User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

No link between childhood vaccinations and allergies or asthma

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A meta-analysis by Australian researchers found no link between childhood vaccinations and an increase in allergies and asthma. In fact, children who received the BCG vaccine actually had a lesser incidence of eczema than other children, but there was no difference shown in any of the allergies or asthma.

The researchers, in a report published in the journal Allergy, write, “We found no evidence that childhood vaccination with commonly administered vaccines was associated with increased risk of later allergic disease.”

“Allergies have increased worldwide in the last 50 years, and in developed countries, earlier,” said study author Caroline J. Lodge, PhD, principal research fellow at the University of Melbourne, in an interview. “In developing countries, it is still a crisis.” No one knows why, she said. That was the reason for the recent study.

Allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and food allergies have a serious influence on quality of life, and the incidence is growing. According to the Global Asthma Network, there are 334 million people living with asthma. Between 2%-10% of adults have atopic eczema, and more than a 250,000 people have food allergies. This coincides temporally with an increase in mass vaccination of children.

Unlike the controversy surrounding vaccinations and autism, which has long been debunked as baseless, a hygiene hypothesis postulates that when children acquire immunity from many diseases, they become vulnerable to allergic reactions. Thanks to vaccinations, children in the developed world now are routinely immune to dozens of diseases.

That immunity leads to suppression of a major antibody response, increasing sensitivity to allergens and allergic disease. Suspicion of a link with childhood vaccinations has been used by opponents of vaccines in lobbying campaigns jeopardizing the sustainability of vaccine programs. In recent days, for example, the state of Tennessee has halted a program to encourage vaccination for COVID-19 as well as all other vaccinations, the result of pressure on the state by anti-vaccination lobbying.

But the Melbourne researchers reported that the meta-analysis of 42 published research studies doesn’t support the vaccine–allergy hypothesis. Using PubMed and EMBASE records between January 1946 and January 2018, researchers selected studies to be included in the analysis, looking for allergic outcomes in children given BCG or vaccines for measles or pertussis. Thirty-five publications reported cohort studies, and seven were based on randomized controlled trials.

The Australian study is not the only one showing the same lack of linkage between vaccination and allergy. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) found no association between mass vaccination and atopic disease. A 1998 Swedish study of 669 children found no differences in the incidence of allergic diseases between those who received pertussis vaccine and those who did not.

“The bottom line is that vaccines prevent infectious diseases,” said Matthew B. Laurens, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, in an interview. Dr. Laurens was not part of the Australian study.

“Large-scale epidemiological studies do not support the theory that vaccines are associated with an increased risk of allergy or asthma,” he stressed. “Parents should not be deterred from vaccinating their children because of fears that this would increase risks of allergy and/or asthma.”

Dr. Lodge and Dr. Laurens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first signs of elusive dysautonomia may appear on the skin

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.

During the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology, Adelaide A. Hebert, MD, defined dysautonomia as an umbrella term describing conditions that result in a malfunction of the autonomic nervous system. “This encompasses both the sympathetic and the parasympathetic components of the nervous system,” said Dr. Hebert, professor of dermatology and pediatrics, and chief of pediatric dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston. “Clinical findings may be neurometabolic, developmental, and/or degenerative,” representing a “whole constellation of issues” that physicians may encounter in practice, she noted. Of particular interest is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which affects between 1 million and 3 million people in the United States. Typical symptoms include lightheadedness, fainting, and a rapid increase in heartbeat after standing up from a seated position. Other conditions associated with dysautonomia include neurocardiogenic syncope and multiple system atrophy.

Dysautonomia can impact the brain, heart, mouth, blood vessels, eyes, immune cells, and bladder, as well as the skin. Patient presentations vary with symptoms that can range from mild to debilitating. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis of dysautonomia is 7 years. “It is very difficult to put together these mysterious symptoms that patients have unless one really thinks about dysautonomia as a possible diagnosis,” Dr. Hebert said.

One of the common symptoms that she has seen in her clinical practice is joint hypermobility. “There is a known association between dysautonomia and hypermobile-type Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and these patients often have hyperhidrosis,” she said. “So, keep in mind that you could see hypermobility, especially in those with EDS, with associated hyperhidrosis and dysautonomia.” Two key references that she recommends to clinicians when evaluating patients with possible dysautonomia are a study on postural tachycardia in hypermobile EDS, and an article on cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction in hypermobile EDS.

The Beighton Scoring System, which measures joint mobility on a 9-point scale, involves assessment of the joint mobility of the knuckle of both pinky fingers, the base of both thumbs, the elbows, knees, and spine. An instructional video on how to perform a joint hypermobility assessment is available on the Ehler-Danlos Society website.

Literature review

In March 2021, Dr. Hebert and colleagues from other medical specialties published a summary of the literature on cutaneous manifestations in dysautonomia, with an emphasis on syndromes of orthostatic intolerance. “We had neurology, cardiology, along with dermatology involved in contributing the findings they had seen in the UTHealth McGovern Dysautonomia Center of Excellence as there was a dearth of literature that taught us about the cutaneous manifestations of orthostatic intolerance syndromes,” Dr. Hebert said.

One study included in the review showed that 23 out of 26 patients with POTS had at least one of the following cutaneous manifestations: flushing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, evanescent hyperemia, livedo reticularis, erythromelalgia, and hypo- or hyperhidrosis. “If you see a patient with any of these findings, you want to think about the possibility of dysautonomia,” she said, adding that urticaria can also be a finding.

To screen for dysautonomia, she advised, “ask patients if they have difficulty sitting or standing upright, if they have indigestion or other gastric symptoms, abnormal blood vessel functioning such as low or high blood pressure, increased or decreased sweating, changes in urinary frequency or urinary incontinence, or challenges with vision.”

If the patient answers yes to two or more of these questions, she said, consider a referral to neurology and/or cardiology or a center of excellence for further evaluation with tilt-table testing and other screening tools. She also recommended a review published in 2015 that describes the dermatological manifestations of postural tachycardia syndrome and includes illustrated cases.

One of Dr. Hebert’s future dermatology residents assembled a composite of data from the Dysautonomia Center of Excellence, and in the study, found that, compared with males, females with dysautonomia suffer more from excessive sweating, paleness of the face, pale extremities, swelling, cyanosis, cold intolerance, flushing, and hot flashes.

