User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

AAD unveils updated guidelines for topical AD treatment in adults

, and topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. The guidelines also conditionally recommend the use of bathing and wet wrap therapy but recommend against the use of topical antimicrobials, antiseptics, and antihistamines.

The development updates the AAD’s 2014 recommendations for managing AD with topical therapies, published almost 9 years ago. “At that time, the only U.S. FDA–approved systemic medication for atopic dermatitis was prednisone – universally felt amongst dermatologists to be the least appropriate systemic medication for this condition, at least chronically,” Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, who cochaired a 14-member multidisciplinary work group that assembled the updated guidelines, told this news organization in an interview.

“Since 2017, there have been two different biologic medications approved for moderate to severe AD (dupilumab and tralokinumab) with certainly a third or more right around the corner. There have been two new oral agents approved for moderate to severe AD – upadacitinib and abrocitinib – with others on the way,” he noted. While these are not topical therapies, the purview of the newly released guidelines, he said, “there have also been new topical medications approved since that time (crisaborole and ruxolitinib). It was high time for an update.”

For the new guidelines, which were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, guidelines cochair Dawn M. R. Davis, MD, a dermatologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conducted a systematic review of evidence regarding the use of nonprescription topical agents such as moisturizers, bathing practices, and wet wraps, as well as topical pharmacologic modalities such as corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE-4 inhibitors, antimicrobials, and antihistamines.

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

12 recommendations

Of the 12 recommendations made for adults with AD, the work group ranked 7 as “strong” based on the evidence reviewed, and the rest as “conditional.” The “strong” recommendations include the use of moisturizers; the use of tacrolimus 0.03% or 0.1%; the use of pimecrolimus 1% cream for mild to moderate AD; use of topical steroids; intermittent use of medium-potency topical corticosteroids as maintenance therapy to reduce flares and relapse; the use of the topical PDE-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and the use of the topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib.

Regarding ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, the work group advised that the treatment area “should not exceed 20% body surface area, and a maximum of 60 grams should be applied per week; these stipulations are aimed at reducing systemic absorption, as black box warnings include serious infections, mortality, malignancies (for example, lymphoma), major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.”

Conditional recommendations in the guidelines include those for bathing for treatment and maintenance and the use of wet dressings, and those against the use of topical antimicrobials, topical antihistamines, and topical antiseptics.

According to Dr. Sidbury, the topic of bathing generated robust discussion among the work group members. “Though [each group member] has strong opinions and individual practice styles, they were also able to recognize that the evidence is all that matters in a project like this, which led to a ‘conditional’ recommendation regarding bathing frequency backed by ‘low’ evidence,” he said. “While this may seem like ‘guidance’ that doesn’t ‘guide,’ I would argue it informs the guideline consumer exactly where we are in terms of this question and allows them to use their best judgment and experience as their true north here.”

In the realm of topical steroids, Dr. Sidbury said that topical steroid addiction (TSA) and topical steroid withdrawal (TSW) have been a “controversial but persistent concern” from some patients and providers. “Two systematic reviews of this topic were mentioned, and it was made clear that the evidence base [for the concepts] is weak,” he said. “With that important caveat ,the guideline committee delineated both a definition of TSW/TSA and potential risk factors.”

Dr. Sidbury marveled at the potential impact of newer medicines such as crisaborole and ruxolitinib on younger AD patients as well. Crisaborole is now Food and Drug Administration approved down to 3 months of age for mild to moderate AD. “This is extraordinary and expands treatment options for all providers at an age when parents and providers are most conservative in their practice,” he said. “Ruxolitinib, also nonsteroidal, is FDA approved for mild to moderate AD down to 12 years of age. Having spent a good percentage of my practice years either being able to offer only topical steroids, or later topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, having additional options is wonderful.”

In the guidelines, the work group noted that “significant gaps remain” in current understanding of various topical AD therapies. “Studies are needed which examine quality of life and other patient-important outcomes, changes to the cutaneous microbiome, as well as long term follow-up, and use in special and diverse populations (e.g., pregnancy, lactation, immunosuppression, multiple comorbidities, skin of color, pediatric),” they wrote. “Furthermore, increased use of new systemic AD treatment options (dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, upadacitinib) in patients with moderate to severe disease may result in a selection bias toward milder disease in current and future AD topical therapy studies.”

Use of topical therapies to manage AD in pediatric patients will be covered in a forthcoming AAD guideline. The first updated AD guideline, on comorbidities associated with AD in adults, was released in January 2022.

Dr. Sidbury reported that he serves as an advisory board member for Pfizer, a principal investigator for Regeneron, an investigator for Brickell Biotech and Galderma USA, and a consultant for Galderma Global and Microes. Other work group members reported having financial disclosures with many pharmaceutical companies.

, and topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. The guidelines also conditionally recommend the use of bathing and wet wrap therapy but recommend against the use of topical antimicrobials, antiseptics, and antihistamines.

The development updates the AAD’s 2014 recommendations for managing AD with topical therapies, published almost 9 years ago. “At that time, the only U.S. FDA–approved systemic medication for atopic dermatitis was prednisone – universally felt amongst dermatologists to be the least appropriate systemic medication for this condition, at least chronically,” Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, who cochaired a 14-member multidisciplinary work group that assembled the updated guidelines, told this news organization in an interview.

“Since 2017, there have been two different biologic medications approved for moderate to severe AD (dupilumab and tralokinumab) with certainly a third or more right around the corner. There have been two new oral agents approved for moderate to severe AD – upadacitinib and abrocitinib – with others on the way,” he noted. While these are not topical therapies, the purview of the newly released guidelines, he said, “there have also been new topical medications approved since that time (crisaborole and ruxolitinib). It was high time for an update.”

For the new guidelines, which were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, guidelines cochair Dawn M. R. Davis, MD, a dermatologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conducted a systematic review of evidence regarding the use of nonprescription topical agents such as moisturizers, bathing practices, and wet wraps, as well as topical pharmacologic modalities such as corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE-4 inhibitors, antimicrobials, and antihistamines.

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

12 recommendations

Of the 12 recommendations made for adults with AD, the work group ranked 7 as “strong” based on the evidence reviewed, and the rest as “conditional.” The “strong” recommendations include the use of moisturizers; the use of tacrolimus 0.03% or 0.1%; the use of pimecrolimus 1% cream for mild to moderate AD; use of topical steroids; intermittent use of medium-potency topical corticosteroids as maintenance therapy to reduce flares and relapse; the use of the topical PDE-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and the use of the topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib.

Regarding ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, the work group advised that the treatment area “should not exceed 20% body surface area, and a maximum of 60 grams should be applied per week; these stipulations are aimed at reducing systemic absorption, as black box warnings include serious infections, mortality, malignancies (for example, lymphoma), major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.”

Conditional recommendations in the guidelines include those for bathing for treatment and maintenance and the use of wet dressings, and those against the use of topical antimicrobials, topical antihistamines, and topical antiseptics.

According to Dr. Sidbury, the topic of bathing generated robust discussion among the work group members. “Though [each group member] has strong opinions and individual practice styles, they were also able to recognize that the evidence is all that matters in a project like this, which led to a ‘conditional’ recommendation regarding bathing frequency backed by ‘low’ evidence,” he said. “While this may seem like ‘guidance’ that doesn’t ‘guide,’ I would argue it informs the guideline consumer exactly where we are in terms of this question and allows them to use their best judgment and experience as their true north here.”

In the realm of topical steroids, Dr. Sidbury said that topical steroid addiction (TSA) and topical steroid withdrawal (TSW) have been a “controversial but persistent concern” from some patients and providers. “Two systematic reviews of this topic were mentioned, and it was made clear that the evidence base [for the concepts] is weak,” he said. “With that important caveat ,the guideline committee delineated both a definition of TSW/TSA and potential risk factors.”

Dr. Sidbury marveled at the potential impact of newer medicines such as crisaborole and ruxolitinib on younger AD patients as well. Crisaborole is now Food and Drug Administration approved down to 3 months of age for mild to moderate AD. “This is extraordinary and expands treatment options for all providers at an age when parents and providers are most conservative in their practice,” he said. “Ruxolitinib, also nonsteroidal, is FDA approved for mild to moderate AD down to 12 years of age. Having spent a good percentage of my practice years either being able to offer only topical steroids, or later topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, having additional options is wonderful.”

In the guidelines, the work group noted that “significant gaps remain” in current understanding of various topical AD therapies. “Studies are needed which examine quality of life and other patient-important outcomes, changes to the cutaneous microbiome, as well as long term follow-up, and use in special and diverse populations (e.g., pregnancy, lactation, immunosuppression, multiple comorbidities, skin of color, pediatric),” they wrote. “Furthermore, increased use of new systemic AD treatment options (dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, upadacitinib) in patients with moderate to severe disease may result in a selection bias toward milder disease in current and future AD topical therapy studies.”

