year period, she has only required cryotherapy as spot treatment for AKs.

For 1 to a few discrete AKs, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy is considered first-line therapy.7 However, if multiple AKs are present, surrounding photodamaged skin also should be treated with field-directed therapy due to surrounding keratinocytes bearing a high mutational burden and risk of cancerization.8 Common field-directed therapies include topical 5-FU, topical imiquimod, topical tirbanibulin, PDT, retinoids, and topical diclofenac 3%.

One challenge in field-directed treatment of AKs is the side-effect profile seen in some patients, causing them to prematurely discontinue treatment. In our patient, 5-FU cream, tretinoin cream, and oral acitretin were not well tolerated. Topical diclofenac generally is well tolerated, with mostly mild local skin reactions and low risk for systemic adverse events. Adverse effects mainly consist of mild local skin reactions including pruritus (reported in 31%-52% of patients who used topical diclofenac), dryness (25%-27%), and irritation (less than 1%).9,10 Although diclofenac carries a black-box warning for serious cardiovascular thrombotic events and serious gastrointestinal tract bleeding, systemic absorption of topical diclofenac has been proven to be substantially lower (5- to 17-fold) compared to the oral formulation, and resulting serious adverse effects have been found to be largely reduced compared to the oral formulation.11,12 If allergic contact dermatitis develops, diclofenac should be discontinued.9,13

Diclofenac’s antineoplastic mechanism of action of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition involves induction of apoptosis as well as reduction in tumor cell proliferation and tumor angiogenesis.14,15 Topical diclofenac may result in decreased levels of lactate and amino acid in AK lesions, particularly in lesions responding to treatment.16 Topical diclofenac may alter immune infiltration by inducing infiltration of dermal CD8+ T cells along with high IFN-γ messenger RNA expression, suggesting improvement of T-cell function after topical diclofenac treatment.16

Although diclofenac gel 3% has been shown to be effective in treatment of AKs,5,6 diclofenac gel 1% has not yet been well studied. Use of the 1% gel is indicated for osteoarthritis and musculoskeletal pain by the US Food and Drug Administration.10,17 Efficacy of the 1% gel has been documented for these and other conditions including seborrheic keratoses.18-20

Because the 1% diclofenac formulation is available over-the-counter, it is more accessible to patients compared to the 3% formulation and often substantially decreases the cost of the medication for the patient. The cost of diclofenac gel 1% in the United States ranges from $0.04 to $0.31 per gram compared to $1.07 to $11.79 per gram for the 3% gel prescription formulation.17 Efficacy of the 1% formulation compared to the 3% formulation could represent an avenue to increase accessibility to field-directed therapy in the population for the treatment of AKs with a potentially well-tolerated, effective, and low-cost medication formulation.

This case represents the effectiveness of diclofenac gel 1% in treating AKs. Several treatment modalities failed in our case, but she experienced improvement with use of over-the-counter diclofenac gel 1%. She also noted no difference in response between the prescription 3% diclofenac formulation and the over-the-counter 1% formulation. Diclofenac gel 1% may represent an excellent therapeutic option in treatment-refractory cases of AKs. Larger randomized trials should be considered to assess safety and efficacy.

- FEisen DB, Asgari MM, Bennett DD, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:e209-e233.

- Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33: 1099-1101.

- Dianzani C, Conforti C, Giuffrida R, et al. Current therapies for actinic keratosis. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:677-684.

- Javor S, Cozzani E, Parodi A. Topical treatment of actinic keratosis with 3.0% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan gel: review of the literature about the cumulative evidence of its efficacy and safety. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2016;151:275-280.

- Martin GM, Stockfleth E. Diclofenac sodium 3% gel for the management of actinic keratosis: 10+ years of cumulative evidence of efficacy and safety. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:600-608.

- Arisi M, Guasco Pisani E, et al. Cryotherapy for actinic keratosis: basic principles and literature review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:357-365.

- Calzavara-Pinton P, Calzavara-Pinton I, Rovati C, et al. Topical pharmacotherapy for actinic keratoses in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2022;39:143-152.

- Beutner C, Forkel S, Kreipe K, et al. Contact allergy to topical diclofenac with systemic tolerance. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;86:41-43.

- Voltaren gel (diclofenac sodium topical gel). Prescribing information. Novartis Consumer Health, Inc; 2009. Accessed May 21, 2025. https:// www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022122s006lbl.pdf

- Moreira SA, Liu DJ. Diclofenac systemic bioavailability of a topical 1% diclofenac + 3% menthol combination gel vs. an oral diclofenac tablet in healthy volunteers: a randomized, open-label, crossover study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;55:368-372.