Dr. Hebert disclosed that she has been a consultant to and an adviser for several pharmaceutical companies.

FROM SPD 2021

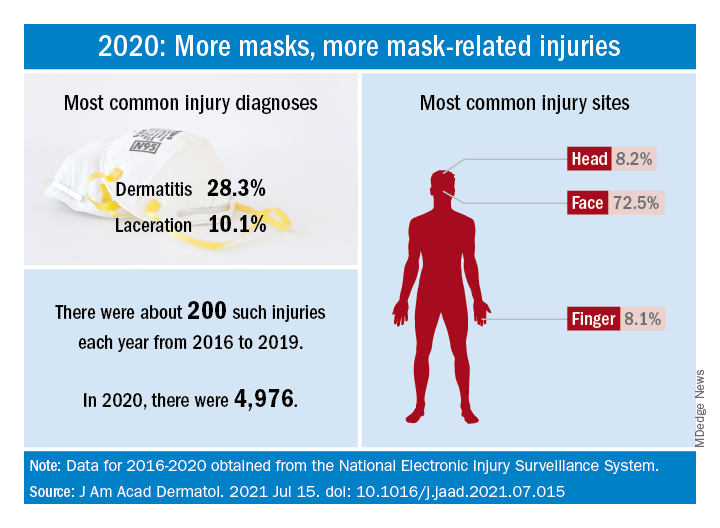

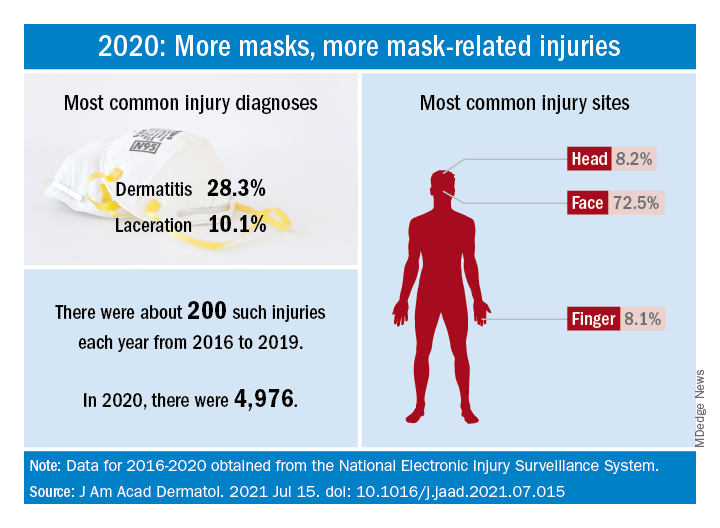

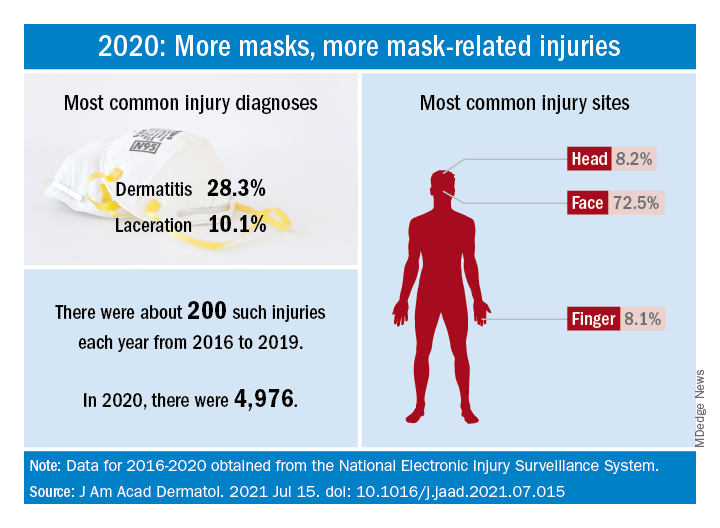

Face mask–related injuries rose dramatically in 2020

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

How dramatic? The number of mask-related injuries treated in U.S. emergency departments averaged about 200 per year from 2016 to 2019. In 2020, that figure soared to 4,976 – an increase of almost 2,400%, Gerald McGwin Jr., PhD, and associates said in a research letter published in the Journal to the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic the use of respiratory protection equipment was largely limited to healthcare and industrial settings. As [face mask] use by the general population increased, so too have reports of dermatologic reactions,” said Dr. McGwin and associates of the department of epidemiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Dermatitis was the most common mask-related injury treated last year, affecting 28.3% of those presenting to EDs, followed by lacerations at 10.1%. Injuries were more common in women than men, but while and black patients “were equally represented,” they noted, based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System, which includes about 100 hospitals and EDs.

Most injuries were caused by rashes/allergic reactions (38%) from prolonged use, poorly fitting masks (19%), and obscured vision (14%). “There was a small (5%) but meaningful number of injuries, all among children, attributable to consuming pieces of a mask or inserting dismantled pieces of a mask into body orifices,” the investigators said.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is available “to aid in the choice and proper fit of face masks,” they wrote, and “increased awareness of these resources [could] minimize the future occurrence of mask-related injuries.”

There was no funding source for the study, and the investigators did not declare any conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Dyspigmentation common in SOC patients with bullous pemphigoid

Patients of skin of color (SOC) with bullous pemphigoid presented significantly more often with dyspigmentation than did White patients in a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with BP at New York University Langone Health and Bellevue Hospital, also in New York.

“Dyspigmentation in the skin-of-color patient population is important to recognize not only for an objective evaluation of the disease process, but also from a quality of life perspective ... to ensure there is timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the skin-of-color population,” said medical student Payal Shah, BS, of New York University, in presenting the findings at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium.

Ms. Shah and coresearchers identified 94 cases of BP through retrospective view of electronic health records – 59 in White patients and 35 in SOC patients. The physical examination features most commonly found at initial presentation were bullae or vesicles in both White patients (64.4% ) and SOC patients (80%). Erosions or ulcers were also commonly found in both groups (42.4% of White patients and 60% of SOC patients).