Use of topical therapies to manage AD in pediatric patients will be covered in a forthcoming AAD guideline. The first updated AD guideline, on comorbidities associated with AD in adults, was released in January 2022.

Dr. Sidbury reported that he serves as an advisory board member for Pfizer, a principal investigator for Regeneron, an investigator for Brickell Biotech and Galderma USA, and a consultant for Galderma Global and Microes. Other work group members reported having financial disclosures with many pharmaceutical companies.

, and topical phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors. The guidelines also conditionally recommend the use of bathing and wet wrap therapy but recommend against the use of topical antimicrobials, antiseptics, and antihistamines.

The development updates the AAD’s 2014 recommendations for managing AD with topical therapies, published almost 9 years ago. “At that time, the only U.S. FDA–approved systemic medication for atopic dermatitis was prednisone – universally felt amongst dermatologists to be the least appropriate systemic medication for this condition, at least chronically,” Robert Sidbury, MD, MPH, who cochaired a 14-member multidisciplinary work group that assembled the updated guidelines, told this news organization in an interview.

“Since 2017, there have been two different biologic medications approved for moderate to severe AD (dupilumab and tralokinumab) with certainly a third or more right around the corner. There have been two new oral agents approved for moderate to severe AD – upadacitinib and abrocitinib – with others on the way,” he noted. While these are not topical therapies, the purview of the newly released guidelines, he said, “there have also been new topical medications approved since that time (crisaborole and ruxolitinib). It was high time for an update.”

For the new guidelines, which were published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Sidbury, chief of the division of dermatology at Seattle Children’s Hospital, guidelines cochair Dawn M. R. Davis, MD, a dermatologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues conducted a systematic review of evidence regarding the use of nonprescription topical agents such as moisturizers, bathing practices, and wet wraps, as well as topical pharmacologic modalities such as corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, PDE-4 inhibitors, antimicrobials, and antihistamines.

Next, the work group applied the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for assessing the certainty of the evidence and formulating and grading clinical recommendations based on relevant randomized trials in the medical literature.

12 recommendations

Of the 12 recommendations made for adults with AD, the work group ranked 7 as “strong” based on the evidence reviewed, and the rest as “conditional.” The “strong” recommendations include the use of moisturizers; the use of tacrolimus 0.03% or 0.1%; the use of pimecrolimus 1% cream for mild to moderate AD; use of topical steroids; intermittent use of medium-potency topical corticosteroids as maintenance therapy to reduce flares and relapse; the use of the topical PDE-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and the use of the topical JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib.

Regarding ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, the work group advised that the treatment area “should not exceed 20% body surface area, and a maximum of 60 grams should be applied per week; these stipulations are aimed at reducing systemic absorption, as black box warnings include serious infections, mortality, malignancies (for example, lymphoma), major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis.”

Conditional recommendations in the guidelines include those for bathing for treatment and maintenance and the use of wet dressings, and those against the use of topical antimicrobials, topical antihistamines, and topical antiseptics.

According to Dr. Sidbury, the topic of bathing generated robust discussion among the work group members. “Though [each group member] has strong opinions and individual practice styles, they were also able to recognize that the evidence is all that matters in a project like this, which led to a ‘conditional’ recommendation regarding bathing frequency backed by ‘low’ evidence,” he said. “While this may seem like ‘guidance’ that doesn’t ‘guide,’ I would argue it informs the guideline consumer exactly where we are in terms of this question and allows them to use their best judgment and experience as their true north here.”

In the realm of topical steroids, Dr. Sidbury said that topical steroid addiction (TSA) and topical steroid withdrawal (TSW) have been a “controversial but persistent concern” from some patients and providers. “Two systematic reviews of this topic were mentioned, and it was made clear that the evidence base [for the concepts] is weak,” he said. “With that important caveat ,the guideline committee delineated both a definition of TSW/TSA and potential risk factors.”

Dr. Sidbury marveled at the potential impact of newer medicines such as crisaborole and ruxolitinib on younger AD patients as well. Crisaborole is now Food and Drug Administration approved down to 3 months of age for mild to moderate AD. “This is extraordinary and expands treatment options for all providers at an age when parents and providers are most conservative in their practice,” he said. “Ruxolitinib, also nonsteroidal, is FDA approved for mild to moderate AD down to 12 years of age. Having spent a good percentage of my practice years either being able to offer only topical steroids, or later topical steroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors like tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, having additional options is wonderful.”

In the guidelines, the work group noted that “significant gaps remain” in current understanding of various topical AD therapies. “Studies are needed which examine quality of life and other patient-important outcomes, changes to the cutaneous microbiome, as well as long term follow-up, and use in special and diverse populations (e.g., pregnancy, lactation, immunosuppression, multiple comorbidities, skin of color, pediatric),” they wrote. “Furthermore, increased use of new systemic AD treatment options (dupilumab, tralokinumab, abrocitinib, upadacitinib) in patients with moderate to severe disease may result in a selection bias toward milder disease in current and future AD topical therapy studies.”

Use of topical therapies to manage AD in pediatric patients will be covered in a forthcoming AAD guideline. The first updated AD guideline, on comorbidities associated with AD in adults, was released in January 2022.

Dr. Sidbury reported that he serves as an advisory board member for Pfizer, a principal investigator for Regeneron, an investigator for Brickell Biotech and Galderma USA, and a consultant for Galderma Global and Microes. Other work group members reported having financial disclosures with many pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Methacrylate Polymer Powder Dressing for a Lower Leg Surgical Defect

