User login

T2D: Dapagliflozin consistently reduces CV and kidney disease risk irrespective of background therapy

Key clinical point: Dapagliflozin consistently reduced the risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) and kidney disease progression irrespective of the background CV medication in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) with a consistent safety profile.

Major finding: Dapagliflozin vs placebo led to a consistent reduction in the composite of CV death/HHF, HHF alone, and kidney-specific outcomes irrespective of the background CV medications (Pinteraction > .05), with patients not using diuretics showing better kidney specific outcomes (Pinteraction = .003). Serious adverse events were not significantly different between the dapagliflozin and placebo groups.

Study details: Findings are from a prespecified secondary analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial including 17,160 patients with T2D and either atherosclerotic disease or multiple CV risk factors.

Disclosures: The DECLAR-TIMI 58 trial was supported by AstraZeneca. One author reported being an employee and shareholder of AstraZeneca. Some authors reported receiving research funding or support, honoraria, personal fees, or consulting or speaker fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AstraZeneca.

Source: Oyama K et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to background use of cardiovascular medications in patients with type 2 diabetes: A prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2006

Key clinical point: Dapagliflozin consistently reduced the risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) and kidney disease progression irrespective of the background CV medication in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) with a consistent safety profile.

Major finding: Dapagliflozin vs placebo led to a consistent reduction in the composite of CV death/HHF, HHF alone, and kidney-specific outcomes irrespective of the background CV medications (Pinteraction > .05), with patients not using diuretics showing better kidney specific outcomes (Pinteraction = .003). Serious adverse events were not significantly different between the dapagliflozin and placebo groups.

Study details: Findings are from a prespecified secondary analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial including 17,160 patients with T2D and either atherosclerotic disease or multiple CV risk factors.

Disclosures: The DECLAR-TIMI 58 trial was supported by AstraZeneca. One author reported being an employee and shareholder of AstraZeneca. Some authors reported receiving research funding or support, honoraria, personal fees, or consulting or speaker fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AstraZeneca.

Source: Oyama K et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to background use of cardiovascular medications in patients with type 2 diabetes: A prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2006

Key clinical point: Dapagliflozin consistently reduced the risk for cardiovascular (CV) death or hospitalization for heart failure (HHF) and kidney disease progression irrespective of the background CV medication in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) with a consistent safety profile.

Major finding: Dapagliflozin vs placebo led to a consistent reduction in the composite of CV death/HHF, HHF alone, and kidney-specific outcomes irrespective of the background CV medications (Pinteraction > .05), with patients not using diuretics showing better kidney specific outcomes (Pinteraction = .003). Serious adverse events were not significantly different between the dapagliflozin and placebo groups.

Study details: Findings are from a prespecified secondary analysis of the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial including 17,160 patients with T2D and either atherosclerotic disease or multiple CV risk factors.

Disclosures: The DECLAR-TIMI 58 trial was supported by AstraZeneca. One author reported being an employee and shareholder of AstraZeneca. Some authors reported receiving research funding or support, honoraria, personal fees, or consulting or speaker fees, or serving as advisory board members for various sources, including AstraZeneca.

Source: Oyama K et al. Efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin according to background use of cardiovascular medications in patients with type 2 diabetes: A prespecified secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022 (Jul 20). Doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.2006

Comparative efficacy and safety of Gla-300 and Deg-100 in T2D

Key clinical point: Initiation of 300 units/mL insulin glargine (Gla-300) or 100 units/mL degludec (Deg-100) was associated with similar improvements in glycemic control, no weight gain, and low rates of hypoglycemia in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Major finding: After 6 months, both Gla-300 and Deg-100 led to a significant and similar reduction in glycated hemoglobin (between group difference [Δ] −0.01%; P = .49) and fasting blood glucose (Δ −2.09 mg/dL; P = .74) levels, with no significant changes in body weight in both treatment groups. Overall, the incidence of hypoglycemia was low, with no severe episodes reported.

Study details: This was a retrospective study including insulin-naive patients with T2D who initiated Gla-300 and were propensity matched with those who initiated Deg-100 (n = 357).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi S.r.l., Milan, Italy. Some authors declared receiving lecture fees, consulting fees, research funding, or speaking honoraria from various sources, including Sanofi. M Larosa declared being an employee and holding stock in Sanofi.

Source: Fadini GP et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of glargine 300 U/mL versus degludec 100 U/mL in insulin-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes. A multicenter retrospective real-world study (RESTORE-2 NAIVE STUDY). Acta Diabetol. 2022 (Jul 21). Doi: 10.1007/s00592-022-01925-9

Key clinical point: Initiation of 300 units/mL insulin glargine (Gla-300) or 100 units/mL degludec (Deg-100) was associated with similar improvements in glycemic control, no weight gain, and low rates of hypoglycemia in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Major finding: After 6 months, both Gla-300 and Deg-100 led to a significant and similar reduction in glycated hemoglobin (between group difference [Δ] −0.01%; P = .49) and fasting blood glucose (Δ −2.09 mg/dL; P = .74) levels, with no significant changes in body weight in both treatment groups. Overall, the incidence of hypoglycemia was low, with no severe episodes reported.

Study details: This was a retrospective study including insulin-naive patients with T2D who initiated Gla-300 and were propensity matched with those who initiated Deg-100 (n = 357).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi S.r.l., Milan, Italy. Some authors declared receiving lecture fees, consulting fees, research funding, or speaking honoraria from various sources, including Sanofi. M Larosa declared being an employee and holding stock in Sanofi.

Source: Fadini GP et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of glargine 300 U/mL versus degludec 100 U/mL in insulin-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes. A multicenter retrospective real-world study (RESTORE-2 NAIVE STUDY). Acta Diabetol. 2022 (Jul 21). Doi: 10.1007/s00592-022-01925-9

Key clinical point: Initiation of 300 units/mL insulin glargine (Gla-300) or 100 units/mL degludec (Deg-100) was associated with similar improvements in glycemic control, no weight gain, and low rates of hypoglycemia in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Major finding: After 6 months, both Gla-300 and Deg-100 led to a significant and similar reduction in glycated hemoglobin (between group difference [Δ] −0.01%; P = .49) and fasting blood glucose (Δ −2.09 mg/dL; P = .74) levels, with no significant changes in body weight in both treatment groups. Overall, the incidence of hypoglycemia was low, with no severe episodes reported.

Study details: This was a retrospective study including insulin-naive patients with T2D who initiated Gla-300 and were propensity matched with those who initiated Deg-100 (n = 357).

Disclosures: This study was funded by Sanofi S.r.l., Milan, Italy. Some authors declared receiving lecture fees, consulting fees, research funding, or speaking honoraria from various sources, including Sanofi. M Larosa declared being an employee and holding stock in Sanofi.

Source: Fadini GP et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of glargine 300 U/mL versus degludec 100 U/mL in insulin-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes. A multicenter retrospective real-world study (RESTORE-2 NAIVE STUDY). Acta Diabetol. 2022 (Jul 21). Doi: 10.1007/s00592-022-01925-9

T2D: No evidence to suggest increased fracture risk with DPP-4i, GLP-1 RA, and SGLT-2i

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) did not increase the risk for fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared with other antidiabetic agents or placebo.

Major finding: DPP-4i was not associated with a higher risk for total fracture compared with insulin (odds ratio [OR] 0.86; 95% CI 0.39-1.90), metformin (OR 1.41; 95% CI 0.48-4.19), sulfonylureas (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.50-1.20), thiazolidinediones (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.27-2.44), α-glucosidase inhibitor (OR 4.92; 95% CI 0.23-103.83), and placebo (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.84-1.29), with findings being similar for GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2i.

Study details: The data come from a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 177 randomized controlled trials including 165,081 patients with T2D.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, China, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chai S et al. Risk of fracture with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis combining 177 randomized controlled trials with a median follow-up of 26 weeks. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:825417 (Jul 1). Doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.825417

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) did not increase the risk for fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared with other antidiabetic agents or placebo.

Major finding: DPP-4i was not associated with a higher risk for total fracture compared with insulin (odds ratio [OR] 0.86; 95% CI 0.39-1.90), metformin (OR 1.41; 95% CI 0.48-4.19), sulfonylureas (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.50-1.20), thiazolidinediones (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.27-2.44), α-glucosidase inhibitor (OR 4.92; 95% CI 0.23-103.83), and placebo (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.84-1.29), with findings being similar for GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2i.

Study details: The data come from a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 177 randomized controlled trials including 165,081 patients with T2D.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, China, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chai S et al. Risk of fracture with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis combining 177 randomized controlled trials with a median follow-up of 26 weeks. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:825417 (Jul 1). Doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.825417

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) did not increase the risk for fracture in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared with other antidiabetic agents or placebo.

Major finding: DPP-4i was not associated with a higher risk for total fracture compared with insulin (odds ratio [OR] 0.86; 95% CI 0.39-1.90), metformin (OR 1.41; 95% CI 0.48-4.19), sulfonylureas (OR 0.77; 95% CI 0.50-1.20), thiazolidinediones (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.27-2.44), α-glucosidase inhibitor (OR 4.92; 95% CI 0.23-103.83), and placebo (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.84-1.29), with findings being similar for GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2i.

Study details: The data come from a systematic review and network meta-analysis of 177 randomized controlled trials including 165,081 patients with T2D.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation, China, and others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chai S et al. Risk of fracture with dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis combining 177 randomized controlled trials with a median follow-up of 26 weeks. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:825417 (Jul 1). Doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.825417

DPP-4 inhibitor but not GLP-1 RA raises risk for acute liver injury in T2D

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), but not glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), significantly increased the risk for acute liver injury in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i).