Erythema was more commonly found in White patients at initial presentation: 35.6% vs. 14.3% of SOC patients (P = .032). Dyspigmentation, defined as areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, was more commonly found in SOC patients: 54.3% versus 10.2% in White patients (P < .001). The difference in erythema of inflammatory bullae in BP may stem from the fact that erythema is more difficult to discern in patients with darker skin types, Ms. Shah said.

SOC patients also were significantly younger at the time of initial presentation; their mean age was 63 years, compared with 77 years in the White population (P < .001).

The time to diagnosis, defined as the time from initial symptoms to dermatologic diagnosis, was greater for the SOC population –7.6 months vs. 6.2 months for white patients –though the difference was not statistically significant, they said in the abstract .

Dyspigmentation has been shown to be among the top dermatologic concerns of Black patients and has important quality of life implications. “Early diagnosis to prevent difficult-to-treat dyspigmentation is therefore of utmost importance,” they said in the abstract.

Prior research has demonstrated that non-White populations are at greater risk for hospitalization secondary to BP and have a greater risk of disease mortality, Ms. Shah noted in her presentation.

Patients of skin of color (SOC) with bullous pemphigoid presented significantly more often with dyspigmentation than did White patients in a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with BP at New York University Langone Health and Bellevue Hospital, also in New York.

“Dyspigmentation in the skin-of-color patient population is important to recognize not only for an objective evaluation of the disease process, but also from a quality of life perspective ... to ensure there is timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the skin-of-color population,” said medical student Payal Shah, BS, of New York University, in presenting the findings at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium.

Ms. Shah and coresearchers identified 94 cases of BP through retrospective view of electronic health records – 59 in White patients and 35 in SOC patients. The physical examination features most commonly found at initial presentation were bullae or vesicles in both White patients (64.4% ) and SOC patients (80%). Erosions or ulcers were also commonly found in both groups (42.4% of White patients and 60% of SOC patients).

Erythema was more commonly found in White patients at initial presentation: 35.6% vs. 14.3% of SOC patients (P = .032). Dyspigmentation, defined as areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, was more commonly found in SOC patients: 54.3% versus 10.2% in White patients (P < .001). The difference in erythema of inflammatory bullae in BP may stem from the fact that erythema is more difficult to discern in patients with darker skin types, Ms. Shah said.

SOC patients also were significantly younger at the time of initial presentation; their mean age was 63 years, compared with 77 years in the White population (P < .001).

The time to diagnosis, defined as the time from initial symptoms to dermatologic diagnosis, was greater for the SOC population –7.6 months vs. 6.2 months for white patients –though the difference was not statistically significant, they said in the abstract .

Dyspigmentation has been shown to be among the top dermatologic concerns of Black patients and has important quality of life implications. “Early diagnosis to prevent difficult-to-treat dyspigmentation is therefore of utmost importance,” they said in the abstract.

Prior research has demonstrated that non-White populations are at greater risk for hospitalization secondary to BP and have a greater risk of disease mortality, Ms. Shah noted in her presentation.

Patients of skin of color (SOC) with bullous pemphigoid presented significantly more often with dyspigmentation than did White patients in a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with BP at New York University Langone Health and Bellevue Hospital, also in New York.

“Dyspigmentation in the skin-of-color patient population is important to recognize not only for an objective evaluation of the disease process, but also from a quality of life perspective ... to ensure there is timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment in the skin-of-color population,” said medical student Payal Shah, BS, of New York University, in presenting the findings at the annual Skin of Color Society symposium.

Ms. Shah and coresearchers identified 94 cases of BP through retrospective view of electronic health records – 59 in White patients and 35 in SOC patients. The physical examination features most commonly found at initial presentation were bullae or vesicles in both White patients (64.4% ) and SOC patients (80%). Erosions or ulcers were also commonly found in both groups (42.4% of White patients and 60% of SOC patients).

Erythema was more commonly found in White patients at initial presentation: 35.6% vs. 14.3% of SOC patients (P = .032). Dyspigmentation, defined as areas of hyper- or hypopigmentation, was more commonly found in SOC patients: 54.3% versus 10.2% in White patients (P < .001). The difference in erythema of inflammatory bullae in BP may stem from the fact that erythema is more difficult to discern in patients with darker skin types, Ms. Shah said.

SOC patients also were significantly younger at the time of initial presentation; their mean age was 63 years, compared with 77 years in the White population (P < .001).

The time to diagnosis, defined as the time from initial symptoms to dermatologic diagnosis, was greater for the SOC population –7.6 months vs. 6.2 months for white patients –though the difference was not statistically significant, they said in the abstract .

Dyspigmentation has been shown to be among the top dermatologic concerns of Black patients and has important quality of life implications. “Early diagnosis to prevent difficult-to-treat dyspigmentation is therefore of utmost importance,” they said in the abstract.

Prior research has demonstrated that non-White populations are at greater risk for hospitalization secondary to BP and have a greater risk of disease mortality, Ms. Shah noted in her presentation.

FROM SOC 2021

Autoinflammatory diseases ‘not so rare after all,’ expert says

Not long ago, after all.

“Patients with autoinflammatory diseases are all around us, but many go several years without a diagnosis,” Dr. Dissanayake, a rheumatologist at the Autoinflammatory Disease Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The median time to diagnosis has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 5 years. You can imagine that this type of delay can lead to significant issues, not only with quality of life but also morbidity due to unchecked inflammation that can cause organ damage, and in the most severe cases, can result in an early death.”

Effective treatment options such as biologic medications, however, can prevent these negative sequelae if the disease is recognized early. “Dermatologists are in a unique position because they will often be the first specialist to see these patients and therefore make the diagnosis early on and really alter the lives of these patients,” he said.

While it’s common to classify autoinflammatory diseases by presenting features, such as age of onset, associated symptoms, family history/ethnicity, and triggers/alleviating factors for episodes, Dr. Dissanayake prefers to classify them into one of three groups based on pathophysiology, the first being inflammasomopathies. “When activated, an inflammasome is responsible for processing cytokines from the [interleukin]-1 family from the pro form to the active form,” he explained. As a result, if there is dysregulation and overactivity of the inflammasome, there is excessive production of cytokines like IL-1 beta and IL-18 driving the disease.

Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably abdominal pain, nonvasculitic rashes, uveitis, arthritis, elevated white blood cell count/neutrophils, and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Potential treatments include IL-1 blockers.

The second category of autoinflammatory diseases are the interferonopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the antiviral side of the innate immune system. “For example, if you have overactivity of a sensor for a nucleic acid in your cytosol, the cell misinterprets this as a viral infection and will turn on type 1 interferon production,” said Dr. Dissanayake, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “As a result, if you have dysregulation of these pathways, you will get excessive type 1 interferon that contributes to your disease manifestations.” Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably vasculitic rashes, interstitial lung disease, and intracranial calcifications. Inflammatory markers may not be as elevated, and autoantibodies may be present. Janus kinase inhibitors are a potential treatment, he said.

The third category of autoinflammatory diseases are the NF-kappaBopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Clinical characteristics can include fevers with organ involvement that can be highly variable but may include mucocutaneous lesions or granulomatous disease as potential clues. Treatment options depend on the pathway that is involved but tumor necrosis factor blockers often play a role because of the importance of NF-KB in this signaling pathway.

From a skin perspective, most of the rashes Dr. Dissanayake and colleagues see in the rheumatology clinic consist of nonspecific dermohypodermatitis: macules, papules, patches, or plaques. The most common monogenic autoinflammatory disease is Familial Mediterranean Fever syndrome, which “commonly presents as an erysipelas-like rash of the lower extremities, typically below the knee, often over the malleolus,” he said.

Other monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with similar rashes include TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome, Hyper-IgD syndrome, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Other patients present with urticarial rashes, most commonly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). “This is a neutrophilic urticaria, so it tends not to be pruritic and can actually sometimes be tender,” he said. “It also tends not to be as transient as your typical urticaria.” Urticarial rashes can also appear with NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome–2), PLCgamma2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, and Schnitzler syndrome (monoclonal IgM gammopathy).

Patients can also present with pyogenic or pustular lesions, which can appear with pyoderma gangrenosum–related diseases, such as pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis (PAPA) syndrome; pyrin-associated inflammation with neutrophilic dermatosis; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist; deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist; and Majeed syndrome, a mutation in the LPIN2 gene.

The mucocutaneous system can also be affected in autoinflammatory diseases, often presenting with symptoms such as periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, and pharyngitis. Cervical adenitis syndrome is the most common autoinflammatory disease in childhood and can present with aphthous stomatitis, he said, while Behcet’s disease typically presents with oral and genital ulcers. “More recently, monogenic forms of Behcet’s disease have been described, with haploinsufficiency of A20 and RelA, which are both part of the NF-KB pathway,” he said.

Finally, the presence of vasculitic lesions often suggest interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy in infancy, proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2.

Dr. Dissanayake noted that dermatologists should suspect an autoimmune disease if a patient has recurrent fevers, evidence of systemic inflammation on blood work, and if multiple organ systems are involved, especially the lungs, gut, joints, CNS system, and eyes. “Many of these patients have episodic and stereotypical attacks,” he said.

“One of the tools we use in the autoinflammatory clinic is to have patients and families keep a symptom diary where they track the dates of the various symptoms. We can review this during their appointment and try to come up with a diagnosis based on the pattern,” he said.

Since many of these diseases are due to a single gene defect, if there’s any evidence to suggest a monogenic cause, consider an autoinflammatory disease, he added. “If there’s a family history, if there’s consanguinity, or if there’s early age of onset – these may all lead you to think about monogenic autoinflammatory disease.”

During a question-and-answer session, a meeting attendee asked what type of workup he recommends when an autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected. “It partially depends on what organ systems you suspect to be involved,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “As a routine baseline, typically what we would check is CBC and differential, [erythrocyte sedimentation rate] and [C-reactive protein], and we screen for liver transaminases and creatinine to check for liver and kidney issues. A serum albumin will also tell you if the patient is hypoalbuminemic, that there’s been some chronic inflammation and they’re starting to leak the protein out. It’s good to check blood work during the flare and off the flare, to get a sense of the persistence of that inflammation.”

Dr. Dissanayake disclosed that he has received research finding from Gilead Sciences and speaker fees from Novartis.

*This story was updated on 9/20/2021.

Not long ago, after all.

“Patients with autoinflammatory diseases are all around us, but many go several years without a diagnosis,” Dr. Dissanayake, a rheumatologist at the Autoinflammatory Disease Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The median time to diagnosis has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 5 years. You can imagine that this type of delay can lead to significant issues, not only with quality of life but also morbidity due to unchecked inflammation that can cause organ damage, and in the most severe cases, can result in an early death.”

Effective treatment options such as biologic medications, however, can prevent these negative sequelae if the disease is recognized early. “Dermatologists are in a unique position because they will often be the first specialist to see these patients and therefore make the diagnosis early on and really alter the lives of these patients,” he said.

While it’s common to classify autoinflammatory diseases by presenting features, such as age of onset, associated symptoms, family history/ethnicity, and triggers/alleviating factors for episodes, Dr. Dissanayake prefers to classify them into one of three groups based on pathophysiology, the first being inflammasomopathies. “When activated, an inflammasome is responsible for processing cytokines from the [interleukin]-1 family from the pro form to the active form,” he explained. As a result, if there is dysregulation and overactivity of the inflammasome, there is excessive production of cytokines like IL-1 beta and IL-18 driving the disease.

Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably abdominal pain, nonvasculitic rashes, uveitis, arthritis, elevated white blood cell count/neutrophils, and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Potential treatments include IL-1 blockers.

The second category of autoinflammatory diseases are the interferonopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the antiviral side of the innate immune system. “For example, if you have overactivity of a sensor for a nucleic acid in your cytosol, the cell misinterprets this as a viral infection and will turn on type 1 interferon production,” said Dr. Dissanayake, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “As a result, if you have dysregulation of these pathways, you will get excessive type 1 interferon that contributes to your disease manifestations.” Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably vasculitic rashes, interstitial lung disease, and intracranial calcifications. Inflammatory markers may not be as elevated, and autoantibodies may be present. Janus kinase inhibitors are a potential treatment, he said.