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

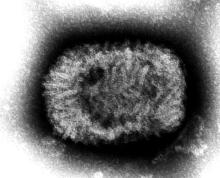

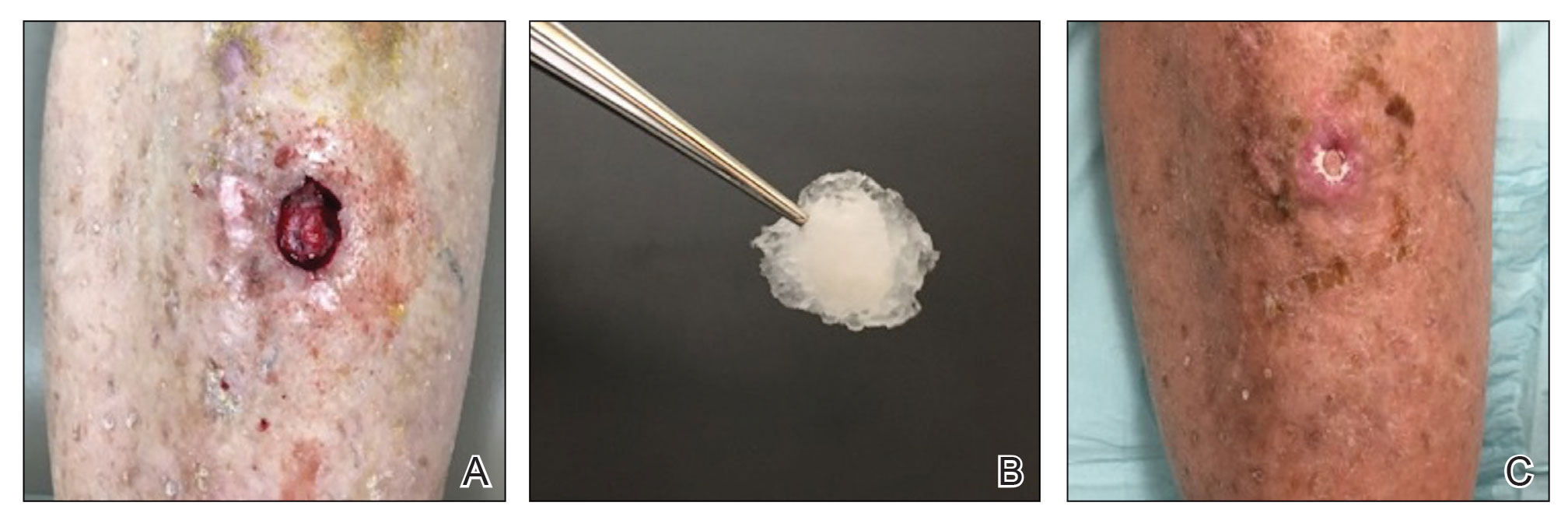

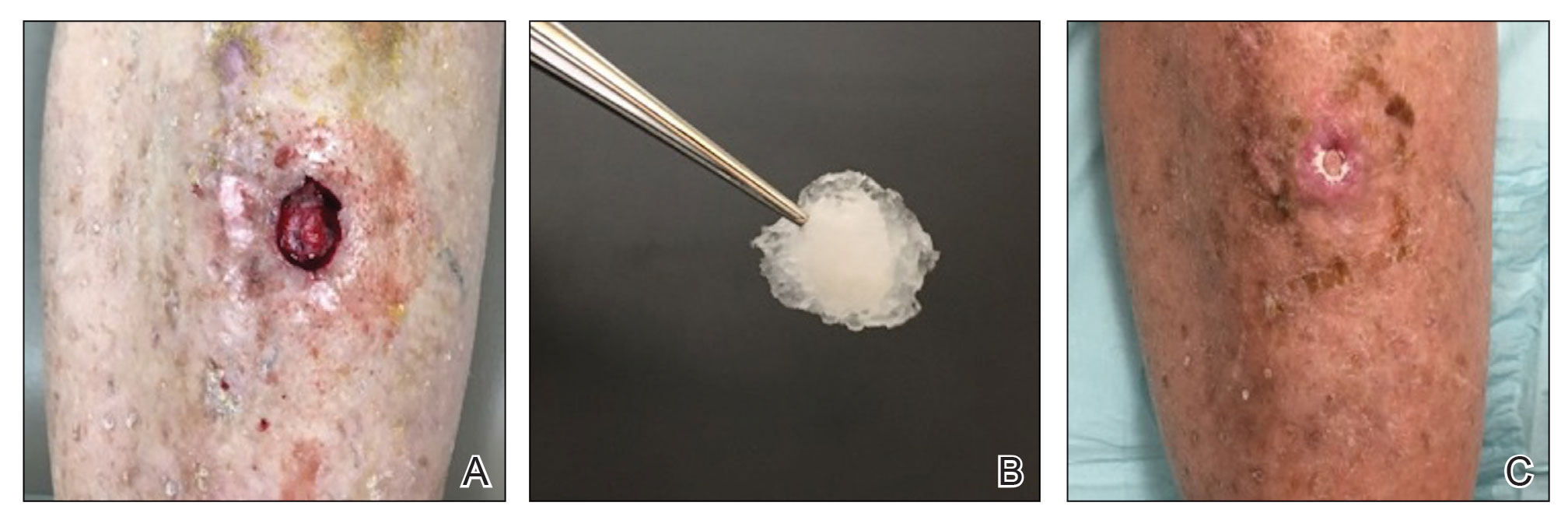

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

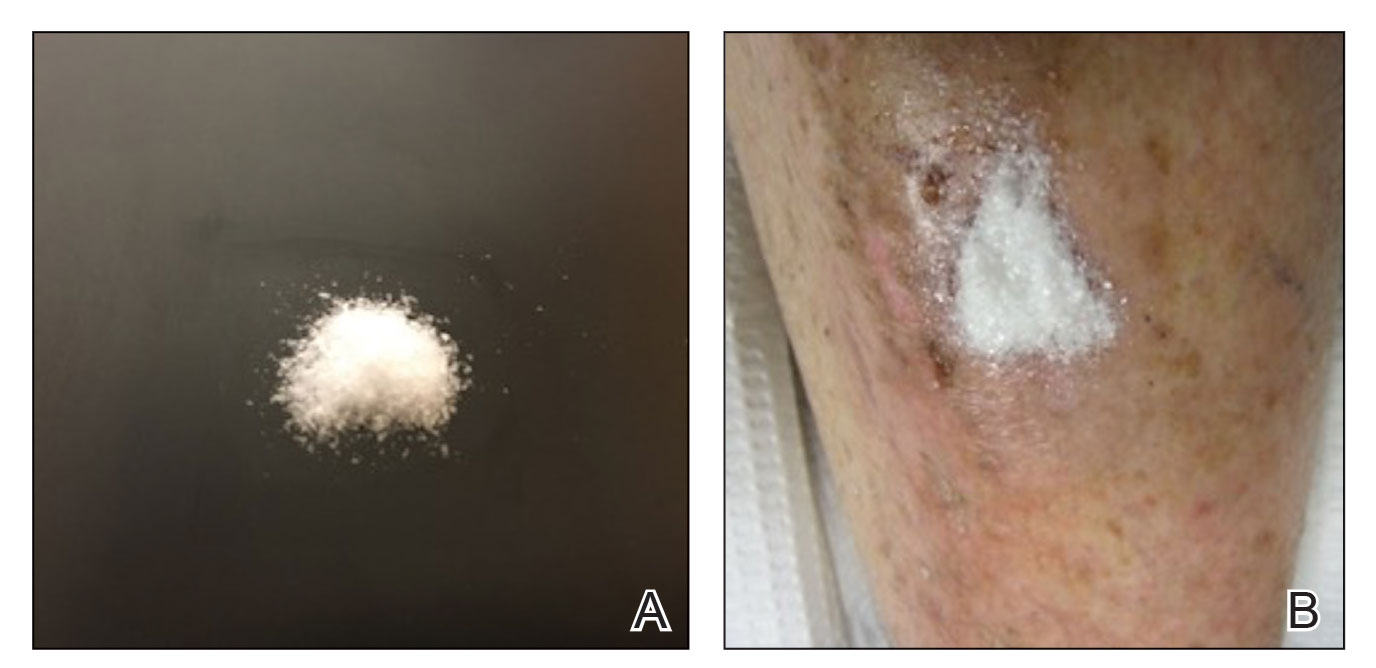

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

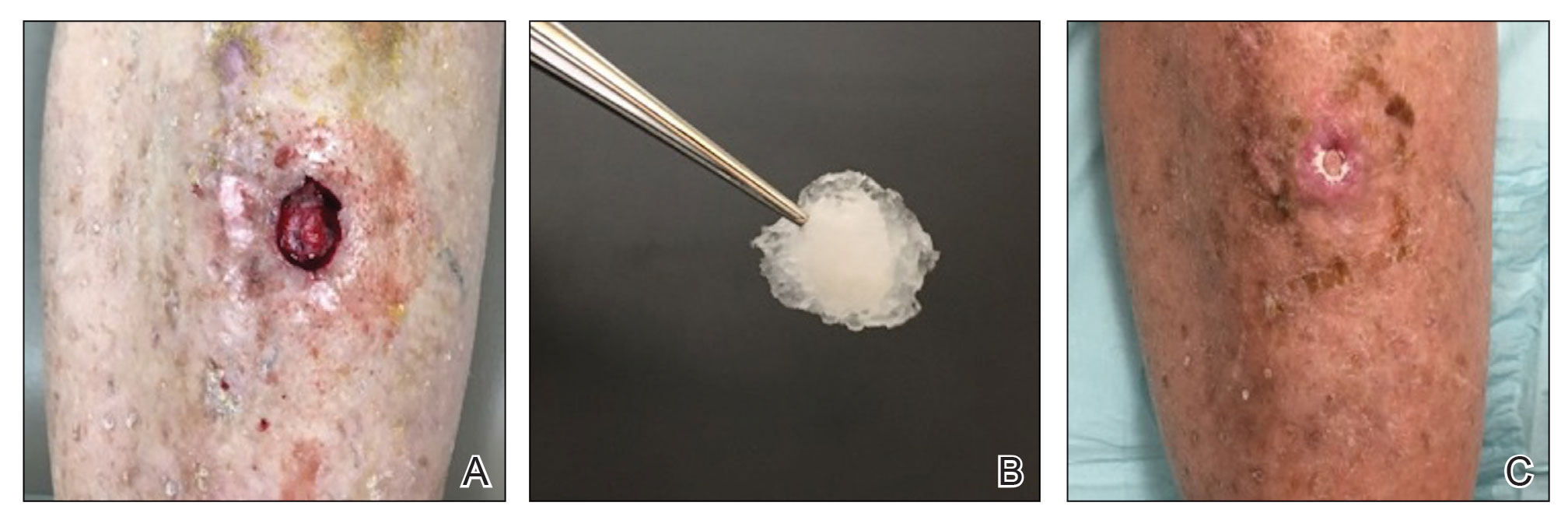

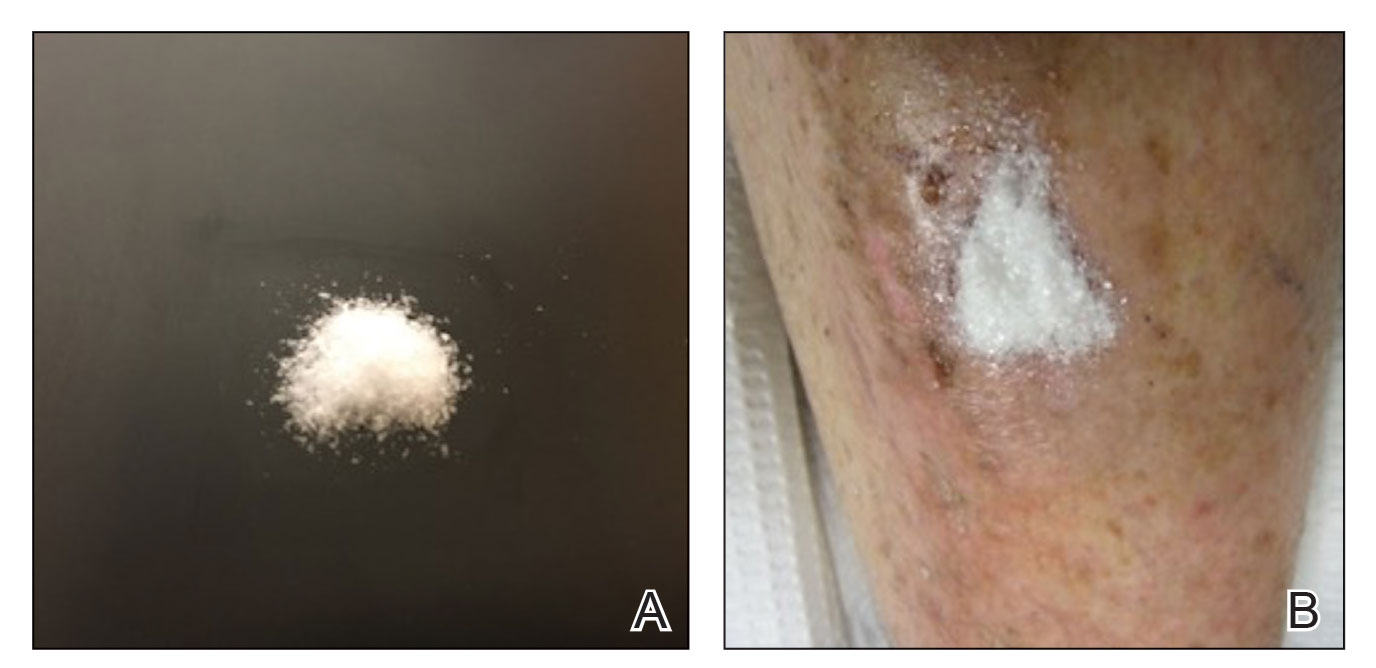

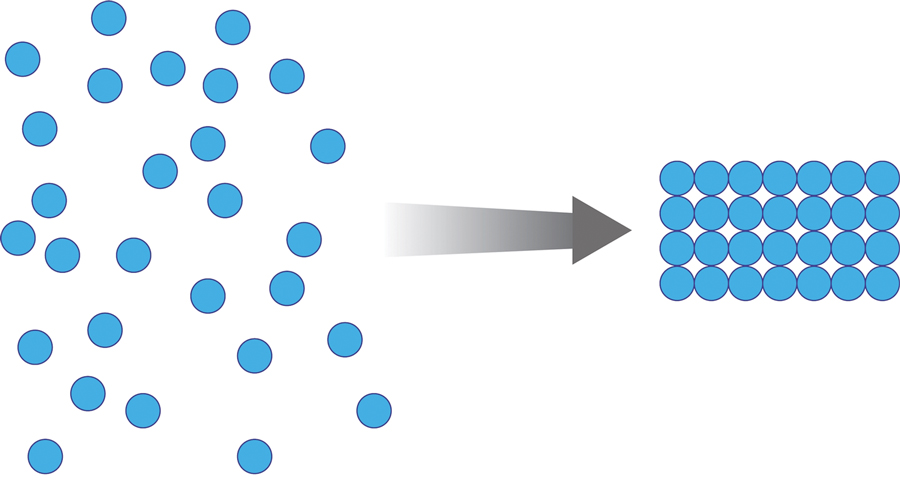

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

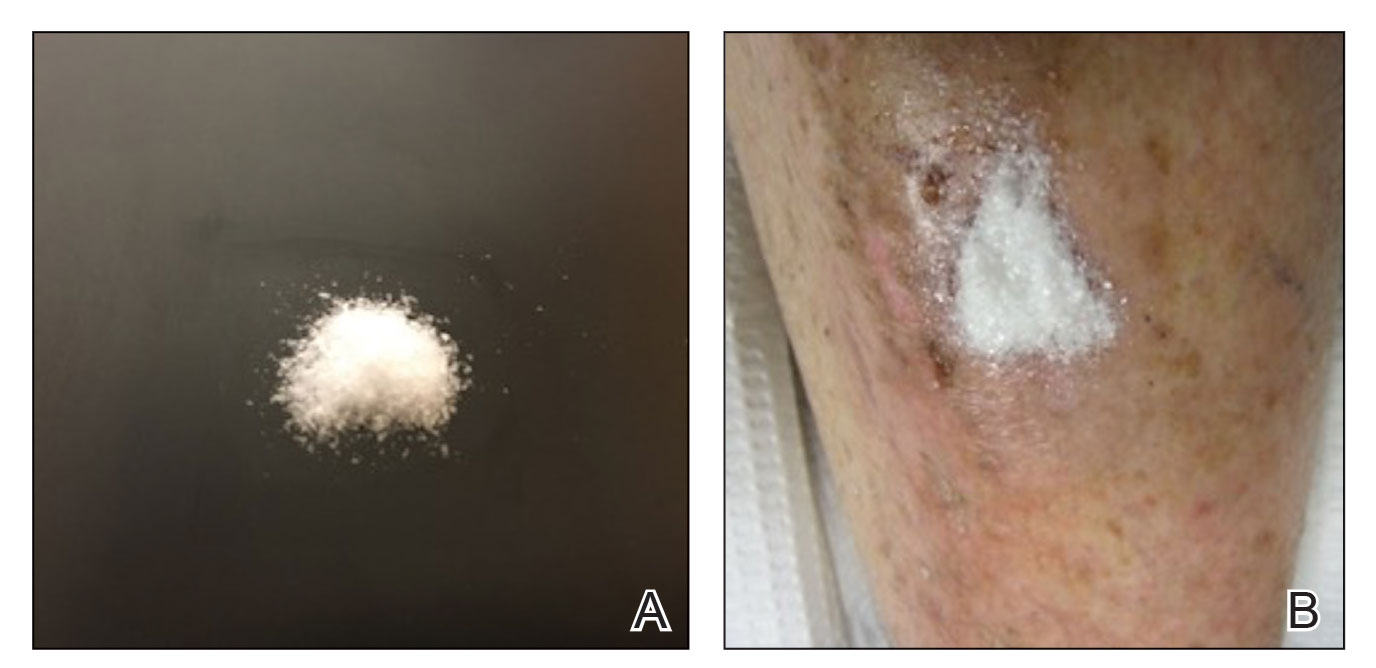

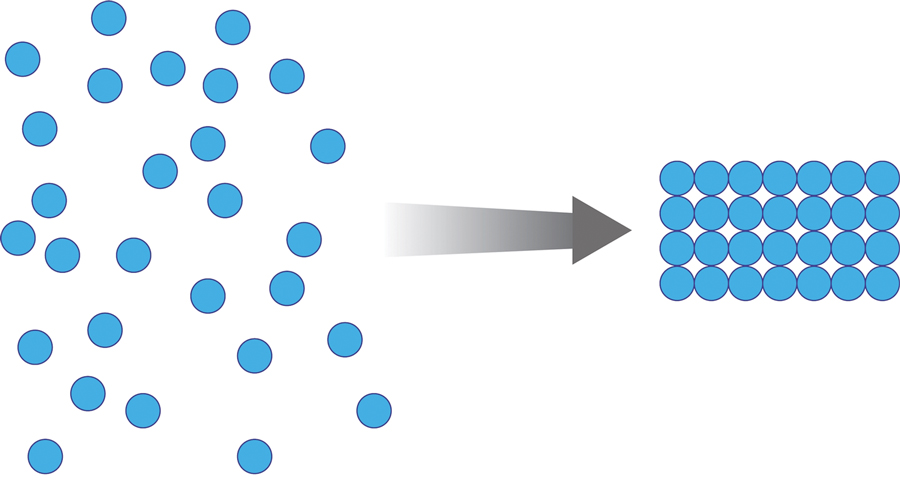

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

To the Editor:

Surgical wounds on the lower leg are challenging to manage because venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing. Advances in technology led to the development of novel, polymer-based wound-healing modalities that hold promise for the management of these wounds.

A 75-year-old man presented with a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with a 3-mm depth of invasion on the left pretibial region. His comorbidities were notable for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, varicose veins, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, and a 32 pack-year cigarette smoking history. Current medications included clopidogrel bisulfate and warfarin sodium to manage a recently placed coronary artery stent.

The tumor was cleared after 2 stages of Mohs micrographic surgery with excision down to tibialis anterior fascia (Figure 1A). The resultant defect measured 43×33 mm in area and 9 mm in depth (wound size, 12,771 mm3). Reconstructive options were discussed, including random-pattern flap repair and skin graft. Given the patient’s risk of bleeding, the decision was made to forego a flap repair. Additionally, the patient was a heavy smoker and could not comply with the wound care and elevation and ambulation restrictions required for optimal skin graft care. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with secondary intention healing using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing.