Major finding: Compared with SGLT-2i, DPP-4i (hazard ratio [HR] 1.53; 95% CI 1.02-2.30), but not GLP-1 RA (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.57-2.16), were associated with a higher risk for acute liver injury; however, the risk was significantly higher in women receiving DPP-4i (HR 3.22; 95% CI 1.67-6.21) and GLP-1 RA (HR 3.23; 95% CI 1.44-7.25).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based study including 2 new-user, active-comparator cohorts; the first cohort included 106,310 and 27,277 new users of DPP-4i and SGLT-2i, respectively, and the second cohort included 9470 and 26,936 new users of GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2i, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Scheme grant. L Azoulay declared receiving consulting fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer outside this work.

Source: Pradhan R et al. Incretin-based drugs and the risk of acute liver injury among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022 (Jul 22). Doi: 10.2337/dc22-0712

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), but not glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), significantly increased the risk for acute liver injury in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i).

Major finding: Compared with SGLT-2i, DPP-4i (hazard ratio [HR] 1.53; 95% CI 1.02-2.30), but not GLP-1 RA (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.57-2.16), were associated with a higher risk for acute liver injury; however, the risk was significantly higher in women receiving DPP-4i (HR 3.22; 95% CI 1.67-6.21) and GLP-1 RA (HR 3.23; 95% CI 1.44-7.25).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based study including 2 new-user, active-comparator cohorts; the first cohort included 106,310 and 27,277 new users of DPP-4i and SGLT-2i, respectively, and the second cohort included 9470 and 26,936 new users of GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2i, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Scheme grant. L Azoulay declared receiving consulting fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer outside this work.

Source: Pradhan R et al. Incretin-based drugs and the risk of acute liver injury among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022 (Jul 22). Doi: 10.2337/dc22-0712

Key clinical point: Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP-4i), but not glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA), significantly increased the risk for acute liver injury in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) compared with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i).

Major finding: Compared with SGLT-2i, DPP-4i (hazard ratio [HR] 1.53; 95% CI 1.02-2.30), but not GLP-1 RA (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.57-2.16), were associated with a higher risk for acute liver injury; however, the risk was significantly higher in women receiving DPP-4i (HR 3.22; 95% CI 1.67-6.21) and GLP-1 RA (HR 3.23; 95% CI 1.44-7.25).

Study details: Findings are from a population-based study including 2 new-user, active-comparator cohorts; the first cohort included 106,310 and 27,277 new users of DPP-4i and SGLT-2i, respectively, and the second cohort included 9470 and 26,936 new users of GLP-1 RA and SGLT-2i, respectively.

Disclosures: This study was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Scheme grant. L Azoulay declared receiving consulting fees from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer outside this work.

Source: Pradhan R et al. Incretin-based drugs and the risk of acute liver injury among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022 (Jul 22). Doi: 10.2337/dc22-0712

Exenatide as a new treatment option for youth with T2D

Key clinical point: Once-weekly exenatide was superior to placebo in improving glycemic control and was well tolerated in youth with type 2 diabetes (T2D) who were suboptimally controlled with current treatments. It had a safety profile similar to that in adults.

Major finding: At 24 weeks, the least squares mean change in the glycated hemoglobin level in the exenatide vs placebo group was −0.36% vs 0.49%, respectively, with a between-group difference of −0.85% (P = .012) showing the superiority of exenatide over placebo. Adverse events were reported by 61.0% and 73.9% of participants in the exenatide and placebo groups, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, parallel-group, phase 3 study including 72 patients with T2D suboptimally controlled with current treatments who were randomly assigned to receive once-weekly exenatide (n = 49) or placebo (n = 23).

Disclosures: This study was funded by AstraZeneca. N Shehadeh and O Doehring declared receiving support from AstraZeneca. The other authors declared being employees or holding stocks in AstraZeneca.

Source: Tamborlane WV et al. Once-weekly exenatide in youth with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(8):1833–1840 (Jul 26). Doi: 10.2337/dc21-2275

Key clinical point: Once-weekly exenatide was superior to placebo in improving glycemic control and was well tolerated in youth with type 2 diabetes (T2D) who were suboptimally controlled with current treatments. It had a safety profile similar to that in adults.

Major finding: At 24 weeks, the least squares mean change in the glycated hemoglobin level in the exenatide vs placebo group was −0.36% vs 0.49%, respectively, with a between-group difference of −0.85% (P = .012) showing the superiority of exenatide over placebo. Adverse events were reported by 61.0% and 73.9% of participants in the exenatide and placebo groups, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, parallel-group, phase 3 study including 72 patients with T2D suboptimally controlled with current treatments who were randomly assigned to receive once-weekly exenatide (n = 49) or placebo (n = 23).

Disclosures: This study was funded by AstraZeneca. N Shehadeh and O Doehring declared receiving support from AstraZeneca. The other authors declared being employees or holding stocks in AstraZeneca.

Source: Tamborlane WV et al. Once-weekly exenatide in youth with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(8):1833–1840 (Jul 26). Doi: 10.2337/dc21-2275

Key clinical point: Once-weekly exenatide was superior to placebo in improving glycemic control and was well tolerated in youth with type 2 diabetes (T2D) who were suboptimally controlled with current treatments. It had a safety profile similar to that in adults.

Major finding: At 24 weeks, the least squares mean change in the glycated hemoglobin level in the exenatide vs placebo group was −0.36% vs 0.49%, respectively, with a between-group difference of −0.85% (P = .012) showing the superiority of exenatide over placebo. Adverse events were reported by 61.0% and 73.9% of participants in the exenatide and placebo groups, respectively.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, parallel-group, phase 3 study including 72 patients with T2D suboptimally controlled with current treatments who were randomly assigned to receive once-weekly exenatide (n = 49) or placebo (n = 23).

Disclosures: This study was funded by AstraZeneca. N Shehadeh and O Doehring declared receiving support from AstraZeneca. The other authors declared being employees or holding stocks in AstraZeneca.

Source: Tamborlane WV et al. Once-weekly exenatide in youth with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2022;45(8):1833–1840 (Jul 26). Doi: 10.2337/dc21-2275

The Ethical Implications of Dermatology Residents Treating Attending Physicians

Residents are confronted daily with situations in clinic that require a foundation in medical ethics to assist in decision-making. Attending physicians require health care services and at times may seek care from resident physicians. If the attending physician has direct oversight over the resident, however, the ethics of the resident treating them need to be addressed. Although patients have autonomy to choose whoever they want as a physician, nonmaleficence dictates that the resident may forego treatment due to concerns for providing suboptimal care; however, this same attending may be treated under specific circumstances. This column explores the ethical implications of both situations.

The Ethical Dilemma of Treating an Attending

Imagine this scenario: You are in your resident general dermatology clinic seeing patients with an attending overseeing your clinical decisions following each encounter. You look on your schedule and see that the next patient is one of your pediatric dermatology attendings for a total-body skin examination (TBSE). You have never treated a physician that oversees you, and you ponder whether you should perform the examination or fetch your attending to perform the encounter alone.

This conundrum then brings other questions to mind: Would changing the reason for the appointment (ie, an acute problem vs a TBSE) alter your decision as to whether or not you would treat this attending? Would the situation be different if this was an attending in a different department?

Ethics Curriculum for Residents

Medical providers face ethical dilemmas daily, and dermatologists and dermatology residents are not excluded. Dermatoethics can provide a framework for the best approach to this hypothetical situation. To equip residents with resources on ethics and a cognitive framework to approach similar situations, the American Board of Dermatology has created an ethics curriculum for residents to learn over their 3 years of training.1

One study that analyzed the ethical themes portrayed in essays by fourth-year medical students showed that the most common themes included autonomy, social justice, nonmaleficence, beneficence, honesty, and respect.2 These themes must be considered in different permutations throughout ethical conundrums.

In the situation of an attending physician who supervises a resident in another clinic voluntarily attending the resident clinic, the physician is aware of the resident’s skills and qualifications and knows that supervision is being provided by an attending physician, which allows informed consent to be made, as a study by Unruh et al3 shows. The patient’s autonomy allows them to choose their treating provider.

However, there are several reasons why the resident may be hesitant to enter the room. One concern may be that during a TBSE the provider usually examines the patient’s genitals, rectum, and breasts.4 Because the resident knows the individual personally, the patient and/or the provider may be uncomfortable checking these areas, leaving a portion of the examination unperformed. This neglect may harm the patient (eg, a genital melanoma is missed), violating the tenant of nonmaleficence.

The effect of the medical hierarchy also should be considered. The de facto hierarchy of attendings supervising residents, interns, and medical students, with each group having some oversight over the next, can have positive effects on education and appropriate patient management but also can prove to be detrimental to the patient and provider in some circumstances. Studies have shown that residents may be less willing to disagree with their superior’s opinions for fear of negative reactions and harmful effects on their future careers.5-7 The hierarchy of medicine also can affect a resident’s moral judgement by intimidating the practitioner to perform tasks or make diagnoses they may not wish to make.5,6,8,9 For example, the resident may send a prescription for a medication that the attending requested despite no clear indication of need. This mingling of patient and supervisor roles can result in a resident treating their attending physician inconsistently with their standard of care.