The third category of autoinflammatory diseases are the NF-kappaBopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Clinical characteristics can include fevers with organ involvement that can be highly variable but may include mucocutaneous lesions or granulomatous disease as potential clues. Treatment options depend on the pathway that is involved but tumor necrosis factor blockers often play a role because of the importance of NF-KB in this signaling pathway.

From a skin perspective, most of the rashes Dr. Dissanayake and colleagues see in the rheumatology clinic consist of nonspecific dermohypodermatitis: macules, papules, patches, or plaques. The most common monogenic autoinflammatory disease is Familial Mediterranean Fever syndrome, which “commonly presents as an erysipelas-like rash of the lower extremities, typically below the knee, often over the malleolus,” he said.

Other monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with similar rashes include TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome, Hyper-IgD syndrome, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Other patients present with urticarial rashes, most commonly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). “This is a neutrophilic urticaria, so it tends not to be pruritic and can actually sometimes be tender,” he said. “It also tends not to be as transient as your typical urticaria.” Urticarial rashes can also appear with NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome–2), PLCgamma2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, and Schnitzler syndrome (monoclonal IgM gammopathy).

Patients can also present with pyogenic or pustular lesions, which can appear with pyoderma gangrenosum–related diseases, such as pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis (PAPA) syndrome; pyrin-associated inflammation with neutrophilic dermatosis; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist; deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist; and Majeed syndrome, a mutation in the LPIN2 gene.

The mucocutaneous system can also be affected in autoinflammatory diseases, often presenting with symptoms such as periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, and pharyngitis. Cervical adenitis syndrome is the most common autoinflammatory disease in childhood and can present with aphthous stomatitis, he said, while Behcet’s disease typically presents with oral and genital ulcers. “More recently, monogenic forms of Behcet’s disease have been described, with haploinsufficiency of A20 and RelA, which are both part of the NF-KB pathway,” he said.

Finally, the presence of vasculitic lesions often suggest interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy in infancy, proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2.

Dr. Dissanayake noted that dermatologists should suspect an autoimmune disease if a patient has recurrent fevers, evidence of systemic inflammation on blood work, and if multiple organ systems are involved, especially the lungs, gut, joints, CNS system, and eyes. “Many of these patients have episodic and stereotypical attacks,” he said.

“One of the tools we use in the autoinflammatory clinic is to have patients and families keep a symptom diary where they track the dates of the various symptoms. We can review this during their appointment and try to come up with a diagnosis based on the pattern,” he said.

Since many of these diseases are due to a single gene defect, if there’s any evidence to suggest a monogenic cause, consider an autoinflammatory disease, he added. “If there’s a family history, if there’s consanguinity, or if there’s early age of onset – these may all lead you to think about monogenic autoinflammatory disease.”

During a question-and-answer session, a meeting attendee asked what type of workup he recommends when an autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected. “It partially depends on what organ systems you suspect to be involved,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “As a routine baseline, typically what we would check is CBC and differential, [erythrocyte sedimentation rate] and [C-reactive protein], and we screen for liver transaminases and creatinine to check for liver and kidney issues. A serum albumin will also tell you if the patient is hypoalbuminemic, that there’s been some chronic inflammation and they’re starting to leak the protein out. It’s good to check blood work during the flare and off the flare, to get a sense of the persistence of that inflammation.”

Dr. Dissanayake disclosed that he has received research finding from Gilead Sciences and speaker fees from Novartis.

*This story was updated on 9/20/2021.

Not long ago, after all.

“Patients with autoinflammatory diseases are all around us, but many go several years without a diagnosis,” Dr. Dissanayake, a rheumatologist at the Autoinflammatory Disease Clinic at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “The median time to diagnosis has been estimated to be between 2.5 and 5 years. You can imagine that this type of delay can lead to significant issues, not only with quality of life but also morbidity due to unchecked inflammation that can cause organ damage, and in the most severe cases, can result in an early death.”

Effective treatment options such as biologic medications, however, can prevent these negative sequelae if the disease is recognized early. “Dermatologists are in a unique position because they will often be the first specialist to see these patients and therefore make the diagnosis early on and really alter the lives of these patients,” he said.

While it’s common to classify autoinflammatory diseases by presenting features, such as age of onset, associated symptoms, family history/ethnicity, and triggers/alleviating factors for episodes, Dr. Dissanayake prefers to classify them into one of three groups based on pathophysiology, the first being inflammasomopathies. “When activated, an inflammasome is responsible for processing cytokines from the [interleukin]-1 family from the pro form to the active form,” he explained. As a result, if there is dysregulation and overactivity of the inflammasome, there is excessive production of cytokines like IL-1 beta and IL-18 driving the disease.

Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably abdominal pain, nonvasculitic rashes, uveitis, arthritis, elevated white blood cell count/neutrophils, and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Potential treatments include IL-1 blockers.

The second category of autoinflammatory diseases are the interferonopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the antiviral side of the innate immune system. “For example, if you have overactivity of a sensor for a nucleic acid in your cytosol, the cell misinterprets this as a viral infection and will turn on type 1 interferon production,” said Dr. Dissanayake, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “As a result, if you have dysregulation of these pathways, you will get excessive type 1 interferon that contributes to your disease manifestations.” Clinical characteristics include fevers and organ involvement, notably vasculitic rashes, interstitial lung disease, and intracranial calcifications. Inflammatory markers may not be as elevated, and autoantibodies may be present. Janus kinase inhibitors are a potential treatment, he said.

The third category of autoinflammatory diseases are the NF-kappaBopathies, which are caused by overactivity of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Clinical characteristics can include fevers with organ involvement that can be highly variable but may include mucocutaneous lesions or granulomatous disease as potential clues. Treatment options depend on the pathway that is involved but tumor necrosis factor blockers often play a role because of the importance of NF-KB in this signaling pathway.

From a skin perspective, most of the rashes Dr. Dissanayake and colleagues see in the rheumatology clinic consist of nonspecific dermohypodermatitis: macules, papules, patches, or plaques. The most common monogenic autoinflammatory disease is Familial Mediterranean Fever syndrome, which “commonly presents as an erysipelas-like rash of the lower extremities, typically below the knee, often over the malleolus,” he said.