After achieving hemostasis, a novel 10-mg sterile, biologically inert methacrylate polymer powder dressing was poured over the wound in a uniform layer to fill and seal the entire wound surface (Figure 1B). Sterile normal saline 0.1 mL was sprayed onto the powder to activate particle aggregation. No secondary dressing was used, and the patient was permitted to get the dressing wet after 48 hours.

The dressing was changed in a similar fashion 4 weeks after application, following gentle debridement with gauze and normal saline. Eight weeks after surgery, the wound exhibited healthy granulation tissue and measured 5×6 mm in area and 2 mm in depth (wound size, 60 mm3), which represented a 99.5% reduction in wound size (Figure 1C). The dressing was not painful, and there were no reported adverse effects. The patient continued to smoke and ambulate fully throughout this period. No antibiotics were used.

Methacrylate polymer powder dressings are a novel and sophisticated dressing modality with great promise for the management of surgical wounds on the lower limb. The dressing is a sterile powder consisting of 84.8% poly-2-hydroxyethylmethacrylate, 14.9% poly-2-hydroxypropylmethacrylate, and 0.3% sodium deoxycholate. These hydrophilic polymers have a covalent methacrylate backbone with a hydroxyl aliphatic side chain. When saline or wound exudate contacts the powder, the spheres hydrate and nonreversibly aggregate to form a moist, flexible dressing that conforms to the topography of the wound and seals it (Figure 2).1

Once the spheres have aggregated, they are designed to orient in a honeycomb formation with 4- to 10-nm openings that serve as capillary channels (Figure 3). This porous architecture of the polymer is essential for adequate moisture management. It allows for vapor transpiration at a rate of 12 L/m2 per day, which ensures the capillary flow from the moist wound surface is evenly distributed through the dressing, contributing to its 68% water content. Notably, this approximately three-fifths water composition is similar to the water makeup of human skin. Optimized moisture management is theorized to enhance epithelial migration, stimulate angiogenesis, retain growth factors, promote autolytic debridement, and maintain ideal voltage and oxygen gradients for wound healing. The risk for infection is not increased by the existence of these pores, as their small size does not allow for bacterial migration.1

This case demonstrates the effectiveness of using a methacrylate polymer powder dressing to promote timely wound healing in a poorly vascularized lower leg surgical wound. The low maintenance, user-friendly dressing was changed at monthly intervals, which spared the patient the inconvenience and pain associated with the repeated application of more conventional primary and secondary dressings. The dressing was well tolerated and resulted in a 99.5% reduction in wound size. Further studies are needed to investigate the utility of this promising technology.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

1. Fitzgerald RH, Bharara M, Mills JL, et al. Use of a nanoflex powder dressing for wound management following debridement for necrotising fasciitis in the diabetic foot. Int Wound J. 2009;6:133-139.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Lower leg surgical wounds are difficult to manage, as venous stasis, bacterial colonization, and high tension may contribute to protracted healing.

- A methacrylate polymer powder dressing is user friendly and facilitates granulation and reduction in size of difficult lower leg wounds.

A 50-year-old woman with no significant history presented with erythematous, annular plaques, and papules on the dorsal hands and arms

. The prevalence and incidence is approximately 0.1%-0.4%. Although the condition is benign, it may be associated with more serious conditions such as HIV and malignancy. GA affects women more frequently than men but can affect any age group, although it most commonly presents in those ages 30 years and younger. While the exact etiology is unknown, GA has been most strongly associated with diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and autoimmune diseases.

The disease presents as localized, annular erythematous plaques and papules on the dorsal hands and feet in approximately 75% of cases. However, eruptions may appear on the trunk and extremities and can be categorized into patchy, generalized, interstitial, subcutaneous, or perforating subtypes. The lesions are often asymptomatic and typically not associated with any other symptoms.

The pathogenesis of GA is still under investigation, but recent studies suggest that a Th1-mediated dysregulation of the JAK-STAT pathway may contribute to the disease. Other hypotheses include a delayed hypersensitivity reaction or cell mediated immune response. The mechanism may be multifaceted, and epidemiologic research suggests a genetic predisposition in White individuals, but these findings may be associated with socioeconomic factors and disparities in health care.

GA presents on histology with palisading histiocytes surrounding focal collagen necrobiosis with mucin deposition. Tissue samples also display leukocytic infiltration of the dermis featuring multinucleated giant cells. There are defining features of the different subtypes, but focal collagen necrosis, the presence of histiocytes, and mucin deposition are consistent findings across all presentations.

GA lesions commonly regress on their own, but they tend to recur and can be functionally and visually unappealing to patients. The most common treatments for GA include topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroid injections, and other anti-inflammatory drugs. These interventions can be administered in a variety of ways as the inflammation caused by GA exists on a spectrum, and less severe cases can be managed with topical or intralesional treatment. Systemic therapy may be necessary for severe and recalcitrant cases. Other interventions that have shown promise in smaller studies include phototherapy, hydroxychloroquine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Tampa Bay Regional Campus, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Joshi TP and Duvic M. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022 Jan;23(1):37-50. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1.

Muse M et al. Dermatol Online J. 2021 Apr 15;27(4):13030/qt0m50398n.

Schmieder SJ et al. Granuloma Annulare. NIH National Center for Biotechnology Information [Updated 2022 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. 7.

. The prevalence and incidence is approximately 0.1%-0.4%. Although the condition is benign, it may be associated with more serious conditions such as HIV and malignancy. GA affects women more frequently than men but can affect any age group, although it most commonly presents in those ages 30 years and younger. While the exact etiology is unknown, GA has been most strongly associated with diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and autoimmune diseases.

The disease presents as localized, annular erythematous plaques and papules on the dorsal hands and feet in approximately 75% of cases. However, eruptions may appear on the trunk and extremities and can be categorized into patchy, generalized, interstitial, subcutaneous, or perforating subtypes. The lesions are often asymptomatic and typically not associated with any other symptoms.

The pathogenesis of GA is still under investigation, but recent studies suggest that a Th1-mediated dysregulation of the JAK-STAT pathway may contribute to the disease. Other hypotheses include a delayed hypersensitivity reaction or cell mediated immune response. The mechanism may be multifaceted, and epidemiologic research suggests a genetic predisposition in White individuals, but these findings may be associated with socioeconomic factors and disparities in health care.

GA presents on histology with palisading histiocytes surrounding focal collagen necrobiosis with mucin deposition. Tissue samples also display leukocytic infiltration of the dermis featuring multinucleated giant cells. There are defining features of the different subtypes, but focal collagen necrosis, the presence of histiocytes, and mucin deposition are consistent findings across all presentations.

GA lesions commonly regress on their own, but they tend to recur and can be functionally and visually unappealing to patients. The most common treatments for GA include topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroid injections, and other anti-inflammatory drugs. These interventions can be administered in a variety of ways as the inflammation caused by GA exists on a spectrum, and less severe cases can be managed with topical or intralesional treatment. Systemic therapy may be necessary for severe and recalcitrant cases. Other interventions that have shown promise in smaller studies include phototherapy, hydroxychloroquine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Tampa Bay Regional Campus, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Joshi TP and Duvic M. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022 Jan;23(1):37-50. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1.

Muse M et al. Dermatol Online J. 2021 Apr 15;27(4):13030/qt0m50398n.

Schmieder SJ et al. Granuloma Annulare. NIH National Center for Biotechnology Information [Updated 2022 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. 7.

. The prevalence and incidence is approximately 0.1%-0.4%. Although the condition is benign, it may be associated with more serious conditions such as HIV and malignancy. GA affects women more frequently than men but can affect any age group, although it most commonly presents in those ages 30 years and younger. While the exact etiology is unknown, GA has been most strongly associated with diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and autoimmune diseases.

The disease presents as localized, annular erythematous plaques and papules on the dorsal hands and feet in approximately 75% of cases. However, eruptions may appear on the trunk and extremities and can be categorized into patchy, generalized, interstitial, subcutaneous, or perforating subtypes. The lesions are often asymptomatic and typically not associated with any other symptoms.

The pathogenesis of GA is still under investigation, but recent studies suggest that a Th1-mediated dysregulation of the JAK-STAT pathway may contribute to the disease. Other hypotheses include a delayed hypersensitivity reaction or cell mediated immune response. The mechanism may be multifaceted, and epidemiologic research suggests a genetic predisposition in White individuals, but these findings may be associated with socioeconomic factors and disparities in health care.

GA presents on histology with palisading histiocytes surrounding focal collagen necrobiosis with mucin deposition. Tissue samples also display leukocytic infiltration of the dermis featuring multinucleated giant cells. There are defining features of the different subtypes, but focal collagen necrosis, the presence of histiocytes, and mucin deposition are consistent findings across all presentations.