Navigating the Ethics of Treating Family Members

The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics Opinions on Patient-Physician Relationships highlights treating family members as an important ethical topic. Although most residents and attendings are not biologically related, a familial-style relationship exists in many dermatology programs between attendings and residents due to the close-knit nature of dermatology programs. Diagnostic and treatment accuracy may be diminished by the discomfort or disbelief that a condition could affect someone the resident cares about.10

The American Medical Association also states that a physician can treat family members in an emergency situation or for short-term minor problems. If these 2 exceptions were to be extrapolated to apply to situations involving residents and attendings in addition to family, there would be situations where a dermatology resident could ethically treat their attending physician.10 If the attending physician was worried about a problem that was deemed potentially life-threatening, such as a rapidly progressive bullous eruption concerning for Stevens-Johnson syndrome following the initiation of a new medication, and they wanted an urgent evaluation and biopsy, an ethicist could argue that urgent treatment is medically indicated as deferring treatment could have negative consequences on the patient’s health. In addition, if the attending found a splinter in their finger following yardwork and needed assistance in removal, this also could be treated by their resident, as it is minimally invasive and has a finite conclusion.

Treating Nonsupervisory Attendings

In the case of performing a TBSE on an attending from another specialty, it would be acceptable and less ethically ambiguous if no close personal relationship existed between the two practitioners, as this patient would have no direct oversight over the resident physician.

Final Thoughts

Each situation that residents face may carry ethical implications with perspectives from the patient, provider, and bystanders. The above scenarios highlight specific instances that a dermatology resident may face and provide insight into how they may approach the situations. At the same time, it is important to remember that every situation is different and requires a unique approach. Fortunately,physicians—specifically dermatologists—are provided many resources to help navigate challenging scenarios.

Acknowledgments—The author thanks Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD (Farmington, Connecticut), for reviewing this paper and providing feedback to improve its content, as well as Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for assisting in the creation of this topic and article.

- Dermatoethics. American Board of Dermatology website. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/dermatoethics

- House JB, Theyyunni N, Barnosky AR, et al. Understanding ethical dilemmas in the emergency department: views from medical students’ essays. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:492-498.

- Unruh KP, Dhulipala SC, Holt GE. Patient understanding of the role of the orthopedic resident. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:345-349.

- Grandhi R, Grant-Kels JM. Naked and vulnerable: the ethics of chaperoning full-body skin examinations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1221-1223.

- Salehi PP, Jacobs D, Suhail-Sindhu T, et al. Consequences of medical hierarchy on medical students, residents, and medical education in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:906-914.

- Lomis KD, Carpenter RO, Miller BM. Moral distress in the third year of medical school: a descriptive review of student case reflections. Am J Surg. 2009;197:107-112.

- Troughton R, Mariano V, Campbell A, et al. Understanding determinants of infection control practices in surgery: the role of shared ownership and team hierarchy. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:116.

- Chiu PP, Hilliard RI, Azzie G, et al. Experience of moral distress among pediatric surgery trainees. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:986-993.

- Martinez W, Lo B. Medical students’ experiences with medical errors: an analysis of medical student essays. Med Educ. 2008;42:733-741.

- Chapter 1. opinions on patient-physician relationships. American Medical Association website. Accessed on August 9, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf

Residents are confronted daily with situations in clinic that require a foundation in medical ethics to assist in decision-making. Attending physicians require health care services and at times may seek care from resident physicians. If the attending physician has direct oversight over the resident, however, the ethics of the resident treating them need to be addressed. Although patients have autonomy to choose whoever they want as a physician, nonmaleficence dictates that the resident may forego treatment due to concerns for providing suboptimal care; however, this same attending may be treated under specific circumstances. This column explores the ethical implications of both situations.

The Ethical Dilemma of Treating an Attending

Imagine this scenario: You are in your resident general dermatology clinic seeing patients with an attending overseeing your clinical decisions following each encounter. You look on your schedule and see that the next patient is one of your pediatric dermatology attendings for a total-body skin examination (TBSE). You have never treated a physician that oversees you, and you ponder whether you should perform the examination or fetch your attending to perform the encounter alone.

This conundrum then brings other questions to mind: Would changing the reason for the appointment (ie, an acute problem vs a TBSE) alter your decision as to whether or not you would treat this attending? Would the situation be different if this was an attending in a different department?

Ethics Curriculum for Residents

Medical providers face ethical dilemmas daily, and dermatologists and dermatology residents are not excluded. Dermatoethics can provide a framework for the best approach to this hypothetical situation. To equip residents with resources on ethics and a cognitive framework to approach similar situations, the American Board of Dermatology has created an ethics curriculum for residents to learn over their 3 years of training.1

One study that analyzed the ethical themes portrayed in essays by fourth-year medical students showed that the most common themes included autonomy, social justice, nonmaleficence, beneficence, honesty, and respect.2 These themes must be considered in different permutations throughout ethical conundrums.

In the situation of an attending physician who supervises a resident in another clinic voluntarily attending the resident clinic, the physician is aware of the resident’s skills and qualifications and knows that supervision is being provided by an attending physician, which allows informed consent to be made, as a study by Unruh et al3 shows. The patient’s autonomy allows them to choose their treating provider.

However, there are several reasons why the resident may be hesitant to enter the room. One concern may be that during a TBSE the provider usually examines the patient’s genitals, rectum, and breasts.4 Because the resident knows the individual personally, the patient and/or the provider may be uncomfortable checking these areas, leaving a portion of the examination unperformed. This neglect may harm the patient (eg, a genital melanoma is missed), violating the tenant of nonmaleficence.

The effect of the medical hierarchy also should be considered. The de facto hierarchy of attendings supervising residents, interns, and medical students, with each group having some oversight over the next, can have positive effects on education and appropriate patient management but also can prove to be detrimental to the patient and provider in some circumstances. Studies have shown that residents may be less willing to disagree with their superior’s opinions for fear of negative reactions and harmful effects on their future careers.5-7 The hierarchy of medicine also can affect a resident’s moral judgement by intimidating the practitioner to perform tasks or make diagnoses they may not wish to make.5,6,8,9 For example, the resident may send a prescription for a medication that the attending requested despite no clear indication of need. This mingling of patient and supervisor roles can result in a resident treating their attending physician inconsistently with their standard of care.

Navigating the Ethics of Treating Family Members

The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics Opinions on Patient-Physician Relationships highlights treating family members as an important ethical topic. Although most residents and attendings are not biologically related, a familial-style relationship exists in many dermatology programs between attendings and residents due to the close-knit nature of dermatology programs. Diagnostic and treatment accuracy may be diminished by the discomfort or disbelief that a condition could affect someone the resident cares about.10

The American Medical Association also states that a physician can treat family members in an emergency situation or for short-term minor problems. If these 2 exceptions were to be extrapolated to apply to situations involving residents and attendings in addition to family, there would be situations where a dermatology resident could ethically treat their attending physician.10 If the attending physician was worried about a problem that was deemed potentially life-threatening, such as a rapidly progressive bullous eruption concerning for Stevens-Johnson syndrome following the initiation of a new medication, and they wanted an urgent evaluation and biopsy, an ethicist could argue that urgent treatment is medically indicated as deferring treatment could have negative consequences on the patient’s health. In addition, if the attending found a splinter in their finger following yardwork and needed assistance in removal, this also could be treated by their resident, as it is minimally invasive and has a finite conclusion.

Treating Nonsupervisory Attendings

In the case of performing a TBSE on an attending from another specialty, it would be acceptable and less ethically ambiguous if no close personal relationship existed between the two practitioners, as this patient would have no direct oversight over the resident physician.

Final Thoughts

Each situation that residents face may carry ethical implications with perspectives from the patient, provider, and bystanders. The above scenarios highlight specific instances that a dermatology resident may face and provide insight into how they may approach the situations. At the same time, it is important to remember that every situation is different and requires a unique approach. Fortunately,physicians—specifically dermatologists—are provided many resources to help navigate challenging scenarios.

Acknowledgments—The author thanks Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD (Farmington, Connecticut), for reviewing this paper and providing feedback to improve its content, as well as Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for assisting in the creation of this topic and article.

Residents are confronted daily with situations in clinic that require a foundation in medical ethics to assist in decision-making. Attending physicians require health care services and at times may seek care from resident physicians. If the attending physician has direct oversight over the resident, however, the ethics of the resident treating them need to be addressed. Although patients have autonomy to choose whoever they want as a physician, nonmaleficence dictates that the resident may forego treatment due to concerns for providing suboptimal care; however, this same attending may be treated under specific circumstances. This column explores the ethical implications of both situations.

The Ethical Dilemma of Treating an Attending

Imagine this scenario: You are in your resident general dermatology clinic seeing patients with an attending overseeing your clinical decisions following each encounter. You look on your schedule and see that the next patient is one of your pediatric dermatology attendings for a total-body skin examination (TBSE). You have never treated a physician that oversees you, and you ponder whether you should perform the examination or fetch your attending to perform the encounter alone.

This conundrum then brings other questions to mind: Would changing the reason for the appointment (ie, an acute problem vs a TBSE) alter your decision as to whether or not you would treat this attending? Would the situation be different if this was an attending in a different department?

Ethics Curriculum for Residents

Medical providers face ethical dilemmas daily, and dermatologists and dermatology residents are not excluded. Dermatoethics can provide a framework for the best approach to this hypothetical situation. To equip residents with resources on ethics and a cognitive framework to approach similar situations, the American Board of Dermatology has created an ethics curriculum for residents to learn over their 3 years of training.1

One study that analyzed the ethical themes portrayed in essays by fourth-year medical students showed that the most common themes included autonomy, social justice, nonmaleficence, beneficence, honesty, and respect.2 These themes must be considered in different permutations throughout ethical conundrums.