Other monogenic autoinflammatory diseases with similar rashes include TNF receptor–associated periodic syndrome, Hyper-IgD syndrome, and systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Other patients present with urticarial rashes, most commonly cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). “This is a neutrophilic urticaria, so it tends not to be pruritic and can actually sometimes be tender,” he said. “It also tends not to be as transient as your typical urticaria.” Urticarial rashes can also appear with NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome–2), PLCgamma2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, and Schnitzler syndrome (monoclonal IgM gammopathy).

Patients can also present with pyogenic or pustular lesions, which can appear with pyoderma gangrenosum–related diseases, such as pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, arthritis (PAPA) syndrome; pyrin-associated inflammation with neutrophilic dermatosis; deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist; deficiency of IL-36 receptor antagonist; and Majeed syndrome, a mutation in the LPIN2 gene.

The mucocutaneous system can also be affected in autoinflammatory diseases, often presenting with symptoms such as periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, and pharyngitis. Cervical adenitis syndrome is the most common autoinflammatory disease in childhood and can present with aphthous stomatitis, he said, while Behcet’s disease typically presents with oral and genital ulcers. “More recently, monogenic forms of Behcet’s disease have been described, with haploinsufficiency of A20 and RelA, which are both part of the NF-KB pathway,” he said.

Finally, the presence of vasculitic lesions often suggest interferonopathies such as STING-associated vasculopathy in infancy, proteasome-associated autoinflammatory syndrome and deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2.

Dr. Dissanayake noted that dermatologists should suspect an autoimmune disease if a patient has recurrent fevers, evidence of systemic inflammation on blood work, and if multiple organ systems are involved, especially the lungs, gut, joints, CNS system, and eyes. “Many of these patients have episodic and stereotypical attacks,” he said.

“One of the tools we use in the autoinflammatory clinic is to have patients and families keep a symptom diary where they track the dates of the various symptoms. We can review this during their appointment and try to come up with a diagnosis based on the pattern,” he said.

Since many of these diseases are due to a single gene defect, if there’s any evidence to suggest a monogenic cause, consider an autoinflammatory disease, he added. “If there’s a family history, if there’s consanguinity, or if there’s early age of onset – these may all lead you to think about monogenic autoinflammatory disease.”

During a question-and-answer session, a meeting attendee asked what type of workup he recommends when an autoinflammatory syndrome is suspected. “It partially depends on what organ systems you suspect to be involved,” Dr. Dissanayake said. “As a routine baseline, typically what we would check is CBC and differential, [erythrocyte sedimentation rate] and [C-reactive protein], and we screen for liver transaminases and creatinine to check for liver and kidney issues. A serum albumin will also tell you if the patient is hypoalbuminemic, that there’s been some chronic inflammation and they’re starting to leak the protein out. It’s good to check blood work during the flare and off the flare, to get a sense of the persistence of that inflammation.”

Dr. Dissanayake disclosed that he has received research finding from Gilead Sciences and speaker fees from Novartis.

*This story was updated on 9/20/2021.

FROM SPD 2021

Expert proposes rethinking the classification of SJS/TEN

In the opinion of Neil H. Shear, MD, a stepwise approach is the best way to diagnose possible drug-induced skin disease and determine the root cause.

“Often, we need to think of more than one cause,” he said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It could be drug X. It could be drug Y. It could be contrast media. We must think broadly and pay special attention to skin of color, overlapping syndromes, and the changing diagnostic assessment over time.”

His suggested diagnostic triangle includes appearance of the rash or lesion(s), systemic impact, and histology. “The first is the appearance,” said Dr. Shear, professor emeritus of dermatology, clinical pharmacology and toxicology, and medicine at the University of Toronto. “Is it exanthem? Is it blistering? Don’t just say drug ‘rash.’ That doesn’t work. You need to know if there are systemic features, and sometimes histologic information can change your approach or diagnosis, but not as often as one might think,” he said, noting that, in his view, the two main factors are appearance and systemic impact.

The presence of fever is a hallmark of systemic problems, he continued, “so if you see fever, you know you’re probably going to be dealing with a complex reaction, so we need to know the morphology.” Consider whether it is simple exanthem (a mild, uncomplicated rash) or complex exanthem (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or fever, malaise, and adenopathy).

As for other morphologies, urticarial lesions could be urticaria or a serum sickness-like reaction, pustular lesions could be acneiform or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, while

Dr. Shear considers SJS/TEN as a spectrum of blistering disease, “because there’s not a single diagnosis,” he said. “There’s a spectrum, if you will, depending on how advanced people are in their disease.” He coauthored a 1991 report describing eight cases of mycoplasma and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “I was surprised at how long that stood up as about the only paper in that area,” he said. “But there’s much more happening now with a proliferation of terms,” he added, referring to MIRM (Mycoplasma pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis), RIME (reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption); and Fuchs syndrome, or SJS without skin lesions.

What was not appreciated in the early classification of SJS, he continued, was a “side basket” of bullous erythema multiforme. “We didn’t know what to call it,” he said. “At one point we called it bullous erythema multiforme. At another point we called it erythema multiforme major. We just didn’t know what it was.”

The appearance and systemic effects of SJS comprise what he termed SJS type 2 – or the early stages of TEN. Taken together, he refers to these two conditions as TEN Spectrum, or TENS. “One of the traps is that TENS can look like varicella, and vice versa, especially in very dark brown or black skin,” Dr. Shear said. “You have to be careful. A biopsy might be worthwhile. Acute lupus has the pathology of TENS but the patients are not as systemically ill as true TENS.”

In 2011, Japanese researchers reported on 38 cases of SJS associated with M. pneumoniae, and 78 cases of drug-induced SJS. They found that 66% of adult patients with M. pneumoniae–associated SJS developed mucocutaneous lesions and fever/respiratory symptoms on the same day, mostly shortness of breath and cough. In contrast, most of the patients aged under 20 years developed fever/respiratory symptoms before mucocutaneous involvement.