GA lesions commonly regress on their own, but they tend to recur and can be functionally and visually unappealing to patients. The most common treatments for GA include topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroid injections, and other anti-inflammatory drugs. These interventions can be administered in a variety of ways as the inflammation caused by GA exists on a spectrum, and less severe cases can be managed with topical or intralesional treatment. Systemic therapy may be necessary for severe and recalcitrant cases. Other interventions that have shown promise in smaller studies include phototherapy, hydroxychloroquine, and TNF-alpha inhibitors.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine, Tampa Bay Regional Campus, and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected].

References

Joshi TP and Duvic M. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022 Jan;23(1):37-50. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1.

Muse M et al. Dermatol Online J. 2021 Apr 15;27(4):13030/qt0m50398n.

Schmieder SJ et al. Granuloma Annulare. NIH National Center for Biotechnology Information [Updated 2022 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. 7.

Regular vitamin D supplements may lower melanoma risk

. They also found a trend for benefit with occasional use.

The study, published in Melanoma Research, involved almost 500 individuals attending a dermatology clinic who reported on their use of vitamin D supplements.

Regular users had a significant 55% reduction in the odds of having a past or present melanoma diagnosis, while occasional use was associated with a nonsignificant 46% reduction. The reduction was similar for all skin cancer types.

However, senior author Ilkka T. Harvima, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio (Finland) University Hospital, warned there are limitations to the study.

Despite adjustment for several possible confounding factors, “it is still possible that some other, yet unidentified or untested, factors can still confound the present result,” he said.

Consequently, “the causal link between vitamin D and melanoma cannot be confirmed by the present results,” Dr. Harvima said in a statement.

Even if the link were to be proven, “the question about the optimal dose of oral vitamin D in order to for it to have beneficial effects remains to be answered,” he said.

“Until we know more, national intake recommendations should be followed.”

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers has been increasing steadily in Western populations, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals, the authors pointed out, and they attributed the rise to an increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

While ultraviolet radiation exposure is a well-known risk factor, “the other side of the coin is that public sun protection campaigns have led to alerts that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem, resulting in insufficient vitamin D status.”

For their study, the team reviewed the records of 498 patients aged 21-79 years at a dermatology outpatient clinic who were deemed by an experienced dermatologist to be at risk of any type of skin cancer.

Among these patients, 295 individuals had a history of past or present cutaneous malignancy, with 100 diagnosed with melanoma, 213 with basal cell carcinoma, and 41 with squamous cell carcinoma. A further 70 subjects had cancer elsewhere, including breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, intestine, and blood cancers.

A subgroup of 96 patients were immunocompromised and were considered separately.

The 402 remaining patients were categorized, based on their self-reported use of oral vitamin D preparations, as nonusers (n = 99), occasional users (n = 126), and regular users (n = 177).

Regular use of vitamin D was associated with being more educated (P = .032), less frequent outdoor working (P = .003), lower tobacco pack years (P = .001), and more frequent solarium exposure (P = .002).

There was no significant association between vitamin D use and photoaging, actinic keratoses, nevi, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, body mass index, or self-estimated lifetime exposure to sunlight or sunburns.

However, there were significant associations between regular use of vitamin D and a lower incidence of melanoma and other cancer types.

There were significantly fewer individuals in the regular vitamin D use group with a past or present history of melanoma when compared with the nonuse group, at 18.1% vs. 32.3% (P = .021), or any type of skin cancer, at 62.1% vs. 74.7% (P = .027).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that regular vitamin D use was significantly associated with a reduced melanoma risk, at an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.447 (P = .016).

Occasional use was associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk, with an odds ratio versus nonuse of 0.540 (P = .08).

For any type of skin cancers, regular vitamin D use was associated with an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.478 (P = .032), while that for occasional vitamin D use was 0.543 (P = .061).

“Somewhat similar” results were obtained when the investigators looked at the subgroup of immunocompromised individuals, although they note that “the number of subjects was low.”

The study was supported by the Cancer Center of Eastern Finland of the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Cancer Research Foundation, and the VTR-funding of Kuopio University Hospital. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. They also found a trend for benefit with occasional use.

The study, published in Melanoma Research, involved almost 500 individuals attending a dermatology clinic who reported on their use of vitamin D supplements.

Regular users had a significant 55% reduction in the odds of having a past or present melanoma diagnosis, while occasional use was associated with a nonsignificant 46% reduction. The reduction was similar for all skin cancer types.

However, senior author Ilkka T. Harvima, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio (Finland) University Hospital, warned there are limitations to the study.

Despite adjustment for several possible confounding factors, “it is still possible that some other, yet unidentified or untested, factors can still confound the present result,” he said.

Consequently, “the causal link between vitamin D and melanoma cannot be confirmed by the present results,” Dr. Harvima said in a statement.

Even if the link were to be proven, “the question about the optimal dose of oral vitamin D in order to for it to have beneficial effects remains to be answered,” he said.

“Until we know more, national intake recommendations should be followed.”

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers has been increasing steadily in Western populations, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals, the authors pointed out, and they attributed the rise to an increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

While ultraviolet radiation exposure is a well-known risk factor, “the other side of the coin is that public sun protection campaigns have led to alerts that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem, resulting in insufficient vitamin D status.”

For their study, the team reviewed the records of 498 patients aged 21-79 years at a dermatology outpatient clinic who were deemed by an experienced dermatologist to be at risk of any type of skin cancer.

Among these patients, 295 individuals had a history of past or present cutaneous malignancy, with 100 diagnosed with melanoma, 213 with basal cell carcinoma, and 41 with squamous cell carcinoma. A further 70 subjects had cancer elsewhere, including breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, intestine, and blood cancers.

A subgroup of 96 patients were immunocompromised and were considered separately.

The 402 remaining patients were categorized, based on their self-reported use of oral vitamin D preparations, as nonusers (n = 99), occasional users (n = 126), and regular users (n = 177).

Regular use of vitamin D was associated with being more educated (P = .032), less frequent outdoor working (P = .003), lower tobacco pack years (P = .001), and more frequent solarium exposure (P = .002).

There was no significant association between vitamin D use and photoaging, actinic keratoses, nevi, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, body mass index, or self-estimated lifetime exposure to sunlight or sunburns.

However, there were significant associations between regular use of vitamin D and a lower incidence of melanoma and other cancer types.

There were significantly fewer individuals in the regular vitamin D use group with a past or present history of melanoma when compared with the nonuse group, at 18.1% vs. 32.3% (P = .021), or any type of skin cancer, at 62.1% vs. 74.7% (P = .027).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that regular vitamin D use was significantly associated with a reduced melanoma risk, at an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.447 (P = .016).

Occasional use was associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk, with an odds ratio versus nonuse of 0.540 (P = .08).

For any type of skin cancers, regular vitamin D use was associated with an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.478 (P = .032), while that for occasional vitamin D use was 0.543 (P = .061).

“Somewhat similar” results were obtained when the investigators looked at the subgroup of immunocompromised individuals, although they note that “the number of subjects was low.”

The study was supported by the Cancer Center of Eastern Finland of the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Cancer Research Foundation, and the VTR-funding of Kuopio University Hospital. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

. They also found a trend for benefit with occasional use.

The study, published in Melanoma Research, involved almost 500 individuals attending a dermatology clinic who reported on their use of vitamin D supplements.

Regular users had a significant 55% reduction in the odds of having a past or present melanoma diagnosis, while occasional use was associated with a nonsignificant 46% reduction. The reduction was similar for all skin cancer types.

However, senior author Ilkka T. Harvima, MD, PhD, department of dermatology, University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio (Finland) University Hospital, warned there are limitations to the study.

Despite adjustment for several possible confounding factors, “it is still possible that some other, yet unidentified or untested, factors can still confound the present result,” he said.

Consequently, “the causal link between vitamin D and melanoma cannot be confirmed by the present results,” Dr. Harvima said in a statement.

Even if the link were to be proven, “the question about the optimal dose of oral vitamin D in order to for it to have beneficial effects remains to be answered,” he said.

“Until we know more, national intake recommendations should be followed.”

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers has been increasing steadily in Western populations, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals, the authors pointed out, and they attributed the rise to an increased exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

While ultraviolet radiation exposure is a well-known risk factor, “the other side of the coin is that public sun protection campaigns have led to alerts that insufficient sun exposure is a significant public health problem, resulting in insufficient vitamin D status.”

For their study, the team reviewed the records of 498 patients aged 21-79 years at a dermatology outpatient clinic who were deemed by an experienced dermatologist to be at risk of any type of skin cancer.

Among these patients, 295 individuals had a history of past or present cutaneous malignancy, with 100 diagnosed with melanoma, 213 with basal cell carcinoma, and 41 with squamous cell carcinoma. A further 70 subjects had cancer elsewhere, including breast, prostate, kidney, bladder, intestine, and blood cancers.