In the situation of an attending physician who supervises a resident in another clinic voluntarily attending the resident clinic, the physician is aware of the resident’s skills and qualifications and knows that supervision is being provided by an attending physician, which allows informed consent to be made, as a study by Unruh et al3 shows. The patient’s autonomy allows them to choose their treating provider.

However, there are several reasons why the resident may be hesitant to enter the room. One concern may be that during a TBSE the provider usually examines the patient’s genitals, rectum, and breasts.4 Because the resident knows the individual personally, the patient and/or the provider may be uncomfortable checking these areas, leaving a portion of the examination unperformed. This neglect may harm the patient (eg, a genital melanoma is missed), violating the tenant of nonmaleficence.

The effect of the medical hierarchy also should be considered. The de facto hierarchy of attendings supervising residents, interns, and medical students, with each group having some oversight over the next, can have positive effects on education and appropriate patient management but also can prove to be detrimental to the patient and provider in some circumstances. Studies have shown that residents may be less willing to disagree with their superior’s opinions for fear of negative reactions and harmful effects on their future careers.5-7 The hierarchy of medicine also can affect a resident’s moral judgement by intimidating the practitioner to perform tasks or make diagnoses they may not wish to make.5,6,8,9 For example, the resident may send a prescription for a medication that the attending requested despite no clear indication of need. This mingling of patient and supervisor roles can result in a resident treating their attending physician inconsistently with their standard of care.

Navigating the Ethics of Treating Family Members

The American Medical Association Code of Medical Ethics Opinions on Patient-Physician Relationships highlights treating family members as an important ethical topic. Although most residents and attendings are not biologically related, a familial-style relationship exists in many dermatology programs between attendings and residents due to the close-knit nature of dermatology programs. Diagnostic and treatment accuracy may be diminished by the discomfort or disbelief that a condition could affect someone the resident cares about.10

The American Medical Association also states that a physician can treat family members in an emergency situation or for short-term minor problems. If these 2 exceptions were to be extrapolated to apply to situations involving residents and attendings in addition to family, there would be situations where a dermatology resident could ethically treat their attending physician.10 If the attending physician was worried about a problem that was deemed potentially life-threatening, such as a rapidly progressive bullous eruption concerning for Stevens-Johnson syndrome following the initiation of a new medication, and they wanted an urgent evaluation and biopsy, an ethicist could argue that urgent treatment is medically indicated as deferring treatment could have negative consequences on the patient’s health. In addition, if the attending found a splinter in their finger following yardwork and needed assistance in removal, this also could be treated by their resident, as it is minimally invasive and has a finite conclusion.

Treating Nonsupervisory Attendings

In the case of performing a TBSE on an attending from another specialty, it would be acceptable and less ethically ambiguous if no close personal relationship existed between the two practitioners, as this patient would have no direct oversight over the resident physician.

Final Thoughts

Each situation that residents face may carry ethical implications with perspectives from the patient, provider, and bystanders. The above scenarios highlight specific instances that a dermatology resident may face and provide insight into how they may approach the situations. At the same time, it is important to remember that every situation is different and requires a unique approach. Fortunately,physicians—specifically dermatologists—are provided many resources to help navigate challenging scenarios.

Acknowledgments—The author thanks Jane M. Grant-Kels, MD (Farmington, Connecticut), for reviewing this paper and providing feedback to improve its content, as well as Warren R. Heymann, MD (Camden, New Jersey), for assisting in the creation of this topic and article.

- Dermatoethics. American Board of Dermatology website. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/dermatoethics

- House JB, Theyyunni N, Barnosky AR, et al. Understanding ethical dilemmas in the emergency department: views from medical students’ essays. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:492-498.

- Unruh KP, Dhulipala SC, Holt GE. Patient understanding of the role of the orthopedic resident. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:345-349.

- Grandhi R, Grant-Kels JM. Naked and vulnerable: the ethics of chaperoning full-body skin examinations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1221-1223.

- Salehi PP, Jacobs D, Suhail-Sindhu T, et al. Consequences of medical hierarchy on medical students, residents, and medical education in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:906-914.

- Lomis KD, Carpenter RO, Miller BM. Moral distress in the third year of medical school: a descriptive review of student case reflections. Am J Surg. 2009;197:107-112.

- Troughton R, Mariano V, Campbell A, et al. Understanding determinants of infection control practices in surgery: the role of shared ownership and team hierarchy. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:116.

- Chiu PP, Hilliard RI, Azzie G, et al. Experience of moral distress among pediatric surgery trainees. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:986-993.

- Martinez W, Lo B. Medical students’ experiences with medical errors: an analysis of medical student essays. Med Educ. 2008;42:733-741.

- Chapter 1. opinions on patient-physician relationships. American Medical Association website. Accessed on August 9, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf

- Dermatoethics. American Board of Dermatology website. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/dermatoethics

- House JB, Theyyunni N, Barnosky AR, et al. Understanding ethical dilemmas in the emergency department: views from medical students’ essays. J Emerg Med. 2015;48:492-498.

- Unruh KP, Dhulipala SC, Holt GE. Patient understanding of the role of the orthopedic resident. J Surg Educ. 2013;70:345-349.

- Grandhi R, Grant-Kels JM. Naked and vulnerable: the ethics of chaperoning full-body skin examinations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1221-1223.

- Salehi PP, Jacobs D, Suhail-Sindhu T, et al. Consequences of medical hierarchy on medical students, residents, and medical education in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163:906-914.

- Lomis KD, Carpenter RO, Miller BM. Moral distress in the third year of medical school: a descriptive review of student case reflections. Am J Surg. 2009;197:107-112.

- Troughton R, Mariano V, Campbell A, et al. Understanding determinants of infection control practices in surgery: the role of shared ownership and team hierarchy. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8:116.

- Chiu PP, Hilliard RI, Azzie G, et al. Experience of moral distress among pediatric surgery trainees. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:986-993.

- Martinez W, Lo B. Medical students’ experiences with medical errors: an analysis of medical student essays. Med Educ. 2008;42:733-741.

- Chapter 1. opinions on patient-physician relationships. American Medical Association website. Accessed on August 9, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/code-of-medical-ethics-chapter-1.pdf

Resident Pearls

- Dermatology residents should not perform total-body skin examinations on or provide long-term care to attending physicians that directly oversee them.

- Residents should only provide care to their attending physicians if the attending’s life is in imminent danger from delay of treatment or if it is a self-limited, minor problem.

FDA authorizes updated COVID boosters to target newest variants

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Scattered Flesh-Colored Papules in a Linear Array in the Setting of Diffuse Skin Thickening