- Kienzler JL, Gold M, Nollevaux F. Systemic bioavailability of topical diclofenac sodium gel 1% versus oral diclofenac sodium in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50:50-61.

- Gulin SJ, Chiriac A. Diclofenac-induced allergic contact dermatitis: a series of four patients. Drug Saf Case Rep. 2016;3:15.

- Fecker LF, Stockfleth E, Nindl I, et al. The role of apoptosis in therapy and prophylaxis of epithelial tumours by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(Suppl 3):25-33.

- Thomas GJ, Herranz P, Cruz SB, et al. Treatment of actinic keratosis through inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2: potential mechanism of action of diclofenac sodium 3% in hyaluronic acid 2.5. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e12800.

- Singer K, Dettmer K, Unger P, et al. Topical diclofenac reprograms metabolism and immune cell infiltration in actinic keratosis. Front Oncol. 2019;9:605.

- Diclofenac (topical). Drug information. UpToDate. https://www-uptodate-com.libraryaccess.elpaso.ttuhsc.edu/contents/diclofenac-topical-drug-information?source=auto_suggest&selectedTitle=1~3---3~4---diclofenac&search=diclofenac%20topical#F8017265

- Afify AA, Hana MR. Comparative evaluation of topical diclofenac sodium versus topical ibuprofen in the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e14370.

- Yin F, Ma J, Xiao H, et al. Randomized, double-blind, noninferiority study of diclofenac diethylamine 2.32% gel applied twice daily versus diclofenac diethylamine 1.16% gel applied four times daily in patients with acute ankle sprain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:1125.

- van Herwaarden N, van den Elsen GAH, de Jong ICA, et al. Topical NSAIDs: ineffective or undervalued? [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2021;165:D5317.

To the Editor:

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are keratinocyte neoplasms that manifest as rough, scaly, erythematous papules with ill-defined borders (commonly known as precancers) and develop due to long-term UV light exposure.1 They must be treated promptly due to the risk for progression to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). One US Department of Veterans Affairs study reported that 0.6% of AKs progress to SCC in 1 year and 2.6% progressed to SCC in 4 years.2 In 10% of AKs that will progress to SCC, one study reported progression in approximately 2 years.3

The risk for progression also increases in patients with multiple AKs; the risk is 4-fold higher in patients with 6 to 20 AKs and 11-fold higher in patients with more than 20 AKs.4 Common treatment options include lesion-directed therapies such as cryotherapy, laser therapy, surgery, and curettage, as well as field-directed therapies such as topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), diclofenac gel 3%, chemical peeling, topical imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).4 When diclofenac gel is chosen as a treatment modality, it is commonly prescribed in the 3% formulation. Diclofenac gel 3% has been shown to be effective in the treatment of AKs,5,6 but diclofenac gel 1% has not been well described in the literature. We report the case of a patient with AKs on the lower legs who was treated with diclofenac gel after other therapies failed.

A 55-year-old woman presented for a routine skin check due to a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Her medical history also included palmar hyperhidrosis, disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis, and extensive actinic damage, as well as numerous biopsy-proven AKs. She had been evaluated every 3 months up to presentation due to the frequency of AK development over the past 5 years. The lesions were mainly localized to both lower legs, where the patient had acquired considerable lifetime sun exposure from tanning beds and sunbathing while boating. She also noted exposure to well water as a child, but none of her family members had a similar issue with AKs.

Prior to this visit, the patient had undergone 5 years of therapy for AKs. She initially was treated with multiple courses of topical 5-FU, but she consequently developed severe allergic contact dermatitis. Subsequent treatments included cryotherapy as well as application of tretinoin cream nightly for 2 weeks followed by PDT. She was unable to tolerate the tretinoin, which she reported led to dryness and irritation. She reported mild improvement after her first session of PDT but only minimal improvement after the next session. Ingenol mebutate was then prescribed for topical use on the legs for 2 days, which did not result in improvement. The patient continued to follow up for unresolved AKs on the legs and was prescribed acitretin to help reduce the risk for progression to SCC. At follow-up 3 months later, she reported decreased soreness from AKs after starting the acitretin and, aside from mild dryness, she tolerated the medication well; however, with continued use of acitretin, she began to experience adverse effects 6 months later, including thyroid suppression and hair loss, leading to discontinuation. Instead, 3 months later, she was recommended to start nicotinamide supplementation for prevention of SCC.