A subgroup of 96 patients were immunocompromised and were considered separately.

The 402 remaining patients were categorized, based on their self-reported use of oral vitamin D preparations, as nonusers (n = 99), occasional users (n = 126), and regular users (n = 177).

Regular use of vitamin D was associated with being more educated (P = .032), less frequent outdoor working (P = .003), lower tobacco pack years (P = .001), and more frequent solarium exposure (P = .002).

There was no significant association between vitamin D use and photoaging, actinic keratoses, nevi, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, body mass index, or self-estimated lifetime exposure to sunlight or sunburns.

However, there were significant associations between regular use of vitamin D and a lower incidence of melanoma and other cancer types.

There were significantly fewer individuals in the regular vitamin D use group with a past or present history of melanoma when compared with the nonuse group, at 18.1% vs. 32.3% (P = .021), or any type of skin cancer, at 62.1% vs. 74.7% (P = .027).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that regular vitamin D use was significantly associated with a reduced melanoma risk, at an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.447 (P = .016).

Occasional use was associated with a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk, with an odds ratio versus nonuse of 0.540 (P = .08).

For any type of skin cancers, regular vitamin D use was associated with an odds ratio vs. nonuse of 0.478 (P = .032), while that for occasional vitamin D use was 0.543 (P = .061).

“Somewhat similar” results were obtained when the investigators looked at the subgroup of immunocompromised individuals, although they note that “the number of subjects was low.”

The study was supported by the Cancer Center of Eastern Finland of the University of Eastern Finland, the Finnish Cancer Research Foundation, and the VTR-funding of Kuopio University Hospital. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MELANOMA RESEARCH

Picosecond lasers for tattoo removal could benefit from enhancements, expert says

SAN DIEGO – When picosecond lasers hit the market about 10 years ago, they became a game-changer for tattoo removal, boasting the delivery of energy that is about threefold faster than with nanosecond lasers.

However, picosecond lasers are far from perfect even in the hands of the most experienced clinicians, according to Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford. “They have been very difficult to build from an engineering perspective,” he said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. It took a long time for these lasers to come to the market, and they are still fairly expensive and require a lot of maintenance, he noted. In addition, “they are also not quite as ‘picosecond’ as they need to be. I think there is definitely room to improve, but this is the gold standard.”

Today, . Tattoo ink particles average about 0.1 mcm in size, and the thermal relaxation size works out to be less than 10 nanoseconds, with shorter pulses better at capturing the ink particles that are smaller than average.

Black is the most common tattoo color dermatologists treat. “For that, you can typically use a 1064, which has the highest absorption, but you can also use many of the other wavelengths,” he said. “Other colors are less common, followed by red, for which you would use a 532-nm wavelength.”

Dr. Ibrahimi underscored the importance of setting realistic expectations during consults with patients seeking options for tattoo removal. Even with picosecond laser technology, many treatments are typically required and “a good patient consultation is key to setting proper expectations,” he said. “If you promise someone results in 4 to 5 treatments like many of the device companies will say you can achieve, you’re going to have a large group of patients who are disappointed.”

The clinical endpoint to strive for during tattoo removal is whitening of the ink, which typically fades about 20 minutes after treatment. That whitening corresponds to cavitation, or the production of gas vacuoles in the cells that were holding the ink. This discovery led to a technique intended to enhance tattoo removal. In 2012, R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and colleagues published results of a study that compared a single Q-switched laser treatment pass with four treatment passes separated by 20 minutes. After treating 18 tattoos in 12 adults, they found that the technique, known as the “R20” method, was more effective than a single-pass treatment (P < .01).

“Subsequent to this, there has been conflicting data on whether this is truly effective or not,” said Dr. Ibrahimi, who is also on the board of directors for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Most of us agree that one additional pass would be helpful, but when you’re doing this in the private practice setting, it’s often challenging because patients aren’t necessarily willing to pay more for more than just one pass for their tattoo removal.”

Another recent advance is use of a topical square silicone patch infused with perfluorodecalin (PFD) for use during tattoo removal, which has been shown to reduce epidermal whitening. The patch contains a fluorocarbon “that is very good at dissolving gas, and it is already widely used in medicine,” he said. When applied, “it almost instantaneously takes the whitening away; you don’t have to wait the 20 minutes to do your second pass.”

A different technology designed to speed up tattoo removal is the Resonic Rapid Acoustic Pulse device (marketed as Resonic, from Allergan Aesthetics), which is cleared by the FDA for use as an accessory to the 1064 nm Q-switched laser for black tattoo removal in patients with skin types I-III. “This uses acoustic pulses of sound waves; they’re rapid and powerful,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “They can clear those cavitation bubbles much like the PFD patches do. It’s also thought that they further disperse the tattoo ink particles by supplementing the laser energy as well. It is also purported to alter the body’s healing response, or immune response, which is important in tattoo clearing.”

Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the Advisory Board for Accure Acne, AbbVie (which owns Allergan), Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – When picosecond lasers hit the market about 10 years ago, they became a game-changer for tattoo removal, boasting the delivery of energy that is about threefold faster than with nanosecond lasers.

However, picosecond lasers are far from perfect even in the hands of the most experienced clinicians, according to Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford. “They have been very difficult to build from an engineering perspective,” he said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. It took a long time for these lasers to come to the market, and they are still fairly expensive and require a lot of maintenance, he noted. In addition, “they are also not quite as ‘picosecond’ as they need to be. I think there is definitely room to improve, but this is the gold standard.”

Today, . Tattoo ink particles average about 0.1 mcm in size, and the thermal relaxation size works out to be less than 10 nanoseconds, with shorter pulses better at capturing the ink particles that are smaller than average.

Black is the most common tattoo color dermatologists treat. “For that, you can typically use a 1064, which has the highest absorption, but you can also use many of the other wavelengths,” he said. “Other colors are less common, followed by red, for which you would use a 532-nm wavelength.”

Dr. Ibrahimi underscored the importance of setting realistic expectations during consults with patients seeking options for tattoo removal. Even with picosecond laser technology, many treatments are typically required and “a good patient consultation is key to setting proper expectations,” he said. “If you promise someone results in 4 to 5 treatments like many of the device companies will say you can achieve, you’re going to have a large group of patients who are disappointed.”

The clinical endpoint to strive for during tattoo removal is whitening of the ink, which typically fades about 20 minutes after treatment. That whitening corresponds to cavitation, or the production of gas vacuoles in the cells that were holding the ink. This discovery led to a technique intended to enhance tattoo removal. In 2012, R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and colleagues published results of a study that compared a single Q-switched laser treatment pass with four treatment passes separated by 20 minutes. After treating 18 tattoos in 12 adults, they found that the technique, known as the “R20” method, was more effective than a single-pass treatment (P < .01).

“Subsequent to this, there has been conflicting data on whether this is truly effective or not,” said Dr. Ibrahimi, who is also on the board of directors for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Most of us agree that one additional pass would be helpful, but when you’re doing this in the private practice setting, it’s often challenging because patients aren’t necessarily willing to pay more for more than just one pass for their tattoo removal.”

Another recent advance is use of a topical square silicone patch infused with perfluorodecalin (PFD) for use during tattoo removal, which has been shown to reduce epidermal whitening. The patch contains a fluorocarbon “that is very good at dissolving gas, and it is already widely used in medicine,” he said. When applied, “it almost instantaneously takes the whitening away; you don’t have to wait the 20 minutes to do your second pass.”

A different technology designed to speed up tattoo removal is the Resonic Rapid Acoustic Pulse device (marketed as Resonic, from Allergan Aesthetics), which is cleared by the FDA for use as an accessory to the 1064 nm Q-switched laser for black tattoo removal in patients with skin types I-III. “This uses acoustic pulses of sound waves; they’re rapid and powerful,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “They can clear those cavitation bubbles much like the PFD patches do. It’s also thought that they further disperse the tattoo ink particles by supplementing the laser energy as well. It is also purported to alter the body’s healing response, or immune response, which is important in tattoo clearing.”

Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the Advisory Board for Accure Acne, AbbVie (which owns Allergan), Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – When picosecond lasers hit the market about 10 years ago, they became a game-changer for tattoo removal, boasting the delivery of energy that is about threefold faster than with nanosecond lasers.

However, picosecond lasers are far from perfect even in the hands of the most experienced clinicians, according to Omar A. Ibrahimi, MD, PhD, medical director of the Connecticut Skin Institute, Stamford. “They have been very difficult to build from an engineering perspective,” he said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. It took a long time for these lasers to come to the market, and they are still fairly expensive and require a lot of maintenance, he noted. In addition, “they are also not quite as ‘picosecond’ as they need to be. I think there is definitely room to improve, but this is the gold standard.”