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

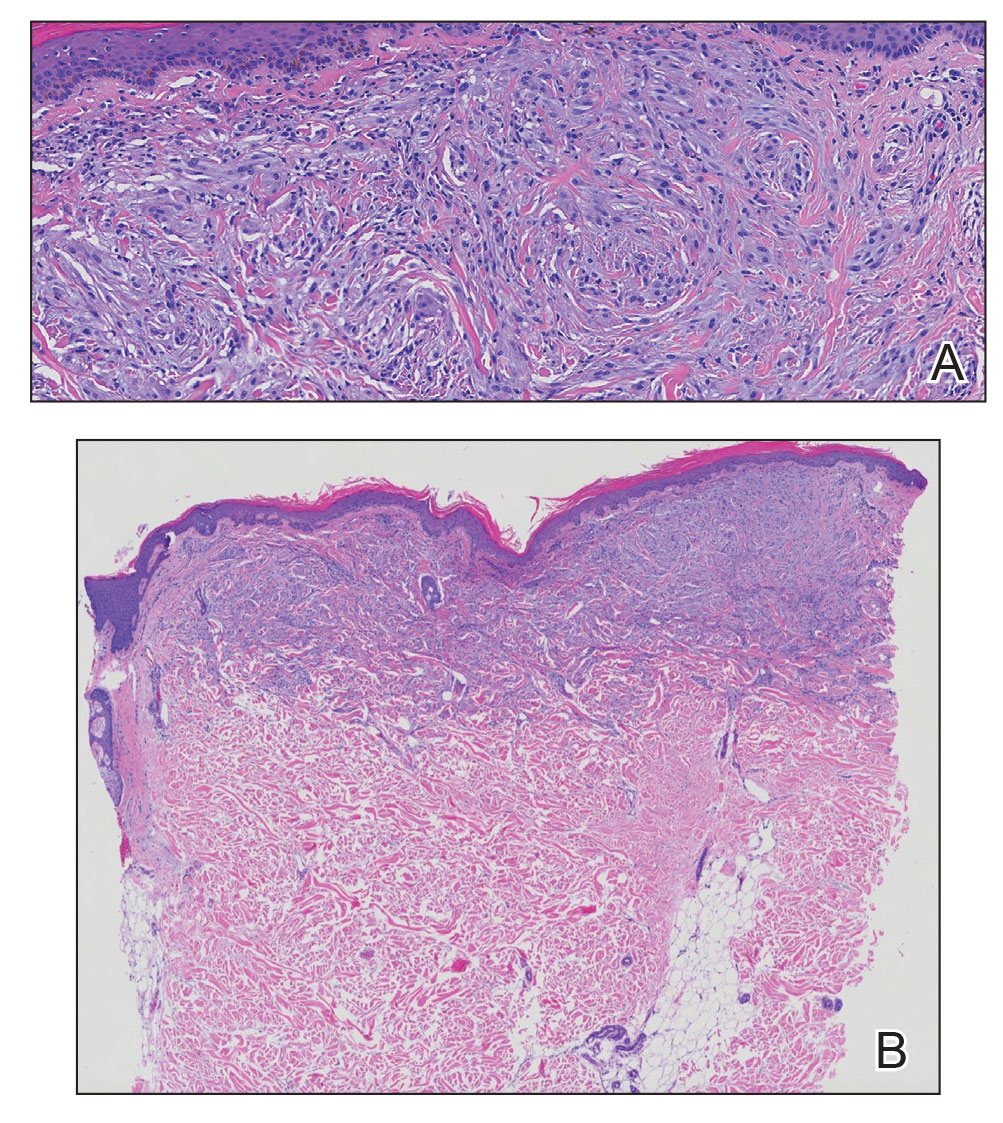

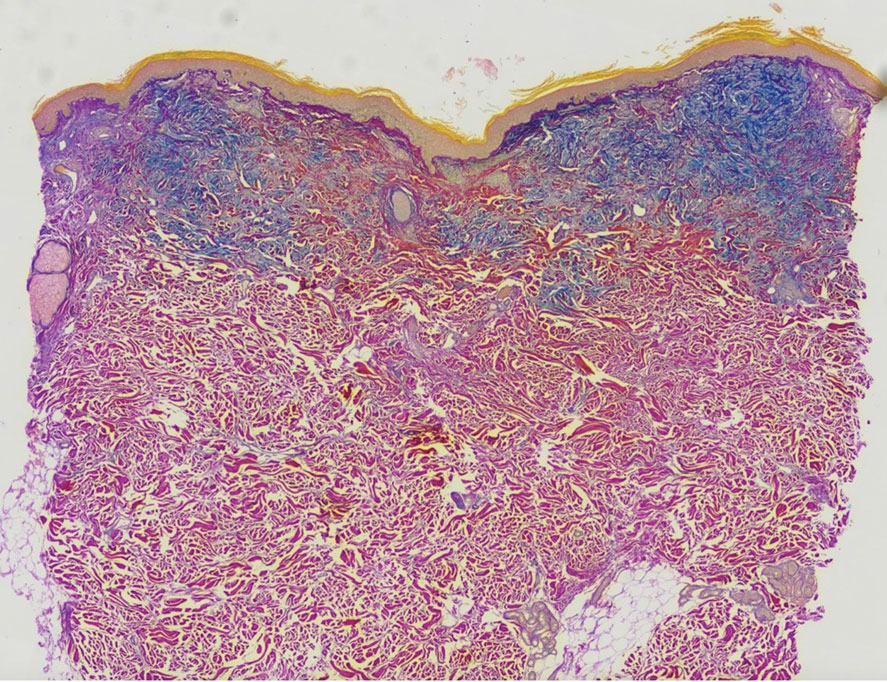

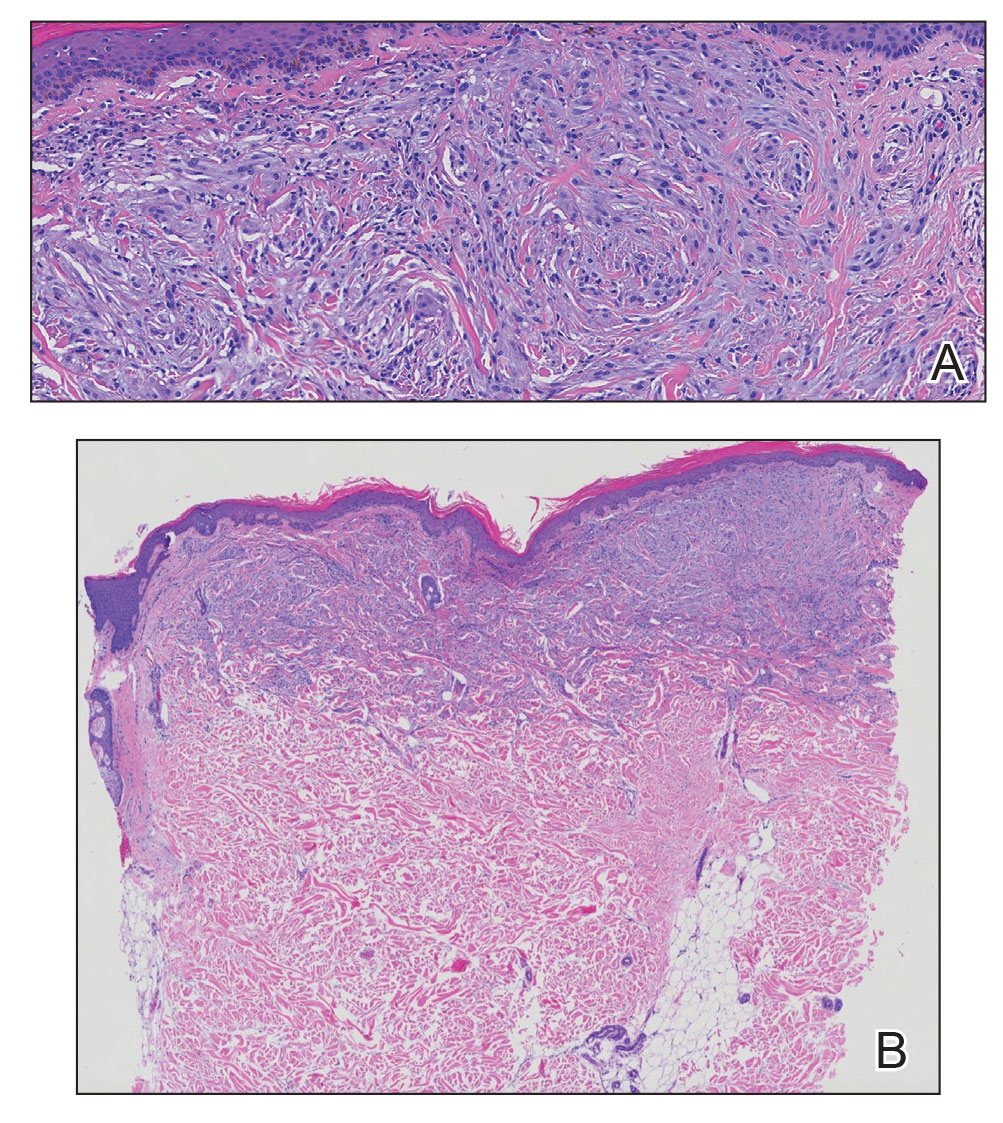

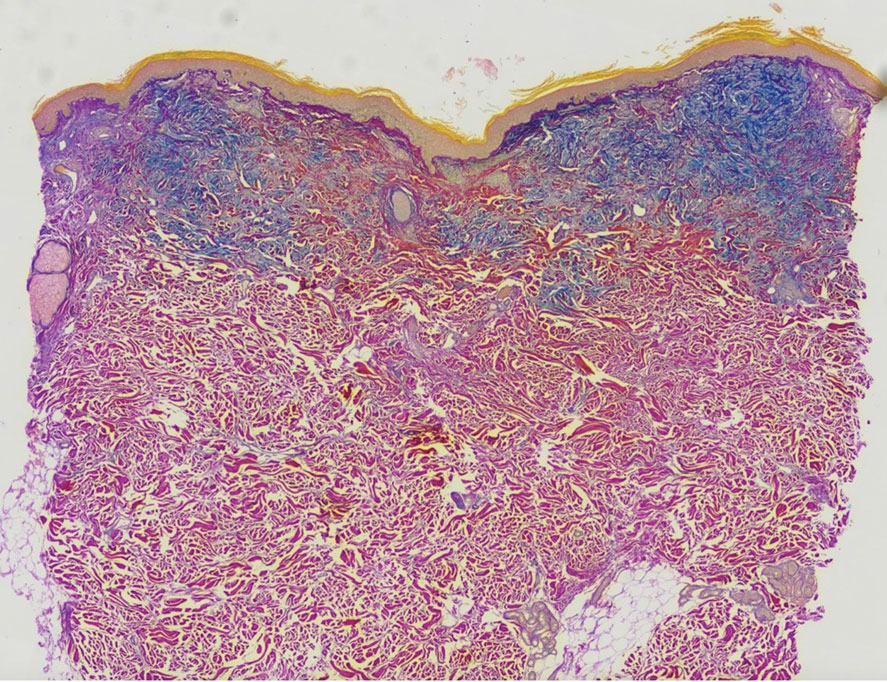

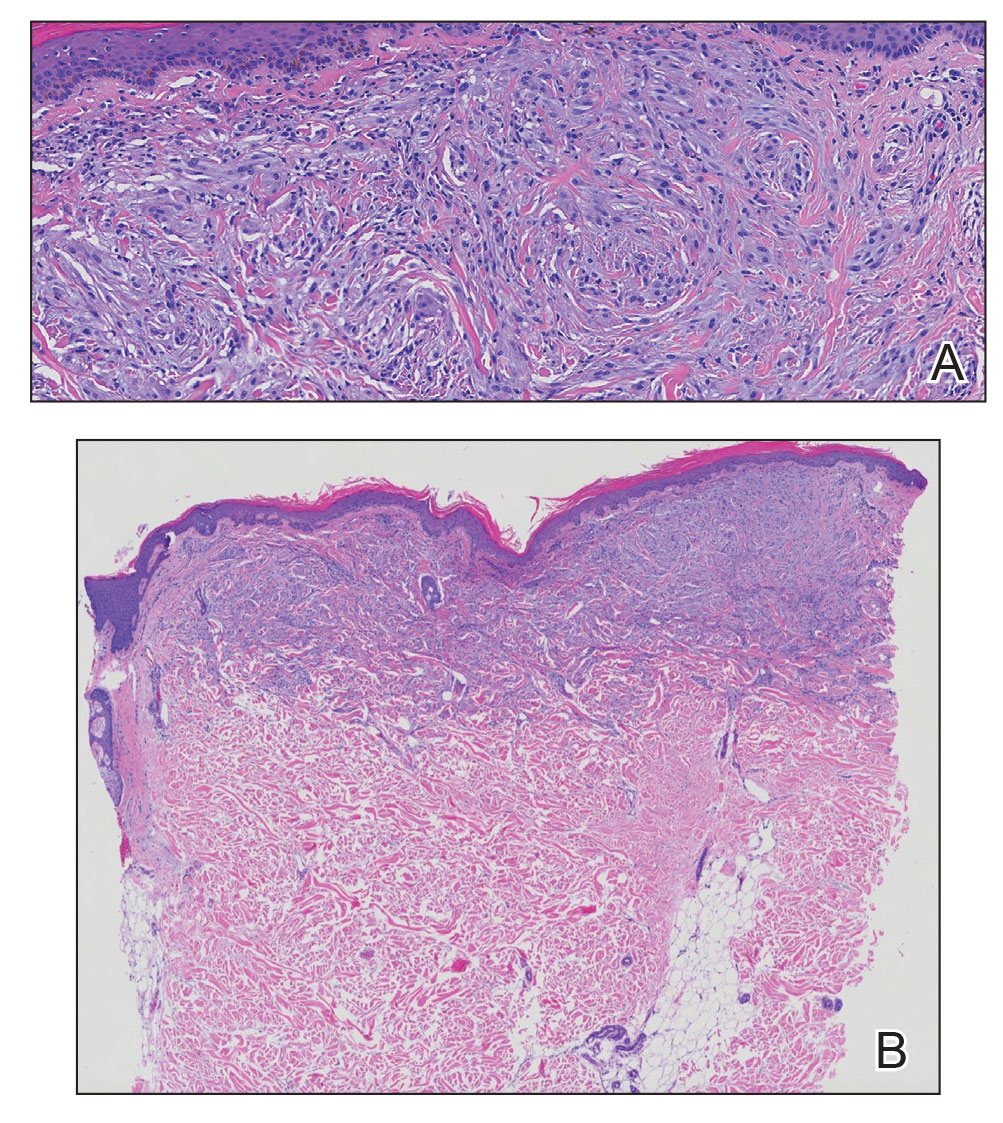

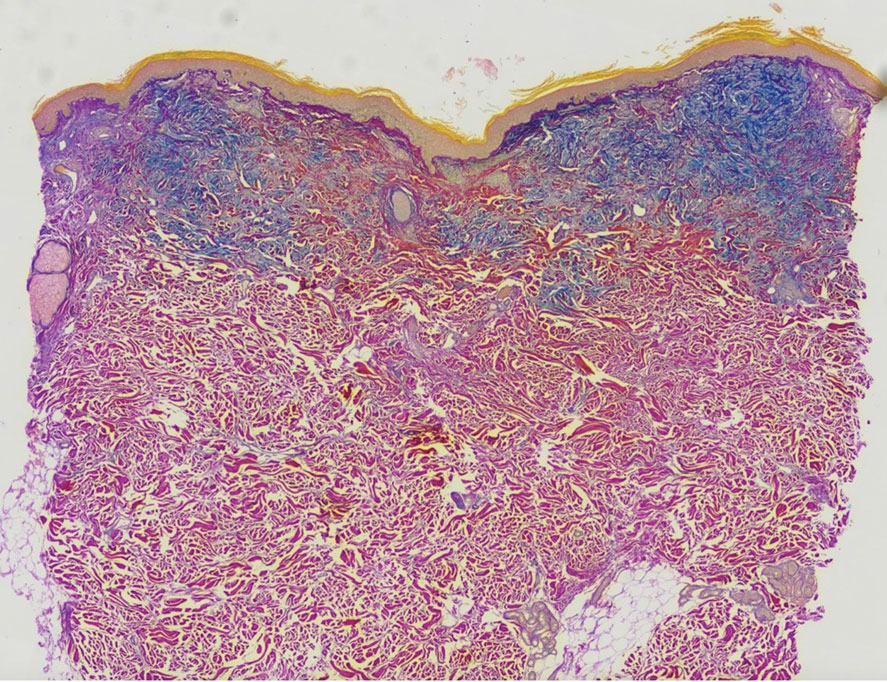

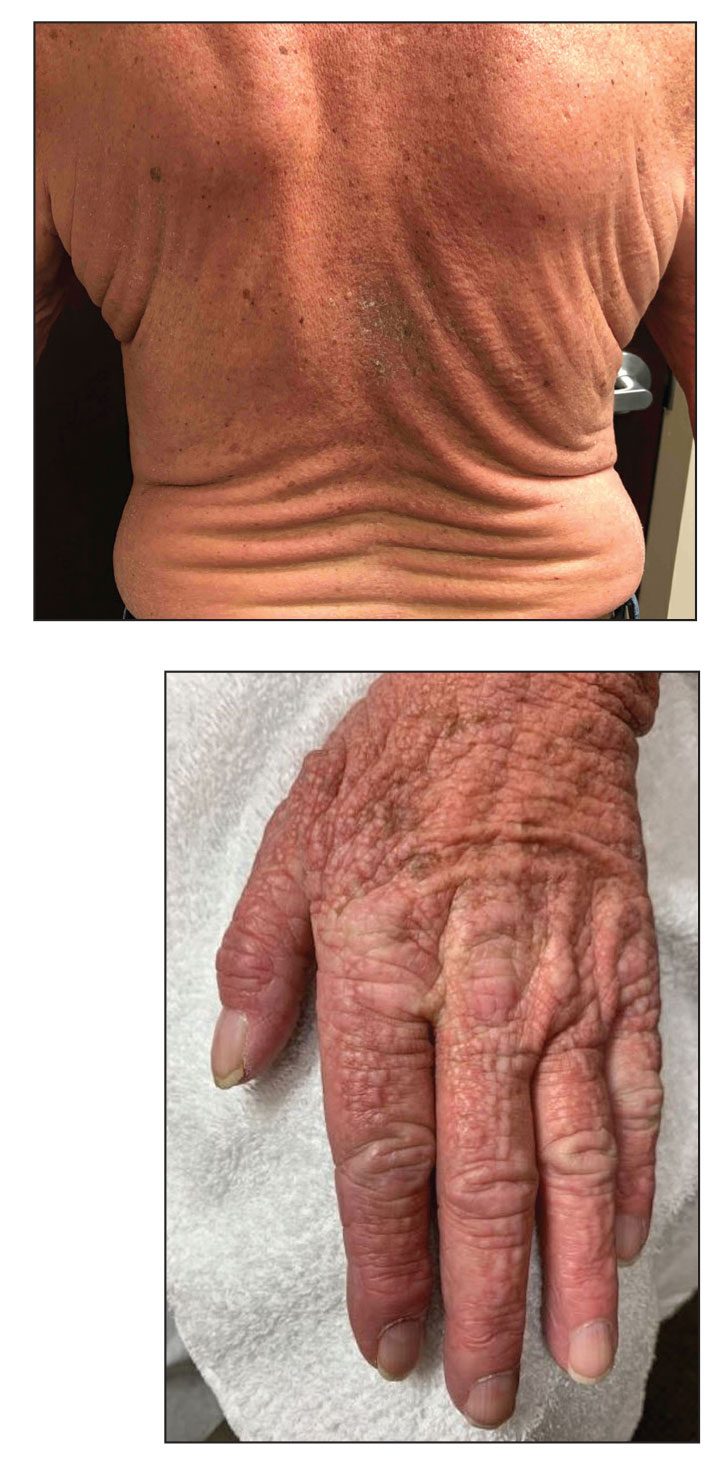

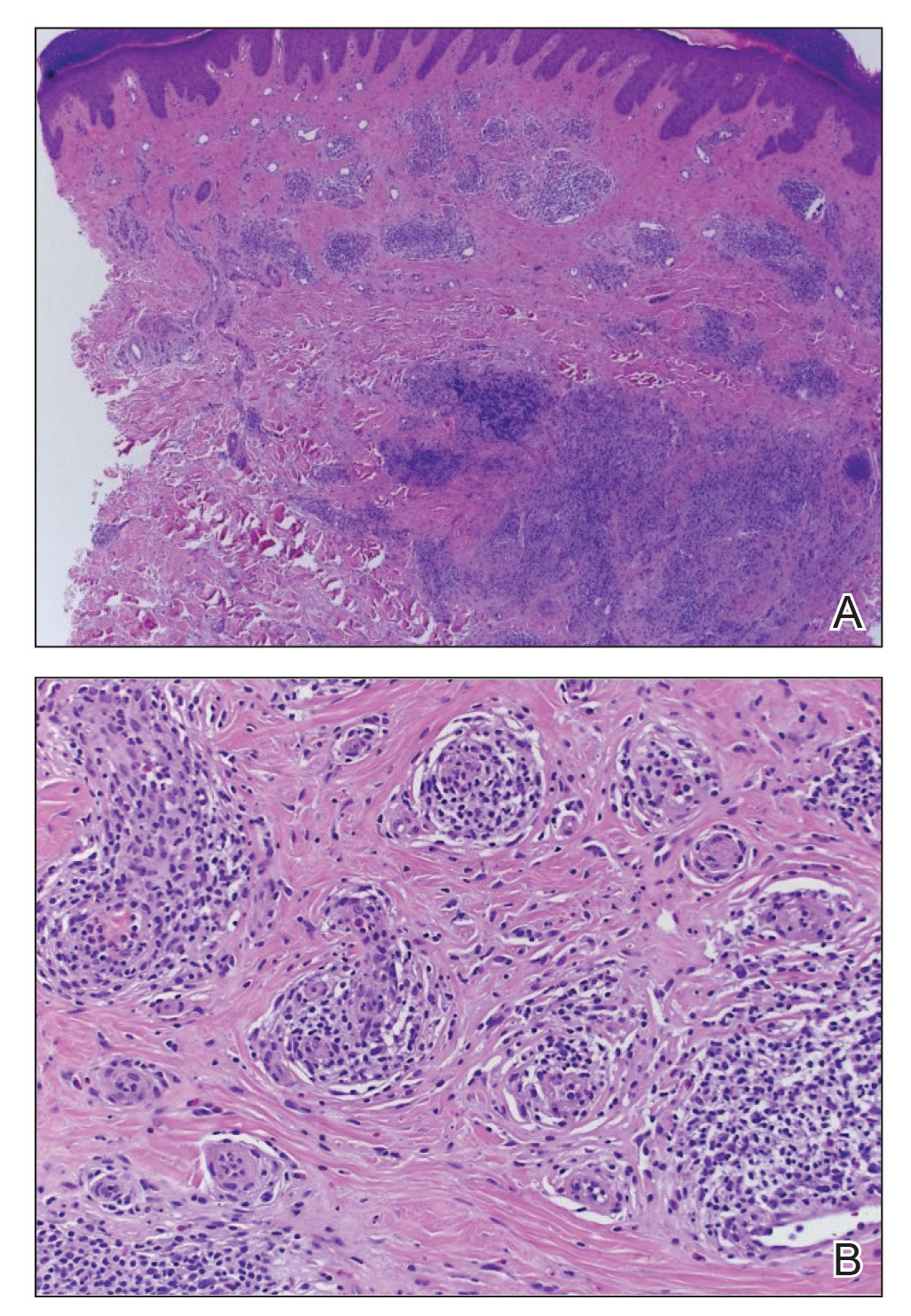

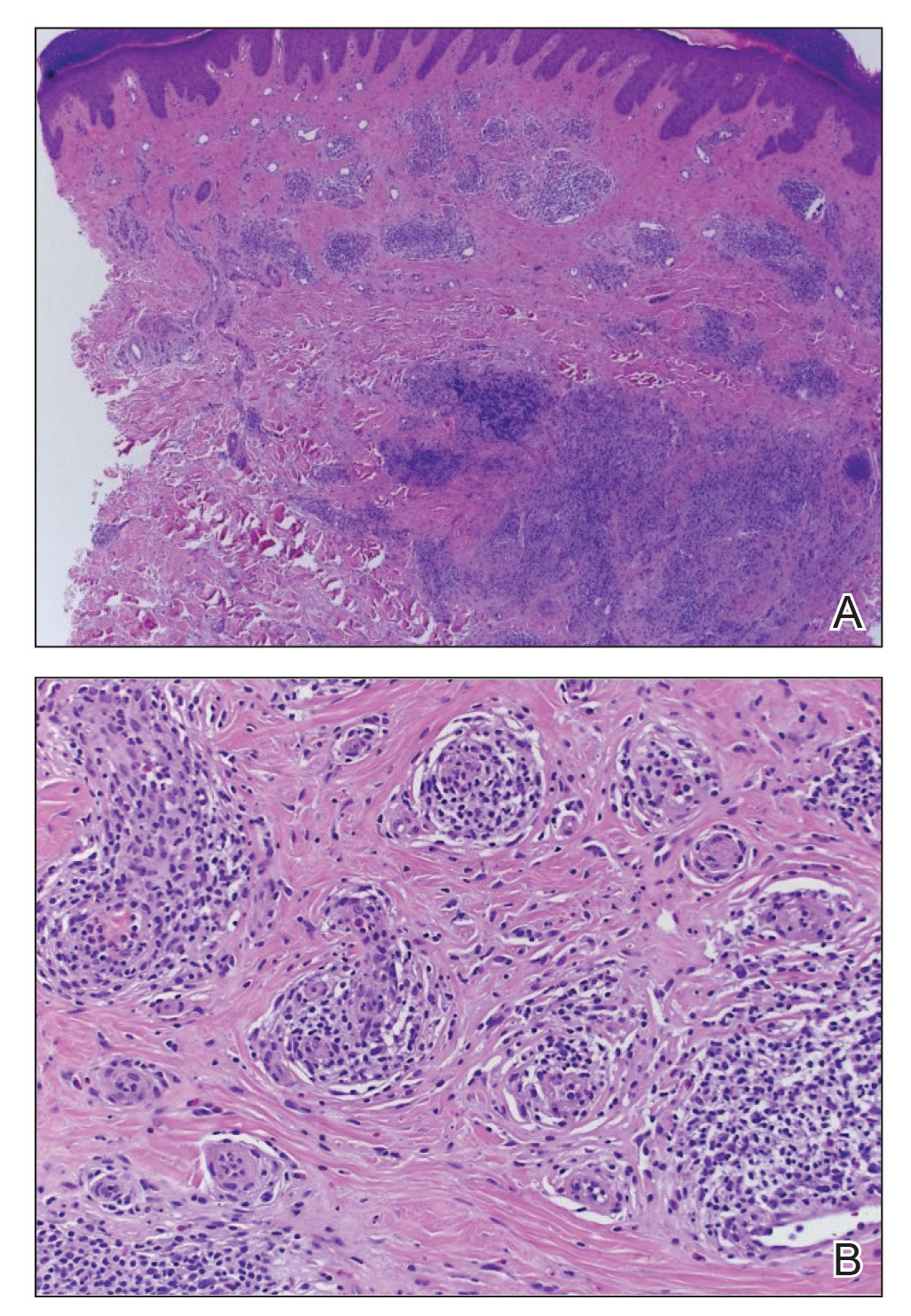

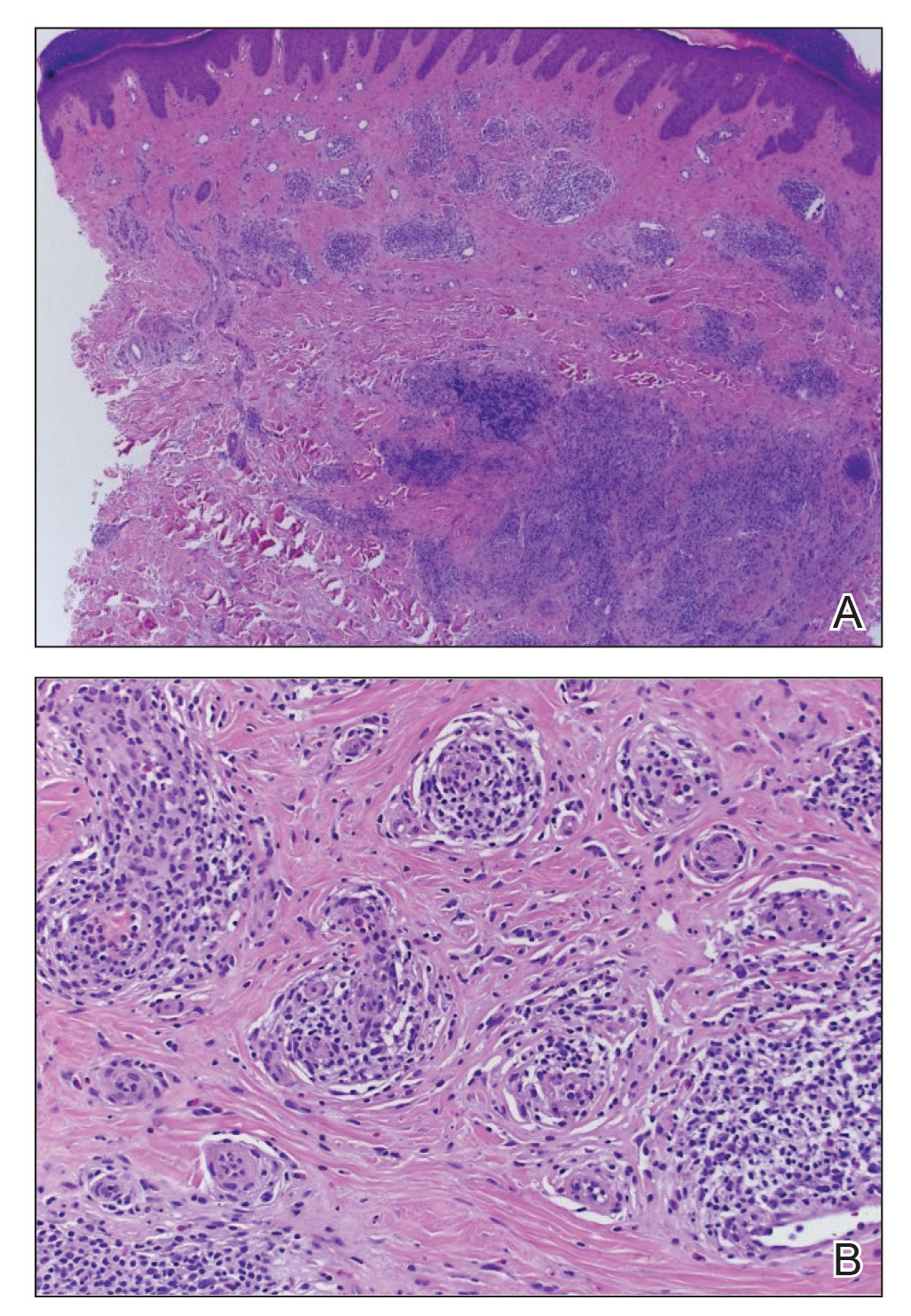

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

The Diagnosis: Scleromyxedema

A punch biopsy of the upper back performed at an outside institution revealed increased histiocytes and abundant interstitial mucin confined to the papillary dermis (Figures 1 and 2), consistent with the lichen myxedematosus (LM) papules that may be seen in scleromyxedema. Serum protein electrophoresis revealed the presence of a protein of restricted mobility on the gamma region that occupied 5.3% of the total protein (0.3 g/dL). Urine protein electrophoresis showed free kappa light chain monoclonal protein in the gamma region. Immunofixation electrophoresis revealed the presence of IgG kappa monoclonal protein in the gamma region with 10% monotype kappa cells. The presence of Raynaud phenomenon and positive antinuclear antibody (1:320, speckled) was noted. Laboratory studies for thyroid-stimulating hormone, C-reactive protein, Scl-70 antibody, myositis panel, ribonucleoprotein antibody, Smith antibody, Sjögren syndrome–related antigens A and B antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and RNA polymerase III antibody all were within reference range. Our patient was treated with monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and he noted substantial improvement in skin findings after 3 months of IVIG.

Localized lichen myxedematosus is a rare idiopathic cutaneous disease that clinically is characterized by waxy indurated papules and histologically is characterized by diffuse mucin deposition and fibroblast proliferation in the upper dermis.1 Scleromyxedema is a diffuse variant of LM in which the papules and plaques of LM are associated with skin thickening involving almost the entire body and associated systemic disease. The exact mechanism of this disease is unknown, but the most widely accepted hypothesis is that immunoglobulins and cytokines contribute to the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans and thereby the deposition of mucin in the dermis.2 Scleromyxedema has a chronic course and generally responds poorly to existing treatments.1 Partial improvement has been demonstrated in treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical steroids.2