“The big clinical differentiator between drug-induced SJS and mycoplasma-induced SJS was respiratory disorder,” said Dr. Shear, who was not affiliated with the study. “That means you’re probably looking at something that’s mycoplasma related [when respiratory problems are present]. Even if you can’t prove it’s mycoplasma related, that probably needs to be the target of your therapy. The idea ... is to make sure it’s clear at the end. One, so they get better, and two, so that we’re not giving drugs needlessly when it was really mycoplasma.”

Noting that HLA-B*15:02 is a marker for carbamazepine-induced SJS and TEN, he said, “a positive HLA test can support the diagnosis, confirm the suspected offending drug, and is valuable for familial genetic counseling.”

As for treatment of SJS, TEN, and other cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions, a randomized Japanese clinical trial evaluating prednisolone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day IV versus etanercept 25-50 mg subcutaneously twice per week in 96 patients with SJS-TEN found that etanercept decreased the mortality rate by 8.3%. In addition, etanercept reduced skin healing time, when compared with prednisolone (a median of 14 vs. 19 days, respectively; P = .010), and was associated with a lower incidence of GI hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 18.2%, respectively; P = .03).

Dr. Shear said that he would like to see better therapeutics for severe, complex patients. “After leaving the hospital, people with SJS or people with TEN need to have ongoing care, consultation, and explanation so they and their families know what drugs are safe in the future.”

Dr. Shear disclosed that he has been a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Medicine, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, LEO Pharma, Otsuka, Janssen, Alpha Laboratories, Lilly, ChemoCentryx, Vivoryon, Galderma, Innovaderm, Chromocell, and Kyowa Kirin.

In the opinion of Neil H. Shear, MD, a stepwise approach is the best way to diagnose possible drug-induced skin disease and determine the root cause.

“Often, we need to think of more than one cause,” he said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It could be drug X. It could be drug Y. It could be contrast media. We must think broadly and pay special attention to skin of color, overlapping syndromes, and the changing diagnostic assessment over time.”

His suggested diagnostic triangle includes appearance of the rash or lesion(s), systemic impact, and histology. “The first is the appearance,” said Dr. Shear, professor emeritus of dermatology, clinical pharmacology and toxicology, and medicine at the University of Toronto. “Is it exanthem? Is it blistering? Don’t just say drug ‘rash.’ That doesn’t work. You need to know if there are systemic features, and sometimes histologic information can change your approach or diagnosis, but not as often as one might think,” he said, noting that, in his view, the two main factors are appearance and systemic impact.

The presence of fever is a hallmark of systemic problems, he continued, “so if you see fever, you know you’re probably going to be dealing with a complex reaction, so we need to know the morphology.” Consider whether it is simple exanthem (a mild, uncomplicated rash) or complex exanthem (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or fever, malaise, and adenopathy).

As for other morphologies, urticarial lesions could be urticaria or a serum sickness-like reaction, pustular lesions could be acneiform or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, while

Dr. Shear considers SJS/TEN as a spectrum of blistering disease, “because there’s not a single diagnosis,” he said. “There’s a spectrum, if you will, depending on how advanced people are in their disease.” He coauthored a 1991 report describing eight cases of mycoplasma and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “I was surprised at how long that stood up as about the only paper in that area,” he said. “But there’s much more happening now with a proliferation of terms,” he added, referring to MIRM (Mycoplasma pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis), RIME (reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption); and Fuchs syndrome, or SJS without skin lesions.

What was not appreciated in the early classification of SJS, he continued, was a “side basket” of bullous erythema multiforme. “We didn’t know what to call it,” he said. “At one point we called it bullous erythema multiforme. At another point we called it erythema multiforme major. We just didn’t know what it was.”

The appearance and systemic effects of SJS comprise what he termed SJS type 2 – or the early stages of TEN. Taken together, he refers to these two conditions as TEN Spectrum, or TENS. “One of the traps is that TENS can look like varicella, and vice versa, especially in very dark brown or black skin,” Dr. Shear said. “You have to be careful. A biopsy might be worthwhile. Acute lupus has the pathology of TENS but the patients are not as systemically ill as true TENS.”

In 2011, Japanese researchers reported on 38 cases of SJS associated with M. pneumoniae, and 78 cases of drug-induced SJS. They found that 66% of adult patients with M. pneumoniae–associated SJS developed mucocutaneous lesions and fever/respiratory symptoms on the same day, mostly shortness of breath and cough. In contrast, most of the patients aged under 20 years developed fever/respiratory symptoms before mucocutaneous involvement.

“The big clinical differentiator between drug-induced SJS and mycoplasma-induced SJS was respiratory disorder,” said Dr. Shear, who was not affiliated with the study. “That means you’re probably looking at something that’s mycoplasma related [when respiratory problems are present]. Even if you can’t prove it’s mycoplasma related, that probably needs to be the target of your therapy. The idea ... is to make sure it’s clear at the end. One, so they get better, and two, so that we’re not giving drugs needlessly when it was really mycoplasma.”

Noting that HLA-B*15:02 is a marker for carbamazepine-induced SJS and TEN, he said, “a positive HLA test can support the diagnosis, confirm the suspected offending drug, and is valuable for familial genetic counseling.”

As for treatment of SJS, TEN, and other cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions, a randomized Japanese clinical trial evaluating prednisolone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day IV versus etanercept 25-50 mg subcutaneously twice per week in 96 patients with SJS-TEN found that etanercept decreased the mortality rate by 8.3%. In addition, etanercept reduced skin healing time, when compared with prednisolone (a median of 14 vs. 19 days, respectively; P = .010), and was associated with a lower incidence of GI hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 18.2%, respectively; P = .03).

Dr. Shear said that he would like to see better therapeutics for severe, complex patients. “After leaving the hospital, people with SJS or people with TEN need to have ongoing care, consultation, and explanation so they and their families know what drugs are safe in the future.”

Dr. Shear disclosed that he has been a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Medicine, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, LEO Pharma, Otsuka, Janssen, Alpha Laboratories, Lilly, ChemoCentryx, Vivoryon, Galderma, Innovaderm, Chromocell, and Kyowa Kirin.

In the opinion of Neil H. Shear, MD, a stepwise approach is the best way to diagnose possible drug-induced skin disease and determine the root cause.