Today, . Tattoo ink particles average about 0.1 mcm in size, and the thermal relaxation size works out to be less than 10 nanoseconds, with shorter pulses better at capturing the ink particles that are smaller than average.

Black is the most common tattoo color dermatologists treat. “For that, you can typically use a 1064, which has the highest absorption, but you can also use many of the other wavelengths,” he said. “Other colors are less common, followed by red, for which you would use a 532-nm wavelength.”

Dr. Ibrahimi underscored the importance of setting realistic expectations during consults with patients seeking options for tattoo removal. Even with picosecond laser technology, many treatments are typically required and “a good patient consultation is key to setting proper expectations,” he said. “If you promise someone results in 4 to 5 treatments like many of the device companies will say you can achieve, you’re going to have a large group of patients who are disappointed.”

The clinical endpoint to strive for during tattoo removal is whitening of the ink, which typically fades about 20 minutes after treatment. That whitening corresponds to cavitation, or the production of gas vacuoles in the cells that were holding the ink. This discovery led to a technique intended to enhance tattoo removal. In 2012, R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, and colleagues published results of a study that compared a single Q-switched laser treatment pass with four treatment passes separated by 20 minutes. After treating 18 tattoos in 12 adults, they found that the technique, known as the “R20” method, was more effective than a single-pass treatment (P < .01).

“Subsequent to this, there has been conflicting data on whether this is truly effective or not,” said Dr. Ibrahimi, who is also on the board of directors for the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery and the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “Most of us agree that one additional pass would be helpful, but when you’re doing this in the private practice setting, it’s often challenging because patients aren’t necessarily willing to pay more for more than just one pass for their tattoo removal.”

Another recent advance is use of a topical square silicone patch infused with perfluorodecalin (PFD) for use during tattoo removal, which has been shown to reduce epidermal whitening. The patch contains a fluorocarbon “that is very good at dissolving gas, and it is already widely used in medicine,” he said. When applied, “it almost instantaneously takes the whitening away; you don’t have to wait the 20 minutes to do your second pass.”

A different technology designed to speed up tattoo removal is the Resonic Rapid Acoustic Pulse device (marketed as Resonic, from Allergan Aesthetics), which is cleared by the FDA for use as an accessory to the 1064 nm Q-switched laser for black tattoo removal in patients with skin types I-III. “This uses acoustic pulses of sound waves; they’re rapid and powerful,” Dr. Ibrahimi said. “They can clear those cavitation bubbles much like the PFD patches do. It’s also thought that they further disperse the tattoo ink particles by supplementing the laser energy as well. It is also purported to alter the body’s healing response, or immune response, which is important in tattoo clearing.”

Dr. Ibrahimi disclosed that he is a member of the Advisory Board for Accure Acne, AbbVie (which owns Allergan), Cutera, Lutronic, Blueberry Therapeutics, Cytrellis, and Quthero. He also holds stock in many device and pharmaceutical companies.

AT MOAS 2022

Early retirement and the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad cognitive decline

The ‘scheme’ in the name should have been a clue

Retirement. The shiny reward to a lifetime’s worth of working and saving. We’re all literally working to get there, some of us more to get there early, but current research reveals that early retirement isn’t the relaxing finish line we dream about, cognitively speaking.

Researchers at Binghamton (N.Y.) University set out to examine just how retirement plans affect cognitive performance. They started off with China’s New Rural Pension Scheme (scheme probably has a less negative connotation in Chinese), a plan that financially aids the growing rural retirement-age population in the country. Then they looked at data from the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, which tests cognition with a focus on episodic memory and parts of intact mental status.

What they found was the opposite of what you would expect out of retirees with nothing but time on their hands.

The pension program, which had been in place for almost a decade, led to delayed recall, especially among women, supporting “the mental retirement hypothesis that decreased mental activity results in worsening cognitive skills,” the investigators said in a written statement.

There also was a drop in social engagement, with lower rates of volunteering and social interaction than people who didn’t receive the pension. Some behaviors, like regular alcohol consumption, did improve over the previous year, as did total health in general, but “the adverse effects of early retirement on mental and social engagement significantly outweigh the program’s protective effect on various health behaviors,” Plamen Nikolov, PhD, said about his research.

So if you’re looking to retire early, don’t skimp on the crosswords and the bingo nights. Stay busy in a good way. Your brain will thank you.

Indiana Jones and the First Smallpox Ancestor

Smallpox was, not that long ago, one of the most devastating diseases known to humanity, killing 300 million people in the 20th century alone. Eradicating it has to be one of medicine’s crowning achievements. Now it can only be found in museums, which is where it belongs.

Here’s the thing with smallpox though: For all it did to us, we know frustratingly little about where it came from. Until very recently, the best available genetic evidence placed its emergence in the 17th century, which clashes with historical data. You know what that means, right? It’s time to dig out the fedora and whip, cue the music, and dig into a recently published study spanning continents in search of the mythical smallpox origin story.

We pick up in 2020, when genetic evidence definitively showed smallpox in a Viking burial site, moving the disease’s emergence a thousand years earlier. Which is all well and good, but there’s solid visual evidence that Egyptian pharaohs were dying of smallpox, as their bodies show the signature scarring. Historians were pretty sure smallpox went back about 4,000 years, but there was no genetic material to prove it.

Since there aren’t any 4,000-year-old smallpox germs laying around, the researchers chose to attack the problem another way – by burning down a Venetian catacomb, er, conducting a analysis of historical smallpox genetics to find the virus’s origin. By analyzing the genomes of various strains at different periods of time, they were able to determine that the variola virus had a definitive common ancestor. Some of the genetic components in the Viking-age sample, for example, persisted until the 18th century.

Armed with this information, the scientists determined that the first smallpox ancestor emerged about 3,800 years ago. That’s very close to the historians’ estimate for the disease’s emergence. Proof at last of smallpox’s truly ancient origin. One might even say the researchers chose wisely.

The only hall of fame that really matters

LOTME loves the holiday season – the food, the gifts, the radio stations that play nothing but Christmas music – but for us the most wonderful time of the year comes just a bit later. No, it’s not our annual Golden Globes slap bet. Nope, not even the “excitement” of the College Football Playoff National Championship. It’s time for the National Inventors Hall of Fame to announce its latest inductees, and we could hardly sleep last night after putting cookies out for Thomas Edison. Fasten your seatbelts!

- Robert G. Bryant is a NASA chemist who developed Langley Research Center-Soluble Imide (yes, that’s the actual name) a polymer used as an insulation material for leads in implantable cardiac resynchronization therapy devices.

- Rory Cooper is a biomedical engineer who was paralyzed in a bicycle accident. His work has improved manual and electric wheelchairs and advanced the health, mobility, and social inclusion of people with disabilities and older adults. He is also the first NIHF inductee named Rory.

- Katalin Karikó, a biochemist, and Drew Weissman, an immunologist, “discovered how to enable messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) to enter cells without triggering the body’s immune system,” NIHF said, and that laid the foundation for the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. That, of course, led to the antivax movement, which has provided so much LOTME fodder over the years.

- Angela Hartley Brodie was a biochemist who discovered and developed a class of drugs called aromatase inhibitors, which can stop the production of hormones that fuel cancer cell growth and are used to treat breast cancer in 500,000 women worldwide each year.

We can’t mention all of the inductees for 2023 (our editor made that very clear), but we would like to offer a special shout-out to brothers Cyril (the first Cyril in the NIHF, by the way) and Louis Keller, who invented the world’s first compact loader, which eventually became the Bobcat skid-steer loader. Not really medical, you’re probably thinking, but we’re sure that someone, somewhere, at some time, used one to build a hospital, landscape a hospital, or clean up after the demolition of a hospital.

The ‘scheme’ in the name should have been a clue

Retirement. The shiny reward to a lifetime’s worth of working and saving. We’re all literally working to get there, some of us more to get there early, but current research reveals that early retirement isn’t the relaxing finish line we dream about, cognitively speaking.

Researchers at Binghamton (N.Y.) University set out to examine just how retirement plans affect cognitive performance. They started off with China’s New Rural Pension Scheme (scheme probably has a less negative connotation in Chinese), a plan that financially aids the growing rural retirement-age population in the country. Then they looked at data from the Chinese Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey, which tests cognition with a focus on episodic memory and parts of intact mental status.

What they found was the opposite of what you would expect out of retirees with nothing but time on their hands.

The pension program, which had been in place for almost a decade, led to delayed recall, especially among women, supporting “the mental retirement hypothesis that decreased mental activity results in worsening cognitive skills,” the investigators said in a written statement.

There also was a drop in social engagement, with lower rates of volunteering and social interaction than people who didn’t receive the pension. Some behaviors, like regular alcohol consumption, did improve over the previous year, as did total health in general, but “the adverse effects of early retirement on mental and social engagement significantly outweigh the program’s protective effect on various health behaviors,” Plamen Nikolov, PhD, said about his research.