The differential diagnosis in our patient included scleromyxedema, scleredema, scleroderma, LM, and reticular erythematosus mucinosis. He was diagnosed with scleromyxedema with kappa monoclonal gammopathy. Scleromyxedema is a rare disorder involving the deposition of mucinous material in the papillary dermis that causes the formation of infiltrative skin lesions.3 The etiology is unknown, but the presence of a monoclonal protein is an important characteristic of this disorder. It is important to rule out thyroid disease as a possible etiology before concluding that the disease process is driven by the monoclonal gammopathy; this will help determine appropriate therapies.4,5 Usually the monoclonal protein is associated with the IgG lambda subtype. Intravenous immunoglobulin often is considered as a first-line treatment of scleromyxedema and usually is administered at a dosage of 2 g/kg divided over 2 to 5 consecutive days per month.3 Previously, our patient had been treated with IVIG for 3 years for chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy and had stopped 1 to 2 years before his cutaneous symptoms started. Generally, scleromyxedema patients must stay on IVIG long-term to prevent relapse, typically every 6 to 8 weeks. Second-line treatments for scleromyxedema include systemic corticosteroids and thalidomide.6 Scleromyxedema and LM have several clinical and histopathologic features in common. Our patient’s biopsy revealed increased mucin deposition associated with fibroblast proliferation confined to the superficial dermis. These histologic changes can be seen in the setting of either LM or scleromyxedema. Our patient’s diffuse skin thickening and monoclonal gammopathy were more characteristic of scleromyxedema. In contrast, LM is a localized eruption with no internal organ manifestations and no associated systemic disease, such as monoclonal gammopathy and thyroid disease.

Scleredema adultorum of Buschke (also referred to as scleredema) is a rare idiopathic dermatologic condition characterized by thickening and tightening of the skin that leads to firm, nonpitting, woody edema that initially involves the upper back and neck but can spread to the face, scalp, and shoulders; importantly, scleredema spares the hands and feet.7 Scleredema has been associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections, and monoclonal gammopathy.8 Although our patient did have a monoclonal gammopathy, he also experienced prominent hand involvement with diffuse skin thickening, which is not typical of scleredema. Additionally, biopsy of scleredema would show increased mucin but would not show the proliferation of fibroblasts that was seen in our patient’s biopsy. Furthermore, scleredema has more profound diffuse superficial and deep mucin deposition compared to scleromyxedema. Scleroderma is an autoimmune cutaneous condition that is divided into 2 categories: localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis (SSc).9 Localized scleroderma (also called morphea) often is characterized by indurated hyperpigmented