“Often, we need to think of more than one cause,” he said during the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “It could be drug X. It could be drug Y. It could be contrast media. We must think broadly and pay special attention to skin of color, overlapping syndromes, and the changing diagnostic assessment over time.”

His suggested diagnostic triangle includes appearance of the rash or lesion(s), systemic impact, and histology. “The first is the appearance,” said Dr. Shear, professor emeritus of dermatology, clinical pharmacology and toxicology, and medicine at the University of Toronto. “Is it exanthem? Is it blistering? Don’t just say drug ‘rash.’ That doesn’t work. You need to know if there are systemic features, and sometimes histologic information can change your approach or diagnosis, but not as often as one might think,” he said, noting that, in his view, the two main factors are appearance and systemic impact.

The presence of fever is a hallmark of systemic problems, he continued, “so if you see fever, you know you’re probably going to be dealing with a complex reaction, so we need to know the morphology.” Consider whether it is simple exanthem (a mild, uncomplicated rash) or complex exanthem (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms or fever, malaise, and adenopathy).

As for other morphologies, urticarial lesions could be urticaria or a serum sickness-like reaction, pustular lesions could be acneiform or acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, while

Dr. Shear considers SJS/TEN as a spectrum of blistering disease, “because there’s not a single diagnosis,” he said. “There’s a spectrum, if you will, depending on how advanced people are in their disease.” He coauthored a 1991 report describing eight cases of mycoplasma and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. “I was surprised at how long that stood up as about the only paper in that area,” he said. “But there’s much more happening now with a proliferation of terms,” he added, referring to MIRM (Mycoplasma pneumonia–induced rash and mucositis), RIME (reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption); and Fuchs syndrome, or SJS without skin lesions.

What was not appreciated in the early classification of SJS, he continued, was a “side basket” of bullous erythema multiforme. “We didn’t know what to call it,” he said. “At one point we called it bullous erythema multiforme. At another point we called it erythema multiforme major. We just didn’t know what it was.”

The appearance and systemic effects of SJS comprise what he termed SJS type 2 – or the early stages of TEN. Taken together, he refers to these two conditions as TEN Spectrum, or TENS. “One of the traps is that TENS can look like varicella, and vice versa, especially in very dark brown or black skin,” Dr. Shear said. “You have to be careful. A biopsy might be worthwhile. Acute lupus has the pathology of TENS but the patients are not as systemically ill as true TENS.”

In 2011, Japanese researchers reported on 38 cases of SJS associated with M. pneumoniae, and 78 cases of drug-induced SJS. They found that 66% of adult patients with M. pneumoniae–associated SJS developed mucocutaneous lesions and fever/respiratory symptoms on the same day, mostly shortness of breath and cough. In contrast, most of the patients aged under 20 years developed fever/respiratory symptoms before mucocutaneous involvement.

“The big clinical differentiator between drug-induced SJS and mycoplasma-induced SJS was respiratory disorder,” said Dr. Shear, who was not affiliated with the study. “That means you’re probably looking at something that’s mycoplasma related [when respiratory problems are present]. Even if you can’t prove it’s mycoplasma related, that probably needs to be the target of your therapy. The idea ... is to make sure it’s clear at the end. One, so they get better, and two, so that we’re not giving drugs needlessly when it was really mycoplasma.”

Noting that HLA-B*15:02 is a marker for carbamazepine-induced SJS and TEN, he said, “a positive HLA test can support the diagnosis, confirm the suspected offending drug, and is valuable for familial genetic counseling.”

As for treatment of SJS, TEN, and other cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–mediated severe cutaneous adverse reactions, a randomized Japanese clinical trial evaluating prednisolone 1-1.5 mg/kg/day IV versus etanercept 25-50 mg subcutaneously twice per week in 96 patients with SJS-TEN found that etanercept decreased the mortality rate by 8.3%. In addition, etanercept reduced skin healing time, when compared with prednisolone (a median of 14 vs. 19 days, respectively; P = .010), and was associated with a lower incidence of GI hemorrhage (2.6% vs. 18.2%, respectively; P = .03).

Dr. Shear said that he would like to see better therapeutics for severe, complex patients. “After leaving the hospital, people with SJS or people with TEN need to have ongoing care, consultation, and explanation so they and their families know what drugs are safe in the future.”

Dr. Shear disclosed that he has been a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Medicine, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, LEO Pharma, Otsuka, Janssen, Alpha Laboratories, Lilly, ChemoCentryx, Vivoryon, Galderma, Innovaderm, Chromocell, and Kyowa Kirin.

FROM SPD 2021

Several uncommon skin disorders related to internal diseases reviewed

and may spawn misdiagnoses, a dermatologist told colleagues.

“Proper diagnosis can lead to an effective management in our patients,” said Jeffrey Callen, MD, professor of medicine and chief of dermatology at the University of Louisville (Ky.), who spoke at the Inaugural Symposium for Inflammatory Skin Disease.

Sarcoidosis

The cause of sarcoidosis, an inflammatory disease that tends to affect the lungs, “is unknown, but it’s probably an immunologic disorder,” Dr. Callen said, “and there probably is a genetic predisposition.” About 20%-25% of patients with sarcoidosis have skin lesions that are either “specific” (a biopsy that reveals a noncaseating – “naked” – granuloma) or “nonspecific” (most commonly, erythema nodosum, or EN).

The specific lesions in sarcoidosis may occur in parts of the body, such as the knees, which were injured earlier in life and may have taken in foreign bodies, Dr. Callen said. As for nonspecific lesions, about 20% of patients with EN have an acute, self-limiting form of sarcoidosis. “These patients will have bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, anterior uveitis, and polyarthritis. It’s generally treated symptomatically because it goes away on its own.”

He cautioned colleagues to beware of indurated, infiltrative facial lesions known as lupus pernio that are commonly found on the nose. They’re more prevalent in Black patients and possibly women, who are at higher risk of manifestations outside the skin, he said. “If you have it along the nasal rim, you should look into the upper respiratory tract for involvement.”

Dr. Callen recommends an extensive workup in patients with suspected sarcoidosis, including biopsy (with the exception of EN lesions), cultures and special stains, and screening when appropriate, for disease in organs such as the eyes, lungs, heart, and kidneys.