or hypopigmented lesions. There is an absence of Raynaud phenomenon, telangiectasia, and systemic disease.9 Systemic sclerosis is further divided into 2 categories—limited cutaneous and diffuse cutaneous—which are differentiated by the extent of organ system involvement. Limited cutaneous SSc involves calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, skin sclerosis distal to the elbows and knees, and telangiectasia.9 Diffuse cutaneous SSc is characterized by Raynaud phenomenon; cutaneous sclerosis proximal to the elbows and knees; and fibrosis of the gastrointestinal, pulmonary, renal, and cardiac systems.9 Scl-70 antibodies are specific for diffuse cutaneous SSc, and centromere antibodies are specific for limited cutaneous SSc. Scleromyxedema shares many of the same clinical symptoms as scleroderma; therefore, histopathologic examination is important for differentiating these disorders. Histologically, scleroderma is characterized by thickened collagen bundles associated with a variable degree of perivascular and interstitial lymphoplasmacytic inflammation. No increased dermal mucin is present.9 Our patient did not have the clinical cutaneous features of localized scleroderma and lacked the signs of internal organ involvement that typically are found in SSc. He did have Raynaud phenomenon but did not have matlike telangiectases or Scl-70 or centromere antibodies.

Reticular erythematosus mucinosis (REM) is a rare inflammatory cutaneous disease that is characterized by diffuse reticular erythematous macules or papules that may be asymptomatic or associated with pruritus.10 Reticular erythematosus mucinosis most frequently affects middle-aged women and appears on the trunk.9 Our patient was not part of the demographic group most frequently affected by REM. More importantly, our patient’s lesions were not erythematous or reticular in appearance, making the diagnosis of REM unlikely. Furthermore, REM has no associated cutaneous sclerosis or induration.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

- Nofal A, Amer H, Alakad R, et al. Lichen myxedematosus: diagnostic criteria, classification, and severity grading. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:284-290.

- Christman MP, Sukhdeo K, Kim RH, et al. Papular mucinosis, or localized lichen myxedematosus (LM)(discrete papular type). Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:8.

- Haber R, Bachour J, El Gemayel M. Scleromyxedema treatment: a systematic review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59:1191-1201.

- Hazan E, Griffin TD Jr, Jabbour SA, et al. Scleromyxedema in a patient with thyroid disease: an atypical case or a case for revised criteria? Cutis. 2020;105:E6-E10.

- Shenoy A, Steixner J, Beltrani V, et al. Discrete papular lichen myxedematosus and scleromyxedema with hypothyroidism: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2019;11:64-70.

- Hoffman JHO, Enk AH. Scleromyxedema. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2020;18:1449-1467.

- Beers WH, Ince AI, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

- Miguel D, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of scleroderma adultorum Buschke: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:305-309.

- Rongioletti F, Ferreli C, Atzori L, et al. Scleroderma with an update about clinicopathological correlation. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2018;153:208-215.

- Ocanha-Xavier JP, Cola-Senra CO, Xavier-Junior JCC. Reticular erythematous mucinosis: literature review and case report of a 24-year-old patient with systemic erythematosus lupus. Lupus. 2021;30:325-335.

A 76-year-old man presented to our clinic with diffusely thickened and tightened skin that worsened over the course of 1 year, as well as numerous scattered small, firm, flesh-colored papules arranged in a linear pattern over the face, ears, neck, chest, abdomen, arms, hands, and knees. His symptoms progressed to include substantial skin thickening initially over the thighs followed by the arms, chest, back (top), and face. He developed confluent cobblestonelike plaques over the elbows and hands (bottom) and eventually developed decreased oral aperture limiting oral intake as well as decreased range of motion in the hands. The patient had a deep furrowed appearance of the brow accompanied by discrete, scattered, flesh-colored papules on the forehead and behind the ears. Deep furrows also were present on the back. When the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hands were extended, elevated rings with central depression were seen instead of horizontal folds.

Men at higher risk than are women for many cancers: Why?

Men have a significantly increased risk of developing 11 different cancers, and the risk is three times greater for men for certain cancers, including those of the esophagus, larynx, gastric cardia, and bladder.

But why?

“There are differences in cancer incidence that are not explained by environmental exposures alone,” said lead author Sarah S. Jackson, PhD, of the division of cancer epidemiology and genetics at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md.

“This suggests that there are intrinsic biological differences between men and women that affect susceptibility to cancer,” she added in a statement.

The study was published online in the journal Cancer.

“Understanding the sex-related biologic mechanisms that lead to the male predominance of cancer at shared anatomic sites could have important implications for etiology and prevention,” the researchers suggested.

In an interview, Dr. Jackson said that the results “do not support changes to existing cancer prevention protocol” to address the disparities in cancer rates between men and women.